User login

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #9 for the ObGyn

For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Continue to the answer...

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Continue to the answer...

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Continue to the answer...

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

AAN updates treatment guidance on painful diabetic neuropathy

Painful diabetic neuropathy is very common and can greatly affect an individual’s quality of life, guideline author Brian Callaghan, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, noted in a news release.

“This guideline aims to help neurologists and other doctors provide the highest quality patient care based on the latest evidence,” Dr. Callaghan said.

The recommendations update the 2011 AAN guideline on the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. The new guidance was published online Dec. 27, 2021, in Neurology and has been endorsed by the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine.

Multiple options

To update the guideline, an expert panel reviewed data from more than 100 randomized controlled trials published from January 2008 to April 2020.

The panel noted that more than 16% of individuals with diabetes experience painful diabetic neuropathy, but it often goes unrecognized and untreated. The guideline recommends clinicians assess patients with diabetes for peripheral neuropathic pain and its effect on their function and quality of life.

Before prescribing treatment, health providers should determine if the patient also has mood or sleep problems as both can influence pain perception.

The guideline recommends offering one of four classes of oral medications found to be effective for neuropathic pain: tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, or imipramine; serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as duloxetine, venlafaxine, or desvenlafaxine; gabapentinoids such as gabapentin or pregabalin; and/or sodium channel blockers such as carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, or lacosamide.

All four classes of medications have “comparable effect sizes just above or just below our cutoff for a medium effect size” (standardized median difference, 0.5), the panel noted.

In addition, “new studies on sodium channel blockers published since the last guideline have resulted in these drugs now being recommended and considered as effective at providing pain relief as the other drug classes recommended in this guideline,” said Dr. Callaghan.

When an initial medication fails to provide meaningful improvement in pain, or produces significant side effects, a trial of another medication from a different class is recommended.

Pain reduction, not elimination

Opioids are not recommended for painful diabetic neuropathy. Not only do they come with risks, there is also no strong evidence they are effective for painful diabetic neuropathy in the long term, the panel wrote. Tramadol and tapentadol are also not recommended for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy.

“Current evidence suggests that the risks of the use of opioids for painful diabetic neuropathy therapy outweigh the benefits, so they should not be prescribed,” Dr. Callaghan said.

For patients interested in trying topical, nontraditional, or nondrug interventions to reduce pain, the guideline recommends a number of options including capsaicin, glyceryl trinitrate spray, and Citrullus colocynthis. Ginkgo biloba, exercise, mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and tai chi are also suggested.

“It is important to note that the recommended drugs and topical treatments in this guideline may not eliminate pain, but they have been shown to reduce pain,” Dr. Callaghan said. “The good news is there are many treatment options for painful diabetic neuropathy, so a treatment plan can be tailored specifically to each person living with this condition.”

Along with the updated guideline, the AAN has also published a new Polyneuropathy Quality Measurement Set to assist neurologists and other health care providers in treating patients with painful diabetic neuropathy.

The updated guideline was developed with financial support from the AAN.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Painful diabetic neuropathy is very common and can greatly affect an individual’s quality of life, guideline author Brian Callaghan, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, noted in a news release.

“This guideline aims to help neurologists and other doctors provide the highest quality patient care based on the latest evidence,” Dr. Callaghan said.

The recommendations update the 2011 AAN guideline on the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. The new guidance was published online Dec. 27, 2021, in Neurology and has been endorsed by the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine.

Multiple options

To update the guideline, an expert panel reviewed data from more than 100 randomized controlled trials published from January 2008 to April 2020.

The panel noted that more than 16% of individuals with diabetes experience painful diabetic neuropathy, but it often goes unrecognized and untreated. The guideline recommends clinicians assess patients with diabetes for peripheral neuropathic pain and its effect on their function and quality of life.

Before prescribing treatment, health providers should determine if the patient also has mood or sleep problems as both can influence pain perception.

The guideline recommends offering one of four classes of oral medications found to be effective for neuropathic pain: tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, or imipramine; serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as duloxetine, venlafaxine, or desvenlafaxine; gabapentinoids such as gabapentin or pregabalin; and/or sodium channel blockers such as carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, or lacosamide.

All four classes of medications have “comparable effect sizes just above or just below our cutoff for a medium effect size” (standardized median difference, 0.5), the panel noted.

In addition, “new studies on sodium channel blockers published since the last guideline have resulted in these drugs now being recommended and considered as effective at providing pain relief as the other drug classes recommended in this guideline,” said Dr. Callaghan.

When an initial medication fails to provide meaningful improvement in pain, or produces significant side effects, a trial of another medication from a different class is recommended.

Pain reduction, not elimination

Opioids are not recommended for painful diabetic neuropathy. Not only do they come with risks, there is also no strong evidence they are effective for painful diabetic neuropathy in the long term, the panel wrote. Tramadol and tapentadol are also not recommended for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy.

“Current evidence suggests that the risks of the use of opioids for painful diabetic neuropathy therapy outweigh the benefits, so they should not be prescribed,” Dr. Callaghan said.

For patients interested in trying topical, nontraditional, or nondrug interventions to reduce pain, the guideline recommends a number of options including capsaicin, glyceryl trinitrate spray, and Citrullus colocynthis. Ginkgo biloba, exercise, mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and tai chi are also suggested.

“It is important to note that the recommended drugs and topical treatments in this guideline may not eliminate pain, but they have been shown to reduce pain,” Dr. Callaghan said. “The good news is there are many treatment options for painful diabetic neuropathy, so a treatment plan can be tailored specifically to each person living with this condition.”

Along with the updated guideline, the AAN has also published a new Polyneuropathy Quality Measurement Set to assist neurologists and other health care providers in treating patients with painful diabetic neuropathy.

The updated guideline was developed with financial support from the AAN.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Painful diabetic neuropathy is very common and can greatly affect an individual’s quality of life, guideline author Brian Callaghan, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, noted in a news release.

“This guideline aims to help neurologists and other doctors provide the highest quality patient care based on the latest evidence,” Dr. Callaghan said.

The recommendations update the 2011 AAN guideline on the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. The new guidance was published online Dec. 27, 2021, in Neurology and has been endorsed by the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine.

Multiple options

To update the guideline, an expert panel reviewed data from more than 100 randomized controlled trials published from January 2008 to April 2020.

The panel noted that more than 16% of individuals with diabetes experience painful diabetic neuropathy, but it often goes unrecognized and untreated. The guideline recommends clinicians assess patients with diabetes for peripheral neuropathic pain and its effect on their function and quality of life.

Before prescribing treatment, health providers should determine if the patient also has mood or sleep problems as both can influence pain perception.

The guideline recommends offering one of four classes of oral medications found to be effective for neuropathic pain: tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, or imipramine; serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as duloxetine, venlafaxine, or desvenlafaxine; gabapentinoids such as gabapentin or pregabalin; and/or sodium channel blockers such as carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, or lacosamide.

All four classes of medications have “comparable effect sizes just above or just below our cutoff for a medium effect size” (standardized median difference, 0.5), the panel noted.

In addition, “new studies on sodium channel blockers published since the last guideline have resulted in these drugs now being recommended and considered as effective at providing pain relief as the other drug classes recommended in this guideline,” said Dr. Callaghan.

When an initial medication fails to provide meaningful improvement in pain, or produces significant side effects, a trial of another medication from a different class is recommended.

Pain reduction, not elimination

Opioids are not recommended for painful diabetic neuropathy. Not only do they come with risks, there is also no strong evidence they are effective for painful diabetic neuropathy in the long term, the panel wrote. Tramadol and tapentadol are also not recommended for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy.

“Current evidence suggests that the risks of the use of opioids for painful diabetic neuropathy therapy outweigh the benefits, so they should not be prescribed,” Dr. Callaghan said.

For patients interested in trying topical, nontraditional, or nondrug interventions to reduce pain, the guideline recommends a number of options including capsaicin, glyceryl trinitrate spray, and Citrullus colocynthis. Ginkgo biloba, exercise, mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and tai chi are also suggested.

“It is important to note that the recommended drugs and topical treatments in this guideline may not eliminate pain, but they have been shown to reduce pain,” Dr. Callaghan said. “The good news is there are many treatment options for painful diabetic neuropathy, so a treatment plan can be tailored specifically to each person living with this condition.”

Along with the updated guideline, the AAN has also published a new Polyneuropathy Quality Measurement Set to assist neurologists and other health care providers in treating patients with painful diabetic neuropathy.

The updated guideline was developed with financial support from the AAN.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Posttraumatic epilepsy is common, even after ‘mild’ TBI

, new research suggests.

Results from a multicenter, prospective cohort study showed 2.7% of nearly 1,500 participants with TBI reported also having posttraumatic epilepsy, and these patients had significantly worse outcomes than those without posttraumatic epilepsy.

“Posttraumatic epilepsy is common even in so-called mild TBI, and we should be on the lookout for patients reporting these kinds of spells,” said coinvestigator Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, PhD, professor of neurology and director of the TBI Clinical Research Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Dr. Diaz-Arrastia said he dislikes the term “mild TBI” because many of these injuries have “pretty substantial consequences.”

The findings were published online Dec. 29 in JAMA Network Open.

Novel study

Seizures can occur after TBI, most commonly after a severe brain injury, such as those leading to coma or bleeding in the brain or requiring surgical intervention. However, there have been “hints” that some patients with milder brain injuries are also at increased risk for epilepsy, said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

To investigate, the researchers assessed data from the large, multicenter Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury (TRACK-TBI) database. Participants with TBI, defined as a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 3-15, had presented to a level I trauma center within 24 hours of a head trauma needing evaluation with a CT scan.

The study included patients with relatively mild TBI (GCS score, 13-15), which is a “novel feature” of the study, the authors noted. Most prior studies of posttraumatic epilepsy focused on moderate to severe TBI.

The researchers included two sex- and age-matched control groups. The orthopedic trauma control (OTC) group consisted of patients with isolated trauma to the limbs, pelvis, and/or ribs. The “friend” or peer control group had backgrounds and lifestyles similar to those with TBI but had no history of TBI, concussion, or traumatic injury in the previous year.

The analysis included 1,885 participants (mean age, 41.3 years; 65.8% men). Of these, 1,493 had TBI, 182 were in the OTC group, and 210 were in the friends group. At 6- and 12-month follow-ups, investigators administered the Epilepsy Screening Questionnaire (ESQ), developed by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

Confirmatory data

Participants were asked about experiencing uncontrolled movements, unexplained changes in mental state, and repeated unusual attacks or convulsions, and whether they had been told they had epilepsy or seizures. If they answered yes to any of these questions, they received second-level screening, which asked about seizures.

Patients were deemed to have posttraumatic epilepsy if they answered affirmatively to any first-level screening item, experienced seizures 7 days after injury, and were diagnosed with epilepsy.

The primary outcome was rate of positive posttraumatic epilepsy diagnoses. At 12 months, 2.7% of those with TBI reported a posttraumatic epilepsy diagnosis compared with none of either of the control groups (P < .001).

This rate is consistent with prior literature and is “pretty close to what we expected,” said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

Among those with TBI and posttraumatic epilepsy, 12.2% had GCS scores of 3-8 (severe), 5.3% had scores of 9-12 (moderate), and 0.9% had scores of 13-15 (mild). That figure for mild TBI is not insignificant, said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

“Probably 90% of all those coming to the emergency room with a brain injury are diagnosed with mild TBI not requiring admission,” he noted.

The risk for posttraumatic epilepsy was higher the more severe the head injury, and among those with hemorrhage on head CT imaging. In patients with mild TBI, hemorrhage was associated with a two- to threefold risk of developing posttraumatic epilepsy.

“This prospective observational study confirms the epidemiologic data that even after mild brain injury, there is an increased risk for epilepsy,” said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

Universal screening?

The researchers also looked at whether seizures worsen other outcomes. Compared with those who had TBI but not posttraumatic epilepsy, those with posttraumatic epilepsy had significantly lower Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE) scores (mean, 4.7 vs. 6.1; P < .001), higher Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) scores (58.6 vs. 50.2; P = .02), and higher Rivermead Cognitive Metric (RCM) scores (5.3 vs. 3.1; P = .002) at 12 months after adjustment for age, initial GCS score, and imaging findings.

Higher GOSE and RCM scores reflect better outcomes, but a higher score on the BSI, which assesses overall mood, reflects a worse outcome, the investigators noted.

Previous evidence suggests prophylactic use of antiepileptic drugs in patients with TBI does not reduce risks. These drugs “are neither 100% safe nor 100% effective,” said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia. Some studies showed that certain agents actually worsen outcomes, he added.

What the field needs instead are antiepileptogenic drugs – those that interfere with the maladaptive synaptic plasticity that ends up in an epileptic circuit, he noted.

The new results suggest screening for posttraumatic epilepsy using the NINDS-ESQ “should be done pretty much routinely as a follow-up for all brain injuries,” Dr. Diaz-Arrastia said.

The investigators plan to have study participants assessed by an epileptologist later. A significant number of people with TBI, he noted, won’t develop posttraumatic epilepsy until 1-5 years after their injury – and even later in some cases.

A limitation of the study was that some patients reporting posttraumatic epilepsy may have had psychogenic nonepileptiform seizures, which are common in TBI patients, the investigators noted.

The study was supported by grants from One Mind, National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS, and Department of Defence. Dr. Diaz-Arrastia reported receiving grants from the NIH, NINDS, and DOD during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a multicenter, prospective cohort study showed 2.7% of nearly 1,500 participants with TBI reported also having posttraumatic epilepsy, and these patients had significantly worse outcomes than those without posttraumatic epilepsy.

“Posttraumatic epilepsy is common even in so-called mild TBI, and we should be on the lookout for patients reporting these kinds of spells,” said coinvestigator Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, PhD, professor of neurology and director of the TBI Clinical Research Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Dr. Diaz-Arrastia said he dislikes the term “mild TBI” because many of these injuries have “pretty substantial consequences.”

The findings were published online Dec. 29 in JAMA Network Open.

Novel study

Seizures can occur after TBI, most commonly after a severe brain injury, such as those leading to coma or bleeding in the brain or requiring surgical intervention. However, there have been “hints” that some patients with milder brain injuries are also at increased risk for epilepsy, said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

To investigate, the researchers assessed data from the large, multicenter Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury (TRACK-TBI) database. Participants with TBI, defined as a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 3-15, had presented to a level I trauma center within 24 hours of a head trauma needing evaluation with a CT scan.

The study included patients with relatively mild TBI (GCS score, 13-15), which is a “novel feature” of the study, the authors noted. Most prior studies of posttraumatic epilepsy focused on moderate to severe TBI.

The researchers included two sex- and age-matched control groups. The orthopedic trauma control (OTC) group consisted of patients with isolated trauma to the limbs, pelvis, and/or ribs. The “friend” or peer control group had backgrounds and lifestyles similar to those with TBI but had no history of TBI, concussion, or traumatic injury in the previous year.

The analysis included 1,885 participants (mean age, 41.3 years; 65.8% men). Of these, 1,493 had TBI, 182 were in the OTC group, and 210 were in the friends group. At 6- and 12-month follow-ups, investigators administered the Epilepsy Screening Questionnaire (ESQ), developed by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

Confirmatory data

Participants were asked about experiencing uncontrolled movements, unexplained changes in mental state, and repeated unusual attacks or convulsions, and whether they had been told they had epilepsy or seizures. If they answered yes to any of these questions, they received second-level screening, which asked about seizures.

Patients were deemed to have posttraumatic epilepsy if they answered affirmatively to any first-level screening item, experienced seizures 7 days after injury, and were diagnosed with epilepsy.

The primary outcome was rate of positive posttraumatic epilepsy diagnoses. At 12 months, 2.7% of those with TBI reported a posttraumatic epilepsy diagnosis compared with none of either of the control groups (P < .001).

This rate is consistent with prior literature and is “pretty close to what we expected,” said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

Among those with TBI and posttraumatic epilepsy, 12.2% had GCS scores of 3-8 (severe), 5.3% had scores of 9-12 (moderate), and 0.9% had scores of 13-15 (mild). That figure for mild TBI is not insignificant, said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

“Probably 90% of all those coming to the emergency room with a brain injury are diagnosed with mild TBI not requiring admission,” he noted.

The risk for posttraumatic epilepsy was higher the more severe the head injury, and among those with hemorrhage on head CT imaging. In patients with mild TBI, hemorrhage was associated with a two- to threefold risk of developing posttraumatic epilepsy.

“This prospective observational study confirms the epidemiologic data that even after mild brain injury, there is an increased risk for epilepsy,” said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

Universal screening?

The researchers also looked at whether seizures worsen other outcomes. Compared with those who had TBI but not posttraumatic epilepsy, those with posttraumatic epilepsy had significantly lower Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE) scores (mean, 4.7 vs. 6.1; P < .001), higher Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) scores (58.6 vs. 50.2; P = .02), and higher Rivermead Cognitive Metric (RCM) scores (5.3 vs. 3.1; P = .002) at 12 months after adjustment for age, initial GCS score, and imaging findings.

Higher GOSE and RCM scores reflect better outcomes, but a higher score on the BSI, which assesses overall mood, reflects a worse outcome, the investigators noted.

Previous evidence suggests prophylactic use of antiepileptic drugs in patients with TBI does not reduce risks. These drugs “are neither 100% safe nor 100% effective,” said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia. Some studies showed that certain agents actually worsen outcomes, he added.

What the field needs instead are antiepileptogenic drugs – those that interfere with the maladaptive synaptic plasticity that ends up in an epileptic circuit, he noted.

The new results suggest screening for posttraumatic epilepsy using the NINDS-ESQ “should be done pretty much routinely as a follow-up for all brain injuries,” Dr. Diaz-Arrastia said.

The investigators plan to have study participants assessed by an epileptologist later. A significant number of people with TBI, he noted, won’t develop posttraumatic epilepsy until 1-5 years after their injury – and even later in some cases.

A limitation of the study was that some patients reporting posttraumatic epilepsy may have had psychogenic nonepileptiform seizures, which are common in TBI patients, the investigators noted.

The study was supported by grants from One Mind, National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS, and Department of Defence. Dr. Diaz-Arrastia reported receiving grants from the NIH, NINDS, and DOD during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a multicenter, prospective cohort study showed 2.7% of nearly 1,500 participants with TBI reported also having posttraumatic epilepsy, and these patients had significantly worse outcomes than those without posttraumatic epilepsy.

“Posttraumatic epilepsy is common even in so-called mild TBI, and we should be on the lookout for patients reporting these kinds of spells,” said coinvestigator Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, PhD, professor of neurology and director of the TBI Clinical Research Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Dr. Diaz-Arrastia said he dislikes the term “mild TBI” because many of these injuries have “pretty substantial consequences.”

The findings were published online Dec. 29 in JAMA Network Open.

Novel study

Seizures can occur after TBI, most commonly after a severe brain injury, such as those leading to coma or bleeding in the brain or requiring surgical intervention. However, there have been “hints” that some patients with milder brain injuries are also at increased risk for epilepsy, said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

To investigate, the researchers assessed data from the large, multicenter Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury (TRACK-TBI) database. Participants with TBI, defined as a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 3-15, had presented to a level I trauma center within 24 hours of a head trauma needing evaluation with a CT scan.

The study included patients with relatively mild TBI (GCS score, 13-15), which is a “novel feature” of the study, the authors noted. Most prior studies of posttraumatic epilepsy focused on moderate to severe TBI.

The researchers included two sex- and age-matched control groups. The orthopedic trauma control (OTC) group consisted of patients with isolated trauma to the limbs, pelvis, and/or ribs. The “friend” or peer control group had backgrounds and lifestyles similar to those with TBI but had no history of TBI, concussion, or traumatic injury in the previous year.

The analysis included 1,885 participants (mean age, 41.3 years; 65.8% men). Of these, 1,493 had TBI, 182 were in the OTC group, and 210 were in the friends group. At 6- and 12-month follow-ups, investigators administered the Epilepsy Screening Questionnaire (ESQ), developed by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

Confirmatory data

Participants were asked about experiencing uncontrolled movements, unexplained changes in mental state, and repeated unusual attacks or convulsions, and whether they had been told they had epilepsy or seizures. If they answered yes to any of these questions, they received second-level screening, which asked about seizures.

Patients were deemed to have posttraumatic epilepsy if they answered affirmatively to any first-level screening item, experienced seizures 7 days after injury, and were diagnosed with epilepsy.

The primary outcome was rate of positive posttraumatic epilepsy diagnoses. At 12 months, 2.7% of those with TBI reported a posttraumatic epilepsy diagnosis compared with none of either of the control groups (P < .001).

This rate is consistent with prior literature and is “pretty close to what we expected,” said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

Among those with TBI and posttraumatic epilepsy, 12.2% had GCS scores of 3-8 (severe), 5.3% had scores of 9-12 (moderate), and 0.9% had scores of 13-15 (mild). That figure for mild TBI is not insignificant, said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

“Probably 90% of all those coming to the emergency room with a brain injury are diagnosed with mild TBI not requiring admission,” he noted.

The risk for posttraumatic epilepsy was higher the more severe the head injury, and among those with hemorrhage on head CT imaging. In patients with mild TBI, hemorrhage was associated with a two- to threefold risk of developing posttraumatic epilepsy.

“This prospective observational study confirms the epidemiologic data that even after mild brain injury, there is an increased risk for epilepsy,” said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia.

Universal screening?

The researchers also looked at whether seizures worsen other outcomes. Compared with those who had TBI but not posttraumatic epilepsy, those with posttraumatic epilepsy had significantly lower Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE) scores (mean, 4.7 vs. 6.1; P < .001), higher Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) scores (58.6 vs. 50.2; P = .02), and higher Rivermead Cognitive Metric (RCM) scores (5.3 vs. 3.1; P = .002) at 12 months after adjustment for age, initial GCS score, and imaging findings.

Higher GOSE and RCM scores reflect better outcomes, but a higher score on the BSI, which assesses overall mood, reflects a worse outcome, the investigators noted.

Previous evidence suggests prophylactic use of antiepileptic drugs in patients with TBI does not reduce risks. These drugs “are neither 100% safe nor 100% effective,” said Dr. Diaz-Arrastia. Some studies showed that certain agents actually worsen outcomes, he added.

What the field needs instead are antiepileptogenic drugs – those that interfere with the maladaptive synaptic plasticity that ends up in an epileptic circuit, he noted.

The new results suggest screening for posttraumatic epilepsy using the NINDS-ESQ “should be done pretty much routinely as a follow-up for all brain injuries,” Dr. Diaz-Arrastia said.

The investigators plan to have study participants assessed by an epileptologist later. A significant number of people with TBI, he noted, won’t develop posttraumatic epilepsy until 1-5 years after their injury – and even later in some cases.

A limitation of the study was that some patients reporting posttraumatic epilepsy may have had psychogenic nonepileptiform seizures, which are common in TBI patients, the investigators noted.

The study was supported by grants from One Mind, National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS, and Department of Defence. Dr. Diaz-Arrastia reported receiving grants from the NIH, NINDS, and DOD during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity prevention in infants benefits second-born too

According to a statement from the National Institutes of Health, who funded the study, it is the first such infant obesity intervention to show the spillover effect. Findings were published online Dec. 21, 2021, in Obesity.

The program is called Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories (INSIGHT) responsive parenting (RP) intervention, and it included guidance on feeding, sleep, interactive play, and regulating emotion.

Parents were given guidance by nurses who came to their homes on how to respond when their child is drowsy, sleeping, fussy, and alert. They also learned how to put infants to bed drowsy, but awake, and avoid feeding infants to get them to sleep; how to respond to infants waking up at night; when to start solid foods; how to limit inactive time; and how to use growth charts.

The control group program focused on safety and matched the guidance categories. For example, early visits included information on prevention of sudden infant death syndrome for sleep, breast milk storage and formula for feeding, and safe bathing.

Jennifer S. Savage, Center for Childhood Obesity Research, Penn State University, University Park, led the study that enrolled 117 infants in a randomized controlled trial. Mother and firstborn children were randomized to the RP or home safety intervention (control) group 10-14 days after delivery. Their second-born siblings were enrolled in an observation-only ancillary study.

Second-born children were delivered 2.5 (standard deviation, 0.9) years after firstborns. Anthropometrics were measured in both siblings at ages 3, 16, 28, and 52 weeks.

Firstborn children at 1 year had a body mass index (BMI) that was 0.44 kg/m2 lower than the control group (95% confidence interval, −0.82 to −0.06), and second-born children whose parents received the RP intervention with their first child had BMI that was 0.36 kg/m2 lower.

“What we saw here is that it worked again,” coauthor Ian Paul, MD, MSc, professor of pediatrics and public health sciences at Penn State University, Hershey, said in an interview.

“Once we imprint them with a certain approach to parenting with the first child, they’re doing the same thing with the second child, which is wonderful to see,” he said.

He noted that this happened with second children without any reinforcements or booster information.

Dr. Paul said it’s still not clear which of the interventions – whether related to feeding techniques or sleeping or activity – helps most. And for each family the problematic behaviors may be different.

Responsive parenting programs have shown success previously among firstborns, the authors wrote, but 80% of those children grow up with younger siblings, so an intervention that also benefits them is important.

Weighing the costs of the intervention

The intervention was extensive. It involved four hour-plus nurse visits a year, often by the same nurse who built a relationship with the family.

But Ms. Savage said that it is possible to replicate INSIGHT on a larger scale in the United States with the dozens of home visitation models.

“Currently, 21 home visitation models meet the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services criteria for evidence of effectiveness, such as Nurse Family Partnership, Family Check-up, and Early Head Start Home Based Option. There is an opportunity to use home visitation models at the national scale to potentially interrupt the cycle of poor multigenerational outcomes such as obesity,” she said.

Dr. Paul said the initial investment “can save money in the long term,” given what’s at stake. “We know that 20%-25% of 2- to 5-year-olds are already overweight or obese and if they are already overweight or obese at that age, that;’s likely to persist.”

However, he acknowledged that staff shortages and costs are a challenge.

“Other countries have made that investment in their health care system,” he said. “In the U.S. only a fraction of new mothers and babies get home visitation. The kind of work that we did for obesity prevention has not yet been incorporated into evidence-based models of home visitation, though it certainly could be.”

Dr. Paul said his team is hoping to collaborate with others in the near future on expanding this program to such models of home visitation.

Telehealth, though a less desirable option, compared with in-home visits, could also be utilized, he said.

Short of the comprehensive intervention, he said, many of the concepts can be put into practice by pediatricians and parents.

Dr. Paul noted that the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has endorsed “responsive feeding” as the preferred approach to feeding infants and toddlers. Responsive feeding – helping parents recognize hunger and satiety cues as opposed to other distress cues – is a big part of the intervention.

“Feeding to soothe is not the preferred approach,” he said. “Food and milk and formula should be used for hunger.” That’s something pediatricians may not be stressing to parents, he said.

Pediatricians can also counsel parents on not using food as a reward. “We shouldn’t be giving kids M&Ms to teach them how to potty train,” he said.

‘Promising’ findings

Charles Wood, MD, a childhood obesity specialist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was not part of the study, called the findings “very promising.”

It also makes sense that the “aha moments” of first-time parents learning from the INSIGHT intervention would carry over to the second sibling, he said.

Dr. Wood agreed costs are a big factor. However, he said, the potential downstream costs of not preventing obesity are worse. And this study indicates the benefits may keep spreading with future siblings.

Dr. Wood said accessing obesity interventions outside the pediatrician visit can also help. Connecting patients with support groups or dietitians or with a counselor from Women, Infants, and Children can help. However, consistent messaging among the providers is key, he noted.

Dr. Wood’s research group is investigating text messaging platforms so parents can get answer to real-time questions, such as those about feeding behaviors.

He pointed to a limitation the authors mention, which is that the study was done in mostly White, highly educated, higher-income families.

“There’s a big problem with racial disparities and obesity,” Dr. Wood noted. “We definitely need solutions that address disparities as well.”

Mothers included in the study had given birth for the first time and their infants were enrolled after birth from a single maternity ward between January 2012 and March 2014. Major eligibility criteria were that the babies were full term (at least 37 weeks’ gestation), single births, and delivered to English-speaking mothers at least 20 years of age. Infants who weighed less than 2,500 g at birth were excluded.

The paper’s authors and Dr. Wood declared no relevant financial relationships.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; and the Department of Agriculture.

According to a statement from the National Institutes of Health, who funded the study, it is the first such infant obesity intervention to show the spillover effect. Findings were published online Dec. 21, 2021, in Obesity.

The program is called Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories (INSIGHT) responsive parenting (RP) intervention, and it included guidance on feeding, sleep, interactive play, and regulating emotion.

Parents were given guidance by nurses who came to their homes on how to respond when their child is drowsy, sleeping, fussy, and alert. They also learned how to put infants to bed drowsy, but awake, and avoid feeding infants to get them to sleep; how to respond to infants waking up at night; when to start solid foods; how to limit inactive time; and how to use growth charts.

The control group program focused on safety and matched the guidance categories. For example, early visits included information on prevention of sudden infant death syndrome for sleep, breast milk storage and formula for feeding, and safe bathing.

Jennifer S. Savage, Center for Childhood Obesity Research, Penn State University, University Park, led the study that enrolled 117 infants in a randomized controlled trial. Mother and firstborn children were randomized to the RP or home safety intervention (control) group 10-14 days after delivery. Their second-born siblings were enrolled in an observation-only ancillary study.

Second-born children were delivered 2.5 (standard deviation, 0.9) years after firstborns. Anthropometrics were measured in both siblings at ages 3, 16, 28, and 52 weeks.

Firstborn children at 1 year had a body mass index (BMI) that was 0.44 kg/m2 lower than the control group (95% confidence interval, −0.82 to −0.06), and second-born children whose parents received the RP intervention with their first child had BMI that was 0.36 kg/m2 lower.

“What we saw here is that it worked again,” coauthor Ian Paul, MD, MSc, professor of pediatrics and public health sciences at Penn State University, Hershey, said in an interview.

“Once we imprint them with a certain approach to parenting with the first child, they’re doing the same thing with the second child, which is wonderful to see,” he said.

He noted that this happened with second children without any reinforcements or booster information.

Dr. Paul said it’s still not clear which of the interventions – whether related to feeding techniques or sleeping or activity – helps most. And for each family the problematic behaviors may be different.

Responsive parenting programs have shown success previously among firstborns, the authors wrote, but 80% of those children grow up with younger siblings, so an intervention that also benefits them is important.

Weighing the costs of the intervention

The intervention was extensive. It involved four hour-plus nurse visits a year, often by the same nurse who built a relationship with the family.

But Ms. Savage said that it is possible to replicate INSIGHT on a larger scale in the United States with the dozens of home visitation models.

“Currently, 21 home visitation models meet the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services criteria for evidence of effectiveness, such as Nurse Family Partnership, Family Check-up, and Early Head Start Home Based Option. There is an opportunity to use home visitation models at the national scale to potentially interrupt the cycle of poor multigenerational outcomes such as obesity,” she said.

Dr. Paul said the initial investment “can save money in the long term,” given what’s at stake. “We know that 20%-25% of 2- to 5-year-olds are already overweight or obese and if they are already overweight or obese at that age, that;’s likely to persist.”

However, he acknowledged that staff shortages and costs are a challenge.

“Other countries have made that investment in their health care system,” he said. “In the U.S. only a fraction of new mothers and babies get home visitation. The kind of work that we did for obesity prevention has not yet been incorporated into evidence-based models of home visitation, though it certainly could be.”

Dr. Paul said his team is hoping to collaborate with others in the near future on expanding this program to such models of home visitation.

Telehealth, though a less desirable option, compared with in-home visits, could also be utilized, he said.

Short of the comprehensive intervention, he said, many of the concepts can be put into practice by pediatricians and parents.

Dr. Paul noted that the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has endorsed “responsive feeding” as the preferred approach to feeding infants and toddlers. Responsive feeding – helping parents recognize hunger and satiety cues as opposed to other distress cues – is a big part of the intervention.

“Feeding to soothe is not the preferred approach,” he said. “Food and milk and formula should be used for hunger.” That’s something pediatricians may not be stressing to parents, he said.

Pediatricians can also counsel parents on not using food as a reward. “We shouldn’t be giving kids M&Ms to teach them how to potty train,” he said.

‘Promising’ findings

Charles Wood, MD, a childhood obesity specialist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was not part of the study, called the findings “very promising.”

It also makes sense that the “aha moments” of first-time parents learning from the INSIGHT intervention would carry over to the second sibling, he said.

Dr. Wood agreed costs are a big factor. However, he said, the potential downstream costs of not preventing obesity are worse. And this study indicates the benefits may keep spreading with future siblings.

Dr. Wood said accessing obesity interventions outside the pediatrician visit can also help. Connecting patients with support groups or dietitians or with a counselor from Women, Infants, and Children can help. However, consistent messaging among the providers is key, he noted.

Dr. Wood’s research group is investigating text messaging platforms so parents can get answer to real-time questions, such as those about feeding behaviors.

He pointed to a limitation the authors mention, which is that the study was done in mostly White, highly educated, higher-income families.

“There’s a big problem with racial disparities and obesity,” Dr. Wood noted. “We definitely need solutions that address disparities as well.”

Mothers included in the study had given birth for the first time and their infants were enrolled after birth from a single maternity ward between January 2012 and March 2014. Major eligibility criteria were that the babies were full term (at least 37 weeks’ gestation), single births, and delivered to English-speaking mothers at least 20 years of age. Infants who weighed less than 2,500 g at birth were excluded.

The paper’s authors and Dr. Wood declared no relevant financial relationships.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; and the Department of Agriculture.

According to a statement from the National Institutes of Health, who funded the study, it is the first such infant obesity intervention to show the spillover effect. Findings were published online Dec. 21, 2021, in Obesity.

The program is called Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories (INSIGHT) responsive parenting (RP) intervention, and it included guidance on feeding, sleep, interactive play, and regulating emotion.

Parents were given guidance by nurses who came to their homes on how to respond when their child is drowsy, sleeping, fussy, and alert. They also learned how to put infants to bed drowsy, but awake, and avoid feeding infants to get them to sleep; how to respond to infants waking up at night; when to start solid foods; how to limit inactive time; and how to use growth charts.

The control group program focused on safety and matched the guidance categories. For example, early visits included information on prevention of sudden infant death syndrome for sleep, breast milk storage and formula for feeding, and safe bathing.

Jennifer S. Savage, Center for Childhood Obesity Research, Penn State University, University Park, led the study that enrolled 117 infants in a randomized controlled trial. Mother and firstborn children were randomized to the RP or home safety intervention (control) group 10-14 days after delivery. Their second-born siblings were enrolled in an observation-only ancillary study.

Second-born children were delivered 2.5 (standard deviation, 0.9) years after firstborns. Anthropometrics were measured in both siblings at ages 3, 16, 28, and 52 weeks.

Firstborn children at 1 year had a body mass index (BMI) that was 0.44 kg/m2 lower than the control group (95% confidence interval, −0.82 to −0.06), and second-born children whose parents received the RP intervention with their first child had BMI that was 0.36 kg/m2 lower.

“What we saw here is that it worked again,” coauthor Ian Paul, MD, MSc, professor of pediatrics and public health sciences at Penn State University, Hershey, said in an interview.

“Once we imprint them with a certain approach to parenting with the first child, they’re doing the same thing with the second child, which is wonderful to see,” he said.

He noted that this happened with second children without any reinforcements or booster information.

Dr. Paul said it’s still not clear which of the interventions – whether related to feeding techniques or sleeping or activity – helps most. And for each family the problematic behaviors may be different.

Responsive parenting programs have shown success previously among firstborns, the authors wrote, but 80% of those children grow up with younger siblings, so an intervention that also benefits them is important.

Weighing the costs of the intervention

The intervention was extensive. It involved four hour-plus nurse visits a year, often by the same nurse who built a relationship with the family.

But Ms. Savage said that it is possible to replicate INSIGHT on a larger scale in the United States with the dozens of home visitation models.

“Currently, 21 home visitation models meet the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services criteria for evidence of effectiveness, such as Nurse Family Partnership, Family Check-up, and Early Head Start Home Based Option. There is an opportunity to use home visitation models at the national scale to potentially interrupt the cycle of poor multigenerational outcomes such as obesity,” she said.

Dr. Paul said the initial investment “can save money in the long term,” given what’s at stake. “We know that 20%-25% of 2- to 5-year-olds are already overweight or obese and if they are already overweight or obese at that age, that;’s likely to persist.”

However, he acknowledged that staff shortages and costs are a challenge.

“Other countries have made that investment in their health care system,” he said. “In the U.S. only a fraction of new mothers and babies get home visitation. The kind of work that we did for obesity prevention has not yet been incorporated into evidence-based models of home visitation, though it certainly could be.”

Dr. Paul said his team is hoping to collaborate with others in the near future on expanding this program to such models of home visitation.

Telehealth, though a less desirable option, compared with in-home visits, could also be utilized, he said.

Short of the comprehensive intervention, he said, many of the concepts can be put into practice by pediatricians and parents.

Dr. Paul noted that the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has endorsed “responsive feeding” as the preferred approach to feeding infants and toddlers. Responsive feeding – helping parents recognize hunger and satiety cues as opposed to other distress cues – is a big part of the intervention.

“Feeding to soothe is not the preferred approach,” he said. “Food and milk and formula should be used for hunger.” That’s something pediatricians may not be stressing to parents, he said.

Pediatricians can also counsel parents on not using food as a reward. “We shouldn’t be giving kids M&Ms to teach them how to potty train,” he said.

‘Promising’ findings

Charles Wood, MD, a childhood obesity specialist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was not part of the study, called the findings “very promising.”

It also makes sense that the “aha moments” of first-time parents learning from the INSIGHT intervention would carry over to the second sibling, he said.

Dr. Wood agreed costs are a big factor. However, he said, the potential downstream costs of not preventing obesity are worse. And this study indicates the benefits may keep spreading with future siblings.

Dr. Wood said accessing obesity interventions outside the pediatrician visit can also help. Connecting patients with support groups or dietitians or with a counselor from Women, Infants, and Children can help. However, consistent messaging among the providers is key, he noted.

Dr. Wood’s research group is investigating text messaging platforms so parents can get answer to real-time questions, such as those about feeding behaviors.

He pointed to a limitation the authors mention, which is that the study was done in mostly White, highly educated, higher-income families.

“There’s a big problem with racial disparities and obesity,” Dr. Wood noted. “We definitely need solutions that address disparities as well.”

Mothers included in the study had given birth for the first time and their infants were enrolled after birth from a single maternity ward between January 2012 and March 2014. Major eligibility criteria were that the babies were full term (at least 37 weeks’ gestation), single births, and delivered to English-speaking mothers at least 20 years of age. Infants who weighed less than 2,500 g at birth were excluded.

The paper’s authors and Dr. Wood declared no relevant financial relationships.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; and the Department of Agriculture.

FROM OBESITY

Herpes Zoster Following a Nucleoside-Modified Messenger RNA COVID-19 Vaccine

Since the end of 2019, COVID-19 infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 has spread in a worldwide pandemic. The first cutaneous manifestations possibly linked to COVID-19 were reported in spring 2020.1 Herpes zoster (HZ) was suspected as a predictive cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 with a debated prognostic significance.2 The end of 2020 was marked with the beginning of vaccination against COVID-19, and safety studies reported few side effects after vaccination with nucleoside-modified messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines.3 Real-life use of vaccines could lead to the occurrence of potential side effects (or fortuitous medical events) that were not observed in these studies. We report a series of 5 cases of HZ occurring after vaccination with a nucleoside-modified mRNA COVID-19 vaccine extracted from a declarative cohort of cutaneous reactions in our vaccination center.

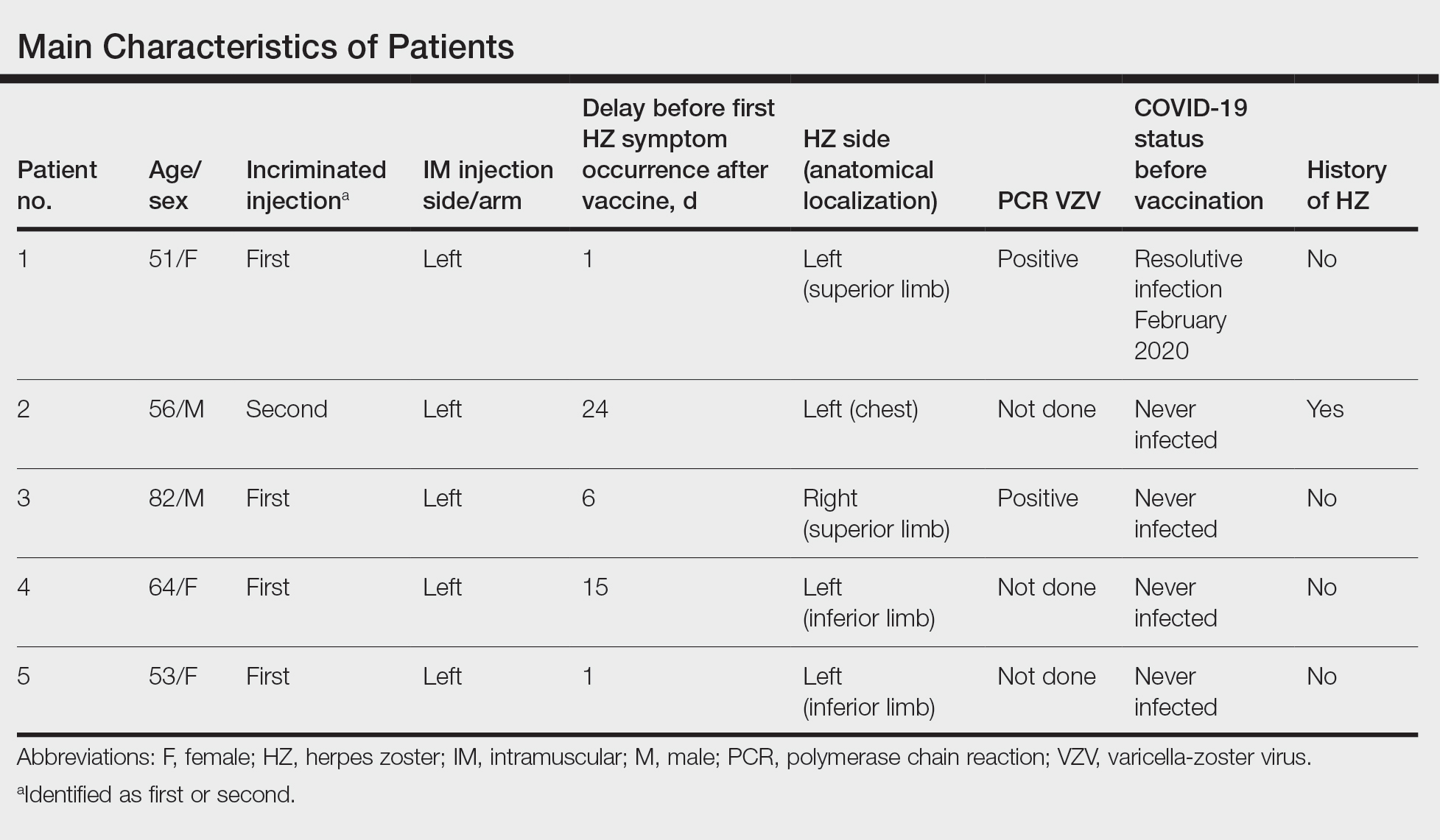

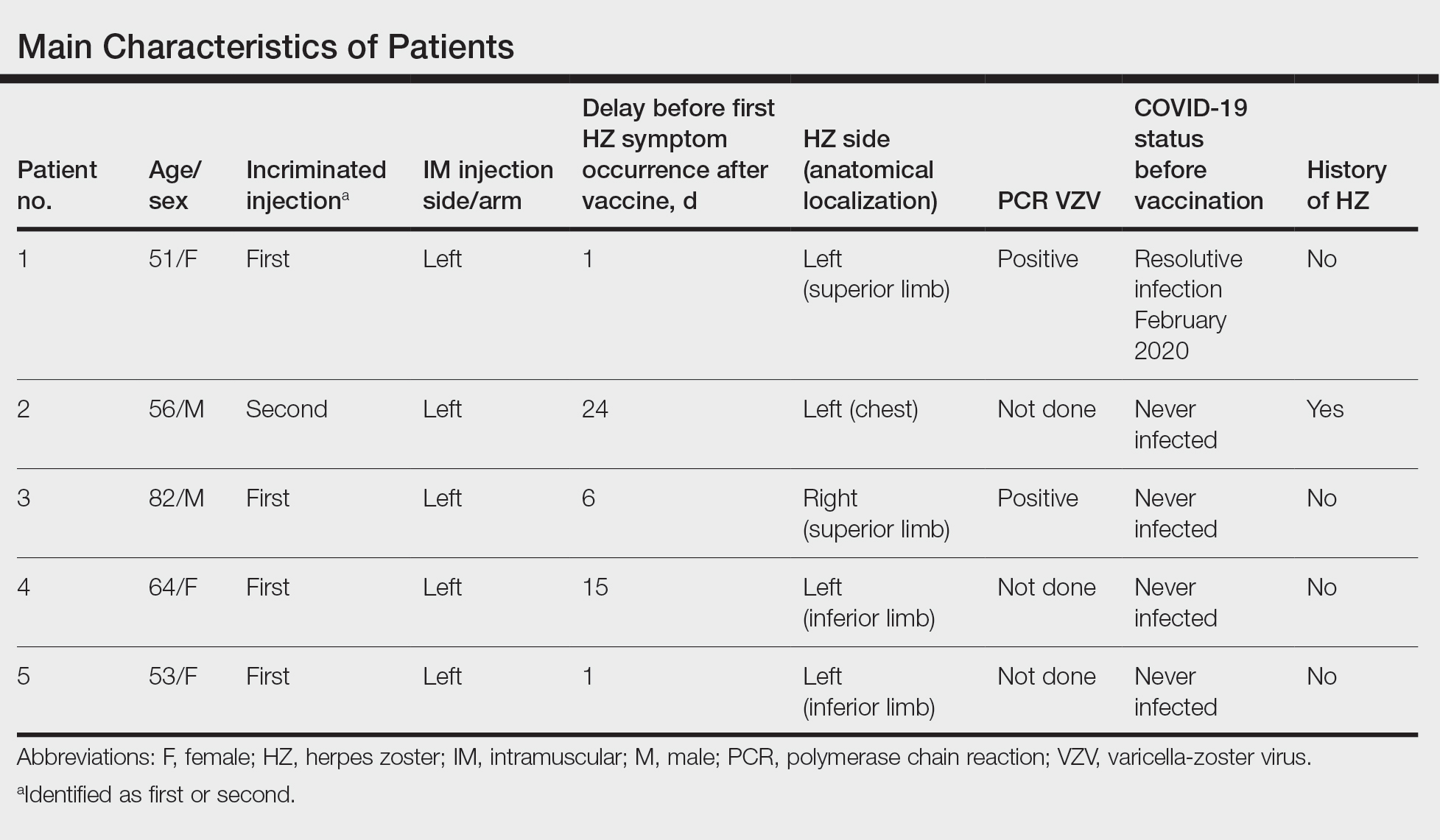

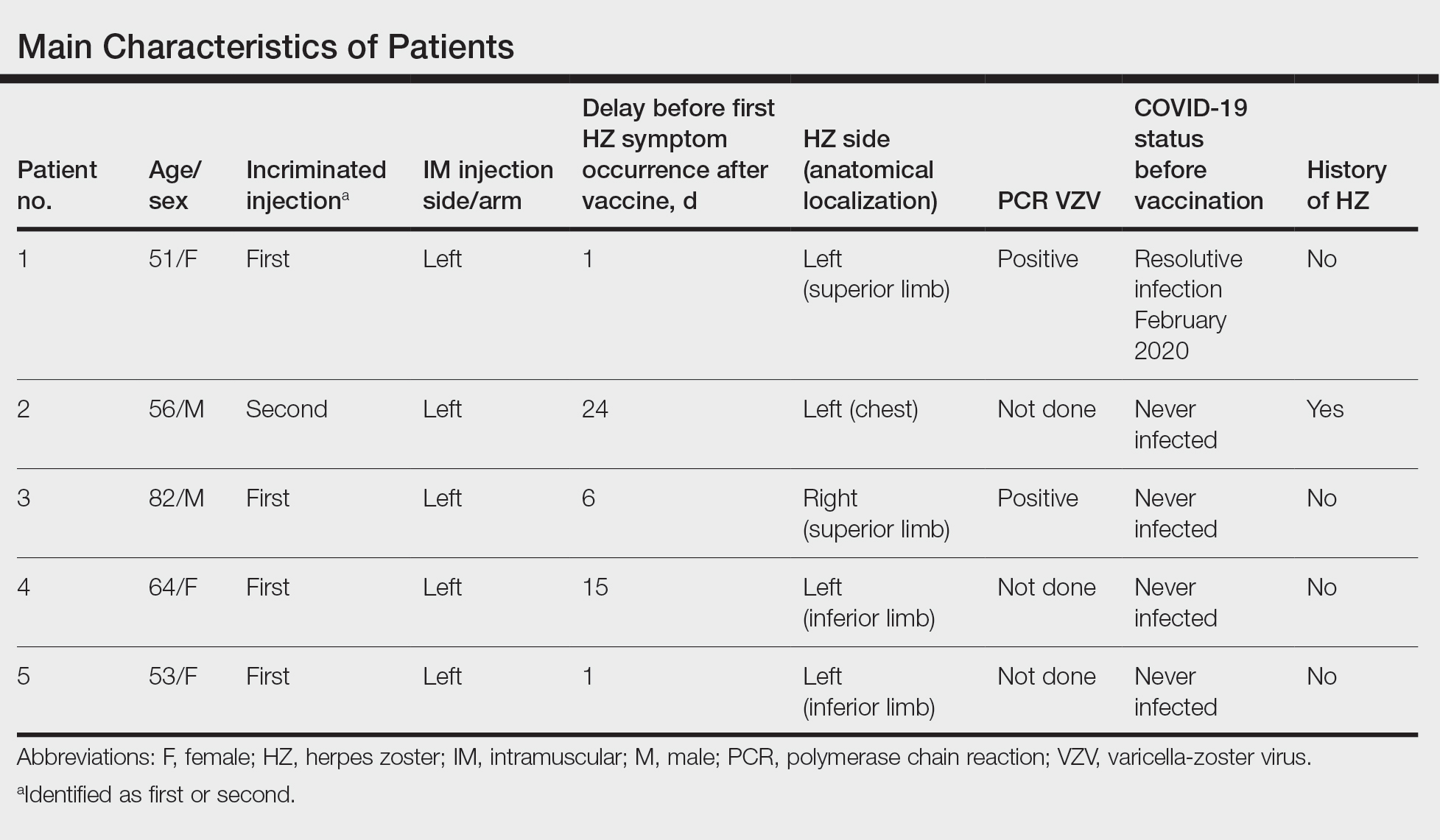

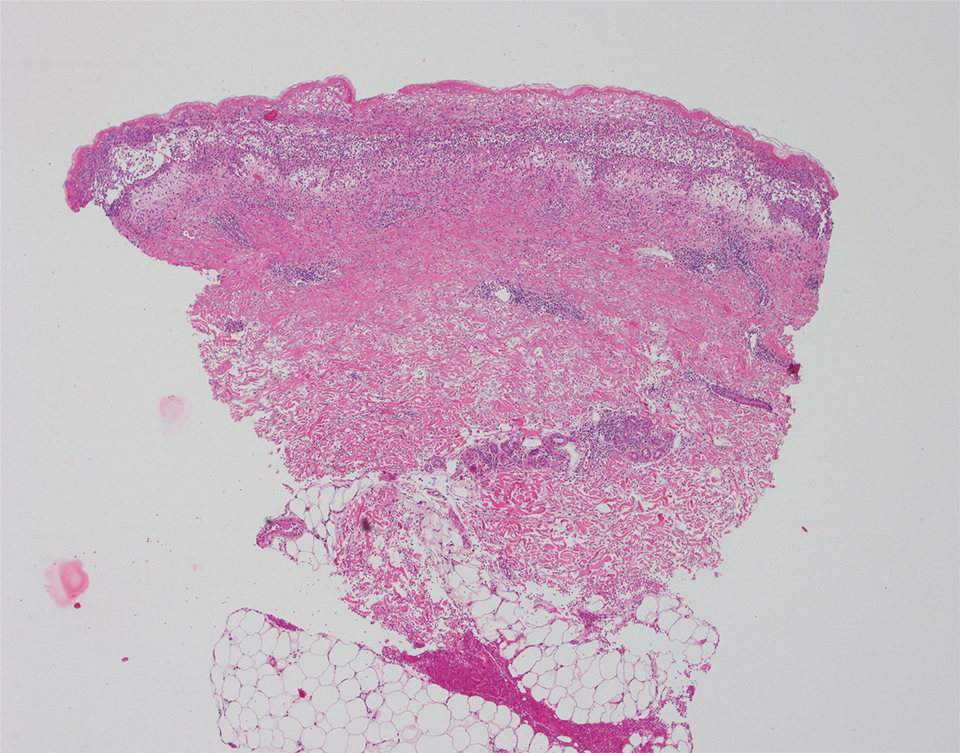

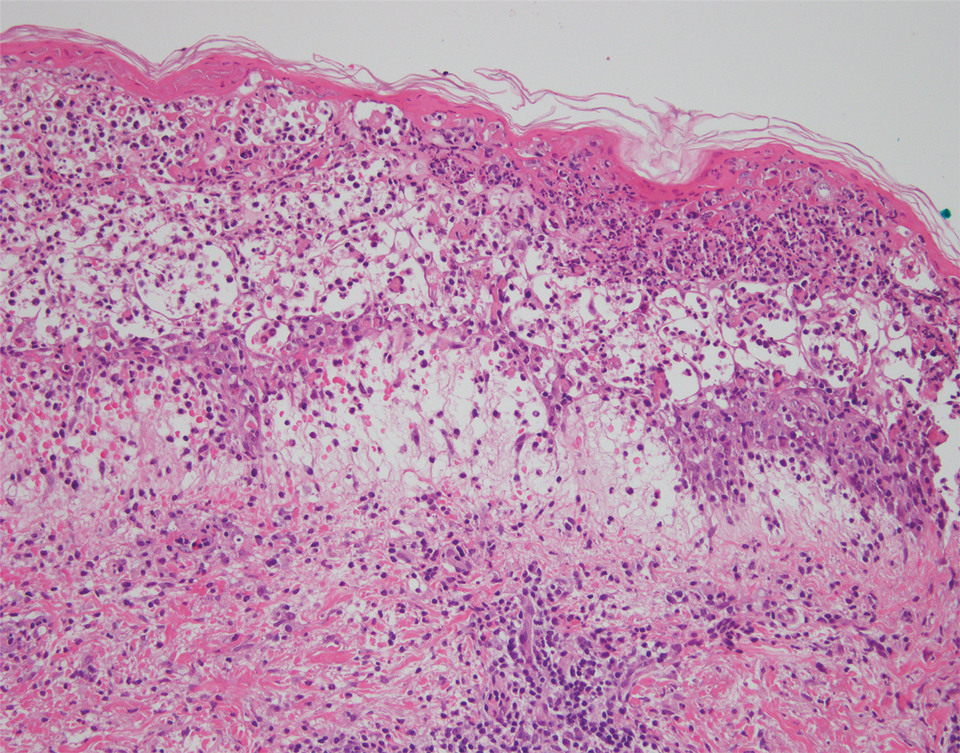

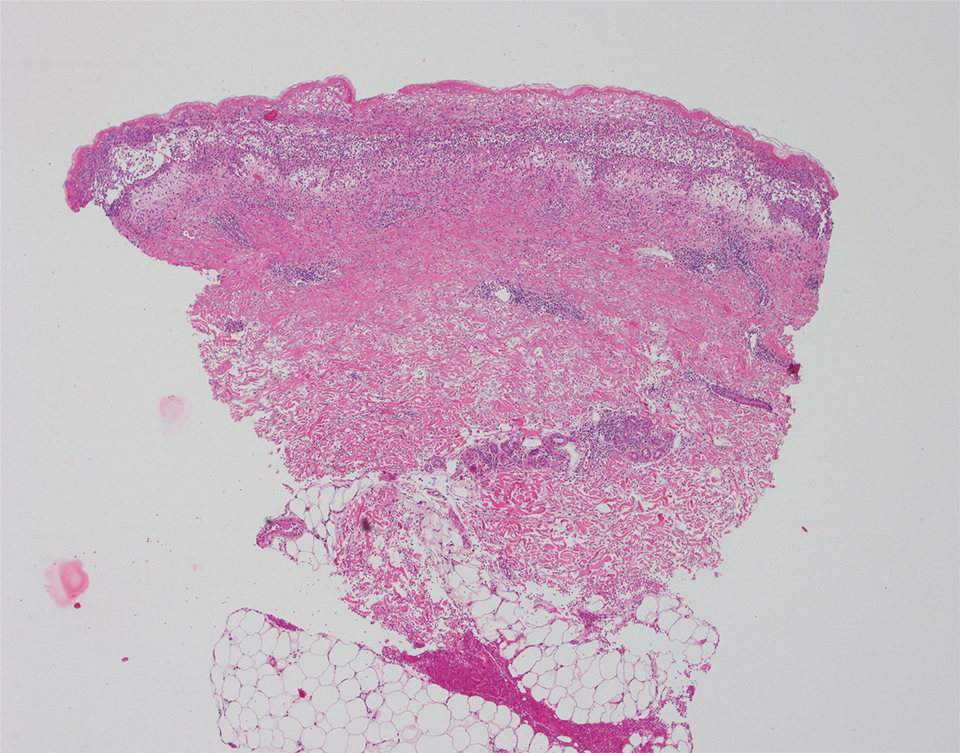

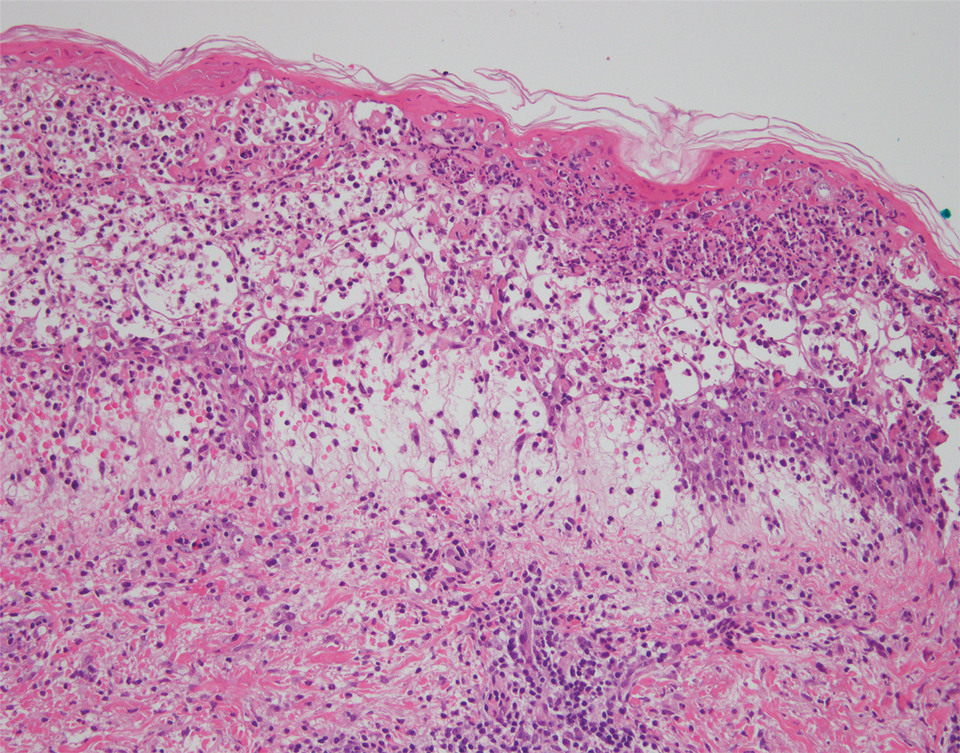

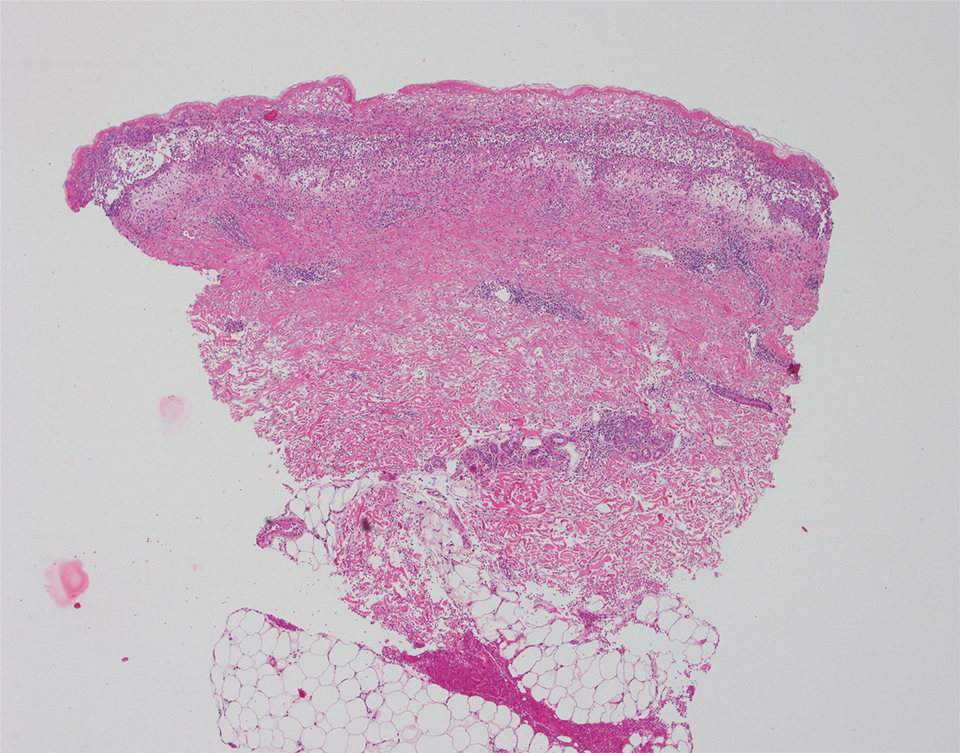

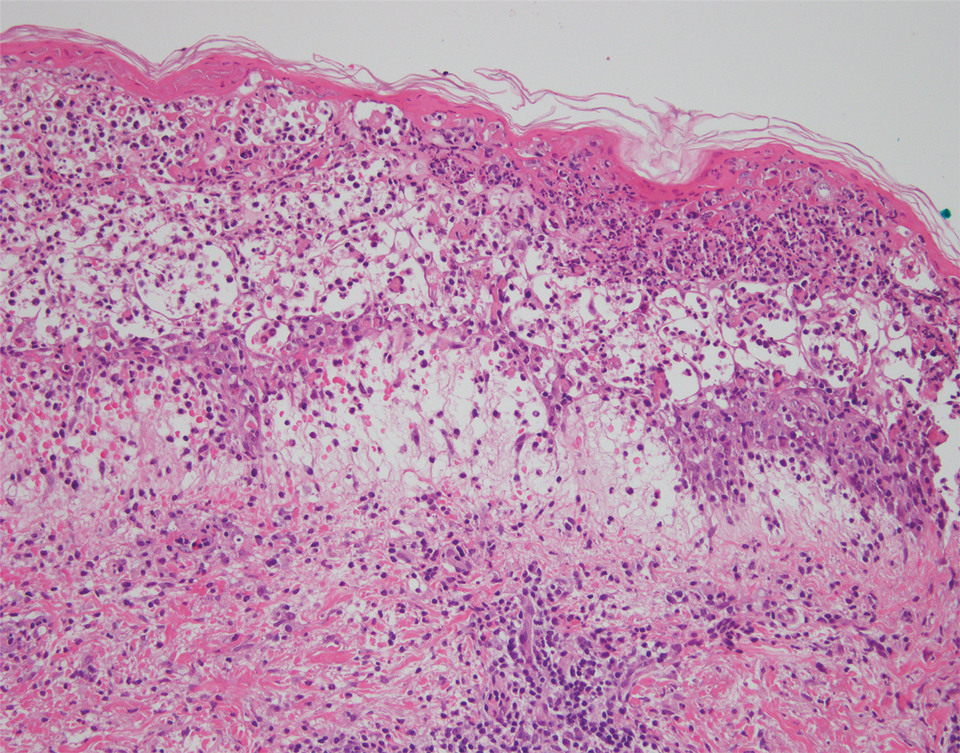

Case Series

We identified 2 men and 3 women (Table) who experienced HZ after vaccination with a nucleoside-modified mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty, Pfizer-BioNTech). Patients fulfilled French governmental criteria for vaccination at the time of the report—older than 75 years or a health care professional—and they were vaccinated at the vaccination center of a French university hospital. The median age of the patients was 56 years (interquartile range [IQR], 51–82 years). One patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 in February 2020. A medical history of HZ was found in 1 patient. No medical history of immunosuppression was noted. Herpes zoster was observed on the same side of the body as the vaccination site in 4 patients. The median delay before the onset of symptoms was 6 days (IQR, 1–15 days) after injection. The median duration of the symptoms was 13 days (IQR, 11.5–16.5 days). Clinical signs of HZ were mild with few vesicles in 4 patients, and we observed a notably long delay between the onset of pain and the eruption of vesicles in 2 cases (4 and 10 days, respectively). The clinical diagnosis of HZ was confirmed by a dermatologist for all patients (Figures 1 and 2). Polymerase chain reaction assays for the detection of the varicella-zoster virus were performed in 2 cases and were positive. A complete blood cell count was performed in 1 patient, and we observed isolated lymphopenia (500/mm3 [reference range, 1000–4000/mm3]). Herpes zoster occurred after the first dose of vaccine in 4 patients and after the second dose for 1 patient. Three patients were treated with antiviral therapy (acyclovir) for 7 days. Three patients recovered from symptoms within 2 weeks and 2 patients within 1 week.

Comment

We report a series of HZ cases occurring after vaccination with a nucleoside-modified mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. We did not observe complicated HZ, and most of the time, HZ lesions were located on the same side of the body as the vaccine injection. One case of HZ after COVID-19 vaccination was reported by Bostan and Yalici-Armagan,4 but it followed injection with an inactivated vaccine, which is different from our series. Herpes zoster remains rarely reported, mainly following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination.5

Cases of HZ after vaccination have been reported after the live attenuated zoster or yellow fever vaccines, but HZ should not appear as a concomitant effect after any type of vaccines.6,7 Kawai et al8 reported that the incidence rate of HZ ranged from 3 to 5 cases per 1000 person-years in North America, Europe, and Asia-Pacific. The risk for recurrence of HZ ranged from 1% to 6% depending on the type of study design, age distribution of studied populations, and definition.8 In another retrospective database analysis in Israel, the incidence density rate of HZ was 3.46 cases per 1000 person-years in the total population and 12.8 cases per 1000 person-years in immunocompromised patients, therefore the immunocompromised status is important to consider.9

In our declarative cohort of skin eruptions before vaccination, we recorded 11 cases of HZ among 148 skin eruptions (7.43%) at the time of the study, but the design of the study did not allow us to estimate the exact incidence of HZ in the global COVID-19–vaccinated population because our study was not based on a systematic and prospective analysis of all vaccinated patients. The comparison between the prevalence of HZ in the COVID-19–vaccinated population and the nonvaccinated population is difficult owing to the lack of data about HZ in the nonvaccinated population at the time of our analysis. Furthermore, we did not include all vaccinated patients in a prospective follow-up. We highlight the importance of medical history of patients that differed between vaccinated patients (at the time of our analysis) and the global population due to French governmental access criteria to vaccination. The link to prior SARS-CoV-2 infection was uncertain because a medical history of COVID-19 was found in only 1 patient. Only 1 patient had a history of HZ, which is not a contraindication of COVID-19 vaccination.

Postinjection pains are frequent with COVID-19 vaccines, but clinical signs such as extension of pain, burning sensation, and eruption of vesicles should lead the physician to consider the diagnosis of HZ, regardless of the delay between the injection and the symptoms. Indeed, the onset of symptoms could be late, and the clinical presentation initially may be mistaken for an injection-site reaction, which is a frequent known side effect of vaccines. These new cases do not prove causality between COVID-19 vaccination and HZ. Varicella-zoster virus remains latent in dorsal-root or ganglia after primary infection, and HZ caused by reactivation of varicella-zoster virus may occur spontaneously or be triggered. In our series, we did not observe medical history of immunosuppression, and no other known risk factors of HZ (eg, radiation therapy, physical trauma, fever after vaccination) were recorded. The pathophysiologic mechanism remains elusive, but local vaccine-induced immunomodulation or an inflammatory state may be involved.

Conclusion

Our case series highlights that clinicians must remain vigilant to diagnose HZ early to prevent potential complications, such as postherpetic neuralgia. Also, vaccination should not be contraindicated in patients with medical history of HZ; the occurrence of HZ does not justify avoiding the second injection of the vaccine due to the benefit of vaccination.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E212-E213.

- Elsaie ML, Youssef EA, Nada HA. Herpes zoster might be an indicator for latent COVID 19 infection. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13666.

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615.

- Bostan E, Yalici-Armagan B. Herpes zoster following inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: a coexistence or coincidence? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1566-1567.

- Desai HD, Sharma K, Shah A, et al. Can SARS-CoV-2 vaccine increase the risk of reactivation of varicella zoster? a systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3350-3361.

- Fahlbusch M, Wesselmann U, Lehmann P. Herpes zoster after varicella-zoster vaccination [in German]. Hautarzt. 2013;64:107-109.

- Bayas JM, González-Alvarez R, Guinovart C. Herpes zoster after yellow fever vaccination. J Travel Med. 2007;14:65-66.

- Kawai K, Gebremeskel BG, Acosta CJ. Systematic review of incidence and complications of herpes zoster: towards a global perspective. BMJ Open. 2014;10;4:E004833.

- Weitzman D, Shavit O, Stein M, et al. A population based study of the epidemiology of herpes zoster and its complications. J Infect. 2013;67:463-469.

Since the end of 2019, COVID-19 infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 has spread in a worldwide pandemic. The first cutaneous manifestations possibly linked to COVID-19 were reported in spring 2020.1 Herpes zoster (HZ) was suspected as a predictive cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 with a debated prognostic significance.2 The end of 2020 was marked with the beginning of vaccination against COVID-19, and safety studies reported few side effects after vaccination with nucleoside-modified messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines.3 Real-life use of vaccines could lead to the occurrence of potential side effects (or fortuitous medical events) that were not observed in these studies. We report a series of 5 cases of HZ occurring after vaccination with a nucleoside-modified mRNA COVID-19 vaccine extracted from a declarative cohort of cutaneous reactions in our vaccination center.

Case Series

We identified 2 men and 3 women (Table) who experienced HZ after vaccination with a nucleoside-modified mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty, Pfizer-BioNTech). Patients fulfilled French governmental criteria for vaccination at the time of the report—older than 75 years or a health care professional—and they were vaccinated at the vaccination center of a French university hospital. The median age of the patients was 56 years (interquartile range [IQR], 51–82 years). One patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 in February 2020. A medical history of HZ was found in 1 patient. No medical history of immunosuppression was noted. Herpes zoster was observed on the same side of the body as the vaccination site in 4 patients. The median delay before the onset of symptoms was 6 days (IQR, 1–15 days) after injection. The median duration of the symptoms was 13 days (IQR, 11.5–16.5 days). Clinical signs of HZ were mild with few vesicles in 4 patients, and we observed a notably long delay between the onset of pain and the eruption of vesicles in 2 cases (4 and 10 days, respectively). The clinical diagnosis of HZ was confirmed by a dermatologist for all patients (Figures 1 and 2). Polymerase chain reaction assays for the detection of the varicella-zoster virus were performed in 2 cases and were positive. A complete blood cell count was performed in 1 patient, and we observed isolated lymphopenia (500/mm3 [reference range, 1000–4000/mm3]). Herpes zoster occurred after the first dose of vaccine in 4 patients and after the second dose for 1 patient. Three patients were treated with antiviral therapy (acyclovir) for 7 days. Three patients recovered from symptoms within 2 weeks and 2 patients within 1 week.

Comment

We report a series of HZ cases occurring after vaccination with a nucleoside-modified mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. We did not observe complicated HZ, and most of the time, HZ lesions were located on the same side of the body as the vaccine injection. One case of HZ after COVID-19 vaccination was reported by Bostan and Yalici-Armagan,4 but it followed injection with an inactivated vaccine, which is different from our series. Herpes zoster remains rarely reported, mainly following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination.5

Cases of HZ after vaccination have been reported after the live attenuated zoster or yellow fever vaccines, but HZ should not appear as a concomitant effect after any type of vaccines.6,7 Kawai et al8 reported that the incidence rate of HZ ranged from 3 to 5 cases per 1000 person-years in North America, Europe, and Asia-Pacific. The risk for recurrence of HZ ranged from 1% to 6% depending on the type of study design, age distribution of studied populations, and definition.8 In another retrospective database analysis in Israel, the incidence density rate of HZ was 3.46 cases per 1000 person-years in the total population and 12.8 cases per 1000 person-years in immunocompromised patients, therefore the immunocompromised status is important to consider.9

In our declarative cohort of skin eruptions before vaccination, we recorded 11 cases of HZ among 148 skin eruptions (7.43%) at the time of the study, but the design of the study did not allow us to estimate the exact incidence of HZ in the global COVID-19–vaccinated population because our study was not based on a systematic and prospective analysis of all vaccinated patients. The comparison between the prevalence of HZ in the COVID-19–vaccinated population and the nonvaccinated population is difficult owing to the lack of data about HZ in the nonvaccinated population at the time of our analysis. Furthermore, we did not include all vaccinated patients in a prospective follow-up. We highlight the importance of medical history of patients that differed between vaccinated patients (at the time of our analysis) and the global population due to French governmental access criteria to vaccination. The link to prior SARS-CoV-2 infection was uncertain because a medical history of COVID-19 was found in only 1 patient. Only 1 patient had a history of HZ, which is not a contraindication of COVID-19 vaccination.

Postinjection pains are frequent with COVID-19 vaccines, but clinical signs such as extension of pain, burning sensation, and eruption of vesicles should lead the physician to consider the diagnosis of HZ, regardless of the delay between the injection and the symptoms. Indeed, the onset of symptoms could be late, and the clinical presentation initially may be mistaken for an injection-site reaction, which is a frequent known side effect of vaccines. These new cases do not prove causality between COVID-19 vaccination and HZ. Varicella-zoster virus remains latent in dorsal-root or ganglia after primary infection, and HZ caused by reactivation of varicella-zoster virus may occur spontaneously or be triggered. In our series, we did not observe medical history of immunosuppression, and no other known risk factors of HZ (eg, radiation therapy, physical trauma, fever after vaccination) were recorded. The pathophysiologic mechanism remains elusive, but local vaccine-induced immunomodulation or an inflammatory state may be involved.

Conclusion

Our case series highlights that clinicians must remain vigilant to diagnose HZ early to prevent potential complications, such as postherpetic neuralgia. Also, vaccination should not be contraindicated in patients with medical history of HZ; the occurrence of HZ does not justify avoiding the second injection of the vaccine due to the benefit of vaccination.

Since the end of 2019, COVID-19 infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 has spread in a worldwide pandemic. The first cutaneous manifestations possibly linked to COVID-19 were reported in spring 2020.1 Herpes zoster (HZ) was suspected as a predictive cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 with a debated prognostic significance.2 The end of 2020 was marked with the beginning of vaccination against COVID-19, and safety studies reported few side effects after vaccination with nucleoside-modified messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines.3 Real-life use of vaccines could lead to the occurrence of potential side effects (or fortuitous medical events) that were not observed in these studies. We report a series of 5 cases of HZ occurring after vaccination with a nucleoside-modified mRNA COVID-19 vaccine extracted from a declarative cohort of cutaneous reactions in our vaccination center.

Case Series

We identified 2 men and 3 women (Table) who experienced HZ after vaccination with a nucleoside-modified mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty, Pfizer-BioNTech). Patients fulfilled French governmental criteria for vaccination at the time of the report—older than 75 years or a health care professional—and they were vaccinated at the vaccination center of a French university hospital. The median age of the patients was 56 years (interquartile range [IQR], 51–82 years). One patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 in February 2020. A medical history of HZ was found in 1 patient. No medical history of immunosuppression was noted. Herpes zoster was observed on the same side of the body as the vaccination site in 4 patients. The median delay before the onset of symptoms was 6 days (IQR, 1–15 days) after injection. The median duration of the symptoms was 13 days (IQR, 11.5–16.5 days). Clinical signs of HZ were mild with few vesicles in 4 patients, and we observed a notably long delay between the onset of pain and the eruption of vesicles in 2 cases (4 and 10 days, respectively). The clinical diagnosis of HZ was confirmed by a dermatologist for all patients (Figures 1 and 2). Polymerase chain reaction assays for the detection of the varicella-zoster virus were performed in 2 cases and were positive. A complete blood cell count was performed in 1 patient, and we observed isolated lymphopenia (500/mm3 [reference range, 1000–4000/mm3]). Herpes zoster occurred after the first dose of vaccine in 4 patients and after the second dose for 1 patient. Three patients were treated with antiviral therapy (acyclovir) for 7 days. Three patients recovered from symptoms within 2 weeks and 2 patients within 1 week.

Comment

We report a series of HZ cases occurring after vaccination with a nucleoside-modified mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. We did not observe complicated HZ, and most of the time, HZ lesions were located on the same side of the body as the vaccine injection. One case of HZ after COVID-19 vaccination was reported by Bostan and Yalici-Armagan,4 but it followed injection with an inactivated vaccine, which is different from our series. Herpes zoster remains rarely reported, mainly following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination.5

Cases of HZ after vaccination have been reported after the live attenuated zoster or yellow fever vaccines, but HZ should not appear as a concomitant effect after any type of vaccines.6,7 Kawai et al8 reported that the incidence rate of HZ ranged from 3 to 5 cases per 1000 person-years in North America, Europe, and Asia-Pacific. The risk for recurrence of HZ ranged from 1% to 6% depending on the type of study design, age distribution of studied populations, and definition.8 In another retrospective database analysis in Israel, the incidence density rate of HZ was 3.46 cases per 1000 person-years in the total population and 12.8 cases per 1000 person-years in immunocompromised patients, therefore the immunocompromised status is important to consider.9

In our declarative cohort of skin eruptions before vaccination, we recorded 11 cases of HZ among 148 skin eruptions (7.43%) at the time of the study, but the design of the study did not allow us to estimate the exact incidence of HZ in the global COVID-19–vaccinated population because our study was not based on a systematic and prospective analysis of all vaccinated patients. The comparison between the prevalence of HZ in the COVID-19–vaccinated population and the nonvaccinated population is difficult owing to the lack of data about HZ in the nonvaccinated population at the time of our analysis. Furthermore, we did not include all vaccinated patients in a prospective follow-up. We highlight the importance of medical history of patients that differed between vaccinated patients (at the time of our analysis) and the global population due to French governmental access criteria to vaccination. The link to prior SARS-CoV-2 infection was uncertain because a medical history of COVID-19 was found in only 1 patient. Only 1 patient had a history of HZ, which is not a contraindication of COVID-19 vaccination.

Postinjection pains are frequent with COVID-19 vaccines, but clinical signs such as extension of pain, burning sensation, and eruption of vesicles should lead the physician to consider the diagnosis of HZ, regardless of the delay between the injection and the symptoms. Indeed, the onset of symptoms could be late, and the clinical presentation initially may be mistaken for an injection-site reaction, which is a frequent known side effect of vaccines. These new cases do not prove causality between COVID-19 vaccination and HZ. Varicella-zoster virus remains latent in dorsal-root or ganglia after primary infection, and HZ caused by reactivation of varicella-zoster virus may occur spontaneously or be triggered. In our series, we did not observe medical history of immunosuppression, and no other known risk factors of HZ (eg, radiation therapy, physical trauma, fever after vaccination) were recorded. The pathophysiologic mechanism remains elusive, but local vaccine-induced immunomodulation or an inflammatory state may be involved.

Conclusion

Our case series highlights that clinicians must remain vigilant to diagnose HZ early to prevent potential complications, such as postherpetic neuralgia. Also, vaccination should not be contraindicated in patients with medical history of HZ; the occurrence of HZ does not justify avoiding the second injection of the vaccine due to the benefit of vaccination.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E212-E213.

- Elsaie ML, Youssef EA, Nada HA. Herpes zoster might be an indicator for latent COVID 19 infection. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13666.

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615.

- Bostan E, Yalici-Armagan B. Herpes zoster following inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: a coexistence or coincidence? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1566-1567.

- Desai HD, Sharma K, Shah A, et al. Can SARS-CoV-2 vaccine increase the risk of reactivation of varicella zoster? a systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3350-3361.

- Fahlbusch M, Wesselmann U, Lehmann P. Herpes zoster after varicella-zoster vaccination [in German]. Hautarzt. 2013;64:107-109.

- Bayas JM, González-Alvarez R, Guinovart C. Herpes zoster after yellow fever vaccination. J Travel Med. 2007;14:65-66.

- Kawai K, Gebremeskel BG, Acosta CJ. Systematic review of incidence and complications of herpes zoster: towards a global perspective. BMJ Open. 2014;10;4:E004833.

- Weitzman D, Shavit O, Stein M, et al. A population based study of the epidemiology of herpes zoster and its complications. J Infect. 2013;67:463-469.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E212-E213.

- Elsaie ML, Youssef EA, Nada HA. Herpes zoster might be an indicator for latent COVID 19 infection. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13666.

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615.

- Bostan E, Yalici-Armagan B. Herpes zoster following inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: a coexistence or coincidence? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1566-1567.

- Desai HD, Sharma K, Shah A, et al. Can SARS-CoV-2 vaccine increase the risk of reactivation of varicella zoster? a systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3350-3361.

- Fahlbusch M, Wesselmann U, Lehmann P. Herpes zoster after varicella-zoster vaccination [in German]. Hautarzt. 2013;64:107-109.

- Bayas JM, González-Alvarez R, Guinovart C. Herpes zoster after yellow fever vaccination. J Travel Med. 2007;14:65-66.

- Kawai K, Gebremeskel BG, Acosta CJ. Systematic review of incidence and complications of herpes zoster: towards a global perspective. BMJ Open. 2014;10;4:E004833.

- Weitzman D, Shavit O, Stein M, et al. A population based study of the epidemiology of herpes zoster and its complications. J Infect. 2013;67:463-469.

Practice Points

- Herpes zoster (HZ) has been reported following COVID-19 vaccination.

- Postinjection pain is common with COVID-19 vaccination, but clinical signs such as extension of pain, burning sensation, and eruption of vesicles should lead the physician to consider the diagnosis of HZ, regardless of the delay in onset between the injection and the symptoms.

- When indicated, the second vaccine dose should not be avoided in patients who are diagnosed with HZ.

Pursuit of a Research Year or Dual Degree by Dermatology Residency Applicants: A Cross-Sectional Study