User login

One-fifth of stem cell transplantation patients develop PTSD

Approximately one-fifth of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), based on a retrospective analysis.

Patient factors at time of transplantation, such as low quality of life and high anxiety, predicted PTSD 6 months later, reported lead author Sarah Griffith, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who presented findings as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program.

“We know that patients admitted for HSCT are often isolated in the hospital for a prolonged period of time, usually about 3-4 weeks, and that they endure substantial toxicities that impact both their physical and psychological well-being,” Dr. Griffith said. “We also know from the literature that HSCT can be considered a traumatic event and that it may lead to clinically significant PTSD symptoms.” But studies evaluating the prevalence and characteristics of PTSD in this patient population have been lacking, she noted.

Dr. Griffith and her colleagues therefore conducted a retrospective analysis involving 250 adults with hematologic malignancies who underwent autologous or allogeneic HSCT during clinical trials conducted from 2014 to 2016. Median patient age was 56 years.

The first objective of the study was to measure the prevalence of PTSD. The second was to characterize features of PTSD such as intrusion, which entails reliving experiences in the form of nightmares or flashbacks, and hypervigilance, which encompasses insomnia, irritability, and hyperarousal for threat. The third objective was to determine risk factors at baseline.

At time of admission for HSCT, after 2 weeks of hospitalization, and again 6 months after transplantation, patients were evaluated using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which measured of quality of life, anxiety, and depression. Six months after HSCT, patients also underwent screening for PTSD with the Post-Traumatic Stress Checklist (PTSD-CL). Multivariate regression models were used to determine predictive risk factors.

Six months after HSCT, 18.9% of patients had clinically significant PTSD symptoms; most common were symptoms of avoidance (92.3%), hypervigilance (92.3%), and intrusion (76.9%). Among those who did not have clinically significant PTSD, almost one-quarter (24.5%) demonstrated significant hypervigilance, while 13.7% showed symptoms of avoidance.

“Clinically significant PTSD symptoms are common in the transplant population,” Dr. Griffith said.

Baseline predictors of PTSD included single status and lower quality of life. More severe PTSD was predicted by single status, younger age, higher baseline scores for anxiety or depression, and increased anxiety during hospitalization.

Concluding her presentation, Dr. Griffith said that the findings, while correlative and not causative, should prompt concern and intervention.

“It is very important to be aware of and to manage PTSD symptoms in these patients,” she said. “There are several baseline factors that can be identified prior to HSCT that may illuminate patients at risk for developing worse PTSD symptoms down the road, and these patients may benefit from tailored supportive care interventions.”

Specifically, Dr. Griffith recommended integrating palliative care into hospitalization, as this has been shown to reduce anxiety.

In a virtual presentation, invited discussant Nirali N. Shah, MD, of the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md., highlighted the importance of the findings, while also noting that the impact of palliative care on risk of PTSD has yet to be demonstrated.

Dr. Shah suggested that future research may be improved through use of a formal diagnosis for PTSD, instead of a PTSD checklist, as was used in the present study.

“And certainly long-term follow-up would be important to evaluate the utility of this tool looking at symptoms beyond 6 months,” she said.

Dr. Shah went on to discuss the relevance of the findings for pediatric populations, as children may face unique risk factors and consequences related to PTSD.

“[PTSD in children] may be impacted by family dynamics and structure,” Dr. Shah said. “Children may also have significant neurocognitive implications as a result of their underlying disease or prior therapy. They may experience chronic pain as they go out into adulthood and long-term survivorship, and may also struggle with symptoms of anxiety and depression.”

According to Dr. Shah, one previous study involving more than 6,000 adult survivors of childhood cancer found that PTSD was relatively common, with prevalence rate of 9%, suggesting that interventional work is necessary.

“Applying the data in the study from Griffith et al. suggests that evaluation in the more proximal posttransplant period for children is needed to specifically evaluate PTSD and symptoms thereof, and to try to use this to identify an opportunity for intervention,” Dr. Shah said.

“Pediatric-specific assessments are essential to optimally capture disease and/or age-specific considerations,” she added.

The study was funded by the Lymphoma and Leukemia Society. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Vector Oncology, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Gaido Health/BCG Digital Ventures.

SOURCE: Griffith et al. ASCO 2020. Abstract # 7505.

Approximately one-fifth of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), based on a retrospective analysis.

Patient factors at time of transplantation, such as low quality of life and high anxiety, predicted PTSD 6 months later, reported lead author Sarah Griffith, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who presented findings as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program.

“We know that patients admitted for HSCT are often isolated in the hospital for a prolonged period of time, usually about 3-4 weeks, and that they endure substantial toxicities that impact both their physical and psychological well-being,” Dr. Griffith said. “We also know from the literature that HSCT can be considered a traumatic event and that it may lead to clinically significant PTSD symptoms.” But studies evaluating the prevalence and characteristics of PTSD in this patient population have been lacking, she noted.

Dr. Griffith and her colleagues therefore conducted a retrospective analysis involving 250 adults with hematologic malignancies who underwent autologous or allogeneic HSCT during clinical trials conducted from 2014 to 2016. Median patient age was 56 years.

The first objective of the study was to measure the prevalence of PTSD. The second was to characterize features of PTSD such as intrusion, which entails reliving experiences in the form of nightmares or flashbacks, and hypervigilance, which encompasses insomnia, irritability, and hyperarousal for threat. The third objective was to determine risk factors at baseline.

At time of admission for HSCT, after 2 weeks of hospitalization, and again 6 months after transplantation, patients were evaluated using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which measured of quality of life, anxiety, and depression. Six months after HSCT, patients also underwent screening for PTSD with the Post-Traumatic Stress Checklist (PTSD-CL). Multivariate regression models were used to determine predictive risk factors.

Six months after HSCT, 18.9% of patients had clinically significant PTSD symptoms; most common were symptoms of avoidance (92.3%), hypervigilance (92.3%), and intrusion (76.9%). Among those who did not have clinically significant PTSD, almost one-quarter (24.5%) demonstrated significant hypervigilance, while 13.7% showed symptoms of avoidance.

“Clinically significant PTSD symptoms are common in the transplant population,” Dr. Griffith said.

Baseline predictors of PTSD included single status and lower quality of life. More severe PTSD was predicted by single status, younger age, higher baseline scores for anxiety or depression, and increased anxiety during hospitalization.

Concluding her presentation, Dr. Griffith said that the findings, while correlative and not causative, should prompt concern and intervention.

“It is very important to be aware of and to manage PTSD symptoms in these patients,” she said. “There are several baseline factors that can be identified prior to HSCT that may illuminate patients at risk for developing worse PTSD symptoms down the road, and these patients may benefit from tailored supportive care interventions.”

Specifically, Dr. Griffith recommended integrating palliative care into hospitalization, as this has been shown to reduce anxiety.

In a virtual presentation, invited discussant Nirali N. Shah, MD, of the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md., highlighted the importance of the findings, while also noting that the impact of palliative care on risk of PTSD has yet to be demonstrated.

Dr. Shah suggested that future research may be improved through use of a formal diagnosis for PTSD, instead of a PTSD checklist, as was used in the present study.

“And certainly long-term follow-up would be important to evaluate the utility of this tool looking at symptoms beyond 6 months,” she said.

Dr. Shah went on to discuss the relevance of the findings for pediatric populations, as children may face unique risk factors and consequences related to PTSD.

“[PTSD in children] may be impacted by family dynamics and structure,” Dr. Shah said. “Children may also have significant neurocognitive implications as a result of their underlying disease or prior therapy. They may experience chronic pain as they go out into adulthood and long-term survivorship, and may also struggle with symptoms of anxiety and depression.”

According to Dr. Shah, one previous study involving more than 6,000 adult survivors of childhood cancer found that PTSD was relatively common, with prevalence rate of 9%, suggesting that interventional work is necessary.

“Applying the data in the study from Griffith et al. suggests that evaluation in the more proximal posttransplant period for children is needed to specifically evaluate PTSD and symptoms thereof, and to try to use this to identify an opportunity for intervention,” Dr. Shah said.

“Pediatric-specific assessments are essential to optimally capture disease and/or age-specific considerations,” she added.

The study was funded by the Lymphoma and Leukemia Society. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Vector Oncology, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Gaido Health/BCG Digital Ventures.

SOURCE: Griffith et al. ASCO 2020. Abstract # 7505.

Approximately one-fifth of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), based on a retrospective analysis.

Patient factors at time of transplantation, such as low quality of life and high anxiety, predicted PTSD 6 months later, reported lead author Sarah Griffith, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who presented findings as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program.

“We know that patients admitted for HSCT are often isolated in the hospital for a prolonged period of time, usually about 3-4 weeks, and that they endure substantial toxicities that impact both their physical and psychological well-being,” Dr. Griffith said. “We also know from the literature that HSCT can be considered a traumatic event and that it may lead to clinically significant PTSD symptoms.” But studies evaluating the prevalence and characteristics of PTSD in this patient population have been lacking, she noted.

Dr. Griffith and her colleagues therefore conducted a retrospective analysis involving 250 adults with hematologic malignancies who underwent autologous or allogeneic HSCT during clinical trials conducted from 2014 to 2016. Median patient age was 56 years.

The first objective of the study was to measure the prevalence of PTSD. The second was to characterize features of PTSD such as intrusion, which entails reliving experiences in the form of nightmares or flashbacks, and hypervigilance, which encompasses insomnia, irritability, and hyperarousal for threat. The third objective was to determine risk factors at baseline.

At time of admission for HSCT, after 2 weeks of hospitalization, and again 6 months after transplantation, patients were evaluated using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which measured of quality of life, anxiety, and depression. Six months after HSCT, patients also underwent screening for PTSD with the Post-Traumatic Stress Checklist (PTSD-CL). Multivariate regression models were used to determine predictive risk factors.

Six months after HSCT, 18.9% of patients had clinically significant PTSD symptoms; most common were symptoms of avoidance (92.3%), hypervigilance (92.3%), and intrusion (76.9%). Among those who did not have clinically significant PTSD, almost one-quarter (24.5%) demonstrated significant hypervigilance, while 13.7% showed symptoms of avoidance.

“Clinically significant PTSD symptoms are common in the transplant population,” Dr. Griffith said.

Baseline predictors of PTSD included single status and lower quality of life. More severe PTSD was predicted by single status, younger age, higher baseline scores for anxiety or depression, and increased anxiety during hospitalization.

Concluding her presentation, Dr. Griffith said that the findings, while correlative and not causative, should prompt concern and intervention.

“It is very important to be aware of and to manage PTSD symptoms in these patients,” she said. “There are several baseline factors that can be identified prior to HSCT that may illuminate patients at risk for developing worse PTSD symptoms down the road, and these patients may benefit from tailored supportive care interventions.”

Specifically, Dr. Griffith recommended integrating palliative care into hospitalization, as this has been shown to reduce anxiety.

In a virtual presentation, invited discussant Nirali N. Shah, MD, of the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md., highlighted the importance of the findings, while also noting that the impact of palliative care on risk of PTSD has yet to be demonstrated.

Dr. Shah suggested that future research may be improved through use of a formal diagnosis for PTSD, instead of a PTSD checklist, as was used in the present study.

“And certainly long-term follow-up would be important to evaluate the utility of this tool looking at symptoms beyond 6 months,” she said.

Dr. Shah went on to discuss the relevance of the findings for pediatric populations, as children may face unique risk factors and consequences related to PTSD.

“[PTSD in children] may be impacted by family dynamics and structure,” Dr. Shah said. “Children may also have significant neurocognitive implications as a result of their underlying disease or prior therapy. They may experience chronic pain as they go out into adulthood and long-term survivorship, and may also struggle with symptoms of anxiety and depression.”

According to Dr. Shah, one previous study involving more than 6,000 adult survivors of childhood cancer found that PTSD was relatively common, with prevalence rate of 9%, suggesting that interventional work is necessary.

“Applying the data in the study from Griffith et al. suggests that evaluation in the more proximal posttransplant period for children is needed to specifically evaluate PTSD and symptoms thereof, and to try to use this to identify an opportunity for intervention,” Dr. Shah said.

“Pediatric-specific assessments are essential to optimally capture disease and/or age-specific considerations,” she added.

The study was funded by the Lymphoma and Leukemia Society. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Vector Oncology, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Gaido Health/BCG Digital Ventures.

SOURCE: Griffith et al. ASCO 2020. Abstract # 7505.

FROM ASCO 2020

Daily Recap: Avoid alcohol to reduce cancer risk, COVID’s lasting health system impact

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

ACS Update: ‘It is best not to drink alcohol’

The American Cancer Society (ACS) is taking its strongest stance yet against drinking. In its updated cancer prevention guidelines, the ACS now recommends that “it is best not to drink alcohol.” Previously, the organizations had suggested that, for those who consume alcoholic beverages, intake should be no more than one drink per day for women or two per day for men. That recommendation is still in place, but is now accompanied by this new, stronger directive. The guidelines also place more emphasis on reducing the consumption of processed and red meat and highly processed foods, and on increasing physical activity. “Individual choice is an important part of a healthy lifestyle, but having the right policies and environmental factors to break down these barriers is also important, and that is something that clinicians can support,” said Laura Makaroff, DO, American Cancer Society senior vice president. The guidelines were published in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. Read more.

COVID health system changes may be here to stay

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced sudden major changes to the nation’s health care system that are unlikely to be reversed. While there’s some good news, there are also some alarming trends. Experts said there are three trends that are likely to stick around: telehealth for all, an exodus of primary care physicians, and less emphasis on hospital care. “I’ve been trying to raise the alarm about the kind of perilous future of primary care,” said Farzad Mostashari, MD, a top Department of Health & Human Services official in the Obama administration. Dr. Mostashari runs Aledade, a company that helps primary care doctors make the transition from fee-for-service medicine to new payment models. The American Academy of Family Physicians reports that 70% of primary care physicians are reporting declines in patient volume of 50% or more since March, and 40% have laid off or furloughed staff. The AAFP has joined other primary care and insurance groups in asking HHS for an infusion of cash. “This is absolutely essential to effectively treat patients today and to maintain their ongoing operations until we overcome this public health emergency,” the groups wrote. Read more.

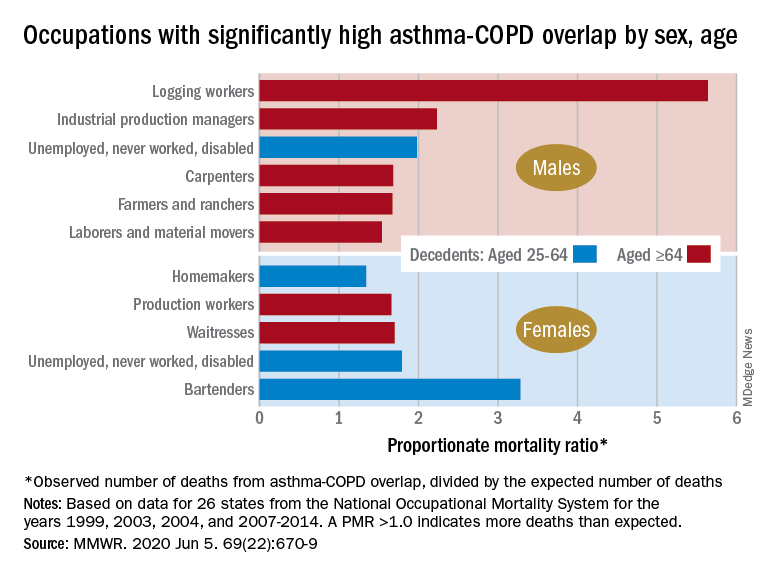

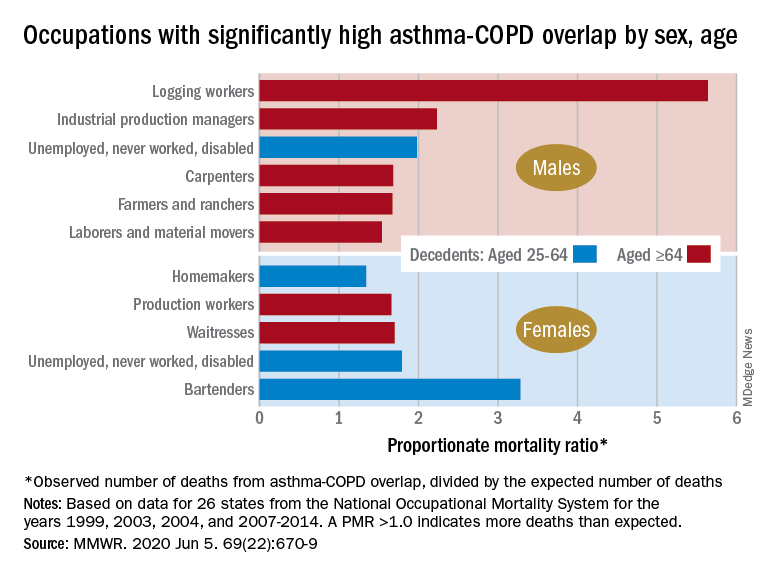

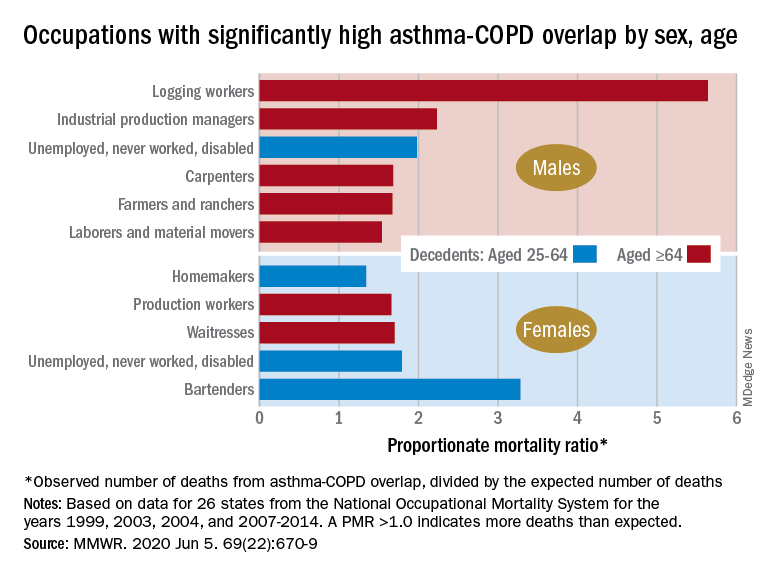

Asthma-COPD overlap deaths

Death rates for combined asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease declined during 1999-2016, but the risk remains higher among women, compared with men, and in certain occupations, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There is also an association between mortality and nonworking status among adults aged 25-64 years, which “suggests that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity,” Katelynn E. Dodd, MPH, and associates at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “These patients have been reported to have worse health outcomes than do those with asthma or COPD alone.” Read more.

Cancer triage in a pandemic: There’s an app for that

Deciding which cancer patients need immediate treatment and who can safely wait is an uncomfortable assessment for cancer clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, a new tool, which appears to be the first of its kind, quantifies that risk-benefit analysis. But its presence immediately raises the question: can it help? OncCOVID is a free tool that was launched in May by the University of Michigan. It allows physicians to individualize risk estimates for delaying treatment of up to 25 early- to late-stage cancers. It includes more than 45 patient characteristics, such as age, location, cancer type, cancer stage, treatment plan, underlying medical conditions, and proposed length of delay in care. “We thought, isn’t it better to at least provide some evidence-based quantification, rather than a back-of-the-envelope three-tier system that is just sort of ‘made up’?“ explained one of the developers, Daniel Spratt, MD, associate professor of radiation oncology at Michigan Medicine. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center . All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com .

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

ACS Update: ‘It is best not to drink alcohol’

The American Cancer Society (ACS) is taking its strongest stance yet against drinking. In its updated cancer prevention guidelines, the ACS now recommends that “it is best not to drink alcohol.” Previously, the organizations had suggested that, for those who consume alcoholic beverages, intake should be no more than one drink per day for women or two per day for men. That recommendation is still in place, but is now accompanied by this new, stronger directive. The guidelines also place more emphasis on reducing the consumption of processed and red meat and highly processed foods, and on increasing physical activity. “Individual choice is an important part of a healthy lifestyle, but having the right policies and environmental factors to break down these barriers is also important, and that is something that clinicians can support,” said Laura Makaroff, DO, American Cancer Society senior vice president. The guidelines were published in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. Read more.

COVID health system changes may be here to stay

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced sudden major changes to the nation’s health care system that are unlikely to be reversed. While there’s some good news, there are also some alarming trends. Experts said there are three trends that are likely to stick around: telehealth for all, an exodus of primary care physicians, and less emphasis on hospital care. “I’ve been trying to raise the alarm about the kind of perilous future of primary care,” said Farzad Mostashari, MD, a top Department of Health & Human Services official in the Obama administration. Dr. Mostashari runs Aledade, a company that helps primary care doctors make the transition from fee-for-service medicine to new payment models. The American Academy of Family Physicians reports that 70% of primary care physicians are reporting declines in patient volume of 50% or more since March, and 40% have laid off or furloughed staff. The AAFP has joined other primary care and insurance groups in asking HHS for an infusion of cash. “This is absolutely essential to effectively treat patients today and to maintain their ongoing operations until we overcome this public health emergency,” the groups wrote. Read more.

Asthma-COPD overlap deaths

Death rates for combined asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease declined during 1999-2016, but the risk remains higher among women, compared with men, and in certain occupations, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There is also an association between mortality and nonworking status among adults aged 25-64 years, which “suggests that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity,” Katelynn E. Dodd, MPH, and associates at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “These patients have been reported to have worse health outcomes than do those with asthma or COPD alone.” Read more.

Cancer triage in a pandemic: There’s an app for that

Deciding which cancer patients need immediate treatment and who can safely wait is an uncomfortable assessment for cancer clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, a new tool, which appears to be the first of its kind, quantifies that risk-benefit analysis. But its presence immediately raises the question: can it help? OncCOVID is a free tool that was launched in May by the University of Michigan. It allows physicians to individualize risk estimates for delaying treatment of up to 25 early- to late-stage cancers. It includes more than 45 patient characteristics, such as age, location, cancer type, cancer stage, treatment plan, underlying medical conditions, and proposed length of delay in care. “We thought, isn’t it better to at least provide some evidence-based quantification, rather than a back-of-the-envelope three-tier system that is just sort of ‘made up’?“ explained one of the developers, Daniel Spratt, MD, associate professor of radiation oncology at Michigan Medicine. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center . All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com .

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

ACS Update: ‘It is best not to drink alcohol’

The American Cancer Society (ACS) is taking its strongest stance yet against drinking. In its updated cancer prevention guidelines, the ACS now recommends that “it is best not to drink alcohol.” Previously, the organizations had suggested that, for those who consume alcoholic beverages, intake should be no more than one drink per day for women or two per day for men. That recommendation is still in place, but is now accompanied by this new, stronger directive. The guidelines also place more emphasis on reducing the consumption of processed and red meat and highly processed foods, and on increasing physical activity. “Individual choice is an important part of a healthy lifestyle, but having the right policies and environmental factors to break down these barriers is also important, and that is something that clinicians can support,” said Laura Makaroff, DO, American Cancer Society senior vice president. The guidelines were published in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. Read more.

COVID health system changes may be here to stay

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced sudden major changes to the nation’s health care system that are unlikely to be reversed. While there’s some good news, there are also some alarming trends. Experts said there are three trends that are likely to stick around: telehealth for all, an exodus of primary care physicians, and less emphasis on hospital care. “I’ve been trying to raise the alarm about the kind of perilous future of primary care,” said Farzad Mostashari, MD, a top Department of Health & Human Services official in the Obama administration. Dr. Mostashari runs Aledade, a company that helps primary care doctors make the transition from fee-for-service medicine to new payment models. The American Academy of Family Physicians reports that 70% of primary care physicians are reporting declines in patient volume of 50% or more since March, and 40% have laid off or furloughed staff. The AAFP has joined other primary care and insurance groups in asking HHS for an infusion of cash. “This is absolutely essential to effectively treat patients today and to maintain their ongoing operations until we overcome this public health emergency,” the groups wrote. Read more.

Asthma-COPD overlap deaths

Death rates for combined asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease declined during 1999-2016, but the risk remains higher among women, compared with men, and in certain occupations, according to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There is also an association between mortality and nonworking status among adults aged 25-64 years, which “suggests that asthma-COPD overlap might be associated with substantial morbidity,” Katelynn E. Dodd, MPH, and associates at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “These patients have been reported to have worse health outcomes than do those with asthma or COPD alone.” Read more.

Cancer triage in a pandemic: There’s an app for that

Deciding which cancer patients need immediate treatment and who can safely wait is an uncomfortable assessment for cancer clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, a new tool, which appears to be the first of its kind, quantifies that risk-benefit analysis. But its presence immediately raises the question: can it help? OncCOVID is a free tool that was launched in May by the University of Michigan. It allows physicians to individualize risk estimates for delaying treatment of up to 25 early- to late-stage cancers. It includes more than 45 patient characteristics, such as age, location, cancer type, cancer stage, treatment plan, underlying medical conditions, and proposed length of delay in care. “We thought, isn’t it better to at least provide some evidence-based quantification, rather than a back-of-the-envelope three-tier system that is just sort of ‘made up’?“ explained one of the developers, Daniel Spratt, MD, associate professor of radiation oncology at Michigan Medicine. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center . All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com .

Irritability strongly linked to suicidal behavior in major depression

Irritability in adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) and stimulant use disorder (SUD) is strongly linked to suicidality and should be assessed by clinicians.

Three clinical trials of adults with MDD and one trial of adults with SUD showed that the link between irritability and suicidality was stronger than the association between depression severity and suicidal behaviors.

“Irritability is an important construct that is not often studied in adults with major depressive disorder,” Manish K. Jha, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

“If you look at current diagnostic convention, irritability is not considered a symptom of major depressive episodes in adults, but below age 18, it is considered one of the two main symptoms,” Dr. Jha said.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2020 annual Meeting.

Clinically useful

Irritability is assessed using age-related norms of behavior, Dr. Jha said.

“The best way to conceptualize it is that it is the propensity to get angry easily or more frequently as compared to peers in response to frustration. I have a 2½-year old, and if he throws a tantrum, that is perfectly age appropriate. But if I do the same thing, it would be extreme irritability. The pediatric literature uses the word ‘grouchiness,’ but it is a little bit difficult to define, in part because it hasn’t been studied extensively,” he said.

To better understand the potential association between irritability and suicidality, the investigators reviewed results of three trials involving adults with MDD. These trials were CO-MED (Combining Medications to Enhance Depression Outcomes), which included 665 patients; EMBARC (Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response in Clinical Care), which included 296 patients; and SAMS (Suicide Assessment Methodology Study), which included 266 patients.

They also examined the STRIDE (Stimulant Reduction Intervention Using Dosed Exercise) study, which was conducted in 302 adults with SUD.

All studies assessed irritability using the Concise Associated Symptom Tracking scale, a 5-point Likert scale. The trials also assessed suicidality with the Concise Health Risk Tracking Suicidal Thoughts.

The investigators found that irritability and suicidality were positively correlated. The association between irritability and suicidality was 2-11 times stronger than the link to overall depression.

Higher irritability at baseline predicted higher levels of suicidality at week 9 in CO-MED (P = .011), EMBARC (P < .0001), and STRIDE (P = .007), but not in SAMS (P = .21).

Greater reduction in irritability from baseline to week 4 predicted lower levels of suicidality at week 8 in CO-MED (P = .007), EMBARC (P < .0001), and STRIDE (P < .0001), but not in SAMS (P = .065).

Similarly, lower baseline levels and greater reductions in irritability were associated with lower levels of suicidality at week 28 of CO-MED, week 16 of EMBARC, and week 36 of STRIDE.

, and he believes that measuring irritability in MDD “has clinical utility.”

A common and disabling symptom

Commenting on the study, Sanjay J. Mathew, MD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said the findings provide further support that irritability is a relatively common and disabling symptom associated with major depression.

“The presence of significant irritability was associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation and is therefore highly relevant for clinicians to assess,” said Dr. Mathew, who was not part of the study.

“Early improvements in irritability are associated with better longer-term outcomes with antidepressant treatments, and this highlights the need for careful clinical evaluation early on in the course of antidepressant therapy, ideally within the first 2 weeks,” he said.

Dr. Jha reports financial relationships with Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Mathew reports financial relationships with Allergan, Vistagen, Janssen, Clexio, and Biohaven.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Irritability in adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) and stimulant use disorder (SUD) is strongly linked to suicidality and should be assessed by clinicians.

Three clinical trials of adults with MDD and one trial of adults with SUD showed that the link between irritability and suicidality was stronger than the association between depression severity and suicidal behaviors.

“Irritability is an important construct that is not often studied in adults with major depressive disorder,” Manish K. Jha, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

“If you look at current diagnostic convention, irritability is not considered a symptom of major depressive episodes in adults, but below age 18, it is considered one of the two main symptoms,” Dr. Jha said.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2020 annual Meeting.

Clinically useful

Irritability is assessed using age-related norms of behavior, Dr. Jha said.

“The best way to conceptualize it is that it is the propensity to get angry easily or more frequently as compared to peers in response to frustration. I have a 2½-year old, and if he throws a tantrum, that is perfectly age appropriate. But if I do the same thing, it would be extreme irritability. The pediatric literature uses the word ‘grouchiness,’ but it is a little bit difficult to define, in part because it hasn’t been studied extensively,” he said.

To better understand the potential association between irritability and suicidality, the investigators reviewed results of three trials involving adults with MDD. These trials were CO-MED (Combining Medications to Enhance Depression Outcomes), which included 665 patients; EMBARC (Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response in Clinical Care), which included 296 patients; and SAMS (Suicide Assessment Methodology Study), which included 266 patients.

They also examined the STRIDE (Stimulant Reduction Intervention Using Dosed Exercise) study, which was conducted in 302 adults with SUD.

All studies assessed irritability using the Concise Associated Symptom Tracking scale, a 5-point Likert scale. The trials also assessed suicidality with the Concise Health Risk Tracking Suicidal Thoughts.

The investigators found that irritability and suicidality were positively correlated. The association between irritability and suicidality was 2-11 times stronger than the link to overall depression.

Higher irritability at baseline predicted higher levels of suicidality at week 9 in CO-MED (P = .011), EMBARC (P < .0001), and STRIDE (P = .007), but not in SAMS (P = .21).

Greater reduction in irritability from baseline to week 4 predicted lower levels of suicidality at week 8 in CO-MED (P = .007), EMBARC (P < .0001), and STRIDE (P < .0001), but not in SAMS (P = .065).

Similarly, lower baseline levels and greater reductions in irritability were associated with lower levels of suicidality at week 28 of CO-MED, week 16 of EMBARC, and week 36 of STRIDE.

, and he believes that measuring irritability in MDD “has clinical utility.”

A common and disabling symptom

Commenting on the study, Sanjay J. Mathew, MD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said the findings provide further support that irritability is a relatively common and disabling symptom associated with major depression.

“The presence of significant irritability was associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation and is therefore highly relevant for clinicians to assess,” said Dr. Mathew, who was not part of the study.

“Early improvements in irritability are associated with better longer-term outcomes with antidepressant treatments, and this highlights the need for careful clinical evaluation early on in the course of antidepressant therapy, ideally within the first 2 weeks,” he said.

Dr. Jha reports financial relationships with Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Mathew reports financial relationships with Allergan, Vistagen, Janssen, Clexio, and Biohaven.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Irritability in adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) and stimulant use disorder (SUD) is strongly linked to suicidality and should be assessed by clinicians.

Three clinical trials of adults with MDD and one trial of adults with SUD showed that the link between irritability and suicidality was stronger than the association between depression severity and suicidal behaviors.

“Irritability is an important construct that is not often studied in adults with major depressive disorder,” Manish K. Jha, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

“If you look at current diagnostic convention, irritability is not considered a symptom of major depressive episodes in adults, but below age 18, it is considered one of the two main symptoms,” Dr. Jha said.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2020 annual Meeting.

Clinically useful

Irritability is assessed using age-related norms of behavior, Dr. Jha said.

“The best way to conceptualize it is that it is the propensity to get angry easily or more frequently as compared to peers in response to frustration. I have a 2½-year old, and if he throws a tantrum, that is perfectly age appropriate. But if I do the same thing, it would be extreme irritability. The pediatric literature uses the word ‘grouchiness,’ but it is a little bit difficult to define, in part because it hasn’t been studied extensively,” he said.

To better understand the potential association between irritability and suicidality, the investigators reviewed results of three trials involving adults with MDD. These trials were CO-MED (Combining Medications to Enhance Depression Outcomes), which included 665 patients; EMBARC (Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response in Clinical Care), which included 296 patients; and SAMS (Suicide Assessment Methodology Study), which included 266 patients.

They also examined the STRIDE (Stimulant Reduction Intervention Using Dosed Exercise) study, which was conducted in 302 adults with SUD.

All studies assessed irritability using the Concise Associated Symptom Tracking scale, a 5-point Likert scale. The trials also assessed suicidality with the Concise Health Risk Tracking Suicidal Thoughts.

The investigators found that irritability and suicidality were positively correlated. The association between irritability and suicidality was 2-11 times stronger than the link to overall depression.

Higher irritability at baseline predicted higher levels of suicidality at week 9 in CO-MED (P = .011), EMBARC (P < .0001), and STRIDE (P = .007), but not in SAMS (P = .21).

Greater reduction in irritability from baseline to week 4 predicted lower levels of suicidality at week 8 in CO-MED (P = .007), EMBARC (P < .0001), and STRIDE (P < .0001), but not in SAMS (P = .065).

Similarly, lower baseline levels and greater reductions in irritability were associated with lower levels of suicidality at week 28 of CO-MED, week 16 of EMBARC, and week 36 of STRIDE.

, and he believes that measuring irritability in MDD “has clinical utility.”

A common and disabling symptom

Commenting on the study, Sanjay J. Mathew, MD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said the findings provide further support that irritability is a relatively common and disabling symptom associated with major depression.

“The presence of significant irritability was associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation and is therefore highly relevant for clinicians to assess,” said Dr. Mathew, who was not part of the study.

“Early improvements in irritability are associated with better longer-term outcomes with antidepressant treatments, and this highlights the need for careful clinical evaluation early on in the course of antidepressant therapy, ideally within the first 2 weeks,” he said.

Dr. Jha reports financial relationships with Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Mathew reports financial relationships with Allergan, Vistagen, Janssen, Clexio, and Biohaven.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Human sitters in the COVID era

Data collection needed for care of suicidal hospitalized patients

I am writing this commentary to bring to readers’ attention a medical and ethical complexity related to human sitters for presumably suicidal, COVID-19–positive hospitalized patients.

To shape and bundle the ethics issues addressed here into a single question, I offer the following: Should policies and practices requiring that patients in presumed need of a sitter because of assessed suicidality change when the patient is COVID-19–positive? Although the analysis might be similar when a sitter is monitoring a Patient Under Investigation (PUI), here I focus only on COVID-19–positive patients. Similarly, there are other reasons for sitters, of course, such as to prevent elopement, or, if a patient is in restraints, to prevent the patient from pulling out lines or tubes. Again, discussion of some of these ethical complications is beyond the scope of this piece. Just considering the matter of potential suicidality and sitters is complex enough. And so, to start, I sought out existing sources for guidance.

In looking for such sources, I first turned to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services before COVID-19. CMS has required that there be a sitter for a patient who is suicidal and that the sitter remain in the room so that the sitter can intervene expeditiously if the patient tries to hurt himself or herself. There has been no change in this guidance since the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. To the best of my knowledge, there is no substantive guidance for protecting sitters from contagion other than PPE. Given this, it begs the question:

In my hospital, I already have begun discussing the potential risks of harm and potential benefits to our suicidal patients of having a sitter directly outside the patient’s room. I also have considered whether to have one sitter watching several room cameras at once, commonly referred to as “telehealth strategies.”

To be sure, sitting for hours in the room of a COVID-19–positive patient is onerous. The sitter is required to be in full PPE (N-95 mask, gown, and gloves), which is hot and uncomfortable. Current practice is resource intensive in other ways. It requires changing out the sitter every 2 hours, which uses substantial amounts of PPE and multiple sitters.

Regardless, however, there are really no data upon which to base any sound ethics judgment about what should or should not be tried. We just have no information on how to attempt to balance potential risks and prospects for the benefit of whom and when. And, given that good clinical ethics always begin with the facts, I write this piece to see whether readers have thought about these issues before – and whether any of clinicians have started collecting the valuable data needed to begin making sound ethical judgments about how to care for our presumably suicidal COVID-19–positive patients and the sitters who watch over them.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

This column is an outcome of a discussion that occurred during Psych/Ethics rounds on June 5, and does not represent any official statements of Medstar Washington Hospital Center or any entity of the MedStar Corp. Dr. Ritchie would like to thank Evan G. DeRenzo, PhD, of the John J. Lynch Center for Ethics, for her thoughtful review of a previous draft of this commentary.

Data collection needed for care of suicidal hospitalized patients

Data collection needed for care of suicidal hospitalized patients

I am writing this commentary to bring to readers’ attention a medical and ethical complexity related to human sitters for presumably suicidal, COVID-19–positive hospitalized patients.

To shape and bundle the ethics issues addressed here into a single question, I offer the following: Should policies and practices requiring that patients in presumed need of a sitter because of assessed suicidality change when the patient is COVID-19–positive? Although the analysis might be similar when a sitter is monitoring a Patient Under Investigation (PUI), here I focus only on COVID-19–positive patients. Similarly, there are other reasons for sitters, of course, such as to prevent elopement, or, if a patient is in restraints, to prevent the patient from pulling out lines or tubes. Again, discussion of some of these ethical complications is beyond the scope of this piece. Just considering the matter of potential suicidality and sitters is complex enough. And so, to start, I sought out existing sources for guidance.

In looking for such sources, I first turned to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services before COVID-19. CMS has required that there be a sitter for a patient who is suicidal and that the sitter remain in the room so that the sitter can intervene expeditiously if the patient tries to hurt himself or herself. There has been no change in this guidance since the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. To the best of my knowledge, there is no substantive guidance for protecting sitters from contagion other than PPE. Given this, it begs the question:

In my hospital, I already have begun discussing the potential risks of harm and potential benefits to our suicidal patients of having a sitter directly outside the patient’s room. I also have considered whether to have one sitter watching several room cameras at once, commonly referred to as “telehealth strategies.”

To be sure, sitting for hours in the room of a COVID-19–positive patient is onerous. The sitter is required to be in full PPE (N-95 mask, gown, and gloves), which is hot and uncomfortable. Current practice is resource intensive in other ways. It requires changing out the sitter every 2 hours, which uses substantial amounts of PPE and multiple sitters.

Regardless, however, there are really no data upon which to base any sound ethics judgment about what should or should not be tried. We just have no information on how to attempt to balance potential risks and prospects for the benefit of whom and when. And, given that good clinical ethics always begin with the facts, I write this piece to see whether readers have thought about these issues before – and whether any of clinicians have started collecting the valuable data needed to begin making sound ethical judgments about how to care for our presumably suicidal COVID-19–positive patients and the sitters who watch over them.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

This column is an outcome of a discussion that occurred during Psych/Ethics rounds on June 5, and does not represent any official statements of Medstar Washington Hospital Center or any entity of the MedStar Corp. Dr. Ritchie would like to thank Evan G. DeRenzo, PhD, of the John J. Lynch Center for Ethics, for her thoughtful review of a previous draft of this commentary.

I am writing this commentary to bring to readers’ attention a medical and ethical complexity related to human sitters for presumably suicidal, COVID-19–positive hospitalized patients.

To shape and bundle the ethics issues addressed here into a single question, I offer the following: Should policies and practices requiring that patients in presumed need of a sitter because of assessed suicidality change when the patient is COVID-19–positive? Although the analysis might be similar when a sitter is monitoring a Patient Under Investigation (PUI), here I focus only on COVID-19–positive patients. Similarly, there are other reasons for sitters, of course, such as to prevent elopement, or, if a patient is in restraints, to prevent the patient from pulling out lines or tubes. Again, discussion of some of these ethical complications is beyond the scope of this piece. Just considering the matter of potential suicidality and sitters is complex enough. And so, to start, I sought out existing sources for guidance.

In looking for such sources, I first turned to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services before COVID-19. CMS has required that there be a sitter for a patient who is suicidal and that the sitter remain in the room so that the sitter can intervene expeditiously if the patient tries to hurt himself or herself. There has been no change in this guidance since the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. To the best of my knowledge, there is no substantive guidance for protecting sitters from contagion other than PPE. Given this, it begs the question:

In my hospital, I already have begun discussing the potential risks of harm and potential benefits to our suicidal patients of having a sitter directly outside the patient’s room. I also have considered whether to have one sitter watching several room cameras at once, commonly referred to as “telehealth strategies.”

To be sure, sitting for hours in the room of a COVID-19–positive patient is onerous. The sitter is required to be in full PPE (N-95 mask, gown, and gloves), which is hot and uncomfortable. Current practice is resource intensive in other ways. It requires changing out the sitter every 2 hours, which uses substantial amounts of PPE and multiple sitters.

Regardless, however, there are really no data upon which to base any sound ethics judgment about what should or should not be tried. We just have no information on how to attempt to balance potential risks and prospects for the benefit of whom and when. And, given that good clinical ethics always begin with the facts, I write this piece to see whether readers have thought about these issues before – and whether any of clinicians have started collecting the valuable data needed to begin making sound ethical judgments about how to care for our presumably suicidal COVID-19–positive patients and the sitters who watch over them.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

This column is an outcome of a discussion that occurred during Psych/Ethics rounds on June 5, and does not represent any official statements of Medstar Washington Hospital Center or any entity of the MedStar Corp. Dr. Ritchie would like to thank Evan G. DeRenzo, PhD, of the John J. Lynch Center for Ethics, for her thoughtful review of a previous draft of this commentary.

Petechial Rash on the Thighs in an Immunosuppressed Patient

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloidiasis is a parasitic infection caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. In the United States it is most prevalent in the Appalachian region. During the filariform larval stage of the parasite's life cycle, larvae from contaminated soil infect the human skin and spread to the intestinal epithelium,1 then the larvae mature into adult female worms that can produce eggs asexually. Rhabditiform larvae hatch from the eggs and are either excreted in the stool or develop into infectious filariform larvae. The latter can cause autoinfection of the intestinal mucosa or nearby skin; in addition, if the larvae enter the bloodstream, they can spread throughout the body and lead to disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.2 This often fatal progression most commonly occurs in immunosuppressed individuals.3 The mortality rate has been reported to be up to 87%.2,4

Fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea are clinically common in disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.5 Patients also may exhibit dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis.2 Cutaneous manifestations are rare and typically include pruritus and petechiae.6 Eosinophilia may be present but is not a reliable indicator.1

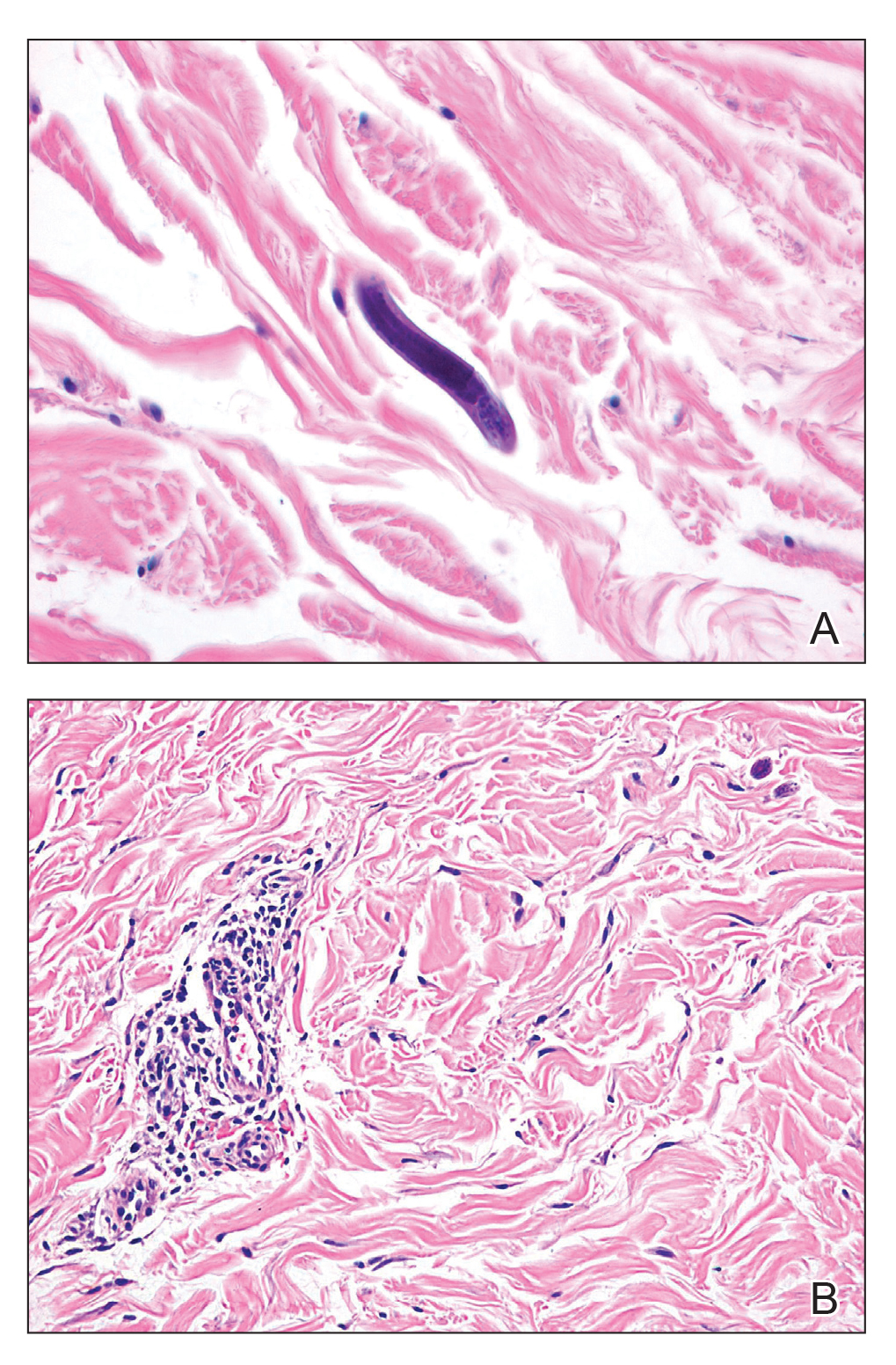

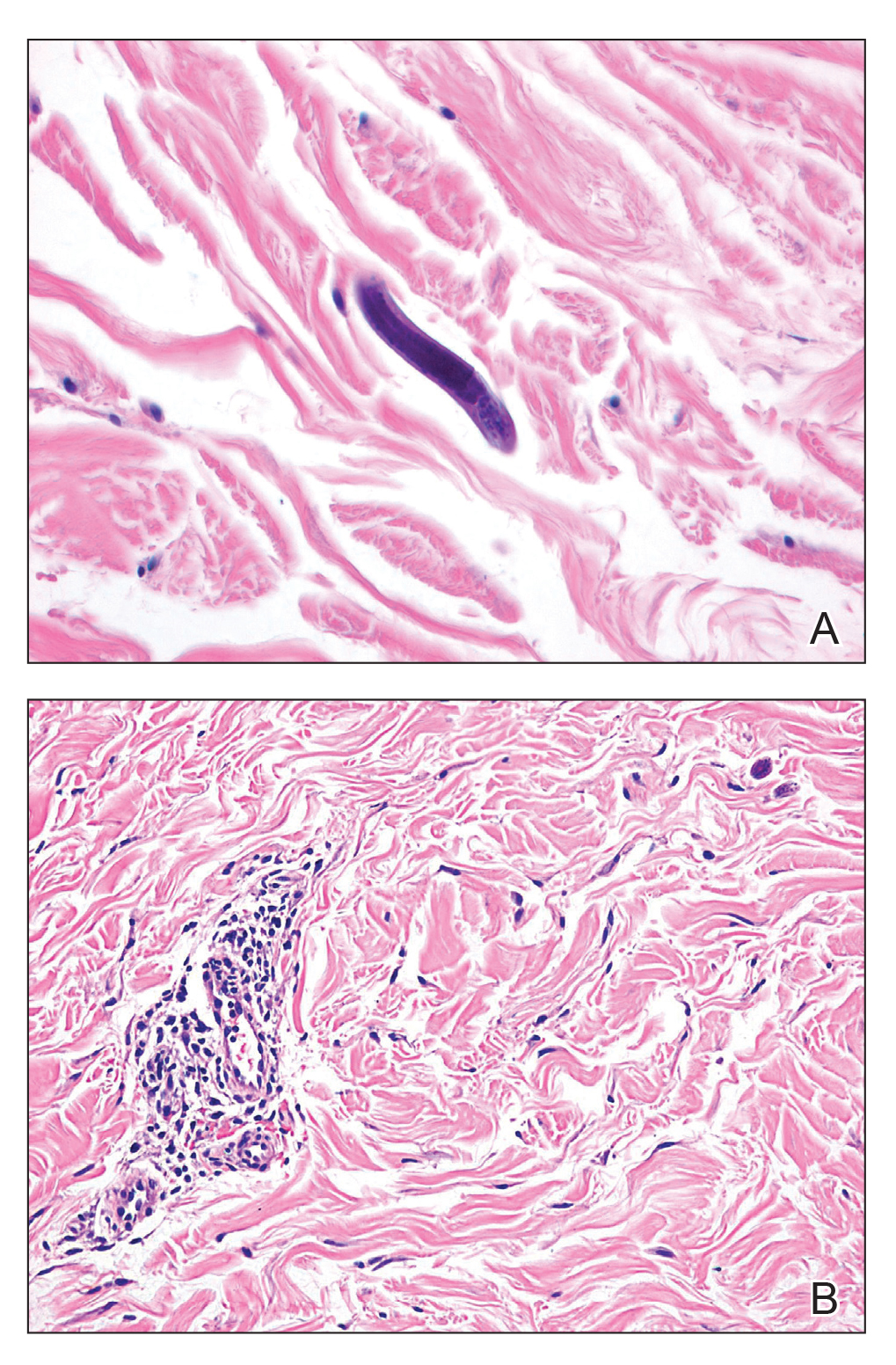

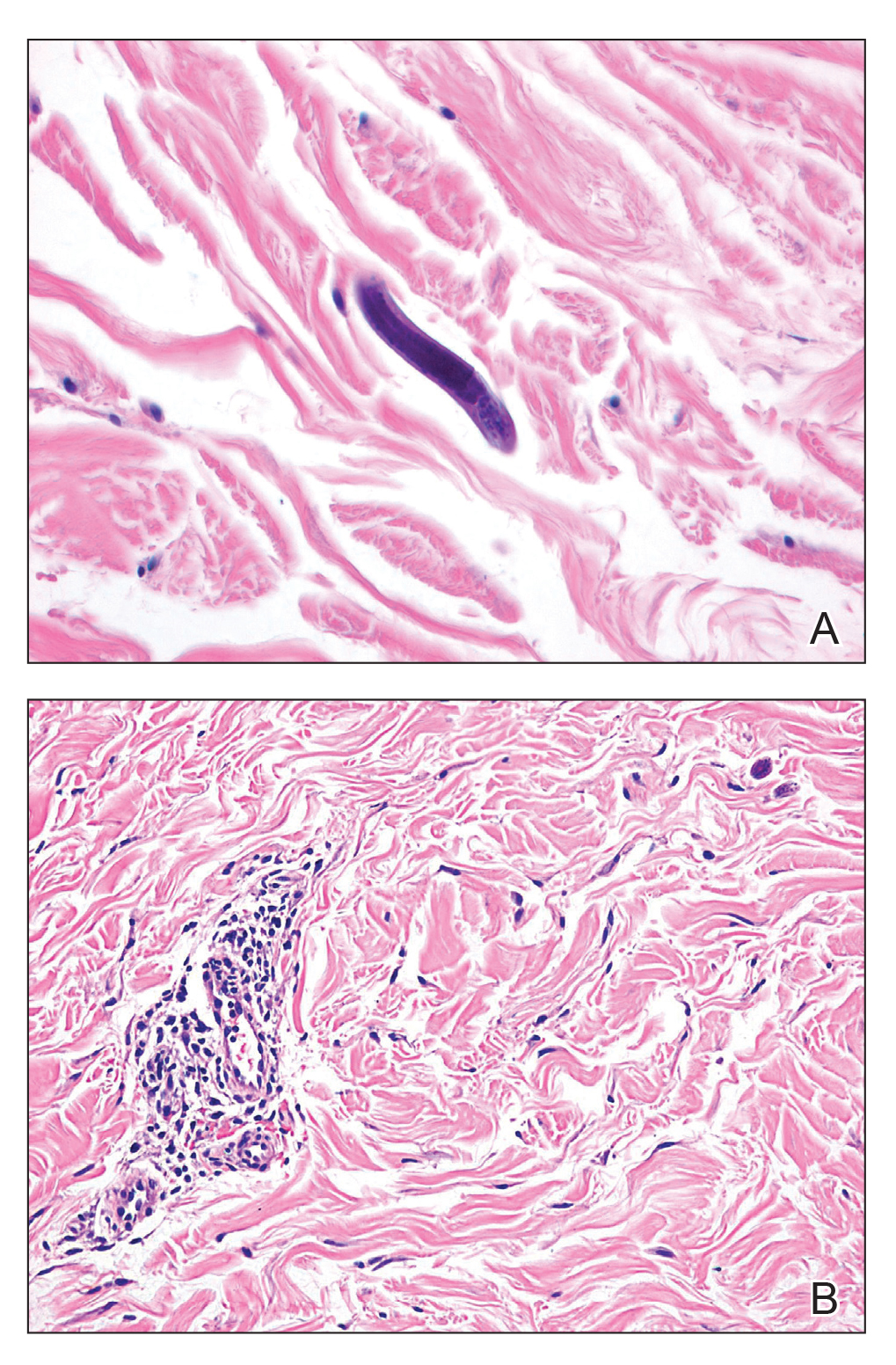

Our patient displayed several risk factors and an early clinical presentation for disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, which evolved over the course of hospitalization. Clues to the diagnosis included an immunosuppressed state; erythematous pruritic macules at presentation that later developed into reticulated petechial patches; and fever, general abdominal symptoms, and dyspnea. However, the patient's overall physical examination findings were subtle and nonspecific. Additionally, the patient did not display the classic larva currens for strongyloidiasis or the pathognomonic periumbilical thumbprint purpura of disseminated infection,6,7 which may indicate that the latter is a later-stage finding. Although graft-vs-host disease initially was suspected, a third skin biopsy revealed basophilic Strongyloides larvae, extravasated erythrocytes, and mild perivascular inflammation (Figure).

Subsequent gastric aspirates and stool cultures revealed S stercoralis. A bronchoalveolar lavage specimen and serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Strongyloides antibody were negative. The patient was treated with an extended 16-day course of ivermectin 12 mg daily until gastric aspirates and stool cultures were negative for the parasite. The rash receded by the end of the patient's 32-day hospital stay.

Because of the high mortality rate of untreated disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, early diagnosis and initiation of anthelmintic treatment is vital in improving patient outcomes. As such, the diagnosis of disseminated strongyloidiasis should be considered in any immunosuppressed patient with multisystemic symptoms and/or petechiae. The differential diagnosis includes graft-vs-host disease, drug-induced urticaria, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and other opportunistic parasites.6,8,9

- Concha R, Harrington W Jr, Rogers AI. Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management, and determinants of outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:203-211.

- Vadlamudi RS, Chi DS, Krishnaswamy G. Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome. Clin Mol Allergy. 2006;4:8.

- Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208-217.

- Chan FLY, Kennedy B, Nelson R. Fatal Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in an immunocompetent adult with review of the literature. Intern Med J. 2018;48:872-875.

- Scowden EB, Schaffner W, Stone WJ. Overwhelming strongyloidiasis: an unappreciated opportunistic infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 1978;57:527-544.

- von Kuster LC, Genta RM. Cutaneous manifestations of strongyloidiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1826-1830.

- Weiser JA, Scully BE, Bulman WA, et al. Periumbilical parasitic thumbprint purpura: Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome acquired from a cadaveric renal transplant. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13:58-62.

- Berenson CS, Dobuler KJ, Bia FJ. Fever, petechiae, and pulmonary infiltrates in an immunocompromised Peruvian man. Yale J Biol Med. 1987;60:437-445.

- Ly MN, Bethel SL, Usmani AS, et al. Cutaneous Strongyloides stercoralis infection: an unusual presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 suppl case reports):S157-S160.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloidiasis is a parasitic infection caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. In the United States it is most prevalent in the Appalachian region. During the filariform larval stage of the parasite's life cycle, larvae from contaminated soil infect the human skin and spread to the intestinal epithelium,1 then the larvae mature into adult female worms that can produce eggs asexually. Rhabditiform larvae hatch from the eggs and are either excreted in the stool or develop into infectious filariform larvae. The latter can cause autoinfection of the intestinal mucosa or nearby skin; in addition, if the larvae enter the bloodstream, they can spread throughout the body and lead to disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.2 This often fatal progression most commonly occurs in immunosuppressed individuals.3 The mortality rate has been reported to be up to 87%.2,4

Fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea are clinically common in disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.5 Patients also may exhibit dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis.2 Cutaneous manifestations are rare and typically include pruritus and petechiae.6 Eosinophilia may be present but is not a reliable indicator.1

Our patient displayed several risk factors and an early clinical presentation for disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, which evolved over the course of hospitalization. Clues to the diagnosis included an immunosuppressed state; erythematous pruritic macules at presentation that later developed into reticulated petechial patches; and fever, general abdominal symptoms, and dyspnea. However, the patient's overall physical examination findings were subtle and nonspecific. Additionally, the patient did not display the classic larva currens for strongyloidiasis or the pathognomonic periumbilical thumbprint purpura of disseminated infection,6,7 which may indicate that the latter is a later-stage finding. Although graft-vs-host disease initially was suspected, a third skin biopsy revealed basophilic Strongyloides larvae, extravasated erythrocytes, and mild perivascular inflammation (Figure).

Subsequent gastric aspirates and stool cultures revealed S stercoralis. A bronchoalveolar lavage specimen and serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Strongyloides antibody were negative. The patient was treated with an extended 16-day course of ivermectin 12 mg daily until gastric aspirates and stool cultures were negative for the parasite. The rash receded by the end of the patient's 32-day hospital stay.

Because of the high mortality rate of untreated disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, early diagnosis and initiation of anthelmintic treatment is vital in improving patient outcomes. As such, the diagnosis of disseminated strongyloidiasis should be considered in any immunosuppressed patient with multisystemic symptoms and/or petechiae. The differential diagnosis includes graft-vs-host disease, drug-induced urticaria, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and other opportunistic parasites.6,8,9

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloidiasis is a parasitic infection caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. In the United States it is most prevalent in the Appalachian region. During the filariform larval stage of the parasite's life cycle, larvae from contaminated soil infect the human skin and spread to the intestinal epithelium,1 then the larvae mature into adult female worms that can produce eggs asexually. Rhabditiform larvae hatch from the eggs and are either excreted in the stool or develop into infectious filariform larvae. The latter can cause autoinfection of the intestinal mucosa or nearby skin; in addition, if the larvae enter the bloodstream, they can spread throughout the body and lead to disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.2 This often fatal progression most commonly occurs in immunosuppressed individuals.3 The mortality rate has been reported to be up to 87%.2,4

Fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea are clinically common in disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.5 Patients also may exhibit dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis.2 Cutaneous manifestations are rare and typically include pruritus and petechiae.6 Eosinophilia may be present but is not a reliable indicator.1

Our patient displayed several risk factors and an early clinical presentation for disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, which evolved over the course of hospitalization. Clues to the diagnosis included an immunosuppressed state; erythematous pruritic macules at presentation that later developed into reticulated petechial patches; and fever, general abdominal symptoms, and dyspnea. However, the patient's overall physical examination findings were subtle and nonspecific. Additionally, the patient did not display the classic larva currens for strongyloidiasis or the pathognomonic periumbilical thumbprint purpura of disseminated infection,6,7 which may indicate that the latter is a later-stage finding. Although graft-vs-host disease initially was suspected, a third skin biopsy revealed basophilic Strongyloides larvae, extravasated erythrocytes, and mild perivascular inflammation (Figure).

Subsequent gastric aspirates and stool cultures revealed S stercoralis. A bronchoalveolar lavage specimen and serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Strongyloides antibody were negative. The patient was treated with an extended 16-day course of ivermectin 12 mg daily until gastric aspirates and stool cultures were negative for the parasite. The rash receded by the end of the patient's 32-day hospital stay.

Because of the high mortality rate of untreated disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, early diagnosis and initiation of anthelmintic treatment is vital in improving patient outcomes. As such, the diagnosis of disseminated strongyloidiasis should be considered in any immunosuppressed patient with multisystemic symptoms and/or petechiae. The differential diagnosis includes graft-vs-host disease, drug-induced urticaria, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and other opportunistic parasites.6,8,9

- Concha R, Harrington W Jr, Rogers AI. Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management, and determinants of outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:203-211.

- Vadlamudi RS, Chi DS, Krishnaswamy G. Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome. Clin Mol Allergy. 2006;4:8.

- Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208-217.

- Chan FLY, Kennedy B, Nelson R. Fatal Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in an immunocompetent adult with review of the literature. Intern Med J. 2018;48:872-875.

- Scowden EB, Schaffner W, Stone WJ. Overwhelming strongyloidiasis: an unappreciated opportunistic infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 1978;57:527-544.

- von Kuster LC, Genta RM. Cutaneous manifestations of strongyloidiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1826-1830.

- Weiser JA, Scully BE, Bulman WA, et al. Periumbilical parasitic thumbprint purpura: Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome acquired from a cadaveric renal transplant. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13:58-62.

- Berenson CS, Dobuler KJ, Bia FJ. Fever, petechiae, and pulmonary infiltrates in an immunocompromised Peruvian man. Yale J Biol Med. 1987;60:437-445.

- Ly MN, Bethel SL, Usmani AS, et al. Cutaneous Strongyloides stercoralis infection: an unusual presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 suppl case reports):S157-S160.

- Concha R, Harrington W Jr, Rogers AI. Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management, and determinants of outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:203-211.

- Vadlamudi RS, Chi DS, Krishnaswamy G. Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome. Clin Mol Allergy. 2006;4:8.

- Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208-217.

- Chan FLY, Kennedy B, Nelson R. Fatal Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in an immunocompetent adult with review of the literature. Intern Med J. 2018;48:872-875.

- Scowden EB, Schaffner W, Stone WJ. Overwhelming strongyloidiasis: an unappreciated opportunistic infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 1978;57:527-544.

- von Kuster LC, Genta RM. Cutaneous manifestations of strongyloidiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1826-1830.

- Weiser JA, Scully BE, Bulman WA, et al. Periumbilical parasitic thumbprint purpura: Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome acquired from a cadaveric renal transplant. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13:58-62.

- Berenson CS, Dobuler KJ, Bia FJ. Fever, petechiae, and pulmonary infiltrates in an immunocompromised Peruvian man. Yale J Biol Med. 1987;60:437-445.

- Ly MN, Bethel SL, Usmani AS, et al. Cutaneous Strongyloides stercoralis infection: an unusual presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 suppl case reports):S157-S160.

A 48-year-old woman from rural Virginia presented with centrifugally spreading, pruritic, blanchable macules over the lower abdomen and upper thighs noted 4 months after a pancreas transplant. After 3 weeks, the macules coalesced into reticulated nonblanching petechial patches. Fever, dyspnea, increasing xerosis, abdominal pain, and constipation were present. The patient had a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus requiring a pancreas transplant. Initial skin biopsy and fluorescence in situ hybridization to test for immune reaction to the XY-donor pancreas were negative. Mild transient eosinophilia was present at admission.

Elevated inflammation common in children’s severe COVID-19 disease

according to data from 50 patients at a single tertiary care center.

“Risk factors for severe disease in pediatric populations have not been clearly identified and the high prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in NYC offers an opportunity to describe severe pediatric disease in more detail,” wrote Philip Zachariah, MD, of New York–Presbyterian Hospital, New York, and colleagues.

In a retrospective case series published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 50 patients: 41 classified as severe and 9 classified as nonsevere. Among the patients, 27 were male and 25 were Hispanic. The patient population had a median of 2 days from symptom onset to hospital admission. The most common symptoms were fever (80%) and respiratory symptoms (64%). Seventy-six percent of patients had a median length of stay of 3 days (range 1-30 days).

At hospital admission, children with severe disease had significantly higher levels of several inflammatory markers compared with those without severe disease, notably C-reactive protein (median 8.978 mg/dL vs. 0.64 mg/dL) and procalcitonin (median 0.31 ng/mL vs. 0.17 ng/mL, (P < .001 for both). High mean peak levels of C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, interleukin 6, ferritin, and D-dimer were seen among the nine children (16%) who required mechanical ventilation, Dr. Zachariah and associates said.

None of the 14 infants and 1 of the 8 immunocompromised children in the study had severe disease, the researchers wrote.

Bacterial coinfections detected while patients were hospitalized were bacteremia in 6%, suspected bacterial pneumonia in 18%, urinary tract infections in 10%, skin and soft tissue infections in 6%, and streptococcus pharyngitis in 2%, Dr. Zachariah and associates reported.

Overall, 61% of the children had comorbidities identified in previous COVID-19 studies, of which obesity was the most common (22%); other comorbidities included asthma, sickle cell disease, cardiac disease, and diabetes. Obesity also was significantly associated with the need for mechanical ventilation in children aged 2 years and older (67%). A total of 16 patients required respiratory support, 9 of these were placed on mechanical ventilation; 6 of these 9 children were obese.

Fifteen patients (30%) who met criteria for increased oxygen requirements and respiratory distress received hydroxychloroquine, but the small sample size did not allow for assessment of treatment efficacy, the researchers said.

“Expanding our knowledge of COVID-19 [disease] in children will potentially permit early recognition of SARS-CoV-2 infection, understanding of the natural history of disease, and potential complications, said Stephen I. Pelton, MD, professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. This review of 50 SARS-CoV-2 infected children (less than 21 years of age) “provides insight into the short period of symptoms prior to hospitalization, challenges the concept that infants less than 1 year are at greatest risk of severe disease (as from the experience in China), and suggests rapid recovery in many children, as median length of stay was 3 days.

“The review revealed two findings that were surprising to me. First, the median length of stay of 3 days. As nearly 20% of the children required mechanical ventilation, it suggests many of the children were discharged quickly after evaluation, suggesting that we need to identify markers of severity to predict those children likely to have progressive disease and require respiratory support,” Dr. Pelton noted.

“The second observation suggests high rates of bacterial infection (bacteremia, pneumonia, UTI, and skin and soft tissue infection). I do not think this has been widely reported in adults, and may represent a difference between child and adult disease. More studies such as this will be required to identify how common coinfection with bacteria is,” he said.

“The take-home message is that although most children with COVID-19 have a mild or even asymptomatic course, some become severely ill requiring ventilator support and potentially ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation]. Potential predictors of severity include high C-reactive protein, obesity, and older age [adolescence], said Dr. Pelton, who was not involved in the study.

What additional research is needed? Dr. Pelton said that better markers of severe disease are needed, as well as an understanding of why obesity is a risk factor for severe disease in both children and adults. Are these prediabetic patients? he asked.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size and high proportion of Hispanic patients, which may limit generalizability, and some symptoms and comorbidities may have been missed because of the retrospective nature of the study, the researchers noted. However, the results support the need for hospitals to remain vigilant to the variable presentations of COVID-19 infections in children.

“Therapeutic considerations need to [include] the risk of toxicity, control of antiviral replication, and early recognition and management of immune dysregulation,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Zachariah had no financial conflicts to disclose. Two coauthors reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies and organizations. Dr. Pelton said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zachariah P et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 June 3. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2430.

according to data from 50 patients at a single tertiary care center.

“Risk factors for severe disease in pediatric populations have not been clearly identified and the high prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in NYC offers an opportunity to describe severe pediatric disease in more detail,” wrote Philip Zachariah, MD, of New York–Presbyterian Hospital, New York, and colleagues.

In a retrospective case series published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 50 patients: 41 classified as severe and 9 classified as nonsevere. Among the patients, 27 were male and 25 were Hispanic. The patient population had a median of 2 days from symptom onset to hospital admission. The most common symptoms were fever (80%) and respiratory symptoms (64%). Seventy-six percent of patients had a median length of stay of 3 days (range 1-30 days).

At hospital admission, children with severe disease had significantly higher levels of several inflammatory markers compared with those without severe disease, notably C-reactive protein (median 8.978 mg/dL vs. 0.64 mg/dL) and procalcitonin (median 0.31 ng/mL vs. 0.17 ng/mL, (P < .001 for both). High mean peak levels of C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, interleukin 6, ferritin, and D-dimer were seen among the nine children (16%) who required mechanical ventilation, Dr. Zachariah and associates said.

None of the 14 infants and 1 of the 8 immunocompromised children in the study had severe disease, the researchers wrote.

Bacterial coinfections detected while patients were hospitalized were bacteremia in 6%, suspected bacterial pneumonia in 18%, urinary tract infections in 10%, skin and soft tissue infections in 6%, and streptococcus pharyngitis in 2%, Dr. Zachariah and associates reported.

Overall, 61% of the children had comorbidities identified in previous COVID-19 studies, of which obesity was the most common (22%); other comorbidities included asthma, sickle cell disease, cardiac disease, and diabetes. Obesity also was significantly associated with the need for mechanical ventilation in children aged 2 years and older (67%). A total of 16 patients required respiratory support, 9 of these were placed on mechanical ventilation; 6 of these 9 children were obese.

Fifteen patients (30%) who met criteria for increased oxygen requirements and respiratory distress received hydroxychloroquine, but the small sample size did not allow for assessment of treatment efficacy, the researchers said.

“Expanding our knowledge of COVID-19 [disease] in children will potentially permit early recognition of SARS-CoV-2 infection, understanding of the natural history of disease, and potential complications, said Stephen I. Pelton, MD, professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. This review of 50 SARS-CoV-2 infected children (less than 21 years of age) “provides insight into the short period of symptoms prior to hospitalization, challenges the concept that infants less than 1 year are at greatest risk of severe disease (as from the experience in China), and suggests rapid recovery in many children, as median length of stay was 3 days.

“The review revealed two findings that were surprising to me. First, the median length of stay of 3 days. As nearly 20% of the children required mechanical ventilation, it suggests many of the children were discharged quickly after evaluation, suggesting that we need to identify markers of severity to predict those children likely to have progressive disease and require respiratory support,” Dr. Pelton noted.

“The second observation suggests high rates of bacterial infection (bacteremia, pneumonia, UTI, and skin and soft tissue infection). I do not think this has been widely reported in adults, and may represent a difference between child and adult disease. More studies such as this will be required to identify how common coinfection with bacteria is,” he said.

“The take-home message is that although most children with COVID-19 have a mild or even asymptomatic course, some become severely ill requiring ventilator support and potentially ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation]. Potential predictors of severity include high C-reactive protein, obesity, and older age [adolescence], said Dr. Pelton, who was not involved in the study.

What additional research is needed? Dr. Pelton said that better markers of severe disease are needed, as well as an understanding of why obesity is a risk factor for severe disease in both children and adults. Are these prediabetic patients? he asked.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size and high proportion of Hispanic patients, which may limit generalizability, and some symptoms and comorbidities may have been missed because of the retrospective nature of the study, the researchers noted. However, the results support the need for hospitals to remain vigilant to the variable presentations of COVID-19 infections in children.

“Therapeutic considerations need to [include] the risk of toxicity, control of antiviral replication, and early recognition and management of immune dysregulation,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Zachariah had no financial conflicts to disclose. Two coauthors reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies and organizations. Dr. Pelton said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zachariah P et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 June 3. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2430.

according to data from 50 patients at a single tertiary care center.

“Risk factors for severe disease in pediatric populations have not been clearly identified and the high prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in NYC offers an opportunity to describe severe pediatric disease in more detail,” wrote Philip Zachariah, MD, of New York–Presbyterian Hospital, New York, and colleagues.

In a retrospective case series published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 50 patients: 41 classified as severe and 9 classified as nonsevere. Among the patients, 27 were male and 25 were Hispanic. The patient population had a median of 2 days from symptom onset to hospital admission. The most common symptoms were fever (80%) and respiratory symptoms (64%). Seventy-six percent of patients had a median length of stay of 3 days (range 1-30 days).