User login

No link found between sleep position, pregnancy outcomes

such as stillbirth, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) newborns, and gestational hypertensive disorders. The finding, published in the October issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology, conflicts with previous retrospective case-control studies that suggested left-side sleeping may lead to reduced risk. The disagreement may be due to the prospective nature of the new study, which followed 8,706 women over 4 years.

Right-side or back sleeping had attracted suspicion because of its potential to compress uterine blood vessels and decrease uterine blood flow, and various public health campaigns urge pregnant women to sleep on their left side. Although case-control studies backed up those worries, those retrospective approaches can suffer from limitations including recall bias, in which grieving mothers overreport suspect sleeping behaviors, perhaps in search of an explanation for their loss.

Prospective analyses can counter some of those limitations. The researchers, led by Robert Silver, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, conducted a secondary analysis of the nuMoM2b study, examining adverse pregnancy outcomes and risk factors. It was a multicenter observational cohort study of 8,706 nulliparous women with singleton gestations who completed two sleep questionnaires: one between 6 and 13 weeks of gestation, and one between 22 and 29 weeks.

Adverse outcomes occurred in 1,903 women, including 178 cases of both SGA and hypertensive disorders, 8 with SGA plus stillbirth, 3 with hypertensive disorders plus stillbirth, and 2 cases with all three complications.

The researchers found no association between any adverse outcomes and sleep position either at the first visit in early pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.14) or the third visit in midpregnancy (aOR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.89-1.11). Propensity score matching to adjust non-left lateral positioning to the composite outcome also showed no association.

In midpregnancy, there was an association between non-left lateral sleeping and reduced risk of stillbirth (aOR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.09-0.75). “This observation is likely spurious owing to small numbers of stillbirths, Dr. Silver and associates said.

A post hoc analysis indicated that the study was sufficiently powered to detect clinically meaningful risks; ORs of 1.2 for hypertensive disorders, 1.23 for SGA, 2.4 for stillbirth, and 1.2 for the composite outcome.

Let sleeping mothers lie

Pregnant women have enough on their minds. They shouldn’t have to worry about sleep position as well, according to Nathan Fox, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive science at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Emily Oster, PhD, economist at Brown University, Providence, R.I., who wrote an accompanying editorial.

It may seem harmless to direct women to sleep on their left side even if it has no benefit, but restricting a woman’s sleep options may leave her less well rested at a time when she is about to enter a period of sleep deprivation, as well as contribute to general discomfort, in their opinion.

Also, in the rare cases of a bad outcome, advice based on limited or poor quality evidence contributes to “devastating and unwarranted feelings of responsibility and guilt, and this harm to women already suffering from sadness and despair must not be minimized,” they said.

The study received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and grants from multiple universities. One author received research funding from Kyndermed through her institution. Another receives royalties from UpToDate.com. Dr. Fox and Dr. Oster have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Silver RM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003458; Fox N and Oster E. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019 Oct. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003466

such as stillbirth, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) newborns, and gestational hypertensive disorders. The finding, published in the October issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology, conflicts with previous retrospective case-control studies that suggested left-side sleeping may lead to reduced risk. The disagreement may be due to the prospective nature of the new study, which followed 8,706 women over 4 years.

Right-side or back sleeping had attracted suspicion because of its potential to compress uterine blood vessels and decrease uterine blood flow, and various public health campaigns urge pregnant women to sleep on their left side. Although case-control studies backed up those worries, those retrospective approaches can suffer from limitations including recall bias, in which grieving mothers overreport suspect sleeping behaviors, perhaps in search of an explanation for their loss.

Prospective analyses can counter some of those limitations. The researchers, led by Robert Silver, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, conducted a secondary analysis of the nuMoM2b study, examining adverse pregnancy outcomes and risk factors. It was a multicenter observational cohort study of 8,706 nulliparous women with singleton gestations who completed two sleep questionnaires: one between 6 and 13 weeks of gestation, and one between 22 and 29 weeks.

Adverse outcomes occurred in 1,903 women, including 178 cases of both SGA and hypertensive disorders, 8 with SGA plus stillbirth, 3 with hypertensive disorders plus stillbirth, and 2 cases with all three complications.

The researchers found no association between any adverse outcomes and sleep position either at the first visit in early pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.14) or the third visit in midpregnancy (aOR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.89-1.11). Propensity score matching to adjust non-left lateral positioning to the composite outcome also showed no association.

In midpregnancy, there was an association between non-left lateral sleeping and reduced risk of stillbirth (aOR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.09-0.75). “This observation is likely spurious owing to small numbers of stillbirths, Dr. Silver and associates said.

A post hoc analysis indicated that the study was sufficiently powered to detect clinically meaningful risks; ORs of 1.2 for hypertensive disorders, 1.23 for SGA, 2.4 for stillbirth, and 1.2 for the composite outcome.

Let sleeping mothers lie

Pregnant women have enough on their minds. They shouldn’t have to worry about sleep position as well, according to Nathan Fox, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive science at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Emily Oster, PhD, economist at Brown University, Providence, R.I., who wrote an accompanying editorial.

It may seem harmless to direct women to sleep on their left side even if it has no benefit, but restricting a woman’s sleep options may leave her less well rested at a time when she is about to enter a period of sleep deprivation, as well as contribute to general discomfort, in their opinion.

Also, in the rare cases of a bad outcome, advice based on limited or poor quality evidence contributes to “devastating and unwarranted feelings of responsibility and guilt, and this harm to women already suffering from sadness and despair must not be minimized,” they said.

The study received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and grants from multiple universities. One author received research funding from Kyndermed through her institution. Another receives royalties from UpToDate.com. Dr. Fox and Dr. Oster have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Silver RM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003458; Fox N and Oster E. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019 Oct. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003466

such as stillbirth, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) newborns, and gestational hypertensive disorders. The finding, published in the October issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology, conflicts with previous retrospective case-control studies that suggested left-side sleeping may lead to reduced risk. The disagreement may be due to the prospective nature of the new study, which followed 8,706 women over 4 years.

Right-side or back sleeping had attracted suspicion because of its potential to compress uterine blood vessels and decrease uterine blood flow, and various public health campaigns urge pregnant women to sleep on their left side. Although case-control studies backed up those worries, those retrospective approaches can suffer from limitations including recall bias, in which grieving mothers overreport suspect sleeping behaviors, perhaps in search of an explanation for their loss.

Prospective analyses can counter some of those limitations. The researchers, led by Robert Silver, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, conducted a secondary analysis of the nuMoM2b study, examining adverse pregnancy outcomes and risk factors. It was a multicenter observational cohort study of 8,706 nulliparous women with singleton gestations who completed two sleep questionnaires: one between 6 and 13 weeks of gestation, and one between 22 and 29 weeks.

Adverse outcomes occurred in 1,903 women, including 178 cases of both SGA and hypertensive disorders, 8 with SGA plus stillbirth, 3 with hypertensive disorders plus stillbirth, and 2 cases with all three complications.

The researchers found no association between any adverse outcomes and sleep position either at the first visit in early pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.14) or the third visit in midpregnancy (aOR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.89-1.11). Propensity score matching to adjust non-left lateral positioning to the composite outcome also showed no association.

In midpregnancy, there was an association between non-left lateral sleeping and reduced risk of stillbirth (aOR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.09-0.75). “This observation is likely spurious owing to small numbers of stillbirths, Dr. Silver and associates said.

A post hoc analysis indicated that the study was sufficiently powered to detect clinically meaningful risks; ORs of 1.2 for hypertensive disorders, 1.23 for SGA, 2.4 for stillbirth, and 1.2 for the composite outcome.

Let sleeping mothers lie

Pregnant women have enough on their minds. They shouldn’t have to worry about sleep position as well, according to Nathan Fox, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive science at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Emily Oster, PhD, economist at Brown University, Providence, R.I., who wrote an accompanying editorial.

It may seem harmless to direct women to sleep on their left side even if it has no benefit, but restricting a woman’s sleep options may leave her less well rested at a time when she is about to enter a period of sleep deprivation, as well as contribute to general discomfort, in their opinion.

Also, in the rare cases of a bad outcome, advice based on limited or poor quality evidence contributes to “devastating and unwarranted feelings of responsibility and guilt, and this harm to women already suffering from sadness and despair must not be minimized,” they said.

The study received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and grants from multiple universities. One author received research funding from Kyndermed through her institution. Another receives royalties from UpToDate.com. Dr. Fox and Dr. Oster have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Silver RM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003458; Fox N and Oster E. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019 Oct. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003466

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

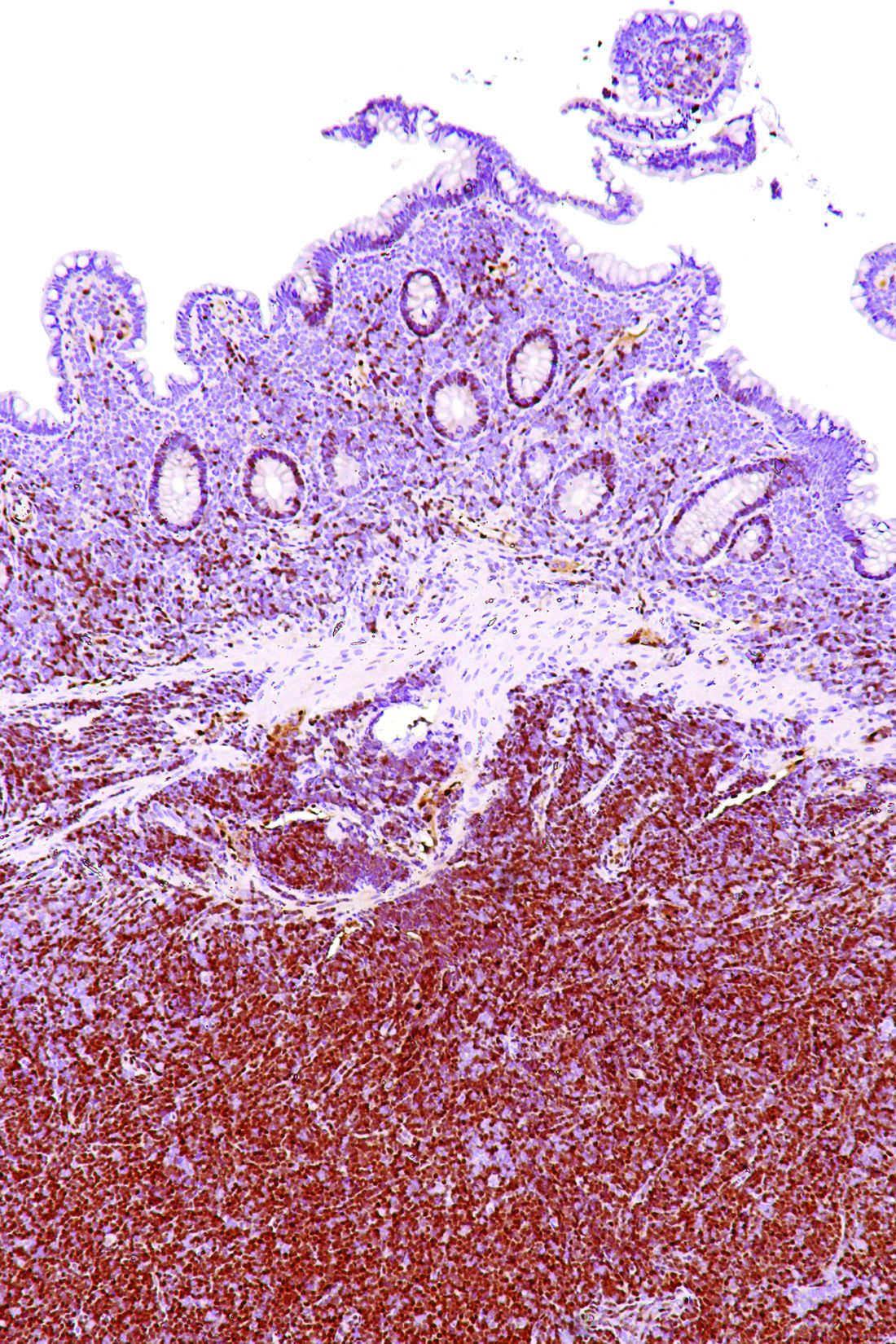

Staging PET/CT better defines extent of mantle cell lymphoma

Use of staging PET/CT better defines the extent of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) in certain compartments, adding important information for treatment decisions, a cohort study suggests. However, patient selection and evaluation criteria are important for its utility.

“A correct and early identification of initial disease could be crucial because it could affect patient management and therapeutic choice,” Domenico Albano, MD, a nuclear medicine physician at the University of Brescia (Italy) and Spedali Civili Brescia, and colleagues wrote in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma, & Leukemia.

Using retrospective data from two centers and 122 patients with MCL, the investigators compared the utility of staging 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT with that of other modalities used for detecting disease in specific compartments. They also assessed its impact on patient management.

The study results showed that, with the exception of a single patient having bone marrow involvement, all patients had positive PET/CT results, with detection of at least one hypermetabolic lesion.

For assessing nodal involvement, compared with CT alone, PET/CT detected additional lesions in 21% of patients. Splenic lesions were detected by PET/CT in 49% of patients and by CT alone in 47%.

For assessing bone marrow involvement, compared with bone marrow biopsy, PET/CT had a sensitivity of 52%, a specificity of 98%, a positive predictive value of 97%, a negative predictive value of 65%, and an overall accuracy of 74%.

For gastrointestinal involvement, compared with endoscopy, PET/CT had a sensitivity of 64% (78% after excluding diabetic patients taking metformin), a specificity of 91% (92%), a positive predictive value of 69% (72%), a negative predictive value of 90% (94%), and an overall accuracy of 85% (89%).

Ultimately, relative to CT alone, PET/CT altered stage and management in 19% of patients. Specifically, this imaging led to up-staging in 17% of patients, prompting clinicians to switch to more-aggressive chemotherapy, and down-staging in 2% of patients, prompting clinicians to skip unnecessary invasive therapies.

“We demonstrated that 18F-FDG pathologic uptake in MCL occurred in almost all patients, with excellent detection rate in nodal and splenic disease – indeed, better than CT,” the researchers wrote. “When we analyzed bone marrow and gastrointestinal involvement, the selection of patients excluding all conditions potentially affecting organ uptake and the use of specific criteria for the evaluation of these organs seemed to be crucial. Within these caveats, PET/CT showed good specificity for bone marrow and gastrointestinal evaluation.”

Study funding was not disclosed. Dr. Albano reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Albano D et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019 Aug;19(8):e457-64.

Use of staging PET/CT better defines the extent of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) in certain compartments, adding important information for treatment decisions, a cohort study suggests. However, patient selection and evaluation criteria are important for its utility.

“A correct and early identification of initial disease could be crucial because it could affect patient management and therapeutic choice,” Domenico Albano, MD, a nuclear medicine physician at the University of Brescia (Italy) and Spedali Civili Brescia, and colleagues wrote in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma, & Leukemia.

Using retrospective data from two centers and 122 patients with MCL, the investigators compared the utility of staging 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT with that of other modalities used for detecting disease in specific compartments. They also assessed its impact on patient management.

The study results showed that, with the exception of a single patient having bone marrow involvement, all patients had positive PET/CT results, with detection of at least one hypermetabolic lesion.

For assessing nodal involvement, compared with CT alone, PET/CT detected additional lesions in 21% of patients. Splenic lesions were detected by PET/CT in 49% of patients and by CT alone in 47%.

For assessing bone marrow involvement, compared with bone marrow biopsy, PET/CT had a sensitivity of 52%, a specificity of 98%, a positive predictive value of 97%, a negative predictive value of 65%, and an overall accuracy of 74%.

For gastrointestinal involvement, compared with endoscopy, PET/CT had a sensitivity of 64% (78% after excluding diabetic patients taking metformin), a specificity of 91% (92%), a positive predictive value of 69% (72%), a negative predictive value of 90% (94%), and an overall accuracy of 85% (89%).

Ultimately, relative to CT alone, PET/CT altered stage and management in 19% of patients. Specifically, this imaging led to up-staging in 17% of patients, prompting clinicians to switch to more-aggressive chemotherapy, and down-staging in 2% of patients, prompting clinicians to skip unnecessary invasive therapies.

“We demonstrated that 18F-FDG pathologic uptake in MCL occurred in almost all patients, with excellent detection rate in nodal and splenic disease – indeed, better than CT,” the researchers wrote. “When we analyzed bone marrow and gastrointestinal involvement, the selection of patients excluding all conditions potentially affecting organ uptake and the use of specific criteria for the evaluation of these organs seemed to be crucial. Within these caveats, PET/CT showed good specificity for bone marrow and gastrointestinal evaluation.”

Study funding was not disclosed. Dr. Albano reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Albano D et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019 Aug;19(8):e457-64.

Use of staging PET/CT better defines the extent of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) in certain compartments, adding important information for treatment decisions, a cohort study suggests. However, patient selection and evaluation criteria are important for its utility.

“A correct and early identification of initial disease could be crucial because it could affect patient management and therapeutic choice,” Domenico Albano, MD, a nuclear medicine physician at the University of Brescia (Italy) and Spedali Civili Brescia, and colleagues wrote in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma, & Leukemia.

Using retrospective data from two centers and 122 patients with MCL, the investigators compared the utility of staging 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT with that of other modalities used for detecting disease in specific compartments. They also assessed its impact on patient management.

The study results showed that, with the exception of a single patient having bone marrow involvement, all patients had positive PET/CT results, with detection of at least one hypermetabolic lesion.

For assessing nodal involvement, compared with CT alone, PET/CT detected additional lesions in 21% of patients. Splenic lesions were detected by PET/CT in 49% of patients and by CT alone in 47%.

For assessing bone marrow involvement, compared with bone marrow biopsy, PET/CT had a sensitivity of 52%, a specificity of 98%, a positive predictive value of 97%, a negative predictive value of 65%, and an overall accuracy of 74%.

For gastrointestinal involvement, compared with endoscopy, PET/CT had a sensitivity of 64% (78% after excluding diabetic patients taking metformin), a specificity of 91% (92%), a positive predictive value of 69% (72%), a negative predictive value of 90% (94%), and an overall accuracy of 85% (89%).

Ultimately, relative to CT alone, PET/CT altered stage and management in 19% of patients. Specifically, this imaging led to up-staging in 17% of patients, prompting clinicians to switch to more-aggressive chemotherapy, and down-staging in 2% of patients, prompting clinicians to skip unnecessary invasive therapies.

“We demonstrated that 18F-FDG pathologic uptake in MCL occurred in almost all patients, with excellent detection rate in nodal and splenic disease – indeed, better than CT,” the researchers wrote. “When we analyzed bone marrow and gastrointestinal involvement, the selection of patients excluding all conditions potentially affecting organ uptake and the use of specific criteria for the evaluation of these organs seemed to be crucial. Within these caveats, PET/CT showed good specificity for bone marrow and gastrointestinal evaluation.”

Study funding was not disclosed. Dr. Albano reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Albano D et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019 Aug;19(8):e457-64.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA, & LEUKEMIA

Baby beverage 101: New recommendations on what young children should drink

entirely. A coalition of health and nutrition organizations offered all this and more in a new set of sometimes surprising recommendations about beverage consumption in children from birth to age 5 years.

The recommendations “are based on the best available evidence, combined with sound expert judgment, and provide consistent messages that can be used by a variety of stakeholders to improve the beverage intake patterns of young children,” the report authors wrote. “It is imperative to capitalize on early childhood as a critical window of opportunity during which dietary patterns are both impressionable and capable of setting the stage for lifelong eating behaviors.”

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Heart Association released their recommendations titled “Healthy Beverage Consumption in Early Childhood” in a report published Sept. 18.

The organizations convened expert panels and analyzed research to develop consensus beverage recommendations. Here are some highlights from the report, the writing of which was led by Megan Lott, MPH, RDN, of Healthy Eating Research and Duke Global Health Institute at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

- Breast milk or formula. This is what babies should be drinking for the first year of life.

- Plain drinking water. None is needed in the first 6 months of life. Introduce 0.5-1.0 cups/day over the next 6 months in cups and during meals when solid food is introduced. Then 1-4 cups/day are recommended from age 1-3 years, then 1.5-5 cups by age 4-5 years.

- Plain, pasteurized milk. None during the first year, then 2-3 cups a day of whole milk at age 12-24 months; if weight gain is excessive or family history is positive for obesity, dyslipidemia, or other cardiovascular disease, the pediatrician may recommend skim or lowfat milk at 12-24 months. Then provide up to 2 cups (age 2-3 years) then 2.5 cups (age 4-5 years) per day of skim /fat-free milk or low fat/1% milk

- 100% juice. None until 12 months. Then it can be provided, although whole fruit is preferred. No more than 0.5 cup per day until age 4-5 years, when no more than 0.5-0.75 cup per day is recommended.

- Plant-based milks and non-dairy beverages. None from age 0-1 year. And at ages 1-5 years, they only should be consumed when medically indicated, such as when a child has an allergy or per a preferred diet such as a vegan one. The panel didn’t recommend them as full replacements for dairy milk from age 12-24 months, and it noted that “consumption of these beverages as a full replacement for dairy milk should be undertaken in consultation with a health care provider so that adequate intake of key nutrients commonly obtained from dairy milk can be considered in dietary planning.”

- Other beverages. Flavored milk (like chocolate milk), “toddler milk,” sugar-sweetened drinks (including soft drinks, flavored water, and various fruit drinks), low-calorie sweetened drinks, and caffeinated drinks are not recommended at any age from 0-5 years. Toddler milk products “offer no unique nutritional value beyond what a nutritionally adequate diet provides and may contribute added sugars to the diet and undermine sustained breastfeeding,” the report authors said.

Lillian M. Beard, MD, said in an interview, “Pediatricians and other child health providers have major roles of influence in parents’ choices of foods and beverages for their infants and young children.

“Following these first-ever consensus recommendations on healthy drinks will alter family grocery shopping patterns, and not only improve the overall health of children under age 5 years, but also may improve the health outcomes of everyone in the household.” Dr. Beard is a clinical professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington. She was not one of the report authors and was asked to comment on the report.

The report was supported by the Healthy Eating Research, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

SOURCE: Lott M et al. Healthy Beverage Consumption in Early Childhood: Recommendations from Key National Health and Nutrition Organizations. Technical Scientific Report. (Durham, NC: Healthy Eating Research, 2019).

entirely. A coalition of health and nutrition organizations offered all this and more in a new set of sometimes surprising recommendations about beverage consumption in children from birth to age 5 years.

The recommendations “are based on the best available evidence, combined with sound expert judgment, and provide consistent messages that can be used by a variety of stakeholders to improve the beverage intake patterns of young children,” the report authors wrote. “It is imperative to capitalize on early childhood as a critical window of opportunity during which dietary patterns are both impressionable and capable of setting the stage for lifelong eating behaviors.”

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Heart Association released their recommendations titled “Healthy Beverage Consumption in Early Childhood” in a report published Sept. 18.

The organizations convened expert panels and analyzed research to develop consensus beverage recommendations. Here are some highlights from the report, the writing of which was led by Megan Lott, MPH, RDN, of Healthy Eating Research and Duke Global Health Institute at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

- Breast milk or formula. This is what babies should be drinking for the first year of life.

- Plain drinking water. None is needed in the first 6 months of life. Introduce 0.5-1.0 cups/day over the next 6 months in cups and during meals when solid food is introduced. Then 1-4 cups/day are recommended from age 1-3 years, then 1.5-5 cups by age 4-5 years.

- Plain, pasteurized milk. None during the first year, then 2-3 cups a day of whole milk at age 12-24 months; if weight gain is excessive or family history is positive for obesity, dyslipidemia, or other cardiovascular disease, the pediatrician may recommend skim or lowfat milk at 12-24 months. Then provide up to 2 cups (age 2-3 years) then 2.5 cups (age 4-5 years) per day of skim /fat-free milk or low fat/1% milk

- 100% juice. None until 12 months. Then it can be provided, although whole fruit is preferred. No more than 0.5 cup per day until age 4-5 years, when no more than 0.5-0.75 cup per day is recommended.

- Plant-based milks and non-dairy beverages. None from age 0-1 year. And at ages 1-5 years, they only should be consumed when medically indicated, such as when a child has an allergy or per a preferred diet such as a vegan one. The panel didn’t recommend them as full replacements for dairy milk from age 12-24 months, and it noted that “consumption of these beverages as a full replacement for dairy milk should be undertaken in consultation with a health care provider so that adequate intake of key nutrients commonly obtained from dairy milk can be considered in dietary planning.”

- Other beverages. Flavored milk (like chocolate milk), “toddler milk,” sugar-sweetened drinks (including soft drinks, flavored water, and various fruit drinks), low-calorie sweetened drinks, and caffeinated drinks are not recommended at any age from 0-5 years. Toddler milk products “offer no unique nutritional value beyond what a nutritionally adequate diet provides and may contribute added sugars to the diet and undermine sustained breastfeeding,” the report authors said.

Lillian M. Beard, MD, said in an interview, “Pediatricians and other child health providers have major roles of influence in parents’ choices of foods and beverages for their infants and young children.

“Following these first-ever consensus recommendations on healthy drinks will alter family grocery shopping patterns, and not only improve the overall health of children under age 5 years, but also may improve the health outcomes of everyone in the household.” Dr. Beard is a clinical professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington. She was not one of the report authors and was asked to comment on the report.

The report was supported by the Healthy Eating Research, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

SOURCE: Lott M et al. Healthy Beverage Consumption in Early Childhood: Recommendations from Key National Health and Nutrition Organizations. Technical Scientific Report. (Durham, NC: Healthy Eating Research, 2019).

entirely. A coalition of health and nutrition organizations offered all this and more in a new set of sometimes surprising recommendations about beverage consumption in children from birth to age 5 years.

The recommendations “are based on the best available evidence, combined with sound expert judgment, and provide consistent messages that can be used by a variety of stakeholders to improve the beverage intake patterns of young children,” the report authors wrote. “It is imperative to capitalize on early childhood as a critical window of opportunity during which dietary patterns are both impressionable and capable of setting the stage for lifelong eating behaviors.”

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Heart Association released their recommendations titled “Healthy Beverage Consumption in Early Childhood” in a report published Sept. 18.

The organizations convened expert panels and analyzed research to develop consensus beverage recommendations. Here are some highlights from the report, the writing of which was led by Megan Lott, MPH, RDN, of Healthy Eating Research and Duke Global Health Institute at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

- Breast milk or formula. This is what babies should be drinking for the first year of life.

- Plain drinking water. None is needed in the first 6 months of life. Introduce 0.5-1.0 cups/day over the next 6 months in cups and during meals when solid food is introduced. Then 1-4 cups/day are recommended from age 1-3 years, then 1.5-5 cups by age 4-5 years.

- Plain, pasteurized milk. None during the first year, then 2-3 cups a day of whole milk at age 12-24 months; if weight gain is excessive or family history is positive for obesity, dyslipidemia, or other cardiovascular disease, the pediatrician may recommend skim or lowfat milk at 12-24 months. Then provide up to 2 cups (age 2-3 years) then 2.5 cups (age 4-5 years) per day of skim /fat-free milk or low fat/1% milk

- 100% juice. None until 12 months. Then it can be provided, although whole fruit is preferred. No more than 0.5 cup per day until age 4-5 years, when no more than 0.5-0.75 cup per day is recommended.

- Plant-based milks and non-dairy beverages. None from age 0-1 year. And at ages 1-5 years, they only should be consumed when medically indicated, such as when a child has an allergy or per a preferred diet such as a vegan one. The panel didn’t recommend them as full replacements for dairy milk from age 12-24 months, and it noted that “consumption of these beverages as a full replacement for dairy milk should be undertaken in consultation with a health care provider so that adequate intake of key nutrients commonly obtained from dairy milk can be considered in dietary planning.”

- Other beverages. Flavored milk (like chocolate milk), “toddler milk,” sugar-sweetened drinks (including soft drinks, flavored water, and various fruit drinks), low-calorie sweetened drinks, and caffeinated drinks are not recommended at any age from 0-5 years. Toddler milk products “offer no unique nutritional value beyond what a nutritionally adequate diet provides and may contribute added sugars to the diet and undermine sustained breastfeeding,” the report authors said.

Lillian M. Beard, MD, said in an interview, “Pediatricians and other child health providers have major roles of influence in parents’ choices of foods and beverages for their infants and young children.

“Following these first-ever consensus recommendations on healthy drinks will alter family grocery shopping patterns, and not only improve the overall health of children under age 5 years, but also may improve the health outcomes of everyone in the household.” Dr. Beard is a clinical professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington. She was not one of the report authors and was asked to comment on the report.

The report was supported by the Healthy Eating Research, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

SOURCE: Lott M et al. Healthy Beverage Consumption in Early Childhood: Recommendations from Key National Health and Nutrition Organizations. Technical Scientific Report. (Durham, NC: Healthy Eating Research, 2019).

Secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures lacking

The report by independent actuarial firm Milliman examined the economic and clinical burden of new osteoporotic fractures in 2015 in the Medicare fee-for-service population, with data from a large medical claims database.

More than 10 million adults aged 50 years and older in the United States are thought to have osteoporosis, and 43.9% of adults are affected by low bone mass.

This report found that about 1.4 million Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries experienced more than 1.6 million osteoporotic fractures in that year, which if extrapolated to include Medicare Advantage beneficiaries would increase to a total of 2.3 million fractures in 2 million individuals.

The most common types of fractures were of the spine (23%) and hip (17%), although the authors noted that the spinal fracture figure did not account for potential underdiagnosis of vertebral fractures.

Women had a 79% higher rate of osteoporotic fractures than that of men, and one-third of people who experienced at least one osteoporotic fracture were aged 74-85 years.

Dane Hansen and colleagues from Milliman from drew particular attention to the lack of secondary prevention in people who had experienced a first osteoporotic fracture. They estimated that 15% of those who had a new osteoporotic fracture experienced one or more subsequent fractures within 12 months, yet only 9% of women received a bone mineral density test within 6 months to evaluate them for osteoporosis.

Overall, 21% of individuals who had a new osteoporotic fracture underwent bone mineral density testing during the fracture episode.

The authors pointed out that their analysis wasn’t able to look at pharmaceutical treatment, and so did not present “a full picture of the overall rate of BMD [bone mineral density] testing and appropriate treatment after a fracture for surviving patients.”

Nearly one in five Medicare beneficiaries experienced at least one new pressure ulcer during the fracture episode, and beneficiaries with osteoporotic fracture were two times more likely than were other Medicare beneficiaries to experience pressure ulcers. “This is significant because research has found that pressure ulcers are clinically difficult and expensive to manage,” the authors wrote. They also saw that nearly 20% of Medicare beneficiaries who experienced an osteoporotic fracture died within 12 months, with the highest mortality (30%) seen in those with hip fracture.

Osteoporotic fractures presented a significant cost burden, with 45% of beneficiaries having at least one acute inpatient hospital stay within 30 days of having a new osteoporotic fracture. The hospitalization rate was as high as 92% for individuals with hip fracture, while 11% of those with wrist fractures were hospitalized within 7 days of the fracture.

The annual allowed medical costs in the 12 months after a new fracture were more than twice the costs of the 12-month period before the fracture in the same individual, and each new fracture was associated with an incremental annual medical cost greater than $21,800.

“An osteoporotic fracture is a sentinel event that should trigger appropriate clinical attention directed to reducing the risk of future subsequent fractures,” the authors said. “Therefore, the months following an osteoporotic fracture, in which the risk of a subsequent fracture is high, provide an important opportunity to identify and treat osteoporosis and to perform other interventions, such as patient education and care coordination, in order to reduce the individual’s risk of a subsequent fracture.”

The report estimated that preventing 5% of subsequent osteoporotic fractures could have saved the Medicare program $310 million just in the 2-3 years after a new fracture, while preventing 20% of subsequent fractures could have saved $1,230 million. These figures included the cost of the additional bone mineral density testing, but did not account for the increased costs of treatment or fracture prevention.

“In future analysis, it will be important to net the total cost of the intervention and additional pharmaceutical treatment for osteoporosis against Medicare savings from avoided subsequent fractures to comprehensively measure the savings from secondary fracture prevention initiatives.”

SOURCE: Milliman Research Report, “Medicare Report of Osteoporotic Fractures,” August 2019.

The report by independent actuarial firm Milliman examined the economic and clinical burden of new osteoporotic fractures in 2015 in the Medicare fee-for-service population, with data from a large medical claims database.

More than 10 million adults aged 50 years and older in the United States are thought to have osteoporosis, and 43.9% of adults are affected by low bone mass.

This report found that about 1.4 million Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries experienced more than 1.6 million osteoporotic fractures in that year, which if extrapolated to include Medicare Advantage beneficiaries would increase to a total of 2.3 million fractures in 2 million individuals.

The most common types of fractures were of the spine (23%) and hip (17%), although the authors noted that the spinal fracture figure did not account for potential underdiagnosis of vertebral fractures.

Women had a 79% higher rate of osteoporotic fractures than that of men, and one-third of people who experienced at least one osteoporotic fracture were aged 74-85 years.

Dane Hansen and colleagues from Milliman from drew particular attention to the lack of secondary prevention in people who had experienced a first osteoporotic fracture. They estimated that 15% of those who had a new osteoporotic fracture experienced one or more subsequent fractures within 12 months, yet only 9% of women received a bone mineral density test within 6 months to evaluate them for osteoporosis.

Overall, 21% of individuals who had a new osteoporotic fracture underwent bone mineral density testing during the fracture episode.

The authors pointed out that their analysis wasn’t able to look at pharmaceutical treatment, and so did not present “a full picture of the overall rate of BMD [bone mineral density] testing and appropriate treatment after a fracture for surviving patients.”

Nearly one in five Medicare beneficiaries experienced at least one new pressure ulcer during the fracture episode, and beneficiaries with osteoporotic fracture were two times more likely than were other Medicare beneficiaries to experience pressure ulcers. “This is significant because research has found that pressure ulcers are clinically difficult and expensive to manage,” the authors wrote. They also saw that nearly 20% of Medicare beneficiaries who experienced an osteoporotic fracture died within 12 months, with the highest mortality (30%) seen in those with hip fracture.

Osteoporotic fractures presented a significant cost burden, with 45% of beneficiaries having at least one acute inpatient hospital stay within 30 days of having a new osteoporotic fracture. The hospitalization rate was as high as 92% for individuals with hip fracture, while 11% of those with wrist fractures were hospitalized within 7 days of the fracture.

The annual allowed medical costs in the 12 months after a new fracture were more than twice the costs of the 12-month period before the fracture in the same individual, and each new fracture was associated with an incremental annual medical cost greater than $21,800.

“An osteoporotic fracture is a sentinel event that should trigger appropriate clinical attention directed to reducing the risk of future subsequent fractures,” the authors said. “Therefore, the months following an osteoporotic fracture, in which the risk of a subsequent fracture is high, provide an important opportunity to identify and treat osteoporosis and to perform other interventions, such as patient education and care coordination, in order to reduce the individual’s risk of a subsequent fracture.”

The report estimated that preventing 5% of subsequent osteoporotic fractures could have saved the Medicare program $310 million just in the 2-3 years after a new fracture, while preventing 20% of subsequent fractures could have saved $1,230 million. These figures included the cost of the additional bone mineral density testing, but did not account for the increased costs of treatment or fracture prevention.

“In future analysis, it will be important to net the total cost of the intervention and additional pharmaceutical treatment for osteoporosis against Medicare savings from avoided subsequent fractures to comprehensively measure the savings from secondary fracture prevention initiatives.”

SOURCE: Milliman Research Report, “Medicare Report of Osteoporotic Fractures,” August 2019.

The report by independent actuarial firm Milliman examined the economic and clinical burden of new osteoporotic fractures in 2015 in the Medicare fee-for-service population, with data from a large medical claims database.

More than 10 million adults aged 50 years and older in the United States are thought to have osteoporosis, and 43.9% of adults are affected by low bone mass.

This report found that about 1.4 million Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries experienced more than 1.6 million osteoporotic fractures in that year, which if extrapolated to include Medicare Advantage beneficiaries would increase to a total of 2.3 million fractures in 2 million individuals.

The most common types of fractures were of the spine (23%) and hip (17%), although the authors noted that the spinal fracture figure did not account for potential underdiagnosis of vertebral fractures.

Women had a 79% higher rate of osteoporotic fractures than that of men, and one-third of people who experienced at least one osteoporotic fracture were aged 74-85 years.

Dane Hansen and colleagues from Milliman from drew particular attention to the lack of secondary prevention in people who had experienced a first osteoporotic fracture. They estimated that 15% of those who had a new osteoporotic fracture experienced one or more subsequent fractures within 12 months, yet only 9% of women received a bone mineral density test within 6 months to evaluate them for osteoporosis.

Overall, 21% of individuals who had a new osteoporotic fracture underwent bone mineral density testing during the fracture episode.

The authors pointed out that their analysis wasn’t able to look at pharmaceutical treatment, and so did not present “a full picture of the overall rate of BMD [bone mineral density] testing and appropriate treatment after a fracture for surviving patients.”

Nearly one in five Medicare beneficiaries experienced at least one new pressure ulcer during the fracture episode, and beneficiaries with osteoporotic fracture were two times more likely than were other Medicare beneficiaries to experience pressure ulcers. “This is significant because research has found that pressure ulcers are clinically difficult and expensive to manage,” the authors wrote. They also saw that nearly 20% of Medicare beneficiaries who experienced an osteoporotic fracture died within 12 months, with the highest mortality (30%) seen in those with hip fracture.

Osteoporotic fractures presented a significant cost burden, with 45% of beneficiaries having at least one acute inpatient hospital stay within 30 days of having a new osteoporotic fracture. The hospitalization rate was as high as 92% for individuals with hip fracture, while 11% of those with wrist fractures were hospitalized within 7 days of the fracture.

The annual allowed medical costs in the 12 months after a new fracture were more than twice the costs of the 12-month period before the fracture in the same individual, and each new fracture was associated with an incremental annual medical cost greater than $21,800.

“An osteoporotic fracture is a sentinel event that should trigger appropriate clinical attention directed to reducing the risk of future subsequent fractures,” the authors said. “Therefore, the months following an osteoporotic fracture, in which the risk of a subsequent fracture is high, provide an important opportunity to identify and treat osteoporosis and to perform other interventions, such as patient education and care coordination, in order to reduce the individual’s risk of a subsequent fracture.”

The report estimated that preventing 5% of subsequent osteoporotic fractures could have saved the Medicare program $310 million just in the 2-3 years after a new fracture, while preventing 20% of subsequent fractures could have saved $1,230 million. These figures included the cost of the additional bone mineral density testing, but did not account for the increased costs of treatment or fracture prevention.

“In future analysis, it will be important to net the total cost of the intervention and additional pharmaceutical treatment for osteoporosis against Medicare savings from avoided subsequent fractures to comprehensively measure the savings from secondary fracture prevention initiatives.”

SOURCE: Milliman Research Report, “Medicare Report of Osteoporotic Fractures,” August 2019.

FROM THE NATIONAL OSTEOPOROSIS FOUNDATION

Increased levels of a bacterial strain may cause nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

A new study involving both human patients and mice has confirmed a long-believed association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and an alteration in the gut microbiome that produces high levels of alcohol.

The study was initiated after the treatment of a rare case: a patient who presented with severe nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) plus auto-brewery syndrome. The patient had a very high blood alcohol concentration but an alcohol-free, high-carbohydrate diet. It was determined that strains of high alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (HiAlc Kpn) rather than a fungal infection were the catalyst for the high blood alcohol level. As such, Jing Yuan of the Capital Institute of Pediatrics in Beijing and coauthors attempted to “connect these commensal HiAlc Kpn to the pathogenesis of hepatic damage” through this study, which was published in Cell Metabolism.

The researchers began by examining 43 patients with NAFLD and 48 healthy controls. Among the patients with NAFLD, 11 had nonalcoholic fatty liver and 32 had NASH. Specifically, they analyzed the presence and effects of HiAlc Kpn, determining that the abundance of Klebsiella pneumoniae was slightly higher in the feces of NAFLD patients, compared with healthy patients, but that their alcohol-producing ability in NAFLD patients was significantly stronger. Of the patients with NAFLD, 61% carried HiAlc and medium-alcohol-producing Kpn, compared with 6.25% of the controls.

Another phase of their study involved feeding specific pathogen-free mice either HiAlc Kpn, ethanol, or yeast extract peptone dextrose medium (pair-fed) for 4, 6, and 8 weeks. The mice that were fed HiAlc Kpn or ethanol showed clear microsteatosis and macrosteatosis in their livers at 4 and 8 weeks, compared with the pair-fed mice. In addition, the HiAlc-Kpn-fed and ethanol-fed mice had increased levels of aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase in their serum and increased levels of triglycerides and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances in their liver. The results overall indicated that the HiAlc-Kpn-fed mice had developed hepatic steatosis.

An additional phase included the intestinal flora from a NASH patient with a specific Kpn strain being fed to germ-free mice. At the same time, two types of intestinal flora from mice with NAFLD were transplanted into healthy mice: one induced by two other specific Kpn strains and one in which those strains had been selectively eliminated. The results saw obvious steatosis in the mice who received the flora from either mice with NAFLD induced by Kpn or the NASH patient at 4 weeks and 8 weeks, respectively. The mice who received the flora win which Kpn had been eliminated saw no fat-related changes in the liver. “These results further suggest that HiAlc Kpn might be one of the major causes of NAFLD development,” the researchers wrote.

The authors acknowledged the study’s limitations, chiefly including the lack of a clinical cohort of individuals with auto brewery syndrome but without NAFLD that could be used as a control. However, they also noted a belief that “causality was shown by the transfer experiments of HiAlc Kpn” while adding that “the further analysis of the impact of ethanol in ABS [auto brewery syndrome] patients should be investigated.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation for Key Programs of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Megaprojects of Science and Technology Research of China, and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Yuan J et al. Cell Metab. 2019 Sep 19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.018.

A new study involving both human patients and mice has confirmed a long-believed association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and an alteration in the gut microbiome that produces high levels of alcohol.

The study was initiated after the treatment of a rare case: a patient who presented with severe nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) plus auto-brewery syndrome. The patient had a very high blood alcohol concentration but an alcohol-free, high-carbohydrate diet. It was determined that strains of high alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (HiAlc Kpn) rather than a fungal infection were the catalyst for the high blood alcohol level. As such, Jing Yuan of the Capital Institute of Pediatrics in Beijing and coauthors attempted to “connect these commensal HiAlc Kpn to the pathogenesis of hepatic damage” through this study, which was published in Cell Metabolism.

The researchers began by examining 43 patients with NAFLD and 48 healthy controls. Among the patients with NAFLD, 11 had nonalcoholic fatty liver and 32 had NASH. Specifically, they analyzed the presence and effects of HiAlc Kpn, determining that the abundance of Klebsiella pneumoniae was slightly higher in the feces of NAFLD patients, compared with healthy patients, but that their alcohol-producing ability in NAFLD patients was significantly stronger. Of the patients with NAFLD, 61% carried HiAlc and medium-alcohol-producing Kpn, compared with 6.25% of the controls.

Another phase of their study involved feeding specific pathogen-free mice either HiAlc Kpn, ethanol, or yeast extract peptone dextrose medium (pair-fed) for 4, 6, and 8 weeks. The mice that were fed HiAlc Kpn or ethanol showed clear microsteatosis and macrosteatosis in their livers at 4 and 8 weeks, compared with the pair-fed mice. In addition, the HiAlc-Kpn-fed and ethanol-fed mice had increased levels of aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase in their serum and increased levels of triglycerides and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances in their liver. The results overall indicated that the HiAlc-Kpn-fed mice had developed hepatic steatosis.

An additional phase included the intestinal flora from a NASH patient with a specific Kpn strain being fed to germ-free mice. At the same time, two types of intestinal flora from mice with NAFLD were transplanted into healthy mice: one induced by two other specific Kpn strains and one in which those strains had been selectively eliminated. The results saw obvious steatosis in the mice who received the flora from either mice with NAFLD induced by Kpn or the NASH patient at 4 weeks and 8 weeks, respectively. The mice who received the flora win which Kpn had been eliminated saw no fat-related changes in the liver. “These results further suggest that HiAlc Kpn might be one of the major causes of NAFLD development,” the researchers wrote.

The authors acknowledged the study’s limitations, chiefly including the lack of a clinical cohort of individuals with auto brewery syndrome but without NAFLD that could be used as a control. However, they also noted a belief that “causality was shown by the transfer experiments of HiAlc Kpn” while adding that “the further analysis of the impact of ethanol in ABS [auto brewery syndrome] patients should be investigated.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation for Key Programs of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Megaprojects of Science and Technology Research of China, and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Yuan J et al. Cell Metab. 2019 Sep 19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.018.

A new study involving both human patients and mice has confirmed a long-believed association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and an alteration in the gut microbiome that produces high levels of alcohol.

The study was initiated after the treatment of a rare case: a patient who presented with severe nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) plus auto-brewery syndrome. The patient had a very high blood alcohol concentration but an alcohol-free, high-carbohydrate diet. It was determined that strains of high alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (HiAlc Kpn) rather than a fungal infection were the catalyst for the high blood alcohol level. As such, Jing Yuan of the Capital Institute of Pediatrics in Beijing and coauthors attempted to “connect these commensal HiAlc Kpn to the pathogenesis of hepatic damage” through this study, which was published in Cell Metabolism.

The researchers began by examining 43 patients with NAFLD and 48 healthy controls. Among the patients with NAFLD, 11 had nonalcoholic fatty liver and 32 had NASH. Specifically, they analyzed the presence and effects of HiAlc Kpn, determining that the abundance of Klebsiella pneumoniae was slightly higher in the feces of NAFLD patients, compared with healthy patients, but that their alcohol-producing ability in NAFLD patients was significantly stronger. Of the patients with NAFLD, 61% carried HiAlc and medium-alcohol-producing Kpn, compared with 6.25% of the controls.

Another phase of their study involved feeding specific pathogen-free mice either HiAlc Kpn, ethanol, or yeast extract peptone dextrose medium (pair-fed) for 4, 6, and 8 weeks. The mice that were fed HiAlc Kpn or ethanol showed clear microsteatosis and macrosteatosis in their livers at 4 and 8 weeks, compared with the pair-fed mice. In addition, the HiAlc-Kpn-fed and ethanol-fed mice had increased levels of aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase in their serum and increased levels of triglycerides and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances in their liver. The results overall indicated that the HiAlc-Kpn-fed mice had developed hepatic steatosis.

An additional phase included the intestinal flora from a NASH patient with a specific Kpn strain being fed to germ-free mice. At the same time, two types of intestinal flora from mice with NAFLD were transplanted into healthy mice: one induced by two other specific Kpn strains and one in which those strains had been selectively eliminated. The results saw obvious steatosis in the mice who received the flora from either mice with NAFLD induced by Kpn or the NASH patient at 4 weeks and 8 weeks, respectively. The mice who received the flora win which Kpn had been eliminated saw no fat-related changes in the liver. “These results further suggest that HiAlc Kpn might be one of the major causes of NAFLD development,” the researchers wrote.

The authors acknowledged the study’s limitations, chiefly including the lack of a clinical cohort of individuals with auto brewery syndrome but without NAFLD that could be used as a control. However, they also noted a belief that “causality was shown by the transfer experiments of HiAlc Kpn” while adding that “the further analysis of the impact of ethanol in ABS [auto brewery syndrome] patients should be investigated.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation for Key Programs of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Megaprojects of Science and Technology Research of China, and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Yuan J et al. Cell Metab. 2019 Sep 19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.018.

FROM CELL METABOLISM

Key clinical point: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease can be caused or exacerbated by excess levels of a high-alcohol-producing bacterial strain.

Major finding: 61% of patients with NAFLD carried high alcohol- and medium alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (HiAlc Kpn), compared to 6.25% of healthy controls.

Study details: A multiphase study that included analysis of a 43-patient cohort with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as well as experiments with mice and HiAlc Kpn.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation for Key Programs of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Megaprojects of Science and Technology Research of China, and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Yuan J et al. Cell Metab. 2019 Sep 19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.018.

Helping patients find balance between self and other

Cultural considerations require careful assessments on therapists’ part

This column is dedicated to the late Carl C. Bell, MD.

When we work with patients and their families from cultures that are not the culture in which we ourselves were raised, we think more deeply about this balance. In this column, I offer a simple but solid framework for this inquiry.

The first family therapist to crystallize the dialectic between the self and its relationship to others was Murray Bowen, MD. He believed that the differentiation of self from the family was the major task of human development. Dr. Bowen worked in a time when vilification of the “other” was common practice in individual psychotherapies and the goal of individual psychotherapy was the development of a healthy sense of self rather than repairing or developing relationships.

When faced with patients from cultures that are unfamiliar to us, we are less confident about how to assess the balance between self and other. In many cultures, marriages are based on social class and perceived social opportunities and are arranged by the respective families. If you come from a collectivist culture, where the focus is on the belief that the group is more important than the individual, the focus is more on self in relation to a group, belonging to a group, and participating in a group than self-striving. This is most evident in the role of women in many families (as well as in other organizations), in which women shoulder the responsibility for keeping families functional and together.

American culture is focused on serious self-striving. From kindergarten, children are expected to excel and to become the best self that they can be – regardless of the toll this takes on relationships. Self-expression and self-actualization frequently are considered the pinnacle of a life’s achievement. Relationships may take a backseat, often being transitory or utilitarian. This leads to switching relationships, peer groups, and friends – and a strong emphasis on cultivating work relationships.

Exploring Dr. Bowen’s theories

Dr. Bowen posited that the family relational pull affects individual development in a negative way. Despite this, his model is considered one of the most comprehensive explanations for the development of psychological problems from a systemic, relational, and multigenerational perspective.1 He identified the basic self (B-self), which strives for differentiation in contrast to the false/pseudo/relational self (R-self), which strives to meet group or family norms.

Dr. Bowen was the oldest of three and grew up in a small town in Tennessee. His father was the mayor of the town and owned several properties, including the funeral home. Following medical training, Dr. Bowen served during World War II. He accepted a fellowship in surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., but his wartime experiences resulted in a change of interest to psychiatry. Dr. Bowen trained at the Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kan., and in 1954 became the first director of the family division at the National Institute of Mental Health. He and his colleagues studied the families of patients with schizophrenia. They described eight fundamental concepts that supported the important aspects of individual growth. When he moved to Georgetown University in Washington, he developed the Bowen Family Systems Theory.2

Dr. Bowen’s eight concepts

1. Nuclear Family Emotional Process

2. Differentiation of self

3. Triangles

4. Emotional cutoff

5. Family projection process

6. Multigenerational transmission process

7. Sibling position

8. Societal Emotional Process

According to Dr. Bowen, the B-self makes decisions on facts, principles, and intrinsic motivation and decides what they are willing to do/not willing to do based on their own internal ethics. On the other hand, the R-self goes along with everybody else, even when the person internally disagrees. He considered the R-self as wanting acceptance in relationship, possibly changing beliefs to find approval, and striving to be liked. Carmen Knudson-Martin, PhD,3 explored the relationship between the B-self and the R-self and suggested that they exist along two dimensions, both of which are important. My contention is that the R-self is undertheorized and deserves much more exploration.

Developmental psychologists and psychiatrists have focused on understanding the process of psychological maturation of the individual throughout life. However, there is little study of the development of a healthy relationship between self and other. We have, instead, gathered examples and descriptors of the pathological examples of the “other.” We can readily call out enmeshment, the manipulations of the borderline personality disordered, the cold withholding mother – to name the most vilified. What do we know about the healthy R-self?

Measuring the relational self

We have understood the R-self mostly through the study of pathological relationships. For example, pathological parenting has been shown to “result” in individual pathology and as a factor in the development of psychiatric illness. The measurement of the relationship between patient and family member/partner is aimed at elucidating pathology. The supreme example is emotional overinvolvement (EOI).

EOI is an integral part of the construct called expressed emotion and is often measured using the Camberwell Family Interview.4 High EOI has been identified routinely as predictive of worsening of psychiatric illness.5 However, exceptions are found (when you look for them)! In African American families, for example, high EOI is predictive of better outcomes in patients with schizophrenia.6 Jill M. Hooley, DPhil, also has identified that patients with borderline personality disorders do better in families with high EOI.7

A shorter equivalent research tool is the 5-minute speech sample (FMSS). The FMSS analyses 5 minutes of the speech of a parent/family member who is asked to describe the identified patient. EOI is identified by expressions of excessive worry or concern, self-sacrifice, or exaggerated praise. In a study of 223 child-mother dyads, 56.5% of which were Hispanic, use of the FMSS found high EOI predicted externalizing behaviors.8

More recently, psychiatry has sought to identify and measure positive factors, such as family warmth. In Puerto Rican children, high parental warmth was found to be protective against psychiatric disorders.9 In a study of Burmese migrant families from 20 communities in Thailand (513 caregivers and 479 patients with schizophrenia, aged 7-15 years), families were randomized to a waitlist or a 12-week family intervention that promoted warmth.10 The family intervention resulted in increased parental warmth and affection and increased family well-being.

Applying the theories to practice

An adolescent, Jan, does not speak when her mother is in the room. Jan has a small B-self, and her mother has a large B-self. Not only does Jan have to develop a strong B, but she also has to change how she is in relation – she has to change her R-self. For Jan, individual therapy supports the development of a stronger B-self. Working with the patient and her mother, the balance between both B-selves and the joined R-self can be reworked. In essence, the therapist encourages Jan to speak and helps the mother keep her own counsel. This is a situation in which the individual and family intervention are best implemented by the same therapist.

Systemic family therapy, a specific type of family intervention, focuses on how all the R-selves in a family work together as a unit called the family, or F-self. The F-self also has its own family history, as relationship patterns are transmitted and played out through families and play out through subsequent generations. A new type of family therapy called family constellation therapy (FCT) focuses on the F-self as a collection of ancestral selves. This resonates strongly with families who have experienced significant trauma, such as war and Holocaust survivors. FCT is popular in collectivist cultures, where there is a strong belief in the power and influence of ancestors and where the self is understood as an “assemblage of ancestral relationships that often creates problems in the present day.”11 Dr. Bowen recognized this multigenerational pattern as one of his eight fundamental principles.

The patients whom we see often have failing or fractured relationships. They might be stuck in dysfunctional transactional patterns with intimate partners, or they might fail to find a suitable intimate partner. We recognize relational dysfunction such as “codependency,” “symbiosis,” and “enmeshment.” We recognize too much distance, identifying family cutoffs. We still have a long way to go before clinical practice incorporates the importance of assessment and development of healthy relationships in a deep way. A typical question heard across all clinics: Is your partner/family supportive? Not much else is asked in regard to relationships, unless the answer is no. We have yet to develop a good set of inquiring questions that focus on the assessment of healthy relationships.

What can the therapist do to help the patient manage this continual dialectic? The therapist can ask the questions: How important is your B-self versus your R-self? What is the balance between your B-self and your R-self? What do you know about your family or F-self? Is your F-self important to you?

References

1. Nichols MP and Davis S. Family Therapy: Concepts & Methods, 8th ed. (Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2008).

2. The Bowen Center for the Study of the Family.

3. Knudson-Martin C. Fam J. 1996 Jul 1. doi: 1066480796043002.

4. Leff J and Vaughn C. Expressed Emotion in Families. (New York: The Guilford Press, 1985).

5. Breitborde NJK et al. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013 Oct;201(10):833-40.

6. Gurak K and de Mamani AW. Fam Process. 2017;56(2):476-86.

7. Hooley JM et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010 Aug;71(8):1017-24.

8. Khafi TY et al. J Fam Psychol. 2015 Aug;29(4):585-94.

9. Santesteban-Echarr et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2017 Apr;87:30-6.

10. Puffer ES et al. PLoS One. 2017 Mar 28;12(3):e0172611.

11. Pritzker SE and WL Duncan. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2019 Sep;43(3):468-95.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of Working With Families in Family Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest.

Cultural considerations require careful assessments on therapists’ part

Cultural considerations require careful assessments on therapists’ part

This column is dedicated to the late Carl C. Bell, MD.

When we work with patients and their families from cultures that are not the culture in which we ourselves were raised, we think more deeply about this balance. In this column, I offer a simple but solid framework for this inquiry.

The first family therapist to crystallize the dialectic between the self and its relationship to others was Murray Bowen, MD. He believed that the differentiation of self from the family was the major task of human development. Dr. Bowen worked in a time when vilification of the “other” was common practice in individual psychotherapies and the goal of individual psychotherapy was the development of a healthy sense of self rather than repairing or developing relationships.

When faced with patients from cultures that are unfamiliar to us, we are less confident about how to assess the balance between self and other. In many cultures, marriages are based on social class and perceived social opportunities and are arranged by the respective families. If you come from a collectivist culture, where the focus is on the belief that the group is more important than the individual, the focus is more on self in relation to a group, belonging to a group, and participating in a group than self-striving. This is most evident in the role of women in many families (as well as in other organizations), in which women shoulder the responsibility for keeping families functional and together.

American culture is focused on serious self-striving. From kindergarten, children are expected to excel and to become the best self that they can be – regardless of the toll this takes on relationships. Self-expression and self-actualization frequently are considered the pinnacle of a life’s achievement. Relationships may take a backseat, often being transitory or utilitarian. This leads to switching relationships, peer groups, and friends – and a strong emphasis on cultivating work relationships.

Exploring Dr. Bowen’s theories

Dr. Bowen posited that the family relational pull affects individual development in a negative way. Despite this, his model is considered one of the most comprehensive explanations for the development of psychological problems from a systemic, relational, and multigenerational perspective.1 He identified the basic self (B-self), which strives for differentiation in contrast to the false/pseudo/relational self (R-self), which strives to meet group or family norms.

Dr. Bowen was the oldest of three and grew up in a small town in Tennessee. His father was the mayor of the town and owned several properties, including the funeral home. Following medical training, Dr. Bowen served during World War II. He accepted a fellowship in surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., but his wartime experiences resulted in a change of interest to psychiatry. Dr. Bowen trained at the Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kan., and in 1954 became the first director of the family division at the National Institute of Mental Health. He and his colleagues studied the families of patients with schizophrenia. They described eight fundamental concepts that supported the important aspects of individual growth. When he moved to Georgetown University in Washington, he developed the Bowen Family Systems Theory.2

Dr. Bowen’s eight concepts

1. Nuclear Family Emotional Process

2. Differentiation of self

3. Triangles

4. Emotional cutoff

5. Family projection process

6. Multigenerational transmission process

7. Sibling position

8. Societal Emotional Process

According to Dr. Bowen, the B-self makes decisions on facts, principles, and intrinsic motivation and decides what they are willing to do/not willing to do based on their own internal ethics. On the other hand, the R-self goes along with everybody else, even when the person internally disagrees. He considered the R-self as wanting acceptance in relationship, possibly changing beliefs to find approval, and striving to be liked. Carmen Knudson-Martin, PhD,3 explored the relationship between the B-self and the R-self and suggested that they exist along two dimensions, both of which are important. My contention is that the R-self is undertheorized and deserves much more exploration.

Developmental psychologists and psychiatrists have focused on understanding the process of psychological maturation of the individual throughout life. However, there is little study of the development of a healthy relationship between self and other. We have, instead, gathered examples and descriptors of the pathological examples of the “other.” We can readily call out enmeshment, the manipulations of the borderline personality disordered, the cold withholding mother – to name the most vilified. What do we know about the healthy R-self?

Measuring the relational self

We have understood the R-self mostly through the study of pathological relationships. For example, pathological parenting has been shown to “result” in individual pathology and as a factor in the development of psychiatric illness. The measurement of the relationship between patient and family member/partner is aimed at elucidating pathology. The supreme example is emotional overinvolvement (EOI).

EOI is an integral part of the construct called expressed emotion and is often measured using the Camberwell Family Interview.4 High EOI has been identified routinely as predictive of worsening of psychiatric illness.5 However, exceptions are found (when you look for them)! In African American families, for example, high EOI is predictive of better outcomes in patients with schizophrenia.6 Jill M. Hooley, DPhil, also has identified that patients with borderline personality disorders do better in families with high EOI.7

A shorter equivalent research tool is the 5-minute speech sample (FMSS). The FMSS analyses 5 minutes of the speech of a parent/family member who is asked to describe the identified patient. EOI is identified by expressions of excessive worry or concern, self-sacrifice, or exaggerated praise. In a study of 223 child-mother dyads, 56.5% of which were Hispanic, use of the FMSS found high EOI predicted externalizing behaviors.8

More recently, psychiatry has sought to identify and measure positive factors, such as family warmth. In Puerto Rican children, high parental warmth was found to be protective against psychiatric disorders.9 In a study of Burmese migrant families from 20 communities in Thailand (513 caregivers and 479 patients with schizophrenia, aged 7-15 years), families were randomized to a waitlist or a 12-week family intervention that promoted warmth.10 The family intervention resulted in increased parental warmth and affection and increased family well-being.

Applying the theories to practice

An adolescent, Jan, does not speak when her mother is in the room. Jan has a small B-self, and her mother has a large B-self. Not only does Jan have to develop a strong B, but she also has to change how she is in relation – she has to change her R-self. For Jan, individual therapy supports the development of a stronger B-self. Working with the patient and her mother, the balance between both B-selves and the joined R-self can be reworked. In essence, the therapist encourages Jan to speak and helps the mother keep her own counsel. This is a situation in which the individual and family intervention are best implemented by the same therapist.

Systemic family therapy, a specific type of family intervention, focuses on how all the R-selves in a family work together as a unit called the family, or F-self. The F-self also has its own family history, as relationship patterns are transmitted and played out through families and play out through subsequent generations. A new type of family therapy called family constellation therapy (FCT) focuses on the F-self as a collection of ancestral selves. This resonates strongly with families who have experienced significant trauma, such as war and Holocaust survivors. FCT is popular in collectivist cultures, where there is a strong belief in the power and influence of ancestors and where the self is understood as an “assemblage of ancestral relationships that often creates problems in the present day.”11 Dr. Bowen recognized this multigenerational pattern as one of his eight fundamental principles.

The patients whom we see often have failing or fractured relationships. They might be stuck in dysfunctional transactional patterns with intimate partners, or they might fail to find a suitable intimate partner. We recognize relational dysfunction such as “codependency,” “symbiosis,” and “enmeshment.” We recognize too much distance, identifying family cutoffs. We still have a long way to go before clinical practice incorporates the importance of assessment and development of healthy relationships in a deep way. A typical question heard across all clinics: Is your partner/family supportive? Not much else is asked in regard to relationships, unless the answer is no. We have yet to develop a good set of inquiring questions that focus on the assessment of healthy relationships.

What can the therapist do to help the patient manage this continual dialectic? The therapist can ask the questions: How important is your B-self versus your R-self? What is the balance between your B-self and your R-self? What do you know about your family or F-self? Is your F-self important to you?

References