User login

Xanthogranulomatous Reaction to Trametinib for Metastatic Malignant Melanoma

A decade ago, the few agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of metastatic melanoma demonstrated low therapeutic success rates (ie, <15%–20%).1 Since then, advances in molecular biology have identified oncogenes that contribute to melanoma progression.2 Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by targeting mutant BRAF and mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) has created promising pharmacologic treatment opportunities.3 Due to the recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of these therapies for treatment of melanoma, it is important to better characterize these adverse events (AEs) so that we can manage them. We present the development of an unusual cutaneous reaction to trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, in a man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma.

Case Report

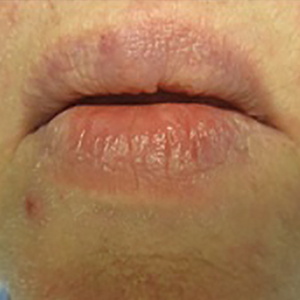

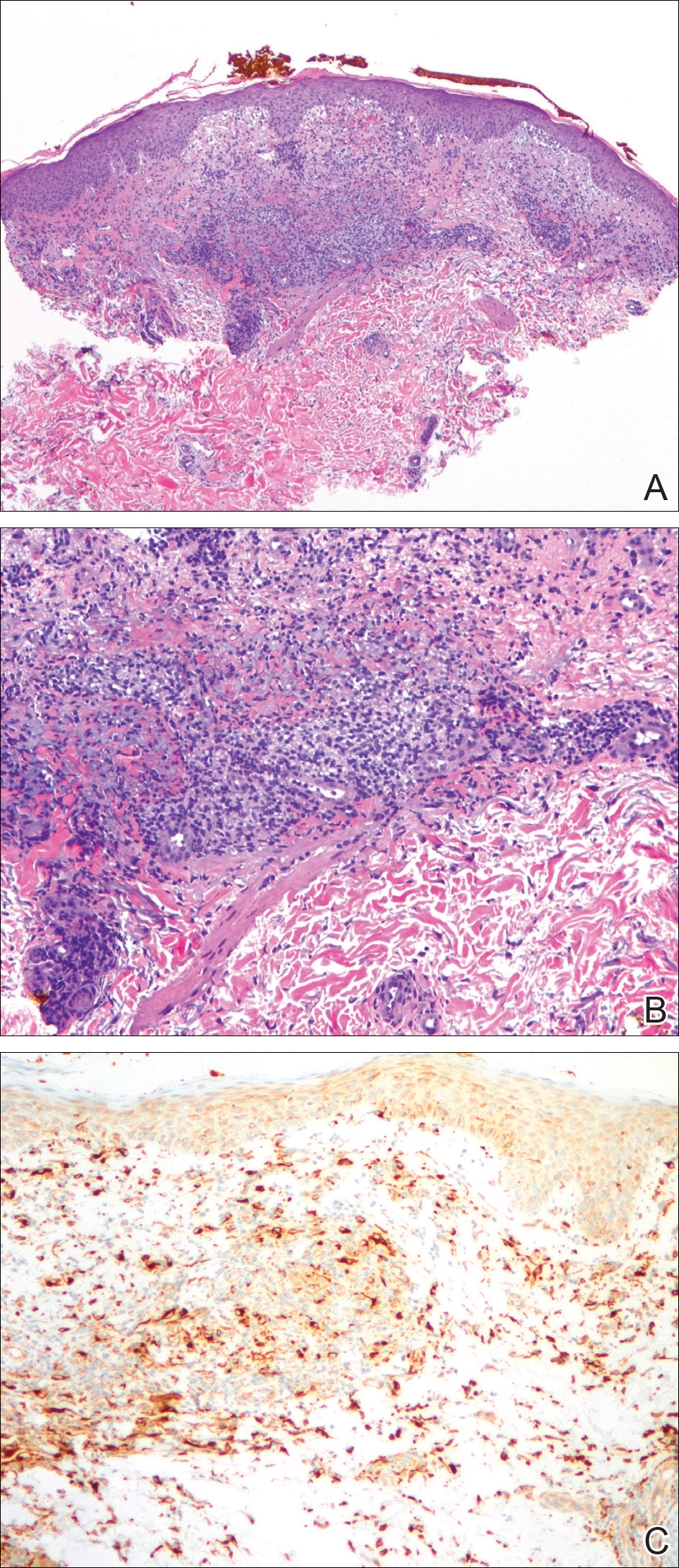

A 66-year-old man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma with metastases to the brain and lungs presented with recurring pruritic erythematous papules on the face and bilateral forearms that began shortly after initiating therapy with trametinib. The cutaneous eruption had initially presented on the face, forearms, and dorsal hands when trametinib was used in combination with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, and ipilimumab, a human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4–blocking antibody; however, lesions initially were minimal and self-resolving. When trametinib was reintroduced as monotherapy due to fever attributed to the combination treatment regimen, the cutaneous eruption recurred more severely. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly papules limited to the face and bilateral upper extremities, including the flexural surfaces.

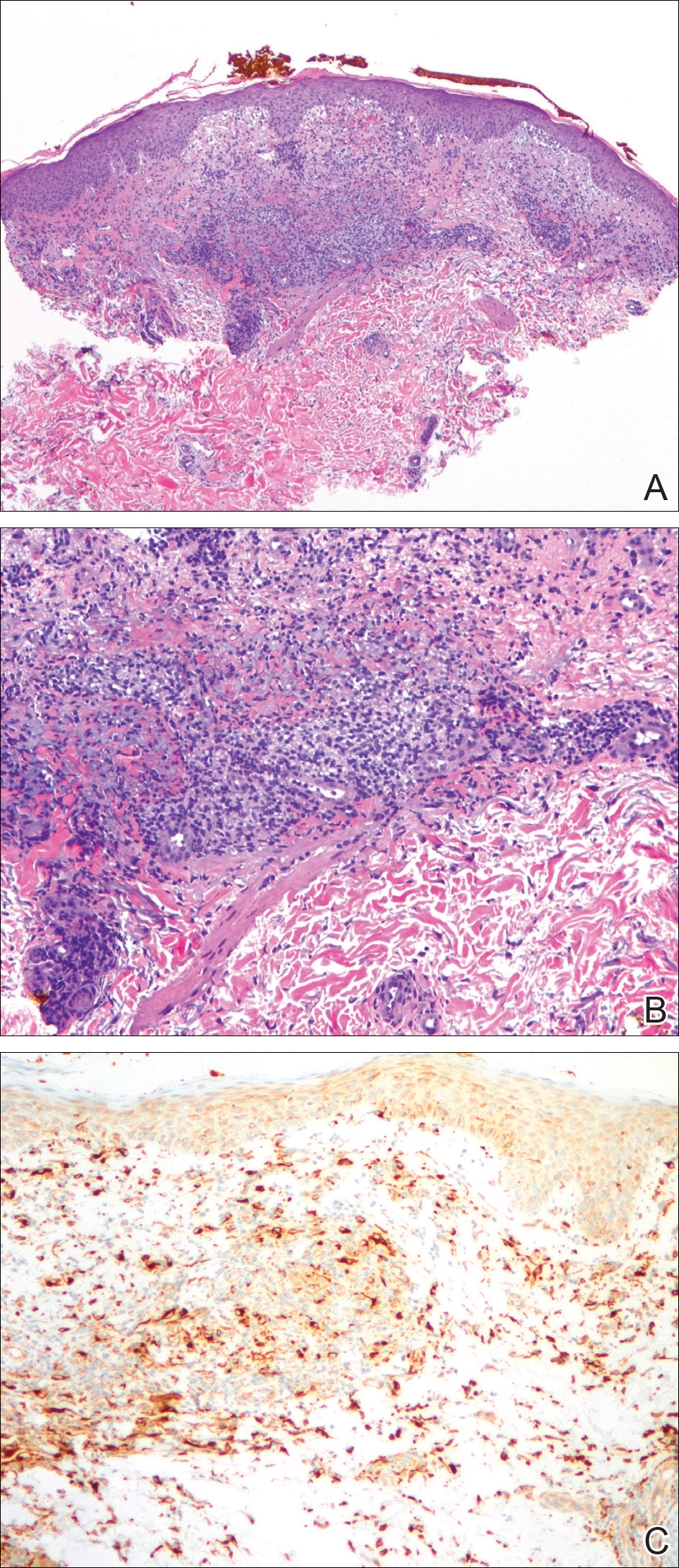

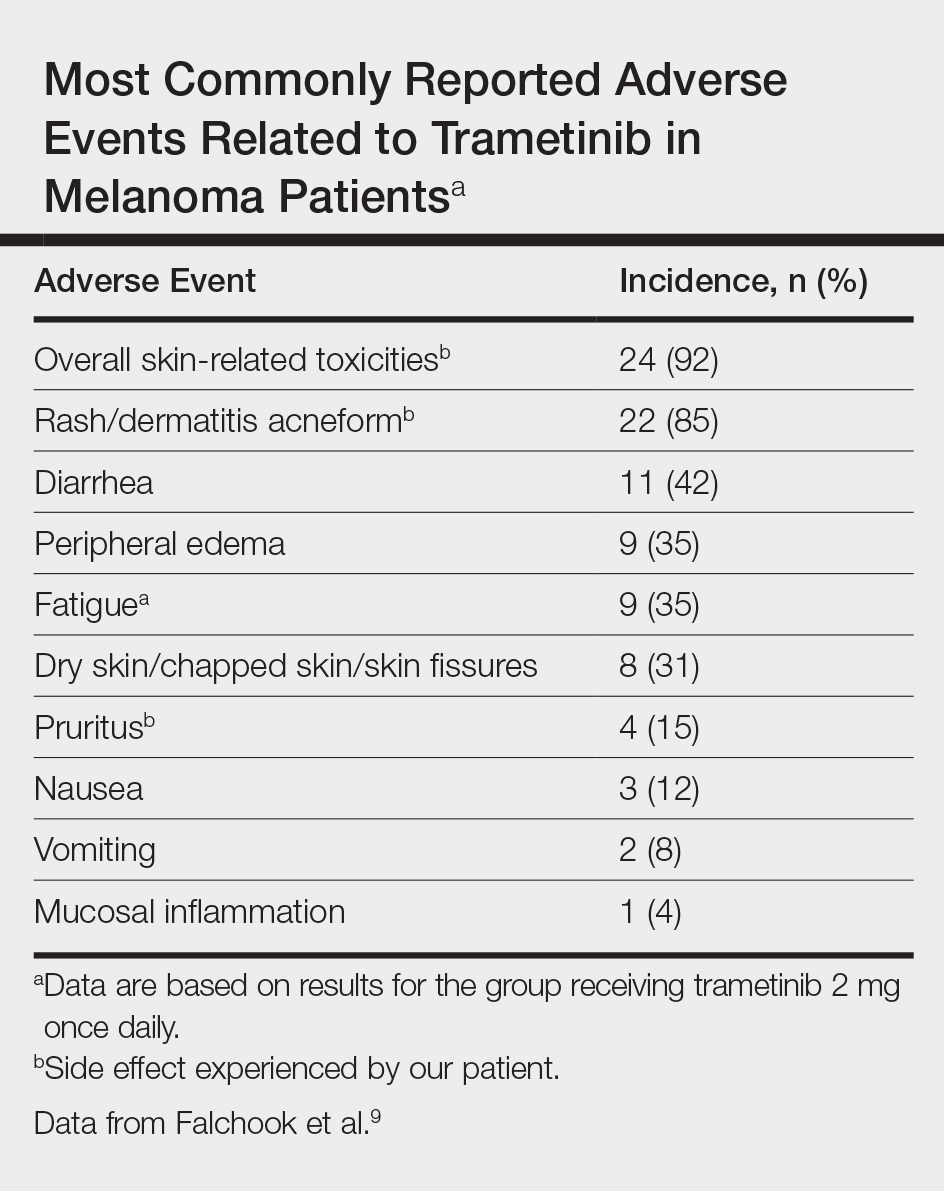

A biopsy from the flexural surface of the right forearm revealed a dense perivascular lymphoid and xanthomatous infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1). Poorly formed granulomas within the mid reticular dermis demonstrated focal palisading of histiocytes with prominent giant cells at the periphery. Histiocytes and giant cells showed foamy or xanthomatous cytoplasm. Within the reaction, degenerative and swollen collagen fibers were noted with no mucin deposition, which was confirmed with negative colloidal iron staining.

Brief cessation of trametinib along with application of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% resulted in resolution of the cutaneous eruption. Later, trametinib was reintroduced in combination with vemurafenib, though therapy was intermittently discontinued due to various side effects. Skin lesions continued to recur (Figure 2) while the patient was on trametinib but remained minimal and continued to respond to topical clobetasol propionate. One year later, the patient continues to tolerate combination therapy with trametinib and vemurafenib.

Comment

BRAF Inhibitors

Normally, activated BRAF phosphorylates and stimulates MEK proteins, ultimately influencing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.3-5 BRAF mutations that constitutively activate this pathway have been detected in several malignancies, including papillary thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer, and brain tumors, but they are particularly prevalent in melanoma.4,6 The majority of BRAF-positive malignant melanomas are associated with V600E, in which valine is substituted for glutamic acid at codon 600. The next most common BRAF mutation is V600K, in which valine is substituted for lysine.2,7 Together these constitute approximately 95% of BRAF mutations in melanoma patients.5

MEK Inhibitors

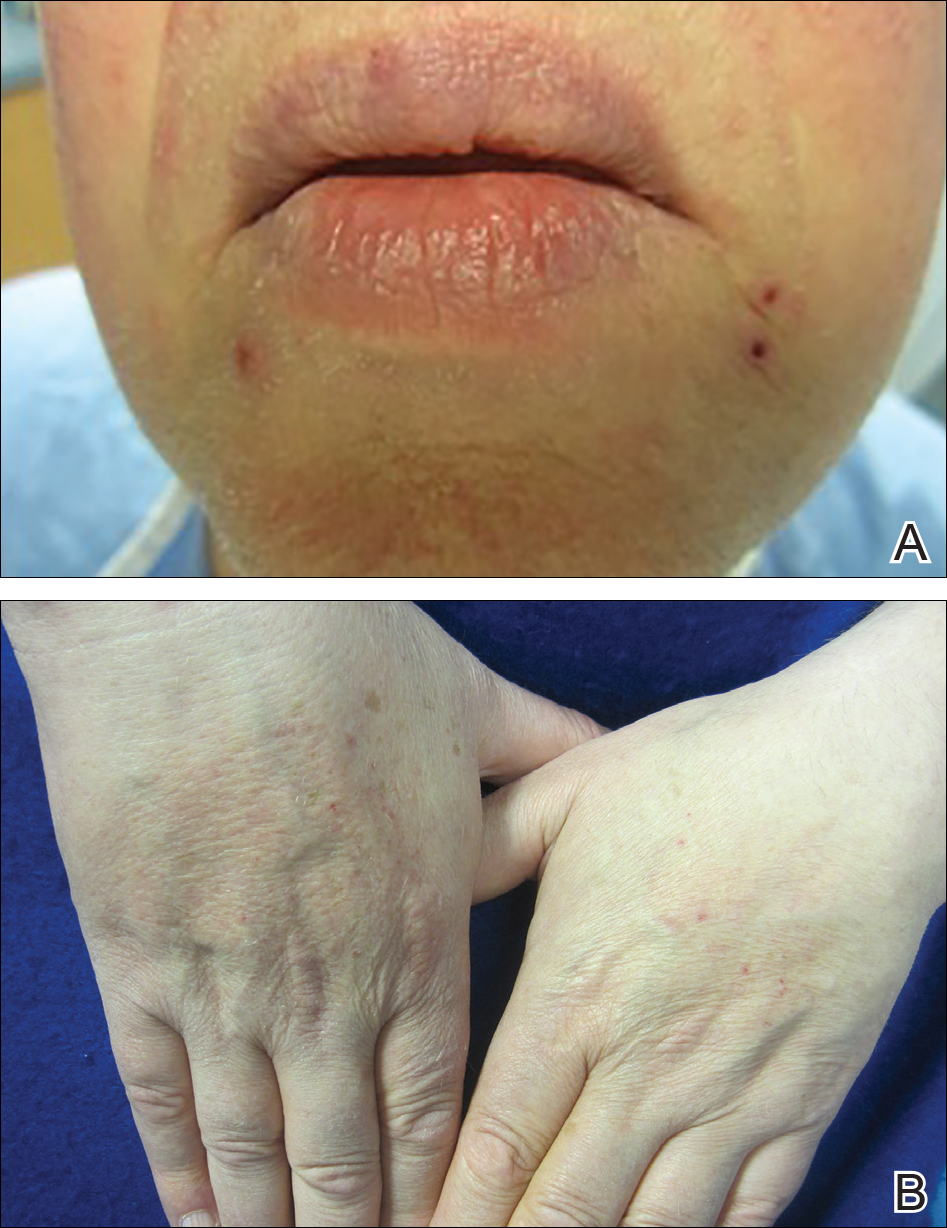

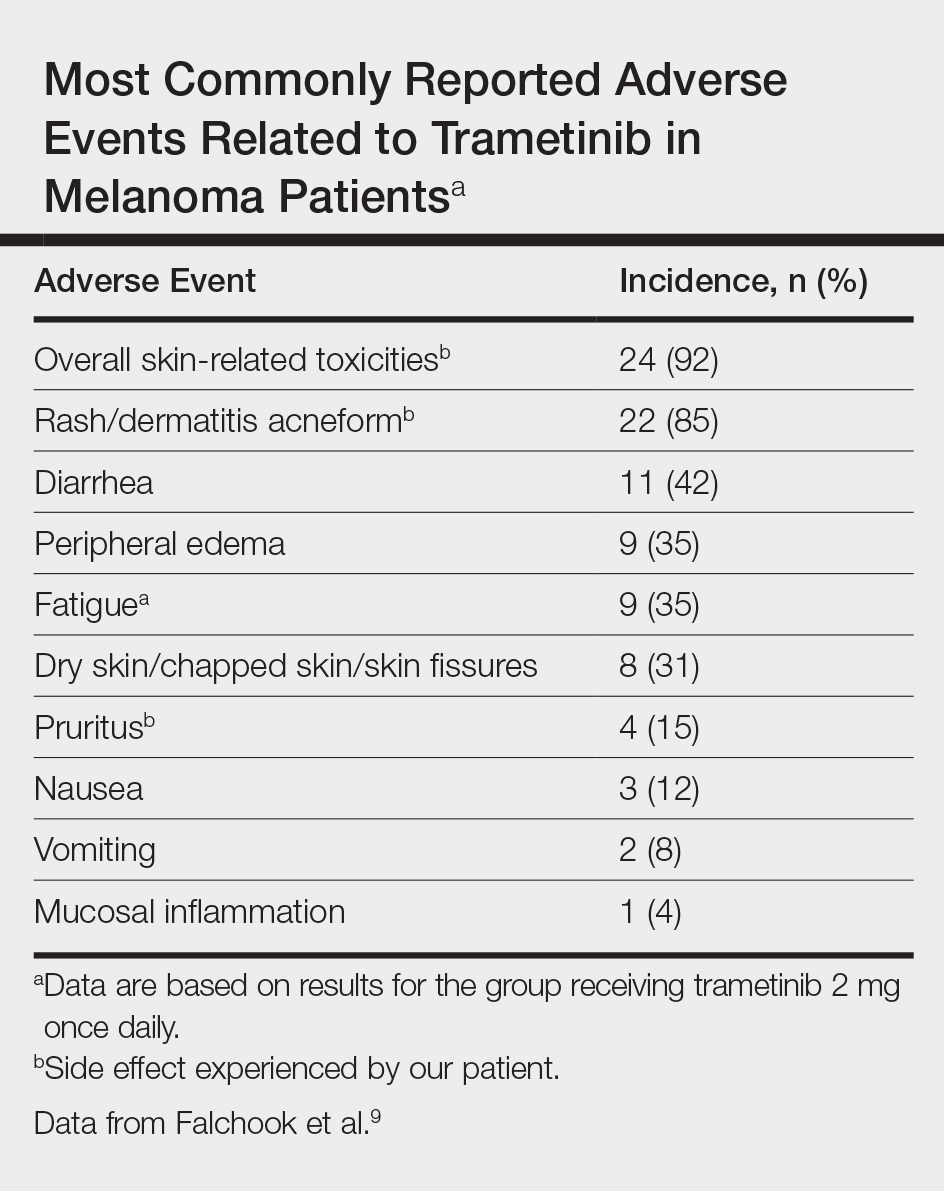

Initially, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) were introduced to the market for treating melanoma with great success; however, resistance to BRAFi therapy quickly was identified within months of initiating therapy, leading to investigations for combination therapy with MEK inhibitors (MEKi).2,5 MEK inhibition decreases cellular proliferation and also leads to apoptosis of melanoma cells in patients with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations.2,8 Trametinib, in particular, is a reversible, highly selective allosteric inhibitor of both MEK1 and MEK2. While on trametinib, patients with metastatic melanoma have experienced 3 times as long progression-free survival as well as 81% overall survival compared to 67% overall survival at 6 months in patients on chemotherapy, dacarbazine, or paclitaxel.5 However, AEs are quite common with trametinib, with cutaneous AEs being a leading side effect. Several large trials have reported that 57% to 92% of patients on trametinib report cutaneous AEs, with the majority of cases being described as papulopustular or acneform (Table).5,9

Combination Therapy

Fortunately, combination treatment with a BRAFi may alleviate MEKi-induced cutaneous drug reactions. In one study, acneform eruptions were identified in only 10% of those on combination therapy—trametinib with the BRAFi dabrafenib—compared to 77% of patients on trametinib monotherapy.10 Strikingly, cutaneous AEs occurred in 100% of trametinib-treated mice compared to 30% of combination-treated mice in another study, while the benefits of MEKi remained similar in both groups.11 Because BRAFi and MEKi combination therapy improves progression-free survival while minimizing AEs, we support the use of combination therapy instead of BRAFi or MEKi monotherapy.5

Histologic Evidence of AEs

Histology of trametinib-associated cutaneous reactions is not well characterized, which is in contrast to our understanding of cutaneous AEs associated with BRAFi in which transient acantholytic dermatosis (seen in 45% of patients) and verrucal keratosis (seen in 18% of patients) have been well characterized on histology.12 Interestingly, cutaneous granulomatous eruptions have been attributed to BRAFi therapy in 4 patients.13,14 One patient was on monotherapy with vemurafenib and granulomatous dermatitis with focal necrosis was seen on histology.13 The other 3 patients were on combination therapy with trametinib; 2 had histology-proven sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation, and 1 demonstrated perifollicular granulomatous inflammation and granulomatous inflammation surrounding a focus of melanoma cells.13,14 Although these granulomatous reactions were attributed to BRAFi or combination therapy, the association with trametinib remains unclear. On the other hand, our patient’s granulomatous reaction was exacerbated on trametinib monotherapy, suggesting a relationship to trametinib itself rather than BRAFi.

Conclusion

With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAFi and MEKi therapies provide major milestones in metastatic melanoma management. As more patients are treated with these agents, it is important that we better characterize their associated side effects. Our case of an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction to trametinib adds to the knowledge base of possible cutaneous reactions caused by this drug. We hope that prospective studies will further investigate and differentiate the cutaneous AEs described so that we can better manage these patients.

- Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D. Melanoma and immunotherapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:547-564.

- Chung C, Reilly S. Trametinib: a novel signal transduction inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:101-110.

- Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy [published online February 12, 2009]. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125-134.

- Hertzman Johansson C, Egyhazi Brage S. BRAF inhibitors in cancer therapy [published online December 8, 2013]. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:176-182.

- Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al; METRIC Study Group. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma [published online June 4, 2012]. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107-114.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer [published online June 9, 2002]. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3:6.

- Roberts PF, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291-3310.

- Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR, et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 2 dose-escalation trial [published online July 16, 2012]. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782-789.

- Anforth R, Liu M, Nguyen B, et al. Acneiform eruptions: a common cutaneous toxicity of the MEK inhibitor trametinib [published online December 9, 2013]. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:250-254.

- Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Deken MA, et al. Synchronous BRAF(V600E) and MEK inhibition leads to superior control of murine melanoma by limiting MEK inhibitor induced skin toxicity. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1649-1658.

- Anforth R, Carlos G, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in patients treated with BRAF inhibitor-based therapies for metastatic melanoma for longer than 52 weeks [published online November 21, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:239-243.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307-311.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell K. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

A decade ago, the few agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of metastatic melanoma demonstrated low therapeutic success rates (ie, <15%–20%).1 Since then, advances in molecular biology have identified oncogenes that contribute to melanoma progression.2 Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by targeting mutant BRAF and mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) has created promising pharmacologic treatment opportunities.3 Due to the recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of these therapies for treatment of melanoma, it is important to better characterize these adverse events (AEs) so that we can manage them. We present the development of an unusual cutaneous reaction to trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, in a man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma.

Case Report

A 66-year-old man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma with metastases to the brain and lungs presented with recurring pruritic erythematous papules on the face and bilateral forearms that began shortly after initiating therapy with trametinib. The cutaneous eruption had initially presented on the face, forearms, and dorsal hands when trametinib was used in combination with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, and ipilimumab, a human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4–blocking antibody; however, lesions initially were minimal and self-resolving. When trametinib was reintroduced as monotherapy due to fever attributed to the combination treatment regimen, the cutaneous eruption recurred more severely. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly papules limited to the face and bilateral upper extremities, including the flexural surfaces.

A biopsy from the flexural surface of the right forearm revealed a dense perivascular lymphoid and xanthomatous infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1). Poorly formed granulomas within the mid reticular dermis demonstrated focal palisading of histiocytes with prominent giant cells at the periphery. Histiocytes and giant cells showed foamy or xanthomatous cytoplasm. Within the reaction, degenerative and swollen collagen fibers were noted with no mucin deposition, which was confirmed with negative colloidal iron staining.

Brief cessation of trametinib along with application of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% resulted in resolution of the cutaneous eruption. Later, trametinib was reintroduced in combination with vemurafenib, though therapy was intermittently discontinued due to various side effects. Skin lesions continued to recur (Figure 2) while the patient was on trametinib but remained minimal and continued to respond to topical clobetasol propionate. One year later, the patient continues to tolerate combination therapy with trametinib and vemurafenib.

Comment

BRAF Inhibitors

Normally, activated BRAF phosphorylates and stimulates MEK proteins, ultimately influencing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.3-5 BRAF mutations that constitutively activate this pathway have been detected in several malignancies, including papillary thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer, and brain tumors, but they are particularly prevalent in melanoma.4,6 The majority of BRAF-positive malignant melanomas are associated with V600E, in which valine is substituted for glutamic acid at codon 600. The next most common BRAF mutation is V600K, in which valine is substituted for lysine.2,7 Together these constitute approximately 95% of BRAF mutations in melanoma patients.5

MEK Inhibitors

Initially, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) were introduced to the market for treating melanoma with great success; however, resistance to BRAFi therapy quickly was identified within months of initiating therapy, leading to investigations for combination therapy with MEK inhibitors (MEKi).2,5 MEK inhibition decreases cellular proliferation and also leads to apoptosis of melanoma cells in patients with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations.2,8 Trametinib, in particular, is a reversible, highly selective allosteric inhibitor of both MEK1 and MEK2. While on trametinib, patients with metastatic melanoma have experienced 3 times as long progression-free survival as well as 81% overall survival compared to 67% overall survival at 6 months in patients on chemotherapy, dacarbazine, or paclitaxel.5 However, AEs are quite common with trametinib, with cutaneous AEs being a leading side effect. Several large trials have reported that 57% to 92% of patients on trametinib report cutaneous AEs, with the majority of cases being described as papulopustular or acneform (Table).5,9

Combination Therapy

Fortunately, combination treatment with a BRAFi may alleviate MEKi-induced cutaneous drug reactions. In one study, acneform eruptions were identified in only 10% of those on combination therapy—trametinib with the BRAFi dabrafenib—compared to 77% of patients on trametinib monotherapy.10 Strikingly, cutaneous AEs occurred in 100% of trametinib-treated mice compared to 30% of combination-treated mice in another study, while the benefits of MEKi remained similar in both groups.11 Because BRAFi and MEKi combination therapy improves progression-free survival while minimizing AEs, we support the use of combination therapy instead of BRAFi or MEKi monotherapy.5

Histologic Evidence of AEs

Histology of trametinib-associated cutaneous reactions is not well characterized, which is in contrast to our understanding of cutaneous AEs associated with BRAFi in which transient acantholytic dermatosis (seen in 45% of patients) and verrucal keratosis (seen in 18% of patients) have been well characterized on histology.12 Interestingly, cutaneous granulomatous eruptions have been attributed to BRAFi therapy in 4 patients.13,14 One patient was on monotherapy with vemurafenib and granulomatous dermatitis with focal necrosis was seen on histology.13 The other 3 patients were on combination therapy with trametinib; 2 had histology-proven sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation, and 1 demonstrated perifollicular granulomatous inflammation and granulomatous inflammation surrounding a focus of melanoma cells.13,14 Although these granulomatous reactions were attributed to BRAFi or combination therapy, the association with trametinib remains unclear. On the other hand, our patient’s granulomatous reaction was exacerbated on trametinib monotherapy, suggesting a relationship to trametinib itself rather than BRAFi.

Conclusion

With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAFi and MEKi therapies provide major milestones in metastatic melanoma management. As more patients are treated with these agents, it is important that we better characterize their associated side effects. Our case of an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction to trametinib adds to the knowledge base of possible cutaneous reactions caused by this drug. We hope that prospective studies will further investigate and differentiate the cutaneous AEs described so that we can better manage these patients.

A decade ago, the few agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of metastatic melanoma demonstrated low therapeutic success rates (ie, <15%–20%).1 Since then, advances in molecular biology have identified oncogenes that contribute to melanoma progression.2 Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by targeting mutant BRAF and mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) has created promising pharmacologic treatment opportunities.3 Due to the recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of these therapies for treatment of melanoma, it is important to better characterize these adverse events (AEs) so that we can manage them. We present the development of an unusual cutaneous reaction to trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, in a man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma.

Case Report

A 66-year-old man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma with metastases to the brain and lungs presented with recurring pruritic erythematous papules on the face and bilateral forearms that began shortly after initiating therapy with trametinib. The cutaneous eruption had initially presented on the face, forearms, and dorsal hands when trametinib was used in combination with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, and ipilimumab, a human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4–blocking antibody; however, lesions initially were minimal and self-resolving. When trametinib was reintroduced as monotherapy due to fever attributed to the combination treatment regimen, the cutaneous eruption recurred more severely. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly papules limited to the face and bilateral upper extremities, including the flexural surfaces.

A biopsy from the flexural surface of the right forearm revealed a dense perivascular lymphoid and xanthomatous infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1). Poorly formed granulomas within the mid reticular dermis demonstrated focal palisading of histiocytes with prominent giant cells at the periphery. Histiocytes and giant cells showed foamy or xanthomatous cytoplasm. Within the reaction, degenerative and swollen collagen fibers were noted with no mucin deposition, which was confirmed with negative colloidal iron staining.

Brief cessation of trametinib along with application of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% resulted in resolution of the cutaneous eruption. Later, trametinib was reintroduced in combination with vemurafenib, though therapy was intermittently discontinued due to various side effects. Skin lesions continued to recur (Figure 2) while the patient was on trametinib but remained minimal and continued to respond to topical clobetasol propionate. One year later, the patient continues to tolerate combination therapy with trametinib and vemurafenib.

Comment

BRAF Inhibitors

Normally, activated BRAF phosphorylates and stimulates MEK proteins, ultimately influencing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.3-5 BRAF mutations that constitutively activate this pathway have been detected in several malignancies, including papillary thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer, and brain tumors, but they are particularly prevalent in melanoma.4,6 The majority of BRAF-positive malignant melanomas are associated with V600E, in which valine is substituted for glutamic acid at codon 600. The next most common BRAF mutation is V600K, in which valine is substituted for lysine.2,7 Together these constitute approximately 95% of BRAF mutations in melanoma patients.5

MEK Inhibitors

Initially, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) were introduced to the market for treating melanoma with great success; however, resistance to BRAFi therapy quickly was identified within months of initiating therapy, leading to investigations for combination therapy with MEK inhibitors (MEKi).2,5 MEK inhibition decreases cellular proliferation and also leads to apoptosis of melanoma cells in patients with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations.2,8 Trametinib, in particular, is a reversible, highly selective allosteric inhibitor of both MEK1 and MEK2. While on trametinib, patients with metastatic melanoma have experienced 3 times as long progression-free survival as well as 81% overall survival compared to 67% overall survival at 6 months in patients on chemotherapy, dacarbazine, or paclitaxel.5 However, AEs are quite common with trametinib, with cutaneous AEs being a leading side effect. Several large trials have reported that 57% to 92% of patients on trametinib report cutaneous AEs, with the majority of cases being described as papulopustular or acneform (Table).5,9

Combination Therapy

Fortunately, combination treatment with a BRAFi may alleviate MEKi-induced cutaneous drug reactions. In one study, acneform eruptions were identified in only 10% of those on combination therapy—trametinib with the BRAFi dabrafenib—compared to 77% of patients on trametinib monotherapy.10 Strikingly, cutaneous AEs occurred in 100% of trametinib-treated mice compared to 30% of combination-treated mice in another study, while the benefits of MEKi remained similar in both groups.11 Because BRAFi and MEKi combination therapy improves progression-free survival while minimizing AEs, we support the use of combination therapy instead of BRAFi or MEKi monotherapy.5

Histologic Evidence of AEs

Histology of trametinib-associated cutaneous reactions is not well characterized, which is in contrast to our understanding of cutaneous AEs associated with BRAFi in which transient acantholytic dermatosis (seen in 45% of patients) and verrucal keratosis (seen in 18% of patients) have been well characterized on histology.12 Interestingly, cutaneous granulomatous eruptions have been attributed to BRAFi therapy in 4 patients.13,14 One patient was on monotherapy with vemurafenib and granulomatous dermatitis with focal necrosis was seen on histology.13 The other 3 patients were on combination therapy with trametinib; 2 had histology-proven sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation, and 1 demonstrated perifollicular granulomatous inflammation and granulomatous inflammation surrounding a focus of melanoma cells.13,14 Although these granulomatous reactions were attributed to BRAFi or combination therapy, the association with trametinib remains unclear. On the other hand, our patient’s granulomatous reaction was exacerbated on trametinib monotherapy, suggesting a relationship to trametinib itself rather than BRAFi.

Conclusion

With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAFi and MEKi therapies provide major milestones in metastatic melanoma management. As more patients are treated with these agents, it is important that we better characterize their associated side effects. Our case of an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction to trametinib adds to the knowledge base of possible cutaneous reactions caused by this drug. We hope that prospective studies will further investigate and differentiate the cutaneous AEs described so that we can better manage these patients.

- Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D. Melanoma and immunotherapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:547-564.

- Chung C, Reilly S. Trametinib: a novel signal transduction inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:101-110.

- Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy [published online February 12, 2009]. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125-134.

- Hertzman Johansson C, Egyhazi Brage S. BRAF inhibitors in cancer therapy [published online December 8, 2013]. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:176-182.

- Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al; METRIC Study Group. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma [published online June 4, 2012]. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107-114.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer [published online June 9, 2002]. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3:6.

- Roberts PF, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291-3310.

- Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR, et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 2 dose-escalation trial [published online July 16, 2012]. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782-789.

- Anforth R, Liu M, Nguyen B, et al. Acneiform eruptions: a common cutaneous toxicity of the MEK inhibitor trametinib [published online December 9, 2013]. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:250-254.

- Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Deken MA, et al. Synchronous BRAF(V600E) and MEK inhibition leads to superior control of murine melanoma by limiting MEK inhibitor induced skin toxicity. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1649-1658.

- Anforth R, Carlos G, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in patients treated with BRAF inhibitor-based therapies for metastatic melanoma for longer than 52 weeks [published online November 21, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:239-243.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307-311.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell K. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

- Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D. Melanoma and immunotherapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:547-564.

- Chung C, Reilly S. Trametinib: a novel signal transduction inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:101-110.

- Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy [published online February 12, 2009]. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125-134.

- Hertzman Johansson C, Egyhazi Brage S. BRAF inhibitors in cancer therapy [published online December 8, 2013]. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:176-182.

- Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al; METRIC Study Group. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma [published online June 4, 2012]. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107-114.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer [published online June 9, 2002]. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3:6.

- Roberts PF, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291-3310.

- Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR, et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 2 dose-escalation trial [published online July 16, 2012]. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782-789.

- Anforth R, Liu M, Nguyen B, et al. Acneiform eruptions: a common cutaneous toxicity of the MEK inhibitor trametinib [published online December 9, 2013]. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:250-254.

- Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Deken MA, et al. Synchronous BRAF(V600E) and MEK inhibition leads to superior control of murine melanoma by limiting MEK inhibitor induced skin toxicity. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1649-1658.

- Anforth R, Carlos G, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in patients treated with BRAF inhibitor-based therapies for metastatic melanoma for longer than 52 weeks [published online November 21, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:239-243.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307-311.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell K. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

Practice Points

- With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAF and MEK inhibitors have been increasingly utilized as therapies in metastatic melanoma management.

- Trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, is commonly associated with cutaneous adverse reactions, particularly acneform eruptions.

- We report a patient on trametinib who developed an eruption with an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction pattern noted on histology.

Acquired Perforating Dermatosis in a Skin Graft

Case Report

A 57-year-old black woman with a history of dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, diastolic congestive heart failure, and chronic bronchitis was admitted to Howard University Hospital (Washington, DC) for acute chest pain and shortness of breath. During her hospital stay the dermatology team was consulted for evaluation of two 1.6-cm teardrop-shaped, yellow-white-chalky plaques noted in the center of an atrophic, hyperpigmented, shiny, contracted split-thickness skin graft (STSG) on the right posterior forearm (Figure 1). Twenty years prior, the patient received STSGs on the right and left forearm secondary to caustic burns. Two months before the current admission she noticed 2 adjacent teardrop-shaped white plaques within the center of the STSG on the right forearm. At a 3-month follow-up, she had developed more lesions within both graft sites of the bilateral forearm. There was no notable pruritus associated with the lesions.

A 4-mm punch biopsy showed an orthokeratotic plug with basophilic inflammatory debris adjacent to acanthotic epidermis, necrotic basophilic debris at the superficial dermis with epidermal canals extending from the base of the lesion superiorly, and transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers (Figure 2A). A Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed the necrotic basophilic debris located in the superficial dermis admixed with a cluster of black wavy elastic fibers establishing the identity of the perforating substance (Figure 2B). Masson trichrome stain revealed loss of collagen structure within the aggregate of elastic fibers adjacent to the epidermis and no collagen within epidermal canals (Figure 2C). These histopathologic findings together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis (APD).

Comment

Presentation

Acquired perforating dermatosis is a dermatologic condition characterized by multiple pruritic, dome-shaped papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs giving a craterlike appearance.1-4 A green-brown or black crust with an erythematous border typically surrounds the primary lesions.4 Acquired perforating dermatosis favors a distribution over the trunk, gluteal region, and the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities. Palmoplantar, intertriginous, and mucous membrane regions typically are spared.4 Occasionally, APD may present as generalized nodules and papules. Our case consisting of lesions that were localized to STSGs on the forearms supports the typical distribution; however, the presentation of APD occurring within a skin graft is unique.

From an epidemiologic standpoint, APD is more likely to affect men than women (1.5:1 ratio). Additionally, APD’s affected age range is 29 to 96 years (mean, 56.8 years),5 which is consistent with our patient’s age. Acquired perforating dermatosis has no racial predilection, though there is a predominance among black patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, as seen in our patient.3

Pathogenesis

The etiology of APD remains unknown.6 Some believe that the uremic or calcium deposits on the skin of patients with chronic kidney disease may trigger chronic pruritus, leading to epithelial hyperplasia and the development of perforating lesions.1,3 A prominent theory in the literature is that superficial trauma, such as scratching, induces necrosis of tissue, facilitating transepidermal elimination of connective tissue components.7 The Köbner phenomenon, which can easily be induced by scratching the skin, supports this idea.8 Fujimoto et al9 suggested that scratching exposes keratinocytes to advanced glycation end product–modified extracellular matrix proteins, particularly types I and III collagen. This exposure leads to the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes with the advanced glycation end receptor (CD36) followed by the upward movement of keratinocytes with glycated collagen. Others postulate fibronectin, involved in epidermal cell signaling, locomotion, and differentiation, is an antigenic trigger because patients with DM and uremia have increased levels of fibronectin in the serum and at sites of perforating skin lesions.10

Diseases Associated With APD

Acquired perforating dermatosis is an umbrella term for perforating disease found in adults. It is associated with systemic diseases, such as DM and pruritus of renal failure.11 Our patient had both dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease and DM. Acquired perforating dermatosis is observed in 4.5% to 11% of patients on hemodialysis12,13; however, APD may occur prior to or in the absence of dialysis.3 Other examples of systemic conditions associated with APD include obstructive uropathy, chronic nephritis, anuria, and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Koebnerization also may trigger lesions to manifest in a linear pattern after localized trauma to the skin.7 Acquired perforating dermatosis is associated with other types of trauma, such as healing herpes zoster, or following exposure to drugs, such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, bevacizumab, telaprevir, sorafenib, sirolimus, and indinavir.14-16 Rarely, there have been associations with a history of insect bites, scabies, lymphoma, and hepatobiliary disease.1-3

Histopathology

Acquired perforating dermatosis is classified as a perforating disease, along with reactive perforating collagenosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), perforating folliculitis, and perforating calcific elastosis. Perforating diseases are histologically characterized by the transepidermal penetration and elimination of altered connective tissue and inflammatory cells.5 Each disease differs based on their clinical and histological characteristics.

Histologic sections of APD show a plug of crusting or hyperkeratosis with variable parakeratosis, acanthosis, and occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes. In the dermis, aggregates of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells may be found.17 The histologic findings vary depending on the stage of evolution of the individual lesion. Early lesions show a concave depression with acanthosis, vacuolation of basal keratinocytes, and dermal inflammation.4 Additionally, transepidermal channels filled with keratin, pyknotic nuclear debris, inflammatory cells, elastin, or collagen can be noted.3 Over time, the elastic fibers, as detected by the Verhoeff-van Gieson stain, dissipate and the collagen acquires a basophilic staining. Adjacent to the channels, the basement membrane remains intact in early lesions but later shows discontinuities and electron-dense fibrinlike material.3 Occasionally, amorphous degenerated material within the perforations is the major histologic finding.11 Usually, the material cannot be clearly identified as collagen or elastin, but sometimes both are present.

In our case, we identified elastin as the perforating substance, which is less common than collagen, the typical perforating substance in APD. Elastin has occasionally been seen to serve as the only perforating substance from APD lesions among patients. Abe et al18 reported that the biopsy of a Japanese patient with keratotic follicular papules and serpiginous-arranged papules demonstrated elimination of atypical elastin fibers from the transepidermal channels. This patient was diagnosed with APD as well as EPS and perforating folliculitis based on the clinical presentation.18 Kim et al19 studied 30 Korean patients with APD. One had serpiginous hyperkeratotic plaques along the upper extremity and trunk that revealed transepidermal channels containing coarse elastic fibers and basophilic debris; however, due to the serpiginous morphology of lesions, both Abe et al18 and Kim et al19 favored a diagnosis of acquired EPS. Saray et al20 conducted a retrospective study of 22 Turkish patients with APD; 1 patient had a painful hyperkeratotic papule on the auricle that on histopathology showed degenerated elastin perforating through the keratotic plug, features similar to our case.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses include perforating diseases14,19 as well as other disorders that exhibit the Köbner phenomenon, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and verruca vulgaris.21,22 Also, it is not uncommon for patients with APD to have coexisting folliculitis or prurigo nodularis.22

Treatment

Management is focused on treating the symptoms. For pruritus, sedating antihistamines and other antipruritic agents are efficacious.23 Topical, intra-lesional, or systemic corticosteroids and topical retinoids have shown variable resolution in APD lesions.24 Some case reports describe topical menthol, salicylic acid, sulfur, benzoyl peroxide, systemic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, doxycycline), and allopurinol for elevated uric acid levels as effective treatment methods.6 Narrowband UVB phototherapy is beneficial for APD and renal disease.25,26 Renal transplantation has been curative for some patients with APD.27 Given that our patient’s lesions were asymptomatic, no treatment was offered at the time.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with APD localized exclusively to the site of a skin graft, and histologic examination identified elastin as the primary perforating substance. A medical history of DM and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

- Rodney IJ, Taylor CS, Cohen G. Derm Dx: what are these pruritic nodules? The Dermatologist. October 15, 2009. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/derm-dx-what-are-these-pruritic-nodules. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- Gagnon, AL, Desai T. Dermatological diseases in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephropathol. 2013;2:104-109.

- Kurban MS, Boueiz A, Kibbi AG. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic kidney disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:255-264.

- Wagner G, Sachse MM. Acquired reactive perforating dermatosis [published online May 29, 2013]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:723-729; 723-730.

- Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592.

- Healy R, Cerio R, Hollingsworth A, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:621-623.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, et al. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22:45-55.

- Satchell AC, Crotty K, Lee S. Reactive perforating collagenosis: a condition that may be underdiagnosed. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:284-287.

- Fujimoto E, Kobayashi T, Fujimoto N, et al. AGE-modified collagens I and III induce keratinocyte terminal differentiation through AGE receptor CD36: epidermal-dermal interaction in acquired perforating dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:405-414.

- Bilezikci B, Sechkin D, Demirhan B. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure: a possible role for fibronectin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:230-232.

- Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1074-1078.

- Hurwitz RM, Melton ME, Creech FT, et al. Perforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:101-108.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Lübbe J, Sorg O, Malé PJ, et al. Sirolimus-induced inflammatory papules with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis [published online January 9, 2008]. Dermatology. 2008;216:239-242.

- Pernet C, Pageaux GP, Guillot B, et al. Telaprevir-induced acquired perforating dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1371-1372.

- Severino-Freire M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with sorafenib therapy [published online September 11, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:328-330.

- Zelger B, Hintner H, Auböck J, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis. transepidermal elimination of DNA material and possible role of leukocytes in pathogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:695-700.

- Abe R, Murase S, Nomura Y, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis appearing as elastosis perforans serpiginosa and perforating folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:653-654.

- Kim SW, Kim MS, Lee JH, et al. A clinicopathologic study of thirty cases of acquired perforating dermatosis in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:162-171.

- Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:679-688.

- Carter VH, Constantine VS. Kyrle’s disease. I. clinical findings in five cases and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:624-632.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Digiovanna JJ. Cutaneous manifestations of end-stage renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:975-986.

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Ohe S, Danno K, Sasaki H, et al. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:892-894.

- Sezer E, Erkek E. Acquired perforating dermatosis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:50-52.

- Saldanha LF, Gonick HC, Rodriguez HJ, et al. Silicon-related syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1997;77:48-56.

Case Report

A 57-year-old black woman with a history of dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, diastolic congestive heart failure, and chronic bronchitis was admitted to Howard University Hospital (Washington, DC) for acute chest pain and shortness of breath. During her hospital stay the dermatology team was consulted for evaluation of two 1.6-cm teardrop-shaped, yellow-white-chalky plaques noted in the center of an atrophic, hyperpigmented, shiny, contracted split-thickness skin graft (STSG) on the right posterior forearm (Figure 1). Twenty years prior, the patient received STSGs on the right and left forearm secondary to caustic burns. Two months before the current admission she noticed 2 adjacent teardrop-shaped white plaques within the center of the STSG on the right forearm. At a 3-month follow-up, she had developed more lesions within both graft sites of the bilateral forearm. There was no notable pruritus associated with the lesions.

A 4-mm punch biopsy showed an orthokeratotic plug with basophilic inflammatory debris adjacent to acanthotic epidermis, necrotic basophilic debris at the superficial dermis with epidermal canals extending from the base of the lesion superiorly, and transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers (Figure 2A). A Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed the necrotic basophilic debris located in the superficial dermis admixed with a cluster of black wavy elastic fibers establishing the identity of the perforating substance (Figure 2B). Masson trichrome stain revealed loss of collagen structure within the aggregate of elastic fibers adjacent to the epidermis and no collagen within epidermal canals (Figure 2C). These histopathologic findings together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis (APD).

Comment

Presentation

Acquired perforating dermatosis is a dermatologic condition characterized by multiple pruritic, dome-shaped papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs giving a craterlike appearance.1-4 A green-brown or black crust with an erythematous border typically surrounds the primary lesions.4 Acquired perforating dermatosis favors a distribution over the trunk, gluteal region, and the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities. Palmoplantar, intertriginous, and mucous membrane regions typically are spared.4 Occasionally, APD may present as generalized nodules and papules. Our case consisting of lesions that were localized to STSGs on the forearms supports the typical distribution; however, the presentation of APD occurring within a skin graft is unique.

From an epidemiologic standpoint, APD is more likely to affect men than women (1.5:1 ratio). Additionally, APD’s affected age range is 29 to 96 years (mean, 56.8 years),5 which is consistent with our patient’s age. Acquired perforating dermatosis has no racial predilection, though there is a predominance among black patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, as seen in our patient.3

Pathogenesis

The etiology of APD remains unknown.6 Some believe that the uremic or calcium deposits on the skin of patients with chronic kidney disease may trigger chronic pruritus, leading to epithelial hyperplasia and the development of perforating lesions.1,3 A prominent theory in the literature is that superficial trauma, such as scratching, induces necrosis of tissue, facilitating transepidermal elimination of connective tissue components.7 The Köbner phenomenon, which can easily be induced by scratching the skin, supports this idea.8 Fujimoto et al9 suggested that scratching exposes keratinocytes to advanced glycation end product–modified extracellular matrix proteins, particularly types I and III collagen. This exposure leads to the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes with the advanced glycation end receptor (CD36) followed by the upward movement of keratinocytes with glycated collagen. Others postulate fibronectin, involved in epidermal cell signaling, locomotion, and differentiation, is an antigenic trigger because patients with DM and uremia have increased levels of fibronectin in the serum and at sites of perforating skin lesions.10

Diseases Associated With APD

Acquired perforating dermatosis is an umbrella term for perforating disease found in adults. It is associated with systemic diseases, such as DM and pruritus of renal failure.11 Our patient had both dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease and DM. Acquired perforating dermatosis is observed in 4.5% to 11% of patients on hemodialysis12,13; however, APD may occur prior to or in the absence of dialysis.3 Other examples of systemic conditions associated with APD include obstructive uropathy, chronic nephritis, anuria, and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Koebnerization also may trigger lesions to manifest in a linear pattern after localized trauma to the skin.7 Acquired perforating dermatosis is associated with other types of trauma, such as healing herpes zoster, or following exposure to drugs, such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, bevacizumab, telaprevir, sorafenib, sirolimus, and indinavir.14-16 Rarely, there have been associations with a history of insect bites, scabies, lymphoma, and hepatobiliary disease.1-3

Histopathology

Acquired perforating dermatosis is classified as a perforating disease, along with reactive perforating collagenosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), perforating folliculitis, and perforating calcific elastosis. Perforating diseases are histologically characterized by the transepidermal penetration and elimination of altered connective tissue and inflammatory cells.5 Each disease differs based on their clinical and histological characteristics.

Histologic sections of APD show a plug of crusting or hyperkeratosis with variable parakeratosis, acanthosis, and occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes. In the dermis, aggregates of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells may be found.17 The histologic findings vary depending on the stage of evolution of the individual lesion. Early lesions show a concave depression with acanthosis, vacuolation of basal keratinocytes, and dermal inflammation.4 Additionally, transepidermal channels filled with keratin, pyknotic nuclear debris, inflammatory cells, elastin, or collagen can be noted.3 Over time, the elastic fibers, as detected by the Verhoeff-van Gieson stain, dissipate and the collagen acquires a basophilic staining. Adjacent to the channels, the basement membrane remains intact in early lesions but later shows discontinuities and electron-dense fibrinlike material.3 Occasionally, amorphous degenerated material within the perforations is the major histologic finding.11 Usually, the material cannot be clearly identified as collagen or elastin, but sometimes both are present.

In our case, we identified elastin as the perforating substance, which is less common than collagen, the typical perforating substance in APD. Elastin has occasionally been seen to serve as the only perforating substance from APD lesions among patients. Abe et al18 reported that the biopsy of a Japanese patient with keratotic follicular papules and serpiginous-arranged papules demonstrated elimination of atypical elastin fibers from the transepidermal channels. This patient was diagnosed with APD as well as EPS and perforating folliculitis based on the clinical presentation.18 Kim et al19 studied 30 Korean patients with APD. One had serpiginous hyperkeratotic plaques along the upper extremity and trunk that revealed transepidermal channels containing coarse elastic fibers and basophilic debris; however, due to the serpiginous morphology of lesions, both Abe et al18 and Kim et al19 favored a diagnosis of acquired EPS. Saray et al20 conducted a retrospective study of 22 Turkish patients with APD; 1 patient had a painful hyperkeratotic papule on the auricle that on histopathology showed degenerated elastin perforating through the keratotic plug, features similar to our case.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses include perforating diseases14,19 as well as other disorders that exhibit the Köbner phenomenon, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and verruca vulgaris.21,22 Also, it is not uncommon for patients with APD to have coexisting folliculitis or prurigo nodularis.22

Treatment

Management is focused on treating the symptoms. For pruritus, sedating antihistamines and other antipruritic agents are efficacious.23 Topical, intra-lesional, or systemic corticosteroids and topical retinoids have shown variable resolution in APD lesions.24 Some case reports describe topical menthol, salicylic acid, sulfur, benzoyl peroxide, systemic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, doxycycline), and allopurinol for elevated uric acid levels as effective treatment methods.6 Narrowband UVB phototherapy is beneficial for APD and renal disease.25,26 Renal transplantation has been curative for some patients with APD.27 Given that our patient’s lesions were asymptomatic, no treatment was offered at the time.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with APD localized exclusively to the site of a skin graft, and histologic examination identified elastin as the primary perforating substance. A medical history of DM and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

Case Report

A 57-year-old black woman with a history of dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, diastolic congestive heart failure, and chronic bronchitis was admitted to Howard University Hospital (Washington, DC) for acute chest pain and shortness of breath. During her hospital stay the dermatology team was consulted for evaluation of two 1.6-cm teardrop-shaped, yellow-white-chalky plaques noted in the center of an atrophic, hyperpigmented, shiny, contracted split-thickness skin graft (STSG) on the right posterior forearm (Figure 1). Twenty years prior, the patient received STSGs on the right and left forearm secondary to caustic burns. Two months before the current admission she noticed 2 adjacent teardrop-shaped white plaques within the center of the STSG on the right forearm. At a 3-month follow-up, she had developed more lesions within both graft sites of the bilateral forearm. There was no notable pruritus associated with the lesions.

A 4-mm punch biopsy showed an orthokeratotic plug with basophilic inflammatory debris adjacent to acanthotic epidermis, necrotic basophilic debris at the superficial dermis with epidermal canals extending from the base of the lesion superiorly, and transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers (Figure 2A). A Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed the necrotic basophilic debris located in the superficial dermis admixed with a cluster of black wavy elastic fibers establishing the identity of the perforating substance (Figure 2B). Masson trichrome stain revealed loss of collagen structure within the aggregate of elastic fibers adjacent to the epidermis and no collagen within epidermal canals (Figure 2C). These histopathologic findings together with the clinical presentation were consistent with a diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis (APD).

Comment

Presentation

Acquired perforating dermatosis is a dermatologic condition characterized by multiple pruritic, dome-shaped papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs giving a craterlike appearance.1-4 A green-brown or black crust with an erythematous border typically surrounds the primary lesions.4 Acquired perforating dermatosis favors a distribution over the trunk, gluteal region, and the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities. Palmoplantar, intertriginous, and mucous membrane regions typically are spared.4 Occasionally, APD may present as generalized nodules and papules. Our case consisting of lesions that were localized to STSGs on the forearms supports the typical distribution; however, the presentation of APD occurring within a skin graft is unique.

From an epidemiologic standpoint, APD is more likely to affect men than women (1.5:1 ratio). Additionally, APD’s affected age range is 29 to 96 years (mean, 56.8 years),5 which is consistent with our patient’s age. Acquired perforating dermatosis has no racial predilection, though there is a predominance among black patients with concomitant chronic renal failure, as seen in our patient.3

Pathogenesis

The etiology of APD remains unknown.6 Some believe that the uremic or calcium deposits on the skin of patients with chronic kidney disease may trigger chronic pruritus, leading to epithelial hyperplasia and the development of perforating lesions.1,3 A prominent theory in the literature is that superficial trauma, such as scratching, induces necrosis of tissue, facilitating transepidermal elimination of connective tissue components.7 The Köbner phenomenon, which can easily be induced by scratching the skin, supports this idea.8 Fujimoto et al9 suggested that scratching exposes keratinocytes to advanced glycation end product–modified extracellular matrix proteins, particularly types I and III collagen. This exposure leads to the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes with the advanced glycation end receptor (CD36) followed by the upward movement of keratinocytes with glycated collagen. Others postulate fibronectin, involved in epidermal cell signaling, locomotion, and differentiation, is an antigenic trigger because patients with DM and uremia have increased levels of fibronectin in the serum and at sites of perforating skin lesions.10

Diseases Associated With APD

Acquired perforating dermatosis is an umbrella term for perforating disease found in adults. It is associated with systemic diseases, such as DM and pruritus of renal failure.11 Our patient had both dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease and DM. Acquired perforating dermatosis is observed in 4.5% to 11% of patients on hemodialysis12,13; however, APD may occur prior to or in the absence of dialysis.3 Other examples of systemic conditions associated with APD include obstructive uropathy, chronic nephritis, anuria, and hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Koebnerization also may trigger lesions to manifest in a linear pattern after localized trauma to the skin.7 Acquired perforating dermatosis is associated with other types of trauma, such as healing herpes zoster, or following exposure to drugs, such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, bevacizumab, telaprevir, sorafenib, sirolimus, and indinavir.14-16 Rarely, there have been associations with a history of insect bites, scabies, lymphoma, and hepatobiliary disease.1-3

Histopathology

Acquired perforating dermatosis is classified as a perforating disease, along with reactive perforating collagenosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), perforating folliculitis, and perforating calcific elastosis. Perforating diseases are histologically characterized by the transepidermal penetration and elimination of altered connective tissue and inflammatory cells.5 Each disease differs based on their clinical and histological characteristics.

Histologic sections of APD show a plug of crusting or hyperkeratosis with variable parakeratosis, acanthosis, and occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes. In the dermis, aggregates of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells may be found.17 The histologic findings vary depending on the stage of evolution of the individual lesion. Early lesions show a concave depression with acanthosis, vacuolation of basal keratinocytes, and dermal inflammation.4 Additionally, transepidermal channels filled with keratin, pyknotic nuclear debris, inflammatory cells, elastin, or collagen can be noted.3 Over time, the elastic fibers, as detected by the Verhoeff-van Gieson stain, dissipate and the collagen acquires a basophilic staining. Adjacent to the channels, the basement membrane remains intact in early lesions but later shows discontinuities and electron-dense fibrinlike material.3 Occasionally, amorphous degenerated material within the perforations is the major histologic finding.11 Usually, the material cannot be clearly identified as collagen or elastin, but sometimes both are present.

In our case, we identified elastin as the perforating substance, which is less common than collagen, the typical perforating substance in APD. Elastin has occasionally been seen to serve as the only perforating substance from APD lesions among patients. Abe et al18 reported that the biopsy of a Japanese patient with keratotic follicular papules and serpiginous-arranged papules demonstrated elimination of atypical elastin fibers from the transepidermal channels. This patient was diagnosed with APD as well as EPS and perforating folliculitis based on the clinical presentation.18 Kim et al19 studied 30 Korean patients with APD. One had serpiginous hyperkeratotic plaques along the upper extremity and trunk that revealed transepidermal channels containing coarse elastic fibers and basophilic debris; however, due to the serpiginous morphology of lesions, both Abe et al18 and Kim et al19 favored a diagnosis of acquired EPS. Saray et al20 conducted a retrospective study of 22 Turkish patients with APD; 1 patient had a painful hyperkeratotic papule on the auricle that on histopathology showed degenerated elastin perforating through the keratotic plug, features similar to our case.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses include perforating diseases14,19 as well as other disorders that exhibit the Köbner phenomenon, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and verruca vulgaris.21,22 Also, it is not uncommon for patients with APD to have coexisting folliculitis or prurigo nodularis.22

Treatment

Management is focused on treating the symptoms. For pruritus, sedating antihistamines and other antipruritic agents are efficacious.23 Topical, intra-lesional, or systemic corticosteroids and topical retinoids have shown variable resolution in APD lesions.24 Some case reports describe topical menthol, salicylic acid, sulfur, benzoyl peroxide, systemic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, doxycycline), and allopurinol for elevated uric acid levels as effective treatment methods.6 Narrowband UVB phototherapy is beneficial for APD and renal disease.25,26 Renal transplantation has been curative for some patients with APD.27 Given that our patient’s lesions were asymptomatic, no treatment was offered at the time.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with APD localized exclusively to the site of a skin graft, and histologic examination identified elastin as the primary perforating substance. A medical history of DM and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

- Rodney IJ, Taylor CS, Cohen G. Derm Dx: what are these pruritic nodules? The Dermatologist. October 15, 2009. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/derm-dx-what-are-these-pruritic-nodules. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- Gagnon, AL, Desai T. Dermatological diseases in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephropathol. 2013;2:104-109.

- Kurban MS, Boueiz A, Kibbi AG. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic kidney disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:255-264.

- Wagner G, Sachse MM. Acquired reactive perforating dermatosis [published online May 29, 2013]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:723-729; 723-730.

- Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592.

- Healy R, Cerio R, Hollingsworth A, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:621-623.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, et al. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22:45-55.

- Satchell AC, Crotty K, Lee S. Reactive perforating collagenosis: a condition that may be underdiagnosed. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:284-287.

- Fujimoto E, Kobayashi T, Fujimoto N, et al. AGE-modified collagens I and III induce keratinocyte terminal differentiation through AGE receptor CD36: epidermal-dermal interaction in acquired perforating dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:405-414.

- Bilezikci B, Sechkin D, Demirhan B. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure: a possible role for fibronectin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:230-232.

- Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1074-1078.

- Hurwitz RM, Melton ME, Creech FT, et al. Perforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:101-108.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Lübbe J, Sorg O, Malé PJ, et al. Sirolimus-induced inflammatory papules with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis [published online January 9, 2008]. Dermatology. 2008;216:239-242.

- Pernet C, Pageaux GP, Guillot B, et al. Telaprevir-induced acquired perforating dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1371-1372.

- Severino-Freire M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with sorafenib therapy [published online September 11, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:328-330.

- Zelger B, Hintner H, Auböck J, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis. transepidermal elimination of DNA material and possible role of leukocytes in pathogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:695-700.

- Abe R, Murase S, Nomura Y, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis appearing as elastosis perforans serpiginosa and perforating folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:653-654.

- Kim SW, Kim MS, Lee JH, et al. A clinicopathologic study of thirty cases of acquired perforating dermatosis in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:162-171.

- Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:679-688.

- Carter VH, Constantine VS. Kyrle’s disease. I. clinical findings in five cases and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:624-632.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Digiovanna JJ. Cutaneous manifestations of end-stage renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:975-986.

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Ohe S, Danno K, Sasaki H, et al. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:892-894.

- Sezer E, Erkek E. Acquired perforating dermatosis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:50-52.

- Saldanha LF, Gonick HC, Rodriguez HJ, et al. Silicon-related syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1997;77:48-56.

- Rodney IJ, Taylor CS, Cohen G. Derm Dx: what are these pruritic nodules? The Dermatologist. October 15, 2009. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/derm-dx-what-are-these-pruritic-nodules. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- Gagnon, AL, Desai T. Dermatological diseases in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephropathol. 2013;2:104-109.

- Kurban MS, Boueiz A, Kibbi AG. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic kidney disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:255-264.

- Wagner G, Sachse MM. Acquired reactive perforating dermatosis [published online May 29, 2013]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:723-729; 723-730.

- Karpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. J Dermatol. 2010;37:585-592.

- Healy R, Cerio R, Hollingsworth A, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:621-623.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, et al. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22:45-55.

- Satchell AC, Crotty K, Lee S. Reactive perforating collagenosis: a condition that may be underdiagnosed. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:284-287.

- Fujimoto E, Kobayashi T, Fujimoto N, et al. AGE-modified collagens I and III induce keratinocyte terminal differentiation through AGE receptor CD36: epidermal-dermal interaction in acquired perforating dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:405-414.

- Bilezikci B, Sechkin D, Demirhan B. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure: a possible role for fibronectin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:230-232.

- Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1074-1078.

- Hurwitz RM, Melton ME, Creech FT, et al. Perforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:101-108.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Lübbe J, Sorg O, Malé PJ, et al. Sirolimus-induced inflammatory papules with acquired reactive perforating collagenosis [published online January 9, 2008]. Dermatology. 2008;216:239-242.

- Pernet C, Pageaux GP, Guillot B, et al. Telaprevir-induced acquired perforating dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1371-1372.

- Severino-Freire M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis associated with sorafenib therapy [published online September 11, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:328-330.

- Zelger B, Hintner H, Auböck J, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis. transepidermal elimination of DNA material and possible role of leukocytes in pathogenesis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:695-700.

- Abe R, Murase S, Nomura Y, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis appearing as elastosis perforans serpiginosa and perforating folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:653-654.

- Kim SW, Kim MS, Lee JH, et al. A clinicopathologic study of thirty cases of acquired perforating dermatosis in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:162-171.

- Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:679-688.

- Carter VH, Constantine VS. Kyrle’s disease. I. clinical findings in five cases and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:624-632.

- Robinson-Bostom L, Digiovanna JJ. Cutaneous manifestations of end-stage renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:975-986.

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288.

- Morton CA, Henderson IS, Jones MC, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a British dialysis population. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:671-677.

- Ohe S, Danno K, Sasaki H, et al. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:892-894.

- Sezer E, Erkek E. Acquired perforating dermatosis successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:50-52.

- Saldanha LF, Gonick HC, Rodriguez HJ, et al. Silicon-related syndrome in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1997;77:48-56.

Practice Points

- Acquired perforating dermatosis (APD) presents as pruritic crateriform papules and plaques with central keratotic plugs.

- A medical history of diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease predisposes patients to APD. This case suggests that skin graft sites may be predisposed to the development of APD.

TKI discontinuation appears safe in CML

NEW YORK – Despite initial concerns that stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment would be ill-advised in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), clinical trial data suggest it is a safe and reasonable strategy, according to a leading expert.

“About 95% of people in all of these trials will regain their original response when they start off on therapy again,” said Jerald P. Radich, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

“There’s been a few that don’t, but blast crisis has been very, very rare, thank goodness, so it looks to be fairly safe for now,” Dr. Radich said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Hematologic Malignancies Annual Congress.

That being said, careful follow up is still required, Dr. Radich cautioned, noting that there was still an excess of CML in Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors evident decades after radiation exposure.

“CML is a very strange disease,” he said. “You can’t eliminate the possibility of some slow-growing clone that, once you take [a patient] off tyrosine kinase therapy, is going into an accelerated phase and might take years to manifest itself.”

In one of the latest reports to shed light on what happens after discontinuation, investigators for the ENESTop study reported that treatment-free remission “seems achievable” in patients who have sustained, deep remissions after discontinuing nilotinib second-line therapy (Ann Intern Med. 2018 Apr 3;168[7]:461-70).

In ENESTop, chronic phase CML patients on tyrosine kinase inhibitors for at least 3 years were eligible to discontinue therapy if they achieved MR4.5 (BCR-ABL1IS of 0.0032% or less) and maintained that response level during a 1-year consolidation phase.

Out of 163 patients in the study, 126 met the criteria to enter the treatment-free remission phase; of that subset, 58% maintained treatment-free remission at 48 weeks, while 53% maintained it at 96 weeks, investigators said.

For 56 patients who restarted nilotinib, 55 regained at least major molecular response (MMR), and 52 regained MR4.5, while none had progression to accelerated phase or blast crisis, according to the report.

Similarly, earlier reported results from the ENESTfreedom trial showed that, of 190 patients entering the treatment-free remission phase after a median duration of 43.5 months on nilotinib, more than half remained in MMR or better at 48 weeks (Leukemia. 2017 Jul;31[7]:1525-31).

Of 86 patients who started nilotinib again after losing MMR, 98.8% regained MMR and 88.4% regained MR4.5 by the data cutoff date for the trial.

Duration and depth of response may make a “little bit of difference” in likelihood of relapse, Dr. Radich added.

In an interim analysis of a prospective multicenter, nonrandomized European discontinuation trial (EURO-SKI), investigators found that patients achieving deep molecular responses had good molecular relapse-free survival (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Jun;19[6]:747-57).

Based on that, investigators suggested that patients with deep molecular responses should be considered for discontinuation to spare them from side effects and to reduce health expenditures.

Results of these and other trials are “pretty much unbelievable,” Dr. Radich said. That’s in part because mathematical modeling – extrapolated from early trials – had suggested it could take nearly 50 years to completely eradicate minimal residual disease with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and that the cumulative cure rate after 30 years of treatment could be as low as 31%.

Dr. Radich reported financial disclosures related to Amgen, Novartis, and Seattle Genetics.

NEW YORK – Despite initial concerns that stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment would be ill-advised in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), clinical trial data suggest it is a safe and reasonable strategy, according to a leading expert.

“About 95% of people in all of these trials will regain their original response when they start off on therapy again,” said Jerald P. Radich, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

“There’s been a few that don’t, but blast crisis has been very, very rare, thank goodness, so it looks to be fairly safe for now,” Dr. Radich said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Hematologic Malignancies Annual Congress.

That being said, careful follow up is still required, Dr. Radich cautioned, noting that there was still an excess of CML in Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors evident decades after radiation exposure.

“CML is a very strange disease,” he said. “You can’t eliminate the possibility of some slow-growing clone that, once you take [a patient] off tyrosine kinase therapy, is going into an accelerated phase and might take years to manifest itself.”

In one of the latest reports to shed light on what happens after discontinuation, investigators for the ENESTop study reported that treatment-free remission “seems achievable” in patients who have sustained, deep remissions after discontinuing nilotinib second-line therapy (Ann Intern Med. 2018 Apr 3;168[7]:461-70).

In ENESTop, chronic phase CML patients on tyrosine kinase inhibitors for at least 3 years were eligible to discontinue therapy if they achieved MR4.5 (BCR-ABL1IS of 0.0032% or less) and maintained that response level during a 1-year consolidation phase.

Out of 163 patients in the study, 126 met the criteria to enter the treatment-free remission phase; of that subset, 58% maintained treatment-free remission at 48 weeks, while 53% maintained it at 96 weeks, investigators said.

For 56 patients who restarted nilotinib, 55 regained at least major molecular response (MMR), and 52 regained MR4.5, while none had progression to accelerated phase or blast crisis, according to the report.

Similarly, earlier reported results from the ENESTfreedom trial showed that, of 190 patients entering the treatment-free remission phase after a median duration of 43.5 months on nilotinib, more than half remained in MMR or better at 48 weeks (Leukemia. 2017 Jul;31[7]:1525-31).

Of 86 patients who started nilotinib again after losing MMR, 98.8% regained MMR and 88.4% regained MR4.5 by the data cutoff date for the trial.

Duration and depth of response may make a “little bit of difference” in likelihood of relapse, Dr. Radich added.

In an interim analysis of a prospective multicenter, nonrandomized European discontinuation trial (EURO-SKI), investigators found that patients achieving deep molecular responses had good molecular relapse-free survival (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Jun;19[6]:747-57).

Based on that, investigators suggested that patients with deep molecular responses should be considered for discontinuation to spare them from side effects and to reduce health expenditures.

Results of these and other trials are “pretty much unbelievable,” Dr. Radich said. That’s in part because mathematical modeling – extrapolated from early trials – had suggested it could take nearly 50 years to completely eradicate minimal residual disease with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and that the cumulative cure rate after 30 years of treatment could be as low as 31%.

Dr. Radich reported financial disclosures related to Amgen, Novartis, and Seattle Genetics.

NEW YORK – Despite initial concerns that stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment would be ill-advised in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), clinical trial data suggest it is a safe and reasonable strategy, according to a leading expert.

“About 95% of people in all of these trials will regain their original response when they start off on therapy again,” said Jerald P. Radich, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

“There’s been a few that don’t, but blast crisis has been very, very rare, thank goodness, so it looks to be fairly safe for now,” Dr. Radich said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Hematologic Malignancies Annual Congress.