User login

Consider measles vaccine booster in HIV-positive patients

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A “surprisingly low” prevalence of protective antibodies against measles is present in adolescents and adults living with HIV infection despite their prior vaccination against the resurgent disease, Raquel M. Simakawa, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“With the present concern about the global reemergence of measles, we should consider measuring measles antibodies in people living with HIV, especially those who acquired the infection vertically, and then revaccinating those with low titers,” said Dr. Simakawa of the Federal University of São Paolo.

She presented interim findings of an ongoing study of the measles immunologic status of persons living with HIV, which for this analysis included 57 patients who acquired HIV from their mother via vertical transmission and 24 with horizontally acquired HIV. The vertical-transmission group was significantly younger, with a median age of 20 years, compared with 31 years in the horizontal group, who were diagnosed with HIV infection at an average age of 24 years. The vast majority of subjects were on combination antiretroviral therapy. No detectable HIV viral load had been present for a median of 70 months in the vertical group and 25 months in the horizontal group.

Only a mere 7% of the vertical transmission group had protective levels of measles IgG antibodies as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as did 29% of the horizontal group. The likely explanation for the higher rate of protection in the horizontal group, she said, is that they received their routine measles vaccination before they acquired HIV infection, and some of them didn’t lose their protective antibodies during their immune system’s fight against HIV infection.

Session chair Nico G. Hartwig, MD, of Franciscus Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, posed a question: Given the sky-high rate of measles seronegativity status among the vertically transmitted HIV-positive group – the patient population pediatricians focus on – why bother to measure their measles antibody level? Why not just give them all a measles booster?

Dr. Simakawa replied that that’s worth considering in routine clinical practice now that her study has shown that this group is more vulnerable to measles because of their poor response to immunization. But the study is ongoing, with larger numbers of patients to be enrolled. Also, in the second phase of the study, which will include a control group, measles IgG antibodies will be remeasured 1 month after administration of a new dose of measles vaccine.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A “surprisingly low” prevalence of protective antibodies against measles is present in adolescents and adults living with HIV infection despite their prior vaccination against the resurgent disease, Raquel M. Simakawa, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“With the present concern about the global reemergence of measles, we should consider measuring measles antibodies in people living with HIV, especially those who acquired the infection vertically, and then revaccinating those with low titers,” said Dr. Simakawa of the Federal University of São Paolo.

She presented interim findings of an ongoing study of the measles immunologic status of persons living with HIV, which for this analysis included 57 patients who acquired HIV from their mother via vertical transmission and 24 with horizontally acquired HIV. The vertical-transmission group was significantly younger, with a median age of 20 years, compared with 31 years in the horizontal group, who were diagnosed with HIV infection at an average age of 24 years. The vast majority of subjects were on combination antiretroviral therapy. No detectable HIV viral load had been present for a median of 70 months in the vertical group and 25 months in the horizontal group.

Only a mere 7% of the vertical transmission group had protective levels of measles IgG antibodies as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as did 29% of the horizontal group. The likely explanation for the higher rate of protection in the horizontal group, she said, is that they received their routine measles vaccination before they acquired HIV infection, and some of them didn’t lose their protective antibodies during their immune system’s fight against HIV infection.

Session chair Nico G. Hartwig, MD, of Franciscus Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, posed a question: Given the sky-high rate of measles seronegativity status among the vertically transmitted HIV-positive group – the patient population pediatricians focus on – why bother to measure their measles antibody level? Why not just give them all a measles booster?

Dr. Simakawa replied that that’s worth considering in routine clinical practice now that her study has shown that this group is more vulnerable to measles because of their poor response to immunization. But the study is ongoing, with larger numbers of patients to be enrolled. Also, in the second phase of the study, which will include a control group, measles IgG antibodies will be remeasured 1 month after administration of a new dose of measles vaccine.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A “surprisingly low” prevalence of protective antibodies against measles is present in adolescents and adults living with HIV infection despite their prior vaccination against the resurgent disease, Raquel M. Simakawa, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“With the present concern about the global reemergence of measles, we should consider measuring measles antibodies in people living with HIV, especially those who acquired the infection vertically, and then revaccinating those with low titers,” said Dr. Simakawa of the Federal University of São Paolo.

She presented interim findings of an ongoing study of the measles immunologic status of persons living with HIV, which for this analysis included 57 patients who acquired HIV from their mother via vertical transmission and 24 with horizontally acquired HIV. The vertical-transmission group was significantly younger, with a median age of 20 years, compared with 31 years in the horizontal group, who were diagnosed with HIV infection at an average age of 24 years. The vast majority of subjects were on combination antiretroviral therapy. No detectable HIV viral load had been present for a median of 70 months in the vertical group and 25 months in the horizontal group.

Only a mere 7% of the vertical transmission group had protective levels of measles IgG antibodies as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as did 29% of the horizontal group. The likely explanation for the higher rate of protection in the horizontal group, she said, is that they received their routine measles vaccination before they acquired HIV infection, and some of them didn’t lose their protective antibodies during their immune system’s fight against HIV infection.

Session chair Nico G. Hartwig, MD, of Franciscus Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, posed a question: Given the sky-high rate of measles seronegativity status among the vertically transmitted HIV-positive group – the patient population pediatricians focus on – why bother to measure their measles antibody level? Why not just give them all a measles booster?

Dr. Simakawa replied that that’s worth considering in routine clinical practice now that her study has shown that this group is more vulnerable to measles because of their poor response to immunization. But the study is ongoing, with larger numbers of patients to be enrolled. Also, in the second phase of the study, which will include a control group, measles IgG antibodies will be remeasured 1 month after administration of a new dose of measles vaccine.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Breastfeeding protects against intussusception

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – in a German case-control study.

Two other potent risk factors for intussusception in children less than 1 year old were identified: a family history of intussusception, and an episode of gastroenteritis, Doris F. Oberle, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Oberle, of the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Langen, Germany, presented a retrospective study of 116 meticulously validated cases of intussusception in infancy treated at 19 German pediatric centers during 2010-2014 and 272 controls matched by birth month, sex, and location. A standardized interview was conducted with the parents of all study participants.

Rotavirus vaccine was added to the German national vaccination schedule in 2013. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, the risk of intussusception was increased by 5.4-fold following the first dose of the vaccine, compared with nonrecipients. However, subsequent doses of rotavirus vaccine were not associated with any excess risk.

In addition, a family history of intussusception was linked to a 4.2-fold increased risk, while an episode of gastroenteritis during the first year of life was associated with a 4.7-fold elevated risk.

In a novel finding, breastfeeding was independently associated with a 44% reduction in the risk of intussusception, compared with that of bottle-fed babies.

The most common presenting signs and symptoms of intussusception were vomiting, abdominal pain, hematochezia, pallor, and reduced appetite, each present in at least half of affected infants.

Dr. Oberle reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, supported by the Paul Ehrlich Institute.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – in a German case-control study.

Two other potent risk factors for intussusception in children less than 1 year old were identified: a family history of intussusception, and an episode of gastroenteritis, Doris F. Oberle, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Oberle, of the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Langen, Germany, presented a retrospective study of 116 meticulously validated cases of intussusception in infancy treated at 19 German pediatric centers during 2010-2014 and 272 controls matched by birth month, sex, and location. A standardized interview was conducted with the parents of all study participants.

Rotavirus vaccine was added to the German national vaccination schedule in 2013. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, the risk of intussusception was increased by 5.4-fold following the first dose of the vaccine, compared with nonrecipients. However, subsequent doses of rotavirus vaccine were not associated with any excess risk.

In addition, a family history of intussusception was linked to a 4.2-fold increased risk, while an episode of gastroenteritis during the first year of life was associated with a 4.7-fold elevated risk.

In a novel finding, breastfeeding was independently associated with a 44% reduction in the risk of intussusception, compared with that of bottle-fed babies.

The most common presenting signs and symptoms of intussusception were vomiting, abdominal pain, hematochezia, pallor, and reduced appetite, each present in at least half of affected infants.

Dr. Oberle reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, supported by the Paul Ehrlich Institute.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – in a German case-control study.

Two other potent risk factors for intussusception in children less than 1 year old were identified: a family history of intussusception, and an episode of gastroenteritis, Doris F. Oberle, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Oberle, of the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Langen, Germany, presented a retrospective study of 116 meticulously validated cases of intussusception in infancy treated at 19 German pediatric centers during 2010-2014 and 272 controls matched by birth month, sex, and location. A standardized interview was conducted with the parents of all study participants.

Rotavirus vaccine was added to the German national vaccination schedule in 2013. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, the risk of intussusception was increased by 5.4-fold following the first dose of the vaccine, compared with nonrecipients. However, subsequent doses of rotavirus vaccine were not associated with any excess risk.

In addition, a family history of intussusception was linked to a 4.2-fold increased risk, while an episode of gastroenteritis during the first year of life was associated with a 4.7-fold elevated risk.

In a novel finding, breastfeeding was independently associated with a 44% reduction in the risk of intussusception, compared with that of bottle-fed babies.

The most common presenting signs and symptoms of intussusception were vomiting, abdominal pain, hematochezia, pallor, and reduced appetite, each present in at least half of affected infants.

Dr. Oberle reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, supported by the Paul Ehrlich Institute.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Selecting First-line TKI Therapy

From the Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: To outline the approach to selecting a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) for initial treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and monitoring patients following initiation of therapy.

- Methods: Review of the literature and evidence-based guidelines.

- Results: The development and availability of TKIs has improved survival for patients diagnosed with CML. The life expectancy of patients diagnosed with chronic-phase CML (CP-CML) is similar to that of the general population, provided they receive appropriate TKI therapy and adhere to treatment. Selection of the most appropriate first-line TKI for newly diagnosed CP-CML requires incorporation of the patient’s baseline karyotype and Sokal or EURO risk score, and a clear understanding of the patient’s comorbidities. The adverse effect profile of all TKIs must be considered in conjunction with the patient’s ongoing medical issues to decrease the likelihood of worsening their current symptoms or causing a severe complication from TKI therapy. After confirming a diagnosis of CML and selecting the most appropriate TKI for first-line therapy, close monitoring and follow-up are necessary to ensure patients are meeting the desired treatment milestones. Responses in CML can be assessed based on hematologic parameters, cytogenetic results, and molecular responses.

- Conclusion: Given the successful treatments available for patients with CML, it is crucial to identify patients with this diagnosis; ensure they receive a complete, appropriate diagnostic workup including a bone marrow biopsy and aspiration with cytogenetic testing; and select the best therapy for each individual patient.

Keywords: chronic myeloid leukemia; CML; tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TKI; cancer; BCR-ABL protein.

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm that is characterized by the presence of the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome and uninhibited expansion of bone marrow stem cells. The Ph chromosome arises from a reciprocal translocation between the Abelson (ABL) region on chromosome 9 and the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) of chromosome 22 (t(9;22)(q34;q11.2)), resulting in the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene and its protein product, BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase.1 BCR-ABL has constitutive tyrosine kinase activity that promotes growth, replication, and survival of hematopoietic cells through downstream pathways, which is the driving factor in the pathogenesis of CML.1

CML is divided into 3 phases based on the number of myeloblasts observed in the blood or bone marrow: chronic, accelerated, and blast. Most cases of CML are diagnosed in the chronic phase (CP), which is marked by proliferation of primarily the myeloid element.

Typical treatment for CML involves lifelong use of oral BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Currently, 5 TKIs have regulatory approval for treatment of this disease. The advent of TKIs, a class of small molecules targeting the tyrosine kinases, particularly the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase, led to rapid changes in the management of CML and improved survival for patients. Patients diagnosed with chronic-phase CML (CP-CML) now have a life expectancy that is similar to that of the general population, as long as they receive appropriate TKI therapy and adhere to treatment. As such, it is crucial to identify patients with CML; ensure they receive a complete, appropriate diagnostic workup; and select the best therapy for each patient.

Epidemiology

According to SEER data estimates, 8430 new cases of CML were diagnosed in the United States in 2018. CML is a disease of older adults, with a median age of 65 years at diagnosis, and there is a slight male predominance. Between 2011 and 2015, the number of new CML cases was 1.8 per 100,000 persons. The median overall survival (OS) in patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML has not been reached.2 Given the effective treatments available for managing CML, it is estimated that the prevalence of CML in the United States will plateau at 180,000 patients by 2050.3

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

The diagnosis of CML is often suspected based on an incidental finding of leukocytosis and, in some cases, thrombocytosis. In many cases, this is an incidental finding on routine blood work, but approximately 50% of patients will present with constitutional symptoms associated with the disease. Characteristic features of the white blood cell differential include left-shifted maturation with neutrophilia and immature circulating myeloid cells. Basophilia and eosinophilia are often present as well. Splenomegaly is a common sign, present in 50% to 90% of patients at diagnosis. In those patients with symptoms related to CML at diagnosis, the most common presentation includes increasing fatigue, fevers, night sweats, early satiety, and weight loss. The diagnosis is confirmed by cytogenetic studies showing the Ph chromosome abnormality, t(9; 22)(q3.4;q1.1), and/or reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) showing BCR-ABL1 transcripts.

Testing

Bone marrow biopsy. There are 3 distinct phases of CML: CP, accelerated phase (AP), and blast phase (BP). Bone marrow biopsy and aspiration at diagnosis are mandatory in order to determine the phase of the disease at diagnosis. This distinction is based on the percentage of blasts, promyelocytes, and basophils present as well as the platelet count and presence or absence of extramedullary disease.4 The vast majority of patients at diagnosis have CML that is in the chronic phase. The typical appearance in CP-CML is a hypercellular marrow with granulocytic and occasionally megakaryocytic hyperplasia. In many cases, basophilia and/or eosinophilia are noted as well. Dysplasia is not a typical finding in CML.5 Bone marrow fibrosis can be seen in up to one-third of patients at diagnosis, and may indicate a slightly worse prognosis.6 Although a diagnosis of CML can be made without a bone marrow biopsy, complete staging and prognostication are only possible with information gained from this test, including baseline karyotype and confirmation of CP versus a more advanced phase of CML.

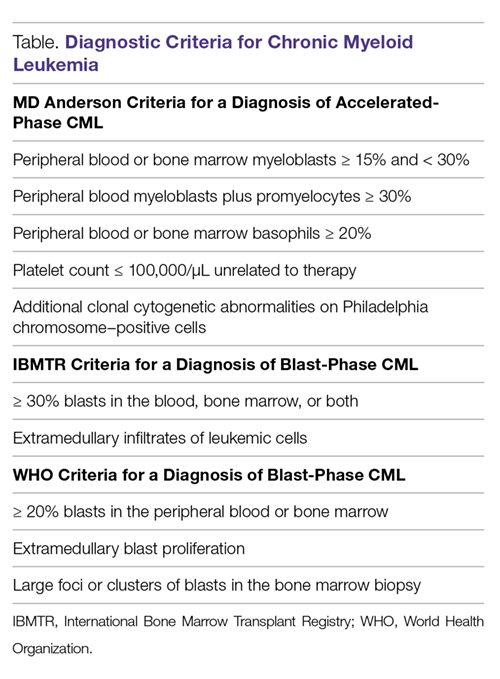

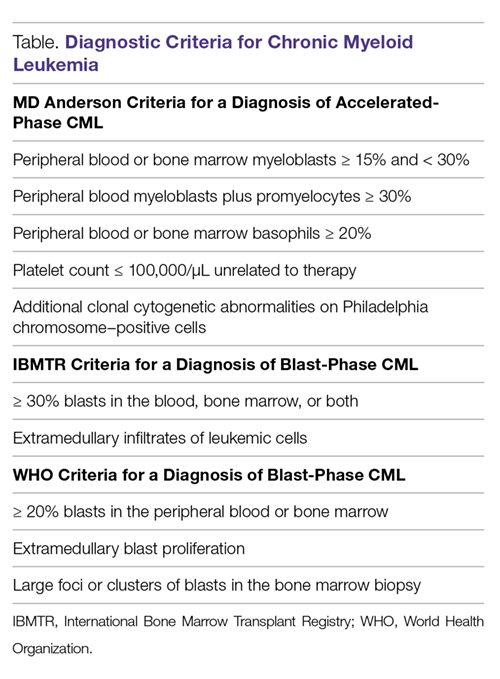

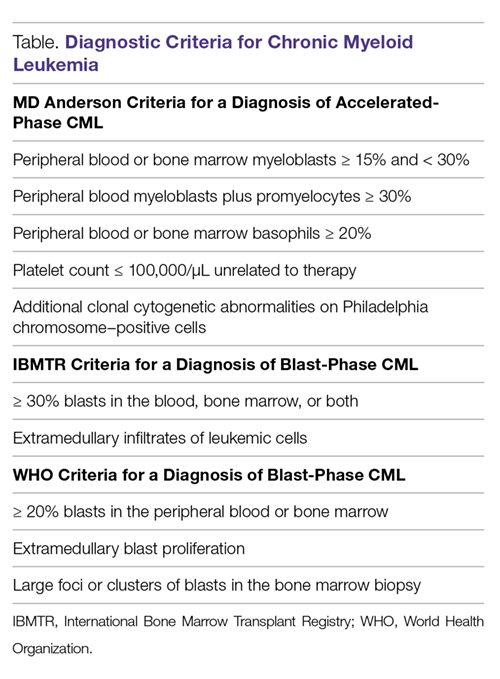

Diagnostic criteria. The criteria for diagnosing AP-CML has not been agreed upon by various groups, but the modified MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) criteria are used in the majority of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of TKIs in preventing progression to advanced phases of CML. MDACC criteria define AP-CML as the presence of 1 of the following: 15% to 29% blasts in the peripheral blood or bone marrow, ≥ 30% peripheral blasts plus promyelocytes, ≥ 20% basophils in the blood or bone marrow, platelet count ≤ 100,000/μL unrelated to therapy, and clonal cytogenetic evolution in Ph-positive metaphases (Table).7

BP-CML is typically defined using the criteria developed by the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry (IBMTR): ≥ 30% blasts in the peripheral blood and/or the bone marrow or the presence of extramedullary disease.8 Although not typically used in clinical trials, the revised World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for BP-CML include ≥ 20% blasts in the peripheral blood or bone marrow, extramedullary blast proliferation, and large foci or clusters of blasts in the bone marrow biopsy sample (Table).9

The defining feature of CML is the presence of the Ph chromosome abnormality. In a small subset of patients, additional chromosome abnormalities (ACA) in the Ph-positive cells may be identified at diagnosis. Some reports indicate that the presence of “major route” ACA (trisomy 8, isochromosome 17q, a second Ph chromosome, or trisomy 19) at diagnosis may negatively impact prognosis, but other reports contradict these findings.10,11

PCR assay. The typical BCR breakpoint in CML is the major breakpoint cluster region (M-BCR), which results in a 210-kDa protein (p210). Alternate breakpoints that are less frequently identified are the minor BCR (mBCR or p190), which is more commonly found in Ph-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and the micro BCR (µBCR or p230), which is much less common and is often characterized by chronic neutrophilia.12 Identifying which BCR-ABL1 transcript is present in each patient using qualitative PCR is crucial in order to ensure proper monitoring during treatment.

The most sensitive method for detecting BCR-ABL1 mRNA transcripts is the quantitative real-time PCR (RQ-PCR) assay, which is typically done on peripheral blood. RQ-PCR is capable of detecting a single CML cell in the presence of ≥ 100,000 normal cells. This test should be done during the initial diagnostic workup in order to confirm the presence of BCR-ABL1 transcripts, and it is used as a standard method for monitoring response to TKI therapy.13 The International Scale (IS) is a standardized approach to reporting RQ-PCR results that was developed to allow comparison of results across various laboratories and has become the gold standard for reporting BCR-ABL1 transcript values.14

Determining Risk Scores

Calculating a patient’s Sokal score or EURO risk score at diagnosis remains an important component of the diagnostic workup in CP-CML, as this information has prognostic and therapeutic implications (an online calculator is available through European LeukemiaNet [ELN]). The risk for disease progression to the accelerated or blast phases is higher in patients with intermediate or high risk scores compared to those with a low risk score at diagnosis. The risk of progression in intermediate- or high-risk patients is lower when a second-generation TKI (dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib) is used as frontline therapy compared to imatinib, and therefore, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) CML Panel recommends starting with a second-generation TKI in these patients.15-19

Monitoring Response to Therapy

After confirming a diagnosis of CML and selecting the most appropriate TKI for first-line therapy, the successful management of CML patients relies on close monitoring and follow-up to ensure they are meeting the desired treatment milestones. Responses in CML can be assessed based on hematologic parameters, cytogenetic results, and molecular responses. A complete hematologic response (CHR) implies complete normalization of peripheral blood counts (with the exception of TKI-induced cytopenias) and resolution of any palpable splenomegaly. The majority of patients will achieve a CHR within 4 to 6 weeks after initiating CML-directed therapy.20

Cytogenetic Response

Cytogenetic responses are defined by the decrease in the number of Ph chromosome–positive metaphases when assessed on bone marrow cytogenetics. A partial cytogenetic response (PCyR) is defined as having 1% to 35% Ph-positive metaphases, a major cytogenetic response (MCyR) as having 0% to 35% Ph-positive metaphases, and a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) implies that no Ph-positive metaphases are identified on bone marrow cytogenetics. An ideal response is the achievement of PCyR after 3 months on a TKI and a CCyR after 12 months on a TKI.21

Molecular Response

Once a patient has achieved a CCyR, monitoring their response to therapy can only be done using RQ-PCR to measure BCR-ABL1 transcripts in the peripheral blood. The NCCN and the ELN recommend monitoring RQ-PCR from the peripheral blood every 3 months in order to assess response to TKIs.19,22 As noted, the IS has become the gold standard reporting system for all BCR-ABL1 transcript levels in the majority of laboratories worldwide.14,23 Molecular responses are based on a log reduction in BCR-ABL1 transcripts from a standardized baseline. Many molecular responses can be correlated with cytogenetic responses such that, if reliable RQ-PCR testing is available, monitoring can be done using only peripheral blood RQ-PCR rather than repeat bone marrow biopsies. For example, an early molecular response (EMR) is defined as a RQ-PCR value of ≤ 10% IS, which is approximately equivalent to a PCyR.24 A value of 1% IS is approximately equivalent to a CCyR. A major molecular response (MMR) is a ≥ 3-log reduction in BCR-ABL1 transcripts from baseline and is a value of ≤ 0.1% IS. Deeper levels of molecular response are best described by the log reduction in BCR-ABL1 transcripts, with a 4-log reduction denoted as MR4.0, a 4.5-log reduction as MR4.5, and so forth. Complete molecular response (CMR) is defined by the level of sensitivity of the RQ-PCR assay being used.14

The definition of relapsed disease in CML is dependent on the type of response the patient had previously achieved. Relapse could be the loss of a hematologic or cytogenetic response, but fluctuations in BCR-ABL1 transcripts on routine RQ-PCR do not necessarily indicate relapsed CML. A 1-log increase in the level of BCR-ABL1 transcripts with a concurrent loss of MMR should prompt a bone marrow biopsy in order to assess for the loss of CCyR, and thus a cytogenetic relapse; however, this loss of MMR does not define relapse in and of itself. In the setting of relapsed disease, testing should be done to look for possible ABL kinase domain mutations, and alternate therapy should be selected.19

Multiple reports have identified the prognostic relevance of achieving an EMR at 3 and 6 months after starting TKI therapy. Marin and colleagues reported that in 282 imatinib-treated patients, there was a significant improvement in 8-year OS, progression-free survival (PFS), and cumulative incidence of CCyR and CMR in patients who had BCR-ABL1 transcripts < 9.84% IS after 3 months on treatment.24 This data highlights the importance of early molecular monitoring in order to ensure the best outcomes for patients with CP-CML.

The NCCN CML guidelines and ELN recommendations both agree that an ideal response after 3 months on a TKI is BCR-ABL1 transcripts < 10% IS, but treatment is not considered to be failing at this point if the patient marginally misses this milestone. After 6 months on treatment, an ideal response is considered BCR-ABL1 transcripts < 1%–10% IS. Ideally, patients will have BCR-ABL1 transcripts < 0.1%–1% IS by the time they complete 12 months of TKI therapy, suggesting that these patients have at least achieved a CCyR.19,22 Even after patients achieve these early milestones, frequent monitoring by RQ-PCR is required to ensure that they are maintaining their response to treatment. This will help to ensure patient compliance with treatment and will also help to identify a select subset of patients who could potentially be considered for an attempt at TKI cessation (not discussed in detail here) after a minimum of 3 years on therapy.19,25

Selecting First-line TKI Therapy

Selection of the most appropriate first-line TKI for newly diagnosed CP-CML patients requires incorporation of many patient-specific factors. These factors include baseline karyotype and confirmation of CP-CML through bone marrow biopsy, Sokal or EURO risk score, and a thorough patient history, including a clear understanding of the patient’s comorbidities. The adverse effect profile of all TKIs must be considered in conjunction with the patient’s ongoing medical issues in order to decrease the likelihood of worsening their current symptoms or causing a severe complication from TKI therapy.

Imatinib

The management of CML was revolutionized by the development and ultimate regulatory approval of imatinib mesylate in 2001. Imatinib was the first small-molecule cancer therapy developed and approved. It acts by binding to the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding site in the catalytic domain of BCR-ABL, thus inhibiting the oncoprotein’s tyrosine kinase activity.26

The International Randomized Study of Interferon versus STI571 (IRIS) trial was a randomized phase 3 study that compared imatinib 400 mg daily to interferon alfa (IFNa) plus cytarabine. More than 1000 CP-CML patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to either imatinib or IFNa plus cytarabine and were assessed for event-free survival, hematologic and cytogenetic responses, freedom from progression to AP or BP, and toxicity. Imatinib was superior to the prior standard of care for all these outcomes.21 The long-term follow-up of the IRIS trial reported an 83% estimated 10-year OS and 79% estimated event-free survival for patients on the imatinib arm of this study.15 The cumulative rate of CCyR was 82.8%. Of the 204 imatinib-treated patients who could undergo a molecular response evaluation at 10 years, 93.1% had a MMR and 63.2% had a MR4.5, suggesting durable, deep molecular responses for many patients. The estimated 10-year rate of freedom from progression to AP or BP was 92.1%.

Higher doses of imatinib (600-800 mg daily) have been studied in an attempt to overcome resistance and improve cytogenetic and molecular response rates. The Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Optimization and Selectivity (TOPS) trial was a randomized phase 3 study that compared imatinib 800 mg daily to imatinib 400 mg daily. Although the 6-month assessments found increased rates of CCyR and a MMR in the higher-dose imatinib arm, these differences were no longer present at the 12-month assessment. Furthermore, the higher dose of imatinib led to a significantly higher incidence of grade 3/4 hematologic adverse events, and approximately 50% of patients on imatinib 800 mg daily required a dose reduction to less than 600 mg daily because of toxicity.27

The Therapeutic Intensification in De Novo Leukaemia (TIDEL)-II study used plasma trough levels of imatinib on day 22 of treatment with imatinib 600 mg daily to determine if patients should escalate the imatinib dose to 800 mg daily. In patients who did not meet molecular milestones at 3, 6, or 12 months, cohort 1 was dose escalated to imatinib 800 mg daily and subsequently switched to nilotinib 400 mg twice daily for failing the same target 3 months later, and cohort 2 was switched to nilotinib. At 2 years, 73% of patients achieved MMR and 34% achieved MR4.5, suggesting that initial treatment with higher-dose imatinib, followed by a switch to nilotinib in those failing to achieve desired milestones, could be an effective strategy for managing newly diagnosed CP-CML.28

Toxicity. The standard starting dose of imatinib in CP-CML patients is 400 mg. The safety profile of imatinib has been very well established. In the IRIS trial, the most common adverse events (all grades in decreasing order of frequency) were peripheral and periorbital edema (60%), nausea (50%), muscle cramps (49%), musculoskeletal pain (47%), diarrhea (45%), rash (40%), fatigue (39%), abdominal pain (37%), headache (37%), and joint pain (31%). Grade 3/4 liver enzyme elevation can occur in 5% of patients.29 In the event of severe liver toxicity or fluid retention, imatinib should be held until the event resolves. At that time, imatinib can be restarted if deemed appropriate, but this is dependent on the severity of the inciting event. Fluid retention can be managed by the use of supportive care, diuretics, imatinib dose reduction, dose interruption, or imatinib discontinuation if the fluid retention is severe. Muscle cramps can be managed by the use of calcium supplements or tonic water. Management of rash can include topical or systemic steroids, or in some cases imatinib dose reduction, interruption, or discontinuation.19

Grade 3/4 imatinib-induced hematologic toxicity is not uncommon, with 17% of patients experiencing neutropenia, 9% thrombocytopenia, and 4% anemia. These adverse events occurred most commonly during the first year of therapy, and the frequency decreased over time.15,29 Depending on the degree of cytopenias, imatinib dosing should be interrupted until recovery of the absolute neutrophil count or platelet count, and can often be resumed at 400 mg daily. However, if cytopenias recur, imatinib should be held and subsequently restarted at 300 mg daily.19

Dasatinib

Dasatinib is a second-generation TKI that has regulatory approval for treatment of adult patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML or CP-CML in patients with resistance or intolerance to prior TKIs. In addition to dasatinib’s ability to inhibit ABL kinases, it is also known to be a potent inhibitor of Src family kinases. Dasatinib has shown efficacy in patients who have developed imatinib-resistant ABL kinase domain mutations.

Dasatinib was initially approved as second-line therapy in patients with resistance or intolerance to imatinib. This indication was based on the results of the phase 3 CA180-034 trial, which ultimately identified dasatinib 100 mg daily as the optimal dose. In this trial, 74% of patients enrolled had resistance to imatinib and the remainder were intolerant. The 7-year follow-up of patients randomized to dasatinib 100 mg (n = 167) daily indicated that 46% achieved MMR while on study. Of the 124 imatinib-resistant patients on dasatinib 100 mg daily, the 7-year PFS was 39% and OS was 63%. In the 43 imatinib-intolerant patients, the 7-year PFS was 51% and OS was 70%.30

Dasatinib 100 mg daily was compared to imatinib 400 mg daily in newly diagnosed CP-CML patients in the randomized phase 3 DASISION (Dasatinib versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naive CML Patients) trial. More patients on the dasatinib arm achieved an EMR of BCR-ABL1 transcripts ≤ 10% IS after 3 months on treatment compared to imatinib (84% versus 64%). Furthermore, the 5-year follow-up reports that the cumulative incidence of MMR and MR4.5 in dasatinib-treated patients was 76% and 42%, and was 64% and 33% with imatinib (P = 0.0022 and P = 0.0251, respectively). Fewer patients treated with dasatinib progressed to AP or BP (4.6%) compared to imatinib (7.3%), but the estimated 5-year OS was similar between the 2 arms (91% for dasatinib versus 90% for imatinib).16 Regulatory approval for dasatinib as first-line therapy in newly diagnosed CML patients was based on results of the DASISION trial.

Toxicity. Most dasatinib-related toxicities are reported as grade 1 or grade 2, but grade 3/4 hematologic adverse events are fairly common. In the DASISION trial, grade 3/4 neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia occurred in 29%, 13%, and 22% of dasatinib-treated patients, respectively. Cytopenias can generally be managed with temporary dose interruptions or dose reductions.

During the 5-year follow-up of the DASISION trial, pleural effusions were reported in 28% of patients, most of which were grade 1/2. This occurred at a rate of approximately ≤ 8% per year, suggesting a stable incidence over time, and the effusions appear to be dose-dependent.16 Depending on the severity, pleural effusion may be treated with diuretics, dose interruption, and, in some instances, steroids or a thoracentesis. Typically, dasatinib can be restarted at 1 dose level lower than the previous dose once the effusion has resolved.19 Other, less common side effects of dasatinib include pulmonary hypertension (5% of patients), as well as abdominal pain, fluid retention, headaches, fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, rash, nausea, and diarrhea. Pulmonary hypertension is typically reversible after cessation of dasatinib, and thus dasatinib should be permanently discontinued once the diagnosis is confirmed. Fluid retention is often treated with diuretics and supportive care. Nausea and diarrhea are generally manageable and occur less frequently when dasatinib is taken with food and a large glass of water. Antiemetics and antidiarrheals can be used as needed. Troublesome rash can be best managed with topical or systemic steroids as well as possible dose reduction or dose interruption.16,19 In the DASISION trial, adverse events led to therapy discontinuation more often in the dasatinib group than in the imatinib group (16% versus 7%).16 Bleeding, particularly in the setting of thrombocytopenia, has been reported in patients being treated with dasatinib as a result of the drug-induced reversible inhibition of platelet aggregation.31

Nilotinib

The structure of nilotinib is similar to that of imatinib; however, it has a markedly increased affinity for the ATP‐binding site on the BCR-ABL1 protein. It was initially given regulatory approval in the setting of imatinib failure. Nilotinib was studied at a dose of 400 mg twice daily in 321 patients who were imatinib-resistant or -intolerant. It proved to be highly effective at inducing cytogenetic remissions in the second-line setting, with 59% of patients achieving a MCyR and 45% achieving a CCyR. With a median follow-up time of 4 years, the OS was 78%.32

Nilotinib gained regulatory approval for use as a first-line TKI after completion of the randomized phase 3 ENESTnd (Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials-Newly Diagnosed Patients) trial. ENESTnd was a 3-arm study comparing nilotinib 300 mg twice daily versus nilotinib 400 mg twice daily versus imatinib 400 mg daily in newly diagnosed, previously untreated patients diagnosed with CP-CML. The primary endpoint of this clinical trial was rate of MMR at 12 months.33 Nilotinib surpassed imatinib in this regard, with 44% of patients on nilotinib 300 mg twice daily achieving MMR at 12 months versus 43% of nilotinib 400 mg twice daily patients versus 22% of the imatinib-treated patients (P < 0.001 for both comparisons). Furthermore, the rate of CCyR by 12 months was significantly higher for both nilotinib arms compared with imatinib (80% for nilotinib 300 mg, 78% for nilotinib 400 mg, and 65% for imatinib) (P < 0.001).12 Based on this data, nilotinib 300 mg twice daily was chosen as the standard dose of nilotinib in the first-line setting. After 5 years of follow-up on the ENESTnd study, there were fewer progressions to AP/BP CML in nilotinib-treated patients compared with imatinib. MMR was achieved in 77% of nilotinib 300 mg patients compared with 60.4% of patients on the imatinib arm. MR4.5 was also more common in patients treated with nilotinib 300 mg twice daily, with a rate of 53.5% at 5 years versus 31.4% in the imatinib arm.17 In spite of the deeper cytogenetic and molecular responses achieved with nilotinib, this did not translate into a significant improvement in OS. The 5-year OS rate was 93.7% in nilotinib 300 mg patients versus 91.7% in imatinib-treated patients, and this difference lacked statistical significance.17

Toxicity. Although some similarities exist between the toxicity profiles of nilotinib and imatinib, each drug has some distinct adverse events. On the ENESTnd trial, the rate of any grade 3/4 non-hematologic adverse event was fairly low; however, lower-grade toxicities were not uncommon. Patients treated with nilotinib 300 mg twice daily experienced rash (31%), headache (14%), pruritis (15%), and fatigue (11%) most commonly. The most frequently reported laboratory abnormalities included increased total bilirubin (53%), hypophosphatemia (32%), hyperglycemia (36%), elevated lipase (24%), increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT; 66%), and increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST; 40%). Any grade of neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, or anemia occurred at rates of 43%, 48%, and 38%, respectively.33 Although nilotinib has a Black Box Warning from the US Food and Drug Administration for QT interval prolongation, no patients on the ENESTnd trial experienced a QT interval corrected for heart rate greater than 500 msec.12

More recent concerns have emerged regarding the potential for cardiovascular toxicity after long-term use of nilotinib. The 5-year update of ENESTnd reports cardiovascular events, including ischemic heart disease, ischemic cerebrovascular events, or peripheral arterial disease occurring in 7.5% of patients treated with nilotinib 300 mg twice daily, as compared with a rate of 2.1% in imatinib-treated patients. The frequency of these cardiovascular events increased linearly over time in both arms. Elevations in total cholesterol from baseline occurred in 27.6% of nilotinib patients compared with 3.9% of imatinib patients. Furthermore, clinically meaningful increases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and glycated hemoglobin occurred more frequently with nilotinib therapy.33

Nilotinib should be taken on an empty stomach; therefore, patients should be made aware of the need to fast for 2 hours prior to each dose and 1 hour after each dose. Given the potential risk of QT interval prolongation, a baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) is recommended prior to initiating treatment to ensure the QT interval is within a normal range. A repeat ECG should be done approximately 7 days after nilotinib initiation to ensure no prolongation of the QT interval after starting. Close monitoring of potassium and magnesium levels is important to decrease the risk of cardiac arrhythmias, and concomitant use of drugs considered strong CYP3A4 inhibitors should be avoided.19

If the patient experiences any grade 3 or higher laboratory abnormalities, nilotinib should be held until resolution of the toxicity, and then restarted at a lower dose. Similarly, if patients develop significant neutropenia or thrombocytopenia, nilotinib doses should be interrupted until resolution of the cytopenias. At that point, nilotinib can be reinitiated at either the same or a lower dose. Rash can be managed by the use of topical or systemic steroids as well as potential dose reduction, interruption, or discontinuation.

Given the concerns for potential cardiovascular events with long-term use of nilotinib, caution is advised when prescribing it to any patient with a history of cardiovascular disease or peripheral arterial occlusive disease. At the first sign of new occlusive disease, nilotinib should be discontinued.19

Bosutinib

Bosutinib is a second-generation BCR-ABL TKI with activity against the Src family of kinases; it was initially approved to treat patients with CP-, AP-, or BP-CML after resistance or intolerance to imatinib. Long-term data has been reported from the phase 1/2 trial of bosutinib therapy in patients with CP-CML who developed resistance or intolerance to imatinib plus dasatinib and/or nilotinib. A total of 119 patients were included in the 4-year follow-up; 38 were resistant/intolerant to imatinib and resistant to dasatinib, 50 were resistant/intolerant to imatinib and intolerant to dasatinib, 26 were resistant/intolerant to imatinib and resistant to nilotinib, and 5 were resistant/intolerant to imatinib and intolerant to nilotinib or resistant/intolerant to dasatinib and nilotinib. Bosutinib 400 mg daily was studied in this setting. Of the 38 patients with imatinib resistance/intolerance and dasatinib resistance, 39% achieved MCyR, 22% achieved CCyR, and the OS was 67%. Of the 50 patients with imatinib resistance/intolerance and dasatinib intolerance, 42% achieved MCyR, 40% achieved CCyR, and the OS was 80%. Finally, in the 26 patients with imatinib resistance/intolerance and nilotinib resistance, 38% achieved MCyR, 31% achieved CCyR, and the OS was 87%.34

Five-year follow-up from the phase 1/2 clinical trial that studied bosutinib 500 mg daily in CP-CML patients after imatinib failure reported data on 284 patients. By 5 years on study, 60% of patients had achieved MCyR and 50% achieved CCyR with a 71% and 69% probability, respectively, of maintaining these responses at 5 years. The 5-year OS was 84%.35 These data led to the regulatory approval of bosutinib 500 mg daily as second-line or later therapy.

Bosutinib was initially studied in the first-line setting in the randomized phase 3 BELA (Bosutinib Efficacy and Safety in Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia) trial. This trial compared bosutinib 500 mg daily to imatinib 400 mg daily in newly diagnosed, previously untreated CP-CML patients. This trial failed to meet its primary endpoint of increased rate of CCyR at 12 months, with 70% of bosutinib patients achieving this response, compared to 68% of imatinib-treated patients (P = 0.601). In spite of this, the rate of MMR at 12 months was significantly higher in the bosutinib arm (41%) compared to the imatinib arm (27%; P = 0.001).36

A second phase 3 trial (BFORE) was designed to study bosutinib 400 mg daily versus imatinib in newly diagnosed, previously untreated CP-CML patients. This study enrolled 536 patients who were randomly assigned 1:1 to bosutinib versus imatinib. The primary endpoint of this trial was rate of MMR at 12 months. A significantly higher number of bosutinib-treated patients achieved this response (47.2%) compared with imatinib-treated patients (36.9%, P = 0.02). Furthermore, by 12 months 77.2% of patients on the bosutinib arm had achieved CCyR compared with 66.4% on the imatinib arm, and this difference did meet statistical significance (P = 0.0075). A lower rate of progression to AP- or BP-CML was noted in bosutinib-treated patients as well (1.6% versus 2.5%). Based on this data, bosutinib gained regulatory approval for first-line therapy in CP-CML at a dose of 400 mg daily.18

Toxicity. On the BFORE trial, the most common treatment-emergent adverse events of any grade reported in the bosutinib-treated patients were diarrhea (70.1%), nausea (35.1%), increased ALT (30.6%), and increased AST (22.8%). Musculoskeletal pain or spasms occurred in 29.5% of patients, rash in 19.8%, fatigue in 19.4%, and headache in 18.7%. Hematologic toxicity was also reported, but most was grade 1/2. Thrombocytopenia was reported in 35.1%, anemia in 18.7%, and neutropenia in 11.2%.18

Cardiovascular events occurred in 5.2% of patients on the bosutinib arm of the BFORE trial, which was similar to the rate observed in imatinib patients. The most common cardiovascular event was QT interval prolongation, which occurred in 1.5% of patients. Pleural effusions were reported in 1.9% of patients treated with bosutinib, and none were grade 3 or higher.18

If liver enzyme elevation occurs at a value greater than 5 times the institutional upper limit of normal, bosutinib should be held until the level recovers to ≤ 2.5 times the upper limit of normal, at which point bosutinib can be restarted at a lower dose. If recovery takes longer than 4 weeks, bosutinib should be permanently discontinued. Liver enzymes elevated greater than 3 times the institutional upper limit of normal and a concurrent elevation in total bilirubin to 2 times the upper limit of normal are consistent with Hy’s law, and bosutinib should be discontinued. Although diarrhea is the most common toxicity associated with bosutinib, it is commonly low grade and transient. Diarrhea occurs most frequently in the first few days after initiating bosutinib. It can often be managed with over-the-counter antidiarrheal medications, but if the diarrhea is grade 3 or higher, bosutinib should be held until recovery to grade 1 or lower. Gastrointestinal side effects may be improved by taking bosutinib with a meal and a large glass of water. Fluid retention can be managed with diuretics and supportive care. Finally, if rash occurs, this can be addressed with topical or systemic steroids as well as bosutinib dose reduction, interruption, or discontinuation.19

Similar to other TKIs, if bosutinib-induced cytopenias occur, treatment should be held and restarted at the same or a lower dose upon blood count recovery.19

Ponatinib

The most common cause of TKI resistance in CP-CML is the development of ABL kinase domain mutations. The majority of imatinib-resistant mutations can be overcome by the use of second-generation TKIs, including dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib. However, ponatinib is the only BCR-ABL TKI able to overcome a T315I mutation. The phase 2 PACE (Ponatinib Ph-positive ALL and CML Evaluation) trial enrolled patients with CP-, AP-, or BP-CML as well as patients with Ph-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who were resistant or intolerant to nilotinib or dasatinib, or who had evidence of a T315I mutation. The starting dose of ponatinib on this trial was 45 mg daily.37 The PACE trial enrolled 267 patients with CP-CML: 203 with resistance or intolerance to nilotinib or dasatinib, and 64 with a T315I mutation. The primary endpoint in the CP cohort was rate of MCyR at any time within 12 months of starting ponatinib. The overall rate of MCyR by 12 months in the CP-CML patients was 56%. In those with a T315I mutation, 70% achieved MCyR, which compared favorably with those with resistance or intolerance to nilotinib or dasatinib, 51% of whom achieved MCyR. CCyR was achieved in 46% of CP-CML patients (40% in the resistant/intolerant cohort and 66% in the T315I cohort). In general, patients with T315I mutations received fewer prior therapies than those in the resistant/intolerant cohort, which likely contributed to the higher response rates in the T315I patients. MR4.5 was achieved in 15% of CP-CML patients by 12 months on the PACE trial.37 The 5-year update to this study reported that 60%, 40%, and 24% of CP-CML patients achieved MCyR, MMR, and MR4.5, respectively. In the patients who achieved MCyR, the probability of maintaining this response for 5 years was 82% and the estimated 5-year OS was 73%.19

Toxicity. In 2013, after the regulatory approval of ponatinib, reports became available that the drug can cause an increase in arterial occlusive events, including fatal myocardial infarctions and cerebrovascular accidents. For this reason, dose reductions were implemented in patients who were deriving clinical benefit from ponatinib. In spite of these dose reductions, ≥ 90% of responders maintained their response for up to 40 months.38 Although the likelihood of developing an arterial occlusive event appears higher in the first year after starting ponatinib than in later years, the cumulative incidence of events continues to increase. The 5-year follow-up to the PACE trial reports 31% of patients experiencing any grade of arterial occlusive event while on ponatinib. Aside from these events, the most common treatment-emergent adverse events in ponatinib-treated patients on the PACE trial included rash (47%), abdominal pain (46%), headache (43%), dry skin (42%), constipation (41%), and hypertension (37%). Hematologic toxicity was also common, with 46% of patients experiencing any grade of thrombocytopenia, 20% experiencing neutropenia, and 20% anemia.38

Patients receiving ponatinib therapy should be monitored closely for any evidence of arterial or venous thrombosis. If an occlusive event occurs, ponatinib should be discontinued. Similarly, in the setting of any new or worsening heart failure symptoms, ponatinib should be promptly discontinued. Management of any underlying cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, or smoking history, is recommended, and these patients should be referred to a cardiologist for a full evaluation. In the absence of any contraindications to aspirin, low-dose aspirin should be considered as a means of decreasing cardiovascular risks associated with ponatinib. In patients with known risk factors, a ponatinib starting dose of 30 mg daily rather than the standard 45 mg daily may be a safer option, resulting in fewer arterial occlusive events, although the efficacy of this dose is still being studied in comparison to 45 mg daily.19

If ponatinib-induced transaminitis greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal occurs, ponatinib should be held until resolution to less than 3 times the upper limit of normal, at which point it should be resumed at a lower dose. Similarly, in the setting of elevated serum lipase or symptomatic pancreatitis, ponatinib should be held and restarted at a lower dose after resolution of symptoms.19

In the event of neutropenia or thrombocytopenia, ponatinib should be held until blood count recovery and then restarted at the same dose. If cytopenias occur for a second time, the dose of ponatinib should be lowered at the time of treatment reinitiation. If rash occurs, it can be addressed with topical or systemic steroids as well as dose reduction, interruption, or discontinuation.19

Conclusion

With the development of imatinib and the subsequent TKIs, dasatinib, nilotinib, bosutinib, and ponatinib, CP-CML has become a chronic disease with a life expectancy that is similar to that of the general population. Given the successful treatments available for these patients, it is crucial to identify patients with this diagnosis, ensure they receive a complete, appropriate diagnostic workup including a bone marrow biopsy and aspiration with cytogenetic testing, and select the best therapy for each individual patient. Once on treatment, the importance of frequent monitoring cannot be overstated. This is the only way to be certain patients are achieving the desired treatment milestones that correlate with the favorable long-term outcomes that have been observed with TKI-based treatment of CP-CML.

Corresponding author: Kendra Sweet, MD, MS, Department of Malignant Hematology, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Sweet has served on the Advisory Board and Speakers Bureau of Novartis, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Ariad Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer, and has served as a consultant to Pfizer.

1. Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, et al. The biology of chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:164-172.

2. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Leukemia - Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML). 2018.

3. Huang X, Cortes J, Kantarjian H. Estimations of the increasing prevalence and plateau prevalence of chronic myeloid leukemia in the era of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Cancer. 2012;118:3123-3127.

4. Savage DG, Szydlo RM, Chase A, et al. Bone marrow transplantation for chronic myeloid leukaemia: the effects of differing criteria for defining chronic phase on probabilities of survival and relapse. Br J Haematol. 1997;99:30-35.

5. Knox WF, Bhavnani M, Davson J, Geary CG. Histological classification of chronic granulocytic leukaemia. Clin Lab Haematol. 1984;6:171-175.

6. Kvasnicka HM, Thiele J, Schmitt-Graeff A, et al. Impact of bone marrow morphology on multivariate risk classification in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Acta Haematol. 2003;109:53-56.

7. Cortes JE, Talpaz M, O’Brien S, et al. Staging of chronic myeloid leukemia in the imatinib era: an evaluation of the World Health Organization proposal. Cancer. 2006;106:1306-1315.

8. Druker BJ. Chronic myeloid leukemia. In: DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, eds. DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg’s Cancer Principles & Practice of Oncology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2007:2267-2304.

9. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391-2405.

10. Fabarius A, Leitner A, Hochhaus A, et al. Impact of additional cytogenetic aberrations at diagnosis on prognosis of CML: long-term observation of 1151 patients from the randomized CML Study IV. Blood. 2011;118:6760-6768.

11. Alhuraiji A, Kantarjian H, Boddu P, et al. Prognostic significance of additional chromosomal abnormalities at the time of diagnosis in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with frontline tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Hematol. 2018;93:84-90.

12. Melo JV. BCR-ABL gene variants. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1997;10:203-222.

13. Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, Cortes J, et al. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction monitoring of BCR-ABL during therapy with imatinib mesylate (STI571; gleevec) in chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:160-166.

14. Hughes T, Deininger M, Hochhaus A, et al. Monitoring CML patients responding to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: review and recommendations for harmonizing current methodology for detecting BCR-ABL transcripts and kinase domain mutations and for expressing results. Blood. 2006;108:28-37.

15. Hochhaus A, Larson RA, Guilhot F, et al. Long-term outcomes of imatinib treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:917-927.

16. Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, et al. Final 5-year study results of DASISION: the Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naive Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2333-2340.

17. Hochhaus A, Saglio G, Hughes TP, et al. Long-term benefits and risks of frontline nilotinib vs imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: 5-year update of the randomized ENESTnd trial. Leukemia. 2016;30:1044-1054.

18. Cortes JE, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Deininger MW, et al. Bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: results from the randomized BFORE trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:231-237.

19. Radich JP, Deininger M, Abboud CN, et al. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, Version 1.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1108-1135.

20. Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, Kantarjian HM. Chronic myelogenous leukemia: biology and therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:207-219.

21. O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:994-1004.

22. Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood. 2013;122:872-884.

23. Larripa I, Ruiz MS, Gutierrez M, Bianchini M. [Guidelines for molecular monitoring of BCR-ABL1 in chronic myeloid leukemia patients by RT-qPCR]. Medicina (B Aires). 2017;77:61-72.

24. Marin D, Ibrahim AR, Lucas C, et al. Assessment of BCR-ABL1 transcript levels at 3 months is the only requirement for predicting outcome for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:232-238.

25. Hughes TP, Ross DM. Moving treatment-free remission into mainstream clinical practice in CML. Blood. 2016;128:17-23.

26. Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031-1037.

27. Baccarani M, Druker BJ, Branford S, et al. Long-term response to imatinib is not affected by the initial dose in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: final update from the Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Optimization and Selectivity (TOPS) study. Int J Hematol. 2014;99:616-624.

28. Yeung DT, Osborn MP, White DL, et al. TIDEL-II: first-line use of imatinib in CML with early switch to nilotinib for failure to achieve time-dependent molecular targets. Blood. 2015;125:915-923.

29. Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O’Brien SG, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2408-2417.

30. Shah NP, Rousselot P, Schiffer C, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant or -intolerant chronic-phase, chronic myeloid leukemia patients: 7-year follow-up of study CA180-034. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:869-874.

31. Quintas-Cardama A, Han X, Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced platelet dysfunction in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:261-263.

32. Giles FJ, le Coutre PD, Pinilla-Ibarz J, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant or imatinib-intolerant patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: 48-month follow-up results of a phase II study. Leukemia. 2013;27:107-112.

33. Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2251-2259.

34. Cortes JE, Khoury HJ, Kantarjian HM, et al. Long-term bosutinib for chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia after failure of imatinib plus dasatinib and/or nilotinib. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1206-1214.

35. Gambacorti-Passerini C, Cortes JE, Lipton JH, et al. Safety and efficacy of second-line bosutinib for chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia over a five-year period: final results of a phase I/II study. Haematologica. 2018;103:1298-1307.

36. Cortes JE, Kim DW, Kantarjian HM, et al. Bosutinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: results from the BELA trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3486-3492.

37. Cortes JE, Kim DW, Pinilla-Ibarz J, et al. A phase 2 trial of ponatinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1783-1796.

38. Cortes JE, Kim DW, Pinilla-Ibarz J, et al. Ponatinib efficacy and safety in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia: final 5-year results of the phase 2 PACE trial. Blood. 2018;132:393-404.

From the Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: To outline the approach to selecting a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) for initial treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and monitoring patients following initiation of therapy.

- Methods: Review of the literature and evidence-based guidelines.

- Results: The development and availability of TKIs has improved survival for patients diagnosed with CML. The life expectancy of patients diagnosed with chronic-phase CML (CP-CML) is similar to that of the general population, provided they receive appropriate TKI therapy and adhere to treatment. Selection of the most appropriate first-line TKI for newly diagnosed CP-CML requires incorporation of the patient’s baseline karyotype and Sokal or EURO risk score, and a clear understanding of the patient’s comorbidities. The adverse effect profile of all TKIs must be considered in conjunction with the patient’s ongoing medical issues to decrease the likelihood of worsening their current symptoms or causing a severe complication from TKI therapy. After confirming a diagnosis of CML and selecting the most appropriate TKI for first-line therapy, close monitoring and follow-up are necessary to ensure patients are meeting the desired treatment milestones. Responses in CML can be assessed based on hematologic parameters, cytogenetic results, and molecular responses.

- Conclusion: Given the successful treatments available for patients with CML, it is crucial to identify patients with this diagnosis; ensure they receive a complete, appropriate diagnostic workup including a bone marrow biopsy and aspiration with cytogenetic testing; and select the best therapy for each individual patient.

Keywords: chronic myeloid leukemia; CML; tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TKI; cancer; BCR-ABL protein.

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm that is characterized by the presence of the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome and uninhibited expansion of bone marrow stem cells. The Ph chromosome arises from a reciprocal translocation between the Abelson (ABL) region on chromosome 9 and the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) of chromosome 22 (t(9;22)(q34;q11.2)), resulting in the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene and its protein product, BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase.1 BCR-ABL has constitutive tyrosine kinase activity that promotes growth, replication, and survival of hematopoietic cells through downstream pathways, which is the driving factor in the pathogenesis of CML.1

CML is divided into 3 phases based on the number of myeloblasts observed in the blood or bone marrow: chronic, accelerated, and blast. Most cases of CML are diagnosed in the chronic phase (CP), which is marked by proliferation of primarily the myeloid element.

Typical treatment for CML involves lifelong use of oral BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Currently, 5 TKIs have regulatory approval for treatment of this disease. The advent of TKIs, a class of small molecules targeting the tyrosine kinases, particularly the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase, led to rapid changes in the management of CML and improved survival for patients. Patients diagnosed with chronic-phase CML (CP-CML) now have a life expectancy that is similar to that of the general population, as long as they receive appropriate TKI therapy and adhere to treatment. As such, it is crucial to identify patients with CML; ensure they receive a complete, appropriate diagnostic workup; and select the best therapy for each patient.

Epidemiology

According to SEER data estimates, 8430 new cases of CML were diagnosed in the United States in 2018. CML is a disease of older adults, with a median age of 65 years at diagnosis, and there is a slight male predominance. Between 2011 and 2015, the number of new CML cases was 1.8 per 100,000 persons. The median overall survival (OS) in patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML has not been reached.2 Given the effective treatments available for managing CML, it is estimated that the prevalence of CML in the United States will plateau at 180,000 patients by 2050.3

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

The diagnosis of CML is often suspected based on an incidental finding of leukocytosis and, in some cases, thrombocytosis. In many cases, this is an incidental finding on routine blood work, but approximately 50% of patients will present with constitutional symptoms associated with the disease. Characteristic features of the white blood cell differential include left-shifted maturation with neutrophilia and immature circulating myeloid cells. Basophilia and eosinophilia are often present as well. Splenomegaly is a common sign, present in 50% to 90% of patients at diagnosis. In those patients with symptoms related to CML at diagnosis, the most common presentation includes increasing fatigue, fevers, night sweats, early satiety, and weight loss. The diagnosis is confirmed by cytogenetic studies showing the Ph chromosome abnormality, t(9; 22)(q3.4;q1.1), and/or reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) showing BCR-ABL1 transcripts.

Testing

Bone marrow biopsy. There are 3 distinct phases of CML: CP, accelerated phase (AP), and blast phase (BP). Bone marrow biopsy and aspiration at diagnosis are mandatory in order to determine the phase of the disease at diagnosis. This distinction is based on the percentage of blasts, promyelocytes, and basophils present as well as the platelet count and presence or absence of extramedullary disease.4 The vast majority of patients at diagnosis have CML that is in the chronic phase. The typical appearance in CP-CML is a hypercellular marrow with granulocytic and occasionally megakaryocytic hyperplasia. In many cases, basophilia and/or eosinophilia are noted as well. Dysplasia is not a typical finding in CML.5 Bone marrow fibrosis can be seen in up to one-third of patients at diagnosis, and may indicate a slightly worse prognosis.6 Although a diagnosis of CML can be made without a bone marrow biopsy, complete staging and prognostication are only possible with information gained from this test, including baseline karyotype and confirmation of CP versus a more advanced phase of CML.

Diagnostic criteria. The criteria for diagnosing AP-CML has not been agreed upon by various groups, but the modified MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) criteria are used in the majority of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of TKIs in preventing progression to advanced phases of CML. MDACC criteria define AP-CML as the presence of 1 of the following: 15% to 29% blasts in the peripheral blood or bone marrow, ≥ 30% peripheral blasts plus promyelocytes, ≥ 20% basophils in the blood or bone marrow, platelet count ≤ 100,000/μL unrelated to therapy, and clonal cytogenetic evolution in Ph-positive metaphases (Table).7

BP-CML is typically defined using the criteria developed by the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry (IBMTR): ≥ 30% blasts in the peripheral blood and/or the bone marrow or the presence of extramedullary disease.8 Although not typically used in clinical trials, the revised World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for BP-CML include ≥ 20% blasts in the peripheral blood or bone marrow, extramedullary blast proliferation, and large foci or clusters of blasts in the bone marrow biopsy sample (Table).9

The defining feature of CML is the presence of the Ph chromosome abnormality. In a small subset of patients, additional chromosome abnormalities (ACA) in the Ph-positive cells may be identified at diagnosis. Some reports indicate that the presence of “major route” ACA (trisomy 8, isochromosome 17q, a second Ph chromosome, or trisomy 19) at diagnosis may negatively impact prognosis, but other reports contradict these findings.10,11

PCR assay. The typical BCR breakpoint in CML is the major breakpoint cluster region (M-BCR), which results in a 210-kDa protein (p210). Alternate breakpoints that are less frequently identified are the minor BCR (mBCR or p190), which is more commonly found in Ph-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and the micro BCR (µBCR or p230), which is much less common and is often characterized by chronic neutrophilia.12 Identifying which BCR-ABL1 transcript is present in each patient using qualitative PCR is crucial in order to ensure proper monitoring during treatment.

The most sensitive method for detecting BCR-ABL1 mRNA transcripts is the quantitative real-time PCR (RQ-PCR) assay, which is typically done on peripheral blood. RQ-PCR is capable of detecting a single CML cell in the presence of ≥ 100,000 normal cells. This test should be done during the initial diagnostic workup in order to confirm the presence of BCR-ABL1 transcripts, and it is used as a standard method for monitoring response to TKI therapy.13 The International Scale (IS) is a standardized approach to reporting RQ-PCR results that was developed to allow comparison of results across various laboratories and has become the gold standard for reporting BCR-ABL1 transcript values.14

Determining Risk Scores

Calculating a patient’s Sokal score or EURO risk score at diagnosis remains an important component of the diagnostic workup in CP-CML, as this information has prognostic and therapeutic implications (an online calculator is available through European LeukemiaNet [ELN]). The risk for disease progression to the accelerated or blast phases is higher in patients with intermediate or high risk scores compared to those with a low risk score at diagnosis. The risk of progression in intermediate- or high-risk patients is lower when a second-generation TKI (dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib) is used as frontline therapy compared to imatinib, and therefore, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) CML Panel recommends starting with a second-generation TKI in these patients.15-19

Monitoring Response to Therapy

After confirming a diagnosis of CML and selecting the most appropriate TKI for first-line therapy, the successful management of CML patients relies on close monitoring and follow-up to ensure they are meeting the desired treatment milestones. Responses in CML can be assessed based on hematologic parameters, cytogenetic results, and molecular responses. A complete hematologic response (CHR) implies complete normalization of peripheral blood counts (with the exception of TKI-induced cytopenias) and resolution of any palpable splenomegaly. The majority of patients will achieve a CHR within 4 to 6 weeks after initiating CML-directed therapy.20

Cytogenetic Response

Cytogenetic responses are defined by the decrease in the number of Ph chromosome–positive metaphases when assessed on bone marrow cytogenetics. A partial cytogenetic response (PCyR) is defined as having 1% to 35% Ph-positive metaphases, a major cytogenetic response (MCyR) as having 0% to 35% Ph-positive metaphases, and a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) implies that no Ph-positive metaphases are identified on bone marrow cytogenetics. An ideal response is the achievement of PCyR after 3 months on a TKI and a CCyR after 12 months on a TKI.21

Molecular Response

Once a patient has achieved a CCyR, monitoring their response to therapy can only be done using RQ-PCR to measure BCR-ABL1 transcripts in the peripheral blood. The NCCN and the ELN recommend monitoring RQ-PCR from the peripheral blood every 3 months in order to assess response to TKIs.19,22 As noted, the IS has become the gold standard reporting system for all BCR-ABL1 transcript levels in the majority of laboratories worldwide.14,23 Molecular responses are based on a log reduction in BCR-ABL1 transcripts from a standardized baseline. Many molecular responses can be correlated with cytogenetic responses such that, if reliable RQ-PCR testing is available, monitoring can be done using only peripheral blood RQ-PCR rather than repeat bone marrow biopsies. For example, an early molecular response (EMR) is defined as a RQ-PCR value of ≤ 10% IS, which is approximately equivalent to a PCyR.24 A value of 1% IS is approximately equivalent to a CCyR. A major molecular response (MMR) is a ≥ 3-log reduction in BCR-ABL1 transcripts from baseline and is a value of ≤ 0.1% IS. Deeper levels of molecular response are best described by the log reduction in BCR-ABL1 transcripts, with a 4-log reduction denoted as MR4.0, a 4.5-log reduction as MR4.5, and so forth. Complete molecular response (CMR) is defined by the level of sensitivity of the RQ-PCR assay being used.14

The definition of relapsed disease in CML is dependent on the type of response the patient had previously achieved. Relapse could be the loss of a hematologic or cytogenetic response, but fluctuations in BCR-ABL1 transcripts on routine RQ-PCR do not necessarily indicate relapsed CML. A 1-log increase in the level of BCR-ABL1 transcripts with a concurrent loss of MMR should prompt a bone marrow biopsy in order to assess for the loss of CCyR, and thus a cytogenetic relapse; however, this loss of MMR does not define relapse in and of itself. In the setting of relapsed disease, testing should be done to look for possible ABL kinase domain mutations, and alternate therapy should be selected.19

Multiple reports have identified the prognostic relevance of achieving an EMR at 3 and 6 months after starting TKI therapy. Marin and colleagues reported that in 282 imatinib-treated patients, there was a significant improvement in 8-year OS, progression-free survival (PFS), and cumulative incidence of CCyR and CMR in patients who had BCR-ABL1 transcripts < 9.84% IS after 3 months on treatment.24 This data highlights the importance of early molecular monitoring in order to ensure the best outcomes for patients with CP-CML.

The NCCN CML guidelines and ELN recommendations both agree that an ideal response after 3 months on a TKI is BCR-ABL1 transcripts < 10% IS, but treatment is not considered to be failing at this point if the patient marginally misses this milestone. After 6 months on treatment, an ideal response is considered BCR-ABL1 transcripts < 1%–10% IS. Ideally, patients will have BCR-ABL1 transcripts < 0.1%–1% IS by the time they complete 12 months of TKI therapy, suggesting that these patients have at least achieved a CCyR.19,22 Even after patients achieve these early milestones, frequent monitoring by RQ-PCR is required to ensure that they are maintaining their response to treatment. This will help to ensure patient compliance with treatment and will also help to identify a select subset of patients who could potentially be considered for an attempt at TKI cessation (not discussed in detail here) after a minimum of 3 years on therapy.19,25

Selecting First-line TKI Therapy

Selection of the most appropriate first-line TKI for newly diagnosed CP-CML patients requires incorporation of many patient-specific factors. These factors include baseline karyotype and confirmation of CP-CML through bone marrow biopsy, Sokal or EURO risk score, and a thorough patient history, including a clear understanding of the patient’s comorbidities. The adverse effect profile of all TKIs must be considered in conjunction with the patient’s ongoing medical issues in order to decrease the likelihood of worsening their current symptoms or causing a severe complication from TKI therapy.

Imatinib

The management of CML was revolutionized by the development and ultimate regulatory approval of imatinib mesylate in 2001. Imatinib was the first small-molecule cancer therapy developed and approved. It acts by binding to the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding site in the catalytic domain of BCR-ABL, thus inhibiting the oncoprotein’s tyrosine kinase activity.26

The International Randomized Study of Interferon versus STI571 (IRIS) trial was a randomized phase 3 study that compared imatinib 400 mg daily to interferon alfa (IFNa) plus cytarabine. More than 1000 CP-CML patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to either imatinib or IFNa plus cytarabine and were assessed for event-free survival, hematologic and cytogenetic responses, freedom from progression to AP or BP, and toxicity. Imatinib was superior to the prior standard of care for all these outcomes.21 The long-term follow-up of the IRIS trial reported an 83% estimated 10-year OS and 79% estimated event-free survival for patients on the imatinib arm of this study.15 The cumulative rate of CCyR was 82.8%. Of the 204 imatinib-treated patients who could undergo a molecular response evaluation at 10 years, 93.1% had a MMR and 63.2% had a MR4.5, suggesting durable, deep molecular responses for many patients. The estimated 10-year rate of freedom from progression to AP or BP was 92.1%.