User login

Is It Time to Revisit Pediatric Postdischarge Home Visits for Readmissions Reduction?

Despite concerted national efforts to decrease pediatric readmissions, recent data suggest that preventable and all-cause readmission rates of hospitalized children remain unchanged.1 Because some readmissions may be caused by inadequate postdischarge follow-up, nurse (RN) home visits offer the prospect of addressing unresolved clinical issues after discharge and ameliorating patient and family concerns that may otherwise prompt re-presentation for acute care. Yet a recent trial of this approach, the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial,2 found the opposite to be true: participants receiving home nurse visits had higher reutilization rates than did participants in the control group. This raises interesting questions: Is it time to revisit postdischarge outreach as an intervention to reduce pediatric readmissions—and even pediatric readmissions altogether as an outcome metric?

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Riddle et al3 explored the perspectives of key stakeholders to understand the factors driving increased reutilization after postdischarge home visits in the H2O trial and obtained feedback for improving potential interventions. The investigators used a qualitative approach that consisted of telephone interviews with 33 parents who were enrolled in the H2O trial and in-person focus groups with 10 home care RNs involved in the trial, 12 hospital medicine physicians, and 7 primary care physicians (PCPs). Inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze responses to open-ended questions through a rigorous, iterative and multidisciplinary process. Key themes elicited from stakeholders included questions about the clinical appropriateness of reutilization episodes; the influence of insufficiently contextualized “red flag,” or warning sign, instructions given to parents in facilitating reutilization; the potential for hospital-employed home care nurses to inadvertently promote emergency department rather than PCP follow-up; and escalation of care exceeding that expected in a PCP office. Stakeholders suggested the intervention could be improved by enhancing postdischarge communication between home care RNs, hospital medicine physicians, and PCPs; tailoring home visits to specific clinical, patient, and family scenarios; and more clearly framing “red flags.”

We welcome the work of Riddle and colleagues in exposing the elements of home visits that may have led to increased utilization, and their proposed next steps to improve the intervention—enhancing contact with PCP offices and focusing interventions on specific populations—unquestionably have merit. We agree that this may be particularly true in children with medical complexity (a population that was excluded from this study), who have unique discharge needs and account for over half of pediatric readmissions.4 However, we suggest that the instinct to refine the design of the study intervention should be weighed against alternative possibilities: that postdischarge interventions are simply not effective in decreasing reutilization or, at the very least, that the findings of the H2O trial should not lead us to invest the resources required to further discern the efficacy of postdischarge interventions.

This counter-intuitive possibility is only compounded by the fact that reutilization rates were not improved in the study group’s H2O II trial, a follow-up study that focused on postdischarge nurse telephone calls as the intervention of interest5; and indeed, the results of these two, well-designed negative trials have been previously cited to propose postdischarge nurse contact as a potential target of deimplementation efforts.6 In the pediatric population, in which caregivers rather than patients themselves are generally responsible for seeking out care, postdischarge outreach may inevitably escalate concerning findings that will result in reutilization. Instead, perhaps the H2O study findings should prompt a broader exploration for alternative solutions to pediatric readmission reduction. One such solution could build on the finding by Riddle et al that stakeholders perceive ambiguity in whether discharging physicians, or rather PCPs, have ownership of clinical issues after discharge. Rather than asking visiting RNs to triangulate between inpatient and outpatient physicians, developing systems to directly integrate PCPs in the hospital discharge process for select patients—for instance, through leveraging the rapid expansion of telemedicine services during the COVID-19 crisis—may promote shared understanding of a patient’s illness trajectory and follow-up needs.

Importantly, the authors also noted that despite the findings of increased reutilization, parents who received home visits expressed their wishes to receive home visits in the future. While not a central finding of the study, this validates a hypothesis expressed in prior work by the H2O study group: “Hospital quality readmission metrics may not be well aligned with family desires for improved postdischarge transitions.”5 Given that efforts to reduce pediatric readmission have been largely unsuccessful and that readmission events are relatively uncommon in the general pediatric population,4 the parental wishes resonate with existing calls in the literature to consider looking beyond readmissions reduction in isolation as a quality metric. In contrast to the increasing presence of hospital reimbursement penalties among state Medicaid agencies for readmissions, a shift in focus toward outcome measures that are patient- and family-centered is imperative.1,7 If home visits are not ultimately a solution to pediatric reutilization reduction, they may nonetheless still enable families to effectively manage the concerns that families endorse following discharge, including medication safety and social hardships.8

In summary, Riddle et al not only provided important context for the unexpected outcome of a well-designed randomized clinical trial but also provided a rich source of qualitative data that furthers our understanding of a child’s discharge home from the hospital through the perspective of multiple stakeholders. While the authors offer well-reasoned next steps in narrowing the intervention population of interest and enhancing connections of families with PCP care, it may be time to broadly revisit postdischarge interventions and outcomes to identify new approaches and redefine quality measures for hospital-to-home transitions of children and their families.

1. Auger KA, Harris JM, Gay JC, et al. Progress (?) toward reducing pediatric readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):618-621. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3210

2. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: the hospital to home outcomes (H2O) trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0092

3. Riddle SW, Sherman SN, Moore MJ, et al. A qualitative study of increased pediatric reutilization after a postdischarge home nurse visit. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:518-525. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3370

4. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351

5. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482

6. Bonafide CP, Keren R. Negative studies and the science of deimplementation. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):807-809. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2077

7. Leyenaar JK, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK. Are pediatric readmission reduction efforts falling flat? J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):644-645. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3269

8. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Riddle SW, Gold JM, et al. Paediatric clinical and social concerns identified by home visit nurses in the immediate postdischarge period. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(6):1394-1403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14341

Despite concerted national efforts to decrease pediatric readmissions, recent data suggest that preventable and all-cause readmission rates of hospitalized children remain unchanged.1 Because some readmissions may be caused by inadequate postdischarge follow-up, nurse (RN) home visits offer the prospect of addressing unresolved clinical issues after discharge and ameliorating patient and family concerns that may otherwise prompt re-presentation for acute care. Yet a recent trial of this approach, the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial,2 found the opposite to be true: participants receiving home nurse visits had higher reutilization rates than did participants in the control group. This raises interesting questions: Is it time to revisit postdischarge outreach as an intervention to reduce pediatric readmissions—and even pediatric readmissions altogether as an outcome metric?

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Riddle et al3 explored the perspectives of key stakeholders to understand the factors driving increased reutilization after postdischarge home visits in the H2O trial and obtained feedback for improving potential interventions. The investigators used a qualitative approach that consisted of telephone interviews with 33 parents who were enrolled in the H2O trial and in-person focus groups with 10 home care RNs involved in the trial, 12 hospital medicine physicians, and 7 primary care physicians (PCPs). Inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze responses to open-ended questions through a rigorous, iterative and multidisciplinary process. Key themes elicited from stakeholders included questions about the clinical appropriateness of reutilization episodes; the influence of insufficiently contextualized “red flag,” or warning sign, instructions given to parents in facilitating reutilization; the potential for hospital-employed home care nurses to inadvertently promote emergency department rather than PCP follow-up; and escalation of care exceeding that expected in a PCP office. Stakeholders suggested the intervention could be improved by enhancing postdischarge communication between home care RNs, hospital medicine physicians, and PCPs; tailoring home visits to specific clinical, patient, and family scenarios; and more clearly framing “red flags.”

We welcome the work of Riddle and colleagues in exposing the elements of home visits that may have led to increased utilization, and their proposed next steps to improve the intervention—enhancing contact with PCP offices and focusing interventions on specific populations—unquestionably have merit. We agree that this may be particularly true in children with medical complexity (a population that was excluded from this study), who have unique discharge needs and account for over half of pediatric readmissions.4 However, we suggest that the instinct to refine the design of the study intervention should be weighed against alternative possibilities: that postdischarge interventions are simply not effective in decreasing reutilization or, at the very least, that the findings of the H2O trial should not lead us to invest the resources required to further discern the efficacy of postdischarge interventions.

This counter-intuitive possibility is only compounded by the fact that reutilization rates were not improved in the study group’s H2O II trial, a follow-up study that focused on postdischarge nurse telephone calls as the intervention of interest5; and indeed, the results of these two, well-designed negative trials have been previously cited to propose postdischarge nurse contact as a potential target of deimplementation efforts.6 In the pediatric population, in which caregivers rather than patients themselves are generally responsible for seeking out care, postdischarge outreach may inevitably escalate concerning findings that will result in reutilization. Instead, perhaps the H2O study findings should prompt a broader exploration for alternative solutions to pediatric readmission reduction. One such solution could build on the finding by Riddle et al that stakeholders perceive ambiguity in whether discharging physicians, or rather PCPs, have ownership of clinical issues after discharge. Rather than asking visiting RNs to triangulate between inpatient and outpatient physicians, developing systems to directly integrate PCPs in the hospital discharge process for select patients—for instance, through leveraging the rapid expansion of telemedicine services during the COVID-19 crisis—may promote shared understanding of a patient’s illness trajectory and follow-up needs.

Importantly, the authors also noted that despite the findings of increased reutilization, parents who received home visits expressed their wishes to receive home visits in the future. While not a central finding of the study, this validates a hypothesis expressed in prior work by the H2O study group: “Hospital quality readmission metrics may not be well aligned with family desires for improved postdischarge transitions.”5 Given that efforts to reduce pediatric readmission have been largely unsuccessful and that readmission events are relatively uncommon in the general pediatric population,4 the parental wishes resonate with existing calls in the literature to consider looking beyond readmissions reduction in isolation as a quality metric. In contrast to the increasing presence of hospital reimbursement penalties among state Medicaid agencies for readmissions, a shift in focus toward outcome measures that are patient- and family-centered is imperative.1,7 If home visits are not ultimately a solution to pediatric reutilization reduction, they may nonetheless still enable families to effectively manage the concerns that families endorse following discharge, including medication safety and social hardships.8

In summary, Riddle et al not only provided important context for the unexpected outcome of a well-designed randomized clinical trial but also provided a rich source of qualitative data that furthers our understanding of a child’s discharge home from the hospital through the perspective of multiple stakeholders. While the authors offer well-reasoned next steps in narrowing the intervention population of interest and enhancing connections of families with PCP care, it may be time to broadly revisit postdischarge interventions and outcomes to identify new approaches and redefine quality measures for hospital-to-home transitions of children and their families.

Despite concerted national efforts to decrease pediatric readmissions, recent data suggest that preventable and all-cause readmission rates of hospitalized children remain unchanged.1 Because some readmissions may be caused by inadequate postdischarge follow-up, nurse (RN) home visits offer the prospect of addressing unresolved clinical issues after discharge and ameliorating patient and family concerns that may otherwise prompt re-presentation for acute care. Yet a recent trial of this approach, the Hospital to Home Outcomes (H2O) trial,2 found the opposite to be true: participants receiving home nurse visits had higher reutilization rates than did participants in the control group. This raises interesting questions: Is it time to revisit postdischarge outreach as an intervention to reduce pediatric readmissions—and even pediatric readmissions altogether as an outcome metric?

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Riddle et al3 explored the perspectives of key stakeholders to understand the factors driving increased reutilization after postdischarge home visits in the H2O trial and obtained feedback for improving potential interventions. The investigators used a qualitative approach that consisted of telephone interviews with 33 parents who were enrolled in the H2O trial and in-person focus groups with 10 home care RNs involved in the trial, 12 hospital medicine physicians, and 7 primary care physicians (PCPs). Inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze responses to open-ended questions through a rigorous, iterative and multidisciplinary process. Key themes elicited from stakeholders included questions about the clinical appropriateness of reutilization episodes; the influence of insufficiently contextualized “red flag,” or warning sign, instructions given to parents in facilitating reutilization; the potential for hospital-employed home care nurses to inadvertently promote emergency department rather than PCP follow-up; and escalation of care exceeding that expected in a PCP office. Stakeholders suggested the intervention could be improved by enhancing postdischarge communication between home care RNs, hospital medicine physicians, and PCPs; tailoring home visits to specific clinical, patient, and family scenarios; and more clearly framing “red flags.”

We welcome the work of Riddle and colleagues in exposing the elements of home visits that may have led to increased utilization, and their proposed next steps to improve the intervention—enhancing contact with PCP offices and focusing interventions on specific populations—unquestionably have merit. We agree that this may be particularly true in children with medical complexity (a population that was excluded from this study), who have unique discharge needs and account for over half of pediatric readmissions.4 However, we suggest that the instinct to refine the design of the study intervention should be weighed against alternative possibilities: that postdischarge interventions are simply not effective in decreasing reutilization or, at the very least, that the findings of the H2O trial should not lead us to invest the resources required to further discern the efficacy of postdischarge interventions.

This counter-intuitive possibility is only compounded by the fact that reutilization rates were not improved in the study group’s H2O II trial, a follow-up study that focused on postdischarge nurse telephone calls as the intervention of interest5; and indeed, the results of these two, well-designed negative trials have been previously cited to propose postdischarge nurse contact as a potential target of deimplementation efforts.6 In the pediatric population, in which caregivers rather than patients themselves are generally responsible for seeking out care, postdischarge outreach may inevitably escalate concerning findings that will result in reutilization. Instead, perhaps the H2O study findings should prompt a broader exploration for alternative solutions to pediatric readmission reduction. One such solution could build on the finding by Riddle et al that stakeholders perceive ambiguity in whether discharging physicians, or rather PCPs, have ownership of clinical issues after discharge. Rather than asking visiting RNs to triangulate between inpatient and outpatient physicians, developing systems to directly integrate PCPs in the hospital discharge process for select patients—for instance, through leveraging the rapid expansion of telemedicine services during the COVID-19 crisis—may promote shared understanding of a patient’s illness trajectory and follow-up needs.

Importantly, the authors also noted that despite the findings of increased reutilization, parents who received home visits expressed their wishes to receive home visits in the future. While not a central finding of the study, this validates a hypothesis expressed in prior work by the H2O study group: “Hospital quality readmission metrics may not be well aligned with family desires for improved postdischarge transitions.”5 Given that efforts to reduce pediatric readmission have been largely unsuccessful and that readmission events are relatively uncommon in the general pediatric population,4 the parental wishes resonate with existing calls in the literature to consider looking beyond readmissions reduction in isolation as a quality metric. In contrast to the increasing presence of hospital reimbursement penalties among state Medicaid agencies for readmissions, a shift in focus toward outcome measures that are patient- and family-centered is imperative.1,7 If home visits are not ultimately a solution to pediatric reutilization reduction, they may nonetheless still enable families to effectively manage the concerns that families endorse following discharge, including medication safety and social hardships.8

In summary, Riddle et al not only provided important context for the unexpected outcome of a well-designed randomized clinical trial but also provided a rich source of qualitative data that furthers our understanding of a child’s discharge home from the hospital through the perspective of multiple stakeholders. While the authors offer well-reasoned next steps in narrowing the intervention population of interest and enhancing connections of families with PCP care, it may be time to broadly revisit postdischarge interventions and outcomes to identify new approaches and redefine quality measures for hospital-to-home transitions of children and their families.

1. Auger KA, Harris JM, Gay JC, et al. Progress (?) toward reducing pediatric readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):618-621. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3210

2. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: the hospital to home outcomes (H2O) trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0092

3. Riddle SW, Sherman SN, Moore MJ, et al. A qualitative study of increased pediatric reutilization after a postdischarge home nurse visit. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:518-525. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3370

4. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351

5. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482

6. Bonafide CP, Keren R. Negative studies and the science of deimplementation. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):807-809. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2077

7. Leyenaar JK, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK. Are pediatric readmission reduction efforts falling flat? J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):644-645. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3269

8. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Riddle SW, Gold JM, et al. Paediatric clinical and social concerns identified by home visit nurses in the immediate postdischarge period. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(6):1394-1403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14341

1. Auger KA, Harris JM, Gay JC, et al. Progress (?) toward reducing pediatric readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):618-621. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3210

2. Auger KA, Simmons JM, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Postdischarge nurse home visits and reuse: the hospital to home outcomes (H2O) trial. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173919. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0092

3. Riddle SW, Sherman SN, Moore MJ, et al. A qualitative study of increased pediatric reutilization after a postdischarge home nurse visit. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:518-525. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3370

4. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.188351

5. Auger KA, Shah SS, Tubbs-Cooley HL, et al. Effects of a 1-time nurse-led telephone call after pediatric discharge: the H2O II randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):e181482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1482

6. Bonafide CP, Keren R. Negative studies and the science of deimplementation. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):807-809. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2077

7. Leyenaar JK, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK. Are pediatric readmission reduction efforts falling flat? J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):644-645. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3269

8. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Riddle SW, Gold JM, et al. Paediatric clinical and social concerns identified by home visit nurses in the immediate postdischarge period. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(6):1394-1403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14341

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Leadership & Professional Development: Having a Backup Plan

“Confidence comes from being prepared.”

—John Wooden

Hospital medicine is a field that requires a constant state of readiness and flexibility. With respect to patient care, constant preparedness is required because conditions change. This necessitates always having a backup plan, or Plan B. For example, your patient with a gastrointestinal (GI) bleed should have two large-bore intravenous (IV) catheters and packed red blood cells (RBCs) typed and crossed. If the patient becomes unstable, the response is not just doing more of the same (IV fluids and proton pump inhibitors); the focus shifts to your Plan B: call GI, transfuse blood, transfer the patient to the intensive care unit.

In contrast to clinical scenarios, there is often a lack of readiness to deal with rapid changes in workflow. Without a plan, efficiency decreases, stress levels rise, and both patients and providers alike suffer the consequences. Patients spending extended periods of time in the Emergency Department (ED) receive less timely services and often don’t benefit from the expertise that they would receive in inpatient units.1 This is particularly true in an era in which many hospitals are experiencing higher overall volume and surges are more common.

Ideally, readiness should manifest as the ability to adapt to changes at the individual, hospitalist team, and leadership levels. Having a Plan B in the practice of hospital medicine is a focused exercise for anticipating future problems and addressing them prospectively. When thinking about a Plan B, the following are some steps to consider:

1. Identify Triggers. In the earlier example of the GI bleed, our triggers for Plan B would be a change in vitals or a brisk drop in hemoglobin. Regarding hospital workflow, the triggers might include low service or bed capacity or a decreased number of expected discharges for the day. Perhaps a high ED census or increased surgical volume will trigger your plan to handle the surge.

2. Define Your Response. At both an individual and service level, there are steps you might consider in your Plan B. On teaching services, this might mean prioritizing rounding on patients that you’re expecting to discharge so they’re able to leave the hospital sooner. For patients on observation status who are boarding in the ED for extended periods, there might be opportunities to safely discharge them with follow-up or even complete their work-up in the ED. There may be circumstances in which providers should exceed the usual service capacity and conditions in which it is truly unsafe to exceed that limit. If there are resources available to increase staffing, consider how to best utilize them.

3. Engage Broadly and Proactively. It is very difficult to execute a Plan B (or frankly a Plan A) without buy-in from your stakeholders. This starts with the rank and file, those on your team who will actually execute the plan. The leadership of your department or division, the ED, and nursing will also likely need to provide input. If financial resources for flexing up staff are part of your plan, the hospital administration might need to weigh in. It is best to engage stakeholders early on rather than during a crisis.

4. Constant Assessment and Improvement. Going back to our example of our patient with a GI bleed, you’re constantly reevaluating your patient to determine if your Plan B is working. Similarly, you should collect data and reassess the effectiveness of your plan. There are likely opportunities to improve it.

There are no textbook chapters or medical school lectures to prepare hospitalists for these real-world crises. Yet failing to have a Plan B is to surrender a tremendous amount of personal control in the face of chaos, to jeopardize patient care, and to ultimately forgo the opportunity to achieve a level of mastery in a field predicated on readiness.

1. Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Hospital-Based Emergency Care at the Breaking Point. Washington, District of Columbia: The National Academies Press; 2006.

“Confidence comes from being prepared.”

—John Wooden

Hospital medicine is a field that requires a constant state of readiness and flexibility. With respect to patient care, constant preparedness is required because conditions change. This necessitates always having a backup plan, or Plan B. For example, your patient with a gastrointestinal (GI) bleed should have two large-bore intravenous (IV) catheters and packed red blood cells (RBCs) typed and crossed. If the patient becomes unstable, the response is not just doing more of the same (IV fluids and proton pump inhibitors); the focus shifts to your Plan B: call GI, transfuse blood, transfer the patient to the intensive care unit.

In contrast to clinical scenarios, there is often a lack of readiness to deal with rapid changes in workflow. Without a plan, efficiency decreases, stress levels rise, and both patients and providers alike suffer the consequences. Patients spending extended periods of time in the Emergency Department (ED) receive less timely services and often don’t benefit from the expertise that they would receive in inpatient units.1 This is particularly true in an era in which many hospitals are experiencing higher overall volume and surges are more common.

Ideally, readiness should manifest as the ability to adapt to changes at the individual, hospitalist team, and leadership levels. Having a Plan B in the practice of hospital medicine is a focused exercise for anticipating future problems and addressing them prospectively. When thinking about a Plan B, the following are some steps to consider:

1. Identify Triggers. In the earlier example of the GI bleed, our triggers for Plan B would be a change in vitals or a brisk drop in hemoglobin. Regarding hospital workflow, the triggers might include low service or bed capacity or a decreased number of expected discharges for the day. Perhaps a high ED census or increased surgical volume will trigger your plan to handle the surge.

2. Define Your Response. At both an individual and service level, there are steps you might consider in your Plan B. On teaching services, this might mean prioritizing rounding on patients that you’re expecting to discharge so they’re able to leave the hospital sooner. For patients on observation status who are boarding in the ED for extended periods, there might be opportunities to safely discharge them with follow-up or even complete their work-up in the ED. There may be circumstances in which providers should exceed the usual service capacity and conditions in which it is truly unsafe to exceed that limit. If there are resources available to increase staffing, consider how to best utilize them.

3. Engage Broadly and Proactively. It is very difficult to execute a Plan B (or frankly a Plan A) without buy-in from your stakeholders. This starts with the rank and file, those on your team who will actually execute the plan. The leadership of your department or division, the ED, and nursing will also likely need to provide input. If financial resources for flexing up staff are part of your plan, the hospital administration might need to weigh in. It is best to engage stakeholders early on rather than during a crisis.

4. Constant Assessment and Improvement. Going back to our example of our patient with a GI bleed, you’re constantly reevaluating your patient to determine if your Plan B is working. Similarly, you should collect data and reassess the effectiveness of your plan. There are likely opportunities to improve it.

There are no textbook chapters or medical school lectures to prepare hospitalists for these real-world crises. Yet failing to have a Plan B is to surrender a tremendous amount of personal control in the face of chaos, to jeopardize patient care, and to ultimately forgo the opportunity to achieve a level of mastery in a field predicated on readiness.

“Confidence comes from being prepared.”

—John Wooden

Hospital medicine is a field that requires a constant state of readiness and flexibility. With respect to patient care, constant preparedness is required because conditions change. This necessitates always having a backup plan, or Plan B. For example, your patient with a gastrointestinal (GI) bleed should have two large-bore intravenous (IV) catheters and packed red blood cells (RBCs) typed and crossed. If the patient becomes unstable, the response is not just doing more of the same (IV fluids and proton pump inhibitors); the focus shifts to your Plan B: call GI, transfuse blood, transfer the patient to the intensive care unit.

In contrast to clinical scenarios, there is often a lack of readiness to deal with rapid changes in workflow. Without a plan, efficiency decreases, stress levels rise, and both patients and providers alike suffer the consequences. Patients spending extended periods of time in the Emergency Department (ED) receive less timely services and often don’t benefit from the expertise that they would receive in inpatient units.1 This is particularly true in an era in which many hospitals are experiencing higher overall volume and surges are more common.

Ideally, readiness should manifest as the ability to adapt to changes at the individual, hospitalist team, and leadership levels. Having a Plan B in the practice of hospital medicine is a focused exercise for anticipating future problems and addressing them prospectively. When thinking about a Plan B, the following are some steps to consider:

1. Identify Triggers. In the earlier example of the GI bleed, our triggers for Plan B would be a change in vitals or a brisk drop in hemoglobin. Regarding hospital workflow, the triggers might include low service or bed capacity or a decreased number of expected discharges for the day. Perhaps a high ED census or increased surgical volume will trigger your plan to handle the surge.

2. Define Your Response. At both an individual and service level, there are steps you might consider in your Plan B. On teaching services, this might mean prioritizing rounding on patients that you’re expecting to discharge so they’re able to leave the hospital sooner. For patients on observation status who are boarding in the ED for extended periods, there might be opportunities to safely discharge them with follow-up or even complete their work-up in the ED. There may be circumstances in which providers should exceed the usual service capacity and conditions in which it is truly unsafe to exceed that limit. If there are resources available to increase staffing, consider how to best utilize them.

3. Engage Broadly and Proactively. It is very difficult to execute a Plan B (or frankly a Plan A) without buy-in from your stakeholders. This starts with the rank and file, those on your team who will actually execute the plan. The leadership of your department or division, the ED, and nursing will also likely need to provide input. If financial resources for flexing up staff are part of your plan, the hospital administration might need to weigh in. It is best to engage stakeholders early on rather than during a crisis.

4. Constant Assessment and Improvement. Going back to our example of our patient with a GI bleed, you’re constantly reevaluating your patient to determine if your Plan B is working. Similarly, you should collect data and reassess the effectiveness of your plan. There are likely opportunities to improve it.

There are no textbook chapters or medical school lectures to prepare hospitalists for these real-world crises. Yet failing to have a Plan B is to surrender a tremendous amount of personal control in the face of chaos, to jeopardize patient care, and to ultimately forgo the opportunity to achieve a level of mastery in a field predicated on readiness.

1. Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Hospital-Based Emergency Care at the Breaking Point. Washington, District of Columbia: The National Academies Press; 2006.

1. Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Hospital-Based Emergency Care at the Breaking Point. Washington, District of Columbia: The National Academies Press; 2006.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Promoting Gender Equity at the Journal of Hospital Medicine

Last year we pledged to lead by example and improve representation within the Journal of Hospital Medicine community.1 By emphasizing diversity, we expand the pool of faculty to whom leadership opportunities are available. A diverse team will put forth a broader range of ideas for consideration, spur greater innovation, and promote diversity in both published content and authorship, ensuring that the spectrum of content we publish reflects and benefits all patients to whom we provide care.

We write to share our progress, first reporting on gender equity. Currently, 45% of the journal leadership team are women, increased from 30% in 2018. In the past year, we also developed processes to collect peer reviewer and author demographic information through our manuscript management system. These processes helped us understand our baseline state.

Prior to developing these processes, we discussed our goals and potential approaches with Society of Hospital Medicine leaders; medical school deans of diversity, equity, and inclusion; department chairs in pediatrics and internal medicine; women, underrepresented minorities, and LGBTQ+ faculty; and trainees. We achieved consensus as a journal leadership team and implemented a new data collection system in July 2019. We focused on first and last authors given the importance of these positions for promotion and tenure. We requested that peer reviewers and authors provide demographic data, including gender (with nonbinary as an option), race, and ethnicity; “prefer not to answer” was a response option for each question. These data were not available during the manuscript decision process. Authors who did not submit information received up to three reminder emails from the Editor-in-Chief encouraging them to provide demographic information and stating the rationale for the request. We did not use gender identifying algorithms (eg, assignment of gender probability based on name) or visit professional websites; our intent was author self-identification.

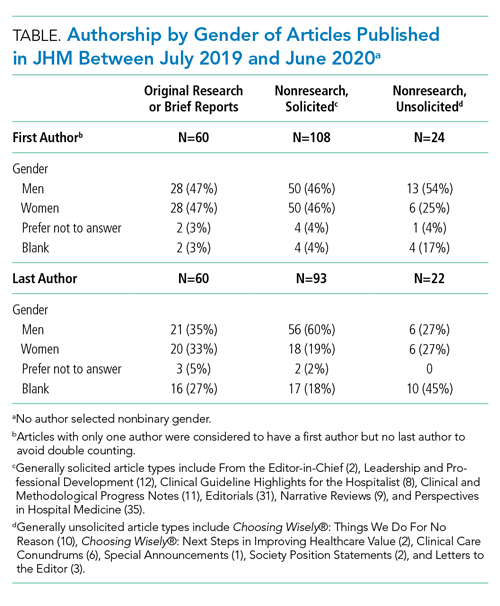

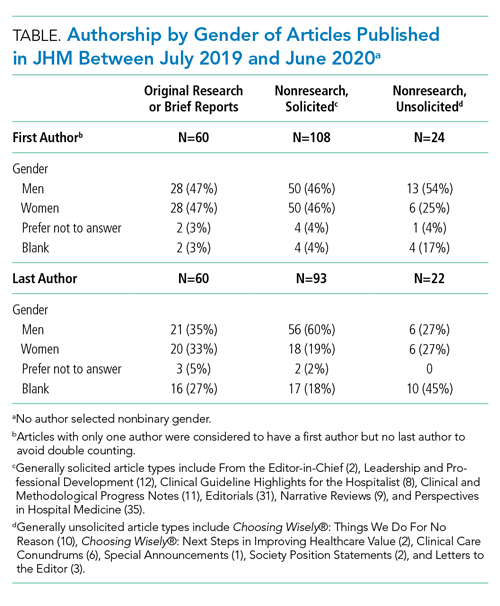

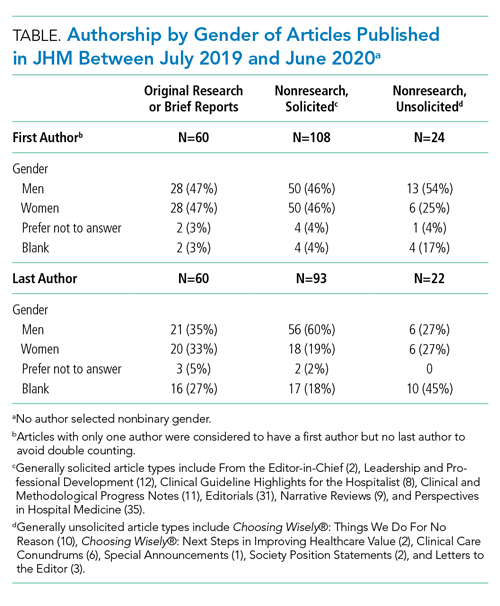

We categorized Journal of Hospital Medicine article types as research, generally solicited, and generally unsolicited (Table). Among research articles, the proportion of women and men were similar with women accounting for 47% of first authors (vs 47% men) and 33% of last authors (vs 35% men) (Table). However, 27% of last authors left this field blank. Among solicited article types, there was an equal proportion of women and men for first but not for last authors. Among unsolicited article types, a smaller proportion of women accounted for first authors. While the proportion of women and men was equal among last authors, 45% left this field blank.

Collecting author demographics and reporting our data on gender represent an important first step for the journal. In the upcoming year, we will develop strategies to obtain more complete data and report our performance on race, ethnicity, and intersectionality, and continue deliberate efforts to improve equity within all areas of the journal, including reviewer, author, and editorial roles. We are committed to continue sharing our progress.

1. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

Last year we pledged to lead by example and improve representation within the Journal of Hospital Medicine community.1 By emphasizing diversity, we expand the pool of faculty to whom leadership opportunities are available. A diverse team will put forth a broader range of ideas for consideration, spur greater innovation, and promote diversity in both published content and authorship, ensuring that the spectrum of content we publish reflects and benefits all patients to whom we provide care.

We write to share our progress, first reporting on gender equity. Currently, 45% of the journal leadership team are women, increased from 30% in 2018. In the past year, we also developed processes to collect peer reviewer and author demographic information through our manuscript management system. These processes helped us understand our baseline state.

Prior to developing these processes, we discussed our goals and potential approaches with Society of Hospital Medicine leaders; medical school deans of diversity, equity, and inclusion; department chairs in pediatrics and internal medicine; women, underrepresented minorities, and LGBTQ+ faculty; and trainees. We achieved consensus as a journal leadership team and implemented a new data collection system in July 2019. We focused on first and last authors given the importance of these positions for promotion and tenure. We requested that peer reviewers and authors provide demographic data, including gender (with nonbinary as an option), race, and ethnicity; “prefer not to answer” was a response option for each question. These data were not available during the manuscript decision process. Authors who did not submit information received up to three reminder emails from the Editor-in-Chief encouraging them to provide demographic information and stating the rationale for the request. We did not use gender identifying algorithms (eg, assignment of gender probability based on name) or visit professional websites; our intent was author self-identification.

We categorized Journal of Hospital Medicine article types as research, generally solicited, and generally unsolicited (Table). Among research articles, the proportion of women and men were similar with women accounting for 47% of first authors (vs 47% men) and 33% of last authors (vs 35% men) (Table). However, 27% of last authors left this field blank. Among solicited article types, there was an equal proportion of women and men for first but not for last authors. Among unsolicited article types, a smaller proportion of women accounted for first authors. While the proportion of women and men was equal among last authors, 45% left this field blank.

Collecting author demographics and reporting our data on gender represent an important first step for the journal. In the upcoming year, we will develop strategies to obtain more complete data and report our performance on race, ethnicity, and intersectionality, and continue deliberate efforts to improve equity within all areas of the journal, including reviewer, author, and editorial roles. We are committed to continue sharing our progress.

Last year we pledged to lead by example and improve representation within the Journal of Hospital Medicine community.1 By emphasizing diversity, we expand the pool of faculty to whom leadership opportunities are available. A diverse team will put forth a broader range of ideas for consideration, spur greater innovation, and promote diversity in both published content and authorship, ensuring that the spectrum of content we publish reflects and benefits all patients to whom we provide care.

We write to share our progress, first reporting on gender equity. Currently, 45% of the journal leadership team are women, increased from 30% in 2018. In the past year, we also developed processes to collect peer reviewer and author demographic information through our manuscript management system. These processes helped us understand our baseline state.

Prior to developing these processes, we discussed our goals and potential approaches with Society of Hospital Medicine leaders; medical school deans of diversity, equity, and inclusion; department chairs in pediatrics and internal medicine; women, underrepresented minorities, and LGBTQ+ faculty; and trainees. We achieved consensus as a journal leadership team and implemented a new data collection system in July 2019. We focused on first and last authors given the importance of these positions for promotion and tenure. We requested that peer reviewers and authors provide demographic data, including gender (with nonbinary as an option), race, and ethnicity; “prefer not to answer” was a response option for each question. These data were not available during the manuscript decision process. Authors who did not submit information received up to three reminder emails from the Editor-in-Chief encouraging them to provide demographic information and stating the rationale for the request. We did not use gender identifying algorithms (eg, assignment of gender probability based on name) or visit professional websites; our intent was author self-identification.

We categorized Journal of Hospital Medicine article types as research, generally solicited, and generally unsolicited (Table). Among research articles, the proportion of women and men were similar with women accounting for 47% of first authors (vs 47% men) and 33% of last authors (vs 35% men) (Table). However, 27% of last authors left this field blank. Among solicited article types, there was an equal proportion of women and men for first but not for last authors. Among unsolicited article types, a smaller proportion of women accounted for first authors. While the proportion of women and men was equal among last authors, 45% left this field blank.

Collecting author demographics and reporting our data on gender represent an important first step for the journal. In the upcoming year, we will develop strategies to obtain more complete data and report our performance on race, ethnicity, and intersectionality, and continue deliberate efforts to improve equity within all areas of the journal, including reviewer, author, and editorial roles. We are committed to continue sharing our progress.

1. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

1. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

SARS-CoV-2 appears unlikely to pass through breast milk

Breast milk is an unlikely source of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from mothers to infants, according to data from case reports and breast milk samples from 18 women.

“To date, SARS-CoV-2 has not been isolated from breast milk, and there are no documented cases of transmission of infectious virus to the infant through breast milk,” but the potential for transmission remains a concern among women who want to breastfeed, wrote Christina Chambers, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA, the investigators identified 18 women with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections (all but 1 of the women had symptomatic COVID-19 disease) and infants aged 0-19 months between March 27 and May 6, 2020. The average age of the mothers was 34 years, and 78% were non-Hispanic White. The women provided 1-12 samples of breast milk for a total of 64 samples collected before and after positive COVID-19 tests.

One sample yielded detectable RNA from SARS-CoV-2 and was collected on the day of the woman’s symptom onset. However, one sample taken 2 days prior to symptom onset and two samples collected 12 and 41 days later tested negative for viral RNA, the researchers said. In addition, no replication-competent virus was identified in the positive sample or any of the other samples.

The researchers spiked two stored milk samples collected prior to the pandemic with replication-competent SARS-CoV-2. Virus was not detected by culture in the samples after Holder pasteurization, but was detected by culture in nonpasteurized aliquots of the same samples.

“These data suggest that SARS-CoV-2 RNA does not represent replication-competent virus and that breast milk may not be a source of infection for the infant,” Dr. Chambers and associates said.

The results were limited by several factors including the small sample size and potential for selection bias, as well as the use of self-reports of positive tests and self-collection of breast milk, the researchers noted. However, the findings are reassuring in light of the known benefits of breastfeeding and the use of milk banks.

“This research is important because the pandemic is ongoing and has far-reaching consequences: as the authors indicate, the potential for viral transmission through breast milk remains a critical question for women infected with SARS-CoV-2 who wish to breastfeed,” Janet R. Hardy, PhD, MPH, MSc, a consultant on global maternal-child health and pharmacoepidemiology, said in an interview.

“This virus has everyone on a rapid learning track, and all information that helps build evidence to support women’s decision-making in the care of their children is valuable,” she said. “These findings suggest that breast milk may not be a source of SARS-CoV-2 infection for the infant. They provide some reassurance given the recognized benefits of breastfeeding and human milk.”

However, “This study is very specific to breast milk,” she emphasized. “In advising women infected with SARS-CoV-2, clinicians may want to include a discussion of protection methods to prevent maternal transmission of the virus through respiratory droplets.”

Although the data are preliminary, “the investigators established and validated an RT-PCR [reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction] assay and developed tissue culture methods for replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 in breast milk, both valuable tools for further studies. Next steps will include controlled studies of greater sample size with independent verification of RT-PCR positivity,” said Dr. Hardy, a consultant to Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, New Haven, Conn.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Mental Health. Medela Corporation provided milk sample collection materials. The Family Larsson-Rosenquist Foundation provided an unrestricted COVID19 emergency gift fund. The Mothers’ Milk Bank at Austin paid for shipping costs.

SOURCE: Chambers C et al. JAMA. 2020 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15580.

Breast milk is an unlikely source of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from mothers to infants, according to data from case reports and breast milk samples from 18 women.

“To date, SARS-CoV-2 has not been isolated from breast milk, and there are no documented cases of transmission of infectious virus to the infant through breast milk,” but the potential for transmission remains a concern among women who want to breastfeed, wrote Christina Chambers, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA, the investigators identified 18 women with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections (all but 1 of the women had symptomatic COVID-19 disease) and infants aged 0-19 months between March 27 and May 6, 2020. The average age of the mothers was 34 years, and 78% were non-Hispanic White. The women provided 1-12 samples of breast milk for a total of 64 samples collected before and after positive COVID-19 tests.

One sample yielded detectable RNA from SARS-CoV-2 and was collected on the day of the woman’s symptom onset. However, one sample taken 2 days prior to symptom onset and two samples collected 12 and 41 days later tested negative for viral RNA, the researchers said. In addition, no replication-competent virus was identified in the positive sample or any of the other samples.

The researchers spiked two stored milk samples collected prior to the pandemic with replication-competent SARS-CoV-2. Virus was not detected by culture in the samples after Holder pasteurization, but was detected by culture in nonpasteurized aliquots of the same samples.

“These data suggest that SARS-CoV-2 RNA does not represent replication-competent virus and that breast milk may not be a source of infection for the infant,” Dr. Chambers and associates said.

The results were limited by several factors including the small sample size and potential for selection bias, as well as the use of self-reports of positive tests and self-collection of breast milk, the researchers noted. However, the findings are reassuring in light of the known benefits of breastfeeding and the use of milk banks.

“This research is important because the pandemic is ongoing and has far-reaching consequences: as the authors indicate, the potential for viral transmission through breast milk remains a critical question for women infected with SARS-CoV-2 who wish to breastfeed,” Janet R. Hardy, PhD, MPH, MSc, a consultant on global maternal-child health and pharmacoepidemiology, said in an interview.

“This virus has everyone on a rapid learning track, and all information that helps build evidence to support women’s decision-making in the care of their children is valuable,” she said. “These findings suggest that breast milk may not be a source of SARS-CoV-2 infection for the infant. They provide some reassurance given the recognized benefits of breastfeeding and human milk.”

However, “This study is very specific to breast milk,” she emphasized. “In advising women infected with SARS-CoV-2, clinicians may want to include a discussion of protection methods to prevent maternal transmission of the virus through respiratory droplets.”

Although the data are preliminary, “the investigators established and validated an RT-PCR [reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction] assay and developed tissue culture methods for replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 in breast milk, both valuable tools for further studies. Next steps will include controlled studies of greater sample size with independent verification of RT-PCR positivity,” said Dr. Hardy, a consultant to Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, New Haven, Conn.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Mental Health. Medela Corporation provided milk sample collection materials. The Family Larsson-Rosenquist Foundation provided an unrestricted COVID19 emergency gift fund. The Mothers’ Milk Bank at Austin paid for shipping costs.

SOURCE: Chambers C et al. JAMA. 2020 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15580.

Breast milk is an unlikely source of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from mothers to infants, according to data from case reports and breast milk samples from 18 women.

“To date, SARS-CoV-2 has not been isolated from breast milk, and there are no documented cases of transmission of infectious virus to the infant through breast milk,” but the potential for transmission remains a concern among women who want to breastfeed, wrote Christina Chambers, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA, the investigators identified 18 women with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections (all but 1 of the women had symptomatic COVID-19 disease) and infants aged 0-19 months between March 27 and May 6, 2020. The average age of the mothers was 34 years, and 78% were non-Hispanic White. The women provided 1-12 samples of breast milk for a total of 64 samples collected before and after positive COVID-19 tests.

One sample yielded detectable RNA from SARS-CoV-2 and was collected on the day of the woman’s symptom onset. However, one sample taken 2 days prior to symptom onset and two samples collected 12 and 41 days later tested negative for viral RNA, the researchers said. In addition, no replication-competent virus was identified in the positive sample or any of the other samples.

The researchers spiked two stored milk samples collected prior to the pandemic with replication-competent SARS-CoV-2. Virus was not detected by culture in the samples after Holder pasteurization, but was detected by culture in nonpasteurized aliquots of the same samples.

“These data suggest that SARS-CoV-2 RNA does not represent replication-competent virus and that breast milk may not be a source of infection for the infant,” Dr. Chambers and associates said.

The results were limited by several factors including the small sample size and potential for selection bias, as well as the use of self-reports of positive tests and self-collection of breast milk, the researchers noted. However, the findings are reassuring in light of the known benefits of breastfeeding and the use of milk banks.

“This research is important because the pandemic is ongoing and has far-reaching consequences: as the authors indicate, the potential for viral transmission through breast milk remains a critical question for women infected with SARS-CoV-2 who wish to breastfeed,” Janet R. Hardy, PhD, MPH, MSc, a consultant on global maternal-child health and pharmacoepidemiology, said in an interview.

“This virus has everyone on a rapid learning track, and all information that helps build evidence to support women’s decision-making in the care of their children is valuable,” she said. “These findings suggest that breast milk may not be a source of SARS-CoV-2 infection for the infant. They provide some reassurance given the recognized benefits of breastfeeding and human milk.”

However, “This study is very specific to breast milk,” she emphasized. “In advising women infected with SARS-CoV-2, clinicians may want to include a discussion of protection methods to prevent maternal transmission of the virus through respiratory droplets.”

Although the data are preliminary, “the investigators established and validated an RT-PCR [reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction] assay and developed tissue culture methods for replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 in breast milk, both valuable tools for further studies. Next steps will include controlled studies of greater sample size with independent verification of RT-PCR positivity,” said Dr. Hardy, a consultant to Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, New Haven, Conn.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Mental Health. Medela Corporation provided milk sample collection materials. The Family Larsson-Rosenquist Foundation provided an unrestricted COVID19 emergency gift fund. The Mothers’ Milk Bank at Austin paid for shipping costs.

SOURCE: Chambers C et al. JAMA. 2020 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15580.

FROM JAMA

Hospitalists balance work, family as pandemic boosts stress

In a Q&A session at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine, Heather Nye, MD, PhD, SFHM, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and David J. Alfandre, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at New York University Langone, discussed strategies to help hospitalists tend to their personal wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The speakers described the complicated logistics and emotional and psychological strain that has come from working during the pandemic, while balancing home responsibilities and parenting. The session was an opportunity to humanize hospitalists’ experience as they straddle work and family.

Dr. Nye said she was still “warming up to personal wellness” because there have been so many other demands over the past several months, but that taking the time to go for walks – to bring on a feeling of health even more than the physical benefits – has been helpful. Even before the pandemic, she said, she brought a guitar to the office to take a few minutes for a hobby for which she can’t seem to find uninterrupted time at home.

“Bringing a little bit of yourself into your work life goes a long way for a lot of people,” she said.

Child care and odd hours always have been a challenge for hospitalists, the presenters said, and for those in academia, any “wiggle room” in the schedule is often taken up by education, administration, and research projects.

Dr. Alfandre said etching out time for yourself must be “a priority, or it won’t happen.” Doing so, he said, “feels indulgent but it’s not. It’s central to being able to do the kind of work you do when you’re at the hospital, at the office, and when you’re back home again.”

Dr. Nye observed that, while working from home on nonclinical work, “recognizing how little I got done was a big surprise,” and she had to “grow comfortable with that” and learn to live with the uncertainty about when that was going to change.

Both physicians described the emotional toll of worrying about their children if they have to continue distance learning.

Dr. Alfandre said that a shared Google calendar for his wife and him – with appointments, work obligations, children’s doctor’s appointments, recitals – has been helpful, removing the strain of having to remind each other. He said that there are skills used at work that hospitalists can use at home – such as not getting upset with a child for crying about a spilled drink – in the same way that a physician wouldn’t get upset with a patient concerned about a test.

“We empathize with our patients, and we empathize with our kids and what their experience is,” he said. Similarly, seeing family members crowd around a smartphone video call to check in with a COVID-19 patient can be a helpful reminder to appreciate going home to family at the end of the day.

When her children get upset that she has to go in to work, Dr. Nye said, it has been helpful to explain that her many patients are suffering and scared and need her help.

“I feel like sharing that part of our job [with] our kids helps them understand that there are very, very big problems out there – that they don’t have to know too much about and be frightened about – but [that knowledge] just gives them a little perspective.”

Dr. Nye and Dr. Alfandre said they had no financial conflicts of interest.

In a Q&A session at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine, Heather Nye, MD, PhD, SFHM, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and David J. Alfandre, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at New York University Langone, discussed strategies to help hospitalists tend to their personal wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The speakers described the complicated logistics and emotional and psychological strain that has come from working during the pandemic, while balancing home responsibilities and parenting. The session was an opportunity to humanize hospitalists’ experience as they straddle work and family.

Dr. Nye said she was still “warming up to personal wellness” because there have been so many other demands over the past several months, but that taking the time to go for walks – to bring on a feeling of health even more than the physical benefits – has been helpful. Even before the pandemic, she said, she brought a guitar to the office to take a few minutes for a hobby for which she can’t seem to find uninterrupted time at home.

“Bringing a little bit of yourself into your work life goes a long way for a lot of people,” she said.

Child care and odd hours always have been a challenge for hospitalists, the presenters said, and for those in academia, any “wiggle room” in the schedule is often taken up by education, administration, and research projects.

Dr. Alfandre said etching out time for yourself must be “a priority, or it won’t happen.” Doing so, he said, “feels indulgent but it’s not. It’s central to being able to do the kind of work you do when you’re at the hospital, at the office, and when you’re back home again.”

Dr. Nye observed that, while working from home on nonclinical work, “recognizing how little I got done was a big surprise,” and she had to “grow comfortable with that” and learn to live with the uncertainty about when that was going to change.

Both physicians described the emotional toll of worrying about their children if they have to continue distance learning.

Dr. Alfandre said that a shared Google calendar for his wife and him – with appointments, work obligations, children’s doctor’s appointments, recitals – has been helpful, removing the strain of having to remind each other. He said that there are skills used at work that hospitalists can use at home – such as not getting upset with a child for crying about a spilled drink – in the same way that a physician wouldn’t get upset with a patient concerned about a test.

“We empathize with our patients, and we empathize with our kids and what their experience is,” he said. Similarly, seeing family members crowd around a smartphone video call to check in with a COVID-19 patient can be a helpful reminder to appreciate going home to family at the end of the day.

When her children get upset that she has to go in to work, Dr. Nye said, it has been helpful to explain that her many patients are suffering and scared and need her help.

“I feel like sharing that part of our job [with] our kids helps them understand that there are very, very big problems out there – that they don’t have to know too much about and be frightened about – but [that knowledge] just gives them a little perspective.”

Dr. Nye and Dr. Alfandre said they had no financial conflicts of interest.

In a Q&A session at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine, Heather Nye, MD, PhD, SFHM, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and David J. Alfandre, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at New York University Langone, discussed strategies to help hospitalists tend to their personal wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The speakers described the complicated logistics and emotional and psychological strain that has come from working during the pandemic, while balancing home responsibilities and parenting. The session was an opportunity to humanize hospitalists’ experience as they straddle work and family.

Dr. Nye said she was still “warming up to personal wellness” because there have been so many other demands over the past several months, but that taking the time to go for walks – to bring on a feeling of health even more than the physical benefits – has been helpful. Even before the pandemic, she said, she brought a guitar to the office to take a few minutes for a hobby for which she can’t seem to find uninterrupted time at home.

“Bringing a little bit of yourself into your work life goes a long way for a lot of people,” she said.

Child care and odd hours always have been a challenge for hospitalists, the presenters said, and for those in academia, any “wiggle room” in the schedule is often taken up by education, administration, and research projects.

Dr. Alfandre said etching out time for yourself must be “a priority, or it won’t happen.” Doing so, he said, “feels indulgent but it’s not. It’s central to being able to do the kind of work you do when you’re at the hospital, at the office, and when you’re back home again.”

Dr. Nye observed that, while working from home on nonclinical work, “recognizing how little I got done was a big surprise,” and she had to “grow comfortable with that” and learn to live with the uncertainty about when that was going to change.

Both physicians described the emotional toll of worrying about their children if they have to continue distance learning.

Dr. Alfandre said that a shared Google calendar for his wife and him – with appointments, work obligations, children’s doctor’s appointments, recitals – has been helpful, removing the strain of having to remind each other. He said that there are skills used at work that hospitalists can use at home – such as not getting upset with a child for crying about a spilled drink – in the same way that a physician wouldn’t get upset with a patient concerned about a test.

“We empathize with our patients, and we empathize with our kids and what their experience is,” he said. Similarly, seeing family members crowd around a smartphone video call to check in with a COVID-19 patient can be a helpful reminder to appreciate going home to family at the end of the day.

When her children get upset that she has to go in to work, Dr. Nye said, it has been helpful to explain that her many patients are suffering and scared and need her help.

“I feel like sharing that part of our job [with] our kids helps them understand that there are very, very big problems out there – that they don’t have to know too much about and be frightened about – but [that knowledge] just gives them a little perspective.”

Dr. Nye and Dr. Alfandre said they had no financial conflicts of interest.

FROM HM20 VIRTUAL

Reducing maternal mortality with prenatal care

As in its typical fashion, the question sprang out from a young Black patient after some meandering conversation during preconception counseling: “How do y’all prevent Black maternal mortality?” At the beginning of my career, I used to think preparing a patient for pregnancy involved recommending prenatal vitamins and rubella immunity screening. Now, having worked in a society with substantial racial health disparities for 14 years, there is greater awareness that pregnancy can be a matter of life or death that disproportionately affects people of color.

For Black patients in the United States, the maternal mortality ratio is almost four times higher than the ratio for White patients, 42 deaths versus 13 deaths per 100,000 live births, respectively.1 Georgia has the highest maternal mortality ratio in the United States at 67 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. However, if you are a Black woman in Georgia, your chance of dying of pregnancy-related causes is 2.7 times that of a non-Hispanic White woman living in Georgia.2

Black patients often are not taken seriously, even when they are wealthy, have attained high levels of education, or are famous. Serena Williams, a Black woman and one of the most talented tennis players of all time, was ignored when complaining that she felt a blood clot had returned in her lungs post partum. As a recognition of this crisis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a new campaign to improve recognition of the warning signs of problems in pregnancy called the HEAR HER campaign. This issue is a pervasive problem in our lives that runs across the spectrum of Black experience. I have had Black friends, patients, and colleagues who have been ignored when complaining about labor pain, workplace discrimination, and even when trying to advocate for their patients. We need to uplift Black voices so they can be heard and support the initiatives and interventions they are asking for.

We practice standardized responses to emergencies and to health conditions. We use drills to practice our responses to life-threatening emergencies such as STAT cesarean delivery, shoulder dystocia, obstetrical hemorrhage, or treatment of preeclampsia and eclampsia. The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health has organized evidence-driven protocols called AIM bundles to reduce preventable maternal morbidity and mortality when implemented. Standardization is an important component of equitable treatment and reduction of disparities. The concept has been used across industries to reduce error and bias. The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health bundles even include a section on Reduction of Peripartum and Ethnic Disparities.

We admit that bias exists and that we need training to recognize and eliminate it. According to a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America about racial bias in pain assessment more than 20% of White residents and medical students surveyed believed that Black people had less sensitive nerve endings than Whites.3 Studies show that this stereotype leads to inappropriate pain management in Black patients, a chief concern when considering how patients are treated on labor and delivery or after surgery.4 Additionally, unconscious bias can be addressed by hiring a diverse workforce at all levels. Familiarity with a diverse group can help us learn from one another in our day-to-day lives.

We need to offer the same high-quality preconception counseling to all of our patients. A patient’s perceived race or ethnicity is a poor indicator of their actual health needs. The amount of melanin in our skin is highly variable but our genetics are remarkably similar, therefore our health concerns are similar. All patients deserve a focus on prevention. Folic acid supplements in the form of prenatal vitamins should be recommended. Routine vaccinations and rubella immunity checks should be offered. Basic carrier screening for diseases of hemoglobin (which includes sickle cell trait), fragile X, spinomuscular atrophy, and cystic fibrosis should be offered. Finally, an emphasis on safety, mental health, and daily low-level exercise (i.e., walking) should be promoted to help prevent illness and injury in this age group. The leading causes of death for people of reproductive age are accidents, suicide, homicide, and heart disease – all preventable.

We treat the social determinants of health, not just the patient in front of us. When “race” is a risk factor for disease, it’s usually racism that’s the problem. As stated earlier, how much melanin is in our skin has little to do with our genetics – if we removed our skin, we’d have similar life expectancies and die of similar things. However, it has everything to do with how we navigate our society and access health care. The stress associated with being Black in America is the likely cause of preterm birth rates – leading to infant illness and death – and maternal mortality being higher in Black patients. This is referred to as “weathering” – the cumulative effects of stress as we age. It explains why Black women are more likely to die in pregnancy despite higher levels of education and increasing age – factors that are protective for other groups. Improving access to quality education, reforming the criminal justice system, affordable housing and child care, living wages, family planning, and universal basic health care exemplify the intersectionality of some of our greatest societal challenges. Addressing these root causes will reduce weathering and ultimately, save Black lives.

We strive to train more “underrepresented minorities” in medicine. According to the American Association of Medical Colleges, only 7.3% of medical students in 2019-2020 identified as Black or African American. This is way below their representation of 13% of the U.S. population. I’m proud that my division and department as a whole have hired and promoted diverse faculty with 30% of my generalist ob.gyn. colleagues being people of color. This shows that we have the input of diverse experiences as well as recognize the special concerns of patients of color. Underrepresented students interested in the health professions need us to do more to get their “foot in the door.” They are less likely to have connections to the field of medicine (family members, mentors), have access to prep courses or advisors, or have the finances to support the expensive application process. Reach out to your alma maters and ask how you can help mentor students at a young age and continue through adulthood, support scholarships, support unpaid internship recipients, and promote interconnectedness throughout this community.

I hope I answered my patient’s question in that moment, but I know what needs to be done is bigger that taking care of one patient. It will require small progress, by us, every single day. Until these interventions and others reshape our society, I’ll still have Black patients who say: “Don’t let me die, okay?” with a look right into my soul and a tight grip on my hand. And I’ll feel the immense weight of that trust, and squeeze the hand back.

Dr. Collins (she/her/hers) is assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology, generalist division, at Emory University, Atlanta. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Collins at [email protected].

References

1. CDC Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm.

2. Maternal Mortality Fact Sheet, 2012-2015. https://dph.georgia.gov/maternal-mortality.

3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Apr 19;113(16):4296-301.

4. Pain Med. 2012 Feb;13(2):150-74.

As in its typical fashion, the question sprang out from a young Black patient after some meandering conversation during preconception counseling: “How do y’all prevent Black maternal mortality?” At the beginning of my career, I used to think preparing a patient for pregnancy involved recommending prenatal vitamins and rubella immunity screening. Now, having worked in a society with substantial racial health disparities for 14 years, there is greater awareness that pregnancy can be a matter of life or death that disproportionately affects people of color.

For Black patients in the United States, the maternal mortality ratio is almost four times higher than the ratio for White patients, 42 deaths versus 13 deaths per 100,000 live births, respectively.1 Georgia has the highest maternal mortality ratio in the United States at 67 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. However, if you are a Black woman in Georgia, your chance of dying of pregnancy-related causes is 2.7 times that of a non-Hispanic White woman living in Georgia.2