User login

Signs of an ‘October vaccine surprise’ alarm career scientists

who have pledged not to release any vaccine unless it’s proved safe and effective.

In podcasts, public forums, social media and medical journals, a growing number of prominent health leaders say they fear that Mr. Trump – who has repeatedly signaled his desire for the swift approval of a vaccine and his displeasure with perceived delays at the FDA – will take matters into his own hands, running roughshod over the usual regulatory process.

It would reflect another attempt by a norm-breaking administration, poised to ram through a Supreme Court nominee opposed to existing abortion rights and the Affordable Care Act, to inject politics into sensitive public health decisions. Mr. Trump has repeatedly contradicted the advice of senior scientists on COVID-19 while pushing controversial treatments for the disease.

If the executive branch were to overrule the FDA’s scientific judgment, a vaccine of limited efficacy and, worse, unknown side effects could be rushed to market.

The worries intensified over the weekend, after Alex Azar, the administration’s secretary of Health & Human Services, asserted his agency’s rule-making authority over the FDA. HHS spokesperson Caitlin Oakley said Mr. Azar’s decision had no bearing on the vaccine approval process.

Vaccines are typically approved by the FDA. Alternatively, Mr. Azar – who reports directly to Mr. Trump – can issue an emergency use authorization, even before any vaccines have been shown to be safe and effective in late-stage clinical trials.

“Yes, this scenario is certainly possible legally and politically,” said Jerry Avorn, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who outlined such an event in the New England Journal of Medicine. He said it “seems frighteningly more plausible each day.”

Vaccine experts and public health officials are particularly vexed by the possibility because it could ruin the fragile public confidence in a COVID-19 vaccine. It might put scientific authorities in the position of urging people not to be vaccinated after years of coaxing hesitant parents to ignore baseless fears.

Physicians might refuse to administer a vaccine approved with inadequate data, said Preeti Malani, MD, chief health officer and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, in a recent webinar. “You could have a safe, effective vaccine that no one wants to take.” A recent KFF poll found that 54% of Americans would not submit to a COVID-19 vaccine authorized before Election Day.

After this story was published, an HHS official said that Mr. Azar “will defer completely to the FDA” as the agency weighs whether to approve a vaccine produced through the government’s Operation Warp Speed effort.

“The idea the Secretary would approve or authorize a vaccine over the FDA’s objections is preposterous and betrays ignorance of the transparent process that we’re following for the development of the OWS vaccines,” HHS chief of staff Brian Harrison wrote in an email.

White House spokesperson Judd Deere dismissed the scientists’ concerns, saying Trump cared only about the public’s safety and health. “This false narrative that the media and Democrats have created that politics is influencing approvals is not only false but is a danger to the American public,” he said.

Usually, the FDA approves vaccines only after companies submit years of data proving that a vaccine is safe and effective. But a 2004 law allows the FDA to issue an emergency use authorization with much less evidence, as long as the vaccine “may be effective” and its “known and potential benefits” outweigh its “known and potential risks.”

Many scientists doubt a vaccine could meet those criteria before the election. But the terms might be legally vague enough to allow the administration to take such steps.

Moncef Slaoui, chief scientific adviser to Operation Warp Speed, the government program aiming to more quickly develop COVID-19 vaccines, said it’s “extremely unlikely” that vaccine trial results will be ready before the end of October.

Mr. Trump, however, has insisted repeatedly that a vaccine to fight the pandemic that has claimed 200,000 American lives will be distributed starting next month. He reiterated that claim Saturday at a campaign rally in Fayetteville, N.C.

The vaccine will be ready “in a matter of weeks,” he said. “We will end the pandemic from China.”

Although pharmaceutical companies have launched three clinical trials in the United States, no one can say with certainty when those trials will have enough data to determine whether the vaccines are safe and effective.

Officials at Moderna, whose vaccine is being tested in 30,000 volunteers, have said their studies could produce a result by the end of the year, although the final analysis could take place next spring.

Pfizer executives, who have expanded their clinical trial to 44,000 participants, boast that they could know their vaccine works by the end of October.

AstraZeneca’s U.S. vaccine trial, which was scheduled to enroll 30,000 volunteers, is on hold pending an investigation of a possible vaccine-related illness.

Scientists have warned for months that the Trump administration could try to win the election with an “October surprise,” authorizing a vaccine that hasn’t been fully tested. “I don’t think people are crazy to be thinking about all of this,” said William Schultz, a partner in a Washington, D.C., law firm who served as a former FDA commissioner for policy and as general counsel for HHS.

“You’ve got a president saying you’ll have an approval in October. Everybody’s wondering how that could happen.”

In an opinion piece published in the Wall Street Journal, conservative former FDA commissioners Scott Gottlieb and Mark McClellan argued that presidential intrusion was unlikely because the FDA’s “thorough and transparent process doesn’t lend itself to meddling. Any deviation would quickly be apparent.”

But the administration has demonstrated a willingness to bend the agency to its will. The FDA has been criticized for issuing emergency authorizations for two COVID-19 treatments that were boosted by the president but lacked strong evidence to support them: hydroxychloroquine and convalescent plasma.

Mr. Azar has sidelined the FDA in other ways, such as by blocking the agency from regulating lab-developed tests, including tests for the novel coronavirus.

Although FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn told the Financial Times he would be willing to approve emergency use of a vaccine before large-scale studies conclude, agency officials also have pledged to ensure the safety of any COVID-19 vaccines.

A senior FDA official who oversees vaccine approvals, Peter Marks, MD, has said he will quit if his agency rubber-stamps an unproven COVID-19 vaccine.

“I think there would be an outcry from the public health community second to none, which is my worst nightmare – my worst nightmare – because we will so confuse the public,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, in his weekly podcast.

Still, “even if a company did not want it to be done, even if the FDA did not want it to be done, he could still do that,” said Dr. Osterholm, in his podcast. “I hope that we’d never see that happen, but we have to entertain that’s a possibility.”

In the New England Journal editorial, Dr. Avorn and coauthor Aaron Kesselheim, MD, wondered whether Mr. Trump might invoke the 1950 Defense Production Act to force reluctant drug companies to manufacture their vaccines.

But Mr. Trump would have to sue a company to enforce the Defense Production Act, and the company would have a strong case in refusing, said Lawrence Gostin, director of Georgetown’s O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.

Also, he noted that Mr. Trump could not invoke the Defense Production Act unless a vaccine were “scientifically justified and approved by the FDA.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

who have pledged not to release any vaccine unless it’s proved safe and effective.

In podcasts, public forums, social media and medical journals, a growing number of prominent health leaders say they fear that Mr. Trump – who has repeatedly signaled his desire for the swift approval of a vaccine and his displeasure with perceived delays at the FDA – will take matters into his own hands, running roughshod over the usual regulatory process.

It would reflect another attempt by a norm-breaking administration, poised to ram through a Supreme Court nominee opposed to existing abortion rights and the Affordable Care Act, to inject politics into sensitive public health decisions. Mr. Trump has repeatedly contradicted the advice of senior scientists on COVID-19 while pushing controversial treatments for the disease.

If the executive branch were to overrule the FDA’s scientific judgment, a vaccine of limited efficacy and, worse, unknown side effects could be rushed to market.

The worries intensified over the weekend, after Alex Azar, the administration’s secretary of Health & Human Services, asserted his agency’s rule-making authority over the FDA. HHS spokesperson Caitlin Oakley said Mr. Azar’s decision had no bearing on the vaccine approval process.

Vaccines are typically approved by the FDA. Alternatively, Mr. Azar – who reports directly to Mr. Trump – can issue an emergency use authorization, even before any vaccines have been shown to be safe and effective in late-stage clinical trials.

“Yes, this scenario is certainly possible legally and politically,” said Jerry Avorn, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who outlined such an event in the New England Journal of Medicine. He said it “seems frighteningly more plausible each day.”

Vaccine experts and public health officials are particularly vexed by the possibility because it could ruin the fragile public confidence in a COVID-19 vaccine. It might put scientific authorities in the position of urging people not to be vaccinated after years of coaxing hesitant parents to ignore baseless fears.

Physicians might refuse to administer a vaccine approved with inadequate data, said Preeti Malani, MD, chief health officer and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, in a recent webinar. “You could have a safe, effective vaccine that no one wants to take.” A recent KFF poll found that 54% of Americans would not submit to a COVID-19 vaccine authorized before Election Day.

After this story was published, an HHS official said that Mr. Azar “will defer completely to the FDA” as the agency weighs whether to approve a vaccine produced through the government’s Operation Warp Speed effort.

“The idea the Secretary would approve or authorize a vaccine over the FDA’s objections is preposterous and betrays ignorance of the transparent process that we’re following for the development of the OWS vaccines,” HHS chief of staff Brian Harrison wrote in an email.

White House spokesperson Judd Deere dismissed the scientists’ concerns, saying Trump cared only about the public’s safety and health. “This false narrative that the media and Democrats have created that politics is influencing approvals is not only false but is a danger to the American public,” he said.

Usually, the FDA approves vaccines only after companies submit years of data proving that a vaccine is safe and effective. But a 2004 law allows the FDA to issue an emergency use authorization with much less evidence, as long as the vaccine “may be effective” and its “known and potential benefits” outweigh its “known and potential risks.”

Many scientists doubt a vaccine could meet those criteria before the election. But the terms might be legally vague enough to allow the administration to take such steps.

Moncef Slaoui, chief scientific adviser to Operation Warp Speed, the government program aiming to more quickly develop COVID-19 vaccines, said it’s “extremely unlikely” that vaccine trial results will be ready before the end of October.

Mr. Trump, however, has insisted repeatedly that a vaccine to fight the pandemic that has claimed 200,000 American lives will be distributed starting next month. He reiterated that claim Saturday at a campaign rally in Fayetteville, N.C.

The vaccine will be ready “in a matter of weeks,” he said. “We will end the pandemic from China.”

Although pharmaceutical companies have launched three clinical trials in the United States, no one can say with certainty when those trials will have enough data to determine whether the vaccines are safe and effective.

Officials at Moderna, whose vaccine is being tested in 30,000 volunteers, have said their studies could produce a result by the end of the year, although the final analysis could take place next spring.

Pfizer executives, who have expanded their clinical trial to 44,000 participants, boast that they could know their vaccine works by the end of October.

AstraZeneca’s U.S. vaccine trial, which was scheduled to enroll 30,000 volunteers, is on hold pending an investigation of a possible vaccine-related illness.

Scientists have warned for months that the Trump administration could try to win the election with an “October surprise,” authorizing a vaccine that hasn’t been fully tested. “I don’t think people are crazy to be thinking about all of this,” said William Schultz, a partner in a Washington, D.C., law firm who served as a former FDA commissioner for policy and as general counsel for HHS.

“You’ve got a president saying you’ll have an approval in October. Everybody’s wondering how that could happen.”

In an opinion piece published in the Wall Street Journal, conservative former FDA commissioners Scott Gottlieb and Mark McClellan argued that presidential intrusion was unlikely because the FDA’s “thorough and transparent process doesn’t lend itself to meddling. Any deviation would quickly be apparent.”

But the administration has demonstrated a willingness to bend the agency to its will. The FDA has been criticized for issuing emergency authorizations for two COVID-19 treatments that were boosted by the president but lacked strong evidence to support them: hydroxychloroquine and convalescent plasma.

Mr. Azar has sidelined the FDA in other ways, such as by blocking the agency from regulating lab-developed tests, including tests for the novel coronavirus.

Although FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn told the Financial Times he would be willing to approve emergency use of a vaccine before large-scale studies conclude, agency officials also have pledged to ensure the safety of any COVID-19 vaccines.

A senior FDA official who oversees vaccine approvals, Peter Marks, MD, has said he will quit if his agency rubber-stamps an unproven COVID-19 vaccine.

“I think there would be an outcry from the public health community second to none, which is my worst nightmare – my worst nightmare – because we will so confuse the public,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, in his weekly podcast.

Still, “even if a company did not want it to be done, even if the FDA did not want it to be done, he could still do that,” said Dr. Osterholm, in his podcast. “I hope that we’d never see that happen, but we have to entertain that’s a possibility.”

In the New England Journal editorial, Dr. Avorn and coauthor Aaron Kesselheim, MD, wondered whether Mr. Trump might invoke the 1950 Defense Production Act to force reluctant drug companies to manufacture their vaccines.

But Mr. Trump would have to sue a company to enforce the Defense Production Act, and the company would have a strong case in refusing, said Lawrence Gostin, director of Georgetown’s O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.

Also, he noted that Mr. Trump could not invoke the Defense Production Act unless a vaccine were “scientifically justified and approved by the FDA.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

who have pledged not to release any vaccine unless it’s proved safe and effective.

In podcasts, public forums, social media and medical journals, a growing number of prominent health leaders say they fear that Mr. Trump – who has repeatedly signaled his desire for the swift approval of a vaccine and his displeasure with perceived delays at the FDA – will take matters into his own hands, running roughshod over the usual regulatory process.

It would reflect another attempt by a norm-breaking administration, poised to ram through a Supreme Court nominee opposed to existing abortion rights and the Affordable Care Act, to inject politics into sensitive public health decisions. Mr. Trump has repeatedly contradicted the advice of senior scientists on COVID-19 while pushing controversial treatments for the disease.

If the executive branch were to overrule the FDA’s scientific judgment, a vaccine of limited efficacy and, worse, unknown side effects could be rushed to market.

The worries intensified over the weekend, after Alex Azar, the administration’s secretary of Health & Human Services, asserted his agency’s rule-making authority over the FDA. HHS spokesperson Caitlin Oakley said Mr. Azar’s decision had no bearing on the vaccine approval process.

Vaccines are typically approved by the FDA. Alternatively, Mr. Azar – who reports directly to Mr. Trump – can issue an emergency use authorization, even before any vaccines have been shown to be safe and effective in late-stage clinical trials.

“Yes, this scenario is certainly possible legally and politically,” said Jerry Avorn, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who outlined such an event in the New England Journal of Medicine. He said it “seems frighteningly more plausible each day.”

Vaccine experts and public health officials are particularly vexed by the possibility because it could ruin the fragile public confidence in a COVID-19 vaccine. It might put scientific authorities in the position of urging people not to be vaccinated after years of coaxing hesitant parents to ignore baseless fears.

Physicians might refuse to administer a vaccine approved with inadequate data, said Preeti Malani, MD, chief health officer and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, in a recent webinar. “You could have a safe, effective vaccine that no one wants to take.” A recent KFF poll found that 54% of Americans would not submit to a COVID-19 vaccine authorized before Election Day.

After this story was published, an HHS official said that Mr. Azar “will defer completely to the FDA” as the agency weighs whether to approve a vaccine produced through the government’s Operation Warp Speed effort.

“The idea the Secretary would approve or authorize a vaccine over the FDA’s objections is preposterous and betrays ignorance of the transparent process that we’re following for the development of the OWS vaccines,” HHS chief of staff Brian Harrison wrote in an email.

White House spokesperson Judd Deere dismissed the scientists’ concerns, saying Trump cared only about the public’s safety and health. “This false narrative that the media and Democrats have created that politics is influencing approvals is not only false but is a danger to the American public,” he said.

Usually, the FDA approves vaccines only after companies submit years of data proving that a vaccine is safe and effective. But a 2004 law allows the FDA to issue an emergency use authorization with much less evidence, as long as the vaccine “may be effective” and its “known and potential benefits” outweigh its “known and potential risks.”

Many scientists doubt a vaccine could meet those criteria before the election. But the terms might be legally vague enough to allow the administration to take such steps.

Moncef Slaoui, chief scientific adviser to Operation Warp Speed, the government program aiming to more quickly develop COVID-19 vaccines, said it’s “extremely unlikely” that vaccine trial results will be ready before the end of October.

Mr. Trump, however, has insisted repeatedly that a vaccine to fight the pandemic that has claimed 200,000 American lives will be distributed starting next month. He reiterated that claim Saturday at a campaign rally in Fayetteville, N.C.

The vaccine will be ready “in a matter of weeks,” he said. “We will end the pandemic from China.”

Although pharmaceutical companies have launched three clinical trials in the United States, no one can say with certainty when those trials will have enough data to determine whether the vaccines are safe and effective.

Officials at Moderna, whose vaccine is being tested in 30,000 volunteers, have said their studies could produce a result by the end of the year, although the final analysis could take place next spring.

Pfizer executives, who have expanded their clinical trial to 44,000 participants, boast that they could know their vaccine works by the end of October.

AstraZeneca’s U.S. vaccine trial, which was scheduled to enroll 30,000 volunteers, is on hold pending an investigation of a possible vaccine-related illness.

Scientists have warned for months that the Trump administration could try to win the election with an “October surprise,” authorizing a vaccine that hasn’t been fully tested. “I don’t think people are crazy to be thinking about all of this,” said William Schultz, a partner in a Washington, D.C., law firm who served as a former FDA commissioner for policy and as general counsel for HHS.

“You’ve got a president saying you’ll have an approval in October. Everybody’s wondering how that could happen.”

In an opinion piece published in the Wall Street Journal, conservative former FDA commissioners Scott Gottlieb and Mark McClellan argued that presidential intrusion was unlikely because the FDA’s “thorough and transparent process doesn’t lend itself to meddling. Any deviation would quickly be apparent.”

But the administration has demonstrated a willingness to bend the agency to its will. The FDA has been criticized for issuing emergency authorizations for two COVID-19 treatments that were boosted by the president but lacked strong evidence to support them: hydroxychloroquine and convalescent plasma.

Mr. Azar has sidelined the FDA in other ways, such as by blocking the agency from regulating lab-developed tests, including tests for the novel coronavirus.

Although FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn told the Financial Times he would be willing to approve emergency use of a vaccine before large-scale studies conclude, agency officials also have pledged to ensure the safety of any COVID-19 vaccines.

A senior FDA official who oversees vaccine approvals, Peter Marks, MD, has said he will quit if his agency rubber-stamps an unproven COVID-19 vaccine.

“I think there would be an outcry from the public health community second to none, which is my worst nightmare – my worst nightmare – because we will so confuse the public,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, in his weekly podcast.

Still, “even if a company did not want it to be done, even if the FDA did not want it to be done, he could still do that,” said Dr. Osterholm, in his podcast. “I hope that we’d never see that happen, but we have to entertain that’s a possibility.”

In the New England Journal editorial, Dr. Avorn and coauthor Aaron Kesselheim, MD, wondered whether Mr. Trump might invoke the 1950 Defense Production Act to force reluctant drug companies to manufacture their vaccines.

But Mr. Trump would have to sue a company to enforce the Defense Production Act, and the company would have a strong case in refusing, said Lawrence Gostin, director of Georgetown’s O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.

Also, he noted that Mr. Trump could not invoke the Defense Production Act unless a vaccine were “scientifically justified and approved by the FDA.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

COVID-19 Screening and Testing Among Patients With Neurologic Dysfunction: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist

From the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, Division of Neuroscience Intensive Care, Jackson, MS.

Abstract

Objective: To test a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening tool to identify patients who qualify for testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction who are unable to answer the usual screening questions, which could help to prevent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers to COVID-19.

Methods: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) was implemented at our institution for 1 week as a quality improvement project to improve the pathway for COVID-19 screening and testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction.

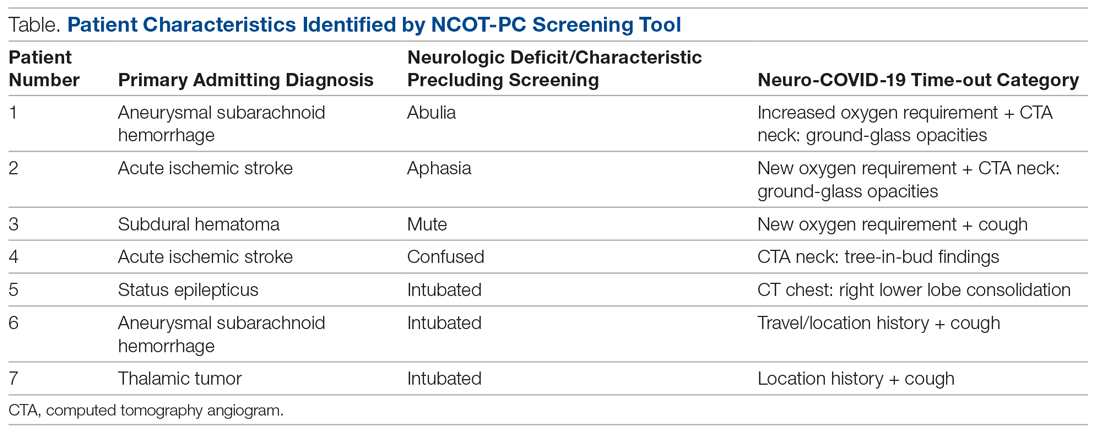

Results: A total of 14 new patients were admitted into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) service during the pilot period. The NCOT-PC was utilized on 9 (64%) patients with neurologic dysfunction; 7 of these patients were found to have a likelihood of requiring testing based on the NCOT-PC and were subsequently screened for COVID-19 testing by contacting the institution’s COVID-19 testing hotline (Med-Com). All these patients were subsequently transitioned into person-under-investigation status based on the determination from Med-Com. The NSICU staff involved were able to utilize NCOT-PC without issues. The NCOT-PC was immediately adopted into the NSICU process.

Conclusion: Use of the NCOT-PC tool was found to be feasible and improved the screening methodology of patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Keywords: coronavirus; health care planning; quality improvement; patient safety; medical decision-making; neuroscience intensive care unit.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered various standard emergent care pathways. Current recommendations regarding COVID-19 screening for testing involve asking patients about their symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.1 This standard screening method poses a problem when caring for patients with neurologic dysfunction. COVID-19 patients may pre-sent with conditions that affect their ability to answer questions, such as stroke, encephalitis, neuromuscular disorders, or headache, and that may preclude the use of standard screening for testing.2 Patients with acute neurologic dysfunction who cannot undergo standard screening may leave the emergency department (ED) and transition into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) or any intensive care unit (ICU) without a reliable COVID-19 screening test.

The Protected Code Stroke pathway offers protection in the emergent setting for patients with stroke when their COVID-19 status is unknown.3 A similar process has been applied at our institution for emergent management of patients with cerebrovascular disease (stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, the process from the ED after designating “difficult to screen” patients as persons under investigation (PUI) is unclear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has delineated the priorities for testing, with not all declared PUIs requiring testing.4 This poses a great challenge, because patients designated as PUIs require the same management as a COVID-19-positive patient, with negative-pressure isolation rooms as well as use of protective personal equipment (PPE), which may not be readily available. It was also recognized that, because the ED staff can be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, there may not be enough time to perform detailed screening of patients with neurologic dysfunction and that “reverse masking” may not be done consistently for nonintubated patients. This may place patients and health care workers at risk of unprotected exposure.

Recognizing these challenges, we created a Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) as a quality improvement project. The aim of this project was to improve and standardize the current process of identifying patients with neurologic dysfunction who require COVID-19 testing to decrease the risk of unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

Methods

Patients and Definitions

This quality improvement project was undertaken at the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU. Because this was a quality improvement project, an Institutional Review Board exemption was granted.

The NCOT-PC was utilized in consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU during a period of 1 week. “Neurologic dysfunction” encompasses any neurologic illness affecting the mental status and/or level of alertness, subsequently precluding the ability to reliably screen the patient utilizing standard COVID-19 screening. “Med-Com” at our institution is the equivalent of the national COVID-19 testing hotline, where our institution’s infectious diseases experts screen calls for testing and determine whether testing is warranted. “Unprotected exposure” means exposure to COVID-19 without adequate and appropriate PPE.

Quality Improvement Process

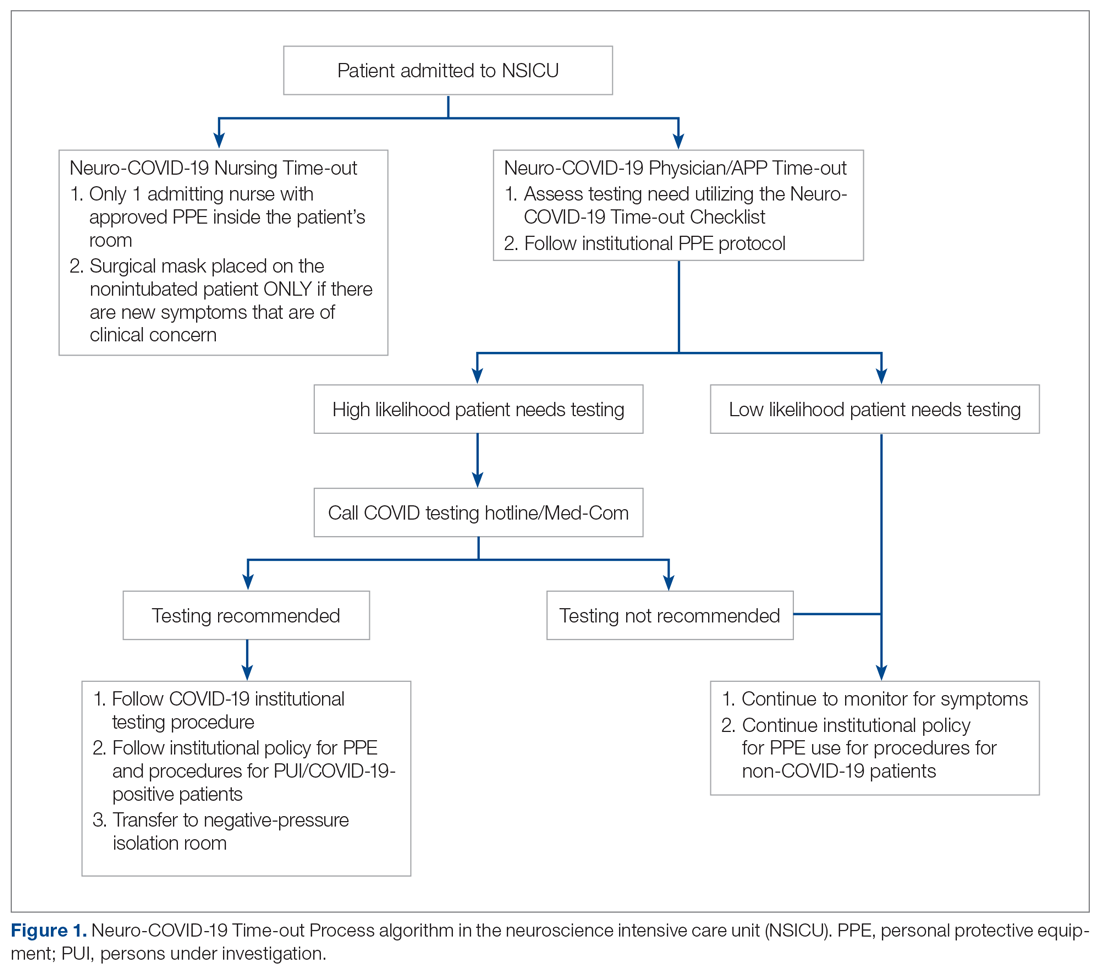

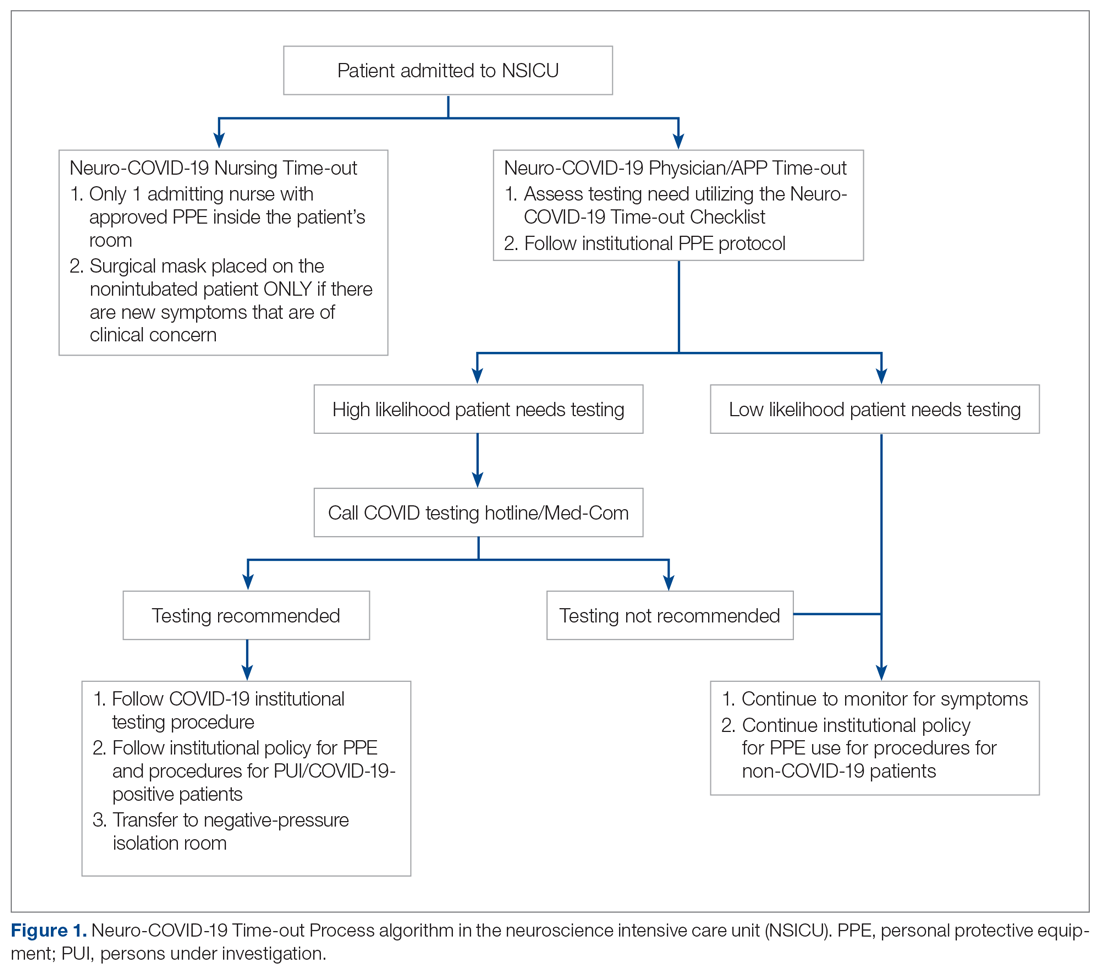

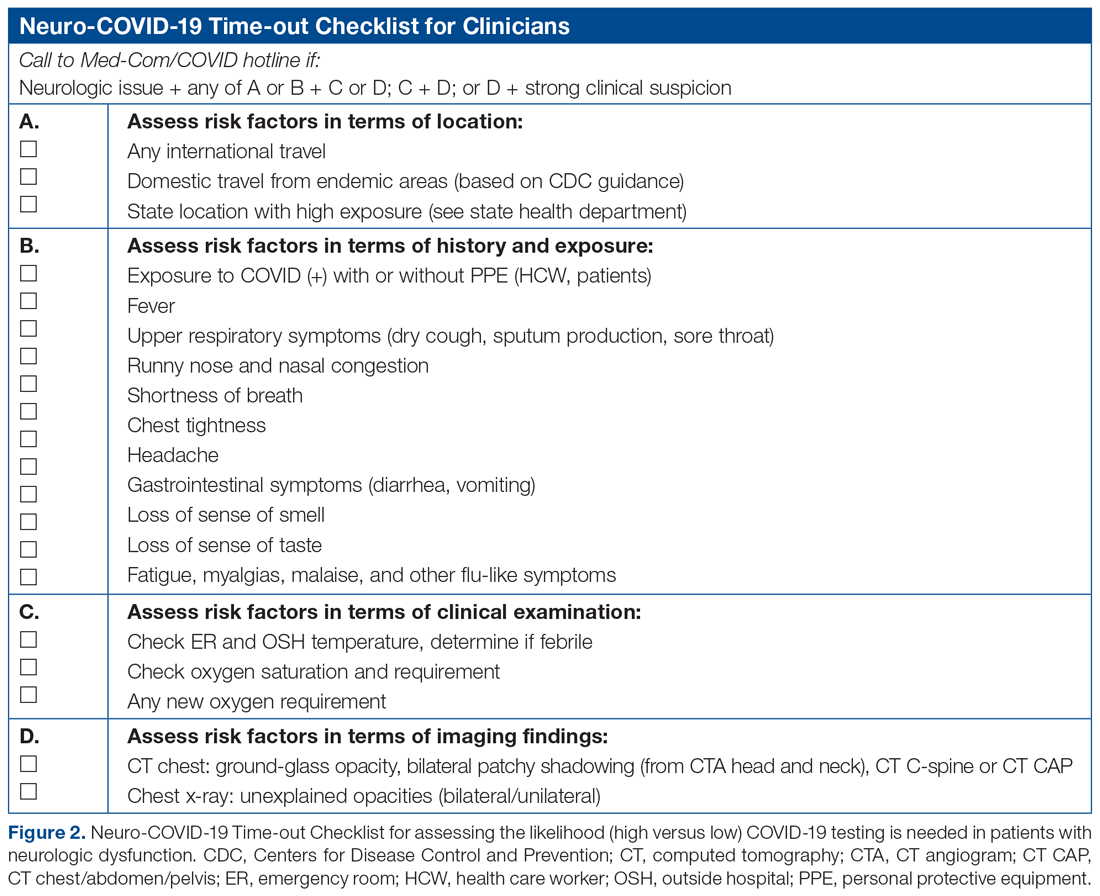

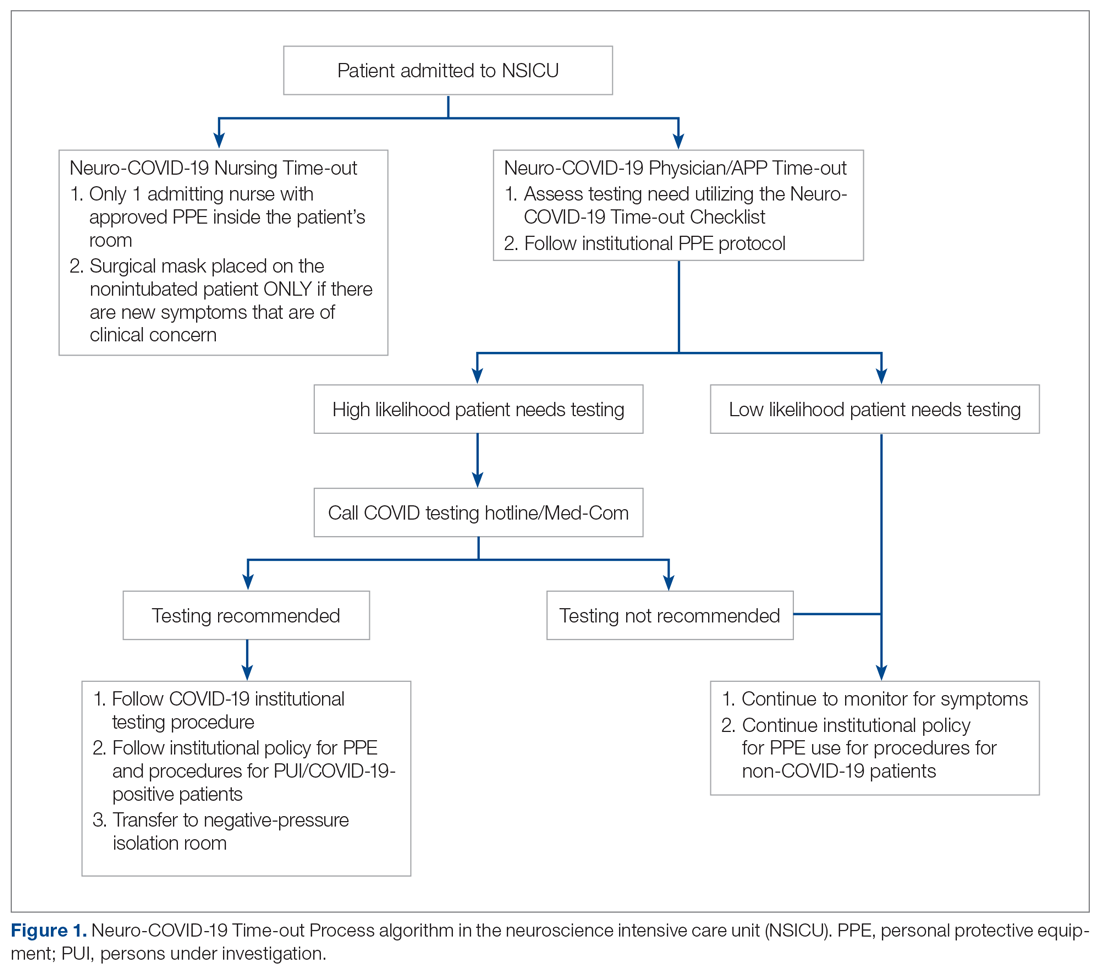

As more PUIs were being admitted to the institution, we used the Plan-Do-Study-Act method for process improvements in the NSICU.5 NSICU stakeholders, including attendings, the nurse manager, and nurse practitioners (NPs), developed an algorithm to facilitate the coordination of the NSICU staff in screening patients to identify those with a high likelihood of needing COVID-19 testing upon arrival in the NSICU (Figure 1). Once the NCOT-PC was finalized, NSICU stakeholders were educated regarding the use of this screening tool.

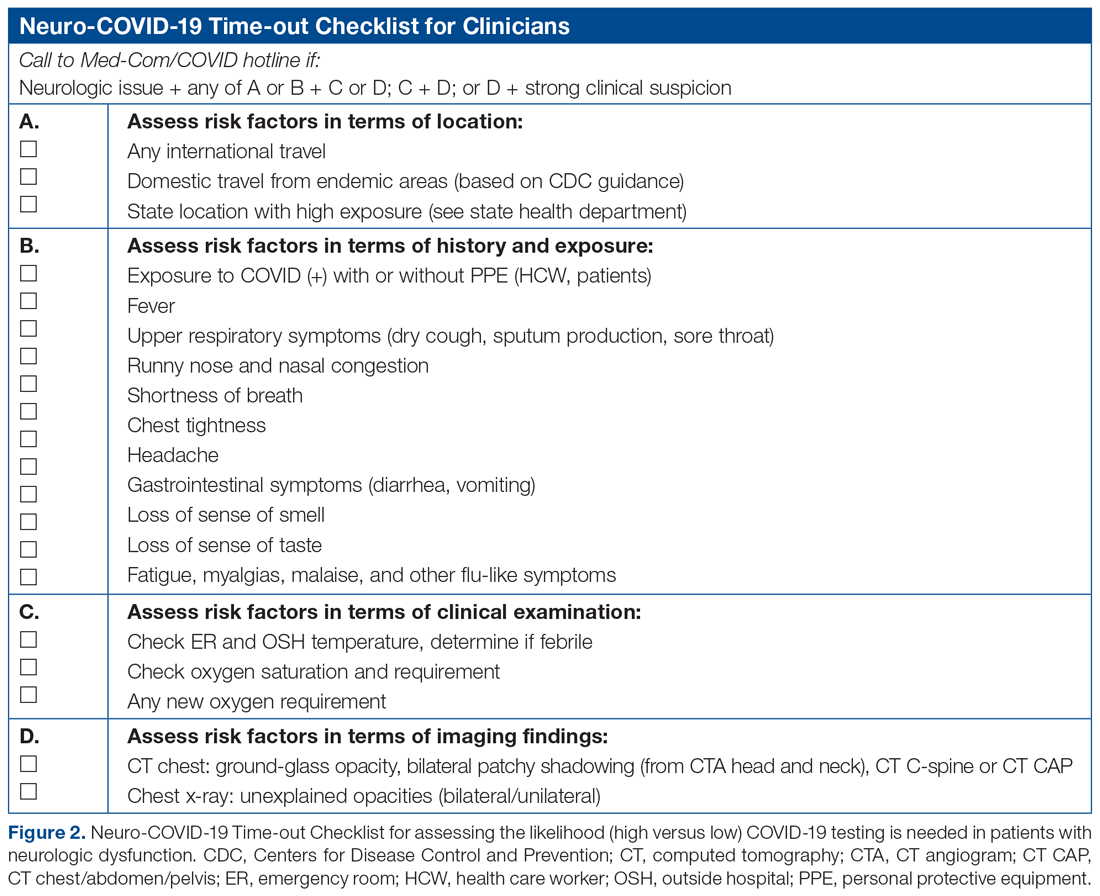

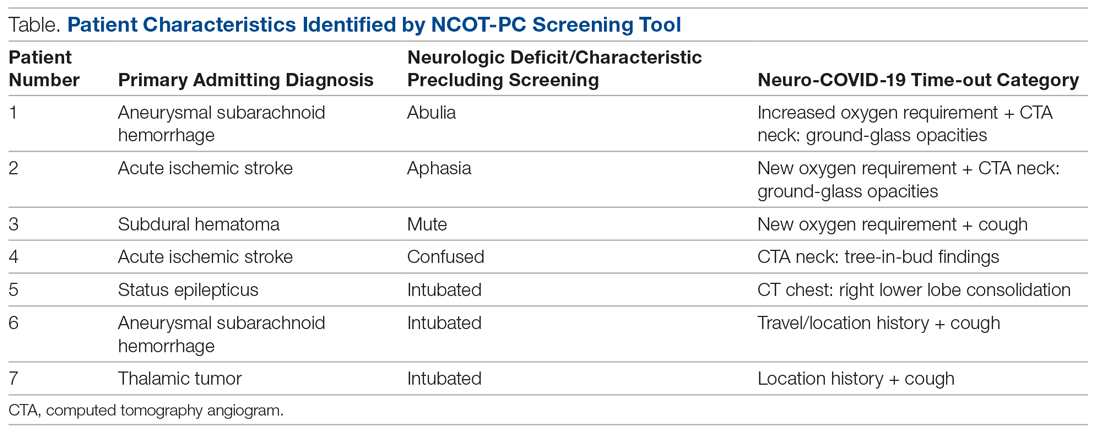

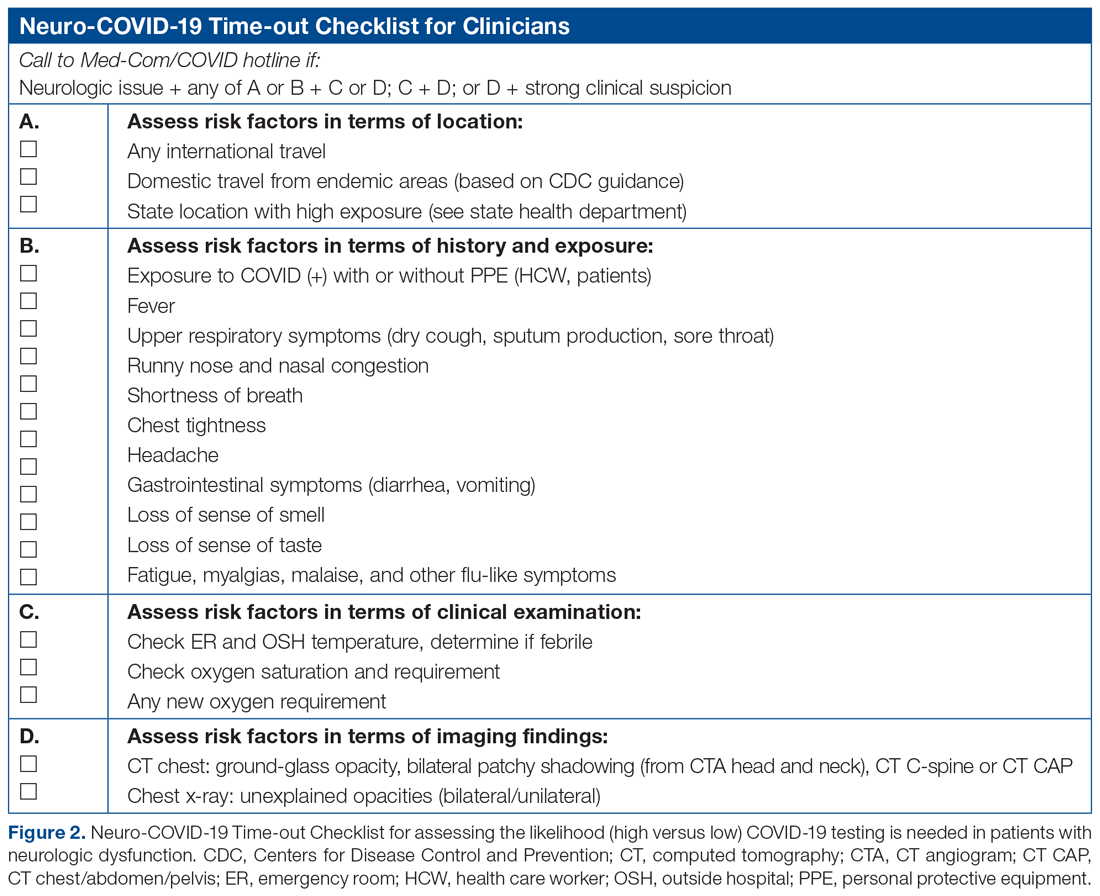

The checklist clinicians review when screening patients is shown in Figure 2. The risk factors comprising the checklist include patient history and clinical and radiographic characteristics that have been shown to be relevant for identifying patients with COVID-19.6,7 The imaging criteria utilize imaging that is part of the standard of care for NSICU patients. For example, computed tomography angiogram of the head and neck performed as part of the acute stroke protocol captures the upper part of the chest. These images are utilized for their incidental findings, such as apical ground-glass opacities and tree-in-bud formation. The risk factors applicable to the patient determine whether the clinician will call Med-Com for testing approval. Institutional COVID-19 processes were then followed accordingly.8 The decision from Med-Com was considered final, and no deviation from institutional policies was allowed.

NCOT-PC was utilized for consecutive days for 1 week before re-evaluation of its feasibility and adaptability.

Data Collection and Analysis

Consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted into the NSICU were assigned nonlinkable patient numbers. No identifiers were collected for the purpose of this project. The primary diagnosis for admission, the neurologic dysfunction that precluded standard screening, and checklist components that the patient fulfilled were collected.

To assess the tool’s feasibility, feedback regarding the ease of use of the NCOT-PC was gathered from the nurses, NPs, charge nurses, fellows, and other attendings. To assess the utility of the NCOT-PC in identifying patients who will be approved for COVID-19 testing, we calculated the proportion of patients who were deemed to have a high likelihood of testing and the proportion of patients who were approved for testing. Descriptive statistics were used, as applicable for the project, to summarize the utility of the NCOT-PC.

Results

We found that the NCOT-PC can be easily used by clinicians. The NSICU staff did not communicate any implementation issues, and since the NCOT-PC was implemented, no problems have been identified.

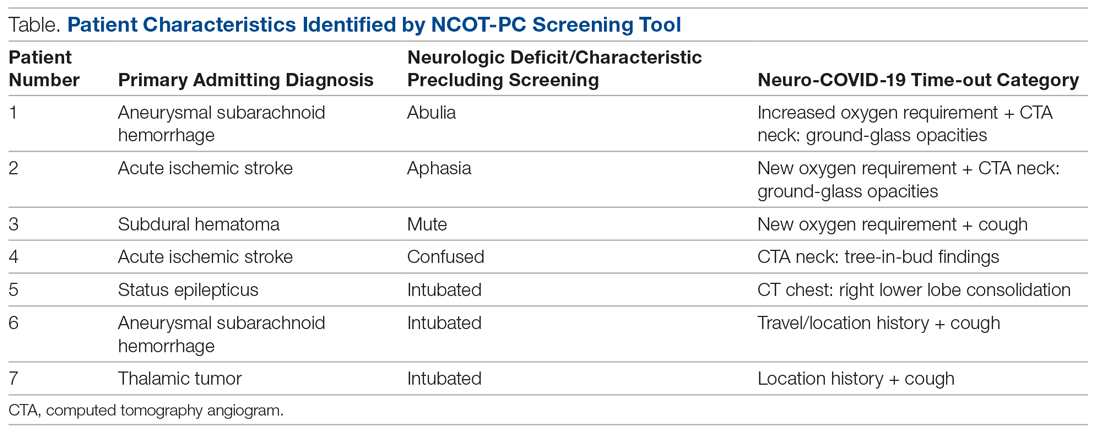

During the pilot period of the NCOT-PC, 14 new patients were admitted to the NSICU service. Nine (64%) of these had neurologic dysfunction, and the NCOT-PC was used to determine whether Med-Com should be called based on the patients’ likelihood (high vs low) of needing a COVID-19 test. Of those patients with neurologic dysfunction, 7 (78%) were deemed to have a high likelihood of needing a COVID-19 test based on the NCOT-PC. Med-Com was contacted regarding these patients, and all were deemed to require the COVID-19 test by Med-Com and were transitioned into PUI status per institutional policy (Table).

Discussion

The NCOT-PC project improved and standardized the process of identifying and screening patients with neurologic dysfunction for COVID-19 testing. The screening tool is feasible to use, and it decreased inadvertent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

The NCOT-PC was easy to administer. Educating the staff regarding the new process took only a few minutes and involved a meeting with the nurse manager, NPs, fellows, residents, and attendings. We found that this process works well in tandem with the standard institutional processes in place in terms of Protected Code Stroke pathway, PUI isolation, PPE use, and Med-Com screening for COVID-19 testing. Med-Com was called only if the patient fulfilled the checklist criteria. In addition, no extra cost was attributed to implementing the NCOT-PC, since we utilized imaging that was already done as part of the standard of care for patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The standardization of the process of screening for COVID-19 testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction improved patient selection. Before the NCOT-PC, there was no consistency in terms of who should get tested and the reason for testing patients with neurologic dysfunction. Patients can pass through the ED and arrive in the NSICU with an unclear screening status, which may cause inadvertent patient and health care worker exposure to COVID-19. With the NCOT-PC, we have avoided instances of inadvertent staff or patient exposure in the NSICU.

The NCOT-PC was adopted into the NSICU process after the first week it was piloted. Beyond the NSICU, the application of the NCOT-PC can be extended to any patient presentation that precludes standard screening, such as ED and interhospital transfers for stroke codes, trauma codes, code blue, or myocardial infarction codes. In our department, as we started the process of PCS for stroke codes, we included NCOT-PC for stroke patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The results of our initiative are largely limited by the decision-making process of Med-Com when patients are called in for testing. At the time of our project, there were no specific criteria used for patients with altered mental status, except for the standard screening methods, and it was through clinician-to-clinician discussion that testing decisions were made. Another limitation is the short period of time that the NCOT-PC was applied before adoption.

In summary, the NCOT-PC tool improved the screening process for COVID-19 testing in patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU. It was feasible and prevented unprotected staff and patient exposure to COVID-19. The NCOT-PC functionality was compatible with institutional COVID-19 policies in place, which contributed to its overall sustainability.

The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) were utilized in preparing this manuscript.9

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU staff for their input with implementation of the NCOT-PC.

Corresponding author: Prashant A. Natteru, MD, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 2500 North State St., Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Symptoms. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

2. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1-9.

3. Khosravani H, Rajendram P, Notario L, et al. Protected code stroke: hyperacute stroke management during the coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19) pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51:1891-1895.

4. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) evaluation and testing. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

5. Plan-Do-Study-Act Worksheet. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PlanDoStudyActWorksheet.aspx. Accessed March 31,2020.

6. Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;10.1002/jmv.25728.

7. Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;101623.

8. UMMC’s COVID-19 Clinical Processes. www.umc.edu/CoronaVirus/Mississippi-Health-Care-Professionals/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Resources.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

9. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. The EQUATOR Network. www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/squire/. Accessed May 12, 2020.

From the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, Division of Neuroscience Intensive Care, Jackson, MS.

Abstract

Objective: To test a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening tool to identify patients who qualify for testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction who are unable to answer the usual screening questions, which could help to prevent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers to COVID-19.

Methods: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) was implemented at our institution for 1 week as a quality improvement project to improve the pathway for COVID-19 screening and testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Results: A total of 14 new patients were admitted into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) service during the pilot period. The NCOT-PC was utilized on 9 (64%) patients with neurologic dysfunction; 7 of these patients were found to have a likelihood of requiring testing based on the NCOT-PC and were subsequently screened for COVID-19 testing by contacting the institution’s COVID-19 testing hotline (Med-Com). All these patients were subsequently transitioned into person-under-investigation status based on the determination from Med-Com. The NSICU staff involved were able to utilize NCOT-PC without issues. The NCOT-PC was immediately adopted into the NSICU process.

Conclusion: Use of the NCOT-PC tool was found to be feasible and improved the screening methodology of patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Keywords: coronavirus; health care planning; quality improvement; patient safety; medical decision-making; neuroscience intensive care unit.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered various standard emergent care pathways. Current recommendations regarding COVID-19 screening for testing involve asking patients about their symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.1 This standard screening method poses a problem when caring for patients with neurologic dysfunction. COVID-19 patients may pre-sent with conditions that affect their ability to answer questions, such as stroke, encephalitis, neuromuscular disorders, or headache, and that may preclude the use of standard screening for testing.2 Patients with acute neurologic dysfunction who cannot undergo standard screening may leave the emergency department (ED) and transition into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) or any intensive care unit (ICU) without a reliable COVID-19 screening test.

The Protected Code Stroke pathway offers protection in the emergent setting for patients with stroke when their COVID-19 status is unknown.3 A similar process has been applied at our institution for emergent management of patients with cerebrovascular disease (stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, the process from the ED after designating “difficult to screen” patients as persons under investigation (PUI) is unclear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has delineated the priorities for testing, with not all declared PUIs requiring testing.4 This poses a great challenge, because patients designated as PUIs require the same management as a COVID-19-positive patient, with negative-pressure isolation rooms as well as use of protective personal equipment (PPE), which may not be readily available. It was also recognized that, because the ED staff can be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, there may not be enough time to perform detailed screening of patients with neurologic dysfunction and that “reverse masking” may not be done consistently for nonintubated patients. This may place patients and health care workers at risk of unprotected exposure.

Recognizing these challenges, we created a Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) as a quality improvement project. The aim of this project was to improve and standardize the current process of identifying patients with neurologic dysfunction who require COVID-19 testing to decrease the risk of unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

Methods

Patients and Definitions

This quality improvement project was undertaken at the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU. Because this was a quality improvement project, an Institutional Review Board exemption was granted.

The NCOT-PC was utilized in consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU during a period of 1 week. “Neurologic dysfunction” encompasses any neurologic illness affecting the mental status and/or level of alertness, subsequently precluding the ability to reliably screen the patient utilizing standard COVID-19 screening. “Med-Com” at our institution is the equivalent of the national COVID-19 testing hotline, where our institution’s infectious diseases experts screen calls for testing and determine whether testing is warranted. “Unprotected exposure” means exposure to COVID-19 without adequate and appropriate PPE.

Quality Improvement Process

As more PUIs were being admitted to the institution, we used the Plan-Do-Study-Act method for process improvements in the NSICU.5 NSICU stakeholders, including attendings, the nurse manager, and nurse practitioners (NPs), developed an algorithm to facilitate the coordination of the NSICU staff in screening patients to identify those with a high likelihood of needing COVID-19 testing upon arrival in the NSICU (Figure 1). Once the NCOT-PC was finalized, NSICU stakeholders were educated regarding the use of this screening tool.

The checklist clinicians review when screening patients is shown in Figure 2. The risk factors comprising the checklist include patient history and clinical and radiographic characteristics that have been shown to be relevant for identifying patients with COVID-19.6,7 The imaging criteria utilize imaging that is part of the standard of care for NSICU patients. For example, computed tomography angiogram of the head and neck performed as part of the acute stroke protocol captures the upper part of the chest. These images are utilized for their incidental findings, such as apical ground-glass opacities and tree-in-bud formation. The risk factors applicable to the patient determine whether the clinician will call Med-Com for testing approval. Institutional COVID-19 processes were then followed accordingly.8 The decision from Med-Com was considered final, and no deviation from institutional policies was allowed.

NCOT-PC was utilized for consecutive days for 1 week before re-evaluation of its feasibility and adaptability.

Data Collection and Analysis

Consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted into the NSICU were assigned nonlinkable patient numbers. No identifiers were collected for the purpose of this project. The primary diagnosis for admission, the neurologic dysfunction that precluded standard screening, and checklist components that the patient fulfilled were collected.

To assess the tool’s feasibility, feedback regarding the ease of use of the NCOT-PC was gathered from the nurses, NPs, charge nurses, fellows, and other attendings. To assess the utility of the NCOT-PC in identifying patients who will be approved for COVID-19 testing, we calculated the proportion of patients who were deemed to have a high likelihood of testing and the proportion of patients who were approved for testing. Descriptive statistics were used, as applicable for the project, to summarize the utility of the NCOT-PC.

Results

We found that the NCOT-PC can be easily used by clinicians. The NSICU staff did not communicate any implementation issues, and since the NCOT-PC was implemented, no problems have been identified.

During the pilot period of the NCOT-PC, 14 new patients were admitted to the NSICU service. Nine (64%) of these had neurologic dysfunction, and the NCOT-PC was used to determine whether Med-Com should be called based on the patients’ likelihood (high vs low) of needing a COVID-19 test. Of those patients with neurologic dysfunction, 7 (78%) were deemed to have a high likelihood of needing a COVID-19 test based on the NCOT-PC. Med-Com was contacted regarding these patients, and all were deemed to require the COVID-19 test by Med-Com and were transitioned into PUI status per institutional policy (Table).

Discussion

The NCOT-PC project improved and standardized the process of identifying and screening patients with neurologic dysfunction for COVID-19 testing. The screening tool is feasible to use, and it decreased inadvertent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

The NCOT-PC was easy to administer. Educating the staff regarding the new process took only a few minutes and involved a meeting with the nurse manager, NPs, fellows, residents, and attendings. We found that this process works well in tandem with the standard institutional processes in place in terms of Protected Code Stroke pathway, PUI isolation, PPE use, and Med-Com screening for COVID-19 testing. Med-Com was called only if the patient fulfilled the checklist criteria. In addition, no extra cost was attributed to implementing the NCOT-PC, since we utilized imaging that was already done as part of the standard of care for patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The standardization of the process of screening for COVID-19 testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction improved patient selection. Before the NCOT-PC, there was no consistency in terms of who should get tested and the reason for testing patients with neurologic dysfunction. Patients can pass through the ED and arrive in the NSICU with an unclear screening status, which may cause inadvertent patient and health care worker exposure to COVID-19. With the NCOT-PC, we have avoided instances of inadvertent staff or patient exposure in the NSICU.

The NCOT-PC was adopted into the NSICU process after the first week it was piloted. Beyond the NSICU, the application of the NCOT-PC can be extended to any patient presentation that precludes standard screening, such as ED and interhospital transfers for stroke codes, trauma codes, code blue, or myocardial infarction codes. In our department, as we started the process of PCS for stroke codes, we included NCOT-PC for stroke patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The results of our initiative are largely limited by the decision-making process of Med-Com when patients are called in for testing. At the time of our project, there were no specific criteria used for patients with altered mental status, except for the standard screening methods, and it was through clinician-to-clinician discussion that testing decisions were made. Another limitation is the short period of time that the NCOT-PC was applied before adoption.

In summary, the NCOT-PC tool improved the screening process for COVID-19 testing in patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU. It was feasible and prevented unprotected staff and patient exposure to COVID-19. The NCOT-PC functionality was compatible with institutional COVID-19 policies in place, which contributed to its overall sustainability.

The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) were utilized in preparing this manuscript.9

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU staff for their input with implementation of the NCOT-PC.

Corresponding author: Prashant A. Natteru, MD, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 2500 North State St., Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, Division of Neuroscience Intensive Care, Jackson, MS.

Abstract

Objective: To test a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening tool to identify patients who qualify for testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction who are unable to answer the usual screening questions, which could help to prevent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers to COVID-19.

Methods: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) was implemented at our institution for 1 week as a quality improvement project to improve the pathway for COVID-19 screening and testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Results: A total of 14 new patients were admitted into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) service during the pilot period. The NCOT-PC was utilized on 9 (64%) patients with neurologic dysfunction; 7 of these patients were found to have a likelihood of requiring testing based on the NCOT-PC and were subsequently screened for COVID-19 testing by contacting the institution’s COVID-19 testing hotline (Med-Com). All these patients were subsequently transitioned into person-under-investigation status based on the determination from Med-Com. The NSICU staff involved were able to utilize NCOT-PC without issues. The NCOT-PC was immediately adopted into the NSICU process.

Conclusion: Use of the NCOT-PC tool was found to be feasible and improved the screening methodology of patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Keywords: coronavirus; health care planning; quality improvement; patient safety; medical decision-making; neuroscience intensive care unit.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered various standard emergent care pathways. Current recommendations regarding COVID-19 screening for testing involve asking patients about their symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.1 This standard screening method poses a problem when caring for patients with neurologic dysfunction. COVID-19 patients may pre-sent with conditions that affect their ability to answer questions, such as stroke, encephalitis, neuromuscular disorders, or headache, and that may preclude the use of standard screening for testing.2 Patients with acute neurologic dysfunction who cannot undergo standard screening may leave the emergency department (ED) and transition into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) or any intensive care unit (ICU) without a reliable COVID-19 screening test.

The Protected Code Stroke pathway offers protection in the emergent setting for patients with stroke when their COVID-19 status is unknown.3 A similar process has been applied at our institution for emergent management of patients with cerebrovascular disease (stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, the process from the ED after designating “difficult to screen” patients as persons under investigation (PUI) is unclear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has delineated the priorities for testing, with not all declared PUIs requiring testing.4 This poses a great challenge, because patients designated as PUIs require the same management as a COVID-19-positive patient, with negative-pressure isolation rooms as well as use of protective personal equipment (PPE), which may not be readily available. It was also recognized that, because the ED staff can be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, there may not be enough time to perform detailed screening of patients with neurologic dysfunction and that “reverse masking” may not be done consistently for nonintubated patients. This may place patients and health care workers at risk of unprotected exposure.

Recognizing these challenges, we created a Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) as a quality improvement project. The aim of this project was to improve and standardize the current process of identifying patients with neurologic dysfunction who require COVID-19 testing to decrease the risk of unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

Methods

Patients and Definitions

This quality improvement project was undertaken at the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU. Because this was a quality improvement project, an Institutional Review Board exemption was granted.

The NCOT-PC was utilized in consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU during a period of 1 week. “Neurologic dysfunction” encompasses any neurologic illness affecting the mental status and/or level of alertness, subsequently precluding the ability to reliably screen the patient utilizing standard COVID-19 screening. “Med-Com” at our institution is the equivalent of the national COVID-19 testing hotline, where our institution’s infectious diseases experts screen calls for testing and determine whether testing is warranted. “Unprotected exposure” means exposure to COVID-19 without adequate and appropriate PPE.

Quality Improvement Process

As more PUIs were being admitted to the institution, we used the Plan-Do-Study-Act method for process improvements in the NSICU.5 NSICU stakeholders, including attendings, the nurse manager, and nurse practitioners (NPs), developed an algorithm to facilitate the coordination of the NSICU staff in screening patients to identify those with a high likelihood of needing COVID-19 testing upon arrival in the NSICU (Figure 1). Once the NCOT-PC was finalized, NSICU stakeholders were educated regarding the use of this screening tool.

The checklist clinicians review when screening patients is shown in Figure 2. The risk factors comprising the checklist include patient history and clinical and radiographic characteristics that have been shown to be relevant for identifying patients with COVID-19.6,7 The imaging criteria utilize imaging that is part of the standard of care for NSICU patients. For example, computed tomography angiogram of the head and neck performed as part of the acute stroke protocol captures the upper part of the chest. These images are utilized for their incidental findings, such as apical ground-glass opacities and tree-in-bud formation. The risk factors applicable to the patient determine whether the clinician will call Med-Com for testing approval. Institutional COVID-19 processes were then followed accordingly.8 The decision from Med-Com was considered final, and no deviation from institutional policies was allowed.

NCOT-PC was utilized for consecutive days for 1 week before re-evaluation of its feasibility and adaptability.

Data Collection and Analysis

Consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted into the NSICU were assigned nonlinkable patient numbers. No identifiers were collected for the purpose of this project. The primary diagnosis for admission, the neurologic dysfunction that precluded standard screening, and checklist components that the patient fulfilled were collected.

To assess the tool’s feasibility, feedback regarding the ease of use of the NCOT-PC was gathered from the nurses, NPs, charge nurses, fellows, and other attendings. To assess the utility of the NCOT-PC in identifying patients who will be approved for COVID-19 testing, we calculated the proportion of patients who were deemed to have a high likelihood of testing and the proportion of patients who were approved for testing. Descriptive statistics were used, as applicable for the project, to summarize the utility of the NCOT-PC.

Results

We found that the NCOT-PC can be easily used by clinicians. The NSICU staff did not communicate any implementation issues, and since the NCOT-PC was implemented, no problems have been identified.

During the pilot period of the NCOT-PC, 14 new patients were admitted to the NSICU service. Nine (64%) of these had neurologic dysfunction, and the NCOT-PC was used to determine whether Med-Com should be called based on the patients’ likelihood (high vs low) of needing a COVID-19 test. Of those patients with neurologic dysfunction, 7 (78%) were deemed to have a high likelihood of needing a COVID-19 test based on the NCOT-PC. Med-Com was contacted regarding these patients, and all were deemed to require the COVID-19 test by Med-Com and were transitioned into PUI status per institutional policy (Table).

Discussion

The NCOT-PC project improved and standardized the process of identifying and screening patients with neurologic dysfunction for COVID-19 testing. The screening tool is feasible to use, and it decreased inadvertent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

The NCOT-PC was easy to administer. Educating the staff regarding the new process took only a few minutes and involved a meeting with the nurse manager, NPs, fellows, residents, and attendings. We found that this process works well in tandem with the standard institutional processes in place in terms of Protected Code Stroke pathway, PUI isolation, PPE use, and Med-Com screening for COVID-19 testing. Med-Com was called only if the patient fulfilled the checklist criteria. In addition, no extra cost was attributed to implementing the NCOT-PC, since we utilized imaging that was already done as part of the standard of care for patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The standardization of the process of screening for COVID-19 testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction improved patient selection. Before the NCOT-PC, there was no consistency in terms of who should get tested and the reason for testing patients with neurologic dysfunction. Patients can pass through the ED and arrive in the NSICU with an unclear screening status, which may cause inadvertent patient and health care worker exposure to COVID-19. With the NCOT-PC, we have avoided instances of inadvertent staff or patient exposure in the NSICU.

The NCOT-PC was adopted into the NSICU process after the first week it was piloted. Beyond the NSICU, the application of the NCOT-PC can be extended to any patient presentation that precludes standard screening, such as ED and interhospital transfers for stroke codes, trauma codes, code blue, or myocardial infarction codes. In our department, as we started the process of PCS for stroke codes, we included NCOT-PC for stroke patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The results of our initiative are largely limited by the decision-making process of Med-Com when patients are called in for testing. At the time of our project, there were no specific criteria used for patients with altered mental status, except for the standard screening methods, and it was through clinician-to-clinician discussion that testing decisions were made. Another limitation is the short period of time that the NCOT-PC was applied before adoption.

In summary, the NCOT-PC tool improved the screening process for COVID-19 testing in patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU. It was feasible and prevented unprotected staff and patient exposure to COVID-19. The NCOT-PC functionality was compatible with institutional COVID-19 policies in place, which contributed to its overall sustainability.

The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) were utilized in preparing this manuscript.9

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU staff for their input with implementation of the NCOT-PC.

Corresponding author: Prashant A. Natteru, MD, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 2500 North State St., Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Symptoms. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

2. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1-9.

3. Khosravani H, Rajendram P, Notario L, et al. Protected code stroke: hyperacute stroke management during the coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19) pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51:1891-1895.

4. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) evaluation and testing. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

5. Plan-Do-Study-Act Worksheet. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PlanDoStudyActWorksheet.aspx. Accessed March 31,2020.

6. Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;10.1002/jmv.25728.

7. Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;101623.

8. UMMC’s COVID-19 Clinical Processes. www.umc.edu/CoronaVirus/Mississippi-Health-Care-Professionals/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Resources.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

9. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. The EQUATOR Network. www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/squire/. Accessed May 12, 2020.

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Symptoms. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

2. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1-9.

3. Khosravani H, Rajendram P, Notario L, et al. Protected code stroke: hyperacute stroke management during the coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19) pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51:1891-1895.

4. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) evaluation and testing. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

5. Plan-Do-Study-Act Worksheet. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PlanDoStudyActWorksheet.aspx. Accessed March 31,2020.

6. Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;10.1002/jmv.25728.

7. Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;101623.

8. UMMC’s COVID-19 Clinical Processes. www.umc.edu/CoronaVirus/Mississippi-Health-Care-Professionals/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Resources.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

9. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. The EQUATOR Network. www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/squire/. Accessed May 12, 2020.

Clinical Utility of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Polymerase Chain Reaction Nasal Swab Testing in Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

From the Hospital of Central Connecticut, New Britain, CT (Dr. Caulfield and Dr. Shepard); Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT (Dr. Linder and Dr. Dempsey); and the Hartford HealthCare Research Program, Hartford, CT (Dr. O’Sullivan).

Abstract

- Objective: To assess the utility of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nasal swab testing in patients with lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI).

- Design and setting: Multicenter, retrospective, electronic chart review conducted within the Hartford HealthCare system.

- Participants: Patients who were treated for LRTIs at the Hospital of Central Connecticut or Hartford Hospital between July 1, 2018, and June 30, 2019.

- Measurements: The primary outcome was anti-MRSA days of therapy (DOT) in patients who underwent MRSA PCR testing versus those who did not. In a subgroup analysis, we compared anti-MRSA DOT among patients with appropriate versus inappropriate utilization of the MRSA PCR test.

- Results: Of the 319 patients treated for LRTIs, 155 (48.6%) had a MRSA PCR ordered, and appropriate utilization occurred in 94 (60.6%) of these patients. Anti-MRSA DOT in the MRSA PCR group (n = 155) was shorter than in the group that did not undergo MRSA PCR testing (n = 164), but this difference did not reach statistical significance (1.68 days [interquartile range {IQR}, 0.80-2.74] vs 1.86 days [IQR, 0.56-3.33], P = 0.458). In the subgroup analysis, anti-MRSA DOT was significantly shorter in the MRSA PCR group with appropriate utilization compared to the inappropriate utilization group (1.16 [IQR, 0.44-1.88] vs 2.68 [IQR, 1.75-3.76], P < 0.001)

- Conclusion: Appropriate utilization of MRSA PCR nasal swab testing can reduce DOT in patients with LRTI. Further education is necessary to expand the appropriate use of the MRSA PCR test across our health system.

Keywords: MRSA; LRTI; pneumonia; antimicrobial stewardship; antibiotic resistance.

More than 300,000 patients were hospitalized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections in the United States in 2017, and at least 10,000 of these cases resulted in mortality.1 While MRSA infections overall are decreasing, it is crucial to continue to employ antimicrobial stewardship tactics to keep these infections at bay. Recently, strains of S. aureus have become resistant to vancomycin, making this bacterium even more difficult to treat.2

A novel tactic in antimicrobial stewardship involves the use of MRSA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nasal swab testing to rule out the presence of MRSA in patients with lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI). If used appropriately, this approach may decrease the number of days patients are treated with anti-MRSA antimicrobials. Waiting for cultures to speciate can take up to 72 hours,3 meaning that patients may be exposed to 3 days of unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotics. Results of MRSA PCR assay of nasal swab specimens can be available in 1 to 2 hours,4 allowing for more rapid de-escalation of therapy. Numerous studies have shown that this test has a negative predictive value (NPV) greater than 95%, indicating that a negative nasal swab result may be useful to guide de-escalation of antibiotic therapy.5-8 The purpose of this study was to assess the utility of MRSA PCR nasal swab testing in patients with LRTI throughout the Hartford HealthCare system.

Methods

Design

This study was a multicenter, retrospective, electronic chart review. It was approved by the Hartford HealthCare Institutional Review Board (HHC-2019-0169).

Selection of Participants

Patients were identified through electronic medical record reports based on ICD-10 codes. Records were categorized into 2 groups: patients who received a MRSA PCR nasal swab testing and patients who did not. Patients who received the MRSA PCR were further categorized by appropriate or inappropriate utilization. Appropriate utilization of the MRSA PCR was defined as MRSA PCR ordered within 48 hours of a new vancomycin or linezolid order, and anti-MRSA therapy discontinued within 24 hours of a negative result. Inappropriate utilization of the MRSA PCR was defined as MRSA PCR ordered more than 48 hours after a new vancomycin or linezolid order, or continuation of anti-MRSA therapy despite a negative MRSA PCR and no other evidence of a MRSA infection.

Patients were included if they met all of the following criteria: age 18 years or older, with no upper age limit; treated for a LRTI, identified by ICD-10 codes (J13-22, J44, J85); treated with empiric antibiotics active against MRSA, specifically vancomycin or linezolid; and treated at the Hospital of Central Connecticut (HOCC) or Hartford Hospital (HH) between July 1, 2018, and June 30, 2019, inclusive. Patients were excluded if they met 1 or more of the following criteria: age less than 18 years old; admitted for 48 hours or fewer or discharged from the emergency department; not treated at either facility; treated before July 1, 2018, or after June 30, 2019; treated for ventilator-associated pneumonia; received anti-MRSA therapy within 30 days prior to admission; or treated for a concurrent bacterial infection requiring anti-MRSA therapy.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was anti-MRSA days of therapy (DOT) in patients who underwent MRSA PCR testing compared to patients who did not undergo MRSA PCR testing. A subgroup analysis was completed to compare anti-MRSA DOT within patients in the MRSA PCR group. Patients in the subgroup were categorized by appropriate or inappropriate utilization, and anti-MRSA DOT were compared between these groups. Secondary outcomes that were evaluated included length of stay (LOS), 30-day readmission rate, and incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI). Thirty-day readmission was defined as admission to HOCC, HH, or any institution within Hartford HealthCare within 30 days of discharge. AKI was defined as an increase in serum creatinine by ≥ 0.3 mg/dL in 48 hours, increase ≥ 1.5 times baseline, or a urine volume < 0.5 mL/kg/hr for 6 hours.

Statistical Analyses

The study was powered for the primary outcome, anti-MRSA DOT, with a clinically meaningful difference of 1 day. Group sample sizes of 240 in the MRSA PCR group and 160 in the no MRSA PCR group would have afforded 92% power to detect that difference, if the null hypothesis was that both group means were 4 days and the alternative hypothesis was that the mean of the MRSA PCR group was 3 days, with estimated group standard deviations of 80% of each mean. This estimate used an alpha level of 0.05 with a 2-sided t-test. Among those who received a MRSA PCR test, a clinically meaningful difference between appropriate and inappropriate utilization was 5%.

Descriptive statistics were provided for all variables as a function of the individual hospital and for the combined data set. Continuous data were summarized with means and standard deviations (SD), or with median and interquartile ranges (IQR), depending on distribution. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies, using percentages. All data were evaluated for normality of distribution. Inferential statistics comprised a Student’s t-test to compare normally distributed, continuous data between groups. Nonparametric distributions were compared using a Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical comparisons were made using a Fisher’s exact test for 2×2 tables and a Pearson chi-square test for comparisons involving more than 2 groups.

Since anti-MRSA DOT (primary outcome) and LOS (secondary outcome) are often non-normally distributed, they have been transformed (eg, log or square root, again depending on distribution). Whichever native variable or transformation variable was appropriate was used as the outcome measure in a linear regression model to account for the influence of factors (covariates) that show significant univariate differences. Given the relatively small sample size, a maximum of 10 variables were included in the model. All factors were iterated in a forward regression model (most influential first) until no significant changes were observed.

All calculations were performed with SPSS v. 21 (IBM; Armonk, NY) using an a priori alpha level of 0.05, such that all results yielding P < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Results

Of the 561 patient records reviewed, 319 patients were included and 242 patients were excluded. Reasons for exclusion included 65 patients admitted for a duration of 48 hours or less or discharged from the emergency department; 61 patients having another infection requiring anti-MRSA therapy; 60 patients not having a diagnosis of a LRTI or not receiving anti-MRSA therapy; 52 patients having received anti-MRSA therapy within 30 days prior to admission; and 4 patients treated outside of the specified date range.

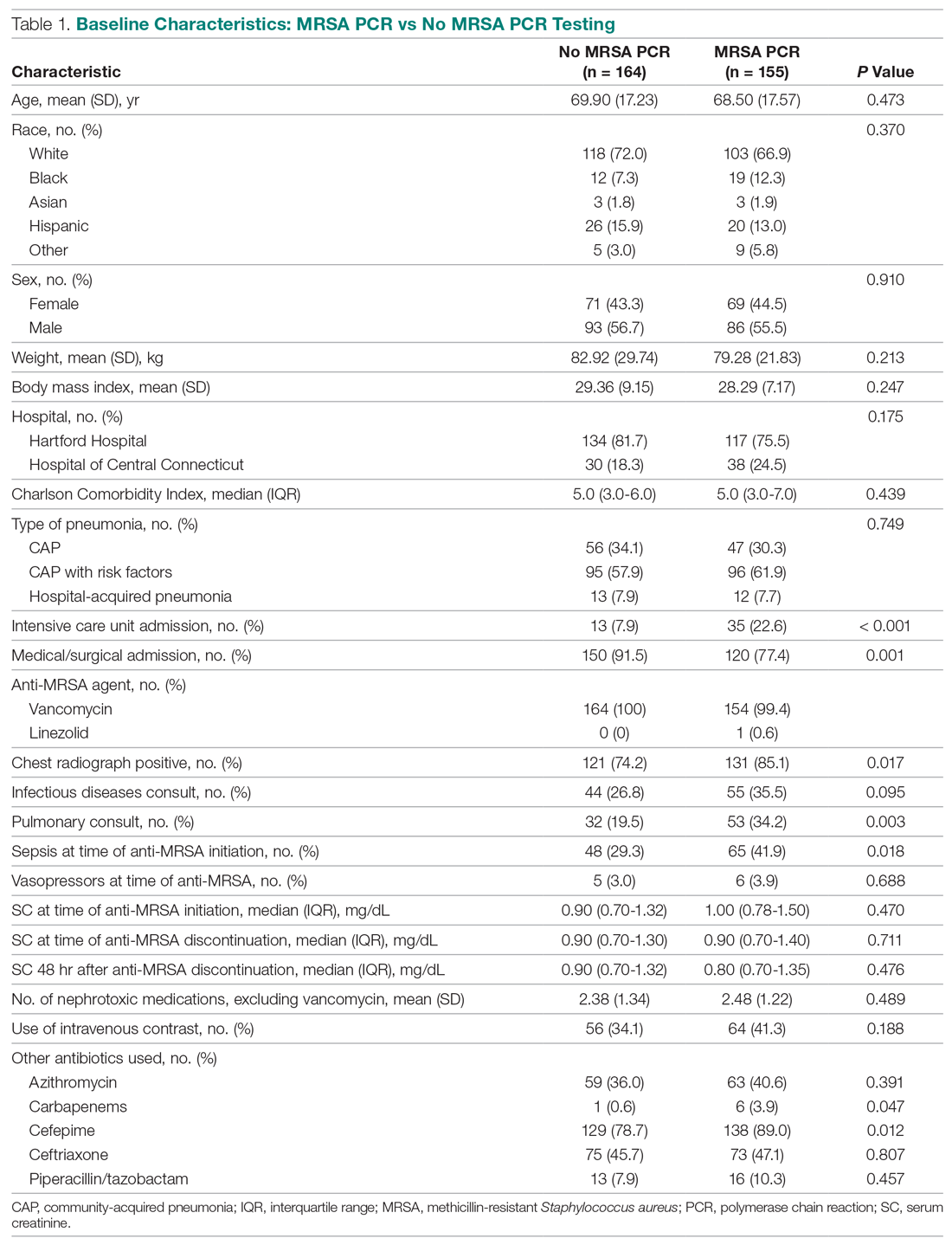

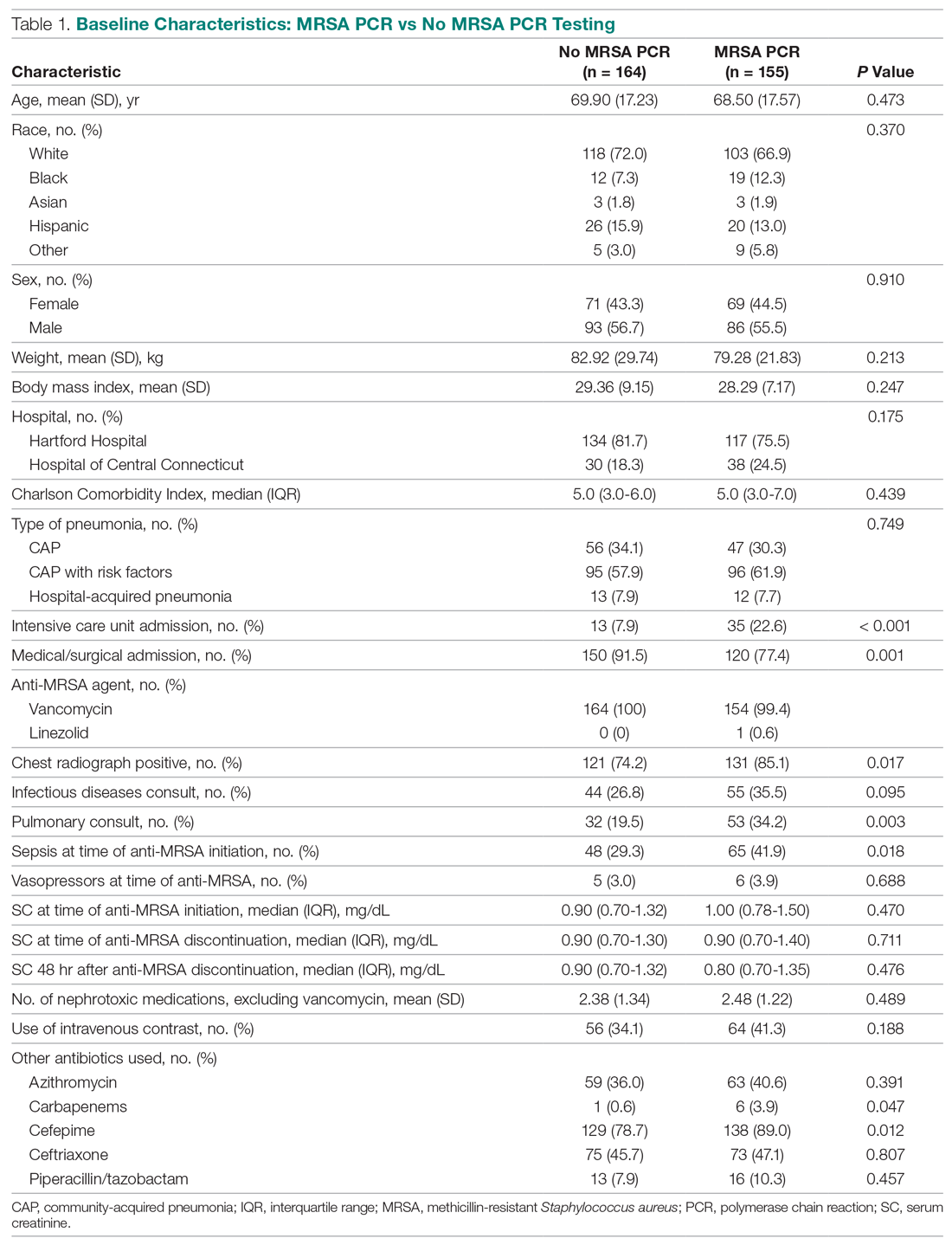

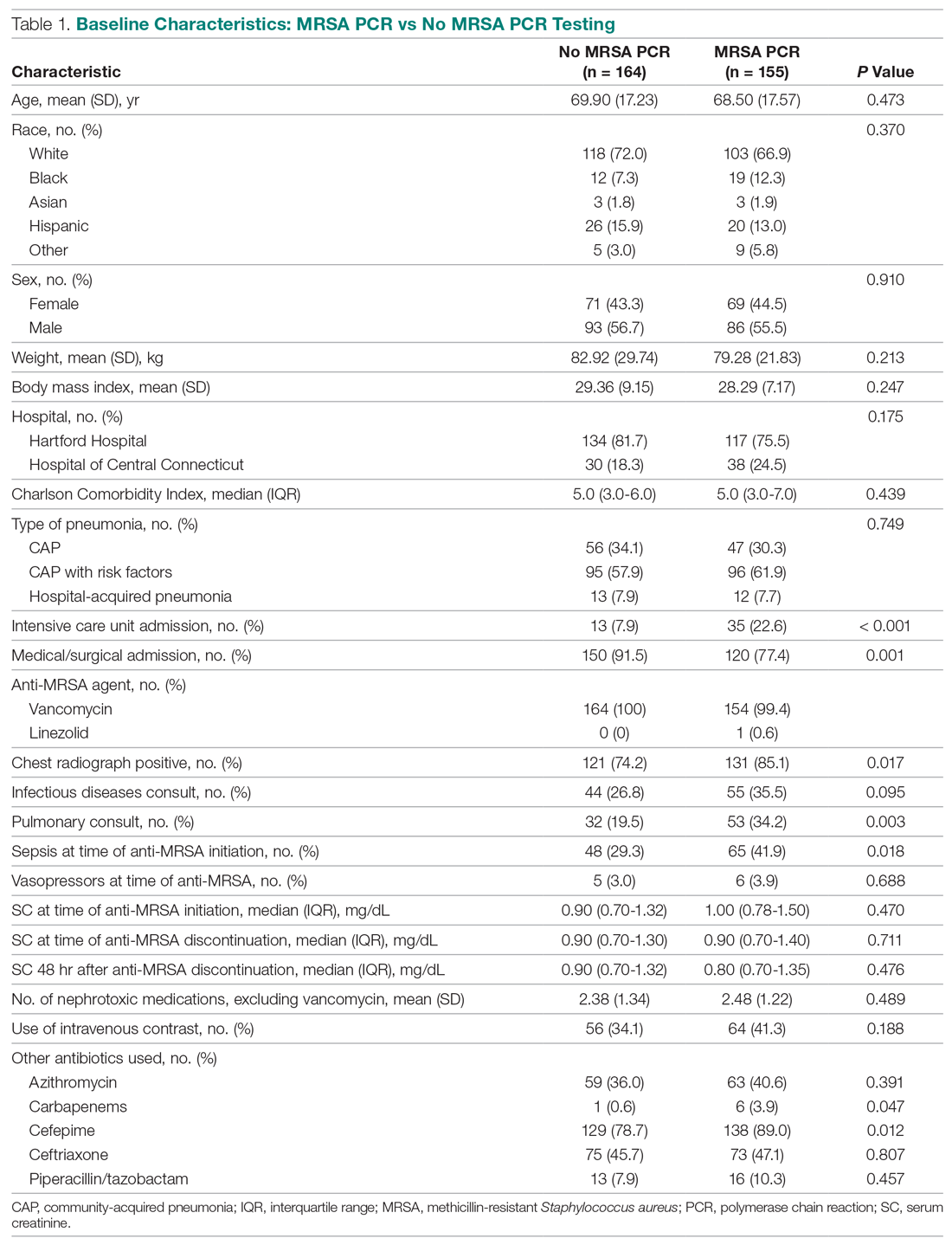

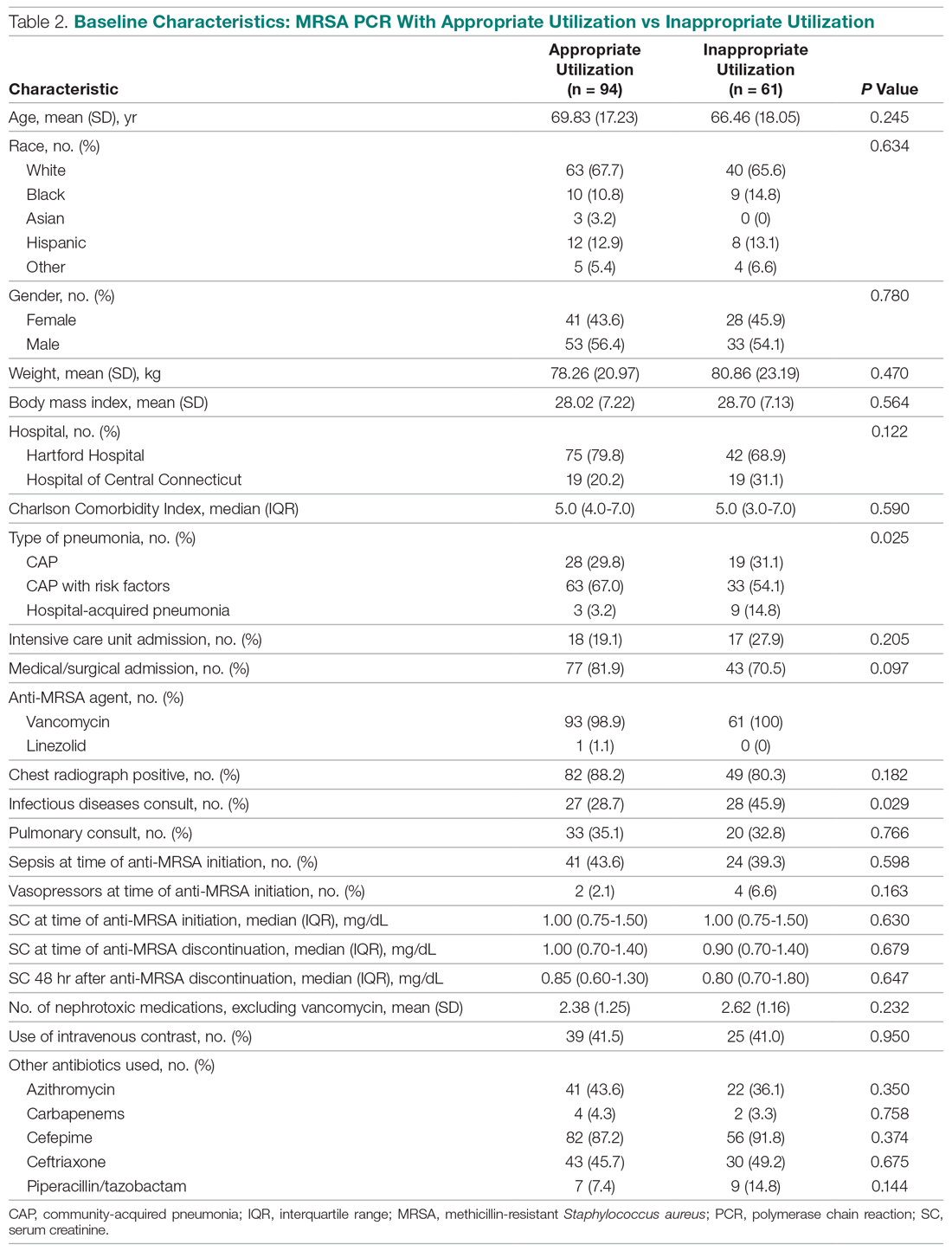

Of the 319 patients included, 155 (48.6%) were in the MRSA PCR group and 164 (51.4%) were in the group that did not undergo MRSA PCR (Table 1). Of the 155 patients with a MRSA PCR ordered, the test was utilized appropriately in 94 (60.6%) patients and inappropriately in 61 (39.4%) patients (Table 2). In the MRSA PCR group, 135 patients had a negative result on PCR assay, with 133 of those patients having negative respiratory cultures, resulting in a NPV of 98.5%. Differences in baseline characteristics between the MRSA PCR and no MRSA PCR groups were observed. The patients in the MRSA PCR group appeared to be significantly more ill than those in the no MRSA PCR group, as indicated by statistically significant differences in intensive care unit (ICU) admissions (P = 0.001), positive chest radiographs (P = 0.034), sepsis at time of anti-MRSA initiation (P = 0.013), pulmonary consults placed (P = 0.003), and carbapenem usage (P = 0.047).

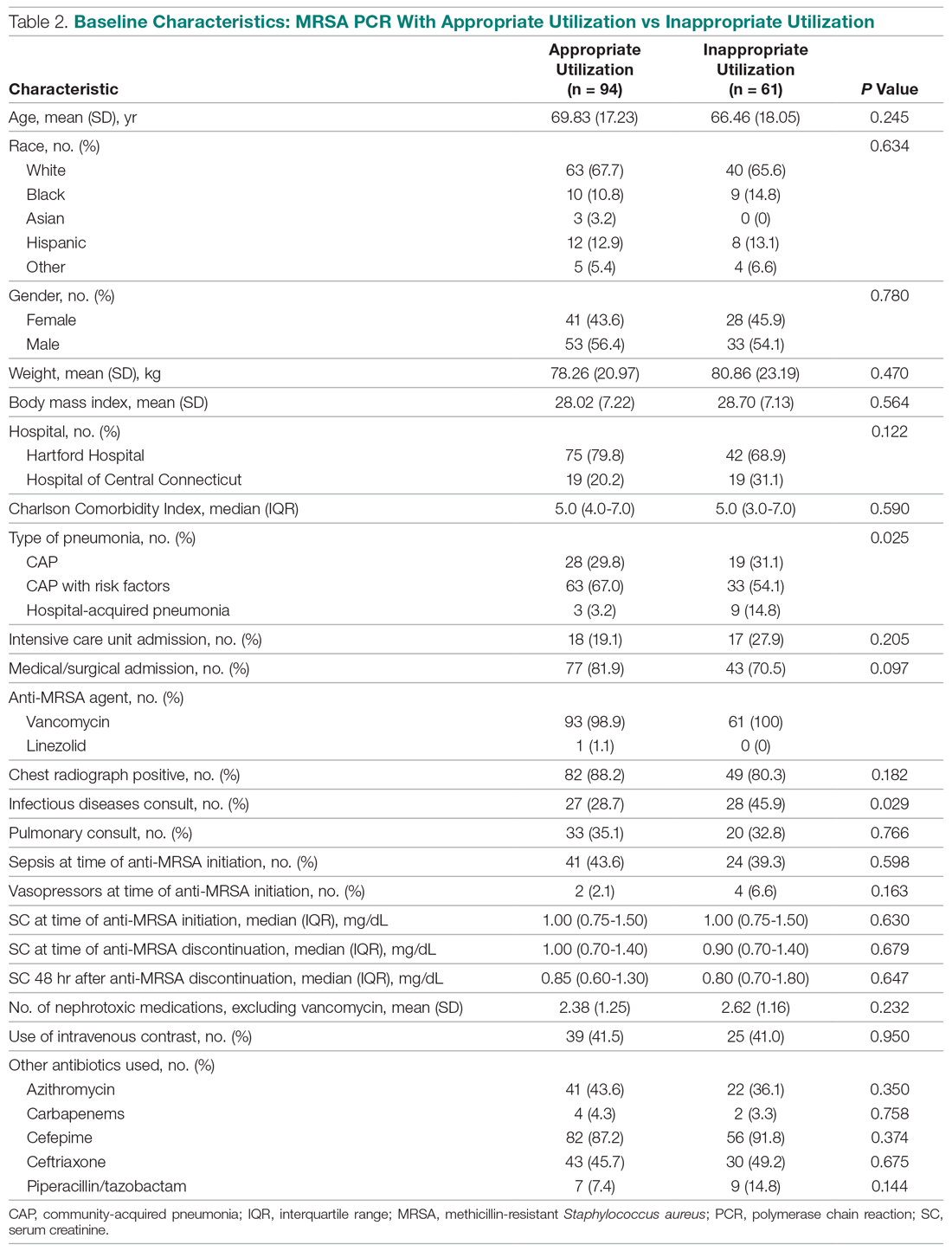

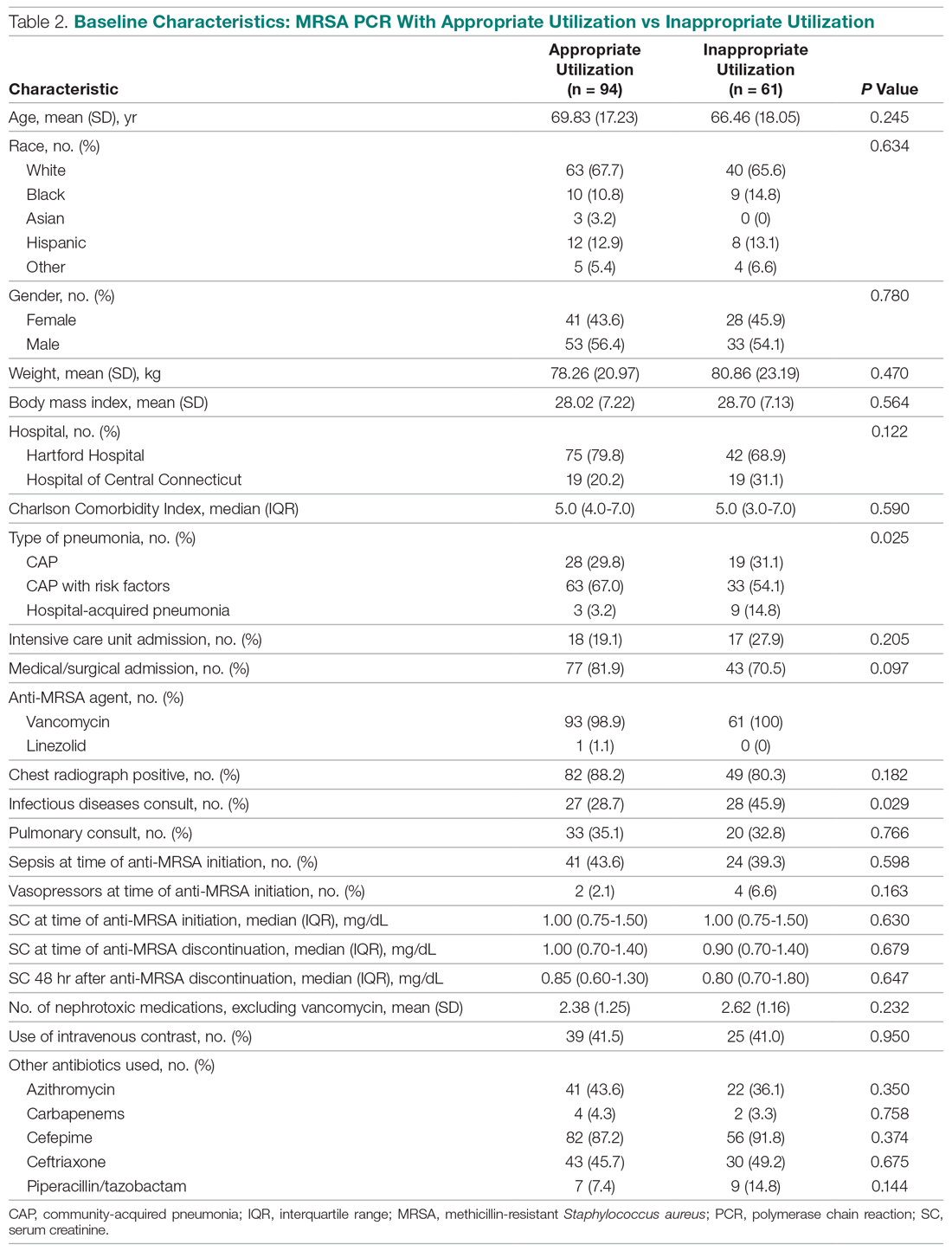

In the subgroup analysis comparing appropriate and inappropriate utilization within the MRSA PCR group, the inappropriate utilization group had significantly higher numbers of infectious diseases consults placed, patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia, and patients with community-acquired pneumonia with risk factors.

Outcomes

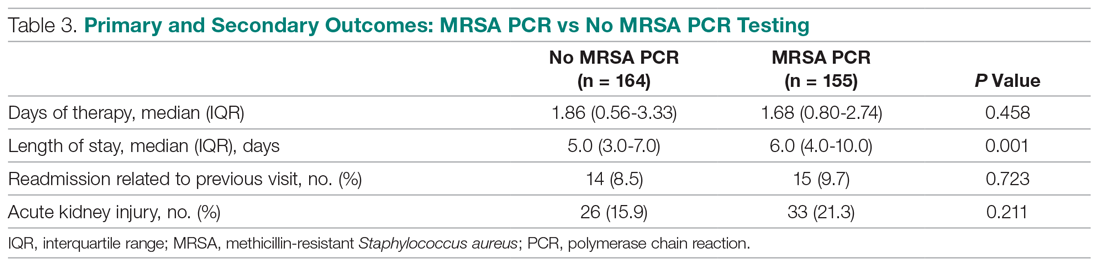

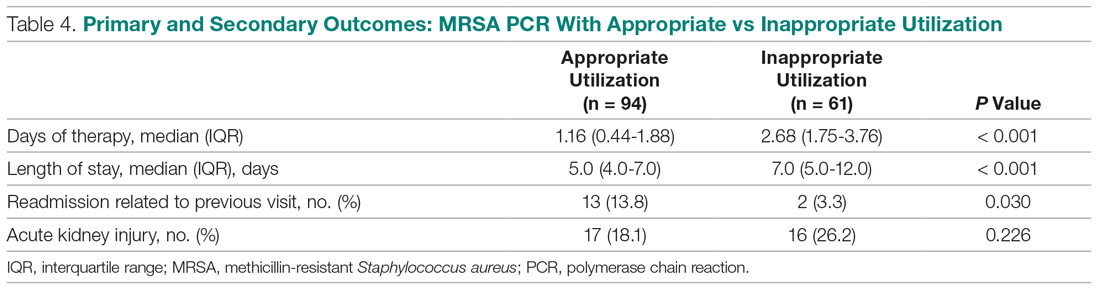

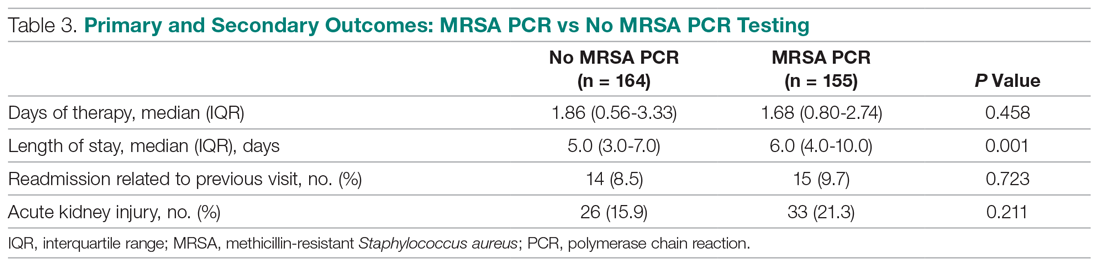

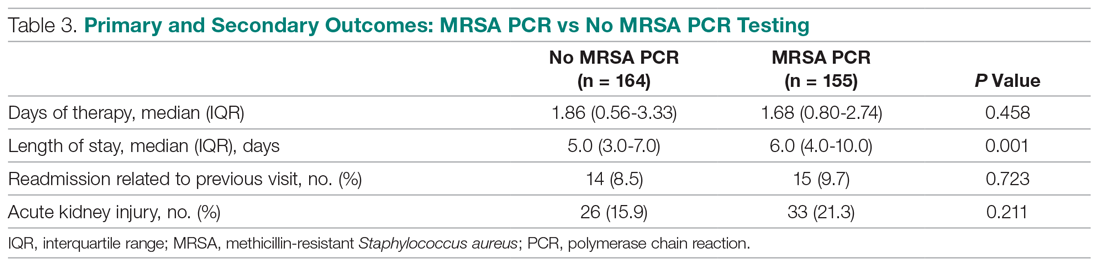

Median anti-MRSA DOT in the MRSA PCR group was shorter than DOT in the no MRSA PCR group, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (1.68 [IQR, 0.80-2.74] vs 1.86 days [IQR, 0.56-3.33], P = 0.458; Table 3). LOS in the MRSA PCR group was longer than in the no MRSA PCR group (6.0 [IQR, 4.0-10.0] vs 5.0 [IQR, 3.0-7.0] days, P = 0.001). There was no difference in 30-day readmissions that were related to the previous visit or incidence of AKI between groups.

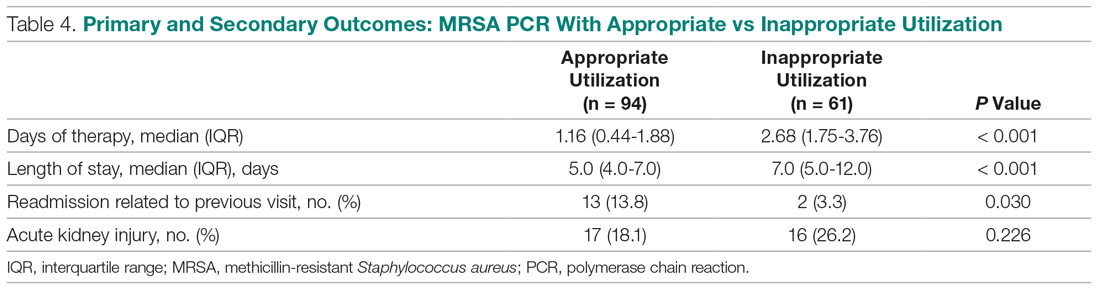

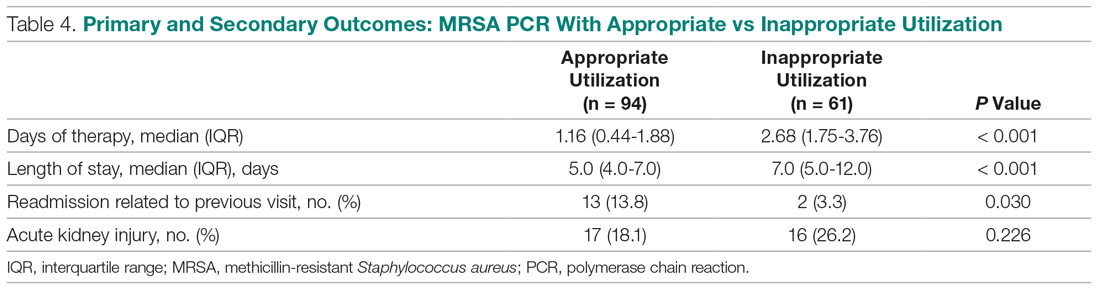

In the subgroup analysis, anti-MRSA DOT in the MRSA PCR group with appropriate utilization was shorter than DOT in the MRSA PCR group with inappropriate utilization (1.16 [IQR, 0.44-1.88] vs 2.68 [IQR, 1.75-3.76] days, P < 0.001; Table 4). LOS in the MRSA PCR group with appropriate utilization was shorter than LOS in the inappropriate utilization group (5.0 [IQR, 4.0-7.0] vs 7.0 [IQR, 5.0-12.0] days, P < 0.001). Thirty-day readmissions that were related to the previous visit were significantly higher in patients in the MRSA PCR group with appropriate utilization (13 vs 2, P = 0.030). There was no difference in incidence of AKI between the groups.

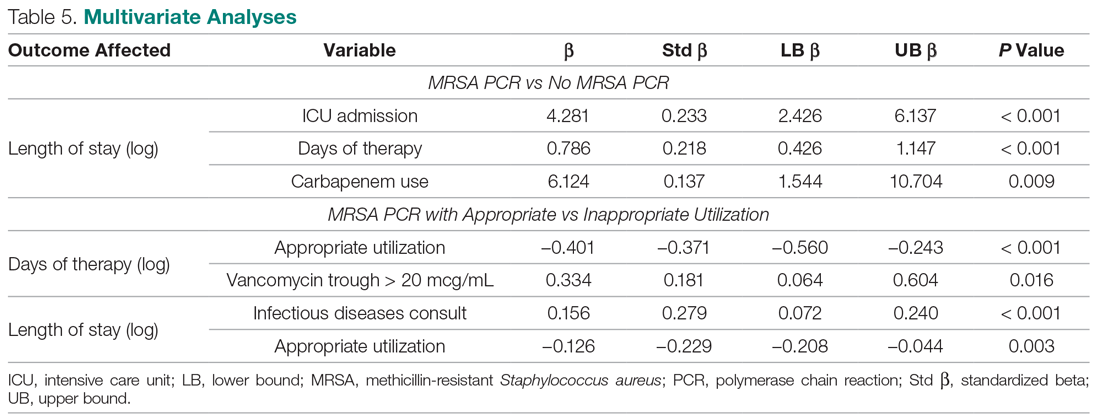

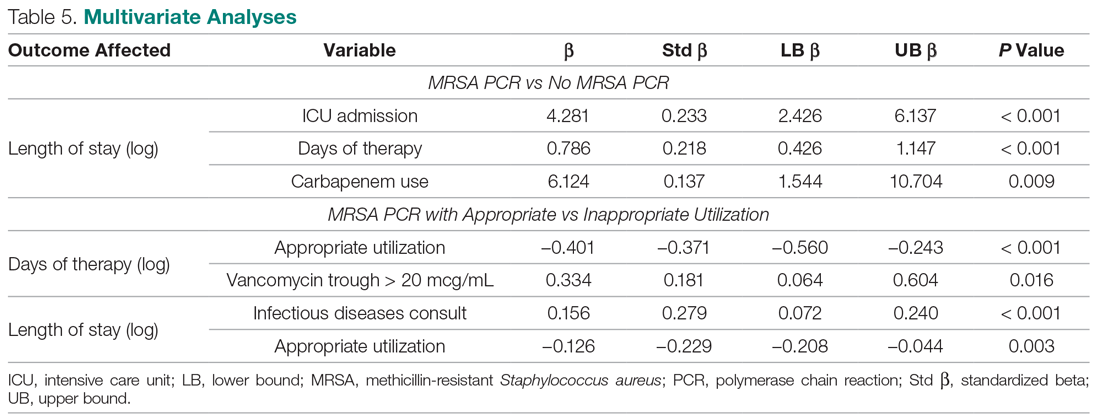

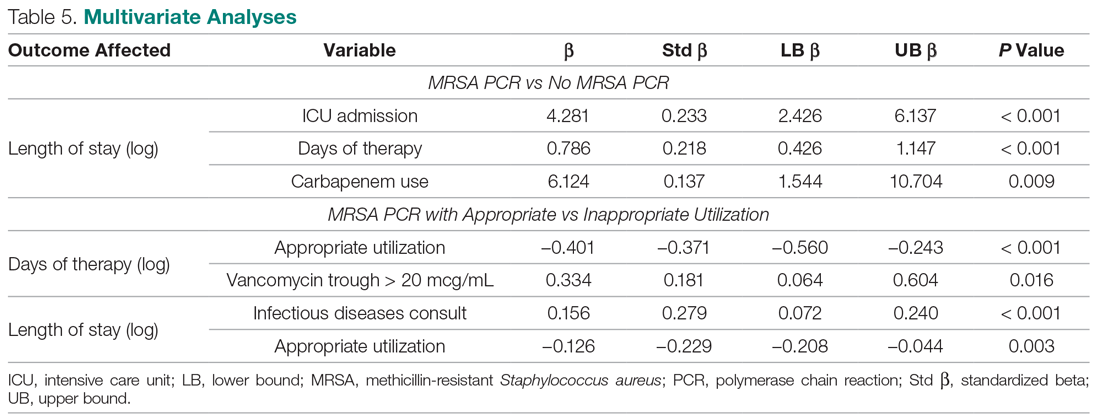

A multivariate analysis was completed to determine whether the sicker MRSA PCR population was confounding outcomes, particularly the secondary outcome of LOS, which was noted to be longer in the MRSA PCR group (Table 5). When comparing LOS in the MRSA PCR and the no MRSA PCR patients, the multivariate analysis showed that admission to the ICU and carbapenem use were associated with a longer LOS (P < 0.001 and P = 0.009, respectively). The incidence of admission to the ICU and carbapenem use were higher in the MRSA PCR group (P = 0.001 and P = 0.047). Therefore, longer LOS in the MRSA PCR patients could be a result of the higher prevalence of ICU admissions and infections requiring carbapenem therapy rather than the result of the MRSA PCR itself.

Discussion

A MRSA PCR nasal swab protocol can be used to minimize a patient’s exposure to unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotics, thereby preventing antimicrobial resistance. Thus, it is important to assess how our health system is utilizing this antimicrobial stewardship tactic. With the MRSA PCR’s high NPV, providers can be confident that MRSA pneumonia is unlikely in the absence of MRSA colonization. Our study established a NPV of 98.5%, which is similar to other studies, all of which have shown NPVs greater than 95%.5-8 Despite the high NPV, this study demonstrated that only 51.4% of patients with LRTI had orders for a MRSA PCR. Of the 155 patients with a MRSA PCR, the test was utilized appropriately only 60.6% of the time. A majority of the inappropriately utilized tests were due to MRSA PCR orders placed more than 48 hours after anti-MRSA therapy initiation. To our knowledge, no other studies have assessed the clinical utility of MRSA PCR nasal swabs as an antimicrobial stewardship tool in a diverse health system; therefore, these results are useful to guide future practices at our institution. There is a clear need for provider and pharmacist education to increase the use of MRSA PCR nasal swab testing for patients with LRTI being treated with anti-MRSA therapy. Additionally, clinician education regarding the initial timing of the MRSA PCR order and the proper utilization of the results of the MRSA PCR likely will benefit patient outcomes at our institution.