User login

TNF inhibitors cut odds of VTE in RA patients

The risk for venous thromboembolism is almost 50% lower in patients with RA taking TNF inhibitors than in those taking conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), according to data from the German RABBIT registry.

“Some rheumatologists have thought TNF inhibitors could increase the risk for venous thromboembolism events, but we don’t think this is true, based on our findings,” said investigator Anja Strangfeld, MD, PhD, from the German Rheumatism Research Center in Berlin.

The risk is more than one-third lower in RA patients treated with other newer biologics, such as abatacept, rituximab, sarilumab, and tocilizumab.

However, risk for a serious venous thromboembolism is twice as high in patients with C-reactive protein (CRP) levels above 5 mg/L and is nearly three times as high in patients 65 years and older.

For the study, Dr. Strangfeld and her colleagues followed about 11,000 patients for more than 10 years. The findings were presented at the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) 2020 Congress.

“Patients with RA have a greater risk for venous thromboembolism compared with the general population, but we didn’t know the risk conveyed by different DMARD treatments,” Dr. Strangfeld told Medscape Medical News. “It is also evident that higher age and lower capacity for physical function increase the risk, which was not so surprising.”

Chronic inflammation in RA patients elevates the risk for deep vein and pulmonary thrombosis by two to three times, said John Isaacs, MBBS, PhD, from Newcastle University in Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom, who is chair of the EULAR scientific program committee.

Among the supporting studies Dr. Isaacs discussed during an online press conference was a Swedish trial of more than 46,000 RA patients, which had been presented earlier by Viktor Molander, a PhD candidate from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm (abstract OP0034).

Mr. Molander’s team showed that one in 100 patients with high disease activity will develop venous thromboembolism within a year, which is twice the number of events seen among patients in remission.

Combined with the RABBIT data, both studies “show if you can control their disease in the right way, you’re not only helping rheumatoid arthritis patients feel better, but you could be prolonging their lives,” Dr. Isaacs said.

The prospective RABBIT study followed RA patients who began receiving a new DMARD after treatment failed with at least one conventional synthetic DMARD, such as methotrexate or leflunomide. At baseline, those taking TNF inhibitors or other biologics had higher CRP levels on average, as well as a higher rate of existing cardiovascular disease. They also received glucocorticoids, such as prednisone, more often.

The observational nature of the RABBIT study is a weakness, Dr. Strangfeld said, and it could not prove cause and effect. But the methodology had several strengths, including input on patient factors from participating rheumatologists at least every 6 months.

“We enrolled patients at the start of treatment and observed them, regardless of any treatment changes, for up to 10 years,” she added. “That’s a really long observation period.”

The RABBIT data can help shape treatment decisions, said Loreto Carmona, MD, PhD, from the Musculoskeletal Health Institute in Madrid, who is chair of the EULAR abstract selection committee.

For a woman with RA who smokes and takes oral contraceptives, for example, “if she has high levels of inflammation, I think it’s okay to use TNF inhibitors, where maybe in the past we wouldn’t have thought that,” she said.

“The TNF inhibitors are actually reducing the inflammation and, therefore, reducing the risk,” Dr. Carmona told Medscape Medical News. “It could be an effect of using the drugs on people with higher levels of inflammation. It’s an indirect protective effect.”

The study was funded by a joint unconditional grant from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Fresenius-Kabi, Hexal, Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung Bioepis, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB. Dr. Strangfeld is on the speakers bureau of AbbVie, BMS, Pfizer, Roche and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Isaacs is a consultant or has received honoraria or grants from Pfizer, AbbVie, Amgen, Merck, Roche, and UCB. Dr. Carmona has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The risk for venous thromboembolism is almost 50% lower in patients with RA taking TNF inhibitors than in those taking conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), according to data from the German RABBIT registry.

“Some rheumatologists have thought TNF inhibitors could increase the risk for venous thromboembolism events, but we don’t think this is true, based on our findings,” said investigator Anja Strangfeld, MD, PhD, from the German Rheumatism Research Center in Berlin.

The risk is more than one-third lower in RA patients treated with other newer biologics, such as abatacept, rituximab, sarilumab, and tocilizumab.

However, risk for a serious venous thromboembolism is twice as high in patients with C-reactive protein (CRP) levels above 5 mg/L and is nearly three times as high in patients 65 years and older.

For the study, Dr. Strangfeld and her colleagues followed about 11,000 patients for more than 10 years. The findings were presented at the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) 2020 Congress.

“Patients with RA have a greater risk for venous thromboembolism compared with the general population, but we didn’t know the risk conveyed by different DMARD treatments,” Dr. Strangfeld told Medscape Medical News. “It is also evident that higher age and lower capacity for physical function increase the risk, which was not so surprising.”

Chronic inflammation in RA patients elevates the risk for deep vein and pulmonary thrombosis by two to three times, said John Isaacs, MBBS, PhD, from Newcastle University in Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom, who is chair of the EULAR scientific program committee.

Among the supporting studies Dr. Isaacs discussed during an online press conference was a Swedish trial of more than 46,000 RA patients, which had been presented earlier by Viktor Molander, a PhD candidate from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm (abstract OP0034).

Mr. Molander’s team showed that one in 100 patients with high disease activity will develop venous thromboembolism within a year, which is twice the number of events seen among patients in remission.

Combined with the RABBIT data, both studies “show if you can control their disease in the right way, you’re not only helping rheumatoid arthritis patients feel better, but you could be prolonging their lives,” Dr. Isaacs said.

The prospective RABBIT study followed RA patients who began receiving a new DMARD after treatment failed with at least one conventional synthetic DMARD, such as methotrexate or leflunomide. At baseline, those taking TNF inhibitors or other biologics had higher CRP levels on average, as well as a higher rate of existing cardiovascular disease. They also received glucocorticoids, such as prednisone, more often.

The observational nature of the RABBIT study is a weakness, Dr. Strangfeld said, and it could not prove cause and effect. But the methodology had several strengths, including input on patient factors from participating rheumatologists at least every 6 months.

“We enrolled patients at the start of treatment and observed them, regardless of any treatment changes, for up to 10 years,” she added. “That’s a really long observation period.”

The RABBIT data can help shape treatment decisions, said Loreto Carmona, MD, PhD, from the Musculoskeletal Health Institute in Madrid, who is chair of the EULAR abstract selection committee.

For a woman with RA who smokes and takes oral contraceptives, for example, “if she has high levels of inflammation, I think it’s okay to use TNF inhibitors, where maybe in the past we wouldn’t have thought that,” she said.

“The TNF inhibitors are actually reducing the inflammation and, therefore, reducing the risk,” Dr. Carmona told Medscape Medical News. “It could be an effect of using the drugs on people with higher levels of inflammation. It’s an indirect protective effect.”

The study was funded by a joint unconditional grant from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Fresenius-Kabi, Hexal, Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung Bioepis, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB. Dr. Strangfeld is on the speakers bureau of AbbVie, BMS, Pfizer, Roche and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Isaacs is a consultant or has received honoraria or grants from Pfizer, AbbVie, Amgen, Merck, Roche, and UCB. Dr. Carmona has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The risk for venous thromboembolism is almost 50% lower in patients with RA taking TNF inhibitors than in those taking conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), according to data from the German RABBIT registry.

“Some rheumatologists have thought TNF inhibitors could increase the risk for venous thromboembolism events, but we don’t think this is true, based on our findings,” said investigator Anja Strangfeld, MD, PhD, from the German Rheumatism Research Center in Berlin.

The risk is more than one-third lower in RA patients treated with other newer biologics, such as abatacept, rituximab, sarilumab, and tocilizumab.

However, risk for a serious venous thromboembolism is twice as high in patients with C-reactive protein (CRP) levels above 5 mg/L and is nearly three times as high in patients 65 years and older.

For the study, Dr. Strangfeld and her colleagues followed about 11,000 patients for more than 10 years. The findings were presented at the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) 2020 Congress.

“Patients with RA have a greater risk for venous thromboembolism compared with the general population, but we didn’t know the risk conveyed by different DMARD treatments,” Dr. Strangfeld told Medscape Medical News. “It is also evident that higher age and lower capacity for physical function increase the risk, which was not so surprising.”

Chronic inflammation in RA patients elevates the risk for deep vein and pulmonary thrombosis by two to three times, said John Isaacs, MBBS, PhD, from Newcastle University in Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom, who is chair of the EULAR scientific program committee.

Among the supporting studies Dr. Isaacs discussed during an online press conference was a Swedish trial of more than 46,000 RA patients, which had been presented earlier by Viktor Molander, a PhD candidate from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm (abstract OP0034).

Mr. Molander’s team showed that one in 100 patients with high disease activity will develop venous thromboembolism within a year, which is twice the number of events seen among patients in remission.

Combined with the RABBIT data, both studies “show if you can control their disease in the right way, you’re not only helping rheumatoid arthritis patients feel better, but you could be prolonging their lives,” Dr. Isaacs said.

The prospective RABBIT study followed RA patients who began receiving a new DMARD after treatment failed with at least one conventional synthetic DMARD, such as methotrexate or leflunomide. At baseline, those taking TNF inhibitors or other biologics had higher CRP levels on average, as well as a higher rate of existing cardiovascular disease. They also received glucocorticoids, such as prednisone, more often.

The observational nature of the RABBIT study is a weakness, Dr. Strangfeld said, and it could not prove cause and effect. But the methodology had several strengths, including input on patient factors from participating rheumatologists at least every 6 months.

“We enrolled patients at the start of treatment and observed them, regardless of any treatment changes, for up to 10 years,” she added. “That’s a really long observation period.”

The RABBIT data can help shape treatment decisions, said Loreto Carmona, MD, PhD, from the Musculoskeletal Health Institute in Madrid, who is chair of the EULAR abstract selection committee.

For a woman with RA who smokes and takes oral contraceptives, for example, “if she has high levels of inflammation, I think it’s okay to use TNF inhibitors, where maybe in the past we wouldn’t have thought that,” she said.

“The TNF inhibitors are actually reducing the inflammation and, therefore, reducing the risk,” Dr. Carmona told Medscape Medical News. “It could be an effect of using the drugs on people with higher levels of inflammation. It’s an indirect protective effect.”

The study was funded by a joint unconditional grant from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Fresenius-Kabi, Hexal, Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung Bioepis, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB. Dr. Strangfeld is on the speakers bureau of AbbVie, BMS, Pfizer, Roche and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Isaacs is a consultant or has received honoraria or grants from Pfizer, AbbVie, Amgen, Merck, Roche, and UCB. Dr. Carmona has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tandem transplantation, long-term maintenance may extend MM remission

Tandem autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) could extend progression-free survival (PFS) for some patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, based on long-term data from the phase 3 STaMINA trial.

While the intent-to-treat analysis showed no difference in 6-year PFS rate between single versus tandem HSCT, the as-treated analysis showed that patients who received two transplants had a 6-year PFS rate that was approximately 10% higher than those who received just one transplant, reported lead author Parameswaran Hari, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, who presented the findings as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program.

The STaMINA trial, also known as BMT CTN 0702, involved 758 patients who were randomized to receive one of three treatment regimens followed by 3 years of maintenance lenalidomide: tandem HSCT (auto/auto), single HSCT plus consolidation with lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone (auto/RVD), and single HSCT (auto/len).

“At the time, we intended the study to stop approximately 38 months from randomization, allowing for the time for transplant, and then 3 years of maintenance,” Dr. Hari said. However, as the results of lenalidomide maintenance in CALGB 00104 study were reported, they allowed for a follow-on protocol, which provided patients who are progression-free at the completion of the original STaMINA trial to go on to a second follow-on trial, which allowed lenalidomide maintenance on an indefinite basis, he added.

The present analysis looked at the long-term results of this follow-on trial, including the impact of discontinuing lenalidomide.

Aligning with the original study, the present intent-to-treat analysis showed no significant difference between treatment arms for 6-year PFS rate or overall survival. Respectively, PFS rates for auto/auto, auto/RVD, and auto/len were 43.9%, 39.7%, and 40.9% (P = .6).

But 32% of patients in the tandem group never underwent second HSCT, Dr. Hari noted, prompting the as-treated analysis. Although overall survival remained similar between groups, the 6-year PFS was significantly higher for patients who underwent tandem HSCT, at 49.4%, compared with 39.7% for auto/RVD and 38.6% for auto/len (P = .03).

Subgroup analysis showed the statistical benefit of tandem HSCT was driven by high-risk patients, who had a significantly better PFS after tandem transplant, compared with standard-risk patients, who showed no significant benefit.

Dr. Hari called the findings “provocative.”

“The tandem auto approach may still be relevant in high-risk multiple myeloma patients,” he said.

Dr. Hari and his colleagues also found that patients who stayed on maintenance lenalidomide after 38 months had a better 5-year PFS rate than those who discontinued maintenance therapy (79.5% vs. 61%; P = .0004). Subgroup analysis showed this benefit was statistically significant among patients with standard-risk disease (86.3% vs. 66%; P less than .001) but not among those in the high-risk subgroup (86.7% vs. 67.8%; P = .2).

However, Dr. Hari suggested that, based on the similarity of proportions between subgroups, the lack of significance in the high-risk subgroup was likely because of small sample size, suggesting the benefit of maintenance was actually shared across risk strata.

“Lenalidomide maintenance becomes a significant factor for preventing patients from progression,” Dr. Hari said, noting that the tandem transplant approach requires further study, and that he and his colleagues would soon publish minimal residual disease data.

He finished his presentation with a clear clinical recommendation. “Preplanned lenalidomide discontinuation at 3 years is not recommended based on inferior progression-free survival among those who stopped such therapy,” he said.

Invited discussant Joshua R. Richter, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the findings encourage high-dose maintenance therapy, and for some, tandem HSCT.

“The STaMINA study presented today supports the notion that some patients with high-risk disease still may benefit and have further tumor burden reduction with the second transplant that leads to deeper remissions and hopefully abrogates diminished outcomes,” Dr. Richter said during a virtual presentation.

But improvements are needed to better identify such patients, Dr. Richter added. He highlighted a lack of standardization in risk modeling, with various factors currently employed, such as patient characteristics and genomic markers, among several others.

“Better definitions will allow us to cross compare and make true analyses about how to manage these patients,” Dr. Richter said. “Despite the improvements across the board that we’ve seen in myeloma patients, high-risk disease continues to represent a more complicated arena. And patients continue to suffer from worse outcomes, despite all of the other advances.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Amgen, Celgene, Novartis, and others. Dr. Richter disclosed affiliations with Takeda, Sanofi, Janssen, and others.

SOURCE: Hari et al. ASCO 2020. Abstract 8506.

Tandem autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) could extend progression-free survival (PFS) for some patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, based on long-term data from the phase 3 STaMINA trial.

While the intent-to-treat analysis showed no difference in 6-year PFS rate between single versus tandem HSCT, the as-treated analysis showed that patients who received two transplants had a 6-year PFS rate that was approximately 10% higher than those who received just one transplant, reported lead author Parameswaran Hari, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, who presented the findings as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program.

The STaMINA trial, also known as BMT CTN 0702, involved 758 patients who were randomized to receive one of three treatment regimens followed by 3 years of maintenance lenalidomide: tandem HSCT (auto/auto), single HSCT plus consolidation with lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone (auto/RVD), and single HSCT (auto/len).

“At the time, we intended the study to stop approximately 38 months from randomization, allowing for the time for transplant, and then 3 years of maintenance,” Dr. Hari said. However, as the results of lenalidomide maintenance in CALGB 00104 study were reported, they allowed for a follow-on protocol, which provided patients who are progression-free at the completion of the original STaMINA trial to go on to a second follow-on trial, which allowed lenalidomide maintenance on an indefinite basis, he added.

The present analysis looked at the long-term results of this follow-on trial, including the impact of discontinuing lenalidomide.

Aligning with the original study, the present intent-to-treat analysis showed no significant difference between treatment arms for 6-year PFS rate or overall survival. Respectively, PFS rates for auto/auto, auto/RVD, and auto/len were 43.9%, 39.7%, and 40.9% (P = .6).

But 32% of patients in the tandem group never underwent second HSCT, Dr. Hari noted, prompting the as-treated analysis. Although overall survival remained similar between groups, the 6-year PFS was significantly higher for patients who underwent tandem HSCT, at 49.4%, compared with 39.7% for auto/RVD and 38.6% for auto/len (P = .03).

Subgroup analysis showed the statistical benefit of tandem HSCT was driven by high-risk patients, who had a significantly better PFS after tandem transplant, compared with standard-risk patients, who showed no significant benefit.

Dr. Hari called the findings “provocative.”

“The tandem auto approach may still be relevant in high-risk multiple myeloma patients,” he said.

Dr. Hari and his colleagues also found that patients who stayed on maintenance lenalidomide after 38 months had a better 5-year PFS rate than those who discontinued maintenance therapy (79.5% vs. 61%; P = .0004). Subgroup analysis showed this benefit was statistically significant among patients with standard-risk disease (86.3% vs. 66%; P less than .001) but not among those in the high-risk subgroup (86.7% vs. 67.8%; P = .2).

However, Dr. Hari suggested that, based on the similarity of proportions between subgroups, the lack of significance in the high-risk subgroup was likely because of small sample size, suggesting the benefit of maintenance was actually shared across risk strata.

“Lenalidomide maintenance becomes a significant factor for preventing patients from progression,” Dr. Hari said, noting that the tandem transplant approach requires further study, and that he and his colleagues would soon publish minimal residual disease data.

He finished his presentation with a clear clinical recommendation. “Preplanned lenalidomide discontinuation at 3 years is not recommended based on inferior progression-free survival among those who stopped such therapy,” he said.

Invited discussant Joshua R. Richter, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the findings encourage high-dose maintenance therapy, and for some, tandem HSCT.

“The STaMINA study presented today supports the notion that some patients with high-risk disease still may benefit and have further tumor burden reduction with the second transplant that leads to deeper remissions and hopefully abrogates diminished outcomes,” Dr. Richter said during a virtual presentation.

But improvements are needed to better identify such patients, Dr. Richter added. He highlighted a lack of standardization in risk modeling, with various factors currently employed, such as patient characteristics and genomic markers, among several others.

“Better definitions will allow us to cross compare and make true analyses about how to manage these patients,” Dr. Richter said. “Despite the improvements across the board that we’ve seen in myeloma patients, high-risk disease continues to represent a more complicated arena. And patients continue to suffer from worse outcomes, despite all of the other advances.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Amgen, Celgene, Novartis, and others. Dr. Richter disclosed affiliations with Takeda, Sanofi, Janssen, and others.

SOURCE: Hari et al. ASCO 2020. Abstract 8506.

Tandem autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) could extend progression-free survival (PFS) for some patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, based on long-term data from the phase 3 STaMINA trial.

While the intent-to-treat analysis showed no difference in 6-year PFS rate between single versus tandem HSCT, the as-treated analysis showed that patients who received two transplants had a 6-year PFS rate that was approximately 10% higher than those who received just one transplant, reported lead author Parameswaran Hari, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, who presented the findings as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program.

The STaMINA trial, also known as BMT CTN 0702, involved 758 patients who were randomized to receive one of three treatment regimens followed by 3 years of maintenance lenalidomide: tandem HSCT (auto/auto), single HSCT plus consolidation with lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone (auto/RVD), and single HSCT (auto/len).

“At the time, we intended the study to stop approximately 38 months from randomization, allowing for the time for transplant, and then 3 years of maintenance,” Dr. Hari said. However, as the results of lenalidomide maintenance in CALGB 00104 study were reported, they allowed for a follow-on protocol, which provided patients who are progression-free at the completion of the original STaMINA trial to go on to a second follow-on trial, which allowed lenalidomide maintenance on an indefinite basis, he added.

The present analysis looked at the long-term results of this follow-on trial, including the impact of discontinuing lenalidomide.

Aligning with the original study, the present intent-to-treat analysis showed no significant difference between treatment arms for 6-year PFS rate or overall survival. Respectively, PFS rates for auto/auto, auto/RVD, and auto/len were 43.9%, 39.7%, and 40.9% (P = .6).

But 32% of patients in the tandem group never underwent second HSCT, Dr. Hari noted, prompting the as-treated analysis. Although overall survival remained similar between groups, the 6-year PFS was significantly higher for patients who underwent tandem HSCT, at 49.4%, compared with 39.7% for auto/RVD and 38.6% for auto/len (P = .03).

Subgroup analysis showed the statistical benefit of tandem HSCT was driven by high-risk patients, who had a significantly better PFS after tandem transplant, compared with standard-risk patients, who showed no significant benefit.

Dr. Hari called the findings “provocative.”

“The tandem auto approach may still be relevant in high-risk multiple myeloma patients,” he said.

Dr. Hari and his colleagues also found that patients who stayed on maintenance lenalidomide after 38 months had a better 5-year PFS rate than those who discontinued maintenance therapy (79.5% vs. 61%; P = .0004). Subgroup analysis showed this benefit was statistically significant among patients with standard-risk disease (86.3% vs. 66%; P less than .001) but not among those in the high-risk subgroup (86.7% vs. 67.8%; P = .2).

However, Dr. Hari suggested that, based on the similarity of proportions between subgroups, the lack of significance in the high-risk subgroup was likely because of small sample size, suggesting the benefit of maintenance was actually shared across risk strata.

“Lenalidomide maintenance becomes a significant factor for preventing patients from progression,” Dr. Hari said, noting that the tandem transplant approach requires further study, and that he and his colleagues would soon publish minimal residual disease data.

He finished his presentation with a clear clinical recommendation. “Preplanned lenalidomide discontinuation at 3 years is not recommended based on inferior progression-free survival among those who stopped such therapy,” he said.

Invited discussant Joshua R. Richter, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the findings encourage high-dose maintenance therapy, and for some, tandem HSCT.

“The STaMINA study presented today supports the notion that some patients with high-risk disease still may benefit and have further tumor burden reduction with the second transplant that leads to deeper remissions and hopefully abrogates diminished outcomes,” Dr. Richter said during a virtual presentation.

But improvements are needed to better identify such patients, Dr. Richter added. He highlighted a lack of standardization in risk modeling, with various factors currently employed, such as patient characteristics and genomic markers, among several others.

“Better definitions will allow us to cross compare and make true analyses about how to manage these patients,” Dr. Richter said. “Despite the improvements across the board that we’ve seen in myeloma patients, high-risk disease continues to represent a more complicated arena. And patients continue to suffer from worse outcomes, despite all of the other advances.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Amgen, Celgene, Novartis, and others. Dr. Richter disclosed affiliations with Takeda, Sanofi, Janssen, and others.

SOURCE: Hari et al. ASCO 2020. Abstract 8506.

FROM ASCO 2020

Baloxavir effective, well tolerated for influenza treatment in children

according to Jeffrey Baker, MD, of Clinical Research Prime, Idaho Falls, and associates.

In the double-blind, randomized, controlled MiniSTONE-2 phase 3 trial, the investigators randomized 112 children aged 1-12 years to baloxavir and 57 to oseltamivir. The predominant influenza A subtype was H3N2 for both groups, followed by H1N1pdm09. Demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between treatment groups, the investigators wrote in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.

The time to alleviation of signs and symptoms was a median 138 hours for those receiving baloxavir and 150 hours for those receiving oseltamivir, a nonsignificant difference. Duration of fever and of all symptoms also were similar between groups, as was the time to return to normal health and activity.

A total of 122 adverse events were reported in 84 children, with 95% of adverse events being resolved or resolving by the end of the study. The incidence of adverse events was 46% in those receiving baloxavir and 53% in those receiving oseltamivir, a nonsignificant difference, with the most common adverse event in both groups being gastrointestinal disorders. No deaths, serious adverse events, or hospitalizations were reported, but two patients receiving oseltamivir discontinued because of adverse events.

The study was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Baker and a coauthor received funding through their institutions for the conduct of the study; several coauthors reported being employed by and owning stocks in F. Hoffmann–La Roche. One coauthor reported receiving consultancy fees from F. Hoffmann–La Roche and grants from Shionogi.

SOURCE: Baker J et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020 Jun 5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002747.

according to Jeffrey Baker, MD, of Clinical Research Prime, Idaho Falls, and associates.

In the double-blind, randomized, controlled MiniSTONE-2 phase 3 trial, the investigators randomized 112 children aged 1-12 years to baloxavir and 57 to oseltamivir. The predominant influenza A subtype was H3N2 for both groups, followed by H1N1pdm09. Demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between treatment groups, the investigators wrote in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.

The time to alleviation of signs and symptoms was a median 138 hours for those receiving baloxavir and 150 hours for those receiving oseltamivir, a nonsignificant difference. Duration of fever and of all symptoms also were similar between groups, as was the time to return to normal health and activity.

A total of 122 adverse events were reported in 84 children, with 95% of adverse events being resolved or resolving by the end of the study. The incidence of adverse events was 46% in those receiving baloxavir and 53% in those receiving oseltamivir, a nonsignificant difference, with the most common adverse event in both groups being gastrointestinal disorders. No deaths, serious adverse events, or hospitalizations were reported, but two patients receiving oseltamivir discontinued because of adverse events.

The study was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Baker and a coauthor received funding through their institutions for the conduct of the study; several coauthors reported being employed by and owning stocks in F. Hoffmann–La Roche. One coauthor reported receiving consultancy fees from F. Hoffmann–La Roche and grants from Shionogi.

SOURCE: Baker J et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020 Jun 5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002747.

according to Jeffrey Baker, MD, of Clinical Research Prime, Idaho Falls, and associates.

In the double-blind, randomized, controlled MiniSTONE-2 phase 3 trial, the investigators randomized 112 children aged 1-12 years to baloxavir and 57 to oseltamivir. The predominant influenza A subtype was H3N2 for both groups, followed by H1N1pdm09. Demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between treatment groups, the investigators wrote in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.

The time to alleviation of signs and symptoms was a median 138 hours for those receiving baloxavir and 150 hours for those receiving oseltamivir, a nonsignificant difference. Duration of fever and of all symptoms also were similar between groups, as was the time to return to normal health and activity.

A total of 122 adverse events were reported in 84 children, with 95% of adverse events being resolved or resolving by the end of the study. The incidence of adverse events was 46% in those receiving baloxavir and 53% in those receiving oseltamivir, a nonsignificant difference, with the most common adverse event in both groups being gastrointestinal disorders. No deaths, serious adverse events, or hospitalizations were reported, but two patients receiving oseltamivir discontinued because of adverse events.

The study was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Baker and a coauthor received funding through their institutions for the conduct of the study; several coauthors reported being employed by and owning stocks in F. Hoffmann–La Roche. One coauthor reported receiving consultancy fees from F. Hoffmann–La Roche and grants from Shionogi.

SOURCE: Baker J et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020 Jun 5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002747.

FROM THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASE JOURNAL

VICTORIA results deepen mystery of vericiguat in low-EF heart failure

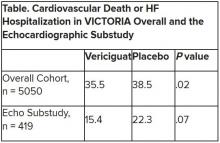

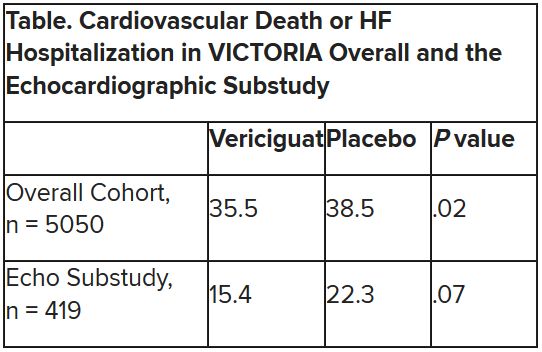

Although clinical outcomes improved for patients with high-risk heart failure (HF) who received vericiguat (Merck/Bayer) on top of standard therapy in a major randomized trial, a subgroup study failed to show any corresponding gains in ventricular function.

The discordant results from the 5,050-patient VICTORIA trial and its echocardiographic substudy highlight something of a mystery as to the mechanism of the investigational oral soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator’s clinical effects. In the overall trial, they included a drop in risk of cardiovascular (CV) death or first HF hospitalization, the primary endpoint.

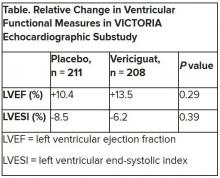

In the echo substudy, which assessed patients with evaluable echocardiograms at both baseline and 8 months, vericiguat, compared with placebo, had no significant effect on two measures of left ventricular (LV) function. Patients in the prospectively conducted substudy made up less than 10% of the total trial population.

Both LV ejection fraction (LVEF) and LV end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) significantly improved in the vericiguat and control groups, but vericiguat “had no additional significant effect,” said Burkert Pieske, MD, of Charité University Medicine Berlin.

Still, he said, there was “evidence of a lower risk of events, evidence of a clinical benefit,” for those who received vericiguat, although it fell slightly short of significance in the substudy cohort of fewer than 500 patients.

Dr. Pieske reported the VICTORIA echo substudy results June 5 in a Late-Breaking Science Session during HFA Discoveries, the online backup for the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology annual scientific meeting.

The traditional live HFA meeting had been scheduled for Barcelona but was canceled this year as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pointing to the significant echo improvements in both treatment groups, invited discussant Rudolf A. de Boer, MD, PhD, University of Groningen (the Netherlands), said the substudy shows that HF in high-risk patients “is associated with a transient deterioration of LV function and geometry, which can to a certain extent be reversed over time.”

That the effect apparently wasn’t influenced by vericiguat “may be explained by the fact that, in randomized controlled trials, patients – including those on placebo – tend to be treated very well.” In clinical practice, he said, “less complete reverse remodeling may be expected.”

Dr. de Boer also pointed to likely survivor bias in the study, in that only patients who survived to at least 8 months were included. That meant, among other things, that they were likely at lower overall risk than the total VICTORIA population, leaving less room for any treatment effect.

“Further, likely because of the play of chance in this substudy, the LV volumes were smaller in the vericiguat group at baseline, creating less of an opportunity for vericiguat to make a difference,” he said. “It could be speculated that, with larger volumes, the window of opportunity for vericiguat would have been wider.”

But “most strikingly,” the lack of vericiguat effect on echo parameters contrasts with the clinical benefits associated with the drug in the main trial, and possibly in the echo substudy, Dr. de Boer said, “creating a dissociation between the surrogate echo parameters and the clinical hard endpoints. And it could be imagined that the rather crude echo measures presented here, LVEF and LV volume, miss a more subtle effect of vericiguat.”

For example, it’s possible that the drug’s clinical effect in heart failure does not depend on any improvements in ventricular function, Dr. de Boer said, adding that vericiguat “may potentially also have important effects on pulmonary and peripheral vasculature,” so he recommended future studies look for any changes in arterial and right ventricular function from the drug.

VICTORIA enrolled only patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction who had previously experienced a decompensation event, usually only within the last 3 months, as it turned out. Those assigned to vericiguat on top of standard drug and device therapies showed a modest 10% decline in adjusted relative risk (P = .019) for the trial’s primary endpoint, CV death or first HF hospitalization.

But when the results were unveiled at a meeting, trialists and observers were more enthused about the drug’s effect in absolute terms, which by one measure was 4.2 fewer events on vericiguat per 100 patient-years. That translated to a number to treat of 24 to prevent one event, said to be impressive, given that the study’s patients were so high risk.

The echo substudy included 419 prospectively selected patients, 208 on vericiguat and 211 assigned to placebo, who had evaluable echocardiograms at both baseline and 8 months, as assessed at the VICTORIA echo core lab. They averaged 64.5 years in age with a mean baseline LVEF of 29%; about 27% were women.

Their clinical outcomes paralleled the overall study, with lower event rates overall and a difference between treatment groups that fell short of significance.

Neither of the study’s primary endpoints, the two echo parameters, responded differently to vericiguat, compared with placebo.

The overall VICTORIA trial “showed a modest but useful benefit in the combined endpoint of hospitalizations and mortality, but all due to fewer hospitalizations,” Andrew J. Coats, MD, DSc, MBA, told this news organization.

“The echo substudy was smaller, and many drugs that reduce hospitalization do not do it through effects on LV function,” said Dr. Coats of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, who wasn’t a part of VICTORIA. “Other mechanisms may be via improved peripheral vascular or renal effects.”

VICTORIA and the echocardiographic substudy were supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme and Bayer AG. Dr. Pieske disclosed serving on a speakers bureau, advisory board, or committee for Bayer Healthcare, Merck, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Stealth, Servier, Daiichi-Sankyo, Biotronic, Abbott Vascular, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. de Boer disclosed receiving speaker fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Roche. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from Actimed, AstraZeneca, Faraday, WL Gore, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Respicardia, Servier, Stealth Peptides, Verona, and Vifor.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Although clinical outcomes improved for patients with high-risk heart failure (HF) who received vericiguat (Merck/Bayer) on top of standard therapy in a major randomized trial, a subgroup study failed to show any corresponding gains in ventricular function.

The discordant results from the 5,050-patient VICTORIA trial and its echocardiographic substudy highlight something of a mystery as to the mechanism of the investigational oral soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator’s clinical effects. In the overall trial, they included a drop in risk of cardiovascular (CV) death or first HF hospitalization, the primary endpoint.

In the echo substudy, which assessed patients with evaluable echocardiograms at both baseline and 8 months, vericiguat, compared with placebo, had no significant effect on two measures of left ventricular (LV) function. Patients in the prospectively conducted substudy made up less than 10% of the total trial population.

Both LV ejection fraction (LVEF) and LV end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) significantly improved in the vericiguat and control groups, but vericiguat “had no additional significant effect,” said Burkert Pieske, MD, of Charité University Medicine Berlin.

Still, he said, there was “evidence of a lower risk of events, evidence of a clinical benefit,” for those who received vericiguat, although it fell slightly short of significance in the substudy cohort of fewer than 500 patients.

Dr. Pieske reported the VICTORIA echo substudy results June 5 in a Late-Breaking Science Session during HFA Discoveries, the online backup for the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology annual scientific meeting.

The traditional live HFA meeting had been scheduled for Barcelona but was canceled this year as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pointing to the significant echo improvements in both treatment groups, invited discussant Rudolf A. de Boer, MD, PhD, University of Groningen (the Netherlands), said the substudy shows that HF in high-risk patients “is associated with a transient deterioration of LV function and geometry, which can to a certain extent be reversed over time.”

That the effect apparently wasn’t influenced by vericiguat “may be explained by the fact that, in randomized controlled trials, patients – including those on placebo – tend to be treated very well.” In clinical practice, he said, “less complete reverse remodeling may be expected.”

Dr. de Boer also pointed to likely survivor bias in the study, in that only patients who survived to at least 8 months were included. That meant, among other things, that they were likely at lower overall risk than the total VICTORIA population, leaving less room for any treatment effect.

“Further, likely because of the play of chance in this substudy, the LV volumes were smaller in the vericiguat group at baseline, creating less of an opportunity for vericiguat to make a difference,” he said. “It could be speculated that, with larger volumes, the window of opportunity for vericiguat would have been wider.”

But “most strikingly,” the lack of vericiguat effect on echo parameters contrasts with the clinical benefits associated with the drug in the main trial, and possibly in the echo substudy, Dr. de Boer said, “creating a dissociation between the surrogate echo parameters and the clinical hard endpoints. And it could be imagined that the rather crude echo measures presented here, LVEF and LV volume, miss a more subtle effect of vericiguat.”

For example, it’s possible that the drug’s clinical effect in heart failure does not depend on any improvements in ventricular function, Dr. de Boer said, adding that vericiguat “may potentially also have important effects on pulmonary and peripheral vasculature,” so he recommended future studies look for any changes in arterial and right ventricular function from the drug.

VICTORIA enrolled only patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction who had previously experienced a decompensation event, usually only within the last 3 months, as it turned out. Those assigned to vericiguat on top of standard drug and device therapies showed a modest 10% decline in adjusted relative risk (P = .019) for the trial’s primary endpoint, CV death or first HF hospitalization.

But when the results were unveiled at a meeting, trialists and observers were more enthused about the drug’s effect in absolute terms, which by one measure was 4.2 fewer events on vericiguat per 100 patient-years. That translated to a number to treat of 24 to prevent one event, said to be impressive, given that the study’s patients were so high risk.

The echo substudy included 419 prospectively selected patients, 208 on vericiguat and 211 assigned to placebo, who had evaluable echocardiograms at both baseline and 8 months, as assessed at the VICTORIA echo core lab. They averaged 64.5 years in age with a mean baseline LVEF of 29%; about 27% were women.

Their clinical outcomes paralleled the overall study, with lower event rates overall and a difference between treatment groups that fell short of significance.

Neither of the study’s primary endpoints, the two echo parameters, responded differently to vericiguat, compared with placebo.

The overall VICTORIA trial “showed a modest but useful benefit in the combined endpoint of hospitalizations and mortality, but all due to fewer hospitalizations,” Andrew J. Coats, MD, DSc, MBA, told this news organization.

“The echo substudy was smaller, and many drugs that reduce hospitalization do not do it through effects on LV function,” said Dr. Coats of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, who wasn’t a part of VICTORIA. “Other mechanisms may be via improved peripheral vascular or renal effects.”

VICTORIA and the echocardiographic substudy were supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme and Bayer AG. Dr. Pieske disclosed serving on a speakers bureau, advisory board, or committee for Bayer Healthcare, Merck, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Stealth, Servier, Daiichi-Sankyo, Biotronic, Abbott Vascular, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. de Boer disclosed receiving speaker fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Roche. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from Actimed, AstraZeneca, Faraday, WL Gore, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Respicardia, Servier, Stealth Peptides, Verona, and Vifor.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Although clinical outcomes improved for patients with high-risk heart failure (HF) who received vericiguat (Merck/Bayer) on top of standard therapy in a major randomized trial, a subgroup study failed to show any corresponding gains in ventricular function.

The discordant results from the 5,050-patient VICTORIA trial and its echocardiographic substudy highlight something of a mystery as to the mechanism of the investigational oral soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator’s clinical effects. In the overall trial, they included a drop in risk of cardiovascular (CV) death or first HF hospitalization, the primary endpoint.

In the echo substudy, which assessed patients with evaluable echocardiograms at both baseline and 8 months, vericiguat, compared with placebo, had no significant effect on two measures of left ventricular (LV) function. Patients in the prospectively conducted substudy made up less than 10% of the total trial population.

Both LV ejection fraction (LVEF) and LV end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) significantly improved in the vericiguat and control groups, but vericiguat “had no additional significant effect,” said Burkert Pieske, MD, of Charité University Medicine Berlin.

Still, he said, there was “evidence of a lower risk of events, evidence of a clinical benefit,” for those who received vericiguat, although it fell slightly short of significance in the substudy cohort of fewer than 500 patients.

Dr. Pieske reported the VICTORIA echo substudy results June 5 in a Late-Breaking Science Session during HFA Discoveries, the online backup for the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology annual scientific meeting.

The traditional live HFA meeting had been scheduled for Barcelona but was canceled this year as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pointing to the significant echo improvements in both treatment groups, invited discussant Rudolf A. de Boer, MD, PhD, University of Groningen (the Netherlands), said the substudy shows that HF in high-risk patients “is associated with a transient deterioration of LV function and geometry, which can to a certain extent be reversed over time.”

That the effect apparently wasn’t influenced by vericiguat “may be explained by the fact that, in randomized controlled trials, patients – including those on placebo – tend to be treated very well.” In clinical practice, he said, “less complete reverse remodeling may be expected.”

Dr. de Boer also pointed to likely survivor bias in the study, in that only patients who survived to at least 8 months were included. That meant, among other things, that they were likely at lower overall risk than the total VICTORIA population, leaving less room for any treatment effect.

“Further, likely because of the play of chance in this substudy, the LV volumes were smaller in the vericiguat group at baseline, creating less of an opportunity for vericiguat to make a difference,” he said. “It could be speculated that, with larger volumes, the window of opportunity for vericiguat would have been wider.”

But “most strikingly,” the lack of vericiguat effect on echo parameters contrasts with the clinical benefits associated with the drug in the main trial, and possibly in the echo substudy, Dr. de Boer said, “creating a dissociation between the surrogate echo parameters and the clinical hard endpoints. And it could be imagined that the rather crude echo measures presented here, LVEF and LV volume, miss a more subtle effect of vericiguat.”

For example, it’s possible that the drug’s clinical effect in heart failure does not depend on any improvements in ventricular function, Dr. de Boer said, adding that vericiguat “may potentially also have important effects on pulmonary and peripheral vasculature,” so he recommended future studies look for any changes in arterial and right ventricular function from the drug.

VICTORIA enrolled only patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction who had previously experienced a decompensation event, usually only within the last 3 months, as it turned out. Those assigned to vericiguat on top of standard drug and device therapies showed a modest 10% decline in adjusted relative risk (P = .019) for the trial’s primary endpoint, CV death or first HF hospitalization.

But when the results were unveiled at a meeting, trialists and observers were more enthused about the drug’s effect in absolute terms, which by one measure was 4.2 fewer events on vericiguat per 100 patient-years. That translated to a number to treat of 24 to prevent one event, said to be impressive, given that the study’s patients were so high risk.

The echo substudy included 419 prospectively selected patients, 208 on vericiguat and 211 assigned to placebo, who had evaluable echocardiograms at both baseline and 8 months, as assessed at the VICTORIA echo core lab. They averaged 64.5 years in age with a mean baseline LVEF of 29%; about 27% were women.

Their clinical outcomes paralleled the overall study, with lower event rates overall and a difference between treatment groups that fell short of significance.

Neither of the study’s primary endpoints, the two echo parameters, responded differently to vericiguat, compared with placebo.

The overall VICTORIA trial “showed a modest but useful benefit in the combined endpoint of hospitalizations and mortality, but all due to fewer hospitalizations,” Andrew J. Coats, MD, DSc, MBA, told this news organization.

“The echo substudy was smaller, and many drugs that reduce hospitalization do not do it through effects on LV function,” said Dr. Coats of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, who wasn’t a part of VICTORIA. “Other mechanisms may be via improved peripheral vascular or renal effects.”

VICTORIA and the echocardiographic substudy were supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme and Bayer AG. Dr. Pieske disclosed serving on a speakers bureau, advisory board, or committee for Bayer Healthcare, Merck, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Stealth, Servier, Daiichi-Sankyo, Biotronic, Abbott Vascular, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. de Boer disclosed receiving speaker fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Roche. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from Actimed, AstraZeneca, Faraday, WL Gore, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Respicardia, Servier, Stealth Peptides, Verona, and Vifor.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC HEART FAILURE 2020

Food deserts linked to greater pregnancy morbidity

according to a retrospective observational study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Previous research has linked so-called “food deserts” to higher systolic blood pressure and an increased risk of cardiovascular events in people with coronary artery disease, the authors note.

“Research on populations in the United States confirm that increased access to supermarkets is associated with lower prevalence of overweight and obesity, and improved fruit and vegetable consumption,” said Matthew J. Tipton, MD, of Loyola University Medical Center in Chicago, and colleagues.

“With our study showing an association between living in a food desert and increased pregnancy morbidity, it is our hope that with future work, an unhealthy food environment could prove to be a modifiable factor that does contribute to disparities in pregnancy morbidity,” the authors said. “Perhaps then, one could question whether greater access to healthier foods could reduce unexplained pregnancy morbidity for this population of patients,” paving the way toward developing interventions that can then improve vulnerable women’s health.

The researchers reviewed the electronic medical records of all the pregnant patients who delivered at Loyola University Medical Center in 2014. To determine who lived in a food desert, the authors relied on data about grocery food availability within Census tracts from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Access Research Atlas.

Dr. Tipton and associates defined living in a food desert as living in a low-income Census tract “where at least 33% of the population is more than half a mile from the nearest large grocery store for an urban area or more than 10 miles for a rural area.” Low-income Census tracts are those where “at least 20% of the population has a median family income at or below 80% of the metropolitan area or state median income.”

The authors compared women’s residence within a food desert (or not) with six different pregnancy morbidities: preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, prelabor rupture of membranes, preterm labor, and intrauterine growth restriction.

Among 1,001 deliveries, about 1 in 5 women (20%) lived in a food desert. These women tended to be slightly younger than those not living in a food desert (28 vs. 30 years old), and a higher proportion of women in food deserts were black (44%) rather than white (32%). They also had a lower average income ($44,694) than those not living in food deserts ($67,005).

After adjustment for age, race, and medical insurance type (private, Medicaid, other), the researchers found that women who lived in a food desert had 1.6 times greater odds of pregnancy comorbidity than if they did not (odds ratio, 1.64; P = .004). Nearly half the women living in food deserts had any type of comorbidity (47%), compared with just over a third of women who did not (36%).

Among the six comorbidities studied, preterm rupture of membranes was significantly different before adjustment between those who lived in food deserts (16%) and those who did not (10%) (P = .015). An association with preeclampsia had borderline significance before adjustment: 13% of women in food deserts had preeclampsia, compared with 9% of women not (P = .049). After adjustment for age, race, and medical insurance, however, neither of these associations retained statistically significant differences.

The study was limited by leaving out consideration of other factors besides local food access that might influence pregnancy health, including “quality of patient-doctor communication, implicit bias, structural racism, and stress owing to concern for neighborhood safety,” Dr. Tipton and associates said.

“An additional, albeit less obvious factor that may be unique to patients suffering disproportionately from obstetric morbidity is exposure to toxic elements,” the researchers add. “It has been shown in a previous study that low-income, predominately black communities of pregnant women may suffer disproportionately from lead or arsenic exposure.”

The study did not note external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Tipton MJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003868.

according to a retrospective observational study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Previous research has linked so-called “food deserts” to higher systolic blood pressure and an increased risk of cardiovascular events in people with coronary artery disease, the authors note.

“Research on populations in the United States confirm that increased access to supermarkets is associated with lower prevalence of overweight and obesity, and improved fruit and vegetable consumption,” said Matthew J. Tipton, MD, of Loyola University Medical Center in Chicago, and colleagues.

“With our study showing an association between living in a food desert and increased pregnancy morbidity, it is our hope that with future work, an unhealthy food environment could prove to be a modifiable factor that does contribute to disparities in pregnancy morbidity,” the authors said. “Perhaps then, one could question whether greater access to healthier foods could reduce unexplained pregnancy morbidity for this population of patients,” paving the way toward developing interventions that can then improve vulnerable women’s health.

The researchers reviewed the electronic medical records of all the pregnant patients who delivered at Loyola University Medical Center in 2014. To determine who lived in a food desert, the authors relied on data about grocery food availability within Census tracts from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Access Research Atlas.

Dr. Tipton and associates defined living in a food desert as living in a low-income Census tract “where at least 33% of the population is more than half a mile from the nearest large grocery store for an urban area or more than 10 miles for a rural area.” Low-income Census tracts are those where “at least 20% of the population has a median family income at or below 80% of the metropolitan area or state median income.”

The authors compared women’s residence within a food desert (or not) with six different pregnancy morbidities: preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, prelabor rupture of membranes, preterm labor, and intrauterine growth restriction.

Among 1,001 deliveries, about 1 in 5 women (20%) lived in a food desert. These women tended to be slightly younger than those not living in a food desert (28 vs. 30 years old), and a higher proportion of women in food deserts were black (44%) rather than white (32%). They also had a lower average income ($44,694) than those not living in food deserts ($67,005).

After adjustment for age, race, and medical insurance type (private, Medicaid, other), the researchers found that women who lived in a food desert had 1.6 times greater odds of pregnancy comorbidity than if they did not (odds ratio, 1.64; P = .004). Nearly half the women living in food deserts had any type of comorbidity (47%), compared with just over a third of women who did not (36%).

Among the six comorbidities studied, preterm rupture of membranes was significantly different before adjustment between those who lived in food deserts (16%) and those who did not (10%) (P = .015). An association with preeclampsia had borderline significance before adjustment: 13% of women in food deserts had preeclampsia, compared with 9% of women not (P = .049). After adjustment for age, race, and medical insurance, however, neither of these associations retained statistically significant differences.

The study was limited by leaving out consideration of other factors besides local food access that might influence pregnancy health, including “quality of patient-doctor communication, implicit bias, structural racism, and stress owing to concern for neighborhood safety,” Dr. Tipton and associates said.

“An additional, albeit less obvious factor that may be unique to patients suffering disproportionately from obstetric morbidity is exposure to toxic elements,” the researchers add. “It has been shown in a previous study that low-income, predominately black communities of pregnant women may suffer disproportionately from lead or arsenic exposure.”

The study did not note external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Tipton MJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003868.

according to a retrospective observational study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Previous research has linked so-called “food deserts” to higher systolic blood pressure and an increased risk of cardiovascular events in people with coronary artery disease, the authors note.

“Research on populations in the United States confirm that increased access to supermarkets is associated with lower prevalence of overweight and obesity, and improved fruit and vegetable consumption,” said Matthew J. Tipton, MD, of Loyola University Medical Center in Chicago, and colleagues.

“With our study showing an association between living in a food desert and increased pregnancy morbidity, it is our hope that with future work, an unhealthy food environment could prove to be a modifiable factor that does contribute to disparities in pregnancy morbidity,” the authors said. “Perhaps then, one could question whether greater access to healthier foods could reduce unexplained pregnancy morbidity for this population of patients,” paving the way toward developing interventions that can then improve vulnerable women’s health.

The researchers reviewed the electronic medical records of all the pregnant patients who delivered at Loyola University Medical Center in 2014. To determine who lived in a food desert, the authors relied on data about grocery food availability within Census tracts from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Access Research Atlas.

Dr. Tipton and associates defined living in a food desert as living in a low-income Census tract “where at least 33% of the population is more than half a mile from the nearest large grocery store for an urban area or more than 10 miles for a rural area.” Low-income Census tracts are those where “at least 20% of the population has a median family income at or below 80% of the metropolitan area or state median income.”

The authors compared women’s residence within a food desert (or not) with six different pregnancy morbidities: preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, prelabor rupture of membranes, preterm labor, and intrauterine growth restriction.

Among 1,001 deliveries, about 1 in 5 women (20%) lived in a food desert. These women tended to be slightly younger than those not living in a food desert (28 vs. 30 years old), and a higher proportion of women in food deserts were black (44%) rather than white (32%). They also had a lower average income ($44,694) than those not living in food deserts ($67,005).

After adjustment for age, race, and medical insurance type (private, Medicaid, other), the researchers found that women who lived in a food desert had 1.6 times greater odds of pregnancy comorbidity than if they did not (odds ratio, 1.64; P = .004). Nearly half the women living in food deserts had any type of comorbidity (47%), compared with just over a third of women who did not (36%).

Among the six comorbidities studied, preterm rupture of membranes was significantly different before adjustment between those who lived in food deserts (16%) and those who did not (10%) (P = .015). An association with preeclampsia had borderline significance before adjustment: 13% of women in food deserts had preeclampsia, compared with 9% of women not (P = .049). After adjustment for age, race, and medical insurance, however, neither of these associations retained statistically significant differences.

The study was limited by leaving out consideration of other factors besides local food access that might influence pregnancy health, including “quality of patient-doctor communication, implicit bias, structural racism, and stress owing to concern for neighborhood safety,” Dr. Tipton and associates said.

“An additional, albeit less obvious factor that may be unique to patients suffering disproportionately from obstetric morbidity is exposure to toxic elements,” the researchers add. “It has been shown in a previous study that low-income, predominately black communities of pregnant women may suffer disproportionately from lead or arsenic exposure.”

The study did not note external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Tipton MJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003868.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

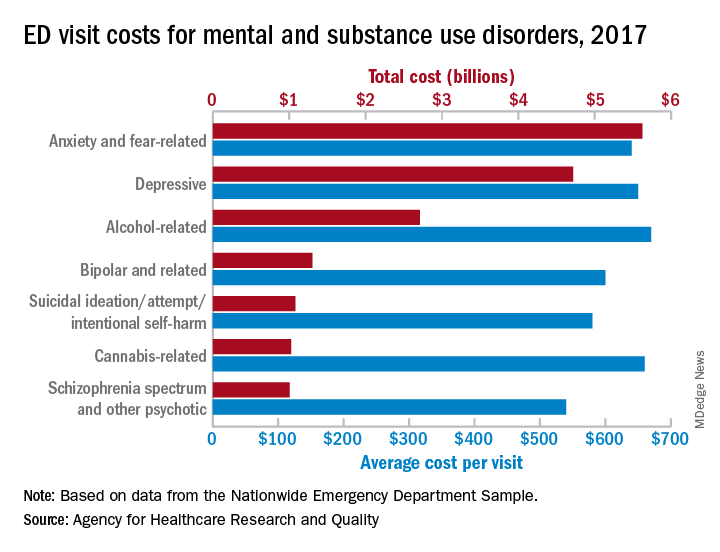

Mental health visits account for 19% of ED costs

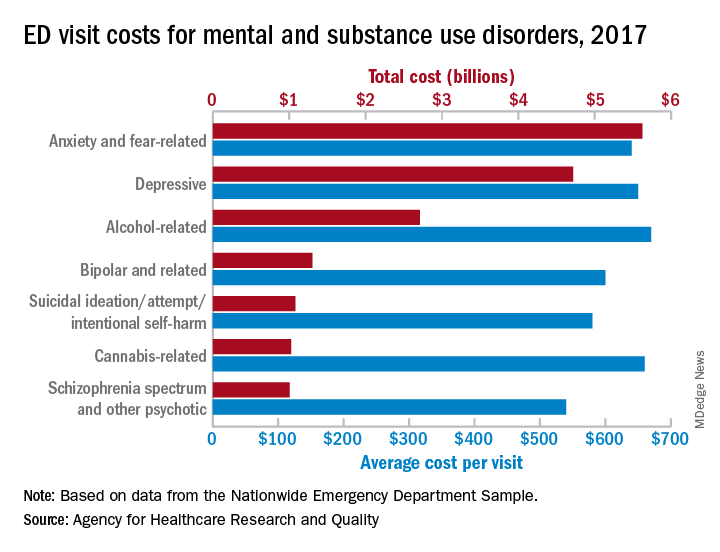

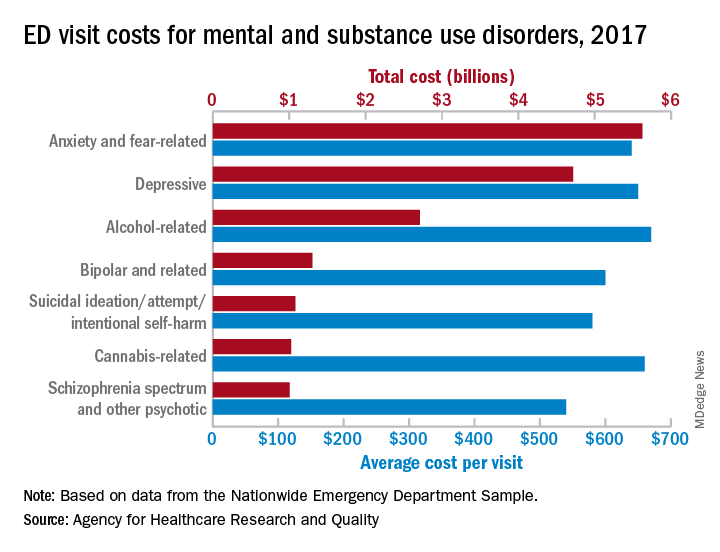

Emergency department visits for mental and substance use disorders (MUSDs) cost $14.6 billion in 2017, representing 19% of the total for all ED visits that year, according to the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research.

In terms of the total number of visits for MUSDs, 23.1 million, the proportion was slightly lower: 16% of all ED visits for the year, Zeynal Karaca, PhD, a senior economist with AHRQ, and Brian J. Moore, PhD, a senior research leader at IBM Watson Health, said in a recent statistical brief.

Put those figures together and the average visit for an MUSD diagnosis cost $630 and that is 19% higher than the average of $530 for all 145 million ED visits, they reported based on data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

The most costly MUSD diagnosis in 2017 was anxiety and fear-related disorders, with a total of $5.6 billion for ED visits, followed by depressive disorders at $4.7 billion and alcohol-related disorders at $2.7 billion. Some ED visits may involve more than one MUSD diagnosis, so the sum of all the individual diagnoses does not agree with the total for the entire MUSD category, the researchers noted.

On a per-visit basis, in 2017. [It was not included in the graph because it was 13th.] Other disorders with high per-visit costs were alcohol-related ($670), cannabis-related ($660), and depressive and stimulant-related (both with $650), Dr. Karaca and Dr. Moore said.

Patients with MUSDs who were routinely discharged after an ED visit in 2017 represented a much lower share of the total MUSD cost (68.0%), compared with the overall group of ED visitors (81.4%), but MUSD visits resulting in an inpatient admission made up a larger proportion of costs (19.0%), compared with all visits (9.5%), they said.

Costs between MUSD visits and all ED visits also differed by patient age. Visits by patients aged 0-9 years represented only 0.7% of MUSD-related ED costs but 5.6% of the overall cost, but the respective figures for those aged 45-64 were 36.2% for MUSD costs and 28.5% for the total ED cost, they reported.

SOURCE: Karaca Z and Moore BJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #257. May 12, 2020.

Emergency department visits for mental and substance use disorders (MUSDs) cost $14.6 billion in 2017, representing 19% of the total for all ED visits that year, according to the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research.

In terms of the total number of visits for MUSDs, 23.1 million, the proportion was slightly lower: 16% of all ED visits for the year, Zeynal Karaca, PhD, a senior economist with AHRQ, and Brian J. Moore, PhD, a senior research leader at IBM Watson Health, said in a recent statistical brief.

Put those figures together and the average visit for an MUSD diagnosis cost $630 and that is 19% higher than the average of $530 for all 145 million ED visits, they reported based on data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

The most costly MUSD diagnosis in 2017 was anxiety and fear-related disorders, with a total of $5.6 billion for ED visits, followed by depressive disorders at $4.7 billion and alcohol-related disorders at $2.7 billion. Some ED visits may involve more than one MUSD diagnosis, so the sum of all the individual diagnoses does not agree with the total for the entire MUSD category, the researchers noted.

On a per-visit basis, in 2017. [It was not included in the graph because it was 13th.] Other disorders with high per-visit costs were alcohol-related ($670), cannabis-related ($660), and depressive and stimulant-related (both with $650), Dr. Karaca and Dr. Moore said.

Patients with MUSDs who were routinely discharged after an ED visit in 2017 represented a much lower share of the total MUSD cost (68.0%), compared with the overall group of ED visitors (81.4%), but MUSD visits resulting in an inpatient admission made up a larger proportion of costs (19.0%), compared with all visits (9.5%), they said.

Costs between MUSD visits and all ED visits also differed by patient age. Visits by patients aged 0-9 years represented only 0.7% of MUSD-related ED costs but 5.6% of the overall cost, but the respective figures for those aged 45-64 were 36.2% for MUSD costs and 28.5% for the total ED cost, they reported.

SOURCE: Karaca Z and Moore BJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #257. May 12, 2020.

Emergency department visits for mental and substance use disorders (MUSDs) cost $14.6 billion in 2017, representing 19% of the total for all ED visits that year, according to the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research.

In terms of the total number of visits for MUSDs, 23.1 million, the proportion was slightly lower: 16% of all ED visits for the year, Zeynal Karaca, PhD, a senior economist with AHRQ, and Brian J. Moore, PhD, a senior research leader at IBM Watson Health, said in a recent statistical brief.

Put those figures together and the average visit for an MUSD diagnosis cost $630 and that is 19% higher than the average of $530 for all 145 million ED visits, they reported based on data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

The most costly MUSD diagnosis in 2017 was anxiety and fear-related disorders, with a total of $5.6 billion for ED visits, followed by depressive disorders at $4.7 billion and alcohol-related disorders at $2.7 billion. Some ED visits may involve more than one MUSD diagnosis, so the sum of all the individual diagnoses does not agree with the total for the entire MUSD category, the researchers noted.

On a per-visit basis, in 2017. [It was not included in the graph because it was 13th.] Other disorders with high per-visit costs were alcohol-related ($670), cannabis-related ($660), and depressive and stimulant-related (both with $650), Dr. Karaca and Dr. Moore said.

Patients with MUSDs who were routinely discharged after an ED visit in 2017 represented a much lower share of the total MUSD cost (68.0%), compared with the overall group of ED visitors (81.4%), but MUSD visits resulting in an inpatient admission made up a larger proportion of costs (19.0%), compared with all visits (9.5%), they said.

Costs between MUSD visits and all ED visits also differed by patient age. Visits by patients aged 0-9 years represented only 0.7% of MUSD-related ED costs but 5.6% of the overall cost, but the respective figures for those aged 45-64 were 36.2% for MUSD costs and 28.5% for the total ED cost, they reported.

SOURCE: Karaca Z and Moore BJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #257. May 12, 2020.

ACR to hold all-virtual annual meeting in November

The American College of Rheumatology will hold its annual meeting as a completely online event during Nov. 5-9, 2020, rather than in Washington, Nov. 6-11, as originally planned “due to public health/safety concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic,” according to an announcement from the organization.

“We’ve given our annual meeting a new name, ACR Convergence 2020, and a fresh look, and we have reimagined #ACR20 without losing the elements you care about most: stellar rheumatology education, cutting-edge advances in science, and outstanding networking opportunities,” according to the announcement.

A frequently asked questions page for the meeting says that “ACR Convergence will include oral and poster discussion presentations, track-based clinical and basic science symposia, opportunities to engage with speakers and participants, as well as an exhibition and several special events.”

The ACR said that the meeting will be held on a new online platform, with more details to come in August, when registration will open. The final program for the virtual meeting will be available on the ACR website in July.

The American College of Rheumatology will hold its annual meeting as a completely online event during Nov. 5-9, 2020, rather than in Washington, Nov. 6-11, as originally planned “due to public health/safety concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic,” according to an announcement from the organization.

“We’ve given our annual meeting a new name, ACR Convergence 2020, and a fresh look, and we have reimagined #ACR20 without losing the elements you care about most: stellar rheumatology education, cutting-edge advances in science, and outstanding networking opportunities,” according to the announcement.

A frequently asked questions page for the meeting says that “ACR Convergence will include oral and poster discussion presentations, track-based clinical and basic science symposia, opportunities to engage with speakers and participants, as well as an exhibition and several special events.”

The ACR said that the meeting will be held on a new online platform, with more details to come in August, when registration will open. The final program for the virtual meeting will be available on the ACR website in July.

The American College of Rheumatology will hold its annual meeting as a completely online event during Nov. 5-9, 2020, rather than in Washington, Nov. 6-11, as originally planned “due to public health/safety concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic,” according to an announcement from the organization.

“We’ve given our annual meeting a new name, ACR Convergence 2020, and a fresh look, and we have reimagined #ACR20 without losing the elements you care about most: stellar rheumatology education, cutting-edge advances in science, and outstanding networking opportunities,” according to the announcement.

A frequently asked questions page for the meeting says that “ACR Convergence will include oral and poster discussion presentations, track-based clinical and basic science symposia, opportunities to engage with speakers and participants, as well as an exhibition and several special events.”

The ACR said that the meeting will be held on a new online platform, with more details to come in August, when registration will open. The final program for the virtual meeting will be available on the ACR website in July.

COVID-19: Where doctors can get help for emotional distress

Nisha Mehta, MD, said her phone has been ringing with calls from tearful and shaken physicians who are distressed and unsettled about their work and home situation and don’t know what to do.

What’s more, many frontline physicians are living apart from family to protect them from infection. “So many physicians have called me crying. ... They can’t even come home and get a hug,” Dr. Mehta said. “What I’m hearing from a lot of people who are in New York and New Jersey is not just that they go to work all day and it’s this exhausting process throughout the entire day, not only physically but also emotionally.”

Physician burnout has held a steady spotlight since long before the COVID-19 crisis began, Dr. Mehta said. “The reason for that is multifold, but in part, it’s hard for physicians to find an appropriate way to be able to process a lot of the emotions related to their work,” she said. “A lot of that brews below the surface, but COVID-19 has really brought many of these issues above that surface.”

Frustrated that governments weren’t doing enough to support health care workers during the pandemic, Dr. Mehta, a radiologist in Charlotte, N.C., decided there needed to be change. On April 4, Dr. Mehta and two physician colleagues submitted to Congress the COVID-19 Pandemic Physician Protection Act, which ensures, among other provisions, mental health coverage for health care workers. An accompanying petition on change.org had received nearly 300,000 signatures as of May 29.

Don’t suffer in silence

A career in medicine comes with immense stress in the best of times, she notes, and managing a pandemic in an already strained system has taken those challenges to newer heights. “We need better support structures at baseline for physician mental health,” said Dr. Mehta.

“That’s something we’ve always been lacking because it’s been against the culture of medicine for so long to say, ‘I’m having a hard time.’ ”