User login

What’s the best VTE treatment for patients with cancer?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No head-to-head studies or umbrella meta-analyses assess all the main treatments for VTE against each other.

Long-term LMWH decreases VTE recurrence compared with VKA

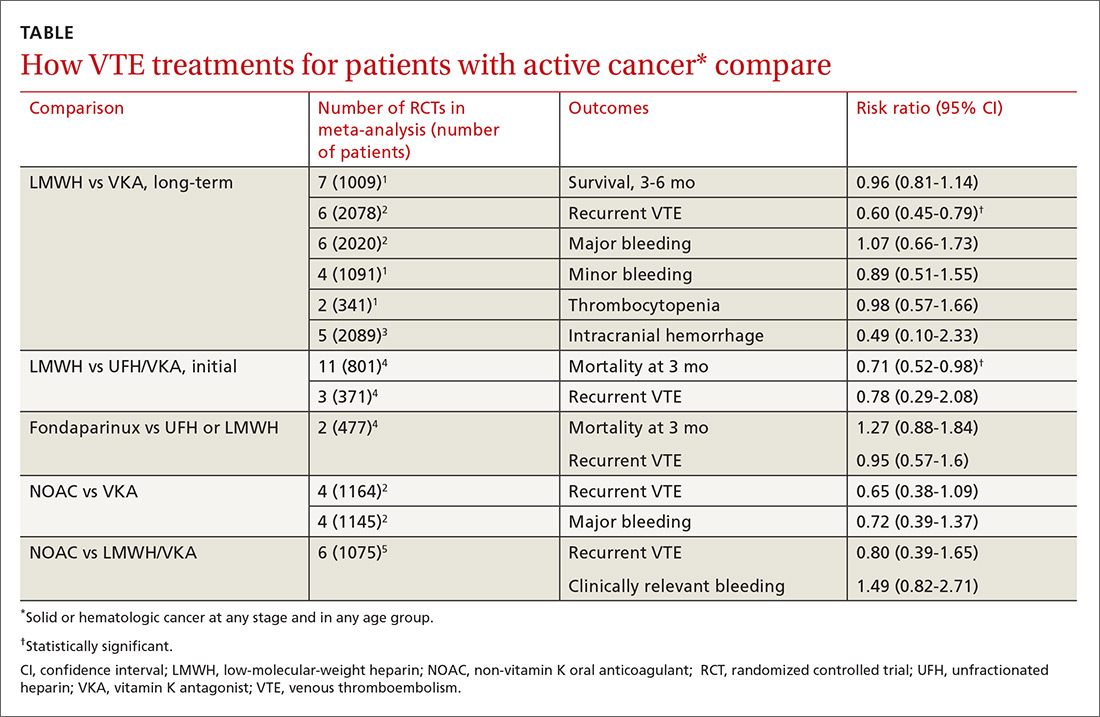

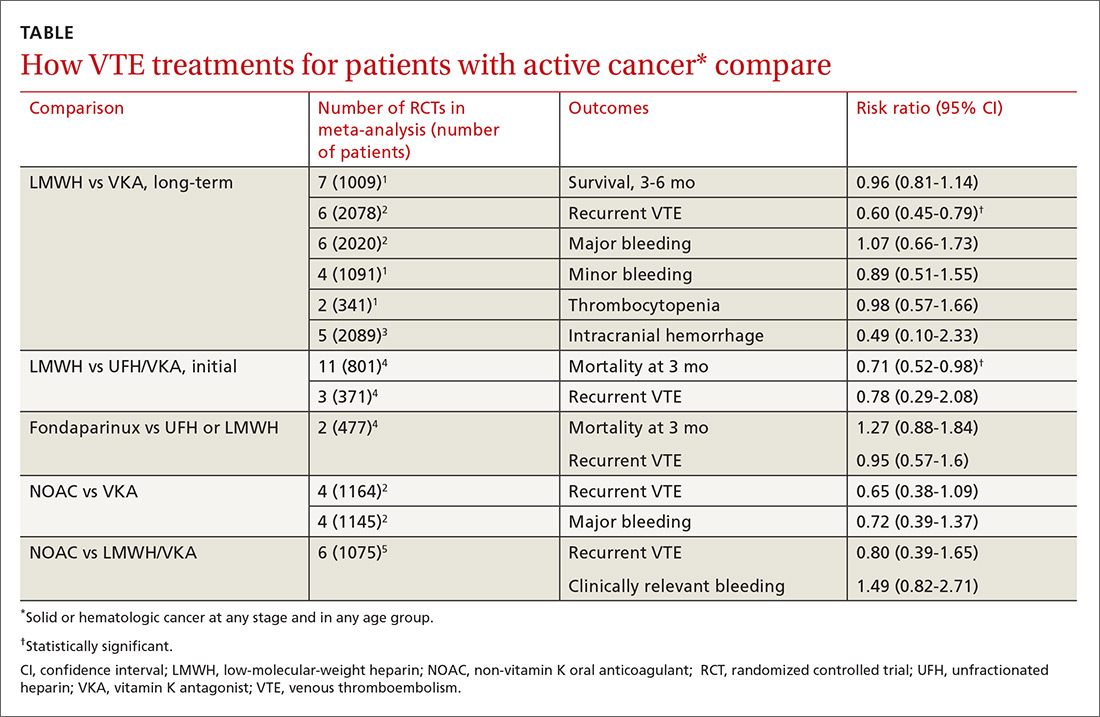

Two meta-analyses of RCTs evaluating LMWH and VKA for long-term treatment (3-12 months) of confirmed VTE in patients with cancer found that LMWH didn’t change mortality, but reduced the rate of VTE recurrence compared with VKA (40% relative reduction).1,2 The comparison showed no differences in major or minor bleeding or thrombocytopenia between LMWH and VKA (TABLE1-5).

The studies included patients with any solid or hematologic cancer at any stage and from any age group, including children. Overall, the mean age of patients was in the mid 60s; approximately 50% were male when specified. Investigators rated the evidence quality as moderate for VTE, but low for the other outcomes.1

The most recent meta-analysis of the same RCTs comparing LMWH with VKA evaluated intracranial hemorrhage rates and found no difference.3

Initial therapy with LMWH: A look at mortality

A meta-analysis of RCTs that compared LMWH with UFH/VKA for initial treatment of confirmed VTE in adult cancer patients (any type or stage of cancer, mean ages not specified) found that LMWH reduced mortality by 30%, but didn’t affect VTE recurrence or major bleeding.4

The control groups received UFH for 5 to 10 days and then continued with VKA, whereas the experimental groups received different types of LMWH (reviparin, nadroparin, tinzaparin, enoxaparin) initially and for 3 months thereafter. Investigators rated all studies low quality because of imprecision and publication bias favoring LMWH.

Fondaparinux shows no advantage for initial therapy

The same meta-analysis compared initial treatment with fondaparinux and initial therapy with enoxaparin or UFH transitioning to warfarin.4 It found no differences in any outcomes at 3 months. Investigators rated both studies as low quality for recurrent VTE and moderate for mortality and bleeding.

Continue to: Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA

Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA: No differences

A meta-analysis of RCTs comparing NOACs (dabigatran, edoxaban, apixaban, rivaroxaban) with VKA for 6 months found no differences in recurrent VTE or major bleeding.2

A second meta-analysis of RCTs that compared NOACs (rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban) with control (LMWH followed by VKA) in adult cancer patients (mean ages, 54-66 years; 50%-60% men) reported no difference in the composite outcome of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death nor clinically significant bleeding over 1 to 36 months (most RCTs ran 3-12 months).5 Separate comparisons for rivaroxaban and dabigatran found no difference in the composite outcome, and rivaroxaban also produced no difference in clinically-significant bleeding.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2016 CHEST guidelines recommend LMWH as first-line treatment for VTE in patients with cancer and indicate no preference between NOACs and VKA for second-line treatment.6

1. Akl EA, Kahale L, Barba M, et al. Anticoagulation for the long-term treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD006650.

2. Posch F, Königsbrügge O, Zielinski C, et al. Treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: A network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2015;136:582-589.

3. Rojas-Hernandez CM, Oo TH, García-Perdomo HA. Risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with therapeutic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;43:233-240.

4. Akl EA, Kahale L, Neumann I, et al. Anticoagulation for the initial treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD006649.

5. Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Herzog E, et al. New oral anticoagulants in patients with cancer: current state of evidence. Am J Ther. 2015;22:460-468.

6. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149:315-352.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No head-to-head studies or umbrella meta-analyses assess all the main treatments for VTE against each other.

Long-term LMWH decreases VTE recurrence compared with VKA

Two meta-analyses of RCTs evaluating LMWH and VKA for long-term treatment (3-12 months) of confirmed VTE in patients with cancer found that LMWH didn’t change mortality, but reduced the rate of VTE recurrence compared with VKA (40% relative reduction).1,2 The comparison showed no differences in major or minor bleeding or thrombocytopenia between LMWH and VKA (TABLE1-5).

The studies included patients with any solid or hematologic cancer at any stage and from any age group, including children. Overall, the mean age of patients was in the mid 60s; approximately 50% were male when specified. Investigators rated the evidence quality as moderate for VTE, but low for the other outcomes.1

The most recent meta-analysis of the same RCTs comparing LMWH with VKA evaluated intracranial hemorrhage rates and found no difference.3

Initial therapy with LMWH: A look at mortality

A meta-analysis of RCTs that compared LMWH with UFH/VKA for initial treatment of confirmed VTE in adult cancer patients (any type or stage of cancer, mean ages not specified) found that LMWH reduced mortality by 30%, but didn’t affect VTE recurrence or major bleeding.4

The control groups received UFH for 5 to 10 days and then continued with VKA, whereas the experimental groups received different types of LMWH (reviparin, nadroparin, tinzaparin, enoxaparin) initially and for 3 months thereafter. Investigators rated all studies low quality because of imprecision and publication bias favoring LMWH.

Fondaparinux shows no advantage for initial therapy

The same meta-analysis compared initial treatment with fondaparinux and initial therapy with enoxaparin or UFH transitioning to warfarin.4 It found no differences in any outcomes at 3 months. Investigators rated both studies as low quality for recurrent VTE and moderate for mortality and bleeding.

Continue to: Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA

Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA: No differences

A meta-analysis of RCTs comparing NOACs (dabigatran, edoxaban, apixaban, rivaroxaban) with VKA for 6 months found no differences in recurrent VTE or major bleeding.2

A second meta-analysis of RCTs that compared NOACs (rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban) with control (LMWH followed by VKA) in adult cancer patients (mean ages, 54-66 years; 50%-60% men) reported no difference in the composite outcome of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death nor clinically significant bleeding over 1 to 36 months (most RCTs ran 3-12 months).5 Separate comparisons for rivaroxaban and dabigatran found no difference in the composite outcome, and rivaroxaban also produced no difference in clinically-significant bleeding.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2016 CHEST guidelines recommend LMWH as first-line treatment for VTE in patients with cancer and indicate no preference between NOACs and VKA for second-line treatment.6

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No head-to-head studies or umbrella meta-analyses assess all the main treatments for VTE against each other.

Long-term LMWH decreases VTE recurrence compared with VKA

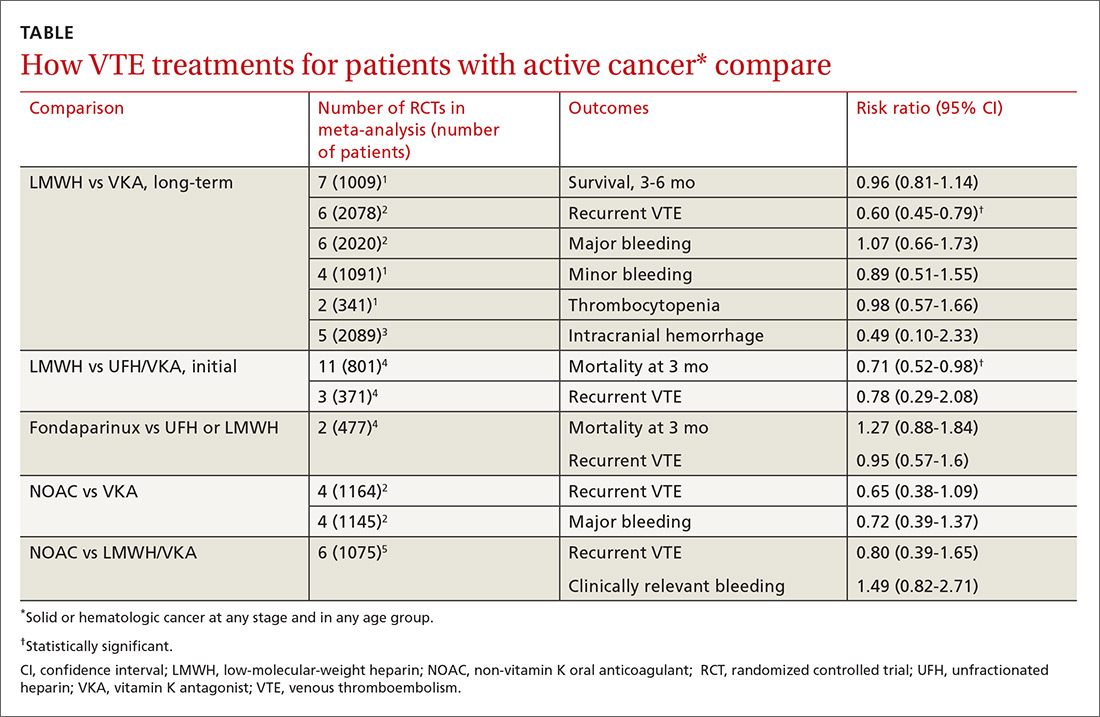

Two meta-analyses of RCTs evaluating LMWH and VKA for long-term treatment (3-12 months) of confirmed VTE in patients with cancer found that LMWH didn’t change mortality, but reduced the rate of VTE recurrence compared with VKA (40% relative reduction).1,2 The comparison showed no differences in major or minor bleeding or thrombocytopenia between LMWH and VKA (TABLE1-5).

The studies included patients with any solid or hematologic cancer at any stage and from any age group, including children. Overall, the mean age of patients was in the mid 60s; approximately 50% were male when specified. Investigators rated the evidence quality as moderate for VTE, but low for the other outcomes.1

The most recent meta-analysis of the same RCTs comparing LMWH with VKA evaluated intracranial hemorrhage rates and found no difference.3

Initial therapy with LMWH: A look at mortality

A meta-analysis of RCTs that compared LMWH with UFH/VKA for initial treatment of confirmed VTE in adult cancer patients (any type or stage of cancer, mean ages not specified) found that LMWH reduced mortality by 30%, but didn’t affect VTE recurrence or major bleeding.4

The control groups received UFH for 5 to 10 days and then continued with VKA, whereas the experimental groups received different types of LMWH (reviparin, nadroparin, tinzaparin, enoxaparin) initially and for 3 months thereafter. Investigators rated all studies low quality because of imprecision and publication bias favoring LMWH.

Fondaparinux shows no advantage for initial therapy

The same meta-analysis compared initial treatment with fondaparinux and initial therapy with enoxaparin or UFH transitioning to warfarin.4 It found no differences in any outcomes at 3 months. Investigators rated both studies as low quality for recurrent VTE and moderate for mortality and bleeding.

Continue to: Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA

Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA: No differences

A meta-analysis of RCTs comparing NOACs (dabigatran, edoxaban, apixaban, rivaroxaban) with VKA for 6 months found no differences in recurrent VTE or major bleeding.2

A second meta-analysis of RCTs that compared NOACs (rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban) with control (LMWH followed by VKA) in adult cancer patients (mean ages, 54-66 years; 50%-60% men) reported no difference in the composite outcome of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death nor clinically significant bleeding over 1 to 36 months (most RCTs ran 3-12 months).5 Separate comparisons for rivaroxaban and dabigatran found no difference in the composite outcome, and rivaroxaban also produced no difference in clinically-significant bleeding.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2016 CHEST guidelines recommend LMWH as first-line treatment for VTE in patients with cancer and indicate no preference between NOACs and VKA for second-line treatment.6

1. Akl EA, Kahale L, Barba M, et al. Anticoagulation for the long-term treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD006650.

2. Posch F, Königsbrügge O, Zielinski C, et al. Treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: A network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2015;136:582-589.

3. Rojas-Hernandez CM, Oo TH, García-Perdomo HA. Risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with therapeutic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;43:233-240.

4. Akl EA, Kahale L, Neumann I, et al. Anticoagulation for the initial treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD006649.

5. Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Herzog E, et al. New oral anticoagulants in patients with cancer: current state of evidence. Am J Ther. 2015;22:460-468.

6. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149:315-352.

1. Akl EA, Kahale L, Barba M, et al. Anticoagulation for the long-term treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD006650.

2. Posch F, Königsbrügge O, Zielinski C, et al. Treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: A network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2015;136:582-589.

3. Rojas-Hernandez CM, Oo TH, García-Perdomo HA. Risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with therapeutic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;43:233-240.

4. Akl EA, Kahale L, Neumann I, et al. Anticoagulation for the initial treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD006649.

5. Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Herzog E, et al. New oral anticoagulants in patients with cancer: current state of evidence. Am J Ther. 2015;22:460-468.

6. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149:315-352.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No head-to-head studies directly compare all the main treatments for venous thromboembolism (VTE) in cancer patients. Long-term treatment (3-12 months) with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) reduces recurrence of VTE by 40% compared with vitamin K antagonists (VKA), but doesn’t change rates of mortality, major or minor bleeding, or intracranial hemorrhage in patients with solid or hematologic cancer at any stage or in any age group. Initial treatment with LMWH reduces mortality by 30% compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH) for 5 to 10 days followed by warfarin, but doesn’t alter recurrent VTE or bleeding. Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have risks of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death (composite outcome) and clinically significant bleeding comparable to VKA or LMWH/VKA (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs], mostly of low quality).

Astonished by physician hourly rate calculation

Astonished by physician hourly rate calculation

I always enjoy the articles and incredible insights presented in OBG Management. Some very sophisticated, well-founded ideas are presented in the article on deciding on purchasing medical equipment. Then, however, you get to the calculations: $50 for 30 minutes of physician time!

My plumber charges me $100 for the first half hour of a visit (okay, there are lots of cliched jokes about this), but on average a physician assistant costs almost that much. It is a sad day in the business of medicine when experts value the time of highly educated physicians at $100 per hour. Maybe someday we can expect to be reasonably compensated for our efforts and training. When I advise my colleagues, I calculate their time, depending on their practice model, between $300 and $400 per hour.

Hamid Banooni, MD

Farmington Hills, Michigan

Dr. Kim responds

I thank Dr. Banooni for his comment. I agree that physicians are highly skilled and educated and that their time deserves to be valued at more than $100 per hour. In the article and the example provided, the values (revenues, costs, and so on) were not meant to be exactly representative of the marketplace, but instead were used merely as an example for understanding the calculation tools for purchasing medical equipment. That being said, I arrived at the $100 per hour cost for physician time (included in the variable cost in the Figure, “Breakeven analysis for hysteroscope purchase for use in tubal sterilization”) for 2 primary reasons. First, to simplify the calculation, and second, to use an equivalent universal hourly salary ($100 per hour) for a physician’s comparative labor cost in the marketplace. Currently, the median hourly compensation for an ObGyn laborist is $110 per hour.1 To simplify, I rounded down to $100. I wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Banooni, however, that a physician’s time should be valued higher in society.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists. SOGH 2016 hospitalist employment and salary survey. 2016. https://www.societyofobgynhospitalists.org/assets/SOGH%202016%20Salary%20%20Employment%20Survey.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2018.

Astonished by physician hourly rate calculation

I always enjoy the articles and incredible insights presented in OBG Management. Some very sophisticated, well-founded ideas are presented in the article on deciding on purchasing medical equipment. Then, however, you get to the calculations: $50 for 30 minutes of physician time!

My plumber charges me $100 for the first half hour of a visit (okay, there are lots of cliched jokes about this), but on average a physician assistant costs almost that much. It is a sad day in the business of medicine when experts value the time of highly educated physicians at $100 per hour. Maybe someday we can expect to be reasonably compensated for our efforts and training. When I advise my colleagues, I calculate their time, depending on their practice model, between $300 and $400 per hour.

Hamid Banooni, MD

Farmington Hills, Michigan

Dr. Kim responds

I thank Dr. Banooni for his comment. I agree that physicians are highly skilled and educated and that their time deserves to be valued at more than $100 per hour. In the article and the example provided, the values (revenues, costs, and so on) were not meant to be exactly representative of the marketplace, but instead were used merely as an example for understanding the calculation tools for purchasing medical equipment. That being said, I arrived at the $100 per hour cost for physician time (included in the variable cost in the Figure, “Breakeven analysis for hysteroscope purchase for use in tubal sterilization”) for 2 primary reasons. First, to simplify the calculation, and second, to use an equivalent universal hourly salary ($100 per hour) for a physician’s comparative labor cost in the marketplace. Currently, the median hourly compensation for an ObGyn laborist is $110 per hour.1 To simplify, I rounded down to $100. I wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Banooni, however, that a physician’s time should be valued higher in society.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Astonished by physician hourly rate calculation

I always enjoy the articles and incredible insights presented in OBG Management. Some very sophisticated, well-founded ideas are presented in the article on deciding on purchasing medical equipment. Then, however, you get to the calculations: $50 for 30 minutes of physician time!

My plumber charges me $100 for the first half hour of a visit (okay, there are lots of cliched jokes about this), but on average a physician assistant costs almost that much. It is a sad day in the business of medicine when experts value the time of highly educated physicians at $100 per hour. Maybe someday we can expect to be reasonably compensated for our efforts and training. When I advise my colleagues, I calculate their time, depending on their practice model, between $300 and $400 per hour.

Hamid Banooni, MD

Farmington Hills, Michigan

Dr. Kim responds

I thank Dr. Banooni for his comment. I agree that physicians are highly skilled and educated and that their time deserves to be valued at more than $100 per hour. In the article and the example provided, the values (revenues, costs, and so on) were not meant to be exactly representative of the marketplace, but instead were used merely as an example for understanding the calculation tools for purchasing medical equipment. That being said, I arrived at the $100 per hour cost for physician time (included in the variable cost in the Figure, “Breakeven analysis for hysteroscope purchase for use in tubal sterilization”) for 2 primary reasons. First, to simplify the calculation, and second, to use an equivalent universal hourly salary ($100 per hour) for a physician’s comparative labor cost in the marketplace. Currently, the median hourly compensation for an ObGyn laborist is $110 per hour.1 To simplify, I rounded down to $100. I wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Banooni, however, that a physician’s time should be valued higher in society.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists. SOGH 2016 hospitalist employment and salary survey. 2016. https://www.societyofobgynhospitalists.org/assets/SOGH%202016%20Salary%20%20Employment%20Survey.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2018.

- Society of Ob/Gyn Hospitalists. SOGH 2016 hospitalist employment and salary survey. 2016. https://www.societyofobgynhospitalists.org/assets/SOGH%202016%20Salary%20%20Employment%20Survey.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2018.

How effectively do ACE inhibitors and ARBs prevent migraines?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

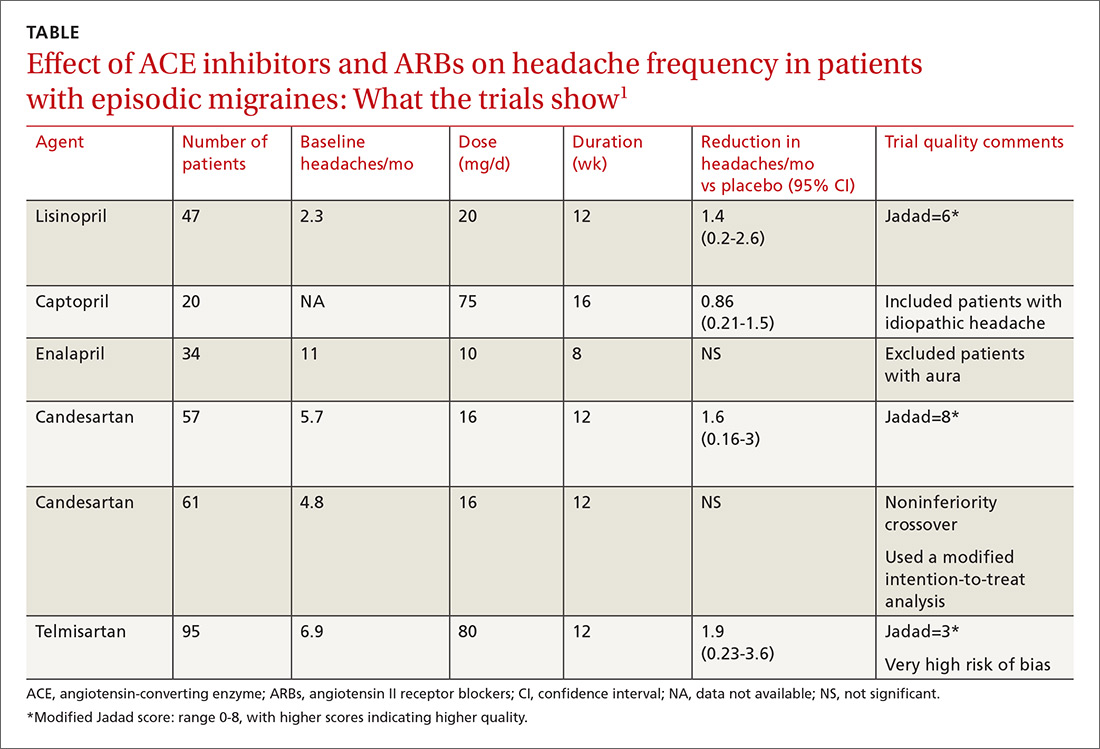

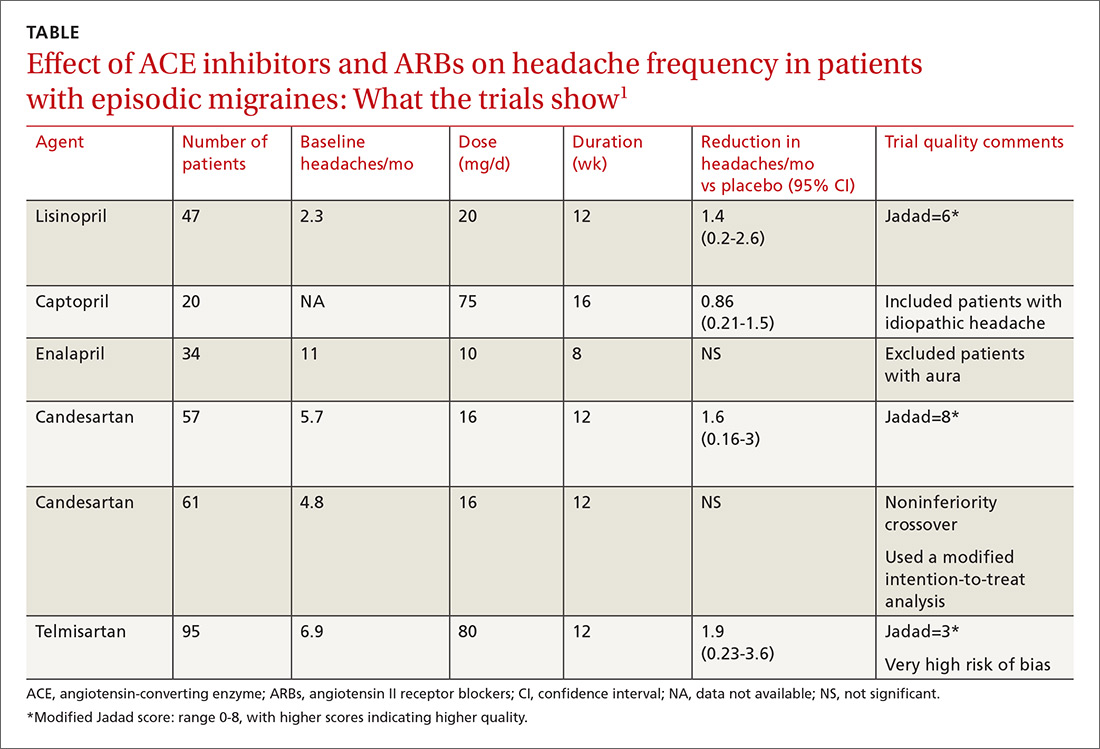

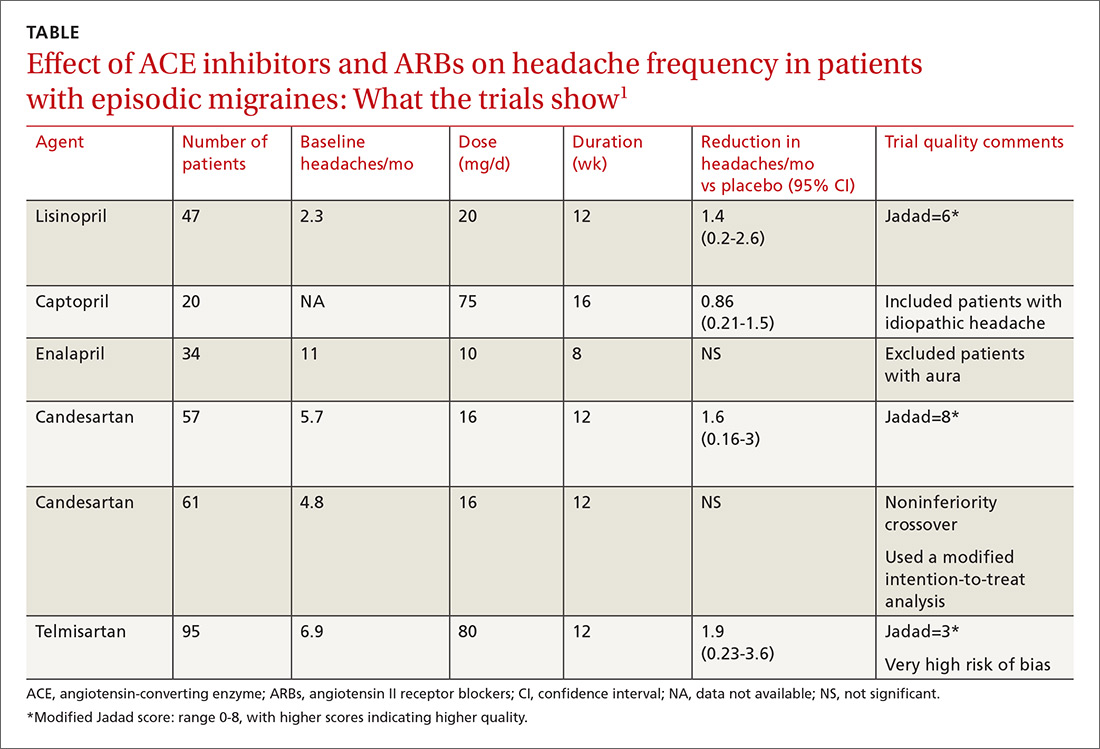

A network meta-analysis of 179 placebo-controlled trials of medications to treat migraine1 headache identified 3 trials involving ACE inhibitors and 3 involving ARBs (TABLE1). The authors of the meta-analysis gave 2 trials (one of lisinopril and one of candesartan) relatively high scores for methodologic quality.

Lisinopril reduces hours, days with headache and days with migraine

The first, a placebo-controlled lisinopril crossover trial, included 60 patients, 19 to 59 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.2 Thirty patients received lisinopril 10 mg once daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg once daily (using 10-mg tablets) for 11 weeks. The other 30 patients received a similarly titrated placebo for 12 weeks. After a 2-week washout period, the groups were given the other therapy. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. Primary outcomes, extracted from headache diaries, included the number of hours and days with headache (of any type) and number of days with migraine specifically.

Out of the initial 60 participants, 47 completed the study. Using intention-to-treat analysis, lisinopril therapy resulted in fewer hours with headache (162 vs 138, a 15% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0-30), fewer days with headache (25 vs 21, a 16% difference; 95% CI, 5-27), and fewer days with migraine (19 vs 15, a 22% change; 95% CI, 11-33), compared with placebo. Three patients discontinued lisinopril because of adverse events. Mean blood pressure reduction with lisinopril was 7 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic more than placebo (P<.0001 for both comparisons).

Candesartan also decreases headaches and migraine

The other study given a high methodologic quality score by the network-meta-analysis authors was a placebo-controlled candesartan crossover trial.3 It enrolled 60 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.

Thirty patients received 16 mg candesartan daily for 12 weeks, followed by a 4-week washout period before taking a placebo tablet daily for 12 weeks. The other 30 received placebo followed by candesartan. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. The primary outcome measure was days with headache, recorded by patients using daily diaries. Three patients didn’t complete the study.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, the mean number of days with headache was 18.5 with placebo and 13.6 with candesartan (P=.001). Secondary end points that also favored candesartan were hours with migraine (92 vs 59; P<.001), hours with headache (139 vs 95; P<.001), days with migraine (13 vs 9; P<.001), and days of sick leave (3.9 vs 1.4; P=.01). Adverse events, including dizziness, were similar with candesartan and placebo. Mean blood pressure reduction with candesartan was 11 mm Hg systolic and 7 mm Hg diastolic over placebo (P<.001 for both comparisons).

Continue to: Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Among all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials in the review, a network meta-analysis (designed to compare interventions never studied head-to-head) could be performed only on candesartan, which had a small effect size on headache frequency relative to placebo (2 trials, 118 patients; standardized mean difference [SMD]= −0.33; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.7).1 (An SMD of 0.2 is considered small, 0.6 moderate, and 1.2 large). Combining data from all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials together in a standard meta-analysis yielded a large effect size on number of headaches per month compared with placebo (6 trials, 351 patients; SMD= −1.12; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.27).1

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society published guidelines on pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults.4 The guidelines stated that lisinopril and candesartan were “possibly effective” for migraine prevention (level C recommendation based on a single lower-quality randomized clinical trial). They further advised clinicians to be “mindful of comorbid and coexistent conditions in patients with migraine to maximize potential treatment efficacy.”

1. Jackson JL, Cogbil E, Santana-Davila R, et al. A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis of drugs for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. PloS One. 2015;10:e0130733.

2. Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ. 2001;322:19-22.

3. Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:65-69.

4. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis of 179 placebo-controlled trials of medications to treat migraine1 headache identified 3 trials involving ACE inhibitors and 3 involving ARBs (TABLE1). The authors of the meta-analysis gave 2 trials (one of lisinopril and one of candesartan) relatively high scores for methodologic quality.

Lisinopril reduces hours, days with headache and days with migraine

The first, a placebo-controlled lisinopril crossover trial, included 60 patients, 19 to 59 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.2 Thirty patients received lisinopril 10 mg once daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg once daily (using 10-mg tablets) for 11 weeks. The other 30 patients received a similarly titrated placebo for 12 weeks. After a 2-week washout period, the groups were given the other therapy. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. Primary outcomes, extracted from headache diaries, included the number of hours and days with headache (of any type) and number of days with migraine specifically.

Out of the initial 60 participants, 47 completed the study. Using intention-to-treat analysis, lisinopril therapy resulted in fewer hours with headache (162 vs 138, a 15% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0-30), fewer days with headache (25 vs 21, a 16% difference; 95% CI, 5-27), and fewer days with migraine (19 vs 15, a 22% change; 95% CI, 11-33), compared with placebo. Three patients discontinued lisinopril because of adverse events. Mean blood pressure reduction with lisinopril was 7 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic more than placebo (P<.0001 for both comparisons).

Candesartan also decreases headaches and migraine

The other study given a high methodologic quality score by the network-meta-analysis authors was a placebo-controlled candesartan crossover trial.3 It enrolled 60 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.

Thirty patients received 16 mg candesartan daily for 12 weeks, followed by a 4-week washout period before taking a placebo tablet daily for 12 weeks. The other 30 received placebo followed by candesartan. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. The primary outcome measure was days with headache, recorded by patients using daily diaries. Three patients didn’t complete the study.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, the mean number of days with headache was 18.5 with placebo and 13.6 with candesartan (P=.001). Secondary end points that also favored candesartan were hours with migraine (92 vs 59; P<.001), hours with headache (139 vs 95; P<.001), days with migraine (13 vs 9; P<.001), and days of sick leave (3.9 vs 1.4; P=.01). Adverse events, including dizziness, were similar with candesartan and placebo. Mean blood pressure reduction with candesartan was 11 mm Hg systolic and 7 mm Hg diastolic over placebo (P<.001 for both comparisons).

Continue to: Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Among all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials in the review, a network meta-analysis (designed to compare interventions never studied head-to-head) could be performed only on candesartan, which had a small effect size on headache frequency relative to placebo (2 trials, 118 patients; standardized mean difference [SMD]= −0.33; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.7).1 (An SMD of 0.2 is considered small, 0.6 moderate, and 1.2 large). Combining data from all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials together in a standard meta-analysis yielded a large effect size on number of headaches per month compared with placebo (6 trials, 351 patients; SMD= −1.12; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.27).1

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society published guidelines on pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults.4 The guidelines stated that lisinopril and candesartan were “possibly effective” for migraine prevention (level C recommendation based on a single lower-quality randomized clinical trial). They further advised clinicians to be “mindful of comorbid and coexistent conditions in patients with migraine to maximize potential treatment efficacy.”

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis of 179 placebo-controlled trials of medications to treat migraine1 headache identified 3 trials involving ACE inhibitors and 3 involving ARBs (TABLE1). The authors of the meta-analysis gave 2 trials (one of lisinopril and one of candesartan) relatively high scores for methodologic quality.

Lisinopril reduces hours, days with headache and days with migraine

The first, a placebo-controlled lisinopril crossover trial, included 60 patients, 19 to 59 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.2 Thirty patients received lisinopril 10 mg once daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg once daily (using 10-mg tablets) for 11 weeks. The other 30 patients received a similarly titrated placebo for 12 weeks. After a 2-week washout period, the groups were given the other therapy. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. Primary outcomes, extracted from headache diaries, included the number of hours and days with headache (of any type) and number of days with migraine specifically.

Out of the initial 60 participants, 47 completed the study. Using intention-to-treat analysis, lisinopril therapy resulted in fewer hours with headache (162 vs 138, a 15% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0-30), fewer days with headache (25 vs 21, a 16% difference; 95% CI, 5-27), and fewer days with migraine (19 vs 15, a 22% change; 95% CI, 11-33), compared with placebo. Three patients discontinued lisinopril because of adverse events. Mean blood pressure reduction with lisinopril was 7 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic more than placebo (P<.0001 for both comparisons).

Candesartan also decreases headaches and migraine

The other study given a high methodologic quality score by the network-meta-analysis authors was a placebo-controlled candesartan crossover trial.3 It enrolled 60 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.

Thirty patients received 16 mg candesartan daily for 12 weeks, followed by a 4-week washout period before taking a placebo tablet daily for 12 weeks. The other 30 received placebo followed by candesartan. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. The primary outcome measure was days with headache, recorded by patients using daily diaries. Three patients didn’t complete the study.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, the mean number of days with headache was 18.5 with placebo and 13.6 with candesartan (P=.001). Secondary end points that also favored candesartan were hours with migraine (92 vs 59; P<.001), hours with headache (139 vs 95; P<.001), days with migraine (13 vs 9; P<.001), and days of sick leave (3.9 vs 1.4; P=.01). Adverse events, including dizziness, were similar with candesartan and placebo. Mean blood pressure reduction with candesartan was 11 mm Hg systolic and 7 mm Hg diastolic over placebo (P<.001 for both comparisons).

Continue to: Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Among all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials in the review, a network meta-analysis (designed to compare interventions never studied head-to-head) could be performed only on candesartan, which had a small effect size on headache frequency relative to placebo (2 trials, 118 patients; standardized mean difference [SMD]= −0.33; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.7).1 (An SMD of 0.2 is considered small, 0.6 moderate, and 1.2 large). Combining data from all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials together in a standard meta-analysis yielded a large effect size on number of headaches per month compared with placebo (6 trials, 351 patients; SMD= −1.12; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.27).1

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society published guidelines on pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults.4 The guidelines stated that lisinopril and candesartan were “possibly effective” for migraine prevention (level C recommendation based on a single lower-quality randomized clinical trial). They further advised clinicians to be “mindful of comorbid and coexistent conditions in patients with migraine to maximize potential treatment efficacy.”

1. Jackson JL, Cogbil E, Santana-Davila R, et al. A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis of drugs for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. PloS One. 2015;10:e0130733.

2. Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ. 2001;322:19-22.

3. Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:65-69.

4. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

1. Jackson JL, Cogbil E, Santana-Davila R, et al. A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis of drugs for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. PloS One. 2015;10:e0130733.

2. Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ. 2001;322:19-22.

3. Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:65-69.

4. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

The angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor lisinopril reduces the number of migraines by about 1.5 per month in patients experiencing 2 to 6 migraines monthly (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small crossover trial); the angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) candesartan may produce a similar reduction (SOR: C, conflicting crossover trials).

Considered as a group, ACE inhibitors and ARBs have a moderate to large effect on the frequency of migraine headaches (SOR: B, meta-analysis of small clinical trials), although only lisinopril and candesartan show fair to good evidence of efficacy.

Providers may consider lisinopril or candesartan for migraine prevention, taking into account their effect on other medical conditions (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Agrees that OC use clearly reduces mortality

Agrees that OC use clearly reduces mortality

Recent evidence from long-term observations of hundreds of thousands of women, in 10 European countries, clearly demonstrated that the use of oral contraceptives (OCs) reduced mortality by roughly 10%.1,2 Newer OCs increase women’s overall survival.

In comparison, reducing obesity by 5 body mass index points would reduce mortality by only 5%, from 1.05 to 1.3

Dr. Stavros Saripanidis

Thessaloniki, Greece

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Merritt MA, Riboli E, Murphy N, et al. Reproductive factors and risk of mortality in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition: a cohort study. BMC Med. 2015;13:252.

- Iversen L, Sivasubramaniam S, Lee AJ, Fielding S, Hannaford PC. Lifetime cancer risk and combined oral contraceptives: the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(6):580.e1–580.e9.

- Aune D, Sen A, Prasad M, et al. BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants. BMJ. 2016;353:i2156.

Agrees that OC use clearly reduces mortality

Recent evidence from long-term observations of hundreds of thousands of women, in 10 European countries, clearly demonstrated that the use of oral contraceptives (OCs) reduced mortality by roughly 10%.1,2 Newer OCs increase women’s overall survival.

In comparison, reducing obesity by 5 body mass index points would reduce mortality by only 5%, from 1.05 to 1.3

Dr. Stavros Saripanidis

Thessaloniki, Greece

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Agrees that OC use clearly reduces mortality

Recent evidence from long-term observations of hundreds of thousands of women, in 10 European countries, clearly demonstrated that the use of oral contraceptives (OCs) reduced mortality by roughly 10%.1,2 Newer OCs increase women’s overall survival.

In comparison, reducing obesity by 5 body mass index points would reduce mortality by only 5%, from 1.05 to 1.3

Dr. Stavros Saripanidis

Thessaloniki, Greece

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Merritt MA, Riboli E, Murphy N, et al. Reproductive factors and risk of mortality in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition: a cohort study. BMC Med. 2015;13:252.

- Iversen L, Sivasubramaniam S, Lee AJ, Fielding S, Hannaford PC. Lifetime cancer risk and combined oral contraceptives: the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(6):580.e1–580.e9.

- Aune D, Sen A, Prasad M, et al. BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants. BMJ. 2016;353:i2156.

- Merritt MA, Riboli E, Murphy N, et al. Reproductive factors and risk of mortality in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition: a cohort study. BMC Med. 2015;13:252.

- Iversen L, Sivasubramaniam S, Lee AJ, Fielding S, Hannaford PC. Lifetime cancer risk and combined oral contraceptives: the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(6):580.e1–580.e9.

- Aune D, Sen A, Prasad M, et al. BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants. BMJ. 2016;353:i2156.

Dehydration in terminal illness: Which path forward?

CASE 1

A 94-year-old white woman, who had been in excellent health (other than pernicious anemia, treated with monthly cyanocobalamin injections), suddenly developed gastrointestinal distress 2 weeks earlier. A work-up performed by her physician revealed advanced pancreatic cancer.

Over the next 2 weeks, she experienced pain and nausea. A left-sided fistula developed externally at her flank that drained feces and induced considerable discomfort. An indwelling drain was placed, which provided some relief, but the patient’s dyspepsia, pain, and nausea escalated.

One month into her disease course, an oncologist reported on her potential treatment options and prognosis. Her life expectancy was about 3 months without treatment. This could be extended by 1 to 2 months with extensive surgical and chemotherapeutic interventions, but would further diminish her quality of life. The patient declined further treatment.

Her clinical status declined, and her quality of life significantly deteriorated. At 3 months, she felt life had lost meaning and was not worth living. She began asking for a morphine overdose, stating a desire to end her life.

After several discussions with the oncologist, one of the patient’s adult children suggested that her mother stop eating and drinking in order to diminish discomfort and hasten her demise. This plan was adopted, and the patient declined food and drank only enough to swish for oral comfort.

CASE 2

An 83-year-old woman with advanced Parkinson’s disease had become increasingly disabled. Her gait and motor skills were dramatically and progressively compromised. Pharmacotherapy yielded only transient improvement and considerable adverse effects of choreiform hyperkinesia and hallucinations, which were troublesome and embarrassing. Her social, physical, and personal well-being declined to the point that she was placed in a nursing home.

Despite this help, worsening parkinsonism progressively diminished her physical capacity. She became largely bedridden and developed decubitus ulcerations, especially at the coccyx, which produced severe pain and distress.

Continue to: The confluence of pain...

The confluence of pain, bedfastness, constipation, and social isolation yielded a loss of interest and joy in life. The patient required assistance with almost every aspect of daily life, including eating. As the illness progressed, she prayed at night that God would “take her.” Each morning, she spoke of disappointment upon reawakening. She overtly expressed her lack of desire to live to her family. Medical interventions were increasingly ineffective.

After repeated family and physician discussions had focused on her death wishes, one adult daughter recommended her mother stop eating and drinking; her food intake was already minimal. Although she did not endorse this plan verbally, the patient’s oral intake significantly diminished. Within 2 weeks, her physical state had declined, and she died one night during sleep.

Adequate hydration is stressed in physician education and practice. A conventional expectation to normalize fluid balance is important to restore health and improve well-being. In addition to being good medical practice, it can also show patients (and their families) that we care about their well-being.1-3

Treating dehydration in individuals with terminal illness is controversial from both medical and ethical standpoints. While the natural tendency of physicians is to restore full hydration to their patients, in select cases of imminent death, being fully hydrated may prolong discomfort.1,2 Emphasis in this population should be consistently placed on improving comfort care and quality of life, rather than prolonging life or delaying death.3-5

Continue to: A multifactorial, patient-based decision

A multifactorial, patient-based decision

Years ago, before the advent of hospitalizing people with terminal illnesses, dying at home amongst loved ones was believed to be peaceful. Nevertheless, questions arise about the practical vs ethical approach to caring for patients with terminal illness.2 Sometimes it is difficult to find a balance between potential health care benefits and the burdens induced by medical, legal, moral, and/or social pressures. Our medical communities and the general population uphold preserving dignity at the end of life, which is supported by organizations such as Compassion & Choices (a nonprofit group that seeks to improve and expand options for end of life care; https://www.compassionandchoices.org).

Allowing for voluntary, patient-determined dehydration in those with terminal illness can offer greater comfort than maintaining the physiologic degrees of fluid balance. There are 3 key considerations to bear in mind:

- Hydration is usually a standard part of quality medical care.1

- Selectively allowing dehydration in patients who are dying can facilitate comfort.1-5

- Dehydration may be a deliberate strategy to hasten death.6

When is dehydration appropriate?

Hydration is not favored whenever doing so may increase discomfort and prolong pain without meaningful life.3 In people with terminal illness, hydration may reduce quality of life.7

The data support dehydration in certain patients. A randomized controlled trial involving 129 patients receiving hospice care compared parenteral hydration with placebo, documenting that rehydration did not improve symptoms or quality of life; there was no significant difference between patients who were hydrated and those who were dehydrated.7 In fact, dehydration may even yield greater patient comfort.8

Case reports, retrospective chart reviews, and testimonials from health care professionals have reported that being less hydrated can diminish nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, ascites, edema, and urinary or bowel incontinence, with less skin breakdown.8 Hydration, on the other hand, may exacerbate dyspnea, coughing, and choking, increasing the need for suctioning.

Continue to: A component of palliative care

A component of palliative care. When death is imminent, palliation becomes key. Pain may be more manageable with less fluids, an important goal for this population.6,8 Dehydration is associated with an accumulation of opioids throughout body fluid volumes, which may decrease pain, consciousness, and/or agony.2 Pharmacotherapies might also have greater efficacy in a dehydrated patient.9 In addition, tissue shrinkage might mitigate pain from tumors, especially those in confined spaces.8

Hospice care and palliative medicine confirm that routine hydration is not always advisable; allowing for dehydration is a conventional practice, especially in older adults with terminal illness.7 However, do not deny access to liquids if a patient wants them, and never force unwanted fluids by any route.8 Facilitate oral care in the form of swishing fluids, elective drinking, or providing mouth lubrication for any patients selectively allowed to become dehydrated.3,8

The role of the physician in decision-making

Patients with terminal illness sometimes do not want fluids and may actively decline food and drink.10 This can be emotionally distressing for family members and/or caregivers to witness. Physicians can address this concern by compassionately explaining: “I know you are concerned that your relative is not eating or drinking, but there is no indication that hydration or parenteral feeding will improve function or quality of life.”10 This can generate a discussion between physicians and families by acknowledging concerns, relieving distress, and leading to what is ultimately best for the patient.

Implications for practice: Individualized autonomy

Physicians must identify patients who wish to die by purposely becoming dehydrated and uphold the important physician obligation to hydrate those with a recoverable illness. Allowing for a moderate degree of dehydration might provide greater comfort in select people with terminal illness. Some individuals for whom life has lost meaning may choose dehydration as a means to hasten their departure.4-6 Allowing individualized autonomy over life and death choices is part of a physician’s obligation to their patients. It can be difficult for caregivers, but it is medically indicated to comply with a patient’s desire for comfort when death is imminent.

Providing palliation as a priority over treatment is sometimes challenging, but comfort care takes preference and is always coordinated with the person’s own wishes. Facilitating dehydration removes assisted-suicide issues or requests and thus affords everyone involved more emotional comfort. An advantage of this method is that a decisional patient maintains full control over the direction of their choices and helps preserve dignity during the end of life.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Lippmann, MD, Department of Psychiatry, University of Louisville School of Medicine, 401 East Chestnut Street, Suite 610, Louisville, KY 40202; [email protected]

1. Burge FI. Dehydration and provision of fluids in palliative care. What is the evidence? Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:2383-2388.

2. Printz LA. Is withholding hydration a valid comfort measure in the terminally ill? Geriatrics. 1988;43:84-88.

3. Lippmann S. Palliative dehydration. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17: doi: 10.4088/PCC.15101797.

4. Bernat JL, Gert B, Mogielnicki RP. Patient refusal of hydration and nutrition: an alternative to physician-assisted suicide or voluntary active euthanasia. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2723-2728.

5. Sullivan RJ. Accepting death without artificial nutrition or hydration. J Gen Intern Med.1993;8:220-224.

6. Miller FG, Meier DE. Voluntary death: a comparison of terminal dehydration and physician-assisted suicide. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:559-562.

7. Bruera E, Hui D, Dalal S, et al. Parenteral hydration in patients with advanced cancer: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:111-118.

8. Forrow L, Smith HS. Pain management in end of life: palliative care. In: Warfield CA, Bajwa ZH, ed. Principles and Practice of Pain Management. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004.

9. Zerwekh JV. The dehydration question. Nursing. 1983;13:47-51.

10. Bailey F, Harman S. Palliative care: The last hours and days of life. www.uptodate.com. September, 2016. Accessed on September 11, 2018.

CASE 1

A 94-year-old white woman, who had been in excellent health (other than pernicious anemia, treated with monthly cyanocobalamin injections), suddenly developed gastrointestinal distress 2 weeks earlier. A work-up performed by her physician revealed advanced pancreatic cancer.

Over the next 2 weeks, she experienced pain and nausea. A left-sided fistula developed externally at her flank that drained feces and induced considerable discomfort. An indwelling drain was placed, which provided some relief, but the patient’s dyspepsia, pain, and nausea escalated.

One month into her disease course, an oncologist reported on her potential treatment options and prognosis. Her life expectancy was about 3 months without treatment. This could be extended by 1 to 2 months with extensive surgical and chemotherapeutic interventions, but would further diminish her quality of life. The patient declined further treatment.

Her clinical status declined, and her quality of life significantly deteriorated. At 3 months, she felt life had lost meaning and was not worth living. She began asking for a morphine overdose, stating a desire to end her life.

After several discussions with the oncologist, one of the patient’s adult children suggested that her mother stop eating and drinking in order to diminish discomfort and hasten her demise. This plan was adopted, and the patient declined food and drank only enough to swish for oral comfort.

CASE 2

An 83-year-old woman with advanced Parkinson’s disease had become increasingly disabled. Her gait and motor skills were dramatically and progressively compromised. Pharmacotherapy yielded only transient improvement and considerable adverse effects of choreiform hyperkinesia and hallucinations, which were troublesome and embarrassing. Her social, physical, and personal well-being declined to the point that she was placed in a nursing home.

Despite this help, worsening parkinsonism progressively diminished her physical capacity. She became largely bedridden and developed decubitus ulcerations, especially at the coccyx, which produced severe pain and distress.

Continue to: The confluence of pain...

The confluence of pain, bedfastness, constipation, and social isolation yielded a loss of interest and joy in life. The patient required assistance with almost every aspect of daily life, including eating. As the illness progressed, she prayed at night that God would “take her.” Each morning, she spoke of disappointment upon reawakening. She overtly expressed her lack of desire to live to her family. Medical interventions were increasingly ineffective.

After repeated family and physician discussions had focused on her death wishes, one adult daughter recommended her mother stop eating and drinking; her food intake was already minimal. Although she did not endorse this plan verbally, the patient’s oral intake significantly diminished. Within 2 weeks, her physical state had declined, and she died one night during sleep.

Adequate hydration is stressed in physician education and practice. A conventional expectation to normalize fluid balance is important to restore health and improve well-being. In addition to being good medical practice, it can also show patients (and their families) that we care about their well-being.1-3

Treating dehydration in individuals with terminal illness is controversial from both medical and ethical standpoints. While the natural tendency of physicians is to restore full hydration to their patients, in select cases of imminent death, being fully hydrated may prolong discomfort.1,2 Emphasis in this population should be consistently placed on improving comfort care and quality of life, rather than prolonging life or delaying death.3-5

Continue to: A multifactorial, patient-based decision

A multifactorial, patient-based decision

Years ago, before the advent of hospitalizing people with terminal illnesses, dying at home amongst loved ones was believed to be peaceful. Nevertheless, questions arise about the practical vs ethical approach to caring for patients with terminal illness.2 Sometimes it is difficult to find a balance between potential health care benefits and the burdens induced by medical, legal, moral, and/or social pressures. Our medical communities and the general population uphold preserving dignity at the end of life, which is supported by organizations such as Compassion & Choices (a nonprofit group that seeks to improve and expand options for end of life care; https://www.compassionandchoices.org).

Allowing for voluntary, patient-determined dehydration in those with terminal illness can offer greater comfort than maintaining the physiologic degrees of fluid balance. There are 3 key considerations to bear in mind:

- Hydration is usually a standard part of quality medical care.1

- Selectively allowing dehydration in patients who are dying can facilitate comfort.1-5

- Dehydration may be a deliberate strategy to hasten death.6

When is dehydration appropriate?

Hydration is not favored whenever doing so may increase discomfort and prolong pain without meaningful life.3 In people with terminal illness, hydration may reduce quality of life.7

The data support dehydration in certain patients. A randomized controlled trial involving 129 patients receiving hospice care compared parenteral hydration with placebo, documenting that rehydration did not improve symptoms or quality of life; there was no significant difference between patients who were hydrated and those who were dehydrated.7 In fact, dehydration may even yield greater patient comfort.8

Case reports, retrospective chart reviews, and testimonials from health care professionals have reported that being less hydrated can diminish nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, ascites, edema, and urinary or bowel incontinence, with less skin breakdown.8 Hydration, on the other hand, may exacerbate dyspnea, coughing, and choking, increasing the need for suctioning.

Continue to: A component of palliative care

A component of palliative care. When death is imminent, palliation becomes key. Pain may be more manageable with less fluids, an important goal for this population.6,8 Dehydration is associated with an accumulation of opioids throughout body fluid volumes, which may decrease pain, consciousness, and/or agony.2 Pharmacotherapies might also have greater efficacy in a dehydrated patient.9 In addition, tissue shrinkage might mitigate pain from tumors, especially those in confined spaces.8

Hospice care and palliative medicine confirm that routine hydration is not always advisable; allowing for dehydration is a conventional practice, especially in older adults with terminal illness.7 However, do not deny access to liquids if a patient wants them, and never force unwanted fluids by any route.8 Facilitate oral care in the form of swishing fluids, elective drinking, or providing mouth lubrication for any patients selectively allowed to become dehydrated.3,8

The role of the physician in decision-making

Patients with terminal illness sometimes do not want fluids and may actively decline food and drink.10 This can be emotionally distressing for family members and/or caregivers to witness. Physicians can address this concern by compassionately explaining: “I know you are concerned that your relative is not eating or drinking, but there is no indication that hydration or parenteral feeding will improve function or quality of life.”10 This can generate a discussion between physicians and families by acknowledging concerns, relieving distress, and leading to what is ultimately best for the patient.

Implications for practice: Individualized autonomy

Physicians must identify patients who wish to die by purposely becoming dehydrated and uphold the important physician obligation to hydrate those with a recoverable illness. Allowing for a moderate degree of dehydration might provide greater comfort in select people with terminal illness. Some individuals for whom life has lost meaning may choose dehydration as a means to hasten their departure.4-6 Allowing individualized autonomy over life and death choices is part of a physician’s obligation to their patients. It can be difficult for caregivers, but it is medically indicated to comply with a patient’s desire for comfort when death is imminent.

Providing palliation as a priority over treatment is sometimes challenging, but comfort care takes preference and is always coordinated with the person’s own wishes. Facilitating dehydration removes assisted-suicide issues or requests and thus affords everyone involved more emotional comfort. An advantage of this method is that a decisional patient maintains full control over the direction of their choices and helps preserve dignity during the end of life.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Lippmann, MD, Department of Psychiatry, University of Louisville School of Medicine, 401 East Chestnut Street, Suite 610, Louisville, KY 40202; [email protected]

CASE 1

A 94-year-old white woman, who had been in excellent health (other than pernicious anemia, treated with monthly cyanocobalamin injections), suddenly developed gastrointestinal distress 2 weeks earlier. A work-up performed by her physician revealed advanced pancreatic cancer.

Over the next 2 weeks, she experienced pain and nausea. A left-sided fistula developed externally at her flank that drained feces and induced considerable discomfort. An indwelling drain was placed, which provided some relief, but the patient’s dyspepsia, pain, and nausea escalated.

One month into her disease course, an oncologist reported on her potential treatment options and prognosis. Her life expectancy was about 3 months without treatment. This could be extended by 1 to 2 months with extensive surgical and chemotherapeutic interventions, but would further diminish her quality of life. The patient declined further treatment.

Her clinical status declined, and her quality of life significantly deteriorated. At 3 months, she felt life had lost meaning and was not worth living. She began asking for a morphine overdose, stating a desire to end her life.

After several discussions with the oncologist, one of the patient’s adult children suggested that her mother stop eating and drinking in order to diminish discomfort and hasten her demise. This plan was adopted, and the patient declined food and drank only enough to swish for oral comfort.

CASE 2

An 83-year-old woman with advanced Parkinson’s disease had become increasingly disabled. Her gait and motor skills were dramatically and progressively compromised. Pharmacotherapy yielded only transient improvement and considerable adverse effects of choreiform hyperkinesia and hallucinations, which were troublesome and embarrassing. Her social, physical, and personal well-being declined to the point that she was placed in a nursing home.

Despite this help, worsening parkinsonism progressively diminished her physical capacity. She became largely bedridden and developed decubitus ulcerations, especially at the coccyx, which produced severe pain and distress.

Continue to: The confluence of pain...

The confluence of pain, bedfastness, constipation, and social isolation yielded a loss of interest and joy in life. The patient required assistance with almost every aspect of daily life, including eating. As the illness progressed, she prayed at night that God would “take her.” Each morning, she spoke of disappointment upon reawakening. She overtly expressed her lack of desire to live to her family. Medical interventions were increasingly ineffective.

After repeated family and physician discussions had focused on her death wishes, one adult daughter recommended her mother stop eating and drinking; her food intake was already minimal. Although she did not endorse this plan verbally, the patient’s oral intake significantly diminished. Within 2 weeks, her physical state had declined, and she died one night during sleep.

Adequate hydration is stressed in physician education and practice. A conventional expectation to normalize fluid balance is important to restore health and improve well-being. In addition to being good medical practice, it can also show patients (and their families) that we care about their well-being.1-3

Treating dehydration in individuals with terminal illness is controversial from both medical and ethical standpoints. While the natural tendency of physicians is to restore full hydration to their patients, in select cases of imminent death, being fully hydrated may prolong discomfort.1,2 Emphasis in this population should be consistently placed on improving comfort care and quality of life, rather than prolonging life or delaying death.3-5

Continue to: A multifactorial, patient-based decision

A multifactorial, patient-based decision

Years ago, before the advent of hospitalizing people with terminal illnesses, dying at home amongst loved ones was believed to be peaceful. Nevertheless, questions arise about the practical vs ethical approach to caring for patients with terminal illness.2 Sometimes it is difficult to find a balance between potential health care benefits and the burdens induced by medical, legal, moral, and/or social pressures. Our medical communities and the general population uphold preserving dignity at the end of life, which is supported by organizations such as Compassion & Choices (a nonprofit group that seeks to improve and expand options for end of life care; https://www.compassionandchoices.org).

Allowing for voluntary, patient-determined dehydration in those with terminal illness can offer greater comfort than maintaining the physiologic degrees of fluid balance. There are 3 key considerations to bear in mind:

- Hydration is usually a standard part of quality medical care.1

- Selectively allowing dehydration in patients who are dying can facilitate comfort.1-5

- Dehydration may be a deliberate strategy to hasten death.6

When is dehydration appropriate?

Hydration is not favored whenever doing so may increase discomfort and prolong pain without meaningful life.3 In people with terminal illness, hydration may reduce quality of life.7

The data support dehydration in certain patients. A randomized controlled trial involving 129 patients receiving hospice care compared parenteral hydration with placebo, documenting that rehydration did not improve symptoms or quality of life; there was no significant difference between patients who were hydrated and those who were dehydrated.7 In fact, dehydration may even yield greater patient comfort.8

Case reports, retrospective chart reviews, and testimonials from health care professionals have reported that being less hydrated can diminish nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, ascites, edema, and urinary or bowel incontinence, with less skin breakdown.8 Hydration, on the other hand, may exacerbate dyspnea, coughing, and choking, increasing the need for suctioning.

Continue to: A component of palliative care

A component of palliative care. When death is imminent, palliation becomes key. Pain may be more manageable with less fluids, an important goal for this population.6,8 Dehydration is associated with an accumulation of opioids throughout body fluid volumes, which may decrease pain, consciousness, and/or agony.2 Pharmacotherapies might also have greater efficacy in a dehydrated patient.9 In addition, tissue shrinkage might mitigate pain from tumors, especially those in confined spaces.8

Hospice care and palliative medicine confirm that routine hydration is not always advisable; allowing for dehydration is a conventional practice, especially in older adults with terminal illness.7 However, do not deny access to liquids if a patient wants them, and never force unwanted fluids by any route.8 Facilitate oral care in the form of swishing fluids, elective drinking, or providing mouth lubrication for any patients selectively allowed to become dehydrated.3,8

The role of the physician in decision-making

Patients with terminal illness sometimes do not want fluids and may actively decline food and drink.10 This can be emotionally distressing for family members and/or caregivers to witness. Physicians can address this concern by compassionately explaining: “I know you are concerned that your relative is not eating or drinking, but there is no indication that hydration or parenteral feeding will improve function or quality of life.”10 This can generate a discussion between physicians and families by acknowledging concerns, relieving distress, and leading to what is ultimately best for the patient.

Implications for practice: Individualized autonomy

Physicians must identify patients who wish to die by purposely becoming dehydrated and uphold the important physician obligation to hydrate those with a recoverable illness. Allowing for a moderate degree of dehydration might provide greater comfort in select people with terminal illness. Some individuals for whom life has lost meaning may choose dehydration as a means to hasten their departure.4-6 Allowing individualized autonomy over life and death choices is part of a physician’s obligation to their patients. It can be difficult for caregivers, but it is medically indicated to comply with a patient’s desire for comfort when death is imminent.

Providing palliation as a priority over treatment is sometimes challenging, but comfort care takes preference and is always coordinated with the person’s own wishes. Facilitating dehydration removes assisted-suicide issues or requests and thus affords everyone involved more emotional comfort. An advantage of this method is that a decisional patient maintains full control over the direction of their choices and helps preserve dignity during the end of life.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Lippmann, MD, Department of Psychiatry, University of Louisville School of Medicine, 401 East Chestnut Street, Suite 610, Louisville, KY 40202; [email protected]

1. Burge FI. Dehydration and provision of fluids in palliative care. What is the evidence? Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:2383-2388.

2. Printz LA. Is withholding hydration a valid comfort measure in the terminally ill? Geriatrics. 1988;43:84-88.

3. Lippmann S. Palliative dehydration. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17: doi: 10.4088/PCC.15101797.

4. Bernat JL, Gert B, Mogielnicki RP. Patient refusal of hydration and nutrition: an alternative to physician-assisted suicide or voluntary active euthanasia. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2723-2728.

5. Sullivan RJ. Accepting death without artificial nutrition or hydration. J Gen Intern Med.1993;8:220-224.

6. Miller FG, Meier DE. Voluntary death: a comparison of terminal dehydration and physician-assisted suicide. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:559-562.

7. Bruera E, Hui D, Dalal S, et al. Parenteral hydration in patients with advanced cancer: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:111-118.

8. Forrow L, Smith HS. Pain management in end of life: palliative care. In: Warfield CA, Bajwa ZH, ed. Principles and Practice of Pain Management. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004.

9. Zerwekh JV. The dehydration question. Nursing. 1983;13:47-51.

10. Bailey F, Harman S. Palliative care: The last hours and days of life. www.uptodate.com. September, 2016. Accessed on September 11, 2018.

1. Burge FI. Dehydration and provision of fluids in palliative care. What is the evidence? Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:2383-2388.

2. Printz LA. Is withholding hydration a valid comfort measure in the terminally ill? Geriatrics. 1988;43:84-88.

3. Lippmann S. Palliative dehydration. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17: doi: 10.4088/PCC.15101797.

4. Bernat JL, Gert B, Mogielnicki RP. Patient refusal of hydration and nutrition: an alternative to physician-assisted suicide or voluntary active euthanasia. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2723-2728.

5. Sullivan RJ. Accepting death without artificial nutrition or hydration. J Gen Intern Med.1993;8:220-224.

6. Miller FG, Meier DE. Voluntary death: a comparison of terminal dehydration and physician-assisted suicide. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:559-562.

7. Bruera E, Hui D, Dalal S, et al. Parenteral hydration in patients with advanced cancer: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:111-118.

8. Forrow L, Smith HS. Pain management in end of life: palliative care. In: Warfield CA, Bajwa ZH, ed. Principles and Practice of Pain Management. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004.

9. Zerwekh JV. The dehydration question. Nursing. 1983;13:47-51.

10. Bailey F, Harman S. Palliative care: The last hours and days of life. www.uptodate.com. September, 2016. Accessed on September 11, 2018.

Use metrics for populations, not individuals

Use metrics for populations, not individuals

Dr. Kanofsky’s commentary on CD metrics is 100% correct. As an ethical question for physicians and society alike, I would ask, is applying metrics to physicians even moral?

As an ObGyn for most of 4 decades, my approach to obstetrics has not changed. In some years, my CD rate was very low, and in others my rate was average. Women must be treated as individuals. Although the industrial revolution increased quality and decreased costs in manufacturing, I do not believe that we can or should apply those principles to our patients.

Government regulators, insurance companies, and many physician leaders have lost sight of the Oath of Maimonides, which states, “May the love of my art actuate me at all times; may neither avarice nor miserliness…engage my mind,”1 as well as Hippocrates’ ancient observation, “Whatsoever house I may enter, my visit shall be for the convenience and advantage of the patient.”2 In addition, in the modern version of the Hippocratic Oath that most schools use today, physicians swear to “apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures [that] are required...”3—not to the benefit of the government, the federal budget, or an accountable care organization (ACO).

Clearly, the informed consent of a 42-year-old who had in vitro fertilization and has a floating presentation with a low Bishop score and an estimated fetal weight of 4,000 at 40 6/7 weeks must include not only the risks of primary CD but also the risks of a long labor that may result in a CD, the occasional risk of shoulder dystocia, or third- or fourth-degree extension. Not having had a case of shoulder dystocia or a third- or fourth-degree in more than a decade clearly justifies my rationale.

The morbidity of a multiple repeat CD or even a primary CD in an obese woman is significantly more risky than a non-labored elective CD in a woman of normal weight who plans to have only 1 or 2 children. We must individualize our care. Metrics are for populations, not individuals.

Health economists who aggressively advocate lower cesarean rates accept stillbirths and babies with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, cerebral palsy, or Erb’s palsy as long as governmental expenditures are lowered. Do the parents of these children get a vote? The majority of practicing physicians like myself feel more aligned with the Hippocratic Oath and the Oath of Maimonides. We believe that we have a moral, ethical, and medical responsibility to the individual patient and not to an ACO or government bean counter.

I would suggest an overarching theme: choice—the freedom to make our own intelligent decisions based on reasonable data and interpretation of the medical literature.

One size does not fit all. So why do those pushing comparative metrics tell us there is only one way to practice obstetrics?

Howard C. Mandel, MD

Los Angeles, California

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Tan SY, Yeow ME. Moses Maimonides (1135–1204): rabbi, philosopher, physician. Singapore Med J. 2002;43(11):551–553.

- Copland J, ed. The Hippocratic Oath. In: The London Medical Repository, Monthly Journal, and Review, Volume III. 1825;23:258.

- Tyson P. The Hippocratic Oath today. Nova. March 27, 2001. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/hippocratic-oath-today.html. Accessed September 21, 2018.

Use metrics for populations, not individuals

Dr. Kanofsky’s commentary on CD metrics is 100% correct. As an ethical question for physicians and society alike, I would ask, is applying metrics to physicians even moral?

As an ObGyn for most of 4 decades, my approach to obstetrics has not changed. In some years, my CD rate was very low, and in others my rate was average. Women must be treated as individuals. Although the industrial revolution increased quality and decreased costs in manufacturing, I do not believe that we can or should apply those principles to our patients.

Government regulators, insurance companies, and many physician leaders have lost sight of the Oath of Maimonides, which states, “May the love of my art actuate me at all times; may neither avarice nor miserliness…engage my mind,”1 as well as Hippocrates’ ancient observation, “Whatsoever house I may enter, my visit shall be for the convenience and advantage of the patient.”2 In addition, in the modern version of the Hippocratic Oath that most schools use today, physicians swear to “apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures [that] are required...”3—not to the benefit of the government, the federal budget, or an accountable care organization (ACO).

Clearly, the informed consent of a 42-year-old who had in vitro fertilization and has a floating presentation with a low Bishop score and an estimated fetal weight of 4,000 at 40 6/7 weeks must include not only the risks of primary CD but also the risks of a long labor that may result in a CD, the occasional risk of shoulder dystocia, or third- or fourth-degree extension. Not having had a case of shoulder dystocia or a third- or fourth-degree in more than a decade clearly justifies my rationale.

The morbidity of a multiple repeat CD or even a primary CD in an obese woman is significantly more risky than a non-labored elective CD in a woman of normal weight who plans to have only 1 or 2 children. We must individualize our care. Metrics are for populations, not individuals.

Health economists who aggressively advocate lower cesarean rates accept stillbirths and babies with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, cerebral palsy, or Erb’s palsy as long as governmental expenditures are lowered. Do the parents of these children get a vote? The majority of practicing physicians like myself feel more aligned with the Hippocratic Oath and the Oath of Maimonides. We believe that we have a moral, ethical, and medical responsibility to the individual patient and not to an ACO or government bean counter.

I would suggest an overarching theme: choice—the freedom to make our own intelligent decisions based on reasonable data and interpretation of the medical literature.

One size does not fit all. So why do those pushing comparative metrics tell us there is only one way to practice obstetrics?

Howard C. Mandel, MD

Los Angeles, California

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.