User login

A high proportion of SARS-CoV-2–infected university students are asymptomatic

Many individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 never become symptomatic. In a South Korean study, these infected individuals remained asymptomatic for a prolonged period while maintaining the same viral load as symptomatic patients, suggesting that they are just as infectious.1 A narrative review found high rates of asymptomatic disease in several younger populations, including women in an obstetric ward (88%), the crew of an aircraft carrier (58%), and prisoners (96%).2 However, there is no published research on the percentage of university students who are asymptomatic.

Methods

The University of Georgia (UGA) began classes on August 20, 2020. Shortly before the beginning of classes, UGA implemented a surveillance program for asymptomatic students, faculty, and staff, testing 300 to 450 people per day. Initially, during Weeks 1 and 2 of data collection, anyone could choose to be tested. In Weeks 3 and 4, students, faculty, and staff were randomly invited to participate.

Over the 4-week period beginning on August 17, we calculated the percent of positive cases in surveillance testing and applied this percentage to the entire UGA student population (n = 38,920) to estimate the total number of asymptomatic COVID-19 students each week.3 Data for symptomatic cases were also reported by the university on a weekly basis. This included positive tests from the University Health Center, as well as voluntary reporting using a smartphone app from other sites.

Positive tests in symptomatic individuals were not stratified by student vs nonstudent until Week 3; students comprised 95% of positive symptomatic reports in Week 3 and 99% in Week 4, so we conservatively estimated that 95% of symptomatic cases in Weeks 1 and 2 were students. These data were used to estimate the percentage of SARS-CoV-2–positive students who were asymptomatic.

Results

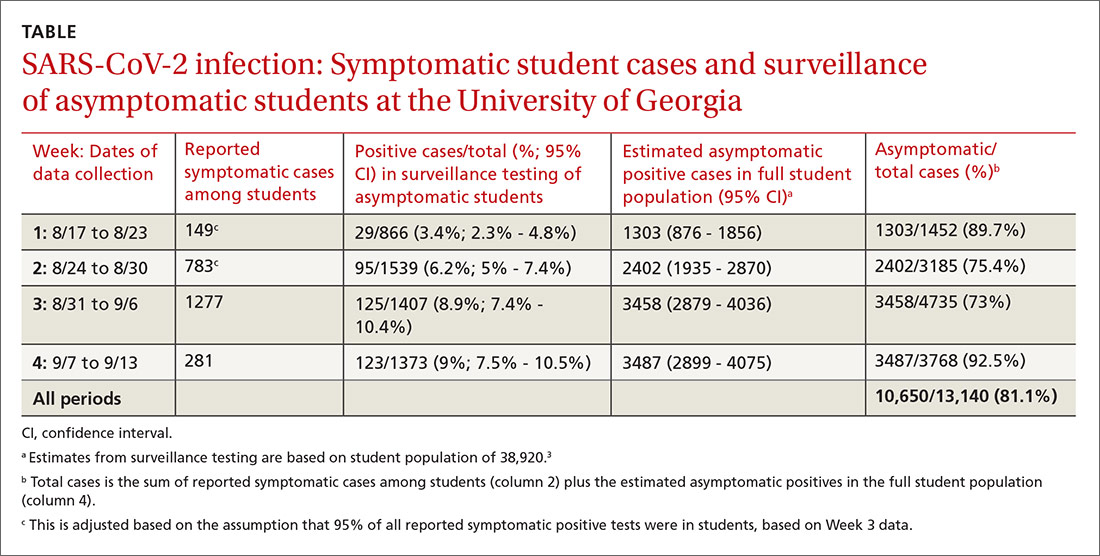

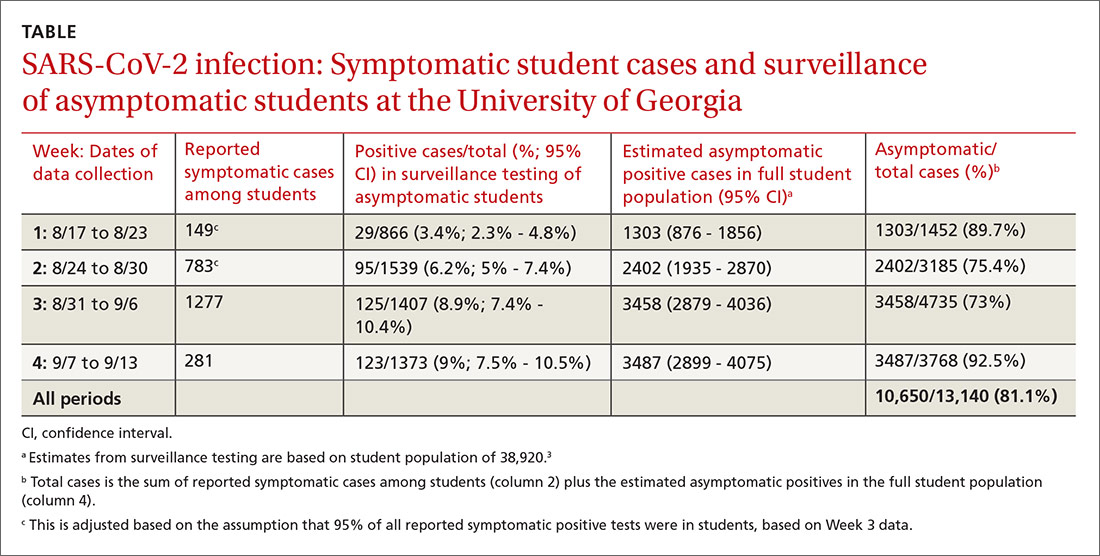

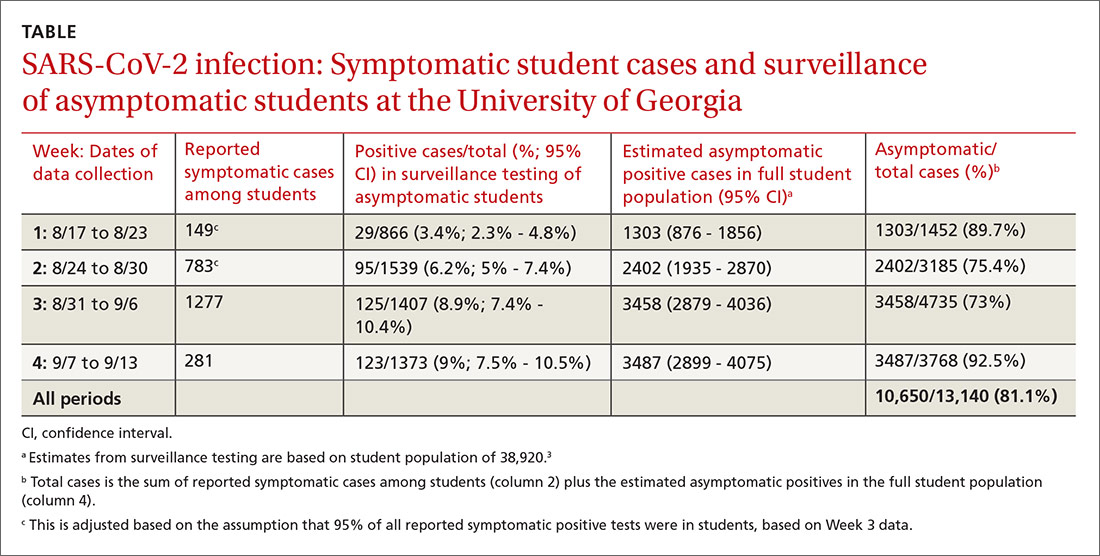

Our results are summarized in the table. The percentage of asymptomatic students testing positive in surveillance testing was 3.4% in Week 1 and rose steadily to 9% by Week 4. We estimated that there were 1303 asymptomatic cases among students in Week 1, increasing to 3487 asymptomatic positive students on campus by Week 4. The estimated percentage of asymptomatic students infected with SARS-CoV-2 ranged from 73% to 92.5% by week and was 81.1% overall.

Discussion

During the reporting period from August 17 to September 13, the 7-day moving average of new cases in Clarke County (home of UGA) increased from 30 to 83 per 100,000 persons/day (https://dph.georgia.gov/covid-19-daily-status-report). During this period, there were large increases in the number of infected students, more than 80% of whom were asymptomatic. With the assumption that anyone could be infected even if asymptomatic, these numbers highlight the importance for infection control to prevent potential spread within a community by taking universal precautions such as wearing a mask, following physical distancing guidelines, and handwashing.

Limitations. First, reporting of positive tests in symptomatic individuals is highly encouraged but not required. The large drop in symptomatic positive test reports between Weeks 3 and 4, with no change in test positivity in surveillance of asymptomatic students (8.9% vs 9%), suggests that students may have chosen to be tested elsewhere in conjunction with evaluation of their symptoms and/or not reported positive tests, possibly to avoid mandatory isolation and other restrictions on their activities. Further evidence to support no change in actual infection rates comes from testing for virus in wastewater, which also remained unchanged.4

Continue to: Second, each week's surveillance...

Second, each week’s surveillance population is not a true random sample, so extrapolating this estimate to the full student population could over- or undercount asymptomatic cases depending on the direction of bias (ie, healthy volunteer bias vs test avoidance by those with high-risk behaviors).

Finally, some students who were positive in surveillance testing may have been presymptomatic, rather than asymptomatic.

In conclusion, we estimate that approximately 80% of students infected with SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic. This is consistent with other studies in young adult populations.2

Mark H. Ebell, MD, MS

Cassie Chupp, MPH

Michelle Bentivegna, MPH

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of Georgia, Athens

[email protected]

The authors reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

1. Lee S, Kim T, Lee E, et al. Clinical course and molecular viral shedding among asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community treatment center in the Republic of Korea [published online ahead of print August 6, 2020]. JAMA Intern Med. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3862

2. Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection : a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:362-367.

3. UGA by the Numbers. University of Georgia Web site. www.uga.edu/facts.php. Updated August 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020.

4. Lott M, Norfolk W, Robertson M, et al. Wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 in Athens, GA. COVID-19 Portal: Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases, University of Georgia Web site. www.covid19.uga.edu/wastewater-athens.html. Updated October 15, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020.

Many individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 never become symptomatic. In a South Korean study, these infected individuals remained asymptomatic for a prolonged period while maintaining the same viral load as symptomatic patients, suggesting that they are just as infectious.1 A narrative review found high rates of asymptomatic disease in several younger populations, including women in an obstetric ward (88%), the crew of an aircraft carrier (58%), and prisoners (96%).2 However, there is no published research on the percentage of university students who are asymptomatic.

Methods

The University of Georgia (UGA) began classes on August 20, 2020. Shortly before the beginning of classes, UGA implemented a surveillance program for asymptomatic students, faculty, and staff, testing 300 to 450 people per day. Initially, during Weeks 1 and 2 of data collection, anyone could choose to be tested. In Weeks 3 and 4, students, faculty, and staff were randomly invited to participate.

Over the 4-week period beginning on August 17, we calculated the percent of positive cases in surveillance testing and applied this percentage to the entire UGA student population (n = 38,920) to estimate the total number of asymptomatic COVID-19 students each week.3 Data for symptomatic cases were also reported by the university on a weekly basis. This included positive tests from the University Health Center, as well as voluntary reporting using a smartphone app from other sites.

Positive tests in symptomatic individuals were not stratified by student vs nonstudent until Week 3; students comprised 95% of positive symptomatic reports in Week 3 and 99% in Week 4, so we conservatively estimated that 95% of symptomatic cases in Weeks 1 and 2 were students. These data were used to estimate the percentage of SARS-CoV-2–positive students who were asymptomatic.

Results

Our results are summarized in the table. The percentage of asymptomatic students testing positive in surveillance testing was 3.4% in Week 1 and rose steadily to 9% by Week 4. We estimated that there were 1303 asymptomatic cases among students in Week 1, increasing to 3487 asymptomatic positive students on campus by Week 4. The estimated percentage of asymptomatic students infected with SARS-CoV-2 ranged from 73% to 92.5% by week and was 81.1% overall.

Discussion

During the reporting period from August 17 to September 13, the 7-day moving average of new cases in Clarke County (home of UGA) increased from 30 to 83 per 100,000 persons/day (https://dph.georgia.gov/covid-19-daily-status-report). During this period, there were large increases in the number of infected students, more than 80% of whom were asymptomatic. With the assumption that anyone could be infected even if asymptomatic, these numbers highlight the importance for infection control to prevent potential spread within a community by taking universal precautions such as wearing a mask, following physical distancing guidelines, and handwashing.

Limitations. First, reporting of positive tests in symptomatic individuals is highly encouraged but not required. The large drop in symptomatic positive test reports between Weeks 3 and 4, with no change in test positivity in surveillance of asymptomatic students (8.9% vs 9%), suggests that students may have chosen to be tested elsewhere in conjunction with evaluation of their symptoms and/or not reported positive tests, possibly to avoid mandatory isolation and other restrictions on their activities. Further evidence to support no change in actual infection rates comes from testing for virus in wastewater, which also remained unchanged.4

Continue to: Second, each week's surveillance...

Second, each week’s surveillance population is not a true random sample, so extrapolating this estimate to the full student population could over- or undercount asymptomatic cases depending on the direction of bias (ie, healthy volunteer bias vs test avoidance by those with high-risk behaviors).

Finally, some students who were positive in surveillance testing may have been presymptomatic, rather than asymptomatic.

In conclusion, we estimate that approximately 80% of students infected with SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic. This is consistent with other studies in young adult populations.2

Mark H. Ebell, MD, MS

Cassie Chupp, MPH

Michelle Bentivegna, MPH

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of Georgia, Athens

[email protected]

The authors reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

Many individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 never become symptomatic. In a South Korean study, these infected individuals remained asymptomatic for a prolonged period while maintaining the same viral load as symptomatic patients, suggesting that they are just as infectious.1 A narrative review found high rates of asymptomatic disease in several younger populations, including women in an obstetric ward (88%), the crew of an aircraft carrier (58%), and prisoners (96%).2 However, there is no published research on the percentage of university students who are asymptomatic.

Methods

The University of Georgia (UGA) began classes on August 20, 2020. Shortly before the beginning of classes, UGA implemented a surveillance program for asymptomatic students, faculty, and staff, testing 300 to 450 people per day. Initially, during Weeks 1 and 2 of data collection, anyone could choose to be tested. In Weeks 3 and 4, students, faculty, and staff were randomly invited to participate.

Over the 4-week period beginning on August 17, we calculated the percent of positive cases in surveillance testing and applied this percentage to the entire UGA student population (n = 38,920) to estimate the total number of asymptomatic COVID-19 students each week.3 Data for symptomatic cases were also reported by the university on a weekly basis. This included positive tests from the University Health Center, as well as voluntary reporting using a smartphone app from other sites.

Positive tests in symptomatic individuals were not stratified by student vs nonstudent until Week 3; students comprised 95% of positive symptomatic reports in Week 3 and 99% in Week 4, so we conservatively estimated that 95% of symptomatic cases in Weeks 1 and 2 were students. These data were used to estimate the percentage of SARS-CoV-2–positive students who were asymptomatic.

Results

Our results are summarized in the table. The percentage of asymptomatic students testing positive in surveillance testing was 3.4% in Week 1 and rose steadily to 9% by Week 4. We estimated that there were 1303 asymptomatic cases among students in Week 1, increasing to 3487 asymptomatic positive students on campus by Week 4. The estimated percentage of asymptomatic students infected with SARS-CoV-2 ranged from 73% to 92.5% by week and was 81.1% overall.

Discussion

During the reporting period from August 17 to September 13, the 7-day moving average of new cases in Clarke County (home of UGA) increased from 30 to 83 per 100,000 persons/day (https://dph.georgia.gov/covid-19-daily-status-report). During this period, there were large increases in the number of infected students, more than 80% of whom were asymptomatic. With the assumption that anyone could be infected even if asymptomatic, these numbers highlight the importance for infection control to prevent potential spread within a community by taking universal precautions such as wearing a mask, following physical distancing guidelines, and handwashing.

Limitations. First, reporting of positive tests in symptomatic individuals is highly encouraged but not required. The large drop in symptomatic positive test reports between Weeks 3 and 4, with no change in test positivity in surveillance of asymptomatic students (8.9% vs 9%), suggests that students may have chosen to be tested elsewhere in conjunction with evaluation of their symptoms and/or not reported positive tests, possibly to avoid mandatory isolation and other restrictions on their activities. Further evidence to support no change in actual infection rates comes from testing for virus in wastewater, which also remained unchanged.4

Continue to: Second, each week's surveillance...

Second, each week’s surveillance population is not a true random sample, so extrapolating this estimate to the full student population could over- or undercount asymptomatic cases depending on the direction of bias (ie, healthy volunteer bias vs test avoidance by those with high-risk behaviors).

Finally, some students who were positive in surveillance testing may have been presymptomatic, rather than asymptomatic.

In conclusion, we estimate that approximately 80% of students infected with SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic. This is consistent with other studies in young adult populations.2

Mark H. Ebell, MD, MS

Cassie Chupp, MPH

Michelle Bentivegna, MPH

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, College of Public Health, University of Georgia, Athens

[email protected]

The authors reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

1. Lee S, Kim T, Lee E, et al. Clinical course and molecular viral shedding among asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community treatment center in the Republic of Korea [published online ahead of print August 6, 2020]. JAMA Intern Med. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3862

2. Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection : a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:362-367.

3. UGA by the Numbers. University of Georgia Web site. www.uga.edu/facts.php. Updated August 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020.

4. Lott M, Norfolk W, Robertson M, et al. Wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 in Athens, GA. COVID-19 Portal: Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases, University of Georgia Web site. www.covid19.uga.edu/wastewater-athens.html. Updated October 15, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020.

1. Lee S, Kim T, Lee E, et al. Clinical course and molecular viral shedding among asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community treatment center in the Republic of Korea [published online ahead of print August 6, 2020]. JAMA Intern Med. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3862

2. Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection : a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:362-367.

3. UGA by the Numbers. University of Georgia Web site. www.uga.edu/facts.php. Updated August 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020.

4. Lott M, Norfolk W, Robertson M, et al. Wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 in Athens, GA. COVID-19 Portal: Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases, University of Georgia Web site. www.covid19.uga.edu/wastewater-athens.html. Updated October 15, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2020.

Pfizer vaccine data show 90% efficacy in early results

A vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2 has been found to be 90% effective in preventing COVID-19 in trial volunteers who were without evidence of prior infection of the virus, results from an interim analysis of a phase 3 study demonstrated.

BTN162b2, a messenger RNA–based vaccine candidate that requires two doses, is being developed by Pfizer and BioNTech SE independently of the Trump administration’s Operation Warp Speed. A global phase 3 clinical trial of BTN162b2 began on July 27 and has enrolled 43,538 participants to date; 42% of enrollees have racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds.

According to a press release issued by the two companies, 38,955 trial volunteers had received a second dose of either vaccine or placebo as of Nov. 8. An interim analysis of 94 individuals conducted by an independent data monitoring committee (DMC) found that the vaccine efficacy rate was above 90% 7 days after the second dose. This means that protection was achieved 28 days after the first vaccine dose.

“It’s promising in that it validates the genetic strategy – whether it’s mRNA vaccines or DNA vaccines,” Paul A. Offit, MD, told Medscape Medical News. Offit is a member of the US Food and Drug Administraiton’s COVID-19 Vaccine Advisory Committee. “All of them have the same approach, which is that they introduce the gene that codes for the coronavirus spike protein into the cell. Your cell makes the spike protein, and your immune system makes antibodies to the spike protein. At least in these preliminary data, which involved 94 people getting sick, it looks like it’s effective. That’s good. We knew that it seemed to work in experimental animals, but you never know until you put it into people.”

According to Pfizer and BioNTech SE, a final data analysis is planned once 164 confirmed COVID-19 cases have accrued. So far, the DMC has not reported any serious safety concerns. It recommends that the study continue to collect safety and efficacy data as planned. The companies plan to apply to the FDA for emergency use authorization soon after the required safety milestone is achieved.

Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla, DVM, PhD, added in a separate press release, “It’s important to note that we cannot apply for FDA Emergency Use Authorization based on these efficacy results alone. More data on safety is also needed, and we are continuing to accumulate that safety data as part of our ongoing clinical study.

“We estimate that a median of two months of safety data following the second and final dose of the vaccine candidate – required by FDA’s guidance for potential Emergency Use Authorization – will be available by the third week of November.”

Offit, professor of pediatrics in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said that, if BTN162b2 is approved, administering it will be tricky. “This particular vaccine has to be shipped and stored at –70° C or –80° C, which we’ve never done before in this country,” he said. “That means maintaining the product on dry ice. That’s going to be a challenge for distribution, I think.”

Good news, but…

In the press release, BioNTech SE’s cofounder and CEO, Ugur Sahin, MD, characterized the findings as “a victory for innovation, science and a global collaborative effort. When we embarked on this journey 10 months ago this is what we aspired to achieve. Especially today, while we are all in the midst of a second wave and many of us in lockdown, we appreciate even more how important this milestone is on our path towards ending this pandemic and for all of us to regain a sense of normality.”

President-elect Joe Biden also weighed in, calling the results “excellent news” in a news release.

“At the same time, it is also important to understand that the end of the battle against COVID-19 is still months away,” he said. “This news follows a previously announced timeline by industry officials that forecast vaccine approval by late November. Even if that is achieved, and some Americans are vaccinated later this year, it will be many more months before there is widespread vaccination in this country.

“Today’s news does not change this urgent reality. Americans will have to rely on masking, distancing, contact tracing, hand washing, and other measures to keep themselves safe well into next year,” Biden added.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2 has been found to be 90% effective in preventing COVID-19 in trial volunteers who were without evidence of prior infection of the virus, results from an interim analysis of a phase 3 study demonstrated.

BTN162b2, a messenger RNA–based vaccine candidate that requires two doses, is being developed by Pfizer and BioNTech SE independently of the Trump administration’s Operation Warp Speed. A global phase 3 clinical trial of BTN162b2 began on July 27 and has enrolled 43,538 participants to date; 42% of enrollees have racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds.

According to a press release issued by the two companies, 38,955 trial volunteers had received a second dose of either vaccine or placebo as of Nov. 8. An interim analysis of 94 individuals conducted by an independent data monitoring committee (DMC) found that the vaccine efficacy rate was above 90% 7 days after the second dose. This means that protection was achieved 28 days after the first vaccine dose.

“It’s promising in that it validates the genetic strategy – whether it’s mRNA vaccines or DNA vaccines,” Paul A. Offit, MD, told Medscape Medical News. Offit is a member of the US Food and Drug Administraiton’s COVID-19 Vaccine Advisory Committee. “All of them have the same approach, which is that they introduce the gene that codes for the coronavirus spike protein into the cell. Your cell makes the spike protein, and your immune system makes antibodies to the spike protein. At least in these preliminary data, which involved 94 people getting sick, it looks like it’s effective. That’s good. We knew that it seemed to work in experimental animals, but you never know until you put it into people.”

According to Pfizer and BioNTech SE, a final data analysis is planned once 164 confirmed COVID-19 cases have accrued. So far, the DMC has not reported any serious safety concerns. It recommends that the study continue to collect safety and efficacy data as planned. The companies plan to apply to the FDA for emergency use authorization soon after the required safety milestone is achieved.

Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla, DVM, PhD, added in a separate press release, “It’s important to note that we cannot apply for FDA Emergency Use Authorization based on these efficacy results alone. More data on safety is also needed, and we are continuing to accumulate that safety data as part of our ongoing clinical study.

“We estimate that a median of two months of safety data following the second and final dose of the vaccine candidate – required by FDA’s guidance for potential Emergency Use Authorization – will be available by the third week of November.”

Offit, professor of pediatrics in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said that, if BTN162b2 is approved, administering it will be tricky. “This particular vaccine has to be shipped and stored at –70° C or –80° C, which we’ve never done before in this country,” he said. “That means maintaining the product on dry ice. That’s going to be a challenge for distribution, I think.”

Good news, but…

In the press release, BioNTech SE’s cofounder and CEO, Ugur Sahin, MD, characterized the findings as “a victory for innovation, science and a global collaborative effort. When we embarked on this journey 10 months ago this is what we aspired to achieve. Especially today, while we are all in the midst of a second wave and many of us in lockdown, we appreciate even more how important this milestone is on our path towards ending this pandemic and for all of us to regain a sense of normality.”

President-elect Joe Biden also weighed in, calling the results “excellent news” in a news release.

“At the same time, it is also important to understand that the end of the battle against COVID-19 is still months away,” he said. “This news follows a previously announced timeline by industry officials that forecast vaccine approval by late November. Even if that is achieved, and some Americans are vaccinated later this year, it will be many more months before there is widespread vaccination in this country.

“Today’s news does not change this urgent reality. Americans will have to rely on masking, distancing, contact tracing, hand washing, and other measures to keep themselves safe well into next year,” Biden added.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2 has been found to be 90% effective in preventing COVID-19 in trial volunteers who were without evidence of prior infection of the virus, results from an interim analysis of a phase 3 study demonstrated.

BTN162b2, a messenger RNA–based vaccine candidate that requires two doses, is being developed by Pfizer and BioNTech SE independently of the Trump administration’s Operation Warp Speed. A global phase 3 clinical trial of BTN162b2 began on July 27 and has enrolled 43,538 participants to date; 42% of enrollees have racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds.

According to a press release issued by the two companies, 38,955 trial volunteers had received a second dose of either vaccine or placebo as of Nov. 8. An interim analysis of 94 individuals conducted by an independent data monitoring committee (DMC) found that the vaccine efficacy rate was above 90% 7 days after the second dose. This means that protection was achieved 28 days after the first vaccine dose.

“It’s promising in that it validates the genetic strategy – whether it’s mRNA vaccines or DNA vaccines,” Paul A. Offit, MD, told Medscape Medical News. Offit is a member of the US Food and Drug Administraiton’s COVID-19 Vaccine Advisory Committee. “All of them have the same approach, which is that they introduce the gene that codes for the coronavirus spike protein into the cell. Your cell makes the spike protein, and your immune system makes antibodies to the spike protein. At least in these preliminary data, which involved 94 people getting sick, it looks like it’s effective. That’s good. We knew that it seemed to work in experimental animals, but you never know until you put it into people.”

According to Pfizer and BioNTech SE, a final data analysis is planned once 164 confirmed COVID-19 cases have accrued. So far, the DMC has not reported any serious safety concerns. It recommends that the study continue to collect safety and efficacy data as planned. The companies plan to apply to the FDA for emergency use authorization soon after the required safety milestone is achieved.

Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla, DVM, PhD, added in a separate press release, “It’s important to note that we cannot apply for FDA Emergency Use Authorization based on these efficacy results alone. More data on safety is also needed, and we are continuing to accumulate that safety data as part of our ongoing clinical study.

“We estimate that a median of two months of safety data following the second and final dose of the vaccine candidate – required by FDA’s guidance for potential Emergency Use Authorization – will be available by the third week of November.”

Offit, professor of pediatrics in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said that, if BTN162b2 is approved, administering it will be tricky. “This particular vaccine has to be shipped and stored at –70° C or –80° C, which we’ve never done before in this country,” he said. “That means maintaining the product on dry ice. That’s going to be a challenge for distribution, I think.”

Good news, but…

In the press release, BioNTech SE’s cofounder and CEO, Ugur Sahin, MD, characterized the findings as “a victory for innovation, science and a global collaborative effort. When we embarked on this journey 10 months ago this is what we aspired to achieve. Especially today, while we are all in the midst of a second wave and many of us in lockdown, we appreciate even more how important this milestone is on our path towards ending this pandemic and for all of us to regain a sense of normality.”

President-elect Joe Biden also weighed in, calling the results “excellent news” in a news release.

“At the same time, it is also important to understand that the end of the battle against COVID-19 is still months away,” he said. “This news follows a previously announced timeline by industry officials that forecast vaccine approval by late November. Even if that is achieved, and some Americans are vaccinated later this year, it will be many more months before there is widespread vaccination in this country.

“Today’s news does not change this urgent reality. Americans will have to rely on masking, distancing, contact tracing, hand washing, and other measures to keep themselves safe well into next year,” Biden added.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Methotrexate users need tuberculosis tests in high-TB areas

People taking even low-dose methotrexate need tuberculosis screening and ongoing clinical care if they live in areas where TB is common, results of a study presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology suggest.

Coauthor Carol Hitchon, MD, MSc, a rheumatologist with the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, who presented the findings, warned that methotrexate (MTX) users who also take corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants are at particular risk and need TB screening.

Current management guidelines for rheumatic disease address TB in relation to biologics, but not in relation to methotrexate, Dr. Hitchon said.

“We know that methotrexate is the foundational DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] for many rheumatic diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Hitchon noted at a press conference. “It’s safe and effective when dosed properly. However, methotrexate does have the potential for significant liver toxicity as well as infection, particularly for infectious organisms that are targeted by cell-mediated immunity, and TB is one of those agents.”

Using multiple databases, researchers conducted a systematic review of the literature published from 1990 to 2018 on TB rates among people who take less than 30 mg of methotrexate a week. Of the 4,700 studies they examined, 31 fit the criteria for this analysis.

They collected data on tuberculosis incidence or new TB diagnoses vs. reactivation of latent TB infection as well as TB outcomes, such as pulmonary symptoms, dissemination, and mortality.

They found a modest increase in the risk of TB infections in the setting of low-dose methotrexate. In addition, rates of TB in people with rheumatic disease who are treated with either methotrexate or biologics are generally higher than in the general population.

They also found that methotrexate users had higher rates of the type of TB that spreads beyond a patient’s lungs, compared with the general population.

Safety of INH with methotrexate

Researchers also looked at the safety of isoniazid (INH), the antibiotic used to treat TB, and found that isoniazid-related liver toxicity and neutropenia were more common when people took the antibiotic along with methotrexate, but those effects were usually reversible.

TB is endemic in various regions around the world. Historically there hasn’t been much rheumatology capacity in many of these areas, but as that capacity increases more people who are at high risk for developing or reactivating TB will be receiving methotrexate for rheumatic diseases, Dr. Hitchon said.

“It’s prudent for people managing patients who may be at higher risk for TB either from where they live or from where they travel that we should have a high suspicion for TB and consider screening as part of our workup in the course of initiating treatment like methotrexate,” she said.

Narender Annapureddy, MD, a rheumatologist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who was not involved in the research, pointed out that a limitation of the work is that only 27% of the studies are from developing countries, which are more likely to have endemic TB, and those studies had very few cases.

“This finding needs to be studied in larger populations in TB-endemic areas and in high-risk populations,” he said in an interview.

As for practice implications in the United States, Dr. Annapureddy noted that TB is rare in the United States and most of the cases occur in people born in other countries.

“This population may be at risk for TB and should probably be screened for TB before initiating methotrexate,” he said. “Since biologics are usually the next step, especially in RA after patients fail methotrexate, having information on TB status may also help guide management options after MTX failure.

“Since high-dose steroids are another important risk factor for TB activation,” Dr. Annapureddy continued, “rheumatologists should likely consider screening patients who are going to be on moderate to high doses of steroids with MTX.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

People taking even low-dose methotrexate need tuberculosis screening and ongoing clinical care if they live in areas where TB is common, results of a study presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology suggest.

Coauthor Carol Hitchon, MD, MSc, a rheumatologist with the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, who presented the findings, warned that methotrexate (MTX) users who also take corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants are at particular risk and need TB screening.

Current management guidelines for rheumatic disease address TB in relation to biologics, but not in relation to methotrexate, Dr. Hitchon said.

“We know that methotrexate is the foundational DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] for many rheumatic diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Hitchon noted at a press conference. “It’s safe and effective when dosed properly. However, methotrexate does have the potential for significant liver toxicity as well as infection, particularly for infectious organisms that are targeted by cell-mediated immunity, and TB is one of those agents.”

Using multiple databases, researchers conducted a systematic review of the literature published from 1990 to 2018 on TB rates among people who take less than 30 mg of methotrexate a week. Of the 4,700 studies they examined, 31 fit the criteria for this analysis.

They collected data on tuberculosis incidence or new TB diagnoses vs. reactivation of latent TB infection as well as TB outcomes, such as pulmonary symptoms, dissemination, and mortality.

They found a modest increase in the risk of TB infections in the setting of low-dose methotrexate. In addition, rates of TB in people with rheumatic disease who are treated with either methotrexate or biologics are generally higher than in the general population.

They also found that methotrexate users had higher rates of the type of TB that spreads beyond a patient’s lungs, compared with the general population.

Safety of INH with methotrexate

Researchers also looked at the safety of isoniazid (INH), the antibiotic used to treat TB, and found that isoniazid-related liver toxicity and neutropenia were more common when people took the antibiotic along with methotrexate, but those effects were usually reversible.

TB is endemic in various regions around the world. Historically there hasn’t been much rheumatology capacity in many of these areas, but as that capacity increases more people who are at high risk for developing or reactivating TB will be receiving methotrexate for rheumatic diseases, Dr. Hitchon said.

“It’s prudent for people managing patients who may be at higher risk for TB either from where they live or from where they travel that we should have a high suspicion for TB and consider screening as part of our workup in the course of initiating treatment like methotrexate,” she said.

Narender Annapureddy, MD, a rheumatologist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who was not involved in the research, pointed out that a limitation of the work is that only 27% of the studies are from developing countries, which are more likely to have endemic TB, and those studies had very few cases.

“This finding needs to be studied in larger populations in TB-endemic areas and in high-risk populations,” he said in an interview.

As for practice implications in the United States, Dr. Annapureddy noted that TB is rare in the United States and most of the cases occur in people born in other countries.

“This population may be at risk for TB and should probably be screened for TB before initiating methotrexate,” he said. “Since biologics are usually the next step, especially in RA after patients fail methotrexate, having information on TB status may also help guide management options after MTX failure.

“Since high-dose steroids are another important risk factor for TB activation,” Dr. Annapureddy continued, “rheumatologists should likely consider screening patients who are going to be on moderate to high doses of steroids with MTX.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

People taking even low-dose methotrexate need tuberculosis screening and ongoing clinical care if they live in areas where TB is common, results of a study presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology suggest.

Coauthor Carol Hitchon, MD, MSc, a rheumatologist with the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, who presented the findings, warned that methotrexate (MTX) users who also take corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants are at particular risk and need TB screening.

Current management guidelines for rheumatic disease address TB in relation to biologics, but not in relation to methotrexate, Dr. Hitchon said.

“We know that methotrexate is the foundational DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] for many rheumatic diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Hitchon noted at a press conference. “It’s safe and effective when dosed properly. However, methotrexate does have the potential for significant liver toxicity as well as infection, particularly for infectious organisms that are targeted by cell-mediated immunity, and TB is one of those agents.”

Using multiple databases, researchers conducted a systematic review of the literature published from 1990 to 2018 on TB rates among people who take less than 30 mg of methotrexate a week. Of the 4,700 studies they examined, 31 fit the criteria for this analysis.

They collected data on tuberculosis incidence or new TB diagnoses vs. reactivation of latent TB infection as well as TB outcomes, such as pulmonary symptoms, dissemination, and mortality.

They found a modest increase in the risk of TB infections in the setting of low-dose methotrexate. In addition, rates of TB in people with rheumatic disease who are treated with either methotrexate or biologics are generally higher than in the general population.

They also found that methotrexate users had higher rates of the type of TB that spreads beyond a patient’s lungs, compared with the general population.

Safety of INH with methotrexate

Researchers also looked at the safety of isoniazid (INH), the antibiotic used to treat TB, and found that isoniazid-related liver toxicity and neutropenia were more common when people took the antibiotic along with methotrexate, but those effects were usually reversible.

TB is endemic in various regions around the world. Historically there hasn’t been much rheumatology capacity in many of these areas, but as that capacity increases more people who are at high risk for developing or reactivating TB will be receiving methotrexate for rheumatic diseases, Dr. Hitchon said.

“It’s prudent for people managing patients who may be at higher risk for TB either from where they live or from where they travel that we should have a high suspicion for TB and consider screening as part of our workup in the course of initiating treatment like methotrexate,” she said.

Narender Annapureddy, MD, a rheumatologist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who was not involved in the research, pointed out that a limitation of the work is that only 27% of the studies are from developing countries, which are more likely to have endemic TB, and those studies had very few cases.

“This finding needs to be studied in larger populations in TB-endemic areas and in high-risk populations,” he said in an interview.

As for practice implications in the United States, Dr. Annapureddy noted that TB is rare in the United States and most of the cases occur in people born in other countries.

“This population may be at risk for TB and should probably be screened for TB before initiating methotrexate,” he said. “Since biologics are usually the next step, especially in RA after patients fail methotrexate, having information on TB status may also help guide management options after MTX failure.

“Since high-dose steroids are another important risk factor for TB activation,” Dr. Annapureddy continued, “rheumatologists should likely consider screening patients who are going to be on moderate to high doses of steroids with MTX.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

What’s Eating You? Human Flea (Pulex irritans)

Characteristics

The ubiquitous human flea, Pulex irritans, is a hematophagous wingless ectoparasite in the order Siphonaptera (wingless siphon) that survives by consuming the blood of its mammalian and avian hosts. Due to diseases such as the bubonic plague, fleas have claimed more victims than all the wars ever fought; in the 14th century, the Black Death caused more than 200 million deaths. Fleas fossilized in amber have been found to be 200 million years old and closely resemble the modern human flea, demonstrating the resilience of the species.

The adult human flea is a small, reddish brown, laterally compressed, wingless insect that is approximately 2- to 3.5-mm long (females, 2.5–3.5 mm; males, 2–2.5 mm) and enclosed by a tough cuticle. Compared to the dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis) and cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), P irritans has no combs or ctenidia (Figure 1). Fleas have large powerful hind legs enabling them to jump horizontally or vertically 200 times their body length (equivalent to a 6-foot human jumping 1200 feet) using stored muscle energy in a pad on the hind legs composed of the elastic protein resilin.1 They feed off a wide variety of hosts, including humans, pigs, cats, dogs, goats, sheep, cattle, chickens, owls, foxes, rabbits, mice, and feral cats. The flea’s mouthparts are highly specialized for piercing the skin and sucking its blood meal via direct capillary cannulation.

Life Cycle

There are 4 stages of the flea life cycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Most adult flea species mate on the host; the female will lay an average of 4 to 8 small white eggs on the host after each blood meal, laying more than 400 eggs during her lifetime. The eggs then drop from the host and hatch in approximately 4 to 6 days to become larvae. The active larvae feed on available organic matter in their environment, such as their parents’ feces and detritus, while undergoing 3 molts within 1 week to several months.2 The larva then spins a silken cocoon from modified salivary glands to form the pupa. In favorable conditions, the pupa lasts only a few weeks; however, it can last for a year or more in unfavorable conditions. Triggers for emergence of the adult flea from the pupa include high humidity, warm temperatures, increased levels of carbon dioxide, and vibrations including sound. An adult P irritans flea can live for a few weeks to more than 1.5 years in favorable conditions of lower air temperature, high relative humidity, and access to a host.3

Related Diseases

Pulex irritans can be a vector for several human diseases. Yersinia pestis is a gram-negative bacteria that causes plague, a highly virulent disease that killed millions of people during its 3 largest human pandemics. The black rat (Rattus rattus) and the oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) have been implicated as initial vectors; however, transmission may be human-to-human with pneumonic plague, and septicemic plague may be spread via Pulex fleas or body lice.4,5 In 1971, Y pestis was isolated from P irritans on a dog in the home of a plague patient in Kayenta, Arizona.6Yersinia pestis bacterial DNA also was extracted from P irritans during a plague outbreak in Madagascar in 20147 and was implicated in epidemiologic studies of plague in Tanzania from 1986 to 2004, suggesting it also plays a role in endemic disease.8

Bartonellosis is an emerging disease caused by different species of the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Bartonella transmitted by lice, ticks, and fleas. Bartonella quintana causes trench fever primarily transmitted by the human body louse, Pediculus humanus corporis, and resulted in more than 1 million cases during World War I. Trench fever is characterized by headache, fever, dizziness, and shin pain that lasts 1 to 3 days and recurs in cycles every 4 to 6 days. Other clinical manifestations of B quintana include chronic bacteremia, endocarditis, lymphadenopathy, and bacillary angiomatosis.9Bartonella henselae causes cat scratch fever, characterized by lymphadenopathy, fever, headache, joint pain, and lethargy from infected cat scratches or the bite of an infected flea. Bartonella rochalimae also has been found to cause a trench fever–like bacteremia.10Bartonella species have been found in P irritans, and the flea is implicated as a vector of bartonellosis in humans.11-15

Rickettsioses are worldwide diseases caused by the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Rickettsia transmitted to humans via hematophagous arthropods. The rickettsiae traditionally have been classified into the spotted fever or typhus groups. The spotted fever group (ie, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Mediterranean spotted fever) is transmitted via ticks. The typhus group is transmitted via lice (epidemic typhus) and fleas (endemic or murine typhus). Murine typhus can be caused by Rickettsia typhi in warm coastal areas around the world where the main mammal reservoir is the rat and the rat flea vector X cheopis. Clinical signs of infection are abrupt onset of fever, headaches, myalgia, malaise, and chills, with a truncal maculopapular rash progressing peripherally several days after the initial clinical signs. Rash is present in up to 50% of cases.16Rickettsia felis is an emerging flea-borne pathogen causing an acute febrile illness usually transmitted via the cat flea C felis.17Rickettsia species DNA have been found to be present in P irritans from dogs18 and livestock19 and pose a risk for causing rickettsioses in humans.

Environmental Treatment and Prevention

Flea bites present as intense, pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that usually are located on the lower extremities but also can be present on exposed areas of the upper extremities and hands (Figure 2). Human fleas infest clothing, and bites can be widespread. Topical antipruritics and corticosteroids can be used for controlling itch and the intense cutaneous inflammatory response. The flea host should be identified in areas of the home, school, farm, work, or local environment. House pets should be examined and treated by a veterinarian. The pet’s bedding should be washed and dried at high temperatures, and carpets and floors should be routinely vacuumed or cleaned to remove eggs, larvae, flea feces, and/or pupae. The killing of adult fleas with insecticidal products (eg, imidacloprid, fipronil, spinosad, selamectin, lufenuron, ivermectin) is the primary method of flea control. Use of insect growth regulators such as pyriproxyfen inhibits adult reproduction and blocks the organogenesis of immature larval stages via hormonal or enzymatic actions.20 The combination of an insecticide and an insect growth regulator appears to be most effective in their synergistic actions against adult fleas and larvae. There have been reports of insecticidal resistance in the flea population, especially with pyrethroids.21,22 A professional exterminator and veterinarian should be consulted. In recalcitrant cases, evaluation for other wild mammals or birds should be performed in unoccupied areas of the home such as the attic, crawl spaces, and basements, as well as inside walls.

Conclusion

The human flea, P irritans, is an important vector in the transmission of human diseases such as the bubonic plague, bartonellosis, and rickettsioses. Flea bites present as intensely pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that most commonly present on the lower extremities. Flea bites can be treated with topical steroids, and fleas can be controlled by a combination of insecticidal products and insect growth regulators.

- Burrow M. How fleas jump. J Exp Biol. 2009;18:2881-2883.

- Buckland PC, Sandler JP. A biogeography of the human flea, Pulex irritans L (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J Biogeogr. 1989;16:115-120.

- Krasnov BR. Life cycles. In: Krasnov BR, ed. Functional and Evolutional Ecology of Fleas. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ Press; 2008:45-67.

- Dean KR, Krauer F, Walloe L, et al. Human ectoparasites and the spread of plague in Europe during the second pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:1304-1309.

- Hufthammer AK, Walloe L. Rats cannot have been intermediate hosts for Yersinia pestis during medieval plague epidemics in Northern Europe. J Archeol Sci. 2013;40:1752-1759.

- Archibald WS, Kunitz SJ. Detection of plague by testing serums of dogs on the Navajo Reservation. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971;86:377-380.

- Ratovonjato J, Rajerison M, Rahelinirina S, et al. Yersinia pestis in Pulex irritans fleas during plague outbreak, Madagascar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1414-1415.

- Laudisoit A, Leirs H, Makundi RH, et al. Plague and the human flea, Tanzania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:687-693.

- Foucault C, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Bartonella quintana characteristics and clinical management. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:217-223.

- Eremeeva ME, Gerns HL, Lydy SL, et al. Bacteremia, fever, and splenomegaly caused by a newly recognized bartonella species. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:2381-2387.11.

- Marquez FJ, Millan J, Rodriguez-Liebana JJ, et al. Detection and identification of Bartonella sp. in fleas from carnivorous mammals in Andalusia, Spain. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:393-398.

- Perez-Martinez L, Venzal JM, Portillo A, et al. Bartonella rochalimae and other Bartonella spp. in fleas, Chile. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1150-1152.

- Sofer S, Gutierrez DM, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Molecular detection of zoonotic bartonellae (B. henselae, B. elizabethae and B. rochalimae) in fleas collected from dogs in Israel. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:344-348.

- Zouari S, Khrouf F, M’ghirbi Y, et al. First molecular detection and characterization of zoonotic Bartonella species in fleas infesting domestic animals in Tunisia. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:436.

- Rolain JM, Bourry, O, Davoust B, et al. Bartonella quintana and Rickettsia felis in Gabon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1742-1744.

- Tsioutis C, Zafeiri M, Avramopoulos A, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics, epidemiology, and outcomes of murine typhus: a systematic review. Acta Trop. 2017;166:16-24.

- Brown L, Macaluso KR. Rickettsia felis, an emerging flea-borne rickettsiosis. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:27-39.

- Oteo JA, Portillo A, Potero F, et al. ‘Candidatus Rickettsia asemboensis’ and Wolbachia spp. in Ctenocephalides felis and Pulex irritans fleas removed from dogs in Ecuador. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:455.

- Ghavami MB, Mirzadeh H, Mohammadi J, et al. Molecular survey of ITS spacer and Rickettsia infection in human flea, Pulex irritans. Parasitol Res. 2018;117:1433-1442.

- Traversa D. Fleas infesting pets in the era of emerging extra-intestinal nematodes. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:59.

- Rust MK. Insecticide resistance in fleas. Insects. 2016;7:10.

- Ghavami MB, Haghi FP, Alibabaei Z, et al. First report of target site insensitivity to pyrethroids in human flea, Pulex irritans (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Pest Biochem Physiol. 2018;146:97-105.

Characteristics

The ubiquitous human flea, Pulex irritans, is a hematophagous wingless ectoparasite in the order Siphonaptera (wingless siphon) that survives by consuming the blood of its mammalian and avian hosts. Due to diseases such as the bubonic plague, fleas have claimed more victims than all the wars ever fought; in the 14th century, the Black Death caused more than 200 million deaths. Fleas fossilized in amber have been found to be 200 million years old and closely resemble the modern human flea, demonstrating the resilience of the species.

The adult human flea is a small, reddish brown, laterally compressed, wingless insect that is approximately 2- to 3.5-mm long (females, 2.5–3.5 mm; males, 2–2.5 mm) and enclosed by a tough cuticle. Compared to the dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis) and cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), P irritans has no combs or ctenidia (Figure 1). Fleas have large powerful hind legs enabling them to jump horizontally or vertically 200 times their body length (equivalent to a 6-foot human jumping 1200 feet) using stored muscle energy in a pad on the hind legs composed of the elastic protein resilin.1 They feed off a wide variety of hosts, including humans, pigs, cats, dogs, goats, sheep, cattle, chickens, owls, foxes, rabbits, mice, and feral cats. The flea’s mouthparts are highly specialized for piercing the skin and sucking its blood meal via direct capillary cannulation.

Life Cycle

There are 4 stages of the flea life cycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Most adult flea species mate on the host; the female will lay an average of 4 to 8 small white eggs on the host after each blood meal, laying more than 400 eggs during her lifetime. The eggs then drop from the host and hatch in approximately 4 to 6 days to become larvae. The active larvae feed on available organic matter in their environment, such as their parents’ feces and detritus, while undergoing 3 molts within 1 week to several months.2 The larva then spins a silken cocoon from modified salivary glands to form the pupa. In favorable conditions, the pupa lasts only a few weeks; however, it can last for a year or more in unfavorable conditions. Triggers for emergence of the adult flea from the pupa include high humidity, warm temperatures, increased levels of carbon dioxide, and vibrations including sound. An adult P irritans flea can live for a few weeks to more than 1.5 years in favorable conditions of lower air temperature, high relative humidity, and access to a host.3

Related Diseases

Pulex irritans can be a vector for several human diseases. Yersinia pestis is a gram-negative bacteria that causes plague, a highly virulent disease that killed millions of people during its 3 largest human pandemics. The black rat (Rattus rattus) and the oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) have been implicated as initial vectors; however, transmission may be human-to-human with pneumonic plague, and septicemic plague may be spread via Pulex fleas or body lice.4,5 In 1971, Y pestis was isolated from P irritans on a dog in the home of a plague patient in Kayenta, Arizona.6Yersinia pestis bacterial DNA also was extracted from P irritans during a plague outbreak in Madagascar in 20147 and was implicated in epidemiologic studies of plague in Tanzania from 1986 to 2004, suggesting it also plays a role in endemic disease.8

Bartonellosis is an emerging disease caused by different species of the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Bartonella transmitted by lice, ticks, and fleas. Bartonella quintana causes trench fever primarily transmitted by the human body louse, Pediculus humanus corporis, and resulted in more than 1 million cases during World War I. Trench fever is characterized by headache, fever, dizziness, and shin pain that lasts 1 to 3 days and recurs in cycles every 4 to 6 days. Other clinical manifestations of B quintana include chronic bacteremia, endocarditis, lymphadenopathy, and bacillary angiomatosis.9Bartonella henselae causes cat scratch fever, characterized by lymphadenopathy, fever, headache, joint pain, and lethargy from infected cat scratches or the bite of an infected flea. Bartonella rochalimae also has been found to cause a trench fever–like bacteremia.10Bartonella species have been found in P irritans, and the flea is implicated as a vector of bartonellosis in humans.11-15

Rickettsioses are worldwide diseases caused by the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Rickettsia transmitted to humans via hematophagous arthropods. The rickettsiae traditionally have been classified into the spotted fever or typhus groups. The spotted fever group (ie, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Mediterranean spotted fever) is transmitted via ticks. The typhus group is transmitted via lice (epidemic typhus) and fleas (endemic or murine typhus). Murine typhus can be caused by Rickettsia typhi in warm coastal areas around the world where the main mammal reservoir is the rat and the rat flea vector X cheopis. Clinical signs of infection are abrupt onset of fever, headaches, myalgia, malaise, and chills, with a truncal maculopapular rash progressing peripherally several days after the initial clinical signs. Rash is present in up to 50% of cases.16Rickettsia felis is an emerging flea-borne pathogen causing an acute febrile illness usually transmitted via the cat flea C felis.17Rickettsia species DNA have been found to be present in P irritans from dogs18 and livestock19 and pose a risk for causing rickettsioses in humans.

Environmental Treatment and Prevention

Flea bites present as intense, pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that usually are located on the lower extremities but also can be present on exposed areas of the upper extremities and hands (Figure 2). Human fleas infest clothing, and bites can be widespread. Topical antipruritics and corticosteroids can be used for controlling itch and the intense cutaneous inflammatory response. The flea host should be identified in areas of the home, school, farm, work, or local environment. House pets should be examined and treated by a veterinarian. The pet’s bedding should be washed and dried at high temperatures, and carpets and floors should be routinely vacuumed or cleaned to remove eggs, larvae, flea feces, and/or pupae. The killing of adult fleas with insecticidal products (eg, imidacloprid, fipronil, spinosad, selamectin, lufenuron, ivermectin) is the primary method of flea control. Use of insect growth regulators such as pyriproxyfen inhibits adult reproduction and blocks the organogenesis of immature larval stages via hormonal or enzymatic actions.20 The combination of an insecticide and an insect growth regulator appears to be most effective in their synergistic actions against adult fleas and larvae. There have been reports of insecticidal resistance in the flea population, especially with pyrethroids.21,22 A professional exterminator and veterinarian should be consulted. In recalcitrant cases, evaluation for other wild mammals or birds should be performed in unoccupied areas of the home such as the attic, crawl spaces, and basements, as well as inside walls.

Conclusion

The human flea, P irritans, is an important vector in the transmission of human diseases such as the bubonic plague, bartonellosis, and rickettsioses. Flea bites present as intensely pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that most commonly present on the lower extremities. Flea bites can be treated with topical steroids, and fleas can be controlled by a combination of insecticidal products and insect growth regulators.

Characteristics

The ubiquitous human flea, Pulex irritans, is a hematophagous wingless ectoparasite in the order Siphonaptera (wingless siphon) that survives by consuming the blood of its mammalian and avian hosts. Due to diseases such as the bubonic plague, fleas have claimed more victims than all the wars ever fought; in the 14th century, the Black Death caused more than 200 million deaths. Fleas fossilized in amber have been found to be 200 million years old and closely resemble the modern human flea, demonstrating the resilience of the species.

The adult human flea is a small, reddish brown, laterally compressed, wingless insect that is approximately 2- to 3.5-mm long (females, 2.5–3.5 mm; males, 2–2.5 mm) and enclosed by a tough cuticle. Compared to the dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis) and cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), P irritans has no combs or ctenidia (Figure 1). Fleas have large powerful hind legs enabling them to jump horizontally or vertically 200 times their body length (equivalent to a 6-foot human jumping 1200 feet) using stored muscle energy in a pad on the hind legs composed of the elastic protein resilin.1 They feed off a wide variety of hosts, including humans, pigs, cats, dogs, goats, sheep, cattle, chickens, owls, foxes, rabbits, mice, and feral cats. The flea’s mouthparts are highly specialized for piercing the skin and sucking its blood meal via direct capillary cannulation.

Life Cycle

There are 4 stages of the flea life cycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Most adult flea species mate on the host; the female will lay an average of 4 to 8 small white eggs on the host after each blood meal, laying more than 400 eggs during her lifetime. The eggs then drop from the host and hatch in approximately 4 to 6 days to become larvae. The active larvae feed on available organic matter in their environment, such as their parents’ feces and detritus, while undergoing 3 molts within 1 week to several months.2 The larva then spins a silken cocoon from modified salivary glands to form the pupa. In favorable conditions, the pupa lasts only a few weeks; however, it can last for a year or more in unfavorable conditions. Triggers for emergence of the adult flea from the pupa include high humidity, warm temperatures, increased levels of carbon dioxide, and vibrations including sound. An adult P irritans flea can live for a few weeks to more than 1.5 years in favorable conditions of lower air temperature, high relative humidity, and access to a host.3

Related Diseases

Pulex irritans can be a vector for several human diseases. Yersinia pestis is a gram-negative bacteria that causes plague, a highly virulent disease that killed millions of people during its 3 largest human pandemics. The black rat (Rattus rattus) and the oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) have been implicated as initial vectors; however, transmission may be human-to-human with pneumonic plague, and septicemic plague may be spread via Pulex fleas or body lice.4,5 In 1971, Y pestis was isolated from P irritans on a dog in the home of a plague patient in Kayenta, Arizona.6Yersinia pestis bacterial DNA also was extracted from P irritans during a plague outbreak in Madagascar in 20147 and was implicated in epidemiologic studies of plague in Tanzania from 1986 to 2004, suggesting it also plays a role in endemic disease.8

Bartonellosis is an emerging disease caused by different species of the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Bartonella transmitted by lice, ticks, and fleas. Bartonella quintana causes trench fever primarily transmitted by the human body louse, Pediculus humanus corporis, and resulted in more than 1 million cases during World War I. Trench fever is characterized by headache, fever, dizziness, and shin pain that lasts 1 to 3 days and recurs in cycles every 4 to 6 days. Other clinical manifestations of B quintana include chronic bacteremia, endocarditis, lymphadenopathy, and bacillary angiomatosis.9Bartonella henselae causes cat scratch fever, characterized by lymphadenopathy, fever, headache, joint pain, and lethargy from infected cat scratches or the bite of an infected flea. Bartonella rochalimae also has been found to cause a trench fever–like bacteremia.10Bartonella species have been found in P irritans, and the flea is implicated as a vector of bartonellosis in humans.11-15

Rickettsioses are worldwide diseases caused by the gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Rickettsia transmitted to humans via hematophagous arthropods. The rickettsiae traditionally have been classified into the spotted fever or typhus groups. The spotted fever group (ie, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Mediterranean spotted fever) is transmitted via ticks. The typhus group is transmitted via lice (epidemic typhus) and fleas (endemic or murine typhus). Murine typhus can be caused by Rickettsia typhi in warm coastal areas around the world where the main mammal reservoir is the rat and the rat flea vector X cheopis. Clinical signs of infection are abrupt onset of fever, headaches, myalgia, malaise, and chills, with a truncal maculopapular rash progressing peripherally several days after the initial clinical signs. Rash is present in up to 50% of cases.16Rickettsia felis is an emerging flea-borne pathogen causing an acute febrile illness usually transmitted via the cat flea C felis.17Rickettsia species DNA have been found to be present in P irritans from dogs18 and livestock19 and pose a risk for causing rickettsioses in humans.

Environmental Treatment and Prevention

Flea bites present as intense, pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that usually are located on the lower extremities but also can be present on exposed areas of the upper extremities and hands (Figure 2). Human fleas infest clothing, and bites can be widespread. Topical antipruritics and corticosteroids can be used for controlling itch and the intense cutaneous inflammatory response. The flea host should be identified in areas of the home, school, farm, work, or local environment. House pets should be examined and treated by a veterinarian. The pet’s bedding should be washed and dried at high temperatures, and carpets and floors should be routinely vacuumed or cleaned to remove eggs, larvae, flea feces, and/or pupae. The killing of adult fleas with insecticidal products (eg, imidacloprid, fipronil, spinosad, selamectin, lufenuron, ivermectin) is the primary method of flea control. Use of insect growth regulators such as pyriproxyfen inhibits adult reproduction and blocks the organogenesis of immature larval stages via hormonal or enzymatic actions.20 The combination of an insecticide and an insect growth regulator appears to be most effective in their synergistic actions against adult fleas and larvae. There have been reports of insecticidal resistance in the flea population, especially with pyrethroids.21,22 A professional exterminator and veterinarian should be consulted. In recalcitrant cases, evaluation for other wild mammals or birds should be performed in unoccupied areas of the home such as the attic, crawl spaces, and basements, as well as inside walls.

Conclusion

The human flea, P irritans, is an important vector in the transmission of human diseases such as the bubonic plague, bartonellosis, and rickettsioses. Flea bites present as intensely pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules that most commonly present on the lower extremities. Flea bites can be treated with topical steroids, and fleas can be controlled by a combination of insecticidal products and insect growth regulators.

- Burrow M. How fleas jump. J Exp Biol. 2009;18:2881-2883.

- Buckland PC, Sandler JP. A biogeography of the human flea, Pulex irritans L (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J Biogeogr. 1989;16:115-120.

- Krasnov BR. Life cycles. In: Krasnov BR, ed. Functional and Evolutional Ecology of Fleas. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ Press; 2008:45-67.

- Dean KR, Krauer F, Walloe L, et al. Human ectoparasites and the spread of plague in Europe during the second pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:1304-1309.

- Hufthammer AK, Walloe L. Rats cannot have been intermediate hosts for Yersinia pestis during medieval plague epidemics in Northern Europe. J Archeol Sci. 2013;40:1752-1759.

- Archibald WS, Kunitz SJ. Detection of plague by testing serums of dogs on the Navajo Reservation. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971;86:377-380.

- Ratovonjato J, Rajerison M, Rahelinirina S, et al. Yersinia pestis in Pulex irritans fleas during plague outbreak, Madagascar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1414-1415.

- Laudisoit A, Leirs H, Makundi RH, et al. Plague and the human flea, Tanzania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:687-693.

- Foucault C, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Bartonella quintana characteristics and clinical management. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:217-223.

- Eremeeva ME, Gerns HL, Lydy SL, et al. Bacteremia, fever, and splenomegaly caused by a newly recognized bartonella species. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:2381-2387.11.

- Marquez FJ, Millan J, Rodriguez-Liebana JJ, et al. Detection and identification of Bartonella sp. in fleas from carnivorous mammals in Andalusia, Spain. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:393-398.

- Perez-Martinez L, Venzal JM, Portillo A, et al. Bartonella rochalimae and other Bartonella spp. in fleas, Chile. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1150-1152.

- Sofer S, Gutierrez DM, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Molecular detection of zoonotic bartonellae (B. henselae, B. elizabethae and B. rochalimae) in fleas collected from dogs in Israel. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:344-348.

- Zouari S, Khrouf F, M’ghirbi Y, et al. First molecular detection and characterization of zoonotic Bartonella species in fleas infesting domestic animals in Tunisia. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:436.

- Rolain JM, Bourry, O, Davoust B, et al. Bartonella quintana and Rickettsia felis in Gabon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1742-1744.

- Tsioutis C, Zafeiri M, Avramopoulos A, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics, epidemiology, and outcomes of murine typhus: a systematic review. Acta Trop. 2017;166:16-24.

- Brown L, Macaluso KR. Rickettsia felis, an emerging flea-borne rickettsiosis. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:27-39.

- Oteo JA, Portillo A, Potero F, et al. ‘Candidatus Rickettsia asemboensis’ and Wolbachia spp. in Ctenocephalides felis and Pulex irritans fleas removed from dogs in Ecuador. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:455.

- Ghavami MB, Mirzadeh H, Mohammadi J, et al. Molecular survey of ITS spacer and Rickettsia infection in human flea, Pulex irritans. Parasitol Res. 2018;117:1433-1442.

- Traversa D. Fleas infesting pets in the era of emerging extra-intestinal nematodes. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:59.

- Rust MK. Insecticide resistance in fleas. Insects. 2016;7:10.

- Ghavami MB, Haghi FP, Alibabaei Z, et al. First report of target site insensitivity to pyrethroids in human flea, Pulex irritans (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Pest Biochem Physiol. 2018;146:97-105.

- Burrow M. How fleas jump. J Exp Biol. 2009;18:2881-2883.

- Buckland PC, Sandler JP. A biogeography of the human flea, Pulex irritans L (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J Biogeogr. 1989;16:115-120.

- Krasnov BR. Life cycles. In: Krasnov BR, ed. Functional and Evolutional Ecology of Fleas. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ Press; 2008:45-67.

- Dean KR, Krauer F, Walloe L, et al. Human ectoparasites and the spread of plague in Europe during the second pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:1304-1309.

- Hufthammer AK, Walloe L. Rats cannot have been intermediate hosts for Yersinia pestis during medieval plague epidemics in Northern Europe. J Archeol Sci. 2013;40:1752-1759.

- Archibald WS, Kunitz SJ. Detection of plague by testing serums of dogs on the Navajo Reservation. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971;86:377-380.

- Ratovonjato J, Rajerison M, Rahelinirina S, et al. Yersinia pestis in Pulex irritans fleas during plague outbreak, Madagascar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1414-1415.

- Laudisoit A, Leirs H, Makundi RH, et al. Plague and the human flea, Tanzania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:687-693.

- Foucault C, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Bartonella quintana characteristics and clinical management. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:217-223.

- Eremeeva ME, Gerns HL, Lydy SL, et al. Bacteremia, fever, and splenomegaly caused by a newly recognized bartonella species. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:2381-2387.11.

- Marquez FJ, Millan J, Rodriguez-Liebana JJ, et al. Detection and identification of Bartonella sp. in fleas from carnivorous mammals in Andalusia, Spain. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:393-398.

- Perez-Martinez L, Venzal JM, Portillo A, et al. Bartonella rochalimae and other Bartonella spp. in fleas, Chile. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1150-1152.

- Sofer S, Gutierrez DM, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Molecular detection of zoonotic bartonellae (B. henselae, B. elizabethae and B. rochalimae) in fleas collected from dogs in Israel. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:344-348.

- Zouari S, Khrouf F, M’ghirbi Y, et al. First molecular detection and characterization of zoonotic Bartonella species in fleas infesting domestic animals in Tunisia. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:436.

- Rolain JM, Bourry, O, Davoust B, et al. Bartonella quintana and Rickettsia felis in Gabon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1742-1744.

- Tsioutis C, Zafeiri M, Avramopoulos A, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics, epidemiology, and outcomes of murine typhus: a systematic review. Acta Trop. 2017;166:16-24.

- Brown L, Macaluso KR. Rickettsia felis, an emerging flea-borne rickettsiosis. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:27-39.

- Oteo JA, Portillo A, Potero F, et al. ‘Candidatus Rickettsia asemboensis’ and Wolbachia spp. in Ctenocephalides felis and Pulex irritans fleas removed from dogs in Ecuador. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:455.

- Ghavami MB, Mirzadeh H, Mohammadi J, et al. Molecular survey of ITS spacer and Rickettsia infection in human flea, Pulex irritans. Parasitol Res. 2018;117:1433-1442.

- Traversa D. Fleas infesting pets in the era of emerging extra-intestinal nematodes. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:59.

- Rust MK. Insecticide resistance in fleas. Insects. 2016;7:10.

- Ghavami MB, Haghi FP, Alibabaei Z, et al. First report of target site insensitivity to pyrethroids in human flea, Pulex irritans (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). Pest Biochem Physiol. 2018;146:97-105.

Practice Points

- The human flea, Pulex irritans, is a vector for various human diseases including the bubonic plague, bartonellosis, and rickettsioses.

- Presenting symptoms of flea bites include intensely pruritic, urticarial to vesicular papules on exposed areas of skin.

- The primary method of flea control includes a combination of insecticidal products and insect growth regulators.

Aging with HIV adds to comorbidity burden

The age of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV is in its third decade, and many of the patients who live in areas of the world fortunate enough to have had early access to therapy have now lived for several decades with complications of HIV and viral suppressive therapy.

But while the life-expectancy of persons with HIV has approached that of noninfected persons over the last 20 years, the higher burden of comorbidities for aging patients with HIV has remained largely the same, according to an epidemiologist who specializes in HIV/AIDS research and aging.

“The pathways from HIV and its treatments to comorbidities are very long and winding, spanning a life course. Social determinants of health and individual risk factors also play an important role, and must be considered,” said Keri N. Althoff, PhD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Althoff discussed long-term complications of HIV and its treatment in a virtual symposium during an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Many urban HIV providers have an increased proportion of patients who are older long-term survivors of the epidemic. Many, but not all of the comorbidities (including cardiovascular, neurocognitive, renal, and malignancies) have been associated with age, long-term HIV infection, especially uncontrolled HIV infection, and low CD4 nadirs,” commented Harry Lampiris, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

“An increasing number of patients are experiencing geriatric syndromes (especially problems with mobility, cognitive decline, food insecurity, polypharmacy, and social isolation) at younger ages than HIV-negative populations,” he added.

Dr. Lampiris, who moderated the session where Dr. Althoff presented her findings, commented on it in an interview, but was not involved in her research.

Pathways to comorbidity

The three primary pathways to comorbidities in people with HIV infections are as follows, according to Dr. Athloff:

- The virus itself, with its associated inflammation, immunosuppression, immune activation, and AIDS.

- HIV therapies, beginning with the notoriously toxic dideoxynucleoside analogues or “d-drugs,” and following with subsequent generations of newer, less toxic agents.

- Individual risk factors, including smoking, stress, diet, exercise, and environment.

Cardiovascular and renal complications

Persons with HIV have an approximately twofold higher risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke) compared with persons without HIV. Conditions contributing to cardiovascular disease including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia are also significantly higher among persons with HIV, Dr. Althoff said.

Hypertension among persons with HIV from the ages 60-69 years is especially high for Black men and to a lesser degree non-Black men, compared with either White or Black women, she noted.

Pathways to renal disease in persons with HIV include diabetes and hypertension, as well as therapies to treat them, hepatitis B and C coinfection, HIV-associated nephropathy, and immune complex kidney disease, as well as chronic kidney disease resulting from acute kidney injury related to therapy.