User login

What medical therapies work for gastroparesis?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

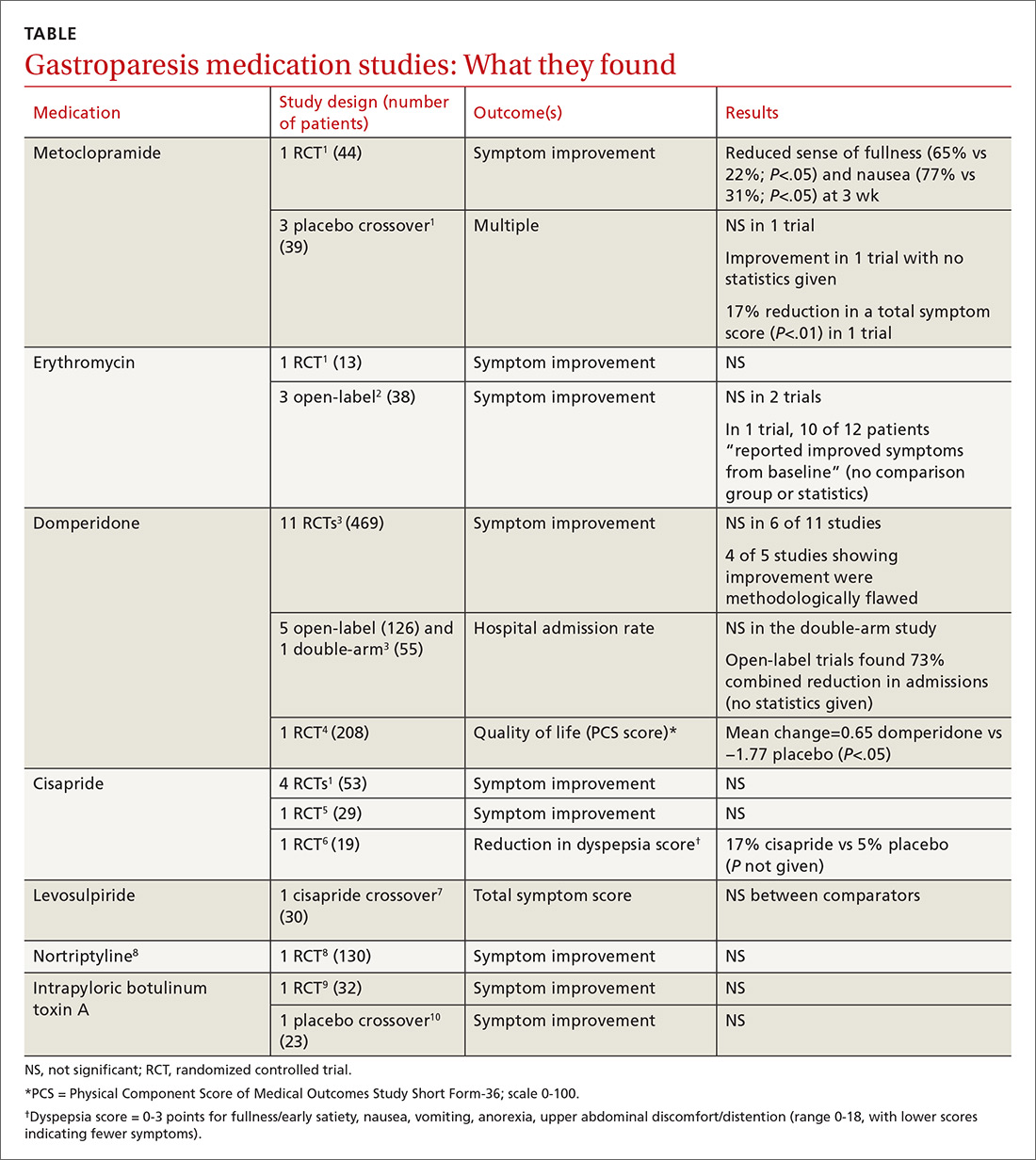

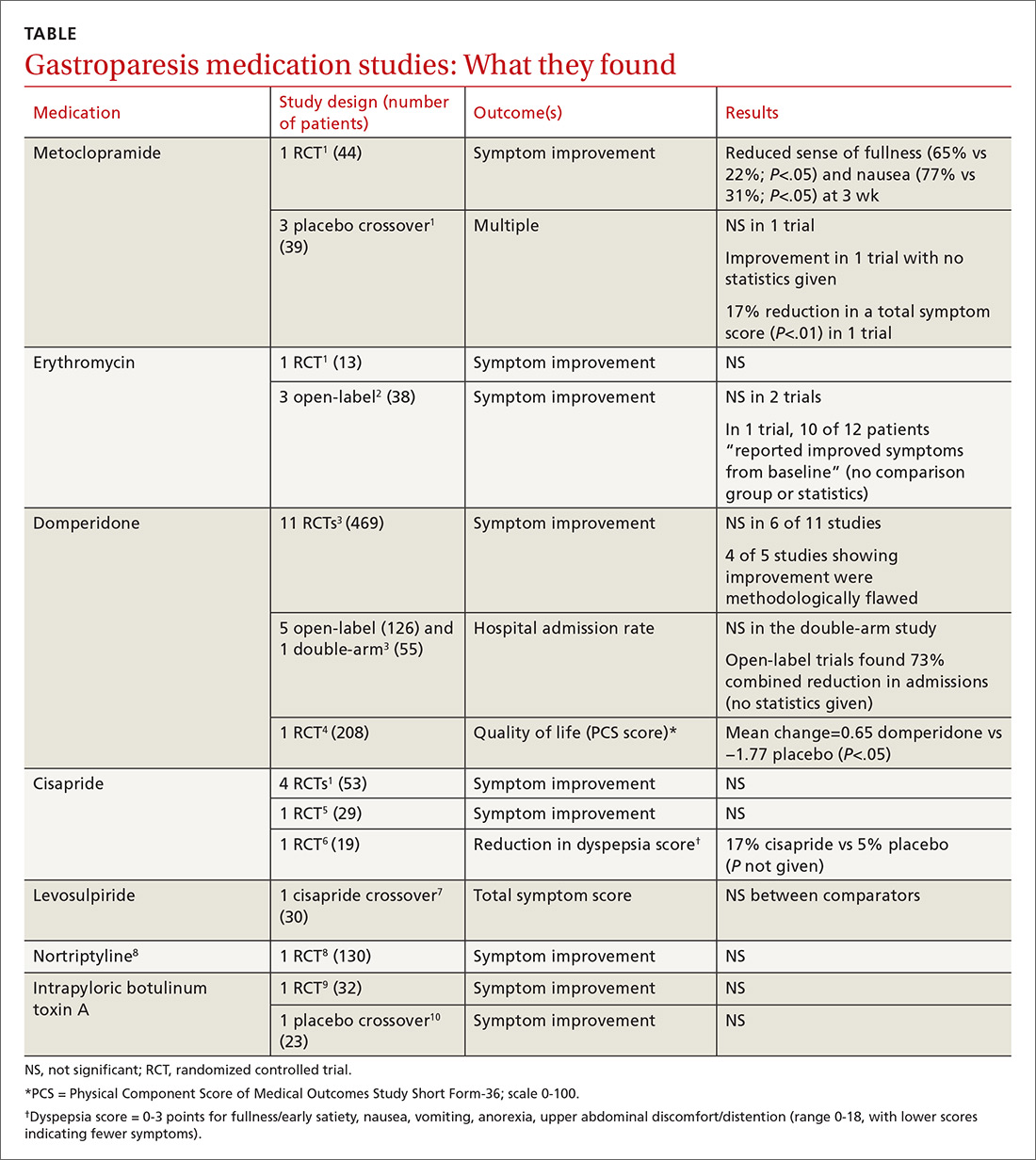

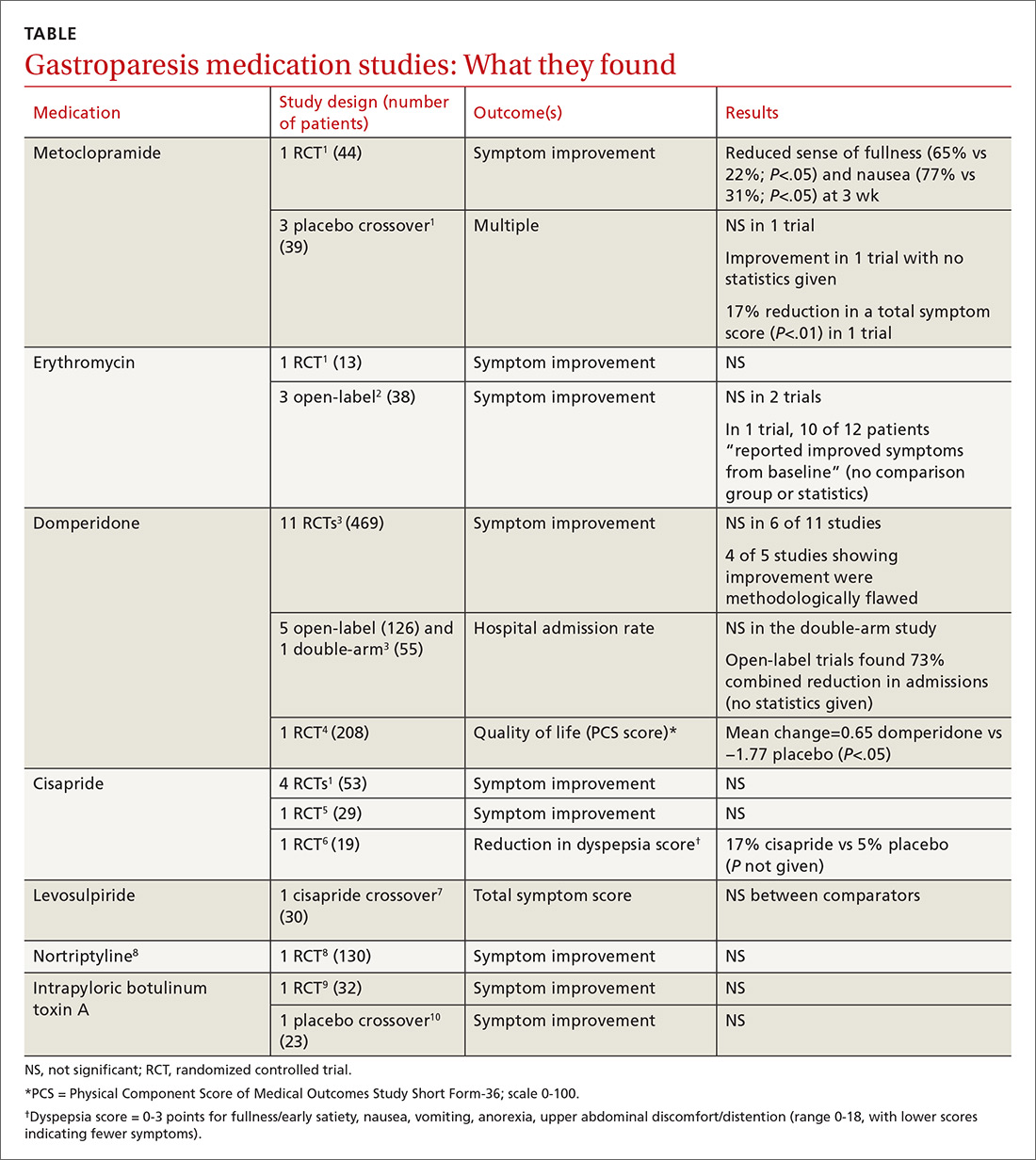

Metoclopramide. One systematic review that looked at the efficacy of metoclopramide for gastroparesis identified one small RCT and 3 smaller placebo-controlled crossover trials.1 The RCT (using 10 mg of metoclopramide after meals and at bedtime) found consistent improvement in the sense of fullness over 3 weeks of therapy, with reduction of nausea at one and 3 weeks, but not at 2 weeks. Vomiting, anorexia, and early satiety didn’t improve. The crossover trials had inconsistent results. The largest one, with only 16 patients, didn’t find an improvement in symptoms.

Erythromycin. Two systematic reviews looked at the efficacy of erythromycin, primarily identifying studies 20- to 30-years old. The first systematic review identified only one small (single-blind) RCT in which erythromycin treatment didn’t change symptoms.1 A second review identified 3 trials described as “open label,” all with fewer than 14 subjects and all lasting a month or less.2 Erythromycin improved patient symptoms in only 1 of the 3, and this trial (like the others) had significant methodologic flaws. The authors of the second review concluded that “the true efficacy of erythromycin in relieving symptoms … remains to be determined.”

Domperidone. A systematic review and one subsequent RCT evaluated domperidone. The systematic review identified 11 randomized, placebo-controlled trials (469 patients).3 Six studies found no impact on patient symptoms, while 5 reported a positive effect. The review also identified 6 trials that evaluated domperidone treatment on hospitalization rates. Open-label (single-arm, unblinded) trials tended to find a reduction in hospitalizations with domperidone, an effect not seen in the one double-arm study that evaluated this outcome.

The review authors noted that given the small size and low methodologic quality of most studies “it is not surprising … that there continues to be controversy about the efficacy of this drug” for symptoms of gastroparesis.

One subsequent RCT, using domperidone 20 mg 4 times daily for 4 weeks, found a 2% improvement over placebo in the physical component of a multifaceted quality-of-life measure.4 The improvement was statistically significant, but of unclear clinical importance.

Cisapride. One systematic review and 2 subsequent RCTs evaluated the clinical effects of cisapride. The systematic review included 4 small RCTs (53 patients) that didn’t individually find changes in patient symptoms.

In one subsequent RCT, comparing 10 mg cisapride 3 times daily to placebo for 2 weeks, cisapride yielded no significant change in symptoms.5 The other RCT compared oral cisapride 10 mg 3 times daily to placebo for one year. Cisapride treatment produced a 17% reduction in symptoms (P<.002 vs baseline), and placebo produced a 5% reduction (P=NS vs baseline). The study didn’t state if the difference between the 2 outcomes was statistically significant.6

Continue to: Levosulpiride

Levosulpiride. One crossover study compared 25 mg levosulpiride with 10 mg cisapride (both given orally 3 times a day) on gastroparesis symptoms and gastric emptying. Each medication was given for one month (washout duration not given). The study found similar efficacy between levosulpiride and cisapride in terms of improvement in gastric emptying rates and total symptom scores.7 No studies compare levosulpiride to placebo.

Nortriptyline. A multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind RCT comparing 75 mg/d nortriptyline for 15 weeks with placebo in adult patients with moderate to severe symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis for at least 6 months found that nortriptyline didn’t improve symptoms.8

Botulinum toxin A. An RCT comparing a single injection of 200 units intrapyloric botulinum toxin A with placebo in adult patients with severe gastroparesis symptoms found that botulinum toxin A didn’t result in symptomatic improvement.9 A crossover trial comparing 100 units monthly intrapyloric botulinum toxin A for 3 months with placebo in patients with gastroparesis found that neither symptoms nor rate of gastric emptying changed with the toxin.10

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2013 guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology list metoclopramide as the first-line agent for gastroparesis requiring medical therapy, followed by domperidone and then erythromycin (all based on “moderate quality evidence”). Antiemetic agents are also recommended for symptom control.11

1. Sturm A, Holtmann G, Goebell H, et al. Prokinetics in patients with gastroparesis: a systematic analysis. Digestion. 1999;60:422-427.

2. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:259-263.

3. Sugumar A, Singh A, Pasricha PJ. A systematic review of the efficacy of domperidone for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:726-733.

4. Farup CE, Leidy NK, Murray M, et al. Effect of domperidone on the health-related quality of life of patients with symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1699-1706.

5. Dutta U, Padhy AK, Ahuja V, et al. Double blind controlled trial of effect of cisapride on gastric emptying in diabetics. Trop Gastroenterol. 1999;20:116-119.

6. Braden B, Enghofer M, Schaub M, et al. Long-term cisapride treatment improves diabetic gastroparesis but not glycaemic control. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1341-1346.

7. Mansi C, Borro P, Giacomini M, et al. Comparative effects of levosulpiride and cisapride on gastric emptying and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:561-569.

8. Parkman HP, Van Natta ML, Abell TL, et al. Effect of nortriptyline on symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis: the NORIG randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2640-2649.

9. Friedenberg FK, Palit A, Parkman HP, et al. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of delayed gastric emptying. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:416-423.

10. Arts J, Holvoet L, Caenepeel P, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized-controlled crossover study of intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin in gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1251-1258.

11. Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, et al. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-38.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Metoclopramide. One systematic review that looked at the efficacy of metoclopramide for gastroparesis identified one small RCT and 3 smaller placebo-controlled crossover trials.1 The RCT (using 10 mg of metoclopramide after meals and at bedtime) found consistent improvement in the sense of fullness over 3 weeks of therapy, with reduction of nausea at one and 3 weeks, but not at 2 weeks. Vomiting, anorexia, and early satiety didn’t improve. The crossover trials had inconsistent results. The largest one, with only 16 patients, didn’t find an improvement in symptoms.

Erythromycin. Two systematic reviews looked at the efficacy of erythromycin, primarily identifying studies 20- to 30-years old. The first systematic review identified only one small (single-blind) RCT in which erythromycin treatment didn’t change symptoms.1 A second review identified 3 trials described as “open label,” all with fewer than 14 subjects and all lasting a month or less.2 Erythromycin improved patient symptoms in only 1 of the 3, and this trial (like the others) had significant methodologic flaws. The authors of the second review concluded that “the true efficacy of erythromycin in relieving symptoms … remains to be determined.”

Domperidone. A systematic review and one subsequent RCT evaluated domperidone. The systematic review identified 11 randomized, placebo-controlled trials (469 patients).3 Six studies found no impact on patient symptoms, while 5 reported a positive effect. The review also identified 6 trials that evaluated domperidone treatment on hospitalization rates. Open-label (single-arm, unblinded) trials tended to find a reduction in hospitalizations with domperidone, an effect not seen in the one double-arm study that evaluated this outcome.

The review authors noted that given the small size and low methodologic quality of most studies “it is not surprising … that there continues to be controversy about the efficacy of this drug” for symptoms of gastroparesis.

One subsequent RCT, using domperidone 20 mg 4 times daily for 4 weeks, found a 2% improvement over placebo in the physical component of a multifaceted quality-of-life measure.4 The improvement was statistically significant, but of unclear clinical importance.

Cisapride. One systematic review and 2 subsequent RCTs evaluated the clinical effects of cisapride. The systematic review included 4 small RCTs (53 patients) that didn’t individually find changes in patient symptoms.

In one subsequent RCT, comparing 10 mg cisapride 3 times daily to placebo for 2 weeks, cisapride yielded no significant change in symptoms.5 The other RCT compared oral cisapride 10 mg 3 times daily to placebo for one year. Cisapride treatment produced a 17% reduction in symptoms (P<.002 vs baseline), and placebo produced a 5% reduction (P=NS vs baseline). The study didn’t state if the difference between the 2 outcomes was statistically significant.6

Continue to: Levosulpiride

Levosulpiride. One crossover study compared 25 mg levosulpiride with 10 mg cisapride (both given orally 3 times a day) on gastroparesis symptoms and gastric emptying. Each medication was given for one month (washout duration not given). The study found similar efficacy between levosulpiride and cisapride in terms of improvement in gastric emptying rates and total symptom scores.7 No studies compare levosulpiride to placebo.

Nortriptyline. A multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind RCT comparing 75 mg/d nortriptyline for 15 weeks with placebo in adult patients with moderate to severe symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis for at least 6 months found that nortriptyline didn’t improve symptoms.8

Botulinum toxin A. An RCT comparing a single injection of 200 units intrapyloric botulinum toxin A with placebo in adult patients with severe gastroparesis symptoms found that botulinum toxin A didn’t result in symptomatic improvement.9 A crossover trial comparing 100 units monthly intrapyloric botulinum toxin A for 3 months with placebo in patients with gastroparesis found that neither symptoms nor rate of gastric emptying changed with the toxin.10

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2013 guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology list metoclopramide as the first-line agent for gastroparesis requiring medical therapy, followed by domperidone and then erythromycin (all based on “moderate quality evidence”). Antiemetic agents are also recommended for symptom control.11

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Metoclopramide. One systematic review that looked at the efficacy of metoclopramide for gastroparesis identified one small RCT and 3 smaller placebo-controlled crossover trials.1 The RCT (using 10 mg of metoclopramide after meals and at bedtime) found consistent improvement in the sense of fullness over 3 weeks of therapy, with reduction of nausea at one and 3 weeks, but not at 2 weeks. Vomiting, anorexia, and early satiety didn’t improve. The crossover trials had inconsistent results. The largest one, with only 16 patients, didn’t find an improvement in symptoms.

Erythromycin. Two systematic reviews looked at the efficacy of erythromycin, primarily identifying studies 20- to 30-years old. The first systematic review identified only one small (single-blind) RCT in which erythromycin treatment didn’t change symptoms.1 A second review identified 3 trials described as “open label,” all with fewer than 14 subjects and all lasting a month or less.2 Erythromycin improved patient symptoms in only 1 of the 3, and this trial (like the others) had significant methodologic flaws. The authors of the second review concluded that “the true efficacy of erythromycin in relieving symptoms … remains to be determined.”

Domperidone. A systematic review and one subsequent RCT evaluated domperidone. The systematic review identified 11 randomized, placebo-controlled trials (469 patients).3 Six studies found no impact on patient symptoms, while 5 reported a positive effect. The review also identified 6 trials that evaluated domperidone treatment on hospitalization rates. Open-label (single-arm, unblinded) trials tended to find a reduction in hospitalizations with domperidone, an effect not seen in the one double-arm study that evaluated this outcome.

The review authors noted that given the small size and low methodologic quality of most studies “it is not surprising … that there continues to be controversy about the efficacy of this drug” for symptoms of gastroparesis.

One subsequent RCT, using domperidone 20 mg 4 times daily for 4 weeks, found a 2% improvement over placebo in the physical component of a multifaceted quality-of-life measure.4 The improvement was statistically significant, but of unclear clinical importance.

Cisapride. One systematic review and 2 subsequent RCTs evaluated the clinical effects of cisapride. The systematic review included 4 small RCTs (53 patients) that didn’t individually find changes in patient symptoms.

In one subsequent RCT, comparing 10 mg cisapride 3 times daily to placebo for 2 weeks, cisapride yielded no significant change in symptoms.5 The other RCT compared oral cisapride 10 mg 3 times daily to placebo for one year. Cisapride treatment produced a 17% reduction in symptoms (P<.002 vs baseline), and placebo produced a 5% reduction (P=NS vs baseline). The study didn’t state if the difference between the 2 outcomes was statistically significant.6

Continue to: Levosulpiride

Levosulpiride. One crossover study compared 25 mg levosulpiride with 10 mg cisapride (both given orally 3 times a day) on gastroparesis symptoms and gastric emptying. Each medication was given for one month (washout duration not given). The study found similar efficacy between levosulpiride and cisapride in terms of improvement in gastric emptying rates and total symptom scores.7 No studies compare levosulpiride to placebo.

Nortriptyline. A multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind RCT comparing 75 mg/d nortriptyline for 15 weeks with placebo in adult patients with moderate to severe symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis for at least 6 months found that nortriptyline didn’t improve symptoms.8

Botulinum toxin A. An RCT comparing a single injection of 200 units intrapyloric botulinum toxin A with placebo in adult patients with severe gastroparesis symptoms found that botulinum toxin A didn’t result in symptomatic improvement.9 A crossover trial comparing 100 units monthly intrapyloric botulinum toxin A for 3 months with placebo in patients with gastroparesis found that neither symptoms nor rate of gastric emptying changed with the toxin.10

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2013 guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology list metoclopramide as the first-line agent for gastroparesis requiring medical therapy, followed by domperidone and then erythromycin (all based on “moderate quality evidence”). Antiemetic agents are also recommended for symptom control.11

1. Sturm A, Holtmann G, Goebell H, et al. Prokinetics in patients with gastroparesis: a systematic analysis. Digestion. 1999;60:422-427.

2. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:259-263.

3. Sugumar A, Singh A, Pasricha PJ. A systematic review of the efficacy of domperidone for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:726-733.

4. Farup CE, Leidy NK, Murray M, et al. Effect of domperidone on the health-related quality of life of patients with symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1699-1706.

5. Dutta U, Padhy AK, Ahuja V, et al. Double blind controlled trial of effect of cisapride on gastric emptying in diabetics. Trop Gastroenterol. 1999;20:116-119.

6. Braden B, Enghofer M, Schaub M, et al. Long-term cisapride treatment improves diabetic gastroparesis but not glycaemic control. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1341-1346.

7. Mansi C, Borro P, Giacomini M, et al. Comparative effects of levosulpiride and cisapride on gastric emptying and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:561-569.

8. Parkman HP, Van Natta ML, Abell TL, et al. Effect of nortriptyline on symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis: the NORIG randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2640-2649.

9. Friedenberg FK, Palit A, Parkman HP, et al. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of delayed gastric emptying. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:416-423.

10. Arts J, Holvoet L, Caenepeel P, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized-controlled crossover study of intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin in gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1251-1258.

11. Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, et al. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-38.

1. Sturm A, Holtmann G, Goebell H, et al. Prokinetics in patients with gastroparesis: a systematic analysis. Digestion. 1999;60:422-427.

2. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:259-263.

3. Sugumar A, Singh A, Pasricha PJ. A systematic review of the efficacy of domperidone for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:726-733.

4. Farup CE, Leidy NK, Murray M, et al. Effect of domperidone on the health-related quality of life of patients with symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1699-1706.

5. Dutta U, Padhy AK, Ahuja V, et al. Double blind controlled trial of effect of cisapride on gastric emptying in diabetics. Trop Gastroenterol. 1999;20:116-119.

6. Braden B, Enghofer M, Schaub M, et al. Long-term cisapride treatment improves diabetic gastroparesis but not glycaemic control. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1341-1346.

7. Mansi C, Borro P, Giacomini M, et al. Comparative effects of levosulpiride and cisapride on gastric emptying and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:561-569.

8. Parkman HP, Van Natta ML, Abell TL, et al. Effect of nortriptyline on symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis: the NORIG randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2640-2649.

9. Friedenberg FK, Palit A, Parkman HP, et al. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of delayed gastric emptying. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:416-423.

10. Arts J, Holvoet L, Caenepeel P, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized-controlled crossover study of intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin in gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1251-1258.

11. Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, et al. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-38.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

It’s unclear if there are any highly effective medications for gastroparesis (TABLE1-10). Metoclopramide improves the sense of fullness by about 40% for as long as 3 weeks, may improve nausea, and doesn’t affect vomiting or anorexia (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Whether or not erythromycin has an effect on symptoms is unclear (SOR: C, conflicting trials and expert opinion).

Domperidone may improve quality of life (by 2%) for as long as a year, but its effect on symptoms is also unclear (SOR: C, small RCTs).

Cisapride may not be effective for symptom relief (SOR: C, small conflicting RCTs), and levosulpiride is likely similar to cisapride (SOR: C, single small crossover trial).

Nortriptyline (SOR: B, single RCT) and intrapyloric botulinum toxin A (SOR: B, small RCT and crossover trial) aren’t effective for symptom relief.

Progressive discoloration over the right shoulder

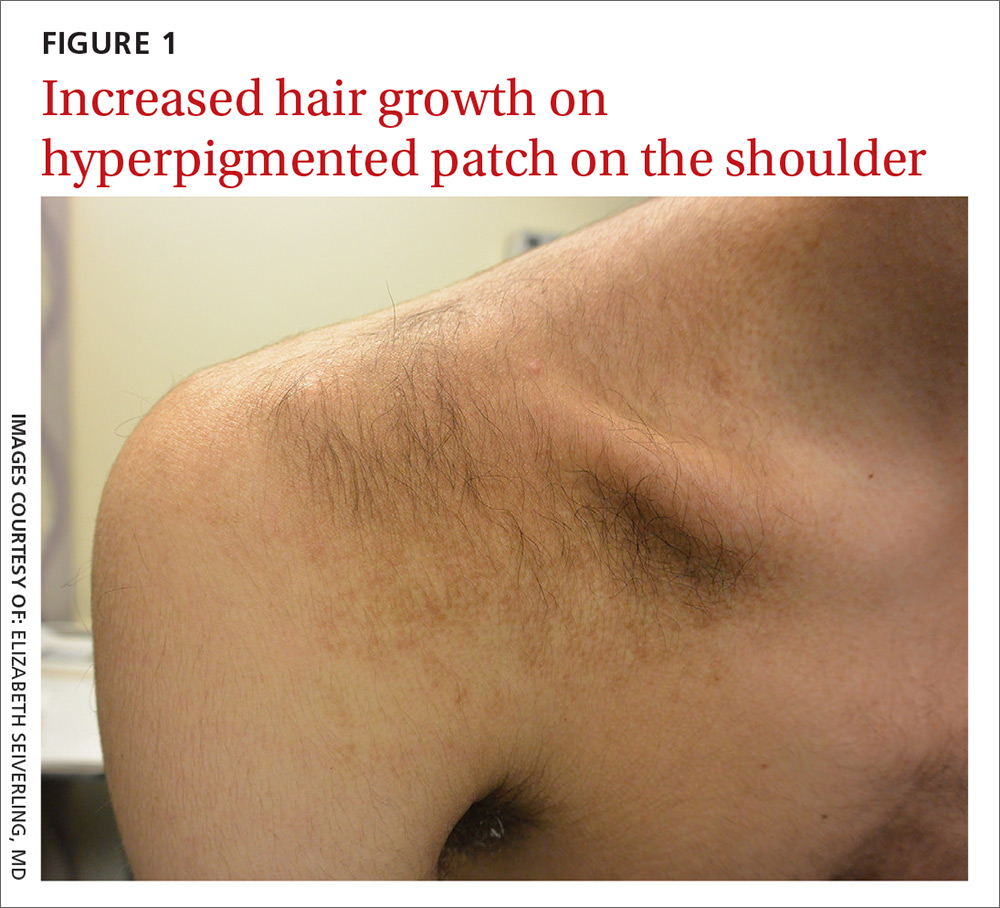

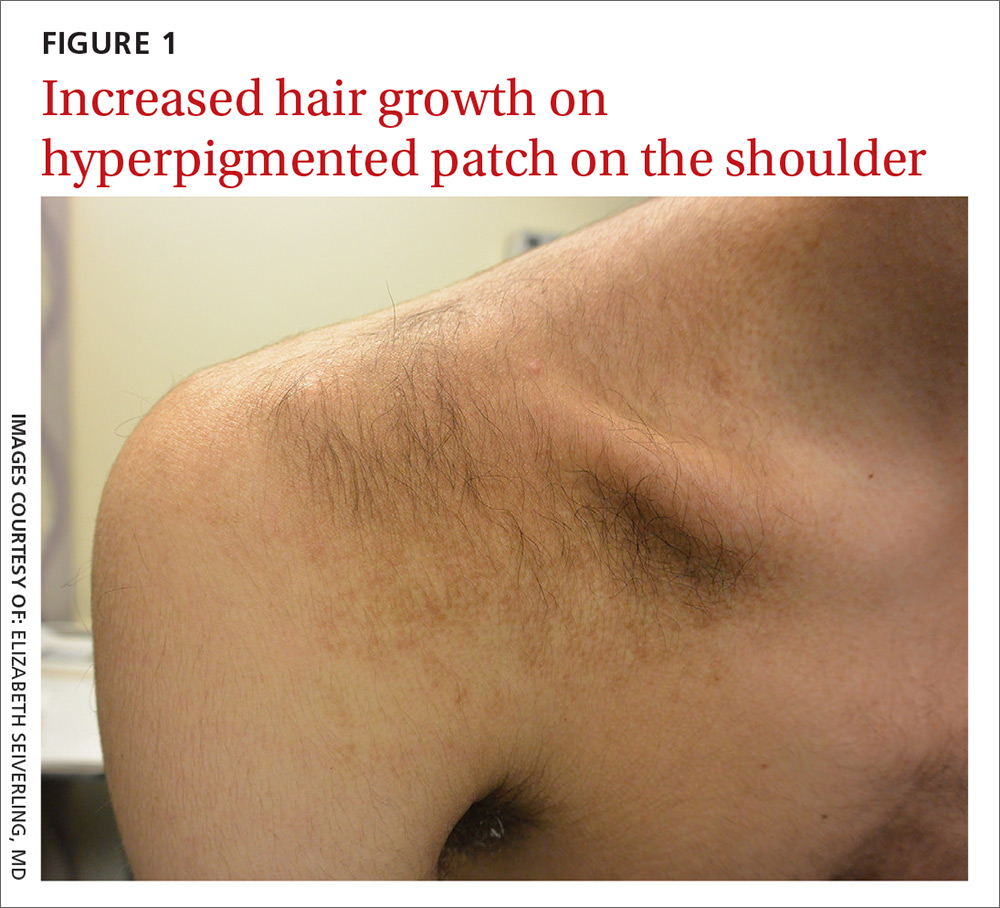

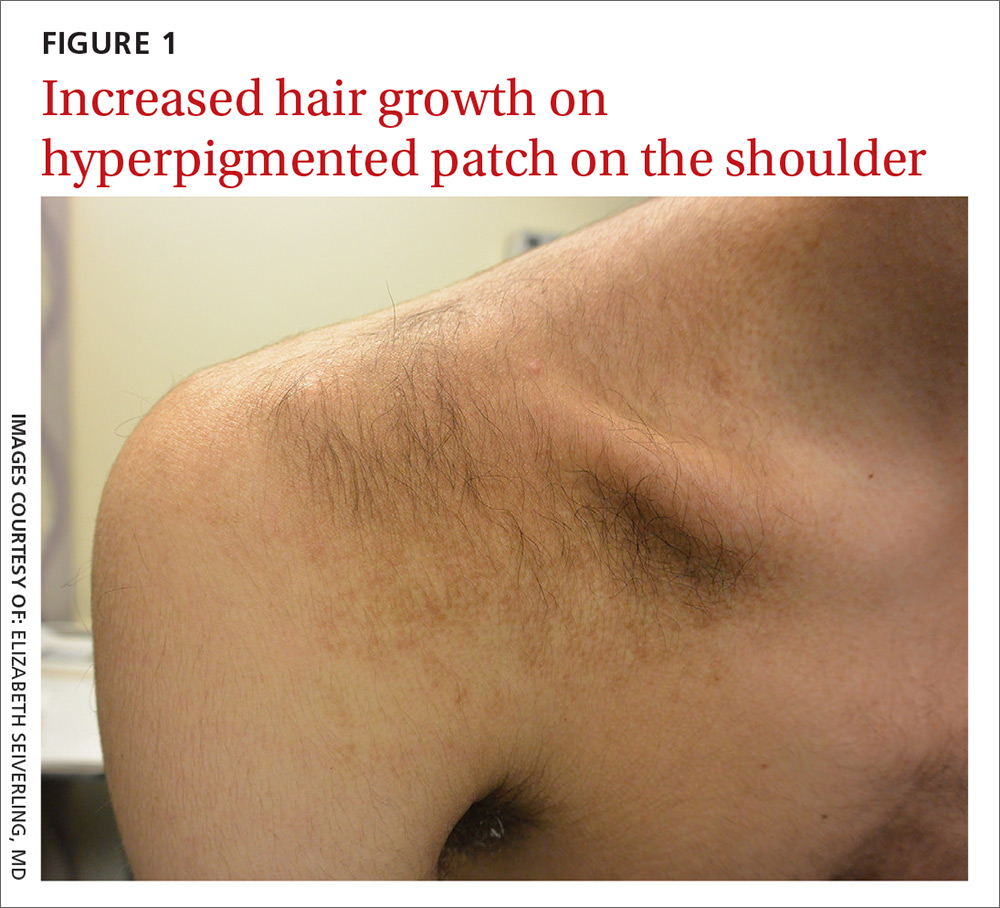

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

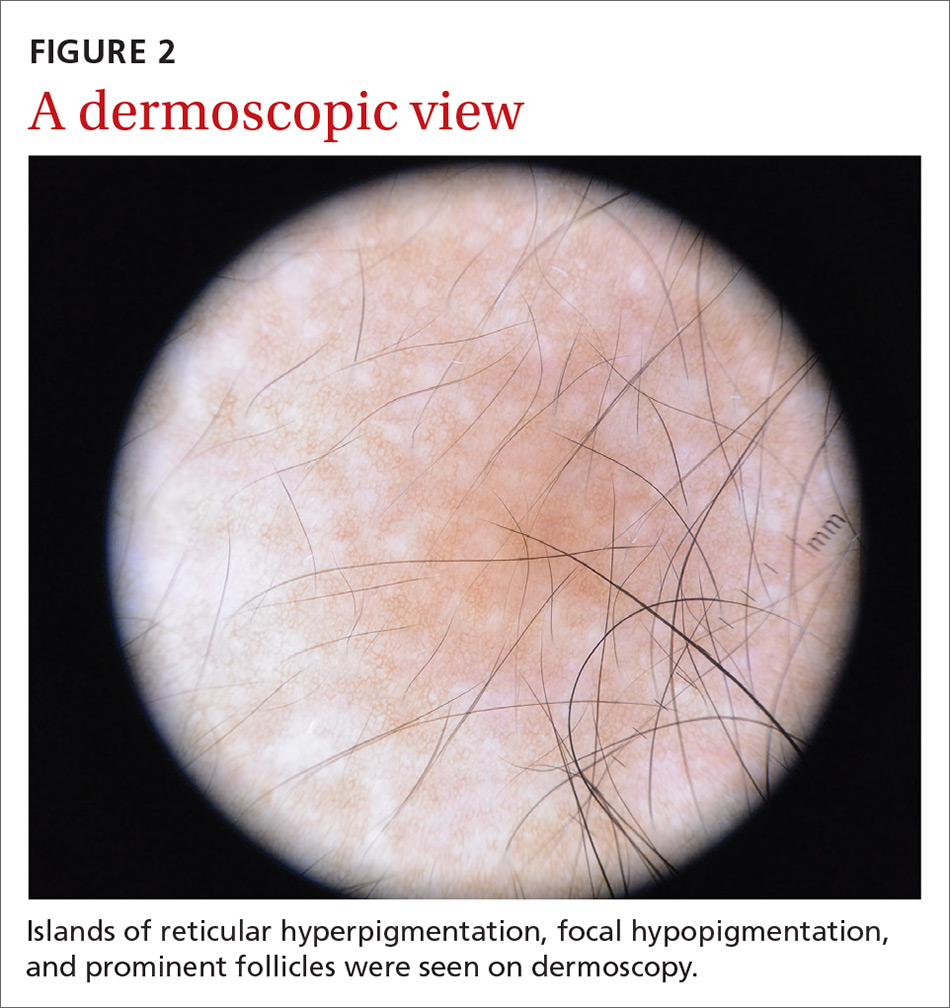

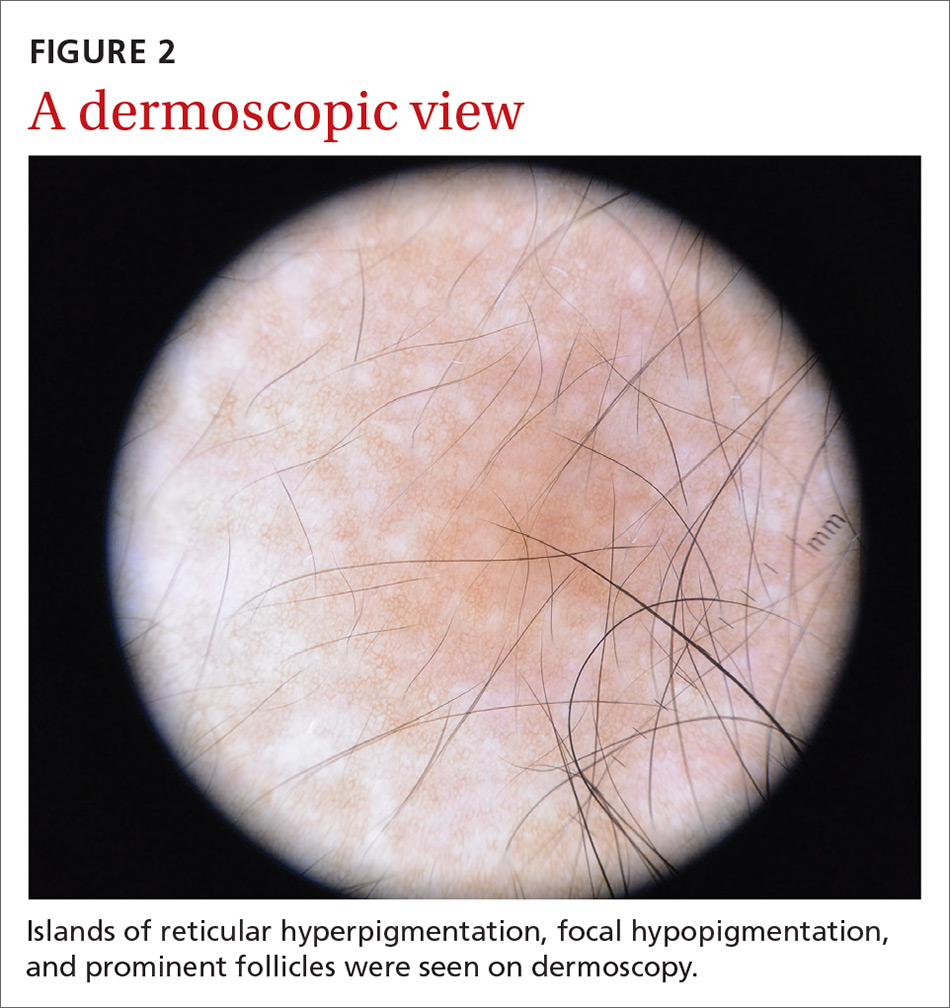

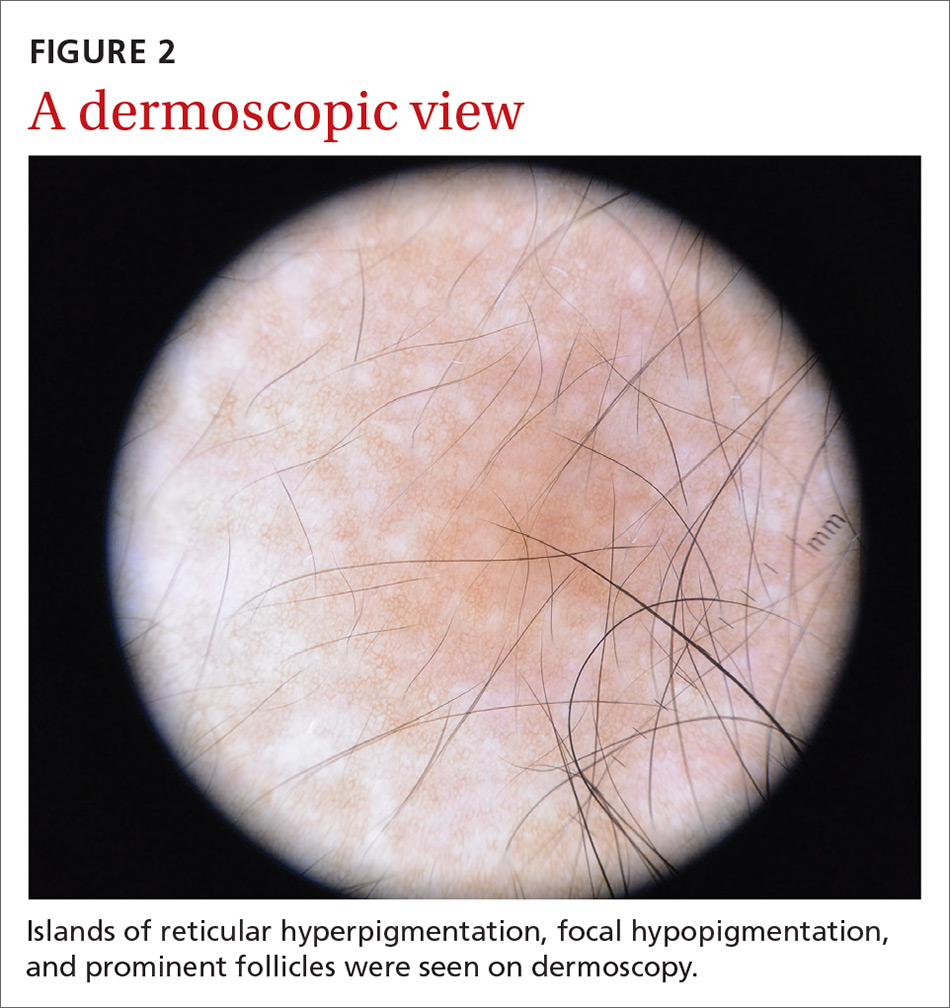

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

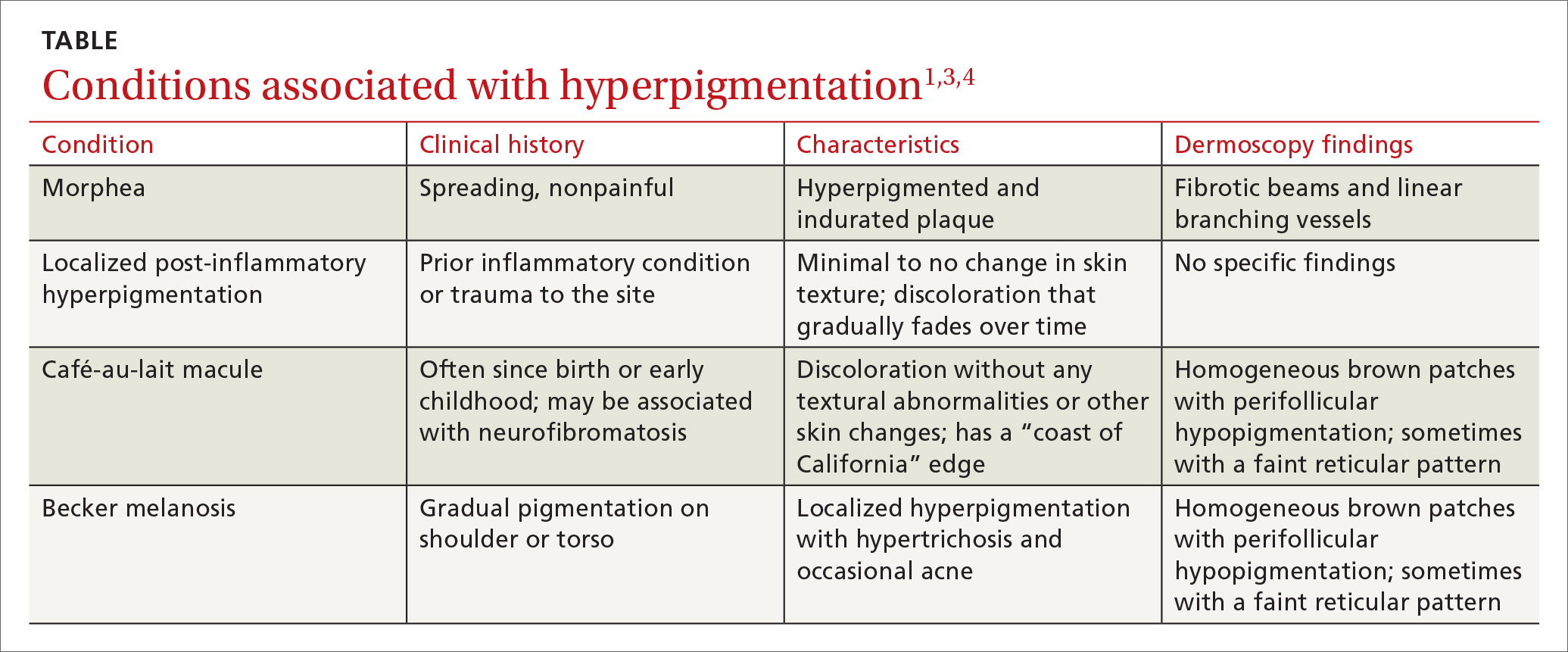

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

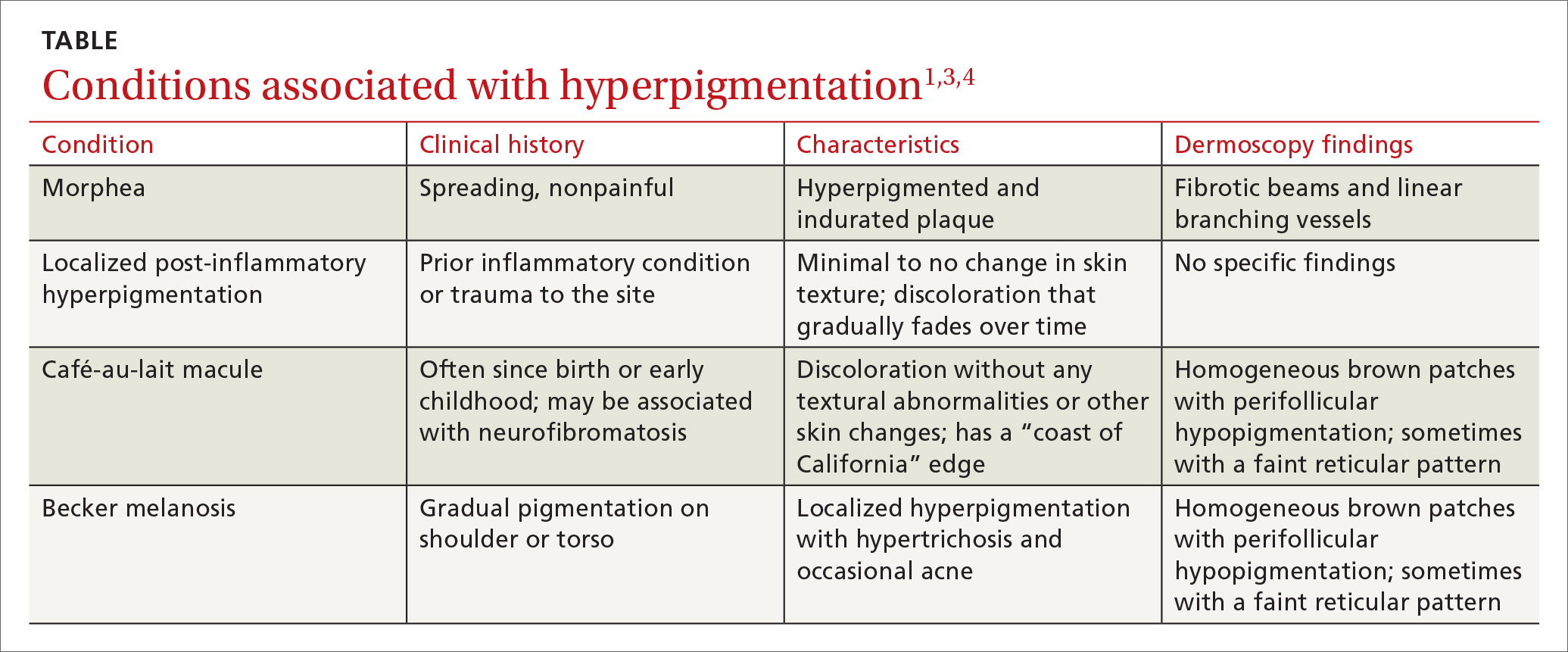

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; [email protected]

1. Rabinovitz HS, Barnhill RL. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012;112:1853-1854.

2. Person JR, Longcope C. Becker’s nevus: an androgen-mediated hyperplasia with increased androgen receptors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:235-238.

3. Cosendey FE, Martinez NS, Bernhard GA, et al. Becker nevus syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:379-384.

4. Ingordo V, Iannazzone SS, Cusano F, et al. Dermoscopic features of congenital melanocytic nevus and Becker nevus in an adult male population: an analysis with 10-fold magnification. Dermatology. 2006;212:354-360.

5. Luk DC, Lam SY, Cheung PC, et al. Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong-made dermoscope. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:495-503.

6. Balaraman B, Friedman PM. Hypertrichotic Becker’s nevi treated with combination 1,550nm non-ablative fractional photothermolysis and laser hair removal. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:350-353.

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; [email protected]

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; [email protected]

1. Rabinovitz HS, Barnhill RL. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012;112:1853-1854.

2. Person JR, Longcope C. Becker’s nevus: an androgen-mediated hyperplasia with increased androgen receptors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:235-238.

3. Cosendey FE, Martinez NS, Bernhard GA, et al. Becker nevus syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:379-384.

4. Ingordo V, Iannazzone SS, Cusano F, et al. Dermoscopic features of congenital melanocytic nevus and Becker nevus in an adult male population: an analysis with 10-fold magnification. Dermatology. 2006;212:354-360.

5. Luk DC, Lam SY, Cheung PC, et al. Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong-made dermoscope. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:495-503.

6. Balaraman B, Friedman PM. Hypertrichotic Becker’s nevi treated with combination 1,550nm non-ablative fractional photothermolysis and laser hair removal. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:350-353.

1. Rabinovitz HS, Barnhill RL. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012;112:1853-1854.

2. Person JR, Longcope C. Becker’s nevus: an androgen-mediated hyperplasia with increased androgen receptors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:235-238.

3. Cosendey FE, Martinez NS, Bernhard GA, et al. Becker nevus syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:379-384.

4. Ingordo V, Iannazzone SS, Cusano F, et al. Dermoscopic features of congenital melanocytic nevus and Becker nevus in an adult male population: an analysis with 10-fold magnification. Dermatology. 2006;212:354-360.

5. Luk DC, Lam SY, Cheung PC, et al. Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong-made dermoscope. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:495-503.

6. Balaraman B, Friedman PM. Hypertrichotic Becker’s nevi treated with combination 1,550nm non-ablative fractional photothermolysis and laser hair removal. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:350-353.

How could improved provider communication have improved the care this patient received?

THE CASE

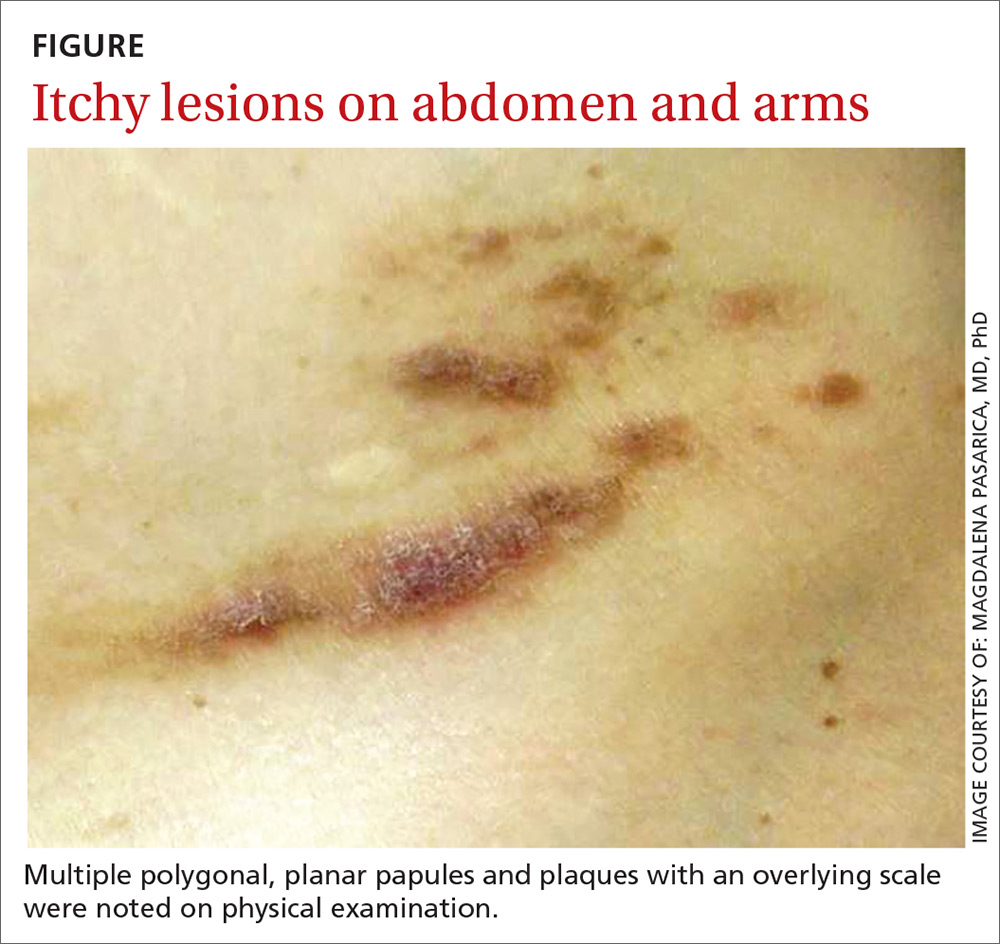

A 40-year-old white woman presented to clinic with multiple pruritic skin lesions on her abdomen, arms, and legs that had developed over a 2-month period. The patient reported that she’d been feeling tired and had been experiencing psychological stressors in her personal life. Her medical history was significant for psoriasis (which was controlled), and her family history was significant for breast and bone cancer (mother) and asbestos-related lung cancer (maternal grandfather).

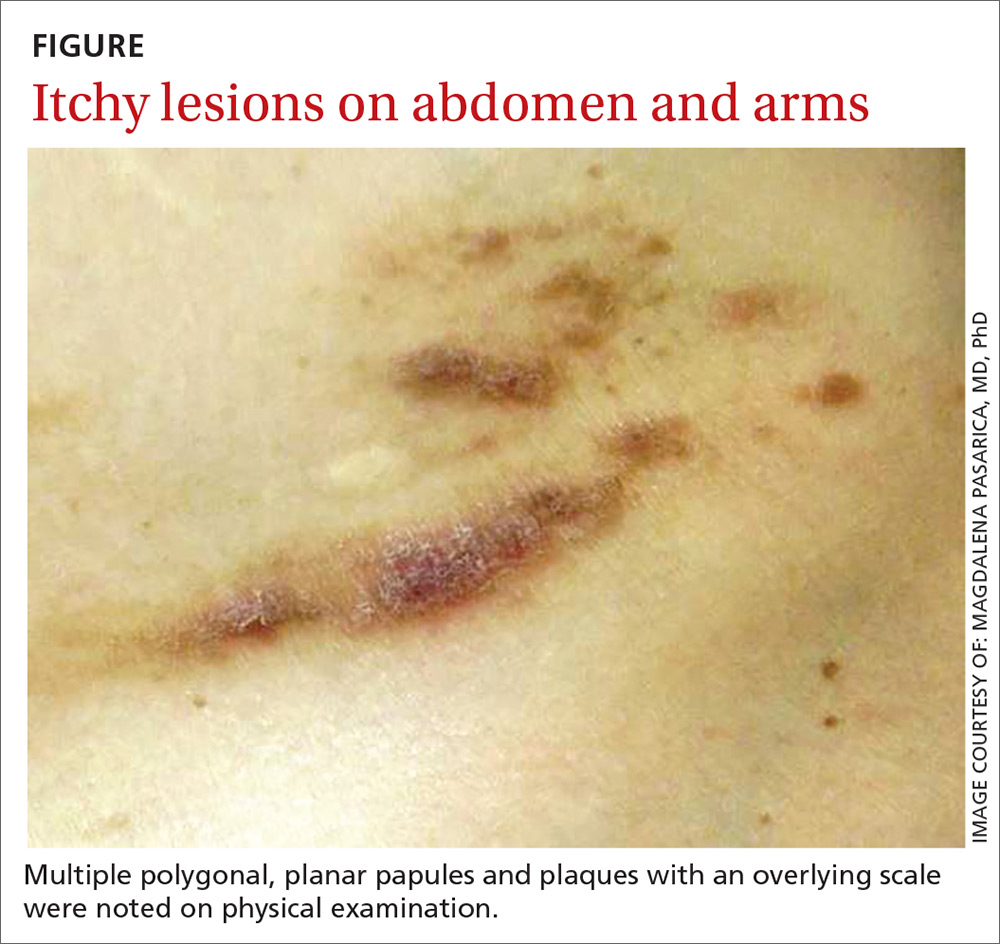

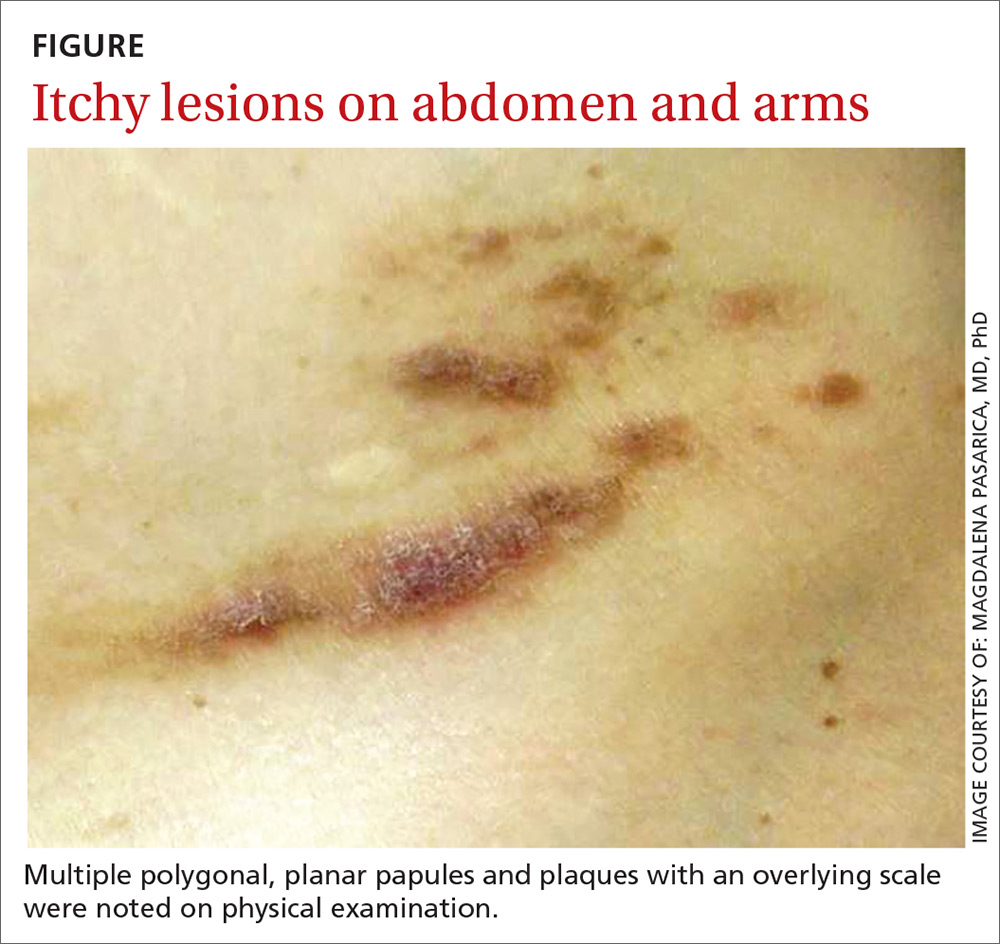

A physical examination, which included breast and pelvic exams, was unremarkable apart from the lesions located on her abdomen, arms, and legs. On skin examination, we noted multiple polygonal, planar papules and plaques of varying size with an overlying scale (FIGURE).

THE DIAGNOSIS

The physician obtained a biopsy of one of the skin lesions, and it was sent to a dermatopathologist to evaluate. Unfortunately, though, the patient’s history and a description of the lesion were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form. Based on the biopsy sample alone, the dermatopathologist’s report indicated a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.

A search for malignancy. Any case of sudden, extensive seborrheic keratosis is suspected to be a Leser-Trélat sign, which is known to be associated with human immunodeficiency virus or underlying malignancy—especially in the gastrointestinal system. The physician talked to the patient about the possibility of malignancy, and an extensive work-up was performed, including multiple laboratory tests, computed tomography (CT) imaging, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, a colonoscopy, and mammography. None of the test results showed signs of an underlying malignancy.

In light of the negative findings, the physician reached out to the dermatopathologist to further discuss the case. It was determined that the dermatopathologist did not receive any clinical information (prior to this discussion) from the primary care office. This was surprising to the primary care physician, who was under the assumption that the clinical chart would be sent along with the biopsy sample. With this new information, the dermatopathologist reexamined the slides and diagnosed the lesion as lichen planus, a rather common skin disease not associated with cancer.

[polldaddy:10153197]

DISCUSSION

A root-cause analysis of this case identified multiple system failures, focused mainly on a lack of communication between providers:

- The description of the lesion and of the patient’s history were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form due to a lack of communication between the nurse and the physician performing the procedure.

- The dermatopathologist did not seek additional clinical information from the referring physician after receiving the sample.

- When the various providers did communicate, an accurate diagnosis was reached—but only after extensive investigation (and worry).

Communication is key to an accurate diagnosis

In 2000, it was estimated that health care costs due to preventable adverse events represent more than half of the $37.6 billion spent on health care.1 Since then, considerable effort has been made to address patient safety, misdiagnosis, and cost-effectiveness. Root cause analysis is one of the most popular methods used to evaluate and prevent future serious adverse events.2

Continue to: Diagnostic errors are often unreported...

Diagnostic errors are often unreported or unrecognized, especially in the outpatient setting.3 Studies focused on reducing diagnostic error show that a second review of pathology slides reduces error, controls costs, and improves quality of health care.4

Don’t rely (exclusively) on the health record. Gaps in effective communication between providers are a leading cause of preventable adverse events.5,6 The incorporation of electronic health records has allowed for more streamlined communication between providers. However, the mere presence of patient records in a common system does not guarantee the receipt or communication of information. The next step after entering the information into the record is to communicate it.

Our patient underwent a battery of costly and unnecessary tests and procedures, many of which were unwarranted at her age. In addition to being exposed to harmful radiation, she also experienced significant stress secondary to the tests and anticipation of the results. However, a root cause analysis of the case led to an improved protocol for communication between providers at the outpatient clinic. We now emphasize the necessity of including a clinical history and corresponding physical findings with all biopsies. We also encourage more direct communication between nursing staff, primary care physicians, and specialists.

THE TAKEAWAY

As medical professionals become increasingly reliant on the many emerging studies available to them, we sometimes forget that communication is key to optimal medical care, an accurate diagnosis, and patient safety.

Continue to: In addition, a second review...

In addition, a second review of dermatopathologic slides may be warranted if the pathologic diagnosis is inconsistent with the clinical picture or if the diagnosed condition is resistant to the usual therapies of choice. Incorrect diagnoses are more likely to occur when tests are interpreted in a vacuum without the corresponding clinical correlation. The weight of these mistakes is felt not only by the health care system, but by the patients themselves.

CORRESPONDENCE

Magdalena Pasarica, MD, PhD, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, 6850 Lake Nona Boulevard, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected]

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Patient safety primer: root cause analysis. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/10/root-cause-analysis. Updated August 2018. Accessed September 27, 2018.

3. Newman-Toker DE, Pronovost PJ. Diagnostic errors-the next frontier for patient safety. JAMA. 2009;301:1060-1062.

4. Kuijpers CC, Burger G, Al-Janabi S, et al. Improved quality of patient care through routine second review of histopathology specimens prior to multidisciplinary meetings. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:866-871.

5. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:85-90.

6. Robinson NL. Promoting patient safety with perioperative hand-off communication. J Perianesth Nurs. 2016;31:245-253.

THE CASE

A 40-year-old white woman presented to clinic with multiple pruritic skin lesions on her abdomen, arms, and legs that had developed over a 2-month period. The patient reported that she’d been feeling tired and had been experiencing psychological stressors in her personal life. Her medical history was significant for psoriasis (which was controlled), and her family history was significant for breast and bone cancer (mother) and asbestos-related lung cancer (maternal grandfather).

A physical examination, which included breast and pelvic exams, was unremarkable apart from the lesions located on her abdomen, arms, and legs. On skin examination, we noted multiple polygonal, planar papules and plaques of varying size with an overlying scale (FIGURE).

THE DIAGNOSIS

The physician obtained a biopsy of one of the skin lesions, and it was sent to a dermatopathologist to evaluate. Unfortunately, though, the patient’s history and a description of the lesion were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form. Based on the biopsy sample alone, the dermatopathologist’s report indicated a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.

A search for malignancy. Any case of sudden, extensive seborrheic keratosis is suspected to be a Leser-Trélat sign, which is known to be associated with human immunodeficiency virus or underlying malignancy—especially in the gastrointestinal system. The physician talked to the patient about the possibility of malignancy, and an extensive work-up was performed, including multiple laboratory tests, computed tomography (CT) imaging, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, a colonoscopy, and mammography. None of the test results showed signs of an underlying malignancy.

In light of the negative findings, the physician reached out to the dermatopathologist to further discuss the case. It was determined that the dermatopathologist did not receive any clinical information (prior to this discussion) from the primary care office. This was surprising to the primary care physician, who was under the assumption that the clinical chart would be sent along with the biopsy sample. With this new information, the dermatopathologist reexamined the slides and diagnosed the lesion as lichen planus, a rather common skin disease not associated with cancer.

[polldaddy:10153197]

DISCUSSION

A root-cause analysis of this case identified multiple system failures, focused mainly on a lack of communication between providers:

- The description of the lesion and of the patient’s history were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form due to a lack of communication between the nurse and the physician performing the procedure.

- The dermatopathologist did not seek additional clinical information from the referring physician after receiving the sample.

- When the various providers did communicate, an accurate diagnosis was reached—but only after extensive investigation (and worry).

Communication is key to an accurate diagnosis

In 2000, it was estimated that health care costs due to preventable adverse events represent more than half of the $37.6 billion spent on health care.1 Since then, considerable effort has been made to address patient safety, misdiagnosis, and cost-effectiveness. Root cause analysis is one of the most popular methods used to evaluate and prevent future serious adverse events.2

Continue to: Diagnostic errors are often unreported...

Diagnostic errors are often unreported or unrecognized, especially in the outpatient setting.3 Studies focused on reducing diagnostic error show that a second review of pathology slides reduces error, controls costs, and improves quality of health care.4

Don’t rely (exclusively) on the health record. Gaps in effective communication between providers are a leading cause of preventable adverse events.5,6 The incorporation of electronic health records has allowed for more streamlined communication between providers. However, the mere presence of patient records in a common system does not guarantee the receipt or communication of information. The next step after entering the information into the record is to communicate it.

Our patient underwent a battery of costly and unnecessary tests and procedures, many of which were unwarranted at her age. In addition to being exposed to harmful radiation, she also experienced significant stress secondary to the tests and anticipation of the results. However, a root cause analysis of the case led to an improved protocol for communication between providers at the outpatient clinic. We now emphasize the necessity of including a clinical history and corresponding physical findings with all biopsies. We also encourage more direct communication between nursing staff, primary care physicians, and specialists.

THE TAKEAWAY

As medical professionals become increasingly reliant on the many emerging studies available to them, we sometimes forget that communication is key to optimal medical care, an accurate diagnosis, and patient safety.

Continue to: In addition, a second review...

In addition, a second review of dermatopathologic slides may be warranted if the pathologic diagnosis is inconsistent with the clinical picture or if the diagnosed condition is resistant to the usual therapies of choice. Incorrect diagnoses are more likely to occur when tests are interpreted in a vacuum without the corresponding clinical correlation. The weight of these mistakes is felt not only by the health care system, but by the patients themselves.

CORRESPONDENCE

Magdalena Pasarica, MD, PhD, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, 6850 Lake Nona Boulevard, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 40-year-old white woman presented to clinic with multiple pruritic skin lesions on her abdomen, arms, and legs that had developed over a 2-month period. The patient reported that she’d been feeling tired and had been experiencing psychological stressors in her personal life. Her medical history was significant for psoriasis (which was controlled), and her family history was significant for breast and bone cancer (mother) and asbestos-related lung cancer (maternal grandfather).

A physical examination, which included breast and pelvic exams, was unremarkable apart from the lesions located on her abdomen, arms, and legs. On skin examination, we noted multiple polygonal, planar papules and plaques of varying size with an overlying scale (FIGURE).

THE DIAGNOSIS

The physician obtained a biopsy of one of the skin lesions, and it was sent to a dermatopathologist to evaluate. Unfortunately, though, the patient’s history and a description of the lesion were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form. Based on the biopsy sample alone, the dermatopathologist’s report indicated a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.

A search for malignancy. Any case of sudden, extensive seborrheic keratosis is suspected to be a Leser-Trélat sign, which is known to be associated with human immunodeficiency virus or underlying malignancy—especially in the gastrointestinal system. The physician talked to the patient about the possibility of malignancy, and an extensive work-up was performed, including multiple laboratory tests, computed tomography (CT) imaging, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, a colonoscopy, and mammography. None of the test results showed signs of an underlying malignancy.

In light of the negative findings, the physician reached out to the dermatopathologist to further discuss the case. It was determined that the dermatopathologist did not receive any clinical information (prior to this discussion) from the primary care office. This was surprising to the primary care physician, who was under the assumption that the clinical chart would be sent along with the biopsy sample. With this new information, the dermatopathologist reexamined the slides and diagnosed the lesion as lichen planus, a rather common skin disease not associated with cancer.

[polldaddy:10153197]

DISCUSSION

A root-cause analysis of this case identified multiple system failures, focused mainly on a lack of communication between providers:

- The description of the lesion and of the patient’s history were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form due to a lack of communication between the nurse and the physician performing the procedure.

- The dermatopathologist did not seek additional clinical information from the referring physician after receiving the sample.

- When the various providers did communicate, an accurate diagnosis was reached—but only after extensive investigation (and worry).

Communication is key to an accurate diagnosis

In 2000, it was estimated that health care costs due to preventable adverse events represent more than half of the $37.6 billion spent on health care.1 Since then, considerable effort has been made to address patient safety, misdiagnosis, and cost-effectiveness. Root cause analysis is one of the most popular methods used to evaluate and prevent future serious adverse events.2

Continue to: Diagnostic errors are often unreported...

Diagnostic errors are often unreported or unrecognized, especially in the outpatient setting.3 Studies focused on reducing diagnostic error show that a second review of pathology slides reduces error, controls costs, and improves quality of health care.4

Don’t rely (exclusively) on the health record. Gaps in effective communication between providers are a leading cause of preventable adverse events.5,6 The incorporation of electronic health records has allowed for more streamlined communication between providers. However, the mere presence of patient records in a common system does not guarantee the receipt or communication of information. The next step after entering the information into the record is to communicate it.

Our patient underwent a battery of costly and unnecessary tests and procedures, many of which were unwarranted at her age. In addition to being exposed to harmful radiation, she also experienced significant stress secondary to the tests and anticipation of the results. However, a root cause analysis of the case led to an improved protocol for communication between providers at the outpatient clinic. We now emphasize the necessity of including a clinical history and corresponding physical findings with all biopsies. We also encourage more direct communication between nursing staff, primary care physicians, and specialists.

THE TAKEAWAY

As medical professionals become increasingly reliant on the many emerging studies available to them, we sometimes forget that communication is key to optimal medical care, an accurate diagnosis, and patient safety.

Continue to: In addition, a second review...

In addition, a second review of dermatopathologic slides may be warranted if the pathologic diagnosis is inconsistent with the clinical picture or if the diagnosed condition is resistant to the usual therapies of choice. Incorrect diagnoses are more likely to occur when tests are interpreted in a vacuum without the corresponding clinical correlation. The weight of these mistakes is felt not only by the health care system, but by the patients themselves.

CORRESPONDENCE

Magdalena Pasarica, MD, PhD, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, 6850 Lake Nona Boulevard, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected]

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Patient safety primer: root cause analysis. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/10/root-cause-analysis. Updated August 2018. Accessed September 27, 2018.

3. Newman-Toker DE, Pronovost PJ. Diagnostic errors-the next frontier for patient safety. JAMA. 2009;301:1060-1062.

4. Kuijpers CC, Burger G, Al-Janabi S, et al. Improved quality of patient care through routine second review of histopathology specimens prior to multidisciplinary meetings. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:866-871.

5. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:85-90.

6. Robinson NL. Promoting patient safety with perioperative hand-off communication. J Perianesth Nurs. 2016;31:245-253.

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Patient safety primer: root cause analysis. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/10/root-cause-analysis. Updated August 2018. Accessed September 27, 2018.

3. Newman-Toker DE, Pronovost PJ. Diagnostic errors-the next frontier for patient safety. JAMA. 2009;301:1060-1062.

4. Kuijpers CC, Burger G, Al-Janabi S, et al. Improved quality of patient care through routine second review of histopathology specimens prior to multidisciplinary meetings. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:866-871.

5. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:85-90.

6. Robinson NL. Promoting patient safety with perioperative hand-off communication. J Perianesth Nurs. 2016;31:245-253.

Should you reassess your patient’s asthma diagnosis?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 45-year-old woman presents to your office for a yearly visit. Two years ago she was started on an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a bronchodilator rescue inhaler after being diagnosed with asthma based on her history and physical exam findings. She has had no exacerbations since then. Should you consider weaning her off the inhalers?

Asthma is a prevalent problem; 8% of adults ages 18 to 64 years have the chronic lung disease.2 Diagnosis can be challenging, partially because it requires measurement of transient airway resistance. And treatment entails significant costs and possible adverse effects. Without some sort of pulmonary function measurements or trials off medication, there is no clinical way to differentiate patients with well-controlled asthma from those who are being treated unnecessarily. Not surprisingly, studies have shown that ruling out active asthma and reducing medication usage is cost effective.3,4 This study followed a cohort of patients to see how many could be weaned off their asthma medications, and how they did in the subsequent year.

STUDY SUMMARY

About one-third of adults with asthma are “undiagnosed” within 5 years

The researchers recruited participants from the general population of the 10 largest cities and surrounding areas in Canada by randomly dialing cellular and landline phone numbers and asking about adult household members with asthma.1 The researchers focused on people with a recent (<5 years) asthma diagnosis, so as to represent contemporary diagnostic practice and to make it easier to collect medical records. Participants lived within 90 minutes of 10 medical centers in Canada. Patients were excluded if they were using long-term oral steroids, pregnant or breastfeeding, unable to tolerate spirometry or methacholine challenges, or had a history of more than 10 pack-years of smoking.

Of the 701 patients enrolled, 613 (87.4%) completed all study assessments. Patients progressed through a series of spirometry tests and were then tapered off their asthma-controlling medications.

The initial spirometry test confirmed asthma if bronchodilators caused a significant improvement in forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration (FEV1). If there was no improvement, the patient took a methacholine challenge 1 week later; if they did well, their maintenance medications were reduced by half. If the patient did well with another methacholine challenge about 1 month later, maintenance medications were stopped, and the patient underwent a third methacholine challenge 3 weeks later.

Asthma was confirmed at any methacholine challenge if there was a 20% decrease in FEV1 from baseline at a methacholine concentration of ≤8 mg/mL; these patients were restarted on appropriate medications. If current asthma was ruled out, follow-up bronchial challenges were repeated at 6 and 12 months.

Results. Among the adults with physician-diagnosed asthma, 33.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 29.4%-36.8%) no longer met criteria for an asthma diagnosis. Of those who no longer had asthma, 44% had previously undergone objective testing of airflow limitation. The investigators also found 12 patients (2%) had other serious cardiorespiratory conditions instead of asthma, including ischemic heart disease, subglottic stenosis, and bronchiectasis.

Continue to: During the 1-year follow-up period...

During the 1-year follow-up period, 22 (10.8%) of the 203 patients who were initially judged to no longer have asthma had a positive bronchial challenge test; 16 had no symptoms and continued to do well off all asthma medications. Six (3%) presented with respiratory symptoms and resumed treatment with asthma medications, but only 1 (0.5%) required oral corticosteroid therapy.

WHAT’S NEW?

Asthma meds are of no benefit for about one-third of patients taking them

This study found that one-third of patients with asthma diagnosed in the last 5 years no longer had symptoms or spirometry results consistent with asthma and did well in the subsequent year. For those patients, there appears to be no benefit to using asthma medications. The Global Institute for Asthma recommends stepping down treatment in adults with asthma that is well controlled for 3 months or more.5 While patients with objectively confirmed asthma diagnoses were more likely to still have asthma in this study, over 40% of patients who no longer had asthma were objectively proven to have had asthma at their original diagnosis.

CAVEATS

High level of rigor and the absence of a randomized trial

This study used a very structured protocol for tapering patients off their medications, including multiple spirometry tests, most including methacholine challenges, as well as oversight by pulmonologists. It is unclear whether this level of rigor is necessary for weaning in other clinical settings.

Also, this study was not a randomized trial, which is the gold standard for withdrawal of therapy. However, a cohort study is adequate to assess diagnostic testing, and this could be considered a trial of “undiagnosing” asthma in adults. The results here are consistent with those of a study that looked at asthma disappearance in groups of patients with and without obesity. In that study, approximately 30% of both groups of patients no longer had a diagnosis of asthma.6

Using random dialing is likely to have broadened the pool of patients this study drew upon. Also, there is a possibility that the patients who were lost to follow-up in this study represented those who had worsening symptoms. Some patients with mild asthma may have a waxing and waning course; it is possible that the study period was not long enough to capture this. In this study, only about 3% of patients who had their medications stopped reported worsening of symptoms.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

“Undiagnosis” is unusual

Using objective testing may provide some logistical or financial challenges for patients. Furthermore, “undiagnosing” a chronic disease like asthma is not a physician’s typical work, and it may take some time and effort to educate and monitor patients through the process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

2. QuickStats: percentage of adults aged 18-64 years with current asthma,* by state - National Health Interview Survey,† 2014-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:590.

3. Pakhale S, Sumner A, Coyle D, et al. (Correcting) misdiagnoses of asthma: a cost effectiveness analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:27.

4. Rank MA, Liesinger JT, Branda ME, et al. Comparative safety and costs of stepping down asthma medications in patients with controlled asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1373-1379.

5. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2018. https://ginasthma.org. Accessed June 15, 2018.

6. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Boulet LP, et al. Overdiagnosis of asthma in obese and nonobese adults. CMAJ. 2008;179:1121-1131.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 45-year-old woman presents to your office for a yearly visit. Two years ago she was started on an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a bronchodilator rescue inhaler after being diagnosed with asthma based on her history and physical exam findings. She has had no exacerbations since then. Should you consider weaning her off the inhalers?

Asthma is a prevalent problem; 8% of adults ages 18 to 64 years have the chronic lung disease.2 Diagnosis can be challenging, partially because it requires measurement of transient airway resistance. And treatment entails significant costs and possible adverse effects. Without some sort of pulmonary function measurements or trials off medication, there is no clinical way to differentiate patients with well-controlled asthma from those who are being treated unnecessarily. Not surprisingly, studies have shown that ruling out active asthma and reducing medication usage is cost effective.3,4 This study followed a cohort of patients to see how many could be weaned off their asthma medications, and how they did in the subsequent year.

STUDY SUMMARY

About one-third of adults with asthma are “undiagnosed” within 5 years

The researchers recruited participants from the general population of the 10 largest cities and surrounding areas in Canada by randomly dialing cellular and landline phone numbers and asking about adult household members with asthma.1 The researchers focused on people with a recent (<5 years) asthma diagnosis, so as to represent contemporary diagnostic practice and to make it easier to collect medical records. Participants lived within 90 minutes of 10 medical centers in Canada. Patients were excluded if they were using long-term oral steroids, pregnant or breastfeeding, unable to tolerate spirometry or methacholine challenges, or had a history of more than 10 pack-years of smoking.

Of the 701 patients enrolled, 613 (87.4%) completed all study assessments. Patients progressed through a series of spirometry tests and were then tapered off their asthma-controlling medications.

The initial spirometry test confirmed asthma if bronchodilators caused a significant improvement in forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration (FEV1). If there was no improvement, the patient took a methacholine challenge 1 week later; if they did well, their maintenance medications were reduced by half. If the patient did well with another methacholine challenge about 1 month later, maintenance medications were stopped, and the patient underwent a third methacholine challenge 3 weeks later.

Asthma was confirmed at any methacholine challenge if there was a 20% decrease in FEV1 from baseline at a methacholine concentration of ≤8 mg/mL; these patients were restarted on appropriate medications. If current asthma was ruled out, follow-up bronchial challenges were repeated at 6 and 12 months.

Results. Among the adults with physician-diagnosed asthma, 33.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 29.4%-36.8%) no longer met criteria for an asthma diagnosis. Of those who no longer had asthma, 44% had previously undergone objective testing of airflow limitation. The investigators also found 12 patients (2%) had other serious cardiorespiratory conditions instead of asthma, including ischemic heart disease, subglottic stenosis, and bronchiectasis.

Continue to: During the 1-year follow-up period...

During the 1-year follow-up period, 22 (10.8%) of the 203 patients who were initially judged to no longer have asthma had a positive bronchial challenge test; 16 had no symptoms and continued to do well off all asthma medications. Six (3%) presented with respiratory symptoms and resumed treatment with asthma medications, but only 1 (0.5%) required oral corticosteroid therapy.

WHAT’S NEW?

Asthma meds are of no benefit for about one-third of patients taking them

This study found that one-third of patients with asthma diagnosed in the last 5 years no longer had symptoms or spirometry results consistent with asthma and did well in the subsequent year. For those patients, there appears to be no benefit to using asthma medications. The Global Institute for Asthma recommends stepping down treatment in adults with asthma that is well controlled for 3 months or more.5 While patients with objectively confirmed asthma diagnoses were more likely to still have asthma in this study, over 40% of patients who no longer had asthma were objectively proven to have had asthma at their original diagnosis.

CAVEATS

High level of rigor and the absence of a randomized trial

This study used a very structured protocol for tapering patients off their medications, including multiple spirometry tests, most including methacholine challenges, as well as oversight by pulmonologists. It is unclear whether this level of rigor is necessary for weaning in other clinical settings.

Also, this study was not a randomized trial, which is the gold standard for withdrawal of therapy. However, a cohort study is adequate to assess diagnostic testing, and this could be considered a trial of “undiagnosing” asthma in adults. The results here are consistent with those of a study that looked at asthma disappearance in groups of patients with and without obesity. In that study, approximately 30% of both groups of patients no longer had a diagnosis of asthma.6

Using random dialing is likely to have broadened the pool of patients this study drew upon. Also, there is a possibility that the patients who were lost to follow-up in this study represented those who had worsening symptoms. Some patients with mild asthma may have a waxing and waning course; it is possible that the study period was not long enough to capture this. In this study, only about 3% of patients who had their medications stopped reported worsening of symptoms.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

“Undiagnosis” is unusual

Using objective testing may provide some logistical or financial challenges for patients. Furthermore, “undiagnosing” a chronic disease like asthma is not a physician’s typical work, and it may take some time and effort to educate and monitor patients through the process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 45-year-old woman presents to your office for a yearly visit. Two years ago she was started on an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a bronchodilator rescue inhaler after being diagnosed with asthma based on her history and physical exam findings. She has had no exacerbations since then. Should you consider weaning her off the inhalers?

Asthma is a prevalent problem; 8% of adults ages 18 to 64 years have the chronic lung disease.2 Diagnosis can be challenging, partially because it requires measurement of transient airway resistance. And treatment entails significant costs and possible adverse effects. Without some sort of pulmonary function measurements or trials off medication, there is no clinical way to differentiate patients with well-controlled asthma from those who are being treated unnecessarily. Not surprisingly, studies have shown that ruling out active asthma and reducing medication usage is cost effective.3,4 This study followed a cohort of patients to see how many could be weaned off their asthma medications, and how they did in the subsequent year.

STUDY SUMMARY

About one-third of adults with asthma are “undiagnosed” within 5 years

The researchers recruited participants from the general population of the 10 largest cities and surrounding areas in Canada by randomly dialing cellular and landline phone numbers and asking about adult household members with asthma.1 The researchers focused on people with a recent (<5 years) asthma diagnosis, so as to represent contemporary diagnostic practice and to make it easier to collect medical records. Participants lived within 90 minutes of 10 medical centers in Canada. Patients were excluded if they were using long-term oral steroids, pregnant or breastfeeding, unable to tolerate spirometry or methacholine challenges, or had a history of more than 10 pack-years of smoking.

Of the 701 patients enrolled, 613 (87.4%) completed all study assessments. Patients progressed through a series of spirometry tests and were then tapered off their asthma-controlling medications.

The initial spirometry test confirmed asthma if bronchodilators caused a significant improvement in forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration (FEV1). If there was no improvement, the patient took a methacholine challenge 1 week later; if they did well, their maintenance medications were reduced by half. If the patient did well with another methacholine challenge about 1 month later, maintenance medications were stopped, and the patient underwent a third methacholine challenge 3 weeks later.

Asthma was confirmed at any methacholine challenge if there was a 20% decrease in FEV1 from baseline at a methacholine concentration of ≤8 mg/mL; these patients were restarted on appropriate medications. If current asthma was ruled out, follow-up bronchial challenges were repeated at 6 and 12 months.

Results. Among the adults with physician-diagnosed asthma, 33.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 29.4%-36.8%) no longer met criteria for an asthma diagnosis. Of those who no longer had asthma, 44% had previously undergone objective testing of airflow limitation. The investigators also found 12 patients (2%) had other serious cardiorespiratory conditions instead of asthma, including ischemic heart disease, subglottic stenosis, and bronchiectasis.

Continue to: During the 1-year follow-up period...

During the 1-year follow-up period, 22 (10.8%) of the 203 patients who were initially judged to no longer have asthma had a positive bronchial challenge test; 16 had no symptoms and continued to do well off all asthma medications. Six (3%) presented with respiratory symptoms and resumed treatment with asthma medications, but only 1 (0.5%) required oral corticosteroid therapy.

WHAT’S NEW?

Asthma meds are of no benefit for about one-third of patients taking them

This study found that one-third of patients with asthma diagnosed in the last 5 years no longer had symptoms or spirometry results consistent with asthma and did well in the subsequent year. For those patients, there appears to be no benefit to using asthma medications. The Global Institute for Asthma recommends stepping down treatment in adults with asthma that is well controlled for 3 months or more.5 While patients with objectively confirmed asthma diagnoses were more likely to still have asthma in this study, over 40% of patients who no longer had asthma were objectively proven to have had asthma at their original diagnosis.

CAVEATS

High level of rigor and the absence of a randomized trial

This study used a very structured protocol for tapering patients off their medications, including multiple spirometry tests, most including methacholine challenges, as well as oversight by pulmonologists. It is unclear whether this level of rigor is necessary for weaning in other clinical settings.

Also, this study was not a randomized trial, which is the gold standard for withdrawal of therapy. However, a cohort study is adequate to assess diagnostic testing, and this could be considered a trial of “undiagnosing” asthma in adults. The results here are consistent with those of a study that looked at asthma disappearance in groups of patients with and without obesity. In that study, approximately 30% of both groups of patients no longer had a diagnosis of asthma.6

Using random dialing is likely to have broadened the pool of patients this study drew upon. Also, there is a possibility that the patients who were lost to follow-up in this study represented those who had worsening symptoms. Some patients with mild asthma may have a waxing and waning course; it is possible that the study period was not long enough to capture this. In this study, only about 3% of patients who had their medications stopped reported worsening of symptoms.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

“Undiagnosis” is unusual

Using objective testing may provide some logistical or financial challenges for patients. Furthermore, “undiagnosing” a chronic disease like asthma is not a physician’s typical work, and it may take some time and effort to educate and monitor patients through the process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

2. QuickStats: percentage of adults aged 18-64 years with current asthma,* by state - National Health Interview Survey,† 2014-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:590.

3. Pakhale S, Sumner A, Coyle D, et al. (Correcting) misdiagnoses of asthma: a cost effectiveness analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:27.

4. Rank MA, Liesinger JT, Branda ME, et al. Comparative safety and costs of stepping down asthma medications in patients with controlled asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1373-1379.

5. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2018. https://ginasthma.org. Accessed June 15, 2018.

6. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Boulet LP, et al. Overdiagnosis of asthma in obese and nonobese adults. CMAJ. 2008;179:1121-1131.

1. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

2. QuickStats: percentage of adults aged 18-64 years with current asthma,* by state - National Health Interview Survey,† 2014-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:590.

3. Pakhale S, Sumner A, Coyle D, et al. (Correcting) misdiagnoses of asthma: a cost effectiveness analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:27.