User login

Clinical Pearl: Advantages of the Scalp as a Split-Thickness Skin Graft Donor Site

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

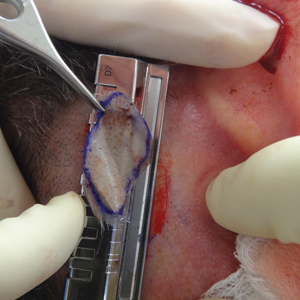

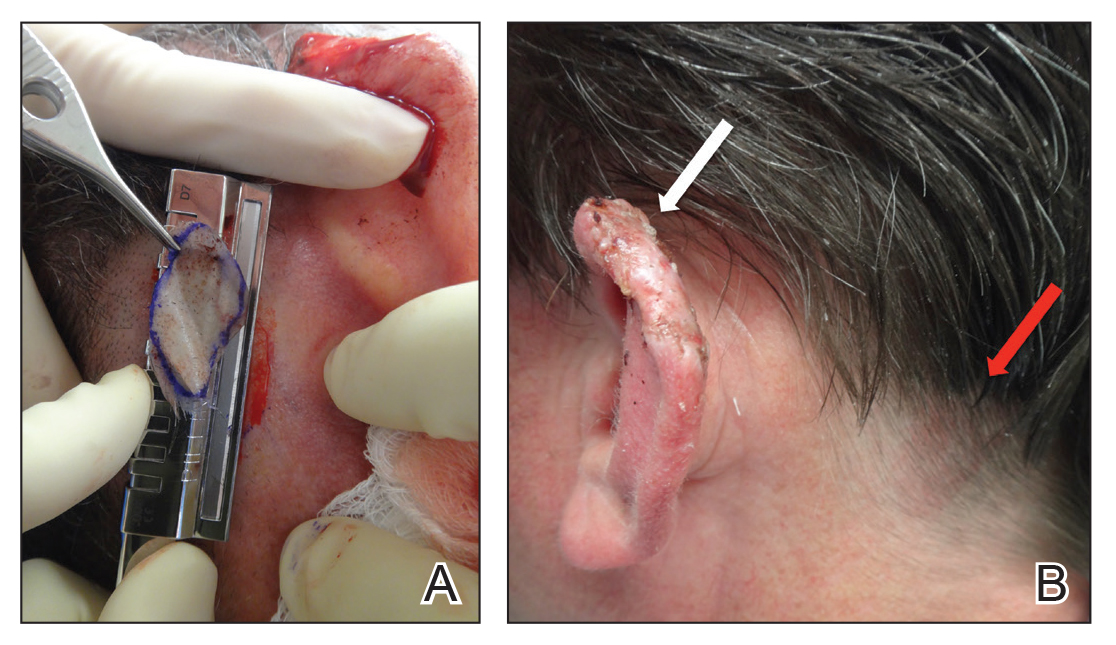

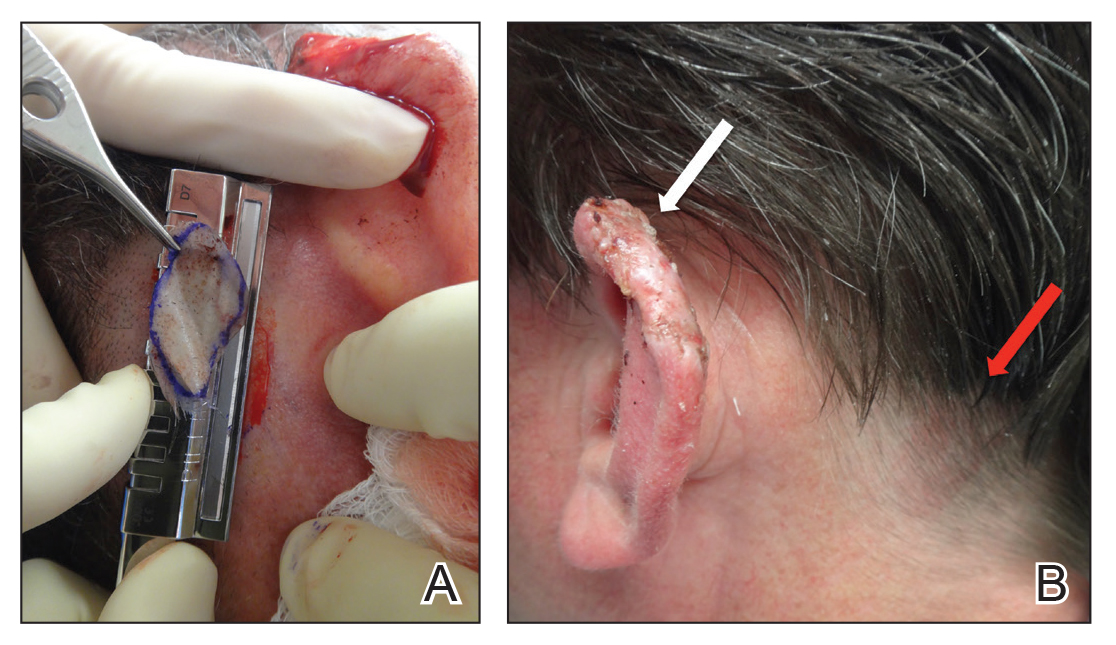

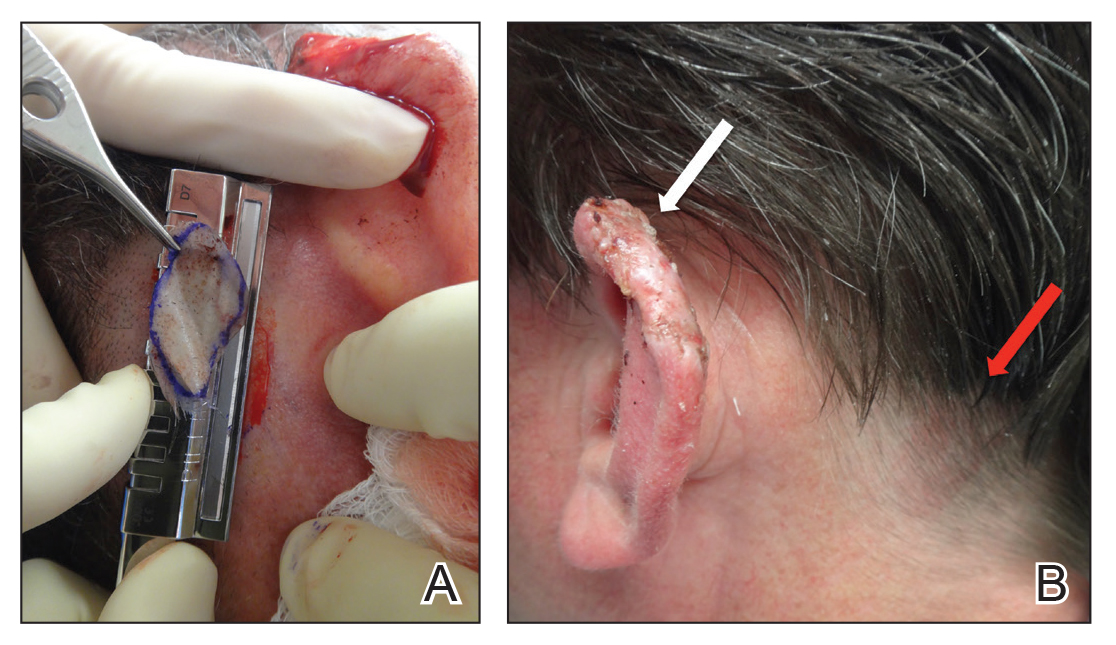

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.

- Goulian D. A new economical dermatome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:85-86.

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.

- Goulian D. A new economical dermatome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:85-86.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.

- Goulian D. A new economical dermatome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:85-86.

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis Confined to the Oral Mucosa

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant and is commonly used to treat or prevent venous thrombosis or the extension of thrombosis.

Adverse effects of heparin administration include bleeding, injection-site pain, and thrombocytopenia. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a serious side effect wherein antibodies are formed against platelet antigens and predispose the patient to venous and arterial thrombosis.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a poorly understood idiosyncratic drug reaction characterized by tense, blood-filled blisters that arise following the administration of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH). First reported in 2006 by Perrinaud et al

Case Report

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the cardiology service with severe substernal chest pain. An electrocardiogram did not show any ST-segment elevations; however, he had elevated troponin T levels. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease complicated by myocardial infarction (MI), as well as ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic stroke, and pulmonary embolism for which he was on long-term anticoagulation for years with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. The patient was diagnosed with a non–ST-segment elevation MI. Accordingly, the patient’s warfarin was discontinued, and he was administered a bolus and continuous infusion of UFH. He also was continued on aspirin and clopidogrel. Within 6 hours of initiation of UFH, the patient noted multiple discrete swollen lesions in the mouth. Dermatology consultation and biopsy of the lesions were deferred due to acute management of the patient’s MI.

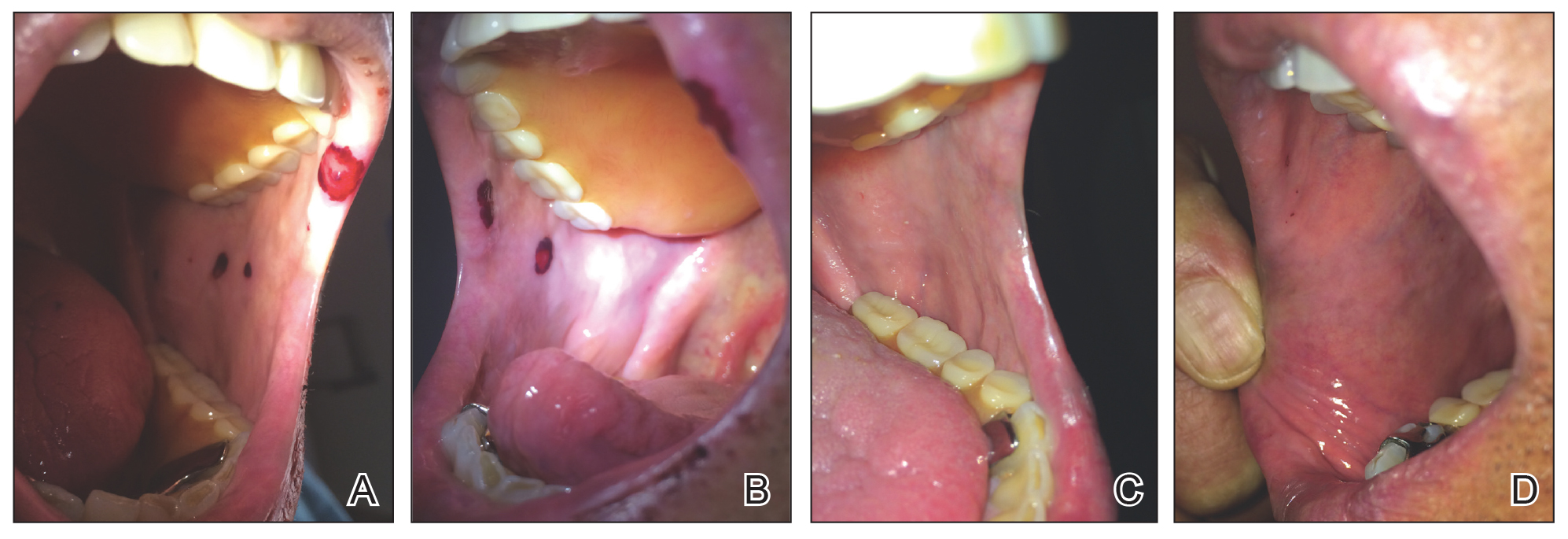

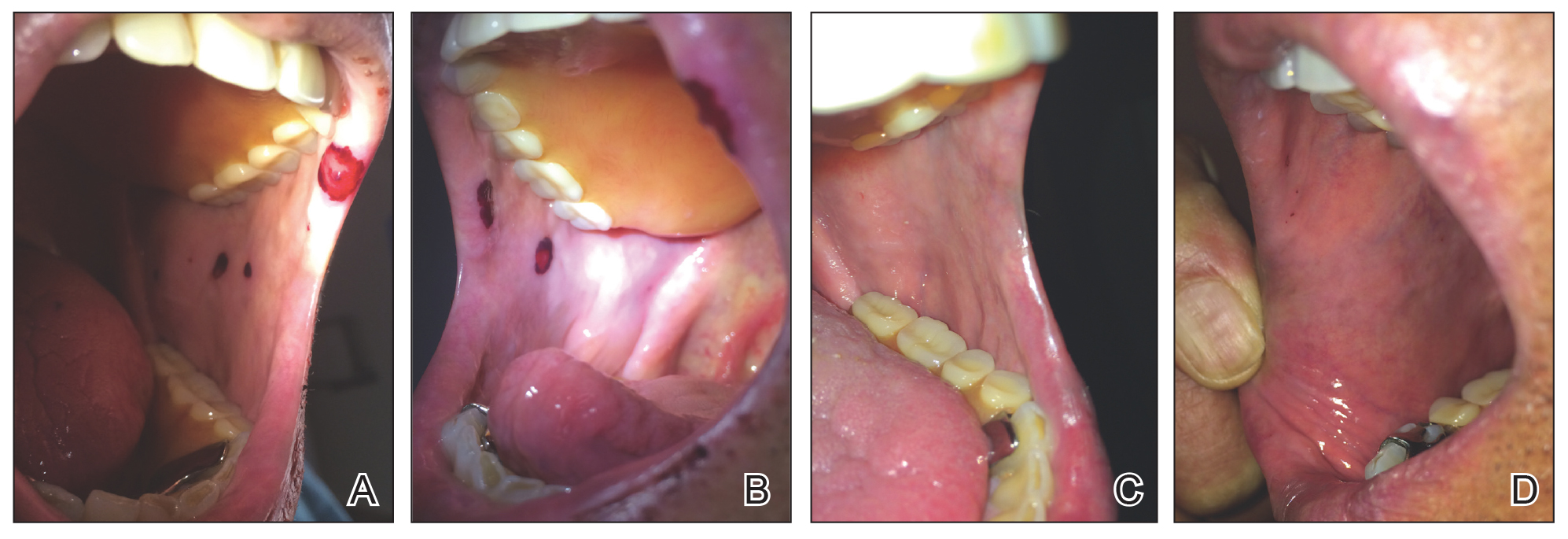

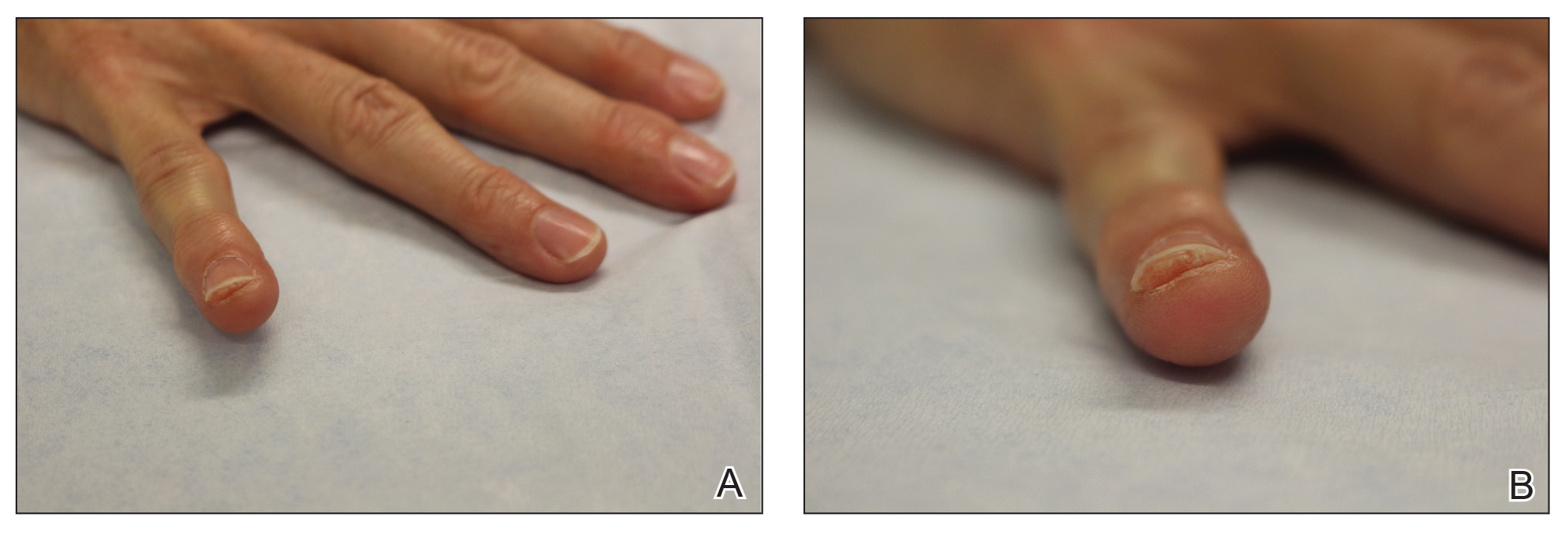

Physical examination revealed a moist oral mucosa with 7 slightly raised, hemorrhagic bullae ranging from 2 to 7 mm in diameter (Figure, A and B). One oral lesion was tense and had become denuded prior to evaluation. Laboratory testing included a normal platelet count (160,000/µL), a nearly therapeutic international normalized ratio (1.9), and a partial thromboplastin time that was initially normal (27 seconds) prior to admission and development of the oral lesions but found to be elevated (176 seconds) after admission and initial UFH bolus.

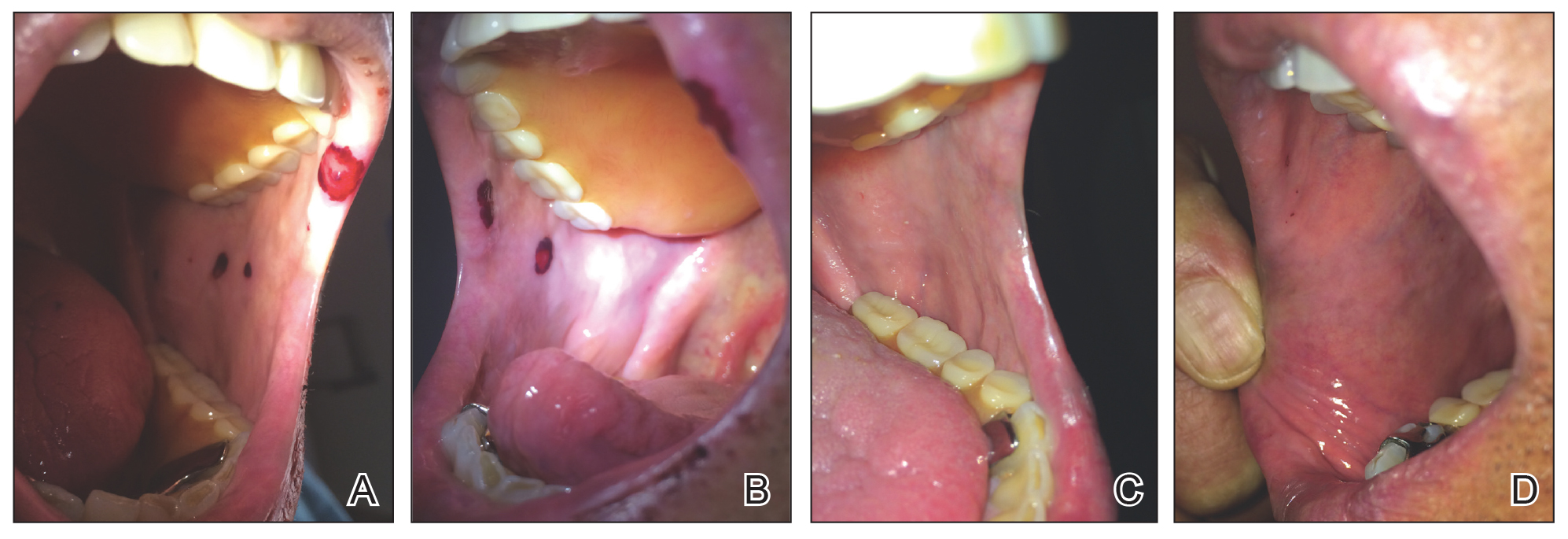

Upon further questioning, the patient revealed a history of similar oral lesions 1 year prior, following exposure to subcutaneous enoxaparin. At that time, formal evaluation by dermatology was deferred due to the rapid resolution of the blisters. Despite these new oral lesions, the patient was continued on a heparin drip for the next 48 hours because of the mortality benefit of heparin in non–ST-segment elevation MI. The patient was discharged from the hospital on a regimen of aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. At 2-week follow-up, the oral lesions had resolved (Figure, C and D).

Comment

Heparin-Induced Skin Lesions

The 2 most common types of heparin-induced skin lesions are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and immune-mediated HIT. A 2009 Canadian study found that the overwhelming majority of heparin-induced skin lesions are due to delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

Types of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is one of the most serious adverse reactions to heparin administration. There are 2 subtypes of HIT, which differ in their clinical significance and pathophysiology.

Type II HIT is an immune-mediated response caused by the formation of IgG autoantibodies against the heparin–platelet factor 4 complex. Antibody formation and thrombocytopenia typically occur after 4 to 10 days of heparin exposure, and there can be devastating arterial and venous thrombotic complications.

Diagnosis of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia should be suspected in patients with a lowered platelet count, particularly if the decrease is more than 50% from baseline, and in patients who develop stroke, MI, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis while on heparin. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was not observed in our patient, as his platelet count remained stable between 160,000 and 164,000/µL throughout his hospital stay and he did not develop any evidence of thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Our patient’s lesions appeared morphologically similar to

Bullous pemphigoid also was considered given the presence of tense bullae in an elderly patient. However, the rapid and spontaneous resolution of these lesions with complete lack of skin involvement made this diagnosis less likely.12

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Because our patient described a similar reaction while taking enoxaparin in the past, this case represents an idiosyncratic drug reaction, possibly from antibodies to a heparin-antigen complex. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rarely reported condition with the majority of lesions presenting on the extremities.

Conclusion

We describe a rare side effect of heparin therapy characterized by discrete blisters on the oral mucosa. However, familiarity with the spectrum of reactions to heparin allowed the patient to continue heparin therapy despite this side effect, as the eruption was not life-threatening and the benefit of continuing heparin outweighed this adverse effect.

- Gómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML, Calvo-Rojas G, et al. Discovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspective. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2012;9:83-104.

- Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chemical approaches to define the structure-activity relationship of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. Chem Biol. 2005;12:731-756.

- Bakchoul T. An update on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:787-797.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:477-481.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S5-S7.

- Naveen KN, Rai V. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:423.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Villanueva CA, Nájera L, Espinosa P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites: a report of 2 new cases due to enoxaparin injection and a review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:816-819.

- Ahmed I, Majeed A, Powell R. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management update. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:575-582.

- Horie N, Kawano R, Inaba J, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of the soft palate: a clinical study of 16 cases. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:33-36.

- Rai S, Kaur M, Goel S. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica: report of 2 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:503.

- Lawson W. Bullous oral lesions: clues to identifying—and managing—the cause. Consultant. 2013;53:168-176.

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant and is commonly used to treat or prevent venous thrombosis or the extension of thrombosis.

Adverse effects of heparin administration include bleeding, injection-site pain, and thrombocytopenia. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a serious side effect wherein antibodies are formed against platelet antigens and predispose the patient to venous and arterial thrombosis.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a poorly understood idiosyncratic drug reaction characterized by tense, blood-filled blisters that arise following the administration of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH). First reported in 2006 by Perrinaud et al

Case Report

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the cardiology service with severe substernal chest pain. An electrocardiogram did not show any ST-segment elevations; however, he had elevated troponin T levels. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease complicated by myocardial infarction (MI), as well as ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic stroke, and pulmonary embolism for which he was on long-term anticoagulation for years with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. The patient was diagnosed with a non–ST-segment elevation MI. Accordingly, the patient’s warfarin was discontinued, and he was administered a bolus and continuous infusion of UFH. He also was continued on aspirin and clopidogrel. Within 6 hours of initiation of UFH, the patient noted multiple discrete swollen lesions in the mouth. Dermatology consultation and biopsy of the lesions were deferred due to acute management of the patient’s MI.

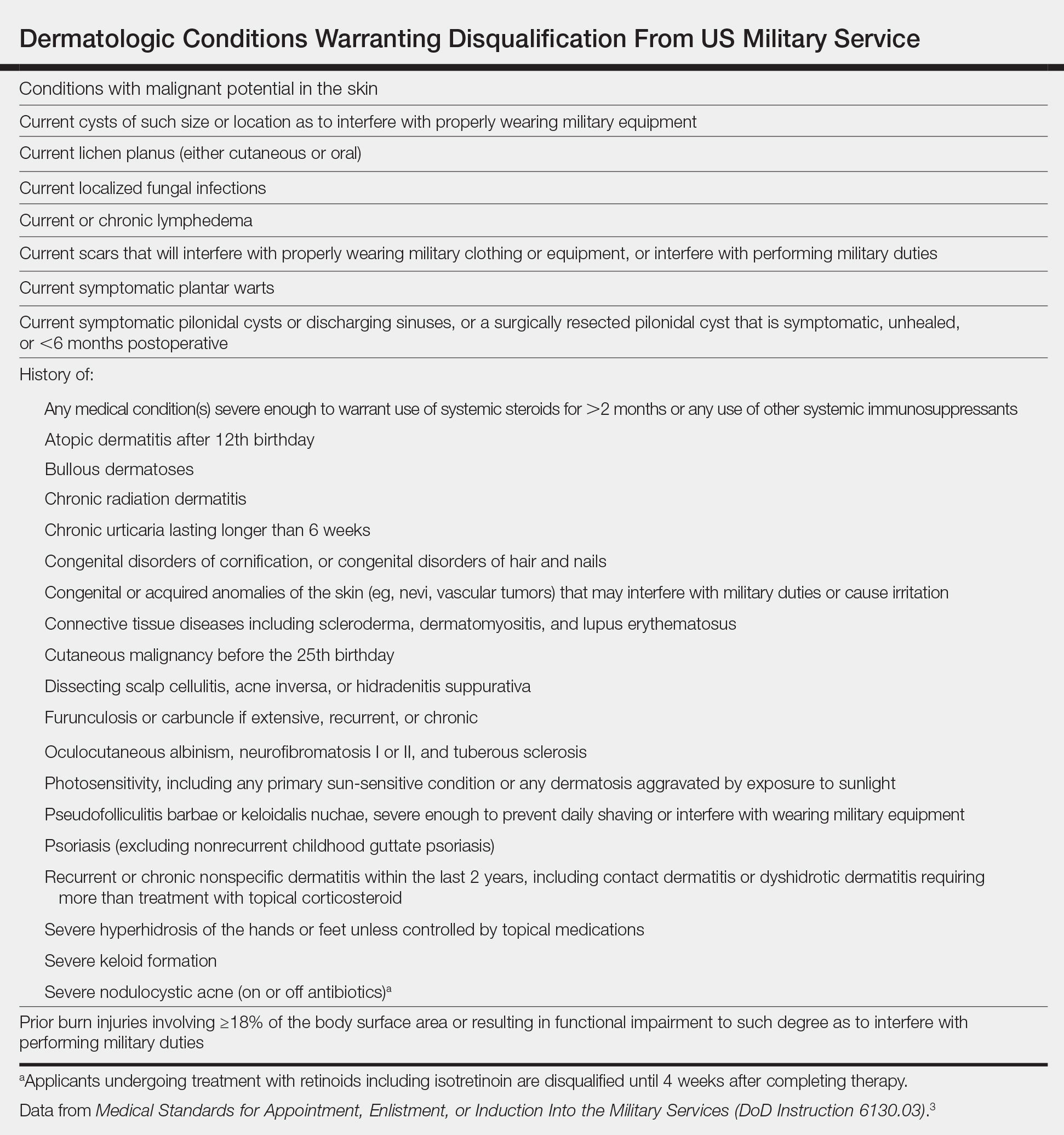

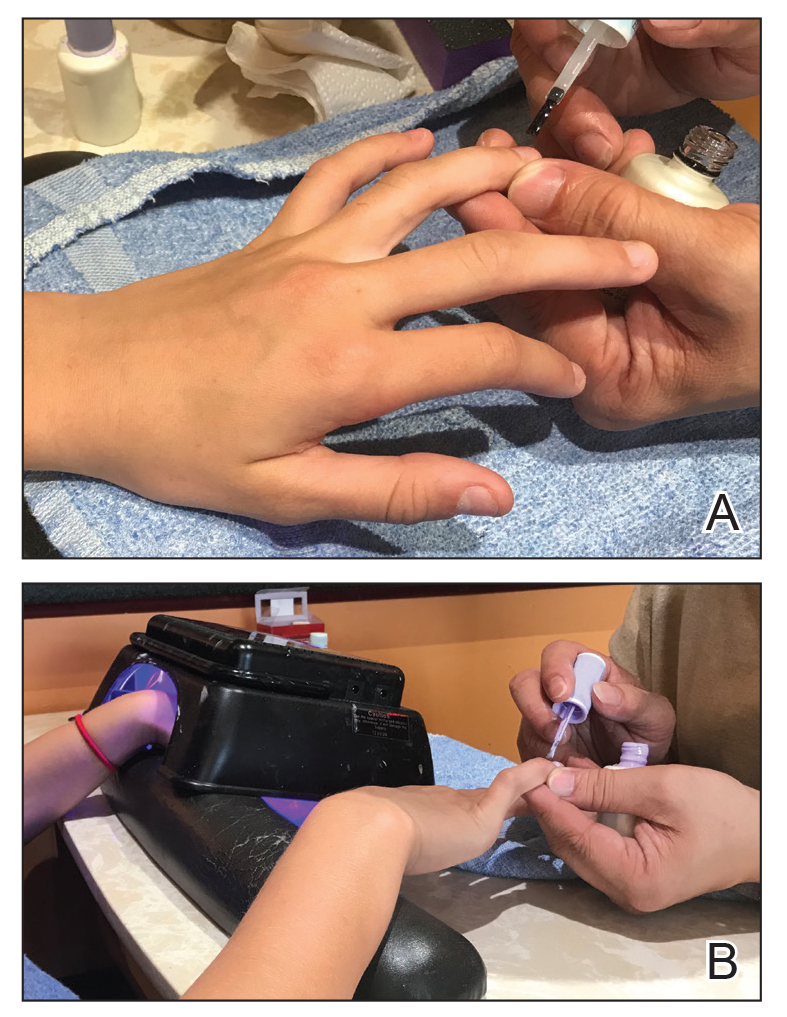

Physical examination revealed a moist oral mucosa with 7 slightly raised, hemorrhagic bullae ranging from 2 to 7 mm in diameter (Figure, A and B). One oral lesion was tense and had become denuded prior to evaluation. Laboratory testing included a normal platelet count (160,000/µL), a nearly therapeutic international normalized ratio (1.9), and a partial thromboplastin time that was initially normal (27 seconds) prior to admission and development of the oral lesions but found to be elevated (176 seconds) after admission and initial UFH bolus.

Upon further questioning, the patient revealed a history of similar oral lesions 1 year prior, following exposure to subcutaneous enoxaparin. At that time, formal evaluation by dermatology was deferred due to the rapid resolution of the blisters. Despite these new oral lesions, the patient was continued on a heparin drip for the next 48 hours because of the mortality benefit of heparin in non–ST-segment elevation MI. The patient was discharged from the hospital on a regimen of aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. At 2-week follow-up, the oral lesions had resolved (Figure, C and D).

Comment

Heparin-Induced Skin Lesions

The 2 most common types of heparin-induced skin lesions are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and immune-mediated HIT. A 2009 Canadian study found that the overwhelming majority of heparin-induced skin lesions are due to delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

Types of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is one of the most serious adverse reactions to heparin administration. There are 2 subtypes of HIT, which differ in their clinical significance and pathophysiology.

Type II HIT is an immune-mediated response caused by the formation of IgG autoantibodies against the heparin–platelet factor 4 complex. Antibody formation and thrombocytopenia typically occur after 4 to 10 days of heparin exposure, and there can be devastating arterial and venous thrombotic complications.

Diagnosis of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia should be suspected in patients with a lowered platelet count, particularly if the decrease is more than 50% from baseline, and in patients who develop stroke, MI, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis while on heparin. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was not observed in our patient, as his platelet count remained stable between 160,000 and 164,000/µL throughout his hospital stay and he did not develop any evidence of thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Our patient’s lesions appeared morphologically similar to

Bullous pemphigoid also was considered given the presence of tense bullae in an elderly patient. However, the rapid and spontaneous resolution of these lesions with complete lack of skin involvement made this diagnosis less likely.12

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Because our patient described a similar reaction while taking enoxaparin in the past, this case represents an idiosyncratic drug reaction, possibly from antibodies to a heparin-antigen complex. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rarely reported condition with the majority of lesions presenting on the extremities.

Conclusion

We describe a rare side effect of heparin therapy characterized by discrete blisters on the oral mucosa. However, familiarity with the spectrum of reactions to heparin allowed the patient to continue heparin therapy despite this side effect, as the eruption was not life-threatening and the benefit of continuing heparin outweighed this adverse effect.

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant and is commonly used to treat or prevent venous thrombosis or the extension of thrombosis.

Adverse effects of heparin administration include bleeding, injection-site pain, and thrombocytopenia. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a serious side effect wherein antibodies are formed against platelet antigens and predispose the patient to venous and arterial thrombosis.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a poorly understood idiosyncratic drug reaction characterized by tense, blood-filled blisters that arise following the administration of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH). First reported in 2006 by Perrinaud et al

Case Report

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the cardiology service with severe substernal chest pain. An electrocardiogram did not show any ST-segment elevations; however, he had elevated troponin T levels. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease complicated by myocardial infarction (MI), as well as ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic stroke, and pulmonary embolism for which he was on long-term anticoagulation for years with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. The patient was diagnosed with a non–ST-segment elevation MI. Accordingly, the patient’s warfarin was discontinued, and he was administered a bolus and continuous infusion of UFH. He also was continued on aspirin and clopidogrel. Within 6 hours of initiation of UFH, the patient noted multiple discrete swollen lesions in the mouth. Dermatology consultation and biopsy of the lesions were deferred due to acute management of the patient’s MI.

Physical examination revealed a moist oral mucosa with 7 slightly raised, hemorrhagic bullae ranging from 2 to 7 mm in diameter (Figure, A and B). One oral lesion was tense and had become denuded prior to evaluation. Laboratory testing included a normal platelet count (160,000/µL), a nearly therapeutic international normalized ratio (1.9), and a partial thromboplastin time that was initially normal (27 seconds) prior to admission and development of the oral lesions but found to be elevated (176 seconds) after admission and initial UFH bolus.

Upon further questioning, the patient revealed a history of similar oral lesions 1 year prior, following exposure to subcutaneous enoxaparin. At that time, formal evaluation by dermatology was deferred due to the rapid resolution of the blisters. Despite these new oral lesions, the patient was continued on a heparin drip for the next 48 hours because of the mortality benefit of heparin in non–ST-segment elevation MI. The patient was discharged from the hospital on a regimen of aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. At 2-week follow-up, the oral lesions had resolved (Figure, C and D).

Comment

Heparin-Induced Skin Lesions

The 2 most common types of heparin-induced skin lesions are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and immune-mediated HIT. A 2009 Canadian study found that the overwhelming majority of heparin-induced skin lesions are due to delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

Types of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is one of the most serious adverse reactions to heparin administration. There are 2 subtypes of HIT, which differ in their clinical significance and pathophysiology.

Type II HIT is an immune-mediated response caused by the formation of IgG autoantibodies against the heparin–platelet factor 4 complex. Antibody formation and thrombocytopenia typically occur after 4 to 10 days of heparin exposure, and there can be devastating arterial and venous thrombotic complications.

Diagnosis of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia should be suspected in patients with a lowered platelet count, particularly if the decrease is more than 50% from baseline, and in patients who develop stroke, MI, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis while on heparin. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was not observed in our patient, as his platelet count remained stable between 160,000 and 164,000/µL throughout his hospital stay and he did not develop any evidence of thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Our patient’s lesions appeared morphologically similar to

Bullous pemphigoid also was considered given the presence of tense bullae in an elderly patient. However, the rapid and spontaneous resolution of these lesions with complete lack of skin involvement made this diagnosis less likely.12

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Because our patient described a similar reaction while taking enoxaparin in the past, this case represents an idiosyncratic drug reaction, possibly from antibodies to a heparin-antigen complex. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rarely reported condition with the majority of lesions presenting on the extremities.

Conclusion

We describe a rare side effect of heparin therapy characterized by discrete blisters on the oral mucosa. However, familiarity with the spectrum of reactions to heparin allowed the patient to continue heparin therapy despite this side effect, as the eruption was not life-threatening and the benefit of continuing heparin outweighed this adverse effect.

- Gómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML, Calvo-Rojas G, et al. Discovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspective. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2012;9:83-104.

- Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chemical approaches to define the structure-activity relationship of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. Chem Biol. 2005;12:731-756.

- Bakchoul T. An update on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:787-797.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:477-481.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S5-S7.

- Naveen KN, Rai V. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:423.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Villanueva CA, Nájera L, Espinosa P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites: a report of 2 new cases due to enoxaparin injection and a review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:816-819.

- Ahmed I, Majeed A, Powell R. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management update. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:575-582.

- Horie N, Kawano R, Inaba J, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of the soft palate: a clinical study of 16 cases. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:33-36.

- Rai S, Kaur M, Goel S. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica: report of 2 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:503.

- Lawson W. Bullous oral lesions: clues to identifying—and managing—the cause. Consultant. 2013;53:168-176.

- Gómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML, Calvo-Rojas G, et al. Discovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspective. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2012;9:83-104.

- Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chemical approaches to define the structure-activity relationship of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. Chem Biol. 2005;12:731-756.

- Bakchoul T. An update on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:787-797.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:477-481.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S5-S7.

- Naveen KN, Rai V. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:423.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Villanueva CA, Nájera L, Espinosa P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites: a report of 2 new cases due to enoxaparin injection and a review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:816-819.

- Ahmed I, Majeed A, Powell R. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management update. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:575-582.

- Horie N, Kawano R, Inaba J, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of the soft palate: a clinical study of 16 cases. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:33-36.

- Rai S, Kaur M, Goel S. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica: report of 2 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:503.

- Lawson W. Bullous oral lesions: clues to identifying—and managing—the cause. Consultant. 2013;53:168-176.

Practice Points

- It is important for physicians to recognize the clinical appearance of cutaneous adverse reactions to heparin, including bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis.

- Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis tends to self-resolve, even with continuation of unfractionated heparin.

Air-conditioned cognition, brain worm, and six-fingered success

(Women’s) Winter is coming

Summer approaches and the Great Freeze begins to make its way through offices across the country.

Women everywhere start dragging out those cardigans stored in desks long ago. Blankets start appearing draped over the backs of chairs. “God, it’s freezing in here” becomes the oft-repeated refrain. It’s women’s winter … and a recent study has shown it has a marked effect on productivity.

Published last month in PlosOne, the study examined the effect of temperature on cognitive performance in both men and women. After studying participants’ performances on math and verbal tasks at various temperatures, researchers found that the women performed better at higher temps while the men performed worse. However, the performance increase for women was much larger than the decrease for men.

The authors concluded that workplaces with mixed genders might increase productivity (and overall office happiness) by cranking that thermostat a little higher than current standards. Perhaps this will be the beginning of the end of the thermostat war.

Need a hand – or finger?

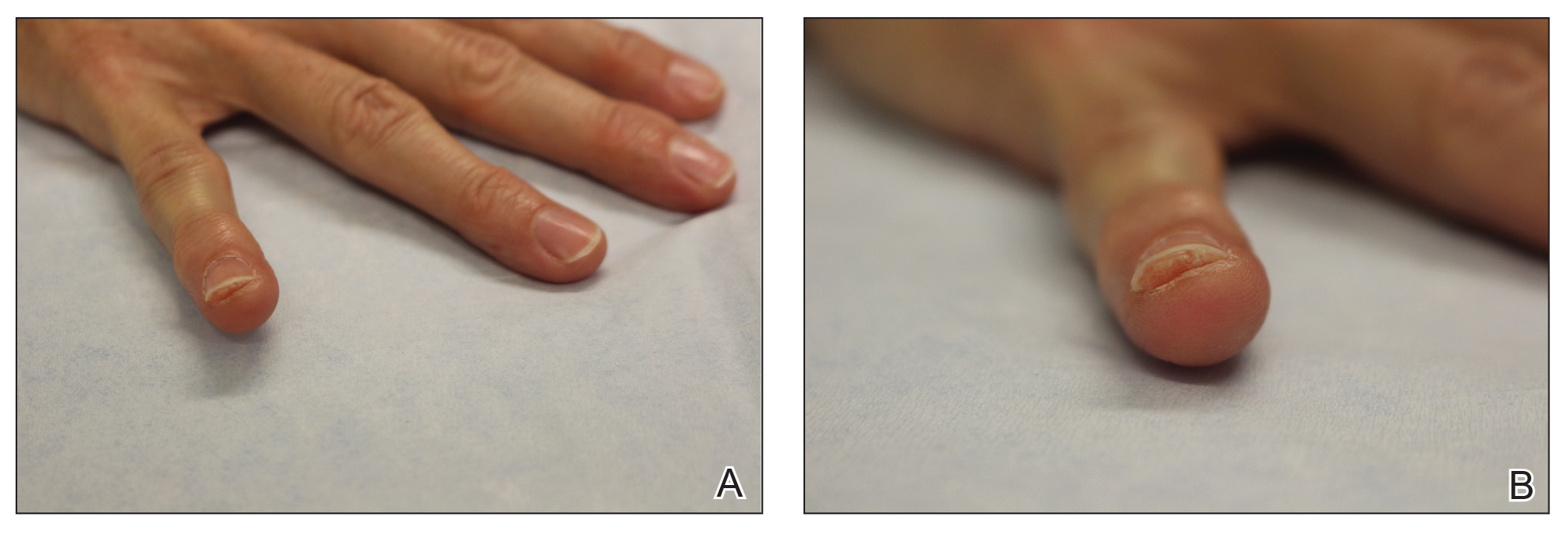

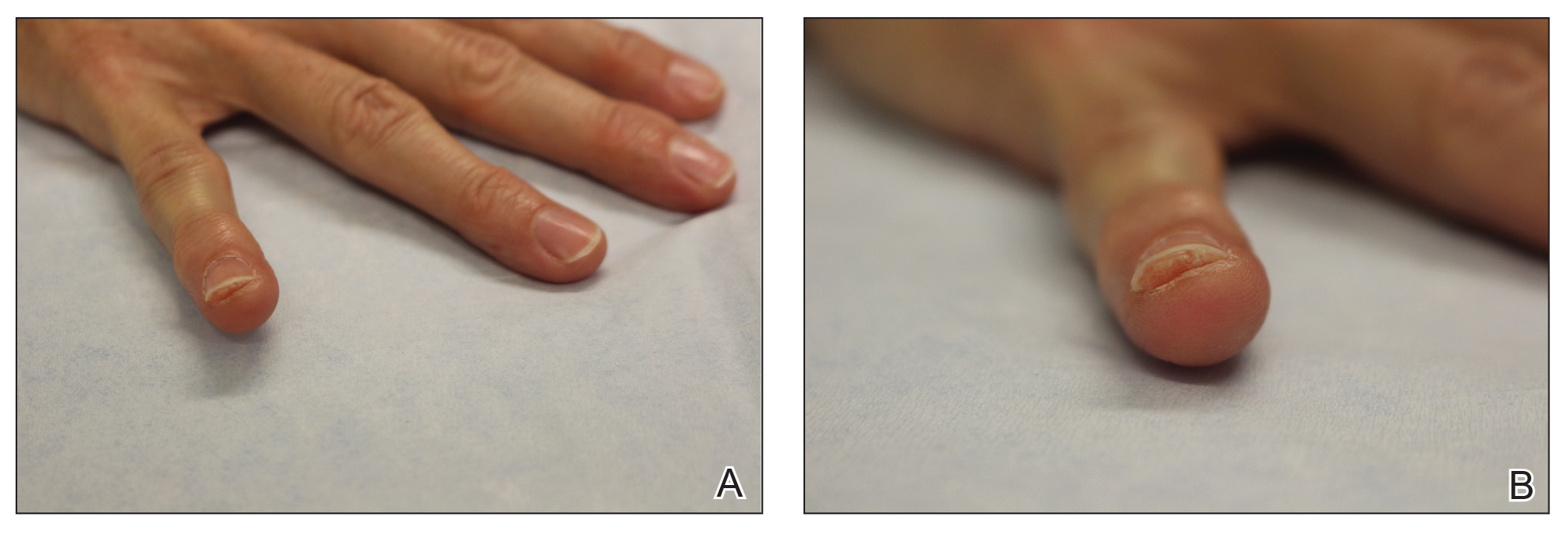

Polydactyly. No, not the flying dinosaur – the congenital condition of having extra fingers or toes. One in every 2,000-3,000 babies is born with polydactyly, and while most doctors quickly remove the extra digits, a German study found that maybe they shouldn’t be so quick to the chopping block.

Researchers found that polydactyl people have more dexterity of movement, and the subjects’ brains showed a distinct representation of the extra digit. The subjects were able to carry out two-handed tasks with just one hand, and the study authors concluded that the subjects’ hand movements “had increased complexity relative to common five-fingered hands.”

Researchers also designed a special video game to test the six-fingered hand vs. using both hands. Video game results were the same with one hand or two, proving that more fingers equals more fun.

Cooking up controversy

If you had a giant spoon, what would you do with it?

Boston artist Domenic Esposito has just such a spoon – being an artist, he made it himself – and he’s been using it to draw attention to the opioid use disorder crisis by placing it “on the doorsteps of corporations and individuals whose recklessness and irresponsibility have fueled the epidemic,” according to the spoon’s website, The Opioid Spoon Project.

Since its creation, the 800-lb, 10.5-foot-long steel heroin spoon has visited Purdue Pharma headquarters in Stamford, Conn. – the spoon was hauled off by the city and taken to a police evidence lot – and Rhodes Pharmaceuticals in Coventry, R.I.

More recently, Mr. Esposito has taken the spoon on a 14-city “Honor Tour.” At each stop, individuals have the opportunity to sign the spoon in memory of “those who have lost their opioid addiction battles.”

The tour, which began in Marlborough, Mass., on May 11 and has been to such cities as Providence, R.I., and Boston, ends on June 7 in Rockville, Md., which happens to be the home of LOTME world headquarters. So, who doesn’t want to see a spoon over 10 feet long?

Worms on (or in) my mind

It sounds like a bad riddle: What looks like a brain tumor, acts like a brain tumor, but isn’t a brain tumor?

Rachel Palma, a 42-year-old woman from Middletown, N.Y., had the joy of finding out the answer.

For months, she’d been having strange symptoms: hallucinations, nightmares, trouble remembering words, memory blackouts, occasional loss of motor control. Her doctors were stumped, until they performed an MRI of her brain, discovering a marble-sized lesion in her brain. Another MRI, performed with contrast, caused the lesion to light up, a surefire sign of a malignant brain tumor. Treatment would require surgery, then chemo and radiation therapy.

But when the surgeons opened her head, they were greeted not with a tumor, but with something they described as looking “like a quail egg.” The object was removed and opened up, and to the delight of the doctors, a tapeworm popped out.

The condition – neurocysticercosis – is common in developing countries but rare in the United States. We won’t share all the details on how tapeworms end up in the brain, but needless to say, poor washing of hands is involved.

On the one hand, Mrs. Palma has made a full recovery with no need for chemo or radiation. On the other hand, she had a tapeworm in her brain. Somehow, she’s managed to make the brain tumor seem like the less unpleasant option. And for that, we salute her.

(Women’s) Winter is coming

Summer approaches and the Great Freeze begins to make its way through offices across the country.

Women everywhere start dragging out those cardigans stored in desks long ago. Blankets start appearing draped over the backs of chairs. “God, it’s freezing in here” becomes the oft-repeated refrain. It’s women’s winter … and a recent study has shown it has a marked effect on productivity.

Published last month in PlosOne, the study examined the effect of temperature on cognitive performance in both men and women. After studying participants’ performances on math and verbal tasks at various temperatures, researchers found that the women performed better at higher temps while the men performed worse. However, the performance increase for women was much larger than the decrease for men.

The authors concluded that workplaces with mixed genders might increase productivity (and overall office happiness) by cranking that thermostat a little higher than current standards. Perhaps this will be the beginning of the end of the thermostat war.

Need a hand – or finger?

Polydactyly. No, not the flying dinosaur – the congenital condition of having extra fingers or toes. One in every 2,000-3,000 babies is born with polydactyly, and while most doctors quickly remove the extra digits, a German study found that maybe they shouldn’t be so quick to the chopping block.

Researchers found that polydactyl people have more dexterity of movement, and the subjects’ brains showed a distinct representation of the extra digit. The subjects were able to carry out two-handed tasks with just one hand, and the study authors concluded that the subjects’ hand movements “had increased complexity relative to common five-fingered hands.”

Researchers also designed a special video game to test the six-fingered hand vs. using both hands. Video game results were the same with one hand or two, proving that more fingers equals more fun.

Cooking up controversy

If you had a giant spoon, what would you do with it?

Boston artist Domenic Esposito has just such a spoon – being an artist, he made it himself – and he’s been using it to draw attention to the opioid use disorder crisis by placing it “on the doorsteps of corporations and individuals whose recklessness and irresponsibility have fueled the epidemic,” according to the spoon’s website, The Opioid Spoon Project.

Since its creation, the 800-lb, 10.5-foot-long steel heroin spoon has visited Purdue Pharma headquarters in Stamford, Conn. – the spoon was hauled off by the city and taken to a police evidence lot – and Rhodes Pharmaceuticals in Coventry, R.I.

More recently, Mr. Esposito has taken the spoon on a 14-city “Honor Tour.” At each stop, individuals have the opportunity to sign the spoon in memory of “those who have lost their opioid addiction battles.”

The tour, which began in Marlborough, Mass., on May 11 and has been to such cities as Providence, R.I., and Boston, ends on June 7 in Rockville, Md., which happens to be the home of LOTME world headquarters. So, who doesn’t want to see a spoon over 10 feet long?

Worms on (or in) my mind

It sounds like a bad riddle: What looks like a brain tumor, acts like a brain tumor, but isn’t a brain tumor?

Rachel Palma, a 42-year-old woman from Middletown, N.Y., had the joy of finding out the answer.

For months, she’d been having strange symptoms: hallucinations, nightmares, trouble remembering words, memory blackouts, occasional loss of motor control. Her doctors were stumped, until they performed an MRI of her brain, discovering a marble-sized lesion in her brain. Another MRI, performed with contrast, caused the lesion to light up, a surefire sign of a malignant brain tumor. Treatment would require surgery, then chemo and radiation therapy.

But when the surgeons opened her head, they were greeted not with a tumor, but with something they described as looking “like a quail egg.” The object was removed and opened up, and to the delight of the doctors, a tapeworm popped out.

The condition – neurocysticercosis – is common in developing countries but rare in the United States. We won’t share all the details on how tapeworms end up in the brain, but needless to say, poor washing of hands is involved.

On the one hand, Mrs. Palma has made a full recovery with no need for chemo or radiation. On the other hand, she had a tapeworm in her brain. Somehow, she’s managed to make the brain tumor seem like the less unpleasant option. And for that, we salute her.

(Women’s) Winter is coming

Summer approaches and the Great Freeze begins to make its way through offices across the country.

Women everywhere start dragging out those cardigans stored in desks long ago. Blankets start appearing draped over the backs of chairs. “God, it’s freezing in here” becomes the oft-repeated refrain. It’s women’s winter … and a recent study has shown it has a marked effect on productivity.

Published last month in PlosOne, the study examined the effect of temperature on cognitive performance in both men and women. After studying participants’ performances on math and verbal tasks at various temperatures, researchers found that the women performed better at higher temps while the men performed worse. However, the performance increase for women was much larger than the decrease for men.

The authors concluded that workplaces with mixed genders might increase productivity (and overall office happiness) by cranking that thermostat a little higher than current standards. Perhaps this will be the beginning of the end of the thermostat war.

Need a hand – or finger?

Polydactyly. No, not the flying dinosaur – the congenital condition of having extra fingers or toes. One in every 2,000-3,000 babies is born with polydactyly, and while most doctors quickly remove the extra digits, a German study found that maybe they shouldn’t be so quick to the chopping block.

Researchers found that polydactyl people have more dexterity of movement, and the subjects’ brains showed a distinct representation of the extra digit. The subjects were able to carry out two-handed tasks with just one hand, and the study authors concluded that the subjects’ hand movements “had increased complexity relative to common five-fingered hands.”

Researchers also designed a special video game to test the six-fingered hand vs. using both hands. Video game results were the same with one hand or two, proving that more fingers equals more fun.

Cooking up controversy

If you had a giant spoon, what would you do with it?

Boston artist Domenic Esposito has just such a spoon – being an artist, he made it himself – and he’s been using it to draw attention to the opioid use disorder crisis by placing it “on the doorsteps of corporations and individuals whose recklessness and irresponsibility have fueled the epidemic,” according to the spoon’s website, The Opioid Spoon Project.

Since its creation, the 800-lb, 10.5-foot-long steel heroin spoon has visited Purdue Pharma headquarters in Stamford, Conn. – the spoon was hauled off by the city and taken to a police evidence lot – and Rhodes Pharmaceuticals in Coventry, R.I.

More recently, Mr. Esposito has taken the spoon on a 14-city “Honor Tour.” At each stop, individuals have the opportunity to sign the spoon in memory of “those who have lost their opioid addiction battles.”

The tour, which began in Marlborough, Mass., on May 11 and has been to such cities as Providence, R.I., and Boston, ends on June 7 in Rockville, Md., which happens to be the home of LOTME world headquarters. So, who doesn’t want to see a spoon over 10 feet long?

Worms on (or in) my mind

It sounds like a bad riddle: What looks like a brain tumor, acts like a brain tumor, but isn’t a brain tumor?

Rachel Palma, a 42-year-old woman from Middletown, N.Y., had the joy of finding out the answer.

For months, she’d been having strange symptoms: hallucinations, nightmares, trouble remembering words, memory blackouts, occasional loss of motor control. Her doctors were stumped, until they performed an MRI of her brain, discovering a marble-sized lesion in her brain. Another MRI, performed with contrast, caused the lesion to light up, a surefire sign of a malignant brain tumor. Treatment would require surgery, then chemo and radiation therapy.

But when the surgeons opened her head, they were greeted not with a tumor, but with something they described as looking “like a quail egg.” The object was removed and opened up, and to the delight of the doctors, a tapeworm popped out.

The condition – neurocysticercosis – is common in developing countries but rare in the United States. We won’t share all the details on how tapeworms end up in the brain, but needless to say, poor washing of hands is involved.

On the one hand, Mrs. Palma has made a full recovery with no need for chemo or radiation. On the other hand, she had a tapeworm in her brain. Somehow, she’s managed to make the brain tumor seem like the less unpleasant option. And for that, we salute her.

Erythema Gyratum Repens–like Eruption in Sézary Syndrome: Evidence for the Role of a Dermatophyte

Case Report

A 65-year-old woman presented with stage IVA2 mycosis fungoides (MF)(T4N3M0B2)/Sézary syndrome (SS). A peripheral blood count contained 6000 Sézary cells with cerebriform nuclei, a CD2+/−CD3+CD4+CD5+/−CD7+CD8−CD26−immunophenotype, and a highly abnormal CD4 to CD8 ratio (70:1). Positron emission tomography and computed tomography demonstrated hypermetabolic subcutaneous nodules in the base of the neck and generalized lymphadenopathy. Lymph node biopsy showed involvement by T-cell lymphoma and dominant T-cell receptor γ clonality by polymerase chain reaction.

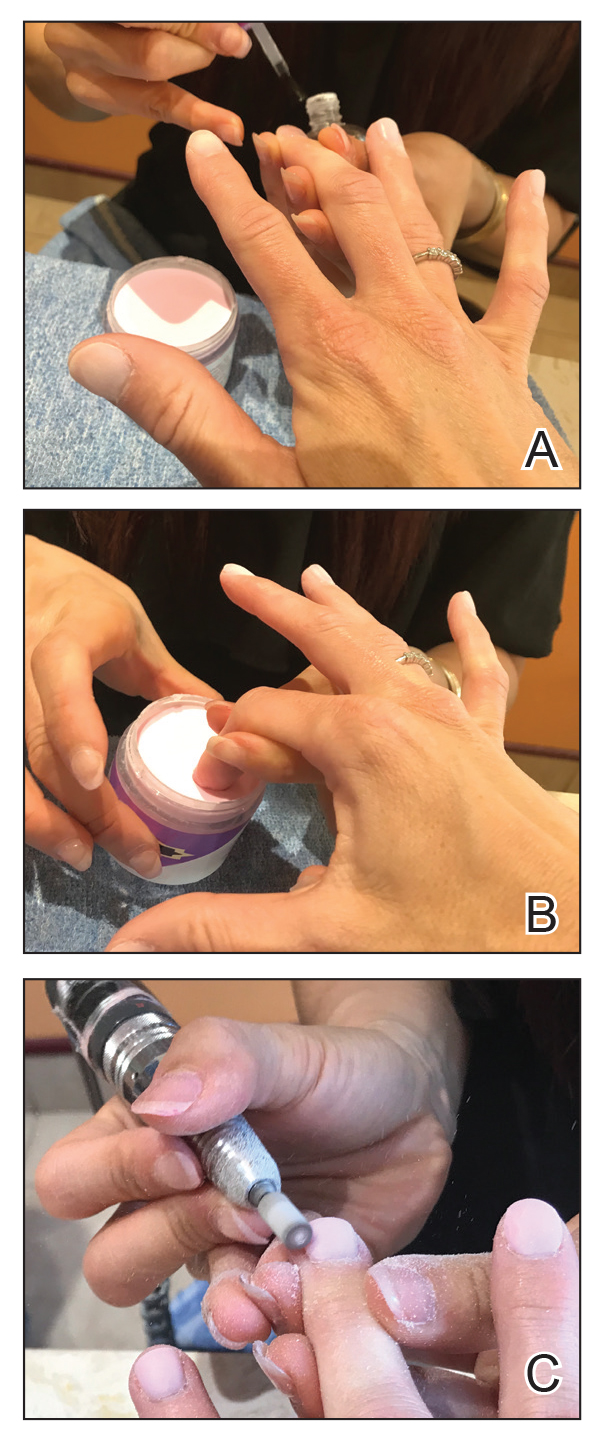

On initial presentation to the Cutaneous Lymphoma Clinic at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the patient was erythrodermic. She also was noted to have undulating wavy bands and concentric annular, ringlike, thin, erythematous plaques with trailing scale, giving a wood grain, zebra hide–like appearance involving the buttocks, abdomen, and lower extremities (Figure 1). Lesions were markedly pruritic and were advancing rapidly. A diagnosis of erythema gyratum repens (EGR)–like eruption was made.

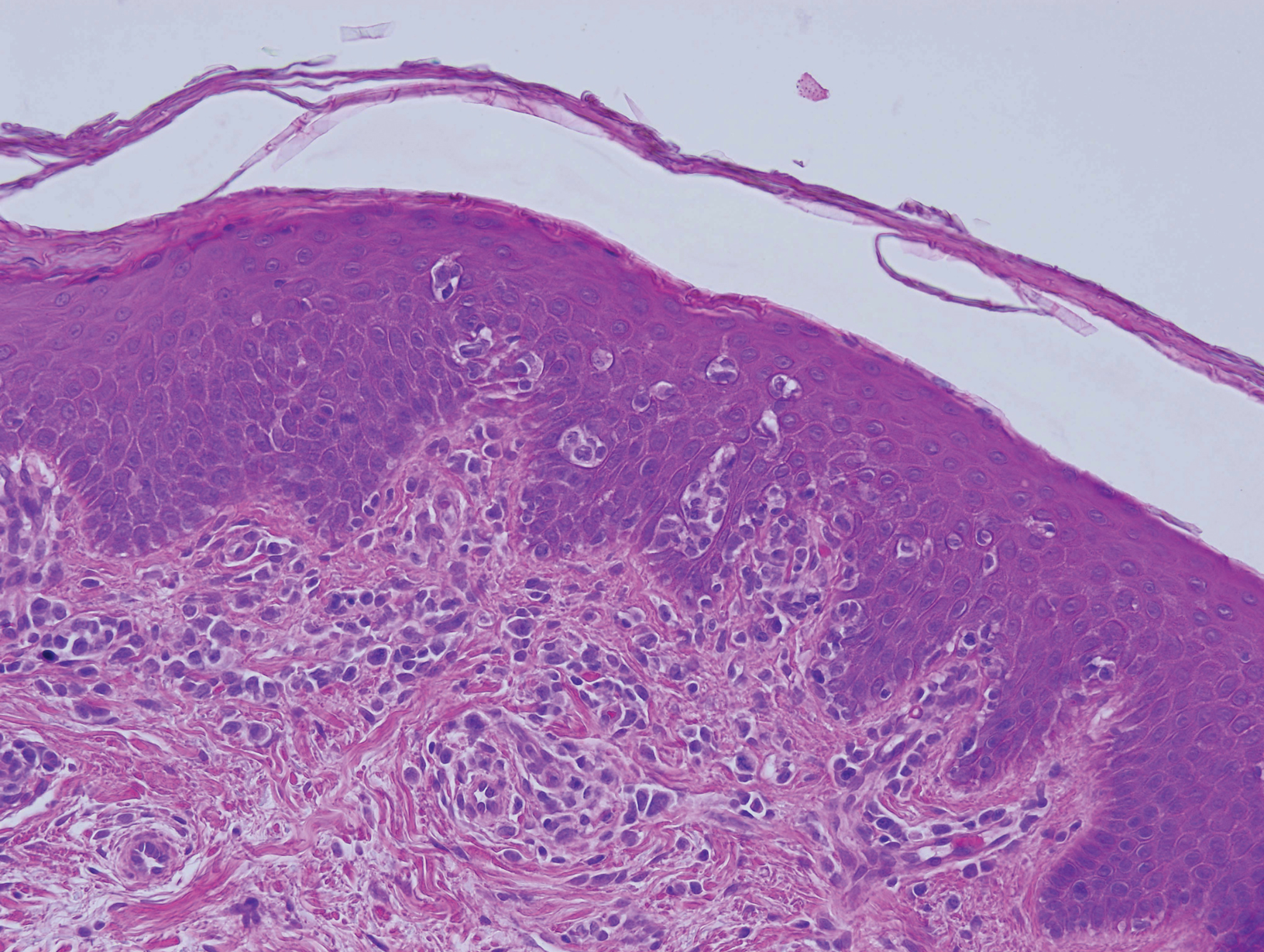

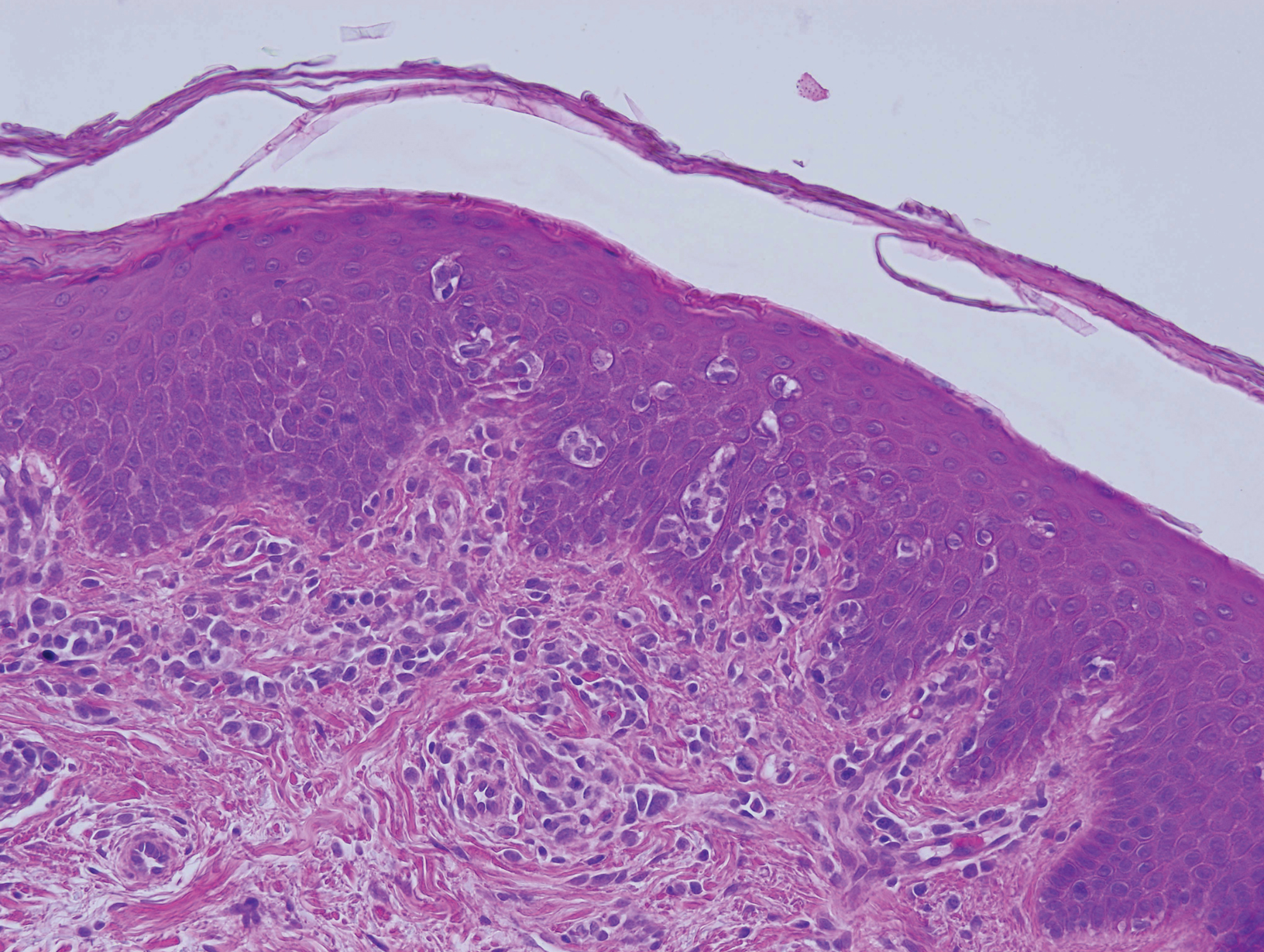

Biopsy of an EGR-like area on the leg showed a superficial perivascular and somewhat lichenoid lymphoid infiltrate (Figure 2). Lymphocytes were lined up along the basal layer, occasionally forming nests within the epidermis. Nearly all mononuclear cells in the epidermis and dermis exhibited positive CD3 and CD4 staining, with only scattered CD8 cells. These features were compatible with cutaneous involvement in SS. A concurrent biopsy from diffusely erythrodermic forearm skin, which lacked EGR-like morphology, showed similar histopathologic and immunophenotypic features.

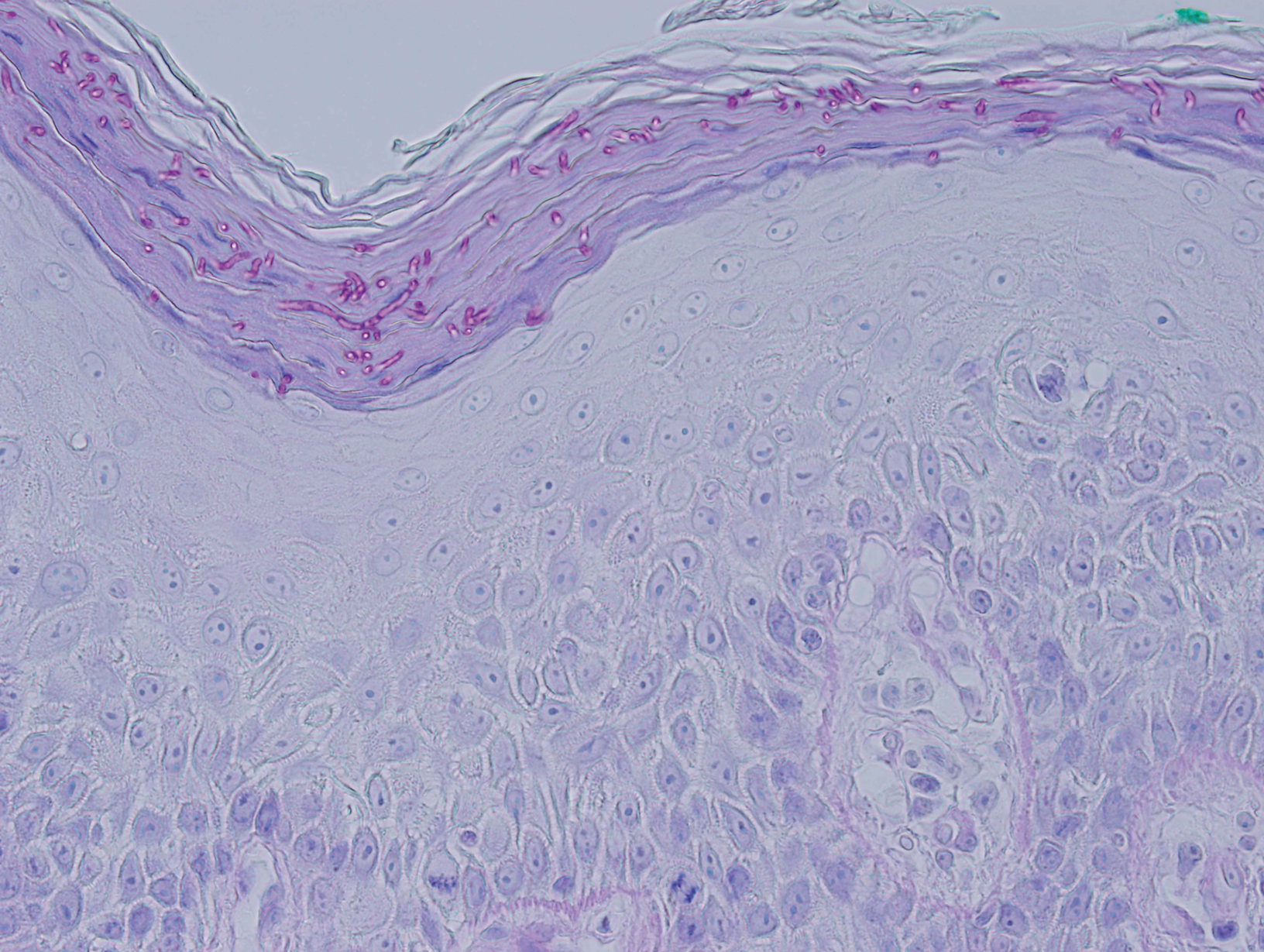

Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase stain revealed numerous septate hyphae within the stratum corneum in both skin biopsy specimens (Figure 3). Fungal culture of EGR-like lesions was positive for a nonsporulating filamentous fungus, identified as Trichophyton rubrum by DNA sequencing.

A diagnosis of EGR-like eruption secondary to tinea corporis in SS was made. The possibility of tinea incognito also was considered to explain the presence of dermatophytes in the biopsy from skin that exhibited only erythroderma clinically; however, the patient did not have a history of corticosteroid use.

Interferon alfa-2b and methotrexate therapy was initiated. Additionally, oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) was initiated for 14 days, resulting in complete resolution of the EGR-like eruption; nevertheless, diffuse erythema remained. Subsequently, within 3 months of treatment, the cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) improved with continued interferon alfa-2b and methotrexate. Erythroderma became minimal; the circulating Sézary cell count decreased by 50%. The patient ultimately had multiple relapses in erythroderma and progression of SS. Erythema gyratum repens–like lesions recurred on multiple occasions, with a temporary response to repeat courses of oral terbinafine.

Comment

Defining True EGR vs EGR-like Eruption

Sézary syndrome represents the leukemic stage of CTCL, which is defined by the triad of erythroderma; generalized lymphadenopathy; and neoplastic T cells in the skin, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood. It is well known that CTCL can mimic multiple benign and malignant dermatoses. One rare presentation of CTCL is an EGR-like eruption.

Erythema gyratum repens presents as rapidly advancing, erythematous, concentric bands that can be figurate, gyrate, or annular, with a fine trailing edge of scale (wood grain pattern). The diagnosis is based on the characteristic clinical pattern of EGR and by ruling out other mimicking conditions with biopsy.1 Patients with the characteristic clinical pattern but with an alternate underlying dermatosis are described as having an EGR-like eruption rather than true EGR.

True EGR is most often but not always associated with underlying malignancy. Biopsy of true EGR eruptions show nonspecific histopathologic features, with perivascular superficial mononuclear dermatitis, occasional mild spongiosis, and focal parakeratosis; specific features of an alternate dermatosis are lacking.2 In addition to CTCL, EGR-like eruptions have been described in a number of diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, erythema annulare centrifugum, bullous dermatosis, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, urticarial vasculitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and neutrophilic dermatoses.

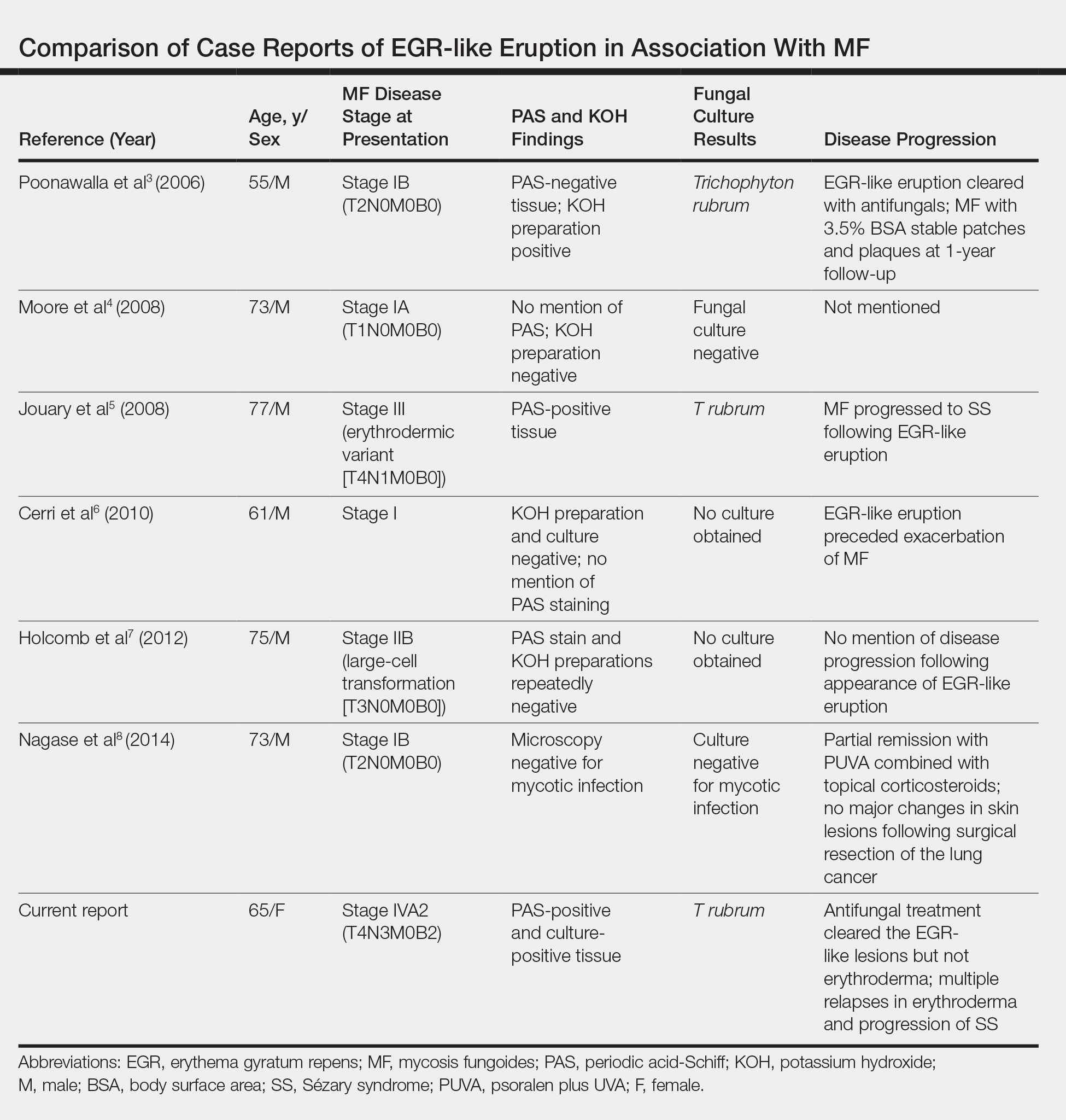

Prior Reports of EGR-like Eruption in Association With MF

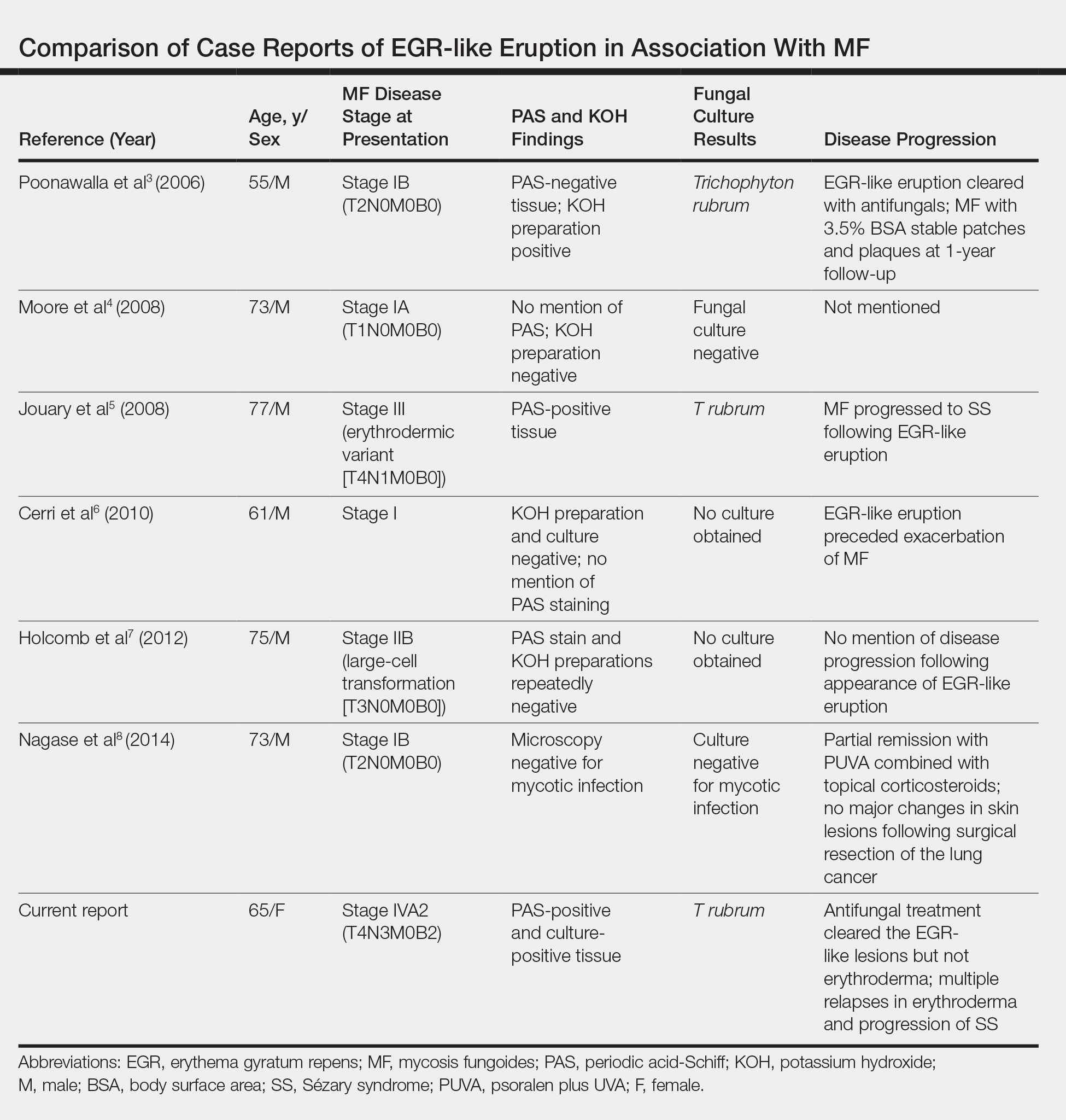

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erythema gyratum repens in mycosis fungoides, mycosis fungoides with tinea, and concentric wood grain erythema, there have been 6 other cases of an EGR-like eruption in association with MF (Table). Poonawalla et al3 first described an EGR-like eruption (utilizing the term tinea pseudoimbricata) in a 55-year-old man with stage IB MF (T2N0M0B0). The patient had a preceding history of tinea pedis and tinea corporis that preceded the diagnosis of MF. At the time of MF diagnosis, the patient presented with extensive concentric, gyrate, wood grain, annular lesions. His MF was resistant to topical mechlorethamine, psoralen plus UVA, and oral bexarotene. The body surface area involvement decreased from 60% to less than 1% after institution of oral and topical antifungal therapy. It was postulated that the widespread dermatophytosis that preceded the development of MF may have been the persistent antigen leading to his disease. Preceding the diagnosis of MF, skin scrapings were floridly positive for dermatophyte hyphae. Fungal cultures from the affected areas of skin grew T rubrum.3

Moore et al4 described an EGR-like eruption on the trunk of a 73-year-old man with stage IA MF (T1N0M0B0). Biopsy was consistent with MF, but no fungal organisms were seen. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal cultures of the lesions also were negative for organisms. The patient was successfully treated with topical betamethasone.4Jouary et al5 described an EGR-like eruption in a 77-year-old man with stage III erythrodermic MF (T4N1M0B0). Biopsy showed mycelia on PAS stain. Subsequent culture isolated T rubrum. Terbinafine (250 mg/d) and ketoconazole cream 2% daily were initiated and the patient’s EGR-like rash quickly cleared, while MF progressed to SS.5

Cerri et al6 later described a case of EGR-like eruption in a 61-year-old man with stage I MF and an EGR-like eruption. Microscopic examination of potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations and fungal culture of the lesions failed to demonstrate mycotic infection. There was no mention of PAS stain of skin biopsy specimens. In this case, the authors mentioned that EGR-like lesions preceded exacerbation of MF and questioned the prognostic significance of the EGR-like eruption in relation to MF.6

Holcomb et al7 reported the next case of a 75-year-old man with stage IIB MF (T3N0M0B0) with CD25+ and CD30+ large cell transformation who presented with an EGR-like eruption. In this case, PAS stain and KOH preparations were repeatedly negative for mycotic infection. Disease progression was not mentioned following the appearance of the EGR-like eruption.7

Nagase et al8 most recently described a case of a 73-year-old Japanese man with stage IB (T2N0M0B0) CD4−CD8− MF and lung cancer who developed a cutaneous eruption mimicking EGR. Microscopy and culture excluded the presence of a mycotic infection. The patient achieved partial remission with photochemotherapy (psoralen plus UVA) combined with topical corticosteroids. No major changes in the patient’s skin lesions were noted following surgical resection of the lung cancer.8

Dermatophyte Infection

It is known that conventional tinea corporis can occur in the setting of CTCL. However, EGR-like eruptions in CTCL can be distinguished from standard tinea corporis by the classic morphology of EGR and clinical history of rapid migration of these characteristic lesions.

Tinea imbricata is known to have a clinical appearance that is similar to EGR, but the infection is caused by Tinea concentricum, which is limited to southwest Polynesia, Melanesia, Southeast Asia, India, and Central America. Although T rubrum was the dermatophyte isolated by Poonawalla et al,3 Jouary et al,5 and in our case, whether T rubrum infection in the setting of CTCL has any impact on prognosis needs further study.

Our case of an EGR-like eruption presented in a patient with SS and tinea corporis. Biopsy specimens showed CTCL and concomitant dermatophytic infection that was confirmed with PAS stain and identified as T rubrum. Interestingly, our patient’s EGR-like eruption cleared with oral terbinafine therapy, consistent with findings described by Poonawalla et al3 and Jouary et al5 in which treatment of the dermatophytic infection led to resolution of the EGR-like eruption, suggesting a causative role.

However, testing for dermatophytes was negative in the other reported cases of EGR-like eruptions in patients with MF, despite screening for the presence of fungal microorganisms using KOH preparation, PAS staining, or fungal culture, or a combination of these methods,3-8 which raises the question: Do the cases reported without dermatophytic infection represent false-negative test results, or can the distinct clinical appearance of EGR indeed be seen in patients with CTCL who lack superimposed dermatophytosis? In 3 prior reported cases of EGR-like eruptions in MF, the eruption was preceded by immunosuppressive therapy.5-7

Further investigation is needed to correlate the role of dermatophytic infection in EGR-like eruptions. Our case and the Jouary et al5 case reported dermatophyte-positive EGR-like eruptions in MF and SS detected with histopathologic analysis and PAS stain. This low-cost screening method should be considered in future cases. If the test result is dermatophyte positive, a 14-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) might induce resolution of the EGR-like eruption.

Conclusion

The role of dermatophyte-induced EGR or EGR-like eruptions in other settings also warrants further investigation to shed light on this poorly understood yet striking dermatologic condition. Our patient showed both MF and dermatophytes in skin biopsy results, regardless of whether those sites showed erythroderma or EGR-like features clinically. On 3 occasions, antifungal treatment cleared the EGR-like lesions and associated pruritus but not erythroderma. Therefore, it appears that the mere presence of dermatophytes was necessary but not sufficient to produce the EGR-like lesions observed in our case.

- Rongioletti F, Fausti V, Parodi A. Erythema gyratum repens is not an obligate paraneoplastic disease: a systematic review of the literature and personal experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;28:112-115.

- Albers SE, Fenske NA, Glass LF. Erythema gyratum repens: direct immunofluorescence microscopic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:493-494.

- Poonawalla T, Chen W, Duvic M. Mycosis fungoides with tinea pseudoimbricata owing to Trichophyton rubrum infection. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:52-56.

- Moore E, McFarlane R, Olerud J. Concentric wood grain erythema on the trunk. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:673-678.

- Jouary T, Lalanne N, Stanislas S, et al. Erythema gyratum repens-like eruption in mycosis fungoides: is dermatophyte superinfection underdiagnosed in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1276-1278.

- Cerri A, Vezzoli P, Serini SM, et al. Mycosis fungoides mimicking erythema gyratum repens: an additional variant? Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:540-541.

- Holcomb M, Duvic M, Cutlan J. Erythema gyratum repens-like eruptions with large cell transformation in a patient with mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1231-1233.

- Nagase K, Shirai R, Okawa T, et al. CD4/CD8 double-negative mycosis fungoides mimicking erythema gyratum repens in a patient with underlying lung cancer. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:89-90.

Case Report

A 65-year-old woman presented with stage IVA2 mycosis fungoides (MF)(T4N3M0B2)/Sézary syndrome (SS). A peripheral blood count contained 6000 Sézary cells with cerebriform nuclei, a CD2+/−CD3+CD4+CD5+/−CD7+CD8−CD26−immunophenotype, and a highly abnormal CD4 to CD8 ratio (70:1). Positron emission tomography and computed tomography demonstrated hypermetabolic subcutaneous nodules in the base of the neck and generalized lymphadenopathy. Lymph node biopsy showed involvement by T-cell lymphoma and dominant T-cell receptor γ clonality by polymerase chain reaction.

On initial presentation to the Cutaneous Lymphoma Clinic at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the patient was erythrodermic. She also was noted to have undulating wavy bands and concentric annular, ringlike, thin, erythematous plaques with trailing scale, giving a wood grain, zebra hide–like appearance involving the buttocks, abdomen, and lower extremities (Figure 1). Lesions were markedly pruritic and were advancing rapidly. A diagnosis of erythema gyratum repens (EGR)–like eruption was made.

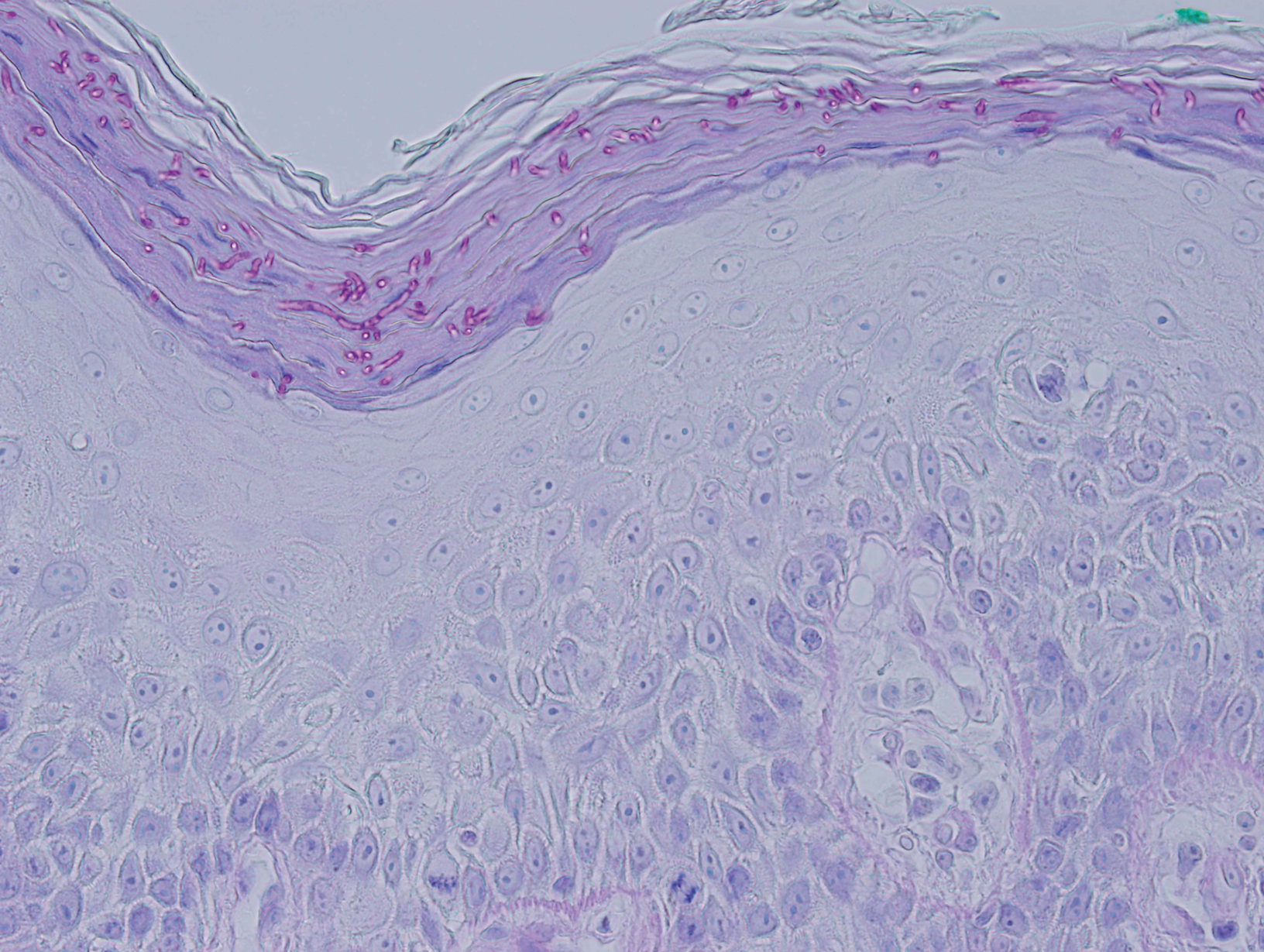

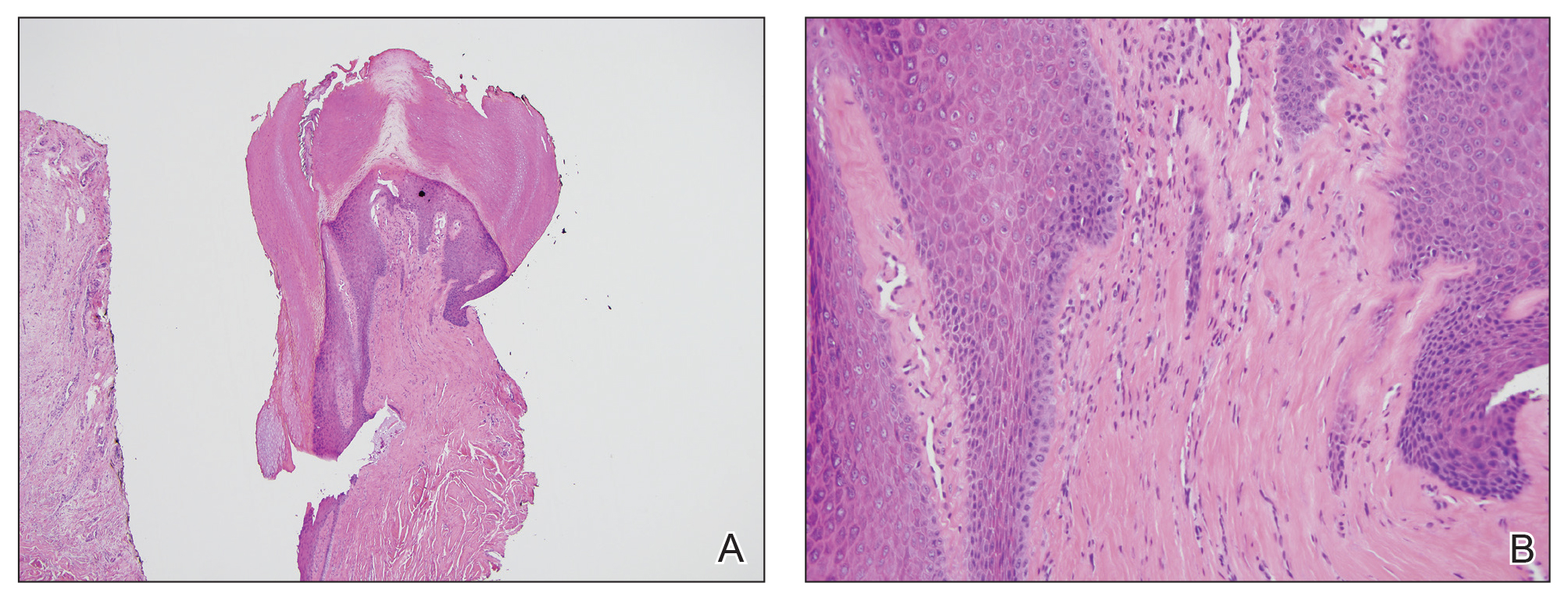

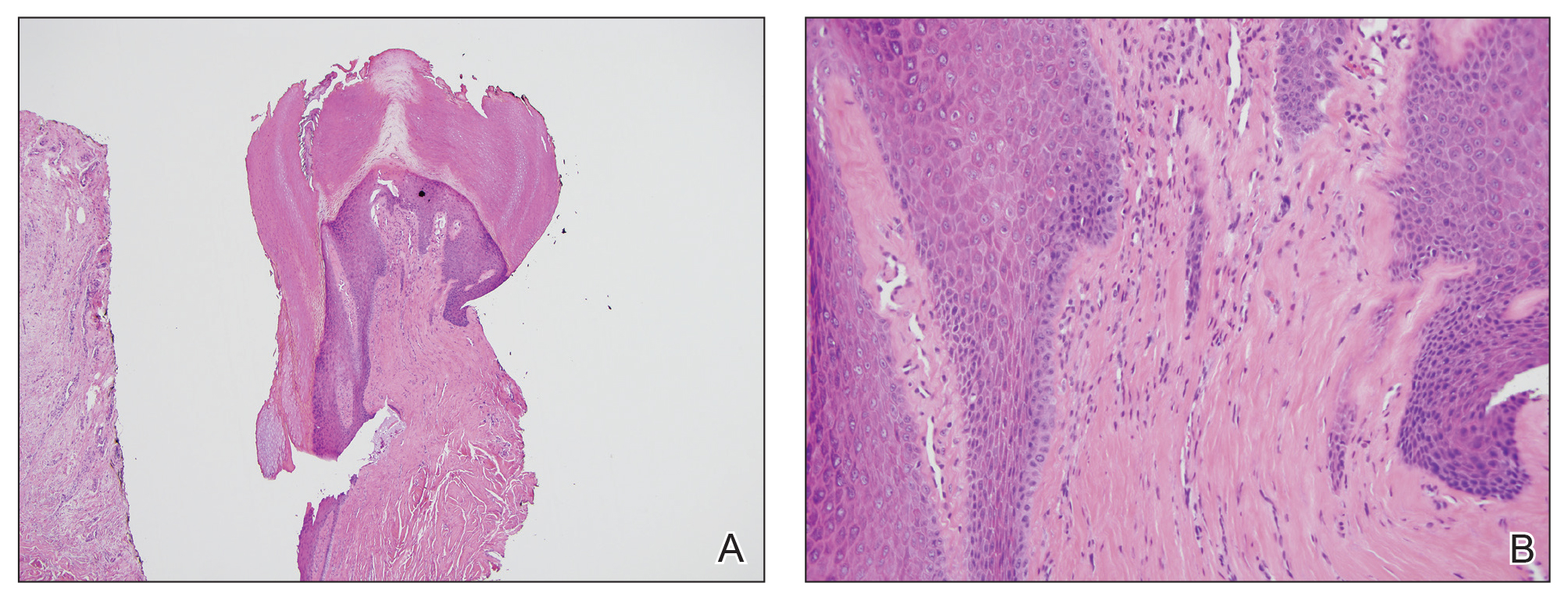

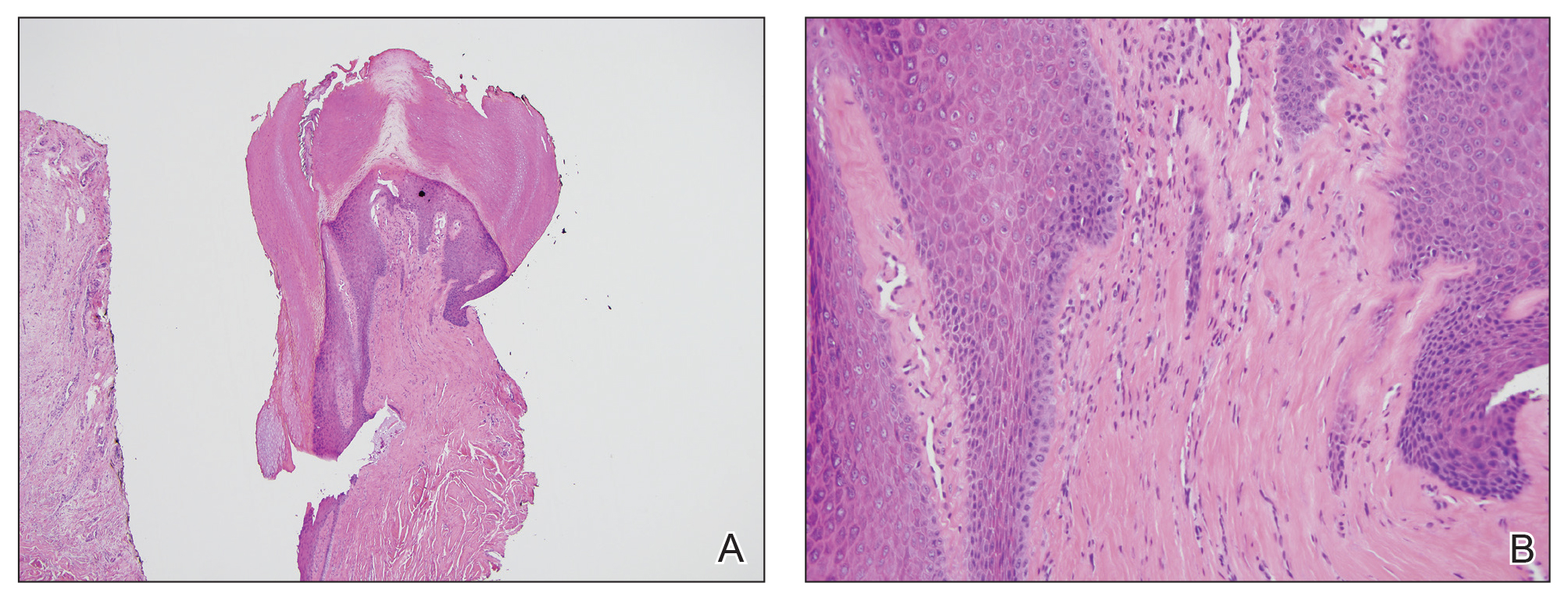

Biopsy of an EGR-like area on the leg showed a superficial perivascular and somewhat lichenoid lymphoid infiltrate (Figure 2). Lymphocytes were lined up along the basal layer, occasionally forming nests within the epidermis. Nearly all mononuclear cells in the epidermis and dermis exhibited positive CD3 and CD4 staining, with only scattered CD8 cells. These features were compatible with cutaneous involvement in SS. A concurrent biopsy from diffusely erythrodermic forearm skin, which lacked EGR-like morphology, showed similar histopathologic and immunophenotypic features.

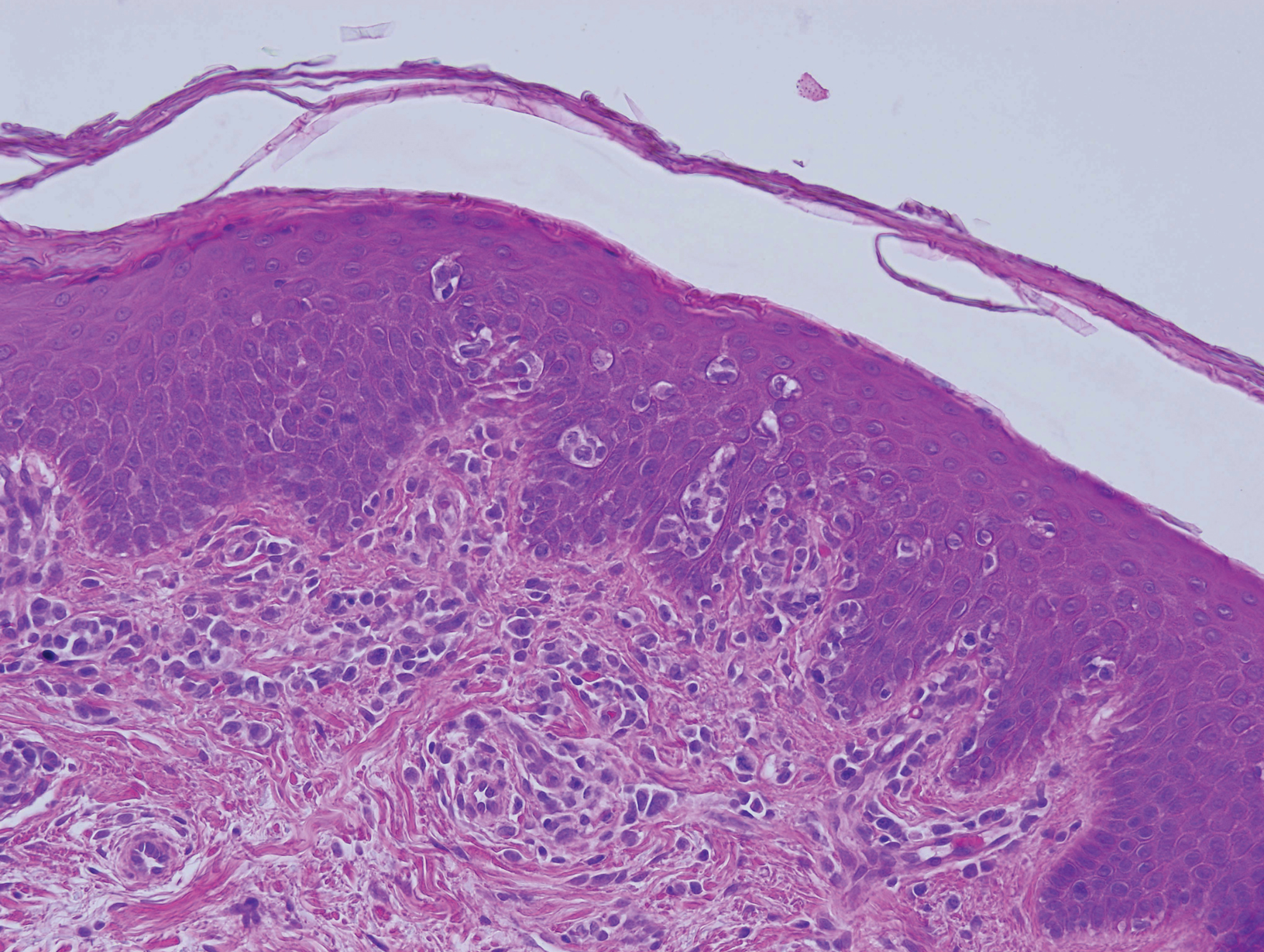

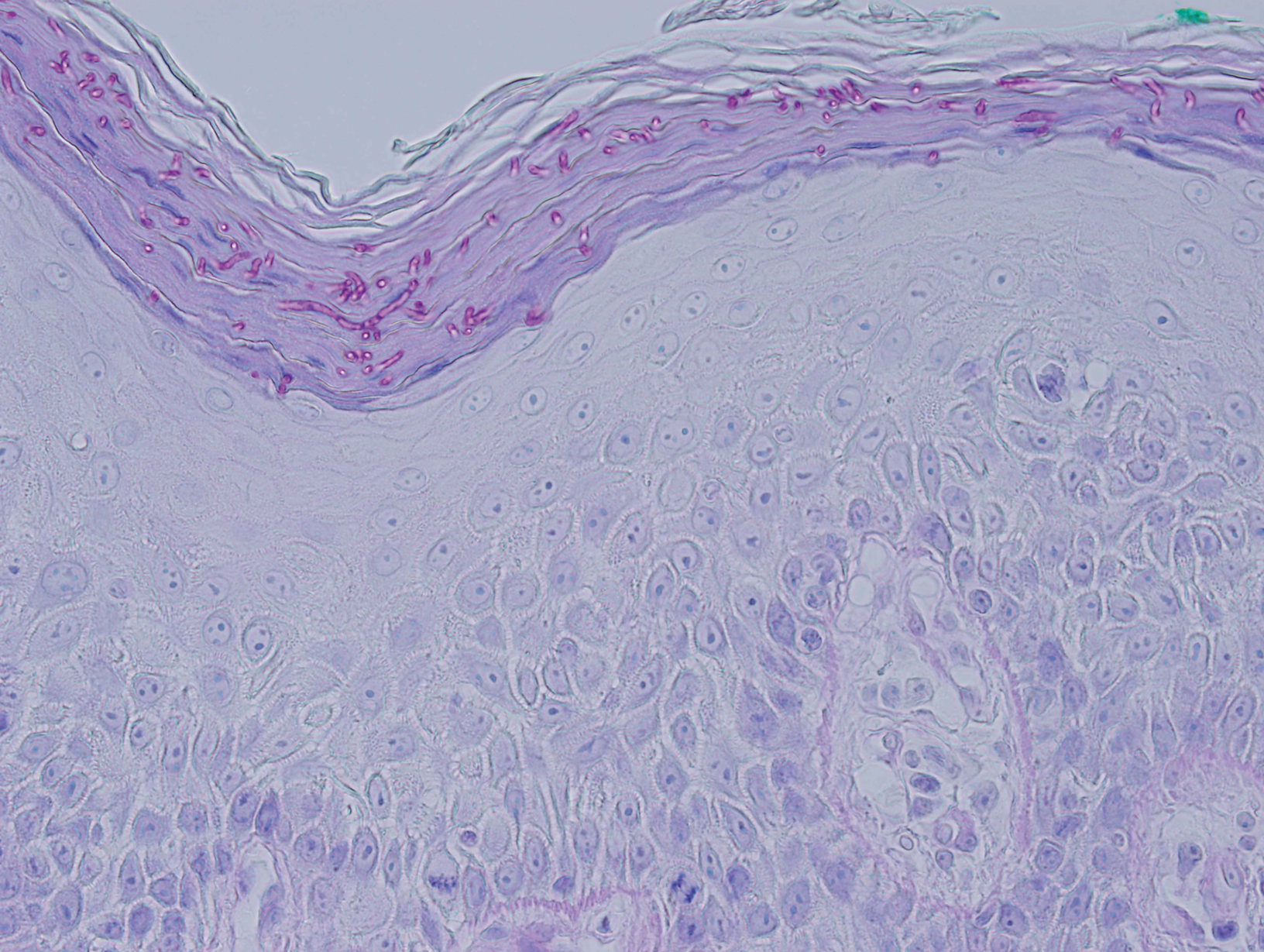

Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase stain revealed numerous septate hyphae within the stratum corneum in both skin biopsy specimens (Figure 3). Fungal culture of EGR-like lesions was positive for a nonsporulating filamentous fungus, identified as Trichophyton rubrum by DNA sequencing.

A diagnosis of EGR-like eruption secondary to tinea corporis in SS was made. The possibility of tinea incognito also was considered to explain the presence of dermatophytes in the biopsy from skin that exhibited only erythroderma clinically; however, the patient did not have a history of corticosteroid use.

Interferon alfa-2b and methotrexate therapy was initiated. Additionally, oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) was initiated for 14 days, resulting in complete resolution of the EGR-like eruption; nevertheless, diffuse erythema remained. Subsequently, within 3 months of treatment, the cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) improved with continued interferon alfa-2b and methotrexate. Erythroderma became minimal; the circulating Sézary cell count decreased by 50%. The patient ultimately had multiple relapses in erythroderma and progression of SS. Erythema gyratum repens–like lesions recurred on multiple occasions, with a temporary response to repeat courses of oral terbinafine.

Comment

Defining True EGR vs EGR-like Eruption

Sézary syndrome represents the leukemic stage of CTCL, which is defined by the triad of erythroderma; generalized lymphadenopathy; and neoplastic T cells in the skin, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood. It is well known that CTCL can mimic multiple benign and malignant dermatoses. One rare presentation of CTCL is an EGR-like eruption.

Erythema gyratum repens presents as rapidly advancing, erythematous, concentric bands that can be figurate, gyrate, or annular, with a fine trailing edge of scale (wood grain pattern). The diagnosis is based on the characteristic clinical pattern of EGR and by ruling out other mimicking conditions with biopsy.1 Patients with the characteristic clinical pattern but with an alternate underlying dermatosis are described as having an EGR-like eruption rather than true EGR.

True EGR is most often but not always associated with underlying malignancy. Biopsy of true EGR eruptions show nonspecific histopathologic features, with perivascular superficial mononuclear dermatitis, occasional mild spongiosis, and focal parakeratosis; specific features of an alternate dermatosis are lacking.2 In addition to CTCL, EGR-like eruptions have been described in a number of diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, erythema annulare centrifugum, bullous dermatosis, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, urticarial vasculitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and neutrophilic dermatoses.

Prior Reports of EGR-like Eruption in Association With MF

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erythema gyratum repens in mycosis fungoides, mycosis fungoides with tinea, and concentric wood grain erythema, there have been 6 other cases of an EGR-like eruption in association with MF (Table). Poonawalla et al3 first described an EGR-like eruption (utilizing the term tinea pseudoimbricata) in a 55-year-old man with stage IB MF (T2N0M0B0). The patient had a preceding history of tinea pedis and tinea corporis that preceded the diagnosis of MF. At the time of MF diagnosis, the patient presented with extensive concentric, gyrate, wood grain, annular lesions. His MF was resistant to topical mechlorethamine, psoralen plus UVA, and oral bexarotene. The body surface area involvement decreased from 60% to less than 1% after institution of oral and topical antifungal therapy. It was postulated that the widespread dermatophytosis that preceded the development of MF may have been the persistent antigen leading to his disease. Preceding the diagnosis of MF, skin scrapings were floridly positive for dermatophyte hyphae. Fungal cultures from the affected areas of skin grew T rubrum.3

Moore et al4 described an EGR-like eruption on the trunk of a 73-year-old man with stage IA MF (T1N0M0B0). Biopsy was consistent with MF, but no fungal organisms were seen. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal cultures of the lesions also were negative for organisms. The patient was successfully treated with topical betamethasone.4Jouary et al5 described an EGR-like eruption in a 77-year-old man with stage III erythrodermic MF (T4N1M0B0). Biopsy showed mycelia on PAS stain. Subsequent culture isolated T rubrum. Terbinafine (250 mg/d) and ketoconazole cream 2% daily were initiated and the patient’s EGR-like rash quickly cleared, while MF progressed to SS.5

Cerri et al6 later described a case of EGR-like eruption in a 61-year-old man with stage I MF and an EGR-like eruption. Microscopic examination of potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations and fungal culture of the lesions failed to demonstrate mycotic infection. There was no mention of PAS stain of skin biopsy specimens. In this case, the authors mentioned that EGR-like lesions preceded exacerbation of MF and questioned the prognostic significance of the EGR-like eruption in relation to MF.6

Holcomb et al7 reported the next case of a 75-year-old man with stage IIB MF (T3N0M0B0) with CD25+ and CD30+ large cell transformation who presented with an EGR-like eruption. In this case, PAS stain and KOH preparations were repeatedly negative for mycotic infection. Disease progression was not mentioned following the appearance of the EGR-like eruption.7

Nagase et al8 most recently described a case of a 73-year-old Japanese man with stage IB (T2N0M0B0) CD4−CD8− MF and lung cancer who developed a cutaneous eruption mimicking EGR. Microscopy and culture excluded the presence of a mycotic infection. The patient achieved partial remission with photochemotherapy (psoralen plus UVA) combined with topical corticosteroids. No major changes in the patient’s skin lesions were noted following surgical resection of the lung cancer.8

Dermatophyte Infection

It is known that conventional tinea corporis can occur in the setting of CTCL. However, EGR-like eruptions in CTCL can be distinguished from standard tinea corporis by the classic morphology of EGR and clinical history of rapid migration of these characteristic lesions.

Tinea imbricata is known to have a clinical appearance that is similar to EGR, but the infection is caused by Tinea concentricum, which is limited to southwest Polynesia, Melanesia, Southeast Asia, India, and Central America. Although T rubrum was the dermatophyte isolated by Poonawalla et al,3 Jouary et al,5 and in our case, whether T rubrum infection in the setting of CTCL has any impact on prognosis needs further study.

Our case of an EGR-like eruption presented in a patient with SS and tinea corporis. Biopsy specimens showed CTCL and concomitant dermatophytic infection that was confirmed with PAS stain and identified as T rubrum. Interestingly, our patient’s EGR-like eruption cleared with oral terbinafine therapy, consistent with findings described by Poonawalla et al3 and Jouary et al5 in which treatment of the dermatophytic infection led to resolution of the EGR-like eruption, suggesting a causative role.

However, testing for dermatophytes was negative in the other reported cases of EGR-like eruptions in patients with MF, despite screening for the presence of fungal microorganisms using KOH preparation, PAS staining, or fungal culture, or a combination of these methods,3-8 which raises the question: Do the cases reported without dermatophytic infection represent false-negative test results, or can the distinct clinical appearance of EGR indeed be seen in patients with CTCL who lack superimposed dermatophytosis? In 3 prior reported cases of EGR-like eruptions in MF, the eruption was preceded by immunosuppressive therapy.5-7

Further investigation is needed to correlate the role of dermatophytic infection in EGR-like eruptions. Our case and the Jouary et al5 case reported dermatophyte-positive EGR-like eruptions in MF and SS detected with histopathologic analysis and PAS stain. This low-cost screening method should be considered in future cases. If the test result is dermatophyte positive, a 14-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) might induce resolution of the EGR-like eruption.

Conclusion

The role of dermatophyte-induced EGR or EGR-like eruptions in other settings also warrants further investigation to shed light on this poorly understood yet striking dermatologic condition. Our patient showed both MF and dermatophytes in skin biopsy results, regardless of whether those sites showed erythroderma or EGR-like features clinically. On 3 occasions, antifungal treatment cleared the EGR-like lesions and associated pruritus but not erythroderma. Therefore, it appears that the mere presence of dermatophytes was necessary but not sufficient to produce the EGR-like lesions observed in our case.

Case Report

A 65-year-old woman presented with stage IVA2 mycosis fungoides (MF)(T4N3M0B2)/Sézary syndrome (SS). A peripheral blood count contained 6000 Sézary cells with cerebriform nuclei, a CD2+/−CD3+CD4+CD5+/−CD7+CD8−CD26−immunophenotype, and a highly abnormal CD4 to CD8 ratio (70:1). Positron emission tomography and computed tomography demonstrated hypermetabolic subcutaneous nodules in the base of the neck and generalized lymphadenopathy. Lymph node biopsy showed involvement by T-cell lymphoma and dominant T-cell receptor γ clonality by polymerase chain reaction.

On initial presentation to the Cutaneous Lymphoma Clinic at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the patient was erythrodermic. She also was noted to have undulating wavy bands and concentric annular, ringlike, thin, erythematous plaques with trailing scale, giving a wood grain, zebra hide–like appearance involving the buttocks, abdomen, and lower extremities (Figure 1). Lesions were markedly pruritic and were advancing rapidly. A diagnosis of erythema gyratum repens (EGR)–like eruption was made.

Biopsy of an EGR-like area on the leg showed a superficial perivascular and somewhat lichenoid lymphoid infiltrate (Figure 2). Lymphocytes were lined up along the basal layer, occasionally forming nests within the epidermis. Nearly all mononuclear cells in the epidermis and dermis exhibited positive CD3 and CD4 staining, with only scattered CD8 cells. These features were compatible with cutaneous involvement in SS. A concurrent biopsy from diffusely erythrodermic forearm skin, which lacked EGR-like morphology, showed similar histopathologic and immunophenotypic features.

Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase stain revealed numerous septate hyphae within the stratum corneum in both skin biopsy specimens (Figure 3). Fungal culture of EGR-like lesions was positive for a nonsporulating filamentous fungus, identified as Trichophyton rubrum by DNA sequencing.

A diagnosis of EGR-like eruption secondary to tinea corporis in SS was made. The possibility of tinea incognito also was considered to explain the presence of dermatophytes in the biopsy from skin that exhibited only erythroderma clinically; however, the patient did not have a history of corticosteroid use.

Interferon alfa-2b and methotrexate therapy was initiated. Additionally, oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) was initiated for 14 days, resulting in complete resolution of the EGR-like eruption; nevertheless, diffuse erythema remained. Subsequently, within 3 months of treatment, the cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) improved with continued interferon alfa-2b and methotrexate. Erythroderma became minimal; the circulating Sézary cell count decreased by 50%. The patient ultimately had multiple relapses in erythroderma and progression of SS. Erythema gyratum repens–like lesions recurred on multiple occasions, with a temporary response to repeat courses of oral terbinafine.

Comment

Defining True EGR vs EGR-like Eruption

Sézary syndrome represents the leukemic stage of CTCL, which is defined by the triad of erythroderma; generalized lymphadenopathy; and neoplastic T cells in the skin, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood. It is well known that CTCL can mimic multiple benign and malignant dermatoses. One rare presentation of CTCL is an EGR-like eruption.

Erythema gyratum repens presents as rapidly advancing, erythematous, concentric bands that can be figurate, gyrate, or annular, with a fine trailing edge of scale (wood grain pattern). The diagnosis is based on the characteristic clinical pattern of EGR and by ruling out other mimicking conditions with biopsy.1 Patients with the characteristic clinical pattern but with an alternate underlying dermatosis are described as having an EGR-like eruption rather than true EGR.

True EGR is most often but not always associated with underlying malignancy. Biopsy of true EGR eruptions show nonspecific histopathologic features, with perivascular superficial mononuclear dermatitis, occasional mild spongiosis, and focal parakeratosis; specific features of an alternate dermatosis are lacking.2 In addition to CTCL, EGR-like eruptions have been described in a number of diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, erythema annulare centrifugum, bullous dermatosis, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, urticarial vasculitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and neutrophilic dermatoses.

Prior Reports of EGR-like Eruption in Association With MF

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erythema gyratum repens in mycosis fungoides, mycosis fungoides with tinea, and concentric wood grain erythema, there have been 6 other cases of an EGR-like eruption in association with MF (Table). Poonawalla et al3 first described an EGR-like eruption (utilizing the term tinea pseudoimbricata) in a 55-year-old man with stage IB MF (T2N0M0B0). The patient had a preceding history of tinea pedis and tinea corporis that preceded the diagnosis of MF. At the time of MF diagnosis, the patient presented with extensive concentric, gyrate, wood grain, annular lesions. His MF was resistant to topical mechlorethamine, psoralen plus UVA, and oral bexarotene. The body surface area involvement decreased from 60% to less than 1% after institution of oral and topical antifungal therapy. It was postulated that the widespread dermatophytosis that preceded the development of MF may have been the persistent antigen leading to his disease. Preceding the diagnosis of MF, skin scrapings were floridly positive for dermatophyte hyphae. Fungal cultures from the affected areas of skin grew T rubrum.3

Moore et al4 described an EGR-like eruption on the trunk of a 73-year-old man with stage IA MF (T1N0M0B0). Biopsy was consistent with MF, but no fungal organisms were seen. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal cultures of the lesions also were negative for organisms. The patient was successfully treated with topical betamethasone.4Jouary et al5 described an EGR-like eruption in a 77-year-old man with stage III erythrodermic MF (T4N1M0B0). Biopsy showed mycelia on PAS stain. Subsequent culture isolated T rubrum. Terbinafine (250 mg/d) and ketoconazole cream 2% daily were initiated and the patient’s EGR-like rash quickly cleared, while MF progressed to SS.5

Cerri et al6 later described a case of EGR-like eruption in a 61-year-old man with stage I MF and an EGR-like eruption. Microscopic examination of potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations and fungal culture of the lesions failed to demonstrate mycotic infection. There was no mention of PAS stain of skin biopsy specimens. In this case, the authors mentioned that EGR-like lesions preceded exacerbation of MF and questioned the prognostic significance of the EGR-like eruption in relation to MF.6

Holcomb et al7 reported the next case of a 75-year-old man with stage IIB MF (T3N0M0B0) with CD25+ and CD30+ large cell transformation who presented with an EGR-like eruption. In this case, PAS stain and KOH preparations were repeatedly negative for mycotic infection. Disease progression was not mentioned following the appearance of the EGR-like eruption.7

Nagase et al8 most recently described a case of a 73-year-old Japanese man with stage IB (T2N0M0B0) CD4−CD8− MF and lung cancer who developed a cutaneous eruption mimicking EGR. Microscopy and culture excluded the presence of a mycotic infection. The patient achieved partial remission with photochemotherapy (psoralen plus UVA) combined with topical corticosteroids. No major changes in the patient’s skin lesions were noted following surgical resection of the lung cancer.8

Dermatophyte Infection

It is known that conventional tinea corporis can occur in the setting of CTCL. However, EGR-like eruptions in CTCL can be distinguished from standard tinea corporis by the classic morphology of EGR and clinical history of rapid migration of these characteristic lesions.