User login

Crusted Papules on the Bilateral Helices and Lobules

The Diagnosis: Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease

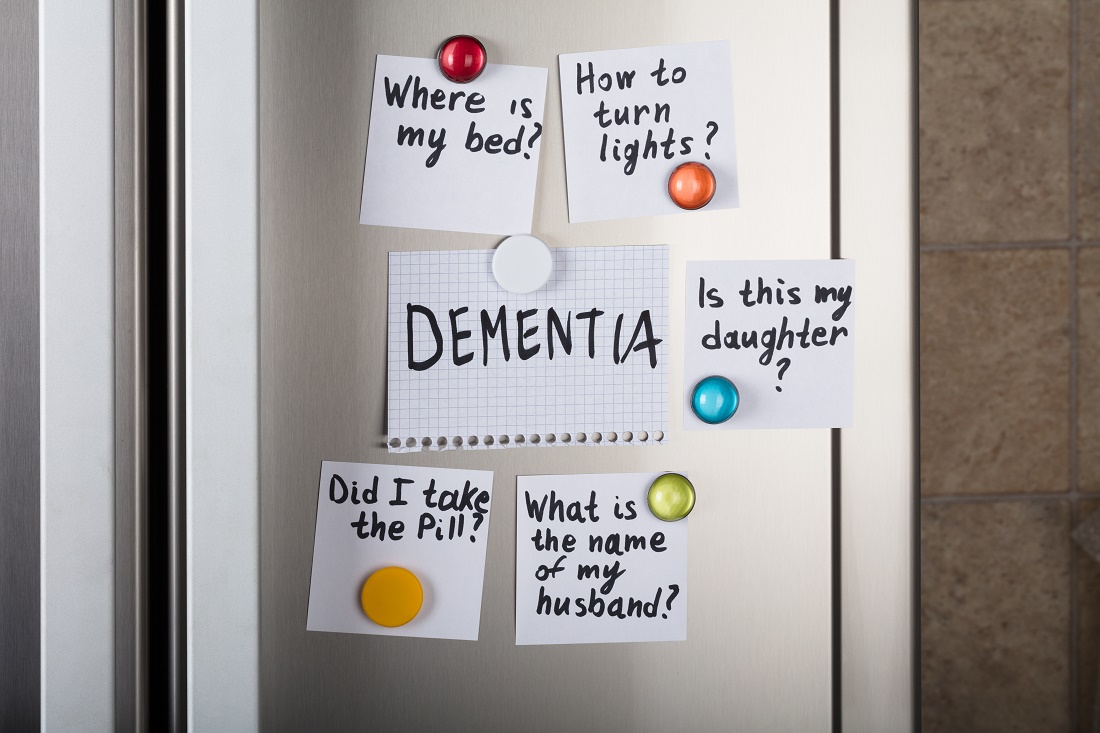

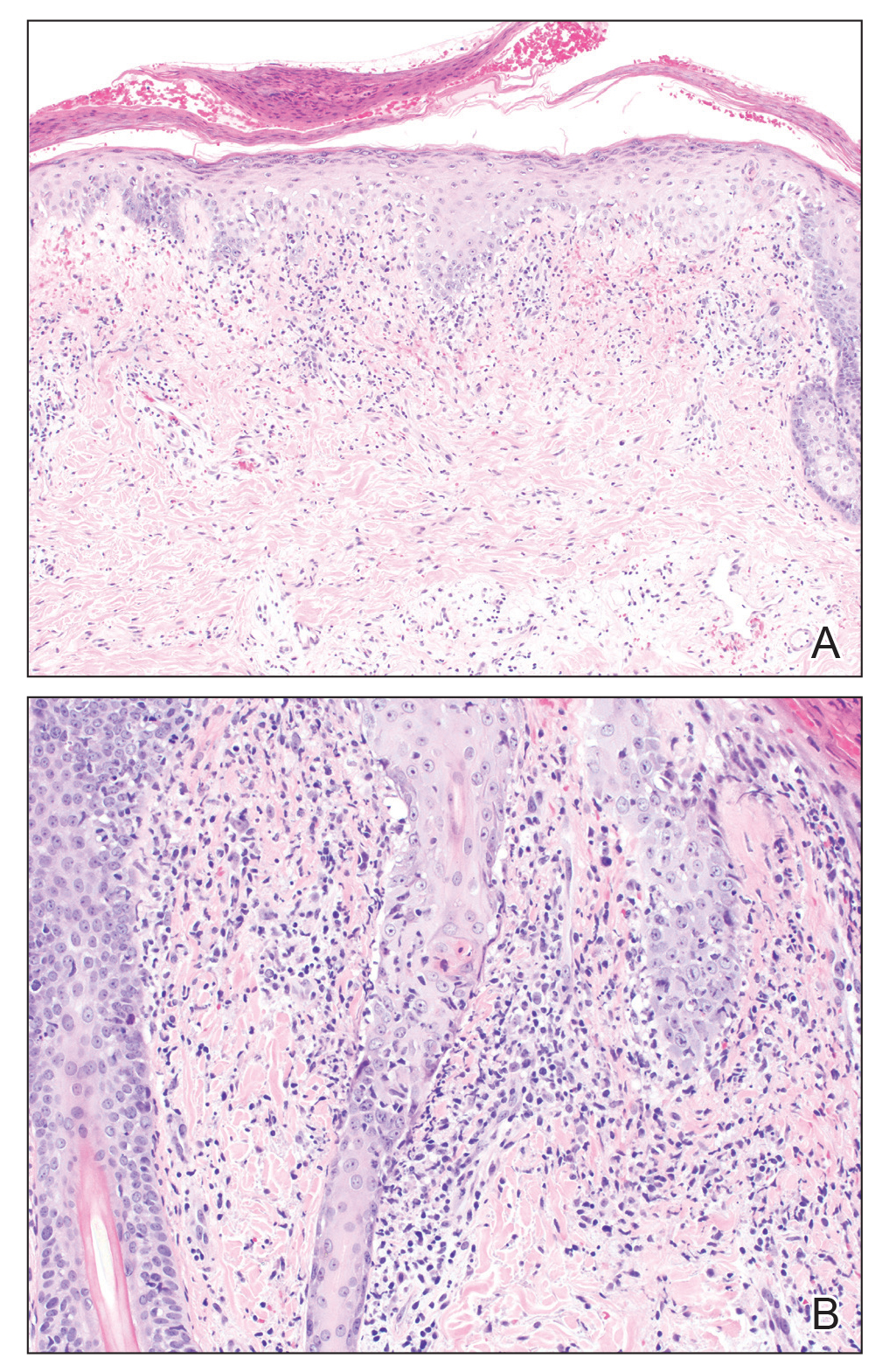

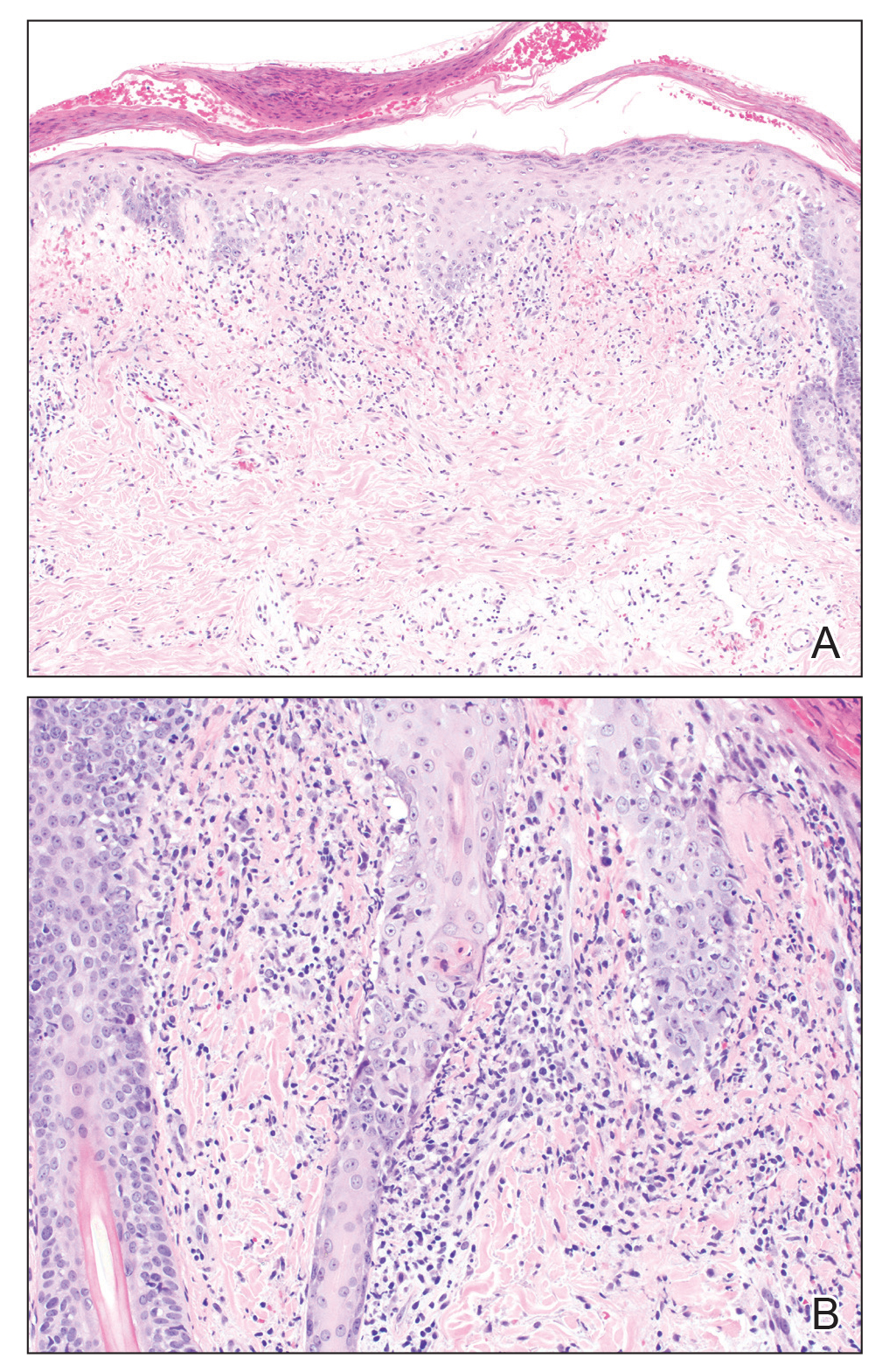

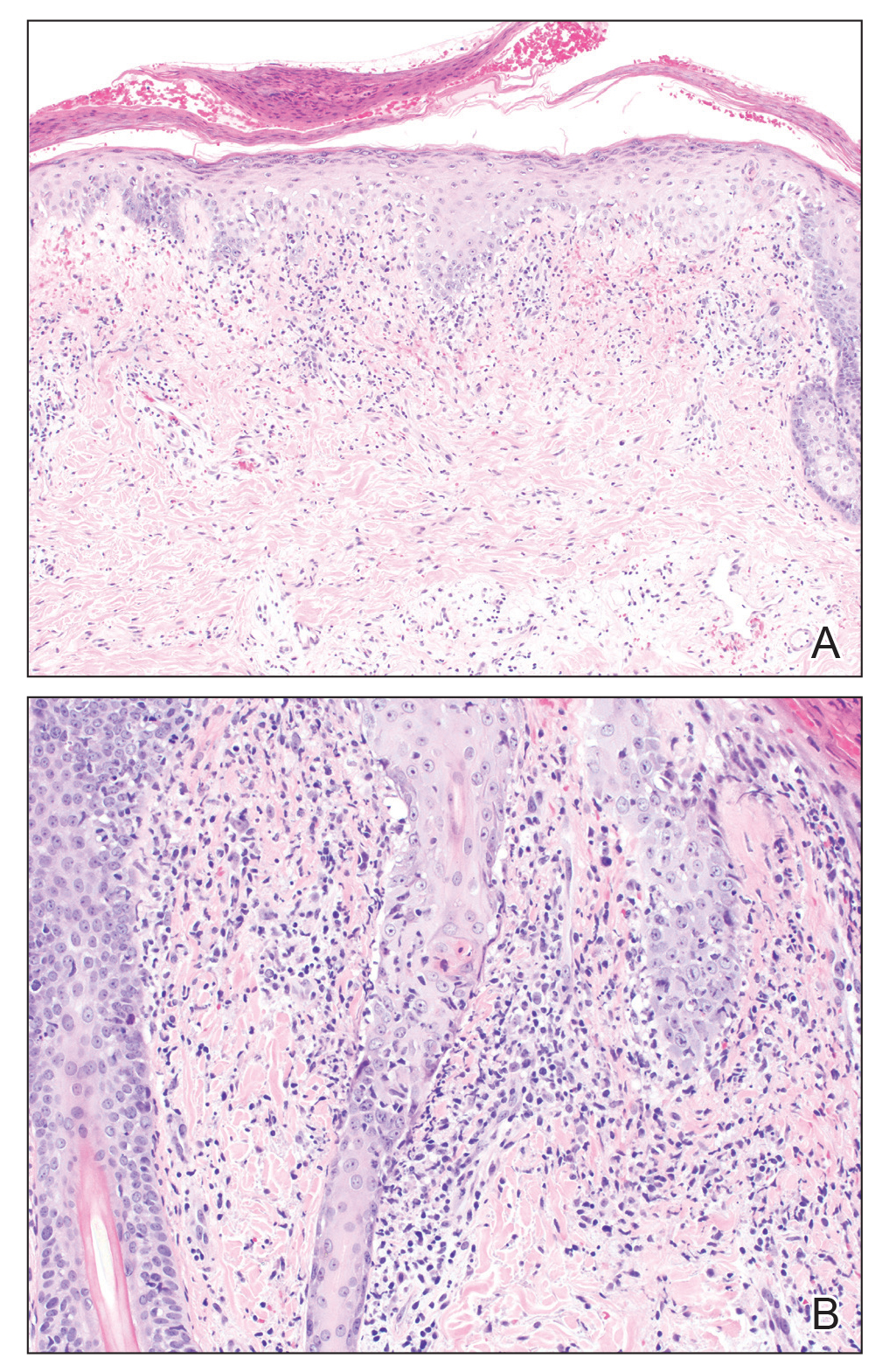

A skin biopsy from the left helix was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a vacuolar interface reaction with marked papillary dermal edema and a patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate. The dermis was free of increased mucin (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–encoded small nuclear RNA chromogenic in situ hybridization were negative. Laboratory workup was remarkable for elevated transaminases and inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) but negative for rheumatologic markers (eg, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, myeloperoxidase antibodies, serine protease IgG). An extensive infectious workup was unrevealing. Computed tomography highlighted prominent lymphadenopathy throughout the cervical and supraclavicular chains and a large necrotic lymph node in the porta hepatis (Figure 2). Right neck lymph node aspiration revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis in a background of histiocytes and mixed lymphocytes. Coupling the clinical presentation and histomorphology with imaging, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KD) was rendered.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare illness of unknown etiology characterized by cervical lymphadenopathy and fever. Originally described in Japan, KD affects all racial and ethnic groups1,2 but more commonly is seen in women and patients younger than 40 years.3 It can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (eg, relapsing polychondritis, adult-onset Still disease),3 and lymphoma.4 Multiple infections have been implicated in the pathogenesis of KD, including EBV and other human herpesviruses; HIV; human T-cell leukemia virus type 1; dengue virus; parvovirus B19; and Yersinia enterocolitica, Bartonella, Brucella, and Toxoplasma infections.3,5,6

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease classically presents with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. In a retrospective review of 244 patients with KD, the 3 most common manifestations included lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.7 A diagnosis of KD is rendered based on clinical presentation and lymph node histopathologic findings of paracortical necrosis and florid histiocytic infiltrate.1

The cutaneous manifestations of KD are heterogeneous yet mostly transient. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 16.6% to 40% of patients.3,5,6 Common cutaneous manifestations include erythematous macules, papules, patches, and plaques; erosions, nodules, and bullae less commonly can occur.6 A variety of cutaneous manifestations have been reported in KD, including lesions mimicking pigmented purpuric dermatoses, vasculitis, Sweet syndrome, drug eruptions, and viral exanthems.6 Signs and symptoms of KD usually resolve within 1 to 4 months. Although there are no established treatments for this disease, patients with severe or persistent symptoms can be treated with steroids or hydroxychloroquine. Recurrences after treatment have been reported.8

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multiorgan disease with protean manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of SLE include malar erythema and discoid, annular, and papulosquamous lesions. Histopathologic patterns frequently observed in cutaneous lesions associated with SLE include interface dermatitis with perivascular infiltrates, dermal mucin, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (marked by CD123 staining); these findings were notably absent in our case.6

Lupus vulgaris is a form of cutaneous tuberculosis that results from reactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tubercles formed during preceding hematogenous dissemination. The head and neck region is the most common location, particularly the nose, cheeks, and earlobes. Small, brown-red, soft papules coalesce into gelatinous plaques, demonstrating a characteristic apple jelly appearance on diascopy. Other clinical manifestations include the plaque/plane, hypertrophic/tumorlike, and ulcerative/scarring forms.9 Delayed-type hypersensitivity testing by tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assay, or polymerase chain reaction–based assays can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Histopathology shows well-formed granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells and central necrosis.

Hydroa vacciniforme–like (HV-like) eruption is a rare photosensitive disorder characterized by vesiculopapules on sun-exposed areas. Hydroa vacciniforme–like eruptions rarely have been reported to progress to EBVassociated malignant lymphoma.10 Unlike typical hydroa vacciniforme, which resolves by early adulthood, HV-like eruptions can become more severe with age and are associated with systemic manifestations, including fevers, lymphadenopathy, and liver damage. Histopathologic examination reveals a dense infiltrate of atypical T lymphocytes or natural killer cells (CD56+), which stain positive for EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA,10 in contrast to the patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate seen in KD.

This case highlights the protean cutaneous manifestations of a rare rheumatologic entity. It demonstrates the importance of a full systemic workup when considering an enigmatic disease. Our patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily. Within 24 hours, the fevers and rash both improved.

- Turner RR, Martin J, Dorfman RF. Necrotizing lymphadenitis. a study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:115-123.

- Dorfman RF, Berry GJ. Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis: an analysis of 108 cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:329-345.

- Atwater AR, Longley BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yoshino T, Mannami T, Ichimura K, et al. Two cases of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease) following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1328-1331.

- Yen A, Fearneyhough P, Raimer SS, et al. EBV-associated Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis with cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:342-346.

- Kim JH, Kim YB, In SI, et al. The cutaneous lesions of Kikuchi’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of 16 cases based on the clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence studies with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1245-1254.

- Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Smith KG, Becker GJ, Busmanis I. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease. Lancet. 1992;340:124.

- Macgregor R. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:245-255.

- Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Harada H, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1081-1086.

The Diagnosis: Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease

A skin biopsy from the left helix was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a vacuolar interface reaction with marked papillary dermal edema and a patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate. The dermis was free of increased mucin (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–encoded small nuclear RNA chromogenic in situ hybridization were negative. Laboratory workup was remarkable for elevated transaminases and inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) but negative for rheumatologic markers (eg, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, myeloperoxidase antibodies, serine protease IgG). An extensive infectious workup was unrevealing. Computed tomography highlighted prominent lymphadenopathy throughout the cervical and supraclavicular chains and a large necrotic lymph node in the porta hepatis (Figure 2). Right neck lymph node aspiration revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis in a background of histiocytes and mixed lymphocytes. Coupling the clinical presentation and histomorphology with imaging, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KD) was rendered.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare illness of unknown etiology characterized by cervical lymphadenopathy and fever. Originally described in Japan, KD affects all racial and ethnic groups1,2 but more commonly is seen in women and patients younger than 40 years.3 It can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (eg, relapsing polychondritis, adult-onset Still disease),3 and lymphoma.4 Multiple infections have been implicated in the pathogenesis of KD, including EBV and other human herpesviruses; HIV; human T-cell leukemia virus type 1; dengue virus; parvovirus B19; and Yersinia enterocolitica, Bartonella, Brucella, and Toxoplasma infections.3,5,6

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease classically presents with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. In a retrospective review of 244 patients with KD, the 3 most common manifestations included lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.7 A diagnosis of KD is rendered based on clinical presentation and lymph node histopathologic findings of paracortical necrosis and florid histiocytic infiltrate.1

The cutaneous manifestations of KD are heterogeneous yet mostly transient. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 16.6% to 40% of patients.3,5,6 Common cutaneous manifestations include erythematous macules, papules, patches, and plaques; erosions, nodules, and bullae less commonly can occur.6 A variety of cutaneous manifestations have been reported in KD, including lesions mimicking pigmented purpuric dermatoses, vasculitis, Sweet syndrome, drug eruptions, and viral exanthems.6 Signs and symptoms of KD usually resolve within 1 to 4 months. Although there are no established treatments for this disease, patients with severe or persistent symptoms can be treated with steroids or hydroxychloroquine. Recurrences after treatment have been reported.8

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multiorgan disease with protean manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of SLE include malar erythema and discoid, annular, and papulosquamous lesions. Histopathologic patterns frequently observed in cutaneous lesions associated with SLE include interface dermatitis with perivascular infiltrates, dermal mucin, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (marked by CD123 staining); these findings were notably absent in our case.6

Lupus vulgaris is a form of cutaneous tuberculosis that results from reactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tubercles formed during preceding hematogenous dissemination. The head and neck region is the most common location, particularly the nose, cheeks, and earlobes. Small, brown-red, soft papules coalesce into gelatinous plaques, demonstrating a characteristic apple jelly appearance on diascopy. Other clinical manifestations include the plaque/plane, hypertrophic/tumorlike, and ulcerative/scarring forms.9 Delayed-type hypersensitivity testing by tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assay, or polymerase chain reaction–based assays can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Histopathology shows well-formed granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells and central necrosis.

Hydroa vacciniforme–like (HV-like) eruption is a rare photosensitive disorder characterized by vesiculopapules on sun-exposed areas. Hydroa vacciniforme–like eruptions rarely have been reported to progress to EBVassociated malignant lymphoma.10 Unlike typical hydroa vacciniforme, which resolves by early adulthood, HV-like eruptions can become more severe with age and are associated with systemic manifestations, including fevers, lymphadenopathy, and liver damage. Histopathologic examination reveals a dense infiltrate of atypical T lymphocytes or natural killer cells (CD56+), which stain positive for EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA,10 in contrast to the patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate seen in KD.

This case highlights the protean cutaneous manifestations of a rare rheumatologic entity. It demonstrates the importance of a full systemic workup when considering an enigmatic disease. Our patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily. Within 24 hours, the fevers and rash both improved.

The Diagnosis: Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease

A skin biopsy from the left helix was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a vacuolar interface reaction with marked papillary dermal edema and a patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate. The dermis was free of increased mucin (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–encoded small nuclear RNA chromogenic in situ hybridization were negative. Laboratory workup was remarkable for elevated transaminases and inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) but negative for rheumatologic markers (eg, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, myeloperoxidase antibodies, serine protease IgG). An extensive infectious workup was unrevealing. Computed tomography highlighted prominent lymphadenopathy throughout the cervical and supraclavicular chains and a large necrotic lymph node in the porta hepatis (Figure 2). Right neck lymph node aspiration revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis in a background of histiocytes and mixed lymphocytes. Coupling the clinical presentation and histomorphology with imaging, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KD) was rendered.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare illness of unknown etiology characterized by cervical lymphadenopathy and fever. Originally described in Japan, KD affects all racial and ethnic groups1,2 but more commonly is seen in women and patients younger than 40 years.3 It can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (eg, relapsing polychondritis, adult-onset Still disease),3 and lymphoma.4 Multiple infections have been implicated in the pathogenesis of KD, including EBV and other human herpesviruses; HIV; human T-cell leukemia virus type 1; dengue virus; parvovirus B19; and Yersinia enterocolitica, Bartonella, Brucella, and Toxoplasma infections.3,5,6

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease classically presents with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. In a retrospective review of 244 patients with KD, the 3 most common manifestations included lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.7 A diagnosis of KD is rendered based on clinical presentation and lymph node histopathologic findings of paracortical necrosis and florid histiocytic infiltrate.1

The cutaneous manifestations of KD are heterogeneous yet mostly transient. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 16.6% to 40% of patients.3,5,6 Common cutaneous manifestations include erythematous macules, papules, patches, and plaques; erosions, nodules, and bullae less commonly can occur.6 A variety of cutaneous manifestations have been reported in KD, including lesions mimicking pigmented purpuric dermatoses, vasculitis, Sweet syndrome, drug eruptions, and viral exanthems.6 Signs and symptoms of KD usually resolve within 1 to 4 months. Although there are no established treatments for this disease, patients with severe or persistent symptoms can be treated with steroids or hydroxychloroquine. Recurrences after treatment have been reported.8

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multiorgan disease with protean manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of SLE include malar erythema and discoid, annular, and papulosquamous lesions. Histopathologic patterns frequently observed in cutaneous lesions associated with SLE include interface dermatitis with perivascular infiltrates, dermal mucin, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (marked by CD123 staining); these findings were notably absent in our case.6

Lupus vulgaris is a form of cutaneous tuberculosis that results from reactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tubercles formed during preceding hematogenous dissemination. The head and neck region is the most common location, particularly the nose, cheeks, and earlobes. Small, brown-red, soft papules coalesce into gelatinous plaques, demonstrating a characteristic apple jelly appearance on diascopy. Other clinical manifestations include the plaque/plane, hypertrophic/tumorlike, and ulcerative/scarring forms.9 Delayed-type hypersensitivity testing by tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assay, or polymerase chain reaction–based assays can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Histopathology shows well-formed granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells and central necrosis.

Hydroa vacciniforme–like (HV-like) eruption is a rare photosensitive disorder characterized by vesiculopapules on sun-exposed areas. Hydroa vacciniforme–like eruptions rarely have been reported to progress to EBVassociated malignant lymphoma.10 Unlike typical hydroa vacciniforme, which resolves by early adulthood, HV-like eruptions can become more severe with age and are associated with systemic manifestations, including fevers, lymphadenopathy, and liver damage. Histopathologic examination reveals a dense infiltrate of atypical T lymphocytes or natural killer cells (CD56+), which stain positive for EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA,10 in contrast to the patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate seen in KD.

This case highlights the protean cutaneous manifestations of a rare rheumatologic entity. It demonstrates the importance of a full systemic workup when considering an enigmatic disease. Our patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily. Within 24 hours, the fevers and rash both improved.

- Turner RR, Martin J, Dorfman RF. Necrotizing lymphadenitis. a study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:115-123.

- Dorfman RF, Berry GJ. Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis: an analysis of 108 cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:329-345.

- Atwater AR, Longley BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yoshino T, Mannami T, Ichimura K, et al. Two cases of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease) following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1328-1331.

- Yen A, Fearneyhough P, Raimer SS, et al. EBV-associated Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis with cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:342-346.

- Kim JH, Kim YB, In SI, et al. The cutaneous lesions of Kikuchi’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of 16 cases based on the clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence studies with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1245-1254.

- Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Smith KG, Becker GJ, Busmanis I. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease. Lancet. 1992;340:124.

- Macgregor R. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:245-255.

- Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Harada H, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1081-1086.

- Turner RR, Martin J, Dorfman RF. Necrotizing lymphadenitis. a study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:115-123.

- Dorfman RF, Berry GJ. Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis: an analysis of 108 cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:329-345.

- Atwater AR, Longley BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yoshino T, Mannami T, Ichimura K, et al. Two cases of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease) following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1328-1331.

- Yen A, Fearneyhough P, Raimer SS, et al. EBV-associated Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis with cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:342-346.

- Kim JH, Kim YB, In SI, et al. The cutaneous lesions of Kikuchi’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of 16 cases based on the clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence studies with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1245-1254.

- Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Smith KG, Becker GJ, Busmanis I. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease. Lancet. 1992;340:124.

- Macgregor R. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:245-255.

- Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Harada H, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1081-1086.

A healthy 42-year-old Japanese man presented with painful lymphadenopathy and fevers of 1 month’s duration as well as a pruritic rash and bilateral ear redness and crusting of 1 week’s duration. He initially was seen at an outside facility and was treated with antibiotics and supportive care for cervical adenitis. During clinical evaluation, he denied joint pain, photosensitivity, and oral lesions. His medical and family history were noncontributory. Although he reported recent travel to multiple countries, he denied exposure to animals, ticks, or sick individuals. Physical examination revealed erythematous blanching papules on the nose and cheeks (top) as well as crusted papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral helices and lobules (bottom).

Depression screening after ACS does not change outcomes

Background: Depression after ACS is common and is associated with increased mortality. Professional societies have recommended routine depression screening in these patients; however, this has not been consistently implemented because there is a lack of data to support routine screening.

Study design: Multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Four geographically diverse health systems in the United States.

Synopsis: In the CODIACS-QoL trial, 1,500 patients were randomized to three groups within 12 months of documented ACS: depression screening with notification to primary care and treatment, screening and notification to primary care, and no screening. Only 7.7% of the patients in the screen, notify, and treat group and 6.6% of screen and notify group screened positive for depression. There were no differences for the primary outcome of quality-adjusted life-years or the secondary outcome of depression-free days between groups. Additionally, there was no difference in mortality or patient-reported harms of screening between groups. The study excluded patients who already had a history of depression, psychiatric history, or other severe life-threatening medical conditions, which may have affected the outcomes.

Depression remains a substantial factor in coronary disease and quality of life; however, systematic depression screening appears to have limited population-level benefits.

Bottom line: Systematic depression screening with or without treatment offerings did not alter quality of life, depression-free days, or mortality in patients with ACS.

Citation: Kronish IM et al. Effect of depression screening after acute coronary syndrome on quality of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):45-53.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: Depression after ACS is common and is associated with increased mortality. Professional societies have recommended routine depression screening in these patients; however, this has not been consistently implemented because there is a lack of data to support routine screening.

Study design: Multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Four geographically diverse health systems in the United States.

Synopsis: In the CODIACS-QoL trial, 1,500 patients were randomized to three groups within 12 months of documented ACS: depression screening with notification to primary care and treatment, screening and notification to primary care, and no screening. Only 7.7% of the patients in the screen, notify, and treat group and 6.6% of screen and notify group screened positive for depression. There were no differences for the primary outcome of quality-adjusted life-years or the secondary outcome of depression-free days between groups. Additionally, there was no difference in mortality or patient-reported harms of screening between groups. The study excluded patients who already had a history of depression, psychiatric history, or other severe life-threatening medical conditions, which may have affected the outcomes.

Depression remains a substantial factor in coronary disease and quality of life; however, systematic depression screening appears to have limited population-level benefits.

Bottom line: Systematic depression screening with or without treatment offerings did not alter quality of life, depression-free days, or mortality in patients with ACS.

Citation: Kronish IM et al. Effect of depression screening after acute coronary syndrome on quality of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):45-53.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Background: Depression after ACS is common and is associated with increased mortality. Professional societies have recommended routine depression screening in these patients; however, this has not been consistently implemented because there is a lack of data to support routine screening.

Study design: Multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Four geographically diverse health systems in the United States.

Synopsis: In the CODIACS-QoL trial, 1,500 patients were randomized to three groups within 12 months of documented ACS: depression screening with notification to primary care and treatment, screening and notification to primary care, and no screening. Only 7.7% of the patients in the screen, notify, and treat group and 6.6% of screen and notify group screened positive for depression. There were no differences for the primary outcome of quality-adjusted life-years or the secondary outcome of depression-free days between groups. Additionally, there was no difference in mortality or patient-reported harms of screening between groups. The study excluded patients who already had a history of depression, psychiatric history, or other severe life-threatening medical conditions, which may have affected the outcomes.

Depression remains a substantial factor in coronary disease and quality of life; however, systematic depression screening appears to have limited population-level benefits.

Bottom line: Systematic depression screening with or without treatment offerings did not alter quality of life, depression-free days, or mortality in patients with ACS.

Citation: Kronish IM et al. Effect of depression screening after acute coronary syndrome on quality of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):45-53.

Dr. Ciarkowski is a hospitalist and clinical instructor of medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

High-intensity interval training cuts cardiometabolic risks in women with PCOS

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) was better than moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) for improving several measures of cardiometabolic health in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in a prospective, randomized, single-center study with 27 women.

After 12 weeks on a supervised exercise regimen, the women with PCOS who followed the HIIT program had significantly better improvements in aerobic capacity, insulin sensitivity, and level of sex hormone–binding globulin, Rhiannon K. Patten, MSc, said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“HIIT can offer superior improvements in health outcomes, and should be considered as an effective tool to reduce cardiometabolic risk in women with PCOS,” concluded Ms. Patten, a researcher in the Institute for Health and Sport at Victoria University in Melbourne in her presentation (Abstract OR10-1).

“The changes we see [after 12 weeks on the HIIT regimen] seem to occur despite no change in body mass index, so rather than focus on weight loss we encourage participants to focus on the health improvements that seem to be greater with HIIT. We actively encourage the HIIT protocol right now,” she said.

Both regimens use a stationary cycle ergometer. In the HIIT protocol patients twice weekly pedal through 12 1-minute intervals at a heart rate of 90%-100% maximum, interspersed with 1 minute rest intervals. On a third day per week, patients pedal to a heart rate of 90%-95% maximum for 6-8 intervals maintained for 2 minutes and interspersed with rest intervals of 2 minutes. The MICT regimen used as a comparator has participants pedal to 60%-70% of their maximum heart rate continuously for 50 minutes 3 days weekly.

HIIT saves time

“These findings are relevant to clinical practice, because they demonstrate that HIIT is effective in women with PCOS. Reducing the time devoted to exercise to achieve fitness goals is attractive to patients. The reduced time to achieve training benefits with HIIT should improve patient compliance,” commented Andrea Dunaif, MD, professor and chief of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and bone disease of the Mount Sinai Health System in New York, who was not involved with the study.

The overall weekly exercise time on the MICT regimen, 150 minutes, halves down to 75 minutes a week in the HIIT program. Guideline recommendations released in 2018 by the International PCOS Network recommended these as acceptable alternative exercise strategies. Ms. Patten and her associates sought to determine whether one strategy surpassed the other, the first time this has been examined in women with PCOS, she said.

They randomized 27 sedentary women 18-45 years old with a body mass index (BMI) above 25 kg/m2 and diagnosed with PCOS by the Rotterdam criteria to a 12-week supervised exercise program on either the HIIT or MICT protocol. Their average BMI at entry was 36-37 kg/m2. The study excluded women who smoked, were pregnant, had an illness or injury that would prevent exercise, or were on an oral contraceptive or insulin-sensitizing medication.

At the end of 12 weeks, neither group had a significant change in average weight or BMI, and waist circumference dropped by an average of just over 2 cm in both treatment groups. Lean mass increased by a mean 1 kg in the HIIT group, a significant change, compared with a nonsignificant 0.3 kg average increase in the MICT group.

Increased aerobic capacity ‘partially explains’ improved insulin sensitivity

Aerobic capacity, measured as peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak), increased by an average 5.7 mL/kg per min among the HIIT patients, significantly more than the mean 3.2 mL/kg per min increase among those in the MICT program.

The insulin sensitivity index rose by a significant, relative 35% among the HIIT patients, but barely budged in the MICT group. Fasting glucose fell significantly and the glucose infusion rate increased significantly among the women who performed HIIT, but again showed little change among those doing MICT.

Analysis showed a significant link between the increase in VO2peak and the increase in insulin sensitivity among the women engaged in HIIT, Ms. Patten reported. The improvement in the insulin sensitivity index was “partially explained” by the increase in VO2peak, she said.

Assessment of hormone levels showed a significant increase in sex hormone–binding globulin in the HIIT patients while those in the MICT group showed a small decline in this level. The free androgen index fell by a relative 39% on average in the HIIT group, a significant drop, but decreased by a much smaller and not significant amount among the women who did MICT. The women who performed HIIT also showed a significant drop in their free testosterone level, a change not seen with MICT.

Women who performed the HIIT protocol also had a significant improvement in their menstrual cyclicity, and significant improvements in depression, stress, and anxiety, Ms Patten reported. She next plans to do longer follow-up on study participants, out to 6 and 12 months after the end of the exercise protocol.

“Overall, the findings suggest that HIIT is superior to MICT for improving fitness and insulin sensitivity in the short term. Results from a number of studies in individuals without PCOS suggest that HIIT is superior to MICT for improving fitness short term,” commented Dr. Dunaif. “This study makes an important contribution by directly investigating the impact of training intensity in women with PCOS. Larger studies will be needed before the superiority of HIIT is established for women with PCOS, and study durations of at least several months will be needed to assess the impact on reproductive outcomes such as ovulation,” she said in an interview. She also called for assessing the effects of HIIT in more diverse populations of women with PCOS.

Ms. Patten had no disclosures. Dr. Dunaif has been a consultant to Equator Therapeutics, Fractyl Laboratories, and Globe Life Sciences.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) was better than moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) for improving several measures of cardiometabolic health in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in a prospective, randomized, single-center study with 27 women.

After 12 weeks on a supervised exercise regimen, the women with PCOS who followed the HIIT program had significantly better improvements in aerobic capacity, insulin sensitivity, and level of sex hormone–binding globulin, Rhiannon K. Patten, MSc, said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“HIIT can offer superior improvements in health outcomes, and should be considered as an effective tool to reduce cardiometabolic risk in women with PCOS,” concluded Ms. Patten, a researcher in the Institute for Health and Sport at Victoria University in Melbourne in her presentation (Abstract OR10-1).

“The changes we see [after 12 weeks on the HIIT regimen] seem to occur despite no change in body mass index, so rather than focus on weight loss we encourage participants to focus on the health improvements that seem to be greater with HIIT. We actively encourage the HIIT protocol right now,” she said.

Both regimens use a stationary cycle ergometer. In the HIIT protocol patients twice weekly pedal through 12 1-minute intervals at a heart rate of 90%-100% maximum, interspersed with 1 minute rest intervals. On a third day per week, patients pedal to a heart rate of 90%-95% maximum for 6-8 intervals maintained for 2 minutes and interspersed with rest intervals of 2 minutes. The MICT regimen used as a comparator has participants pedal to 60%-70% of their maximum heart rate continuously for 50 minutes 3 days weekly.

HIIT saves time

“These findings are relevant to clinical practice, because they demonstrate that HIIT is effective in women with PCOS. Reducing the time devoted to exercise to achieve fitness goals is attractive to patients. The reduced time to achieve training benefits with HIIT should improve patient compliance,” commented Andrea Dunaif, MD, professor and chief of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and bone disease of the Mount Sinai Health System in New York, who was not involved with the study.

The overall weekly exercise time on the MICT regimen, 150 minutes, halves down to 75 minutes a week in the HIIT program. Guideline recommendations released in 2018 by the International PCOS Network recommended these as acceptable alternative exercise strategies. Ms. Patten and her associates sought to determine whether one strategy surpassed the other, the first time this has been examined in women with PCOS, she said.

They randomized 27 sedentary women 18-45 years old with a body mass index (BMI) above 25 kg/m2 and diagnosed with PCOS by the Rotterdam criteria to a 12-week supervised exercise program on either the HIIT or MICT protocol. Their average BMI at entry was 36-37 kg/m2. The study excluded women who smoked, were pregnant, had an illness or injury that would prevent exercise, or were on an oral contraceptive or insulin-sensitizing medication.

At the end of 12 weeks, neither group had a significant change in average weight or BMI, and waist circumference dropped by an average of just over 2 cm in both treatment groups. Lean mass increased by a mean 1 kg in the HIIT group, a significant change, compared with a nonsignificant 0.3 kg average increase in the MICT group.

Increased aerobic capacity ‘partially explains’ improved insulin sensitivity

Aerobic capacity, measured as peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak), increased by an average 5.7 mL/kg per min among the HIIT patients, significantly more than the mean 3.2 mL/kg per min increase among those in the MICT program.

The insulin sensitivity index rose by a significant, relative 35% among the HIIT patients, but barely budged in the MICT group. Fasting glucose fell significantly and the glucose infusion rate increased significantly among the women who performed HIIT, but again showed little change among those doing MICT.

Analysis showed a significant link between the increase in VO2peak and the increase in insulin sensitivity among the women engaged in HIIT, Ms. Patten reported. The improvement in the insulin sensitivity index was “partially explained” by the increase in VO2peak, she said.

Assessment of hormone levels showed a significant increase in sex hormone–binding globulin in the HIIT patients while those in the MICT group showed a small decline in this level. The free androgen index fell by a relative 39% on average in the HIIT group, a significant drop, but decreased by a much smaller and not significant amount among the women who did MICT. The women who performed HIIT also showed a significant drop in their free testosterone level, a change not seen with MICT.

Women who performed the HIIT protocol also had a significant improvement in their menstrual cyclicity, and significant improvements in depression, stress, and anxiety, Ms Patten reported. She next plans to do longer follow-up on study participants, out to 6 and 12 months after the end of the exercise protocol.

“Overall, the findings suggest that HIIT is superior to MICT for improving fitness and insulin sensitivity in the short term. Results from a number of studies in individuals without PCOS suggest that HIIT is superior to MICT for improving fitness short term,” commented Dr. Dunaif. “This study makes an important contribution by directly investigating the impact of training intensity in women with PCOS. Larger studies will be needed before the superiority of HIIT is established for women with PCOS, and study durations of at least several months will be needed to assess the impact on reproductive outcomes such as ovulation,” she said in an interview. She also called for assessing the effects of HIIT in more diverse populations of women with PCOS.

Ms. Patten had no disclosures. Dr. Dunaif has been a consultant to Equator Therapeutics, Fractyl Laboratories, and Globe Life Sciences.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) was better than moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) for improving several measures of cardiometabolic health in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in a prospective, randomized, single-center study with 27 women.

After 12 weeks on a supervised exercise regimen, the women with PCOS who followed the HIIT program had significantly better improvements in aerobic capacity, insulin sensitivity, and level of sex hormone–binding globulin, Rhiannon K. Patten, MSc, said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“HIIT can offer superior improvements in health outcomes, and should be considered as an effective tool to reduce cardiometabolic risk in women with PCOS,” concluded Ms. Patten, a researcher in the Institute for Health and Sport at Victoria University in Melbourne in her presentation (Abstract OR10-1).

“The changes we see [after 12 weeks on the HIIT regimen] seem to occur despite no change in body mass index, so rather than focus on weight loss we encourage participants to focus on the health improvements that seem to be greater with HIIT. We actively encourage the HIIT protocol right now,” she said.

Both regimens use a stationary cycle ergometer. In the HIIT protocol patients twice weekly pedal through 12 1-minute intervals at a heart rate of 90%-100% maximum, interspersed with 1 minute rest intervals. On a third day per week, patients pedal to a heart rate of 90%-95% maximum for 6-8 intervals maintained for 2 minutes and interspersed with rest intervals of 2 minutes. The MICT regimen used as a comparator has participants pedal to 60%-70% of their maximum heart rate continuously for 50 minutes 3 days weekly.

HIIT saves time

“These findings are relevant to clinical practice, because they demonstrate that HIIT is effective in women with PCOS. Reducing the time devoted to exercise to achieve fitness goals is attractive to patients. The reduced time to achieve training benefits with HIIT should improve patient compliance,” commented Andrea Dunaif, MD, professor and chief of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and bone disease of the Mount Sinai Health System in New York, who was not involved with the study.

The overall weekly exercise time on the MICT regimen, 150 minutes, halves down to 75 minutes a week in the HIIT program. Guideline recommendations released in 2018 by the International PCOS Network recommended these as acceptable alternative exercise strategies. Ms. Patten and her associates sought to determine whether one strategy surpassed the other, the first time this has been examined in women with PCOS, she said.

They randomized 27 sedentary women 18-45 years old with a body mass index (BMI) above 25 kg/m2 and diagnosed with PCOS by the Rotterdam criteria to a 12-week supervised exercise program on either the HIIT or MICT protocol. Their average BMI at entry was 36-37 kg/m2. The study excluded women who smoked, were pregnant, had an illness or injury that would prevent exercise, or were on an oral contraceptive or insulin-sensitizing medication.

At the end of 12 weeks, neither group had a significant change in average weight or BMI, and waist circumference dropped by an average of just over 2 cm in both treatment groups. Lean mass increased by a mean 1 kg in the HIIT group, a significant change, compared with a nonsignificant 0.3 kg average increase in the MICT group.

Increased aerobic capacity ‘partially explains’ improved insulin sensitivity

Aerobic capacity, measured as peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak), increased by an average 5.7 mL/kg per min among the HIIT patients, significantly more than the mean 3.2 mL/kg per min increase among those in the MICT program.

The insulin sensitivity index rose by a significant, relative 35% among the HIIT patients, but barely budged in the MICT group. Fasting glucose fell significantly and the glucose infusion rate increased significantly among the women who performed HIIT, but again showed little change among those doing MICT.

Analysis showed a significant link between the increase in VO2peak and the increase in insulin sensitivity among the women engaged in HIIT, Ms. Patten reported. The improvement in the insulin sensitivity index was “partially explained” by the increase in VO2peak, she said.

Assessment of hormone levels showed a significant increase in sex hormone–binding globulin in the HIIT patients while those in the MICT group showed a small decline in this level. The free androgen index fell by a relative 39% on average in the HIIT group, a significant drop, but decreased by a much smaller and not significant amount among the women who did MICT. The women who performed HIIT also showed a significant drop in their free testosterone level, a change not seen with MICT.

Women who performed the HIIT protocol also had a significant improvement in their menstrual cyclicity, and significant improvements in depression, stress, and anxiety, Ms Patten reported. She next plans to do longer follow-up on study participants, out to 6 and 12 months after the end of the exercise protocol.

“Overall, the findings suggest that HIIT is superior to MICT for improving fitness and insulin sensitivity in the short term. Results from a number of studies in individuals without PCOS suggest that HIIT is superior to MICT for improving fitness short term,” commented Dr. Dunaif. “This study makes an important contribution by directly investigating the impact of training intensity in women with PCOS. Larger studies will be needed before the superiority of HIIT is established for women with PCOS, and study durations of at least several months will be needed to assess the impact on reproductive outcomes such as ovulation,” she said in an interview. She also called for assessing the effects of HIIT in more diverse populations of women with PCOS.

Ms. Patten had no disclosures. Dr. Dunaif has been a consultant to Equator Therapeutics, Fractyl Laboratories, and Globe Life Sciences.

FROM ENDO 2021

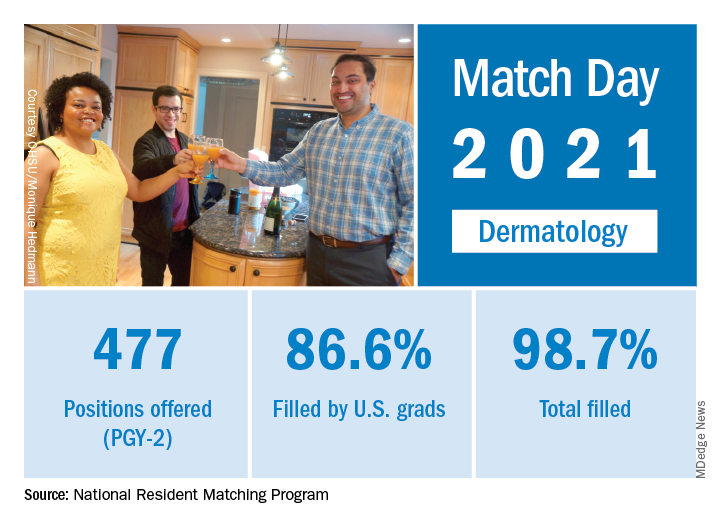

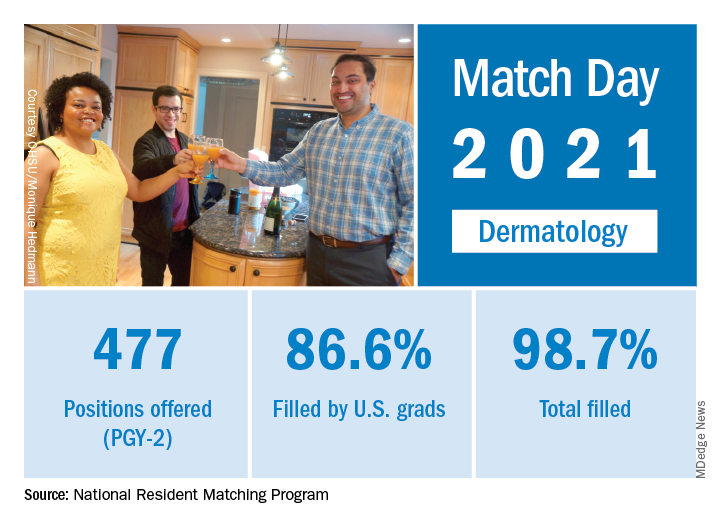

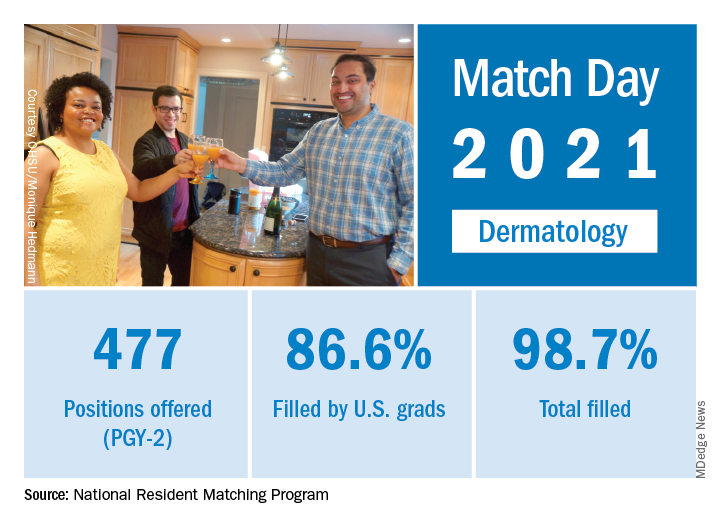

Match Day 2021: Dermatology holds steady

Despite the pandemic, , according to the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

Available dermatology PGY-2 slots fell by 0.2% from 478 in 2020 to 477 in 2021, but 471 slots were filled in 2021, 2 more than last year, for an increase of 0.4%. The overall fill rate was 98.7% in 2021, with 86.6% being filled by U.S. graduates. Just under 88% of filled positions went to MD and DO seniors.

While Match Day 2021 set a record for positions offered and filled at 38,106 slots and 36,179, respectively, an overall total of 2,699 PGY-2 slots were offered in 2021, which is a decrease of 1.6% from last year’s total of 2,742 slots. Of the available PGY-2 slots, 97.6% were filled in 2021, compared with 96.6% in 2020.

“The NRMP is honored to have delivered a strong Match to the many applicants pursuing their dreams of medicine. We admire all the Match participants for their hard work and their commitment to train and serve alongside their peers. The application and recruitment cycle was upended as a result of the pandemic, yet the results of the Match continue to demonstrate strong and consistent outcomes for participants,” Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, MBA, BSN, NRMP President and CEO, said in a press release.

Despite the pandemic, , according to the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

Available dermatology PGY-2 slots fell by 0.2% from 478 in 2020 to 477 in 2021, but 471 slots were filled in 2021, 2 more than last year, for an increase of 0.4%. The overall fill rate was 98.7% in 2021, with 86.6% being filled by U.S. graduates. Just under 88% of filled positions went to MD and DO seniors.

While Match Day 2021 set a record for positions offered and filled at 38,106 slots and 36,179, respectively, an overall total of 2,699 PGY-2 slots were offered in 2021, which is a decrease of 1.6% from last year’s total of 2,742 slots. Of the available PGY-2 slots, 97.6% were filled in 2021, compared with 96.6% in 2020.

“The NRMP is honored to have delivered a strong Match to the many applicants pursuing their dreams of medicine. We admire all the Match participants for their hard work and their commitment to train and serve alongside their peers. The application and recruitment cycle was upended as a result of the pandemic, yet the results of the Match continue to demonstrate strong and consistent outcomes for participants,” Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, MBA, BSN, NRMP President and CEO, said in a press release.

Despite the pandemic, , according to the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

Available dermatology PGY-2 slots fell by 0.2% from 478 in 2020 to 477 in 2021, but 471 slots were filled in 2021, 2 more than last year, for an increase of 0.4%. The overall fill rate was 98.7% in 2021, with 86.6% being filled by U.S. graduates. Just under 88% of filled positions went to MD and DO seniors.

While Match Day 2021 set a record for positions offered and filled at 38,106 slots and 36,179, respectively, an overall total of 2,699 PGY-2 slots were offered in 2021, which is a decrease of 1.6% from last year’s total of 2,742 slots. Of the available PGY-2 slots, 97.6% were filled in 2021, compared with 96.6% in 2020.

“The NRMP is honored to have delivered a strong Match to the many applicants pursuing their dreams of medicine. We admire all the Match participants for their hard work and their commitment to train and serve alongside their peers. The application and recruitment cycle was upended as a result of the pandemic, yet the results of the Match continue to demonstrate strong and consistent outcomes for participants,” Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, MBA, BSN, NRMP President and CEO, said in a press release.

New analysis eyes the surgical landscape for hidradenitis suppurativa

yet these options should be balanced against potentially higher morbidity of extensive procedures.

Those are among the key findings of a systematic review and meta-analysis published online in Dermatologic Surgery.

“There is a major need to better understand the best surgical approaches to HS,” one of the study authors, Christopher Sayed, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview. Previous studies have mostly reviewed outcomes for procedure types in individual cohorts, “but no recent reports have combined and analyzed data from recent studies.”

When Dr. Sayed and colleagues set out to summarize the literature on HS surgery regarding patient characteristics, surgical approaches, and study quality, as well as compare postsurgical recurrence rates, the most recent meta-analysis on postoperative recurrence rates of HS included studies published between 1990 and 2015. “In the past few years, surgical management of HS has become an increasingly popular area of study,” corresponding author Ashley Riddle, MD, MPH, who is currently an internal medicine resident at the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, said in an interview. “We sought to provide an updated picture of the HS surgical landscape by analyzing studies published between 2004 to 2019. We also limited our analysis to studies with follow-up periods of greater than 1 year and included information on disease severity, adverse events, and patient satisfaction when available.”

Of 715 relevant studies identified in the medical literature, the researchers included 59 in the review and 33 in the meta-analysis. Of these 59 studies, 56 were case series, 2 were randomized, controlled trials, and one was a retrospective cohort study.

Of the 50 studies reporting gender and age at time of surgery, 61% of patients were female and their average age was 37 years. Of the 25 studies that reported Hurley scores, 73% had Hurley stage 3 HS. Of the 38 studies reporting the number of procedures per anatomic region, the most commonly operated on regions were the axilla (59%) and the inguinal region (20%).

The researchers found that 22 studies of wide excision had the lowest pooled recurrence rate at 8%, while local excision had the highest pooled recurrence rate at 34%. Meanwhile, among studies of wide/radical excision, flap repair had a pooled recurrence rate of 0%, while delayed primary closure had the highest pooled recurrence rate at 38%.

“Extensive excisions of HS seem to portend a lower risk of postoperative recurrence, but there are many approaches available that may be more appropriate for certain patients,” Dr. Riddle said. “The influence of patient factors such as comorbidities and disease severity on surgical outcomes is unclear and is a potential area of future study.”

Dr. Sayed, an author of the 2019 North American guidelines for the clinical management of HS, pointed out that most studies in the review and meta-analysis included patients who had diabetes, were on biologics or other therapy, were actively smoking, or had other comorbidities that sometimes influence surgeons to delay surgical treatment because they consider it elective. “Most studies indicated minimal or no risk of significant complications relating to these factors, so they should ideally not become obstacles for patients interested in surgical care,” he said.

Dr. Riddle said that she was surprised by how relatively few studies had been published on more conservative surgical approaches such as skin tissue–sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, deroofing, local excision, and CO2 laser–based evaporation.

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of their work, including the high risk of bias for most included studies. “Almost all studies were retrospective with substantial methodological limitations, and there were no head-to-head comparisons of different surgical approaches,” Dr. Riddle said. “Patient comorbidities and postoperative complications were variably reported.”

Dr. Sayed disclosed that he is a speaker for AbbVie and Novartis; an investigator for AbbVie, Novartis, InflaRx, and UCB; and on the advisory board of AbbVie and InflaRx. The remaining authors reported having no financial disclosures.

yet these options should be balanced against potentially higher morbidity of extensive procedures.

Those are among the key findings of a systematic review and meta-analysis published online in Dermatologic Surgery.

“There is a major need to better understand the best surgical approaches to HS,” one of the study authors, Christopher Sayed, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview. Previous studies have mostly reviewed outcomes for procedure types in individual cohorts, “but no recent reports have combined and analyzed data from recent studies.”

When Dr. Sayed and colleagues set out to summarize the literature on HS surgery regarding patient characteristics, surgical approaches, and study quality, as well as compare postsurgical recurrence rates, the most recent meta-analysis on postoperative recurrence rates of HS included studies published between 1990 and 2015. “In the past few years, surgical management of HS has become an increasingly popular area of study,” corresponding author Ashley Riddle, MD, MPH, who is currently an internal medicine resident at the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, said in an interview. “We sought to provide an updated picture of the HS surgical landscape by analyzing studies published between 2004 to 2019. We also limited our analysis to studies with follow-up periods of greater than 1 year and included information on disease severity, adverse events, and patient satisfaction when available.”

Of 715 relevant studies identified in the medical literature, the researchers included 59 in the review and 33 in the meta-analysis. Of these 59 studies, 56 were case series, 2 were randomized, controlled trials, and one was a retrospective cohort study.

Of the 50 studies reporting gender and age at time of surgery, 61% of patients were female and their average age was 37 years. Of the 25 studies that reported Hurley scores, 73% had Hurley stage 3 HS. Of the 38 studies reporting the number of procedures per anatomic region, the most commonly operated on regions were the axilla (59%) and the inguinal region (20%).

The researchers found that 22 studies of wide excision had the lowest pooled recurrence rate at 8%, while local excision had the highest pooled recurrence rate at 34%. Meanwhile, among studies of wide/radical excision, flap repair had a pooled recurrence rate of 0%, while delayed primary closure had the highest pooled recurrence rate at 38%.

“Extensive excisions of HS seem to portend a lower risk of postoperative recurrence, but there are many approaches available that may be more appropriate for certain patients,” Dr. Riddle said. “The influence of patient factors such as comorbidities and disease severity on surgical outcomes is unclear and is a potential area of future study.”

Dr. Sayed, an author of the 2019 North American guidelines for the clinical management of HS, pointed out that most studies in the review and meta-analysis included patients who had diabetes, were on biologics or other therapy, were actively smoking, or had other comorbidities that sometimes influence surgeons to delay surgical treatment because they consider it elective. “Most studies indicated minimal or no risk of significant complications relating to these factors, so they should ideally not become obstacles for patients interested in surgical care,” he said.

Dr. Riddle said that she was surprised by how relatively few studies had been published on more conservative surgical approaches such as skin tissue–sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, deroofing, local excision, and CO2 laser–based evaporation.

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of their work, including the high risk of bias for most included studies. “Almost all studies were retrospective with substantial methodological limitations, and there were no head-to-head comparisons of different surgical approaches,” Dr. Riddle said. “Patient comorbidities and postoperative complications were variably reported.”

Dr. Sayed disclosed that he is a speaker for AbbVie and Novartis; an investigator for AbbVie, Novartis, InflaRx, and UCB; and on the advisory board of AbbVie and InflaRx. The remaining authors reported having no financial disclosures.

yet these options should be balanced against potentially higher morbidity of extensive procedures.

Those are among the key findings of a systematic review and meta-analysis published online in Dermatologic Surgery.

“There is a major need to better understand the best surgical approaches to HS,” one of the study authors, Christopher Sayed, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview. Previous studies have mostly reviewed outcomes for procedure types in individual cohorts, “but no recent reports have combined and analyzed data from recent studies.”

When Dr. Sayed and colleagues set out to summarize the literature on HS surgery regarding patient characteristics, surgical approaches, and study quality, as well as compare postsurgical recurrence rates, the most recent meta-analysis on postoperative recurrence rates of HS included studies published between 1990 and 2015. “In the past few years, surgical management of HS has become an increasingly popular area of study,” corresponding author Ashley Riddle, MD, MPH, who is currently an internal medicine resident at the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, said in an interview. “We sought to provide an updated picture of the HS surgical landscape by analyzing studies published between 2004 to 2019. We also limited our analysis to studies with follow-up periods of greater than 1 year and included information on disease severity, adverse events, and patient satisfaction when available.”

Of 715 relevant studies identified in the medical literature, the researchers included 59 in the review and 33 in the meta-analysis. Of these 59 studies, 56 were case series, 2 were randomized, controlled trials, and one was a retrospective cohort study.

Of the 50 studies reporting gender and age at time of surgery, 61% of patients were female and their average age was 37 years. Of the 25 studies that reported Hurley scores, 73% had Hurley stage 3 HS. Of the 38 studies reporting the number of procedures per anatomic region, the most commonly operated on regions were the axilla (59%) and the inguinal region (20%).

The researchers found that 22 studies of wide excision had the lowest pooled recurrence rate at 8%, while local excision had the highest pooled recurrence rate at 34%. Meanwhile, among studies of wide/radical excision, flap repair had a pooled recurrence rate of 0%, while delayed primary closure had the highest pooled recurrence rate at 38%.

“Extensive excisions of HS seem to portend a lower risk of postoperative recurrence, but there are many approaches available that may be more appropriate for certain patients,” Dr. Riddle said. “The influence of patient factors such as comorbidities and disease severity on surgical outcomes is unclear and is a potential area of future study.”

Dr. Sayed, an author of the 2019 North American guidelines for the clinical management of HS, pointed out that most studies in the review and meta-analysis included patients who had diabetes, were on biologics or other therapy, were actively smoking, or had other comorbidities that sometimes influence surgeons to delay surgical treatment because they consider it elective. “Most studies indicated minimal or no risk of significant complications relating to these factors, so they should ideally not become obstacles for patients interested in surgical care,” he said.

Dr. Riddle said that she was surprised by how relatively few studies had been published on more conservative surgical approaches such as skin tissue–sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, deroofing, local excision, and CO2 laser–based evaporation.

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of their work, including the high risk of bias for most included studies. “Almost all studies were retrospective with substantial methodological limitations, and there were no head-to-head comparisons of different surgical approaches,” Dr. Riddle said. “Patient comorbidities and postoperative complications were variably reported.”

Dr. Sayed disclosed that he is a speaker for AbbVie and Novartis; an investigator for AbbVie, Novartis, InflaRx, and UCB; and on the advisory board of AbbVie and InflaRx. The remaining authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Prenatal dietary folate not enough to offset AEDs’ effect on kids’ cognition

New research underscores the importance of folic acid supplementation for pregnant women with epilepsy who are taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs).

Dietary folate alone, even in the United States, where food is fortified with folic acid, is “not sufficient” to improve cognitive outcomes for children of women who take AEDs during pregnancy, the researchers report.

“We found that dietary folate was not related to outcomes,” study investigator Kimford Meador, MD, professor of neurology and neurologic sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization.

“Only when the mother was taking extra folate did we see an improvement in child outcomes,” he added.

The findings were published online Feb. 23 in Epilepsy and Behavior.

Cognitive boost

“Daily folate is recommended to women in the general populations to reduce congenital malformations,” Dr. Meador said. In addition, periconceptional use of folate has been shown in previous research to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes for children of mothers with epilepsy who are taking AEDs.

Whether folate-fortified food alone, without supplements, has any effect on cognitive outcomes in this population of children has not been examined previously.

To investigate, the researchers assessed 117 children from the Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (NEAD) study, a prospective, observational study of women with epilepsy who were taking one of four AEDs: carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin, or valproate.

Results showed that dietary folate from fortified food alone, without supplements, had no significant impact on IQ at age 6 years among children with prenatal exposure to AEDs.

In contrast, use of periconceptual folate supplements was significantly associated with a 10-point higher IQ at age 6 in the adjusted analyses (95% confidence interval, 5.2-15.0; P < .001).

These six other nutrients from food and supplements had no significant association with IQ at age 6 years: vitamins C, D, and E, omega-3, gamma tocopherol, and vitamin B12.

Optimal dose unclear

The findings indicate that folates, including natural folate and folic acid, in food do not have positive cognitive effects for children of women with epilepsy who take AEDs, the researchers write.

Dr. Meador noted that the optimal dose of folic acid supplementation to provide a cognitive benefit remains unclear.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control recommends 0.4 mg/d for the general population of women of childbearing age. In Europe, the recommendation is 1 mg/d.

“Higher doses are recommended if there is a personal or family history of spina bifida in prior pregnancies, but there is some concern that very high doses of folate may be detrimental,” Dr. Meador said.

For women with epilepsy, he would recommend “at least 1 mg/d and not more than 4 mg/d.”

Proves a point?

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Derek Chong, MD, vice chair of neurology and director of epilepsy at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, said the finding that folate fortification of food alone is not adequate for women with epilepsy is “not groundbreaking” but does prove something previously thought.

“Folic acid is important for all women, but it does seem like folic acid may be even more important in the epilepsy population,” said Dr. Chong, who was not involved with the research.

He cautioned that the current analysis included only four medications, three of which are not used very often anymore.

“Lamotrigine is probably the most commonly used one now. It’s unfortunate that this study did not include Keppra [levetiracetam], which probably is the number one medication that we use now,” Dr. Chong said.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Meador and Dr. Chong have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research underscores the importance of folic acid supplementation for pregnant women with epilepsy who are taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs).

Dietary folate alone, even in the United States, where food is fortified with folic acid, is “not sufficient” to improve cognitive outcomes for children of women who take AEDs during pregnancy, the researchers report.

“We found that dietary folate was not related to outcomes,” study investigator Kimford Meador, MD, professor of neurology and neurologic sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization.

“Only when the mother was taking extra folate did we see an improvement in child outcomes,” he added.

The findings were published online Feb. 23 in Epilepsy and Behavior.

Cognitive boost

“Daily folate is recommended to women in the general populations to reduce congenital malformations,” Dr. Meador said. In addition, periconceptional use of folate has been shown in previous research to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes for children of mothers with epilepsy who are taking AEDs.

Whether folate-fortified food alone, without supplements, has any effect on cognitive outcomes in this population of children has not been examined previously.

To investigate, the researchers assessed 117 children from the Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (NEAD) study, a prospective, observational study of women with epilepsy who were taking one of four AEDs: carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin, or valproate.

Results showed that dietary folate from fortified food alone, without supplements, had no significant impact on IQ at age 6 years among children with prenatal exposure to AEDs.

In contrast, use of periconceptual folate supplements was significantly associated with a 10-point higher IQ at age 6 in the adjusted analyses (95% confidence interval, 5.2-15.0; P < .001).

These six other nutrients from food and supplements had no significant association with IQ at age 6 years: vitamins C, D, and E, omega-3, gamma tocopherol, and vitamin B12.

Optimal dose unclear

The findings indicate that folates, including natural folate and folic acid, in food do not have positive cognitive effects for children of women with epilepsy who take AEDs, the researchers write.

Dr. Meador noted that the optimal dose of folic acid supplementation to provide a cognitive benefit remains unclear.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control recommends 0.4 mg/d for the general population of women of childbearing age. In Europe, the recommendation is 1 mg/d.

“Higher doses are recommended if there is a personal or family history of spina bifida in prior pregnancies, but there is some concern that very high doses of folate may be detrimental,” Dr. Meador said.

For women with epilepsy, he would recommend “at least 1 mg/d and not more than 4 mg/d.”

Proves a point?

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Derek Chong, MD, vice chair of neurology and director of epilepsy at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, said the finding that folate fortification of food alone is not adequate for women with epilepsy is “not groundbreaking” but does prove something previously thought.

“Folic acid is important for all women, but it does seem like folic acid may be even more important in the epilepsy population,” said Dr. Chong, who was not involved with the research.

He cautioned that the current analysis included only four medications, three of which are not used very often anymore.

“Lamotrigine is probably the most commonly used one now. It’s unfortunate that this study did not include Keppra [levetiracetam], which probably is the number one medication that we use now,” Dr. Chong said.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Meador and Dr. Chong have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research underscores the importance of folic acid supplementation for pregnant women with epilepsy who are taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs).

Dietary folate alone, even in the United States, where food is fortified with folic acid, is “not sufficient” to improve cognitive outcomes for children of women who take AEDs during pregnancy, the researchers report.

“We found that dietary folate was not related to outcomes,” study investigator Kimford Meador, MD, professor of neurology and neurologic sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization.

“Only when the mother was taking extra folate did we see an improvement in child outcomes,” he added.

The findings were published online Feb. 23 in Epilepsy and Behavior.

Cognitive boost

“Daily folate is recommended to women in the general populations to reduce congenital malformations,” Dr. Meador said. In addition, periconceptional use of folate has been shown in previous research to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes for children of mothers with epilepsy who are taking AEDs.

Whether folate-fortified food alone, without supplements, has any effect on cognitive outcomes in this population of children has not been examined previously.

To investigate, the researchers assessed 117 children from the Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (NEAD) study, a prospective, observational study of women with epilepsy who were taking one of four AEDs: carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin, or valproate.

Results showed that dietary folate from fortified food alone, without supplements, had no significant impact on IQ at age 6 years among children with prenatal exposure to AEDs.

In contrast, use of periconceptual folate supplements was significantly associated with a 10-point higher IQ at age 6 in the adjusted analyses (95% confidence interval, 5.2-15.0; P < .001).

These six other nutrients from food and supplements had no significant association with IQ at age 6 years: vitamins C, D, and E, omega-3, gamma tocopherol, and vitamin B12.

Optimal dose unclear

The findings indicate that folates, including natural folate and folic acid, in food do not have positive cognitive effects for children of women with epilepsy who take AEDs, the researchers write.

Dr. Meador noted that the optimal dose of folic acid supplementation to provide a cognitive benefit remains unclear.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control recommends 0.4 mg/d for the general population of women of childbearing age. In Europe, the recommendation is 1 mg/d.

“Higher doses are recommended if there is a personal or family history of spina bifida in prior pregnancies, but there is some concern that very high doses of folate may be detrimental,” Dr. Meador said.

For women with epilepsy, he would recommend “at least 1 mg/d and not more than 4 mg/d.”

Proves a point?

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Derek Chong, MD, vice chair of neurology and director of epilepsy at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, said the finding that folate fortification of food alone is not adequate for women with epilepsy is “not groundbreaking” but does prove something previously thought.

“Folic acid is important for all women, but it does seem like folic acid may be even more important in the epilepsy population,” said Dr. Chong, who was not involved with the research.

He cautioned that the current analysis included only four medications, three of which are not used very often anymore.

“Lamotrigine is probably the most commonly used one now. It’s unfortunate that this study did not include Keppra [levetiracetam], which probably is the number one medication that we use now,” Dr. Chong said.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Meador and Dr. Chong have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cannabinoids promising for improving appetite, behavior in dementia

For patients with dementia, cannabinoids may be a promising intervention for treating neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) and the refusing of food, new research suggests.

Results of a systematic literature review, presented at the 2021 meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, showed that cannabinoids were associated with reduced agitation, longer sleep, and lower NPS. They were also linked to increased meal consumption and weight gain.

Refusing food is a common problem for patients with dementia, often resulting in worsening sleep, agitation, and mood, study investigator Niraj Asthana, MD, a second-year resident in the department of psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, said in an interview. Dr. Asthana noted that certain cannabinoid analogues are now used to stimulate appetite for patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Filling a treatment gap

After years of legal and other problems affecting cannabinoid research, there is renewed interest in investigating its use for patients with dementia. Early evidence suggests that cannabinoids may also be beneficial for pain, sleep, and aggression.

The researchers noted that cannabinoids may be especially valuable in areas where there are currently limited therapies, including food refusal and NPS.

“Unfortunately, there are limited treatments available for food refusal, so we’re left with appetite stimulants and electroconvulsive therapy, and although atypical antipsychotics are commonly used to treat NPS, they’re associated with an increased risk of serious adverse events and mortality in older patients,” said Dr. Asthana.

Dr. Asthana and colleague Dan Sewell, MD, carried out a systematic literature review of relevant studies of the use of cannabinoids for dementia patients.

“We found there are lot of studies, but they’re small scale; I’d say the largest was probably about 50 patients, with most studies having 10-50 patients,” said Dr. Asthana. In part, this may be because, until very recently, research on cannabinoids was controversial.

To review the current literature on the potential applications of cannabinoids in the treatment of food refusal and NPS in dementia patients, the researchers conducted a literature review.

They identified 23 relevant studies of the use of synthetic cannabinoids, including dronabinol and nabilone, for dementia patients. These products contain tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive compound in cannabis.

More research coming

Several studies showed that cannabinoid use was associated with reduced nighttime motor activity, improved sleep duration, reduced agitation, and lower Neuropsychiatric Inventory scores.

One crossover placebo-controlled trial showed an overall increase in body weight among dementia patients who took dronabinol.

This suggests there might be something to the “colloquial cultural association between cannabinoids and the munchies,” said Dr. Asthana.

Possible mechanisms for the effects on appetite may be that cannabinoids increase levels of the hormone ghrelin, which is also known as the “hunger hormone,” and decrease leptin levels, a hormone that inhibits hunger. Dr. Asthana noted that, in these studies, the dose of THC was low and that overall, cannabinoids appeared to be safe.

“We found that, at least in these small-scale studies, cannabinoid analogues are well tolerated,” possibly because of the relatively low doses of THC, said Dr. Asthana. “They generally don’t seem to have a ton of side effects; they may make people a little sleepy, which is actually good, because these patents also have a lot of trouble sleeping.”

He noted that more recent research suggests cannabidiol oil may reduce agitation by up to 40%.

“Now that cannabis is losing a lot of its stigma, both culturally and in the scientific community, you’re seeing a lot of grant applications for clinical trials,” said Dr. Asthana. “I’m excited to see what we find in the next 5-10 years.”

In a comment, Kirsten Wilkins, MD, associate professor of psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who is also a geriatric psychiatrist at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Health Care System, welcomed the new research in this area.

“With limited safe and effective treatments for food refusal and neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, Dr. Asthana and Dr. Sewell highlight the growing body of literature suggesting cannabinoids may be a novel treatment option,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with dementia, cannabinoids may be a promising intervention for treating neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) and the refusing of food, new research suggests.

Results of a systematic literature review, presented at the 2021 meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, showed that cannabinoids were associated with reduced agitation, longer sleep, and lower NPS. They were also linked to increased meal consumption and weight gain.