User login

Gynecologic cancer patients at risk of insurance loss, ‘catastrophic’ costs

A retrospective study of respondents to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey showed that more than one in five gynecologic cancer patients reported losing health insurance for at least 1 month every year, and more than one in four reported having catastrophic health expenses annually.

Benjamin Albright, MD, of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., presented these results at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Virtual Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer (Abstract 10303).

“We found gynecologic cancer patients to have high rates of insurance churn and catastrophic health expenditures, particularly among the poor,” Dr. Albright said. “Traditional static measurements clearly underestimate the impact of uninsurance, with over 20% of patients reporting some period of uninsurance annually.”

There was no evidence of improvement in any outcome after the implementation of the ACA, compared with the pre-ACA period, “though our assessment was limited in estimate precision by small sample size,” Dr. Albright acknowledged.

Dynamic, not static

Oncology researchers who study access to care and financial toxicities often consider insurance status as a static characteristic, but in the U.S. health care system, the reality is quite different, with insurance status fluctuating by employment or ability to pay, sometimes on a month-to-month basis, according to Dr. Albright.

Citing the Commonwealth Fund’s definition of catastrophic health expenditures as “spending over 10% of income on health care,” Dr. Albright noted that the prevalence of catastrophic out-of-pocket costs “is also relatively poorly described among cancer patients, particularly in accounting for family spending and income dynamics.

“The Affordable Care Act contained measures to address both of these concerns, including coverage protections and expansions, and spending regulations,” he said.

Dr. Albright and colleagues at Duke and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York assessed insurance churn and catastrophic health expenditures among gynecologic cancer patients, attempting to determine whether the ACA had helped to limit insurance churn and keep costs manageable.

Representative sample

The investigators conducted a retrospective study of data from Medical Expenditure Panel Survey respondents from 2006 through 2017, a period that spanned the implementation of the ACA in 2010.

The sample included 684 women younger than 65 years reporting care in the given year related to a gynecologic cancer diagnosis. The civilian, noninstitutionalized sample was weighted to represent an estimated average annual population of 533,000 persons. The population was majority White (87%) and non-Hispanic (85.5%).

The investigators found that, compared with the overall U.S. population of people under 65, gynecologic cancer patients were more likely to have incomes of 250% or less of the federal poverty line (45.1% vs. 32.2%, P < .001).

The cancer patients were more likely than was the general population to have less than full-time employment, with 15.2% and 10.5%, respectively, reporting a job change or job loss; 55.3% and 44.1%, respectively, being employed only part of a given year; and 38.6% and 32.4%, respectively, being unemployed for a full year (P < .05 for each comparison).

Gynecologic cancer patients continued to experience insurance troubles and financial hardships after the ACA went into effect, with 8.8% reporting loss of insurance, 18.7% reporting a change in insurance, 21.7% being uninsured for at least 1 month, and 8.4% being uninsured for an entire year.

In addition, 12.8% of gynecologic cancer patients reported catastrophic health expenditures in out-of-pocket costs alone, and 28.0% spent more than 10% of their income on health care when the cost of premiums was factored in.

The numbers were even worse for non-White and Hispanic patients, with 25.9% reporting an insurance change (vs. 16.3% for non-Hispanic Whites) and 30.2% reporting a period of not being insured (vs. 18.7% for non-Hispanic Whites). There were no differences in catastrophic health expenditures by race/ethnicity, however.

Not surprisingly, patients from low-income families had significantly higher probability of having catastrophic expenditures, at 22.7% vs. 3.0% for higher-income families for out-of-pocket expenses alone (P < .001), and 35.3% vs. 20.8%, respectively, when the cost of premiums was included (P = .01).

On the other hand, patients with full-year Medicaid coverage were less likely to suffer from catastrophic costs than were privately-insured patients, at 15.3% vs. 31.3% in the overall sample (P = .02), and 11.5% vs. 62.1% of low-income vs. higher-income patients (P < .001).

There was a trend toward lower catastrophic health expenditures among low-income patients after full implementation of the ACA – 2014-2017 – compared with 2006-2009, but this difference was not statistically significant.

How to change it

In a panel discussion following the presentation, comoderator Eloise Chapman-Davis, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, said to Dr. Albright, “As we look to improve equity within our subspecialty, I would like to ask you to comment on how you believe your abstract will inform our gyn-oncology culture and speak to what changes that you believe are needed to better advocate for our patients.”

“I think that our abstract really shows the prevalence of the problems of financial toxicity and of instability in the insurance market in the U.S.,” he replied. “I think it points out that we need to be more proactive about identifying patients and seeking out patients who may be having issues related to financial toxicity, to try to refer people to resources sooner and upfront.”

The investigators did not list a funding source for the study. Dr. Albright and Dr. Chapman-Davis reported having no conflicts of interest.

A retrospective study of respondents to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey showed that more than one in five gynecologic cancer patients reported losing health insurance for at least 1 month every year, and more than one in four reported having catastrophic health expenses annually.

Benjamin Albright, MD, of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., presented these results at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Virtual Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer (Abstract 10303).

“We found gynecologic cancer patients to have high rates of insurance churn and catastrophic health expenditures, particularly among the poor,” Dr. Albright said. “Traditional static measurements clearly underestimate the impact of uninsurance, with over 20% of patients reporting some period of uninsurance annually.”

There was no evidence of improvement in any outcome after the implementation of the ACA, compared with the pre-ACA period, “though our assessment was limited in estimate precision by small sample size,” Dr. Albright acknowledged.

Dynamic, not static

Oncology researchers who study access to care and financial toxicities often consider insurance status as a static characteristic, but in the U.S. health care system, the reality is quite different, with insurance status fluctuating by employment or ability to pay, sometimes on a month-to-month basis, according to Dr. Albright.

Citing the Commonwealth Fund’s definition of catastrophic health expenditures as “spending over 10% of income on health care,” Dr. Albright noted that the prevalence of catastrophic out-of-pocket costs “is also relatively poorly described among cancer patients, particularly in accounting for family spending and income dynamics.

“The Affordable Care Act contained measures to address both of these concerns, including coverage protections and expansions, and spending regulations,” he said.

Dr. Albright and colleagues at Duke and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York assessed insurance churn and catastrophic health expenditures among gynecologic cancer patients, attempting to determine whether the ACA had helped to limit insurance churn and keep costs manageable.

Representative sample

The investigators conducted a retrospective study of data from Medical Expenditure Panel Survey respondents from 2006 through 2017, a period that spanned the implementation of the ACA in 2010.

The sample included 684 women younger than 65 years reporting care in the given year related to a gynecologic cancer diagnosis. The civilian, noninstitutionalized sample was weighted to represent an estimated average annual population of 533,000 persons. The population was majority White (87%) and non-Hispanic (85.5%).

The investigators found that, compared with the overall U.S. population of people under 65, gynecologic cancer patients were more likely to have incomes of 250% or less of the federal poverty line (45.1% vs. 32.2%, P < .001).

The cancer patients were more likely than was the general population to have less than full-time employment, with 15.2% and 10.5%, respectively, reporting a job change or job loss; 55.3% and 44.1%, respectively, being employed only part of a given year; and 38.6% and 32.4%, respectively, being unemployed for a full year (P < .05 for each comparison).

Gynecologic cancer patients continued to experience insurance troubles and financial hardships after the ACA went into effect, with 8.8% reporting loss of insurance, 18.7% reporting a change in insurance, 21.7% being uninsured for at least 1 month, and 8.4% being uninsured for an entire year.

In addition, 12.8% of gynecologic cancer patients reported catastrophic health expenditures in out-of-pocket costs alone, and 28.0% spent more than 10% of their income on health care when the cost of premiums was factored in.

The numbers were even worse for non-White and Hispanic patients, with 25.9% reporting an insurance change (vs. 16.3% for non-Hispanic Whites) and 30.2% reporting a period of not being insured (vs. 18.7% for non-Hispanic Whites). There were no differences in catastrophic health expenditures by race/ethnicity, however.

Not surprisingly, patients from low-income families had significantly higher probability of having catastrophic expenditures, at 22.7% vs. 3.0% for higher-income families for out-of-pocket expenses alone (P < .001), and 35.3% vs. 20.8%, respectively, when the cost of premiums was included (P = .01).

On the other hand, patients with full-year Medicaid coverage were less likely to suffer from catastrophic costs than were privately-insured patients, at 15.3% vs. 31.3% in the overall sample (P = .02), and 11.5% vs. 62.1% of low-income vs. higher-income patients (P < .001).

There was a trend toward lower catastrophic health expenditures among low-income patients after full implementation of the ACA – 2014-2017 – compared with 2006-2009, but this difference was not statistically significant.

How to change it

In a panel discussion following the presentation, comoderator Eloise Chapman-Davis, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, said to Dr. Albright, “As we look to improve equity within our subspecialty, I would like to ask you to comment on how you believe your abstract will inform our gyn-oncology culture and speak to what changes that you believe are needed to better advocate for our patients.”

“I think that our abstract really shows the prevalence of the problems of financial toxicity and of instability in the insurance market in the U.S.,” he replied. “I think it points out that we need to be more proactive about identifying patients and seeking out patients who may be having issues related to financial toxicity, to try to refer people to resources sooner and upfront.”

The investigators did not list a funding source for the study. Dr. Albright and Dr. Chapman-Davis reported having no conflicts of interest.

A retrospective study of respondents to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey showed that more than one in five gynecologic cancer patients reported losing health insurance for at least 1 month every year, and more than one in four reported having catastrophic health expenses annually.

Benjamin Albright, MD, of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., presented these results at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Virtual Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer (Abstract 10303).

“We found gynecologic cancer patients to have high rates of insurance churn and catastrophic health expenditures, particularly among the poor,” Dr. Albright said. “Traditional static measurements clearly underestimate the impact of uninsurance, with over 20% of patients reporting some period of uninsurance annually.”

There was no evidence of improvement in any outcome after the implementation of the ACA, compared with the pre-ACA period, “though our assessment was limited in estimate precision by small sample size,” Dr. Albright acknowledged.

Dynamic, not static

Oncology researchers who study access to care and financial toxicities often consider insurance status as a static characteristic, but in the U.S. health care system, the reality is quite different, with insurance status fluctuating by employment or ability to pay, sometimes on a month-to-month basis, according to Dr. Albright.

Citing the Commonwealth Fund’s definition of catastrophic health expenditures as “spending over 10% of income on health care,” Dr. Albright noted that the prevalence of catastrophic out-of-pocket costs “is also relatively poorly described among cancer patients, particularly in accounting for family spending and income dynamics.

“The Affordable Care Act contained measures to address both of these concerns, including coverage protections and expansions, and spending regulations,” he said.

Dr. Albright and colleagues at Duke and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York assessed insurance churn and catastrophic health expenditures among gynecologic cancer patients, attempting to determine whether the ACA had helped to limit insurance churn and keep costs manageable.

Representative sample

The investigators conducted a retrospective study of data from Medical Expenditure Panel Survey respondents from 2006 through 2017, a period that spanned the implementation of the ACA in 2010.

The sample included 684 women younger than 65 years reporting care in the given year related to a gynecologic cancer diagnosis. The civilian, noninstitutionalized sample was weighted to represent an estimated average annual population of 533,000 persons. The population was majority White (87%) and non-Hispanic (85.5%).

The investigators found that, compared with the overall U.S. population of people under 65, gynecologic cancer patients were more likely to have incomes of 250% or less of the federal poverty line (45.1% vs. 32.2%, P < .001).

The cancer patients were more likely than was the general population to have less than full-time employment, with 15.2% and 10.5%, respectively, reporting a job change or job loss; 55.3% and 44.1%, respectively, being employed only part of a given year; and 38.6% and 32.4%, respectively, being unemployed for a full year (P < .05 for each comparison).

Gynecologic cancer patients continued to experience insurance troubles and financial hardships after the ACA went into effect, with 8.8% reporting loss of insurance, 18.7% reporting a change in insurance, 21.7% being uninsured for at least 1 month, and 8.4% being uninsured for an entire year.

In addition, 12.8% of gynecologic cancer patients reported catastrophic health expenditures in out-of-pocket costs alone, and 28.0% spent more than 10% of their income on health care when the cost of premiums was factored in.

The numbers were even worse for non-White and Hispanic patients, with 25.9% reporting an insurance change (vs. 16.3% for non-Hispanic Whites) and 30.2% reporting a period of not being insured (vs. 18.7% for non-Hispanic Whites). There were no differences in catastrophic health expenditures by race/ethnicity, however.

Not surprisingly, patients from low-income families had significantly higher probability of having catastrophic expenditures, at 22.7% vs. 3.0% for higher-income families for out-of-pocket expenses alone (P < .001), and 35.3% vs. 20.8%, respectively, when the cost of premiums was included (P = .01).

On the other hand, patients with full-year Medicaid coverage were less likely to suffer from catastrophic costs than were privately-insured patients, at 15.3% vs. 31.3% in the overall sample (P = .02), and 11.5% vs. 62.1% of low-income vs. higher-income patients (P < .001).

There was a trend toward lower catastrophic health expenditures among low-income patients after full implementation of the ACA – 2014-2017 – compared with 2006-2009, but this difference was not statistically significant.

How to change it

In a panel discussion following the presentation, comoderator Eloise Chapman-Davis, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, said to Dr. Albright, “As we look to improve equity within our subspecialty, I would like to ask you to comment on how you believe your abstract will inform our gyn-oncology culture and speak to what changes that you believe are needed to better advocate for our patients.”

“I think that our abstract really shows the prevalence of the problems of financial toxicity and of instability in the insurance market in the U.S.,” he replied. “I think it points out that we need to be more proactive about identifying patients and seeking out patients who may be having issues related to financial toxicity, to try to refer people to resources sooner and upfront.”

The investigators did not list a funding source for the study. Dr. Albright and Dr. Chapman-Davis reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM SGO 2021

Recurrent miscarriage: What’s the evidence-based evaluation and management?

A pregnancy loss at any gestational age is devastating. Women and/or couples may, unfairly, self-blame as they desperately seek substantive answers. Their support systems, including health care providers, offer some, albeit fleeting, comfort. Conception is merely the start of an emotionally arduous first trimester that often results in a learned helplessness. This month, we focus on the comprehensive evaluation and the medical evidence–based approach to recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL).

RPL is defined by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine as two or more clinical pregnancy losses of less than 20 weeks’ gestation with a prevalence of approximately 5%. Embryo aneuploidy is the most common reason for a spontaneous miscarriage, occurring in 50%-70% of losses. The risk of spontaneous miscarriage during the reproductive years follows a J-shaped pattern. The lowest percentage is in women aged 25-29 years (9.8%), with a nadir at age 27 (9.5%), then an increasingly steep rise after age 35 to a peak at age 45 and over (53.6%). The loss rate is closer to 50% of all fertilizations since many spontaneous miscarriages occur at 2-4 weeks, before a pregnancy can be clinically diagnosed. The frequency of embryo aneuploidy significantly decreases and embryo euploidy increases with successive numbers of spontaneous miscarriages.

After three or more spontaneous miscarriages, nulliparous women appear to have a higher rate of subsequent pregnancy loss, compared with parous women (BMJ. 2000;320:1708). We recommend an evaluation following two losses given the lack of evidence for a difference in diagnostic yield following two versus three miscarriages and particularly because of the emotional effects of impact of RPL.

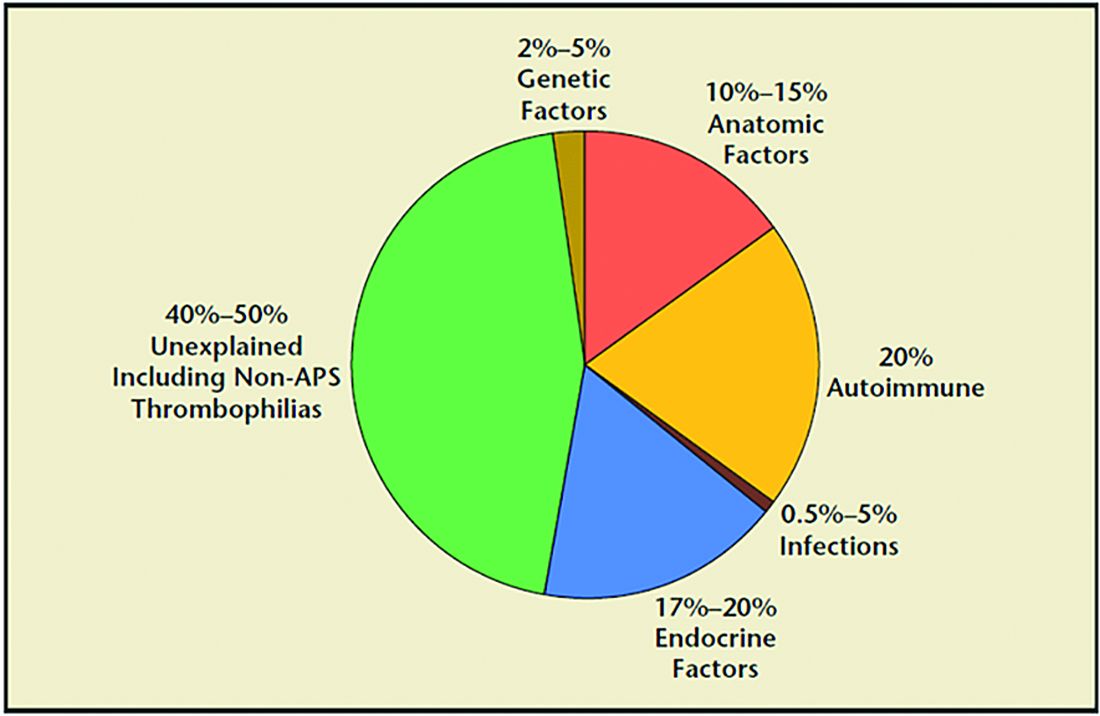

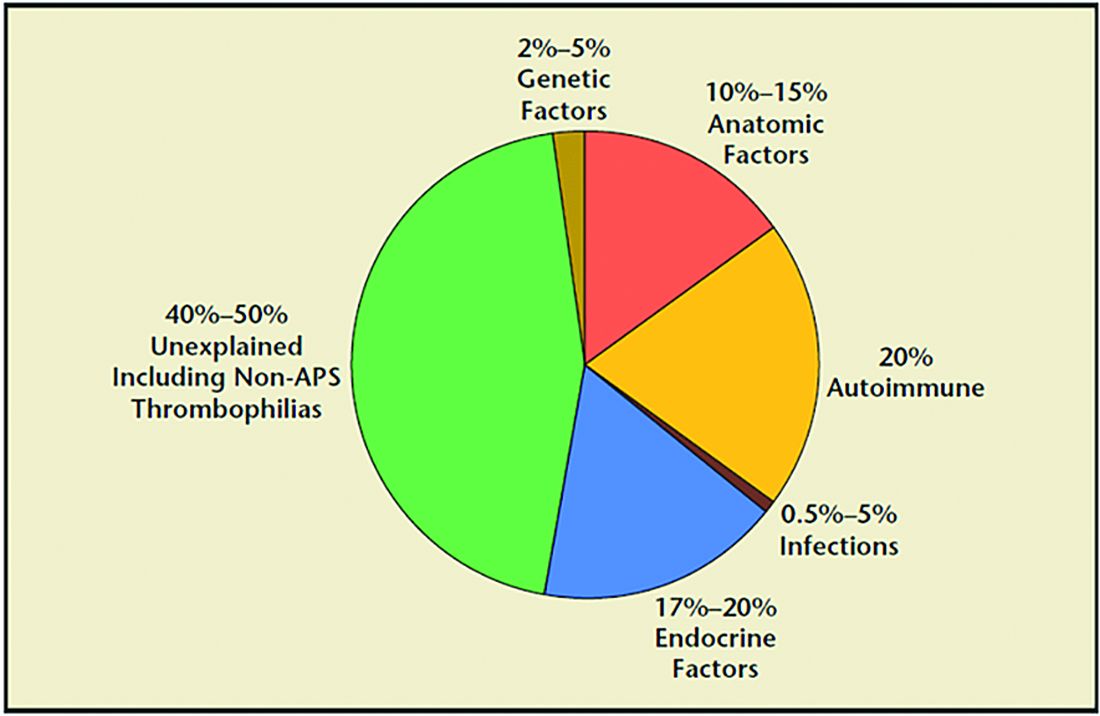

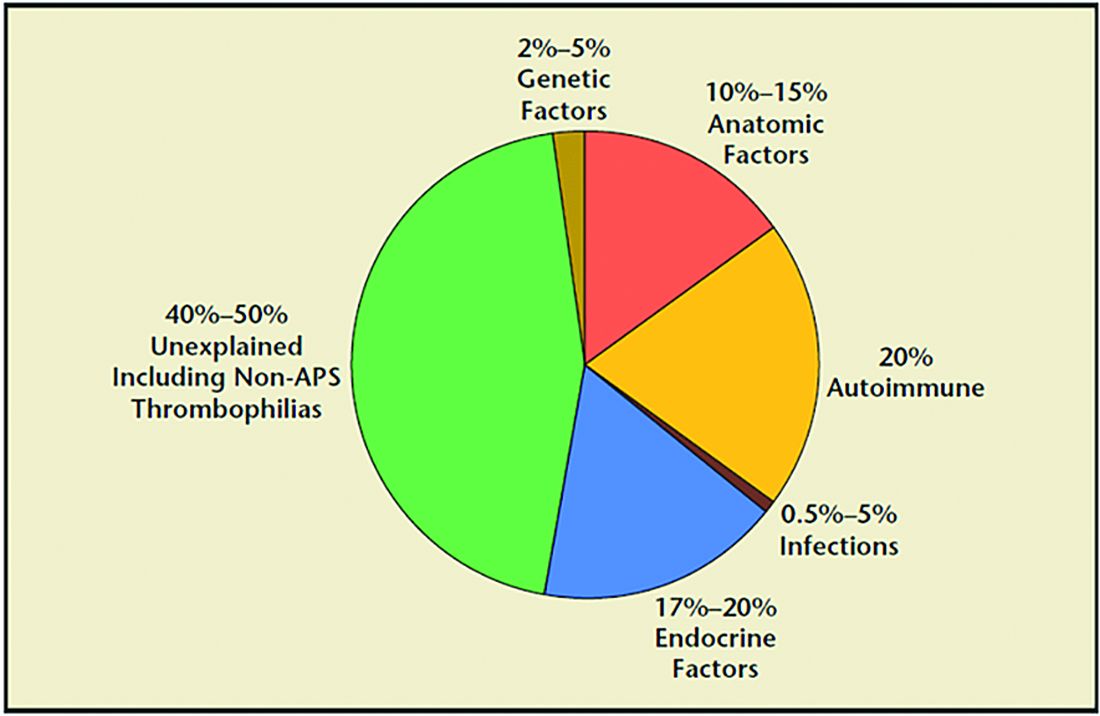

RPL causes, percentages of contribution, and evaluation

1. Genetic (2%-5%). Because of the risk of an embryo with an unbalanced chromosomal rearrangement inherited from a translocation present in either of the couple, a blood karyotype of the couple is essential despite a history of one or more successful live births. While in vitro fertilization (IVF) with preimplantation genetic testing for structural rearrangements (PGT-SR) can successfully diagnose affected embryos to avoid their intrauterine transfer, overall live birth rates are similar when comparing natural conception attempts with PGT-SR, although the latter may reduce miscarriages.

2. Anatomic (10%-15%). Hysteroscopy, hysterosalpingogram, or saline ultrasound can be used to image the uterine cavity to evaluate for polyps, fibroids, scarring, or a congenital septum – all of which can be surgically corrected. Chronic endometritis has been found in 27% of patients with recurrent miscarriage (and in 14% with recurrent implantation failure), therefore testing by biopsy is reasonable. An elevated level of homocysteine has been reported to impair DNA methylation and gene expression, causing defective chorionic villous vascularization in spontaneous miscarriage tissues. We recommend folic acid supplementation and the avoidance of testing for MTHFR (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase). Of note, the recent TRUST study showed no significant benefit from metroplasty in comparison with expectant management in 12 months of observation resulting in a live birth rate of 31% versus 35%, respectively.

3. Acquired thrombophilias (20%). Medical evidence supports testing for the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), i.e., RPL with either the presence of lupus anticoagulant (LAC), anticardiolipin antibodies, or anti-beta2 glycoprotein for IgG and IgM. Persistent LAC or elevations of antibodies greater than 40 GPL or greater than the 99th percentile for more than 12 weeks justifies the use of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). APS has been shown to cause RPL, thrombosis, and/or autoimmune thrombocytopenia. There is no definitive evidence to support testing for MTHFR or any other thrombophilias for first trimester RPL. APS has up to a 90% fetal loss rate without therapeutic intervention. Treatment includes low-dose aspirin (81 mg daily) and LMWH. These medications are thought to help prevent thrombosis in the placenta, helping to maintain pregnancies.

4. Hormonal (17%-20%). The most common hormonal disorders increasing the risk for miscarriage is thyroid dysfunction (both hyper- and hypothyroid), prolactin elevations, and lack of glucose control. While the concern for a luteal phase (LPD) prevails, there is no accepted definition or treatment. There is recent evidence that antibodies to thyroid peroxidase may increase miscarriage and that low-dose thyroid replacement may reduce this risk. One other important area is the polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). This hormonal abnormality affects 6%-20% of all reproductive aged women and may increase miscarriage.

5. Unexplained (40%-50%). The most frustrating but most common reason for RPL. Nevertheless, close monitoring and supportive care throughout the first trimester has been demonstrated in medical studies to improve outcome.

Seven surprising facts about recurrent miscarriage

1. Folic acid 4 mg daily may decrease embryo chromosomal abnormalities and miscarriage.

Folic acid in doses of at least 0.4 mg daily have long been advocated to reduce spina bifida and neural tube defects. It is optimal to begin folic acid for several months prior to conception attempts. There is evidence it may help treat RPL by reducing the chance for chromosomal errors.

2. A randomized trial did not demonstrate an improved live birth rate using progesterone in the first trimester. However, women enrolled may not have begun progesterone until 6 weeks of pregnancy, begging the question if earlier progesterone would have demonstrated improvement.

Dydrogesterone, a progestogen that is highly selective for the progesterone receptor, lacks estrogenic, androgenic, anabolic, and corticoid properties. Although not available in the United States, dydrogesterone appears to reduce the rate of idiopathic recurrent miscarriage (two or more losses). Also, progesterone support has been shown to reduce loss in threatened miscarriage – 17 OHPC 500 mg IM weekly in the first trimester.

3. No benefit of aspirin and/or heparin to treat unexplained RM.

The use of aspirin and/or heparin-like medication has convincingly been shown to not improve live birth rates in RPL.

4. Inherited thrombophilias are NOT associated with RM and should not be tested.

Screening for factor V (Leiden mutation), factor II (Prothrombin G20210A), and MTHFR have not been shown to cause RM and no treatment, such as aspirin and/or heparin-like medications, improves the live birth rate.

5. Close monitoring and empathetic care improves outcomes.

For unknown reasons, clinics providing close monitoring, emotional support, and education to patients with unexplained RM report higher live birth rates, compared with patients not receiving this level of care.

6. Behavior changes reduce miscarriage.

Elevations in body mass index (BMI) and cigarette smoking both increase the risk of miscarriage. As a result, a healthy BMI and eliminating tobacco use reduce the risk of pregnancy loss. Excessive caffeine use (more than two equivalent cups of caffeine in coffee per day) also may increase spontaneous miscarriage.

7. Fertility medications, intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization, or preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) do not improve outcomes.

While patients and, often, health care providers, feel compelled to proceed with fertility treatment, ovulation induction medications, intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization, or PGT-A have not been shown to improve the chance for a live birth. PGT-A did not reduce the risk of miscarriage in women with recurrent pregnancy loss.

In summary, following two or more pregnancy losses, I recommend obtaining chromosomal testing of the couple, viewing the uterine cavity, blood testing for thyroid, prolactin, and glucose control, and acquired thrombophilias (as above). Fortunately, when the cause is unexplained, the woman has a 70%-80% chance of a spontaneous live birth over the next 10 years from diagnosis. By further understanding, knowing how to diagnose, and, finally, treating the cause of RPL we can hopefully prevent the heartbreak women and couples endure.

Dr. Trolice is director of Fertility CARE – The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

A pregnancy loss at any gestational age is devastating. Women and/or couples may, unfairly, self-blame as they desperately seek substantive answers. Their support systems, including health care providers, offer some, albeit fleeting, comfort. Conception is merely the start of an emotionally arduous first trimester that often results in a learned helplessness. This month, we focus on the comprehensive evaluation and the medical evidence–based approach to recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL).

RPL is defined by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine as two or more clinical pregnancy losses of less than 20 weeks’ gestation with a prevalence of approximately 5%. Embryo aneuploidy is the most common reason for a spontaneous miscarriage, occurring in 50%-70% of losses. The risk of spontaneous miscarriage during the reproductive years follows a J-shaped pattern. The lowest percentage is in women aged 25-29 years (9.8%), with a nadir at age 27 (9.5%), then an increasingly steep rise after age 35 to a peak at age 45 and over (53.6%). The loss rate is closer to 50% of all fertilizations since many spontaneous miscarriages occur at 2-4 weeks, before a pregnancy can be clinically diagnosed. The frequency of embryo aneuploidy significantly decreases and embryo euploidy increases with successive numbers of spontaneous miscarriages.

After three or more spontaneous miscarriages, nulliparous women appear to have a higher rate of subsequent pregnancy loss, compared with parous women (BMJ. 2000;320:1708). We recommend an evaluation following two losses given the lack of evidence for a difference in diagnostic yield following two versus three miscarriages and particularly because of the emotional effects of impact of RPL.

RPL causes, percentages of contribution, and evaluation

1. Genetic (2%-5%). Because of the risk of an embryo with an unbalanced chromosomal rearrangement inherited from a translocation present in either of the couple, a blood karyotype of the couple is essential despite a history of one or more successful live births. While in vitro fertilization (IVF) with preimplantation genetic testing for structural rearrangements (PGT-SR) can successfully diagnose affected embryos to avoid their intrauterine transfer, overall live birth rates are similar when comparing natural conception attempts with PGT-SR, although the latter may reduce miscarriages.

2. Anatomic (10%-15%). Hysteroscopy, hysterosalpingogram, or saline ultrasound can be used to image the uterine cavity to evaluate for polyps, fibroids, scarring, or a congenital septum – all of which can be surgically corrected. Chronic endometritis has been found in 27% of patients with recurrent miscarriage (and in 14% with recurrent implantation failure), therefore testing by biopsy is reasonable. An elevated level of homocysteine has been reported to impair DNA methylation and gene expression, causing defective chorionic villous vascularization in spontaneous miscarriage tissues. We recommend folic acid supplementation and the avoidance of testing for MTHFR (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase). Of note, the recent TRUST study showed no significant benefit from metroplasty in comparison with expectant management in 12 months of observation resulting in a live birth rate of 31% versus 35%, respectively.

3. Acquired thrombophilias (20%). Medical evidence supports testing for the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), i.e., RPL with either the presence of lupus anticoagulant (LAC), anticardiolipin antibodies, or anti-beta2 glycoprotein for IgG and IgM. Persistent LAC or elevations of antibodies greater than 40 GPL or greater than the 99th percentile for more than 12 weeks justifies the use of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). APS has been shown to cause RPL, thrombosis, and/or autoimmune thrombocytopenia. There is no definitive evidence to support testing for MTHFR or any other thrombophilias for first trimester RPL. APS has up to a 90% fetal loss rate without therapeutic intervention. Treatment includes low-dose aspirin (81 mg daily) and LMWH. These medications are thought to help prevent thrombosis in the placenta, helping to maintain pregnancies.

4. Hormonal (17%-20%). The most common hormonal disorders increasing the risk for miscarriage is thyroid dysfunction (both hyper- and hypothyroid), prolactin elevations, and lack of glucose control. While the concern for a luteal phase (LPD) prevails, there is no accepted definition or treatment. There is recent evidence that antibodies to thyroid peroxidase may increase miscarriage and that low-dose thyroid replacement may reduce this risk. One other important area is the polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). This hormonal abnormality affects 6%-20% of all reproductive aged women and may increase miscarriage.

5. Unexplained (40%-50%). The most frustrating but most common reason for RPL. Nevertheless, close monitoring and supportive care throughout the first trimester has been demonstrated in medical studies to improve outcome.

Seven surprising facts about recurrent miscarriage

1. Folic acid 4 mg daily may decrease embryo chromosomal abnormalities and miscarriage.

Folic acid in doses of at least 0.4 mg daily have long been advocated to reduce spina bifida and neural tube defects. It is optimal to begin folic acid for several months prior to conception attempts. There is evidence it may help treat RPL by reducing the chance for chromosomal errors.

2. A randomized trial did not demonstrate an improved live birth rate using progesterone in the first trimester. However, women enrolled may not have begun progesterone until 6 weeks of pregnancy, begging the question if earlier progesterone would have demonstrated improvement.

Dydrogesterone, a progestogen that is highly selective for the progesterone receptor, lacks estrogenic, androgenic, anabolic, and corticoid properties. Although not available in the United States, dydrogesterone appears to reduce the rate of idiopathic recurrent miscarriage (two or more losses). Also, progesterone support has been shown to reduce loss in threatened miscarriage – 17 OHPC 500 mg IM weekly in the first trimester.

3. No benefit of aspirin and/or heparin to treat unexplained RM.

The use of aspirin and/or heparin-like medication has convincingly been shown to not improve live birth rates in RPL.

4. Inherited thrombophilias are NOT associated with RM and should not be tested.

Screening for factor V (Leiden mutation), factor II (Prothrombin G20210A), and MTHFR have not been shown to cause RM and no treatment, such as aspirin and/or heparin-like medications, improves the live birth rate.

5. Close monitoring and empathetic care improves outcomes.

For unknown reasons, clinics providing close monitoring, emotional support, and education to patients with unexplained RM report higher live birth rates, compared with patients not receiving this level of care.

6. Behavior changes reduce miscarriage.

Elevations in body mass index (BMI) and cigarette smoking both increase the risk of miscarriage. As a result, a healthy BMI and eliminating tobacco use reduce the risk of pregnancy loss. Excessive caffeine use (more than two equivalent cups of caffeine in coffee per day) also may increase spontaneous miscarriage.

7. Fertility medications, intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization, or preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) do not improve outcomes.

While patients and, often, health care providers, feel compelled to proceed with fertility treatment, ovulation induction medications, intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization, or PGT-A have not been shown to improve the chance for a live birth. PGT-A did not reduce the risk of miscarriage in women with recurrent pregnancy loss.

In summary, following two or more pregnancy losses, I recommend obtaining chromosomal testing of the couple, viewing the uterine cavity, blood testing for thyroid, prolactin, and glucose control, and acquired thrombophilias (as above). Fortunately, when the cause is unexplained, the woman has a 70%-80% chance of a spontaneous live birth over the next 10 years from diagnosis. By further understanding, knowing how to diagnose, and, finally, treating the cause of RPL we can hopefully prevent the heartbreak women and couples endure.

Dr. Trolice is director of Fertility CARE – The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

A pregnancy loss at any gestational age is devastating. Women and/or couples may, unfairly, self-blame as they desperately seek substantive answers. Their support systems, including health care providers, offer some, albeit fleeting, comfort. Conception is merely the start of an emotionally arduous first trimester that often results in a learned helplessness. This month, we focus on the comprehensive evaluation and the medical evidence–based approach to recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL).

RPL is defined by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine as two or more clinical pregnancy losses of less than 20 weeks’ gestation with a prevalence of approximately 5%. Embryo aneuploidy is the most common reason for a spontaneous miscarriage, occurring in 50%-70% of losses. The risk of spontaneous miscarriage during the reproductive years follows a J-shaped pattern. The lowest percentage is in women aged 25-29 years (9.8%), with a nadir at age 27 (9.5%), then an increasingly steep rise after age 35 to a peak at age 45 and over (53.6%). The loss rate is closer to 50% of all fertilizations since many spontaneous miscarriages occur at 2-4 weeks, before a pregnancy can be clinically diagnosed. The frequency of embryo aneuploidy significantly decreases and embryo euploidy increases with successive numbers of spontaneous miscarriages.

After three or more spontaneous miscarriages, nulliparous women appear to have a higher rate of subsequent pregnancy loss, compared with parous women (BMJ. 2000;320:1708). We recommend an evaluation following two losses given the lack of evidence for a difference in diagnostic yield following two versus three miscarriages and particularly because of the emotional effects of impact of RPL.

RPL causes, percentages of contribution, and evaluation

1. Genetic (2%-5%). Because of the risk of an embryo with an unbalanced chromosomal rearrangement inherited from a translocation present in either of the couple, a blood karyotype of the couple is essential despite a history of one or more successful live births. While in vitro fertilization (IVF) with preimplantation genetic testing for structural rearrangements (PGT-SR) can successfully diagnose affected embryos to avoid their intrauterine transfer, overall live birth rates are similar when comparing natural conception attempts with PGT-SR, although the latter may reduce miscarriages.

2. Anatomic (10%-15%). Hysteroscopy, hysterosalpingogram, or saline ultrasound can be used to image the uterine cavity to evaluate for polyps, fibroids, scarring, or a congenital septum – all of which can be surgically corrected. Chronic endometritis has been found in 27% of patients with recurrent miscarriage (and in 14% with recurrent implantation failure), therefore testing by biopsy is reasonable. An elevated level of homocysteine has been reported to impair DNA methylation and gene expression, causing defective chorionic villous vascularization in spontaneous miscarriage tissues. We recommend folic acid supplementation and the avoidance of testing for MTHFR (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase). Of note, the recent TRUST study showed no significant benefit from metroplasty in comparison with expectant management in 12 months of observation resulting in a live birth rate of 31% versus 35%, respectively.

3. Acquired thrombophilias (20%). Medical evidence supports testing for the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), i.e., RPL with either the presence of lupus anticoagulant (LAC), anticardiolipin antibodies, or anti-beta2 glycoprotein for IgG and IgM. Persistent LAC or elevations of antibodies greater than 40 GPL or greater than the 99th percentile for more than 12 weeks justifies the use of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). APS has been shown to cause RPL, thrombosis, and/or autoimmune thrombocytopenia. There is no definitive evidence to support testing for MTHFR or any other thrombophilias for first trimester RPL. APS has up to a 90% fetal loss rate without therapeutic intervention. Treatment includes low-dose aspirin (81 mg daily) and LMWH. These medications are thought to help prevent thrombosis in the placenta, helping to maintain pregnancies.

4. Hormonal (17%-20%). The most common hormonal disorders increasing the risk for miscarriage is thyroid dysfunction (both hyper- and hypothyroid), prolactin elevations, and lack of glucose control. While the concern for a luteal phase (LPD) prevails, there is no accepted definition or treatment. There is recent evidence that antibodies to thyroid peroxidase may increase miscarriage and that low-dose thyroid replacement may reduce this risk. One other important area is the polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). This hormonal abnormality affects 6%-20% of all reproductive aged women and may increase miscarriage.

5. Unexplained (40%-50%). The most frustrating but most common reason for RPL. Nevertheless, close monitoring and supportive care throughout the first trimester has been demonstrated in medical studies to improve outcome.

Seven surprising facts about recurrent miscarriage

1. Folic acid 4 mg daily may decrease embryo chromosomal abnormalities and miscarriage.

Folic acid in doses of at least 0.4 mg daily have long been advocated to reduce spina bifida and neural tube defects. It is optimal to begin folic acid for several months prior to conception attempts. There is evidence it may help treat RPL by reducing the chance for chromosomal errors.

2. A randomized trial did not demonstrate an improved live birth rate using progesterone in the first trimester. However, women enrolled may not have begun progesterone until 6 weeks of pregnancy, begging the question if earlier progesterone would have demonstrated improvement.

Dydrogesterone, a progestogen that is highly selective for the progesterone receptor, lacks estrogenic, androgenic, anabolic, and corticoid properties. Although not available in the United States, dydrogesterone appears to reduce the rate of idiopathic recurrent miscarriage (two or more losses). Also, progesterone support has been shown to reduce loss in threatened miscarriage – 17 OHPC 500 mg IM weekly in the first trimester.

3. No benefit of aspirin and/or heparin to treat unexplained RM.

The use of aspirin and/or heparin-like medication has convincingly been shown to not improve live birth rates in RPL.

4. Inherited thrombophilias are NOT associated with RM and should not be tested.

Screening for factor V (Leiden mutation), factor II (Prothrombin G20210A), and MTHFR have not been shown to cause RM and no treatment, such as aspirin and/or heparin-like medications, improves the live birth rate.

5. Close monitoring and empathetic care improves outcomes.

For unknown reasons, clinics providing close monitoring, emotional support, and education to patients with unexplained RM report higher live birth rates, compared with patients not receiving this level of care.

6. Behavior changes reduce miscarriage.

Elevations in body mass index (BMI) and cigarette smoking both increase the risk of miscarriage. As a result, a healthy BMI and eliminating tobacco use reduce the risk of pregnancy loss. Excessive caffeine use (more than two equivalent cups of caffeine in coffee per day) also may increase spontaneous miscarriage.

7. Fertility medications, intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization, or preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) do not improve outcomes.

While patients and, often, health care providers, feel compelled to proceed with fertility treatment, ovulation induction medications, intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization, or PGT-A have not been shown to improve the chance for a live birth. PGT-A did not reduce the risk of miscarriage in women with recurrent pregnancy loss.

In summary, following two or more pregnancy losses, I recommend obtaining chromosomal testing of the couple, viewing the uterine cavity, blood testing for thyroid, prolactin, and glucose control, and acquired thrombophilias (as above). Fortunately, when the cause is unexplained, the woman has a 70%-80% chance of a spontaneous live birth over the next 10 years from diagnosis. By further understanding, knowing how to diagnose, and, finally, treating the cause of RPL we can hopefully prevent the heartbreak women and couples endure.

Dr. Trolice is director of Fertility CARE – The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

Contact allergen of the year found in foam in shin guards, footwear

.

The announcement was made by Donald V. Belsito, MD, professor of dermatology, Columbia University, New York, during a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society, held virtually this year. In his opinion, he said, the most exciting selections occur when international cooperation results in the identification of a new allergen that could become problematic, and acetophenone azine falls into this category.

The chemical formula of acetophenone azine is C16H16N2.

Acetophenone azine was highlighted as a contact allergen in a recent report in Dermatitis. The authors, Nadia Raison-Peyron, MD, from the department of dermatology at the University of Montpelier (France), and Denis Sasseville, MD, from the division of dermatology at McGill University Health Center, Quebec, described publications and reports of about 12 cases of severe allergic contact dermatitis secondary to shin pads or footwear, mainly in children and teens in Europe (one case was in Canada).

A common feature of these cases was the presence of a foam used for cushioning, made of ethyl vinyl acetate (EVA) used in the relevant products.

In one case, a 13-year-old boy who wore shin pads for soccer developed contact dermatitis on both shins that spread, and was described as severe. Patch testing revealed the EVA foam in the shin pads as the only positive reaction. Similar cases have been reported after exposure to EVA-containing products, including shin pads, sneakers, flip-flops, ski boots, insoles, swimming goggles, and bicycle seats, according to the authors.

In some reports, cases related to footwear presented as dyshidrosiform, vesiculobullous eczema, with or without palmar lesions, or presented as plantar hyperkeratotic dermatitis, they wrote. In other cases, patients experienced scarring and postinflammatory hypopigmentation.

The compound is likely not added to EVA intentionally, they added, but instead is thought to result from reactions between additives during the manufacturing process. The presence of acetophenone azine is not well explained, but the current theory is that it results from a combination of “the degradation of the initiator dicumylperoxide and hydrazine from the foaming agent azodicarbonamide,” the authors said.

In the paper, Dr. Raison-Peyron and Dr. Sasseville recommended a patch testing concentration of 0.1% in acetone or petrolatum, as acetophenone azine is not currently available from path test suppliers, although it can be obtained from chemical product distributors.

“Given the recent discovery of this allergen, it is presumed that cases of allergic contact dermatitis would have been missed and labeled irritant contact dermatitis or dyshidrosis,” they noted. To avoid missing more cases, acetophenone azine should be added to the patch testing shoe series, as well as plastics and glues series, they emphasized.

Although no cases of allergic reactions to acetophenone azine have been reported in the United States to date, it is an emerging allergen that should be on the radar for U.S. dermatologists, Amber Atwater, MD, outgoing ACDS president, said in an interview. The lack of reported cases may be in part attributed to the fact that acetophenone azine is not yet available to purchase for testing in the United States, and the allergen could be present in shin guards and other products identified in reported cases, added Dr. Atwater, associate professor of dermatology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

.

The announcement was made by Donald V. Belsito, MD, professor of dermatology, Columbia University, New York, during a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society, held virtually this year. In his opinion, he said, the most exciting selections occur when international cooperation results in the identification of a new allergen that could become problematic, and acetophenone azine falls into this category.

The chemical formula of acetophenone azine is C16H16N2.

Acetophenone azine was highlighted as a contact allergen in a recent report in Dermatitis. The authors, Nadia Raison-Peyron, MD, from the department of dermatology at the University of Montpelier (France), and Denis Sasseville, MD, from the division of dermatology at McGill University Health Center, Quebec, described publications and reports of about 12 cases of severe allergic contact dermatitis secondary to shin pads or footwear, mainly in children and teens in Europe (one case was in Canada).

A common feature of these cases was the presence of a foam used for cushioning, made of ethyl vinyl acetate (EVA) used in the relevant products.

In one case, a 13-year-old boy who wore shin pads for soccer developed contact dermatitis on both shins that spread, and was described as severe. Patch testing revealed the EVA foam in the shin pads as the only positive reaction. Similar cases have been reported after exposure to EVA-containing products, including shin pads, sneakers, flip-flops, ski boots, insoles, swimming goggles, and bicycle seats, according to the authors.

In some reports, cases related to footwear presented as dyshidrosiform, vesiculobullous eczema, with or without palmar lesions, or presented as plantar hyperkeratotic dermatitis, they wrote. In other cases, patients experienced scarring and postinflammatory hypopigmentation.

The compound is likely not added to EVA intentionally, they added, but instead is thought to result from reactions between additives during the manufacturing process. The presence of acetophenone azine is not well explained, but the current theory is that it results from a combination of “the degradation of the initiator dicumylperoxide and hydrazine from the foaming agent azodicarbonamide,” the authors said.

In the paper, Dr. Raison-Peyron and Dr. Sasseville recommended a patch testing concentration of 0.1% in acetone or petrolatum, as acetophenone azine is not currently available from path test suppliers, although it can be obtained from chemical product distributors.

“Given the recent discovery of this allergen, it is presumed that cases of allergic contact dermatitis would have been missed and labeled irritant contact dermatitis or dyshidrosis,” they noted. To avoid missing more cases, acetophenone azine should be added to the patch testing shoe series, as well as plastics and glues series, they emphasized.

Although no cases of allergic reactions to acetophenone azine have been reported in the United States to date, it is an emerging allergen that should be on the radar for U.S. dermatologists, Amber Atwater, MD, outgoing ACDS president, said in an interview. The lack of reported cases may be in part attributed to the fact that acetophenone azine is not yet available to purchase for testing in the United States, and the allergen could be present in shin guards and other products identified in reported cases, added Dr. Atwater, associate professor of dermatology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

.

The announcement was made by Donald V. Belsito, MD, professor of dermatology, Columbia University, New York, during a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society, held virtually this year. In his opinion, he said, the most exciting selections occur when international cooperation results in the identification of a new allergen that could become problematic, and acetophenone azine falls into this category.

The chemical formula of acetophenone azine is C16H16N2.

Acetophenone azine was highlighted as a contact allergen in a recent report in Dermatitis. The authors, Nadia Raison-Peyron, MD, from the department of dermatology at the University of Montpelier (France), and Denis Sasseville, MD, from the division of dermatology at McGill University Health Center, Quebec, described publications and reports of about 12 cases of severe allergic contact dermatitis secondary to shin pads or footwear, mainly in children and teens in Europe (one case was in Canada).

A common feature of these cases was the presence of a foam used for cushioning, made of ethyl vinyl acetate (EVA) used in the relevant products.

In one case, a 13-year-old boy who wore shin pads for soccer developed contact dermatitis on both shins that spread, and was described as severe. Patch testing revealed the EVA foam in the shin pads as the only positive reaction. Similar cases have been reported after exposure to EVA-containing products, including shin pads, sneakers, flip-flops, ski boots, insoles, swimming goggles, and bicycle seats, according to the authors.

In some reports, cases related to footwear presented as dyshidrosiform, vesiculobullous eczema, with or without palmar lesions, or presented as plantar hyperkeratotic dermatitis, they wrote. In other cases, patients experienced scarring and postinflammatory hypopigmentation.

The compound is likely not added to EVA intentionally, they added, but instead is thought to result from reactions between additives during the manufacturing process. The presence of acetophenone azine is not well explained, but the current theory is that it results from a combination of “the degradation of the initiator dicumylperoxide and hydrazine from the foaming agent azodicarbonamide,” the authors said.

In the paper, Dr. Raison-Peyron and Dr. Sasseville recommended a patch testing concentration of 0.1% in acetone or petrolatum, as acetophenone azine is not currently available from path test suppliers, although it can be obtained from chemical product distributors.

“Given the recent discovery of this allergen, it is presumed that cases of allergic contact dermatitis would have been missed and labeled irritant contact dermatitis or dyshidrosis,” they noted. To avoid missing more cases, acetophenone azine should be added to the patch testing shoe series, as well as plastics and glues series, they emphasized.

Although no cases of allergic reactions to acetophenone azine have been reported in the United States to date, it is an emerging allergen that should be on the radar for U.S. dermatologists, Amber Atwater, MD, outgoing ACDS president, said in an interview. The lack of reported cases may be in part attributed to the fact that acetophenone azine is not yet available to purchase for testing in the United States, and the allergen could be present in shin guards and other products identified in reported cases, added Dr. Atwater, associate professor of dermatology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

FROM ACDS 2021

A ‘scary’ side effect

Memantine (aka Namenda) is Food and Drug Administration–approved for Alzheimer’s disease, though its benefits are modest, at best.

It’s also, 18 years after first coming to market, relatively inexpensive.

I occasionally use it off label, as neurologists tend to do with a wide variety of medications. There are small studies that suggest it’s effective for migraine prevention and painful neuropathies. It also has a relatively benign side-effect profile.

As a result, once in a while I prescribe it for migraines or neuropathy where more typical agents haven’t helped. Like any of these drugs, sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. A lot of neurology, as one of my colleagues puts it, is “guessing and voodoo.”

Since I’ve started this, however, I’ve noticed an unusual, and somewhat scary, side effect – one that has nothing to do the drug reactions.

While I don’t use any type of commercial chart system, most doctors in my area do, as well as all the hospitals. So I often see my patients’ notes from their general practitioners or after they’ve been in the hospital for whatever reason.

Those notes often list – as they should – current medications. Which includes the memantine I’ve prescribed.

But in the patient problem list I often then see “Alzheimer’s disease” or “dementia” show up, even in people who clearly have no history of such.

I’ve seen it way too many times to think it’s an accident. So one of two things is happening:

1. The computer chart system, when it sees “memantine” entered, searches its database, finds what it’s FDA-approved for, and automatically puts that in a list of current diagnoses.

2. The person entering the data, upon hearing the patient takes memantine, just enters the more commonly used indication as well, without bothering to ask the patient why they’re taking it.

Neither of these is good.

At the very least, they show a lack of proper history taking (or interest in doing so) by the person entering things in the chart (which these days could be someone with no medical training at all). It doesn’t take that much effort to say “what are you on this for?” I do it several times a day. It’s part of my job.

It’s bad form for any incorrect diagnosis to get into a chart. It can have serious repercussions on someone’s ability to get health, disability, or life insurance, not to mention the immediate impact on their care when that shows up. Someone who doesn’t know the patient opens the chart and immediately assumes it’s what they’ve got. I mean, it’s the chart. People treat it like it’s infallible and inviolable.

This isn’t a new issue – I trained at the VA when sometimes an H&P simply said “see old chart” and there were four volumes of it. But now, in the age of digital records, entries are forever. The toe you fractured surfing 8 years ago still shows up as a “current problem,” and will likely follow you to the grave. The same with any other diagnosis entered – it’s yours to keep, regardless of accuracy.

Medicine, like life, is mostly gray. But computers, and many times those who enter their data, only see things as black and white. In this field that’s liable to backfire. I’m just seeing the tip of the iceberg by using memantine off-label.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Memantine (aka Namenda) is Food and Drug Administration–approved for Alzheimer’s disease, though its benefits are modest, at best.

It’s also, 18 years after first coming to market, relatively inexpensive.

I occasionally use it off label, as neurologists tend to do with a wide variety of medications. There are small studies that suggest it’s effective for migraine prevention and painful neuropathies. It also has a relatively benign side-effect profile.

As a result, once in a while I prescribe it for migraines or neuropathy where more typical agents haven’t helped. Like any of these drugs, sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. A lot of neurology, as one of my colleagues puts it, is “guessing and voodoo.”

Since I’ve started this, however, I’ve noticed an unusual, and somewhat scary, side effect – one that has nothing to do the drug reactions.

While I don’t use any type of commercial chart system, most doctors in my area do, as well as all the hospitals. So I often see my patients’ notes from their general practitioners or after they’ve been in the hospital for whatever reason.

Those notes often list – as they should – current medications. Which includes the memantine I’ve prescribed.

But in the patient problem list I often then see “Alzheimer’s disease” or “dementia” show up, even in people who clearly have no history of such.

I’ve seen it way too many times to think it’s an accident. So one of two things is happening:

1. The computer chart system, when it sees “memantine” entered, searches its database, finds what it’s FDA-approved for, and automatically puts that in a list of current diagnoses.

2. The person entering the data, upon hearing the patient takes memantine, just enters the more commonly used indication as well, without bothering to ask the patient why they’re taking it.

Neither of these is good.

At the very least, they show a lack of proper history taking (or interest in doing so) by the person entering things in the chart (which these days could be someone with no medical training at all). It doesn’t take that much effort to say “what are you on this for?” I do it several times a day. It’s part of my job.

It’s bad form for any incorrect diagnosis to get into a chart. It can have serious repercussions on someone’s ability to get health, disability, or life insurance, not to mention the immediate impact on their care when that shows up. Someone who doesn’t know the patient opens the chart and immediately assumes it’s what they’ve got. I mean, it’s the chart. People treat it like it’s infallible and inviolable.

This isn’t a new issue – I trained at the VA when sometimes an H&P simply said “see old chart” and there were four volumes of it. But now, in the age of digital records, entries are forever. The toe you fractured surfing 8 years ago still shows up as a “current problem,” and will likely follow you to the grave. The same with any other diagnosis entered – it’s yours to keep, regardless of accuracy.

Medicine, like life, is mostly gray. But computers, and many times those who enter their data, only see things as black and white. In this field that’s liable to backfire. I’m just seeing the tip of the iceberg by using memantine off-label.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Memantine (aka Namenda) is Food and Drug Administration–approved for Alzheimer’s disease, though its benefits are modest, at best.

It’s also, 18 years after first coming to market, relatively inexpensive.

I occasionally use it off label, as neurologists tend to do with a wide variety of medications. There are small studies that suggest it’s effective for migraine prevention and painful neuropathies. It also has a relatively benign side-effect profile.

As a result, once in a while I prescribe it for migraines or neuropathy where more typical agents haven’t helped. Like any of these drugs, sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. A lot of neurology, as one of my colleagues puts it, is “guessing and voodoo.”

Since I’ve started this, however, I’ve noticed an unusual, and somewhat scary, side effect – one that has nothing to do the drug reactions.

While I don’t use any type of commercial chart system, most doctors in my area do, as well as all the hospitals. So I often see my patients’ notes from their general practitioners or after they’ve been in the hospital for whatever reason.

Those notes often list – as they should – current medications. Which includes the memantine I’ve prescribed.

But in the patient problem list I often then see “Alzheimer’s disease” or “dementia” show up, even in people who clearly have no history of such.

I’ve seen it way too many times to think it’s an accident. So one of two things is happening:

1. The computer chart system, when it sees “memantine” entered, searches its database, finds what it’s FDA-approved for, and automatically puts that in a list of current diagnoses.

2. The person entering the data, upon hearing the patient takes memantine, just enters the more commonly used indication as well, without bothering to ask the patient why they’re taking it.

Neither of these is good.

At the very least, they show a lack of proper history taking (or interest in doing so) by the person entering things in the chart (which these days could be someone with no medical training at all). It doesn’t take that much effort to say “what are you on this for?” I do it several times a day. It’s part of my job.

It’s bad form for any incorrect diagnosis to get into a chart. It can have serious repercussions on someone’s ability to get health, disability, or life insurance, not to mention the immediate impact on their care when that shows up. Someone who doesn’t know the patient opens the chart and immediately assumes it’s what they’ve got. I mean, it’s the chart. People treat it like it’s infallible and inviolable.

This isn’t a new issue – I trained at the VA when sometimes an H&P simply said “see old chart” and there were four volumes of it. But now, in the age of digital records, entries are forever. The toe you fractured surfing 8 years ago still shows up as a “current problem,” and will likely follow you to the grave. The same with any other diagnosis entered – it’s yours to keep, regardless of accuracy.

Medicine, like life, is mostly gray. But computers, and many times those who enter their data, only see things as black and white. In this field that’s liable to backfire. I’m just seeing the tip of the iceberg by using memantine off-label.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Baricitinib hits mark for severe alopecia areata

in the phase 2/3 BRAVE-AA1 randomized trial, Brett King, MD, PhD, reported at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

The results with the 4-mg/day dose of the Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and -2 inhibitor were even more impressive. However, this higher dose, while approved in Europe and elsewhere for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, was rejected by the Food and Drug Administration because of safety concerns and is not available in the United States. The 2-mg dose of baricitinib is approved for RA in the United States.

There are currently no FDA-approved treatments for alopecia areata, noted Dr. King, a dermatologist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

He reported on 110 adults with severe alopecia areata as defined by a baseline Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score of 87, meaning they averaged 87% scalp hair loss. They averaged a 16-year history of the autoimmune disease. The duration of the current episode was at least 4 years in more than one-third of participants. Clinicians rated more than three-quarters of patients as having no eyebrow or eyelash hair, or significant gaps and uneven distribution.

The primary outcome in this interim analysis was achievement of a SALT score of 20 or less at week 36, meaning hair loss had shrunk to 20% or less of the scalp. Fifty-two percent of patients on baricitinib 4 mg achieved this outcome, as did 33% of those randomized to baricitinib 2 mg and 4% of placebo-treated controls.

In addition, 60% of patients on the higher dose of the JAK inhibitor and 40% on the lower dose rated themselves as having either full eyebrows and eyelashes on both eyes at 36 weeks, or only minimal gaps with even distribution. None of the controls reported comparable improvement, Dr. King said at the conference, which was sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

There were no serious adverse events in this relatively small study. Six cases of herpes simplex and two of herpes zoster occurred in baricitinib-treated patients; there were none in controls.

Session moderator Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatric dermatology at Penn State University, Hershey, said that she was very impressed that baricitinib could achieve substantial hair regrowth in patients with a median duration of hair loss of about 16 years.

“It’s very interesting,” agreed comoderator Ashfaq A. Marghoob, MD, director of clinical dermatology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Hauppauge, N.Y. “Having this kind of hair regrowth goes against what we learned in our residency, that the longer you’ve gone with hair loss, the less likely it is to ever come back.”

Separately, Eli Lilly issued a press release announcing that both the 2- and 4-mg doses of baricitinib had met the primary endpoint in the phase 3 BRAVE-AA2 trial, showing significantly greater hair regrowth compared with placebo in the 546-patient study. However, the company provided no data, instead stating that the full results will be presented at an upcoming medical conference.

in the phase 2/3 BRAVE-AA1 randomized trial, Brett King, MD, PhD, reported at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

The results with the 4-mg/day dose of the Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and -2 inhibitor were even more impressive. However, this higher dose, while approved in Europe and elsewhere for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, was rejected by the Food and Drug Administration because of safety concerns and is not available in the United States. The 2-mg dose of baricitinib is approved for RA in the United States.

There are currently no FDA-approved treatments for alopecia areata, noted Dr. King, a dermatologist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

He reported on 110 adults with severe alopecia areata as defined by a baseline Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score of 87, meaning they averaged 87% scalp hair loss. They averaged a 16-year history of the autoimmune disease. The duration of the current episode was at least 4 years in more than one-third of participants. Clinicians rated more than three-quarters of patients as having no eyebrow or eyelash hair, or significant gaps and uneven distribution.

The primary outcome in this interim analysis was achievement of a SALT score of 20 or less at week 36, meaning hair loss had shrunk to 20% or less of the scalp. Fifty-two percent of patients on baricitinib 4 mg achieved this outcome, as did 33% of those randomized to baricitinib 2 mg and 4% of placebo-treated controls.

In addition, 60% of patients on the higher dose of the JAK inhibitor and 40% on the lower dose rated themselves as having either full eyebrows and eyelashes on both eyes at 36 weeks, or only minimal gaps with even distribution. None of the controls reported comparable improvement, Dr. King said at the conference, which was sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

There were no serious adverse events in this relatively small study. Six cases of herpes simplex and two of herpes zoster occurred in baricitinib-treated patients; there were none in controls.

Session moderator Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatric dermatology at Penn State University, Hershey, said that she was very impressed that baricitinib could achieve substantial hair regrowth in patients with a median duration of hair loss of about 16 years.

“It’s very interesting,” agreed comoderator Ashfaq A. Marghoob, MD, director of clinical dermatology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Hauppauge, N.Y. “Having this kind of hair regrowth goes against what we learned in our residency, that the longer you’ve gone with hair loss, the less likely it is to ever come back.”

Separately, Eli Lilly issued a press release announcing that both the 2- and 4-mg doses of baricitinib had met the primary endpoint in the phase 3 BRAVE-AA2 trial, showing significantly greater hair regrowth compared with placebo in the 546-patient study. However, the company provided no data, instead stating that the full results will be presented at an upcoming medical conference.

in the phase 2/3 BRAVE-AA1 randomized trial, Brett King, MD, PhD, reported at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

The results with the 4-mg/day dose of the Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and -2 inhibitor were even more impressive. However, this higher dose, while approved in Europe and elsewhere for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, was rejected by the Food and Drug Administration because of safety concerns and is not available in the United States. The 2-mg dose of baricitinib is approved for RA in the United States.

There are currently no FDA-approved treatments for alopecia areata, noted Dr. King, a dermatologist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

He reported on 110 adults with severe alopecia areata as defined by a baseline Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score of 87, meaning they averaged 87% scalp hair loss. They averaged a 16-year history of the autoimmune disease. The duration of the current episode was at least 4 years in more than one-third of participants. Clinicians rated more than three-quarters of patients as having no eyebrow or eyelash hair, or significant gaps and uneven distribution.

The primary outcome in this interim analysis was achievement of a SALT score of 20 or less at week 36, meaning hair loss had shrunk to 20% or less of the scalp. Fifty-two percent of patients on baricitinib 4 mg achieved this outcome, as did 33% of those randomized to baricitinib 2 mg and 4% of placebo-treated controls.

In addition, 60% of patients on the higher dose of the JAK inhibitor and 40% on the lower dose rated themselves as having either full eyebrows and eyelashes on both eyes at 36 weeks, or only minimal gaps with even distribution. None of the controls reported comparable improvement, Dr. King said at the conference, which was sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

There were no serious adverse events in this relatively small study. Six cases of herpes simplex and two of herpes zoster occurred in baricitinib-treated patients; there were none in controls.

Session moderator Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatric dermatology at Penn State University, Hershey, said that she was very impressed that baricitinib could achieve substantial hair regrowth in patients with a median duration of hair loss of about 16 years.

“It’s very interesting,” agreed comoderator Ashfaq A. Marghoob, MD, director of clinical dermatology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Hauppauge, N.Y. “Having this kind of hair regrowth goes against what we learned in our residency, that the longer you’ve gone with hair loss, the less likely it is to ever come back.”

Separately, Eli Lilly issued a press release announcing that both the 2- and 4-mg doses of baricitinib had met the primary endpoint in the phase 3 BRAVE-AA2 trial, showing significantly greater hair regrowth compared with placebo in the 546-patient study. However, the company provided no data, instead stating that the full results will be presented at an upcoming medical conference.

FROM INNOVATIONS IN DERMATOLOGY

Systemic racism in medical education

Resources:

"How Medical Education Is Missing the Bull’s-eye" by LaShyra Nolen

Becoming by Michelle Obama

Resources:

"How Medical Education Is Missing the Bull’s-eye" by LaShyra Nolen

Becoming by Michelle Obama

Resources:

"How Medical Education Is Missing the Bull’s-eye" by LaShyra Nolen

Becoming by Michelle Obama

COVID-19 variants now detected in more animals, may find hosts in mice

The new SARS-CoV-2 variants are not just problems for humans.

New research shows they can also infect animals, and for the first time, variants have been able to infect mice, a development that may complicate efforts to rein in the global spread of the virus.

In addition, two new studies have implications for pets. Veterinarians in Texas and the United Kingdom have documented infections of B.1.1.7 – the fast-spreading variant first found in the United Kingdom – in dogs and cats. The animals in the U.K. study also had heart damage, but it’s unclear if the damage was caused by the virus or was already there and was found as a result of their infections.

Animal studies of SARS-CoV-2 and its emerging variants are urgent, said Sarah Hamer, DVM, PhD, a veterinarian and epidemiologist at Texas A&M University, College Station.

She’s part of a network of scientists who are swabbing the pets of people who are diagnosed with COVID-19 to find out how often the virus passes from people to animals.

The collaboration is part of the One Health initiative through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One Health aims to tackle infectious diseases by recognizing that people can’t be fully protected from pathogens unless animals and the environment are also safeguarded. “Over 70% of emerging diseases of humans have their origins in animal populations,” Dr. Hamer said. “So if we are only focusing on studying disease as it emerges in humans and ignoring where those pathogens have been transmitted or circulating for years, then we might miss the ability to detect early emergence. We might miss the ability to control these diseases before they become problems for human health.”

Variants move to mice

In new work, researchers at the Institut Pasteur in Paris have shown that the B.1.351 and P.1 variants of concern, which were first identified in South Africa and Brazil, respectively, can infect mice, giving the virus a potential new host. Older versions of the virus couldn’t infect mice because they weren’t able bind to receptors on their cells. These two variants can.

On one hand, that’s a good thing, because it will help scientists more easily conduct experiments in mice. Before, if they wanted to do an experiment with SARS-CoV-2 in mice, they had to use a special strain of mouse that was bred to carry human ACE2 receptors on their lung cells. Now that mice can become naturally infected, any breed will do, making it less costly and time-consuming to study the virus in animals.

On the other hand, the idea that the virus could have more and different ways to spread isn’t good news.

“From the beginning of the epidemic and since human coronaviruses emerged from animals, it has been very important to establish in which species the virus can replicate, in particular the species that live close to humans,” said Xavier Montagutelli, DVM, PhD, head of the Mouse Genetics Laboratory at the Institut Pasteur. His study was published as a preprint ahead of peer review on BioRXIV.

Once a virus establishes itself within a population of animals, it will continue to spread and change and may eventually be passed back to humans. It’s the reason that birds and pigs are closely monitored for influenza viruses.

So far, with SARS-CoV-2, only one animal has been found to catch and spread the virus and pass it back to people – farmed mink. Researchers have also documented SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in escaped mink living near mink farms in Utah, suggesting the virus has the potential to be transmitted to wild populations.

And the move of the virus into mice suggests that SARS-CoV-2 could establish itself in a population of wild animals that live close to humans.

“At this point, we have no evidence that wild mice are infected, or can become infected from humans,” Dr. Montagutelli said. He added that his findings emphasize the need to regularly test animals for signs of the infection. He said these surveys will need to be updated as more variants emerge.

“So far, we’ve been lucky that our livestock species aren’t really susceptible to this,” said Scott Weese, DVM, a professor at Ontario Veterinary College at the University of Guelph, who studies emerging infectious diseases that pass between animals and people.

While the outbreaks on mink farms have been bad, imagine what would happen, Dr. Weese said, if the virus moved to pigs.

“If this infects a barn with a few thousand pigs – which is like the mink scenario – but we have a lot more pig farms than mink farms,” he said.

“With these variants, we have to reset,” he said. “We’ve figured all this about animals and how it spreads or how it doesn’t, but now we need to repeat all those studies to make sure it’s the same thing.”

Pets catch variants, too

Pets living with people who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 can catch it from their owners, and cats are particularly susceptible, Dr. Weese said.