User login

For MD-IQ use only

The SHM 2019 Chapter Excellence Awards

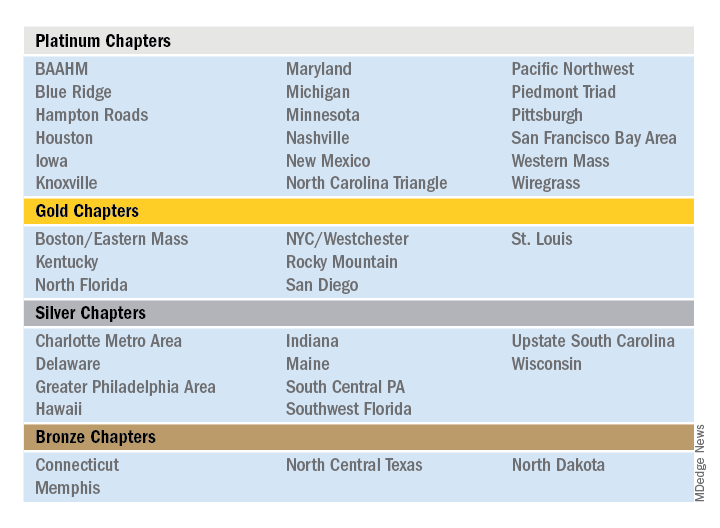

The Society of Hospital Medicine is proud to recognize its chapters for their hard work and dedication in 2019 through Chapter Excellence Awards. Each year, chapters strive to demonstrate growth, sustenance, and innovation within their chapter activities, which are then applauded for their successes throughout the subsequent year. In 2019, a new Bronze category was established, for a total of four Status Awards that chapters can earn.

Please join SHM in congratulating the following chapters on their year of success in 2019!

Outstanding Chapter of the Year

The Outstanding Chapter of the Year Award goes to one chapter who exemplifies high performance, going above and beyond the basic chapter requirements. The recipient of the Outstanding Chapter of the Year Award for 2019 is the Wiregrass Chapter of SHM. The chapter has a strong and engaged leadership which includes representation at all levels of the hospital medicine team, including physician hospitalists, advanced care provider hospitalists, practice administrators, nurses, residents, and medical students.

In the last year, the Wiregrass leadership team has organized programs and events to cater to and engage all the chapter’s members. This includes a variety of innovative ideas that catered toward medical education, health care provider well-being, engagement, mentorship, and community involvement.

The SHM Wiregrass Chapter’s biggest accomplishment in 2019 was the creation of an exchange program for physician and advanced practice provider hospitalists between the SHM New Mexico Chapter and the SHM Wiregrass Chapter. This idea first arose at HM19, where the chapter leaders had met during a networking event and debated the role of clinician wellbeing, quality of medical education, and faculty development to individual hospital medicine group (HMG) practice styles.

Clinician well-being is the prerequisite to the triple aim of improving the health of populations, enhancing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care. Each HMG faces similar challenges but approaches to solving them vary. Professional challenges can affect the well-being of the individual clinicians. Having interinstitutional exchange programs provides a platform to exchange ideas and establish mentors. Also, the quality of medical education is directly linked to the quality of faculty development. Improving the quality of medical education requires a multifaceted approach by highly developed faculty. The complex factors affecting medical education and faculty development are further complicated by geographic location, patient characteristics, and professional growth opportunities. Overcoming these obstacles requires an innovative and collaborative approach. Although faculty exchanges are common in academic medicine, they are not commonly attempted with HMGs.

Hospitalists are responsible for a significant part of inpatient training for residents, medical students, and nurse practitioners/physician assistants (NPs/PAs), but their faculty training can vary based on location. Being a young specialty, only 2 decades old, hospital medicine is still evolving and incorporating NP/PA and physician hospitalists in varied practice models. Each HMG addresses common obstacles differently based on their culture and practice styles. The chapter leaders determined an exchange program would afford the opportunity for visiting faculty members to experience these differences. This emphasized the role and importance of exchanging ideas and contemplated a solution to benefit more practicing hospitalists.

The chapter leaders researched the characteristics of individual academic HMGs and structured a tailored faculty exchange involving physicians and NPs/PAs. During the exchange program planning, the visiting faculty itinerary was tailored to a well-planned agenda for 1 week, with separate tracks for physicians and NPs/PAs giving increased access to their individual peer practice styles. Additionally, the visiting faculty had meetings and discussions with HMG and hospital leadership, to specifically address each visiting faculty institution’s challenges. The overall goal of this exchange program was to promote cross-institutional collaboration, increase engagement, improve medical education through faculty development, and improve the quality of care. The focus of the exchange program was to share ideas and innovation and learn the approaches to unique challenges at each institution. Out of this also came collaboration and mentoring opportunities.

The evaluation process of the exchange involved interviews, a survey, and the establishment of shared QI projects in mutual areas of challenge. The survey provided feedback, lessons learned from the exchange, and areas to be improved. Collaborative QI projects currently underway as a result of the exchange include paging etiquette, quality of sleep for hospitalized patients, and onboarding of NPs/PAs in HMGs.

This innovation addressed faculty development and medical education via clinician well-being. The physician and NP/PA Faculty Exchange was an essential and meaningful innovation that resulted in increased SHM member engagement, cross-institutional collaboration, networking, and mentorship.

Additional projects that the SHM Wiregrass Chapter successfully implemented in 2019 include a “Women in Medicine” event that recognized women physician and advanced practice provider hospitalist leaders, a poster competition that expanded its research, clinical vignettes, and quality categories to include a fourth category of innovation, featuring 75 posters. Additionally, the chapter held a policy meeting with six Alabama state legislators, creating new channels of collaboration between the legislators and the chapter. Lastly, the chapter held a successful community event and launched a mentor program targeting medical students and residents.

Rising Star Chapter

The Rising Star Chapter Award goes to one chapter who has been active for 2 years or less, who in the past 12 months have made improvements to their leadership, stability and growth, and membership. The recipient of the Rising Star Chapter Award for 2019 is the Blue Ridge Chapter of SHM, which has made significant strides to develop since its launch in the fall of 2018. The chapter represents counties in northwest Tennessee, southwest Virginia, and western North Carolina.

The chapter held three meetings in 2019 which were well attended by hospitalists, residents/fellows, administrators, advanced practice providers, and nurses. On average, attendees from five to six different hospitalist groups are represented. The chapter hosted both Dr. Chris Frost, immediate past president of the SHM board of directors, and Dr. Ron Greeno, a past president of the SHM board of directors.

The SHM Blue Ridge Chapter has collaborated with both the ACP Tennessee Chapter and the Healthcare MBA program at Haslam College of Business at the University of Tennessee.

The chapter leadership regularly attends local medical residency programs at noon conferences to attract and recruit young physicians into chapter activities. Overall, the chapter has seen a growth in membership in 2019. The Blue Ridge Chapter is an active, enthusiastic chapter that is rapidly growing and thriving.

Outstanding Membership Recruitment and Retention

The Outstanding Membership Recruitment and Retention Award is a new exemplary award for 2019 that goes to one chapter who has gone above and beyond to implement initiatives to recruit and retain SHM members in their chapter. The recipient of the Outstanding Membership Recruitment and Retention Award for 2019 is the Western Massachusetts Chapter of SHM, which has done outstanding work to recruit and retain the membership. In 2019, the SHM membership in the chapter grew by 24%. The chapter utilized Chapter Development Funds to launch new initiatives to conduct outreach to nonmember hospitalists in the community and invite them to meetings to obtain the SHM experience. Additionally, the chapter encouraged residents to join and get involved by hosting a poster competition.

The Western Massachusetts Chapter focused on being innovative, inclusive, and creative to retain their existing meetings. For example, the chapter hosted a new “Jeopardy Session” event that featured a nontraditional jeopardy game that attracted a large attendance including local residents. Additionally, the chapter insured that all clinical and nonclinical members of the hospital medicine team were included and encouraged to participate in all chapter meetings. Lastly, the chapter launched a local awards program to recognize senior hospitalist and early career hospitalist who contributed to chapter development.

Most Engaged Chapter Leader

The Most Engaged Chapter Leader Award is a new exemplary award for 2019 that goes to one chapter leader or district chair who is either nominated or self-nominated and has demonstrated how they or their nominee has gone above and beyond in the past year to grow and sustain their chapter and/or district and continues to carry out the SHM mission. The recipient of the Most Engaged Chapter Leader Award for 2019 goes to Thérèse Franco, MD, SFHM, president of the Pacific Northwest Chapter.

Dr. Franco has served as the chapter’s president for 2 years and has served on the SHM Chapter Support Committee for 3 years. She has previously participated as a mentor in the glycemic control mentored implementation program, and as chair and cochair of the RIV contest. She continues to review abstracts, volunteer as a judge and offer local education on glycemic control through the Washington State Hospital Association, promoting SHM’s work there. One of Dr. Franco’s core strengths has been effective collaboration with past leaders (such as Rachel Thompson, MD, and Kimberly Bell, MD), future leaders, and other organizations (such as the Washington State Medical Association and the King County Medical Association). Dr. Franco has recruited an outstanding leadership team and new advisory committee for the Pacific Northwest Chapter, resulting a fantastic year of growth, innovation, and development.

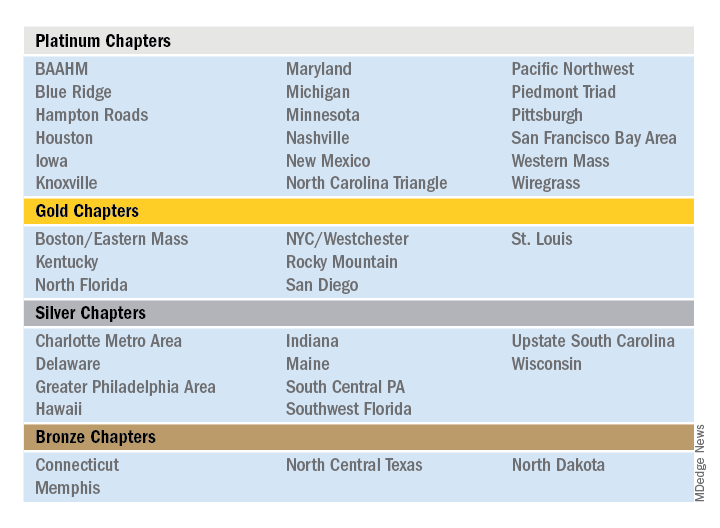

The Society of Hospital Medicine is proud to recognize its chapters for their hard work and dedication in 2019 through Chapter Excellence Awards. Each year, chapters strive to demonstrate growth, sustenance, and innovation within their chapter activities, which are then applauded for their successes throughout the subsequent year. In 2019, a new Bronze category was established, for a total of four Status Awards that chapters can earn.

Please join SHM in congratulating the following chapters on their year of success in 2019!

Outstanding Chapter of the Year

The Outstanding Chapter of the Year Award goes to one chapter who exemplifies high performance, going above and beyond the basic chapter requirements. The recipient of the Outstanding Chapter of the Year Award for 2019 is the Wiregrass Chapter of SHM. The chapter has a strong and engaged leadership which includes representation at all levels of the hospital medicine team, including physician hospitalists, advanced care provider hospitalists, practice administrators, nurses, residents, and medical students.

In the last year, the Wiregrass leadership team has organized programs and events to cater to and engage all the chapter’s members. This includes a variety of innovative ideas that catered toward medical education, health care provider well-being, engagement, mentorship, and community involvement.

The SHM Wiregrass Chapter’s biggest accomplishment in 2019 was the creation of an exchange program for physician and advanced practice provider hospitalists between the SHM New Mexico Chapter and the SHM Wiregrass Chapter. This idea first arose at HM19, where the chapter leaders had met during a networking event and debated the role of clinician wellbeing, quality of medical education, and faculty development to individual hospital medicine group (HMG) practice styles.

Clinician well-being is the prerequisite to the triple aim of improving the health of populations, enhancing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care. Each HMG faces similar challenges but approaches to solving them vary. Professional challenges can affect the well-being of the individual clinicians. Having interinstitutional exchange programs provides a platform to exchange ideas and establish mentors. Also, the quality of medical education is directly linked to the quality of faculty development. Improving the quality of medical education requires a multifaceted approach by highly developed faculty. The complex factors affecting medical education and faculty development are further complicated by geographic location, patient characteristics, and professional growth opportunities. Overcoming these obstacles requires an innovative and collaborative approach. Although faculty exchanges are common in academic medicine, they are not commonly attempted with HMGs.

Hospitalists are responsible for a significant part of inpatient training for residents, medical students, and nurse practitioners/physician assistants (NPs/PAs), but their faculty training can vary based on location. Being a young specialty, only 2 decades old, hospital medicine is still evolving and incorporating NP/PA and physician hospitalists in varied practice models. Each HMG addresses common obstacles differently based on their culture and practice styles. The chapter leaders determined an exchange program would afford the opportunity for visiting faculty members to experience these differences. This emphasized the role and importance of exchanging ideas and contemplated a solution to benefit more practicing hospitalists.

The chapter leaders researched the characteristics of individual academic HMGs and structured a tailored faculty exchange involving physicians and NPs/PAs. During the exchange program planning, the visiting faculty itinerary was tailored to a well-planned agenda for 1 week, with separate tracks for physicians and NPs/PAs giving increased access to their individual peer practice styles. Additionally, the visiting faculty had meetings and discussions with HMG and hospital leadership, to specifically address each visiting faculty institution’s challenges. The overall goal of this exchange program was to promote cross-institutional collaboration, increase engagement, improve medical education through faculty development, and improve the quality of care. The focus of the exchange program was to share ideas and innovation and learn the approaches to unique challenges at each institution. Out of this also came collaboration and mentoring opportunities.

The evaluation process of the exchange involved interviews, a survey, and the establishment of shared QI projects in mutual areas of challenge. The survey provided feedback, lessons learned from the exchange, and areas to be improved. Collaborative QI projects currently underway as a result of the exchange include paging etiquette, quality of sleep for hospitalized patients, and onboarding of NPs/PAs in HMGs.

This innovation addressed faculty development and medical education via clinician well-being. The physician and NP/PA Faculty Exchange was an essential and meaningful innovation that resulted in increased SHM member engagement, cross-institutional collaboration, networking, and mentorship.

Additional projects that the SHM Wiregrass Chapter successfully implemented in 2019 include a “Women in Medicine” event that recognized women physician and advanced practice provider hospitalist leaders, a poster competition that expanded its research, clinical vignettes, and quality categories to include a fourth category of innovation, featuring 75 posters. Additionally, the chapter held a policy meeting with six Alabama state legislators, creating new channels of collaboration between the legislators and the chapter. Lastly, the chapter held a successful community event and launched a mentor program targeting medical students and residents.

Rising Star Chapter

The Rising Star Chapter Award goes to one chapter who has been active for 2 years or less, who in the past 12 months have made improvements to their leadership, stability and growth, and membership. The recipient of the Rising Star Chapter Award for 2019 is the Blue Ridge Chapter of SHM, which has made significant strides to develop since its launch in the fall of 2018. The chapter represents counties in northwest Tennessee, southwest Virginia, and western North Carolina.

The chapter held three meetings in 2019 which were well attended by hospitalists, residents/fellows, administrators, advanced practice providers, and nurses. On average, attendees from five to six different hospitalist groups are represented. The chapter hosted both Dr. Chris Frost, immediate past president of the SHM board of directors, and Dr. Ron Greeno, a past president of the SHM board of directors.

The SHM Blue Ridge Chapter has collaborated with both the ACP Tennessee Chapter and the Healthcare MBA program at Haslam College of Business at the University of Tennessee.

The chapter leadership regularly attends local medical residency programs at noon conferences to attract and recruit young physicians into chapter activities. Overall, the chapter has seen a growth in membership in 2019. The Blue Ridge Chapter is an active, enthusiastic chapter that is rapidly growing and thriving.

Outstanding Membership Recruitment and Retention

The Outstanding Membership Recruitment and Retention Award is a new exemplary award for 2019 that goes to one chapter who has gone above and beyond to implement initiatives to recruit and retain SHM members in their chapter. The recipient of the Outstanding Membership Recruitment and Retention Award for 2019 is the Western Massachusetts Chapter of SHM, which has done outstanding work to recruit and retain the membership. In 2019, the SHM membership in the chapter grew by 24%. The chapter utilized Chapter Development Funds to launch new initiatives to conduct outreach to nonmember hospitalists in the community and invite them to meetings to obtain the SHM experience. Additionally, the chapter encouraged residents to join and get involved by hosting a poster competition.

The Western Massachusetts Chapter focused on being innovative, inclusive, and creative to retain their existing meetings. For example, the chapter hosted a new “Jeopardy Session” event that featured a nontraditional jeopardy game that attracted a large attendance including local residents. Additionally, the chapter insured that all clinical and nonclinical members of the hospital medicine team were included and encouraged to participate in all chapter meetings. Lastly, the chapter launched a local awards program to recognize senior hospitalist and early career hospitalist who contributed to chapter development.

Most Engaged Chapter Leader

The Most Engaged Chapter Leader Award is a new exemplary award for 2019 that goes to one chapter leader or district chair who is either nominated or self-nominated and has demonstrated how they or their nominee has gone above and beyond in the past year to grow and sustain their chapter and/or district and continues to carry out the SHM mission. The recipient of the Most Engaged Chapter Leader Award for 2019 goes to Thérèse Franco, MD, SFHM, president of the Pacific Northwest Chapter.

Dr. Franco has served as the chapter’s president for 2 years and has served on the SHM Chapter Support Committee for 3 years. She has previously participated as a mentor in the glycemic control mentored implementation program, and as chair and cochair of the RIV contest. She continues to review abstracts, volunteer as a judge and offer local education on glycemic control through the Washington State Hospital Association, promoting SHM’s work there. One of Dr. Franco’s core strengths has been effective collaboration with past leaders (such as Rachel Thompson, MD, and Kimberly Bell, MD), future leaders, and other organizations (such as the Washington State Medical Association and the King County Medical Association). Dr. Franco has recruited an outstanding leadership team and new advisory committee for the Pacific Northwest Chapter, resulting a fantastic year of growth, innovation, and development.

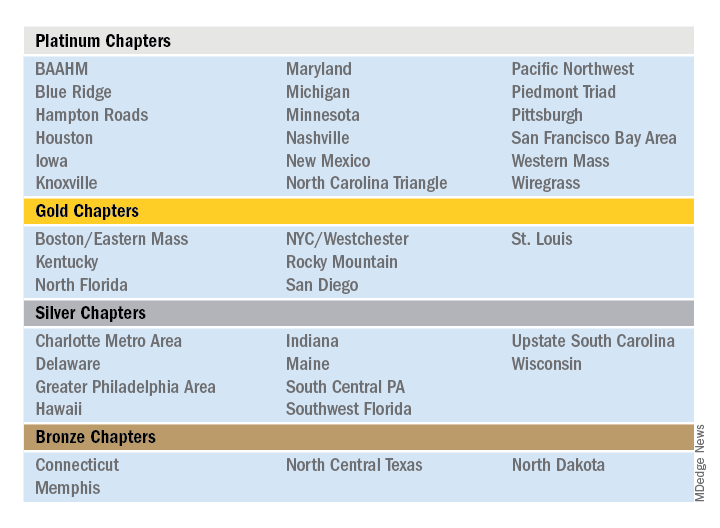

The Society of Hospital Medicine is proud to recognize its chapters for their hard work and dedication in 2019 through Chapter Excellence Awards. Each year, chapters strive to demonstrate growth, sustenance, and innovation within their chapter activities, which are then applauded for their successes throughout the subsequent year. In 2019, a new Bronze category was established, for a total of four Status Awards that chapters can earn.

Please join SHM in congratulating the following chapters on their year of success in 2019!

Outstanding Chapter of the Year

The Outstanding Chapter of the Year Award goes to one chapter who exemplifies high performance, going above and beyond the basic chapter requirements. The recipient of the Outstanding Chapter of the Year Award for 2019 is the Wiregrass Chapter of SHM. The chapter has a strong and engaged leadership which includes representation at all levels of the hospital medicine team, including physician hospitalists, advanced care provider hospitalists, practice administrators, nurses, residents, and medical students.

In the last year, the Wiregrass leadership team has organized programs and events to cater to and engage all the chapter’s members. This includes a variety of innovative ideas that catered toward medical education, health care provider well-being, engagement, mentorship, and community involvement.

The SHM Wiregrass Chapter’s biggest accomplishment in 2019 was the creation of an exchange program for physician and advanced practice provider hospitalists between the SHM New Mexico Chapter and the SHM Wiregrass Chapter. This idea first arose at HM19, where the chapter leaders had met during a networking event and debated the role of clinician wellbeing, quality of medical education, and faculty development to individual hospital medicine group (HMG) practice styles.

Clinician well-being is the prerequisite to the triple aim of improving the health of populations, enhancing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care. Each HMG faces similar challenges but approaches to solving them vary. Professional challenges can affect the well-being of the individual clinicians. Having interinstitutional exchange programs provides a platform to exchange ideas and establish mentors. Also, the quality of medical education is directly linked to the quality of faculty development. Improving the quality of medical education requires a multifaceted approach by highly developed faculty. The complex factors affecting medical education and faculty development are further complicated by geographic location, patient characteristics, and professional growth opportunities. Overcoming these obstacles requires an innovative and collaborative approach. Although faculty exchanges are common in academic medicine, they are not commonly attempted with HMGs.

Hospitalists are responsible for a significant part of inpatient training for residents, medical students, and nurse practitioners/physician assistants (NPs/PAs), but their faculty training can vary based on location. Being a young specialty, only 2 decades old, hospital medicine is still evolving and incorporating NP/PA and physician hospitalists in varied practice models. Each HMG addresses common obstacles differently based on their culture and practice styles. The chapter leaders determined an exchange program would afford the opportunity for visiting faculty members to experience these differences. This emphasized the role and importance of exchanging ideas and contemplated a solution to benefit more practicing hospitalists.

The chapter leaders researched the characteristics of individual academic HMGs and structured a tailored faculty exchange involving physicians and NPs/PAs. During the exchange program planning, the visiting faculty itinerary was tailored to a well-planned agenda for 1 week, with separate tracks for physicians and NPs/PAs giving increased access to their individual peer practice styles. Additionally, the visiting faculty had meetings and discussions with HMG and hospital leadership, to specifically address each visiting faculty institution’s challenges. The overall goal of this exchange program was to promote cross-institutional collaboration, increase engagement, improve medical education through faculty development, and improve the quality of care. The focus of the exchange program was to share ideas and innovation and learn the approaches to unique challenges at each institution. Out of this also came collaboration and mentoring opportunities.

The evaluation process of the exchange involved interviews, a survey, and the establishment of shared QI projects in mutual areas of challenge. The survey provided feedback, lessons learned from the exchange, and areas to be improved. Collaborative QI projects currently underway as a result of the exchange include paging etiquette, quality of sleep for hospitalized patients, and onboarding of NPs/PAs in HMGs.

This innovation addressed faculty development and medical education via clinician well-being. The physician and NP/PA Faculty Exchange was an essential and meaningful innovation that resulted in increased SHM member engagement, cross-institutional collaboration, networking, and mentorship.

Additional projects that the SHM Wiregrass Chapter successfully implemented in 2019 include a “Women in Medicine” event that recognized women physician and advanced practice provider hospitalist leaders, a poster competition that expanded its research, clinical vignettes, and quality categories to include a fourth category of innovation, featuring 75 posters. Additionally, the chapter held a policy meeting with six Alabama state legislators, creating new channels of collaboration between the legislators and the chapter. Lastly, the chapter held a successful community event and launched a mentor program targeting medical students and residents.

Rising Star Chapter

The Rising Star Chapter Award goes to one chapter who has been active for 2 years or less, who in the past 12 months have made improvements to their leadership, stability and growth, and membership. The recipient of the Rising Star Chapter Award for 2019 is the Blue Ridge Chapter of SHM, which has made significant strides to develop since its launch in the fall of 2018. The chapter represents counties in northwest Tennessee, southwest Virginia, and western North Carolina.

The chapter held three meetings in 2019 which were well attended by hospitalists, residents/fellows, administrators, advanced practice providers, and nurses. On average, attendees from five to six different hospitalist groups are represented. The chapter hosted both Dr. Chris Frost, immediate past president of the SHM board of directors, and Dr. Ron Greeno, a past president of the SHM board of directors.

The SHM Blue Ridge Chapter has collaborated with both the ACP Tennessee Chapter and the Healthcare MBA program at Haslam College of Business at the University of Tennessee.

The chapter leadership regularly attends local medical residency programs at noon conferences to attract and recruit young physicians into chapter activities. Overall, the chapter has seen a growth in membership in 2019. The Blue Ridge Chapter is an active, enthusiastic chapter that is rapidly growing and thriving.

Outstanding Membership Recruitment and Retention

The Outstanding Membership Recruitment and Retention Award is a new exemplary award for 2019 that goes to one chapter who has gone above and beyond to implement initiatives to recruit and retain SHM members in their chapter. The recipient of the Outstanding Membership Recruitment and Retention Award for 2019 is the Western Massachusetts Chapter of SHM, which has done outstanding work to recruit and retain the membership. In 2019, the SHM membership in the chapter grew by 24%. The chapter utilized Chapter Development Funds to launch new initiatives to conduct outreach to nonmember hospitalists in the community and invite them to meetings to obtain the SHM experience. Additionally, the chapter encouraged residents to join and get involved by hosting a poster competition.

The Western Massachusetts Chapter focused on being innovative, inclusive, and creative to retain their existing meetings. For example, the chapter hosted a new “Jeopardy Session” event that featured a nontraditional jeopardy game that attracted a large attendance including local residents. Additionally, the chapter insured that all clinical and nonclinical members of the hospital medicine team were included and encouraged to participate in all chapter meetings. Lastly, the chapter launched a local awards program to recognize senior hospitalist and early career hospitalist who contributed to chapter development.

Most Engaged Chapter Leader

The Most Engaged Chapter Leader Award is a new exemplary award for 2019 that goes to one chapter leader or district chair who is either nominated or self-nominated and has demonstrated how they or their nominee has gone above and beyond in the past year to grow and sustain their chapter and/or district and continues to carry out the SHM mission. The recipient of the Most Engaged Chapter Leader Award for 2019 goes to Thérèse Franco, MD, SFHM, president of the Pacific Northwest Chapter.

Dr. Franco has served as the chapter’s president for 2 years and has served on the SHM Chapter Support Committee for 3 years. She has previously participated as a mentor in the glycemic control mentored implementation program, and as chair and cochair of the RIV contest. She continues to review abstracts, volunteer as a judge and offer local education on glycemic control through the Washington State Hospital Association, promoting SHM’s work there. One of Dr. Franco’s core strengths has been effective collaboration with past leaders (such as Rachel Thompson, MD, and Kimberly Bell, MD), future leaders, and other organizations (such as the Washington State Medical Association and the King County Medical Association). Dr. Franco has recruited an outstanding leadership team and new advisory committee for the Pacific Northwest Chapter, resulting a fantastic year of growth, innovation, and development.

COVID-19 exacerbating challenges for Latino patients

Disproportionate burden of pandemic complicates mental health care

Pamela Montano, MD, recalls the recent case of a patient with bipolar II disorder who was improving after treatment with medication and therapy when her life was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The patient, who is Puerto Rican, lost two cousins to the virus, two of her brothers fell ill, and her sister became sick with coronavirus, said Dr. Montano, director of the Latino Bicultural Clinic at Gouverneur Health in New York. The patient was then left to care for her sister’s toddlers along with the patient’s own children, one of whom has special needs.

“After this happened, it increased her anxiety,” Dr. Montano said in an interview. “She’s not sleeping, and she started having panic attacks. My main concern was how to help her cope.”

Across the country, clinicians who treat mental illness and behavioral disorders in Latino patients are facing similar experiences and challenges associated with COVID-19 and the ensuing pandemic response. Current data suggest a disproportionate burden of illness and death from the novel coronavirus among racial and ethnic groups, particularly black and Hispanic patients. The disparities are likely attributable to economic and social conditions more common among such populations, compared with non-Hispanic whites, in addition to isolation from resources, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A recent New York City Department of Health study based on data that were available in late April found that deaths from COVID-19 were substantially higher for black and Hispanic/Latino patients than for white and Asian patients. The death rate per 100,000 population was 209.4 for blacks, 195.3 for Hispanics/Latinos, 107.7 for whites, and 90.8 for Asians.

“The COVID pandemic has highlighted the structural inequities that affect the Latino population [both] immigrant and nonimmigrant,” said Dr. Montano, a board member of the American Society of Hispanic Psychiatry and the officer of infrastructure and advocacy for the Hispanic Caucus of the American Psychiatric Association. “This includes income inequality, poor nutrition, history of trauma and discrimination, employment issues, quality education, access to technology, and overall access to appropriate cultural linguistic health care.”

Navigating challenges

For mental health professionals treating Latino patients, COVID-19 and the pandemic response have generated a range of treatment obstacles.

The transition to telehealth for example, has not been easy for some patients, said Jacqueline Posada, MD, consultation-liaison psychiatry fellow at the Inova Fairfax Hospital–George Washington University program in Falls Church, Va., and an APA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration minority fellow. Some patients lack Internet services, others forget virtual visits, and some do not have working phones, she said.

“I’ve had to be very flexible,” she said in an interview. “Ideally, I’d love to see everybody via video chat, but a lot of people either don’t have a stable Internet connection or Internet, so I meet the patient where they are. Whatever they have available, that’s what I’m going to use. If they don’t answer on the first call, I will call again at least three to five times in the first 15 minutes to make sure I’m giving them an opportunity to pick up the phone.”

In addition, Dr. Posada has encountered disconnected phones when calling patients for appointments. In such cases, Dr. Posada contacts the patient’s primary care physician to relay medication recommendations in case the patient resurfaces at the clinic.

In other instances, patients are not familiar with video technology, or they must travel to a friend or neighbor’s house to access the technology, said Hector Colón-Rivera, MD, an addiction psychiatrist and medical director of the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha Behavioral Health Program, a nonprofit organization based in the Philadelphia area. Telehealth visits frequently include appearances by children, family members, barking dogs, and other distractions, said Dr. Colón-Rivera, president of the APA Hispanic Caucus.

“We’re seeing things that we didn’t used to see when they came to our office – for good or for bad,” said Dr. Colón-Rivera, an attending telemedicine physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “It could be a good chance to meet our patient in a different way. Of course, it creates different stressors. If you have five kids on top of you and you’re the only one at home, it’s hard to do therapy.”

Psychiatrists are also seeing prior health conditions in patients exacerbated by COVID-19 fears and new health problems arising from the current pandemic environment. Dr. Posada recalls a patient whom she successfully treated for premenstrual dysphoric disorder who recently descended into severe clinical depression. The patient, from Colombia, was attending school in the United States on a student visa and supporting herself through child care jobs.

“So much of her depression was based on her social circumstance,” Dr. Posada said. “She had lost her job, her sister had lost her job so they were scraping by on her sister’s husband’s income, and the thing that brought her joy, which was going to school and studying so she could make a different life for herself than what her parents had in Colombia, also seemed like it was out of reach.”

Dr. Colón-Rivera recently received a call from a hospital where one of his patients was admitted after becoming delusional and psychotic. The patient was correctly taking medication prescribed by Dr. Colón-Rivera, but her diabetes had become uncontrolled because she was unable to reach her primary care doctor and couldn’t access the pharmacy. Her blood sugar level became elevated, leading to the delusions.

“A patient that was perfectly stable now is unstable,” he said. “Her diet has not been good enough through the pandemic, exacerbating her diabetes. She was admitted to the hospital for delirium.

Compounding of traumas

For many Latino patients, the adverse impacts of the pandemic comes on top of multiple prior traumas, such as violence exposures, discrimination, and economic issues, said Lisa Fortuna, MD, MPH, MDiv, chief of psychiatry and vice chair at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. A 2017 analysis found that nearly four in five Latino youth face at least one traumatic childhood experience, like poverty or abuse, and that about 29% of Latino youth experience four or more of these traumas.

Immigrants in particular, may have faced trauma in their home country and/or immigration trauma, Dr. Fortuna added. A 2013 study on immigrant Latino adolescents for example, found that 29% of foreign-born adolescents and 34% of foreign-born parents experienced trauma during the migration process (Int Migr Rev. 2013 Dec;47(4):10).

“All of these things are cumulative,” Dr. Fortuna said. “Then when you’re hit with a pandemic, all of the disparities that you already have and all the stress that you already have are compounded. This is for the kids, too, who have been exposed to a lot of stressors and now maybe have family members that have been ill or have died. All of these things definitely put people at risk for increased depression [and] the worsening of any preexisting posttraumatic stress disorder. We’ve seen this in previous disasters, and I expect that’s what we’re going to see more of with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

At the same time, a central cultural value of many Latinos is family unity, Dr. Montano said, a foundation that is now being strained by social distancing and severed connections.

“This has separated many families,” she said. “There has been a lot of loneliness and grief.”

Mistrust and fear toward the government, public agencies, and even the health system itself act as further hurdles for some Latinos in the face of COVID-19. In areas with large immigrant populations such as San Francisco, Dr. Fortuna noted, it’s not uncommon for undocumented patients to avoid accessing medical care and social services, or visiting emergency departments for needed care for fear of drawing attention to themselves or possible detainment.

“The fact that so many people showed up at our hospital so ill and ended up in the ICU – that could be a combination of factors. Because the population has high rates of diabetes and hypertension, that might have put people at increased risk for severe illness,” she said. “But some people may have been holding out for care because they wanted to avoid being in places out of fear of immigration scrutiny.”

Overcoming language barriers

Compounding the challenging pandemic landscape for Latino patients is the fact that many state resources about COVID-19 have not been translated to Spanish, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. He was troubled recently when he went to several state websites and found limited to no information in Spanish about the coronavirus. Some data about COVID-19 from the federal government were not translated to Spanish until officials received pushback, he added. Even now, press releases and other information disseminated by the federal government about the virus appear to be translated by an automated service – and lack sense and context.

The state agencies in Pennsylvania have been alerted to the absence of Spanish information, but change has been slow, he noted.

“In Philadelphia, 23% speaks a language other than English,” he said. “So we missed a lot of critical information that could have helped to avoid spreading the illness and access support.”

Dr. Fortuna said that California has done better with providing COVID-19–related information in Spanish, compared with some other states, but misinformation about the virus and lingering myths have still been a problem among the Latino community. The University of California, San Francisco, recently launched a Latino Task Force resource website for the Latino community that includes information in English, Spanish, and Yucatec Maya about COVID-19, health and wellness tips, and resources for various assistance needs.

The concerning lack of COVID-19 information translated to Spanish led Dr. Montano to start a Facebook page in Spanish about mental health tips and guidance for managing COVID-19–related issues. She and her team of clinicians share information, videos, relaxation exercises, and community resources on the page, among other posts. “There is also general info and recommendations about COVID-19 that I think can be useful for the community,” she said. “The idea is that patients, the general community, and providers can have share information, hope messages, and ask questions in Spanish.”

Feeling ‘helpless’

A central part of caring for Latino patients during the COVID-19 crisis has been referring them to outside agencies and social services, psychiatrists say. But finding the right resources amid a pandemic and ensuring that patients connect with the correct aid has been an uphill battle.

“We sometimes feel like our hands are tied,” Dr. Colón-Rivera said. “Sometimes, we need to call a place to bring food. Some of the state agencies and nonprofits don’t have delivery systems, so the patient has to go pick up for food or medication. Some of our patients don’t want to go outside. Some do not have cars.”

As a clinician, it can be easy to feel helpless when trying to navigate new challenges posed by the pandemic in addition to other longstanding barriers, Dr. Posada said.

“Already, mental health disorders are so influenced by social situations like poverty, job insecurity, or family issues, and now it just seems those obstacles are even more insurmountable,” she said. “At the end of the day, I can feel like: ‘Did I make a difference?’ That’s a big struggle.”

Dr. Montano’s team, which includes psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, have come to rely on virtual debriefings to vent, express frustrations, and support one another, she said. She also recently joined a virtual mind-body skills group as a participant.

“I recognize the importance of getting additional support and ways to alleviate burnout,” she said. “We need to take care of ourselves or we won’t be able to help others.”

Focusing on resilience during the current crisis can be beneficial for both patients and providers in coping and drawing strength, Dr. Posada said.

“When it comes to fostering resilience during times of hardship, I think it’s most helpful to reflect on what skills or attributes have helped during past crises and apply those now – whether it’s turning to comfort from close relationships, looking to religion and spirituality, practicing self-care like rest or exercise, or really tapping into one’s purpose and reason for practicing psychiatry and being a physician,” she said. “The same advice goes for clinicians: We’ve all been through hard times in the past, it’s part of the human condition and we’ve also witnessed a lot of suffering in our patients, so now is the time to practice those skills that have gotten us through hard times in the past.”

Learning lessons from COVID-19

Despite the challenges with moving to telehealth, Dr. Fortuna said the tool has proved beneficial overall for mental health care. For Dr. Fortuna’s team for example, telehealth by phone has decreased the no-show rate, compared with clinic visits, and improved care access.

“We need to figure out how to maintain that,” she said. “If we can build ways for equity and access to Internet, especially equipment, I think that’s going to help.”

In addition, more data are needed about the ways in which COVID-19 is affecting Latino patients, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. Mortality statistics have been published, but information is needed about the rates of infection and manifestation of illness.

Most importantly, the COVID-19 crisis has emphasized the critical need to address and improve the underlying inequity issues among Latino patients, psychiatrists say.

“We really need to think about how there can be partnerships, in terms of community-based Latino business and leaders, multisector resources, trying to think about how we can improve conditions both work and safety for Latinos,” Dr. Fortuna said. “How can schools get support in integrating mental health and support for families, especially now after COVID-19? And really looking at some of these underlying inequities that are the underpinnings of why people were at risk for the disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Disproportionate burden of pandemic complicates mental health care

Disproportionate burden of pandemic complicates mental health care

Pamela Montano, MD, recalls the recent case of a patient with bipolar II disorder who was improving after treatment with medication and therapy when her life was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The patient, who is Puerto Rican, lost two cousins to the virus, two of her brothers fell ill, and her sister became sick with coronavirus, said Dr. Montano, director of the Latino Bicultural Clinic at Gouverneur Health in New York. The patient was then left to care for her sister’s toddlers along with the patient’s own children, one of whom has special needs.

“After this happened, it increased her anxiety,” Dr. Montano said in an interview. “She’s not sleeping, and she started having panic attacks. My main concern was how to help her cope.”

Across the country, clinicians who treat mental illness and behavioral disorders in Latino patients are facing similar experiences and challenges associated with COVID-19 and the ensuing pandemic response. Current data suggest a disproportionate burden of illness and death from the novel coronavirus among racial and ethnic groups, particularly black and Hispanic patients. The disparities are likely attributable to economic and social conditions more common among such populations, compared with non-Hispanic whites, in addition to isolation from resources, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A recent New York City Department of Health study based on data that were available in late April found that deaths from COVID-19 were substantially higher for black and Hispanic/Latino patients than for white and Asian patients. The death rate per 100,000 population was 209.4 for blacks, 195.3 for Hispanics/Latinos, 107.7 for whites, and 90.8 for Asians.

“The COVID pandemic has highlighted the structural inequities that affect the Latino population [both] immigrant and nonimmigrant,” said Dr. Montano, a board member of the American Society of Hispanic Psychiatry and the officer of infrastructure and advocacy for the Hispanic Caucus of the American Psychiatric Association. “This includes income inequality, poor nutrition, history of trauma and discrimination, employment issues, quality education, access to technology, and overall access to appropriate cultural linguistic health care.”

Navigating challenges

For mental health professionals treating Latino patients, COVID-19 and the pandemic response have generated a range of treatment obstacles.

The transition to telehealth for example, has not been easy for some patients, said Jacqueline Posada, MD, consultation-liaison psychiatry fellow at the Inova Fairfax Hospital–George Washington University program in Falls Church, Va., and an APA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration minority fellow. Some patients lack Internet services, others forget virtual visits, and some do not have working phones, she said.

“I’ve had to be very flexible,” she said in an interview. “Ideally, I’d love to see everybody via video chat, but a lot of people either don’t have a stable Internet connection or Internet, so I meet the patient where they are. Whatever they have available, that’s what I’m going to use. If they don’t answer on the first call, I will call again at least three to five times in the first 15 minutes to make sure I’m giving them an opportunity to pick up the phone.”

In addition, Dr. Posada has encountered disconnected phones when calling patients for appointments. In such cases, Dr. Posada contacts the patient’s primary care physician to relay medication recommendations in case the patient resurfaces at the clinic.

In other instances, patients are not familiar with video technology, or they must travel to a friend or neighbor’s house to access the technology, said Hector Colón-Rivera, MD, an addiction psychiatrist and medical director of the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha Behavioral Health Program, a nonprofit organization based in the Philadelphia area. Telehealth visits frequently include appearances by children, family members, barking dogs, and other distractions, said Dr. Colón-Rivera, president of the APA Hispanic Caucus.

“We’re seeing things that we didn’t used to see when they came to our office – for good or for bad,” said Dr. Colón-Rivera, an attending telemedicine physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “It could be a good chance to meet our patient in a different way. Of course, it creates different stressors. If you have five kids on top of you and you’re the only one at home, it’s hard to do therapy.”

Psychiatrists are also seeing prior health conditions in patients exacerbated by COVID-19 fears and new health problems arising from the current pandemic environment. Dr. Posada recalls a patient whom she successfully treated for premenstrual dysphoric disorder who recently descended into severe clinical depression. The patient, from Colombia, was attending school in the United States on a student visa and supporting herself through child care jobs.

“So much of her depression was based on her social circumstance,” Dr. Posada said. “She had lost her job, her sister had lost her job so they were scraping by on her sister’s husband’s income, and the thing that brought her joy, which was going to school and studying so she could make a different life for herself than what her parents had in Colombia, also seemed like it was out of reach.”

Dr. Colón-Rivera recently received a call from a hospital where one of his patients was admitted after becoming delusional and psychotic. The patient was correctly taking medication prescribed by Dr. Colón-Rivera, but her diabetes had become uncontrolled because she was unable to reach her primary care doctor and couldn’t access the pharmacy. Her blood sugar level became elevated, leading to the delusions.

“A patient that was perfectly stable now is unstable,” he said. “Her diet has not been good enough through the pandemic, exacerbating her diabetes. She was admitted to the hospital for delirium.

Compounding of traumas

For many Latino patients, the adverse impacts of the pandemic comes on top of multiple prior traumas, such as violence exposures, discrimination, and economic issues, said Lisa Fortuna, MD, MPH, MDiv, chief of psychiatry and vice chair at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. A 2017 analysis found that nearly four in five Latino youth face at least one traumatic childhood experience, like poverty or abuse, and that about 29% of Latino youth experience four or more of these traumas.

Immigrants in particular, may have faced trauma in their home country and/or immigration trauma, Dr. Fortuna added. A 2013 study on immigrant Latino adolescents for example, found that 29% of foreign-born adolescents and 34% of foreign-born parents experienced trauma during the migration process (Int Migr Rev. 2013 Dec;47(4):10).

“All of these things are cumulative,” Dr. Fortuna said. “Then when you’re hit with a pandemic, all of the disparities that you already have and all the stress that you already have are compounded. This is for the kids, too, who have been exposed to a lot of stressors and now maybe have family members that have been ill or have died. All of these things definitely put people at risk for increased depression [and] the worsening of any preexisting posttraumatic stress disorder. We’ve seen this in previous disasters, and I expect that’s what we’re going to see more of with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

At the same time, a central cultural value of many Latinos is family unity, Dr. Montano said, a foundation that is now being strained by social distancing and severed connections.

“This has separated many families,” she said. “There has been a lot of loneliness and grief.”

Mistrust and fear toward the government, public agencies, and even the health system itself act as further hurdles for some Latinos in the face of COVID-19. In areas with large immigrant populations such as San Francisco, Dr. Fortuna noted, it’s not uncommon for undocumented patients to avoid accessing medical care and social services, or visiting emergency departments for needed care for fear of drawing attention to themselves or possible detainment.

“The fact that so many people showed up at our hospital so ill and ended up in the ICU – that could be a combination of factors. Because the population has high rates of diabetes and hypertension, that might have put people at increased risk for severe illness,” she said. “But some people may have been holding out for care because they wanted to avoid being in places out of fear of immigration scrutiny.”

Overcoming language barriers

Compounding the challenging pandemic landscape for Latino patients is the fact that many state resources about COVID-19 have not been translated to Spanish, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. He was troubled recently when he went to several state websites and found limited to no information in Spanish about the coronavirus. Some data about COVID-19 from the federal government were not translated to Spanish until officials received pushback, he added. Even now, press releases and other information disseminated by the federal government about the virus appear to be translated by an automated service – and lack sense and context.

The state agencies in Pennsylvania have been alerted to the absence of Spanish information, but change has been slow, he noted.

“In Philadelphia, 23% speaks a language other than English,” he said. “So we missed a lot of critical information that could have helped to avoid spreading the illness and access support.”

Dr. Fortuna said that California has done better with providing COVID-19–related information in Spanish, compared with some other states, but misinformation about the virus and lingering myths have still been a problem among the Latino community. The University of California, San Francisco, recently launched a Latino Task Force resource website for the Latino community that includes information in English, Spanish, and Yucatec Maya about COVID-19, health and wellness tips, and resources for various assistance needs.

The concerning lack of COVID-19 information translated to Spanish led Dr. Montano to start a Facebook page in Spanish about mental health tips and guidance for managing COVID-19–related issues. She and her team of clinicians share information, videos, relaxation exercises, and community resources on the page, among other posts. “There is also general info and recommendations about COVID-19 that I think can be useful for the community,” she said. “The idea is that patients, the general community, and providers can have share information, hope messages, and ask questions in Spanish.”

Feeling ‘helpless’

A central part of caring for Latino patients during the COVID-19 crisis has been referring them to outside agencies and social services, psychiatrists say. But finding the right resources amid a pandemic and ensuring that patients connect with the correct aid has been an uphill battle.

“We sometimes feel like our hands are tied,” Dr. Colón-Rivera said. “Sometimes, we need to call a place to bring food. Some of the state agencies and nonprofits don’t have delivery systems, so the patient has to go pick up for food or medication. Some of our patients don’t want to go outside. Some do not have cars.”

As a clinician, it can be easy to feel helpless when trying to navigate new challenges posed by the pandemic in addition to other longstanding barriers, Dr. Posada said.

“Already, mental health disorders are so influenced by social situations like poverty, job insecurity, or family issues, and now it just seems those obstacles are even more insurmountable,” she said. “At the end of the day, I can feel like: ‘Did I make a difference?’ That’s a big struggle.”

Dr. Montano’s team, which includes psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, have come to rely on virtual debriefings to vent, express frustrations, and support one another, she said. She also recently joined a virtual mind-body skills group as a participant.

“I recognize the importance of getting additional support and ways to alleviate burnout,” she said. “We need to take care of ourselves or we won’t be able to help others.”

Focusing on resilience during the current crisis can be beneficial for both patients and providers in coping and drawing strength, Dr. Posada said.

“When it comes to fostering resilience during times of hardship, I think it’s most helpful to reflect on what skills or attributes have helped during past crises and apply those now – whether it’s turning to comfort from close relationships, looking to religion and spirituality, practicing self-care like rest or exercise, or really tapping into one’s purpose and reason for practicing psychiatry and being a physician,” she said. “The same advice goes for clinicians: We’ve all been through hard times in the past, it’s part of the human condition and we’ve also witnessed a lot of suffering in our patients, so now is the time to practice those skills that have gotten us through hard times in the past.”

Learning lessons from COVID-19

Despite the challenges with moving to telehealth, Dr. Fortuna said the tool has proved beneficial overall for mental health care. For Dr. Fortuna’s team for example, telehealth by phone has decreased the no-show rate, compared with clinic visits, and improved care access.

“We need to figure out how to maintain that,” she said. “If we can build ways for equity and access to Internet, especially equipment, I think that’s going to help.”

In addition, more data are needed about the ways in which COVID-19 is affecting Latino patients, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. Mortality statistics have been published, but information is needed about the rates of infection and manifestation of illness.

Most importantly, the COVID-19 crisis has emphasized the critical need to address and improve the underlying inequity issues among Latino patients, psychiatrists say.

“We really need to think about how there can be partnerships, in terms of community-based Latino business and leaders, multisector resources, trying to think about how we can improve conditions both work and safety for Latinos,” Dr. Fortuna said. “How can schools get support in integrating mental health and support for families, especially now after COVID-19? And really looking at some of these underlying inequities that are the underpinnings of why people were at risk for the disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Pamela Montano, MD, recalls the recent case of a patient with bipolar II disorder who was improving after treatment with medication and therapy when her life was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The patient, who is Puerto Rican, lost two cousins to the virus, two of her brothers fell ill, and her sister became sick with coronavirus, said Dr. Montano, director of the Latino Bicultural Clinic at Gouverneur Health in New York. The patient was then left to care for her sister’s toddlers along with the patient’s own children, one of whom has special needs.

“After this happened, it increased her anxiety,” Dr. Montano said in an interview. “She’s not sleeping, and she started having panic attacks. My main concern was how to help her cope.”

Across the country, clinicians who treat mental illness and behavioral disorders in Latino patients are facing similar experiences and challenges associated with COVID-19 and the ensuing pandemic response. Current data suggest a disproportionate burden of illness and death from the novel coronavirus among racial and ethnic groups, particularly black and Hispanic patients. The disparities are likely attributable to economic and social conditions more common among such populations, compared with non-Hispanic whites, in addition to isolation from resources, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A recent New York City Department of Health study based on data that were available in late April found that deaths from COVID-19 were substantially higher for black and Hispanic/Latino patients than for white and Asian patients. The death rate per 100,000 population was 209.4 for blacks, 195.3 for Hispanics/Latinos, 107.7 for whites, and 90.8 for Asians.

“The COVID pandemic has highlighted the structural inequities that affect the Latino population [both] immigrant and nonimmigrant,” said Dr. Montano, a board member of the American Society of Hispanic Psychiatry and the officer of infrastructure and advocacy for the Hispanic Caucus of the American Psychiatric Association. “This includes income inequality, poor nutrition, history of trauma and discrimination, employment issues, quality education, access to technology, and overall access to appropriate cultural linguistic health care.”

Navigating challenges

For mental health professionals treating Latino patients, COVID-19 and the pandemic response have generated a range of treatment obstacles.

The transition to telehealth for example, has not been easy for some patients, said Jacqueline Posada, MD, consultation-liaison psychiatry fellow at the Inova Fairfax Hospital–George Washington University program in Falls Church, Va., and an APA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration minority fellow. Some patients lack Internet services, others forget virtual visits, and some do not have working phones, she said.

“I’ve had to be very flexible,” she said in an interview. “Ideally, I’d love to see everybody via video chat, but a lot of people either don’t have a stable Internet connection or Internet, so I meet the patient where they are. Whatever they have available, that’s what I’m going to use. If they don’t answer on the first call, I will call again at least three to five times in the first 15 minutes to make sure I’m giving them an opportunity to pick up the phone.”

In addition, Dr. Posada has encountered disconnected phones when calling patients for appointments. In such cases, Dr. Posada contacts the patient’s primary care physician to relay medication recommendations in case the patient resurfaces at the clinic.

In other instances, patients are not familiar with video technology, or they must travel to a friend or neighbor’s house to access the technology, said Hector Colón-Rivera, MD, an addiction psychiatrist and medical director of the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha Behavioral Health Program, a nonprofit organization based in the Philadelphia area. Telehealth visits frequently include appearances by children, family members, barking dogs, and other distractions, said Dr. Colón-Rivera, president of the APA Hispanic Caucus.

“We’re seeing things that we didn’t used to see when they came to our office – for good or for bad,” said Dr. Colón-Rivera, an attending telemedicine physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “It could be a good chance to meet our patient in a different way. Of course, it creates different stressors. If you have five kids on top of you and you’re the only one at home, it’s hard to do therapy.”

Psychiatrists are also seeing prior health conditions in patients exacerbated by COVID-19 fears and new health problems arising from the current pandemic environment. Dr. Posada recalls a patient whom she successfully treated for premenstrual dysphoric disorder who recently descended into severe clinical depression. The patient, from Colombia, was attending school in the United States on a student visa and supporting herself through child care jobs.

“So much of her depression was based on her social circumstance,” Dr. Posada said. “She had lost her job, her sister had lost her job so they were scraping by on her sister’s husband’s income, and the thing that brought her joy, which was going to school and studying so she could make a different life for herself than what her parents had in Colombia, also seemed like it was out of reach.”

Dr. Colón-Rivera recently received a call from a hospital where one of his patients was admitted after becoming delusional and psychotic. The patient was correctly taking medication prescribed by Dr. Colón-Rivera, but her diabetes had become uncontrolled because she was unable to reach her primary care doctor and couldn’t access the pharmacy. Her blood sugar level became elevated, leading to the delusions.

“A patient that was perfectly stable now is unstable,” he said. “Her diet has not been good enough through the pandemic, exacerbating her diabetes. She was admitted to the hospital for delirium.

Compounding of traumas

For many Latino patients, the adverse impacts of the pandemic comes on top of multiple prior traumas, such as violence exposures, discrimination, and economic issues, said Lisa Fortuna, MD, MPH, MDiv, chief of psychiatry and vice chair at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. A 2017 analysis found that nearly four in five Latino youth face at least one traumatic childhood experience, like poverty or abuse, and that about 29% of Latino youth experience four or more of these traumas.

Immigrants in particular, may have faced trauma in their home country and/or immigration trauma, Dr. Fortuna added. A 2013 study on immigrant Latino adolescents for example, found that 29% of foreign-born adolescents and 34% of foreign-born parents experienced trauma during the migration process (Int Migr Rev. 2013 Dec;47(4):10).

“All of these things are cumulative,” Dr. Fortuna said. “Then when you’re hit with a pandemic, all of the disparities that you already have and all the stress that you already have are compounded. This is for the kids, too, who have been exposed to a lot of stressors and now maybe have family members that have been ill or have died. All of these things definitely put people at risk for increased depression [and] the worsening of any preexisting posttraumatic stress disorder. We’ve seen this in previous disasters, and I expect that’s what we’re going to see more of with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

At the same time, a central cultural value of many Latinos is family unity, Dr. Montano said, a foundation that is now being strained by social distancing and severed connections.

“This has separated many families,” she said. “There has been a lot of loneliness and grief.”

Mistrust and fear toward the government, public agencies, and even the health system itself act as further hurdles for some Latinos in the face of COVID-19. In areas with large immigrant populations such as San Francisco, Dr. Fortuna noted, it’s not uncommon for undocumented patients to avoid accessing medical care and social services, or visiting emergency departments for needed care for fear of drawing attention to themselves or possible detainment.

“The fact that so many people showed up at our hospital so ill and ended up in the ICU – that could be a combination of factors. Because the population has high rates of diabetes and hypertension, that might have put people at increased risk for severe illness,” she said. “But some people may have been holding out for care because they wanted to avoid being in places out of fear of immigration scrutiny.”

Overcoming language barriers

Compounding the challenging pandemic landscape for Latino patients is the fact that many state resources about COVID-19 have not been translated to Spanish, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. He was troubled recently when he went to several state websites and found limited to no information in Spanish about the coronavirus. Some data about COVID-19 from the federal government were not translated to Spanish until officials received pushback, he added. Even now, press releases and other information disseminated by the federal government about the virus appear to be translated by an automated service – and lack sense and context.

The state agencies in Pennsylvania have been alerted to the absence of Spanish information, but change has been slow, he noted.

“In Philadelphia, 23% speaks a language other than English,” he said. “So we missed a lot of critical information that could have helped to avoid spreading the illness and access support.”

Dr. Fortuna said that California has done better with providing COVID-19–related information in Spanish, compared with some other states, but misinformation about the virus and lingering myths have still been a problem among the Latino community. The University of California, San Francisco, recently launched a Latino Task Force resource website for the Latino community that includes information in English, Spanish, and Yucatec Maya about COVID-19, health and wellness tips, and resources for various assistance needs.

The concerning lack of COVID-19 information translated to Spanish led Dr. Montano to start a Facebook page in Spanish about mental health tips and guidance for managing COVID-19–related issues. She and her team of clinicians share information, videos, relaxation exercises, and community resources on the page, among other posts. “There is also general info and recommendations about COVID-19 that I think can be useful for the community,” she said. “The idea is that patients, the general community, and providers can have share information, hope messages, and ask questions in Spanish.”

Feeling ‘helpless’

A central part of caring for Latino patients during the COVID-19 crisis has been referring them to outside agencies and social services, psychiatrists say. But finding the right resources amid a pandemic and ensuring that patients connect with the correct aid has been an uphill battle.

“We sometimes feel like our hands are tied,” Dr. Colón-Rivera said. “Sometimes, we need to call a place to bring food. Some of the state agencies and nonprofits don’t have delivery systems, so the patient has to go pick up for food or medication. Some of our patients don’t want to go outside. Some do not have cars.”

As a clinician, it can be easy to feel helpless when trying to navigate new challenges posed by the pandemic in addition to other longstanding barriers, Dr. Posada said.

“Already, mental health disorders are so influenced by social situations like poverty, job insecurity, or family issues, and now it just seems those obstacles are even more insurmountable,” she said. “At the end of the day, I can feel like: ‘Did I make a difference?’ That’s a big struggle.”

Dr. Montano’s team, which includes psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, have come to rely on virtual debriefings to vent, express frustrations, and support one another, she said. She also recently joined a virtual mind-body skills group as a participant.

“I recognize the importance of getting additional support and ways to alleviate burnout,” she said. “We need to take care of ourselves or we won’t be able to help others.”

Focusing on resilience during the current crisis can be beneficial for both patients and providers in coping and drawing strength, Dr. Posada said.

“When it comes to fostering resilience during times of hardship, I think it’s most helpful to reflect on what skills or attributes have helped during past crises and apply those now – whether it’s turning to comfort from close relationships, looking to religion and spirituality, practicing self-care like rest or exercise, or really tapping into one’s purpose and reason for practicing psychiatry and being a physician,” she said. “The same advice goes for clinicians: We’ve all been through hard times in the past, it’s part of the human condition and we’ve also witnessed a lot of suffering in our patients, so now is the time to practice those skills that have gotten us through hard times in the past.”

Learning lessons from COVID-19

Despite the challenges with moving to telehealth, Dr. Fortuna said the tool has proved beneficial overall for mental health care. For Dr. Fortuna’s team for example, telehealth by phone has decreased the no-show rate, compared with clinic visits, and improved care access.

“We need to figure out how to maintain that,” she said. “If we can build ways for equity and access to Internet, especially equipment, I think that’s going to help.”

In addition, more data are needed about the ways in which COVID-19 is affecting Latino patients, Dr. Colón-Rivera said. Mortality statistics have been published, but information is needed about the rates of infection and manifestation of illness.

Most importantly, the COVID-19 crisis has emphasized the critical need to address and improve the underlying inequity issues among Latino patients, psychiatrists say.

“We really need to think about how there can be partnerships, in terms of community-based Latino business and leaders, multisector resources, trying to think about how we can improve conditions both work and safety for Latinos,” Dr. Fortuna said. “How can schools get support in integrating mental health and support for families, especially now after COVID-19? And really looking at some of these underlying inequities that are the underpinnings of why people were at risk for the disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Psoriasis patients with mental illness report lower satisfaction with physicians

according to a retrospective analysis of survey data.

The findings highlight the importance of clinicians being supportive and adaptable in their communication style when interacting with psoriasis patients with mental illness.

“This study aims to evaluate whether an association exists between a patient’s psychological state and the perception of patient-clinician encounters,” wrote Charlotte Read, MBBS, of Imperial College London, and April W. Armstrong, MD, MPH, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, in JAMA Dermatology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed longitudinal data from over 8.8 million U.S. adults (unweighted, 652) with psoriasis who participated in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 2004 to 2017. The nationally representative database includes various clinical information, such as data on patient demographics, health care use, and mental health comorbidities.

The primary outcome, patient satisfaction with their physician, was assessed using a patient-physician communication composite score. Mental health comorbidities were evaluated using standard questionnaires.

The mean age of study patients was 52.1 years (range, 0.7 years), and most were female (54%). In all, 73% of participants had no or mild psychological distress symptoms, and 27% had moderate or severe symptoms.

After analysis, the researchers found that patients with moderate psychological distress symptoms were 2.8 times more likely to report lower satisfaction with their physician than were those with no or mild symptoms (adjusted odds ratio, 2.8; P = .001). They also reported that patients with severe symptoms were more likely to report lower satisfaction (aOR, 2.3; P = .03).

“Patients with moderate or severe depression symptoms were less satisfied with their clinicians, compared with those with no or mild depression symptoms,” they further explained.

Based on the results, the coinvestigators emphasized the importance of bettering the patient experience for those with mental illness given the potential association with improved health outcomes.

“Because depressed patients can be more sensitive to negative communication, the clinician needs to be more conscious about using a positive and supportive communication style,” they recommended.

The authors acknowledged the inadequacy of evaluating clinician performance using patient satisfaction alone. As a result, the findings may not be generalizable to all clinical settings.

The study was funded by the National Psoriasis Foundation. Dr. Armstrong reported financial affiliations with several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Read C, Armstrong AW. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1054.

according to a retrospective analysis of survey data.

The findings highlight the importance of clinicians being supportive and adaptable in their communication style when interacting with psoriasis patients with mental illness.

“This study aims to evaluate whether an association exists between a patient’s psychological state and the perception of patient-clinician encounters,” wrote Charlotte Read, MBBS, of Imperial College London, and April W. Armstrong, MD, MPH, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, in JAMA Dermatology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed longitudinal data from over 8.8 million U.S. adults (unweighted, 652) with psoriasis who participated in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey from 2004 to 2017. The nationally representative database includes various clinical information, such as data on patient demographics, health care use, and mental health comorbidities.

The primary outcome, patient satisfaction with their physician, was assessed using a patient-physician communication composite score. Mental health comorbidities were evaluated using standard questionnaires.

The mean age of study patients was 52.1 years (range, 0.7 years), and most were female (54%). In all, 73% of participants had no or mild psychological distress symptoms, and 27% had moderate or severe symptoms.

After analysis, the researchers found that patients with moderate psychological distress symptoms were 2.8 times more likely to report lower satisfaction with their physician than were those with no or mild symptoms (adjusted odds ratio, 2.8; P = .001). They also reported that patients with severe symptoms were more likely to report lower satisfaction (aOR, 2.3; P = .03).