User login

Acne and Rosacea: A Supplement to Dermatology News 2020

This Acne and Rosacea supplement to Dermatology News includes commentary from Dr Hilary E. Baldwin

Topics Included:

Pathogenic Pathway As Target In Rosacea Treatment / 5

Acne In Skin Of Color / 6

Under FDA Review Of Novel Acne Treatment / 7

Chemical Peels For Acne / 8

Isotretinoin And Psychiatric Conditions / 10

Pregnancy Reports For Isotretinoin / 11

Rosacea Triggers / 12

Topical Treatment Of Demodex / 13

Social Media And Acne / 14

This Acne and Rosacea supplement to Dermatology News includes commentary from Dr Hilary E. Baldwin

Topics Included:

Pathogenic Pathway As Target In Rosacea Treatment / 5

Acne In Skin Of Color / 6

Under FDA Review Of Novel Acne Treatment / 7

Chemical Peels For Acne / 8

Isotretinoin And Psychiatric Conditions / 10

Pregnancy Reports For Isotretinoin / 11

Rosacea Triggers / 12

Topical Treatment Of Demodex / 13

Social Media And Acne / 14

This Acne and Rosacea supplement to Dermatology News includes commentary from Dr Hilary E. Baldwin

Topics Included:

Pathogenic Pathway As Target In Rosacea Treatment / 5

Acne In Skin Of Color / 6

Under FDA Review Of Novel Acne Treatment / 7

Chemical Peels For Acne / 8

Isotretinoin And Psychiatric Conditions / 10

Pregnancy Reports For Isotretinoin / 11

Rosacea Triggers / 12

Topical Treatment Of Demodex / 13

Social Media And Acne / 14

How aging affects melanoma development and treatment response

There are several mechanisms by which the aging microenvironment can drive cancer and influence response to therapy, according to a plenary presentation at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Ashani T. Weeraratna, PhD, highlighted research showing how the aging microenvironment affects tumor cell metabolism, angiogenesis, and treatment resistance in melanoma.

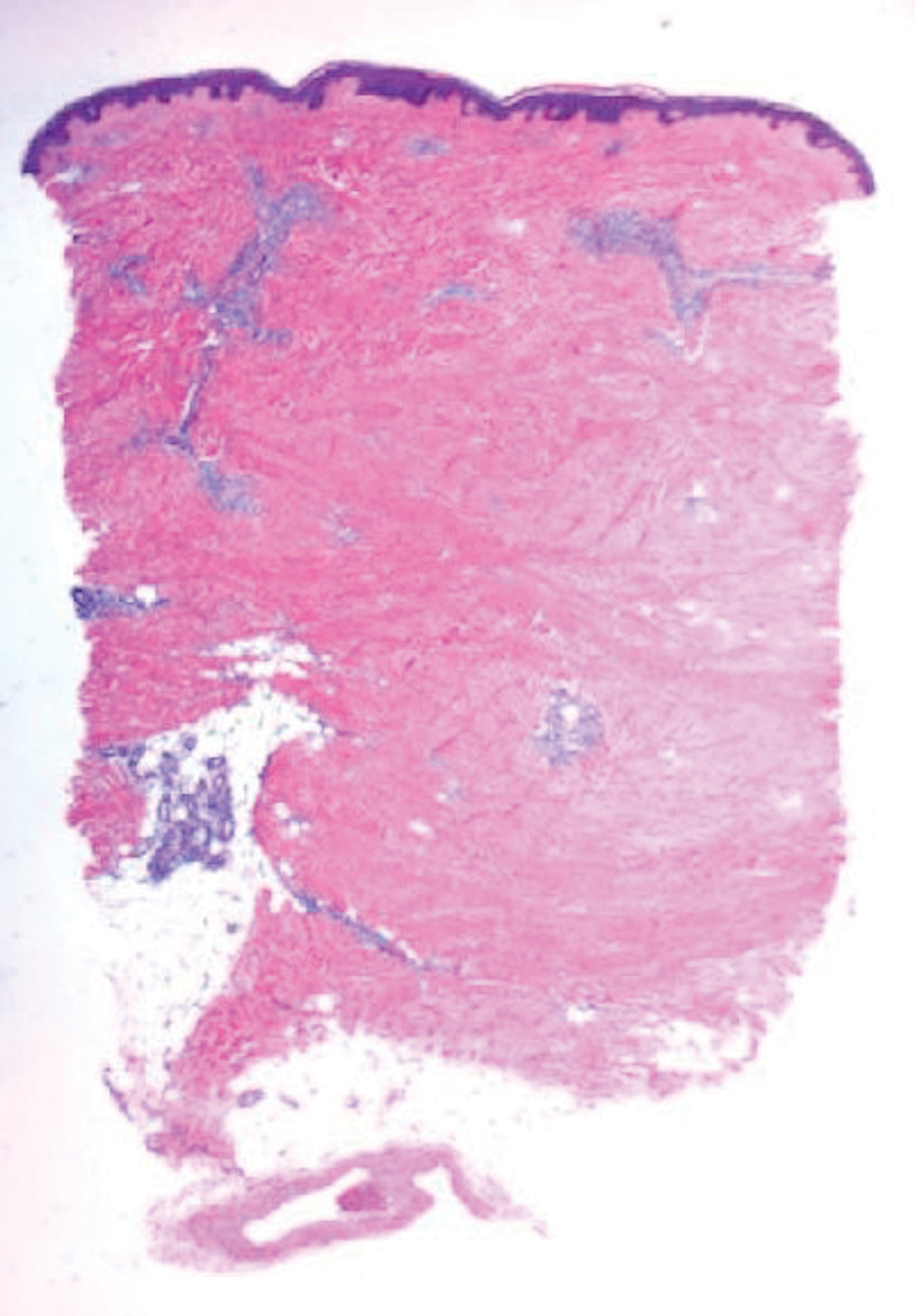

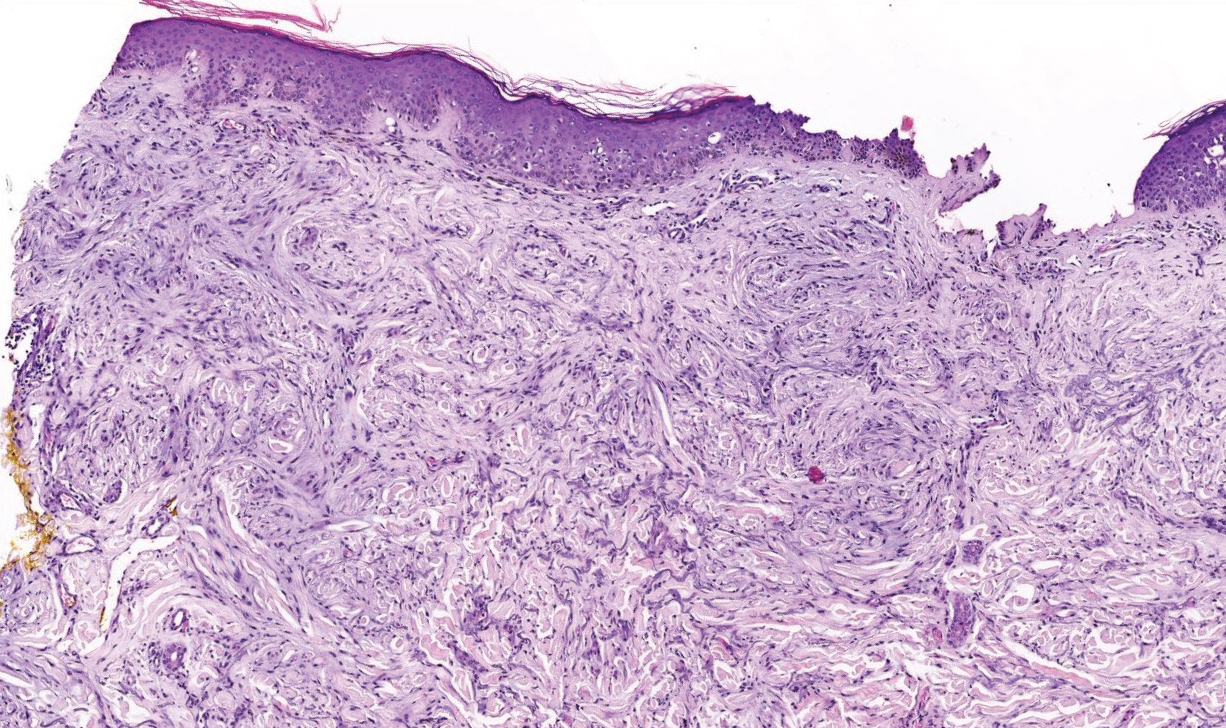

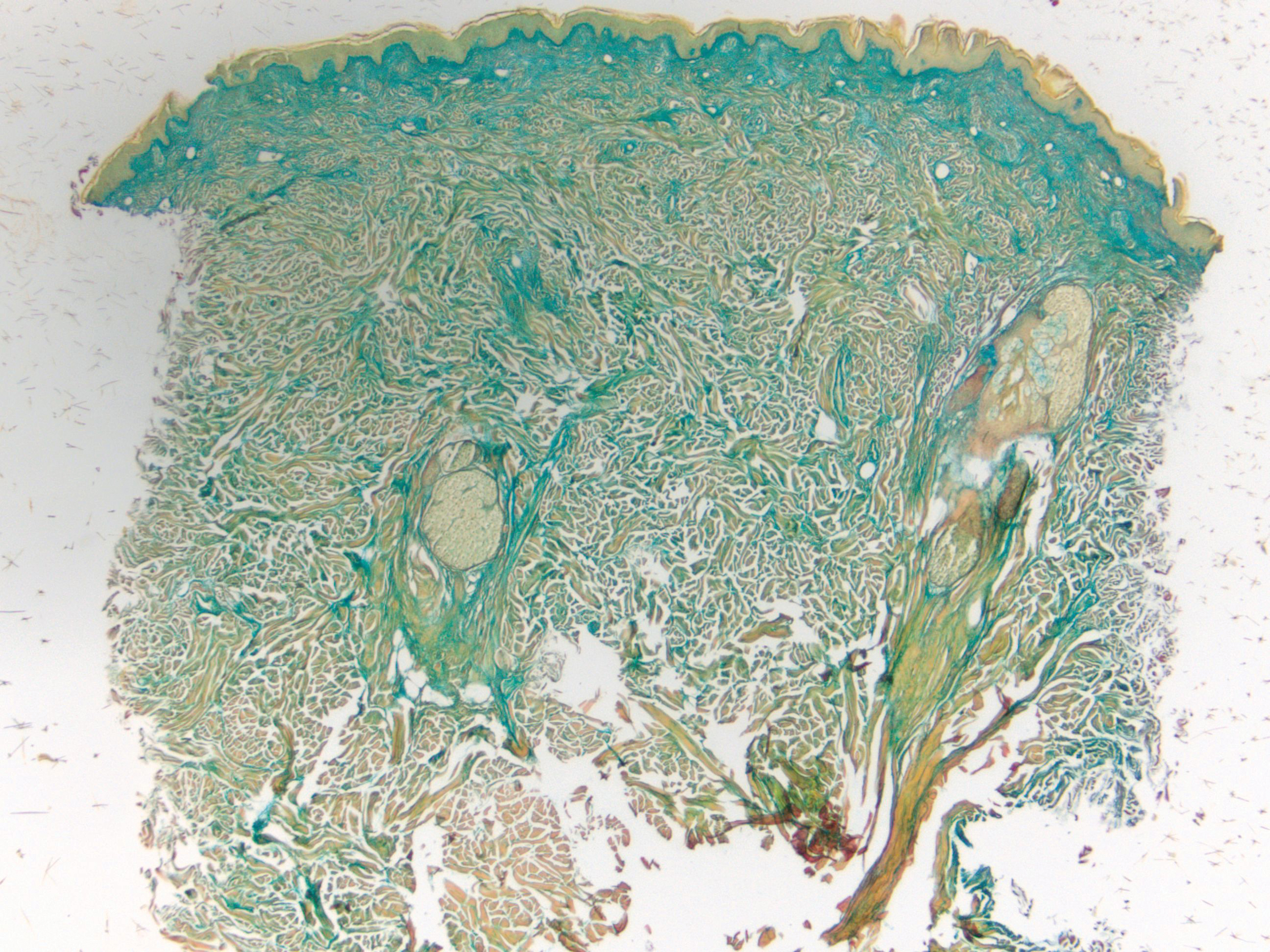

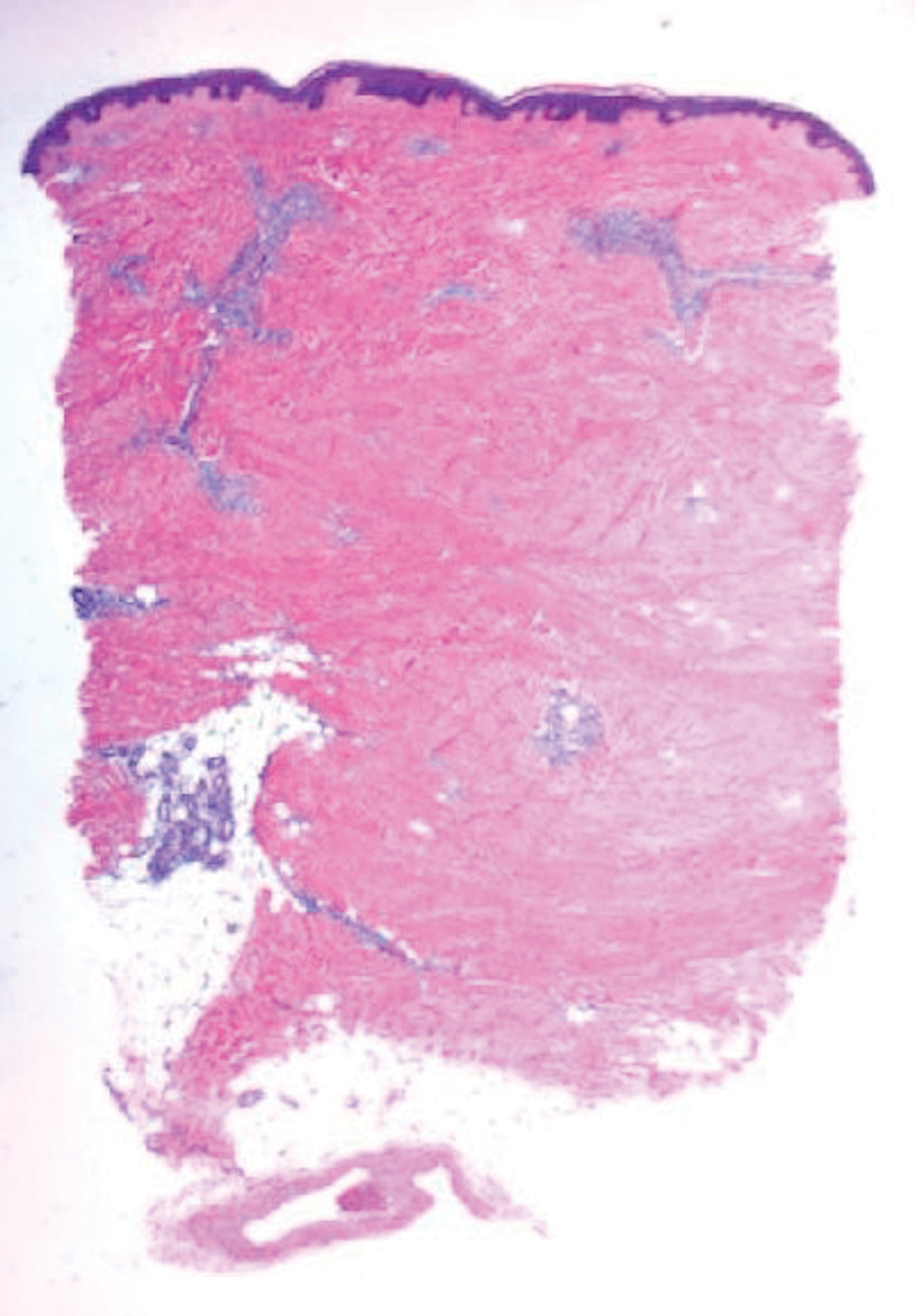

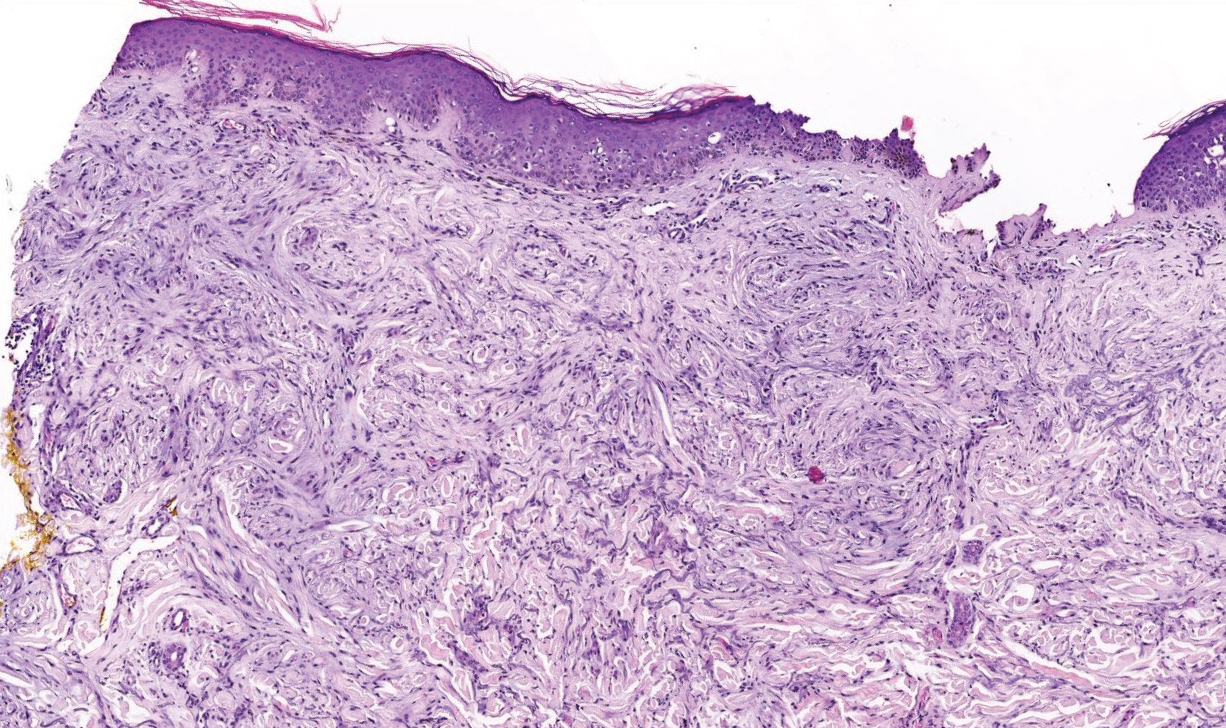

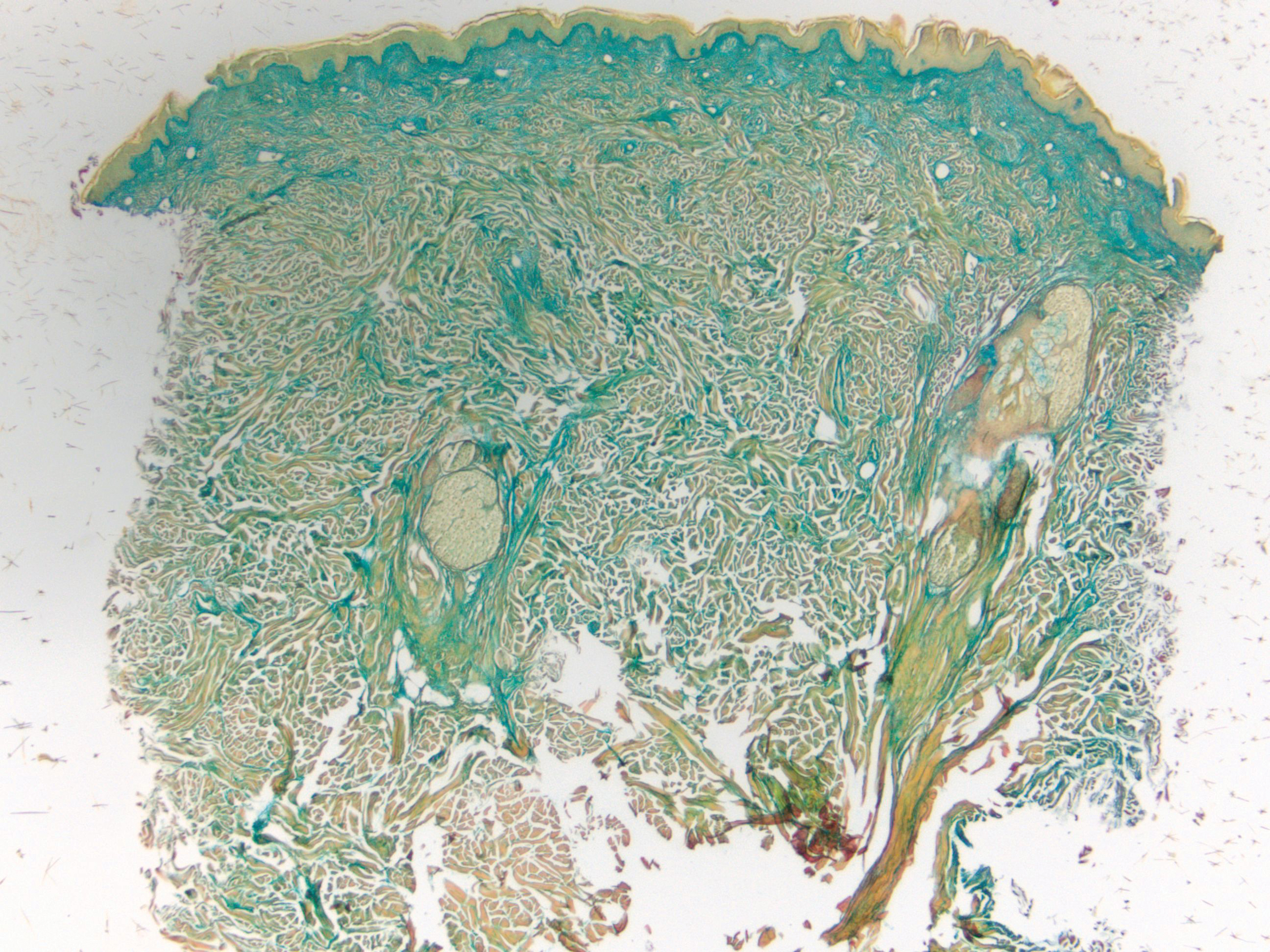

Dr. Weeraratna, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, first described a study showing how fibroblasts in the aged microenvironment contribute to tumor progression in models of melanoma (Nature. 2016 Apr 14;532[7598]:250-4).

Dr. Weeraratna and colleagues isolated dermal fibroblasts from young human donors (aged 25-35 years) and older donors (55-65 years) and used these cells to produce artificial skin.

Melanoma cells placed in the artificial skin created with young fibroblasts remained “very tightly nested at the surface,” Dr. Weeraratna said. On the other hand, melanoma cells migrated “very rapidly” through the artificial dermis created from aged fibroblasts.

In mouse models of melanoma, tumors grew much faster in young mice (6-8 weeks) than in old mice (12-18 months). However, tumors metastasized to the lung at a “much greater rate in the aged mice than in the young mice,” Dr. Weeraratna said.

Angiogenesis, SFRP2, and VEGF

Dr. Weeraratna went on to explain how a member of her lab conducted proteomic analyses of young and aged lung fibroblasts. The results were compared with results from prior analyses of young and aged skin fibroblasts.

The results showed that aged skin fibroblasts promote noncanonical WNT signaling via expression of SFRP2, SERPINE2, DKK1, Wnt5A, and ROR2. On the other hand, aged lung fibroblasts promote canonical WNT signaling via some of the same family members, including SFRP1, DKK3, and ROR1.

Research by another group showed that SFRP2 stimulates angiogenesis via a calcineurin/NFAT signaling pathway (Cancer Res. 2009 Jun 1;69[11]:4621-8).

Research in Dr. Weeraratna’s lab showed that SFRP2 and VEGF are inversely correlated with aging. Tumors in aged mice had an abundance of SFRP2 but little VEGF. Tumors in young mice had an abundance of VEGF but little SFRP2.

Dr. Weeraratna’s team wanted to determine if results would be similar in melanoma patients, so the researchers analyzed data from the TCGA database. They found that VEGF and two of its key receptors are decreased in older melanoma patients, in comparison with younger melanoma patients.

The clinical relevancy of this finding is reflected in an analysis of data from the AVAST-M study (Ann Oncol. 2019;30[12]:2013-4). When compared with observation, bevacizumab did not improve survival overall or for older patients, but the EGFR inhibitor was associated with longer survival in patients younger than 45 years.

Dr. Weeraratna said this finding and her group’s prior findings suggest younger melanoma patients have more VEGF but less angiogenesis than older patients. The older patients have less VEGF and more SFRP2, which drives angiogenesis.

Dr. Weeraratna’s lab then conducted experiments in young mice, which suggested that an anti-VEGF antibody can reduce angiogenesis, but not in the presence of SFRP2.

Lipid metabolism and treatment resistance

A recently published study by Dr. Weeraratna and colleagues tied changes in aged fibroblast lipid metabolism to treatment resistance in melanoma (Cancer Discov. 2020 Jun 4;CD-20-0329).

The research showed that melanoma cells accumulate lipids when incubated with aged, rather than young, fibroblasts in vitro.

Lipid uptake is mediated by fatty acid transporters (FATPs), and the researchers found that most FATPs were unchanged by age. However, FATP2 was elevated in melanoma cells exposed to aged media, aged mice, and melanoma patients older than 50 years of age.

When melanoma cells were incubated with conditioned media from aged fibroblasts and a FATP2 inhibitor, they no longer took up lipids.

When FATP2 was knocked down in aged mice with melanoma, BRAF and MEK inhibitors (which are not very effective ordinarily) caused dramatic and prolonged tumor regression. These effects were not seen with FATP2 inhibition in young mice.

These results suggest FATP2 is a key transporter of lipids in the aged microenvironment, and inhibiting FATP2 can delay the onset of treatment resistance.

Striving to understand a complex system

For many years, the dogma was that cancer cells behaved like unwelcome invaders, co-opting the metabolic machinery of the sites of spread, with crowding of the normal structures within those organs.

To say that concept was primitive is an understatement. Clearly, the relationship between tumor cells and the surrounding stroma is complex. Changes that occur in an aging microenvironment can influence cancer outcomes in older adults.

Dr. Weeraratna’s presentation adds further impetus to efforts to broaden eligibility criteria for clinical trials so the median age and the metabolic milieu of trial participants more closely parallels the general population.

She highlighted the importance of data analysis by age cohorts and the need to design preclinical studies so that investigators can study the microenvironment of cancer cells in in vitro models and in young and older laboratory animals.

As management expert W. Edwards Deming is believed to have said, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” Cancer is likely not an independent, hostile invader, overtaking the failing machinery of aging cells. To understand the intersection of cancer and aging, we need a more perfect understanding of the system in which tumors develop and are treated.

Dr. Weeraratna reported having no disclosures.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Weeraratna A. AACR 2020. Age against the machine: How the aging microenvironment governs response to therapy.

There are several mechanisms by which the aging microenvironment can drive cancer and influence response to therapy, according to a plenary presentation at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Ashani T. Weeraratna, PhD, highlighted research showing how the aging microenvironment affects tumor cell metabolism, angiogenesis, and treatment resistance in melanoma.

Dr. Weeraratna, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, first described a study showing how fibroblasts in the aged microenvironment contribute to tumor progression in models of melanoma (Nature. 2016 Apr 14;532[7598]:250-4).

Dr. Weeraratna and colleagues isolated dermal fibroblasts from young human donors (aged 25-35 years) and older donors (55-65 years) and used these cells to produce artificial skin.

Melanoma cells placed in the artificial skin created with young fibroblasts remained “very tightly nested at the surface,” Dr. Weeraratna said. On the other hand, melanoma cells migrated “very rapidly” through the artificial dermis created from aged fibroblasts.

In mouse models of melanoma, tumors grew much faster in young mice (6-8 weeks) than in old mice (12-18 months). However, tumors metastasized to the lung at a “much greater rate in the aged mice than in the young mice,” Dr. Weeraratna said.

Angiogenesis, SFRP2, and VEGF

Dr. Weeraratna went on to explain how a member of her lab conducted proteomic analyses of young and aged lung fibroblasts. The results were compared with results from prior analyses of young and aged skin fibroblasts.

The results showed that aged skin fibroblasts promote noncanonical WNT signaling via expression of SFRP2, SERPINE2, DKK1, Wnt5A, and ROR2. On the other hand, aged lung fibroblasts promote canonical WNT signaling via some of the same family members, including SFRP1, DKK3, and ROR1.

Research by another group showed that SFRP2 stimulates angiogenesis via a calcineurin/NFAT signaling pathway (Cancer Res. 2009 Jun 1;69[11]:4621-8).

Research in Dr. Weeraratna’s lab showed that SFRP2 and VEGF are inversely correlated with aging. Tumors in aged mice had an abundance of SFRP2 but little VEGF. Tumors in young mice had an abundance of VEGF but little SFRP2.

Dr. Weeraratna’s team wanted to determine if results would be similar in melanoma patients, so the researchers analyzed data from the TCGA database. They found that VEGF and two of its key receptors are decreased in older melanoma patients, in comparison with younger melanoma patients.

The clinical relevancy of this finding is reflected in an analysis of data from the AVAST-M study (Ann Oncol. 2019;30[12]:2013-4). When compared with observation, bevacizumab did not improve survival overall or for older patients, but the EGFR inhibitor was associated with longer survival in patients younger than 45 years.

Dr. Weeraratna said this finding and her group’s prior findings suggest younger melanoma patients have more VEGF but less angiogenesis than older patients. The older patients have less VEGF and more SFRP2, which drives angiogenesis.

Dr. Weeraratna’s lab then conducted experiments in young mice, which suggested that an anti-VEGF antibody can reduce angiogenesis, but not in the presence of SFRP2.

Lipid metabolism and treatment resistance

A recently published study by Dr. Weeraratna and colleagues tied changes in aged fibroblast lipid metabolism to treatment resistance in melanoma (Cancer Discov. 2020 Jun 4;CD-20-0329).

The research showed that melanoma cells accumulate lipids when incubated with aged, rather than young, fibroblasts in vitro.

Lipid uptake is mediated by fatty acid transporters (FATPs), and the researchers found that most FATPs were unchanged by age. However, FATP2 was elevated in melanoma cells exposed to aged media, aged mice, and melanoma patients older than 50 years of age.

When melanoma cells were incubated with conditioned media from aged fibroblasts and a FATP2 inhibitor, they no longer took up lipids.

When FATP2 was knocked down in aged mice with melanoma, BRAF and MEK inhibitors (which are not very effective ordinarily) caused dramatic and prolonged tumor regression. These effects were not seen with FATP2 inhibition in young mice.

These results suggest FATP2 is a key transporter of lipids in the aged microenvironment, and inhibiting FATP2 can delay the onset of treatment resistance.

Striving to understand a complex system

For many years, the dogma was that cancer cells behaved like unwelcome invaders, co-opting the metabolic machinery of the sites of spread, with crowding of the normal structures within those organs.

To say that concept was primitive is an understatement. Clearly, the relationship between tumor cells and the surrounding stroma is complex. Changes that occur in an aging microenvironment can influence cancer outcomes in older adults.

Dr. Weeraratna’s presentation adds further impetus to efforts to broaden eligibility criteria for clinical trials so the median age and the metabolic milieu of trial participants more closely parallels the general population.

She highlighted the importance of data analysis by age cohorts and the need to design preclinical studies so that investigators can study the microenvironment of cancer cells in in vitro models and in young and older laboratory animals.

As management expert W. Edwards Deming is believed to have said, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” Cancer is likely not an independent, hostile invader, overtaking the failing machinery of aging cells. To understand the intersection of cancer and aging, we need a more perfect understanding of the system in which tumors develop and are treated.

Dr. Weeraratna reported having no disclosures.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Weeraratna A. AACR 2020. Age against the machine: How the aging microenvironment governs response to therapy.

There are several mechanisms by which the aging microenvironment can drive cancer and influence response to therapy, according to a plenary presentation at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Ashani T. Weeraratna, PhD, highlighted research showing how the aging microenvironment affects tumor cell metabolism, angiogenesis, and treatment resistance in melanoma.

Dr. Weeraratna, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, first described a study showing how fibroblasts in the aged microenvironment contribute to tumor progression in models of melanoma (Nature. 2016 Apr 14;532[7598]:250-4).

Dr. Weeraratna and colleagues isolated dermal fibroblasts from young human donors (aged 25-35 years) and older donors (55-65 years) and used these cells to produce artificial skin.

Melanoma cells placed in the artificial skin created with young fibroblasts remained “very tightly nested at the surface,” Dr. Weeraratna said. On the other hand, melanoma cells migrated “very rapidly” through the artificial dermis created from aged fibroblasts.

In mouse models of melanoma, tumors grew much faster in young mice (6-8 weeks) than in old mice (12-18 months). However, tumors metastasized to the lung at a “much greater rate in the aged mice than in the young mice,” Dr. Weeraratna said.

Angiogenesis, SFRP2, and VEGF

Dr. Weeraratna went on to explain how a member of her lab conducted proteomic analyses of young and aged lung fibroblasts. The results were compared with results from prior analyses of young and aged skin fibroblasts.

The results showed that aged skin fibroblasts promote noncanonical WNT signaling via expression of SFRP2, SERPINE2, DKK1, Wnt5A, and ROR2. On the other hand, aged lung fibroblasts promote canonical WNT signaling via some of the same family members, including SFRP1, DKK3, and ROR1.

Research by another group showed that SFRP2 stimulates angiogenesis via a calcineurin/NFAT signaling pathway (Cancer Res. 2009 Jun 1;69[11]:4621-8).

Research in Dr. Weeraratna’s lab showed that SFRP2 and VEGF are inversely correlated with aging. Tumors in aged mice had an abundance of SFRP2 but little VEGF. Tumors in young mice had an abundance of VEGF but little SFRP2.

Dr. Weeraratna’s team wanted to determine if results would be similar in melanoma patients, so the researchers analyzed data from the TCGA database. They found that VEGF and two of its key receptors are decreased in older melanoma patients, in comparison with younger melanoma patients.

The clinical relevancy of this finding is reflected in an analysis of data from the AVAST-M study (Ann Oncol. 2019;30[12]:2013-4). When compared with observation, bevacizumab did not improve survival overall or for older patients, but the EGFR inhibitor was associated with longer survival in patients younger than 45 years.

Dr. Weeraratna said this finding and her group’s prior findings suggest younger melanoma patients have more VEGF but less angiogenesis than older patients. The older patients have less VEGF and more SFRP2, which drives angiogenesis.

Dr. Weeraratna’s lab then conducted experiments in young mice, which suggested that an anti-VEGF antibody can reduce angiogenesis, but not in the presence of SFRP2.

Lipid metabolism and treatment resistance

A recently published study by Dr. Weeraratna and colleagues tied changes in aged fibroblast lipid metabolism to treatment resistance in melanoma (Cancer Discov. 2020 Jun 4;CD-20-0329).

The research showed that melanoma cells accumulate lipids when incubated with aged, rather than young, fibroblasts in vitro.

Lipid uptake is mediated by fatty acid transporters (FATPs), and the researchers found that most FATPs were unchanged by age. However, FATP2 was elevated in melanoma cells exposed to aged media, aged mice, and melanoma patients older than 50 years of age.

When melanoma cells were incubated with conditioned media from aged fibroblasts and a FATP2 inhibitor, they no longer took up lipids.

When FATP2 was knocked down in aged mice with melanoma, BRAF and MEK inhibitors (which are not very effective ordinarily) caused dramatic and prolonged tumor regression. These effects were not seen with FATP2 inhibition in young mice.

These results suggest FATP2 is a key transporter of lipids in the aged microenvironment, and inhibiting FATP2 can delay the onset of treatment resistance.

Striving to understand a complex system

For many years, the dogma was that cancer cells behaved like unwelcome invaders, co-opting the metabolic machinery of the sites of spread, with crowding of the normal structures within those organs.

To say that concept was primitive is an understatement. Clearly, the relationship between tumor cells and the surrounding stroma is complex. Changes that occur in an aging microenvironment can influence cancer outcomes in older adults.

Dr. Weeraratna’s presentation adds further impetus to efforts to broaden eligibility criteria for clinical trials so the median age and the metabolic milieu of trial participants more closely parallels the general population.

She highlighted the importance of data analysis by age cohorts and the need to design preclinical studies so that investigators can study the microenvironment of cancer cells in in vitro models and in young and older laboratory animals.

As management expert W. Edwards Deming is believed to have said, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” Cancer is likely not an independent, hostile invader, overtaking the failing machinery of aging cells. To understand the intersection of cancer and aging, we need a more perfect understanding of the system in which tumors develop and are treated.

Dr. Weeraratna reported having no disclosures.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Weeraratna A. AACR 2020. Age against the machine: How the aging microenvironment governs response to therapy.

FROM AACR 2020

PHM fellowship changes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 surge and pandemic have changed many things in medicine, from how we round on the wards to our increased use of telemedicine in outpatient and inpatient care. This not only changed our interactions with patients, but it also changed our learners’ education. From March to May 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, many Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) fellowship directors were required to adjust clinical responsibilities and scholarly activities. These changes led to unique challenges and learning opportunities for fellows and faculty.

Many fellowships were asked to make changes to patient care for patient/provider safety. Because of low censuses, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Pittsburgh Children’s Hospital closed their observation unit; as a result, Elise Lu, MD, PhD, PHM fellow, spent time rounding on inpatient units instead of the observation unit. At the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, PHM fellow Brandon Palmer, MD, said his in-person child abuse elective was switched to a virtual elective. Dr. Adam Cohen, chief PHM fellow at Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, offered to care for adult patients and provide telehealth services to pediatric patients, but was never called to participate.

At other programs, fellows experienced greater changes to patient care and systems-based practice. Carlos Plancarte, MD, PHM fellow at Children’s Hospital of Montefiore, New York, provided care for patients up to the age of 30 years as his training hospital began admitting adult patients. Jeremiah Cleveland, MD, PHM fellowship director at Maimonides Children’s Hospital, New York, shared that his fellow’s “away elective” at a pediatric long-term acute care facility was canceled. Dr. Cleveland changed the fellow’s rotation to an infectious disease rotation, which gave her a unique opportunity to evaluate the clinical and nonclinical aspects of pandemic and disaster response.

PHM fellows also experienced changes to their scholarly activities. Matthew Shapiro, MD, a fellow at Anne and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, had to place his quality improvement research on hold and is writing a commentary with his mentors. Marie Pfarr, MD, a fellow at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, changed her plans from a simulation-based research project to studying compassion fatigue. Many fellows had workshops, platform and/or poster presentations at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting and/or the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference, both of which were canceled.

Some fellows felt the pandemic provided them an opportunity to learn communication and interpersonal skills. Dr. Shapiro observed his mentors effectively communicating while managing a crisis. Dr. Plancarte shared that he learned that saying “I don’t know” can be helpful when effectively leading a team.

Despite the changes, the COVID-19 pandemic’s most important lesson was the creation of a supportive community. Across the country, PHM fellows were supported by faculty, and faculty by their fellows. Dr. Plancarte observed how his colleagues united during a challenging situation to support each other. Ritu Patel, MD, PHM fellowship director at Kaiser Oakland shared that her fellowship’s weekly informal meetings helped bring her fellowship’s fellows and faculty closer. Joel Forman, MD, PHM fellowship director and vice chair of education at Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital in New York stressed the importance of camaraderie amongst faculty and learners.

While the pandemic continues, and long after it has passed, fellowship programs have learned that fostering community across training lines is important for both fellows and faculty.

Dr. Kumar is a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and serves as the pediatrics editor for the Hospitalist.

The COVID-19 surge and pandemic have changed many things in medicine, from how we round on the wards to our increased use of telemedicine in outpatient and inpatient care. This not only changed our interactions with patients, but it also changed our learners’ education. From March to May 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, many Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) fellowship directors were required to adjust clinical responsibilities and scholarly activities. These changes led to unique challenges and learning opportunities for fellows and faculty.

Many fellowships were asked to make changes to patient care for patient/provider safety. Because of low censuses, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Pittsburgh Children’s Hospital closed their observation unit; as a result, Elise Lu, MD, PhD, PHM fellow, spent time rounding on inpatient units instead of the observation unit. At the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, PHM fellow Brandon Palmer, MD, said his in-person child abuse elective was switched to a virtual elective. Dr. Adam Cohen, chief PHM fellow at Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, offered to care for adult patients and provide telehealth services to pediatric patients, but was never called to participate.

At other programs, fellows experienced greater changes to patient care and systems-based practice. Carlos Plancarte, MD, PHM fellow at Children’s Hospital of Montefiore, New York, provided care for patients up to the age of 30 years as his training hospital began admitting adult patients. Jeremiah Cleveland, MD, PHM fellowship director at Maimonides Children’s Hospital, New York, shared that his fellow’s “away elective” at a pediatric long-term acute care facility was canceled. Dr. Cleveland changed the fellow’s rotation to an infectious disease rotation, which gave her a unique opportunity to evaluate the clinical and nonclinical aspects of pandemic and disaster response.

PHM fellows also experienced changes to their scholarly activities. Matthew Shapiro, MD, a fellow at Anne and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, had to place his quality improvement research on hold and is writing a commentary with his mentors. Marie Pfarr, MD, a fellow at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, changed her plans from a simulation-based research project to studying compassion fatigue. Many fellows had workshops, platform and/or poster presentations at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting and/or the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference, both of which were canceled.

Some fellows felt the pandemic provided them an opportunity to learn communication and interpersonal skills. Dr. Shapiro observed his mentors effectively communicating while managing a crisis. Dr. Plancarte shared that he learned that saying “I don’t know” can be helpful when effectively leading a team.

Despite the changes, the COVID-19 pandemic’s most important lesson was the creation of a supportive community. Across the country, PHM fellows were supported by faculty, and faculty by their fellows. Dr. Plancarte observed how his colleagues united during a challenging situation to support each other. Ritu Patel, MD, PHM fellowship director at Kaiser Oakland shared that her fellowship’s weekly informal meetings helped bring her fellowship’s fellows and faculty closer. Joel Forman, MD, PHM fellowship director and vice chair of education at Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital in New York stressed the importance of camaraderie amongst faculty and learners.

While the pandemic continues, and long after it has passed, fellowship programs have learned that fostering community across training lines is important for both fellows and faculty.

Dr. Kumar is a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and serves as the pediatrics editor for the Hospitalist.

The COVID-19 surge and pandemic have changed many things in medicine, from how we round on the wards to our increased use of telemedicine in outpatient and inpatient care. This not only changed our interactions with patients, but it also changed our learners’ education. From March to May 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, many Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) fellowship directors were required to adjust clinical responsibilities and scholarly activities. These changes led to unique challenges and learning opportunities for fellows and faculty.

Many fellowships were asked to make changes to patient care for patient/provider safety. Because of low censuses, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Pittsburgh Children’s Hospital closed their observation unit; as a result, Elise Lu, MD, PhD, PHM fellow, spent time rounding on inpatient units instead of the observation unit. At the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, PHM fellow Brandon Palmer, MD, said his in-person child abuse elective was switched to a virtual elective. Dr. Adam Cohen, chief PHM fellow at Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, offered to care for adult patients and provide telehealth services to pediatric patients, but was never called to participate.

At other programs, fellows experienced greater changes to patient care and systems-based practice. Carlos Plancarte, MD, PHM fellow at Children’s Hospital of Montefiore, New York, provided care for patients up to the age of 30 years as his training hospital began admitting adult patients. Jeremiah Cleveland, MD, PHM fellowship director at Maimonides Children’s Hospital, New York, shared that his fellow’s “away elective” at a pediatric long-term acute care facility was canceled. Dr. Cleveland changed the fellow’s rotation to an infectious disease rotation, which gave her a unique opportunity to evaluate the clinical and nonclinical aspects of pandemic and disaster response.

PHM fellows also experienced changes to their scholarly activities. Matthew Shapiro, MD, a fellow at Anne and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, had to place his quality improvement research on hold and is writing a commentary with his mentors. Marie Pfarr, MD, a fellow at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, changed her plans from a simulation-based research project to studying compassion fatigue. Many fellows had workshops, platform and/or poster presentations at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting and/or the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Conference, both of which were canceled.

Some fellows felt the pandemic provided them an opportunity to learn communication and interpersonal skills. Dr. Shapiro observed his mentors effectively communicating while managing a crisis. Dr. Plancarte shared that he learned that saying “I don’t know” can be helpful when effectively leading a team.

Despite the changes, the COVID-19 pandemic’s most important lesson was the creation of a supportive community. Across the country, PHM fellows were supported by faculty, and faculty by their fellows. Dr. Plancarte observed how his colleagues united during a challenging situation to support each other. Ritu Patel, MD, PHM fellowship director at Kaiser Oakland shared that her fellowship’s weekly informal meetings helped bring her fellowship’s fellows and faculty closer. Joel Forman, MD, PHM fellowship director and vice chair of education at Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital in New York stressed the importance of camaraderie amongst faculty and learners.

While the pandemic continues, and long after it has passed, fellowship programs have learned that fostering community across training lines is important for both fellows and faculty.

Dr. Kumar is a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and serves as the pediatrics editor for the Hospitalist.

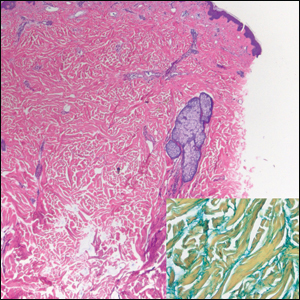

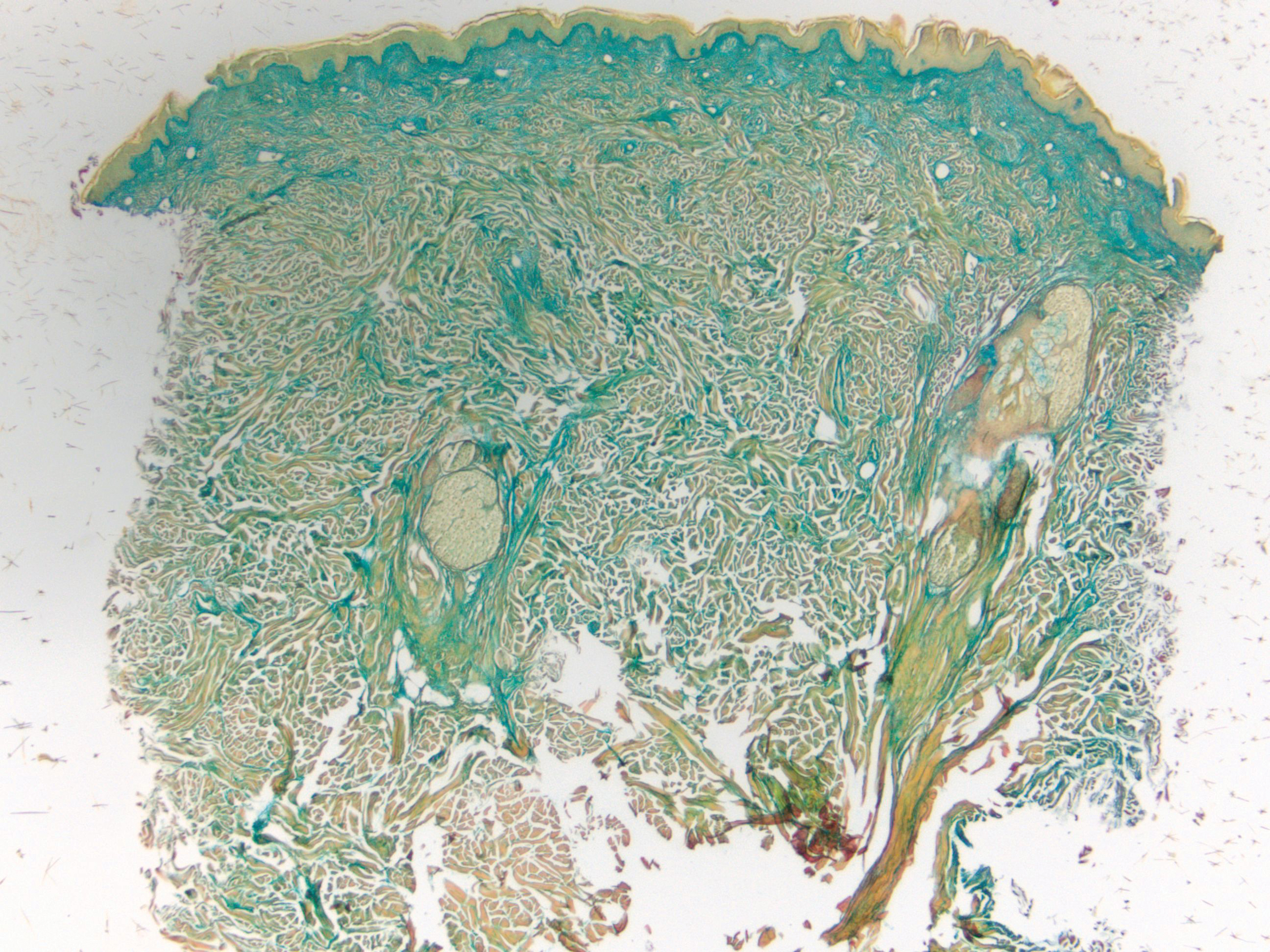

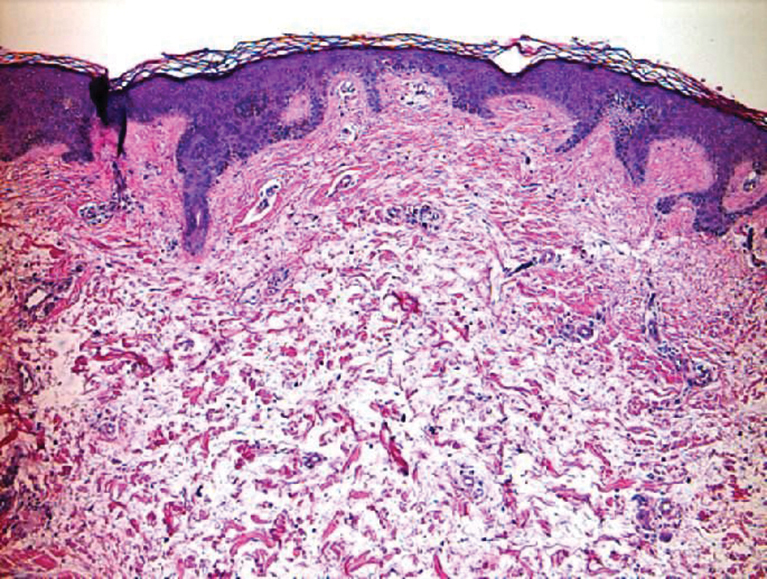

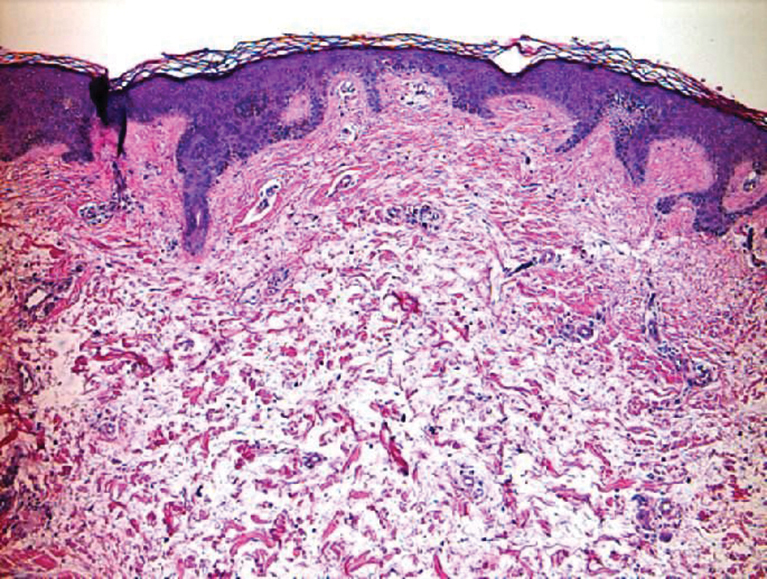

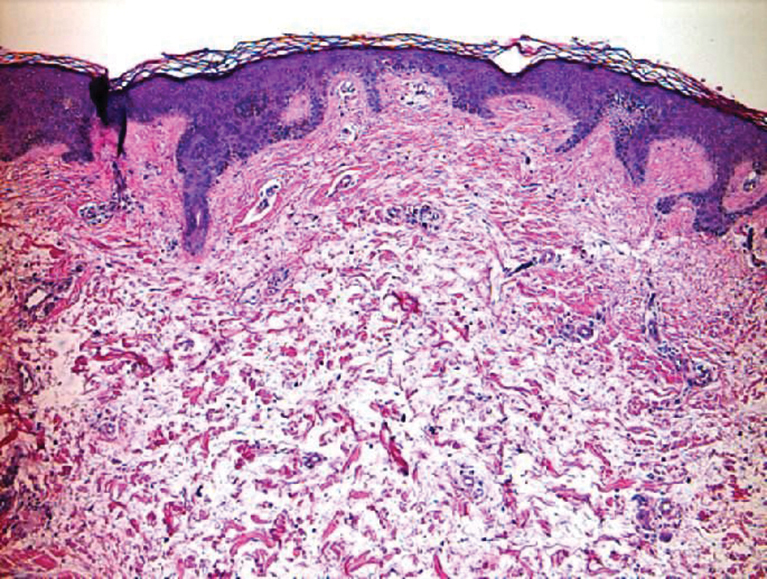

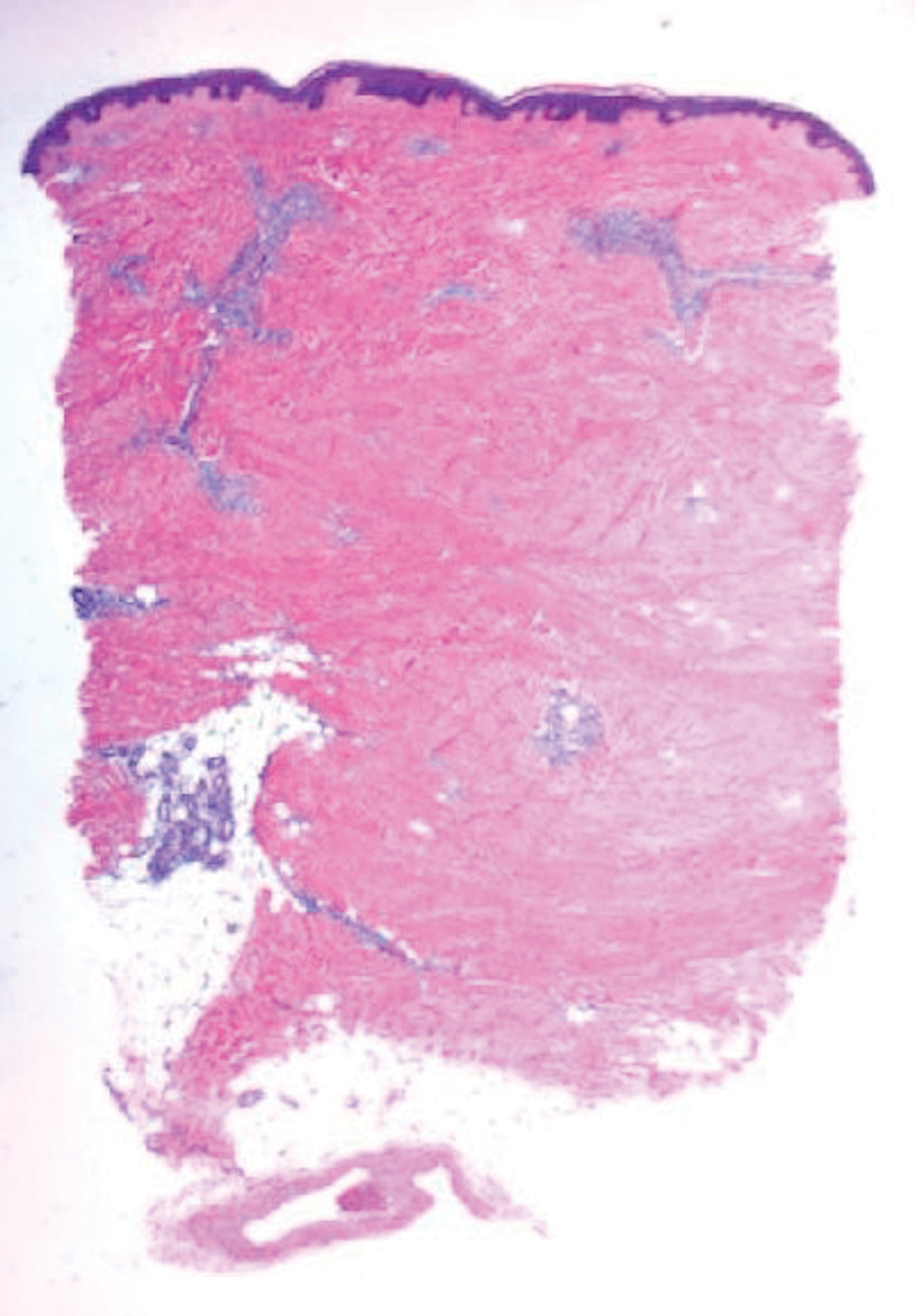

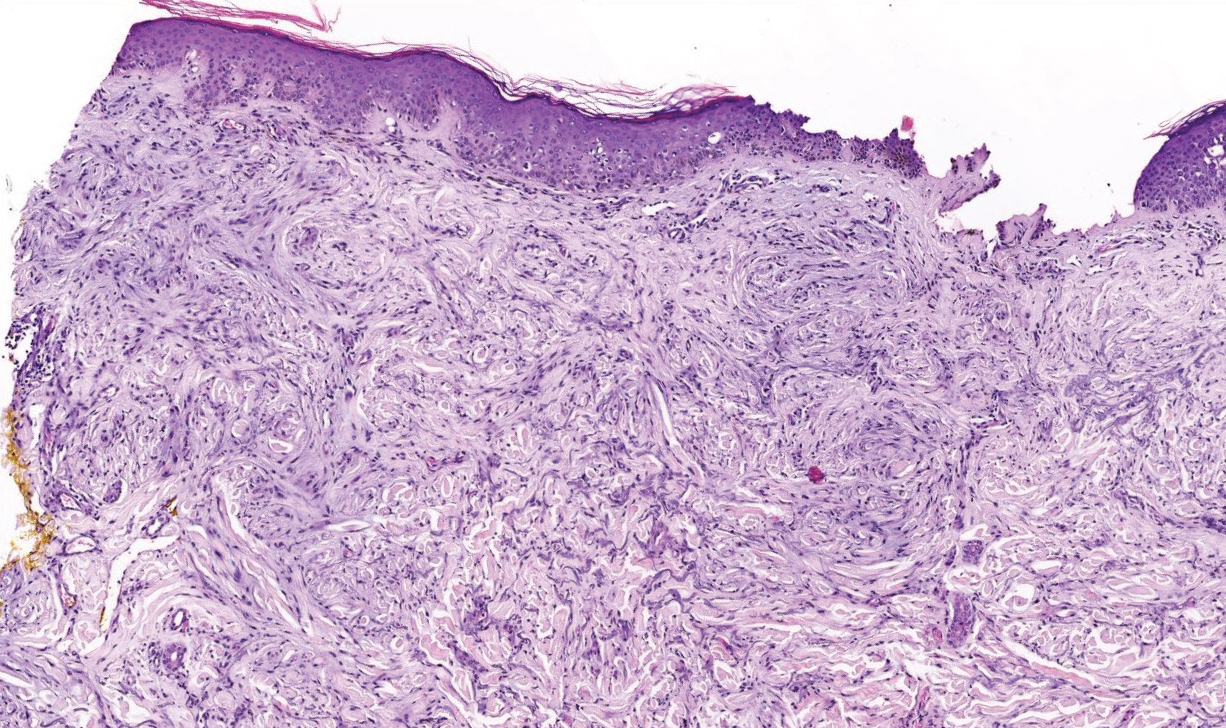

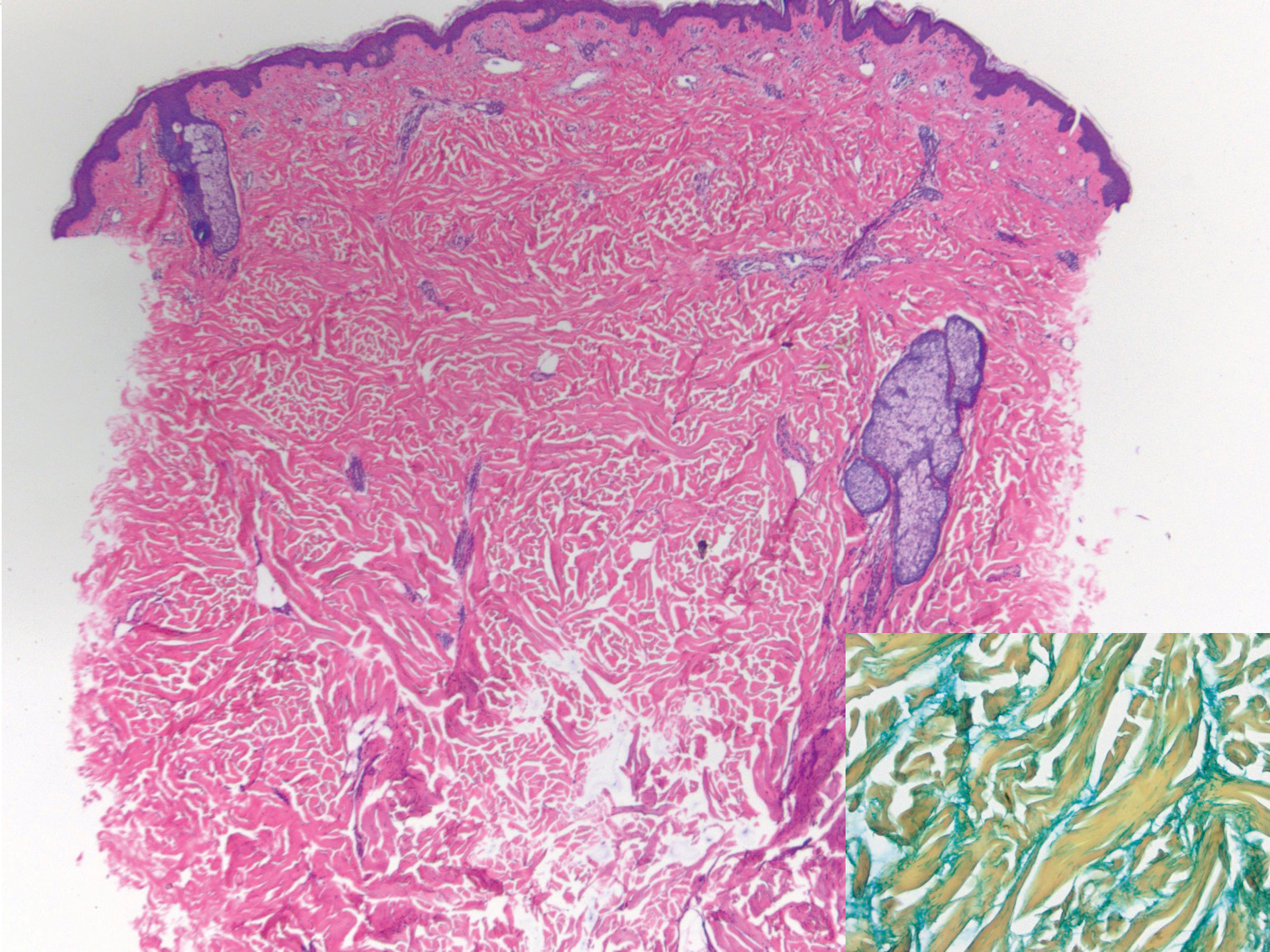

Cutaneous Metastases Masquerading as Solitary or Multiple Keratoacanthomas

To the Editor:

We read with interest the excellent Cutis articles on cutaneous metastases by Tarantino et al1 and Agnetta et al.2 Tarantino et al1 reported a 59-year-old man who developed cutaneous metastases on the scalp from an esophageal adenocarcinoma. Agnetta et al2 described a 76-year-old woman with metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.

Cutaneous metastases are not common. They may herald the unsuspected diagnosis of a solid tumor recurrence or progression of systemic disease in an oncology patient. Occasionally, they are the primary manifestation of a visceral tumor in a previously cancer-free patient. Less often, skin lesions are the manifestation of a new or recurrent hematologic malignancy.3,4

The morphology of cutaneous metastases is variable. Most commonly they appear as papules and nodules. However, they can mimic bacterial (eg, erysipelas) and viral (eg, herpes zoster) infections or present as scalp alopecia.5-7

Cutaneous metastases also can mimic benign (eg, epidermoid cysts) or malignant (eg, keratoacanthoma) neoplasms. Keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases are rare.8 They can present as single or multiple tumors.9,10

In the case reported by Tarantino et al,1 the patient had a history of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. His unsuspected recurrence presented not only with a single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastasis on the scalp but also with another metastasis-related scalp lesion that appeared as a smooth pearly papule. We also observed a 53-year-old man whose metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma presented with a keratoacanthomalike nodule on the right upper lip; additionally, the patient had other cutaneous metastases that appeared as an erythematous papule on the forehead and a cystic nodule on the scalp.8 Other investigators also observed a single keratoacanthomalike lesion on the left cheek of a 49-year-old man with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma.11

Agnetta et al2 described a patient with a history of malignant melanoma on the left upper back that had been excised 2 years prior. She presented with the eruptive onset of multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases on the chest, back, and right arm.2 The important observation of metastatic malignant melanoma presenting as multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases pointed out by Agnetta et al2 confirms a similar occurrence reported by Reed et al12 in a patient with metastatic malignant melanoma.

We also previously reported the case of a 68-year-old man with metastatic laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) who developed more than 10 keratoacanthomalike nodules within a radiation port that extended from the face to the mid chest.10 In addition, other researchers have noted a similar phenomenon of keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.13 Gil et al14 described a 40-year-old woman whose metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor initially presented as 11 keratoacanthomalike scalp nodules; interestingly, the first nodule spontaneously regressed. Araghi et al15 reported a 58-year-old woman--with a stable SCC of the larynx that had been diagnosed 2 years prior and treated with chemoradiotherapy--in whom cancer progression presented as multiple keratoacanthomalike lesions in an area of prior radiotherapy.

In conclusion, cutaneous metastases presenting as new-onset solitary or multiple keratoacanthomalike nodules in either a cancer-free individual or a patient with a prior history of a visceral malignancy is uncommon. Although the clinical features mimic those of a single or eruptive keratoacanthomas, a biopsy will readily establish the diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic cancer. Metastatic esophageal carcinoma--either adenocarcinoma or SCC--can present, albeit rarely, with cutaneous lesions that can have various morphologies.8 Whether there is an increased predilection for patients with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma to present with single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases with or without concurrent additional skin lesions of cutaneous metastases of other morphologies remains to be determined.

- Tarantino IS, Tennill T, Fraga G, et al. Cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma on the scalp. Cutis. 2020;105:E3-E5.

- Agnetta V, Hamstra A, Hirokane J, et al. Metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas. Cutis. 2020;105:E29-E31.

- Cohen PR. Skin clues to primary and metastatic malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51:1199-1204.

- Cohen PR. Leukemia cutis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. Cutis. 2019;103:212.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The "shield sign" in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Manteaux A, Cohen PR, Rapini RP. Zosteriform and epidermotropic metastasis. report of two cases. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:97-100.

- Conner KB, Cohen PR. Cutaneous metastases of breast carcinoma presenting as alopecia neoplastica. South Med J. 2009;102:385-389.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Malignancies with skin lesions mimicking keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20397.

- Ellis DL, Riahi RR, Murina AT, et al. Metastatic laryngeal carcinoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas: report of keratoacanthoma-like cutaneous metastases in a radiation port. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt3s43b81f.

- Hani AC, Nuñez E, Cuellar I, et al. Cutaneous metastases as a manifestation of esophageal adenocarcinoma recurrence: a case report [published online September 5, 2019]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. doi:10.1016/j.rgmx.2019.06.002.

- Reed KB, Cook-Norris RH, Brewer JD. The cutaneous manifestations of metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:243-249.

- Cohen PR, Riahi RR. Cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E320-E322.

- Gil F, Elvas L, Raposo S, et al. Keratoacanthoma-like nodules as first manifestation of metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25. pii:13030/qt9xx6p2tt.

- Araghi F, Fatemi A, Rakhshan A, et al. Skin metastasis of laryngeal carcinoma presenting as multiple eruptive nodules [published online February 10, 2020]. Head Neck Pathol. doi:10.1007/s12105-020-01143-1.

To the Editor:

We read with interest the excellent Cutis articles on cutaneous metastases by Tarantino et al1 and Agnetta et al.2 Tarantino et al1 reported a 59-year-old man who developed cutaneous metastases on the scalp from an esophageal adenocarcinoma. Agnetta et al2 described a 76-year-old woman with metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.

Cutaneous metastases are not common. They may herald the unsuspected diagnosis of a solid tumor recurrence or progression of systemic disease in an oncology patient. Occasionally, they are the primary manifestation of a visceral tumor in a previously cancer-free patient. Less often, skin lesions are the manifestation of a new or recurrent hematologic malignancy.3,4

The morphology of cutaneous metastases is variable. Most commonly they appear as papules and nodules. However, they can mimic bacterial (eg, erysipelas) and viral (eg, herpes zoster) infections or present as scalp alopecia.5-7

Cutaneous metastases also can mimic benign (eg, epidermoid cysts) or malignant (eg, keratoacanthoma) neoplasms. Keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases are rare.8 They can present as single or multiple tumors.9,10

In the case reported by Tarantino et al,1 the patient had a history of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. His unsuspected recurrence presented not only with a single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastasis on the scalp but also with another metastasis-related scalp lesion that appeared as a smooth pearly papule. We also observed a 53-year-old man whose metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma presented with a keratoacanthomalike nodule on the right upper lip; additionally, the patient had other cutaneous metastases that appeared as an erythematous papule on the forehead and a cystic nodule on the scalp.8 Other investigators also observed a single keratoacanthomalike lesion on the left cheek of a 49-year-old man with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma.11

Agnetta et al2 described a patient with a history of malignant melanoma on the left upper back that had been excised 2 years prior. She presented with the eruptive onset of multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases on the chest, back, and right arm.2 The important observation of metastatic malignant melanoma presenting as multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases pointed out by Agnetta et al2 confirms a similar occurrence reported by Reed et al12 in a patient with metastatic malignant melanoma.

We also previously reported the case of a 68-year-old man with metastatic laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) who developed more than 10 keratoacanthomalike nodules within a radiation port that extended from the face to the mid chest.10 In addition, other researchers have noted a similar phenomenon of keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.13 Gil et al14 described a 40-year-old woman whose metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor initially presented as 11 keratoacanthomalike scalp nodules; interestingly, the first nodule spontaneously regressed. Araghi et al15 reported a 58-year-old woman--with a stable SCC of the larynx that had been diagnosed 2 years prior and treated with chemoradiotherapy--in whom cancer progression presented as multiple keratoacanthomalike lesions in an area of prior radiotherapy.

In conclusion, cutaneous metastases presenting as new-onset solitary or multiple keratoacanthomalike nodules in either a cancer-free individual or a patient with a prior history of a visceral malignancy is uncommon. Although the clinical features mimic those of a single or eruptive keratoacanthomas, a biopsy will readily establish the diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic cancer. Metastatic esophageal carcinoma--either adenocarcinoma or SCC--can present, albeit rarely, with cutaneous lesions that can have various morphologies.8 Whether there is an increased predilection for patients with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma to present with single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases with or without concurrent additional skin lesions of cutaneous metastases of other morphologies remains to be determined.

To the Editor:

We read with interest the excellent Cutis articles on cutaneous metastases by Tarantino et al1 and Agnetta et al.2 Tarantino et al1 reported a 59-year-old man who developed cutaneous metastases on the scalp from an esophageal adenocarcinoma. Agnetta et al2 described a 76-year-old woman with metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.

Cutaneous metastases are not common. They may herald the unsuspected diagnosis of a solid tumor recurrence or progression of systemic disease in an oncology patient. Occasionally, they are the primary manifestation of a visceral tumor in a previously cancer-free patient. Less often, skin lesions are the manifestation of a new or recurrent hematologic malignancy.3,4

The morphology of cutaneous metastases is variable. Most commonly they appear as papules and nodules. However, they can mimic bacterial (eg, erysipelas) and viral (eg, herpes zoster) infections or present as scalp alopecia.5-7

Cutaneous metastases also can mimic benign (eg, epidermoid cysts) or malignant (eg, keratoacanthoma) neoplasms. Keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases are rare.8 They can present as single or multiple tumors.9,10

In the case reported by Tarantino et al,1 the patient had a history of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. His unsuspected recurrence presented not only with a single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastasis on the scalp but also with another metastasis-related scalp lesion that appeared as a smooth pearly papule. We also observed a 53-year-old man whose metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma presented with a keratoacanthomalike nodule on the right upper lip; additionally, the patient had other cutaneous metastases that appeared as an erythematous papule on the forehead and a cystic nodule on the scalp.8 Other investigators also observed a single keratoacanthomalike lesion on the left cheek of a 49-year-old man with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma.11

Agnetta et al2 described a patient with a history of malignant melanoma on the left upper back that had been excised 2 years prior. She presented with the eruptive onset of multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases on the chest, back, and right arm.2 The important observation of metastatic malignant melanoma presenting as multiple keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases pointed out by Agnetta et al2 confirms a similar occurrence reported by Reed et al12 in a patient with metastatic malignant melanoma.

We also previously reported the case of a 68-year-old man with metastatic laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) who developed more than 10 keratoacanthomalike nodules within a radiation port that extended from the face to the mid chest.10 In addition, other researchers have noted a similar phenomenon of keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas.13 Gil et al14 described a 40-year-old woman whose metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor initially presented as 11 keratoacanthomalike scalp nodules; interestingly, the first nodule spontaneously regressed. Araghi et al15 reported a 58-year-old woman--with a stable SCC of the larynx that had been diagnosed 2 years prior and treated with chemoradiotherapy--in whom cancer progression presented as multiple keratoacanthomalike lesions in an area of prior radiotherapy.

In conclusion, cutaneous metastases presenting as new-onset solitary or multiple keratoacanthomalike nodules in either a cancer-free individual or a patient with a prior history of a visceral malignancy is uncommon. Although the clinical features mimic those of a single or eruptive keratoacanthomas, a biopsy will readily establish the diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic cancer. Metastatic esophageal carcinoma--either adenocarcinoma or SCC--can present, albeit rarely, with cutaneous lesions that can have various morphologies.8 Whether there is an increased predilection for patients with metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma to present with single keratoacanthomalike cutaneous metastases with or without concurrent additional skin lesions of cutaneous metastases of other morphologies remains to be determined.

- Tarantino IS, Tennill T, Fraga G, et al. Cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma on the scalp. Cutis. 2020;105:E3-E5.

- Agnetta V, Hamstra A, Hirokane J, et al. Metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas. Cutis. 2020;105:E29-E31.

- Cohen PR. Skin clues to primary and metastatic malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51:1199-1204.

- Cohen PR. Leukemia cutis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. Cutis. 2019;103:212.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The "shield sign" in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Manteaux A, Cohen PR, Rapini RP. Zosteriform and epidermotropic metastasis. report of two cases. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:97-100.

- Conner KB, Cohen PR. Cutaneous metastases of breast carcinoma presenting as alopecia neoplastica. South Med J. 2009;102:385-389.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Malignancies with skin lesions mimicking keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20397.

- Ellis DL, Riahi RR, Murina AT, et al. Metastatic laryngeal carcinoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas: report of keratoacanthoma-like cutaneous metastases in a radiation port. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt3s43b81f.

- Hani AC, Nuñez E, Cuellar I, et al. Cutaneous metastases as a manifestation of esophageal adenocarcinoma recurrence: a case report [published online September 5, 2019]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. doi:10.1016/j.rgmx.2019.06.002.

- Reed KB, Cook-Norris RH, Brewer JD. The cutaneous manifestations of metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:243-249.

- Cohen PR, Riahi RR. Cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E320-E322.

- Gil F, Elvas L, Raposo S, et al. Keratoacanthoma-like nodules as first manifestation of metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25. pii:13030/qt9xx6p2tt.

- Araghi F, Fatemi A, Rakhshan A, et al. Skin metastasis of laryngeal carcinoma presenting as multiple eruptive nodules [published online February 10, 2020]. Head Neck Pathol. doi:10.1007/s12105-020-01143-1.

- Tarantino IS, Tennill T, Fraga G, et al. Cutaneous metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma on the scalp. Cutis. 2020;105:E3-E5.

- Agnetta V, Hamstra A, Hirokane J, et al. Metastatic melanoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas. Cutis. 2020;105:E29-E31.

- Cohen PR. Skin clues to primary and metastatic malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51:1199-1204.

- Cohen PR. Leukemia cutis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. Cutis. 2019;103:212.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The "shield sign" in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Manteaux A, Cohen PR, Rapini RP. Zosteriform and epidermotropic metastasis. report of two cases. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:97-100.

- Conner KB, Cohen PR. Cutaneous metastases of breast carcinoma presenting as alopecia neoplastica. South Med J. 2009;102:385-389.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Malignancies with skin lesions mimicking keratoacanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20397.

- Ellis DL, Riahi RR, Murina AT, et al. Metastatic laryngeal carcinoma mimicking eruptive keratoacanthomas: report of keratoacanthoma-like cutaneous metastases in a radiation port. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt3s43b81f.

- Hani AC, Nuñez E, Cuellar I, et al. Cutaneous metastases as a manifestation of esophageal adenocarcinoma recurrence: a case report [published online September 5, 2019]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. doi:10.1016/j.rgmx.2019.06.002.

- Reed KB, Cook-Norris RH, Brewer JD. The cutaneous manifestations of metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:243-249.

- Cohen PR, Riahi RR. Cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E320-E322.

- Gil F, Elvas L, Raposo S, et al. Keratoacanthoma-like nodules as first manifestation of metastatic epithelioid trophoblastic tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25. pii:13030/qt9xx6p2tt.

- Araghi F, Fatemi A, Rakhshan A, et al. Skin metastasis of laryngeal carcinoma presenting as multiple eruptive nodules [published online February 10, 2020]. Head Neck Pathol. doi:10.1007/s12105-020-01143-1.

AGA releases BRCA risk guidance

BRCA carrier status alone should not influence screening recommendations for colorectal cancer or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, according to an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update.

Relationships between BRCA carrier status and risks of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) remain unclear, reported lead author Sonia S. Kupfer, MD, AGAF, of the University of Chicago, and colleagues.

“Pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have ... been associated with variable risk of GI cancer, including CRC, PDAC, biliary, and gastric cancers,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, the magnitude of GI cancer risks is not well established and there is minimal evidence or guidance on screening for GI cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers.”

According to the investigators, personalized screening for CRC is well supported by evidence, as higher-risk individuals, such as those with a family history of CRC, have been shown to benefit from earlier and more frequent colonoscopies. Although the value of risk-based screening is less clear for other types of GI cancer, the investigators cited a growing body of evidence that supports screening individuals at high risk of PDAC.

Still, data illuminating the role of BRCA carrier status are relatively scarce, which has led to variability in clinical practice.

“Lack of accurate CRC and PDAC risk estimates in BRCA1 and BRCA2 leave physicians and patients without guidance, and result in a range of screening recommendations and practices in this population,” wrote Dr. Kupfer and colleagues.

To offer some clarity, they drafted the present clinical practice update on behalf of the AGA. The recommendations are framed within a discussion of relevant publications.

Data from multiple studies, for instance, suggest that BRCA pathogenic variants are found in 1.3% of patients with early-onset CRC, 0.2% of those with high-risk CRC, and 1.0% of those with any type of CRC, all of which are higher rates “than would be expected by chance.

“However,” the investigators added, “this association is not proof that the observed BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants play a causative role in CRC.”

The investigators went on to discuss a 2018 meta-analysis by Oho et al., which included 14 studies evaluating risk of CRC among BRCA carriers. The analysis found that BRCA carriers had a 24% increased risk of CRC, which Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described as “small but statistically significant.” Subgroup analysis suggested that BRCA1 carriers drove this association, with a 49% increased risk of CRC, whereas no significant link was found with BRCA2.

Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described the 49% increase as “very modest,” and therefore insufficient to warrant more intensive screening, particularly when considered in the context of other risk factors, such as Lynch syndrome, which may entail a 1,600% increased risk of CRC. For PDAC, no such meta-analysis has been conducted; however, multiple studies have pointed to associations between BRCA and risk of PDAC.

For example, a 2018 case-control study by Hu et al. showed that BRCA1 and BRCA2 had relative prevalence rates of 0.59% and 1.95% among patients with PDAC. These rates translated to a 158% increased risk of PDAC for BRCA1, and a 520% increase risk for BRCA2; but Dr. Kupfer and colleagues noted that the BRCA2 carriers were from high-risk families, so the findings may not extend to the general population.

In light of these findings, the update recommends PDAC screening for BRCA carriers only if they have a family history of PDAC, with the caveat that the association between risk and degree of family involvement remains unknown.

Ultimately, for both CRC and PDAC, the investigators called for further BRCA research, based on the conclusion that “results from published studies provide inconsistent levels of evidence.”

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kupfer SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr 23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.086.

BRCA carrier status alone should not influence screening recommendations for colorectal cancer or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, according to an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update.

Relationships between BRCA carrier status and risks of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) remain unclear, reported lead author Sonia S. Kupfer, MD, AGAF, of the University of Chicago, and colleagues.

“Pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have ... been associated with variable risk of GI cancer, including CRC, PDAC, biliary, and gastric cancers,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, the magnitude of GI cancer risks is not well established and there is minimal evidence or guidance on screening for GI cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers.”

According to the investigators, personalized screening for CRC is well supported by evidence, as higher-risk individuals, such as those with a family history of CRC, have been shown to benefit from earlier and more frequent colonoscopies. Although the value of risk-based screening is less clear for other types of GI cancer, the investigators cited a growing body of evidence that supports screening individuals at high risk of PDAC.

Still, data illuminating the role of BRCA carrier status are relatively scarce, which has led to variability in clinical practice.

“Lack of accurate CRC and PDAC risk estimates in BRCA1 and BRCA2 leave physicians and patients without guidance, and result in a range of screening recommendations and practices in this population,” wrote Dr. Kupfer and colleagues.

To offer some clarity, they drafted the present clinical practice update on behalf of the AGA. The recommendations are framed within a discussion of relevant publications.

Data from multiple studies, for instance, suggest that BRCA pathogenic variants are found in 1.3% of patients with early-onset CRC, 0.2% of those with high-risk CRC, and 1.0% of those with any type of CRC, all of which are higher rates “than would be expected by chance.

“However,” the investigators added, “this association is not proof that the observed BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants play a causative role in CRC.”

The investigators went on to discuss a 2018 meta-analysis by Oho et al., which included 14 studies evaluating risk of CRC among BRCA carriers. The analysis found that BRCA carriers had a 24% increased risk of CRC, which Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described as “small but statistically significant.” Subgroup analysis suggested that BRCA1 carriers drove this association, with a 49% increased risk of CRC, whereas no significant link was found with BRCA2.

Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described the 49% increase as “very modest,” and therefore insufficient to warrant more intensive screening, particularly when considered in the context of other risk factors, such as Lynch syndrome, which may entail a 1,600% increased risk of CRC. For PDAC, no such meta-analysis has been conducted; however, multiple studies have pointed to associations between BRCA and risk of PDAC.

For example, a 2018 case-control study by Hu et al. showed that BRCA1 and BRCA2 had relative prevalence rates of 0.59% and 1.95% among patients with PDAC. These rates translated to a 158% increased risk of PDAC for BRCA1, and a 520% increase risk for BRCA2; but Dr. Kupfer and colleagues noted that the BRCA2 carriers were from high-risk families, so the findings may not extend to the general population.

In light of these findings, the update recommends PDAC screening for BRCA carriers only if they have a family history of PDAC, with the caveat that the association between risk and degree of family involvement remains unknown.

Ultimately, for both CRC and PDAC, the investigators called for further BRCA research, based on the conclusion that “results from published studies provide inconsistent levels of evidence.”

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kupfer SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr 23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.086.

BRCA carrier status alone should not influence screening recommendations for colorectal cancer or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, according to an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update.

Relationships between BRCA carrier status and risks of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) remain unclear, reported lead author Sonia S. Kupfer, MD, AGAF, of the University of Chicago, and colleagues.

“Pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have ... been associated with variable risk of GI cancer, including CRC, PDAC, biliary, and gastric cancers,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, the magnitude of GI cancer risks is not well established and there is minimal evidence or guidance on screening for GI cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers.”

According to the investigators, personalized screening for CRC is well supported by evidence, as higher-risk individuals, such as those with a family history of CRC, have been shown to benefit from earlier and more frequent colonoscopies. Although the value of risk-based screening is less clear for other types of GI cancer, the investigators cited a growing body of evidence that supports screening individuals at high risk of PDAC.

Still, data illuminating the role of BRCA carrier status are relatively scarce, which has led to variability in clinical practice.

“Lack of accurate CRC and PDAC risk estimates in BRCA1 and BRCA2 leave physicians and patients without guidance, and result in a range of screening recommendations and practices in this population,” wrote Dr. Kupfer and colleagues.

To offer some clarity, they drafted the present clinical practice update on behalf of the AGA. The recommendations are framed within a discussion of relevant publications.

Data from multiple studies, for instance, suggest that BRCA pathogenic variants are found in 1.3% of patients with early-onset CRC, 0.2% of those with high-risk CRC, and 1.0% of those with any type of CRC, all of which are higher rates “than would be expected by chance.

“However,” the investigators added, “this association is not proof that the observed BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants play a causative role in CRC.”

The investigators went on to discuss a 2018 meta-analysis by Oho et al., which included 14 studies evaluating risk of CRC among BRCA carriers. The analysis found that BRCA carriers had a 24% increased risk of CRC, which Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described as “small but statistically significant.” Subgroup analysis suggested that BRCA1 carriers drove this association, with a 49% increased risk of CRC, whereas no significant link was found with BRCA2.

Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described the 49% increase as “very modest,” and therefore insufficient to warrant more intensive screening, particularly when considered in the context of other risk factors, such as Lynch syndrome, which may entail a 1,600% increased risk of CRC. For PDAC, no such meta-analysis has been conducted; however, multiple studies have pointed to associations between BRCA and risk of PDAC.

For example, a 2018 case-control study by Hu et al. showed that BRCA1 and BRCA2 had relative prevalence rates of 0.59% and 1.95% among patients with PDAC. These rates translated to a 158% increased risk of PDAC for BRCA1, and a 520% increase risk for BRCA2; but Dr. Kupfer and colleagues noted that the BRCA2 carriers were from high-risk families, so the findings may not extend to the general population.

In light of these findings, the update recommends PDAC screening for BRCA carriers only if they have a family history of PDAC, with the caveat that the association between risk and degree of family involvement remains unknown.

Ultimately, for both CRC and PDAC, the investigators called for further BRCA research, based on the conclusion that “results from published studies provide inconsistent levels of evidence.”

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kupfer SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr 23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.086.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

AGA probiotic guideline reveals shortage of high-quality data

The role of probiotics in the management of gastrointestinal disorders remains largely unclear, according to a clinical practice guideline published by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).

Out of eight disorders reviewed by the guideline panel, four had enough relevant data to support conditional recommendations, while the other four were associated with knowledge gaps that precluded guidance, reported lead author Grace L. Su, MD, AGAF, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“It is estimated that 3.9 million American adults used some form of probiotics or prebiotics ... in 2015, an amount which is four times that in 2007,” the guideline panelists wrote. Their report is in Gastroenterology. “Given widespread use and often biased sources of information, it is essential that clinicians have objective guidance for their patients about the appropriate use of and indications for probiotics.”

The creation of such guidance, however, proved a challenging task for the panel, who faced an “extremely varied” evidence base.

Dr. Su and colleagues, who were selected by the AGA Governing Board and Clinical Guidelines Committee, encountered “differences in the strain of microbe(s) used, dose, and route of administration.”

They noted that such differences can significantly affect clinical outcomes.

“Within species, different strains can have widely different activities and biologic effects,” they wrote. “Many immunologic, neurologic, and biochemical effects of gut microbiota are likely not only to be strain specific, but also dose specific. Furthermore, combinations of different microbial strains may also have widely different activity as some microbial activities are dependent on interactions between different strains.”

Beyond differences in treatments, the investigators also reported wide variability in endpoints and outcomes, as well as relatively small study populations compared with pharmacological trials.

Still, data were sufficient to provide some conditional recommendations.

The guideline supports probiotics for patients with pouchitis, those receiving antibiotic therapy, and preterm/low-birthweight infants. In contrast, the panel recommended against probiotics for children with acute infectious gastroenteritis, noting that this recommendation differs from those made by other medical organizations.

“While other society guidelines have previously recommended the use of probiotics in [children with acute infectious gastroenteritis], these guidelines were developed without utilizing GRADE methodology and also relied on data outside of North America which became available after the recommendations were made,” wrote Dr. Su and colleagues. They described a moderate quality of evidence relevant to this indication.

In comparison, the quality of evidence was very low for patients with pouchitis, low for those receiving antibiotics, and moderate/high for preterm/low-birthweight infants.

For Clostridioides difficile infection, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and irritable bowel syndrome, the panel recommended probiotics only in the context of a clinical trial, citing knowledge gaps in these areas.

They also noted that probiotics may not be suitable for those at high risk of infection.

“[F]or patients who place a high value on avoidance of potential harms, particularly those with severe illnesses or immunosuppression, it would be reasonable to select not to use probiotics,” the panelists wrote.

Concluding their discussion, Dr. Su and colleagues called for more high-quality research.

“We identified that significant knowledge gaps exist in this very promising and important area of research due to the significant heterogeneity between studies and variability in the probiotic strains studied,” they wrote. “The lack of consistent harms reporting makes it difficult to assess true harms. The lack of product manufacturing details prohibits true comparisons and decreases the feasibility of obtaining certain products by patients. Future high-quality studies are urgently needed which address these pitfalls.”

According to the panelists, the probiotic guideline will be updated in 3-5 years, or possibly earlier if practice-altering findings are published.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Nestex, AbbVie, Takeda, and others.

The role of probiotics in the management of gastrointestinal disorders remains largely unclear, according to a clinical practice guideline published by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).

Out of eight disorders reviewed by the guideline panel, four had enough relevant data to support conditional recommendations, while the other four were associated with knowledge gaps that precluded guidance, reported lead author Grace L. Su, MD, AGAF, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“It is estimated that 3.9 million American adults used some form of probiotics or prebiotics ... in 2015, an amount which is four times that in 2007,” the guideline panelists wrote. Their report is in Gastroenterology. “Given widespread use and often biased sources of information, it is essential that clinicians have objective guidance for their patients about the appropriate use of and indications for probiotics.”

The creation of such guidance, however, proved a challenging task for the panel, who faced an “extremely varied” evidence base.

Dr. Su and colleagues, who were selected by the AGA Governing Board and Clinical Guidelines Committee, encountered “differences in the strain of microbe(s) used, dose, and route of administration.”

They noted that such differences can significantly affect clinical outcomes.

“Within species, different strains can have widely different activities and biologic effects,” they wrote. “Many immunologic, neurologic, and biochemical effects of gut microbiota are likely not only to be strain specific, but also dose specific. Furthermore, combinations of different microbial strains may also have widely different activity as some microbial activities are dependent on interactions between different strains.”

Beyond differences in treatments, the investigators also reported wide variability in endpoints and outcomes, as well as relatively small study populations compared with pharmacological trials.

Still, data were sufficient to provide some conditional recommendations.

The guideline supports probiotics for patients with pouchitis, those receiving antibiotic therapy, and preterm/low-birthweight infants. In contrast, the panel recommended against probiotics for children with acute infectious gastroenteritis, noting that this recommendation differs from those made by other medical organizations.

“While other society guidelines have previously recommended the use of probiotics in [children with acute infectious gastroenteritis], these guidelines were developed without utilizing GRADE methodology and also relied on data outside of North America which became available after the recommendations were made,” wrote Dr. Su and colleagues. They described a moderate quality of evidence relevant to this indication.

In comparison, the quality of evidence was very low for patients with pouchitis, low for those receiving antibiotics, and moderate/high for preterm/low-birthweight infants.

For Clostridioides difficile infection, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and irritable bowel syndrome, the panel recommended probiotics only in the context of a clinical trial, citing knowledge gaps in these areas.

They also noted that probiotics may not be suitable for those at high risk of infection.

“[F]or patients who place a high value on avoidance of potential harms, particularly those with severe illnesses or immunosuppression, it would be reasonable to select not to use probiotics,” the panelists wrote.

Concluding their discussion, Dr. Su and colleagues called for more high-quality research.

“We identified that significant knowledge gaps exist in this very promising and important area of research due to the significant heterogeneity between studies and variability in the probiotic strains studied,” they wrote. “The lack of consistent harms reporting makes it difficult to assess true harms. The lack of product manufacturing details prohibits true comparisons and decreases the feasibility of obtaining certain products by patients. Future high-quality studies are urgently needed which address these pitfalls.”

According to the panelists, the probiotic guideline will be updated in 3-5 years, or possibly earlier if practice-altering findings are published.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Nestex, AbbVie, Takeda, and others.

The role of probiotics in the management of gastrointestinal disorders remains largely unclear, according to a clinical practice guideline published by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).

Out of eight disorders reviewed by the guideline panel, four had enough relevant data to support conditional recommendations, while the other four were associated with knowledge gaps that precluded guidance, reported lead author Grace L. Su, MD, AGAF, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“It is estimated that 3.9 million American adults used some form of probiotics or prebiotics ... in 2015, an amount which is four times that in 2007,” the guideline panelists wrote. Their report is in Gastroenterology. “Given widespread use and often biased sources of information, it is essential that clinicians have objective guidance for their patients about the appropriate use of and indications for probiotics.”

The creation of such guidance, however, proved a challenging task for the panel, who faced an “extremely varied” evidence base.

Dr. Su and colleagues, who were selected by the AGA Governing Board and Clinical Guidelines Committee, encountered “differences in the strain of microbe(s) used, dose, and route of administration.”

They noted that such differences can significantly affect clinical outcomes.

“Within species, different strains can have widely different activities and biologic effects,” they wrote. “Many immunologic, neurologic, and biochemical effects of gut microbiota are likely not only to be strain specific, but also dose specific. Furthermore, combinations of different microbial strains may also have widely different activity as some microbial activities are dependent on interactions between different strains.”

Beyond differences in treatments, the investigators also reported wide variability in endpoints and outcomes, as well as relatively small study populations compared with pharmacological trials.

Still, data were sufficient to provide some conditional recommendations.

The guideline supports probiotics for patients with pouchitis, those receiving antibiotic therapy, and preterm/low-birthweight infants. In contrast, the panel recommended against probiotics for children with acute infectious gastroenteritis, noting that this recommendation differs from those made by other medical organizations.

“While other society guidelines have previously recommended the use of probiotics in [children with acute infectious gastroenteritis], these guidelines were developed without utilizing GRADE methodology and also relied on data outside of North America which became available after the recommendations were made,” wrote Dr. Su and colleagues. They described a moderate quality of evidence relevant to this indication.

In comparison, the quality of evidence was very low for patients with pouchitis, low for those receiving antibiotics, and moderate/high for preterm/low-birthweight infants.

For Clostridioides difficile infection, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and irritable bowel syndrome, the panel recommended probiotics only in the context of a clinical trial, citing knowledge gaps in these areas.

They also noted that probiotics may not be suitable for those at high risk of infection.

“[F]or patients who place a high value on avoidance of potential harms, particularly those with severe illnesses or immunosuppression, it would be reasonable to select not to use probiotics,” the panelists wrote.

Concluding their discussion, Dr. Su and colleagues called for more high-quality research.

“We identified that significant knowledge gaps exist in this very promising and important area of research due to the significant heterogeneity between studies and variability in the probiotic strains studied,” they wrote. “The lack of consistent harms reporting makes it difficult to assess true harms. The lack of product manufacturing details prohibits true comparisons and decreases the feasibility of obtaining certain products by patients. Future high-quality studies are urgently needed which address these pitfalls.”

According to the panelists, the probiotic guideline will be updated in 3-5 years, or possibly earlier if practice-altering findings are published.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Nestex, AbbVie, Takeda, and others.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Patients who refuse to wear masks: Responses that won’t get you sued

What do you do now?

Your waiting room is filled with mask-wearing individuals, except for one person. Your staff offers a mask to this person, citing your office policy of requiring masks for all persons in order to prevent asymptomatic COVID-19 spread, and the patient refuses to put it on.

What can you/should you/must you do? Are you required to see a patient who refuses to wear a mask? If you ask the patient to leave without being seen, can you be accused of patient abandonment? If you allow the patient to stay, could you be liable for negligence for exposing others to a deadly illness?

The rules on mask-wearing, while initially downright confusing, have inexorably come to a rough consensus. By governors’ orders, masks are now mandatory in most states, though when and where they are required varies. For example, effective July 7, the governor of Washington has ordered that a business not allow a customer to enter without a face covering.

Nor do we have case law to help us determine whether patient abandonment would apply if a patient is sent home without being seen.

We can apply the legal principles and cases from other situations to this one, however, to tell us what constitutes negligence or patient abandonment. The practical questions, legally, are who might sue and on what basis?

Who might sue?