User login

For MD-IQ use only

Screening Tool to Reduce Anticoagulant Clinic Encounters

Metrics from 2017 at the Fayetteville Veterans Affairs Heath Care Center (FVAHCC) Anticoagulation Clinic indicate that 43% of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who are prescribed warfarin have difficulty maintaining a therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR). These patients require frequent clinic appointments to adjust their regimens to ensure anticoagulation efficacy. FVAHCC policy requires a patient to return to the clinic for repeat INR evaluation within 5 to 14 days of the visit where INR was outside of the established therapeutic range.1 These frequent INR monitoring appointments increase patient and health care provider burden.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are an alternative to warfarin for patients with AF who require anticoagulation. DOACs, which do not require regular efficacy monitoring, can be beneficial to patients who struggle to maintain a therapeutic INR when taking warfarin. FVAHCC policy regarding warfarin therapy monitoring allows for a maximum of 6 weeks between appointments. This period is often extended to 3 to 6 months for patients on DOACs.1

At FVAHCC, patients prescribed warfarin are managed in a centralized Anticoagulation Clinic led by a clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS). When a patient reports for an appointment, a clinical pharmacy technician performs point-of-care INR testing and asks standardized questions regarding therapy, including an assessment of adherence. The CPS then evaluates the patient’s INR test results, adjusts the dosage of warfarin as indicated, and determines appropriate follow-up.

A patient who is prescribed a DOAC is monitored by a CPS who works within a patient aligned care team (PACT). The PACT, a multidisciplinary team providing health care to veterans, includes physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dieticians, and mental health providers. Each CPS covers 3 or 4 PACTs. These pharmacists monitor all aspects of DOAC therapy at regular intervals, including renal and hepatic function, complete blood counts, medication adherence, and adverse effects.

Clinic and patient INR data are tracked using a time in therapeutic range (TTR) report generated by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The TTR report provides clinical information to enhance patient anticoagulation care.2 The TTR report identifies patients with an active order for warfarin and a diagnosis of AF or venous thromboembolism (VTE) whose INR is within therapeutic range (between 2 and 3) < 60% of the time over the previous 160 days.2 The patient must have had at least 3 INR levels drawn within that time frame for a TTR report calculation.2 The report excludes patients who were first prescribed warfarin within the previous 42 days and those with mechanical heart valves. The TTR report is used by the VA to see concrete facility-level results for quality improvement efforts.2

A quality improvement screening tool was developed to identify patients with AF being treated with warfarin who may appropriately transition to DOAC therapy. Anticoagulation Clinic patients were eligible for further evaluation if they had a TTR report level of < 60% and were prescribed indefinite warfarin therapy for AF.

The national VA goal is to have patient TTR report levels read > 60%. Therefore, the primary objective of this project was to improve Anticoagulation Clinic TTR metrics by targeting patients with TTR levels below the national goal.2

Patients who were successfully converted from warfarin to a DOAC were no longer included in Anticoagulation Clinic metrics and instead were followed by a PACT CPS. Thus, it was hypothesized that the average number of monthly Anticoagulation Clinic encounters would decrease on successful implementation of the screening tool. A secondary endpoint of the study evaluated the change in the total number of encounters of those who converted from warfarin to a DOAC.

Fewer clinic encounters could increase time available for the CPS to incorporate other initiatives into workflow and could increase clinic availability for newly referred veterans.

Methods

As this undertaking was considered to be a quality improvement project, institutional review board approval was not required. During an 8-week screening period (August to September 2018), the DOAC screening tool was implemented into the Anticoagulation Clinic workflow. This screening tool (Figure 1) was established based on VA Pharmacy Benefit Management (PBM) Service’s Criteria for Use for Stroke Prevention in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation, a national set of standards used to determine appropriate candidates for DOAC therapy.3

Exclusion criteria included patients with INR goals < 2 or > 3, patients with a diagnosis of VTE, and patients with weight > 120 kg. Patients with a diagnosis of VTE were excluded due to the variability in therapy duration. Weight cutoffs were based on recommendations by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Due to a lack of available data, it was suggested that clinical judgment be used in patients whose weight was > 120 kg.4

During the screening period, weekly TTR reports identified patients in the clinic who had TTR < 60%. When a patient with a TTR report results of < 60% also had a scheduled appointment within a week, a CPS then further reviewed patient eligibility using the DOAC screening tool. On arrival for an appointment, the eligible patient was counseled on DOAC medications and the differences between warfarin and DOACs, including monitoring requirements. Patients had the option to switch to DOAC therapy or remain on warfarin.

The change in the average number of monthly Anticoagulation Clinic encounters for 3 months prior to the screening period (May to July 2018) and 2 months following screening (October to November 2018) was evaluated to measure the impact of the DOAC screening tool. The total number of encounters in the clinic was assessed using the monthly VA reports and were averaged for each period. Then data from the 2 periods were compared.

The monthly encounter reports, a data tool that monitors the number of unique visits per veteran each calendar month, also were used to generate a secondary endpoint showing the number of encounters in the Anticoagulation Clinic associated with patients who switched to a DOAC, including visits prior to changing therapy, and before and after the screening period.

Student’s t test was used to compare the change in encounter frequency before and after screening tool implementation for both primary and secondary endpoints. α was defined as .05 a priori. Continuous data were presented as means and standard deviations. Data were calculated with Microsoft Excel 2016.

Results

For the 3 months before the 8-week screening period, an average of 476 Anticoagulation Clinic encounters per month were documented. Two months of data following the screening period averaged 546 encounters per month. There were an average of 70 additional encounters per month after screening tool implementation (P = .15), reflecting the study’s primary objective.

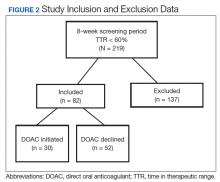

A total of 219 patients in the Anticoagulation Clinic were identified as having a TTR report results of < 60% during the 8-week screening period (Figure 2). Eighty-two of those patients (37.4%) were considered eligible to switch from warfarin to DOAC therapy. Thirty of those eligible patients (13.7%) switched to a DOAC. A total of 107 clinic encounters (22.5%) was associated with these 30 patients prior to screening and 32 associated encounters (5.9%) following screening (P = .01). Of the remaining 137 patients (62.6%) who were ineligible for DOAC therapy, the most common reason for disqualification was a diagnosis of VTE (Table).

Discussion

The general results of this quality improvement project showed that implementation of a screening tool designed to identify patients eligible for DOAC therapy did not decrease the average number of Anticoagulation Clinic encounters. Thirty of 82 eligible patients (36.6%) decided to switch to DOAC therapy during the study period. For those 30 patients, there was a statistically significant decrease in the number of individual clinic encounters. This suggests that the screening tool may positively impact Anticoagulation Clinic metrics when evaluating individual patients, potentially increasing clinic appointment availability.

Confounding Factors

Multiple confounding factors may have affected this project’s results. First, Class I recall for point-of-care test strips used by the clinic was mandated by the US Food and Drug Administration on November 1, 2018.5 Before the recall, investigators found that many nontherapeutic INRs using point-of-care testing later showed results that were within the therapeutic INR range using same-day venous blood collection. This may have led to increases in falsely recorded nontherapeutic INRs and lowered TTR report results. Initially, the project was designed to collect monthly clinic encounter data for 3 months following the 8-week screening period; however, data collection was stopped after 2 months because of the test strip recall.

In addition, in early December 2018, all patients were moved from the Anticoagulation Clinic to the Anticoagulation Telephone Clinic that uses venous blood draws and telephone appointments. Data from venous blood draw results had previously been excluded from this project because results were not available on the same day. Patients in this program are contacted by telephone rather than being offered a face-to-face appointment, thus reducing in-clinic encounters.

Another confounding factor was a FVAHCC policy change in August 2018 requiring that any patient initiated on a DOAC make a onetime visit to the Anticoagulation Clinic prior to establishing care with a PACT CPS. Investigators were unable to exclude these patients from monthly encounter data. Some patients transitioning from warfarin to DOAC therapy were required to continue receiving anticoagulation monitoring from the clinic because of limited PACT CPS clinic availability, thus further increasing postscreening encounters.

Health care providers outside of the Anticoagulation Clinic and uninvolved with the quality improvement project also were switching patients from warfarin to DOAC therapies. Although this may have affected encounter data positively, investigators cannot guarantee these patients would have met criteria outlined by the screening tool.

In September 2018 Hurricane Florence disrupted health care delivery during the 8-week screening period. This event disrupted numerous clinic appointments. Although screening of patients was completed during the 8-week screening period, some patients did not switch to DOAC therapies until November 2018.

Secondary Endpoint Results

Promising results can be seen by specifically looking at the secondary endpoint: the number of encounters associated with patients who chose DOAC therapy. There were 107 encounters associated with the 30 patients who switched to a DOAC prior to screening and only 32 associated encounters after screening, a reduction of 70.1%. This suggests that multiple appointment slots were freed when the screening tool led to successful conversion from warfarin to a DOAC. Further assessment is warranted.

Future Project Development

Future areas for quality improvement project development include expanding project criteria to include patients taking warfarin for VTE. Eighty-nine of 137 patients (65%) who were deemed ineligible to switch to DOAC therapy were excluded due to a diagnosis of VTE. There are existing VA/Department of Defense Criteria for Use for DOAC use in VTE recommendations. Straightforward modification of the screening tool could include this patient group and may be especially useful for patients on indefinite warfarin therapy for recurrent VTE who have poor TTR report results.6

Given the number of confounding factors caused by unforeseen changes to the Anticoagulation Clinic workflow, use of the DOAC screening tool was placed on hold at the conclusion of data collection. This limited the ability to analyze encounter data in the months following project conclusion. Future plans include reimplementation of the screening tool with minor adjustments to include patients on warfarin for VTE and patients with a TTR report results above 60%.

Conclusion

This quality improvement project sought to determine the impact of a screening tool on effecting Anticoagulation Clinic encounter metrics. Results of this project show that the screening tool was unsuccessful in reducing the number of overall clinic encounters. Some promise was shown when evaluating clinic encounters for patients who switched anticoagulation therapies. Numerous confounding factors may have contributed to these results.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Fayetteville Veterans Affairs Health Care Center. MCM 11-188 Anticoagulation Management Program. Revised July 11, 2017. [Source not verified.]

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Management Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office. Anticoagulation percent time in therapeutic range reports. https://spsites.cdw.va.gov/sites/PBM_CPPO/Pages/AnticoagulationTTR.aspx. Revised May 24, 2017. Accessed April 20, 2020. [Source not verified.]

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis) and edoxaban (SAVAYSA) criteria for use for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF). https://www.pbm.va.gov/apps/VANationalFormulary/. Updated December 2017. Accessed April 30, 2020.

4. Martin K, Beyer-Westendorf J, Davidson BL, Huisman MV, Sandset PM, Moll S. Use of the direct oral anticoagulants in obese patients: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(6):1308-1313.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Roche Diagnostics recalls CoaguChek XS PT Test Strips due to naccurate INR test results. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/ListofRecalls/ucm624822.htm. Published November 1, 2018. Accessed April 16, 2019.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) (formerly called TSOACs) dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and edoxaban(Savaysa) criteria for use for *treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE)* https://www.pbm.va.gov/apps/VANationalFormulary/. Updated December 2017. Accessed April 30, 2020.

Metrics from 2017 at the Fayetteville Veterans Affairs Heath Care Center (FVAHCC) Anticoagulation Clinic indicate that 43% of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who are prescribed warfarin have difficulty maintaining a therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR). These patients require frequent clinic appointments to adjust their regimens to ensure anticoagulation efficacy. FVAHCC policy requires a patient to return to the clinic for repeat INR evaluation within 5 to 14 days of the visit where INR was outside of the established therapeutic range.1 These frequent INR monitoring appointments increase patient and health care provider burden.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are an alternative to warfarin for patients with AF who require anticoagulation. DOACs, which do not require regular efficacy monitoring, can be beneficial to patients who struggle to maintain a therapeutic INR when taking warfarin. FVAHCC policy regarding warfarin therapy monitoring allows for a maximum of 6 weeks between appointments. This period is often extended to 3 to 6 months for patients on DOACs.1

At FVAHCC, patients prescribed warfarin are managed in a centralized Anticoagulation Clinic led by a clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS). When a patient reports for an appointment, a clinical pharmacy technician performs point-of-care INR testing and asks standardized questions regarding therapy, including an assessment of adherence. The CPS then evaluates the patient’s INR test results, adjusts the dosage of warfarin as indicated, and determines appropriate follow-up.

A patient who is prescribed a DOAC is monitored by a CPS who works within a patient aligned care team (PACT). The PACT, a multidisciplinary team providing health care to veterans, includes physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dieticians, and mental health providers. Each CPS covers 3 or 4 PACTs. These pharmacists monitor all aspects of DOAC therapy at regular intervals, including renal and hepatic function, complete blood counts, medication adherence, and adverse effects.

Clinic and patient INR data are tracked using a time in therapeutic range (TTR) report generated by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The TTR report provides clinical information to enhance patient anticoagulation care.2 The TTR report identifies patients with an active order for warfarin and a diagnosis of AF or venous thromboembolism (VTE) whose INR is within therapeutic range (between 2 and 3) < 60% of the time over the previous 160 days.2 The patient must have had at least 3 INR levels drawn within that time frame for a TTR report calculation.2 The report excludes patients who were first prescribed warfarin within the previous 42 days and those with mechanical heart valves. The TTR report is used by the VA to see concrete facility-level results for quality improvement efforts.2

A quality improvement screening tool was developed to identify patients with AF being treated with warfarin who may appropriately transition to DOAC therapy. Anticoagulation Clinic patients were eligible for further evaluation if they had a TTR report level of < 60% and were prescribed indefinite warfarin therapy for AF.

The national VA goal is to have patient TTR report levels read > 60%. Therefore, the primary objective of this project was to improve Anticoagulation Clinic TTR metrics by targeting patients with TTR levels below the national goal.2

Patients who were successfully converted from warfarin to a DOAC were no longer included in Anticoagulation Clinic metrics and instead were followed by a PACT CPS. Thus, it was hypothesized that the average number of monthly Anticoagulation Clinic encounters would decrease on successful implementation of the screening tool. A secondary endpoint of the study evaluated the change in the total number of encounters of those who converted from warfarin to a DOAC.

Fewer clinic encounters could increase time available for the CPS to incorporate other initiatives into workflow and could increase clinic availability for newly referred veterans.

Methods

As this undertaking was considered to be a quality improvement project, institutional review board approval was not required. During an 8-week screening period (August to September 2018), the DOAC screening tool was implemented into the Anticoagulation Clinic workflow. This screening tool (Figure 1) was established based on VA Pharmacy Benefit Management (PBM) Service’s Criteria for Use for Stroke Prevention in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation, a national set of standards used to determine appropriate candidates for DOAC therapy.3

Exclusion criteria included patients with INR goals < 2 or > 3, patients with a diagnosis of VTE, and patients with weight > 120 kg. Patients with a diagnosis of VTE were excluded due to the variability in therapy duration. Weight cutoffs were based on recommendations by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Due to a lack of available data, it was suggested that clinical judgment be used in patients whose weight was > 120 kg.4

During the screening period, weekly TTR reports identified patients in the clinic who had TTR < 60%. When a patient with a TTR report results of < 60% also had a scheduled appointment within a week, a CPS then further reviewed patient eligibility using the DOAC screening tool. On arrival for an appointment, the eligible patient was counseled on DOAC medications and the differences between warfarin and DOACs, including monitoring requirements. Patients had the option to switch to DOAC therapy or remain on warfarin.

The change in the average number of monthly Anticoagulation Clinic encounters for 3 months prior to the screening period (May to July 2018) and 2 months following screening (October to November 2018) was evaluated to measure the impact of the DOAC screening tool. The total number of encounters in the clinic was assessed using the monthly VA reports and were averaged for each period. Then data from the 2 periods were compared.

The monthly encounter reports, a data tool that monitors the number of unique visits per veteran each calendar month, also were used to generate a secondary endpoint showing the number of encounters in the Anticoagulation Clinic associated with patients who switched to a DOAC, including visits prior to changing therapy, and before and after the screening period.

Student’s t test was used to compare the change in encounter frequency before and after screening tool implementation for both primary and secondary endpoints. α was defined as .05 a priori. Continuous data were presented as means and standard deviations. Data were calculated with Microsoft Excel 2016.

Results

For the 3 months before the 8-week screening period, an average of 476 Anticoagulation Clinic encounters per month were documented. Two months of data following the screening period averaged 546 encounters per month. There were an average of 70 additional encounters per month after screening tool implementation (P = .15), reflecting the study’s primary objective.

A total of 219 patients in the Anticoagulation Clinic were identified as having a TTR report results of < 60% during the 8-week screening period (Figure 2). Eighty-two of those patients (37.4%) were considered eligible to switch from warfarin to DOAC therapy. Thirty of those eligible patients (13.7%) switched to a DOAC. A total of 107 clinic encounters (22.5%) was associated with these 30 patients prior to screening and 32 associated encounters (5.9%) following screening (P = .01). Of the remaining 137 patients (62.6%) who were ineligible for DOAC therapy, the most common reason for disqualification was a diagnosis of VTE (Table).

Discussion

The general results of this quality improvement project showed that implementation of a screening tool designed to identify patients eligible for DOAC therapy did not decrease the average number of Anticoagulation Clinic encounters. Thirty of 82 eligible patients (36.6%) decided to switch to DOAC therapy during the study period. For those 30 patients, there was a statistically significant decrease in the number of individual clinic encounters. This suggests that the screening tool may positively impact Anticoagulation Clinic metrics when evaluating individual patients, potentially increasing clinic appointment availability.

Confounding Factors

Multiple confounding factors may have affected this project’s results. First, Class I recall for point-of-care test strips used by the clinic was mandated by the US Food and Drug Administration on November 1, 2018.5 Before the recall, investigators found that many nontherapeutic INRs using point-of-care testing later showed results that were within the therapeutic INR range using same-day venous blood collection. This may have led to increases in falsely recorded nontherapeutic INRs and lowered TTR report results. Initially, the project was designed to collect monthly clinic encounter data for 3 months following the 8-week screening period; however, data collection was stopped after 2 months because of the test strip recall.

In addition, in early December 2018, all patients were moved from the Anticoagulation Clinic to the Anticoagulation Telephone Clinic that uses venous blood draws and telephone appointments. Data from venous blood draw results had previously been excluded from this project because results were not available on the same day. Patients in this program are contacted by telephone rather than being offered a face-to-face appointment, thus reducing in-clinic encounters.

Another confounding factor was a FVAHCC policy change in August 2018 requiring that any patient initiated on a DOAC make a onetime visit to the Anticoagulation Clinic prior to establishing care with a PACT CPS. Investigators were unable to exclude these patients from monthly encounter data. Some patients transitioning from warfarin to DOAC therapy were required to continue receiving anticoagulation monitoring from the clinic because of limited PACT CPS clinic availability, thus further increasing postscreening encounters.

Health care providers outside of the Anticoagulation Clinic and uninvolved with the quality improvement project also were switching patients from warfarin to DOAC therapies. Although this may have affected encounter data positively, investigators cannot guarantee these patients would have met criteria outlined by the screening tool.

In September 2018 Hurricane Florence disrupted health care delivery during the 8-week screening period. This event disrupted numerous clinic appointments. Although screening of patients was completed during the 8-week screening period, some patients did not switch to DOAC therapies until November 2018.

Secondary Endpoint Results

Promising results can be seen by specifically looking at the secondary endpoint: the number of encounters associated with patients who chose DOAC therapy. There were 107 encounters associated with the 30 patients who switched to a DOAC prior to screening and only 32 associated encounters after screening, a reduction of 70.1%. This suggests that multiple appointment slots were freed when the screening tool led to successful conversion from warfarin to a DOAC. Further assessment is warranted.

Future Project Development

Future areas for quality improvement project development include expanding project criteria to include patients taking warfarin for VTE. Eighty-nine of 137 patients (65%) who were deemed ineligible to switch to DOAC therapy were excluded due to a diagnosis of VTE. There are existing VA/Department of Defense Criteria for Use for DOAC use in VTE recommendations. Straightforward modification of the screening tool could include this patient group and may be especially useful for patients on indefinite warfarin therapy for recurrent VTE who have poor TTR report results.6

Given the number of confounding factors caused by unforeseen changes to the Anticoagulation Clinic workflow, use of the DOAC screening tool was placed on hold at the conclusion of data collection. This limited the ability to analyze encounter data in the months following project conclusion. Future plans include reimplementation of the screening tool with minor adjustments to include patients on warfarin for VTE and patients with a TTR report results above 60%.

Conclusion

This quality improvement project sought to determine the impact of a screening tool on effecting Anticoagulation Clinic encounter metrics. Results of this project show that the screening tool was unsuccessful in reducing the number of overall clinic encounters. Some promise was shown when evaluating clinic encounters for patients who switched anticoagulation therapies. Numerous confounding factors may have contributed to these results.

Metrics from 2017 at the Fayetteville Veterans Affairs Heath Care Center (FVAHCC) Anticoagulation Clinic indicate that 43% of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who are prescribed warfarin have difficulty maintaining a therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR). These patients require frequent clinic appointments to adjust their regimens to ensure anticoagulation efficacy. FVAHCC policy requires a patient to return to the clinic for repeat INR evaluation within 5 to 14 days of the visit where INR was outside of the established therapeutic range.1 These frequent INR monitoring appointments increase patient and health care provider burden.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are an alternative to warfarin for patients with AF who require anticoagulation. DOACs, which do not require regular efficacy monitoring, can be beneficial to patients who struggle to maintain a therapeutic INR when taking warfarin. FVAHCC policy regarding warfarin therapy monitoring allows for a maximum of 6 weeks between appointments. This period is often extended to 3 to 6 months for patients on DOACs.1

At FVAHCC, patients prescribed warfarin are managed in a centralized Anticoagulation Clinic led by a clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS). When a patient reports for an appointment, a clinical pharmacy technician performs point-of-care INR testing and asks standardized questions regarding therapy, including an assessment of adherence. The CPS then evaluates the patient’s INR test results, adjusts the dosage of warfarin as indicated, and determines appropriate follow-up.

A patient who is prescribed a DOAC is monitored by a CPS who works within a patient aligned care team (PACT). The PACT, a multidisciplinary team providing health care to veterans, includes physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dieticians, and mental health providers. Each CPS covers 3 or 4 PACTs. These pharmacists monitor all aspects of DOAC therapy at regular intervals, including renal and hepatic function, complete blood counts, medication adherence, and adverse effects.

Clinic and patient INR data are tracked using a time in therapeutic range (TTR) report generated by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The TTR report provides clinical information to enhance patient anticoagulation care.2 The TTR report identifies patients with an active order for warfarin and a diagnosis of AF or venous thromboembolism (VTE) whose INR is within therapeutic range (between 2 and 3) < 60% of the time over the previous 160 days.2 The patient must have had at least 3 INR levels drawn within that time frame for a TTR report calculation.2 The report excludes patients who were first prescribed warfarin within the previous 42 days and those with mechanical heart valves. The TTR report is used by the VA to see concrete facility-level results for quality improvement efforts.2

A quality improvement screening tool was developed to identify patients with AF being treated with warfarin who may appropriately transition to DOAC therapy. Anticoagulation Clinic patients were eligible for further evaluation if they had a TTR report level of < 60% and were prescribed indefinite warfarin therapy for AF.

The national VA goal is to have patient TTR report levels read > 60%. Therefore, the primary objective of this project was to improve Anticoagulation Clinic TTR metrics by targeting patients with TTR levels below the national goal.2

Patients who were successfully converted from warfarin to a DOAC were no longer included in Anticoagulation Clinic metrics and instead were followed by a PACT CPS. Thus, it was hypothesized that the average number of monthly Anticoagulation Clinic encounters would decrease on successful implementation of the screening tool. A secondary endpoint of the study evaluated the change in the total number of encounters of those who converted from warfarin to a DOAC.

Fewer clinic encounters could increase time available for the CPS to incorporate other initiatives into workflow and could increase clinic availability for newly referred veterans.

Methods

As this undertaking was considered to be a quality improvement project, institutional review board approval was not required. During an 8-week screening period (August to September 2018), the DOAC screening tool was implemented into the Anticoagulation Clinic workflow. This screening tool (Figure 1) was established based on VA Pharmacy Benefit Management (PBM) Service’s Criteria for Use for Stroke Prevention in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation, a national set of standards used to determine appropriate candidates for DOAC therapy.3

Exclusion criteria included patients with INR goals < 2 or > 3, patients with a diagnosis of VTE, and patients with weight > 120 kg. Patients with a diagnosis of VTE were excluded due to the variability in therapy duration. Weight cutoffs were based on recommendations by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Due to a lack of available data, it was suggested that clinical judgment be used in patients whose weight was > 120 kg.4

During the screening period, weekly TTR reports identified patients in the clinic who had TTR < 60%. When a patient with a TTR report results of < 60% also had a scheduled appointment within a week, a CPS then further reviewed patient eligibility using the DOAC screening tool. On arrival for an appointment, the eligible patient was counseled on DOAC medications and the differences between warfarin and DOACs, including monitoring requirements. Patients had the option to switch to DOAC therapy or remain on warfarin.

The change in the average number of monthly Anticoagulation Clinic encounters for 3 months prior to the screening period (May to July 2018) and 2 months following screening (October to November 2018) was evaluated to measure the impact of the DOAC screening tool. The total number of encounters in the clinic was assessed using the monthly VA reports and were averaged for each period. Then data from the 2 periods were compared.

The monthly encounter reports, a data tool that monitors the number of unique visits per veteran each calendar month, also were used to generate a secondary endpoint showing the number of encounters in the Anticoagulation Clinic associated with patients who switched to a DOAC, including visits prior to changing therapy, and before and after the screening period.

Student’s t test was used to compare the change in encounter frequency before and after screening tool implementation for both primary and secondary endpoints. α was defined as .05 a priori. Continuous data were presented as means and standard deviations. Data were calculated with Microsoft Excel 2016.

Results

For the 3 months before the 8-week screening period, an average of 476 Anticoagulation Clinic encounters per month were documented. Two months of data following the screening period averaged 546 encounters per month. There were an average of 70 additional encounters per month after screening tool implementation (P = .15), reflecting the study’s primary objective.

A total of 219 patients in the Anticoagulation Clinic were identified as having a TTR report results of < 60% during the 8-week screening period (Figure 2). Eighty-two of those patients (37.4%) were considered eligible to switch from warfarin to DOAC therapy. Thirty of those eligible patients (13.7%) switched to a DOAC. A total of 107 clinic encounters (22.5%) was associated with these 30 patients prior to screening and 32 associated encounters (5.9%) following screening (P = .01). Of the remaining 137 patients (62.6%) who were ineligible for DOAC therapy, the most common reason for disqualification was a diagnosis of VTE (Table).

Discussion

The general results of this quality improvement project showed that implementation of a screening tool designed to identify patients eligible for DOAC therapy did not decrease the average number of Anticoagulation Clinic encounters. Thirty of 82 eligible patients (36.6%) decided to switch to DOAC therapy during the study period. For those 30 patients, there was a statistically significant decrease in the number of individual clinic encounters. This suggests that the screening tool may positively impact Anticoagulation Clinic metrics when evaluating individual patients, potentially increasing clinic appointment availability.

Confounding Factors

Multiple confounding factors may have affected this project’s results. First, Class I recall for point-of-care test strips used by the clinic was mandated by the US Food and Drug Administration on November 1, 2018.5 Before the recall, investigators found that many nontherapeutic INRs using point-of-care testing later showed results that were within the therapeutic INR range using same-day venous blood collection. This may have led to increases in falsely recorded nontherapeutic INRs and lowered TTR report results. Initially, the project was designed to collect monthly clinic encounter data for 3 months following the 8-week screening period; however, data collection was stopped after 2 months because of the test strip recall.

In addition, in early December 2018, all patients were moved from the Anticoagulation Clinic to the Anticoagulation Telephone Clinic that uses venous blood draws and telephone appointments. Data from venous blood draw results had previously been excluded from this project because results were not available on the same day. Patients in this program are contacted by telephone rather than being offered a face-to-face appointment, thus reducing in-clinic encounters.

Another confounding factor was a FVAHCC policy change in August 2018 requiring that any patient initiated on a DOAC make a onetime visit to the Anticoagulation Clinic prior to establishing care with a PACT CPS. Investigators were unable to exclude these patients from monthly encounter data. Some patients transitioning from warfarin to DOAC therapy were required to continue receiving anticoagulation monitoring from the clinic because of limited PACT CPS clinic availability, thus further increasing postscreening encounters.

Health care providers outside of the Anticoagulation Clinic and uninvolved with the quality improvement project also were switching patients from warfarin to DOAC therapies. Although this may have affected encounter data positively, investigators cannot guarantee these patients would have met criteria outlined by the screening tool.

In September 2018 Hurricane Florence disrupted health care delivery during the 8-week screening period. This event disrupted numerous clinic appointments. Although screening of patients was completed during the 8-week screening period, some patients did not switch to DOAC therapies until November 2018.

Secondary Endpoint Results

Promising results can be seen by specifically looking at the secondary endpoint: the number of encounters associated with patients who chose DOAC therapy. There were 107 encounters associated with the 30 patients who switched to a DOAC prior to screening and only 32 associated encounters after screening, a reduction of 70.1%. This suggests that multiple appointment slots were freed when the screening tool led to successful conversion from warfarin to a DOAC. Further assessment is warranted.

Future Project Development

Future areas for quality improvement project development include expanding project criteria to include patients taking warfarin for VTE. Eighty-nine of 137 patients (65%) who were deemed ineligible to switch to DOAC therapy were excluded due to a diagnosis of VTE. There are existing VA/Department of Defense Criteria for Use for DOAC use in VTE recommendations. Straightforward modification of the screening tool could include this patient group and may be especially useful for patients on indefinite warfarin therapy for recurrent VTE who have poor TTR report results.6

Given the number of confounding factors caused by unforeseen changes to the Anticoagulation Clinic workflow, use of the DOAC screening tool was placed on hold at the conclusion of data collection. This limited the ability to analyze encounter data in the months following project conclusion. Future plans include reimplementation of the screening tool with minor adjustments to include patients on warfarin for VTE and patients with a TTR report results above 60%.

Conclusion

This quality improvement project sought to determine the impact of a screening tool on effecting Anticoagulation Clinic encounter metrics. Results of this project show that the screening tool was unsuccessful in reducing the number of overall clinic encounters. Some promise was shown when evaluating clinic encounters for patients who switched anticoagulation therapies. Numerous confounding factors may have contributed to these results.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Fayetteville Veterans Affairs Health Care Center. MCM 11-188 Anticoagulation Management Program. Revised July 11, 2017. [Source not verified.]

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Management Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office. Anticoagulation percent time in therapeutic range reports. https://spsites.cdw.va.gov/sites/PBM_CPPO/Pages/AnticoagulationTTR.aspx. Revised May 24, 2017. Accessed April 20, 2020. [Source not verified.]

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis) and edoxaban (SAVAYSA) criteria for use for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF). https://www.pbm.va.gov/apps/VANationalFormulary/. Updated December 2017. Accessed April 30, 2020.

4. Martin K, Beyer-Westendorf J, Davidson BL, Huisman MV, Sandset PM, Moll S. Use of the direct oral anticoagulants in obese patients: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(6):1308-1313.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Roche Diagnostics recalls CoaguChek XS PT Test Strips due to naccurate INR test results. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/ListofRecalls/ucm624822.htm. Published November 1, 2018. Accessed April 16, 2019.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) (formerly called TSOACs) dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and edoxaban(Savaysa) criteria for use for *treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE)* https://www.pbm.va.gov/apps/VANationalFormulary/. Updated December 2017. Accessed April 30, 2020.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Fayetteville Veterans Affairs Health Care Center. MCM 11-188 Anticoagulation Management Program. Revised July 11, 2017. [Source not verified.]

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Management Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office. Anticoagulation percent time in therapeutic range reports. https://spsites.cdw.va.gov/sites/PBM_CPPO/Pages/AnticoagulationTTR.aspx. Revised May 24, 2017. Accessed April 20, 2020. [Source not verified.]

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis) and edoxaban (SAVAYSA) criteria for use for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF). https://www.pbm.va.gov/apps/VANationalFormulary/. Updated December 2017. Accessed April 30, 2020.

4. Martin K, Beyer-Westendorf J, Davidson BL, Huisman MV, Sandset PM, Moll S. Use of the direct oral anticoagulants in obese patients: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(6):1308-1313.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Roche Diagnostics recalls CoaguChek XS PT Test Strips due to naccurate INR test results. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/ListofRecalls/ucm624822.htm. Published November 1, 2018. Accessed April 16, 2019.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) (formerly called TSOACs) dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and edoxaban(Savaysa) criteria for use for *treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE)* https://www.pbm.va.gov/apps/VANationalFormulary/. Updated December 2017. Accessed April 30, 2020.

Urgent and Emergent Eye Care Strategies to Protect Against COVID-19

COVID-19 is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and its symptoms range from mild to severe respiratory illness, fever, cough, fatigue, and shortness of breath.1 Diarrhea is common early on with infection and loss of taste and smell have also been reported.1 Follicular conjunctivitis has also been reported, either as an early sign of infection or during hospitalization for severe COVID-19 disease.2-4 The incubation period of COVID-19 falls within 2 to 14 days according to the CDC.5

It has been confirmed that COVID-19 is transmitted through both respiratory droplets and direct contact. Another possible route of viral transmission is entry through aerosolized droplets into the tears, which then pass through the nasolacrimal ducts and into the respiratory tract.6

Preparations Prior to Office Visit

It is essential for the eye care provider to prioritize patient care in order of absolute necessity, such as sudden vision loss, sudden onset flashes and floaters, and eye trauma. In cases of potentially sight threatening pathology, it is in the best interest of the patient to conduct a face-to-face appointment. Therefore, it is important to implement new guidelines and protocols as we continue to see these patients (Figure 1).

Prior to the patient entering the medical facility, measures should be implemented to minimize exposure risk. This can be done over the telephone or at vehicle entrance screening stations. The triage technician answering the telephone should have a script of questions to ask. The patient should be instructed to come into the office alone unless, for physical or mental reasons, a caregiver is required.

SARS-CoV-2 Screening Questions

Preparedness through risk mitigation strategies are recommended with a targeted questionnaire and noncontact temperature check at the clinic or hospital entrance. Below are some general questions to further triage patients exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

- Do you have fever or any respiratory symptoms?

- Do you have new or worsening cough or shortness of breath?

- Do you have flulike symptoms?

- Have you been in close contact with someone, including health care workers, confirmed to have the COVID-19?

If the patient answers yes to any of the above questions, the CDC urges health care providers to immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department.1,2 In regions currently managing significant outbreaks of COVID-19, the AAO recommends that eye care providers assume that any patient could be infected with SARS-CoV-2 and to proceed accordingly.2 If urgent eye care is needed, a referral call should be made to a hospital or center equipped to deal with COVID-19 and urgent eye conditions. When calling the referral center, ensure adequate staffing and space and relay all pertinent information along with receiving approval from the treating physician.

Face-to-Face Office Visits

Once it has been determined that it is in the best interest of the patient to be seen in a face-to-face visit, the patient should be instructed to call the office when they arrive in the parking lot. The CDC recommends limiting points of entry upon arrival and during the visit.1 As soon as an examination lane is ready, the patient can then be messaged to come into the office and escorted into the examination room.

An urgent or emergent ophthalmic examination for a patient with no respiratory symptoms, no fever, and no COVID-19 risk factors should include proper hand hygiene, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and proper disinfection. Several studies have documented SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic and presymptomatic patients, making PPE of the up most importance.2,7,8 PPE should include mask, face shield, and gloves. Currently, there are national and international shortages on PPE and a heightened topic of discussion concerning mask use, effectiveness with extended wear, and reuse. Please refer to the CDC and AAO websites for up-to-date guidelines (Table).1,2 According to the CDC, N95 respirators are restricted to those performing or present for an aerosol-generating procedure.9

It is recommended that the eye care provider should only perform necessary tests and procedures. Noncontact tonometry should be avoided, as this might cause aerosolization of virus particles. The close proximity between eye care providers and their patients during slit-lamp examination may require further precautions to lower the risk of transmission via droplets or through hand to eye contact. The patient should be advised not to speak during the examination portion and the AAO also recommends a surgical mask or cloth face covering for the patient.2 An additional protective device that may be used during the slit-lamp exam is a breath shield or a barrier shield (Figures 2 and 3).2 Some manufacturers are offering clinicians free slit-lamp breath shields online.

Infection Prevention and Control Measures

Last, once the patient leaves the examination room, it should be properly disinfected. A disinfection checklist may be made to ensure uniform systematic cleaning. Alcohol and bleach-based disinfectants commonly used in health care settings are likely very effective against virus particles that cause COVID-19.10 During the disinfection process, gloves should be worn and careful attention paid to the contact time. Contact time is the amount of time the surface should appear visibly wet for proper disinfection. For example, Metrex CaviWipes have a recommended contact time of 3 minutes; however, this varies depending on type of virus and formulation, check labels or manufacturers’ websites for further directions.10 Also, the US Environmental Protection Agency has a database search available for disinfectants that meet their criteria for use against SARS-CoV-2.11

In an ever-changing environment, we offer this article to help equip providers to deliver the best possible patient care when face-to-face encounters are necessary. Currently nonurgent eye care follow-up visits are being conducted by telephone or video clinics. It is our goal to inform fellow practitioners on options and strategies to elevate the safety of staff and patients while minimizing the risk of exposure.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): for healthcare professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/index.html. Updated April 7, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

2. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Important coronavirus context for ophthalmologists. https://www.aao.org/headline/alert-important-coronavirus-context. Updated April 12, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. Zhou Y, Zeng Y, Tong Y, Chen CZ. Ophthalmologic evidence against the interpersonal transmission of 2019 novel coronavirus through conjunctiva [preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.11.20021956. Published February 12, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

4. Lu CW, Liu XF, Jia ZF. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. Lancet. 2020; 395(10224):e39.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptoms of coronavirus. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Updated March 20, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

6. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMc2004973. [Published online ahead of print, March 17, 2020].

7. Kimball A, Hatfield KM, Arons M, et al. Asymptomatic and Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-Infections in Residents of a Long-Term Care Skilled Nursing Facility - King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):377-381.

8. Li R, Pei S, Chen B, et al. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 16]. Science. 2020; eabb3221.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html. Updated April 9, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cleaning and disinfection for households interim recommendations for U.S. households with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cleaning-disinfection.html. Updated March 28, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

11. US Environmental Protection Agency. Pesticide registration: List N: disinfectants for use against SARS-CoV-2. https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2. Updated April 10, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

COVID-19 is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and its symptoms range from mild to severe respiratory illness, fever, cough, fatigue, and shortness of breath.1 Diarrhea is common early on with infection and loss of taste and smell have also been reported.1 Follicular conjunctivitis has also been reported, either as an early sign of infection or during hospitalization for severe COVID-19 disease.2-4 The incubation period of COVID-19 falls within 2 to 14 days according to the CDC.5

It has been confirmed that COVID-19 is transmitted through both respiratory droplets and direct contact. Another possible route of viral transmission is entry through aerosolized droplets into the tears, which then pass through the nasolacrimal ducts and into the respiratory tract.6

Preparations Prior to Office Visit

It is essential for the eye care provider to prioritize patient care in order of absolute necessity, such as sudden vision loss, sudden onset flashes and floaters, and eye trauma. In cases of potentially sight threatening pathology, it is in the best interest of the patient to conduct a face-to-face appointment. Therefore, it is important to implement new guidelines and protocols as we continue to see these patients (Figure 1).

Prior to the patient entering the medical facility, measures should be implemented to minimize exposure risk. This can be done over the telephone or at vehicle entrance screening stations. The triage technician answering the telephone should have a script of questions to ask. The patient should be instructed to come into the office alone unless, for physical or mental reasons, a caregiver is required.

SARS-CoV-2 Screening Questions

Preparedness through risk mitigation strategies are recommended with a targeted questionnaire and noncontact temperature check at the clinic or hospital entrance. Below are some general questions to further triage patients exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

- Do you have fever or any respiratory symptoms?

- Do you have new or worsening cough or shortness of breath?

- Do you have flulike symptoms?

- Have you been in close contact with someone, including health care workers, confirmed to have the COVID-19?

If the patient answers yes to any of the above questions, the CDC urges health care providers to immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department.1,2 In regions currently managing significant outbreaks of COVID-19, the AAO recommends that eye care providers assume that any patient could be infected with SARS-CoV-2 and to proceed accordingly.2 If urgent eye care is needed, a referral call should be made to a hospital or center equipped to deal with COVID-19 and urgent eye conditions. When calling the referral center, ensure adequate staffing and space and relay all pertinent information along with receiving approval from the treating physician.

Face-to-Face Office Visits

Once it has been determined that it is in the best interest of the patient to be seen in a face-to-face visit, the patient should be instructed to call the office when they arrive in the parking lot. The CDC recommends limiting points of entry upon arrival and during the visit.1 As soon as an examination lane is ready, the patient can then be messaged to come into the office and escorted into the examination room.

An urgent or emergent ophthalmic examination for a patient with no respiratory symptoms, no fever, and no COVID-19 risk factors should include proper hand hygiene, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and proper disinfection. Several studies have documented SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic and presymptomatic patients, making PPE of the up most importance.2,7,8 PPE should include mask, face shield, and gloves. Currently, there are national and international shortages on PPE and a heightened topic of discussion concerning mask use, effectiveness with extended wear, and reuse. Please refer to the CDC and AAO websites for up-to-date guidelines (Table).1,2 According to the CDC, N95 respirators are restricted to those performing or present for an aerosol-generating procedure.9

It is recommended that the eye care provider should only perform necessary tests and procedures. Noncontact tonometry should be avoided, as this might cause aerosolization of virus particles. The close proximity between eye care providers and their patients during slit-lamp examination may require further precautions to lower the risk of transmission via droplets or through hand to eye contact. The patient should be advised not to speak during the examination portion and the AAO also recommends a surgical mask or cloth face covering for the patient.2 An additional protective device that may be used during the slit-lamp exam is a breath shield or a barrier shield (Figures 2 and 3).2 Some manufacturers are offering clinicians free slit-lamp breath shields online.

Infection Prevention and Control Measures

Last, once the patient leaves the examination room, it should be properly disinfected. A disinfection checklist may be made to ensure uniform systematic cleaning. Alcohol and bleach-based disinfectants commonly used in health care settings are likely very effective against virus particles that cause COVID-19.10 During the disinfection process, gloves should be worn and careful attention paid to the contact time. Contact time is the amount of time the surface should appear visibly wet for proper disinfection. For example, Metrex CaviWipes have a recommended contact time of 3 minutes; however, this varies depending on type of virus and formulation, check labels or manufacturers’ websites for further directions.10 Also, the US Environmental Protection Agency has a database search available for disinfectants that meet their criteria for use against SARS-CoV-2.11

In an ever-changing environment, we offer this article to help equip providers to deliver the best possible patient care when face-to-face encounters are necessary. Currently nonurgent eye care follow-up visits are being conducted by telephone or video clinics. It is our goal to inform fellow practitioners on options and strategies to elevate the safety of staff and patients while minimizing the risk of exposure.

COVID-19 is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and its symptoms range from mild to severe respiratory illness, fever, cough, fatigue, and shortness of breath.1 Diarrhea is common early on with infection and loss of taste and smell have also been reported.1 Follicular conjunctivitis has also been reported, either as an early sign of infection or during hospitalization for severe COVID-19 disease.2-4 The incubation period of COVID-19 falls within 2 to 14 days according to the CDC.5

It has been confirmed that COVID-19 is transmitted through both respiratory droplets and direct contact. Another possible route of viral transmission is entry through aerosolized droplets into the tears, which then pass through the nasolacrimal ducts and into the respiratory tract.6

Preparations Prior to Office Visit

It is essential for the eye care provider to prioritize patient care in order of absolute necessity, such as sudden vision loss, sudden onset flashes and floaters, and eye trauma. In cases of potentially sight threatening pathology, it is in the best interest of the patient to conduct a face-to-face appointment. Therefore, it is important to implement new guidelines and protocols as we continue to see these patients (Figure 1).

Prior to the patient entering the medical facility, measures should be implemented to minimize exposure risk. This can be done over the telephone or at vehicle entrance screening stations. The triage technician answering the telephone should have a script of questions to ask. The patient should be instructed to come into the office alone unless, for physical or mental reasons, a caregiver is required.

SARS-CoV-2 Screening Questions

Preparedness through risk mitigation strategies are recommended with a targeted questionnaire and noncontact temperature check at the clinic or hospital entrance. Below are some general questions to further triage patients exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

- Do you have fever or any respiratory symptoms?

- Do you have new or worsening cough or shortness of breath?

- Do you have flulike symptoms?

- Have you been in close contact with someone, including health care workers, confirmed to have the COVID-19?

If the patient answers yes to any of the above questions, the CDC urges health care providers to immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department.1,2 In regions currently managing significant outbreaks of COVID-19, the AAO recommends that eye care providers assume that any patient could be infected with SARS-CoV-2 and to proceed accordingly.2 If urgent eye care is needed, a referral call should be made to a hospital or center equipped to deal with COVID-19 and urgent eye conditions. When calling the referral center, ensure adequate staffing and space and relay all pertinent information along with receiving approval from the treating physician.

Face-to-Face Office Visits

Once it has been determined that it is in the best interest of the patient to be seen in a face-to-face visit, the patient should be instructed to call the office when they arrive in the parking lot. The CDC recommends limiting points of entry upon arrival and during the visit.1 As soon as an examination lane is ready, the patient can then be messaged to come into the office and escorted into the examination room.

An urgent or emergent ophthalmic examination for a patient with no respiratory symptoms, no fever, and no COVID-19 risk factors should include proper hand hygiene, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and proper disinfection. Several studies have documented SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic and presymptomatic patients, making PPE of the up most importance.2,7,8 PPE should include mask, face shield, and gloves. Currently, there are national and international shortages on PPE and a heightened topic of discussion concerning mask use, effectiveness with extended wear, and reuse. Please refer to the CDC and AAO websites for up-to-date guidelines (Table).1,2 According to the CDC, N95 respirators are restricted to those performing or present for an aerosol-generating procedure.9

It is recommended that the eye care provider should only perform necessary tests and procedures. Noncontact tonometry should be avoided, as this might cause aerosolization of virus particles. The close proximity between eye care providers and their patients during slit-lamp examination may require further precautions to lower the risk of transmission via droplets or through hand to eye contact. The patient should be advised not to speak during the examination portion and the AAO also recommends a surgical mask or cloth face covering for the patient.2 An additional protective device that may be used during the slit-lamp exam is a breath shield or a barrier shield (Figures 2 and 3).2 Some manufacturers are offering clinicians free slit-lamp breath shields online.

Infection Prevention and Control Measures

Last, once the patient leaves the examination room, it should be properly disinfected. A disinfection checklist may be made to ensure uniform systematic cleaning. Alcohol and bleach-based disinfectants commonly used in health care settings are likely very effective against virus particles that cause COVID-19.10 During the disinfection process, gloves should be worn and careful attention paid to the contact time. Contact time is the amount of time the surface should appear visibly wet for proper disinfection. For example, Metrex CaviWipes have a recommended contact time of 3 minutes; however, this varies depending on type of virus and formulation, check labels or manufacturers’ websites for further directions.10 Also, the US Environmental Protection Agency has a database search available for disinfectants that meet their criteria for use against SARS-CoV-2.11

In an ever-changing environment, we offer this article to help equip providers to deliver the best possible patient care when face-to-face encounters are necessary. Currently nonurgent eye care follow-up visits are being conducted by telephone or video clinics. It is our goal to inform fellow practitioners on options and strategies to elevate the safety of staff and patients while minimizing the risk of exposure.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): for healthcare professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/index.html. Updated April 7, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

2. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Important coronavirus context for ophthalmologists. https://www.aao.org/headline/alert-important-coronavirus-context. Updated April 12, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. Zhou Y, Zeng Y, Tong Y, Chen CZ. Ophthalmologic evidence against the interpersonal transmission of 2019 novel coronavirus through conjunctiva [preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.11.20021956. Published February 12, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

4. Lu CW, Liu XF, Jia ZF. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. Lancet. 2020; 395(10224):e39.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptoms of coronavirus. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Updated March 20, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

6. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMc2004973. [Published online ahead of print, March 17, 2020].

7. Kimball A, Hatfield KM, Arons M, et al. Asymptomatic and Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-Infections in Residents of a Long-Term Care Skilled Nursing Facility - King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):377-381.

8. Li R, Pei S, Chen B, et al. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 16]. Science. 2020; eabb3221.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html. Updated April 9, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cleaning and disinfection for households interim recommendations for U.S. households with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cleaning-disinfection.html. Updated March 28, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

11. US Environmental Protection Agency. Pesticide registration: List N: disinfectants for use against SARS-CoV-2. https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2. Updated April 10, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): for healthcare professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/index.html. Updated April 7, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

2. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Important coronavirus context for ophthalmologists. https://www.aao.org/headline/alert-important-coronavirus-context. Updated April 12, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. Zhou Y, Zeng Y, Tong Y, Chen CZ. Ophthalmologic evidence against the interpersonal transmission of 2019 novel coronavirus through conjunctiva [preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.11.20021956. Published February 12, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

4. Lu CW, Liu XF, Jia ZF. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. Lancet. 2020; 395(10224):e39.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptoms of coronavirus. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Updated March 20, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

6. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMc2004973. [Published online ahead of print, March 17, 2020].

7. Kimball A, Hatfield KM, Arons M, et al. Asymptomatic and Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-Infections in Residents of a Long-Term Care Skilled Nursing Facility - King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):377-381.

8. Li R, Pei S, Chen B, et al. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 16]. Science. 2020; eabb3221.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html. Updated April 9, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cleaning and disinfection for households interim recommendations for U.S. households with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cleaning-disinfection.html. Updated March 28, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

11. US Environmental Protection Agency. Pesticide registration: List N: disinfectants for use against SARS-CoV-2. https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2. Updated April 10, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020.

The Duty to Care and Its Exceptions in a Pandemic

As of April 9, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 9,282 health care providers in the US had contracted COVID-19, and 27 had died of the virus.2 Medscape reports the toll as much higher. Thousands more nurses, doctors, epidemiologists, social workers, physician assistants, dentists, pharmacists, and other health care workers from Italy, China, and dozens of other countries have died fighting this plague.3

The truth is no one knows how many health care workers are actually sick or even have died. State and federal governments have not been routinely and specifically tracking that data, making these already grim statistics likely a gross underestimation.4 While not all of these health care providers were exposed to COVID-19 in the line of duty, many were, and many more will be as the pandemic subsides in one epicenter only to erupt in another, and smolders for months until a vaccine quenches it.

Each of those lost lives of promise had a story of hard work and sacrifice to become a health care professional, of friends and family who loved and cared for them when ill, who need and grieve for them, now gone far too soon. Nor should we forget to mourn all of the administrative professionals, the line and support staff of health care facilities, who also perished fighting the pestilence. It is fitting then, that this second editorial in my pledge to write each month about COVID-19 until the pandemic ends, be about the duty to care and its limits.

The duty to care is among the most fundamental and ancient ethical obligations of health care providers. It is included even in modern codes of ethics like that of the American Medical Association and American Nurses Association. The obligation to not abandon patients is even more compelling for the Military Health System, Veterans Health Administration (VHA), and the US Public Health Service whose health care mission also is a public trust. The duty is rooted in the fiduciary nature of the health professions in which the interests of the patient should take priority over other considerations, including a risk to their own health and life. Prioritization though has exceptions. Physician and attorney David Orentlicher points out the unconditional obligation that bound physicians in the 14th century Black Death, or the 1918 Spanish influenza, now admits exceptions and qualifications.5

The exception that has become the object of greatest concern to health care workers is personal protective equipment (PPE). In modern public health ethics, health care systems and state and federal governments have a corresponding ethical obligation of reciprocity toward their employees whose work places them at elevated risk of harm—in this case, COVID-19 exposure. The principle of reciprocity encompasses the measures and materials that health care institutions need to provide to health care workers to reasonably minimize the risk of viral transmission. The reasonableness standard does not demand that there be zero risk. It does require that health care workers have adequate and appropriate PPE so that in fulfilling their duty to care they are not exposed to a disproportionate risk.

This last assertion has been the subject of controversy in the media and consternation on the part of health care professionals for several disconcerting reasons. First and foremost, a cascade failure on the part of government and industry has resulted in PPE being the scarcest health care resource in this pandemic.6 The shortage is as serious as that of the life-saving ventilators that are rightly at the center of most crisis standards resource allocation plans.7 Second, the guidance from the CDC and other authoritative sources continues to change. This is, in part, to adjust to the even more rapid pace of knowledge about the virus and its behavior and to adapt to the reality of insufficient PPE.8

Understandably, health care providers, especially those on the frontlines, may lose trust in the scientific experts and the leadership of their institutions, compounding the climate of moral distress in a public health crisis. Health care workers in the community, and even in federal service, have launched socially distanced protests and taken to social media to voice their concern and rally assistance.9,10 In response, VHA Executive-in-Charge Richard Stone, MD, admitted that VHA does have a shortage of PPE in a Washington Post interview.11 He outlined how the organization plans to address staff concerns. The article also reported only a 4% absentee rate of VHA staff as opposed to the 40% that plans predicted was possible. This demonstrates once more the dedication of VHA health care professionals and workers to fulfill their duty to care for veterans even amid fears about inadequate PPE.

In the epigraph, Albert Camus captures the uncertainty and fear that as humans all health care providers experience as they face the unpredictable but very real threat of COVID-19.1 Camus expresses even more strongly the devotion to duty of health care providers to care for vulnerable ill patients in need despite the inherent threat in a highly transmissible and potentially deadly infection that is inextricably linked to that caring. Orentlicher wisely opines that the integrity of the health professions and their respected role in society benefit from a strong duty to care.5 The best way to promote that duty is to do all in our power to protect those who willingly brave the pestilence to treat, and hope and pray someday to cure COVID-19.

1. Camus A. The Plague. Vintage Books: New York; 1948:120.

2. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Characteristics of Health Care Personnel with COVID-19— United States, February 12-April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):477-481.

3. In memoriam: healthcare workers who have died of COVID-19. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/927976. Updated April 21, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2020.

4. Galvin G. The great unknown: how many health care workers have coronavirus? https://www.usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/2020-04-03/how-many-health-care-workers-have-coronavirus. Published April 3, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2020.

5. Orentlicher D. The physician’s duty to treat during pandemics. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(11):1459-1461.

6. Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages—the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. [Published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 25.] N Engl J Med. 2020;10.1056/NEJMp2006141.

7. New York State Task Force on Life and the Law, New York State Department of Health. Ventilator allocation guidelines. https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/task_force/reports_publications/docs/ventilator_guidelines.pdf. Published November 2015. Accessed April 22, 2020.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-2019): Strategies to optimize PPE and equipment. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/index.html. Updated April 3, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2020.

9. Wentling N. ‘It’s out of control’: VA nurses demand more protection against coronavirus. https://www.stripes.com/news/veterans/va-nurses-demand-more-protection-against-coronavirus-1.626910. Updated April 21, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2020.

10. Padilla M. ‘It feels like a war zone’: doctors and nurses plead for masks on social media. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/us/hospitals-coronavirus-ppe-shortage.html. Updated March 22, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2020.

11. Rein L. VA health chief acknowledges a shortage of protective gear for its hospital workers. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/va-health-chief-acknowledges-a-shortage-of-protective-gear-for-its-hospital-workers/2020/04/24/4c1bcd5e-84bf-11ea-ae26-989cfce1c7c7_story.html. Published April 25, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020.