User login

Progestin-only systemic hormone therapy for menopausal hot flashes

The field of menopause medicine is dominated by studies documenting the effectiveness of systemic estrogen or estrogen-progestin hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes caused by hypoestrogenism. The effectiveness of progestin-only systemic hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes is much less studied and seldom is utilized in clinical practice. A small number of studies have reported that progestins, including micronized progesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and norethindrone acetate, are effective treatment for hot flashes. Progestin-only systemic hormone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment.

Micronized progesterone

Micronized progesterone (Prometrium) 300 mg daily taken at bedtime has been reported to effectively treat hot flashes in postmenopausal women. In one study, 133 postmenopausal women with an average age of 55 years and approximately 3 years from their last menstrual period were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with placebo or micronized progesterone 300 mg daily taken at bedtime.1 Mean serum progesterone levels were 0.28 ng/mL (0.89 nM) and 27 ng/mL (86 nM) in the women taking placebo and micronized progesterone, respectively. Compared with placebo, micronized progesterone reduced daytime and nighttime hot flash frequency and severity. In addition, compared with placebo, micronized progesterone improved the quality of sleep.1

Most reviews conclude that micronized progesterone has minimal cardiovascular risk.2 Micronized progesterone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment such as those at increased risk for cardiovascular disease or women with a thrombophilia. Many experts believe that systemic estrogen therapy is contraindicated in postmenopausal women with an American Heart Association risk score greater than 10% over 10 years.3 Additional contraindications to systemic estrogen include women with cardiac disease who have a thrombophilia, such as the Factor V Leiden mutation.4

For women who are at high risk for estrogen-induced cardiovascular events, micronized progesterone may be a better option than systemic estrogen for treating hot flashes. Alternatively, in these women at risk of cardiovascular disease a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, such as escitalopram, 10 mg to 20 mg daily, may be a good option for treating postmenopausal hot flashes.5

Medroxyprogesterone acetate

Medroxyprogesterone acetate, at a dosage of 20 mg daily, is an effective treatment for hot flashes. In a randomized clinical trial 27 postmenopausal women with hot flashes were randomly assigned to treatment with placebo or medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg daily for 4 weeks. Vasomotor flushes were decreased by 26% and 74% in the placebo and medroxyprogesterone groups, respectively.6

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections at dosages from 150 mg to 400 mg also have been reported to effectively treat hot flashes.7,8 In a trial comparing the effectiveness of estrogen monotherapy (conjugated equine estrogen 0.6 mg daily) with progestin monotherapy (medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg daily), both treatments were equally effective in reducing hot flashes.9

Continue to: Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate...

Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate

Experts in menopause medicine have suggested that in postmenopausal women micronized progesterone has a better pattern of benefits and fewer risks than medroxyprogesterone acetate.10,11 For example, in the E3N observational study of hormones and breast cancer risk, among 80,377 French postmenopausal women followed for a mean of 8 years, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone was associated with no significantly increased risk of breast cancer (relative risk [RR], 1.08, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.89–1.31) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy.12 By contrast, the combination of oral estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.02–2.16) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy. The E3N study indicates that micronized progesterone may have a more favorable breast health profile than medroxyprogesterone acetate.12

Norethindrone acetate

Norethindrone acetate monotherapy is not commonly prescribed for the treatment of menopausal hot flashes. However, a large clinical trial has demonstrated that norethindrone acetate effectively suppresses hot flashes in women with endometriosis treated with depot leuprolide acetate (LA). In one trial 201 women with endometriosis were randomly assigned to 12 months of treatment with13:

- LA plus placebo pills

- LA plus norethindrone acetate (NEA) 5 mg daily

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily, or

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus CEE 1.25 mg daily.

The median number of hot flashes in 24 hours was 6 in the LA plus placebo group and 0 in both the LA plus NEA 5 mg daily group and the LA plus NEA 5 mg plus CEE 1.25 mg daily group. This study demonstrates that NEA 5 mg daily is an effective treatment for hot flashes.

In the same study, LA plus placebo was associated with a significant decrease in lumbar spine bone mineral density. No significant decrease in bone mineral density was observed in the women who received LA plus NEA 5 mg daily. This finding indicates that NEA 5 mg reduces bone absorption caused by hypoestrogenism. In humans, norethindrone is a substrate for the aromatase enzyme system.14 Small quantities of ethinyl estradiol may be formed by aromatization of norethindrone in vivo,15,16 contributing to the effectiveness of NEA in suppressing hot flashes and preserving bone density.

Progestin: The estrogen alternative to hot flashes

For postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, estrogen treatment reliably suppresses hot flashes and often improves sleep quality and mood. For postmenopausal women with a contraindication to estrogen treatment, progestin-only treatment with micronized progesterone or norethindrone acetate may be an effective option.

- Hitchcock CL, Prior JC. Oral micronized progesterone for vasomotor symptoms—a placebo-controlled randomized trial in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2012;19:886-893.

- Spark MJ, Willis J. Systematic review of progesterone use by midlife menopausal women. Maturitas 2012; 72: 192-202.

- Manson JE, Ames JM, Shapiro M, et al. Algorithm and mobile app for menopausal symptom management and hormonal/nonhormonal therapy decision making: a clinical decision-suport tool from The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:247-253.

- Herrington DM, Vittinghoff E, Howard TD, et al. Factor V Leiden, hormone replacement therapy, and risk of venous thromboembolic events in women with coronary disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1012-1017.

- Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19:848-855.

- Schiff I, Tulchinsky D, Cramer D, et al. Oral medroxyprogesterone in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms. JAMA. 1980;244:1443-1445.

- Bullock JL, Massey FM, Gambrell RD Jr. Use of medroxyprogesterone acetate to prevent menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:165-168.

- Loprinzi CL, Levitt R, Barton D, et al. Phase III comparison of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate to venlafaxine for managing hot flashes: North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial N99C7. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1409-1414.

- Prior JC, Nielsen JD, Hitchcock CL, et al. Medroxyprogesterone and conjugated oestrogen are equivalent for hot flushes: 1-year randomized double-blind trial following premenopausal ovariectomy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2007;112:517-525.

- L’hermite M, Simoncini T, Fuller S, et al. Could transdermal estradiol + progesterone be a safer postmenopausal HRT? A review. Maturitas. 2008;60:185-201.

- Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? Menopause. 2014;21:769-783.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107:103-111.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, et al. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16-24.

- Barbieri RL, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. High-affinity steroid binding to rat testis 17 alpha-hydroxylase and human placental aromatase. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;14:387-393.

- Chu MC, Zhang X, Gentzschein E, et al. Formation of ethinyl estradiol in women during treatment with norethindrone acetate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2205-2207.

- Chwalisz K, Surrey E, Stanczyk FZ. The hormonal profile of norethindrone acetate: rationale for add-back therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in women with endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2012;19:563-571.

The field of menopause medicine is dominated by studies documenting the effectiveness of systemic estrogen or estrogen-progestin hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes caused by hypoestrogenism. The effectiveness of progestin-only systemic hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes is much less studied and seldom is utilized in clinical practice. A small number of studies have reported that progestins, including micronized progesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and norethindrone acetate, are effective treatment for hot flashes. Progestin-only systemic hormone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment.

Micronized progesterone

Micronized progesterone (Prometrium) 300 mg daily taken at bedtime has been reported to effectively treat hot flashes in postmenopausal women. In one study, 133 postmenopausal women with an average age of 55 years and approximately 3 years from their last menstrual period were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with placebo or micronized progesterone 300 mg daily taken at bedtime.1 Mean serum progesterone levels were 0.28 ng/mL (0.89 nM) and 27 ng/mL (86 nM) in the women taking placebo and micronized progesterone, respectively. Compared with placebo, micronized progesterone reduced daytime and nighttime hot flash frequency and severity. In addition, compared with placebo, micronized progesterone improved the quality of sleep.1

Most reviews conclude that micronized progesterone has minimal cardiovascular risk.2 Micronized progesterone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment such as those at increased risk for cardiovascular disease or women with a thrombophilia. Many experts believe that systemic estrogen therapy is contraindicated in postmenopausal women with an American Heart Association risk score greater than 10% over 10 years.3 Additional contraindications to systemic estrogen include women with cardiac disease who have a thrombophilia, such as the Factor V Leiden mutation.4

For women who are at high risk for estrogen-induced cardiovascular events, micronized progesterone may be a better option than systemic estrogen for treating hot flashes. Alternatively, in these women at risk of cardiovascular disease a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, such as escitalopram, 10 mg to 20 mg daily, may be a good option for treating postmenopausal hot flashes.5

Medroxyprogesterone acetate

Medroxyprogesterone acetate, at a dosage of 20 mg daily, is an effective treatment for hot flashes. In a randomized clinical trial 27 postmenopausal women with hot flashes were randomly assigned to treatment with placebo or medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg daily for 4 weeks. Vasomotor flushes were decreased by 26% and 74% in the placebo and medroxyprogesterone groups, respectively.6

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections at dosages from 150 mg to 400 mg also have been reported to effectively treat hot flashes.7,8 In a trial comparing the effectiveness of estrogen monotherapy (conjugated equine estrogen 0.6 mg daily) with progestin monotherapy (medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg daily), both treatments were equally effective in reducing hot flashes.9

Continue to: Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate...

Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate

Experts in menopause medicine have suggested that in postmenopausal women micronized progesterone has a better pattern of benefits and fewer risks than medroxyprogesterone acetate.10,11 For example, in the E3N observational study of hormones and breast cancer risk, among 80,377 French postmenopausal women followed for a mean of 8 years, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone was associated with no significantly increased risk of breast cancer (relative risk [RR], 1.08, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.89–1.31) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy.12 By contrast, the combination of oral estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.02–2.16) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy. The E3N study indicates that micronized progesterone may have a more favorable breast health profile than medroxyprogesterone acetate.12

Norethindrone acetate

Norethindrone acetate monotherapy is not commonly prescribed for the treatment of menopausal hot flashes. However, a large clinical trial has demonstrated that norethindrone acetate effectively suppresses hot flashes in women with endometriosis treated with depot leuprolide acetate (LA). In one trial 201 women with endometriosis were randomly assigned to 12 months of treatment with13:

- LA plus placebo pills

- LA plus norethindrone acetate (NEA) 5 mg daily

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily, or

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus CEE 1.25 mg daily.

The median number of hot flashes in 24 hours was 6 in the LA plus placebo group and 0 in both the LA plus NEA 5 mg daily group and the LA plus NEA 5 mg plus CEE 1.25 mg daily group. This study demonstrates that NEA 5 mg daily is an effective treatment for hot flashes.

In the same study, LA plus placebo was associated with a significant decrease in lumbar spine bone mineral density. No significant decrease in bone mineral density was observed in the women who received LA plus NEA 5 mg daily. This finding indicates that NEA 5 mg reduces bone absorption caused by hypoestrogenism. In humans, norethindrone is a substrate for the aromatase enzyme system.14 Small quantities of ethinyl estradiol may be formed by aromatization of norethindrone in vivo,15,16 contributing to the effectiveness of NEA in suppressing hot flashes and preserving bone density.

Progestin: The estrogen alternative to hot flashes

For postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, estrogen treatment reliably suppresses hot flashes and often improves sleep quality and mood. For postmenopausal women with a contraindication to estrogen treatment, progestin-only treatment with micronized progesterone or norethindrone acetate may be an effective option.

The field of menopause medicine is dominated by studies documenting the effectiveness of systemic estrogen or estrogen-progestin hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes caused by hypoestrogenism. The effectiveness of progestin-only systemic hormone therapy for the treatment of hot flashes is much less studied and seldom is utilized in clinical practice. A small number of studies have reported that progestins, including micronized progesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and norethindrone acetate, are effective treatment for hot flashes. Progestin-only systemic hormone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment.

Micronized progesterone

Micronized progesterone (Prometrium) 300 mg daily taken at bedtime has been reported to effectively treat hot flashes in postmenopausal women. In one study, 133 postmenopausal women with an average age of 55 years and approximately 3 years from their last menstrual period were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with placebo or micronized progesterone 300 mg daily taken at bedtime.1 Mean serum progesterone levels were 0.28 ng/mL (0.89 nM) and 27 ng/mL (86 nM) in the women taking placebo and micronized progesterone, respectively. Compared with placebo, micronized progesterone reduced daytime and nighttime hot flash frequency and severity. In addition, compared with placebo, micronized progesterone improved the quality of sleep.1

Most reviews conclude that micronized progesterone has minimal cardiovascular risk.2 Micronized progesterone therapy might be especially helpful for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes who have a contraindication to estrogen treatment such as those at increased risk for cardiovascular disease or women with a thrombophilia. Many experts believe that systemic estrogen therapy is contraindicated in postmenopausal women with an American Heart Association risk score greater than 10% over 10 years.3 Additional contraindications to systemic estrogen include women with cardiac disease who have a thrombophilia, such as the Factor V Leiden mutation.4

For women who are at high risk for estrogen-induced cardiovascular events, micronized progesterone may be a better option than systemic estrogen for treating hot flashes. Alternatively, in these women at risk of cardiovascular disease a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, such as escitalopram, 10 mg to 20 mg daily, may be a good option for treating postmenopausal hot flashes.5

Medroxyprogesterone acetate

Medroxyprogesterone acetate, at a dosage of 20 mg daily, is an effective treatment for hot flashes. In a randomized clinical trial 27 postmenopausal women with hot flashes were randomly assigned to treatment with placebo or medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg daily for 4 weeks. Vasomotor flushes were decreased by 26% and 74% in the placebo and medroxyprogesterone groups, respectively.6

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections at dosages from 150 mg to 400 mg also have been reported to effectively treat hot flashes.7,8 In a trial comparing the effectiveness of estrogen monotherapy (conjugated equine estrogen 0.6 mg daily) with progestin monotherapy (medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg daily), both treatments were equally effective in reducing hot flashes.9

Continue to: Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate...

Micronized progesterone vs medroxyprogesterone acetate

Experts in menopause medicine have suggested that in postmenopausal women micronized progesterone has a better pattern of benefits and fewer risks than medroxyprogesterone acetate.10,11 For example, in the E3N observational study of hormones and breast cancer risk, among 80,377 French postmenopausal women followed for a mean of 8 years, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone was associated with no significantly increased risk of breast cancer (relative risk [RR], 1.08, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.89–1.31) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy.12 By contrast, the combination of oral estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.02–2.16) compared with never users of postmenopausal hormone therapy. The E3N study indicates that micronized progesterone may have a more favorable breast health profile than medroxyprogesterone acetate.12

Norethindrone acetate

Norethindrone acetate monotherapy is not commonly prescribed for the treatment of menopausal hot flashes. However, a large clinical trial has demonstrated that norethindrone acetate effectively suppresses hot flashes in women with endometriosis treated with depot leuprolide acetate (LA). In one trial 201 women with endometriosis were randomly assigned to 12 months of treatment with13:

- LA plus placebo pills

- LA plus norethindrone acetate (NEA) 5 mg daily

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily, or

- LA plus NEA 5 mg daily plus CEE 1.25 mg daily.

The median number of hot flashes in 24 hours was 6 in the LA plus placebo group and 0 in both the LA plus NEA 5 mg daily group and the LA plus NEA 5 mg plus CEE 1.25 mg daily group. This study demonstrates that NEA 5 mg daily is an effective treatment for hot flashes.

In the same study, LA plus placebo was associated with a significant decrease in lumbar spine bone mineral density. No significant decrease in bone mineral density was observed in the women who received LA plus NEA 5 mg daily. This finding indicates that NEA 5 mg reduces bone absorption caused by hypoestrogenism. In humans, norethindrone is a substrate for the aromatase enzyme system.14 Small quantities of ethinyl estradiol may be formed by aromatization of norethindrone in vivo,15,16 contributing to the effectiveness of NEA in suppressing hot flashes and preserving bone density.

Progestin: The estrogen alternative to hot flashes

For postmenopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, estrogen treatment reliably suppresses hot flashes and often improves sleep quality and mood. For postmenopausal women with a contraindication to estrogen treatment, progestin-only treatment with micronized progesterone or norethindrone acetate may be an effective option.

- Hitchcock CL, Prior JC. Oral micronized progesterone for vasomotor symptoms—a placebo-controlled randomized trial in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2012;19:886-893.

- Spark MJ, Willis J. Systematic review of progesterone use by midlife menopausal women. Maturitas 2012; 72: 192-202.

- Manson JE, Ames JM, Shapiro M, et al. Algorithm and mobile app for menopausal symptom management and hormonal/nonhormonal therapy decision making: a clinical decision-suport tool from The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:247-253.

- Herrington DM, Vittinghoff E, Howard TD, et al. Factor V Leiden, hormone replacement therapy, and risk of venous thromboembolic events in women with coronary disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1012-1017.

- Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19:848-855.

- Schiff I, Tulchinsky D, Cramer D, et al. Oral medroxyprogesterone in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms. JAMA. 1980;244:1443-1445.

- Bullock JL, Massey FM, Gambrell RD Jr. Use of medroxyprogesterone acetate to prevent menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:165-168.

- Loprinzi CL, Levitt R, Barton D, et al. Phase III comparison of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate to venlafaxine for managing hot flashes: North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial N99C7. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1409-1414.

- Prior JC, Nielsen JD, Hitchcock CL, et al. Medroxyprogesterone and conjugated oestrogen are equivalent for hot flushes: 1-year randomized double-blind trial following premenopausal ovariectomy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2007;112:517-525.

- L’hermite M, Simoncini T, Fuller S, et al. Could transdermal estradiol + progesterone be a safer postmenopausal HRT? A review. Maturitas. 2008;60:185-201.

- Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? Menopause. 2014;21:769-783.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107:103-111.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, et al. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16-24.

- Barbieri RL, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. High-affinity steroid binding to rat testis 17 alpha-hydroxylase and human placental aromatase. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;14:387-393.

- Chu MC, Zhang X, Gentzschein E, et al. Formation of ethinyl estradiol in women during treatment with norethindrone acetate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2205-2207.

- Chwalisz K, Surrey E, Stanczyk FZ. The hormonal profile of norethindrone acetate: rationale for add-back therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in women with endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2012;19:563-571.

- Hitchcock CL, Prior JC. Oral micronized progesterone for vasomotor symptoms—a placebo-controlled randomized trial in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2012;19:886-893.

- Spark MJ, Willis J. Systematic review of progesterone use by midlife menopausal women. Maturitas 2012; 72: 192-202.

- Manson JE, Ames JM, Shapiro M, et al. Algorithm and mobile app for menopausal symptom management and hormonal/nonhormonal therapy decision making: a clinical decision-suport tool from The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:247-253.

- Herrington DM, Vittinghoff E, Howard TD, et al. Factor V Leiden, hormone replacement therapy, and risk of venous thromboembolic events in women with coronary disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1012-1017.

- Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19:848-855.

- Schiff I, Tulchinsky D, Cramer D, et al. Oral medroxyprogesterone in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms. JAMA. 1980;244:1443-1445.

- Bullock JL, Massey FM, Gambrell RD Jr. Use of medroxyprogesterone acetate to prevent menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:165-168.

- Loprinzi CL, Levitt R, Barton D, et al. Phase III comparison of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate to venlafaxine for managing hot flashes: North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial N99C7. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1409-1414.

- Prior JC, Nielsen JD, Hitchcock CL, et al. Medroxyprogesterone and conjugated oestrogen are equivalent for hot flushes: 1-year randomized double-blind trial following premenopausal ovariectomy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2007;112:517-525.

- L’hermite M, Simoncini T, Fuller S, et al. Could transdermal estradiol + progesterone be a safer postmenopausal HRT? A review. Maturitas. 2008;60:185-201.

- Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? Menopause. 2014;21:769-783.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107:103-111.

- Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, et al. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16-24.

- Barbieri RL, Canick JA, Ryan KJ. High-affinity steroid binding to rat testis 17 alpha-hydroxylase and human placental aromatase. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;14:387-393.

- Chu MC, Zhang X, Gentzschein E, et al. Formation of ethinyl estradiol in women during treatment with norethindrone acetate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2205-2207.

- Chwalisz K, Surrey E, Stanczyk FZ. The hormonal profile of norethindrone acetate: rationale for add-back therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in women with endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2012;19:563-571.

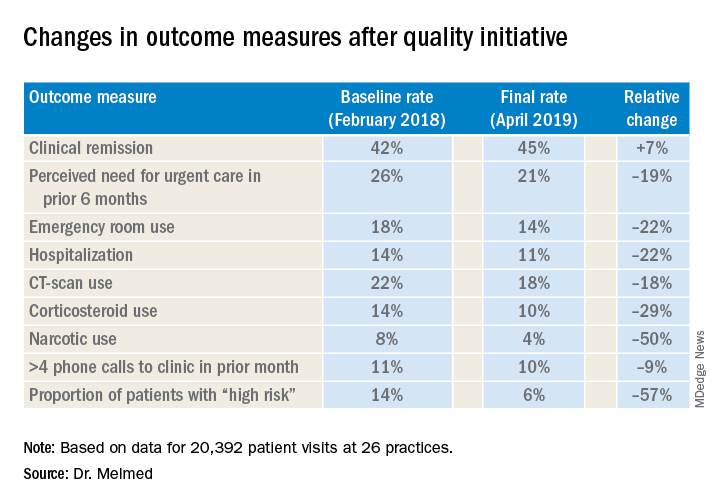

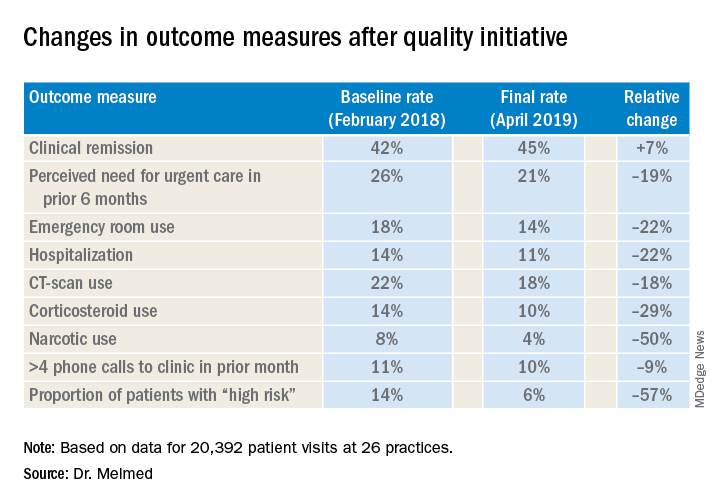

IBD quality initiative slashes ED utilization

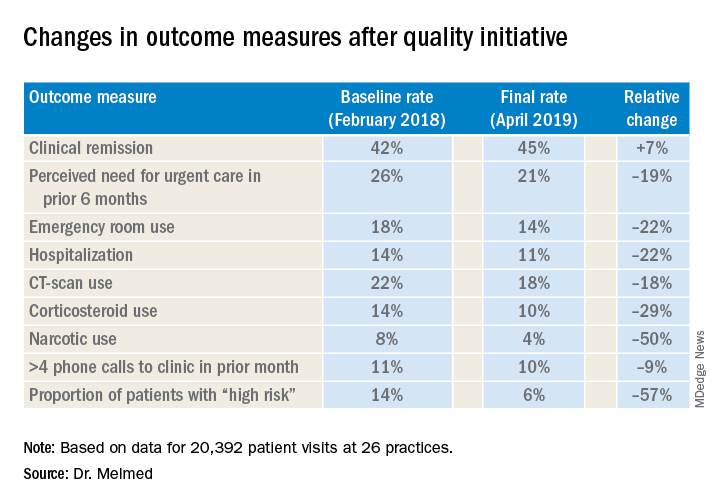

AUSTIN, TEX. – A quality improvement initiative aimed at patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has reduced emergency department visits and hospitalizations by 20% or more and slashed opioid use by half, according to study results presented at the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

After 15 months, the quality improvement program saw emergency department visit rates decline from 18% to 14%, a 22% relative decrease, Gil Y. Melmed, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said. Additionally, the study documented a similar decrease in the rate of hospitalization, declining from 14% to 11%, while opioid utilization rates declined from 8% to 4%. “We also found decreases in special-cause variation in other measures of interest, including CT scan utilization as well as corticosteroid use, which was reduced 29% during the course of the program,” he said.

The quality initiative was conducted through the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation as an outgrowth of its IBD Qorus quality improvement program. The 15-month study involved 20,392 patient visits at 15 academic and 11 private/community practices from January 2018 to April 2019. “This specific project within Qorus is focused specifically around the concept of improving access during times of urgent care need,” Dr. Melmed told this news organization. The goal was to identify practice changes that can drive improvement.

The intervention consisted of 19 different strategies, called a “Change Package,” and participating sites could choose to test and implement one or more of them, Dr. Melmed said. Some examples included designating urgent care slots in the clinic schedule, installing a nurse hotline, a weekly “huddle” to review high-risk patients, and patient education on using urgent care.

One of the drivers of the program was to provide immediate care improvement to patients, Dr. Melmed said in the interview. “As opposed to investments into the cure of IBD that we need, but which can take years to develop, this research has immediate, practical applicability for patients today,” he said.

“The fact that we were able to demonstrate reduction in emergency room utilization and hospitalization, steroid use, and narcotic use has really energized the work that we were doing. We can now show that very-low-cost process changes at a site level lead to robust improvement in patient outcomes. These changes are potentially implementable in any practice setting,” Dr. Melmed said in the interview.

After Dr. Melmed’s presentation, Maria T. Abreu, MD, director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center at the University of Miami, asked about the cost of the interventions. Dr. Melmed said the costs were nominal, such as paying for a new phone line for a patient hotline. “But overall the cost really involved in the program was the time that it took to review the high-risk list on a weekly basis with the team, and that is essentially a 15-minute huddle,” he said.

Later, Dr. Abreu said in an interview that the program was “a terrific example of how measuring outcomes and sharing ideas can make huge impacts in the lives of patients.” She added, “An enormous amount of money is spent on clinical trials of expensive biologics which have revolutionized treatment, yet the humanistic aspects of our care have just as great of an impact. In this study, each center focused on ways they could lower ER visits and hospitalizations. One size did not fit all, yet they could learn from each other. The very platform they used to conduct the study is a model for all of us.”

Corey A. Siegel, MD, of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and Dr. Melmed's coprincipal investigator on Qorus, said the quality initiative now includes 49 GI practices across the country with plans to grow to 60 by the end of the year. "We have created this 'collaboratory' for providers from actross the country to work togetherr to learn how to best deliver high-qulaity care for patients with IBD," he said.

Another feature of the quality initiative allowed participating sites to see how they compared with others anonymously, Dr. Melmed said. “Using the data, we called out high-performing sites to teach the rest of us what they were doing that enabled them to improve, so that all of us could learn from their successes,” he said.

The researchers are aiming to evaluate costs and identify the most successful interventions, with the plan to present the latter at Digestive Disease Week® 2020 and use them to develop a toolkit practices can use. “Ultimately,” said Dr. Melmed, “this is scalable.”

Dr. Melmed disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Jannsen, GSK, Medtronic, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Takeda, and Techlab; IBD Qorus receives support from Abbvie, AMAG, Helmsley Charitable Trust, Janssen, Nephoroceuticals, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB.

SOURCE: Melmed GT et al. Crohn’s & Colitis Congress 2020, Session 28.

AUSTIN, TEX. – A quality improvement initiative aimed at patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has reduced emergency department visits and hospitalizations by 20% or more and slashed opioid use by half, according to study results presented at the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

After 15 months, the quality improvement program saw emergency department visit rates decline from 18% to 14%, a 22% relative decrease, Gil Y. Melmed, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said. Additionally, the study documented a similar decrease in the rate of hospitalization, declining from 14% to 11%, while opioid utilization rates declined from 8% to 4%. “We also found decreases in special-cause variation in other measures of interest, including CT scan utilization as well as corticosteroid use, which was reduced 29% during the course of the program,” he said.

The quality initiative was conducted through the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation as an outgrowth of its IBD Qorus quality improvement program. The 15-month study involved 20,392 patient visits at 15 academic and 11 private/community practices from January 2018 to April 2019. “This specific project within Qorus is focused specifically around the concept of improving access during times of urgent care need,” Dr. Melmed told this news organization. The goal was to identify practice changes that can drive improvement.

The intervention consisted of 19 different strategies, called a “Change Package,” and participating sites could choose to test and implement one or more of them, Dr. Melmed said. Some examples included designating urgent care slots in the clinic schedule, installing a nurse hotline, a weekly “huddle” to review high-risk patients, and patient education on using urgent care.

One of the drivers of the program was to provide immediate care improvement to patients, Dr. Melmed said in the interview. “As opposed to investments into the cure of IBD that we need, but which can take years to develop, this research has immediate, practical applicability for patients today,” he said.

“The fact that we were able to demonstrate reduction in emergency room utilization and hospitalization, steroid use, and narcotic use has really energized the work that we were doing. We can now show that very-low-cost process changes at a site level lead to robust improvement in patient outcomes. These changes are potentially implementable in any practice setting,” Dr. Melmed said in the interview.

After Dr. Melmed’s presentation, Maria T. Abreu, MD, director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center at the University of Miami, asked about the cost of the interventions. Dr. Melmed said the costs were nominal, such as paying for a new phone line for a patient hotline. “But overall the cost really involved in the program was the time that it took to review the high-risk list on a weekly basis with the team, and that is essentially a 15-minute huddle,” he said.

Later, Dr. Abreu said in an interview that the program was “a terrific example of how measuring outcomes and sharing ideas can make huge impacts in the lives of patients.” She added, “An enormous amount of money is spent on clinical trials of expensive biologics which have revolutionized treatment, yet the humanistic aspects of our care have just as great of an impact. In this study, each center focused on ways they could lower ER visits and hospitalizations. One size did not fit all, yet they could learn from each other. The very platform they used to conduct the study is a model for all of us.”

Corey A. Siegel, MD, of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and Dr. Melmed's coprincipal investigator on Qorus, said the quality initiative now includes 49 GI practices across the country with plans to grow to 60 by the end of the year. "We have created this 'collaboratory' for providers from actross the country to work togetherr to learn how to best deliver high-qulaity care for patients with IBD," he said.

Another feature of the quality initiative allowed participating sites to see how they compared with others anonymously, Dr. Melmed said. “Using the data, we called out high-performing sites to teach the rest of us what they were doing that enabled them to improve, so that all of us could learn from their successes,” he said.

The researchers are aiming to evaluate costs and identify the most successful interventions, with the plan to present the latter at Digestive Disease Week® 2020 and use them to develop a toolkit practices can use. “Ultimately,” said Dr. Melmed, “this is scalable.”

Dr. Melmed disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Jannsen, GSK, Medtronic, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Takeda, and Techlab; IBD Qorus receives support from Abbvie, AMAG, Helmsley Charitable Trust, Janssen, Nephoroceuticals, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB.

SOURCE: Melmed GT et al. Crohn’s & Colitis Congress 2020, Session 28.

AUSTIN, TEX. – A quality improvement initiative aimed at patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has reduced emergency department visits and hospitalizations by 20% or more and slashed opioid use by half, according to study results presented at the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

After 15 months, the quality improvement program saw emergency department visit rates decline from 18% to 14%, a 22% relative decrease, Gil Y. Melmed, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said. Additionally, the study documented a similar decrease in the rate of hospitalization, declining from 14% to 11%, while opioid utilization rates declined from 8% to 4%. “We also found decreases in special-cause variation in other measures of interest, including CT scan utilization as well as corticosteroid use, which was reduced 29% during the course of the program,” he said.

The quality initiative was conducted through the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation as an outgrowth of its IBD Qorus quality improvement program. The 15-month study involved 20,392 patient visits at 15 academic and 11 private/community practices from January 2018 to April 2019. “This specific project within Qorus is focused specifically around the concept of improving access during times of urgent care need,” Dr. Melmed told this news organization. The goal was to identify practice changes that can drive improvement.

The intervention consisted of 19 different strategies, called a “Change Package,” and participating sites could choose to test and implement one or more of them, Dr. Melmed said. Some examples included designating urgent care slots in the clinic schedule, installing a nurse hotline, a weekly “huddle” to review high-risk patients, and patient education on using urgent care.

One of the drivers of the program was to provide immediate care improvement to patients, Dr. Melmed said in the interview. “As opposed to investments into the cure of IBD that we need, but which can take years to develop, this research has immediate, practical applicability for patients today,” he said.

“The fact that we were able to demonstrate reduction in emergency room utilization and hospitalization, steroid use, and narcotic use has really energized the work that we were doing. We can now show that very-low-cost process changes at a site level lead to robust improvement in patient outcomes. These changes are potentially implementable in any practice setting,” Dr. Melmed said in the interview.

After Dr. Melmed’s presentation, Maria T. Abreu, MD, director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center at the University of Miami, asked about the cost of the interventions. Dr. Melmed said the costs were nominal, such as paying for a new phone line for a patient hotline. “But overall the cost really involved in the program was the time that it took to review the high-risk list on a weekly basis with the team, and that is essentially a 15-minute huddle,” he said.

Later, Dr. Abreu said in an interview that the program was “a terrific example of how measuring outcomes and sharing ideas can make huge impacts in the lives of patients.” She added, “An enormous amount of money is spent on clinical trials of expensive biologics which have revolutionized treatment, yet the humanistic aspects of our care have just as great of an impact. In this study, each center focused on ways they could lower ER visits and hospitalizations. One size did not fit all, yet they could learn from each other. The very platform they used to conduct the study is a model for all of us.”

Corey A. Siegel, MD, of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and Dr. Melmed's coprincipal investigator on Qorus, said the quality initiative now includes 49 GI practices across the country with plans to grow to 60 by the end of the year. "We have created this 'collaboratory' for providers from actross the country to work togetherr to learn how to best deliver high-qulaity care for patients with IBD," he said.

Another feature of the quality initiative allowed participating sites to see how they compared with others anonymously, Dr. Melmed said. “Using the data, we called out high-performing sites to teach the rest of us what they were doing that enabled them to improve, so that all of us could learn from their successes,” he said.

The researchers are aiming to evaluate costs and identify the most successful interventions, with the plan to present the latter at Digestive Disease Week® 2020 and use them to develop a toolkit practices can use. “Ultimately,” said Dr. Melmed, “this is scalable.”

Dr. Melmed disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Jannsen, GSK, Medtronic, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Takeda, and Techlab; IBD Qorus receives support from Abbvie, AMAG, Helmsley Charitable Trust, Janssen, Nephoroceuticals, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB.

SOURCE: Melmed GT et al. Crohn’s & Colitis Congress 2020, Session 28.

REPORTING FROM CROHN’S & COLITIS CONGRESS

Treating those who taught us

I was surprised when the name came up on my hospital census as a new consult.

Many years ago he’d been one of my attendings in residency. Someone I’d trained under. He’d been patient, almost grandfatherly, in the way he taught residents on his service. Never angry or impatient. I’d genuinely liked him as a person and respected him as a teacher.

And here he was now, a new consult on my daily hospital patient list.

A quick look at his chart brought the irony that I’m the same age now that he was when I worked under him. Time flies.

He didn’t remember me, nor did I expect him to. In my training from 1993 to 1997, I’d only dealt with him directly for a few months here and there. He’d seen a lot of residents come and go over his career.

He was, like me, older now. I wouldn’t have recognized him if I didn’t know the name in advance. He was frail now, seemingly smaller than I remembered, his mind and health damaged by his own neurologic issues.

Like all of us, I’ve taken care of other physicians, but this was the first time I’d encountered one of my former teachers in that role, and felt bad that he was in a situation I really couldn’t do much about.

I wrote some orders and moved on to the next consult, but haven’t stopped thinking about him.

Time comes for all of us sooner or later, though it’s never easy to reflect on. I’d certainly do what I could to help him, but was well aware (as I’m sure he was) that there was only so much I could.

When I came back the next day he’d left. At his own insistence, he wanted us to stop what we were doing and opted to be kept comfortable. It was certainly not an easy choice to make for any of us, but in character with the person and physician I still liked and respected.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I was surprised when the name came up on my hospital census as a new consult.

Many years ago he’d been one of my attendings in residency. Someone I’d trained under. He’d been patient, almost grandfatherly, in the way he taught residents on his service. Never angry or impatient. I’d genuinely liked him as a person and respected him as a teacher.

And here he was now, a new consult on my daily hospital patient list.

A quick look at his chart brought the irony that I’m the same age now that he was when I worked under him. Time flies.

He didn’t remember me, nor did I expect him to. In my training from 1993 to 1997, I’d only dealt with him directly for a few months here and there. He’d seen a lot of residents come and go over his career.

He was, like me, older now. I wouldn’t have recognized him if I didn’t know the name in advance. He was frail now, seemingly smaller than I remembered, his mind and health damaged by his own neurologic issues.

Like all of us, I’ve taken care of other physicians, but this was the first time I’d encountered one of my former teachers in that role, and felt bad that he was in a situation I really couldn’t do much about.

I wrote some orders and moved on to the next consult, but haven’t stopped thinking about him.

Time comes for all of us sooner or later, though it’s never easy to reflect on. I’d certainly do what I could to help him, but was well aware (as I’m sure he was) that there was only so much I could.

When I came back the next day he’d left. At his own insistence, he wanted us to stop what we were doing and opted to be kept comfortable. It was certainly not an easy choice to make for any of us, but in character with the person and physician I still liked and respected.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I was surprised when the name came up on my hospital census as a new consult.

Many years ago he’d been one of my attendings in residency. Someone I’d trained under. He’d been patient, almost grandfatherly, in the way he taught residents on his service. Never angry or impatient. I’d genuinely liked him as a person and respected him as a teacher.

And here he was now, a new consult on my daily hospital patient list.

A quick look at his chart brought the irony that I’m the same age now that he was when I worked under him. Time flies.

He didn’t remember me, nor did I expect him to. In my training from 1993 to 1997, I’d only dealt with him directly for a few months here and there. He’d seen a lot of residents come and go over his career.

He was, like me, older now. I wouldn’t have recognized him if I didn’t know the name in advance. He was frail now, seemingly smaller than I remembered, his mind and health damaged by his own neurologic issues.

Like all of us, I’ve taken care of other physicians, but this was the first time I’d encountered one of my former teachers in that role, and felt bad that he was in a situation I really couldn’t do much about.

I wrote some orders and moved on to the next consult, but haven’t stopped thinking about him.

Time comes for all of us sooner or later, though it’s never easy to reflect on. I’d certainly do what I could to help him, but was well aware (as I’m sure he was) that there was only so much I could.

When I came back the next day he’d left. At his own insistence, he wanted us to stop what we were doing and opted to be kept comfortable. It was certainly not an easy choice to make for any of us, but in character with the person and physician I still liked and respected.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

EEG abnormalities may indicate increased risk for epilepsy in patients with autism

BALTIMORE – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. In addition, a positive family history of febrile seizures also is associated with an increased risk of epilepsy in this population.

The literature suggests that the prevalence of epilepsy in patients with ASD ranges from 5% to 40%. This broad range may result from the heterogeneity of epilepsy risk factors among patients with ASD. These risk factors include intellectual disability, age, and syndromic forms of ASD such as tuberous sclerosis complex. Regardless of whether they have epilepsy, approximately 60% of patients with ASD have EEG abnormalities. The prognostic implications of these abnormalities are uncertain.

Investigators reviewed patients’ charts retrospectively

Divya Nadkarni, MD, a neurologist at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, and colleagues sought to clarify the relationship between risk factors such as EEG abnormalities and subsequent epilepsy in patients with ASD. They retrospectively identified patients who were followed jointly at UCLA and at Pediatric Minds, a neurodevelopmental clinic in Torrance, Calif. Eligible patients had a diagnosis of ASD, based on criteria from DSM-IV, DSM-5, or the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. In addition, patients had overnight, continuous video EEG evaluation and a minimum follow-up of 1 week after EEG. Patients with a history of epilepsy before the initial EEG evaluation were excluded. Dr. Nadkarni and colleagues collected clinical and electrographic data by chart review.

The study’s primary outcome was time to onset of epilepsy. Among the variables that the investigators analyzed were EEG abnormalities, which they defined as focal slowing or generalized or focal epileptiform discharges. The other variables were history of febrile seizures, family history of epilepsy, family history of febrile seizures, and family history of ASD. Dr. Nadkarni and colleagues analyzed the data using the Kaplan–Meier method and Cox proportional hazards models.

In all, 164 patients met the study’s inclusion criteria. The population’s median age at the initial EEG evaluation was 4.5 years. The median follow-up after this evaluation was 2.4 years. The investigators found 63 patients (38.4%) with abnormal EEGs, and 18 patients (11%) subsequently developed epilepsy after a median of 1.9 years.

Family history of febrile seizures was associated with time to epilepsy onset

The time to epilepsy onset was associated with abnormalities on the initial overnight continuous EEG. The hazard ratio of epilepsy among patients with EEG abnormalities was 8.0. Approximately one-third of patients with EEG abnormalities developed subsequent epilepsy, compared with approximately 5% of patients without EEG abnormalities, said Dr. Nadkarni.

In addition, time to epilepsy onset was independently associated with a positive family history of febrile seizures. This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Nadkarni. The hazard ratio of epilepsy among patients with a positive family history of febrile seizures was 12.6.

The patient’s own history of febrile seizures was not associated with time to epilepsy onset. One potential explanation for this result is that it is difficult to distinguish between febrile seizure and seizure with fever in the general pediatric population. Making this distinction in children with ASD, who may have atypical febrile seizures, might be still more difficult, said Dr. Nadkarni.

Time for guideline updates?

“Statements from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Neurology, and the Child Neurology Society do not currently recommend routine EEG screening for all children with ASD,” said Dr. Nadkarni. Investigators are suggesting that the guidelines should be reevaluated, however. “Research shows that EEG abnormalities, particularly epileptiform abnormalities, are associated with worse outcome, in terms of developmental and adaptive functioning. EEG endophenotypes in ASD are starting to be elucidated ... That’s one reason to consider EEG screening.” Furthermore, preliminary connectivity research suggests that EEG screening of high-risk siblings of children with ASD may predict the development of ASD.

The small cohort and retrospective design were among the study’s limitations, said Dr. Nadkarni. Some patients were lost to follow-up, and some data were missing from patients’ charts.

“In our opinion, further study – ideally, a prospective, observational cohort study – might be warranted to determine whether overnight continuous EEG monitoring might be useful as a screening tool for epilepsy in patients with ASD,” Dr. Nadkarni concluded.

The study was conducted without external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nadkarni D et al. AES 2019. Abstract 1.29.

BALTIMORE – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. In addition, a positive family history of febrile seizures also is associated with an increased risk of epilepsy in this population.

The literature suggests that the prevalence of epilepsy in patients with ASD ranges from 5% to 40%. This broad range may result from the heterogeneity of epilepsy risk factors among patients with ASD. These risk factors include intellectual disability, age, and syndromic forms of ASD such as tuberous sclerosis complex. Regardless of whether they have epilepsy, approximately 60% of patients with ASD have EEG abnormalities. The prognostic implications of these abnormalities are uncertain.

Investigators reviewed patients’ charts retrospectively

Divya Nadkarni, MD, a neurologist at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, and colleagues sought to clarify the relationship between risk factors such as EEG abnormalities and subsequent epilepsy in patients with ASD. They retrospectively identified patients who were followed jointly at UCLA and at Pediatric Minds, a neurodevelopmental clinic in Torrance, Calif. Eligible patients had a diagnosis of ASD, based on criteria from DSM-IV, DSM-5, or the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. In addition, patients had overnight, continuous video EEG evaluation and a minimum follow-up of 1 week after EEG. Patients with a history of epilepsy before the initial EEG evaluation were excluded. Dr. Nadkarni and colleagues collected clinical and electrographic data by chart review.

The study’s primary outcome was time to onset of epilepsy. Among the variables that the investigators analyzed were EEG abnormalities, which they defined as focal slowing or generalized or focal epileptiform discharges. The other variables were history of febrile seizures, family history of epilepsy, family history of febrile seizures, and family history of ASD. Dr. Nadkarni and colleagues analyzed the data using the Kaplan–Meier method and Cox proportional hazards models.

In all, 164 patients met the study’s inclusion criteria. The population’s median age at the initial EEG evaluation was 4.5 years. The median follow-up after this evaluation was 2.4 years. The investigators found 63 patients (38.4%) with abnormal EEGs, and 18 patients (11%) subsequently developed epilepsy after a median of 1.9 years.

Family history of febrile seizures was associated with time to epilepsy onset

The time to epilepsy onset was associated with abnormalities on the initial overnight continuous EEG. The hazard ratio of epilepsy among patients with EEG abnormalities was 8.0. Approximately one-third of patients with EEG abnormalities developed subsequent epilepsy, compared with approximately 5% of patients without EEG abnormalities, said Dr. Nadkarni.

In addition, time to epilepsy onset was independently associated with a positive family history of febrile seizures. This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Nadkarni. The hazard ratio of epilepsy among patients with a positive family history of febrile seizures was 12.6.

The patient’s own history of febrile seizures was not associated with time to epilepsy onset. One potential explanation for this result is that it is difficult to distinguish between febrile seizure and seizure with fever in the general pediatric population. Making this distinction in children with ASD, who may have atypical febrile seizures, might be still more difficult, said Dr. Nadkarni.

Time for guideline updates?

“Statements from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Neurology, and the Child Neurology Society do not currently recommend routine EEG screening for all children with ASD,” said Dr. Nadkarni. Investigators are suggesting that the guidelines should be reevaluated, however. “Research shows that EEG abnormalities, particularly epileptiform abnormalities, are associated with worse outcome, in terms of developmental and adaptive functioning. EEG endophenotypes in ASD are starting to be elucidated ... That’s one reason to consider EEG screening.” Furthermore, preliminary connectivity research suggests that EEG screening of high-risk siblings of children with ASD may predict the development of ASD.

The small cohort and retrospective design were among the study’s limitations, said Dr. Nadkarni. Some patients were lost to follow-up, and some data were missing from patients’ charts.

“In our opinion, further study – ideally, a prospective, observational cohort study – might be warranted to determine whether overnight continuous EEG monitoring might be useful as a screening tool for epilepsy in patients with ASD,” Dr. Nadkarni concluded.

The study was conducted without external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nadkarni D et al. AES 2019. Abstract 1.29.

BALTIMORE – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. In addition, a positive family history of febrile seizures also is associated with an increased risk of epilepsy in this population.

The literature suggests that the prevalence of epilepsy in patients with ASD ranges from 5% to 40%. This broad range may result from the heterogeneity of epilepsy risk factors among patients with ASD. These risk factors include intellectual disability, age, and syndromic forms of ASD such as tuberous sclerosis complex. Regardless of whether they have epilepsy, approximately 60% of patients with ASD have EEG abnormalities. The prognostic implications of these abnormalities are uncertain.

Investigators reviewed patients’ charts retrospectively

Divya Nadkarni, MD, a neurologist at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, and colleagues sought to clarify the relationship between risk factors such as EEG abnormalities and subsequent epilepsy in patients with ASD. They retrospectively identified patients who were followed jointly at UCLA and at Pediatric Minds, a neurodevelopmental clinic in Torrance, Calif. Eligible patients had a diagnosis of ASD, based on criteria from DSM-IV, DSM-5, or the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. In addition, patients had overnight, continuous video EEG evaluation and a minimum follow-up of 1 week after EEG. Patients with a history of epilepsy before the initial EEG evaluation were excluded. Dr. Nadkarni and colleagues collected clinical and electrographic data by chart review.

The study’s primary outcome was time to onset of epilepsy. Among the variables that the investigators analyzed were EEG abnormalities, which they defined as focal slowing or generalized or focal epileptiform discharges. The other variables were history of febrile seizures, family history of epilepsy, family history of febrile seizures, and family history of ASD. Dr. Nadkarni and colleagues analyzed the data using the Kaplan–Meier method and Cox proportional hazards models.

In all, 164 patients met the study’s inclusion criteria. The population’s median age at the initial EEG evaluation was 4.5 years. The median follow-up after this evaluation was 2.4 years. The investigators found 63 patients (38.4%) with abnormal EEGs, and 18 patients (11%) subsequently developed epilepsy after a median of 1.9 years.

Family history of febrile seizures was associated with time to epilepsy onset

The time to epilepsy onset was associated with abnormalities on the initial overnight continuous EEG. The hazard ratio of epilepsy among patients with EEG abnormalities was 8.0. Approximately one-third of patients with EEG abnormalities developed subsequent epilepsy, compared with approximately 5% of patients without EEG abnormalities, said Dr. Nadkarni.

In addition, time to epilepsy onset was independently associated with a positive family history of febrile seizures. This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Nadkarni. The hazard ratio of epilepsy among patients with a positive family history of febrile seizures was 12.6.

The patient’s own history of febrile seizures was not associated with time to epilepsy onset. One potential explanation for this result is that it is difficult to distinguish between febrile seizure and seizure with fever in the general pediatric population. Making this distinction in children with ASD, who may have atypical febrile seizures, might be still more difficult, said Dr. Nadkarni.

Time for guideline updates?

“Statements from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Neurology, and the Child Neurology Society do not currently recommend routine EEG screening for all children with ASD,” said Dr. Nadkarni. Investigators are suggesting that the guidelines should be reevaluated, however. “Research shows that EEG abnormalities, particularly epileptiform abnormalities, are associated with worse outcome, in terms of developmental and adaptive functioning. EEG endophenotypes in ASD are starting to be elucidated ... That’s one reason to consider EEG screening.” Furthermore, preliminary connectivity research suggests that EEG screening of high-risk siblings of children with ASD may predict the development of ASD.

The small cohort and retrospective design were among the study’s limitations, said Dr. Nadkarni. Some patients were lost to follow-up, and some data were missing from patients’ charts.

“In our opinion, further study – ideally, a prospective, observational cohort study – might be warranted to determine whether overnight continuous EEG monitoring might be useful as a screening tool for epilepsy in patients with ASD,” Dr. Nadkarni concluded.

The study was conducted without external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nadkarni D et al. AES 2019. Abstract 1.29.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Less gestational weight gain seen with metformin

GRAPEVINE, TEX.* – Pregnant women with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes had significantly less gestational weight gain if they had metformin exposure at any point in their pregnancies, with no differences in infant birth weight or postnatal infant hypoglycemia, according to research presented at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

In a retrospective single-center review of 284 women without metformin exposure and 227 with metformin exposure in pregnancy, metformin exposure at any point in pregnancy was associated with a significantly greater chance of appropriate – rather than excessive – weight gain.

The relationship held true for the 169 women who had metformin in their first trimester of pregnancy. Here, 69% of women had appropriate weight gain using Institute of Medicine and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists standards, compared with 54% of the 282 women who had no metformin exposure (adjusted odds ratio 1.92, P = .003). A further 22% of women receiving metformin in their first trimester of pregnancy lost weight, compared with 9% of women without metformin exposure (aOR 2.11, P = .019). There was no significant difference between the two groups in infant birth weight.

Separately, study author Jacquelyn Adams, MD, and her colleagues analyzed outcomes for the full cohort of 227 women who received metformin at any point in their pregnancy, comparing them again to the 282 women who had not received metformin. Most women (85%) were on 2 g of metformin at the time of delivery. These results again showed a greater likelihood of appropriate weight gain in the metformin group (69%; aOR 1.85; P = .002). Maternal weight loss was seen in 20% of this group (aOR 1.98, P = .018). Infant birth weights were not significantly different between these two groups.

“We found that women who had been on metformin at any point in their pregnancy had more appropriate weight gain and less excessive weight gain,” said Dr. Adams, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “Actually, some women on metformin had even had a little bit of weight loss, with no difference in their baby’s birth weight. So that’s really exciting, because our starting prepregnancy body mass index was 33-36 [kg/m2], which is considered obese,” she said in an interview.

This is an important finding, said Dr. Adams, because previous work has shown that less weight gain in pregnancy is associated with lower risk for hypertension and preeclampsia, and lower rates of fetal macrosomia.

What about infant outcomes? Dr. Adams said that there were many concerns about metformin: “Would it affect baby outcome? Were those babies more likely to be hypoglycemic? Were they more likely to be growth restricted? Were they more likely to have issues in the NICU? And the answer was really, ‘No.’ ”

“So we can both help these women have appropriate weight gain and not have any negative effects on these babies,” she added.

Specifically, Dr. Adams and her coinvestigators found no significant differences between the groups in gestational age at birth, likelihood of neonatal ICU admission, Apgar scores, neonatal hypoglycemia, respiratory distress syndrome, or fetal death. Fetal growth restriction and anomalies occurred at a low and similar rate between the groups.

Dr. Adams said that she was not surprised to see that metformin was associated with less weight gain in pregnancy, but she was surprised at how highly significant the differences were with metformin use. “Metformin is first-line for diabetes in nonpregnant individuals because it’s associated with things like weight loss, and because of ease of use and lack of hypoglycemia – so I was really hoping to see this kind of result.”

Women receiving metformin were a mean 34 years old, while those who didn’t get metformin were 32 years old, a significant difference. Prepregnancy body mass index also was higher in those receiving metformin, and they were more likely to have a type 2 diabetes diagnosis. A similar proportion of both groups – about two-thirds – were white, and about 20% were Hispanic.

The lower weight gain seen in metformin-takers also might smooth the way post partum, said Dr. Adams. “My perception is that, when these women leave us, they might not have any primary care follow-up; they might not have anybody following their diabetes; and metformin is a very viable way to help them in their life outside of pregnancy.

“Not to mention that all the weight you gain in pregnancy, you do eventually have to lose post partum,” she added, “so having less pregnancy weight gain kind of sets them up for success in their postpregnancy life as well.”

Asked whether these results inform the ongoing question of whether insulin or metformin is the most appropriate first-line treatment for gestational diabetes, Dr. Adams first noted that “there’s a lot of crossover,” pointing out that over 60% of the participants in her study eventually also required insulin.

“It’s a question I would love to address in a head-to-head trial,” she said, adding that questions about metformin’s effects on the placenta and the potential for later deleterious effects require more study.

In her practice, Dr. Adams said that patients generally are discharged with a metformin prescription, and then meet with a diabetes educator 1 week after delivery to assess blood glucose levels and adjust medical management. Following that, a warm hand-off to a primary care practice who can continue management and education is optimal, she said.

In terms of next steps, “We would really love to look at metformin in the postpartum period,” said Dr. Adams. Ideally, future work could look for outcomes that extend beyond the 6- to 8-week postpartum follow-up visit. For example, she said, there are indications that women with insulin insensitivity might benefit from metformin while breastfeeding; it’s also possible that metformin might reduce the risk of postpartum preeclampsia.

Dr. Adams reported that she had no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding.

SOURCE: Adams J et al. SMFM 2020, Abstract 335.

*This story was updated 2/10/2020.

GRAPEVINE, TEX.* – Pregnant women with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes had significantly less gestational weight gain if they had metformin exposure at any point in their pregnancies, with no differences in infant birth weight or postnatal infant hypoglycemia, according to research presented at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

In a retrospective single-center review of 284 women without metformin exposure and 227 with metformin exposure in pregnancy, metformin exposure at any point in pregnancy was associated with a significantly greater chance of appropriate – rather than excessive – weight gain.

The relationship held true for the 169 women who had metformin in their first trimester of pregnancy. Here, 69% of women had appropriate weight gain using Institute of Medicine and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists standards, compared with 54% of the 282 women who had no metformin exposure (adjusted odds ratio 1.92, P = .003). A further 22% of women receiving metformin in their first trimester of pregnancy lost weight, compared with 9% of women without metformin exposure (aOR 2.11, P = .019). There was no significant difference between the two groups in infant birth weight.

Separately, study author Jacquelyn Adams, MD, and her colleagues analyzed outcomes for the full cohort of 227 women who received metformin at any point in their pregnancy, comparing them again to the 282 women who had not received metformin. Most women (85%) were on 2 g of metformin at the time of delivery. These results again showed a greater likelihood of appropriate weight gain in the metformin group (69%; aOR 1.85; P = .002). Maternal weight loss was seen in 20% of this group (aOR 1.98, P = .018). Infant birth weights were not significantly different between these two groups.

“We found that women who had been on metformin at any point in their pregnancy had more appropriate weight gain and less excessive weight gain,” said Dr. Adams, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “Actually, some women on metformin had even had a little bit of weight loss, with no difference in their baby’s birth weight. So that’s really exciting, because our starting prepregnancy body mass index was 33-36 [kg/m2], which is considered obese,” she said in an interview.

This is an important finding, said Dr. Adams, because previous work has shown that less weight gain in pregnancy is associated with lower risk for hypertension and preeclampsia, and lower rates of fetal macrosomia.

What about infant outcomes? Dr. Adams said that there were many concerns about metformin: “Would it affect baby outcome? Were those babies more likely to be hypoglycemic? Were they more likely to be growth restricted? Were they more likely to have issues in the NICU? And the answer was really, ‘No.’ ”

“So we can both help these women have appropriate weight gain and not have any negative effects on these babies,” she added.

Specifically, Dr. Adams and her coinvestigators found no significant differences between the groups in gestational age at birth, likelihood of neonatal ICU admission, Apgar scores, neonatal hypoglycemia, respiratory distress syndrome, or fetal death. Fetal growth restriction and anomalies occurred at a low and similar rate between the groups.

Dr. Adams said that she was not surprised to see that metformin was associated with less weight gain in pregnancy, but she was surprised at how highly significant the differences were with metformin use. “Metformin is first-line for diabetes in nonpregnant individuals because it’s associated with things like weight loss, and because of ease of use and lack of hypoglycemia – so I was really hoping to see this kind of result.”

Women receiving metformin were a mean 34 years old, while those who didn’t get metformin were 32 years old, a significant difference. Prepregnancy body mass index also was higher in those receiving metformin, and they were more likely to have a type 2 diabetes diagnosis. A similar proportion of both groups – about two-thirds – were white, and about 20% were Hispanic.

The lower weight gain seen in metformin-takers also might smooth the way post partum, said Dr. Adams. “My perception is that, when these women leave us, they might not have any primary care follow-up; they might not have anybody following their diabetes; and metformin is a very viable way to help them in their life outside of pregnancy.

“Not to mention that all the weight you gain in pregnancy, you do eventually have to lose post partum,” she added, “so having less pregnancy weight gain kind of sets them up for success in their postpregnancy life as well.”

Asked whether these results inform the ongoing question of whether insulin or metformin is the most appropriate first-line treatment for gestational diabetes, Dr. Adams first noted that “there’s a lot of crossover,” pointing out that over 60% of the participants in her study eventually also required insulin.

“It’s a question I would love to address in a head-to-head trial,” she said, adding that questions about metformin’s effects on the placenta and the potential for later deleterious effects require more study.

In her practice, Dr. Adams said that patients generally are discharged with a metformin prescription, and then meet with a diabetes educator 1 week after delivery to assess blood glucose levels and adjust medical management. Following that, a warm hand-off to a primary care practice who can continue management and education is optimal, she said.

In terms of next steps, “We would really love to look at metformin in the postpartum period,” said Dr. Adams. Ideally, future work could look for outcomes that extend beyond the 6- to 8-week postpartum follow-up visit. For example, she said, there are indications that women with insulin insensitivity might benefit from metformin while breastfeeding; it’s also possible that metformin might reduce the risk of postpartum preeclampsia.

Dr. Adams reported that she had no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding.

SOURCE: Adams J et al. SMFM 2020, Abstract 335.

*This story was updated 2/10/2020.

GRAPEVINE, TEX.* – Pregnant women with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes had significantly less gestational weight gain if they had metformin exposure at any point in their pregnancies, with no differences in infant birth weight or postnatal infant hypoglycemia, according to research presented at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

In a retrospective single-center review of 284 women without metformin exposure and 227 with metformin exposure in pregnancy, metformin exposure at any point in pregnancy was associated with a significantly greater chance of appropriate – rather than excessive – weight gain.

The relationship held true for the 169 women who had metformin in their first trimester of pregnancy. Here, 69% of women had appropriate weight gain using Institute of Medicine and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists standards, compared with 54% of the 282 women who had no metformin exposure (adjusted odds ratio 1.92, P = .003). A further 22% of women receiving metformin in their first trimester of pregnancy lost weight, compared with 9% of women without metformin exposure (aOR 2.11, P = .019). There was no significant difference between the two groups in infant birth weight.

Separately, study author Jacquelyn Adams, MD, and her colleagues analyzed outcomes for the full cohort of 227 women who received metformin at any point in their pregnancy, comparing them again to the 282 women who had not received metformin. Most women (85%) were on 2 g of metformin at the time of delivery. These results again showed a greater likelihood of appropriate weight gain in the metformin group (69%; aOR 1.85; P = .002). Maternal weight loss was seen in 20% of this group (aOR 1.98, P = .018). Infant birth weights were not significantly different between these two groups.

“We found that women who had been on metformin at any point in their pregnancy had more appropriate weight gain and less excessive weight gain,” said Dr. Adams, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “Actually, some women on metformin had even had a little bit of weight loss, with no difference in their baby’s birth weight. So that’s really exciting, because our starting prepregnancy body mass index was 33-36 [kg/m2], which is considered obese,” she said in an interview.

This is an important finding, said Dr. Adams, because previous work has shown that less weight gain in pregnancy is associated with lower risk for hypertension and preeclampsia, and lower rates of fetal macrosomia.