User login

Caring for patients with autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is an umbrella term used to describe lifelong neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by impairment in social interactions and communication coupled with restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviors or interests that appear to share a common developmental course.1 In this article, we examine psychiatric care of patients with ASD and the most common symptom clusters treated with pharmacotherapy: irritability, anxiety, and hyperactivity/inattention.

First step: Keep the diagnosis in mind

Prior to 2013, ASD was comprised of 3 separate disorders distinguished by language delay and overall severity: autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified.2 With the release of DSM-5 in 2013, these disorders were essentially collapsed into a single ASD.3 ASD prevalence is estimated to be 1 in 59 children,4 which represents a 20- to 30-fold increase since the 1960s.

In order to provide adequate psychiatric care for individuals with ASD, the first step is to remember the diagnosis; keep it in mind. This may be particularly important for clinicians who primarily care for adults, because such clinicians often receive limited training in disorders first manifesting in childhood and may not consider ASD in patients who have not been previously diagnosed. However, ASD diagnostic criteria have become broader, and public knowledge of the diagnosis has grown. DSM-5 acknowledges that although symptoms begin in early childhood, they may become more recognizable later in life with increasing social demand. The result is that many adults are likely undiagnosed. The estimated prevalence of ASD in adult psychiatric settings range from 1.5% to 4%.5-7 These patients have different treatment needs and unfortunately are often misdiagnosed with other psychiatric conditions.

A recent study in a state psychiatric facility found that 10% of patients in this setting met criteria for ASD.8 Almost all of those patients had been misdiagnosed with some form of schizophrenia, including one patient who had been previously diagnosed with autism by the father of autism himself, Leo Kanner, MD. Through the years, this patient’s autism diagnosis had fallen away, and at the time of the study, the patient carried a diagnosis of undifferentiated schizophrenia and was prescribed 8 psychotropic medications. The patient had repeatedly denied auditory or visual hallucinations; however, his stereotypies and odd behaviors were taken as evidence that he was responding to internal stimuli. This case highlights the importance of keeping the ASD diagnosis in mind when evaluating and treating patients.

Addressing 3 key symptom clusters

Even for patients with an established ASD diagnosis, comprehensive treatment is complex. It typically involves a multimodal approach that includes speech therapy, occupational therapy, applied behavioral analysis (ABA), and vocational training and support as well as management of associated medical conditions. Because medical comorbidities may play an important role in exacerbation of severe behaviors in ASD, often leading to acute behavioral regression and psychiatric admission, it is essential that they not be overlooked during evaluations.9,10

There are no effective pharmacologic treatments for the core social deficits seen in ASD. Novel pharmacotherapies to improve social impairment are in the early stages of research,11,12 but currently social impairment is best addressed through behavioral therapy and social skills training. Our role as psychiatrists is most often to treat co-occurring psychiatric symptoms so that individuals with ASD can fully participate in behavioral and school-based treatments that lead to improved social skills, activities of daily living, and quality of life. Three of the most common of these symptoms are irritability, anxiety, and hyperactivity/inattention.

Irritability

Irritability, marked by aggression, self-injury, and severe tantrums, causes serious distress for both patients and families, and this behavior cluster is the most frequently reported comorbid symptom in ASD.13-15 Nonpharmacologic treatment of irritability often involves ABA-based therapy and communication training.

Continued to: ABA includes an initial functional behavior assessment...

ABA includes an initial functional behavior assessment (FBA) of maladaptive behavior followed by the application of specific schedules of reinforcement for positive behavior. The FBA allows the therapist to determine what desirable consequences maintain a behavior. Without this knowledge, there is the risk of inadvertently rewarding a maladaptive behavior. For instance, if you are recommending a time-out for escape-motivated aggression, the result will likely be an increase rather than decrease in aggression.

Communication training teaches the patient to use communicative means to request a desired outcome to reduce inappropriate behaviors and improve independent functioning. Communication training can include speech therapy, teaching sign language, using picture exchange programs, or navigating communication devices. Consideration of nonpharmacologic management is vital in treatment planning. Continual inadvertent reward of behaviors will limit the effects of medications. Evidence suggests that pharmacotherapy is more effective when it occurs in the context of appropriate behavioral management techniques.16

Irritability has been the focus of significant pharmacotherapy research in ASD. Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are first-line pharmacotherapy for severe irritability. Risperidone and aripiprazole are both FDA-approved for addressing irritability in youth with ASD. Their efficacy has been established in several large, placebo-controlled trials.17-23

Given issues with tolerability and cases refractory to the use of first-line agents,24 other SGAs are frequently used off-label for this indication with limited safety or efficacy data. Olanzapine demonstrated high response rates in early open-label studies,25,26 followed by efficacy over an 8-week double-blind placebo-controlled trial, although with significant weight gain.27 No other SGAs have been examined in double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Paliperidone demonstrated a particularly high response rate (84%) in a prospective open-label study of 25 adolescents and young adults with ASD.28 In a retrospective study of ziprasidone in 42 youth with ASD and irritability, we reported a response rate of 40%, which is lower than that seen for some other SGAs; however, ziprasidone can be an appealing option for patients for whom SGA-associated weight gain has been significant, because it is much more likely to be weight-neutral.29,30 Open-label studies with quetiapine in ASD have generally revealed only minimal efficacy for aggression,31,32 although sleep improvement may be more substantial.32 The safety and tolerability of lurasidone in treating irritability in youth with ASD has yet to be established.33 It is the only SGA with a published negative placebo-controlled trial in ASD.34 Use of SGAs may be limited by adverse effects, including weight gain, increased appetite, sedation, enuresis, and elevated prolactin. Monitoring of body mass index and metabolic profiles is indicated with all SGAs.

Haloperidol is the only first-generation antipsychotic with significant evidence (from multiple studies dating back to 1978) to support its use for ASD-associated irritability.35 However, due to the high incidence of dyskinesias and potential dystonias, use of haloperidol is reserved for severe treatment-refractory symptoms that have often not improved after multiple SGA trials.

Continued to: When severe self-inury and aggression fail to improve...

When severe self-injury and aggression fail to improve with multiple medication trials, the next steps include combination treatment with multiple antipsychotics,36 followed by clozapine, often as a last option.37 Research suggests that clozapine is effective and well-tolerated in ASD38-42; however, it has many potential severe adverse effects, including cardiomyopathy, lowered seizure threshold, severe constipation, weight gain, and agranulocytosis; due to risk of the latter, patients require regular blood draws for monitoring.

There is very little evidence to support the use of antiepileptic medications (AEDs) and mood stabilizers for irritability in ASD.43 Placebo-controlled trials have had mixed results. Some evidence suggests that AEDS may have more utility in individuals with ASD and abnormal EEGs without epilepsy44 or as an adjunct to SGA treatment.45 One study found that lithium may be beneficial for patients with ASD whose clinical presentation includes 2 or more mood symptoms.46

Anxiety

Anxiety is a significant issue for many individuals with ASD.47 Anxiety symptoms and disorders, including specific phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), social anxiety, and generalized anxiety disorder, are commonly seen in persons with ASD.48 Anxiety is often combined with restricted, repetitive behaviors (RBs) in ASD literature. Some evidence suggests that in individuals with ASD, sameness behaviors may limit sensory input and modulate anxiety.49 However, the core RBs symptom domain may not be related solely to anxiety, but rather represents deficits in executive processes that include cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control seen across multiple disorders with prominent RBs.50-54 Research indicates that anxiety is an independent and separable construct in ASD.55

Studies of treatments for both RBs and anxiety have focused primarily on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), hoping that the promising results for anxiety and OCD behaviors seen in neurotypical patients would translate to patients with ASD.56 Unfortunately, there is little evidence for effective pharmacologic management of ASD-associated anxiety.57 Large, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are lacking. A Cochrane Database review of SSRIs for ASD58 examined 9 RCTs with a total of 320 patients. The authors concluded that there is no evidence to support the use of SSRIs for children with ASD, and limited evidence of utility in adults. Youth with ASD are particularly vulnerable to adverse effects from SSRIs, specifically impulsivity and agitation.57,59 However, SSRIs are among the most commonly prescribed medications for youth with ASD. Because there is limited evidence supporting SSRIs’ efficacy for this indication and issues with tolerability, there is significant concern for the overprescribing of SSRIs to patients with ASD. In comparison, there is some compelling evidence of efficacy for modified cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for patients with high-functioning ASD. Seven RCTs have shown that CBT is superior to treatment as usual and waiting list control groups, with most effect sizes >0.8 and with no treatment-associated adverse effects.57

Risperidone has been shown to reduce RBs17,60 and anxiety17 in patients with ASD. In young children with co-occurring irritability, risperidone monotherapy is likely best to address both symptoms. When anxiety occurs in isolation and is severe, clinical experience suggests that SSRIs can be effective in a limited percentage of cases, though we recommend starting at low doses with frequent monitoring for activation and irritability. Treatment of anxiety is further complicated by the significant challenges presented by the diagnosis of true anxiety in the context of ASD.

Continued to: Hyperactivity and impulsivity

Hyperactivity and impulsivity

Hyperactivity and impulsivity are common among patients with ASD, with rates estimated from 41% to 78%.61 Hyperactivity and inattention are treated with a variety of medications. Research examining methylphenidate in ASD has demonstrated modest effects compared with placebo, though with frequent adverse effects, such as increased irritability and insomnia62,63 Other smaller studies have confirmed these results.64-66 One additional study found improvements not only in hyperactivity but also in joint attention and self-regulation of affective state following stimulant treatment.67 There is limited data on the efficacy and tolerability of amphetamine for treating hyperactivity and impulsivity in ASD. Stimulant medications often are avoided as the first-line treatment for hyperactivity because of concerns about increased irritability. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists often are used before stimulants because of their relatively benign adverse effect profile. Clonidine, guanfacine, and guanfacine ER all have demonstrated effectiveness in double-blind, placebo-controls trials in patients with ASD.68-70 In these trails, sedation was the most common adverse effect, although some studies have reported increased irritability with guanfacine.70,71

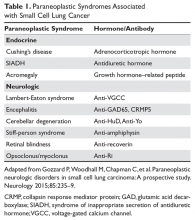

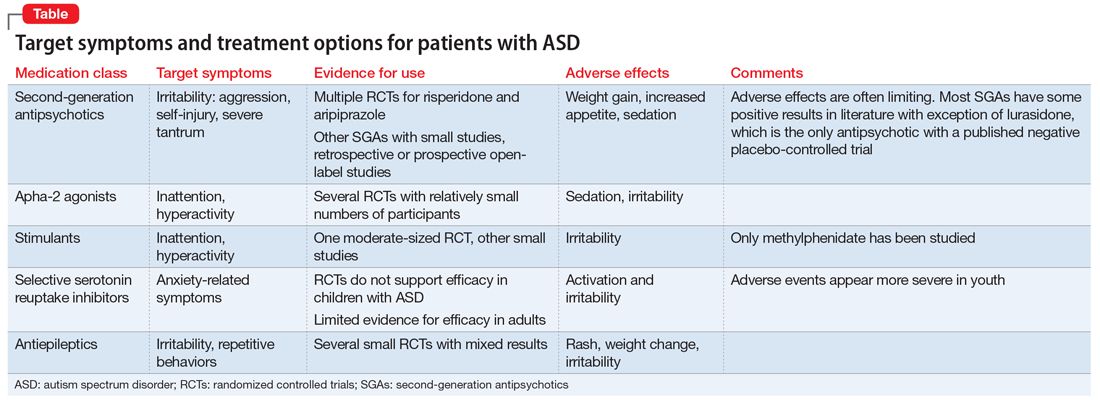

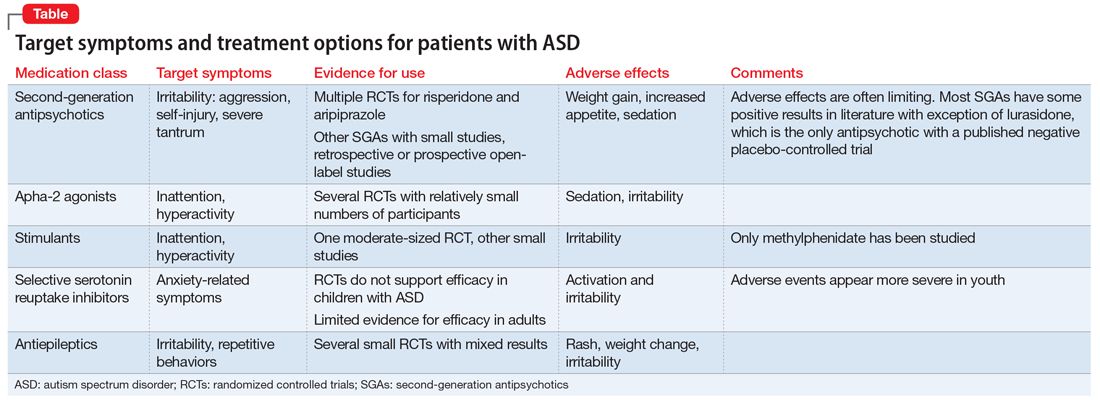

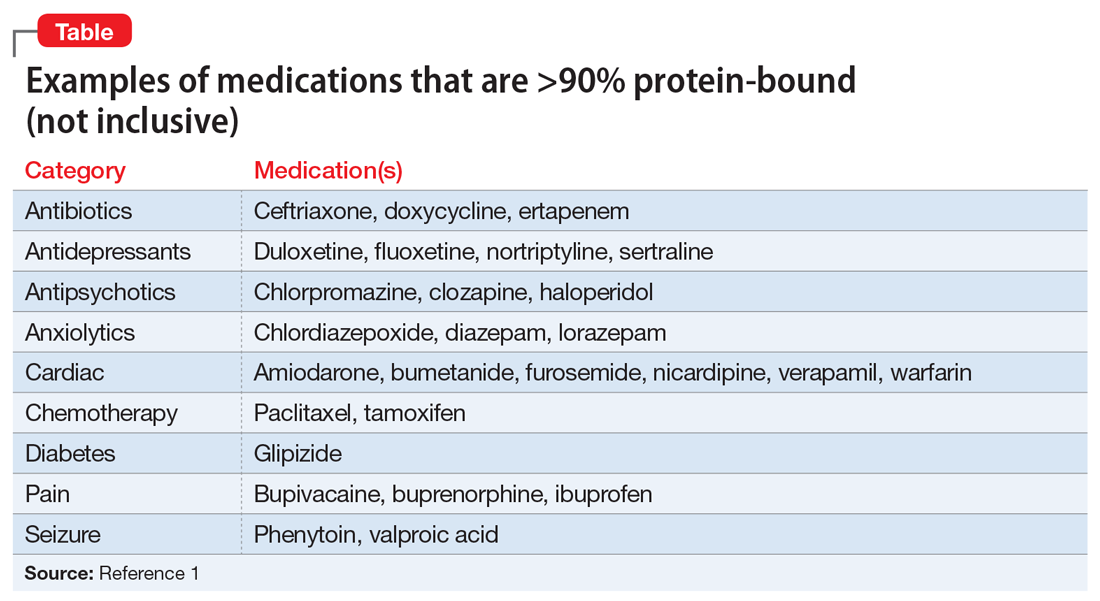

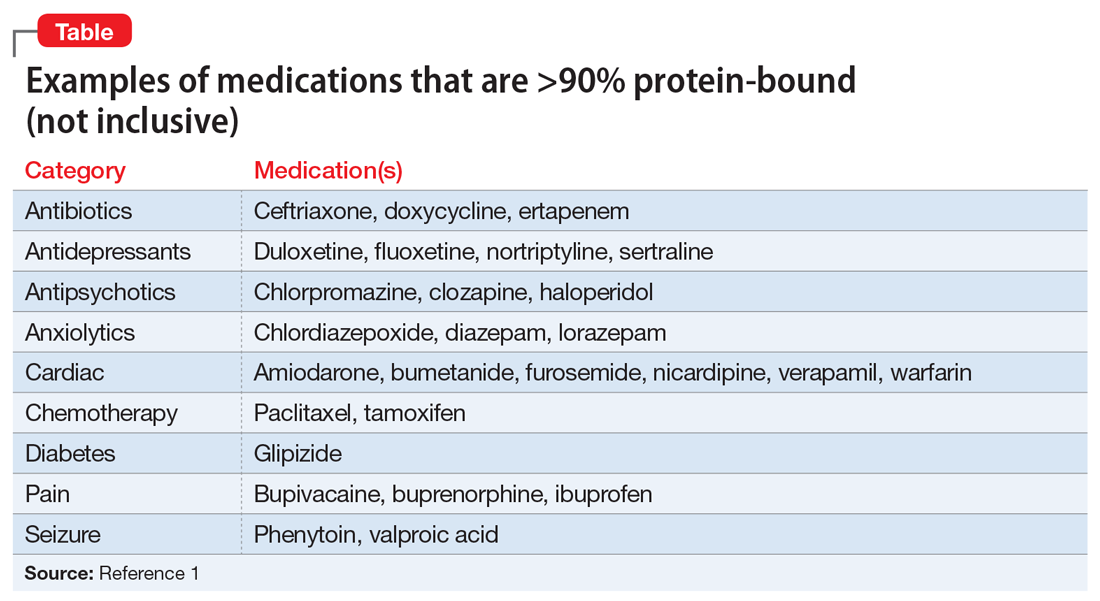

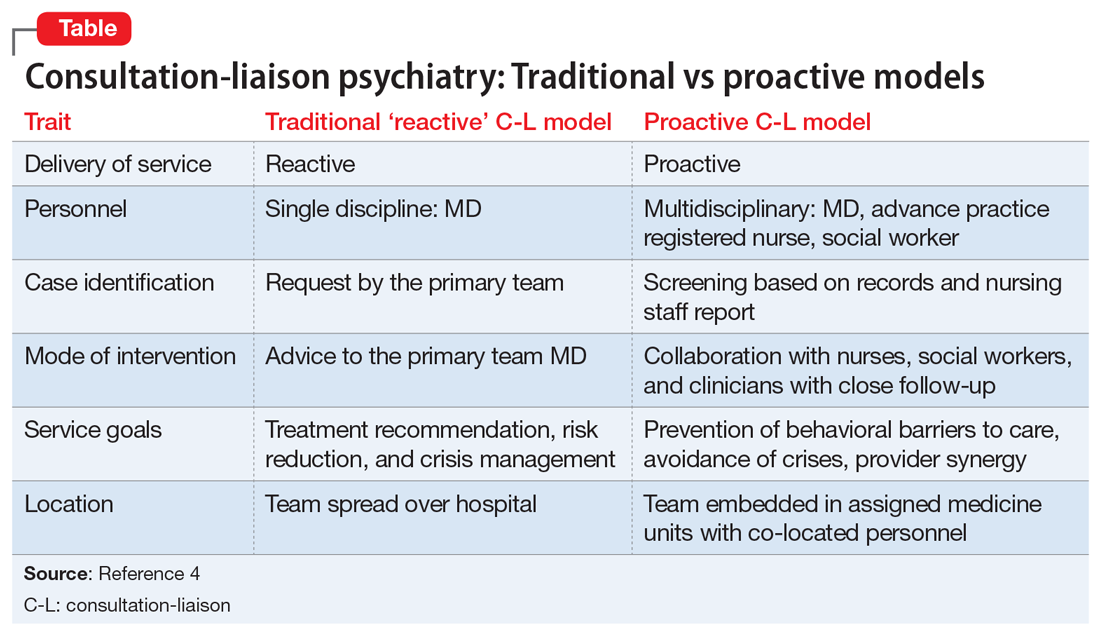

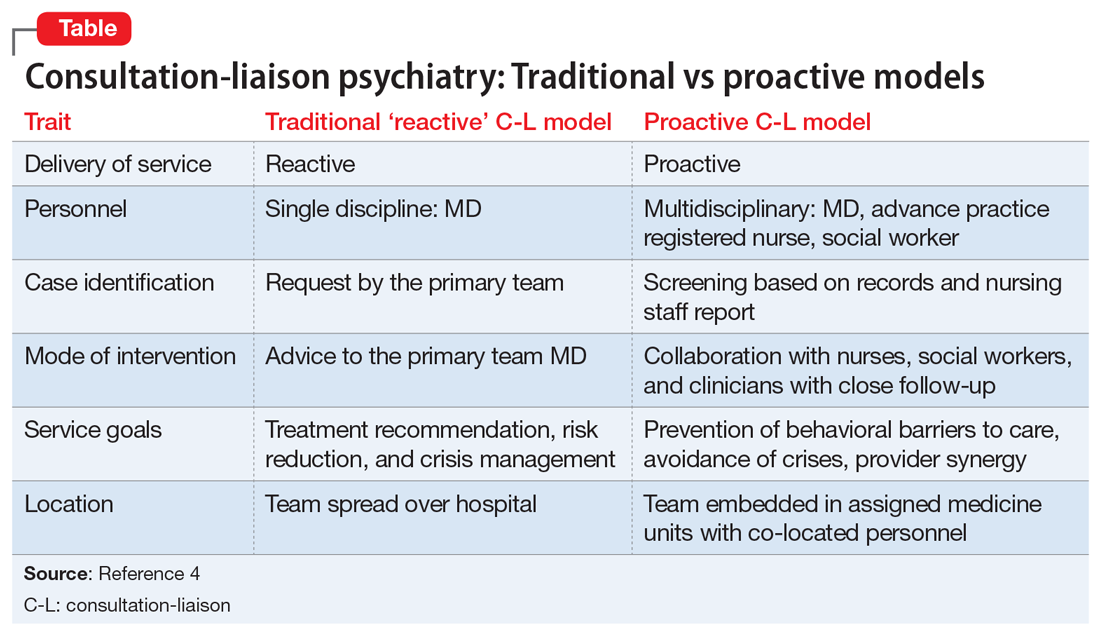

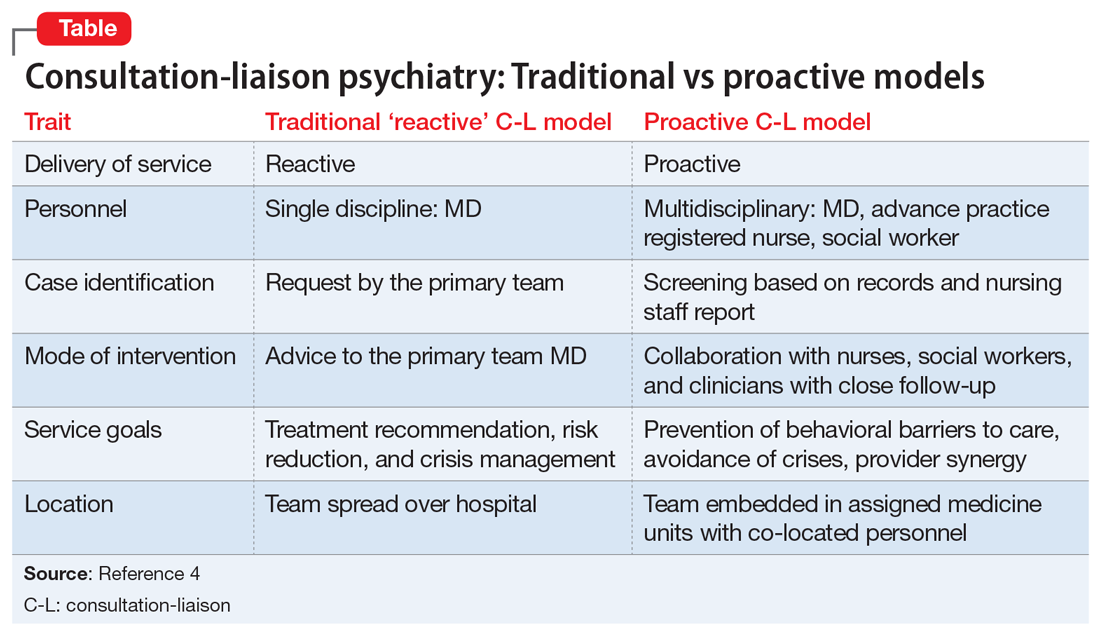

The Table provides a summary of the target symptoms and their treatment options for patients with ASD.

Improved diagnosis, but few evidence-based treatments

The rise in ASD cases observed over the past 20 years can be explained in part by a broader diagnostic algorithm and increased awareness. We are better at identifying ASD; however, there are still considerable gaps in identifying ASD in high-functioning patients and adults. One percent of the population has ASD,72,73 and this group is overrepresented in psychiatric clinic and hospital settings.74 Therefore, we must be aware of and understand the diagnosis.

Medication treatments are often less effective and less tolerable in patients with ASD than in patients without neurodevelopmental disability. There are differences in pharmacotherapy response and tolerability across development in ASD and limited evidence to guide prescribing in adults with ASD. SGAs appear to be effective across multiple symptom domains, but carry the risk of significant adverse effects. For anxiety and irritability, there is compelling evidence supporting the use of nonpharmacologic treatments.

Bottom Line

A subset of patients seen in psychiatry will have undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder (ASD). When evaluating worsening behaviors, first rule out organic causes. Second-generation antipsychotics have the most evidence for efficacy in ASD across multiple symptom domains. To sustain improvement in symptoms, it is vital to incorporate nonpharmacologic treatments.

Related Resources

- National Institute of Mental Health. Autism spectrum disorder. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/autismspectrum-disorder/index.shtml.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD). https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/ autism/index.html.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Guanfacine • Tenex

Guanfacine Extended Release • Intuniv

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Volkmar FR, Lord C, Bailey A, et al. Autism and pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(1):135-170.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018;67(6):1-23.

5. Scragg P, Shah A. Prevalence of Asperger’s syndrome in a secure hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165(5):679-682.

6. Hare DJ, Gould J, Mills R, et al. A preliminary study of individuals with autistic spectrum disorders in three special hospitals in England. London, UK: National Autistic Society; 1999.

7. Shah A, Holmes N, Wing L. Prevalence of autism and related conditions in adults in a mental handicap hospital. Appl Res Ment Retard. 1982;3(3):303-317.

8. Mandell DS, Lawer LJ, Branch K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of autism in a state psychiatric hospital. Autism. 2012;16(6):557-567.

9. Guinchat V, Cravero C, Diaz L, et al. Acute behavioral crises in psychiatric inpatients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): recognition of concomitant medical or non-ASD psychiatric conditions predicts enhanced improvement. Res Devel Disabil. 2015;38:242-255.

10. Perisse D, Amiet C, Consoli A, et al. Risk factors of acute behavioral regression in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents with autism. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):100-108.

11. Canitano R. New experimental treatments for core social domain in autism spectrum disorders. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:61.

12. Wink LK, Plawecki MH, Erickson CA, et al. Emerging drugs for the treatment of symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorders. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2010;15(3):481-494.

13. Fitzpatrick SE, Srivorakiat L, Wink LK, et al. Aggression in autism spectrum disorder: presentation and treatment options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1525-1538.

14. Lecavalier L, Leone S, Wiltz J. The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2006;50(pt 3):172-183.

15. Mills R, Wing L. Researching interventions in ASD and priorities for research: surveying the membership of the NAS. London, UK: National Autistic Society; 2005.

16. Aman MG, McDougle CJ, Scahill L, et al. Medication and parent training in children with pervasive developmental disorders and serious behavior problems: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(12):1143-1154.

17. McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Carlson DC, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(7):633-641.

18. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Risperidone treatment of autistic disorder: longer-term benefits and blinded discontinuation after 6 months. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1361-1369.

19. Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e634-e641.

20. Zuddas A, Zanni R, Usala T. Second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) for non-psychotic disorders in children and adolescents: a review of the randomized controlled studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(8):600-620.

21. Benton TD. Aripiprazole to treat irritability associated with autism: a placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(2):77-79.

22. Marcus RN, Owen R, Kamen L, et al. A placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(11):1110-1119.

23. Owen R, Sikich L, Marcus RN, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1533-1540.

24. Adler BA, Wink LK, Early M, et al. Drug-refractory aggression, self-injurious behavior, and severe tantrums in autism spectrum disorders: a chart review study. Autism. 2015;19(1):102-106.

25. Malone RP, Cater J, Sheikh RM, et al. Olanzapine versus haloperidol in children with autistic disorder: an open pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):887-894.

26. Potenza MN, Holmes JP, Kanes SJ, et al. Olanzapine treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with pervasive developmental disorders: an open-label pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(1):37-44.

27. Hollander E, Wasserman S, Swanson EN, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of olanzapine in childhood/adolescent pervasive developmental disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(5):541-548.

28. Stigler KA, Erickson CA, Mullett JE, et al. Paliperidone for irritability in autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(1):75-78.

29. Dominick K, Wink LK, McDougle CJ, et al. A retrospective naturalistic study of ziprasidone for irritability in youth with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(5):397-401.

30. Malone RP, Delaney MA, Hyman SB, et al. Ziprasidone in adolescents with autism: an open-label pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(6):779-790.

31. Findling RL, McNamara NK, Gracious BL, et al. Quetiapine in nine youths with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;14(2):287-294.

32. Golubchik P, Sever J, Weizman A. Low-dose quetiapine for adolescents with autistic spectrum disorder and aggressive behavior: open-label trial. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(6):216-219.

33. McClellan L, Dominick KC, Pedapati EV, et al. Lurasidone for the treatment of irritability and anger in autism spectrum disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26(8):985-989.

34. Loebel A, Brams M, Goldman RS, et al. Lurasidone for the treatment of irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(4):1153-1163.

35. Campbell M, Anderson LT, Meier M, et al. A comparison of haloperidol and behavior therapy and their interaction in autistic children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1978;17(4):640-655.

36. Wink LK, Pedapati EV, Horn PS, et al. Multiple antipsychotic medication use in autism spectrum disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(1):91-94.

37. Wink LK, Badran I, Pedapati EV, et al. Clozapine for drug-refractory irritability in individuals with developmental disability. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(9):843-846.

38. Chen NC, Bedair HS, McKay B, et al. Clozapine in the treatment of aggression in an adolescent with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(6):479-480.

39. Gobbi G, Pulvirenti L. Long-term treatment with clozapine in an adult with autistic disorder accompanied by aggressive behaviour. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26(4):340-341.

40. Lambrey S, Falissard B, Martin-Barrero M, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine for the treatment of aggression in an adolescent with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(1):79-80.

41. Yalcin O, Kaymak G, Erdogan A, et al. a retrospective investigation of clozapine treatment in autistic and nonautistic children and adolescents in an inpatient clinic in Turkey. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(9):815-821.

42. Beherec L, Lambrey S, Quilici G, et al. Retrospective review of clozapine in the treatment of patients with autism spectrum disorder and severe disruptive behaviors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(3):341-344.

43. Hirota T, Veenstra-Vanderweele J, Hollander E, et al, Antiepileptic medications in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(4):948-957.

44. Hollander E, Chaplin W, Soorya L, et al. Divalproex sodium vs placebo for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(4):990-998.

45. Rezaei V, Mohammadi MR, Ghanizadeh A, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone plus topiramate in children with autistic disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(7):1269-1272.

46. Siegel M, Beresford CA, Bunker M, et al. Preliminary investigation of lithium for mood disorder symptoms in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(7):399-402.

47. Costello EJ, Egger HL, Angold A. The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2005;14(4):631-648,vii.

48. van Steensel FJ, Deutschman AA, Bogels SM. Examining the Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorder-71 as an assessment tool for anxiety in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2013;17(6):681-692.

49. Lidstone J, Uljarevic M, Sullivan J, et al. Relations among restricted and repetitive behaviors, anxiety and sensory features in children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2014;8(2):82-92.

50. Turner M. Annotation: Repetitive behaviour in autism: a review of psychological research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(6):839-849.

51. Kuelz AK, Hohagen F, Voderholzer U. Neuropsychological performance in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a critical review. Biol Psychol. 2004;65(3):185-236.

52. Olley A, Malhi G, Sachdev P. Memory and executive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a selective review. J Affect Disord. 2007;104(1-3):15-23.

53. Channon S, Gunning A, Frankl J, et al. Tourette’s syndrome (TS): cognitive performance in adults with uncomplicated TS. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(1):58-65.

54. Crawford S, Channon S, Robertson MM. Tourette’s syndrome: performance on tests of behavioural inhibition, working memory and gambling. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(12):1327-1336.

55. Renno P, Wood JJ. Discriminant and convergent validity of the anxiety construct in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(9):2135-2146.

56. Wink LK, Erickson CA, Stigler KA, et al. Riluzole in autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(4):375-379.

57. Vasa RA, Carroll LM, Nozzolillo AA, et al. A systematic review of treatments for anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(12):3215-3229.

58. Williams K, Brignell A, Randall M, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD004677.

59. Wink LK, Erickson CA, McDougle CJ. Pharmacologic treatment of behavioral symptoms associated with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2010;12(6):529-538.

60. McDougle CJ, Scahill L, Aman MG, et al. Risperidone for the core symptom domains of autism: results from the study by the autism network of the research units on pediatric psychopharmacology. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1142-1148.

61. Murray MJ, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the context of autism spectrum disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(5):382-388.

62. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Randomized, controlled, crossover trial of methylphenidate in pervasive developmental disorders with hyperactivity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1266-1274.

63. Posey DJ, Aman MG, McCracken JT, et al. Positive effects of methylphenidate on inattention and hyperactivity in pervasive developmental disorders: an analysis of secondary measures. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(4):538-544.

64. Aman MG, Langworthy KS. Pharmacotherapy for hyperactivity in children with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(5):451-459.

65. Handen BL, Johnson CR, Lubetsky M. Efficacy of methylphenidate among children with autism and symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):245-255.

66. Quintana H, Birmaher B, Stedge D, et al. Use of methylphenidate in the treatment of children with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25(3):283-294.

67. Jahromi LB, Kasari CL, McCracken JT, et al. Positive effects of methylphenidate on social communication and self-regulation in children with pervasive developmental disorders and hyperactivity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(3):395-404.

68. Fankhauser MP, Karumanchi VC, German ML, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of transdermal clonidine in autism. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(3):77-82.

69. Scahill L, McCracken JT, King BH, et al. Extended-release guanfacine for hyperactivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(12):1197-1206.

70. Handen BL, Sahl R, Hardan AY. Guanfacine in children with autism and/or intellectual disabilities. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(4):303-308.

71. Scahill L, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, et al. A prospective open trial of guanfacine in children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(5):589-598.

72. Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2010 Principal Investigators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(2):1-21.

73. Brugha TS, McManus S, Bankart J, et al. Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders in adults in the community in England. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(5):459-465.

74. Mandell DS, Psychiatric hospitalization among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(6):1059-1065.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is an umbrella term used to describe lifelong neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by impairment in social interactions and communication coupled with restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviors or interests that appear to share a common developmental course.1 In this article, we examine psychiatric care of patients with ASD and the most common symptom clusters treated with pharmacotherapy: irritability, anxiety, and hyperactivity/inattention.

First step: Keep the diagnosis in mind

Prior to 2013, ASD was comprised of 3 separate disorders distinguished by language delay and overall severity: autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified.2 With the release of DSM-5 in 2013, these disorders were essentially collapsed into a single ASD.3 ASD prevalence is estimated to be 1 in 59 children,4 which represents a 20- to 30-fold increase since the 1960s.

In order to provide adequate psychiatric care for individuals with ASD, the first step is to remember the diagnosis; keep it in mind. This may be particularly important for clinicians who primarily care for adults, because such clinicians often receive limited training in disorders first manifesting in childhood and may not consider ASD in patients who have not been previously diagnosed. However, ASD diagnostic criteria have become broader, and public knowledge of the diagnosis has grown. DSM-5 acknowledges that although symptoms begin in early childhood, they may become more recognizable later in life with increasing social demand. The result is that many adults are likely undiagnosed. The estimated prevalence of ASD in adult psychiatric settings range from 1.5% to 4%.5-7 These patients have different treatment needs and unfortunately are often misdiagnosed with other psychiatric conditions.

A recent study in a state psychiatric facility found that 10% of patients in this setting met criteria for ASD.8 Almost all of those patients had been misdiagnosed with some form of schizophrenia, including one patient who had been previously diagnosed with autism by the father of autism himself, Leo Kanner, MD. Through the years, this patient’s autism diagnosis had fallen away, and at the time of the study, the patient carried a diagnosis of undifferentiated schizophrenia and was prescribed 8 psychotropic medications. The patient had repeatedly denied auditory or visual hallucinations; however, his stereotypies and odd behaviors were taken as evidence that he was responding to internal stimuli. This case highlights the importance of keeping the ASD diagnosis in mind when evaluating and treating patients.

Addressing 3 key symptom clusters

Even for patients with an established ASD diagnosis, comprehensive treatment is complex. It typically involves a multimodal approach that includes speech therapy, occupational therapy, applied behavioral analysis (ABA), and vocational training and support as well as management of associated medical conditions. Because medical comorbidities may play an important role in exacerbation of severe behaviors in ASD, often leading to acute behavioral regression and psychiatric admission, it is essential that they not be overlooked during evaluations.9,10

There are no effective pharmacologic treatments for the core social deficits seen in ASD. Novel pharmacotherapies to improve social impairment are in the early stages of research,11,12 but currently social impairment is best addressed through behavioral therapy and social skills training. Our role as psychiatrists is most often to treat co-occurring psychiatric symptoms so that individuals with ASD can fully participate in behavioral and school-based treatments that lead to improved social skills, activities of daily living, and quality of life. Three of the most common of these symptoms are irritability, anxiety, and hyperactivity/inattention.

Irritability

Irritability, marked by aggression, self-injury, and severe tantrums, causes serious distress for both patients and families, and this behavior cluster is the most frequently reported comorbid symptom in ASD.13-15 Nonpharmacologic treatment of irritability often involves ABA-based therapy and communication training.

Continued to: ABA includes an initial functional behavior assessment...

ABA includes an initial functional behavior assessment (FBA) of maladaptive behavior followed by the application of specific schedules of reinforcement for positive behavior. The FBA allows the therapist to determine what desirable consequences maintain a behavior. Without this knowledge, there is the risk of inadvertently rewarding a maladaptive behavior. For instance, if you are recommending a time-out for escape-motivated aggression, the result will likely be an increase rather than decrease in aggression.

Communication training teaches the patient to use communicative means to request a desired outcome to reduce inappropriate behaviors and improve independent functioning. Communication training can include speech therapy, teaching sign language, using picture exchange programs, or navigating communication devices. Consideration of nonpharmacologic management is vital in treatment planning. Continual inadvertent reward of behaviors will limit the effects of medications. Evidence suggests that pharmacotherapy is more effective when it occurs in the context of appropriate behavioral management techniques.16

Irritability has been the focus of significant pharmacotherapy research in ASD. Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are first-line pharmacotherapy for severe irritability. Risperidone and aripiprazole are both FDA-approved for addressing irritability in youth with ASD. Their efficacy has been established in several large, placebo-controlled trials.17-23

Given issues with tolerability and cases refractory to the use of first-line agents,24 other SGAs are frequently used off-label for this indication with limited safety or efficacy data. Olanzapine demonstrated high response rates in early open-label studies,25,26 followed by efficacy over an 8-week double-blind placebo-controlled trial, although with significant weight gain.27 No other SGAs have been examined in double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Paliperidone demonstrated a particularly high response rate (84%) in a prospective open-label study of 25 adolescents and young adults with ASD.28 In a retrospective study of ziprasidone in 42 youth with ASD and irritability, we reported a response rate of 40%, which is lower than that seen for some other SGAs; however, ziprasidone can be an appealing option for patients for whom SGA-associated weight gain has been significant, because it is much more likely to be weight-neutral.29,30 Open-label studies with quetiapine in ASD have generally revealed only minimal efficacy for aggression,31,32 although sleep improvement may be more substantial.32 The safety and tolerability of lurasidone in treating irritability in youth with ASD has yet to be established.33 It is the only SGA with a published negative placebo-controlled trial in ASD.34 Use of SGAs may be limited by adverse effects, including weight gain, increased appetite, sedation, enuresis, and elevated prolactin. Monitoring of body mass index and metabolic profiles is indicated with all SGAs.

Haloperidol is the only first-generation antipsychotic with significant evidence (from multiple studies dating back to 1978) to support its use for ASD-associated irritability.35 However, due to the high incidence of dyskinesias and potential dystonias, use of haloperidol is reserved for severe treatment-refractory symptoms that have often not improved after multiple SGA trials.

Continued to: When severe self-inury and aggression fail to improve...

When severe self-injury and aggression fail to improve with multiple medication trials, the next steps include combination treatment with multiple antipsychotics,36 followed by clozapine, often as a last option.37 Research suggests that clozapine is effective and well-tolerated in ASD38-42; however, it has many potential severe adverse effects, including cardiomyopathy, lowered seizure threshold, severe constipation, weight gain, and agranulocytosis; due to risk of the latter, patients require regular blood draws for monitoring.

There is very little evidence to support the use of antiepileptic medications (AEDs) and mood stabilizers for irritability in ASD.43 Placebo-controlled trials have had mixed results. Some evidence suggests that AEDS may have more utility in individuals with ASD and abnormal EEGs without epilepsy44 or as an adjunct to SGA treatment.45 One study found that lithium may be beneficial for patients with ASD whose clinical presentation includes 2 or more mood symptoms.46

Anxiety

Anxiety is a significant issue for many individuals with ASD.47 Anxiety symptoms and disorders, including specific phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), social anxiety, and generalized anxiety disorder, are commonly seen in persons with ASD.48 Anxiety is often combined with restricted, repetitive behaviors (RBs) in ASD literature. Some evidence suggests that in individuals with ASD, sameness behaviors may limit sensory input and modulate anxiety.49 However, the core RBs symptom domain may not be related solely to anxiety, but rather represents deficits in executive processes that include cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control seen across multiple disorders with prominent RBs.50-54 Research indicates that anxiety is an independent and separable construct in ASD.55

Studies of treatments for both RBs and anxiety have focused primarily on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), hoping that the promising results for anxiety and OCD behaviors seen in neurotypical patients would translate to patients with ASD.56 Unfortunately, there is little evidence for effective pharmacologic management of ASD-associated anxiety.57 Large, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are lacking. A Cochrane Database review of SSRIs for ASD58 examined 9 RCTs with a total of 320 patients. The authors concluded that there is no evidence to support the use of SSRIs for children with ASD, and limited evidence of utility in adults. Youth with ASD are particularly vulnerable to adverse effects from SSRIs, specifically impulsivity and agitation.57,59 However, SSRIs are among the most commonly prescribed medications for youth with ASD. Because there is limited evidence supporting SSRIs’ efficacy for this indication and issues with tolerability, there is significant concern for the overprescribing of SSRIs to patients with ASD. In comparison, there is some compelling evidence of efficacy for modified cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for patients with high-functioning ASD. Seven RCTs have shown that CBT is superior to treatment as usual and waiting list control groups, with most effect sizes >0.8 and with no treatment-associated adverse effects.57

Risperidone has been shown to reduce RBs17,60 and anxiety17 in patients with ASD. In young children with co-occurring irritability, risperidone monotherapy is likely best to address both symptoms. When anxiety occurs in isolation and is severe, clinical experience suggests that SSRIs can be effective in a limited percentage of cases, though we recommend starting at low doses with frequent monitoring for activation and irritability. Treatment of anxiety is further complicated by the significant challenges presented by the diagnosis of true anxiety in the context of ASD.

Continued to: Hyperactivity and impulsivity

Hyperactivity and impulsivity

Hyperactivity and impulsivity are common among patients with ASD, with rates estimated from 41% to 78%.61 Hyperactivity and inattention are treated with a variety of medications. Research examining methylphenidate in ASD has demonstrated modest effects compared with placebo, though with frequent adverse effects, such as increased irritability and insomnia62,63 Other smaller studies have confirmed these results.64-66 One additional study found improvements not only in hyperactivity but also in joint attention and self-regulation of affective state following stimulant treatment.67 There is limited data on the efficacy and tolerability of amphetamine for treating hyperactivity and impulsivity in ASD. Stimulant medications often are avoided as the first-line treatment for hyperactivity because of concerns about increased irritability. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists often are used before stimulants because of their relatively benign adverse effect profile. Clonidine, guanfacine, and guanfacine ER all have demonstrated effectiveness in double-blind, placebo-controls trials in patients with ASD.68-70 In these trails, sedation was the most common adverse effect, although some studies have reported increased irritability with guanfacine.70,71

The Table provides a summary of the target symptoms and their treatment options for patients with ASD.

Improved diagnosis, but few evidence-based treatments

The rise in ASD cases observed over the past 20 years can be explained in part by a broader diagnostic algorithm and increased awareness. We are better at identifying ASD; however, there are still considerable gaps in identifying ASD in high-functioning patients and adults. One percent of the population has ASD,72,73 and this group is overrepresented in psychiatric clinic and hospital settings.74 Therefore, we must be aware of and understand the diagnosis.

Medication treatments are often less effective and less tolerable in patients with ASD than in patients without neurodevelopmental disability. There are differences in pharmacotherapy response and tolerability across development in ASD and limited evidence to guide prescribing in adults with ASD. SGAs appear to be effective across multiple symptom domains, but carry the risk of significant adverse effects. For anxiety and irritability, there is compelling evidence supporting the use of nonpharmacologic treatments.

Bottom Line

A subset of patients seen in psychiatry will have undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder (ASD). When evaluating worsening behaviors, first rule out organic causes. Second-generation antipsychotics have the most evidence for efficacy in ASD across multiple symptom domains. To sustain improvement in symptoms, it is vital to incorporate nonpharmacologic treatments.

Related Resources

- National Institute of Mental Health. Autism spectrum disorder. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/autismspectrum-disorder/index.shtml.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD). https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/ autism/index.html.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Guanfacine • Tenex

Guanfacine Extended Release • Intuniv

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is an umbrella term used to describe lifelong neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by impairment in social interactions and communication coupled with restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviors or interests that appear to share a common developmental course.1 In this article, we examine psychiatric care of patients with ASD and the most common symptom clusters treated with pharmacotherapy: irritability, anxiety, and hyperactivity/inattention.

First step: Keep the diagnosis in mind

Prior to 2013, ASD was comprised of 3 separate disorders distinguished by language delay and overall severity: autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified.2 With the release of DSM-5 in 2013, these disorders were essentially collapsed into a single ASD.3 ASD prevalence is estimated to be 1 in 59 children,4 which represents a 20- to 30-fold increase since the 1960s.

In order to provide adequate psychiatric care for individuals with ASD, the first step is to remember the diagnosis; keep it in mind. This may be particularly important for clinicians who primarily care for adults, because such clinicians often receive limited training in disorders first manifesting in childhood and may not consider ASD in patients who have not been previously diagnosed. However, ASD diagnostic criteria have become broader, and public knowledge of the diagnosis has grown. DSM-5 acknowledges that although symptoms begin in early childhood, they may become more recognizable later in life with increasing social demand. The result is that many adults are likely undiagnosed. The estimated prevalence of ASD in adult psychiatric settings range from 1.5% to 4%.5-7 These patients have different treatment needs and unfortunately are often misdiagnosed with other psychiatric conditions.

A recent study in a state psychiatric facility found that 10% of patients in this setting met criteria for ASD.8 Almost all of those patients had been misdiagnosed with some form of schizophrenia, including one patient who had been previously diagnosed with autism by the father of autism himself, Leo Kanner, MD. Through the years, this patient’s autism diagnosis had fallen away, and at the time of the study, the patient carried a diagnosis of undifferentiated schizophrenia and was prescribed 8 psychotropic medications. The patient had repeatedly denied auditory or visual hallucinations; however, his stereotypies and odd behaviors were taken as evidence that he was responding to internal stimuli. This case highlights the importance of keeping the ASD diagnosis in mind when evaluating and treating patients.

Addressing 3 key symptom clusters

Even for patients with an established ASD diagnosis, comprehensive treatment is complex. It typically involves a multimodal approach that includes speech therapy, occupational therapy, applied behavioral analysis (ABA), and vocational training and support as well as management of associated medical conditions. Because medical comorbidities may play an important role in exacerbation of severe behaviors in ASD, often leading to acute behavioral regression and psychiatric admission, it is essential that they not be overlooked during evaluations.9,10

There are no effective pharmacologic treatments for the core social deficits seen in ASD. Novel pharmacotherapies to improve social impairment are in the early stages of research,11,12 but currently social impairment is best addressed through behavioral therapy and social skills training. Our role as psychiatrists is most often to treat co-occurring psychiatric symptoms so that individuals with ASD can fully participate in behavioral and school-based treatments that lead to improved social skills, activities of daily living, and quality of life. Three of the most common of these symptoms are irritability, anxiety, and hyperactivity/inattention.

Irritability

Irritability, marked by aggression, self-injury, and severe tantrums, causes serious distress for both patients and families, and this behavior cluster is the most frequently reported comorbid symptom in ASD.13-15 Nonpharmacologic treatment of irritability often involves ABA-based therapy and communication training.

Continued to: ABA includes an initial functional behavior assessment...

ABA includes an initial functional behavior assessment (FBA) of maladaptive behavior followed by the application of specific schedules of reinforcement for positive behavior. The FBA allows the therapist to determine what desirable consequences maintain a behavior. Without this knowledge, there is the risk of inadvertently rewarding a maladaptive behavior. For instance, if you are recommending a time-out for escape-motivated aggression, the result will likely be an increase rather than decrease in aggression.

Communication training teaches the patient to use communicative means to request a desired outcome to reduce inappropriate behaviors and improve independent functioning. Communication training can include speech therapy, teaching sign language, using picture exchange programs, or navigating communication devices. Consideration of nonpharmacologic management is vital in treatment planning. Continual inadvertent reward of behaviors will limit the effects of medications. Evidence suggests that pharmacotherapy is more effective when it occurs in the context of appropriate behavioral management techniques.16

Irritability has been the focus of significant pharmacotherapy research in ASD. Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are first-line pharmacotherapy for severe irritability. Risperidone and aripiprazole are both FDA-approved for addressing irritability in youth with ASD. Their efficacy has been established in several large, placebo-controlled trials.17-23

Given issues with tolerability and cases refractory to the use of first-line agents,24 other SGAs are frequently used off-label for this indication with limited safety or efficacy data. Olanzapine demonstrated high response rates in early open-label studies,25,26 followed by efficacy over an 8-week double-blind placebo-controlled trial, although with significant weight gain.27 No other SGAs have been examined in double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Paliperidone demonstrated a particularly high response rate (84%) in a prospective open-label study of 25 adolescents and young adults with ASD.28 In a retrospective study of ziprasidone in 42 youth with ASD and irritability, we reported a response rate of 40%, which is lower than that seen for some other SGAs; however, ziprasidone can be an appealing option for patients for whom SGA-associated weight gain has been significant, because it is much more likely to be weight-neutral.29,30 Open-label studies with quetiapine in ASD have generally revealed only minimal efficacy for aggression,31,32 although sleep improvement may be more substantial.32 The safety and tolerability of lurasidone in treating irritability in youth with ASD has yet to be established.33 It is the only SGA with a published negative placebo-controlled trial in ASD.34 Use of SGAs may be limited by adverse effects, including weight gain, increased appetite, sedation, enuresis, and elevated prolactin. Monitoring of body mass index and metabolic profiles is indicated with all SGAs.

Haloperidol is the only first-generation antipsychotic with significant evidence (from multiple studies dating back to 1978) to support its use for ASD-associated irritability.35 However, due to the high incidence of dyskinesias and potential dystonias, use of haloperidol is reserved for severe treatment-refractory symptoms that have often not improved after multiple SGA trials.

Continued to: When severe self-inury and aggression fail to improve...

When severe self-injury and aggression fail to improve with multiple medication trials, the next steps include combination treatment with multiple antipsychotics,36 followed by clozapine, often as a last option.37 Research suggests that clozapine is effective and well-tolerated in ASD38-42; however, it has many potential severe adverse effects, including cardiomyopathy, lowered seizure threshold, severe constipation, weight gain, and agranulocytosis; due to risk of the latter, patients require regular blood draws for monitoring.

There is very little evidence to support the use of antiepileptic medications (AEDs) and mood stabilizers for irritability in ASD.43 Placebo-controlled trials have had mixed results. Some evidence suggests that AEDS may have more utility in individuals with ASD and abnormal EEGs without epilepsy44 or as an adjunct to SGA treatment.45 One study found that lithium may be beneficial for patients with ASD whose clinical presentation includes 2 or more mood symptoms.46

Anxiety

Anxiety is a significant issue for many individuals with ASD.47 Anxiety symptoms and disorders, including specific phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), social anxiety, and generalized anxiety disorder, are commonly seen in persons with ASD.48 Anxiety is often combined with restricted, repetitive behaviors (RBs) in ASD literature. Some evidence suggests that in individuals with ASD, sameness behaviors may limit sensory input and modulate anxiety.49 However, the core RBs symptom domain may not be related solely to anxiety, but rather represents deficits in executive processes that include cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control seen across multiple disorders with prominent RBs.50-54 Research indicates that anxiety is an independent and separable construct in ASD.55

Studies of treatments for both RBs and anxiety have focused primarily on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), hoping that the promising results for anxiety and OCD behaviors seen in neurotypical patients would translate to patients with ASD.56 Unfortunately, there is little evidence for effective pharmacologic management of ASD-associated anxiety.57 Large, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are lacking. A Cochrane Database review of SSRIs for ASD58 examined 9 RCTs with a total of 320 patients. The authors concluded that there is no evidence to support the use of SSRIs for children with ASD, and limited evidence of utility in adults. Youth with ASD are particularly vulnerable to adverse effects from SSRIs, specifically impulsivity and agitation.57,59 However, SSRIs are among the most commonly prescribed medications for youth with ASD. Because there is limited evidence supporting SSRIs’ efficacy for this indication and issues with tolerability, there is significant concern for the overprescribing of SSRIs to patients with ASD. In comparison, there is some compelling evidence of efficacy for modified cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for patients with high-functioning ASD. Seven RCTs have shown that CBT is superior to treatment as usual and waiting list control groups, with most effect sizes >0.8 and with no treatment-associated adverse effects.57

Risperidone has been shown to reduce RBs17,60 and anxiety17 in patients with ASD. In young children with co-occurring irritability, risperidone monotherapy is likely best to address both symptoms. When anxiety occurs in isolation and is severe, clinical experience suggests that SSRIs can be effective in a limited percentage of cases, though we recommend starting at low doses with frequent monitoring for activation and irritability. Treatment of anxiety is further complicated by the significant challenges presented by the diagnosis of true anxiety in the context of ASD.

Continued to: Hyperactivity and impulsivity

Hyperactivity and impulsivity

Hyperactivity and impulsivity are common among patients with ASD, with rates estimated from 41% to 78%.61 Hyperactivity and inattention are treated with a variety of medications. Research examining methylphenidate in ASD has demonstrated modest effects compared with placebo, though with frequent adverse effects, such as increased irritability and insomnia62,63 Other smaller studies have confirmed these results.64-66 One additional study found improvements not only in hyperactivity but also in joint attention and self-regulation of affective state following stimulant treatment.67 There is limited data on the efficacy and tolerability of amphetamine for treating hyperactivity and impulsivity in ASD. Stimulant medications often are avoided as the first-line treatment for hyperactivity because of concerns about increased irritability. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists often are used before stimulants because of their relatively benign adverse effect profile. Clonidine, guanfacine, and guanfacine ER all have demonstrated effectiveness in double-blind, placebo-controls trials in patients with ASD.68-70 In these trails, sedation was the most common adverse effect, although some studies have reported increased irritability with guanfacine.70,71

The Table provides a summary of the target symptoms and their treatment options for patients with ASD.

Improved diagnosis, but few evidence-based treatments

The rise in ASD cases observed over the past 20 years can be explained in part by a broader diagnostic algorithm and increased awareness. We are better at identifying ASD; however, there are still considerable gaps in identifying ASD in high-functioning patients and adults. One percent of the population has ASD,72,73 and this group is overrepresented in psychiatric clinic and hospital settings.74 Therefore, we must be aware of and understand the diagnosis.

Medication treatments are often less effective and less tolerable in patients with ASD than in patients without neurodevelopmental disability. There are differences in pharmacotherapy response and tolerability across development in ASD and limited evidence to guide prescribing in adults with ASD. SGAs appear to be effective across multiple symptom domains, but carry the risk of significant adverse effects. For anxiety and irritability, there is compelling evidence supporting the use of nonpharmacologic treatments.

Bottom Line

A subset of patients seen in psychiatry will have undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder (ASD). When evaluating worsening behaviors, first rule out organic causes. Second-generation antipsychotics have the most evidence for efficacy in ASD across multiple symptom domains. To sustain improvement in symptoms, it is vital to incorporate nonpharmacologic treatments.

Related Resources

- National Institute of Mental Health. Autism spectrum disorder. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/autismspectrum-disorder/index.shtml.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD). https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/ autism/index.html.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Guanfacine • Tenex

Guanfacine Extended Release • Intuniv

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Volkmar FR, Lord C, Bailey A, et al. Autism and pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(1):135-170.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018;67(6):1-23.

5. Scragg P, Shah A. Prevalence of Asperger’s syndrome in a secure hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165(5):679-682.

6. Hare DJ, Gould J, Mills R, et al. A preliminary study of individuals with autistic spectrum disorders in three special hospitals in England. London, UK: National Autistic Society; 1999.

7. Shah A, Holmes N, Wing L. Prevalence of autism and related conditions in adults in a mental handicap hospital. Appl Res Ment Retard. 1982;3(3):303-317.

8. Mandell DS, Lawer LJ, Branch K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of autism in a state psychiatric hospital. Autism. 2012;16(6):557-567.

9. Guinchat V, Cravero C, Diaz L, et al. Acute behavioral crises in psychiatric inpatients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): recognition of concomitant medical or non-ASD psychiatric conditions predicts enhanced improvement. Res Devel Disabil. 2015;38:242-255.

10. Perisse D, Amiet C, Consoli A, et al. Risk factors of acute behavioral regression in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents with autism. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):100-108.

11. Canitano R. New experimental treatments for core social domain in autism spectrum disorders. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:61.

12. Wink LK, Plawecki MH, Erickson CA, et al. Emerging drugs for the treatment of symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorders. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2010;15(3):481-494.

13. Fitzpatrick SE, Srivorakiat L, Wink LK, et al. Aggression in autism spectrum disorder: presentation and treatment options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1525-1538.

14. Lecavalier L, Leone S, Wiltz J. The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2006;50(pt 3):172-183.

15. Mills R, Wing L. Researching interventions in ASD and priorities for research: surveying the membership of the NAS. London, UK: National Autistic Society; 2005.

16. Aman MG, McDougle CJ, Scahill L, et al. Medication and parent training in children with pervasive developmental disorders and serious behavior problems: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(12):1143-1154.

17. McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Carlson DC, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(7):633-641.

18. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Risperidone treatment of autistic disorder: longer-term benefits and blinded discontinuation after 6 months. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1361-1369.

19. Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e634-e641.

20. Zuddas A, Zanni R, Usala T. Second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) for non-psychotic disorders in children and adolescents: a review of the randomized controlled studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(8):600-620.

21. Benton TD. Aripiprazole to treat irritability associated with autism: a placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(2):77-79.

22. Marcus RN, Owen R, Kamen L, et al. A placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(11):1110-1119.

23. Owen R, Sikich L, Marcus RN, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1533-1540.

24. Adler BA, Wink LK, Early M, et al. Drug-refractory aggression, self-injurious behavior, and severe tantrums in autism spectrum disorders: a chart review study. Autism. 2015;19(1):102-106.

25. Malone RP, Cater J, Sheikh RM, et al. Olanzapine versus haloperidol in children with autistic disorder: an open pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):887-894.

26. Potenza MN, Holmes JP, Kanes SJ, et al. Olanzapine treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with pervasive developmental disorders: an open-label pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(1):37-44.

27. Hollander E, Wasserman S, Swanson EN, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of olanzapine in childhood/adolescent pervasive developmental disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(5):541-548.

28. Stigler KA, Erickson CA, Mullett JE, et al. Paliperidone for irritability in autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(1):75-78.

29. Dominick K, Wink LK, McDougle CJ, et al. A retrospective naturalistic study of ziprasidone for irritability in youth with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(5):397-401.

30. Malone RP, Delaney MA, Hyman SB, et al. Ziprasidone in adolescents with autism: an open-label pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(6):779-790.

31. Findling RL, McNamara NK, Gracious BL, et al. Quetiapine in nine youths with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;14(2):287-294.

32. Golubchik P, Sever J, Weizman A. Low-dose quetiapine for adolescents with autistic spectrum disorder and aggressive behavior: open-label trial. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(6):216-219.

33. McClellan L, Dominick KC, Pedapati EV, et al. Lurasidone for the treatment of irritability and anger in autism spectrum disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26(8):985-989.

34. Loebel A, Brams M, Goldman RS, et al. Lurasidone for the treatment of irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(4):1153-1163.

35. Campbell M, Anderson LT, Meier M, et al. A comparison of haloperidol and behavior therapy and their interaction in autistic children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1978;17(4):640-655.

36. Wink LK, Pedapati EV, Horn PS, et al. Multiple antipsychotic medication use in autism spectrum disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(1):91-94.

37. Wink LK, Badran I, Pedapati EV, et al. Clozapine for drug-refractory irritability in individuals with developmental disability. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(9):843-846.

38. Chen NC, Bedair HS, McKay B, et al. Clozapine in the treatment of aggression in an adolescent with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(6):479-480.

39. Gobbi G, Pulvirenti L. Long-term treatment with clozapine in an adult with autistic disorder accompanied by aggressive behaviour. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26(4):340-341.

40. Lambrey S, Falissard B, Martin-Barrero M, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine for the treatment of aggression in an adolescent with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(1):79-80.

41. Yalcin O, Kaymak G, Erdogan A, et al. a retrospective investigation of clozapine treatment in autistic and nonautistic children and adolescents in an inpatient clinic in Turkey. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(9):815-821.

42. Beherec L, Lambrey S, Quilici G, et al. Retrospective review of clozapine in the treatment of patients with autism spectrum disorder and severe disruptive behaviors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(3):341-344.

43. Hirota T, Veenstra-Vanderweele J, Hollander E, et al, Antiepileptic medications in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(4):948-957.

44. Hollander E, Chaplin W, Soorya L, et al. Divalproex sodium vs placebo for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(4):990-998.

45. Rezaei V, Mohammadi MR, Ghanizadeh A, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone plus topiramate in children with autistic disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(7):1269-1272.

46. Siegel M, Beresford CA, Bunker M, et al. Preliminary investigation of lithium for mood disorder symptoms in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(7):399-402.

47. Costello EJ, Egger HL, Angold A. The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2005;14(4):631-648,vii.

48. van Steensel FJ, Deutschman AA, Bogels SM. Examining the Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorder-71 as an assessment tool for anxiety in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2013;17(6):681-692.

49. Lidstone J, Uljarevic M, Sullivan J, et al. Relations among restricted and repetitive behaviors, anxiety and sensory features in children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2014;8(2):82-92.

50. Turner M. Annotation: Repetitive behaviour in autism: a review of psychological research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(6):839-849.

51. Kuelz AK, Hohagen F, Voderholzer U. Neuropsychological performance in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a critical review. Biol Psychol. 2004;65(3):185-236.

52. Olley A, Malhi G, Sachdev P. Memory and executive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a selective review. J Affect Disord. 2007;104(1-3):15-23.

53. Channon S, Gunning A, Frankl J, et al. Tourette’s syndrome (TS): cognitive performance in adults with uncomplicated TS. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(1):58-65.

54. Crawford S, Channon S, Robertson MM. Tourette’s syndrome: performance on tests of behavioural inhibition, working memory and gambling. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(12):1327-1336.

55. Renno P, Wood JJ. Discriminant and convergent validity of the anxiety construct in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(9):2135-2146.

56. Wink LK, Erickson CA, Stigler KA, et al. Riluzole in autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(4):375-379.

57. Vasa RA, Carroll LM, Nozzolillo AA, et al. A systematic review of treatments for anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(12):3215-3229.

58. Williams K, Brignell A, Randall M, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD004677.

59. Wink LK, Erickson CA, McDougle CJ. Pharmacologic treatment of behavioral symptoms associated with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2010;12(6):529-538.

60. McDougle CJ, Scahill L, Aman MG, et al. Risperidone for the core symptom domains of autism: results from the study by the autism network of the research units on pediatric psychopharmacology. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1142-1148.

61. Murray MJ, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the context of autism spectrum disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(5):382-388.

62. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Randomized, controlled, crossover trial of methylphenidate in pervasive developmental disorders with hyperactivity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1266-1274.

63. Posey DJ, Aman MG, McCracken JT, et al. Positive effects of methylphenidate on inattention and hyperactivity in pervasive developmental disorders: an analysis of secondary measures. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(4):538-544.

64. Aman MG, Langworthy KS. Pharmacotherapy for hyperactivity in children with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(5):451-459.

65. Handen BL, Johnson CR, Lubetsky M. Efficacy of methylphenidate among children with autism and symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):245-255.

66. Quintana H, Birmaher B, Stedge D, et al. Use of methylphenidate in the treatment of children with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25(3):283-294.

67. Jahromi LB, Kasari CL, McCracken JT, et al. Positive effects of methylphenidate on social communication and self-regulation in children with pervasive developmental disorders and hyperactivity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(3):395-404.

68. Fankhauser MP, Karumanchi VC, German ML, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of transdermal clonidine in autism. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(3):77-82.

69. Scahill L, McCracken JT, King BH, et al. Extended-release guanfacine for hyperactivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(12):1197-1206.

70. Handen BL, Sahl R, Hardan AY. Guanfacine in children with autism and/or intellectual disabilities. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(4):303-308.

71. Scahill L, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, et al. A prospective open trial of guanfacine in children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(5):589-598.

72. Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2010 Principal Investigators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(2):1-21.

73. Brugha TS, McManus S, Bankart J, et al. Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders in adults in the community in England. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(5):459-465.

74. Mandell DS, Psychiatric hospitalization among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(6):1059-1065.

1. Volkmar FR, Lord C, Bailey A, et al. Autism and pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(1):135-170.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018;67(6):1-23.

5. Scragg P, Shah A. Prevalence of Asperger’s syndrome in a secure hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165(5):679-682.

6. Hare DJ, Gould J, Mills R, et al. A preliminary study of individuals with autistic spectrum disorders in three special hospitals in England. London, UK: National Autistic Society; 1999.

7. Shah A, Holmes N, Wing L. Prevalence of autism and related conditions in adults in a mental handicap hospital. Appl Res Ment Retard. 1982;3(3):303-317.

8. Mandell DS, Lawer LJ, Branch K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of autism in a state psychiatric hospital. Autism. 2012;16(6):557-567.

9. Guinchat V, Cravero C, Diaz L, et al. Acute behavioral crises in psychiatric inpatients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): recognition of concomitant medical or non-ASD psychiatric conditions predicts enhanced improvement. Res Devel Disabil. 2015;38:242-255.

10. Perisse D, Amiet C, Consoli A, et al. Risk factors of acute behavioral regression in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents with autism. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):100-108.

11. Canitano R. New experimental treatments for core social domain in autism spectrum disorders. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:61.

12. Wink LK, Plawecki MH, Erickson CA, et al. Emerging drugs for the treatment of symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorders. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2010;15(3):481-494.

13. Fitzpatrick SE, Srivorakiat L, Wink LK, et al. Aggression in autism spectrum disorder: presentation and treatment options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1525-1538.

14. Lecavalier L, Leone S, Wiltz J. The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2006;50(pt 3):172-183.

15. Mills R, Wing L. Researching interventions in ASD and priorities for research: surveying the membership of the NAS. London, UK: National Autistic Society; 2005.

16. Aman MG, McDougle CJ, Scahill L, et al. Medication and parent training in children with pervasive developmental disorders and serious behavior problems: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(12):1143-1154.

17. McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Carlson DC, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(7):633-641.

18. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Risperidone treatment of autistic disorder: longer-term benefits and blinded discontinuation after 6 months. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1361-1369.

19. Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e634-e641.

20. Zuddas A, Zanni R, Usala T. Second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) for non-psychotic disorders in children and adolescents: a review of the randomized controlled studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(8):600-620.

21. Benton TD. Aripiprazole to treat irritability associated with autism: a placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(2):77-79.

22. Marcus RN, Owen R, Kamen L, et al. A placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(11):1110-1119.

23. Owen R, Sikich L, Marcus RN, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1533-1540.

24. Adler BA, Wink LK, Early M, et al. Drug-refractory aggression, self-injurious behavior, and severe tantrums in autism spectrum disorders: a chart review study. Autism. 2015;19(1):102-106.

25. Malone RP, Cater J, Sheikh RM, et al. Olanzapine versus haloperidol in children with autistic disorder: an open pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):887-894.

26. Potenza MN, Holmes JP, Kanes SJ, et al. Olanzapine treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with pervasive developmental disorders: an open-label pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(1):37-44.

27. Hollander E, Wasserman S, Swanson EN, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of olanzapine in childhood/adolescent pervasive developmental disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(5):541-548.

28. Stigler KA, Erickson CA, Mullett JE, et al. Paliperidone for irritability in autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(1):75-78.

29. Dominick K, Wink LK, McDougle CJ, et al. A retrospective naturalistic study of ziprasidone for irritability in youth with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(5):397-401.