User login

Even a few days of steroids may be risky, new study suggests

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.

Given the findings, physicians should weigh the benefits against the risks of rare but potentially serious consequences of these anti-inflammatory drugs, according to the authors.

“After initiating patients on oral steroid bursts, physicians should be on the lookout for these severe adverse events, particularly within the first month after initiation of steroid therapy,” Dr. Yao said in an interview.

The findings were published online July 6 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Of the 15,859,129 adult Asians in the Taiwanese database, the study included 2,623,327 adults aged 20-64 years who received single steroid bursts (14 days or less) between Jan. 1, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2015.

Almost 60% of the indications were for skin disorders, such as eczema and urticaria, and for respiratory tract infections, such as sinusitis and acute pharyngitis. Among specialties, dermatology, otolaryngology, family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics accounted for 88% of prescriptions.

“Our findings are important for physicians and guideline developers because short-term use of oral corticosteroids is common and the real-world safety of this approach remains unclear,” the authors wrote. They acknowledged that the database did not provide information on such potential confounders as disease severity and lifestyle factors, nor did it include children and vulnerable individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the results.

The findings echo those of a 2017 cohort study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That study, by Akbar K. Waljee, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues, included data on more than 1.5 million privately insured U.S. adults. The researchers included somewhat longer steroid bursts of up to 30 days’ duration and found that use of the drugs was associated with a greater than fivefold increased risk for sepsis, a more than threefold increased risk for venous thromboembolism, and a nearly twofold increased risk for fracture within 30 days of starting treatment.

Furthermore, the elevated risk persisted at prednisone-equivalent doses of less than 20 mg/d (IRR, 4.02 for sepsis, 3.61 for venous thromboembolism, and 1.83 for fracture; all P < .001).

The U.S. study also found that during the 3-year period from 2012 to 2014, more than 20% of patients were prescribed short-term oral corticosteroids.

“Both studies indicate that these short-term regimens are more common in the real world than was previously thought and are not risk free,” Dr. Yao said.

Recognition that corticosteroids are associated with adverse events has been building for decades, according to the authors of an editorial that accompanies the new study.

“However, we commonly use short corticosteroid ‘bursts’ for minor ailments despite a lack of evidence for meaningful benefit. We are now learning that bursts as short as 3 days may increase risk for serious AEs, even in young and healthy people,” wrote editorialists Beth I. Wallace, MD, of the Center for Clinical Management Research at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Waljee, who led the 2017 study.

Dr. Wallace and Dr. Waljee drew parallels between corticosteroid bursts and other short-term regimens, such as of antibiotics and opiates, in which prescriber preference and sometimes patient pressure play a role. “All of these treatments have well-defined indications but can cause net harm when used. We can thus conceive of a corticosteroid stewardship model of targeted interventions that aims to reduce inappropriate prescribing,” they wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Wallace, a rheumatologist who prescribes oral steroids fairly frequently, noted that the Taiwan study is the first to investigate steroid bursts. “Up till now, these very short courses have flown under the radar. Clinicians very commonly prescribe short courses to help relieve symptoms of self-limited conditions like bronchitis, and we assume that because the exposure duration is short, the risks are low, especially for patients who are otherwise healthy.”

She warned that the data in the current study indicate that these short bursts – even at the lower end of the 1- to 2-week courses American physicians prescribe most often – carry small but real increases in risk for serious AEs. “And these increases were seen in young, healthy people, not just in people with preexisting conditions,” she said. “So, we might need to start thinking harder about how we are prescribing even these very short courses of steroids and try to use steroids only when their meaningful benefits really outweigh the risk.”

She noted that a patient with a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit substantially from short-term steroids to treat a disease flare. In that specific case, the benefits of short-term steroids may outweigh the risks, Dr. Wallace said.

But not everyone thinks a new strategy is needed. For Whitney A. High, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pathology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, the overprescribing of short-term corticosteroids is not a problem, and dermatologists are already exercising caution.

“I only prescribe these drugs short term to, at a guess, about 1 in 40 patients and only when a patient is miserable and quality of life is being seriously affected,” he said in an interview. “And that’s something that can’t be measured in a database study like the one from Taiwan but only in a risk-benefit analysis,” he said.

Furthermore, dermatologists have other drugs and technologies in their armamentarium, including topical steroids with occlusion or with wet wraps, phototherapy, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcipotriene, methotrexate and other immunosuppressive agents, and biologics. “In fact, many of these agents are specifically referred to as steroid-sparing,” Dr. High said.

Nor does he experience much pressure from patients to prescribe these drugs. “While occasionally I may encounter a patient who places pressure on me for oral steroids, it’s probably not nearly as frequently as providers in other fields are pressured to prescribe antibiotics or narcotics,” he said.

According to the Taiwanese researchers, the next step is to conduct more studies, including clinical trials, to determine optimal use of corticosteroids by monitoring adverse events. In the meantime, for practitioners such as Dr. Wallace and Dr. High, there is ample evidence from several recent studies of the harms of short-term corticosteroids, whereas the benefits for patients with self-limiting conditions remain uncertain. “This and other studies like it quite appropriately remind providers to avoid oral steroids when they’re not necessary and to seek alternatives where possible,” Dr. High said.

The study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan, the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, the Chang Gung Medical Foundation, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Yao has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wu has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. The editorialists and Dr. High have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace received an NIH grant during the writing of the editorial.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.

Given the findings, physicians should weigh the benefits against the risks of rare but potentially serious consequences of these anti-inflammatory drugs, according to the authors.

“After initiating patients on oral steroid bursts, physicians should be on the lookout for these severe adverse events, particularly within the first month after initiation of steroid therapy,” Dr. Yao said in an interview.

The findings were published online July 6 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Of the 15,859,129 adult Asians in the Taiwanese database, the study included 2,623,327 adults aged 20-64 years who received single steroid bursts (14 days or less) between Jan. 1, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2015.

Almost 60% of the indications were for skin disorders, such as eczema and urticaria, and for respiratory tract infections, such as sinusitis and acute pharyngitis. Among specialties, dermatology, otolaryngology, family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics accounted for 88% of prescriptions.

“Our findings are important for physicians and guideline developers because short-term use of oral corticosteroids is common and the real-world safety of this approach remains unclear,” the authors wrote. They acknowledged that the database did not provide information on such potential confounders as disease severity and lifestyle factors, nor did it include children and vulnerable individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the results.

The findings echo those of a 2017 cohort study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That study, by Akbar K. Waljee, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues, included data on more than 1.5 million privately insured U.S. adults. The researchers included somewhat longer steroid bursts of up to 30 days’ duration and found that use of the drugs was associated with a greater than fivefold increased risk for sepsis, a more than threefold increased risk for venous thromboembolism, and a nearly twofold increased risk for fracture within 30 days of starting treatment.

Furthermore, the elevated risk persisted at prednisone-equivalent doses of less than 20 mg/d (IRR, 4.02 for sepsis, 3.61 for venous thromboembolism, and 1.83 for fracture; all P < .001).

The U.S. study also found that during the 3-year period from 2012 to 2014, more than 20% of patients were prescribed short-term oral corticosteroids.

“Both studies indicate that these short-term regimens are more common in the real world than was previously thought and are not risk free,” Dr. Yao said.

Recognition that corticosteroids are associated with adverse events has been building for decades, according to the authors of an editorial that accompanies the new study.

“However, we commonly use short corticosteroid ‘bursts’ for minor ailments despite a lack of evidence for meaningful benefit. We are now learning that bursts as short as 3 days may increase risk for serious AEs, even in young and healthy people,” wrote editorialists Beth I. Wallace, MD, of the Center for Clinical Management Research at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Waljee, who led the 2017 study.

Dr. Wallace and Dr. Waljee drew parallels between corticosteroid bursts and other short-term regimens, such as of antibiotics and opiates, in which prescriber preference and sometimes patient pressure play a role. “All of these treatments have well-defined indications but can cause net harm when used. We can thus conceive of a corticosteroid stewardship model of targeted interventions that aims to reduce inappropriate prescribing,” they wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Wallace, a rheumatologist who prescribes oral steroids fairly frequently, noted that the Taiwan study is the first to investigate steroid bursts. “Up till now, these very short courses have flown under the radar. Clinicians very commonly prescribe short courses to help relieve symptoms of self-limited conditions like bronchitis, and we assume that because the exposure duration is short, the risks are low, especially for patients who are otherwise healthy.”

She warned that the data in the current study indicate that these short bursts – even at the lower end of the 1- to 2-week courses American physicians prescribe most often – carry small but real increases in risk for serious AEs. “And these increases were seen in young, healthy people, not just in people with preexisting conditions,” she said. “So, we might need to start thinking harder about how we are prescribing even these very short courses of steroids and try to use steroids only when their meaningful benefits really outweigh the risk.”

She noted that a patient with a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit substantially from short-term steroids to treat a disease flare. In that specific case, the benefits of short-term steroids may outweigh the risks, Dr. Wallace said.

But not everyone thinks a new strategy is needed. For Whitney A. High, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pathology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, the overprescribing of short-term corticosteroids is not a problem, and dermatologists are already exercising caution.

“I only prescribe these drugs short term to, at a guess, about 1 in 40 patients and only when a patient is miserable and quality of life is being seriously affected,” he said in an interview. “And that’s something that can’t be measured in a database study like the one from Taiwan but only in a risk-benefit analysis,” he said.

Furthermore, dermatologists have other drugs and technologies in their armamentarium, including topical steroids with occlusion or with wet wraps, phototherapy, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcipotriene, methotrexate and other immunosuppressive agents, and biologics. “In fact, many of these agents are specifically referred to as steroid-sparing,” Dr. High said.

Nor does he experience much pressure from patients to prescribe these drugs. “While occasionally I may encounter a patient who places pressure on me for oral steroids, it’s probably not nearly as frequently as providers in other fields are pressured to prescribe antibiotics or narcotics,” he said.

According to the Taiwanese researchers, the next step is to conduct more studies, including clinical trials, to determine optimal use of corticosteroids by monitoring adverse events. In the meantime, for practitioners such as Dr. Wallace and Dr. High, there is ample evidence from several recent studies of the harms of short-term corticosteroids, whereas the benefits for patients with self-limiting conditions remain uncertain. “This and other studies like it quite appropriately remind providers to avoid oral steroids when they’re not necessary and to seek alternatives where possible,” Dr. High said.

The study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan, the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, the Chang Gung Medical Foundation, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Yao has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wu has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. The editorialists and Dr. High have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace received an NIH grant during the writing of the editorial.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.

Given the findings, physicians should weigh the benefits against the risks of rare but potentially serious consequences of these anti-inflammatory drugs, according to the authors.

“After initiating patients on oral steroid bursts, physicians should be on the lookout for these severe adverse events, particularly within the first month after initiation of steroid therapy,” Dr. Yao said in an interview.

The findings were published online July 6 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Of the 15,859,129 adult Asians in the Taiwanese database, the study included 2,623,327 adults aged 20-64 years who received single steroid bursts (14 days or less) between Jan. 1, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2015.

Almost 60% of the indications were for skin disorders, such as eczema and urticaria, and for respiratory tract infections, such as sinusitis and acute pharyngitis. Among specialties, dermatology, otolaryngology, family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics accounted for 88% of prescriptions.

“Our findings are important for physicians and guideline developers because short-term use of oral corticosteroids is common and the real-world safety of this approach remains unclear,” the authors wrote. They acknowledged that the database did not provide information on such potential confounders as disease severity and lifestyle factors, nor did it include children and vulnerable individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the results.

The findings echo those of a 2017 cohort study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That study, by Akbar K. Waljee, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues, included data on more than 1.5 million privately insured U.S. adults. The researchers included somewhat longer steroid bursts of up to 30 days’ duration and found that use of the drugs was associated with a greater than fivefold increased risk for sepsis, a more than threefold increased risk for venous thromboembolism, and a nearly twofold increased risk for fracture within 30 days of starting treatment.

Furthermore, the elevated risk persisted at prednisone-equivalent doses of less than 20 mg/d (IRR, 4.02 for sepsis, 3.61 for venous thromboembolism, and 1.83 for fracture; all P < .001).

The U.S. study also found that during the 3-year period from 2012 to 2014, more than 20% of patients were prescribed short-term oral corticosteroids.

“Both studies indicate that these short-term regimens are more common in the real world than was previously thought and are not risk free,” Dr. Yao said.

Recognition that corticosteroids are associated with adverse events has been building for decades, according to the authors of an editorial that accompanies the new study.

“However, we commonly use short corticosteroid ‘bursts’ for minor ailments despite a lack of evidence for meaningful benefit. We are now learning that bursts as short as 3 days may increase risk for serious AEs, even in young and healthy people,” wrote editorialists Beth I. Wallace, MD, of the Center for Clinical Management Research at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Waljee, who led the 2017 study.

Dr. Wallace and Dr. Waljee drew parallels between corticosteroid bursts and other short-term regimens, such as of antibiotics and opiates, in which prescriber preference and sometimes patient pressure play a role. “All of these treatments have well-defined indications but can cause net harm when used. We can thus conceive of a corticosteroid stewardship model of targeted interventions that aims to reduce inappropriate prescribing,” they wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Wallace, a rheumatologist who prescribes oral steroids fairly frequently, noted that the Taiwan study is the first to investigate steroid bursts. “Up till now, these very short courses have flown under the radar. Clinicians very commonly prescribe short courses to help relieve symptoms of self-limited conditions like bronchitis, and we assume that because the exposure duration is short, the risks are low, especially for patients who are otherwise healthy.”

She warned that the data in the current study indicate that these short bursts – even at the lower end of the 1- to 2-week courses American physicians prescribe most often – carry small but real increases in risk for serious AEs. “And these increases were seen in young, healthy people, not just in people with preexisting conditions,” she said. “So, we might need to start thinking harder about how we are prescribing even these very short courses of steroids and try to use steroids only when their meaningful benefits really outweigh the risk.”

She noted that a patient with a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit substantially from short-term steroids to treat a disease flare. In that specific case, the benefits of short-term steroids may outweigh the risks, Dr. Wallace said.

But not everyone thinks a new strategy is needed. For Whitney A. High, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pathology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, the overprescribing of short-term corticosteroids is not a problem, and dermatologists are already exercising caution.

“I only prescribe these drugs short term to, at a guess, about 1 in 40 patients and only when a patient is miserable and quality of life is being seriously affected,” he said in an interview. “And that’s something that can’t be measured in a database study like the one from Taiwan but only in a risk-benefit analysis,” he said.

Furthermore, dermatologists have other drugs and technologies in their armamentarium, including topical steroids with occlusion or with wet wraps, phototherapy, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcipotriene, methotrexate and other immunosuppressive agents, and biologics. “In fact, many of these agents are specifically referred to as steroid-sparing,” Dr. High said.

Nor does he experience much pressure from patients to prescribe these drugs. “While occasionally I may encounter a patient who places pressure on me for oral steroids, it’s probably not nearly as frequently as providers in other fields are pressured to prescribe antibiotics or narcotics,” he said.

According to the Taiwanese researchers, the next step is to conduct more studies, including clinical trials, to determine optimal use of corticosteroids by monitoring adverse events. In the meantime, for practitioners such as Dr. Wallace and Dr. High, there is ample evidence from several recent studies of the harms of short-term corticosteroids, whereas the benefits for patients with self-limiting conditions remain uncertain. “This and other studies like it quite appropriately remind providers to avoid oral steroids when they’re not necessary and to seek alternatives where possible,” Dr. High said.

The study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan, the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, the Chang Gung Medical Foundation, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Yao has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wu has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. The editorialists and Dr. High have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace received an NIH grant during the writing of the editorial.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Access to Pain Care From Compensation Clinics: A Relational Coordination Perspective

Chronic pain is common in veterans, and early engagement in pain treatment is recommended to forestall consequences of untreated pain, including depression, disability, and substance use disorders. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) employs a stepped care model of pain treatment, with the majority of pain care based in primary care (step 1), and an array of specialty/multimodal treatment options made available at each step in the model for patients with more complex problems, or those who do not respond to more conservative interventions.1

Recognizing the need for comprehensive pain care, the US Congress passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, 21 USC §1521 (2016), which included provisions for VHA facilities to offer multimodal pain treatment and to report the availability of pain care options at each step in the stepped care model.2, With the passage of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, 38 USC §101 (2014) and now the MISSION Act of 2018, 38 USC §703 (2018) veterans whose VHA facilities are too distant, who require care unavailable at that facility, or who have to wait too long to receive care are eligible for treatment at either VHA or non-VHA facilities.3 These laws allocate the same pool of funds to both VHA and community care and thus create an incentive to engage veterans in care within the VHA network so the funds are not spent out of network.4

An opportunity to connect veterans with VHA care arises at specialized VHA Compensation and Pension (C&P) clinics during examinations that determine whether a veteran’s health conditions were caused or exacerbated by their military service. Veterans file claims with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), which sends the patient to either a VHA facility or private practitioners for these examinations. Although the number of examinations conducted each year is not available, there were 274,528 veterans newly awarded compensation in fiscal year 2018, and a substantial number of the total of 4,743,108 veterans with C&P awards had reevaluation examinations for at least 1 of their conditions during that year.5 Based largely on the compensation examination results, military service records, and medical records, veterans are granted a service-connected rating for conditions deemed related to military service. A service-connection rating between 0% and 100% is assigned by the VBA, with higher ratings indicating more impairment and, consequently, more financial compensation. Service-connection ratings also are used to decide which veterans are in the highest priority groups for receipt of VHA health care services and are exempt from copayments.

Although traditionally thought of as a forensic evaluation with no clinical purpose, the C&P examination process affords many opportunities to explain VHA care to veterans in distress who file claims.6 A randomized clinical trials (RCT) involving veterans with mental health claims and a second RCT including veterans with musculoskeletal claims each found that veterans use more VHA services if offered outreach at the time of the C&P examination.7,8 In addition to clinical benefits, outreach around the time of C&P examinations also might mitigate the well documented adversarial aspects of the service-connection claims process.6,9,10 Currently, such outreach is not part of routine VHA procedures. Ironically, it is the VBA and not VHA that contacts veterans who are awarded service-connection with information about their eligibility for VHA care based on their award.

Connecting veterans to pain treatment can involve clarifying eligibility for VHA care for veterans in whom eligibility is unknown, involving primary care providers (PCPs) who are the fulcrum of VHA pain care referrals, and motivating veterans to seek specific pain treatment modalities. Connecting veterans to treatment at the time of their compensation examinations also likely involves bidirectional cooperation between the specialized C&P clinics where veterans are examined and the clinics that provide treatment.

Relational coordination is a theoretical framework that can describe the horizontal relationships between different teams within the same medical facility. Relational coordination theorizes that communication between workgroups is related synergistically to the quality of relationships between workgroups. Relational coordination is better between workgroups that share goals and often have high levels of relational coordination, which is thought to be especially important when activities are ambiguous, require cooperation, and are conducted under time pressure.11 High relational coordination also has been associated with high staff job satisfaction, high satisfaction with delivered services, and adherence to treatment guidelines.12-14 An observational cohort study suggested that relational coordination can be improved by targeted interventions that bring workgroups together and facilitate intercommunication.15

To better understand referral and engagement for pain treatment at compensation examinations, VA staff from primary care, mental health, pain management, and C&P teams at the 8 VHA medical centers in New England were invited to complete a validated relational coordination survey.11,16 A subset of invited staff participated in a semistructured interview about pain treatment referral practices within their medical centers.

Assessments were conducted as part of a mixed methods formative evaluation involving quantitative and qualitative methods for a clinical trial at the 8 VHA medical centers in New England. The trial is testing an intervention in which veterans presenting for service-connection examinations for musculoskeletal conditions receive brief counseling to engage them in nonopioid pain treatments. The VHA Central Institutional Review Board approved this formative evaluation and the clinical trial has begun (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04062214).

Potential interviewees were involved in referrals to and provision of nonpharmacologic pain treatment and were identified by site investigators in the randomized trial. Identified interviewees were clinical and administrative staff belonging to VHA Primary Care, Pain Management, and Compensation and Pension clinics. A total of 83 staff were identified.

Semistructured Interviews

A subset of the 83 staff were invited to participate in a semistructured interview because their position impacted coordination of pain care at their facilities or they worked in C&P. Staff at a site were interviewed until no new themes emerged from additional interviews, and each of the 8 sites was represented. Interviews were conducted between June and August 2018. Standardized scripts describing the study and inviting participation in a semistructured interview were e-mailed to VA staff. At the time of the interview the study purpose was restated and consent for audiotaping was obtained. The interviews followed a guide designed to assess a relational coordination framework among various workgroups. The data in this manuscript were elicited by specific prompts concerning: (1) How veterans learn about pain care when they come through C&P; and (2) How staff in C&P communicate with treatment providers about veterans who have chronic pain. Each interview lasted about 30 minutes.

Relational Coordination Survey

All identified staff were invited to participate in a relational coordination survey. The survey was administered through VA REDCap. Survey invitations were e-mailed from REDCap to VA staff and included a description of the study and assurances of the confidentiality of data collected. Surveys took < 10 minutes to complete. To begin, respondents identified their primary workgroup (C&P, primary care, pain management, or administrative leadership or staff), secondary workgroup (if they were in > 1), and site. Respondents provided no other identifying information and were assured their responses would be confidential.

The survey consisted of 7 questions regarding beliefs about the quality of communication and interactions among workgroup members in obtaining a shared goal.11 The shared goal in the survey used in this study was providing pain care services for veterans with musculoskeletal conditions. Using a 5-point Likert scale, the 7 questions concerned frequency, timeliness, and accuracy of communication; response to problems providing pain services; sharing goals; and knowledge and respect for respondent’s job function. Higher scores indicated better relational coordination among members of a workgroup. Using the survey’s 7 items, composite mean relational coordination scores were calculated for each of the 4 primary workgroups. To account for the possibility that a member rated their own workgroups, 2 scores were created for each workgroup; one included members of the workgroup and another excluded them.

Data Analysis

The audio-recorded semistructured interviews were transcribed and entered into Atlas.ti qualitative data analysis software. To identify cross-cutting themes, a semistructured telephone interview guide was developed by the qualitative study team that emphasized interrelationships between different clinical teams. The transcripts were then analyzed using the grounded theory approach, a systematic methodology to reduce themes from collected qualitative data. Two research staff read each transcript twice; first to familiarize themselves with the text and then, using open coding, to identify important concepts that emerged from the language and assign codes to segments of text. To ensure accuracy, researchers included suitable contextual information in the coding. Using the constant comparative method, research staff then met to examine the themes that emerged in the interviews, discuss and coalesce coding discrepancies, and compare perspectives.17

The composite score (mean of the 7 items and 95% CI) of the survey responses was analyzed to identify significant differences in coordination across the 4 workgroups. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine each relational coordination score by respondents’ workgroup. Post hoc analyses examined relational coordination survey differences among the 4 respondent groups.

Results

Thirty-nine survey respondents participated in the semistructured interviews. C&P examiners expressed varying degrees of comfort with their role in extending access to pain care for veterans. Some of the examiners strongly believed that their role was purely forensic, and going beyond this forensic role to refer or recommend treatment to veterans would be a violation of their role to conduct a forensic examination. “We don’t have an ongoing therapeutic relationship with any of the patients,” a C&P examiner explained: “We see them once; they’re out the door. It’s forensic. We’re investigating the person as a claimant, we’re investigating it and using our tools to go and review information from 30, 40 years ago.”

Other examiners had a less strict approach for working with veterans in C&P, even though examiners are asked not to provide advice or therapy. One C&P examiner noted that because he “can’t watch people in pain,” during the examination this doctor recommends that patients go to the office that determines whether they are eligible for benefits and choose a PCP. Another C&P examiner concurred with this approach. “I certainly spend a little time with the veteran talking to them about their personal life, who they are, what they do, what they’ve done, what they’re going to do to kind of break the ice between us,” the second examiner explained. “At the end, I will make some suggestions to them. I’m comfortable doing that. I don’t know that everybody is.”

Many of the VHA providers we interviewed had little knowledge of the C&P process or whether C&P examiners had any role or responsibilities in referring veterans for pain care. Most VHA providers could not name any C&P examiners at their facility and were generally unfamiliar with the content of C&P examinations. One provider bluntly said, “I’ve never communicated with anyone in comp and pen [C&P].”

Another PCP also expressed concerns with referrals, suggesting that C&P and primary care “are totally separate and should remain separate,” the PCP explained. “My concern with getting referral from comp and pen is that is it then they’re seeking all sorts of treatment that they wouldn’t necessarily need or ask for otherwise.”

Conversely a different PCP had a positive outlook on how C&P examiners might help ease the transition into the VHA for veterans with pain, especially for newly discharged veterans. “Having comp and pen address these issues is really going to be helpful. I think it could be significant that the topic is introduced early on.”

Relational Coordination Survey

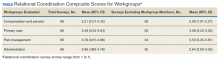

Relational coordination surveys were sent to 83 participants of whom 66 responded. Respondents were from

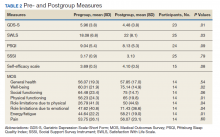

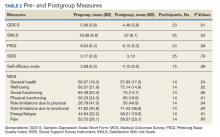

The relational coordination composite scores were lowest for C&P. This finding remained whether C&P staff surveys were included or removed from the C&P responses. As demonstrated by the 95% CI, when team members’ surveys were included, C&P scores (95% CI, 2.01-2.42) were significantly lower than the primary care (95% CI, 3.34-3.64) and pain management (95% CI, 3.61-3.96) groups. All the relational coordination composite scores were slightly lower when staff who described their own workgroup were removed (ie, respondents rated their own workgroups as having higher relational coordination than others did). Using the composite scores excluding same workgroup members, the composite scores of the C&P remained significantly lower than all 3 other workgroups (Table). Means values for each individual item in the C&P group were significantly less than all other group means for each item except for the question on responses to problems providing pain services (data not shown). On this item only, the mean C&P rating was > 3 (3.19), but this was still lower than the means of the primary care and pain management workgroups.

Further analyses were undertaken to understand the importance of stakeholders’ ratings of their own workgroup compared with ratings by others of that workgroup. A 1-way ANOVA of workgroup was conducted and displayed significant workgroup differences between member and nonmember relational coordination ratings on 3 of the 4 workgroup’s scores C&P (F = 5.75, 3, 62 df; P < .01) primary care (F = 4.30, 3, 62 df; P < .008) and pain management (F = 8.22, 3, 62 df; P < .001). Post hoc contrasts between the different workgroups doing the rating revealed: (1) significant differences in the assessment of the C&P workgroup between the C&P workgroup and both the primary care (P < .01) and pain management groups (P < .001) with C&P rating their own workgroup significantly higher; (2) a significant difference in the scoring of the primary care workgroup with the primary care group rating themselves significantly higher than the C&P group; and (3) significant differences in the scoring of the pain management workgroup with both pain management and primary care groups rating the pain management group significantly higher than the C&P group. The results were not substantially changed by removing the 18 respondents who identified themselves as being part of > 1 workgroup .

Discussion

Mixed methods revealed disparate viewpoints about the role of C&P in referring veterans to pain care services. Overall, C&P teams coordinated less with other workgroups than the other groups coordinated with each other, and the C&P clinics took only limited steps to engage veterans in VHA treatment. The relational coordination results appeared to be valid. The mean scores were near the middle of the relational coordination rating scale, with standard deviations indicating a range of responses. The lower relational coordination scores of the C&P group remained after removing stakeholders who were rating their own workgroup. Further support for the validity of the relational coordination survey results is that they were consistent with the reports of C&P clinic isolation in the semistructured interviews.

The interview data suggest that one reason the C&P teams had low relational coordination scores is that VA staff interpret the emphasis on evaluative rather than therapeutic examinations to preclude other attempts to engage veterans into VHA treatment, even though such treatment engagement is permitted within existing guidelines. VBA referrals for examinations say nothing, either way, about engaging veterans in VHA care. The relational coordination results suggest that an intervention that might increase treatment referrals from the C&P clinics would be to explain the (existing) policy allowing for outreach around the time of compensation examinations to VHA staff so this goal is clearly agreed-upon. Another approach to facilitating treatment engagement at the C&P examination is to use other interventions that have been associated with better relational coordination such as intergroup meetings, horizontal integration more generally, and an atmosphere is which people from different backgrounds feel empowered to speak frankly to each other.15,18,19 An important linkage to forge is between C&P teams and the administrative workgroups responsible for verifying a veteran’s eligibility for VHA care and enrolling eligible veterans in VHA treatment. Having C&P clinicians who are familiar with the eligibility and treatment engagement processes would facilitate providing that information to veterans, without compromising the evaluative format of the compensation examination.

An interesting ancillary finding is that relational coordination ratings by members of 3 of the 4 workgroups were higher than ratings by other staff of that workgroup. A possible explanation for this finding is that workgroup members are more aware of the relational coordination efforts made by their own workgroup than those by other workgroups, and therefore rate their own workgroup higher. This also might be part of a broader self-aggrandizement heuristic that has been described in multiple domains.20 Staff may apply this heuristic in reporting that their staff engage in more relational coordination, reflecting the social desirability of being cooperative.

There are simple facility-level interventions that would facilitate veterans access to care such as conducting C&P examinations for potentially treatment-eligible veterans at VHA facilities (vs conducted outside VHA) and having access to materials that explain the treatment options to veterans when they check in for their compensation examinations. The approach to C&P-based treatment engagement that was successfully employed in 2 clinical trials involved having counselors not connected with the C&P clinic contact veterans around the time of their compensation examination to explain VA treatment options and motivate veterans to pursue treatment.8,9 This independent counselor approach is being evaluated in a larger study.

Limitations

These data are from a small number of VA staff evaluating veterans in a single region of the US. They do not show causation, and it is possible that relational coordination is not necessary for referrals from C&P clinics. Relational coordination might not be necessary when referral processes can be simply routinized with little need for communication.11 However, other analyses in these clinics have found that pain treatment referrals in fact are not routinized, with substantial variability within and across institutions. Another possibility is that features that have been associated with less relational coordination, such as male gender and medical specialist guild, were disproportionately present in C&P clinics compared to the other clinics.21

Conclusions

There have been public calls to improve the evaluation of service-connection claims such that this process includes approaches to engage veterans in treatment.22 Referring veterans to treatment when they come for C&P examinations will likely involve improving relational coordination between the C&P service and other parts of VHA. Nationwide, sites that integrate C&P more fully may have valuable lessons to impart about the benefits of such integration. An important step towards better relational coordination will be clarifying that engaging veterans in VHA care around the time of their C&P examinations is a facility-wide goal.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brian Linde and Efia James for their perspectives on C&P procedures. This work was supported by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 1 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) and National Institute of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Project # 5UG3AT009758-02. (MIR, SM mPIs).

1. US Department Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 2009-053: pain management. https://www.va.gov/painmanagement/docs/vha09paindirective.pdf. Published October 28, 2019. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Rosenberger PH, Phillip EJ, Lee A, Kerns RD. The VHA’s national pain management strategy: implementing the stepped care model. Fed Pract. 2011;28(8):39-42.

3. Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, Bastian L. The Veterans Choice Act: A Qualitative Examination of Rapid Policy Implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 7 Suppl 1:S71-S75. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000667

4. Rieselbach RE, Epperly T, Nycz G, Shin P. Community health centers could provide better outsourced primary care for veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(1):150-153. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4691-4

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefit Administration. VBA annual benefits report fiscal year 2018. https://www.benefits.va.gov/REPORTS/abr/docs/2018-abr.pdf. Updated March 29, 2019. Accessed June 17, 2020.

6. Rosen MI. Compensation examinations for PTSD-an opportunity for treatment? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(5):xv-xxii. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2010.04.0075

7. Rosen MI, Ablondi K, Black AC, et al. Work outcomes after benefits counseling among veterans applying for service connection for a psychiatric condition. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(12):1426-1432. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201300478

8. Rosen MI, Becker WC, Black AC, Martino S, Edens EL, Kerns RD. Brief counseling for veterans with musculoskeletal disorder, risky substance use, and service connection claims. Pain Med. 2019;20(3):528-542. doi:10.1093/pm/pny071

9. Meshberg-Cohen S, DeViva JC, Rosen MI. Counseling veterans applying for service connection status for mental health conditions. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(4):396-399. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201500533

10. Sayer NA, Spoont M, Nelson DB. Post-traumatic stress disorder claims from the viewpoint of veterans service officers. Mil Med. 2005;170(10):867-870. doi:10.7205/milmed.170.10.867

11. Gittell JH. Coordinating mechanisms in care provider groups: relational coordination as a mediator and input uncertainty as a moderator of performance effects. Manage Sci. 2002;48(11):1408-1426. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.48.11.1408.268

12. Havens DS, Gittell JH, Vasey J. Impact of relational coordination on nurse job satisfaction, work engagement and burnout: achieving the quadruple aim. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(3):132-140. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000587

13. Gittell JH, Logan C, Cronenwett J, et al. Impact of relational coordination on staff and patient outcomes in outpatient surgical clinics. Health Care Manage Rev. 2020;45(1):12-20. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000192

14. Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Relational coordination promotes quality of chronic care delivery in Dutch disease-management programs. Health Care Manage Rev. 2012;37(4):301-309. doi:10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182355ea4

15. Abu-Rish Blakeney E, Lavallee DC, Baik D, Pambianco S, O’Brien KD, Zierler BK. Purposeful interprofessional team intervention improves relational coordination among advanced heart failure care teams. J Interprof Care. 2019;33(5):481-489. doi:10.1080/13561820.2018.1560248

16. Valentine MA, Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Measuring teamwork in health care settings: a review of survey instruments. Med Care. 2015;53(4):e16-e30. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827feef6

17. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL. Transaction Publishers; 2009.

18. Gittell JH. How interdependent parties build relational coordination to achieve their desired outcomes. Negot J. 2015;31(4):387-391. doi: 10.1111/nejo.12114

19. Solberg MT, Hansen TW, Bjørk IT. The need for predictability in coordination of ventilator treatment of newborn infants--a qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2015;31(4):205-212. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2014.12.003

20. Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol Bull. 1988;103(2):193-210.

21. Hartgerink JM, Cramm JM, Bakker TJ, van Eijsden AM, Mackenbach JP, Nieboer AP. The importance of multidisciplinary teamwork and team climate for relational coordination among teams delivering care to older patients. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(4):791-799. doi:10.1111/jan.12233

22. Bilmes L. soldiers returning from iraq and afghanistan: the long-term costs of providing veterans medical care and disability benefits RWP07-001. https://research.hks.harvard.edu/publications/getFile.aspx?Id=237. Published January 2007. Accessed June 18, 2020.

Chronic pain is common in veterans, and early engagement in pain treatment is recommended to forestall consequences of untreated pain, including depression, disability, and substance use disorders. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) employs a stepped care model of pain treatment, with the majority of pain care based in primary care (step 1), and an array of specialty/multimodal treatment options made available at each step in the model for patients with more complex problems, or those who do not respond to more conservative interventions.1

Recognizing the need for comprehensive pain care, the US Congress passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, 21 USC §1521 (2016), which included provisions for VHA facilities to offer multimodal pain treatment and to report the availability of pain care options at each step in the stepped care model.2, With the passage of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, 38 USC §101 (2014) and now the MISSION Act of 2018, 38 USC §703 (2018) veterans whose VHA facilities are too distant, who require care unavailable at that facility, or who have to wait too long to receive care are eligible for treatment at either VHA or non-VHA facilities.3 These laws allocate the same pool of funds to both VHA and community care and thus create an incentive to engage veterans in care within the VHA network so the funds are not spent out of network.4

An opportunity to connect veterans with VHA care arises at specialized VHA Compensation and Pension (C&P) clinics during examinations that determine whether a veteran’s health conditions were caused or exacerbated by their military service. Veterans file claims with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), which sends the patient to either a VHA facility or private practitioners for these examinations. Although the number of examinations conducted each year is not available, there were 274,528 veterans newly awarded compensation in fiscal year 2018, and a substantial number of the total of 4,743,108 veterans with C&P awards had reevaluation examinations for at least 1 of their conditions during that year.5 Based largely on the compensation examination results, military service records, and medical records, veterans are granted a service-connected rating for conditions deemed related to military service. A service-connection rating between 0% and 100% is assigned by the VBA, with higher ratings indicating more impairment and, consequently, more financial compensation. Service-connection ratings also are used to decide which veterans are in the highest priority groups for receipt of VHA health care services and are exempt from copayments.

Although traditionally thought of as a forensic evaluation with no clinical purpose, the C&P examination process affords many opportunities to explain VHA care to veterans in distress who file claims.6 A randomized clinical trials (RCT) involving veterans with mental health claims and a second RCT including veterans with musculoskeletal claims each found that veterans use more VHA services if offered outreach at the time of the C&P examination.7,8 In addition to clinical benefits, outreach around the time of C&P examinations also might mitigate the well documented adversarial aspects of the service-connection claims process.6,9,10 Currently, such outreach is not part of routine VHA procedures. Ironically, it is the VBA and not VHA that contacts veterans who are awarded service-connection with information about their eligibility for VHA care based on their award.

Connecting veterans to pain treatment can involve clarifying eligibility for VHA care for veterans in whom eligibility is unknown, involving primary care providers (PCPs) who are the fulcrum of VHA pain care referrals, and motivating veterans to seek specific pain treatment modalities. Connecting veterans to treatment at the time of their compensation examinations also likely involves bidirectional cooperation between the specialized C&P clinics where veterans are examined and the clinics that provide treatment.

Relational coordination is a theoretical framework that can describe the horizontal relationships between different teams within the same medical facility. Relational coordination theorizes that communication between workgroups is related synergistically to the quality of relationships between workgroups. Relational coordination is better between workgroups that share goals and often have high levels of relational coordination, which is thought to be especially important when activities are ambiguous, require cooperation, and are conducted under time pressure.11 High relational coordination also has been associated with high staff job satisfaction, high satisfaction with delivered services, and adherence to treatment guidelines.12-14 An observational cohort study suggested that relational coordination can be improved by targeted interventions that bring workgroups together and facilitate intercommunication.15

To better understand referral and engagement for pain treatment at compensation examinations, VA staff from primary care, mental health, pain management, and C&P teams at the 8 VHA medical centers in New England were invited to complete a validated relational coordination survey.11,16 A subset of invited staff participated in a semistructured interview about pain treatment referral practices within their medical centers.

Assessments were conducted as part of a mixed methods formative evaluation involving quantitative and qualitative methods for a clinical trial at the 8 VHA medical centers in New England. The trial is testing an intervention in which veterans presenting for service-connection examinations for musculoskeletal conditions receive brief counseling to engage them in nonopioid pain treatments. The VHA Central Institutional Review Board approved this formative evaluation and the clinical trial has begun (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04062214).

Potential interviewees were involved in referrals to and provision of nonpharmacologic pain treatment and were identified by site investigators in the randomized trial. Identified interviewees were clinical and administrative staff belonging to VHA Primary Care, Pain Management, and Compensation and Pension clinics. A total of 83 staff were identified.

Semistructured Interviews

A subset of the 83 staff were invited to participate in a semistructured interview because their position impacted coordination of pain care at their facilities or they worked in C&P. Staff at a site were interviewed until no new themes emerged from additional interviews, and each of the 8 sites was represented. Interviews were conducted between June and August 2018. Standardized scripts describing the study and inviting participation in a semistructured interview were e-mailed to VA staff. At the time of the interview the study purpose was restated and consent for audiotaping was obtained. The interviews followed a guide designed to assess a relational coordination framework among various workgroups. The data in this manuscript were elicited by specific prompts concerning: (1) How veterans learn about pain care when they come through C&P; and (2) How staff in C&P communicate with treatment providers about veterans who have chronic pain. Each interview lasted about 30 minutes.

Relational Coordination Survey

All identified staff were invited to participate in a relational coordination survey. The survey was administered through VA REDCap. Survey invitations were e-mailed from REDCap to VA staff and included a description of the study and assurances of the confidentiality of data collected. Surveys took < 10 minutes to complete. To begin, respondents identified their primary workgroup (C&P, primary care, pain management, or administrative leadership or staff), secondary workgroup (if they were in > 1), and site. Respondents provided no other identifying information and were assured their responses would be confidential.

The survey consisted of 7 questions regarding beliefs about the quality of communication and interactions among workgroup members in obtaining a shared goal.11 The shared goal in the survey used in this study was providing pain care services for veterans with musculoskeletal conditions. Using a 5-point Likert scale, the 7 questions concerned frequency, timeliness, and accuracy of communication; response to problems providing pain services; sharing goals; and knowledge and respect for respondent’s job function. Higher scores indicated better relational coordination among members of a workgroup. Using the survey’s 7 items, composite mean relational coordination scores were calculated for each of the 4 primary workgroups. To account for the possibility that a member rated their own workgroups, 2 scores were created for each workgroup; one included members of the workgroup and another excluded them.

Data Analysis

The audio-recorded semistructured interviews were transcribed and entered into Atlas.ti qualitative data analysis software. To identify cross-cutting themes, a semistructured telephone interview guide was developed by the qualitative study team that emphasized interrelationships between different clinical teams. The transcripts were then analyzed using the grounded theory approach, a systematic methodology to reduce themes from collected qualitative data. Two research staff read each transcript twice; first to familiarize themselves with the text and then, using open coding, to identify important concepts that emerged from the language and assign codes to segments of text. To ensure accuracy, researchers included suitable contextual information in the coding. Using the constant comparative method, research staff then met to examine the themes that emerged in the interviews, discuss and coalesce coding discrepancies, and compare perspectives.17

The composite score (mean of the 7 items and 95% CI) of the survey responses was analyzed to identify significant differences in coordination across the 4 workgroups. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine each relational coordination score by respondents’ workgroup. Post hoc analyses examined relational coordination survey differences among the 4 respondent groups.

Results

Thirty-nine survey respondents participated in the semistructured interviews. C&P examiners expressed varying degrees of comfort with their role in extending access to pain care for veterans. Some of the examiners strongly believed that their role was purely forensic, and going beyond this forensic role to refer or recommend treatment to veterans would be a violation of their role to conduct a forensic examination. “We don’t have an ongoing therapeutic relationship with any of the patients,” a C&P examiner explained: “We see them once; they’re out the door. It’s forensic. We’re investigating the person as a claimant, we’re investigating it and using our tools to go and review information from 30, 40 years ago.”

Other examiners had a less strict approach for working with veterans in C&P, even though examiners are asked not to provide advice or therapy. One C&P examiner noted that because he “can’t watch people in pain,” during the examination this doctor recommends that patients go to the office that determines whether they are eligible for benefits and choose a PCP. Another C&P examiner concurred with this approach. “I certainly spend a little time with the veteran talking to them about their personal life, who they are, what they do, what they’ve done, what they’re going to do to kind of break the ice between us,” the second examiner explained. “At the end, I will make some suggestions to them. I’m comfortable doing that. I don’t know that everybody is.”

Many of the VHA providers we interviewed had little knowledge of the C&P process or whether C&P examiners had any role or responsibilities in referring veterans for pain care. Most VHA providers could not name any C&P examiners at their facility and were generally unfamiliar with the content of C&P examinations. One provider bluntly said, “I’ve never communicated with anyone in comp and pen [C&P].”

Another PCP also expressed concerns with referrals, suggesting that C&P and primary care “are totally separate and should remain separate,” the PCP explained. “My concern with getting referral from comp and pen is that is it then they’re seeking all sorts of treatment that they wouldn’t necessarily need or ask for otherwise.”

Conversely a different PCP had a positive outlook on how C&P examiners might help ease the transition into the VHA for veterans with pain, especially for newly discharged veterans. “Having comp and pen address these issues is really going to be helpful. I think it could be significant that the topic is introduced early on.”

Relational Coordination Survey

Relational coordination surveys were sent to 83 participants of whom 66 responded. Respondents were from

The relational coordination composite scores were lowest for C&P. This finding remained whether C&P staff surveys were included or removed from the C&P responses. As demonstrated by the 95% CI, when team members’ surveys were included, C&P scores (95% CI, 2.01-2.42) were significantly lower than the primary care (95% CI, 3.34-3.64) and pain management (95% CI, 3.61-3.96) groups. All the relational coordination composite scores were slightly lower when staff who described their own workgroup were removed (ie, respondents rated their own workgroups as having higher relational coordination than others did). Using the composite scores excluding same workgroup members, the composite scores of the C&P remained significantly lower than all 3 other workgroups (Table). Means values for each individual item in the C&P group were significantly less than all other group means for each item except for the question on responses to problems providing pain services (data not shown). On this item only, the mean C&P rating was > 3 (3.19), but this was still lower than the means of the primary care and pain management workgroups.

Further analyses were undertaken to understand the importance of stakeholders’ ratings of their own workgroup compared with ratings by others of that workgroup. A 1-way ANOVA of workgroup was conducted and displayed significant workgroup differences between member and nonmember relational coordination ratings on 3 of the 4 workgroup’s scores C&P (F = 5.75, 3, 62 df; P < .01) primary care (F = 4.30, 3, 62 df; P < .008) and pain management (F = 8.22, 3, 62 df; P < .001). Post hoc contrasts between the different workgroups doing the rating revealed: (1) significant differences in the assessment of the C&P workgroup between the C&P workgroup and both the primary care (P < .01) and pain management groups (P < .001) with C&P rating their own workgroup significantly higher; (2) a significant difference in the scoring of the primary care workgroup with the primary care group rating themselves significantly higher than the C&P group; and (3) significant differences in the scoring of the pain management workgroup with both pain management and primary care groups rating the pain management group significantly higher than the C&P group. The results were not substantially changed by removing the 18 respondents who identified themselves as being part of > 1 workgroup .

Discussion

Mixed methods revealed disparate viewpoints about the role of C&P in referring veterans to pain care services. Overall, C&P teams coordinated less with other workgroups than the other groups coordinated with each other, and the C&P clinics took only limited steps to engage veterans in VHA treatment. The relational coordination results appeared to be valid. The mean scores were near the middle of the relational coordination rating scale, with standard deviations indicating a range of responses. The lower relational coordination scores of the C&P group remained after removing stakeholders who were rating their own workgroup. Further support for the validity of the relational coordination survey results is that they were consistent with the reports of C&P clinic isolation in the semistructured interviews.

The interview data suggest that one reason the C&P teams had low relational coordination scores is that VA staff interpret the emphasis on evaluative rather than therapeutic examinations to preclude other attempts to engage veterans into VHA treatment, even though such treatment engagement is permitted within existing guidelines. VBA referrals for examinations say nothing, either way, about engaging veterans in VHA care. The relational coordination results suggest that an intervention that might increase treatment referrals from the C&P clinics would be to explain the (existing) policy allowing for outreach around the time of compensation examinations to VHA staff so this goal is clearly agreed-upon. Another approach to facilitating treatment engagement at the C&P examination is to use other interventions that have been associated with better relational coordination such as intergroup meetings, horizontal integration more generally, and an atmosphere is which people from different backgrounds feel empowered to speak frankly to each other.15,18,19 An important linkage to forge is between C&P teams and the administrative workgroups responsible for verifying a veteran’s eligibility for VHA care and enrolling eligible veterans in VHA treatment. Having C&P clinicians who are familiar with the eligibility and treatment engagement processes would facilitate providing that information to veterans, without compromising the evaluative format of the compensation examination.

An interesting ancillary finding is that relational coordination ratings by members of 3 of the 4 workgroups were higher than ratings by other staff of that workgroup. A possible explanation for this finding is that workgroup members are more aware of the relational coordination efforts made by their own workgroup than those by other workgroups, and therefore rate their own workgroup higher. This also might be part of a broader self-aggrandizement heuristic that has been described in multiple domains.20 Staff may apply this heuristic in reporting that their staff engage in more relational coordination, reflecting the social desirability of being cooperative.

There are simple facility-level interventions that would facilitate veterans access to care such as conducting C&P examinations for potentially treatment-eligible veterans at VHA facilities (vs conducted outside VHA) and having access to materials that explain the treatment options to veterans when they check in for their compensation examinations. The approach to C&P-based treatment engagement that was successfully employed in 2 clinical trials involved having counselors not connected with the C&P clinic contact veterans around the time of their compensation examination to explain VA treatment options and motivate veterans to pursue treatment.8,9 This independent counselor approach is being evaluated in a larger study.

Limitations

These data are from a small number of VA staff evaluating veterans in a single region of the US. They do not show causation, and it is possible that relational coordination is not necessary for referrals from C&P clinics. Relational coordination might not be necessary when referral processes can be simply routinized with little need for communication.11 However, other analyses in these clinics have found that pain treatment referrals in fact are not routinized, with substantial variability within and across institutions. Another possibility is that features that have been associated with less relational coordination, such as male gender and medical specialist guild, were disproportionately present in C&P clinics compared to the other clinics.21

Conclusions

There have been public calls to improve the evaluation of service-connection claims such that this process includes approaches to engage veterans in treatment.22 Referring veterans to treatment when they come for C&P examinations will likely involve improving relational coordination between the C&P service and other parts of VHA. Nationwide, sites that integrate C&P more fully may have valuable lessons to impart about the benefits of such integration. An important step towards better relational coordination will be clarifying that engaging veterans in VHA care around the time of their C&P examinations is a facility-wide goal.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brian Linde and Efia James for their perspectives on C&P procedures. This work was supported by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 1 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) and National Institute of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Project # 5UG3AT009758-02. (MIR, SM mPIs).

Chronic pain is common in veterans, and early engagement in pain treatment is recommended to forestall consequences of untreated pain, including depression, disability, and substance use disorders. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) employs a stepped care model of pain treatment, with the majority of pain care based in primary care (step 1), and an array of specialty/multimodal treatment options made available at each step in the model for patients with more complex problems, or those who do not respond to more conservative interventions.1

Recognizing the need for comprehensive pain care, the US Congress passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, 21 USC §1521 (2016), which included provisions for VHA facilities to offer multimodal pain treatment and to report the availability of pain care options at each step in the stepped care model.2, With the passage of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, 38 USC §101 (2014) and now the MISSION Act of 2018, 38 USC §703 (2018) veterans whose VHA facilities are too distant, who require care unavailable at that facility, or who have to wait too long to receive care are eligible for treatment at either VHA or non-VHA facilities.3 These laws allocate the same pool of funds to both VHA and community care and thus create an incentive to engage veterans in care within the VHA network so the funds are not spent out of network.4

An opportunity to connect veterans with VHA care arises at specialized VHA Compensation and Pension (C&P) clinics during examinations that determine whether a veteran’s health conditions were caused or exacerbated by their military service. Veterans file claims with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), which sends the patient to either a VHA facility or private practitioners for these examinations. Although the number of examinations conducted each year is not available, there were 274,528 veterans newly awarded compensation in fiscal year 2018, and a substantial number of the total of 4,743,108 veterans with C&P awards had reevaluation examinations for at least 1 of their conditions during that year.5 Based largely on the compensation examination results, military service records, and medical records, veterans are granted a service-connected rating for conditions deemed related to military service. A service-connection rating between 0% and 100% is assigned by the VBA, with higher ratings indicating more impairment and, consequently, more financial compensation. Service-connection ratings also are used to decide which veterans are in the highest priority groups for receipt of VHA health care services and are exempt from copayments.

Although traditionally thought of as a forensic evaluation with no clinical purpose, the C&P examination process affords many opportunities to explain VHA care to veterans in distress who file claims.6 A randomized clinical trials (RCT) involving veterans with mental health claims and a second RCT including veterans with musculoskeletal claims each found that veterans use more VHA services if offered outreach at the time of the C&P examination.7,8 In addition to clinical benefits, outreach around the time of C&P examinations also might mitigate the well documented adversarial aspects of the service-connection claims process.6,9,10 Currently, such outreach is not part of routine VHA procedures. Ironically, it is the VBA and not VHA that contacts veterans who are awarded service-connection with information about their eligibility for VHA care based on their award.

Connecting veterans to pain treatment can involve clarifying eligibility for VHA care for veterans in whom eligibility is unknown, involving primary care providers (PCPs) who are the fulcrum of VHA pain care referrals, and motivating veterans to seek specific pain treatment modalities. Connecting veterans to treatment at the time of their compensation examinations also likely involves bidirectional cooperation between the specialized C&P clinics where veterans are examined and the clinics that provide treatment.

Relational coordination is a theoretical framework that can describe the horizontal relationships between different teams within the same medical facility. Relational coordination theorizes that communication between workgroups is related synergistically to the quality of relationships between workgroups. Relational coordination is better between workgroups that share goals and often have high levels of relational coordination, which is thought to be especially important when activities are ambiguous, require cooperation, and are conducted under time pressure.11 High relational coordination also has been associated with high staff job satisfaction, high satisfaction with delivered services, and adherence to treatment guidelines.12-14 An observational cohort study suggested that relational coordination can be improved by targeted interventions that bring workgroups together and facilitate intercommunication.15

To better understand referral and engagement for pain treatment at compensation examinations, VA staff from primary care, mental health, pain management, and C&P teams at the 8 VHA medical centers in New England were invited to complete a validated relational coordination survey.11,16 A subset of invited staff participated in a semistructured interview about pain treatment referral practices within their medical centers.