User login

ED visits related to psychiatric complaints are up 20% among elderly

SAN DIEGO – Between 2011 and 2015, the proportion of elderly patients presenting to the emergency department with psychiatric complaints increased by 20%, according to a retrospective analysis of national hospital data.

In addition, 10-year increases in age, male sex, nursing home status, and Medicare insurance were associated with an increased likelihood of hospital admission.

“The growing geriatric patient population is a well-known phenomenon across every developed country,” lead researcher Derrick Huang said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians. “A potent mix of increasing life expectancy, greater disease severity and comorbidities in the elderly, and large-scale demographic shifts has placed a significant strain on both our financial and health care resources. This study corroborates these trends in the emergency department and is a preliminary exploration of potential, newly evolving clinical challenges that the ED team will increasingly face into the future.”

For the study, Mr. Huang, a fourth-year medical student at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine in Rochester, Mich., and his colleagues examined National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) data between 2011 and 2015. They limited the analysis to emergency department visits with patients in the age groups of 65-74, 75-84, and 85 or older. For the primary outcome of interest, the researchers evaluated demographic variables of age group, sex, residential status, race and ethnicity, and insurance for association with hospital admission. For the secondary outcome of interest, they evaluated presenting ED complaints related to the clinical domains of cardiopulmonary disease, psychiatric disease, and fractures and dislocations for potential trends in the ED geriatric age group between 2011 and 2015.

Mr. Huang and his associates found that, as a percentage of total ED visits, those among patients aged 65 or older rose from 14.9% in 2011 to 15.6% in 2015, an increase of 4.7%. By age group, the proportion of visits during the study period was highest for those aged 65-74 years (43.8%), followed by those aged 75-84 years (34.7%) and those aged 85 and older (21.5%). On multivariate analysis, the 75-84 and age-85-and-older groups were 1.30 and 1.71 times more likely to be admitted to the hospital, compared with the 65-74 group, respectively (P less than .000 for both).

Men were 1.19 times more likely than were women to be admitted (P less than .000). In addition, elderly patients who reside in nursing homes were 1.70 times more likely to be admitted to the hospital, compared with those who lived in private homes (P less than .000), while those with Medicare insurance were 1.57 more likely to be admitted, compared with those who did not have insurance (P = .004).

On trend analysis, ED psychiatric complaints rose incrementally during the study period, from 3.9% in 2011 to 4.7% in 2015, a relative increase of 20.5%. The researchers identified no consistent trend with visit complaints related to cardiopulmonary disease, and fractures and dislocations.

“This was not too surprising, because these difficulties with older patients are not new and many investigators have sought out solutions,” Mr. Huang said. “For example, there have been many interventions both in the ED as well as in the primary care setting designed to identify risk factors and facilitate postdischarge care to prevent falls. These approaches are constantly evolving and will be of increasing importance.”

“For example, we may be seeing a larger of proportion of patients with acute mental health complaints,” Mr. Huang said. “We will need to continue developing our multidisciplinary approach to care by improving coordination with different specialties – and especially outpatient and community health care providers.”

The study’s senior author was Jason Wasserman, PhD of Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Huang D et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.08.212.

SAN DIEGO – Between 2011 and 2015, the proportion of elderly patients presenting to the emergency department with psychiatric complaints increased by 20%, according to a retrospective analysis of national hospital data.

In addition, 10-year increases in age, male sex, nursing home status, and Medicare insurance were associated with an increased likelihood of hospital admission.

“The growing geriatric patient population is a well-known phenomenon across every developed country,” lead researcher Derrick Huang said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians. “A potent mix of increasing life expectancy, greater disease severity and comorbidities in the elderly, and large-scale demographic shifts has placed a significant strain on both our financial and health care resources. This study corroborates these trends in the emergency department and is a preliminary exploration of potential, newly evolving clinical challenges that the ED team will increasingly face into the future.”

For the study, Mr. Huang, a fourth-year medical student at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine in Rochester, Mich., and his colleagues examined National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) data between 2011 and 2015. They limited the analysis to emergency department visits with patients in the age groups of 65-74, 75-84, and 85 or older. For the primary outcome of interest, the researchers evaluated demographic variables of age group, sex, residential status, race and ethnicity, and insurance for association with hospital admission. For the secondary outcome of interest, they evaluated presenting ED complaints related to the clinical domains of cardiopulmonary disease, psychiatric disease, and fractures and dislocations for potential trends in the ED geriatric age group between 2011 and 2015.

Mr. Huang and his associates found that, as a percentage of total ED visits, those among patients aged 65 or older rose from 14.9% in 2011 to 15.6% in 2015, an increase of 4.7%. By age group, the proportion of visits during the study period was highest for those aged 65-74 years (43.8%), followed by those aged 75-84 years (34.7%) and those aged 85 and older (21.5%). On multivariate analysis, the 75-84 and age-85-and-older groups were 1.30 and 1.71 times more likely to be admitted to the hospital, compared with the 65-74 group, respectively (P less than .000 for both).

Men were 1.19 times more likely than were women to be admitted (P less than .000). In addition, elderly patients who reside in nursing homes were 1.70 times more likely to be admitted to the hospital, compared with those who lived in private homes (P less than .000), while those with Medicare insurance were 1.57 more likely to be admitted, compared with those who did not have insurance (P = .004).

On trend analysis, ED psychiatric complaints rose incrementally during the study period, from 3.9% in 2011 to 4.7% in 2015, a relative increase of 20.5%. The researchers identified no consistent trend with visit complaints related to cardiopulmonary disease, and fractures and dislocations.

“This was not too surprising, because these difficulties with older patients are not new and many investigators have sought out solutions,” Mr. Huang said. “For example, there have been many interventions both in the ED as well as in the primary care setting designed to identify risk factors and facilitate postdischarge care to prevent falls. These approaches are constantly evolving and will be of increasing importance.”

“For example, we may be seeing a larger of proportion of patients with acute mental health complaints,” Mr. Huang said. “We will need to continue developing our multidisciplinary approach to care by improving coordination with different specialties – and especially outpatient and community health care providers.”

The study’s senior author was Jason Wasserman, PhD of Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Huang D et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.08.212.

SAN DIEGO – Between 2011 and 2015, the proportion of elderly patients presenting to the emergency department with psychiatric complaints increased by 20%, according to a retrospective analysis of national hospital data.

In addition, 10-year increases in age, male sex, nursing home status, and Medicare insurance were associated with an increased likelihood of hospital admission.

“The growing geriatric patient population is a well-known phenomenon across every developed country,” lead researcher Derrick Huang said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians. “A potent mix of increasing life expectancy, greater disease severity and comorbidities in the elderly, and large-scale demographic shifts has placed a significant strain on both our financial and health care resources. This study corroborates these trends in the emergency department and is a preliminary exploration of potential, newly evolving clinical challenges that the ED team will increasingly face into the future.”

For the study, Mr. Huang, a fourth-year medical student at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine in Rochester, Mich., and his colleagues examined National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) data between 2011 and 2015. They limited the analysis to emergency department visits with patients in the age groups of 65-74, 75-84, and 85 or older. For the primary outcome of interest, the researchers evaluated demographic variables of age group, sex, residential status, race and ethnicity, and insurance for association with hospital admission. For the secondary outcome of interest, they evaluated presenting ED complaints related to the clinical domains of cardiopulmonary disease, psychiatric disease, and fractures and dislocations for potential trends in the ED geriatric age group between 2011 and 2015.

Mr. Huang and his associates found that, as a percentage of total ED visits, those among patients aged 65 or older rose from 14.9% in 2011 to 15.6% in 2015, an increase of 4.7%. By age group, the proportion of visits during the study period was highest for those aged 65-74 years (43.8%), followed by those aged 75-84 years (34.7%) and those aged 85 and older (21.5%). On multivariate analysis, the 75-84 and age-85-and-older groups were 1.30 and 1.71 times more likely to be admitted to the hospital, compared with the 65-74 group, respectively (P less than .000 for both).

Men were 1.19 times more likely than were women to be admitted (P less than .000). In addition, elderly patients who reside in nursing homes were 1.70 times more likely to be admitted to the hospital, compared with those who lived in private homes (P less than .000), while those with Medicare insurance were 1.57 more likely to be admitted, compared with those who did not have insurance (P = .004).

On trend analysis, ED psychiatric complaints rose incrementally during the study period, from 3.9% in 2011 to 4.7% in 2015, a relative increase of 20.5%. The researchers identified no consistent trend with visit complaints related to cardiopulmonary disease, and fractures and dislocations.

“This was not too surprising, because these difficulties with older patients are not new and many investigators have sought out solutions,” Mr. Huang said. “For example, there have been many interventions both in the ED as well as in the primary care setting designed to identify risk factors and facilitate postdischarge care to prevent falls. These approaches are constantly evolving and will be of increasing importance.”

“For example, we may be seeing a larger of proportion of patients with acute mental health complaints,” Mr. Huang said. “We will need to continue developing our multidisciplinary approach to care by improving coordination with different specialties – and especially outpatient and community health care providers.”

The study’s senior author was Jason Wasserman, PhD of Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Huang D et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.08.212.

REPORTING FROM ACEP18

Key clinical point: An increasing proportion of elderly patients are presenting to the emergency department with mental health complaints.

Major finding: Emergency department psychiatric complaints among elderly patients rose from 3.9% in 2011, to 4.7% in 2015, a relative increase of 20.5%.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data between 2011 and 2015.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Huang D et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.08.212.

The In Vivo Impact of Leukocyte Injections on Normal Rat Achilles Tendons: Potential Detriment to Tendon Morphology, Cellularity, and Vascularity

ABSTRACT

In this study, we determine the in vivo effects of injecting sub-populations of leukocytes into normal rat Achilles tendons via a controlled laboratory study. Allogenic monocytes, granulocytes, or plasma were injected into 24 healthy rat Achilles tendons. Treated and contralateral un-treated control tendons then assessed for cellularity, histologic morphology, and vascularity after 7 and 14 days. Significant increases of 221% and 249% in cellularity (P = 0.014) were seen on day 14 within Achilles tendons injected with granulocytes as compared to plasma and monocytes, respectively. Also, significant improvement in morphology (P = 0.029) between days 7 and 14 was seen for the granulocyte injected Achilles tendons. Significant increases in cellularity after an injection of granulocytes, compared to monocytes and plasma, corresponds to a significant increase in inflammation within the tissue, suggesting that leukocyte-rich platelet-rich plasma (PRP) preparations are proinflammatory and potentially catabolic when injected into tendon tissue. The concentration and composition of white blood cells within PRP preparations is variable and needs to be better understood in order to optimize clinical utility of PRP injections.

Continue to: Tendinopathies are debilitating conditions...

Tendinopathies are debilitating conditions affecting patients worldwide every day. They arise most frequently from tendon overuse resulting in pathology.1 There are 2 major subtypes of tendinopathy: tendinosis and tendinitis. Tendinosis, the more common condition, is characterized by long-term, chronic degradation of tendon tissue resulting in fibrosis from infiltrating fibroblasts.2 Tendinitis, the less common condition, is characterized by an acute inflammatory response and inflammatory cell infiltrate.2 Both conditions are common, with Achilles tendinopathy affecting 11% of runners and lateral epicondylitis affecting 1% to 3% of the general population.3,4 Many sports-related overuse injuries, such as tendinopathies, go undiagnosed for extended periods of time because medical attention is avoided in order to prevent time loss from training or competing.5 These delays could be eliminated if a non-surgical option for treating tendon pathology was available.

Tendinopathies are believed to result from tendon overuse that causes micro-damage to collagen, as well as from significant changes in protein and enzyme composition within the tendon.6 The damage accumulates over time and eventually leads to chronic inflammation or fibrotic change within tendons, in both cases weakening the tendon and causing pain. Currently, accepted treatments for tendinopathies include: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, ultrasound, laser-therapy, corticosteroids, glyceryl trinitrate patches, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, sclerotherapy, and surgery.7 Recently, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy has emerged as a promising treatment for tendinopathies, as well as a variety of other orthopedic indications.

PRP consists of autologous blood from the patient, centrifuged to increase the amount of platelets in the sample above baseline, and subsequently injected around an affected tendon or joint.8 PRP is used to treat tendinopathy because it can supply injured tendons with blood components that aid in healing, which tendons do not receive due to poor vascularity.9 These components include growth factors, such as platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), endothelial growth factor, and leukocytes that can stimulate an inflammatory response within the injured tissue.10 The inflammatory response from the PRP induces a more robust reconstruction and revascularization of the injured tissue, stimulating proliferation, and remodeling.11,12However, significant variability exists within the platelets, leukocytes, and growth factors that comprise PRP. This is attributed to 3 major causes. First, current commercial preparations of PRP result in differing platelet concentrations, as well as leukocyte-rich and leukocyte-poor compositions.13,14 Variability in platelet concentrations results in unreliable amounts of growth factors, including cytokines, TGF-β, PDGF, VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor in each preparation, while leukocyte levels affect inflammation, all leading to variable effects for each preparation.15,16Second, despite sex and age of the PRP donor not being significant factors influencing variation in growth factor concentrations, the existence of an unexplained variation in concentrations of growth factors between different donors has been observed.17 Third, the selection of activating agents, bovine thrombin or calcium chloride, and their application, whether to the elbow, shoulder, or knee, produces variability.18

While the effects of platelets and growth factors in PRP have been well studied, less is known about the effects of differing cell types. Recently it was reported that the concentrations of leukocytes directly affect the outcomes of PRP injections. McCarrel and colleagues19,20 found that as the number of leukocytes increased, there was a concomitant increase in the expression of inflammatory cytokines and catabolic activity. This effect may result in inferior healing of injured tissues and is attributed to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β from the leukocytes.21 There is also evidence that minimizing the catabolic effect of leukocytes may be just as important to tissue healing as the maximizing anabolic effect of platelets and growth factors.22

The use of PRP has been highly disputed in recent years due to conflicting reports of its success in treating orthopedic conditions. Numerous favorable studies have shown benefit for treating chronic and acute orthopedic injuries including; rotator cuff tear repair, chronic refractory patellar tendinopathy, and chronic lateral tendinosis/epicondylitis.23-26 Concurrently, articles demonstrating no significant effects from PRP have also been published. One study claiming that PRP injections did not improve outcomes of chronic Achilles tendinopathy did not differentiate whether patients had tendinosis or tendinitis, and did not consider leukocyte concentration in their PRP preparations27 Another study that determined PRP is not beneficial to the healing of ruptured Achilles tendons after surgical repair also failed to consider the concentration of leukocytes in their PRP preparations.28 One of the difficulties in comparing these studies is their heterogeneous nature. This arises from the use of different conditions in each study that makes the studies incomparable. Variations in PRP preparations lead to different concentrations of growth factors, platelets, and leukocyte concentrations. Additionally, tendinopathy models were not specified as tendinosis and tendonitis, and models or patients were not controlled for age, sex, or comorbidities. Given that leukocyte-rich and leukocyte-poor PRP preparations are currently widely used in clinical practice, the discovery of which type of preparation is indicated in which setting is paramount to evidence-based use of this treatment modality. Due to reports suggesting that leukocytes may be detrimental to tendon healing, determining which types of leukocytes are responsible for these effects is vital. As such, the purpose of this study is to determine the in vivo effects of sub-populations of leukocytes on normal rat tendons. This study design allowed us to isolate the effects of the injections to induce a response and remove confounding effects of normal healing response to a damaged tendon and effects from the injection itself. Our hypothesis was that the injection of leukocytes would cause an inflammatory response in rat tendons, leading to catabolic outcomes.

Continue to: METHODS...

METHODS

This was a prospective, in vivo, placebo controlled, randomized animal study. The University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures prior to initiation. Twenty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized to 3 treatment groups (n = 8): monocytes; granulocytes, and; plasma, as a negative control.

Allogenic blood from 6 additional rats was collected into K2EDTA tubes via cardiac puncture. Allogenic, as opposed to autogenic, blood is commonly used in rat models because of low immunogenic response to blood from rats of the same strain and litter.29,30 The blood was then pooled and the red cells lysed by incubation with Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (Roche). The samples were then sorted into fractions containing monocytes and granulocytes using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Cells were sorted using Purified PE Mouse Anti-Rat CD11b/c antibodies (BD Pharmingen) specific to monocytes, granulocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and microglia, APC-Cy7 Mouse Anti-Rat CD45 antibodies (BD Pharmingen) specific to all hematopoietic cells except erythrocytes, and FITC Mouse Anti-Rat CD42d antibodies (BD Pharmingen) specific to megakaryocytes and platelets. 20 μL of 0.2 mg/mL CD11b/c, 20 μL of 0.2 mg/mL CD 45, and 10 μL of 0.5 mg/mL CD42d antibodies were added to 1 mL of condensed non-red cells collected from the 6 rats and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 minutes. A fraction containing only platelet-poor plasma was also collected. For all treatments the injection volume was 75 μL. Rats in the monocyte group were injected with 200,000 cells in platelet-poor plasma, those in the granulocyte group were injected with 900,000 cells in platelet-poor plasma, and rats in the plasma control group received only platelet-poor plasma. The cell concentrations were based on previous studies that documented these concentrations that are found in typical leukocyte-rich PRP preparations.13

The animals were anesthetized with isoflurane gas and then injected aseptically once into their right Achilles tendon. The left Achilles tendon was used as an un-injected control, giving a total of 48 total Achilles tendons studied. At days 7 and 14 post-injection, 4 rats from each group were euthanized and the Achilles tendons were harvested.

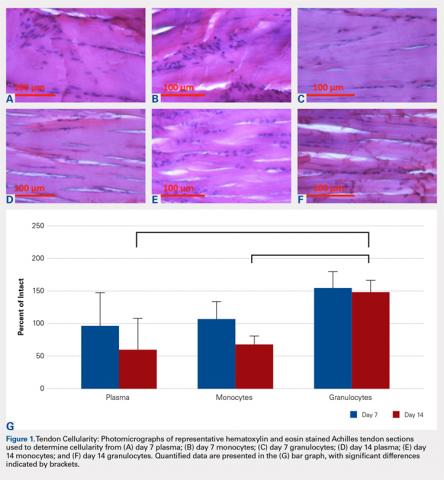

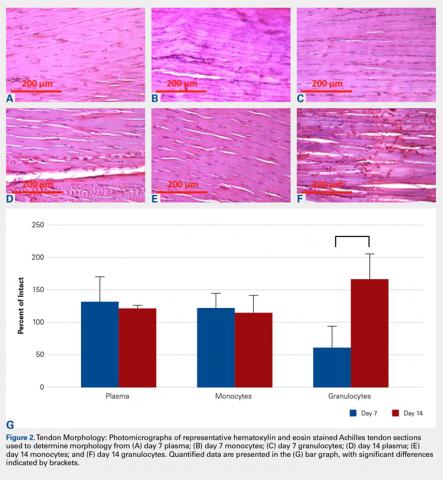

The tendons were fixed in neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours and then embedded in paraffin and sectioned sagittally at 12 μm. The tendons were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard histological protocols and examined by 3 individuals trained to assess cellularity and morphology. All samples were assigned unrecognizable numbers and randomized prior to examination by individuals. Cell counts were based on the number of nuclei present in 3 mid-tendon high-power fields (400x) per sample. Morphology was graded on a scale of 1 to 3, with 1 being a normal tendon and 3 having severe pathology with total loss of alignment and crimping on 3 low-power fields (100x) per sample (Figures 1A-1G).

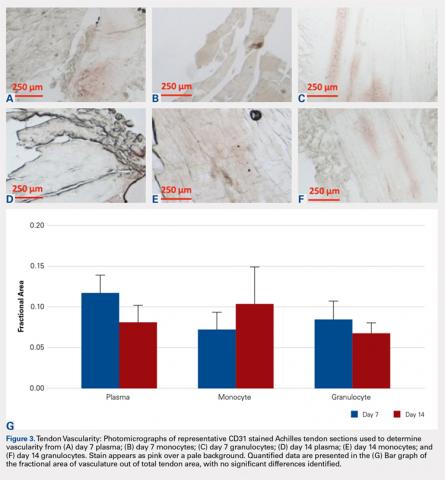

Vascularity was assessed by immunohistochemical staining using Rabbit Polyclonal Anti-CD31 antibodies (Abcam), a marker for vascular endothelial cells, using a Vectastain ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories) system and the ImmPACT AEC Peroxidase (HRP) Substrate (Vector Laboratories). Following staining, automated image analysis was performed (Bioquant). Briefly, all areas that did not contain tendon were masked. CD31 positive areas were then quantified using global thresholding. Vascularity was then calculated as ratio of CD31 positive area to total tendon area. Analyses were performed on 3 mid-tendon medium-power (200x) fields per sample.

For cellularity and morphology, the results for the injected tendons were normalized to those of their contralateral untreated controls and reported as a percentage. Results for vascularity were compared directly between treated tendons. Differences were assessed between groups at each time-point using Independent Samples Median Tests. When significant differences were identified, pairwise comparisons were performed to identify the source of the differences. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (V22, SAS Institute) with significant differences determined for values of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

No significant differences in cellularity between groups were seen at day 7 (P = 0.368) (Figures 1A-1G). However, a significant difference in cellularity between groups was seen at day 14 (P = 0.014). Pairwise tests showed there to be a significant increase in the number of cells in the tendons treated with granulocytes from 221% and 249% in cellularity (P = 0.014) on day 14, as compared to both monocytes and plasma, respectively. Morphologically, no significant differences were seen between groups at either time-point (P = 0.091 for day 7 and P = 1.000 for day 14) (Figures 2A-2G). However, a significant improvement in morphology was observed from day 7 to day 14 in the granulocyte group from 60% to 165% (P = 0.029). Finally, no differences were seen in vascularity between treatment groups at either time-point (P = 0.368 for day 7 and P = 0.535 for day 14) (Figures 3A-3G).

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Our hypothesis that the injection of leukocytes would cause an inflammatory response in rat tendons leading to catabolic outcomes was confirmed in the granulocyte group. It should be noted that prior to the catabolic outcome, there was a transient anabolic effect in the granulocyte group during the second week. Deterioration in morphology was observed in the tendons injected with granulocytes on day 7, which subsequently recovered in the following week. We found that injecting granulocytes into normal tendons resulted in an increase in inflammatory cellularity, when compared to monocytes and plasma injections.

Limitations inherent in this study are those similar to other in vivo studies. To begin with, the results of injections into rat tendons may not be translatable to human tendons. Despite this limitation, the rat is a common model for tendon research.31 Another limitation is that this study injected healthy Achilles tendons, rather than tendons with preexisting tendinopathy. In a naturally occurring tendinopathy, there may be other factors present that interact with PRP, and this model negates the contribution of these factors. Finally, while the immunohistochemistry (IHC) and morphological data are clear, the cellularity data are not clear in identifying the type of cells that were increased by granulocyte injection. However, the cells appeared rounded, resembling inflammatory infiltrate; a common cell type seen in tendons.2 While fibroblasts are also a common infiltrate during chronic tendinopathy, they are generally flat and appear on H&E as long spindle shaped cells. Thus, we believe the increased cellularity of the tendons after granulocyte injections is representative of an increase in inflammation. The increased cellularity could be due to the increased number of cells injected into the tendon; however, our conclusions are consistent with the increased inflammation previously reported linking leukocytes to tendon inflammation.20,22,32

In terms of morphology, we hypothesized that degenerative changes would be seen in the tendons that were injected with granulocytes due to the inflammatory action of these cells. As part of the granulocyte response, neutrophils release proteases and macrophages can stimulate collagen synthesis via fibroblasts, both causing change within the extracellular matrix.33,34 Indeed, we observed a significant change in tissue morphology in the granulocyte group over the course of 14 days. As the degenerative and regenerative effects of granulocytes take time to present, this is likely what we observed to occur between day 7 and 14 after treatment. These observations are also consistent with prior observations that leukocyte-rich PRP injections can be detrimental to tendon healing, but beneficial to tissue degeneration in the setting of chronic tendonitis.20

We hypothesized that the vascularity of the tendons would be similar in all preparations. This was based on previous studies demonstrating that the lack of platelets in the platelet-poor plasma fraction is sufficient to deplete VEGF, the angiogenic agent in PRP.35 In this study, there were no observable differences in vascularity of platelet-poor plasma, monocyte, and granulocyte injections. We attribute this to the lack of VEGF in any of these preparations. The aforementioned study also showed that the lack of platelets in injection was enough to prevent the angiogenic effect of this treatment.35

Continue to: The goal of this study was...

The goal of this study was to assess the morphology, cellularity, and vascularity of normal tendons after injections of different leukocyte populations. This is clinically important because of the potential to tailor future PRP injections on a patient-by-patient basis. In patients requiring an anabolic response, leukocyte-poor PRP may be the best option. In contrast, when patient pathology requires an inflammatory response to improve healing36 or breakdown fibrotic tissue, as seen in tendinosis, leukocyte-rich PRP may be warranted. Further, properly controlled clinical studies are needed to validate these recommendations.

Limitations inherent in this study are those similar to other in vivo studies. First, the results of injections into rat tendons may not be translatable to human tendons. Despite this limitation, the rat is a common model for tendon research.31 A second limitation is that this study injected healthy Achilles tendons, rather than tendons with preexisting tendinopathy. In a naturally occurring tendinopathy, there may be other factors present that interact with PRP, and this model negates the contribution of these factors. Finally, while the IHC and morphological data show clear changes, the cellularity data are not clear in identifying the type of cells that were increased by granulocyte injection. However, the cells appeared rounded, resembling inflammatory infiltrate; a common cell type seen in tendons.2 While fibroblasts are also a common infiltrate during chronic tendinopathy, they are generally flat and appear on H&E as long spindle shaped cells. The last limitation of this study is the lack of functional mechanical testing since, clinically, healing of the tendon is also related to the strength of the tendon. Thus, we believe the increased cellularity of the tendons after granulocyte injections is representative of an increase in inflammation. Moreover, our results are consistent with the increased inflammation previously reported linking leukocytes to tendon inflammation.20,22,32 It is interesting to note that the increase in inflammation does not lead to an increase in vascularity as could be expected.

CONCLUSION

We found that the injection of leukocytes into healthy rat Achilles tendons increases inflammation, as evidenced by increased cellularity and disrupted morphology, which suggests that leukocyte-rich PRP preparations may be contraindicated in settings of acute tendonitis. However, these preparations may be useful for a specific subset of tendinopathies, including chronic tendinosis.

1. Herring SA, Nilson KL. Introduction to overuse injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1987;6(2):225-239.

2. Bass E. Tendinopathy: why the difference between tendinitis and tendinosis matters. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork. 2012;5(1):14-17.

3. James SL, Bates BT, Osternig LR. Injuries to runners. Am J Sports Med. 1978;6(2):40-50.

4. Allander E. Prevalence, incidence, and remission rates of some common rheumatic diseases or syndromes. Scand J Rheumatol. 1974;3(3):145-153.

5. Bahr R. No injuries, but plenty of pain? On the methodology for recording overuse symptoms in sports. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(13):966-972.

6. Rees JD, Maffulli N, Cook J. Management of tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(9):1855-1867.

7. Andres BM, Murrell GA. Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1539-1554.

8. Hall MP, Band PA, Meislin RJ, Jazrawi LM, Cardone DA. Platelet-rich plasma: current concepts and application in sports medicine. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(10):602-608.

9. Smith JW. Blood Supply of Tendons. Am J Surg. 1965;109:272-276.

10. Wu PI, Diaz R, Borg-Stein J. Platelet-rich plasma. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2016;27(4):825-853.

11. Nguyen RT, Borg-Stein J, McInnis K. Applications of platelet-rich plasma in musculoskeletal and sports medicine: an evidence-based approach. PM R. 2011;3(3):226-250.

12. Broughton G 2nd, Janis JE, Attinger CE. Wound healing: an overview. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7 Suppl):1e-S-32e-S.

13. Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, et al. Platelet-rich plasma differs according to preparation method and human variability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(4):308-316.

14. Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, et al. The positive effects of different platelet-rich plasma methods on human muscle, bone, and tendon cells. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(8):1742-1749.

15. Castillo TN, Pouliot MA, Kim HJ, Dragoo JL. Comparison of growth factor and platelet concentration from commercial platelet-rich plasma separation systems. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):266-271.

16. Cho HS, Song IH, Park SY, Sung MC, Ahn MW, Song KE. Individual variation in growth factor concentrations in platelet-rich plasma and its influence on human mesenchymal stem cells. Korean J Lab Med. 2011;31(3):212-218.

17. Weibrich G, Kleis WK, Hafner G, Hitzler WE. Growth factor levels in platelet-rich plasma and correlations with donor age, sex, and platelet count. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2002;30(2):97-102.

18. Taylor DW, Petrera M, Hendry M, Theodoropoulos JS. A systematic review of the use of platelet-rich plasma in sports medicine as a new treatment for tendon and ligament injuries. Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21(4):344-352.

19. McCarrel T, Fortier L. Temporal growth factor release from platelet-rich plasma, trehalose lyophilized platelets, and bone marrow aspirate and their effect on tendon and ligament gene expression. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(8):1033-1042.

20. McCarrel TM, Minas T, Fortier LA. Optimization of leukocyte concentration in platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(19):e143(141-148).

21. Pillitteri D, Bassus S, Boller K, et al. Thrombin-induced interleukin 1beta synthesis in platelet suspensions: impact of contaminating leukocytes. Platelets. 2007;18(2):119-127.

22. Boswell SG, Schnabel LV, Mohammed HO, Sundman EA, Minas T, Fortier LA. Increasing platelet concentrations in leukocyte-reduced platelet-rich plasma decrease collagen gene synthesis in tendons. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(1):42-49.

23. Mishra A, Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(11):1774-1778.

24. Maniscalco P, Gambera D, Lunati A, et al. The "Cascade" membrane: a new PRP device for tendon ruptures. Description and case report on rotator cuff tendon. Acta Biomed. 2008;79(3):223-226.

25. Filardo G, Kon E, Della Villa S, Vincentelli F, Fornasari PM, Marcacci M. Use of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of refractory jumper's knee. Int Orthop. 2010;34(6):909-915.

26. Peerbooms JC, Sluimer J, Bruijn DJ, Gosens T. Positive effect of an autologous platelet concentrate in lateral epicondylitis in a double-blind randomized controlled trial: platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection with a 1-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(2):255-262.

27. de Vos RJ, Weir A, van Schie HT, et al. Platelet-rich plasma injection for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303(2):144-149.

28. Schepull T, Kvist J, Norrman H, Trinks M, Berlin G, Aspenberg P. Autologous platelets have no effect on the healing of human achilles tendon ruptures: a randomized single-blind study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(1):38-47.

29. Welsh KI, Burgos H, Batchelor JR. The immune response to allogeneic rat platelets; Ag-B antigens in matrix form lacking Ia. Eur J Immunol. 1977;7(5):267-272.

30. Xue M, Del Bigio MR. Intracortical hemorrhage injury in rats : relationship between blood fractions and brain cell death. Stroke. 2000;31(7):1721-1727.

31. Voleti PB, Buckley MR, Soslowsky LJ. Tendon healing: repair and regeneration. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2012;14:47-71.

32. Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Fortier LA. Growth factor and catabolic cytokine concentrations are influenced by the cellular composition of platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2135-2140.

33. Palmgren MS, deShazo RD, Carter RM, Zimny ML, Shah SV. Mechanisms of neutrophil damage to human alveolar extracellular matrix: the role of serine and metalloproteases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;89(4):905-915.

34. Khalil N, Bereznay O, Sporn M, Greenberg AH. Macrophage production of transforming growth factor beta and fibroblast collagen synthesis in chronic pulmonary inflammation. J Exp Med. 1989;170(3):727-737.

35. Zhou Y, Zhang J, Wu H, Hogan MV, Wang JH. The differential effects of leukocyte-containing and pure platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on tendon stem/progenitor cells - implications of PRP application for the clinical treatment of tendon injuries. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:173.

36. Su B, O'Connor JP. NSAID therapy effects on healing of bone, tendon, and the enthesis. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2013;115(6):892-899.

ABSTRACT

In this study, we determine the in vivo effects of injecting sub-populations of leukocytes into normal rat Achilles tendons via a controlled laboratory study. Allogenic monocytes, granulocytes, or plasma were injected into 24 healthy rat Achilles tendons. Treated and contralateral un-treated control tendons then assessed for cellularity, histologic morphology, and vascularity after 7 and 14 days. Significant increases of 221% and 249% in cellularity (P = 0.014) were seen on day 14 within Achilles tendons injected with granulocytes as compared to plasma and monocytes, respectively. Also, significant improvement in morphology (P = 0.029) between days 7 and 14 was seen for the granulocyte injected Achilles tendons. Significant increases in cellularity after an injection of granulocytes, compared to monocytes and plasma, corresponds to a significant increase in inflammation within the tissue, suggesting that leukocyte-rich platelet-rich plasma (PRP) preparations are proinflammatory and potentially catabolic when injected into tendon tissue. The concentration and composition of white blood cells within PRP preparations is variable and needs to be better understood in order to optimize clinical utility of PRP injections.

Continue to: Tendinopathies are debilitating conditions...

Tendinopathies are debilitating conditions affecting patients worldwide every day. They arise most frequently from tendon overuse resulting in pathology.1 There are 2 major subtypes of tendinopathy: tendinosis and tendinitis. Tendinosis, the more common condition, is characterized by long-term, chronic degradation of tendon tissue resulting in fibrosis from infiltrating fibroblasts.2 Tendinitis, the less common condition, is characterized by an acute inflammatory response and inflammatory cell infiltrate.2 Both conditions are common, with Achilles tendinopathy affecting 11% of runners and lateral epicondylitis affecting 1% to 3% of the general population.3,4 Many sports-related overuse injuries, such as tendinopathies, go undiagnosed for extended periods of time because medical attention is avoided in order to prevent time loss from training or competing.5 These delays could be eliminated if a non-surgical option for treating tendon pathology was available.

Tendinopathies are believed to result from tendon overuse that causes micro-damage to collagen, as well as from significant changes in protein and enzyme composition within the tendon.6 The damage accumulates over time and eventually leads to chronic inflammation or fibrotic change within tendons, in both cases weakening the tendon and causing pain. Currently, accepted treatments for tendinopathies include: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, ultrasound, laser-therapy, corticosteroids, glyceryl trinitrate patches, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, sclerotherapy, and surgery.7 Recently, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy has emerged as a promising treatment for tendinopathies, as well as a variety of other orthopedic indications.

PRP consists of autologous blood from the patient, centrifuged to increase the amount of platelets in the sample above baseline, and subsequently injected around an affected tendon or joint.8 PRP is used to treat tendinopathy because it can supply injured tendons with blood components that aid in healing, which tendons do not receive due to poor vascularity.9 These components include growth factors, such as platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), endothelial growth factor, and leukocytes that can stimulate an inflammatory response within the injured tissue.10 The inflammatory response from the PRP induces a more robust reconstruction and revascularization of the injured tissue, stimulating proliferation, and remodeling.11,12However, significant variability exists within the platelets, leukocytes, and growth factors that comprise PRP. This is attributed to 3 major causes. First, current commercial preparations of PRP result in differing platelet concentrations, as well as leukocyte-rich and leukocyte-poor compositions.13,14 Variability in platelet concentrations results in unreliable amounts of growth factors, including cytokines, TGF-β, PDGF, VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor in each preparation, while leukocyte levels affect inflammation, all leading to variable effects for each preparation.15,16Second, despite sex and age of the PRP donor not being significant factors influencing variation in growth factor concentrations, the existence of an unexplained variation in concentrations of growth factors between different donors has been observed.17 Third, the selection of activating agents, bovine thrombin or calcium chloride, and their application, whether to the elbow, shoulder, or knee, produces variability.18

While the effects of platelets and growth factors in PRP have been well studied, less is known about the effects of differing cell types. Recently it was reported that the concentrations of leukocytes directly affect the outcomes of PRP injections. McCarrel and colleagues19,20 found that as the number of leukocytes increased, there was a concomitant increase in the expression of inflammatory cytokines and catabolic activity. This effect may result in inferior healing of injured tissues and is attributed to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β from the leukocytes.21 There is also evidence that minimizing the catabolic effect of leukocytes may be just as important to tissue healing as the maximizing anabolic effect of platelets and growth factors.22

The use of PRP has been highly disputed in recent years due to conflicting reports of its success in treating orthopedic conditions. Numerous favorable studies have shown benefit for treating chronic and acute orthopedic injuries including; rotator cuff tear repair, chronic refractory patellar tendinopathy, and chronic lateral tendinosis/epicondylitis.23-26 Concurrently, articles demonstrating no significant effects from PRP have also been published. One study claiming that PRP injections did not improve outcomes of chronic Achilles tendinopathy did not differentiate whether patients had tendinosis or tendinitis, and did not consider leukocyte concentration in their PRP preparations27 Another study that determined PRP is not beneficial to the healing of ruptured Achilles tendons after surgical repair also failed to consider the concentration of leukocytes in their PRP preparations.28 One of the difficulties in comparing these studies is their heterogeneous nature. This arises from the use of different conditions in each study that makes the studies incomparable. Variations in PRP preparations lead to different concentrations of growth factors, platelets, and leukocyte concentrations. Additionally, tendinopathy models were not specified as tendinosis and tendonitis, and models or patients were not controlled for age, sex, or comorbidities. Given that leukocyte-rich and leukocyte-poor PRP preparations are currently widely used in clinical practice, the discovery of which type of preparation is indicated in which setting is paramount to evidence-based use of this treatment modality. Due to reports suggesting that leukocytes may be detrimental to tendon healing, determining which types of leukocytes are responsible for these effects is vital. As such, the purpose of this study is to determine the in vivo effects of sub-populations of leukocytes on normal rat tendons. This study design allowed us to isolate the effects of the injections to induce a response and remove confounding effects of normal healing response to a damaged tendon and effects from the injection itself. Our hypothesis was that the injection of leukocytes would cause an inflammatory response in rat tendons, leading to catabolic outcomes.

Continue to: METHODS...

METHODS

This was a prospective, in vivo, placebo controlled, randomized animal study. The University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures prior to initiation. Twenty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized to 3 treatment groups (n = 8): monocytes; granulocytes, and; plasma, as a negative control.

Allogenic blood from 6 additional rats was collected into K2EDTA tubes via cardiac puncture. Allogenic, as opposed to autogenic, blood is commonly used in rat models because of low immunogenic response to blood from rats of the same strain and litter.29,30 The blood was then pooled and the red cells lysed by incubation with Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (Roche). The samples were then sorted into fractions containing monocytes and granulocytes using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Cells were sorted using Purified PE Mouse Anti-Rat CD11b/c antibodies (BD Pharmingen) specific to monocytes, granulocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and microglia, APC-Cy7 Mouse Anti-Rat CD45 antibodies (BD Pharmingen) specific to all hematopoietic cells except erythrocytes, and FITC Mouse Anti-Rat CD42d antibodies (BD Pharmingen) specific to megakaryocytes and platelets. 20 μL of 0.2 mg/mL CD11b/c, 20 μL of 0.2 mg/mL CD 45, and 10 μL of 0.5 mg/mL CD42d antibodies were added to 1 mL of condensed non-red cells collected from the 6 rats and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 minutes. A fraction containing only platelet-poor plasma was also collected. For all treatments the injection volume was 75 μL. Rats in the monocyte group were injected with 200,000 cells in platelet-poor plasma, those in the granulocyte group were injected with 900,000 cells in platelet-poor plasma, and rats in the plasma control group received only platelet-poor plasma. The cell concentrations were based on previous studies that documented these concentrations that are found in typical leukocyte-rich PRP preparations.13

The animals were anesthetized with isoflurane gas and then injected aseptically once into their right Achilles tendon. The left Achilles tendon was used as an un-injected control, giving a total of 48 total Achilles tendons studied. At days 7 and 14 post-injection, 4 rats from each group were euthanized and the Achilles tendons were harvested.

The tendons were fixed in neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours and then embedded in paraffin and sectioned sagittally at 12 μm. The tendons were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard histological protocols and examined by 3 individuals trained to assess cellularity and morphology. All samples were assigned unrecognizable numbers and randomized prior to examination by individuals. Cell counts were based on the number of nuclei present in 3 mid-tendon high-power fields (400x) per sample. Morphology was graded on a scale of 1 to 3, with 1 being a normal tendon and 3 having severe pathology with total loss of alignment and crimping on 3 low-power fields (100x) per sample (Figures 1A-1G).

Vascularity was assessed by immunohistochemical staining using Rabbit Polyclonal Anti-CD31 antibodies (Abcam), a marker for vascular endothelial cells, using a Vectastain ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories) system and the ImmPACT AEC Peroxidase (HRP) Substrate (Vector Laboratories). Following staining, automated image analysis was performed (Bioquant). Briefly, all areas that did not contain tendon were masked. CD31 positive areas were then quantified using global thresholding. Vascularity was then calculated as ratio of CD31 positive area to total tendon area. Analyses were performed on 3 mid-tendon medium-power (200x) fields per sample.

For cellularity and morphology, the results for the injected tendons were normalized to those of their contralateral untreated controls and reported as a percentage. Results for vascularity were compared directly between treated tendons. Differences were assessed between groups at each time-point using Independent Samples Median Tests. When significant differences were identified, pairwise comparisons were performed to identify the source of the differences. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (V22, SAS Institute) with significant differences determined for values of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

No significant differences in cellularity between groups were seen at day 7 (P = 0.368) (Figures 1A-1G). However, a significant difference in cellularity between groups was seen at day 14 (P = 0.014). Pairwise tests showed there to be a significant increase in the number of cells in the tendons treated with granulocytes from 221% and 249% in cellularity (P = 0.014) on day 14, as compared to both monocytes and plasma, respectively. Morphologically, no significant differences were seen between groups at either time-point (P = 0.091 for day 7 and P = 1.000 for day 14) (Figures 2A-2G). However, a significant improvement in morphology was observed from day 7 to day 14 in the granulocyte group from 60% to 165% (P = 0.029). Finally, no differences were seen in vascularity between treatment groups at either time-point (P = 0.368 for day 7 and P = 0.535 for day 14) (Figures 3A-3G).

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Our hypothesis that the injection of leukocytes would cause an inflammatory response in rat tendons leading to catabolic outcomes was confirmed in the granulocyte group. It should be noted that prior to the catabolic outcome, there was a transient anabolic effect in the granulocyte group during the second week. Deterioration in morphology was observed in the tendons injected with granulocytes on day 7, which subsequently recovered in the following week. We found that injecting granulocytes into normal tendons resulted in an increase in inflammatory cellularity, when compared to monocytes and plasma injections.

Limitations inherent in this study are those similar to other in vivo studies. To begin with, the results of injections into rat tendons may not be translatable to human tendons. Despite this limitation, the rat is a common model for tendon research.31 Another limitation is that this study injected healthy Achilles tendons, rather than tendons with preexisting tendinopathy. In a naturally occurring tendinopathy, there may be other factors present that interact with PRP, and this model negates the contribution of these factors. Finally, while the immunohistochemistry (IHC) and morphological data are clear, the cellularity data are not clear in identifying the type of cells that were increased by granulocyte injection. However, the cells appeared rounded, resembling inflammatory infiltrate; a common cell type seen in tendons.2 While fibroblasts are also a common infiltrate during chronic tendinopathy, they are generally flat and appear on H&E as long spindle shaped cells. Thus, we believe the increased cellularity of the tendons after granulocyte injections is representative of an increase in inflammation. The increased cellularity could be due to the increased number of cells injected into the tendon; however, our conclusions are consistent with the increased inflammation previously reported linking leukocytes to tendon inflammation.20,22,32

In terms of morphology, we hypothesized that degenerative changes would be seen in the tendons that were injected with granulocytes due to the inflammatory action of these cells. As part of the granulocyte response, neutrophils release proteases and macrophages can stimulate collagen synthesis via fibroblasts, both causing change within the extracellular matrix.33,34 Indeed, we observed a significant change in tissue morphology in the granulocyte group over the course of 14 days. As the degenerative and regenerative effects of granulocytes take time to present, this is likely what we observed to occur between day 7 and 14 after treatment. These observations are also consistent with prior observations that leukocyte-rich PRP injections can be detrimental to tendon healing, but beneficial to tissue degeneration in the setting of chronic tendonitis.20

We hypothesized that the vascularity of the tendons would be similar in all preparations. This was based on previous studies demonstrating that the lack of platelets in the platelet-poor plasma fraction is sufficient to deplete VEGF, the angiogenic agent in PRP.35 In this study, there were no observable differences in vascularity of platelet-poor plasma, monocyte, and granulocyte injections. We attribute this to the lack of VEGF in any of these preparations. The aforementioned study also showed that the lack of platelets in injection was enough to prevent the angiogenic effect of this treatment.35

Continue to: The goal of this study was...

The goal of this study was to assess the morphology, cellularity, and vascularity of normal tendons after injections of different leukocyte populations. This is clinically important because of the potential to tailor future PRP injections on a patient-by-patient basis. In patients requiring an anabolic response, leukocyte-poor PRP may be the best option. In contrast, when patient pathology requires an inflammatory response to improve healing36 or breakdown fibrotic tissue, as seen in tendinosis, leukocyte-rich PRP may be warranted. Further, properly controlled clinical studies are needed to validate these recommendations.

Limitations inherent in this study are those similar to other in vivo studies. First, the results of injections into rat tendons may not be translatable to human tendons. Despite this limitation, the rat is a common model for tendon research.31 A second limitation is that this study injected healthy Achilles tendons, rather than tendons with preexisting tendinopathy. In a naturally occurring tendinopathy, there may be other factors present that interact with PRP, and this model negates the contribution of these factors. Finally, while the IHC and morphological data show clear changes, the cellularity data are not clear in identifying the type of cells that were increased by granulocyte injection. However, the cells appeared rounded, resembling inflammatory infiltrate; a common cell type seen in tendons.2 While fibroblasts are also a common infiltrate during chronic tendinopathy, they are generally flat and appear on H&E as long spindle shaped cells. The last limitation of this study is the lack of functional mechanical testing since, clinically, healing of the tendon is also related to the strength of the tendon. Thus, we believe the increased cellularity of the tendons after granulocyte injections is representative of an increase in inflammation. Moreover, our results are consistent with the increased inflammation previously reported linking leukocytes to tendon inflammation.20,22,32 It is interesting to note that the increase in inflammation does not lead to an increase in vascularity as could be expected.

CONCLUSION

We found that the injection of leukocytes into healthy rat Achilles tendons increases inflammation, as evidenced by increased cellularity and disrupted morphology, which suggests that leukocyte-rich PRP preparations may be contraindicated in settings of acute tendonitis. However, these preparations may be useful for a specific subset of tendinopathies, including chronic tendinosis.

ABSTRACT

In this study, we determine the in vivo effects of injecting sub-populations of leukocytes into normal rat Achilles tendons via a controlled laboratory study. Allogenic monocytes, granulocytes, or plasma were injected into 24 healthy rat Achilles tendons. Treated and contralateral un-treated control tendons then assessed for cellularity, histologic morphology, and vascularity after 7 and 14 days. Significant increases of 221% and 249% in cellularity (P = 0.014) were seen on day 14 within Achilles tendons injected with granulocytes as compared to plasma and monocytes, respectively. Also, significant improvement in morphology (P = 0.029) between days 7 and 14 was seen for the granulocyte injected Achilles tendons. Significant increases in cellularity after an injection of granulocytes, compared to monocytes and plasma, corresponds to a significant increase in inflammation within the tissue, suggesting that leukocyte-rich platelet-rich plasma (PRP) preparations are proinflammatory and potentially catabolic when injected into tendon tissue. The concentration and composition of white blood cells within PRP preparations is variable and needs to be better understood in order to optimize clinical utility of PRP injections.

Continue to: Tendinopathies are debilitating conditions...

Tendinopathies are debilitating conditions affecting patients worldwide every day. They arise most frequently from tendon overuse resulting in pathology.1 There are 2 major subtypes of tendinopathy: tendinosis and tendinitis. Tendinosis, the more common condition, is characterized by long-term, chronic degradation of tendon tissue resulting in fibrosis from infiltrating fibroblasts.2 Tendinitis, the less common condition, is characterized by an acute inflammatory response and inflammatory cell infiltrate.2 Both conditions are common, with Achilles tendinopathy affecting 11% of runners and lateral epicondylitis affecting 1% to 3% of the general population.3,4 Many sports-related overuse injuries, such as tendinopathies, go undiagnosed for extended periods of time because medical attention is avoided in order to prevent time loss from training or competing.5 These delays could be eliminated if a non-surgical option for treating tendon pathology was available.

Tendinopathies are believed to result from tendon overuse that causes micro-damage to collagen, as well as from significant changes in protein and enzyme composition within the tendon.6 The damage accumulates over time and eventually leads to chronic inflammation or fibrotic change within tendons, in both cases weakening the tendon and causing pain. Currently, accepted treatments for tendinopathies include: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, ultrasound, laser-therapy, corticosteroids, glyceryl trinitrate patches, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, sclerotherapy, and surgery.7 Recently, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy has emerged as a promising treatment for tendinopathies, as well as a variety of other orthopedic indications.

PRP consists of autologous blood from the patient, centrifuged to increase the amount of platelets in the sample above baseline, and subsequently injected around an affected tendon or joint.8 PRP is used to treat tendinopathy because it can supply injured tendons with blood components that aid in healing, which tendons do not receive due to poor vascularity.9 These components include growth factors, such as platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), endothelial growth factor, and leukocytes that can stimulate an inflammatory response within the injured tissue.10 The inflammatory response from the PRP induces a more robust reconstruction and revascularization of the injured tissue, stimulating proliferation, and remodeling.11,12However, significant variability exists within the platelets, leukocytes, and growth factors that comprise PRP. This is attributed to 3 major causes. First, current commercial preparations of PRP result in differing platelet concentrations, as well as leukocyte-rich and leukocyte-poor compositions.13,14 Variability in platelet concentrations results in unreliable amounts of growth factors, including cytokines, TGF-β, PDGF, VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor in each preparation, while leukocyte levels affect inflammation, all leading to variable effects for each preparation.15,16Second, despite sex and age of the PRP donor not being significant factors influencing variation in growth factor concentrations, the existence of an unexplained variation in concentrations of growth factors between different donors has been observed.17 Third, the selection of activating agents, bovine thrombin or calcium chloride, and their application, whether to the elbow, shoulder, or knee, produces variability.18

While the effects of platelets and growth factors in PRP have been well studied, less is known about the effects of differing cell types. Recently it was reported that the concentrations of leukocytes directly affect the outcomes of PRP injections. McCarrel and colleagues19,20 found that as the number of leukocytes increased, there was a concomitant increase in the expression of inflammatory cytokines and catabolic activity. This effect may result in inferior healing of injured tissues and is attributed to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β from the leukocytes.21 There is also evidence that minimizing the catabolic effect of leukocytes may be just as important to tissue healing as the maximizing anabolic effect of platelets and growth factors.22

The use of PRP has been highly disputed in recent years due to conflicting reports of its success in treating orthopedic conditions. Numerous favorable studies have shown benefit for treating chronic and acute orthopedic injuries including; rotator cuff tear repair, chronic refractory patellar tendinopathy, and chronic lateral tendinosis/epicondylitis.23-26 Concurrently, articles demonstrating no significant effects from PRP have also been published. One study claiming that PRP injections did not improve outcomes of chronic Achilles tendinopathy did not differentiate whether patients had tendinosis or tendinitis, and did not consider leukocyte concentration in their PRP preparations27 Another study that determined PRP is not beneficial to the healing of ruptured Achilles tendons after surgical repair also failed to consider the concentration of leukocytes in their PRP preparations.28 One of the difficulties in comparing these studies is their heterogeneous nature. This arises from the use of different conditions in each study that makes the studies incomparable. Variations in PRP preparations lead to different concentrations of growth factors, platelets, and leukocyte concentrations. Additionally, tendinopathy models were not specified as tendinosis and tendonitis, and models or patients were not controlled for age, sex, or comorbidities. Given that leukocyte-rich and leukocyte-poor PRP preparations are currently widely used in clinical practice, the discovery of which type of preparation is indicated in which setting is paramount to evidence-based use of this treatment modality. Due to reports suggesting that leukocytes may be detrimental to tendon healing, determining which types of leukocytes are responsible for these effects is vital. As such, the purpose of this study is to determine the in vivo effects of sub-populations of leukocytes on normal rat tendons. This study design allowed us to isolate the effects of the injections to induce a response and remove confounding effects of normal healing response to a damaged tendon and effects from the injection itself. Our hypothesis was that the injection of leukocytes would cause an inflammatory response in rat tendons, leading to catabolic outcomes.

Continue to: METHODS...

METHODS

This was a prospective, in vivo, placebo controlled, randomized animal study. The University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures prior to initiation. Twenty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized to 3 treatment groups (n = 8): monocytes; granulocytes, and; plasma, as a negative control.

Allogenic blood from 6 additional rats was collected into K2EDTA tubes via cardiac puncture. Allogenic, as opposed to autogenic, blood is commonly used in rat models because of low immunogenic response to blood from rats of the same strain and litter.29,30 The blood was then pooled and the red cells lysed by incubation with Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (Roche). The samples were then sorted into fractions containing monocytes and granulocytes using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Cells were sorted using Purified PE Mouse Anti-Rat CD11b/c antibodies (BD Pharmingen) specific to monocytes, granulocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and microglia, APC-Cy7 Mouse Anti-Rat CD45 antibodies (BD Pharmingen) specific to all hematopoietic cells except erythrocytes, and FITC Mouse Anti-Rat CD42d antibodies (BD Pharmingen) specific to megakaryocytes and platelets. 20 μL of 0.2 mg/mL CD11b/c, 20 μL of 0.2 mg/mL CD 45, and 10 μL of 0.5 mg/mL CD42d antibodies were added to 1 mL of condensed non-red cells collected from the 6 rats and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 minutes. A fraction containing only platelet-poor plasma was also collected. For all treatments the injection volume was 75 μL. Rats in the monocyte group were injected with 200,000 cells in platelet-poor plasma, those in the granulocyte group were injected with 900,000 cells in platelet-poor plasma, and rats in the plasma control group received only platelet-poor plasma. The cell concentrations were based on previous studies that documented these concentrations that are found in typical leukocyte-rich PRP preparations.13

The animals were anesthetized with isoflurane gas and then injected aseptically once into their right Achilles tendon. The left Achilles tendon was used as an un-injected control, giving a total of 48 total Achilles tendons studied. At days 7 and 14 post-injection, 4 rats from each group were euthanized and the Achilles tendons were harvested.

The tendons were fixed in neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours and then embedded in paraffin and sectioned sagittally at 12 μm. The tendons were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard histological protocols and examined by 3 individuals trained to assess cellularity and morphology. All samples were assigned unrecognizable numbers and randomized prior to examination by individuals. Cell counts were based on the number of nuclei present in 3 mid-tendon high-power fields (400x) per sample. Morphology was graded on a scale of 1 to 3, with 1 being a normal tendon and 3 having severe pathology with total loss of alignment and crimping on 3 low-power fields (100x) per sample (Figures 1A-1G).

Vascularity was assessed by immunohistochemical staining using Rabbit Polyclonal Anti-CD31 antibodies (Abcam), a marker for vascular endothelial cells, using a Vectastain ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories) system and the ImmPACT AEC Peroxidase (HRP) Substrate (Vector Laboratories). Following staining, automated image analysis was performed (Bioquant). Briefly, all areas that did not contain tendon were masked. CD31 positive areas were then quantified using global thresholding. Vascularity was then calculated as ratio of CD31 positive area to total tendon area. Analyses were performed on 3 mid-tendon medium-power (200x) fields per sample.

For cellularity and morphology, the results for the injected tendons were normalized to those of their contralateral untreated controls and reported as a percentage. Results for vascularity were compared directly between treated tendons. Differences were assessed between groups at each time-point using Independent Samples Median Tests. When significant differences were identified, pairwise comparisons were performed to identify the source of the differences. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (V22, SAS Institute) with significant differences determined for values of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

No significant differences in cellularity between groups were seen at day 7 (P = 0.368) (Figures 1A-1G). However, a significant difference in cellularity between groups was seen at day 14 (P = 0.014). Pairwise tests showed there to be a significant increase in the number of cells in the tendons treated with granulocytes from 221% and 249% in cellularity (P = 0.014) on day 14, as compared to both monocytes and plasma, respectively. Morphologically, no significant differences were seen between groups at either time-point (P = 0.091 for day 7 and P = 1.000 for day 14) (Figures 2A-2G). However, a significant improvement in morphology was observed from day 7 to day 14 in the granulocyte group from 60% to 165% (P = 0.029). Finally, no differences were seen in vascularity between treatment groups at either time-point (P = 0.368 for day 7 and P = 0.535 for day 14) (Figures 3A-3G).

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Our hypothesis that the injection of leukocytes would cause an inflammatory response in rat tendons leading to catabolic outcomes was confirmed in the granulocyte group. It should be noted that prior to the catabolic outcome, there was a transient anabolic effect in the granulocyte group during the second week. Deterioration in morphology was observed in the tendons injected with granulocytes on day 7, which subsequently recovered in the following week. We found that injecting granulocytes into normal tendons resulted in an increase in inflammatory cellularity, when compared to monocytes and plasma injections.

Limitations inherent in this study are those similar to other in vivo studies. To begin with, the results of injections into rat tendons may not be translatable to human tendons. Despite this limitation, the rat is a common model for tendon research.31 Another limitation is that this study injected healthy Achilles tendons, rather than tendons with preexisting tendinopathy. In a naturally occurring tendinopathy, there may be other factors present that interact with PRP, and this model negates the contribution of these factors. Finally, while the immunohistochemistry (IHC) and morphological data are clear, the cellularity data are not clear in identifying the type of cells that were increased by granulocyte injection. However, the cells appeared rounded, resembling inflammatory infiltrate; a common cell type seen in tendons.2 While fibroblasts are also a common infiltrate during chronic tendinopathy, they are generally flat and appear on H&E as long spindle shaped cells. Thus, we believe the increased cellularity of the tendons after granulocyte injections is representative of an increase in inflammation. The increased cellularity could be due to the increased number of cells injected into the tendon; however, our conclusions are consistent with the increased inflammation previously reported linking leukocytes to tendon inflammation.20,22,32

In terms of morphology, we hypothesized that degenerative changes would be seen in the tendons that were injected with granulocytes due to the inflammatory action of these cells. As part of the granulocyte response, neutrophils release proteases and macrophages can stimulate collagen synthesis via fibroblasts, both causing change within the extracellular matrix.33,34 Indeed, we observed a significant change in tissue morphology in the granulocyte group over the course of 14 days. As the degenerative and regenerative effects of granulocytes take time to present, this is likely what we observed to occur between day 7 and 14 after treatment. These observations are also consistent with prior observations that leukocyte-rich PRP injections can be detrimental to tendon healing, but beneficial to tissue degeneration in the setting of chronic tendonitis.20

We hypothesized that the vascularity of the tendons would be similar in all preparations. This was based on previous studies demonstrating that the lack of platelets in the platelet-poor plasma fraction is sufficient to deplete VEGF, the angiogenic agent in PRP.35 In this study, there were no observable differences in vascularity of platelet-poor plasma, monocyte, and granulocyte injections. We attribute this to the lack of VEGF in any of these preparations. The aforementioned study also showed that the lack of platelets in injection was enough to prevent the angiogenic effect of this treatment.35

Continue to: The goal of this study was...

The goal of this study was to assess the morphology, cellularity, and vascularity of normal tendons after injections of different leukocyte populations. This is clinically important because of the potential to tailor future PRP injections on a patient-by-patient basis. In patients requiring an anabolic response, leukocyte-poor PRP may be the best option. In contrast, when patient pathology requires an inflammatory response to improve healing36 or breakdown fibrotic tissue, as seen in tendinosis, leukocyte-rich PRP may be warranted. Further, properly controlled clinical studies are needed to validate these recommendations.

Limitations inherent in this study are those similar to other in vivo studies. First, the results of injections into rat tendons may not be translatable to human tendons. Despite this limitation, the rat is a common model for tendon research.31 A second limitation is that this study injected healthy Achilles tendons, rather than tendons with preexisting tendinopathy. In a naturally occurring tendinopathy, there may be other factors present that interact with PRP, and this model negates the contribution of these factors. Finally, while the IHC and morphological data show clear changes, the cellularity data are not clear in identifying the type of cells that were increased by granulocyte injection. However, the cells appeared rounded, resembling inflammatory infiltrate; a common cell type seen in tendons.2 While fibroblasts are also a common infiltrate during chronic tendinopathy, they are generally flat and appear on H&E as long spindle shaped cells. The last limitation of this study is the lack of functional mechanical testing since, clinically, healing of the tendon is also related to the strength of the tendon. Thus, we believe the increased cellularity of the tendons after granulocyte injections is representative of an increase in inflammation. Moreover, our results are consistent with the increased inflammation previously reported linking leukocytes to tendon inflammation.20,22,32 It is interesting to note that the increase in inflammation does not lead to an increase in vascularity as could be expected.

CONCLUSION

We found that the injection of leukocytes into healthy rat Achilles tendons increases inflammation, as evidenced by increased cellularity and disrupted morphology, which suggests that leukocyte-rich PRP preparations may be contraindicated in settings of acute tendonitis. However, these preparations may be useful for a specific subset of tendinopathies, including chronic tendinosis.

1. Herring SA, Nilson KL. Introduction to overuse injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1987;6(2):225-239.

2. Bass E. Tendinopathy: why the difference between tendinitis and tendinosis matters. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork. 2012;5(1):14-17.

3. James SL, Bates BT, Osternig LR. Injuries to runners. Am J Sports Med. 1978;6(2):40-50.

4. Allander E. Prevalence, incidence, and remission rates of some common rheumatic diseases or syndromes. Scand J Rheumatol. 1974;3(3):145-153.

5. Bahr R. No injuries, but plenty of pain? On the methodology for recording overuse symptoms in sports. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(13):966-972.

6. Rees JD, Maffulli N, Cook J. Management of tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(9):1855-1867.

7. Andres BM, Murrell GA. Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1539-1554.

8. Hall MP, Band PA, Meislin RJ, Jazrawi LM, Cardone DA. Platelet-rich plasma: current concepts and application in sports medicine. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(10):602-608.

9. Smith JW. Blood Supply of Tendons. Am J Surg. 1965;109:272-276.

10. Wu PI, Diaz R, Borg-Stein J. Platelet-rich plasma. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2016;27(4):825-853.

11. Nguyen RT, Borg-Stein J, McInnis K. Applications of platelet-rich plasma in musculoskeletal and sports medicine: an evidence-based approach. PM R. 2011;3(3):226-250.

12. Broughton G 2nd, Janis JE, Attinger CE. Wound healing: an overview. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7 Suppl):1e-S-32e-S.

13. Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, et al. Platelet-rich plasma differs according to preparation method and human variability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(4):308-316.

14. Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, et al. The positive effects of different platelet-rich plasma methods on human muscle, bone, and tendon cells. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(8):1742-1749.

15. Castillo TN, Pouliot MA, Kim HJ, Dragoo JL. Comparison of growth factor and platelet concentration from commercial platelet-rich plasma separation systems. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):266-271.