User login

B-cell maturation antigen targeted in myeloma trials

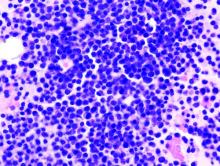

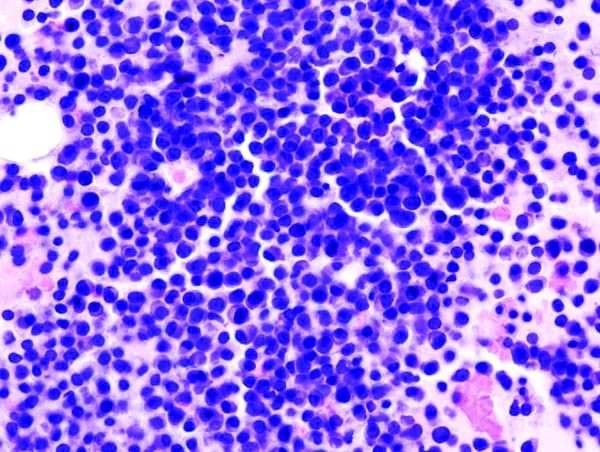

NEW YORK – Three novel treatment strategies that target B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) have shown promise in recent multiple myeloma clinical trials, according to Shaji K. Kumar, MD, of the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center in Rochester, Minn.

These strategies include B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies, bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs), and a BCMA antibody–drug conjugate, Dr. Kumar said at the annual congress on Hematologic Malignancies held by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“Clearly, there are a lot of exciting drugs that are currently in clinical trials, but these three platforms appear to be much more advanced than the others, and hopefully we will see that in the clinic in the near future,” Dr. Kumar said.

The antibody-drug conjugate, GSK2857916, is a humanized IgG1 anti-BCMA antibody conjugated to a microtubule-disrupting agent that has produced an overall response rate in 67% in a group of myeloma patients who had previously received multiple standard-of-care agents.

“Some of the responses were quite durable, lasting several months,” he said.

Now, GSK2857916 is being evaluated in a variety of different combinations, including in a phase 2 study of the antibody-drug conjugate in combination with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone, or bortezomib plus dexamethasone, in patients with relapsed or refractory disease.

Some of the most “exciting” data with anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy in myeloma involves bb2121, which showed durable clinical responses in heavily pretreated patients, according to data presented at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“The overall response rate is quite significant,” said Dr. Kumar, who related a 94% rate of overall response that was even higher in patients treated with doses of 150 x 106 CAR+ T cells or more. Many of the response were lasting, he said, with five patients in ongoing response for more than 1 year.

“The results are exciting enough that this is actually moving forward with registration trials,” Dr. Kumar said.

Additionally, promising results have been presented on a novel CAR T-cell product, LCAR-B38M, which principally targets BCMA and led to a significant number of patients who achieved stringent complete response that lasted beyond 1 year.

Multiple BCMA-targeting CAR T-cell products that use different vectors and costimulatory molecules are currently undergoing clinical trials, Dr. Kumar said.

In contrast to CAR T-cell products that must be customized to each patient in a process that takes weeks, BiTEs are a ready-made approach to allow T cells to engage with tumor cells.

“In patients with advanced disease, a lot can change in that short time frame, so having an approach that is off the shelf, which is not patient specific, is quite attractive,” Dr. Kumar said.

BCMA-directed BiTE therapies under investigation include AMG 420 and PF-06863135, he added.

Dr. Kumar reported one disclosure related to Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories.

NEW YORK – Three novel treatment strategies that target B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) have shown promise in recent multiple myeloma clinical trials, according to Shaji K. Kumar, MD, of the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center in Rochester, Minn.

These strategies include B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies, bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs), and a BCMA antibody–drug conjugate, Dr. Kumar said at the annual congress on Hematologic Malignancies held by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“Clearly, there are a lot of exciting drugs that are currently in clinical trials, but these three platforms appear to be much more advanced than the others, and hopefully we will see that in the clinic in the near future,” Dr. Kumar said.

The antibody-drug conjugate, GSK2857916, is a humanized IgG1 anti-BCMA antibody conjugated to a microtubule-disrupting agent that has produced an overall response rate in 67% in a group of myeloma patients who had previously received multiple standard-of-care agents.

“Some of the responses were quite durable, lasting several months,” he said.

Now, GSK2857916 is being evaluated in a variety of different combinations, including in a phase 2 study of the antibody-drug conjugate in combination with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone, or bortezomib plus dexamethasone, in patients with relapsed or refractory disease.

Some of the most “exciting” data with anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy in myeloma involves bb2121, which showed durable clinical responses in heavily pretreated patients, according to data presented at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“The overall response rate is quite significant,” said Dr. Kumar, who related a 94% rate of overall response that was even higher in patients treated with doses of 150 x 106 CAR+ T cells or more. Many of the response were lasting, he said, with five patients in ongoing response for more than 1 year.

“The results are exciting enough that this is actually moving forward with registration trials,” Dr. Kumar said.

Additionally, promising results have been presented on a novel CAR T-cell product, LCAR-B38M, which principally targets BCMA and led to a significant number of patients who achieved stringent complete response that lasted beyond 1 year.

Multiple BCMA-targeting CAR T-cell products that use different vectors and costimulatory molecules are currently undergoing clinical trials, Dr. Kumar said.

In contrast to CAR T-cell products that must be customized to each patient in a process that takes weeks, BiTEs are a ready-made approach to allow T cells to engage with tumor cells.

“In patients with advanced disease, a lot can change in that short time frame, so having an approach that is off the shelf, which is not patient specific, is quite attractive,” Dr. Kumar said.

BCMA-directed BiTE therapies under investigation include AMG 420 and PF-06863135, he added.

Dr. Kumar reported one disclosure related to Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories.

NEW YORK – Three novel treatment strategies that target B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) have shown promise in recent multiple myeloma clinical trials, according to Shaji K. Kumar, MD, of the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center in Rochester, Minn.

These strategies include B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)–specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies, bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs), and a BCMA antibody–drug conjugate, Dr. Kumar said at the annual congress on Hematologic Malignancies held by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“Clearly, there are a lot of exciting drugs that are currently in clinical trials, but these three platforms appear to be much more advanced than the others, and hopefully we will see that in the clinic in the near future,” Dr. Kumar said.

The antibody-drug conjugate, GSK2857916, is a humanized IgG1 anti-BCMA antibody conjugated to a microtubule-disrupting agent that has produced an overall response rate in 67% in a group of myeloma patients who had previously received multiple standard-of-care agents.

“Some of the responses were quite durable, lasting several months,” he said.

Now, GSK2857916 is being evaluated in a variety of different combinations, including in a phase 2 study of the antibody-drug conjugate in combination with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone, or bortezomib plus dexamethasone, in patients with relapsed or refractory disease.

Some of the most “exciting” data with anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy in myeloma involves bb2121, which showed durable clinical responses in heavily pretreated patients, according to data presented at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“The overall response rate is quite significant,” said Dr. Kumar, who related a 94% rate of overall response that was even higher in patients treated with doses of 150 x 106 CAR+ T cells or more. Many of the response were lasting, he said, with five patients in ongoing response for more than 1 year.

“The results are exciting enough that this is actually moving forward with registration trials,” Dr. Kumar said.

Additionally, promising results have been presented on a novel CAR T-cell product, LCAR-B38M, which principally targets BCMA and led to a significant number of patients who achieved stringent complete response that lasted beyond 1 year.

Multiple BCMA-targeting CAR T-cell products that use different vectors and costimulatory molecules are currently undergoing clinical trials, Dr. Kumar said.

In contrast to CAR T-cell products that must be customized to each patient in a process that takes weeks, BiTEs are a ready-made approach to allow T cells to engage with tumor cells.

“In patients with advanced disease, a lot can change in that short time frame, so having an approach that is off the shelf, which is not patient specific, is quite attractive,” Dr. Kumar said.

BCMA-directed BiTE therapies under investigation include AMG 420 and PF-06863135, he added.

Dr. Kumar reported one disclosure related to Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NCCN HEMATOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES CONGRESS

Pazopanib is active against renal, other neoplasms of von Hippel-Lindau disease

The oral, multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor pazopanib (Votrient) is active and safe in patients with renal cell carcinoma and other neoplasms caused by von Hippel-Lindau disease, a phase 2 trial has found.

Eric Jonasch, MD, and his coinvestigators at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, conducted the single-arm trial among 31 adult patients with clinical manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease, an autosomal dominant disorder that currently has no approved treatment.

All patients were treated with open-label pazopanib (800 mg daily with dose reductions permitted) for 24 weeks, with an option to continue thereafter. Pazopanib derives its antiangiogenic and antineoplastic activity from its selective inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR)–1, –2, and –3; c-KIT; and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR). It is currently approved by the FDA for treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma and advanced soft-tissue sarcoma.

The trial was stopped before attaining planned enrollment because accrual slowed and it met a prespecified toxicity stopping threshold, according to results reported in Lancet Oncology.

At a median follow-up of 12 months, 42% of patients overall had an objective response to pazopanib. By site, response was seen in 52% of 59 renal cell carcinomas, 53% of 17 pancreatic lesions (mainly serous cystadenomas), and 4% of 49 CNS hemangioblastomas; the median reduction in tumor size was 40.5%, 30.5%, and 13%, respectively.

Slightly more than half of patients, 52%, opted to stay on pazopanib after 24 weeks, with the longest duration being 60 months at data cutoff.

Some 13% of patients withdrew from the study because of grade 3 or 4 transaminitis, and 10% stopped treatment because of general intolerance related to multiple grade 1 and 2 toxicities. There were three treatment-related serious adverse events: one case of appendicitis, one case of gastritis, and one case of fatal CNS bleeding after a fall.

“Pazopanib was associated with encouraging preliminary activity in von Hippel-Lindau disease, with a side effect profile consistent with that seen in previous trials,” the investigators concluded. “Pazopanib could be considered as a treatment choice for patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease and growing lesions, or to reduce the size of unresectable lesions in these patients.”

Dr. Jonasch disclosed that he receives research support and honoraria from Novartis. The study was funded by Novartis and by a National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute core grant.

SOURCE: Jonasch E et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30487-X,

The oral, multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor pazopanib (Votrient) is active and safe in patients with renal cell carcinoma and other neoplasms caused by von Hippel-Lindau disease, a phase 2 trial has found.

Eric Jonasch, MD, and his coinvestigators at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, conducted the single-arm trial among 31 adult patients with clinical manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease, an autosomal dominant disorder that currently has no approved treatment.

All patients were treated with open-label pazopanib (800 mg daily with dose reductions permitted) for 24 weeks, with an option to continue thereafter. Pazopanib derives its antiangiogenic and antineoplastic activity from its selective inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR)–1, –2, and –3; c-KIT; and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR). It is currently approved by the FDA for treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma and advanced soft-tissue sarcoma.

The trial was stopped before attaining planned enrollment because accrual slowed and it met a prespecified toxicity stopping threshold, according to results reported in Lancet Oncology.

At a median follow-up of 12 months, 42% of patients overall had an objective response to pazopanib. By site, response was seen in 52% of 59 renal cell carcinomas, 53% of 17 pancreatic lesions (mainly serous cystadenomas), and 4% of 49 CNS hemangioblastomas; the median reduction in tumor size was 40.5%, 30.5%, and 13%, respectively.

Slightly more than half of patients, 52%, opted to stay on pazopanib after 24 weeks, with the longest duration being 60 months at data cutoff.

Some 13% of patients withdrew from the study because of grade 3 or 4 transaminitis, and 10% stopped treatment because of general intolerance related to multiple grade 1 and 2 toxicities. There were three treatment-related serious adverse events: one case of appendicitis, one case of gastritis, and one case of fatal CNS bleeding after a fall.

“Pazopanib was associated with encouraging preliminary activity in von Hippel-Lindau disease, with a side effect profile consistent with that seen in previous trials,” the investigators concluded. “Pazopanib could be considered as a treatment choice for patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease and growing lesions, or to reduce the size of unresectable lesions in these patients.”

Dr. Jonasch disclosed that he receives research support and honoraria from Novartis. The study was funded by Novartis and by a National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute core grant.

SOURCE: Jonasch E et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30487-X,

The oral, multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor pazopanib (Votrient) is active and safe in patients with renal cell carcinoma and other neoplasms caused by von Hippel-Lindau disease, a phase 2 trial has found.

Eric Jonasch, MD, and his coinvestigators at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, conducted the single-arm trial among 31 adult patients with clinical manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease, an autosomal dominant disorder that currently has no approved treatment.

All patients were treated with open-label pazopanib (800 mg daily with dose reductions permitted) for 24 weeks, with an option to continue thereafter. Pazopanib derives its antiangiogenic and antineoplastic activity from its selective inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR)–1, –2, and –3; c-KIT; and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR). It is currently approved by the FDA for treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma and advanced soft-tissue sarcoma.

The trial was stopped before attaining planned enrollment because accrual slowed and it met a prespecified toxicity stopping threshold, according to results reported in Lancet Oncology.

At a median follow-up of 12 months, 42% of patients overall had an objective response to pazopanib. By site, response was seen in 52% of 59 renal cell carcinomas, 53% of 17 pancreatic lesions (mainly serous cystadenomas), and 4% of 49 CNS hemangioblastomas; the median reduction in tumor size was 40.5%, 30.5%, and 13%, respectively.

Slightly more than half of patients, 52%, opted to stay on pazopanib after 24 weeks, with the longest duration being 60 months at data cutoff.

Some 13% of patients withdrew from the study because of grade 3 or 4 transaminitis, and 10% stopped treatment because of general intolerance related to multiple grade 1 and 2 toxicities. There were three treatment-related serious adverse events: one case of appendicitis, one case of gastritis, and one case of fatal CNS bleeding after a fall.

“Pazopanib was associated with encouraging preliminary activity in von Hippel-Lindau disease, with a side effect profile consistent with that seen in previous trials,” the investigators concluded. “Pazopanib could be considered as a treatment choice for patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease and growing lesions, or to reduce the size of unresectable lesions in these patients.”

Dr. Jonasch disclosed that he receives research support and honoraria from Novartis. The study was funded by Novartis and by a National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute core grant.

SOURCE: Jonasch E et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30487-X,

FROM LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Pazopanib appears efficacious and safe for treating neoplasms associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease.

Major finding: The objective response rate was 42% overall, with response seen in 52% of renal cell carcinomas.

Study details: Single-center, single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial among 31 adult patients with clinical manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease who were treated with pazopanib for at least 24 weeks.

Disclosures: Dr. Jonasch disclosed that he receives research support and honoraria from Novartis. The study was funded by Novartis and by a National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute core grant.

Source: Jonasch E et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30487-X.

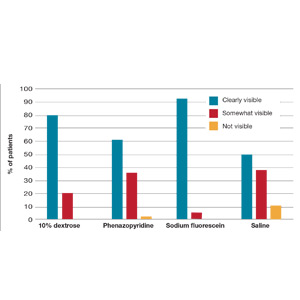

Mobile App Rankings in Dermatology

As technology continues to advance, so too does its accessibility to the general population. In 2013, 56% of Americans owned a smartphone versus 77% in 2017.1With the increase in mobile applications (apps) available, it is no surprise that the market has extended into the medical field, with dermatology being no exception.2 The majority of dermatology apps can be classified as teledermatology apps, followed by self-surveillance, disease guide, and reference apps. Additional types of dermatology apps include dermoscopy, conference, education, photograph storage and sharing, and journal apps, and others.2 In this study, we examined Apple App Store rankings to determine the types of dermatology apps that are most popular among patients and physicians.

METHODS

A popular app rankings analyzer (App Annie) was used to search for dermatology apps along with their App Store rankings.3 Although iOS is not the most popular mobile device operating system, we chose to evaluate app rankings via the App Store because iPhones are the top-selling individual phones of any kind in the United States.4

We performed our analysis on a single day (July 14, 2018) given that app rankings can change daily. We incorporated the following keywords, which were commonly used in other dermatology app studies: dermatology, psoriasis, rosacea, acne, skin cancer, melanoma, eczema, and teledermatology. The category ranking was defined as the rank of a free or paid app in the App Store’s top charts for the selected country (United States), market (Apple), and device (iPhone) within their app category (Medical). Inclusion criteria required a ranking in the top 1500 Medical apps and being categorized in the App Store as a Medical app. Exclusion criteria included apps that focused on cosmetics, private practice, direct advertisements, photograph editing, or claims to cure skin disease, as well as non–English-language apps. The App Store descriptions were assessed to determine the type of each app (eg, teledermatology, disease guide) and target audience (patient, physician, or both).

Another search was performed using the same keywords but within the Health and Fitness category to capture potentially more highly ranked apps among patients. We also conducted separate searches within the Medical category using the keywords billing, coding, and ICD (International Classification of Diseases) to evaluate rankings for billing/coding apps, as well as EMR and electronic medical records for electronic medical record (EMR) apps.

RESULTS

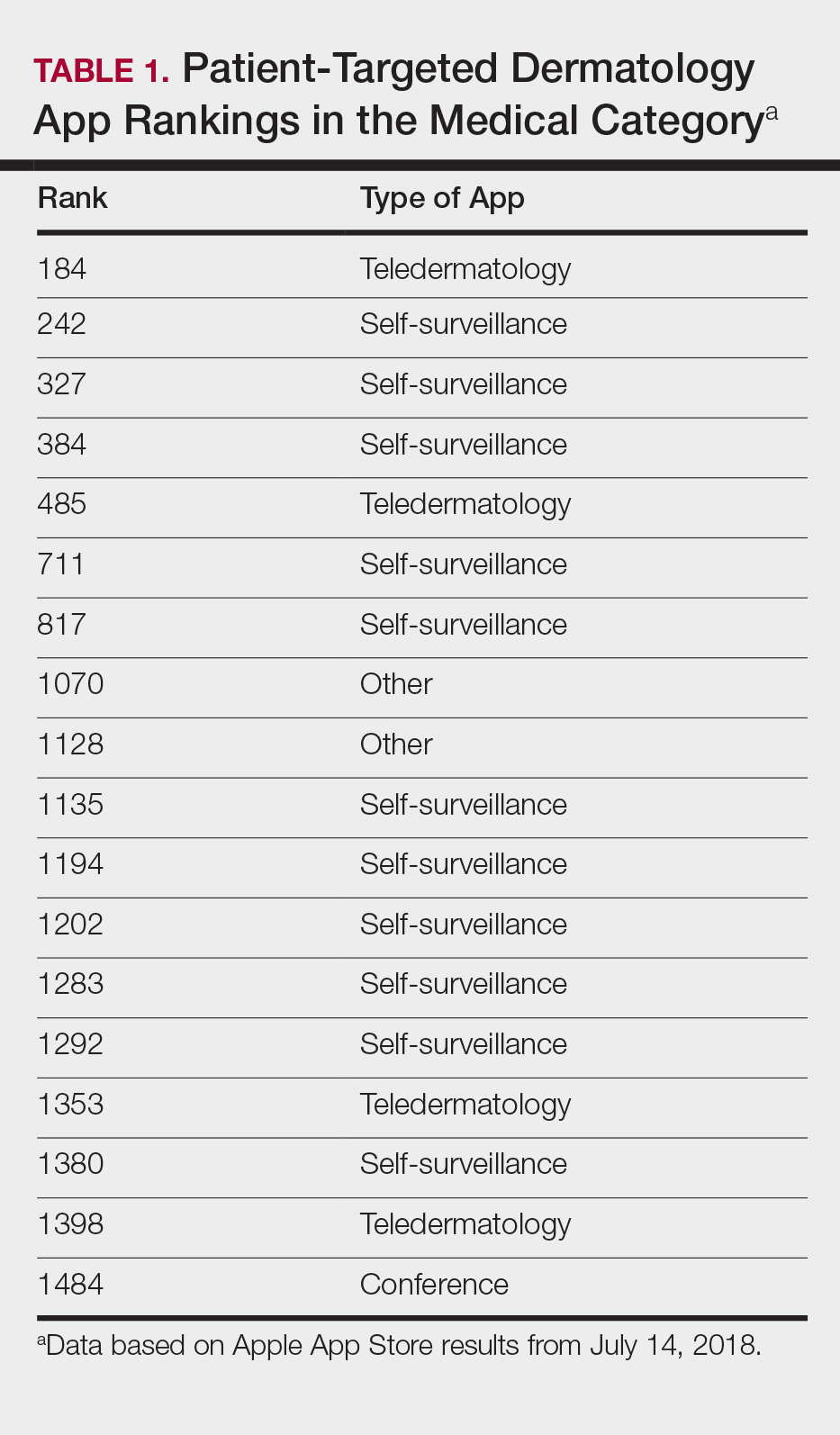

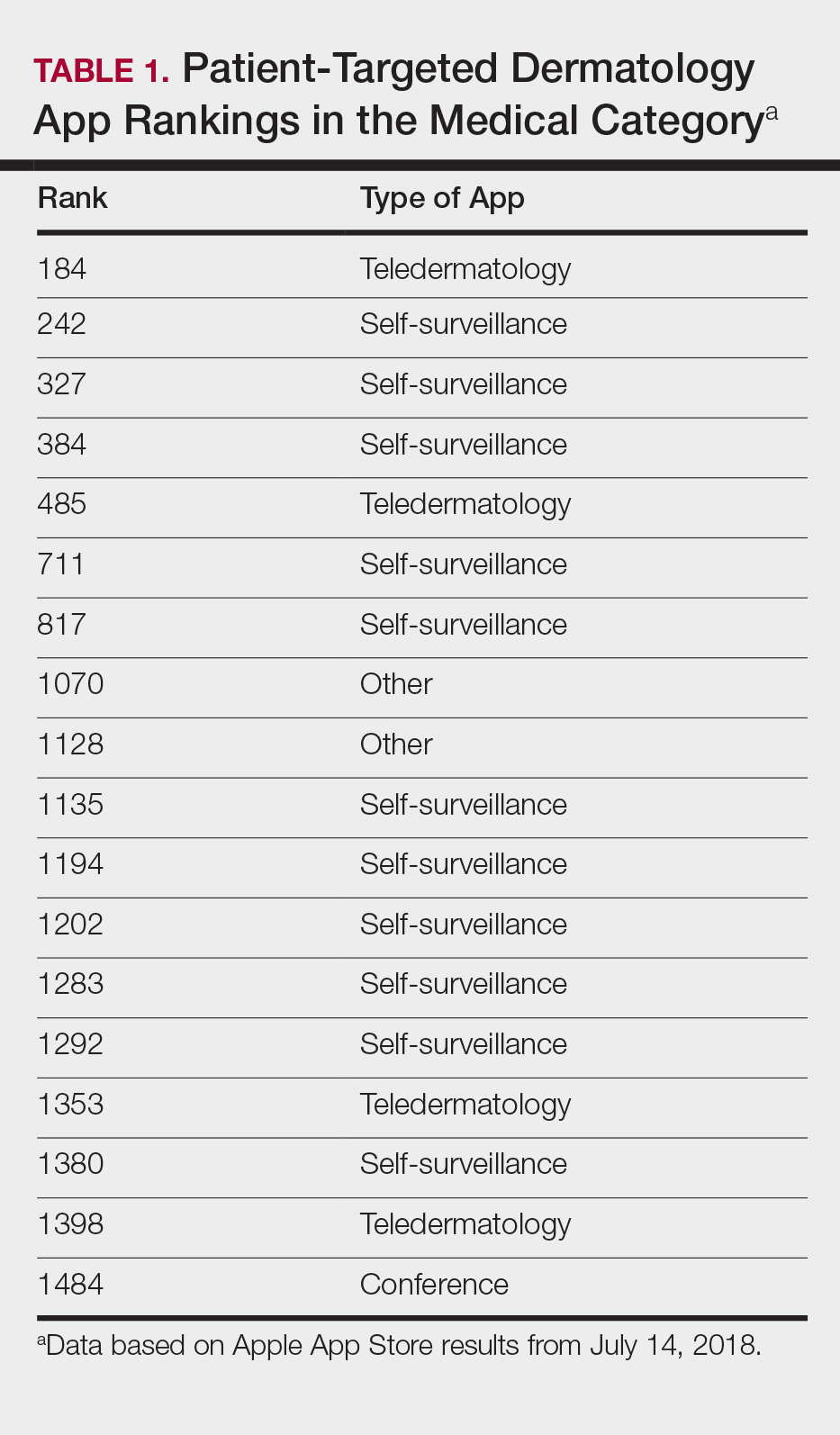

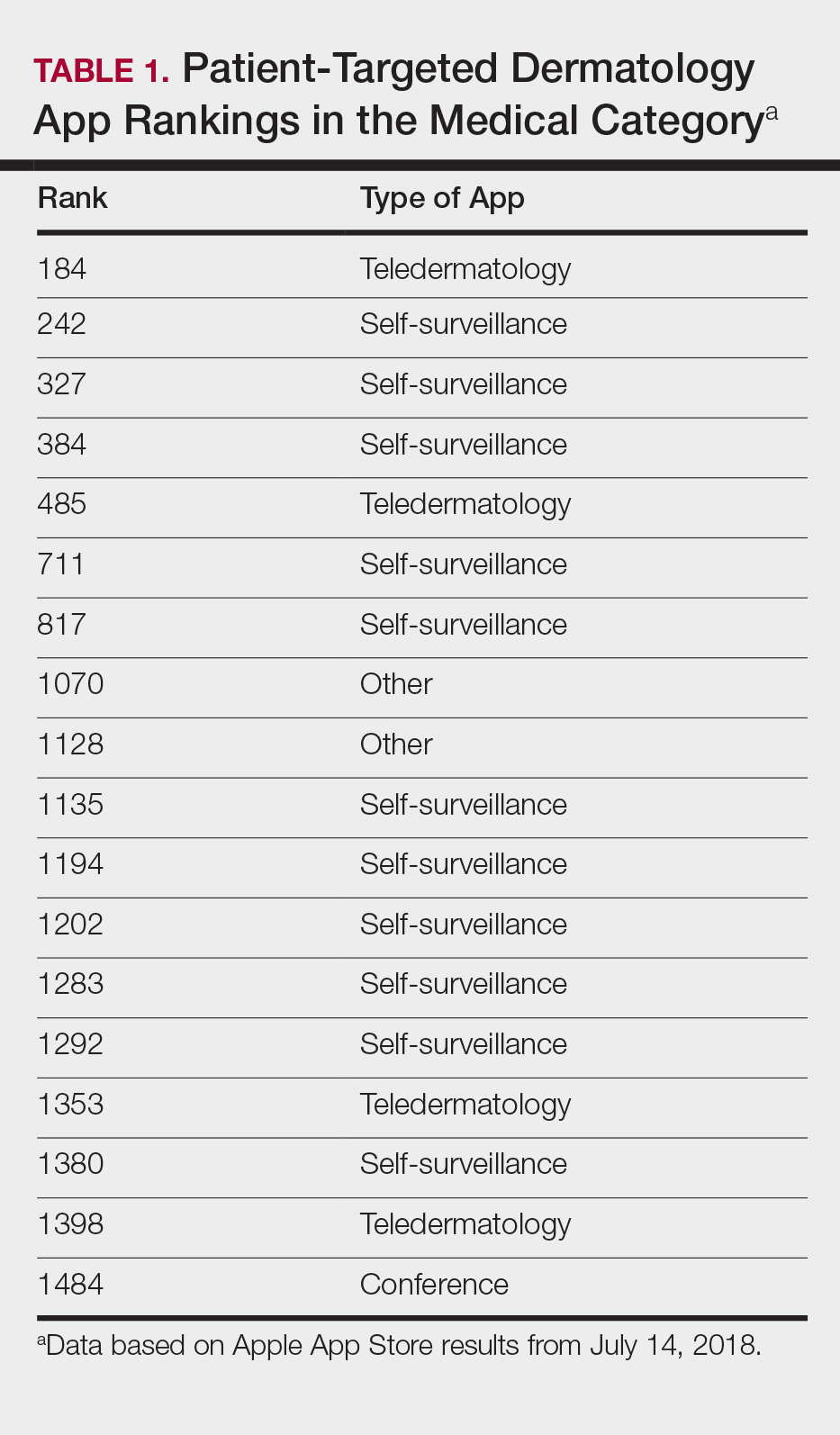

The initial search yielded 851 results, which was narrowed down to 29 apps after applying the exclusion criteria. Of note, prior to application of the exclusion criteria, one dermatology app that was considered to be a direct advertisement app claiming to cure acne was ranked fourth of 1500 apps in the Medical category. However, the majority of the search results were excluded because they were not popular enough to be ranked among the top 1500 apps. There were more ranked dermatology apps in the Medical category targeting patients than physicians; 18 of 29 (62%) qualifying apps targeted patients and 11 (38%) targeted physicians (Tables 1 and 2). No apps targeted both groups. The most common type of ranked app targeting patients was self-surveillance (11/18), and the most common type targeting physicians was reference (8/11). The highest ranked app targeting patients was a teledermatology app with a ranking of 184, and the highest ranked app targeting physicians was educational, ranked 353. The least common type of ranked apps targeting patients were “other” (2/18 [11%]; 1 prescription and 1 UV monitor app) and conference (1/18 [6%]). The least common type of ranked apps targeting physicians were education (2/11 [18%]) and dermoscopy (1/11 [9%]).

Our search of the Health and Fitness category yielded 6 apps, all targeting patients; 3 (50%) were self-surveillance apps, and 3 (50%) were classified as other (2 UV monitors and a conferencing app for cancer emotional support)(Table 3).

Our search of the Medical category for billing/coding and EMR apps yielded 232 and 164 apps, respectively; of them, 49 (21%) and 54 (33%) apps were ranked. These apps did not overlap with the dermatology-related search criteria; thus, we were not able to ascertain how many of these apps were used specifically by health care providers in dermatology.

COMMENT

Patient Apps

The most common apps used by patients are fitness and nutrition tracker apps categorized as Health and Fitness5,6; however, the majority of ranked dermatology apps are categorized as Medical per our findings. In a study of 557 dermatology patients, it was found that among the health-related apps they used, the most common apps after fitness/nutrition were references, followed by patient portals, self-surveillance, and emotional assistance apps.6 Our search was consistent with these findings, suggesting that the most desired dermatology apps by patients are those that allow them to be proactive with their health. It is no surprise that the top-ranked app targeting patients was a teledermatology app, followed by multiple self-surveillance apps. The highest ranked self-surveillance app in the Health and Fitness category focused on monitoring the effects of nutrition on symptoms of diseases including skin disorders, while the highest ranked (as well as the majority of) self-surveillance apps in the Medical category encompassed mole monitoring and cancer risk calculators.

Benefits of the ranked dermatology apps in the Medical and Health and Fitness categories targeting patients include more immediate access to health care and education. Despite this popularity among patients, Masud et al7 demonstrated that only 20.5% (9/44) of dermatology apps targeting patients may be reliable resources based on a rubric created by the investigators. Overall, there remains a research gap for a standardized scientific approach to evaluating app validity and reliability.

Teledermatology

Teledermatology apps are the most common dermatology apps,2 allowing for remote evaluation of patients through either live consultations or transmittance of medical information for later review by board-certified physicians.8 Features common to many teledermatology apps include accessibility on Android (Google Inc) and iOS as well as a web version. Security and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliance is especially important and is enforced through user authentications, data encryption, and automatic logout features. Data is not stored locally and is secured on a private server with backup. Referring providers and consultants often can communicate within the app. Insurance providers also may cover teledermatology services, and if not, the out-of-pocket costs often are affordable.

The highest-ranked patient app (ranked 184 in the Medical category) was a teledermatology app that did not meet the American Telemedicine Association standards for teledermatology apps.9 The popularity of this app among patients may have been attributable to multiple ease-of-use and turnaround time features. The user interface was simplistic, and the design was appealing to the eye. The entry field options were minimal to avoid confusion. The turnaround time to receive a diagnosis depended on 1 of 3 options, including a more rapid response for an increased cost. Ease of use was the highlight of this app at the cost of accuracy, as the limited amount of information that users were required to provide physicians compromised diagnostic accuracy in this app.

For comparison, we chose a nonranked (and thus less frequently used) teledermatology app that had previously undergone scientific evaluation using 13 evaluation criteria specific to teledermatology.10 The app also met the American Telemedicine Association standard for teledermatology apps.9 The app was originally a broader telemedicine app but featured a section specific to teledermatology. The user interface was simple but professional, almost resembling an EMR. The input fields included a comprehensive history that permitted a better evaluation of a lesion but might be tedious for users. This app boasted professionalism and accuracy, but from a user standpoint, it may have been too time-consuming.

Striking a balance between ensuring proper care versus appealing to patients is a difficult but important task. Based on this study, it appears that popular patient apps may in fact have less scientific rationale and therefore potentially less accuracy.

Self-surveillance

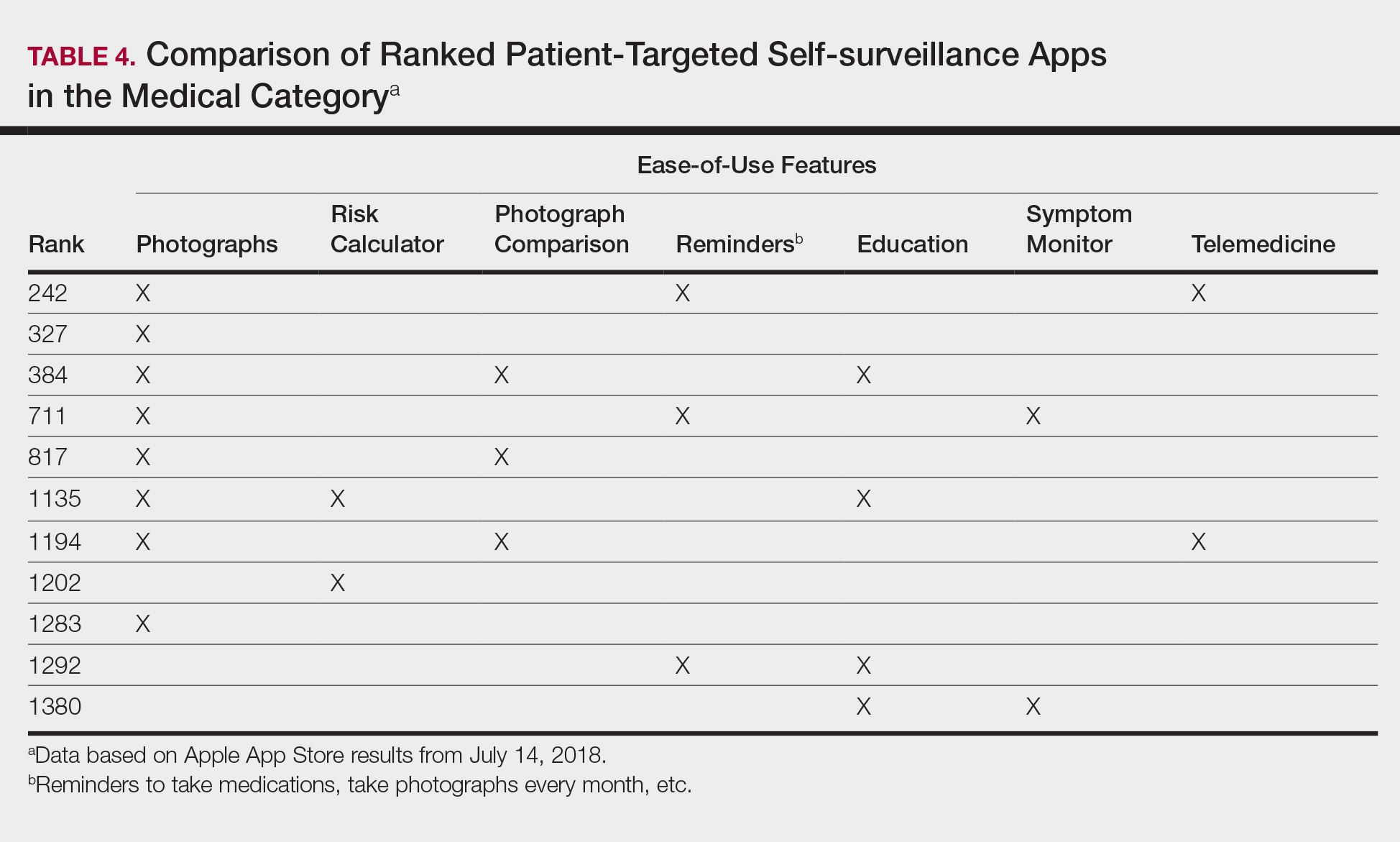

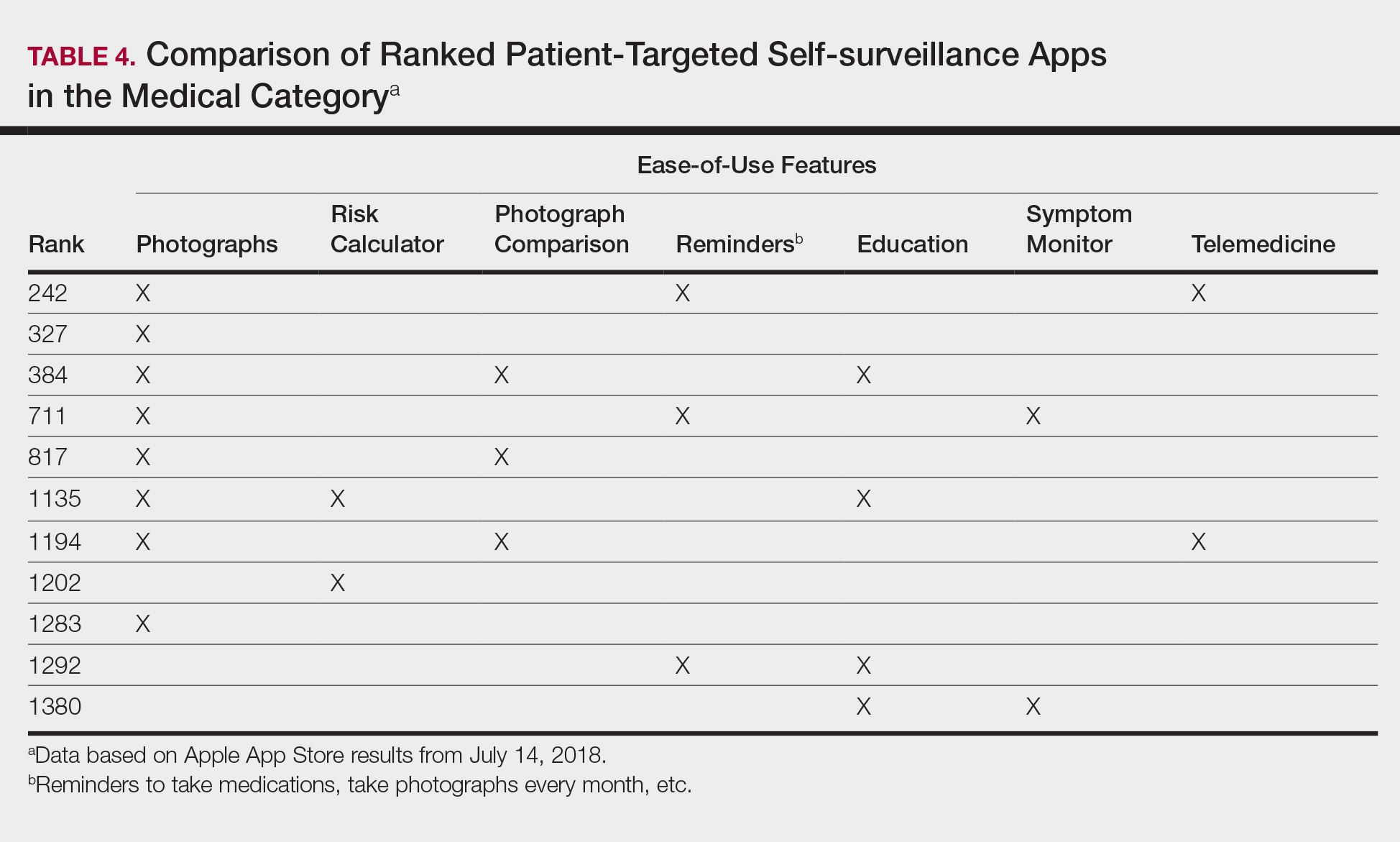

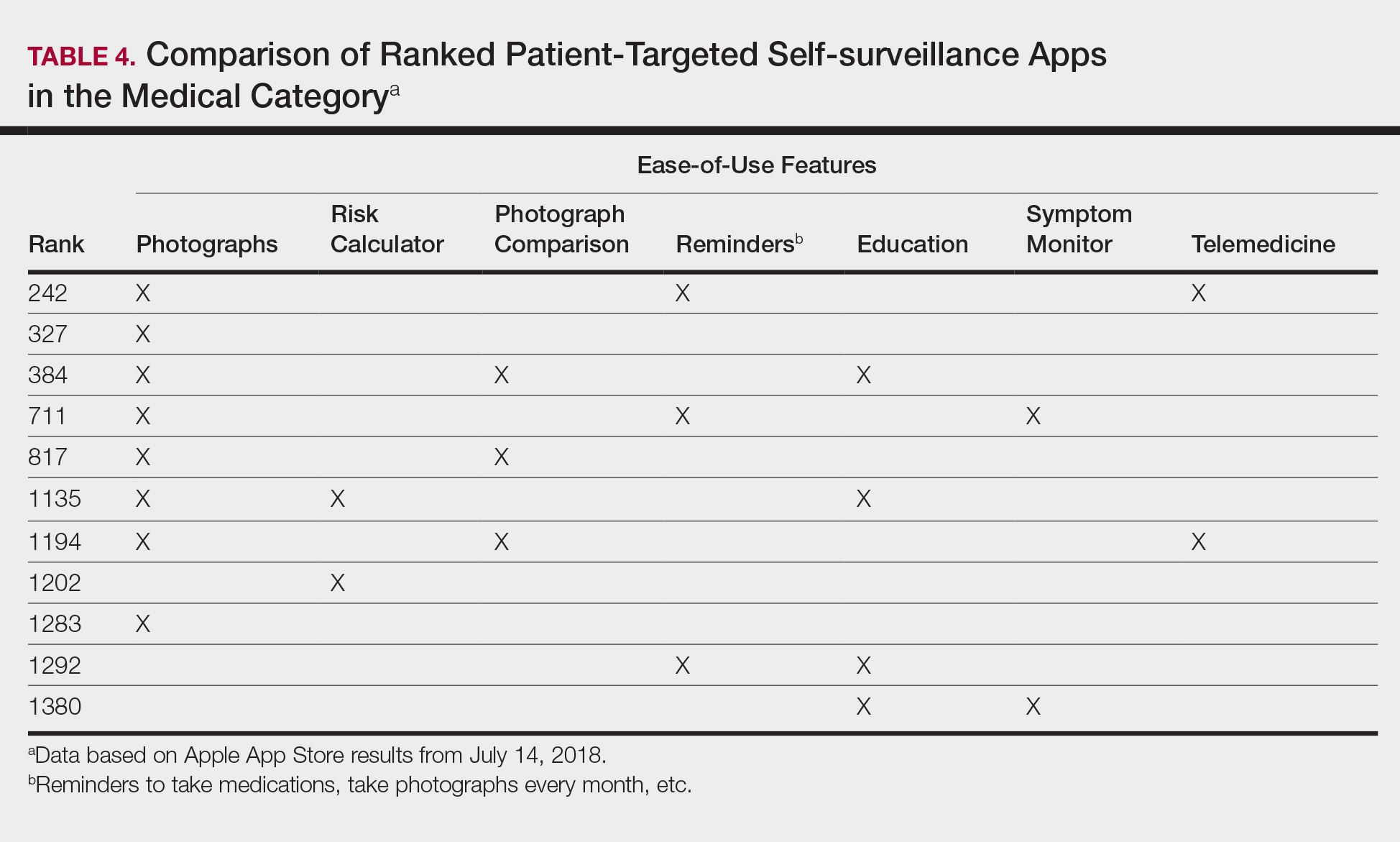

Although self-surveillance apps did not account for the highest-ranked app, they were the most frequently ranked app type in our study. Most of the ranked self-surveillance apps in the Medical category were for monitoring lesions over time to assess for changes. These apps help users take photographs that are well organized in a single, easy-to-find location. Some apps were risk calculators that assessed the risk for malignancies using a questionnaire. The majority of these self-surveillance apps were specific to skin cancer detection. Of note, one of the ranked self-surveillance apps assessed drug effectiveness by monitoring clinical appearance and symptoms. The lowest ranked self-surveillance app in the top 1500 ranked Medical apps in our search monitored cancer symptoms not specific to dermatology. Although this app had a low ranking (1380/1500), it received a high number of reviews and was well rated at 4.8 out of 5 stars; therefore, it seemed more helpful than the other higher-ranked apps targeting patients, which had higher rankings but minimal to no reviews or ratings. A comparison of the ease-of-use features of all the ranked patient-targeted self-surveillance apps in the Medical category is provided in Table 4.

Physician Apps

After examining the results of apps targeting physicians, we realized that the data may be accurate but may not be as representative of all currently practicing dermatology providers. Given the increased usage of apps among younger age groups,11 our data may be skewed toward medical students and residents, supported by the fact that the top-ranked physician app in our study was an education app and the majority were reference apps. Future studies are needed to reexamine app ranking as this age group transitions from entry-level health care providers in the next 5 to 10 years. These findings also suggest less frequent app use among more veteran health care providers within our specific search parameters. Therefore, we decided to do subsequent searches for available billing/coding and EMR apps, which were many, but as mentioned above, none were specific to dermatology.

General Dermatology References

Most of the dermatology reference apps were formatted as e-books; however, other apps such as the Amazon Kindle app (categorized under Books) providing access to multiple e-books within one app were not included. Some apps included study aid features (eg, flash cards, quizzes), and topics spanned both dermatology and dermatopathology. Apps provide a unique way for on-the-go studying for dermatologists in training, and if the usage continues to grow, there may be a need for increased formal integration in dermatology education in the future.

Journals

Journal apps were not among those listed in the top-ranked apps we evaluated, which we suspect may be because journals were categorized differently from one journal to the next; for example, the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology was ranked 1168 in the Magazines and Newspapers category. On the other hand, Dermatology World was ranked 1363 in the Reference category. An article’s citation affects the publishing journal’s impact factor, which is one of the most important variables in measuring a journal’s influence. In the future, there may be other variables that could aid in understanding journal impact as it relates to the journal’s accessibility.

Limitations

Our study did not look at Android apps. The top chart apps in the Android and Apple App Stores use undisclosed algorithms likely involving different characteristics such as number of downloads, frequency of updates, number of reviews, ratings, and more. Thus, the rankings across these different markets would not be comparable. Although our choice of keywords stemmed from the majority of prior studies looking at dermatology apps, our search was limited due to the use of these specific keywords. To avoid skewing data by cross-comparison of noncomparable categories, we could not compare apps in the Medical category versus those in other categories.

CONCLUSION

There seems to be a disconnect between the apps that are popular among patients and the scientific validity of the apps. As app usage increases among dermatology providers, whose demographic is shifting younger and younger, apps may become more incorporated in our education, and as such, it will become more critical to develop formal scientific standards. Given these future trends, we may need to increase our current literature and understanding of apps in dermatology with regard to their impact on both patients and health care providers.

- Poushter J, Bishop C, Chwe H. Social media use continues to rise in developing countries but plateaus across developed ones. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewglobal.org/2018/06/19/social-media-use-continues-to-rise-in-developing-countries-but-plateaus-across-developed-ones/#table. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, et al. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology—2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. pii:13030/qt3hs7n9z6.

- App Annie website. https://www.appannie.com/top/. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Number of iPhone users in the United States from 2012 to 2016 (in millions). Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/232790/forecast-of-apple-users-in-the-us/. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Burkhart C. Medical mobile apps and dermatology. Cutis. 2012;90:278-281.

- Wolf JA, Moreau JF, Patton TJ, et al. Prevalence and impact of health-related internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients. Cutis. 2015;95:323-328.

- Masud A, Shafi S, Rao BK. Mobile medical apps for patient education: a graded review of available dermatology apps. Cutis. 2018;101:141-144.

- Walocko FM, Tejasvi T. Teledermatology applications in skin cancer diagnosis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:559-563.

- Krupinski E, Burdick A, Pak H, et al. American Telemedicine Association’s practice guidelines for teledermatology. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:289-302.

- Ho B, Lee M, Armstrong AW. Evaluation criteria for mobile teledermatology applications and comparison of major mobile teledermatology applications. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19:678-682.

- Number of mobile app hours per smartphone and tablet app user in the United States in June 2016, by age group. Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/323522/us-user-mobile-app-engagement-age/. Accessed September 18, 2018.

As technology continues to advance, so too does its accessibility to the general population. In 2013, 56% of Americans owned a smartphone versus 77% in 2017.1With the increase in mobile applications (apps) available, it is no surprise that the market has extended into the medical field, with dermatology being no exception.2 The majority of dermatology apps can be classified as teledermatology apps, followed by self-surveillance, disease guide, and reference apps. Additional types of dermatology apps include dermoscopy, conference, education, photograph storage and sharing, and journal apps, and others.2 In this study, we examined Apple App Store rankings to determine the types of dermatology apps that are most popular among patients and physicians.

METHODS

A popular app rankings analyzer (App Annie) was used to search for dermatology apps along with their App Store rankings.3 Although iOS is not the most popular mobile device operating system, we chose to evaluate app rankings via the App Store because iPhones are the top-selling individual phones of any kind in the United States.4

We performed our analysis on a single day (July 14, 2018) given that app rankings can change daily. We incorporated the following keywords, which were commonly used in other dermatology app studies: dermatology, psoriasis, rosacea, acne, skin cancer, melanoma, eczema, and teledermatology. The category ranking was defined as the rank of a free or paid app in the App Store’s top charts for the selected country (United States), market (Apple), and device (iPhone) within their app category (Medical). Inclusion criteria required a ranking in the top 1500 Medical apps and being categorized in the App Store as a Medical app. Exclusion criteria included apps that focused on cosmetics, private practice, direct advertisements, photograph editing, or claims to cure skin disease, as well as non–English-language apps. The App Store descriptions were assessed to determine the type of each app (eg, teledermatology, disease guide) and target audience (patient, physician, or both).

Another search was performed using the same keywords but within the Health and Fitness category to capture potentially more highly ranked apps among patients. We also conducted separate searches within the Medical category using the keywords billing, coding, and ICD (International Classification of Diseases) to evaluate rankings for billing/coding apps, as well as EMR and electronic medical records for electronic medical record (EMR) apps.

RESULTS

The initial search yielded 851 results, which was narrowed down to 29 apps after applying the exclusion criteria. Of note, prior to application of the exclusion criteria, one dermatology app that was considered to be a direct advertisement app claiming to cure acne was ranked fourth of 1500 apps in the Medical category. However, the majority of the search results were excluded because they were not popular enough to be ranked among the top 1500 apps. There were more ranked dermatology apps in the Medical category targeting patients than physicians; 18 of 29 (62%) qualifying apps targeted patients and 11 (38%) targeted physicians (Tables 1 and 2). No apps targeted both groups. The most common type of ranked app targeting patients was self-surveillance (11/18), and the most common type targeting physicians was reference (8/11). The highest ranked app targeting patients was a teledermatology app with a ranking of 184, and the highest ranked app targeting physicians was educational, ranked 353. The least common type of ranked apps targeting patients were “other” (2/18 [11%]; 1 prescription and 1 UV monitor app) and conference (1/18 [6%]). The least common type of ranked apps targeting physicians were education (2/11 [18%]) and dermoscopy (1/11 [9%]).

Our search of the Health and Fitness category yielded 6 apps, all targeting patients; 3 (50%) were self-surveillance apps, and 3 (50%) were classified as other (2 UV monitors and a conferencing app for cancer emotional support)(Table 3).

Our search of the Medical category for billing/coding and EMR apps yielded 232 and 164 apps, respectively; of them, 49 (21%) and 54 (33%) apps were ranked. These apps did not overlap with the dermatology-related search criteria; thus, we were not able to ascertain how many of these apps were used specifically by health care providers in dermatology.

COMMENT

Patient Apps

The most common apps used by patients are fitness and nutrition tracker apps categorized as Health and Fitness5,6; however, the majority of ranked dermatology apps are categorized as Medical per our findings. In a study of 557 dermatology patients, it was found that among the health-related apps they used, the most common apps after fitness/nutrition were references, followed by patient portals, self-surveillance, and emotional assistance apps.6 Our search was consistent with these findings, suggesting that the most desired dermatology apps by patients are those that allow them to be proactive with their health. It is no surprise that the top-ranked app targeting patients was a teledermatology app, followed by multiple self-surveillance apps. The highest ranked self-surveillance app in the Health and Fitness category focused on monitoring the effects of nutrition on symptoms of diseases including skin disorders, while the highest ranked (as well as the majority of) self-surveillance apps in the Medical category encompassed mole monitoring and cancer risk calculators.

Benefits of the ranked dermatology apps in the Medical and Health and Fitness categories targeting patients include more immediate access to health care and education. Despite this popularity among patients, Masud et al7 demonstrated that only 20.5% (9/44) of dermatology apps targeting patients may be reliable resources based on a rubric created by the investigators. Overall, there remains a research gap for a standardized scientific approach to evaluating app validity and reliability.

Teledermatology

Teledermatology apps are the most common dermatology apps,2 allowing for remote evaluation of patients through either live consultations or transmittance of medical information for later review by board-certified physicians.8 Features common to many teledermatology apps include accessibility on Android (Google Inc) and iOS as well as a web version. Security and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliance is especially important and is enforced through user authentications, data encryption, and automatic logout features. Data is not stored locally and is secured on a private server with backup. Referring providers and consultants often can communicate within the app. Insurance providers also may cover teledermatology services, and if not, the out-of-pocket costs often are affordable.

The highest-ranked patient app (ranked 184 in the Medical category) was a teledermatology app that did not meet the American Telemedicine Association standards for teledermatology apps.9 The popularity of this app among patients may have been attributable to multiple ease-of-use and turnaround time features. The user interface was simplistic, and the design was appealing to the eye. The entry field options were minimal to avoid confusion. The turnaround time to receive a diagnosis depended on 1 of 3 options, including a more rapid response for an increased cost. Ease of use was the highlight of this app at the cost of accuracy, as the limited amount of information that users were required to provide physicians compromised diagnostic accuracy in this app.

For comparison, we chose a nonranked (and thus less frequently used) teledermatology app that had previously undergone scientific evaluation using 13 evaluation criteria specific to teledermatology.10 The app also met the American Telemedicine Association standard for teledermatology apps.9 The app was originally a broader telemedicine app but featured a section specific to teledermatology. The user interface was simple but professional, almost resembling an EMR. The input fields included a comprehensive history that permitted a better evaluation of a lesion but might be tedious for users. This app boasted professionalism and accuracy, but from a user standpoint, it may have been too time-consuming.

Striking a balance between ensuring proper care versus appealing to patients is a difficult but important task. Based on this study, it appears that popular patient apps may in fact have less scientific rationale and therefore potentially less accuracy.

Self-surveillance

Although self-surveillance apps did not account for the highest-ranked app, they were the most frequently ranked app type in our study. Most of the ranked self-surveillance apps in the Medical category were for monitoring lesions over time to assess for changes. These apps help users take photographs that are well organized in a single, easy-to-find location. Some apps were risk calculators that assessed the risk for malignancies using a questionnaire. The majority of these self-surveillance apps were specific to skin cancer detection. Of note, one of the ranked self-surveillance apps assessed drug effectiveness by monitoring clinical appearance and symptoms. The lowest ranked self-surveillance app in the top 1500 ranked Medical apps in our search monitored cancer symptoms not specific to dermatology. Although this app had a low ranking (1380/1500), it received a high number of reviews and was well rated at 4.8 out of 5 stars; therefore, it seemed more helpful than the other higher-ranked apps targeting patients, which had higher rankings but minimal to no reviews or ratings. A comparison of the ease-of-use features of all the ranked patient-targeted self-surveillance apps in the Medical category is provided in Table 4.

Physician Apps

After examining the results of apps targeting physicians, we realized that the data may be accurate but may not be as representative of all currently practicing dermatology providers. Given the increased usage of apps among younger age groups,11 our data may be skewed toward medical students and residents, supported by the fact that the top-ranked physician app in our study was an education app and the majority were reference apps. Future studies are needed to reexamine app ranking as this age group transitions from entry-level health care providers in the next 5 to 10 years. These findings also suggest less frequent app use among more veteran health care providers within our specific search parameters. Therefore, we decided to do subsequent searches for available billing/coding and EMR apps, which were many, but as mentioned above, none were specific to dermatology.

General Dermatology References

Most of the dermatology reference apps were formatted as e-books; however, other apps such as the Amazon Kindle app (categorized under Books) providing access to multiple e-books within one app were not included. Some apps included study aid features (eg, flash cards, quizzes), and topics spanned both dermatology and dermatopathology. Apps provide a unique way for on-the-go studying for dermatologists in training, and if the usage continues to grow, there may be a need for increased formal integration in dermatology education in the future.

Journals

Journal apps were not among those listed in the top-ranked apps we evaluated, which we suspect may be because journals were categorized differently from one journal to the next; for example, the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology was ranked 1168 in the Magazines and Newspapers category. On the other hand, Dermatology World was ranked 1363 in the Reference category. An article’s citation affects the publishing journal’s impact factor, which is one of the most important variables in measuring a journal’s influence. In the future, there may be other variables that could aid in understanding journal impact as it relates to the journal’s accessibility.

Limitations

Our study did not look at Android apps. The top chart apps in the Android and Apple App Stores use undisclosed algorithms likely involving different characteristics such as number of downloads, frequency of updates, number of reviews, ratings, and more. Thus, the rankings across these different markets would not be comparable. Although our choice of keywords stemmed from the majority of prior studies looking at dermatology apps, our search was limited due to the use of these specific keywords. To avoid skewing data by cross-comparison of noncomparable categories, we could not compare apps in the Medical category versus those in other categories.

CONCLUSION

There seems to be a disconnect between the apps that are popular among patients and the scientific validity of the apps. As app usage increases among dermatology providers, whose demographic is shifting younger and younger, apps may become more incorporated in our education, and as such, it will become more critical to develop formal scientific standards. Given these future trends, we may need to increase our current literature and understanding of apps in dermatology with regard to their impact on both patients and health care providers.

As technology continues to advance, so too does its accessibility to the general population. In 2013, 56% of Americans owned a smartphone versus 77% in 2017.1With the increase in mobile applications (apps) available, it is no surprise that the market has extended into the medical field, with dermatology being no exception.2 The majority of dermatology apps can be classified as teledermatology apps, followed by self-surveillance, disease guide, and reference apps. Additional types of dermatology apps include dermoscopy, conference, education, photograph storage and sharing, and journal apps, and others.2 In this study, we examined Apple App Store rankings to determine the types of dermatology apps that are most popular among patients and physicians.

METHODS

A popular app rankings analyzer (App Annie) was used to search for dermatology apps along with their App Store rankings.3 Although iOS is not the most popular mobile device operating system, we chose to evaluate app rankings via the App Store because iPhones are the top-selling individual phones of any kind in the United States.4

We performed our analysis on a single day (July 14, 2018) given that app rankings can change daily. We incorporated the following keywords, which were commonly used in other dermatology app studies: dermatology, psoriasis, rosacea, acne, skin cancer, melanoma, eczema, and teledermatology. The category ranking was defined as the rank of a free or paid app in the App Store’s top charts for the selected country (United States), market (Apple), and device (iPhone) within their app category (Medical). Inclusion criteria required a ranking in the top 1500 Medical apps and being categorized in the App Store as a Medical app. Exclusion criteria included apps that focused on cosmetics, private practice, direct advertisements, photograph editing, or claims to cure skin disease, as well as non–English-language apps. The App Store descriptions were assessed to determine the type of each app (eg, teledermatology, disease guide) and target audience (patient, physician, or both).

Another search was performed using the same keywords but within the Health and Fitness category to capture potentially more highly ranked apps among patients. We also conducted separate searches within the Medical category using the keywords billing, coding, and ICD (International Classification of Diseases) to evaluate rankings for billing/coding apps, as well as EMR and electronic medical records for electronic medical record (EMR) apps.

RESULTS

The initial search yielded 851 results, which was narrowed down to 29 apps after applying the exclusion criteria. Of note, prior to application of the exclusion criteria, one dermatology app that was considered to be a direct advertisement app claiming to cure acne was ranked fourth of 1500 apps in the Medical category. However, the majority of the search results were excluded because they were not popular enough to be ranked among the top 1500 apps. There were more ranked dermatology apps in the Medical category targeting patients than physicians; 18 of 29 (62%) qualifying apps targeted patients and 11 (38%) targeted physicians (Tables 1 and 2). No apps targeted both groups. The most common type of ranked app targeting patients was self-surveillance (11/18), and the most common type targeting physicians was reference (8/11). The highest ranked app targeting patients was a teledermatology app with a ranking of 184, and the highest ranked app targeting physicians was educational, ranked 353. The least common type of ranked apps targeting patients were “other” (2/18 [11%]; 1 prescription and 1 UV monitor app) and conference (1/18 [6%]). The least common type of ranked apps targeting physicians were education (2/11 [18%]) and dermoscopy (1/11 [9%]).

Our search of the Health and Fitness category yielded 6 apps, all targeting patients; 3 (50%) were self-surveillance apps, and 3 (50%) were classified as other (2 UV monitors and a conferencing app for cancer emotional support)(Table 3).

Our search of the Medical category for billing/coding and EMR apps yielded 232 and 164 apps, respectively; of them, 49 (21%) and 54 (33%) apps were ranked. These apps did not overlap with the dermatology-related search criteria; thus, we were not able to ascertain how many of these apps were used specifically by health care providers in dermatology.

COMMENT

Patient Apps

The most common apps used by patients are fitness and nutrition tracker apps categorized as Health and Fitness5,6; however, the majority of ranked dermatology apps are categorized as Medical per our findings. In a study of 557 dermatology patients, it was found that among the health-related apps they used, the most common apps after fitness/nutrition were references, followed by patient portals, self-surveillance, and emotional assistance apps.6 Our search was consistent with these findings, suggesting that the most desired dermatology apps by patients are those that allow them to be proactive with their health. It is no surprise that the top-ranked app targeting patients was a teledermatology app, followed by multiple self-surveillance apps. The highest ranked self-surveillance app in the Health and Fitness category focused on monitoring the effects of nutrition on symptoms of diseases including skin disorders, while the highest ranked (as well as the majority of) self-surveillance apps in the Medical category encompassed mole monitoring and cancer risk calculators.

Benefits of the ranked dermatology apps in the Medical and Health and Fitness categories targeting patients include more immediate access to health care and education. Despite this popularity among patients, Masud et al7 demonstrated that only 20.5% (9/44) of dermatology apps targeting patients may be reliable resources based on a rubric created by the investigators. Overall, there remains a research gap for a standardized scientific approach to evaluating app validity and reliability.

Teledermatology

Teledermatology apps are the most common dermatology apps,2 allowing for remote evaluation of patients through either live consultations or transmittance of medical information for later review by board-certified physicians.8 Features common to many teledermatology apps include accessibility on Android (Google Inc) and iOS as well as a web version. Security and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliance is especially important and is enforced through user authentications, data encryption, and automatic logout features. Data is not stored locally and is secured on a private server with backup. Referring providers and consultants often can communicate within the app. Insurance providers also may cover teledermatology services, and if not, the out-of-pocket costs often are affordable.

The highest-ranked patient app (ranked 184 in the Medical category) was a teledermatology app that did not meet the American Telemedicine Association standards for teledermatology apps.9 The popularity of this app among patients may have been attributable to multiple ease-of-use and turnaround time features. The user interface was simplistic, and the design was appealing to the eye. The entry field options were minimal to avoid confusion. The turnaround time to receive a diagnosis depended on 1 of 3 options, including a more rapid response for an increased cost. Ease of use was the highlight of this app at the cost of accuracy, as the limited amount of information that users were required to provide physicians compromised diagnostic accuracy in this app.

For comparison, we chose a nonranked (and thus less frequently used) teledermatology app that had previously undergone scientific evaluation using 13 evaluation criteria specific to teledermatology.10 The app also met the American Telemedicine Association standard for teledermatology apps.9 The app was originally a broader telemedicine app but featured a section specific to teledermatology. The user interface was simple but professional, almost resembling an EMR. The input fields included a comprehensive history that permitted a better evaluation of a lesion but might be tedious for users. This app boasted professionalism and accuracy, but from a user standpoint, it may have been too time-consuming.

Striking a balance between ensuring proper care versus appealing to patients is a difficult but important task. Based on this study, it appears that popular patient apps may in fact have less scientific rationale and therefore potentially less accuracy.

Self-surveillance

Although self-surveillance apps did not account for the highest-ranked app, they were the most frequently ranked app type in our study. Most of the ranked self-surveillance apps in the Medical category were for monitoring lesions over time to assess for changes. These apps help users take photographs that are well organized in a single, easy-to-find location. Some apps were risk calculators that assessed the risk for malignancies using a questionnaire. The majority of these self-surveillance apps were specific to skin cancer detection. Of note, one of the ranked self-surveillance apps assessed drug effectiveness by monitoring clinical appearance and symptoms. The lowest ranked self-surveillance app in the top 1500 ranked Medical apps in our search monitored cancer symptoms not specific to dermatology. Although this app had a low ranking (1380/1500), it received a high number of reviews and was well rated at 4.8 out of 5 stars; therefore, it seemed more helpful than the other higher-ranked apps targeting patients, which had higher rankings but minimal to no reviews or ratings. A comparison of the ease-of-use features of all the ranked patient-targeted self-surveillance apps in the Medical category is provided in Table 4.

Physician Apps

After examining the results of apps targeting physicians, we realized that the data may be accurate but may not be as representative of all currently practicing dermatology providers. Given the increased usage of apps among younger age groups,11 our data may be skewed toward medical students and residents, supported by the fact that the top-ranked physician app in our study was an education app and the majority were reference apps. Future studies are needed to reexamine app ranking as this age group transitions from entry-level health care providers in the next 5 to 10 years. These findings also suggest less frequent app use among more veteran health care providers within our specific search parameters. Therefore, we decided to do subsequent searches for available billing/coding and EMR apps, which were many, but as mentioned above, none were specific to dermatology.

General Dermatology References

Most of the dermatology reference apps were formatted as e-books; however, other apps such as the Amazon Kindle app (categorized under Books) providing access to multiple e-books within one app were not included. Some apps included study aid features (eg, flash cards, quizzes), and topics spanned both dermatology and dermatopathology. Apps provide a unique way for on-the-go studying for dermatologists in training, and if the usage continues to grow, there may be a need for increased formal integration in dermatology education in the future.

Journals

Journal apps were not among those listed in the top-ranked apps we evaluated, which we suspect may be because journals were categorized differently from one journal to the next; for example, the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology was ranked 1168 in the Magazines and Newspapers category. On the other hand, Dermatology World was ranked 1363 in the Reference category. An article’s citation affects the publishing journal’s impact factor, which is one of the most important variables in measuring a journal’s influence. In the future, there may be other variables that could aid in understanding journal impact as it relates to the journal’s accessibility.

Limitations

Our study did not look at Android apps. The top chart apps in the Android and Apple App Stores use undisclosed algorithms likely involving different characteristics such as number of downloads, frequency of updates, number of reviews, ratings, and more. Thus, the rankings across these different markets would not be comparable. Although our choice of keywords stemmed from the majority of prior studies looking at dermatology apps, our search was limited due to the use of these specific keywords. To avoid skewing data by cross-comparison of noncomparable categories, we could not compare apps in the Medical category versus those in other categories.

CONCLUSION

There seems to be a disconnect between the apps that are popular among patients and the scientific validity of the apps. As app usage increases among dermatology providers, whose demographic is shifting younger and younger, apps may become more incorporated in our education, and as such, it will become more critical to develop formal scientific standards. Given these future trends, we may need to increase our current literature and understanding of apps in dermatology with regard to their impact on both patients and health care providers.

- Poushter J, Bishop C, Chwe H. Social media use continues to rise in developing countries but plateaus across developed ones. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewglobal.org/2018/06/19/social-media-use-continues-to-rise-in-developing-countries-but-plateaus-across-developed-ones/#table. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, et al. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology—2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. pii:13030/qt3hs7n9z6.

- App Annie website. https://www.appannie.com/top/. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Number of iPhone users in the United States from 2012 to 2016 (in millions). Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/232790/forecast-of-apple-users-in-the-us/. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Burkhart C. Medical mobile apps and dermatology. Cutis. 2012;90:278-281.

- Wolf JA, Moreau JF, Patton TJ, et al. Prevalence and impact of health-related internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients. Cutis. 2015;95:323-328.

- Masud A, Shafi S, Rao BK. Mobile medical apps for patient education: a graded review of available dermatology apps. Cutis. 2018;101:141-144.

- Walocko FM, Tejasvi T. Teledermatology applications in skin cancer diagnosis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:559-563.

- Krupinski E, Burdick A, Pak H, et al. American Telemedicine Association’s practice guidelines for teledermatology. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:289-302.

- Ho B, Lee M, Armstrong AW. Evaluation criteria for mobile teledermatology applications and comparison of major mobile teledermatology applications. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19:678-682.

- Number of mobile app hours per smartphone and tablet app user in the United States in June 2016, by age group. Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/323522/us-user-mobile-app-engagement-age/. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- Poushter J, Bishop C, Chwe H. Social media use continues to rise in developing countries but plateaus across developed ones. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewglobal.org/2018/06/19/social-media-use-continues-to-rise-in-developing-countries-but-plateaus-across-developed-ones/#table. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, et al. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology—2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. pii:13030/qt3hs7n9z6.

- App Annie website. https://www.appannie.com/top/. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Number of iPhone users in the United States from 2012 to 2016 (in millions). Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/232790/forecast-of-apple-users-in-the-us/. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- Burkhart C. Medical mobile apps and dermatology. Cutis. 2012;90:278-281.

- Wolf JA, Moreau JF, Patton TJ, et al. Prevalence and impact of health-related internet and smartphone use among dermatology patients. Cutis. 2015;95:323-328.

- Masud A, Shafi S, Rao BK. Mobile medical apps for patient education: a graded review of available dermatology apps. Cutis. 2018;101:141-144.

- Walocko FM, Tejasvi T. Teledermatology applications in skin cancer diagnosis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:559-563.

- Krupinski E, Burdick A, Pak H, et al. American Telemedicine Association’s practice guidelines for teledermatology. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:289-302.

- Ho B, Lee M, Armstrong AW. Evaluation criteria for mobile teledermatology applications and comparison of major mobile teledermatology applications. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19:678-682.

- Number of mobile app hours per smartphone and tablet app user in the United States in June 2016, by age group. Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/323522/us-user-mobile-app-engagement-age/. Accessed September 18, 2018.

Practice Points

- As mobile application (app) usage increases among dermatology providers, whose demographic is shifting younger and younger, apps may become more incorporated in dermatology education. As such, it will become more critical to develop formal scientific standards.

- The most desired dermatology apps for patients were apps that allowed them to be proactive with their health.

- There seems to be a disconnect between the apps that are popular among patients and the scientific validity of the apps.

On-site coverage of CHEST 2018

CHEST Physician reporting staff will provide on-site coverage of CHEST 2018, the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held in San Antonio, Tex., Oct. 6 through Oct. 10. They are planning to report on a wide variety of sessions covering the latest research on treating COPD, sleep medicine, pulmonary hypertension, asthma, and other pulmonary disease. Panels, plenaries, original research presentations, and late-breaking studies will all be covered in depth. Stories will be posted daily during the meeting on the CHEST Physician website. They will also be talking to presenters and discussants about their work, so be sure to watch for video interviews, which also will be published daily.

Among the sessions on the coverage calendar are the following:

The Impact of Obesity on Pulmonary Disorders. Sunday, Oct. 7, 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., Convention Center 207B

GAMES: Games Augmenting Medical Education. Sunday, Oct. 7, 10:45 a.m. to 11:45 a.m., Convention Center 207B

Current Trends and Controversies in the Practice of Sleep Medicine. Monday, Oct. 8, 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., Convention Center 214A

Futility? Responding to Nonbeneficial Treatment Requests. Monday, Oct. 8, 11:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m., Convention Center 212A

Update on Diagnosis and Management of Diffuse Cystic Lung Disease. Tuesday, Oct. 9, 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., Convention Center 214A

Lung Cancer Screening: News Questions and New Answers. Tuesday, Oct. 9, 8:45 a.m. to 9:45 a.m., Convention Center 207A

Check here on the CHEST Physician website for the latest news from CHEST 2018!

CHEST Physician reporting staff will provide on-site coverage of CHEST 2018, the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held in San Antonio, Tex., Oct. 6 through Oct. 10. They are planning to report on a wide variety of sessions covering the latest research on treating COPD, sleep medicine, pulmonary hypertension, asthma, and other pulmonary disease. Panels, plenaries, original research presentations, and late-breaking studies will all be covered in depth. Stories will be posted daily during the meeting on the CHEST Physician website. They will also be talking to presenters and discussants about their work, so be sure to watch for video interviews, which also will be published daily.

Among the sessions on the coverage calendar are the following:

The Impact of Obesity on Pulmonary Disorders. Sunday, Oct. 7, 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., Convention Center 207B

GAMES: Games Augmenting Medical Education. Sunday, Oct. 7, 10:45 a.m. to 11:45 a.m., Convention Center 207B

Current Trends and Controversies in the Practice of Sleep Medicine. Monday, Oct. 8, 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., Convention Center 214A

Futility? Responding to Nonbeneficial Treatment Requests. Monday, Oct. 8, 11:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m., Convention Center 212A

Update on Diagnosis and Management of Diffuse Cystic Lung Disease. Tuesday, Oct. 9, 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., Convention Center 214A

Lung Cancer Screening: News Questions and New Answers. Tuesday, Oct. 9, 8:45 a.m. to 9:45 a.m., Convention Center 207A

Check here on the CHEST Physician website for the latest news from CHEST 2018!

CHEST Physician reporting staff will provide on-site coverage of CHEST 2018, the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians, held in San Antonio, Tex., Oct. 6 through Oct. 10. They are planning to report on a wide variety of sessions covering the latest research on treating COPD, sleep medicine, pulmonary hypertension, asthma, and other pulmonary disease. Panels, plenaries, original research presentations, and late-breaking studies will all be covered in depth. Stories will be posted daily during the meeting on the CHEST Physician website. They will also be talking to presenters and discussants about their work, so be sure to watch for video interviews, which also will be published daily.

Among the sessions on the coverage calendar are the following:

The Impact of Obesity on Pulmonary Disorders. Sunday, Oct. 7, 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., Convention Center 207B

GAMES: Games Augmenting Medical Education. Sunday, Oct. 7, 10:45 a.m. to 11:45 a.m., Convention Center 207B

Current Trends and Controversies in the Practice of Sleep Medicine. Monday, Oct. 8, 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., Convention Center 214A

Futility? Responding to Nonbeneficial Treatment Requests. Monday, Oct. 8, 11:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m., Convention Center 212A

Update on Diagnosis and Management of Diffuse Cystic Lung Disease. Tuesday, Oct. 9, 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m., Convention Center 214A

Lung Cancer Screening: News Questions and New Answers. Tuesday, Oct. 9, 8:45 a.m. to 9:45 a.m., Convention Center 207A

Check here on the CHEST Physician website for the latest news from CHEST 2018!

IMpower133: Atezolizumab plus standard chemotherapy boosted survival in ES-SCLC

TORONTO – Adding the humanized monoclonal programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody atezolizumab to standard first-line treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) significantly improved overall and progression-free survival in the phase 1/3 IMpower133 trial.

The combination may represent a new standard-of-care regimen for patients with untreated ES-SCLC, which is highly lethal – with 5-year survival of about 1%-3% – and represents about 13% of all lung cancers, Stephen V. Liu, MD, reported at the World Conference on Lung Cancer.

The findings were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The median overall survival in 201 patients randomized to receive atezolizumab in addition to carboplatin and etoposide was 12.3 months, compared with 10.3 months in 202 patients who received placebo plus carboplatin and etoposide (hazard ratio, 0.7), Dr. Liu of Georgetown University, Washington, and a member of the trial steering committee said at the meeting, sponsored by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

“That translates to a 30% reduction in the risk of patient death,” he said at a press briefing during the conference. “Patients receiving atezolizumab had a much greater likelihood of being alive at 1 year, with a 1-year survival rate of 51.7% versus 38.2%.”

Median progression-free survival(PFS) also improved with atezolizumab (5.2 months vs. 4.3 months with placebo; HR, 0.77), as did 6-month PFS. At 12 months there was more than a doubling of PFS in the atezolizumab group (5.0% vs. 12.6%), he said.

Participants in the double-blind trial were treatment-naive all-comers with measurable ES-SCLC and good performance status. They received four 21-day cycles of intravenous carboplatin (area under the curve, 5 mg/mL per minute) on day 1 plus intravenous etoposide (100 mg/m2) on days 1-3 with either concurrent 1,200 mg of atezolizumab on day 1 or placebo, followed by maintenance therapy with atezolizumab or placebo until intolerable toxicity or disease progression.

The treatment benefits were seen across many patient subgroups and regardless of tumor mutational burden.

The atezolizumab safety profile was as expected with no new safety signals and did not compromise patients’ ability to complete four treatment cycles, Dr. Liu noted.

The findings are exciting in that they represent the first in decades to show a significant improvement in survival in patients with ES-SCLC, he said. Although most patients have an initial response to standard-of-care chemotherapy, that response isn’t durable. “As much as we expect a response, we also know that it’s transient; we expect a response, we expect relapse. There hasn’t been a change really in the past 20 years, at least, with this regimen that we’ve been using since the 1980s.”

That’s not for lack of trying, he added, noting that more than 40 phase 3 studies have looked at more than 60 different drugs since the 1970s and have “failed to move the needle.”

Immunotherapy, however, has dramatically improved the therapeutic landscape in non–small cell lung cancer, and preclinical data and clinical experience suggest “a possible synergy between checkpoint inhibition and chemotherapy,” which led to this global study, he explained.

“This is the first study in over 20 years to show a significant improvement in survival and progression-free survival in initial treatment of small cell lung cancer. The concurrent administration of atezolizumab with chemotherapy helped people live longer, compared to chemotherapy alone,” Dr. Liu concluded, adding in a press statement that “this is an exciting time in oncology, and we are thrilled to finally see real progress in the SCLC space.”

When questioned about the role of PD-L1 in this population and the possibility of identifying a subgroup in which this treatment may be more cost effective, he noted that tissue samples weren’t required at enrollment in this study, but were collected from some patients, and future analyses will assess those samples to try to determine if there are subsets of patients who derive particular benefit from immunotherapy in this setting.

“But today, in an all-comer population, this combination has improved survival,” he said.

IMpower133 was sponsored by F. Hoffman–La Roche. Dr. Liu is a speaker or advisory board member for Genentech, Pfizer, Takeda, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, and Ignyta, and has received research or grant support from Genentech, Pfizer, Threshold Pharmaceuticals, Clovis Oncology, Corvus Pharmaceuticals, Esanex, Bayer, OncoMed Pharmaceuticals, Ignyta, Merck, Lycera, AstraZeneca, and Molecular Partners.

SOURCE: Liu SV et al. WCLC 2018, Abstract PL02.07.

Invited discussant Natasha B. Leighl, MD, said that, while many questions remain, the IMpower133 findings do present a new standard of care for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer given the hazard ratio of 0.70 for survival, the unmet need in this population, and the 4 decades without progress.

“We have a long way to go to catch up with non–small cell lung cancer, and it starts today,” she said, noting, however, that uptake will vary depending on regulatory and economic thresholds in different areas. “I think that really highlights the urgent need for progress in patient selection, biomarker research, and the need to change our culture to one of tissue collection at trial.

“Finally, small cell lung cancer ... is a preventable disease and we need urgent steps in tobacco control to help us eradicate this killer,” she concluded.

Dr. Leighl is a medical oncologist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto. She has received research, grant, or other support from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer, and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

Invited discussant Natasha B. Leighl, MD, said that, while many questions remain, the IMpower133 findings do present a new standard of care for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer given the hazard ratio of 0.70 for survival, the unmet need in this population, and the 4 decades without progress.

“We have a long way to go to catch up with non–small cell lung cancer, and it starts today,” she said, noting, however, that uptake will vary depending on regulatory and economic thresholds in different areas. “I think that really highlights the urgent need for progress in patient selection, biomarker research, and the need to change our culture to one of tissue collection at trial.

“Finally, small cell lung cancer ... is a preventable disease and we need urgent steps in tobacco control to help us eradicate this killer,” she concluded.

Dr. Leighl is a medical oncologist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto. She has received research, grant, or other support from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer, and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

Invited discussant Natasha B. Leighl, MD, said that, while many questions remain, the IMpower133 findings do present a new standard of care for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer given the hazard ratio of 0.70 for survival, the unmet need in this population, and the 4 decades without progress.

“We have a long way to go to catch up with non–small cell lung cancer, and it starts today,” she said, noting, however, that uptake will vary depending on regulatory and economic thresholds in different areas. “I think that really highlights the urgent need for progress in patient selection, biomarker research, and the need to change our culture to one of tissue collection at trial.

“Finally, small cell lung cancer ... is a preventable disease and we need urgent steps in tobacco control to help us eradicate this killer,” she concluded.

Dr. Leighl is a medical oncologist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto. She has received research, grant, or other support from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer, and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

TORONTO – Adding the humanized monoclonal programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody atezolizumab to standard first-line treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) significantly improved overall and progression-free survival in the phase 1/3 IMpower133 trial.

The combination may represent a new standard-of-care regimen for patients with untreated ES-SCLC, which is highly lethal – with 5-year survival of about 1%-3% – and represents about 13% of all lung cancers, Stephen V. Liu, MD, reported at the World Conference on Lung Cancer.

The findings were published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The median overall survival in 201 patients randomized to receive atezolizumab in addition to carboplatin and etoposide was 12.3 months, compared with 10.3 months in 202 patients who received placebo plus carboplatin and etoposide (hazard ratio, 0.7), Dr. Liu of Georgetown University, Washington, and a member of the trial steering committee said at the meeting, sponsored by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

“That translates to a 30% reduction in the risk of patient death,” he said at a press briefing during the conference. “Patients receiving atezolizumab had a much greater likelihood of being alive at 1 year, with a 1-year survival rate of 51.7% versus 38.2%.”

Median progression-free survival(PFS) also improved with atezolizumab (5.2 months vs. 4.3 months with placebo; HR, 0.77), as did 6-month PFS. At 12 months there was more than a doubling of PFS in the atezolizumab group (5.0% vs. 12.6%), he said.