User login

Flesh-Colored Pinpoint Papules With Fine White Spicules on the Upper Body

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

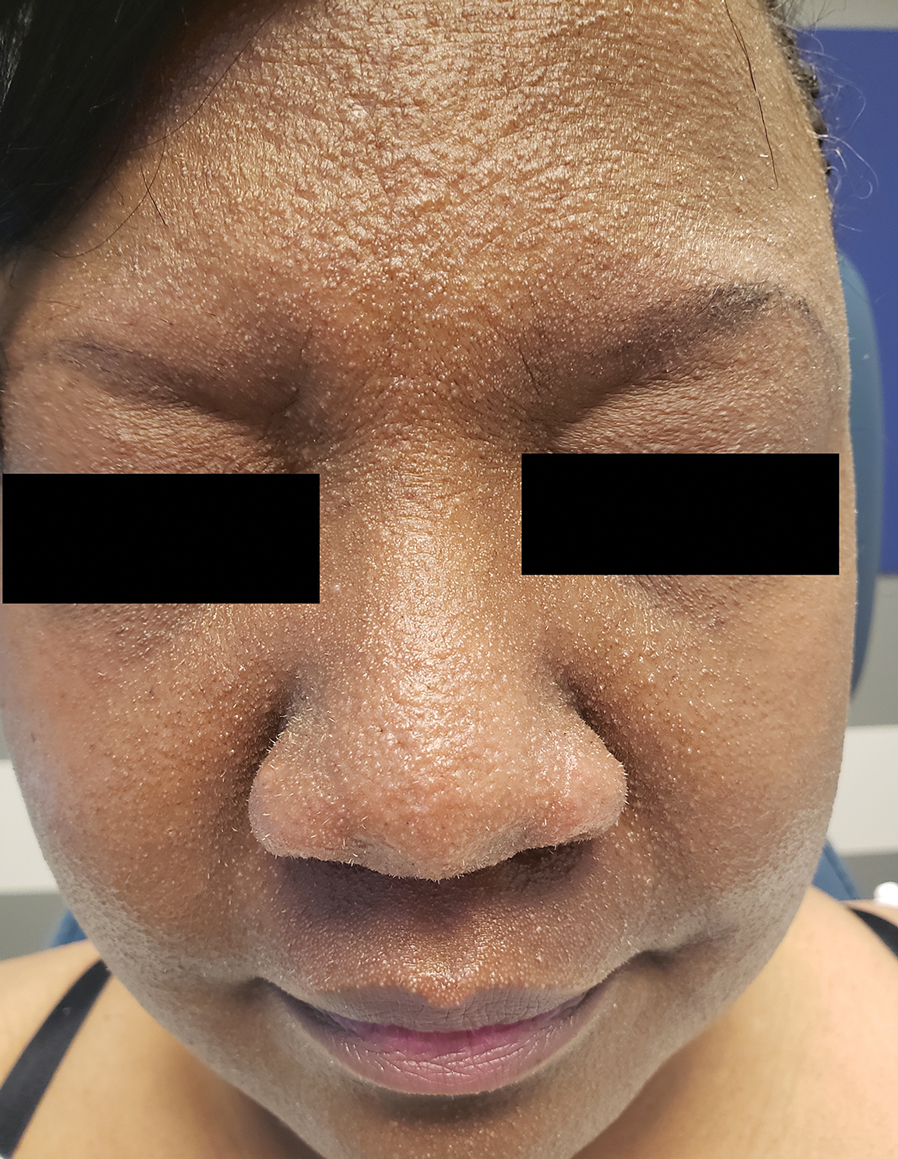

A diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS) was rendered based on the clinical presentation— diffuse folliculocentric keratotic papules with spicules and leonine facies—coinciding with cyclosporine initiation. Biopsy was deferred given the classic presentation. The patient applied cidofovir cream 1% daily to lesions on the face. She was prescribed leflunomide 10 mg daily, which was later increased to 20 mg daily, for polyarthritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Her transplant physician increased her cyclosporine dosage from 50 mg twice daily to 75 mg each morning and 50 mg each evening due to rising creatinine and donor-specific antibodies from the renal transplant. The patient’s TS eruption mildly improved 3 months after the cyclosporine dose was increased. To treat persistent lesions, oral valganciclovir was started at 450 mg once daily and later reduced to every other day due to leukopenia. After 3 months of taking valganciclovir 450 mg every other day, the patient’s TS rash resolved.

Trichodysplasia spinulosa is a rare condition caused by TS-associated polyomavirus1 that may arise in immunosuppressed patients, especially in solid organ transplant recipients.2 It is characterized by spiculated and folliculocentric papules, mainly on the face,1 and often is diagnosed clinically, but if the presentation is not classic, a skin biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis. Because of its rarity, treatment options do not have well-established efficacy1 but include reducing immunosuppression and using the antivirals cidofovir1 or valganciclovir3 to treat the polyomavirus. Topical retinoids,3 photodynamic therapy, 4 and leflunomide5 also may be effective.

Although the typical approach to treating TS is to reduce immunosuppression, this was not an option for our patient, as she required increased immunosuppression for the treatment of active SLE. Leflunomide can be used for SLE, and in some reports it can be effective for BK viremia in kidney transplant recipients5 as well as for TS in solid organ transplant recipients.6 Our patient showed improvement of the TS, BK viremia, renal function, and SLE while taking leflunomide and valganciclovir.

The differential diagnosis includes keratosis pilaris, lichen nitidus, scleromyxedema, and trichostasis spinulosa. Keratosis pilaris is a benign skin disorder consisting of patches of keratotic papules with varying degrees of erythema and inflammation that are formed by dead keratinocytes plugging the hair follicles and often are seen on the extremities, face, and trunk.7 Our patient’s papules were flesh colored with no notable background erythema. Additionally, the presence of leonine facies was atypical for keratosis pilaris. Acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors are the most frequently used treatments for keratosis pilaris.8

Lichen nitidus is a skin condition characterized by multiple shiny, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules usually found on the flexor surfaces of the arms, anterior trunk, and genitalia. It is mostly asymptomatic, but patients may experience pruritus. Most cases occur in children and young adults, with no obvious racial or gender predilection. The diagnosis often is clinical, but biopsy shows downward enlargement of the epidermal rete ridges surrounding a focal inflammatory infiltrate, known as a ball-in-claw configuration.9-11 Lichen nitidus spontaneously resolves within a few years without treatment. Our patient did have flesh-colored papules on the arms and chest; however, major involvement of the face is not typical in lichen nitidus. Additionally, fine white spicules would not be seen in lichen nitidus. For severe generalized lichen nitidus, treatment options include topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, oral antihistamines, or UV light to decrease inflammation.9-11

Scleromyxedema is a rare condition involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis to cause the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.12 It is thought that immunoglobulins and cytokines secreted by inflammatory cells lead to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans, which then causes deposition of mucin in the dermis.13 The classic cutaneous features of scleromyxedema include waxy indurated papules and plaques with skin thickening throughout the entire body.12 Our patient’s papules were not notably indurated and involved less than 50% of the total body surface area. An important diagnostic feature of scleromyxedema is monoclonal gammopathy, which our patient did not have. Intravenous immunoglobulin is the first-line treatment of scleromyxedema, and second-line treatments include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.14 Our patient also did not require treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, as her rash improved with antiviral medication, which would not address the underlying inflammatory processes associated with scleromyxedema.

Trichostasis spinulosa is a rare hair follicle disorder consisting of dark, spiny, hyperkeratotic follicular papules that can be found on the extremities and face, especially the nose. The etiology is unknown, but risk factors include congenital dysplasia of hair follicles; exposure to UV light, dust, oil, or heat; chronic renal failure; Malassezia yeast; and Propionibacterium acnes. Adult women with darker skin types are most commonly affected by trichostasis spinulosa.15,16 Our patient fit the epidemiologic demographic of trichostasis spinulosa, including a history of chronic renal failure. Her rash covered the face, nose, and arms; however, the papules were flesh colored, whereas trichostasis spinulosa would appear as black papules. Furthermore, yeast and bacterial infections have been identified as potential agents associated with trichostasis spinulosa; therefore, antiviral agents would be ineffective. Viable treatments for trichostasis spinulosa include emollients, topical keratolytic agents, retinoic acids, and lasers to remove abnormal hair follicles.15,16

- Curman P, Näsman A, Brauner H. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a comprehensive disease and its treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:1067-1076.

- Fischer MK, Kao GF, Nguyen HP, et al. Specific detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus DNA in skin and renal allograft tissues in a patient with trichodysplasia spinulosa. Arch Dermatol. 2021;148:726-733.

- Shah PR, Esaa FS, Gupta P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa successfully treated with adapalene 0.1% gel and oral valganciclovir in a renal transplant recipient. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:23-25.

- Liew YCC, Kee TYS, Kwek JL, et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in an Asian renal transplant recipient: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;7:74-83.

- Pierrotti LC, Urbano PRP, da Silva Nali LH, et al. Viremia and viuria of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus before the development of clinical disease in a kidney transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21:E13133.

- Kassar R, Chang J, Chan AW, et al. Leflunomide for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in a liver transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19:E12702.

- Eckburg A, Kazemi T, Maguiness S. Keratosis pilaris rubra successfully treated with topical sirolimus: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:429-431.

- Reddy S, Brahmbhatt H. A narrative review on the role of acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors in the treatment of keratosis pilaris. Cureus. 2021;13:E18917.

- Jordan AS, Green MC, Sulit DJ. Lichen nitidus. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119:704.

- Arizaga AT, Gaughan MD, Bang RH. Generalized lichen nitidus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:115-117.

- Chu J, Lam JM. Lichen nitidus. CMAJ. 2014;186:E688.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosis (LM) (discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Kositkuljorn C, Suchonwanit P. Trichostasis spinulosa: a case report with an unusual presentation. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:178-185.

- Ramteke MN, Bhide AA. Trichostasis spinulosa at an unusual site. Int J Trichology. 2016;8:78-80.

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

A diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS) was rendered based on the clinical presentation— diffuse folliculocentric keratotic papules with spicules and leonine facies—coinciding with cyclosporine initiation. Biopsy was deferred given the classic presentation. The patient applied cidofovir cream 1% daily to lesions on the face. She was prescribed leflunomide 10 mg daily, which was later increased to 20 mg daily, for polyarthritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Her transplant physician increased her cyclosporine dosage from 50 mg twice daily to 75 mg each morning and 50 mg each evening due to rising creatinine and donor-specific antibodies from the renal transplant. The patient’s TS eruption mildly improved 3 months after the cyclosporine dose was increased. To treat persistent lesions, oral valganciclovir was started at 450 mg once daily and later reduced to every other day due to leukopenia. After 3 months of taking valganciclovir 450 mg every other day, the patient’s TS rash resolved.

Trichodysplasia spinulosa is a rare condition caused by TS-associated polyomavirus1 that may arise in immunosuppressed patients, especially in solid organ transplant recipients.2 It is characterized by spiculated and folliculocentric papules, mainly on the face,1 and often is diagnosed clinically, but if the presentation is not classic, a skin biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis. Because of its rarity, treatment options do not have well-established efficacy1 but include reducing immunosuppression and using the antivirals cidofovir1 or valganciclovir3 to treat the polyomavirus. Topical retinoids,3 photodynamic therapy, 4 and leflunomide5 also may be effective.

Although the typical approach to treating TS is to reduce immunosuppression, this was not an option for our patient, as she required increased immunosuppression for the treatment of active SLE. Leflunomide can be used for SLE, and in some reports it can be effective for BK viremia in kidney transplant recipients5 as well as for TS in solid organ transplant recipients.6 Our patient showed improvement of the TS, BK viremia, renal function, and SLE while taking leflunomide and valganciclovir.

The differential diagnosis includes keratosis pilaris, lichen nitidus, scleromyxedema, and trichostasis spinulosa. Keratosis pilaris is a benign skin disorder consisting of patches of keratotic papules with varying degrees of erythema and inflammation that are formed by dead keratinocytes plugging the hair follicles and often are seen on the extremities, face, and trunk.7 Our patient’s papules were flesh colored with no notable background erythema. Additionally, the presence of leonine facies was atypical for keratosis pilaris. Acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors are the most frequently used treatments for keratosis pilaris.8

Lichen nitidus is a skin condition characterized by multiple shiny, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules usually found on the flexor surfaces of the arms, anterior trunk, and genitalia. It is mostly asymptomatic, but patients may experience pruritus. Most cases occur in children and young adults, with no obvious racial or gender predilection. The diagnosis often is clinical, but biopsy shows downward enlargement of the epidermal rete ridges surrounding a focal inflammatory infiltrate, known as a ball-in-claw configuration.9-11 Lichen nitidus spontaneously resolves within a few years without treatment. Our patient did have flesh-colored papules on the arms and chest; however, major involvement of the face is not typical in lichen nitidus. Additionally, fine white spicules would not be seen in lichen nitidus. For severe generalized lichen nitidus, treatment options include topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, oral antihistamines, or UV light to decrease inflammation.9-11

Scleromyxedema is a rare condition involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis to cause the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.12 It is thought that immunoglobulins and cytokines secreted by inflammatory cells lead to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans, which then causes deposition of mucin in the dermis.13 The classic cutaneous features of scleromyxedema include waxy indurated papules and plaques with skin thickening throughout the entire body.12 Our patient’s papules were not notably indurated and involved less than 50% of the total body surface area. An important diagnostic feature of scleromyxedema is monoclonal gammopathy, which our patient did not have. Intravenous immunoglobulin is the first-line treatment of scleromyxedema, and second-line treatments include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.14 Our patient also did not require treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, as her rash improved with antiviral medication, which would not address the underlying inflammatory processes associated with scleromyxedema.

Trichostasis spinulosa is a rare hair follicle disorder consisting of dark, spiny, hyperkeratotic follicular papules that can be found on the extremities and face, especially the nose. The etiology is unknown, but risk factors include congenital dysplasia of hair follicles; exposure to UV light, dust, oil, or heat; chronic renal failure; Malassezia yeast; and Propionibacterium acnes. Adult women with darker skin types are most commonly affected by trichostasis spinulosa.15,16 Our patient fit the epidemiologic demographic of trichostasis spinulosa, including a history of chronic renal failure. Her rash covered the face, nose, and arms; however, the papules were flesh colored, whereas trichostasis spinulosa would appear as black papules. Furthermore, yeast and bacterial infections have been identified as potential agents associated with trichostasis spinulosa; therefore, antiviral agents would be ineffective. Viable treatments for trichostasis spinulosa include emollients, topical keratolytic agents, retinoic acids, and lasers to remove abnormal hair follicles.15,16

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

A diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS) was rendered based on the clinical presentation— diffuse folliculocentric keratotic papules with spicules and leonine facies—coinciding with cyclosporine initiation. Biopsy was deferred given the classic presentation. The patient applied cidofovir cream 1% daily to lesions on the face. She was prescribed leflunomide 10 mg daily, which was later increased to 20 mg daily, for polyarthritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Her transplant physician increased her cyclosporine dosage from 50 mg twice daily to 75 mg each morning and 50 mg each evening due to rising creatinine and donor-specific antibodies from the renal transplant. The patient’s TS eruption mildly improved 3 months after the cyclosporine dose was increased. To treat persistent lesions, oral valganciclovir was started at 450 mg once daily and later reduced to every other day due to leukopenia. After 3 months of taking valganciclovir 450 mg every other day, the patient’s TS rash resolved.

Trichodysplasia spinulosa is a rare condition caused by TS-associated polyomavirus1 that may arise in immunosuppressed patients, especially in solid organ transplant recipients.2 It is characterized by spiculated and folliculocentric papules, mainly on the face,1 and often is diagnosed clinically, but if the presentation is not classic, a skin biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis. Because of its rarity, treatment options do not have well-established efficacy1 but include reducing immunosuppression and using the antivirals cidofovir1 or valganciclovir3 to treat the polyomavirus. Topical retinoids,3 photodynamic therapy, 4 and leflunomide5 also may be effective.

Although the typical approach to treating TS is to reduce immunosuppression, this was not an option for our patient, as she required increased immunosuppression for the treatment of active SLE. Leflunomide can be used for SLE, and in some reports it can be effective for BK viremia in kidney transplant recipients5 as well as for TS in solid organ transplant recipients.6 Our patient showed improvement of the TS, BK viremia, renal function, and SLE while taking leflunomide and valganciclovir.

The differential diagnosis includes keratosis pilaris, lichen nitidus, scleromyxedema, and trichostasis spinulosa. Keratosis pilaris is a benign skin disorder consisting of patches of keratotic papules with varying degrees of erythema and inflammation that are formed by dead keratinocytes plugging the hair follicles and often are seen on the extremities, face, and trunk.7 Our patient’s papules were flesh colored with no notable background erythema. Additionally, the presence of leonine facies was atypical for keratosis pilaris. Acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors are the most frequently used treatments for keratosis pilaris.8

Lichen nitidus is a skin condition characterized by multiple shiny, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules usually found on the flexor surfaces of the arms, anterior trunk, and genitalia. It is mostly asymptomatic, but patients may experience pruritus. Most cases occur in children and young adults, with no obvious racial or gender predilection. The diagnosis often is clinical, but biopsy shows downward enlargement of the epidermal rete ridges surrounding a focal inflammatory infiltrate, known as a ball-in-claw configuration.9-11 Lichen nitidus spontaneously resolves within a few years without treatment. Our patient did have flesh-colored papules on the arms and chest; however, major involvement of the face is not typical in lichen nitidus. Additionally, fine white spicules would not be seen in lichen nitidus. For severe generalized lichen nitidus, treatment options include topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, oral antihistamines, or UV light to decrease inflammation.9-11

Scleromyxedema is a rare condition involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis to cause the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.12 It is thought that immunoglobulins and cytokines secreted by inflammatory cells lead to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans, which then causes deposition of mucin in the dermis.13 The classic cutaneous features of scleromyxedema include waxy indurated papules and plaques with skin thickening throughout the entire body.12 Our patient’s papules were not notably indurated and involved less than 50% of the total body surface area. An important diagnostic feature of scleromyxedema is monoclonal gammopathy, which our patient did not have. Intravenous immunoglobulin is the first-line treatment of scleromyxedema, and second-line treatments include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.14 Our patient also did not require treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, as her rash improved with antiviral medication, which would not address the underlying inflammatory processes associated with scleromyxedema.

Trichostasis spinulosa is a rare hair follicle disorder consisting of dark, spiny, hyperkeratotic follicular papules that can be found on the extremities and face, especially the nose. The etiology is unknown, but risk factors include congenital dysplasia of hair follicles; exposure to UV light, dust, oil, or heat; chronic renal failure; Malassezia yeast; and Propionibacterium acnes. Adult women with darker skin types are most commonly affected by trichostasis spinulosa.15,16 Our patient fit the epidemiologic demographic of trichostasis spinulosa, including a history of chronic renal failure. Her rash covered the face, nose, and arms; however, the papules were flesh colored, whereas trichostasis spinulosa would appear as black papules. Furthermore, yeast and bacterial infections have been identified as potential agents associated with trichostasis spinulosa; therefore, antiviral agents would be ineffective. Viable treatments for trichostasis spinulosa include emollients, topical keratolytic agents, retinoic acids, and lasers to remove abnormal hair follicles.15,16

- Curman P, Näsman A, Brauner H. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a comprehensive disease and its treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:1067-1076.

- Fischer MK, Kao GF, Nguyen HP, et al. Specific detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus DNA in skin and renal allograft tissues in a patient with trichodysplasia spinulosa. Arch Dermatol. 2021;148:726-733.

- Shah PR, Esaa FS, Gupta P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa successfully treated with adapalene 0.1% gel and oral valganciclovir in a renal transplant recipient. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:23-25.

- Liew YCC, Kee TYS, Kwek JL, et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in an Asian renal transplant recipient: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;7:74-83.

- Pierrotti LC, Urbano PRP, da Silva Nali LH, et al. Viremia and viuria of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus before the development of clinical disease in a kidney transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21:E13133.

- Kassar R, Chang J, Chan AW, et al. Leflunomide for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in a liver transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19:E12702.

- Eckburg A, Kazemi T, Maguiness S. Keratosis pilaris rubra successfully treated with topical sirolimus: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:429-431.

- Reddy S, Brahmbhatt H. A narrative review on the role of acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors in the treatment of keratosis pilaris. Cureus. 2021;13:E18917.

- Jordan AS, Green MC, Sulit DJ. Lichen nitidus. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119:704.

- Arizaga AT, Gaughan MD, Bang RH. Generalized lichen nitidus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:115-117.

- Chu J, Lam JM. Lichen nitidus. CMAJ. 2014;186:E688.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosis (LM) (discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Kositkuljorn C, Suchonwanit P. Trichostasis spinulosa: a case report with an unusual presentation. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:178-185.

- Ramteke MN, Bhide AA. Trichostasis spinulosa at an unusual site. Int J Trichology. 2016;8:78-80.

- Curman P, Näsman A, Brauner H. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a comprehensive disease and its treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:1067-1076.

- Fischer MK, Kao GF, Nguyen HP, et al. Specific detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus DNA in skin and renal allograft tissues in a patient with trichodysplasia spinulosa. Arch Dermatol. 2021;148:726-733.

- Shah PR, Esaa FS, Gupta P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa successfully treated with adapalene 0.1% gel and oral valganciclovir in a renal transplant recipient. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:23-25.

- Liew YCC, Kee TYS, Kwek JL, et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in an Asian renal transplant recipient: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;7:74-83.

- Pierrotti LC, Urbano PRP, da Silva Nali LH, et al. Viremia and viuria of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus before the development of clinical disease in a kidney transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21:E13133.

- Kassar R, Chang J, Chan AW, et al. Leflunomide for the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa in a liver transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19:E12702.

- Eckburg A, Kazemi T, Maguiness S. Keratosis pilaris rubra successfully treated with topical sirolimus: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:429-431.

- Reddy S, Brahmbhatt H. A narrative review on the role of acids, steroids, and kinase inhibitors in the treatment of keratosis pilaris. Cureus. 2021;13:E18917.

- Jordan AS, Green MC, Sulit DJ. Lichen nitidus. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119:704.

- Arizaga AT, Gaughan MD, Bang RH. Generalized lichen nitidus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:115-117.

- Chu J, Lam JM. Lichen nitidus. CMAJ. 2014;186:E688.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosis (LM) (discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Kositkuljorn C, Suchonwanit P. Trichostasis spinulosa: a case report with an unusual presentation. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:178-185.

- Ramteke MN, Bhide AA. Trichostasis spinulosa at an unusual site. Int J Trichology. 2016;8:78-80.

A 54-year-old Black woman presented with a rash that developed 6 months after a renal transplant due to a history of systemic lupus erythematosus with lupus nephritis. She was started on mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus after the transplant but was switched to cyclosporine because of BK viremia. The rash developed 1 week after cyclosporine was initiated and consisted of pruritic papules that started on the face and spread to the trunk and arms. Physical examination revealed innumerable follicular-based, keratotic, flesh-colored, pinpoint papules with fine white spicules on the face (top), neck, chest, arms, and back. Leonine facies was seen along the glabella with madarosis of the lateral eyebrows (top) and ears (bottom).

Doctors Endorsing Products on X May Not Disclose Company Ties

Lead author Aaron Mitchell, MD, MPH, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, told this news organization that he and his colleagues undertook the study in part to see whether physicians were adhering to professional and industry guidelines regarding marketing communications.

The team reviewed posts by physicians on X during 2022, looking for key words that might indicate that the posts were intended as endorsements of a product. The researchers then delved into the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open Payments database to see how many of those identified as having endorsed a product were paid by the manufacturers.

What Dr. Mitchell found concerned him, he said.

Overall, the researchers identified 28 physician endorsers who received a total of $1.4 million from sponsors in 2022. Among these, 26 physicians (93%) received payments from the product’s manufacturer, totaling $713,976, and 24 physicians (86%) accepted payments related to the endorsed drug or device, totaling $492,098.

While most did disclose that the posts were sponsored — by adding the word “sponsored” or using #sponsored — nine physicians did not.

Although 28 physician endorsers represent a “small fraction” of the overall number of physicians who use X, each endorsement was ultimately posted dozens, if not hundreds of times, said Dr. Mitchell. In fact, he said he saw the same particular endorsement post every time he opened his X app for months.

Overall, Dr. Mitchell noted that it’s less about the fact that the endorsements are occurring on social media and more that there are these paid endorsements taking place at all.

Among the physician specialties promoting a product, urologists and oncologists dominated. Almost one third were urologists, and 57% were oncologists — six medical oncologists, six radiation oncologists, and four gynecologic oncologists. Of the remaining three physicians, two were internists and one was a pulmonary and critical care medicine specialist.

The authors tracked posts from physicians and industry accounts. Many of the posts on industry accounts were physician testimonials, usually videos. Almost half — 8 of 17 — of those testimonials did not disclose that the doctor was being paid by the manufacturer. In another case, a physician did not disclose that they were paid to endorse a white paper.

Fifteen promotional posts were for a Boston Scientific product, followed by six for GlaxoSmithKline, two for Eisai, two for Exelixis, and one each for AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Pfizer.

In general, Dr. Mitchell said, industry guidelines suggest that manufacturer-paid speakers or consultants should have well-regarded expertise in the area they are being asked to weigh in on, but most physician endorsers in the study were not key opinion leaders or experts.

The authors examined the paid endorsers’ H-index — a measure of academic productivity provided by Scopus. Overall, 19 of the 28 physicians had an H-index below 20, which is considered less accomplished, and 14 had no published research related to the endorsed product.

Ten received payments from manufacturers for research purposes, and only one received research payments related to the endorsed product ($224,577).

“Physicians’ participation in industry marketing raises questions regarding professionalism and their responsibilities as patient advocates,” the JAMA authors wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Mitchell reported no relevant financial relationships. Coauthors Samer Al Hadidi, MD, reported receiving personal fees from Pfizer, Sanofi, and Janssen during the conduct of the study, and Timothy S. Anderson, MD, reported receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging, the American Heart Association, and the American College of Cardiology, and receiving consulting fees from the American Medical Student Association. Dr. Anderson is also an associate editor of JAMA Internal Medicine.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Lead author Aaron Mitchell, MD, MPH, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, told this news organization that he and his colleagues undertook the study in part to see whether physicians were adhering to professional and industry guidelines regarding marketing communications.

The team reviewed posts by physicians on X during 2022, looking for key words that might indicate that the posts were intended as endorsements of a product. The researchers then delved into the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open Payments database to see how many of those identified as having endorsed a product were paid by the manufacturers.

What Dr. Mitchell found concerned him, he said.

Overall, the researchers identified 28 physician endorsers who received a total of $1.4 million from sponsors in 2022. Among these, 26 physicians (93%) received payments from the product’s manufacturer, totaling $713,976, and 24 physicians (86%) accepted payments related to the endorsed drug or device, totaling $492,098.

While most did disclose that the posts were sponsored — by adding the word “sponsored” or using #sponsored — nine physicians did not.

Although 28 physician endorsers represent a “small fraction” of the overall number of physicians who use X, each endorsement was ultimately posted dozens, if not hundreds of times, said Dr. Mitchell. In fact, he said he saw the same particular endorsement post every time he opened his X app for months.

Overall, Dr. Mitchell noted that it’s less about the fact that the endorsements are occurring on social media and more that there are these paid endorsements taking place at all.

Among the physician specialties promoting a product, urologists and oncologists dominated. Almost one third were urologists, and 57% were oncologists — six medical oncologists, six radiation oncologists, and four gynecologic oncologists. Of the remaining three physicians, two were internists and one was a pulmonary and critical care medicine specialist.

The authors tracked posts from physicians and industry accounts. Many of the posts on industry accounts were physician testimonials, usually videos. Almost half — 8 of 17 — of those testimonials did not disclose that the doctor was being paid by the manufacturer. In another case, a physician did not disclose that they were paid to endorse a white paper.

Fifteen promotional posts were for a Boston Scientific product, followed by six for GlaxoSmithKline, two for Eisai, two for Exelixis, and one each for AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Pfizer.

In general, Dr. Mitchell said, industry guidelines suggest that manufacturer-paid speakers or consultants should have well-regarded expertise in the area they are being asked to weigh in on, but most physician endorsers in the study were not key opinion leaders or experts.

The authors examined the paid endorsers’ H-index — a measure of academic productivity provided by Scopus. Overall, 19 of the 28 physicians had an H-index below 20, which is considered less accomplished, and 14 had no published research related to the endorsed product.

Ten received payments from manufacturers for research purposes, and only one received research payments related to the endorsed product ($224,577).

“Physicians’ participation in industry marketing raises questions regarding professionalism and their responsibilities as patient advocates,” the JAMA authors wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Mitchell reported no relevant financial relationships. Coauthors Samer Al Hadidi, MD, reported receiving personal fees from Pfizer, Sanofi, and Janssen during the conduct of the study, and Timothy S. Anderson, MD, reported receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging, the American Heart Association, and the American College of Cardiology, and receiving consulting fees from the American Medical Student Association. Dr. Anderson is also an associate editor of JAMA Internal Medicine.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Lead author Aaron Mitchell, MD, MPH, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, told this news organization that he and his colleagues undertook the study in part to see whether physicians were adhering to professional and industry guidelines regarding marketing communications.

The team reviewed posts by physicians on X during 2022, looking for key words that might indicate that the posts were intended as endorsements of a product. The researchers then delved into the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open Payments database to see how many of those identified as having endorsed a product were paid by the manufacturers.

What Dr. Mitchell found concerned him, he said.

Overall, the researchers identified 28 physician endorsers who received a total of $1.4 million from sponsors in 2022. Among these, 26 physicians (93%) received payments from the product’s manufacturer, totaling $713,976, and 24 physicians (86%) accepted payments related to the endorsed drug or device, totaling $492,098.

While most did disclose that the posts were sponsored — by adding the word “sponsored” or using #sponsored — nine physicians did not.

Although 28 physician endorsers represent a “small fraction” of the overall number of physicians who use X, each endorsement was ultimately posted dozens, if not hundreds of times, said Dr. Mitchell. In fact, he said he saw the same particular endorsement post every time he opened his X app for months.

Overall, Dr. Mitchell noted that it’s less about the fact that the endorsements are occurring on social media and more that there are these paid endorsements taking place at all.

Among the physician specialties promoting a product, urologists and oncologists dominated. Almost one third were urologists, and 57% were oncologists — six medical oncologists, six radiation oncologists, and four gynecologic oncologists. Of the remaining three physicians, two were internists and one was a pulmonary and critical care medicine specialist.

The authors tracked posts from physicians and industry accounts. Many of the posts on industry accounts were physician testimonials, usually videos. Almost half — 8 of 17 — of those testimonials did not disclose that the doctor was being paid by the manufacturer. In another case, a physician did not disclose that they were paid to endorse a white paper.

Fifteen promotional posts were for a Boston Scientific product, followed by six for GlaxoSmithKline, two for Eisai, two for Exelixis, and one each for AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Pfizer.

In general, Dr. Mitchell said, industry guidelines suggest that manufacturer-paid speakers or consultants should have well-regarded expertise in the area they are being asked to weigh in on, but most physician endorsers in the study were not key opinion leaders or experts.

The authors examined the paid endorsers’ H-index — a measure of academic productivity provided by Scopus. Overall, 19 of the 28 physicians had an H-index below 20, which is considered less accomplished, and 14 had no published research related to the endorsed product.

Ten received payments from manufacturers for research purposes, and only one received research payments related to the endorsed product ($224,577).

“Physicians’ participation in industry marketing raises questions regarding professionalism and their responsibilities as patient advocates,” the JAMA authors wrote.

The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Mitchell reported no relevant financial relationships. Coauthors Samer Al Hadidi, MD, reported receiving personal fees from Pfizer, Sanofi, and Janssen during the conduct of the study, and Timothy S. Anderson, MD, reported receiving grants from the National Institute on Aging, the American Heart Association, and the American College of Cardiology, and receiving consulting fees from the American Medical Student Association. Dr. Anderson is also an associate editor of JAMA Internal Medicine.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

One Patient Changed This Oncologist’s View of Hope. Here’s How.

CHICAGO — Carlos, a 21-year-old, lay in a hospital bed, barely clinging to life. Following a stem cell transplant for leukemia, Carlos had developed a life-threatening case of graft-vs-host disease.

But Carlos’ mother had faith.

“I have hope things will get better,” she said, via interpreter, to Richard Leiter, MD, a palliative care doctor in training at that time.

“I hope they will,” Dr. Leiter told her.

“I should have stopped there,” said Dr. Leiter, recounting an early-career lesson on hope during the ASCO Voices session at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. “But in my eagerness to show my attending and myself that I could handle this conversation, I kept going, mistakenly.”

“But none of us think they will,” Dr. Leiter continued.

Carlos’ mother looked Dr. Leiter in the eye. “You want him to die,” she said.

“I knew, even then, that she was right,” recalled Dr. Leiter, now a palliative care physician at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although there was nothing he could do to save Carlos, Dr. Leiter also couldn’t sit with the extreme suffering. “The pain was too great,” Dr. Leiter said. “I needed her to adopt our narrative that we had done everything we could to help him live, and now, we would do everything we could to help his death be a comfortable one.”

But looking back, Dr. Leiter realized, “How could we have asked her to accept what was fundamentally unacceptable, to comprehend the incomprehensible?”

The Importance of Hope

Alan B. Astrow, MD, said during an ASCO symposium on “The Art and Science of Hope.”

“How we think about hope directly influences patient care,” said Dr. Astrow, chief of hematology and medical oncology at NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital and a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City.

Hope, whatever it turns out to be neurobiologically, is “very much a gift” that underlies human existence, he said.

Physicians have the capacity to restore or shatter a patient’s hopes, and those who come to understand the importance of hope will wish to extend the gift to others, Dr. Astrow said.

Asking patients about their hopes is the “golden question,” Steven Z. Pantilat, MD, said at the symposium. “When you think about the future, what do you hope for?”

Often, the answers reveal not only “things beyond a cure that matter tremendously to the patient but things that we can help with,” said Dr. Pantilat, professor and chief of the Division of Palliative Medicine at the University of California San Francisco.

Dr. Pantilat recalled a patient with advanced pancreatic cancer who wished to see her daughter’s wedding in 10 months. He knew that was unlikely, but the discussion led to another solution.

Her daughter moved the wedding to the ICU.

Hope can persist and uplift even in the darkest of times, and “as clinicians, we need to be in the true hope business,” he said.

While some patients may wish for a cure, others may want more time with family or comfort in the face of suffering. People can “hope for all the things that can still be, despite the fact that there’s a lot of things that can’t,” he said.

However, fear that a patient will hope for a cure, and that the difficult discussions to follow might destroy hope or lead to false hope, sometimes means physicians won’t begin the conversation.

“We want to be honest with our patients — compassionate and kind, but honest — when we talk about their hopes,” Dr. Pantilat explained. Sometimes that means he needs to tell patients, “I wish that could happen. I wish I had a treatment that could make your cancer go away, but unfortunately, I don’t. So let’s think about what else we can do to help you.”

Having these difficult discussions matters. The evidence, although limited, indicates that feeling hopeful can improve patients’ well-being and may even boost their cancer outcomes.

One recent study found, for instance, that patients who reported feeling more hopeful also had lower levels of depression and anxiety. Early research also suggests that greater levels of hope may have a hand in reducing inflammation in patients with ovarian cancer and could even improve survival in some patients with advanced cancer.

For Dr. Leiter, while these lessons came early in his career as a palliative care physician, they persist and influence his practice today.

“I know that I could not have prevented Carlos’ death. None of us could have, and none of us could have protected his mother from the unimaginable grief that will stay with her for the rest of her life,” he said. “But I could have made things just a little bit less difficult for her.

“I could have acted as her guide rather than her cross-examiner,” he continued, explaining that he now sees hope as “a generous collaborator” that can coexist with rising creatinine levels, failing livers, and fears about intubation.

“As clinicians, we can always find space to hope with our patients and their families,” he said. “So now, years later when I sit with a terrified and grieving family and they tell me they hope their loved one gets better, I remember Carlos’ mother’s eyes piercing mine ... and I know how to respond: ‘I hope so, too.’ And I do.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO — Carlos, a 21-year-old, lay in a hospital bed, barely clinging to life. Following a stem cell transplant for leukemia, Carlos had developed a life-threatening case of graft-vs-host disease.

But Carlos’ mother had faith.

“I have hope things will get better,” she said, via interpreter, to Richard Leiter, MD, a palliative care doctor in training at that time.

“I hope they will,” Dr. Leiter told her.

“I should have stopped there,” said Dr. Leiter, recounting an early-career lesson on hope during the ASCO Voices session at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. “But in my eagerness to show my attending and myself that I could handle this conversation, I kept going, mistakenly.”

“But none of us think they will,” Dr. Leiter continued.

Carlos’ mother looked Dr. Leiter in the eye. “You want him to die,” she said.

“I knew, even then, that she was right,” recalled Dr. Leiter, now a palliative care physician at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although there was nothing he could do to save Carlos, Dr. Leiter also couldn’t sit with the extreme suffering. “The pain was too great,” Dr. Leiter said. “I needed her to adopt our narrative that we had done everything we could to help him live, and now, we would do everything we could to help his death be a comfortable one.”

But looking back, Dr. Leiter realized, “How could we have asked her to accept what was fundamentally unacceptable, to comprehend the incomprehensible?”

The Importance of Hope

Alan B. Astrow, MD, said during an ASCO symposium on “The Art and Science of Hope.”

“How we think about hope directly influences patient care,” said Dr. Astrow, chief of hematology and medical oncology at NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital and a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City.

Hope, whatever it turns out to be neurobiologically, is “very much a gift” that underlies human existence, he said.

Physicians have the capacity to restore or shatter a patient’s hopes, and those who come to understand the importance of hope will wish to extend the gift to others, Dr. Astrow said.

Asking patients about their hopes is the “golden question,” Steven Z. Pantilat, MD, said at the symposium. “When you think about the future, what do you hope for?”

Often, the answers reveal not only “things beyond a cure that matter tremendously to the patient but things that we can help with,” said Dr. Pantilat, professor and chief of the Division of Palliative Medicine at the University of California San Francisco.

Dr. Pantilat recalled a patient with advanced pancreatic cancer who wished to see her daughter’s wedding in 10 months. He knew that was unlikely, but the discussion led to another solution.

Her daughter moved the wedding to the ICU.

Hope can persist and uplift even in the darkest of times, and “as clinicians, we need to be in the true hope business,” he said.

While some patients may wish for a cure, others may want more time with family or comfort in the face of suffering. People can “hope for all the things that can still be, despite the fact that there’s a lot of things that can’t,” he said.

However, fear that a patient will hope for a cure, and that the difficult discussions to follow might destroy hope or lead to false hope, sometimes means physicians won’t begin the conversation.

“We want to be honest with our patients — compassionate and kind, but honest — when we talk about their hopes,” Dr. Pantilat explained. Sometimes that means he needs to tell patients, “I wish that could happen. I wish I had a treatment that could make your cancer go away, but unfortunately, I don’t. So let’s think about what else we can do to help you.”

Having these difficult discussions matters. The evidence, although limited, indicates that feeling hopeful can improve patients’ well-being and may even boost their cancer outcomes.

One recent study found, for instance, that patients who reported feeling more hopeful also had lower levels of depression and anxiety. Early research also suggests that greater levels of hope may have a hand in reducing inflammation in patients with ovarian cancer and could even improve survival in some patients with advanced cancer.

For Dr. Leiter, while these lessons came early in his career as a palliative care physician, they persist and influence his practice today.

“I know that I could not have prevented Carlos’ death. None of us could have, and none of us could have protected his mother from the unimaginable grief that will stay with her for the rest of her life,” he said. “But I could have made things just a little bit less difficult for her.

“I could have acted as her guide rather than her cross-examiner,” he continued, explaining that he now sees hope as “a generous collaborator” that can coexist with rising creatinine levels, failing livers, and fears about intubation.

“As clinicians, we can always find space to hope with our patients and their families,” he said. “So now, years later when I sit with a terrified and grieving family and they tell me they hope their loved one gets better, I remember Carlos’ mother’s eyes piercing mine ... and I know how to respond: ‘I hope so, too.’ And I do.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO — Carlos, a 21-year-old, lay in a hospital bed, barely clinging to life. Following a stem cell transplant for leukemia, Carlos had developed a life-threatening case of graft-vs-host disease.

But Carlos’ mother had faith.

“I have hope things will get better,” she said, via interpreter, to Richard Leiter, MD, a palliative care doctor in training at that time.

“I hope they will,” Dr. Leiter told her.

“I should have stopped there,” said Dr. Leiter, recounting an early-career lesson on hope during the ASCO Voices session at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. “But in my eagerness to show my attending and myself that I could handle this conversation, I kept going, mistakenly.”

“But none of us think they will,” Dr. Leiter continued.

Carlos’ mother looked Dr. Leiter in the eye. “You want him to die,” she said.

“I knew, even then, that she was right,” recalled Dr. Leiter, now a palliative care physician at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although there was nothing he could do to save Carlos, Dr. Leiter also couldn’t sit with the extreme suffering. “The pain was too great,” Dr. Leiter said. “I needed her to adopt our narrative that we had done everything we could to help him live, and now, we would do everything we could to help his death be a comfortable one.”

But looking back, Dr. Leiter realized, “How could we have asked her to accept what was fundamentally unacceptable, to comprehend the incomprehensible?”

The Importance of Hope

Alan B. Astrow, MD, said during an ASCO symposium on “The Art and Science of Hope.”

“How we think about hope directly influences patient care,” said Dr. Astrow, chief of hematology and medical oncology at NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital and a professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City.

Hope, whatever it turns out to be neurobiologically, is “very much a gift” that underlies human existence, he said.

Physicians have the capacity to restore or shatter a patient’s hopes, and those who come to understand the importance of hope will wish to extend the gift to others, Dr. Astrow said.

Asking patients about their hopes is the “golden question,” Steven Z. Pantilat, MD, said at the symposium. “When you think about the future, what do you hope for?”

Often, the answers reveal not only “things beyond a cure that matter tremendously to the patient but things that we can help with,” said Dr. Pantilat, professor and chief of the Division of Palliative Medicine at the University of California San Francisco.

Dr. Pantilat recalled a patient with advanced pancreatic cancer who wished to see her daughter’s wedding in 10 months. He knew that was unlikely, but the discussion led to another solution.

Her daughter moved the wedding to the ICU.

Hope can persist and uplift even in the darkest of times, and “as clinicians, we need to be in the true hope business,” he said.

While some patients may wish for a cure, others may want more time with family or comfort in the face of suffering. People can “hope for all the things that can still be, despite the fact that there’s a lot of things that can’t,” he said.

However, fear that a patient will hope for a cure, and that the difficult discussions to follow might destroy hope or lead to false hope, sometimes means physicians won’t begin the conversation.

“We want to be honest with our patients — compassionate and kind, but honest — when we talk about their hopes,” Dr. Pantilat explained. Sometimes that means he needs to tell patients, “I wish that could happen. I wish I had a treatment that could make your cancer go away, but unfortunately, I don’t. So let’s think about what else we can do to help you.”

Having these difficult discussions matters. The evidence, although limited, indicates that feeling hopeful can improve patients’ well-being and may even boost their cancer outcomes.

One recent study found, for instance, that patients who reported feeling more hopeful also had lower levels of depression and anxiety. Early research also suggests that greater levels of hope may have a hand in reducing inflammation in patients with ovarian cancer and could even improve survival in some patients with advanced cancer.

For Dr. Leiter, while these lessons came early in his career as a palliative care physician, they persist and influence his practice today.

“I know that I could not have prevented Carlos’ death. None of us could have, and none of us could have protected his mother from the unimaginable grief that will stay with her for the rest of her life,” he said. “But I could have made things just a little bit less difficult for her.

“I could have acted as her guide rather than her cross-examiner,” he continued, explaining that he now sees hope as “a generous collaborator” that can coexist with rising creatinine levels, failing livers, and fears about intubation.

“As clinicians, we can always find space to hope with our patients and their families,” he said. “So now, years later when I sit with a terrified and grieving family and they tell me they hope their loved one gets better, I remember Carlos’ mother’s eyes piercing mine ... and I know how to respond: ‘I hope so, too.’ And I do.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASCO 2024

Lidocaine Effective Against Pediatric Migraine

SAN DIEGO — The treatment has long been used in adults, and frequently in children on the strength of observational evidence.

Prior Research

Most of the studies have been conducted in adults, and these were often in specific settings like the emergency department for status migrainosus, while outpatient studies were generally conducted in chronic migraine, according to presenting author Christina Szperka, MD. “The assumptions were a little bit different,” Dr. Szperka, director of the pediatric headache program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview.

Retrospective studies are also fraught with bias. “We’ve tried to look at retrospective data. People don’t necessarily report how they’re doing unless they come back, and so you lose a huge portion of kids,” said Dr. Szperka, who presented the research at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

“From a clinical perspective, I think it gives us additional evidence that what we’re doing makes a difference, and I think that will help us in terms of insurance coverage, because that’s really been a major barrier,” said Dr. Szperka.

The study also opens other avenues for research. “Just doing the greater occipital nerves only reduces the pain so much. So what’s the next step? Do I study additional injections? Do I do a study where I compare different medications?”

She previously conducted a study of how providers were using lidocaine injections, and “there was a large amount of variability, both in terms of what nerves are being injected, what medications they were using, the patient population, et cetera,” said Dr. Szperka. Previous observational studies have suggested efficacy in pediatric populations for transition and prevention of migraine, new daily persistent headache, posttraumatic headache, and post-shunt occipital neuralgia.

A Randomized, Controlled Trial

In the new study, 58 adolescents aged 7 to 21 (mean age, 16.0 years; 44 female) were initially treated with lidocaine cream. The patients were “relatively refractory,” said Dr. Szperka, with 25 having received intravenous medications and 6 having been inpatients. After 30 minutes, if they still had pain and consented to further treatment, Dr. Szperka performed bilateral greater occipital nerve injections with lidocaine or a saline placebo, and did additional injections after 30 minutes if there wasn’t sufficient improvement.

There was no significant change in pain after the lidocaine cream treatment, and all patients proceeded to be randomized to lidocaine or placebo injections. The primary outcome of 30-minute reduction in pain score ranked 0-10 favored the lidocaine group (2.3 vs 1.1; P = .013). There was a 2-point reduction in pain scores in 69% of the lidocaine group and 34% of the saline group (P = .009) and a higher frequency of pain relief from moderate/severe to no pain or mild (52% versus 24%; P = .03). There was no significant difference in pain freedom.

After 24 hours, the treatment group was more likely to experience pain relief from moderate/severe to no pain or mild (24% vs 3%; P = .05) and to be free from associated symptoms (48% vs 21%; P = .027). Pain at the injection site was significantly higher in the placebo group (5.4 vs 3.2), prompting a change in plans for future trials. “I don’t think I would do saline again, because I think it hurt them, and I don’t want to cause them harm,” said Dr. Szperka.

Adverse events were common, with all but one patient in the study experiencing at least one. “I think this is a couple of things: One, kids don’t like needles in their head. Nerve blocks hurt. And so it was not surprising in some ways that we had a very high rate of adverse events. We also consented them, and that had a long wait period, and there’s a lot of anxiety in the room. However, most of the adverse events were mild,” said Dr. Szperka.

Important Research in an Understudied Population

Laine Greene, MD, who moderated the session, was asked for comment. “I think it’s an important study. Occipital nerve blocks have been used for a long period of time in management of migraine and other headache disorders. The quality of the evidence has always been brought into question, especially from payers, but also a very important aspect to this is that a lot of clinical trials over time have not specifically been done in children or adolescents, so any work that is done in that age category is significantly helpful to advancing therapeutics,” said Dr. Greene, associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic Arizona.

Dr. Szperka has consulted for AbbVie and Teva, and serves on data safety and monitoring boards for Eli Lilly and Upsher-Smith. She has been a principal investigator in trials sponsored by Abbvie, Amgen, Biohaven/Pfizer, Teva, and Theranica. Dr. Greene has no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO — The treatment has long been used in adults, and frequently in children on the strength of observational evidence.

Prior Research

Most of the studies have been conducted in adults, and these were often in specific settings like the emergency department for status migrainosus, while outpatient studies were generally conducted in chronic migraine, according to presenting author Christina Szperka, MD. “The assumptions were a little bit different,” Dr. Szperka, director of the pediatric headache program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview.

Retrospective studies are also fraught with bias. “We’ve tried to look at retrospective data. People don’t necessarily report how they’re doing unless they come back, and so you lose a huge portion of kids,” said Dr. Szperka, who presented the research at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

“From a clinical perspective, I think it gives us additional evidence that what we’re doing makes a difference, and I think that will help us in terms of insurance coverage, because that’s really been a major barrier,” said Dr. Szperka.

The study also opens other avenues for research. “Just doing the greater occipital nerves only reduces the pain so much. So what’s the next step? Do I study additional injections? Do I do a study where I compare different medications?”

She previously conducted a study of how providers were using lidocaine injections, and “there was a large amount of variability, both in terms of what nerves are being injected, what medications they were using, the patient population, et cetera,” said Dr. Szperka. Previous observational studies have suggested efficacy in pediatric populations for transition and prevention of migraine, new daily persistent headache, posttraumatic headache, and post-shunt occipital neuralgia.

A Randomized, Controlled Trial

In the new study, 58 adolescents aged 7 to 21 (mean age, 16.0 years; 44 female) were initially treated with lidocaine cream. The patients were “relatively refractory,” said Dr. Szperka, with 25 having received intravenous medications and 6 having been inpatients. After 30 minutes, if they still had pain and consented to further treatment, Dr. Szperka performed bilateral greater occipital nerve injections with lidocaine or a saline placebo, and did additional injections after 30 minutes if there wasn’t sufficient improvement.

There was no significant change in pain after the lidocaine cream treatment, and all patients proceeded to be randomized to lidocaine or placebo injections. The primary outcome of 30-minute reduction in pain score ranked 0-10 favored the lidocaine group (2.3 vs 1.1; P = .013). There was a 2-point reduction in pain scores in 69% of the lidocaine group and 34% of the saline group (P = .009) and a higher frequency of pain relief from moderate/severe to no pain or mild (52% versus 24%; P = .03). There was no significant difference in pain freedom.

After 24 hours, the treatment group was more likely to experience pain relief from moderate/severe to no pain or mild (24% vs 3%; P = .05) and to be free from associated symptoms (48% vs 21%; P = .027). Pain at the injection site was significantly higher in the placebo group (5.4 vs 3.2), prompting a change in plans for future trials. “I don’t think I would do saline again, because I think it hurt them, and I don’t want to cause them harm,” said Dr. Szperka.

Adverse events were common, with all but one patient in the study experiencing at least one. “I think this is a couple of things: One, kids don’t like needles in their head. Nerve blocks hurt. And so it was not surprising in some ways that we had a very high rate of adverse events. We also consented them, and that had a long wait period, and there’s a lot of anxiety in the room. However, most of the adverse events were mild,” said Dr. Szperka.

Important Research in an Understudied Population

Laine Greene, MD, who moderated the session, was asked for comment. “I think it’s an important study. Occipital nerve blocks have been used for a long period of time in management of migraine and other headache disorders. The quality of the evidence has always been brought into question, especially from payers, but also a very important aspect to this is that a lot of clinical trials over time have not specifically been done in children or adolescents, so any work that is done in that age category is significantly helpful to advancing therapeutics,” said Dr. Greene, associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic Arizona.

Dr. Szperka has consulted for AbbVie and Teva, and serves on data safety and monitoring boards for Eli Lilly and Upsher-Smith. She has been a principal investigator in trials sponsored by Abbvie, Amgen, Biohaven/Pfizer, Teva, and Theranica. Dr. Greene has no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO — The treatment has long been used in adults, and frequently in children on the strength of observational evidence.

Prior Research

Most of the studies have been conducted in adults, and these were often in specific settings like the emergency department for status migrainosus, while outpatient studies were generally conducted in chronic migraine, according to presenting author Christina Szperka, MD. “The assumptions were a little bit different,” Dr. Szperka, director of the pediatric headache program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview.

Retrospective studies are also fraught with bias. “We’ve tried to look at retrospective data. People don’t necessarily report how they’re doing unless they come back, and so you lose a huge portion of kids,” said Dr. Szperka, who presented the research at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

“From a clinical perspective, I think it gives us additional evidence that what we’re doing makes a difference, and I think that will help us in terms of insurance coverage, because that’s really been a major barrier,” said Dr. Szperka.

The study also opens other avenues for research. “Just doing the greater occipital nerves only reduces the pain so much. So what’s the next step? Do I study additional injections? Do I do a study where I compare different medications?”

She previously conducted a study of how providers were using lidocaine injections, and “there was a large amount of variability, both in terms of what nerves are being injected, what medications they were using, the patient population, et cetera,” said Dr. Szperka. Previous observational studies have suggested efficacy in pediatric populations for transition and prevention of migraine, new daily persistent headache, posttraumatic headache, and post-shunt occipital neuralgia.

A Randomized, Controlled Trial

In the new study, 58 adolescents aged 7 to 21 (mean age, 16.0 years; 44 female) were initially treated with lidocaine cream. The patients were “relatively refractory,” said Dr. Szperka, with 25 having received intravenous medications and 6 having been inpatients. After 30 minutes, if they still had pain and consented to further treatment, Dr. Szperka performed bilateral greater occipital nerve injections with lidocaine or a saline placebo, and did additional injections after 30 minutes if there wasn’t sufficient improvement.

There was no significant change in pain after the lidocaine cream treatment, and all patients proceeded to be randomized to lidocaine or placebo injections. The primary outcome of 30-minute reduction in pain score ranked 0-10 favored the lidocaine group (2.3 vs 1.1; P = .013). There was a 2-point reduction in pain scores in 69% of the lidocaine group and 34% of the saline group (P = .009) and a higher frequency of pain relief from moderate/severe to no pain or mild (52% versus 24%; P = .03). There was no significant difference in pain freedom.

After 24 hours, the treatment group was more likely to experience pain relief from moderate/severe to no pain or mild (24% vs 3%; P = .05) and to be free from associated symptoms (48% vs 21%; P = .027). Pain at the injection site was significantly higher in the placebo group (5.4 vs 3.2), prompting a change in plans for future trials. “I don’t think I would do saline again, because I think it hurt them, and I don’t want to cause them harm,” said Dr. Szperka.

Adverse events were common, with all but one patient in the study experiencing at least one. “I think this is a couple of things: One, kids don’t like needles in their head. Nerve blocks hurt. And so it was not surprising in some ways that we had a very high rate of adverse events. We also consented them, and that had a long wait period, and there’s a lot of anxiety in the room. However, most of the adverse events were mild,” said Dr. Szperka.

Important Research in an Understudied Population

Laine Greene, MD, who moderated the session, was asked for comment. “I think it’s an important study. Occipital nerve blocks have been used for a long period of time in management of migraine and other headache disorders. The quality of the evidence has always been brought into question, especially from payers, but also a very important aspect to this is that a lot of clinical trials over time have not specifically been done in children or adolescents, so any work that is done in that age category is significantly helpful to advancing therapeutics,” said Dr. Greene, associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic Arizona.

Dr. Szperka has consulted for AbbVie and Teva, and serves on data safety and monitoring boards for Eli Lilly and Upsher-Smith. She has been a principal investigator in trials sponsored by Abbvie, Amgen, Biohaven/Pfizer, Teva, and Theranica. Dr. Greene has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AHS 2024

ChatGPT Enhances Readability of Cancer Information for Patients

TOPLINE:

The artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot ChatGPT can significantly improve the readability of online cancer-related patient information while maintaining the content’s quality, a recent study found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Patients with cancer often search for cancer information online after their diagnosis, with most seeking information from their oncologists’ websites. However, the online materials often exceed the average reading level of the US population, limiting accessibility and comprehension.

- Researchers asked ChatGPT 4.0 to rewrite content about breast, colon, lung, prostate, and pancreas cancer, aiming for a sixth-grade readability level. The content came from a random sample of documents from 34 patient-facing websites associated with National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) member institutions.

- Readability, accuracy, similarity, and quality of the rewritten content were assessed using several established metrics and tools, including an F1 score, which assesses the precision and recall of a machine-learning model; a cosine similarity score, which measures similarities and is often used to detect plagiarism; and the DISCERN instrument, which helps assess the quality of the AI-rewritten information.

- The primary outcome was the mean readability score for the original and AI-generated content.

TAKEAWAY:

- The original content had an average readability level equivalent to a university freshman (grade 13). Following the AI revision, the readability level improved to a high school freshman level (grade 9).

- The rewritten content had high accuracy, with an overall F1 score of 0.87 (a good score is 0.8-0.9).

- The rewritten content had a high cosine similarity score of 0.915 (scores range from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no similarity and 1 indicating complete similarity). Researchers attributed the improved readability to the use of simpler words and shorter sentences.

- Quality assessment using the DISCERN instrument showed that the AI-rewritten content maintained a “good” quality rating, similar to that of the original content.

IN PRACTICE:

Society has become increasingly dependent on online educational materials, and considering that more than half of Americans may not be literate beyond an eighth-grade level, our AI intervention offers a potential low-cost solution to narrow the gap between patient health literacy and content received from the nation’s leading cancer centers, the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Andres A. Abreu, MD, with UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, was published online in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was limited to English-language content from NCCN member websites, so the findings may not be generalizable to other sources or languages. Readability alone cannot guarantee comprehension. Factors such as material design and audiovisual aids were not evaluated.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not report a funding source. The authors reported several disclosures but none related to the study. Herbert J. Zeh disclosed serving as a scientific advisor for Surgical Safety Technologies; Dr. Polanco disclosed serving as a consultant for Iota Biosciences and Palisade Bio and as a proctor for Intuitive Surgical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot ChatGPT can significantly improve the readability of online cancer-related patient information while maintaining the content’s quality, a recent study found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Patients with cancer often search for cancer information online after their diagnosis, with most seeking information from their oncologists’ websites. However, the online materials often exceed the average reading level of the US population, limiting accessibility and comprehension.

- Researchers asked ChatGPT 4.0 to rewrite content about breast, colon, lung, prostate, and pancreas cancer, aiming for a sixth-grade readability level. The content came from a random sample of documents from 34 patient-facing websites associated with National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) member institutions.

- Readability, accuracy, similarity, and quality of the rewritten content were assessed using several established metrics and tools, including an F1 score, which assesses the precision and recall of a machine-learning model; a cosine similarity score, which measures similarities and is often used to detect plagiarism; and the DISCERN instrument, which helps assess the quality of the AI-rewritten information.

- The primary outcome was the mean readability score for the original and AI-generated content.

TAKEAWAY:

- The original content had an average readability level equivalent to a university freshman (grade 13). Following the AI revision, the readability level improved to a high school freshman level (grade 9).

- The rewritten content had high accuracy, with an overall F1 score of 0.87 (a good score is 0.8-0.9).

- The rewritten content had a high cosine similarity score of 0.915 (scores range from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no similarity and 1 indicating complete similarity). Researchers attributed the improved readability to the use of simpler words and shorter sentences.

- Quality assessment using the DISCERN instrument showed that the AI-rewritten content maintained a “good” quality rating, similar to that of the original content.

IN PRACTICE:

Society has become increasingly dependent on online educational materials, and considering that more than half of Americans may not be literate beyond an eighth-grade level, our AI intervention offers a potential low-cost solution to narrow the gap between patient health literacy and content received from the nation’s leading cancer centers, the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Andres A. Abreu, MD, with UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, was published online in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was limited to English-language content from NCCN member websites, so the findings may not be generalizable to other sources or languages. Readability alone cannot guarantee comprehension. Factors such as material design and audiovisual aids were not evaluated.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not report a funding source. The authors reported several disclosures but none related to the study. Herbert J. Zeh disclosed serving as a scientific advisor for Surgical Safety Technologies; Dr. Polanco disclosed serving as a consultant for Iota Biosciences and Palisade Bio and as a proctor for Intuitive Surgical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot ChatGPT can significantly improve the readability of online cancer-related patient information while maintaining the content’s quality, a recent study found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Patients with cancer often search for cancer information online after their diagnosis, with most seeking information from their oncologists’ websites. However, the online materials often exceed the average reading level of the US population, limiting accessibility and comprehension.

- Researchers asked ChatGPT 4.0 to rewrite content about breast, colon, lung, prostate, and pancreas cancer, aiming for a sixth-grade readability level. The content came from a random sample of documents from 34 patient-facing websites associated with National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) member institutions.

- Readability, accuracy, similarity, and quality of the rewritten content were assessed using several established metrics and tools, including an F1 score, which assesses the precision and recall of a machine-learning model; a cosine similarity score, which measures similarities and is often used to detect plagiarism; and the DISCERN instrument, which helps assess the quality of the AI-rewritten information.

- The primary outcome was the mean readability score for the original and AI-generated content.

TAKEAWAY:

- The original content had an average readability level equivalent to a university freshman (grade 13). Following the AI revision, the readability level improved to a high school freshman level (grade 9).

- The rewritten content had high accuracy, with an overall F1 score of 0.87 (a good score is 0.8-0.9).

- The rewritten content had a high cosine similarity score of 0.915 (scores range from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no similarity and 1 indicating complete similarity). Researchers attributed the improved readability to the use of simpler words and shorter sentences.

- Quality assessment using the DISCERN instrument showed that the AI-rewritten content maintained a “good” quality rating, similar to that of the original content.

IN PRACTICE:

Society has become increasingly dependent on online educational materials, and considering that more than half of Americans may not be literate beyond an eighth-grade level, our AI intervention offers a potential low-cost solution to narrow the gap between patient health literacy and content received from the nation’s leading cancer centers, the authors wrote.

SOURCE: