User login

Food for thought: Dangerous weight loss in an older adult

CASE Fixated on health and nutrition

At the insistence of her daughter, Ms. L, age 75, presents to the emergency department (ED) for self-neglect and severe weight loss, with a body mass index (BMI) of 13.5 kg/m2 (normal: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). When asked why she is in the ED, Ms. L says she doesn’t know. She attributes her significant weight loss (approximately 20 pounds in the last few months) to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). She constantly worries about her esophagus. She had been diagnosed with esophageal dysphagia 7 years ago after undergoing radiofrequency ablation for esophageal cancer. Ms. L fixates on the negative effects certain foods and ingredients might have on her stomach and esophagus.

Following transfer from the ED, Ms. L is involuntarily admitted to our inpatient unit. Although she acknowledges weight loss, she minimizes the severity of her illness and indicates she would like to gain weight, but only by eating healthy foods she is comfortable with, including kale, quinoa, and vegetables. Ms. L says that she has always been interested in “healthful foods” and that she “loves sugar,” but “it’s bad for you,” mentioning that “sugar fuels cancer.” She has daily thoughts about sugar causing cancer. Ms. L also mentions that she stopped eating flour, sugar, fried food, and oils because those foods affect her “stomach acid” and cause “pimples on my face and weight loss.” While in the inpatient unit, Ms. L requests a special diet and demands to know the origin and ingredients of the foods she is offered. She emphasizes that her esophageal cancer diagnosis and dysphagia exacerbate worries that certain foods cause cancer, and wants to continue her diet restrictions. Nonetheless, she says she wants to get healthy, and denies an intense fear of gaining weight or feeling fat.

HISTORY Multiple psychiatric diagnoses

Ms. L lives alone and enjoys spending time with her grandchildren, visiting museums, and listening to classical music. However, her family, social workers, and records from a previous psychiatric hospitalization reveal that Ms. L has a history of psychiatric illness and fears regarding certain types of foods for much of her adult life. Ms. L’s family also described a range of compulsive behaviors, including shoplifting, hoarding art, multiple plastic surgeries, and phases where Ms. L ate only frozen yogurt without sugar.

Ms. L’s daughter reported that Ms. L had seen a psychologist in the late 1990s for depression and had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the early 2000s. In 2006, during a depressive episode after her divorce, Ms. L had a suicide attempt with pills and alcohol, and was hospitalized. Records from that stay described a history of mood dysregulation with fears regarding food and nutrition. Ms. L was treated with aripiprazole 5 mg/d. A trial of trazodone 25 mg/d did not have any effect. When discharged, she was receiving lamotrigine 100 mg/d. However, her daughter believes she stopped taking all psychiatric medications shortly after discharge.

Her daughter says that in the past 2 years, Ms. L has seen multiple doctors for treatment of somatic gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. A 2018 note from a social worker indicated that Ms. L endorsed taking >80 supplements per day and constantly researched nutrition online. In the months leading to her current hospitalization, Ms. L suffered from severe self-neglect and fear regarding foods she felt were not healthy for her. She had stopped leaving her apartment.

Continue to: EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results...

EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results

During her evaluation, Ms. L appears cachectic and frail. She has a heavily constricted affect and is guarded, dismissive, and vague. Although her thought processes are linear and goal-directed, her insight into her condition is extremely poor and she appears surprised when clinicians inform her that her self-neglect would lead to death. Instead, Ms. L insists she is eating healthily and demonstrates severe anxiety in relation to her GI symptoms.

Ms. L is oriented to person, place, and time. She scores 27/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, indicating normal cognition. She denies any depressive symptoms or suicidal intent. She does not appear to be internally preoccupied and denies having auditory or visual hallucinations or manic symptoms.

A neurologic examination reveals that her cranial nerves are normal, and cerebellar function, strength, and sensory testing are intact. Her gait is steady and she walks without a walker. Despite her severely low BMI and recent history of self-neglect, Ms. L’s laboratory results are remarkably normal and show no liver, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no signs of infection, and normal vitamin B12 levels. She has slightly elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, but a normal glomerular filtration rate.

Her medical history is significant for squamous cell esophageal cancer, treated with radiofrequency ablation. Although Ms. L is constantly worried about the recurrence of cancer, pathology reports demonstrate no esophageal dysplasia. However, she does show evidence of an approximately 1 cm × 1 cm mild, noncircumferential esophageal stenosis, likely resulting from radiofrequency ablation.

[polldaddy:11079394]

The authors’ observations

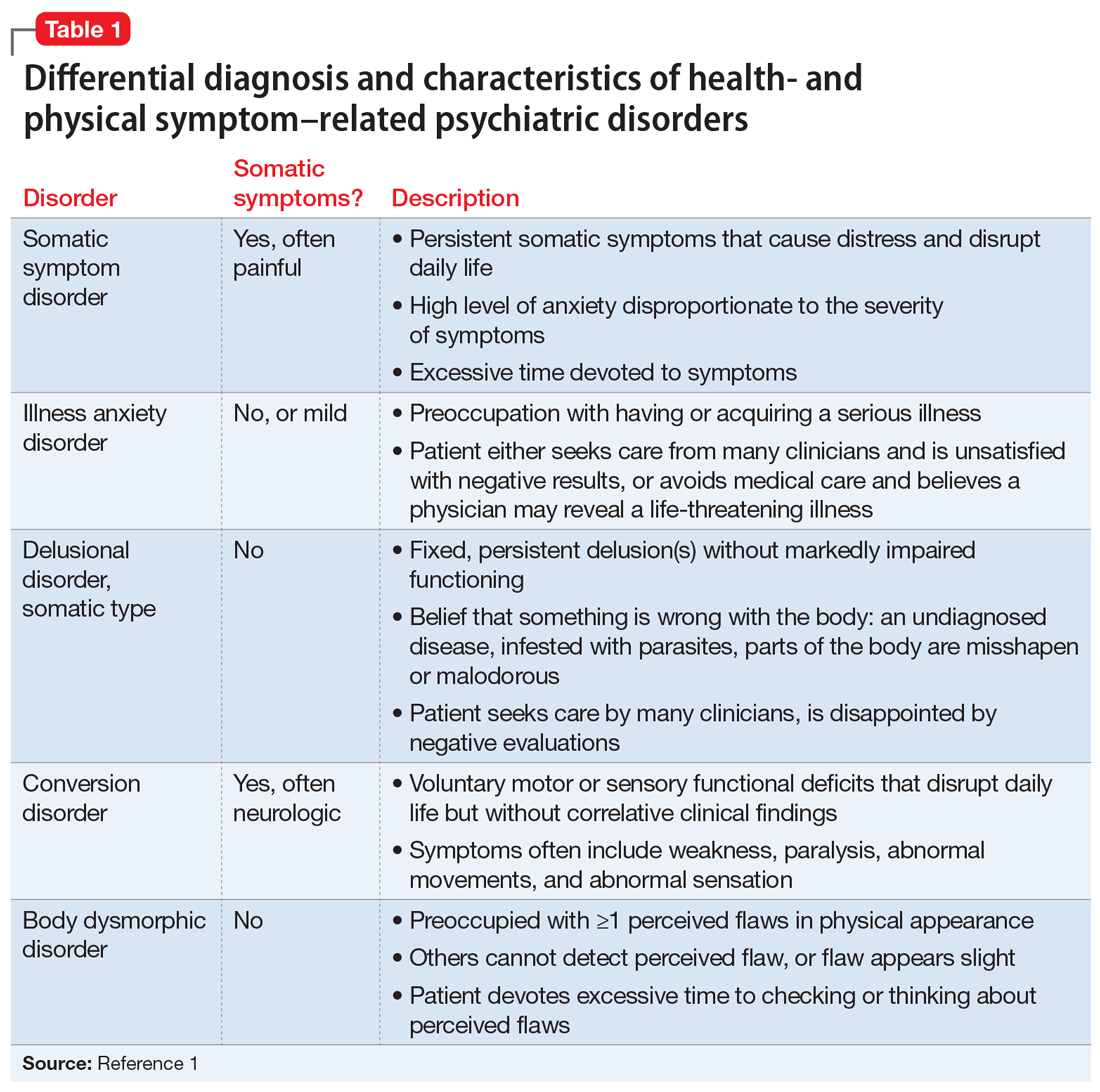

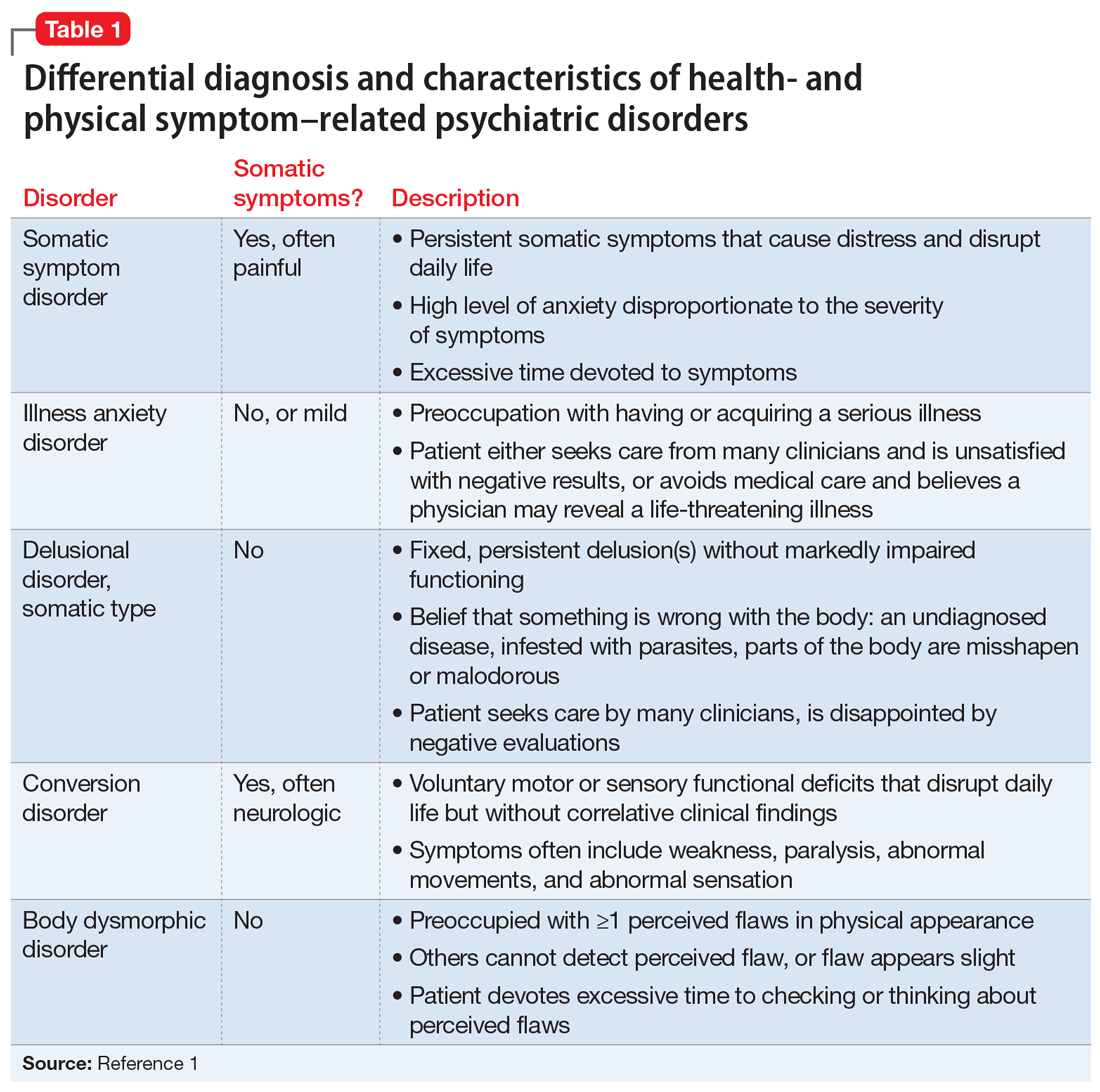

Several health- and physical symptom-related psychiatric disorders have overlapping features, which can complicate the differential diagnosis (Table 11). Ms. L presented to the ED with a severely low BMI of 13.5 kg/m2, obsessions regarding specific types of food, and preoccupations regarding her esophagus. Despite her extensive psychiatric history (including intense fears regarding food), we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder because she did not describe auditory or visual hallucinations and never appeared internally preoccupied. While her BMI and persistent minimization of the extent of her disease meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, she denied body dysmorphia and did not have any fear of gaining weight.

A central element of Ms. L’s presentation was her anxiety regarding how certain types of foods impact her health as well as her anxieties regarding her esophagus. While Ms. L was in remission from esophageal cancer and had a diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia, these preoccupations and obsessions regarding how certain types of foods affect her esophagus drove her to self-neglect and thus represent pathologic thought processes out of proportion to her symptoms. Illness anxiety disorder was considered because Ms. L met many of its criteria: preoccupation with having a serious illness, disproportionate preoccupation with somatic symptoms if they are present, extreme anxiety over health, and performance of health-related behaviors.1 However, illness anxiety disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion, and 1 criterion is that these symptoms cannot be explained by another mental disorder. We felt other diagnoses better fit Ms. L’s condition and ruled out illness anxiety disorder.

Ms. L’s long history of food and non-food–related obsessions and compulsions that interrupted her ability to perform daily activities were strongly suggestive for OCD. Additionally, her intense preoccupation, high level of anxiety, amount of time and energy spent seeking care for her esophagus and GERD symptoms, and the resulting significant disruption of daily life, met criteria for somatic symptom disorder (SSD). However, we did not believe that a diagnosis of OCD and SSD alone explained the entirety of Ms. L’s clinical picture. Despite ruling out anorexia nervosa, Ms. L nonetheless demonstrated disordered eating.

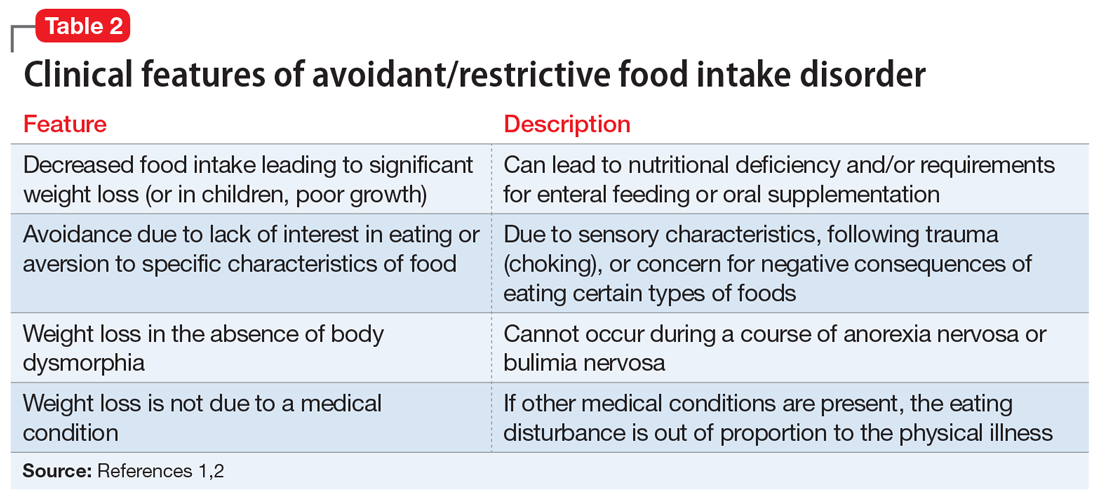

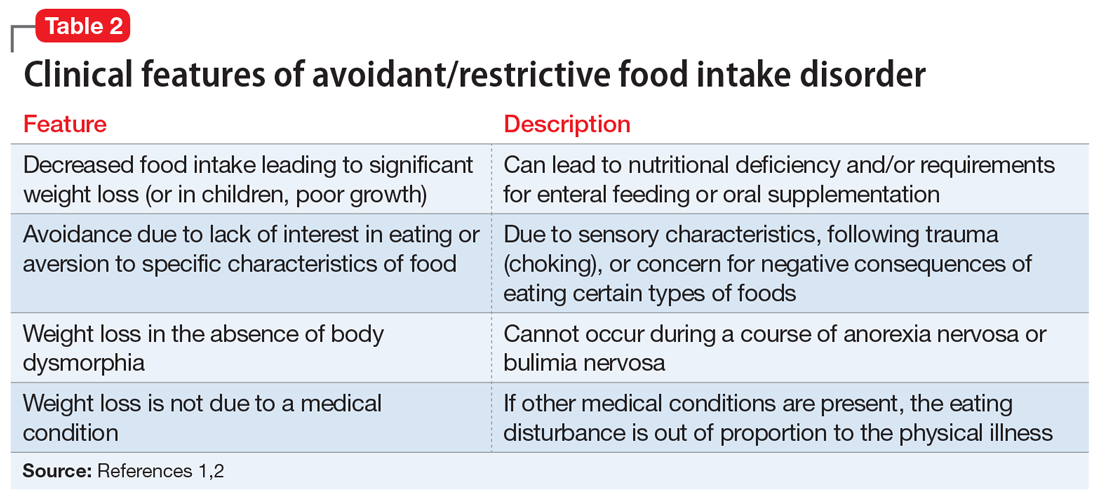

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder in which patients restrict their diet and do not meet nutritional needs for any number of reasons, do not experience body dysmorphia, and do not fear weight gain.1 A common feature of ARFID is a fear of negative consequences from eating specific types of food.2 Table 21,2 summarizes additional clinical features of ARFID. Although ARFID is typically diagnosed in children and adolescents, particularly in individuals with autism with heightened sensory sensitivities, ARFID is also common among adult patients with GI disorders.3 In a retrospective chart review of 410 adults ages 18 to 90 (73% women) referred to a neurogastroenterology care center, 6.3% met the full criteria for ARFID and 17.3% had clinically significant avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors. Among patients with ARFID symptoms, 93% stated that a fear of GI symptoms was the driver of their avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors.2 Patients with GI diseases often develop dietary control and avoidance coping mechanisms to alleviate their symptoms.4 These strategies can exacerbate health anxieties and have a detrimental effect on mental health.5 Patients with GI disorders have a high degree of comorbidity with affective disorders, including anxiety disorders.6 These trends may arise from hypervigilance and the need to gain control over physical symptoms.7 Feeling a need for control, actions driven by anxiety and fear, and the need for compensatory behaviors are cardinal features of OCD and eating disorders.8 Multiple studies have demonstrated comorbidities between irritable bowel syndrome and eating disorders,9 SSD,10 and OCD.11 Taken together with observations that ARFID is also found in patients with GI disorders,2 these findings demonstrate that patients with a history of GI disease are at high risk of developing extreme health anxieties and behavioral coping strategies that can lead to disordered eating.

The rise in “healthy” eating materials online—particularly on social media—has created an atmosphere in which misinformation regarding diet and health is common and widespread. For patients with OCD and a predisposition to health anxiety, such as Ms. L, searching online for nutrition information and healthy living habits can exacerbate food-related anxieties and can lead to a pathological drive for purity and health.12Although not included in DSM-5, orthorexia nervosa was identified in 1997 as a proposed eating disorder best characterized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors.13 Patients with this disorder are rarely focused on losing weight, and orthorexic eating behaviors have been associated with both SSD and OCD.12,14 As in Ms. L’s case, patients with orthorexia nervosa demonstrate intrusive obsessions with nutrition, spend excessive amount of time researching nutrition, and fixate on food quality.12 Throughout Ms. L’s hospitalization, even as her food-related magical thinking symptoms improved, she constantly informed her care team that she had been “eating healthily” even though she was severely cachectic. Patients with SSD and OCD prone to health anxieties are at risk of developing pathologic food beliefs and dangerous eating behaviors. These patients may benefit from psychoeducation regarding nutrition and media literacy, which are components of effective eating disorder programs.15

[polldaddy:11079399]

Continue to: The authors' observations...

The authors’ observations

How do we approach the pharmacologic treatment of patients with co-occurring eating, somatic symptom, and anxiety disorders? Olanzapine facilitates recovery in children and adolescents with ARFID by promoting eating and weight gain, and decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety.16 Patients with orthorexia nervosa also may benefit from treatment with olanzapine, which has decreased food-related fixations, magical thinking, and delusions regarding food.17 Further, orthorexic patients with ARFID have also been shown to respond to SSRIs due to those agents’ efficacy for treating intrusive thoughts, obsessions, and preoccupations from OCD and SSD.18,19 Thus, treating Ms. L’s symptoms with olanzapine and fluoxetine targeted the intersection of several diagnoses on our differential. Olanzapine’s propensity to cause weight gain is favorable in this population, particularly patients such as Ms. L, who do not exhibit body dysmorphia or fear of gaining weight.

OUTCOME Weight gain and fewer fears

Ms. L is prescribed olanzapine 5 mg/d and fluoxetine 20 mg/d. She gains 20.6 pounds in 4 weeks. Importantly, she endorses fewer fears related to foods and expands her palate to include foods she previously considered to be unhealthy, including white bread and farm-raised salmon. Further, she spends less time thinking about food and says she has less anxiety regarding the recurrence of GI symptoms.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Murray HB, Bailey AP, Keshishian AC. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in adult neurogastroenterology patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1995-2002.e1.

3. Görmez A, Kılıç A, Kırpınar İ. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: an adult case responding to cognitive behavioral therapy. Clinical Case Studies. 2018;17(6):443-452.

4. Reed-Knight B, Squires M, Chitkara DK, et al. Adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome report increased eating-associated symptoms, changes in dietary composition, and altered eating behaviors: a pilot comparison study to healthy adolescents. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(12):1915-1920.

5. Melchior C, Desprez C, Riachi G, et al. Anxiety and depression profile is associated with eating disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:928.

6. Mayer EA, Craske M, Naliboff BD. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 Suppl 8:28-37.

7. Abraham S, Kellow J. Exploring eating disorder quality of life and functional gastrointestinal disorders among eating disorder patients. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(4):372-377.

8. Swinbourne JM, Touyz SW. The co-morbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(4):253-274.

9. Perkins SJ, Keville S, Schmidt U, et al. Eating disorders and irritable bowel syndrome: is there a link? J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(2):57-64.

10. Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Henningsen P. Irritable bowel syndrome: relations with functional, mental, and somatoform disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(2):6024-6030.

11. Masand PS, Keuthen NJ, Gupta S, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(1):21-25.

12. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

13. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga Journal. 1997;136:42-50.

14. Barthels F, Müller R, Schüth T, et al. Orthorexic eating behavior in patients with somatoform disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26(1):135-143.

15. Ciao AC, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing eating disorder pathology: common and unique features of successful eating disorders prevention programs. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(7):453.

16. Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive use of olanzapine in the treatment of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents in an eating disorders program. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(10):920-922.

17. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, et al. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

18. Spettigue W, Norris ML, Santos A, et al. Treatment of children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a case series examining the feasibility of family therapy and adjunctive treatments. J Eat Disord. 2018;6:20.

19. Niedzielski A, Kaźmierczak-Wojtaś N. Prevalence of Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Diagnostic Tools-A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488. Published 2021 May 20. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105488 Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa and its diagnostic tools-a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488.

CASE Fixated on health and nutrition

At the insistence of her daughter, Ms. L, age 75, presents to the emergency department (ED) for self-neglect and severe weight loss, with a body mass index (BMI) of 13.5 kg/m2 (normal: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). When asked why she is in the ED, Ms. L says she doesn’t know. She attributes her significant weight loss (approximately 20 pounds in the last few months) to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). She constantly worries about her esophagus. She had been diagnosed with esophageal dysphagia 7 years ago after undergoing radiofrequency ablation for esophageal cancer. Ms. L fixates on the negative effects certain foods and ingredients might have on her stomach and esophagus.

Following transfer from the ED, Ms. L is involuntarily admitted to our inpatient unit. Although she acknowledges weight loss, she minimizes the severity of her illness and indicates she would like to gain weight, but only by eating healthy foods she is comfortable with, including kale, quinoa, and vegetables. Ms. L says that she has always been interested in “healthful foods” and that she “loves sugar,” but “it’s bad for you,” mentioning that “sugar fuels cancer.” She has daily thoughts about sugar causing cancer. Ms. L also mentions that she stopped eating flour, sugar, fried food, and oils because those foods affect her “stomach acid” and cause “pimples on my face and weight loss.” While in the inpatient unit, Ms. L requests a special diet and demands to know the origin and ingredients of the foods she is offered. She emphasizes that her esophageal cancer diagnosis and dysphagia exacerbate worries that certain foods cause cancer, and wants to continue her diet restrictions. Nonetheless, she says she wants to get healthy, and denies an intense fear of gaining weight or feeling fat.

HISTORY Multiple psychiatric diagnoses

Ms. L lives alone and enjoys spending time with her grandchildren, visiting museums, and listening to classical music. However, her family, social workers, and records from a previous psychiatric hospitalization reveal that Ms. L has a history of psychiatric illness and fears regarding certain types of foods for much of her adult life. Ms. L’s family also described a range of compulsive behaviors, including shoplifting, hoarding art, multiple plastic surgeries, and phases where Ms. L ate only frozen yogurt without sugar.

Ms. L’s daughter reported that Ms. L had seen a psychologist in the late 1990s for depression and had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the early 2000s. In 2006, during a depressive episode after her divorce, Ms. L had a suicide attempt with pills and alcohol, and was hospitalized. Records from that stay described a history of mood dysregulation with fears regarding food and nutrition. Ms. L was treated with aripiprazole 5 mg/d. A trial of trazodone 25 mg/d did not have any effect. When discharged, she was receiving lamotrigine 100 mg/d. However, her daughter believes she stopped taking all psychiatric medications shortly after discharge.

Her daughter says that in the past 2 years, Ms. L has seen multiple doctors for treatment of somatic gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. A 2018 note from a social worker indicated that Ms. L endorsed taking >80 supplements per day and constantly researched nutrition online. In the months leading to her current hospitalization, Ms. L suffered from severe self-neglect and fear regarding foods she felt were not healthy for her. She had stopped leaving her apartment.

Continue to: EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results...

EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results

During her evaluation, Ms. L appears cachectic and frail. She has a heavily constricted affect and is guarded, dismissive, and vague. Although her thought processes are linear and goal-directed, her insight into her condition is extremely poor and she appears surprised when clinicians inform her that her self-neglect would lead to death. Instead, Ms. L insists she is eating healthily and demonstrates severe anxiety in relation to her GI symptoms.

Ms. L is oriented to person, place, and time. She scores 27/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, indicating normal cognition. She denies any depressive symptoms or suicidal intent. She does not appear to be internally preoccupied and denies having auditory or visual hallucinations or manic symptoms.

A neurologic examination reveals that her cranial nerves are normal, and cerebellar function, strength, and sensory testing are intact. Her gait is steady and she walks without a walker. Despite her severely low BMI and recent history of self-neglect, Ms. L’s laboratory results are remarkably normal and show no liver, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no signs of infection, and normal vitamin B12 levels. She has slightly elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, but a normal glomerular filtration rate.

Her medical history is significant for squamous cell esophageal cancer, treated with radiofrequency ablation. Although Ms. L is constantly worried about the recurrence of cancer, pathology reports demonstrate no esophageal dysplasia. However, she does show evidence of an approximately 1 cm × 1 cm mild, noncircumferential esophageal stenosis, likely resulting from radiofrequency ablation.

[polldaddy:11079394]

The authors’ observations

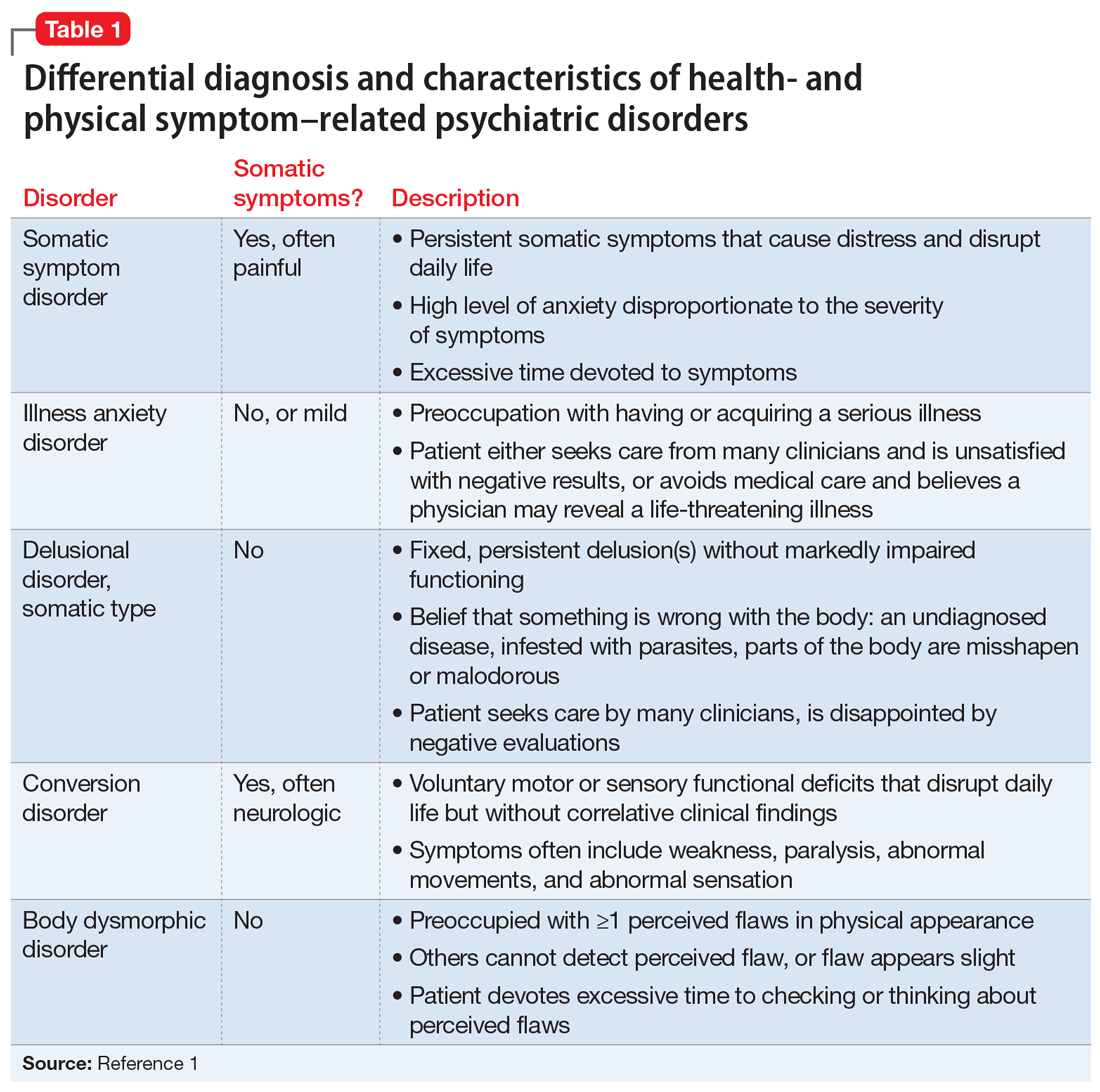

Several health- and physical symptom-related psychiatric disorders have overlapping features, which can complicate the differential diagnosis (Table 11). Ms. L presented to the ED with a severely low BMI of 13.5 kg/m2, obsessions regarding specific types of food, and preoccupations regarding her esophagus. Despite her extensive psychiatric history (including intense fears regarding food), we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder because she did not describe auditory or visual hallucinations and never appeared internally preoccupied. While her BMI and persistent minimization of the extent of her disease meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, she denied body dysmorphia and did not have any fear of gaining weight.

A central element of Ms. L’s presentation was her anxiety regarding how certain types of foods impact her health as well as her anxieties regarding her esophagus. While Ms. L was in remission from esophageal cancer and had a diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia, these preoccupations and obsessions regarding how certain types of foods affect her esophagus drove her to self-neglect and thus represent pathologic thought processes out of proportion to her symptoms. Illness anxiety disorder was considered because Ms. L met many of its criteria: preoccupation with having a serious illness, disproportionate preoccupation with somatic symptoms if they are present, extreme anxiety over health, and performance of health-related behaviors.1 However, illness anxiety disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion, and 1 criterion is that these symptoms cannot be explained by another mental disorder. We felt other diagnoses better fit Ms. L’s condition and ruled out illness anxiety disorder.

Ms. L’s long history of food and non-food–related obsessions and compulsions that interrupted her ability to perform daily activities were strongly suggestive for OCD. Additionally, her intense preoccupation, high level of anxiety, amount of time and energy spent seeking care for her esophagus and GERD symptoms, and the resulting significant disruption of daily life, met criteria for somatic symptom disorder (SSD). However, we did not believe that a diagnosis of OCD and SSD alone explained the entirety of Ms. L’s clinical picture. Despite ruling out anorexia nervosa, Ms. L nonetheless demonstrated disordered eating.

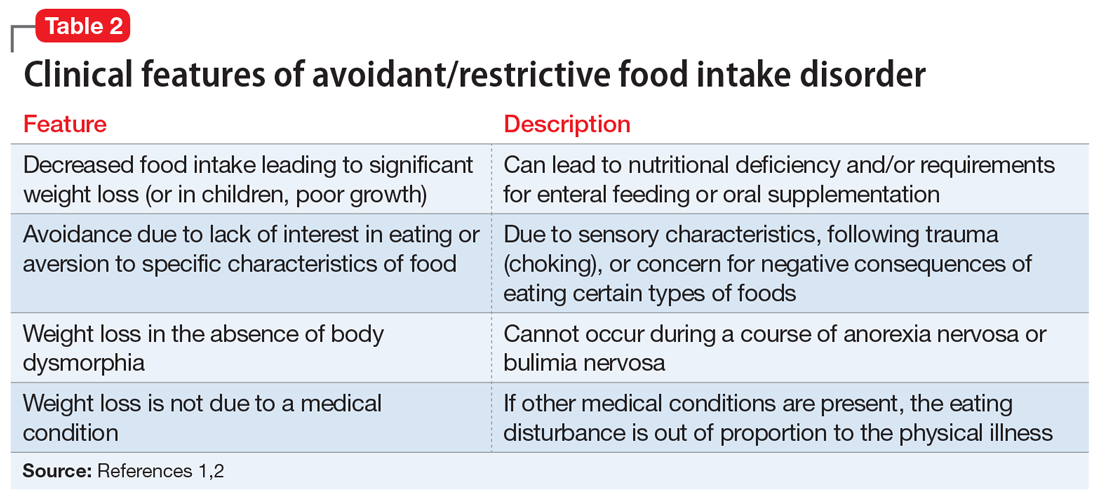

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder in which patients restrict their diet and do not meet nutritional needs for any number of reasons, do not experience body dysmorphia, and do not fear weight gain.1 A common feature of ARFID is a fear of negative consequences from eating specific types of food.2 Table 21,2 summarizes additional clinical features of ARFID. Although ARFID is typically diagnosed in children and adolescents, particularly in individuals with autism with heightened sensory sensitivities, ARFID is also common among adult patients with GI disorders.3 In a retrospective chart review of 410 adults ages 18 to 90 (73% women) referred to a neurogastroenterology care center, 6.3% met the full criteria for ARFID and 17.3% had clinically significant avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors. Among patients with ARFID symptoms, 93% stated that a fear of GI symptoms was the driver of their avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors.2 Patients with GI diseases often develop dietary control and avoidance coping mechanisms to alleviate their symptoms.4 These strategies can exacerbate health anxieties and have a detrimental effect on mental health.5 Patients with GI disorders have a high degree of comorbidity with affective disorders, including anxiety disorders.6 These trends may arise from hypervigilance and the need to gain control over physical symptoms.7 Feeling a need for control, actions driven by anxiety and fear, and the need for compensatory behaviors are cardinal features of OCD and eating disorders.8 Multiple studies have demonstrated comorbidities between irritable bowel syndrome and eating disorders,9 SSD,10 and OCD.11 Taken together with observations that ARFID is also found in patients with GI disorders,2 these findings demonstrate that patients with a history of GI disease are at high risk of developing extreme health anxieties and behavioral coping strategies that can lead to disordered eating.

The rise in “healthy” eating materials online—particularly on social media—has created an atmosphere in which misinformation regarding diet and health is common and widespread. For patients with OCD and a predisposition to health anxiety, such as Ms. L, searching online for nutrition information and healthy living habits can exacerbate food-related anxieties and can lead to a pathological drive for purity and health.12Although not included in DSM-5, orthorexia nervosa was identified in 1997 as a proposed eating disorder best characterized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors.13 Patients with this disorder are rarely focused on losing weight, and orthorexic eating behaviors have been associated with both SSD and OCD.12,14 As in Ms. L’s case, patients with orthorexia nervosa demonstrate intrusive obsessions with nutrition, spend excessive amount of time researching nutrition, and fixate on food quality.12 Throughout Ms. L’s hospitalization, even as her food-related magical thinking symptoms improved, she constantly informed her care team that she had been “eating healthily” even though she was severely cachectic. Patients with SSD and OCD prone to health anxieties are at risk of developing pathologic food beliefs and dangerous eating behaviors. These patients may benefit from psychoeducation regarding nutrition and media literacy, which are components of effective eating disorder programs.15

[polldaddy:11079399]

Continue to: The authors' observations...

The authors’ observations

How do we approach the pharmacologic treatment of patients with co-occurring eating, somatic symptom, and anxiety disorders? Olanzapine facilitates recovery in children and adolescents with ARFID by promoting eating and weight gain, and decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety.16 Patients with orthorexia nervosa also may benefit from treatment with olanzapine, which has decreased food-related fixations, magical thinking, and delusions regarding food.17 Further, orthorexic patients with ARFID have also been shown to respond to SSRIs due to those agents’ efficacy for treating intrusive thoughts, obsessions, and preoccupations from OCD and SSD.18,19 Thus, treating Ms. L’s symptoms with olanzapine and fluoxetine targeted the intersection of several diagnoses on our differential. Olanzapine’s propensity to cause weight gain is favorable in this population, particularly patients such as Ms. L, who do not exhibit body dysmorphia or fear of gaining weight.

OUTCOME Weight gain and fewer fears

Ms. L is prescribed olanzapine 5 mg/d and fluoxetine 20 mg/d. She gains 20.6 pounds in 4 weeks. Importantly, she endorses fewer fears related to foods and expands her palate to include foods she previously considered to be unhealthy, including white bread and farm-raised salmon. Further, she spends less time thinking about food and says she has less anxiety regarding the recurrence of GI symptoms.

CASE Fixated on health and nutrition

At the insistence of her daughter, Ms. L, age 75, presents to the emergency department (ED) for self-neglect and severe weight loss, with a body mass index (BMI) of 13.5 kg/m2 (normal: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). When asked why she is in the ED, Ms. L says she doesn’t know. She attributes her significant weight loss (approximately 20 pounds in the last few months) to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). She constantly worries about her esophagus. She had been diagnosed with esophageal dysphagia 7 years ago after undergoing radiofrequency ablation for esophageal cancer. Ms. L fixates on the negative effects certain foods and ingredients might have on her stomach and esophagus.

Following transfer from the ED, Ms. L is involuntarily admitted to our inpatient unit. Although she acknowledges weight loss, she minimizes the severity of her illness and indicates she would like to gain weight, but only by eating healthy foods she is comfortable with, including kale, quinoa, and vegetables. Ms. L says that she has always been interested in “healthful foods” and that she “loves sugar,” but “it’s bad for you,” mentioning that “sugar fuels cancer.” She has daily thoughts about sugar causing cancer. Ms. L also mentions that she stopped eating flour, sugar, fried food, and oils because those foods affect her “stomach acid” and cause “pimples on my face and weight loss.” While in the inpatient unit, Ms. L requests a special diet and demands to know the origin and ingredients of the foods she is offered. She emphasizes that her esophageal cancer diagnosis and dysphagia exacerbate worries that certain foods cause cancer, and wants to continue her diet restrictions. Nonetheless, she says she wants to get healthy, and denies an intense fear of gaining weight or feeling fat.

HISTORY Multiple psychiatric diagnoses

Ms. L lives alone and enjoys spending time with her grandchildren, visiting museums, and listening to classical music. However, her family, social workers, and records from a previous psychiatric hospitalization reveal that Ms. L has a history of psychiatric illness and fears regarding certain types of foods for much of her adult life. Ms. L’s family also described a range of compulsive behaviors, including shoplifting, hoarding art, multiple plastic surgeries, and phases where Ms. L ate only frozen yogurt without sugar.

Ms. L’s daughter reported that Ms. L had seen a psychologist in the late 1990s for depression and had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the early 2000s. In 2006, during a depressive episode after her divorce, Ms. L had a suicide attempt with pills and alcohol, and was hospitalized. Records from that stay described a history of mood dysregulation with fears regarding food and nutrition. Ms. L was treated with aripiprazole 5 mg/d. A trial of trazodone 25 mg/d did not have any effect. When discharged, she was receiving lamotrigine 100 mg/d. However, her daughter believes she stopped taking all psychiatric medications shortly after discharge.

Her daughter says that in the past 2 years, Ms. L has seen multiple doctors for treatment of somatic gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. A 2018 note from a social worker indicated that Ms. L endorsed taking >80 supplements per day and constantly researched nutrition online. In the months leading to her current hospitalization, Ms. L suffered from severe self-neglect and fear regarding foods she felt were not healthy for her. She had stopped leaving her apartment.

Continue to: EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results...

EVALUATION Poor insight, normal lab results

During her evaluation, Ms. L appears cachectic and frail. She has a heavily constricted affect and is guarded, dismissive, and vague. Although her thought processes are linear and goal-directed, her insight into her condition is extremely poor and she appears surprised when clinicians inform her that her self-neglect would lead to death. Instead, Ms. L insists she is eating healthily and demonstrates severe anxiety in relation to her GI symptoms.

Ms. L is oriented to person, place, and time. She scores 27/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, indicating normal cognition. She denies any depressive symptoms or suicidal intent. She does not appear to be internally preoccupied and denies having auditory or visual hallucinations or manic symptoms.

A neurologic examination reveals that her cranial nerves are normal, and cerebellar function, strength, and sensory testing are intact. Her gait is steady and she walks without a walker. Despite her severely low BMI and recent history of self-neglect, Ms. L’s laboratory results are remarkably normal and show no liver, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no signs of infection, and normal vitamin B12 levels. She has slightly elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, but a normal glomerular filtration rate.

Her medical history is significant for squamous cell esophageal cancer, treated with radiofrequency ablation. Although Ms. L is constantly worried about the recurrence of cancer, pathology reports demonstrate no esophageal dysplasia. However, she does show evidence of an approximately 1 cm × 1 cm mild, noncircumferential esophageal stenosis, likely resulting from radiofrequency ablation.

[polldaddy:11079394]

The authors’ observations

Several health- and physical symptom-related psychiatric disorders have overlapping features, which can complicate the differential diagnosis (Table 11). Ms. L presented to the ED with a severely low BMI of 13.5 kg/m2, obsessions regarding specific types of food, and preoccupations regarding her esophagus. Despite her extensive psychiatric history (including intense fears regarding food), we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder because she did not describe auditory or visual hallucinations and never appeared internally preoccupied. While her BMI and persistent minimization of the extent of her disease meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, she denied body dysmorphia and did not have any fear of gaining weight.

A central element of Ms. L’s presentation was her anxiety regarding how certain types of foods impact her health as well as her anxieties regarding her esophagus. While Ms. L was in remission from esophageal cancer and had a diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia, these preoccupations and obsessions regarding how certain types of foods affect her esophagus drove her to self-neglect and thus represent pathologic thought processes out of proportion to her symptoms. Illness anxiety disorder was considered because Ms. L met many of its criteria: preoccupation with having a serious illness, disproportionate preoccupation with somatic symptoms if they are present, extreme anxiety over health, and performance of health-related behaviors.1 However, illness anxiety disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion, and 1 criterion is that these symptoms cannot be explained by another mental disorder. We felt other diagnoses better fit Ms. L’s condition and ruled out illness anxiety disorder.

Ms. L’s long history of food and non-food–related obsessions and compulsions that interrupted her ability to perform daily activities were strongly suggestive for OCD. Additionally, her intense preoccupation, high level of anxiety, amount of time and energy spent seeking care for her esophagus and GERD symptoms, and the resulting significant disruption of daily life, met criteria for somatic symptom disorder (SSD). However, we did not believe that a diagnosis of OCD and SSD alone explained the entirety of Ms. L’s clinical picture. Despite ruling out anorexia nervosa, Ms. L nonetheless demonstrated disordered eating.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder in which patients restrict their diet and do not meet nutritional needs for any number of reasons, do not experience body dysmorphia, and do not fear weight gain.1 A common feature of ARFID is a fear of negative consequences from eating specific types of food.2 Table 21,2 summarizes additional clinical features of ARFID. Although ARFID is typically diagnosed in children and adolescents, particularly in individuals with autism with heightened sensory sensitivities, ARFID is also common among adult patients with GI disorders.3 In a retrospective chart review of 410 adults ages 18 to 90 (73% women) referred to a neurogastroenterology care center, 6.3% met the full criteria for ARFID and 17.3% had clinically significant avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors. Among patients with ARFID symptoms, 93% stated that a fear of GI symptoms was the driver of their avoidant or restrictive eating behaviors.2 Patients with GI diseases often develop dietary control and avoidance coping mechanisms to alleviate their symptoms.4 These strategies can exacerbate health anxieties and have a detrimental effect on mental health.5 Patients with GI disorders have a high degree of comorbidity with affective disorders, including anxiety disorders.6 These trends may arise from hypervigilance and the need to gain control over physical symptoms.7 Feeling a need for control, actions driven by anxiety and fear, and the need for compensatory behaviors are cardinal features of OCD and eating disorders.8 Multiple studies have demonstrated comorbidities between irritable bowel syndrome and eating disorders,9 SSD,10 and OCD.11 Taken together with observations that ARFID is also found in patients with GI disorders,2 these findings demonstrate that patients with a history of GI disease are at high risk of developing extreme health anxieties and behavioral coping strategies that can lead to disordered eating.

The rise in “healthy” eating materials online—particularly on social media—has created an atmosphere in which misinformation regarding diet and health is common and widespread. For patients with OCD and a predisposition to health anxiety, such as Ms. L, searching online for nutrition information and healthy living habits can exacerbate food-related anxieties and can lead to a pathological drive for purity and health.12Although not included in DSM-5, orthorexia nervosa was identified in 1997 as a proposed eating disorder best characterized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors.13 Patients with this disorder are rarely focused on losing weight, and orthorexic eating behaviors have been associated with both SSD and OCD.12,14 As in Ms. L’s case, patients with orthorexia nervosa demonstrate intrusive obsessions with nutrition, spend excessive amount of time researching nutrition, and fixate on food quality.12 Throughout Ms. L’s hospitalization, even as her food-related magical thinking symptoms improved, she constantly informed her care team that she had been “eating healthily” even though she was severely cachectic. Patients with SSD and OCD prone to health anxieties are at risk of developing pathologic food beliefs and dangerous eating behaviors. These patients may benefit from psychoeducation regarding nutrition and media literacy, which are components of effective eating disorder programs.15

[polldaddy:11079399]

Continue to: The authors' observations...

The authors’ observations

How do we approach the pharmacologic treatment of patients with co-occurring eating, somatic symptom, and anxiety disorders? Olanzapine facilitates recovery in children and adolescents with ARFID by promoting eating and weight gain, and decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety.16 Patients with orthorexia nervosa also may benefit from treatment with olanzapine, which has decreased food-related fixations, magical thinking, and delusions regarding food.17 Further, orthorexic patients with ARFID have also been shown to respond to SSRIs due to those agents’ efficacy for treating intrusive thoughts, obsessions, and preoccupations from OCD and SSD.18,19 Thus, treating Ms. L’s symptoms with olanzapine and fluoxetine targeted the intersection of several diagnoses on our differential. Olanzapine’s propensity to cause weight gain is favorable in this population, particularly patients such as Ms. L, who do not exhibit body dysmorphia or fear of gaining weight.

OUTCOME Weight gain and fewer fears

Ms. L is prescribed olanzapine 5 mg/d and fluoxetine 20 mg/d. She gains 20.6 pounds in 4 weeks. Importantly, she endorses fewer fears related to foods and expands her palate to include foods she previously considered to be unhealthy, including white bread and farm-raised salmon. Further, she spends less time thinking about food and says she has less anxiety regarding the recurrence of GI symptoms.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Murray HB, Bailey AP, Keshishian AC. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in adult neurogastroenterology patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1995-2002.e1.

3. Görmez A, Kılıç A, Kırpınar İ. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: an adult case responding to cognitive behavioral therapy. Clinical Case Studies. 2018;17(6):443-452.

4. Reed-Knight B, Squires M, Chitkara DK, et al. Adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome report increased eating-associated symptoms, changes in dietary composition, and altered eating behaviors: a pilot comparison study to healthy adolescents. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(12):1915-1920.

5. Melchior C, Desprez C, Riachi G, et al. Anxiety and depression profile is associated with eating disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:928.

6. Mayer EA, Craske M, Naliboff BD. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 Suppl 8:28-37.

7. Abraham S, Kellow J. Exploring eating disorder quality of life and functional gastrointestinal disorders among eating disorder patients. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(4):372-377.

8. Swinbourne JM, Touyz SW. The co-morbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(4):253-274.

9. Perkins SJ, Keville S, Schmidt U, et al. Eating disorders and irritable bowel syndrome: is there a link? J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(2):57-64.

10. Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Henningsen P. Irritable bowel syndrome: relations with functional, mental, and somatoform disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(2):6024-6030.

11. Masand PS, Keuthen NJ, Gupta S, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(1):21-25.

12. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

13. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga Journal. 1997;136:42-50.

14. Barthels F, Müller R, Schüth T, et al. Orthorexic eating behavior in patients with somatoform disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26(1):135-143.

15. Ciao AC, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing eating disorder pathology: common and unique features of successful eating disorders prevention programs. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(7):453.

16. Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive use of olanzapine in the treatment of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents in an eating disorders program. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(10):920-922.

17. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, et al. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

18. Spettigue W, Norris ML, Santos A, et al. Treatment of children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a case series examining the feasibility of family therapy and adjunctive treatments. J Eat Disord. 2018;6:20.

19. Niedzielski A, Kaźmierczak-Wojtaś N. Prevalence of Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Diagnostic Tools-A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488. Published 2021 May 20. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105488 Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa and its diagnostic tools-a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Murray HB, Bailey AP, Keshishian AC. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in adult neurogastroenterology patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1995-2002.e1.

3. Görmez A, Kılıç A, Kırpınar İ. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: an adult case responding to cognitive behavioral therapy. Clinical Case Studies. 2018;17(6):443-452.

4. Reed-Knight B, Squires M, Chitkara DK, et al. Adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome report increased eating-associated symptoms, changes in dietary composition, and altered eating behaviors: a pilot comparison study to healthy adolescents. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(12):1915-1920.

5. Melchior C, Desprez C, Riachi G, et al. Anxiety and depression profile is associated with eating disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:928.

6. Mayer EA, Craske M, Naliboff BD. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 Suppl 8:28-37.

7. Abraham S, Kellow J. Exploring eating disorder quality of life and functional gastrointestinal disorders among eating disorder patients. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(4):372-377.

8. Swinbourne JM, Touyz SW. The co-morbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(4):253-274.

9. Perkins SJ, Keville S, Schmidt U, et al. Eating disorders and irritable bowel syndrome: is there a link? J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(2):57-64.

10. Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Henningsen P. Irritable bowel syndrome: relations with functional, mental, and somatoform disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(2):6024-6030.

11. Masand PS, Keuthen NJ, Gupta S, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(1):21-25.

12. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

13. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga Journal. 1997;136:42-50.

14. Barthels F, Müller R, Schüth T, et al. Orthorexic eating behavior in patients with somatoform disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26(1):135-143.

15. Ciao AC, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing eating disorder pathology: common and unique features of successful eating disorders prevention programs. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(7):453.

16. Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive use of olanzapine in the treatment of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents in an eating disorders program. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(10):920-922.

17. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, et al. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

18. Spettigue W, Norris ML, Santos A, et al. Treatment of children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a case series examining the feasibility of family therapy and adjunctive treatments. J Eat Disord. 2018;6:20.

19. Niedzielski A, Kaźmierczak-Wojtaś N. Prevalence of Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Diagnostic Tools-A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488. Published 2021 May 20. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105488 Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa and its diagnostic tools-a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5488.

I STEP: Recognizing cognitive distortions in posttraumatic stress disorder

Evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may employ cognitive restructuring. This psychotherapeutic technique entails recognizing and correcting maladaptive, inaccurate thoughts that perpetuate illness.1 For example, a clinician helps a patient recognize that the negative thought “Nobody loves me” following a romantic breakup is an overgeneralization. The patient is taught to self-correct this to “While my ex-girlfriend doesn’t love me, others do. It only feels like nobody loves me.”2

We introduce the acronym I STEP to help clinicians recognize several common distorted thoughts in PTSD. These tend to occur within stereotyped themes in PTSD,3 as outlined and illustrated below. Recognizing distorted thoughts in these patients will help clinicians understand and address psychological distress following trauma.

Intimacy/In-touch. Intimacy involves comfort in relationships, including but not limited to sexual intimacy. This requires being in touch emotionally with self and others. In trauma involving loss, fear of further loss may impair intimacy with others. Difficulty with self-intimacy impairs commitment to life’s goals and prompts unhelpful avoidance behaviors, such as difficulty being alone or self-injurious use of drugs or alcohol. Comfort in spending some portion of time alone with one’s thoughts and emotions is a life skill necessary to attain optimum function. Patients who are unable to tolerate their own emotions without constant company might have excessive anxiety when social supports are otherwise occupied. Such patients might seek excessive and repeated reassurance rather than learning to tolerate their own emotions and thoughts. They would then find it difficult to engage successfully in solo activities.

Safety. After trauma, patients may view themselves and others as unsafe, and may overestimate risk. For example, a pedestrian who is struck by a vehicle may believe that crossing a street will again result in getting hit by a car without appreciating that people frequently cross streets without injury or that crossing cautiously is an essential life skill. Parents who have suffered from trauma may unduly believe that their children are in danger when engaging in an activity generally considered to be safe. This may create challenges in parenting and impede their children’s ability to develop a sense of independence.

Trust. Trauma victims may unfairly blame themselves, leading them to mistrust their own judgment. Such patients may have difficulty making decisions confidently and independently, such as choosing a job or a romantic partner. When traumatized by another person or people, it can be difficult to maintain positive views of others or to accept others’ positive behaviors as genuine. For example, a common reaction following rape may be a generalized mistrust of all men.

Esteem. Patients’ self-esteem may suffer following trauma due to irrational self-blame or believing the “just world hypothesis”—the idea that bad things only happen to bad people. For example, a patient who suffers an assault by an acquaintance might think “I must be stupid if I couldn’t figure out that my friend was dangerous.”

Power. Traumatic events usually occur outside of one’s control. Survivors of trauma may lose confidence in their ability to control any aspect of their lives. Conversely, they may attempt to gain control of all of life’s circumstances, including those that are beyond anyone’s control. Control can be applied to emotions, behaviors, or events. A driver struck by a vehicle may think “I can’t control other drivers, so I have no power to control my safety while driving,” and hence give up driving. While there are things that are beyond our control, this extreme thought ignores things that we can control, such as wearing seatbelts or having the vehicle’s brakes regularly serviced.

1. Wenzel A. Basic strategies of cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):597-609.

2. Beck J. Cognitive behavioral therapy: basics and beyond. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; 2011.

3. Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. A comprehensive manual. The Guilford Press; 2017.

Evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may employ cognitive restructuring. This psychotherapeutic technique entails recognizing and correcting maladaptive, inaccurate thoughts that perpetuate illness.1 For example, a clinician helps a patient recognize that the negative thought “Nobody loves me” following a romantic breakup is an overgeneralization. The patient is taught to self-correct this to “While my ex-girlfriend doesn’t love me, others do. It only feels like nobody loves me.”2

We introduce the acronym I STEP to help clinicians recognize several common distorted thoughts in PTSD. These tend to occur within stereotyped themes in PTSD,3 as outlined and illustrated below. Recognizing distorted thoughts in these patients will help clinicians understand and address psychological distress following trauma.

Intimacy/In-touch. Intimacy involves comfort in relationships, including but not limited to sexual intimacy. This requires being in touch emotionally with self and others. In trauma involving loss, fear of further loss may impair intimacy with others. Difficulty with self-intimacy impairs commitment to life’s goals and prompts unhelpful avoidance behaviors, such as difficulty being alone or self-injurious use of drugs or alcohol. Comfort in spending some portion of time alone with one’s thoughts and emotions is a life skill necessary to attain optimum function. Patients who are unable to tolerate their own emotions without constant company might have excessive anxiety when social supports are otherwise occupied. Such patients might seek excessive and repeated reassurance rather than learning to tolerate their own emotions and thoughts. They would then find it difficult to engage successfully in solo activities.

Safety. After trauma, patients may view themselves and others as unsafe, and may overestimate risk. For example, a pedestrian who is struck by a vehicle may believe that crossing a street will again result in getting hit by a car without appreciating that people frequently cross streets without injury or that crossing cautiously is an essential life skill. Parents who have suffered from trauma may unduly believe that their children are in danger when engaging in an activity generally considered to be safe. This may create challenges in parenting and impede their children’s ability to develop a sense of independence.

Trust. Trauma victims may unfairly blame themselves, leading them to mistrust their own judgment. Such patients may have difficulty making decisions confidently and independently, such as choosing a job or a romantic partner. When traumatized by another person or people, it can be difficult to maintain positive views of others or to accept others’ positive behaviors as genuine. For example, a common reaction following rape may be a generalized mistrust of all men.

Esteem. Patients’ self-esteem may suffer following trauma due to irrational self-blame or believing the “just world hypothesis”—the idea that bad things only happen to bad people. For example, a patient who suffers an assault by an acquaintance might think “I must be stupid if I couldn’t figure out that my friend was dangerous.”

Power. Traumatic events usually occur outside of one’s control. Survivors of trauma may lose confidence in their ability to control any aspect of their lives. Conversely, they may attempt to gain control of all of life’s circumstances, including those that are beyond anyone’s control. Control can be applied to emotions, behaviors, or events. A driver struck by a vehicle may think “I can’t control other drivers, so I have no power to control my safety while driving,” and hence give up driving. While there are things that are beyond our control, this extreme thought ignores things that we can control, such as wearing seatbelts or having the vehicle’s brakes regularly serviced.

Evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may employ cognitive restructuring. This psychotherapeutic technique entails recognizing and correcting maladaptive, inaccurate thoughts that perpetuate illness.1 For example, a clinician helps a patient recognize that the negative thought “Nobody loves me” following a romantic breakup is an overgeneralization. The patient is taught to self-correct this to “While my ex-girlfriend doesn’t love me, others do. It only feels like nobody loves me.”2

We introduce the acronym I STEP to help clinicians recognize several common distorted thoughts in PTSD. These tend to occur within stereotyped themes in PTSD,3 as outlined and illustrated below. Recognizing distorted thoughts in these patients will help clinicians understand and address psychological distress following trauma.

Intimacy/In-touch. Intimacy involves comfort in relationships, including but not limited to sexual intimacy. This requires being in touch emotionally with self and others. In trauma involving loss, fear of further loss may impair intimacy with others. Difficulty with self-intimacy impairs commitment to life’s goals and prompts unhelpful avoidance behaviors, such as difficulty being alone or self-injurious use of drugs or alcohol. Comfort in spending some portion of time alone with one’s thoughts and emotions is a life skill necessary to attain optimum function. Patients who are unable to tolerate their own emotions without constant company might have excessive anxiety when social supports are otherwise occupied. Such patients might seek excessive and repeated reassurance rather than learning to tolerate their own emotions and thoughts. They would then find it difficult to engage successfully in solo activities.

Safety. After trauma, patients may view themselves and others as unsafe, and may overestimate risk. For example, a pedestrian who is struck by a vehicle may believe that crossing a street will again result in getting hit by a car without appreciating that people frequently cross streets without injury or that crossing cautiously is an essential life skill. Parents who have suffered from trauma may unduly believe that their children are in danger when engaging in an activity generally considered to be safe. This may create challenges in parenting and impede their children’s ability to develop a sense of independence.

Trust. Trauma victims may unfairly blame themselves, leading them to mistrust their own judgment. Such patients may have difficulty making decisions confidently and independently, such as choosing a job or a romantic partner. When traumatized by another person or people, it can be difficult to maintain positive views of others or to accept others’ positive behaviors as genuine. For example, a common reaction following rape may be a generalized mistrust of all men.

Esteem. Patients’ self-esteem may suffer following trauma due to irrational self-blame or believing the “just world hypothesis”—the idea that bad things only happen to bad people. For example, a patient who suffers an assault by an acquaintance might think “I must be stupid if I couldn’t figure out that my friend was dangerous.”

Power. Traumatic events usually occur outside of one’s control. Survivors of trauma may lose confidence in their ability to control any aspect of their lives. Conversely, they may attempt to gain control of all of life’s circumstances, including those that are beyond anyone’s control. Control can be applied to emotions, behaviors, or events. A driver struck by a vehicle may think “I can’t control other drivers, so I have no power to control my safety while driving,” and hence give up driving. While there are things that are beyond our control, this extreme thought ignores things that we can control, such as wearing seatbelts or having the vehicle’s brakes regularly serviced.

1. Wenzel A. Basic strategies of cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):597-609.

2. Beck J. Cognitive behavioral therapy: basics and beyond. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; 2011.

3. Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. A comprehensive manual. The Guilford Press; 2017.

1. Wenzel A. Basic strategies of cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):597-609.

2. Beck J. Cognitive behavioral therapy: basics and beyond. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; 2011.

3. Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. A comprehensive manual. The Guilford Press; 2017.

Managing a COVID-19–positive psychiatric patient on a medical unit

With the COVID-19 pandemic turning the world on its head, we have seen more first-episode psychotic breaks and quick deterioration in previously stable patients. Early in the pandemic, care was particularly complicated for psychiatric patients who had been infected with the virus. Many of these patients required immediate psychiatric hospitalization. At that time, many community hospital psychiatric inpatient units did not have the capacity, staffing, or infrastructure to safely admit such patients, so they needed to be managed on a medical unit. Here, I discuss the case of a COVID-19–positive woman with psychiatric illness who we managed while she was in quarantine on a medical unit.

Case report

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Ms. B, a 35-year-old teacher with a history of depression, was evaluated in the emergency department for bizarre behavior and paranoid delusions regarding her family. Initial laboratory and imaging testing was negative for any potential medical causes of her psychiatric symptoms. Psychiatric hospitalization was recommended, but before Ms. B could be transferred to the psychiatric unit, she tested positive for COVID-19. At that time, our community hospital did not have a designated wing on our psychiatric unit for patients infected with COVID-19. Thus, Ms. B was admitted to the medical floor, where she was quarantined in her room. She would need to remain asymptomatic and test negative for COVID-19 before she could be transferred to the psychiatric unit.

Upon arriving at the medical unit, Ms. B was hostile and uncooperative. She frequently attempted to leave her room and required restraints throughout the day. Our consultation-liaison (CL) team was consulted to assist in managing her. During the initial interview, we noticed that she had covered all 4 walls of her room with papers filled with handwritten notes. Ms. B had cut her gown to expose her stomach and legs. She had pressured speech, tangential thinking, and was religiously preoccupied. She denied any visual and auditory hallucinations, but her persecutory delusions involving her family persisted. We believed that her signs and symptoms were consistent with a manic episode from underlying, and likely undiagnosed, bipolar I disorder that was precipitated by her COVID-19 infection.

We first addressed Ms. B’s and the staff’s safety by transferring her to a larger room with a vestibule at the end of the hallway so she had more room to walk and minimal exposure to the stimuli of the medical unit. We initiated one-on-one observation to redirect her and prevent elopement. We incentivized her cooperation with staff by providing her with paper, pencils, reading material, and phone privileges. We started oral risperidone 2 mg twice daily and lorazepam 2 mg 3 times daily for short-term behavioral control and acute treatment of her symptoms, with the goal of deferring additional treatment decisions to the inpatient psychiatry team after she was transferred to the psychiatric unit. Ms. B’s agitation and impulsivity improved. She began participating with the medical team and was eventually transferred out of our medical unit to a psychiatric unit at a different facility.

COVID-19 and psychiatric illness: Clinical concerns

While infection from COVID-19 and widespread social distancing of the general population have been linked to depression and anxiety, manic and psychotic symptoms secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic have not been well described. The association between influenza infection and psychosis has been reported since the Spanish Flu pandemic,1 but there is limited data on the association between COVID-19 and psychosis. A review of 14 studies found that 0.9% to 4% of people exposed to a virus during an epidemic or pandemic develop psychosis or psychotic symptoms.1 Psychosis was associated with viral exposure, treatments used to manage the infection (steroid therapy), and psychosocial stress. This study also found that treatment with low doses of antipsychotic medication—notably aripiprazole—seemed to have been effective.1

Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind a thorough differential diagnosis and rule out any potential organic etiologies in a COVID-19–positive patient who presents with psychiatric symptoms.2 For Ms. B, we began by ruling out drug-induced psychosis and electrolyte imbalance, and obtained brain imaging to rule out malignancy. We considered an interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy, a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by alterations in sexual behavior, religiosity, and extensive and compulsive writing and drawing.3 Neurology was consulted to evaluate the patient and possibly use EEG to detect interictal spikes, a tall task given the patient’s restlessness and paranoia. Ultimately, we determined the patient was most likely exhibiting symptoms of previously undetected bipolar disorder.

Managing patients with psychiatric illness on a medical floor during a pandemic such as COVID-19 requires the psychiatrist to truly serve as a consultant and liaison between the patient and the treatment team.4 Clinical management should address both infection control and psychiatric symptoms.5 We visited with Ms. B frequently, provided psychoeducation, engaged her in treatment, and updated her on the treatment plan.

As the medical world continues to adjust to treating patients during the pandemic, CL psychiatrists may be tasked with managing patients with acute psychiatric illness on the medical unit while they await transfer to a psychiatric unit. A creative, multifaceted, and team-based approach is key to ensure effective care and safety for all involved.

1. Brown E, Gray R, Lo Monaco S, et al. The potential impact of COVID-19 on psychosis: a rapid review of contemporary epidemic and pandemic research. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:79-87. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.005

2. Byrne P. Managing the acute psychotic episode. BMJ. 2007;334(7595):686-692. doi:10.1136/bmj.39148.668160.80

3. Waxman SG, Geschwind N. The interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(12):1580-1586. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760300118011

4. Stern TA, Freudenreich O, Smith FA, et al. Psychotic patients. In: Massachusetts General Hospital: Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. Mosby; 1997:109-121.

5. Deshpande S, Livingstone A. First-onset psychosis in older adults: social isolation influence during COVID pandemic—a UK case series. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry. 2021;25(1):14-18. doi:10.1002/pnp.692

With the COVID-19 pandemic turning the world on its head, we have seen more first-episode psychotic breaks and quick deterioration in previously stable patients. Early in the pandemic, care was particularly complicated for psychiatric patients who had been infected with the virus. Many of these patients required immediate psychiatric hospitalization. At that time, many community hospital psychiatric inpatient units did not have the capacity, staffing, or infrastructure to safely admit such patients, so they needed to be managed on a medical unit. Here, I discuss the case of a COVID-19–positive woman with psychiatric illness who we managed while she was in quarantine on a medical unit.

Case report

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Ms. B, a 35-year-old teacher with a history of depression, was evaluated in the emergency department for bizarre behavior and paranoid delusions regarding her family. Initial laboratory and imaging testing was negative for any potential medical causes of her psychiatric symptoms. Psychiatric hospitalization was recommended, but before Ms. B could be transferred to the psychiatric unit, she tested positive for COVID-19. At that time, our community hospital did not have a designated wing on our psychiatric unit for patients infected with COVID-19. Thus, Ms. B was admitted to the medical floor, where she was quarantined in her room. She would need to remain asymptomatic and test negative for COVID-19 before she could be transferred to the psychiatric unit.

Upon arriving at the medical unit, Ms. B was hostile and uncooperative. She frequently attempted to leave her room and required restraints throughout the day. Our consultation-liaison (CL) team was consulted to assist in managing her. During the initial interview, we noticed that she had covered all 4 walls of her room with papers filled with handwritten notes. Ms. B had cut her gown to expose her stomach and legs. She had pressured speech, tangential thinking, and was religiously preoccupied. She denied any visual and auditory hallucinations, but her persecutory delusions involving her family persisted. We believed that her signs and symptoms were consistent with a manic episode from underlying, and likely undiagnosed, bipolar I disorder that was precipitated by her COVID-19 infection.

We first addressed Ms. B’s and the staff’s safety by transferring her to a larger room with a vestibule at the end of the hallway so she had more room to walk and minimal exposure to the stimuli of the medical unit. We initiated one-on-one observation to redirect her and prevent elopement. We incentivized her cooperation with staff by providing her with paper, pencils, reading material, and phone privileges. We started oral risperidone 2 mg twice daily and lorazepam 2 mg 3 times daily for short-term behavioral control and acute treatment of her symptoms, with the goal of deferring additional treatment decisions to the inpatient psychiatry team after she was transferred to the psychiatric unit. Ms. B’s agitation and impulsivity improved. She began participating with the medical team and was eventually transferred out of our medical unit to a psychiatric unit at a different facility.

COVID-19 and psychiatric illness: Clinical concerns

While infection from COVID-19 and widespread social distancing of the general population have been linked to depression and anxiety, manic and psychotic symptoms secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic have not been well described. The association between influenza infection and psychosis has been reported since the Spanish Flu pandemic,1 but there is limited data on the association between COVID-19 and psychosis. A review of 14 studies found that 0.9% to 4% of people exposed to a virus during an epidemic or pandemic develop psychosis or psychotic symptoms.1 Psychosis was associated with viral exposure, treatments used to manage the infection (steroid therapy), and psychosocial stress. This study also found that treatment with low doses of antipsychotic medication—notably aripiprazole—seemed to have been effective.1

Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind a thorough differential diagnosis and rule out any potential organic etiologies in a COVID-19–positive patient who presents with psychiatric symptoms.2 For Ms. B, we began by ruling out drug-induced psychosis and electrolyte imbalance, and obtained brain imaging to rule out malignancy. We considered an interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy, a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by alterations in sexual behavior, religiosity, and extensive and compulsive writing and drawing.3 Neurology was consulted to evaluate the patient and possibly use EEG to detect interictal spikes, a tall task given the patient’s restlessness and paranoia. Ultimately, we determined the patient was most likely exhibiting symptoms of previously undetected bipolar disorder.

Managing patients with psychiatric illness on a medical floor during a pandemic such as COVID-19 requires the psychiatrist to truly serve as a consultant and liaison between the patient and the treatment team.4 Clinical management should address both infection control and psychiatric symptoms.5 We visited with Ms. B frequently, provided psychoeducation, engaged her in treatment, and updated her on the treatment plan.

As the medical world continues to adjust to treating patients during the pandemic, CL psychiatrists may be tasked with managing patients with acute psychiatric illness on the medical unit while they await transfer to a psychiatric unit. A creative, multifaceted, and team-based approach is key to ensure effective care and safety for all involved.

With the COVID-19 pandemic turning the world on its head, we have seen more first-episode psychotic breaks and quick deterioration in previously stable patients. Early in the pandemic, care was particularly complicated for psychiatric patients who had been infected with the virus. Many of these patients required immediate psychiatric hospitalization. At that time, many community hospital psychiatric inpatient units did not have the capacity, staffing, or infrastructure to safely admit such patients, so they needed to be managed on a medical unit. Here, I discuss the case of a COVID-19–positive woman with psychiatric illness who we managed while she was in quarantine on a medical unit.

Case report

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Ms. B, a 35-year-old teacher with a history of depression, was evaluated in the emergency department for bizarre behavior and paranoid delusions regarding her family. Initial laboratory and imaging testing was negative for any potential medical causes of her psychiatric symptoms. Psychiatric hospitalization was recommended, but before Ms. B could be transferred to the psychiatric unit, she tested positive for COVID-19. At that time, our community hospital did not have a designated wing on our psychiatric unit for patients infected with COVID-19. Thus, Ms. B was admitted to the medical floor, where she was quarantined in her room. She would need to remain asymptomatic and test negative for COVID-19 before she could be transferred to the psychiatric unit.

Upon arriving at the medical unit, Ms. B was hostile and uncooperative. She frequently attempted to leave her room and required restraints throughout the day. Our consultation-liaison (CL) team was consulted to assist in managing her. During the initial interview, we noticed that she had covered all 4 walls of her room with papers filled with handwritten notes. Ms. B had cut her gown to expose her stomach and legs. She had pressured speech, tangential thinking, and was religiously preoccupied. She denied any visual and auditory hallucinations, but her persecutory delusions involving her family persisted. We believed that her signs and symptoms were consistent with a manic episode from underlying, and likely undiagnosed, bipolar I disorder that was precipitated by her COVID-19 infection.

We first addressed Ms. B’s and the staff’s safety by transferring her to a larger room with a vestibule at the end of the hallway so she had more room to walk and minimal exposure to the stimuli of the medical unit. We initiated one-on-one observation to redirect her and prevent elopement. We incentivized her cooperation with staff by providing her with paper, pencils, reading material, and phone privileges. We started oral risperidone 2 mg twice daily and lorazepam 2 mg 3 times daily for short-term behavioral control and acute treatment of her symptoms, with the goal of deferring additional treatment decisions to the inpatient psychiatry team after she was transferred to the psychiatric unit. Ms. B’s agitation and impulsivity improved. She began participating with the medical team and was eventually transferred out of our medical unit to a psychiatric unit at a different facility.

COVID-19 and psychiatric illness: Clinical concerns

While infection from COVID-19 and widespread social distancing of the general population have been linked to depression and anxiety, manic and psychotic symptoms secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic have not been well described. The association between influenza infection and psychosis has been reported since the Spanish Flu pandemic,1 but there is limited data on the association between COVID-19 and psychosis. A review of 14 studies found that 0.9% to 4% of people exposed to a virus during an epidemic or pandemic develop psychosis or psychotic symptoms.1 Psychosis was associated with viral exposure, treatments used to manage the infection (steroid therapy), and psychosocial stress. This study also found that treatment with low doses of antipsychotic medication—notably aripiprazole—seemed to have been effective.1

Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind a thorough differential diagnosis and rule out any potential organic etiologies in a COVID-19–positive patient who presents with psychiatric symptoms.2 For Ms. B, we began by ruling out drug-induced psychosis and electrolyte imbalance, and obtained brain imaging to rule out malignancy. We considered an interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy, a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by alterations in sexual behavior, religiosity, and extensive and compulsive writing and drawing.3 Neurology was consulted to evaluate the patient and possibly use EEG to detect interictal spikes, a tall task given the patient’s restlessness and paranoia. Ultimately, we determined the patient was most likely exhibiting symptoms of previously undetected bipolar disorder.

Managing patients with psychiatric illness on a medical floor during a pandemic such as COVID-19 requires the psychiatrist to truly serve as a consultant and liaison between the patient and the treatment team.4 Clinical management should address both infection control and psychiatric symptoms.5 We visited with Ms. B frequently, provided psychoeducation, engaged her in treatment, and updated her on the treatment plan.