User login

Diuretic agents equal to prevent CV events in hypertension: DCP

There was no difference in major cardiovascular outcomes with the use of two different diuretics – chlorthalidone or hydrochlorothiazide – in the treatment of hypertension in a new large randomized real-world study.

The Diuretic Comparison Project (DCP), which was conducted in more than 13,500 U.S. veterans age 65 years or over, showed almost identical rates of the primary composite endpoint, including myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, noncancer death, hospitalization for acute heart failure, or urgent revascularization, after a median of 2.4 years of follow-up.

There was no difference in any of the individual endpoints or other secondary cardiovascular outcomes.

However, in the subgroup of patients who had a history of MI or stroke (who made up about 10% of the study population), there was a significant reduction in the primary endpoint with chlorthalidone, whereas those without a history of MI or stroke appeared to have an increased risk for primary outcome events while receiving chlorthalidone compared with those receiving hydrochlorothiazide.

The DCP trial was presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions by Areef Ishani, MD, director of the Minneapolis Primary Care and Specialty Care Integrated Care Community and director of the Veterans Affairs (VA) Midwest Health Care Network.

Asked how to interpret the result for clinical practice, Dr. Ishani said, “I think we can now say that either of these two drugs is appropriate to use for the treatment of hypertension.”

But he added that the decision on what to do with the subgroup of patients with previous MI or stroke was more “challenging.”

“We saw a highly significant benefit in this subgroup, but this was in the context of an overall negative trial,” he noted. “I think this is a discussion with the patients on how they want to hedge their bets. Because these two drugs are so similar, if they wanted to take one or the other because of this subgroup result I think that is a conversation to have, but I think we now need to conduct another trial specifically in this subgroup of patients to see if chlorthalidone really is of benefit in that group.”

Dr. Ishani explained that both chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide have been around for more than 50 years and are considered first-line treatments for hypertension. Early studies suggested better cardiovascular outcomes and 24-hour blood pressure control with chlorthalidone, but recent observational studies have not shown more benefit with chlorthalidone. These studies have suggested that chlorthalidone may be associated with an increase in adverse events, such as hypokalemia, acute kidney injury, and chronic kidney disease.

Pragmatic study

The DCP trial was conducted to try to definitively answer this question of whether chlorthalidone is superior to hydrochlorothiazide. The pragmatic study had a “point-of-care” design that allowed participants and health care professionals to know which medication was being prescribed and to administer the medication in a real-world setting.

“Patients can continue with their normal care with their usual care team because we integrated this trial into primary care clinics,” Dr. Ishani said. “We followed participant results using their electronic health record. This study was nonintrusive, cost-effective, and inexpensive. Plus, we were able to recruit a large rural population, which is unusual for large, randomized trials, where we usually rely on big academic medical centers.”

Using VA electronic medical records, the investigators recruited primary care physicians who identified patients older than age 65 years who were receiving hydrochlorothiazide (25 mg or 50 mg) for hypertension. These patients (97% of whom were male) were then randomly assigned to continue receiving hydrochlorothiazide or to switch to an equivalent dose of chlorthalidone. Patients were followed through the electronic medical record as well as Medicare claims and the National Death Index.

Results after a median follow-up of 2.4 years showed no difference in blood pressure control between the two groups.

In terms of clinical events, the primary composite outcome of MI, stroke, noncancer death, hospitalization for acute heart failure, or urgent revascularization occurred in 10.4% of the chlorthalidone group and in 10.0% of the hydrochlorothiazide group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.94-1.16; P = .4).

There was no difference in any individual components of the primary endpoint or the secondary outcomes of all-cause mortality, any revascularization, or erectile dysfunction.

In terms of adverse events, chlorthalidone was associated with an increase in hypokalemia (6% vs. 4.4%; HR, 1.38), but there was no difference in hospitalization for acute kidney injury.

Benefit in MI, stroke subgroup?

In the subgroup analysis, patients with a history of MI or stroke who were receiving chlorthalidone had a significant 27% reduction in the primary endpoint (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57-0.94). Conversely, patients without a history of MI or stroke appeared to do worse while taking chlorthalidone (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26).

“We were surprised by these results,” Dr. Ishani said. “We expected chlorthalidone to be more effective overall. However, learning about these differences in patients who have a history of cardiovascular disease may affect patient care. It’s best for people to talk with their health care clinicians about which of these medications is better for their individual needs.”

He added: “More research is needed to explore these results further because we don’t know how they may fit into treating the general population.”

Dr. Ishani noted that a limitations of this study was that most patients were receiving the low dose of chlorthalidone, and previous studies that suggested benefits with chlorthalidone used the higher dose.

“But the world has voted – we had 4,000 clinicians involved in this study, and the vast majority are using the low dose of hydrochlorothiazide. And this is a definitively negative study,” he said. “The world has also voted in that 10 times more patients were on hydrochlorothiazide than on chlorthalidone.”

Commenting on the study at an AHA press conference, Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, pointed out that in all of the landmark National Institutes of Health hypertension trials, there was a signal for benefit with chlorthalidone compared with other antihypertensives.

“We’ve always had this concept that chlorthalidone is better,” she said. “But this study shows no difference in major cardiovascular endpoints. There was more hypokalemia with chlorthalidone, but that’s recognizable as chlorthalidone is a more potent diuretic.”

Other limitations of the DCP trial are its open-label design, which could interject some bias; the enduring effects of hydrochlorothiazide – most of these patients were receiving this agent as background therapy; and inability to look at the effectiveness of decongestion of the agents in such a pragmatic study, Dr. Bozkurt noted.

She said she would like to see more analysis in the subgroup of patients with previous MI or stroke. “Does this result mean that chlorthalidone is better for sicker patients or is this result just due to chance?” she asked.

“While this study demonstrates equal effectiveness of these two diuretics in the targeted population, the question of subgroups of patients for which we use a more potent diuretic I think remains unanswered,” she concluded.

Designated discussant of the DCP trial at the late-breaking trial session, Daniel Levy, MD, director of the Framingham Heart Study at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, reminded attendees that chlorthalidone had shown impressive results in previous important hypertension studies including SHEP and ALLHAT.

He said the current DCP was a pragmatic study addressing a knowledge gap that “would never have been performed by industry.”

Dr. Levy concluded that the results showing no difference in outcomes between the two diuretics were “compelling,” although a few questions remain.

These include a possible bias toward hydrochlorothiazide – patients were selected who were already taking that drug and so would have already had a favorable response to it. In addition, because the trial was conducted in an older male population, he questioned whether the results could be generalized to women and younger patients.

The DCP study was funded by the VA Cooperative Studies Program. Dr. Ishani reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There was no difference in major cardiovascular outcomes with the use of two different diuretics – chlorthalidone or hydrochlorothiazide – in the treatment of hypertension in a new large randomized real-world study.

The Diuretic Comparison Project (DCP), which was conducted in more than 13,500 U.S. veterans age 65 years or over, showed almost identical rates of the primary composite endpoint, including myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, noncancer death, hospitalization for acute heart failure, or urgent revascularization, after a median of 2.4 years of follow-up.

There was no difference in any of the individual endpoints or other secondary cardiovascular outcomes.

However, in the subgroup of patients who had a history of MI or stroke (who made up about 10% of the study population), there was a significant reduction in the primary endpoint with chlorthalidone, whereas those without a history of MI or stroke appeared to have an increased risk for primary outcome events while receiving chlorthalidone compared with those receiving hydrochlorothiazide.

The DCP trial was presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions by Areef Ishani, MD, director of the Minneapolis Primary Care and Specialty Care Integrated Care Community and director of the Veterans Affairs (VA) Midwest Health Care Network.

Asked how to interpret the result for clinical practice, Dr. Ishani said, “I think we can now say that either of these two drugs is appropriate to use for the treatment of hypertension.”

But he added that the decision on what to do with the subgroup of patients with previous MI or stroke was more “challenging.”

“We saw a highly significant benefit in this subgroup, but this was in the context of an overall negative trial,” he noted. “I think this is a discussion with the patients on how they want to hedge their bets. Because these two drugs are so similar, if they wanted to take one or the other because of this subgroup result I think that is a conversation to have, but I think we now need to conduct another trial specifically in this subgroup of patients to see if chlorthalidone really is of benefit in that group.”

Dr. Ishani explained that both chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide have been around for more than 50 years and are considered first-line treatments for hypertension. Early studies suggested better cardiovascular outcomes and 24-hour blood pressure control with chlorthalidone, but recent observational studies have not shown more benefit with chlorthalidone. These studies have suggested that chlorthalidone may be associated with an increase in adverse events, such as hypokalemia, acute kidney injury, and chronic kidney disease.

Pragmatic study

The DCP trial was conducted to try to definitively answer this question of whether chlorthalidone is superior to hydrochlorothiazide. The pragmatic study had a “point-of-care” design that allowed participants and health care professionals to know which medication was being prescribed and to administer the medication in a real-world setting.

“Patients can continue with their normal care with their usual care team because we integrated this trial into primary care clinics,” Dr. Ishani said. “We followed participant results using their electronic health record. This study was nonintrusive, cost-effective, and inexpensive. Plus, we were able to recruit a large rural population, which is unusual for large, randomized trials, where we usually rely on big academic medical centers.”

Using VA electronic medical records, the investigators recruited primary care physicians who identified patients older than age 65 years who were receiving hydrochlorothiazide (25 mg or 50 mg) for hypertension. These patients (97% of whom were male) were then randomly assigned to continue receiving hydrochlorothiazide or to switch to an equivalent dose of chlorthalidone. Patients were followed through the electronic medical record as well as Medicare claims and the National Death Index.

Results after a median follow-up of 2.4 years showed no difference in blood pressure control between the two groups.

In terms of clinical events, the primary composite outcome of MI, stroke, noncancer death, hospitalization for acute heart failure, or urgent revascularization occurred in 10.4% of the chlorthalidone group and in 10.0% of the hydrochlorothiazide group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.94-1.16; P = .4).

There was no difference in any individual components of the primary endpoint or the secondary outcomes of all-cause mortality, any revascularization, or erectile dysfunction.

In terms of adverse events, chlorthalidone was associated with an increase in hypokalemia (6% vs. 4.4%; HR, 1.38), but there was no difference in hospitalization for acute kidney injury.

Benefit in MI, stroke subgroup?

In the subgroup analysis, patients with a history of MI or stroke who were receiving chlorthalidone had a significant 27% reduction in the primary endpoint (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57-0.94). Conversely, patients without a history of MI or stroke appeared to do worse while taking chlorthalidone (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26).

“We were surprised by these results,” Dr. Ishani said. “We expected chlorthalidone to be more effective overall. However, learning about these differences in patients who have a history of cardiovascular disease may affect patient care. It’s best for people to talk with their health care clinicians about which of these medications is better for their individual needs.”

He added: “More research is needed to explore these results further because we don’t know how they may fit into treating the general population.”

Dr. Ishani noted that a limitations of this study was that most patients were receiving the low dose of chlorthalidone, and previous studies that suggested benefits with chlorthalidone used the higher dose.

“But the world has voted – we had 4,000 clinicians involved in this study, and the vast majority are using the low dose of hydrochlorothiazide. And this is a definitively negative study,” he said. “The world has also voted in that 10 times more patients were on hydrochlorothiazide than on chlorthalidone.”

Commenting on the study at an AHA press conference, Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, pointed out that in all of the landmark National Institutes of Health hypertension trials, there was a signal for benefit with chlorthalidone compared with other antihypertensives.

“We’ve always had this concept that chlorthalidone is better,” she said. “But this study shows no difference in major cardiovascular endpoints. There was more hypokalemia with chlorthalidone, but that’s recognizable as chlorthalidone is a more potent diuretic.”

Other limitations of the DCP trial are its open-label design, which could interject some bias; the enduring effects of hydrochlorothiazide – most of these patients were receiving this agent as background therapy; and inability to look at the effectiveness of decongestion of the agents in such a pragmatic study, Dr. Bozkurt noted.

She said she would like to see more analysis in the subgroup of patients with previous MI or stroke. “Does this result mean that chlorthalidone is better for sicker patients or is this result just due to chance?” she asked.

“While this study demonstrates equal effectiveness of these two diuretics in the targeted population, the question of subgroups of patients for which we use a more potent diuretic I think remains unanswered,” she concluded.

Designated discussant of the DCP trial at the late-breaking trial session, Daniel Levy, MD, director of the Framingham Heart Study at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, reminded attendees that chlorthalidone had shown impressive results in previous important hypertension studies including SHEP and ALLHAT.

He said the current DCP was a pragmatic study addressing a knowledge gap that “would never have been performed by industry.”

Dr. Levy concluded that the results showing no difference in outcomes between the two diuretics were “compelling,” although a few questions remain.

These include a possible bias toward hydrochlorothiazide – patients were selected who were already taking that drug and so would have already had a favorable response to it. In addition, because the trial was conducted in an older male population, he questioned whether the results could be generalized to women and younger patients.

The DCP study was funded by the VA Cooperative Studies Program. Dr. Ishani reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There was no difference in major cardiovascular outcomes with the use of two different diuretics – chlorthalidone or hydrochlorothiazide – in the treatment of hypertension in a new large randomized real-world study.

The Diuretic Comparison Project (DCP), which was conducted in more than 13,500 U.S. veterans age 65 years or over, showed almost identical rates of the primary composite endpoint, including myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, noncancer death, hospitalization for acute heart failure, or urgent revascularization, after a median of 2.4 years of follow-up.

There was no difference in any of the individual endpoints or other secondary cardiovascular outcomes.

However, in the subgroup of patients who had a history of MI or stroke (who made up about 10% of the study population), there was a significant reduction in the primary endpoint with chlorthalidone, whereas those without a history of MI or stroke appeared to have an increased risk for primary outcome events while receiving chlorthalidone compared with those receiving hydrochlorothiazide.

The DCP trial was presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions by Areef Ishani, MD, director of the Minneapolis Primary Care and Specialty Care Integrated Care Community and director of the Veterans Affairs (VA) Midwest Health Care Network.

Asked how to interpret the result for clinical practice, Dr. Ishani said, “I think we can now say that either of these two drugs is appropriate to use for the treatment of hypertension.”

But he added that the decision on what to do with the subgroup of patients with previous MI or stroke was more “challenging.”

“We saw a highly significant benefit in this subgroup, but this was in the context of an overall negative trial,” he noted. “I think this is a discussion with the patients on how they want to hedge their bets. Because these two drugs are so similar, if they wanted to take one or the other because of this subgroup result I think that is a conversation to have, but I think we now need to conduct another trial specifically in this subgroup of patients to see if chlorthalidone really is of benefit in that group.”

Dr. Ishani explained that both chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide have been around for more than 50 years and are considered first-line treatments for hypertension. Early studies suggested better cardiovascular outcomes and 24-hour blood pressure control with chlorthalidone, but recent observational studies have not shown more benefit with chlorthalidone. These studies have suggested that chlorthalidone may be associated with an increase in adverse events, such as hypokalemia, acute kidney injury, and chronic kidney disease.

Pragmatic study

The DCP trial was conducted to try to definitively answer this question of whether chlorthalidone is superior to hydrochlorothiazide. The pragmatic study had a “point-of-care” design that allowed participants and health care professionals to know which medication was being prescribed and to administer the medication in a real-world setting.

“Patients can continue with their normal care with their usual care team because we integrated this trial into primary care clinics,” Dr. Ishani said. “We followed participant results using their electronic health record. This study was nonintrusive, cost-effective, and inexpensive. Plus, we were able to recruit a large rural population, which is unusual for large, randomized trials, where we usually rely on big academic medical centers.”

Using VA electronic medical records, the investigators recruited primary care physicians who identified patients older than age 65 years who were receiving hydrochlorothiazide (25 mg or 50 mg) for hypertension. These patients (97% of whom were male) were then randomly assigned to continue receiving hydrochlorothiazide or to switch to an equivalent dose of chlorthalidone. Patients were followed through the electronic medical record as well as Medicare claims and the National Death Index.

Results after a median follow-up of 2.4 years showed no difference in blood pressure control between the two groups.

In terms of clinical events, the primary composite outcome of MI, stroke, noncancer death, hospitalization for acute heart failure, or urgent revascularization occurred in 10.4% of the chlorthalidone group and in 10.0% of the hydrochlorothiazide group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.94-1.16; P = .4).

There was no difference in any individual components of the primary endpoint or the secondary outcomes of all-cause mortality, any revascularization, or erectile dysfunction.

In terms of adverse events, chlorthalidone was associated with an increase in hypokalemia (6% vs. 4.4%; HR, 1.38), but there was no difference in hospitalization for acute kidney injury.

Benefit in MI, stroke subgroup?

In the subgroup analysis, patients with a history of MI or stroke who were receiving chlorthalidone had a significant 27% reduction in the primary endpoint (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57-0.94). Conversely, patients without a history of MI or stroke appeared to do worse while taking chlorthalidone (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26).

“We were surprised by these results,” Dr. Ishani said. “We expected chlorthalidone to be more effective overall. However, learning about these differences in patients who have a history of cardiovascular disease may affect patient care. It’s best for people to talk with their health care clinicians about which of these medications is better for their individual needs.”

He added: “More research is needed to explore these results further because we don’t know how they may fit into treating the general population.”

Dr. Ishani noted that a limitations of this study was that most patients were receiving the low dose of chlorthalidone, and previous studies that suggested benefits with chlorthalidone used the higher dose.

“But the world has voted – we had 4,000 clinicians involved in this study, and the vast majority are using the low dose of hydrochlorothiazide. And this is a definitively negative study,” he said. “The world has also voted in that 10 times more patients were on hydrochlorothiazide than on chlorthalidone.”

Commenting on the study at an AHA press conference, Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, pointed out that in all of the landmark National Institutes of Health hypertension trials, there was a signal for benefit with chlorthalidone compared with other antihypertensives.

“We’ve always had this concept that chlorthalidone is better,” she said. “But this study shows no difference in major cardiovascular endpoints. There was more hypokalemia with chlorthalidone, but that’s recognizable as chlorthalidone is a more potent diuretic.”

Other limitations of the DCP trial are its open-label design, which could interject some bias; the enduring effects of hydrochlorothiazide – most of these patients were receiving this agent as background therapy; and inability to look at the effectiveness of decongestion of the agents in such a pragmatic study, Dr. Bozkurt noted.

She said she would like to see more analysis in the subgroup of patients with previous MI or stroke. “Does this result mean that chlorthalidone is better for sicker patients or is this result just due to chance?” she asked.

“While this study demonstrates equal effectiveness of these two diuretics in the targeted population, the question of subgroups of patients for which we use a more potent diuretic I think remains unanswered,” she concluded.

Designated discussant of the DCP trial at the late-breaking trial session, Daniel Levy, MD, director of the Framingham Heart Study at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, reminded attendees that chlorthalidone had shown impressive results in previous important hypertension studies including SHEP and ALLHAT.

He said the current DCP was a pragmatic study addressing a knowledge gap that “would never have been performed by industry.”

Dr. Levy concluded that the results showing no difference in outcomes between the two diuretics were “compelling,” although a few questions remain.

These include a possible bias toward hydrochlorothiazide – patients were selected who were already taking that drug and so would have already had a favorable response to it. In addition, because the trial was conducted in an older male population, he questioned whether the results could be generalized to women and younger patients.

The DCP study was funded by the VA Cooperative Studies Program. Dr. Ishani reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AHA 2022

Triglyceride-lowering fails to show CV benefit in large fibrate trial

Twenty-five percent reduction has no effect

CHICAGO – Despite a 25% reduction in triglycerides (TGs) along with similar reductions in very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), and remnant cholesterol, a novel agent failed to provide any protection in a multinational trial against a composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with type 2 diabetes.

“Our data further highlight the complexity of lipid mediators of residual risk among patients with insulin resistance who are receiving statin therapy,” reported Aruna Das Pradhan, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Queen Mary University, London.

It is the most recent in a series of trials that have failed to associate a meaningful reduction in TGs with protection from a composite MACE endpoint. This is a pattern that dates back 20 years, even though earlier trials did suggest that hypertriglyceridemia was a targetable risk factor.

No benefit from fibrates seen in statin era

“We have not seen a significant cardiovascular event reduction with a fibrate in the statin era,” according to Karol Watson, MD, PhD, director of the UCLA Women’s Cardiovascular Health Center, Los Angeles.

In the statin era, which began soon after the Helsinki Heart Study was published in 1987, Dr. Watson counted at least five studies with fibrates that had a null result.

In the setting of good control of LDL cholesterol, “fibrates have not been shown to further lower CV risk,” said Dr. Watson, who was invited by the AHA to discuss the PROMINENT trial.

In PROMINENT, 10,497 patients with type 2 diabetes were randomized to pemafibrate, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a (PPAR-a) agonist, or placebo. Pemafibrate is not currently available in North America or Europe, but it is licensed in Japan for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia.

The primary efficacy endpoint of the double-blind trial was a composite endpoint of nonfatal myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, coronary revascularization, or death.

The patients were eligible if they had TG levels from 200 to 400 mg/dL and HDL cholesterol levels of 40 mg/dL or below. Pemafibrate in a dose of 0.2 mg or placebo were taken twice daily. About two-thirds had a prior history of coronary heart disease. The goal was primary prevention in the remainder.

After a median follow-up of 3.4 years when the study was stopped for futility, the proportion of patients reaching a primary endpoint was slightly greater in the experimental arm (3.60 vs. 3.51 events per 100 patient-years). The hazard ratio, although not significant, was nominally in favor of placebo (hazard ratio, 1.03; P = .67).

When events within the composite endpoint were assessed individually, there was no signal of benefit for any outcome. The rates of death from any cause, although numerically higher in the pemafibrate group (2.44 vs. 2.34 per 100 patient years), were also comparable.

Lipid profile improved as predicted

Yet, in regard to an improvement in the lipid profile, pemafibrate performed as predicted. When compared to placebo 4 months into the trial, pemafibrate was associated with median reductions of 26.2% in TGs, 25.8% in VLDL, and 25.6% in remnant cholesterol, which is cholesterol transported in TG-rich lipoproteins after lipolysis and lipoprotein remodeling.

Furthermore, pemafibrate was associated with a median 27.6% reduction relative to placebo in apolipoprotein C-III and a median 4.8% reduction in apolipoprotein E, all of which would be expected to reduce CV risk.

The findings of PROMINENT were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine immediately after their presentation.

The findings of this study do not eliminate any hope for lowering residual CV risk with TG reductions, but they do suggest the relationship with other lipid subfractions is complex, according to Salim S. Virani, MD, PhD, a professor of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

“I think that the lack of efficacy despite TG lowering may be largely due to a lack of an overall decrease in the apolipoprotein B level,” speculated Dr. Virani, who wrote an editorial that accompanied publication of the PROMINENT results.

He noted that pemafibrate is implicated in converting remnant cholesterol to LDL cholesterol, which might be one reason for a counterproductive effect on CV risk.

“In order for therapies that lower TG levels to be effective, they probably have to have mechanisms to increase clearance of TG-rich remnant lipoprotein cholesterol particles rather than just converting remnant lipoproteins to LDL,” Dr. Virani explained in an attempt to unravel the interplay of these variables.

Although this study enrolled patients “who would be predicted to have the most benefit from a TG-lowering strategy,” Dr. Watson agreed that these results do not necessarily extend to other means of lowering TG. However, it might draw into question the value of pemafibrate and perhaps other drugs in this class for treatment of hypertriglyceridemia. In addition to a lack of CV benefit, treatment was not without risks, including a higher rate of thromboembolism and adverse renal events.

Dr. Das Pradhan reported financial relationships with Denka, Medtelligence, Optum, Novo Nordisk, and Kowa, which provided funding for this trial. Dr. Watson reported financial relationships with Amarin, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Esperion.

Twenty-five percent reduction has no effect

Twenty-five percent reduction has no effect

CHICAGO – Despite a 25% reduction in triglycerides (TGs) along with similar reductions in very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), and remnant cholesterol, a novel agent failed to provide any protection in a multinational trial against a composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with type 2 diabetes.

“Our data further highlight the complexity of lipid mediators of residual risk among patients with insulin resistance who are receiving statin therapy,” reported Aruna Das Pradhan, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Queen Mary University, London.

It is the most recent in a series of trials that have failed to associate a meaningful reduction in TGs with protection from a composite MACE endpoint. This is a pattern that dates back 20 years, even though earlier trials did suggest that hypertriglyceridemia was a targetable risk factor.

No benefit from fibrates seen in statin era

“We have not seen a significant cardiovascular event reduction with a fibrate in the statin era,” according to Karol Watson, MD, PhD, director of the UCLA Women’s Cardiovascular Health Center, Los Angeles.

In the statin era, which began soon after the Helsinki Heart Study was published in 1987, Dr. Watson counted at least five studies with fibrates that had a null result.

In the setting of good control of LDL cholesterol, “fibrates have not been shown to further lower CV risk,” said Dr. Watson, who was invited by the AHA to discuss the PROMINENT trial.

In PROMINENT, 10,497 patients with type 2 diabetes were randomized to pemafibrate, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a (PPAR-a) agonist, or placebo. Pemafibrate is not currently available in North America or Europe, but it is licensed in Japan for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia.

The primary efficacy endpoint of the double-blind trial was a composite endpoint of nonfatal myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, coronary revascularization, or death.

The patients were eligible if they had TG levels from 200 to 400 mg/dL and HDL cholesterol levels of 40 mg/dL or below. Pemafibrate in a dose of 0.2 mg or placebo were taken twice daily. About two-thirds had a prior history of coronary heart disease. The goal was primary prevention in the remainder.

After a median follow-up of 3.4 years when the study was stopped for futility, the proportion of patients reaching a primary endpoint was slightly greater in the experimental arm (3.60 vs. 3.51 events per 100 patient-years). The hazard ratio, although not significant, was nominally in favor of placebo (hazard ratio, 1.03; P = .67).

When events within the composite endpoint were assessed individually, there was no signal of benefit for any outcome. The rates of death from any cause, although numerically higher in the pemafibrate group (2.44 vs. 2.34 per 100 patient years), were also comparable.

Lipid profile improved as predicted

Yet, in regard to an improvement in the lipid profile, pemafibrate performed as predicted. When compared to placebo 4 months into the trial, pemafibrate was associated with median reductions of 26.2% in TGs, 25.8% in VLDL, and 25.6% in remnant cholesterol, which is cholesterol transported in TG-rich lipoproteins after lipolysis and lipoprotein remodeling.

Furthermore, pemafibrate was associated with a median 27.6% reduction relative to placebo in apolipoprotein C-III and a median 4.8% reduction in apolipoprotein E, all of which would be expected to reduce CV risk.

The findings of PROMINENT were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine immediately after their presentation.

The findings of this study do not eliminate any hope for lowering residual CV risk with TG reductions, but they do suggest the relationship with other lipid subfractions is complex, according to Salim S. Virani, MD, PhD, a professor of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

“I think that the lack of efficacy despite TG lowering may be largely due to a lack of an overall decrease in the apolipoprotein B level,” speculated Dr. Virani, who wrote an editorial that accompanied publication of the PROMINENT results.

He noted that pemafibrate is implicated in converting remnant cholesterol to LDL cholesterol, which might be one reason for a counterproductive effect on CV risk.

“In order for therapies that lower TG levels to be effective, they probably have to have mechanisms to increase clearance of TG-rich remnant lipoprotein cholesterol particles rather than just converting remnant lipoproteins to LDL,” Dr. Virani explained in an attempt to unravel the interplay of these variables.

Although this study enrolled patients “who would be predicted to have the most benefit from a TG-lowering strategy,” Dr. Watson agreed that these results do not necessarily extend to other means of lowering TG. However, it might draw into question the value of pemafibrate and perhaps other drugs in this class for treatment of hypertriglyceridemia. In addition to a lack of CV benefit, treatment was not without risks, including a higher rate of thromboembolism and adverse renal events.

Dr. Das Pradhan reported financial relationships with Denka, Medtelligence, Optum, Novo Nordisk, and Kowa, which provided funding for this trial. Dr. Watson reported financial relationships with Amarin, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Esperion.

CHICAGO – Despite a 25% reduction in triglycerides (TGs) along with similar reductions in very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), and remnant cholesterol, a novel agent failed to provide any protection in a multinational trial against a composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with type 2 diabetes.

“Our data further highlight the complexity of lipid mediators of residual risk among patients with insulin resistance who are receiving statin therapy,” reported Aruna Das Pradhan, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Queen Mary University, London.

It is the most recent in a series of trials that have failed to associate a meaningful reduction in TGs with protection from a composite MACE endpoint. This is a pattern that dates back 20 years, even though earlier trials did suggest that hypertriglyceridemia was a targetable risk factor.

No benefit from fibrates seen in statin era

“We have not seen a significant cardiovascular event reduction with a fibrate in the statin era,” according to Karol Watson, MD, PhD, director of the UCLA Women’s Cardiovascular Health Center, Los Angeles.

In the statin era, which began soon after the Helsinki Heart Study was published in 1987, Dr. Watson counted at least five studies with fibrates that had a null result.

In the setting of good control of LDL cholesterol, “fibrates have not been shown to further lower CV risk,” said Dr. Watson, who was invited by the AHA to discuss the PROMINENT trial.

In PROMINENT, 10,497 patients with type 2 diabetes were randomized to pemafibrate, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a (PPAR-a) agonist, or placebo. Pemafibrate is not currently available in North America or Europe, but it is licensed in Japan for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia.

The primary efficacy endpoint of the double-blind trial was a composite endpoint of nonfatal myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, coronary revascularization, or death.

The patients were eligible if they had TG levels from 200 to 400 mg/dL and HDL cholesterol levels of 40 mg/dL or below. Pemafibrate in a dose of 0.2 mg or placebo were taken twice daily. About two-thirds had a prior history of coronary heart disease. The goal was primary prevention in the remainder.

After a median follow-up of 3.4 years when the study was stopped for futility, the proportion of patients reaching a primary endpoint was slightly greater in the experimental arm (3.60 vs. 3.51 events per 100 patient-years). The hazard ratio, although not significant, was nominally in favor of placebo (hazard ratio, 1.03; P = .67).

When events within the composite endpoint were assessed individually, there was no signal of benefit for any outcome. The rates of death from any cause, although numerically higher in the pemafibrate group (2.44 vs. 2.34 per 100 patient years), were also comparable.

Lipid profile improved as predicted

Yet, in regard to an improvement in the lipid profile, pemafibrate performed as predicted. When compared to placebo 4 months into the trial, pemafibrate was associated with median reductions of 26.2% in TGs, 25.8% in VLDL, and 25.6% in remnant cholesterol, which is cholesterol transported in TG-rich lipoproteins after lipolysis and lipoprotein remodeling.

Furthermore, pemafibrate was associated with a median 27.6% reduction relative to placebo in apolipoprotein C-III and a median 4.8% reduction in apolipoprotein E, all of which would be expected to reduce CV risk.

The findings of PROMINENT were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine immediately after their presentation.

The findings of this study do not eliminate any hope for lowering residual CV risk with TG reductions, but they do suggest the relationship with other lipid subfractions is complex, according to Salim S. Virani, MD, PhD, a professor of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

“I think that the lack of efficacy despite TG lowering may be largely due to a lack of an overall decrease in the apolipoprotein B level,” speculated Dr. Virani, who wrote an editorial that accompanied publication of the PROMINENT results.

He noted that pemafibrate is implicated in converting remnant cholesterol to LDL cholesterol, which might be one reason for a counterproductive effect on CV risk.

“In order for therapies that lower TG levels to be effective, they probably have to have mechanisms to increase clearance of TG-rich remnant lipoprotein cholesterol particles rather than just converting remnant lipoproteins to LDL,” Dr. Virani explained in an attempt to unravel the interplay of these variables.

Although this study enrolled patients “who would be predicted to have the most benefit from a TG-lowering strategy,” Dr. Watson agreed that these results do not necessarily extend to other means of lowering TG. However, it might draw into question the value of pemafibrate and perhaps other drugs in this class for treatment of hypertriglyceridemia. In addition to a lack of CV benefit, treatment was not without risks, including a higher rate of thromboembolism and adverse renal events.

Dr. Das Pradhan reported financial relationships with Denka, Medtelligence, Optum, Novo Nordisk, and Kowa, which provided funding for this trial. Dr. Watson reported financial relationships with Amarin, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Esperion.

AT AHA 2022

Hairdressers have ‘excess risk’ of contact allergies

.

“Research has shown that up to 70% of hairdressers suffer from work-related skin damage, mostly hand dermatitis, at some point during their career,” write Wolfgang Uter of Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg and coauthors. In general, they write, occupational skin diseases such as hand dermatitis represent up to 35% of reported occupational diseases. The study was published online in Contact Dermatitis.

Wet work and skin contact with detergents and hairdressing chemicals are top risk factors for developing occupational skin disease in this population, according to the researchers.

To further understand the burden of occupational contact allergy in hairdressers, the investigators gathered evidence published since 2000 on contact allergies to hair cosmetic chemicals. They searched the literature for nine substances selected beforehand by experts and stakeholders. The researchers also examined the prevalence of sensitization between hairdressers and other individuals given skin patch tests.

Substance by substance

Common potentially sensitizing cosmetic ingredients reported across studies included p-phenylenediamine (PPD), persulfates (mostly ammonium persulfate [APS]), glyceryl thioglycolate (GMTG), and ammonium thioglycolate (ATG).

In a pooled analysis, the overall prevalence of contact allergy to PPD was 4.3% in consecutively patch-tested patients, but in hairdressers specifically, the overall prevalence of contact allergy to this ingredient was 28.6%, reviewers reported.

The pooled prevalence of contact allergy to APS was 5.5% in consumers and 17.2% in hairdressers. In other review studies, contact allergy risks to APS, GMTG, and ATG were also elevated in hairdressers compared with all controls.

The calculated relative risk (RR) of contact allergy to PPD was approximately 5.4 higher for hairdressers, while the RR for ATG sensitization was 3.4 in hairdressers compared with consumers.

Commenting on these findings, James A. Yiannias, MD, professor of dermatology at the Mayo Medical School, Phoenix, told this news organization in an email that many providers and patients are concerned only about hair dye molecules such as PPD and aminophenol, as well as permanent, wave, and straightening chemicals such as GMTG.

“Although these are common allergens in hairdressers, allergens such as fragrances and some preservatives found in daily hair care products such as shampoos, conditioners, and hair sprays are also common causes of contact dermatitis,” said Dr. Yiannias, who wasn’t involved in the research.

Consequences of exposure

Dr. Yiannias explained that progressive worsening of the dermatitis can occur with ongoing allergen exposure and, if not properly mitigated, can lead to bigger issues. “Initial nuisances of mild irritation and hyperkeratosis can evolve to a state of fissuring with the risk of bleeding and significant pain,” he said.

But once severe and untreated dermatitis occurs, Dr. Yiannias said that hairdressers “may need to change careers” or at least face short- or long-term unemployment.

The researchers suggest reducing exposure to the allergen is key for prevention of symptoms, adding that adequate guidance on the safe use of new products is needed. Also, the researchers suggested that vocational schools should more rigorously implement education for hairdressers that addresses how to protect the skin appropriately at work.

“Hairdressers are taught during their training to be cautious about allergen exposure by avoiding touching high-risk ingredients such as hair dyes,” Dr. Yiannias added. “However, in practice, this is very difficult since the wearing of gloves can impair the tactile sensations that hairdressers often feel is essential in performing their job.”

The study received no industry funding. Dr. Yiannias reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

“Research has shown that up to 70% of hairdressers suffer from work-related skin damage, mostly hand dermatitis, at some point during their career,” write Wolfgang Uter of Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg and coauthors. In general, they write, occupational skin diseases such as hand dermatitis represent up to 35% of reported occupational diseases. The study was published online in Contact Dermatitis.

Wet work and skin contact with detergents and hairdressing chemicals are top risk factors for developing occupational skin disease in this population, according to the researchers.

To further understand the burden of occupational contact allergy in hairdressers, the investigators gathered evidence published since 2000 on contact allergies to hair cosmetic chemicals. They searched the literature for nine substances selected beforehand by experts and stakeholders. The researchers also examined the prevalence of sensitization between hairdressers and other individuals given skin patch tests.

Substance by substance

Common potentially sensitizing cosmetic ingredients reported across studies included p-phenylenediamine (PPD), persulfates (mostly ammonium persulfate [APS]), glyceryl thioglycolate (GMTG), and ammonium thioglycolate (ATG).

In a pooled analysis, the overall prevalence of contact allergy to PPD was 4.3% in consecutively patch-tested patients, but in hairdressers specifically, the overall prevalence of contact allergy to this ingredient was 28.6%, reviewers reported.

The pooled prevalence of contact allergy to APS was 5.5% in consumers and 17.2% in hairdressers. In other review studies, contact allergy risks to APS, GMTG, and ATG were also elevated in hairdressers compared with all controls.

The calculated relative risk (RR) of contact allergy to PPD was approximately 5.4 higher for hairdressers, while the RR for ATG sensitization was 3.4 in hairdressers compared with consumers.

Commenting on these findings, James A. Yiannias, MD, professor of dermatology at the Mayo Medical School, Phoenix, told this news organization in an email that many providers and patients are concerned only about hair dye molecules such as PPD and aminophenol, as well as permanent, wave, and straightening chemicals such as GMTG.

“Although these are common allergens in hairdressers, allergens such as fragrances and some preservatives found in daily hair care products such as shampoos, conditioners, and hair sprays are also common causes of contact dermatitis,” said Dr. Yiannias, who wasn’t involved in the research.

Consequences of exposure

Dr. Yiannias explained that progressive worsening of the dermatitis can occur with ongoing allergen exposure and, if not properly mitigated, can lead to bigger issues. “Initial nuisances of mild irritation and hyperkeratosis can evolve to a state of fissuring with the risk of bleeding and significant pain,” he said.

But once severe and untreated dermatitis occurs, Dr. Yiannias said that hairdressers “may need to change careers” or at least face short- or long-term unemployment.

The researchers suggest reducing exposure to the allergen is key for prevention of symptoms, adding that adequate guidance on the safe use of new products is needed. Also, the researchers suggested that vocational schools should more rigorously implement education for hairdressers that addresses how to protect the skin appropriately at work.

“Hairdressers are taught during their training to be cautious about allergen exposure by avoiding touching high-risk ingredients such as hair dyes,” Dr. Yiannias added. “However, in practice, this is very difficult since the wearing of gloves can impair the tactile sensations that hairdressers often feel is essential in performing their job.”

The study received no industry funding. Dr. Yiannias reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

“Research has shown that up to 70% of hairdressers suffer from work-related skin damage, mostly hand dermatitis, at some point during their career,” write Wolfgang Uter of Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg and coauthors. In general, they write, occupational skin diseases such as hand dermatitis represent up to 35% of reported occupational diseases. The study was published online in Contact Dermatitis.

Wet work and skin contact with detergents and hairdressing chemicals are top risk factors for developing occupational skin disease in this population, according to the researchers.

To further understand the burden of occupational contact allergy in hairdressers, the investigators gathered evidence published since 2000 on contact allergies to hair cosmetic chemicals. They searched the literature for nine substances selected beforehand by experts and stakeholders. The researchers also examined the prevalence of sensitization between hairdressers and other individuals given skin patch tests.

Substance by substance

Common potentially sensitizing cosmetic ingredients reported across studies included p-phenylenediamine (PPD), persulfates (mostly ammonium persulfate [APS]), glyceryl thioglycolate (GMTG), and ammonium thioglycolate (ATG).

In a pooled analysis, the overall prevalence of contact allergy to PPD was 4.3% in consecutively patch-tested patients, but in hairdressers specifically, the overall prevalence of contact allergy to this ingredient was 28.6%, reviewers reported.

The pooled prevalence of contact allergy to APS was 5.5% in consumers and 17.2% in hairdressers. In other review studies, contact allergy risks to APS, GMTG, and ATG were also elevated in hairdressers compared with all controls.

The calculated relative risk (RR) of contact allergy to PPD was approximately 5.4 higher for hairdressers, while the RR for ATG sensitization was 3.4 in hairdressers compared with consumers.

Commenting on these findings, James A. Yiannias, MD, professor of dermatology at the Mayo Medical School, Phoenix, told this news organization in an email that many providers and patients are concerned only about hair dye molecules such as PPD and aminophenol, as well as permanent, wave, and straightening chemicals such as GMTG.

“Although these are common allergens in hairdressers, allergens such as fragrances and some preservatives found in daily hair care products such as shampoos, conditioners, and hair sprays are also common causes of contact dermatitis,” said Dr. Yiannias, who wasn’t involved in the research.

Consequences of exposure

Dr. Yiannias explained that progressive worsening of the dermatitis can occur with ongoing allergen exposure and, if not properly mitigated, can lead to bigger issues. “Initial nuisances of mild irritation and hyperkeratosis can evolve to a state of fissuring with the risk of bleeding and significant pain,” he said.

But once severe and untreated dermatitis occurs, Dr. Yiannias said that hairdressers “may need to change careers” or at least face short- or long-term unemployment.

The researchers suggest reducing exposure to the allergen is key for prevention of symptoms, adding that adequate guidance on the safe use of new products is needed. Also, the researchers suggested that vocational schools should more rigorously implement education for hairdressers that addresses how to protect the skin appropriately at work.

“Hairdressers are taught during their training to be cautious about allergen exposure by avoiding touching high-risk ingredients such as hair dyes,” Dr. Yiannias added. “However, in practice, this is very difficult since the wearing of gloves can impair the tactile sensations that hairdressers often feel is essential in performing their job.”

The study received no industry funding. Dr. Yiannias reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Do scare tactics work?

I suspect that you have heard about or maybe read the recent Associated Press story reporting that four daycare workers in Hamilton, Miss., have been charged with felony child abuse for intentionally scaring the children “who didn’t clean up or act good” by wearing a Halloween mask and yelling in their faces. I can have some sympathy for those among us who choose to spend their days tending a flock of sometimes unruly and mischievous toddlers and preschoolers. But, I think one would be hard pressed to find very many adults who would condone the strategy of these misguided daycare providers. Not surprisingly, the parents of some of these children describe their children as traumatized and having disordered sleep.

The news report of this incident in Mississippi doesn’t tell us if these daycare providers had used this tactic in the past. One wonders whether they had found less dramatic verbal threats just weren’t as effective as they had hoped and so decided to go all out.

How effective is fear in changing behavior? Certainly, we have all experienced situations in which a frightening experience has caused us to avoid places, people, and activities. But, is a fear-focused strategy one that health care providers should include in their quiver as we try to mold patient behavior? As luck would have it, 2 weeks before this news story broke I encountered a global study from 84 countries that sought to answer this question (Affect Sci. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1007/s42761-022-00128-3).

Using the WHO four-point advice about COVID prevention (stay home/avoid shops/use face covering/isolate if exposed) as a model the researchers around the world reviewed the responses of 16,000 individuals. They found that there was no difference in the effectiveness of the message whether it was framed as a negative (“you have so much to lose”) or a positive (“you have so much to gain”). However, investigators observed that the negatively framed presentations generated significantly more anxiety in the respondents. The authors of the paper conclude that if there is no significant difference in the effectiveness, why would we chose a negatively framed presentation that is likely to generate anxiety that we know is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. From a purely public health perspective, it doesn’t make sense and is counterproductive.

I guess if we look back to the old carrot and stick metaphor we shouldn’t be surprised by the findings in this paper. If one’s only goal is to get a group of young preschoolers to behave by scaring the b’geezes out of them with a mask or a threat of bodily punishment, then go for it. Scare tactics will probably work just as well as offering a well-chosen reward system. However, the devil is in the side effects. It’s the same argument that I give to parents who argue that spanking works. Of course it does, but it has a narrow margin for safety and can set up ripples of negative side effects that can destroy healthy parent-child relationships.

The bottom line of this story is the sad truth that somewhere along the line someone failed to effectively train these four daycare workers. But, do we as health care providers need to rethink our training? Have we forgotten our commitment to “First do no harm?” As we craft our messaging have we thought enough about the potential side effects of our attempts at scaring the public into following our suggestions?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

I suspect that you have heard about or maybe read the recent Associated Press story reporting that four daycare workers in Hamilton, Miss., have been charged with felony child abuse for intentionally scaring the children “who didn’t clean up or act good” by wearing a Halloween mask and yelling in their faces. I can have some sympathy for those among us who choose to spend their days tending a flock of sometimes unruly and mischievous toddlers and preschoolers. But, I think one would be hard pressed to find very many adults who would condone the strategy of these misguided daycare providers. Not surprisingly, the parents of some of these children describe their children as traumatized and having disordered sleep.

The news report of this incident in Mississippi doesn’t tell us if these daycare providers had used this tactic in the past. One wonders whether they had found less dramatic verbal threats just weren’t as effective as they had hoped and so decided to go all out.

How effective is fear in changing behavior? Certainly, we have all experienced situations in which a frightening experience has caused us to avoid places, people, and activities. But, is a fear-focused strategy one that health care providers should include in their quiver as we try to mold patient behavior? As luck would have it, 2 weeks before this news story broke I encountered a global study from 84 countries that sought to answer this question (Affect Sci. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1007/s42761-022-00128-3).

Using the WHO four-point advice about COVID prevention (stay home/avoid shops/use face covering/isolate if exposed) as a model the researchers around the world reviewed the responses of 16,000 individuals. They found that there was no difference in the effectiveness of the message whether it was framed as a negative (“you have so much to lose”) or a positive (“you have so much to gain”). However, investigators observed that the negatively framed presentations generated significantly more anxiety in the respondents. The authors of the paper conclude that if there is no significant difference in the effectiveness, why would we chose a negatively framed presentation that is likely to generate anxiety that we know is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. From a purely public health perspective, it doesn’t make sense and is counterproductive.

I guess if we look back to the old carrot and stick metaphor we shouldn’t be surprised by the findings in this paper. If one’s only goal is to get a group of young preschoolers to behave by scaring the b’geezes out of them with a mask or a threat of bodily punishment, then go for it. Scare tactics will probably work just as well as offering a well-chosen reward system. However, the devil is in the side effects. It’s the same argument that I give to parents who argue that spanking works. Of course it does, but it has a narrow margin for safety and can set up ripples of negative side effects that can destroy healthy parent-child relationships.

The bottom line of this story is the sad truth that somewhere along the line someone failed to effectively train these four daycare workers. But, do we as health care providers need to rethink our training? Have we forgotten our commitment to “First do no harm?” As we craft our messaging have we thought enough about the potential side effects of our attempts at scaring the public into following our suggestions?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

I suspect that you have heard about or maybe read the recent Associated Press story reporting that four daycare workers in Hamilton, Miss., have been charged with felony child abuse for intentionally scaring the children “who didn’t clean up or act good” by wearing a Halloween mask and yelling in their faces. I can have some sympathy for those among us who choose to spend their days tending a flock of sometimes unruly and mischievous toddlers and preschoolers. But, I think one would be hard pressed to find very many adults who would condone the strategy of these misguided daycare providers. Not surprisingly, the parents of some of these children describe their children as traumatized and having disordered sleep.

The news report of this incident in Mississippi doesn’t tell us if these daycare providers had used this tactic in the past. One wonders whether they had found less dramatic verbal threats just weren’t as effective as they had hoped and so decided to go all out.

How effective is fear in changing behavior? Certainly, we have all experienced situations in which a frightening experience has caused us to avoid places, people, and activities. But, is a fear-focused strategy one that health care providers should include in their quiver as we try to mold patient behavior? As luck would have it, 2 weeks before this news story broke I encountered a global study from 84 countries that sought to answer this question (Affect Sci. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1007/s42761-022-00128-3).

Using the WHO four-point advice about COVID prevention (stay home/avoid shops/use face covering/isolate if exposed) as a model the researchers around the world reviewed the responses of 16,000 individuals. They found that there was no difference in the effectiveness of the message whether it was framed as a negative (“you have so much to lose”) or a positive (“you have so much to gain”). However, investigators observed that the negatively framed presentations generated significantly more anxiety in the respondents. The authors of the paper conclude that if there is no significant difference in the effectiveness, why would we chose a negatively framed presentation that is likely to generate anxiety that we know is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. From a purely public health perspective, it doesn’t make sense and is counterproductive.

I guess if we look back to the old carrot and stick metaphor we shouldn’t be surprised by the findings in this paper. If one’s only goal is to get a group of young preschoolers to behave by scaring the b’geezes out of them with a mask or a threat of bodily punishment, then go for it. Scare tactics will probably work just as well as offering a well-chosen reward system. However, the devil is in the side effects. It’s the same argument that I give to parents who argue that spanking works. Of course it does, but it has a narrow margin for safety and can set up ripples of negative side effects that can destroy healthy parent-child relationships.

The bottom line of this story is the sad truth that somewhere along the line someone failed to effectively train these four daycare workers. But, do we as health care providers need to rethink our training? Have we forgotten our commitment to “First do no harm?” As we craft our messaging have we thought enough about the potential side effects of our attempts at scaring the public into following our suggestions?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Perineuriomas in 2 Pediatric Patients

Perineuriomas are benign, slow-growing tumors derived from perineurial cells,1 which form the structurally supportive perineurium that surrounds individual nerve fascicles.2,3 Perineuriomas are classified into 2 main forms: intraneural or extraneural.4 Intraneural perineuriomas are found within the border of the peripheral nerve,5 while extraneural perineuriomas usually are found in soft tissue and skin. Extraneural perineuriomas can be further classified into variants based on their histologic appearance, including reticular, sclerosing, and plexiform subtypes. Extraneural perineuriomas usually present on the extremities or trunk of young to middle-aged adults as a well-circumscribed, painless, subcutaneous masses.1 These tumors are especially unusual in children.4 We present 2 extraneural perineurioma cases in children, and we review the pertinent diagnostic features of perineurioma as well as the presentation in the pediatric population.

Case Reports

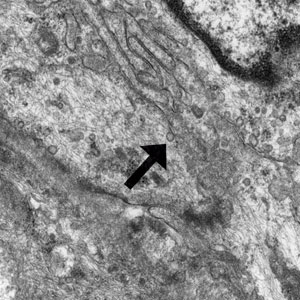

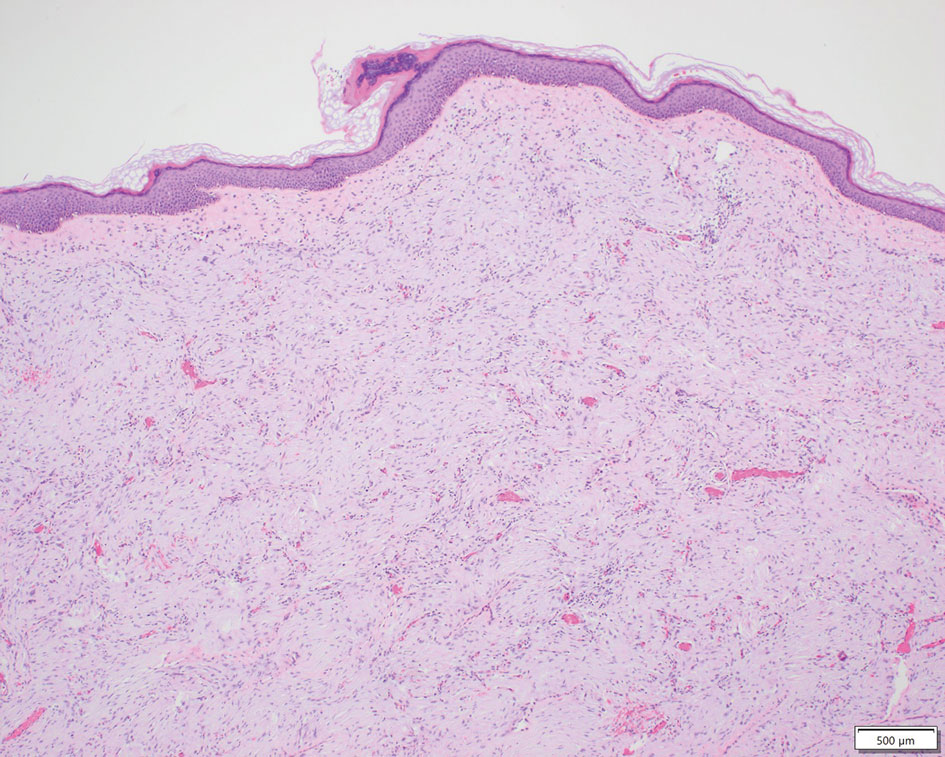

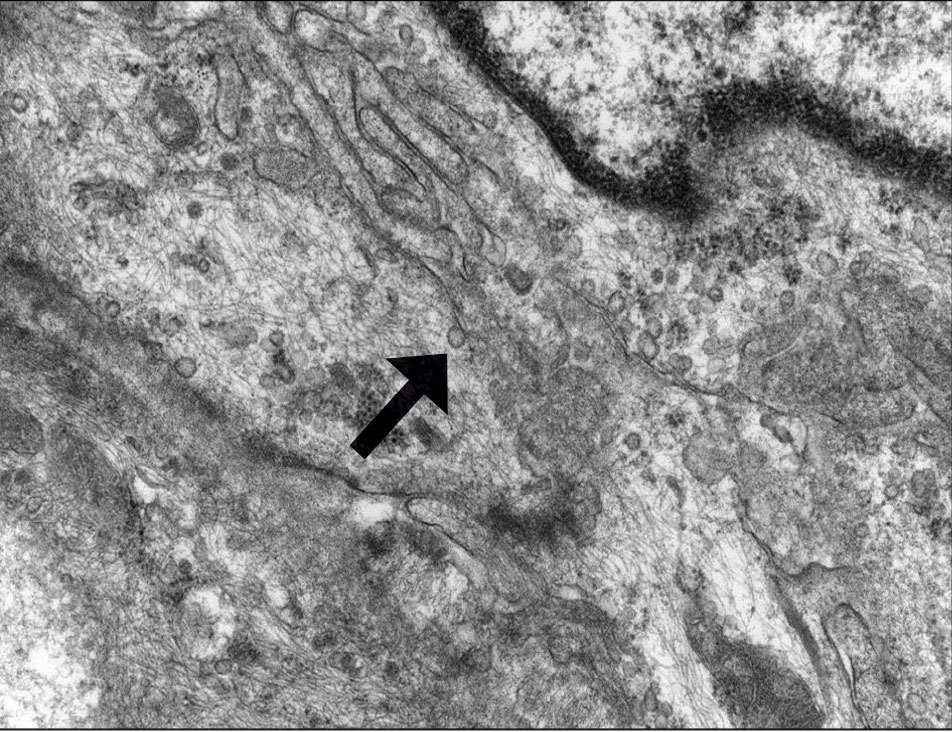

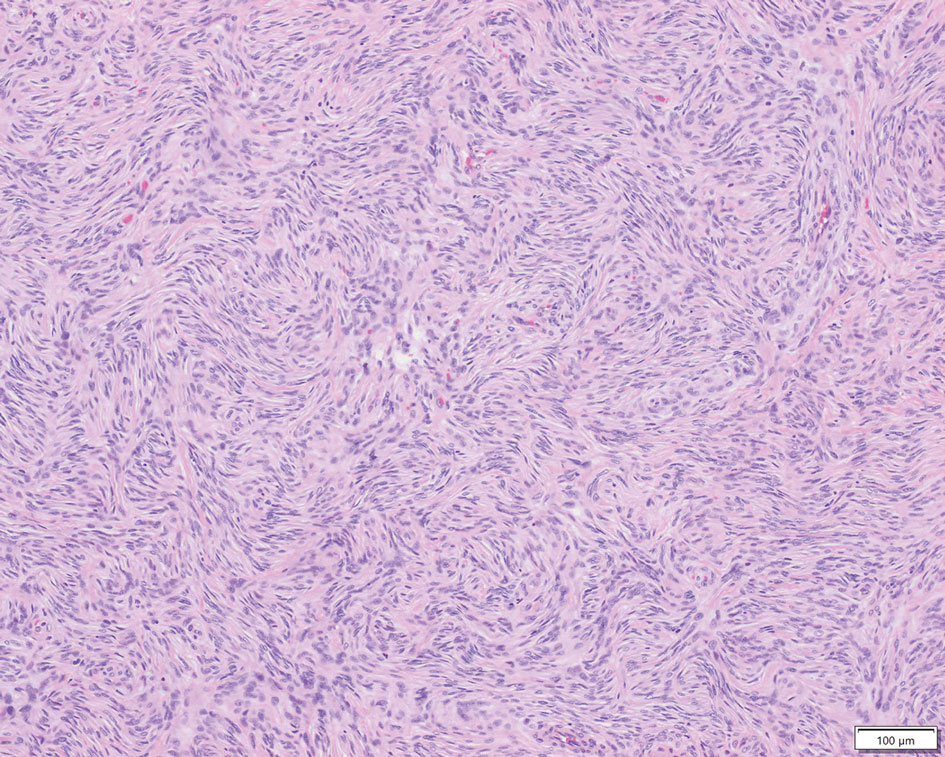

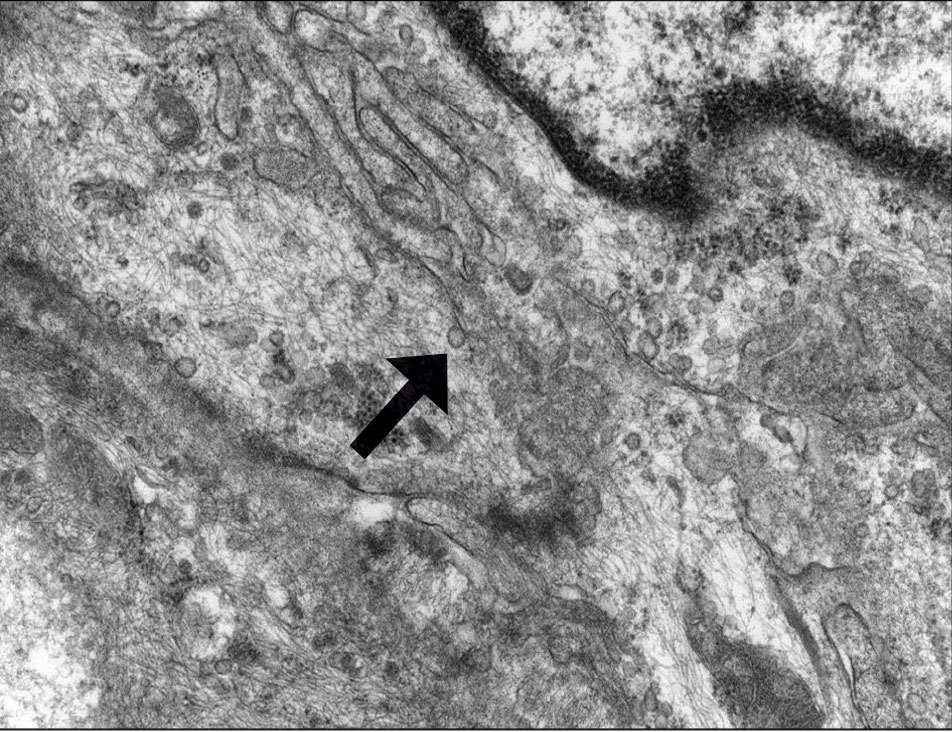

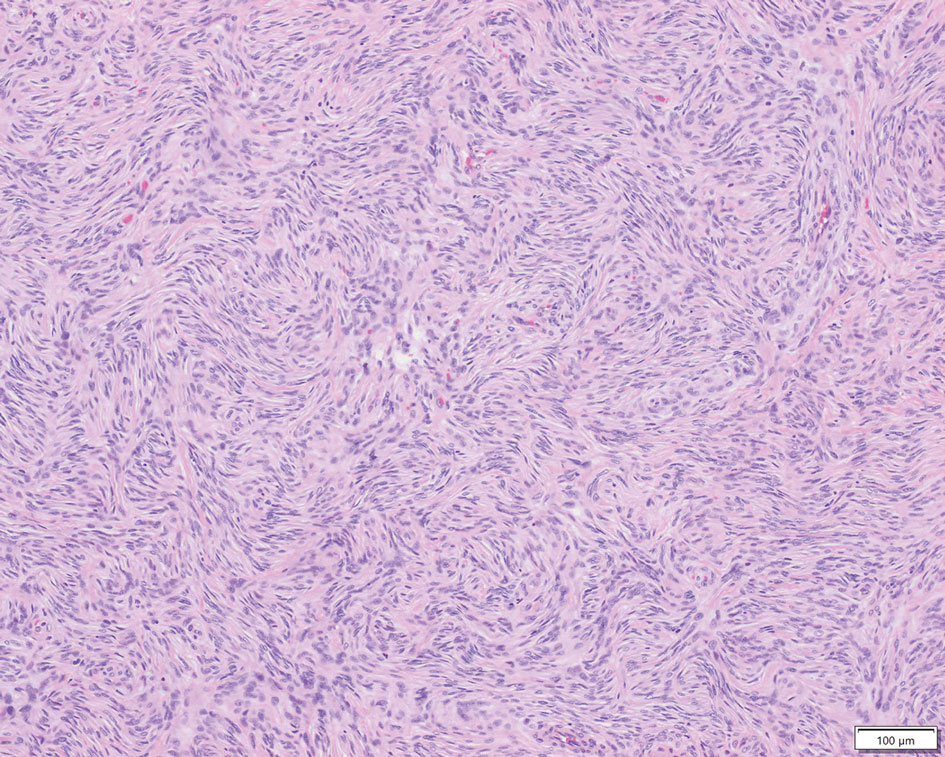

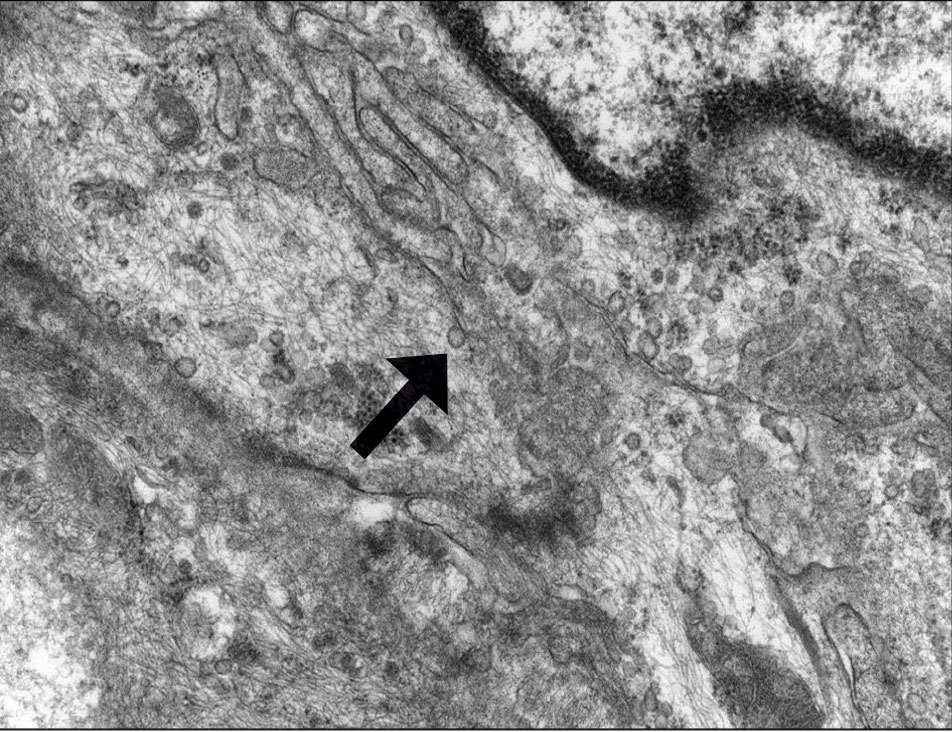

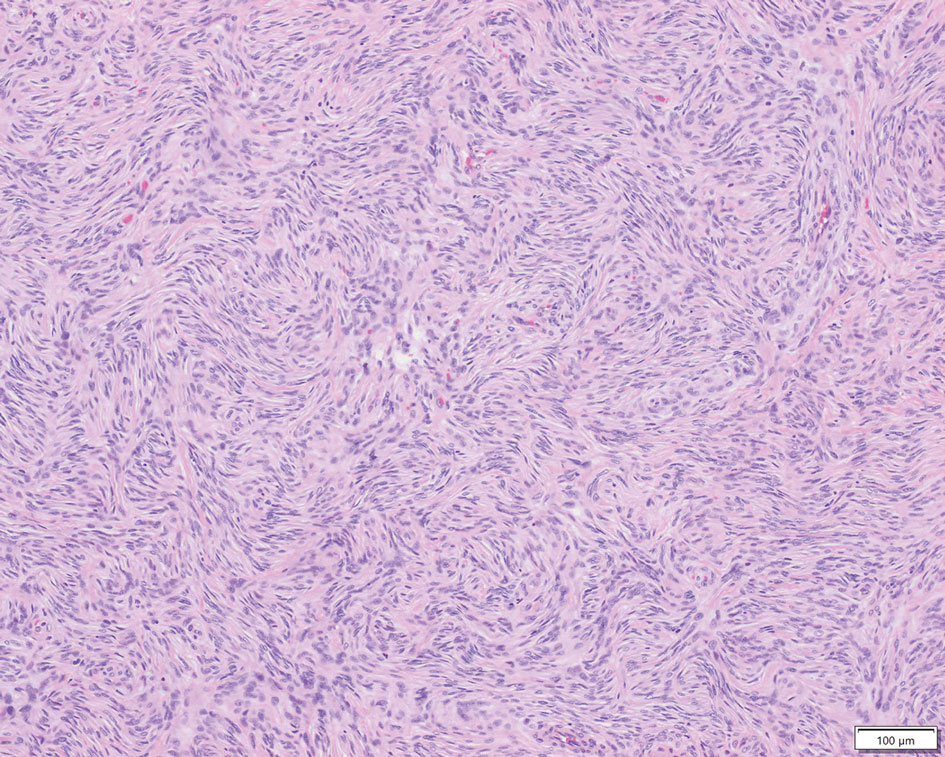

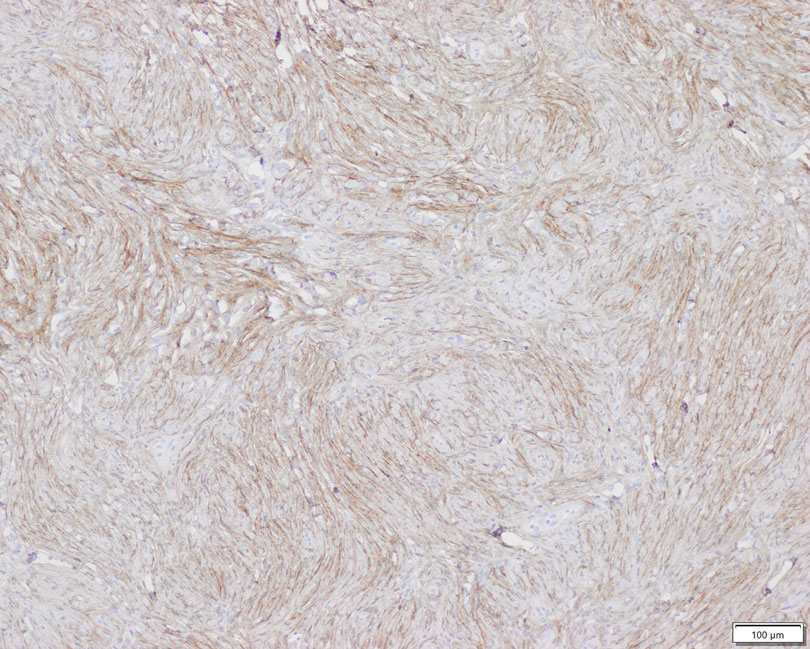

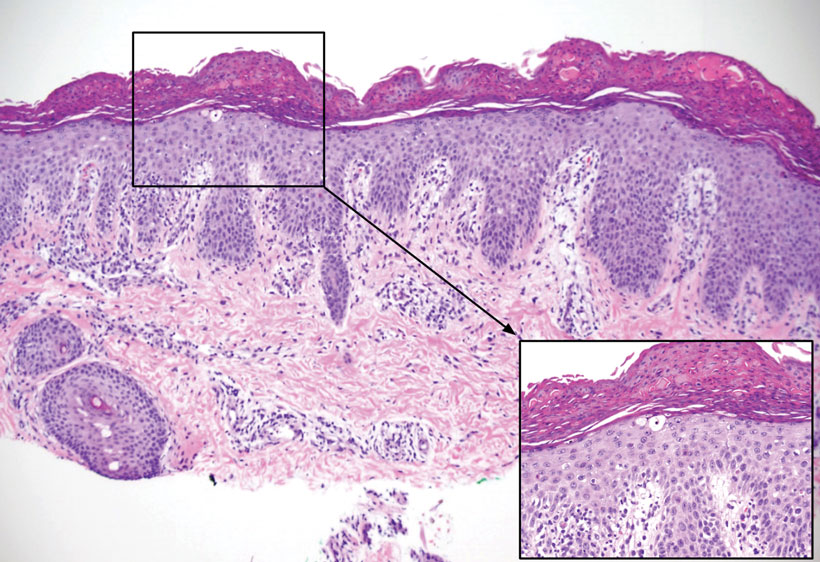

Patient 1—A 10-year-old boy with a history of cerebral palsy and related comorbidities presented to the clinic for evaluation of a lesion on the thigh with no associated pain, irritation, erythema, or drainage. Physical examination revealed a soft, pedunculated, mobile nodule on the right medial thigh. An elliptical excision was performed. Gross examination demonstrated a 2.0×2.0×1.8-cm polypoid nodule. Histologic examination showed a dermal-based proliferation of bland spindle cells (Figure 1). The cytomorphology was characterized by elongated tapering nuclei and many areas with delicate bipolar cytoplasmic processes. The constituent cells were arranged in a whorled pattern in a variably myxoid to collagenous stroma. The tumor cells were multifocally positive for CD34; focally positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA); and negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), GLUT1, claudin-1, STAT6, and desmin. Rb protein was intact. The CD34 immunostain highlighted the cytoplasmic processes. Electron microscopy was performed because the immunohistochemical results were nonspecific despite the favorable histologic features for perineurioma and showed pinocytic vesicles with delicate cytoplasmic processes, characteristic of perineurioma (Figure 2). Follow-up visits were related to the management of multiple comorbidities; no known recurrence of the lesion was documented.

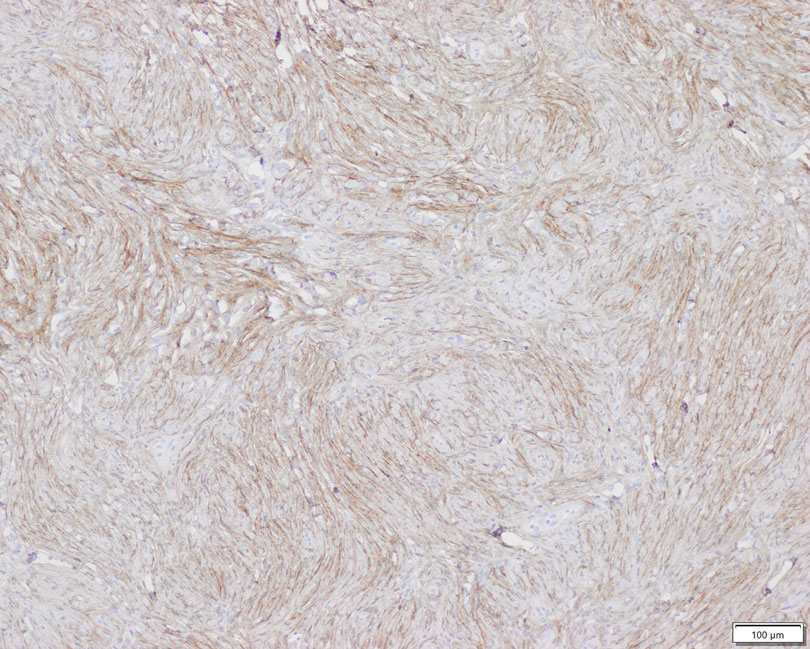

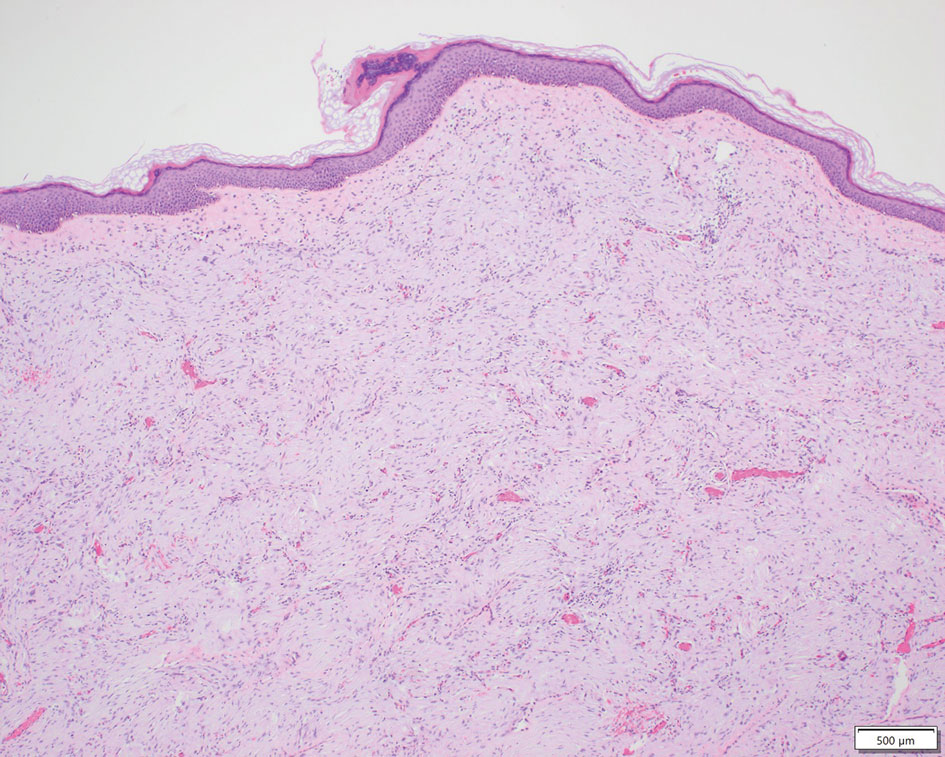

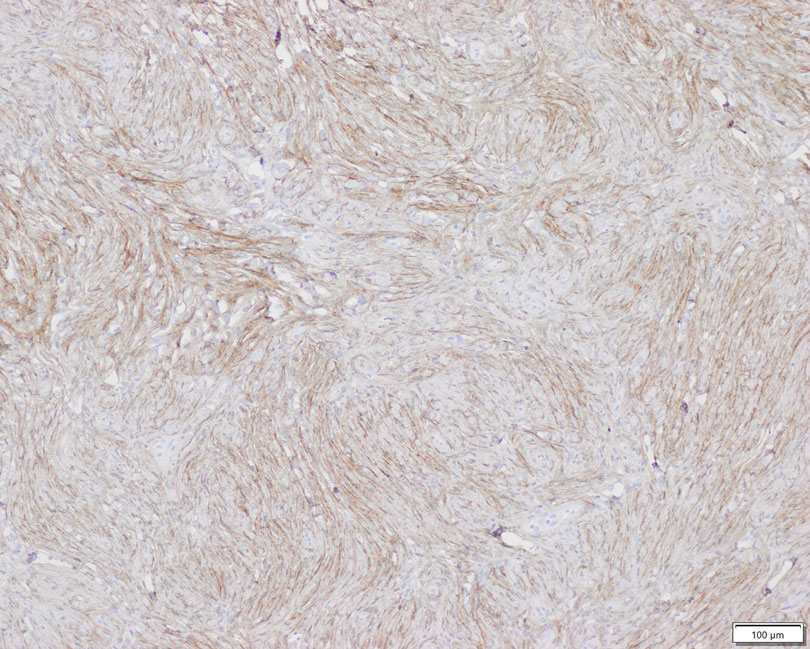

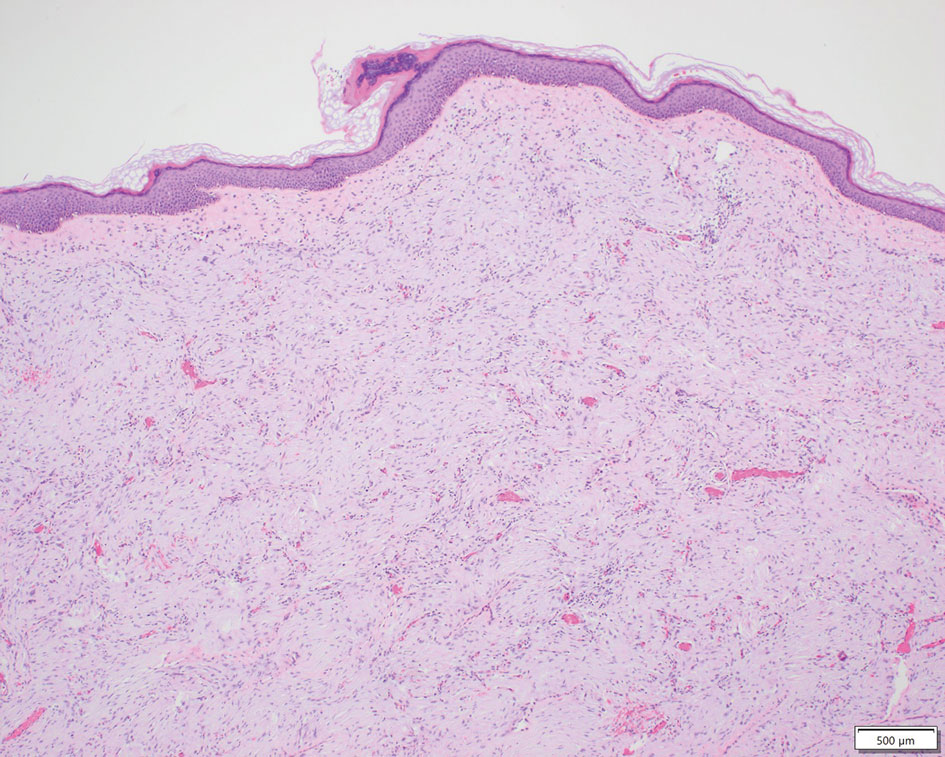

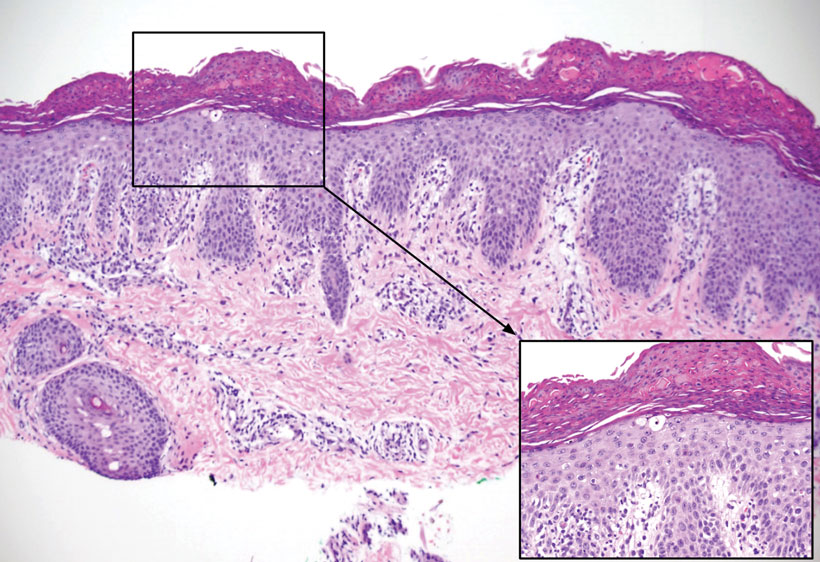

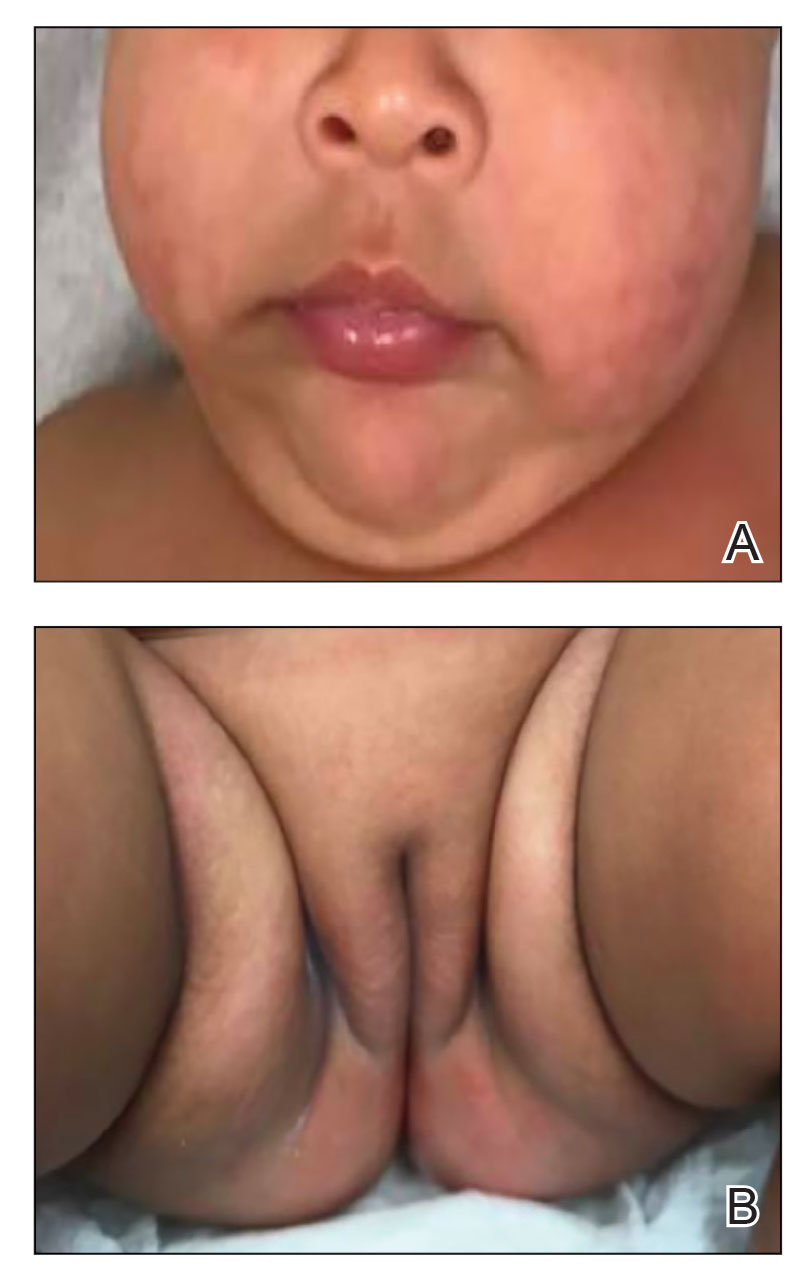

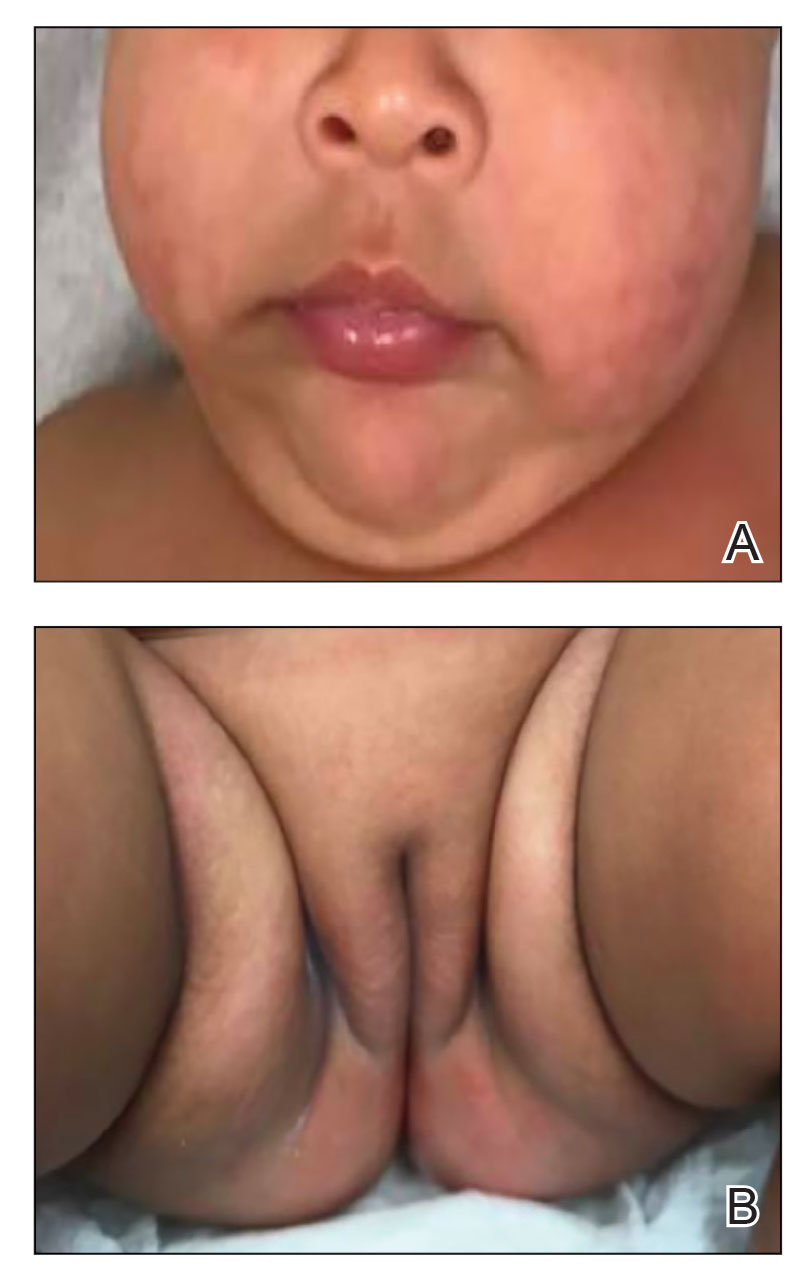

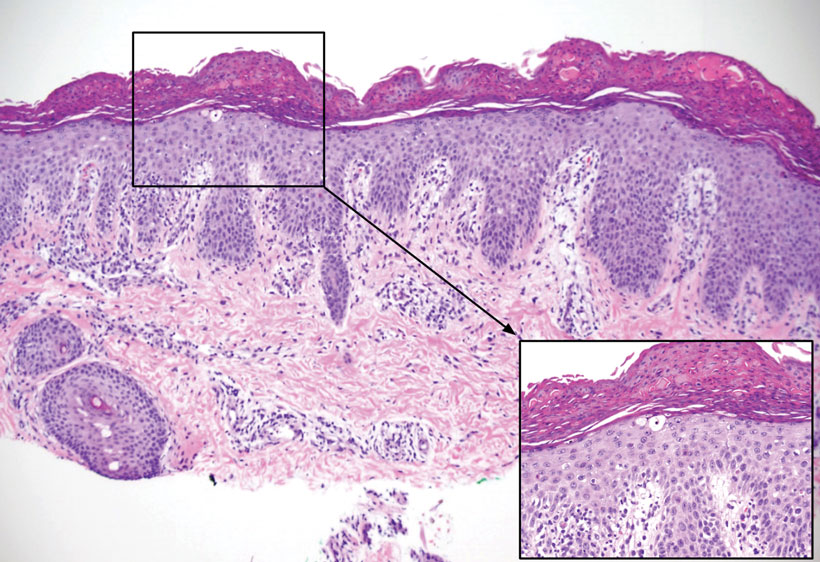

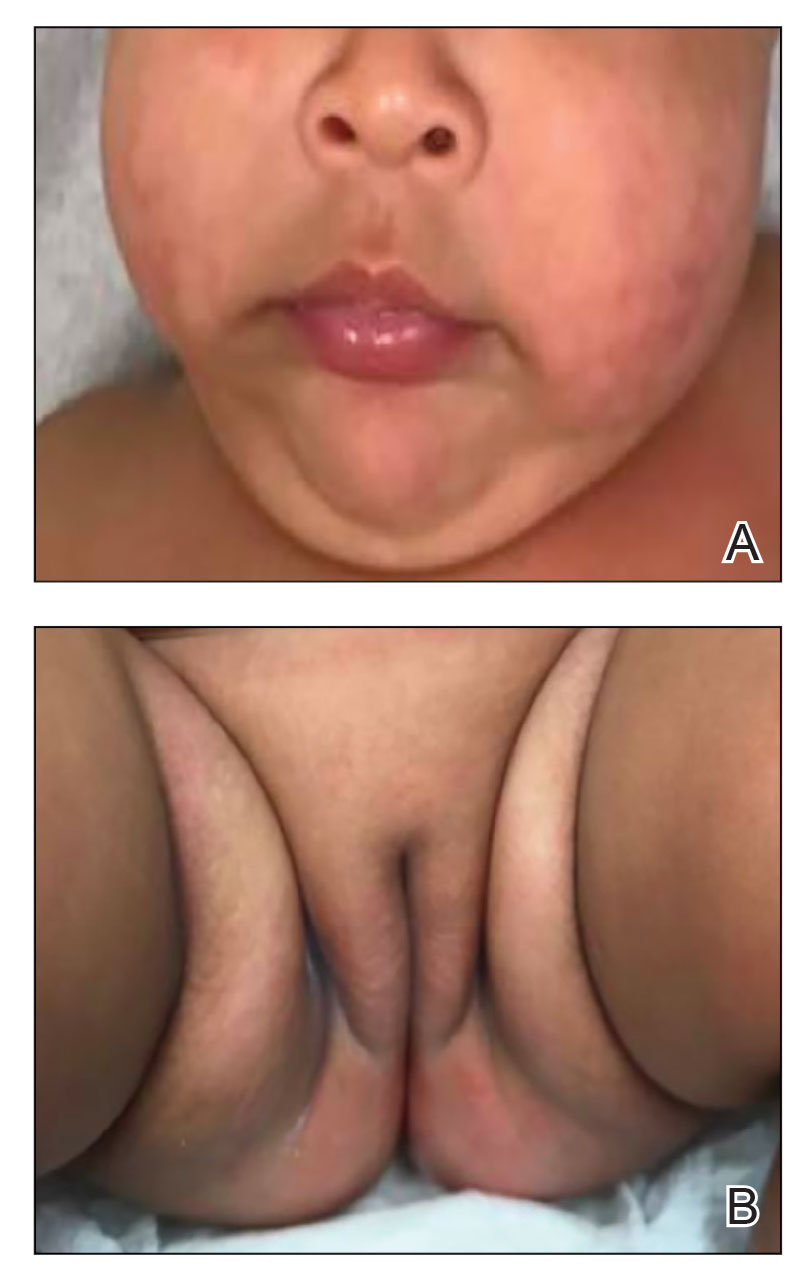

Patient 2—A 15-year-old adolescent boy with no notable medical history presented to the pediatric clinic for a bump on the right upper arm of 4 to 5 months’ duration. He did not recall an injury to the area and denied change in size, redness, bruising, or pain of the lesion. Ultrasonography demonstrated a 2.6×2.3×1.3-cm hypoechoic and slightly heterogeneous, well-circumscribed, subcutaneous mass with internal vascularity. The patient was then referred to a pediatric surgeon. The clinical differential included a lipoma, lymphadenopathy, or sebaceous cyst. An excision was performed. Gross inspection demonstrated a 7-g, 2.8×2.6×1.8-cm, homogeneous, tan-pink, rubbery nodule with minimal surrounding soft tissue. Histologic examination showed a bland proliferation of spindle cells with storiform and whorled patterns (Figure 3). No notable nuclear atypia or necrosis was identified. The tumor cells were focally positive for EMA (Figure 4), claudin-1, and CD34 and negative for S-100, SOX10, GLUT1, desmin, STAT6, pankeratin AE1/AE3, and SMA. The diagnosis of perineurioma was rendered. No recurrence of the lesion was appreciated clinically on a 6-month follow-up examination.

Comment

Characteristics of Perineuriomas—On gross evaluation, perineuriomas are firm, gray-white, and well circumscribed but not encapsulated. Histologically, perineuriomas can have a storiform, whorled, or lamellar pattern of spindle cells. Perivascular whorls can be a histologic clue. The spindle cells are bland appearing and typically are elongated and slender but can appear slightly ovoid and plump. The background stroma can be myxoid, collagenous, or mixed. There usually is no atypia, and mitotic figures are rare.2,3,6,7 Intraneural perineuriomas vary architecturally in that they display a unique onion bulb–like appearance in which whorls of cytoplasmic material of variable sizes surround central axons.3

Diagnosis—The diagnosis of perineuriomas usually requires characteristic immunohistochemical and sometimes ultrastructural features. Perineuriomas are positive for EMA and GLUT1 and variable for CD34.6 Approximately 20% to 91% will be positive for claudin-1, a tight junction protein associated with perineuriomas.8 Of note, EMA and GLUT1 usually are positive in both neoplastic and nonneoplastic perineurial cells.9,10 Occasionally, these tumors can be focally positive for SMA and negative for S-100 and glial fibrillary acidic protein. The bipolar, thin, delicate, cytoplasmic processes with long-tapering nuclei may be easier to appreciate on electron microscopy than on conventional light microscopy. In addition, the cells contain pinocytotic vesicles and a discontinuous external lamina, which may be helpful for diagnosis.10

Genetics—Genetic alterations in perineurioma continue to be elucidated. Although many soft tissue perineuriomas possess deletion of chromosome 22q material, this is not a consistent finding and is not pathognomonic. Notably, the NF2 tumor suppressor gene is found on chromosome 22.11 For the sclerosing variant of perineurioma, rearrangements or deletions of chromosome 10q have been described. A study of 14 soft tissue/extraneural perineuriomas using whole-exome sequencing and single nucleotide polymorphism array showed 6 cases of recurrent chromosome 22q deletions containing the NF2 locus and 4 cases with a previously unreported finding of chromosome 17q deletions containing the NF1 locus that were mutually exclusive events in all but 1 case.12 Although perineuriomas can harbor NF1 or NF2 mutations, perineuriomas are not considered to be associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 or 2 (NF1 or NF2, respectively). Patients with NF1 or NF2 and perineurioma are exceedingly rare. One pediatric patient with both soft tissue perineurioma and NF1 has been reported in the literature.13

Differential Diagnosis—Perineuriomas should be distinguished from other benign neural neoplasms of the skin and soft tissue. Commonly considered in the differential diagnosis is schwannoma and neurofibroma. Schwannomas are encapsulated epineurial nerve sheath tumors comprised of a neoplastic proliferation of Schwann cells. Schwannomas morphologically differ from perineuriomas because of the presence of the hypercellular Antoni A with Verocay bodies and the hypocellular myxoid Antoni B patterns of spindle cells with elongated wavy nuclei and tapered ends. Other features include hyalinized vessels, hemosiderin deposition, cystic degeneration, and/or degenerative atypia.3,14 Importantly, the constituent cells of schwannomas are positive for S-100 and SOX10 and negative for EMA.3 Neurofibromas consist of fascicles and whorls of Schwann cells in a background myxoid stroma with scattered mast cells, lymphocytes, fibroblasts, and perineurial cells. Similar to schwannomas, neurofibromas also are positive for S-100 and negative for EMA.3,14 Neurofibromas can have either a somatic or germline mutation of the biallelic NF1 gene on chromosome 17q11.2 with subsequent loss of protein neurofibromin activity.15 Less common but still a consideration are the hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors that may present with a biphasic or intermingled morphology. Combinations include neurofibroma-schwannoma, schwannoma-perineurioma, and neurofibroma-perineurioma. The hybrid schwannoma-perineurioma has a mixture of thin and plump spindle cells with tapered nuclei as well as patchy S-100 positivity corresponding to schwannian areas. Similarly, S-100 will highlight the wavy Schwann cells in neurofibroma-perineurioma as well as CD34-highlighting fibroblasts.7,15 In both aforementioned hybrid tumors, EMA will be positive in the perineurial areas. Another potential diagnostic consideration that can occur in both pediatric and adult populations is dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), which is comprised of a dermal proliferation of monomorphic fusiform spindle cells. Although both perineuriomas and DFSP can have a storiform architecture, DFSP is more asymmetric and infiltrative. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is recognized in areas of individual adipocyte trapping, referred to as honeycombing. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans typically does not express EMA, though the sclerosing variant of DFSP has been reported to sometimes demonstrate focal EMA reactivity.11,14,16 For morphologically challenging cases, cytogenetic studies will show t(17;22) translocation fusing the COL1A1 and PDGFRB genes.16 Finally, for subcutaneous or deep-seated tumors, one also may consider other mesenchymal neoplasms, including solitary fibrous tumor, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, or low-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST).11

Management—Perineuriomas are considered benign. The presence of mitotic figures, pleomorphism, and degenerative nuclear atypia akin to ancient change, as seen in ancient schwannoma, does not affect their benign clinical behavior. Treatment of a perineurioma typically is surgical excision with conservative margins and minimal chance of recurrence.1,11 So-called malignant perineuriomas are better classified as MPNSTs with perineural differentiation or perineurial MPNST. They also are positive for EMA and may be distinguished from perineurioma by the presence of major atypia and an infiltrative growth pattern.17,18

Considerations in the Pediatric Population—Few pediatric soft tissue perineuriomas have been reported. A clinicopathologic analysis by Hornick and Fletcher1 of patients with soft tissue perineurioma showed that only 6 of 81 patients were younger than 20 years. The youngest reported case of perineurioma occurred as an extraneural perineurioma on the scalp in an infant.19 Only 1 soft tissue perineural MPNST has been reported in the pediatric population, arising on the face of an 11-year-old boy. In a case series of 11 pediatric perineuriomas, including extraneural and intraneural, there was no evidence of recurrence or metastasis at follow-up.4

Conclusion

Perineuriomas are rare benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors with unique histologic and immunohistochemical features. Soft tissue perineuriomas in the pediatric population are an important diagnostic consideration, especially for the pediatrician or dermatologist when encountering a well-circumscribed nodular soft tissue lesion of the extremity or when encountering a neural-appearing tumor in the subcutaneous tissue.

Acknowledgment—We would like to thank Christopher Fletcher, MD (Boston, Massachusetts), for his expertise in outside consultation for patient 1.

- Hornick J, Fletcher C. Soft tissue perineurioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:845-858.

- Tsang WY, Chan JK, Chow LT, et al. Perineurioma: an uncommon soft tissue neoplasm distinct from localized hypertrophic neuropathy and neurofibroma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:756-763.

- Belakhoua SM, Rodriguez FJ. Diagnostic pathology of tumors of peripheral nerve. Neurosurgery. 2021;88:443-456.

- Balarezo FS, Muller RC, Weiss RG, et al. Soft tissue perineuriomas in children: report of three cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2003;6:137-141. Published correction appears in Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2003;6:following 364.

- Macarenco R, Ellinger F, Oliveira A. Perineurioma: a distinctive and underrecognized peripheral nerve sheath neoplasm. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:625-636.

- Agaimy A, Buslei R, Coras R, et al. Comparative study of soft tissue perineurioma and meningioma using a five-marker immunohistochemical panel. Histopathology. 2014;65:60-70.

- Greenson JK, Hornick JL, Longacre TA, et al. Sternberg’s Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Folpe A, Billings S, McKenney J, et al. Expression of claudin-1, a recently described tight junction-associated protein, distinguishes soft tissue perineurioma from potential mimics. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1620-1626.

- Hirose T, Tani T, Shimada T, et al. Immunohistochemical demonstration of EMA/Glut1-positive perineurial cells and CD34-positive fibroblastic cells in peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:293-298.

- Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al. Perineurioma. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. IARC Press; 2013:176-178.

- Hornick JL. Practical Soft Tissue Pathology: A Diagnostic Approach. Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- Carter JM, Wu Y, Blessing MM, et al. Recurrent genomic alterations in soft tissue perineuriomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1708-1714.

- Al-Adnani M. Soft tissue perineurioma in a child with neurofibromatosis type 1: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2017;20:444-448.

- Reddy VB, David O, Spitz DJ, et al. Gattuso’s Differential Diagnosis in Surgical Pathology. Elsevier Saunders; 2022.

- Michal M, Kazakov DV, Michal M. Hybrid peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a review. Cesk Patol. 2017;53:81-88.