User login

Ibrutinib associated with decreased circulating malignant cells and restored T-cell function in CLL patients

Ibrutinib showed significant impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and was found to restore healthy T-cell function in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to the results of a comparative study of CLL patients and healthy controls.

Researchers compared circulating counts of 21 immune blood cell subsets throughout the first year of treatment in 55 patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL from the RESONATE trial and 50 previously untreated CLL patients from the RESONATE-2 trial with 20 untreated age-matched healthy donors, according to a report published online in Leukemia Research.

In addition, T-cell function was assessed in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation in 21 patients with R/R CLL, compared with 18 age-matched healthy donors, according to Isabelle G. Solman, MS, an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. and colleagues.

Positive indicators

Ibrutinib significantly decreased pathologically high circulating B cells, regulatory T cells, effector/memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (including exhausted and chronically activated T cells), natural killer (NK) T cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells; preserved naive T cells and NK cells; and increased circulating classical monocytes, according to the researchers.

Ibrutinib also significantly restored T-cell proliferative ability, degranulation, and cytokine secretion. Over the same period, ofatumumab or chlorambucil did not confer the same spectrum of normalization as ibrutinib in multiple immune subsets that were examined, they added.

“These results establish that ibrutinib has a significant and likely positive impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and restores healthy T-cell function,” the researchers indicated.

“Ibrutinib has a significant, progressively positive impact on both malignant and nonmalignant immune cells in CLL. These positive effects on circulating nonmalignant immune cells may contribute to long-term CLL disease control, overall health status, and decreased susceptibility to infection,” they concluded.

The study was funded by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie Company. Ms. Solman is an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. as were several other authors.

SOURCE: Solman IG et al. Leuk Res. 2020;97. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106432.

Ibrutinib showed significant impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and was found to restore healthy T-cell function in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to the results of a comparative study of CLL patients and healthy controls.

Researchers compared circulating counts of 21 immune blood cell subsets throughout the first year of treatment in 55 patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL from the RESONATE trial and 50 previously untreated CLL patients from the RESONATE-2 trial with 20 untreated age-matched healthy donors, according to a report published online in Leukemia Research.

In addition, T-cell function was assessed in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation in 21 patients with R/R CLL, compared with 18 age-matched healthy donors, according to Isabelle G. Solman, MS, an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. and colleagues.

Positive indicators

Ibrutinib significantly decreased pathologically high circulating B cells, regulatory T cells, effector/memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (including exhausted and chronically activated T cells), natural killer (NK) T cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells; preserved naive T cells and NK cells; and increased circulating classical monocytes, according to the researchers.

Ibrutinib also significantly restored T-cell proliferative ability, degranulation, and cytokine secretion. Over the same period, ofatumumab or chlorambucil did not confer the same spectrum of normalization as ibrutinib in multiple immune subsets that were examined, they added.

“These results establish that ibrutinib has a significant and likely positive impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and restores healthy T-cell function,” the researchers indicated.

“Ibrutinib has a significant, progressively positive impact on both malignant and nonmalignant immune cells in CLL. These positive effects on circulating nonmalignant immune cells may contribute to long-term CLL disease control, overall health status, and decreased susceptibility to infection,” they concluded.

The study was funded by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie Company. Ms. Solman is an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. as were several other authors.

SOURCE: Solman IG et al. Leuk Res. 2020;97. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106432.

Ibrutinib showed significant impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and was found to restore healthy T-cell function in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to the results of a comparative study of CLL patients and healthy controls.

Researchers compared circulating counts of 21 immune blood cell subsets throughout the first year of treatment in 55 patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL from the RESONATE trial and 50 previously untreated CLL patients from the RESONATE-2 trial with 20 untreated age-matched healthy donors, according to a report published online in Leukemia Research.

In addition, T-cell function was assessed in response to T-cell–receptor stimulation in 21 patients with R/R CLL, compared with 18 age-matched healthy donors, according to Isabelle G. Solman, MS, an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. and colleagues.

Positive indicators

Ibrutinib significantly decreased pathologically high circulating B cells, regulatory T cells, effector/memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (including exhausted and chronically activated T cells), natural killer (NK) T cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells; preserved naive T cells and NK cells; and increased circulating classical monocytes, according to the researchers.

Ibrutinib also significantly restored T-cell proliferative ability, degranulation, and cytokine secretion. Over the same period, ofatumumab or chlorambucil did not confer the same spectrum of normalization as ibrutinib in multiple immune subsets that were examined, they added.

“These results establish that ibrutinib has a significant and likely positive impact on circulating malignant and nonmalignant immune cells and restores healthy T-cell function,” the researchers indicated.

“Ibrutinib has a significant, progressively positive impact on both malignant and nonmalignant immune cells in CLL. These positive effects on circulating nonmalignant immune cells may contribute to long-term CLL disease control, overall health status, and decreased susceptibility to infection,” they concluded.

The study was funded by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie Company. Ms. Solman is an employee of Translational Medicine, Pharmacyclics, Sunnyvale, Calif. as were several other authors.

SOURCE: Solman IG et al. Leuk Res. 2020;97. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2020.106432.

FROM LEUKEMIA RESEARCH

Beat AML: Precision medicine strategy feasible, superior to SOC for AML

The 30-day mortality rates were 3.7% versus 20.4% in 224 patients who enrolled in the Beat AML trial precision medicine substudies within 7 days of prospective genomic profiling and 103 who elected SOC chemotherapy, respectively, Amy Burd, PhD, vice president of research strategy for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Rye Brook, N.Y. and her colleagues reported online in Nature Medicine.

Overall survival (OS) at a median of 7.1 months was also significantly longer with precision medicine than with SOC chemotherapy (median, 12.8 vs. 3.9 months), the investigators found.

In an additional 28 patients who selected an investigational therapy rather than a precision medicine strategy or SOC chemotherapy, median OS was not reached, and in 38 who chose palliative care, median OS was 0.6 months, they noted. Care type was unknown in two patients.

The results were similar after controlling for demographic, clinical, and molecular variables and did not change when patients with adverse events of special interest were excluded from the analysis or when only those with survival greater than 2 weeks were included in the analysis.

AML confers an adverse outcome in older adults and therefore is typically treated rapidly after diagnosis. This has precluded consideration of patients’ mutational profile for treatment decisions.

Beat AML, however, sought to prospectively assess the feasibility of quickly ascertaining cytogenetic and mutational data for the purpose of improving outcomes through targeted treatment.

“The study shows that delaying treatment up to 7 days is feasible and safe, and that patients who opted for the precision medicine approach experienced a lower early death rate and superior overall survival, compared with patients who opted for standard of care,” lead study author John C. Byrd, MD, the D. Warren Brown Chair of Leukemia Research of the Ohio State University, Columbus, noted in a press statement from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, which conducted the trial. “This patient-centric study shows that we can move away from chemotherapy treatment for patients who won’t respond or can’t withstand the harsh effects of the same chemotherapies we’ve been using for 40 years and match them with a treatment better suited for their individual cases.”

The ongoing Beat AML trial was launched by LLS in 2016 to assess various novel targeted therapies in newly diagnosed AML patients aged 60 years and older. Participants underwent next-generation genomic sequencing, were matched to the appropriate targeted therapy, and were given the option of enrolling on the relevant substudy or selecting an alternate treatment strategy. There are currently 11 substudies assessing novel therapies that have emerged in the wake of “significant progress in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of AML.”

The current findings represent outcomes in patients enrolled between Nov. 2016 and Jan. 2018. The patients had a mean age of 72 years, and those selecting precision medicine vs. SOC had similar demographic and genetic features, the authors noted.

LLS president and chief executive officer Louis J. DeGennaro, PhD, said the findings are practice changing and provide a template for studying precision medicine in other cancers.

“The study is changing significantly the way we look at treating patients with AML, showing that precision medicine ... can improve short- and long-term outcomes for patients with this deadly blood cancer,” he said in the LLS statement. “Further, BEAT AML has proven to be a viable model for other cancer clinical trials to emulate.”

In fact, the model has been applied to the recently launched Beat COVID trial, which looks at acalabrutinib in patients with hematologic cancers and COVID-19 infection, and other trials, including the LLS PedAL global precision medicine trial for children with relapsed acute leukemia, are planned.

“This study sets the path to establish the safety of precision medicine in AML and sets the stage to extend this same approach to younger patients with this disease and other cancers that are urgently treated as a single disease despite recognition of multiple subtypes, the authors concluded.

Dr. Burd is an employee of LLS, which received funding from AbbVie, Agios Pharmaceuticals, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, and a variety of other pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. Dr. Byrd has received research support from Acerta Pharma, Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pharmacyclics and has served on the advisory board of Syndax Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Burd A et al. Nature Medicine 2020 Oct 26. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1089-8.

The 30-day mortality rates were 3.7% versus 20.4% in 224 patients who enrolled in the Beat AML trial precision medicine substudies within 7 days of prospective genomic profiling and 103 who elected SOC chemotherapy, respectively, Amy Burd, PhD, vice president of research strategy for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Rye Brook, N.Y. and her colleagues reported online in Nature Medicine.

Overall survival (OS) at a median of 7.1 months was also significantly longer with precision medicine than with SOC chemotherapy (median, 12.8 vs. 3.9 months), the investigators found.

In an additional 28 patients who selected an investigational therapy rather than a precision medicine strategy or SOC chemotherapy, median OS was not reached, and in 38 who chose palliative care, median OS was 0.6 months, they noted. Care type was unknown in two patients.

The results were similar after controlling for demographic, clinical, and molecular variables and did not change when patients with adverse events of special interest were excluded from the analysis or when only those with survival greater than 2 weeks were included in the analysis.

AML confers an adverse outcome in older adults and therefore is typically treated rapidly after diagnosis. This has precluded consideration of patients’ mutational profile for treatment decisions.

Beat AML, however, sought to prospectively assess the feasibility of quickly ascertaining cytogenetic and mutational data for the purpose of improving outcomes through targeted treatment.

“The study shows that delaying treatment up to 7 days is feasible and safe, and that patients who opted for the precision medicine approach experienced a lower early death rate and superior overall survival, compared with patients who opted for standard of care,” lead study author John C. Byrd, MD, the D. Warren Brown Chair of Leukemia Research of the Ohio State University, Columbus, noted in a press statement from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, which conducted the trial. “This patient-centric study shows that we can move away from chemotherapy treatment for patients who won’t respond or can’t withstand the harsh effects of the same chemotherapies we’ve been using for 40 years and match them with a treatment better suited for their individual cases.”

The ongoing Beat AML trial was launched by LLS in 2016 to assess various novel targeted therapies in newly diagnosed AML patients aged 60 years and older. Participants underwent next-generation genomic sequencing, were matched to the appropriate targeted therapy, and were given the option of enrolling on the relevant substudy or selecting an alternate treatment strategy. There are currently 11 substudies assessing novel therapies that have emerged in the wake of “significant progress in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of AML.”

The current findings represent outcomes in patients enrolled between Nov. 2016 and Jan. 2018. The patients had a mean age of 72 years, and those selecting precision medicine vs. SOC had similar demographic and genetic features, the authors noted.

LLS president and chief executive officer Louis J. DeGennaro, PhD, said the findings are practice changing and provide a template for studying precision medicine in other cancers.

“The study is changing significantly the way we look at treating patients with AML, showing that precision medicine ... can improve short- and long-term outcomes for patients with this deadly blood cancer,” he said in the LLS statement. “Further, BEAT AML has proven to be a viable model for other cancer clinical trials to emulate.”

In fact, the model has been applied to the recently launched Beat COVID trial, which looks at acalabrutinib in patients with hematologic cancers and COVID-19 infection, and other trials, including the LLS PedAL global precision medicine trial for children with relapsed acute leukemia, are planned.

“This study sets the path to establish the safety of precision medicine in AML and sets the stage to extend this same approach to younger patients with this disease and other cancers that are urgently treated as a single disease despite recognition of multiple subtypes, the authors concluded.

Dr. Burd is an employee of LLS, which received funding from AbbVie, Agios Pharmaceuticals, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, and a variety of other pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. Dr. Byrd has received research support from Acerta Pharma, Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pharmacyclics and has served on the advisory board of Syndax Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Burd A et al. Nature Medicine 2020 Oct 26. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1089-8.

The 30-day mortality rates were 3.7% versus 20.4% in 224 patients who enrolled in the Beat AML trial precision medicine substudies within 7 days of prospective genomic profiling and 103 who elected SOC chemotherapy, respectively, Amy Burd, PhD, vice president of research strategy for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Rye Brook, N.Y. and her colleagues reported online in Nature Medicine.

Overall survival (OS) at a median of 7.1 months was also significantly longer with precision medicine than with SOC chemotherapy (median, 12.8 vs. 3.9 months), the investigators found.

In an additional 28 patients who selected an investigational therapy rather than a precision medicine strategy or SOC chemotherapy, median OS was not reached, and in 38 who chose palliative care, median OS was 0.6 months, they noted. Care type was unknown in two patients.

The results were similar after controlling for demographic, clinical, and molecular variables and did not change when patients with adverse events of special interest were excluded from the analysis or when only those with survival greater than 2 weeks were included in the analysis.

AML confers an adverse outcome in older adults and therefore is typically treated rapidly after diagnosis. This has precluded consideration of patients’ mutational profile for treatment decisions.

Beat AML, however, sought to prospectively assess the feasibility of quickly ascertaining cytogenetic and mutational data for the purpose of improving outcomes through targeted treatment.

“The study shows that delaying treatment up to 7 days is feasible and safe, and that patients who opted for the precision medicine approach experienced a lower early death rate and superior overall survival, compared with patients who opted for standard of care,” lead study author John C. Byrd, MD, the D. Warren Brown Chair of Leukemia Research of the Ohio State University, Columbus, noted in a press statement from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, which conducted the trial. “This patient-centric study shows that we can move away from chemotherapy treatment for patients who won’t respond or can’t withstand the harsh effects of the same chemotherapies we’ve been using for 40 years and match them with a treatment better suited for their individual cases.”

The ongoing Beat AML trial was launched by LLS in 2016 to assess various novel targeted therapies in newly diagnosed AML patients aged 60 years and older. Participants underwent next-generation genomic sequencing, were matched to the appropriate targeted therapy, and were given the option of enrolling on the relevant substudy or selecting an alternate treatment strategy. There are currently 11 substudies assessing novel therapies that have emerged in the wake of “significant progress in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of AML.”

The current findings represent outcomes in patients enrolled between Nov. 2016 and Jan. 2018. The patients had a mean age of 72 years, and those selecting precision medicine vs. SOC had similar demographic and genetic features, the authors noted.

LLS president and chief executive officer Louis J. DeGennaro, PhD, said the findings are practice changing and provide a template for studying precision medicine in other cancers.

“The study is changing significantly the way we look at treating patients with AML, showing that precision medicine ... can improve short- and long-term outcomes for patients with this deadly blood cancer,” he said in the LLS statement. “Further, BEAT AML has proven to be a viable model for other cancer clinical trials to emulate.”

In fact, the model has been applied to the recently launched Beat COVID trial, which looks at acalabrutinib in patients with hematologic cancers and COVID-19 infection, and other trials, including the LLS PedAL global precision medicine trial for children with relapsed acute leukemia, are planned.

“This study sets the path to establish the safety of precision medicine in AML and sets the stage to extend this same approach to younger patients with this disease and other cancers that are urgently treated as a single disease despite recognition of multiple subtypes, the authors concluded.

Dr. Burd is an employee of LLS, which received funding from AbbVie, Agios Pharmaceuticals, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, and a variety of other pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. Dr. Byrd has received research support from Acerta Pharma, Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pharmacyclics and has served on the advisory board of Syndax Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Burd A et al. Nature Medicine 2020 Oct 26. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1089-8.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Rising IBD rates in minorities heighten need for awareness, strategies to close treatment gaps

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is rapidly increasing among racial and ethnic minorities, which makes it important to consider for patients with compatible symptoms, experts wrote in Gastroenterology.

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are “chronic diseases with intermittent periods of flare and remission, so access to specialists, appropriate therapies, and frequent follow-up visits are vital to good outcomes,” wrote Edward L. Barnes, MD, MPH, of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with his associates. However, Blacks with IBD tend to be diagnosed later than Whites, are less likely to receive recommended biologics and immunomodulators, and are more likely to receive care at an emergency department, to experience delays in colectomy, and to miss regular visits to IBD specialists because of financial and transportation barriers, they added.

These disparities are known to worsen outcomes. Compared with Whites, for example, Black patients with Crohn’s disease have higher rates of stricture and penetrating lesions and are at greater risk for postsurgical complications and death, even after potential confounders such age, sex, smoking status, time to operation, and obesity are controlled for. To help close these gaps, Dr. Barnes and his associates recommended enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols, which “streamline [the] multidisciplinary management of patients with IBD before surgery, incorporating evidence-based practices focused on nutrition, prevention of postoperative ileus, and use of nonopioid analgesia and goal-directed fluid therapy.”

Similar approaches also might improve nonsurgical outcomes in minorities with IBD, the experts said. In the Sinai-Helmsley Alliance for Research Excellence (SHARE) study, Black patients had more complicated IBD at baseline but similar clinical outcomes and patterns of medication use as Whites when they were treated at academic IBD centers. In other studies, race and ethnicity did not affect patterns of medication use, surgery, or surgical outcomes if patients had similar access to care. Such findings “indicate that when patients of minority races and ethnicities have access to appropriate specialty care and IBD-related therapy, many previously identified disparities are resolved or reduced,” the experts said.

However, race and ethnicity do affect some aspects of IBD disease activity, genetics, and treatment safety and efficacy. Since White patients have made up the vast majority of research participants, studies of racial and ethnic minorities are needed to improve their IBD diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Such research is particularly vital because IBD incidence is rising three times faster rates in racial and ethnic minorities than Whites, said Aline Charabaty, MD, AGAF, clinical director of the gastroenterology division at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and director of the IBD Center at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington.

She explained that, when immigrants from countries where IBD is rare adopt the United States’ sedentary lifestyle and Western diet (low in fruits and vegetables; high in proinflammatory saturated fats, sugars, and processed foods), their gut microbiome shifts and their IBD risk increases markedly. Studies in other countries have produced similar findings, said Dr. Charabaty, who did not help author the review article.

She also noted that patients from communities with a historically low prevalence of IBD may not understand its chronicity or the need for long-term treatment. However, treatment adherence is a common issue for patients of all backgrounds with IBD, she said. “What is unique is barriers to continuity of care – not being able to get to the treatment center, not being able to afford treatment or take time off work if you live paycheck to paycheck, not being able to pay someone to care for your kids while you see the doctor.”

Other potential barriers to seeking IBD treatment include cultural taboos against discussing lower GI symptoms or concerns that chronic disease will harm marriage prospects, Dr. Charabaty said. Such challenges only heighten the need to ascertain IBD symptoms: “Studies show that minorities have less follow-up care and their symptoms tend to be minimized. There is a lot of unconscious bias among providers that factors into this. The barriers are multiple, and it is important to define them and find strategies to overcome them at the level of the patient, the clinician, and the health system.”

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation supported the work. Dr. Barnes disclosed ties to AbbVie, Gilead, Takeda, and Target Pharmasolutions. Two coauthors also disclosed relevant ties to pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Charabaty disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Takeda, Pfizer, Janssen, and UCB.

SOURCE: Barnes EL et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Oct 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.064.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is rapidly increasing among racial and ethnic minorities, which makes it important to consider for patients with compatible symptoms, experts wrote in Gastroenterology.

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are “chronic diseases with intermittent periods of flare and remission, so access to specialists, appropriate therapies, and frequent follow-up visits are vital to good outcomes,” wrote Edward L. Barnes, MD, MPH, of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with his associates. However, Blacks with IBD tend to be diagnosed later than Whites, are less likely to receive recommended biologics and immunomodulators, and are more likely to receive care at an emergency department, to experience delays in colectomy, and to miss regular visits to IBD specialists because of financial and transportation barriers, they added.

These disparities are known to worsen outcomes. Compared with Whites, for example, Black patients with Crohn’s disease have higher rates of stricture and penetrating lesions and are at greater risk for postsurgical complications and death, even after potential confounders such age, sex, smoking status, time to operation, and obesity are controlled for. To help close these gaps, Dr. Barnes and his associates recommended enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols, which “streamline [the] multidisciplinary management of patients with IBD before surgery, incorporating evidence-based practices focused on nutrition, prevention of postoperative ileus, and use of nonopioid analgesia and goal-directed fluid therapy.”

Similar approaches also might improve nonsurgical outcomes in minorities with IBD, the experts said. In the Sinai-Helmsley Alliance for Research Excellence (SHARE) study, Black patients had more complicated IBD at baseline but similar clinical outcomes and patterns of medication use as Whites when they were treated at academic IBD centers. In other studies, race and ethnicity did not affect patterns of medication use, surgery, or surgical outcomes if patients had similar access to care. Such findings “indicate that when patients of minority races and ethnicities have access to appropriate specialty care and IBD-related therapy, many previously identified disparities are resolved or reduced,” the experts said.

However, race and ethnicity do affect some aspects of IBD disease activity, genetics, and treatment safety and efficacy. Since White patients have made up the vast majority of research participants, studies of racial and ethnic minorities are needed to improve their IBD diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Such research is particularly vital because IBD incidence is rising three times faster rates in racial and ethnic minorities than Whites, said Aline Charabaty, MD, AGAF, clinical director of the gastroenterology division at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and director of the IBD Center at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington.

She explained that, when immigrants from countries where IBD is rare adopt the United States’ sedentary lifestyle and Western diet (low in fruits and vegetables; high in proinflammatory saturated fats, sugars, and processed foods), their gut microbiome shifts and their IBD risk increases markedly. Studies in other countries have produced similar findings, said Dr. Charabaty, who did not help author the review article.

She also noted that patients from communities with a historically low prevalence of IBD may not understand its chronicity or the need for long-term treatment. However, treatment adherence is a common issue for patients of all backgrounds with IBD, she said. “What is unique is barriers to continuity of care – not being able to get to the treatment center, not being able to afford treatment or take time off work if you live paycheck to paycheck, not being able to pay someone to care for your kids while you see the doctor.”

Other potential barriers to seeking IBD treatment include cultural taboos against discussing lower GI symptoms or concerns that chronic disease will harm marriage prospects, Dr. Charabaty said. Such challenges only heighten the need to ascertain IBD symptoms: “Studies show that minorities have less follow-up care and their symptoms tend to be minimized. There is a lot of unconscious bias among providers that factors into this. The barriers are multiple, and it is important to define them and find strategies to overcome them at the level of the patient, the clinician, and the health system.”

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation supported the work. Dr. Barnes disclosed ties to AbbVie, Gilead, Takeda, and Target Pharmasolutions. Two coauthors also disclosed relevant ties to pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Charabaty disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Takeda, Pfizer, Janssen, and UCB.

SOURCE: Barnes EL et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Oct 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.064.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is rapidly increasing among racial and ethnic minorities, which makes it important to consider for patients with compatible symptoms, experts wrote in Gastroenterology.

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are “chronic diseases with intermittent periods of flare and remission, so access to specialists, appropriate therapies, and frequent follow-up visits are vital to good outcomes,” wrote Edward L. Barnes, MD, MPH, of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with his associates. However, Blacks with IBD tend to be diagnosed later than Whites, are less likely to receive recommended biologics and immunomodulators, and are more likely to receive care at an emergency department, to experience delays in colectomy, and to miss regular visits to IBD specialists because of financial and transportation barriers, they added.

These disparities are known to worsen outcomes. Compared with Whites, for example, Black patients with Crohn’s disease have higher rates of stricture and penetrating lesions and are at greater risk for postsurgical complications and death, even after potential confounders such age, sex, smoking status, time to operation, and obesity are controlled for. To help close these gaps, Dr. Barnes and his associates recommended enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols, which “streamline [the] multidisciplinary management of patients with IBD before surgery, incorporating evidence-based practices focused on nutrition, prevention of postoperative ileus, and use of nonopioid analgesia and goal-directed fluid therapy.”

Similar approaches also might improve nonsurgical outcomes in minorities with IBD, the experts said. In the Sinai-Helmsley Alliance for Research Excellence (SHARE) study, Black patients had more complicated IBD at baseline but similar clinical outcomes and patterns of medication use as Whites when they were treated at academic IBD centers. In other studies, race and ethnicity did not affect patterns of medication use, surgery, or surgical outcomes if patients had similar access to care. Such findings “indicate that when patients of minority races and ethnicities have access to appropriate specialty care and IBD-related therapy, many previously identified disparities are resolved or reduced,” the experts said.

However, race and ethnicity do affect some aspects of IBD disease activity, genetics, and treatment safety and efficacy. Since White patients have made up the vast majority of research participants, studies of racial and ethnic minorities are needed to improve their IBD diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Such research is particularly vital because IBD incidence is rising three times faster rates in racial and ethnic minorities than Whites, said Aline Charabaty, MD, AGAF, clinical director of the gastroenterology division at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and director of the IBD Center at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington.

She explained that, when immigrants from countries where IBD is rare adopt the United States’ sedentary lifestyle and Western diet (low in fruits and vegetables; high in proinflammatory saturated fats, sugars, and processed foods), their gut microbiome shifts and their IBD risk increases markedly. Studies in other countries have produced similar findings, said Dr. Charabaty, who did not help author the review article.

She also noted that patients from communities with a historically low prevalence of IBD may not understand its chronicity or the need for long-term treatment. However, treatment adherence is a common issue for patients of all backgrounds with IBD, she said. “What is unique is barriers to continuity of care – not being able to get to the treatment center, not being able to afford treatment or take time off work if you live paycheck to paycheck, not being able to pay someone to care for your kids while you see the doctor.”

Other potential barriers to seeking IBD treatment include cultural taboos against discussing lower GI symptoms or concerns that chronic disease will harm marriage prospects, Dr. Charabaty said. Such challenges only heighten the need to ascertain IBD symptoms: “Studies show that minorities have less follow-up care and their symptoms tend to be minimized. There is a lot of unconscious bias among providers that factors into this. The barriers are multiple, and it is important to define them and find strategies to overcome them at the level of the patient, the clinician, and the health system.”

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation supported the work. Dr. Barnes disclosed ties to AbbVie, Gilead, Takeda, and Target Pharmasolutions. Two coauthors also disclosed relevant ties to pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Charabaty disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Takeda, Pfizer, Janssen, and UCB.

SOURCE: Barnes EL et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Oct 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.064.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Template Design and Analysis: Integrating Informatics Solutions to Improve Clinical Documentation

Standardized template design is a useful tool to improve clinical documentation and reliable reporting of health care outcomes when constructed with clear objectives and with collaboration of key stakeholders. A standardized template should not only capture accurate diagnostic information, but also inform quality improvement (QI) measures and best practices.

Kang and colleagues showed that a correlation exists between organizational satisfaction and improved quality outcomes.1 A new initiative should have a well-defined purpose reinforced by collaborative workgroups and engaged employees who understand their clinical care role with electronic health record (EHR) modifications.

Several studies have shown how the usefulness of templates achieve multipurpose goals, such as accurate documentation and improved care. Valluru and colleagues showed a significant increase in vaccination rates for patients with inflammatory bowel disease after implementing a standardized template.2 By using a standardized template, Thaker and colleagues showed improved documentation regarding obesity and increased nutritional and physical activity counseling.3 Furthermore, Grogan and colleagues showed that templates are useful for house staff education on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) terminology and demonstrated improved documentation in the postintervention group.4,5

This article discusses the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS) integrated informatics solutions within template design in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) EHR system that was associated with an increase in its case severity index (CSI) through improved clinical documentation capture.

Methods

According to policy activities that constitute research at NF/SGVHS, institutional review board approval was not required as this work met the criteria for operational improvement activities exempt from ethics review.

NF/SGVHS includes 2 hospitals: Malcom Randall VA Medical Center (MRVAMC) in Gainesville, Florida, and Lake City VA Medical Center (LCVAMC) in Lake City, Florida. MRVAMC is a large, 1a, academic VA facility composed of rotating residents and fellows and includes multiple specialty care services. LCVAMC is a smaller, nonteaching facility.

Template Design Impact

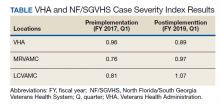

CSI is a risk-adjusted formula developed by the Inpatient Evaluation Center within VHA. CSI is incorporated into the VHA quality metrics reporting system, Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL). CSI risk-adjusts metrics such as length of stay and mortality before releasing SAIL reports. CSI is calculated separately for acute level of care (LOC) and for the intensive care unit (ICU). In fiscal year (FY) 2017, acute LOC preimplementation data for CSI at NF/SGVHS were 0.76 for MRVAMC and 0.81 for LCVAMC, which was significantly below the national VHA average of 0.96 (Table).

A below-average CSI conveys a less complicated case mix compared with most other VA facilities. Although smaller VA facilities may have a less complicated case mix, it is unusual for large, tertiary care 1a VA facilities to have a low CSI. This low CSI is usually due to inadequate documentation, which affects not only risk-adjusted quality metrics outcomes, but also potential reimbursement.6

An interdisciplinary team composed of attendings, residents, and a clinical document improvement specialist identified the below-average acute LOC CSI for MRVAMC and LCVAMC compared with that of the national VHA average. Further analysis by chart reviews showed inconsistencies with standardized documentation despite prior health care provider education on ICD terminology and specific groups of common comorbidities analyzed in administrative data reviews for risk-adjustment purposes, known as Elixhauser comorbidities.5,7

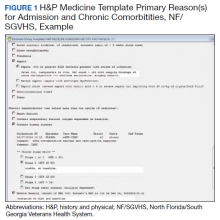

A chart review showed lack of clarity regarding primary reason(s) for admission and chronic comorbidities within NF/SGVHS. Using Pareto chart analysis, the template team designed a standardized history and physical (H&P) medicine template based on NF/SGVHS common medicine admissions (Figure 1). A Pareto chart is a valuable QI tool that assists with identifying majority contributors to a problem(s) being analyzed when evaluating a large set of data points. Subsequently, this tool helps focus direction on QI efforts.8

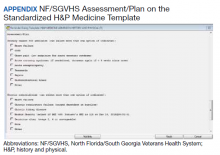

The template had the usual H&P elements not shown (eg, chief complaint, history of present illness, etc), and highlights the assessment/plan section containing primary reason(s) for admission and chronic comorbidities (Figure 1). The complete assessment and plan section on the template can be found in the Appendix.

To simplify the template interface, only single clicks were required to expand diagnostic and chronic comorbidity checkboxes. Subcategories then appeared to select diagnosis and chronic comorbidities along with free text for additional documentation.

In addition, data objects were created within the template that permitted the ability to retrieve information from the VHA EHR and insert specific data points of interest in the template; for example, body mass index to assess degree of obesity and estimated glomerular filtration rate to determine the stage of chronic kidney disease. This allowed users to easily reference data in one template in lieu of searching for data in multiple places in the EHR.9

Results

The standardized H&P medicine template was implemented at MRVAMC and LCVAMC in June 2018 (the final month of the third quarter of FY 2018). As clinical providers throughout NF/SGVHS used the standardized template, acute LOC postimplementation data for CSI significantly improved. Although the national VHA average slightly decreased from 0.96 in the first quarter of FY 2017 to 0.89, in the first quarter of FY 2019, MRVAMC acute LOC CSI improved from 0.76 to 0.97, and LCVAMC acute LOC CSI improved from 0.81 to 1.07 during the same period.

In addition, compliance also was monitored within MRVAMC and LCVAMC for about 1 year after standardized H&P medicine template implementation. Compliance was determined by how often the standardized H&P medicine template was used for inpatient medicine admissions to the acute care wards vs other H&P notes used (such as personalized templates).

Methodology for compliance analysis included acquisition of completed H&P medicine notes from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, within the VHA Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) clinical and business information system using the search strings: “H&P admission history and physical” and “history of present illness.”10

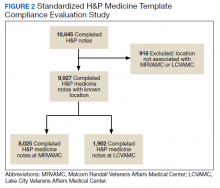

A review identified 10,845 completed medicine H&P notes. Nine hundred eighteen notes were excluded as their search function yielded a location not corresponding to MRVAMC or LCVAMC. Of the 9,927 notes remaining, 8,025 of these were completed medicine H&P notes at MRVAMC and 1,902 were completed medicine H&P notes at LCVAMC (Figure 2).

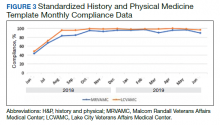

From June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019 at MRVAMC, compliance was reviewed monthly for the 8,025 completed H&P medicine notes. Of the completed H&P medicine notes, the standardized H&P medicine template was used 43.2% in June 2018. By June 2019, MRVAMC clinical providers demonstrated significant improvement for standardized H&P medicine template use at 89.9% (Figure 3). Total average compliance from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, was 88.4%, which doubled compliance from the initial introduction of the standardized H&P medicine template.

Compliance was reviewed monthly for the 1,902 completed H&P medicine notes from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, at LCVAMC. Of the completed H&P medicine notes, the standardized template was used 48.2% of the time in June 2018. By June 2019, LCVAMC clinical providers demonstrated significant improvement for standardized H&P medicine template use, which increased to 96.9%. Total average compliance from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, was 93.8%, which was almost double the baseline compliance rate.

Discussion

Template design with clear objectives, strategic collaboration, and integrated informatics solutions has the potential to increase accuracy of documentation. As shown, the NF/SGVHS template design was associated with significant improvement in acute LOC CSI for both MRVAMC and LCVAMC due to more accurate documentation using the standardized H&P medicine template.

Numerous factors contributed to the success of this template design. First, a clear vision for application of the template was communicated with key stakeholders. In addition, the template design team was focused on specific goals rather than a one size fits all approach, which was crucial for sustainable execution. Although interdisciplinary teamwork has the potential to result in innovative practices, large multidisciplinary teams also may have difficulty establishing a shared vision that can result in barriers to achieving project goals.

Balancing standardization and customization was essential for user buy-in. As noted by Gardner and Pearce, inviting clinical providers to participate in template design and allowing for customization has the potential to increase acceptance and use of templates.11 Although the original design for the standardized H&P medicine template started with the medicine service at NF/SGVHS, the design framework is applicable to numerous services where various clinical care elements can be customized.

Explaining the informatics tools built into the template allowed clinicians to see opportunities to improve clinical documentation and the impact it has on reporting health care outcomes. When improvement work involves integrating clinical care delivery and administrative expectations, it is essential that health care systems understand and strategically execute project initiatives at this critical juncture.

Finally, incorporation of a sustainability plan when process improvement strategies are implemented is vital. In addition to collaboration with the clinical providers during design and implementation of the standardized template, leadership buy-in was key. Compliance with standardized H&P medicine template use was monitored monthly and reviewed by the NF/SGVHS Chief of Staff.

As noted, LCVAMC postimplementation acute LOC CSI was higher than that of MRVAMC despite being a smaller facility. This might be due to the MRVAMC designation as a teaching institution. Medicine is the only inpatient service at LCVAMC staffed by hospitalists with limited specialists available for consultation, whereas MRVAMC is a tertiary care teaching facility with numerous inpatient services and subspecialties. As LCVAMC has more continuity, house staff rotating at MRVAMC require continued training/education on new templates and process changes.

Limitations

Although standardized template design was successful at NF/SGVHS, limitations should be noted. Our clinical documentation improvement (CDI) program also was expanded about the same time as the new templates were released. The expansion of the CDI program in addition to new template design likely had a synergistic effect on acute LOC CSI.

CSI is a complex, risk-adjusted model that includes numerous factors, including but not limited to diagnosis and comorbid conditions. Other factors include age, marital status, procedures, source of admission, specific laboratory values, medical or surgical diagnosis-related group, intensive care unit stays, and immunosuppressive status. CSI also includes operative and nonoperative components that average into an overall CSI. As the majority of CSI is composed of nonoperative constituents within NF/SGVHS, we do not believe this had any substantial impact on reporting of CSI improvements.

In addition, template entry into VHA EHR requires a location selection (such as a clinic name or ward name following an inpatient admission). Of the 10,845 completed H&P medicine notes identified in VistA, 918 notes were excluded from analysis as their search function yielded a location not corresponding to MRVAMC or LCVAMC. For the 918 notes excluded, we believe this was likely due to user error where locations not related to MRVAMC or LCVAMC were selected during standardized H&P medicine template entry.

Conclusions

After the NF/SGVHS implementation of a uniquely designed template embedded with informatics solutions within the VHA EHR, the CSI increased due to more accurate documentation.

Next steps include determining the impact of the NF/SGVHS template design on potential reimbursement and expanding template design into the outpatient setting where there are additional opportunities to improve clinical documentation and reliable reporting of health care outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals for their experience and contribution: Beverley White is the Clinical Documentation Improvement Coordinator at North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System and provided expertise on documentation requirements. Russell Jacobitz and Susan Rozelle provided technical expertise on electronic health record system enhancements and implemented the template design. Jess Delaune, MD, and Robert Carroll, MD, provided additional physician input during template design. We also acknowledge the Inpatient Evaluation Center (IPEC) within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). IPEC developed the case severity index, a risk-adjusted formula incorporated into the VHA quality metric reporting system, Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL).

1. Kang R, Kunkel S, Columbo J, et al. Association of Hospital Employee satisfaction with patient safety and satisfaction within Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. Am J Med. 2019;132(4):530-534.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.11.031

2. Valluru, N, Kang L, Gaidos JK. Health maintenance documentation improves for veterans with IBD using a template in the Computerized Patient Record System. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(7):1782-1786. doi:10.1007%2Fs10620-018-5093-5

3. Thaker VV, Lee F, Bottino CJ, et al. Impact of an electronic template on documentation of obesity in a primary care clinic. Clin Pediatr. 2016;55(12):1152-1159. doi:10.1177/0009922815621331

4. Grogan EL, Speroff T, Deppen S, et al. Improving documentation of patient acuity level using a progress note template. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(3):468-475. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.05.254

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Classification of diseases, functioning, and disability. https://www .cdc.gov/nchs/icd/index.htm. Updated June 30, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2020.

6. Marill K A, Gauharou ES, Nelson BK, et al. Prospective, randomized trial of template-assisted versus undirected written recording of physician records in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(5):500- 509. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70336-7

7. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004

8. Hart KA, Steinfeldt BA, Braun RD. Formulation and applications of a probalistic Pareto chart. AIAA. 2015;0804. doi:10.2514/6.2015-0804

9. IBM. IBM knowledge center: overview of data objects. https://www.ibm.com/support/knowledgecenter /en/SSLTBW_2.3.0/com.ibm.zos.v2r3.cbclx01/data _objects.htm. Accessed October 12, 2020.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. History of IT at VA. https://www.oit.va.gov/about/history.cfm. Accessed October 18, 2020.

11. Gardner CL, Pearce PF. Customization of electronic medical record templates to improve end-user satisfaction. Comput Inform Nurs. 2013;31(3):115-121. doi:10.1097/NXN.0b013e3182771814

Standardized template design is a useful tool to improve clinical documentation and reliable reporting of health care outcomes when constructed with clear objectives and with collaboration of key stakeholders. A standardized template should not only capture accurate diagnostic information, but also inform quality improvement (QI) measures and best practices.

Kang and colleagues showed that a correlation exists between organizational satisfaction and improved quality outcomes.1 A new initiative should have a well-defined purpose reinforced by collaborative workgroups and engaged employees who understand their clinical care role with electronic health record (EHR) modifications.

Several studies have shown how the usefulness of templates achieve multipurpose goals, such as accurate documentation and improved care. Valluru and colleagues showed a significant increase in vaccination rates for patients with inflammatory bowel disease after implementing a standardized template.2 By using a standardized template, Thaker and colleagues showed improved documentation regarding obesity and increased nutritional and physical activity counseling.3 Furthermore, Grogan and colleagues showed that templates are useful for house staff education on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) terminology and demonstrated improved documentation in the postintervention group.4,5

This article discusses the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS) integrated informatics solutions within template design in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) EHR system that was associated with an increase in its case severity index (CSI) through improved clinical documentation capture.

Methods

According to policy activities that constitute research at NF/SGVHS, institutional review board approval was not required as this work met the criteria for operational improvement activities exempt from ethics review.

NF/SGVHS includes 2 hospitals: Malcom Randall VA Medical Center (MRVAMC) in Gainesville, Florida, and Lake City VA Medical Center (LCVAMC) in Lake City, Florida. MRVAMC is a large, 1a, academic VA facility composed of rotating residents and fellows and includes multiple specialty care services. LCVAMC is a smaller, nonteaching facility.

Template Design Impact

CSI is a risk-adjusted formula developed by the Inpatient Evaluation Center within VHA. CSI is incorporated into the VHA quality metrics reporting system, Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL). CSI risk-adjusts metrics such as length of stay and mortality before releasing SAIL reports. CSI is calculated separately for acute level of care (LOC) and for the intensive care unit (ICU). In fiscal year (FY) 2017, acute LOC preimplementation data for CSI at NF/SGVHS were 0.76 for MRVAMC and 0.81 for LCVAMC, which was significantly below the national VHA average of 0.96 (Table).

A below-average CSI conveys a less complicated case mix compared with most other VA facilities. Although smaller VA facilities may have a less complicated case mix, it is unusual for large, tertiary care 1a VA facilities to have a low CSI. This low CSI is usually due to inadequate documentation, which affects not only risk-adjusted quality metrics outcomes, but also potential reimbursement.6

An interdisciplinary team composed of attendings, residents, and a clinical document improvement specialist identified the below-average acute LOC CSI for MRVAMC and LCVAMC compared with that of the national VHA average. Further analysis by chart reviews showed inconsistencies with standardized documentation despite prior health care provider education on ICD terminology and specific groups of common comorbidities analyzed in administrative data reviews for risk-adjustment purposes, known as Elixhauser comorbidities.5,7

A chart review showed lack of clarity regarding primary reason(s) for admission and chronic comorbidities within NF/SGVHS. Using Pareto chart analysis, the template team designed a standardized history and physical (H&P) medicine template based on NF/SGVHS common medicine admissions (Figure 1). A Pareto chart is a valuable QI tool that assists with identifying majority contributors to a problem(s) being analyzed when evaluating a large set of data points. Subsequently, this tool helps focus direction on QI efforts.8

The template had the usual H&P elements not shown (eg, chief complaint, history of present illness, etc), and highlights the assessment/plan section containing primary reason(s) for admission and chronic comorbidities (Figure 1). The complete assessment and plan section on the template can be found in the Appendix.

To simplify the template interface, only single clicks were required to expand diagnostic and chronic comorbidity checkboxes. Subcategories then appeared to select diagnosis and chronic comorbidities along with free text for additional documentation.

In addition, data objects were created within the template that permitted the ability to retrieve information from the VHA EHR and insert specific data points of interest in the template; for example, body mass index to assess degree of obesity and estimated glomerular filtration rate to determine the stage of chronic kidney disease. This allowed users to easily reference data in one template in lieu of searching for data in multiple places in the EHR.9

Results

The standardized H&P medicine template was implemented at MRVAMC and LCVAMC in June 2018 (the final month of the third quarter of FY 2018). As clinical providers throughout NF/SGVHS used the standardized template, acute LOC postimplementation data for CSI significantly improved. Although the national VHA average slightly decreased from 0.96 in the first quarter of FY 2017 to 0.89, in the first quarter of FY 2019, MRVAMC acute LOC CSI improved from 0.76 to 0.97, and LCVAMC acute LOC CSI improved from 0.81 to 1.07 during the same period.

In addition, compliance also was monitored within MRVAMC and LCVAMC for about 1 year after standardized H&P medicine template implementation. Compliance was determined by how often the standardized H&P medicine template was used for inpatient medicine admissions to the acute care wards vs other H&P notes used (such as personalized templates).

Methodology for compliance analysis included acquisition of completed H&P medicine notes from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, within the VHA Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) clinical and business information system using the search strings: “H&P admission history and physical” and “history of present illness.”10

A review identified 10,845 completed medicine H&P notes. Nine hundred eighteen notes were excluded as their search function yielded a location not corresponding to MRVAMC or LCVAMC. Of the 9,927 notes remaining, 8,025 of these were completed medicine H&P notes at MRVAMC and 1,902 were completed medicine H&P notes at LCVAMC (Figure 2).

From June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019 at MRVAMC, compliance was reviewed monthly for the 8,025 completed H&P medicine notes. Of the completed H&P medicine notes, the standardized H&P medicine template was used 43.2% in June 2018. By June 2019, MRVAMC clinical providers demonstrated significant improvement for standardized H&P medicine template use at 89.9% (Figure 3). Total average compliance from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, was 88.4%, which doubled compliance from the initial introduction of the standardized H&P medicine template.

Compliance was reviewed monthly for the 1,902 completed H&P medicine notes from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, at LCVAMC. Of the completed H&P medicine notes, the standardized template was used 48.2% of the time in June 2018. By June 2019, LCVAMC clinical providers demonstrated significant improvement for standardized H&P medicine template use, which increased to 96.9%. Total average compliance from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, was 93.8%, which was almost double the baseline compliance rate.

Discussion

Template design with clear objectives, strategic collaboration, and integrated informatics solutions has the potential to increase accuracy of documentation. As shown, the NF/SGVHS template design was associated with significant improvement in acute LOC CSI for both MRVAMC and LCVAMC due to more accurate documentation using the standardized H&P medicine template.

Numerous factors contributed to the success of this template design. First, a clear vision for application of the template was communicated with key stakeholders. In addition, the template design team was focused on specific goals rather than a one size fits all approach, which was crucial for sustainable execution. Although interdisciplinary teamwork has the potential to result in innovative practices, large multidisciplinary teams also may have difficulty establishing a shared vision that can result in barriers to achieving project goals.

Balancing standardization and customization was essential for user buy-in. As noted by Gardner and Pearce, inviting clinical providers to participate in template design and allowing for customization has the potential to increase acceptance and use of templates.11 Although the original design for the standardized H&P medicine template started with the medicine service at NF/SGVHS, the design framework is applicable to numerous services where various clinical care elements can be customized.

Explaining the informatics tools built into the template allowed clinicians to see opportunities to improve clinical documentation and the impact it has on reporting health care outcomes. When improvement work involves integrating clinical care delivery and administrative expectations, it is essential that health care systems understand and strategically execute project initiatives at this critical juncture.

Finally, incorporation of a sustainability plan when process improvement strategies are implemented is vital. In addition to collaboration with the clinical providers during design and implementation of the standardized template, leadership buy-in was key. Compliance with standardized H&P medicine template use was monitored monthly and reviewed by the NF/SGVHS Chief of Staff.

As noted, LCVAMC postimplementation acute LOC CSI was higher than that of MRVAMC despite being a smaller facility. This might be due to the MRVAMC designation as a teaching institution. Medicine is the only inpatient service at LCVAMC staffed by hospitalists with limited specialists available for consultation, whereas MRVAMC is a tertiary care teaching facility with numerous inpatient services and subspecialties. As LCVAMC has more continuity, house staff rotating at MRVAMC require continued training/education on new templates and process changes.

Limitations

Although standardized template design was successful at NF/SGVHS, limitations should be noted. Our clinical documentation improvement (CDI) program also was expanded about the same time as the new templates were released. The expansion of the CDI program in addition to new template design likely had a synergistic effect on acute LOC CSI.

CSI is a complex, risk-adjusted model that includes numerous factors, including but not limited to diagnosis and comorbid conditions. Other factors include age, marital status, procedures, source of admission, specific laboratory values, medical or surgical diagnosis-related group, intensive care unit stays, and immunosuppressive status. CSI also includes operative and nonoperative components that average into an overall CSI. As the majority of CSI is composed of nonoperative constituents within NF/SGVHS, we do not believe this had any substantial impact on reporting of CSI improvements.

In addition, template entry into VHA EHR requires a location selection (such as a clinic name or ward name following an inpatient admission). Of the 10,845 completed H&P medicine notes identified in VistA, 918 notes were excluded from analysis as their search function yielded a location not corresponding to MRVAMC or LCVAMC. For the 918 notes excluded, we believe this was likely due to user error where locations not related to MRVAMC or LCVAMC were selected during standardized H&P medicine template entry.

Conclusions

After the NF/SGVHS implementation of a uniquely designed template embedded with informatics solutions within the VHA EHR, the CSI increased due to more accurate documentation.

Next steps include determining the impact of the NF/SGVHS template design on potential reimbursement and expanding template design into the outpatient setting where there are additional opportunities to improve clinical documentation and reliable reporting of health care outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals for their experience and contribution: Beverley White is the Clinical Documentation Improvement Coordinator at North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System and provided expertise on documentation requirements. Russell Jacobitz and Susan Rozelle provided technical expertise on electronic health record system enhancements and implemented the template design. Jess Delaune, MD, and Robert Carroll, MD, provided additional physician input during template design. We also acknowledge the Inpatient Evaluation Center (IPEC) within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). IPEC developed the case severity index, a risk-adjusted formula incorporated into the VHA quality metric reporting system, Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL).

Standardized template design is a useful tool to improve clinical documentation and reliable reporting of health care outcomes when constructed with clear objectives and with collaboration of key stakeholders. A standardized template should not only capture accurate diagnostic information, but also inform quality improvement (QI) measures and best practices.

Kang and colleagues showed that a correlation exists between organizational satisfaction and improved quality outcomes.1 A new initiative should have a well-defined purpose reinforced by collaborative workgroups and engaged employees who understand their clinical care role with electronic health record (EHR) modifications.

Several studies have shown how the usefulness of templates achieve multipurpose goals, such as accurate documentation and improved care. Valluru and colleagues showed a significant increase in vaccination rates for patients with inflammatory bowel disease after implementing a standardized template.2 By using a standardized template, Thaker and colleagues showed improved documentation regarding obesity and increased nutritional and physical activity counseling.3 Furthermore, Grogan and colleagues showed that templates are useful for house staff education on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) terminology and demonstrated improved documentation in the postintervention group.4,5

This article discusses the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS) integrated informatics solutions within template design in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) EHR system that was associated with an increase in its case severity index (CSI) through improved clinical documentation capture.

Methods

According to policy activities that constitute research at NF/SGVHS, institutional review board approval was not required as this work met the criteria for operational improvement activities exempt from ethics review.

NF/SGVHS includes 2 hospitals: Malcom Randall VA Medical Center (MRVAMC) in Gainesville, Florida, and Lake City VA Medical Center (LCVAMC) in Lake City, Florida. MRVAMC is a large, 1a, academic VA facility composed of rotating residents and fellows and includes multiple specialty care services. LCVAMC is a smaller, nonteaching facility.

Template Design Impact

CSI is a risk-adjusted formula developed by the Inpatient Evaluation Center within VHA. CSI is incorporated into the VHA quality metrics reporting system, Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL). CSI risk-adjusts metrics such as length of stay and mortality before releasing SAIL reports. CSI is calculated separately for acute level of care (LOC) and for the intensive care unit (ICU). In fiscal year (FY) 2017, acute LOC preimplementation data for CSI at NF/SGVHS were 0.76 for MRVAMC and 0.81 for LCVAMC, which was significantly below the national VHA average of 0.96 (Table).

A below-average CSI conveys a less complicated case mix compared with most other VA facilities. Although smaller VA facilities may have a less complicated case mix, it is unusual for large, tertiary care 1a VA facilities to have a low CSI. This low CSI is usually due to inadequate documentation, which affects not only risk-adjusted quality metrics outcomes, but also potential reimbursement.6

An interdisciplinary team composed of attendings, residents, and a clinical document improvement specialist identified the below-average acute LOC CSI for MRVAMC and LCVAMC compared with that of the national VHA average. Further analysis by chart reviews showed inconsistencies with standardized documentation despite prior health care provider education on ICD terminology and specific groups of common comorbidities analyzed in administrative data reviews for risk-adjustment purposes, known as Elixhauser comorbidities.5,7

A chart review showed lack of clarity regarding primary reason(s) for admission and chronic comorbidities within NF/SGVHS. Using Pareto chart analysis, the template team designed a standardized history and physical (H&P) medicine template based on NF/SGVHS common medicine admissions (Figure 1). A Pareto chart is a valuable QI tool that assists with identifying majority contributors to a problem(s) being analyzed when evaluating a large set of data points. Subsequently, this tool helps focus direction on QI efforts.8

The template had the usual H&P elements not shown (eg, chief complaint, history of present illness, etc), and highlights the assessment/plan section containing primary reason(s) for admission and chronic comorbidities (Figure 1). The complete assessment and plan section on the template can be found in the Appendix.

To simplify the template interface, only single clicks were required to expand diagnostic and chronic comorbidity checkboxes. Subcategories then appeared to select diagnosis and chronic comorbidities along with free text for additional documentation.

In addition, data objects were created within the template that permitted the ability to retrieve information from the VHA EHR and insert specific data points of interest in the template; for example, body mass index to assess degree of obesity and estimated glomerular filtration rate to determine the stage of chronic kidney disease. This allowed users to easily reference data in one template in lieu of searching for data in multiple places in the EHR.9

Results

The standardized H&P medicine template was implemented at MRVAMC and LCVAMC in June 2018 (the final month of the third quarter of FY 2018). As clinical providers throughout NF/SGVHS used the standardized template, acute LOC postimplementation data for CSI significantly improved. Although the national VHA average slightly decreased from 0.96 in the first quarter of FY 2017 to 0.89, in the first quarter of FY 2019, MRVAMC acute LOC CSI improved from 0.76 to 0.97, and LCVAMC acute LOC CSI improved from 0.81 to 1.07 during the same period.

In addition, compliance also was monitored within MRVAMC and LCVAMC for about 1 year after standardized H&P medicine template implementation. Compliance was determined by how often the standardized H&P medicine template was used for inpatient medicine admissions to the acute care wards vs other H&P notes used (such as personalized templates).

Methodology for compliance analysis included acquisition of completed H&P medicine notes from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, within the VHA Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA) clinical and business information system using the search strings: “H&P admission history and physical” and “history of present illness.”10

A review identified 10,845 completed medicine H&P notes. Nine hundred eighteen notes were excluded as their search function yielded a location not corresponding to MRVAMC or LCVAMC. Of the 9,927 notes remaining, 8,025 of these were completed medicine H&P notes at MRVAMC and 1,902 were completed medicine H&P notes at LCVAMC (Figure 2).

From June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019 at MRVAMC, compliance was reviewed monthly for the 8,025 completed H&P medicine notes. Of the completed H&P medicine notes, the standardized H&P medicine template was used 43.2% in June 2018. By June 2019, MRVAMC clinical providers demonstrated significant improvement for standardized H&P medicine template use at 89.9% (Figure 3). Total average compliance from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, was 88.4%, which doubled compliance from the initial introduction of the standardized H&P medicine template.

Compliance was reviewed monthly for the 1,902 completed H&P medicine notes from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, at LCVAMC. Of the completed H&P medicine notes, the standardized template was used 48.2% of the time in June 2018. By June 2019, LCVAMC clinical providers demonstrated significant improvement for standardized H&P medicine template use, which increased to 96.9%. Total average compliance from June 18, 2018 to June 30, 2019, was 93.8%, which was almost double the baseline compliance rate.

Discussion

Template design with clear objectives, strategic collaboration, and integrated informatics solutions has the potential to increase accuracy of documentation. As shown, the NF/SGVHS template design was associated with significant improvement in acute LOC CSI for both MRVAMC and LCVAMC due to more accurate documentation using the standardized H&P medicine template.

Numerous factors contributed to the success of this template design. First, a clear vision for application of the template was communicated with key stakeholders. In addition, the template design team was focused on specific goals rather than a one size fits all approach, which was crucial for sustainable execution. Although interdisciplinary teamwork has the potential to result in innovative practices, large multidisciplinary teams also may have difficulty establishing a shared vision that can result in barriers to achieving project goals.

Balancing standardization and customization was essential for user buy-in. As noted by Gardner and Pearce, inviting clinical providers to participate in template design and allowing for customization has the potential to increase acceptance and use of templates.11 Although the original design for the standardized H&P medicine template started with the medicine service at NF/SGVHS, the design framework is applicable to numerous services where various clinical care elements can be customized.

Explaining the informatics tools built into the template allowed clinicians to see opportunities to improve clinical documentation and the impact it has on reporting health care outcomes. When improvement work involves integrating clinical care delivery and administrative expectations, it is essential that health care systems understand and strategically execute project initiatives at this critical juncture.

Finally, incorporation of a sustainability plan when process improvement strategies are implemented is vital. In addition to collaboration with the clinical providers during design and implementation of the standardized template, leadership buy-in was key. Compliance with standardized H&P medicine template use was monitored monthly and reviewed by the NF/SGVHS Chief of Staff.

As noted, LCVAMC postimplementation acute LOC CSI was higher than that of MRVAMC despite being a smaller facility. This might be due to the MRVAMC designation as a teaching institution. Medicine is the only inpatient service at LCVAMC staffed by hospitalists with limited specialists available for consultation, whereas MRVAMC is a tertiary care teaching facility with numerous inpatient services and subspecialties. As LCVAMC has more continuity, house staff rotating at MRVAMC require continued training/education on new templates and process changes.

Limitations

Although standardized template design was successful at NF/SGVHS, limitations should be noted. Our clinical documentation improvement (CDI) program also was expanded about the same time as the new templates were released. The expansion of the CDI program in addition to new template design likely had a synergistic effect on acute LOC CSI.

CSI is a complex, risk-adjusted model that includes numerous factors, including but not limited to diagnosis and comorbid conditions. Other factors include age, marital status, procedures, source of admission, specific laboratory values, medical or surgical diagnosis-related group, intensive care unit stays, and immunosuppressive status. CSI also includes operative and nonoperative components that average into an overall CSI. As the majority of CSI is composed of nonoperative constituents within NF/SGVHS, we do not believe this had any substantial impact on reporting of CSI improvements.

In addition, template entry into VHA EHR requires a location selection (such as a clinic name or ward name following an inpatient admission). Of the 10,845 completed H&P medicine notes identified in VistA, 918 notes were excluded from analysis as their search function yielded a location not corresponding to MRVAMC or LCVAMC. For the 918 notes excluded, we believe this was likely due to user error where locations not related to MRVAMC or LCVAMC were selected during standardized H&P medicine template entry.

Conclusions

After the NF/SGVHS implementation of a uniquely designed template embedded with informatics solutions within the VHA EHR, the CSI increased due to more accurate documentation.

Next steps include determining the impact of the NF/SGVHS template design on potential reimbursement and expanding template design into the outpatient setting where there are additional opportunities to improve clinical documentation and reliable reporting of health care outcomes.

Acknowledgments