User login

Evaluation of Interventions by Clinical Pharmacy Specialists in Cardiology at a VA Ambulatory Cardiology Clinic

Integration of CPSs into an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for other cardiology health care providers.

Health care providers face many challenges in utilizing cardiovascular therapies, such as anticipated shortages in physicians, patients with more complicated conditions, shifting medication regimens, management needs, and increased accountability for quality and performance measures.1 To meet the potential increase in service demand, cardiology practices are embracing cardiovascular team-based care.1 Advanced practice providers, such as advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), physician assistants (PAs), and clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs), have education, training, and experience to extend the team’s capability to meet these complex management needs.1

The role of CPSs within a cardiovascular care team includes providing a variety of patient-specific services, such as collaborating with other cardiology providers, to optimize evidence-based pharmacotherapy, preventing medication-related adverse events/errors, improving patient understanding of their medication regimen, and ultimately, improving patient outcomes.2 Health care systems, such as Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) by implementing a multidisciplinary collaborative cardiac care service, including a clinical pharmacy cardiac risk service, in which CPSs assisted with management of cholesterol-lowering, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and smoking-cessation therapies, which resulted in a 76% to 89% reduction in all-cause mortality associated with CAD in multiple evaluations.3,4

Pharmacists providing medication therapy management (MTM) services in Minnesota had higher goal attainment for patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia than did pharmacists who did not provide MTM services.5 MTM services provided by pharmacists led to an improvement in clinical outcomes for patients as well as a reduction in overall health care expenditures compared with that of a control group of patients who did not receive MTM services.5 Furthermore, CPS integration in the heart failure (HF) setting has led to improvements in utilization and optimization of guideline-directed medical therapies, an area in which recent data have suggested deficiencies exist.6-8 A full review of the outcomes associated with CPS involvement in cardiovascular care is beyond the scope of this article; but the recent review by Dunn and colleagues provides more detail.2

With the increasing number of patients with cardiovascular disease,expanding integration of CPSs in the cardiovascular team providing MTM services may reduce the burden of other providers (MD, PA, APRN, etc), thereby increasing access for not only new patients, but also diagnostic and interventional work, while potentially improving clinical and economic outcomes.2 The value of integrating CPSs as members of the cardiovascular care team is recognized in a variety of inpatient and ambulatory practice settings.2-6 However, data are limited on the number and types of interventions made per encounter as direct patient care providers. Expanded granularity regarding the effect of CPSs as active members of the cardiovascular team is an essential component to evaluate the potential benefit of CPS integration into direct patient care.

Methods

The West Palm Beach (WPB) Veteran Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) outpatient cardiology clinic consists of 6 full-time employee (FTE) cardiologists, 4 PAs or APRNs, 10 other cardiology health care staff members (registered/license practical nurses and technicians), and 2 cardiology CPSs providing direct patient care

The cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic is open 20.5 hours per week with 41 appointment slots (30 minutes each), of which 7 appointments are delivered via clinic video telehealth and 34 appointments are traditional face-to-face visits.9 The remaining CPS time is assigned to other clinical care and administrative areas to fit facility need, including oversight of the CPS-run 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure clinic, postgraduate year 2 cardiology pharmacy practice residency program directorship, and other administrative activities for the facility.10

The cardiology CPSs practice under an advanced scope of practice in which they independently manage medications (initiate, modify, discontinue), order diagnostic testing (laboratory, monitoring, imaging, etc) needed for medication management, and create monitoring and treatment plans for patients referred to the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic by other cardiology providers. The diseases managed within the clinic vary based on patient-specific needs, but may include HF, dyslipidemia, hypertension, anticoagulation, CAD, arrhythmias, cardiovascular risk factor assessment and reduction, and medication reconciliation and teaching. Patients are referred for CPS management directly from facility cardiologist and cardiology clinic PAs and APRNs. Workload and interventions carried out are captured in the Pharmacists Achieve Results with Medications Demonstration (PhARMD) tool and patient care encounter tracking.9

Data Collection

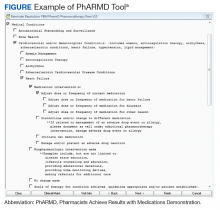

Using local data from workload tracking, the number of CPS encounters was determined from July 6, 2015, to October 1, 2015. Data were collected on the types and volume of interventions made by CPSs in the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic using the PhARMD tool (Figure).

The PhARMD tool was initially developed and implemented for CPSs in primary care pharmacotherapy clinics and was used to evaluate the types and volume of CPS interventions made in this setting.11 Since this initial evaluation, the tool has been updated, standardized nationally by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy Benefits Management Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office, and integrated across numerous VAMCs and associated outpatient clinics. The tool remains embedded within the VA electronic health record (EHR) and allows the capture of specific CPS interventions of several types (ie, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, including adjust dose or frequency; change or discontinue medication; initiate medication; monitor medication; counsel on adherence, contraindications, drug interactions, and drugs not indicated; reconcile medication; and prevent or manage adverse drug events [ADEs]) specific to certain diseases, such as anemia, anticoagulation, HF, type 2 DM (T2DM), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and tobacco cessation.

Given that the interventions captured by the PhARMD tool are based on self-report of the CPS performing the intervention, a quality assurance (QA) measure was taken to audit a random sample of interventions to validate the accuracy of reported data. A Pharmacy Benefits Management PhARMD Project QA report provided the 20% random sample of encounters for each cardiology CPS to be reviewed. This percentage was determined by VAMC Clinical Pharmacy Program Office (CPPO) directives on implementation of the PhARMD tool. During the QA period, the provided sample was reviewed to determine whether the intervention(s) recorded with the PhARMD tool matched the actions documented in the EHR. The QA review was done through a manual chart review by an author not involved in recording the original interventions. Both WPB VAMC cardiology CPSs passed the QA review (> 80% concurrence with tool logged and chart documented interventions as required by VA CPPO directive), with a 90.9% concurrence between the EHR and PhARMD tool documentation.

Statistical Analyses

Data on intervention type and encounter number were evaluated with descriptive statistics. The information was characterized and diagrammed with Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) charts and graphs.

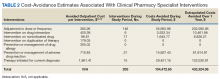

Cost-avoidance calculations were done using previously described methods and are included for exploratory analysis.11,12 Briefly, published estimates of cost avoidance associated with various interventions from the outpatient setting within a VAMC setting were applied as appropriate to the various interventions captured with the PhARMD tool.11,12 These estimates from Lee and colleagues were derived from detailed chart review of interventions made and the potential harm prevented.12 Costs or cost avoidances associated with interventions were calculated from pooled examination of 600 interventions in a VAMC with drug costs before and after the intervention, costs associated with harms prevented by the intervention, as well as the VAMC hourly pharmacist wages associated with making an intervention and processing and filling original vs recommended therapies.

The costs presented represent a “best-case” scenario in which all interventions made are expected to prevent patient harms. The costs related to avoided outcomes, facility overhead, and auxiliary staff cannot be included but highlight the many considerations that must be considered when examining potential cost-avoidance calculations. The estimates and methods at hand were chosen because, to our knowledge, no other consensus model exists that would be more appropriate for use in the situation and health care system at hand. Cost-avoidance estimates were calculated by extrapolating the 88-day study period values to a yearly estimate. All cost estimates were adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index calculator as per convention in previous analyses using the cost-avoidance estimates at hand.11-13

Results

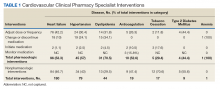

From July 6, 2015, through October 1, 2015, 301 patient encounters occurred, and 529 interventions were documented with the PhARMD tool. The mean number of interventions per encounter was 1.8. Interventions were 65.2% pharmacologic and 34.8% nonpharmacologic. Of pharmacologic interventions, 27.1% were for HF, 12.7% for hypertension, 8.8% for dyslipidemia, 2.8% for anticoagulation, 1.4% for tobacco cessation, 1.1% for T2DM, 0.3% for anemia, and 45.8% for other conditions (Table 1).

The main types of pharmacologic interventions across all diseases were related to adjustments in medication dose or frequency (42.3%) and change or discontinuation of medications (20.0%).

Discussion

Evaluation of the interventions and encounters at the WPB VAMC ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic suggests that CPSs are able to contribute to direct patient care independently of interventions performed by other cardiology providers. Specifically, 1.8 interventions per encounter were made by CPSs in this study. In a prior evaluation of CPS interventions recorded with the PhARMD tool in a VAMC primary care setting, 2.3 interventions per encounter were recorded.11 In comparing the present volume of interventions with the volume recorded in the study by Hough and colleagues, the difference in practice setting may account for differences seen.11

The primary care medication management setting would capture a broader array of clinical interventions than would the ambulatory cardiology clinic of the present study, so it is reasonable that more interventions would be captured per encounter in the primary care clinic. The difference in practice settings affecting the character of collected interventions can be seen because most interventions in this study at an ambulatory cardiology clinic were related to HF, whereas in Hough and colleagues 39.2% of the disease-specific interventions were related to DM, and only 2.9% were related to HF.11 The differences inherent in the intervention populations can also be seen by comparing the percentage of interventions related to hypertension and dyslipidemia: 30% and 28% in the study by Hough and colleagues compared with 13% and 9%, respectively, in the present study.11

Comparison of the present evaluation and Hough and colleagues is also hindered by the PhARMD tool used. The PhARMD tool used in the initial evaluation has been modified on a national level to improve the granularity of intervention data collected.

Our cost-avoidance estimate of $433,324.06 per year seems lower than that estimated in the previous evaluation when all applicable interventions were included.11 However, this study had several differences compared with those of previous VAMC studies looking at clinical interventions performed by CPSs. The main differences are the volume and setting in which interventions were being made. For example, in comparison with Hough and colleagues, the studies include different practice settings (primary care vs cardiology specialty clinic) and number of FTEs involved in the study (4.65 vs 1). If the cost avoidance is distributed evenly per FTE in the previous study, the following calculation is observed: $649,551.99 per FTE, which is closer to this study’s estimation. Given that primary care is a broader setting than is ambulatory cardiology, it is not surprising that more types of interventions and the overall volume/absolute number of interventions would be higher. Thus, the lower estimated cost avoidance in our study may be attributed to the lower volume of intervention opportunities availed to the cardiology CPS. Another difference is that detailed types of interventions related to hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, and HF were not included in Hough and colleagues, whereas our study included all applicable interventions regardless of relation to diseases, which may account for a degree of the variation in intervention breakdown between the 2 studies.11 However, as noted previously, some interventions for these particular diseases may not fully capture the rationale for pharmacotherapy interventions, such as drug dose changes or discontinuations, which may misrepresent the potential cost avoidance associated with them in reality.

Limitations

Of general importance, the PhARMD tool may underestimate the number of interventions made such that multiple interventions for a medical condition may have been completed but only captured as 1 intervention, which may represent a limitation of the tool when multiple interventions are made for the same disease (eg, titration of both β-blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor doses at a single appointment in a patient with HF with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction). Improved clarity about interventions made would require laborious chart review, which was not feasible. The evaluation at hand included a preliminary QA review, adding confidence that overdocumentation was not being done and the values represented at worst an underestimation of actual CPS intervention impact. Because this study was an initial evaluation of interventions made by CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy setting, whether these same outcomes would exist in other patient cohorts is unclear. However, these data do provide a foundational understanding of what may be expected from CPS integration into a cardiovascular care team.

These findings may be limited in generalizability to other health care systems and situations in which CPSs are afforded the regulatory opportunity to practice independently within an established scope of practice or collaborative practice agreements. The Veterans Health Administration system has been a leader in integrating CPSs into direct patient care roles and serves as a potential model for application by other groups. This evaluation’s data support continued efforts to create such independent practice environments as they allow for qualified CPSs to practice to their full clinical potential and have the fullest possible effect on cardiovascular outcomes.

Previous studies looking at cost savings in MTM programs have established a substantial return in economic investment with patients being managed by pharmacists.5,14 Given that the interventions made in this study were not tied to attainment of clinical outcomes, a limitation to our study, the cost-avoidance estimates should be interpreted cautiously. However, we know of no such tool that is available to allow accurate capture of clinical event reduction in a single center with consistent CPS involvement in care. A clear opportunity exists regarding design of a model that measures clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes related to the interventions performed by cardiology CPSs, but developing and deploying such a model may be challenging because guideline-directed medical therapies vary significantly based on many patient-specific issues, and identifying optimal or truly optimized medical therapy is at times a subjective task, especially in a single center. Using the types and volumes of interventions made by CPSs as a surrogate for these higher-level outcomes is still of value in order to understand the effect and role of CPSs in cardiovascular care. At present, the cost-avoidance estimates presented in this evaluation are based on the most appropriate system-specific data at hand, with the realization that actual cost avoidance in practice may vary widely and should be the topic of future research.

Conclusion

As cardiovascular team-based care continues to expand with the support of large organizations, such as the American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Failure Society of America, and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network, the need for understanding the effect of CPSs on patient care measures and health care costs becomes more pronounced.2,15 The results of this study demonstrate how integration of CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for cardiology physicians and providers, allowing more availability for diagnostic testing and care.

Interventions made by CPSs functioning as independent providers

1. Brush JE Jr, Handberg EM, Biga C, et al. 2015 ACC health policy statement on cardiovascular team-based care and the role of advanced practice providers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2118-2136.

2. Dunn SP, Birtcher KK, Beavers CJ, et al. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the care of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(19):2129-2139.

3. Sandoff BG, Kuca S, Rasmussen J, Merenich JA. Collaborative cardiac care service: a multidisciplinary approach to caring for patients with coronary artery disease. Perm J. 2008;12(3):4-11.

4. Merenich JA, Olson KL, Delate T, Rasmussen J, Helling DK, Ward DG; Clinical Pharmacy Cardiac Risk Service Study Group. Mortality reduction benefits of a comprehensive cardiac care program for patients with occlusive coronary disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(10):1370-1378.

5. Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience.

6. Martinez AS, Saef J, Paszcuzuk A, Bhatt-Chugani H. Implementation of a pharmacist-managed heart failure medication titration clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(12):1070-1076.

7. Roth GA, Poole JE, Zaha R, Zhou W, Skinner J, Morden NE. Use of guideline-directed medications for heart failure before cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(9):1062-1069.

8. Noschese LA, Bergman CL, Brar CK, Kansal MM. The pharmacist’s role in medication optimization for patients with chronic heart failure. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 10):S10-S15.

9. Coakley C, Hough A, Dwyer D, Parra D. Clinical video telehealth in a cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(22):1974-1975.

10. Khazan E, Anastasia E, Hough A, Parra D. Pharmacist-managed ambulatory blood pressure monitoring service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(4):190-195.

11. Hough A, Vartan CM, Groppi JA, Reyes S, Beckey NP. Evaluation of clinical pharmacy interventions in a Veterans Affairs medical center primary care clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(13):1168-1172.

12. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070-2077.

13. US Department of Labor. CPI inflation calculator. www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed January 18, 2019.

14. Perez A, Doloresco F, Hoffman JM, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2001-2005. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;29(1):128.

15. Milfred-LaForest SK, Chow SL, DiDomenico RJ, et al. Clinical pharmacy services in heart failure: an opinion paper from the Heart Failure Society of America and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(5):529-548.

Integration of CPSs into an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for other cardiology health care providers.

Integration of CPSs into an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for other cardiology health care providers.

Health care providers face many challenges in utilizing cardiovascular therapies, such as anticipated shortages in physicians, patients with more complicated conditions, shifting medication regimens, management needs, and increased accountability for quality and performance measures.1 To meet the potential increase in service demand, cardiology practices are embracing cardiovascular team-based care.1 Advanced practice providers, such as advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), physician assistants (PAs), and clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs), have education, training, and experience to extend the team’s capability to meet these complex management needs.1

The role of CPSs within a cardiovascular care team includes providing a variety of patient-specific services, such as collaborating with other cardiology providers, to optimize evidence-based pharmacotherapy, preventing medication-related adverse events/errors, improving patient understanding of their medication regimen, and ultimately, improving patient outcomes.2 Health care systems, such as Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) by implementing a multidisciplinary collaborative cardiac care service, including a clinical pharmacy cardiac risk service, in which CPSs assisted with management of cholesterol-lowering, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and smoking-cessation therapies, which resulted in a 76% to 89% reduction in all-cause mortality associated with CAD in multiple evaluations.3,4

Pharmacists providing medication therapy management (MTM) services in Minnesota had higher goal attainment for patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia than did pharmacists who did not provide MTM services.5 MTM services provided by pharmacists led to an improvement in clinical outcomes for patients as well as a reduction in overall health care expenditures compared with that of a control group of patients who did not receive MTM services.5 Furthermore, CPS integration in the heart failure (HF) setting has led to improvements in utilization and optimization of guideline-directed medical therapies, an area in which recent data have suggested deficiencies exist.6-8 A full review of the outcomes associated with CPS involvement in cardiovascular care is beyond the scope of this article; but the recent review by Dunn and colleagues provides more detail.2

With the increasing number of patients with cardiovascular disease,expanding integration of CPSs in the cardiovascular team providing MTM services may reduce the burden of other providers (MD, PA, APRN, etc), thereby increasing access for not only new patients, but also diagnostic and interventional work, while potentially improving clinical and economic outcomes.2 The value of integrating CPSs as members of the cardiovascular care team is recognized in a variety of inpatient and ambulatory practice settings.2-6 However, data are limited on the number and types of interventions made per encounter as direct patient care providers. Expanded granularity regarding the effect of CPSs as active members of the cardiovascular team is an essential component to evaluate the potential benefit of CPS integration into direct patient care.

Methods

The West Palm Beach (WPB) Veteran Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) outpatient cardiology clinic consists of 6 full-time employee (FTE) cardiologists, 4 PAs or APRNs, 10 other cardiology health care staff members (registered/license practical nurses and technicians), and 2 cardiology CPSs providing direct patient care

The cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic is open 20.5 hours per week with 41 appointment slots (30 minutes each), of which 7 appointments are delivered via clinic video telehealth and 34 appointments are traditional face-to-face visits.9 The remaining CPS time is assigned to other clinical care and administrative areas to fit facility need, including oversight of the CPS-run 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure clinic, postgraduate year 2 cardiology pharmacy practice residency program directorship, and other administrative activities for the facility.10

The cardiology CPSs practice under an advanced scope of practice in which they independently manage medications (initiate, modify, discontinue), order diagnostic testing (laboratory, monitoring, imaging, etc) needed for medication management, and create monitoring and treatment plans for patients referred to the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic by other cardiology providers. The diseases managed within the clinic vary based on patient-specific needs, but may include HF, dyslipidemia, hypertension, anticoagulation, CAD, arrhythmias, cardiovascular risk factor assessment and reduction, and medication reconciliation and teaching. Patients are referred for CPS management directly from facility cardiologist and cardiology clinic PAs and APRNs. Workload and interventions carried out are captured in the Pharmacists Achieve Results with Medications Demonstration (PhARMD) tool and patient care encounter tracking.9

Data Collection

Using local data from workload tracking, the number of CPS encounters was determined from July 6, 2015, to October 1, 2015. Data were collected on the types and volume of interventions made by CPSs in the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic using the PhARMD tool (Figure).

The PhARMD tool was initially developed and implemented for CPSs in primary care pharmacotherapy clinics and was used to evaluate the types and volume of CPS interventions made in this setting.11 Since this initial evaluation, the tool has been updated, standardized nationally by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy Benefits Management Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office, and integrated across numerous VAMCs and associated outpatient clinics. The tool remains embedded within the VA electronic health record (EHR) and allows the capture of specific CPS interventions of several types (ie, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, including adjust dose or frequency; change or discontinue medication; initiate medication; monitor medication; counsel on adherence, contraindications, drug interactions, and drugs not indicated; reconcile medication; and prevent or manage adverse drug events [ADEs]) specific to certain diseases, such as anemia, anticoagulation, HF, type 2 DM (T2DM), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and tobacco cessation.

Given that the interventions captured by the PhARMD tool are based on self-report of the CPS performing the intervention, a quality assurance (QA) measure was taken to audit a random sample of interventions to validate the accuracy of reported data. A Pharmacy Benefits Management PhARMD Project QA report provided the 20% random sample of encounters for each cardiology CPS to be reviewed. This percentage was determined by VAMC Clinical Pharmacy Program Office (CPPO) directives on implementation of the PhARMD tool. During the QA period, the provided sample was reviewed to determine whether the intervention(s) recorded with the PhARMD tool matched the actions documented in the EHR. The QA review was done through a manual chart review by an author not involved in recording the original interventions. Both WPB VAMC cardiology CPSs passed the QA review (> 80% concurrence with tool logged and chart documented interventions as required by VA CPPO directive), with a 90.9% concurrence between the EHR and PhARMD tool documentation.

Statistical Analyses

Data on intervention type and encounter number were evaluated with descriptive statistics. The information was characterized and diagrammed with Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) charts and graphs.

Cost-avoidance calculations were done using previously described methods and are included for exploratory analysis.11,12 Briefly, published estimates of cost avoidance associated with various interventions from the outpatient setting within a VAMC setting were applied as appropriate to the various interventions captured with the PhARMD tool.11,12 These estimates from Lee and colleagues were derived from detailed chart review of interventions made and the potential harm prevented.12 Costs or cost avoidances associated with interventions were calculated from pooled examination of 600 interventions in a VAMC with drug costs before and after the intervention, costs associated with harms prevented by the intervention, as well as the VAMC hourly pharmacist wages associated with making an intervention and processing and filling original vs recommended therapies.

The costs presented represent a “best-case” scenario in which all interventions made are expected to prevent patient harms. The costs related to avoided outcomes, facility overhead, and auxiliary staff cannot be included but highlight the many considerations that must be considered when examining potential cost-avoidance calculations. The estimates and methods at hand were chosen because, to our knowledge, no other consensus model exists that would be more appropriate for use in the situation and health care system at hand. Cost-avoidance estimates were calculated by extrapolating the 88-day study period values to a yearly estimate. All cost estimates were adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index calculator as per convention in previous analyses using the cost-avoidance estimates at hand.11-13

Results

From July 6, 2015, through October 1, 2015, 301 patient encounters occurred, and 529 interventions were documented with the PhARMD tool. The mean number of interventions per encounter was 1.8. Interventions were 65.2% pharmacologic and 34.8% nonpharmacologic. Of pharmacologic interventions, 27.1% were for HF, 12.7% for hypertension, 8.8% for dyslipidemia, 2.8% for anticoagulation, 1.4% for tobacco cessation, 1.1% for T2DM, 0.3% for anemia, and 45.8% for other conditions (Table 1).

The main types of pharmacologic interventions across all diseases were related to adjustments in medication dose or frequency (42.3%) and change or discontinuation of medications (20.0%).

Discussion

Evaluation of the interventions and encounters at the WPB VAMC ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic suggests that CPSs are able to contribute to direct patient care independently of interventions performed by other cardiology providers. Specifically, 1.8 interventions per encounter were made by CPSs in this study. In a prior evaluation of CPS interventions recorded with the PhARMD tool in a VAMC primary care setting, 2.3 interventions per encounter were recorded.11 In comparing the present volume of interventions with the volume recorded in the study by Hough and colleagues, the difference in practice setting may account for differences seen.11

The primary care medication management setting would capture a broader array of clinical interventions than would the ambulatory cardiology clinic of the present study, so it is reasonable that more interventions would be captured per encounter in the primary care clinic. The difference in practice settings affecting the character of collected interventions can be seen because most interventions in this study at an ambulatory cardiology clinic were related to HF, whereas in Hough and colleagues 39.2% of the disease-specific interventions were related to DM, and only 2.9% were related to HF.11 The differences inherent in the intervention populations can also be seen by comparing the percentage of interventions related to hypertension and dyslipidemia: 30% and 28% in the study by Hough and colleagues compared with 13% and 9%, respectively, in the present study.11

Comparison of the present evaluation and Hough and colleagues is also hindered by the PhARMD tool used. The PhARMD tool used in the initial evaluation has been modified on a national level to improve the granularity of intervention data collected.

Our cost-avoidance estimate of $433,324.06 per year seems lower than that estimated in the previous evaluation when all applicable interventions were included.11 However, this study had several differences compared with those of previous VAMC studies looking at clinical interventions performed by CPSs. The main differences are the volume and setting in which interventions were being made. For example, in comparison with Hough and colleagues, the studies include different practice settings (primary care vs cardiology specialty clinic) and number of FTEs involved in the study (4.65 vs 1). If the cost avoidance is distributed evenly per FTE in the previous study, the following calculation is observed: $649,551.99 per FTE, which is closer to this study’s estimation. Given that primary care is a broader setting than is ambulatory cardiology, it is not surprising that more types of interventions and the overall volume/absolute number of interventions would be higher. Thus, the lower estimated cost avoidance in our study may be attributed to the lower volume of intervention opportunities availed to the cardiology CPS. Another difference is that detailed types of interventions related to hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, and HF were not included in Hough and colleagues, whereas our study included all applicable interventions regardless of relation to diseases, which may account for a degree of the variation in intervention breakdown between the 2 studies.11 However, as noted previously, some interventions for these particular diseases may not fully capture the rationale for pharmacotherapy interventions, such as drug dose changes or discontinuations, which may misrepresent the potential cost avoidance associated with them in reality.

Limitations

Of general importance, the PhARMD tool may underestimate the number of interventions made such that multiple interventions for a medical condition may have been completed but only captured as 1 intervention, which may represent a limitation of the tool when multiple interventions are made for the same disease (eg, titration of both β-blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor doses at a single appointment in a patient with HF with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction). Improved clarity about interventions made would require laborious chart review, which was not feasible. The evaluation at hand included a preliminary QA review, adding confidence that overdocumentation was not being done and the values represented at worst an underestimation of actual CPS intervention impact. Because this study was an initial evaluation of interventions made by CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy setting, whether these same outcomes would exist in other patient cohorts is unclear. However, these data do provide a foundational understanding of what may be expected from CPS integration into a cardiovascular care team.

These findings may be limited in generalizability to other health care systems and situations in which CPSs are afforded the regulatory opportunity to practice independently within an established scope of practice or collaborative practice agreements. The Veterans Health Administration system has been a leader in integrating CPSs into direct patient care roles and serves as a potential model for application by other groups. This evaluation’s data support continued efforts to create such independent practice environments as they allow for qualified CPSs to practice to their full clinical potential and have the fullest possible effect on cardiovascular outcomes.

Previous studies looking at cost savings in MTM programs have established a substantial return in economic investment with patients being managed by pharmacists.5,14 Given that the interventions made in this study were not tied to attainment of clinical outcomes, a limitation to our study, the cost-avoidance estimates should be interpreted cautiously. However, we know of no such tool that is available to allow accurate capture of clinical event reduction in a single center with consistent CPS involvement in care. A clear opportunity exists regarding design of a model that measures clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes related to the interventions performed by cardiology CPSs, but developing and deploying such a model may be challenging because guideline-directed medical therapies vary significantly based on many patient-specific issues, and identifying optimal or truly optimized medical therapy is at times a subjective task, especially in a single center. Using the types and volumes of interventions made by CPSs as a surrogate for these higher-level outcomes is still of value in order to understand the effect and role of CPSs in cardiovascular care. At present, the cost-avoidance estimates presented in this evaluation are based on the most appropriate system-specific data at hand, with the realization that actual cost avoidance in practice may vary widely and should be the topic of future research.

Conclusion

As cardiovascular team-based care continues to expand with the support of large organizations, such as the American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Failure Society of America, and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network, the need for understanding the effect of CPSs on patient care measures and health care costs becomes more pronounced.2,15 The results of this study demonstrate how integration of CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for cardiology physicians and providers, allowing more availability for diagnostic testing and care.

Interventions made by CPSs functioning as independent providers

Health care providers face many challenges in utilizing cardiovascular therapies, such as anticipated shortages in physicians, patients with more complicated conditions, shifting medication regimens, management needs, and increased accountability for quality and performance measures.1 To meet the potential increase in service demand, cardiology practices are embracing cardiovascular team-based care.1 Advanced practice providers, such as advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), physician assistants (PAs), and clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs), have education, training, and experience to extend the team’s capability to meet these complex management needs.1

The role of CPSs within a cardiovascular care team includes providing a variety of patient-specific services, such as collaborating with other cardiology providers, to optimize evidence-based pharmacotherapy, preventing medication-related adverse events/errors, improving patient understanding of their medication regimen, and ultimately, improving patient outcomes.2 Health care systems, such as Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) by implementing a multidisciplinary collaborative cardiac care service, including a clinical pharmacy cardiac risk service, in which CPSs assisted with management of cholesterol-lowering, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and smoking-cessation therapies, which resulted in a 76% to 89% reduction in all-cause mortality associated with CAD in multiple evaluations.3,4

Pharmacists providing medication therapy management (MTM) services in Minnesota had higher goal attainment for patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia than did pharmacists who did not provide MTM services.5 MTM services provided by pharmacists led to an improvement in clinical outcomes for patients as well as a reduction in overall health care expenditures compared with that of a control group of patients who did not receive MTM services.5 Furthermore, CPS integration in the heart failure (HF) setting has led to improvements in utilization and optimization of guideline-directed medical therapies, an area in which recent data have suggested deficiencies exist.6-8 A full review of the outcomes associated with CPS involvement in cardiovascular care is beyond the scope of this article; but the recent review by Dunn and colleagues provides more detail.2

With the increasing number of patients with cardiovascular disease,expanding integration of CPSs in the cardiovascular team providing MTM services may reduce the burden of other providers (MD, PA, APRN, etc), thereby increasing access for not only new patients, but also diagnostic and interventional work, while potentially improving clinical and economic outcomes.2 The value of integrating CPSs as members of the cardiovascular care team is recognized in a variety of inpatient and ambulatory practice settings.2-6 However, data are limited on the number and types of interventions made per encounter as direct patient care providers. Expanded granularity regarding the effect of CPSs as active members of the cardiovascular team is an essential component to evaluate the potential benefit of CPS integration into direct patient care.

Methods

The West Palm Beach (WPB) Veteran Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) outpatient cardiology clinic consists of 6 full-time employee (FTE) cardiologists, 4 PAs or APRNs, 10 other cardiology health care staff members (registered/license practical nurses and technicians), and 2 cardiology CPSs providing direct patient care

The cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic is open 20.5 hours per week with 41 appointment slots (30 minutes each), of which 7 appointments are delivered via clinic video telehealth and 34 appointments are traditional face-to-face visits.9 The remaining CPS time is assigned to other clinical care and administrative areas to fit facility need, including oversight of the CPS-run 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure clinic, postgraduate year 2 cardiology pharmacy practice residency program directorship, and other administrative activities for the facility.10

The cardiology CPSs practice under an advanced scope of practice in which they independently manage medications (initiate, modify, discontinue), order diagnostic testing (laboratory, monitoring, imaging, etc) needed for medication management, and create monitoring and treatment plans for patients referred to the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic by other cardiology providers. The diseases managed within the clinic vary based on patient-specific needs, but may include HF, dyslipidemia, hypertension, anticoagulation, CAD, arrhythmias, cardiovascular risk factor assessment and reduction, and medication reconciliation and teaching. Patients are referred for CPS management directly from facility cardiologist and cardiology clinic PAs and APRNs. Workload and interventions carried out are captured in the Pharmacists Achieve Results with Medications Demonstration (PhARMD) tool and patient care encounter tracking.9

Data Collection

Using local data from workload tracking, the number of CPS encounters was determined from July 6, 2015, to October 1, 2015. Data were collected on the types and volume of interventions made by CPSs in the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic using the PhARMD tool (Figure).

The PhARMD tool was initially developed and implemented for CPSs in primary care pharmacotherapy clinics and was used to evaluate the types and volume of CPS interventions made in this setting.11 Since this initial evaluation, the tool has been updated, standardized nationally by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy Benefits Management Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office, and integrated across numerous VAMCs and associated outpatient clinics. The tool remains embedded within the VA electronic health record (EHR) and allows the capture of specific CPS interventions of several types (ie, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, including adjust dose or frequency; change or discontinue medication; initiate medication; monitor medication; counsel on adherence, contraindications, drug interactions, and drugs not indicated; reconcile medication; and prevent or manage adverse drug events [ADEs]) specific to certain diseases, such as anemia, anticoagulation, HF, type 2 DM (T2DM), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and tobacco cessation.

Given that the interventions captured by the PhARMD tool are based on self-report of the CPS performing the intervention, a quality assurance (QA) measure was taken to audit a random sample of interventions to validate the accuracy of reported data. A Pharmacy Benefits Management PhARMD Project QA report provided the 20% random sample of encounters for each cardiology CPS to be reviewed. This percentage was determined by VAMC Clinical Pharmacy Program Office (CPPO) directives on implementation of the PhARMD tool. During the QA period, the provided sample was reviewed to determine whether the intervention(s) recorded with the PhARMD tool matched the actions documented in the EHR. The QA review was done through a manual chart review by an author not involved in recording the original interventions. Both WPB VAMC cardiology CPSs passed the QA review (> 80% concurrence with tool logged and chart documented interventions as required by VA CPPO directive), with a 90.9% concurrence between the EHR and PhARMD tool documentation.

Statistical Analyses

Data on intervention type and encounter number were evaluated with descriptive statistics. The information was characterized and diagrammed with Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) charts and graphs.

Cost-avoidance calculations were done using previously described methods and are included for exploratory analysis.11,12 Briefly, published estimates of cost avoidance associated with various interventions from the outpatient setting within a VAMC setting were applied as appropriate to the various interventions captured with the PhARMD tool.11,12 These estimates from Lee and colleagues were derived from detailed chart review of interventions made and the potential harm prevented.12 Costs or cost avoidances associated with interventions were calculated from pooled examination of 600 interventions in a VAMC with drug costs before and after the intervention, costs associated with harms prevented by the intervention, as well as the VAMC hourly pharmacist wages associated with making an intervention and processing and filling original vs recommended therapies.

The costs presented represent a “best-case” scenario in which all interventions made are expected to prevent patient harms. The costs related to avoided outcomes, facility overhead, and auxiliary staff cannot be included but highlight the many considerations that must be considered when examining potential cost-avoidance calculations. The estimates and methods at hand were chosen because, to our knowledge, no other consensus model exists that would be more appropriate for use in the situation and health care system at hand. Cost-avoidance estimates were calculated by extrapolating the 88-day study period values to a yearly estimate. All cost estimates were adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index calculator as per convention in previous analyses using the cost-avoidance estimates at hand.11-13

Results

From July 6, 2015, through October 1, 2015, 301 patient encounters occurred, and 529 interventions were documented with the PhARMD tool. The mean number of interventions per encounter was 1.8. Interventions were 65.2% pharmacologic and 34.8% nonpharmacologic. Of pharmacologic interventions, 27.1% were for HF, 12.7% for hypertension, 8.8% for dyslipidemia, 2.8% for anticoagulation, 1.4% for tobacco cessation, 1.1% for T2DM, 0.3% for anemia, and 45.8% for other conditions (Table 1).

The main types of pharmacologic interventions across all diseases were related to adjustments in medication dose or frequency (42.3%) and change or discontinuation of medications (20.0%).

Discussion

Evaluation of the interventions and encounters at the WPB VAMC ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic suggests that CPSs are able to contribute to direct patient care independently of interventions performed by other cardiology providers. Specifically, 1.8 interventions per encounter were made by CPSs in this study. In a prior evaluation of CPS interventions recorded with the PhARMD tool in a VAMC primary care setting, 2.3 interventions per encounter were recorded.11 In comparing the present volume of interventions with the volume recorded in the study by Hough and colleagues, the difference in practice setting may account for differences seen.11

The primary care medication management setting would capture a broader array of clinical interventions than would the ambulatory cardiology clinic of the present study, so it is reasonable that more interventions would be captured per encounter in the primary care clinic. The difference in practice settings affecting the character of collected interventions can be seen because most interventions in this study at an ambulatory cardiology clinic were related to HF, whereas in Hough and colleagues 39.2% of the disease-specific interventions were related to DM, and only 2.9% were related to HF.11 The differences inherent in the intervention populations can also be seen by comparing the percentage of interventions related to hypertension and dyslipidemia: 30% and 28% in the study by Hough and colleagues compared with 13% and 9%, respectively, in the present study.11

Comparison of the present evaluation and Hough and colleagues is also hindered by the PhARMD tool used. The PhARMD tool used in the initial evaluation has been modified on a national level to improve the granularity of intervention data collected.

Our cost-avoidance estimate of $433,324.06 per year seems lower than that estimated in the previous evaluation when all applicable interventions were included.11 However, this study had several differences compared with those of previous VAMC studies looking at clinical interventions performed by CPSs. The main differences are the volume and setting in which interventions were being made. For example, in comparison with Hough and colleagues, the studies include different practice settings (primary care vs cardiology specialty clinic) and number of FTEs involved in the study (4.65 vs 1). If the cost avoidance is distributed evenly per FTE in the previous study, the following calculation is observed: $649,551.99 per FTE, which is closer to this study’s estimation. Given that primary care is a broader setting than is ambulatory cardiology, it is not surprising that more types of interventions and the overall volume/absolute number of interventions would be higher. Thus, the lower estimated cost avoidance in our study may be attributed to the lower volume of intervention opportunities availed to the cardiology CPS. Another difference is that detailed types of interventions related to hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, and HF were not included in Hough and colleagues, whereas our study included all applicable interventions regardless of relation to diseases, which may account for a degree of the variation in intervention breakdown between the 2 studies.11 However, as noted previously, some interventions for these particular diseases may not fully capture the rationale for pharmacotherapy interventions, such as drug dose changes or discontinuations, which may misrepresent the potential cost avoidance associated with them in reality.

Limitations

Of general importance, the PhARMD tool may underestimate the number of interventions made such that multiple interventions for a medical condition may have been completed but only captured as 1 intervention, which may represent a limitation of the tool when multiple interventions are made for the same disease (eg, titration of both β-blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor doses at a single appointment in a patient with HF with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction). Improved clarity about interventions made would require laborious chart review, which was not feasible. The evaluation at hand included a preliminary QA review, adding confidence that overdocumentation was not being done and the values represented at worst an underestimation of actual CPS intervention impact. Because this study was an initial evaluation of interventions made by CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy setting, whether these same outcomes would exist in other patient cohorts is unclear. However, these data do provide a foundational understanding of what may be expected from CPS integration into a cardiovascular care team.

These findings may be limited in generalizability to other health care systems and situations in which CPSs are afforded the regulatory opportunity to practice independently within an established scope of practice or collaborative practice agreements. The Veterans Health Administration system has been a leader in integrating CPSs into direct patient care roles and serves as a potential model for application by other groups. This evaluation’s data support continued efforts to create such independent practice environments as they allow for qualified CPSs to practice to their full clinical potential and have the fullest possible effect on cardiovascular outcomes.

Previous studies looking at cost savings in MTM programs have established a substantial return in economic investment with patients being managed by pharmacists.5,14 Given that the interventions made in this study were not tied to attainment of clinical outcomes, a limitation to our study, the cost-avoidance estimates should be interpreted cautiously. However, we know of no such tool that is available to allow accurate capture of clinical event reduction in a single center with consistent CPS involvement in care. A clear opportunity exists regarding design of a model that measures clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes related to the interventions performed by cardiology CPSs, but developing and deploying such a model may be challenging because guideline-directed medical therapies vary significantly based on many patient-specific issues, and identifying optimal or truly optimized medical therapy is at times a subjective task, especially in a single center. Using the types and volumes of interventions made by CPSs as a surrogate for these higher-level outcomes is still of value in order to understand the effect and role of CPSs in cardiovascular care. At present, the cost-avoidance estimates presented in this evaluation are based on the most appropriate system-specific data at hand, with the realization that actual cost avoidance in practice may vary widely and should be the topic of future research.

Conclusion

As cardiovascular team-based care continues to expand with the support of large organizations, such as the American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Failure Society of America, and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network, the need for understanding the effect of CPSs on patient care measures and health care costs becomes more pronounced.2,15 The results of this study demonstrate how integration of CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for cardiology physicians and providers, allowing more availability for diagnostic testing and care.

Interventions made by CPSs functioning as independent providers

1. Brush JE Jr, Handberg EM, Biga C, et al. 2015 ACC health policy statement on cardiovascular team-based care and the role of advanced practice providers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2118-2136.

2. Dunn SP, Birtcher KK, Beavers CJ, et al. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the care of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(19):2129-2139.

3. Sandoff BG, Kuca S, Rasmussen J, Merenich JA. Collaborative cardiac care service: a multidisciplinary approach to caring for patients with coronary artery disease. Perm J. 2008;12(3):4-11.

4. Merenich JA, Olson KL, Delate T, Rasmussen J, Helling DK, Ward DG; Clinical Pharmacy Cardiac Risk Service Study Group. Mortality reduction benefits of a comprehensive cardiac care program for patients with occlusive coronary disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(10):1370-1378.

5. Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience.

6. Martinez AS, Saef J, Paszcuzuk A, Bhatt-Chugani H. Implementation of a pharmacist-managed heart failure medication titration clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(12):1070-1076.

7. Roth GA, Poole JE, Zaha R, Zhou W, Skinner J, Morden NE. Use of guideline-directed medications for heart failure before cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(9):1062-1069.

8. Noschese LA, Bergman CL, Brar CK, Kansal MM. The pharmacist’s role in medication optimization for patients with chronic heart failure. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 10):S10-S15.

9. Coakley C, Hough A, Dwyer D, Parra D. Clinical video telehealth in a cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(22):1974-1975.

10. Khazan E, Anastasia E, Hough A, Parra D. Pharmacist-managed ambulatory blood pressure monitoring service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(4):190-195.

11. Hough A, Vartan CM, Groppi JA, Reyes S, Beckey NP. Evaluation of clinical pharmacy interventions in a Veterans Affairs medical center primary care clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(13):1168-1172.

12. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070-2077.

13. US Department of Labor. CPI inflation calculator. www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed January 18, 2019.

14. Perez A, Doloresco F, Hoffman JM, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2001-2005. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;29(1):128.

15. Milfred-LaForest SK, Chow SL, DiDomenico RJ, et al. Clinical pharmacy services in heart failure: an opinion paper from the Heart Failure Society of America and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(5):529-548.

1. Brush JE Jr, Handberg EM, Biga C, et al. 2015 ACC health policy statement on cardiovascular team-based care and the role of advanced practice providers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2118-2136.

2. Dunn SP, Birtcher KK, Beavers CJ, et al. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the care of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(19):2129-2139.

3. Sandoff BG, Kuca S, Rasmussen J, Merenich JA. Collaborative cardiac care service: a multidisciplinary approach to caring for patients with coronary artery disease. Perm J. 2008;12(3):4-11.

4. Merenich JA, Olson KL, Delate T, Rasmussen J, Helling DK, Ward DG; Clinical Pharmacy Cardiac Risk Service Study Group. Mortality reduction benefits of a comprehensive cardiac care program for patients with occlusive coronary disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(10):1370-1378.

5. Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience.

6. Martinez AS, Saef J, Paszcuzuk A, Bhatt-Chugani H. Implementation of a pharmacist-managed heart failure medication titration clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(12):1070-1076.

7. Roth GA, Poole JE, Zaha R, Zhou W, Skinner J, Morden NE. Use of guideline-directed medications for heart failure before cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(9):1062-1069.

8. Noschese LA, Bergman CL, Brar CK, Kansal MM. The pharmacist’s role in medication optimization for patients with chronic heart failure. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 10):S10-S15.

9. Coakley C, Hough A, Dwyer D, Parra D. Clinical video telehealth in a cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(22):1974-1975.

10. Khazan E, Anastasia E, Hough A, Parra D. Pharmacist-managed ambulatory blood pressure monitoring service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(4):190-195.

11. Hough A, Vartan CM, Groppi JA, Reyes S, Beckey NP. Evaluation of clinical pharmacy interventions in a Veterans Affairs medical center primary care clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(13):1168-1172.

12. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070-2077.

13. US Department of Labor. CPI inflation calculator. www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed January 18, 2019.

14. Perez A, Doloresco F, Hoffman JM, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2001-2005. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;29(1):128.

15. Milfred-LaForest SK, Chow SL, DiDomenico RJ, et al. Clinical pharmacy services in heart failure: an opinion paper from the Heart Failure Society of America and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(5):529-548.

The Best of 2018 Is Also the Worst

I am a doctor, not an engineer.Dr. McCoy, Star Trek “Mirror, Mirror” episode

Last year in my annual wrap-up, I wrote back-to-back editorials (December 2017 and January 2018) on the worst and best of 2017 from a federal health care perspective, emphasizing ethics or the lack thereof. I featured the altruism of federal health care providers (HCPs) responding to natural disasters and the terrible outcome of seemingly banal moral lapses.

This year the best and worst are one and the same, and I am not sure how it could be otherwise: the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) electronic health record (EHR) contract with Cerner (North Kansas City, MO). Former VA Secretary David Shulkin, MD, announced the deal in 2017 shortly before his departure, and it was signed under then Acting VA Secretary Robert Wilkie in May of 2018.1 But the reason the Cerner contract is the most impactful and momentous ethical event of the year is perhaps not what readers expect. Search engines will efficiently unearth plentiful drama with ethical import about the contract. There were conspiracy charges that the shadow regime improperly engineered the selection.2 The usual Congressional hearings on the VA leadership mismanagement of the EHR culminated in Sen Jon Tester’s (D-MO) martial declaration in a letter to the newly sworn-in VA Chief Information Officer James Paul Gfrerer that “EHR modernization cannot fail.”3

While all this is obviously important, it is not why the annual awards for ethical and unethical behaviors are bestowed on what is essentially an information technology acquisition. The Cerner contract is chosen because of its enormous potential to change the human practice of health care for good or ill; hence, the dual nomination. This column is not about Cerner qua Cerner but about how the EHR has transformed—or deformed—the humanistic aspects of medical practice.

I am old enough to remember the original transition from paper charts to VistA EHR. As an intern with illegible handwriting, I can remember breathing a sigh of relief when the blue screen appeared for the first time. The commands were cumbersome and the code laborious, but it was a technologic marvel to see the clean, organized progress notes and be able to print your medication list or discharge summary. However, it also was the first stuttering waves of a tsunami that would alter medical practice forever. The human cost of the revolution could be seen almost immediately as older clinicians or those who could not type struggled to complete work that with paper and pen would have been easily accomplished.

For many years there was a steady stream of updates to VistA, including the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). For a relatively long time in technology terms, VistA and CPRS were the envy of the medical world, which rushed to catch up. Gradually though, VA fell behind; the wizard IT guys could not patch and fix new versions fast enough, and eventually, like all things created, VistA and CPRS became obsolete.4 Attitudes toward this microcosm of the modernization of an aging organization were intense and diverse. Some of us held onto CPRS as though it was a transitional object that we had personalized and became attached to with all its quirks and problems. Others could not wait to get rid of it, believing anything new and streamlined had to be better.

Yet the opposite also is true. EHRs have been, and could be again, incredible time-savers, enabling HCPs to deliver more evidence-based, patient-centered care in a more accurate, integrated, timely, and comprehensive manner. For example, Cerner finally could discover the Holy Grail of VA-DoD interoperability and even—dare we dream—integrate with the community. Yet as science fiction aficionados know, the machine designed to free humankind of drudgery may also end up controlling us.

The other commonplace year-end practice is for ersatz prophets to predict the future. I have no idea whether the Cerner EHR will be good or bad for VA and DoD. According to the insightful critic of medical culture, Atul Gawande, MD, who has examined the practitioner-computer interface, what we must guard against is that it does not replace the practitioner-patient relationship.5 The most common complaint I hear from patients in VA mental health care is: “They never listen to me, they just sit there typing.” Similarly, clinicians complain: “I spend all my time looking at a screen not at a patient.” As an ethicist, I cannot tell you how many times the blight of copy and paste has thwarted or damaged a patient’s care. And the direct correlation between medical computing and burnout has been well documented as all health care systems struggle with a doctor shortage particularly in primary care—arguably where computer fatigue hits hardest.6

What will decide whether EHR modernization will be a positive or negative development for VA and DoD patients? And is there anything we as federal HCPs can do to tip the scales in favor of the what is best for patients and clinicians? The most encouraging step has already been taken: VA and Cerner have set up EHR Councils composed of 60% practicing VA HCPs to provide the clinical perspective and 40% from VA Central Office to encourage synchronization of the top-down and bottom-up processes.7

Many experts have pointed out the inherent tension between how computers and human beings work, which I will simplify as the battle between the 3 S’s and the 3 F’s.5 The optimal operation of EHRs requires systems, structure, stability; to function successfully human beings need flexibility, freedom, and fragmentation. VistA had more than 100 versions according to a report from the Federal News Network (FNN), which is a striking example of the challenge EHR modernization faces in bridging the 2 orientations. As former VA Chief Information Officer Roger Baker told FNN, replacing this approach of EHR tinkering with a locked-down commercial system will require “a culture change that is orders of magnitude bigger than expected.”8

Think of the 2 domains as a Venn diagram. Where the circles overlap is all the things we and patients want and need in health care: empathic listening, strong enduring relationships, accurate diagnosis, accessibility, personalized treatment, continuity of care, mutual respect, patient safety, room to exercise professional judgment, and the data needed to promote shared decision making. Our contribution and duty are to make that inner circle where we all dwell together as wide and full as possible and the overlap between the 2 outer circles as seamless as human imperfection and artificial intelligence permit.

The Gawande article is titled “Why Doctors Hate Their Computers.” Of course, his piece shows that we also love them. None of the proposed liberations from our EHR domination—be they medical scribes or dictation programs—has solved the problem, probably because they are all technologic and just move the slavery downstream. We have come too far, and medicine is too complex, to go back to the age of paper. If we can no longer do the good work of healing and caring without computers, then we have to learn to live with them as our allies not our enemies. After all, even Dr. McCoy had a tricorder.

1. VA Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Statement by Acting Secretary Robert Wilkie—VA signs contract with Cerner for an electronic health record system. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4061. Published May 17, 2018. Accessed January 15, 2019.

2. Arnsdorf I. The VA shadow ruler’s signature program is “trending towards red.” https://www.propublica.org/article/va-shadow-rulers-program-is-trending-towards-red. Published November 1, 2018. Accessed January 15, 2019.

3. Murphy K. Senate committee says EHR modernization cannot be allowed to fail. https://ehrintelligence.com/news/senate-committee-says-ehr-modernization-cannot-be-allowed-to-fail. Published January 14, 2019. Accessed January 15, 2019.

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs. A history of the electronic health record. https://www.ehrm.va.gov/about/history. Updated September 28, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2019.

5. Gawande A. Why doctors hate their computers. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/11/12/why-doctors-hate-their-computers. Published November 12, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2019.

6. Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care results from the MEMO study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):100-106.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. EHRM councils. https://www.ehrm.va.gov/deployment/councils. Updated July 17, 2018. Accessed January 15, 2019.

8. Ogrysko N. In abandoning VistA, VA faces culture change that’s ‘orders of magnitude bigger’ than expected. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/veterans-affairs/2017/06/in-abandoning-vista-va-faces-culture-change-thats-orders-of-magnitude-bigger-than-expected. Published June 26, 2017. Accessed January 16, 2018.

I am a doctor, not an engineer.Dr. McCoy, Star Trek “Mirror, Mirror” episode

Last year in my annual wrap-up, I wrote back-to-back editorials (December 2017 and January 2018) on the worst and best of 2017 from a federal health care perspective, emphasizing ethics or the lack thereof. I featured the altruism of federal health care providers (HCPs) responding to natural disasters and the terrible outcome of seemingly banal moral lapses.

This year the best and worst are one and the same, and I am not sure how it could be otherwise: the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) electronic health record (EHR) contract with Cerner (North Kansas City, MO). Former VA Secretary David Shulkin, MD, announced the deal in 2017 shortly before his departure, and it was signed under then Acting VA Secretary Robert Wilkie in May of 2018.1 But the reason the Cerner contract is the most impactful and momentous ethical event of the year is perhaps not what readers expect. Search engines will efficiently unearth plentiful drama with ethical import about the contract. There were conspiracy charges that the shadow regime improperly engineered the selection.2 The usual Congressional hearings on the VA leadership mismanagement of the EHR culminated in Sen Jon Tester’s (D-MO) martial declaration in a letter to the newly sworn-in VA Chief Information Officer James Paul Gfrerer that “EHR modernization cannot fail.”3

While all this is obviously important, it is not why the annual awards for ethical and unethical behaviors are bestowed on what is essentially an information technology acquisition. The Cerner contract is chosen because of its enormous potential to change the human practice of health care for good or ill; hence, the dual nomination. This column is not about Cerner qua Cerner but about how the EHR has transformed—or deformed—the humanistic aspects of medical practice.

I am old enough to remember the original transition from paper charts to VistA EHR. As an intern with illegible handwriting, I can remember breathing a sigh of relief when the blue screen appeared for the first time. The commands were cumbersome and the code laborious, but it was a technologic marvel to see the clean, organized progress notes and be able to print your medication list or discharge summary. However, it also was the first stuttering waves of a tsunami that would alter medical practice forever. The human cost of the revolution could be seen almost immediately as older clinicians or those who could not type struggled to complete work that with paper and pen would have been easily accomplished.

For many years there was a steady stream of updates to VistA, including the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). For a relatively long time in technology terms, VistA and CPRS were the envy of the medical world, which rushed to catch up. Gradually though, VA fell behind; the wizard IT guys could not patch and fix new versions fast enough, and eventually, like all things created, VistA and CPRS became obsolete.4 Attitudes toward this microcosm of the modernization of an aging organization were intense and diverse. Some of us held onto CPRS as though it was a transitional object that we had personalized and became attached to with all its quirks and problems. Others could not wait to get rid of it, believing anything new and streamlined had to be better.

Yet the opposite also is true. EHRs have been, and could be again, incredible time-savers, enabling HCPs to deliver more evidence-based, patient-centered care in a more accurate, integrated, timely, and comprehensive manner. For example, Cerner finally could discover the Holy Grail of VA-DoD interoperability and even—dare we dream—integrate with the community. Yet as science fiction aficionados know, the machine designed to free humankind of drudgery may also end up controlling us.

The other commonplace year-end practice is for ersatz prophets to predict the future. I have no idea whether the Cerner EHR will be good or bad for VA and DoD. According to the insightful critic of medical culture, Atul Gawande, MD, who has examined the practitioner-computer interface, what we must guard against is that it does not replace the practitioner-patient relationship.5 The most common complaint I hear from patients in VA mental health care is: “They never listen to me, they just sit there typing.” Similarly, clinicians complain: “I spend all my time looking at a screen not at a patient.” As an ethicist, I cannot tell you how many times the blight of copy and paste has thwarted or damaged a patient’s care. And the direct correlation between medical computing and burnout has been well documented as all health care systems struggle with a doctor shortage particularly in primary care—arguably where computer fatigue hits hardest.6

What will decide whether EHR modernization will be a positive or negative development for VA and DoD patients? And is there anything we as federal HCPs can do to tip the scales in favor of the what is best for patients and clinicians? The most encouraging step has already been taken: VA and Cerner have set up EHR Councils composed of 60% practicing VA HCPs to provide the clinical perspective and 40% from VA Central Office to encourage synchronization of the top-down and bottom-up processes.7

Many experts have pointed out the inherent tension between how computers and human beings work, which I will simplify as the battle between the 3 S’s and the 3 F’s.5 The optimal operation of EHRs requires systems, structure, stability; to function successfully human beings need flexibility, freedom, and fragmentation. VistA had more than 100 versions according to a report from the Federal News Network (FNN), which is a striking example of the challenge EHR modernization faces in bridging the 2 orientations. As former VA Chief Information Officer Roger Baker told FNN, replacing this approach of EHR tinkering with a locked-down commercial system will require “a culture change that is orders of magnitude bigger than expected.”8

Think of the 2 domains as a Venn diagram. Where the circles overlap is all the things we and patients want and need in health care: empathic listening, strong enduring relationships, accurate diagnosis, accessibility, personalized treatment, continuity of care, mutual respect, patient safety, room to exercise professional judgment, and the data needed to promote shared decision making. Our contribution and duty are to make that inner circle where we all dwell together as wide and full as possible and the overlap between the 2 outer circles as seamless as human imperfection and artificial intelligence permit.

The Gawande article is titled “Why Doctors Hate Their Computers.” Of course, his piece shows that we also love them. None of the proposed liberations from our EHR domination—be they medical scribes or dictation programs—has solved the problem, probably because they are all technologic and just move the slavery downstream. We have come too far, and medicine is too complex, to go back to the age of paper. If we can no longer do the good work of healing and caring without computers, then we have to learn to live with them as our allies not our enemies. After all, even Dr. McCoy had a tricorder.

I am a doctor, not an engineer.Dr. McCoy, Star Trek “Mirror, Mirror” episode

Last year in my annual wrap-up, I wrote back-to-back editorials (December 2017 and January 2018) on the worst and best of 2017 from a federal health care perspective, emphasizing ethics or the lack thereof. I featured the altruism of federal health care providers (HCPs) responding to natural disasters and the terrible outcome of seemingly banal moral lapses.