User login

CBO predicts more Medicare spending with drug rebate proposal

Medicare spending on pharmaceuticals is projected to increase if the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services finalizes changes to drug rebates in the Medicare program.

The Congressional Budget Office is estimating that Medicare spending would increase by $170 billion from 2020-2029 if the rebate rule goes into effect, according to a report released May 2.

The proposed rule, issued Jan. 31, would make it illegal for drug manufacturers to pay rebates to health plans and pharmacy benefit managers in return for better formulary placement. Instead of rebates, manufacturers could offer discounts directly to beneficiaries by lowering list prices or making a payment to the pharmacy for the full amount of the negotiated discount – a chargeback. Under the proposal, a beneficiary’s cost sharing would be based on the lower list price or the price after the chargeback.

The CBO’s projected spending increases are based on the assumption that manufacturers will withhold 15% of current-law rebates, as well as increases in federal subsidies for premiums, changes in annual thresholds to beneficiary cost sharing, and the cost of implementing the chargeback system.

The agency expects premiums to rise, as many plans currently use the rebates they receive from drug companies to lower premiums across the board.

However, some beneficiaries “would pay lower prices on their prescription drugs, and for some beneficiaries, those reductions would be greater than their premium increases,” the CBO stated in its report. For beneficiaries who use few drugs or who use drugs that have no significant rebates, “the premium increase would outweigh the price reduction.”

Another reason federal spending would increase under this proposal is an expected increase in utilization that would come with the lowering of prices.

“In CBO’s estimate, the additional Part D utilization stemming from implementing the proposed rule would increase federal spending for beneficiaries who are not enrolled in the low-income subsidy program over the 2020-2029 period by a total of about 2% or $10 billion,” the report noted.

But the increase in utilization would have a net positive effect on Medicare spending for this population, as more beneficiaries followed their drug regimens resulting in lower spending for physician and hospital services under Medicare Part A and Part B by an estimated $20 billion over the same period, according to the CBO.

“On net, those effects are projected to reduce Medicare spending by $10 billion over the 2020-2029 period,” according to the report.

Medicare spending on pharmaceuticals is projected to increase if the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services finalizes changes to drug rebates in the Medicare program.

The Congressional Budget Office is estimating that Medicare spending would increase by $170 billion from 2020-2029 if the rebate rule goes into effect, according to a report released May 2.

The proposed rule, issued Jan. 31, would make it illegal for drug manufacturers to pay rebates to health plans and pharmacy benefit managers in return for better formulary placement. Instead of rebates, manufacturers could offer discounts directly to beneficiaries by lowering list prices or making a payment to the pharmacy for the full amount of the negotiated discount – a chargeback. Under the proposal, a beneficiary’s cost sharing would be based on the lower list price or the price after the chargeback.

The CBO’s projected spending increases are based on the assumption that manufacturers will withhold 15% of current-law rebates, as well as increases in federal subsidies for premiums, changes in annual thresholds to beneficiary cost sharing, and the cost of implementing the chargeback system.

The agency expects premiums to rise, as many plans currently use the rebates they receive from drug companies to lower premiums across the board.

However, some beneficiaries “would pay lower prices on their prescription drugs, and for some beneficiaries, those reductions would be greater than their premium increases,” the CBO stated in its report. For beneficiaries who use few drugs or who use drugs that have no significant rebates, “the premium increase would outweigh the price reduction.”

Another reason federal spending would increase under this proposal is an expected increase in utilization that would come with the lowering of prices.

“In CBO’s estimate, the additional Part D utilization stemming from implementing the proposed rule would increase federal spending for beneficiaries who are not enrolled in the low-income subsidy program over the 2020-2029 period by a total of about 2% or $10 billion,” the report noted.

But the increase in utilization would have a net positive effect on Medicare spending for this population, as more beneficiaries followed their drug regimens resulting in lower spending for physician and hospital services under Medicare Part A and Part B by an estimated $20 billion over the same period, according to the CBO.

“On net, those effects are projected to reduce Medicare spending by $10 billion over the 2020-2029 period,” according to the report.

Medicare spending on pharmaceuticals is projected to increase if the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services finalizes changes to drug rebates in the Medicare program.

The Congressional Budget Office is estimating that Medicare spending would increase by $170 billion from 2020-2029 if the rebate rule goes into effect, according to a report released May 2.

The proposed rule, issued Jan. 31, would make it illegal for drug manufacturers to pay rebates to health plans and pharmacy benefit managers in return for better formulary placement. Instead of rebates, manufacturers could offer discounts directly to beneficiaries by lowering list prices or making a payment to the pharmacy for the full amount of the negotiated discount – a chargeback. Under the proposal, a beneficiary’s cost sharing would be based on the lower list price or the price after the chargeback.

The CBO’s projected spending increases are based on the assumption that manufacturers will withhold 15% of current-law rebates, as well as increases in federal subsidies for premiums, changes in annual thresholds to beneficiary cost sharing, and the cost of implementing the chargeback system.

The agency expects premiums to rise, as many plans currently use the rebates they receive from drug companies to lower premiums across the board.

However, some beneficiaries “would pay lower prices on their prescription drugs, and for some beneficiaries, those reductions would be greater than their premium increases,” the CBO stated in its report. For beneficiaries who use few drugs or who use drugs that have no significant rebates, “the premium increase would outweigh the price reduction.”

Another reason federal spending would increase under this proposal is an expected increase in utilization that would come with the lowering of prices.

“In CBO’s estimate, the additional Part D utilization stemming from implementing the proposed rule would increase federal spending for beneficiaries who are not enrolled in the low-income subsidy program over the 2020-2029 period by a total of about 2% or $10 billion,” the report noted.

But the increase in utilization would have a net positive effect on Medicare spending for this population, as more beneficiaries followed their drug regimens resulting in lower spending for physician and hospital services under Medicare Part A and Part B by an estimated $20 billion over the same period, according to the CBO.

“On net, those effects are projected to reduce Medicare spending by $10 billion over the 2020-2029 period,” according to the report.

In a tight vote, FDA panel backs mannitol for CF

A Food and Drug Administration Advisory Committee voted that the benefit-risk profile of an inhaled treatment for cystic fibrosis merits approval of the drug – dry powder mannitol (DPM).

Mannitol is a naturally occurring sugar alcohol that is used as a low-calorie sweetener; it is generally recognized as safe when taken enterically. Inhaled DPM, marketed as Aridol, is currently approved as a bronchoprovocation agent. For the current indication, DPM is given as 10x40-mg capsules twice daily.

In a 9-7 vote, the FDA’s Pulmonary-Allergy Drugs Advisory Committee (PADAC) decided that DPM’s modest potential to improve pulmonary function in adults with cystic fibrosis (CF) outweighed a potential signal for increased exacerbations seen in clinical trials.

Chiesi USA Inc. is seeking approval of DPM for the management of cystic fibrosis to improve pulmonary function in patients 18 years of age and older in conjunction with standard therapies. It plans to market DPM as Bronchitol.

Some committee members who voted against approval, including PADAC chair David H. Au, MD, worried that DPM’s ease of use might prompt patients and caregivers to substitute it for inhaled hypertonic saline, a medication that’s more burdensome to use but has a longer track record for efficacy and safety. While hypertonic saline requires cumbersome equipment and cleaning regimens and takes 20-30 minutes to administer, DPM is administered over about 5 minutes via a series of capsules inserted into a small inhaler device.

“I was very impressed by conversations that we heard from the community that this will be viewed as a substitute drug [for hypertonic saline],” said Dr. Au, professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “Before we make that leap of faith ... we have to better understand how it has to be used.” He also acknowledged that making the call for DPM was “challenging.”

Other committee members were reassured by the fact that DPM is approved for adult use in 35 countries; it’s been in use since 2011 in Australia for adults and children.

Some members also noted an unmet need in CF therapies and placed confidence in those treating CF patients to find ways to use DPM safely and effectively. “I’m really counting on the cystic fibrosis clinicians who do this for a living to figure out where to use this in their armamentarium,” said John M. Kelso, MD, an allergist at Scripps Clinic, San Diego.

In 2012, the initial new drug application submitted by Pharmaxis, which then held marketing rights to DPM, resulted in a “no” vote for approval from PADAC, and eventual FDA denial of approval. The initial submission was supported by two phase 3 clinical trials, 301 and 302, that included pediatric patients. In the pediatric population, there was concern for increased hemoptysis with DPM, so the FDA advised the drug’s marketers to consider seeking approval for an adult population only in its reapplication. The current submission followed a new double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, study 303, that included adults with CF aged 18 or over.

All three studies had similar designs, tracking change from baseline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) from baseline to the end of the 26-week study period. In addition to this primary endpoint, secondary endpoints included other pulmonary function measures, as well as the number of protocol-defined pulmonary exacerbations (PDPEs). Participants also reported quality of life and symptom measures on the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire–Revised (CFQ-R).

In study 301, the dropout rate approached one in three participants with higher discontinuation in the intervention than the control arm, causing significant statistical problems in dealing with missing data. Thus, said the FDA’s Robert Lim, MD, though this study had positive results for FEV1, it was not “statistically robust.”

The second study, 302, did not meet its primary endpoint, and there was “no support from secondary endpoints” for efficacy, said Dr. Lim, a clinical team leader in the FDA’s Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Rheumatology Products.

The current submission was also supported by a new post hoc subgroup analysis of adults in studies 301 and 302. A total of 414 patients receiving DPM and 347 receiving placebo (DPM at a nontherapeutic level) were included in the integrated analysis of patients from all three studies. Studies 301 and 302 both had open-label extension arms, allowing more patients to be included in safety data.

The problems caused by the missing data from study 301 were addressed in the design of study 303 by encouraging patients who discontinued the study drug to continue data collection efforts for the study. Dropout rates were lower overall in study 303 and balanced between arms.

Over the 26-week duration of study 303, investigators saw a statistically significant improvement in FEV1 of about 50 mL, according to the FDA’s analysis. Post hoc analyses of studies 301 and 302 showed point estimate increases of approximately 80 mL, according to Dr. Lim.

In its presentations, Chiesi USA presented its integrated analysis of adult data from the three clinical trials. The analysis showed an increase in FEV1 from baseline of 73 mL for the DPM group, compared with an increase of 7 mL for the control group, using an intention-to-treat population (P less than .001). The committee heard evidence that in adults with CF, pulmonary function typically decreases by 1%-3% annually.

The PDPE rate was slightly higher in the DPM group than in the control group in studies 302 and 303, but the differences were not statistically significant. These findings have a backdrop of an overall low rate of PDPEs ranging from 0.221 to 0.995 per year, according to Chiesi presenter Scott Donaldson, MD, a pulmonologist who directs the adult cystic fibrosis center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

When looking at the subgroup of United States study participants, the DPM integrated cohort included more patients with a history of prior pulmonary exacerbations. In the DPM group, 45% of U.S. participants had at least one exacerbation in the prior year, and 20% had two or more exacerbations, compared with 38% and 14%, respectively, in the control group. Chiesi argued that this imbalance was likely responsible for the increased exacerbation rate.

The sponsor and the FDA used different imputation methods to account for missing data from the earlier studies, complicating interpretation of the potential signal for increased exacerbations.

Quality of life data were similar between groups across the studies.

In the end, the view of the “yes” voters was encapsulated by James M. Tracy, DO, an allergist in private practice in Omaha, Neb. “This is not a drug for everybody; but absolutely, it’s a drug for somebody. Ultimately we have to make that decision – I do think that we study populations, but we really take care of people.”

The FDA usually follows the recommendations of its advisory panels.

A Food and Drug Administration Advisory Committee voted that the benefit-risk profile of an inhaled treatment for cystic fibrosis merits approval of the drug – dry powder mannitol (DPM).

Mannitol is a naturally occurring sugar alcohol that is used as a low-calorie sweetener; it is generally recognized as safe when taken enterically. Inhaled DPM, marketed as Aridol, is currently approved as a bronchoprovocation agent. For the current indication, DPM is given as 10x40-mg capsules twice daily.

In a 9-7 vote, the FDA’s Pulmonary-Allergy Drugs Advisory Committee (PADAC) decided that DPM’s modest potential to improve pulmonary function in adults with cystic fibrosis (CF) outweighed a potential signal for increased exacerbations seen in clinical trials.

Chiesi USA Inc. is seeking approval of DPM for the management of cystic fibrosis to improve pulmonary function in patients 18 years of age and older in conjunction with standard therapies. It plans to market DPM as Bronchitol.

Some committee members who voted against approval, including PADAC chair David H. Au, MD, worried that DPM’s ease of use might prompt patients and caregivers to substitute it for inhaled hypertonic saline, a medication that’s more burdensome to use but has a longer track record for efficacy and safety. While hypertonic saline requires cumbersome equipment and cleaning regimens and takes 20-30 minutes to administer, DPM is administered over about 5 minutes via a series of capsules inserted into a small inhaler device.

“I was very impressed by conversations that we heard from the community that this will be viewed as a substitute drug [for hypertonic saline],” said Dr. Au, professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “Before we make that leap of faith ... we have to better understand how it has to be used.” He also acknowledged that making the call for DPM was “challenging.”

Other committee members were reassured by the fact that DPM is approved for adult use in 35 countries; it’s been in use since 2011 in Australia for adults and children.

Some members also noted an unmet need in CF therapies and placed confidence in those treating CF patients to find ways to use DPM safely and effectively. “I’m really counting on the cystic fibrosis clinicians who do this for a living to figure out where to use this in their armamentarium,” said John M. Kelso, MD, an allergist at Scripps Clinic, San Diego.

In 2012, the initial new drug application submitted by Pharmaxis, which then held marketing rights to DPM, resulted in a “no” vote for approval from PADAC, and eventual FDA denial of approval. The initial submission was supported by two phase 3 clinical trials, 301 and 302, that included pediatric patients. In the pediatric population, there was concern for increased hemoptysis with DPM, so the FDA advised the drug’s marketers to consider seeking approval for an adult population only in its reapplication. The current submission followed a new double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, study 303, that included adults with CF aged 18 or over.

All three studies had similar designs, tracking change from baseline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) from baseline to the end of the 26-week study period. In addition to this primary endpoint, secondary endpoints included other pulmonary function measures, as well as the number of protocol-defined pulmonary exacerbations (PDPEs). Participants also reported quality of life and symptom measures on the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire–Revised (CFQ-R).

In study 301, the dropout rate approached one in three participants with higher discontinuation in the intervention than the control arm, causing significant statistical problems in dealing with missing data. Thus, said the FDA’s Robert Lim, MD, though this study had positive results for FEV1, it was not “statistically robust.”

The second study, 302, did not meet its primary endpoint, and there was “no support from secondary endpoints” for efficacy, said Dr. Lim, a clinical team leader in the FDA’s Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Rheumatology Products.

The current submission was also supported by a new post hoc subgroup analysis of adults in studies 301 and 302. A total of 414 patients receiving DPM and 347 receiving placebo (DPM at a nontherapeutic level) were included in the integrated analysis of patients from all three studies. Studies 301 and 302 both had open-label extension arms, allowing more patients to be included in safety data.

The problems caused by the missing data from study 301 were addressed in the design of study 303 by encouraging patients who discontinued the study drug to continue data collection efforts for the study. Dropout rates were lower overall in study 303 and balanced between arms.

Over the 26-week duration of study 303, investigators saw a statistically significant improvement in FEV1 of about 50 mL, according to the FDA’s analysis. Post hoc analyses of studies 301 and 302 showed point estimate increases of approximately 80 mL, according to Dr. Lim.

In its presentations, Chiesi USA presented its integrated analysis of adult data from the three clinical trials. The analysis showed an increase in FEV1 from baseline of 73 mL for the DPM group, compared with an increase of 7 mL for the control group, using an intention-to-treat population (P less than .001). The committee heard evidence that in adults with CF, pulmonary function typically decreases by 1%-3% annually.

The PDPE rate was slightly higher in the DPM group than in the control group in studies 302 and 303, but the differences were not statistically significant. These findings have a backdrop of an overall low rate of PDPEs ranging from 0.221 to 0.995 per year, according to Chiesi presenter Scott Donaldson, MD, a pulmonologist who directs the adult cystic fibrosis center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

When looking at the subgroup of United States study participants, the DPM integrated cohort included more patients with a history of prior pulmonary exacerbations. In the DPM group, 45% of U.S. participants had at least one exacerbation in the prior year, and 20% had two or more exacerbations, compared with 38% and 14%, respectively, in the control group. Chiesi argued that this imbalance was likely responsible for the increased exacerbation rate.

The sponsor and the FDA used different imputation methods to account for missing data from the earlier studies, complicating interpretation of the potential signal for increased exacerbations.

Quality of life data were similar between groups across the studies.

In the end, the view of the “yes” voters was encapsulated by James M. Tracy, DO, an allergist in private practice in Omaha, Neb. “This is not a drug for everybody; but absolutely, it’s a drug for somebody. Ultimately we have to make that decision – I do think that we study populations, but we really take care of people.”

The FDA usually follows the recommendations of its advisory panels.

A Food and Drug Administration Advisory Committee voted that the benefit-risk profile of an inhaled treatment for cystic fibrosis merits approval of the drug – dry powder mannitol (DPM).

Mannitol is a naturally occurring sugar alcohol that is used as a low-calorie sweetener; it is generally recognized as safe when taken enterically. Inhaled DPM, marketed as Aridol, is currently approved as a bronchoprovocation agent. For the current indication, DPM is given as 10x40-mg capsules twice daily.

In a 9-7 vote, the FDA’s Pulmonary-Allergy Drugs Advisory Committee (PADAC) decided that DPM’s modest potential to improve pulmonary function in adults with cystic fibrosis (CF) outweighed a potential signal for increased exacerbations seen in clinical trials.

Chiesi USA Inc. is seeking approval of DPM for the management of cystic fibrosis to improve pulmonary function in patients 18 years of age and older in conjunction with standard therapies. It plans to market DPM as Bronchitol.

Some committee members who voted against approval, including PADAC chair David H. Au, MD, worried that DPM’s ease of use might prompt patients and caregivers to substitute it for inhaled hypertonic saline, a medication that’s more burdensome to use but has a longer track record for efficacy and safety. While hypertonic saline requires cumbersome equipment and cleaning regimens and takes 20-30 minutes to administer, DPM is administered over about 5 minutes via a series of capsules inserted into a small inhaler device.

“I was very impressed by conversations that we heard from the community that this will be viewed as a substitute drug [for hypertonic saline],” said Dr. Au, professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “Before we make that leap of faith ... we have to better understand how it has to be used.” He also acknowledged that making the call for DPM was “challenging.”

Other committee members were reassured by the fact that DPM is approved for adult use in 35 countries; it’s been in use since 2011 in Australia for adults and children.

Some members also noted an unmet need in CF therapies and placed confidence in those treating CF patients to find ways to use DPM safely and effectively. “I’m really counting on the cystic fibrosis clinicians who do this for a living to figure out where to use this in their armamentarium,” said John M. Kelso, MD, an allergist at Scripps Clinic, San Diego.

In 2012, the initial new drug application submitted by Pharmaxis, which then held marketing rights to DPM, resulted in a “no” vote for approval from PADAC, and eventual FDA denial of approval. The initial submission was supported by two phase 3 clinical trials, 301 and 302, that included pediatric patients. In the pediatric population, there was concern for increased hemoptysis with DPM, so the FDA advised the drug’s marketers to consider seeking approval for an adult population only in its reapplication. The current submission followed a new double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, study 303, that included adults with CF aged 18 or over.

All three studies had similar designs, tracking change from baseline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) from baseline to the end of the 26-week study period. In addition to this primary endpoint, secondary endpoints included other pulmonary function measures, as well as the number of protocol-defined pulmonary exacerbations (PDPEs). Participants also reported quality of life and symptom measures on the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire–Revised (CFQ-R).

In study 301, the dropout rate approached one in three participants with higher discontinuation in the intervention than the control arm, causing significant statistical problems in dealing with missing data. Thus, said the FDA’s Robert Lim, MD, though this study had positive results for FEV1, it was not “statistically robust.”

The second study, 302, did not meet its primary endpoint, and there was “no support from secondary endpoints” for efficacy, said Dr. Lim, a clinical team leader in the FDA’s Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Rheumatology Products.

The current submission was also supported by a new post hoc subgroup analysis of adults in studies 301 and 302. A total of 414 patients receiving DPM and 347 receiving placebo (DPM at a nontherapeutic level) were included in the integrated analysis of patients from all three studies. Studies 301 and 302 both had open-label extension arms, allowing more patients to be included in safety data.

The problems caused by the missing data from study 301 were addressed in the design of study 303 by encouraging patients who discontinued the study drug to continue data collection efforts for the study. Dropout rates were lower overall in study 303 and balanced between arms.

Over the 26-week duration of study 303, investigators saw a statistically significant improvement in FEV1 of about 50 mL, according to the FDA’s analysis. Post hoc analyses of studies 301 and 302 showed point estimate increases of approximately 80 mL, according to Dr. Lim.

In its presentations, Chiesi USA presented its integrated analysis of adult data from the three clinical trials. The analysis showed an increase in FEV1 from baseline of 73 mL for the DPM group, compared with an increase of 7 mL for the control group, using an intention-to-treat population (P less than .001). The committee heard evidence that in adults with CF, pulmonary function typically decreases by 1%-3% annually.

The PDPE rate was slightly higher in the DPM group than in the control group in studies 302 and 303, but the differences were not statistically significant. These findings have a backdrop of an overall low rate of PDPEs ranging from 0.221 to 0.995 per year, according to Chiesi presenter Scott Donaldson, MD, a pulmonologist who directs the adult cystic fibrosis center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

When looking at the subgroup of United States study participants, the DPM integrated cohort included more patients with a history of prior pulmonary exacerbations. In the DPM group, 45% of U.S. participants had at least one exacerbation in the prior year, and 20% had two or more exacerbations, compared with 38% and 14%, respectively, in the control group. Chiesi argued that this imbalance was likely responsible for the increased exacerbation rate.

The sponsor and the FDA used different imputation methods to account for missing data from the earlier studies, complicating interpretation of the potential signal for increased exacerbations.

Quality of life data were similar between groups across the studies.

In the end, the view of the “yes” voters was encapsulated by James M. Tracy, DO, an allergist in private practice in Omaha, Neb. “This is not a drug for everybody; but absolutely, it’s a drug for somebody. Ultimately we have to make that decision – I do think that we study populations, but we really take care of people.”

The FDA usually follows the recommendations of its advisory panels.

FROM AN FDA ADVISORY COMMITTEE HEARING

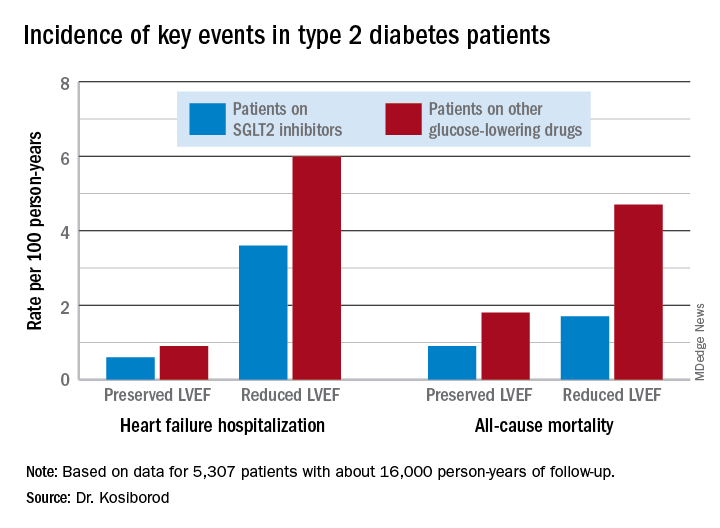

SGLT2 inhibitors prevent HF hospitalization regardless of baseline LVEF

NEW ORLEANS – based on data from a large real-world patient registry.

“The observed beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on heart failure may extend across the range of baseline ejection fractions,” Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, observed at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

This is an important new insight. The major randomized cardiovascular outcome trials that showed lower risks of heart failure hospitalization and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetic patients on an SGLT2 inhibitor, such as EMPA-REG OUTCOME for empagliflozin (Jardiance) and CANVAS for canagliflozin (Invokana), didn’t include information on baseline LVEF. So until now it has been unclear whether the beneficial effects of the SGLT2 inhibitors preventing heart failure hospitalization vary depending upon LVEF, explained Dr. Kosiborod, a cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Mo.

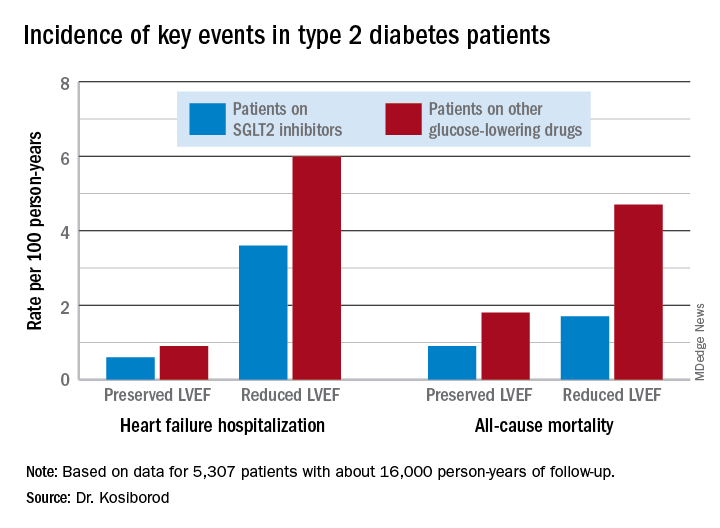

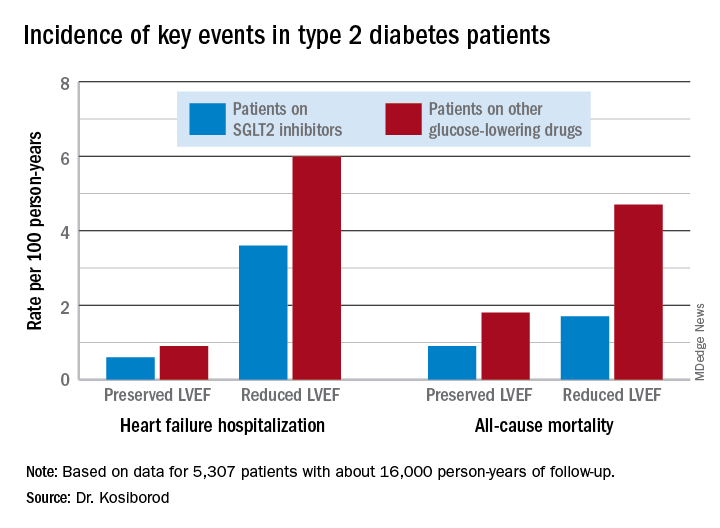

He presented an analysis drawn from the patient database kept by Maccabi Healthcare Services in Israel. The study included 5,307 patients with type 2 diabetes and an LVEF measurement recorded in their chart at the time they started on either empagliflozin or dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and an equal number of propensity-matched type 2 diabetic controls who started on other glucose-lowering drugs, most commonly an oral dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor.

During roughly 16,000 person-years of follow-up, 239 deaths occurred. Compared with patients on another glucose-lowering drug, the risk of death from all causes was reduced by 47% among patients who were on an SGLT2 inhibitor and had a baseline LVEF of 50% or greater and by 62% among the 9% of subjects who had a baseline LVEF less than 50%.

Similarly, the risk of heart failure hospitalization was reduced by 29% in SGLT2 inhibitor users with a preserved LVEF and by 27% if they had a reduced LVEF.

For the composite endpoint of heart failure hospitalization or all-cause mortality, the risk reductions associated with SGLT2 inhibitor therapy were 45% with preserved and 39% with reduced LVEF.

Session comoderator Prakash C. Deedwania, MD, noted that there are ongoing major randomized trials of various SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with known heart failure, with cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization as primary endpoints. He asked Dr. Kosiborod whether, given that the results of these studies aren’t in yet, he thinks clinicians should be prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors to diabetic or prediabetic patients who don’t have clinical symptoms of heart failure but may have a marker of increased risk, such as an elevated B-type natriuretic peptide.

“At least in my mind, we have more than enough evidence at this point to say that SGLT2 inhibitors are effective in preventing heart failure,” Dr. Kosiborod replied.

“Obviously, if your risk for developing a condition is higher at baseline, then the absolute benefit that you’re going to get from using an agent that’s effective in preventing that event is going to be higher and the number needed to treat is going to be lower. So if you have a patient at high risk for heart failure by whatever risk predictor you’re using and the patient doesn’t yet have heart failure but does have diabetes, which is already a risk factor for heart failure, I think we have pretty solid data now that SGLT2 inhibitors will likely be effective in preventing heart failure in that kind of patient population. But I don’t think we have definitive data at this point to say that the drugs are effective in treating heart failure in people who already have a manifest clinical syndrome of heart failure, which is why we’re doing all these clinical trials now,” he continued.

Dr. Deedwania urged audience members to make the effort to become comfortable in prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors for their patients with type 2 diabetes.

“Many different surveys show that these drugs are not being utilized effectively by cardiologists,” noted Dr. Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of the heart failure program at the university’s Fresno campus.

“As cardiologists, we may not want to own diabetes, but we at least have to feel that we have the ownership of treating the diabetic patient with cardiovascular disease with appropriate drugs. We don’t need to depend on endocrinologists because if we do these patients may become lost,” he said.

Dr. Kosiborod concurred, citing evidence that diabetic patients with cardiovascular disease are much more likely to see a cardiologist than an endocrinologist in the course of usual care.

“There’s definitely a golden opportunity here to intervene to reduce risk,” he said.

Dr. Kosiborod reported serving as a consultant to roughly a dozen pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kosiborod M. ACC 19, Abstract #1024-07.

NEW ORLEANS – based on data from a large real-world patient registry.

“The observed beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on heart failure may extend across the range of baseline ejection fractions,” Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, observed at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

This is an important new insight. The major randomized cardiovascular outcome trials that showed lower risks of heart failure hospitalization and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetic patients on an SGLT2 inhibitor, such as EMPA-REG OUTCOME for empagliflozin (Jardiance) and CANVAS for canagliflozin (Invokana), didn’t include information on baseline LVEF. So until now it has been unclear whether the beneficial effects of the SGLT2 inhibitors preventing heart failure hospitalization vary depending upon LVEF, explained Dr. Kosiborod, a cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Mo.

He presented an analysis drawn from the patient database kept by Maccabi Healthcare Services in Israel. The study included 5,307 patients with type 2 diabetes and an LVEF measurement recorded in their chart at the time they started on either empagliflozin or dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and an equal number of propensity-matched type 2 diabetic controls who started on other glucose-lowering drugs, most commonly an oral dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor.

During roughly 16,000 person-years of follow-up, 239 deaths occurred. Compared with patients on another glucose-lowering drug, the risk of death from all causes was reduced by 47% among patients who were on an SGLT2 inhibitor and had a baseline LVEF of 50% or greater and by 62% among the 9% of subjects who had a baseline LVEF less than 50%.

Similarly, the risk of heart failure hospitalization was reduced by 29% in SGLT2 inhibitor users with a preserved LVEF and by 27% if they had a reduced LVEF.

For the composite endpoint of heart failure hospitalization or all-cause mortality, the risk reductions associated with SGLT2 inhibitor therapy were 45% with preserved and 39% with reduced LVEF.

Session comoderator Prakash C. Deedwania, MD, noted that there are ongoing major randomized trials of various SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with known heart failure, with cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization as primary endpoints. He asked Dr. Kosiborod whether, given that the results of these studies aren’t in yet, he thinks clinicians should be prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors to diabetic or prediabetic patients who don’t have clinical symptoms of heart failure but may have a marker of increased risk, such as an elevated B-type natriuretic peptide.

“At least in my mind, we have more than enough evidence at this point to say that SGLT2 inhibitors are effective in preventing heart failure,” Dr. Kosiborod replied.

“Obviously, if your risk for developing a condition is higher at baseline, then the absolute benefit that you’re going to get from using an agent that’s effective in preventing that event is going to be higher and the number needed to treat is going to be lower. So if you have a patient at high risk for heart failure by whatever risk predictor you’re using and the patient doesn’t yet have heart failure but does have diabetes, which is already a risk factor for heart failure, I think we have pretty solid data now that SGLT2 inhibitors will likely be effective in preventing heart failure in that kind of patient population. But I don’t think we have definitive data at this point to say that the drugs are effective in treating heart failure in people who already have a manifest clinical syndrome of heart failure, which is why we’re doing all these clinical trials now,” he continued.

Dr. Deedwania urged audience members to make the effort to become comfortable in prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors for their patients with type 2 diabetes.

“Many different surveys show that these drugs are not being utilized effectively by cardiologists,” noted Dr. Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of the heart failure program at the university’s Fresno campus.

“As cardiologists, we may not want to own diabetes, but we at least have to feel that we have the ownership of treating the diabetic patient with cardiovascular disease with appropriate drugs. We don’t need to depend on endocrinologists because if we do these patients may become lost,” he said.

Dr. Kosiborod concurred, citing evidence that diabetic patients with cardiovascular disease are much more likely to see a cardiologist than an endocrinologist in the course of usual care.

“There’s definitely a golden opportunity here to intervene to reduce risk,” he said.

Dr. Kosiborod reported serving as a consultant to roughly a dozen pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kosiborod M. ACC 19, Abstract #1024-07.

NEW ORLEANS – based on data from a large real-world patient registry.

“The observed beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on heart failure may extend across the range of baseline ejection fractions,” Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, observed at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

This is an important new insight. The major randomized cardiovascular outcome trials that showed lower risks of heart failure hospitalization and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetic patients on an SGLT2 inhibitor, such as EMPA-REG OUTCOME for empagliflozin (Jardiance) and CANVAS for canagliflozin (Invokana), didn’t include information on baseline LVEF. So until now it has been unclear whether the beneficial effects of the SGLT2 inhibitors preventing heart failure hospitalization vary depending upon LVEF, explained Dr. Kosiborod, a cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Mo.

He presented an analysis drawn from the patient database kept by Maccabi Healthcare Services in Israel. The study included 5,307 patients with type 2 diabetes and an LVEF measurement recorded in their chart at the time they started on either empagliflozin or dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and an equal number of propensity-matched type 2 diabetic controls who started on other glucose-lowering drugs, most commonly an oral dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor.

During roughly 16,000 person-years of follow-up, 239 deaths occurred. Compared with patients on another glucose-lowering drug, the risk of death from all causes was reduced by 47% among patients who were on an SGLT2 inhibitor and had a baseline LVEF of 50% or greater and by 62% among the 9% of subjects who had a baseline LVEF less than 50%.

Similarly, the risk of heart failure hospitalization was reduced by 29% in SGLT2 inhibitor users with a preserved LVEF and by 27% if they had a reduced LVEF.

For the composite endpoint of heart failure hospitalization or all-cause mortality, the risk reductions associated with SGLT2 inhibitor therapy were 45% with preserved and 39% with reduced LVEF.

Session comoderator Prakash C. Deedwania, MD, noted that there are ongoing major randomized trials of various SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with known heart failure, with cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization as primary endpoints. He asked Dr. Kosiborod whether, given that the results of these studies aren’t in yet, he thinks clinicians should be prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors to diabetic or prediabetic patients who don’t have clinical symptoms of heart failure but may have a marker of increased risk, such as an elevated B-type natriuretic peptide.

“At least in my mind, we have more than enough evidence at this point to say that SGLT2 inhibitors are effective in preventing heart failure,” Dr. Kosiborod replied.

“Obviously, if your risk for developing a condition is higher at baseline, then the absolute benefit that you’re going to get from using an agent that’s effective in preventing that event is going to be higher and the number needed to treat is going to be lower. So if you have a patient at high risk for heart failure by whatever risk predictor you’re using and the patient doesn’t yet have heart failure but does have diabetes, which is already a risk factor for heart failure, I think we have pretty solid data now that SGLT2 inhibitors will likely be effective in preventing heart failure in that kind of patient population. But I don’t think we have definitive data at this point to say that the drugs are effective in treating heart failure in people who already have a manifest clinical syndrome of heart failure, which is why we’re doing all these clinical trials now,” he continued.

Dr. Deedwania urged audience members to make the effort to become comfortable in prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors for their patients with type 2 diabetes.

“Many different surveys show that these drugs are not being utilized effectively by cardiologists,” noted Dr. Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of the heart failure program at the university’s Fresno campus.

“As cardiologists, we may not want to own diabetes, but we at least have to feel that we have the ownership of treating the diabetic patient with cardiovascular disease with appropriate drugs. We don’t need to depend on endocrinologists because if we do these patients may become lost,” he said.

Dr. Kosiborod concurred, citing evidence that diabetic patients with cardiovascular disease are much more likely to see a cardiologist than an endocrinologist in the course of usual care.

“There’s definitely a golden opportunity here to intervene to reduce risk,” he said.

Dr. Kosiborod reported serving as a consultant to roughly a dozen pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Kosiborod M. ACC 19, Abstract #1024-07.

REPORTING FROM ACC 19

Short-term use of CGMs can deliver life-changing data for patients with type 2 diabetes

LOS ANGELES – Cardiology patients can strap on a Holter monitor for a day or two to track their heart activity and get a brief but helpful glimpse at their cardiac health. Could patients with type 2 diabetes benefit by monitoring their blood sugar for a short period? Absolutely, according to an endocrinologist who says he’s had tremendous success with the temporary use of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) in appropriate patients.

“There’s an actionable surprise with almost every patient,” said Daniel Einhorn, MD, FACP, FACE, medical director of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute and clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

The key is to use CGM data to pinpoint glucose spikes and then quickly make adjustments, typically over a period of 2 weeks. “This is about pattern recognition. We can do [CGM] over a week, see what the pattern is, and then try to fix something. Then they come back after the second week or send [the monitor] in, and they have the problem fixed. You have a happy patient and a happy family,” said Dr. Einhorn, who spoke in a presentation at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

He highlighted how CGM data allow patients to track their blood sugar over extended periods of time and detect patterns. The data can uncover hidden hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, he said, and is much more useful to patients than the self-monitoring of glucose levels or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) data.

Reading the patterns, adjusting behavior

Dr. Einhorn discussed several specific cases of patients who had changed their behavior in regard to food or medicine after CGM data disclosed certain blood sugar patterns.

Often, he said, patients say they’re surprised to find their well-being improves after they make adjustments, saying something along the lines of “I didn’t feel badly, but I feel better now.” According to Dr. Einhorn, “You hear that all the time.”

For example, he said, one patient knew his blood sugar occasionally topped 200 mg/dL, but he felt all right and didn’t want to take insulin. CGM monitoring over 6 days showed the patient had continuous glucose levels well over 200 mg/dL, especially at night. The patient accepted insulin, and a few months later his HbA1c dropped from 10.4% to 6.6%, and his blood sugar level stayed near or below the target range of 154 mg/dL.

Dr. Einhorn said the CGM data can reveal a range of problems, including:

- The “breakfast bump” after carbohydrate-heavy breakfasts of cereal, toast, and juice. “Breakfast cereal is diabolical,” he said.

- Hypoglycemia hours after exercise.

- Nocturnal hypoglycemia.

- Hypoglycemia unawareness.

Insurance coverage of the CGM device varies widely, he said, and insurers may not cover it at all in type 2 diabetes or only pay if the patient takes insulin. Fortunately, he said, the devices can be inexpensive.

Temporary use is not for everyone

Dr. Einhorn cautioned that temporary use of CGM is not appropriate for every patient with type 2 diabetes. “There’s absolutely a place for [permanent] monitoring for those people who have to make decisions throughout the day, especially if they are taking insulin,” he said.

And anyone with type 1 diabetes should use CGM on an ongoing basis, he emphasized. “Type 1 is a different world, a different universe,” he said.

He also noted that some patients don’t fare well on CGM, even on a temporary basis. That would include patients who hate to wear devices (possibly out of embarrassment), those who can’t manage to switch over from self-monitoring, and those who can’t manage to understand the data.

Dr. Einhorn disclosed various types of relationships with a number of drug makers, including Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo, Sanofi, Janssen, and others.

LOS ANGELES – Cardiology patients can strap on a Holter monitor for a day or two to track their heart activity and get a brief but helpful glimpse at their cardiac health. Could patients with type 2 diabetes benefit by monitoring their blood sugar for a short period? Absolutely, according to an endocrinologist who says he’s had tremendous success with the temporary use of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) in appropriate patients.

“There’s an actionable surprise with almost every patient,” said Daniel Einhorn, MD, FACP, FACE, medical director of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute and clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

The key is to use CGM data to pinpoint glucose spikes and then quickly make adjustments, typically over a period of 2 weeks. “This is about pattern recognition. We can do [CGM] over a week, see what the pattern is, and then try to fix something. Then they come back after the second week or send [the monitor] in, and they have the problem fixed. You have a happy patient and a happy family,” said Dr. Einhorn, who spoke in a presentation at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

He highlighted how CGM data allow patients to track their blood sugar over extended periods of time and detect patterns. The data can uncover hidden hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, he said, and is much more useful to patients than the self-monitoring of glucose levels or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) data.

Reading the patterns, adjusting behavior

Dr. Einhorn discussed several specific cases of patients who had changed their behavior in regard to food or medicine after CGM data disclosed certain blood sugar patterns.

Often, he said, patients say they’re surprised to find their well-being improves after they make adjustments, saying something along the lines of “I didn’t feel badly, but I feel better now.” According to Dr. Einhorn, “You hear that all the time.”

For example, he said, one patient knew his blood sugar occasionally topped 200 mg/dL, but he felt all right and didn’t want to take insulin. CGM monitoring over 6 days showed the patient had continuous glucose levels well over 200 mg/dL, especially at night. The patient accepted insulin, and a few months later his HbA1c dropped from 10.4% to 6.6%, and his blood sugar level stayed near or below the target range of 154 mg/dL.

Dr. Einhorn said the CGM data can reveal a range of problems, including:

- The “breakfast bump” after carbohydrate-heavy breakfasts of cereal, toast, and juice. “Breakfast cereal is diabolical,” he said.

- Hypoglycemia hours after exercise.

- Nocturnal hypoglycemia.

- Hypoglycemia unawareness.

Insurance coverage of the CGM device varies widely, he said, and insurers may not cover it at all in type 2 diabetes or only pay if the patient takes insulin. Fortunately, he said, the devices can be inexpensive.

Temporary use is not for everyone

Dr. Einhorn cautioned that temporary use of CGM is not appropriate for every patient with type 2 diabetes. “There’s absolutely a place for [permanent] monitoring for those people who have to make decisions throughout the day, especially if they are taking insulin,” he said.

And anyone with type 1 diabetes should use CGM on an ongoing basis, he emphasized. “Type 1 is a different world, a different universe,” he said.

He also noted that some patients don’t fare well on CGM, even on a temporary basis. That would include patients who hate to wear devices (possibly out of embarrassment), those who can’t manage to switch over from self-monitoring, and those who can’t manage to understand the data.

Dr. Einhorn disclosed various types of relationships with a number of drug makers, including Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo, Sanofi, Janssen, and others.

LOS ANGELES – Cardiology patients can strap on a Holter monitor for a day or two to track their heart activity and get a brief but helpful glimpse at their cardiac health. Could patients with type 2 diabetes benefit by monitoring their blood sugar for a short period? Absolutely, according to an endocrinologist who says he’s had tremendous success with the temporary use of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) in appropriate patients.

“There’s an actionable surprise with almost every patient,” said Daniel Einhorn, MD, FACP, FACE, medical director of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute and clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

The key is to use CGM data to pinpoint glucose spikes and then quickly make adjustments, typically over a period of 2 weeks. “This is about pattern recognition. We can do [CGM] over a week, see what the pattern is, and then try to fix something. Then they come back after the second week or send [the monitor] in, and they have the problem fixed. You have a happy patient and a happy family,” said Dr. Einhorn, who spoke in a presentation at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

He highlighted how CGM data allow patients to track their blood sugar over extended periods of time and detect patterns. The data can uncover hidden hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, he said, and is much more useful to patients than the self-monitoring of glucose levels or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) data.

Reading the patterns, adjusting behavior

Dr. Einhorn discussed several specific cases of patients who had changed their behavior in regard to food or medicine after CGM data disclosed certain blood sugar patterns.

Often, he said, patients say they’re surprised to find their well-being improves after they make adjustments, saying something along the lines of “I didn’t feel badly, but I feel better now.” According to Dr. Einhorn, “You hear that all the time.”

For example, he said, one patient knew his blood sugar occasionally topped 200 mg/dL, but he felt all right and didn’t want to take insulin. CGM monitoring over 6 days showed the patient had continuous glucose levels well over 200 mg/dL, especially at night. The patient accepted insulin, and a few months later his HbA1c dropped from 10.4% to 6.6%, and his blood sugar level stayed near or below the target range of 154 mg/dL.

Dr. Einhorn said the CGM data can reveal a range of problems, including:

- The “breakfast bump” after carbohydrate-heavy breakfasts of cereal, toast, and juice. “Breakfast cereal is diabolical,” he said.

- Hypoglycemia hours after exercise.

- Nocturnal hypoglycemia.

- Hypoglycemia unawareness.

Insurance coverage of the CGM device varies widely, he said, and insurers may not cover it at all in type 2 diabetes or only pay if the patient takes insulin. Fortunately, he said, the devices can be inexpensive.

Temporary use is not for everyone

Dr. Einhorn cautioned that temporary use of CGM is not appropriate for every patient with type 2 diabetes. “There’s absolutely a place for [permanent] monitoring for those people who have to make decisions throughout the day, especially if they are taking insulin,” he said.

And anyone with type 1 diabetes should use CGM on an ongoing basis, he emphasized. “Type 1 is a different world, a different universe,” he said.

He also noted that some patients don’t fare well on CGM, even on a temporary basis. That would include patients who hate to wear devices (possibly out of embarrassment), those who can’t manage to switch over from self-monitoring, and those who can’t manage to understand the data.

Dr. Einhorn disclosed various types of relationships with a number of drug makers, including Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo, Sanofi, Janssen, and others.

REPORTING FROM AACE 2019

HM19: Pediatric clinical conundrums

Atypical symptoms and diagnoses

Presenters

Yemisi Jones, MD; Mirna Giordano, MD

Session title

Pediatric Clinical Conundrums

Session summary

Dr. Mirna Giordano of Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, and Dr. Yemisi Jones of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, moderated the Pediatric Clinical Conundrums session at HM19. After reviewing multiple submissions, they invited four trainees to present their interesting cases.

Malignancy or infection? Dr. Jeremy Brown, a resident at the University of Louisville, presented a case of a 15-year-old male with right upper quadrant abdominal pain with associated weight loss and intermittent fevers, over the course of several weeks. CT revealed multiple liver lesions, providing concern for possible malignancy, although liver biopsy proved otherwise, with mostly liquefactive tissue and benign liver parenchyma. After a large infectious work-up ensued, the patient was diagnosed with disseminated Bartonella. He was treated with a 10-day course of azithromycin, and his symptoms resolved.

Leg blisters as an uncommon manifestation of a common childhood disease. Dr. Stefan Mammele, a resident at Kapi’olani Medical Center in Honolulu, and the University of Hawaii, presented a case of an 11-year-old boy with a painful and pruritic rash associated with multiple 5- to 10-mm tense bullae located on the patient’s bilateral lower extremities with extension to the trunk. The patient was also found to have hematuria and proteinuria. The bullae drained both serosanguinous and purulent material. Fluid culture grew group A Streptococcus and skin biopsy confirmed IgA vasculitis. Bullae are a rare characteristic of Henoch Schönlein pupura in children, but are more commonly seen as a disease manifestation in adults. The patient was treated with cefazolin, and his lesions improved over the course of several weeks with resolution of his hematuria by 6 months.

Is she crying blood? Dr. Joshua Price, a resident at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., described a 12-year-old female who presented with 7 days of left-sided hemolacria with acute vision loss and unilateral eye pain. This patient did not respond to outpatient topical steroids and antibiotics, as prescribed by ophthalmology. For this reason, she underwent further work-up and imaging. MRI of the head and orbits revealed left maxillary sinus disease. She was treated with antibiotics for acute left maxillary sinusitis and her hemolacria resolved within 24 hours. While the differential diagnosis for hemolacria is broad, rarely acute sinusitis has been reported as a cause in medical literature.

Recurrent bronchiolitis or something more? Dr. Moira Black, a resident at Children’s Memorial Hermann in Houston, presented a case of a 7-month-old female with a history of recurrent admissions for increased work of breathing believed to be secondary to viral bronchiolitis. Her first hospitalization occurred at 7 weeks of age and was complicated by spontaneous pneumothorax requiring chest tube placement. She was again hospitalized at 5 months of age with resolution of her increased work of breathing with high-flow nasal cannula. She presented again at 7 months of age with presumed bronchiolitis, however, she decompensated and required intubation on the 5th day of hospitalization. A bronchoscopy was performed and revealed a significantly narrowed left bronchus at the carina and a blind pouch on the right with notable pulsation of the walls. She underwent further imaging and was ultimately diagnosed with a left pulmonary artery sling. Left pulmonary artery slings are a rare, but potentially fatal anomaly that can present with wheezing, stridor, and recurrent respiratory infections. Patient underwent correction by cardiovascular surgery and has since been doing well.

Key takeaways for HM

• Bartonella is a common cause of fever of unknown origin, and should be considered in unusual presentations of febrile illnesses.

• Bullae in IgA vasculitis are rare in children and do not have prognostic value, but streptococcal infection may be a trigger for IgA vasculitis.

• Hemolacria is an atypical presentation of rare and common diagnoses that should prompt further work-up.

• Acute respiratory distress can be caused by underlying cardiac or vascular anomalies and can be mistaken for common viral illnesses.

Dr. Marsicek is a pediatric hospital medicine fellow at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla. Dr. Wysocka is a pediatric resident at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital.

Atypical symptoms and diagnoses

Atypical symptoms and diagnoses

Presenters

Yemisi Jones, MD; Mirna Giordano, MD

Session title

Pediatric Clinical Conundrums

Session summary

Dr. Mirna Giordano of Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, and Dr. Yemisi Jones of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, moderated the Pediatric Clinical Conundrums session at HM19. After reviewing multiple submissions, they invited four trainees to present their interesting cases.

Malignancy or infection? Dr. Jeremy Brown, a resident at the University of Louisville, presented a case of a 15-year-old male with right upper quadrant abdominal pain with associated weight loss and intermittent fevers, over the course of several weeks. CT revealed multiple liver lesions, providing concern for possible malignancy, although liver biopsy proved otherwise, with mostly liquefactive tissue and benign liver parenchyma. After a large infectious work-up ensued, the patient was diagnosed with disseminated Bartonella. He was treated with a 10-day course of azithromycin, and his symptoms resolved.

Leg blisters as an uncommon manifestation of a common childhood disease. Dr. Stefan Mammele, a resident at Kapi’olani Medical Center in Honolulu, and the University of Hawaii, presented a case of an 11-year-old boy with a painful and pruritic rash associated with multiple 5- to 10-mm tense bullae located on the patient’s bilateral lower extremities with extension to the trunk. The patient was also found to have hematuria and proteinuria. The bullae drained both serosanguinous and purulent material. Fluid culture grew group A Streptococcus and skin biopsy confirmed IgA vasculitis. Bullae are a rare characteristic of Henoch Schönlein pupura in children, but are more commonly seen as a disease manifestation in adults. The patient was treated with cefazolin, and his lesions improved over the course of several weeks with resolution of his hematuria by 6 months.

Is she crying blood? Dr. Joshua Price, a resident at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., described a 12-year-old female who presented with 7 days of left-sided hemolacria with acute vision loss and unilateral eye pain. This patient did not respond to outpatient topical steroids and antibiotics, as prescribed by ophthalmology. For this reason, she underwent further work-up and imaging. MRI of the head and orbits revealed left maxillary sinus disease. She was treated with antibiotics for acute left maxillary sinusitis and her hemolacria resolved within 24 hours. While the differential diagnosis for hemolacria is broad, rarely acute sinusitis has been reported as a cause in medical literature.

Recurrent bronchiolitis or something more? Dr. Moira Black, a resident at Children’s Memorial Hermann in Houston, presented a case of a 7-month-old female with a history of recurrent admissions for increased work of breathing believed to be secondary to viral bronchiolitis. Her first hospitalization occurred at 7 weeks of age and was complicated by spontaneous pneumothorax requiring chest tube placement. She was again hospitalized at 5 months of age with resolution of her increased work of breathing with high-flow nasal cannula. She presented again at 7 months of age with presumed bronchiolitis, however, she decompensated and required intubation on the 5th day of hospitalization. A bronchoscopy was performed and revealed a significantly narrowed left bronchus at the carina and a blind pouch on the right with notable pulsation of the walls. She underwent further imaging and was ultimately diagnosed with a left pulmonary artery sling. Left pulmonary artery slings are a rare, but potentially fatal anomaly that can present with wheezing, stridor, and recurrent respiratory infections. Patient underwent correction by cardiovascular surgery and has since been doing well.

Key takeaways for HM

• Bartonella is a common cause of fever of unknown origin, and should be considered in unusual presentations of febrile illnesses.

• Bullae in IgA vasculitis are rare in children and do not have prognostic value, but streptococcal infection may be a trigger for IgA vasculitis.

• Hemolacria is an atypical presentation of rare and common diagnoses that should prompt further work-up.

• Acute respiratory distress can be caused by underlying cardiac or vascular anomalies and can be mistaken for common viral illnesses.

Dr. Marsicek is a pediatric hospital medicine fellow at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla. Dr. Wysocka is a pediatric resident at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital.

Presenters

Yemisi Jones, MD; Mirna Giordano, MD

Session title

Pediatric Clinical Conundrums

Session summary

Dr. Mirna Giordano of Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, and Dr. Yemisi Jones of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, moderated the Pediatric Clinical Conundrums session at HM19. After reviewing multiple submissions, they invited four trainees to present their interesting cases.

Malignancy or infection? Dr. Jeremy Brown, a resident at the University of Louisville, presented a case of a 15-year-old male with right upper quadrant abdominal pain with associated weight loss and intermittent fevers, over the course of several weeks. CT revealed multiple liver lesions, providing concern for possible malignancy, although liver biopsy proved otherwise, with mostly liquefactive tissue and benign liver parenchyma. After a large infectious work-up ensued, the patient was diagnosed with disseminated Bartonella. He was treated with a 10-day course of azithromycin, and his symptoms resolved.

Leg blisters as an uncommon manifestation of a common childhood disease. Dr. Stefan Mammele, a resident at Kapi’olani Medical Center in Honolulu, and the University of Hawaii, presented a case of an 11-year-old boy with a painful and pruritic rash associated with multiple 5- to 10-mm tense bullae located on the patient’s bilateral lower extremities with extension to the trunk. The patient was also found to have hematuria and proteinuria. The bullae drained both serosanguinous and purulent material. Fluid culture grew group A Streptococcus and skin biopsy confirmed IgA vasculitis. Bullae are a rare characteristic of Henoch Schönlein pupura in children, but are more commonly seen as a disease manifestation in adults. The patient was treated with cefazolin, and his lesions improved over the course of several weeks with resolution of his hematuria by 6 months.

Is she crying blood? Dr. Joshua Price, a resident at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., described a 12-year-old female who presented with 7 days of left-sided hemolacria with acute vision loss and unilateral eye pain. This patient did not respond to outpatient topical steroids and antibiotics, as prescribed by ophthalmology. For this reason, she underwent further work-up and imaging. MRI of the head and orbits revealed left maxillary sinus disease. She was treated with antibiotics for acute left maxillary sinusitis and her hemolacria resolved within 24 hours. While the differential diagnosis for hemolacria is broad, rarely acute sinusitis has been reported as a cause in medical literature.

Recurrent bronchiolitis or something more? Dr. Moira Black, a resident at Children’s Memorial Hermann in Houston, presented a case of a 7-month-old female with a history of recurrent admissions for increased work of breathing believed to be secondary to viral bronchiolitis. Her first hospitalization occurred at 7 weeks of age and was complicated by spontaneous pneumothorax requiring chest tube placement. She was again hospitalized at 5 months of age with resolution of her increased work of breathing with high-flow nasal cannula. She presented again at 7 months of age with presumed bronchiolitis, however, she decompensated and required intubation on the 5th day of hospitalization. A bronchoscopy was performed and revealed a significantly narrowed left bronchus at the carina and a blind pouch on the right with notable pulsation of the walls. She underwent further imaging and was ultimately diagnosed with a left pulmonary artery sling. Left pulmonary artery slings are a rare, but potentially fatal anomaly that can present with wheezing, stridor, and recurrent respiratory infections. Patient underwent correction by cardiovascular surgery and has since been doing well.

Key takeaways for HM

• Bartonella is a common cause of fever of unknown origin, and should be considered in unusual presentations of febrile illnesses.

• Bullae in IgA vasculitis are rare in children and do not have prognostic value, but streptococcal infection may be a trigger for IgA vasculitis.

• Hemolacria is an atypical presentation of rare and common diagnoses that should prompt further work-up.

• Acute respiratory distress can be caused by underlying cardiac or vascular anomalies and can be mistaken for common viral illnesses.

Dr. Marsicek is a pediatric hospital medicine fellow at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla. Dr. Wysocka is a pediatric resident at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital.

ctDNA predicts recurrence in nonmetastatic colorectal cancer

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) could be used to predict disease recurrence in patients with nonmetastatic colorectal cancer (CRC), according to investigators following an observational study.

About three out of four patients with a positive ctDNA test went on to have disease recurrence, reported lead author Yuxuan Wang, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, and her colleagues. On average, positive tests preceded clinical and radiologic evidence of recurrence by 3 months.

“[T]he optimal protocol for surveillance of resected colorectal cancer remains uncertain,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Oncology.

“The only recommended blood marker for CRC surveillance is serum [carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)], an oncofetal protein that is elevated in the serum of patients with a variety of disease conditions, including CRC. Unfortunately, its utility is limited by the lack of sensitivity and specificity.” Although computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can improve disease detection, these techniques also have their own shortcomings, the investigators noted, setting the stage for the present study.

The investigators recruited 63 patients with stage I, II, or III CRC who underwent surgical resection in Sweden between 2007 and 2013. Blood samples for ctDNA testing were collected 1 month after surgery, then every 3-6 months. CT was performed every 6-12 months. During this process, 5 patients were excluded, leaving 58 patients in the final dataset, 18 (31%) of whom received adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients were followed until metastasis or a median of 49 months.

Among all patients, 13 tested positive for ctDNA, and 10 of these relapsed (77%), with a median time of 3 months between ctDNA positivity and CT or clinical evidence of recurrence. Three of the 48 patients (6%) who did not relapse had a positive ctDNA result that later dropped to an undetectable level. Of the 45 patients who tested negative for ctDNA, none had recurrence, although 1 was positive for CEA.

Results were also divided into patients who received or did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Among the 40 patients who did not receive chemotherapy, 8 had disease recurrence after a positive ctDNA test, although only 5 tested positive for CEA. Among the 18 patients who did receive chemotherapy, 2 tested positive for ctDNA and later relapsed, although only 1 tested positive for CEA. These figures translated to a ctDNA sensitivity for recurrence of 100%, compared with 60% for CEA testing.

“Serial ctDNA levels during follow-up can precede disease recurrence prior to routine radiographic imaging,” the investigators concluded. “Because ctDNA measurements can be obtained from blood samples collected during routine follow-up, they may be easily incorporated into routine follow-up to complement a CEA test, radiographic imaging, and other conventional modalities to help stratify patients on the basis of the risk of disease recurrence. Such a personalized surveillance strategy may allow for earlier detection of relapse and minimize unnecessary testing.”

The study was funded by the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, the Commonwealth Foundation, the John Templeton Foundation, and others. The investigators reported financial relationships with PapGene, Sysmex, Eisai, and others.

SOURCE: Wang et al. JAMA Onc. 2019 May 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0512.

Based on recent findings of a study conducted by Wang et al. and an increasing amount of research, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing “will likely revolutionize” postoperative management for patients with early-stage colorectal cancer (CRC), according to Van Morris, MD; Arvind Dasari, MD; and Scott Kopetz, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“The ability to optimize adjuvant chemotherapy recommendations for patients with resected CRC has been historically limited by the use of clinicopathologic characteristics, which imperfectly prognosticate the risk for recurrence,” the doctors wrote in a JAMA Oncology editorial accompanying the article by Wang et al.

In the study by Dr. Wang and associates, “clinical recurrence was strongly linked with ctDNA detection at the time of recurrence,” the doctors wrote, adding that “the absence of ctDNA was highly associated with excellent oncologic outcomes.” These associations translated to predictive advantages, as “[ctDNA] status outperformed traditional risk factors, including the pathological stage, in stratifying patients’ risk for recurrence.”

“With the implications of ctDNA status for recurrence risk, the question remains regarding how this exciting technology can be used to improve the standard practices for CRC,” the authors of the editorial wrote, noting that the National Comprehensive Cancer Network currently recommends monitoring with imaging studies, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) tests, and endoscopies. “ctDNA positivity may eventually serve as a biomarker for high-risk patients for whom a more aggressive systemic treatment against residual micrometastatic disease may be advantageous,” they wrote.

They also highlighted how, in the Wang et al. study, chemotherapy was associated with conversion from ctDNA positivity to negativity in one patient, a phenomenon that has been observed in other trials. “Interpretation of these data is limited by a small sample size of patients,” the doctors wrote, “but these findings nonetheless begin to provide important insight into the ability of chemotherapy to clear minimal residual disease, as tracked by serial changes in ctDNA status over time, which is associated with favorable prognostic implications for patients with early-stage CRC. Future trials in CRC and other solid cancers should assess ctDNA clearance more robustly as a surrogate marker for disease-free survival in patients undergoing definitive therapies for their solid tumors.”

“At present, payers in the United States have not yet approved the routine use of ctDNA technologies in patients with early-stage CRC after resection,” the doctors wrote. “However, compelling data on ctDNA as a robust prognostic marker should be a reason to reassess coverage.”

“[With payer support and improved techniques], then this exciting ctDNA technology will likely revolutionize the routine postoperative management of early-stage CRC by providing a reliable, objective tool for oncologists,” they concluded.

Dr. Morris, Dr. Dasari, and Dr. Kopetz are affiliated with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Dr. Morris reported financial relationships with GuardantHealth and Array Biopharma. Dr. Kopetz reported relationships with Symphogen, Amgen, Merck, and Holy Stone.

Based on recent findings of a study conducted by Wang et al. and an increasing amount of research, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing “will likely revolutionize” postoperative management for patients with early-stage colorectal cancer (CRC), according to Van Morris, MD; Arvind Dasari, MD; and Scott Kopetz, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“The ability to optimize adjuvant chemotherapy recommendations for patients with resected CRC has been historically limited by the use of clinicopathologic characteristics, which imperfectly prognosticate the risk for recurrence,” the doctors wrote in a JAMA Oncology editorial accompanying the article by Wang et al.

In the study by Dr. Wang and associates, “clinical recurrence was strongly linked with ctDNA detection at the time of recurrence,” the doctors wrote, adding that “the absence of ctDNA was highly associated with excellent oncologic outcomes.” These associations translated to predictive advantages, as “[ctDNA] status outperformed traditional risk factors, including the pathological stage, in stratifying patients’ risk for recurrence.”

“With the implications of ctDNA status for recurrence risk, the question remains regarding how this exciting technology can be used to improve the standard practices for CRC,” the authors of the editorial wrote, noting that the National Comprehensive Cancer Network currently recommends monitoring with imaging studies, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) tests, and endoscopies. “ctDNA positivity may eventually serve as a biomarker for high-risk patients for whom a more aggressive systemic treatment against residual micrometastatic disease may be advantageous,” they wrote.

They also highlighted how, in the Wang et al. study, chemotherapy was associated with conversion from ctDNA positivity to negativity in one patient, a phenomenon that has been observed in other trials. “Interpretation of these data is limited by a small sample size of patients,” the doctors wrote, “but these findings nonetheless begin to provide important insight into the ability of chemotherapy to clear minimal residual disease, as tracked by serial changes in ctDNA status over time, which is associated with favorable prognostic implications for patients with early-stage CRC. Future trials in CRC and other solid cancers should assess ctDNA clearance more robustly as a surrogate marker for disease-free survival in patients undergoing definitive therapies for their solid tumors.”

“At present, payers in the United States have not yet approved the routine use of ctDNA technologies in patients with early-stage CRC after resection,” the doctors wrote. “However, compelling data on ctDNA as a robust prognostic marker should be a reason to reassess coverage.”