User login

Analysis: Why Alexa’s bedside manner is bad for health care

Amazon has opened a new health care frontier: Now Alexa can be used to transmit patient data. Using this new feature – which Amazon labeled as a “skill” – a company named Livongo will allow diabetes patients – which it calls “members” – to use the device to “query their last blood sugar reading, blood sugar measurement trends, and receive insights and Health Nudges that are personalized to them.”

Private equity and venture capital firms are in love with a legion of companies and startups touting the benefits of virtual doctors’ visits and telemedicine to revolutionize health care, investing almost $10 billion in 2018, a record for the sector. Without stepping into a gym or a clinic, a startup called Kinetxx will provide patients with virtual physical therapy, along with messaging and exercise logging. And Maven Clinic (which is not actually a physical place) offers online medical guidance and personal advice focusing on women’s health needs.

In April, at Fortune’s Brainstorm Health conference in San Diego, Bruce Broussard, CEO of health insurer Humana, said he believes technology will help patients receive help during medical crises, citing the benefits of home monitoring and the ability of doctors’ visits to be conducted by video conference.

But when I returned from Brainstorm Health, I was confronted by an alternative reality of virtual medicine: a $235 medical bill for a telehealth visit that resulted from one of my kids calling a longtime doctor’s office. It was for a five-minute phone call answering a question about a possible infection.

Virtual communications have streamlined life and transformed many of our relationships for the better. There is little need anymore to sit across the desk from a tax accountant or travel agent or to stand in a queue for a bank teller. And there is certainly room for disruptive digital innovation in our confusing and overpriced health care system.

But it remains an open question whether virtual medicine will prove a valuable, convenient adjunct to health care. Or, instead, will it be a way for the U.S. profit-driven health care system to make big bucks by outsourcing core duties – while providing a paler version of actual medical treatment?

After all, my doctors have long answered my questions and dispensed phone and email advice for free – as part of our doctor-patient relationship – though it didn’t have a cool branding moniker like telehealth. And my obstetrician’s office offered great support and advice through two difficult pregnancies – maybe they should have been paid for that valuable service. But $235 for a phone call (which works out to over $2,000 per hour)? Not even a corporate lawyer bills that.

Logic holds that some digital health tools have tremendous potential: A neurologist can view a patient by video to see if lopsided facial movements suggest a stroke. A patient with an irregular heart rhythm could send in digital tracings to see if a new prescription drug is working. But the tangible benefit of many other virtual services offered is less certain. Some people may like receiving feedback about their sleep from an Apple Watch, but I’m not sure that’s medicine.

And if virtual medicine is pursued in the name of business efficiency or just profit, it has enormous potential to make health care worse.

My doctor’s nurse is far better equipped to answer a question about my ongoing health problem than someone at a call center reading from a script. And, however thorough a virtual visit may be, it forsakes some of the diagnostic information that comes when you see and touch the patient.

A study published recently in Pediatrics found that children who had a telemedicine visit for an upper respiratory infection were far more likely to get an antibiotic than those who physically saw a doctor, suggesting overprescribing is at work. It makes sense: A doctor can’t use a stethoscope to listen to lungs or wiggle an otoscope into a kid’s ear by video. Similarly, a virtual physical therapist can’t feel the knots in muscle or notice a fleeting wince on a patient’s face via camera.

More important, perhaps, virtual medicine means losing the support that has long been a crucial part of the profession. There are programs to provide iPads to people in home hospice for resources about grief and chatbots that purport to treat depression. Maybe people at such challenging moments need – and deserve – human contact.

Of course, companies like those mentioned are expecting to be reimbursed for the remote monitoring and virtual advice they provide. Investors, in turn, get generous payback without having to employ so many actual doctors or other health professionals. Livongo, for instance, has raised a total of $235 million in funding over six rounds. And, as of 2018, Medicare announced it would allow such digital monitoring tools to “qualify for reimbursement,” if they are “clinically endorsed.” But, ultimately, will the well-being of patients or investors decide which tools are clinically endorsed?

So far, with its new so-called skill, Alexa will be able to perform a half-dozen health-related services. In addition to diabetes coaching, it can find the earliest urgent care appointment in a given area and check the status of a prescription drug delivery.

But it will not provide many things patients desperately want, which technology should be able to readily deliver, such as a reliable price estimate for an upcoming surgery, the infection rates at the local hospital, the location of the cheapest cholesterol test nearby. And if we’re trying to bring health care into the tech-enabled 21st century, how about starting with low-hanging fruit: Does any other sector still use paper bills and faxes?

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Amazon has opened a new health care frontier: Now Alexa can be used to transmit patient data. Using this new feature – which Amazon labeled as a “skill” – a company named Livongo will allow diabetes patients – which it calls “members” – to use the device to “query their last blood sugar reading, blood sugar measurement trends, and receive insights and Health Nudges that are personalized to them.”

Private equity and venture capital firms are in love with a legion of companies and startups touting the benefits of virtual doctors’ visits and telemedicine to revolutionize health care, investing almost $10 billion in 2018, a record for the sector. Without stepping into a gym or a clinic, a startup called Kinetxx will provide patients with virtual physical therapy, along with messaging and exercise logging. And Maven Clinic (which is not actually a physical place) offers online medical guidance and personal advice focusing on women’s health needs.

In April, at Fortune’s Brainstorm Health conference in San Diego, Bruce Broussard, CEO of health insurer Humana, said he believes technology will help patients receive help during medical crises, citing the benefits of home monitoring and the ability of doctors’ visits to be conducted by video conference.

But when I returned from Brainstorm Health, I was confronted by an alternative reality of virtual medicine: a $235 medical bill for a telehealth visit that resulted from one of my kids calling a longtime doctor’s office. It was for a five-minute phone call answering a question about a possible infection.

Virtual communications have streamlined life and transformed many of our relationships for the better. There is little need anymore to sit across the desk from a tax accountant or travel agent or to stand in a queue for a bank teller. And there is certainly room for disruptive digital innovation in our confusing and overpriced health care system.

But it remains an open question whether virtual medicine will prove a valuable, convenient adjunct to health care. Or, instead, will it be a way for the U.S. profit-driven health care system to make big bucks by outsourcing core duties – while providing a paler version of actual medical treatment?

After all, my doctors have long answered my questions and dispensed phone and email advice for free – as part of our doctor-patient relationship – though it didn’t have a cool branding moniker like telehealth. And my obstetrician’s office offered great support and advice through two difficult pregnancies – maybe they should have been paid for that valuable service. But $235 for a phone call (which works out to over $2,000 per hour)? Not even a corporate lawyer bills that.

Logic holds that some digital health tools have tremendous potential: A neurologist can view a patient by video to see if lopsided facial movements suggest a stroke. A patient with an irregular heart rhythm could send in digital tracings to see if a new prescription drug is working. But the tangible benefit of many other virtual services offered is less certain. Some people may like receiving feedback about their sleep from an Apple Watch, but I’m not sure that’s medicine.

And if virtual medicine is pursued in the name of business efficiency or just profit, it has enormous potential to make health care worse.

My doctor’s nurse is far better equipped to answer a question about my ongoing health problem than someone at a call center reading from a script. And, however thorough a virtual visit may be, it forsakes some of the diagnostic information that comes when you see and touch the patient.

A study published recently in Pediatrics found that children who had a telemedicine visit for an upper respiratory infection were far more likely to get an antibiotic than those who physically saw a doctor, suggesting overprescribing is at work. It makes sense: A doctor can’t use a stethoscope to listen to lungs or wiggle an otoscope into a kid’s ear by video. Similarly, a virtual physical therapist can’t feel the knots in muscle or notice a fleeting wince on a patient’s face via camera.

More important, perhaps, virtual medicine means losing the support that has long been a crucial part of the profession. There are programs to provide iPads to people in home hospice for resources about grief and chatbots that purport to treat depression. Maybe people at such challenging moments need – and deserve – human contact.

Of course, companies like those mentioned are expecting to be reimbursed for the remote monitoring and virtual advice they provide. Investors, in turn, get generous payback without having to employ so many actual doctors or other health professionals. Livongo, for instance, has raised a total of $235 million in funding over six rounds. And, as of 2018, Medicare announced it would allow such digital monitoring tools to “qualify for reimbursement,” if they are “clinically endorsed.” But, ultimately, will the well-being of patients or investors decide which tools are clinically endorsed?

So far, with its new so-called skill, Alexa will be able to perform a half-dozen health-related services. In addition to diabetes coaching, it can find the earliest urgent care appointment in a given area and check the status of a prescription drug delivery.

But it will not provide many things patients desperately want, which technology should be able to readily deliver, such as a reliable price estimate for an upcoming surgery, the infection rates at the local hospital, the location of the cheapest cholesterol test nearby. And if we’re trying to bring health care into the tech-enabled 21st century, how about starting with low-hanging fruit: Does any other sector still use paper bills and faxes?

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Amazon has opened a new health care frontier: Now Alexa can be used to transmit patient data. Using this new feature – which Amazon labeled as a “skill” – a company named Livongo will allow diabetes patients – which it calls “members” – to use the device to “query their last blood sugar reading, blood sugar measurement trends, and receive insights and Health Nudges that are personalized to them.”

Private equity and venture capital firms are in love with a legion of companies and startups touting the benefits of virtual doctors’ visits and telemedicine to revolutionize health care, investing almost $10 billion in 2018, a record for the sector. Without stepping into a gym or a clinic, a startup called Kinetxx will provide patients with virtual physical therapy, along with messaging and exercise logging. And Maven Clinic (which is not actually a physical place) offers online medical guidance and personal advice focusing on women’s health needs.

In April, at Fortune’s Brainstorm Health conference in San Diego, Bruce Broussard, CEO of health insurer Humana, said he believes technology will help patients receive help during medical crises, citing the benefits of home monitoring and the ability of doctors’ visits to be conducted by video conference.

But when I returned from Brainstorm Health, I was confronted by an alternative reality of virtual medicine: a $235 medical bill for a telehealth visit that resulted from one of my kids calling a longtime doctor’s office. It was for a five-minute phone call answering a question about a possible infection.

Virtual communications have streamlined life and transformed many of our relationships for the better. There is little need anymore to sit across the desk from a tax accountant or travel agent or to stand in a queue for a bank teller. And there is certainly room for disruptive digital innovation in our confusing and overpriced health care system.

But it remains an open question whether virtual medicine will prove a valuable, convenient adjunct to health care. Or, instead, will it be a way for the U.S. profit-driven health care system to make big bucks by outsourcing core duties – while providing a paler version of actual medical treatment?

After all, my doctors have long answered my questions and dispensed phone and email advice for free – as part of our doctor-patient relationship – though it didn’t have a cool branding moniker like telehealth. And my obstetrician’s office offered great support and advice through two difficult pregnancies – maybe they should have been paid for that valuable service. But $235 for a phone call (which works out to over $2,000 per hour)? Not even a corporate lawyer bills that.

Logic holds that some digital health tools have tremendous potential: A neurologist can view a patient by video to see if lopsided facial movements suggest a stroke. A patient with an irregular heart rhythm could send in digital tracings to see if a new prescription drug is working. But the tangible benefit of many other virtual services offered is less certain. Some people may like receiving feedback about their sleep from an Apple Watch, but I’m not sure that’s medicine.

And if virtual medicine is pursued in the name of business efficiency or just profit, it has enormous potential to make health care worse.

My doctor’s nurse is far better equipped to answer a question about my ongoing health problem than someone at a call center reading from a script. And, however thorough a virtual visit may be, it forsakes some of the diagnostic information that comes when you see and touch the patient.

A study published recently in Pediatrics found that children who had a telemedicine visit for an upper respiratory infection were far more likely to get an antibiotic than those who physically saw a doctor, suggesting overprescribing is at work. It makes sense: A doctor can’t use a stethoscope to listen to lungs or wiggle an otoscope into a kid’s ear by video. Similarly, a virtual physical therapist can’t feel the knots in muscle or notice a fleeting wince on a patient’s face via camera.

More important, perhaps, virtual medicine means losing the support that has long been a crucial part of the profession. There are programs to provide iPads to people in home hospice for resources about grief and chatbots that purport to treat depression. Maybe people at such challenging moments need – and deserve – human contact.

Of course, companies like those mentioned are expecting to be reimbursed for the remote monitoring and virtual advice they provide. Investors, in turn, get generous payback without having to employ so many actual doctors or other health professionals. Livongo, for instance, has raised a total of $235 million in funding over six rounds. And, as of 2018, Medicare announced it would allow such digital monitoring tools to “qualify for reimbursement,” if they are “clinically endorsed.” But, ultimately, will the well-being of patients or investors decide which tools are clinically endorsed?

So far, with its new so-called skill, Alexa will be able to perform a half-dozen health-related services. In addition to diabetes coaching, it can find the earliest urgent care appointment in a given area and check the status of a prescription drug delivery.

But it will not provide many things patients desperately want, which technology should be able to readily deliver, such as a reliable price estimate for an upcoming surgery, the infection rates at the local hospital, the location of the cheapest cholesterol test nearby. And if we’re trying to bring health care into the tech-enabled 21st century, how about starting with low-hanging fruit: Does any other sector still use paper bills and faxes?

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Modern surgical techniques for gastrointestinal endometriosis

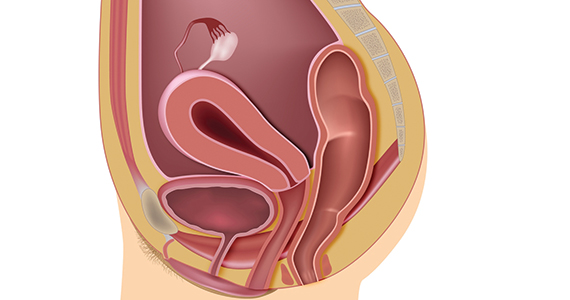

About 10% of all reproductive-aged women and 35% to 50% of women with pelvic pain and infertility are affected by endometriosis.1,2 The disease typically involves the reproductive tract organs, anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and uterosacral ligaments. However, disease outside of the reproductive tract occurs frequently and has been found on all organs except the spleen.3

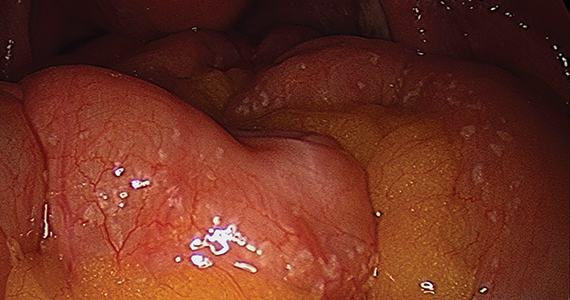

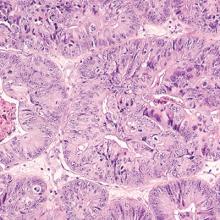

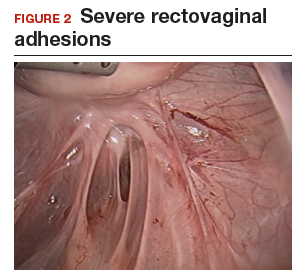

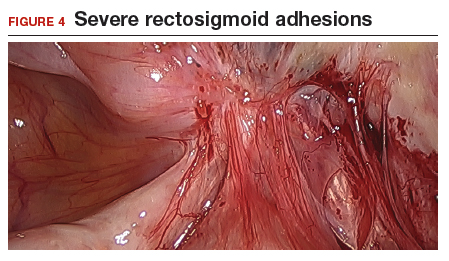

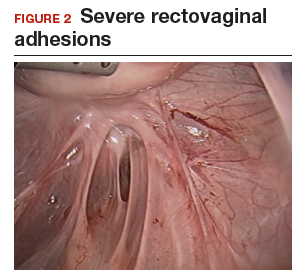

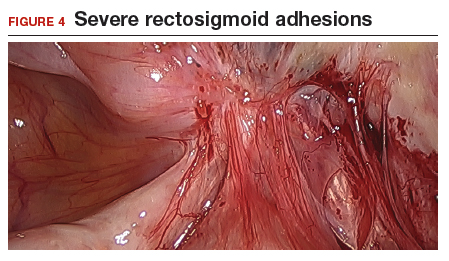

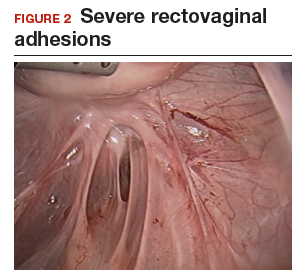

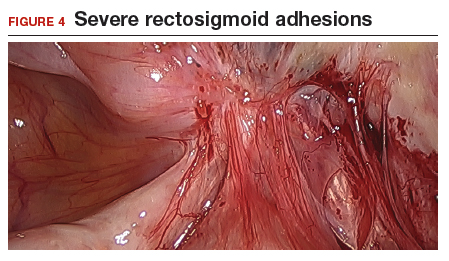

The bowel is the most common site for extragenital endometriosis, affected in an estimated 3.8% to 37% of patients with known endometriosis.4-7 Implants may be superficial, involving the bowel serosa and subserosa (FIGURE 1), or they can manifest as deeply infiltrating lesions involving the muscularis and mucosa (FIGURE 2). The rectosigmoid colon is the most common location for bowel endometriosis, followed by the rectum, ileum, appendix, and cecum4,8 (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5). Case reports also have described endometrial implants on the stomach and transverse colon.9 Although isolated bowel involvement has been recognized, most patients with bowel endometriosis have concurrent disease elsewhere.2,4

Historically, segmental resection was performed regardless of the anatomical location of the lesion.10 Even today, many surgeons continue to routinely perform segmental bowel resection as a first-line surgical approach.11 Unnecessary segmental resection, however, places patients at risk for short- and long-term postoperative morbidity, including the possibility of permanent ostomy. Modern surgical techniques, such as shaving excision and disc resection, have been performed to successfully treat bowel endometriosis with excellent long-term outcomes and fewer complications when compared with traditional segmental resection.2,12-16

In this article, we focus on the clinical indications and surgical techniques for video-laparoscopic management, but first we describe the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of bowel endometriosis.

Pathophysiology of bowel endometriosis

The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains unknown, as no single mechanism explains all clinical cases of the disease. The most popular proposed theory describes retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.17 Once inside the peritoneal cavity, endometrial cells attach to and invade healthy peritoneum, establishing a blood supply necessary for growth and survival.

In the case of bowel endometriosis, deposition of effluxed endometrial cells may lead to an inflammatory response that increases the risk of adhesion formation, leading to potential cul-de-sac obliteration. Lesions may originate as Allen-Masters peritoneal defects, developing into deeply infiltrative rectovaginal septum lesions. The anatomical shelter theory contributes to lesions within the pelvis, with the rectosigmoid colon blocking the cephalad flow of effluxed menstrual blood from the pelvis, thus leading to a preponderance of lesions in the pelvis and along the rectosigmoid colon.2

Continue to: Clinical presentation and diagnosis...

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Women presenting with endometriosis of the bowel are typically of reproductive age and commonly report symptoms of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dyschezia. Some women also experience catamenial diarrhea, constipation, hematochezia, and bloating.2 The differential diagnosis of these symptoms is broad and includes irritable bowel disease, ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and malignancy.

Because of its nonspecific symptoms, bowel endometriosis is often misdiagnosed and the disease goes untreated for years.18 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating reproductive-aged women with gastrointestinal symptoms and pelvic pain.

Physical examination can be helpful in making the diagnosis of endometriosis. During bimanual examination, findings such as a fixed, tender, or retroverted uterus, uterosacral ligament nodularity, or an enlarged adnexal mass representing an ovarian endometrioma may be appreciated. Rectovaginal exam can identify areas of tenderness and nodularity along the rectovaginal septum. Speculum exam may reveal a laterally displaced cervix or blue powder-burn lesions along the cervix or posterior fornix.19 Rarely, endometriosis is found on the perineum within an episiotomy scar.20

Imaging studies can be used in conjunction with physical examination findings to aid in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Images also guide preoperative planning by characterizing lesions based on their size, location, and depth of invasion. Hudelist and colleagues found transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) to have an overall sensitivity of 71% to 98% and a specificity of 92% to 100%.21 However, it was noted that the accuracy of the diagnosis was directly related to the experience of the sonographer, and lesions above the sigmoid colon were generally unable to be diagnosed. Other imaging modalities that have been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing bowel endometriosis include rectal water contrast TVUS,22,23 rectal endoscopic sonography,22 magnetic resonance imaging,22 and barium enema.24

Medical management

Medical therapy for patients with endometriosis is utilized with the goal of suppressing ovulation, lowering circulating hormone levels, and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly employed include gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists, anabolic steriods such as danazol, combined oral contraceptive pills, progestins, and aromatase inhibitors.

Continue to: To date, no optimal hormonal regimen...

To date, no optimal hormonal regimen has been established for the treatment of bowel endometriosis. Vercellini and colleagues demonstrated that progestins with and without low-dose estrogen improved symptoms of dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia.25 Ferrero and colleagues reported that 2.5 mg of norethindrone daily resulted in 53% of women with colorectal endometriosis reporting improved gastrointestinal symptoms.26 However, by 12 months of follow-up, 33% of these patients had elected to undergo surgical management.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, such as leuprolide acetate, also can be used to mitigate symptoms of bowel endometriosis or to decrease disease burden at the time of surgery, and they can be used with add-back norethindrone acetate. The use of these medications is limited by adverse effects, such as vasomotor symptoms and decreased bone mineral density when used for longer than 6 months.2

Medical therapy is commonly used for patients with mild to moderate symptoms and in those who are poor surgical candidates or decline surgical intervention. Medical therapy is especially useful when employed postoperatively to suppress the regrowth of microscopic ectopic endometrial tissue.

Patients must be counseled, however, that even with medical management, they may still require surgery in the future to control their symptoms and/or to preserve organ function.2

Surgical management

Surgical treatment for bowel endometriosis depends on the disease location, the size and depth of the lesion, the presence or absence of stricture, and the surgeon’s level of expertise.2,12,27-30

In our group, we advocate for video-laparoscopy, with or without robotic as sistance. Minimally invasive surgery offers reduced blood loss, shorter recovery time, and fewer postoperative complications compared with laparotomy.2,16,27,31-33 The conversion rate to laparotomy has been reported to be about 3% when performed by an experienced surgeon.12

Darai and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of 52 patients undergoing surgery for colorectal endometriosis via either laparoscopic or open colon resection.33 Blood loss was significantly lower in the laparoscopy group (1.6 vs 2.7 mg/L, P <.05). No difference was noted in long-term outcomes. In a retrospective study of 436 cases, Ruffo and colleagues showed that those who underwent laparoscopic colorectal resection had higher postoperative pregnancy rates compared with those who had laparotomy (57.6% vs 23.1%, P <.035).32

The goal of surgical management of bowel endometriosis is to remove as many of the endometriotic lesions as possible while minimizing short- and long-term complications. Three surgical approaches have been described: shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection.2

Some surgeons prefer traditional segmental resection of the bowel regardless of the anatomical site, citing reduced disease recurrence with this approach; however, traditional segmental resection confers increased risk of complications. Increasingly, in an effort to reduce morbidity, more surgeons are advocating for the less aggressive methods of shaving excision and disc resection.

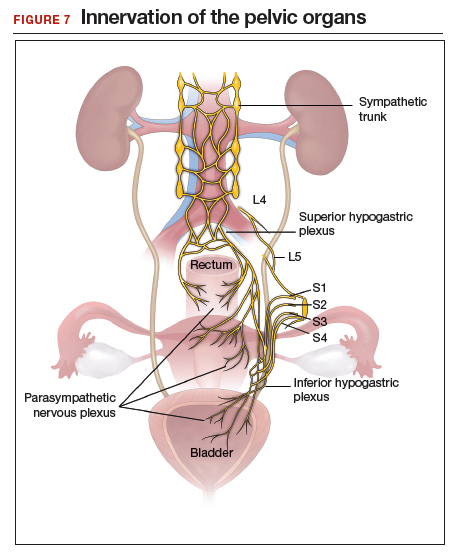

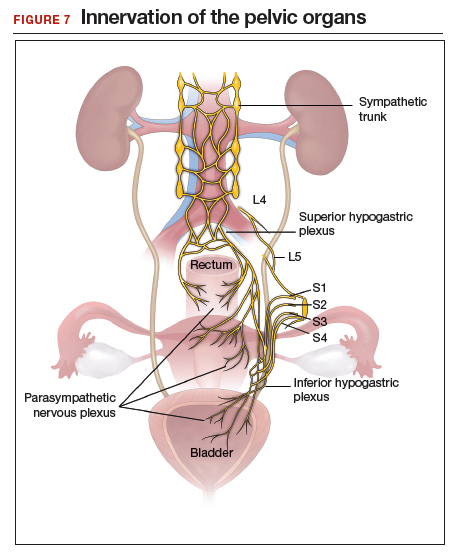

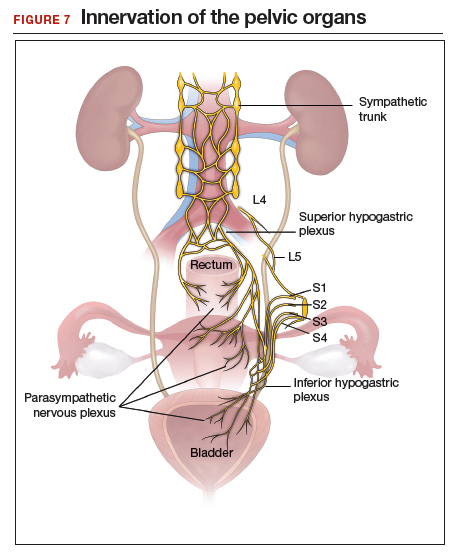

Aggressive resection at the level of the low rectum requires extensive surgical dissection of the retrorectal space, with the potential for inadvertent injury to surrounding neurovascular structures, such as the pelvic splanchnic nerves and superior and inferior hypogastric plexus.29 Injury to these structures can lead to significant complications, including bowel stenosis, fistula formation, constipation, and urinary retention. Complete resection of other areas, such as the small bowel, do not carry the same risks and may have more significant benefit to the patient than less aggressive techniques.

Our group recommends carefully balancing the risks and benefits of aggressive surgical treatment for each individual and treating the patient with the appropriate technique. Regardless of technique, surgical treatment of bowel endometriosis can lead to long-term improvements in pain and infertility.29,30,34,35

- The clinical presentation of bowel endometriosis is often nonspecific, with a broad differential diagnosis. Maintain a high index of suspicion when reproductive-aged women present for evaluation of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, bloating, dyschezia, or hematochezia.

- Symptomatic patients not desiring fertility, poor surgical candidates, and those declining surgical intervention may benefit from medical management. Patients who fail medical therapy, have severe symptoms, or experience infertility are candidates for surgical intervention.

- Surgical management involves shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection. Some surgeons advocate for aggressive segmental resection regardless of the endometriotic lesion's location. Based on our extensive experience, we prefer shaving excision for lesions below the sigmoid to avoid dissection into the retrorectal space and inadvertent injury to nerve tissue controlling bowel and bladder function.

- Following shaving excision, patients experience low complication rates29,39,40 and favorable long-term outcomes.15,40,56 For lesions above the sigmoid colon, including the small bowel, segmental resection or disc resection for smaller lesions are reasonable surgical approaches.

Continue to: Shaving excision...

Shaving excision

The most conservative approach to resection of bowel endometriosis is shaving excision; this involves removing endometriotic tissue layer-by-layer until healthy, underlying tissue is encountered.2 With bowel endometriosis, the goal of shaving excision is to remove as much of the diseased tissue as possible while leaving behind the mucosal layer and a portion of the muscularis.2,15,16,36-38 This is the most conservative of the 3 surgical techniques and is associated with the lowest complication rate.2,14,15,36,37

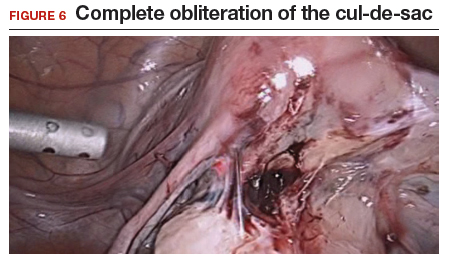

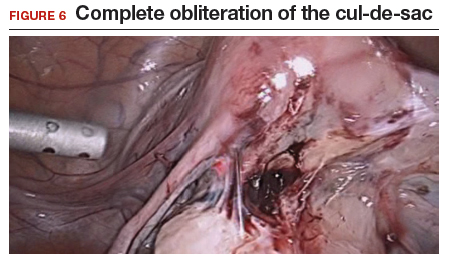

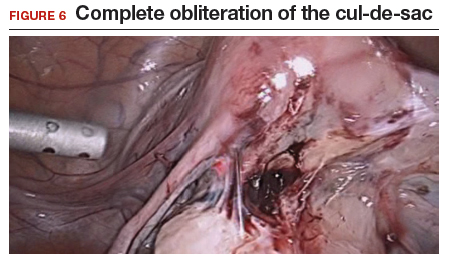

Our group reported on 185 women who underwent shaving excision for bowel endometriosis. At the time of surgery, 80 women had complete obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURE 6). Of the study patients, 174 patients were available for follow-up, with 93% reporting moderate to complete pain relief.15

In a retrospective analysis of 3,298 surgeries for rectovaginal endometriosis in which shaving excision was used on all but 1% of patients, Donnez and colleagues reported a very low complication rate, with 1 case of rectal perforation, 1 case of fecal peritonitis, and 3 cases of ureteral injury.39

Roman and colleagues described the use of shaving excision for rectal endometriosis using plasma energy (n = 54) and laparoscopic scissors (n = 68).40 Only 4% of patients reported experiencing symptom recurrence, and the pregnancy rate was 65.4%, with 59% of those patients spontaneously conceiving. Two cases of rectal fistula were noted.

Disc resection

Laparoscopic disc excision has been described in the literature since the 1980s, and the technique involves the full-thickness removal of the diseased portion of the bowel, followed by closure of the remaining defect.2,12-14,28,29,31,41-45 To be appropriate for this technique, a lesion should involve only a portion of the bowel wall and, preferably, less than one-half of the bowel circumference.2,42 Disc excision results in excellent outcomes with fewer postoperative complications than segmental resection, but with more complications when compared to shaving excision.2,12,13,29,45,46

We reported on a series of 141 women with bowel endometriosis who underwent disc excision.2 At 1-month follow-up, 87% of patients experienced an improvement in their symptoms. No cases required conversion to laparotomy or were complicated by rectovaginal fistula formation, ureteral injury, bowel perforation, or pelvic abscess.2

Continue to: Segmental resection...

Segmental resection

The most aggressive surgical approach, segmental resection involves complete removal of a diseased portion of bowel, followed by side-to-side or end-to-end reanastomosis of the adjacent segments.2 For this procedure, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended, with involvement of a colorectal surgeon or gynecologic oncologist trained in performing bowel resections. Segmental resection is indicated for lesions that are larger than 3 cm, circumferential, obstructive, or multifocal.

Given the higher complication rate associated with this procedure and the good outcomes associated with less invasive techniques, we avoid segmental resection whenever possible, especially for lesions near the anal verge.2

Complications associated with surgical approach

In 2005, our group reported on a cohort of 178 women who underwent laparoscopic treatment of deeply infiltrative bowel endometriosis with shaving excision (n = 93), disc excision (n = 38), and segmental resection (n = 47).34 The major complication rate was significantly higher for those undergoing segmental resection (12.5%, P <.001); only 7.7% of those who underwent disc resection experienced a major complication; and none were observed in the group treated with shaving excision.

In 2011, De Cicco and colleagues conducted a systematic review of 1,889 patients who underwent segmental bowel resection.35 The major complication rate was 11%, with a leakage rate of 2.7%, fistula rate of 1.8%, major obstruction rate of 2.7%, and hemorrhage rate of 2.5%. Many of these complications, however, occurred in patients who had low rectal resections.

Regardless of surgical approach, the complication rate is related to the surgeon’s ability to preserve the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses and the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve bundles (FIGURE 7). Nerve-sparing techniques should be used to decrease the incidence of postoperative bowel, bladder, and sexual function complications.2

Our group’s preferences

In our practice, we emphasize that the choice of surgical technique depends on the location, size, and depth of the lesion, as well as the extent of bowel wall circumferential invasion.2

We categorize lesions by their anatomic location: those above the sigmoid colon, on the sigmoid colon, on the rectosigmoid colon, and on the rectum. For lesions above the sigmoid colon, segmental or disc resection is appropriate.2 We recommend segmental resection for multifocal lesions, lesions larger than 3 cm, or for lesions involving more than one-third of the bowel lumen.37,44,45,47 Disc resection is appropriate for lesions smaller than 3 cm even if the bowel lumen is involved.44,45,48 If endometriosis is encountered in any location along the bowel, appendectomy can be performed even without visible disease, due to a high incidence of occult disease of the appendix.49,50

When lesions involve the sigmoid colon, we prefer utilizing shaving excision when possible to limit dissection of the retrorectal space and pelvic sidewall nerves.2 Segmental resection at or below the sigmoid colon has been associated with postoperative surgical site leakage51 and long-term bowel and bladder dysfunction with risk of permanent colostomy.52,53 For lesions smaller than 3 cm or involving less than one-third of the bowel lumen, disc resection can be performed. Segmental resection is required if multifocal disease or obstruction are present, if lesions are larger than 3 cm, or if more than one-third of the bowel lumen is involved.

For lesions along the rectosigmoid colon, we prefer utilizing shaving excision when possible.2 Disc excision can be performed utilizing a transanal approach, being mindful to minimize dissection of the retroperitoneal space and pelvic sidewall nerves.48 Segmental resection is avoided even with lesions larger than 3 cm, unless prior surgery has failed. Approaches for segmental resection can utilize laparoscopy or the natural orifices of the rectum or vagina.31,51

For lesions on the rectum, we strongly advise shaving excision.2 Evidence fails to show that the benefits of segmental resection outweigh the risks when compared to conservative techniques at the rectum.30,39,54 There is evidence indicating that aggressive surgery 5 to 8 cm from the anal verge is predictive of postoperative complications.55 In our group, we use shaving excision to remove as much disease as possible without compromising the integrity of the bowel wall or surrounding neurovascular structures. We err on the side of caution, leaving some of the disease on the rectum to avoid rectal perforation, and plan for postoperative hormonal suppression in these patients.

For patients desiring fertility, successful pregnancy is often achieved using the shaving technique.41

- Giudice LC. Clinical practice. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2389-2398.

- Nezhat C, Li A, Falik R, et al. Bowel endometriosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:549-562.

- Markham SM, Carpenter SE, Rock JA. Extrapelvic endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:193-219.

- Veeraswamy A, Lewis M, Mann A, et al. Extragenital endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:449-466.

- Redwine DB. Ovarian endometriosis: a marker for more extensive pelvic and intestinal disease. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:310-315.

- Weed JC, Ray JE. Endometriosis of the bowel. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:727-730.

- Wheeler JM. Epidemiology of endometriosis-associated infertility. J Reprod Med. 1989;34:41-46.

- Redwine DB. Intestinal endometriosis. In: Redwine DB. Surgical Management of Endometriosis. New York, NY: Martin Dunitz; 2004:196.

- Hartmann D, Schilling D, Roth SU, et al. [Endometriosis of the transverse colon--a rare localization]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2002;127:2317-2320.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Endometriosis: ancient disease, ancient treatments. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(6 suppl):S1-62.

- Macafee CH, Greer HL. Intestinal endometriosis. A report of 29 cases and a survey of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1960;67:539-555.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Ambroze W, et al. Laparoscopic repair of small bowel and colon. A report of 26 cases. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:88-89.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Pennington E, et al. Laparoscopic disk excision and primary repair of the anterior rectal wall for the treatment of full-thickness bowel endometriosis. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:682-685.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Evaluation of safety of videolaseroscopic treatment of bowel endometriosis. Presented at: 44th Annual Meeting of the American Fertility Society; October, 1988; Atlanta, GA.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Pennington E. Laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative rectosigmoid colon and rectovaginal septum endometriosis by the technique of videolaparoscopy and the CO2 laser. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:664-667.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1986;45:778-783.

- Sourial S, Tempest N, Hapangama DK. Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:179515.

- Skoog SM, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Levy MJ, et al. Intestinal endometriosis: the great masquerader. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6:405-409.

- Alabiso G, Alio L, Arena S, et al. How to manage bowel endometriosis: the ETIC approach. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:517-529.

- Heller DS, Lespinasse P, Mirani N. Endometriosis of the perineum: a rare diagnosis usually associated with episiotomy. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:e48-e49.

- Hudelist G, English J, Thomas AE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for non-invasive diagnosis of bowel endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:257-263.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, et al. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591.

- Menada MV, Remorgida V, Abbamonte LH, et al. Transvaginal ultrasonography combined with water-contrast in the rectum in the diagnosis of rectovaginal endometriosis infiltrating the bowel. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:699-700.

- Gordon RL, Evers K, Kressel HY, et al. Double-contrast enema in pelvic endometriosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;138:549-552.

- Vercellini P, Pietropaolo G, De Giorgi O, et al. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen-progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1375-1387.

- Ferrero S, Camerini G, Ragni N, et al. Norethisterone acetate in the treatment of colorectal endometriosis: a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:94-100.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic treatment of bowel, bladder, and ureteral endometriosis. JSLS. 2011;15:387-392.

- Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Laparoscopic management of bowel endometriosis: predictors of severe disease and recurrence. JSLS. 2011;15:431-438.

- Roman H, Milles M, Vassilieff M, et al. Long-term functional outcomes following colorectal resection versus shaving for rectal endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:762.e1-762.e9.

- Kent A, Shakir F, Rockall T, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for severe rectovaginal endometriosis compromising the bowel: a prospective cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:526-534.

- Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Pennington E. Laparoscopic proctectomy for infiltrating endometriosis of the rectum. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:1129-1132.

- Ruffo G, Scopelliti F, Scioscia M, et al. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis: analysis of 436 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:63-67.

- Darai E, Dubernard G, Coutant C, et al. Randomized trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open colorectal resection for endometriosis: morbidity, symptoms, quality of life, and fertility. Ann Surg. 2010;251:1018-1023.

- Mohr C, Nezhat FR, Nezhat CH, et al. Fertility considerations in laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative bowel endometriosis. JSLS. 2005;9:16-24.

- De Cicco C, Corona R, Schonman R, et al. Bowel resection for deep endometriosis: a systematic review. BJOG. 2011;118:285-291.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat FR. Safe laser endoscopic excision or vaporization of peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:149-151.

- Donnez J, Squifflet J. Complications, pregnancy and recurrence in a prospective series of 500 patients operated on by the shaving technique for deep rectovaginal endometriotic nodules. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1949-1958.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy and videolaseroscopy. Contrib Gynecol Obstet. 1987;16:303-312.

- Donnez J, Jadoul P, Colette S, et al. Deep rectovaginal endometriotic nodules: perioperative complications from a series of 3,298 patients operated on by the shaving technique. Gynecol Surg. 2013;10:31-40.

- Roman H, Moatassim-Drissa S, Marty N, et al. Rectal shaving for deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum: a 5-year continuous retrospective series. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:1438-1445.e2.

- Mohr C, Nezhat FR, Nezhat CH, et al. Fertility considerations in laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative bowel endometriosis. JSLS. 2005;9:16-24.

- Jerby BL, Kessler H, Falcone T, et al. Laparoscopic management of colorectal endometriosis. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1125-1128.

- Coronado C, Franklin RR, Lotze EC, et al. Surgical treatment of symptomatic colorectal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:411-416.

- Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Gagliardi ML, et al. Discoid or segmental rectosigmoid resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis: a case-control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:444-449.

- Landi S, Pontrelli G, Surico D, et al. Laparoscopic disk resection for bowel endometriosis using a circular stapler and a new endoscopic method to control postoperative bleeding from the stapler line. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:205-209.

- Slack A, Child T, Lindsey I, et al. Urological and colorectal complications following surgery for rectovaginal endometriosis. BJOG. 2007;114:1278-1282.

- Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Bruni F, et al. Nerve-sparing laparoscopic eradication of deep endometriosis with segmental rectal and parametrial resection: the Negrar method. A single-center, prospective, clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2029-2045.

- Roman H, Abo C, Huet E, et al. Deep shaving and transanal disc excision in large endometriosis of mid and lower rectum: the Rouen technique. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2626-2627.

- Gustofson RL, Kim N, Liu S, et al. Endometriosis and the appendix: a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:298-303.

- Berker B, Lashay N, Davarpanah R, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy in patients with endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:206-209.

- Ret Dávalos ML, De Cicco C, D'Hoore A, et al. Outcome after rectum or sigmoid resection: a review for gynecologists. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:33-38.

- Alves A, Panis Y, Mathieu P, et al; Association Française de Chirurgie (AFC). Mortality and morbidity after surgery of mid and low rectal cancer. Results of a French prospective multicentric study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:509-514.

- Camilleri-Brennan J, Steele RJ. Objective assessment of morbidity and quality of life after surgery for low rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:61-66.

- Acien P, Núñez C, Quereda F, et al. Is a bowel resection necessary for deep endometriosis with rectovaginal or colorectal involvement? Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:449-455.

- Abrão MS, Petraglia F, Falcone T, et al. Deep endometriosis infiltrating the recto-sigmoid: critical factors to consider before management. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:329-339.

- Donnez J, Nisolle M, Gillerot S, et al. Rectovaginal septum adenomyotic nodules: a series of 500 cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1014-1018.

About 10% of all reproductive-aged women and 35% to 50% of women with pelvic pain and infertility are affected by endometriosis.1,2 The disease typically involves the reproductive tract organs, anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and uterosacral ligaments. However, disease outside of the reproductive tract occurs frequently and has been found on all organs except the spleen.3

The bowel is the most common site for extragenital endometriosis, affected in an estimated 3.8% to 37% of patients with known endometriosis.4-7 Implants may be superficial, involving the bowel serosa and subserosa (FIGURE 1), or they can manifest as deeply infiltrating lesions involving the muscularis and mucosa (FIGURE 2). The rectosigmoid colon is the most common location for bowel endometriosis, followed by the rectum, ileum, appendix, and cecum4,8 (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5). Case reports also have described endometrial implants on the stomach and transverse colon.9 Although isolated bowel involvement has been recognized, most patients with bowel endometriosis have concurrent disease elsewhere.2,4

Historically, segmental resection was performed regardless of the anatomical location of the lesion.10 Even today, many surgeons continue to routinely perform segmental bowel resection as a first-line surgical approach.11 Unnecessary segmental resection, however, places patients at risk for short- and long-term postoperative morbidity, including the possibility of permanent ostomy. Modern surgical techniques, such as shaving excision and disc resection, have been performed to successfully treat bowel endometriosis with excellent long-term outcomes and fewer complications when compared with traditional segmental resection.2,12-16

In this article, we focus on the clinical indications and surgical techniques for video-laparoscopic management, but first we describe the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of bowel endometriosis.

Pathophysiology of bowel endometriosis

The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains unknown, as no single mechanism explains all clinical cases of the disease. The most popular proposed theory describes retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.17 Once inside the peritoneal cavity, endometrial cells attach to and invade healthy peritoneum, establishing a blood supply necessary for growth and survival.

In the case of bowel endometriosis, deposition of effluxed endometrial cells may lead to an inflammatory response that increases the risk of adhesion formation, leading to potential cul-de-sac obliteration. Lesions may originate as Allen-Masters peritoneal defects, developing into deeply infiltrative rectovaginal septum lesions. The anatomical shelter theory contributes to lesions within the pelvis, with the rectosigmoid colon blocking the cephalad flow of effluxed menstrual blood from the pelvis, thus leading to a preponderance of lesions in the pelvis and along the rectosigmoid colon.2

Continue to: Clinical presentation and diagnosis...

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Women presenting with endometriosis of the bowel are typically of reproductive age and commonly report symptoms of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dyschezia. Some women also experience catamenial diarrhea, constipation, hematochezia, and bloating.2 The differential diagnosis of these symptoms is broad and includes irritable bowel disease, ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and malignancy.

Because of its nonspecific symptoms, bowel endometriosis is often misdiagnosed and the disease goes untreated for years.18 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating reproductive-aged women with gastrointestinal symptoms and pelvic pain.

Physical examination can be helpful in making the diagnosis of endometriosis. During bimanual examination, findings such as a fixed, tender, or retroverted uterus, uterosacral ligament nodularity, or an enlarged adnexal mass representing an ovarian endometrioma may be appreciated. Rectovaginal exam can identify areas of tenderness and nodularity along the rectovaginal septum. Speculum exam may reveal a laterally displaced cervix or blue powder-burn lesions along the cervix or posterior fornix.19 Rarely, endometriosis is found on the perineum within an episiotomy scar.20

Imaging studies can be used in conjunction with physical examination findings to aid in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Images also guide preoperative planning by characterizing lesions based on their size, location, and depth of invasion. Hudelist and colleagues found transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) to have an overall sensitivity of 71% to 98% and a specificity of 92% to 100%.21 However, it was noted that the accuracy of the diagnosis was directly related to the experience of the sonographer, and lesions above the sigmoid colon were generally unable to be diagnosed. Other imaging modalities that have been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing bowel endometriosis include rectal water contrast TVUS,22,23 rectal endoscopic sonography,22 magnetic resonance imaging,22 and barium enema.24

Medical management

Medical therapy for patients with endometriosis is utilized with the goal of suppressing ovulation, lowering circulating hormone levels, and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly employed include gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists, anabolic steriods such as danazol, combined oral contraceptive pills, progestins, and aromatase inhibitors.

Continue to: To date, no optimal hormonal regimen...

To date, no optimal hormonal regimen has been established for the treatment of bowel endometriosis. Vercellini and colleagues demonstrated that progestins with and without low-dose estrogen improved symptoms of dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia.25 Ferrero and colleagues reported that 2.5 mg of norethindrone daily resulted in 53% of women with colorectal endometriosis reporting improved gastrointestinal symptoms.26 However, by 12 months of follow-up, 33% of these patients had elected to undergo surgical management.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, such as leuprolide acetate, also can be used to mitigate symptoms of bowel endometriosis or to decrease disease burden at the time of surgery, and they can be used with add-back norethindrone acetate. The use of these medications is limited by adverse effects, such as vasomotor symptoms and decreased bone mineral density when used for longer than 6 months.2

Medical therapy is commonly used for patients with mild to moderate symptoms and in those who are poor surgical candidates or decline surgical intervention. Medical therapy is especially useful when employed postoperatively to suppress the regrowth of microscopic ectopic endometrial tissue.

Patients must be counseled, however, that even with medical management, they may still require surgery in the future to control their symptoms and/or to preserve organ function.2

Surgical management

Surgical treatment for bowel endometriosis depends on the disease location, the size and depth of the lesion, the presence or absence of stricture, and the surgeon’s level of expertise.2,12,27-30

In our group, we advocate for video-laparoscopy, with or without robotic as sistance. Minimally invasive surgery offers reduced blood loss, shorter recovery time, and fewer postoperative complications compared with laparotomy.2,16,27,31-33 The conversion rate to laparotomy has been reported to be about 3% when performed by an experienced surgeon.12

Darai and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of 52 patients undergoing surgery for colorectal endometriosis via either laparoscopic or open colon resection.33 Blood loss was significantly lower in the laparoscopy group (1.6 vs 2.7 mg/L, P <.05). No difference was noted in long-term outcomes. In a retrospective study of 436 cases, Ruffo and colleagues showed that those who underwent laparoscopic colorectal resection had higher postoperative pregnancy rates compared with those who had laparotomy (57.6% vs 23.1%, P <.035).32

The goal of surgical management of bowel endometriosis is to remove as many of the endometriotic lesions as possible while minimizing short- and long-term complications. Three surgical approaches have been described: shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection.2

Some surgeons prefer traditional segmental resection of the bowel regardless of the anatomical site, citing reduced disease recurrence with this approach; however, traditional segmental resection confers increased risk of complications. Increasingly, in an effort to reduce morbidity, more surgeons are advocating for the less aggressive methods of shaving excision and disc resection.

Aggressive resection at the level of the low rectum requires extensive surgical dissection of the retrorectal space, with the potential for inadvertent injury to surrounding neurovascular structures, such as the pelvic splanchnic nerves and superior and inferior hypogastric plexus.29 Injury to these structures can lead to significant complications, including bowel stenosis, fistula formation, constipation, and urinary retention. Complete resection of other areas, such as the small bowel, do not carry the same risks and may have more significant benefit to the patient than less aggressive techniques.

Our group recommends carefully balancing the risks and benefits of aggressive surgical treatment for each individual and treating the patient with the appropriate technique. Regardless of technique, surgical treatment of bowel endometriosis can lead to long-term improvements in pain and infertility.29,30,34,35

- The clinical presentation of bowel endometriosis is often nonspecific, with a broad differential diagnosis. Maintain a high index of suspicion when reproductive-aged women present for evaluation of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, bloating, dyschezia, or hematochezia.

- Symptomatic patients not desiring fertility, poor surgical candidates, and those declining surgical intervention may benefit from medical management. Patients who fail medical therapy, have severe symptoms, or experience infertility are candidates for surgical intervention.

- Surgical management involves shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection. Some surgeons advocate for aggressive segmental resection regardless of the endometriotic lesion's location. Based on our extensive experience, we prefer shaving excision for lesions below the sigmoid to avoid dissection into the retrorectal space and inadvertent injury to nerve tissue controlling bowel and bladder function.

- Following shaving excision, patients experience low complication rates29,39,40 and favorable long-term outcomes.15,40,56 For lesions above the sigmoid colon, including the small bowel, segmental resection or disc resection for smaller lesions are reasonable surgical approaches.

Continue to: Shaving excision...

Shaving excision

The most conservative approach to resection of bowel endometriosis is shaving excision; this involves removing endometriotic tissue layer-by-layer until healthy, underlying tissue is encountered.2 With bowel endometriosis, the goal of shaving excision is to remove as much of the diseased tissue as possible while leaving behind the mucosal layer and a portion of the muscularis.2,15,16,36-38 This is the most conservative of the 3 surgical techniques and is associated with the lowest complication rate.2,14,15,36,37

Our group reported on 185 women who underwent shaving excision for bowel endometriosis. At the time of surgery, 80 women had complete obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURE 6). Of the study patients, 174 patients were available for follow-up, with 93% reporting moderate to complete pain relief.15

In a retrospective analysis of 3,298 surgeries for rectovaginal endometriosis in which shaving excision was used on all but 1% of patients, Donnez and colleagues reported a very low complication rate, with 1 case of rectal perforation, 1 case of fecal peritonitis, and 3 cases of ureteral injury.39

Roman and colleagues described the use of shaving excision for rectal endometriosis using plasma energy (n = 54) and laparoscopic scissors (n = 68).40 Only 4% of patients reported experiencing symptom recurrence, and the pregnancy rate was 65.4%, with 59% of those patients spontaneously conceiving. Two cases of rectal fistula were noted.

Disc resection

Laparoscopic disc excision has been described in the literature since the 1980s, and the technique involves the full-thickness removal of the diseased portion of the bowel, followed by closure of the remaining defect.2,12-14,28,29,31,41-45 To be appropriate for this technique, a lesion should involve only a portion of the bowel wall and, preferably, less than one-half of the bowel circumference.2,42 Disc excision results in excellent outcomes with fewer postoperative complications than segmental resection, but with more complications when compared to shaving excision.2,12,13,29,45,46

We reported on a series of 141 women with bowel endometriosis who underwent disc excision.2 At 1-month follow-up, 87% of patients experienced an improvement in their symptoms. No cases required conversion to laparotomy or were complicated by rectovaginal fistula formation, ureteral injury, bowel perforation, or pelvic abscess.2

Continue to: Segmental resection...

Segmental resection

The most aggressive surgical approach, segmental resection involves complete removal of a diseased portion of bowel, followed by side-to-side or end-to-end reanastomosis of the adjacent segments.2 For this procedure, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended, with involvement of a colorectal surgeon or gynecologic oncologist trained in performing bowel resections. Segmental resection is indicated for lesions that are larger than 3 cm, circumferential, obstructive, or multifocal.

Given the higher complication rate associated with this procedure and the good outcomes associated with less invasive techniques, we avoid segmental resection whenever possible, especially for lesions near the anal verge.2

Complications associated with surgical approach

In 2005, our group reported on a cohort of 178 women who underwent laparoscopic treatment of deeply infiltrative bowel endometriosis with shaving excision (n = 93), disc excision (n = 38), and segmental resection (n = 47).34 The major complication rate was significantly higher for those undergoing segmental resection (12.5%, P <.001); only 7.7% of those who underwent disc resection experienced a major complication; and none were observed in the group treated with shaving excision.

In 2011, De Cicco and colleagues conducted a systematic review of 1,889 patients who underwent segmental bowel resection.35 The major complication rate was 11%, with a leakage rate of 2.7%, fistula rate of 1.8%, major obstruction rate of 2.7%, and hemorrhage rate of 2.5%. Many of these complications, however, occurred in patients who had low rectal resections.

Regardless of surgical approach, the complication rate is related to the surgeon’s ability to preserve the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses and the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve bundles (FIGURE 7). Nerve-sparing techniques should be used to decrease the incidence of postoperative bowel, bladder, and sexual function complications.2

Our group’s preferences

In our practice, we emphasize that the choice of surgical technique depends on the location, size, and depth of the lesion, as well as the extent of bowel wall circumferential invasion.2

We categorize lesions by their anatomic location: those above the sigmoid colon, on the sigmoid colon, on the rectosigmoid colon, and on the rectum. For lesions above the sigmoid colon, segmental or disc resection is appropriate.2 We recommend segmental resection for multifocal lesions, lesions larger than 3 cm, or for lesions involving more than one-third of the bowel lumen.37,44,45,47 Disc resection is appropriate for lesions smaller than 3 cm even if the bowel lumen is involved.44,45,48 If endometriosis is encountered in any location along the bowel, appendectomy can be performed even without visible disease, due to a high incidence of occult disease of the appendix.49,50

When lesions involve the sigmoid colon, we prefer utilizing shaving excision when possible to limit dissection of the retrorectal space and pelvic sidewall nerves.2 Segmental resection at or below the sigmoid colon has been associated with postoperative surgical site leakage51 and long-term bowel and bladder dysfunction with risk of permanent colostomy.52,53 For lesions smaller than 3 cm or involving less than one-third of the bowel lumen, disc resection can be performed. Segmental resection is required if multifocal disease or obstruction are present, if lesions are larger than 3 cm, or if more than one-third of the bowel lumen is involved.

For lesions along the rectosigmoid colon, we prefer utilizing shaving excision when possible.2 Disc excision can be performed utilizing a transanal approach, being mindful to minimize dissection of the retroperitoneal space and pelvic sidewall nerves.48 Segmental resection is avoided even with lesions larger than 3 cm, unless prior surgery has failed. Approaches for segmental resection can utilize laparoscopy or the natural orifices of the rectum or vagina.31,51

For lesions on the rectum, we strongly advise shaving excision.2 Evidence fails to show that the benefits of segmental resection outweigh the risks when compared to conservative techniques at the rectum.30,39,54 There is evidence indicating that aggressive surgery 5 to 8 cm from the anal verge is predictive of postoperative complications.55 In our group, we use shaving excision to remove as much disease as possible without compromising the integrity of the bowel wall or surrounding neurovascular structures. We err on the side of caution, leaving some of the disease on the rectum to avoid rectal perforation, and plan for postoperative hormonal suppression in these patients.

For patients desiring fertility, successful pregnancy is often achieved using the shaving technique.41

About 10% of all reproductive-aged women and 35% to 50% of women with pelvic pain and infertility are affected by endometriosis.1,2 The disease typically involves the reproductive tract organs, anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, and uterosacral ligaments. However, disease outside of the reproductive tract occurs frequently and has been found on all organs except the spleen.3

The bowel is the most common site for extragenital endometriosis, affected in an estimated 3.8% to 37% of patients with known endometriosis.4-7 Implants may be superficial, involving the bowel serosa and subserosa (FIGURE 1), or they can manifest as deeply infiltrating lesions involving the muscularis and mucosa (FIGURE 2). The rectosigmoid colon is the most common location for bowel endometriosis, followed by the rectum, ileum, appendix, and cecum4,8 (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5). Case reports also have described endometrial implants on the stomach and transverse colon.9 Although isolated bowel involvement has been recognized, most patients with bowel endometriosis have concurrent disease elsewhere.2,4

Historically, segmental resection was performed regardless of the anatomical location of the lesion.10 Even today, many surgeons continue to routinely perform segmental bowel resection as a first-line surgical approach.11 Unnecessary segmental resection, however, places patients at risk for short- and long-term postoperative morbidity, including the possibility of permanent ostomy. Modern surgical techniques, such as shaving excision and disc resection, have been performed to successfully treat bowel endometriosis with excellent long-term outcomes and fewer complications when compared with traditional segmental resection.2,12-16

In this article, we focus on the clinical indications and surgical techniques for video-laparoscopic management, but first we describe the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of bowel endometriosis.

Pathophysiology of bowel endometriosis

The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains unknown, as no single mechanism explains all clinical cases of the disease. The most popular proposed theory describes retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.17 Once inside the peritoneal cavity, endometrial cells attach to and invade healthy peritoneum, establishing a blood supply necessary for growth and survival.

In the case of bowel endometriosis, deposition of effluxed endometrial cells may lead to an inflammatory response that increases the risk of adhesion formation, leading to potential cul-de-sac obliteration. Lesions may originate as Allen-Masters peritoneal defects, developing into deeply infiltrative rectovaginal septum lesions. The anatomical shelter theory contributes to lesions within the pelvis, with the rectosigmoid colon blocking the cephalad flow of effluxed menstrual blood from the pelvis, thus leading to a preponderance of lesions in the pelvis and along the rectosigmoid colon.2

Continue to: Clinical presentation and diagnosis...

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Women presenting with endometriosis of the bowel are typically of reproductive age and commonly report symptoms of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dyschezia. Some women also experience catamenial diarrhea, constipation, hematochezia, and bloating.2 The differential diagnosis of these symptoms is broad and includes irritable bowel disease, ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and malignancy.

Because of its nonspecific symptoms, bowel endometriosis is often misdiagnosed and the disease goes untreated for years.18 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating reproductive-aged women with gastrointestinal symptoms and pelvic pain.

Physical examination can be helpful in making the diagnosis of endometriosis. During bimanual examination, findings such as a fixed, tender, or retroverted uterus, uterosacral ligament nodularity, or an enlarged adnexal mass representing an ovarian endometrioma may be appreciated. Rectovaginal exam can identify areas of tenderness and nodularity along the rectovaginal septum. Speculum exam may reveal a laterally displaced cervix or blue powder-burn lesions along the cervix or posterior fornix.19 Rarely, endometriosis is found on the perineum within an episiotomy scar.20

Imaging studies can be used in conjunction with physical examination findings to aid in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Images also guide preoperative planning by characterizing lesions based on their size, location, and depth of invasion. Hudelist and colleagues found transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) to have an overall sensitivity of 71% to 98% and a specificity of 92% to 100%.21 However, it was noted that the accuracy of the diagnosis was directly related to the experience of the sonographer, and lesions above the sigmoid colon were generally unable to be diagnosed. Other imaging modalities that have been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing bowel endometriosis include rectal water contrast TVUS,22,23 rectal endoscopic sonography,22 magnetic resonance imaging,22 and barium enema.24

Medical management

Medical therapy for patients with endometriosis is utilized with the goal of suppressing ovulation, lowering circulating hormone levels, and inducing endometrial atrophy. Medications commonly employed include gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists, anabolic steriods such as danazol, combined oral contraceptive pills, progestins, and aromatase inhibitors.

Continue to: To date, no optimal hormonal regimen...

To date, no optimal hormonal regimen has been established for the treatment of bowel endometriosis. Vercellini and colleagues demonstrated that progestins with and without low-dose estrogen improved symptoms of dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia.25 Ferrero and colleagues reported that 2.5 mg of norethindrone daily resulted in 53% of women with colorectal endometriosis reporting improved gastrointestinal symptoms.26 However, by 12 months of follow-up, 33% of these patients had elected to undergo surgical management.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, such as leuprolide acetate, also can be used to mitigate symptoms of bowel endometriosis or to decrease disease burden at the time of surgery, and they can be used with add-back norethindrone acetate. The use of these medications is limited by adverse effects, such as vasomotor symptoms and decreased bone mineral density when used for longer than 6 months.2

Medical therapy is commonly used for patients with mild to moderate symptoms and in those who are poor surgical candidates or decline surgical intervention. Medical therapy is especially useful when employed postoperatively to suppress the regrowth of microscopic ectopic endometrial tissue.

Patients must be counseled, however, that even with medical management, they may still require surgery in the future to control their symptoms and/or to preserve organ function.2

Surgical management

Surgical treatment for bowel endometriosis depends on the disease location, the size and depth of the lesion, the presence or absence of stricture, and the surgeon’s level of expertise.2,12,27-30

In our group, we advocate for video-laparoscopy, with or without robotic as sistance. Minimally invasive surgery offers reduced blood loss, shorter recovery time, and fewer postoperative complications compared with laparotomy.2,16,27,31-33 The conversion rate to laparotomy has been reported to be about 3% when performed by an experienced surgeon.12

Darai and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of 52 patients undergoing surgery for colorectal endometriosis via either laparoscopic or open colon resection.33 Blood loss was significantly lower in the laparoscopy group (1.6 vs 2.7 mg/L, P <.05). No difference was noted in long-term outcomes. In a retrospective study of 436 cases, Ruffo and colleagues showed that those who underwent laparoscopic colorectal resection had higher postoperative pregnancy rates compared with those who had laparotomy (57.6% vs 23.1%, P <.035).32

The goal of surgical management of bowel endometriosis is to remove as many of the endometriotic lesions as possible while minimizing short- and long-term complications. Three surgical approaches have been described: shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection.2

Some surgeons prefer traditional segmental resection of the bowel regardless of the anatomical site, citing reduced disease recurrence with this approach; however, traditional segmental resection confers increased risk of complications. Increasingly, in an effort to reduce morbidity, more surgeons are advocating for the less aggressive methods of shaving excision and disc resection.

Aggressive resection at the level of the low rectum requires extensive surgical dissection of the retrorectal space, with the potential for inadvertent injury to surrounding neurovascular structures, such as the pelvic splanchnic nerves and superior and inferior hypogastric plexus.29 Injury to these structures can lead to significant complications, including bowel stenosis, fistula formation, constipation, and urinary retention. Complete resection of other areas, such as the small bowel, do not carry the same risks and may have more significant benefit to the patient than less aggressive techniques.

Our group recommends carefully balancing the risks and benefits of aggressive surgical treatment for each individual and treating the patient with the appropriate technique. Regardless of technique, surgical treatment of bowel endometriosis can lead to long-term improvements in pain and infertility.29,30,34,35

- The clinical presentation of bowel endometriosis is often nonspecific, with a broad differential diagnosis. Maintain a high index of suspicion when reproductive-aged women present for evaluation of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, bloating, dyschezia, or hematochezia.

- Symptomatic patients not desiring fertility, poor surgical candidates, and those declining surgical intervention may benefit from medical management. Patients who fail medical therapy, have severe symptoms, or experience infertility are candidates for surgical intervention.

- Surgical management involves shaving excision, disc resection, and segmental resection. Some surgeons advocate for aggressive segmental resection regardless of the endometriotic lesion's location. Based on our extensive experience, we prefer shaving excision for lesions below the sigmoid to avoid dissection into the retrorectal space and inadvertent injury to nerve tissue controlling bowel and bladder function.

- Following shaving excision, patients experience low complication rates29,39,40 and favorable long-term outcomes.15,40,56 For lesions above the sigmoid colon, including the small bowel, segmental resection or disc resection for smaller lesions are reasonable surgical approaches.

Continue to: Shaving excision...

Shaving excision

The most conservative approach to resection of bowel endometriosis is shaving excision; this involves removing endometriotic tissue layer-by-layer until healthy, underlying tissue is encountered.2 With bowel endometriosis, the goal of shaving excision is to remove as much of the diseased tissue as possible while leaving behind the mucosal layer and a portion of the muscularis.2,15,16,36-38 This is the most conservative of the 3 surgical techniques and is associated with the lowest complication rate.2,14,15,36,37

Our group reported on 185 women who underwent shaving excision for bowel endometriosis. At the time of surgery, 80 women had complete obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURE 6). Of the study patients, 174 patients were available for follow-up, with 93% reporting moderate to complete pain relief.15

In a retrospective analysis of 3,298 surgeries for rectovaginal endometriosis in which shaving excision was used on all but 1% of patients, Donnez and colleagues reported a very low complication rate, with 1 case of rectal perforation, 1 case of fecal peritonitis, and 3 cases of ureteral injury.39

Roman and colleagues described the use of shaving excision for rectal endometriosis using plasma energy (n = 54) and laparoscopic scissors (n = 68).40 Only 4% of patients reported experiencing symptom recurrence, and the pregnancy rate was 65.4%, with 59% of those patients spontaneously conceiving. Two cases of rectal fistula were noted.

Disc resection

Laparoscopic disc excision has been described in the literature since the 1980s, and the technique involves the full-thickness removal of the diseased portion of the bowel, followed by closure of the remaining defect.2,12-14,28,29,31,41-45 To be appropriate for this technique, a lesion should involve only a portion of the bowel wall and, preferably, less than one-half of the bowel circumference.2,42 Disc excision results in excellent outcomes with fewer postoperative complications than segmental resection, but with more complications when compared to shaving excision.2,12,13,29,45,46

We reported on a series of 141 women with bowel endometriosis who underwent disc excision.2 At 1-month follow-up, 87% of patients experienced an improvement in their symptoms. No cases required conversion to laparotomy or were complicated by rectovaginal fistula formation, ureteral injury, bowel perforation, or pelvic abscess.2

Continue to: Segmental resection...

Segmental resection

The most aggressive surgical approach, segmental resection involves complete removal of a diseased portion of bowel, followed by side-to-side or end-to-end reanastomosis of the adjacent segments.2 For this procedure, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended, with involvement of a colorectal surgeon or gynecologic oncologist trained in performing bowel resections. Segmental resection is indicated for lesions that are larger than 3 cm, circumferential, obstructive, or multifocal.

Given the higher complication rate associated with this procedure and the good outcomes associated with less invasive techniques, we avoid segmental resection whenever possible, especially for lesions near the anal verge.2

Complications associated with surgical approach

In 2005, our group reported on a cohort of 178 women who underwent laparoscopic treatment of deeply infiltrative bowel endometriosis with shaving excision (n = 93), disc excision (n = 38), and segmental resection (n = 47).34 The major complication rate was significantly higher for those undergoing segmental resection (12.5%, P <.001); only 7.7% of those who underwent disc resection experienced a major complication; and none were observed in the group treated with shaving excision.

In 2011, De Cicco and colleagues conducted a systematic review of 1,889 patients who underwent segmental bowel resection.35 The major complication rate was 11%, with a leakage rate of 2.7%, fistula rate of 1.8%, major obstruction rate of 2.7%, and hemorrhage rate of 2.5%. Many of these complications, however, occurred in patients who had low rectal resections.