User login

Have you heard of VEXAS syndrome?

Its name is an acronym: Vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, Autoinflammatory, Somatic. The prevalence of this syndrome is unknown, but it is not so rare. As it is an X-linked disease, men are predominantly affected.

First identification

The NIH team screened the exomes and genomes of 2,560 individuals. Of this group, 1,477 had been referred because of undiagnosed recurrent fevers, systemic inflammation, or both, and 1,083 were affected by atypical, unclassified disorders. The researchers identified 25 men with a somatic mutation in the ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1 (UBA1) gene, which is involved in the protein ubiquitylation system. This posttranslational modification has a pleiotropic function that likely explains the clinical heterogeneity seen in VEXAS patients: regulation of protein turnover, especially those involved in the cell cycle, cell death, and signal transduction. Ubiquitylation is also involved in nonproteolytic functions, such as assembly of multiprotein complexes, intracellular signaling, inflammatory signaling, and DNA repair.

Clinical presentation

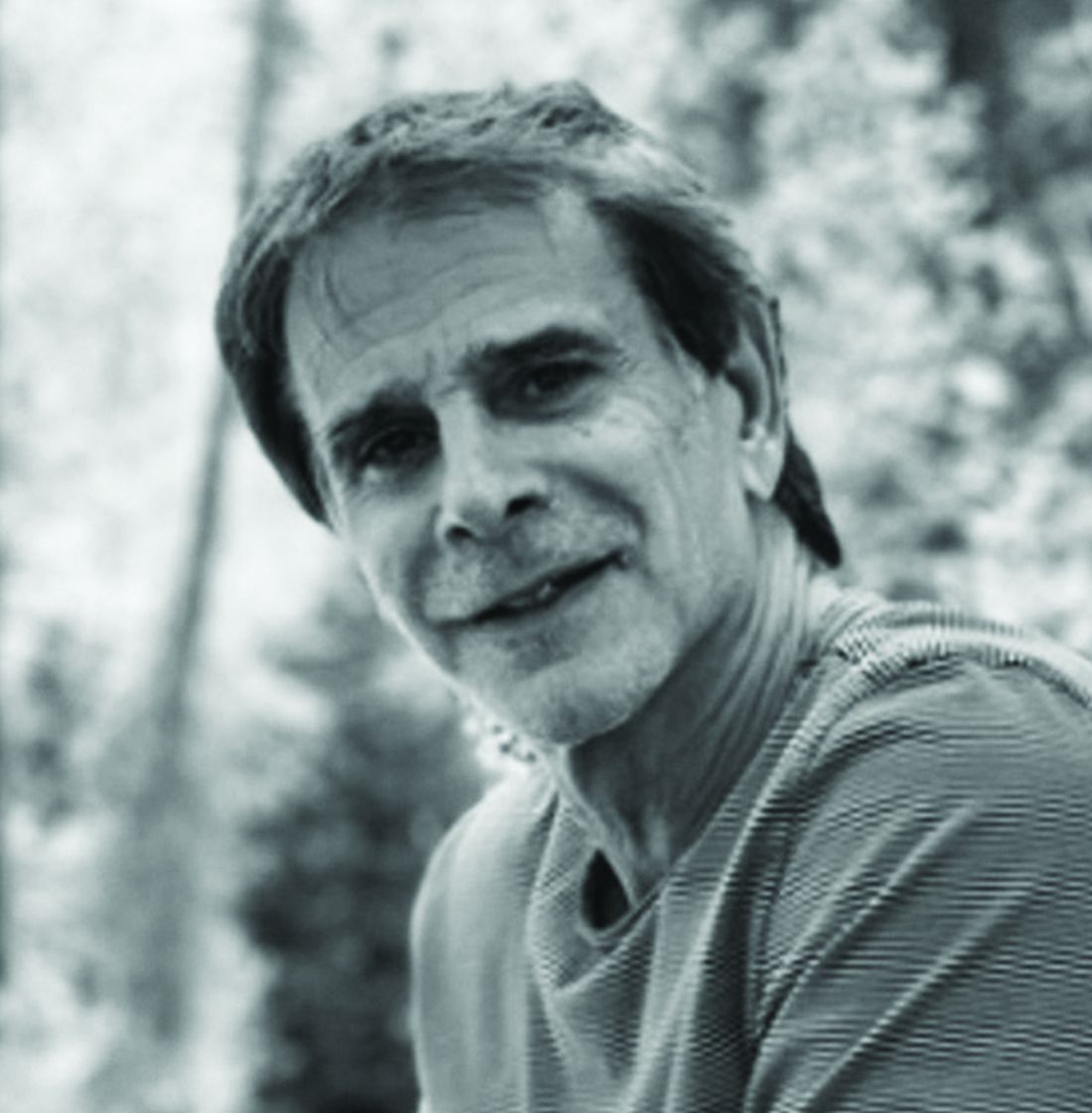

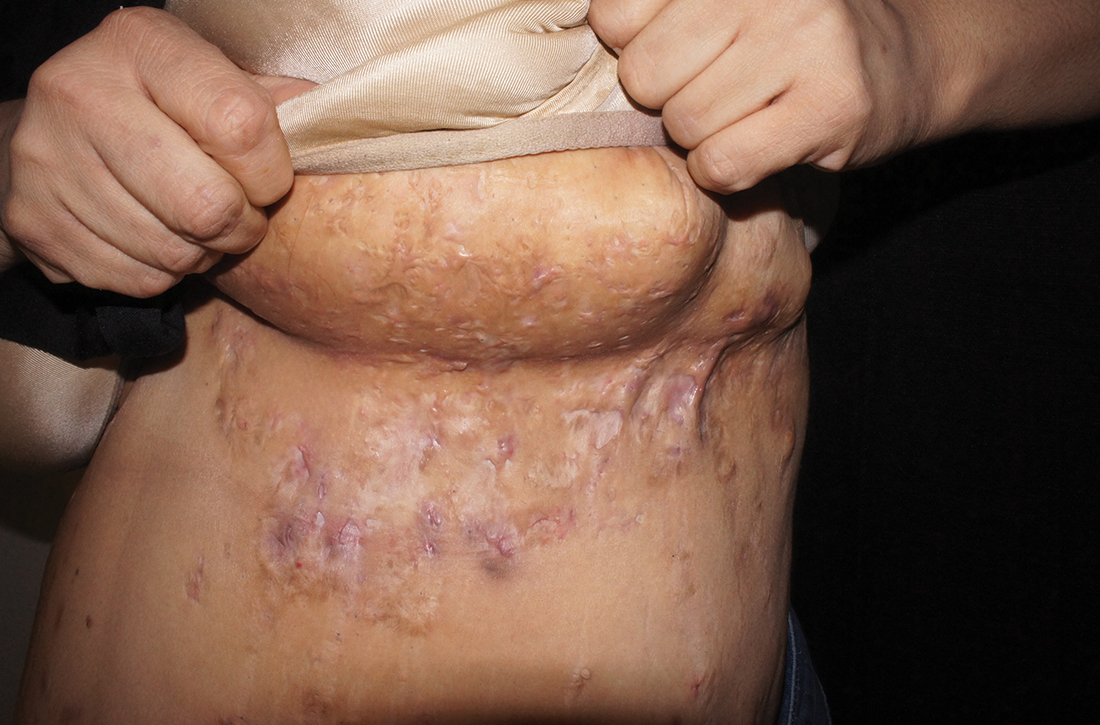

The clinicobiological presentation of VEXAS syndrome is very heterogeneous. Typically, patients present with a systemic inflammatory disease with unexplained episodes of fever, involvement of the lungs, skin, blood vessels, and joints. Molecular diagnosis is made by the sequencing of UBA1.

Most patients present with the characteristic clinical signs of other inflammatory diseases, such as polyarteritis nodosa and recurrent polychondritis. But VEXAS patients are at high risk of developing hematologic conditions. Indeed, the following were seen among the 25 participants in the NIH study: macrocytic anemia (96%), venous thromboembolism (44%), myelodysplastic syndrome (24%), and multiple myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (20%).

In VEXAS patients, levels of serum inflammatory markers are increased. These markers include tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-8, interleukin-6, interferon-inducible protein-10, interferon-gamma, C-reactive protein. In addition, there is aberrant activation of innate immune-signaling pathways.

In a large-scale analysis of a multicenter case series of 116 French patients, researchers found that VEXAS syndrome primarily affected men. The disease was progressive, and onset occurred after age 50 years. These patients can be divided into three phenotypically distinct clusters on the basis of integration of clinical and biological data. In the 58 cases in which myelodysplastic syndrome was present, the mortality rates were higher. The researchers also reported that the UBA1 p.Met41L mutation was associated with a better prognosis.

Treatment data

VEXAS syndrome resists the classical therapeutic arsenal. Patients require high-dose glucocorticoids, and prognosis appears to be poor. The available treatment data are retrospective. Of the 25 participants in the NIH study, 40% died within 5 years from disease-related causes or complications related to treatment. Among the promising therapeutic avenues is the use of inhibitors of the Janus kinase pathway.

This article was translated from Univadis France. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Its name is an acronym: Vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, Autoinflammatory, Somatic. The prevalence of this syndrome is unknown, but it is not so rare. As it is an X-linked disease, men are predominantly affected.

First identification

The NIH team screened the exomes and genomes of 2,560 individuals. Of this group, 1,477 had been referred because of undiagnosed recurrent fevers, systemic inflammation, or both, and 1,083 were affected by atypical, unclassified disorders. The researchers identified 25 men with a somatic mutation in the ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1 (UBA1) gene, which is involved in the protein ubiquitylation system. This posttranslational modification has a pleiotropic function that likely explains the clinical heterogeneity seen in VEXAS patients: regulation of protein turnover, especially those involved in the cell cycle, cell death, and signal transduction. Ubiquitylation is also involved in nonproteolytic functions, such as assembly of multiprotein complexes, intracellular signaling, inflammatory signaling, and DNA repair.

Clinical presentation

The clinicobiological presentation of VEXAS syndrome is very heterogeneous. Typically, patients present with a systemic inflammatory disease with unexplained episodes of fever, involvement of the lungs, skin, blood vessels, and joints. Molecular diagnosis is made by the sequencing of UBA1.

Most patients present with the characteristic clinical signs of other inflammatory diseases, such as polyarteritis nodosa and recurrent polychondritis. But VEXAS patients are at high risk of developing hematologic conditions. Indeed, the following were seen among the 25 participants in the NIH study: macrocytic anemia (96%), venous thromboembolism (44%), myelodysplastic syndrome (24%), and multiple myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (20%).

In VEXAS patients, levels of serum inflammatory markers are increased. These markers include tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-8, interleukin-6, interferon-inducible protein-10, interferon-gamma, C-reactive protein. In addition, there is aberrant activation of innate immune-signaling pathways.

In a large-scale analysis of a multicenter case series of 116 French patients, researchers found that VEXAS syndrome primarily affected men. The disease was progressive, and onset occurred after age 50 years. These patients can be divided into three phenotypically distinct clusters on the basis of integration of clinical and biological data. In the 58 cases in which myelodysplastic syndrome was present, the mortality rates were higher. The researchers also reported that the UBA1 p.Met41L mutation was associated with a better prognosis.

Treatment data

VEXAS syndrome resists the classical therapeutic arsenal. Patients require high-dose glucocorticoids, and prognosis appears to be poor. The available treatment data are retrospective. Of the 25 participants in the NIH study, 40% died within 5 years from disease-related causes or complications related to treatment. Among the promising therapeutic avenues is the use of inhibitors of the Janus kinase pathway.

This article was translated from Univadis France. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Its name is an acronym: Vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, Autoinflammatory, Somatic. The prevalence of this syndrome is unknown, but it is not so rare. As it is an X-linked disease, men are predominantly affected.

First identification

The NIH team screened the exomes and genomes of 2,560 individuals. Of this group, 1,477 had been referred because of undiagnosed recurrent fevers, systemic inflammation, or both, and 1,083 were affected by atypical, unclassified disorders. The researchers identified 25 men with a somatic mutation in the ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1 (UBA1) gene, which is involved in the protein ubiquitylation system. This posttranslational modification has a pleiotropic function that likely explains the clinical heterogeneity seen in VEXAS patients: regulation of protein turnover, especially those involved in the cell cycle, cell death, and signal transduction. Ubiquitylation is also involved in nonproteolytic functions, such as assembly of multiprotein complexes, intracellular signaling, inflammatory signaling, and DNA repair.

Clinical presentation

The clinicobiological presentation of VEXAS syndrome is very heterogeneous. Typically, patients present with a systemic inflammatory disease with unexplained episodes of fever, involvement of the lungs, skin, blood vessels, and joints. Molecular diagnosis is made by the sequencing of UBA1.

Most patients present with the characteristic clinical signs of other inflammatory diseases, such as polyarteritis nodosa and recurrent polychondritis. But VEXAS patients are at high risk of developing hematologic conditions. Indeed, the following were seen among the 25 participants in the NIH study: macrocytic anemia (96%), venous thromboembolism (44%), myelodysplastic syndrome (24%), and multiple myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (20%).

In VEXAS patients, levels of serum inflammatory markers are increased. These markers include tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-8, interleukin-6, interferon-inducible protein-10, interferon-gamma, C-reactive protein. In addition, there is aberrant activation of innate immune-signaling pathways.

In a large-scale analysis of a multicenter case series of 116 French patients, researchers found that VEXAS syndrome primarily affected men. The disease was progressive, and onset occurred after age 50 years. These patients can be divided into three phenotypically distinct clusters on the basis of integration of clinical and biological data. In the 58 cases in which myelodysplastic syndrome was present, the mortality rates were higher. The researchers also reported that the UBA1 p.Met41L mutation was associated with a better prognosis.

Treatment data

VEXAS syndrome resists the classical therapeutic arsenal. Patients require high-dose glucocorticoids, and prognosis appears to be poor. The available treatment data are retrospective. Of the 25 participants in the NIH study, 40% died within 5 years from disease-related causes or complications related to treatment. Among the promising therapeutic avenues is the use of inhibitors of the Janus kinase pathway.

This article was translated from Univadis France. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Toward a healthy and sustainable critical care workforce in the COVID-19 era: A call for action

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused unprecedented and unpredictable strain on health care systems worldwide, forcing rapid organizational modifications and innovations to ensure availability of critical care resources during acute surge events. Yet, while much attention has been paid to the availability of ICU beds and ventilators, COVID-19 has insidiously and significantly harmed the most precious critical care resource of all – the human beings who are the lifeblood of critical care delivery. We are now at a crucial moment in history to better understand the pandemic’s impact on our human resources and enact changes to reverse the damage that it has inflicted on our workforce.

ICUs, where critical care delivery predominantly occurs, increasingly utilize interprofessional staffing models in which clinicians from multiple disciplines – physicians, nurses, clinical pharmacists, respiratory therapists, and dieticians, among others – bring their unique expertise to team-based clinical decisions and care delivery. Such a multidisciplinary approach helps enable the provision of more comprehensive, higher-quality critical care. In this way, the interprofessional ICU care team is an embodiment of the notion that the “whole” is more than just the sum of its parts. Therefore, we must consider the impact of the pandemic on interprofessional critical care clinicians as the team that they are.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the well-being of critical care clinicians was compromised. Across multiple disciplines, they had among the highest rates of burnout syndrome of all health care professionals (Moss M, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194[1]:106-113). As the pandemic has dragged on, their well-being has only further declined. Burnout rates are at all-time highs, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression are common and have increased with each subsequent surge (Azoulay E, et al. Chest. 2021;160[3]:944-955). Offsets to burnout, such as fulfillment and recognition, have declined over time (Kerlin MP, et al. Ann Amer Thorac Soc. 2022;19[2]:329-331). These worrisome trends pose a significant threat to critical care delivery. Clinician burnout is associated with worse patient outcomes, increased medical errors, and lower patient satisfaction (Moss M, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194[1]:106-113; Poghosyan L, et al. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33[4]:288-298). It is also associated with mental illness and substance use disorders among clinicians (Dyrbye LN, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149[5]:334-341). Finally, it has contributed to a workforce crisis: nearly 500,000 health care workers have left the US health care sector since the beginning of the pandemic, and approximately two-thirds of acute and critical care nurses have considered doing so (Wong E. “Why Healthcare Workers are Quitting in Droves”. The Atlantic. Accessed November 7, 2022). Such a “brain drain” of clinicians – whose expertise cannot be easily replicated or replaced – represents a staffing crisis that threatens our ability to provide high-quality, safe care for the foreseeable future.

To combat burnout, it is first necessary to identify the mechanisms by which the pandemic has induced harm. Early during the pandemic, critical care clinicians feared for their own safety with little information of how the virus was spread. At a time when the world was under lockdown, vaccines were not yet available, and hospitals were overwhelmed with surges of critically ill patients, clinicians struggled like the rest of the world to meet their own basic needs such as childcare, grocery shopping, and time with family. They experienced distress from high volumes of patients with extreme mortality rates, helplessness due to lack of treatment options, and moral injury over restrictive visitation policies (Vranas KC, et al. Chest. 2022;162[2]:331-345; Vranas KC, et al. Chest. 2021;160[5]:1714-1728). Over time, critical care clinicians have no doubt experienced further exhaustion related to the duration of the pandemic, often without adequate time to recover and process the trauma they have experienced. More recently, a new source of distress for clinicians has emerged from variability in vaccine uptake among the public. Clinicians have experienced compassion fatigue and even moral outrage toward those who chose not to receive a vaccine that is highly effective at preventing severe illness. They also suffered from ethical conflicts over how to treat unvaccinated patients and whether they should be given equal priority and access to limited therapies (Shaw D. Bioethics. 2022;36[8]:883-890).

Furthermore, the pandemic has damaged the relationship between clinicians and their institutions. Early in the pandemic, the widespread shortages of personal protective equipment harmed trust among clinicians due to their perception that their safety was not prioritized. Hospitals have also struggled with having to make rapid decisions on how to equitably allocate fixed resources in response to unanticipated and unpredictable demands, while also maintaining financial solvency. In some cases, these challenging policy decisions (eg, whether to continue elective procedures during acute surge events) lacked transparency and input from the team at the frontlines of patient care. As a result, clinicians have felt undervalued and without a voice in decisions that directly impact both the care they can provide their patients and their own well-being.

It is incumbent upon us now to take steps to repair the damage inflicted on our critical care workforce by the pandemic. To this end, there have been calls for the urgent implementation of strategies to mitigate the psychological burden experienced by critical care clinicians. However, many of these focus on interventions to increase coping strategies and resilience among individual clinicians. While programs such as mindfulness apps and resilience training are valuable, they are not sufficient. The very nature of these solutions implies that the solution (and therefore, the problem) of burnout lies in the individual clinician. Yet, as described above, many of the mechanisms of harm to clinicians’ well-being are systems-level issues that will necessarily require systems-level solutions.

Therefore, we propose a comprehensive, layered approach to begin to reverse the damage inflicted by the pandemic on critical care clinicians’ well-being, with solutions organized by ecological levels of individual clinicians, departments, institutions, and society. With this approach, we hope to address specific aspects of our critical care delivery system that, taken together, will fortify the well-being of our critical care workforce as a whole. We offer suggestions below that are both informed by existing evidence, as well as our own opinions as intensivists and researchers.

At the level of the individual clinician:

- Proactively provide access to mental health resources. Clinicians have limited time or energy to navigate mental health and support services and find it helpful when others proactively reach out to them.

- Provide opportunities for clinicians to experience community and support among peers. Clinicians find benefit in town halls, debrief sessions, and peer support groups, particularly during times of acute strain.

At the level of the department:

- Allow more flexibility in work schedules. Even prior to the pandemic, the lack of scheduling flexibility and the number of consecutive days worked had been identified as key contributors to burnout; these have been exacerbated during times of caseload surges, when clinicians have been asked or even required to increase their hours and work extra shifts.

- Promote a culture of psychological safety in which clinicians feel empowered to say “I cannot work” for whatever reason. This will require the establishment of formalized backup systems that easily accommodate call-outs without relying on individual clinicians to find their own coverage.

At the level of the health care system:

- Prioritize transparency, and bring administrators and clinicians together for policy decisions. Break down silos between the frontline workers involved in direct patient care and hospital executives, both to inform those decisions and demonstrate the value of clinicians’ perspectives.

- Compensate clinicians for extra work. Consider hazard pay or ensure extra time off for extra time worked.

- Make it “easier” for clinicians to do their jobs by helping them meet their basic needs. Create schedules with designated breaks during shifts. Provide adequate office space and call rooms. Facilitate access to childcare. Provide parking.

- Minimize moral injury. Develop protocols for scarce resource allocation that exclude the treatment team from making decisions about allocation of scarce resources. Avoid visitor restrictions given the harm these policies inflict on patients, families, and members of the care team.

At the level of society:

- Study mechanisms to improve communication about public health with the public. Both science and communication are essential to promoting and protecting public health; more research is needed to improve the way scientific knowledge and evidence-based recommendations are communicated to the public.

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has forever changed our critical care workforce and the way we deliver care. The time is now to act on the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic through implementation of systems-level solutions to combat burnout and ensure both the health and sustainability of our critical care workforce for the season ahead.

Dr. Vranas is with the Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care, VA Portland Health Care System, the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, Oregon Health & Science University; Portland, OR; and the Palliative and Advanced Illness Research (PAIR) Center, University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, PA. Dr. Kerlin is with the Palliative and Advanced Illness Research (PAIR) Center, and Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, PA.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused unprecedented and unpredictable strain on health care systems worldwide, forcing rapid organizational modifications and innovations to ensure availability of critical care resources during acute surge events. Yet, while much attention has been paid to the availability of ICU beds and ventilators, COVID-19 has insidiously and significantly harmed the most precious critical care resource of all – the human beings who are the lifeblood of critical care delivery. We are now at a crucial moment in history to better understand the pandemic’s impact on our human resources and enact changes to reverse the damage that it has inflicted on our workforce.

ICUs, where critical care delivery predominantly occurs, increasingly utilize interprofessional staffing models in which clinicians from multiple disciplines – physicians, nurses, clinical pharmacists, respiratory therapists, and dieticians, among others – bring their unique expertise to team-based clinical decisions and care delivery. Such a multidisciplinary approach helps enable the provision of more comprehensive, higher-quality critical care. In this way, the interprofessional ICU care team is an embodiment of the notion that the “whole” is more than just the sum of its parts. Therefore, we must consider the impact of the pandemic on interprofessional critical care clinicians as the team that they are.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the well-being of critical care clinicians was compromised. Across multiple disciplines, they had among the highest rates of burnout syndrome of all health care professionals (Moss M, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194[1]:106-113). As the pandemic has dragged on, their well-being has only further declined. Burnout rates are at all-time highs, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression are common and have increased with each subsequent surge (Azoulay E, et al. Chest. 2021;160[3]:944-955). Offsets to burnout, such as fulfillment and recognition, have declined over time (Kerlin MP, et al. Ann Amer Thorac Soc. 2022;19[2]:329-331). These worrisome trends pose a significant threat to critical care delivery. Clinician burnout is associated with worse patient outcomes, increased medical errors, and lower patient satisfaction (Moss M, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194[1]:106-113; Poghosyan L, et al. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33[4]:288-298). It is also associated with mental illness and substance use disorders among clinicians (Dyrbye LN, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149[5]:334-341). Finally, it has contributed to a workforce crisis: nearly 500,000 health care workers have left the US health care sector since the beginning of the pandemic, and approximately two-thirds of acute and critical care nurses have considered doing so (Wong E. “Why Healthcare Workers are Quitting in Droves”. The Atlantic. Accessed November 7, 2022). Such a “brain drain” of clinicians – whose expertise cannot be easily replicated or replaced – represents a staffing crisis that threatens our ability to provide high-quality, safe care for the foreseeable future.

To combat burnout, it is first necessary to identify the mechanisms by which the pandemic has induced harm. Early during the pandemic, critical care clinicians feared for their own safety with little information of how the virus was spread. At a time when the world was under lockdown, vaccines were not yet available, and hospitals were overwhelmed with surges of critically ill patients, clinicians struggled like the rest of the world to meet their own basic needs such as childcare, grocery shopping, and time with family. They experienced distress from high volumes of patients with extreme mortality rates, helplessness due to lack of treatment options, and moral injury over restrictive visitation policies (Vranas KC, et al. Chest. 2022;162[2]:331-345; Vranas KC, et al. Chest. 2021;160[5]:1714-1728). Over time, critical care clinicians have no doubt experienced further exhaustion related to the duration of the pandemic, often without adequate time to recover and process the trauma they have experienced. More recently, a new source of distress for clinicians has emerged from variability in vaccine uptake among the public. Clinicians have experienced compassion fatigue and even moral outrage toward those who chose not to receive a vaccine that is highly effective at preventing severe illness. They also suffered from ethical conflicts over how to treat unvaccinated patients and whether they should be given equal priority and access to limited therapies (Shaw D. Bioethics. 2022;36[8]:883-890).

Furthermore, the pandemic has damaged the relationship between clinicians and their institutions. Early in the pandemic, the widespread shortages of personal protective equipment harmed trust among clinicians due to their perception that their safety was not prioritized. Hospitals have also struggled with having to make rapid decisions on how to equitably allocate fixed resources in response to unanticipated and unpredictable demands, while also maintaining financial solvency. In some cases, these challenging policy decisions (eg, whether to continue elective procedures during acute surge events) lacked transparency and input from the team at the frontlines of patient care. As a result, clinicians have felt undervalued and without a voice in decisions that directly impact both the care they can provide their patients and their own well-being.

It is incumbent upon us now to take steps to repair the damage inflicted on our critical care workforce by the pandemic. To this end, there have been calls for the urgent implementation of strategies to mitigate the psychological burden experienced by critical care clinicians. However, many of these focus on interventions to increase coping strategies and resilience among individual clinicians. While programs such as mindfulness apps and resilience training are valuable, they are not sufficient. The very nature of these solutions implies that the solution (and therefore, the problem) of burnout lies in the individual clinician. Yet, as described above, many of the mechanisms of harm to clinicians’ well-being are systems-level issues that will necessarily require systems-level solutions.

Therefore, we propose a comprehensive, layered approach to begin to reverse the damage inflicted by the pandemic on critical care clinicians’ well-being, with solutions organized by ecological levels of individual clinicians, departments, institutions, and society. With this approach, we hope to address specific aspects of our critical care delivery system that, taken together, will fortify the well-being of our critical care workforce as a whole. We offer suggestions below that are both informed by existing evidence, as well as our own opinions as intensivists and researchers.

At the level of the individual clinician:

- Proactively provide access to mental health resources. Clinicians have limited time or energy to navigate mental health and support services and find it helpful when others proactively reach out to them.

- Provide opportunities for clinicians to experience community and support among peers. Clinicians find benefit in town halls, debrief sessions, and peer support groups, particularly during times of acute strain.

At the level of the department:

- Allow more flexibility in work schedules. Even prior to the pandemic, the lack of scheduling flexibility and the number of consecutive days worked had been identified as key contributors to burnout; these have been exacerbated during times of caseload surges, when clinicians have been asked or even required to increase their hours and work extra shifts.

- Promote a culture of psychological safety in which clinicians feel empowered to say “I cannot work” for whatever reason. This will require the establishment of formalized backup systems that easily accommodate call-outs without relying on individual clinicians to find their own coverage.

At the level of the health care system:

- Prioritize transparency, and bring administrators and clinicians together for policy decisions. Break down silos between the frontline workers involved in direct patient care and hospital executives, both to inform those decisions and demonstrate the value of clinicians’ perspectives.

- Compensate clinicians for extra work. Consider hazard pay or ensure extra time off for extra time worked.

- Make it “easier” for clinicians to do their jobs by helping them meet their basic needs. Create schedules with designated breaks during shifts. Provide adequate office space and call rooms. Facilitate access to childcare. Provide parking.

- Minimize moral injury. Develop protocols for scarce resource allocation that exclude the treatment team from making decisions about allocation of scarce resources. Avoid visitor restrictions given the harm these policies inflict on patients, families, and members of the care team.

At the level of society:

- Study mechanisms to improve communication about public health with the public. Both science and communication are essential to promoting and protecting public health; more research is needed to improve the way scientific knowledge and evidence-based recommendations are communicated to the public.

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has forever changed our critical care workforce and the way we deliver care. The time is now to act on the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic through implementation of systems-level solutions to combat burnout and ensure both the health and sustainability of our critical care workforce for the season ahead.

Dr. Vranas is with the Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care, VA Portland Health Care System, the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, Oregon Health & Science University; Portland, OR; and the Palliative and Advanced Illness Research (PAIR) Center, University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, PA. Dr. Kerlin is with the Palliative and Advanced Illness Research (PAIR) Center, and Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, PA.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused unprecedented and unpredictable strain on health care systems worldwide, forcing rapid organizational modifications and innovations to ensure availability of critical care resources during acute surge events. Yet, while much attention has been paid to the availability of ICU beds and ventilators, COVID-19 has insidiously and significantly harmed the most precious critical care resource of all – the human beings who are the lifeblood of critical care delivery. We are now at a crucial moment in history to better understand the pandemic’s impact on our human resources and enact changes to reverse the damage that it has inflicted on our workforce.

ICUs, where critical care delivery predominantly occurs, increasingly utilize interprofessional staffing models in which clinicians from multiple disciplines – physicians, nurses, clinical pharmacists, respiratory therapists, and dieticians, among others – bring their unique expertise to team-based clinical decisions and care delivery. Such a multidisciplinary approach helps enable the provision of more comprehensive, higher-quality critical care. In this way, the interprofessional ICU care team is an embodiment of the notion that the “whole” is more than just the sum of its parts. Therefore, we must consider the impact of the pandemic on interprofessional critical care clinicians as the team that they are.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the well-being of critical care clinicians was compromised. Across multiple disciplines, they had among the highest rates of burnout syndrome of all health care professionals (Moss M, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194[1]:106-113). As the pandemic has dragged on, their well-being has only further declined. Burnout rates are at all-time highs, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression are common and have increased with each subsequent surge (Azoulay E, et al. Chest. 2021;160[3]:944-955). Offsets to burnout, such as fulfillment and recognition, have declined over time (Kerlin MP, et al. Ann Amer Thorac Soc. 2022;19[2]:329-331). These worrisome trends pose a significant threat to critical care delivery. Clinician burnout is associated with worse patient outcomes, increased medical errors, and lower patient satisfaction (Moss M, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194[1]:106-113; Poghosyan L, et al. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33[4]:288-298). It is also associated with mental illness and substance use disorders among clinicians (Dyrbye LN, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149[5]:334-341). Finally, it has contributed to a workforce crisis: nearly 500,000 health care workers have left the US health care sector since the beginning of the pandemic, and approximately two-thirds of acute and critical care nurses have considered doing so (Wong E. “Why Healthcare Workers are Quitting in Droves”. The Atlantic. Accessed November 7, 2022). Such a “brain drain” of clinicians – whose expertise cannot be easily replicated or replaced – represents a staffing crisis that threatens our ability to provide high-quality, safe care for the foreseeable future.

To combat burnout, it is first necessary to identify the mechanisms by which the pandemic has induced harm. Early during the pandemic, critical care clinicians feared for their own safety with little information of how the virus was spread. At a time when the world was under lockdown, vaccines were not yet available, and hospitals were overwhelmed with surges of critically ill patients, clinicians struggled like the rest of the world to meet their own basic needs such as childcare, grocery shopping, and time with family. They experienced distress from high volumes of patients with extreme mortality rates, helplessness due to lack of treatment options, and moral injury over restrictive visitation policies (Vranas KC, et al. Chest. 2022;162[2]:331-345; Vranas KC, et al. Chest. 2021;160[5]:1714-1728). Over time, critical care clinicians have no doubt experienced further exhaustion related to the duration of the pandemic, often without adequate time to recover and process the trauma they have experienced. More recently, a new source of distress for clinicians has emerged from variability in vaccine uptake among the public. Clinicians have experienced compassion fatigue and even moral outrage toward those who chose not to receive a vaccine that is highly effective at preventing severe illness. They also suffered from ethical conflicts over how to treat unvaccinated patients and whether they should be given equal priority and access to limited therapies (Shaw D. Bioethics. 2022;36[8]:883-890).

Furthermore, the pandemic has damaged the relationship between clinicians and their institutions. Early in the pandemic, the widespread shortages of personal protective equipment harmed trust among clinicians due to their perception that their safety was not prioritized. Hospitals have also struggled with having to make rapid decisions on how to equitably allocate fixed resources in response to unanticipated and unpredictable demands, while also maintaining financial solvency. In some cases, these challenging policy decisions (eg, whether to continue elective procedures during acute surge events) lacked transparency and input from the team at the frontlines of patient care. As a result, clinicians have felt undervalued and without a voice in decisions that directly impact both the care they can provide their patients and their own well-being.

It is incumbent upon us now to take steps to repair the damage inflicted on our critical care workforce by the pandemic. To this end, there have been calls for the urgent implementation of strategies to mitigate the psychological burden experienced by critical care clinicians. However, many of these focus on interventions to increase coping strategies and resilience among individual clinicians. While programs such as mindfulness apps and resilience training are valuable, they are not sufficient. The very nature of these solutions implies that the solution (and therefore, the problem) of burnout lies in the individual clinician. Yet, as described above, many of the mechanisms of harm to clinicians’ well-being are systems-level issues that will necessarily require systems-level solutions.

Therefore, we propose a comprehensive, layered approach to begin to reverse the damage inflicted by the pandemic on critical care clinicians’ well-being, with solutions organized by ecological levels of individual clinicians, departments, institutions, and society. With this approach, we hope to address specific aspects of our critical care delivery system that, taken together, will fortify the well-being of our critical care workforce as a whole. We offer suggestions below that are both informed by existing evidence, as well as our own opinions as intensivists and researchers.

At the level of the individual clinician:

- Proactively provide access to mental health resources. Clinicians have limited time or energy to navigate mental health and support services and find it helpful when others proactively reach out to them.

- Provide opportunities for clinicians to experience community and support among peers. Clinicians find benefit in town halls, debrief sessions, and peer support groups, particularly during times of acute strain.

At the level of the department:

- Allow more flexibility in work schedules. Even prior to the pandemic, the lack of scheduling flexibility and the number of consecutive days worked had been identified as key contributors to burnout; these have been exacerbated during times of caseload surges, when clinicians have been asked or even required to increase their hours and work extra shifts.

- Promote a culture of psychological safety in which clinicians feel empowered to say “I cannot work” for whatever reason. This will require the establishment of formalized backup systems that easily accommodate call-outs without relying on individual clinicians to find their own coverage.

At the level of the health care system:

- Prioritize transparency, and bring administrators and clinicians together for policy decisions. Break down silos between the frontline workers involved in direct patient care and hospital executives, both to inform those decisions and demonstrate the value of clinicians’ perspectives.

- Compensate clinicians for extra work. Consider hazard pay or ensure extra time off for extra time worked.

- Make it “easier” for clinicians to do their jobs by helping them meet their basic needs. Create schedules with designated breaks during shifts. Provide adequate office space and call rooms. Facilitate access to childcare. Provide parking.

- Minimize moral injury. Develop protocols for scarce resource allocation that exclude the treatment team from making decisions about allocation of scarce resources. Avoid visitor restrictions given the harm these policies inflict on patients, families, and members of the care team.

At the level of society:

- Study mechanisms to improve communication about public health with the public. Both science and communication are essential to promoting and protecting public health; more research is needed to improve the way scientific knowledge and evidence-based recommendations are communicated to the public.

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has forever changed our critical care workforce and the way we deliver care. The time is now to act on the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic through implementation of systems-level solutions to combat burnout and ensure both the health and sustainability of our critical care workforce for the season ahead.

Dr. Vranas is with the Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care, VA Portland Health Care System, the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, Oregon Health & Science University; Portland, OR; and the Palliative and Advanced Illness Research (PAIR) Center, University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, PA. Dr. Kerlin is with the Palliative and Advanced Illness Research (PAIR) Center, and Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, PA.

A single pediatric CT scan raises brain cancer risk

Children and young adults who are exposed to a single CT scan of the head or neck before age 22 years are at significantly increased risk of developing a brain tumor, particularly glioma, after at least 5 years, according to results of the large EPI-CT study.

“Translation of our risk estimates to the clinical setting indicates that per 10,000 children who received one head CT examination, about one radiation-induced brain cancer is expected during the 5-15 years following the CT examination,” noted lead author Michael Hauptmann, PhD, from the Institute of Biostatistics and Registry Research, Brandenburg Medical School, Neuruppin, Germany, and coauthors.

“Next to the clinical benefit of most CT scans, there is a small risk of cancer from the radiation exposure,” Dr. Hauptmann told this news organization.

“So, CT examinations should only be used when necessary, and if they are used, the lowest achievable dose should be applied,” he said.

The study was published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“This is a thoughtful and well-conducted study by an outstanding multinational team of scientists that adds further weight to the growing body of evidence that has found exposure to CT scanning increases a child’s risk of developing brain cancer,” commented Rebecca Bindman-Smith, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the research.

“The results are real, and important,” she told this news organization, adding that “the authors were conservative in their assumptions, and performed a very large number of sensitivity analyses ... to check that the results were robust to a large range of assumptions – and the results changed relatively little.”

“I do not think there is enough awareness [about this risk],” Dr. Hauptmann said. “There is evidence that a nonnegligible number of CTs is unjustified according to guidelines, and there is evidence that doses vary substantially for the same CT between institutions in the same or different countries.”

Indeed, particularly in the United States, “we perform many CT scans in children and even more so in adults that are simply unnecessary,” agreed Dr. Bindman-Smith, who is professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “It is important for patients and providers to understand that nothing we do in medicine is risk free, including CT scanning. If a CT is necessary, the benefit almost certainly outweighs the risk. But if [not], then it should not be obtained. Both patients and providers must make thoroughly considered decisions before asking for or agreeing to a CT.”

She also pointed out that while this study evaluated the risk only for brain cancer, children who undergo head CTs are also at increased risk for leukemia.

Dose/response relationship

The study included 658,752 individuals from nine European countries and 276 hospitals. Each patient had received at least one CT scan between 1977 and 2014 before they turned 22 years of age. Eligibility requirements included their being alive at least 5 years after the first scan and that they had not previously been diagnosed with cancer or benign brain tumor.

The radiation dose absorbed to the brain and 33 other organs and tissues was estimated for each participant using a dose reconstruction model that included historical information on CT machine settings, questionnaire data, and Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine header metadata. “Mean brain dose per head or neck CT examination increased from 1984 until about 1991, following the introduction of multislice CT scanners at which point thereafter the mean dose decreased and then stabilized around 2010,” note the authors.

During a median follow-up of 5.6 years (starting 5 years after the first scan), 165 brain cancers occurred, including 121 (73%) gliomas, as well as a variety of other morphologic changes.

The mean cumulative brain dose, which lagged by 5 years, was 47.4 mGy overall and 76.0 mGy among people with brain cancer.

“We observed a significant positive association between the cumulative number of head or neck CT examinations and the risk of all brain cancers combined (P < .0001), and of gliomas separately (P = .0002),” the team reports, adding that, for a brain dose of 38 mGy, which was the average dose per head or neck CT in 2012-2014, the relative risk of developing brain cancer was 1.5, compared with not undergoing a CT scan, and the excess absolute risk per 100,000 person-years was 1.1.

These findings “can be used to give the patients and their parents important information on the risks of CT examination to balance against the known benefits,” noted Nobuyuki Hamada, PhD, from the Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry, Tokyo, and Lydia B. Zablotska, MD, PhD, from the University of California, San Francisco, writing in a linked commentary.

“In recent years, rates of CT use have been steady or declined, and various efforts (for instance, in terms of diagnostic reference levels) have been made to justify and optimize CT examinations. Such continued efforts, along with extended epidemiological investigations, would be needed to minimize the risk of brain cancer after pediatric CT examination,” they add.

Keeping dose to a minimum

The study’s finding of a dose-response relationship underscores the importance of keeping doses to a minimum, Dr. Bindman-Smith commented. “I do not believe we are doing this nearly enough,” she added.

“In the UCSF International CT Dose Registry, where we have collected CT scans from 165 hospitals on many millions of patients, we found that the average brain dose for a head CT in a 1-year-old is 42 mGy but that this dose varies tremendously, where some children receive a dose of 100 mGy.

“So, a second message is that not only should CT scans be justified and used judiciously, but also they should be optimized, meaning using the lowest dose possible. I personally think there should be regulatory oversight to ensure that patients receive the absolutely lowest doses possible,” she added. “My team at UCSF has written quality measures endorsed by the National Quality Forum as a start for setting explicit standards for how CT should be performed in order to ensure the cancer risks are as low as possible.”

The study was funded through the Belgian Cancer Registry; La Ligue contre le Cancer, L’Institut National du Cancer, France; the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan; the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; Worldwide Cancer Research; the Dutch Cancer Society; the Research Council of Norway; Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear, Generalitat deCatalunya, Spain; the U.S. National Cancer Institute; the U.K. National Institute for Health Research; and Public Health England. Dr. Hauptmann has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Other investigators’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article. Dr. Hamada and Dr. Zablotska disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and young adults who are exposed to a single CT scan of the head or neck before age 22 years are at significantly increased risk of developing a brain tumor, particularly glioma, after at least 5 years, according to results of the large EPI-CT study.

“Translation of our risk estimates to the clinical setting indicates that per 10,000 children who received one head CT examination, about one radiation-induced brain cancer is expected during the 5-15 years following the CT examination,” noted lead author Michael Hauptmann, PhD, from the Institute of Biostatistics and Registry Research, Brandenburg Medical School, Neuruppin, Germany, and coauthors.

“Next to the clinical benefit of most CT scans, there is a small risk of cancer from the radiation exposure,” Dr. Hauptmann told this news organization.

“So, CT examinations should only be used when necessary, and if they are used, the lowest achievable dose should be applied,” he said.

The study was published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“This is a thoughtful and well-conducted study by an outstanding multinational team of scientists that adds further weight to the growing body of evidence that has found exposure to CT scanning increases a child’s risk of developing brain cancer,” commented Rebecca Bindman-Smith, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the research.

“The results are real, and important,” she told this news organization, adding that “the authors were conservative in their assumptions, and performed a very large number of sensitivity analyses ... to check that the results were robust to a large range of assumptions – and the results changed relatively little.”

“I do not think there is enough awareness [about this risk],” Dr. Hauptmann said. “There is evidence that a nonnegligible number of CTs is unjustified according to guidelines, and there is evidence that doses vary substantially for the same CT between institutions in the same or different countries.”

Indeed, particularly in the United States, “we perform many CT scans in children and even more so in adults that are simply unnecessary,” agreed Dr. Bindman-Smith, who is professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “It is important for patients and providers to understand that nothing we do in medicine is risk free, including CT scanning. If a CT is necessary, the benefit almost certainly outweighs the risk. But if [not], then it should not be obtained. Both patients and providers must make thoroughly considered decisions before asking for or agreeing to a CT.”

She also pointed out that while this study evaluated the risk only for brain cancer, children who undergo head CTs are also at increased risk for leukemia.

Dose/response relationship

The study included 658,752 individuals from nine European countries and 276 hospitals. Each patient had received at least one CT scan between 1977 and 2014 before they turned 22 years of age. Eligibility requirements included their being alive at least 5 years after the first scan and that they had not previously been diagnosed with cancer or benign brain tumor.

The radiation dose absorbed to the brain and 33 other organs and tissues was estimated for each participant using a dose reconstruction model that included historical information on CT machine settings, questionnaire data, and Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine header metadata. “Mean brain dose per head or neck CT examination increased from 1984 until about 1991, following the introduction of multislice CT scanners at which point thereafter the mean dose decreased and then stabilized around 2010,” note the authors.

During a median follow-up of 5.6 years (starting 5 years after the first scan), 165 brain cancers occurred, including 121 (73%) gliomas, as well as a variety of other morphologic changes.

The mean cumulative brain dose, which lagged by 5 years, was 47.4 mGy overall and 76.0 mGy among people with brain cancer.

“We observed a significant positive association between the cumulative number of head or neck CT examinations and the risk of all brain cancers combined (P < .0001), and of gliomas separately (P = .0002),” the team reports, adding that, for a brain dose of 38 mGy, which was the average dose per head or neck CT in 2012-2014, the relative risk of developing brain cancer was 1.5, compared with not undergoing a CT scan, and the excess absolute risk per 100,000 person-years was 1.1.

These findings “can be used to give the patients and their parents important information on the risks of CT examination to balance against the known benefits,” noted Nobuyuki Hamada, PhD, from the Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry, Tokyo, and Lydia B. Zablotska, MD, PhD, from the University of California, San Francisco, writing in a linked commentary.

“In recent years, rates of CT use have been steady or declined, and various efforts (for instance, in terms of diagnostic reference levels) have been made to justify and optimize CT examinations. Such continued efforts, along with extended epidemiological investigations, would be needed to minimize the risk of brain cancer after pediatric CT examination,” they add.

Keeping dose to a minimum

The study’s finding of a dose-response relationship underscores the importance of keeping doses to a minimum, Dr. Bindman-Smith commented. “I do not believe we are doing this nearly enough,” she added.

“In the UCSF International CT Dose Registry, where we have collected CT scans from 165 hospitals on many millions of patients, we found that the average brain dose for a head CT in a 1-year-old is 42 mGy but that this dose varies tremendously, where some children receive a dose of 100 mGy.

“So, a second message is that not only should CT scans be justified and used judiciously, but also they should be optimized, meaning using the lowest dose possible. I personally think there should be regulatory oversight to ensure that patients receive the absolutely lowest doses possible,” she added. “My team at UCSF has written quality measures endorsed by the National Quality Forum as a start for setting explicit standards for how CT should be performed in order to ensure the cancer risks are as low as possible.”

The study was funded through the Belgian Cancer Registry; La Ligue contre le Cancer, L’Institut National du Cancer, France; the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan; the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; Worldwide Cancer Research; the Dutch Cancer Society; the Research Council of Norway; Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear, Generalitat deCatalunya, Spain; the U.S. National Cancer Institute; the U.K. National Institute for Health Research; and Public Health England. Dr. Hauptmann has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Other investigators’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article. Dr. Hamada and Dr. Zablotska disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and young adults who are exposed to a single CT scan of the head or neck before age 22 years are at significantly increased risk of developing a brain tumor, particularly glioma, after at least 5 years, according to results of the large EPI-CT study.

“Translation of our risk estimates to the clinical setting indicates that per 10,000 children who received one head CT examination, about one radiation-induced brain cancer is expected during the 5-15 years following the CT examination,” noted lead author Michael Hauptmann, PhD, from the Institute of Biostatistics and Registry Research, Brandenburg Medical School, Neuruppin, Germany, and coauthors.

“Next to the clinical benefit of most CT scans, there is a small risk of cancer from the radiation exposure,” Dr. Hauptmann told this news organization.

“So, CT examinations should only be used when necessary, and if they are used, the lowest achievable dose should be applied,” he said.

The study was published online in The Lancet Oncology.

“This is a thoughtful and well-conducted study by an outstanding multinational team of scientists that adds further weight to the growing body of evidence that has found exposure to CT scanning increases a child’s risk of developing brain cancer,” commented Rebecca Bindman-Smith, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the research.

“The results are real, and important,” she told this news organization, adding that “the authors were conservative in their assumptions, and performed a very large number of sensitivity analyses ... to check that the results were robust to a large range of assumptions – and the results changed relatively little.”

“I do not think there is enough awareness [about this risk],” Dr. Hauptmann said. “There is evidence that a nonnegligible number of CTs is unjustified according to guidelines, and there is evidence that doses vary substantially for the same CT between institutions in the same or different countries.”

Indeed, particularly in the United States, “we perform many CT scans in children and even more so in adults that are simply unnecessary,” agreed Dr. Bindman-Smith, who is professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “It is important for patients and providers to understand that nothing we do in medicine is risk free, including CT scanning. If a CT is necessary, the benefit almost certainly outweighs the risk. But if [not], then it should not be obtained. Both patients and providers must make thoroughly considered decisions before asking for or agreeing to a CT.”

She also pointed out that while this study evaluated the risk only for brain cancer, children who undergo head CTs are also at increased risk for leukemia.

Dose/response relationship

The study included 658,752 individuals from nine European countries and 276 hospitals. Each patient had received at least one CT scan between 1977 and 2014 before they turned 22 years of age. Eligibility requirements included their being alive at least 5 years after the first scan and that they had not previously been diagnosed with cancer or benign brain tumor.

The radiation dose absorbed to the brain and 33 other organs and tissues was estimated for each participant using a dose reconstruction model that included historical information on CT machine settings, questionnaire data, and Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine header metadata. “Mean brain dose per head or neck CT examination increased from 1984 until about 1991, following the introduction of multislice CT scanners at which point thereafter the mean dose decreased and then stabilized around 2010,” note the authors.

During a median follow-up of 5.6 years (starting 5 years after the first scan), 165 brain cancers occurred, including 121 (73%) gliomas, as well as a variety of other morphologic changes.

The mean cumulative brain dose, which lagged by 5 years, was 47.4 mGy overall and 76.0 mGy among people with brain cancer.

“We observed a significant positive association between the cumulative number of head or neck CT examinations and the risk of all brain cancers combined (P < .0001), and of gliomas separately (P = .0002),” the team reports, adding that, for a brain dose of 38 mGy, which was the average dose per head or neck CT in 2012-2014, the relative risk of developing brain cancer was 1.5, compared with not undergoing a CT scan, and the excess absolute risk per 100,000 person-years was 1.1.

These findings “can be used to give the patients and their parents important information on the risks of CT examination to balance against the known benefits,” noted Nobuyuki Hamada, PhD, from the Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry, Tokyo, and Lydia B. Zablotska, MD, PhD, from the University of California, San Francisco, writing in a linked commentary.

“In recent years, rates of CT use have been steady or declined, and various efforts (for instance, in terms of diagnostic reference levels) have been made to justify and optimize CT examinations. Such continued efforts, along with extended epidemiological investigations, would be needed to minimize the risk of brain cancer after pediatric CT examination,” they add.

Keeping dose to a minimum

The study’s finding of a dose-response relationship underscores the importance of keeping doses to a minimum, Dr. Bindman-Smith commented. “I do not believe we are doing this nearly enough,” she added.

“In the UCSF International CT Dose Registry, where we have collected CT scans from 165 hospitals on many millions of patients, we found that the average brain dose for a head CT in a 1-year-old is 42 mGy but that this dose varies tremendously, where some children receive a dose of 100 mGy.

“So, a second message is that not only should CT scans be justified and used judiciously, but also they should be optimized, meaning using the lowest dose possible. I personally think there should be regulatory oversight to ensure that patients receive the absolutely lowest doses possible,” she added. “My team at UCSF has written quality measures endorsed by the National Quality Forum as a start for setting explicit standards for how CT should be performed in order to ensure the cancer risks are as low as possible.”

The study was funded through the Belgian Cancer Registry; La Ligue contre le Cancer, L’Institut National du Cancer, France; the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan; the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; Worldwide Cancer Research; the Dutch Cancer Society; the Research Council of Norway; Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear, Generalitat deCatalunya, Spain; the U.S. National Cancer Institute; the U.K. National Institute for Health Research; and Public Health England. Dr. Hauptmann has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Other investigators’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article. Dr. Hamada and Dr. Zablotska disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET ONCOLOGY

Digital treatment may help relieve PTSD, panic disorder

The 28-day home-based treatment, known as the capnometry guided respiratory intervention (CGRI), uses an app-based feedback protocol to normalize respiration and increase patients’ ability to cope with symptoms of stress, anxiety, and panic by providing real time breath-to-breath feedback of respiratory rate and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels via a nasal cannula.

Results from the large real-world study showed that over 65% of patients with PD and over 72% of those with PTSD responded to the treatment. In addition, almost 75% of participants adhered to the study protocol, with low dropout rates.

“The brief duration of treatment, high adherence rates, and clinical benefit suggests that CGRI provides an important addition to treatment options for PD and PTSD,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Digital Health.

‘New kid on the block’

The “respiratory dysregulation hypothesis” links CO2 sensitivity to panic attacks and PD, and similar reactivity has been identified in PTSD, but a “common limitation of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic approaches to PD and PTSD is that neither address the role of respiratory physiology and breathing style,” the investigators note.

The most widely studied treatment for PTSD is trauma-focused psychotherapy, in which the patient reviews and revisits the trauma, but it has a high dropout rate, study investigator Michael Telch, PhD, director of the Laboratory for the Study of Anxiety Disorders, University of Texas, Austin, told this news organization.

He described CGRI for PTSD as a “relatively new kid on the block, so to speak.” The intervention was cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of PD and PTSD in 2013 and 2018, respectively, and is currently available through the Veterans Administration for veterans with PTSD. It is also covered by some commercial insurance plans.

“The underlying assumption [of CGRI] is that a person can learn to develop skills for controlling some of their physiological reactions that are triggered as a result of trauma,” said Dr. Telch.

The device uses a biofeedback approach to give patients “greater control over their physiological reactions, such as hyperventilation and increased respiration rate, and the focus is on providing a sense of mastery,” he said.

Participants with PTSD were assigned to a health coach. The device was delivered to the patient’s home, and patients met with the trained coach weekly and could check in between visits via text or e-mail. Twice-daily sessions were recommended.

“The coach gets feedback about what’s happening with the patient’s respiration and end-tidal CO2 levels [etCO2] and instructs participants how to keep their respiration rate and etCO2 at a more normal level,” said Dr. Telch.

The CGRI “teaches a specific breathing style via a system providing real-time feedback of respiratory rate (RR) and exhaled carbon dioxide levels facilitated by data capture,” the authors note.

Sense of mastery

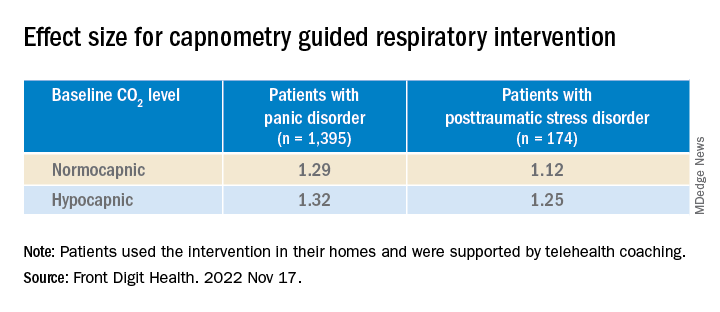

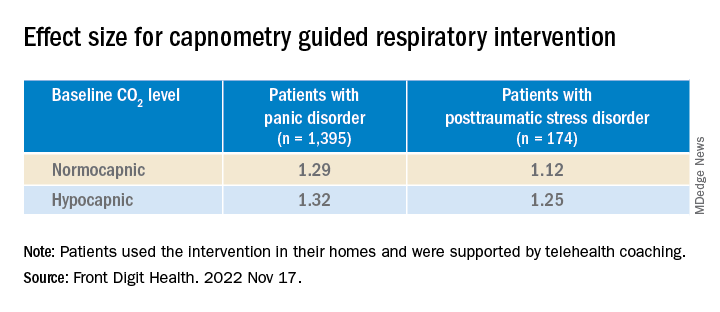

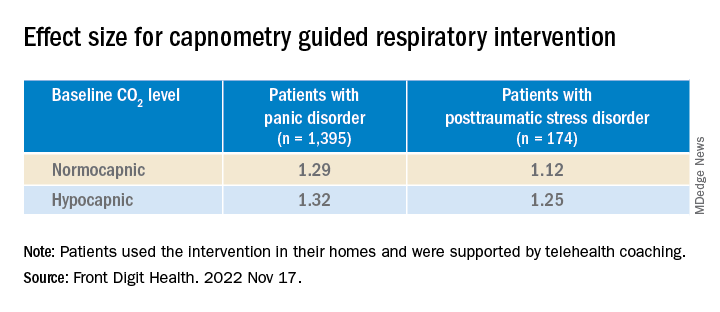

Of the 1,569 participants, 1,395 had PD and 174 had PTSD (mean age, 39.2 [standard deviation, 13.9] years and 40.9 [SD, 14.9] years, respectively; 76% and 73% female, respectively). Those with PD completed the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) and those with PTSD completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), before and after the intervention.

The treatment response rate for PD was defined as a 40% or greater reduction in PDSS total scores, whereas treatment response rate for PTSD was defined as a 10-point or greater reduction in PCL-5 scores.

At baseline, patients were classified either as normocapnic or hypocapnic (etCO2 ≥ 37 or < 37, respectively), with 65% classified as normocapnic and 35% classified as hypocapnic.

Among patients with PD, there was a 50.2% mean pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PDSS scores (P < .001; d = 1.31), with a treatment response rate of 65.3% of patients.

Among patients with PTSD, there was a 41.1% pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PCL-5 scores (P < .001; d = 1.16), with a treatment response rate of 72.4%.

When investigators analyzed the response at the individual level, they found that 55.7% of patients with PD and 53.5% of those with PTSD were classified as treatment responders. This determination was based on a two-pronged approach that first calculated the Reliable Change Index (RCI) for each participant, and, in participants showing statistically reliable improvement, whether the posttreatment score was closer to the distribution of scores for patients without or with the given disorder.

“Patients with both normal and below-normal baseline exhaled CO2 levels experienced comparable benefit,” the authors report.

There were high levels of adherence across the full treatment period in both the PD and the PTSD groups (74.8% and 74.9%, respectively), with low dropout rates (10% and 11%, respectively).

“Not every single patient who undergoes any treatment has a perfect response, but the response rates to this treatment have, surprisingly, been quite positive and there have been no negative side effects,” Dr. Telch remarked.

He noted that one of the effects of PTSD is that the “patient has negative beliefs about their ability to control the world. ‘I can’t control my reactions. At any time, I could have a flashback.’ Helping the patient to develop any sense of mastery over some of their reactions can spill over and give them a greater sense of mastery and control, which can have a positive effect in reducing PTSD symptoms.”

‘A viable alternative’

Commenting on the research, Charles Marmar, MD, chair and Peter H. Schub Professor of Psychiatry, department of psychiatry, New York University, said that the study has some limitations, probably the most significant of which is that most participants had normal baseline CO2 levels.

“The treatment is fundamentally designed for people who hyperventilate and blow off too much CO2 so they can breathe in a more calm, relaxed way, but most people in the trial had normal CO2 to begin with,” said Dr. Marmar, who was not involved with the study.

“It’s likely that the major benefits were the relaxation from doing the breathing exercises rather than the change in CO2 levels,” he speculated.

The treatment is “probably a good thing for those patients who actually have abnormal CO2 levels. This treatment could be used in precision medicine, where you tailor treatments to those who actually need them rather than giving the same treatment to everyone,” he said.

“For patients who don’t respond to trauma-focused therapy or it’s too aversive for them to undergo, this new intervention provides a viable alternative,” Dr. Telch added.

The study was internally funded by Freespira. Dr. Telch is a scientific advisor at Freespira and receives compensation by way of stock options. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. Dr. Marmar has declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 28-day home-based treatment, known as the capnometry guided respiratory intervention (CGRI), uses an app-based feedback protocol to normalize respiration and increase patients’ ability to cope with symptoms of stress, anxiety, and panic by providing real time breath-to-breath feedback of respiratory rate and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels via a nasal cannula.

Results from the large real-world study showed that over 65% of patients with PD and over 72% of those with PTSD responded to the treatment. In addition, almost 75% of participants adhered to the study protocol, with low dropout rates.

“The brief duration of treatment, high adherence rates, and clinical benefit suggests that CGRI provides an important addition to treatment options for PD and PTSD,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Digital Health.

‘New kid on the block’

The “respiratory dysregulation hypothesis” links CO2 sensitivity to panic attacks and PD, and similar reactivity has been identified in PTSD, but a “common limitation of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic approaches to PD and PTSD is that neither address the role of respiratory physiology and breathing style,” the investigators note.

The most widely studied treatment for PTSD is trauma-focused psychotherapy, in which the patient reviews and revisits the trauma, but it has a high dropout rate, study investigator Michael Telch, PhD, director of the Laboratory for the Study of Anxiety Disorders, University of Texas, Austin, told this news organization.

He described CGRI for PTSD as a “relatively new kid on the block, so to speak.” The intervention was cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of PD and PTSD in 2013 and 2018, respectively, and is currently available through the Veterans Administration for veterans with PTSD. It is also covered by some commercial insurance plans.

“The underlying assumption [of CGRI] is that a person can learn to develop skills for controlling some of their physiological reactions that are triggered as a result of trauma,” said Dr. Telch.

The device uses a biofeedback approach to give patients “greater control over their physiological reactions, such as hyperventilation and increased respiration rate, and the focus is on providing a sense of mastery,” he said.

Participants with PTSD were assigned to a health coach. The device was delivered to the patient’s home, and patients met with the trained coach weekly and could check in between visits via text or e-mail. Twice-daily sessions were recommended.

“The coach gets feedback about what’s happening with the patient’s respiration and end-tidal CO2 levels [etCO2] and instructs participants how to keep their respiration rate and etCO2 at a more normal level,” said Dr. Telch.

The CGRI “teaches a specific breathing style via a system providing real-time feedback of respiratory rate (RR) and exhaled carbon dioxide levels facilitated by data capture,” the authors note.

Sense of mastery

Of the 1,569 participants, 1,395 had PD and 174 had PTSD (mean age, 39.2 [standard deviation, 13.9] years and 40.9 [SD, 14.9] years, respectively; 76% and 73% female, respectively). Those with PD completed the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) and those with PTSD completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), before and after the intervention.

The treatment response rate for PD was defined as a 40% or greater reduction in PDSS total scores, whereas treatment response rate for PTSD was defined as a 10-point or greater reduction in PCL-5 scores.

At baseline, patients were classified either as normocapnic or hypocapnic (etCO2 ≥ 37 or < 37, respectively), with 65% classified as normocapnic and 35% classified as hypocapnic.

Among patients with PD, there was a 50.2% mean pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PDSS scores (P < .001; d = 1.31), with a treatment response rate of 65.3% of patients.

Among patients with PTSD, there was a 41.1% pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PCL-5 scores (P < .001; d = 1.16), with a treatment response rate of 72.4%.

When investigators analyzed the response at the individual level, they found that 55.7% of patients with PD and 53.5% of those with PTSD were classified as treatment responders. This determination was based on a two-pronged approach that first calculated the Reliable Change Index (RCI) for each participant, and, in participants showing statistically reliable improvement, whether the posttreatment score was closer to the distribution of scores for patients without or with the given disorder.

“Patients with both normal and below-normal baseline exhaled CO2 levels experienced comparable benefit,” the authors report.

There were high levels of adherence across the full treatment period in both the PD and the PTSD groups (74.8% and 74.9%, respectively), with low dropout rates (10% and 11%, respectively).

“Not every single patient who undergoes any treatment has a perfect response, but the response rates to this treatment have, surprisingly, been quite positive and there have been no negative side effects,” Dr. Telch remarked.

He noted that one of the effects of PTSD is that the “patient has negative beliefs about their ability to control the world. ‘I can’t control my reactions. At any time, I could have a flashback.’ Helping the patient to develop any sense of mastery over some of their reactions can spill over and give them a greater sense of mastery and control, which can have a positive effect in reducing PTSD symptoms.”

‘A viable alternative’

Commenting on the research, Charles Marmar, MD, chair and Peter H. Schub Professor of Psychiatry, department of psychiatry, New York University, said that the study has some limitations, probably the most significant of which is that most participants had normal baseline CO2 levels.

“The treatment is fundamentally designed for people who hyperventilate and blow off too much CO2 so they can breathe in a more calm, relaxed way, but most people in the trial had normal CO2 to begin with,” said Dr. Marmar, who was not involved with the study.

“It’s likely that the major benefits were the relaxation from doing the breathing exercises rather than the change in CO2 levels,” he speculated.

The treatment is “probably a good thing for those patients who actually have abnormal CO2 levels. This treatment could be used in precision medicine, where you tailor treatments to those who actually need them rather than giving the same treatment to everyone,” he said.

“For patients who don’t respond to trauma-focused therapy or it’s too aversive for them to undergo, this new intervention provides a viable alternative,” Dr. Telch added.

The study was internally funded by Freespira. Dr. Telch is a scientific advisor at Freespira and receives compensation by way of stock options. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. Dr. Marmar has declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 28-day home-based treatment, known as the capnometry guided respiratory intervention (CGRI), uses an app-based feedback protocol to normalize respiration and increase patients’ ability to cope with symptoms of stress, anxiety, and panic by providing real time breath-to-breath feedback of respiratory rate and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels via a nasal cannula.

Results from the large real-world study showed that over 65% of patients with PD and over 72% of those with PTSD responded to the treatment. In addition, almost 75% of participants adhered to the study protocol, with low dropout rates.

“The brief duration of treatment, high adherence rates, and clinical benefit suggests that CGRI provides an important addition to treatment options for PD and PTSD,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Digital Health.

‘New kid on the block’

The “respiratory dysregulation hypothesis” links CO2 sensitivity to panic attacks and PD, and similar reactivity has been identified in PTSD, but a “common limitation of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic approaches to PD and PTSD is that neither address the role of respiratory physiology and breathing style,” the investigators note.

The most widely studied treatment for PTSD is trauma-focused psychotherapy, in which the patient reviews and revisits the trauma, but it has a high dropout rate, study investigator Michael Telch, PhD, director of the Laboratory for the Study of Anxiety Disorders, University of Texas, Austin, told this news organization.

He described CGRI for PTSD as a “relatively new kid on the block, so to speak.” The intervention was cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of PD and PTSD in 2013 and 2018, respectively, and is currently available through the Veterans Administration for veterans with PTSD. It is also covered by some commercial insurance plans.

“The underlying assumption [of CGRI] is that a person can learn to develop skills for controlling some of their physiological reactions that are triggered as a result of trauma,” said Dr. Telch.

The device uses a biofeedback approach to give patients “greater control over their physiological reactions, such as hyperventilation and increased respiration rate, and the focus is on providing a sense of mastery,” he said.

Participants with PTSD were assigned to a health coach. The device was delivered to the patient’s home, and patients met with the trained coach weekly and could check in between visits via text or e-mail. Twice-daily sessions were recommended.

“The coach gets feedback about what’s happening with the patient’s respiration and end-tidal CO2 levels [etCO2] and instructs participants how to keep their respiration rate and etCO2 at a more normal level,” said Dr. Telch.