User login

ctDNA clearance tracks with PFS in NSCLC subtype

The median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for those without ctDNA clearance three to four cycles after starting treatment with osimertinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), and savolitinib, a MET TKI (P = 0.0146).

“[O]ur findings indicate that EGFR-mutant ctDNA clearance may be predictive of longer PFS for patients with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified non–small cell lung cancer and detectable ctDNA at baseline,” said investigator Ryan Hartmaier, PhD, of AstraZeneca in Boston, Mass.

Dr. Hartmaier presented these findings at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Prior results of TATTON

Interim results of the TATTON study were published earlier this year (Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar;21[3]:373-386). The trial enrolled patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified NSCLC who had progressed on a prior EGFR TKI. Results included patients enrolled in parts B and D.

Part B consisted of patients who had previously received a third-generation EGFR TKI and patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were either Thr790Met negative or Thr790Met positive. There were 144 patients in part B. All received oral osimertinib at 80 mg, 138 received savolitinib at 600 mg, and 8 received savolitinib at 300 mg daily. Part D included 42 patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were Thr790Met negative. In this cohort, patients received osimertinib at 80 mg and savolitinib at 300 mg daily.

The objective response rate (all partial responses) was 48% in part B and 64% in part D. The median PFS was 7.6 months and 9.1 months, respectively.

Alexander E. Drilon, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said results of the TATTON study demonstrate that MET dependence is an actionable EGFR TKI resistance mechanism in EGFR-mutant lung cancers.

“We all would welcome the approval of an EGFR and MET TKI combination in the future,” Dr. Drilon said in a discussion of the study at the AACR meeting.

According to Dr. Hartmaier, MET-based resistance mechanisms are seen in up to 10% of patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC following progression on first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs, and up to 25% of those progressing on osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR TKI.

“Nonclinical and clinical evidence suggests that combined treatment of a MET inhibitor and an EGFR TKI could overcome acquired MET-mediated resistance,” he said.

ctDNA analysis

Patients in the TATTON study had ctDNA samples collected at various time points from baseline through cycle five of treatment and until disease progression or treatment discontinuation.

Dr. Hartmaier’s analysis focused on ctDNA changes from baseline to day 1 of the third or fourth treatment cycle, time points at which the bulk of ctDNA could be observed, he said.

Among 34 evaluable patients in part B who received savolitinib at 600 mg, 22 had ctDNA clearance, and 12 had not. Among 16 evaluable patients in part D who received savolitinib at 300 mg, 13 had ctDNA clearance, and 3 had not.

Rates of ctDNA clearance were “remarkably similar” among the dosing groups, Dr. Hartmaier said.

In part B, the median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for patients without clearance (hazard ratio, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.14-0.81; P = 0.0146).

Dr. Hartmaier did not present PFS results according to ctDNA clearance for patients in part D.

Dr. Drilon said serial ctDNA analyses can provide information on mechanisms of primary or acquired resistance, intra- and inter-tumoral heterogeneity, and the potential durability of benefit that can be achieved with combination targeted therapy. He acknowledged, however, that more work needs to be done in the field of MET-targeted therapy development.

“We need to work on standardizing diagnostic definitions of MET dependence, recognizing that loose definitions and poly-assay use make data challenging to interpret,” he said.

The TATTON study was supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Hartmaier is an AstraZeneca employee and shareholder. Dr. Drilon disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Helsinn, Beigene, and other companies.

SOURCE: Hartmaier R, et al. AACR 2020, Abstract CT303.

The median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for those without ctDNA clearance three to four cycles after starting treatment with osimertinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), and savolitinib, a MET TKI (P = 0.0146).

“[O]ur findings indicate that EGFR-mutant ctDNA clearance may be predictive of longer PFS for patients with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified non–small cell lung cancer and detectable ctDNA at baseline,” said investigator Ryan Hartmaier, PhD, of AstraZeneca in Boston, Mass.

Dr. Hartmaier presented these findings at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Prior results of TATTON

Interim results of the TATTON study were published earlier this year (Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar;21[3]:373-386). The trial enrolled patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified NSCLC who had progressed on a prior EGFR TKI. Results included patients enrolled in parts B and D.

Part B consisted of patients who had previously received a third-generation EGFR TKI and patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were either Thr790Met negative or Thr790Met positive. There were 144 patients in part B. All received oral osimertinib at 80 mg, 138 received savolitinib at 600 mg, and 8 received savolitinib at 300 mg daily. Part D included 42 patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were Thr790Met negative. In this cohort, patients received osimertinib at 80 mg and savolitinib at 300 mg daily.

The objective response rate (all partial responses) was 48% in part B and 64% in part D. The median PFS was 7.6 months and 9.1 months, respectively.

Alexander E. Drilon, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said results of the TATTON study demonstrate that MET dependence is an actionable EGFR TKI resistance mechanism in EGFR-mutant lung cancers.

“We all would welcome the approval of an EGFR and MET TKI combination in the future,” Dr. Drilon said in a discussion of the study at the AACR meeting.

According to Dr. Hartmaier, MET-based resistance mechanisms are seen in up to 10% of patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC following progression on first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs, and up to 25% of those progressing on osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR TKI.

“Nonclinical and clinical evidence suggests that combined treatment of a MET inhibitor and an EGFR TKI could overcome acquired MET-mediated resistance,” he said.

ctDNA analysis

Patients in the TATTON study had ctDNA samples collected at various time points from baseline through cycle five of treatment and until disease progression or treatment discontinuation.

Dr. Hartmaier’s analysis focused on ctDNA changes from baseline to day 1 of the third or fourth treatment cycle, time points at which the bulk of ctDNA could be observed, he said.

Among 34 evaluable patients in part B who received savolitinib at 600 mg, 22 had ctDNA clearance, and 12 had not. Among 16 evaluable patients in part D who received savolitinib at 300 mg, 13 had ctDNA clearance, and 3 had not.

Rates of ctDNA clearance were “remarkably similar” among the dosing groups, Dr. Hartmaier said.

In part B, the median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for patients without clearance (hazard ratio, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.14-0.81; P = 0.0146).

Dr. Hartmaier did not present PFS results according to ctDNA clearance for patients in part D.

Dr. Drilon said serial ctDNA analyses can provide information on mechanisms of primary or acquired resistance, intra- and inter-tumoral heterogeneity, and the potential durability of benefit that can be achieved with combination targeted therapy. He acknowledged, however, that more work needs to be done in the field of MET-targeted therapy development.

“We need to work on standardizing diagnostic definitions of MET dependence, recognizing that loose definitions and poly-assay use make data challenging to interpret,” he said.

The TATTON study was supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Hartmaier is an AstraZeneca employee and shareholder. Dr. Drilon disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Helsinn, Beigene, and other companies.

SOURCE: Hartmaier R, et al. AACR 2020, Abstract CT303.

The median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for those without ctDNA clearance three to four cycles after starting treatment with osimertinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), and savolitinib, a MET TKI (P = 0.0146).

“[O]ur findings indicate that EGFR-mutant ctDNA clearance may be predictive of longer PFS for patients with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified non–small cell lung cancer and detectable ctDNA at baseline,” said investigator Ryan Hartmaier, PhD, of AstraZeneca in Boston, Mass.

Dr. Hartmaier presented these findings at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Prior results of TATTON

Interim results of the TATTON study were published earlier this year (Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar;21[3]:373-386). The trial enrolled patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified NSCLC who had progressed on a prior EGFR TKI. Results included patients enrolled in parts B and D.

Part B consisted of patients who had previously received a third-generation EGFR TKI and patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were either Thr790Met negative or Thr790Met positive. There were 144 patients in part B. All received oral osimertinib at 80 mg, 138 received savolitinib at 600 mg, and 8 received savolitinib at 300 mg daily. Part D included 42 patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were Thr790Met negative. In this cohort, patients received osimertinib at 80 mg and savolitinib at 300 mg daily.

The objective response rate (all partial responses) was 48% in part B and 64% in part D. The median PFS was 7.6 months and 9.1 months, respectively.

Alexander E. Drilon, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said results of the TATTON study demonstrate that MET dependence is an actionable EGFR TKI resistance mechanism in EGFR-mutant lung cancers.

“We all would welcome the approval of an EGFR and MET TKI combination in the future,” Dr. Drilon said in a discussion of the study at the AACR meeting.

According to Dr. Hartmaier, MET-based resistance mechanisms are seen in up to 10% of patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC following progression on first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs, and up to 25% of those progressing on osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR TKI.

“Nonclinical and clinical evidence suggests that combined treatment of a MET inhibitor and an EGFR TKI could overcome acquired MET-mediated resistance,” he said.

ctDNA analysis

Patients in the TATTON study had ctDNA samples collected at various time points from baseline through cycle five of treatment and until disease progression or treatment discontinuation.

Dr. Hartmaier’s analysis focused on ctDNA changes from baseline to day 1 of the third or fourth treatment cycle, time points at which the bulk of ctDNA could be observed, he said.

Among 34 evaluable patients in part B who received savolitinib at 600 mg, 22 had ctDNA clearance, and 12 had not. Among 16 evaluable patients in part D who received savolitinib at 300 mg, 13 had ctDNA clearance, and 3 had not.

Rates of ctDNA clearance were “remarkably similar” among the dosing groups, Dr. Hartmaier said.

In part B, the median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for patients without clearance (hazard ratio, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.14-0.81; P = 0.0146).

Dr. Hartmaier did not present PFS results according to ctDNA clearance for patients in part D.

Dr. Drilon said serial ctDNA analyses can provide information on mechanisms of primary or acquired resistance, intra- and inter-tumoral heterogeneity, and the potential durability of benefit that can be achieved with combination targeted therapy. He acknowledged, however, that more work needs to be done in the field of MET-targeted therapy development.

“We need to work on standardizing diagnostic definitions of MET dependence, recognizing that loose definitions and poly-assay use make data challenging to interpret,” he said.

The TATTON study was supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Hartmaier is an AstraZeneca employee and shareholder. Dr. Drilon disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Helsinn, Beigene, and other companies.

SOURCE: Hartmaier R, et al. AACR 2020, Abstract CT303.

FROM AACR 2020

Hep C sofosbuvir/daclatasvir combo promising for COVID-19

research from an open-label Iranian study shows.

And the good news is that the treatment combination “already has a well-established safety profile in the treatment of hepatitis C,” said investigator Andrew Hill, PhD, from the University of Liverpool, United Kingdom.

But although the results look promising, they are preliminary, he cautioned. The combination could follow the path of ritonavir plus lopinavir (Kaletra, AbbVie Pharmaceuticals) or hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil, Sanofi Pharmaceuticals), which showed promise early but did not perform as hoped in large randomized controlled trials.

“We need to remember that conducting research amidst a pandemic with overwhelmed hospitals is a clear challenge, and we cannot be sure of success,” he added.

Three Trials, 176 Patients

Data collected during a four-site trial of the combination treatment in Tehran during an early spike in cases in Iran were presented at the Virtual COVID-19 Conference 2020 by Hannah Wentzel, a masters student in public health at Imperial College London and a member of Hill’s team.

All 66 study participants were diagnosed with moderate to severe COVID-19 and were treated with standard care, which consisted of hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily with or without the combination of lopinavir plus ritonavir 250 mg twice daily.

The 33 patients randomized to the treatment group also received the combination of sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir 460 mg once daily. These patients were slightly younger and more likely to be men than were those in the standard-care group, but the differences were not significant.

All participants were treated for 14 days, and then the researchers assessed fever, respiration rate, and blood oxygen saturation.

More patients in the treatment group than in the standard-care group had recovered at 14 days (88% vs 67%), but the difference was not significant.

However, median time to clinical recovery, which took into account death as a competing risk, was significantly faster in the treatment group than in the standard-care group (6 vs 11 days; P = .041).

The researchers then pooled their Tehran data with those from two other trials of the sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir combination conducted in Iran: one in the city of Sari with 48 patients and one in the city of Abadan with 62 patients.

A meta-analysis showed that clinical recovery in 14 days was 14% better in the treatment group than in the control group in the Sari study, 32% better in the Tehran study, and 82% better in the Abadan study. However, in a sensitivity analysis, because “the trial in Abadan was not properly randomized,” only the improvements in the Sari and Tehran studies were significant, Wentzel reported.

The meta-analysis also showed that patients in the treatment groups were 70% more likely than those in the standard-care groups to survive.

However, the treatment regimens in the standard-care groups of the three studies were all different, reflecting evolving national treatment guidelines in Iran at the time. And SARS-CoV-2 viral loads were not measured in any of the trials, so the effects of the different drugs on the virus itself could not be assessed.

Still, overall, “sofosbuvir and daclatasvir is associated with faster discharge from hospital and improved survival,” Wentzel said.

These findings are hopeful, “provocative, and encouraging,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and he echoed Hill’s call to “get these kinds of studies into randomized controlled trials.”

But he cautioned that more data are needed before the sofosbuvir and daclatasvir combination can be added to the National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines, which clinicians who might be under-resourced and overwhelmed with spikes in COVID-19 cases rely on.

Results from three double-blind randomized controlled trials – one each in Iran, Egypt, and South Africa – with an estimated cumulative enrollment of about 2,000 patients, are expected in October, Hill reported.

“Having gone through feeling so desperate to help people and try new things, it’s really important to do these trials,” said Kristen Marks, MD, from Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City.

“You get tempted to just kind of throw anything at people. And I think we really have to have science to guide us,” she told Medscape Medical News.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

research from an open-label Iranian study shows.

And the good news is that the treatment combination “already has a well-established safety profile in the treatment of hepatitis C,” said investigator Andrew Hill, PhD, from the University of Liverpool, United Kingdom.

But although the results look promising, they are preliminary, he cautioned. The combination could follow the path of ritonavir plus lopinavir (Kaletra, AbbVie Pharmaceuticals) or hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil, Sanofi Pharmaceuticals), which showed promise early but did not perform as hoped in large randomized controlled trials.

“We need to remember that conducting research amidst a pandemic with overwhelmed hospitals is a clear challenge, and we cannot be sure of success,” he added.

Three Trials, 176 Patients

Data collected during a four-site trial of the combination treatment in Tehran during an early spike in cases in Iran were presented at the Virtual COVID-19 Conference 2020 by Hannah Wentzel, a masters student in public health at Imperial College London and a member of Hill’s team.

All 66 study participants were diagnosed with moderate to severe COVID-19 and were treated with standard care, which consisted of hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily with or without the combination of lopinavir plus ritonavir 250 mg twice daily.

The 33 patients randomized to the treatment group also received the combination of sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir 460 mg once daily. These patients were slightly younger and more likely to be men than were those in the standard-care group, but the differences were not significant.

All participants were treated for 14 days, and then the researchers assessed fever, respiration rate, and blood oxygen saturation.

More patients in the treatment group than in the standard-care group had recovered at 14 days (88% vs 67%), but the difference was not significant.

However, median time to clinical recovery, which took into account death as a competing risk, was significantly faster in the treatment group than in the standard-care group (6 vs 11 days; P = .041).

The researchers then pooled their Tehran data with those from two other trials of the sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir combination conducted in Iran: one in the city of Sari with 48 patients and one in the city of Abadan with 62 patients.

A meta-analysis showed that clinical recovery in 14 days was 14% better in the treatment group than in the control group in the Sari study, 32% better in the Tehran study, and 82% better in the Abadan study. However, in a sensitivity analysis, because “the trial in Abadan was not properly randomized,” only the improvements in the Sari and Tehran studies were significant, Wentzel reported.

The meta-analysis also showed that patients in the treatment groups were 70% more likely than those in the standard-care groups to survive.

However, the treatment regimens in the standard-care groups of the three studies were all different, reflecting evolving national treatment guidelines in Iran at the time. And SARS-CoV-2 viral loads were not measured in any of the trials, so the effects of the different drugs on the virus itself could not be assessed.

Still, overall, “sofosbuvir and daclatasvir is associated with faster discharge from hospital and improved survival,” Wentzel said.

These findings are hopeful, “provocative, and encouraging,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and he echoed Hill’s call to “get these kinds of studies into randomized controlled trials.”

But he cautioned that more data are needed before the sofosbuvir and daclatasvir combination can be added to the National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines, which clinicians who might be under-resourced and overwhelmed with spikes in COVID-19 cases rely on.

Results from three double-blind randomized controlled trials – one each in Iran, Egypt, and South Africa – with an estimated cumulative enrollment of about 2,000 patients, are expected in October, Hill reported.

“Having gone through feeling so desperate to help people and try new things, it’s really important to do these trials,” said Kristen Marks, MD, from Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City.

“You get tempted to just kind of throw anything at people. And I think we really have to have science to guide us,” she told Medscape Medical News.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

research from an open-label Iranian study shows.

And the good news is that the treatment combination “already has a well-established safety profile in the treatment of hepatitis C,” said investigator Andrew Hill, PhD, from the University of Liverpool, United Kingdom.

But although the results look promising, they are preliminary, he cautioned. The combination could follow the path of ritonavir plus lopinavir (Kaletra, AbbVie Pharmaceuticals) or hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil, Sanofi Pharmaceuticals), which showed promise early but did not perform as hoped in large randomized controlled trials.

“We need to remember that conducting research amidst a pandemic with overwhelmed hospitals is a clear challenge, and we cannot be sure of success,” he added.

Three Trials, 176 Patients

Data collected during a four-site trial of the combination treatment in Tehran during an early spike in cases in Iran were presented at the Virtual COVID-19 Conference 2020 by Hannah Wentzel, a masters student in public health at Imperial College London and a member of Hill’s team.

All 66 study participants were diagnosed with moderate to severe COVID-19 and were treated with standard care, which consisted of hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily with or without the combination of lopinavir plus ritonavir 250 mg twice daily.

The 33 patients randomized to the treatment group also received the combination of sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir 460 mg once daily. These patients were slightly younger and more likely to be men than were those in the standard-care group, but the differences were not significant.

All participants were treated for 14 days, and then the researchers assessed fever, respiration rate, and blood oxygen saturation.

More patients in the treatment group than in the standard-care group had recovered at 14 days (88% vs 67%), but the difference was not significant.

However, median time to clinical recovery, which took into account death as a competing risk, was significantly faster in the treatment group than in the standard-care group (6 vs 11 days; P = .041).

The researchers then pooled their Tehran data with those from two other trials of the sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir combination conducted in Iran: one in the city of Sari with 48 patients and one in the city of Abadan with 62 patients.

A meta-analysis showed that clinical recovery in 14 days was 14% better in the treatment group than in the control group in the Sari study, 32% better in the Tehran study, and 82% better in the Abadan study. However, in a sensitivity analysis, because “the trial in Abadan was not properly randomized,” only the improvements in the Sari and Tehran studies were significant, Wentzel reported.

The meta-analysis also showed that patients in the treatment groups were 70% more likely than those in the standard-care groups to survive.

However, the treatment regimens in the standard-care groups of the three studies were all different, reflecting evolving national treatment guidelines in Iran at the time. And SARS-CoV-2 viral loads were not measured in any of the trials, so the effects of the different drugs on the virus itself could not be assessed.

Still, overall, “sofosbuvir and daclatasvir is associated with faster discharge from hospital and improved survival,” Wentzel said.

These findings are hopeful, “provocative, and encouraging,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and he echoed Hill’s call to “get these kinds of studies into randomized controlled trials.”

But he cautioned that more data are needed before the sofosbuvir and daclatasvir combination can be added to the National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines, which clinicians who might be under-resourced and overwhelmed with spikes in COVID-19 cases rely on.

Results from three double-blind randomized controlled trials – one each in Iran, Egypt, and South Africa – with an estimated cumulative enrollment of about 2,000 patients, are expected in October, Hill reported.

“Having gone through feeling so desperate to help people and try new things, it’s really important to do these trials,” said Kristen Marks, MD, from Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City.

“You get tempted to just kind of throw anything at people. And I think we really have to have science to guide us,” she told Medscape Medical News.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Helping families understand internalized racism

Ms. Jones brings her 15-year-old daughter, Angela, to the resident clinic. Angela is becoming increasingly anxious, withdrawn, and difficult to manage. As part of the initial interview, the resident, Dr. Sota, asks about the sociocultural background of the family. Ms. Jones is African American and recently began a relationship with a white man. Her daughter, Angela, is biracial; her biological father is white and has moved out of state with little ongoing contact with Angela and her mother.

At interview, Angela expresses a lot of anger at her mother, her biological father, and her new “stepfather.” Ms. Jones says: “I do not want Angela growing up as an ‘angry black woman.’ ” When asked for an explanation, she stated that she doesn’t want her daughter to be stereotyped, to be perceived as an angry black person. “She needs to fit in with our new life. She has lots of opportunities if only she would take them.”

Dr. Sota recognizes that Angela’s struggle, and perhaps also the struggle of Ms. Jones, has a component of internalized racism. How should Dr. Sota proceed? Dr. Sota puts herself in Angela’s shoes: How does Angela see herself? Angela has light brown skin, and

The term internalized racism (IR) first appeared in the 1980s. IR was compared to the oppression of black people in the 1800s: “The slavery that captures the mind and incarcerates the motivation, perception, aspiration, and identity in a web of anti-self images, generating a personal and collective self destruction, is more cruel than the shackles on the wrists and ankles.”1 According to Susanne Lipsky,2 IR “in African Americans manifests as internalizing stereotypes, mistrusting the self and other Blacks, and narrows one’s view of authentic Black culture.”

IR refers to the internalization and acceptance of the dominant white culture’s actions and beliefs, while rejecting one’s own cultural background. There is a long history of negative cultural representations of African Americans in popular American culture, and IR has a detrimental impact on the emotional well-being of African Americans.3

IR is associated with poorer metabolic health4 and psychological distress, depression and anxiety,5-8 and decreased self-esteem.9 However, protective processes can reduce one’s response to risk and can be developed through the psychotherapeutic relationship.

Interventions at an individual, family, or community levels

Angela: Tell me about yourself: What type of person are you? How do you identify? How do you feel about yourself/your appearance/your language?

Tell me about your friends/family? What interests do you have?

“Tell me more” questions can reveal conflicted feelings, etc., even if Angela does not answer. A good therapist can talk about IR; even if Angela does not bring it up, it is important for the therapist to find language suitable for the age of the patient.

Dr. Sota has some luck with Angela, who nods her head but says little. Dr. Sota then turns to Ms. Jones and asks whether she can answer these questions, too, and rephrases the questions for an adult. Interviewing parents in the presence of their children gives Dr. Sota and Angela an idea of what is permitted to talk about in the family.

A therapist can also note other permissions in the family: How do Angela and her mother use language? Do they claim or reject words and phrases such as “angry black woman” and choose, instead, to use language to “fit in” with the dominant white culture?

Dr. Sota notices that Ms. Jones presents herself as keen to fit in with her new future husband’s life. She wants Angela to do likewise. Dr. Sota notices that Angela vacillates between wanting to claim her black identity and having to navigate what that means in this family (not a good thing) – and wanting to assimilate into white culture. Her peers fall into two separate groups: a set of black friends and a set of white friends. Her mother prefers that she see her white friends, mistrusting her black friends.

Dr. Sota’s supervisor suggests that she introduce IR more forcefully because this seems to be a major course of conflict for Angela and encourage a frank discussion between mother and daughter. Dr. Sota starts the next session in the following way: “I noticed last week that the way you each identify yourselves is quite different. Ms. Jones, you want Angela to ‘fit in’ and perhaps just embrace white culture, whereas Angela, perhaps you vacillate between a white identity and a black identity?”

The following questions can help Dr. Sota elicit IR:

- What information about yourself would you like others to know – about your heritage, country of origin, family, class background, and so on?

- What makes you proud about being a member of this group, and what do you love about other members of this group?

- What has been hard about being a member of this group, and what don’t you like about others in this group?

- What were your early life experiences with people in this group? How were you treated? How did you feel about others in your group when you were young?

At a community level, family workshops support positive cultural identities that strengthen family functioning and reducing behavioral health risks. In a study of 575 urban American Indian (AI) families from diverse tribal backgrounds, the AI families who participated in such a workshop had significant increases in their ethnic identity, improved sense of spirituality, and a more positive cultural identification. The workshops provided culturally adaptive parenting interventions.10

IR is a serious determinant of both physical and mental health. Assessment of IR can be done using rating scales, such as the Nadanolitization Scale11 or the Internalized Racial Oppression Scale.12 IR also can also be assessed using a more formalized interview guide, such as the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI).13 This 16-question interview guide helps behavioral health providers better understand the way service users and their social networks (e.g., families, friends) understand what is happening to them and why, as well as the barriers they experience, such as racism, discrimination, stigma, and financial stressors.

Individuals’ cultures and experiences have a profound impact on their understanding of their symptoms and their engagement in care. The American Psychiatric Association considers it to be part of mental health providers’ duty of care to engage all individuals in culturally relevant conversations about their past experiences and care expectations. More relevant, I submit that you cannot treat someone without having made this inquiry. A cultural assessment improves understanding but also shifts power relationships between providers and patients. The DSM-5 CFI and training guides are widely available and provide additional information for those who want to improve their cultural literacy.

Conclusion

Internalized racism is the component of racism that is the most difficult to discern. Psychiatrists and mental health professionals are uniquely poised to address IR, and any subsequent internal conflict and identity difficulties. Each program, office, and clinic can easily find the resources to do this through the APA. If you would like help providing education, contact me at [email protected].

References

1. Akbar N. J Black Studies. 1984. doi: 10.11771002193478401400401.

2. Lipsky S. Internalized Racism. Seattle: Rational Island Publishers, 1987.

3. Williams DR and Mohammed SA. Am Behav Sci. 2013 May 8. doi: 10.1177/00027642134873340.

4. DeLilly CR and Flaskerud JH. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012 Nov;33(11):804-11.

5. Molina KM and James D. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016 Jul;19(4):439-61.

6. Szymanski D and Obiri O. Couns Psychologist. 2011;39(3):438-62.

7. Carter RT et al. J Multicul Couns Dev. 2017 Oct 5;45(4):232-59.

8. Mouzon DM and McLean JS. Ethn Health. 2017 Feb;22(1):36-48.

9. Szymanski DM and Gupta A. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(1):110-18.

10. Kulis SS et al. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychol. 2019. doi: 10.1037/cpd000315.

11. Taylor J and Grundy C. “Measuring black internalization of white stereotypes about African Americans: The Nadanolization Scale.” In: Jones RL, ed. Handbook of Tests and Measurements of Black Populations. Hampton, Va.: Cobb & Henry, 1996.

12. Bailey T-K M et al. J Couns Psychol. 2011 Oct;58(4):481-93.

13. American Psychiatric Association. Cultural Formulation Interview. DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, Va. 2013.

Various aspects about the case described above have been changed to protect the clinician’s and patients’ identities. Thanks to the following individuals for their contributions to this article: Suzanne Huberty, MD, and Shiona Heru, JD.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ms. Jones brings her 15-year-old daughter, Angela, to the resident clinic. Angela is becoming increasingly anxious, withdrawn, and difficult to manage. As part of the initial interview, the resident, Dr. Sota, asks about the sociocultural background of the family. Ms. Jones is African American and recently began a relationship with a white man. Her daughter, Angela, is biracial; her biological father is white and has moved out of state with little ongoing contact with Angela and her mother.

At interview, Angela expresses a lot of anger at her mother, her biological father, and her new “stepfather.” Ms. Jones says: “I do not want Angela growing up as an ‘angry black woman.’ ” When asked for an explanation, she stated that she doesn’t want her daughter to be stereotyped, to be perceived as an angry black person. “She needs to fit in with our new life. She has lots of opportunities if only she would take them.”

Dr. Sota recognizes that Angela’s struggle, and perhaps also the struggle of Ms. Jones, has a component of internalized racism. How should Dr. Sota proceed? Dr. Sota puts herself in Angela’s shoes: How does Angela see herself? Angela has light brown skin, and

The term internalized racism (IR) first appeared in the 1980s. IR was compared to the oppression of black people in the 1800s: “The slavery that captures the mind and incarcerates the motivation, perception, aspiration, and identity in a web of anti-self images, generating a personal and collective self destruction, is more cruel than the shackles on the wrists and ankles.”1 According to Susanne Lipsky,2 IR “in African Americans manifests as internalizing stereotypes, mistrusting the self and other Blacks, and narrows one’s view of authentic Black culture.”

IR refers to the internalization and acceptance of the dominant white culture’s actions and beliefs, while rejecting one’s own cultural background. There is a long history of negative cultural representations of African Americans in popular American culture, and IR has a detrimental impact on the emotional well-being of African Americans.3

IR is associated with poorer metabolic health4 and psychological distress, depression and anxiety,5-8 and decreased self-esteem.9 However, protective processes can reduce one’s response to risk and can be developed through the psychotherapeutic relationship.

Interventions at an individual, family, or community levels

Angela: Tell me about yourself: What type of person are you? How do you identify? How do you feel about yourself/your appearance/your language?

Tell me about your friends/family? What interests do you have?

“Tell me more” questions can reveal conflicted feelings, etc., even if Angela does not answer. A good therapist can talk about IR; even if Angela does not bring it up, it is important for the therapist to find language suitable for the age of the patient.

Dr. Sota has some luck with Angela, who nods her head but says little. Dr. Sota then turns to Ms. Jones and asks whether she can answer these questions, too, and rephrases the questions for an adult. Interviewing parents in the presence of their children gives Dr. Sota and Angela an idea of what is permitted to talk about in the family.

A therapist can also note other permissions in the family: How do Angela and her mother use language? Do they claim or reject words and phrases such as “angry black woman” and choose, instead, to use language to “fit in” with the dominant white culture?

Dr. Sota notices that Ms. Jones presents herself as keen to fit in with her new future husband’s life. She wants Angela to do likewise. Dr. Sota notices that Angela vacillates between wanting to claim her black identity and having to navigate what that means in this family (not a good thing) – and wanting to assimilate into white culture. Her peers fall into two separate groups: a set of black friends and a set of white friends. Her mother prefers that she see her white friends, mistrusting her black friends.

Dr. Sota’s supervisor suggests that she introduce IR more forcefully because this seems to be a major course of conflict for Angela and encourage a frank discussion between mother and daughter. Dr. Sota starts the next session in the following way: “I noticed last week that the way you each identify yourselves is quite different. Ms. Jones, you want Angela to ‘fit in’ and perhaps just embrace white culture, whereas Angela, perhaps you vacillate between a white identity and a black identity?”

The following questions can help Dr. Sota elicit IR:

- What information about yourself would you like others to know – about your heritage, country of origin, family, class background, and so on?

- What makes you proud about being a member of this group, and what do you love about other members of this group?

- What has been hard about being a member of this group, and what don’t you like about others in this group?

- What were your early life experiences with people in this group? How were you treated? How did you feel about others in your group when you were young?

At a community level, family workshops support positive cultural identities that strengthen family functioning and reducing behavioral health risks. In a study of 575 urban American Indian (AI) families from diverse tribal backgrounds, the AI families who participated in such a workshop had significant increases in their ethnic identity, improved sense of spirituality, and a more positive cultural identification. The workshops provided culturally adaptive parenting interventions.10

IR is a serious determinant of both physical and mental health. Assessment of IR can be done using rating scales, such as the Nadanolitization Scale11 or the Internalized Racial Oppression Scale.12 IR also can also be assessed using a more formalized interview guide, such as the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI).13 This 16-question interview guide helps behavioral health providers better understand the way service users and their social networks (e.g., families, friends) understand what is happening to them and why, as well as the barriers they experience, such as racism, discrimination, stigma, and financial stressors.

Individuals’ cultures and experiences have a profound impact on their understanding of their symptoms and their engagement in care. The American Psychiatric Association considers it to be part of mental health providers’ duty of care to engage all individuals in culturally relevant conversations about their past experiences and care expectations. More relevant, I submit that you cannot treat someone without having made this inquiry. A cultural assessment improves understanding but also shifts power relationships between providers and patients. The DSM-5 CFI and training guides are widely available and provide additional information for those who want to improve their cultural literacy.

Conclusion

Internalized racism is the component of racism that is the most difficult to discern. Psychiatrists and mental health professionals are uniquely poised to address IR, and any subsequent internal conflict and identity difficulties. Each program, office, and clinic can easily find the resources to do this through the APA. If you would like help providing education, contact me at [email protected].

References

1. Akbar N. J Black Studies. 1984. doi: 10.11771002193478401400401.

2. Lipsky S. Internalized Racism. Seattle: Rational Island Publishers, 1987.

3. Williams DR and Mohammed SA. Am Behav Sci. 2013 May 8. doi: 10.1177/00027642134873340.

4. DeLilly CR and Flaskerud JH. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012 Nov;33(11):804-11.

5. Molina KM and James D. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016 Jul;19(4):439-61.

6. Szymanski D and Obiri O. Couns Psychologist. 2011;39(3):438-62.

7. Carter RT et al. J Multicul Couns Dev. 2017 Oct 5;45(4):232-59.

8. Mouzon DM and McLean JS. Ethn Health. 2017 Feb;22(1):36-48.

9. Szymanski DM and Gupta A. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(1):110-18.

10. Kulis SS et al. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychol. 2019. doi: 10.1037/cpd000315.

11. Taylor J and Grundy C. “Measuring black internalization of white stereotypes about African Americans: The Nadanolization Scale.” In: Jones RL, ed. Handbook of Tests and Measurements of Black Populations. Hampton, Va.: Cobb & Henry, 1996.

12. Bailey T-K M et al. J Couns Psychol. 2011 Oct;58(4):481-93.

13. American Psychiatric Association. Cultural Formulation Interview. DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, Va. 2013.

Various aspects about the case described above have been changed to protect the clinician’s and patients’ identities. Thanks to the following individuals for their contributions to this article: Suzanne Huberty, MD, and Shiona Heru, JD.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ms. Jones brings her 15-year-old daughter, Angela, to the resident clinic. Angela is becoming increasingly anxious, withdrawn, and difficult to manage. As part of the initial interview, the resident, Dr. Sota, asks about the sociocultural background of the family. Ms. Jones is African American and recently began a relationship with a white man. Her daughter, Angela, is biracial; her biological father is white and has moved out of state with little ongoing contact with Angela and her mother.

At interview, Angela expresses a lot of anger at her mother, her biological father, and her new “stepfather.” Ms. Jones says: “I do not want Angela growing up as an ‘angry black woman.’ ” When asked for an explanation, she stated that she doesn’t want her daughter to be stereotyped, to be perceived as an angry black person. “She needs to fit in with our new life. She has lots of opportunities if only she would take them.”

Dr. Sota recognizes that Angela’s struggle, and perhaps also the struggle of Ms. Jones, has a component of internalized racism. How should Dr. Sota proceed? Dr. Sota puts herself in Angela’s shoes: How does Angela see herself? Angela has light brown skin, and

The term internalized racism (IR) first appeared in the 1980s. IR was compared to the oppression of black people in the 1800s: “The slavery that captures the mind and incarcerates the motivation, perception, aspiration, and identity in a web of anti-self images, generating a personal and collective self destruction, is more cruel than the shackles on the wrists and ankles.”1 According to Susanne Lipsky,2 IR “in African Americans manifests as internalizing stereotypes, mistrusting the self and other Blacks, and narrows one’s view of authentic Black culture.”

IR refers to the internalization and acceptance of the dominant white culture’s actions and beliefs, while rejecting one’s own cultural background. There is a long history of negative cultural representations of African Americans in popular American culture, and IR has a detrimental impact on the emotional well-being of African Americans.3

IR is associated with poorer metabolic health4 and psychological distress, depression and anxiety,5-8 and decreased self-esteem.9 However, protective processes can reduce one’s response to risk and can be developed through the psychotherapeutic relationship.

Interventions at an individual, family, or community levels

Angela: Tell me about yourself: What type of person are you? How do you identify? How do you feel about yourself/your appearance/your language?

Tell me about your friends/family? What interests do you have?

“Tell me more” questions can reveal conflicted feelings, etc., even if Angela does not answer. A good therapist can talk about IR; even if Angela does not bring it up, it is important for the therapist to find language suitable for the age of the patient.

Dr. Sota has some luck with Angela, who nods her head but says little. Dr. Sota then turns to Ms. Jones and asks whether she can answer these questions, too, and rephrases the questions for an adult. Interviewing parents in the presence of their children gives Dr. Sota and Angela an idea of what is permitted to talk about in the family.

A therapist can also note other permissions in the family: How do Angela and her mother use language? Do they claim or reject words and phrases such as “angry black woman” and choose, instead, to use language to “fit in” with the dominant white culture?

Dr. Sota notices that Ms. Jones presents herself as keen to fit in with her new future husband’s life. She wants Angela to do likewise. Dr. Sota notices that Angela vacillates between wanting to claim her black identity and having to navigate what that means in this family (not a good thing) – and wanting to assimilate into white culture. Her peers fall into two separate groups: a set of black friends and a set of white friends. Her mother prefers that she see her white friends, mistrusting her black friends.

Dr. Sota’s supervisor suggests that she introduce IR more forcefully because this seems to be a major course of conflict for Angela and encourage a frank discussion between mother and daughter. Dr. Sota starts the next session in the following way: “I noticed last week that the way you each identify yourselves is quite different. Ms. Jones, you want Angela to ‘fit in’ and perhaps just embrace white culture, whereas Angela, perhaps you vacillate between a white identity and a black identity?”

The following questions can help Dr. Sota elicit IR:

- What information about yourself would you like others to know – about your heritage, country of origin, family, class background, and so on?

- What makes you proud about being a member of this group, and what do you love about other members of this group?

- What has been hard about being a member of this group, and what don’t you like about others in this group?

- What were your early life experiences with people in this group? How were you treated? How did you feel about others in your group when you were young?

At a community level, family workshops support positive cultural identities that strengthen family functioning and reducing behavioral health risks. In a study of 575 urban American Indian (AI) families from diverse tribal backgrounds, the AI families who participated in such a workshop had significant increases in their ethnic identity, improved sense of spirituality, and a more positive cultural identification. The workshops provided culturally adaptive parenting interventions.10

IR is a serious determinant of both physical and mental health. Assessment of IR can be done using rating scales, such as the Nadanolitization Scale11 or the Internalized Racial Oppression Scale.12 IR also can also be assessed using a more formalized interview guide, such as the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI).13 This 16-question interview guide helps behavioral health providers better understand the way service users and their social networks (e.g., families, friends) understand what is happening to them and why, as well as the barriers they experience, such as racism, discrimination, stigma, and financial stressors.

Individuals’ cultures and experiences have a profound impact on their understanding of their symptoms and their engagement in care. The American Psychiatric Association considers it to be part of mental health providers’ duty of care to engage all individuals in culturally relevant conversations about their past experiences and care expectations. More relevant, I submit that you cannot treat someone without having made this inquiry. A cultural assessment improves understanding but also shifts power relationships between providers and patients. The DSM-5 CFI and training guides are widely available and provide additional information for those who want to improve their cultural literacy.

Conclusion

Internalized racism is the component of racism that is the most difficult to discern. Psychiatrists and mental health professionals are uniquely poised to address IR, and any subsequent internal conflict and identity difficulties. Each program, office, and clinic can easily find the resources to do this through the APA. If you would like help providing education, contact me at [email protected].

References

1. Akbar N. J Black Studies. 1984. doi: 10.11771002193478401400401.

2. Lipsky S. Internalized Racism. Seattle: Rational Island Publishers, 1987.

3. Williams DR and Mohammed SA. Am Behav Sci. 2013 May 8. doi: 10.1177/00027642134873340.

4. DeLilly CR and Flaskerud JH. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012 Nov;33(11):804-11.

5. Molina KM and James D. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016 Jul;19(4):439-61.

6. Szymanski D and Obiri O. Couns Psychologist. 2011;39(3):438-62.

7. Carter RT et al. J Multicul Couns Dev. 2017 Oct 5;45(4):232-59.

8. Mouzon DM and McLean JS. Ethn Health. 2017 Feb;22(1):36-48.

9. Szymanski DM and Gupta A. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(1):110-18.

10. Kulis SS et al. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychol. 2019. doi: 10.1037/cpd000315.

11. Taylor J and Grundy C. “Measuring black internalization of white stereotypes about African Americans: The Nadanolization Scale.” In: Jones RL, ed. Handbook of Tests and Measurements of Black Populations. Hampton, Va.: Cobb & Henry, 1996.

12. Bailey T-K M et al. J Couns Psychol. 2011 Oct;58(4):481-93.

13. American Psychiatric Association. Cultural Formulation Interview. DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, Va. 2013.

Various aspects about the case described above have been changed to protect the clinician’s and patients’ identities. Thanks to the following individuals for their contributions to this article: Suzanne Huberty, MD, and Shiona Heru, JD.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Calculations of an academic hospitalist

The term “academic hospitalist” has come to mean more than a mere affiliation to an academic medical center (AMC). Academic hospitalists perform various clinical roles like staffing house staff teams, covering nonteaching services, critical care services, procedure teams, night services, medical consultation, and comanagement services.

Over the last decade, academic hospitalists have successfully managed many nonclinical roles in areas like research, medical unit leadership, faculty development, faculty affairs, quality, safety, informatics, utilization review, clinical documentation, throughput, group management, hospital administration, and educational leadership. The role of an academic hospital is as clear as a chocolate martini these days. Here we present some recent trends in academic hospital medicine.

Compensation

From SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM)2014 to 2018 data, the median compensation for U.S. academic hospitalists has risen by an average of 5.15% every year, although increases vary by rank.1 From 2016 to 2018, clinical instructors saw the most significant growth, 11.23% per year, suggesting a need to remain competitive for junior hospitalists. Compensation also varies by geographic area, with the Southern region reporting the highest compensation. Over the last decade, academic hospitalists received, on average, a 28%-35% lower salary, compared with community hospitalists.

Patient population and census

Lower patient encounters and compensation of the academic hospitalists poses the chicken or the egg dilemma. In the 2018 SoHM report, academic hospitalists had an average of 17% fewer encounters. Of note, AMC patients tend to have higher complexity, as measured by the Case Mix Index (CMI – the average diagnosis-related group weight of a hospital).2 A higher CMI is a surrogate marker for the diagnostic diversity, clinical complexity, and resource needs of the patient population in the hospital.

Productivity and financial metrics

The financial bottom line is a critical aspect, and as a report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine described, all health care executives look at business metrics while making decisions.3 Below are some significant academic and community comparisons from SoHM 2018.

- Collections, encounters, and wRVUs (work relative value units) were highly correlated. All of them were lower for academic hospitalists, corroborating the fact that they see a smaller number of patients. Clinical full-time equivalents (cFTE) is a vernacular of how much of the faculty time is devoted to clinical activities. The academic data from SoHM achieves the same target, as it is standardized to 100% billable clinical activity, so the fact that many academic hospitalists do not work a full-time clinical schedule is not a factor in their lower production.

- Charges had a smaller gap likely because of sicker patients in AMCs. The higher acuity difference can also explain 12% higher wRVU/encounter for academic hospitalists.

- The wRVU/encounter ratio can indicate a few patterns: high acuity of patients in AMCs, higher levels of evaluation and management documentation, or both. As the encounters and charges have the same percentage differences, we would place our bets on the former.

- Compensation per encounter and compensation per wRVU showed that academic hospitalists do get a slight advantage.

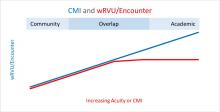

CMI and wRVUs

Although the SoHM does not capture information on patient acuity or CMI, we speculate that the relationship between CMI and wRVUs may be more or less linear at lower levels of acuity. However, once level III E/M billing is achieved (assuming there is no critical care provided), wRVUs/encounter plateau, even as acuity continues to increase. This plateau effect may be seen more often in high-acuity AMC settings than in community hospitals.

So, in our opinion, compensation models based solely on wRVU production would not do justice for hospitalists in AMC settings since these models would fail to capture the extra work involved with very-high-acuity patients. SoHM 2018 shows the financial support per wRVU for AMC is $45.81, and for the community is $41.28, an 11% difference. We think the higher financial support per wRVU for academic practices may be related to the lost wRVU potential of caring for very-high-acuity patients.

Conclusion

In an academic setting, hospitalists are reforming the field of hospital medicine and defining the ways we could deliver care. They are the pillars of collaboration, education, research, innovation, quality, and safety. It would be increasingly crucial for academic hospitalist leaders to use comparative metrics from SoHM to advocate for their group. The bottom line can be explained by the title of the qualitative study in JHM referenced above: “Collaboration, not calculation.”3

Dr. Chadha is division chief for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the practice analysis committee. Ms. Dede is division administrator for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare. She prepares and manages budgets, liaisons with the downstream revenue teams, and contributes to the building of academic compensation models. She is serving in the practice administrators committee for the second year and is currently vice chair of the Executive Council for the Practice Administrators special interest group.

References

1. State of Hospital Medicine Report. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

2. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Academic Medical Centers: Joining forces with community providers for broad benefits and positive outcomes. 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/academic-medical-centers-consolidation.html

3. White AA et al. Collaboration, not calculation: A qualitative study of how hospital executives value hospital medicine groups. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):662‐7.

The term “academic hospitalist” has come to mean more than a mere affiliation to an academic medical center (AMC). Academic hospitalists perform various clinical roles like staffing house staff teams, covering nonteaching services, critical care services, procedure teams, night services, medical consultation, and comanagement services.

Over the last decade, academic hospitalists have successfully managed many nonclinical roles in areas like research, medical unit leadership, faculty development, faculty affairs, quality, safety, informatics, utilization review, clinical documentation, throughput, group management, hospital administration, and educational leadership. The role of an academic hospital is as clear as a chocolate martini these days. Here we present some recent trends in academic hospital medicine.

Compensation

From SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM)2014 to 2018 data, the median compensation for U.S. academic hospitalists has risen by an average of 5.15% every year, although increases vary by rank.1 From 2016 to 2018, clinical instructors saw the most significant growth, 11.23% per year, suggesting a need to remain competitive for junior hospitalists. Compensation also varies by geographic area, with the Southern region reporting the highest compensation. Over the last decade, academic hospitalists received, on average, a 28%-35% lower salary, compared with community hospitalists.

Patient population and census

Lower patient encounters and compensation of the academic hospitalists poses the chicken or the egg dilemma. In the 2018 SoHM report, academic hospitalists had an average of 17% fewer encounters. Of note, AMC patients tend to have higher complexity, as measured by the Case Mix Index (CMI – the average diagnosis-related group weight of a hospital).2 A higher CMI is a surrogate marker for the diagnostic diversity, clinical complexity, and resource needs of the patient population in the hospital.

Productivity and financial metrics

The financial bottom line is a critical aspect, and as a report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine described, all health care executives look at business metrics while making decisions.3 Below are some significant academic and community comparisons from SoHM 2018.

- Collections, encounters, and wRVUs (work relative value units) were highly correlated. All of them were lower for academic hospitalists, corroborating the fact that they see a smaller number of patients. Clinical full-time equivalents (cFTE) is a vernacular of how much of the faculty time is devoted to clinical activities. The academic data from SoHM achieves the same target, as it is standardized to 100% billable clinical activity, so the fact that many academic hospitalists do not work a full-time clinical schedule is not a factor in their lower production.

- Charges had a smaller gap likely because of sicker patients in AMCs. The higher acuity difference can also explain 12% higher wRVU/encounter for academic hospitalists.

- The wRVU/encounter ratio can indicate a few patterns: high acuity of patients in AMCs, higher levels of evaluation and management documentation, or both. As the encounters and charges have the same percentage differences, we would place our bets on the former.

- Compensation per encounter and compensation per wRVU showed that academic hospitalists do get a slight advantage.

CMI and wRVUs

Although the SoHM does not capture information on patient acuity or CMI, we speculate that the relationship between CMI and wRVUs may be more or less linear at lower levels of acuity. However, once level III E/M billing is achieved (assuming there is no critical care provided), wRVUs/encounter plateau, even as acuity continues to increase. This plateau effect may be seen more often in high-acuity AMC settings than in community hospitals.

So, in our opinion, compensation models based solely on wRVU production would not do justice for hospitalists in AMC settings since these models would fail to capture the extra work involved with very-high-acuity patients. SoHM 2018 shows the financial support per wRVU for AMC is $45.81, and for the community is $41.28, an 11% difference. We think the higher financial support per wRVU for academic practices may be related to the lost wRVU potential of caring for very-high-acuity patients.

Conclusion

In an academic setting, hospitalists are reforming the field of hospital medicine and defining the ways we could deliver care. They are the pillars of collaboration, education, research, innovation, quality, and safety. It would be increasingly crucial for academic hospitalist leaders to use comparative metrics from SoHM to advocate for their group. The bottom line can be explained by the title of the qualitative study in JHM referenced above: “Collaboration, not calculation.”3

Dr. Chadha is division chief for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the practice analysis committee. Ms. Dede is division administrator for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare. She prepares and manages budgets, liaisons with the downstream revenue teams, and contributes to the building of academic compensation models. She is serving in the practice administrators committee for the second year and is currently vice chair of the Executive Council for the Practice Administrators special interest group.

References

1. State of Hospital Medicine Report. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

2. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Academic Medical Centers: Joining forces with community providers for broad benefits and positive outcomes. 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/academic-medical-centers-consolidation.html

3. White AA et al. Collaboration, not calculation: A qualitative study of how hospital executives value hospital medicine groups. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):662‐7.

The term “academic hospitalist” has come to mean more than a mere affiliation to an academic medical center (AMC). Academic hospitalists perform various clinical roles like staffing house staff teams, covering nonteaching services, critical care services, procedure teams, night services, medical consultation, and comanagement services.

Over the last decade, academic hospitalists have successfully managed many nonclinical roles in areas like research, medical unit leadership, faculty development, faculty affairs, quality, safety, informatics, utilization review, clinical documentation, throughput, group management, hospital administration, and educational leadership. The role of an academic hospital is as clear as a chocolate martini these days. Here we present some recent trends in academic hospital medicine.

Compensation

From SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM)2014 to 2018 data, the median compensation for U.S. academic hospitalists has risen by an average of 5.15% every year, although increases vary by rank.1 From 2016 to 2018, clinical instructors saw the most significant growth, 11.23% per year, suggesting a need to remain competitive for junior hospitalists. Compensation also varies by geographic area, with the Southern region reporting the highest compensation. Over the last decade, academic hospitalists received, on average, a 28%-35% lower salary, compared with community hospitalists.

Patient population and census

Lower patient encounters and compensation of the academic hospitalists poses the chicken or the egg dilemma. In the 2018 SoHM report, academic hospitalists had an average of 17% fewer encounters. Of note, AMC patients tend to have higher complexity, as measured by the Case Mix Index (CMI – the average diagnosis-related group weight of a hospital).2 A higher CMI is a surrogate marker for the diagnostic diversity, clinical complexity, and resource needs of the patient population in the hospital.

Productivity and financial metrics

The financial bottom line is a critical aspect, and as a report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine described, all health care executives look at business metrics while making decisions.3 Below are some significant academic and community comparisons from SoHM 2018.

- Collections, encounters, and wRVUs (work relative value units) were highly correlated. All of them were lower for academic hospitalists, corroborating the fact that they see a smaller number of patients. Clinical full-time equivalents (cFTE) is a vernacular of how much of the faculty time is devoted to clinical activities. The academic data from SoHM achieves the same target, as it is standardized to 100% billable clinical activity, so the fact that many academic hospitalists do not work a full-time clinical schedule is not a factor in their lower production.

- Charges had a smaller gap likely because of sicker patients in AMCs. The higher acuity difference can also explain 12% higher wRVU/encounter for academic hospitalists.

- The wRVU/encounter ratio can indicate a few patterns: high acuity of patients in AMCs, higher levels of evaluation and management documentation, or both. As the encounters and charges have the same percentage differences, we would place our bets on the former.

- Compensation per encounter and compensation per wRVU showed that academic hospitalists do get a slight advantage.

CMI and wRVUs

Although the SoHM does not capture information on patient acuity or CMI, we speculate that the relationship between CMI and wRVUs may be more or less linear at lower levels of acuity. However, once level III E/M billing is achieved (assuming there is no critical care provided), wRVUs/encounter plateau, even as acuity continues to increase. This plateau effect may be seen more often in high-acuity AMC settings than in community hospitals.

So, in our opinion, compensation models based solely on wRVU production would not do justice for hospitalists in AMC settings since these models would fail to capture the extra work involved with very-high-acuity patients. SoHM 2018 shows the financial support per wRVU for AMC is $45.81, and for the community is $41.28, an 11% difference. We think the higher financial support per wRVU for academic practices may be related to the lost wRVU potential of caring for very-high-acuity patients.

Conclusion

In an academic setting, hospitalists are reforming the field of hospital medicine and defining the ways we could deliver care. They are the pillars of collaboration, education, research, innovation, quality, and safety. It would be increasingly crucial for academic hospitalist leaders to use comparative metrics from SoHM to advocate for their group. The bottom line can be explained by the title of the qualitative study in JHM referenced above: “Collaboration, not calculation.”3

Dr. Chadha is division chief for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the practice analysis committee. Ms. Dede is division administrator for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare. She prepares and manages budgets, liaisons with the downstream revenue teams, and contributes to the building of academic compensation models. She is serving in the practice administrators committee for the second year and is currently vice chair of the Executive Council for the Practice Administrators special interest group.

References

1. State of Hospital Medicine Report. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

2. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Academic Medical Centers: Joining forces with community providers for broad benefits and positive outcomes. 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/academic-medical-centers-consolidation.html

3. White AA et al. Collaboration, not calculation: A qualitative study of how hospital executives value hospital medicine groups. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):662‐7.

Relapsing MS: Lower disability progression in long-term users of fingolimod

Key clinical point: Long-term exposure to fingolimod is associated with lower disability progression in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS).

Major finding: The high (≥8 years) vs. low (<8 years) exposure groups showed a smaller increase in the mean Expanded Disability Status Scale (+0.55 vs. +1.21) and lower frequencies of disability progression (34.7% vs. 56.1%; P less than .01) and wheelchair use (4.9% vs. 16.9%; P less than .0276) at 10 years.

Study details: ACROSS was a cross-sectional follow-up study of patients with relapsing MS enrolled in a phase 2 proof-of-concept study. Disability outcomes were assessed in patients grouped as per fingolimod exposure: high exposure (n=104) and low exposure (n=71).

Disclosures: The study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Amin Azmon and Davorka Tomic are employees of Novartis. The other authors reported relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Citation: Derfuss T et al. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2020 Mar 30. doi: 10.1177/2055217320907951.

Key clinical point: Long-term exposure to fingolimod is associated with lower disability progression in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS).

Major finding: The high (≥8 years) vs. low (<8 years) exposure groups showed a smaller increase in the mean Expanded Disability Status Scale (+0.55 vs. +1.21) and lower frequencies of disability progression (34.7% vs. 56.1%; P less than .01) and wheelchair use (4.9% vs. 16.9%; P less than .0276) at 10 years.

Study details: ACROSS was a cross-sectional follow-up study of patients with relapsing MS enrolled in a phase 2 proof-of-concept study. Disability outcomes were assessed in patients grouped as per fingolimod exposure: high exposure (n=104) and low exposure (n=71).

Disclosures: The study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Amin Azmon and Davorka Tomic are employees of Novartis. The other authors reported relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Citation: Derfuss T et al. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2020 Mar 30. doi: 10.1177/2055217320907951.

Key clinical point: Long-term exposure to fingolimod is associated with lower disability progression in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS).

Major finding: The high (≥8 years) vs. low (<8 years) exposure groups showed a smaller increase in the mean Expanded Disability Status Scale (+0.55 vs. +1.21) and lower frequencies of disability progression (34.7% vs. 56.1%; P less than .01) and wheelchair use (4.9% vs. 16.9%; P less than .0276) at 10 years.

Study details: ACROSS was a cross-sectional follow-up study of patients with relapsing MS enrolled in a phase 2 proof-of-concept study. Disability outcomes were assessed in patients grouped as per fingolimod exposure: high exposure (n=104) and low exposure (n=71).

Disclosures: The study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Amin Azmon and Davorka Tomic are employees of Novartis. The other authors reported relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Citation: Derfuss T et al. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2020 Mar 30. doi: 10.1177/2055217320907951.

Obesity tied to accelerated retinal atrophy in MS

Key clinical point: Elevated body mass index (BMI) is independently associated with an accelerated rate of ganglion cell+inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) atrophy in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Major findings: Obese (n=146; BMI, ≥30 kg/m2) vs. normal weight (n=214; BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) patients showed accelerated rate of GCIPL atrophy (−0.57%/year vs. −0.42%/year; P = .012). Atrophy rates were not significantly different between overweight (n=153; BMI, 25-29.9 kg/m2) and normal weight patients (−0.47%/year vs. −0.42%/year; P = .41). GCIPL atrophy rate accelerated by −0.011% per year with each 1 kg/m2 higher BMI (P =.003).

Study details: This observational study included 522 patients with MS from Johns Hopkins MS Center who were followed with retinal imaging for a median of 4.4 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National MS Society, Race to Erase MS, and NIH/NINDS. The presenting author had no disclosures. One coauthor reported receiving support from the Race to Erase MS foundation.

Citation: Filippatou AG et al. Mult Scler. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1177/1352458519900942.

Key clinical point: Elevated body mass index (BMI) is independently associated with an accelerated rate of ganglion cell+inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) atrophy in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Major findings: Obese (n=146; BMI, ≥30 kg/m2) vs. normal weight (n=214; BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) patients showed accelerated rate of GCIPL atrophy (−0.57%/year vs. −0.42%/year; P = .012). Atrophy rates were not significantly different between overweight (n=153; BMI, 25-29.9 kg/m2) and normal weight patients (−0.47%/year vs. −0.42%/year; P = .41). GCIPL atrophy rate accelerated by −0.011% per year with each 1 kg/m2 higher BMI (P =.003).

Study details: This observational study included 522 patients with MS from Johns Hopkins MS Center who were followed with retinal imaging for a median of 4.4 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National MS Society, Race to Erase MS, and NIH/NINDS. The presenting author had no disclosures. One coauthor reported receiving support from the Race to Erase MS foundation.

Citation: Filippatou AG et al. Mult Scler. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1177/1352458519900942.

Key clinical point: Elevated body mass index (BMI) is independently associated with an accelerated rate of ganglion cell+inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) atrophy in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Major findings: Obese (n=146; BMI, ≥30 kg/m2) vs. normal weight (n=214; BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) patients showed accelerated rate of GCIPL atrophy (−0.57%/year vs. −0.42%/year; P = .012). Atrophy rates were not significantly different between overweight (n=153; BMI, 25-29.9 kg/m2) and normal weight patients (−0.47%/year vs. −0.42%/year; P = .41). GCIPL atrophy rate accelerated by −0.011% per year with each 1 kg/m2 higher BMI (P =.003).

Study details: This observational study included 522 patients with MS from Johns Hopkins MS Center who were followed with retinal imaging for a median of 4.4 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National MS Society, Race to Erase MS, and NIH/NINDS. The presenting author had no disclosures. One coauthor reported receiving support from the Race to Erase MS foundation.