User login

No link between cell phones and brain tumors in large U.K. study

“These results support the accumulating evidence that mobile phone use under usual conditions does not increase brain tumor risk,” study author Kirstin Pirie, MSc, from the cancer epidemiology unit at Oxford (England) Population Health, said in a statement.

However, an important limitation of the study is that it involved only women who were middle-aged and older; these people generally use cell phones less than younger women or men, the authors noted. In this study’s cohort, mobile phone use was low, with only 18% of users talking on the phone for 30 minutes or more each week.

The results were published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

This study is a “welcome addition to the body of knowledge looking at the risk from mobile phones, and specifically in relation to certain types of tumor genesis. It is a well-designed, prospective study that identifies no causal link,” commented Malcolm Sperrin from Oxford University Hospitals, who was not involved in the research.

“There is always a need for further research work, especially as phones, wireless, etc., become ubiquitous, but this study should allay many existing concerns,” he commented on the UK Science Media Centre.

Concerns about a cancer risk, particularly brain tumors, have been circulating for decades, and to date, there have been some 30 epidemiologic studies on this issue.

In 2011, the International Agency for Research on Cancer announced that cell phones are “possibly carcinogenic.” That conclusion was based largely on the results of the large INTERPHONE international case-control study and a series of Swedish studies led by Hardell Lennart, MD.

In the latest article, the U.K. researchers suggest that a “likely explanation for the previous positive results is that for a very slow growing tumor, there may be detection bias if cellular telephone users seek medical advice because of awareness of typical symptoms of acoustic neuroma, such as unilateral hearing problems, earlier than nonusers.

“The totality of human evidence, from observational studies, time trends, and bioassays, suggests little or no increase in the risk of cellular telephone users developing a brain tumor,” the U.K. researchers concluded.

Commenting on the U.K. study, Joachim Schüz, PhD, branch head of the section of environment and radiation at the IARC, noted that “mobile technologies are improving all the time, so that the more recent generations emit substantially lower output power.

“Nevertheless, given the lack of evidence for heavy users, advising mobile phone users to reduce unnecessary exposures remains a good precautionary approach,” Dr. Schuz said in a statement.

Details of U.K. study

The U.K. study was conducted by researchers from Oxford Population Health and IARC, who used data from the ongoing UK Million Women Study. This study began in 1996 and has recruited 1.3 million women born from 1935 to 1950 (which amounts to 1 in every 4 women) through the U.K. National Health Service Breast Screening Programme. These women complete regular postal questionnaires about sociodemographic, medical, and lifestyle factors.

Questions about cell phone use were completed by about 776,000 women in 2001 (when they were 50-65 years old). About half of these women also answered these questions about mobile phone use 10 years later, in 2011 (when they were aged 60-75).

The answers indicated that by 2011, the majority of women (75%) aged between 60 and 64 years used a mobile phone, while just under half of those aged between 75 and 79 years used one.

These women were then followed for an average of 14 years through linkage to their NHS records.

The researchers looked for any mention of brain tumors, including glioma, acoustic neuroma, meningioma, and pituitary gland tumors, as well as eye tumors.

During the 14 year follow-up period, 3,268 (0.42%) of the participants developed a brain tumor, but there was no significant difference in that risk between individuals who had never used a mobile phone and those who were mobile phone users. These included tumors in the temporal and parietal lobes, which are the most exposed areas of the brain.

There was also no difference in the risk of developing tumors between women who reported using a mobile phone daily, those who used them for at least 20 minutes a week, and those who had used a mobile phone for over 10 years.

In addition, among the individuals who did develop a tumor, the incidence of right- and left-sided tumors was similar among mobile phone users, even though mobile phone use tends to involve the right side considerably more than the left side, the researchers noted.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council and Cancer Research UK.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“These results support the accumulating evidence that mobile phone use under usual conditions does not increase brain tumor risk,” study author Kirstin Pirie, MSc, from the cancer epidemiology unit at Oxford (England) Population Health, said in a statement.

However, an important limitation of the study is that it involved only women who were middle-aged and older; these people generally use cell phones less than younger women or men, the authors noted. In this study’s cohort, mobile phone use was low, with only 18% of users talking on the phone for 30 minutes or more each week.

The results were published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

This study is a “welcome addition to the body of knowledge looking at the risk from mobile phones, and specifically in relation to certain types of tumor genesis. It is a well-designed, prospective study that identifies no causal link,” commented Malcolm Sperrin from Oxford University Hospitals, who was not involved in the research.

“There is always a need for further research work, especially as phones, wireless, etc., become ubiquitous, but this study should allay many existing concerns,” he commented on the UK Science Media Centre.

Concerns about a cancer risk, particularly brain tumors, have been circulating for decades, and to date, there have been some 30 epidemiologic studies on this issue.

In 2011, the International Agency for Research on Cancer announced that cell phones are “possibly carcinogenic.” That conclusion was based largely on the results of the large INTERPHONE international case-control study and a series of Swedish studies led by Hardell Lennart, MD.

In the latest article, the U.K. researchers suggest that a “likely explanation for the previous positive results is that for a very slow growing tumor, there may be detection bias if cellular telephone users seek medical advice because of awareness of typical symptoms of acoustic neuroma, such as unilateral hearing problems, earlier than nonusers.

“The totality of human evidence, from observational studies, time trends, and bioassays, suggests little or no increase in the risk of cellular telephone users developing a brain tumor,” the U.K. researchers concluded.

Commenting on the U.K. study, Joachim Schüz, PhD, branch head of the section of environment and radiation at the IARC, noted that “mobile technologies are improving all the time, so that the more recent generations emit substantially lower output power.

“Nevertheless, given the lack of evidence for heavy users, advising mobile phone users to reduce unnecessary exposures remains a good precautionary approach,” Dr. Schuz said in a statement.

Details of U.K. study

The U.K. study was conducted by researchers from Oxford Population Health and IARC, who used data from the ongoing UK Million Women Study. This study began in 1996 and has recruited 1.3 million women born from 1935 to 1950 (which amounts to 1 in every 4 women) through the U.K. National Health Service Breast Screening Programme. These women complete regular postal questionnaires about sociodemographic, medical, and lifestyle factors.

Questions about cell phone use were completed by about 776,000 women in 2001 (when they were 50-65 years old). About half of these women also answered these questions about mobile phone use 10 years later, in 2011 (when they were aged 60-75).

The answers indicated that by 2011, the majority of women (75%) aged between 60 and 64 years used a mobile phone, while just under half of those aged between 75 and 79 years used one.

These women were then followed for an average of 14 years through linkage to their NHS records.

The researchers looked for any mention of brain tumors, including glioma, acoustic neuroma, meningioma, and pituitary gland tumors, as well as eye tumors.

During the 14 year follow-up period, 3,268 (0.42%) of the participants developed a brain tumor, but there was no significant difference in that risk between individuals who had never used a mobile phone and those who were mobile phone users. These included tumors in the temporal and parietal lobes, which are the most exposed areas of the brain.

There was also no difference in the risk of developing tumors between women who reported using a mobile phone daily, those who used them for at least 20 minutes a week, and those who had used a mobile phone for over 10 years.

In addition, among the individuals who did develop a tumor, the incidence of right- and left-sided tumors was similar among mobile phone users, even though mobile phone use tends to involve the right side considerably more than the left side, the researchers noted.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council and Cancer Research UK.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“These results support the accumulating evidence that mobile phone use under usual conditions does not increase brain tumor risk,” study author Kirstin Pirie, MSc, from the cancer epidemiology unit at Oxford (England) Population Health, said in a statement.

However, an important limitation of the study is that it involved only women who were middle-aged and older; these people generally use cell phones less than younger women or men, the authors noted. In this study’s cohort, mobile phone use was low, with only 18% of users talking on the phone for 30 minutes or more each week.

The results were published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

This study is a “welcome addition to the body of knowledge looking at the risk from mobile phones, and specifically in relation to certain types of tumor genesis. It is a well-designed, prospective study that identifies no causal link,” commented Malcolm Sperrin from Oxford University Hospitals, who was not involved in the research.

“There is always a need for further research work, especially as phones, wireless, etc., become ubiquitous, but this study should allay many existing concerns,” he commented on the UK Science Media Centre.

Concerns about a cancer risk, particularly brain tumors, have been circulating for decades, and to date, there have been some 30 epidemiologic studies on this issue.

In 2011, the International Agency for Research on Cancer announced that cell phones are “possibly carcinogenic.” That conclusion was based largely on the results of the large INTERPHONE international case-control study and a series of Swedish studies led by Hardell Lennart, MD.

In the latest article, the U.K. researchers suggest that a “likely explanation for the previous positive results is that for a very slow growing tumor, there may be detection bias if cellular telephone users seek medical advice because of awareness of typical symptoms of acoustic neuroma, such as unilateral hearing problems, earlier than nonusers.

“The totality of human evidence, from observational studies, time trends, and bioassays, suggests little or no increase in the risk of cellular telephone users developing a brain tumor,” the U.K. researchers concluded.

Commenting on the U.K. study, Joachim Schüz, PhD, branch head of the section of environment and radiation at the IARC, noted that “mobile technologies are improving all the time, so that the more recent generations emit substantially lower output power.

“Nevertheless, given the lack of evidence for heavy users, advising mobile phone users to reduce unnecessary exposures remains a good precautionary approach,” Dr. Schuz said in a statement.

Details of U.K. study

The U.K. study was conducted by researchers from Oxford Population Health and IARC, who used data from the ongoing UK Million Women Study. This study began in 1996 and has recruited 1.3 million women born from 1935 to 1950 (which amounts to 1 in every 4 women) through the U.K. National Health Service Breast Screening Programme. These women complete regular postal questionnaires about sociodemographic, medical, and lifestyle factors.

Questions about cell phone use were completed by about 776,000 women in 2001 (when they were 50-65 years old). About half of these women also answered these questions about mobile phone use 10 years later, in 2011 (when they were aged 60-75).

The answers indicated that by 2011, the majority of women (75%) aged between 60 and 64 years used a mobile phone, while just under half of those aged between 75 and 79 years used one.

These women were then followed for an average of 14 years through linkage to their NHS records.

The researchers looked for any mention of brain tumors, including glioma, acoustic neuroma, meningioma, and pituitary gland tumors, as well as eye tumors.

During the 14 year follow-up period, 3,268 (0.42%) of the participants developed a brain tumor, but there was no significant difference in that risk between individuals who had never used a mobile phone and those who were mobile phone users. These included tumors in the temporal and parietal lobes, which are the most exposed areas of the brain.

There was also no difference in the risk of developing tumors between women who reported using a mobile phone daily, those who used them for at least 20 minutes a week, and those who had used a mobile phone for over 10 years.

In addition, among the individuals who did develop a tumor, the incidence of right- and left-sided tumors was similar among mobile phone users, even though mobile phone use tends to involve the right side considerably more than the left side, the researchers noted.

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council and Cancer Research UK.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

Fingers take the fight to COVID-19

Pointing a finger at COVID-19

The battle against COVID-19 is seemingly never ending. It’s been 2 years and still we struggle against the virus. But now, a new hero rises against the eternal menace, a powerful weapon against this scourge of humanity. And that weapon? Finger length.

Before you break out the sad trombone, hear us out. One of the big questions around COVID-19 is the role testosterone plays in its severity: Does low testosterone increase or decrease the odds of contracting severe COVID-19? To help answer that question, English researchers have published a study analyzing finger length ratios in both COVID-19 patients and a healthy control group. That seems random, but high testosterone in the womb leads to longer ring fingers in adulthood, while high estrogen leads to longer index fingers.

According to the researchers, those who had significant left hand–right hand differences in the ratio between the second and fourth digits, as well as the third and fifth digits, were significantly more likely to have severe COVID-19 compared with those with more even ratios. Those with “feminized” short little fingers were also at risk. Those large ratio differences indicate low testosterone and high estrogen, which may explain why elderly men are at such high risk for severe COVID-19. Testosterone naturally falls off as men get older.

The results add credence to clinical trials looking to use testosterone-boosting drugs against COVID-19, the researchers said. It also gives credence to LOTME’s brand-new 12-step finger strength fitness routine and our branded finger weights. Now just $19.95! It’s the bargain of the century! Boost your testosterone naturally and protect yourself from COVID-19! We promise it’s not a scam.

Some emergencies need a superhero

Last week, we learned about the most boring person in the world. This week just happens to be opposite week, so we’re looking at a candidate for the most interesting person. Someone who can swoop down from the sky to save the injured and helpless. Someone who can go where helicopters fear to tread. Someone with jet engines for arms. Superhero-type stuff.

The Great North Air Ambulance Service (GNAAS), a charitable organization located in the United Kingdom, recently announced that one of its members has completed training on the Gravity Industries Jet Suit. The suit “has two engines on each arm and a larger engine on the back [that] provide up to 317 pounds of thrust,” Interesting Engineering explained.

GNAAS is putting the suit into operation in England’s Lake District National Park, which includes mountainous terrain that is not very hospitable to helicopter landings. A paramedic using the suit can reach hikers stranded on mountainsides much faster than rescuers who have to run or hike from the nearest helicopter landing site.

“Everyone looks at the wow factor and the fact we are the world’s first jet suit paramedics, but for us, it’s about delivering patient care,” GNAAS’ Andy Mawson told Interesting Engineering. Sounds like superhero-speak to us.

So if you’re in the Lake District and have taken a bit of a tumble, you can call a superhero on your cell phone or you can use this to summon one.

Why we’re rejecting food as medicine

Humans have been using food to treat ailments much longer than we’ve had the advances of modern medicine. So why have we rejected its worth in our treatment processes? And what can be done to change that? The Center for Food as Medicine and the Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center just released a 335-page report that answers those questions.

First, the why: Meals in health care settings are not medically designed to help with the specific needs of the patient. Produce-prescription and nutrition-incentive programs don’t have the government funds to fully support them. And a lot of medical schools don’t even require students to take a basic nutrition course. So there’s a lack of knowledge and a disconnect between health care providers and food as a resource.

Then there’s a lack of trust in the food industry and their validity. Social media uses food as a means of promoting “pseudoscientific alternative medicine” or spreading false info, pushing away legitimate providers. The food industry has had its fingers in food science studies and an almost mafia-esque chokehold on American dietary guidelines. No wonder food for medicine is getting the boot!

To change the situation, the report offers 10 key recommendations on how to advance the idea of incorporating food into medicine for treatment and prevention. They include boosting the funding for research, making hospitals more food-as-medicine focused, expanding federal programs, and improving public awareness on the role nutrition can play in medical treatment or prevention.

So maybe instead of rejecting food outright, we should be looking a little deeper at how we can use it to our advantage. Just a thought: Ice cream as an antidepressant.

Being rude is a good thing, apparently

If you’ve ever been called argumentative, stubborn, or unpleasant, then this LOTME is for you. Researchers at the University of Geneva have found that people who are more stubborn and hate to conform have brains that are more protected against Alzheimer’s disease. That type of personality seems to preserve the part of the brain that usually deteriorates as we grow older.

The original hypothesis that personality may have a protective effect against brain degeneration led the investigators to conduct cognitive and personality assessments of 65 elderly participants over a 5-year period. Researchers have been attempting to create vaccines to protect against Alzheimer’s disease, but these new findings offer a nonbiological way to help.

“For a long time, the brain is able to compensate by activating alternative networks; when the first clinical signs appear, however, it is unfortunately often too late. The identification of early biomarkers is therefore essential for … effective disease management,” lead author Panteleimon Giannakopoulos, MD, said in a Study Finds report.

You may be wondering how people with more agreeable and less confrontational personalities can seek help. Well, researchers are working on that, too. It’s a complex situation, but as always, we’re rooting for you, science!

At least now you can take solace in the fact that your elderly next-door neighbor who yells at you for stepping on his lawn is probably more protected against Alzheimer’s disease.

Pointing a finger at COVID-19

The battle against COVID-19 is seemingly never ending. It’s been 2 years and still we struggle against the virus. But now, a new hero rises against the eternal menace, a powerful weapon against this scourge of humanity. And that weapon? Finger length.

Before you break out the sad trombone, hear us out. One of the big questions around COVID-19 is the role testosterone plays in its severity: Does low testosterone increase or decrease the odds of contracting severe COVID-19? To help answer that question, English researchers have published a study analyzing finger length ratios in both COVID-19 patients and a healthy control group. That seems random, but high testosterone in the womb leads to longer ring fingers in adulthood, while high estrogen leads to longer index fingers.

According to the researchers, those who had significant left hand–right hand differences in the ratio between the second and fourth digits, as well as the third and fifth digits, were significantly more likely to have severe COVID-19 compared with those with more even ratios. Those with “feminized” short little fingers were also at risk. Those large ratio differences indicate low testosterone and high estrogen, which may explain why elderly men are at such high risk for severe COVID-19. Testosterone naturally falls off as men get older.

The results add credence to clinical trials looking to use testosterone-boosting drugs against COVID-19, the researchers said. It also gives credence to LOTME’s brand-new 12-step finger strength fitness routine and our branded finger weights. Now just $19.95! It’s the bargain of the century! Boost your testosterone naturally and protect yourself from COVID-19! We promise it’s not a scam.

Some emergencies need a superhero

Last week, we learned about the most boring person in the world. This week just happens to be opposite week, so we’re looking at a candidate for the most interesting person. Someone who can swoop down from the sky to save the injured and helpless. Someone who can go where helicopters fear to tread. Someone with jet engines for arms. Superhero-type stuff.

The Great North Air Ambulance Service (GNAAS), a charitable organization located in the United Kingdom, recently announced that one of its members has completed training on the Gravity Industries Jet Suit. The suit “has two engines on each arm and a larger engine on the back [that] provide up to 317 pounds of thrust,” Interesting Engineering explained.

GNAAS is putting the suit into operation in England’s Lake District National Park, which includes mountainous terrain that is not very hospitable to helicopter landings. A paramedic using the suit can reach hikers stranded on mountainsides much faster than rescuers who have to run or hike from the nearest helicopter landing site.

“Everyone looks at the wow factor and the fact we are the world’s first jet suit paramedics, but for us, it’s about delivering patient care,” GNAAS’ Andy Mawson told Interesting Engineering. Sounds like superhero-speak to us.

So if you’re in the Lake District and have taken a bit of a tumble, you can call a superhero on your cell phone or you can use this to summon one.

Why we’re rejecting food as medicine

Humans have been using food to treat ailments much longer than we’ve had the advances of modern medicine. So why have we rejected its worth in our treatment processes? And what can be done to change that? The Center for Food as Medicine and the Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center just released a 335-page report that answers those questions.

First, the why: Meals in health care settings are not medically designed to help with the specific needs of the patient. Produce-prescription and nutrition-incentive programs don’t have the government funds to fully support them. And a lot of medical schools don’t even require students to take a basic nutrition course. So there’s a lack of knowledge and a disconnect between health care providers and food as a resource.

Then there’s a lack of trust in the food industry and their validity. Social media uses food as a means of promoting “pseudoscientific alternative medicine” or spreading false info, pushing away legitimate providers. The food industry has had its fingers in food science studies and an almost mafia-esque chokehold on American dietary guidelines. No wonder food for medicine is getting the boot!

To change the situation, the report offers 10 key recommendations on how to advance the idea of incorporating food into medicine for treatment and prevention. They include boosting the funding for research, making hospitals more food-as-medicine focused, expanding federal programs, and improving public awareness on the role nutrition can play in medical treatment or prevention.

So maybe instead of rejecting food outright, we should be looking a little deeper at how we can use it to our advantage. Just a thought: Ice cream as an antidepressant.

Being rude is a good thing, apparently

If you’ve ever been called argumentative, stubborn, or unpleasant, then this LOTME is for you. Researchers at the University of Geneva have found that people who are more stubborn and hate to conform have brains that are more protected against Alzheimer’s disease. That type of personality seems to preserve the part of the brain that usually deteriorates as we grow older.

The original hypothesis that personality may have a protective effect against brain degeneration led the investigators to conduct cognitive and personality assessments of 65 elderly participants over a 5-year period. Researchers have been attempting to create vaccines to protect against Alzheimer’s disease, but these new findings offer a nonbiological way to help.

“For a long time, the brain is able to compensate by activating alternative networks; when the first clinical signs appear, however, it is unfortunately often too late. The identification of early biomarkers is therefore essential for … effective disease management,” lead author Panteleimon Giannakopoulos, MD, said in a Study Finds report.

You may be wondering how people with more agreeable and less confrontational personalities can seek help. Well, researchers are working on that, too. It’s a complex situation, but as always, we’re rooting for you, science!

At least now you can take solace in the fact that your elderly next-door neighbor who yells at you for stepping on his lawn is probably more protected against Alzheimer’s disease.

Pointing a finger at COVID-19

The battle against COVID-19 is seemingly never ending. It’s been 2 years and still we struggle against the virus. But now, a new hero rises against the eternal menace, a powerful weapon against this scourge of humanity. And that weapon? Finger length.

Before you break out the sad trombone, hear us out. One of the big questions around COVID-19 is the role testosterone plays in its severity: Does low testosterone increase or decrease the odds of contracting severe COVID-19? To help answer that question, English researchers have published a study analyzing finger length ratios in both COVID-19 patients and a healthy control group. That seems random, but high testosterone in the womb leads to longer ring fingers in adulthood, while high estrogen leads to longer index fingers.

According to the researchers, those who had significant left hand–right hand differences in the ratio between the second and fourth digits, as well as the third and fifth digits, were significantly more likely to have severe COVID-19 compared with those with more even ratios. Those with “feminized” short little fingers were also at risk. Those large ratio differences indicate low testosterone and high estrogen, which may explain why elderly men are at such high risk for severe COVID-19. Testosterone naturally falls off as men get older.

The results add credence to clinical trials looking to use testosterone-boosting drugs against COVID-19, the researchers said. It also gives credence to LOTME’s brand-new 12-step finger strength fitness routine and our branded finger weights. Now just $19.95! It’s the bargain of the century! Boost your testosterone naturally and protect yourself from COVID-19! We promise it’s not a scam.

Some emergencies need a superhero

Last week, we learned about the most boring person in the world. This week just happens to be opposite week, so we’re looking at a candidate for the most interesting person. Someone who can swoop down from the sky to save the injured and helpless. Someone who can go where helicopters fear to tread. Someone with jet engines for arms. Superhero-type stuff.

The Great North Air Ambulance Service (GNAAS), a charitable organization located in the United Kingdom, recently announced that one of its members has completed training on the Gravity Industries Jet Suit. The suit “has two engines on each arm and a larger engine on the back [that] provide up to 317 pounds of thrust,” Interesting Engineering explained.

GNAAS is putting the suit into operation in England’s Lake District National Park, which includes mountainous terrain that is not very hospitable to helicopter landings. A paramedic using the suit can reach hikers stranded on mountainsides much faster than rescuers who have to run or hike from the nearest helicopter landing site.

“Everyone looks at the wow factor and the fact we are the world’s first jet suit paramedics, but for us, it’s about delivering patient care,” GNAAS’ Andy Mawson told Interesting Engineering. Sounds like superhero-speak to us.

So if you’re in the Lake District and have taken a bit of a tumble, you can call a superhero on your cell phone or you can use this to summon one.

Why we’re rejecting food as medicine

Humans have been using food to treat ailments much longer than we’ve had the advances of modern medicine. So why have we rejected its worth in our treatment processes? And what can be done to change that? The Center for Food as Medicine and the Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center just released a 335-page report that answers those questions.

First, the why: Meals in health care settings are not medically designed to help with the specific needs of the patient. Produce-prescription and nutrition-incentive programs don’t have the government funds to fully support them. And a lot of medical schools don’t even require students to take a basic nutrition course. So there’s a lack of knowledge and a disconnect between health care providers and food as a resource.

Then there’s a lack of trust in the food industry and their validity. Social media uses food as a means of promoting “pseudoscientific alternative medicine” or spreading false info, pushing away legitimate providers. The food industry has had its fingers in food science studies and an almost mafia-esque chokehold on American dietary guidelines. No wonder food for medicine is getting the boot!

To change the situation, the report offers 10 key recommendations on how to advance the idea of incorporating food into medicine for treatment and prevention. They include boosting the funding for research, making hospitals more food-as-medicine focused, expanding federal programs, and improving public awareness on the role nutrition can play in medical treatment or prevention.

So maybe instead of rejecting food outright, we should be looking a little deeper at how we can use it to our advantage. Just a thought: Ice cream as an antidepressant.

Being rude is a good thing, apparently

If you’ve ever been called argumentative, stubborn, or unpleasant, then this LOTME is for you. Researchers at the University of Geneva have found that people who are more stubborn and hate to conform have brains that are more protected against Alzheimer’s disease. That type of personality seems to preserve the part of the brain that usually deteriorates as we grow older.

The original hypothesis that personality may have a protective effect against brain degeneration led the investigators to conduct cognitive and personality assessments of 65 elderly participants over a 5-year period. Researchers have been attempting to create vaccines to protect against Alzheimer’s disease, but these new findings offer a nonbiological way to help.

“For a long time, the brain is able to compensate by activating alternative networks; when the first clinical signs appear, however, it is unfortunately often too late. The identification of early biomarkers is therefore essential for … effective disease management,” lead author Panteleimon Giannakopoulos, MD, said in a Study Finds report.

You may be wondering how people with more agreeable and less confrontational personalities can seek help. Well, researchers are working on that, too. It’s a complex situation, but as always, we’re rooting for you, science!

At least now you can take solace in the fact that your elderly next-door neighbor who yells at you for stepping on his lawn is probably more protected against Alzheimer’s disease.

Verrucous Carcinoma of the Foot: A Retrospective Study of 19 Cases and Analysis of Prognostic Factors Influencing Recurrence

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare cancer with the greatest predilection for the foot. Multiple case reports with only a few large case series have been published. 1-3 Plantar verrucous carcinoma is characterized as a slowly but relentlessly enlarging warty tumor with low metastatic potential and high risk for local invasion. The tumor occurs most frequently in patients aged 60 to 70 years, predominantly in White males. 1 It often is misdiagnosed for years as an ulcer or wart that is highly resistant to therapy. Size typically ranges from 1 to 12 cm in greatest dimension. 1

The pathogenesis of plantar verrucous carcinoma remains unclear, but some contributing factors have been proposed, including trauma, chronic irritation, infection, and poor local hygiene.2 This tumor has been reported to occur in chronic foot ulcerations, particularly in the diabetic population.4 It has been proposed that abnormal expression of the p53 tumor suppressor protein and several types of human papillomavirus (HPV) may have a role in the pathogenesis of verrucous carcinoma.5

The pathologic hallmarks of this tumor include a verrucous/hyperkeratotic surface with a deeply endophytic, broad, pushing base. Tumor cells are well differentiated, and atypia is either absent or confined to 1 or 2 layers at the base of the tumor. Overt invasion at the base is lacking, except in cases with a component of conventional invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Human papillomavirus viropathic changes are classically absent.1,3 Studies of the histopathology of verrucous carcinoma have been complicated by similar entities, nomenclatural uncertainty, and variable diagnostic criteria. For example, epithelioma cuniculatum variously has been defined as being synonymous with verrucous carcinoma, a distinct clinical verrucous carcinoma subtype occurring on the soles, a histologic subtype (characterized by prominent burrowing sinuses), or a separate entity entirely.1,2,6,7 Furthermore, in the genital area, several different types of carcinomas have verruciform features but display distinct microscopic findings and outcomes from verrucous carcinoma.8

Verrucous carcinoma represents an unusual variant of squamous cell carcinoma and is treated as such. Treatments have included laser surgery; immunotherapy; retinoid therapy; and chemotherapy by oral, intralesional, or iontophoretic routes in select patients.9 Radiotherapy presents another option, though reports have described progression to aggressive squamous cell carcinoma in some cases.9 Surgery is the best course of treatment, and as more case reports have been published, a transition from radical resection to wide excision with tumor-free margins is the treatment of choice.2,3,10,11 To minimize soft-tissue deficits, Mohs micrographic surgery has been discussed as a treatment option for verrucous carcinoma.11-13

Few studies have described verrucous carcinoma recurrence, and none have systematically examined recurrence rate, risk factors, or prognosis

Methods

Patient cases were

Of the 19 cases, 16 were treated at the University of Michigan and are included in the treatment analyses. Specific attention was then paid to the cases with a clinical recurrence despite negative surgical margins. We compared the clinical and surgical differences between recurrent cases and nonrecurrent cases.

Pathology was rereviewed for selected cases, including 2 cases with recurrence and matched primary, 2 cases with recurrence (for which the matched primary was unavailable for review), and 5 representative primary cases that were not complicated by recurrence. Pathology review was conducted in a blinded manner by one of the authors (P.W.H) who is a board-certified dermatopathologist for approximate depth of invasion from the granular layer, perineural invasion, bone invasion, infiltrative growth, presence of conventional squamous cell carcinoma, and margin status.

Statistical analysis was performed when appropriate using an N1 χ2 test or Student t test.

Results

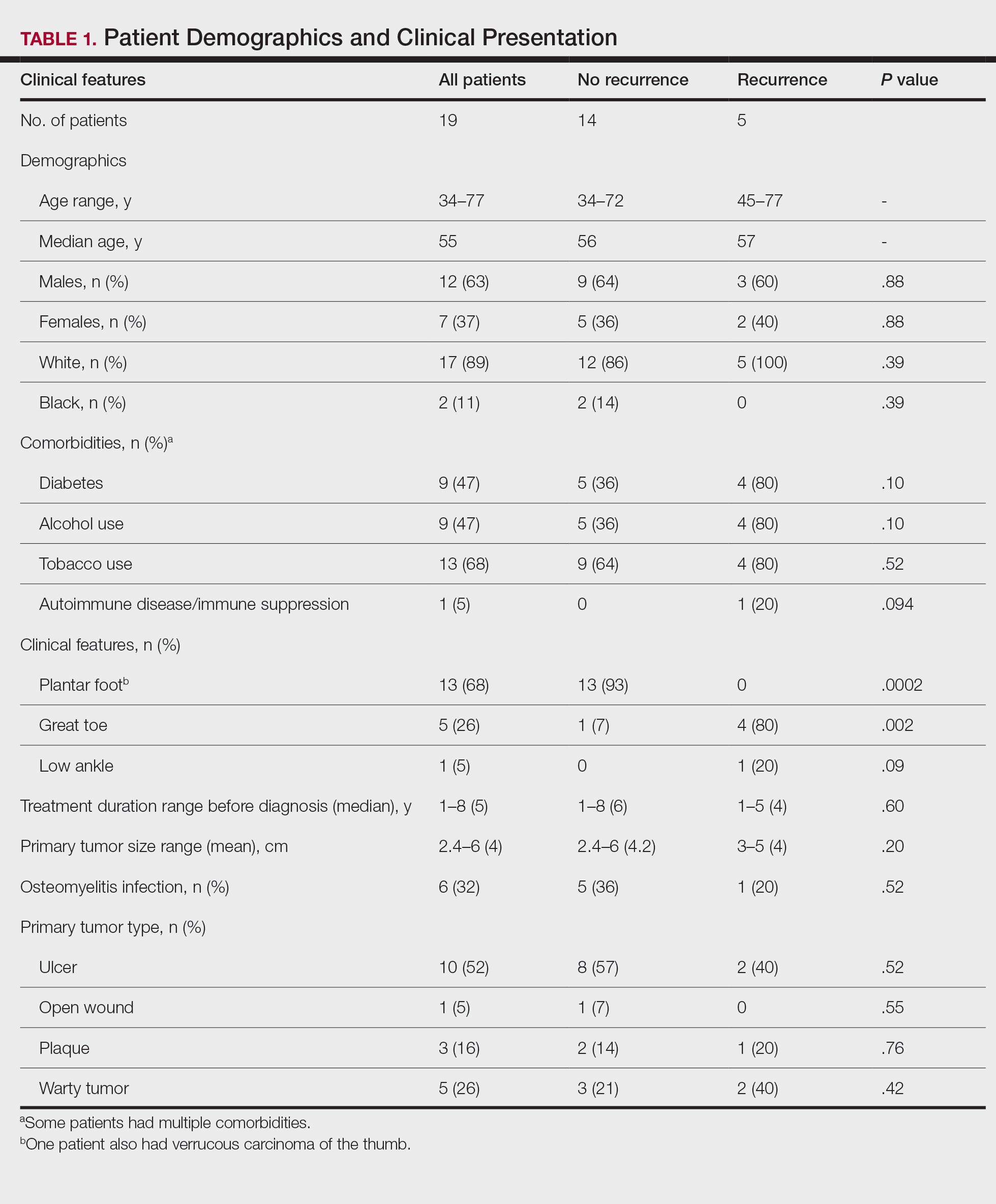

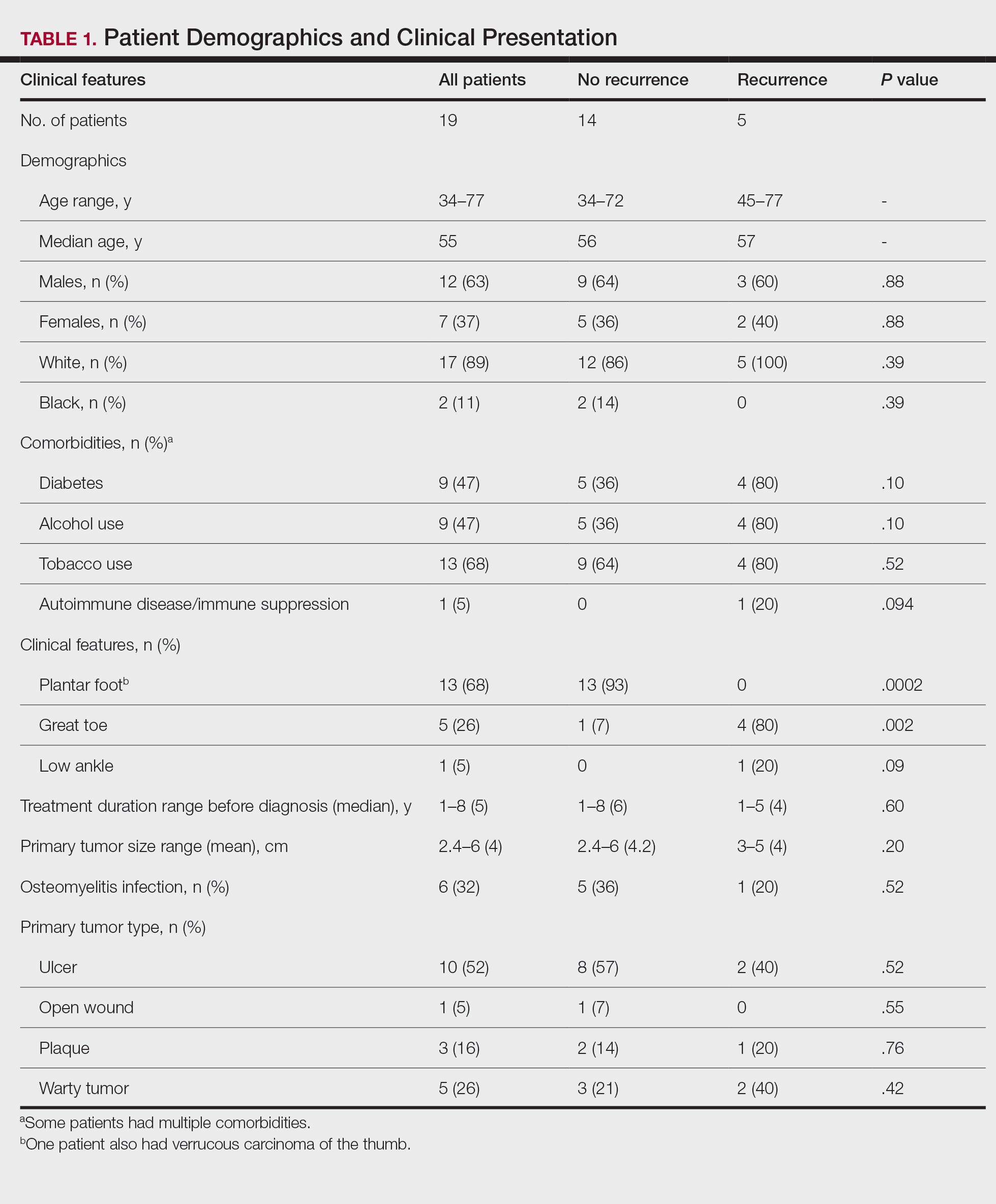

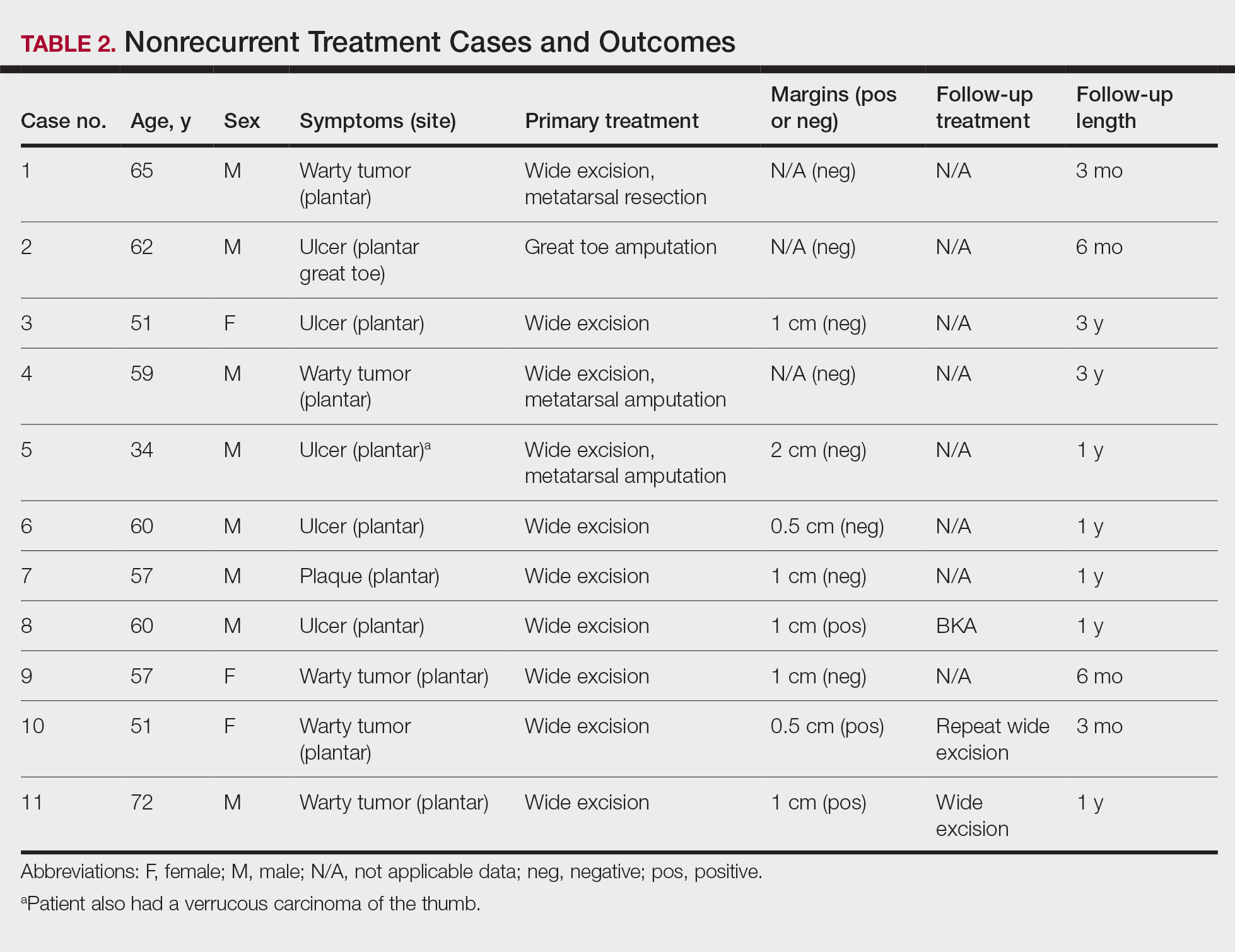

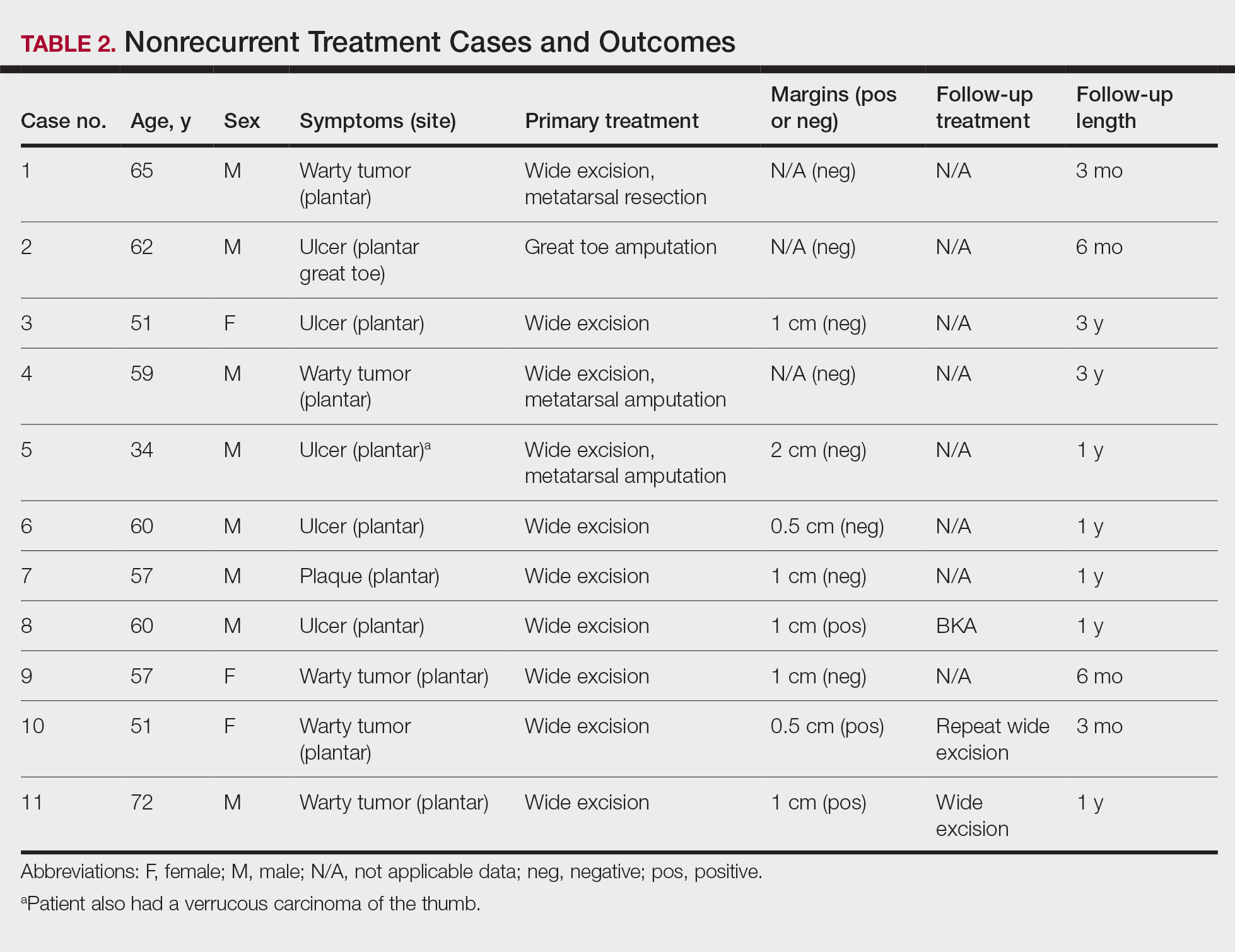

Demographics and Comorbidities—The median age of the patients at the time of diagnosis was 55 years (range, 34–77 years). There were 12 males and 7 females (Table 1). Two patients were Black and 17 were White. Almost all patients had additional comorbidities including tobacco use (68%), alcohol use (47%), and diabetes (47%). Only 1 patient had an autoimmune disease and was on chronic steroids. No significant difference was found between the demographics of patients with recurrent lesions and those without recurrence.

Tumor Location and Clinical Presentation—The most common clinical presentation included a nonhealing ulceration with warty edges, pain, bleeding, and lowered mobility. In most cases, there was history of prior treatment over a duration ranging from 1 to 8 years, with a median of 5 years prior to biopsy-based diagnosis (Table 1). Six patients had a history of osteomyelitis, diagnosed by imaging or biopsy, within a year before tumor diagnosis. The size of the primary tumor ranged from 2.4 to 6 cm, with a mean of 4 cm (P=.20). The clinical presentation, time before diagnosis, and size of the tumors did not differ significantly between recurrent and nonrecurrent cases.

The tumor location for the recurrent cases differed significantly compared to nonrecurrent cases. All 5 of the patients with a recurrence presented with a tumor on the nonglabrous part of the foot. Four patients (80%) had lesions on the dorsal or lateral aspect of the great toe (P=.002), and 1 patient (20%) had a lesion on the low ankle (P=.09)(Table 1). Of the nonrecurrent cases, 1 patient (7%) presented with a tumor on the plantar surface of the great toe (P=.002), 13 patients (93%) presented with tumors on the distal plantar surface of the foot (P=.0002), and 1 patient with a plantar foot tumor (Figure 1) also had verrucous carcinoma on the thumb (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Histopathology—Available pathology slides for recurrent cases of verrucous carcinoma were reviewed alongside representative cases of verrucous carcinomas that did not progress to recurrence. The diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma was confirmed in all cases, with no evidence of conventional squamous cell carcinoma, perineural invasion, extension beyond the dermis, or bone invasion in any case. The median size of the tumors was 4.2 cm and 4 cm for nonrecurrent and recurrent specimens, respectively. Recurrences displayed a trend toward increased depth compared to primary tumors without recurrence (average depth, 5.5 mm vs 3.7 mm); however, this did not reach statistical significance (P=.24). Primary tumors that progressed to recurrence (n=2) displayed similar findings to the other cases, with invasive depths of 3.5 and 5.5 mm, and there was no evidence of conventional squamous cell carcinoma, perineural invasion, or extension beyond the dermis.

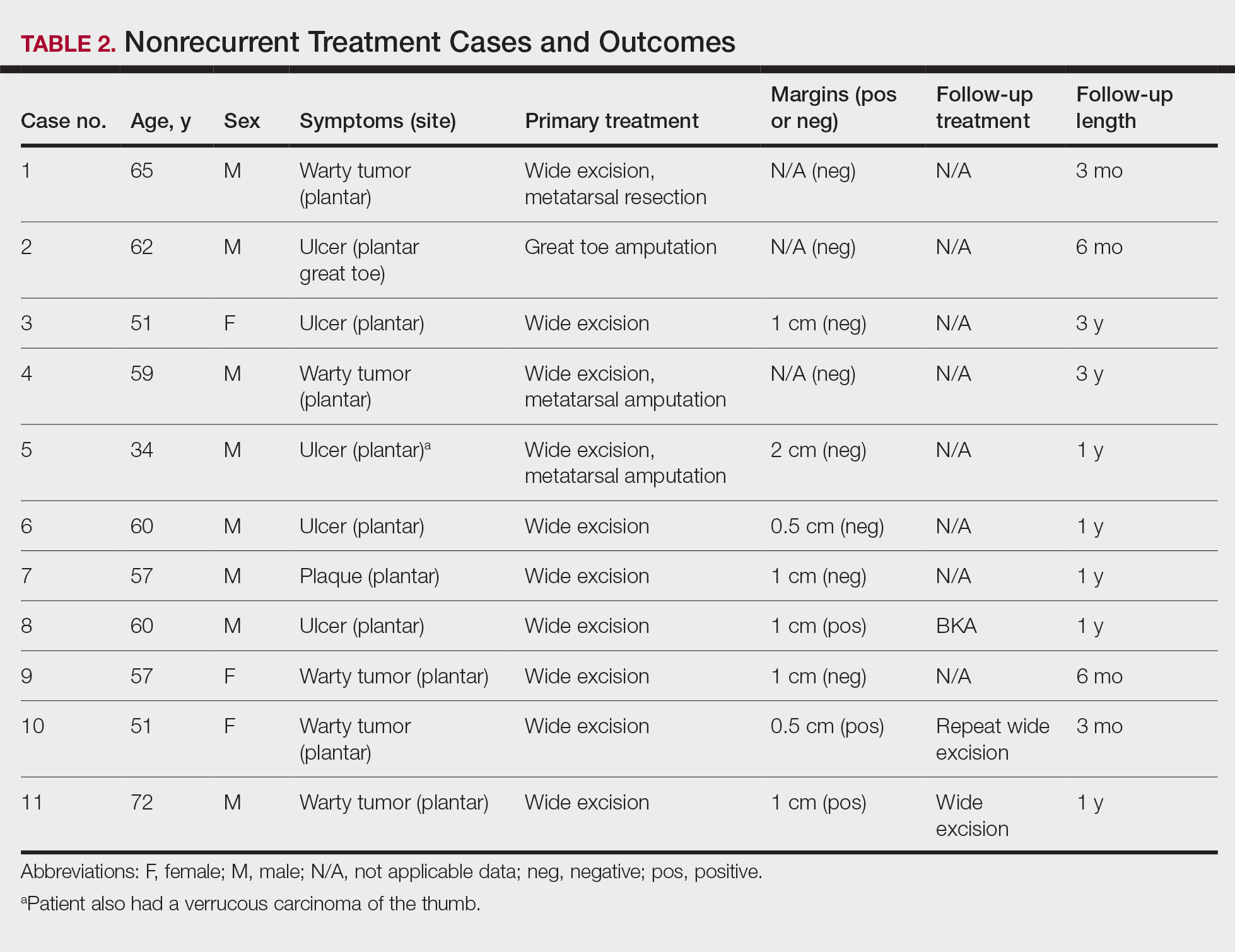

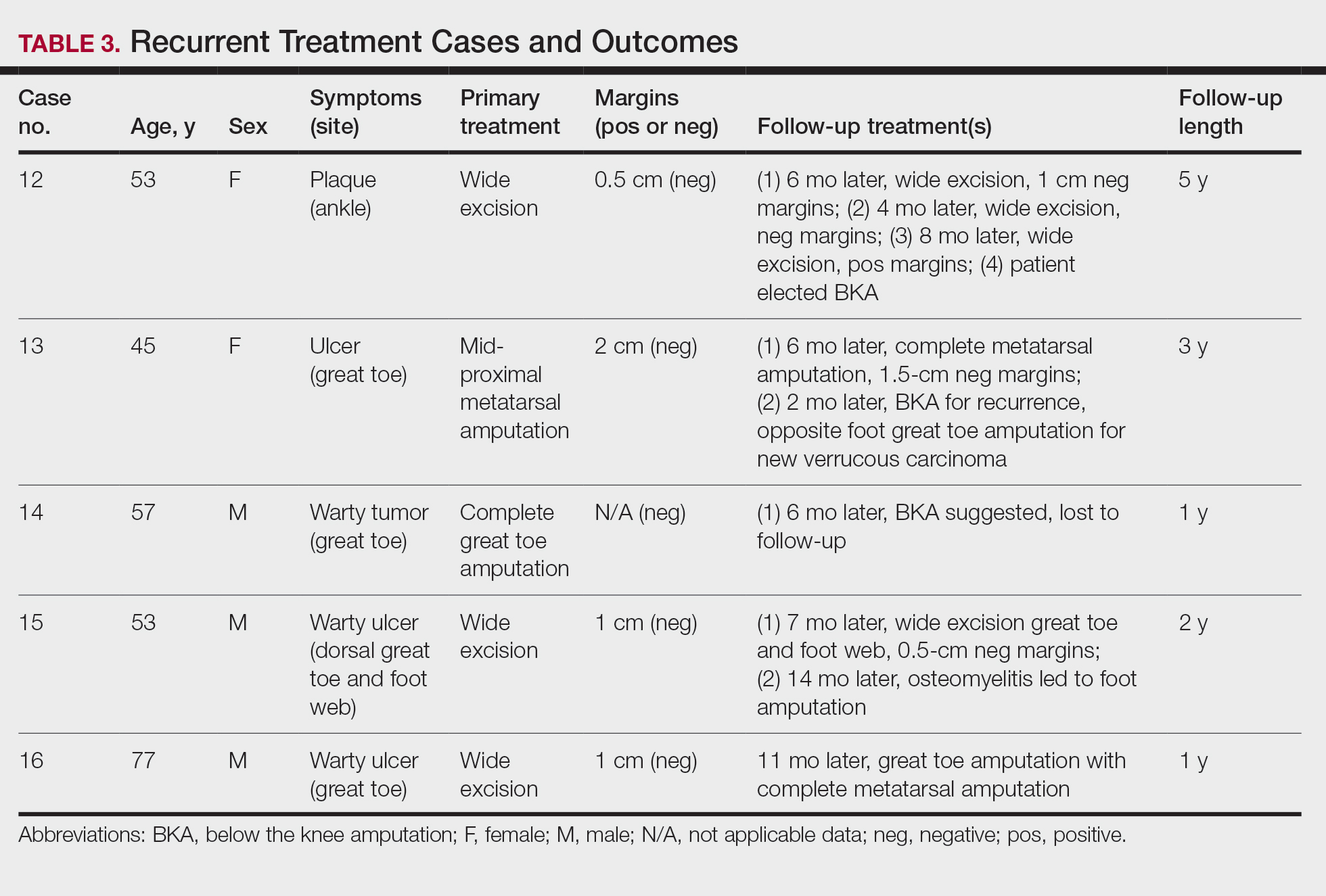

Treatment of Nonrecurrent Cases—Of the 16 total cases treated at the University of Michigan, surgery was the primary mode of therapy in every case (Tables 2 and 3). Of the 11 nonrecurrent cases, 7 patients had wide local excision with a dermal regeneration template, and delayed split-thickness graft reconstruction. Three cases had wide local excision with metatarsal resection, dermal regeneration template, and delayed skin grafting. One case had a great toe amputation

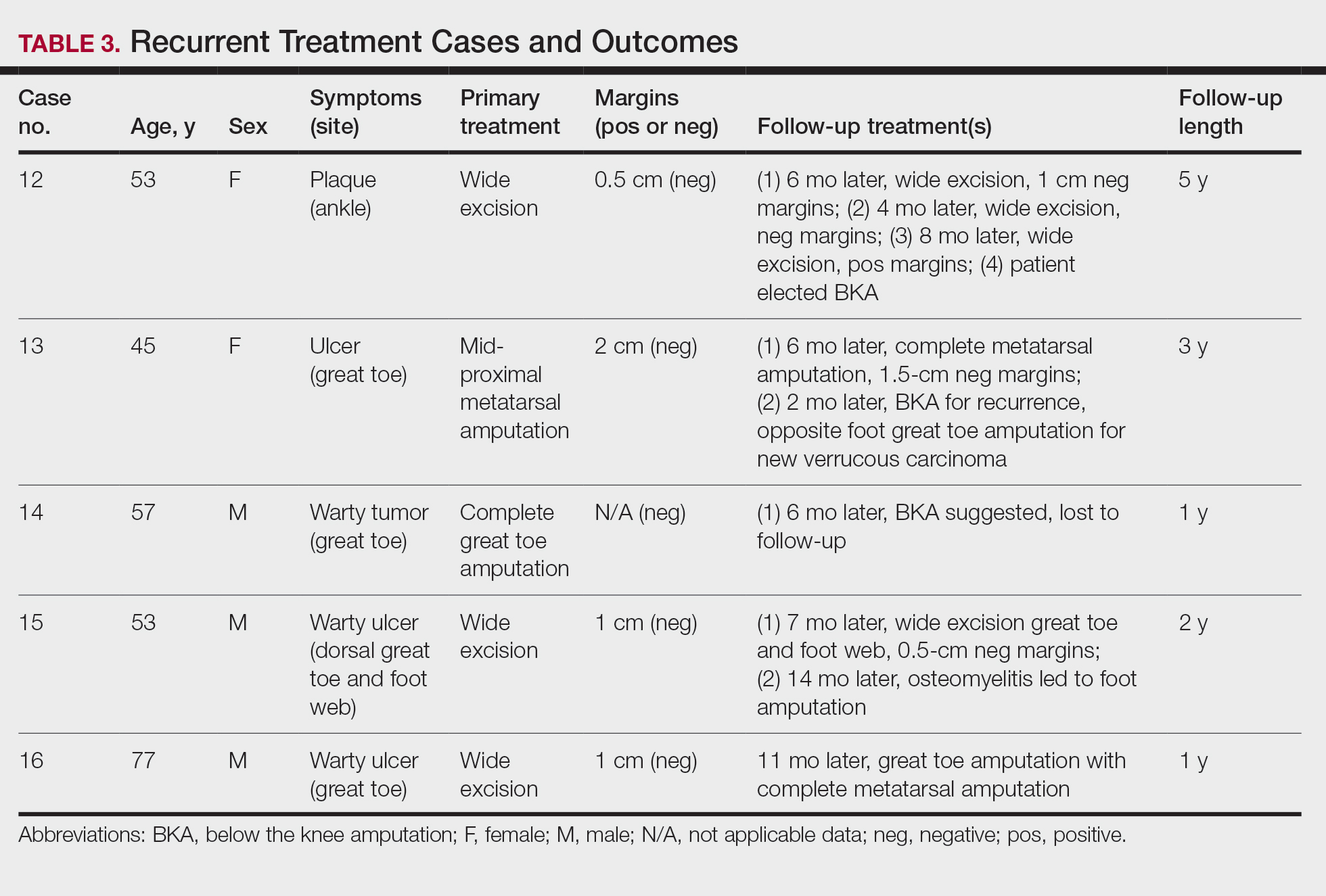

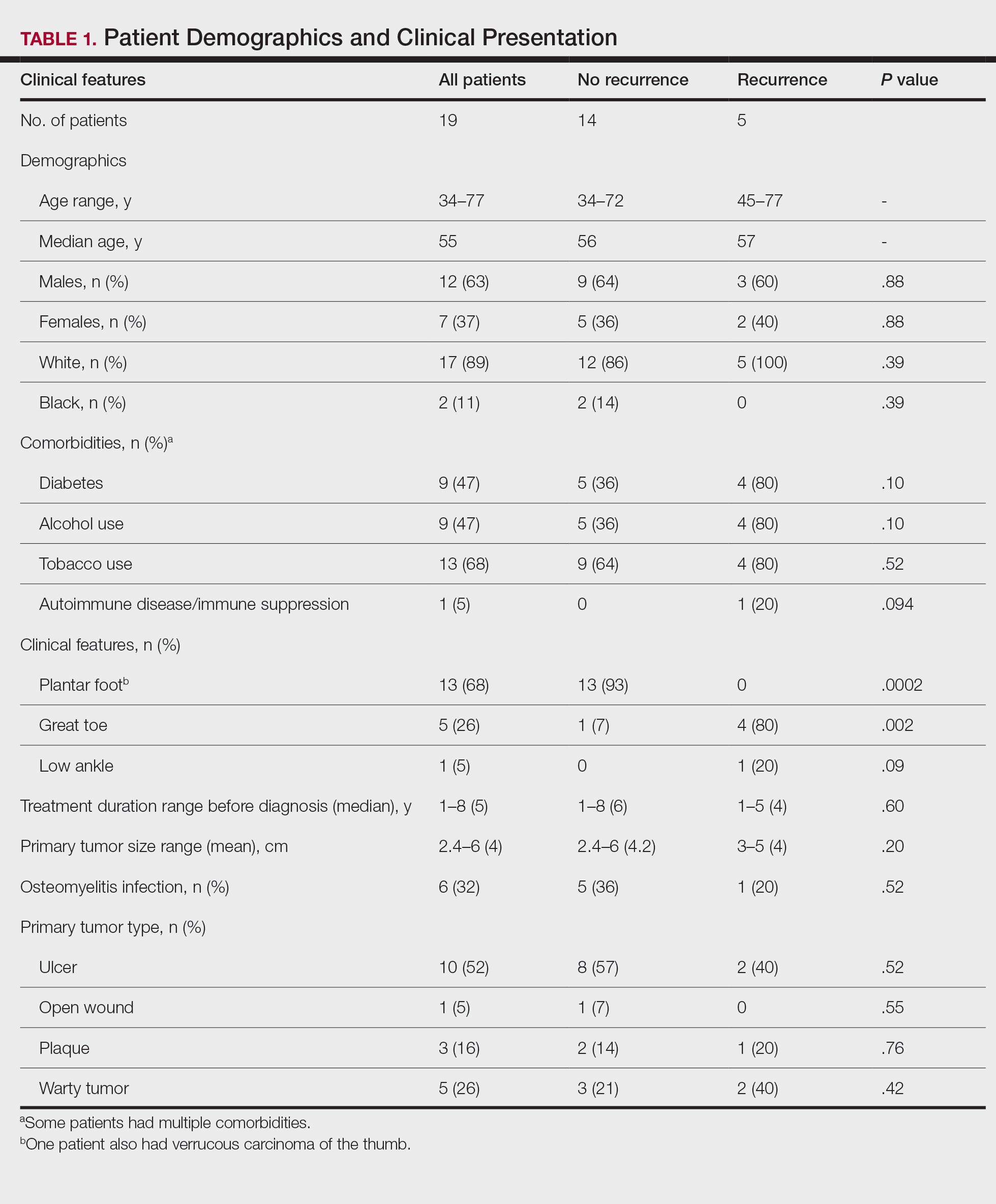

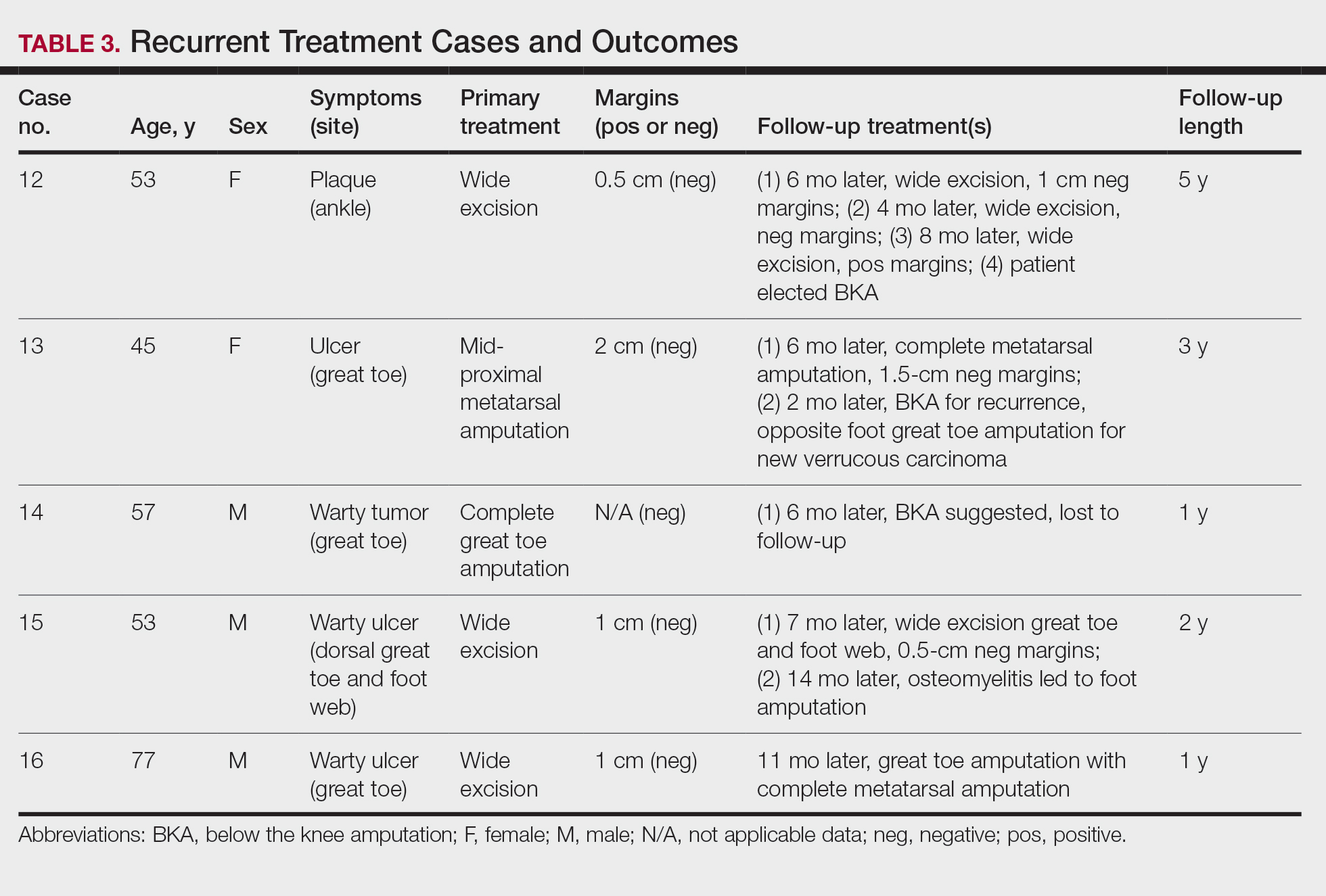

Treatment of Recurrent Cases—For the 5 patients with recurrence, surgical margins were not reported in all the cases but ranged from 0.5 to 2 cm (4/5 [80%] reported). On average, follow-up for this group of patients was 29 months, with a range of 12 to 60 months (Table 3).

The first case with a recurrence (patient 12) initially presented with a chronic calluslike growth of the medial ankle. The lesion initially was treated with wide local excision with negative margins. Reconstruction was performed in a staged fashion with use of a dermal regenerative template followed later by split-thickness skin grafting. Tumor recurrence with negative margins occurred 3 times over the next 2 years despite re-resections with negative pathologic margins. Each recurrence presented as graft breakdown and surrounding hyperkeratosis (Figure 3). After the third graft placement failed, the patient elected for a BKA. There has not been recurrence since the BKA after 5 years total follow-up from the time of primary tumor resection. Of note, this was the only patient in our cohort who was immunosuppressed and evaluated for regional nodal involvement by positron emission tomography.

Another patient with recurrence (patient 13) presented with a chronic great toe ulcer of 5 years’ duration that formed on the dorsal aspect of the great toe after a previously excised wart (Figure 4A). This patient underwent mid-proximal metatarsal amputation with 2-cm margins and subsequent skin graft. Pathologic margins were negative. Within 6 months, there was hyperkeratosis and a draining wound (Figure 4B). Biopsy results confirmed recurrent disease that was treated with re-resection, including complete metatarsal amputation with negative margins and skin graft placement. Verrucous carcinoma recurred at the edges of the graft within 8 months, and the patient elected for a BKA. In addition, this patient also presented with a verrucous carcinoma of the contralateral great toe. The tumor presented as a warty ulcer of 4 months’ duration in the setting of osteomyelitis and was resected by great toe amputation that was performed concurrently with the opposite leg BKA; there has been no recurrence. Of note, this was the only patient to have right inguinal sentinel lymph node tissue sampled and HPV testing conducted, which were negative for verrucous carcinoma and high or low strains of HPV.

Another recurrent case (patient 14) presented with a large warty lesion on the dorsal great toe positive for verrucous carcinoma. He underwent a complete great toe amputation with skin graft placement. Verrucous carcinoma recurred on the edges of the graft within 6 months, and the patient was lost to follow-up when a BKA was suggested.

The fourth recurrent case (patient 15) initially had been treated for 1 year as a viral verruca of the dorsal aspect of the great toe. He had an exophytic mass positive for verrucous carcinoma growing on the dorsal aspect of the great toe around the prior excision site. After primary wide excision with negative 1-cm margins and graft placement, the tumor was re-excised twice within the next 2 years with pathologic negative margins. The patient underwent a foot amputation due to a severe osteomyelitis infection at the reconstruction site.

The final recurrent case (patient 16) presented with a mass on the lateral great toe that initially was treated as a viral verruca (for unknown duration) that had begun to ulcerate. The patient underwent wide excision with 1-cm margins and graft placement. Final pathology was consistent with verrucous carcinoma with negative margins. Recurrence occurred within 11 months on the edge of the graft, and a great toe amputation through the metatarsal phalangeal joint was performed.

Comment

Our series of 19 cases of verrucous carcinoma adds to the limited number of reported cases in the literature. We sought to evaluate the potential risk factors for early recurrence. Consistent with prior studies, our series found verrucous carcinoma of the foot to occur most frequently in patients aged 50 to 70 years, predominantly in White men.1 These tumors grew in the setting of chronic inflammation, tissue regeneration, multiple comorbidities, and poor wound hygiene. Misdiagnosis of verrucous carcinoma often leads to ineffective treatments and local invasion of nerves, muscle, and bone tissue.9,15,16 Our case series also clearly demonstrated the diagnostic challenge verrucous carcinoma presents, with an average delay in diagnosis of 5 years; correct diagnosis often did not occur until the tumor was 4 cm in size (average) and more than 50% had chronic ulceration.

The histologic features of the tumors showed striking uniformity. Within the literature, there is confusion regarding the use of the terms verrucous carcinoma and carcinoma (epithelioma) cuniculatum and the possible pathologic differences between the two. The World Health Organization’s classification of skin tumors describes epithelioma cuniculatum as verrucous carcinoma located on the sole of the foot.7 Kubik and Rhatigan6 pointed out that carcinoma cuniculatum does not have a warty or verrucous surface, which is a defining feature of verrucous carcinoma. Multiple authors have further surmised that the deep burrowing sinus tracts of epithelioma cuniculatum are different than those seen in verrucous carcinoma formed by the undulations extending from the papillomatous and verrucous surface.1,6 We did not observe these notable pathologic differences in recurrent or nonrecurrent primary tumors or differences between primary and recurrent cases. Although our cohort was small, the findings suggest that standard histologic features do not predict aggressive behavior in verrucous carcinomas. Furthermore, our observations support a model wherein recurrence is an inherent property of certain verrucous carcinomas rather than a consequence of histologic progression to conventional squamous cell carcinoma. The lack of overt malignant features in such cases underscores the need for distinction of verrucous carcinoma from benign mimics such as viral verruca or reactive epidermal hyperplasia.

Our recurrent cases showed a greater predilection for nonplantar surfaces and the great toe (P=.002). Five of 6 cases on the nonplantar surface—1 on the ankle and 5 on the great toe—recurred despite negative pathologic margins. There was no significant difference in demographics, pathogenesis, tumor size, chronicity, phenotype, or metastatic spread in recurrent and nonrecurrent cases in our cohort.

The tumor has only been described in rare instances at extrapedal cutaneous sites including the hand, scalp, and abdomen.14,17,18 Our series did include a case of synchronous presentation with a verrucous carcinoma on the thumb. Given the rarity of this presentation, thus far there are no data supporting any atypical locations of verrucous carcinoma having greater instances of recurrence. Our recurrent cases displaying atypical location on nonglabrous skin could suggest an underlying pathologic mechanism distinct from tumors on glabrous skin and relevant to increased recurrence risk. Such a mechanism might relate to distinct genetic insults, tumor-microenvironment interactions, or field effects. There are few studies regarding physiologic differences between the plantar surface and the nonglabrous surface and how that influences cancer genesis. Within acral melanoma studies, nonglabrous skin of more sun-exposed surfaces has a higher burden of genetic insults including BRAF mutations.19 Genetic testing of verrucous carcinoma is highly limited, with abnormal expression of the p53 tumor suppressor protein and possible association with several types of HPV. Verrucous carcinoma in general has been found to contain HPV types 6 and 11, nononcogenic forms, and higher risk from HPV types 16 and 18.9,20 However, only a few cases of HPV type 16 as well as 1 case each of HPV type 2 and type 11 have been found within verrucous carcinoma of the foot.21,22 In squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, HPV-positive tumors have shown better response to treatment. Further investigation of HPV and genetic contributors in verrucous carcinoma is warranted.

There is notable evidence that surgical resection is the best mode of treatment of verrucous carcinoma.2,3,10,11 Our case series was treated with wide local excision, with partial metatarsal amputation or great toe amputation, in cases with bone invasion or osteomyelitis. Surgical margins were not reported in all the cases but ranged from 0.5 to 2 cm with no significant differences between the recurrent and nonrecurrent groups. After excision, closure was conducted by incorporating primary, secondary, and delayed closure techniques, along with skin grafts for larger defects. Lymph node biopsy traditionally has not been recommended due to reported low metastatic potential. In all 5 recurrent cases, the tumors recurred after multiple attempts at wide excision and greater resection of bone and tissue, with negative margins. The tumors regrew quickly, within months, on the edges of the new graft or in the middle of the graft. The sites of recurrent tumor growth would suggest regrowth in the areas of greatest tissue stress and proliferation. We recommend a low threshold for biopsy and aggressive retreatment in the setting of exophytic growth at reconstruction sites.

Recurrence is uncommon in the setting of verrucous carcinoma, with our series being the first to analyze prognostic factors.3,9,14 Our findings indicate that

- Kao GF, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Carcinoma cuniculatum (verrucous carcinoma of the skin): a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases with ultrastructural observations. Cancer. 1982;49:2395-2403.

- McKee PH, Wilkinson JD, Black M, et al. Carcinoma (epithelioma) cuniculatum: a clinic-pathologic study of nineteen cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1981;5:425-436.

- Penera KE, Manji KA, Craig AB, et al. Atypical presentation of verrucous carcinoma: a case study and review of the literature. Foot Ankle Spec. 2013;6:318-322.

- Rosales MA, Martin BR, Armstrong DG, et al. Verrucous hyperplasia: a common and problematic finding in the high-risk diabetic foot. J Am Podiatr Assoc. 2006:4:348-350.

- Noel JC, Peny MO, De Dobbeleer G, et al. p53 Protein overexpression in verrucous carcinoma of the skin. Dermatology. 1996;192:12-15.

- Kubik MJ, Rhatigan RM. Carcinoma cuniculatum: not a verrucous carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:1083-1087

- Elder D, Massi D, Scolver R, et al. Verrucous squamous cell carcinoma. WHO Classification of Tumours (Medicine). Vol 11. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer: 2018;35-57.

- Chan MP. Verruciform and condyloma-like squamous proliferations in the anogenital region. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:821-831

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-21.

- Flynn K, Wiemer D. Treatment of an epithelioma cuniculatum plantare by local excision and a plantar skin flap. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1978;4:773-775.

- Spyriounis P, Tentis D, Sparveri I, et al. Plantar epithelioma cuniculatum: a case report with review of the literature. Eur J Plast Surg. 2004;27:253-256.

- Swanson NA, Taylor WB. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: literature review and treatment by the Moh’s chemosurgery technique. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:794-797.

- Alkalay R, Alcalay J, Shiri J. Plantar verrucous carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report and literature review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006:5:68-73.

- Kotwal M, Poflee S, Bobhate, S. Carcinoma cuniculatum at various anatomical sites. Indian J Dermatol. 2005;50:216-220.

- Nagarajan D, Chandrasekhar M, Jebakumar J, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of foot at an unusual site: lessons to be learnt. South Asian J Cancer. 2017;6:63.

- Pempinello C, Bova A, Pempinello R, et al Verrucous carcinoma of the foot with bone invasion: a case report. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:135307.

- Vandeweyer E, Sales F, Deramaecker R. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma. Br J Plastic Surg. 2001;54:168-170.

- Joybari A, Azadeh P, Honar B. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma superimposed on chronically inflamed ileostomy site skin. Iran J Pathol. 2018;13:285-288.

- Davis EJ, Johnson DB, Sosman JA, et al. Melanoma: what do all the mutations mean? Cancer. 2018;124:3490-3499.

- Gissmann L, Wolnik L, Ikenberg H, et al. Human papillomavirus types 6 and 11 DNA sequences in genital and laryngeal papillomas and in some cervical cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:560-563.

- Knobler RM, Schneider S, Neumann RA, et al. DNA dot-blot hybridization implicates human papillomavirus type 11-DNA in epithelioma cuniculatum. J Med Virol. 1989;29:33-37.

- Noel JC, Peny MO, Detremmerie O, et al. Demonstration of human papillomavirus type 2 in a verrucous carcinoma of the foot. Dermatology. 1993;187:58-61.

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare cancer with the greatest predilection for the foot. Multiple case reports with only a few large case series have been published. 1-3 Plantar verrucous carcinoma is characterized as a slowly but relentlessly enlarging warty tumor with low metastatic potential and high risk for local invasion. The tumor occurs most frequently in patients aged 60 to 70 years, predominantly in White males. 1 It often is misdiagnosed for years as an ulcer or wart that is highly resistant to therapy. Size typically ranges from 1 to 12 cm in greatest dimension. 1

The pathogenesis of plantar verrucous carcinoma remains unclear, but some contributing factors have been proposed, including trauma, chronic irritation, infection, and poor local hygiene.2 This tumor has been reported to occur in chronic foot ulcerations, particularly in the diabetic population.4 It has been proposed that abnormal expression of the p53 tumor suppressor protein and several types of human papillomavirus (HPV) may have a role in the pathogenesis of verrucous carcinoma.5

The pathologic hallmarks of this tumor include a verrucous/hyperkeratotic surface with a deeply endophytic, broad, pushing base. Tumor cells are well differentiated, and atypia is either absent or confined to 1 or 2 layers at the base of the tumor. Overt invasion at the base is lacking, except in cases with a component of conventional invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Human papillomavirus viropathic changes are classically absent.1,3 Studies of the histopathology of verrucous carcinoma have been complicated by similar entities, nomenclatural uncertainty, and variable diagnostic criteria. For example, epithelioma cuniculatum variously has been defined as being synonymous with verrucous carcinoma, a distinct clinical verrucous carcinoma subtype occurring on the soles, a histologic subtype (characterized by prominent burrowing sinuses), or a separate entity entirely.1,2,6,7 Furthermore, in the genital area, several different types of carcinomas have verruciform features but display distinct microscopic findings and outcomes from verrucous carcinoma.8

Verrucous carcinoma represents an unusual variant of squamous cell carcinoma and is treated as such. Treatments have included laser surgery; immunotherapy; retinoid therapy; and chemotherapy by oral, intralesional, or iontophoretic routes in select patients.9 Radiotherapy presents another option, though reports have described progression to aggressive squamous cell carcinoma in some cases.9 Surgery is the best course of treatment, and as more case reports have been published, a transition from radical resection to wide excision with tumor-free margins is the treatment of choice.2,3,10,11 To minimize soft-tissue deficits, Mohs micrographic surgery has been discussed as a treatment option for verrucous carcinoma.11-13

Few studies have described verrucous carcinoma recurrence, and none have systematically examined recurrence rate, risk factors, or prognosis

Methods

Patient cases were

Of the 19 cases, 16 were treated at the University of Michigan and are included in the treatment analyses. Specific attention was then paid to the cases with a clinical recurrence despite negative surgical margins. We compared the clinical and surgical differences between recurrent cases and nonrecurrent cases.

Pathology was rereviewed for selected cases, including 2 cases with recurrence and matched primary, 2 cases with recurrence (for which the matched primary was unavailable for review), and 5 representative primary cases that were not complicated by recurrence. Pathology review was conducted in a blinded manner by one of the authors (P.W.H) who is a board-certified dermatopathologist for approximate depth of invasion from the granular layer, perineural invasion, bone invasion, infiltrative growth, presence of conventional squamous cell carcinoma, and margin status.

Statistical analysis was performed when appropriate using an N1 χ2 test or Student t test.

Results

Demographics and Comorbidities—The median age of the patients at the time of diagnosis was 55 years (range, 34–77 years). There were 12 males and 7 females (Table 1). Two patients were Black and 17 were White. Almost all patients had additional comorbidities including tobacco use (68%), alcohol use (47%), and diabetes (47%). Only 1 patient had an autoimmune disease and was on chronic steroids. No significant difference was found between the demographics of patients with recurrent lesions and those without recurrence.

Tumor Location and Clinical Presentation—The most common clinical presentation included a nonhealing ulceration with warty edges, pain, bleeding, and lowered mobility. In most cases, there was history of prior treatment over a duration ranging from 1 to 8 years, with a median of 5 years prior to biopsy-based diagnosis (Table 1). Six patients had a history of osteomyelitis, diagnosed by imaging or biopsy, within a year before tumor diagnosis. The size of the primary tumor ranged from 2.4 to 6 cm, with a mean of 4 cm (P=.20). The clinical presentation, time before diagnosis, and size of the tumors did not differ significantly between recurrent and nonrecurrent cases.

The tumor location for the recurrent cases differed significantly compared to nonrecurrent cases. All 5 of the patients with a recurrence presented with a tumor on the nonglabrous part of the foot. Four patients (80%) had lesions on the dorsal or lateral aspect of the great toe (P=.002), and 1 patient (20%) had a lesion on the low ankle (P=.09)(Table 1). Of the nonrecurrent cases, 1 patient (7%) presented with a tumor on the plantar surface of the great toe (P=.002), 13 patients (93%) presented with tumors on the distal plantar surface of the foot (P=.0002), and 1 patient with a plantar foot tumor (Figure 1) also had verrucous carcinoma on the thumb (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Histopathology—Available pathology slides for recurrent cases of verrucous carcinoma were reviewed alongside representative cases of verrucous carcinomas that did not progress to recurrence. The diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma was confirmed in all cases, with no evidence of conventional squamous cell carcinoma, perineural invasion, extension beyond the dermis, or bone invasion in any case. The median size of the tumors was 4.2 cm and 4 cm for nonrecurrent and recurrent specimens, respectively. Recurrences displayed a trend toward increased depth compared to primary tumors without recurrence (average depth, 5.5 mm vs 3.7 mm); however, this did not reach statistical significance (P=.24). Primary tumors that progressed to recurrence (n=2) displayed similar findings to the other cases, with invasive depths of 3.5 and 5.5 mm, and there was no evidence of conventional squamous cell carcinoma, perineural invasion, or extension beyond the dermis.

Treatment of Nonrecurrent Cases—Of the 16 total cases treated at the University of Michigan, surgery was the primary mode of therapy in every case (Tables 2 and 3). Of the 11 nonrecurrent cases, 7 patients had wide local excision with a dermal regeneration template, and delayed split-thickness graft reconstruction. Three cases had wide local excision with metatarsal resection, dermal regeneration template, and delayed skin grafting. One case had a great toe amputation

Treatment of Recurrent Cases—For the 5 patients with recurrence, surgical margins were not reported in all the cases but ranged from 0.5 to 2 cm (4/5 [80%] reported). On average, follow-up for this group of patients was 29 months, with a range of 12 to 60 months (Table 3).

The first case with a recurrence (patient 12) initially presented with a chronic calluslike growth of the medial ankle. The lesion initially was treated with wide local excision with negative margins. Reconstruction was performed in a staged fashion with use of a dermal regenerative template followed later by split-thickness skin grafting. Tumor recurrence with negative margins occurred 3 times over the next 2 years despite re-resections with negative pathologic margins. Each recurrence presented as graft breakdown and surrounding hyperkeratosis (Figure 3). After the third graft placement failed, the patient elected for a BKA. There has not been recurrence since the BKA after 5 years total follow-up from the time of primary tumor resection. Of note, this was the only patient in our cohort who was immunosuppressed and evaluated for regional nodal involvement by positron emission tomography.

Another patient with recurrence (patient 13) presented with a chronic great toe ulcer of 5 years’ duration that formed on the dorsal aspect of the great toe after a previously excised wart (Figure 4A). This patient underwent mid-proximal metatarsal amputation with 2-cm margins and subsequent skin graft. Pathologic margins were negative. Within 6 months, there was hyperkeratosis and a draining wound (Figure 4B). Biopsy results confirmed recurrent disease that was treated with re-resection, including complete metatarsal amputation with negative margins and skin graft placement. Verrucous carcinoma recurred at the edges of the graft within 8 months, and the patient elected for a BKA. In addition, this patient also presented with a verrucous carcinoma of the contralateral great toe. The tumor presented as a warty ulcer of 4 months’ duration in the setting of osteomyelitis and was resected by great toe amputation that was performed concurrently with the opposite leg BKA; there has been no recurrence. Of note, this was the only patient to have right inguinal sentinel lymph node tissue sampled and HPV testing conducted, which were negative for verrucous carcinoma and high or low strains of HPV.

Another recurrent case (patient 14) presented with a large warty lesion on the dorsal great toe positive for verrucous carcinoma. He underwent a complete great toe amputation with skin graft placement. Verrucous carcinoma recurred on the edges of the graft within 6 months, and the patient was lost to follow-up when a BKA was suggested.

The fourth recurrent case (patient 15) initially had been treated for 1 year as a viral verruca of the dorsal aspect of the great toe. He had an exophytic mass positive for verrucous carcinoma growing on the dorsal aspect of the great toe around the prior excision site. After primary wide excision with negative 1-cm margins and graft placement, the tumor was re-excised twice within the next 2 years with pathologic negative margins. The patient underwent a foot amputation due to a severe osteomyelitis infection at the reconstruction site.

The final recurrent case (patient 16) presented with a mass on the lateral great toe that initially was treated as a viral verruca (for unknown duration) that had begun to ulcerate. The patient underwent wide excision with 1-cm margins and graft placement. Final pathology was consistent with verrucous carcinoma with negative margins. Recurrence occurred within 11 months on the edge of the graft, and a great toe amputation through the metatarsal phalangeal joint was performed.

Comment

Our series of 19 cases of verrucous carcinoma adds to the limited number of reported cases in the literature. We sought to evaluate the potential risk factors for early recurrence. Consistent with prior studies, our series found verrucous carcinoma of the foot to occur most frequently in patients aged 50 to 70 years, predominantly in White men.1 These tumors grew in the setting of chronic inflammation, tissue regeneration, multiple comorbidities, and poor wound hygiene. Misdiagnosis of verrucous carcinoma often leads to ineffective treatments and local invasion of nerves, muscle, and bone tissue.9,15,16 Our case series also clearly demonstrated the diagnostic challenge verrucous carcinoma presents, with an average delay in diagnosis of 5 years; correct diagnosis often did not occur until the tumor was 4 cm in size (average) and more than 50% had chronic ulceration.

The histologic features of the tumors showed striking uniformity. Within the literature, there is confusion regarding the use of the terms verrucous carcinoma and carcinoma (epithelioma) cuniculatum and the possible pathologic differences between the two. The World Health Organization’s classification of skin tumors describes epithelioma cuniculatum as verrucous carcinoma located on the sole of the foot.7 Kubik and Rhatigan6 pointed out that carcinoma cuniculatum does not have a warty or verrucous surface, which is a defining feature of verrucous carcinoma. Multiple authors have further surmised that the deep burrowing sinus tracts of epithelioma cuniculatum are different than those seen in verrucous carcinoma formed by the undulations extending from the papillomatous and verrucous surface.1,6 We did not observe these notable pathologic differences in recurrent or nonrecurrent primary tumors or differences between primary and recurrent cases. Although our cohort was small, the findings suggest that standard histologic features do not predict aggressive behavior in verrucous carcinomas. Furthermore, our observations support a model wherein recurrence is an inherent property of certain verrucous carcinomas rather than a consequence of histologic progression to conventional squamous cell carcinoma. The lack of overt malignant features in such cases underscores the need for distinction of verrucous carcinoma from benign mimics such as viral verruca or reactive epidermal hyperplasia.

Our recurrent cases showed a greater predilection for nonplantar surfaces and the great toe (P=.002). Five of 6 cases on the nonplantar surface—1 on the ankle and 5 on the great toe—recurred despite negative pathologic margins. There was no significant difference in demographics, pathogenesis, tumor size, chronicity, phenotype, or metastatic spread in recurrent and nonrecurrent cases in our cohort.

The tumor has only been described in rare instances at extrapedal cutaneous sites including the hand, scalp, and abdomen.14,17,18 Our series did include a case of synchronous presentation with a verrucous carcinoma on the thumb. Given the rarity of this presentation, thus far there are no data supporting any atypical locations of verrucous carcinoma having greater instances of recurrence. Our recurrent cases displaying atypical location on nonglabrous skin could suggest an underlying pathologic mechanism distinct from tumors on glabrous skin and relevant to increased recurrence risk. Such a mechanism might relate to distinct genetic insults, tumor-microenvironment interactions, or field effects. There are few studies regarding physiologic differences between the plantar surface and the nonglabrous surface and how that influences cancer genesis. Within acral melanoma studies, nonglabrous skin of more sun-exposed surfaces has a higher burden of genetic insults including BRAF mutations.19 Genetic testing of verrucous carcinoma is highly limited, with abnormal expression of the p53 tumor suppressor protein and possible association with several types of HPV. Verrucous carcinoma in general has been found to contain HPV types 6 and 11, nononcogenic forms, and higher risk from HPV types 16 and 18.9,20 However, only a few cases of HPV type 16 as well as 1 case each of HPV type 2 and type 11 have been found within verrucous carcinoma of the foot.21,22 In squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, HPV-positive tumors have shown better response to treatment. Further investigation of HPV and genetic contributors in verrucous carcinoma is warranted.

There is notable evidence that surgical resection is the best mode of treatment of verrucous carcinoma.2,3,10,11 Our case series was treated with wide local excision, with partial metatarsal amputation or great toe amputation, in cases with bone invasion or osteomyelitis. Surgical margins were not reported in all the cases but ranged from 0.5 to 2 cm with no significant differences between the recurrent and nonrecurrent groups. After excision, closure was conducted by incorporating primary, secondary, and delayed closure techniques, along with skin grafts for larger defects. Lymph node biopsy traditionally has not been recommended due to reported low metastatic potential. In all 5 recurrent cases, the tumors recurred after multiple attempts at wide excision and greater resection of bone and tissue, with negative margins. The tumors regrew quickly, within months, on the edges of the new graft or in the middle of the graft. The sites of recurrent tumor growth would suggest regrowth in the areas of greatest tissue stress and proliferation. We recommend a low threshold for biopsy and aggressive retreatment in the setting of exophytic growth at reconstruction sites.

Recurrence is uncommon in the setting of verrucous carcinoma, with our series being the first to analyze prognostic factors.3,9,14 Our findings indicate that

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare cancer with the greatest predilection for the foot. Multiple case reports with only a few large case series have been published. 1-3 Plantar verrucous carcinoma is characterized as a slowly but relentlessly enlarging warty tumor with low metastatic potential and high risk for local invasion. The tumor occurs most frequently in patients aged 60 to 70 years, predominantly in White males. 1 It often is misdiagnosed for years as an ulcer or wart that is highly resistant to therapy. Size typically ranges from 1 to 12 cm in greatest dimension. 1

The pathogenesis of plantar verrucous carcinoma remains unclear, but some contributing factors have been proposed, including trauma, chronic irritation, infection, and poor local hygiene.2 This tumor has been reported to occur in chronic foot ulcerations, particularly in the diabetic population.4 It has been proposed that abnormal expression of the p53 tumor suppressor protein and several types of human papillomavirus (HPV) may have a role in the pathogenesis of verrucous carcinoma.5

The pathologic hallmarks of this tumor include a verrucous/hyperkeratotic surface with a deeply endophytic, broad, pushing base. Tumor cells are well differentiated, and atypia is either absent or confined to 1 or 2 layers at the base of the tumor. Overt invasion at the base is lacking, except in cases with a component of conventional invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Human papillomavirus viropathic changes are classically absent.1,3 Studies of the histopathology of verrucous carcinoma have been complicated by similar entities, nomenclatural uncertainty, and variable diagnostic criteria. For example, epithelioma cuniculatum variously has been defined as being synonymous with verrucous carcinoma, a distinct clinical verrucous carcinoma subtype occurring on the soles, a histologic subtype (characterized by prominent burrowing sinuses), or a separate entity entirely.1,2,6,7 Furthermore, in the genital area, several different types of carcinomas have verruciform features but display distinct microscopic findings and outcomes from verrucous carcinoma.8

Verrucous carcinoma represents an unusual variant of squamous cell carcinoma and is treated as such. Treatments have included laser surgery; immunotherapy; retinoid therapy; and chemotherapy by oral, intralesional, or iontophoretic routes in select patients.9 Radiotherapy presents another option, though reports have described progression to aggressive squamous cell carcinoma in some cases.9 Surgery is the best course of treatment, and as more case reports have been published, a transition from radical resection to wide excision with tumor-free margins is the treatment of choice.2,3,10,11 To minimize soft-tissue deficits, Mohs micrographic surgery has been discussed as a treatment option for verrucous carcinoma.11-13

Few studies have described verrucous carcinoma recurrence, and none have systematically examined recurrence rate, risk factors, or prognosis

Methods

Patient cases were

Of the 19 cases, 16 were treated at the University of Michigan and are included in the treatment analyses. Specific attention was then paid to the cases with a clinical recurrence despite negative surgical margins. We compared the clinical and surgical differences between recurrent cases and nonrecurrent cases.

Pathology was rereviewed for selected cases, including 2 cases with recurrence and matched primary, 2 cases with recurrence (for which the matched primary was unavailable for review), and 5 representative primary cases that were not complicated by recurrence. Pathology review was conducted in a blinded manner by one of the authors (P.W.H) who is a board-certified dermatopathologist for approximate depth of invasion from the granular layer, perineural invasion, bone invasion, infiltrative growth, presence of conventional squamous cell carcinoma, and margin status.

Statistical analysis was performed when appropriate using an N1 χ2 test or Student t test.

Results

Demographics and Comorbidities—The median age of the patients at the time of diagnosis was 55 years (range, 34–77 years). There were 12 males and 7 females (Table 1). Two patients were Black and 17 were White. Almost all patients had additional comorbidities including tobacco use (68%), alcohol use (47%), and diabetes (47%). Only 1 patient had an autoimmune disease and was on chronic steroids. No significant difference was found between the demographics of patients with recurrent lesions and those without recurrence.

Tumor Location and Clinical Presentation—The most common clinical presentation included a nonhealing ulceration with warty edges, pain, bleeding, and lowered mobility. In most cases, there was history of prior treatment over a duration ranging from 1 to 8 years, with a median of 5 years prior to biopsy-based diagnosis (Table 1). Six patients had a history of osteomyelitis, diagnosed by imaging or biopsy, within a year before tumor diagnosis. The size of the primary tumor ranged from 2.4 to 6 cm, with a mean of 4 cm (P=.20). The clinical presentation, time before diagnosis, and size of the tumors did not differ significantly between recurrent and nonrecurrent cases.

The tumor location for the recurrent cases differed significantly compared to nonrecurrent cases. All 5 of the patients with a recurrence presented with a tumor on the nonglabrous part of the foot. Four patients (80%) had lesions on the dorsal or lateral aspect of the great toe (P=.002), and 1 patient (20%) had a lesion on the low ankle (P=.09)(Table 1). Of the nonrecurrent cases, 1 patient (7%) presented with a tumor on the plantar surface of the great toe (P=.002), 13 patients (93%) presented with tumors on the distal plantar surface of the foot (P=.0002), and 1 patient with a plantar foot tumor (Figure 1) also had verrucous carcinoma on the thumb (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Histopathology—Available pathology slides for recurrent cases of verrucous carcinoma were reviewed alongside representative cases of verrucous carcinomas that did not progress to recurrence. The diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma was confirmed in all cases, with no evidence of conventional squamous cell carcinoma, perineural invasion, extension beyond the dermis, or bone invasion in any case. The median size of the tumors was 4.2 cm and 4 cm for nonrecurrent and recurrent specimens, respectively. Recurrences displayed a trend toward increased depth compared to primary tumors without recurrence (average depth, 5.5 mm vs 3.7 mm); however, this did not reach statistical significance (P=.24). Primary tumors that progressed to recurrence (n=2) displayed similar findings to the other cases, with invasive depths of 3.5 and 5.5 mm, and there was no evidence of conventional squamous cell carcinoma, perineural invasion, or extension beyond the dermis.

Treatment of Nonrecurrent Cases—Of the 16 total cases treated at the University of Michigan, surgery was the primary mode of therapy in every case (Tables 2 and 3). Of the 11 nonrecurrent cases, 7 patients had wide local excision with a dermal regeneration template, and delayed split-thickness graft reconstruction. Three cases had wide local excision with metatarsal resection, dermal regeneration template, and delayed skin grafting. One case had a great toe amputation

Treatment of Recurrent Cases—For the 5 patients with recurrence, surgical margins were not reported in all the cases but ranged from 0.5 to 2 cm (4/5 [80%] reported). On average, follow-up for this group of patients was 29 months, with a range of 12 to 60 months (Table 3).