User login

Screen pregnant women with suspected 2019-nCoV infection

It is too early yet to explicitly determine the effects of the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) on pregnant women and their fetuses. This is a critical concern, because members of the coronavirus family, which have been responsible for previous outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV), have demonstrated their ability to cause severe complications during pregnancy, according to researchers.

The SARS virus outbreak and the more recent MERS virus outbreak provide the best available models with which to examine the potential impact of 2019-nCoV on pregnancy, according to a letter published online in the Lancet.

Twelve pregnant women were infected with SARS-CoV during the 2002-2003 pandemic. Three (25%) of these women died during pregnancy. Overall, four of seven women had a miscarriage in the first trimester. In the second or third trimester, two out of five women had fetal growth restriction, and four of the five had preterm birth (one case was spontaneous and three were induced because of the maternal condition), according to corresponding author David Baud, MD, PhD, of the maternal-fetal and obstetrics research unit at Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, and colleagues.

A review of 11 pregnant women infected with the virus showed that 10 women (91%) presented with adverse outcomes. Six (55%) neonates were admitted to the ICU; three (27%) died. Two neonates were delivered prematurely because their mothers developed severe respiratory failure.

Because 2019-nCov has a potential for similar behavior, “we recommend systematic screening of any suspected 2019-nCoV infection during pregnancy. If 2019-nCoV infection during pregnancy is confirmed, extended follow-up should be recommended for mothers and their fetuses,” concluded Dr. Baud and colleagues.

Dr. Baud and associates are known for their previous research on the impacts of the Zika virus on pregnancy. They reported having no competing interests.

SOURCE: Baud D et al. Lancet. 2020 Feb 6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30311-1.

The coronavirus has been spreading rapidly in China, and recently, international cases have been identified, including within the United States. As the article by Locher et al. suggests, mechanical, physiological, and immune adaptations in pregnancy leave pregnant women at risk of severe complications from respiratory illnesses.

Obstetricians need to be prepared to screen, test, and promptly treat pregnant women with any severe respiratory illness to reduce maternal and perinatal morbidity. At this time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advises that any patient with fever and signs of a lower respiratory infection, as well as an epidemiologic risk factor (such as recent travel to China), should be considered at risk for the coronavirus. Samples are collected and sent to the CDC as testing can be done only at the CDC at this time. Please refer to the CDC website for up-to-date guidance for health care professionals.

Unfortunately, there is no specific treatment for coronavirus. Clinical management includes prompt implementation of recommended infection prevention and control measures. Supportive management of complications, including fever reduction and advanced organ support, should be provided as necessary.

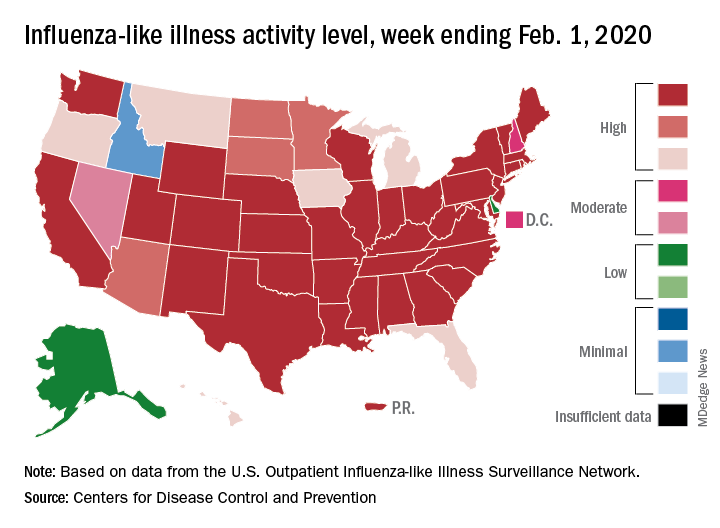

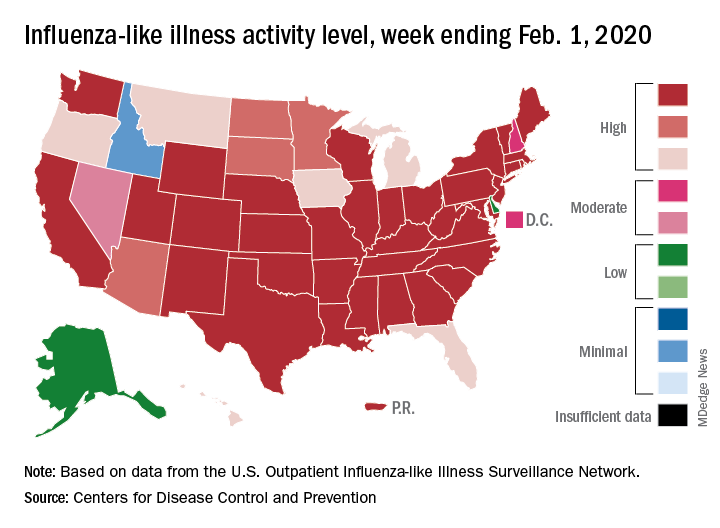

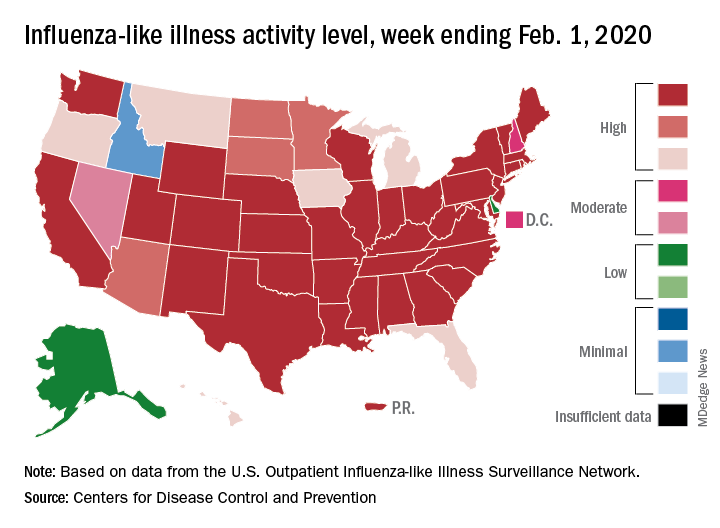

While coronavirus is a terrifying potential threat, it’s worth mentioning that, for most pregnant women, a much more likely threat is influenza. Pregnant women with influenza virus infection are at increased risk for progression to pneumonia, ICU admission, preterm delivery, and maternal death. The influenza vaccine can help reduce these risks, and we should continue to encourage vaccination for all pregnant women. Prompt treatment is important! Treatment within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms is ideal, but treatment should not be withheld if the ideal window is missed.

Finally, don’t forget to remind your pregnant patients to avoid close contact with sick family members and friends, wash hands frequently, and call the doctor’s office with any sign of a flu-like illness!

Angela Martin, MD, is an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

The coronavirus has been spreading rapidly in China, and recently, international cases have been identified, including within the United States. As the article by Locher et al. suggests, mechanical, physiological, and immune adaptations in pregnancy leave pregnant women at risk of severe complications from respiratory illnesses.

Obstetricians need to be prepared to screen, test, and promptly treat pregnant women with any severe respiratory illness to reduce maternal and perinatal morbidity. At this time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advises that any patient with fever and signs of a lower respiratory infection, as well as an epidemiologic risk factor (such as recent travel to China), should be considered at risk for the coronavirus. Samples are collected and sent to the CDC as testing can be done only at the CDC at this time. Please refer to the CDC website for up-to-date guidance for health care professionals.

Unfortunately, there is no specific treatment for coronavirus. Clinical management includes prompt implementation of recommended infection prevention and control measures. Supportive management of complications, including fever reduction and advanced organ support, should be provided as necessary.

While coronavirus is a terrifying potential threat, it’s worth mentioning that, for most pregnant women, a much more likely threat is influenza. Pregnant women with influenza virus infection are at increased risk for progression to pneumonia, ICU admission, preterm delivery, and maternal death. The influenza vaccine can help reduce these risks, and we should continue to encourage vaccination for all pregnant women. Prompt treatment is important! Treatment within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms is ideal, but treatment should not be withheld if the ideal window is missed.

Finally, don’t forget to remind your pregnant patients to avoid close contact with sick family members and friends, wash hands frequently, and call the doctor’s office with any sign of a flu-like illness!

Angela Martin, MD, is an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

The coronavirus has been spreading rapidly in China, and recently, international cases have been identified, including within the United States. As the article by Locher et al. suggests, mechanical, physiological, and immune adaptations in pregnancy leave pregnant women at risk of severe complications from respiratory illnesses.

Obstetricians need to be prepared to screen, test, and promptly treat pregnant women with any severe respiratory illness to reduce maternal and perinatal morbidity. At this time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advises that any patient with fever and signs of a lower respiratory infection, as well as an epidemiologic risk factor (such as recent travel to China), should be considered at risk for the coronavirus. Samples are collected and sent to the CDC as testing can be done only at the CDC at this time. Please refer to the CDC website for up-to-date guidance for health care professionals.

Unfortunately, there is no specific treatment for coronavirus. Clinical management includes prompt implementation of recommended infection prevention and control measures. Supportive management of complications, including fever reduction and advanced organ support, should be provided as necessary.

While coronavirus is a terrifying potential threat, it’s worth mentioning that, for most pregnant women, a much more likely threat is influenza. Pregnant women with influenza virus infection are at increased risk for progression to pneumonia, ICU admission, preterm delivery, and maternal death. The influenza vaccine can help reduce these risks, and we should continue to encourage vaccination for all pregnant women. Prompt treatment is important! Treatment within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms is ideal, but treatment should not be withheld if the ideal window is missed.

Finally, don’t forget to remind your pregnant patients to avoid close contact with sick family members and friends, wash hands frequently, and call the doctor’s office with any sign of a flu-like illness!

Angela Martin, MD, is an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

It is too early yet to explicitly determine the effects of the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) on pregnant women and their fetuses. This is a critical concern, because members of the coronavirus family, which have been responsible for previous outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV), have demonstrated their ability to cause severe complications during pregnancy, according to researchers.

The SARS virus outbreak and the more recent MERS virus outbreak provide the best available models with which to examine the potential impact of 2019-nCoV on pregnancy, according to a letter published online in the Lancet.

Twelve pregnant women were infected with SARS-CoV during the 2002-2003 pandemic. Three (25%) of these women died during pregnancy. Overall, four of seven women had a miscarriage in the first trimester. In the second or third trimester, two out of five women had fetal growth restriction, and four of the five had preterm birth (one case was spontaneous and three were induced because of the maternal condition), according to corresponding author David Baud, MD, PhD, of the maternal-fetal and obstetrics research unit at Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, and colleagues.

A review of 11 pregnant women infected with the virus showed that 10 women (91%) presented with adverse outcomes. Six (55%) neonates were admitted to the ICU; three (27%) died. Two neonates were delivered prematurely because their mothers developed severe respiratory failure.

Because 2019-nCov has a potential for similar behavior, “we recommend systematic screening of any suspected 2019-nCoV infection during pregnancy. If 2019-nCoV infection during pregnancy is confirmed, extended follow-up should be recommended for mothers and their fetuses,” concluded Dr. Baud and colleagues.

Dr. Baud and associates are known for their previous research on the impacts of the Zika virus on pregnancy. They reported having no competing interests.

SOURCE: Baud D et al. Lancet. 2020 Feb 6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30311-1.

It is too early yet to explicitly determine the effects of the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) on pregnant women and their fetuses. This is a critical concern, because members of the coronavirus family, which have been responsible for previous outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV), have demonstrated their ability to cause severe complications during pregnancy, according to researchers.

The SARS virus outbreak and the more recent MERS virus outbreak provide the best available models with which to examine the potential impact of 2019-nCoV on pregnancy, according to a letter published online in the Lancet.

Twelve pregnant women were infected with SARS-CoV during the 2002-2003 pandemic. Three (25%) of these women died during pregnancy. Overall, four of seven women had a miscarriage in the first trimester. In the second or third trimester, two out of five women had fetal growth restriction, and four of the five had preterm birth (one case was spontaneous and three were induced because of the maternal condition), according to corresponding author David Baud, MD, PhD, of the maternal-fetal and obstetrics research unit at Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, and colleagues.

A review of 11 pregnant women infected with the virus showed that 10 women (91%) presented with adverse outcomes. Six (55%) neonates were admitted to the ICU; three (27%) died. Two neonates were delivered prematurely because their mothers developed severe respiratory failure.

Because 2019-nCov has a potential for similar behavior, “we recommend systematic screening of any suspected 2019-nCoV infection during pregnancy. If 2019-nCoV infection during pregnancy is confirmed, extended follow-up should be recommended for mothers and their fetuses,” concluded Dr. Baud and colleagues.

Dr. Baud and associates are known for their previous research on the impacts of the Zika virus on pregnancy. They reported having no competing interests.

SOURCE: Baud D et al. Lancet. 2020 Feb 6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30311-1.

FROM THE LANCET

What you absolutely need to know about tail coverage

A 28-year-old pediatrician working in a large group practice in California found a new job in Pennsylvania. The job would allow her to live with her husband, who was a nonphysician.

On her last day of work at the California job, the practice’s office manager asked her, “Do you know about the tail coverage?”

He explained that it is malpractice insurance for any cases filed against her after leaving the job. Without it, he said, she would not be covered for those claims.

The physician (who asked not to be identified) had very little savings and suddenly had to pay a five-figure bill for tail coverage. To provide the extra malpractice coverage, she and her husband had to use savings they’d set aside to buy a house.

Getting tail coverage, known formally as an extended reporting endorsement, often comes as a complete and costly surprise for new doctors, says Dennis Hursh, Esq, a health care attorney based in Middletown, Penn., who deals with physicians’ employment contracts.

“Having to pay for a tail can disrupt lives,” Hursh said. “A tail can cost about one third of a young doctor’s salary. If you don’t feel you can afford to pay that, you may be forced to stay with a job you don’t like.”

Most medical residents don’t think about tail coverage until they apply for their first job, but last year, residents at Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia got a painful early lesson.

In the summer, the hospital went out of business because of financial problems. Hundreds of medical residents and fellows not only were forced to find new programs but also had to prepare to buy tail coverage for their training years at Hahnemann.

“All the guarantees have been yanked out from under us,” said Tom Sibert, MD, a former internal medicine resident at the hospital, who is now finishing his training in California. “Residents don’t have that kind of money.”

Hahnemann trainees have asked the judge in the bankruptcy proceedings to put them ahead of other creditors and to ensure their tail coverage is paid. As of early February, the issue had not been resolved.

Meanwhile, Sibert and many other former trainees were trying to get quotes for purchasing tail coverage. They have been shocked by the amounts they would have to pay.

How tail coverage works

Medical malpractice tail coverage protects from incidents that took place when doctors were at their previous jobs but that later resulted in malpractice claims after they had left that employer.

One type of malpractice insurance, an occurrence policy, does not need tail coverage. Occurrence policies cover any incident that occurred when the policy was in force, no matter when a claim was filed – even if it is filed many years after the claims-filing period of the policy ends.

However, most malpractice policies – as many as 85%, according to one estimate – are claims-made policies. Claims-made policies are more much common because they’re significantly less expensive than occurrence policies.

Under a claims-made policy, coverage for malpractice claims completely stops when the policy ends. It does not cover incidents that occurred when the policy was in force but for which the patients later filed claims, as the occurrence policy does. So a tail is needed to cover these claims.

Physicians in all stages of their career may need tail coverage when they leave a job, change malpractice carriers, or retire.

But young physicians often have greater problems with tail coverage, for several reasons. They tend to be employed, and as such, they cannot choose the coverage they want. As a result, they most likely get claims-made coverage. In addition, the job turnover tends to be higher for these doctors. When leaving a job, the tail comes into play. More than half of new physicians leave their first job within 5 years, and of those, more than half leave after only 1 or 2 years.

Young physicians have no experience with tails and may not even know what they are. “In training, malpractice coverage is not a problem because the program handles it,” Mr. Hursh said. Accreditation standards require that teaching hospitals buy coverage, including a tail when residents leave.

So when young physicians are offered their first job and are handed an employment contract to sign, they may not even look for tail coverage, says Mr. Hursh, who wrote The Final Hurdle, a Physician’s Guide to Negotiating a Fair Employment Agreement. Instead, “young physicians tend to focus on issues like salary, benefits, and signing bonuses,” he said.

Mr. Hursh says the tail is usually the most expensive potential cost in the contract.

There’s no easy way to get out of paying the tail coverage once it is enshrined in the contract. The full tail can cost five or even six figures, depending on the physicians’ specialty, the local malpractice premium, and the physician’s own claims history.

Can you negotiate your tail coverage?

Negotiating tail coverage in the employment contract involves some familiarity with medical malpractice insurance and a close reading of the contract. First, you have to determine that the employer is providing claims-made coverage, which would require a tail if you leave. Then you have to determine whether the employer will pay for the tail coverage.

Often, the contract does not even mention tail coverage. “It could merely state that the practice will be responsible for malpractice coverage while you are working there,” Mr. Hursh said. Although it never specifies the tail, this language indicates that you will be paying for it, he says.

Therefore, it’s wise to have a conversation with your prospective employer about the tail. “Some new doctors never ask the question ‘What happens if I leave? Do I get tail coverage?’ ” said Israel Teitelbaum, an attorney who is chairman of Contemporary Insurance Services, an insurance broker in Silver Spring, Md.

Talking about the tail, however, can be a touchy subject for many young doctors applying for their first job. The tail matters only if you leave the job, and you may not want to imply that you would ever want to leave. Too much money, however, is on the line for you not to ask, Mr. Teitelbaum said.

Even if the employer verbally agrees to pay for the tail coverage, experts advise that you try to get the employer’s commitment in writing and have it put it into the contract.

Getting the employer to cover the tail in the initial contract is crucial because once you have agreed to work there, “it’s much more difficult to get it changed,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. However, even if tail coverage is not in the first contract, you shouldn’t give up, he says. You should try again in the next contract a few years later.

“It’s never too late to bring it up,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. After a few years of employment, you have a track record at the job. “A doctor who is very desirable to the employer may be able to get tail coverage on contract renewal.”

Coverage: Large employers vs. small employers

Willingness to pay for an employee’s tail coverage varies depending on the size of the employer. Large employers – systems, hospitals, and large practices – are much more likely to cover the tail than small and medium-sized practices.

Large employers tend to pay for at least part of the tail because they realize that it is in their interest to do so. Since they have the deepest pockets, they’re often the first to be named in a lawsuit. They might have to pay the whole claim if the physician did not have tail coverage.

However, many large employers want to use tail coverage as a bargaining chip to make sure doctors stay for a while at least. One typical arrangement, Mr. Hursh says, is to pay only one-fifth of the tail if the physician leaves in the first year of employment and then to pay one fifth more in each succeeding year until year five, when the employer assumes the entire cost of the tail.

Smaller practices, on the other hand, are usually close-fisted about tail coverage. “They tend to view the tail as an unnecessary expense,” Mr. Hursh said. “They don’t want to pay for a doctor who is not generating revenue for them any more.”

Traditionally, when physicians become partners, practices are more generous and agree to pay their tails if they leave, Mr. Hursh says. But he thinks this is changing, too – recent partnership contracts he has reviewed did not provide for tail coverage.

Times you don’t need to pay for tail coverage

Even if you’re responsible for the tail coverage, your insurance arrangement may be such that you don’t have to pay for it, says Michelle Perron, a malpractice insurance broker in North Hampton, N.H.

For example, if the carrier at your new job is the same as the one at your old job, your coverage would continue with no break, and you would not need a tail, she says. Even if you move to another state, your old carrier might also sell policies there, and you would then likely have seamless coverage, Ms. Perron says. This would be handy if you could choose your new carrier.

Even when you change carriers, Ms. Perron says, the new one might agree to pick up the old carrier’s coverage in return for getting your business, assuming you are an independent physician buying your own coverage. The new carrier would issue prior acts coverage, also known as nose coverage.

Older doctors going into retirement also have a potential tail coverage problem, but their tail coverage premium is often waived, Ms. Perron says. The need for a tail has to do with claims arising post retirement, after your coverage has ended. Typically, if you have been with the carrier for at least 5 years and you are age 55 years or older, your carrier will waive the tail coverage premium, she says.

However, if the retired doctor starts practicing again, even part time, the carrier may want to take back the free tail, she says. Some retired doctors get around this by buying a lower-priced tail from another company, but the former carrier may still want its money back, Ms. Perron says.

Can you just go without tail coverage?

What happens if physicians with a tail commitment choose to wing it and not pay for the tail? If a claim was never made against them, they may believe that the expense is unnecessary. The situation, however, is not so simple.

Some states require having tail coverage. Malpractice coverage is required in seven states, and at least some of those states explicitly extend this requirement to tails. They are Colorado, Connecticut, Kansas, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin. Eleven more states tie malpractice coverage, perhaps including tails, to some benefit for the doctor, such as tort reform. These states include Indiana, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, and Pennsylvania.

Many hospitals require tail coverage for privileges, and some insurers do as well. In addition, Ms. Perron says a missing tail reduces your prospects when looking for a job. “For the employer, having to pay coverage for a new hire will cost more than starting fresh with someone else,” she said.

Still, it’s important to remember the risk of being sued. “If you don’t buy the tail coverage, you are at risk for a lawsuit for many years to come,” Mr. Teitelbaum said.

Doctors should consider their potential lifetime risk, not just their current risk. Although only 8% of doctors younger than age 40 have been sued for malpractice, that figure climbs to almost half by the time doctors reach age 55.

The risks are higher in some specialties. About 63% of general surgeons and ob.gyns. have been sued.

Many of these claims are without merit, and doctors pay only the legal expenses of defending the case. Some doctors may think they could risk frivolous suits and cover legal expenses out of pocket. An American Medical Association survey showed that 68% of closed claims against doctors were dropped, dismissed, or withdrawn. It said these claims cost an average of more than $30,000 to defend.

However, Mr. Teitelbaum puts the defense costs for so-called frivolous suits much higher than the AMA, at $250,000 or more. “Even if you’re sure you won’t have to pay a claim, you still have to defend yourself against frivolous suits,” he said. “You won’t recover those expenses.”

How to lower your tail coverage cost

Physicians typically have 60 days to buy tail coverage after their regular coverage has ended. Specialized brokers such as Mr. Teitelbaum and Ms. Perron help physicians look for the best tails to buy.

The cost of the tail depends on how long you’ve been at your job when you leave it, Ms. Perron says. If you leave in the first 1 or 2 years of the policy, she says, the tail price will be lower because the coverage period is shorter.

Usually the most expensive tail available is from the carrier that issued the original policy. Why is this? “Carriers rarely sell a tail that undercuts their retail price,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. “They don’t want to compete with themselves, and in fact doing so could pose regulatory problems for them.”

Instead of buying from their own carrier, doctors can purchase stand-alone tails from competitors, which Mr. Teitelbaum says are 10%-30% less expensive than the policy the original carrier issues. However, stand-alone tails are not always easy to find, especially for high-cost specialties such as neurosurgery and ob.gyn., he says.

Some physicians try to bring down the cost of the tail by limiting the duration of the tail. You can buy tails that only cover claims filed 1-5 years after the incident took place, rather than indefinitely. These limits mirror the typical statute of limitations – the time limit to file a claim in each state. This limit is as little as 2 years in some states, though it can be as long as 6 years in others.

However, some states make exceptions to the statute of limitations. The 2- to 6-year clock doesn’t start ticking until the mistake is discovered or, in the case of children, when they reach adulthood. “This means that with a limited tail, you always have risk,” Perron said.

And yet some doctors insist on these time-limited tails. “If a doctor opts for 3 years’ coverage, that’s better than no years,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. “But I would advise them to take at least 5 years because that gives you coverage for the basic statute of limitations in most states. Three-year tails do yield savings, but often they’re not enough to warrant the risk.”

Another way to reduce costs is to lower the coverage limits of the tail. The standard coverage limit is $1 million per case and $3 million per year, so doctors might be able to save money on the premium by buying limits of $200,000/$600,000. But Mr. Teitelbaum says most companies would refuse to sell a policy with a limit lower than that of the expiring policy.

Further ways to reduce the cost of the tail include buying tail coverage that doesn’t give the physician the right to approve a settlement or that doesn’t include legal fees in the coverage limits. But these options, too, raise the physician’s risks. Whichever option you choose, the important thing is to protect yourself against costly lawsuits.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 28-year-old pediatrician working in a large group practice in California found a new job in Pennsylvania. The job would allow her to live with her husband, who was a nonphysician.

On her last day of work at the California job, the practice’s office manager asked her, “Do you know about the tail coverage?”

He explained that it is malpractice insurance for any cases filed against her after leaving the job. Without it, he said, she would not be covered for those claims.

The physician (who asked not to be identified) had very little savings and suddenly had to pay a five-figure bill for tail coverage. To provide the extra malpractice coverage, she and her husband had to use savings they’d set aside to buy a house.

Getting tail coverage, known formally as an extended reporting endorsement, often comes as a complete and costly surprise for new doctors, says Dennis Hursh, Esq, a health care attorney based in Middletown, Penn., who deals with physicians’ employment contracts.

“Having to pay for a tail can disrupt lives,” Hursh said. “A tail can cost about one third of a young doctor’s salary. If you don’t feel you can afford to pay that, you may be forced to stay with a job you don’t like.”

Most medical residents don’t think about tail coverage until they apply for their first job, but last year, residents at Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia got a painful early lesson.

In the summer, the hospital went out of business because of financial problems. Hundreds of medical residents and fellows not only were forced to find new programs but also had to prepare to buy tail coverage for their training years at Hahnemann.

“All the guarantees have been yanked out from under us,” said Tom Sibert, MD, a former internal medicine resident at the hospital, who is now finishing his training in California. “Residents don’t have that kind of money.”

Hahnemann trainees have asked the judge in the bankruptcy proceedings to put them ahead of other creditors and to ensure their tail coverage is paid. As of early February, the issue had not been resolved.

Meanwhile, Sibert and many other former trainees were trying to get quotes for purchasing tail coverage. They have been shocked by the amounts they would have to pay.

How tail coverage works

Medical malpractice tail coverage protects from incidents that took place when doctors were at their previous jobs but that later resulted in malpractice claims after they had left that employer.

One type of malpractice insurance, an occurrence policy, does not need tail coverage. Occurrence policies cover any incident that occurred when the policy was in force, no matter when a claim was filed – even if it is filed many years after the claims-filing period of the policy ends.

However, most malpractice policies – as many as 85%, according to one estimate – are claims-made policies. Claims-made policies are more much common because they’re significantly less expensive than occurrence policies.

Under a claims-made policy, coverage for malpractice claims completely stops when the policy ends. It does not cover incidents that occurred when the policy was in force but for which the patients later filed claims, as the occurrence policy does. So a tail is needed to cover these claims.

Physicians in all stages of their career may need tail coverage when they leave a job, change malpractice carriers, or retire.

But young physicians often have greater problems with tail coverage, for several reasons. They tend to be employed, and as such, they cannot choose the coverage they want. As a result, they most likely get claims-made coverage. In addition, the job turnover tends to be higher for these doctors. When leaving a job, the tail comes into play. More than half of new physicians leave their first job within 5 years, and of those, more than half leave after only 1 or 2 years.

Young physicians have no experience with tails and may not even know what they are. “In training, malpractice coverage is not a problem because the program handles it,” Mr. Hursh said. Accreditation standards require that teaching hospitals buy coverage, including a tail when residents leave.

So when young physicians are offered their first job and are handed an employment contract to sign, they may not even look for tail coverage, says Mr. Hursh, who wrote The Final Hurdle, a Physician’s Guide to Negotiating a Fair Employment Agreement. Instead, “young physicians tend to focus on issues like salary, benefits, and signing bonuses,” he said.

Mr. Hursh says the tail is usually the most expensive potential cost in the contract.

There’s no easy way to get out of paying the tail coverage once it is enshrined in the contract. The full tail can cost five or even six figures, depending on the physicians’ specialty, the local malpractice premium, and the physician’s own claims history.

Can you negotiate your tail coverage?

Negotiating tail coverage in the employment contract involves some familiarity with medical malpractice insurance and a close reading of the contract. First, you have to determine that the employer is providing claims-made coverage, which would require a tail if you leave. Then you have to determine whether the employer will pay for the tail coverage.

Often, the contract does not even mention tail coverage. “It could merely state that the practice will be responsible for malpractice coverage while you are working there,” Mr. Hursh said. Although it never specifies the tail, this language indicates that you will be paying for it, he says.

Therefore, it’s wise to have a conversation with your prospective employer about the tail. “Some new doctors never ask the question ‘What happens if I leave? Do I get tail coverage?’ ” said Israel Teitelbaum, an attorney who is chairman of Contemporary Insurance Services, an insurance broker in Silver Spring, Md.

Talking about the tail, however, can be a touchy subject for many young doctors applying for their first job. The tail matters only if you leave the job, and you may not want to imply that you would ever want to leave. Too much money, however, is on the line for you not to ask, Mr. Teitelbaum said.

Even if the employer verbally agrees to pay for the tail coverage, experts advise that you try to get the employer’s commitment in writing and have it put it into the contract.

Getting the employer to cover the tail in the initial contract is crucial because once you have agreed to work there, “it’s much more difficult to get it changed,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. However, even if tail coverage is not in the first contract, you shouldn’t give up, he says. You should try again in the next contract a few years later.

“It’s never too late to bring it up,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. After a few years of employment, you have a track record at the job. “A doctor who is very desirable to the employer may be able to get tail coverage on contract renewal.”

Coverage: Large employers vs. small employers

Willingness to pay for an employee’s tail coverage varies depending on the size of the employer. Large employers – systems, hospitals, and large practices – are much more likely to cover the tail than small and medium-sized practices.

Large employers tend to pay for at least part of the tail because they realize that it is in their interest to do so. Since they have the deepest pockets, they’re often the first to be named in a lawsuit. They might have to pay the whole claim if the physician did not have tail coverage.

However, many large employers want to use tail coverage as a bargaining chip to make sure doctors stay for a while at least. One typical arrangement, Mr. Hursh says, is to pay only one-fifth of the tail if the physician leaves in the first year of employment and then to pay one fifth more in each succeeding year until year five, when the employer assumes the entire cost of the tail.

Smaller practices, on the other hand, are usually close-fisted about tail coverage. “They tend to view the tail as an unnecessary expense,” Mr. Hursh said. “They don’t want to pay for a doctor who is not generating revenue for them any more.”

Traditionally, when physicians become partners, practices are more generous and agree to pay their tails if they leave, Mr. Hursh says. But he thinks this is changing, too – recent partnership contracts he has reviewed did not provide for tail coverage.

Times you don’t need to pay for tail coverage

Even if you’re responsible for the tail coverage, your insurance arrangement may be such that you don’t have to pay for it, says Michelle Perron, a malpractice insurance broker in North Hampton, N.H.

For example, if the carrier at your new job is the same as the one at your old job, your coverage would continue with no break, and you would not need a tail, she says. Even if you move to another state, your old carrier might also sell policies there, and you would then likely have seamless coverage, Ms. Perron says. This would be handy if you could choose your new carrier.

Even when you change carriers, Ms. Perron says, the new one might agree to pick up the old carrier’s coverage in return for getting your business, assuming you are an independent physician buying your own coverage. The new carrier would issue prior acts coverage, also known as nose coverage.

Older doctors going into retirement also have a potential tail coverage problem, but their tail coverage premium is often waived, Ms. Perron says. The need for a tail has to do with claims arising post retirement, after your coverage has ended. Typically, if you have been with the carrier for at least 5 years and you are age 55 years or older, your carrier will waive the tail coverage premium, she says.

However, if the retired doctor starts practicing again, even part time, the carrier may want to take back the free tail, she says. Some retired doctors get around this by buying a lower-priced tail from another company, but the former carrier may still want its money back, Ms. Perron says.

Can you just go without tail coverage?

What happens if physicians with a tail commitment choose to wing it and not pay for the tail? If a claim was never made against them, they may believe that the expense is unnecessary. The situation, however, is not so simple.

Some states require having tail coverage. Malpractice coverage is required in seven states, and at least some of those states explicitly extend this requirement to tails. They are Colorado, Connecticut, Kansas, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin. Eleven more states tie malpractice coverage, perhaps including tails, to some benefit for the doctor, such as tort reform. These states include Indiana, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, and Pennsylvania.

Many hospitals require tail coverage for privileges, and some insurers do as well. In addition, Ms. Perron says a missing tail reduces your prospects when looking for a job. “For the employer, having to pay coverage for a new hire will cost more than starting fresh with someone else,” she said.

Still, it’s important to remember the risk of being sued. “If you don’t buy the tail coverage, you are at risk for a lawsuit for many years to come,” Mr. Teitelbaum said.

Doctors should consider their potential lifetime risk, not just their current risk. Although only 8% of doctors younger than age 40 have been sued for malpractice, that figure climbs to almost half by the time doctors reach age 55.

The risks are higher in some specialties. About 63% of general surgeons and ob.gyns. have been sued.

Many of these claims are without merit, and doctors pay only the legal expenses of defending the case. Some doctors may think they could risk frivolous suits and cover legal expenses out of pocket. An American Medical Association survey showed that 68% of closed claims against doctors were dropped, dismissed, or withdrawn. It said these claims cost an average of more than $30,000 to defend.

However, Mr. Teitelbaum puts the defense costs for so-called frivolous suits much higher than the AMA, at $250,000 or more. “Even if you’re sure you won’t have to pay a claim, you still have to defend yourself against frivolous suits,” he said. “You won’t recover those expenses.”

How to lower your tail coverage cost

Physicians typically have 60 days to buy tail coverage after their regular coverage has ended. Specialized brokers such as Mr. Teitelbaum and Ms. Perron help physicians look for the best tails to buy.

The cost of the tail depends on how long you’ve been at your job when you leave it, Ms. Perron says. If you leave in the first 1 or 2 years of the policy, she says, the tail price will be lower because the coverage period is shorter.

Usually the most expensive tail available is from the carrier that issued the original policy. Why is this? “Carriers rarely sell a tail that undercuts their retail price,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. “They don’t want to compete with themselves, and in fact doing so could pose regulatory problems for them.”

Instead of buying from their own carrier, doctors can purchase stand-alone tails from competitors, which Mr. Teitelbaum says are 10%-30% less expensive than the policy the original carrier issues. However, stand-alone tails are not always easy to find, especially for high-cost specialties such as neurosurgery and ob.gyn., he says.

Some physicians try to bring down the cost of the tail by limiting the duration of the tail. You can buy tails that only cover claims filed 1-5 years after the incident took place, rather than indefinitely. These limits mirror the typical statute of limitations – the time limit to file a claim in each state. This limit is as little as 2 years in some states, though it can be as long as 6 years in others.

However, some states make exceptions to the statute of limitations. The 2- to 6-year clock doesn’t start ticking until the mistake is discovered or, in the case of children, when they reach adulthood. “This means that with a limited tail, you always have risk,” Perron said.

And yet some doctors insist on these time-limited tails. “If a doctor opts for 3 years’ coverage, that’s better than no years,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. “But I would advise them to take at least 5 years because that gives you coverage for the basic statute of limitations in most states. Three-year tails do yield savings, but often they’re not enough to warrant the risk.”

Another way to reduce costs is to lower the coverage limits of the tail. The standard coverage limit is $1 million per case and $3 million per year, so doctors might be able to save money on the premium by buying limits of $200,000/$600,000. But Mr. Teitelbaum says most companies would refuse to sell a policy with a limit lower than that of the expiring policy.

Further ways to reduce the cost of the tail include buying tail coverage that doesn’t give the physician the right to approve a settlement or that doesn’t include legal fees in the coverage limits. But these options, too, raise the physician’s risks. Whichever option you choose, the important thing is to protect yourself against costly lawsuits.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 28-year-old pediatrician working in a large group practice in California found a new job in Pennsylvania. The job would allow her to live with her husband, who was a nonphysician.

On her last day of work at the California job, the practice’s office manager asked her, “Do you know about the tail coverage?”

He explained that it is malpractice insurance for any cases filed against her after leaving the job. Without it, he said, she would not be covered for those claims.

The physician (who asked not to be identified) had very little savings and suddenly had to pay a five-figure bill for tail coverage. To provide the extra malpractice coverage, she and her husband had to use savings they’d set aside to buy a house.

Getting tail coverage, known formally as an extended reporting endorsement, often comes as a complete and costly surprise for new doctors, says Dennis Hursh, Esq, a health care attorney based in Middletown, Penn., who deals with physicians’ employment contracts.

“Having to pay for a tail can disrupt lives,” Hursh said. “A tail can cost about one third of a young doctor’s salary. If you don’t feel you can afford to pay that, you may be forced to stay with a job you don’t like.”

Most medical residents don’t think about tail coverage until they apply for their first job, but last year, residents at Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia got a painful early lesson.

In the summer, the hospital went out of business because of financial problems. Hundreds of medical residents and fellows not only were forced to find new programs but also had to prepare to buy tail coverage for their training years at Hahnemann.

“All the guarantees have been yanked out from under us,” said Tom Sibert, MD, a former internal medicine resident at the hospital, who is now finishing his training in California. “Residents don’t have that kind of money.”

Hahnemann trainees have asked the judge in the bankruptcy proceedings to put them ahead of other creditors and to ensure their tail coverage is paid. As of early February, the issue had not been resolved.

Meanwhile, Sibert and many other former trainees were trying to get quotes for purchasing tail coverage. They have been shocked by the amounts they would have to pay.

How tail coverage works

Medical malpractice tail coverage protects from incidents that took place when doctors were at their previous jobs but that later resulted in malpractice claims after they had left that employer.

One type of malpractice insurance, an occurrence policy, does not need tail coverage. Occurrence policies cover any incident that occurred when the policy was in force, no matter when a claim was filed – even if it is filed many years after the claims-filing period of the policy ends.

However, most malpractice policies – as many as 85%, according to one estimate – are claims-made policies. Claims-made policies are more much common because they’re significantly less expensive than occurrence policies.

Under a claims-made policy, coverage for malpractice claims completely stops when the policy ends. It does not cover incidents that occurred when the policy was in force but for which the patients later filed claims, as the occurrence policy does. So a tail is needed to cover these claims.

Physicians in all stages of their career may need tail coverage when they leave a job, change malpractice carriers, or retire.

But young physicians often have greater problems with tail coverage, for several reasons. They tend to be employed, and as such, they cannot choose the coverage they want. As a result, they most likely get claims-made coverage. In addition, the job turnover tends to be higher for these doctors. When leaving a job, the tail comes into play. More than half of new physicians leave their first job within 5 years, and of those, more than half leave after only 1 or 2 years.

Young physicians have no experience with tails and may not even know what they are. “In training, malpractice coverage is not a problem because the program handles it,” Mr. Hursh said. Accreditation standards require that teaching hospitals buy coverage, including a tail when residents leave.

So when young physicians are offered their first job and are handed an employment contract to sign, they may not even look for tail coverage, says Mr. Hursh, who wrote The Final Hurdle, a Physician’s Guide to Negotiating a Fair Employment Agreement. Instead, “young physicians tend to focus on issues like salary, benefits, and signing bonuses,” he said.

Mr. Hursh says the tail is usually the most expensive potential cost in the contract.

There’s no easy way to get out of paying the tail coverage once it is enshrined in the contract. The full tail can cost five or even six figures, depending on the physicians’ specialty, the local malpractice premium, and the physician’s own claims history.

Can you negotiate your tail coverage?

Negotiating tail coverage in the employment contract involves some familiarity with medical malpractice insurance and a close reading of the contract. First, you have to determine that the employer is providing claims-made coverage, which would require a tail if you leave. Then you have to determine whether the employer will pay for the tail coverage.

Often, the contract does not even mention tail coverage. “It could merely state that the practice will be responsible for malpractice coverage while you are working there,” Mr. Hursh said. Although it never specifies the tail, this language indicates that you will be paying for it, he says.

Therefore, it’s wise to have a conversation with your prospective employer about the tail. “Some new doctors never ask the question ‘What happens if I leave? Do I get tail coverage?’ ” said Israel Teitelbaum, an attorney who is chairman of Contemporary Insurance Services, an insurance broker in Silver Spring, Md.

Talking about the tail, however, can be a touchy subject for many young doctors applying for their first job. The tail matters only if you leave the job, and you may not want to imply that you would ever want to leave. Too much money, however, is on the line for you not to ask, Mr. Teitelbaum said.

Even if the employer verbally agrees to pay for the tail coverage, experts advise that you try to get the employer’s commitment in writing and have it put it into the contract.

Getting the employer to cover the tail in the initial contract is crucial because once you have agreed to work there, “it’s much more difficult to get it changed,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. However, even if tail coverage is not in the first contract, you shouldn’t give up, he says. You should try again in the next contract a few years later.

“It’s never too late to bring it up,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. After a few years of employment, you have a track record at the job. “A doctor who is very desirable to the employer may be able to get tail coverage on contract renewal.”

Coverage: Large employers vs. small employers

Willingness to pay for an employee’s tail coverage varies depending on the size of the employer. Large employers – systems, hospitals, and large practices – are much more likely to cover the tail than small and medium-sized practices.

Large employers tend to pay for at least part of the tail because they realize that it is in their interest to do so. Since they have the deepest pockets, they’re often the first to be named in a lawsuit. They might have to pay the whole claim if the physician did not have tail coverage.

However, many large employers want to use tail coverage as a bargaining chip to make sure doctors stay for a while at least. One typical arrangement, Mr. Hursh says, is to pay only one-fifth of the tail if the physician leaves in the first year of employment and then to pay one fifth more in each succeeding year until year five, when the employer assumes the entire cost of the tail.

Smaller practices, on the other hand, are usually close-fisted about tail coverage. “They tend to view the tail as an unnecessary expense,” Mr. Hursh said. “They don’t want to pay for a doctor who is not generating revenue for them any more.”

Traditionally, when physicians become partners, practices are more generous and agree to pay their tails if they leave, Mr. Hursh says. But he thinks this is changing, too – recent partnership contracts he has reviewed did not provide for tail coverage.

Times you don’t need to pay for tail coverage

Even if you’re responsible for the tail coverage, your insurance arrangement may be such that you don’t have to pay for it, says Michelle Perron, a malpractice insurance broker in North Hampton, N.H.

For example, if the carrier at your new job is the same as the one at your old job, your coverage would continue with no break, and you would not need a tail, she says. Even if you move to another state, your old carrier might also sell policies there, and you would then likely have seamless coverage, Ms. Perron says. This would be handy if you could choose your new carrier.

Even when you change carriers, Ms. Perron says, the new one might agree to pick up the old carrier’s coverage in return for getting your business, assuming you are an independent physician buying your own coverage. The new carrier would issue prior acts coverage, also known as nose coverage.

Older doctors going into retirement also have a potential tail coverage problem, but their tail coverage premium is often waived, Ms. Perron says. The need for a tail has to do with claims arising post retirement, after your coverage has ended. Typically, if you have been with the carrier for at least 5 years and you are age 55 years or older, your carrier will waive the tail coverage premium, she says.

However, if the retired doctor starts practicing again, even part time, the carrier may want to take back the free tail, she says. Some retired doctors get around this by buying a lower-priced tail from another company, but the former carrier may still want its money back, Ms. Perron says.

Can you just go without tail coverage?

What happens if physicians with a tail commitment choose to wing it and not pay for the tail? If a claim was never made against them, they may believe that the expense is unnecessary. The situation, however, is not so simple.

Some states require having tail coverage. Malpractice coverage is required in seven states, and at least some of those states explicitly extend this requirement to tails. They are Colorado, Connecticut, Kansas, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin. Eleven more states tie malpractice coverage, perhaps including tails, to some benefit for the doctor, such as tort reform. These states include Indiana, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, and Pennsylvania.

Many hospitals require tail coverage for privileges, and some insurers do as well. In addition, Ms. Perron says a missing tail reduces your prospects when looking for a job. “For the employer, having to pay coverage for a new hire will cost more than starting fresh with someone else,” she said.

Still, it’s important to remember the risk of being sued. “If you don’t buy the tail coverage, you are at risk for a lawsuit for many years to come,” Mr. Teitelbaum said.

Doctors should consider their potential lifetime risk, not just their current risk. Although only 8% of doctors younger than age 40 have been sued for malpractice, that figure climbs to almost half by the time doctors reach age 55.

The risks are higher in some specialties. About 63% of general surgeons and ob.gyns. have been sued.

Many of these claims are without merit, and doctors pay only the legal expenses of defending the case. Some doctors may think they could risk frivolous suits and cover legal expenses out of pocket. An American Medical Association survey showed that 68% of closed claims against doctors were dropped, dismissed, or withdrawn. It said these claims cost an average of more than $30,000 to defend.

However, Mr. Teitelbaum puts the defense costs for so-called frivolous suits much higher than the AMA, at $250,000 or more. “Even if you’re sure you won’t have to pay a claim, you still have to defend yourself against frivolous suits,” he said. “You won’t recover those expenses.”

How to lower your tail coverage cost

Physicians typically have 60 days to buy tail coverage after their regular coverage has ended. Specialized brokers such as Mr. Teitelbaum and Ms. Perron help physicians look for the best tails to buy.

The cost of the tail depends on how long you’ve been at your job when you leave it, Ms. Perron says. If you leave in the first 1 or 2 years of the policy, she says, the tail price will be lower because the coverage period is shorter.

Usually the most expensive tail available is from the carrier that issued the original policy. Why is this? “Carriers rarely sell a tail that undercuts their retail price,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. “They don’t want to compete with themselves, and in fact doing so could pose regulatory problems for them.”

Instead of buying from their own carrier, doctors can purchase stand-alone tails from competitors, which Mr. Teitelbaum says are 10%-30% less expensive than the policy the original carrier issues. However, stand-alone tails are not always easy to find, especially for high-cost specialties such as neurosurgery and ob.gyn., he says.

Some physicians try to bring down the cost of the tail by limiting the duration of the tail. You can buy tails that only cover claims filed 1-5 years after the incident took place, rather than indefinitely. These limits mirror the typical statute of limitations – the time limit to file a claim in each state. This limit is as little as 2 years in some states, though it can be as long as 6 years in others.

However, some states make exceptions to the statute of limitations. The 2- to 6-year clock doesn’t start ticking until the mistake is discovered or, in the case of children, when they reach adulthood. “This means that with a limited tail, you always have risk,” Perron said.

And yet some doctors insist on these time-limited tails. “If a doctor opts for 3 years’ coverage, that’s better than no years,” Mr. Teitelbaum said. “But I would advise them to take at least 5 years because that gives you coverage for the basic statute of limitations in most states. Three-year tails do yield savings, but often they’re not enough to warrant the risk.”

Another way to reduce costs is to lower the coverage limits of the tail. The standard coverage limit is $1 million per case and $3 million per year, so doctors might be able to save money on the premium by buying limits of $200,000/$600,000. But Mr. Teitelbaum says most companies would refuse to sell a policy with a limit lower than that of the expiring policy.

Further ways to reduce the cost of the tail include buying tail coverage that doesn’t give the physician the right to approve a settlement or that doesn’t include legal fees in the coverage limits. But these options, too, raise the physician’s risks. Whichever option you choose, the important thing is to protect yourself against costly lawsuits.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer research foundation awards ‘breakthrough scientists’

The Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation has awarded $100,000 each to six “breakthrough scientists.”

The Damon Runyon–Dale F. Frey Award for Breakthrough Scientists provides additional funding to scientists completing a Damon Runyon Fellowship Award who “are most likely to make paradigm-shifting breakthroughs that transform the way we prevent, diagnose, and treat cancer,” according to the foundation announcement.

Lindsay B. Case, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, received the award for her research investigating the molecular interactions that contribute to integrin signaling and focal adhesion function. This work could reveal new strategies for disrupting integrin signaling in cancer.

Ivana Gasic, DrSc, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was awarded for her research on tubulin autoregulation and the microtubule integrity response. Her research could provide insight into the workings of microtubule-targeting chemotherapeutic drugs and reveal new pathways to target cancer cells.

Natasha M. O’Brown, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was awarded for her research using CRISPR technology and zebrafish to investigate the molecular mechanisms that regulate the blood-brain barrier. This work could reveal new approaches to drug delivery for patients with brain tumors.

Benjamin M. Stinson, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was awarded for his work investigating the mechanisms of two main DNA double-strand break repair pathways. This research could shed light on the causes of cancers and have applications for cancer treatment.

Iva A. Tchasovnikarova, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, was awarded for epigenetics research that may reveal targets for cancer therapy. She developed a method to identify cell-based reporters of any epigenetic process inside the nucleus and aims to use this method to better understand the biology underlying epigenetic mechanisms.

Yi Yin, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, was awarded for work that may help inform the treatment of many cancers. Dr. Yin developed single-cell assays that she will combine with statistical modeling to better understand homologous recombination.

The Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation has awarded $100,000 each to six “breakthrough scientists.”

The Damon Runyon–Dale F. Frey Award for Breakthrough Scientists provides additional funding to scientists completing a Damon Runyon Fellowship Award who “are most likely to make paradigm-shifting breakthroughs that transform the way we prevent, diagnose, and treat cancer,” according to the foundation announcement.

Lindsay B. Case, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, received the award for her research investigating the molecular interactions that contribute to integrin signaling and focal adhesion function. This work could reveal new strategies for disrupting integrin signaling in cancer.

Ivana Gasic, DrSc, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was awarded for her research on tubulin autoregulation and the microtubule integrity response. Her research could provide insight into the workings of microtubule-targeting chemotherapeutic drugs and reveal new pathways to target cancer cells.

Natasha M. O’Brown, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was awarded for her research using CRISPR technology and zebrafish to investigate the molecular mechanisms that regulate the blood-brain barrier. This work could reveal new approaches to drug delivery for patients with brain tumors.

Benjamin M. Stinson, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was awarded for his work investigating the mechanisms of two main DNA double-strand break repair pathways. This research could shed light on the causes of cancers and have applications for cancer treatment.

Iva A. Tchasovnikarova, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, was awarded for epigenetics research that may reveal targets for cancer therapy. She developed a method to identify cell-based reporters of any epigenetic process inside the nucleus and aims to use this method to better understand the biology underlying epigenetic mechanisms.

Yi Yin, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, was awarded for work that may help inform the treatment of many cancers. Dr. Yin developed single-cell assays that she will combine with statistical modeling to better understand homologous recombination.

The Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation has awarded $100,000 each to six “breakthrough scientists.”

The Damon Runyon–Dale F. Frey Award for Breakthrough Scientists provides additional funding to scientists completing a Damon Runyon Fellowship Award who “are most likely to make paradigm-shifting breakthroughs that transform the way we prevent, diagnose, and treat cancer,” according to the foundation announcement.

Lindsay B. Case, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, received the award for her research investigating the molecular interactions that contribute to integrin signaling and focal adhesion function. This work could reveal new strategies for disrupting integrin signaling in cancer.

Ivana Gasic, DrSc, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was awarded for her research on tubulin autoregulation and the microtubule integrity response. Her research could provide insight into the workings of microtubule-targeting chemotherapeutic drugs and reveal new pathways to target cancer cells.

Natasha M. O’Brown, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was awarded for her research using CRISPR technology and zebrafish to investigate the molecular mechanisms that regulate the blood-brain barrier. This work could reveal new approaches to drug delivery for patients with brain tumors.

Benjamin M. Stinson, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, was awarded for his work investigating the mechanisms of two main DNA double-strand break repair pathways. This research could shed light on the causes of cancers and have applications for cancer treatment.

Iva A. Tchasovnikarova, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, was awarded for epigenetics research that may reveal targets for cancer therapy. She developed a method to identify cell-based reporters of any epigenetic process inside the nucleus and aims to use this method to better understand the biology underlying epigenetic mechanisms.

Yi Yin, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, was awarded for work that may help inform the treatment of many cancers. Dr. Yin developed single-cell assays that she will combine with statistical modeling to better understand homologous recombination.

ObGyn malpractice liability risk: 2020 developments and probabilities

In this second in a series of 3 articles discussing medical malpractice and the ObGyn we look at the reasons for malpractice claims and liability, what happens to malpractice claims, and the direction and future of medical malpractice. The first article dealt with 2 sources of major malpractice damages: the “big verdict” and physicians with multiple malpractice paid claims. Next month we look at the place of apology in medicine, in cases in which error, including negligence, may have caused a patient injury.

CASE 1 Long-term brachial plexus injury

Right upper extremity injury occurs in the neonate at delivery with sequela of long-term brachial plexus injury (which is diagnosed around 6 months of age). Physical therapy and orthopedic assessment are rendered. Despite continued treatment, discrepancy in arm lengths (ie, affected side arm is noticeably shorter than opposite side) remains. The child cannot play basketball with his older brother and is the victim of ridicule, the plaintiff’s attorney emphasizes. He is unable to properly pronate or supinate the affected arm.

The defendant ObGyn maintains that there was “no shoulder dystocia [at delivery] and the shoulder did not get obstructed in the pelvis; shoulder was delivered 15 seconds after delivery of the head.” The nursing staff testifies that if shoulder dystocia had been the problem they would have launched upon a series of procedures to address such, in accord with the delivering obstetrician. The defense expert witness testifies that a brachial plexus injury can happen without shoulder dystocia.

A defense verdict is rendered by the Florida jury.1

CASE 2 Shoulder dystocia

During delivery, the obstetrician notes a shoulder dystocia (“turtle sign”). After initial attempts to release the shoulder were unsuccessful, the physician applies traction several times to the head of the child, and the baby is delivered. There is permanent injury to the right brachial plexus. The defendant ObGyn says that traction was necessary to dislodge the shoulder, and that the injury was the result of the forces of labor (not the traction). The expert witness for the plaintiff testifies that the medical standard of care did not permit traction under these circumstances, and that the traction was the likely cause of the injury.

The Virginia jury awards $2.32 million in damages.2

Note: The above vignettes are drawn from actual cases but are only outlines of those cases and are not complete descriptions of the claims in the cases. Because the information comes from informal sources, not formal court records, the facts may be inaccurate and incomplete. They should be viewed as illustrations only.

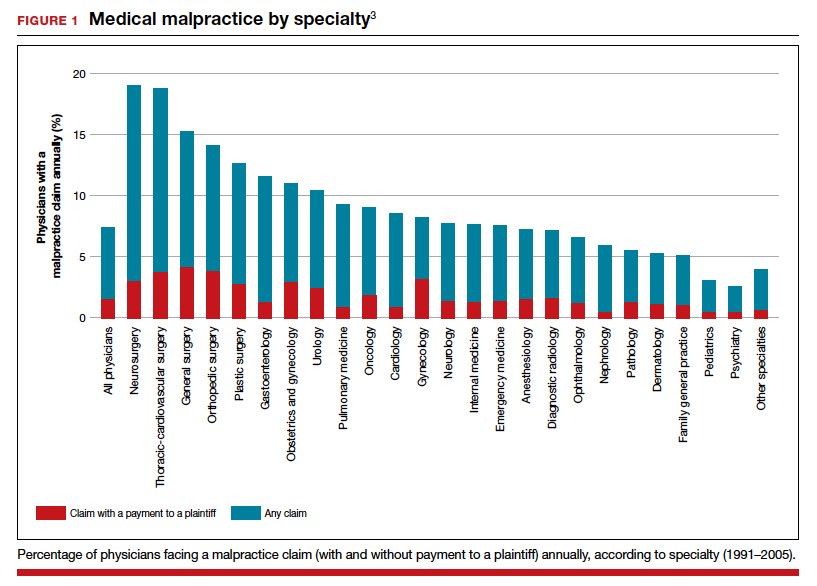

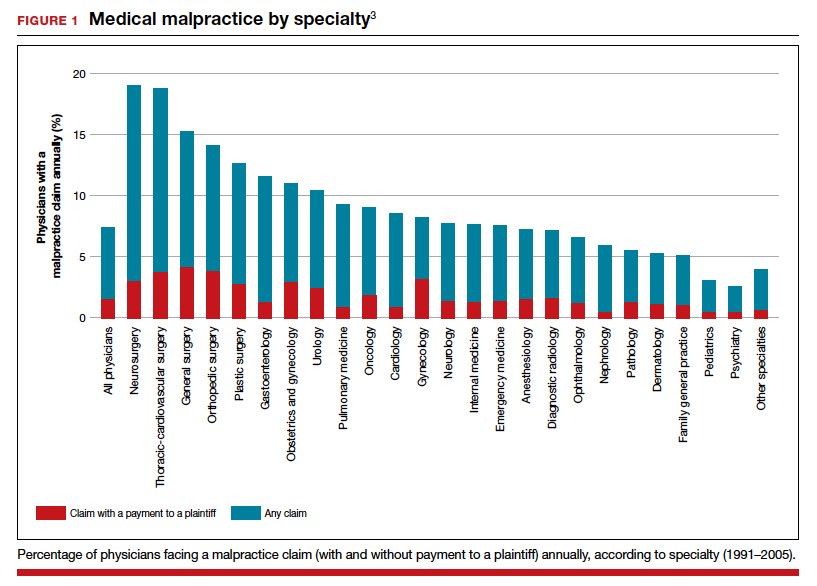

The trend in malpractice

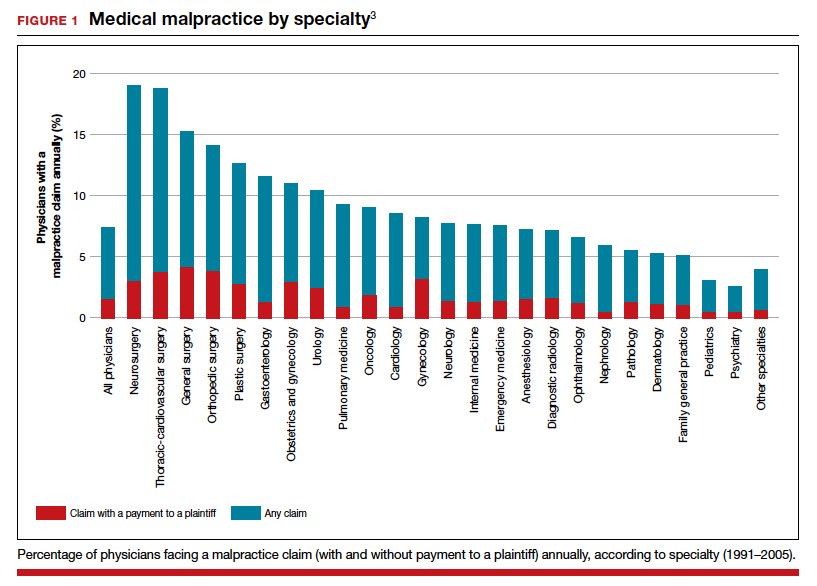

It has been clear for many years that medical malpractice claims are not randomly or evenly distributed among physicians. Notably, the variation among specialties has, and continues to be, substantial (FIGURE 1).3 Recent data suggest that, although paid claims per “1,000 physician-years” averages 14 paid claims per 1,000 physician years, it ranges from 4 or 5 in 1,000 (psychiatry and pediatrics) to 53 and 49 claims per 1,000 (neurology and plastic surgery, respectively). Obstetrics and gynecology has the fourth highest rate at 42.5 paid claims per 1,000 physician years.4 (These data are for the years 1992–2014.)

Continue to: The number of ObGyn paid malpractice claims has decreased over time...

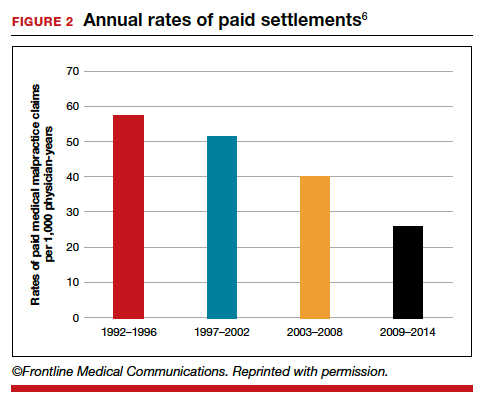

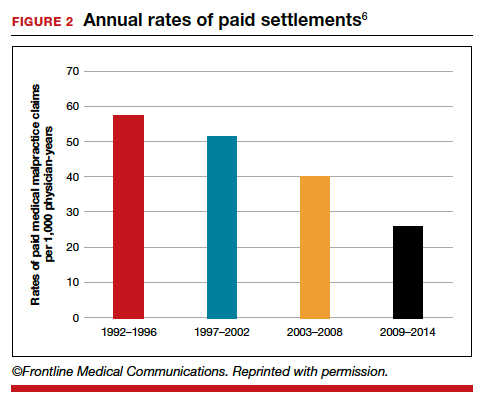

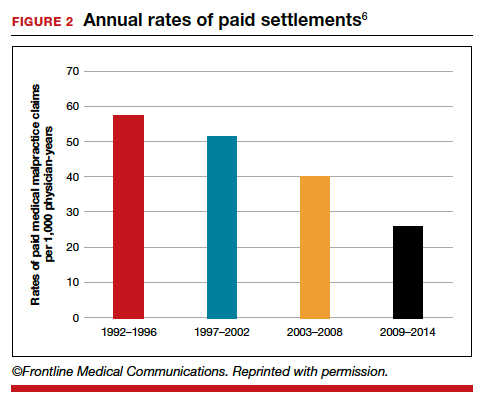

The number of ObGyn paid malpractice claims has decreased over time. Although large verdicts and physicians with multiple paid malpractice claims receive a good deal of attention (as we noted in part 1 of our series), in fact, paid medical malpractice claims have trended downward in recent decades.5 When the data above are disaggregated by 5-year periods, for example, in obstetrics and gynecology, there has been a consistent reduction in paid malpractice claims from 1992 to 2014. Paid claims went from 58 per 1,000 physician-years in 1992–1996 to 25 per 1,000 in 2009–2014 (FIGURE 2).4,6 In short, the rate dropped by half over approximately 20 years.4

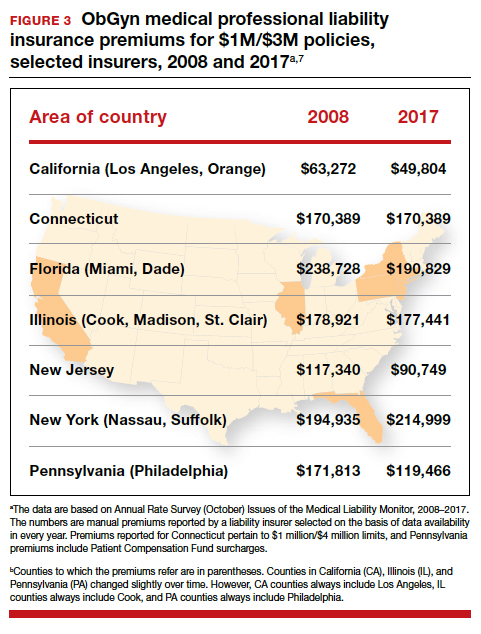

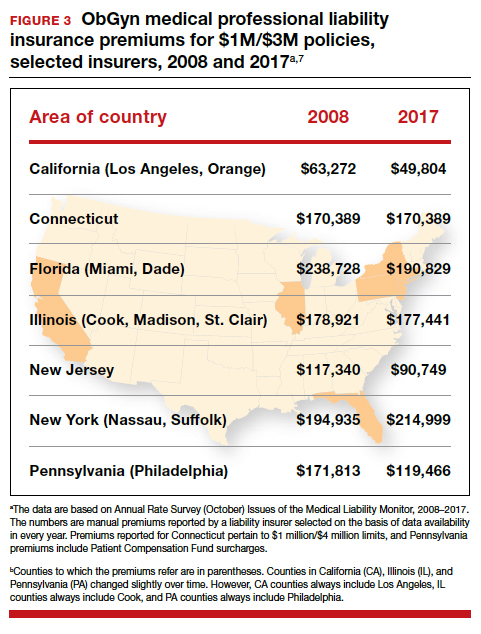

It is reasonable to expect that such a decline in the cost of malpractice insurance premiums would follow. Robert L. Barbieri, MD, who practices in Boston, Massachusetts, in his excellent recent editorial in OBG M

Why have malpractice payouts declined overall?

Have medical errors declined?

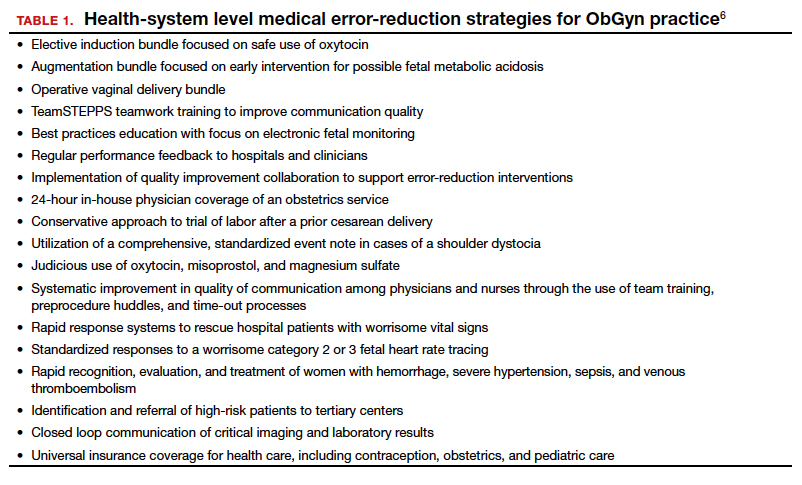

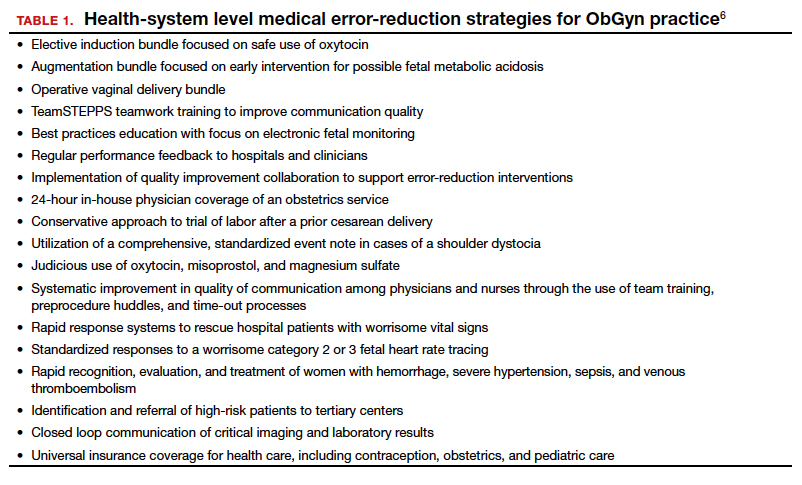

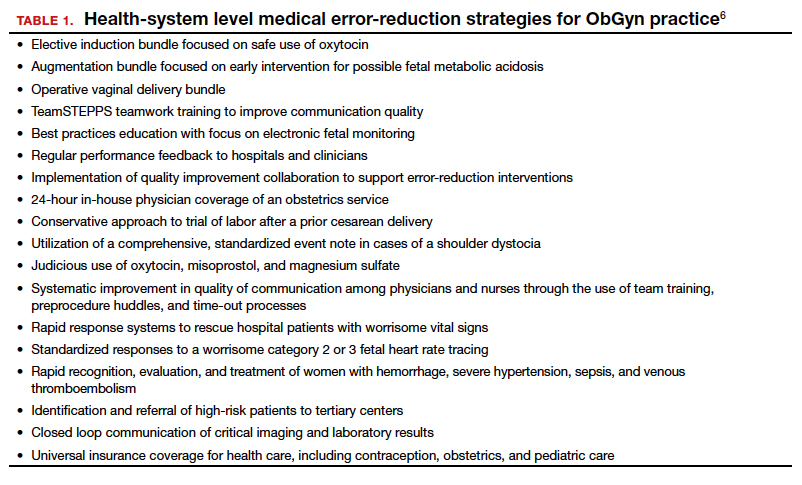

It would be wonderful if the reduction in malpractice claims represented a significant decrease in medical errors. Attention to medical errors was driven by the first widely noticed study of medical error deaths. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) study in 2000, put the number of deaths annually at 44,000 to 98,000.8 There have been many efforts to reduce such errors, and it is possible that those efforts have indeed reduced errors somewhat.4 Barbieri provided a helpful digest of many of the error-reduction suggestions for ObGyn practice (TABLE 1).6 But the number of medical errors remains high. More recent studies have suggested that the IOM’s reported number of injuries may have been low.9 In 2013, one study suggested that 210,000 deaths annually were “associated with preventable harm” in hospitals. Because of how the data were gathered the authors estimated that the actual number of preventable deaths was closer to 400,000 annually. Serious harm to patients was estimated at 10 to 20 times the IOM rate.9

Therefore, a dramatic reduction in preventable medical errors does not appear to explain the reduction in malpractice claims. Some portion of it may be explained by malpractice reforms—see "The medical reform factor" section below.

The collective accountability factor

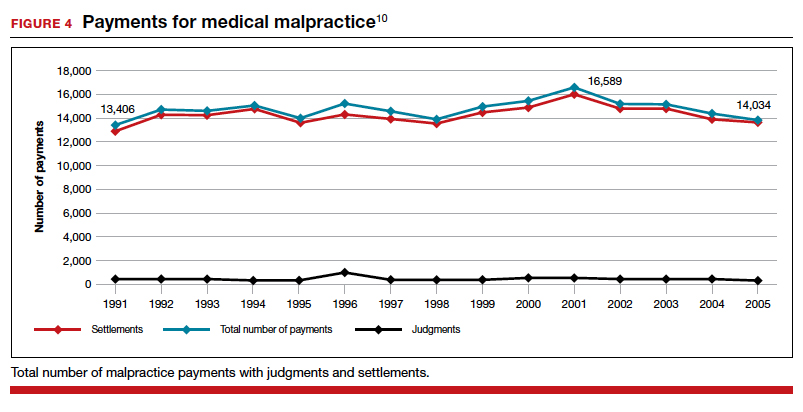

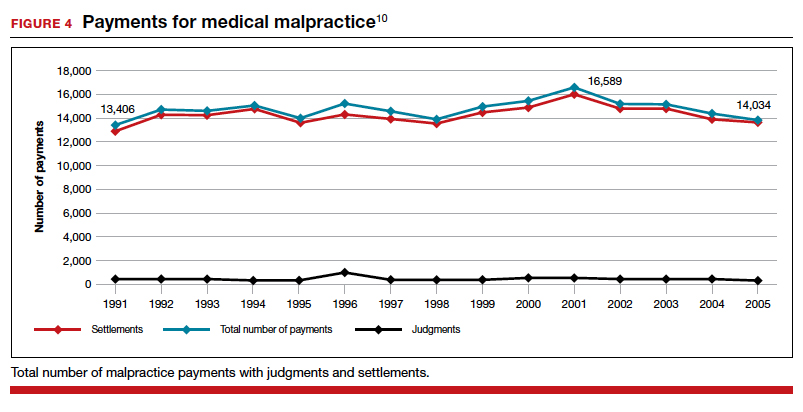

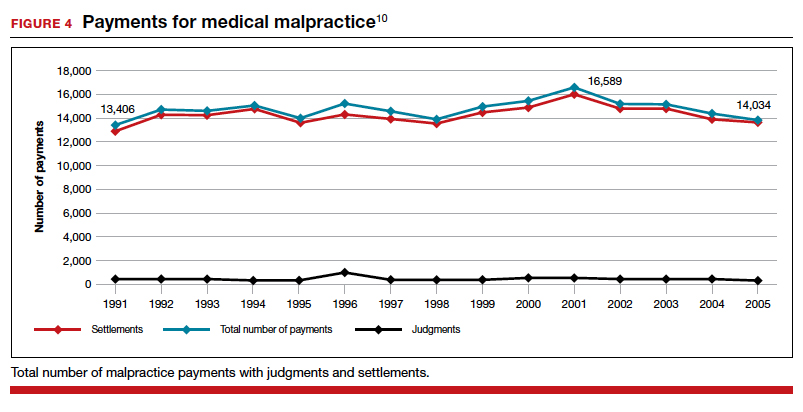

The way malpractice claims are paid (FIGURE 4),10 reported, and handled may explain some of the apparent reduction in overall paid claims. Perhaps the advent of “collective accountability,” in which patient care is rendered by teams and responsibility accepted at a team level, can alleviate a significant amount of individual physician medical malpractice claims.11 This “enterprise liability” may shift the burden of medical error from physicians to health care organizations.12 Collective accountability may, therefore, focus on institutional responsibility rather than individual physician negligence.11,13 Institutions frequently hire multiple specialists and cover their medical malpractice costs as well as stand to be named in suits.

Continue to: The institutional involvement in malpractice cases also may affect...

The institutional involvement in malpractice cases also may affect apparent malpractice rates in another way. The National Practitioner Data Bank, which is the source of information for many malpractice studies, only requires reporting about individual physicians, not institutions.14 If, therefore, claims are settled on behalf of an institution, without implicating the physician, the number of physician malpractice cases may appear to decline without any real change in malpractice rates.14 In addition, institutions have taken the lead in informal resolution of injuries that occur in the institution, and these programs may reduce the direct malpractice claims against physicians. (These “disclosure, apology, and offer,” and similar programs, are discussed in the upcoming third part of this series.)

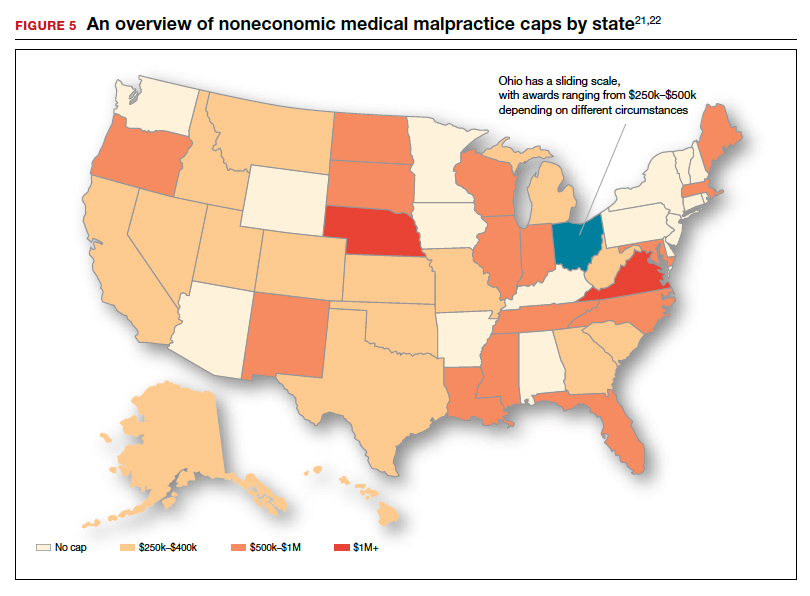

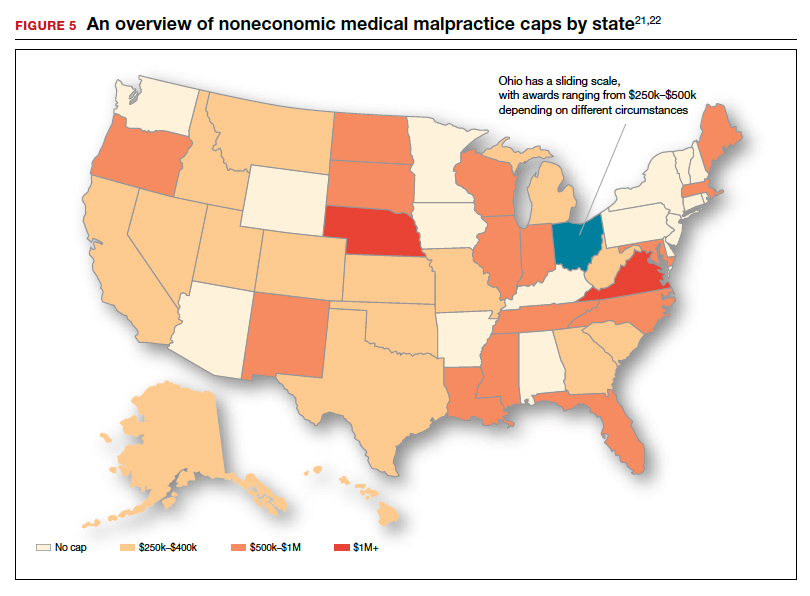

The medical reform factor

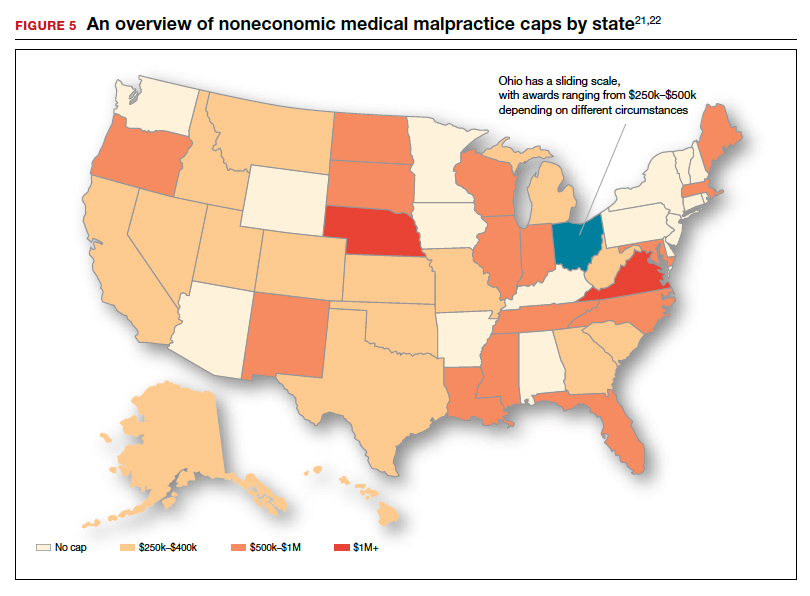

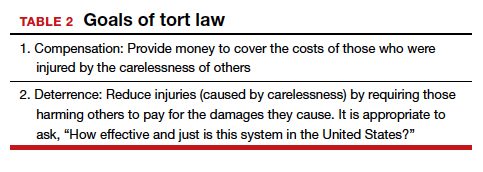

As noted, annual rates paid for medical malpractice in our specialty are trending downward. Many commentators look to malpractice reforms as the reason for the drop in malpractice rates.15-17 Because medical malpractice is essentially a matter of state law, the medical malpractice reform has occurred primarily at the state level.18 There have been many different reforms tried—limits on expert witnesses, review panels, and a variety of procedural limitations.19 Perhaps the most effective reform has been caps being placed on noneconomic damages (generally pain and suffering).20 These caps vary by state (FIGURE 5)21,22 and, of course, affect the “big verdict” cases. (As we saw in the second case scenario above, Virginia is an example of a state with a cap on malpractice awards.) They also have the secondary effect of reducing the number of malpractice cases. They make malpractice cases less attractive to some attorneys because they reduce the opportunity of large contingency fees from large verdicts. (Virtually all medical malpractice cases in the United States are tried on a contingency-fee basis, meaning that the plaintiff does not pay the attorney handling the case but rather the attorney takes a percentage of any recovery—typically in the neighborhood of 35%.) The reform process continues, although, presently, there is less pressure to act on the malpractice crisis.

Medical malpractice cases are emotional and costly

Another reason for the relatively low rate of paid claims is that medical malpractice cases are difficult, emotionally challenging, time consuming, and expensive to pursue.23 They typically drag on for years, require extensive and expensive expert consultants as well as witnesses, and face stiff defense (compared with many other torts). The settlement of medical malpractice cases, for example, is less likely than other kinds of personal injury cases.

The contingency-fee basis does mean that injured patients do not have to pay attorney fees up front; however, plaintiffs may have to pay substantial costs along the way. The other side of this coin is that lawyers can be reluctant to take malpractice cases in which the damages are likely to be small, or where the legal uncertainty reduces the odds of achieving any damages. Thus, many potential malpractice cases are never filed.

A word of caution

The news of a reduction in malpractice paid claims may not be permanent. The numbers can conceivably be cyclical, and political reforms achieved can be changed. In addition, new technology will likely bring new kinds of malpractice claims. That appears to be the case, for example, with electronic health records (EHRs). One insurer reports that EHR malpractice claims have increased over the last 8 years.24 The most common injury in these claims was death (25%), as well as a magnitude of less serious injuries. EHR-related claims result from system failures, copy-paste inaccuracies, faulty drop-down menu use, and uncorrected “auto-populated” fields. Obstetrics is tied for fifth on the list of 14 specialties with claims related to EHRs, and gynecology is tied for eighth place.24

Continue to: A federal court ruled that a hospital that changed from...

A federal court ruled that a hospital that changed from paper records to EHRs for test results had a duty to “‘implement a reasonable procedure during the transition phase’ to ensure the timely delivery of test results” to health care providers.25 We will address this in a future “What’s the Verdict?”.

Rates of harm, malpractice cases, and the disposition of cases

There are many surprises when looking at medical malpractice claims data generally. The first surprise is how few claims are filed relative to the number of error-related injuries. Given the estimate of 210,000 to 400,000 deaths “associated with preventable harm” in hospitals, plus 10 to 20 times that number of serious injuries, it would be reasonable to expect claims of many hundreds of thousands per year. Compare the probability of a malpractice claim from an error-related injury, for example, with the probability of other personal injuries—eg, of traffic deaths associated with preventable harm.

The second key observation is how many of the claims filed are not successful—even when there was evidence in the record of errors associated with the injury. Studies slice the data in different ways but collectively suggest that only a small proportion of malpractice claims filed (a claim is generally regarded as some written demand for compensation for injuries) result in payments, either through settlement or by trial. A 2006 study by Studdert and colleagues determined that 63% of formal malpractice claims filed did involve injuries resulting from errors.26 The study found that in 16% of the claims (not injuries) there was no payment even though there was error. In 10% of the claims there was payment, even in the absence of error.

Overall, in this study, 56% of the claims received some compensation.26 That is higher than a more recent study by Jena and others, which found only 22% of claims resulted in compensation.3

How malpractice claims are decided is also interesting. Jena and colleagues found that only 55% of claims resulted in litigation.27 Presumably, the other 45% may have resulted in the plaintiff dropping the case, or in some form of settlement. Of the claims that were litigated, 54% were dismissed by the court, and another 35% were settled before a trial verdict. The cases that went to trial (about 10%), overwhelmingly (80%) resulted in verdicts for the defense.3,27 A different study found that only 9% of cases went to trial, and 87% were a defense verdict.28 The high level of defense verdicts may suggest that malpractice defense lawyers, and their client physicians, do a good job of assessing cases they are likely to lose, and settling them before trial.