User login

FDA approves topical antiandrogen for acne

Clascoterone is a topical androgen receptor inhibitor indicated for treatment of acne vulgaris in patients aged 12 years and older, according to the labeling from manufacturer Cassiopea. Clascoterone, which will be marketed as Winlevi, targets the androgen hormones that contribute to acne by inhibiting serum production and inflammation, according to a company press release.

“Although clascoterone’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, laboratory studies suggest clascoterone competes with androgens, specifically dihydrotestosterone, for binding to the androgen receptors within the sebaceous gland and hair follicles,” according to the release.

Approval was based in part on a pair of phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 12-week, randomized trials including 1,440 patients aged 9 years and older with moderate to severe facial acne. The findings were published in April, in JAMA Dermatology .

Participants were randomized to twice-daily application of clascoterone or a control vehicle; treatment success was defined as having an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear), as well as at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline, and absolute change in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesion counts at week 12.

At 12 weeks, treatment success rates were 18.4% and 20.3% among those on clascoterone, compared with 9% and 6.5%, respectively, among controls. There were also significant reductions in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesions from baseline at 12 weeks, compared with controls.

In the studies, treatment was well tolerated, with a safety profile similar to safety in controls. Adverse events thought to be related to clascoterone in the studies (a total of 13) included application-site pain; erythema; oropharyngeal pain; hypersensitivity, dryness, or hypertrichosis at the application site; eye irritation; headache; and hair color changes. “Clascoterone targets androgen receptors at the site of application and is quickly metabolized to an inactive form, thus limiting systemic activity,” the authors of the study wrote.

Clascoterone is expected to be available in the United States in early 2021, according to the manufacturer.

Clascoterone is a topical androgen receptor inhibitor indicated for treatment of acne vulgaris in patients aged 12 years and older, according to the labeling from manufacturer Cassiopea. Clascoterone, which will be marketed as Winlevi, targets the androgen hormones that contribute to acne by inhibiting serum production and inflammation, according to a company press release.

“Although clascoterone’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, laboratory studies suggest clascoterone competes with androgens, specifically dihydrotestosterone, for binding to the androgen receptors within the sebaceous gland and hair follicles,” according to the release.

Approval was based in part on a pair of phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 12-week, randomized trials including 1,440 patients aged 9 years and older with moderate to severe facial acne. The findings were published in April, in JAMA Dermatology .

Participants were randomized to twice-daily application of clascoterone or a control vehicle; treatment success was defined as having an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear), as well as at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline, and absolute change in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesion counts at week 12.

At 12 weeks, treatment success rates were 18.4% and 20.3% among those on clascoterone, compared with 9% and 6.5%, respectively, among controls. There were also significant reductions in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesions from baseline at 12 weeks, compared with controls.

In the studies, treatment was well tolerated, with a safety profile similar to safety in controls. Adverse events thought to be related to clascoterone in the studies (a total of 13) included application-site pain; erythema; oropharyngeal pain; hypersensitivity, dryness, or hypertrichosis at the application site; eye irritation; headache; and hair color changes. “Clascoterone targets androgen receptors at the site of application and is quickly metabolized to an inactive form, thus limiting systemic activity,” the authors of the study wrote.

Clascoterone is expected to be available in the United States in early 2021, according to the manufacturer.

Clascoterone is a topical androgen receptor inhibitor indicated for treatment of acne vulgaris in patients aged 12 years and older, according to the labeling from manufacturer Cassiopea. Clascoterone, which will be marketed as Winlevi, targets the androgen hormones that contribute to acne by inhibiting serum production and inflammation, according to a company press release.

“Although clascoterone’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, laboratory studies suggest clascoterone competes with androgens, specifically dihydrotestosterone, for binding to the androgen receptors within the sebaceous gland and hair follicles,” according to the release.

Approval was based in part on a pair of phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 12-week, randomized trials including 1,440 patients aged 9 years and older with moderate to severe facial acne. The findings were published in April, in JAMA Dermatology .

Participants were randomized to twice-daily application of clascoterone or a control vehicle; treatment success was defined as having an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear), as well as at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline, and absolute change in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesion counts at week 12.

At 12 weeks, treatment success rates were 18.4% and 20.3% among those on clascoterone, compared with 9% and 6.5%, respectively, among controls. There were also significant reductions in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesions from baseline at 12 weeks, compared with controls.

In the studies, treatment was well tolerated, with a safety profile similar to safety in controls. Adverse events thought to be related to clascoterone in the studies (a total of 13) included application-site pain; erythema; oropharyngeal pain; hypersensitivity, dryness, or hypertrichosis at the application site; eye irritation; headache; and hair color changes. “Clascoterone targets androgen receptors at the site of application and is quickly metabolized to an inactive form, thus limiting systemic activity,” the authors of the study wrote.

Clascoterone is expected to be available in the United States in early 2021, according to the manufacturer.

Immunotherapy should not be withheld because of sex, age, or PS

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

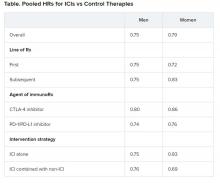

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Diffuse Painful Plaques in the Setting of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare Complex Infection

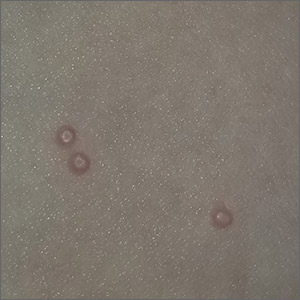

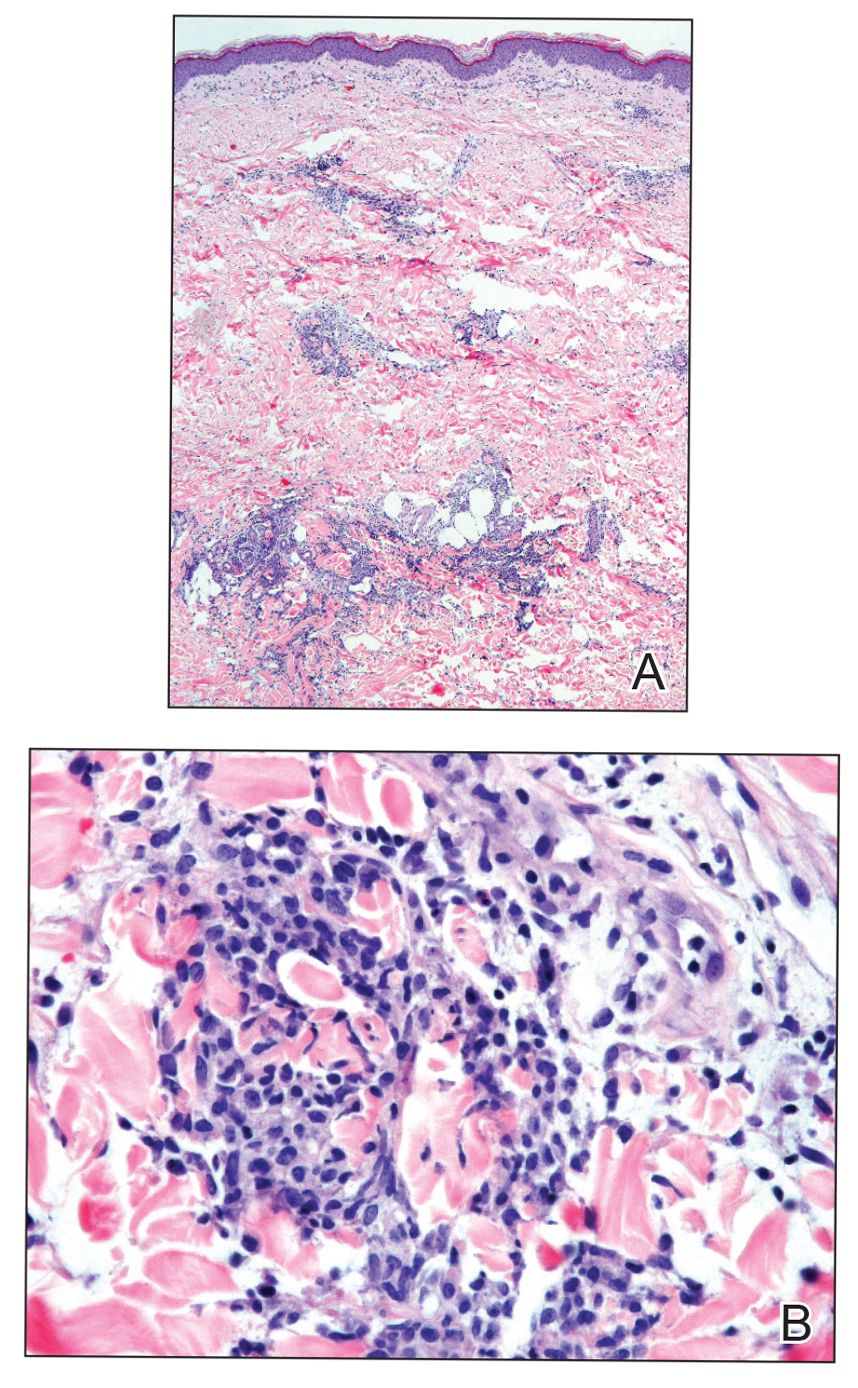

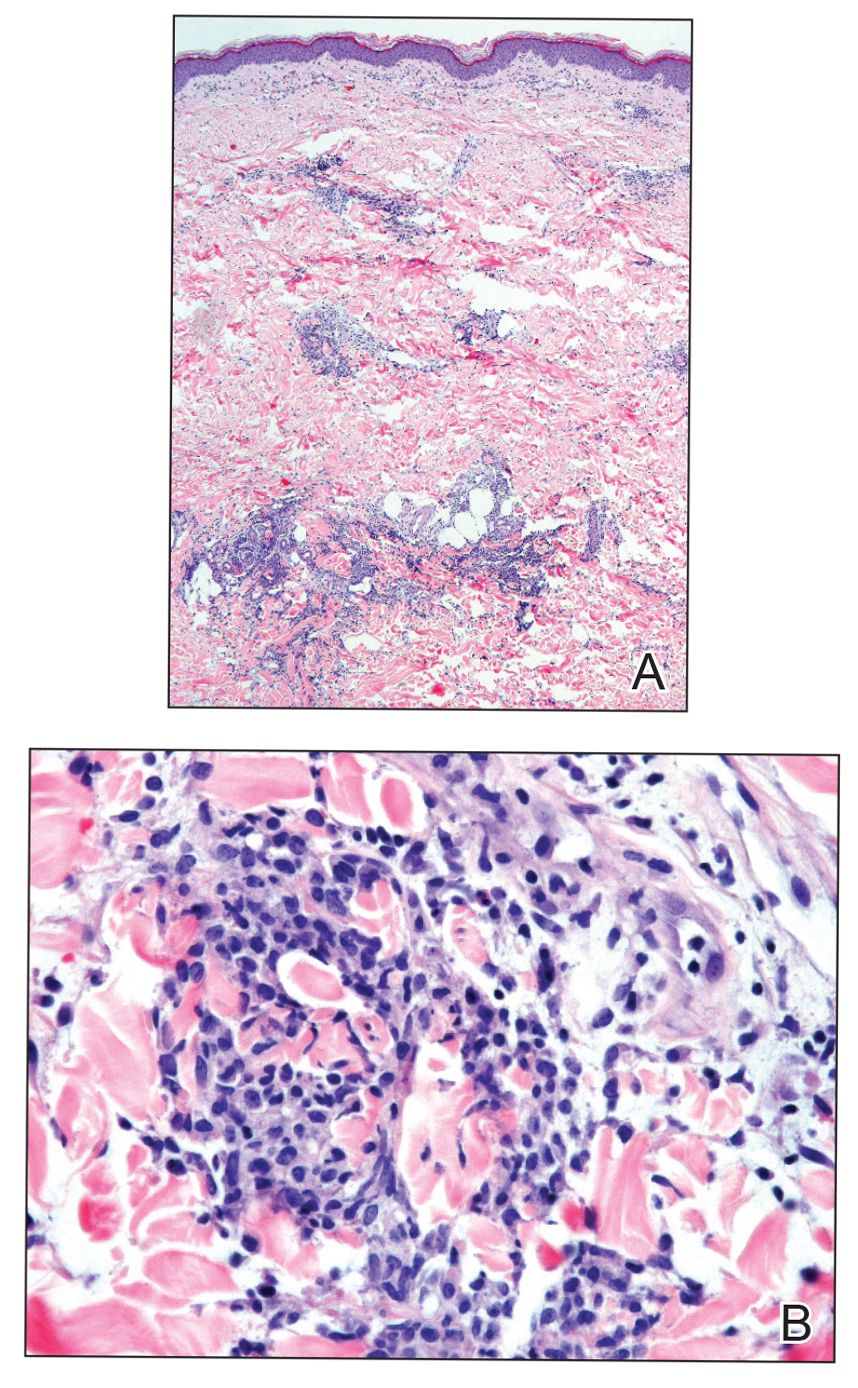

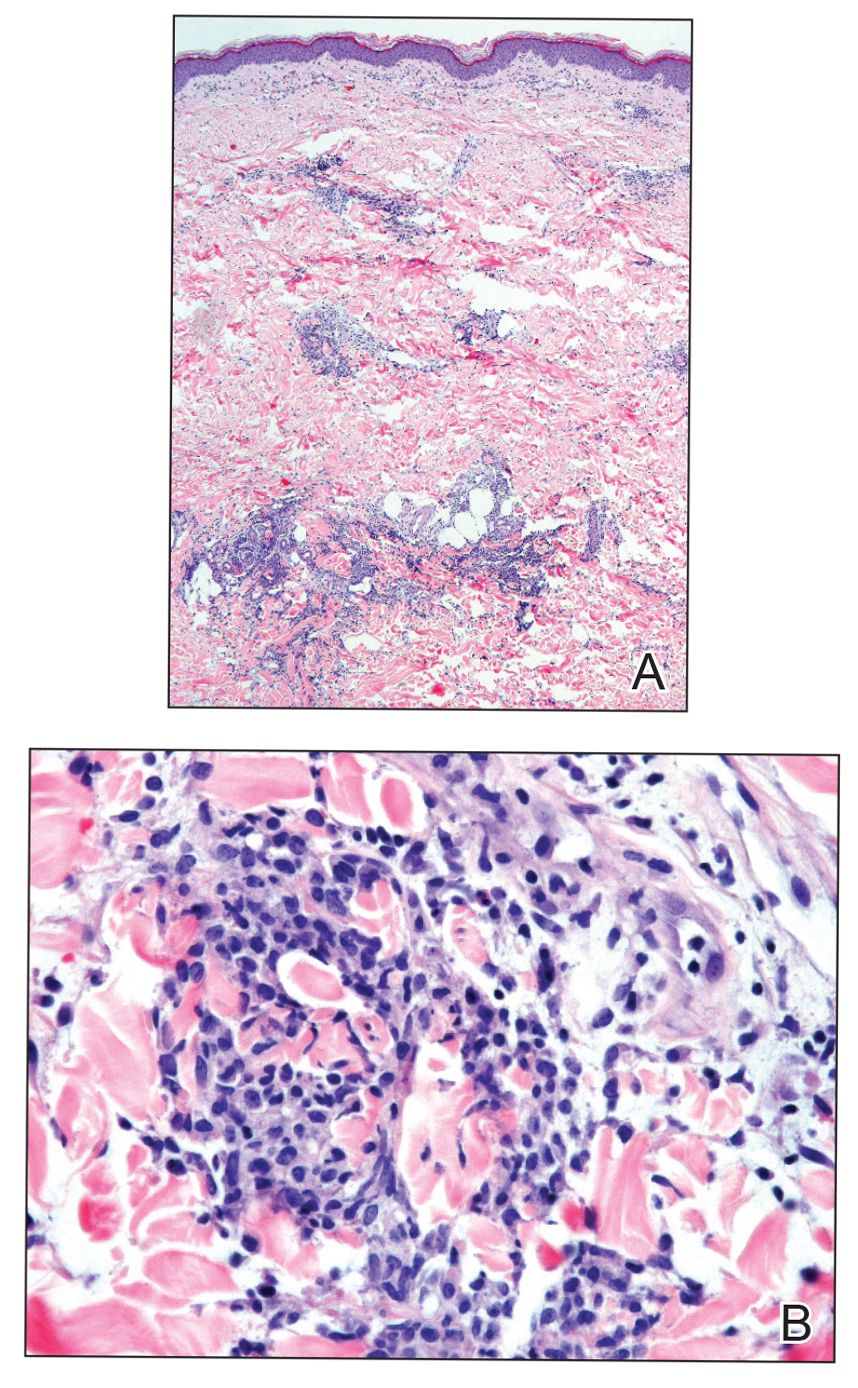

Histopathologic evaluation revealed superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal inflammation. The epidermis exhibited some vacuolar interface change and effacement with relatively sparse dyskeratotic cells. A lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate surrounded the blood vessels, nerves, and adnexal structures and extended into the subcutaneous fat (Figure). Acid-fast, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, Gram, Fite, Treponema pallidum, and Alcian blue stains were performed at our institution and were all negative. Biopsies sent to the National Hansen's Disease (Leprosy) Program demonstrated scattered extracellular acid-fast organisms on Fite staining in the specimen of the forearm. Polymerase chain reaction testing for Mycobacterium leprae DNA was negative. DNA sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene matched Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAC). In the workup of the hepatic mass, the patient incidentally was found to have large-cell transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and therefore was treated with bendamustine and rituximab as an outpatient. The patient received 1 chemotherapy infusion every 4 weeks for a total of 10 rounds. At 10-week follow-up after 2 rounds of chemotherapy, all of the skin lesions had resolved despite no antibiotic therapy for atypical infections.

Disseminated infection with MAC is relatively rare in healthy as well as immunocompromised individuals. Clinical disease most commonly is seen as an opportunistic infection in patients with AIDS who have CD4 counts less than 50/mm3 (reference range, 500-1400/mm3) or in those with preexisting lung disease.1 Cutaneous involvement has been observed in only 14% of non-AIDS patients with disseminated MAC infection.2 In another study of 76 patients with MAC infection, only 2 involved the skin or soft tissue.3 Infection of the skin without concurrent pulmonary MAC infection is rare, though trauma may cause isolated skin infection. The cutaneous presentation of MAC infection is highly variable and may include erythematous papules, pustules, panniculitis, infiltrated plaques, verrucous lesions, and draining sinuses.3 The lesions have been reported to be painful.1

Cutaneous findings occur in up to 25% of patients with CLL, either due to the seeding of leukemic cells or other secondary lesions.4 Leukemia cutis, or skin involvement by B-cell CLL, most commonly presents in the head and neck region as chronic and relapsing erythematous papules and plaques.5 It histologically presents as monomorphic lymphocytic infiltrates accentuated around periadnexal and perivascular structures, with some extending into adipose tissue.2 In our case, histopathology demonstrated a lack of monomorphous infiltrate and thus was inconsistent with leukemia cutis. Similarly, lack of pale pink deposits and lack of neutrophilic infiltrates or degenerated collagen makes amyloidosis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis incorrect diagnoses, respectively.

We hypothesize that the initially undetected worsening of CLL resulted in an immunocompromised state, which facilitated this unique presentation of cutaneous MAC infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient with no clinical symptoms of active pulmonary disease. The rash was the presenting sign of both the cutaneous MAC infection and worsening CLL. Additionally, our patient's cutaneous MAC facial involvement clinically resembled the leonine facies that is classic in lepromatous leprosy. Rare reports have been published addressing this similarity.6

Treatment of MAC pulmonary disease usually includes a combination of clarithromycin or azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol (for nodular/bronchiectatic disease), with or without amikacin or streptomycin.7 For limited pulmonary disease in patients with adequate pulmonary reserve, surgical resection may be considered in combination with the multidrug MAC pulmonary treatment regimen for 3 months to 1 year. Patients with localized MAC disease involving only the skin, soft tissue, tendons, and joints usually are treated with surgical excision in combination with clarithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol for 6 to 12 months.7 In our patient, we believe that chemotherapy and the subsequent reconstituted immune system likely cleared the MAC infection without targeted antibiotic treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Scollard, MD, PhD, and Barbara Stryjewska, MD, from the National Hansen's Disease (Leprosy) Association (Baton Rouge, Louisiana).

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Plaza JA, Comfere NI, Gibson LE, et al. Unusual cutaneous manifestations of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:772-780.

- Sivanesan SP, Khera P, Buckthal-McCuin J, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex associated with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:E25-E26.

- Horsburgh CR, Mason UG, Farhi DC, et al. Disseminated infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare. a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:36-48.

- Bodle EE, Cunningham JA, Della-Latta P, et al. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients without HIV infection, New York City. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:290-296.

- Boyd AS, Robbins J. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection in an HIV+ patient mimicking histoid leprosy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:39-41.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare Complex Infection

Histopathologic evaluation revealed superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal inflammation. The epidermis exhibited some vacuolar interface change and effacement with relatively sparse dyskeratotic cells. A lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate surrounded the blood vessels, nerves, and adnexal structures and extended into the subcutaneous fat (Figure). Acid-fast, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, Gram, Fite, Treponema pallidum, and Alcian blue stains were performed at our institution and were all negative. Biopsies sent to the National Hansen's Disease (Leprosy) Program demonstrated scattered extracellular acid-fast organisms on Fite staining in the specimen of the forearm. Polymerase chain reaction testing for Mycobacterium leprae DNA was negative. DNA sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene matched Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAC). In the workup of the hepatic mass, the patient incidentally was found to have large-cell transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and therefore was treated with bendamustine and rituximab as an outpatient. The patient received 1 chemotherapy infusion every 4 weeks for a total of 10 rounds. At 10-week follow-up after 2 rounds of chemotherapy, all of the skin lesions had resolved despite no antibiotic therapy for atypical infections.

Disseminated infection with MAC is relatively rare in healthy as well as immunocompromised individuals. Clinical disease most commonly is seen as an opportunistic infection in patients with AIDS who have CD4 counts less than 50/mm3 (reference range, 500-1400/mm3) or in those with preexisting lung disease.1 Cutaneous involvement has been observed in only 14% of non-AIDS patients with disseminated MAC infection.2 In another study of 76 patients with MAC infection, only 2 involved the skin or soft tissue.3 Infection of the skin without concurrent pulmonary MAC infection is rare, though trauma may cause isolated skin infection. The cutaneous presentation of MAC infection is highly variable and may include erythematous papules, pustules, panniculitis, infiltrated plaques, verrucous lesions, and draining sinuses.3 The lesions have been reported to be painful.1

Cutaneous findings occur in up to 25% of patients with CLL, either due to the seeding of leukemic cells or other secondary lesions.4 Leukemia cutis, or skin involvement by B-cell CLL, most commonly presents in the head and neck region as chronic and relapsing erythematous papules and plaques.5 It histologically presents as monomorphic lymphocytic infiltrates accentuated around periadnexal and perivascular structures, with some extending into adipose tissue.2 In our case, histopathology demonstrated a lack of monomorphous infiltrate and thus was inconsistent with leukemia cutis. Similarly, lack of pale pink deposits and lack of neutrophilic infiltrates or degenerated collagen makes amyloidosis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis incorrect diagnoses, respectively.

We hypothesize that the initially undetected worsening of CLL resulted in an immunocompromised state, which facilitated this unique presentation of cutaneous MAC infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient with no clinical symptoms of active pulmonary disease. The rash was the presenting sign of both the cutaneous MAC infection and worsening CLL. Additionally, our patient's cutaneous MAC facial involvement clinically resembled the leonine facies that is classic in lepromatous leprosy. Rare reports have been published addressing this similarity.6

Treatment of MAC pulmonary disease usually includes a combination of clarithromycin or azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol (for nodular/bronchiectatic disease), with or without amikacin or streptomycin.7 For limited pulmonary disease in patients with adequate pulmonary reserve, surgical resection may be considered in combination with the multidrug MAC pulmonary treatment regimen for 3 months to 1 year. Patients with localized MAC disease involving only the skin, soft tissue, tendons, and joints usually are treated with surgical excision in combination with clarithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol for 6 to 12 months.7 In our patient, we believe that chemotherapy and the subsequent reconstituted immune system likely cleared the MAC infection without targeted antibiotic treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Scollard, MD, PhD, and Barbara Stryjewska, MD, from the National Hansen's Disease (Leprosy) Association (Baton Rouge, Louisiana).

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare Complex Infection

Histopathologic evaluation revealed superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal inflammation. The epidermis exhibited some vacuolar interface change and effacement with relatively sparse dyskeratotic cells. A lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate surrounded the blood vessels, nerves, and adnexal structures and extended into the subcutaneous fat (Figure). Acid-fast, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, Gram, Fite, Treponema pallidum, and Alcian blue stains were performed at our institution and were all negative. Biopsies sent to the National Hansen's Disease (Leprosy) Program demonstrated scattered extracellular acid-fast organisms on Fite staining in the specimen of the forearm. Polymerase chain reaction testing for Mycobacterium leprae DNA was negative. DNA sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene matched Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAC). In the workup of the hepatic mass, the patient incidentally was found to have large-cell transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and therefore was treated with bendamustine and rituximab as an outpatient. The patient received 1 chemotherapy infusion every 4 weeks for a total of 10 rounds. At 10-week follow-up after 2 rounds of chemotherapy, all of the skin lesions had resolved despite no antibiotic therapy for atypical infections.

Disseminated infection with MAC is relatively rare in healthy as well as immunocompromised individuals. Clinical disease most commonly is seen as an opportunistic infection in patients with AIDS who have CD4 counts less than 50/mm3 (reference range, 500-1400/mm3) or in those with preexisting lung disease.1 Cutaneous involvement has been observed in only 14% of non-AIDS patients with disseminated MAC infection.2 In another study of 76 patients with MAC infection, only 2 involved the skin or soft tissue.3 Infection of the skin without concurrent pulmonary MAC infection is rare, though trauma may cause isolated skin infection. The cutaneous presentation of MAC infection is highly variable and may include erythematous papules, pustules, panniculitis, infiltrated plaques, verrucous lesions, and draining sinuses.3 The lesions have been reported to be painful.1

Cutaneous findings occur in up to 25% of patients with CLL, either due to the seeding of leukemic cells or other secondary lesions.4 Leukemia cutis, or skin involvement by B-cell CLL, most commonly presents in the head and neck region as chronic and relapsing erythematous papules and plaques.5 It histologically presents as monomorphic lymphocytic infiltrates accentuated around periadnexal and perivascular structures, with some extending into adipose tissue.2 In our case, histopathology demonstrated a lack of monomorphous infiltrate and thus was inconsistent with leukemia cutis. Similarly, lack of pale pink deposits and lack of neutrophilic infiltrates or degenerated collagen makes amyloidosis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis incorrect diagnoses, respectively.

We hypothesize that the initially undetected worsening of CLL resulted in an immunocompromised state, which facilitated this unique presentation of cutaneous MAC infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient with no clinical symptoms of active pulmonary disease. The rash was the presenting sign of both the cutaneous MAC infection and worsening CLL. Additionally, our patient's cutaneous MAC facial involvement clinically resembled the leonine facies that is classic in lepromatous leprosy. Rare reports have been published addressing this similarity.6

Treatment of MAC pulmonary disease usually includes a combination of clarithromycin or azithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol (for nodular/bronchiectatic disease), with or without amikacin or streptomycin.7 For limited pulmonary disease in patients with adequate pulmonary reserve, surgical resection may be considered in combination with the multidrug MAC pulmonary treatment regimen for 3 months to 1 year. Patients with localized MAC disease involving only the skin, soft tissue, tendons, and joints usually are treated with surgical excision in combination with clarithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol for 6 to 12 months.7 In our patient, we believe that chemotherapy and the subsequent reconstituted immune system likely cleared the MAC infection without targeted antibiotic treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Scollard, MD, PhD, and Barbara Stryjewska, MD, from the National Hansen's Disease (Leprosy) Association (Baton Rouge, Louisiana).

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Plaza JA, Comfere NI, Gibson LE, et al. Unusual cutaneous manifestations of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:772-780.

- Sivanesan SP, Khera P, Buckthal-McCuin J, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex associated with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:E25-E26.

- Horsburgh CR, Mason UG, Farhi DC, et al. Disseminated infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare. a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:36-48.

- Bodle EE, Cunningham JA, Della-Latta P, et al. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients without HIV infection, New York City. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:290-296.

- Boyd AS, Robbins J. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection in an HIV+ patient mimicking histoid leprosy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:39-41.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Plaza JA, Comfere NI, Gibson LE, et al. Unusual cutaneous manifestations of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:772-780.

- Sivanesan SP, Khera P, Buckthal-McCuin J, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex associated with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:E25-E26.

- Horsburgh CR, Mason UG, Farhi DC, et al. Disseminated infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare. a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:36-48.

- Bodle EE, Cunningham JA, Della-Latta P, et al. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients without HIV infection, New York City. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:290-296.

- Boyd AS, Robbins J. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection in an HIV+ patient mimicking histoid leprosy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:39-41.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

Age, other risk factors predict length of MM survival

Younger age of onset and the use of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (ASCT) treatment were key factors improving the length of survival of newly diagnosed, active multiple myeloma (MM) patients, according to the results of a retrospective analysis.

In addition, multivariable analysis showed that a higher level of blood creatinine, the presence of extramedullary disease, a lower level of partial remission, and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were independent risk factors for shorter survival, according to Virginia Bove, MD, of the Asociación Espanola Primera en Socorros Mutuos, Montevideo, Uruguay and colleagues.

Dr. Bove and colleagues retrospectively analyzed clinical characteristics, response to treatment, and survival of 282 patients from multiple institutions who had active newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. They compared the results between patients age 65 years or younger (53.2%) with those older than 65 years and assessed clinical risk factors, as reported online in Hematology, Transfusion, and Cell Therapy.

The main cause of death in all patients was MM progression and the early mortality rate was not different between the younger and older patients. The main cause of early death in older patients was infection, according to the researchers.

Multiple risk factors

“Although MM patients younger than 66 years of age have an aggressive presentation with an advanced stage, high rate of renal failure and extramedullary disease, this did not translate into an inferior [overall survival] and [progression-free survival],” the researchers reported.

The overall response rate was similar between groups (80.6% vs. 81.4%; P = .866), and the overall survival was significantly longer in young patients (median, 65 months vs. 41 months; P = .001) and higher in those who received autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Multivariate analysis was performed on data from the younger patients. The results showed that a creatinine level of less than or equal to 2 mg/dL (P = .048), extramedullary disease (P = .001), a lower VGPR (P = .003) and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (P = .048) were all independent risk factors for shorter survival.

“Older age is an independent adverse prognostic factor. Adequate risk identification, frontline treatment based on novel drugs and ASCT are the best strategies to improve outcomes, both in young and old patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bove V et al. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2020 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2020.06.014.

Younger age of onset and the use of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (ASCT) treatment were key factors improving the length of survival of newly diagnosed, active multiple myeloma (MM) patients, according to the results of a retrospective analysis.

In addition, multivariable analysis showed that a higher level of blood creatinine, the presence of extramedullary disease, a lower level of partial remission, and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were independent risk factors for shorter survival, according to Virginia Bove, MD, of the Asociación Espanola Primera en Socorros Mutuos, Montevideo, Uruguay and colleagues.

Dr. Bove and colleagues retrospectively analyzed clinical characteristics, response to treatment, and survival of 282 patients from multiple institutions who had active newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. They compared the results between patients age 65 years or younger (53.2%) with those older than 65 years and assessed clinical risk factors, as reported online in Hematology, Transfusion, and Cell Therapy.

The main cause of death in all patients was MM progression and the early mortality rate was not different between the younger and older patients. The main cause of early death in older patients was infection, according to the researchers.

Multiple risk factors

“Although MM patients younger than 66 years of age have an aggressive presentation with an advanced stage, high rate of renal failure and extramedullary disease, this did not translate into an inferior [overall survival] and [progression-free survival],” the researchers reported.

The overall response rate was similar between groups (80.6% vs. 81.4%; P = .866), and the overall survival was significantly longer in young patients (median, 65 months vs. 41 months; P = .001) and higher in those who received autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Multivariate analysis was performed on data from the younger patients. The results showed that a creatinine level of less than or equal to 2 mg/dL (P = .048), extramedullary disease (P = .001), a lower VGPR (P = .003) and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (P = .048) were all independent risk factors for shorter survival.

“Older age is an independent adverse prognostic factor. Adequate risk identification, frontline treatment based on novel drugs and ASCT are the best strategies to improve outcomes, both in young and old patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bove V et al. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2020 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2020.06.014.

Younger age of onset and the use of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (ASCT) treatment were key factors improving the length of survival of newly diagnosed, active multiple myeloma (MM) patients, according to the results of a retrospective analysis.

In addition, multivariable analysis showed that a higher level of blood creatinine, the presence of extramedullary disease, a lower level of partial remission, and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were independent risk factors for shorter survival, according to Virginia Bove, MD, of the Asociación Espanola Primera en Socorros Mutuos, Montevideo, Uruguay and colleagues.

Dr. Bove and colleagues retrospectively analyzed clinical characteristics, response to treatment, and survival of 282 patients from multiple institutions who had active newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. They compared the results between patients age 65 years or younger (53.2%) with those older than 65 years and assessed clinical risk factors, as reported online in Hematology, Transfusion, and Cell Therapy.

The main cause of death in all patients was MM progression and the early mortality rate was not different between the younger and older patients. The main cause of early death in older patients was infection, according to the researchers.

Multiple risk factors

“Although MM patients younger than 66 years of age have an aggressive presentation with an advanced stage, high rate of renal failure and extramedullary disease, this did not translate into an inferior [overall survival] and [progression-free survival],” the researchers reported.

The overall response rate was similar between groups (80.6% vs. 81.4%; P = .866), and the overall survival was significantly longer in young patients (median, 65 months vs. 41 months; P = .001) and higher in those who received autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Multivariate analysis was performed on data from the younger patients. The results showed that a creatinine level of less than or equal to 2 mg/dL (P = .048), extramedullary disease (P = .001), a lower VGPR (P = .003) and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (P = .048) were all independent risk factors for shorter survival.

“Older age is an independent adverse prognostic factor. Adequate risk identification, frontline treatment based on novel drugs and ASCT are the best strategies to improve outcomes, both in young and old patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bove V et al. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2020 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2020.06.014.

FROM HEMATOLOGY, TRANSFUSION, AND CELL THERAPY

Selpercatinib ‘poised to alter the landscape’ of RET+ cancers

Clinical data for the first-ever RET inhibitor, selpercatinib (Retevmo), show efficacy in two groups of patients with cancer – those with RET fusion–positive non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and those with RET-mutant medullary thyroid cancer (MTC).

The drug showed “very good efficacy and also very good tolerability” in both groups, said lead author Lori J. Wirth, MD, medical director of head and neck cancers, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, Boston, in a statement.

“The response rates are high, responses are very durable, and overall, the drug does not cause a lot of toxicity,” she said.

“If you have a clean, RET-specific inhibitor such as selpercatinib, then you can really pound down RET very strongly and hit the driver alteration much harder, with a better side effect profile,” Dr. Wirth added.

Both groups of patients were part of the phase 1/2 LIBRETTO-001 study, which served as the basis for the recent accelerated approval of selpercatinib by the Food and Drug Administration.

Data from LIBRETTO-001 were published in the New England Journal of Medicine as two articles, one on NSCLC patients and one on MTC patients.

There has been a “remarkable increase” in the number of targeted agents that are effective in treating patients with advanced cancers that harbor specific genomic alterations, commented Razelle Kurzrock, MD, from the University of California, San Diego, in an accompanying editorial.

Selpercatinib, a potent RET inhibitor, “is now poised to alter the landscape of another genomic subgroup – RET-altered cancers,” she wrote.

Multikinase inhibitors such as vandetanib and cabozantinib have ancillary RET-inhibitor activity and are also active against RET-driven cancers. But these drugs are limited by off-target side effects, Dr. Krurzrock pointed out. “In contrast, next-generation, highly potent, and selective RET inhibitors such as selpercatinib offer the potential for improved efficacy and a more satisfactory side effect profile.”

In both parts of the study, selpercatinib produced durable responses in a majority of patients. Only about 3% of patients discontinued taking selpercatinib because of drug-related adverse events.

Taken together, these results show that selpercatinib “had marked and durable antitumor activity in most patients with RET-altered thyroid cancer or NSCLC,” wrote Dr. Krurzrock. “RET abnormalities now join other genomic alterations such as NTRK fusions, tumor mutational burden, and deficient mismatchrepair genes across cancers and ALK, BRAF, EGFR, MET, and ROS1 alterations in NSCLC that warrant molecular screening strategies.”

Results in patients with RET-mutated NSCLC

All patients enrolled in the LIBRETTO-001 trial received selpercatinib 160 mg orally twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred.

Of 105 patients with NSCLC who had received at least one platinum-based chemotherapy regimen, the objective response rate was 64%. The median duration of response was 17.5 months.

At a median follow-up of 12.1 months, 63% of the responses were ongoing.

The cohort included 39 treatment-naive patients, among whom the response rate was even higher, at 85%; 90% of the responses were ongoing at 6 months. In addition, 11 patients had measurable central nervous system metastasis at study enrollment. Of this group, 91% achieved an intracranial response.

Common adverse events of grade 3 or higher included hypertension (in 14% of the patients), an increase in ALT level (in 12%), an increase in AST level (in 10%), hyponatremia (in 6%), and lymphopenia (in 6%). The drug was discontinued in 12 patients because of a drug-related adverse event.

Results in patients with RET-mutated MTC

Efficacy for MTC was evaluated in 55 patients with advanced or metastatic RET-mutant MTC who had previously been treated with cabozantinib, vandetanib, or both. The objective response rate was 69%. The 1-year progression-free survival rate was 82%.

For the 88 patients who had not previously received vandetanib or cabozantinib, the response rate was 73%. The 1-year progression-free survival rate was 92%.

In a subgroup of 19 patients with previously treated RET fusion–positive thyroid cancer, 79% responded to the therapy; 1-year progression-free survival was 64%.

The most common adverse events of grade 3 or higher were hypertension (in 21% of the patients), an increase in ALT level (in 11%), an increase in AST level (in 9%), hyponatremia (in 8%), and diarrhea (in 6%). Selpercatinib was discontinued by 12 patients because of drug-related adverse events.

The study was funded by Loxo Oncology (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly) and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Kurzrock and Wirth report relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, as listed in the journal article.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinical data for the first-ever RET inhibitor, selpercatinib (Retevmo), show efficacy in two groups of patients with cancer – those with RET fusion–positive non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and those with RET-mutant medullary thyroid cancer (MTC).

The drug showed “very good efficacy and also very good tolerability” in both groups, said lead author Lori J. Wirth, MD, medical director of head and neck cancers, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, Boston, in a statement.

“The response rates are high, responses are very durable, and overall, the drug does not cause a lot of toxicity,” she said.

“If you have a clean, RET-specific inhibitor such as selpercatinib, then you can really pound down RET very strongly and hit the driver alteration much harder, with a better side effect profile,” Dr. Wirth added.

Both groups of patients were part of the phase 1/2 LIBRETTO-001 study, which served as the basis for the recent accelerated approval of selpercatinib by the Food and Drug Administration.

Data from LIBRETTO-001 were published in the New England Journal of Medicine as two articles, one on NSCLC patients and one on MTC patients.

There has been a “remarkable increase” in the number of targeted agents that are effective in treating patients with advanced cancers that harbor specific genomic alterations, commented Razelle Kurzrock, MD, from the University of California, San Diego, in an accompanying editorial.

Selpercatinib, a potent RET inhibitor, “is now poised to alter the landscape of another genomic subgroup – RET-altered cancers,” she wrote.

Multikinase inhibitors such as vandetanib and cabozantinib have ancillary RET-inhibitor activity and are also active against RET-driven cancers. But these drugs are limited by off-target side effects, Dr. Krurzrock pointed out. “In contrast, next-generation, highly potent, and selective RET inhibitors such as selpercatinib offer the potential for improved efficacy and a more satisfactory side effect profile.”

In both parts of the study, selpercatinib produced durable responses in a majority of patients. Only about 3% of patients discontinued taking selpercatinib because of drug-related adverse events.

Taken together, these results show that selpercatinib “had marked and durable antitumor activity in most patients with RET-altered thyroid cancer or NSCLC,” wrote Dr. Krurzrock. “RET abnormalities now join other genomic alterations such as NTRK fusions, tumor mutational burden, and deficient mismatchrepair genes across cancers and ALK, BRAF, EGFR, MET, and ROS1 alterations in NSCLC that warrant molecular screening strategies.”

Results in patients with RET-mutated NSCLC

All patients enrolled in the LIBRETTO-001 trial received selpercatinib 160 mg orally twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred.

Of 105 patients with NSCLC who had received at least one platinum-based chemotherapy regimen, the objective response rate was 64%. The median duration of response was 17.5 months.

At a median follow-up of 12.1 months, 63% of the responses were ongoing.

The cohort included 39 treatment-naive patients, among whom the response rate was even higher, at 85%; 90% of the responses were ongoing at 6 months. In addition, 11 patients had measurable central nervous system metastasis at study enrollment. Of this group, 91% achieved an intracranial response.

Common adverse events of grade 3 or higher included hypertension (in 14% of the patients), an increase in ALT level (in 12%), an increase in AST level (in 10%), hyponatremia (in 6%), and lymphopenia (in 6%). The drug was discontinued in 12 patients because of a drug-related adverse event.

Results in patients with RET-mutated MTC

Efficacy for MTC was evaluated in 55 patients with advanced or metastatic RET-mutant MTC who had previously been treated with cabozantinib, vandetanib, or both. The objective response rate was 69%. The 1-year progression-free survival rate was 82%.

For the 88 patients who had not previously received vandetanib or cabozantinib, the response rate was 73%. The 1-year progression-free survival rate was 92%.

In a subgroup of 19 patients with previously treated RET fusion–positive thyroid cancer, 79% responded to the therapy; 1-year progression-free survival was 64%.

The most common adverse events of grade 3 or higher were hypertension (in 21% of the patients), an increase in ALT level (in 11%), an increase in AST level (in 9%), hyponatremia (in 8%), and diarrhea (in 6%). Selpercatinib was discontinued by 12 patients because of drug-related adverse events.

The study was funded by Loxo Oncology (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly) and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Kurzrock and Wirth report relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, as listed in the journal article.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinical data for the first-ever RET inhibitor, selpercatinib (Retevmo), show efficacy in two groups of patients with cancer – those with RET fusion–positive non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and those with RET-mutant medullary thyroid cancer (MTC).

The drug showed “very good efficacy and also very good tolerability” in both groups, said lead author Lori J. Wirth, MD, medical director of head and neck cancers, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, Boston, in a statement.

“The response rates are high, responses are very durable, and overall, the drug does not cause a lot of toxicity,” she said.

“If you have a clean, RET-specific inhibitor such as selpercatinib, then you can really pound down RET very strongly and hit the driver alteration much harder, with a better side effect profile,” Dr. Wirth added.

Both groups of patients were part of the phase 1/2 LIBRETTO-001 study, which served as the basis for the recent accelerated approval of selpercatinib by the Food and Drug Administration.

Data from LIBRETTO-001 were published in the New England Journal of Medicine as two articles, one on NSCLC patients and one on MTC patients.

There has been a “remarkable increase” in the number of targeted agents that are effective in treating patients with advanced cancers that harbor specific genomic alterations, commented Razelle Kurzrock, MD, from the University of California, San Diego, in an accompanying editorial.

Selpercatinib, a potent RET inhibitor, “is now poised to alter the landscape of another genomic subgroup – RET-altered cancers,” she wrote.

Multikinase inhibitors such as vandetanib and cabozantinib have ancillary RET-inhibitor activity and are also active against RET-driven cancers. But these drugs are limited by off-target side effects, Dr. Krurzrock pointed out. “In contrast, next-generation, highly potent, and selective RET inhibitors such as selpercatinib offer the potential for improved efficacy and a more satisfactory side effect profile.”

In both parts of the study, selpercatinib produced durable responses in a majority of patients. Only about 3% of patients discontinued taking selpercatinib because of drug-related adverse events.

Taken together, these results show that selpercatinib “had marked and durable antitumor activity in most patients with RET-altered thyroid cancer or NSCLC,” wrote Dr. Krurzrock. “RET abnormalities now join other genomic alterations such as NTRK fusions, tumor mutational burden, and deficient mismatchrepair genes across cancers and ALK, BRAF, EGFR, MET, and ROS1 alterations in NSCLC that warrant molecular screening strategies.”

Results in patients with RET-mutated NSCLC

All patients enrolled in the LIBRETTO-001 trial received selpercatinib 160 mg orally twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred.

Of 105 patients with NSCLC who had received at least one platinum-based chemotherapy regimen, the objective response rate was 64%. The median duration of response was 17.5 months.

At a median follow-up of 12.1 months, 63% of the responses were ongoing.

The cohort included 39 treatment-naive patients, among whom the response rate was even higher, at 85%; 90% of the responses were ongoing at 6 months. In addition, 11 patients had measurable central nervous system metastasis at study enrollment. Of this group, 91% achieved an intracranial response.

Common adverse events of grade 3 or higher included hypertension (in 14% of the patients), an increase in ALT level (in 12%), an increase in AST level (in 10%), hyponatremia (in 6%), and lymphopenia (in 6%). The drug was discontinued in 12 patients because of a drug-related adverse event.

Results in patients with RET-mutated MTC

Efficacy for MTC was evaluated in 55 patients with advanced or metastatic RET-mutant MTC who had previously been treated with cabozantinib, vandetanib, or both. The objective response rate was 69%. The 1-year progression-free survival rate was 82%.

For the 88 patients who had not previously received vandetanib or cabozantinib, the response rate was 73%. The 1-year progression-free survival rate was 92%.

In a subgroup of 19 patients with previously treated RET fusion–positive thyroid cancer, 79% responded to the therapy; 1-year progression-free survival was 64%.

The most common adverse events of grade 3 or higher were hypertension (in 21% of the patients), an increase in ALT level (in 11%), an increase in AST level (in 9%), hyponatremia (in 8%), and diarrhea (in 6%). Selpercatinib was discontinued by 12 patients because of drug-related adverse events.

The study was funded by Loxo Oncology (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly) and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Kurzrock and Wirth report relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, as listed in the journal article.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Bumps on the thighs

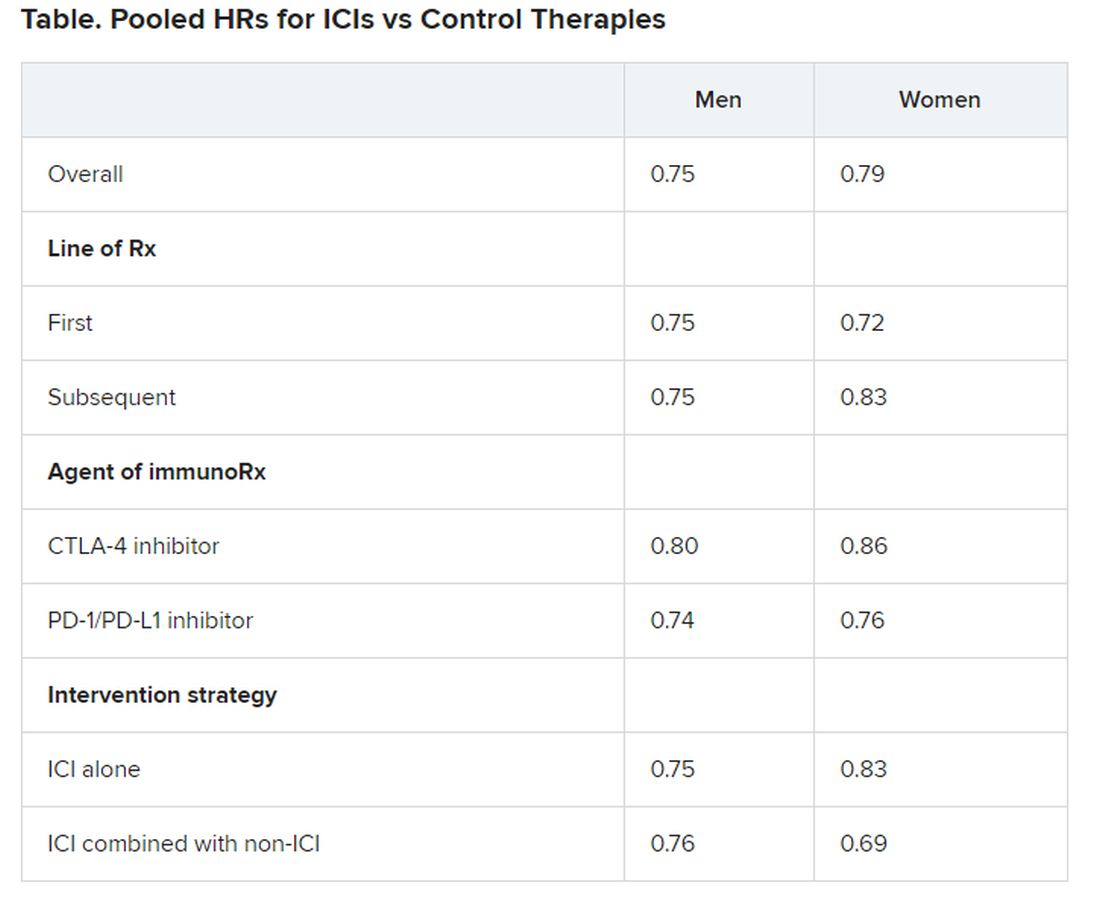

The photograph submitted for the telemedicine visit showed 2 classic umbilicated lesions and 1 dome-shaped papule consistent with molluscum contagiosum. Not all skin conditions can be diagnosed or treated via telehealth, but with a careful history, cooperative patients (and parents in this case), and photos taken on newer cell phones or digital cameras, many conditions can be diagnosed and managed appropriately.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the Molluscipox genus poxvirus and Is commonly seen in preschool and school-aged children. It can be passed through direct contact with infected individuals or spread by fomites. (In this case, the child may have picked up the virus by sharing a towel with an infected individual.)

The flesh-colored lesions are umbilicated or popular, and occur in clusters on the trunk, face, and extremities. Typically, the lesions will resolve spontaneously, but it may take several weeks to many months for resolution.

Given this lengthy time for spontaneous resolution, the risk of spreading to family members or other contacts, and the skin’s appearance, many patients choose to treat the lesions. Treatment options include curettage, cryosurgery, and laser. Available topical destructive agents include podophyllotoxin, trichloroacetic acid, benzoyl peroxide, potassium hydroxide, and cantharidin (which is from the blister beetle and often difficult to obtain). There also are naturopathic topical products and immune system modulators, including topical imiquimod. These treatments are commonly used, but are off-label for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.

The family was counseled that there is debate about the effectiveness of imiquimod for molluscum contagiosum, but that some studies find it to be useful. In this case, the mother chose a prescription for imiquimod cream 5%, to be applied 3 times weekly at bedtime until the lesions resolved. (The cream can be used for up to 16 weeks.) The family was advised that erythema and irritation are expected adverse effects at the application site.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Monastirli A, et al. Topical imiquimod is an effective and safe drug for molluscum contagiosum in children. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:164-166.

The photograph submitted for the telemedicine visit showed 2 classic umbilicated lesions and 1 dome-shaped papule consistent with molluscum contagiosum. Not all skin conditions can be diagnosed or treated via telehealth, but with a careful history, cooperative patients (and parents in this case), and photos taken on newer cell phones or digital cameras, many conditions can be diagnosed and managed appropriately.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the Molluscipox genus poxvirus and Is commonly seen in preschool and school-aged children. It can be passed through direct contact with infected individuals or spread by fomites. (In this case, the child may have picked up the virus by sharing a towel with an infected individual.)

The flesh-colored lesions are umbilicated or popular, and occur in clusters on the trunk, face, and extremities. Typically, the lesions will resolve spontaneously, but it may take several weeks to many months for resolution.

Given this lengthy time for spontaneous resolution, the risk of spreading to family members or other contacts, and the skin’s appearance, many patients choose to treat the lesions. Treatment options include curettage, cryosurgery, and laser. Available topical destructive agents include podophyllotoxin, trichloroacetic acid, benzoyl peroxide, potassium hydroxide, and cantharidin (which is from the blister beetle and often difficult to obtain). There also are naturopathic topical products and immune system modulators, including topical imiquimod. These treatments are commonly used, but are off-label for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.

The family was counseled that there is debate about the effectiveness of imiquimod for molluscum contagiosum, but that some studies find it to be useful. In this case, the mother chose a prescription for imiquimod cream 5%, to be applied 3 times weekly at bedtime until the lesions resolved. (The cream can be used for up to 16 weeks.) The family was advised that erythema and irritation are expected adverse effects at the application site.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The photograph submitted for the telemedicine visit showed 2 classic umbilicated lesions and 1 dome-shaped papule consistent with molluscum contagiosum. Not all skin conditions can be diagnosed or treated via telehealth, but with a careful history, cooperative patients (and parents in this case), and photos taken on newer cell phones or digital cameras, many conditions can be diagnosed and managed appropriately.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the Molluscipox genus poxvirus and Is commonly seen in preschool and school-aged children. It can be passed through direct contact with infected individuals or spread by fomites. (In this case, the child may have picked up the virus by sharing a towel with an infected individual.)

The flesh-colored lesions are umbilicated or popular, and occur in clusters on the trunk, face, and extremities. Typically, the lesions will resolve spontaneously, but it may take several weeks to many months for resolution.

Given this lengthy time for spontaneous resolution, the risk of spreading to family members or other contacts, and the skin’s appearance, many patients choose to treat the lesions. Treatment options include curettage, cryosurgery, and laser. Available topical destructive agents include podophyllotoxin, trichloroacetic acid, benzoyl peroxide, potassium hydroxide, and cantharidin (which is from the blister beetle and often difficult to obtain). There also are naturopathic topical products and immune system modulators, including topical imiquimod. These treatments are commonly used, but are off-label for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.

The family was counseled that there is debate about the effectiveness of imiquimod for molluscum contagiosum, but that some studies find it to be useful. In this case, the mother chose a prescription for imiquimod cream 5%, to be applied 3 times weekly at bedtime until the lesions resolved. (The cream can be used for up to 16 weeks.) The family was advised that erythema and irritation are expected adverse effects at the application site.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Monastirli A, et al. Topical imiquimod is an effective and safe drug for molluscum contagiosum in children. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:164-166.

Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Monastirli A, et al. Topical imiquimod is an effective and safe drug for molluscum contagiosum in children. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:164-166.

Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in kids tied to local rates

As communities wrestle with the decision to send children back to school or opt for distance learning, a key question is how many children are likely to have asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections.

“The strong association between prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in children who are asymptomatic and contemporaneous weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population ... provides a simple means for institutions to estimate local pediatric asymptomatic prevalence from the publicly available Johns Hopkins University database,” researchers say in an article published online August 25 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Ana Marija Sola, BS, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues examined the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among 33,041 children who underwent routine testing in April and May when hospitals resumed elective medical and surgical care. The hospitals performed reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2 RNA before surgery, clinic visits, or hospital admissions. Pediatric otolaryngologists reported the prevalence data through May 29 as part of a quality improvement project.

In all, 250 patients tested positive for the virus, for an overall prevalence of 0.65%. Across 25 geographic areas, the prevalence ranged from 0% to 2.2%. By region, prevalence was highest in the Northeast, at 0.90%, and the Midwest, at 0.87%; prevalence was lower in the West, at 0.59%, and the South, at 0.52%.

To get a sense of how those rates compared with overall rates in the same geographic areas, the researchers used the Johns Hopkins University confirmed cases database to calculate the average weekly incidence of COVID-19 for the entire population for each geographic area.

“Asymptomatic pediatric prevalence was significantly associated with weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population during the 6-week period over which most testing of individuals without symptoms occurred,” Ms. Sola and colleagues reported. An analysis using additional data from 11 geographic areas demonstrated that this association persisted at a later time point.

The study provides “another window on the question of how likely is it that an asymptomatic child will be carrying coronavirus,” said Susan E. Coffin, MD, MPH, an attending physician for the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. However, important related questions remain, said Dr. Coffin, who was not involved with the study.

For one, it is unclear how many children remain asymptomatic in comparison with those who were in a presymptomatic phase at the time of testing. And importantly, “what proportion of these children are infectious?” said Dr. Coffin. “There is some data to suggest that children with asymptomatic infection may be less infectious than children with symptomatic infection.”

It also could be that patients seen at children’s hospitals differ from the general pediatric population. “What does this look like if you do the exact same study in a group of randomly selected children, not children who are queueing up to have a procedure? ... And what do these numbers look like now that stay-at-home orders have been lifted?” Dr. Coffin asked.

Further studies are needed to establish that detection of COVID-19 in the general population is predictive of the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic children, Dr. Coffin said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As communities wrestle with the decision to send children back to school or opt for distance learning, a key question is how many children are likely to have asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections.

“The strong association between prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in children who are asymptomatic and contemporaneous weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population ... provides a simple means for institutions to estimate local pediatric asymptomatic prevalence from the publicly available Johns Hopkins University database,” researchers say in an article published online August 25 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Ana Marija Sola, BS, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues examined the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among 33,041 children who underwent routine testing in April and May when hospitals resumed elective medical and surgical care. The hospitals performed reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2 RNA before surgery, clinic visits, or hospital admissions. Pediatric otolaryngologists reported the prevalence data through May 29 as part of a quality improvement project.

In all, 250 patients tested positive for the virus, for an overall prevalence of 0.65%. Across 25 geographic areas, the prevalence ranged from 0% to 2.2%. By region, prevalence was highest in the Northeast, at 0.90%, and the Midwest, at 0.87%; prevalence was lower in the West, at 0.59%, and the South, at 0.52%.

To get a sense of how those rates compared with overall rates in the same geographic areas, the researchers used the Johns Hopkins University confirmed cases database to calculate the average weekly incidence of COVID-19 for the entire population for each geographic area.

“Asymptomatic pediatric prevalence was significantly associated with weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population during the 6-week period over which most testing of individuals without symptoms occurred,” Ms. Sola and colleagues reported. An analysis using additional data from 11 geographic areas demonstrated that this association persisted at a later time point.

The study provides “another window on the question of how likely is it that an asymptomatic child will be carrying coronavirus,” said Susan E. Coffin, MD, MPH, an attending physician for the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. However, important related questions remain, said Dr. Coffin, who was not involved with the study.

For one, it is unclear how many children remain asymptomatic in comparison with those who were in a presymptomatic phase at the time of testing. And importantly, “what proportion of these children are infectious?” said Dr. Coffin. “There is some data to suggest that children with asymptomatic infection may be less infectious than children with symptomatic infection.”

It also could be that patients seen at children’s hospitals differ from the general pediatric population. “What does this look like if you do the exact same study in a group of randomly selected children, not children who are queueing up to have a procedure? ... And what do these numbers look like now that stay-at-home orders have been lifted?” Dr. Coffin asked.

Further studies are needed to establish that detection of COVID-19 in the general population is predictive of the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic children, Dr. Coffin said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As communities wrestle with the decision to send children back to school or opt for distance learning, a key question is how many children are likely to have asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections.

“The strong association between prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in children who are asymptomatic and contemporaneous weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population ... provides a simple means for institutions to estimate local pediatric asymptomatic prevalence from the publicly available Johns Hopkins University database,” researchers say in an article published online August 25 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Ana Marija Sola, BS, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues examined the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among 33,041 children who underwent routine testing in April and May when hospitals resumed elective medical and surgical care. The hospitals performed reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2 RNA before surgery, clinic visits, or hospital admissions. Pediatric otolaryngologists reported the prevalence data through May 29 as part of a quality improvement project.

In all, 250 patients tested positive for the virus, for an overall prevalence of 0.65%. Across 25 geographic areas, the prevalence ranged from 0% to 2.2%. By region, prevalence was highest in the Northeast, at 0.90%, and the Midwest, at 0.87%; prevalence was lower in the West, at 0.59%, and the South, at 0.52%.

To get a sense of how those rates compared with overall rates in the same geographic areas, the researchers used the Johns Hopkins University confirmed cases database to calculate the average weekly incidence of COVID-19 for the entire population for each geographic area.

“Asymptomatic pediatric prevalence was significantly associated with weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population during the 6-week period over which most testing of individuals without symptoms occurred,” Ms. Sola and colleagues reported. An analysis using additional data from 11 geographic areas demonstrated that this association persisted at a later time point.

The study provides “another window on the question of how likely is it that an asymptomatic child will be carrying coronavirus,” said Susan E. Coffin, MD, MPH, an attending physician for the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. However, important related questions remain, said Dr. Coffin, who was not involved with the study.

For one, it is unclear how many children remain asymptomatic in comparison with those who were in a presymptomatic phase at the time of testing. And importantly, “what proportion of these children are infectious?” said Dr. Coffin. “There is some data to suggest that children with asymptomatic infection may be less infectious than children with symptomatic infection.”

It also could be that patients seen at children’s hospitals differ from the general pediatric population. “What does this look like if you do the exact same study in a group of randomly selected children, not children who are queueing up to have a procedure? ... And what do these numbers look like now that stay-at-home orders have been lifted?” Dr. Coffin asked.

Further studies are needed to establish that detection of COVID-19 in the general population is predictive of the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic children, Dr. Coffin said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Aspirin may accelerate cancer progression in older adults

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.