User login

Quick Byte: Needle-free injections

A start-up operating out of MIT in Cambridge, Mass., called Portal Instruments has developed a needleless injection system.

The device, called PRIME, delivers medication into the bloodstream in a high-pressure stream that travels at Mach 0.7 – the speed of a jet. The makers signed a commercial deal in December 2017, and the device is expected to be available soon.

Reference

1. Kerrigan S. The 16 Most Remarkable Healthcare Innovations, Events, and Discoveries of 2018 For World Health Day. https://interestingengineering.com/the-16-most-remarkable-healthcare-innovations-events-and-discoveries-of-2018-for-world-health-day. April 7, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

A start-up operating out of MIT in Cambridge, Mass., called Portal Instruments has developed a needleless injection system.

The device, called PRIME, delivers medication into the bloodstream in a high-pressure stream that travels at Mach 0.7 – the speed of a jet. The makers signed a commercial deal in December 2017, and the device is expected to be available soon.

Reference

1. Kerrigan S. The 16 Most Remarkable Healthcare Innovations, Events, and Discoveries of 2018 For World Health Day. https://interestingengineering.com/the-16-most-remarkable-healthcare-innovations-events-and-discoveries-of-2018-for-world-health-day. April 7, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

A start-up operating out of MIT in Cambridge, Mass., called Portal Instruments has developed a needleless injection system.

The device, called PRIME, delivers medication into the bloodstream in a high-pressure stream that travels at Mach 0.7 – the speed of a jet. The makers signed a commercial deal in December 2017, and the device is expected to be available soon.

Reference

1. Kerrigan S. The 16 Most Remarkable Healthcare Innovations, Events, and Discoveries of 2018 For World Health Day. https://interestingengineering.com/the-16-most-remarkable-healthcare-innovations-events-and-discoveries-of-2018-for-world-health-day. April 7, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

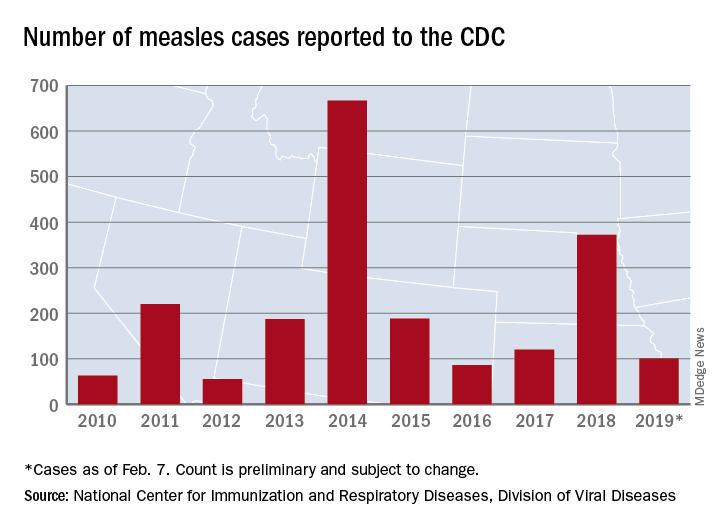

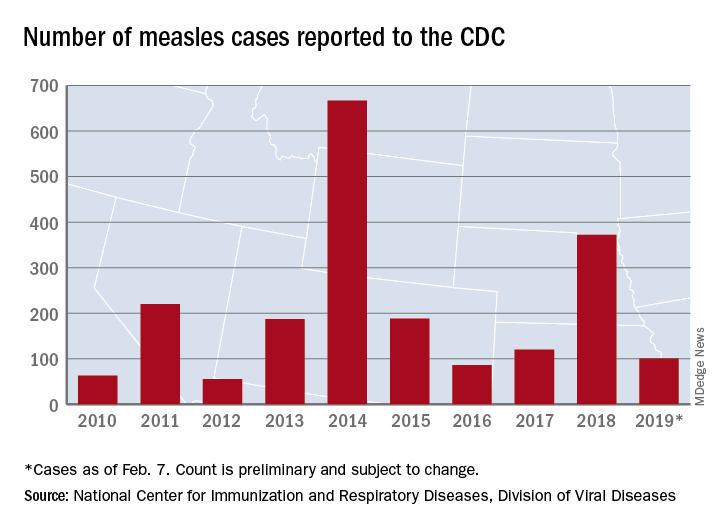

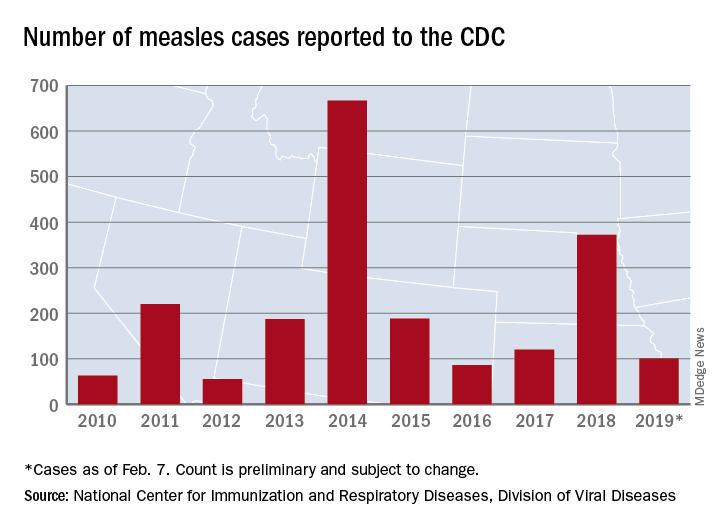

United States now over 100 measles cases for the year

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Just over half of the cases in 2019 have occurred in Clark County, Wash., which has reported 53 cases. That outbreak led Gov. Jay Inslee to declare a public health emergency for the entire state on Jan. 25.

The cases in Washington represent one of the five outbreaks – the CDC defines an outbreak as three or more cases – that have occurred so far this year, with three reported in New York State (Rockland County, Monroe County, and New York City) and one in Texas, which has been spread out over five counties, the CDC reported Feb. 11.

“These outbreaks are linked to travelers who brought measles back from other countries such as Israel and Ukraine, where large measles outbreaks are occurring,” the CDC noted. The other states with confirmed cases are California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, and Oregon.

In a video released Feb. 1, Surgeon General Jerome Adams stressed the importance of getting vaccinated and noted that an infected person can transmit the measles virus up to 4 days before he or she develops symptoms.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Just over half of the cases in 2019 have occurred in Clark County, Wash., which has reported 53 cases. That outbreak led Gov. Jay Inslee to declare a public health emergency for the entire state on Jan. 25.

The cases in Washington represent one of the five outbreaks – the CDC defines an outbreak as three or more cases – that have occurred so far this year, with three reported in New York State (Rockland County, Monroe County, and New York City) and one in Texas, which has been spread out over five counties, the CDC reported Feb. 11.

“These outbreaks are linked to travelers who brought measles back from other countries such as Israel and Ukraine, where large measles outbreaks are occurring,” the CDC noted. The other states with confirmed cases are California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, and Oregon.

In a video released Feb. 1, Surgeon General Jerome Adams stressed the importance of getting vaccinated and noted that an infected person can transmit the measles virus up to 4 days before he or she develops symptoms.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Just over half of the cases in 2019 have occurred in Clark County, Wash., which has reported 53 cases. That outbreak led Gov. Jay Inslee to declare a public health emergency for the entire state on Jan. 25.

The cases in Washington represent one of the five outbreaks – the CDC defines an outbreak as three or more cases – that have occurred so far this year, with three reported in New York State (Rockland County, Monroe County, and New York City) and one in Texas, which has been spread out over five counties, the CDC reported Feb. 11.

“These outbreaks are linked to travelers who brought measles back from other countries such as Israel and Ukraine, where large measles outbreaks are occurring,” the CDC noted. The other states with confirmed cases are California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, and Oregon.

In a video released Feb. 1, Surgeon General Jerome Adams stressed the importance of getting vaccinated and noted that an infected person can transmit the measles virus up to 4 days before he or she develops symptoms.

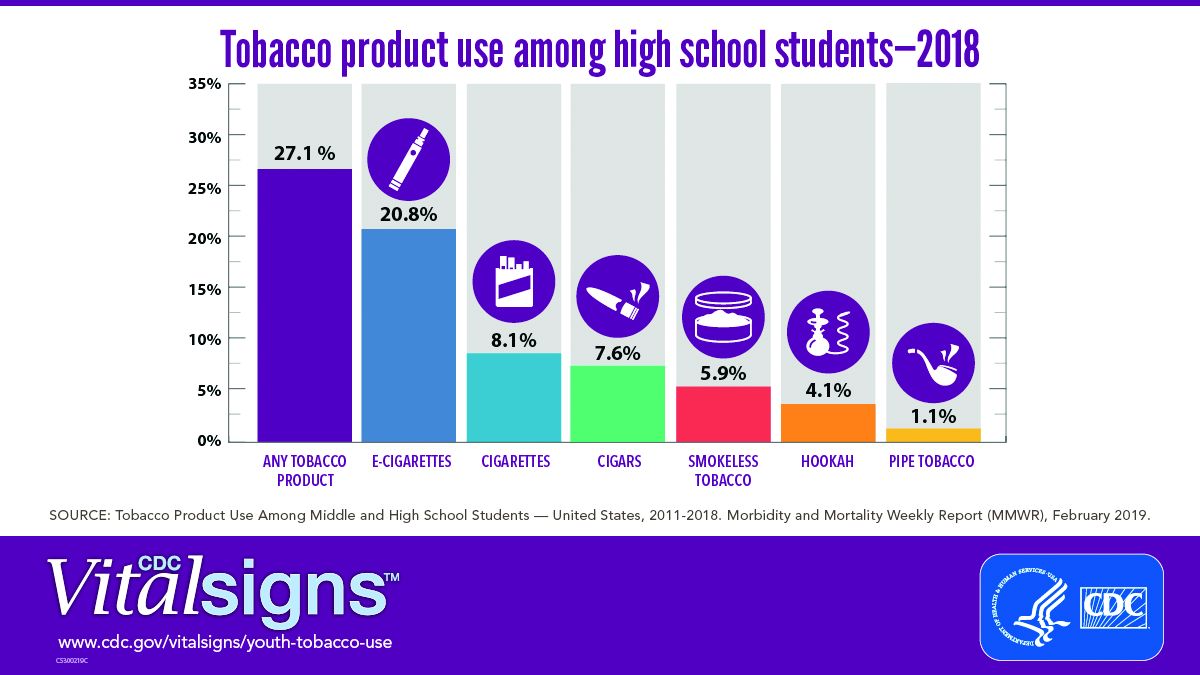

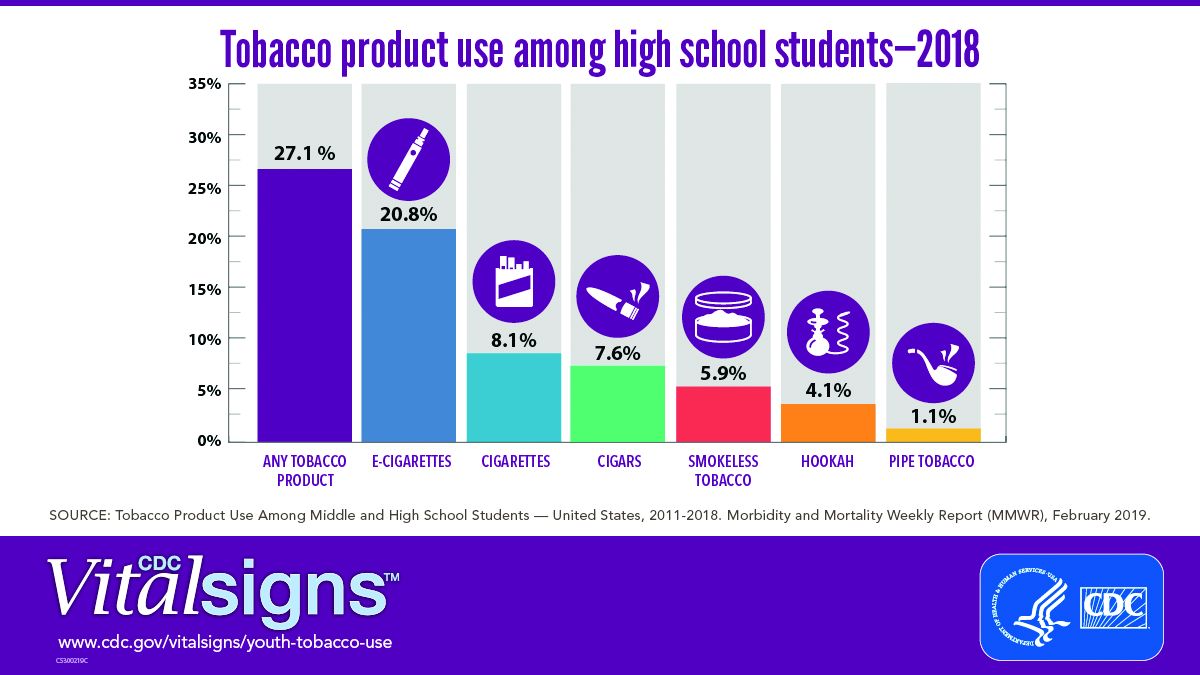

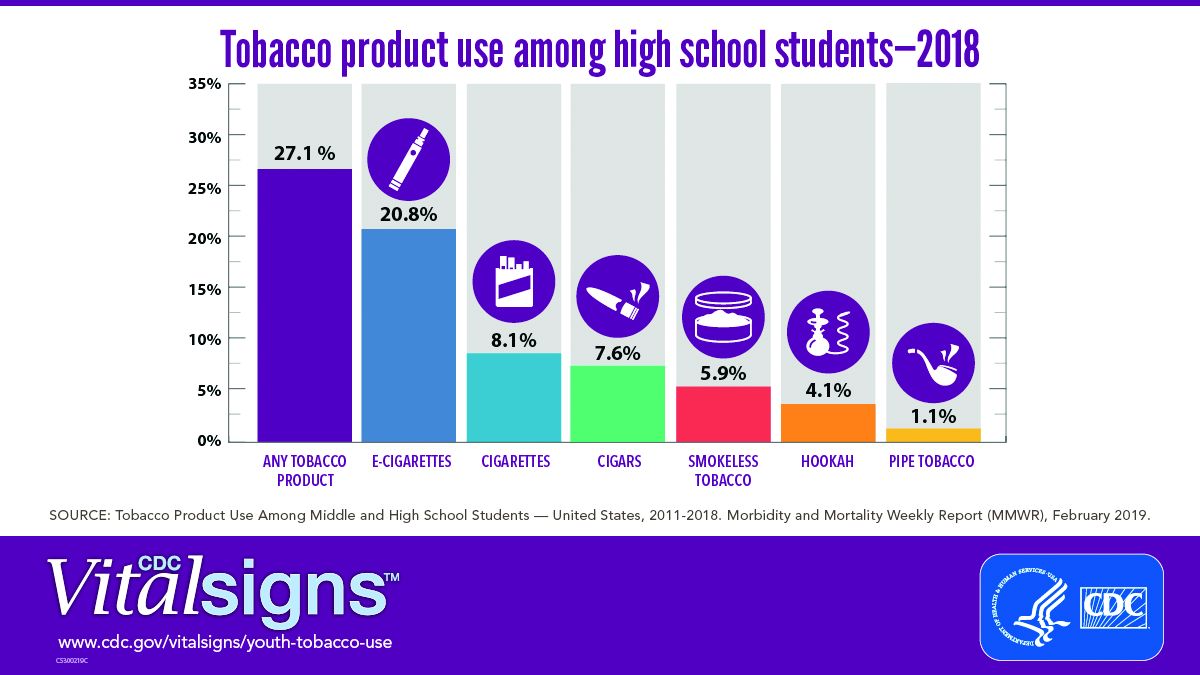

E-cig use reverses progress in reducing tobacco use in teens

A significant increase during 2017-2018 in e-cigarette use among U.S. youths has erased recent progress in reducing overall tobacco product use in this age group, a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found.

E-cigarettes are driving the trend. About 4 million high school students in the United States reported using any tobacco product in the last 30 days, and 3 million of them reported using e-cigarettes, according to a Vital Signs document published by the CDC on Feb. 11 in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.*

In addition, many high school students who use e-cigarettes use them often; 28% reported using the products at least 20 times in the past 28 days, up from 20% in 2017.

“Any use of any tobacco product is unsafe for teens,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, said in a teleconference to present the findings. Nicotine is highly addictive and can harm brain development in youth, including capacity for learning, memory, and attention, she said.

The rise in e-cigarette use corresponds with the rise in marketing and availability of e-cigarette devices such as JUUL, which dispense nicotine via liquid refill pods available in flavors including strawberry and cotton candy, said Brian King, MPH, PhD, deputy director for research translation at the CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health.

“The advertising will lead a horse to water, the flavors will make them drink, and the nicotine will keep them coming back for more,” said Dr. King.

Approximately 27.1% of high school students and 7.2% of middle school students used a tobacco product in 2018, a significant increase from 2017 data, and with a major increase in e-cigarette use.

No change was noted in the use of other tobacco products, including cigarettes, from 2017 to 2018, according to the report. However, conventional cigarettes remained the most common companion product to e-cigarettes for youth who use two or more tobacco products (two in five high school students and one in three middle school students in 2018). From a demographic standpoint, e-cigarette use was highest among males, whites, and high school students.

Tobacco use in teens is trending in the direction of wiping out the progress made in recent years to reduce exposure to youths. The report noted, “The prevalence of e-cigarette use by U.S. high school students had peaked in 2015 before declining by 29% during 2015-2016 (from 16% to 11.3%); this decline was the first ever recorded for e-cigarette use among youths in the NYTS since monitoring began, and it was subsequently sustained during 2016-2017). However, current e-cigarette use increased by 77.8% among high school students and 48.5% among middle school students during 2017-2018, erasing the progress in reducing e-cigarette use, as well as any tobacco product use, that had occurred in prior years.”

The CDC and the Food and Drug Administration are taking action to curb the rise in e-cigarette use in youth in particular by seeking regulations to make the products less accessible, raising prices, and banning most flavorings, said Dr. Schuchat.

“We have targeted companies engaged in kid friendly marketing,” said Mitch Zeller, JD, director of the Center for Tobacco Products for the FDA.

In a statement published simultaneously with the Vital Signs study, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, emphasized the link between e-cigarette use in teens and the potential for future tobacco use. “The kids using e-cigarettes are children who rejected conventional cigarettes, but don’t see the same stigma associated with the use of e-cigarettes. But now, having become exposed to nicotine through e-cigs, they will be more likely to smoke.” Dr. Gottlieb declared, “I will not allow a generation of children to become addicted to nicotine through e-cigarettes. We must stop the trends of youth e-cigarette use from continuing to build and will take whatever action is necessary to ensure these kids don’t become future smokers.” He reviewed steps taken in the past year by the FDA to counter tobacco use in teens but he warned of future actions that may need to be taken: “If these youth use trends continue, we’ll be forced to consider regulatory steps that could constrain or even foreclose the opportunities for currently addicted adult smokers to have the same level of access to these products that they now enjoy. I recognize that such a move could come with significant impacts to adult smokers.”

In the meantime, however, parents, teachers, community leaders, and health care providers are on the front lines and can make a difference in protecting youth and curbing nicotine use, Dr. King said.

One of the most important things clinicians can do is to ask young patients specifically about e-cigarette use, he emphasized. Learn and use the terminology the kids are using; ask, “Do you use JUUL?” If they are using these products, “make sure they know they are dangerous,” and can harm the developing brain, he said.

Although there are no currently approved medications to treat nicotine addiction in youth, research suggests that behavioral counseling, as well as reinforcement of the danger of nicotine from parents and other people of influence, can help, Dr. King said.

The Vital Signs report is based on data from the 2011-2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey, which assesses current use of cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, hookahs, pipe tobacco, and bidis among a nationally representative sample of middle and high school students in the United States. The findings were analyzed by the CDC, FDA, and the National Cancer Institute.

SOURCE: Gentzke AS et al. MMWR 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1.

*Correction 2/13/2019 An earlier version of this article misstated the number of students using e-cigarettes as a proportion of all teen tobacco users.

A significant increase during 2017-2018 in e-cigarette use among U.S. youths has erased recent progress in reducing overall tobacco product use in this age group, a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found.

E-cigarettes are driving the trend. About 4 million high school students in the United States reported using any tobacco product in the last 30 days, and 3 million of them reported using e-cigarettes, according to a Vital Signs document published by the CDC on Feb. 11 in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.*

In addition, many high school students who use e-cigarettes use them often; 28% reported using the products at least 20 times in the past 28 days, up from 20% in 2017.

“Any use of any tobacco product is unsafe for teens,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, said in a teleconference to present the findings. Nicotine is highly addictive and can harm brain development in youth, including capacity for learning, memory, and attention, she said.

The rise in e-cigarette use corresponds with the rise in marketing and availability of e-cigarette devices such as JUUL, which dispense nicotine via liquid refill pods available in flavors including strawberry and cotton candy, said Brian King, MPH, PhD, deputy director for research translation at the CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health.

“The advertising will lead a horse to water, the flavors will make them drink, and the nicotine will keep them coming back for more,” said Dr. King.

Approximately 27.1% of high school students and 7.2% of middle school students used a tobacco product in 2018, a significant increase from 2017 data, and with a major increase in e-cigarette use.

No change was noted in the use of other tobacco products, including cigarettes, from 2017 to 2018, according to the report. However, conventional cigarettes remained the most common companion product to e-cigarettes for youth who use two or more tobacco products (two in five high school students and one in three middle school students in 2018). From a demographic standpoint, e-cigarette use was highest among males, whites, and high school students.

Tobacco use in teens is trending in the direction of wiping out the progress made in recent years to reduce exposure to youths. The report noted, “The prevalence of e-cigarette use by U.S. high school students had peaked in 2015 before declining by 29% during 2015-2016 (from 16% to 11.3%); this decline was the first ever recorded for e-cigarette use among youths in the NYTS since monitoring began, and it was subsequently sustained during 2016-2017). However, current e-cigarette use increased by 77.8% among high school students and 48.5% among middle school students during 2017-2018, erasing the progress in reducing e-cigarette use, as well as any tobacco product use, that had occurred in prior years.”

The CDC and the Food and Drug Administration are taking action to curb the rise in e-cigarette use in youth in particular by seeking regulations to make the products less accessible, raising prices, and banning most flavorings, said Dr. Schuchat.

“We have targeted companies engaged in kid friendly marketing,” said Mitch Zeller, JD, director of the Center for Tobacco Products for the FDA.

In a statement published simultaneously with the Vital Signs study, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, emphasized the link between e-cigarette use in teens and the potential for future tobacco use. “The kids using e-cigarettes are children who rejected conventional cigarettes, but don’t see the same stigma associated with the use of e-cigarettes. But now, having become exposed to nicotine through e-cigs, they will be more likely to smoke.” Dr. Gottlieb declared, “I will not allow a generation of children to become addicted to nicotine through e-cigarettes. We must stop the trends of youth e-cigarette use from continuing to build and will take whatever action is necessary to ensure these kids don’t become future smokers.” He reviewed steps taken in the past year by the FDA to counter tobacco use in teens but he warned of future actions that may need to be taken: “If these youth use trends continue, we’ll be forced to consider regulatory steps that could constrain or even foreclose the opportunities for currently addicted adult smokers to have the same level of access to these products that they now enjoy. I recognize that such a move could come with significant impacts to adult smokers.”

In the meantime, however, parents, teachers, community leaders, and health care providers are on the front lines and can make a difference in protecting youth and curbing nicotine use, Dr. King said.

One of the most important things clinicians can do is to ask young patients specifically about e-cigarette use, he emphasized. Learn and use the terminology the kids are using; ask, “Do you use JUUL?” If they are using these products, “make sure they know they are dangerous,” and can harm the developing brain, he said.

Although there are no currently approved medications to treat nicotine addiction in youth, research suggests that behavioral counseling, as well as reinforcement of the danger of nicotine from parents and other people of influence, can help, Dr. King said.

The Vital Signs report is based on data from the 2011-2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey, which assesses current use of cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, hookahs, pipe tobacco, and bidis among a nationally representative sample of middle and high school students in the United States. The findings were analyzed by the CDC, FDA, and the National Cancer Institute.

SOURCE: Gentzke AS et al. MMWR 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1.

*Correction 2/13/2019 An earlier version of this article misstated the number of students using e-cigarettes as a proportion of all teen tobacco users.

A significant increase during 2017-2018 in e-cigarette use among U.S. youths has erased recent progress in reducing overall tobacco product use in this age group, a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found.

E-cigarettes are driving the trend. About 4 million high school students in the United States reported using any tobacco product in the last 30 days, and 3 million of them reported using e-cigarettes, according to a Vital Signs document published by the CDC on Feb. 11 in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.*

In addition, many high school students who use e-cigarettes use them often; 28% reported using the products at least 20 times in the past 28 days, up from 20% in 2017.

“Any use of any tobacco product is unsafe for teens,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, said in a teleconference to present the findings. Nicotine is highly addictive and can harm brain development in youth, including capacity for learning, memory, and attention, she said.

The rise in e-cigarette use corresponds with the rise in marketing and availability of e-cigarette devices such as JUUL, which dispense nicotine via liquid refill pods available in flavors including strawberry and cotton candy, said Brian King, MPH, PhD, deputy director for research translation at the CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health.

“The advertising will lead a horse to water, the flavors will make them drink, and the nicotine will keep them coming back for more,” said Dr. King.

Approximately 27.1% of high school students and 7.2% of middle school students used a tobacco product in 2018, a significant increase from 2017 data, and with a major increase in e-cigarette use.

No change was noted in the use of other tobacco products, including cigarettes, from 2017 to 2018, according to the report. However, conventional cigarettes remained the most common companion product to e-cigarettes for youth who use two or more tobacco products (two in five high school students and one in three middle school students in 2018). From a demographic standpoint, e-cigarette use was highest among males, whites, and high school students.

Tobacco use in teens is trending in the direction of wiping out the progress made in recent years to reduce exposure to youths. The report noted, “The prevalence of e-cigarette use by U.S. high school students had peaked in 2015 before declining by 29% during 2015-2016 (from 16% to 11.3%); this decline was the first ever recorded for e-cigarette use among youths in the NYTS since monitoring began, and it was subsequently sustained during 2016-2017). However, current e-cigarette use increased by 77.8% among high school students and 48.5% among middle school students during 2017-2018, erasing the progress in reducing e-cigarette use, as well as any tobacco product use, that had occurred in prior years.”

The CDC and the Food and Drug Administration are taking action to curb the rise in e-cigarette use in youth in particular by seeking regulations to make the products less accessible, raising prices, and banning most flavorings, said Dr. Schuchat.

“We have targeted companies engaged in kid friendly marketing,” said Mitch Zeller, JD, director of the Center for Tobacco Products for the FDA.

In a statement published simultaneously with the Vital Signs study, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, emphasized the link between e-cigarette use in teens and the potential for future tobacco use. “The kids using e-cigarettes are children who rejected conventional cigarettes, but don’t see the same stigma associated with the use of e-cigarettes. But now, having become exposed to nicotine through e-cigs, they will be more likely to smoke.” Dr. Gottlieb declared, “I will not allow a generation of children to become addicted to nicotine through e-cigarettes. We must stop the trends of youth e-cigarette use from continuing to build and will take whatever action is necessary to ensure these kids don’t become future smokers.” He reviewed steps taken in the past year by the FDA to counter tobacco use in teens but he warned of future actions that may need to be taken: “If these youth use trends continue, we’ll be forced to consider regulatory steps that could constrain or even foreclose the opportunities for currently addicted adult smokers to have the same level of access to these products that they now enjoy. I recognize that such a move could come with significant impacts to adult smokers.”

In the meantime, however, parents, teachers, community leaders, and health care providers are on the front lines and can make a difference in protecting youth and curbing nicotine use, Dr. King said.

One of the most important things clinicians can do is to ask young patients specifically about e-cigarette use, he emphasized. Learn and use the terminology the kids are using; ask, “Do you use JUUL?” If they are using these products, “make sure they know they are dangerous,” and can harm the developing brain, he said.

Although there are no currently approved medications to treat nicotine addiction in youth, research suggests that behavioral counseling, as well as reinforcement of the danger of nicotine from parents and other people of influence, can help, Dr. King said.

The Vital Signs report is based on data from the 2011-2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey, which assesses current use of cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, hookahs, pipe tobacco, and bidis among a nationally representative sample of middle and high school students in the United States. The findings were analyzed by the CDC, FDA, and the National Cancer Institute.

SOURCE: Gentzke AS et al. MMWR 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1.

*Correction 2/13/2019 An earlier version of this article misstated the number of students using e-cigarettes as a proportion of all teen tobacco users.

FROM CDC VITAL SIGNS REPORT

EC approves dasatinib plus chemo for kids with Ph+ ALL

The European Commission has approved dasatinib (Sprycel) for use in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Philadelphia chromosome–positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Dasatinib will be available in tablet form and as a powder for oral suspension, Bristol-Myers Squib said in a press release.

The approval was based on an event-free survival rate of 65.5% (95% confidence interval, 57.7-73.7) and an overall survival rate of 91.5% (95% CI, 84.2-95.5) in a phase 2 trial that evaluated the addition of dasatinib to a chemotherapy regimen modeled on a Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster high-risk backbone in pediatric patients with newly diagnosed Ph+ ALL.

Patients treated in the study (n = 106) were all aged younger than 18 years and received dasatinib at a daily dose of 60 mg/m2 on a continuous dosing regimen for up to 24 months, in combination with chemotherapy. About 77 % of patients (n = 82) received tablets exclusively; 23% of patients (n = 24) received the powder for oral suspension at least once.

Hematologic adverse events included grade 3 or 4 febrile neutropenia (75.5%), sepsis (23.6%), and bacteremia (24.5%). Nonhematologic, noninfectious grade 3 or 4 adverse events attributed to dasatinib and reported in more than 10% of patients included elevated ALT (21.7%) and AST (10.4%). Additional grade 3 or 4 adverse events attributed to dasatinib were pleural effusion (3.8%), edema (2.8%), hemorrhage (5.7%), and cardiac failure (0.8%). No events of pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary arterial hypertension were reported, the company said in the press release.

Dasatinib is already approved by the European Commission to treat children with Ph+ chronic myeloid leukemia in the chronic phase, which includes newly diagnosed patients and those with resistance or intolerance to imatinib.

The European Commission has approved dasatinib (Sprycel) for use in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Philadelphia chromosome–positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Dasatinib will be available in tablet form and as a powder for oral suspension, Bristol-Myers Squib said in a press release.

The approval was based on an event-free survival rate of 65.5% (95% confidence interval, 57.7-73.7) and an overall survival rate of 91.5% (95% CI, 84.2-95.5) in a phase 2 trial that evaluated the addition of dasatinib to a chemotherapy regimen modeled on a Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster high-risk backbone in pediatric patients with newly diagnosed Ph+ ALL.

Patients treated in the study (n = 106) were all aged younger than 18 years and received dasatinib at a daily dose of 60 mg/m2 on a continuous dosing regimen for up to 24 months, in combination with chemotherapy. About 77 % of patients (n = 82) received tablets exclusively; 23% of patients (n = 24) received the powder for oral suspension at least once.

Hematologic adverse events included grade 3 or 4 febrile neutropenia (75.5%), sepsis (23.6%), and bacteremia (24.5%). Nonhematologic, noninfectious grade 3 or 4 adverse events attributed to dasatinib and reported in more than 10% of patients included elevated ALT (21.7%) and AST (10.4%). Additional grade 3 or 4 adverse events attributed to dasatinib were pleural effusion (3.8%), edema (2.8%), hemorrhage (5.7%), and cardiac failure (0.8%). No events of pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary arterial hypertension were reported, the company said in the press release.

Dasatinib is already approved by the European Commission to treat children with Ph+ chronic myeloid leukemia in the chronic phase, which includes newly diagnosed patients and those with resistance or intolerance to imatinib.

The European Commission has approved dasatinib (Sprycel) for use in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Philadelphia chromosome–positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Dasatinib will be available in tablet form and as a powder for oral suspension, Bristol-Myers Squib said in a press release.

The approval was based on an event-free survival rate of 65.5% (95% confidence interval, 57.7-73.7) and an overall survival rate of 91.5% (95% CI, 84.2-95.5) in a phase 2 trial that evaluated the addition of dasatinib to a chemotherapy regimen modeled on a Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster high-risk backbone in pediatric patients with newly diagnosed Ph+ ALL.

Patients treated in the study (n = 106) were all aged younger than 18 years and received dasatinib at a daily dose of 60 mg/m2 on a continuous dosing regimen for up to 24 months, in combination with chemotherapy. About 77 % of patients (n = 82) received tablets exclusively; 23% of patients (n = 24) received the powder for oral suspension at least once.

Hematologic adverse events included grade 3 or 4 febrile neutropenia (75.5%), sepsis (23.6%), and bacteremia (24.5%). Nonhematologic, noninfectious grade 3 or 4 adverse events attributed to dasatinib and reported in more than 10% of patients included elevated ALT (21.7%) and AST (10.4%). Additional grade 3 or 4 adverse events attributed to dasatinib were pleural effusion (3.8%), edema (2.8%), hemorrhage (5.7%), and cardiac failure (0.8%). No events of pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary arterial hypertension were reported, the company said in the press release.

Dasatinib is already approved by the European Commission to treat children with Ph+ chronic myeloid leukemia in the chronic phase, which includes newly diagnosed patients and those with resistance or intolerance to imatinib.

Treatment missing for U.S. children with mental illness

according to data from a national survey of parents.

Among the estimated 7.7 million children with a treatable mental illness, 49.4% did not receive needed treatment from a psychiatrist, psychologist, psychiatric nurse, or clinical social worker in the previous 12 months, Daniel G. Whitney, PhD, and Mark D. Peterson, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote in JAMA Pediatrics.

State-level data from the National Survey of Children’s Health show considerable variation from the national average. North Carolina had the highest prevalence of nontreatment at 72.2% and Washington, D.C., had the lowest rate at 29.5%. The prevalence of at least one mental health disorder was highest in Maine (27.2%) and lowest in Hawaii (7.6%), the investigators reported.

Four states – Alabama, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Utah – were in the top quartile for both mental health disorder prevalence and prevalence of children with a disorder who did not receive treatment, they noted.

“State-level practices and policies play a role in health care needs and use, which may help to explain the state variability observed in this study. Nevertheless, initiatives that assist systems of care coordination have demonstrated a reduction of mental health–related burdens across multiple domains,” Dr. Whitney and Dr. Peterson wrote.

SOURCE: Whitney DG et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399.

according to data from a national survey of parents.

Among the estimated 7.7 million children with a treatable mental illness, 49.4% did not receive needed treatment from a psychiatrist, psychologist, psychiatric nurse, or clinical social worker in the previous 12 months, Daniel G. Whitney, PhD, and Mark D. Peterson, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote in JAMA Pediatrics.

State-level data from the National Survey of Children’s Health show considerable variation from the national average. North Carolina had the highest prevalence of nontreatment at 72.2% and Washington, D.C., had the lowest rate at 29.5%. The prevalence of at least one mental health disorder was highest in Maine (27.2%) and lowest in Hawaii (7.6%), the investigators reported.

Four states – Alabama, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Utah – were in the top quartile for both mental health disorder prevalence and prevalence of children with a disorder who did not receive treatment, they noted.

“State-level practices and policies play a role in health care needs and use, which may help to explain the state variability observed in this study. Nevertheless, initiatives that assist systems of care coordination have demonstrated a reduction of mental health–related burdens across multiple domains,” Dr. Whitney and Dr. Peterson wrote.

SOURCE: Whitney DG et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399.

according to data from a national survey of parents.

Among the estimated 7.7 million children with a treatable mental illness, 49.4% did not receive needed treatment from a psychiatrist, psychologist, psychiatric nurse, or clinical social worker in the previous 12 months, Daniel G. Whitney, PhD, and Mark D. Peterson, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote in JAMA Pediatrics.

State-level data from the National Survey of Children’s Health show considerable variation from the national average. North Carolina had the highest prevalence of nontreatment at 72.2% and Washington, D.C., had the lowest rate at 29.5%. The prevalence of at least one mental health disorder was highest in Maine (27.2%) and lowest in Hawaii (7.6%), the investigators reported.

Four states – Alabama, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Utah – were in the top quartile for both mental health disorder prevalence and prevalence of children with a disorder who did not receive treatment, they noted.

“State-level practices and policies play a role in health care needs and use, which may help to explain the state variability observed in this study. Nevertheless, initiatives that assist systems of care coordination have demonstrated a reduction of mental health–related burdens across multiple domains,” Dr. Whitney and Dr. Peterson wrote.

SOURCE: Whitney DG et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Herpes zoster could pose special threat to younger IBD patients

LAS VEGAS – Herpes zoster infection could pose a special risk for younger patients with inflammatory bowel disease who are on immunosuppressant or biologic therapies, a new study suggests.

About 3% of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients developed herpes zoster (HZ) over a 5-year period at a single center, researchers found, and their average age was 37 years. The mean national age of HZ diagnosis is 59 years, and the latest guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention do not recommend that people get vaccinated against HZ, or shingles, until age 50.

“Increased efforts should be made to administer herpes zoster vaccine in all eligible IBD patients, and said gastroenterologist and study coauthor Marie L. Borum, MD, MPH, of George Washington University, Washington. She spoke in an interview before presenting the study findings at the the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress – a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Dr. Borum and her associates launched the study, published in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, after noticing an increase in HZ cases among patients with IBD. The authors retrospectively analyzed the medical charts of all patients with IBD who were treated at a single center from 2012 to 2017 (n = 393; 55% female; average age, 44 years). Nearly all had ulcerative colitis (71%) or Crohn’s disease (24%).

Over the 5-year period, 11 patients – 5 with ulcerative colitis, 5 with Crohn’s disease, and 1 patient with unspecified colitis – were diagnosed with HZ. All were taking immunosuppressant or biologic medications, and none had been vaccinated against HZ.

The difference in the average age of diagnosis of the infected patients versus the national mean age (37 years vs. 59 years) was statistically significant (P less than .0001).

The IBD patients with HZ often had postherpetic neuralgia, Dr. Borum said.

Previous studies also have linked IBD to higher rates of HZ. A 2018 retrospective study of veterans found that “the incidence rates of herpes zoster in all age groups and all IBD medication subgroups were substantially higher than that in the oldest group of patients without IBD [older than 60 years]” (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Dec;16[12]:1919-27).

In 2017, researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison received a grant to study immunity to the varicella zoster virus in patients with IBD. A university press release said the results “could support recommendations for universal herpes zoster immunization for all IBD patients above the age of 40.”

Why might IBD boost the risk of HZ? “Individuals with IBD may have an increased risk of developing more episodes of herpes zoster due to immune dysregulation,” Dr. Borum said. “Those on immunosuppressants or biologic therapies have greater risk of more frequent and severe complications. It has been speculated that Janus kinase inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk for developing HZ.”

Dr. Borum noted that the study is limited by its size and single-center design. “However, it supports the recommendations that additional research is needed to fully understand the potential impact of HZ on IBD patients.”

The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Borum ML et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Feb 7. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy393.073.

LAS VEGAS – Herpes zoster infection could pose a special risk for younger patients with inflammatory bowel disease who are on immunosuppressant or biologic therapies, a new study suggests.

About 3% of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients developed herpes zoster (HZ) over a 5-year period at a single center, researchers found, and their average age was 37 years. The mean national age of HZ diagnosis is 59 years, and the latest guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention do not recommend that people get vaccinated against HZ, or shingles, until age 50.

“Increased efforts should be made to administer herpes zoster vaccine in all eligible IBD patients, and said gastroenterologist and study coauthor Marie L. Borum, MD, MPH, of George Washington University, Washington. She spoke in an interview before presenting the study findings at the the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress – a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Dr. Borum and her associates launched the study, published in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, after noticing an increase in HZ cases among patients with IBD. The authors retrospectively analyzed the medical charts of all patients with IBD who were treated at a single center from 2012 to 2017 (n = 393; 55% female; average age, 44 years). Nearly all had ulcerative colitis (71%) or Crohn’s disease (24%).

Over the 5-year period, 11 patients – 5 with ulcerative colitis, 5 with Crohn’s disease, and 1 patient with unspecified colitis – were diagnosed with HZ. All were taking immunosuppressant or biologic medications, and none had been vaccinated against HZ.

The difference in the average age of diagnosis of the infected patients versus the national mean age (37 years vs. 59 years) was statistically significant (P less than .0001).

The IBD patients with HZ often had postherpetic neuralgia, Dr. Borum said.

Previous studies also have linked IBD to higher rates of HZ. A 2018 retrospective study of veterans found that “the incidence rates of herpes zoster in all age groups and all IBD medication subgroups were substantially higher than that in the oldest group of patients without IBD [older than 60 years]” (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Dec;16[12]:1919-27).

In 2017, researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison received a grant to study immunity to the varicella zoster virus in patients with IBD. A university press release said the results “could support recommendations for universal herpes zoster immunization for all IBD patients above the age of 40.”

Why might IBD boost the risk of HZ? “Individuals with IBD may have an increased risk of developing more episodes of herpes zoster due to immune dysregulation,” Dr. Borum said. “Those on immunosuppressants or biologic therapies have greater risk of more frequent and severe complications. It has been speculated that Janus kinase inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk for developing HZ.”

Dr. Borum noted that the study is limited by its size and single-center design. “However, it supports the recommendations that additional research is needed to fully understand the potential impact of HZ on IBD patients.”

The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Borum ML et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Feb 7. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy393.073.

LAS VEGAS – Herpes zoster infection could pose a special risk for younger patients with inflammatory bowel disease who are on immunosuppressant or biologic therapies, a new study suggests.

About 3% of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients developed herpes zoster (HZ) over a 5-year period at a single center, researchers found, and their average age was 37 years. The mean national age of HZ diagnosis is 59 years, and the latest guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention do not recommend that people get vaccinated against HZ, or shingles, until age 50.

“Increased efforts should be made to administer herpes zoster vaccine in all eligible IBD patients, and said gastroenterologist and study coauthor Marie L. Borum, MD, MPH, of George Washington University, Washington. She spoke in an interview before presenting the study findings at the the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress – a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Dr. Borum and her associates launched the study, published in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, after noticing an increase in HZ cases among patients with IBD. The authors retrospectively analyzed the medical charts of all patients with IBD who were treated at a single center from 2012 to 2017 (n = 393; 55% female; average age, 44 years). Nearly all had ulcerative colitis (71%) or Crohn’s disease (24%).

Over the 5-year period, 11 patients – 5 with ulcerative colitis, 5 with Crohn’s disease, and 1 patient with unspecified colitis – were diagnosed with HZ. All were taking immunosuppressant or biologic medications, and none had been vaccinated against HZ.

The difference in the average age of diagnosis of the infected patients versus the national mean age (37 years vs. 59 years) was statistically significant (P less than .0001).

The IBD patients with HZ often had postherpetic neuralgia, Dr. Borum said.

Previous studies also have linked IBD to higher rates of HZ. A 2018 retrospective study of veterans found that “the incidence rates of herpes zoster in all age groups and all IBD medication subgroups were substantially higher than that in the oldest group of patients without IBD [older than 60 years]” (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Dec;16[12]:1919-27).

In 2017, researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison received a grant to study immunity to the varicella zoster virus in patients with IBD. A university press release said the results “could support recommendations for universal herpes zoster immunization for all IBD patients above the age of 40.”

Why might IBD boost the risk of HZ? “Individuals with IBD may have an increased risk of developing more episodes of herpes zoster due to immune dysregulation,” Dr. Borum said. “Those on immunosuppressants or biologic therapies have greater risk of more frequent and severe complications. It has been speculated that Janus kinase inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk for developing HZ.”

Dr. Borum noted that the study is limited by its size and single-center design. “However, it supports the recommendations that additional research is needed to fully understand the potential impact of HZ on IBD patients.”

The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Borum ML et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Feb 7. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy393.073.

REPORTING FROM THE CROHN’S & COLITIS CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Younger patients with inflammatory bowel disease may face a higher risk of infection with herpes zoster.

Major finding: About 3% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease were diagnosed with herpes zoster infection, and their average age was 37 years.

Study details: A retrospective 5-year chart review of 393 patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Source: Borum ML et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Feb 7. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy393.073.

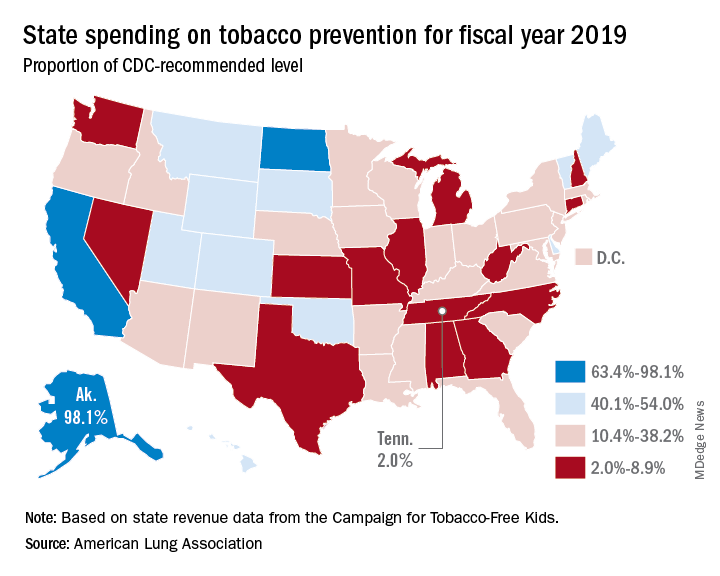

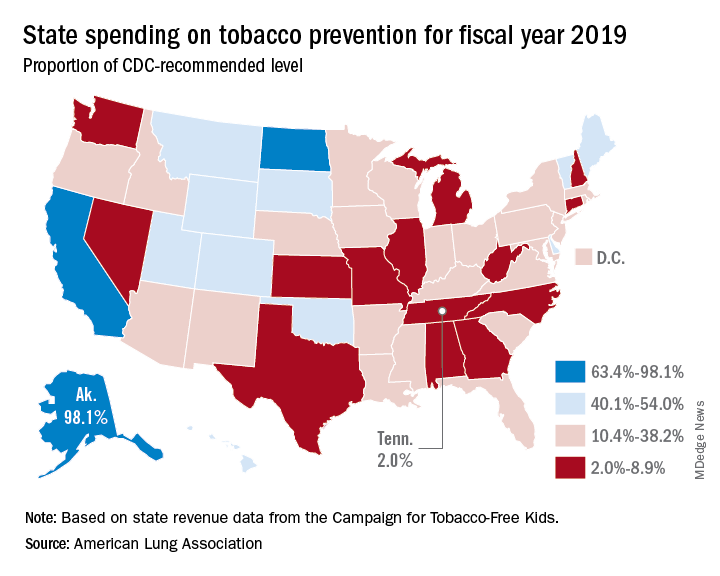

ALA report: Federal and state actions to limit tobacco use fall short

Tobacco use is currently at an all-time low thanks to public and private efforts, but more aggressive action from federal, state, and local governments is needed to protect the public, according to a review of tobacco control trends in the United States.

The American Lung Association (ALA) released “State of Tobacco Control” 2019, its 17th annual state-by-state analysis and list of recommended policy priorities to limit tobacco use. Although the report notes some positive steps taken by the federal and state governments, shortfalls in policy and legislation also are highlighted. The report states, “We know how and are ready to save more lives, but we need our elected officials to do much more. To many, solving America’s tobacco crisis might seem like a complex puzzle with no solution. And yet we have known for years what pieces are needed to reduce the disease and death caused by tobacco use.”

In this report, the federal government and each state are graded on a scale, A through F, for policy actions and laws to limit tobacco use. The grading methodology is based on a detailed point system cataloging the implementation and strength of specific actions and policies to limit tobacco use.

Areas of Impact

The report focused on six areas of public policy that affect exposure to and use of tobacco:

- Smoke-free air: Protecting the public from secondhand smoke should be a priority for policymakers, according the report, but 22 states have no smoke-free workplace laws in place. Laws restricting e-cigarettes in workplaces and public buildings have lagged behind tobacco laws in many states.

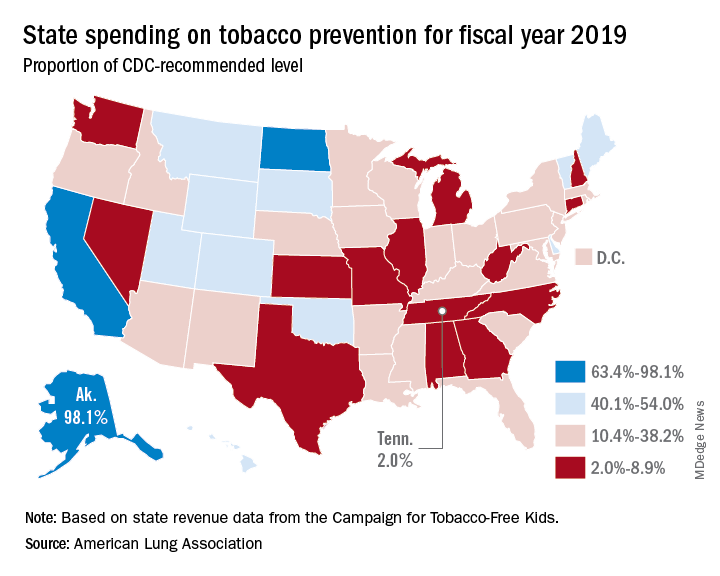

- Tobacco prevention funding: Dedicated funds to prevent tobacco addiction before it starts is a key element of a public health attack on tobacco use, but no U.S. state currently spends what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended. Twenty years ago, the Master Settlement Agreement between the tobacco industry and 46 states and the District of Columbia guaranteed ongoing payments to the states to be used for tobacco prevention and control. Although those funds have been collected in the states to the tune of $27 billion since 1998, overall only 2.4% of those funds have been spent for this purpose, and the rest has been budgeted for other purposes.

- Tobacco taxes: Sales taxes on tobacco products have been highly effective in preventing young people from taking up tobacco use, but those taxation rates have remained unchanged in 2018 in all but the District of Columbia and Oklahoma. The tobacco industry spent $22 million in a successful effort to defeat ballot measures to increase sales taxes on tobacco in Montana and South Dakota.

- Tobacco 21: “Increasing the legal age of sale for tobacco products to 21 would decrease tobacco use by 12% and could prevent 223,000 deaths among those born between 2000 and 2019,” the report noted, citing a 2015 report by the Institute of Medicine. So far, the this restriction has been legislated in six states, the District of Columbia, and numerous local governments. The ALA considers increasing the age for tobacco sales to 21 to be a public health priority.

- Helping smokers quit: The addictive qualities of tobacco mean that many smokers struggle unsuccessfully to quit, and medical intervention is needed to help them. The report notes that current law requires that Medicaid expansion health plans and private insurance plans cover comprehensive smoking cessation treatment. However, not all states have the expanded Medicaid program, and many of those with Medicaid expansion don’t offer coverage of all Food and Drug–approved cessation treatments. Despite laws requiring smoking cessation coverage, many private insurance plans still do not include this coverage. The ALA recommends enforcement of the current law with regard to tobacco cessation insurance coverage.

- FDA regulation of tobacco products: The FDA has announced plans to make a major effort to reduce tobacco use in young people, decrease nicotine in cigarettes, and to restrict flavored tobacco products. But these plans fall short of the aggressive action needed to curb the tobacco “epidemic,” according to the report. Delayed action and timid policy have “resulted in tobacco companies becoming more emboldened to devise new and egregious ways to addict youth and sustain addiction among current users.” The ALA report points to the steep rise in e-cigarette use among youth with a 20.8% rise in high school students using these products in 2018, a rise from 11.7% in 2017. This trend is not likely to be reversed by the FDA proposals to date, which rely on voluntary action by the industry to curb youth use, sales restrictions to youth, and restrictions on some flavored tobacco products.

The report card

Federal government efforts in regulation of tobacco products, taxation, and health insurance coverage of cessation all received an F in this report, while mass media campaigns were given an A.

The states didn’t fare much better. They were graded on prevention and control funding, smoke-free air, taxation, access to cessation services, and minimum age for sales. A total of 19 states received a grade of F in four or five of these areas.

Funding for prevention and control was evaluated as the percentage of the amount recommended by the CDC, adjusted for a variety of state-specific factors such as prevalence of tobacco use, cost and complexity of conducting mass media campaigns, and proportion of the audience below 200% of the federal poverty level. A limitation of this methodology of grading funding is that it doesn’t evaluate effectiveness of the spending or the level of spending in different program categories. The higher spenders on prevention and control were Alaska at 98.1% and California at 74.5% of the CDC recommended level. The lowest spenders were Georgia at 2.8% and Missouri at 3.0%.

All but eight states received an F on minimum age for tobacco sales because most have an age limit 18 instead of the ALA and CDC recommendation of age 21.

Harold Wimmer, the CEO of the American Lung Association, wrote, “Aggressive action by our country’s federal and state policymakers is urgently required. However, ‘State of Tobacco Control’ 2019 has found a disturbing failure by federal and state governments to take action to put in place meaningful and proven-effective policies that would have prevented, and reduced tobacco use during 2018. This failure to act places the lung health and lives of Americans at risk. We have also found that this lack of action has emboldened tobacco companies to be even more brazen in producing and marketing products squarely aimed at kids, such as the JUUL e-cigarettes that look like an easily concealed USB drive, which now dominate the market driven by youth use.”

The full report is available for download at the ALA website.

SOURCE: American Lung Association, “State of Tobacco Control 2019”.

Tobacco use is currently at an all-time low thanks to public and private efforts, but more aggressive action from federal, state, and local governments is needed to protect the public, according to a review of tobacco control trends in the United States.

The American Lung Association (ALA) released “State of Tobacco Control” 2019, its 17th annual state-by-state analysis and list of recommended policy priorities to limit tobacco use. Although the report notes some positive steps taken by the federal and state governments, shortfalls in policy and legislation also are highlighted. The report states, “We know how and are ready to save more lives, but we need our elected officials to do much more. To many, solving America’s tobacco crisis might seem like a complex puzzle with no solution. And yet we have known for years what pieces are needed to reduce the disease and death caused by tobacco use.”

In this report, the federal government and each state are graded on a scale, A through F, for policy actions and laws to limit tobacco use. The grading methodology is based on a detailed point system cataloging the implementation and strength of specific actions and policies to limit tobacco use.

Areas of Impact

The report focused on six areas of public policy that affect exposure to and use of tobacco:

- Smoke-free air: Protecting the public from secondhand smoke should be a priority for policymakers, according the report, but 22 states have no smoke-free workplace laws in place. Laws restricting e-cigarettes in workplaces and public buildings have lagged behind tobacco laws in many states.

- Tobacco prevention funding: Dedicated funds to prevent tobacco addiction before it starts is a key element of a public health attack on tobacco use, but no U.S. state currently spends what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended. Twenty years ago, the Master Settlement Agreement between the tobacco industry and 46 states and the District of Columbia guaranteed ongoing payments to the states to be used for tobacco prevention and control. Although those funds have been collected in the states to the tune of $27 billion since 1998, overall only 2.4% of those funds have been spent for this purpose, and the rest has been budgeted for other purposes.

- Tobacco taxes: Sales taxes on tobacco products have been highly effective in preventing young people from taking up tobacco use, but those taxation rates have remained unchanged in 2018 in all but the District of Columbia and Oklahoma. The tobacco industry spent $22 million in a successful effort to defeat ballot measures to increase sales taxes on tobacco in Montana and South Dakota.

- Tobacco 21: “Increasing the legal age of sale for tobacco products to 21 would decrease tobacco use by 12% and could prevent 223,000 deaths among those born between 2000 and 2019,” the report noted, citing a 2015 report by the Institute of Medicine. So far, the this restriction has been legislated in six states, the District of Columbia, and numerous local governments. The ALA considers increasing the age for tobacco sales to 21 to be a public health priority.

- Helping smokers quit: The addictive qualities of tobacco mean that many smokers struggle unsuccessfully to quit, and medical intervention is needed to help them. The report notes that current law requires that Medicaid expansion health plans and private insurance plans cover comprehensive smoking cessation treatment. However, not all states have the expanded Medicaid program, and many of those with Medicaid expansion don’t offer coverage of all Food and Drug–approved cessation treatments. Despite laws requiring smoking cessation coverage, many private insurance plans still do not include this coverage. The ALA recommends enforcement of the current law with regard to tobacco cessation insurance coverage.

- FDA regulation of tobacco products: The FDA has announced plans to make a major effort to reduce tobacco use in young people, decrease nicotine in cigarettes, and to restrict flavored tobacco products. But these plans fall short of the aggressive action needed to curb the tobacco “epidemic,” according to the report. Delayed action and timid policy have “resulted in tobacco companies becoming more emboldened to devise new and egregious ways to addict youth and sustain addiction among current users.” The ALA report points to the steep rise in e-cigarette use among youth with a 20.8% rise in high school students using these products in 2018, a rise from 11.7% in 2017. This trend is not likely to be reversed by the FDA proposals to date, which rely on voluntary action by the industry to curb youth use, sales restrictions to youth, and restrictions on some flavored tobacco products.

The report card

Federal government efforts in regulation of tobacco products, taxation, and health insurance coverage of cessation all received an F in this report, while mass media campaigns were given an A.

The states didn’t fare much better. They were graded on prevention and control funding, smoke-free air, taxation, access to cessation services, and minimum age for sales. A total of 19 states received a grade of F in four or five of these areas.

Funding for prevention and control was evaluated as the percentage of the amount recommended by the CDC, adjusted for a variety of state-specific factors such as prevalence of tobacco use, cost and complexity of conducting mass media campaigns, and proportion of the audience below 200% of the federal poverty level. A limitation of this methodology of grading funding is that it doesn’t evaluate effectiveness of the spending or the level of spending in different program categories. The higher spenders on prevention and control were Alaska at 98.1% and California at 74.5% of the CDC recommended level. The lowest spenders were Georgia at 2.8% and Missouri at 3.0%.

All but eight states received an F on minimum age for tobacco sales because most have an age limit 18 instead of the ALA and CDC recommendation of age 21.

Harold Wimmer, the CEO of the American Lung Association, wrote, “Aggressive action by our country’s federal and state policymakers is urgently required. However, ‘State of Tobacco Control’ 2019 has found a disturbing failure by federal and state governments to take action to put in place meaningful and proven-effective policies that would have prevented, and reduced tobacco use during 2018. This failure to act places the lung health and lives of Americans at risk. We have also found that this lack of action has emboldened tobacco companies to be even more brazen in producing and marketing products squarely aimed at kids, such as the JUUL e-cigarettes that look like an easily concealed USB drive, which now dominate the market driven by youth use.”

The full report is available for download at the ALA website.

SOURCE: American Lung Association, “State of Tobacco Control 2019”.

Tobacco use is currently at an all-time low thanks to public and private efforts, but more aggressive action from federal, state, and local governments is needed to protect the public, according to a review of tobacco control trends in the United States.

The American Lung Association (ALA) released “State of Tobacco Control” 2019, its 17th annual state-by-state analysis and list of recommended policy priorities to limit tobacco use. Although the report notes some positive steps taken by the federal and state governments, shortfalls in policy and legislation also are highlighted. The report states, “We know how and are ready to save more lives, but we need our elected officials to do much more. To many, solving America’s tobacco crisis might seem like a complex puzzle with no solution. And yet we have known for years what pieces are needed to reduce the disease and death caused by tobacco use.”

In this report, the federal government and each state are graded on a scale, A through F, for policy actions and laws to limit tobacco use. The grading methodology is based on a detailed point system cataloging the implementation and strength of specific actions and policies to limit tobacco use.

Areas of Impact

The report focused on six areas of public policy that affect exposure to and use of tobacco:

- Smoke-free air: Protecting the public from secondhand smoke should be a priority for policymakers, according the report, but 22 states have no smoke-free workplace laws in place. Laws restricting e-cigarettes in workplaces and public buildings have lagged behind tobacco laws in many states.

- Tobacco prevention funding: Dedicated funds to prevent tobacco addiction before it starts is a key element of a public health attack on tobacco use, but no U.S. state currently spends what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended. Twenty years ago, the Master Settlement Agreement between the tobacco industry and 46 states and the District of Columbia guaranteed ongoing payments to the states to be used for tobacco prevention and control. Although those funds have been collected in the states to the tune of $27 billion since 1998, overall only 2.4% of those funds have been spent for this purpose, and the rest has been budgeted for other purposes.

- Tobacco taxes: Sales taxes on tobacco products have been highly effective in preventing young people from taking up tobacco use, but those taxation rates have remained unchanged in 2018 in all but the District of Columbia and Oklahoma. The tobacco industry spent $22 million in a successful effort to defeat ballot measures to increase sales taxes on tobacco in Montana and South Dakota.

- Tobacco 21: “Increasing the legal age of sale for tobacco products to 21 would decrease tobacco use by 12% and could prevent 223,000 deaths among those born between 2000 and 2019,” the report noted, citing a 2015 report by the Institute of Medicine. So far, the this restriction has been legislated in six states, the District of Columbia, and numerous local governments. The ALA considers increasing the age for tobacco sales to 21 to be a public health priority.

- Helping smokers quit: The addictive qualities of tobacco mean that many smokers struggle unsuccessfully to quit, and medical intervention is needed to help them. The report notes that current law requires that Medicaid expansion health plans and private insurance plans cover comprehensive smoking cessation treatment. However, not all states have the expanded Medicaid program, and many of those with Medicaid expansion don’t offer coverage of all Food and Drug–approved cessation treatments. Despite laws requiring smoking cessation coverage, many private insurance plans still do not include this coverage. The ALA recommends enforcement of the current law with regard to tobacco cessation insurance coverage.

- FDA regulation of tobacco products: The FDA has announced plans to make a major effort to reduce tobacco use in young people, decrease nicotine in cigarettes, and to restrict flavored tobacco products. But these plans fall short of the aggressive action needed to curb the tobacco “epidemic,” according to the report. Delayed action and timid policy have “resulted in tobacco companies becoming more emboldened to devise new and egregious ways to addict youth and sustain addiction among current users.” The ALA report points to the steep rise in e-cigarette use among youth with a 20.8% rise in high school students using these products in 2018, a rise from 11.7% in 2017. This trend is not likely to be reversed by the FDA proposals to date, which rely on voluntary action by the industry to curb youth use, sales restrictions to youth, and restrictions on some flavored tobacco products.

The report card

Federal government efforts in regulation of tobacco products, taxation, and health insurance coverage of cessation all received an F in this report, while mass media campaigns were given an A.

The states didn’t fare much better. They were graded on prevention and control funding, smoke-free air, taxation, access to cessation services, and minimum age for sales. A total of 19 states received a grade of F in four or five of these areas.

Funding for prevention and control was evaluated as the percentage of the amount recommended by the CDC, adjusted for a variety of state-specific factors such as prevalence of tobacco use, cost and complexity of conducting mass media campaigns, and proportion of the audience below 200% of the federal poverty level. A limitation of this methodology of grading funding is that it doesn’t evaluate effectiveness of the spending or the level of spending in different program categories. The higher spenders on prevention and control were Alaska at 98.1% and California at 74.5% of the CDC recommended level. The lowest spenders were Georgia at 2.8% and Missouri at 3.0%.

All but eight states received an F on minimum age for tobacco sales because most have an age limit 18 instead of the ALA and CDC recommendation of age 21.

Harold Wimmer, the CEO of the American Lung Association, wrote, “Aggressive action by our country’s federal and state policymakers is urgently required. However, ‘State of Tobacco Control’ 2019 has found a disturbing failure by federal and state governments to take action to put in place meaningful and proven-effective policies that would have prevented, and reduced tobacco use during 2018. This failure to act places the lung health and lives of Americans at risk. We have also found that this lack of action has emboldened tobacco companies to be even more brazen in producing and marketing products squarely aimed at kids, such as the JUUL e-cigarettes that look like an easily concealed USB drive, which now dominate the market driven by youth use.”

The full report is available for download at the ALA website.

SOURCE: American Lung Association, “State of Tobacco Control 2019”.

February 2019 Highlights

Anthracyclines, bendamustine are options for grade 3A follicular lymphoma

While optimal treatment for grade 3A follicular lymphoma remains in question, either anthracycline-based chemotherapy or bendamustine appear to be preferable to cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP), results of a recent analysis suggest.

Time to progression with anthracycline-based chemotherapy was superior to that of CVP in the retrospective, multicenter study.

At the same time, clinical outcomes were comparable between anthracycline-based chemotherapy and bendamustine, according to Nirav N. Shah, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and his coinvestigators.

“Both remain appropriate frontline options for this patient population,” Dr. Shah and his colleagues wrote in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

Frontline therapy for follicular lymphoma has evolved, and recently shifted toward bendamustine-based chemotherapy regimens in light of two large randomized trials, according to the investigators. However, optimal therapy – specifically for grade 3A follicular lymphoma – has been debated for more than 20 years, they added.

“While some approach it as an aggressive malignancy, others treat it as an indolent lymphoma,” they wrote.

Accordingly, Dr. Shah and his colleagues sought to evaluate treatment outcomes with these regimens in 103 advanced stage 3/4 follicular lymphoma patients from six centers seen over a 10-year period.

Of those patients, 65 had received anthracycline-based chemotherapy, 30 received bendamustine, and 8 received CVP. All received either rituximab or ofatumumab in combination with the chemotherapy, and about one-third went on to receive maintenance treatment with one of those two anti-CD20 antibodies.

The proportion of patients not experiencing disease progression at 24 months from the initiation of treatment was significantly different between arms, at 72% for those receiving anthracyclines, 79% for bendamustine, and 50% for CVP (P = .01).

Patients who received CVP had a significantly poorer time-to-progression outcomes versus anthracycline-based chemotherapy, an adjusted analysis showed (hazard ratio, 3.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.26-8.25; P = .01), while by contrast, there was no significant difference between bendamustine and anthracyclines on this endpoint.

Progression-free survival was likewise worse for CVP compared with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, but there was no significant difference in overall survival for either CVP or bendamustine compared with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, the investigators said.

The 5-year overall survival was estimated to be 82% for anthracycline-based chemotherapy, 74% for bendamustine, and 58% for CVP (P = .23).

Optimal treatment of grade 3A follicular lymphoma remains controversial despite these findings, the investigators noted.

“Unfortunately, this specific histology was excluded from pivotal trials comparing anthracycline-based chemotherapy to bendamustine, leaving the question of optimal frontline treatment unanswered in this subset,” they wrote.

The situation could change with a subgroup analysis of GALLIUM, which might provide some prospective data for this histology. Beyond that, it would be helpful to have prospective, randomized studies specifically enrolling grade 3A disease, Dr. Shah and his coauthors wrote.

Dr. Shah reported disclosures related to Exelixis, Oncosec, Geron, Jazz, Kite, Juno, and Lentigen Technology. Coauthors provided disclosures related to Sanofi-Genzyme, Celgene, Takeda, Otsuka, Spectrum, Merck, and Astellas, among others.

SOURCE: Shah NN et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019 Feb;19(2):95-102.

While optimal treatment for grade 3A follicular lymphoma remains in question, either anthracycline-based chemotherapy or bendamustine appear to be preferable to cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP), results of a recent analysis suggest.

Time to progression with anthracycline-based chemotherapy was superior to that of CVP in the retrospective, multicenter study.

At the same time, clinical outcomes were comparable between anthracycline-based chemotherapy and bendamustine, according to Nirav N. Shah, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and his coinvestigators.

“Both remain appropriate frontline options for this patient population,” Dr. Shah and his colleagues wrote in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

Frontline therapy for follicular lymphoma has evolved, and recently shifted toward bendamustine-based chemotherapy regimens in light of two large randomized trials, according to the investigators. However, optimal therapy – specifically for grade 3A follicular lymphoma – has been debated for more than 20 years, they added.

“While some approach it as an aggressive malignancy, others treat it as an indolent lymphoma,” they wrote.

Accordingly, Dr. Shah and his colleagues sought to evaluate treatment outcomes with these regimens in 103 advanced stage 3/4 follicular lymphoma patients from six centers seen over a 10-year period.

Of those patients, 65 had received anthracycline-based chemotherapy, 30 received bendamustine, and 8 received CVP. All received either rituximab or ofatumumab in combination with the chemotherapy, and about one-third went on to receive maintenance treatment with one of those two anti-CD20 antibodies.

The proportion of patients not experiencing disease progression at 24 months from the initiation of treatment was significantly different between arms, at 72% for those receiving anthracyclines, 79% for bendamustine, and 50% for CVP (P = .01).

Patients who received CVP had a significantly poorer time-to-progression outcomes versus anthracycline-based chemotherapy, an adjusted analysis showed (hazard ratio, 3.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.26-8.25; P = .01), while by contrast, there was no significant difference between bendamustine and anthracyclines on this endpoint.

Progression-free survival was likewise worse for CVP compared with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, but there was no significant difference in overall survival for either CVP or bendamustine compared with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, the investigators said.

The 5-year overall survival was estimated to be 82% for anthracycline-based chemotherapy, 74% for bendamustine, and 58% for CVP (P = .23).

Optimal treatment of grade 3A follicular lymphoma remains controversial despite these findings, the investigators noted.

“Unfortunately, this specific histology was excluded from pivotal trials comparing anthracycline-based chemotherapy to bendamustine, leaving the question of optimal frontline treatment unanswered in this subset,” they wrote.

The situation could change with a subgroup analysis of GALLIUM, which might provide some prospective data for this histology. Beyond that, it would be helpful to have prospective, randomized studies specifically enrolling grade 3A disease, Dr. Shah and his coauthors wrote.

Dr. Shah reported disclosures related to Exelixis, Oncosec, Geron, Jazz, Kite, Juno, and Lentigen Technology. Coauthors provided disclosures related to Sanofi-Genzyme, Celgene, Takeda, Otsuka, Spectrum, Merck, and Astellas, among others.

SOURCE: Shah NN et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019 Feb;19(2):95-102.

While optimal treatment for grade 3A follicular lymphoma remains in question, either anthracycline-based chemotherapy or bendamustine appear to be preferable to cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP), results of a recent analysis suggest.

Time to progression with anthracycline-based chemotherapy was superior to that of CVP in the retrospective, multicenter study.

At the same time, clinical outcomes were comparable between anthracycline-based chemotherapy and bendamustine, according to Nirav N. Shah, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and his coinvestigators.

“Both remain appropriate frontline options for this patient population,” Dr. Shah and his colleagues wrote in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

Frontline therapy for follicular lymphoma has evolved, and recently shifted toward bendamustine-based chemotherapy regimens in light of two large randomized trials, according to the investigators. However, optimal therapy – specifically for grade 3A follicular lymphoma – has been debated for more than 20 years, they added.

“While some approach it as an aggressive malignancy, others treat it as an indolent lymphoma,” they wrote.

Accordingly, Dr. Shah and his colleagues sought to evaluate treatment outcomes with these regimens in 103 advanced stage 3/4 follicular lymphoma patients from six centers seen over a 10-year period.

Of those patients, 65 had received anthracycline-based chemotherapy, 30 received bendamustine, and 8 received CVP. All received either rituximab or ofatumumab in combination with the chemotherapy, and about one-third went on to receive maintenance treatment with one of those two anti-CD20 antibodies.

The proportion of patients not experiencing disease progression at 24 months from the initiation of treatment was significantly different between arms, at 72% for those receiving anthracyclines, 79% for bendamustine, and 50% for CVP (P = .01).

Patients who received CVP had a significantly poorer time-to-progression outcomes versus anthracycline-based chemotherapy, an adjusted analysis showed (hazard ratio, 3.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.26-8.25; P = .01), while by contrast, there was no significant difference between bendamustine and anthracyclines on this endpoint.

Progression-free survival was likewise worse for CVP compared with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, but there was no significant difference in overall survival for either CVP or bendamustine compared with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, the investigators said.

The 5-year overall survival was estimated to be 82% for anthracycline-based chemotherapy, 74% for bendamustine, and 58% for CVP (P = .23).

Optimal treatment of grade 3A follicular lymphoma remains controversial despite these findings, the investigators noted.

“Unfortunately, this specific histology was excluded from pivotal trials comparing anthracycline-based chemotherapy to bendamustine, leaving the question of optimal frontline treatment unanswered in this subset,” they wrote.

The situation could change with a subgroup analysis of GALLIUM, which might provide some prospective data for this histology. Beyond that, it would be helpful to have prospective, randomized studies specifically enrolling grade 3A disease, Dr. Shah and his coauthors wrote.

Dr. Shah reported disclosures related to Exelixis, Oncosec, Geron, Jazz, Kite, Juno, and Lentigen Technology. Coauthors provided disclosures related to Sanofi-Genzyme, Celgene, Takeda, Otsuka, Spectrum, Merck, and Astellas, among others.

SOURCE: Shah NN et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019 Feb;19(2):95-102.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA & LEUKEMIA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients who received CVP had a significantly poorer time-to-progression outcome versus anthracycline-based chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 3.22; 95% CI, 1.26-8.25; P = .01), while there was no significant difference between bendamustine and anthracyclines.

Study details: A multicenter analysis including 103 patients with advanced stage grade 3A follicular lymphoma.

Disclosures: The authors reported disclosures related to Exelixis, OncoSec, Geron, Jazz, Kite, Juno, Lentigen Technology, Sanofi-Genzyme, Celgene, Takeda, Otsuka, Spectrum, Merck, and Astellas, among others.

Source: Shah NN et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019 Feb;19(2):95-102.

Ibrutinib-MTX-rituximab combo shows promise in CNS lymphoma

The three-drug combination of ibrutinib, high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX), and rituximab showed positive safety and clinical outcomes in patients with recurrent/refractory primary/secondary CNS lymphoma, according to results from a phase 1b trial.

Ibrutinib has already shown single-agent activity in recurrent/refractory CNS lymphoma, Christian Grommes, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and his colleagues, wrote in Blood. “The primary objective was to determine the maximum tolerated dose of ibrutinib in combination with HD-MTX alone and ibrutinib in combination with HD-MTX and rituximab.”

With respect to ibrutinib dosing, the initial cohort was started at 560 mg daily, which was increased to 840 mg daily in successive cohorts using a 3+3 design. HD-MTX was administered every 2 weeks at 3.5 g/m2 for a total of eight infusions, or four cycles, with each cycle lasting of 28 days.

After no dose-limiting adverse effects were seen with the ibrutinib-MTX combination, the researchers added rituximab at 500 mg/m2 every 2 weeks, for a total of eight infusions, which completed the induction phase. The three-agent induction therapy was followed by daily ibrutinib monotherapy, which was maintained until discontinuation caused by malignancy progression, intolerable adverse events, or death.

“To minimize the risk of adverse events, we held ibrutinib on days of HD-MTX infusion and resumed 5 days after HD-MTX infusion or after MTX clearance,” they wrote.

After analysis, Dr. Grommes and his colleagues reported that no dose-limiting or grade 5 toxicities were detected. At a median follow-up of 19.7 months, they saw an 80% overall response rate in study patients treated with combination therapy. The median progression free survival for all 15 patients was 9.2 months and the median overall survival was not reached, with 11 of 15 patients alive.

The researchers proposed an 840-mg dose of ibrutinib for future studies.

The most frequent adverse events were lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and transaminase elevations. No fungal infections were seen during the study.