User login

Is Vitiligo in Vogue? The Changing Face of Vitiligo

Vitiligo is a disfiguring skin condition that is thought to result from autoimmune destruction of melanocytes in the skin, leading to patchy depigmentation. The prevalence of vitiligo is estimated at 1% worldwide.1 Once seen as merely a cosmetic disorder, it is increasingly recognized for its devastating psychological effects. As skin quality, texture, and color are a few of the first things people notice about others, skin plays a major role in our daily interactions with the world. Vitiligo often affects the face and other visible areas of the body; thus, it is associated with impaired quality of life, and affected individuals often experience psychosocial impairment including anxiety, depression, stigmatization, and self-harm ideation.2 Indeed, vitiligo is a condition with not only a visible skin component but a deeper psychological component that also is important to recognize and address. However, due in large part to recent exposure to vitiligo through mainstream media, general understanding about and attitudes toward this condition are changing. As a result, vitiligo has seen a surge in outreach by those affected by the disease.

Perhaps the most well-known current face of vitiligo is Chantelle Brown-Young, a black fashion model, activist, and vitiligo spokesperson known professionally as Winnie Harlow. Diagnosed with vitiligo in childhood, she revealed she was teased and bullied and at one point contemplated suicide. “The continuous harassment and the despair that [vitiligo] brought on my life was so unbearably dehumanizing that I wanted to kill myself,” she disclosed.3 After competing on America’s Next Top Model in 2014, Winnie Harlow became a household name for redefining global standards of beauty and, in her own words, accepting the differences that make us unique and authentic.4 She went on to speak at the Dove Self-Esteem Project panel at the 2015 Women in the World London Summit and was presented with the Role Model award at the Portuguese GQ Men of the Year event that same year.5

More recently, Amy Deanna, a model with vitiligo, was featured in videos for CoverGirl’s 2018 “I Am What I Make Up” campaign in which she is shown enhancing her various skin tones rather than hiding them by applying both light and dark shades of makeup on her face. In a press release she stated, “Vitiligo awareness is something that is very important to me. Being given a platform to [raise awareness] means so much.”6

Additionally, Brock Elbank, a London-based photographer, recently launched a photograph series of men and women with vitiligo on the digital platform Instagram.7 In a recent interview he stated, “I see beauty in what many see as different. Unique individuals who stand out from the crowd are what inspire me to do what I do.”7

Lee Thomas, a television broadcaster and author of the book Turning White: A Memoir of Change is yet another example of a vitiligo patient who recently stopped hiding his condition. He admitted he has had people refuse to shake his hand due to his condition but has used the experience to educate others. He stated, “Because I’m in this position, I think this is where my next thing is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be about sharing and helping, and hopefully leaving the planet a little better for everybody else who comes along with vitiligo.”8 Thomas is dedicated to inspiring others with the condition and started the Clarity Lee Thomas Foundation to provide emotional and mental support to those with vitiligo.

Critics may say this vitiligo movement is merely another example of exploitation of what is unique or different by mainstream media and the fashion industry, similar to prior movements for plus-sized models, natural hairstyles in black women, and transgender identification. Even if partially true, the ultimate effect has been an increase in attention and representation of individuals with vitiligo in mainstream media. At the time this article was being published (September 2018), an Instagram search for #vitiligo yielded approximately 226,000 posts. For comparison with other much more common dermatologic conditions, #eczema returned approximately 958,000 results, #moles returned approximately 65,000 results, and #skincancer returned approximately 104,000 results. Additionally, the Vitiligo Research Foundation currently has more than 5000 followers on Instagram, which is as many as the Melanoma Research Foundation and almost twice as many as the Skin Cancer Foundation, supporting the idea that mainstream representation of individuals with vitiligo is contributing to raising awareness and backing of organizations aimed at making advancements in this area of dermatology.

As more individuals gain an understanding and curiosity about this disease, perhaps more research and investigation will be done to improve treatment options and outcomes for patients with vitiligo. With this movement, perhaps vitiligo patients will feel more comfortable and confident in their skin.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Tomas‐Aragones L, Marron SE. Body image and body dysmorphic concerns. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:47-50.

- Rodney D. From suicide thoughts to finalist in America’s Next Top Model. The Gleaner. February 25, 2014. http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20140225/news/news1.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Keyes-Bevan B. Winnie Harlow: her emotional story with vitiligo. Personal Health News website. http://www.personalhealthnews.ca/prevention-and-treatment/her-emotional-story-with-vitiligo. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Giles K, Davidson R. ‘I think I’m beautiful’: model Winnie Harlow, who suffers from rare vitiligo skin condition, gives empowering talk at Women in the World event. Daily Mail. October 9, 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3266579/I-think-m-beautiful-Model-Winnie-Harlow-suffers-rare-Vitiligo-skin-condition-gives-empowering-talk-Women-World-event.html. Updated October 13, 2015. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Ruffo J. CoverGirl’s first model with vitiligo stars in new campaign: ‘w

e have to be more inclusive.’ People. February 20, 2018. https://people.com/style/covergirl-first-model-with-vitiligo-interview/. Accessed September 25, 2018. - Blair O. This vitiligo photo series is absolutely breathtaking. Cosmopolitan. March 23, 2018. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/beauty-hair/a19494259/vitiligo-photo-series-instagram/. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Broadcaster opens up about living with vitiligo. People. February 20, 2018. http://people.com/health/lee-thomas-tv-reporter-on-his-vitiligo/. Accessed April 1, 2018.

Vitiligo is a disfiguring skin condition that is thought to result from autoimmune destruction of melanocytes in the skin, leading to patchy depigmentation. The prevalence of vitiligo is estimated at 1% worldwide.1 Once seen as merely a cosmetic disorder, it is increasingly recognized for its devastating psychological effects. As skin quality, texture, and color are a few of the first things people notice about others, skin plays a major role in our daily interactions with the world. Vitiligo often affects the face and other visible areas of the body; thus, it is associated with impaired quality of life, and affected individuals often experience psychosocial impairment including anxiety, depression, stigmatization, and self-harm ideation.2 Indeed, vitiligo is a condition with not only a visible skin component but a deeper psychological component that also is important to recognize and address. However, due in large part to recent exposure to vitiligo through mainstream media, general understanding about and attitudes toward this condition are changing. As a result, vitiligo has seen a surge in outreach by those affected by the disease.

Perhaps the most well-known current face of vitiligo is Chantelle Brown-Young, a black fashion model, activist, and vitiligo spokesperson known professionally as Winnie Harlow. Diagnosed with vitiligo in childhood, she revealed she was teased and bullied and at one point contemplated suicide. “The continuous harassment and the despair that [vitiligo] brought on my life was so unbearably dehumanizing that I wanted to kill myself,” she disclosed.3 After competing on America’s Next Top Model in 2014, Winnie Harlow became a household name for redefining global standards of beauty and, in her own words, accepting the differences that make us unique and authentic.4 She went on to speak at the Dove Self-Esteem Project panel at the 2015 Women in the World London Summit and was presented with the Role Model award at the Portuguese GQ Men of the Year event that same year.5

More recently, Amy Deanna, a model with vitiligo, was featured in videos for CoverGirl’s 2018 “I Am What I Make Up” campaign in which she is shown enhancing her various skin tones rather than hiding them by applying both light and dark shades of makeup on her face. In a press release she stated, “Vitiligo awareness is something that is very important to me. Being given a platform to [raise awareness] means so much.”6

Additionally, Brock Elbank, a London-based photographer, recently launched a photograph series of men and women with vitiligo on the digital platform Instagram.7 In a recent interview he stated, “I see beauty in what many see as different. Unique individuals who stand out from the crowd are what inspire me to do what I do.”7

Lee Thomas, a television broadcaster and author of the book Turning White: A Memoir of Change is yet another example of a vitiligo patient who recently stopped hiding his condition. He admitted he has had people refuse to shake his hand due to his condition but has used the experience to educate others. He stated, “Because I’m in this position, I think this is where my next thing is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be about sharing and helping, and hopefully leaving the planet a little better for everybody else who comes along with vitiligo.”8 Thomas is dedicated to inspiring others with the condition and started the Clarity Lee Thomas Foundation to provide emotional and mental support to those with vitiligo.

Critics may say this vitiligo movement is merely another example of exploitation of what is unique or different by mainstream media and the fashion industry, similar to prior movements for plus-sized models, natural hairstyles in black women, and transgender identification. Even if partially true, the ultimate effect has been an increase in attention and representation of individuals with vitiligo in mainstream media. At the time this article was being published (September 2018), an Instagram search for #vitiligo yielded approximately 226,000 posts. For comparison with other much more common dermatologic conditions, #eczema returned approximately 958,000 results, #moles returned approximately 65,000 results, and #skincancer returned approximately 104,000 results. Additionally, the Vitiligo Research Foundation currently has more than 5000 followers on Instagram, which is as many as the Melanoma Research Foundation and almost twice as many as the Skin Cancer Foundation, supporting the idea that mainstream representation of individuals with vitiligo is contributing to raising awareness and backing of organizations aimed at making advancements in this area of dermatology.

As more individuals gain an understanding and curiosity about this disease, perhaps more research and investigation will be done to improve treatment options and outcomes for patients with vitiligo. With this movement, perhaps vitiligo patients will feel more comfortable and confident in their skin.

Vitiligo is a disfiguring skin condition that is thought to result from autoimmune destruction of melanocytes in the skin, leading to patchy depigmentation. The prevalence of vitiligo is estimated at 1% worldwide.1 Once seen as merely a cosmetic disorder, it is increasingly recognized for its devastating psychological effects. As skin quality, texture, and color are a few of the first things people notice about others, skin plays a major role in our daily interactions with the world. Vitiligo often affects the face and other visible areas of the body; thus, it is associated with impaired quality of life, and affected individuals often experience psychosocial impairment including anxiety, depression, stigmatization, and self-harm ideation.2 Indeed, vitiligo is a condition with not only a visible skin component but a deeper psychological component that also is important to recognize and address. However, due in large part to recent exposure to vitiligo through mainstream media, general understanding about and attitudes toward this condition are changing. As a result, vitiligo has seen a surge in outreach by those affected by the disease.

Perhaps the most well-known current face of vitiligo is Chantelle Brown-Young, a black fashion model, activist, and vitiligo spokesperson known professionally as Winnie Harlow. Diagnosed with vitiligo in childhood, she revealed she was teased and bullied and at one point contemplated suicide. “The continuous harassment and the despair that [vitiligo] brought on my life was so unbearably dehumanizing that I wanted to kill myself,” she disclosed.3 After competing on America’s Next Top Model in 2014, Winnie Harlow became a household name for redefining global standards of beauty and, in her own words, accepting the differences that make us unique and authentic.4 She went on to speak at the Dove Self-Esteem Project panel at the 2015 Women in the World London Summit and was presented with the Role Model award at the Portuguese GQ Men of the Year event that same year.5

More recently, Amy Deanna, a model with vitiligo, was featured in videos for CoverGirl’s 2018 “I Am What I Make Up” campaign in which she is shown enhancing her various skin tones rather than hiding them by applying both light and dark shades of makeup on her face. In a press release she stated, “Vitiligo awareness is something that is very important to me. Being given a platform to [raise awareness] means so much.”6

Additionally, Brock Elbank, a London-based photographer, recently launched a photograph series of men and women with vitiligo on the digital platform Instagram.7 In a recent interview he stated, “I see beauty in what many see as different. Unique individuals who stand out from the crowd are what inspire me to do what I do.”7

Lee Thomas, a television broadcaster and author of the book Turning White: A Memoir of Change is yet another example of a vitiligo patient who recently stopped hiding his condition. He admitted he has had people refuse to shake his hand due to his condition but has used the experience to educate others. He stated, “Because I’m in this position, I think this is where my next thing is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be about sharing and helping, and hopefully leaving the planet a little better for everybody else who comes along with vitiligo.”8 Thomas is dedicated to inspiring others with the condition and started the Clarity Lee Thomas Foundation to provide emotional and mental support to those with vitiligo.

Critics may say this vitiligo movement is merely another example of exploitation of what is unique or different by mainstream media and the fashion industry, similar to prior movements for plus-sized models, natural hairstyles in black women, and transgender identification. Even if partially true, the ultimate effect has been an increase in attention and representation of individuals with vitiligo in mainstream media. At the time this article was being published (September 2018), an Instagram search for #vitiligo yielded approximately 226,000 posts. For comparison with other much more common dermatologic conditions, #eczema returned approximately 958,000 results, #moles returned approximately 65,000 results, and #skincancer returned approximately 104,000 results. Additionally, the Vitiligo Research Foundation currently has more than 5000 followers on Instagram, which is as many as the Melanoma Research Foundation and almost twice as many as the Skin Cancer Foundation, supporting the idea that mainstream representation of individuals with vitiligo is contributing to raising awareness and backing of organizations aimed at making advancements in this area of dermatology.

As more individuals gain an understanding and curiosity about this disease, perhaps more research and investigation will be done to improve treatment options and outcomes for patients with vitiligo. With this movement, perhaps vitiligo patients will feel more comfortable and confident in their skin.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Tomas‐Aragones L, Marron SE. Body image and body dysmorphic concerns. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:47-50.

- Rodney D. From suicide thoughts to finalist in America’s Next Top Model. The Gleaner. February 25, 2014. http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20140225/news/news1.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Keyes-Bevan B. Winnie Harlow: her emotional story with vitiligo. Personal Health News website. http://www.personalhealthnews.ca/prevention-and-treatment/her-emotional-story-with-vitiligo. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Giles K, Davidson R. ‘I think I’m beautiful’: model Winnie Harlow, who suffers from rare vitiligo skin condition, gives empowering talk at Women in the World event. Daily Mail. October 9, 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3266579/I-think-m-beautiful-Model-Winnie-Harlow-suffers-rare-Vitiligo-skin-condition-gives-empowering-talk-Women-World-event.html. Updated October 13, 2015. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Ruffo J. CoverGirl’s first model with vitiligo stars in new campaign: ‘w

e have to be more inclusive.’ People. February 20, 2018. https://people.com/style/covergirl-first-model-with-vitiligo-interview/. Accessed September 25, 2018. - Blair O. This vitiligo photo series is absolutely breathtaking. Cosmopolitan. March 23, 2018. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/beauty-hair/a19494259/vitiligo-photo-series-instagram/. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Broadcaster opens up about living with vitiligo. People. February 20, 2018. http://people.com/health/lee-thomas-tv-reporter-on-his-vitiligo/. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Tomas‐Aragones L, Marron SE. Body image and body dysmorphic concerns. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:47-50.

- Rodney D. From suicide thoughts to finalist in America’s Next Top Model. The Gleaner. February 25, 2014. http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20140225/news/news1.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Keyes-Bevan B. Winnie Harlow: her emotional story with vitiligo. Personal Health News website. http://www.personalhealthnews.ca/prevention-and-treatment/her-emotional-story-with-vitiligo. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Giles K, Davidson R. ‘I think I’m beautiful’: model Winnie Harlow, who suffers from rare vitiligo skin condition, gives empowering talk at Women in the World event. Daily Mail. October 9, 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3266579/I-think-m-beautiful-Model-Winnie-Harlow-suffers-rare-Vitiligo-skin-condition-gives-empowering-talk-Women-World-event.html. Updated October 13, 2015. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Ruffo J. CoverGirl’s first model with vitiligo stars in new campaign: ‘w

e have to be more inclusive.’ People. February 20, 2018. https://people.com/style/covergirl-first-model-with-vitiligo-interview/. Accessed September 25, 2018. - Blair O. This vitiligo photo series is absolutely breathtaking. Cosmopolitan. March 23, 2018. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/beauty-hair/a19494259/vitiligo-photo-series-instagram/. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Broadcaster opens up about living with vitiligo. People. February 20, 2018. http://people.com/health/lee-thomas-tv-reporter-on-his-vitiligo/. Accessed April 1, 2018.

ACOG lends support to bill promoting maternal mortality review committees

The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018 (H.R. 1318) was the subject of a Sept. 27 hearing of the House Energy and Commerce Health Subcommittee. The bill comes at a time when 700 women a year die as a result of pregnancy or pregnancy-related complications with a rate that is increasing, while 157 of 183 countries around the world are reporting decreasing rates of maternal mortality, according to ACOG.

The bill, authored by Rep. Jamie Herrera Beutler (R-Wash.) and Diana DeGette (D-Colo.) would allocate $58 million for each fiscal year from 2019 through 2023 to support the 33 existing states with maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) and help the remaining 17 states develop them, as well as to standardize data collection across the nation.

The goal of having these committees in place is to “improve data collection and reporting around maternal mortality, and to develop or support surveillance systems at the local, state, and national level in order to better understand the burden of maternal complications,” a background memo on the hearing noted. “These surveillance efforts include identifying groups of women with disproportionately high rates of maternal mortality and identifying the determinants of disparities in maternal care, health risks, and health outcomes.”

Necessitating this legislation was a data point that was reiterated throughout the course of the hearing – that maternal mortality rates in the United States were on the rise.

“What’s both surprising and devastating is that, despite massive innovation and advances in health care and technology, we’ve experienced recent reports that have indicated that the number of women dying due to pregnancy complications is actually increasing,” Full Committee Chairman Greg Walden (R-Ore.) said in his opening remarks at the hearing. “According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, maternal mortality rates in America have more than doubled since 1987. I think we are asking, how can that be? This is not a statistic any of us wants to hear.”

Chairman Walden acknowledged that there are questions as to whether the increase was a function of better data collection or whether it was an issue with the delivery of health care.

“The bill before us today will help us answer these really important questions and hopefully ensure that expectant newborn mothers receive even better care,” he said.

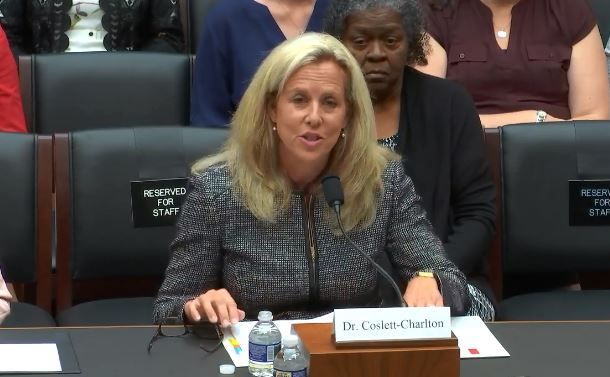

Lynne M. Coslett-Charlton, MD, ACOG Pennsylvania District legislative chair, offered the organization’s support for the bill.

MMRCs “are multidisciplinary groups of local experts in maternal and public health, as well as patient and community advocates, that closely examine maternal death cases and identify locally relevant ways to prevent future deaths,” she testified before the committee. “While traditional public health surveillance using vital statistics can tell us about trends and disparities, MMRCs are best positioned to comprehensively assess maternal deaths and identify opportunities for prevention.”

Dr. Coslett-Charlton added that to clearly understand why women are dying from preventable maternal complications, which she noted that 60% of maternal deaths are, “every state must have a robust MMRC. The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act will help us reach that goal, and ultimately improve maternal health across this nation,” as these committees review every maternal death and can make a determination as to whether they could have been preventable.

Additionally, the fact that black women face a significantly higher rate of maternal mortality was another data point highlighted during the hearing, further adding to the need for this bill that has bipartisan support and more than 170 cosponsors.

Rep. DeGette called it “one of the most striking aspects” that black women “are nearly four times as likely to experience a pregnancy-related death.”

Stacey D. Stewart, president of the March of Dimes, in her written testimony praised the inclusion in H.R. 1318 of a “demonstration project to determine how best to address disparities in maternal health outcomes.”

The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018 (H.R. 1318) was the subject of a Sept. 27 hearing of the House Energy and Commerce Health Subcommittee. The bill comes at a time when 700 women a year die as a result of pregnancy or pregnancy-related complications with a rate that is increasing, while 157 of 183 countries around the world are reporting decreasing rates of maternal mortality, according to ACOG.

The bill, authored by Rep. Jamie Herrera Beutler (R-Wash.) and Diana DeGette (D-Colo.) would allocate $58 million for each fiscal year from 2019 through 2023 to support the 33 existing states with maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) and help the remaining 17 states develop them, as well as to standardize data collection across the nation.

The goal of having these committees in place is to “improve data collection and reporting around maternal mortality, and to develop or support surveillance systems at the local, state, and national level in order to better understand the burden of maternal complications,” a background memo on the hearing noted. “These surveillance efforts include identifying groups of women with disproportionately high rates of maternal mortality and identifying the determinants of disparities in maternal care, health risks, and health outcomes.”

Necessitating this legislation was a data point that was reiterated throughout the course of the hearing – that maternal mortality rates in the United States were on the rise.

“What’s both surprising and devastating is that, despite massive innovation and advances in health care and technology, we’ve experienced recent reports that have indicated that the number of women dying due to pregnancy complications is actually increasing,” Full Committee Chairman Greg Walden (R-Ore.) said in his opening remarks at the hearing. “According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, maternal mortality rates in America have more than doubled since 1987. I think we are asking, how can that be? This is not a statistic any of us wants to hear.”

Chairman Walden acknowledged that there are questions as to whether the increase was a function of better data collection or whether it was an issue with the delivery of health care.

“The bill before us today will help us answer these really important questions and hopefully ensure that expectant newborn mothers receive even better care,” he said.

Lynne M. Coslett-Charlton, MD, ACOG Pennsylvania District legislative chair, offered the organization’s support for the bill.

MMRCs “are multidisciplinary groups of local experts in maternal and public health, as well as patient and community advocates, that closely examine maternal death cases and identify locally relevant ways to prevent future deaths,” she testified before the committee. “While traditional public health surveillance using vital statistics can tell us about trends and disparities, MMRCs are best positioned to comprehensively assess maternal deaths and identify opportunities for prevention.”

Dr. Coslett-Charlton added that to clearly understand why women are dying from preventable maternal complications, which she noted that 60% of maternal deaths are, “every state must have a robust MMRC. The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act will help us reach that goal, and ultimately improve maternal health across this nation,” as these committees review every maternal death and can make a determination as to whether they could have been preventable.

Additionally, the fact that black women face a significantly higher rate of maternal mortality was another data point highlighted during the hearing, further adding to the need for this bill that has bipartisan support and more than 170 cosponsors.

Rep. DeGette called it “one of the most striking aspects” that black women “are nearly four times as likely to experience a pregnancy-related death.”

Stacey D. Stewart, president of the March of Dimes, in her written testimony praised the inclusion in H.R. 1318 of a “demonstration project to determine how best to address disparities in maternal health outcomes.”

The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018 (H.R. 1318) was the subject of a Sept. 27 hearing of the House Energy and Commerce Health Subcommittee. The bill comes at a time when 700 women a year die as a result of pregnancy or pregnancy-related complications with a rate that is increasing, while 157 of 183 countries around the world are reporting decreasing rates of maternal mortality, according to ACOG.

The bill, authored by Rep. Jamie Herrera Beutler (R-Wash.) and Diana DeGette (D-Colo.) would allocate $58 million for each fiscal year from 2019 through 2023 to support the 33 existing states with maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) and help the remaining 17 states develop them, as well as to standardize data collection across the nation.

The goal of having these committees in place is to “improve data collection and reporting around maternal mortality, and to develop or support surveillance systems at the local, state, and national level in order to better understand the burden of maternal complications,” a background memo on the hearing noted. “These surveillance efforts include identifying groups of women with disproportionately high rates of maternal mortality and identifying the determinants of disparities in maternal care, health risks, and health outcomes.”

Necessitating this legislation was a data point that was reiterated throughout the course of the hearing – that maternal mortality rates in the United States were on the rise.

“What’s both surprising and devastating is that, despite massive innovation and advances in health care and technology, we’ve experienced recent reports that have indicated that the number of women dying due to pregnancy complications is actually increasing,” Full Committee Chairman Greg Walden (R-Ore.) said in his opening remarks at the hearing. “According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, maternal mortality rates in America have more than doubled since 1987. I think we are asking, how can that be? This is not a statistic any of us wants to hear.”

Chairman Walden acknowledged that there are questions as to whether the increase was a function of better data collection or whether it was an issue with the delivery of health care.

“The bill before us today will help us answer these really important questions and hopefully ensure that expectant newborn mothers receive even better care,” he said.

Lynne M. Coslett-Charlton, MD, ACOG Pennsylvania District legislative chair, offered the organization’s support for the bill.

MMRCs “are multidisciplinary groups of local experts in maternal and public health, as well as patient and community advocates, that closely examine maternal death cases and identify locally relevant ways to prevent future deaths,” she testified before the committee. “While traditional public health surveillance using vital statistics can tell us about trends and disparities, MMRCs are best positioned to comprehensively assess maternal deaths and identify opportunities for prevention.”

Dr. Coslett-Charlton added that to clearly understand why women are dying from preventable maternal complications, which she noted that 60% of maternal deaths are, “every state must have a robust MMRC. The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act will help us reach that goal, and ultimately improve maternal health across this nation,” as these committees review every maternal death and can make a determination as to whether they could have been preventable.

Additionally, the fact that black women face a significantly higher rate of maternal mortality was another data point highlighted during the hearing, further adding to the need for this bill that has bipartisan support and more than 170 cosponsors.

Rep. DeGette called it “one of the most striking aspects” that black women “are nearly four times as likely to experience a pregnancy-related death.”

Stacey D. Stewart, president of the March of Dimes, in her written testimony praised the inclusion in H.R. 1318 of a “demonstration project to determine how best to address disparities in maternal health outcomes.”

REPORTING FROM A HOUSE ENERGY AND COMMERCE HEALTH SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING

Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology: Is Cognitive Computing the Future of Evidence-Based Medicine?

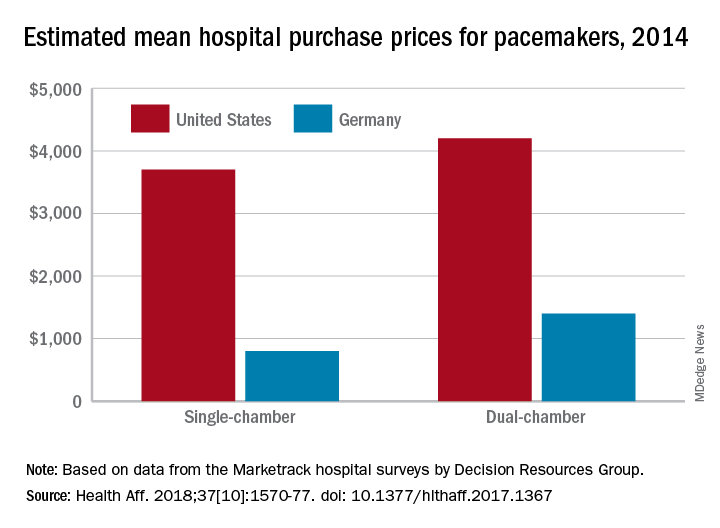

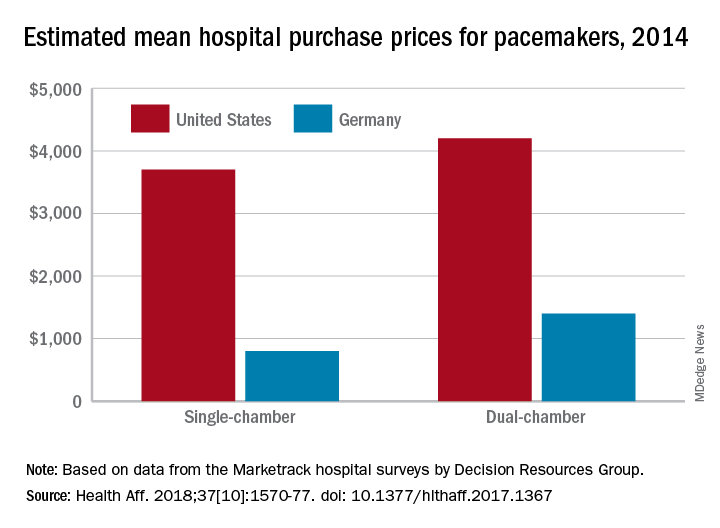

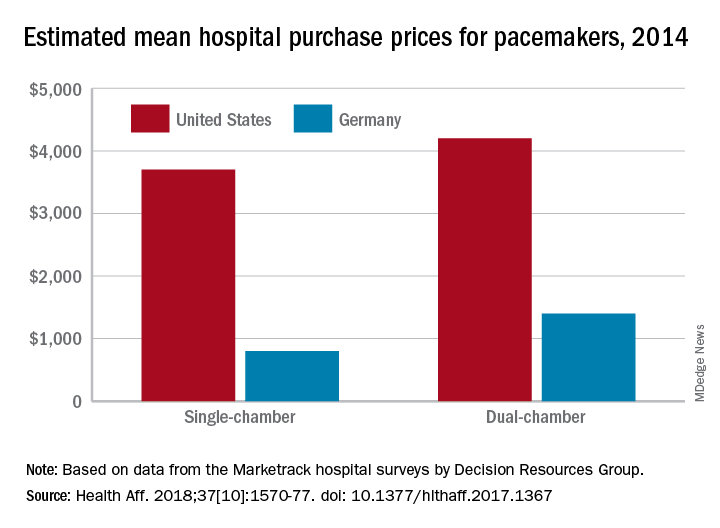

U.S. vs. Europe: Costs of cardiac implant devices compared

Prices that hospitals pay for cardiac implant devices are two to six times higher in the United States than in Europe, according to analysis of a large hospital panel survey.

U.S. hospitals had an estimated mean cost of $670 for a bare-metal stent in 2014, compared with $120 in Germany, and the mean costs for dual-chamber pacemakers that year were $4,200 in the United States and $1,400 in Germany, which had lower costs for cardiac devices than the other three European countries – United Kingdom, France, and Italy – included in the study, Martin Wenzl, MSc, and Elias Mossialos, MD, PhD, reported in Health Affairs.

France generally had the highest costs among the European countries, with Italy next and then the United Kingdom. The estimated cost of bare-metal stents was actually higher for French hospitals ($750) than for those in the United States, and Italy had mean prices similar to the United Sates for dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. The prices of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization devices with defibrillating function were the other exceptions, with the United Kingdom similar to or higher than the United States, said Mr. Wenzl and Dr. Mossialos, both of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The analysis of data from Decision Resources Group’s Marketrack hospital surveys also showed significant variation between the hospitals in each country, with the exception of France, where payments are based on the specific device rather than the procedure and the system “creates weak incentives for hospitals to negotiate lower prices,” they said. In most of the device categories, “variation between hospitals in each country was similar to variation between countries,” they wrote, adding that prices in general “were only weakly correlated with volumes purchased by hospitals.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund. The investigators did not disclose any possible conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wenzi M, Mossialos E. Health Aff. 2018;37[10]:1570-77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1367.

Prices that hospitals pay for cardiac implant devices are two to six times higher in the United States than in Europe, according to analysis of a large hospital panel survey.

U.S. hospitals had an estimated mean cost of $670 for a bare-metal stent in 2014, compared with $120 in Germany, and the mean costs for dual-chamber pacemakers that year were $4,200 in the United States and $1,400 in Germany, which had lower costs for cardiac devices than the other three European countries – United Kingdom, France, and Italy – included in the study, Martin Wenzl, MSc, and Elias Mossialos, MD, PhD, reported in Health Affairs.

France generally had the highest costs among the European countries, with Italy next and then the United Kingdom. The estimated cost of bare-metal stents was actually higher for French hospitals ($750) than for those in the United States, and Italy had mean prices similar to the United Sates for dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. The prices of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization devices with defibrillating function were the other exceptions, with the United Kingdom similar to or higher than the United States, said Mr. Wenzl and Dr. Mossialos, both of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The analysis of data from Decision Resources Group’s Marketrack hospital surveys also showed significant variation between the hospitals in each country, with the exception of France, where payments are based on the specific device rather than the procedure and the system “creates weak incentives for hospitals to negotiate lower prices,” they said. In most of the device categories, “variation between hospitals in each country was similar to variation between countries,” they wrote, adding that prices in general “were only weakly correlated with volumes purchased by hospitals.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund. The investigators did not disclose any possible conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wenzi M, Mossialos E. Health Aff. 2018;37[10]:1570-77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1367.

Prices that hospitals pay for cardiac implant devices are two to six times higher in the United States than in Europe, according to analysis of a large hospital panel survey.

U.S. hospitals had an estimated mean cost of $670 for a bare-metal stent in 2014, compared with $120 in Germany, and the mean costs for dual-chamber pacemakers that year were $4,200 in the United States and $1,400 in Germany, which had lower costs for cardiac devices than the other three European countries – United Kingdom, France, and Italy – included in the study, Martin Wenzl, MSc, and Elias Mossialos, MD, PhD, reported in Health Affairs.

France generally had the highest costs among the European countries, with Italy next and then the United Kingdom. The estimated cost of bare-metal stents was actually higher for French hospitals ($750) than for those in the United States, and Italy had mean prices similar to the United Sates for dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. The prices of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization devices with defibrillating function were the other exceptions, with the United Kingdom similar to or higher than the United States, said Mr. Wenzl and Dr. Mossialos, both of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The analysis of data from Decision Resources Group’s Marketrack hospital surveys also showed significant variation between the hospitals in each country, with the exception of France, where payments are based on the specific device rather than the procedure and the system “creates weak incentives for hospitals to negotiate lower prices,” they said. In most of the device categories, “variation between hospitals in each country was similar to variation between countries,” they wrote, adding that prices in general “were only weakly correlated with volumes purchased by hospitals.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund. The investigators did not disclose any possible conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wenzi M, Mossialos E. Health Aff. 2018;37[10]:1570-77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1367.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

PCV13 moderately effective in older adults

ATLANTA – (IPD) caused by PCV13 vaccine serotypes in adults aged 65 years and older, according to a case-control study involving Medicare beneficiaries.

Conversely, the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) showed limited effectiveness against serotypes unique to that vaccine in the study, which included 699 cases and more than 10,000 controls, Olivia Almendares, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Vaccine efficacy against PCV13 [plus 6C type, which has cross-reactivity with serotype 6A] was 47% in those who received PCV13 vaccine only,” Ms. Almendares said in an interview, noting that efficacy was 26% against serotype 3 and 67% against other PCV13 serotypes (plus 6C). “Vaccine efficacy against PPSV23-unique types was 36% for those who received only PPSV23.”

Neither vaccine showed effectiveness against serotypes not included in the respective vaccines, she said.

The findings are timely given that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is reevaluating its PCV13 recommendation for adults aged 65 years and older, she added.

“Specifically, ACIP is addressing whether PCV13 should be recommended routinely for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 and older given sustained indirect effects,” she said, explaining that, in 2014 when ACIP recommended routine use of the vaccine in series with PPSV23 for adults aged 65 years and older, the committee recognized that herd immunity effects from PCV13 use in children might eventually limit the utility of this recommendation, and therefore it proposed reevaluation and revision as needed after 4 years.

For the current study, she and her colleagues linked IPD cases in persons aged 65 years and older, which were identified through Active Bacterial Core surveillance during 2015-2016, to records for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) beneficiaries. Vaccination and medical histories were obtained through medical records, and vaccine effectiveness was estimated as one minus the odds ratio for vaccination with PCV13 only or PPSV23 only versus neither vaccine using conditional logistic regression, with adjustment for sex and underlying medical conditions.

Of 2,246 IPD cases, 1,017 (45%) were matched to Medicare beneficiaries, and 699 were included in the analysis after those with noncontinuous enrollment in Medicare, long-term care residence, and missing census tract data were excluded. The cases were matched based on age, census tract of residence, and length of Medicare enrollment to 10,152 matched controls identified through CMS.

IPD associated with PCV13 (plus type 6C) accounted for 164 (23% of cases), of which 88 (12% of cases) involved serotype 3, and invasive pneumococcal disease associated with PPSV23 accounted for 350 cases (50%), she said.

PCV13 vaccine was given alone in 14% and 18% of cases and controls, respectively; PPSV23 alone was given in 22% and 21% of case patients and controls, respectively; and both vaccines were given in 8% of cases and controls.

Compared with controls, case patients were more likely to be of nonwhite race (16% vs. 11%), to have more than one chronic medical condition (88% vs. 58%), and to have one or more immunocompromising conditions (54% vs. 32%), she and her colleagues reported.

“PCV13 showed moderate overall effectiveness in preventing IPD caused by PCV13 (including 6C), but effectiveness may be lower for serotype 3 than for other PCV13 types,” she said.

“These results are in agreement with those from CAPiTA – a large clinical trial conducted in the Netherlands, which showed PCV13 to be effective against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older,” she noted. “Additionally, data from CDC surveillance suggest that PCV13-serotype [invasive pneumococcal disease] among children and adults aged 65 and older has declined dramatically following PCV13 introduction for children in 2010, as predicted.”

In fact, among adults aged 65 years and older, PCV13-serotype invasive pneumococcal disease declined by 40% after the vaccine was introduced in children. This corresponds to a change in the annual PCV13-serotype incidence from 14 cases per 100,000 population in 2010 to five cases per 100,000 population in 2014, she said; she added that IPD incidence plateaued in 2014-2016 with vaccine serotypes contributing to a small proportion of overall IPD burden among adults aged 65 years and older.

ACIP’s reevaluation of the PCV13 recommendation is ongoing and will be addressed at upcoming meetings.

“As part of the review process, we look at changes in disease incidence focusing primarily on invasive pneumococcal disease and noninvasive pneumonia, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, and vaccine safety,” she said. She noted that ACIP currently has no plans to consider revising PCV13 recommendations for adults who have immunocompromising conditions, for whom PCV13 has been recommended since 2012.

Ms. Almendares reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Almendares O et al. ICEID 2018, Board 376.

ATLANTA – (IPD) caused by PCV13 vaccine serotypes in adults aged 65 years and older, according to a case-control study involving Medicare beneficiaries.

Conversely, the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) showed limited effectiveness against serotypes unique to that vaccine in the study, which included 699 cases and more than 10,000 controls, Olivia Almendares, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Vaccine efficacy against PCV13 [plus 6C type, which has cross-reactivity with serotype 6A] was 47% in those who received PCV13 vaccine only,” Ms. Almendares said in an interview, noting that efficacy was 26% against serotype 3 and 67% against other PCV13 serotypes (plus 6C). “Vaccine efficacy against PPSV23-unique types was 36% for those who received only PPSV23.”

Neither vaccine showed effectiveness against serotypes not included in the respective vaccines, she said.

The findings are timely given that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is reevaluating its PCV13 recommendation for adults aged 65 years and older, she added.

“Specifically, ACIP is addressing whether PCV13 should be recommended routinely for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 and older given sustained indirect effects,” she said, explaining that, in 2014 when ACIP recommended routine use of the vaccine in series with PPSV23 for adults aged 65 years and older, the committee recognized that herd immunity effects from PCV13 use in children might eventually limit the utility of this recommendation, and therefore it proposed reevaluation and revision as needed after 4 years.

For the current study, she and her colleagues linked IPD cases in persons aged 65 years and older, which were identified through Active Bacterial Core surveillance during 2015-2016, to records for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) beneficiaries. Vaccination and medical histories were obtained through medical records, and vaccine effectiveness was estimated as one minus the odds ratio for vaccination with PCV13 only or PPSV23 only versus neither vaccine using conditional logistic regression, with adjustment for sex and underlying medical conditions.

Of 2,246 IPD cases, 1,017 (45%) were matched to Medicare beneficiaries, and 699 were included in the analysis after those with noncontinuous enrollment in Medicare, long-term care residence, and missing census tract data were excluded. The cases were matched based on age, census tract of residence, and length of Medicare enrollment to 10,152 matched controls identified through CMS.

IPD associated with PCV13 (plus type 6C) accounted for 164 (23% of cases), of which 88 (12% of cases) involved serotype 3, and invasive pneumococcal disease associated with PPSV23 accounted for 350 cases (50%), she said.

PCV13 vaccine was given alone in 14% and 18% of cases and controls, respectively; PPSV23 alone was given in 22% and 21% of case patients and controls, respectively; and both vaccines were given in 8% of cases and controls.

Compared with controls, case patients were more likely to be of nonwhite race (16% vs. 11%), to have more than one chronic medical condition (88% vs. 58%), and to have one or more immunocompromising conditions (54% vs. 32%), she and her colleagues reported.

“PCV13 showed moderate overall effectiveness in preventing IPD caused by PCV13 (including 6C), but effectiveness may be lower for serotype 3 than for other PCV13 types,” she said.

“These results are in agreement with those from CAPiTA – a large clinical trial conducted in the Netherlands, which showed PCV13 to be effective against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older,” she noted. “Additionally, data from CDC surveillance suggest that PCV13-serotype [invasive pneumococcal disease] among children and adults aged 65 and older has declined dramatically following PCV13 introduction for children in 2010, as predicted.”

In fact, among adults aged 65 years and older, PCV13-serotype invasive pneumococcal disease declined by 40% after the vaccine was introduced in children. This corresponds to a change in the annual PCV13-serotype incidence from 14 cases per 100,000 population in 2010 to five cases per 100,000 population in 2014, she said; she added that IPD incidence plateaued in 2014-2016 with vaccine serotypes contributing to a small proportion of overall IPD burden among adults aged 65 years and older.

ACIP’s reevaluation of the PCV13 recommendation is ongoing and will be addressed at upcoming meetings.

“As part of the review process, we look at changes in disease incidence focusing primarily on invasive pneumococcal disease and noninvasive pneumonia, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, and vaccine safety,” she said. She noted that ACIP currently has no plans to consider revising PCV13 recommendations for adults who have immunocompromising conditions, for whom PCV13 has been recommended since 2012.

Ms. Almendares reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Almendares O et al. ICEID 2018, Board 376.

ATLANTA – (IPD) caused by PCV13 vaccine serotypes in adults aged 65 years and older, according to a case-control study involving Medicare beneficiaries.

Conversely, the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) showed limited effectiveness against serotypes unique to that vaccine in the study, which included 699 cases and more than 10,000 controls, Olivia Almendares, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Vaccine efficacy against PCV13 [plus 6C type, which has cross-reactivity with serotype 6A] was 47% in those who received PCV13 vaccine only,” Ms. Almendares said in an interview, noting that efficacy was 26% against serotype 3 and 67% against other PCV13 serotypes (plus 6C). “Vaccine efficacy against PPSV23-unique types was 36% for those who received only PPSV23.”

Neither vaccine showed effectiveness against serotypes not included in the respective vaccines, she said.

The findings are timely given that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is reevaluating its PCV13 recommendation for adults aged 65 years and older, she added.

“Specifically, ACIP is addressing whether PCV13 should be recommended routinely for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 and older given sustained indirect effects,” she said, explaining that, in 2014 when ACIP recommended routine use of the vaccine in series with PPSV23 for adults aged 65 years and older, the committee recognized that herd immunity effects from PCV13 use in children might eventually limit the utility of this recommendation, and therefore it proposed reevaluation and revision as needed after 4 years.

For the current study, she and her colleagues linked IPD cases in persons aged 65 years and older, which were identified through Active Bacterial Core surveillance during 2015-2016, to records for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) beneficiaries. Vaccination and medical histories were obtained through medical records, and vaccine effectiveness was estimated as one minus the odds ratio for vaccination with PCV13 only or PPSV23 only versus neither vaccine using conditional logistic regression, with adjustment for sex and underlying medical conditions.

Of 2,246 IPD cases, 1,017 (45%) were matched to Medicare beneficiaries, and 699 were included in the analysis after those with noncontinuous enrollment in Medicare, long-term care residence, and missing census tract data were excluded. The cases were matched based on age, census tract of residence, and length of Medicare enrollment to 10,152 matched controls identified through CMS.

IPD associated with PCV13 (plus type 6C) accounted for 164 (23% of cases), of which 88 (12% of cases) involved serotype 3, and invasive pneumococcal disease associated with PPSV23 accounted for 350 cases (50%), she said.

PCV13 vaccine was given alone in 14% and 18% of cases and controls, respectively; PPSV23 alone was given in 22% and 21% of case patients and controls, respectively; and both vaccines were given in 8% of cases and controls.

Compared with controls, case patients were more likely to be of nonwhite race (16% vs. 11%), to have more than one chronic medical condition (88% vs. 58%), and to have one or more immunocompromising conditions (54% vs. 32%), she and her colleagues reported.

“PCV13 showed moderate overall effectiveness in preventing IPD caused by PCV13 (including 6C), but effectiveness may be lower for serotype 3 than for other PCV13 types,” she said.

“These results are in agreement with those from CAPiTA – a large clinical trial conducted in the Netherlands, which showed PCV13 to be effective against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older,” she noted. “Additionally, data from CDC surveillance suggest that PCV13-serotype [invasive pneumococcal disease] among children and adults aged 65 and older has declined dramatically following PCV13 introduction for children in 2010, as predicted.”

In fact, among adults aged 65 years and older, PCV13-serotype invasive pneumococcal disease declined by 40% after the vaccine was introduced in children. This corresponds to a change in the annual PCV13-serotype incidence from 14 cases per 100,000 population in 2010 to five cases per 100,000 population in 2014, she said; she added that IPD incidence plateaued in 2014-2016 with vaccine serotypes contributing to a small proportion of overall IPD burden among adults aged 65 years and older.

ACIP’s reevaluation of the PCV13 recommendation is ongoing and will be addressed at upcoming meetings.

“As part of the review process, we look at changes in disease incidence focusing primarily on invasive pneumococcal disease and noninvasive pneumonia, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, and vaccine safety,” she said. She noted that ACIP currently has no plans to consider revising PCV13 recommendations for adults who have immunocompromising conditions, for whom PCV13 has been recommended since 2012.

Ms. Almendares reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Almendares O et al. ICEID 2018, Board 376.

REPORTING FROM ICEID 2018

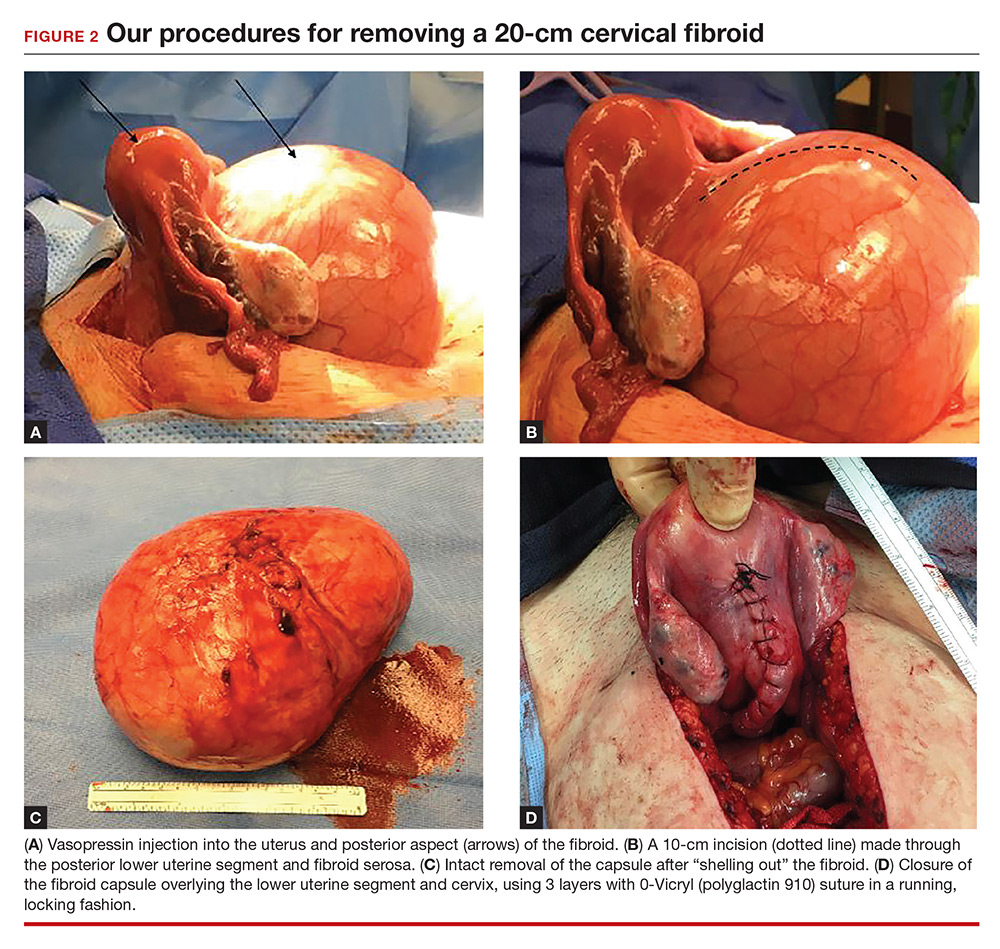

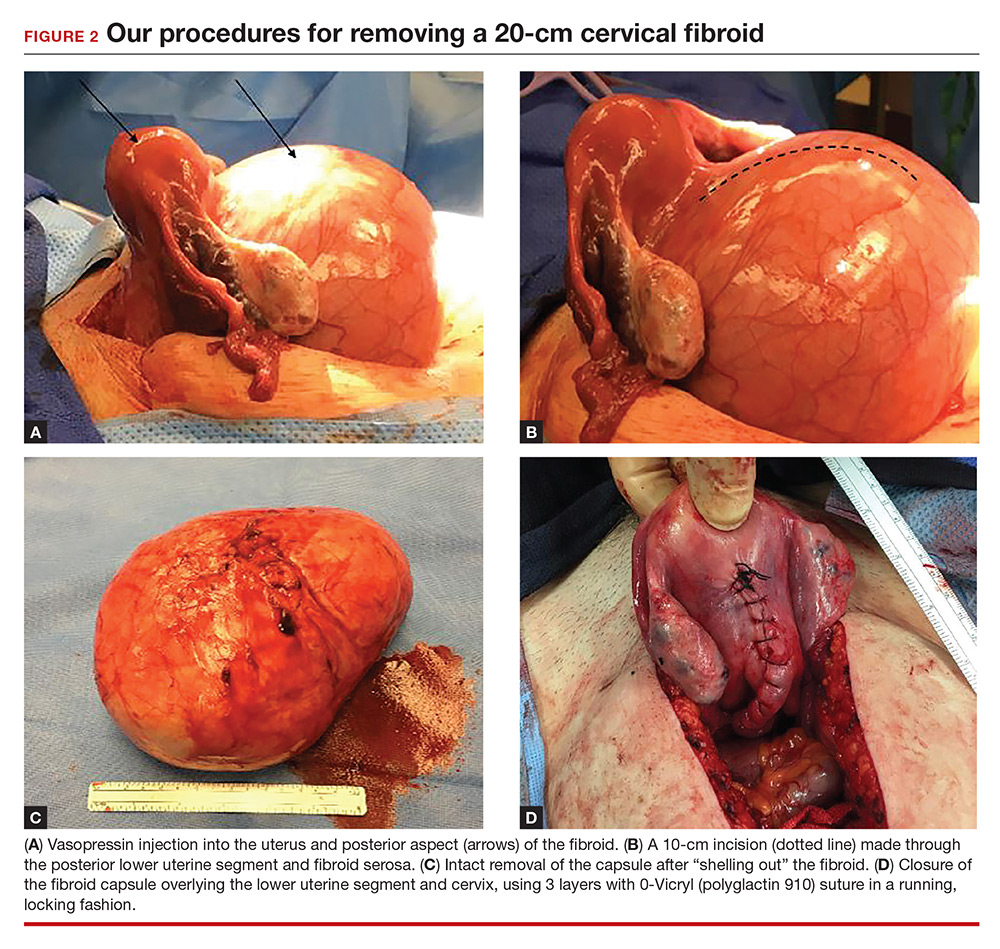

Myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid in a patient desiring future fertility

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

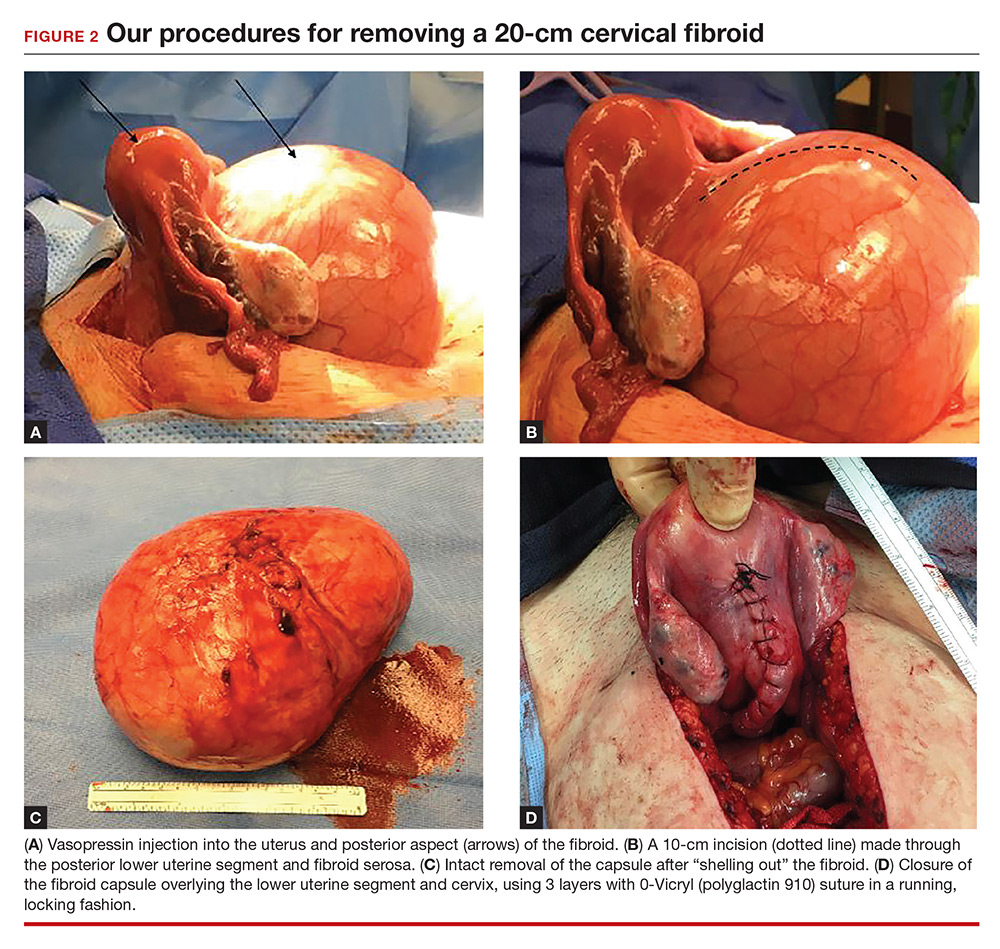

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312–324.

- Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(12):1789–1804.

- Okin CR, Guido RS, Meyn LA, Ramanathan S. Vasopressin during abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):867–872.

- Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N, Wiysonge CS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to reduce hemorrhage during myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):4–9.

- Barbieri RL. Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery. OBG Manage. 2010;22(3):12–15.

- Tian YC, Long TF, Dai YN. Pregnancy outcomes following different surgical approaches of myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):350–357.

- Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of a single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1326–1330.

- Claeys J, Hellendoorn I, Hamerlynck T, Bosteels J, Weyers S. The risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(3):197–206.

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumors of the uterus. Clinically significant fibroids that arise from the cervix are less common.1 Removing large cervical fibroids when a patient desires future fertility is a surgical challenge because of the risks of significant blood loss, bladder and ureteral injury, and unplanned hysterectomy. For women who desire future fertility, myomectomy can improve the chances of pregnancy by restoring normal anatomy.2 In this article, we describe a technique for myomectomy with uterine preservation in a patient with a 20-cm cervical fibroid.

CASE Woman with increasing girth and urinary symptoms is unable to conceive

A 33-year-old white woman with a history of 1 prior vaginal delivery presents with symptoms of increasing abdominal girth, intermittent urinary retention and urgency, and inability to become pregnant. She reports normal monthly menstrual periods. On pelvic examination, the ObGyn notes a large fibroid partially protruding through a dilated cervix. Abdominal examination reveals a fundal height at the level of the umbilicus.

Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a uterus that measures 4.5 x 6.1 x 13.6 cm. Arising from the posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, body, and lower uterine segment is a fibroid that measures 9.7 x 15.5 x 18.9 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging is performed and confirms a fibroid measuring 10 x 16 x 20 cm. The inferior-most aspect of the fibroid appears to be within the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. Most of the fibroid, however, is posterior to the uterus, pressing on and anteriorly displacing the endometrial cavity (FIGURE 1).

What is your surgical approach?

Comprehensive preoperative planning

In this case, the patient should receive extensive preoperative counseling about the significantly increased risk for hysterectomy with an attempted myomectomy. Prior to being scheduled for surgery, she also should have a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist. To optimize visualization during the procedure, we recommend to plan for a midline vertical skin incision. Because of the potential bleeding risks, blood products should be made available in the operating room at the time of surgery.

Techniques for surgery

Intraoperatively, a vertical midline incision exteriorizes the uterus from the peritoneal cavity. Opening of the retroperitoneal spaces allows for identification of the ureters. Perform dissection in the midline away from the ureters. Inject vasopressin (5 U) into the uterine fundus. Incise the uterine serosa over the myoma posteriorly in the midline.

Perform a myomectomy, with gentle “shelling out” of the myoma; in this way the specimen can be removed intact. Reapproximate the fibroid cavity in 3 layers with 0-Vicryl (polyglactin 910) suture in a running fashion (FIGURE 2).

Continue to: CASE Resolved

CASE Resolved

The estimated blood loss during surgery was 50 mL. Final pathology reported a 1,660-g intact myoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Her postoperative evaluation was 1 month later. Her abdominal incision was well healed. Her fibroid-related symptoms had resolved, and she planned to attempt pregnancy. Cesarean delivery for future pregnancies was recommended.

Increase the chances of a good outcome

Advanced planning for attempted myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid can increase the probability of a successful outcome. We suggest the following:

Counsel the patient on risks. Our preoperative strategy includes extensive counseling on the significantly increased surgical risks and the possibility of unavoidable hysterectomy. Given the anatomic distortion with respect to the ureters, bladder, and major blood vessels, involving gynecologic oncology is beneficial to the surgery planning process.

Prepare for possible transfusion. Ensure blood products are made available in the operating room in case transfusion is needed.

Control bleeding. Randomized studies have shown that intrauterine injection of vasopressin, through its action as a vasoconstrictor, decreases surgical bleeding.3,4 While little data are available on vasopressin’s most effective dosage and dilution, 5 U at a very dilute concentration (0.1–0.2 U/mL) has been recommended.5 A midline cervical incision away from lateral structures and gentle shelling out of the cervical fibroid help to avoid intraoperative damage to the bladder, ureters, and vascular supply.

Close in multiple layers. This approach can prevent a potential space for hematoma accumulation.6 Further, a multiple-layer closure of a myometrial incision may decrease the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.7

Advise abstinence postsurgery. There are no consistent data to guide patient counseling regarding recommendations for the timing of conception following myomectomy. We counseled our patient to abstain from vaginal intercourse for 4 weeks, after which time she soon should attempt to conceive. Although there are no published data regarding when it is best to resume sexual relations following such a surgery, we advise a 1-month period primarily to allow healing of the skin incision. Any further delay in attempting to become pregnant may allow for the growth of additional fibroids.

Plan for future deliveries. When the myomais extensively involved, such as in this case, we recommend cesarean delivery for future pregnancies to avoid the known risk of uterine rupture.8 In general, we recommend cesarean delivery in future pregnancies if an incision larger than 50% of the myometrial thickness is made in the contractile portion of the uterus.

Final takeaway. Despite increased surgical risks, myomectomy of a large cervical fibroid is possible and can alleviate symptoms and improve future fertility.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312–324.

- Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(12):1789–1804.

- Okin CR, Guido RS, Meyn LA, Ramanathan S. Vasopressin during abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):867–872.

- Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N, Wiysonge CS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to reduce hemorrhage during myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):4–9.

- Barbieri RL. Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery. OBG Manage. 2010;22(3):12–15.

- Tian YC, Long TF, Dai YN. Pregnancy outcomes following different surgical approaches of myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):350–357.

- Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of a single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1326–1330.

- Claeys J, Hellendoorn I, Hamerlynck T, Bosteels J, Weyers S. The risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(3):197–206.

- Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312–324.

- Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D. Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(12):1789–1804.

- Okin CR, Guido RS, Meyn LA, Ramanathan S. Vasopressin during abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):867–872.

- Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N, Wiysonge CS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to reduce hemorrhage during myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100(1):4–9.

- Barbieri RL. Give vasopressin to reduce bleeding in gynecologic surgery. OBG Manage. 2010;22(3):12–15.

- Tian YC, Long TF, Dai YN. Pregnancy outcomes following different surgical approaches of myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):350–357.

- Bujold E, Bujold C, Hamilton EF, Harel F, Gauthier RJ. The impact of a single-layer or double-layer closure on uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1326–1330.

- Claeys J, Hellendoorn I, Hamerlynck T, Bosteels J, Weyers S. The risk of uterine rupture after myomectomy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11(3):197–206.

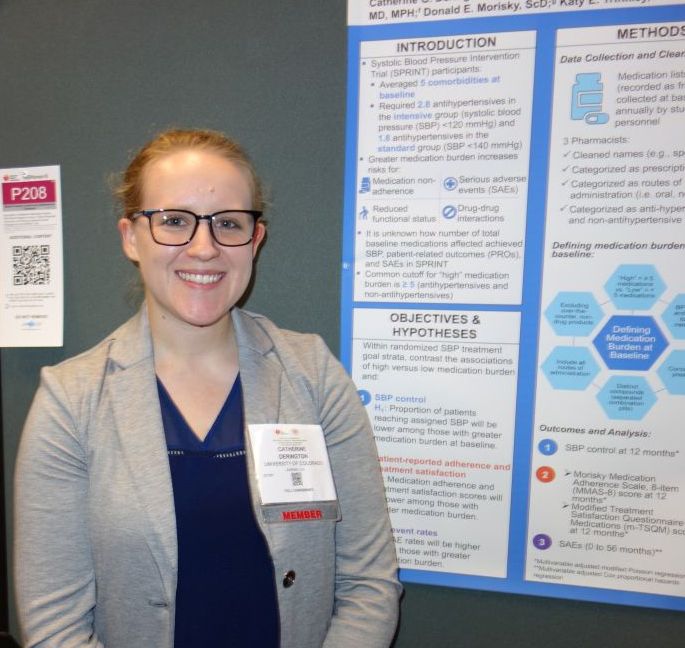

SPRINT: Pill burden affects ability to reach systolic BP control

CHICAGO –

“Five or more medications” meant total drug burden, both for hypertension and comorbidities. “When you are treating a patient for hypertension, you care about blood pressure, but you also need to care about” what else they are on, and their total drug burden, “because it affects their ability to get to their blood pressure goal, especially if you’re targeting intensive control,” said lead investigator Catherine Derington, PharmD, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

Good old-fashioned exercise and weight loss remain potent non–pill options, she noted at the joint scientific sessions of AHA Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

The take-home message is to use more combination drugs for hypertension “to get patients on fewer pills.” Also, “eliminate drugs [patients] don’t need,” said SPRINT investigator William C. Cushman, MD, professor of medicine and physiology at the University of Tennessee, Memphis, when asked what he thought of the new findings.

SPRINT [Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial] found that targeting systolic blood pressures below 120 mm Hg, as compared with less than 140 mm Hg, led to lower rates of MI, stroke, heart failure, and death from any cause.

Medication burden had no effect on patients in the 140 mm Hg group; they achieved a mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 136 mm Hg at 1 year, whether they were on fewer than five drugs a day or more. Hitting that target took an average of 1.8 hypertension medications.

Reaching 120 mm Hg generally took one extra drug (an average of 2.8), and the overall pill burden did matter; 2,463 patients in the intensive arm on fewer than five medications dropped their mean SBP 20 mm Hg at one year, while 1,698 taking more than five had a 15–mm Hg reduction. The group with the lower pill burden had a mean SBP of 120.6 mm Hg and those taking five or more had a mean SBP of 122.5 mm Hg. It’s a small difference but likely important.

Comorbidities in SPRINT included kidney and cardiovascular disease, among others, but the trial excluded patients with diabetes. Many patients were on statins and aspirin.

Pharmacy review is especially a good idea in the elderly.