User login

The cost of postponing medical care during the pandemic

Friends of mine who work in the ED have noticed a drop-off in patients. Granted, so has my office, but theirs is a little less expected.

It’s not just in my region. An article on this site last week mentioned the same phenomenon. Not just minor stuff but visits for more serious conditions also have decreased. This means that either people are currently choosing to ignore those things entirely or are trying to get them handled at a later date in the outpatient setting.

Neither one is good.

One friend pointed out that since a fair percentage of visits to the ED aren’t really “emergencies” maybe this is part of the reason. With all the news about COVID-19, the risk of going to the ED for something minor isn’t worth it. This may apply to some, but not all. Certainly, if it clarifies to people what is and isn’t an emergency, that would be helpful to prevent ED overuse in the future.

Every day we all face a countless number of decisions, each with its own risks and benefits. When the question of whether or not to go to an ED comes up, usually the only perceived drawbacks are costs in time and money, compared with the benefit of believing you’re going to get the problem “fixed.”

In the era of coronavirus, with daily news reports on its spread and casualties, the risk of going to the ED is perceived to be higher, and so people are more willing to stay away. If you were going in for a sinus infection, this is probably a good idea. If you’re having a more serious problem and staying home ...

A cost of the pandemic that will come to light in the future will be people who unknowingly survived mild cardiac events, strokes, and other potentially serious problems. While they may do okay in the short term, in the long run they may not be aware they had a problem and so it will continue to go untreated. Coronary or cerebrovascular arteries that need to be reopened won’t be. People with poorly controlled hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes won’t be started on medications they need until it may be too late to avoid more serious outcomes.

Likewise, I worry about an uptick in cancer-related deaths down the road. With the shutdown of many nonurgent procedures, patients may have missed a window for early diagnosis of a malignancy, either because the procedure wasn’t available or they were reluctant to venture out.

Medical data from 2020 will be analyzed many times in the coming years, not just for coronavirus, but for its effects on medical care as a whole. As the first worldwide pandemic of the information age, there will be a lot of lessons to be learned as to how medicine, science, and society in general should and should not respond. Both good and bad things will be learned, but whatever knowledge is gained will be critical for the inevitable next pandemic.

The future world is watching.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Friends of mine who work in the ED have noticed a drop-off in patients. Granted, so has my office, but theirs is a little less expected.

It’s not just in my region. An article on this site last week mentioned the same phenomenon. Not just minor stuff but visits for more serious conditions also have decreased. This means that either people are currently choosing to ignore those things entirely or are trying to get them handled at a later date in the outpatient setting.

Neither one is good.

One friend pointed out that since a fair percentage of visits to the ED aren’t really “emergencies” maybe this is part of the reason. With all the news about COVID-19, the risk of going to the ED for something minor isn’t worth it. This may apply to some, but not all. Certainly, if it clarifies to people what is and isn’t an emergency, that would be helpful to prevent ED overuse in the future.

Every day we all face a countless number of decisions, each with its own risks and benefits. When the question of whether or not to go to an ED comes up, usually the only perceived drawbacks are costs in time and money, compared with the benefit of believing you’re going to get the problem “fixed.”

In the era of coronavirus, with daily news reports on its spread and casualties, the risk of going to the ED is perceived to be higher, and so people are more willing to stay away. If you were going in for a sinus infection, this is probably a good idea. If you’re having a more serious problem and staying home ...

A cost of the pandemic that will come to light in the future will be people who unknowingly survived mild cardiac events, strokes, and other potentially serious problems. While they may do okay in the short term, in the long run they may not be aware they had a problem and so it will continue to go untreated. Coronary or cerebrovascular arteries that need to be reopened won’t be. People with poorly controlled hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes won’t be started on medications they need until it may be too late to avoid more serious outcomes.

Likewise, I worry about an uptick in cancer-related deaths down the road. With the shutdown of many nonurgent procedures, patients may have missed a window for early diagnosis of a malignancy, either because the procedure wasn’t available or they were reluctant to venture out.

Medical data from 2020 will be analyzed many times in the coming years, not just for coronavirus, but for its effects on medical care as a whole. As the first worldwide pandemic of the information age, there will be a lot of lessons to be learned as to how medicine, science, and society in general should and should not respond. Both good and bad things will be learned, but whatever knowledge is gained will be critical for the inevitable next pandemic.

The future world is watching.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Friends of mine who work in the ED have noticed a drop-off in patients. Granted, so has my office, but theirs is a little less expected.

It’s not just in my region. An article on this site last week mentioned the same phenomenon. Not just minor stuff but visits for more serious conditions also have decreased. This means that either people are currently choosing to ignore those things entirely or are trying to get them handled at a later date in the outpatient setting.

Neither one is good.

One friend pointed out that since a fair percentage of visits to the ED aren’t really “emergencies” maybe this is part of the reason. With all the news about COVID-19, the risk of going to the ED for something minor isn’t worth it. This may apply to some, but not all. Certainly, if it clarifies to people what is and isn’t an emergency, that would be helpful to prevent ED overuse in the future.

Every day we all face a countless number of decisions, each with its own risks and benefits. When the question of whether or not to go to an ED comes up, usually the only perceived drawbacks are costs in time and money, compared with the benefit of believing you’re going to get the problem “fixed.”

In the era of coronavirus, with daily news reports on its spread and casualties, the risk of going to the ED is perceived to be higher, and so people are more willing to stay away. If you were going in for a sinus infection, this is probably a good idea. If you’re having a more serious problem and staying home ...

A cost of the pandemic that will come to light in the future will be people who unknowingly survived mild cardiac events, strokes, and other potentially serious problems. While they may do okay in the short term, in the long run they may not be aware they had a problem and so it will continue to go untreated. Coronary or cerebrovascular arteries that need to be reopened won’t be. People with poorly controlled hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes won’t be started on medications they need until it may be too late to avoid more serious outcomes.

Likewise, I worry about an uptick in cancer-related deaths down the road. With the shutdown of many nonurgent procedures, patients may have missed a window for early diagnosis of a malignancy, either because the procedure wasn’t available or they were reluctant to venture out.

Medical data from 2020 will be analyzed many times in the coming years, not just for coronavirus, but for its effects on medical care as a whole. As the first worldwide pandemic of the information age, there will be a lot of lessons to be learned as to how medicine, science, and society in general should and should not respond. Both good and bad things will be learned, but whatever knowledge is gained will be critical for the inevitable next pandemic.

The future world is watching.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Frontal lobe glucose abnormalities may indicate increased SUDEP risk

, new research suggests.

“The data provide initial evidence that hypometabolism in certain parts of the frontal cortex may be associated with higher SUDEP risk,” said lead author Maysaa M. Basha, MD, associate professor of neurology and director of the Adult Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, Wayne State University/Detroit Medical Center, in Michigan.

If this research is validated, “it potentially can be used to screen patients for higher SUDEP risk,” she said. The idea is to identify those at high risk and then reduce that risk with more aggressive management of seizures or closer monitoring in certain cases, she added.

The research is being presented online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Science Highlights.

Hypometabolism

Dr. Basha and colleagues were encouraged to pursue this new line of research after a pilot [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) study revealed frontal lobe hypometabolism among patients who subsequently died.

“We wanted to determine if such a metabolic abnormality is associated with SUDEP risk,” said Dr. Basha. She noted that no PET studies have addressed this question, only MRI studies.

In this new study, researchers aimed to identify specific patterns of objectively detected brain glucose metabolic abnormalities in patients with refractory focal epilepsy who were at risk for SUDEP.

The study included 80 patients (45 female patients) aged 16 to 61 years (mean age, 37 years) who underwent FDG-PET as part of their presurgical evaluation for epilepsy surgery. Patients with large brain lesions, such as an infarct or a large tumor, were excluded from the study; such lesions can affect the accuracy of an objective PET analysis, explained Dr. Basha.

The researchers assessed risk for SUDEP using the seven-item SUDEP inventory (SUDEP-7), which was developed as a marker of clinical SUDEP risk. The 0- to 10-point scale is used to evaluate the frequency of tonic-clonic and other seizures, the duration of epilepsy, the use of antiepileptic drugs, and intellectual disability.

The researchers calculated SUDEP-7 inventory scores as closely as possible to FDG-PET assessments. The mean score in the patient population was 3.6.

The investigators divided participants into two subgroups: 22 patients had a SUDEP score of 5 or greater; and 58 had a score of less than 5 (higher scores indicate higher risk for SUDEP).

The researchers compared PET scans of each of these subgroups to PET scans from healthy adults to determine whether they showed common areas of metabolic abnormality. For this, they used an image analytic software program called Statistical Parametric Mapping, which compares group values of metabolic activity measured in small units of the brain (voxels) with statistical methods.

The analysis showed that the higher-risk group displayed a common pattern of hypometabolism in certain brain areas.

“The epilepsy patient subgroup with high SUDEP risk showed areas of decreased metabolism, as compared to the control group, in portions of the frontal cortex,” said Dr. Basha. “The statistically most significant decreases were in the right frontal lobe area—both lateral convexity and medial cortex.”

Dr. Basha added that these group abnormalities were “remarkably similar” to the individual metabolic abnormalities found in the four SUDEP patients in the previous pilot study who underwent PET scanning and who subsequently died.

A similar group analysis showed that the group at low SUDEP risk displayed no common metabolic abnormalities.

MRI findings were normal for 40 patients.

Dr. Basha and colleagues believe that “this is the first PET study assessing the metabolic correlates of SUDEP risk on the group level.”

Common feature

Interictal glucose hypometabolism is “common in and around epileptic foci,” noted Dr. Basha. However, this could extend into nonepileptic regions—for example, to remote connected regions where seizures can spread from the primary focus and into subcortical gray matter structures, such the thalamus.

Some of these metabolic abnormalities may indicate subtle, microscopic, structural abnormalities in the affected brain, said Dr. Basha.

Abnormalities that are induced by epilepsy and that result from purely metabolic changes could be partly or fully reversed if seizures are controlled on a long-term basis, she said. “Some metabolic abnormalities can be reversed after better seizure control with antiepileptic drugs, epileptic surgery, or other antiepileptic treatment,” she said.

It’s “quite possible” that the same brain pattern would be evident in children with epilepsy, although her team has not performed the same analysis in a younger pediatric group, said Dr. Basha. She noted that it would be unethical to administer PET scans, which involve radiation, to young, healthy control persons.

It’s too early to recommend that all epilepsy patients undergo FDG-PET scanning to see whether this pattern of brain glucose hypometabolism is present, said Dr. Basha. “But if this is proven to be a good biomarker, the next step would be a prospective study” to see whether this brain marker is a true signal of SUDEP risk.

“I don’t think our single study would do that, but ultimately, that would be the goal,” she added.

One more piece of the SUDEP puzzle

Commenting on the study, William Davis Gaillard, MD, president of the American Epilepsy Society and chief of neurology, Children’s National Medical Center, Chevy Chase, Maryland, said this new information provides one more piece of the SUDEP puzzle but doesn’t complete the picture.

The study authors assessed PET scans of a group of patients and found common abnormalities that implicate the right medial frontal cortex. “That’s a pretty reasonable method” of investigation, said Dr. Gaillard.

“The challenge is that they’re looking at people they believe have a risk of SUDEP as opposed to people who died,” said Dr. Gaillard.

But he agreed that the results might signal “a biomarker” that “allows you to identify who’s at high risk, and then you may be able to intervene to save them.”

It’s not clear that people with frontal lobe epilepsy are at greater risk for SUDEP than those with temporal lobe epilepsy, he said.

“What you don’t know is whether this represents people with a seizure focus in that area or this represents a common network implicated in people with diverse forms of focal epilepsy; so you need to do some more work,” he said.

Dr. Gaillard pointed out that other research has implicated regions other than the mesial frontal cortex in SUDEP risk. These regions include the insula, the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the brain stem.

He also noted that the SUDEP-7, which has not been thoroughly validated, is designed for use only in adults.

In his own practice, he asks patients about the frequency of tonic-clonic seizures and whether they occur at night. The number of antiepileptic medications a patient takes reflects the difficulty of controlling seizures and may not be “an independent variable for risk,” said Dr. Gaillard.

“It’s clear one needs a better assessment and better idea of who is at risk,” he said.

The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SOURCE: Basha A et al. AAN 2020. Abstract P5.001.

, new research suggests.

“The data provide initial evidence that hypometabolism in certain parts of the frontal cortex may be associated with higher SUDEP risk,” said lead author Maysaa M. Basha, MD, associate professor of neurology and director of the Adult Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, Wayne State University/Detroit Medical Center, in Michigan.

If this research is validated, “it potentially can be used to screen patients for higher SUDEP risk,” she said. The idea is to identify those at high risk and then reduce that risk with more aggressive management of seizures or closer monitoring in certain cases, she added.

The research is being presented online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Science Highlights.

Hypometabolism

Dr. Basha and colleagues were encouraged to pursue this new line of research after a pilot [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) study revealed frontal lobe hypometabolism among patients who subsequently died.

“We wanted to determine if such a metabolic abnormality is associated with SUDEP risk,” said Dr. Basha. She noted that no PET studies have addressed this question, only MRI studies.

In this new study, researchers aimed to identify specific patterns of objectively detected brain glucose metabolic abnormalities in patients with refractory focal epilepsy who were at risk for SUDEP.

The study included 80 patients (45 female patients) aged 16 to 61 years (mean age, 37 years) who underwent FDG-PET as part of their presurgical evaluation for epilepsy surgery. Patients with large brain lesions, such as an infarct or a large tumor, were excluded from the study; such lesions can affect the accuracy of an objective PET analysis, explained Dr. Basha.

The researchers assessed risk for SUDEP using the seven-item SUDEP inventory (SUDEP-7), which was developed as a marker of clinical SUDEP risk. The 0- to 10-point scale is used to evaluate the frequency of tonic-clonic and other seizures, the duration of epilepsy, the use of antiepileptic drugs, and intellectual disability.

The researchers calculated SUDEP-7 inventory scores as closely as possible to FDG-PET assessments. The mean score in the patient population was 3.6.

The investigators divided participants into two subgroups: 22 patients had a SUDEP score of 5 or greater; and 58 had a score of less than 5 (higher scores indicate higher risk for SUDEP).

The researchers compared PET scans of each of these subgroups to PET scans from healthy adults to determine whether they showed common areas of metabolic abnormality. For this, they used an image analytic software program called Statistical Parametric Mapping, which compares group values of metabolic activity measured in small units of the brain (voxels) with statistical methods.

The analysis showed that the higher-risk group displayed a common pattern of hypometabolism in certain brain areas.

“The epilepsy patient subgroup with high SUDEP risk showed areas of decreased metabolism, as compared to the control group, in portions of the frontal cortex,” said Dr. Basha. “The statistically most significant decreases were in the right frontal lobe area—both lateral convexity and medial cortex.”

Dr. Basha added that these group abnormalities were “remarkably similar” to the individual metabolic abnormalities found in the four SUDEP patients in the previous pilot study who underwent PET scanning and who subsequently died.

A similar group analysis showed that the group at low SUDEP risk displayed no common metabolic abnormalities.

MRI findings were normal for 40 patients.

Dr. Basha and colleagues believe that “this is the first PET study assessing the metabolic correlates of SUDEP risk on the group level.”

Common feature

Interictal glucose hypometabolism is “common in and around epileptic foci,” noted Dr. Basha. However, this could extend into nonepileptic regions—for example, to remote connected regions where seizures can spread from the primary focus and into subcortical gray matter structures, such the thalamus.

Some of these metabolic abnormalities may indicate subtle, microscopic, structural abnormalities in the affected brain, said Dr. Basha.

Abnormalities that are induced by epilepsy and that result from purely metabolic changes could be partly or fully reversed if seizures are controlled on a long-term basis, she said. “Some metabolic abnormalities can be reversed after better seizure control with antiepileptic drugs, epileptic surgery, or other antiepileptic treatment,” she said.

It’s “quite possible” that the same brain pattern would be evident in children with epilepsy, although her team has not performed the same analysis in a younger pediatric group, said Dr. Basha. She noted that it would be unethical to administer PET scans, which involve radiation, to young, healthy control persons.

It’s too early to recommend that all epilepsy patients undergo FDG-PET scanning to see whether this pattern of brain glucose hypometabolism is present, said Dr. Basha. “But if this is proven to be a good biomarker, the next step would be a prospective study” to see whether this brain marker is a true signal of SUDEP risk.

“I don’t think our single study would do that, but ultimately, that would be the goal,” she added.

One more piece of the SUDEP puzzle

Commenting on the study, William Davis Gaillard, MD, president of the American Epilepsy Society and chief of neurology, Children’s National Medical Center, Chevy Chase, Maryland, said this new information provides one more piece of the SUDEP puzzle but doesn’t complete the picture.

The study authors assessed PET scans of a group of patients and found common abnormalities that implicate the right medial frontal cortex. “That’s a pretty reasonable method” of investigation, said Dr. Gaillard.

“The challenge is that they’re looking at people they believe have a risk of SUDEP as opposed to people who died,” said Dr. Gaillard.

But he agreed that the results might signal “a biomarker” that “allows you to identify who’s at high risk, and then you may be able to intervene to save them.”

It’s not clear that people with frontal lobe epilepsy are at greater risk for SUDEP than those with temporal lobe epilepsy, he said.

“What you don’t know is whether this represents people with a seizure focus in that area or this represents a common network implicated in people with diverse forms of focal epilepsy; so you need to do some more work,” he said.

Dr. Gaillard pointed out that other research has implicated regions other than the mesial frontal cortex in SUDEP risk. These regions include the insula, the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the brain stem.

He also noted that the SUDEP-7, which has not been thoroughly validated, is designed for use only in adults.

In his own practice, he asks patients about the frequency of tonic-clonic seizures and whether they occur at night. The number of antiepileptic medications a patient takes reflects the difficulty of controlling seizures and may not be “an independent variable for risk,” said Dr. Gaillard.

“It’s clear one needs a better assessment and better idea of who is at risk,” he said.

The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SOURCE: Basha A et al. AAN 2020. Abstract P5.001.

, new research suggests.

“The data provide initial evidence that hypometabolism in certain parts of the frontal cortex may be associated with higher SUDEP risk,” said lead author Maysaa M. Basha, MD, associate professor of neurology and director of the Adult Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, Wayne State University/Detroit Medical Center, in Michigan.

If this research is validated, “it potentially can be used to screen patients for higher SUDEP risk,” she said. The idea is to identify those at high risk and then reduce that risk with more aggressive management of seizures or closer monitoring in certain cases, she added.

The research is being presented online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Science Highlights.

Hypometabolism

Dr. Basha and colleagues were encouraged to pursue this new line of research after a pilot [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) study revealed frontal lobe hypometabolism among patients who subsequently died.

“We wanted to determine if such a metabolic abnormality is associated with SUDEP risk,” said Dr. Basha. She noted that no PET studies have addressed this question, only MRI studies.

In this new study, researchers aimed to identify specific patterns of objectively detected brain glucose metabolic abnormalities in patients with refractory focal epilepsy who were at risk for SUDEP.

The study included 80 patients (45 female patients) aged 16 to 61 years (mean age, 37 years) who underwent FDG-PET as part of their presurgical evaluation for epilepsy surgery. Patients with large brain lesions, such as an infarct or a large tumor, were excluded from the study; such lesions can affect the accuracy of an objective PET analysis, explained Dr. Basha.

The researchers assessed risk for SUDEP using the seven-item SUDEP inventory (SUDEP-7), which was developed as a marker of clinical SUDEP risk. The 0- to 10-point scale is used to evaluate the frequency of tonic-clonic and other seizures, the duration of epilepsy, the use of antiepileptic drugs, and intellectual disability.

The researchers calculated SUDEP-7 inventory scores as closely as possible to FDG-PET assessments. The mean score in the patient population was 3.6.

The investigators divided participants into two subgroups: 22 patients had a SUDEP score of 5 or greater; and 58 had a score of less than 5 (higher scores indicate higher risk for SUDEP).

The researchers compared PET scans of each of these subgroups to PET scans from healthy adults to determine whether they showed common areas of metabolic abnormality. For this, they used an image analytic software program called Statistical Parametric Mapping, which compares group values of metabolic activity measured in small units of the brain (voxels) with statistical methods.

The analysis showed that the higher-risk group displayed a common pattern of hypometabolism in certain brain areas.

“The epilepsy patient subgroup with high SUDEP risk showed areas of decreased metabolism, as compared to the control group, in portions of the frontal cortex,” said Dr. Basha. “The statistically most significant decreases were in the right frontal lobe area—both lateral convexity and medial cortex.”

Dr. Basha added that these group abnormalities were “remarkably similar” to the individual metabolic abnormalities found in the four SUDEP patients in the previous pilot study who underwent PET scanning and who subsequently died.

A similar group analysis showed that the group at low SUDEP risk displayed no common metabolic abnormalities.

MRI findings were normal for 40 patients.

Dr. Basha and colleagues believe that “this is the first PET study assessing the metabolic correlates of SUDEP risk on the group level.”

Common feature

Interictal glucose hypometabolism is “common in and around epileptic foci,” noted Dr. Basha. However, this could extend into nonepileptic regions—for example, to remote connected regions where seizures can spread from the primary focus and into subcortical gray matter structures, such the thalamus.

Some of these metabolic abnormalities may indicate subtle, microscopic, structural abnormalities in the affected brain, said Dr. Basha.

Abnormalities that are induced by epilepsy and that result from purely metabolic changes could be partly or fully reversed if seizures are controlled on a long-term basis, she said. “Some metabolic abnormalities can be reversed after better seizure control with antiepileptic drugs, epileptic surgery, or other antiepileptic treatment,” she said.

It’s “quite possible” that the same brain pattern would be evident in children with epilepsy, although her team has not performed the same analysis in a younger pediatric group, said Dr. Basha. She noted that it would be unethical to administer PET scans, which involve radiation, to young, healthy control persons.

It’s too early to recommend that all epilepsy patients undergo FDG-PET scanning to see whether this pattern of brain glucose hypometabolism is present, said Dr. Basha. “But if this is proven to be a good biomarker, the next step would be a prospective study” to see whether this brain marker is a true signal of SUDEP risk.

“I don’t think our single study would do that, but ultimately, that would be the goal,” she added.

One more piece of the SUDEP puzzle

Commenting on the study, William Davis Gaillard, MD, president of the American Epilepsy Society and chief of neurology, Children’s National Medical Center, Chevy Chase, Maryland, said this new information provides one more piece of the SUDEP puzzle but doesn’t complete the picture.

The study authors assessed PET scans of a group of patients and found common abnormalities that implicate the right medial frontal cortex. “That’s a pretty reasonable method” of investigation, said Dr. Gaillard.

“The challenge is that they’re looking at people they believe have a risk of SUDEP as opposed to people who died,” said Dr. Gaillard.

But he agreed that the results might signal “a biomarker” that “allows you to identify who’s at high risk, and then you may be able to intervene to save them.”

It’s not clear that people with frontal lobe epilepsy are at greater risk for SUDEP than those with temporal lobe epilepsy, he said.

“What you don’t know is whether this represents people with a seizure focus in that area or this represents a common network implicated in people with diverse forms of focal epilepsy; so you need to do some more work,” he said.

Dr. Gaillard pointed out that other research has implicated regions other than the mesial frontal cortex in SUDEP risk. These regions include the insula, the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the brain stem.

He also noted that the SUDEP-7, which has not been thoroughly validated, is designed for use only in adults.

In his own practice, he asks patients about the frequency of tonic-clonic seizures and whether they occur at night. The number of antiepileptic medications a patient takes reflects the difficulty of controlling seizures and may not be “an independent variable for risk,” said Dr. Gaillard.

“It’s clear one needs a better assessment and better idea of who is at risk,” he said.

The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SOURCE: Basha A et al. AAN 2020. Abstract P5.001.

Dermatologic changes with COVID-19: What we know and don’t know

The dermatologic manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 are many and varied, with new information virtually daily. Graeme Lipper, MD, a member of the Medscape Dermatology advisory board, discussed what we know and what is still to be learned with Lindy Fox, MD, a professor of dermatology at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry task force.

Graeme M. Lipper, MD

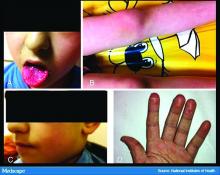

Earlier this spring, before there was any real talk about skin manifestations of COVID, my partner called me in to see an unusual case. His patient was a healthy 20-year-old who had just come back from college and had tender, purple discoloration and swelling on his toes. I shrugged and said “looks like chilblains,” but there was something weird about the case. It seemed more severe, with areas of blistering and erosions, and the discomfort was unusual for run-of-the-mill pernio. This young man had experienced a cough and shortness of breath a few weeks earlier but those symptoms had resolved when we saw him.

That evening, I was on a derm social media site and saw a series of pictures from Italy that blew me away. All of these pictures looked just like this kid’s toes. That’s the first I heard of “COVID toes,” but now they seem to be everywhere. How would you describe this presentation, and how does it differ from typical chilblains?

Lindy P. Fox, MD

I am so proud of dermatologists around the world who have really jumped into action to examine the pathophysiology and immunology behind these findings.

Your experience matches mine. Like you, I first heard about these pernio- or chilblains-like lesions when Europe was experiencing its surge in cases. And while it does indeed look like chilblains, I think the reality is that it is more severe and symptomatic than we would expect. I think your observation is exactly right. There are certainly clinicians who do not believe that this is an association with COVID-19 because the testing is often negative. But to my mind, there are just too many cases at the wrong time of year, all happening concomitantly, and simultaneous with a new virus for me to accept that they are not somehow related.

Dr. Lipper: Some have referred to this as “quarantine toes,” the result of more people at home and walking around barefoot. That doesn’t seem to make a whole lot of sense because it’s happening in both warm and cold climates.

Others have speculated that there is another, unrelated circulating virus causing these pernio cases, but that seems far-fetched.

But the idea of a reporting bias – more patients paying attention to these lesions because they’ve read something in the mass media or seen a report on television and are concerned, and thus present with mild lesions they might otherwise have ignored – may be contributing somewhat. But even that cannot be the sole reason behind the increase.

Dr. Fox: Agree.

Evaluation of the patient with chilblains – then and now

Dr. Lipper: In the past, how did you perform a workup for someone with chilblains?

Dr. Fox: Pre-COVID – and I think we all have divided our world into pre- and post-COVID – the most common thing that I’d be looking for would be a clotting disorder or an autoimmune disease, typically lupus. So I take a good history, review of systems, and look at the skin for signs of lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue diseases. My lab workup is probably limited to an antinuclear antibody (ANA). If the findings are severe and recurrent, I might check for hypercoagulability with an antiphospholipid antibody panel. But that was usually it unless there was something in the history or physical exam that would lead me to look for something less common – for example, cryoglobulins or an underlying hematologic disease that would lead to a predominance of lesions in acral sites.

My approach was the same. In New England, where I practice, I also always look at environmental factors. We would sometimes see chilblains in someone from a warmer climate who came home to the Northeast to ski.

Dr. Lipper: Now, in the post-COVID world, how do you assess these patients? What has changed?

Dr. Fox: That’s a great question. To be frank, our focus now is on not missing a secondary consequence of COVID infection that we might not have picked up before. I’m the first to admit that the workup that we have been doing at UCSF is extremely comprehensive. We may be ordering tests that don’t need to be done. But until we know better what might and might not be affected by COVID, we don’t actually have a sense of whether they’re worth looking for or not.

Right now, my workup includes nasal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for COVID, as well as IgG and IgM serology if available. We have IgG easily available to us. IgM needs approval; at UCSF, it is primarily done in neonates as of now. I also do a workup for autoimmunity and cold-associated disease, which includes an ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulin, and cold agglutinins.

Because of reported concerns about hypercoagulability in COVID patients, particularly in those who are doing poorly in the hospital, we look for elevations in d-dimers and fibrinogen. We check antiphospholipid antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. That is probably too much of a workup for the healthy young person, but as of yet, we are just unable to say that those things are universally normal.

There has also been concern that complement may be involved in patients who do poorly and tend to clot a lot. So we are also checking C3, C4, and CH50.

To date, in my patients who have had this workup, I have found one with a positive ANA that was significant (1:320) who also had low complements.

There have been a couple of patients at my institution, not my own patients, who are otherwise fine but have some slight elevation in d-dimers.

Dr. Lipper: Is COVID toes more than one condition?

Some of the initial reports of finger/toe cyanosis out of China were very alarming, with many patients developing skin necrosis or even gangrene. These were critically ill adults with pneumonia and blood markers of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and five out of seven died. In contrast, the cases of pseudo-pernio reported in Europe, and now the United States, seem to be much milder, usually occurring late in the illness or in asymptomatic young people. Do you think these are two different conditions?

Dr. Fox: I believe you have hit the nail on the head. I think it is really important that we don’t confuse those two things. In the inpatient setting, we are clearly seeing patients with a prothrombotic state with associated retiform purpura. For nondermatologists, that usually means star-like, stellate-like, or even lacy purpuric changes with potential for necrosis of the skin. In hospitalized patients, the fingers and toes are usually affected but, interestingly, also the buttocks. When these lesions are biopsied, as has been done by our colleague at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, Joanna Harp, MD, we tend to find thrombosis.

A study of endothelial cell function in patients with COVID-19, published in the Lancet tried to determine whether viral particles could be found in endothelial cells. And the investigators did indeed find these particles. So it appears that the virus is endothelially active, and this might provide some insight into the thromboses seen in hospitalized patients. These patients can develop purple necrotic toes that may progress to gangrene. But that is completely different from what we’re seeing when we say pernio-like or chilblains-like lesions.

The chilblains-like lesions come in several forms. They may be purple, red bumps, often involving the tops of the toes and sometimes the bottom of the feet. Some have been described as target-like or erythema multiforme–like. In others, there may not be individual discrete lesions but rather a redness or bluish, purplish discoloration accompanied by edema of the entire toe or several toes.

Biopsies that I am aware of have identified features consistent with an inflammatory process, all of which can be seen in a typical biopsy of pernio. You can sometimes see lymphocytes surrounding a vessel (called lymphocytic vasculitis) that may damage a vessel and cause a small clot, but the primary process is an inflammatory rather than thrombotic one. You may get a clot in a little tiny vessel secondary to inflammation, and that may lead to some blisters or little areas of necrosis. But you’re not going to see digital necrosis and gangrene. I think that’s an important distinction.

The patients who get the pernio-like lesions are typically children or young adults and are otherwise healthy. Half of them didn’t even have COVID symptoms. If they did have COVID symptoms they were typically mild. So we think the pernio-like lesions are most often occurring in the late stage of the disease and now represent a secondary inflammatory response.

Managing COVID toes

Dr. Lipper: One question I’ve been struggling with is, what do we tell these otherwise healthy patients with purple toes, especially those with no other symptoms? Many of them are testing SARS-CoV-2 negative, both with viral swabs and serologies. Some have suggestive histories like known COVID exposure, recent cough, or travel to high-risk areas. Do we tell them they’re at risk of transmitting the virus? Should they self-quarantine, and for how long? Is there any consensus emerging?

Dr. Fox: This is a good opportunity to plug the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry, which is run by Esther Freeman, MD, at Massachusetts General Hospital. She has done a phenomenal job in helping us figure out the answers to these exact questions.

I’d encourage any clinicians who have a suspected COVID patient with a skin finding, whether or not infection is confirmed with testing, to enter information about that patient into the registry. That is the only way we will figure out evidence-based answers to a lot of the questions that we’re talking about today.

Based on working with the registry, we know that, rarely, patients who develop pernio-like changes will do so before they get COVID symptoms or at the same time as more typical symptoms. Some patients with these findings are PCR positive, and it is therefore theoretically possible that you could be shedding virus while you’re having the pernio toes. However, more commonly – and this is the experience of most of my colleagues and what we’re seeing at UCSF – pernio is a later finding and most patients are no longer shedding the virus. It appears that pseudo-pernio is an immune reaction and most people are not actively infectious at that point.

The only way to know for sure is to send patients for both PCR testing and antibody testing. If the PCR is negative, the most likely interpretation is that the person is no longer shedding virus, though there can be some false negatives. Therefore, these patients do not need to isolate outside of what I call their COVID pod – family or roommates who have probably been with them the whole time. Any transmission likely would have already occurred.

I tell people who call me concerned about their toes that I do think they should be given a workup for COVID. However, I reassure them that it is usually a good prognostic sign.

What is puzzling is that even in patients with pseudo-chilblains who have a clinical history consistent with COVID or exposure to a COVID-positive family member, antibody testing is often – in fact, most often – negative. There are many hypotheses as to why this is. Maybe the tests just aren’t good. Maybe people with mild disease don’t generate enough antibodies to be detected, Maybe we’re testing at the wrong time. Those are all things that we’re trying to figure out.

But currently, I tell patients that they do not need to strictly isolate. They should still practice social distancing, wear a mask, practice good hand hygiene, and do all of the careful things that we should all be doing. However, they can live within their home environment and be reassured that most likely they are in the convalescent stage.

Dr. Lipper: I find the antibody issue both fascinating and confusing.

In my practice, we’ve noticed a range of symptoms associated with pseudo-pernio. Some people barely realize it’s there and only called because they saw a headline in the news. Others complain of severe burning, throbbing, or itching that keeps them up at night and can sometimes last for weeks. Are there any treatments that seem to help?

Dr. Fox: We can start by saying, as you note, that a lot of patients don’t need interventions. They want reassurance that their toes aren’t going to fall off, that nothing terrible is going to happen to them, and often that’s enough. So far, many patients have contacted us just because they heard about the link between what they were seeing on their feet and COVID. They were likely toward the end of any other symptoms they may have had. But moving forward, I think we’re going to be seeing patients at the more active stage as the public is more aware of this finding.

Most of the time we can manage with clobetasol ointment and low-dose aspirin. I wouldn’t give aspirin to a young child with a high fever, but otherwise I think aspirin is not harmful. A paper published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings in 2014, before COVID, by Jonathan Cappel, MD, and David Wetter, MD, provides a nice therapeutic algorithm. Assuming that the findings we are seeing now are inflammatory, then I think that algorithm should apply. Nifedipine 20-60 mg/day is an option. Hydroxychloroquine, a maximum of 5 mg/kg per day, is an option. I have used hydroxychloroquine most commonly, pre-COVID, in patients who have symptomatic pernio.

I also use pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day, which has a slight anti-inflammatory effect, when I think a blood vessel is incidentally involved or the patient has a predisposition to clotting. Nicotinamide 500 mg three times a day can be used, though I have not used it.

Some topical options are nitroglycerin, tacrolimus, and minoxidil.

However, during this post-COVID period, I have not come across many with pseudo-pernio who needed anything more than a topical steroid and some aspirin. But I do know of other physicians who have been taking care of patients with much more symptomatic disease.

Dr. Lipper: That is a comprehensive list. You’ve mentioned some options that I’ve wondered about, especially pentoxifylline, which I have found to be very helpful for livedoid vasculopathy. I should note that these are all off-label uses.

Let’s talk about some other suspected skin manifestations of COVID. A prospective nationwide study in Spain of 375 patients reported on a number of different skin manifestations of COVID.

You’re part of a team doing critically important work with the American Academy of Dermatology COVID-19 Dermatology Registry. I know it’s early going, but what are some of the other common skin presentations you’re finding?

Dr. Fox: I’m glad you brought up that paper out of Spain. I think it is really good and does highlight the difference in acute versus convalescent cutaneous manifestations and prognosis. It confirms what we’re seeing. Retiform purpura is an early finding associated with ill patients in the hospital. Pseudo pernio-like lesions tend to be later-stage and in younger, healthier patients.

Interestingly, the vesicular eruption that those investigators describe – monomorphic vesicles on the trunk and extremity – can occur in the more acute phase. That’s fascinating to me because widespread vesicular eruptions are not a thing that we commonly see. If it is not an autoimmune blistering disease, and not a drug-induced blistering process, then you’re really left with viral. Rickettsialpox can do that, as can primary varicella, disseminated herpes, disseminated zoster, and now COVID. So that’s intriguing.

I got called to see a patient yesterday who had symptoms of COVID about a month ago. She was not PCR tested at the time but she is now negative. She has a widespread eruption of tiny vesicles on an erythematous base. An IgG for COVID is positive. How do we decide whether her skin lesions have active virus in them?

The many dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19

Dr. Lipper: In the series in Spain, almost 1 out of 10 patients were found to have a widespread vesicular rash. And just under half had maculopapular exanthems. The information arising from the AAD registry will be of great interest and build on this paper.

In England, the National Health Service and the Paediatric Intensive Care Society recently put out a warning about an alarming number of children with COVID-19 who developed symptoms mimicking Kawasaki disease (high fever, abdominal pain, rash, swollen lymph nodes, mucositis, and conjunctivitis). These kids have systemic inflammation and vasculitis and are critically ill. That was followed by an alert from the New York City Health Department about cases there, which as of May 6 numbered 64. Another 25 children with similar findings have been identified in France.

This is such a scary development, especially because children were supposed to be relatively “safe” from this virus. Any thoughts on who is at risk or why?

Dr. Fox: It’s very alarming. It appears that these cases look just like Kawasaki disease.

It was once hypothesized that Coronaviridae was the cause of Kawasaki disease. Then that got debunked. But these cases now raise the question of whether Kawasaki disease may be virally mediated. Is it an immune reaction to an infectious trigger? Is it actually Coronaviridae that triggers it?

As with these pernio cases, I think we’re going to learn about the pathophysiology of these diseases that we currently look at as secondary responses or immune reactions to unknown triggers. We’re going to learn a lot about them and about the immune system because of how this virus is acting on the immune system.

Dr. Lipper: As is the case with patients with pernio-like lesions, some of these children with Kawasaki-like disease are PCR negative for SARS-CoV-2. It will be interesting to see what happens with antibody testing in this population.

Dr. Fox: Agree. While some of the manufacturers of serology tests have claimed that they have very high sensitivity and specificity, that has not been my experience.

Dr. Lipper: I’ve had a number of patients with a clinical picture that strongly suggests COVID whose serology tests have been negative.

Dr. Fox: As have I. While this could be the result of faulty tests, my biggest worry is that it means that people with mild disease do not mount an antibody response. And if people who have disease can’t make antibodies, then there’s no herd immunity. If there’s no herd immunity, we’re stuck in lockdown until there’s a vaccine.

Dr. Lipper: That is a scary but real possibility. We need evidence – evidence like that provided by the AAD registry.

Dr. Fox: Agree. I look forward to sharing those results with you when we have them.

Dr. Lipper is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington, and a partner at Advanced DermCare in Danbury, Conn.

Dr. Fox is a professor in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. She is a hospital-based dermatologist who specializes in the care of patients with complex skin conditions. She is immediate past president of the Medical Dermatology Society and current president of the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists.

This article was first published on Medscape.com.

The dermatologic manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 are many and varied, with new information virtually daily. Graeme Lipper, MD, a member of the Medscape Dermatology advisory board, discussed what we know and what is still to be learned with Lindy Fox, MD, a professor of dermatology at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry task force.

Graeme M. Lipper, MD

Earlier this spring, before there was any real talk about skin manifestations of COVID, my partner called me in to see an unusual case. His patient was a healthy 20-year-old who had just come back from college and had tender, purple discoloration and swelling on his toes. I shrugged and said “looks like chilblains,” but there was something weird about the case. It seemed more severe, with areas of blistering and erosions, and the discomfort was unusual for run-of-the-mill pernio. This young man had experienced a cough and shortness of breath a few weeks earlier but those symptoms had resolved when we saw him.

That evening, I was on a derm social media site and saw a series of pictures from Italy that blew me away. All of these pictures looked just like this kid’s toes. That’s the first I heard of “COVID toes,” but now they seem to be everywhere. How would you describe this presentation, and how does it differ from typical chilblains?

Lindy P. Fox, MD

I am so proud of dermatologists around the world who have really jumped into action to examine the pathophysiology and immunology behind these findings.

Your experience matches mine. Like you, I first heard about these pernio- or chilblains-like lesions when Europe was experiencing its surge in cases. And while it does indeed look like chilblains, I think the reality is that it is more severe and symptomatic than we would expect. I think your observation is exactly right. There are certainly clinicians who do not believe that this is an association with COVID-19 because the testing is often negative. But to my mind, there are just too many cases at the wrong time of year, all happening concomitantly, and simultaneous with a new virus for me to accept that they are not somehow related.

Dr. Lipper: Some have referred to this as “quarantine toes,” the result of more people at home and walking around barefoot. That doesn’t seem to make a whole lot of sense because it’s happening in both warm and cold climates.

Others have speculated that there is another, unrelated circulating virus causing these pernio cases, but that seems far-fetched.

But the idea of a reporting bias – more patients paying attention to these lesions because they’ve read something in the mass media or seen a report on television and are concerned, and thus present with mild lesions they might otherwise have ignored – may be contributing somewhat. But even that cannot be the sole reason behind the increase.

Dr. Fox: Agree.

Evaluation of the patient with chilblains – then and now

Dr. Lipper: In the past, how did you perform a workup for someone with chilblains?

Dr. Fox: Pre-COVID – and I think we all have divided our world into pre- and post-COVID – the most common thing that I’d be looking for would be a clotting disorder or an autoimmune disease, typically lupus. So I take a good history, review of systems, and look at the skin for signs of lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue diseases. My lab workup is probably limited to an antinuclear antibody (ANA). If the findings are severe and recurrent, I might check for hypercoagulability with an antiphospholipid antibody panel. But that was usually it unless there was something in the history or physical exam that would lead me to look for something less common – for example, cryoglobulins or an underlying hematologic disease that would lead to a predominance of lesions in acral sites.

My approach was the same. In New England, where I practice, I also always look at environmental factors. We would sometimes see chilblains in someone from a warmer climate who came home to the Northeast to ski.

Dr. Lipper: Now, in the post-COVID world, how do you assess these patients? What has changed?

Dr. Fox: That’s a great question. To be frank, our focus now is on not missing a secondary consequence of COVID infection that we might not have picked up before. I’m the first to admit that the workup that we have been doing at UCSF is extremely comprehensive. We may be ordering tests that don’t need to be done. But until we know better what might and might not be affected by COVID, we don’t actually have a sense of whether they’re worth looking for or not.

Right now, my workup includes nasal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for COVID, as well as IgG and IgM serology if available. We have IgG easily available to us. IgM needs approval; at UCSF, it is primarily done in neonates as of now. I also do a workup for autoimmunity and cold-associated disease, which includes an ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulin, and cold agglutinins.

Because of reported concerns about hypercoagulability in COVID patients, particularly in those who are doing poorly in the hospital, we look for elevations in d-dimers and fibrinogen. We check antiphospholipid antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. That is probably too much of a workup for the healthy young person, but as of yet, we are just unable to say that those things are universally normal.

There has also been concern that complement may be involved in patients who do poorly and tend to clot a lot. So we are also checking C3, C4, and CH50.

To date, in my patients who have had this workup, I have found one with a positive ANA that was significant (1:320) who also had low complements.

There have been a couple of patients at my institution, not my own patients, who are otherwise fine but have some slight elevation in d-dimers.

Dr. Lipper: Is COVID toes more than one condition?

Some of the initial reports of finger/toe cyanosis out of China were very alarming, with many patients developing skin necrosis or even gangrene. These were critically ill adults with pneumonia and blood markers of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and five out of seven died. In contrast, the cases of pseudo-pernio reported in Europe, and now the United States, seem to be much milder, usually occurring late in the illness or in asymptomatic young people. Do you think these are two different conditions?

Dr. Fox: I believe you have hit the nail on the head. I think it is really important that we don’t confuse those two things. In the inpatient setting, we are clearly seeing patients with a prothrombotic state with associated retiform purpura. For nondermatologists, that usually means star-like, stellate-like, or even lacy purpuric changes with potential for necrosis of the skin. In hospitalized patients, the fingers and toes are usually affected but, interestingly, also the buttocks. When these lesions are biopsied, as has been done by our colleague at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, Joanna Harp, MD, we tend to find thrombosis.

A study of endothelial cell function in patients with COVID-19, published in the Lancet tried to determine whether viral particles could be found in endothelial cells. And the investigators did indeed find these particles. So it appears that the virus is endothelially active, and this might provide some insight into the thromboses seen in hospitalized patients. These patients can develop purple necrotic toes that may progress to gangrene. But that is completely different from what we’re seeing when we say pernio-like or chilblains-like lesions.

The chilblains-like lesions come in several forms. They may be purple, red bumps, often involving the tops of the toes and sometimes the bottom of the feet. Some have been described as target-like or erythema multiforme–like. In others, there may not be individual discrete lesions but rather a redness or bluish, purplish discoloration accompanied by edema of the entire toe or several toes.

Biopsies that I am aware of have identified features consistent with an inflammatory process, all of which can be seen in a typical biopsy of pernio. You can sometimes see lymphocytes surrounding a vessel (called lymphocytic vasculitis) that may damage a vessel and cause a small clot, but the primary process is an inflammatory rather than thrombotic one. You may get a clot in a little tiny vessel secondary to inflammation, and that may lead to some blisters or little areas of necrosis. But you’re not going to see digital necrosis and gangrene. I think that’s an important distinction.

The patients who get the pernio-like lesions are typically children or young adults and are otherwise healthy. Half of them didn’t even have COVID symptoms. If they did have COVID symptoms they were typically mild. So we think the pernio-like lesions are most often occurring in the late stage of the disease and now represent a secondary inflammatory response.

Managing COVID toes

Dr. Lipper: One question I’ve been struggling with is, what do we tell these otherwise healthy patients with purple toes, especially those with no other symptoms? Many of them are testing SARS-CoV-2 negative, both with viral swabs and serologies. Some have suggestive histories like known COVID exposure, recent cough, or travel to high-risk areas. Do we tell them they’re at risk of transmitting the virus? Should they self-quarantine, and for how long? Is there any consensus emerging?

Dr. Fox: This is a good opportunity to plug the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry, which is run by Esther Freeman, MD, at Massachusetts General Hospital. She has done a phenomenal job in helping us figure out the answers to these exact questions.

I’d encourage any clinicians who have a suspected COVID patient with a skin finding, whether or not infection is confirmed with testing, to enter information about that patient into the registry. That is the only way we will figure out evidence-based answers to a lot of the questions that we’re talking about today.

Based on working with the registry, we know that, rarely, patients who develop pernio-like changes will do so before they get COVID symptoms or at the same time as more typical symptoms. Some patients with these findings are PCR positive, and it is therefore theoretically possible that you could be shedding virus while you’re having the pernio toes. However, more commonly – and this is the experience of most of my colleagues and what we’re seeing at UCSF – pernio is a later finding and most patients are no longer shedding the virus. It appears that pseudo-pernio is an immune reaction and most people are not actively infectious at that point.

The only way to know for sure is to send patients for both PCR testing and antibody testing. If the PCR is negative, the most likely interpretation is that the person is no longer shedding virus, though there can be some false negatives. Therefore, these patients do not need to isolate outside of what I call their COVID pod – family or roommates who have probably been with them the whole time. Any transmission likely would have already occurred.

I tell people who call me concerned about their toes that I do think they should be given a workup for COVID. However, I reassure them that it is usually a good prognostic sign.

What is puzzling is that even in patients with pseudo-chilblains who have a clinical history consistent with COVID or exposure to a COVID-positive family member, antibody testing is often – in fact, most often – negative. There are many hypotheses as to why this is. Maybe the tests just aren’t good. Maybe people with mild disease don’t generate enough antibodies to be detected, Maybe we’re testing at the wrong time. Those are all things that we’re trying to figure out.

But currently, I tell patients that they do not need to strictly isolate. They should still practice social distancing, wear a mask, practice good hand hygiene, and do all of the careful things that we should all be doing. However, they can live within their home environment and be reassured that most likely they are in the convalescent stage.

Dr. Lipper: I find the antibody issue both fascinating and confusing.

In my practice, we’ve noticed a range of symptoms associated with pseudo-pernio. Some people barely realize it’s there and only called because they saw a headline in the news. Others complain of severe burning, throbbing, or itching that keeps them up at night and can sometimes last for weeks. Are there any treatments that seem to help?

Dr. Fox: We can start by saying, as you note, that a lot of patients don’t need interventions. They want reassurance that their toes aren’t going to fall off, that nothing terrible is going to happen to them, and often that’s enough. So far, many patients have contacted us just because they heard about the link between what they were seeing on their feet and COVID. They were likely toward the end of any other symptoms they may have had. But moving forward, I think we’re going to be seeing patients at the more active stage as the public is more aware of this finding.

Most of the time we can manage with clobetasol ointment and low-dose aspirin. I wouldn’t give aspirin to a young child with a high fever, but otherwise I think aspirin is not harmful. A paper published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings in 2014, before COVID, by Jonathan Cappel, MD, and David Wetter, MD, provides a nice therapeutic algorithm. Assuming that the findings we are seeing now are inflammatory, then I think that algorithm should apply. Nifedipine 20-60 mg/day is an option. Hydroxychloroquine, a maximum of 5 mg/kg per day, is an option. I have used hydroxychloroquine most commonly, pre-COVID, in patients who have symptomatic pernio.

I also use pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day, which has a slight anti-inflammatory effect, when I think a blood vessel is incidentally involved or the patient has a predisposition to clotting. Nicotinamide 500 mg three times a day can be used, though I have not used it.

Some topical options are nitroglycerin, tacrolimus, and minoxidil.

However, during this post-COVID period, I have not come across many with pseudo-pernio who needed anything more than a topical steroid and some aspirin. But I do know of other physicians who have been taking care of patients with much more symptomatic disease.

Dr. Lipper: That is a comprehensive list. You’ve mentioned some options that I’ve wondered about, especially pentoxifylline, which I have found to be very helpful for livedoid vasculopathy. I should note that these are all off-label uses.

Let’s talk about some other suspected skin manifestations of COVID. A prospective nationwide study in Spain of 375 patients reported on a number of different skin manifestations of COVID.

You’re part of a team doing critically important work with the American Academy of Dermatology COVID-19 Dermatology Registry. I know it’s early going, but what are some of the other common skin presentations you’re finding?

Dr. Fox: I’m glad you brought up that paper out of Spain. I think it is really good and does highlight the difference in acute versus convalescent cutaneous manifestations and prognosis. It confirms what we’re seeing. Retiform purpura is an early finding associated with ill patients in the hospital. Pseudo pernio-like lesions tend to be later-stage and in younger, healthier patients.

Interestingly, the vesicular eruption that those investigators describe – monomorphic vesicles on the trunk and extremity – can occur in the more acute phase. That’s fascinating to me because widespread vesicular eruptions are not a thing that we commonly see. If it is not an autoimmune blistering disease, and not a drug-induced blistering process, then you’re really left with viral. Rickettsialpox can do that, as can primary varicella, disseminated herpes, disseminated zoster, and now COVID. So that’s intriguing.

I got called to see a patient yesterday who had symptoms of COVID about a month ago. She was not PCR tested at the time but she is now negative. She has a widespread eruption of tiny vesicles on an erythematous base. An IgG for COVID is positive. How do we decide whether her skin lesions have active virus in them?

The many dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19

Dr. Lipper: In the series in Spain, almost 1 out of 10 patients were found to have a widespread vesicular rash. And just under half had maculopapular exanthems. The information arising from the AAD registry will be of great interest and build on this paper.

In England, the National Health Service and the Paediatric Intensive Care Society recently put out a warning about an alarming number of children with COVID-19 who developed symptoms mimicking Kawasaki disease (high fever, abdominal pain, rash, swollen lymph nodes, mucositis, and conjunctivitis). These kids have systemic inflammation and vasculitis and are critically ill. That was followed by an alert from the New York City Health Department about cases there, which as of May 6 numbered 64. Another 25 children with similar findings have been identified in France.

This is such a scary development, especially because children were supposed to be relatively “safe” from this virus. Any thoughts on who is at risk or why?

Dr. Fox: It’s very alarming. It appears that these cases look just like Kawasaki disease.

It was once hypothesized that Coronaviridae was the cause of Kawasaki disease. Then that got debunked. But these cases now raise the question of whether Kawasaki disease may be virally mediated. Is it an immune reaction to an infectious trigger? Is it actually Coronaviridae that triggers it?

As with these pernio cases, I think we’re going to learn about the pathophysiology of these diseases that we currently look at as secondary responses or immune reactions to unknown triggers. We’re going to learn a lot about them and about the immune system because of how this virus is acting on the immune system.

Dr. Lipper: As is the case with patients with pernio-like lesions, some of these children with Kawasaki-like disease are PCR negative for SARS-CoV-2. It will be interesting to see what happens with antibody testing in this population.

Dr. Fox: Agree. While some of the manufacturers of serology tests have claimed that they have very high sensitivity and specificity, that has not been my experience.

Dr. Lipper: I’ve had a number of patients with a clinical picture that strongly suggests COVID whose serology tests have been negative.

Dr. Fox: As have I. While this could be the result of faulty tests, my biggest worry is that it means that people with mild disease do not mount an antibody response. And if people who have disease can’t make antibodies, then there’s no herd immunity. If there’s no herd immunity, we’re stuck in lockdown until there’s a vaccine.

Dr. Lipper: That is a scary but real possibility. We need evidence – evidence like that provided by the AAD registry.

Dr. Fox: Agree. I look forward to sharing those results with you when we have them.

Dr. Lipper is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington, and a partner at Advanced DermCare in Danbury, Conn.

Dr. Fox is a professor in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. She is a hospital-based dermatologist who specializes in the care of patients with complex skin conditions. She is immediate past president of the Medical Dermatology Society and current president of the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists.

This article was first published on Medscape.com.

The dermatologic manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 are many and varied, with new information virtually daily. Graeme Lipper, MD, a member of the Medscape Dermatology advisory board, discussed what we know and what is still to be learned with Lindy Fox, MD, a professor of dermatology at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry task force.

Graeme M. Lipper, MD

Earlier this spring, before there was any real talk about skin manifestations of COVID, my partner called me in to see an unusual case. His patient was a healthy 20-year-old who had just come back from college and had tender, purple discoloration and swelling on his toes. I shrugged and said “looks like chilblains,” but there was something weird about the case. It seemed more severe, with areas of blistering and erosions, and the discomfort was unusual for run-of-the-mill pernio. This young man had experienced a cough and shortness of breath a few weeks earlier but those symptoms had resolved when we saw him.

That evening, I was on a derm social media site and saw a series of pictures from Italy that blew me away. All of these pictures looked just like this kid’s toes. That’s the first I heard of “COVID toes,” but now they seem to be everywhere. How would you describe this presentation, and how does it differ from typical chilblains?

Lindy P. Fox, MD

I am so proud of dermatologists around the world who have really jumped into action to examine the pathophysiology and immunology behind these findings.

Your experience matches mine. Like you, I first heard about these pernio- or chilblains-like lesions when Europe was experiencing its surge in cases. And while it does indeed look like chilblains, I think the reality is that it is more severe and symptomatic than we would expect. I think your observation is exactly right. There are certainly clinicians who do not believe that this is an association with COVID-19 because the testing is often negative. But to my mind, there are just too many cases at the wrong time of year, all happening concomitantly, and simultaneous with a new virus for me to accept that they are not somehow related.

Dr. Lipper: Some have referred to this as “quarantine toes,” the result of more people at home and walking around barefoot. That doesn’t seem to make a whole lot of sense because it’s happening in both warm and cold climates.

Others have speculated that there is another, unrelated circulating virus causing these pernio cases, but that seems far-fetched.

But the idea of a reporting bias – more patients paying attention to these lesions because they’ve read something in the mass media or seen a report on television and are concerned, and thus present with mild lesions they might otherwise have ignored – may be contributing somewhat. But even that cannot be the sole reason behind the increase.

Dr. Fox: Agree.

Evaluation of the patient with chilblains – then and now

Dr. Lipper: In the past, how did you perform a workup for someone with chilblains?

Dr. Fox: Pre-COVID – and I think we all have divided our world into pre- and post-COVID – the most common thing that I’d be looking for would be a clotting disorder or an autoimmune disease, typically lupus. So I take a good history, review of systems, and look at the skin for signs of lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue diseases. My lab workup is probably limited to an antinuclear antibody (ANA). If the findings are severe and recurrent, I might check for hypercoagulability with an antiphospholipid antibody panel. But that was usually it unless there was something in the history or physical exam that would lead me to look for something less common – for example, cryoglobulins or an underlying hematologic disease that would lead to a predominance of lesions in acral sites.

My approach was the same. In New England, where I practice, I also always look at environmental factors. We would sometimes see chilblains in someone from a warmer climate who came home to the Northeast to ski.

Dr. Lipper: Now, in the post-COVID world, how do you assess these patients? What has changed?

Dr. Fox: That’s a great question. To be frank, our focus now is on not missing a secondary consequence of COVID infection that we might not have picked up before. I’m the first to admit that the workup that we have been doing at UCSF is extremely comprehensive. We may be ordering tests that don’t need to be done. But until we know better what might and might not be affected by COVID, we don’t actually have a sense of whether they’re worth looking for or not.

Right now, my workup includes nasal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for COVID, as well as IgG and IgM serology if available. We have IgG easily available to us. IgM needs approval; at UCSF, it is primarily done in neonates as of now. I also do a workup for autoimmunity and cold-associated disease, which includes an ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulin, and cold agglutinins.

Because of reported concerns about hypercoagulability in COVID patients, particularly in those who are doing poorly in the hospital, we look for elevations in d-dimers and fibrinogen. We check antiphospholipid antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. That is probably too much of a workup for the healthy young person, but as of yet, we are just unable to say that those things are universally normal.

There has also been concern that complement may be involved in patients who do poorly and tend to clot a lot. So we are also checking C3, C4, and CH50.

To date, in my patients who have had this workup, I have found one with a positive ANA that was significant (1:320) who also had low complements.

There have been a couple of patients at my institution, not my own patients, who are otherwise fine but have some slight elevation in d-dimers.

Dr. Lipper: Is COVID toes more than one condition?

Some of the initial reports of finger/toe cyanosis out of China were very alarming, with many patients developing skin necrosis or even gangrene. These were critically ill adults with pneumonia and blood markers of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and five out of seven died. In contrast, the cases of pseudo-pernio reported in Europe, and now the United States, seem to be much milder, usually occurring late in the illness or in asymptomatic young people. Do you think these are two different conditions?

Dr. Fox: I believe you have hit the nail on the head. I think it is really important that we don’t confuse those two things. In the inpatient setting, we are clearly seeing patients with a prothrombotic state with associated retiform purpura. For nondermatologists, that usually means star-like, stellate-like, or even lacy purpuric changes with potential for necrosis of the skin. In hospitalized patients, the fingers and toes are usually affected but, interestingly, also the buttocks. When these lesions are biopsied, as has been done by our colleague at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, Joanna Harp, MD, we tend to find thrombosis.

A study of endothelial cell function in patients with COVID-19, published in the Lancet tried to determine whether viral particles could be found in endothelial cells. And the investigators did indeed find these particles. So it appears that the virus is endothelially active, and this might provide some insight into the thromboses seen in hospitalized patients. These patients can develop purple necrotic toes that may progress to gangrene. But that is completely different from what we’re seeing when we say pernio-like or chilblains-like lesions.

The chilblains-like lesions come in several forms. They may be purple, red bumps, often involving the tops of the toes and sometimes the bottom of the feet. Some have been described as target-like or erythema multiforme–like. In others, there may not be individual discrete lesions but rather a redness or bluish, purplish discoloration accompanied by edema of the entire toe or several toes.