User login

Vemurafenib-Induced Plantar Hyperkeratosis

To the Editor:

Vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, is a chemotherapeutic agent used in the treatment of metastatic melanoma with BRAF mutations. It has been associated with various cutaneous side effects. We report a case of metastatic melanoma with acquired plantar hyperkeratosis secondary to vemurafenib therapy.

A 49-year-old man presented for evaluation of a pigmented plaque on the left pretibial region that had been enlarging over the last 2 months. The lesion had been diagnosed as folliculitis by his primary care physician 1 month prior to the current presentation and was being treated with oral antibiotics. The patient reported occasional bleeding from the lesion but denied other symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 1.4-cm pigmented plaque distributed over the left shin. Excisional biopsy was performed to rule out melanoma. Histopathology revealed well-circumscribed and symmetric proliferation of nested and single atypical melanocytes throughout all layers to the deep reticular dermis, confirming a clinical diagnosis of malignant melanoma. The lesion demonstrated angiolymphatic invasion, mitotic activity, and a Breslow depth of 2.5 mm. The patient underwent wide local excision with 3-cm margins and left inguinal sentinel lymph node biopsy; 2 of 14 lymph nodes were positive for melanoma. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography was negative for further metastatic disease. The patient underwent isolated limb perfusion with ipilimumab, but treatment was discontinued due to regional progression of multiple cutaneous metastases that were positive for the BRAF V600E mutation.

The patient was then started on vemurafenib therapy. Within 2 weeks, the patient reported various cutaneous symptoms, including morbilliform drug eruption covering approximately 70% of the body surface area that resolved with topical steroids and oral antihistamines, as well as the appearance of melanocytic nevi on the posterior neck, back, and abdomen. After 5 months of vemurafenib therapy, the patient began to develop hyperkeratosis of the bilateral soles of the feet (Figure). A diagnosis of acquired plantar hyperkeratosis secondary to vemurafenib therapy was made. Treatment with keratolytics was initiated and vemurafenib was not discontinued. The patient died approximately 1 year after therapy was started.

Metastatic melanoma is challenging to treat and continues to have a high mortality rate; however, newer chemotherapeutic agents targeting specific mutations found in melanoma, including the BRAF V600E mutation, are promising.

The US Food and Drug Administration first approved vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, in 2011 for treatment of metastatic melanoma. Activating BRAF mutations have been detected in up to 60% of cutaneous melanomas.1 In the majority of these mutations, valine (V) is inserted at codon 600 instead of glutamic acid (E); therefore, the mutation is named V600E.2 In a phase 3 trial of 675 metastatic melanoma patients with positive V600E who were randomized to receive either vemurafenib or dacarbazine, the overall survival rate in the vemurafenib group improved by 84% versus 64% in the dacarbazine group at 6 months.3

Vemurafenib and other BRAF inhibitors have been associated with multiple cutaneous side effects, including rash, alopecia, squamous cell carcinoma, photosensitivity, evolution of existing nevi, and less commonly palmoplantar hyperkeratosis.2-5 Constitutional symptoms including arthralgia, nausea, and fatigue also have been commonly reported.2-5 In several large studies comprising 1138 patients, cutaneous side effects were seen in 92% to 95% of patients.3,5 Adverse effects caused interruption or modification of therapy in 38% of patients.3

Palmoplantar keratoderma is a known side effect of vemurafenib therapy, but it is less commonly reported than other cutaneous adverse effects. It is believed that vemurafenib has the ability to paradoxically activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, leading to keratinocyte proliferation in cells without BRAF mutations.6-8 In the phase 3 trial, approximately 23% to 30% of patients developed some form of hyperkeratosis.5 Comparatively, 64% of patients developed a rash and 23% developed cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Incidence of palmoplantar hyperkeratosis was similar in the vemurafenib and dabrafenib groups (6% vs 8%).3,9 Development of keratoderma also has been associated with other multikinase inhibitors (eg, sorafenib, sunitinib).10,11

In our case, the patient displayed multiple side effects while undergoing vemurafenib therapy. Within the first 2 weeks of therapy, he experienced a drug eruption that affected approximately 70% of the body surface area. The eruption resolved with topical steroids and oral antihistamines. The patient also noted the appearance of several new melanocytic nevi on the posterior neck as well as several evolving nevi on the back and abdomen. Five months into the treatment cycle, the patient began to develop hyperkeratosis on the bilateral plantar feet. Treatment consisted of keratolytics. Vemurafenib therapy was not discontinued secondary to any adverse effects.

Vemurafenib and other BRAF inhibitors are efficacious in the treatment of metastatic melanoma with V600E mutations. The use of these therapies is likely to continue and increase in the future. BRAF inhibitors have been associated with a variety of side effects, including palmoplantar hyperkeratosis. Awareness of and appropriate response to adverse reactions is essential to proper patient care and continuation of potentially life-extending therapies.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations in the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Cohen PR, Bedikian AY, Kim KB. Appearance of new vemurafenib-associated melanocytic nevi on normal-appearing skin: case series and a review of changing or new pigmented lesions in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma after initiating treatment with vemurafenib. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-37.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al; BRIM-3 Study Group. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507-2516.

- Rinderknecht JD, Goldinger SM, Rozati S, et al. RASopathic skin eruptions during vemurafenib therapy [published online March 13, 2014]. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58721.

- Lacouture ME, Duvic M, Hauschild A, et al. Analysis of dermatologic events in vemurafenib-treated patients with melanoma. Oncologist. 2013;18:314-322.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Su F, Bradley WD, Wang Q, et al. Resistance to selective BRAF inhibition can be mediated by modest upstream pathway activation. Cancer Res. 2012;72:969-978.

- Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431-435.

- Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358-365.

- Autier J, Escudier B, Wechsler J, et al. Prospective study of the cutaneous adverse effects of sorafenib, a novel multikinase inhibitor. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:886-892.

- Degen A, Alter M, Schenck F, et al. The hand-foot-syndrome associated with medical tumor therapy—classification and management. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:652-661.

To the Editor:

Vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, is a chemotherapeutic agent used in the treatment of metastatic melanoma with BRAF mutations. It has been associated with various cutaneous side effects. We report a case of metastatic melanoma with acquired plantar hyperkeratosis secondary to vemurafenib therapy.

A 49-year-old man presented for evaluation of a pigmented plaque on the left pretibial region that had been enlarging over the last 2 months. The lesion had been diagnosed as folliculitis by his primary care physician 1 month prior to the current presentation and was being treated with oral antibiotics. The patient reported occasional bleeding from the lesion but denied other symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 1.4-cm pigmented plaque distributed over the left shin. Excisional biopsy was performed to rule out melanoma. Histopathology revealed well-circumscribed and symmetric proliferation of nested and single atypical melanocytes throughout all layers to the deep reticular dermis, confirming a clinical diagnosis of malignant melanoma. The lesion demonstrated angiolymphatic invasion, mitotic activity, and a Breslow depth of 2.5 mm. The patient underwent wide local excision with 3-cm margins and left inguinal sentinel lymph node biopsy; 2 of 14 lymph nodes were positive for melanoma. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography was negative for further metastatic disease. The patient underwent isolated limb perfusion with ipilimumab, but treatment was discontinued due to regional progression of multiple cutaneous metastases that were positive for the BRAF V600E mutation.

The patient was then started on vemurafenib therapy. Within 2 weeks, the patient reported various cutaneous symptoms, including morbilliform drug eruption covering approximately 70% of the body surface area that resolved with topical steroids and oral antihistamines, as well as the appearance of melanocytic nevi on the posterior neck, back, and abdomen. After 5 months of vemurafenib therapy, the patient began to develop hyperkeratosis of the bilateral soles of the feet (Figure). A diagnosis of acquired plantar hyperkeratosis secondary to vemurafenib therapy was made. Treatment with keratolytics was initiated and vemurafenib was not discontinued. The patient died approximately 1 year after therapy was started.

Metastatic melanoma is challenging to treat and continues to have a high mortality rate; however, newer chemotherapeutic agents targeting specific mutations found in melanoma, including the BRAF V600E mutation, are promising.

The US Food and Drug Administration first approved vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, in 2011 for treatment of metastatic melanoma. Activating BRAF mutations have been detected in up to 60% of cutaneous melanomas.1 In the majority of these mutations, valine (V) is inserted at codon 600 instead of glutamic acid (E); therefore, the mutation is named V600E.2 In a phase 3 trial of 675 metastatic melanoma patients with positive V600E who were randomized to receive either vemurafenib or dacarbazine, the overall survival rate in the vemurafenib group improved by 84% versus 64% in the dacarbazine group at 6 months.3

Vemurafenib and other BRAF inhibitors have been associated with multiple cutaneous side effects, including rash, alopecia, squamous cell carcinoma, photosensitivity, evolution of existing nevi, and less commonly palmoplantar hyperkeratosis.2-5 Constitutional symptoms including arthralgia, nausea, and fatigue also have been commonly reported.2-5 In several large studies comprising 1138 patients, cutaneous side effects were seen in 92% to 95% of patients.3,5 Adverse effects caused interruption or modification of therapy in 38% of patients.3

Palmoplantar keratoderma is a known side effect of vemurafenib therapy, but it is less commonly reported than other cutaneous adverse effects. It is believed that vemurafenib has the ability to paradoxically activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, leading to keratinocyte proliferation in cells without BRAF mutations.6-8 In the phase 3 trial, approximately 23% to 30% of patients developed some form of hyperkeratosis.5 Comparatively, 64% of patients developed a rash and 23% developed cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Incidence of palmoplantar hyperkeratosis was similar in the vemurafenib and dabrafenib groups (6% vs 8%).3,9 Development of keratoderma also has been associated with other multikinase inhibitors (eg, sorafenib, sunitinib).10,11

In our case, the patient displayed multiple side effects while undergoing vemurafenib therapy. Within the first 2 weeks of therapy, he experienced a drug eruption that affected approximately 70% of the body surface area. The eruption resolved with topical steroids and oral antihistamines. The patient also noted the appearance of several new melanocytic nevi on the posterior neck as well as several evolving nevi on the back and abdomen. Five months into the treatment cycle, the patient began to develop hyperkeratosis on the bilateral plantar feet. Treatment consisted of keratolytics. Vemurafenib therapy was not discontinued secondary to any adverse effects.

Vemurafenib and other BRAF inhibitors are efficacious in the treatment of metastatic melanoma with V600E mutations. The use of these therapies is likely to continue and increase in the future. BRAF inhibitors have been associated with a variety of side effects, including palmoplantar hyperkeratosis. Awareness of and appropriate response to adverse reactions is essential to proper patient care and continuation of potentially life-extending therapies.

To the Editor:

Vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, is a chemotherapeutic agent used in the treatment of metastatic melanoma with BRAF mutations. It has been associated with various cutaneous side effects. We report a case of metastatic melanoma with acquired plantar hyperkeratosis secondary to vemurafenib therapy.

A 49-year-old man presented for evaluation of a pigmented plaque on the left pretibial region that had been enlarging over the last 2 months. The lesion had been diagnosed as folliculitis by his primary care physician 1 month prior to the current presentation and was being treated with oral antibiotics. The patient reported occasional bleeding from the lesion but denied other symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 1.4-cm pigmented plaque distributed over the left shin. Excisional biopsy was performed to rule out melanoma. Histopathology revealed well-circumscribed and symmetric proliferation of nested and single atypical melanocytes throughout all layers to the deep reticular dermis, confirming a clinical diagnosis of malignant melanoma. The lesion demonstrated angiolymphatic invasion, mitotic activity, and a Breslow depth of 2.5 mm. The patient underwent wide local excision with 3-cm margins and left inguinal sentinel lymph node biopsy; 2 of 14 lymph nodes were positive for melanoma. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography was negative for further metastatic disease. The patient underwent isolated limb perfusion with ipilimumab, but treatment was discontinued due to regional progression of multiple cutaneous metastases that were positive for the BRAF V600E mutation.

The patient was then started on vemurafenib therapy. Within 2 weeks, the patient reported various cutaneous symptoms, including morbilliform drug eruption covering approximately 70% of the body surface area that resolved with topical steroids and oral antihistamines, as well as the appearance of melanocytic nevi on the posterior neck, back, and abdomen. After 5 months of vemurafenib therapy, the patient began to develop hyperkeratosis of the bilateral soles of the feet (Figure). A diagnosis of acquired plantar hyperkeratosis secondary to vemurafenib therapy was made. Treatment with keratolytics was initiated and vemurafenib was not discontinued. The patient died approximately 1 year after therapy was started.

Metastatic melanoma is challenging to treat and continues to have a high mortality rate; however, newer chemotherapeutic agents targeting specific mutations found in melanoma, including the BRAF V600E mutation, are promising.

The US Food and Drug Administration first approved vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, in 2011 for treatment of metastatic melanoma. Activating BRAF mutations have been detected in up to 60% of cutaneous melanomas.1 In the majority of these mutations, valine (V) is inserted at codon 600 instead of glutamic acid (E); therefore, the mutation is named V600E.2 In a phase 3 trial of 675 metastatic melanoma patients with positive V600E who were randomized to receive either vemurafenib or dacarbazine, the overall survival rate in the vemurafenib group improved by 84% versus 64% in the dacarbazine group at 6 months.3

Vemurafenib and other BRAF inhibitors have been associated with multiple cutaneous side effects, including rash, alopecia, squamous cell carcinoma, photosensitivity, evolution of existing nevi, and less commonly palmoplantar hyperkeratosis.2-5 Constitutional symptoms including arthralgia, nausea, and fatigue also have been commonly reported.2-5 In several large studies comprising 1138 patients, cutaneous side effects were seen in 92% to 95% of patients.3,5 Adverse effects caused interruption or modification of therapy in 38% of patients.3

Palmoplantar keratoderma is a known side effect of vemurafenib therapy, but it is less commonly reported than other cutaneous adverse effects. It is believed that vemurafenib has the ability to paradoxically activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, leading to keratinocyte proliferation in cells without BRAF mutations.6-8 In the phase 3 trial, approximately 23% to 30% of patients developed some form of hyperkeratosis.5 Comparatively, 64% of patients developed a rash and 23% developed cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Incidence of palmoplantar hyperkeratosis was similar in the vemurafenib and dabrafenib groups (6% vs 8%).3,9 Development of keratoderma also has been associated with other multikinase inhibitors (eg, sorafenib, sunitinib).10,11

In our case, the patient displayed multiple side effects while undergoing vemurafenib therapy. Within the first 2 weeks of therapy, he experienced a drug eruption that affected approximately 70% of the body surface area. The eruption resolved with topical steroids and oral antihistamines. The patient also noted the appearance of several new melanocytic nevi on the posterior neck as well as several evolving nevi on the back and abdomen. Five months into the treatment cycle, the patient began to develop hyperkeratosis on the bilateral plantar feet. Treatment consisted of keratolytics. Vemurafenib therapy was not discontinued secondary to any adverse effects.

Vemurafenib and other BRAF inhibitors are efficacious in the treatment of metastatic melanoma with V600E mutations. The use of these therapies is likely to continue and increase in the future. BRAF inhibitors have been associated with a variety of side effects, including palmoplantar hyperkeratosis. Awareness of and appropriate response to adverse reactions is essential to proper patient care and continuation of potentially life-extending therapies.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations in the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Cohen PR, Bedikian AY, Kim KB. Appearance of new vemurafenib-associated melanocytic nevi on normal-appearing skin: case series and a review of changing or new pigmented lesions in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma after initiating treatment with vemurafenib. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-37.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al; BRIM-3 Study Group. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507-2516.

- Rinderknecht JD, Goldinger SM, Rozati S, et al. RASopathic skin eruptions during vemurafenib therapy [published online March 13, 2014]. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58721.

- Lacouture ME, Duvic M, Hauschild A, et al. Analysis of dermatologic events in vemurafenib-treated patients with melanoma. Oncologist. 2013;18:314-322.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Su F, Bradley WD, Wang Q, et al. Resistance to selective BRAF inhibition can be mediated by modest upstream pathway activation. Cancer Res. 2012;72:969-978.

- Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431-435.

- Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358-365.

- Autier J, Escudier B, Wechsler J, et al. Prospective study of the cutaneous adverse effects of sorafenib, a novel multikinase inhibitor. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:886-892.

- Degen A, Alter M, Schenck F, et al. The hand-foot-syndrome associated with medical tumor therapy—classification and management. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:652-661.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations in the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Cohen PR, Bedikian AY, Kim KB. Appearance of new vemurafenib-associated melanocytic nevi on normal-appearing skin: case series and a review of changing or new pigmented lesions in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma after initiating treatment with vemurafenib. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-37.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al; BRIM-3 Study Group. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507-2516.

- Rinderknecht JD, Goldinger SM, Rozati S, et al. RASopathic skin eruptions during vemurafenib therapy [published online March 13, 2014]. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58721.

- Lacouture ME, Duvic M, Hauschild A, et al. Analysis of dermatologic events in vemurafenib-treated patients with melanoma. Oncologist. 2013;18:314-322.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Su F, Bradley WD, Wang Q, et al. Resistance to selective BRAF inhibition can be mediated by modest upstream pathway activation. Cancer Res. 2012;72:969-978.

- Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431-435.

- Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358-365.

- Autier J, Escudier B, Wechsler J, et al. Prospective study of the cutaneous adverse effects of sorafenib, a novel multikinase inhibitor. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:886-892.

- Degen A, Alter M, Schenck F, et al. The hand-foot-syndrome associated with medical tumor therapy—classification and management. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:652-661.

Practice Points

- BRAF inhibitors such as vemurafenib are associated with a high incidence of cutaneous side effects, including rash, hyperkeratosis, and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.

- Practitioners should be aware of these side effects and their management to avoid discontinuation or interruption of therapy.

Composite Fixation of Proximal Tibial Nonunions: A Technical Trick

ABSTRACT

Nonunion after a proximal tibia fracture is often associated with poor bone stock, (previous) infection, and compromised soft tissues. These conditions make revision internal fixation with double plating difficult. Combining a plate and contralateral 2-pin external fixator, coined composite fixation, can provide an alternative means of obtaining stability without further compromising soft tissues.

Three patients with a proximal tibia nonunion precluding standard internal fixation with double plating were treated with composite fixation. All 3 patients achieved union with deformity correction at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months). The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°) and postoperative ROM returned to pre-injury levels.

Composite fixation can be a helpful adjunct in the treatment of this challenging problem.

Continue to: Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion...

Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion is challenging, compromised by limited bone stock, pre-existing hardware, stiffness, poor soft tissue conditions, and infection. The goals of treatment include bone union, re-establishment of both joint stability and lower extremity alignment, restoration of an anatomic articular surface, and recovery of function.1 Currently, various treatment options such as plate fixation, bone grafting, intramedullary nailing, external fixation, functional bracing, or a combination of these are available.1-8 Rigid internal fixation is the gold standard for most nonunions. However, sometimes local soft tissues or bone quality preclude standard internal fixation. Bolhofner9 described the combination of a single plate and an external fixator on the contralateral side for the management of extra-articular proximal tibial fractures with compromised soft tissues, and the technique known as composite fixation was coined. The external fixator on 1 side and the plate on the other, generate a balanced, stable environment while limiting the use of foreign hardware, thereby avoiding both additional soft-tissue damage and periosteal stripping.9-11 In this technical article, we describe the indication, technique, and outcomes of 3 patients with proximal tibial nonunions, who were successfully treated with composite fixation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PATIENTS

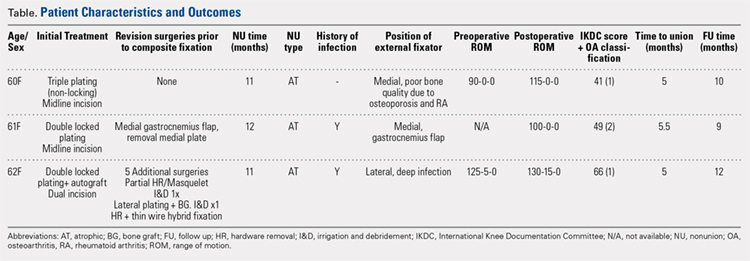

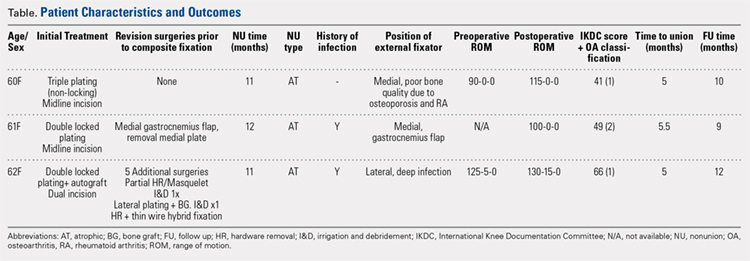

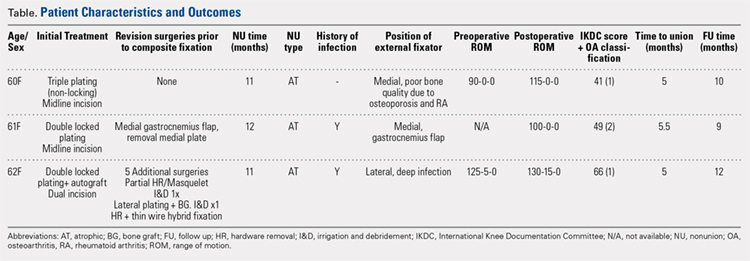

Between January 2014 and July 2016, 3 patients each with a proximal tibial nonunion that developed after a bicondylar tibial plateau fracture (Schatzker type VI) were treated with composite fixation (Table). The 3 patients were female with an average age of 61 years (range, 60-62 years), and a body mass index of 23.7 kg/m2 (range, 19.0-31.9 kg/m2). All 3 patients had sustained a tibial plateau fracture that was primarily treated with open reduction and internal fixation. Two of them had a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and were being treated with methotrexate and Humira (adalimumab) (case 1), and with methotrexate, prednisolone, and etanercept (case 3). The etanercept was discontinued after discussion with the treating rheumatologist when a deep infection developed. Two patients (cases 1 and 2) were referred to us because of their nonunions. All 3 patients developed extra-articular nonunions with compromised bone stock. Two patients had developed deep infections during treatment of their plateau fractures; 1 of these patients underwent a medial gastrocnemius flap for wound coverage (case 1). The second patient (case 3) with a deep infection underwent partial hardware removal, a Masquelet salvage procedure, and revision plate fixation. However, the infection recurred. The hardware was removed, and 2 débridements with conversion to a hybrid external fixator with thin wire fixation were done. Due to her longstanding rheumatoid arthritis, the patient had bilateral valgus knee malalignment causing the ring fixator to strike her contralateral knee when she walked. The period from the initial tibial plateau fracture to our composite fixation averaged 11.3 months (range, 11-12 months). Indications for the use of the composite fixation comprised previously infected soft tissue on the lateral side and inability to walk with a hybrid thin wire fixator because of valgus knees (case 3), a medial gastrocnemius flap (case 2), and poor bone quality (case 1). Follow-up consisted of clinical examination, Timed Up and Go (TUG) test that is a standardized test for mobility, and radiographic evaluation at routine appointments up to 1 year or until healed.12 At the last follow-up visit, patients filled out the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee form.13

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

A fellowship-trained orthopedic trauma surgeon treated all patients. Patients were placed on a radiolucent operating table after general or regional anesthesia. Previous incisions were used. Two patients had a midline incision; the third had both a posteromedial and an anterolateral incision. Five deep tissue cultures were taken after which antibiotics were given intravenously. All unstable or failed hardware was removed. Aggressive débridement of the nonunion was performed. After débridement, multiple holes were drilled with a 2.0 mm drill bit until blood was seen to egress from both sides of the medullary canal. Malalignment of the proximal tibia was corrected and checked fluoroscopically. Fixation was done with an anatomic locking plate (LCP Proximal Tibia Plate 3.5; DePuy Synthes) with a mixture of locking and non-locking screws. In 2 patients, a tricortical graft from the posterior iliac crest was positioned in the defect. Additional autologous bone graft and demineralized bone matrix was added around the nonunion. Although locking screws were used, the fixation did not appear to be strong enough to resist the varus (cases 1 and 2), or the valgus (case 3) deforming forces. Additional fixation was thus needed. However, the contralateral soft tissues were compromised in case 2 (medial gastrocnemius flap), and case 3 (a previously infected area with very tenuous skin laterally), whereas the bone was considered to be of insufficient quality in case 1. The opposite side of the nonunion was stabilized using composite fixation with a 2-pin external fixator to circumvent the need for additional plate fixation. In 2 patients, the plate was placed laterally, and the external fixator medially. In the third patient, the plate was positioned medially, and the external fixator laterally. The plate was always placed first. The external fixator was placed last. Using fluoroscopy, we ensured that the fixator pins would not interfere with the screws. The pins were predrilled and positioned perpendicular to the tibia through small stab incisions. We prefer hydroxyapatite-coated pins (6-mm diameter, XCaliber Bone Screws; Pro-Motion Medical) to increase their holding power in the often osteopenic bone. Postoperative management consisted of toe-touch weight-bearing for 6 weeks and progressed to full weight-bearing at 3 months. Radiographs were taken on postoperative day 1, at 6 weeks, and at 12 weeks until healed. No continuous passive motion was used postoperatively. Antibiotics were continued until cultures were negative. No specific pin care was used. We advised patients to shower daily with the external fixator in place, once the wounds have healed.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

On average, patients were hospitalized for 5 days (range, 3-7 days). There were no postoperative complications. None of the patients developed a clinically significant pin site infection. There were no re-operations during follow-up. All patients achieved union at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months) (Figure 1).

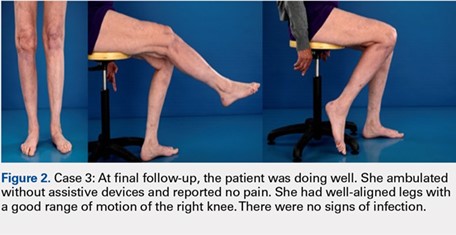

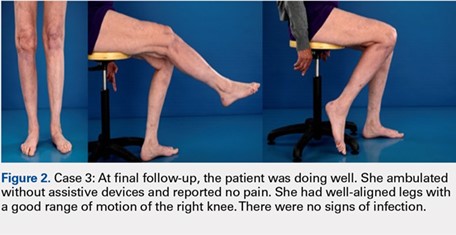

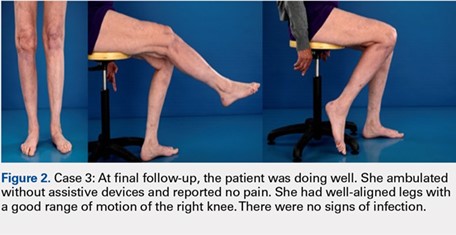

Deformity correction was achieved in all 3 patients. The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°). None of the patients had an extension deficit. TUG test was <8 seconds in all patients. The IKDC knee score averaged 52 (range, 41-66). Of note is that 2 patients already had compromised knee function before the fracture because of rheumatoid arthritis. The Ahlbäck classification of osteoarthritis showed grade 1 in cases 1 and 3, and grade 2 in case 2.14 Postoperative ROM of the knee returned to pre-injury levels in all patients (Figure 2). The 2-pin external fixator was removed at 9 weeks on average (range, 6-12 weeks) postoperatively in the outpatient clinic. At the last follow-up appointment at an average of 10.3 months (range, 9-12 months), all wounds had healed without infection. All patients had a normal neurovascular examination.

DISCUSSION

Nonunion after a proximal tibial fracture is rare.4 In cases when nonunions do develop, they most often pertain to the extra-articular component with the plateau component healed. Surgical exposure for débridements, hardware removal, bone grafting, and revision of fixation carries the risk of wound breakdown, necrosis, and infection. The alternative strategy of composite fixation (a plate combined with a contralateral 2-pin external fixator) to limit additional soft tissue compromise was already described in proximal tibial fractures by Bolhofner.9 He treated 41 extra-articular proximal tibial fractures using this composite fixation technique and attained successful results with an average time to union of 12.1 weeks. There was only 1 malunion, 2 wound infections, and 3 delayed unions.

In our practice, we have extrapolated this idea to an extra-articular nonunion that developed after a tibial plateau fracture. With the use of an external fixator, we provided sufficient mechanical stability of the nonunion without unnecessarily compromising previously infected or tenuous soft tissues, a muscle flap, or further devascularizing poor bone. Limitations of this study include the retrospective data and small sample size prone to bias. However, all patients received the same treatment protocol from 1 orthopedic trauma surgeon, follow-up intervals were similar, and data were acquired consistently.

Meanwhile, we have used this technique in a fourth patient with a septic nonunion of a tibial plateau fracture. All 4 patients in whom we have used this method so far have healed successfully.

CONCLUSION

This technique respects both the demand for minimal soft tissue damage and a maximal stable environment without notable perioperative and postoperative complications. It also offers an alternative option for the treatment of a proximal tibial nonunion that is not amenable to invasive revision dual plate fixation. As such, it can be a useful addition to the existing armamentarium of the treating surgeon.

1. Wu CC. Salvage of proximal tibial malunion or nonunion with the use of angled blade plate. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126(2):82-87. doi:10.1007/s00402-006-0106-9.

2. Carpenter CA, Jupiter JB. Blade plate reconstruction of metaphyseal nonunion of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;332:23-28.

3. Gardner MJ, Toro-Arbelaez JB, Hansen M, Boraiah S, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Surgical treatment and outcomes of extraarticular proximal tibial nonunions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(8):833-839. doi:10.1007/s00402-007-0383-y.

4. Toro-Arbelaez JB, Gardner MJ, Shindle MK, Cabas JM, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Open reduction and internal fixation of intraarticular tibial plateau nonunions. Injury. 2007;38(3):378-383. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2006.11.003.

5. Mechrefe AP, Koh EY, Trafton PG, DiGiovanni CW. Tibial nonunion. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(1):1-18, vii. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2005.12.003.

6. Chin KR, Nagarkatti DG, Miranda MA, Santoro VM, Baumgaertner MR, Jupiter JB. Salvage of distal tibia metaphyseal nonunions with the 90 degrees cannulated blade plate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(409):241-249.

7. Devgan A, Kamboj P, Gupta V, Magu NK, Rohilla R. Pseudoarthrosis of medial tibial plateau fracture-role of alignment procedure. Chin J Traumatol. 2013;16(2):118-121. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-1275.2013.02.011.

8. Helfet DL, Jupiter JB, Gasser S. Indirect reduction and tension-band plating of tibial non-union with deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(9):1286-1297.

9. Bolhofner BR. Indirect reduction and composite fixation of extraarticular proximal tibial fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(315):75-83. doi:10.1097/00003086-199506000-00009.

10. Ries MD, Meinhard BP. Medial external fixation with lateral plate internal fixation in metaphyseal tibia fractures. A report of eight cases associated with severe soft-tissue injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(256):215-223.

11. Weiner LS, Kelley M, Yang E, et al. The use of combination internal fixation and hybrid external fixation in severe proximal tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):244-250.

12. Alghadir A, Anwer S, Brismee JM. The reliability and minimal detectable change of Timed Up and Go test in individuals with grade 1-3 knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:174. doi:10.1186/s12891-015-0637-8.

13. Haverkamp D, Sierevelt IN, Breugem SJ, Lohuis K, Blankevoort L, van Dijk CN. Translation and validation of the Dutch version of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1680-1684. doi:10.1177/0363546506288854.

14. Ahlbäck S. Osteoartrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1968;Suppl 277:7-72.

ABSTRACT

Nonunion after a proximal tibia fracture is often associated with poor bone stock, (previous) infection, and compromised soft tissues. These conditions make revision internal fixation with double plating difficult. Combining a plate and contralateral 2-pin external fixator, coined composite fixation, can provide an alternative means of obtaining stability without further compromising soft tissues.

Three patients with a proximal tibia nonunion precluding standard internal fixation with double plating were treated with composite fixation. All 3 patients achieved union with deformity correction at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months). The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°) and postoperative ROM returned to pre-injury levels.

Composite fixation can be a helpful adjunct in the treatment of this challenging problem.

Continue to: Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion...

Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion is challenging, compromised by limited bone stock, pre-existing hardware, stiffness, poor soft tissue conditions, and infection. The goals of treatment include bone union, re-establishment of both joint stability and lower extremity alignment, restoration of an anatomic articular surface, and recovery of function.1 Currently, various treatment options such as plate fixation, bone grafting, intramedullary nailing, external fixation, functional bracing, or a combination of these are available.1-8 Rigid internal fixation is the gold standard for most nonunions. However, sometimes local soft tissues or bone quality preclude standard internal fixation. Bolhofner9 described the combination of a single plate and an external fixator on the contralateral side for the management of extra-articular proximal tibial fractures with compromised soft tissues, and the technique known as composite fixation was coined. The external fixator on 1 side and the plate on the other, generate a balanced, stable environment while limiting the use of foreign hardware, thereby avoiding both additional soft-tissue damage and periosteal stripping.9-11 In this technical article, we describe the indication, technique, and outcomes of 3 patients with proximal tibial nonunions, who were successfully treated with composite fixation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PATIENTS

Between January 2014 and July 2016, 3 patients each with a proximal tibial nonunion that developed after a bicondylar tibial plateau fracture (Schatzker type VI) were treated with composite fixation (Table). The 3 patients were female with an average age of 61 years (range, 60-62 years), and a body mass index of 23.7 kg/m2 (range, 19.0-31.9 kg/m2). All 3 patients had sustained a tibial plateau fracture that was primarily treated with open reduction and internal fixation. Two of them had a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and were being treated with methotrexate and Humira (adalimumab) (case 1), and with methotrexate, prednisolone, and etanercept (case 3). The etanercept was discontinued after discussion with the treating rheumatologist when a deep infection developed. Two patients (cases 1 and 2) were referred to us because of their nonunions. All 3 patients developed extra-articular nonunions with compromised bone stock. Two patients had developed deep infections during treatment of their plateau fractures; 1 of these patients underwent a medial gastrocnemius flap for wound coverage (case 1). The second patient (case 3) with a deep infection underwent partial hardware removal, a Masquelet salvage procedure, and revision plate fixation. However, the infection recurred. The hardware was removed, and 2 débridements with conversion to a hybrid external fixator with thin wire fixation were done. Due to her longstanding rheumatoid arthritis, the patient had bilateral valgus knee malalignment causing the ring fixator to strike her contralateral knee when she walked. The period from the initial tibial plateau fracture to our composite fixation averaged 11.3 months (range, 11-12 months). Indications for the use of the composite fixation comprised previously infected soft tissue on the lateral side and inability to walk with a hybrid thin wire fixator because of valgus knees (case 3), a medial gastrocnemius flap (case 2), and poor bone quality (case 1). Follow-up consisted of clinical examination, Timed Up and Go (TUG) test that is a standardized test for mobility, and radiographic evaluation at routine appointments up to 1 year or until healed.12 At the last follow-up visit, patients filled out the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee form.13

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

A fellowship-trained orthopedic trauma surgeon treated all patients. Patients were placed on a radiolucent operating table after general or regional anesthesia. Previous incisions were used. Two patients had a midline incision; the third had both a posteromedial and an anterolateral incision. Five deep tissue cultures were taken after which antibiotics were given intravenously. All unstable or failed hardware was removed. Aggressive débridement of the nonunion was performed. After débridement, multiple holes were drilled with a 2.0 mm drill bit until blood was seen to egress from both sides of the medullary canal. Malalignment of the proximal tibia was corrected and checked fluoroscopically. Fixation was done with an anatomic locking plate (LCP Proximal Tibia Plate 3.5; DePuy Synthes) with a mixture of locking and non-locking screws. In 2 patients, a tricortical graft from the posterior iliac crest was positioned in the defect. Additional autologous bone graft and demineralized bone matrix was added around the nonunion. Although locking screws were used, the fixation did not appear to be strong enough to resist the varus (cases 1 and 2), or the valgus (case 3) deforming forces. Additional fixation was thus needed. However, the contralateral soft tissues were compromised in case 2 (medial gastrocnemius flap), and case 3 (a previously infected area with very tenuous skin laterally), whereas the bone was considered to be of insufficient quality in case 1. The opposite side of the nonunion was stabilized using composite fixation with a 2-pin external fixator to circumvent the need for additional plate fixation. In 2 patients, the plate was placed laterally, and the external fixator medially. In the third patient, the plate was positioned medially, and the external fixator laterally. The plate was always placed first. The external fixator was placed last. Using fluoroscopy, we ensured that the fixator pins would not interfere with the screws. The pins were predrilled and positioned perpendicular to the tibia through small stab incisions. We prefer hydroxyapatite-coated pins (6-mm diameter, XCaliber Bone Screws; Pro-Motion Medical) to increase their holding power in the often osteopenic bone. Postoperative management consisted of toe-touch weight-bearing for 6 weeks and progressed to full weight-bearing at 3 months. Radiographs were taken on postoperative day 1, at 6 weeks, and at 12 weeks until healed. No continuous passive motion was used postoperatively. Antibiotics were continued until cultures were negative. No specific pin care was used. We advised patients to shower daily with the external fixator in place, once the wounds have healed.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

On average, patients were hospitalized for 5 days (range, 3-7 days). There were no postoperative complications. None of the patients developed a clinically significant pin site infection. There were no re-operations during follow-up. All patients achieved union at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months) (Figure 1).

Deformity correction was achieved in all 3 patients. The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°). None of the patients had an extension deficit. TUG test was <8 seconds in all patients. The IKDC knee score averaged 52 (range, 41-66). Of note is that 2 patients already had compromised knee function before the fracture because of rheumatoid arthritis. The Ahlbäck classification of osteoarthritis showed grade 1 in cases 1 and 3, and grade 2 in case 2.14 Postoperative ROM of the knee returned to pre-injury levels in all patients (Figure 2). The 2-pin external fixator was removed at 9 weeks on average (range, 6-12 weeks) postoperatively in the outpatient clinic. At the last follow-up appointment at an average of 10.3 months (range, 9-12 months), all wounds had healed without infection. All patients had a normal neurovascular examination.

DISCUSSION

Nonunion after a proximal tibial fracture is rare.4 In cases when nonunions do develop, they most often pertain to the extra-articular component with the plateau component healed. Surgical exposure for débridements, hardware removal, bone grafting, and revision of fixation carries the risk of wound breakdown, necrosis, and infection. The alternative strategy of composite fixation (a plate combined with a contralateral 2-pin external fixator) to limit additional soft tissue compromise was already described in proximal tibial fractures by Bolhofner.9 He treated 41 extra-articular proximal tibial fractures using this composite fixation technique and attained successful results with an average time to union of 12.1 weeks. There was only 1 malunion, 2 wound infections, and 3 delayed unions.

In our practice, we have extrapolated this idea to an extra-articular nonunion that developed after a tibial plateau fracture. With the use of an external fixator, we provided sufficient mechanical stability of the nonunion without unnecessarily compromising previously infected or tenuous soft tissues, a muscle flap, or further devascularizing poor bone. Limitations of this study include the retrospective data and small sample size prone to bias. However, all patients received the same treatment protocol from 1 orthopedic trauma surgeon, follow-up intervals were similar, and data were acquired consistently.

Meanwhile, we have used this technique in a fourth patient with a septic nonunion of a tibial plateau fracture. All 4 patients in whom we have used this method so far have healed successfully.

CONCLUSION

This technique respects both the demand for minimal soft tissue damage and a maximal stable environment without notable perioperative and postoperative complications. It also offers an alternative option for the treatment of a proximal tibial nonunion that is not amenable to invasive revision dual plate fixation. As such, it can be a useful addition to the existing armamentarium of the treating surgeon.

ABSTRACT

Nonunion after a proximal tibia fracture is often associated with poor bone stock, (previous) infection, and compromised soft tissues. These conditions make revision internal fixation with double plating difficult. Combining a plate and contralateral 2-pin external fixator, coined composite fixation, can provide an alternative means of obtaining stability without further compromising soft tissues.

Three patients with a proximal tibia nonunion precluding standard internal fixation with double plating were treated with composite fixation. All 3 patients achieved union with deformity correction at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months). The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°) and postoperative ROM returned to pre-injury levels.

Composite fixation can be a helpful adjunct in the treatment of this challenging problem.

Continue to: Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion...

Operative management of a proximal tibial nonunion is challenging, compromised by limited bone stock, pre-existing hardware, stiffness, poor soft tissue conditions, and infection. The goals of treatment include bone union, re-establishment of both joint stability and lower extremity alignment, restoration of an anatomic articular surface, and recovery of function.1 Currently, various treatment options such as plate fixation, bone grafting, intramedullary nailing, external fixation, functional bracing, or a combination of these are available.1-8 Rigid internal fixation is the gold standard for most nonunions. However, sometimes local soft tissues or bone quality preclude standard internal fixation. Bolhofner9 described the combination of a single plate and an external fixator on the contralateral side for the management of extra-articular proximal tibial fractures with compromised soft tissues, and the technique known as composite fixation was coined. The external fixator on 1 side and the plate on the other, generate a balanced, stable environment while limiting the use of foreign hardware, thereby avoiding both additional soft-tissue damage and periosteal stripping.9-11 In this technical article, we describe the indication, technique, and outcomes of 3 patients with proximal tibial nonunions, who were successfully treated with composite fixation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PATIENTS

Between January 2014 and July 2016, 3 patients each with a proximal tibial nonunion that developed after a bicondylar tibial plateau fracture (Schatzker type VI) were treated with composite fixation (Table). The 3 patients were female with an average age of 61 years (range, 60-62 years), and a body mass index of 23.7 kg/m2 (range, 19.0-31.9 kg/m2). All 3 patients had sustained a tibial plateau fracture that was primarily treated with open reduction and internal fixation. Two of them had a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and were being treated with methotrexate and Humira (adalimumab) (case 1), and with methotrexate, prednisolone, and etanercept (case 3). The etanercept was discontinued after discussion with the treating rheumatologist when a deep infection developed. Two patients (cases 1 and 2) were referred to us because of their nonunions. All 3 patients developed extra-articular nonunions with compromised bone stock. Two patients had developed deep infections during treatment of their plateau fractures; 1 of these patients underwent a medial gastrocnemius flap for wound coverage (case 1). The second patient (case 3) with a deep infection underwent partial hardware removal, a Masquelet salvage procedure, and revision plate fixation. However, the infection recurred. The hardware was removed, and 2 débridements with conversion to a hybrid external fixator with thin wire fixation were done. Due to her longstanding rheumatoid arthritis, the patient had bilateral valgus knee malalignment causing the ring fixator to strike her contralateral knee when she walked. The period from the initial tibial plateau fracture to our composite fixation averaged 11.3 months (range, 11-12 months). Indications for the use of the composite fixation comprised previously infected soft tissue on the lateral side and inability to walk with a hybrid thin wire fixator because of valgus knees (case 3), a medial gastrocnemius flap (case 2), and poor bone quality (case 1). Follow-up consisted of clinical examination, Timed Up and Go (TUG) test that is a standardized test for mobility, and radiographic evaluation at routine appointments up to 1 year or until healed.12 At the last follow-up visit, patients filled out the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee form.13

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

A fellowship-trained orthopedic trauma surgeon treated all patients. Patients were placed on a radiolucent operating table after general or regional anesthesia. Previous incisions were used. Two patients had a midline incision; the third had both a posteromedial and an anterolateral incision. Five deep tissue cultures were taken after which antibiotics were given intravenously. All unstable or failed hardware was removed. Aggressive débridement of the nonunion was performed. After débridement, multiple holes were drilled with a 2.0 mm drill bit until blood was seen to egress from both sides of the medullary canal. Malalignment of the proximal tibia was corrected and checked fluoroscopically. Fixation was done with an anatomic locking plate (LCP Proximal Tibia Plate 3.5; DePuy Synthes) with a mixture of locking and non-locking screws. In 2 patients, a tricortical graft from the posterior iliac crest was positioned in the defect. Additional autologous bone graft and demineralized bone matrix was added around the nonunion. Although locking screws were used, the fixation did not appear to be strong enough to resist the varus (cases 1 and 2), or the valgus (case 3) deforming forces. Additional fixation was thus needed. However, the contralateral soft tissues were compromised in case 2 (medial gastrocnemius flap), and case 3 (a previously infected area with very tenuous skin laterally), whereas the bone was considered to be of insufficient quality in case 1. The opposite side of the nonunion was stabilized using composite fixation with a 2-pin external fixator to circumvent the need for additional plate fixation. In 2 patients, the plate was placed laterally, and the external fixator medially. In the third patient, the plate was positioned medially, and the external fixator laterally. The plate was always placed first. The external fixator was placed last. Using fluoroscopy, we ensured that the fixator pins would not interfere with the screws. The pins were predrilled and positioned perpendicular to the tibia through small stab incisions. We prefer hydroxyapatite-coated pins (6-mm diameter, XCaliber Bone Screws; Pro-Motion Medical) to increase their holding power in the often osteopenic bone. Postoperative management consisted of toe-touch weight-bearing for 6 weeks and progressed to full weight-bearing at 3 months. Radiographs were taken on postoperative day 1, at 6 weeks, and at 12 weeks until healed. No continuous passive motion was used postoperatively. Antibiotics were continued until cultures were negative. No specific pin care was used. We advised patients to shower daily with the external fixator in place, once the wounds have healed.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

On average, patients were hospitalized for 5 days (range, 3-7 days). There were no postoperative complications. None of the patients developed a clinically significant pin site infection. There were no re-operations during follow-up. All patients achieved union at a mean of 5.2 months (range, 5-5.5 months) (Figure 1).

Deformity correction was achieved in all 3 patients. The average range of motion (ROM) arc was 100° (range, 100°-115°). None of the patients had an extension deficit. TUG test was <8 seconds in all patients. The IKDC knee score averaged 52 (range, 41-66). Of note is that 2 patients already had compromised knee function before the fracture because of rheumatoid arthritis. The Ahlbäck classification of osteoarthritis showed grade 1 in cases 1 and 3, and grade 2 in case 2.14 Postoperative ROM of the knee returned to pre-injury levels in all patients (Figure 2). The 2-pin external fixator was removed at 9 weeks on average (range, 6-12 weeks) postoperatively in the outpatient clinic. At the last follow-up appointment at an average of 10.3 months (range, 9-12 months), all wounds had healed without infection. All patients had a normal neurovascular examination.

DISCUSSION

Nonunion after a proximal tibial fracture is rare.4 In cases when nonunions do develop, they most often pertain to the extra-articular component with the plateau component healed. Surgical exposure for débridements, hardware removal, bone grafting, and revision of fixation carries the risk of wound breakdown, necrosis, and infection. The alternative strategy of composite fixation (a plate combined with a contralateral 2-pin external fixator) to limit additional soft tissue compromise was already described in proximal tibial fractures by Bolhofner.9 He treated 41 extra-articular proximal tibial fractures using this composite fixation technique and attained successful results with an average time to union of 12.1 weeks. There was only 1 malunion, 2 wound infections, and 3 delayed unions.

In our practice, we have extrapolated this idea to an extra-articular nonunion that developed after a tibial plateau fracture. With the use of an external fixator, we provided sufficient mechanical stability of the nonunion without unnecessarily compromising previously infected or tenuous soft tissues, a muscle flap, or further devascularizing poor bone. Limitations of this study include the retrospective data and small sample size prone to bias. However, all patients received the same treatment protocol from 1 orthopedic trauma surgeon, follow-up intervals were similar, and data were acquired consistently.

Meanwhile, we have used this technique in a fourth patient with a septic nonunion of a tibial plateau fracture. All 4 patients in whom we have used this method so far have healed successfully.

CONCLUSION

This technique respects both the demand for minimal soft tissue damage and a maximal stable environment without notable perioperative and postoperative complications. It also offers an alternative option for the treatment of a proximal tibial nonunion that is not amenable to invasive revision dual plate fixation. As such, it can be a useful addition to the existing armamentarium of the treating surgeon.

1. Wu CC. Salvage of proximal tibial malunion or nonunion with the use of angled blade plate. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126(2):82-87. doi:10.1007/s00402-006-0106-9.

2. Carpenter CA, Jupiter JB. Blade plate reconstruction of metaphyseal nonunion of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;332:23-28.

3. Gardner MJ, Toro-Arbelaez JB, Hansen M, Boraiah S, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Surgical treatment and outcomes of extraarticular proximal tibial nonunions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(8):833-839. doi:10.1007/s00402-007-0383-y.

4. Toro-Arbelaez JB, Gardner MJ, Shindle MK, Cabas JM, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Open reduction and internal fixation of intraarticular tibial plateau nonunions. Injury. 2007;38(3):378-383. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2006.11.003.

5. Mechrefe AP, Koh EY, Trafton PG, DiGiovanni CW. Tibial nonunion. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(1):1-18, vii. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2005.12.003.

6. Chin KR, Nagarkatti DG, Miranda MA, Santoro VM, Baumgaertner MR, Jupiter JB. Salvage of distal tibia metaphyseal nonunions with the 90 degrees cannulated blade plate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(409):241-249.

7. Devgan A, Kamboj P, Gupta V, Magu NK, Rohilla R. Pseudoarthrosis of medial tibial plateau fracture-role of alignment procedure. Chin J Traumatol. 2013;16(2):118-121. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-1275.2013.02.011.

8. Helfet DL, Jupiter JB, Gasser S. Indirect reduction and tension-band plating of tibial non-union with deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(9):1286-1297.

9. Bolhofner BR. Indirect reduction and composite fixation of extraarticular proximal tibial fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(315):75-83. doi:10.1097/00003086-199506000-00009.

10. Ries MD, Meinhard BP. Medial external fixation with lateral plate internal fixation in metaphyseal tibia fractures. A report of eight cases associated with severe soft-tissue injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(256):215-223.

11. Weiner LS, Kelley M, Yang E, et al. The use of combination internal fixation and hybrid external fixation in severe proximal tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):244-250.

12. Alghadir A, Anwer S, Brismee JM. The reliability and minimal detectable change of Timed Up and Go test in individuals with grade 1-3 knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:174. doi:10.1186/s12891-015-0637-8.

13. Haverkamp D, Sierevelt IN, Breugem SJ, Lohuis K, Blankevoort L, van Dijk CN. Translation and validation of the Dutch version of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1680-1684. doi:10.1177/0363546506288854.

14. Ahlbäck S. Osteoartrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1968;Suppl 277:7-72.

1. Wu CC. Salvage of proximal tibial malunion or nonunion with the use of angled blade plate. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126(2):82-87. doi:10.1007/s00402-006-0106-9.

2. Carpenter CA, Jupiter JB. Blade plate reconstruction of metaphyseal nonunion of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;332:23-28.

3. Gardner MJ, Toro-Arbelaez JB, Hansen M, Boraiah S, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Surgical treatment and outcomes of extraarticular proximal tibial nonunions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(8):833-839. doi:10.1007/s00402-007-0383-y.

4. Toro-Arbelaez JB, Gardner MJ, Shindle MK, Cabas JM, Lorich DG, Helfet DL. Open reduction and internal fixation of intraarticular tibial plateau nonunions. Injury. 2007;38(3):378-383. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2006.11.003.

5. Mechrefe AP, Koh EY, Trafton PG, DiGiovanni CW. Tibial nonunion. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(1):1-18, vii. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2005.12.003.

6. Chin KR, Nagarkatti DG, Miranda MA, Santoro VM, Baumgaertner MR, Jupiter JB. Salvage of distal tibia metaphyseal nonunions with the 90 degrees cannulated blade plate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(409):241-249.

7. Devgan A, Kamboj P, Gupta V, Magu NK, Rohilla R. Pseudoarthrosis of medial tibial plateau fracture-role of alignment procedure. Chin J Traumatol. 2013;16(2):118-121. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-1275.2013.02.011.

8. Helfet DL, Jupiter JB, Gasser S. Indirect reduction and tension-band plating of tibial non-union with deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(9):1286-1297.

9. Bolhofner BR. Indirect reduction and composite fixation of extraarticular proximal tibial fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(315):75-83. doi:10.1097/00003086-199506000-00009.

10. Ries MD, Meinhard BP. Medial external fixation with lateral plate internal fixation in metaphyseal tibia fractures. A report of eight cases associated with severe soft-tissue injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(256):215-223.

11. Weiner LS, Kelley M, Yang E, et al. The use of combination internal fixation and hybrid external fixation in severe proximal tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(3):244-250.

12. Alghadir A, Anwer S, Brismee JM. The reliability and minimal detectable change of Timed Up and Go test in individuals with grade 1-3 knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:174. doi:10.1186/s12891-015-0637-8.

13. Haverkamp D, Sierevelt IN, Breugem SJ, Lohuis K, Blankevoort L, van Dijk CN. Translation and validation of the Dutch version of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1680-1684. doi:10.1177/0363546506288854.

14. Ahlbäck S. Osteoartrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1968;Suppl 277:7-72.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Treatment goals for a nonunion are bone union, re-establishment of (joint) stability, extremity alignment, and recovery of function.

- A nonunion of a tibia plateau fracture is often associated with poor soft tissues from previous surgeries and/or infections.

- Ideally a combination of minimal soft tissue damage and maximal stable fixation is used for salvage.

- There is a high risk of complications when using dual plating in these cases.

- A combination of an external fixator with limited internal fixation can be a good alternative.

Transgender equality: U.S. physicians must lead the way

Physicians have a duty to uphold to all kinds of people we serve, and transgender people are just that: people.

According to the U.S. Transgender Survey of 2015, one-third of transgender individuals have experienced a negative reaction from a health care provider in the past year. About 40% have attempted suicide in their lifetime, nearly nine times the rate of the U.S. general population. HIV positivity in the transgender community is nearly five times the rate of the U.S. general population.

In many states across the United States, including Pennsylvania, there are no comprehensive nondiscrimination laws that protect members of the LGBTQ community from being denied housing or from being fired because of their sexual orientation or gender identity and expression. Members of the transgender community have experienced brutal, unfair judgment and have been denied fair opportunities.

There have been numerous cases where transgender individuals have been treated unfairly by private businesses and public institutions. These instances include people being physically assaulted, verbally harassed, or denied their basic rights.

The denial of these fundamental rights calls for change, and the responsibility of this shift toward equality falls upon a faction of some of the most important people in our society: American physicians.

These patients are at an already vulnerable time of their lives and often need support from those who are in the best position to provide it.

Esteemed medical organizations such as the American Medical Association have iterated their beliefs about the importance of equality in medical treatment several times, mentioning that their support for equal care is blind of gender, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

The AMA has developed numerous policies that support LGBTQ individuals. General policies developed include those on the Continued Support of Human Rights and Freedom, the Nondiscrimination Policy, and Civil Rights Restoration. Several additional physician- and patient-centered policies have also been developed to reinforce the AMA’s support.

As a doctor who can recognize the importance of this initiative, I think it is of utmost importance that physicians support, spearhead, and lead this movement – not as part of a political agenda, but for the purpose of providing aid to a community that has not been receiving the clinical or social acknowledgment it deserves.

Often, transgender patients look to their health care providers for counsel, support, and education when confused about government legislation, insurance policies, and benefits. Yet, many physicians find themselves to be either unaware of the answers or unable to help with current resources at hand when approached about this issue. That is the case despite the wide number of resources and articles that are available to educate physicians to support their patients.

In cases like these, it is imperative that transgender patients, as any other patient would, receive the guidance and support they need. It is a respected obligation to our valued profession that we are continuously learning – exploring, discovering, and seeing the future of treatment for the benefit of those we serve, especially for the growing needs of our transgender patients.

The dynamics of equal treatment for the transgender community require significant action of health care professionals, and it is the will and power of American physicians that will propel this movement toward victory. As a transgender Pennsylvanian and American, I am proud to serve my community, my state, and my nation as the secretary of health for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

In addition to serving as Pennsylvania’s secretary of health, Dr. Levine is professor of pediatrics and psychiatry at Penn State University, Hershey.

Physicians have a duty to uphold to all kinds of people we serve, and transgender people are just that: people.

According to the U.S. Transgender Survey of 2015, one-third of transgender individuals have experienced a negative reaction from a health care provider in the past year. About 40% have attempted suicide in their lifetime, nearly nine times the rate of the U.S. general population. HIV positivity in the transgender community is nearly five times the rate of the U.S. general population.

In many states across the United States, including Pennsylvania, there are no comprehensive nondiscrimination laws that protect members of the LGBTQ community from being denied housing or from being fired because of their sexual orientation or gender identity and expression. Members of the transgender community have experienced brutal, unfair judgment and have been denied fair opportunities.

There have been numerous cases where transgender individuals have been treated unfairly by private businesses and public institutions. These instances include people being physically assaulted, verbally harassed, or denied their basic rights.

The denial of these fundamental rights calls for change, and the responsibility of this shift toward equality falls upon a faction of some of the most important people in our society: American physicians.

These patients are at an already vulnerable time of their lives and often need support from those who are in the best position to provide it.

Esteemed medical organizations such as the American Medical Association have iterated their beliefs about the importance of equality in medical treatment several times, mentioning that their support for equal care is blind of gender, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

The AMA has developed numerous policies that support LGBTQ individuals. General policies developed include those on the Continued Support of Human Rights and Freedom, the Nondiscrimination Policy, and Civil Rights Restoration. Several additional physician- and patient-centered policies have also been developed to reinforce the AMA’s support.

As a doctor who can recognize the importance of this initiative, I think it is of utmost importance that physicians support, spearhead, and lead this movement – not as part of a political agenda, but for the purpose of providing aid to a community that has not been receiving the clinical or social acknowledgment it deserves.

Often, transgender patients look to their health care providers for counsel, support, and education when confused about government legislation, insurance policies, and benefits. Yet, many physicians find themselves to be either unaware of the answers or unable to help with current resources at hand when approached about this issue. That is the case despite the wide number of resources and articles that are available to educate physicians to support their patients.

In cases like these, it is imperative that transgender patients, as any other patient would, receive the guidance and support they need. It is a respected obligation to our valued profession that we are continuously learning – exploring, discovering, and seeing the future of treatment for the benefit of those we serve, especially for the growing needs of our transgender patients.

The dynamics of equal treatment for the transgender community require significant action of health care professionals, and it is the will and power of American physicians that will propel this movement toward victory. As a transgender Pennsylvanian and American, I am proud to serve my community, my state, and my nation as the secretary of health for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

In addition to serving as Pennsylvania’s secretary of health, Dr. Levine is professor of pediatrics and psychiatry at Penn State University, Hershey.

Physicians have a duty to uphold to all kinds of people we serve, and transgender people are just that: people.

According to the U.S. Transgender Survey of 2015, one-third of transgender individuals have experienced a negative reaction from a health care provider in the past year. About 40% have attempted suicide in their lifetime, nearly nine times the rate of the U.S. general population. HIV positivity in the transgender community is nearly five times the rate of the U.S. general population.

In many states across the United States, including Pennsylvania, there are no comprehensive nondiscrimination laws that protect members of the LGBTQ community from being denied housing or from being fired because of their sexual orientation or gender identity and expression. Members of the transgender community have experienced brutal, unfair judgment and have been denied fair opportunities.

There have been numerous cases where transgender individuals have been treated unfairly by private businesses and public institutions. These instances include people being physically assaulted, verbally harassed, or denied their basic rights.

The denial of these fundamental rights calls for change, and the responsibility of this shift toward equality falls upon a faction of some of the most important people in our society: American physicians.

These patients are at an already vulnerable time of their lives and often need support from those who are in the best position to provide it.

Esteemed medical organizations such as the American Medical Association have iterated their beliefs about the importance of equality in medical treatment several times, mentioning that their support for equal care is blind of gender, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

The AMA has developed numerous policies that support LGBTQ individuals. General policies developed include those on the Continued Support of Human Rights and Freedom, the Nondiscrimination Policy, and Civil Rights Restoration. Several additional physician- and patient-centered policies have also been developed to reinforce the AMA’s support.

As a doctor who can recognize the importance of this initiative, I think it is of utmost importance that physicians support, spearhead, and lead this movement – not as part of a political agenda, but for the purpose of providing aid to a community that has not been receiving the clinical or social acknowledgment it deserves.

Often, transgender patients look to their health care providers for counsel, support, and education when confused about government legislation, insurance policies, and benefits. Yet, many physicians find themselves to be either unaware of the answers or unable to help with current resources at hand when approached about this issue. That is the case despite the wide number of resources and articles that are available to educate physicians to support their patients.

In cases like these, it is imperative that transgender patients, as any other patient would, receive the guidance and support they need. It is a respected obligation to our valued profession that we are continuously learning – exploring, discovering, and seeing the future of treatment for the benefit of those we serve, especially for the growing needs of our transgender patients.

The dynamics of equal treatment for the transgender community require significant action of health care professionals, and it is the will and power of American physicians that will propel this movement toward victory. As a transgender Pennsylvanian and American, I am proud to serve my community, my state, and my nation as the secretary of health for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

In addition to serving as Pennsylvania’s secretary of health, Dr. Levine is professor of pediatrics and psychiatry at Penn State University, Hershey.

Data-driven prescribing

Computational psychiatry is an emerging field in which artificial intelligence and machine learning are used to find hidden patterns in big data to better understand, predict, and treat mental illness. The field uses various mathematical models to predict the dependent variable y based on the independent variable x. One application of analytics in medicine was the Framingham Heart Study, which used multivariate logistic regression to predict heart disease.1

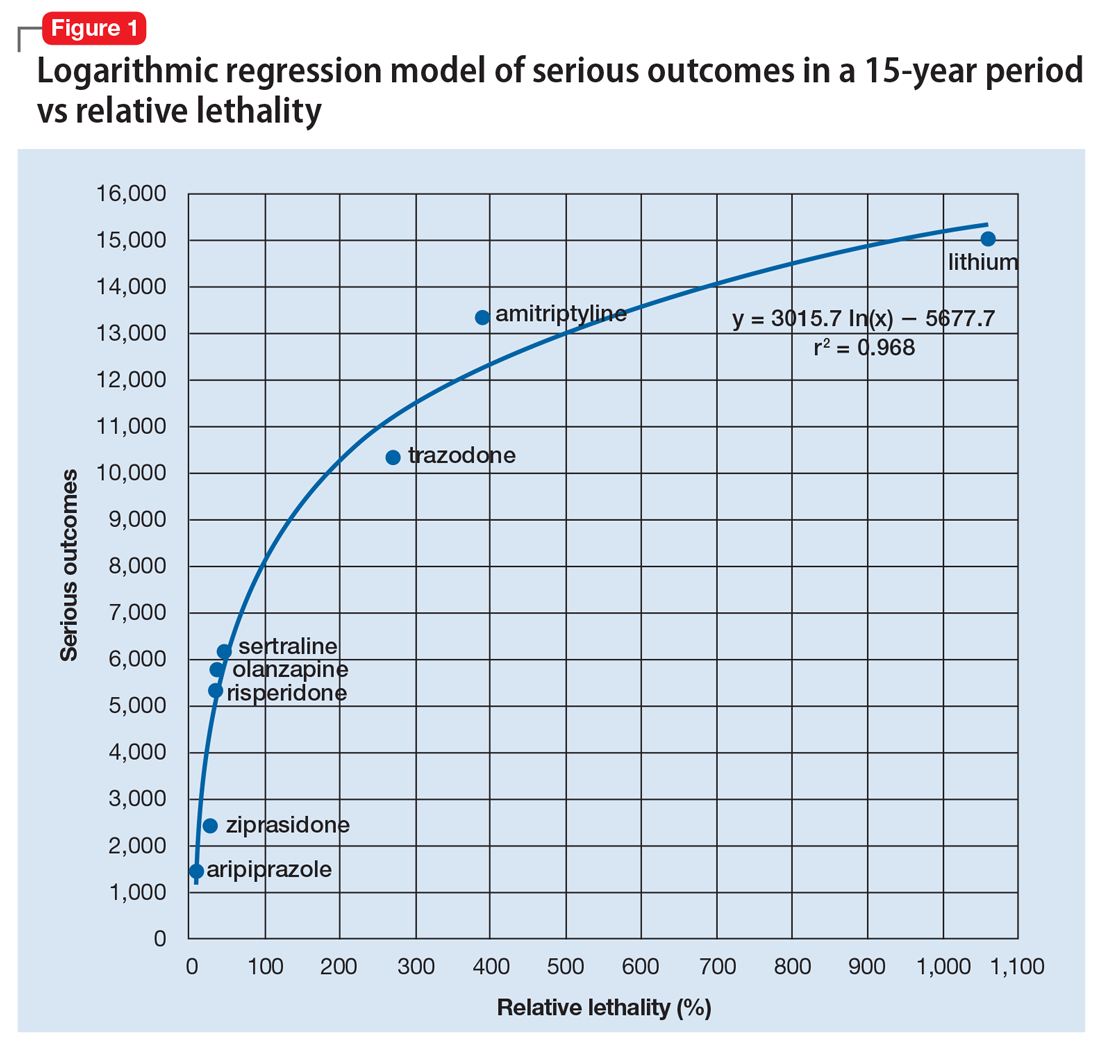

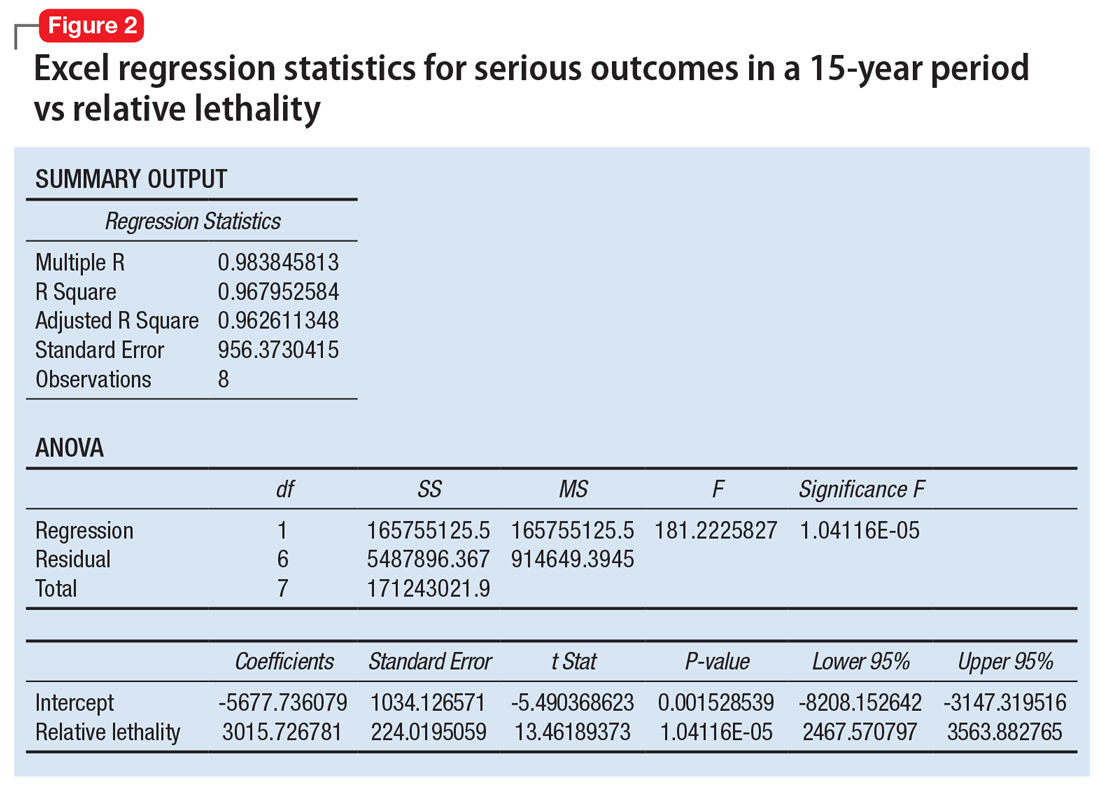

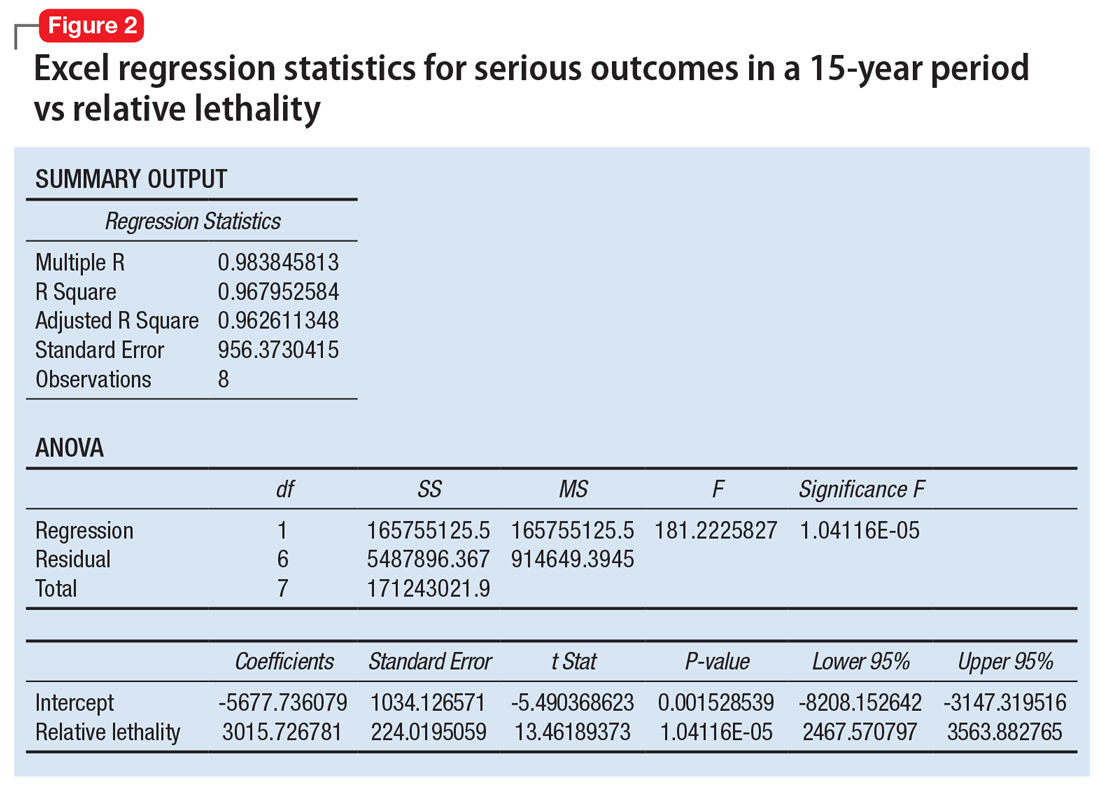

Analytics could be used to predict the number of bad outcomes associated with different psychiatric medications over time. To demonstrate this, I examined a select data set of 8 psychiatric medications (aripiprazole, ziprasidone, risperidone, olanzapine, sertraline, trazodone, amitriptyline, and lithium) accounting for 59,827 bad outcomes during a 15-year period as reported by U.S. poison control centers,2 and plotted these on the y-axis.

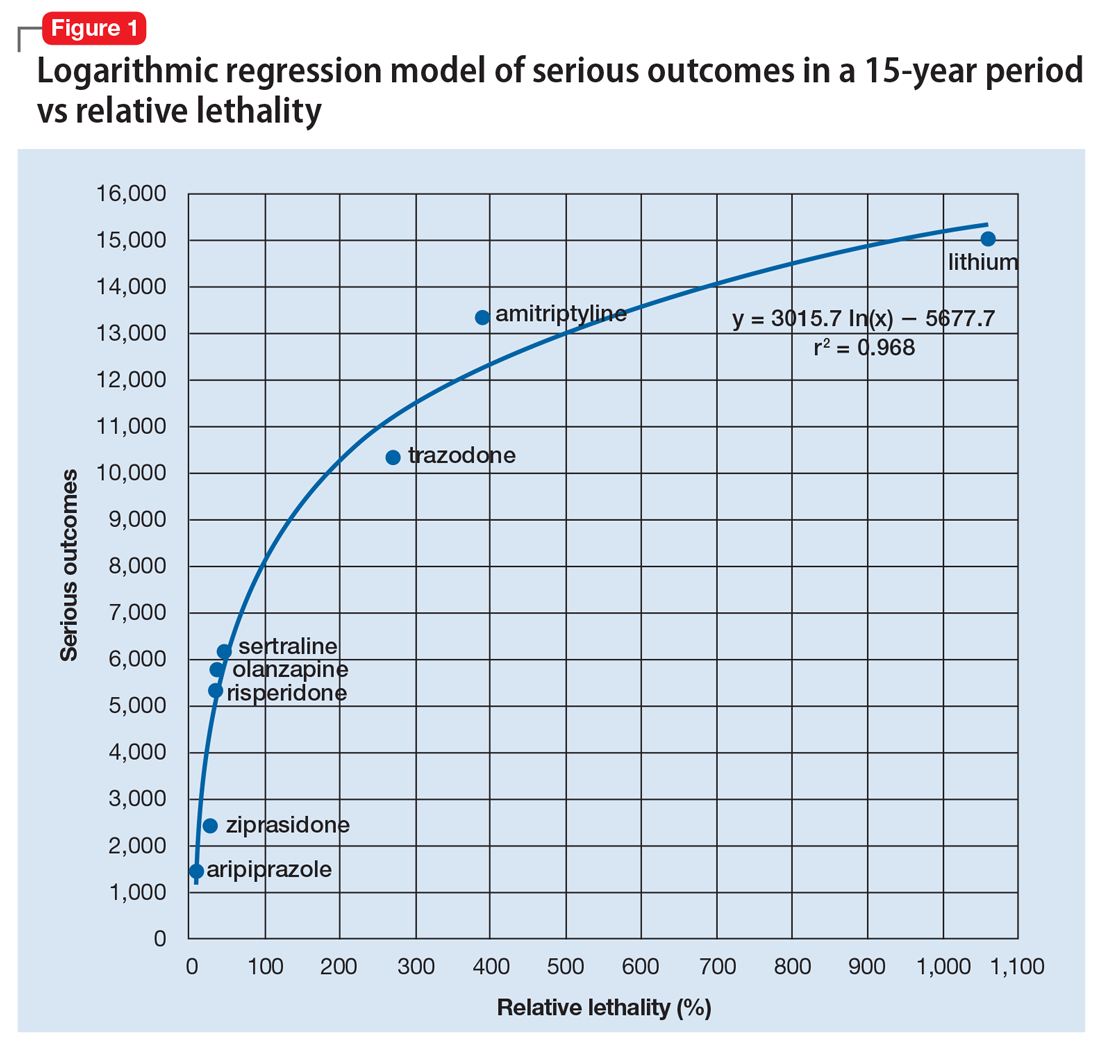

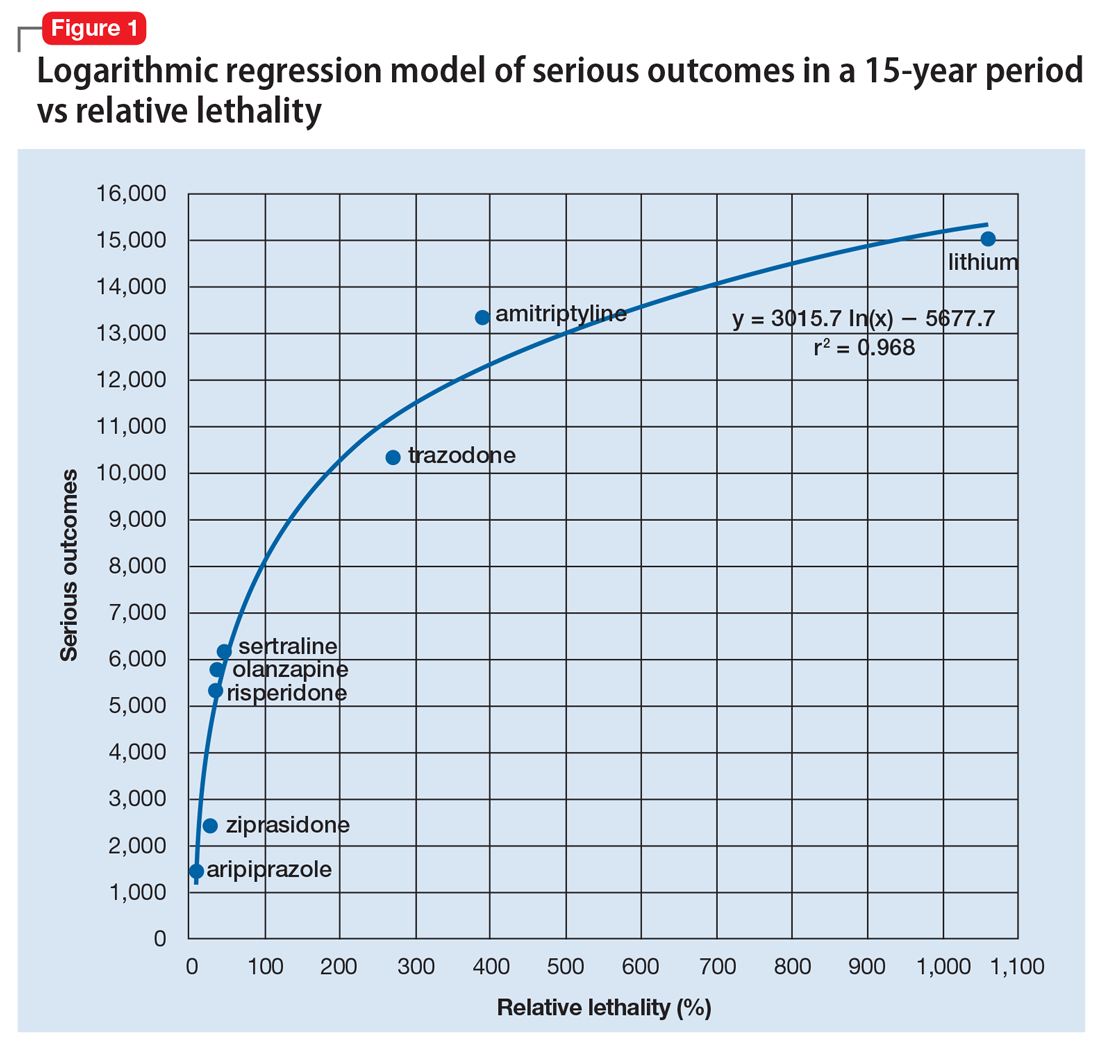

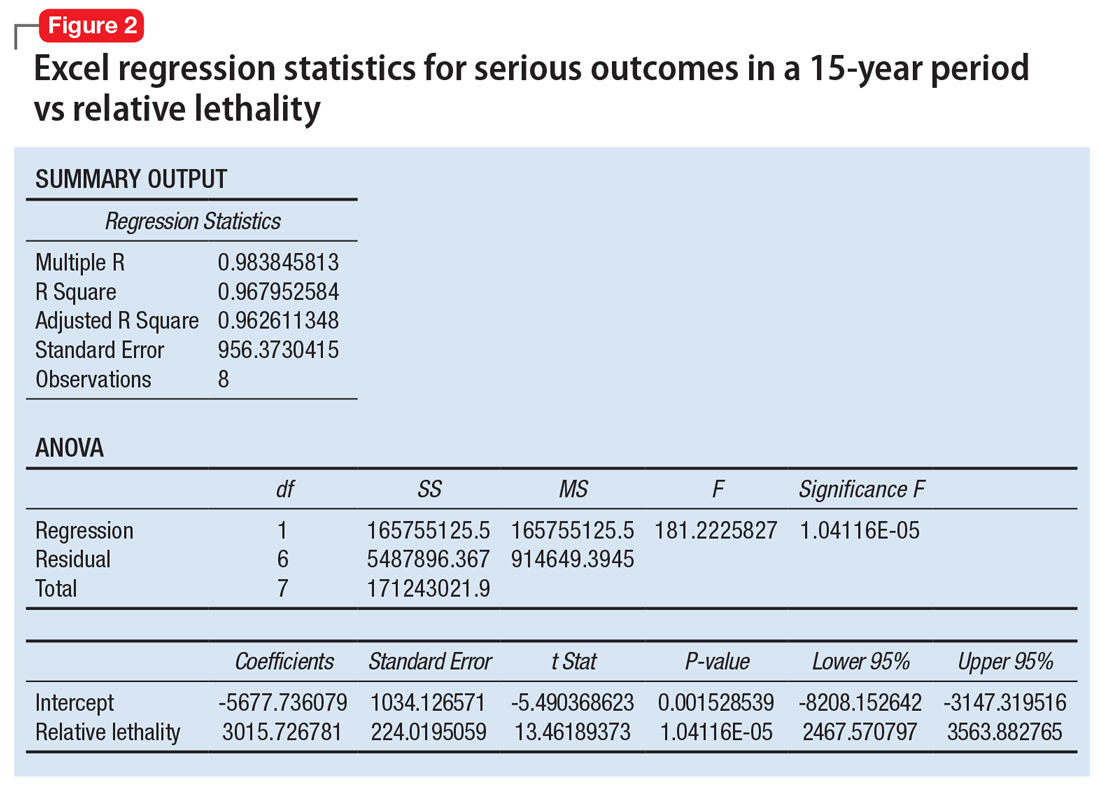

When considering the independent variable to use as a predictor for bad outcomes, I used a composite index derived with the relative lethality (RL) equation, f(x) = 310x /LD50, where x is the daily dose of a medication prescribed for 30 days, and LD50 is the rat oral lethal dose 50.3 I plotted the RL of the 8 medications on the x-axis. Then I attempted to find a mathematical function that would best fit the x and y intersection points (Figure 1). I used the Excel data analysis pack to run a logarithmic regression model (Figure 2).

The model predicts that medications with a lower RL will have fewer serious outcomes, including mortality. The coefficient of determination r2 = 0.968, which indicates that 97% of the variation in serious outcomes is attributed to variation in RL, and 3% may be due to other factors, such as the poor quality of U.S. poison control data. This is a very significant correlation, and the causality is self-evident.

Continued to: The distribution of bad outcomes in the model was...

The distribution of bad outcomes in the model was: 1,446 for aripiprazole (RL = 9.76%), 2,387 for ziprasidone (RL = 24.80%), 5,352 for risperidone (RL = 32.63%), 5,798 for olanzapine (RL = 35.03%), 6,120 for sertraline (RL = 46.72%), 10,343 for trazodone (RL = 269.57%), 13,345 for amitriptyline (RL = 387.50%), and 15,036 for lithium (RL = 1,062.86%). The regression equation is: serious outcomes = –5,677.7 + 3,015.7 × ln (RL).

Some doctors may argue that such a data set is too small to make a meaningful model. However, the number of possible ways of ranking the drugs by bad outcomes is 8! = 40,320, so the probability of guessing the right sequence is P = .000024801. To appreciate how small this probability is, imagine trying to find a person of interest in half a football stadium on Superbowl Sunday.

The RL composite index correctly predicted the ranking order of serious outcomes for the 8 medications and may be useful for finding such outcomes in any drug class. For example, with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (n = 11) the number of possible combinations is 11! = 39,916,800. The probability of guessing the right sequence is like finding a person of interest in Poland. The model predicts the following decreasing sequence: 1) captopril, 2) fosinopril, 3) quinapril, 4) benazepril, 5) enalapril, 6) lisinopril, 7) moexipril, 8) perindopril, 9) cilazapril, 10) ramipril, 11) trandolapril. The predicted number of bad outcomes is highest for captopril, and lowest for trandolapril. The usefulness of the machine learning algorithm becomes immediately apparent.

Data can inform prescribing