User login

Inflammatory back pain likely underrecognized in primary care

according to a review of 239 charts there by rheumatologists and rheumatology fellows.

In more than two-thirds of cases, the reviewers were unable to determine if patients had inflammatory back pain or not based on what was documented. When symptoms relevant to inflammation – such as improvement with movement – were documented, it wasn’t clear if providers were actually trying to solicit a history of inflammation or if they simply recorded what patients volunteered.

Spondyloarthritis was listed in the differential of just five charts (2%), and only eight (3.3%) documented considering a rheumatology referral.

It raises the possibility that, in at least some cases, an opportunity to diagnose and treat spondyloarthritis early was missed. It’s a known problem in the literature; previous studies report a delay of 2-10 years before ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis.

“In our primary care practice, there appears to be poor awareness of inflammatory back pain [that] could lead to diagnostic delay,” said senior investigator and rheumatologist Steven Vlad, MD, PhD, an assistant professor at Tufts. Primary care providers are usually the first to see back pain patients, but they “did not seem to be screening for” inflammation, he said.

Dr. Vlad presented the study results at the virtual annual meeting of the Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network. The meeting was held online this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The findings suggest that a reminder to check for inflammation might be in order. Dr. Vlad and his colleagues have since held educational sessions, and plan to do more, with the idea of repeating the study in a year or 2 to see if the sessions made a difference.

“People take away what they learn as residents. We probably need to focus on resident education if we really want to make a dent in this,” he said.

The generalizability of the single-center results is unclear, and it’s possible at least in some cases that providers asked the right questions but did not document them in the chart. Even so, the issue “deserves future study in other populations,” Dr. Vlad said.

The subjects all had a diagnostic code for low back pain and were seen by Tuft’s primary care at least twice 3 or more months apart, which indicated chronic pain. Chart reviews included clinical notes, labs, imaging studies, and consultation reports. “We looked for specific documentation that primary care physicians had been asking questions related to inflammatory back pain,” Dr. Vlad explained.

Overall, 128 charts (53.6%) documented some feature of inflammatory low back pain. Insidious onset was the most common, but morning stiffness, a cardinal sign, was the least common, noted in only five charts (2%). About 30% of the subjects had a lumbar spine x-ray, which was the most common imaging study, followed by lumbar spine MRI. Only a handful had imaging of the sacroiliac joints.

In 111 charts (46.4%), there was no documentation that primary care providers had looked for inflammatory features or asked questions about them.

Patients were seen from Jan. 2016 to May 2018. The average age in the study was 37.6 years, and two-thirds of the subjects were women.

Funding source and disclosures weren’t reported.

according to a review of 239 charts there by rheumatologists and rheumatology fellows.

In more than two-thirds of cases, the reviewers were unable to determine if patients had inflammatory back pain or not based on what was documented. When symptoms relevant to inflammation – such as improvement with movement – were documented, it wasn’t clear if providers were actually trying to solicit a history of inflammation or if they simply recorded what patients volunteered.

Spondyloarthritis was listed in the differential of just five charts (2%), and only eight (3.3%) documented considering a rheumatology referral.

It raises the possibility that, in at least some cases, an opportunity to diagnose and treat spondyloarthritis early was missed. It’s a known problem in the literature; previous studies report a delay of 2-10 years before ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis.

“In our primary care practice, there appears to be poor awareness of inflammatory back pain [that] could lead to diagnostic delay,” said senior investigator and rheumatologist Steven Vlad, MD, PhD, an assistant professor at Tufts. Primary care providers are usually the first to see back pain patients, but they “did not seem to be screening for” inflammation, he said.

Dr. Vlad presented the study results at the virtual annual meeting of the Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network. The meeting was held online this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The findings suggest that a reminder to check for inflammation might be in order. Dr. Vlad and his colleagues have since held educational sessions, and plan to do more, with the idea of repeating the study in a year or 2 to see if the sessions made a difference.

“People take away what they learn as residents. We probably need to focus on resident education if we really want to make a dent in this,” he said.

The generalizability of the single-center results is unclear, and it’s possible at least in some cases that providers asked the right questions but did not document them in the chart. Even so, the issue “deserves future study in other populations,” Dr. Vlad said.

The subjects all had a diagnostic code for low back pain and were seen by Tuft’s primary care at least twice 3 or more months apart, which indicated chronic pain. Chart reviews included clinical notes, labs, imaging studies, and consultation reports. “We looked for specific documentation that primary care physicians had been asking questions related to inflammatory back pain,” Dr. Vlad explained.

Overall, 128 charts (53.6%) documented some feature of inflammatory low back pain. Insidious onset was the most common, but morning stiffness, a cardinal sign, was the least common, noted in only five charts (2%). About 30% of the subjects had a lumbar spine x-ray, which was the most common imaging study, followed by lumbar spine MRI. Only a handful had imaging of the sacroiliac joints.

In 111 charts (46.4%), there was no documentation that primary care providers had looked for inflammatory features or asked questions about them.

Patients were seen from Jan. 2016 to May 2018. The average age in the study was 37.6 years, and two-thirds of the subjects were women.

Funding source and disclosures weren’t reported.

according to a review of 239 charts there by rheumatologists and rheumatology fellows.

In more than two-thirds of cases, the reviewers were unable to determine if patients had inflammatory back pain or not based on what was documented. When symptoms relevant to inflammation – such as improvement with movement – were documented, it wasn’t clear if providers were actually trying to solicit a history of inflammation or if they simply recorded what patients volunteered.

Spondyloarthritis was listed in the differential of just five charts (2%), and only eight (3.3%) documented considering a rheumatology referral.

It raises the possibility that, in at least some cases, an opportunity to diagnose and treat spondyloarthritis early was missed. It’s a known problem in the literature; previous studies report a delay of 2-10 years before ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis.

“In our primary care practice, there appears to be poor awareness of inflammatory back pain [that] could lead to diagnostic delay,” said senior investigator and rheumatologist Steven Vlad, MD, PhD, an assistant professor at Tufts. Primary care providers are usually the first to see back pain patients, but they “did not seem to be screening for” inflammation, he said.

Dr. Vlad presented the study results at the virtual annual meeting of the Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network. The meeting was held online this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The findings suggest that a reminder to check for inflammation might be in order. Dr. Vlad and his colleagues have since held educational sessions, and plan to do more, with the idea of repeating the study in a year or 2 to see if the sessions made a difference.

“People take away what they learn as residents. We probably need to focus on resident education if we really want to make a dent in this,” he said.

The generalizability of the single-center results is unclear, and it’s possible at least in some cases that providers asked the right questions but did not document them in the chart. Even so, the issue “deserves future study in other populations,” Dr. Vlad said.

The subjects all had a diagnostic code for low back pain and were seen by Tuft’s primary care at least twice 3 or more months apart, which indicated chronic pain. Chart reviews included clinical notes, labs, imaging studies, and consultation reports. “We looked for specific documentation that primary care physicians had been asking questions related to inflammatory back pain,” Dr. Vlad explained.

Overall, 128 charts (53.6%) documented some feature of inflammatory low back pain. Insidious onset was the most common, but morning stiffness, a cardinal sign, was the least common, noted in only five charts (2%). About 30% of the subjects had a lumbar spine x-ray, which was the most common imaging study, followed by lumbar spine MRI. Only a handful had imaging of the sacroiliac joints.

In 111 charts (46.4%), there was no documentation that primary care providers had looked for inflammatory features or asked questions about them.

Patients were seen from Jan. 2016 to May 2018. The average age in the study was 37.6 years, and two-thirds of the subjects were women.

Funding source and disclosures weren’t reported.

REPORTING FROM SPARTAN 2020

COVID-19 exacerbating challenges for Latino patients

Disproportionate burden of pandemic complicates mental health care

Pamela Montano, MD, recalls the recent case of a patient with bipolar II disorder who was improving after treatment with medication and therapy when her life was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The patient, who is Puerto Rican, lost two cousins to the virus, two of her brothers fell ill, and her sister became sick with coronavirus, said Dr. Montano, director of the Latino Bicultural Clinic at Gouverneur Health in New York. The patient was then left to care for her sister’s toddlers along with the patient’s own children, one of whom has special needs.

“After this happened, it increased her anxiety,” Dr. Montano said in an interview. “She’s not sleeping, and she started having panic attacks. My main concern was how to help her cope.”

Across the country, clinicians who treat mental illness and behavioral disorders in Latino patients are facing similar experiences and challenges associated with COVID-19 and the ensuing pandemic response. Current data suggest a disproportionate burden of illness and death from the novel coronavirus among racial and ethnic groups, particularly black and Hispanic patients. The disparities are likely attributable to economic and social conditions more common among such populations, compared with non-Hispanic whites, in addition to isolation from resources, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A recent New York City Department of Health study based on data that were available in late April found that deaths from COVID-19 were substantially higher for black and Hispanic/Latino patients than for white and Asian patients. The death rate per 100,000 population was 209.4 for blacks, 195.3 for Hispanics/Latinos, 107.7 for whites, and 90.8 for Asians.

“The COVID pandemic has highlighted the structural inequities that affect the Latino population [both] immigrant and nonimmigrant,” said Dr. Montano, a board member of the American Society of Hispanic Psychiatry and the officer of infrastructure and advocacy for the Hispanic Caucus of the American Psychiatric Association. “This includes income inequality, poor nutrition, history of trauma and discrimination, employment issues, quality education, access to technology, and overall access to appropriate cultural linguistic health care.”

Navigating challenges

For mental health professionals treating Latino patients, COVID-19 and the pandemic response have generated a range of treatment obstacles.

The transition to telehealth for example, has not been easy for some patients, said Jacqueline Posada, MD, consultation-liaison psychiatry fellow at the Inova Fairfax Hospital–George Washington University program in Falls Church, Va., and an APA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration minority fellow. Some patients lack Internet services, others forget virtual visits, and some do not have working phones, she said.

“I’ve had to be very flexible,” she said in an interview. “Ideally, I’d love to see everybody via video chat, but a lot of people either don’t have a stable Internet connection or Internet, so I meet the patient where they are. Whatever they have available, that’s what I’m going to use. If they don’t answer on the first call, I will call again at least three to five times in the first 15 minutes to make sure I’m giving them an opportunity to pick up the phone.”

In addition, Dr. Posada has encountered disconnected phones when calling patients for appointments. In such cases, Dr. Posada contacts the patient’s primary care physician to relay medication recommendations in case the patient resurfaces at the clinic.

In other instances, patients are not familiar with video technology, or they must travel to a friend or neighbor’s house to access the technology, said Hector Colón-Rivera, MD, an addiction psychiatrist and medical director of the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha Behavioral Health Program, a nonprofit organization based in the Philadelphia area. Telehealth visits frequently include appearances by children, family members, barking dogs, and other distractions, said Dr. Colón-Rivera, president of the APA Hispanic Caucus.

“We’re seeing things that we didn’t used to see when they came to our office – for good or for bad,” said Dr. Colón-Rivera, an attending telemedicine physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “It could be a good chance to meet our patient in a different way. Of course, it creates different stressors. If you have five kids on top of you and you’re the only one at home, it’s hard to do therapy.”

Psychiatrists are also seeing prior health conditions in patients exacerbated by COVID-19 fears and new health problems arising from the current pandemic environment. Dr. Posada recalls a patient whom she successfully treated for premenstrual dysphoric disorder who recently descended into severe clinical depression. The patient, from Colombia, was attending school in the United States on a student visa and supporting herself through child care jobs.

“So much of her depression was based on her social circumstance,” Dr. Posada said. “She had lost her job, her sister had lost her job so they were scraping by on her sister’s husband’s income, and the thing that brought her joy, which was going to school and studying so she could make a different life for herself than what her parents had in Colombia, also seemed like it was out of reach.”

Dr. Colón-Rivera recently received a call from a hospital where one of his patients was admitted after becoming delusional and psychotic. The patient was correctly taking medication prescribed by Dr. Colón-Rivera, but her diabetes had become uncontrolled because she was unable to reach her primary care doctor and couldn’t access the pharmacy. Her blood sugar level became elevated, leading to the delusions.

“A patient that was perfectly stable now is unstable,” he said. “Her diet has not been good enough through the pandemic, exacerbating her diabetes. She was admitted to the hospital for delirium.

Compounding of traumas

For many Latino patients, the adverse impacts of the pandemic comes on top of multiple prior traumas, such as violence exposures, discrimination, and economic issues, said Lisa Fortuna, MD, MPH, MDiv, chief of psychiatry and vice chair at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. A 2017 analysis found that nearly four in five Latino youth face at least one traumatic childhood experience, like poverty or abuse, and that about 29% of Latino youth experience four or more of these traumas.

Immigrants in particular, may have faced trauma in their home country and/or immigration trauma, Dr. Fortuna added. A 2013 study on immigrant Latino adolescents for example, found that 29% of foreign-born adolescents and 34% of foreign-born parents experienced trauma during the migration process (Int Migr Rev. 2013 Dec;47(4):10).

“All of these things are cumulative,” Dr. Fortuna said. “Then when you’re hit with a pandemic, all of the disparities that you already have and all the stress that you already have are compounded. This is for the kids, too, who have been exposed to a lot of stressors and now maybe have family members that have been ill or have died. All of these things definitely put people at risk for increased depression [and] the worsening of any preexisting posttraumatic stress disorder. We’ve seen this in previous disasters, and I expect that’s what we’re going to see more of with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

At the same time, a central cultural value of many Latinos is family unity, Dr. Montano said, a foundation that is now being strained by social distancing and severed connections.

“This has separated many families,” she said. “There has been a lot of loneliness and grief.”

Mistrust and fear toward the government, public agencies, and even the health system itself act as further hurdles for some Latinos in the face of COVID-19. In areas with large immigrant populations such as San Francisco, Dr. Fortuna noted, it’s not uncommon for undocumented patients to avoid accessing medical care and social services, or visiting emergency departments for needed care for fear of drawing attention to themselves or possible detainment.

“The fact that so many people showed up at our hospital so ill and ended up in the ICU – that could be a combination of factors. Because the population has high rates of diabetes and hypertension, that might have put people at increased risk for severe illness,” she said. “But some people may have been holding out for care because they wanted to avoid being in places out of fear of immigration scrutiny.”

Overcoming language barriers

Compounding the challenging pandemic landscape for Latino patients is the fact that many state resources about COVID-19 have not been translated to Spanish, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. He was troubled recently when he went to several state websites and found limited to no information in Spanish about the coronavirus. Some data about COVID-19 from the federal government were not translated to Spanish until officials received pushback, he added. Even now, press releases and other information disseminated by the federal government about the virus appear to be translated by an automated service – and lack sense and context.

The state agencies in Pennsylvania have been alerted to the absence of Spanish information, but change has been slow, he noted.

“In Philadelphia, 23% speaks a language other than English,” he said. “So we missed a lot of critical information that could have helped to avoid spreading the illness and access support.”

Dr. Fortuna said that California has done better with providing COVID-19–related information in Spanish, compared with some other states, but misinformation about the virus and lingering myths have still been a problem among the Latino community. The University of California, San Francisco, recently launched a Latino Task Force resource website for the Latino community that includes information in English, Spanish, and Yucatec Maya about COVID-19, health and wellness tips, and resources for various assistance needs.

The concerning lack of COVID-19 information translated to Spanish led Dr. Montano to start a Facebook page in Spanish about mental health tips and guidance for managing COVID-19–related issues. She and her team of clinicians share information, videos, relaxation exercises, and community resources on the page, among other posts. “There is also general info and recommendations about COVID-19 that I think can be useful for the community,” she said. “The idea is that patients, the general community, and providers can have share information, hope messages, and ask questions in Spanish.”

Feeling ‘helpless’

A central part of caring for Latino patients during the COVID-19 crisis has been referring them to outside agencies and social services, psychiatrists say. But finding the right resources amid a pandemic and ensuring that patients connect with the correct aid has been an uphill battle.

“We sometimes feel like our hands are tied,” Dr. Colón-Rivera said. “Sometimes, we need to call a place to bring food. Some of the state agencies and nonprofits don’t have delivery systems, so the patient has to go pick up for food or medication. Some of our patients don’t want to go outside. Some do not have cars.”

As a clinician, it can be easy to feel helpless when trying to navigate new challenges posed by the pandemic in addition to other longstanding barriers, Dr. Posada said.

“Already, mental health disorders are so influenced by social situations like poverty, job insecurity, or family issues, and now it just seems those obstacles are even more insurmountable,” she said. “At the end of the day, I can feel like: ‘Did I make a difference?’ That’s a big struggle.”

Dr. Montano’s team, which includes psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, have come to rely on virtual debriefings to vent, express frustrations, and support one another, she said. She also recently joined a virtual mind-body skills group as a participant.

“I recognize the importance of getting additional support and ways to alleviate burnout,” she said. “We need to take care of ourselves or we won’t be able to help others.”

Focusing on resilience during the current crisis can be beneficial for both patients and providers in coping and drawing strength, Dr. Posada said.

“When it comes to fostering resilience during times of hardship, I think it’s most helpful to reflect on what skills or attributes have helped during past crises and apply those now – whether it’s turning to comfort from close relationships, looking to religion and spirituality, practicing self-care like rest or exercise, or really tapping into one’s purpose and reason for practicing psychiatry and being a physician,” she said. “The same advice goes for clinicians: We’ve all been through hard times in the past, it’s part of the human condition and we’ve also witnessed a lot of suffering in our patients, so now is the time to practice those skills that have gotten us through hard times in the past.”

Learning lessons from COVID-19

Despite the challenges with moving to telehealth, Dr. Fortuna said the tool has proved beneficial overall for mental health care. For Dr. Fortuna’s team for example, telehealth by phone has decreased the no-show rate, compared with clinic visits, and improved care access.

“We need to figure out how to maintain that,” she said. “If we can build ways for equity and access to Internet, especially equipment, I think that’s going to help.”

In addition, more data are needed about the ways in which COVID-19 is affecting Latino patients, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. Mortality statistics have been published, but information is needed about the rates of infection and manifestation of illness.

Most importantly, the COVID-19 crisis has emphasized the critical need to address and improve the underlying inequity issues among Latino patients, psychiatrists say.

“We really need to think about how there can be partnerships, in terms of community-based Latino business and leaders, multisector resources, trying to think about how we can improve conditions both work and safety for Latinos,” Dr. Fortuna said. “How can schools get support in integrating mental health and support for families, especially now after COVID-19? And really looking at some of these underlying inequities that are the underpinnings of why people were at risk for the disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Disproportionate burden of pandemic complicates mental health care

Disproportionate burden of pandemic complicates mental health care

Pamela Montano, MD, recalls the recent case of a patient with bipolar II disorder who was improving after treatment with medication and therapy when her life was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The patient, who is Puerto Rican, lost two cousins to the virus, two of her brothers fell ill, and her sister became sick with coronavirus, said Dr. Montano, director of the Latino Bicultural Clinic at Gouverneur Health in New York. The patient was then left to care for her sister’s toddlers along with the patient’s own children, one of whom has special needs.

“After this happened, it increased her anxiety,” Dr. Montano said in an interview. “She’s not sleeping, and she started having panic attacks. My main concern was how to help her cope.”

Across the country, clinicians who treat mental illness and behavioral disorders in Latino patients are facing similar experiences and challenges associated with COVID-19 and the ensuing pandemic response. Current data suggest a disproportionate burden of illness and death from the novel coronavirus among racial and ethnic groups, particularly black and Hispanic patients. The disparities are likely attributable to economic and social conditions more common among such populations, compared with non-Hispanic whites, in addition to isolation from resources, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A recent New York City Department of Health study based on data that were available in late April found that deaths from COVID-19 were substantially higher for black and Hispanic/Latino patients than for white and Asian patients. The death rate per 100,000 population was 209.4 for blacks, 195.3 for Hispanics/Latinos, 107.7 for whites, and 90.8 for Asians.

“The COVID pandemic has highlighted the structural inequities that affect the Latino population [both] immigrant and nonimmigrant,” said Dr. Montano, a board member of the American Society of Hispanic Psychiatry and the officer of infrastructure and advocacy for the Hispanic Caucus of the American Psychiatric Association. “This includes income inequality, poor nutrition, history of trauma and discrimination, employment issues, quality education, access to technology, and overall access to appropriate cultural linguistic health care.”

Navigating challenges

For mental health professionals treating Latino patients, COVID-19 and the pandemic response have generated a range of treatment obstacles.

The transition to telehealth for example, has not been easy for some patients, said Jacqueline Posada, MD, consultation-liaison psychiatry fellow at the Inova Fairfax Hospital–George Washington University program in Falls Church, Va., and an APA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration minority fellow. Some patients lack Internet services, others forget virtual visits, and some do not have working phones, she said.

“I’ve had to be very flexible,” she said in an interview. “Ideally, I’d love to see everybody via video chat, but a lot of people either don’t have a stable Internet connection or Internet, so I meet the patient where they are. Whatever they have available, that’s what I’m going to use. If they don’t answer on the first call, I will call again at least three to five times in the first 15 minutes to make sure I’m giving them an opportunity to pick up the phone.”

In addition, Dr. Posada has encountered disconnected phones when calling patients for appointments. In such cases, Dr. Posada contacts the patient’s primary care physician to relay medication recommendations in case the patient resurfaces at the clinic.

In other instances, patients are not familiar with video technology, or they must travel to a friend or neighbor’s house to access the technology, said Hector Colón-Rivera, MD, an addiction psychiatrist and medical director of the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha Behavioral Health Program, a nonprofit organization based in the Philadelphia area. Telehealth visits frequently include appearances by children, family members, barking dogs, and other distractions, said Dr. Colón-Rivera, president of the APA Hispanic Caucus.

“We’re seeing things that we didn’t used to see when they came to our office – for good or for bad,” said Dr. Colón-Rivera, an attending telemedicine physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “It could be a good chance to meet our patient in a different way. Of course, it creates different stressors. If you have five kids on top of you and you’re the only one at home, it’s hard to do therapy.”

Psychiatrists are also seeing prior health conditions in patients exacerbated by COVID-19 fears and new health problems arising from the current pandemic environment. Dr. Posada recalls a patient whom she successfully treated for premenstrual dysphoric disorder who recently descended into severe clinical depression. The patient, from Colombia, was attending school in the United States on a student visa and supporting herself through child care jobs.

“So much of her depression was based on her social circumstance,” Dr. Posada said. “She had lost her job, her sister had lost her job so they were scraping by on her sister’s husband’s income, and the thing that brought her joy, which was going to school and studying so she could make a different life for herself than what her parents had in Colombia, also seemed like it was out of reach.”

Dr. Colón-Rivera recently received a call from a hospital where one of his patients was admitted after becoming delusional and psychotic. The patient was correctly taking medication prescribed by Dr. Colón-Rivera, but her diabetes had become uncontrolled because she was unable to reach her primary care doctor and couldn’t access the pharmacy. Her blood sugar level became elevated, leading to the delusions.

“A patient that was perfectly stable now is unstable,” he said. “Her diet has not been good enough through the pandemic, exacerbating her diabetes. She was admitted to the hospital for delirium.

Compounding of traumas

For many Latino patients, the adverse impacts of the pandemic comes on top of multiple prior traumas, such as violence exposures, discrimination, and economic issues, said Lisa Fortuna, MD, MPH, MDiv, chief of psychiatry and vice chair at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. A 2017 analysis found that nearly four in five Latino youth face at least one traumatic childhood experience, like poverty or abuse, and that about 29% of Latino youth experience four or more of these traumas.

Immigrants in particular, may have faced trauma in their home country and/or immigration trauma, Dr. Fortuna added. A 2013 study on immigrant Latino adolescents for example, found that 29% of foreign-born adolescents and 34% of foreign-born parents experienced trauma during the migration process (Int Migr Rev. 2013 Dec;47(4):10).

“All of these things are cumulative,” Dr. Fortuna said. “Then when you’re hit with a pandemic, all of the disparities that you already have and all the stress that you already have are compounded. This is for the kids, too, who have been exposed to a lot of stressors and now maybe have family members that have been ill or have died. All of these things definitely put people at risk for increased depression [and] the worsening of any preexisting posttraumatic stress disorder. We’ve seen this in previous disasters, and I expect that’s what we’re going to see more of with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

At the same time, a central cultural value of many Latinos is family unity, Dr. Montano said, a foundation that is now being strained by social distancing and severed connections.

“This has separated many families,” she said. “There has been a lot of loneliness and grief.”

Mistrust and fear toward the government, public agencies, and even the health system itself act as further hurdles for some Latinos in the face of COVID-19. In areas with large immigrant populations such as San Francisco, Dr. Fortuna noted, it’s not uncommon for undocumented patients to avoid accessing medical care and social services, or visiting emergency departments for needed care for fear of drawing attention to themselves or possible detainment.

“The fact that so many people showed up at our hospital so ill and ended up in the ICU – that could be a combination of factors. Because the population has high rates of diabetes and hypertension, that might have put people at increased risk for severe illness,” she said. “But some people may have been holding out for care because they wanted to avoid being in places out of fear of immigration scrutiny.”

Overcoming language barriers

Compounding the challenging pandemic landscape for Latino patients is the fact that many state resources about COVID-19 have not been translated to Spanish, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. He was troubled recently when he went to several state websites and found limited to no information in Spanish about the coronavirus. Some data about COVID-19 from the federal government were not translated to Spanish until officials received pushback, he added. Even now, press releases and other information disseminated by the federal government about the virus appear to be translated by an automated service – and lack sense and context.

The state agencies in Pennsylvania have been alerted to the absence of Spanish information, but change has been slow, he noted.

“In Philadelphia, 23% speaks a language other than English,” he said. “So we missed a lot of critical information that could have helped to avoid spreading the illness and access support.”

Dr. Fortuna said that California has done better with providing COVID-19–related information in Spanish, compared with some other states, but misinformation about the virus and lingering myths have still been a problem among the Latino community. The University of California, San Francisco, recently launched a Latino Task Force resource website for the Latino community that includes information in English, Spanish, and Yucatec Maya about COVID-19, health and wellness tips, and resources for various assistance needs.

The concerning lack of COVID-19 information translated to Spanish led Dr. Montano to start a Facebook page in Spanish about mental health tips and guidance for managing COVID-19–related issues. She and her team of clinicians share information, videos, relaxation exercises, and community resources on the page, among other posts. “There is also general info and recommendations about COVID-19 that I think can be useful for the community,” she said. “The idea is that patients, the general community, and providers can have share information, hope messages, and ask questions in Spanish.”

Feeling ‘helpless’

A central part of caring for Latino patients during the COVID-19 crisis has been referring them to outside agencies and social services, psychiatrists say. But finding the right resources amid a pandemic and ensuring that patients connect with the correct aid has been an uphill battle.

“We sometimes feel like our hands are tied,” Dr. Colón-Rivera said. “Sometimes, we need to call a place to bring food. Some of the state agencies and nonprofits don’t have delivery systems, so the patient has to go pick up for food or medication. Some of our patients don’t want to go outside. Some do not have cars.”

As a clinician, it can be easy to feel helpless when trying to navigate new challenges posed by the pandemic in addition to other longstanding barriers, Dr. Posada said.

“Already, mental health disorders are so influenced by social situations like poverty, job insecurity, or family issues, and now it just seems those obstacles are even more insurmountable,” she said. “At the end of the day, I can feel like: ‘Did I make a difference?’ That’s a big struggle.”

Dr. Montano’s team, which includes psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, have come to rely on virtual debriefings to vent, express frustrations, and support one another, she said. She also recently joined a virtual mind-body skills group as a participant.

“I recognize the importance of getting additional support and ways to alleviate burnout,” she said. “We need to take care of ourselves or we won’t be able to help others.”

Focusing on resilience during the current crisis can be beneficial for both patients and providers in coping and drawing strength, Dr. Posada said.

“When it comes to fostering resilience during times of hardship, I think it’s most helpful to reflect on what skills or attributes have helped during past crises and apply those now – whether it’s turning to comfort from close relationships, looking to religion and spirituality, practicing self-care like rest or exercise, or really tapping into one’s purpose and reason for practicing psychiatry and being a physician,” she said. “The same advice goes for clinicians: We’ve all been through hard times in the past, it’s part of the human condition and we’ve also witnessed a lot of suffering in our patients, so now is the time to practice those skills that have gotten us through hard times in the past.”

Learning lessons from COVID-19

Despite the challenges with moving to telehealth, Dr. Fortuna said the tool has proved beneficial overall for mental health care. For Dr. Fortuna’s team for example, telehealth by phone has decreased the no-show rate, compared with clinic visits, and improved care access.

“We need to figure out how to maintain that,” she said. “If we can build ways for equity and access to Internet, especially equipment, I think that’s going to help.”

In addition, more data are needed about the ways in which COVID-19 is affecting Latino patients, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. Mortality statistics have been published, but information is needed about the rates of infection and manifestation of illness.

Most importantly, the COVID-19 crisis has emphasized the critical need to address and improve the underlying inequity issues among Latino patients, psychiatrists say.

“We really need to think about how there can be partnerships, in terms of community-based Latino business and leaders, multisector resources, trying to think about how we can improve conditions both work and safety for Latinos,” Dr. Fortuna said. “How can schools get support in integrating mental health and support for families, especially now after COVID-19? And really looking at some of these underlying inequities that are the underpinnings of why people were at risk for the disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Pamela Montano, MD, recalls the recent case of a patient with bipolar II disorder who was improving after treatment with medication and therapy when her life was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The patient, who is Puerto Rican, lost two cousins to the virus, two of her brothers fell ill, and her sister became sick with coronavirus, said Dr. Montano, director of the Latino Bicultural Clinic at Gouverneur Health in New York. The patient was then left to care for her sister’s toddlers along with the patient’s own children, one of whom has special needs.

“After this happened, it increased her anxiety,” Dr. Montano said in an interview. “She’s not sleeping, and she started having panic attacks. My main concern was how to help her cope.”

Across the country, clinicians who treat mental illness and behavioral disorders in Latino patients are facing similar experiences and challenges associated with COVID-19 and the ensuing pandemic response. Current data suggest a disproportionate burden of illness and death from the novel coronavirus among racial and ethnic groups, particularly black and Hispanic patients. The disparities are likely attributable to economic and social conditions more common among such populations, compared with non-Hispanic whites, in addition to isolation from resources, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A recent New York City Department of Health study based on data that were available in late April found that deaths from COVID-19 were substantially higher for black and Hispanic/Latino patients than for white and Asian patients. The death rate per 100,000 population was 209.4 for blacks, 195.3 for Hispanics/Latinos, 107.7 for whites, and 90.8 for Asians.

“The COVID pandemic has highlighted the structural inequities that affect the Latino population [both] immigrant and nonimmigrant,” said Dr. Montano, a board member of the American Society of Hispanic Psychiatry and the officer of infrastructure and advocacy for the Hispanic Caucus of the American Psychiatric Association. “This includes income inequality, poor nutrition, history of trauma and discrimination, employment issues, quality education, access to technology, and overall access to appropriate cultural linguistic health care.”

Navigating challenges

For mental health professionals treating Latino patients, COVID-19 and the pandemic response have generated a range of treatment obstacles.

The transition to telehealth for example, has not been easy for some patients, said Jacqueline Posada, MD, consultation-liaison psychiatry fellow at the Inova Fairfax Hospital–George Washington University program in Falls Church, Va., and an APA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration minority fellow. Some patients lack Internet services, others forget virtual visits, and some do not have working phones, she said.

“I’ve had to be very flexible,” she said in an interview. “Ideally, I’d love to see everybody via video chat, but a lot of people either don’t have a stable Internet connection or Internet, so I meet the patient where they are. Whatever they have available, that’s what I’m going to use. If they don’t answer on the first call, I will call again at least three to five times in the first 15 minutes to make sure I’m giving them an opportunity to pick up the phone.”

In addition, Dr. Posada has encountered disconnected phones when calling patients for appointments. In such cases, Dr. Posada contacts the patient’s primary care physician to relay medication recommendations in case the patient resurfaces at the clinic.

In other instances, patients are not familiar with video technology, or they must travel to a friend or neighbor’s house to access the technology, said Hector Colón-Rivera, MD, an addiction psychiatrist and medical director of the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha Behavioral Health Program, a nonprofit organization based in the Philadelphia area. Telehealth visits frequently include appearances by children, family members, barking dogs, and other distractions, said Dr. Colón-Rivera, president of the APA Hispanic Caucus.

“We’re seeing things that we didn’t used to see when they came to our office – for good or for bad,” said Dr. Colón-Rivera, an attending telemedicine physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “It could be a good chance to meet our patient in a different way. Of course, it creates different stressors. If you have five kids on top of you and you’re the only one at home, it’s hard to do therapy.”

Psychiatrists are also seeing prior health conditions in patients exacerbated by COVID-19 fears and new health problems arising from the current pandemic environment. Dr. Posada recalls a patient whom she successfully treated for premenstrual dysphoric disorder who recently descended into severe clinical depression. The patient, from Colombia, was attending school in the United States on a student visa and supporting herself through child care jobs.

“So much of her depression was based on her social circumstance,” Dr. Posada said. “She had lost her job, her sister had lost her job so they were scraping by on her sister’s husband’s income, and the thing that brought her joy, which was going to school and studying so she could make a different life for herself than what her parents had in Colombia, also seemed like it was out of reach.”

Dr. Colón-Rivera recently received a call from a hospital where one of his patients was admitted after becoming delusional and psychotic. The patient was correctly taking medication prescribed by Dr. Colón-Rivera, but her diabetes had become uncontrolled because she was unable to reach her primary care doctor and couldn’t access the pharmacy. Her blood sugar level became elevated, leading to the delusions.

“A patient that was perfectly stable now is unstable,” he said. “Her diet has not been good enough through the pandemic, exacerbating her diabetes. She was admitted to the hospital for delirium.

Compounding of traumas

For many Latino patients, the adverse impacts of the pandemic comes on top of multiple prior traumas, such as violence exposures, discrimination, and economic issues, said Lisa Fortuna, MD, MPH, MDiv, chief of psychiatry and vice chair at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. A 2017 analysis found that nearly four in five Latino youth face at least one traumatic childhood experience, like poverty or abuse, and that about 29% of Latino youth experience four or more of these traumas.

Immigrants in particular, may have faced trauma in their home country and/or immigration trauma, Dr. Fortuna added. A 2013 study on immigrant Latino adolescents for example, found that 29% of foreign-born adolescents and 34% of foreign-born parents experienced trauma during the migration process (Int Migr Rev. 2013 Dec;47(4):10).

“All of these things are cumulative,” Dr. Fortuna said. “Then when you’re hit with a pandemic, all of the disparities that you already have and all the stress that you already have are compounded. This is for the kids, too, who have been exposed to a lot of stressors and now maybe have family members that have been ill or have died. All of these things definitely put people at risk for increased depression [and] the worsening of any preexisting posttraumatic stress disorder. We’ve seen this in previous disasters, and I expect that’s what we’re going to see more of with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

At the same time, a central cultural value of many Latinos is family unity, Dr. Montano said, a foundation that is now being strained by social distancing and severed connections.

“This has separated many families,” she said. “There has been a lot of loneliness and grief.”

Mistrust and fear toward the government, public agencies, and even the health system itself act as further hurdles for some Latinos in the face of COVID-19. In areas with large immigrant populations such as San Francisco, Dr. Fortuna noted, it’s not uncommon for undocumented patients to avoid accessing medical care and social services, or visiting emergency departments for needed care for fear of drawing attention to themselves or possible detainment.

“The fact that so many people showed up at our hospital so ill and ended up in the ICU – that could be a combination of factors. Because the population has high rates of diabetes and hypertension, that might have put people at increased risk for severe illness,” she said. “But some people may have been holding out for care because they wanted to avoid being in places out of fear of immigration scrutiny.”

Overcoming language barriers

Compounding the challenging pandemic landscape for Latino patients is the fact that many state resources about COVID-19 have not been translated to Spanish, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. He was troubled recently when he went to several state websites and found limited to no information in Spanish about the coronavirus. Some data about COVID-19 from the federal government were not translated to Spanish until officials received pushback, he added. Even now, press releases and other information disseminated by the federal government about the virus appear to be translated by an automated service – and lack sense and context.

The state agencies in Pennsylvania have been alerted to the absence of Spanish information, but change has been slow, he noted.

“In Philadelphia, 23% speaks a language other than English,” he said. “So we missed a lot of critical information that could have helped to avoid spreading the illness and access support.”

Dr. Fortuna said that California has done better with providing COVID-19–related information in Spanish, compared with some other states, but misinformation about the virus and lingering myths have still been a problem among the Latino community. The University of California, San Francisco, recently launched a Latino Task Force resource website for the Latino community that includes information in English, Spanish, and Yucatec Maya about COVID-19, health and wellness tips, and resources for various assistance needs.

The concerning lack of COVID-19 information translated to Spanish led Dr. Montano to start a Facebook page in Spanish about mental health tips and guidance for managing COVID-19–related issues. She and her team of clinicians share information, videos, relaxation exercises, and community resources on the page, among other posts. “There is also general info and recommendations about COVID-19 that I think can be useful for the community,” she said. “The idea is that patients, the general community, and providers can have share information, hope messages, and ask questions in Spanish.”

Feeling ‘helpless’

A central part of caring for Latino patients during the COVID-19 crisis has been referring them to outside agencies and social services, psychiatrists say. But finding the right resources amid a pandemic and ensuring that patients connect with the correct aid has been an uphill battle.

“We sometimes feel like our hands are tied,” Dr. Colón-Rivera said. “Sometimes, we need to call a place to bring food. Some of the state agencies and nonprofits don’t have delivery systems, so the patient has to go pick up for food or medication. Some of our patients don’t want to go outside. Some do not have cars.”

As a clinician, it can be easy to feel helpless when trying to navigate new challenges posed by the pandemic in addition to other longstanding barriers, Dr. Posada said.

“Already, mental health disorders are so influenced by social situations like poverty, job insecurity, or family issues, and now it just seems those obstacles are even more insurmountable,” she said. “At the end of the day, I can feel like: ‘Did I make a difference?’ That’s a big struggle.”

Dr. Montano’s team, which includes psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, have come to rely on virtual debriefings to vent, express frustrations, and support one another, she said. She also recently joined a virtual mind-body skills group as a participant.

“I recognize the importance of getting additional support and ways to alleviate burnout,” she said. “We need to take care of ourselves or we won’t be able to help others.”

Focusing on resilience during the current crisis can be beneficial for both patients and providers in coping and drawing strength, Dr. Posada said.

“When it comes to fostering resilience during times of hardship, I think it’s most helpful to reflect on what skills or attributes have helped during past crises and apply those now – whether it’s turning to comfort from close relationships, looking to religion and spirituality, practicing self-care like rest or exercise, or really tapping into one’s purpose and reason for practicing psychiatry and being a physician,” she said. “The same advice goes for clinicians: We’ve all been through hard times in the past, it’s part of the human condition and we’ve also witnessed a lot of suffering in our patients, so now is the time to practice those skills that have gotten us through hard times in the past.”

Learning lessons from COVID-19

Despite the challenges with moving to telehealth, Dr. Fortuna said the tool has proved beneficial overall for mental health care. For Dr. Fortuna’s team for example, telehealth by phone has decreased the no-show rate, compared with clinic visits, and improved care access.

“We need to figure out how to maintain that,” she said. “If we can build ways for equity and access to Internet, especially equipment, I think that’s going to help.”

In addition, more data are needed about the ways in which COVID-19 is affecting Latino patients, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. Mortality statistics have been published, but information is needed about the rates of infection and manifestation of illness.

Most importantly, the COVID-19 crisis has emphasized the critical need to address and improve the underlying inequity issues among Latino patients, psychiatrists say.

“We really need to think about how there can be partnerships, in terms of community-based Latino business and leaders, multisector resources, trying to think about how we can improve conditions both work and safety for Latinos,” Dr. Fortuna said. “How can schools get support in integrating mental health and support for families, especially now after COVID-19? And really looking at some of these underlying inequities that are the underpinnings of why people were at risk for the disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Race and location appear to play a role in the incidence of CLL and DLBCL

Exposure to carcinogens has been implicated in the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), suggesting that an examination of the environment on a population-based level might provide some insights. On that basis, researchers performed a study that found that living in an urban vs. rural area was associated with an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) among diverse, urban populations.

The study, published online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia, found an increased incidence of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in urban vs. rural Hispanics, and a similar increased incidence of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in non-metropolitan urban non-Hispanic blacks.

A total of 482,096 adults aged 20 years and older with incident NHL were reported to 21 Surveillance, Epidemiology,and End Results (SEER) population-based registries for the period 2000 to 2016. Deanna Blansky of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, N.Y., and her colleagues compared patients by NHL subtype and urban-rural status, using rural-urban continuum codes from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The researchers found 136,197 DLBCL, 70,882 follicular lymphoma (FL), and 120,319 CLL cases of patients aged ≥ 20 years. The DLBCL patients comprised 73.6% non-Hispanic white, 11.8% Hispanic, and 7.3% non-Hispanic black, with a similar distribution observed for FL and CLL. Patients were adjusted for age, sex, and family poverty.

The study showed that, overall, there was a higher DLBCL incidence rate in metropolitan urban areas, compared with rural areas overall (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.11-1.30). Most pronounced was an increased DLBCL incidence among Hispanics in urban areas, compared with rural areas (rural IRR = 1.00; non-metropolitan urban IRR = 1.32, 95% CI 1.16-1.51; metropolitan urban = 1.55, 95% CI 1.36-1.76).

In contrast, metropolitan urban areas had a lower overall incidence of CLL than rural areas (8.4 vs. 9.7 per 100,000; IRR = .87; 95% CI .86-.89).

However, increased CLL incidence rates were found to be associated with non-metropolitan urban areas, compared with rural areas (IRR = 1.19; 95% CI 1.10-1.28), particularly among non-Hispanic Blacks (IRR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.27-1.72).

Unlike DLBCL and CLL, there were no differences observed in FL incidence rates by urban-rural status after adjusting for age, sex, and family poverty rates, the researchers reported.

“Overall, our findings suggest that factors related to urban status may be associated with DLBCL and CLL pathogenesis. Our results may help provide epidemiological clues to understanding the racial disparities seen among hematological malignancies, particularly regarding the risk of DLBCL in Hispanics and CLL in non-Hispanic Blacks,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The researchers did not report conflict information.

SOURCE: Blansky D et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 May 15; doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2020.05.010.

Exposure to carcinogens has been implicated in the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), suggesting that an examination of the environment on a population-based level might provide some insights. On that basis, researchers performed a study that found that living in an urban vs. rural area was associated with an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) among diverse, urban populations.

The study, published online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia, found an increased incidence of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in urban vs. rural Hispanics, and a similar increased incidence of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in non-metropolitan urban non-Hispanic blacks.

A total of 482,096 adults aged 20 years and older with incident NHL were reported to 21 Surveillance, Epidemiology,and End Results (SEER) population-based registries for the period 2000 to 2016. Deanna Blansky of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, N.Y., and her colleagues compared patients by NHL subtype and urban-rural status, using rural-urban continuum codes from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The researchers found 136,197 DLBCL, 70,882 follicular lymphoma (FL), and 120,319 CLL cases of patients aged ≥ 20 years. The DLBCL patients comprised 73.6% non-Hispanic white, 11.8% Hispanic, and 7.3% non-Hispanic black, with a similar distribution observed for FL and CLL. Patients were adjusted for age, sex, and family poverty.

The study showed that, overall, there was a higher DLBCL incidence rate in metropolitan urban areas, compared with rural areas overall (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.11-1.30). Most pronounced was an increased DLBCL incidence among Hispanics in urban areas, compared with rural areas (rural IRR = 1.00; non-metropolitan urban IRR = 1.32, 95% CI 1.16-1.51; metropolitan urban = 1.55, 95% CI 1.36-1.76).

In contrast, metropolitan urban areas had a lower overall incidence of CLL than rural areas (8.4 vs. 9.7 per 100,000; IRR = .87; 95% CI .86-.89).

However, increased CLL incidence rates were found to be associated with non-metropolitan urban areas, compared with rural areas (IRR = 1.19; 95% CI 1.10-1.28), particularly among non-Hispanic Blacks (IRR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.27-1.72).

Unlike DLBCL and CLL, there were no differences observed in FL incidence rates by urban-rural status after adjusting for age, sex, and family poverty rates, the researchers reported.

“Overall, our findings suggest that factors related to urban status may be associated with DLBCL and CLL pathogenesis. Our results may help provide epidemiological clues to understanding the racial disparities seen among hematological malignancies, particularly regarding the risk of DLBCL in Hispanics and CLL in non-Hispanic Blacks,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The researchers did not report conflict information.

SOURCE: Blansky D et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 May 15; doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2020.05.010.

Exposure to carcinogens has been implicated in the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), suggesting that an examination of the environment on a population-based level might provide some insights. On that basis, researchers performed a study that found that living in an urban vs. rural area was associated with an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) among diverse, urban populations.

The study, published online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia, found an increased incidence of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in urban vs. rural Hispanics, and a similar increased incidence of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in non-metropolitan urban non-Hispanic blacks.

A total of 482,096 adults aged 20 years and older with incident NHL were reported to 21 Surveillance, Epidemiology,and End Results (SEER) population-based registries for the period 2000 to 2016. Deanna Blansky of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, N.Y., and her colleagues compared patients by NHL subtype and urban-rural status, using rural-urban continuum codes from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The researchers found 136,197 DLBCL, 70,882 follicular lymphoma (FL), and 120,319 CLL cases of patients aged ≥ 20 years. The DLBCL patients comprised 73.6% non-Hispanic white, 11.8% Hispanic, and 7.3% non-Hispanic black, with a similar distribution observed for FL and CLL. Patients were adjusted for age, sex, and family poverty.

The study showed that, overall, there was a higher DLBCL incidence rate in metropolitan urban areas, compared with rural areas overall (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.11-1.30). Most pronounced was an increased DLBCL incidence among Hispanics in urban areas, compared with rural areas (rural IRR = 1.00; non-metropolitan urban IRR = 1.32, 95% CI 1.16-1.51; metropolitan urban = 1.55, 95% CI 1.36-1.76).

In contrast, metropolitan urban areas had a lower overall incidence of CLL than rural areas (8.4 vs. 9.7 per 100,000; IRR = .87; 95% CI .86-.89).

However, increased CLL incidence rates were found to be associated with non-metropolitan urban areas, compared with rural areas (IRR = 1.19; 95% CI 1.10-1.28), particularly among non-Hispanic Blacks (IRR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.27-1.72).

Unlike DLBCL and CLL, there were no differences observed in FL incidence rates by urban-rural status after adjusting for age, sex, and family poverty rates, the researchers reported.

“Overall, our findings suggest that factors related to urban status may be associated with DLBCL and CLL pathogenesis. Our results may help provide epidemiological clues to understanding the racial disparities seen among hematological malignancies, particularly regarding the risk of DLBCL in Hispanics and CLL in non-Hispanic Blacks,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The researchers did not report conflict information.

SOURCE: Blansky D et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 May 15; doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2020.05.010.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA & LEUKEMIA

Vulvar Syringoma

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

A 51-year-old woman presented to dermatology (G.G.) and was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of possible vulvar syringoma vs MAC. The patient previously had been evaluated at an outside community practice due to dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities of 1 month’s duration. At that time, a small biopsy was performed, and the histologic differential diagnosis included syringoma vs an adnexal carcinoma. Consequently, she was referred to gynecologic oncology for further management.

Pelvic examination revealed multilobular nodular areas overlying the clitoral hood that extended down to the labia majora. The nodular processes did not involve the clitoris, labia minora, or perineum. A mobile isolated lymph node measuring 2.0×1.0 cm in the right inguinal area also was noted. The patient’s clinical history was notable for right breast carcinoma treated with a right mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection that showed metastatic disease. She also underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin for breast carcinoma.

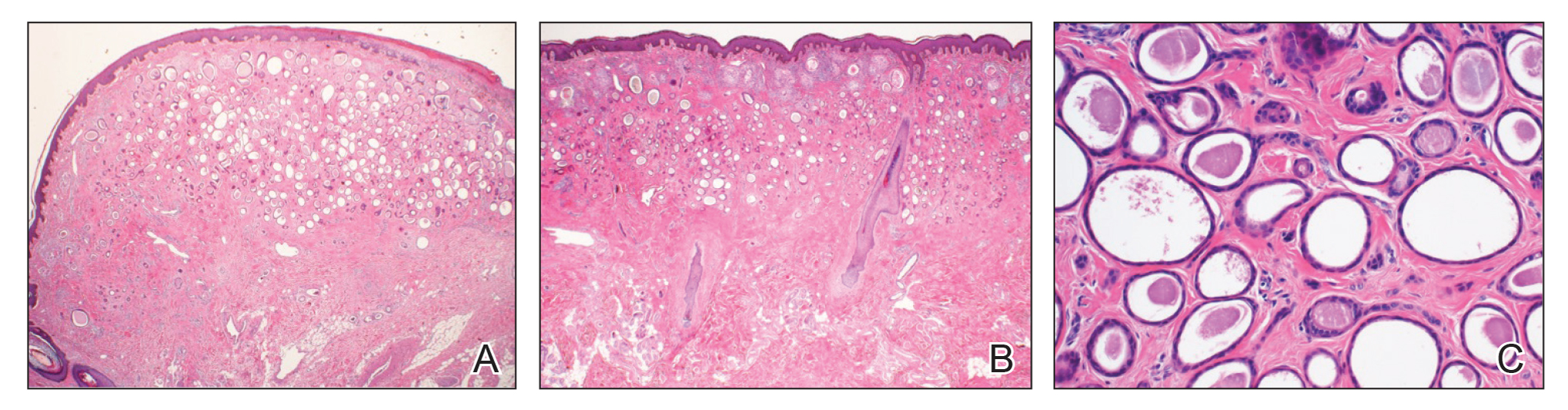

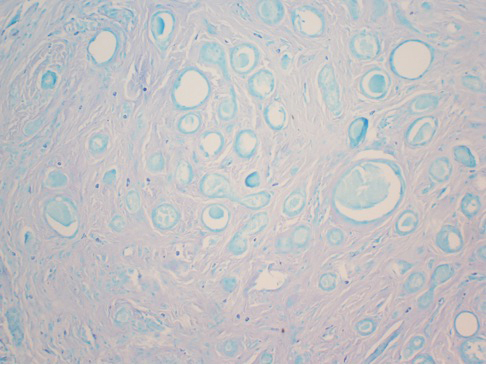

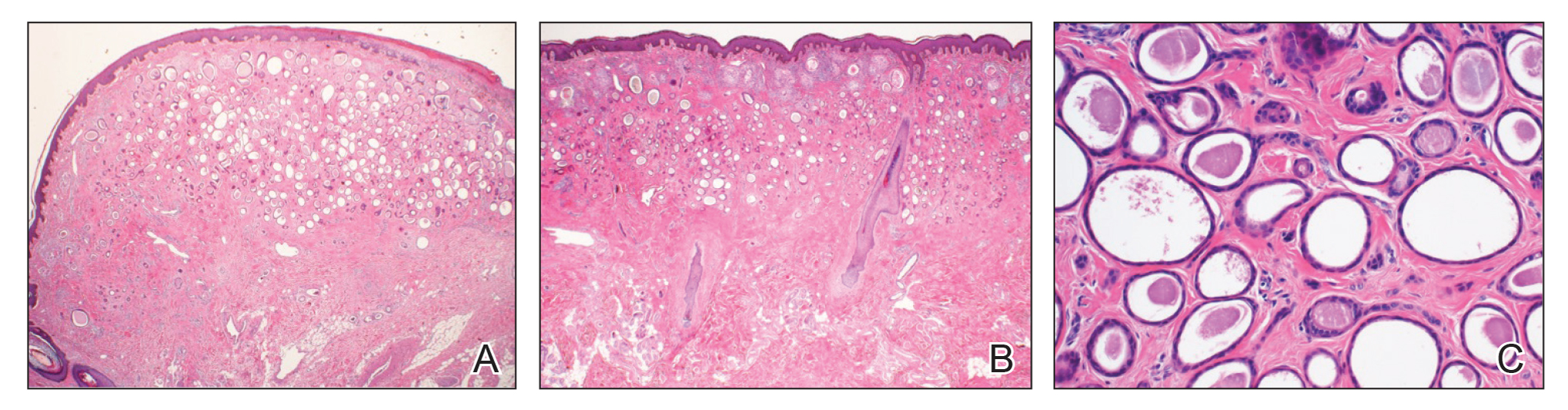

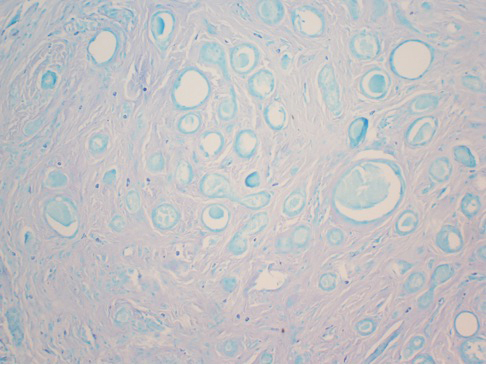

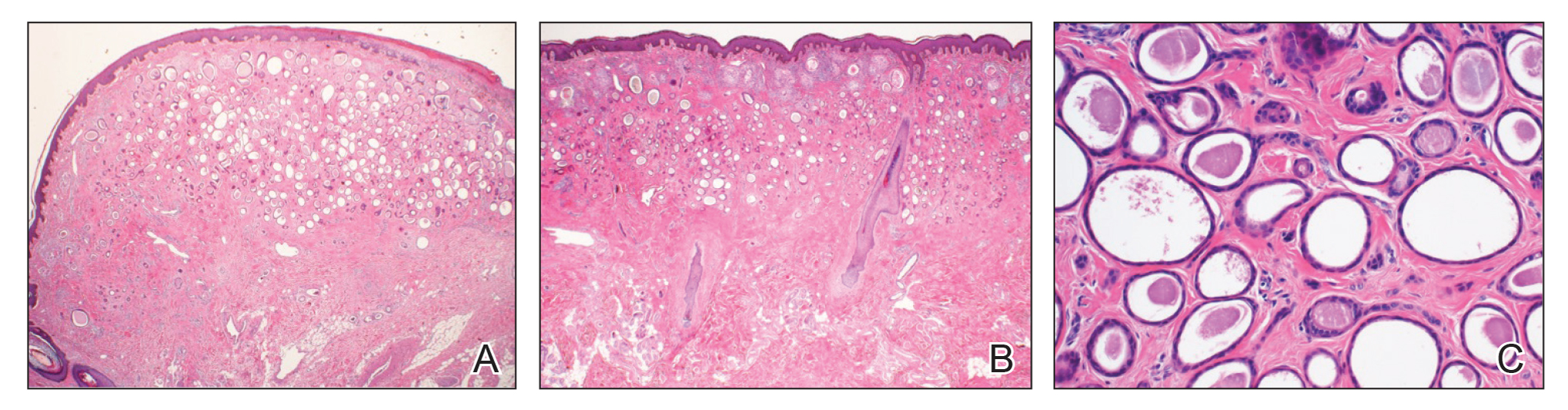

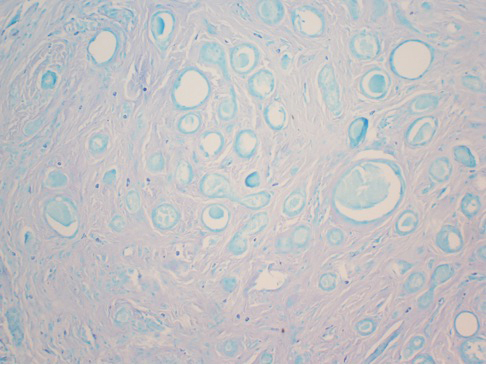

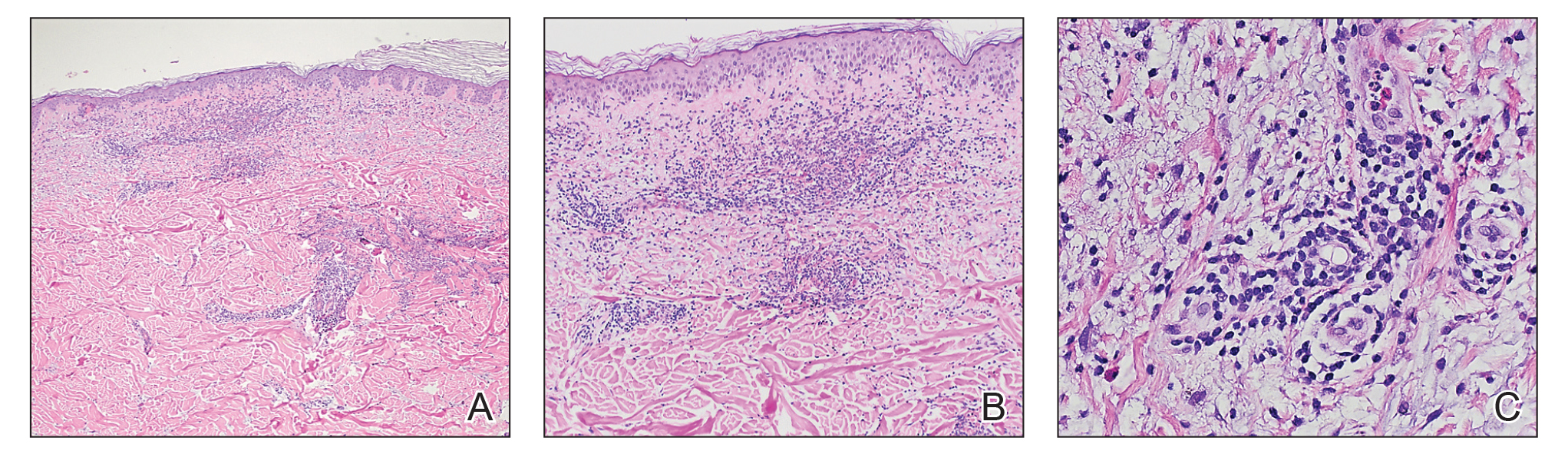

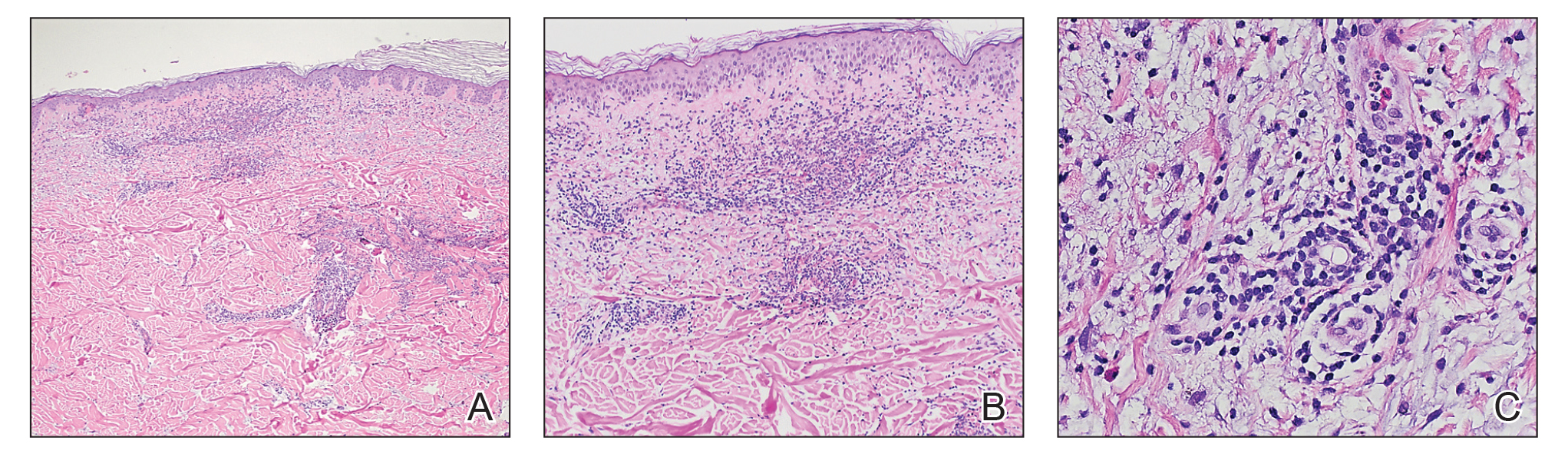

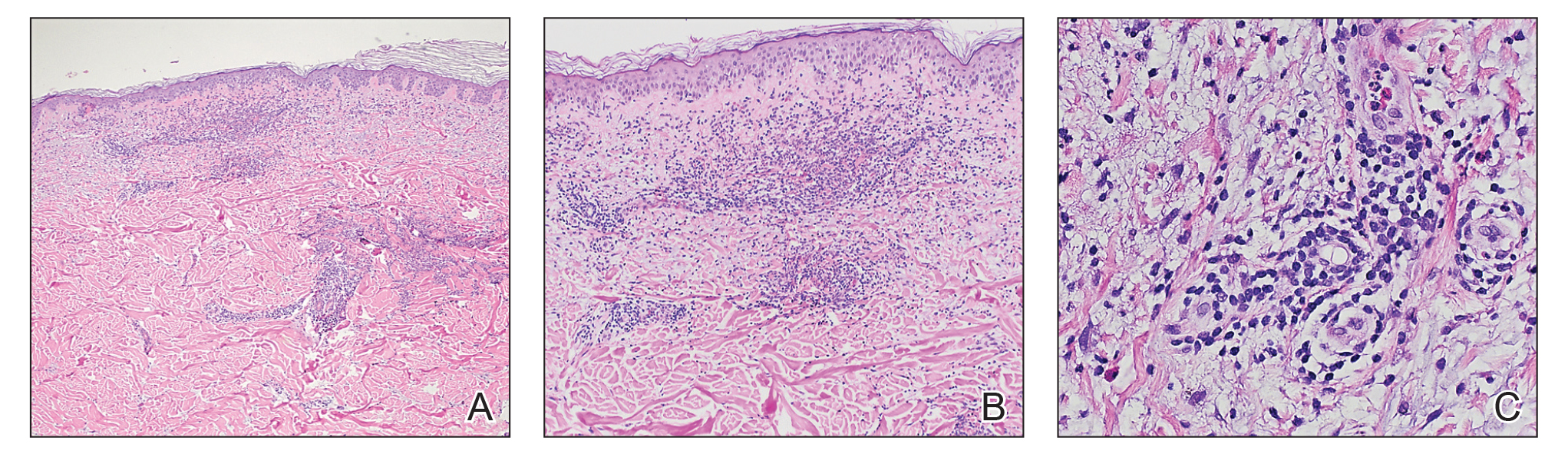

After discussing the diagnostic differential and treatment options, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral partial radical vulvectomy with reconstruction and resection of the right inguinal lymph node. Gross examination of the vulvectomy specimen showed multiple flesh-colored papules (Figure 1). Histologic examination revealed a neoplasm with sweat gland differentiation that was broad and poorly circumscribed but confined to the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The neoplasm was composed of epithelial cells that formed ductlike structures, lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a fibrous stroma (Figure 2C). A toluidine blue special stain was performed and demonstrated an increased amount of mast cells in the tissue (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical stains for gross cystic disease fluid protein, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) were negative in the tumor cells. The lack of cytologic atypia, perineural invasion, and deep infiltration into the subcutis favored a syringoma. One month later, the case was presented at the Tumor Board Conference at the University of Alabama at Birmingham where a final diagnosis of vulvar syringoma was agreed upon and discussed with the patient. At that time, no recurrence was evident and follow-up was recommended.

Syringomas are benign tumors of the sweat glands that are fairly common and appear to have a predilection for women. Although most of the literature classifies them as eccrine neoplasms, the term syringoma can be used to describe neoplasms of either apocrine or eccrine lineage.1 To rule out an apocrine lineage of the tumor in our patient, we performed immunohistochemistry for gross cystic disease fluid protein, a marker of apocrine differentiation. This stain highlighted normal apocrine glands that were not involved in the tumor proliferation.

Syringomas may occur at any site on the body but are prone to occur on the periorbital area, especially the eyelids.1 Some of the atypical locations for a syringoma include the anterior neck, chest, abdomen, genitals, axillae, groin, and buttocks.2 Vulvar syringomas were first reported by Carneiro3 in 1971 as usually affecting adolescent girls and middle-aged women. There have been approximately 40 reported cases affecting women aged 8 to 78 years.4,5 Vulvar syringomas classically appear as firm or soft, flesh-colored to transparent, papular lesions. The 2 other clinical variants are miliumlike, whitish, cystic papules as well as lichenoid papules.6 Pérez-Bustillo et al5 reported a case of the lichenoid papule variant on the labia majora of a 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent vulvar pruritus of 4 years’ duration. Due to this patient’s 9-year history of urinary incontinence, the lesions had been misdiagnosed as irritant dermatitis and associated lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). This case is a reminder to consider vulvar syringoma in patients with LSC who respond poorly to oral antihistamines and topical steroids.5 Rarely, multiple clinical variants may coexist. In a case reported by Dereli et al,7 a 19-year-old woman presented with concurrent classical and miliumlike forms of vulvar syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually present as multiple lesions involving both sides of the labia majora; however, Blasdale and McLelland8 reported a single isolated syringoma of the vulva on the anterior right labia minora that measured 1.0×0.5 cm, leading the lesion to be described as a giant syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually are asymptomatic and noticed during routine gynecologic examination. Therefore, it is believed that they likely are underdiagnosed.5 When symptomatic, they commonly present with constant9 or intermittent5 pruritus, which may intensify during menstruation, pregnancy, and summertime.6,10-12 Gerdsen et al10 documented a 27-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of pruritic vulvar skin lesions that became exacerbated during menstruation, which raised the possibility of cyclical hormonal changes being responsible for periodic exacerbation of vulvar pruritus during menstruation. In addition, patients may experience an increase in size and number of the lesions during pregnancy. Bal et al11 reported a 24-year-old primigravida with vulvar papular lesions that intensified during pregnancy. She had experienced intermittent vulvar pruritus for 12 years but had no change in symptoms during menstruation.11 Few studies have attempted to evaluate the presence of ER and PR in the syringomas. A study of 9 nonvulvar syringomas by Wallace and Smoller13 showed ER positivity in 1 case and PR positivity in 8 cases, lending support to the hormonal theory; however, in another case series of 15 vulvar syringomas, Huang et al6 failed to show ER and PR expression by immunohistochemical staining. A case report published 3 years earlier documented the first case of PR positivity on a vulvar syringoma.14 Our patient also was negative for ER and PR, which suggested that hormonal status is important in some but not all syringomas.

Patients with vulgar syringomas also might have coexisting extragenital syringomas in the neck,4 eyelids,6,7,10 and periorbital area,6 and thorough examination of the body is essential. If an extragenital syringoma is diagnosed, a vulvar syringoma should be considered, especially when the patient presents with unexplained genital symptoms. Although no proven hereditary transmission pattern has been established, family history of syringomas has been established in several cases.15 In a case series reported by Huang et al,6 4 of 18 patients reported a family history of periorbital syringomas. In our case, the patient did not report a family history of syringomas.

The differential diagnosis of vulvar lesions with pruritus is broad and includes Fox-Fordyce disease, lichen planus, LSC, epidermal cysts, senile angiomas, dystrophic calcinosis, xanthomas, steatocytomas, soft fibromas, condyloma acuminatum, and candidiasis. Vulvar syringomas might have a nonspecific appearance, and histologic examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any malignant process such as MAC, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, extramammary Paget disease, or other glandular neoplasms of the vulva.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma was first reported in 1982 by Goldstein et al16 as a locally aggressive neoplasm that can be confused with benign adnexal neoplasms, particularly desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, trichoadenoma, and syringoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinomas present as slow-growing, flesh-colored papules that may resemble syringomas and appear in similar body sites. Histologic examination is essential to differentiate between these two entities. Syringomas are tumors confined to the dermis and are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a dense fibrous stroma. Unlike syringomas, MACs usually infiltrate diffusely into the dermis and subcutis and may extend into the underlying muscle. Although bland cytologic features predominate, perineural invasion frequently is present in MACs. A potential pitfall of misdiagnosis can be caused by a superficial biopsy that may reveal benign histologic appearance, particularly in the upper level of the tumor where it may be confused with a syringoma or a benign follicular neoplasm.17

The initial biopsy performed on our patient was possibly not deep enough to render an unequivocal diagnosis and therefore bilateral partial radical vulvectomy was considered. After surgery, histologic examination of the resection specimen revealed a poorly circumscribed tumor confined to the dermis. The tumor was broad and the lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis and perineural invasion favored a syringoma (Figures 2A and 2B). These findings were consistent with case reports that documented syringomas as being more wide than deep on microscopic examination, whereas the opposite pertained to MAC.18 Cases of plaque-type syringomas that initially were misdiagnosed as MACs also have been reported.19 Because misdiagnosis may affect the treatment plan and potentially result in unnecessary surgery, caution should be taken when differentiating between these two entities. When a definitive diagnosis cannot be rendered on a superficial biopsy, a recommendation should be made for a deeper biopsy sampling the subcutis.

For the majority of the patients with vulvar syringomas, treatment is seldom required due to their asymptomatic nature; however, patients who present with symptoms usually report pruritus of variable intensities and patterns. A standardized treatment does not exist for vulvar syringomas, and oral or topical treatment might be used as an initial approach. Commonly prescribed medications with variable results include topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and topical retinoids. In a case reported by Iwao et al,20 vulvar syringomas were successfully treated with tranilast, which has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. This medication could have a possible dual action—inhibiting the release of chemical mediators from the mast cells and inhibiting the release of IL-1β from the eccrine duct, which could suppress the proliferation of stromal connective tissue. Our case was stained with toluidine blue and showed an increased number of mast cells in the tissue (Figure 3). Patients who are unresponsive to tranilast or have extensive disease resulting in cosmetic disfigurement might benefit from more invasive treatment methods including a variety of lasers, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and excision. Excisions should include the entire tumor to avoid recurrence. In a case reported by Garman and Metry,21 the lesions were surgically excised using small 2- to 3-mm punches; however, several weeks later the lesions recurred. Our patient presented with a 1-month evolution of dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities that were probably not treated with oral or topical medications before being referred for surgery.

We report a case of a vulvar syringoma that presented diagnostic challenges in the initial biopsy, which prevented the exclusion of an MAC. After partial radical vulvectomy, histologic examination was more definitive, showing lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis or perineural invasion that are commonly seen in MAC. This case is an example of a notable pitfall in the diagnosis of vulvar syringoma on a limited biopsy leading to overtreatment. Raising awareness of this entity is the only modality to prevent misdiagnosis. We encourage reporting of further cases of syringomas, particularly those with atypical locations or patterns that may cause diagnostic problems.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

- Carneiro SJ, Gardner HL, Knox JM. Syringoma of the vulva. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:494-496.

- Trager JD, Silvers J, Reed JA, et al. Neck and vulvar papules in an 8-year-old girl. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:203, 206.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Ruiz-González I, Delgado S, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a rare cause of vulvar pruritus. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2008;99:580-581.

- Huang YH, Chuang YH, Kuo TT, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study of 18 patients and results of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:735-739.

- Dereli T, Turk BG, Kazandi AC. Syringomas of the vulva. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:65-66.

- Blasdale C, McLelland J. Solitary giant vulval syringoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:374-375.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Gerdsen R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Periodic genital pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:369-370.

- Bal N, Aslan E, Kayaselcuk F, et al. Vulvar syringoma aggravated by pregnancy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;9:196-197.

- Turan C, Ugur M, Kutluay L, et al. Vulvar syringoma exacerbated during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:141-142.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Yorganci A, Kale A, Dunder I, et al. Vulvar syringoma showing progesterone receptor positivity. BJOG. 2000;107:292-294.

- Draznin M. Hereditary syringomas: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:19.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Hamsch C, Hartschuh W. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma - aggressive infiltrative tumor often with innocent clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:275-278.

- Henner MS, Shapiro PE, Ritter JH, et al. Solitary syringoma. report of five cases and clinicopathologic comparison with microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:465-470.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Iwao F, Onozuka T, Kawashima T. Vulval syringoma successfully treated with tranilast. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1228-1230.

- Garman M, Metry D. Vulvar syringomas in a 9-year-old child with review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:369-372.

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).