User login

Correction: Genitourinary syndrome of menopause

Taurine

Taurine, also known as 2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, is a naturally occurring beta-amino acid (which has a sulphonic acid group instead of carboxylic acid, differentiating it from other amino acids) yielded by methionine and cysteine metabolism in the liver.1,2 An important free beta-amino acid in mammals, it is often the free amino acid present in the greatest concentrations in several cell types in humans.1,2 Dietary intake of taurine also plays an important role in maintaining the body’s taurine levels because of mammals’ limited ability to synthesize it.1

Notably in terms of dermatologic treatment options, the combination product taurine bromamine is known to impart antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities.3 And taurine itself is associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and immunomodulatory characteristics,1,4 and is noted for conferring antiaging benefits.5

Acne and other inflammatory conditions

The use of .6,7

In response to the problem of evolving antibiotic resistance, Marcinkiewicz reported in 2009 on the then-new therapeutic option of topical taurine bromamine for the treatment of inflammatory skin disorders such as acne. The author pointed out that Propionibacterium acnes is particularly sensitive to taurine bromamine, with the substance now known to suppress H2O2 production by activated neutrophils, likely contributing to moderating the severity and lowering the number of inflammatory acne lesions. In a 6-week double-blind pilot clinical study, Marcinkiewicz and his team compared the efficacy of 0.5% taurine bromamine cream with 1% clindamycin gel in 40 patients with mild to moderate acne. Treatments, which were randomly assigned, occurred twice daily through the study. Amelioration of acne symptoms was comparable in the two groups, with more than 90% of patients improving clinically and experiencing similar decreases in acne lesions (65% in the taurine bromamine group and 68% in the clindamycin group). Marcinkiewicz concluded that these results indicate the viability of taurine bromamine as an option for inflammatory acne therapy, particularly for patients who have shown antibiotic resistance.3

Wide-ranging protection potential

In 2003, Janeke et al. conducted analyses that showed that taurine accumulation defended cultured human keratinocytes from osmotically- and UV-induced apoptosis, suggesting the importance of taurine as an epidermal osmolyte necessary for maintaining keratinocyte hydration in a dry environment.2

Three years later, Collin et al. demonstrated the dynamic protective effects of taurine on the human hair follicle in an in vitro study in which taurine promoted hair survival and protected against TGF-beta1-induced damage.1

Taurine has also been found to stabilize and protect the catalytic activity of the hemoprotein cytochrome P450 3A4, which is a key enzyme responsible for metabolizing various endogenous as well as foreign substances, including drugs.8

Penetration enhancement

In 2016, Mueller et al. studied the effects of urea and taurine as hydrophilic penetration enhancers on stratum corneum lipid models as both substances are known to exert such effects. With inconclusive results as to the roots of such activity, they speculated that both entities enhance penetration through the introduction of copious water into the corneocytes, resulting from the robust water-binding capacity of urea and the consequent osmotic pressure related to taurine.9

Possible skin whitening and anti-aging roles and other promising lab results

Based on their previous work demonstrating that azelaic acid, a saturated dicarboxylic acid found naturally in wheat, rye, and barley, suppressed melanogenesis, Yu and Kim investigated the antimelanogenic activity of azelaic acid and taurine in B16F10 mouse melanoma cells in 2010. They found that the combination of the two substances exhibited a greater inhibitory effect in melanocytes than azelaic acid alone, with melanin production and tyrosinase activity suppressed without inducing cytotoxicity. The investigators concluded the combination of azelaic acid and taurine may be an effective approach for treating hyperpigmentation.10

In 2015, Ito et al. investigated the possible anti-aging role of taurine using a taurine transporter knockout mouse model. They noted that aging-related disorders affecting the skin, heart, skeletal muscle, and liver and resulting in a shorter lifespan have been correlated with tissue taurine depletion. The researchers proposed that proper protein folding allows endogenous taurine to perform as an antiaging molecule.5

Also in 2015, Kim et al. investigated potential mechanisms of the antiproliferative activity of taurine on murine B16F10 melanoma cells via the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and neutral red assays and microscopic analysis. They found that taurine prevented cell proliferation and engendered apoptosis in B16F10 cells, concluding that taurine may have a role to play as a chemotherapeutic agent for skin cancer.11

In 2014, Ashkani-Esfahani et al. studied the impact of taurine on cutaneous leishmaniasis wounds in a mouse model. Investigators induced 18 mice with wounds using L. major promastigotes, and divided them into a taurine injection group, taurine gel group, and no treatment group, performing treatments every 24 hours over 21 days. The taurine treatment groups exhibited significantly greater numerical fibroblast density, collagen bundle volume density, and vessel length densities compared with the nontreatment group. The taurine injection group displayed higher fibroblast numerical density than did the taurine gel group. The researchers concluded that taurine has the capacity to enhance wound healing and tissue regeneration but showed no direct anti-leishmaniasis effect.4

Conclusion

Taurine has been found over the last few decades to impart salutary effects for human health. This beta-amino acid that occurs naturally in humans and other mammals also appears to hold promising potential in the dermatologic realm, particularly for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. More research is needed to ascertain just how pivotal this compound can be for skin health.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006 Aug;28(4):289-98.

2. J Invest Dermatol. 2003 Aug;121(2):354-61.

3. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009 Oct;119(10):673-6.

4. Adv Biomed Res. 2014 Oct 7;3:204.

5. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;803:481-7.

6. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012 Dec 1;13(6):357-64.

7. Eur J Dermatol. 2008 Jul-Aug;18(4):433-9.

8. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2015 Mar;80(3):366-73.

9. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 Sep;1858(9):2006-18.

10. J Biomed Sci. 2010 Aug 24;17 Suppl 1:S45.

11. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;803:167-77.

Taurine, also known as 2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, is a naturally occurring beta-amino acid (which has a sulphonic acid group instead of carboxylic acid, differentiating it from other amino acids) yielded by methionine and cysteine metabolism in the liver.1,2 An important free beta-amino acid in mammals, it is often the free amino acid present in the greatest concentrations in several cell types in humans.1,2 Dietary intake of taurine also plays an important role in maintaining the body’s taurine levels because of mammals’ limited ability to synthesize it.1

Notably in terms of dermatologic treatment options, the combination product taurine bromamine is known to impart antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities.3 And taurine itself is associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and immunomodulatory characteristics,1,4 and is noted for conferring antiaging benefits.5

Acne and other inflammatory conditions

The use of .6,7

In response to the problem of evolving antibiotic resistance, Marcinkiewicz reported in 2009 on the then-new therapeutic option of topical taurine bromamine for the treatment of inflammatory skin disorders such as acne. The author pointed out that Propionibacterium acnes is particularly sensitive to taurine bromamine, with the substance now known to suppress H2O2 production by activated neutrophils, likely contributing to moderating the severity and lowering the number of inflammatory acne lesions. In a 6-week double-blind pilot clinical study, Marcinkiewicz and his team compared the efficacy of 0.5% taurine bromamine cream with 1% clindamycin gel in 40 patients with mild to moderate acne. Treatments, which were randomly assigned, occurred twice daily through the study. Amelioration of acne symptoms was comparable in the two groups, with more than 90% of patients improving clinically and experiencing similar decreases in acne lesions (65% in the taurine bromamine group and 68% in the clindamycin group). Marcinkiewicz concluded that these results indicate the viability of taurine bromamine as an option for inflammatory acne therapy, particularly for patients who have shown antibiotic resistance.3

Wide-ranging protection potential

In 2003, Janeke et al. conducted analyses that showed that taurine accumulation defended cultured human keratinocytes from osmotically- and UV-induced apoptosis, suggesting the importance of taurine as an epidermal osmolyte necessary for maintaining keratinocyte hydration in a dry environment.2

Three years later, Collin et al. demonstrated the dynamic protective effects of taurine on the human hair follicle in an in vitro study in which taurine promoted hair survival and protected against TGF-beta1-induced damage.1

Taurine has also been found to stabilize and protect the catalytic activity of the hemoprotein cytochrome P450 3A4, which is a key enzyme responsible for metabolizing various endogenous as well as foreign substances, including drugs.8

Penetration enhancement

In 2016, Mueller et al. studied the effects of urea and taurine as hydrophilic penetration enhancers on stratum corneum lipid models as both substances are known to exert such effects. With inconclusive results as to the roots of such activity, they speculated that both entities enhance penetration through the introduction of copious water into the corneocytes, resulting from the robust water-binding capacity of urea and the consequent osmotic pressure related to taurine.9

Possible skin whitening and anti-aging roles and other promising lab results

Based on their previous work demonstrating that azelaic acid, a saturated dicarboxylic acid found naturally in wheat, rye, and barley, suppressed melanogenesis, Yu and Kim investigated the antimelanogenic activity of azelaic acid and taurine in B16F10 mouse melanoma cells in 2010. They found that the combination of the two substances exhibited a greater inhibitory effect in melanocytes than azelaic acid alone, with melanin production and tyrosinase activity suppressed without inducing cytotoxicity. The investigators concluded the combination of azelaic acid and taurine may be an effective approach for treating hyperpigmentation.10

In 2015, Ito et al. investigated the possible anti-aging role of taurine using a taurine transporter knockout mouse model. They noted that aging-related disorders affecting the skin, heart, skeletal muscle, and liver and resulting in a shorter lifespan have been correlated with tissue taurine depletion. The researchers proposed that proper protein folding allows endogenous taurine to perform as an antiaging molecule.5

Also in 2015, Kim et al. investigated potential mechanisms of the antiproliferative activity of taurine on murine B16F10 melanoma cells via the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and neutral red assays and microscopic analysis. They found that taurine prevented cell proliferation and engendered apoptosis in B16F10 cells, concluding that taurine may have a role to play as a chemotherapeutic agent for skin cancer.11

In 2014, Ashkani-Esfahani et al. studied the impact of taurine on cutaneous leishmaniasis wounds in a mouse model. Investigators induced 18 mice with wounds using L. major promastigotes, and divided them into a taurine injection group, taurine gel group, and no treatment group, performing treatments every 24 hours over 21 days. The taurine treatment groups exhibited significantly greater numerical fibroblast density, collagen bundle volume density, and vessel length densities compared with the nontreatment group. The taurine injection group displayed higher fibroblast numerical density than did the taurine gel group. The researchers concluded that taurine has the capacity to enhance wound healing and tissue regeneration but showed no direct anti-leishmaniasis effect.4

Conclusion

Taurine has been found over the last few decades to impart salutary effects for human health. This beta-amino acid that occurs naturally in humans and other mammals also appears to hold promising potential in the dermatologic realm, particularly for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. More research is needed to ascertain just how pivotal this compound can be for skin health.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006 Aug;28(4):289-98.

2. J Invest Dermatol. 2003 Aug;121(2):354-61.

3. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009 Oct;119(10):673-6.

4. Adv Biomed Res. 2014 Oct 7;3:204.

5. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;803:481-7.

6. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012 Dec 1;13(6):357-64.

7. Eur J Dermatol. 2008 Jul-Aug;18(4):433-9.

8. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2015 Mar;80(3):366-73.

9. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 Sep;1858(9):2006-18.

10. J Biomed Sci. 2010 Aug 24;17 Suppl 1:S45.

11. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;803:167-77.

Taurine, also known as 2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, is a naturally occurring beta-amino acid (which has a sulphonic acid group instead of carboxylic acid, differentiating it from other amino acids) yielded by methionine and cysteine metabolism in the liver.1,2 An important free beta-amino acid in mammals, it is often the free amino acid present in the greatest concentrations in several cell types in humans.1,2 Dietary intake of taurine also plays an important role in maintaining the body’s taurine levels because of mammals’ limited ability to synthesize it.1

Notably in terms of dermatologic treatment options, the combination product taurine bromamine is known to impart antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities.3 And taurine itself is associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and immunomodulatory characteristics,1,4 and is noted for conferring antiaging benefits.5

Acne and other inflammatory conditions

The use of .6,7

In response to the problem of evolving antibiotic resistance, Marcinkiewicz reported in 2009 on the then-new therapeutic option of topical taurine bromamine for the treatment of inflammatory skin disorders such as acne. The author pointed out that Propionibacterium acnes is particularly sensitive to taurine bromamine, with the substance now known to suppress H2O2 production by activated neutrophils, likely contributing to moderating the severity and lowering the number of inflammatory acne lesions. In a 6-week double-blind pilot clinical study, Marcinkiewicz and his team compared the efficacy of 0.5% taurine bromamine cream with 1% clindamycin gel in 40 patients with mild to moderate acne. Treatments, which were randomly assigned, occurred twice daily through the study. Amelioration of acne symptoms was comparable in the two groups, with more than 90% of patients improving clinically and experiencing similar decreases in acne lesions (65% in the taurine bromamine group and 68% in the clindamycin group). Marcinkiewicz concluded that these results indicate the viability of taurine bromamine as an option for inflammatory acne therapy, particularly for patients who have shown antibiotic resistance.3

Wide-ranging protection potential

In 2003, Janeke et al. conducted analyses that showed that taurine accumulation defended cultured human keratinocytes from osmotically- and UV-induced apoptosis, suggesting the importance of taurine as an epidermal osmolyte necessary for maintaining keratinocyte hydration in a dry environment.2

Three years later, Collin et al. demonstrated the dynamic protective effects of taurine on the human hair follicle in an in vitro study in which taurine promoted hair survival and protected against TGF-beta1-induced damage.1

Taurine has also been found to stabilize and protect the catalytic activity of the hemoprotein cytochrome P450 3A4, which is a key enzyme responsible for metabolizing various endogenous as well as foreign substances, including drugs.8

Penetration enhancement

In 2016, Mueller et al. studied the effects of urea and taurine as hydrophilic penetration enhancers on stratum corneum lipid models as both substances are known to exert such effects. With inconclusive results as to the roots of such activity, they speculated that both entities enhance penetration through the introduction of copious water into the corneocytes, resulting from the robust water-binding capacity of urea and the consequent osmotic pressure related to taurine.9

Possible skin whitening and anti-aging roles and other promising lab results

Based on their previous work demonstrating that azelaic acid, a saturated dicarboxylic acid found naturally in wheat, rye, and barley, suppressed melanogenesis, Yu and Kim investigated the antimelanogenic activity of azelaic acid and taurine in B16F10 mouse melanoma cells in 2010. They found that the combination of the two substances exhibited a greater inhibitory effect in melanocytes than azelaic acid alone, with melanin production and tyrosinase activity suppressed without inducing cytotoxicity. The investigators concluded the combination of azelaic acid and taurine may be an effective approach for treating hyperpigmentation.10

In 2015, Ito et al. investigated the possible anti-aging role of taurine using a taurine transporter knockout mouse model. They noted that aging-related disorders affecting the skin, heart, skeletal muscle, and liver and resulting in a shorter lifespan have been correlated with tissue taurine depletion. The researchers proposed that proper protein folding allows endogenous taurine to perform as an antiaging molecule.5

Also in 2015, Kim et al. investigated potential mechanisms of the antiproliferative activity of taurine on murine B16F10 melanoma cells via the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and neutral red assays and microscopic analysis. They found that taurine prevented cell proliferation and engendered apoptosis in B16F10 cells, concluding that taurine may have a role to play as a chemotherapeutic agent for skin cancer.11

In 2014, Ashkani-Esfahani et al. studied the impact of taurine on cutaneous leishmaniasis wounds in a mouse model. Investigators induced 18 mice with wounds using L. major promastigotes, and divided them into a taurine injection group, taurine gel group, and no treatment group, performing treatments every 24 hours over 21 days. The taurine treatment groups exhibited significantly greater numerical fibroblast density, collagen bundle volume density, and vessel length densities compared with the nontreatment group. The taurine injection group displayed higher fibroblast numerical density than did the taurine gel group. The researchers concluded that taurine has the capacity to enhance wound healing and tissue regeneration but showed no direct anti-leishmaniasis effect.4

Conclusion

Taurine has been found over the last few decades to impart salutary effects for human health. This beta-amino acid that occurs naturally in humans and other mammals also appears to hold promising potential in the dermatologic realm, particularly for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. More research is needed to ascertain just how pivotal this compound can be for skin health.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006 Aug;28(4):289-98.

2. J Invest Dermatol. 2003 Aug;121(2):354-61.

3. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009 Oct;119(10):673-6.

4. Adv Biomed Res. 2014 Oct 7;3:204.

5. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;803:481-7.

6. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012 Dec 1;13(6):357-64.

7. Eur J Dermatol. 2008 Jul-Aug;18(4):433-9.

8. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2015 Mar;80(3):366-73.

9. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 Sep;1858(9):2006-18.

10. J Biomed Sci. 2010 Aug 24;17 Suppl 1:S45.

11. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;803:167-77.

November 2018 Digital Edition

Click here to access the November 2018 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

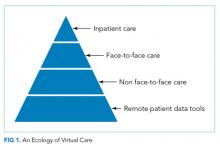

Providing Rural Veterans With Access to Exercise Through Gerofit

Reducing COPD Readmission Rates: Using a COPD Care Service During Care Transitions

Initiative to Minimize Pharmaceutical Risk in Older Veterans (IMPROVE) Polypharmacy Clinic

Click here to access the November 2018 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

Providing Rural Veterans With Access to Exercise Through Gerofit

Reducing COPD Readmission Rates: Using a COPD Care Service During Care Transitions

Initiative to Minimize Pharmaceutical Risk in Older Veterans (IMPROVE) Polypharmacy Clinic

Click here to access the November 2018 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

Providing Rural Veterans With Access to Exercise Through Gerofit

Reducing COPD Readmission Rates: Using a COPD Care Service During Care Transitions

Initiative to Minimize Pharmaceutical Risk in Older Veterans (IMPROVE) Polypharmacy Clinic

Reply to “Increasing Inpatient Consultation: Hospitalist Perceptions and Objective Findings. In Reference to: ‘Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services’”

The finding by Kachman et al. that consultations have decreased at their institution is an interesting and important observation.1 In contrast, our study found that more than a third of hospitalists reported an increase in consultation requests.2 There may be several explanations for this discrepancy. First, as Kachman et al. suggest, there may be differences between hospitalist perception and actual consultation use. Second, a significant variability in consultation may exist between hospitals. Although our study examined four institutions, we were unable to examine the variability between them, which requires further study. Third, there may be considerable variability between individual hospitalist practices, which is consistent with the findings reported by Kachman et al. Finally, the fact that our study examined only nonteaching services may be another explanation as Kachman et al. found that hospitalists on nonteaching services ordered more consultations than those on teaching services. These findings are consistent with a recent study conducted by Perez et al., who found that hospitalists on teaching services utilized fewer consultations and had lower direct care costs and shorter lengths of stay compared with those on nonteaching services.3 This finding raises the question of whether consultations impact care costs and lengths of stay, a topic that should be explored in future studies.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Kachman M, Carter K, Martin S. Increasing inpatient consultation: hospitalist perceptions and objective findings. In Reference to: “Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services”. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):802. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2992.

2. Adams TN, Bonsall J, Hunt D, et al. Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5):318-323. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882. PubMed

3. Perez JA Jr, Awar M, Nezamabadi A, et al. Comparison of direct patient care costs and quality outcomes of the teaching and nonteaching hospitalist services at a large academic medical center. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):491-497. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002026. PubMed

The finding by Kachman et al. that consultations have decreased at their institution is an interesting and important observation.1 In contrast, our study found that more than a third of hospitalists reported an increase in consultation requests.2 There may be several explanations for this discrepancy. First, as Kachman et al. suggest, there may be differences between hospitalist perception and actual consultation use. Second, a significant variability in consultation may exist between hospitals. Although our study examined four institutions, we were unable to examine the variability between them, which requires further study. Third, there may be considerable variability between individual hospitalist practices, which is consistent with the findings reported by Kachman et al. Finally, the fact that our study examined only nonteaching services may be another explanation as Kachman et al. found that hospitalists on nonteaching services ordered more consultations than those on teaching services. These findings are consistent with a recent study conducted by Perez et al., who found that hospitalists on teaching services utilized fewer consultations and had lower direct care costs and shorter lengths of stay compared with those on nonteaching services.3 This finding raises the question of whether consultations impact care costs and lengths of stay, a topic that should be explored in future studies.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The finding by Kachman et al. that consultations have decreased at their institution is an interesting and important observation.1 In contrast, our study found that more than a third of hospitalists reported an increase in consultation requests.2 There may be several explanations for this discrepancy. First, as Kachman et al. suggest, there may be differences between hospitalist perception and actual consultation use. Second, a significant variability in consultation may exist between hospitals. Although our study examined four institutions, we were unable to examine the variability between them, which requires further study. Third, there may be considerable variability between individual hospitalist practices, which is consistent with the findings reported by Kachman et al. Finally, the fact that our study examined only nonteaching services may be another explanation as Kachman et al. found that hospitalists on nonteaching services ordered more consultations than those on teaching services. These findings are consistent with a recent study conducted by Perez et al., who found that hospitalists on teaching services utilized fewer consultations and had lower direct care costs and shorter lengths of stay compared with those on nonteaching services.3 This finding raises the question of whether consultations impact care costs and lengths of stay, a topic that should be explored in future studies.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Kachman M, Carter K, Martin S. Increasing inpatient consultation: hospitalist perceptions and objective findings. In Reference to: “Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services”. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):802. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2992.

2. Adams TN, Bonsall J, Hunt D, et al. Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5):318-323. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882. PubMed

3. Perez JA Jr, Awar M, Nezamabadi A, et al. Comparison of direct patient care costs and quality outcomes of the teaching and nonteaching hospitalist services at a large academic medical center. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):491-497. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002026. PubMed

1. Kachman M, Carter K, Martin S. Increasing inpatient consultation: hospitalist perceptions and objective findings. In Reference to: “Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services”. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):802. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2992.

2. Adams TN, Bonsall J, Hunt D, et al. Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5):318-323. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882. PubMed

3. Perez JA Jr, Awar M, Nezamabadi A, et al. Comparison of direct patient care costs and quality outcomes of the teaching and nonteaching hospitalist services at a large academic medical center. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):491-497. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002026. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

In Reply to “Diving Into Diagnostic Uncertainty: Strategies to Mitigate Cognitive Load. In Reference to: ‘Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers’”

We thank Dr. Santhosh and colleagues for their letter concerning our article.1 We agree that the diagnostic journey includes interactions both between and across teams, not just those within the patient’s team. In an article currently in press in Diagnosis, we examine how systems and cognitive factors interact during the process of diagnosis. Specifically, we reported on how communication between consultants can be both a barrier and facilitator to the diagnostic process.2 We found that the frequency, quality, and pace of communication between and across inpatient teams and specialists are essential to timely diagnoses. As diagnostic errors remain a costly and morbid issue in the hospital setting, efforts to improve communication are clearly needed.3

Santhosh et al. raise an interesting point regarding cognitive load in evaluating diagnosis. Cognitive load is a multidimensional construct that represents the load that performing a specific task poses on a learner’s cognitive system.4 Components often used for measuring load include (a) task characteristics such as format, complexity, and time pressure; (b) subject characteristics such as expertise level, age, and spatial abilities; and (c) mental load and effort that originate from the interaction between task and subject characteristics.5 While there is little doubt that measuring these constructs has face value in diagnosis, we know of no instruments that are nimble

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was supported by grant number P30HS024385 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The funding source played no role in study design, data acquisition, analysis or decision to report these data.

1. Chopra V, Harrod M, Winter S, et al. Focused ethnography of diagnosis in academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):668-672. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2966 PubMed

2. Gupta A, Harrod M, Quinn M, et al. Mind the overlap: how system problems contribute to cognitive failure and diagnostic errors. Diagnosis. 2018; In Press PubMed

3. Gupta A, Snyder A, Kachalia A, et al. Malpractice claims related to diagnostic errors in the hospital [published online ahead of print August 11, 2017]. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006774 PubMed

4. Paas FG, Van Merrienboer JJ, Adam JJ. Measurement of cognitive load in instructional research. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;79(1 Pt 2):419-30. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.79.1.419 PubMed

5. Paas FG, Tuovinen JE, Tabbers H, et al. Cognitive load measurement as a means to advance cognitive load theory. Educational Psychologist. 2003;38(1):63-71. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3801_8

We thank Dr. Santhosh and colleagues for their letter concerning our article.1 We agree that the diagnostic journey includes interactions both between and across teams, not just those within the patient’s team. In an article currently in press in Diagnosis, we examine how systems and cognitive factors interact during the process of diagnosis. Specifically, we reported on how communication between consultants can be both a barrier and facilitator to the diagnostic process.2 We found that the frequency, quality, and pace of communication between and across inpatient teams and specialists are essential to timely diagnoses. As diagnostic errors remain a costly and morbid issue in the hospital setting, efforts to improve communication are clearly needed.3

Santhosh et al. raise an interesting point regarding cognitive load in evaluating diagnosis. Cognitive load is a multidimensional construct that represents the load that performing a specific task poses on a learner’s cognitive system.4 Components often used for measuring load include (a) task characteristics such as format, complexity, and time pressure; (b) subject characteristics such as expertise level, age, and spatial abilities; and (c) mental load and effort that originate from the interaction between task and subject characteristics.5 While there is little doubt that measuring these constructs has face value in diagnosis, we know of no instruments that are nimble

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was supported by grant number P30HS024385 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The funding source played no role in study design, data acquisition, analysis or decision to report these data.

We thank Dr. Santhosh and colleagues for their letter concerning our article.1 We agree that the diagnostic journey includes interactions both between and across teams, not just those within the patient’s team. In an article currently in press in Diagnosis, we examine how systems and cognitive factors interact during the process of diagnosis. Specifically, we reported on how communication between consultants can be both a barrier and facilitator to the diagnostic process.2 We found that the frequency, quality, and pace of communication between and across inpatient teams and specialists are essential to timely diagnoses. As diagnostic errors remain a costly and morbid issue in the hospital setting, efforts to improve communication are clearly needed.3

Santhosh et al. raise an interesting point regarding cognitive load in evaluating diagnosis. Cognitive load is a multidimensional construct that represents the load that performing a specific task poses on a learner’s cognitive system.4 Components often used for measuring load include (a) task characteristics such as format, complexity, and time pressure; (b) subject characteristics such as expertise level, age, and spatial abilities; and (c) mental load and effort that originate from the interaction between task and subject characteristics.5 While there is little doubt that measuring these constructs has face value in diagnosis, we know of no instruments that are nimble

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was supported by grant number P30HS024385 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The funding source played no role in study design, data acquisition, analysis or decision to report these data.

1. Chopra V, Harrod M, Winter S, et al. Focused ethnography of diagnosis in academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):668-672. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2966 PubMed

2. Gupta A, Harrod M, Quinn M, et al. Mind the overlap: how system problems contribute to cognitive failure and diagnostic errors. Diagnosis. 2018; In Press PubMed

3. Gupta A, Snyder A, Kachalia A, et al. Malpractice claims related to diagnostic errors in the hospital [published online ahead of print August 11, 2017]. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006774 PubMed

4. Paas FG, Van Merrienboer JJ, Adam JJ. Measurement of cognitive load in instructional research. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;79(1 Pt 2):419-30. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.79.1.419 PubMed

5. Paas FG, Tuovinen JE, Tabbers H, et al. Cognitive load measurement as a means to advance cognitive load theory. Educational Psychologist. 2003;38(1):63-71. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3801_8

1. Chopra V, Harrod M, Winter S, et al. Focused ethnography of diagnosis in academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):668-672. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2966 PubMed

2. Gupta A, Harrod M, Quinn M, et al. Mind the overlap: how system problems contribute to cognitive failure and diagnostic errors. Diagnosis. 2018; In Press PubMed

3. Gupta A, Snyder A, Kachalia A, et al. Malpractice claims related to diagnostic errors in the hospital [published online ahead of print August 11, 2017]. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006774 PubMed

4. Paas FG, Van Merrienboer JJ, Adam JJ. Measurement of cognitive load in instructional research. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;79(1 Pt 2):419-30. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.79.1.419 PubMed

5. Paas FG, Tuovinen JE, Tabbers H, et al. Cognitive load measurement as a means to advance cognitive load theory. Educational Psychologist. 2003;38(1):63-71. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3801_8

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Diving Into Diagnostic Uncertainty: Strategies to Mitigate Cognitive Load: In Reference to: “Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers”

We read the article by Chopra et al. “Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers” with great interest.1 This ethnographic study provided valuable insights into possible interventions to encourage diagnostic thinking.

Duty hour regulations and the resulting increase in handoffs have shifted the social experience of diagnosis from one that occurs within teams to one that often occurs between teams during handoffs between providers.2 While the article highlighted barriers to diagnosis, including distractions and time pressure, it did not explicitly discuss cognitive load theory. Cognitive load theory is an educational framework that has been described by Young et al.3 to improve instructions in the handoff process. These investigators showed how progressively experienced learners retain more information when using a structured scaffold or framework for information, such as the IPASS mnemonic,4 for example.

To mitigate the effects of distraction on the transfer of information, especially in cases with high diagnostic uncertainty, cognitive load must be explicitly considered. A structured framework for communication about diagnostic uncertainty informed by cognitive load theory would be a novel innovation that would help not only graduate medical education but could also improve diagnostic accuracy.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

1. Chopra V, Harrod M, Winter S, et al. Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):668-672. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2966. PubMed

2. Duong JA, Jensen TP, Morduchowicz, S, Mourad M, Harrison JD, Ranji SR. Exploring physician perspectives of residency holdover handoffs: a qualitative study to understand an increasingly important type of handoff. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):654-659. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4009-y PubMed

3. Young JQ, ten Cate O, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Unpacking the complexity of patient handoffs through the lens of cognitive load theory. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(1):88-96. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2015.1107491. PubMed

4. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1414788. PubMed

We read the article by Chopra et al. “Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers” with great interest.1 This ethnographic study provided valuable insights into possible interventions to encourage diagnostic thinking.

Duty hour regulations and the resulting increase in handoffs have shifted the social experience of diagnosis from one that occurs within teams to one that often occurs between teams during handoffs between providers.2 While the article highlighted barriers to diagnosis, including distractions and time pressure, it did not explicitly discuss cognitive load theory. Cognitive load theory is an educational framework that has been described by Young et al.3 to improve instructions in the handoff process. These investigators showed how progressively experienced learners retain more information when using a structured scaffold or framework for information, such as the IPASS mnemonic,4 for example.

To mitigate the effects of distraction on the transfer of information, especially in cases with high diagnostic uncertainty, cognitive load must be explicitly considered. A structured framework for communication about diagnostic uncertainty informed by cognitive load theory would be a novel innovation that would help not only graduate medical education but could also improve diagnostic accuracy.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

We read the article by Chopra et al. “Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers” with great interest.1 This ethnographic study provided valuable insights into possible interventions to encourage diagnostic thinking.

Duty hour regulations and the resulting increase in handoffs have shifted the social experience of diagnosis from one that occurs within teams to one that often occurs between teams during handoffs between providers.2 While the article highlighted barriers to diagnosis, including distractions and time pressure, it did not explicitly discuss cognitive load theory. Cognitive load theory is an educational framework that has been described by Young et al.3 to improve instructions in the handoff process. These investigators showed how progressively experienced learners retain more information when using a structured scaffold or framework for information, such as the IPASS mnemonic,4 for example.

To mitigate the effects of distraction on the transfer of information, especially in cases with high diagnostic uncertainty, cognitive load must be explicitly considered. A structured framework for communication about diagnostic uncertainty informed by cognitive load theory would be a novel innovation that would help not only graduate medical education but could also improve diagnostic accuracy.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

1. Chopra V, Harrod M, Winter S, et al. Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):668-672. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2966. PubMed

2. Duong JA, Jensen TP, Morduchowicz, S, Mourad M, Harrison JD, Ranji SR. Exploring physician perspectives of residency holdover handoffs: a qualitative study to understand an increasingly important type of handoff. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):654-659. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4009-y PubMed

3. Young JQ, ten Cate O, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Unpacking the complexity of patient handoffs through the lens of cognitive load theory. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(1):88-96. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2015.1107491. PubMed

4. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1414788. PubMed

1. Chopra V, Harrod M, Winter S, et al. Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):668-672. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2966. PubMed

2. Duong JA, Jensen TP, Morduchowicz, S, Mourad M, Harrison JD, Ranji SR. Exploring physician perspectives of residency holdover handoffs: a qualitative study to understand an increasingly important type of handoff. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):654-659. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4009-y PubMed

3. Young JQ, ten Cate O, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Unpacking the complexity of patient handoffs through the lens of cognitive load theory. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(1):88-96. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2015.1107491. PubMed

4. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1414788. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Increasing Inpatient Consultation: Hospitalist Perceptions and Objective Findings. In Reference to: “Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services”

We read with interest the article, “Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services.”1 We applaud the authors for their work, but were surprised by the authors’ findings of hospitalist perceptions of consultation utilization. The authors reported that more hospitalists felt that their personal use of consultation was increasing (38.5%) versus those who reported that use was decreasing (30.3%).1 The lack of true consensus on this issue may hint at significant variability in hospitalist use of inpatient consultation. We examined consultation use in 4,023 general medicine admissions to the University of Chicago from 2011 to 2015. Consultation use varied widely, with a 3.5-fold difference between the lowest and the highest quartiles of use (P < .01).2 Contrary to the survey findings, we found that the number of consultations per admission actually decreased with each year in our sample.2 In addition, a particularly interesting effect was observed in hospitalists; in multivariate regression, hospitalists on nonteaching services ordered more consultations than those on teaching services.2 These findings suggest a gap between hospitalist self-reported perceptions of consultation use and actual use, which is important to understand, and highlight the need for further characterization of factors driving the use of this valuable resource.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Adams TN, Bonsall J, Hunt D, et al. Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services. J Hosp Med. 2018:13(5):318-323. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882. PubMed

2. Kachman M, Carter K, Martin S, et al. Describing variability of inpatient consultation practices on general medicine services: patient, admission and physician-level factors. Abstract from: Hospital Medicine 2018; April 8-11, 2018; Orlando, Florida.

We read with interest the article, “Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services.”1 We applaud the authors for their work, but were surprised by the authors’ findings of hospitalist perceptions of consultation utilization. The authors reported that more hospitalists felt that their personal use of consultation was increasing (38.5%) versus those who reported that use was decreasing (30.3%).1 The lack of true consensus on this issue may hint at significant variability in hospitalist use of inpatient consultation. We examined consultation use in 4,023 general medicine admissions to the University of Chicago from 2011 to 2015. Consultation use varied widely, with a 3.5-fold difference between the lowest and the highest quartiles of use (P < .01).2 Contrary to the survey findings, we found that the number of consultations per admission actually decreased with each year in our sample.2 In addition, a particularly interesting effect was observed in hospitalists; in multivariate regression, hospitalists on nonteaching services ordered more consultations than those on teaching services.2 These findings suggest a gap between hospitalist self-reported perceptions of consultation use and actual use, which is important to understand, and highlight the need for further characterization of factors driving the use of this valuable resource.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

We read with interest the article, “Hospitalist Perspective of Interactions with Medicine Subspecialty Consult Services.”1 We applaud the authors for their work, but were surprised by the authors’ findings of hospitalist perceptions of consultation utilization. The authors reported that more hospitalists felt that their personal use of consultation was increasing (38.5%) versus those who reported that use was decreasing (30.3%).1 The lack of true consensus on this issue may hint at significant variability in hospitalist use of inpatient consultation. We examined consultation use in 4,023 general medicine admissions to the University of Chicago from 2011 to 2015. Consultation use varied widely, with a 3.5-fold difference between the lowest and the highest quartiles of use (P < .01).2 Contrary to the survey findings, we found that the number of consultations per admission actually decreased with each year in our sample.2 In addition, a particularly interesting effect was observed in hospitalists; in multivariate regression, hospitalists on nonteaching services ordered more consultations than those on teaching services.2 These findings suggest a gap between hospitalist self-reported perceptions of consultation use and actual use, which is important to understand, and highlight the need for further characterization of factors driving the use of this valuable resource.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Adams TN, Bonsall J, Hunt D, et al. Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services. J Hosp Med. 2018:13(5):318-323. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882. PubMed

2. Kachman M, Carter K, Martin S, et al. Describing variability of inpatient consultation practices on general medicine services: patient, admission and physician-level factors. Abstract from: Hospital Medicine 2018; April 8-11, 2018; Orlando, Florida.

1. Adams TN, Bonsall J, Hunt D, et al. Hospitalist perspective of interactions with medicine subspecialty consult services. J Hosp Med. 2018:13(5):318-323. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2882. PubMed

2. Kachman M, Carter K, Martin S, et al. Describing variability of inpatient consultation practices on general medicine services: patient, admission and physician-level factors. Abstract from: Hospital Medicine 2018; April 8-11, 2018; Orlando, Florida.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

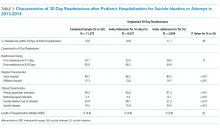

Healthcare Quality for Children and Adolescents with Suicidality Admitted to Acute Care Hospitals in the United States

Suicide is the second most common cause of death among children, adolescents, and young adults in the United States. In 2016, over 6,000 children and youth 5 to 24 years of age succumbed to suicide, thus reflecting a mortality rate nearly three times higher than deaths from malignancies and 28 times higher than deaths from sepsis in this age group.1 Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts are even more common, with 17% of high school students reporting seriously considering suicide and 8% reporting suicide attempts in the previous 12 months.2 These tragic statistics are reflected in our health system use, emergency department (ED) utilization for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation is growing at a tremendous rate, and over 50% of the children seen in EDs are subsequently admitted to the hospital for ongoing care.3,4

In this issue of Journal of Hospital Medicine, Doupnik and colleagues present an analysis of pediatric hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation at acute care hospitals contained within the 2013 and 2014 National Readmissions Dataset.5 This dataset reflects a nationally representative sample of pediatric hospitalizations, weighted to allow for national estimates. Although their focus was on hospital readmission, their analysis yielded additional valuable data about suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in American youth. The investigators identified 181,575 pediatric acute care hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation over the two-year study period, accounting for 9.5% of all acute care hospitalizations among children and adolescents 6 to 17 years of age nationally. This number exceeds the biennial number of pediatric hospitalizations for cellulitis, dehydration, and urinary tract infections, all of which are generally considered the “bread and butter” of pediatric hospital medicine.6

Doupnik and colleagues rightly pointed out that hospital readmission is not a nationally endorsed measure to evaluate the quality of pediatric mental health hospitalizations. At the same time, their work highlights that acute care hospitals need strategies to measure the quality of pediatric hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. Beyond readmissions, how should the quality of these hospital stays be evaluated? A recent review of 15 national quality measure sets identified 257 unique measures to evaluate pediatric quality of care.7 Of these, only one focused on mental health hospitalization. This measure, which was endorsed by the National Quality Forum, determines the percentage of discharges for patients six years of age and older who were hospitalized for mental health diagnoses and who had a follow-up visit with a mental health practitioner within 7 and 30 days of hospital discharge.8 Given Doupnik et al.’s finding that one-third of all 30-day hospital readmissions occurred within seven days of hospital discharge, early follow-up visits with mental health practitioners is arguably essential.

Although evidence-based quality measures to evaluate hospital-based mental healthcare are limited, quality measure development is ongoing, facilitated by recent federal health policy and associated research efforts. Four newly developed measures focus on the quality of inpatient care for suicidality, including two evaluated using data from health records and two derived from caregiver surveys. The first medical records-based measure identifies whether caregivers of patients admitted to hospital for dangerous self-harm or suicidality have documentation that they were counseled on how to restrict their child’s or adolescent’s access to potentially lethal means of suicide before discharge. The second record-based measure evaluates documentation in the medical record of discussion between the hospital provider and the patient’s outpatient provider regarding the plan for follow-up.9 The two survey-based measures ask caregivers whether they were counseled on how to restrict access to potentially lethal means of suicide, and, for children and adolescents started on a new antidepressant medication or dose, whether they were counseled regarding the potential benefits and risks of the medication.10 All measures were field-tested at children’s hospitals to ensure feasibility in data collection. However, as shown by Doupnik et al., only 7.4% of acute care hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation occurred at freestanding children’s hospitals; most occurred at urban nonteaching centers. Evaluation of these new quality measures across structurally diverse hospitals is an important next step.

Beyond the healthcare constructs evaluated by these quality measures, many foundational questions about what constitutes high quality inpatient healthcare for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation remain. An American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) practice parameter, which was published in 2001, established minimal standards for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior.11 This guideline recommends inpatient treatment until the mental state or level of suicidality has stabilized, with discharge considered only when the clinician is satisfied that adequate supervision and support will be available and when a responsible adult has agreed to secure or dispose of potentially lethal medications and firearms. It further recommends that the clinician treating the child or adolescent during the days following a suicide attempt be available to the patient and family – for example, to receive and make telephone calls outside of regular clinic hours. Recognizing the growing prevalence of suicidality in American children and youth, coupled with critical shortages in pediatric psychiatrists and fragmentation of inpatient and outpatient care, these minimal standards may be difficult to implement across the many settings where children receive their mental healthcare.4,12,13

The large number of children and adolescents being hospitalized for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation at acute care hospitals demands that we take stock of how we manage this vulnerable population. Although Doupnik and colleagues suggest that exclusion of specialty psychiatric hospitals from their dataset is a limitation, their presentation of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation epidemiology at acute care hospitals provides valuable data for pediatric hospitalists. Given the presence of pediatric hospitalists at many acute care hospitals, comanagement by hospital medicine and psychiatry services may prove both efficient and effective while breaking down the silos that traditionally separate these specialties. Alternatively, extending the role of collaborative care teams, which are increasingly embedded in pediatric primary care, into inpatient settings may enable continuity of care and improve healthcare quality.14 Finally, nearly 20 years have passed since the AACAP published its practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. An update to reflect contemporary suicide attempts and suicidal ideation statistics and evidence-based practices is needed, and collaboration between professional pediatric and psychiatric organizations in the creation of this update would recognize the growing role of pediatricians, including hospitalists, in the provision of mental healthcare for children.

Updated guidelines must take into account the transitions of care experienced by children and adolescents throughout their hospital stay: at admission, at discharge, and during their hospitalization if they move from medical to psychiatric care. Research is needed to determine what proportion of children and adolescents receive evidence-based mental health therapies while in hospital and how many are connected with wraparound mental health services before hospital discharge.15 Doupnik et al. excluded children and adolescents who were transferred to other hospitals, which included over 18,000 youth. How long did these patients spend “boarding,” and did they receive any mental health assessment or treatment during this period? Although the Joint Commission recommends that holding times for patients awaiting bed placement should not exceed four4 hours, hospitals have described average pediatric inpatient boarding times of 2-3 days while awaiting inpatient psychiatric care.16,17 In one study of children and adolescents awaiting transfer for inpatient psychiatric care, mental health counseling was received by only 6%, which reflects lost time that could have been spent treating this highly vulnerable population.16 Multidisciplinary collaboration is needed to address these issues and inform best practices.

Although mortality is a rare outcome for most conditions we treat in pediatric hospital medicine, mortality following suicide attempts is all too common. The data presented by Doupnik and colleagues provide a powerful call to improve healthcare quality across the diverse settings where children with suicidality receive their care.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Leyenaar was supported by grant number K08HS024133 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of AHRQ.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2016 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released December, 2017.

2. Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2013. MMWR. 2014;63(4):1-168. PubMed

3. Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Marcus SC, Greenberg T, Shaffer D. Emergency treatment of young people following deliberate self-harm. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1122-1128. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1122 PubMed

4. Mercado MC, Holland K, Leemis RW, Stone DM, Wang J. Trends in emergency department visits for nonfatal self-inflicted injuries among youth aged 10 to 24 years in the United States, 2001-2015. JAMA. 2017;318(19):1931-1932. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13317 PubMed

5. Doupnik S, Rodean J, Zima B, et al. Readmissions after pediatric hospitalization for suicide ideation and suicide attempt [published online ahead of print October 31, 2018]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3070

6. Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh M, Pekow PS, Mangione-Smith R, Lindenauer PK. Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):743-749. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2624 PubMed

7. House SA, Coon ER, Schroeder AR, Ralston SL. Categorization of national pediatric quality measures. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20163269. PubMed

8. National Quality Forum. Follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness. Available at www.qualityforum.org. Accessed July 21, 2018.

9. Bardach N, Burkhart Q, Richardson L, et al. Hospital-based quality measures for pediatric mental health care. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20173554. PubMed

10. Parast L, Bardach N, Burkhart Q, et al. Development of new quality measures for hospital-based care of suicidal youth. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(3):248-255. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.017 PubMed

11. Shaffer D, Pfeffer C. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(7 Suppl):24-51. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107001-00003

12. Thomas C, Holtzer C. The continuing shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(9):1023-1031. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000225353.16831.5d PubMed

13. Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008–2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20172426. PubMed

14. Beach SR, Walker J, Celano CM, Mastromauro CA, Sharpe M, Huffman JC. Implementing collaborative care programs for psychiatric disorders in medical settings: a practical guide. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(6):522-527. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.06.015 PubMed

15. Winters N, Pumariega A. Practice parameter on child and adolescent mental health care in community systems of care. J Am Acad Child Adolsc Psychiatry. 2007;46(2):284-299. DOI: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246061.70330.b8 PubMed

16. Claudius I, Donofrio J, Lam CN, Santillanes G. Impact of boarding pediatric psychiatric patients on a medical ward. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(3):125-131. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2013-0079 PubMed

17. Gallagher KAS, Bujoreanu IS, Cheung P, Choi C, Golden S, Brodziak K. Psychiatric boarding in the pediatric inpatient medical setting: a retrospective analysis. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;7(8):444-450. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2017-0005 PubMed

Suicide is the second most common cause of death among children, adolescents, and young adults in the United States. In 2016, over 6,000 children and youth 5 to 24 years of age succumbed to suicide, thus reflecting a mortality rate nearly three times higher than deaths from malignancies and 28 times higher than deaths from sepsis in this age group.1 Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts are even more common, with 17% of high school students reporting seriously considering suicide and 8% reporting suicide attempts in the previous 12 months.2 These tragic statistics are reflected in our health system use, emergency department (ED) utilization for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation is growing at a tremendous rate, and over 50% of the children seen in EDs are subsequently admitted to the hospital for ongoing care.3,4

In this issue of Journal of Hospital Medicine, Doupnik and colleagues present an analysis of pediatric hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation at acute care hospitals contained within the 2013 and 2014 National Readmissions Dataset.5 This dataset reflects a nationally representative sample of pediatric hospitalizations, weighted to allow for national estimates. Although their focus was on hospital readmission, their analysis yielded additional valuable data about suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in American youth. The investigators identified 181,575 pediatric acute care hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation over the two-year study period, accounting for 9.5% of all acute care hospitalizations among children and adolescents 6 to 17 years of age nationally. This number exceeds the biennial number of pediatric hospitalizations for cellulitis, dehydration, and urinary tract infections, all of which are generally considered the “bread and butter” of pediatric hospital medicine.6

Doupnik and colleagues rightly pointed out that hospital readmission is not a nationally endorsed measure to evaluate the quality of pediatric mental health hospitalizations. At the same time, their work highlights that acute care hospitals need strategies to measure the quality of pediatric hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. Beyond readmissions, how should the quality of these hospital stays be evaluated? A recent review of 15 national quality measure sets identified 257 unique measures to evaluate pediatric quality of care.7 Of these, only one focused on mental health hospitalization. This measure, which was endorsed by the National Quality Forum, determines the percentage of discharges for patients six years of age and older who were hospitalized for mental health diagnoses and who had a follow-up visit with a mental health practitioner within 7 and 30 days of hospital discharge.8 Given Doupnik et al.’s finding that one-third of all 30-day hospital readmissions occurred within seven days of hospital discharge, early follow-up visits with mental health practitioners is arguably essential.

Although evidence-based quality measures to evaluate hospital-based mental healthcare are limited, quality measure development is ongoing, facilitated by recent federal health policy and associated research efforts. Four newly developed measures focus on the quality of inpatient care for suicidality, including two evaluated using data from health records and two derived from caregiver surveys. The first medical records-based measure identifies whether caregivers of patients admitted to hospital for dangerous self-harm or suicidality have documentation that they were counseled on how to restrict their child’s or adolescent’s access to potentially lethal means of suicide before discharge. The second record-based measure evaluates documentation in the medical record of discussion between the hospital provider and the patient’s outpatient provider regarding the plan for follow-up.9 The two survey-based measures ask caregivers whether they were counseled on how to restrict access to potentially lethal means of suicide, and, for children and adolescents started on a new antidepressant medication or dose, whether they were counseled regarding the potential benefits and risks of the medication.10 All measures were field-tested at children’s hospitals to ensure feasibility in data collection. However, as shown by Doupnik et al., only 7.4% of acute care hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation occurred at freestanding children’s hospitals; most occurred at urban nonteaching centers. Evaluation of these new quality measures across structurally diverse hospitals is an important next step.

Beyond the healthcare constructs evaluated by these quality measures, many foundational questions about what constitutes high quality inpatient healthcare for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation remain. An American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) practice parameter, which was published in 2001, established minimal standards for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior.11 This guideline recommends inpatient treatment until the mental state or level of suicidality has stabilized, with discharge considered only when the clinician is satisfied that adequate supervision and support will be available and when a responsible adult has agreed to secure or dispose of potentially lethal medications and firearms. It further recommends that the clinician treating the child or adolescent during the days following a suicide attempt be available to the patient and family – for example, to receive and make telephone calls outside of regular clinic hours. Recognizing the growing prevalence of suicidality in American children and youth, coupled with critical shortages in pediatric psychiatrists and fragmentation of inpatient and outpatient care, these minimal standards may be difficult to implement across the many settings where children receive their mental healthcare.4,12,13

The large number of children and adolescents being hospitalized for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation at acute care hospitals demands that we take stock of how we manage this vulnerable population. Although Doupnik and colleagues suggest that exclusion of specialty psychiatric hospitals from their dataset is a limitation, their presentation of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation epidemiology at acute care hospitals provides valuable data for pediatric hospitalists. Given the presence of pediatric hospitalists at many acute care hospitals, comanagement by hospital medicine and psychiatry services may prove both efficient and effective while breaking down the silos that traditionally separate these specialties. Alternatively, extending the role of collaborative care teams, which are increasingly embedded in pediatric primary care, into inpatient settings may enable continuity of care and improve healthcare quality.14 Finally, nearly 20 years have passed since the AACAP published its practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. An update to reflect contemporary suicide attempts and suicidal ideation statistics and evidence-based practices is needed, and collaboration between professional pediatric and psychiatric organizations in the creation of this update would recognize the growing role of pediatricians, including hospitalists, in the provision of mental healthcare for children.

Updated guidelines must take into account the transitions of care experienced by children and adolescents throughout their hospital stay: at admission, at discharge, and during their hospitalization if they move from medical to psychiatric care. Research is needed to determine what proportion of children and adolescents receive evidence-based mental health therapies while in hospital and how many are connected with wraparound mental health services before hospital discharge.15 Doupnik et al. excluded children and adolescents who were transferred to other hospitals, which included over 18,000 youth. How long did these patients spend “boarding,” and did they receive any mental health assessment or treatment during this period? Although the Joint Commission recommends that holding times for patients awaiting bed placement should not exceed four4 hours, hospitals have described average pediatric inpatient boarding times of 2-3 days while awaiting inpatient psychiatric care.16,17 In one study of children and adolescents awaiting transfer for inpatient psychiatric care, mental health counseling was received by only 6%, which reflects lost time that could have been spent treating this highly vulnerable population.16 Multidisciplinary collaboration is needed to address these issues and inform best practices.

Although mortality is a rare outcome for most conditions we treat in pediatric hospital medicine, mortality following suicide attempts is all too common. The data presented by Doupnik and colleagues provide a powerful call to improve healthcare quality across the diverse settings where children with suicidality receive their care.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Leyenaar was supported by grant number K08HS024133 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of AHRQ.

Suicide is the second most common cause of death among children, adolescents, and young adults in the United States. In 2016, over 6,000 children and youth 5 to 24 years of age succumbed to suicide, thus reflecting a mortality rate nearly three times higher than deaths from malignancies and 28 times higher than deaths from sepsis in this age group.1 Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts are even more common, with 17% of high school students reporting seriously considering suicide and 8% reporting suicide attempts in the previous 12 months.2 These tragic statistics are reflected in our health system use, emergency department (ED) utilization for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation is growing at a tremendous rate, and over 50% of the children seen in EDs are subsequently admitted to the hospital for ongoing care.3,4

In this issue of Journal of Hospital Medicine, Doupnik and colleagues present an analysis of pediatric hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation at acute care hospitals contained within the 2013 and 2014 National Readmissions Dataset.5 This dataset reflects a nationally representative sample of pediatric hospitalizations, weighted to allow for national estimates. Although their focus was on hospital readmission, their analysis yielded additional valuable data about suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in American youth. The investigators identified 181,575 pediatric acute care hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation over the two-year study period, accounting for 9.5% of all acute care hospitalizations among children and adolescents 6 to 17 years of age nationally. This number exceeds the biennial number of pediatric hospitalizations for cellulitis, dehydration, and urinary tract infections, all of which are generally considered the “bread and butter” of pediatric hospital medicine.6

Doupnik and colleagues rightly pointed out that hospital readmission is not a nationally endorsed measure to evaluate the quality of pediatric mental health hospitalizations. At the same time, their work highlights that acute care hospitals need strategies to measure the quality of pediatric hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. Beyond readmissions, how should the quality of these hospital stays be evaluated? A recent review of 15 national quality measure sets identified 257 unique measures to evaluate pediatric quality of care.7 Of these, only one focused on mental health hospitalization. This measure, which was endorsed by the National Quality Forum, determines the percentage of discharges for patients six years of age and older who were hospitalized for mental health diagnoses and who had a follow-up visit with a mental health practitioner within 7 and 30 days of hospital discharge.8 Given Doupnik et al.’s finding that one-third of all 30-day hospital readmissions occurred within seven days of hospital discharge, early follow-up visits with mental health practitioners is arguably essential.

Although evidence-based quality measures to evaluate hospital-based mental healthcare are limited, quality measure development is ongoing, facilitated by recent federal health policy and associated research efforts. Four newly developed measures focus on the quality of inpatient care for suicidality, including two evaluated using data from health records and two derived from caregiver surveys. The first medical records-based measure identifies whether caregivers of patients admitted to hospital for dangerous self-harm or suicidality have documentation that they were counseled on how to restrict their child’s or adolescent’s access to potentially lethal means of suicide before discharge. The second record-based measure evaluates documentation in the medical record of discussion between the hospital provider and the patient’s outpatient provider regarding the plan for follow-up.9 The two survey-based measures ask caregivers whether they were counseled on how to restrict access to potentially lethal means of suicide, and, for children and adolescents started on a new antidepressant medication or dose, whether they were counseled regarding the potential benefits and risks of the medication.10 All measures were field-tested at children’s hospitals to ensure feasibility in data collection. However, as shown by Doupnik et al., only 7.4% of acute care hospitalizations for suicide attempts and suicidal ideation occurred at freestanding children’s hospitals; most occurred at urban nonteaching centers. Evaluation of these new quality measures across structurally diverse hospitals is an important next step.