User login

Study IDs microbial signature of celiac disease in children

Eleven operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of fecal bacteria were less abundant in children with celiac disease than in healthy children, according to the findings of a study published in Gastroenterology.

This microbial signature correctly identified approximately four out of five cases of celiac disease, regardless of whether children were newly diagnosed or had already modified their diet, reported Konstantina Zafeiropoulou and Ben Nichols, PhD, of the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. “It is not clear whether the microbes identified [in this study] contribute to the pathogenesis of celiac disease or are the result of it. Future research should explore the role of the disease-specific species identified here,” the researchers wrote in Gastroenterology.

Celiac disease is multifactorial. While up to 40% of people are genetically predisposed, only a small proportion develop it, suggesting that environmental factors are key to pathogenesis. Recent studies have linked celiac disease with alterations in the gut microbiome, but it is unclear whether dysbiosis is pathogenic or a secondary effect of disease processes such as nutrient malabsorption, or whether dysbiosis is present at disease onset or results from a gluten-free diet.

For the study, the researchers performed gas chromatography and 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing of fecal samples from 141 children, including 20 with newly biopsy-confirmed, previously untreated celiac disease, 45 who were previously diagnosed and on a gluten-free diet, 19 unaffected siblings, and 57 healthy children who were not on regular medications and had no history of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. A single fecal sample was tested for all but the previously untreated children, who were tested at baseline and then after 6 and 12 months on a gluten-free diet.

Children with new-onset celiac disease showed no evidence of dysbiosis, while a gluten-free diet explained up to 2.8% of variation in microbiota between patients and controls. Microbial alpha diversity, a measure of species-level diversity, was generally similar among groups, but between 3% and 5% of all taxa differed. Irrespective of treatment, the decreased abundance of the 11 OTUs was diagnostic for celiac disease with an error rate of 21.5% (P < .001 vs. random classification). Notably, most of these 11 discrepant OTUs were associated with nutrient or food group intake and with biomarkers of gluten ingestion, the researchers said. Gas chromatography showed that, after patients started a gluten-free diet, fecal levels of butyrate and ammonia decreased.

“Even though we identified differences in the abundance of a few species between patients with untreated celiac disease and healthy controls, the profound microbial dysbiosis noted in Crohn’s disease was not observed, at least using crude diversity indices,” the investigators commented. “Although several alterations in the intestinal microbiota of children with established celiac disease appear to be effects of a gluten-free diet, there are specific bacteria that are distinct biomarkers of celiac disease.”

Future research might involve performing in vitro tests of “candidate” bacteria, coculturing these bacteria with human immune cells, and studying whether dietary interventions alter the relative abundance of these bacteria in the gut microbiome, the researchers said.

Nutricia Research Foundation, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, and The Catherine McEwan Foundation provided funding. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to Nutricia, 4D Pharma, AbbVie, Celltrion, Janssen, Takeda, and several other pharmaceutical companies. One coinvestigator reported chairing the working group for ISLI Europe. The remaining investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zafeiropoulou K et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Aug 10;S0016-5085(20)35023-X. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.007.

It is well known that gluten ingestion in genetically susceptible individuals does not guarantee celiac disease, and research over the past decade has searched for environmental triggers. Gut microbiota play a role in activation of innate immunity, which leads to the adaptive immune response and the small bowel damage that is characteristic of celiac disease. The authors of this study sought to identify whether there is a distinct microbial pattern among celiac disease patients, both those with treated and untreated disease, in comparison with healthy controls and healthy siblings.

A significantly different microbial profile and metabolites were identified in subjects on gluten-free diets. The consequences of the gluten-free diet are an important consideration when committing a patient to this life-long therapy. The microbiome changes may play a role in persistent symptoms and the increased health conditions we see in treated celiac disease. Those on a gluten-free diet have other micronutrient deficiencies in addition to microbiome changes and the health sequelae of this are not fully understood. A gluten-free diet focused on restoring the normal gut flora through probiotic or gluten-free prebiotic or fiber supplementation in celiac disease patients could prove beneficial.

Dawn Wiese Adams, MD, MS, is assistant professor and medical director, Center for Human Nutrition, department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. She has no conflicts of interest.

It is well known that gluten ingestion in genetically susceptible individuals does not guarantee celiac disease, and research over the past decade has searched for environmental triggers. Gut microbiota play a role in activation of innate immunity, which leads to the adaptive immune response and the small bowel damage that is characteristic of celiac disease. The authors of this study sought to identify whether there is a distinct microbial pattern among celiac disease patients, both those with treated and untreated disease, in comparison with healthy controls and healthy siblings.

A significantly different microbial profile and metabolites were identified in subjects on gluten-free diets. The consequences of the gluten-free diet are an important consideration when committing a patient to this life-long therapy. The microbiome changes may play a role in persistent symptoms and the increased health conditions we see in treated celiac disease. Those on a gluten-free diet have other micronutrient deficiencies in addition to microbiome changes and the health sequelae of this are not fully understood. A gluten-free diet focused on restoring the normal gut flora through probiotic or gluten-free prebiotic or fiber supplementation in celiac disease patients could prove beneficial.

Dawn Wiese Adams, MD, MS, is assistant professor and medical director, Center for Human Nutrition, department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. She has no conflicts of interest.

It is well known that gluten ingestion in genetically susceptible individuals does not guarantee celiac disease, and research over the past decade has searched for environmental triggers. Gut microbiota play a role in activation of innate immunity, which leads to the adaptive immune response and the small bowel damage that is characteristic of celiac disease. The authors of this study sought to identify whether there is a distinct microbial pattern among celiac disease patients, both those with treated and untreated disease, in comparison with healthy controls and healthy siblings.

A significantly different microbial profile and metabolites were identified in subjects on gluten-free diets. The consequences of the gluten-free diet are an important consideration when committing a patient to this life-long therapy. The microbiome changes may play a role in persistent symptoms and the increased health conditions we see in treated celiac disease. Those on a gluten-free diet have other micronutrient deficiencies in addition to microbiome changes and the health sequelae of this are not fully understood. A gluten-free diet focused on restoring the normal gut flora through probiotic or gluten-free prebiotic or fiber supplementation in celiac disease patients could prove beneficial.

Dawn Wiese Adams, MD, MS, is assistant professor and medical director, Center for Human Nutrition, department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. She has no conflicts of interest.

Eleven operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of fecal bacteria were less abundant in children with celiac disease than in healthy children, according to the findings of a study published in Gastroenterology.

This microbial signature correctly identified approximately four out of five cases of celiac disease, regardless of whether children were newly diagnosed or had already modified their diet, reported Konstantina Zafeiropoulou and Ben Nichols, PhD, of the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. “It is not clear whether the microbes identified [in this study] contribute to the pathogenesis of celiac disease or are the result of it. Future research should explore the role of the disease-specific species identified here,” the researchers wrote in Gastroenterology.

Celiac disease is multifactorial. While up to 40% of people are genetically predisposed, only a small proportion develop it, suggesting that environmental factors are key to pathogenesis. Recent studies have linked celiac disease with alterations in the gut microbiome, but it is unclear whether dysbiosis is pathogenic or a secondary effect of disease processes such as nutrient malabsorption, or whether dysbiosis is present at disease onset or results from a gluten-free diet.

For the study, the researchers performed gas chromatography and 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing of fecal samples from 141 children, including 20 with newly biopsy-confirmed, previously untreated celiac disease, 45 who were previously diagnosed and on a gluten-free diet, 19 unaffected siblings, and 57 healthy children who were not on regular medications and had no history of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. A single fecal sample was tested for all but the previously untreated children, who were tested at baseline and then after 6 and 12 months on a gluten-free diet.

Children with new-onset celiac disease showed no evidence of dysbiosis, while a gluten-free diet explained up to 2.8% of variation in microbiota between patients and controls. Microbial alpha diversity, a measure of species-level diversity, was generally similar among groups, but between 3% and 5% of all taxa differed. Irrespective of treatment, the decreased abundance of the 11 OTUs was diagnostic for celiac disease with an error rate of 21.5% (P < .001 vs. random classification). Notably, most of these 11 discrepant OTUs were associated with nutrient or food group intake and with biomarkers of gluten ingestion, the researchers said. Gas chromatography showed that, after patients started a gluten-free diet, fecal levels of butyrate and ammonia decreased.

“Even though we identified differences in the abundance of a few species between patients with untreated celiac disease and healthy controls, the profound microbial dysbiosis noted in Crohn’s disease was not observed, at least using crude diversity indices,” the investigators commented. “Although several alterations in the intestinal microbiota of children with established celiac disease appear to be effects of a gluten-free diet, there are specific bacteria that are distinct biomarkers of celiac disease.”

Future research might involve performing in vitro tests of “candidate” bacteria, coculturing these bacteria with human immune cells, and studying whether dietary interventions alter the relative abundance of these bacteria in the gut microbiome, the researchers said.

Nutricia Research Foundation, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, and The Catherine McEwan Foundation provided funding. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to Nutricia, 4D Pharma, AbbVie, Celltrion, Janssen, Takeda, and several other pharmaceutical companies. One coinvestigator reported chairing the working group for ISLI Europe. The remaining investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zafeiropoulou K et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Aug 10;S0016-5085(20)35023-X. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.007.

Eleven operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of fecal bacteria were less abundant in children with celiac disease than in healthy children, according to the findings of a study published in Gastroenterology.

This microbial signature correctly identified approximately four out of five cases of celiac disease, regardless of whether children were newly diagnosed or had already modified their diet, reported Konstantina Zafeiropoulou and Ben Nichols, PhD, of the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. “It is not clear whether the microbes identified [in this study] contribute to the pathogenesis of celiac disease or are the result of it. Future research should explore the role of the disease-specific species identified here,” the researchers wrote in Gastroenterology.

Celiac disease is multifactorial. While up to 40% of people are genetically predisposed, only a small proportion develop it, suggesting that environmental factors are key to pathogenesis. Recent studies have linked celiac disease with alterations in the gut microbiome, but it is unclear whether dysbiosis is pathogenic or a secondary effect of disease processes such as nutrient malabsorption, or whether dysbiosis is present at disease onset or results from a gluten-free diet.

For the study, the researchers performed gas chromatography and 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing of fecal samples from 141 children, including 20 with newly biopsy-confirmed, previously untreated celiac disease, 45 who were previously diagnosed and on a gluten-free diet, 19 unaffected siblings, and 57 healthy children who were not on regular medications and had no history of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. A single fecal sample was tested for all but the previously untreated children, who were tested at baseline and then after 6 and 12 months on a gluten-free diet.

Children with new-onset celiac disease showed no evidence of dysbiosis, while a gluten-free diet explained up to 2.8% of variation in microbiota between patients and controls. Microbial alpha diversity, a measure of species-level diversity, was generally similar among groups, but between 3% and 5% of all taxa differed. Irrespective of treatment, the decreased abundance of the 11 OTUs was diagnostic for celiac disease with an error rate of 21.5% (P < .001 vs. random classification). Notably, most of these 11 discrepant OTUs were associated with nutrient or food group intake and with biomarkers of gluten ingestion, the researchers said. Gas chromatography showed that, after patients started a gluten-free diet, fecal levels of butyrate and ammonia decreased.

“Even though we identified differences in the abundance of a few species between patients with untreated celiac disease and healthy controls, the profound microbial dysbiosis noted in Crohn’s disease was not observed, at least using crude diversity indices,” the investigators commented. “Although several alterations in the intestinal microbiota of children with established celiac disease appear to be effects of a gluten-free diet, there are specific bacteria that are distinct biomarkers of celiac disease.”

Future research might involve performing in vitro tests of “candidate” bacteria, coculturing these bacteria with human immune cells, and studying whether dietary interventions alter the relative abundance of these bacteria in the gut microbiome, the researchers said.

Nutricia Research Foundation, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, and The Catherine McEwan Foundation provided funding. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to Nutricia, 4D Pharma, AbbVie, Celltrion, Janssen, Takeda, and several other pharmaceutical companies. One coinvestigator reported chairing the working group for ISLI Europe. The remaining investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zafeiropoulou K et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Aug 10;S0016-5085(20)35023-X. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.007.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: A novel microbial signature distinguished children with celiac disease from healthy controls.

Major finding: Eleven operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were less abundant in fecal samples from children with treated and untreated celiac disease than in healthy controls. The microbial signature was diagnostic for celiac disease with an error rate of 21.5% (P < .001 compared with random classification).

Study details: Gas chromatography and 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing of fecal samples from 141 children: 20 with new-onset celiac disease, 45 with an established diagnosis who were on a gluten-free diet, 19 unaffected siblings, and 57 healthy children. Also, a prospective study of fecal samples from 13 newly diagnosed children after 6 and 12 months on a gluten-free diet.

Disclosures: Nutricia Research Foundation, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, and The Catherine McEwan Foundation provided funding. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to Nutricia, 4D Pharma, Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda, Celltrion, and several other pharmaceutical companies. One coinvestigator reported chairing the working group for ISLI Europe. The remaining investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zafeiropoulou K et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Aug 10;S0016-5085(20)35023-X. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.007.

Great Barrington coauthor backs off strict reliance on herd immunity

A coauthor of the Great Barrington Declaration says that he and colleagues have never argued against using mitigation strategies to keep COVID-19 from spreading, and that critics have mischaracterized the document as a “let it rip” strategy.

Jay Bhattacharya, MD, PhD, a professor and public health policy expert in infectious diseases at Stanford University in California, spoke on a JAMA Livestream debate on November 6. Marc Lipsitch, MD, an epidemiology professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, represented the 6900 signatories of the John Snow Memorandum, a rebuttal to the Great Barrington document.

The Great Barrington approach of “Focused Protection” advocates isolation and protection of people who are most vulnerable to COVID-19 while avoiding what they characterize as lockdowns. “The most compassionate approach that balances the risks and benefits of reaching herd immunity, is to allow those who are at minimal risk of death to live their lives normally to build up immunity to the virus through natural infection, while better protecting those who are at highest risk,” the document reads.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and its HIV Medicine Association denounced the declaration, as reported by Medscape Medical News, and the World Health Organization (WHO) Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus called the proposal “unethical.” But the idea has gained some traction at the White House, where Coronavirus Task Force Member and Stanford professor Scott Atlas, MD, has been advising President Donald J. Trump.

On the JAMA debate, Bhattacharya said, “I think all of the mitigation measures are really important,” listing social distancing, hand washing, and masks when distancing is not possible as chief among those strategies for the less vulnerable. “I don’t want to create infections intentionally, but I want us to allow people to go back to their lives as best they can, understanding of the risks they are taking when they do it,” he said, claiming that 99.95% of the population will survive infection.

“The harmful lockdowns are worse for many, many people,” Bhattacharya said.

“I think Jay is moving towards a middle ground which is not really what the Great Barrington Declaration seems to promote,” countered Lipsitch. The declaration does not say use masks or social distance, he said. “It just says we need to go back to a normal life.”

Bhattacharya’s statements to JAMA mean that “maybe we are approaching some common ground,” Lipsitch said.

Definition of a lockdown

Both men were asked to give their definition of a “lockdown.” To Lipsitch, it means people are not allowed out except for essential services and that most businesses are closed, with exceptions for those deemed essential.

Bhattacharya, however, said he views that as a quarantine. Lockdowns “are what we’re currently doing,” he said. Schools, churches, businesses, and arts and culture organizations are shuttered, and “almost every aspect of society is restricted in some way,” Bhattacharya said.

He blamed these lockdowns for most of the excess deaths over and above the COVID-19 deaths and said they had failed to control the pandemic.

Lipsitch said that “it feels to me that Jay is describing as lockdown everything that causes harm, even when it’s not locked down.” He noted that the country was truly closed down for 2 months or so in the spring.

“All of these harms I agree are real,” said Lipsitch. “But they are because the normal life of our society is being interfered with by viral transmission and by people’s inability to live their normal lives.”

Closures and lockdowns are essential to delaying cases and deaths, said Lipsitch. “A case today is worse than a case tomorrow and a lot worse than a case 6 months from now,” he said, noting that a vaccine or improved therapeutics could evolve.

“Delay is not nothing,” Lipsitch added. “It’s actually the goal as I see it, and as the John Snow memo says, we want to keep the virus under control in such a way as that the vulnerable people are not at risk.”

He predicted that cases will continue to grow exponentially because the nation is “not even close to herd immunity.” And, if intensive care units fill up, “there will be a responsive lockdown,” he said, adding that he did not endorse that as a general matter or favor it as a default position.

Bhattacharya claimed that Sweden has tallied only 1800 excess deaths since the pandemic began. “That’s lockdown harm avoided,” he said, advocating a similar strategy for the United States. But, infections have been on the rise in Sweden, and the nation has a higher COVID-19 death rate — with 6000 deaths — than other Nordic countries.

“If we keep this policy of lockdown we will have the same kind of outcomes we’ve already had — high excess deaths and sort of indifferent control of COVID,” Bhattacharya said.

“We’re still going to have misery and death going forward until we reach a point where there’s sufficient immunity either though a vaccine or through natural infection,” he said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A coauthor of the Great Barrington Declaration says that he and colleagues have never argued against using mitigation strategies to keep COVID-19 from spreading, and that critics have mischaracterized the document as a “let it rip” strategy.

Jay Bhattacharya, MD, PhD, a professor and public health policy expert in infectious diseases at Stanford University in California, spoke on a JAMA Livestream debate on November 6. Marc Lipsitch, MD, an epidemiology professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, represented the 6900 signatories of the John Snow Memorandum, a rebuttal to the Great Barrington document.

The Great Barrington approach of “Focused Protection” advocates isolation and protection of people who are most vulnerable to COVID-19 while avoiding what they characterize as lockdowns. “The most compassionate approach that balances the risks and benefits of reaching herd immunity, is to allow those who are at minimal risk of death to live their lives normally to build up immunity to the virus through natural infection, while better protecting those who are at highest risk,” the document reads.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and its HIV Medicine Association denounced the declaration, as reported by Medscape Medical News, and the World Health Organization (WHO) Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus called the proposal “unethical.” But the idea has gained some traction at the White House, where Coronavirus Task Force Member and Stanford professor Scott Atlas, MD, has been advising President Donald J. Trump.

On the JAMA debate, Bhattacharya said, “I think all of the mitigation measures are really important,” listing social distancing, hand washing, and masks when distancing is not possible as chief among those strategies for the less vulnerable. “I don’t want to create infections intentionally, but I want us to allow people to go back to their lives as best they can, understanding of the risks they are taking when they do it,” he said, claiming that 99.95% of the population will survive infection.

“The harmful lockdowns are worse for many, many people,” Bhattacharya said.

“I think Jay is moving towards a middle ground which is not really what the Great Barrington Declaration seems to promote,” countered Lipsitch. The declaration does not say use masks or social distance, he said. “It just says we need to go back to a normal life.”

Bhattacharya’s statements to JAMA mean that “maybe we are approaching some common ground,” Lipsitch said.

Definition of a lockdown

Both men were asked to give their definition of a “lockdown.” To Lipsitch, it means people are not allowed out except for essential services and that most businesses are closed, with exceptions for those deemed essential.

Bhattacharya, however, said he views that as a quarantine. Lockdowns “are what we’re currently doing,” he said. Schools, churches, businesses, and arts and culture organizations are shuttered, and “almost every aspect of society is restricted in some way,” Bhattacharya said.

He blamed these lockdowns for most of the excess deaths over and above the COVID-19 deaths and said they had failed to control the pandemic.

Lipsitch said that “it feels to me that Jay is describing as lockdown everything that causes harm, even when it’s not locked down.” He noted that the country was truly closed down for 2 months or so in the spring.

“All of these harms I agree are real,” said Lipsitch. “But they are because the normal life of our society is being interfered with by viral transmission and by people’s inability to live their normal lives.”

Closures and lockdowns are essential to delaying cases and deaths, said Lipsitch. “A case today is worse than a case tomorrow and a lot worse than a case 6 months from now,” he said, noting that a vaccine or improved therapeutics could evolve.

“Delay is not nothing,” Lipsitch added. “It’s actually the goal as I see it, and as the John Snow memo says, we want to keep the virus under control in such a way as that the vulnerable people are not at risk.”

He predicted that cases will continue to grow exponentially because the nation is “not even close to herd immunity.” And, if intensive care units fill up, “there will be a responsive lockdown,” he said, adding that he did not endorse that as a general matter or favor it as a default position.

Bhattacharya claimed that Sweden has tallied only 1800 excess deaths since the pandemic began. “That’s lockdown harm avoided,” he said, advocating a similar strategy for the United States. But, infections have been on the rise in Sweden, and the nation has a higher COVID-19 death rate — with 6000 deaths — than other Nordic countries.

“If we keep this policy of lockdown we will have the same kind of outcomes we’ve already had — high excess deaths and sort of indifferent control of COVID,” Bhattacharya said.

“We’re still going to have misery and death going forward until we reach a point where there’s sufficient immunity either though a vaccine or through natural infection,” he said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A coauthor of the Great Barrington Declaration says that he and colleagues have never argued against using mitigation strategies to keep COVID-19 from spreading, and that critics have mischaracterized the document as a “let it rip” strategy.

Jay Bhattacharya, MD, PhD, a professor and public health policy expert in infectious diseases at Stanford University in California, spoke on a JAMA Livestream debate on November 6. Marc Lipsitch, MD, an epidemiology professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, represented the 6900 signatories of the John Snow Memorandum, a rebuttal to the Great Barrington document.

The Great Barrington approach of “Focused Protection” advocates isolation and protection of people who are most vulnerable to COVID-19 while avoiding what they characterize as lockdowns. “The most compassionate approach that balances the risks and benefits of reaching herd immunity, is to allow those who are at minimal risk of death to live their lives normally to build up immunity to the virus through natural infection, while better protecting those who are at highest risk,” the document reads.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and its HIV Medicine Association denounced the declaration, as reported by Medscape Medical News, and the World Health Organization (WHO) Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus called the proposal “unethical.” But the idea has gained some traction at the White House, where Coronavirus Task Force Member and Stanford professor Scott Atlas, MD, has been advising President Donald J. Trump.

On the JAMA debate, Bhattacharya said, “I think all of the mitigation measures are really important,” listing social distancing, hand washing, and masks when distancing is not possible as chief among those strategies for the less vulnerable. “I don’t want to create infections intentionally, but I want us to allow people to go back to their lives as best they can, understanding of the risks they are taking when they do it,” he said, claiming that 99.95% of the population will survive infection.

“The harmful lockdowns are worse for many, many people,” Bhattacharya said.

“I think Jay is moving towards a middle ground which is not really what the Great Barrington Declaration seems to promote,” countered Lipsitch. The declaration does not say use masks or social distance, he said. “It just says we need to go back to a normal life.”

Bhattacharya’s statements to JAMA mean that “maybe we are approaching some common ground,” Lipsitch said.

Definition of a lockdown

Both men were asked to give their definition of a “lockdown.” To Lipsitch, it means people are not allowed out except for essential services and that most businesses are closed, with exceptions for those deemed essential.

Bhattacharya, however, said he views that as a quarantine. Lockdowns “are what we’re currently doing,” he said. Schools, churches, businesses, and arts and culture organizations are shuttered, and “almost every aspect of society is restricted in some way,” Bhattacharya said.

He blamed these lockdowns for most of the excess deaths over and above the COVID-19 deaths and said they had failed to control the pandemic.

Lipsitch said that “it feels to me that Jay is describing as lockdown everything that causes harm, even when it’s not locked down.” He noted that the country was truly closed down for 2 months or so in the spring.

“All of these harms I agree are real,” said Lipsitch. “But they are because the normal life of our society is being interfered with by viral transmission and by people’s inability to live their normal lives.”

Closures and lockdowns are essential to delaying cases and deaths, said Lipsitch. “A case today is worse than a case tomorrow and a lot worse than a case 6 months from now,” he said, noting that a vaccine or improved therapeutics could evolve.

“Delay is not nothing,” Lipsitch added. “It’s actually the goal as I see it, and as the John Snow memo says, we want to keep the virus under control in such a way as that the vulnerable people are not at risk.”

He predicted that cases will continue to grow exponentially because the nation is “not even close to herd immunity.” And, if intensive care units fill up, “there will be a responsive lockdown,” he said, adding that he did not endorse that as a general matter or favor it as a default position.

Bhattacharya claimed that Sweden has tallied only 1800 excess deaths since the pandemic began. “That’s lockdown harm avoided,” he said, advocating a similar strategy for the United States. But, infections have been on the rise in Sweden, and the nation has a higher COVID-19 death rate — with 6000 deaths — than other Nordic countries.

“If we keep this policy of lockdown we will have the same kind of outcomes we’ve already had — high excess deaths and sort of indifferent control of COVID,” Bhattacharya said.

“We’re still going to have misery and death going forward until we reach a point where there’s sufficient immunity either though a vaccine or through natural infection,” he said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What imaging can disclose about suspected stroke and its Tx

Stroke ranks second behind heart disease as the leading cause of mortality worldwide, accounting for 1 of every 19 deaths,1 and remains a serious cause of morbidity. Best practices in stroke diagnosis and management can seem elusive to front-line clinicians, for 2 reasons: the rate of proliferation and nuance in stroke medicine and the fact that the typical scope of primary care practice exists apart from much of the diagnostic tools and management schema provided in stroke centers.2 In this article, we describe and update the diagnosis of stroke and review imaging modalities, their nuances, and their application in practice.

Diagnosis of acute stroke

Acute stroke is diagnosed upon observation of new neurologic deficits and congruent neuroimaging. Some updated definitions favor a silent form of cerebral ischemia manifested by imaging pathology only; this form is not discussed in this article. Although there are several characteristically distinct stroke syndromes, there is no way to clinically distinguish ischemic pathology from hemorrhagic pathology.

Some common symptoms that should prompt evaluation for stroke are part of the American Stroke Association FAST mnemonic designed to promote public health awareness3-5:

f ace droopinga rm weaknesss peech difficultyt ime to call 911.

Other commonly reported stroke symptoms include unilateral weakness or numbness, confusion, word-finding difficulty, visual problems, difficulty ambulating, dizziness, loss of balance or coordination, and thunderclap headache. A stroke should also be considered in the presence of any new focal neurologic deficit.3,4

Stroke patients should be triaged by emergency medical services using a stroke screening scale, such as BE-FAST5 (a modification of FAST that adds balance and eye assessments); the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS)6,7; the Rapid Arterial oCclusion Evaluation (RACE)8; and the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Severity Scale (CP-SSS)9,10 (see “Stroke screening scales for early identification and triage"). Studies have not found that any single prehospital stroke scale is superior to the others for reliably predicting large-vessel occlusion; therefore, prehospital assessment is typically based on practice patterns in a given locale.11 A patient (or family member or caregiver) who seeks your care for stroke symptoms should be told to call 911 and get emergency transport to a health care facility that can capably administer intravenous (IV) thrombolysis.a

SIDEBAR

Stroke screening scales for early identification and triage

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

www.stroke.nih.gov/resources/scale.htm

FAST

www.stroke.org/en/help-and-support/resource-library/fast-materials

BE-FAST

www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015169

Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS)

http://stroke.ucla.edu/workfiles/prehospital-screen.pdf

Rapid Artery Occlusion Evaluation (RACE)

www.mdcalc.com/rapid-arterial-occlusion-evaluation-race-scale-stroke

Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Severity Scale (CP-SSS)

https://www.mdcalc.com/cincinnati-prehospital-stroke-severity-scale-cp-sss

First responders should elicit “last-known-normal” time; this critical information can aid in diagnosis and drive therapeutic options, especially if patients are unaccompanied at time of transport to a higher echelon of care. A point-of-care blood glucose test should be performed by emergency medical staff, with dextrose administered for a level < 45 mg/dL. Establishing IV access for fluids, medications, and contrast can be considered if it does not delay transport. A 12-lead electrocardiogram can also be considered, again, as long as it does not delay transport to a facility capable of providing definitive therapy. Notification by emergency services staff before arrival and transport of the patient to such a facility is the essential element of prehospital care, and should be prioritized above ancillary testing beyond the stroke assessment.14

Guidelines recommend use of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS; www.stroke.nih.gov/resources/scale.htm) for clinical evaluation upon arrival at the ED.15 Although no scale has been identified that can reliably predict large-vessel occlusion amenable to endovascular therapy (EVT), no other score has been found to outperform the NIHSS in achieving meaningful patient outcomes.16 Furthermore, NIHSS has been validated to track clinical changes in response to therapy, is widely utilized, and is free.

Continue to: A criticism of the NIHSS...

A criticism of the NIHSS is its bias toward left-hemispheric ischemic pathology.17 NIHSS includes 11 questions on a scale of 0 to 42; typically, a score < 4 is associated with a higher chance of a positive clinical outcome.18 There is no minimum or maximum NIHSS score that precludes treatment with thrombolysis or EVT.

Other commonly used scores in acute stroke include disability assessments. The modified Rankin scale, which is used most often, features a score of 0 (symptom-free) to 6 (death). A modified Rankin scale score of 0 or 1 is considered an indication of a favorable outcome after stroke.19 Note that these functional scores are not always part of an acute assessment but can be done early in the clinical course to gauge the response to treatment, and are collected for stroke-center certification.

Imaging modalities

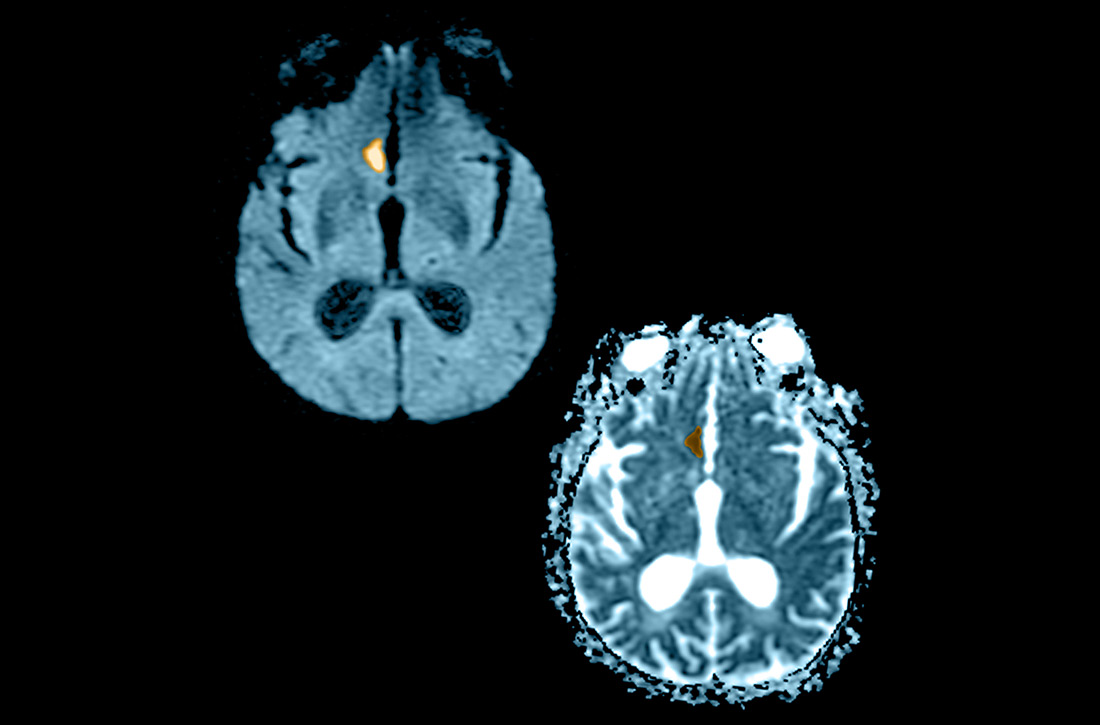

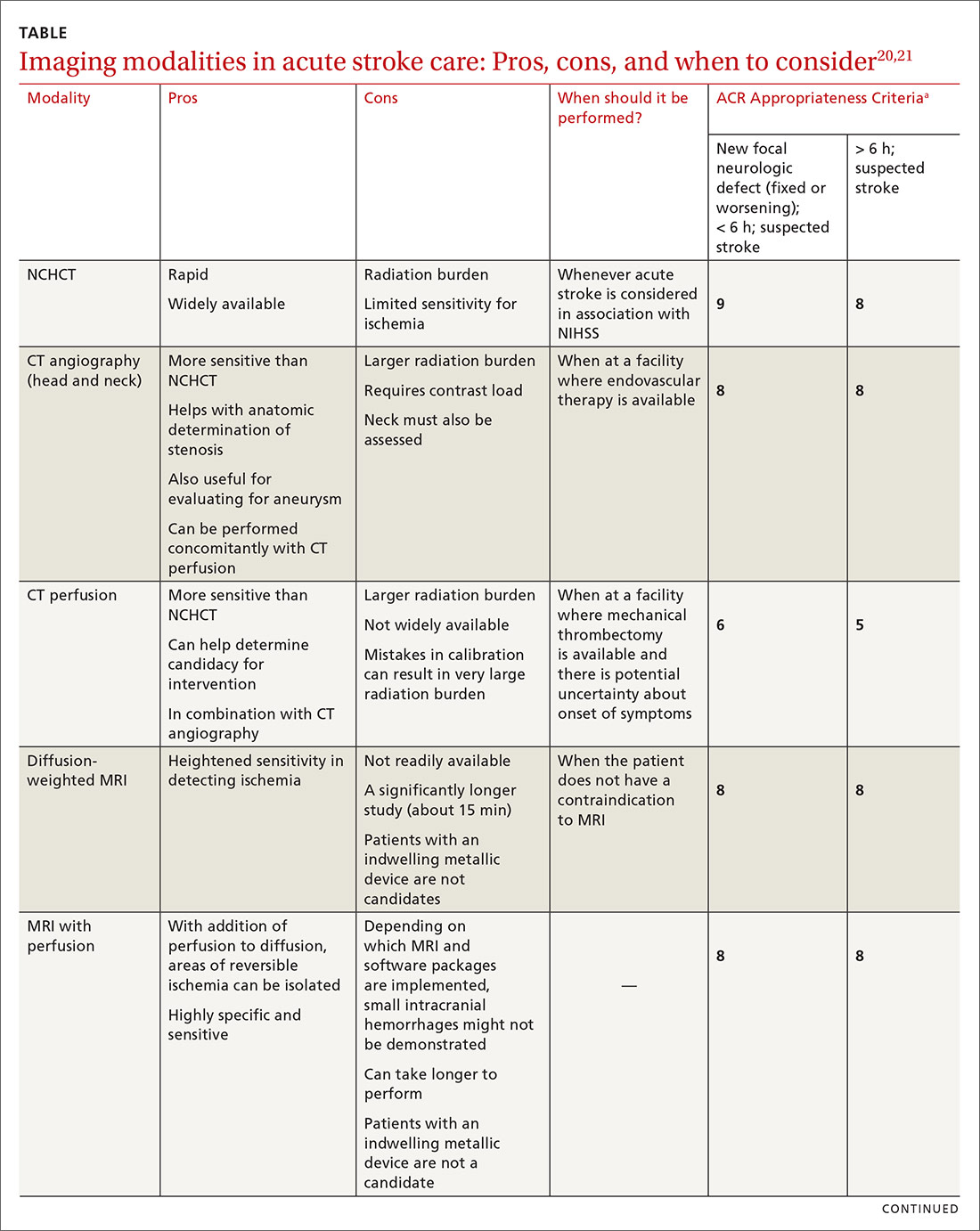

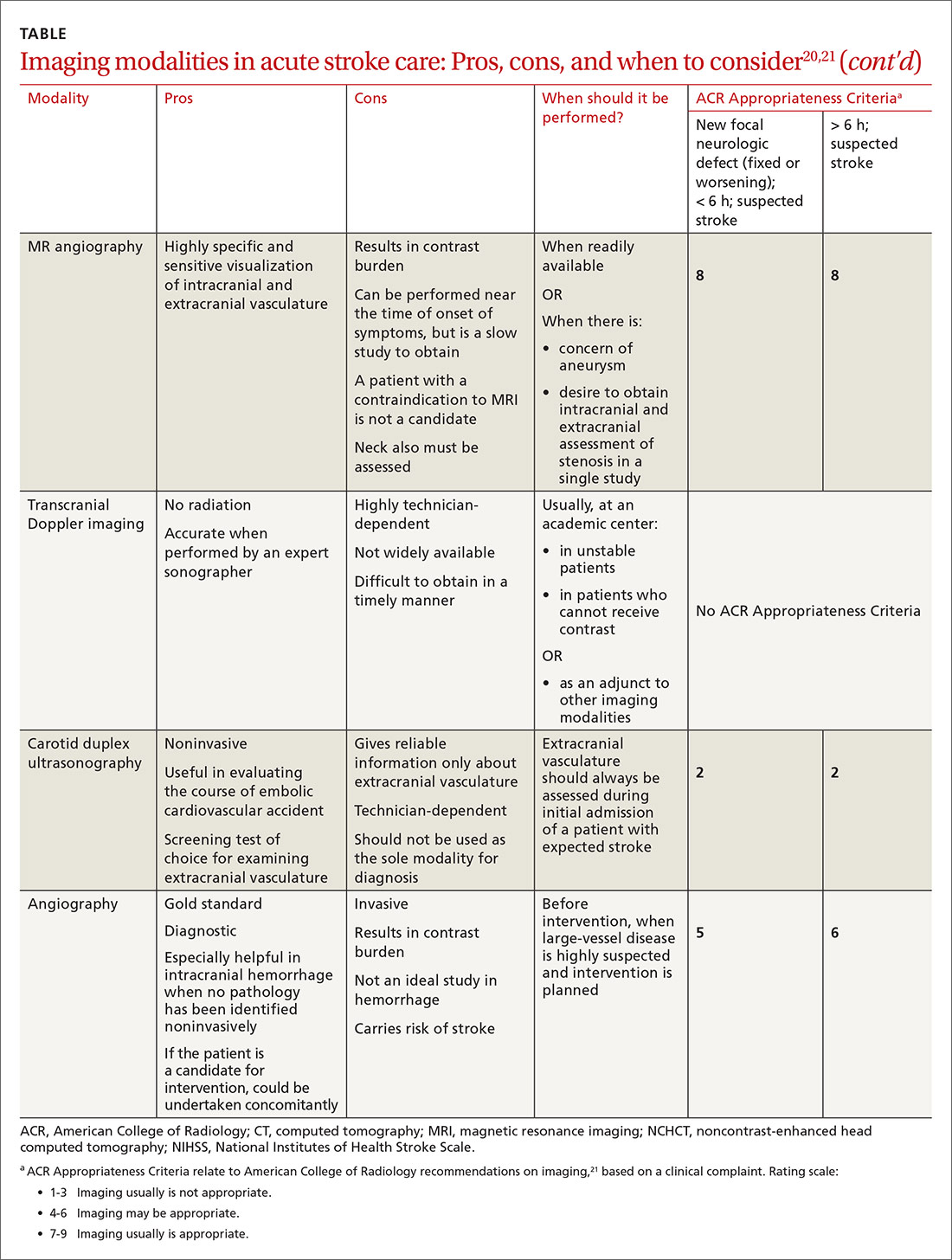

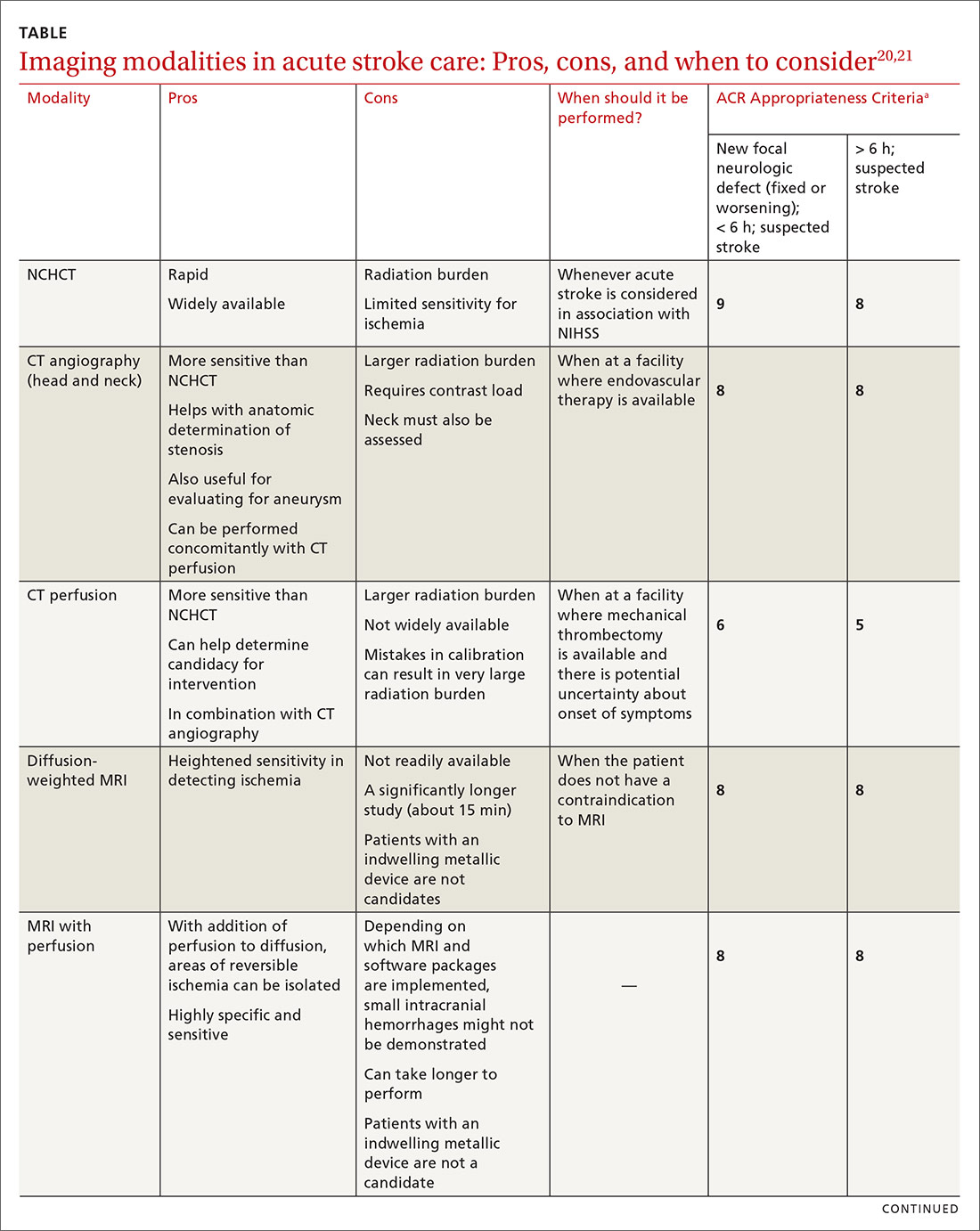

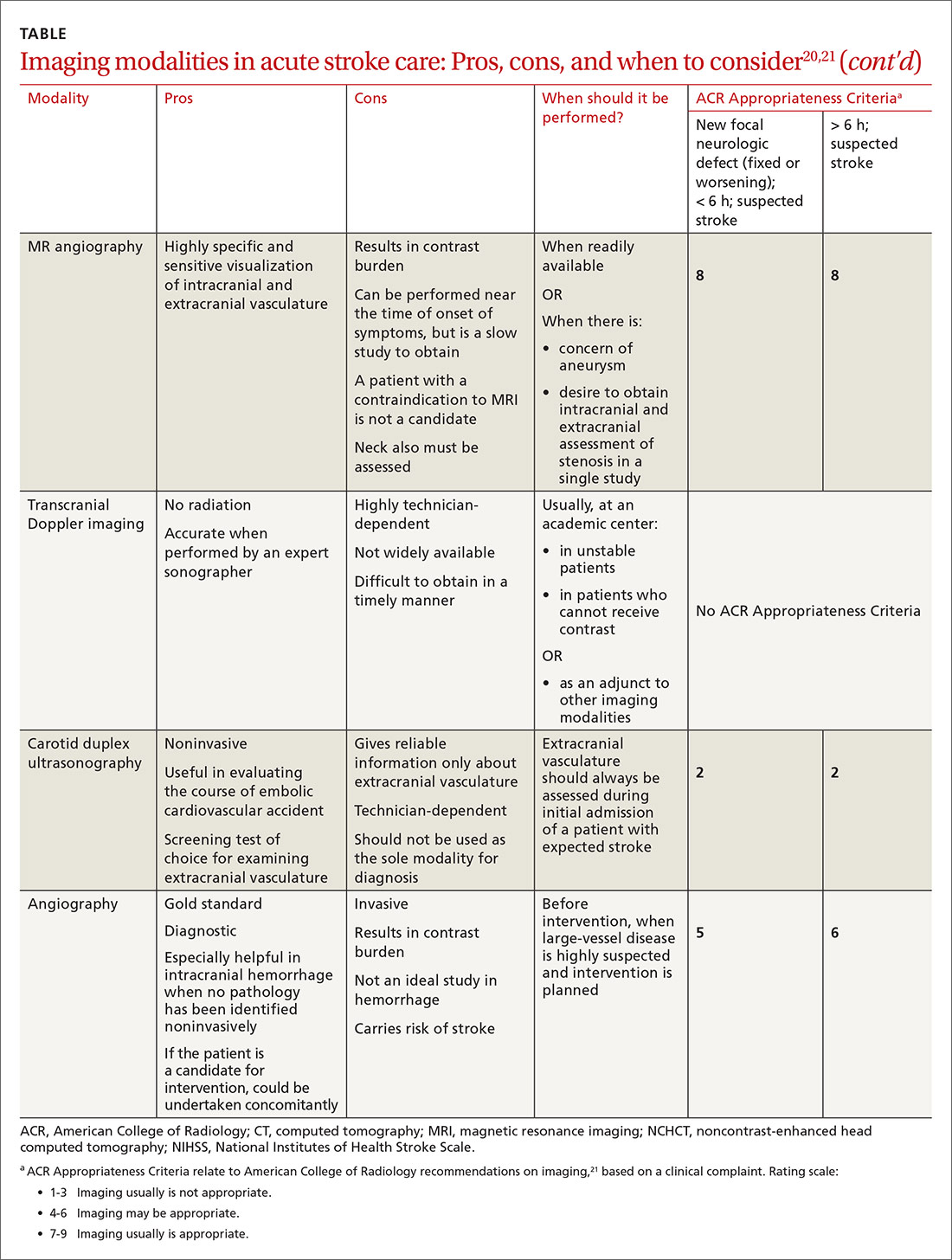

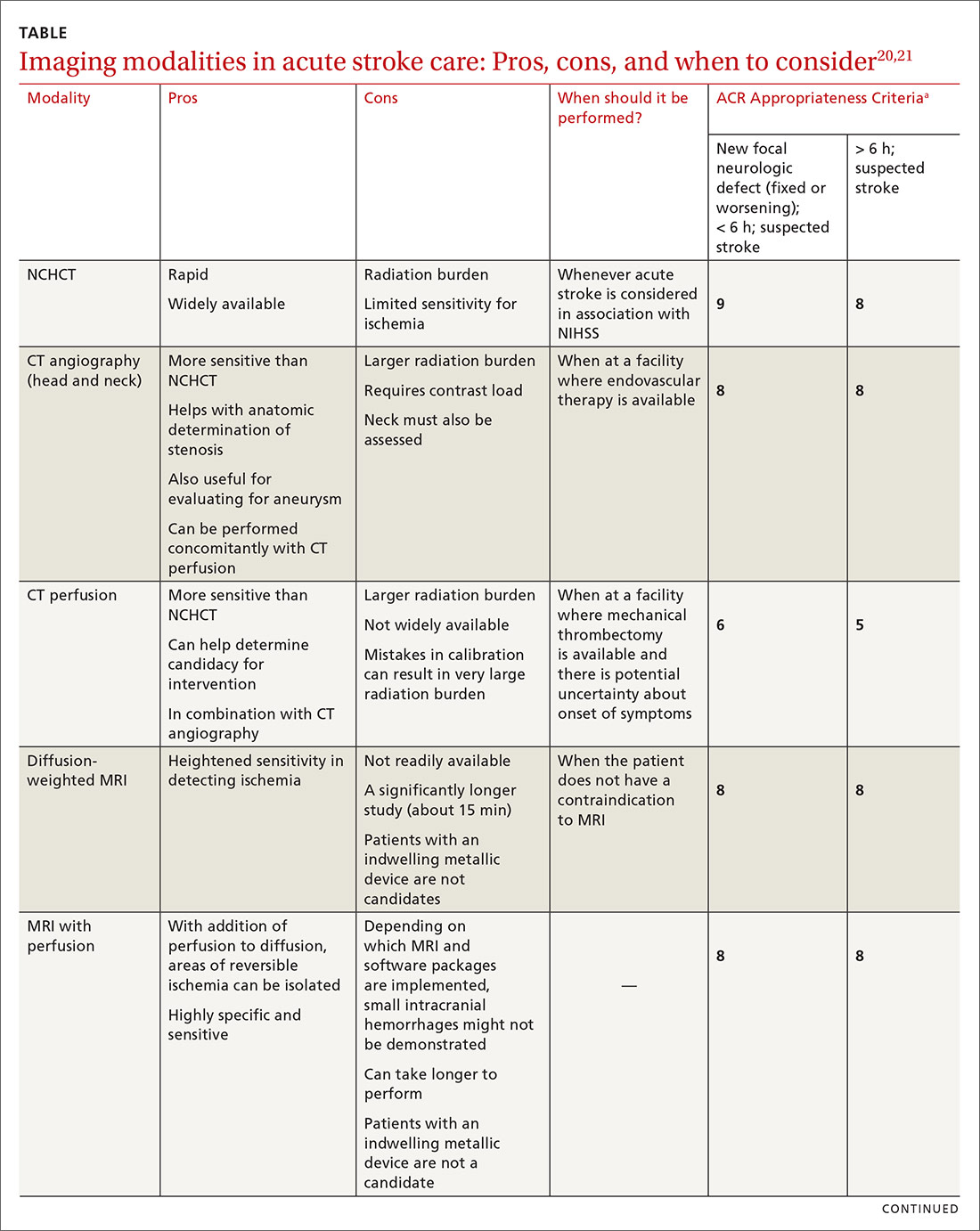

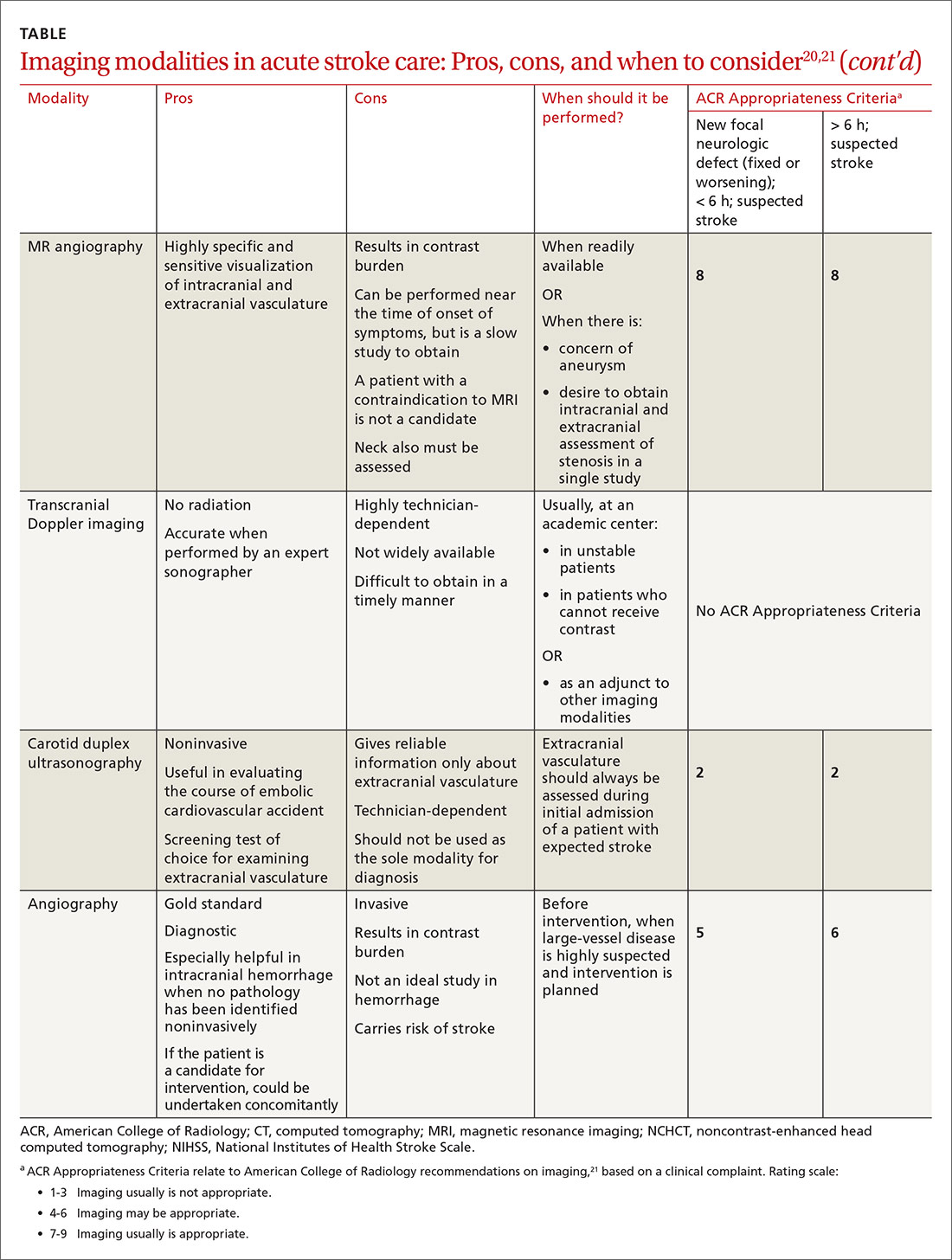

Imaging is recommended within 20 minutes of arrival in the ED in a stroke patient who might be a candidate for thrombolysis or thrombectomy.3 There, imaging modalities commonly performed are noncontrast-enhanced head computed tomography (NCHCT); computed tomography (CT) angiography, with or without perfusion; and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).20,21 In addition, more highly specialized imaging modalities are available for the evaluation of the stroke patient in specific, often limited, circumstances. All these modalities are described below and compared in the TABLE,20,21 using the ACR Appropriateness Criteria (of the American College of Radiology),21 which are guidelines for appropriate imaging of stroke, based on a clinical complaint. Separate recommendations and appraisals are offered by the most recent American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guideline.3

NCHCT. This study should be performed within 20 minutes after arrival at the ED because it provides rapid assessment of intracerebral hemorrhage, can effectively corroborate the diagnosis of some stroke mimickers, and identifies some candidates for EVT or thrombolysis3,21,22 (typically, the decision to proceed with EVT is based on adjunct imaging studies discussed in a bit). Evaluation for intracerebral hemorrhage is required prior to administering thrombolysis. Ischemic changes can be seen with variable specificity and sensitivity on NCHCT, depending on how much time has passed since the original insult. In all historical trials, CT was the only imaging modality used in the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) that suggested benefit from IV thrombolysis.23-25

Acute, subacute, and chronic changes can be seen on NCHCT, although the modality has limited sensitivity for identifying AIS (ie, approximately 75% within 6 hours after the original insult):

- Acute findings on NCHCT include intracellular edema, which causes loss of the gray matter–white matter interface and effacement of the cortical sulci. This occurs as a result of increased cellular uptake of water in response to ischemia and cell death, resulting in a decreased density of tissue (hypoattenuation) in affected areas.

- Subacute changes appear in the 2- to 5-day window, including vasogenic edema with greater mass effect, hypoattenuation, and well-defined margins.3,20,21

- Chronic vascular findings on NCHCT include loss of brain tissue and hypoattenuation.

Continue to: NCHCT is typically performed...

NCHCT is typically performed in advance of other adjunct imaging modalities.3,20,21 Baseline NCHCT can be performed on patients with advanced kidney disease and those who have an indwelling metallic device.

CT angiography is performed with timed contrast, providing a 3-dimensional representation of the cerebral vasculature; the entire intracranial and extracranial vasculature, including the aortic arch, can be mapped in approximately 60 seconds. CT angiography is sensitive in identifying areas of stenosis > 50% and identifies clinically significant areas of stenosis up to approximately 90% of the time.26 For this reason, it is particularly helpful in identifying candidates for an interventional strategy beyond pharmacotherapeutic thrombolysis. In addition, CT angiography can visualize aneurysmal dilation and dissection, and help with the planning of interventions—specifically, the confident administration of thrombolysis or more specific planning for target lesions and EVT.

It also can help identify a host of vascular phenomena, such as arteriovenous malformations, Moyamoya disease (progressive arterial blockage within the basal ganglia and compensatory microvascularization), and some vasculopathies.20,27 In intracranial hemorrhage, CT with angiography can help evaluate for structural malformations and identify patients at risk of hematoma expansion.22

CT perfusion. Many stroke centers will perform a CT perfusion study,28 which encompasses as many as 3 different CT sequences:

- NCHCT

- vertex-to-arch angiography with contrast bolus

- administration of contrast and capture of a dynamic sequence through 1 or 2 slabs of tissue, allowing for the generation of maps of cerebral blood flow (CBF), mean transit time (MTT), and cerebral blood volume (CBV) of the entire cerebral vasculature.

The interplay of these 3 sequences drives characterization of lesions (ie, CBF = CBV/MTT). An infarct is characterized by low CBF, low CBV, and elevated MTT. In penumbral tissue, MTT is elevated but CBF is slightly decreased and CBV is normal or increased. Using CT perfusion, areas throughout the ischemic penumbra can be surveyed for favorable interventional characteristics.20,29

Continue to: A CT perfusion study adds...

A CT perfusion study adds at least 60 seconds to NCHCT. This modality can be useful in planning interventions and for stratifying appropriateness of reperfusion strategies in strokes of unknown duration.3,30 CT perfusion can be performed on any multidetector CT scan but (1) requires specialized software and expertise to interpret and (2) subjects the patient to a significant radiation dose, which, if incorrectly administered, can be considerably higher than intended.20,26,27

Diffusion-weighted MRI. This is the most sensitive study for demonstrating early ischemic changes; however, limitations include lack of availability, contraindication in patients with metallic indwelling implants, and duration of the study—although, at some stroke centers, diffusion-weighted MRI can be performed in ≤ 10 minutes.

MRI and NCHCT have comparable sensitivity in detecting intracranial hemorrhage. MRI is likely more sensitive in identifying areas of microhemorrhage: In diffusion-weighted MRI, the sensitivity of stroke detection increases to > 95%.31 The modality relies on the comparable movement of water through damaged vs normal neuronal tissue. Diffusion-weighted MRI does not require administration of concomitant contrast, which can be a benefit in patients who are allergic to gadolinium-based contrast agents or have advanced kidney disease that precludes the use of contrast. It typically does not result in adequate characterization of extracranial vasculature.

Other MRI modalities. These MRI extensions include magnetic resonance (MR) perfusion and MR angiography. Whereas diffusion-weighted MRI (discussed above) offers the most rapid and sensitive evaluation for ischemia, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging has been utilized as a comparator to isolated diffusion-weighted MRI to help determine stroke duration. FLAIR signal positivity typically occurs 6 to 24 hours after the initial insult but is negative in stroke that occurred < 3 hours earlier.32

MRI is limited, in terms of availability and increased study duration, especially when it comes to timely administration of thrombolysis. A benefit of this modality is less radiation and, as noted, superior sensitivity for ischemia. Diffusion-weighted MRI combined with MR perfusion analysis can help isolate areas of the ischemic penumbra. MR perfusion is performed for a similar reason as CT perfusion, although logistical execution across those modalities is significantly different. Considerations for choosing MR perfusion or CT perfusion should be made on an individual basis and based on available local resources and accepted local practice patterns.26

Continue to: In the subacute setting...

In the subacute setting, MR perfusion and MR angiography of the head and the neck are often performed to identify stenosis, dissection, and more subtle mimickers of cerebrovascular accident not ascertained on initial CT evaluation. These studies are typically performed well outside the window for thrombolysis or intervention.26 No guidelines specifically direct or recommend this practice pattern. The superior sensitivity and cerebral blood flow mapping of MR perfusion and MR angiography might be useful for validating a suspected diagnosis of ischemic stroke and providing phenotypic information about AIS events.

Transcranial Doppler imaging relies on bony windows to assess intracranial vascular flow, velocity, direction, and reactivity. This information can be utilized to diagnose stenosis or occlusion. This modality is principally used to evaluate for stenosis in the anterior circulation (sensitivity, 70%-90%; specificity, 90%-95%).20 Evaluation of the basilar, vertebral, and internal carotid arteries is less accurate (sensitivity, 55%-80%).20 Transcranial Doppler imaging is also used to assess for cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage, monitor sickle cell disease patients’ overall risk for ischemic stroke, and augment thrombolysis. It is limited by the availability of an expert technician, and therefore is typically reserved for unstable patients or those who cannot receive contrast.20

Carotid duplex ultrasonography. A dynamic study such as duplex ultrasonography can be strongly considered for flow imaging of the extracranial carotids to evaluate for stenosis. Indications for carotid stenting or endarterectomy include 50% to 79% occlusion of the carotid artery on the same side as a recent transient ischemic attack or AIS. Carotid stenosis > 80% warrants consideration for intervention independent of a recent cerebrovascular accident. Interventions are typically performed 2 to 14 days after stroke.33 Although this study is of limited utility in the hyperacute setting, it is recommended within 24 hours after nondisabling stroke in the carotid territory, when (1) the patient is otherwise a candidate for a surgical or procedural intervention to address the stenosis and (2) none of the aforementioned studies that focus on neck vasculature have been performed.

Conventional (digital subtraction) angiography is the gold standard for mapping cerebrovascular disease because it is dynamic and highly accurate. It is, however, typically limited by the number of required personnel, its invasive nature, and the requirement for IV contrast. This study is performed during intra-arterial intervention techniques, including stent retrieval and intra-arterial thrombolysis.26

Impact of imaging on treatment

Imaging helps determine the cause and some characteristics of stroke, both of which can help determine therapy. Strokes can be broadly subcategorized as hemorrhagic or ischemic; recent studies suggest that 87% are ischemic.34 Knowledge of the historic details of the event, the patient (eg, known atrial fibrillation, anticoagulant use, history of falls), and findings on imaging can contribute to determine the cause of AIS, and can facilitate communication and consultation between the primary care physician and inpatient teams.35

Continue to: Best practices for stroke treatment...

Best practices for stroke treatment are based on the cause of the event.3 To identify the likely cause, the aforementioned characteristics are incorporated into one of the scoring systems, which seek to clarify either the cause or the phenotypic appearance of the AIS, which helps direct further testing and treatment. (The ASCOD36 and TOAST37 classification schemes are commonly used phenotypic and causative classifications, respectively.) Several (not all) of the broad phenotypic imaging patterns, with myriad clinical manifestations, are reviewed below. They include:

- Embolic stroke, which, classically, involves end circulation and therefore has cortical involvement. Typically, these originate from the heart or large extracranial arteries, and higher rates of atrial fibrillation and hypercoagulable states are implicated.

- Thrombotic stroke, which, typically, is from large vessels or small vessels, and occurs as a result of atherosclerosis. These strokes are more common at the origins or bifurcations of vessels. Symptoms of thrombotic stroke classically wax and wane slightly more frequently. Lacunar strokes are typically from thrombotic causes, although there are rare episodes of an embolic source contributing to a lacunar stroke syndrome.38

There is evidence for using MRI discrepancies between diffusion-weighted and FLAIR imaging to time AIS findings in so-called wake-up strokes.39 The rationale is that strokes < 4.5 hours old can be identified because they would have abnormal diffusion imaging components but normal findings with FLAIR. When these criteria were utilized in considering whether to treat with thrombolysis, there was a statistically significant improvement in 90-day modified Rankin scale (odds ratio = 1.61; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-2.36), but also an increased probability of death and intracerebral hemorrhage.39

A recent multicenter, randomized, open-label trial, with blinded outcomes assessment, showcased the efficacy of thrombectomy as an adjunct when ischemic brain territory was identified without frank infarction, as ascertained by CT perfusion within the anterior circulation. This trial showed that thrombectomy could be performed as long as 16 hours after the patient was last well-appearing and still result in an improved outcome with favorable imaging characteristics (on the modified Rankin scale, an ordinal score of 4 with medical therapy and an ordinal score of 3 with EVT [odds ratio = 2.77; 95% confidence interval, 1.63-4.70]).29 A 2018 multicenter, prospective, randomized trial with blinded assessment of endpoints extended this idea, demonstrating that, when there was mismatch of the clinical deficit (ie, high NIHSS score) and infarct volume (measured on diffusion-weighted MRI or CT perfusion), thrombectomy as late as 24 hours after the patient was last known to be well was beneficial for lesions in the anterior circulation—specifically, the intracranial internal carotid artery or the proximal middle cerebral artery.40

a Whether local emergency departments (EDs) should be bypassed in favor of a specialized stroke center is the subject of debate. The 2019 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines note the AHA’s Mission: Lifeline Stroke EMS algorithm, which bypasses the nearest ED in feared cases of large-vessel occlusion if travel to a comprehensive stroke center can be accomplished within 30 minutes of arrival at the scene. This is based on expert consensus.3,12,13

CORRESPONDENCE

Brian Ford, MD, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD; [email protected].

1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67-e492.

2. Darves B. Collaboration key to post-stroke follow-up. ACP Internist. October 2009. https://acpinternist.org/archives/2009/10/stroke.htm. Accessed September 22, 2020.

3. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50e344-e418.

4. Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:2064-2089.

5. Aroor S, Singh R, Goldstein LB. BE-FAST (Balance, Eyes, Face, Arm, Speech, Time): Reducing the proportion of strokes missed using the FAST mnemonic. 2017;48:479-481.

6. Kidwell CS, Starkman S, Eckstein M, et al. Identifying stroke in the field. Prospective validation of the Los Angeles prehospital stroke screen (LAPSS). Stroke. 2000;31:71-76.

7. Llanes JN, Kidwell CS, Starkman S, et al. The Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS): a new measure to characterize stroke severity in the field. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2004;8:46-50.

8. Pérez de la Ossa N, Carrera D, Gorchs M, et al. Design and validation of a prehospital stroke scale to predict large arterial occlusion: the rapid arterial occlusion evaluation scale. Stroke. 2014;45:87-91.

9. Katz BS, McMullan JT, Sucharew H, et al. Design and validation of a prehospital scale to predict stroke severity: Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Severity Scale. Stroke. 2015;466:1508-1512.

10. Kummer BR, et al. External validation of the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Severity Scale. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:1270-1274.

11. Beume L-A, Hieber M, Kaller CP, et al. Large vessel occlusion in acute stroke. Stroke. 2018;49:2323-2329.

12. Man S, Zhao X, Uchino K, et al. Comparison of acute ischemic stroke care and outcomes between comprehensive stroke centers and primary stroke centers in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e004512.

13. American Heart Association (Mission: Lifeline—Stroke). Emergency medical services acute stroke routing. 2020. www.heart.org/-/media/files/professional/quality-improvement/mission-lifeline/2_25_2020/ds15698-qi-ems-algorithm_update-2142020.pdf?la=en. Accessed October 8, 2020.

14. Glober NK, Sporer KA, Guluma KZ, et al. Acute stroke: current evidence-based recommendations for prehospital care. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17:104-128.

15. NIH stroke scale. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health. www.stroke.nih.gov/resources/scale.htm. Accessed October 10, 2020.

16. Smith EE, Kent DM, Bulsara KR, et al; . Accuracy of prediction instruments for diagnosing large vessel occlusion in individuals with suspected stroke: a systematic review for the 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2018;49:e111-e122.

17. Woo D, Broderick JP, Kothari RU, et al. Does the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale favor left hemisphere strokes? NINDS t-PA Stroke Study Group. Stroke. 1999;30:2355-2359.

18. Adams HP Jr, Davis PH, Leira EC, et al. Baseline NIH Stroke Scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke: a report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). Neurology. 1999;53:126-131.

19. Banks JL, Marotta CA. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: implications for stroke clinical trials: a literature review and synthesis. Stroke. 2007;38:1091-1096.

20. Birenbaum D, Bancroft LW, Felsberg GJ. Imaging in acute stroke. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:67-76.

21. Salmela MB, Mortazavi S, Jagadeesan BD, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Cerebrovascular Disease. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:S34-S61.

22. Hemphill JC 3rd, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015;46:2032-60.

23. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke. The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS). JAMA. 1995;274:1017-1025.

24. The Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med, 1995;333:1581-1587.

25. Albers GW, Clark WM, Madden KP, et al. ATLANTIS trial: results for patients treated within 3 hours of stroke onset. Alteplase Thrombolysis for Acute Noninterventional Therapy in Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2002;33:493-495.

26. Khan R, Nael K, Erly W. Acute stroke imaging: what clinicians need to know. Am J Med. 2013;126:379-386.

27. Latchaw RE, Alberts MJ, Lev MH, et al; . Recommendations for managing of acute ischemic stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40:3646-3678.

28. Vagal A, Meganathan K, Kleindorfer DO, et al. Increasing use of computed tomographic perfusion and computed tomographic angiograms in acute ischemic stroke from 2006 to 2010. Stroke. 2014;45:1029-1034.

29. Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, et al; DEFUSE 3 Investigators. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:708-718.

30. Demeestere J, Wouters A, Christensen S, et al. Review of perfusion imaging in acute ischemic stroke: from time to tissue. Stroke. 2020;51:1017-1024.

31. Chalela JA, Kidwell CS, Nentwich LM, et al, Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: a prospective comparison. Lancet. 2007;369:293-298.

32. Aoki J, Kimura K, Iguchi Y, et al. FLAIR can estimate the onset time in acute ischemic stroke patients. J Neurol Sci. 2010;293:39-44.

33. Wabnitz AM, Turan TN. Symptomatic carotid artery stenosis: surgery, stenting, or medical therapy? Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2017;19:62.

34. Muir KW, Santosh C. Imaging of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(suppl 3):iii19-iii28.

35. Cameron JI, Tsoi C, Marsella A.Optimizing stroke systems of care by enhancing transitions across care environments. Stroke. 2008;39:2637-2643.

36. Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Caplan LR, et al. The ASCOD phenotyping of ischemic stroke (updated ASCO phenotyping). Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36:1-5.

37. Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35-41.

38. Cacciatore A, Russo LS Jr. Lacunar infarction as an embolic complication of cardiac and arch angiography. Stroke. 1991;22:1603-1605.

39. Thomalla G, Simonsen CZ, Boutitie F, et al; WAKE-UP Investigators. MRI-guided thrombolysis for stroke with unknown time of onset. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:611-622.

40. Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, et al; DAWN Trial Investigators. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:11-21.

Stroke ranks second behind heart disease as the leading cause of mortality worldwide, accounting for 1 of every 19 deaths,1 and remains a serious cause of morbidity. Best practices in stroke diagnosis and management can seem elusive to front-line clinicians, for 2 reasons: the rate of proliferation and nuance in stroke medicine and the fact that the typical scope of primary care practice exists apart from much of the diagnostic tools and management schema provided in stroke centers.2 In this article, we describe and update the diagnosis of stroke and review imaging modalities, their nuances, and their application in practice.

Diagnosis of acute stroke

Acute stroke is diagnosed upon observation of new neurologic deficits and congruent neuroimaging. Some updated definitions favor a silent form of cerebral ischemia manifested by imaging pathology only; this form is not discussed in this article. Although there are several characteristically distinct stroke syndromes, there is no way to clinically distinguish ischemic pathology from hemorrhagic pathology.

Some common symptoms that should prompt evaluation for stroke are part of the American Stroke Association FAST mnemonic designed to promote public health awareness3-5:

f ace droopinga rm weaknesss peech difficultyt ime to call 911.

Other commonly reported stroke symptoms include unilateral weakness or numbness, confusion, word-finding difficulty, visual problems, difficulty ambulating, dizziness, loss of balance or coordination, and thunderclap headache. A stroke should also be considered in the presence of any new focal neurologic deficit.3,4

Stroke patients should be triaged by emergency medical services using a stroke screening scale, such as BE-FAST5 (a modification of FAST that adds balance and eye assessments); the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS)6,7; the Rapid Arterial oCclusion Evaluation (RACE)8; and the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Severity Scale (CP-SSS)9,10 (see “Stroke screening scales for early identification and triage"). Studies have not found that any single prehospital stroke scale is superior to the others for reliably predicting large-vessel occlusion; therefore, prehospital assessment is typically based on practice patterns in a given locale.11 A patient (or family member or caregiver) who seeks your care for stroke symptoms should be told to call 911 and get emergency transport to a health care facility that can capably administer intravenous (IV) thrombolysis.a

SIDEBAR

Stroke screening scales for early identification and triage

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

www.stroke.nih.gov/resources/scale.htm

FAST

www.stroke.org/en/help-and-support/resource-library/fast-materials

BE-FAST

www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015169

Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS)

http://stroke.ucla.edu/workfiles/prehospital-screen.pdf

Rapid Artery Occlusion Evaluation (RACE)

www.mdcalc.com/rapid-arterial-occlusion-evaluation-race-scale-stroke

Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Severity Scale (CP-SSS)

https://www.mdcalc.com/cincinnati-prehospital-stroke-severity-scale-cp-sss

First responders should elicit “last-known-normal” time; this critical information can aid in diagnosis and drive therapeutic options, especially if patients are unaccompanied at time of transport to a higher echelon of care. A point-of-care blood glucose test should be performed by emergency medical staff, with dextrose administered for a level < 45 mg/dL. Establishing IV access for fluids, medications, and contrast can be considered if it does not delay transport. A 12-lead electrocardiogram can also be considered, again, as long as it does not delay transport to a facility capable of providing definitive therapy. Notification by emergency services staff before arrival and transport of the patient to such a facility is the essential element of prehospital care, and should be prioritized above ancillary testing beyond the stroke assessment.14

Guidelines recommend use of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS; www.stroke.nih.gov/resources/scale.htm) for clinical evaluation upon arrival at the ED.15 Although no scale has been identified that can reliably predict large-vessel occlusion amenable to endovascular therapy (EVT), no other score has been found to outperform the NIHSS in achieving meaningful patient outcomes.16 Furthermore, NIHSS has been validated to track clinical changes in response to therapy, is widely utilized, and is free.

Continue to: A criticism of the NIHSS...

A criticism of the NIHSS is its bias toward left-hemispheric ischemic pathology.17 NIHSS includes 11 questions on a scale of 0 to 42; typically, a score < 4 is associated with a higher chance of a positive clinical outcome.18 There is no minimum or maximum NIHSS score that precludes treatment with thrombolysis or EVT.

Other commonly used scores in acute stroke include disability assessments. The modified Rankin scale, which is used most often, features a score of 0 (symptom-free) to 6 (death). A modified Rankin scale score of 0 or 1 is considered an indication of a favorable outcome after stroke.19 Note that these functional scores are not always part of an acute assessment but can be done early in the clinical course to gauge the response to treatment, and are collected for stroke-center certification.

Imaging modalities

Imaging is recommended within 20 minutes of arrival in the ED in a stroke patient who might be a candidate for thrombolysis or thrombectomy.3 There, imaging modalities commonly performed are noncontrast-enhanced head computed tomography (NCHCT); computed tomography (CT) angiography, with or without perfusion; and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).20,21 In addition, more highly specialized imaging modalities are available for the evaluation of the stroke patient in specific, often limited, circumstances. All these modalities are described below and compared in the TABLE,20,21 using the ACR Appropriateness Criteria (of the American College of Radiology),21 which are guidelines for appropriate imaging of stroke, based on a clinical complaint. Separate recommendations and appraisals are offered by the most recent American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guideline.3

NCHCT. This study should be performed within 20 minutes after arrival at the ED because it provides rapid assessment of intracerebral hemorrhage, can effectively corroborate the diagnosis of some stroke mimickers, and identifies some candidates for EVT or thrombolysis3,21,22 (typically, the decision to proceed with EVT is based on adjunct imaging studies discussed in a bit). Evaluation for intracerebral hemorrhage is required prior to administering thrombolysis. Ischemic changes can be seen with variable specificity and sensitivity on NCHCT, depending on how much time has passed since the original insult. In all historical trials, CT was the only imaging modality used in the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) that suggested benefit from IV thrombolysis.23-25

Acute, subacute, and chronic changes can be seen on NCHCT, although the modality has limited sensitivity for identifying AIS (ie, approximately 75% within 6 hours after the original insult):

- Acute findings on NCHCT include intracellular edema, which causes loss of the gray matter–white matter interface and effacement of the cortical sulci. This occurs as a result of increased cellular uptake of water in response to ischemia and cell death, resulting in a decreased density of tissue (hypoattenuation) in affected areas.

- Subacute changes appear in the 2- to 5-day window, including vasogenic edema with greater mass effect, hypoattenuation, and well-defined margins.3,20,21

- Chronic vascular findings on NCHCT include loss of brain tissue and hypoattenuation.

Continue to: NCHCT is typically performed...

NCHCT is typically performed in advance of other adjunct imaging modalities.3,20,21 Baseline NCHCT can be performed on patients with advanced kidney disease and those who have an indwelling metallic device.

CT angiography is performed with timed contrast, providing a 3-dimensional representation of the cerebral vasculature; the entire intracranial and extracranial vasculature, including the aortic arch, can be mapped in approximately 60 seconds. CT angiography is sensitive in identifying areas of stenosis > 50% and identifies clinically significant areas of stenosis up to approximately 90% of the time.26 For this reason, it is particularly helpful in identifying candidates for an interventional strategy beyond pharmacotherapeutic thrombolysis. In addition, CT angiography can visualize aneurysmal dilation and dissection, and help with the planning of interventions—specifically, the confident administration of thrombolysis or more specific planning for target lesions and EVT.

It also can help identify a host of vascular phenomena, such as arteriovenous malformations, Moyamoya disease (progressive arterial blockage within the basal ganglia and compensatory microvascularization), and some vasculopathies.20,27 In intracranial hemorrhage, CT with angiography can help evaluate for structural malformations and identify patients at risk of hematoma expansion.22

CT perfusion. Many stroke centers will perform a CT perfusion study,28 which encompasses as many as 3 different CT sequences:

- NCHCT

- vertex-to-arch angiography with contrast bolus

- administration of contrast and capture of a dynamic sequence through 1 or 2 slabs of tissue, allowing for the generation of maps of cerebral blood flow (CBF), mean transit time (MTT), and cerebral blood volume (CBV) of the entire cerebral vasculature.

The interplay of these 3 sequences drives characterization of lesions (ie, CBF = CBV/MTT). An infarct is characterized by low CBF, low CBV, and elevated MTT. In penumbral tissue, MTT is elevated but CBF is slightly decreased and CBV is normal or increased. Using CT perfusion, areas throughout the ischemic penumbra can be surveyed for favorable interventional characteristics.20,29

Continue to: A CT perfusion study adds...

A CT perfusion study adds at least 60 seconds to NCHCT. This modality can be useful in planning interventions and for stratifying appropriateness of reperfusion strategies in strokes of unknown duration.3,30 CT perfusion can be performed on any multidetector CT scan but (1) requires specialized software and expertise to interpret and (2) subjects the patient to a significant radiation dose, which, if incorrectly administered, can be considerably higher than intended.20,26,27

Diffusion-weighted MRI. This is the most sensitive study for demonstrating early ischemic changes; however, limitations include lack of availability, contraindication in patients with metallic indwelling implants, and duration of the study—although, at some stroke centers, diffusion-weighted MRI can be performed in ≤ 10 minutes.

MRI and NCHCT have comparable sensitivity in detecting intracranial hemorrhage. MRI is likely more sensitive in identifying areas of microhemorrhage: In diffusion-weighted MRI, the sensitivity of stroke detection increases to > 95%.31 The modality relies on the comparable movement of water through damaged vs normal neuronal tissue. Diffusion-weighted MRI does not require administration of concomitant contrast, which can be a benefit in patients who are allergic to gadolinium-based contrast agents or have advanced kidney disease that precludes the use of contrast. It typically does not result in adequate characterization of extracranial vasculature.

Other MRI modalities. These MRI extensions include magnetic resonance (MR) perfusion and MR angiography. Whereas diffusion-weighted MRI (discussed above) offers the most rapid and sensitive evaluation for ischemia, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging has been utilized as a comparator to isolated diffusion-weighted MRI to help determine stroke duration. FLAIR signal positivity typically occurs 6 to 24 hours after the initial insult but is negative in stroke that occurred < 3 hours earlier.32

MRI is limited, in terms of availability and increased study duration, especially when it comes to timely administration of thrombolysis. A benefit of this modality is less radiation and, as noted, superior sensitivity for ischemia. Diffusion-weighted MRI combined with MR perfusion analysis can help isolate areas of the ischemic penumbra. MR perfusion is performed for a similar reason as CT perfusion, although logistical execution across those modalities is significantly different. Considerations for choosing MR perfusion or CT perfusion should be made on an individual basis and based on available local resources and accepted local practice patterns.26

Continue to: In the subacute setting...

In the subacute setting, MR perfusion and MR angiography of the head and the neck are often performed to identify stenosis, dissection, and more subtle mimickers of cerebrovascular accident not ascertained on initial CT evaluation. These studies are typically performed well outside the window for thrombolysis or intervention.26 No guidelines specifically direct or recommend this practice pattern. The superior sensitivity and cerebral blood flow mapping of MR perfusion and MR angiography might be useful for validating a suspected diagnosis of ischemic stroke and providing phenotypic information about AIS events.

Transcranial Doppler imaging relies on bony windows to assess intracranial vascular flow, velocity, direction, and reactivity. This information can be utilized to diagnose stenosis or occlusion. This modality is principally used to evaluate for stenosis in the anterior circulation (sensitivity, 70%-90%; specificity, 90%-95%).20 Evaluation of the basilar, vertebral, and internal carotid arteries is less accurate (sensitivity, 55%-80%).20 Transcranial Doppler imaging is also used to assess for cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage, monitor sickle cell disease patients’ overall risk for ischemic stroke, and augment thrombolysis. It is limited by the availability of an expert technician, and therefore is typically reserved for unstable patients or those who cannot receive contrast.20

Carotid duplex ultrasonography. A dynamic study such as duplex ultrasonography can be strongly considered for flow imaging of the extracranial carotids to evaluate for stenosis. Indications for carotid stenting or endarterectomy include 50% to 79% occlusion of the carotid artery on the same side as a recent transient ischemic attack or AIS. Carotid stenosis > 80% warrants consideration for intervention independent of a recent cerebrovascular accident. Interventions are typically performed 2 to 14 days after stroke.33 Although this study is of limited utility in the hyperacute setting, it is recommended within 24 hours after nondisabling stroke in the carotid territory, when (1) the patient is otherwise a candidate for a surgical or procedural intervention to address the stenosis and (2) none of the aforementioned studies that focus on neck vasculature have been performed.

Conventional (digital subtraction) angiography is the gold standard for mapping cerebrovascular disease because it is dynamic and highly accurate. It is, however, typically limited by the number of required personnel, its invasive nature, and the requirement for IV contrast. This study is performed during intra-arterial intervention techniques, including stent retrieval and intra-arterial thrombolysis.26

Impact of imaging on treatment

Imaging helps determine the cause and some characteristics of stroke, both of which can help determine therapy. Strokes can be broadly subcategorized as hemorrhagic or ischemic; recent studies suggest that 87% are ischemic.34 Knowledge of the historic details of the event, the patient (eg, known atrial fibrillation, anticoagulant use, history of falls), and findings on imaging can contribute to determine the cause of AIS, and can facilitate communication and consultation between the primary care physician and inpatient teams.35

Continue to: Best practices for stroke treatment...

Best practices for stroke treatment are based on the cause of the event.3 To identify the likely cause, the aforementioned characteristics are incorporated into one of the scoring systems, which seek to clarify either the cause or the phenotypic appearance of the AIS, which helps direct further testing and treatment. (The ASCOD36 and TOAST37 classification schemes are commonly used phenotypic and causative classifications, respectively.) Several (not all) of the broad phenotypic imaging patterns, with myriad clinical manifestations, are reviewed below. They include:

- Embolic stroke, which, classically, involves end circulation and therefore has cortical involvement. Typically, these originate from the heart or large extracranial arteries, and higher rates of atrial fibrillation and hypercoagulable states are implicated.

- Thrombotic stroke, which, typically, is from large vessels or small vessels, and occurs as a result of atherosclerosis. These strokes are more common at the origins or bifurcations of vessels. Symptoms of thrombotic stroke classically wax and wane slightly more frequently. Lacunar strokes are typically from thrombotic causes, although there are rare episodes of an embolic source contributing to a lacunar stroke syndrome.38