User login

Adult insomnia associated with childhood behavioral problems

Yohannes Adama Melaku, MPH, PhD, of the Adelaide (Australia) Institute for Sleep Health at Flinders University and coauthors drew data from the 1970 UK Birth Cohort Study. This study followed an initial cohort of 16,571 babies who were born during a single week, with follow-up at ages 5, 10, 16, 26, 30, 38, 42, and 46 years. For the purposes of this study, the investigators looked at participants who, at 42 years of age, were alive and not lost to follow-up and who responded to an invitation to be interviewed; the sample sizes in the analysis were 8,050 participants aged 5 years, 9,090 participants aged 10 years, 9,653 participants aged 16 years, and 9,841 participants aged 42 years.

Behavior was measured at ages 5 years and 16 years using the Rutter Behavioral Scale (RBS) and at age 10 years using a visual analog scale, and insomnia symptoms were assessed through interviewing participants in adulthood about duration of sleep, difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and not feeling rested on waking. Participants were organized into normal behavior (less than or equal to 80th percentile on RBS), moderate behavioral problems (greater than the 80th percentile but less than or equal to the 95th percentile), and severe behavioral problems (above 95th percentile). The investigators then devised two models for their analysis: Model 1 adjusted for sex, parent’s social class and educational level, marital status, educational status, and social class, and model 2 adjusted for physical activity level and body mass index (BMI) trajectory (from 10 to 42 years), perceived health status, and number of noncommunicable diseases, although this latter model yielded fewer statistically significant results in some analyses.

Odds for difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep as an adult was increased among participants with severe behavioral problems at age 5 years in model 1 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-1.96; P = .004), as well as for those with severe problems at 10 years (aOR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.14-1.63; P = .001), and at 16 years (aOR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.59-2.91; P less than .001). The aORs also were higher individually for difficulty initiating sleep and for difficulty maintaining sleep in all age groups.

The association with adulthood insomnia was stronger in participants with externalizing behavioral problems such as lying, bullying, restlessness, and fighting than it was in those with internalizing behavioral problems such as worry, fearfulness, and solitariness.

“Although early sleep problems should be identified, we should additionally identify children with moderate to severe behavioral problems that persist throughout childhood as potential beneficiaries of early intervention with a sleep health focus,” the authors wrote.

One of the study’s limitations was a lack of standardized insomnia measures in the cohort study; however, the researchers suggested that the symptoms included reflect those of standardized measures and diagnostic criteria.

“This study is the first, to our knowledge, to suggest an unfavorable association of early-life behavioral problems with adulthood sleep health, underlining the importance of treating behavioral problems in children and addressing insomnia from a life-course perspective,” they concluded.

No study sponsor was identified. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Melaku YA et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10861.

Yohannes Adama Melaku, MPH, PhD, of the Adelaide (Australia) Institute for Sleep Health at Flinders University and coauthors drew data from the 1970 UK Birth Cohort Study. This study followed an initial cohort of 16,571 babies who were born during a single week, with follow-up at ages 5, 10, 16, 26, 30, 38, 42, and 46 years. For the purposes of this study, the investigators looked at participants who, at 42 years of age, were alive and not lost to follow-up and who responded to an invitation to be interviewed; the sample sizes in the analysis were 8,050 participants aged 5 years, 9,090 participants aged 10 years, 9,653 participants aged 16 years, and 9,841 participants aged 42 years.

Behavior was measured at ages 5 years and 16 years using the Rutter Behavioral Scale (RBS) and at age 10 years using a visual analog scale, and insomnia symptoms were assessed through interviewing participants in adulthood about duration of sleep, difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and not feeling rested on waking. Participants were organized into normal behavior (less than or equal to 80th percentile on RBS), moderate behavioral problems (greater than the 80th percentile but less than or equal to the 95th percentile), and severe behavioral problems (above 95th percentile). The investigators then devised two models for their analysis: Model 1 adjusted for sex, parent’s social class and educational level, marital status, educational status, and social class, and model 2 adjusted for physical activity level and body mass index (BMI) trajectory (from 10 to 42 years), perceived health status, and number of noncommunicable diseases, although this latter model yielded fewer statistically significant results in some analyses.

Odds for difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep as an adult was increased among participants with severe behavioral problems at age 5 years in model 1 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-1.96; P = .004), as well as for those with severe problems at 10 years (aOR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.14-1.63; P = .001), and at 16 years (aOR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.59-2.91; P less than .001). The aORs also were higher individually for difficulty initiating sleep and for difficulty maintaining sleep in all age groups.

The association with adulthood insomnia was stronger in participants with externalizing behavioral problems such as lying, bullying, restlessness, and fighting than it was in those with internalizing behavioral problems such as worry, fearfulness, and solitariness.

“Although early sleep problems should be identified, we should additionally identify children with moderate to severe behavioral problems that persist throughout childhood as potential beneficiaries of early intervention with a sleep health focus,” the authors wrote.

One of the study’s limitations was a lack of standardized insomnia measures in the cohort study; however, the researchers suggested that the symptoms included reflect those of standardized measures and diagnostic criteria.

“This study is the first, to our knowledge, to suggest an unfavorable association of early-life behavioral problems with adulthood sleep health, underlining the importance of treating behavioral problems in children and addressing insomnia from a life-course perspective,” they concluded.

No study sponsor was identified. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Melaku YA et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10861.

Yohannes Adama Melaku, MPH, PhD, of the Adelaide (Australia) Institute for Sleep Health at Flinders University and coauthors drew data from the 1970 UK Birth Cohort Study. This study followed an initial cohort of 16,571 babies who were born during a single week, with follow-up at ages 5, 10, 16, 26, 30, 38, 42, and 46 years. For the purposes of this study, the investigators looked at participants who, at 42 years of age, were alive and not lost to follow-up and who responded to an invitation to be interviewed; the sample sizes in the analysis were 8,050 participants aged 5 years, 9,090 participants aged 10 years, 9,653 participants aged 16 years, and 9,841 participants aged 42 years.

Behavior was measured at ages 5 years and 16 years using the Rutter Behavioral Scale (RBS) and at age 10 years using a visual analog scale, and insomnia symptoms were assessed through interviewing participants in adulthood about duration of sleep, difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and not feeling rested on waking. Participants were organized into normal behavior (less than or equal to 80th percentile on RBS), moderate behavioral problems (greater than the 80th percentile but less than or equal to the 95th percentile), and severe behavioral problems (above 95th percentile). The investigators then devised two models for their analysis: Model 1 adjusted for sex, parent’s social class and educational level, marital status, educational status, and social class, and model 2 adjusted for physical activity level and body mass index (BMI) trajectory (from 10 to 42 years), perceived health status, and number of noncommunicable diseases, although this latter model yielded fewer statistically significant results in some analyses.

Odds for difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep as an adult was increased among participants with severe behavioral problems at age 5 years in model 1 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-1.96; P = .004), as well as for those with severe problems at 10 years (aOR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.14-1.63; P = .001), and at 16 years (aOR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.59-2.91; P less than .001). The aORs also were higher individually for difficulty initiating sleep and for difficulty maintaining sleep in all age groups.

The association with adulthood insomnia was stronger in participants with externalizing behavioral problems such as lying, bullying, restlessness, and fighting than it was in those with internalizing behavioral problems such as worry, fearfulness, and solitariness.

“Although early sleep problems should be identified, we should additionally identify children with moderate to severe behavioral problems that persist throughout childhood as potential beneficiaries of early intervention with a sleep health focus,” the authors wrote.

One of the study’s limitations was a lack of standardized insomnia measures in the cohort study; however, the researchers suggested that the symptoms included reflect those of standardized measures and diagnostic criteria.

“This study is the first, to our knowledge, to suggest an unfavorable association of early-life behavioral problems with adulthood sleep health, underlining the importance of treating behavioral problems in children and addressing insomnia from a life-course perspective,” they concluded.

No study sponsor was identified. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Melaku YA et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10861.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Reversal agents for direct-acting oral anticoagulants

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

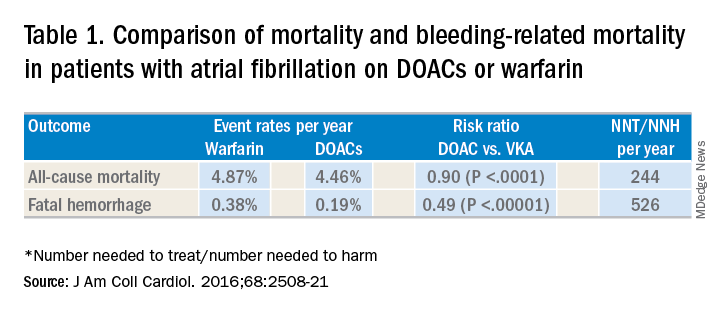

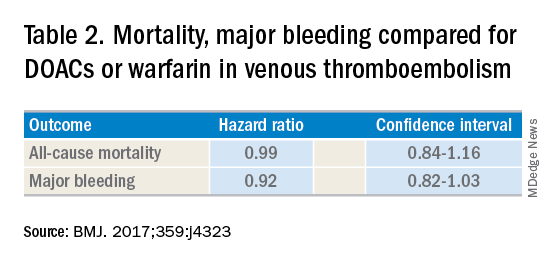

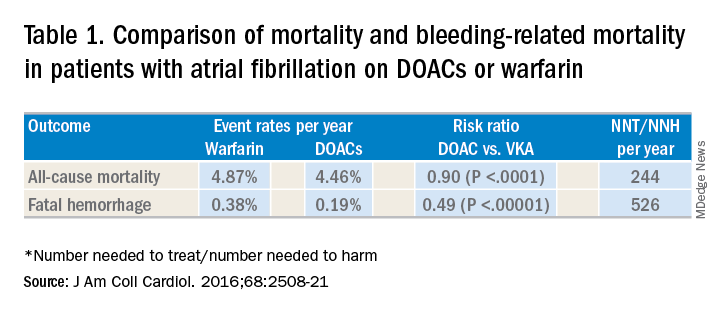

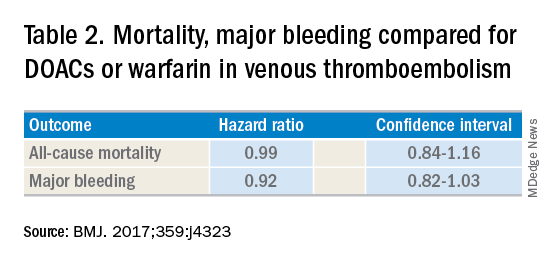

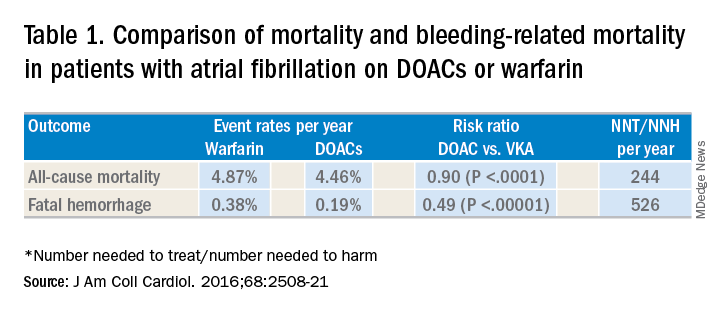

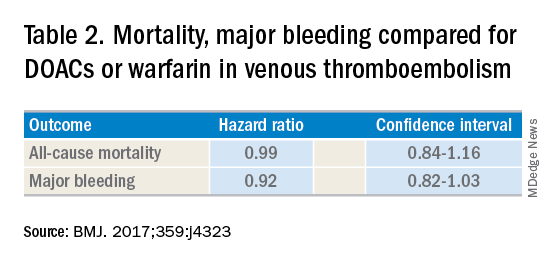

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

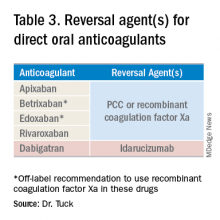

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding in patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban.9 The approval came after a study by the ANNEXA-4 investigators showed that recombinant coagulation factor Xa quickly and effectively achieved hemostasis.10 Full study results were published in April 2019, demonstrating 82% of patients receiving the drug attained clinical hemostasis.11 However, as with idarucizumab, up to 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the follow-up period. Use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to betrixaban and edoxaban is considered off label but is recommended by guidelines.8 Studies on investigational reversal agents for betrixaban and edoxaban are ongoing.

Both unactivated and activated PCC contain clotting factor X. Their use to control bleeding related to DOAC use is based on observational studies. In a systematic review of the nonrandomized studies, the efficacy of PCC to stem major bleeding was 69% and the risk for thromboembolism was 4%.12 There are no head-to-head studies comparing use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa and PCC. Therefore, guidelines are to use either recombinant factor Xa or PCC for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to DOAC use.7

As thrombosis risk heightens after use of any reversal agent, the recommendations are to resume anticoagulation within 90 days if the patient is at moderate or high risk for recurrent thromboembolism.8

After discussion with the hospitalist about the new agents available to reverse anticoagulation, the colleague decided to place the patient on a DOAC and keep the patient in his nursing home. Thankfully, the patient did not thereafter experience sustained bleeding necessitating use of these reversal agents. More importantly for the patient, he was able to stay in the comfort of his home.

Dr. Tuck is associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

References

1. Gómez-Outes A et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2508-21.

2. Jun M et al. Comparative safety of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in venous thromboembolism: multicentre, population-based, observational study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4323.

3. Barnes GD et al. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128:(1300-5).e2.

4. Reddy P et al. Practical approach to VTE management in hospitalized patients. Am J Ther. 2017;24(4):e442-67.

5. Kimachi M et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 6;11:CD011373.

6. Gottenborg E et al. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: The management of anticoagulation in the hospitalized adult. J Hosp Med. 2019; 14(8):499-500.

7. Pollack CV Jr et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal – full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):431-41.

8. Witt DM et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-91.

9. Malarky M et al. FDA accelerated approval letter. Retrieved July 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/113285/download

10. Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1131-41.

11. Connolly SJ et al. Full study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1326-35.

12. Piran S et al. Management of direct factor Xa inhibitor–related major bleeding with prothrombin complex concentrate: A meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(2):158-67.

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

Summary of guidelines published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding in patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban.9 The approval came after a study by the ANNEXA-4 investigators showed that recombinant coagulation factor Xa quickly and effectively achieved hemostasis.10 Full study results were published in April 2019, demonstrating 82% of patients receiving the drug attained clinical hemostasis.11 However, as with idarucizumab, up to 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the follow-up period. Use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to betrixaban and edoxaban is considered off label but is recommended by guidelines.8 Studies on investigational reversal agents for betrixaban and edoxaban are ongoing.

Both unactivated and activated PCC contain clotting factor X. Their use to control bleeding related to DOAC use is based on observational studies. In a systematic review of the nonrandomized studies, the efficacy of PCC to stem major bleeding was 69% and the risk for thromboembolism was 4%.12 There are no head-to-head studies comparing use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa and PCC. Therefore, guidelines are to use either recombinant factor Xa or PCC for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to DOAC use.7

As thrombosis risk heightens after use of any reversal agent, the recommendations are to resume anticoagulation within 90 days if the patient is at moderate or high risk for recurrent thromboembolism.8

After discussion with the hospitalist about the new agents available to reverse anticoagulation, the colleague decided to place the patient on a DOAC and keep the patient in his nursing home. Thankfully, the patient did not thereafter experience sustained bleeding necessitating use of these reversal agents. More importantly for the patient, he was able to stay in the comfort of his home.

Dr. Tuck is associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

References

1. Gómez-Outes A et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2508-21.

2. Jun M et al. Comparative safety of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in venous thromboembolism: multicentre, population-based, observational study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4323.

3. Barnes GD et al. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128:(1300-5).e2.

4. Reddy P et al. Practical approach to VTE management in hospitalized patients. Am J Ther. 2017;24(4):e442-67.

5. Kimachi M et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 6;11:CD011373.

6. Gottenborg E et al. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: The management of anticoagulation in the hospitalized adult. J Hosp Med. 2019; 14(8):499-500.

7. Pollack CV Jr et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal – full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):431-41.

8. Witt DM et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-91.

9. Malarky M et al. FDA accelerated approval letter. Retrieved July 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/113285/download

10. Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1131-41.

11. Connolly SJ et al. Full study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1326-35.

12. Piran S et al. Management of direct factor Xa inhibitor–related major bleeding with prothrombin complex concentrate: A meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(2):158-67.

When on call for admissions, a hospitalist receives a request from a colleague to admit an octogenarian man with an acute uncomplicated deep vein thrombosis to start heparin, bridging to warfarin. The patient has no evidence of postphlebitic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or right-sided heart strain. The hospitalist asks her colleague if he had considered treating the patient in the ambulatory setting using a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC). After all, this would save the patient an unnecessary hospitalization, weekly international normalized ratio checks, and other important lifestyle changes. In response, the colleague voices concern that the “new drugs don’t have antidotes.”

DOACs have several benefits over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and heparins. DOACs have quicker onset of action, can be taken by mouth, in general do not require dosage adjustment, and have fewer dietary and lifestyle modifications, compared with VKAs and heparins. In atrial fibrillation, DOACs have been shown to have lower all-cause and bleeding-related mortality than warfarin (see Table 1).1 Observational studies also suggest less risk of major bleeding with DOACs over warfarin but no difference in overall mortality when used to treat venous thromboembolism (see Table 2).2 Because of these combined advantages, DOACs are increasingly prescribed, accounting for approximately half of all oral anticoagulant prescriptions in 2014.3

Although DOACs have been shown to be as good if not superior to VKAs and heparins in these circumstances, there are situations where a DOAC should not be used. There is limited data on the safety of DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves, liver failure, and chronic kidney disease with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min.4 Therefore, warfarin is still the preferred agent in these settings. There is some data that apixaban may be safe in patients with a creatinine clearance of greater than 10 mL/min, but long-term safety studies have not been performed in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis.5 Finally, in patients requiring concomitant inducers or inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 enzymes like antiepileptics and protease inhibitors, VKAs and heparins are favored.4

Notwithstanding their advantages, when DOACs first hit the market there were concerns that reversal agents were not available. In the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist, Emily Gottenborg, MD, and Gregory Misky, MD, summarized guideline recommendations for reversal of the newer agents.6 This includes use of idarucizumab for patients on dabigatran and use of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) or recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) for patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding.

Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody developed to reverse the effects of dabigatran, the only DOAC that directly inhibits thrombin. In 2017, researchers reported on a cohort of subjects receiving idarucizumab for uncontrolled bleeding or who were on dabigatran and about to undergo an urgent procedure.7 Of those with uncontrolled bleeding, two-thirds had confirmed bleeding cessation within 24 hours. Periprocedural hemostasis was achieved in 93.4% of patients undergoing urgent procedures. However, it should be noted that use of idarucizumab conferred an increase risk (6.3%) of thrombosis within 90 days. Based on these findings, guidelines recommend use of idarucizumab in patients experiencing life-threatening bleeding, balanced against the risk of thrombosis.8

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening or uncontrolled bleeding in patients on apixaban or rivaroxaban.9 The approval came after a study by the ANNEXA-4 investigators showed that recombinant coagulation factor Xa quickly and effectively achieved hemostasis.10 Full study results were published in April 2019, demonstrating 82% of patients receiving the drug attained clinical hemostasis.11 However, as with idarucizumab, up to 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the follow-up period. Use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa for treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to betrixaban and edoxaban is considered off label but is recommended by guidelines.8 Studies on investigational reversal agents for betrixaban and edoxaban are ongoing.

Both unactivated and activated PCC contain clotting factor X. Their use to control bleeding related to DOAC use is based on observational studies. In a systematic review of the nonrandomized studies, the efficacy of PCC to stem major bleeding was 69% and the risk for thromboembolism was 4%.12 There are no head-to-head studies comparing use of recombinant coagulation factor Xa and PCC. Therefore, guidelines are to use either recombinant factor Xa or PCC for the treatment of life-threatening bleeding related to DOAC use.7

As thrombosis risk heightens after use of any reversal agent, the recommendations are to resume anticoagulation within 90 days if the patient is at moderate or high risk for recurrent thromboembolism.8

After discussion with the hospitalist about the new agents available to reverse anticoagulation, the colleague decided to place the patient on a DOAC and keep the patient in his nursing home. Thankfully, the patient did not thereafter experience sustained bleeding necessitating use of these reversal agents. More importantly for the patient, he was able to stay in the comfort of his home.

Dr. Tuck is associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

References

1. Gómez-Outes A et al. Causes of death in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2508-21.

2. Jun M et al. Comparative safety of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in venous thromboembolism: multicentre, population-based, observational study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4323.

3. Barnes GD et al. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128:(1300-5).e2.

4. Reddy P et al. Practical approach to VTE management in hospitalized patients. Am J Ther. 2017;24(4):e442-67.

5. Kimachi M et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 6;11:CD011373.

6. Gottenborg E et al. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: The management of anticoagulation in the hospitalized adult. J Hosp Med. 2019; 14(8):499-500.

7. Pollack CV Jr et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal – full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):431-41.

8. Witt DM et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Optimal management of anticoagulation therapy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-91.

9. Malarky M et al. FDA accelerated approval letter. Retrieved July 15, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/113285/download

10. Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1131-41.

11. Connolly SJ et al. Full study report of andexanet alfa for bleeding associated with factor xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1326-35.

12. Piran S et al. Management of direct factor Xa inhibitor–related major bleeding with prothrombin complex concentrate: A meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2019;3(2):158-67.

Early infusion of mononuclear cells may benefit stroke patients

, results from a single-arm, phase I trial demonstrated. Unlike autologous mesenchymal stem cells, mononuclear cells (MNCs) do not require passage in culture, which allows for testing in the early poststroke time therapy window.

Bone marrow MNCs are attractive in regenerative medicine studies because they can be rapidly isolated; are enriched with hematopoietic, mesenchymal, and endothelial progenitor cells; and permit autologous applications. “The regenerative potential of bone marrow–derived MNCs is attributed to various mechanisms that impact stroke recovery,” researchers led by Sean I. Savitz, MD, wrote in a study published online Sept. 17 in Stem Cells. “These cells migrate to the site of injury, release cytokines and other trophic factors, decrease proinflammatory and upregulate anti-inflammatory pathways, and enhance angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and synaptogenesis.”

For the trial, Dr. Savitz, MD, director of the Institute for Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease at UTHealth, Houston, and colleagues recruited 25 patients to receive an IV dose of their own bone marrow mononuclear cells within 72 hours after stroke onset, a time frame supported by previous preclinical studies. They followed the patients for 1 year and compared the results with a control group of 185 patients who received conventional poststroke treatment. Primary outcomes were study-related serious adverse events and the proportion of patients successfully completing study intervention.

The researchers reported results from 25 patients who received bone marrow MNCs. The mean age of patients in the MNC and control groups were 61 and 63 years, respectively, 53% were female, and 69% were white. No study-related adverse events were observed in the MNC group, but three (12%) had infarct expansion between enrollment and harvest and underwent elective hemicraniectomy after cell infusion.

Advanced magnetic resonance imaging revealed that the average mean fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure of structural integrity and directional coherence of axonal fibers, within the ipsilesional pons was decreased between 1 and 3 months after stroke, “which translated to a relative FA [rFA] comparable with prior reports at this time point,” the researchers wrote. “However, by 6 months, mean rFA began to increase and by 2 years it was significantly higher than at 1 month. This increasing trend in rFA may imply an increase in axonal and fiber coherence as well as thickness in myelin sheets, suggesting microstructural repair. However, without a comparable group of stroke patients not treated with MNCs, we cannot directly ascribe the white matter changes to MNC treatment.”

In light of the findings, the researchers concluded that MNCs “pose no additional harm in ischemic stroke patients when given during the acute phase, doses up to 10 million cells per kilogram are tolerated, and it is feasible to perform a bone marrow harvest and reinfusion of MNCs for a wide range of stroke patients. Well-designed RCTs are needed to further assess safety and efficacy of this novel investigational approach to enhance stroke recovery.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Savitz and many of his coauthors disclosed having numerous financial ties to the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries.

, results from a single-arm, phase I trial demonstrated. Unlike autologous mesenchymal stem cells, mononuclear cells (MNCs) do not require passage in culture, which allows for testing in the early poststroke time therapy window.

Bone marrow MNCs are attractive in regenerative medicine studies because they can be rapidly isolated; are enriched with hematopoietic, mesenchymal, and endothelial progenitor cells; and permit autologous applications. “The regenerative potential of bone marrow–derived MNCs is attributed to various mechanisms that impact stroke recovery,” researchers led by Sean I. Savitz, MD, wrote in a study published online Sept. 17 in Stem Cells. “These cells migrate to the site of injury, release cytokines and other trophic factors, decrease proinflammatory and upregulate anti-inflammatory pathways, and enhance angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and synaptogenesis.”

For the trial, Dr. Savitz, MD, director of the Institute for Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease at UTHealth, Houston, and colleagues recruited 25 patients to receive an IV dose of their own bone marrow mononuclear cells within 72 hours after stroke onset, a time frame supported by previous preclinical studies. They followed the patients for 1 year and compared the results with a control group of 185 patients who received conventional poststroke treatment. Primary outcomes were study-related serious adverse events and the proportion of patients successfully completing study intervention.

The researchers reported results from 25 patients who received bone marrow MNCs. The mean age of patients in the MNC and control groups were 61 and 63 years, respectively, 53% were female, and 69% were white. No study-related adverse events were observed in the MNC group, but three (12%) had infarct expansion between enrollment and harvest and underwent elective hemicraniectomy after cell infusion.

Advanced magnetic resonance imaging revealed that the average mean fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure of structural integrity and directional coherence of axonal fibers, within the ipsilesional pons was decreased between 1 and 3 months after stroke, “which translated to a relative FA [rFA] comparable with prior reports at this time point,” the researchers wrote. “However, by 6 months, mean rFA began to increase and by 2 years it was significantly higher than at 1 month. This increasing trend in rFA may imply an increase in axonal and fiber coherence as well as thickness in myelin sheets, suggesting microstructural repair. However, without a comparable group of stroke patients not treated with MNCs, we cannot directly ascribe the white matter changes to MNC treatment.”

In light of the findings, the researchers concluded that MNCs “pose no additional harm in ischemic stroke patients when given during the acute phase, doses up to 10 million cells per kilogram are tolerated, and it is feasible to perform a bone marrow harvest and reinfusion of MNCs for a wide range of stroke patients. Well-designed RCTs are needed to further assess safety and efficacy of this novel investigational approach to enhance stroke recovery.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Savitz and many of his coauthors disclosed having numerous financial ties to the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries.

, results from a single-arm, phase I trial demonstrated. Unlike autologous mesenchymal stem cells, mononuclear cells (MNCs) do not require passage in culture, which allows for testing in the early poststroke time therapy window.

Bone marrow MNCs are attractive in regenerative medicine studies because they can be rapidly isolated; are enriched with hematopoietic, mesenchymal, and endothelial progenitor cells; and permit autologous applications. “The regenerative potential of bone marrow–derived MNCs is attributed to various mechanisms that impact stroke recovery,” researchers led by Sean I. Savitz, MD, wrote in a study published online Sept. 17 in Stem Cells. “These cells migrate to the site of injury, release cytokines and other trophic factors, decrease proinflammatory and upregulate anti-inflammatory pathways, and enhance angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and synaptogenesis.”

For the trial, Dr. Savitz, MD, director of the Institute for Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease at UTHealth, Houston, and colleagues recruited 25 patients to receive an IV dose of their own bone marrow mononuclear cells within 72 hours after stroke onset, a time frame supported by previous preclinical studies. They followed the patients for 1 year and compared the results with a control group of 185 patients who received conventional poststroke treatment. Primary outcomes were study-related serious adverse events and the proportion of patients successfully completing study intervention.

The researchers reported results from 25 patients who received bone marrow MNCs. The mean age of patients in the MNC and control groups were 61 and 63 years, respectively, 53% were female, and 69% were white. No study-related adverse events were observed in the MNC group, but three (12%) had infarct expansion between enrollment and harvest and underwent elective hemicraniectomy after cell infusion.

Advanced magnetic resonance imaging revealed that the average mean fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure of structural integrity and directional coherence of axonal fibers, within the ipsilesional pons was decreased between 1 and 3 months after stroke, “which translated to a relative FA [rFA] comparable with prior reports at this time point,” the researchers wrote. “However, by 6 months, mean rFA began to increase and by 2 years it was significantly higher than at 1 month. This increasing trend in rFA may imply an increase in axonal and fiber coherence as well as thickness in myelin sheets, suggesting microstructural repair. However, without a comparable group of stroke patients not treated with MNCs, we cannot directly ascribe the white matter changes to MNC treatment.”

In light of the findings, the researchers concluded that MNCs “pose no additional harm in ischemic stroke patients when given during the acute phase, doses up to 10 million cells per kilogram are tolerated, and it is feasible to perform a bone marrow harvest and reinfusion of MNCs for a wide range of stroke patients. Well-designed RCTs are needed to further assess safety and efficacy of this novel investigational approach to enhance stroke recovery.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Savitz and many of his coauthors disclosed having numerous financial ties to the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries.

FROM STEM CELLS

Does this patient have bacterial conjunctivitis?

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

High mortality rates trail tracheostomy patients

findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Current outcome prediction tools to support decision making regarding tracheostomies are limited, wrote Anuj B. Mehta, MD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues. “This study provides novel and in-depth insight into mortality and health care utilization following tracheostomy not previously described at the population-level.”

In a study published in Critical Care Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from 8,343 nonsurgical patients seen in California hospitals from 2012 to 2013 who received a tracheostomy for acute respiratory failure.

Overall, the 1-year mortality rate for patients who had tracheostomies (the primary outcome) was 46.5%, with in-hospital mortality of 18.9% and 30-day mortality of 22.1%. Pneumonia was the most common diagnosis for patients with respiratory failure (79%) and some had an additional diagnosis, such as severe sepsis (56%).

Patients aged 65 years and older had significantly higher mortality than those under 65 (54.7% vs. 36.5%). The average age of the patients was 65 years; approximately 46% were women and 48% were white. The median survival for adults aged 65 years and older was 175 days, compared with median survival of more than a year for younger patients.

Secondary outcomes included discharge destination, hospital readmission, and health care utilization. A majority (86%) of patients were discharged to a long-term care facility, while 11% were sent home and approximately 3% were discharged to other destinations.

Nearly two-thirds (60%) of patients were readmitted to the hospital within a year of tracheostomy, and readmission was more common among older adults, compared with younger (66% vs. 55%).

In addition, just over one-third of all patients (36%) spent more than 50% of their days alive in the hospital in short-term acute care, and this rate was significantly higher for patients aged 65 years and older, compared with those under 65 (43% vs. 29%). On average, the total hospital cost for patients who survived the first year after tracheostomy was $215,369, with no significant difference in average cost among age groups.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single state, possible misclassification of billing codes, and inability to measure quality of life, the researchers noted.

However, “our findings of high mortality, low median survival for older patients, high readmission rates, potentially burdensome cost, and informative outcome trajectories provide significant insight into long-term outcomes following tracheostomy,” they concluded.

Dr. Mehta and several colleagues reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Mehta AB et al. Crit Care Med. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003959.

findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Current outcome prediction tools to support decision making regarding tracheostomies are limited, wrote Anuj B. Mehta, MD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues. “This study provides novel and in-depth insight into mortality and health care utilization following tracheostomy not previously described at the population-level.”

In a study published in Critical Care Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from 8,343 nonsurgical patients seen in California hospitals from 2012 to 2013 who received a tracheostomy for acute respiratory failure.

Overall, the 1-year mortality rate for patients who had tracheostomies (the primary outcome) was 46.5%, with in-hospital mortality of 18.9% and 30-day mortality of 22.1%. Pneumonia was the most common diagnosis for patients with respiratory failure (79%) and some had an additional diagnosis, such as severe sepsis (56%).

Patients aged 65 years and older had significantly higher mortality than those under 65 (54.7% vs. 36.5%). The average age of the patients was 65 years; approximately 46% were women and 48% were white. The median survival for adults aged 65 years and older was 175 days, compared with median survival of more than a year for younger patients.

Secondary outcomes included discharge destination, hospital readmission, and health care utilization. A majority (86%) of patients were discharged to a long-term care facility, while 11% were sent home and approximately 3% were discharged to other destinations.

Nearly two-thirds (60%) of patients were readmitted to the hospital within a year of tracheostomy, and readmission was more common among older adults, compared with younger (66% vs. 55%).

In addition, just over one-third of all patients (36%) spent more than 50% of their days alive in the hospital in short-term acute care, and this rate was significantly higher for patients aged 65 years and older, compared with those under 65 (43% vs. 29%). On average, the total hospital cost for patients who survived the first year after tracheostomy was $215,369, with no significant difference in average cost among age groups.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single state, possible misclassification of billing codes, and inability to measure quality of life, the researchers noted.

However, “our findings of high mortality, low median survival for older patients, high readmission rates, potentially burdensome cost, and informative outcome trajectories provide significant insight into long-term outcomes following tracheostomy,” they concluded.

Dr. Mehta and several colleagues reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Mehta AB et al. Crit Care Med. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003959.

findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Current outcome prediction tools to support decision making regarding tracheostomies are limited, wrote Anuj B. Mehta, MD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues. “This study provides novel and in-depth insight into mortality and health care utilization following tracheostomy not previously described at the population-level.”

In a study published in Critical Care Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from 8,343 nonsurgical patients seen in California hospitals from 2012 to 2013 who received a tracheostomy for acute respiratory failure.

Overall, the 1-year mortality rate for patients who had tracheostomies (the primary outcome) was 46.5%, with in-hospital mortality of 18.9% and 30-day mortality of 22.1%. Pneumonia was the most common diagnosis for patients with respiratory failure (79%) and some had an additional diagnosis, such as severe sepsis (56%).

Patients aged 65 years and older had significantly higher mortality than those under 65 (54.7% vs. 36.5%). The average age of the patients was 65 years; approximately 46% were women and 48% were white. The median survival for adults aged 65 years and older was 175 days, compared with median survival of more than a year for younger patients.

Secondary outcomes included discharge destination, hospital readmission, and health care utilization. A majority (86%) of patients were discharged to a long-term care facility, while 11% were sent home and approximately 3% were discharged to other destinations.

Nearly two-thirds (60%) of patients were readmitted to the hospital within a year of tracheostomy, and readmission was more common among older adults, compared with younger (66% vs. 55%).

In addition, just over one-third of all patients (36%) spent more than 50% of their days alive in the hospital in short-term acute care, and this rate was significantly higher for patients aged 65 years and older, compared with those under 65 (43% vs. 29%). On average, the total hospital cost for patients who survived the first year after tracheostomy was $215,369, with no significant difference in average cost among age groups.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single state, possible misclassification of billing codes, and inability to measure quality of life, the researchers noted.

However, “our findings of high mortality, low median survival for older patients, high readmission rates, potentially burdensome cost, and informative outcome trajectories provide significant insight into long-term outcomes following tracheostomy,” they concluded.

Dr. Mehta and several colleagues reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Mehta AB et al. Crit Care Med. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003959.

FROM CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

Combo could be new standard for transplant-eligible, newly diagnosed myeloma patients

BOSTON — Daratumumab plus bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (D-RVd) may be a new standard of care for transplant-eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, according to a speaker at the International Myeloma Workshop.

In the phase 2 GRIFFIN trial, adding daratumumab to RVd deepened responses at all time points and improved rates of stringent complete response and minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity post consolidation.

These results might convince “early adopters of therapy” to change their practice, said Peter M. Voorhees, MD, of Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., who presented results from GRIFFIN as a late-breaking abstract at the workshop, which is held by the International Myeloma Society.

“But I think you do have to be careful,” Dr. Voorhees added. “We’ll have to see how these patients do over time. Is the MRD sustained, and does that MRD negativity improve progression-free survival?”

Dr. Voorhees presented data on 207 adults with transplant-eligible, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who were enrolled in the GRIFFIN trial. The patients received RVd, with or without daratumumab, for induction (cycles 1-4). They received granulocyte colony stimulating factor, with or without plerixafor, for stem cell mobilization, and melphalan for conditioning prior to transplant.

Patients received consolidation with D-RVd or RVd (cycles 5-6) and maintenance with lenalidomide alone or in combination with daratumumab (cycles 7-32). Patients could continue maintenance with lenalidomide alone beyond cycle 32.

The D-RVd arm comprised 104 patients, and the RVd arm comprised 103 patients. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the treatment arms. The median age was 59 years (range, 29-70 years) in the D-RVd arm and 61 years (range, 40-70 years) in the RVd arm.

Most patients had stage I (47% in the D-RVd arm and 49% in the RVd arm) or stage II disease (39% and 36%, respectively) according to the International Staging System. And most patients had standard risk cytogenetics (84% and 86%, respectively).

Response, MRD, and engraftment

The study’s primary endpoint was stringent complete response by the end of consolidation, which was achieved by 42.4% of patients in the D-RVd arm and 32.0% in the RVd arm (odds ratio [OR] = 1.57; P = .068). The overall response rate at that time point was 99.0% and 91.8%, respectively (P = .0160).

Responses deepened over time, and response rates were greater for D-RVd than for RVd at all time points. The complete response rate was 19.2% in the D-RVd arm and 13.4% in the RVd arm at the end of induction; 27.3% and 19.6%, respectively, at the end of transplant; 51.5% and 42.3%, respectively, at the end of consolidation; and 62.6% and 47.4%, respectively, at the clinical cutoff.

D-RVd also improved MRD negativity (10-5) rates at the end of consolidation. MRD negativity was 44.2% in the D-RVd arm and 14.6% in the RVd arm (OR = 4.70; P less than .0001). The rate of MRD negativity in patients with a complete response or better was 28.8% and 9.7%, respectively (OR = 3.73; P = .0007).

Dr. Voorhees noted that D-RVd was favored across all subgroups for MRD negativity and stringent compete response, except among patients with high-risk cytogenetics and stage III disease.

He also pointed out that stem cell mobilization was “feasible” in the D-RVd arm, and daratumumab did not impact engraftment. The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 12 days in both treatment arms. The median time to platelet engraftment was 13 days in the D-RVd arm and 12 days in the RVd arm.

Safety

“The adverse events are what you would expect,” Dr. Voorhees said. “Grade 3 and 4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were seen more often in the dara arm of the trial compared to the RVd arm.”

The most common grade 3/4 treatment-emergent adverse events (in the D-RVd and RVd arms, respectively) were neutropenia (32% and 15%), lymphopenia (23% in both), thrombocytopenia (16% and 8%), and leukopenia (15% and 7%).

“Nonhematologic toxicities were generally equal between the two groups, but I do want to stress that there was a higher rate of infection in the dara arm,” Dr. Voorhees noted.

The incidence of infection was 82% in the D-RVd arm and 55% in the RVd arm, but the rate of grade 3/4 infection was 17% in both arms. The rate of pneumonia was 10% in the D-RVd arm and 9% in the RVd arm.

All-grade infusion-related reactions occurred in 41% of patients in the D-RVd arm, and grade 3/4 infusion-related reactions occurred in 5%.

The trial was sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Voorhees reported relationships with Janssen and several other companies.

SOURCE: Voorhees PM et al. IMW 2019. Abstract OAB-087.

BOSTON — Daratumumab plus bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (D-RVd) may be a new standard of care for transplant-eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, according to a speaker at the International Myeloma Workshop.

In the phase 2 GRIFFIN trial, adding daratumumab to RVd deepened responses at all time points and improved rates of stringent complete response and minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity post consolidation.

These results might convince “early adopters of therapy” to change their practice, said Peter M. Voorhees, MD, of Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., who presented results from GRIFFIN as a late-breaking abstract at the workshop, which is held by the International Myeloma Society.

“But I think you do have to be careful,” Dr. Voorhees added. “We’ll have to see how these patients do over time. Is the MRD sustained, and does that MRD negativity improve progression-free survival?”

Dr. Voorhees presented data on 207 adults with transplant-eligible, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who were enrolled in the GRIFFIN trial. The patients received RVd, with or without daratumumab, for induction (cycles 1-4). They received granulocyte colony stimulating factor, with or without plerixafor, for stem cell mobilization, and melphalan for conditioning prior to transplant.

Patients received consolidation with D-RVd or RVd (cycles 5-6) and maintenance with lenalidomide alone or in combination with daratumumab (cycles 7-32). Patients could continue maintenance with lenalidomide alone beyond cycle 32.

The D-RVd arm comprised 104 patients, and the RVd arm comprised 103 patients. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the treatment arms. The median age was 59 years (range, 29-70 years) in the D-RVd arm and 61 years (range, 40-70 years) in the RVd arm.

Most patients had stage I (47% in the D-RVd arm and 49% in the RVd arm) or stage II disease (39% and 36%, respectively) according to the International Staging System. And most patients had standard risk cytogenetics (84% and 86%, respectively).

Response, MRD, and engraftment

The study’s primary endpoint was stringent complete response by the end of consolidation, which was achieved by 42.4% of patients in the D-RVd arm and 32.0% in the RVd arm (odds ratio [OR] = 1.57; P = .068). The overall response rate at that time point was 99.0% and 91.8%, respectively (P = .0160).

Responses deepened over time, and response rates were greater for D-RVd than for RVd at all time points. The complete response rate was 19.2% in the D-RVd arm and 13.4% in the RVd arm at the end of induction; 27.3% and 19.6%, respectively, at the end of transplant; 51.5% and 42.3%, respectively, at the end of consolidation; and 62.6% and 47.4%, respectively, at the clinical cutoff.

D-RVd also improved MRD negativity (10-5) rates at the end of consolidation. MRD negativity was 44.2% in the D-RVd arm and 14.6% in the RVd arm (OR = 4.70; P less than .0001). The rate of MRD negativity in patients with a complete response or better was 28.8% and 9.7%, respectively (OR = 3.73; P = .0007).

Dr. Voorhees noted that D-RVd was favored across all subgroups for MRD negativity and stringent compete response, except among patients with high-risk cytogenetics and stage III disease.

He also pointed out that stem cell mobilization was “feasible” in the D-RVd arm, and daratumumab did not impact engraftment. The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 12 days in both treatment arms. The median time to platelet engraftment was 13 days in the D-RVd arm and 12 days in the RVd arm.

Safety

“The adverse events are what you would expect,” Dr. Voorhees said. “Grade 3 and 4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were seen more often in the dara arm of the trial compared to the RVd arm.”

The most common grade 3/4 treatment-emergent adverse events (in the D-RVd and RVd arms, respectively) were neutropenia (32% and 15%), lymphopenia (23% in both), thrombocytopenia (16% and 8%), and leukopenia (15% and 7%).

“Nonhematologic toxicities were generally equal between the two groups, but I do want to stress that there was a higher rate of infection in the dara arm,” Dr. Voorhees noted.

The incidence of infection was 82% in the D-RVd arm and 55% in the RVd arm, but the rate of grade 3/4 infection was 17% in both arms. The rate of pneumonia was 10% in the D-RVd arm and 9% in the RVd arm.

All-grade infusion-related reactions occurred in 41% of patients in the D-RVd arm, and grade 3/4 infusion-related reactions occurred in 5%.

The trial was sponsored by Janssen. Dr. Voorhees reported relationships with Janssen and several other companies.

SOURCE: Voorhees PM et al. IMW 2019. Abstract OAB-087.

BOSTON — Daratumumab plus bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (D-RVd) may be a new standard of care for transplant-eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, according to a speaker at the International Myeloma Workshop.

In the phase 2 GRIFFIN trial, adding daratumumab to RVd deepened responses at all time points and improved rates of stringent complete response and minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity post consolidation.

These results might convince “early adopters of therapy” to change their practice, said Peter M. Voorhees, MD, of Levine Cancer Institute at Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., who presented results from GRIFFIN as a late-breaking abstract at the workshop, which is held by the International Myeloma Society.

“But I think you do have to be careful,” Dr. Voorhees added. “We’ll have to see how these patients do over time. Is the MRD sustained, and does that MRD negativity improve progression-free survival?”

Dr. Voorhees presented data on 207 adults with transplant-eligible, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who were enrolled in the GRIFFIN trial. The patients received RVd, with or without daratumumab, for induction (cycles 1-4). They received granulocyte colony stimulating factor, with or without plerixafor, for stem cell mobilization, and melphalan for conditioning prior to transplant.

Patients received consolidation with D-RVd or RVd (cycles 5-6) and maintenance with lenalidomide alone or in combination with daratumumab (cycles 7-32). Patients could continue maintenance with lenalidomide alone beyond cycle 32.

The D-RVd arm comprised 104 patients, and the RVd arm comprised 103 patients. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the treatment arms. The median age was 59 years (range, 29-70 years) in the D-RVd arm and 61 years (range, 40-70 years) in the RVd arm.

Most patients had stage I (47% in the D-RVd arm and 49% in the RVd arm) or stage II disease (39% and 36%, respectively) according to the International Staging System. And most patients had standard risk cytogenetics (84% and 86%, respectively).

Response, MRD, and engraftment

The study’s primary endpoint was stringent complete response by the end of consolidation, which was achieved by 42.4% of patients in the D-RVd arm and 32.0% in the RVd arm (odds ratio [OR] = 1.57; P = .068). The overall response rate at that time point was 99.0% and 91.8%, respectively (P = .0160).

Responses deepened over time, and response rates were greater for D-RVd than for RVd at all time points. The complete response rate was 19.2% in the D-RVd arm and 13.4% in the RVd arm at the end of induction; 27.3% and 19.6%, respectively, at the end of transplant; 51.5% and 42.3%, respectively, at the end of consolidation; and 62.6% and 47.4%, respectively, at the clinical cutoff.