User login

ID experts urge widespread flu vaccination for 2018-2019 season

WASHINGTON – The flu vaccine may not be perfect, but it can reduce the severity of illness and curb the risk of spreading the disease to others, William Schaffner, MD, emphasized at a press conference held by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

“Give the vaccine credit for softening the blow,” said Dr. Schaffner, medical director of NFID and a professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

Dr. Schaffner and a panel of experts including U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams, MD, encouraged the public and the health care community to follow recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention that everyone aged 6 months and older receive an influenza vaccine.

Dr. Schaffner shared recent data showing that complications from the flu don’t stop when the acute illness resolves. Acute influenza causes a whole-body inflammatory reaction, and consequently “there is an increased risk of heart attack and stroke during the 2-4 weeks of recovery from acute influenza,” he said. In addition, older adults who experience acute flu and are already frail may never regain their pre-flu level of function, as the flu can start a “domino effect of decline and disability.”

Despite last year’s severe flu season that included 180 deaths in children, vaccination remains the most effective protection against the flu, Dr. Adams said.

This year, between 163 million and 168 million doses of vaccine will be available in the United States. The vaccine is available in a range of settings including doctors’ offices, pharmacies, grocery stores, and workplaces, said Dr. Adams.

Flu vaccine choices this year include a return of the live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) given via nasal spray, along with the standard influenza vaccine that includes either three influenza viruses (trivalent, with two influenza A and one influenza B) or four influenza viruses (quadrivalent, with two influenza A and two influenza B). Other options are adjuvanted vaccine and high-dose vaccine for adults aged 65 years and older, and a cell-based and recombinant vaccine as alternatives to egg-based vaccines.

Dr. Adams emphasized the importance of healthy people getting vaccinated to protect the community. “All the people who died from the flu caught it from someone else,” he said.

The message to health care providers remains the same: Recommend the flu vaccine to patients at every opportunity, and lead by example and get vaccinated yourself, Dr. Adams said. He noted this year’s strategies to promote flu vaccination on social media, and encouraged clinicians to recommend the flu shot to their patients and to showcase their own shots via the #FightFlu hashtag.

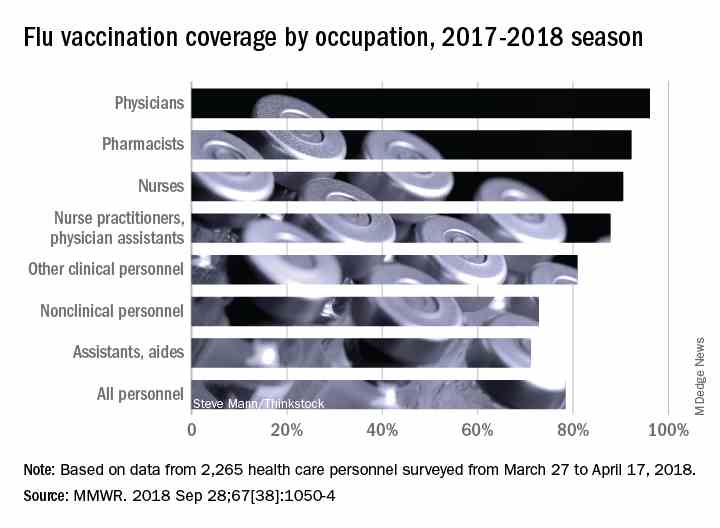

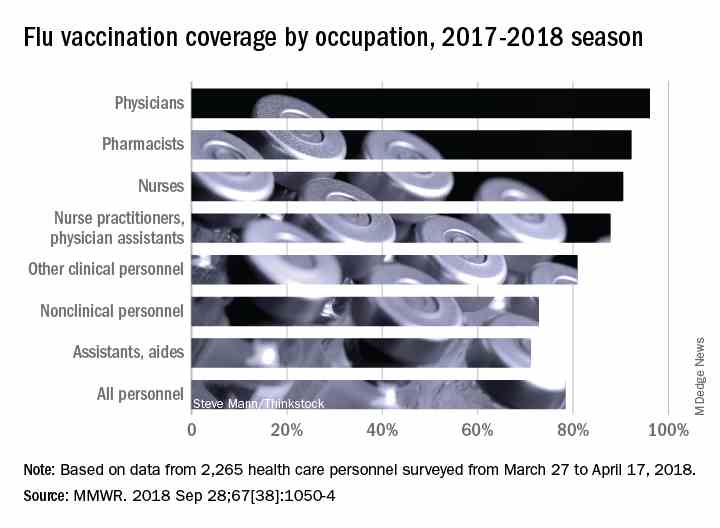

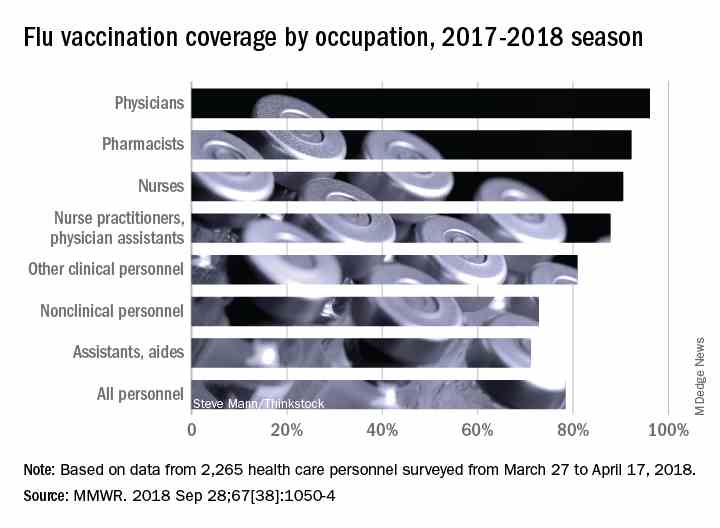

Vaccination among health care personnel last year was approximately 78%, which is a plateau over the past several years (MMWR 2018; 67:1050-54).

Be prepared to offer antivirals to patients as appropriate, and to promote the pneumococcal vaccine to eligible older adults as well, to protect not only themselves, but their contacts and the community, Dr. Adams emphasized. Currently approved antiviral drugs recommended for the 2018-2019 flu season: oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir.

Wendy Sue Swanson, MD, of Seattle Children’s Hospital, stressed the importance of flu vaccination for all children, given their ability to spread viral infections. She noted a concerning 2% drop in vaccinations for children aged 6 months to 4 years, although vaccination coverage in this group was highest among children overall, at approximately 68% last season.

Last year, approximately 80% of the child deaths from flu occurred in unvaccinated children, but the vaccine has been shown to reduce the likelihood of hospitalization or death even if a child does become ill, Dr. Swanson said.

Laura E. Riley, MD, of Weill Cornell Medical Center, noted that vaccination of pregnant women has plateaued in recent years, and was 49% last year. “Our goal is 80% plus,” she said. Data show that pregnant women who received flu vaccination were 40% less likely to be hospitalized for the flu, she noted. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends flu vaccination as safe during any trimester, and valuable to both mothers and newborns because it provides protective antibodies during the first 6 months of life before babies can receive their own vaccinations, Dr. Riley said.

More information about this year’s flu season is available from the CDC and NFID.

WASHINGTON – The flu vaccine may not be perfect, but it can reduce the severity of illness and curb the risk of spreading the disease to others, William Schaffner, MD, emphasized at a press conference held by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

“Give the vaccine credit for softening the blow,” said Dr. Schaffner, medical director of NFID and a professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

Dr. Schaffner and a panel of experts including U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams, MD, encouraged the public and the health care community to follow recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention that everyone aged 6 months and older receive an influenza vaccine.

Dr. Schaffner shared recent data showing that complications from the flu don’t stop when the acute illness resolves. Acute influenza causes a whole-body inflammatory reaction, and consequently “there is an increased risk of heart attack and stroke during the 2-4 weeks of recovery from acute influenza,” he said. In addition, older adults who experience acute flu and are already frail may never regain their pre-flu level of function, as the flu can start a “domino effect of decline and disability.”

Despite last year’s severe flu season that included 180 deaths in children, vaccination remains the most effective protection against the flu, Dr. Adams said.

This year, between 163 million and 168 million doses of vaccine will be available in the United States. The vaccine is available in a range of settings including doctors’ offices, pharmacies, grocery stores, and workplaces, said Dr. Adams.

Flu vaccine choices this year include a return of the live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) given via nasal spray, along with the standard influenza vaccine that includes either three influenza viruses (trivalent, with two influenza A and one influenza B) or four influenza viruses (quadrivalent, with two influenza A and two influenza B). Other options are adjuvanted vaccine and high-dose vaccine for adults aged 65 years and older, and a cell-based and recombinant vaccine as alternatives to egg-based vaccines.

Dr. Adams emphasized the importance of healthy people getting vaccinated to protect the community. “All the people who died from the flu caught it from someone else,” he said.

The message to health care providers remains the same: Recommend the flu vaccine to patients at every opportunity, and lead by example and get vaccinated yourself, Dr. Adams said. He noted this year’s strategies to promote flu vaccination on social media, and encouraged clinicians to recommend the flu shot to their patients and to showcase their own shots via the #FightFlu hashtag.

Vaccination among health care personnel last year was approximately 78%, which is a plateau over the past several years (MMWR 2018; 67:1050-54).

Be prepared to offer antivirals to patients as appropriate, and to promote the pneumococcal vaccine to eligible older adults as well, to protect not only themselves, but their contacts and the community, Dr. Adams emphasized. Currently approved antiviral drugs recommended for the 2018-2019 flu season: oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir.

Wendy Sue Swanson, MD, of Seattle Children’s Hospital, stressed the importance of flu vaccination for all children, given their ability to spread viral infections. She noted a concerning 2% drop in vaccinations for children aged 6 months to 4 years, although vaccination coverage in this group was highest among children overall, at approximately 68% last season.

Last year, approximately 80% of the child deaths from flu occurred in unvaccinated children, but the vaccine has been shown to reduce the likelihood of hospitalization or death even if a child does become ill, Dr. Swanson said.

Laura E. Riley, MD, of Weill Cornell Medical Center, noted that vaccination of pregnant women has plateaued in recent years, and was 49% last year. “Our goal is 80% plus,” she said. Data show that pregnant women who received flu vaccination were 40% less likely to be hospitalized for the flu, she noted. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends flu vaccination as safe during any trimester, and valuable to both mothers and newborns because it provides protective antibodies during the first 6 months of life before babies can receive their own vaccinations, Dr. Riley said.

More information about this year’s flu season is available from the CDC and NFID.

WASHINGTON – The flu vaccine may not be perfect, but it can reduce the severity of illness and curb the risk of spreading the disease to others, William Schaffner, MD, emphasized at a press conference held by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

“Give the vaccine credit for softening the blow,” said Dr. Schaffner, medical director of NFID and a professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

Dr. Schaffner and a panel of experts including U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams, MD, encouraged the public and the health care community to follow recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention that everyone aged 6 months and older receive an influenza vaccine.

Dr. Schaffner shared recent data showing that complications from the flu don’t stop when the acute illness resolves. Acute influenza causes a whole-body inflammatory reaction, and consequently “there is an increased risk of heart attack and stroke during the 2-4 weeks of recovery from acute influenza,” he said. In addition, older adults who experience acute flu and are already frail may never regain their pre-flu level of function, as the flu can start a “domino effect of decline and disability.”

Despite last year’s severe flu season that included 180 deaths in children, vaccination remains the most effective protection against the flu, Dr. Adams said.

This year, between 163 million and 168 million doses of vaccine will be available in the United States. The vaccine is available in a range of settings including doctors’ offices, pharmacies, grocery stores, and workplaces, said Dr. Adams.

Flu vaccine choices this year include a return of the live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) given via nasal spray, along with the standard influenza vaccine that includes either three influenza viruses (trivalent, with two influenza A and one influenza B) or four influenza viruses (quadrivalent, with two influenza A and two influenza B). Other options are adjuvanted vaccine and high-dose vaccine for adults aged 65 years and older, and a cell-based and recombinant vaccine as alternatives to egg-based vaccines.

Dr. Adams emphasized the importance of healthy people getting vaccinated to protect the community. “All the people who died from the flu caught it from someone else,” he said.

The message to health care providers remains the same: Recommend the flu vaccine to patients at every opportunity, and lead by example and get vaccinated yourself, Dr. Adams said. He noted this year’s strategies to promote flu vaccination on social media, and encouraged clinicians to recommend the flu shot to their patients and to showcase their own shots via the #FightFlu hashtag.

Vaccination among health care personnel last year was approximately 78%, which is a plateau over the past several years (MMWR 2018; 67:1050-54).

Be prepared to offer antivirals to patients as appropriate, and to promote the pneumococcal vaccine to eligible older adults as well, to protect not only themselves, but their contacts and the community, Dr. Adams emphasized. Currently approved antiviral drugs recommended for the 2018-2019 flu season: oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir.

Wendy Sue Swanson, MD, of Seattle Children’s Hospital, stressed the importance of flu vaccination for all children, given their ability to spread viral infections. She noted a concerning 2% drop in vaccinations for children aged 6 months to 4 years, although vaccination coverage in this group was highest among children overall, at approximately 68% last season.

Last year, approximately 80% of the child deaths from flu occurred in unvaccinated children, but the vaccine has been shown to reduce the likelihood of hospitalization or death even if a child does become ill, Dr. Swanson said.

Laura E. Riley, MD, of Weill Cornell Medical Center, noted that vaccination of pregnant women has plateaued in recent years, and was 49% last year. “Our goal is 80% plus,” she said. Data show that pregnant women who received flu vaccination were 40% less likely to be hospitalized for the flu, she noted. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends flu vaccination as safe during any trimester, and valuable to both mothers and newborns because it provides protective antibodies during the first 6 months of life before babies can receive their own vaccinations, Dr. Riley said.

More information about this year’s flu season is available from the CDC and NFID.

FROM AN NFID PRESS CONFERENCE

Point-of-care test for respiratory viruses lowers antibiotic use

Routine testing in the ED is advocated

PARIS – Using a point-of-care test for viral pathogens, hospital admissions were avoided in about a third of emergency department patients with suspected respiratory infection when other clinical signs also suggested a low risk of a bacterial pathogen, according to a single-center experience presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“We found that when patients had point-of-care respiratory viral testing soon after they were admitted to the emergency department, we were able to reduce unnecessary admission and improve bed flow in our center,” reported Kay Roy, MBBS, consultant physician in respiratory medicine, West Hertfordshire (England) Hospital NHS Trust.

In a protocol that was launched at Dr. Kay’s institution in January 2018, the point-of-care viral test was combined with other clinical factors, particularly chest x-rays and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), to determine whether patients had a viral pathogen and whether they could be discharged without antibiotics.

“Clinical judgment will always be required in individual patient decisions regarding antibiotic avoidance and early discharge,” Dr. Roy maintained. “But the point-of-care viral assay can be integrated into a strategy that permits more informed and rapid decision-making.”

This assertion is supported by the experience using a protocol anchored with the point-of-care viral test over a 4-month period. During this time, 901 patients with respiratory symptoms suspected of having a viral etiology were evaluated with the proprietary point-of-care device called FilmArray (bioMérieux).

From a sample taken with a nasopharyngeal swab, the test can identify a broad array of viruses using polymerase chain reaction technology in less than 45 minutes. However, the ED protocol for considering discharge without antibiotics requires additional evidence that the pathogen is viral, including a normal chest x-ray and a CRP less than 50 mg/L.

Of the 901 patients tested, a substantial proportion of whom had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, 507 (56%) tested positive for at least one virus, including influenza, rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, and adenovirus. Of these, 239 had normal chest x-rays and CRPs less than 50 mg/L. Because of the severity of symptoms or other clinical considerations, 154 patients were admitted, but 85 (36% of those meeting protocol criteria) were discharged without an antibiotic prescription.

“Antibiotics were continued in 90% of the patients who had an abnormal chest x-ray and abnormal CRP,” Dr. Roy reported. However, an objective strategy that permits clinicians to discharge patients at very low risk of a bacterial infection has many advantages even if it applies to a relatively modest proportion of those tested, according to Dr. Roy.

“Each respiratory admission can cost around [2,000 pounds] at our center,” reported Dr. Kay, referring to a figure equivalent to more than $2,600. In addition, she said that avoiding hospitalization frees up hospital beds and facilitates improved antimicrobial stewardship, which is vital to stem resistance.

Avoiding antibiotic use in patients with viral respiratory infections also is relevant to improved antibiotic stewardship in the community. For this reason, a randomized trial with a similar protocol involving the point-of-care viral test is planned in the outpatient setting. According to Dr. Roy, this will involve a community hub to which patients can be referred for testing and clinical evaluation.

“We hope that the quality of care can be improved with the point-of-care test for respiratory viruses as well as helping to reduce antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Roy said.

This approach is promising, according to Tobias Welte, MD, of the department of respiratory medicine at Hannover (Germany) Medical School, but he cautioned that it is not a standard approach.

“The protocol described by Dr. Roy will have to be compared to guidelines and recommended best clinical practice to confirm its usefulness,” he said, while conceding that any strategy that reduces unnecessary hospitalizations deserves further evaluation.

Routine testing in the ED is advocated

Routine testing in the ED is advocated

PARIS – Using a point-of-care test for viral pathogens, hospital admissions were avoided in about a third of emergency department patients with suspected respiratory infection when other clinical signs also suggested a low risk of a bacterial pathogen, according to a single-center experience presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“We found that when patients had point-of-care respiratory viral testing soon after they were admitted to the emergency department, we were able to reduce unnecessary admission and improve bed flow in our center,” reported Kay Roy, MBBS, consultant physician in respiratory medicine, West Hertfordshire (England) Hospital NHS Trust.

In a protocol that was launched at Dr. Kay’s institution in January 2018, the point-of-care viral test was combined with other clinical factors, particularly chest x-rays and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), to determine whether patients had a viral pathogen and whether they could be discharged without antibiotics.

“Clinical judgment will always be required in individual patient decisions regarding antibiotic avoidance and early discharge,” Dr. Roy maintained. “But the point-of-care viral assay can be integrated into a strategy that permits more informed and rapid decision-making.”

This assertion is supported by the experience using a protocol anchored with the point-of-care viral test over a 4-month period. During this time, 901 patients with respiratory symptoms suspected of having a viral etiology were evaluated with the proprietary point-of-care device called FilmArray (bioMérieux).

From a sample taken with a nasopharyngeal swab, the test can identify a broad array of viruses using polymerase chain reaction technology in less than 45 minutes. However, the ED protocol for considering discharge without antibiotics requires additional evidence that the pathogen is viral, including a normal chest x-ray and a CRP less than 50 mg/L.

Of the 901 patients tested, a substantial proportion of whom had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, 507 (56%) tested positive for at least one virus, including influenza, rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, and adenovirus. Of these, 239 had normal chest x-rays and CRPs less than 50 mg/L. Because of the severity of symptoms or other clinical considerations, 154 patients were admitted, but 85 (36% of those meeting protocol criteria) were discharged without an antibiotic prescription.

“Antibiotics were continued in 90% of the patients who had an abnormal chest x-ray and abnormal CRP,” Dr. Roy reported. However, an objective strategy that permits clinicians to discharge patients at very low risk of a bacterial infection has many advantages even if it applies to a relatively modest proportion of those tested, according to Dr. Roy.

“Each respiratory admission can cost around [2,000 pounds] at our center,” reported Dr. Kay, referring to a figure equivalent to more than $2,600. In addition, she said that avoiding hospitalization frees up hospital beds and facilitates improved antimicrobial stewardship, which is vital to stem resistance.

Avoiding antibiotic use in patients with viral respiratory infections also is relevant to improved antibiotic stewardship in the community. For this reason, a randomized trial with a similar protocol involving the point-of-care viral test is planned in the outpatient setting. According to Dr. Roy, this will involve a community hub to which patients can be referred for testing and clinical evaluation.

“We hope that the quality of care can be improved with the point-of-care test for respiratory viruses as well as helping to reduce antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Roy said.

This approach is promising, according to Tobias Welte, MD, of the department of respiratory medicine at Hannover (Germany) Medical School, but he cautioned that it is not a standard approach.

“The protocol described by Dr. Roy will have to be compared to guidelines and recommended best clinical practice to confirm its usefulness,” he said, while conceding that any strategy that reduces unnecessary hospitalizations deserves further evaluation.

PARIS – Using a point-of-care test for viral pathogens, hospital admissions were avoided in about a third of emergency department patients with suspected respiratory infection when other clinical signs also suggested a low risk of a bacterial pathogen, according to a single-center experience presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

“We found that when patients had point-of-care respiratory viral testing soon after they were admitted to the emergency department, we were able to reduce unnecessary admission and improve bed flow in our center,” reported Kay Roy, MBBS, consultant physician in respiratory medicine, West Hertfordshire (England) Hospital NHS Trust.

In a protocol that was launched at Dr. Kay’s institution in January 2018, the point-of-care viral test was combined with other clinical factors, particularly chest x-rays and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), to determine whether patients had a viral pathogen and whether they could be discharged without antibiotics.

“Clinical judgment will always be required in individual patient decisions regarding antibiotic avoidance and early discharge,” Dr. Roy maintained. “But the point-of-care viral assay can be integrated into a strategy that permits more informed and rapid decision-making.”

This assertion is supported by the experience using a protocol anchored with the point-of-care viral test over a 4-month period. During this time, 901 patients with respiratory symptoms suspected of having a viral etiology were evaluated with the proprietary point-of-care device called FilmArray (bioMérieux).

From a sample taken with a nasopharyngeal swab, the test can identify a broad array of viruses using polymerase chain reaction technology in less than 45 minutes. However, the ED protocol for considering discharge without antibiotics requires additional evidence that the pathogen is viral, including a normal chest x-ray and a CRP less than 50 mg/L.

Of the 901 patients tested, a substantial proportion of whom had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, 507 (56%) tested positive for at least one virus, including influenza, rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, and adenovirus. Of these, 239 had normal chest x-rays and CRPs less than 50 mg/L. Because of the severity of symptoms or other clinical considerations, 154 patients were admitted, but 85 (36% of those meeting protocol criteria) were discharged without an antibiotic prescription.

“Antibiotics were continued in 90% of the patients who had an abnormal chest x-ray and abnormal CRP,” Dr. Roy reported. However, an objective strategy that permits clinicians to discharge patients at very low risk of a bacterial infection has many advantages even if it applies to a relatively modest proportion of those tested, according to Dr. Roy.

“Each respiratory admission can cost around [2,000 pounds] at our center,” reported Dr. Kay, referring to a figure equivalent to more than $2,600. In addition, she said that avoiding hospitalization frees up hospital beds and facilitates improved antimicrobial stewardship, which is vital to stem resistance.

Avoiding antibiotic use in patients with viral respiratory infections also is relevant to improved antibiotic stewardship in the community. For this reason, a randomized trial with a similar protocol involving the point-of-care viral test is planned in the outpatient setting. According to Dr. Roy, this will involve a community hub to which patients can be referred for testing and clinical evaluation.

“We hope that the quality of care can be improved with the point-of-care test for respiratory viruses as well as helping to reduce antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Roy said.

This approach is promising, according to Tobias Welte, MD, of the department of respiratory medicine at Hannover (Germany) Medical School, but he cautioned that it is not a standard approach.

“The protocol described by Dr. Roy will have to be compared to guidelines and recommended best clinical practice to confirm its usefulness,” he said, while conceding that any strategy that reduces unnecessary hospitalizations deserves further evaluation.

REPORTING FROM THE ERS CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of patients with a negative chest x-ray and low CRP level, 36% avoided hospital admission due to a positive test for a virus.

Study details: A case series.

Disclosures: Dr. Roy reports no financial relationships relevant to this study.

Get on top of home BP monitoring now

CHICAGO – Home BP monitoring has proved its worth, and it’s now time to integrate it into health care and get insurers to pay for it, according to Hayden Bosworth, PhD, a population health sciences professor and health services researcher at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The devices are on the shelves of pharmacies and discount stores nationwide, sometimes for less than $50, but what to do with them in the clinic hasn’t been worked out. It’s likely patients are soon going to want help interpreting the results, if they aren’t already, but a leap in technology has left clinicians and payors scratching their heads.

There’s more than enough evidence of benefit. Dr. Bosworth has been involved with several trials of home BP monitoring with good results. He was one of the many authors on a recent meta-analysis that found when patients check their BP at home, it can lead to a “clinically significant” reduction “which persists for at least 12 months” (PLoS Med. 2017 Sep 19;14[9]:e1002389).

“Are we talking about efficacy or proof of concept? I think we are beyond that. Now we have to think about how we put it into the system, how do we integrate it, what’s the best way of delivery. I think that’s where the future is,” he said in an interview at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

Home monitoring came up far more often at this year’s joint sessions than in 2017, which might indicate growing interest, but reimbursement remains a challenge. American Medical Association staff said at this year’s meeting that they are working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for coverage of the devices and their use. It seemed likely to them.

In the meantime, Dr. Bosworth had some useful advice for those who are thinking about incorporating home BP monitoring into their practices.

He shared his tips on how to pick out a device – there’s actually a journal called Blood Pressure Monitoring that can help – as well as his thoughts on how often people should monitor themselves and what to do with the numbers.

He envisions a future when patients routinely check their BP at home; it’s even possible they could adjust their medications based on the results, much like diabetes patients track their blood glucose and adjust their insulin. It’s been shown to work in Britain (JAMA. 2014 Aug 27;312[8]:799-808).

Dr. Bosworth reported no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – Home BP monitoring has proved its worth, and it’s now time to integrate it into health care and get insurers to pay for it, according to Hayden Bosworth, PhD, a population health sciences professor and health services researcher at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The devices are on the shelves of pharmacies and discount stores nationwide, sometimes for less than $50, but what to do with them in the clinic hasn’t been worked out. It’s likely patients are soon going to want help interpreting the results, if they aren’t already, but a leap in technology has left clinicians and payors scratching their heads.

There’s more than enough evidence of benefit. Dr. Bosworth has been involved with several trials of home BP monitoring with good results. He was one of the many authors on a recent meta-analysis that found when patients check their BP at home, it can lead to a “clinically significant” reduction “which persists for at least 12 months” (PLoS Med. 2017 Sep 19;14[9]:e1002389).

“Are we talking about efficacy or proof of concept? I think we are beyond that. Now we have to think about how we put it into the system, how do we integrate it, what’s the best way of delivery. I think that’s where the future is,” he said in an interview at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

Home monitoring came up far more often at this year’s joint sessions than in 2017, which might indicate growing interest, but reimbursement remains a challenge. American Medical Association staff said at this year’s meeting that they are working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for coverage of the devices and their use. It seemed likely to them.

In the meantime, Dr. Bosworth had some useful advice for those who are thinking about incorporating home BP monitoring into their practices.

He shared his tips on how to pick out a device – there’s actually a journal called Blood Pressure Monitoring that can help – as well as his thoughts on how often people should monitor themselves and what to do with the numbers.

He envisions a future when patients routinely check their BP at home; it’s even possible they could adjust their medications based on the results, much like diabetes patients track their blood glucose and adjust their insulin. It’s been shown to work in Britain (JAMA. 2014 Aug 27;312[8]:799-808).

Dr. Bosworth reported no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – Home BP monitoring has proved its worth, and it’s now time to integrate it into health care and get insurers to pay for it, according to Hayden Bosworth, PhD, a population health sciences professor and health services researcher at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The devices are on the shelves of pharmacies and discount stores nationwide, sometimes for less than $50, but what to do with them in the clinic hasn’t been worked out. It’s likely patients are soon going to want help interpreting the results, if they aren’t already, but a leap in technology has left clinicians and payors scratching their heads.

There’s more than enough evidence of benefit. Dr. Bosworth has been involved with several trials of home BP monitoring with good results. He was one of the many authors on a recent meta-analysis that found when patients check their BP at home, it can lead to a “clinically significant” reduction “which persists for at least 12 months” (PLoS Med. 2017 Sep 19;14[9]:e1002389).

“Are we talking about efficacy or proof of concept? I think we are beyond that. Now we have to think about how we put it into the system, how do we integrate it, what’s the best way of delivery. I think that’s where the future is,” he said in an interview at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

Home monitoring came up far more often at this year’s joint sessions than in 2017, which might indicate growing interest, but reimbursement remains a challenge. American Medical Association staff said at this year’s meeting that they are working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for coverage of the devices and their use. It seemed likely to them.

In the meantime, Dr. Bosworth had some useful advice for those who are thinking about incorporating home BP monitoring into their practices.

He shared his tips on how to pick out a device – there’s actually a journal called Blood Pressure Monitoring that can help – as well as his thoughts on how often people should monitor themselves and what to do with the numbers.

He envisions a future when patients routinely check their BP at home; it’s even possible they could adjust their medications based on the results, much like diabetes patients track their blood glucose and adjust their insulin. It’s been shown to work in Britain (JAMA. 2014 Aug 27;312[8]:799-808).

Dr. Bosworth reported no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM JOINT HYPERTENSION 2018

Online diabetes prevention programs as good as face-to-face programs

, researchers report.

Writing in background information to their paper, Tannaz Moin, MD, an endocrinologist at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the Veterans Affairs’ Health Services Research and Development Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation, and Policy, and her associates, said intensive lifestyle interventions such as diabetes prevention programs (DPP) could lower the risk of incident diabetes by 58%, but a lack of reach significantly attenuated their population impact in real-world settings.

“Building evidence for online DPP is important because of its potential for increasing reach because most U.S. adults (87%) use the Internet,” they wrote in their paper, published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

They therefore set out to compare weight loss results from 114 veterans taking part in the Veterans Administration’s face-to-face standard-of-care weight management program MOVE! with an online program involving 268 obese or overweight veterans with prediabetes and 273 people taking part in an in-person program.

MOVE! included 8-12 face-to-face healthy-lifestyle sessions and monthly maintenance sessions but with no specified goals. The online program involved virtual groups of participants: live e-coaches who monitored group interactions and provided the participants with feedback via phone and private online messages; weekly educational modules on healthy eating and exercise; and wireless scales to record participant weights.

The in-person program consisted of 8-22 group-based face-to-face sessions focused on 7% weight loss and at least 150 minutes per session of moderate physical activity.

Weight loss, considered by the authors to be a significant predictor of diabetes risk reduction, was recorded at 6 months and then again at 12 months in all three interventions.

An analysis of 242 participants enrolled in the intensive, multifaceted online DPP intervention (26 were excluded because they did not have more than two available weights) revealed a significant weight change of –4.7 kg at 6 months and –4 kg at 12 months’ follow-up. On average, these participants lost 3.7% of their baseline weight at 12 months.

At both times weight change (kg and percentage) was not significantly different between the online intervention and those taking part in the in-person DPP (–4.8 and –4.1 kg for online vs –4 kg and –3.9 kg in-person for those completing more than one module/session). Both groups also had higher weight loss (percentage and kg) at 6 and 12 months compared with MOVE! participants (–1.1kg and 0.10 kg).

The research team noted that the online program had better participation than did the in-person program, with 87% of online participants completing eight or more sessions, compared with 59% for the in-person program and 55% for MOVE!

They suggested this was because the online program had several user-friendly features that increased the frequency of potential “touches” participants received over time.

“Future studies examining how inline DPP intervention components can work together to impact participation and engagement are key,” they said.

“This is one of the first studies to report weight outcomes irrespective of the level of engagement with an online DPP intervention and to examine outcomes compared with in person DPP. Overall, these findings may have important implications for national efforts to disseminate DPP,” they concluded.

The authors conceded that the generalizability of their study was limited as it included veterans receiving care in the VHA.

SOURCE: Am J Prev Med. 2018 Sep 24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.06.028

, researchers report.

Writing in background information to their paper, Tannaz Moin, MD, an endocrinologist at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the Veterans Affairs’ Health Services Research and Development Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation, and Policy, and her associates, said intensive lifestyle interventions such as diabetes prevention programs (DPP) could lower the risk of incident diabetes by 58%, but a lack of reach significantly attenuated their population impact in real-world settings.

“Building evidence for online DPP is important because of its potential for increasing reach because most U.S. adults (87%) use the Internet,” they wrote in their paper, published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

They therefore set out to compare weight loss results from 114 veterans taking part in the Veterans Administration’s face-to-face standard-of-care weight management program MOVE! with an online program involving 268 obese or overweight veterans with prediabetes and 273 people taking part in an in-person program.

MOVE! included 8-12 face-to-face healthy-lifestyle sessions and monthly maintenance sessions but with no specified goals. The online program involved virtual groups of participants: live e-coaches who monitored group interactions and provided the participants with feedback via phone and private online messages; weekly educational modules on healthy eating and exercise; and wireless scales to record participant weights.

The in-person program consisted of 8-22 group-based face-to-face sessions focused on 7% weight loss and at least 150 minutes per session of moderate physical activity.

Weight loss, considered by the authors to be a significant predictor of diabetes risk reduction, was recorded at 6 months and then again at 12 months in all three interventions.

An analysis of 242 participants enrolled in the intensive, multifaceted online DPP intervention (26 were excluded because they did not have more than two available weights) revealed a significant weight change of –4.7 kg at 6 months and –4 kg at 12 months’ follow-up. On average, these participants lost 3.7% of their baseline weight at 12 months.

At both times weight change (kg and percentage) was not significantly different between the online intervention and those taking part in the in-person DPP (–4.8 and –4.1 kg for online vs –4 kg and –3.9 kg in-person for those completing more than one module/session). Both groups also had higher weight loss (percentage and kg) at 6 and 12 months compared with MOVE! participants (–1.1kg and 0.10 kg).

The research team noted that the online program had better participation than did the in-person program, with 87% of online participants completing eight or more sessions, compared with 59% for the in-person program and 55% for MOVE!

They suggested this was because the online program had several user-friendly features that increased the frequency of potential “touches” participants received over time.

“Future studies examining how inline DPP intervention components can work together to impact participation and engagement are key,” they said.

“This is one of the first studies to report weight outcomes irrespective of the level of engagement with an online DPP intervention and to examine outcomes compared with in person DPP. Overall, these findings may have important implications for national efforts to disseminate DPP,” they concluded.

The authors conceded that the generalizability of their study was limited as it included veterans receiving care in the VHA.

SOURCE: Am J Prev Med. 2018 Sep 24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.06.028

, researchers report.

Writing in background information to their paper, Tannaz Moin, MD, an endocrinologist at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the Veterans Affairs’ Health Services Research and Development Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation, and Policy, and her associates, said intensive lifestyle interventions such as diabetes prevention programs (DPP) could lower the risk of incident diabetes by 58%, but a lack of reach significantly attenuated their population impact in real-world settings.

“Building evidence for online DPP is important because of its potential for increasing reach because most U.S. adults (87%) use the Internet,” they wrote in their paper, published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

They therefore set out to compare weight loss results from 114 veterans taking part in the Veterans Administration’s face-to-face standard-of-care weight management program MOVE! with an online program involving 268 obese or overweight veterans with prediabetes and 273 people taking part in an in-person program.

MOVE! included 8-12 face-to-face healthy-lifestyle sessions and monthly maintenance sessions but with no specified goals. The online program involved virtual groups of participants: live e-coaches who monitored group interactions and provided the participants with feedback via phone and private online messages; weekly educational modules on healthy eating and exercise; and wireless scales to record participant weights.

The in-person program consisted of 8-22 group-based face-to-face sessions focused on 7% weight loss and at least 150 minutes per session of moderate physical activity.

Weight loss, considered by the authors to be a significant predictor of diabetes risk reduction, was recorded at 6 months and then again at 12 months in all three interventions.

An analysis of 242 participants enrolled in the intensive, multifaceted online DPP intervention (26 were excluded because they did not have more than two available weights) revealed a significant weight change of –4.7 kg at 6 months and –4 kg at 12 months’ follow-up. On average, these participants lost 3.7% of their baseline weight at 12 months.

At both times weight change (kg and percentage) was not significantly different between the online intervention and those taking part in the in-person DPP (–4.8 and –4.1 kg for online vs –4 kg and –3.9 kg in-person for those completing more than one module/session). Both groups also had higher weight loss (percentage and kg) at 6 and 12 months compared with MOVE! participants (–1.1kg and 0.10 kg).

The research team noted that the online program had better participation than did the in-person program, with 87% of online participants completing eight or more sessions, compared with 59% for the in-person program and 55% for MOVE!

They suggested this was because the online program had several user-friendly features that increased the frequency of potential “touches” participants received over time.

“Future studies examining how inline DPP intervention components can work together to impact participation and engagement are key,” they said.

“This is one of the first studies to report weight outcomes irrespective of the level of engagement with an online DPP intervention and to examine outcomes compared with in person DPP. Overall, these findings may have important implications for national efforts to disseminate DPP,” they concluded.

The authors conceded that the generalizability of their study was limited as it included veterans receiving care in the VHA.

SOURCE: Am J Prev Med. 2018 Sep 24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.06.028

FROM AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Online diabetes prevention programs (DPP) are as effective as in-person programs in terms of weight loss, and they have a wider reach.

Major finding: Participants enrolled in an intensive, multifaceted online DPP intervention had significant weight change of −4.7 kg at 6 months and −4.0 kg at 12-month follow-up, similar to that of participants enrolled in a face-to face program.

Study details: A large nonrandomized trial and a comparative analysis of individuals from a concurrent trial of two parallel in-person programs.

Disclosures: The Department of Veteran Affairs funded the study. One author reported co-owning shares in Amgen, and another reported receiving personal fees from two pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Am J Prev Med. 2018 Sep 24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.06.028.

Apomorphine Reduces Off Time in First Randomized Trial

The drug reduces motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease without exacerbating troublesome dyskinesia.

Subcutaneous apomorphine infusion significantly reduces off time in patients with Parkinson’s disease and inadequately controlled motor fluctuations, according to data published in the September issue of Lancet Neurology. The data result from the first randomized controlled trial of apomorphine in this population.

In 1988, an open-label study indicated that apomorphine had antiparkinsonian efficacy equivalent to that of levodopa. Several uncontrolled studies have indicated that it effectively reduces off time, improves dyskinesias, and allows doses of oral levodopa to be decreased.

A Multicenter European Study

Regina Katzenschlager, MD, a neurologist at Danube Hospital in Vienna, and colleagues investigated the safety and efficacy of apomorphine infusion in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. They enrolled patients at 23 European hospitals who had received a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease more than three years previously and had motor fluctuations that were inadequately controlled. Patients were randomized in equal groups to 3–8-mg/h infusions of apomorphine or saline for approximately 16 h/day. The treatment period lasted for 12 weeks. During the first four weeks, investigators adjusted the dose according to efficacy and tolerability, and the remaining eight weeks were a maintenance period.

Patients completed home diary assessments of motor status and visited the hospital for regular evaluations. The study’s primary end point was the absolute change in off time from baseline to 12 weeks, based on diary assessments. Secondary end points included response to therapy (ie, a reduction in off time of at least two hours from baseline), absolute change in on time without troublesome dyskinesia, Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) score, change in levodopa dose, change in motor score, and change in quality of life.

Results Were Consistent in Prespecified Subgroups

A total of 53 patients were randomized to apomorphine, and 54 patients were randomized to placebo. The mean final dose of study drug was 4.68 mg/h in the apomorphine group and 5.76 mg/h in the placebo group.

Mean reduction in off time was significantly greater at week 12 in the apomorphine group (−2.47 h/day) than among controls (−0.58 h/day). The results were consistent in sensitivity analyses. Approximately 62% of patients in the apomorphine group responded to therapy, compared with 29% of controls.

Mean on time without troublesome dyskinesia was significantly increased in the apomorphine group (2.77 h/day), compared with the placebo group (0.80 h/day). Apomorphine also improved PGIC scores significantly at 12 weeks, compared with placebo. Mean reduction in oral levodopa dose was greater in the apomorphine group, but the difference between groups was not statistically significant. Changes in motor score and quality of life were not significantly different between groups at 12 weeks.

The treatment was well tolerated, and the researchers found no unexpected safety signals. The rate of treatment-emergent adverse events was 93% in the apomorphine group and 57% among controls. The most common adverse events were skin reactions, nausea, and somnolence. Six patients had an adverse event that prompted study withdrawal; all were in the apomorphine group. Five patients in the apomorphine group had serious adverse events, including severe hypotension, myocardial infarction, and persistently abnormal hematology test results indicating mild leukopenia and moderate anemia.

“From a practical viewpoint, our study shows that some patients tolerate and receive benefit from doses exceeding the common range of hourly flow rates currently used in practice,” said the authors. “Many centers use higher flow rates than the mean dose in our study, and it is possible that the full potential of apomorphine has not been investigated here.”

How Effective Would Apomorphine Monotherapy Be?

The findings of Dr. Katzenschlager and colleagues “should help guide clinicians in making decisions about management of patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease, particularly when considering use of deep brain stimulation or intestinal infusion of levodopa–carbidopa gel,” said Peter A. LeWitt, MD, Director of the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Program at Henry Ford Hospital in West Bloomfield, Michigan, in an accompanying editorial. “In view of its efficacy and safety profile, apomorphine infusion should be considered before embarking on other invasive therapies.”

On average, apomorphine infusion decreased off time by approximately one-third from patients’ baseline levels. “One might ask why the study did not achieve better results,” said Dr. LeWitt. A potential explanation is that impaired brain circuitry in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease loses its long-term response to levodopa and is associated with dyskinesias and freezing of gait, he added. It also is possible that participants’ medical treatment had not been optimized at baseline.

“Despite a heavy load of levodopa and adjunctive medications (most participants in the study also received dopaminergic agonists, and inhibitors of catechol-O-methyltransferase and monoamine oxidase type B were used liberally), many patients continue to be burdened by substantial daily off time fluctuations,” said Dr. LeWitt. “A final question unanswered by this study is the effectiveness of apomorphine monotherapy, which has been previously tested in only a few studies. Future studies might investigate this question and what benefit, if any, is offered by concomitant levodopa treatment.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Katzenschlager R, Poewe W, Rascol O, et al. Apomorphine subcutaneous infusion in patients with Parkinson’s disease with persistent motor fluctuations (TOLEDO): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(9):749-759.

LeWitt PA. At last, a randomised controlled trial of apomorphine infusion. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(9):732-733.

The drug reduces motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease without exacerbating troublesome dyskinesia.

The drug reduces motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease without exacerbating troublesome dyskinesia.

Subcutaneous apomorphine infusion significantly reduces off time in patients with Parkinson’s disease and inadequately controlled motor fluctuations, according to data published in the September issue of Lancet Neurology. The data result from the first randomized controlled trial of apomorphine in this population.

In 1988, an open-label study indicated that apomorphine had antiparkinsonian efficacy equivalent to that of levodopa. Several uncontrolled studies have indicated that it effectively reduces off time, improves dyskinesias, and allows doses of oral levodopa to be decreased.

A Multicenter European Study

Regina Katzenschlager, MD, a neurologist at Danube Hospital in Vienna, and colleagues investigated the safety and efficacy of apomorphine infusion in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. They enrolled patients at 23 European hospitals who had received a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease more than three years previously and had motor fluctuations that were inadequately controlled. Patients were randomized in equal groups to 3–8-mg/h infusions of apomorphine or saline for approximately 16 h/day. The treatment period lasted for 12 weeks. During the first four weeks, investigators adjusted the dose according to efficacy and tolerability, and the remaining eight weeks were a maintenance period.

Patients completed home diary assessments of motor status and visited the hospital for regular evaluations. The study’s primary end point was the absolute change in off time from baseline to 12 weeks, based on diary assessments. Secondary end points included response to therapy (ie, a reduction in off time of at least two hours from baseline), absolute change in on time without troublesome dyskinesia, Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) score, change in levodopa dose, change in motor score, and change in quality of life.

Results Were Consistent in Prespecified Subgroups

A total of 53 patients were randomized to apomorphine, and 54 patients were randomized to placebo. The mean final dose of study drug was 4.68 mg/h in the apomorphine group and 5.76 mg/h in the placebo group.

Mean reduction in off time was significantly greater at week 12 in the apomorphine group (−2.47 h/day) than among controls (−0.58 h/day). The results were consistent in sensitivity analyses. Approximately 62% of patients in the apomorphine group responded to therapy, compared with 29% of controls.

Mean on time without troublesome dyskinesia was significantly increased in the apomorphine group (2.77 h/day), compared with the placebo group (0.80 h/day). Apomorphine also improved PGIC scores significantly at 12 weeks, compared with placebo. Mean reduction in oral levodopa dose was greater in the apomorphine group, but the difference between groups was not statistically significant. Changes in motor score and quality of life were not significantly different between groups at 12 weeks.

The treatment was well tolerated, and the researchers found no unexpected safety signals. The rate of treatment-emergent adverse events was 93% in the apomorphine group and 57% among controls. The most common adverse events were skin reactions, nausea, and somnolence. Six patients had an adverse event that prompted study withdrawal; all were in the apomorphine group. Five patients in the apomorphine group had serious adverse events, including severe hypotension, myocardial infarction, and persistently abnormal hematology test results indicating mild leukopenia and moderate anemia.

“From a practical viewpoint, our study shows that some patients tolerate and receive benefit from doses exceeding the common range of hourly flow rates currently used in practice,” said the authors. “Many centers use higher flow rates than the mean dose in our study, and it is possible that the full potential of apomorphine has not been investigated here.”

How Effective Would Apomorphine Monotherapy Be?

The findings of Dr. Katzenschlager and colleagues “should help guide clinicians in making decisions about management of patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease, particularly when considering use of deep brain stimulation or intestinal infusion of levodopa–carbidopa gel,” said Peter A. LeWitt, MD, Director of the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Program at Henry Ford Hospital in West Bloomfield, Michigan, in an accompanying editorial. “In view of its efficacy and safety profile, apomorphine infusion should be considered before embarking on other invasive therapies.”

On average, apomorphine infusion decreased off time by approximately one-third from patients’ baseline levels. “One might ask why the study did not achieve better results,” said Dr. LeWitt. A potential explanation is that impaired brain circuitry in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease loses its long-term response to levodopa and is associated with dyskinesias and freezing of gait, he added. It also is possible that participants’ medical treatment had not been optimized at baseline.

“Despite a heavy load of levodopa and adjunctive medications (most participants in the study also received dopaminergic agonists, and inhibitors of catechol-O-methyltransferase and monoamine oxidase type B were used liberally), many patients continue to be burdened by substantial daily off time fluctuations,” said Dr. LeWitt. “A final question unanswered by this study is the effectiveness of apomorphine monotherapy, which has been previously tested in only a few studies. Future studies might investigate this question and what benefit, if any, is offered by concomitant levodopa treatment.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Katzenschlager R, Poewe W, Rascol O, et al. Apomorphine subcutaneous infusion in patients with Parkinson’s disease with persistent motor fluctuations (TOLEDO): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(9):749-759.

LeWitt PA. At last, a randomised controlled trial of apomorphine infusion. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(9):732-733.

Subcutaneous apomorphine infusion significantly reduces off time in patients with Parkinson’s disease and inadequately controlled motor fluctuations, according to data published in the September issue of Lancet Neurology. The data result from the first randomized controlled trial of apomorphine in this population.

In 1988, an open-label study indicated that apomorphine had antiparkinsonian efficacy equivalent to that of levodopa. Several uncontrolled studies have indicated that it effectively reduces off time, improves dyskinesias, and allows doses of oral levodopa to be decreased.

A Multicenter European Study

Regina Katzenschlager, MD, a neurologist at Danube Hospital in Vienna, and colleagues investigated the safety and efficacy of apomorphine infusion in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. They enrolled patients at 23 European hospitals who had received a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease more than three years previously and had motor fluctuations that were inadequately controlled. Patients were randomized in equal groups to 3–8-mg/h infusions of apomorphine or saline for approximately 16 h/day. The treatment period lasted for 12 weeks. During the first four weeks, investigators adjusted the dose according to efficacy and tolerability, and the remaining eight weeks were a maintenance period.

Patients completed home diary assessments of motor status and visited the hospital for regular evaluations. The study’s primary end point was the absolute change in off time from baseline to 12 weeks, based on diary assessments. Secondary end points included response to therapy (ie, a reduction in off time of at least two hours from baseline), absolute change in on time without troublesome dyskinesia, Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) score, change in levodopa dose, change in motor score, and change in quality of life.

Results Were Consistent in Prespecified Subgroups

A total of 53 patients were randomized to apomorphine, and 54 patients were randomized to placebo. The mean final dose of study drug was 4.68 mg/h in the apomorphine group and 5.76 mg/h in the placebo group.

Mean reduction in off time was significantly greater at week 12 in the apomorphine group (−2.47 h/day) than among controls (−0.58 h/day). The results were consistent in sensitivity analyses. Approximately 62% of patients in the apomorphine group responded to therapy, compared with 29% of controls.

Mean on time without troublesome dyskinesia was significantly increased in the apomorphine group (2.77 h/day), compared with the placebo group (0.80 h/day). Apomorphine also improved PGIC scores significantly at 12 weeks, compared with placebo. Mean reduction in oral levodopa dose was greater in the apomorphine group, but the difference between groups was not statistically significant. Changes in motor score and quality of life were not significantly different between groups at 12 weeks.

The treatment was well tolerated, and the researchers found no unexpected safety signals. The rate of treatment-emergent adverse events was 93% in the apomorphine group and 57% among controls. The most common adverse events were skin reactions, nausea, and somnolence. Six patients had an adverse event that prompted study withdrawal; all were in the apomorphine group. Five patients in the apomorphine group had serious adverse events, including severe hypotension, myocardial infarction, and persistently abnormal hematology test results indicating mild leukopenia and moderate anemia.

“From a practical viewpoint, our study shows that some patients tolerate and receive benefit from doses exceeding the common range of hourly flow rates currently used in practice,” said the authors. “Many centers use higher flow rates than the mean dose in our study, and it is possible that the full potential of apomorphine has not been investigated here.”

How Effective Would Apomorphine Monotherapy Be?

The findings of Dr. Katzenschlager and colleagues “should help guide clinicians in making decisions about management of patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease, particularly when considering use of deep brain stimulation or intestinal infusion of levodopa–carbidopa gel,” said Peter A. LeWitt, MD, Director of the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Program at Henry Ford Hospital in West Bloomfield, Michigan, in an accompanying editorial. “In view of its efficacy and safety profile, apomorphine infusion should be considered before embarking on other invasive therapies.”

On average, apomorphine infusion decreased off time by approximately one-third from patients’ baseline levels. “One might ask why the study did not achieve better results,” said Dr. LeWitt. A potential explanation is that impaired brain circuitry in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease loses its long-term response to levodopa and is associated with dyskinesias and freezing of gait, he added. It also is possible that participants’ medical treatment had not been optimized at baseline.

“Despite a heavy load of levodopa and adjunctive medications (most participants in the study also received dopaminergic agonists, and inhibitors of catechol-O-methyltransferase and monoamine oxidase type B were used liberally), many patients continue to be burdened by substantial daily off time fluctuations,” said Dr. LeWitt. “A final question unanswered by this study is the effectiveness of apomorphine monotherapy, which has been previously tested in only a few studies. Future studies might investigate this question and what benefit, if any, is offered by concomitant levodopa treatment.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Katzenschlager R, Poewe W, Rascol O, et al. Apomorphine subcutaneous infusion in patients with Parkinson’s disease with persistent motor fluctuations (TOLEDO): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(9):749-759.

LeWitt PA. At last, a randomised controlled trial of apomorphine infusion. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(9):732-733.

Fremanezumab May Improve Migraineurs’ Function on Headache-Free Days

The mechanism underlying the benefit observed in the post hoc analyses is unclear.

Fremanezumab increases the number of headache-free days with normal function for patients with episodic or chronic migraine, according to post hoc analyses published online ahead of print August 17 in Neurology. Fremanezumab appears to improve all measures of function in patients with episodic migraine, and some measures in patients with chronic migraine.

“The results should be considered exploratory,” said Juliana VanderPluym, MD, a neurologist at Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, and colleagues. “Further research is needed to confirm these preliminary findings and to understand the factors contributing to perceived functional status on headache-free days.”

Examining Two Phase II Trials

Fremanezumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). Dr. VanderPluym and colleagues analyzed data from randomized, double-blind phase II trials of the therapy for prevention of high-frequency episodic migraine (ie, eight to 14 headache days per month) and chronic migraine. Patients with high-frequency episodic migraine received placebo or monthly subcutaneous fremanezumab injections of 225 mg or 675 mg. Patients with chronic migraine received placebo or an initial 675-mg fremanezumab dose followed by monthly subcutaneous injections of 225 mg or 900 mg. The treatment period was three months.

Participants entered information into an electronic diary daily. Questions about functional performance elicited information about “work/school/household chore performance” and “concentration/mental fatigue.” For the former category, patients recorded their performance as normal, less than 50% impaired, or at least 50% impaired. For the latter category, patients recorded how much time they had spent working more slowly, finding it difficult to concentrate, and feeling tired or drained.

Fremanezumab Improved Concentration

In the high-frequency episodic migraine study, patients who received fremanezumab had a greater increase in headache-free days with normal concentration and normal performance at work, school, and home, compared with controls.

In the study of chronic migraine, the 900-mg dose was associated with consistent improvements in function on headache-free days. Patients with chronic migraine in the 225-mg dose group had increases compared with controls in the number of headache-free days in which they performed household chores normally and had no time with difficulty concentrating. The 225-mg group had minimal changes in the number of headache-free days in which work/study and household chore performance was impaired by 50% or more, as well as in in time with difficulty concentrating, but its results were better than those of controls.

“One could postulate that patients had more headache-free days with normal functional performance simply because they had more headache-free days on fremanezumab,” said Dr. VanderPluym. “With increased headache-free days, patients may have had reduced interictal anxiety and thus reduced avoidance behavior and lifestyle compromise, allowing them to function normally.”

Patients receiving fremanezumab significantly reduced their intake of acute medications, compared with controls. This reduction likely decreased the number of side effects associated with acute medications and could have contributed to better functional performance, said the authors.

A limitation of the analysis is that the assessment of function was not based on standardized questionnaires such as the Headache Impact Test-6 or the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

VanderPluym J, Dodick DW, Lipton RB, et al. Fremanezumab for preventive treatment of migraine: functional status on headache-free days. Neurology. 2018 Aug 17 [Epub ahead of print].

The mechanism underlying the benefit observed in the post hoc analyses is unclear.

The mechanism underlying the benefit observed in the post hoc analyses is unclear.

Fremanezumab increases the number of headache-free days with normal function for patients with episodic or chronic migraine, according to post hoc analyses published online ahead of print August 17 in Neurology. Fremanezumab appears to improve all measures of function in patients with episodic migraine, and some measures in patients with chronic migraine.

“The results should be considered exploratory,” said Juliana VanderPluym, MD, a neurologist at Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, and colleagues. “Further research is needed to confirm these preliminary findings and to understand the factors contributing to perceived functional status on headache-free days.”

Examining Two Phase II Trials

Fremanezumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). Dr. VanderPluym and colleagues analyzed data from randomized, double-blind phase II trials of the therapy for prevention of high-frequency episodic migraine (ie, eight to 14 headache days per month) and chronic migraine. Patients with high-frequency episodic migraine received placebo or monthly subcutaneous fremanezumab injections of 225 mg or 675 mg. Patients with chronic migraine received placebo or an initial 675-mg fremanezumab dose followed by monthly subcutaneous injections of 225 mg or 900 mg. The treatment period was three months.

Participants entered information into an electronic diary daily. Questions about functional performance elicited information about “work/school/household chore performance” and “concentration/mental fatigue.” For the former category, patients recorded their performance as normal, less than 50% impaired, or at least 50% impaired. For the latter category, patients recorded how much time they had spent working more slowly, finding it difficult to concentrate, and feeling tired or drained.

Fremanezumab Improved Concentration

In the high-frequency episodic migraine study, patients who received fremanezumab had a greater increase in headache-free days with normal concentration and normal performance at work, school, and home, compared with controls.

In the study of chronic migraine, the 900-mg dose was associated with consistent improvements in function on headache-free days. Patients with chronic migraine in the 225-mg dose group had increases compared with controls in the number of headache-free days in which they performed household chores normally and had no time with difficulty concentrating. The 225-mg group had minimal changes in the number of headache-free days in which work/study and household chore performance was impaired by 50% or more, as well as in in time with difficulty concentrating, but its results were better than those of controls.

“One could postulate that patients had more headache-free days with normal functional performance simply because they had more headache-free days on fremanezumab,” said Dr. VanderPluym. “With increased headache-free days, patients may have had reduced interictal anxiety and thus reduced avoidance behavior and lifestyle compromise, allowing them to function normally.”

Patients receiving fremanezumab significantly reduced their intake of acute medications, compared with controls. This reduction likely decreased the number of side effects associated with acute medications and could have contributed to better functional performance, said the authors.

A limitation of the analysis is that the assessment of function was not based on standardized questionnaires such as the Headache Impact Test-6 or the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

VanderPluym J, Dodick DW, Lipton RB, et al. Fremanezumab for preventive treatment of migraine: functional status on headache-free days. Neurology. 2018 Aug 17 [Epub ahead of print].

Fremanezumab increases the number of headache-free days with normal function for patients with episodic or chronic migraine, according to post hoc analyses published online ahead of print August 17 in Neurology. Fremanezumab appears to improve all measures of function in patients with episodic migraine, and some measures in patients with chronic migraine.

“The results should be considered exploratory,” said Juliana VanderPluym, MD, a neurologist at Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, and colleagues. “Further research is needed to confirm these preliminary findings and to understand the factors contributing to perceived functional status on headache-free days.”

Examining Two Phase II Trials

Fremanezumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). Dr. VanderPluym and colleagues analyzed data from randomized, double-blind phase II trials of the therapy for prevention of high-frequency episodic migraine (ie, eight to 14 headache days per month) and chronic migraine. Patients with high-frequency episodic migraine received placebo or monthly subcutaneous fremanezumab injections of 225 mg or 675 mg. Patients with chronic migraine received placebo or an initial 675-mg fremanezumab dose followed by monthly subcutaneous injections of 225 mg or 900 mg. The treatment period was three months.

Participants entered information into an electronic diary daily. Questions about functional performance elicited information about “work/school/household chore performance” and “concentration/mental fatigue.” For the former category, patients recorded their performance as normal, less than 50% impaired, or at least 50% impaired. For the latter category, patients recorded how much time they had spent working more slowly, finding it difficult to concentrate, and feeling tired or drained.

Fremanezumab Improved Concentration

In the high-frequency episodic migraine study, patients who received fremanezumab had a greater increase in headache-free days with normal concentration and normal performance at work, school, and home, compared with controls.

In the study of chronic migraine, the 900-mg dose was associated with consistent improvements in function on headache-free days. Patients with chronic migraine in the 225-mg dose group had increases compared with controls in the number of headache-free days in which they performed household chores normally and had no time with difficulty concentrating. The 225-mg group had minimal changes in the number of headache-free days in which work/study and household chore performance was impaired by 50% or more, as well as in in time with difficulty concentrating, but its results were better than those of controls.

“One could postulate that patients had more headache-free days with normal functional performance simply because they had more headache-free days on fremanezumab,” said Dr. VanderPluym. “With increased headache-free days, patients may have had reduced interictal anxiety and thus reduced avoidance behavior and lifestyle compromise, allowing them to function normally.”

Patients receiving fremanezumab significantly reduced their intake of acute medications, compared with controls. This reduction likely decreased the number of side effects associated with acute medications and could have contributed to better functional performance, said the authors.

A limitation of the analysis is that the assessment of function was not based on standardized questionnaires such as the Headache Impact Test-6 or the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

VanderPluym J, Dodick DW, Lipton RB, et al. Fremanezumab for preventive treatment of migraine: functional status on headache-free days. Neurology. 2018 Aug 17 [Epub ahead of print].

Early Treatment Improves Outcomes in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder

Research has improved understanding of the disorder’s pathology and indicated which treatments are most beneficial.

HILTON HEAD, SC—Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) can result in severe disability, but early diagnosis and treatment increase the likelihood that a patient will regain his or her baseline function, according to an overview provided at the 41st Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium. Increased understanding of NMOSD has led to new diagnostic criteria, and emerging data are clarifying the question of effective treatments.

NMOSD As a Distinct Disorder

NMOSD originally was recognized as an inflammatory disorder of the CNS that causes transverse myelitis and optic neuritis, said Siddharama Pawate, MD, Associate Professor of Neurology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. Although neurologists first considered NMOSD a variant of multiple sclerosis (MS), the former has several features that distinguish it from the latter. These features include exceptionally severe relapses, spinal cord lesions that span more than three vertebral segments, and CSF that reveals pleocytosis and high protein levels. In addition, some MS treatments such as interferons, fingolimod, and natalizumab usually exacerbate, rather than mitigate, NMOSD.

In 2004, researchers found that antibodies against aquaporin-4 (AQP4) were almost 100% specific for NMOSD. Astrocytes and ependymal cells, but not oligodendrocytes or neurons, express AQP4. When anti-AQP4 antibodies bind to the membrane of an astrocyte, they disrupt the blood–brain barrier and eventually cause the astrocyte to die. The death of astrocytes promotes secondary damage of oligodendrocytes and neurons. Because of these processes, swelling in the spinal cord and the optic nerve are prominent features of NMOSD on MRI, said Dr. Pawate. The swelling, in turn, can lead to vascular compromise and necrosis, thus

Clinical Presentations of NMOSD