User login

Case Report: Perianal Streptococcal Infection

Case

The mother of a 3-year-old boy presented her son to the ED for evaluation after she noticed peeling of the skin in his perianal region. She stated that the peeling had started 1 day prior to presentation. Two days earlier, the mother had brought the same patient to the ED for evaluation of a fever, sore throat, and a slight rash over his face. The boy’s vital signs at the initial presentation were: temperature, 101.8°F; heart rate, 102 beats/minute; and respiratory rate, 28 breaths/minute. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

During this first visit, the mother denied the child having had any fever, chills, headache, sore throat, facial rash, joint pain, or pain on defecation. He had no significant medical history and no known drug allergies. After examination, a throat culture was taken, and the patient was given acetaminophen and discharged home with a diagnosis of viral syndrome.

At the second presentation, physical examination revealed a well-developed child in no distress. The examination was negative except for a 4 x 2 cm area of desquamation present over the perianal region (Figure).

The area of desquamation was dry, mildly erythematous without discharge, and nontender. The patient’s vital signs at this presentation were stable, and he was afebrile. The remaining physical examination findings were normal. The throat culture taken during the first ED presentation was reported as negative. A perianal swab was sent for culture and sensitivity. This was later reported to be positive for group A β-hemolytic streptococci (GABHS), which is sensitive to penicillin. The patient was discharged home in the care of his mother with a prescription of penicillin. A 10-day follow-up showed complete resolution of the skin rash.

Discussion

The rash in this case was most likely the result of scarlet fever with an unusual presentation of PSD; the signs and symptoms of which include perianal erythema, itching, rectal pain, sometimes blood-streaked stools, rectal bleeding, irritation or pruritus, tissue loss and exudation, secondary constipation, and cellulitis. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis has also been described in the adult literature.2 As with pediatric cases, PSD in adults is usually caused by GABHS.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

A rapid streptococcal test of suspicious areas can confirm the diagnosis. Fever, sore throat, and arthralgia are rare; however, culture from the perianal region grows GABHS. Titers are usually not elevated in laboratory evaluation. A routine skin culture is an alternative diagnostic aid.

Brilliant2 described the bright red color of PSD as a sharply demarcated rash that is caused by GABHS. As previously stated, symptoms include perianal rash, itching, and rectal pain; blood-streaked stools may also be seen in one-third of patients. It primarily occurs in children between 6 months and 10 years of age and is often misdiagnosed and treated inappropriately.3

Prompt diagnosis of GABHS is important. If untreated, it can cause serious systemic infections, especially in elderly and in newborn patients. Treatment with antibiotics resolves the condition in the majority of patients.2 In the acute stage, a white pseudomembrane may be present. As the rash becomes more chronic, the perianal eruption may consist of painful fissures, a dry mucoid discharge, or psoriasiform plaques. Perianal dermatitis can also be caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Candida. Confirmation of the diagnosis is accomplished by culturing a moderate-to-heavy growth of GABHS on 5% sheep-blood agar.

Treatment

A 10-day course of oral penicillin produces resolution of the dermatitis and other symptoms in most patients, but a relapse rate as high as 39% has been reported. Other treatment plans include amoxicillin, 40 mg/kg per day, divided into three doses, and/or topical applications of mupirocin 2% three times per day for 10 days. Penicillin, clindamycin phosphate, and erythromycin have also been used.

Although penicillin is generally recommended for treatment of GABHS infection, amoxicillin is often better tolerated in the pediatric population due to its superior palatability. Early antibiotic treatment causes a dramatic and rapid improvement of symptoms. However, according to Olson et al,4 PSD initially treated with amoxicillin or penicillin is consistently associated with a high risk of clinical recurrence. Whether treatment with a β-lactamase–resistant agent reduces this risk is uncertain.

Conclusion

This case represents an unusual presentation of scarlet fever manifesting as perianal dermatitis caused by GABHS. Although more common in the pediatric population, adult cases have been documented in the literature. As this case illustrates, early recognition and treatment with penicillin (or amoxicillin) produces rapid improvement and resolution of symptoms.

Dr Nibhanipudi is a professor of clinical emergency medicine at New York Medical College - Metropolitan Hospital Center, New York.

- Case Report: Perianal Streptococcal Infection

- Landolt M, Heininger U. Prevalence of perianal streptococcal dermatitis in children and adolescents [in German]. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2005;94(38):1467-1471.

- Kahlke V, Jongen J, Peleikis HG, Herbst RA. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis in adults: its association with pruritic anorectal diseases is mainly caused by group B Streptococci. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(5):602-607.

- Brilliant LC. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(2):391-393.

- Olson D, Edmonson MB. Outcomes in children treated for perineal group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal dermatitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(11):933-936.

Case

The mother of a 3-year-old boy presented her son to the ED for evaluation after she noticed peeling of the skin in his perianal region. She stated that the peeling had started 1 day prior to presentation. Two days earlier, the mother had brought the same patient to the ED for evaluation of a fever, sore throat, and a slight rash over his face. The boy’s vital signs at the initial presentation were: temperature, 101.8°F; heart rate, 102 beats/minute; and respiratory rate, 28 breaths/minute. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

During this first visit, the mother denied the child having had any fever, chills, headache, sore throat, facial rash, joint pain, or pain on defecation. He had no significant medical history and no known drug allergies. After examination, a throat culture was taken, and the patient was given acetaminophen and discharged home with a diagnosis of viral syndrome.

At the second presentation, physical examination revealed a well-developed child in no distress. The examination was negative except for a 4 x 2 cm area of desquamation present over the perianal region (Figure).

The area of desquamation was dry, mildly erythematous without discharge, and nontender. The patient’s vital signs at this presentation were stable, and he was afebrile. The remaining physical examination findings were normal. The throat culture taken during the first ED presentation was reported as negative. A perianal swab was sent for culture and sensitivity. This was later reported to be positive for group A β-hemolytic streptococci (GABHS), which is sensitive to penicillin. The patient was discharged home in the care of his mother with a prescription of penicillin. A 10-day follow-up showed complete resolution of the skin rash.

Discussion

The rash in this case was most likely the result of scarlet fever with an unusual presentation of PSD; the signs and symptoms of which include perianal erythema, itching, rectal pain, sometimes blood-streaked stools, rectal bleeding, irritation or pruritus, tissue loss and exudation, secondary constipation, and cellulitis. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis has also been described in the adult literature.2 As with pediatric cases, PSD in adults is usually caused by GABHS.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

A rapid streptococcal test of suspicious areas can confirm the diagnosis. Fever, sore throat, and arthralgia are rare; however, culture from the perianal region grows GABHS. Titers are usually not elevated in laboratory evaluation. A routine skin culture is an alternative diagnostic aid.

Brilliant2 described the bright red color of PSD as a sharply demarcated rash that is caused by GABHS. As previously stated, symptoms include perianal rash, itching, and rectal pain; blood-streaked stools may also be seen in one-third of patients. It primarily occurs in children between 6 months and 10 years of age and is often misdiagnosed and treated inappropriately.3

Prompt diagnosis of GABHS is important. If untreated, it can cause serious systemic infections, especially in elderly and in newborn patients. Treatment with antibiotics resolves the condition in the majority of patients.2 In the acute stage, a white pseudomembrane may be present. As the rash becomes more chronic, the perianal eruption may consist of painful fissures, a dry mucoid discharge, or psoriasiform plaques. Perianal dermatitis can also be caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Candida. Confirmation of the diagnosis is accomplished by culturing a moderate-to-heavy growth of GABHS on 5% sheep-blood agar.

Treatment

A 10-day course of oral penicillin produces resolution of the dermatitis and other symptoms in most patients, but a relapse rate as high as 39% has been reported. Other treatment plans include amoxicillin, 40 mg/kg per day, divided into three doses, and/or topical applications of mupirocin 2% three times per day for 10 days. Penicillin, clindamycin phosphate, and erythromycin have also been used.

Although penicillin is generally recommended for treatment of GABHS infection, amoxicillin is often better tolerated in the pediatric population due to its superior palatability. Early antibiotic treatment causes a dramatic and rapid improvement of symptoms. However, according to Olson et al,4 PSD initially treated with amoxicillin or penicillin is consistently associated with a high risk of clinical recurrence. Whether treatment with a β-lactamase–resistant agent reduces this risk is uncertain.

Conclusion

This case represents an unusual presentation of scarlet fever manifesting as perianal dermatitis caused by GABHS. Although more common in the pediatric population, adult cases have been documented in the literature. As this case illustrates, early recognition and treatment with penicillin (or amoxicillin) produces rapid improvement and resolution of symptoms.

Dr Nibhanipudi is a professor of clinical emergency medicine at New York Medical College - Metropolitan Hospital Center, New York.

Case

The mother of a 3-year-old boy presented her son to the ED for evaluation after she noticed peeling of the skin in his perianal region. She stated that the peeling had started 1 day prior to presentation. Two days earlier, the mother had brought the same patient to the ED for evaluation of a fever, sore throat, and a slight rash over his face. The boy’s vital signs at the initial presentation were: temperature, 101.8°F; heart rate, 102 beats/minute; and respiratory rate, 28 breaths/minute. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

During this first visit, the mother denied the child having had any fever, chills, headache, sore throat, facial rash, joint pain, or pain on defecation. He had no significant medical history and no known drug allergies. After examination, a throat culture was taken, and the patient was given acetaminophen and discharged home with a diagnosis of viral syndrome.

At the second presentation, physical examination revealed a well-developed child in no distress. The examination was negative except for a 4 x 2 cm area of desquamation present over the perianal region (Figure).

The area of desquamation was dry, mildly erythematous without discharge, and nontender. The patient’s vital signs at this presentation were stable, and he was afebrile. The remaining physical examination findings were normal. The throat culture taken during the first ED presentation was reported as negative. A perianal swab was sent for culture and sensitivity. This was later reported to be positive for group A β-hemolytic streptococci (GABHS), which is sensitive to penicillin. The patient was discharged home in the care of his mother with a prescription of penicillin. A 10-day follow-up showed complete resolution of the skin rash.

Discussion

The rash in this case was most likely the result of scarlet fever with an unusual presentation of PSD; the signs and symptoms of which include perianal erythema, itching, rectal pain, sometimes blood-streaked stools, rectal bleeding, irritation or pruritus, tissue loss and exudation, secondary constipation, and cellulitis. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis has also been described in the adult literature.2 As with pediatric cases, PSD in adults is usually caused by GABHS.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

A rapid streptococcal test of suspicious areas can confirm the diagnosis. Fever, sore throat, and arthralgia are rare; however, culture from the perianal region grows GABHS. Titers are usually not elevated in laboratory evaluation. A routine skin culture is an alternative diagnostic aid.

Brilliant2 described the bright red color of PSD as a sharply demarcated rash that is caused by GABHS. As previously stated, symptoms include perianal rash, itching, and rectal pain; blood-streaked stools may also be seen in one-third of patients. It primarily occurs in children between 6 months and 10 years of age and is often misdiagnosed and treated inappropriately.3

Prompt diagnosis of GABHS is important. If untreated, it can cause serious systemic infections, especially in elderly and in newborn patients. Treatment with antibiotics resolves the condition in the majority of patients.2 In the acute stage, a white pseudomembrane may be present. As the rash becomes more chronic, the perianal eruption may consist of painful fissures, a dry mucoid discharge, or psoriasiform plaques. Perianal dermatitis can also be caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Candida. Confirmation of the diagnosis is accomplished by culturing a moderate-to-heavy growth of GABHS on 5% sheep-blood agar.

Treatment

A 10-day course of oral penicillin produces resolution of the dermatitis and other symptoms in most patients, but a relapse rate as high as 39% has been reported. Other treatment plans include amoxicillin, 40 mg/kg per day, divided into three doses, and/or topical applications of mupirocin 2% three times per day for 10 days. Penicillin, clindamycin phosphate, and erythromycin have also been used.

Although penicillin is generally recommended for treatment of GABHS infection, amoxicillin is often better tolerated in the pediatric population due to its superior palatability. Early antibiotic treatment causes a dramatic and rapid improvement of symptoms. However, according to Olson et al,4 PSD initially treated with amoxicillin or penicillin is consistently associated with a high risk of clinical recurrence. Whether treatment with a β-lactamase–resistant agent reduces this risk is uncertain.

Conclusion

This case represents an unusual presentation of scarlet fever manifesting as perianal dermatitis caused by GABHS. Although more common in the pediatric population, adult cases have been documented in the literature. As this case illustrates, early recognition and treatment with penicillin (or amoxicillin) produces rapid improvement and resolution of symptoms.

Dr Nibhanipudi is a professor of clinical emergency medicine at New York Medical College - Metropolitan Hospital Center, New York.

- Case Report: Perianal Streptococcal Infection

- Landolt M, Heininger U. Prevalence of perianal streptococcal dermatitis in children and adolescents [in German]. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2005;94(38):1467-1471.

- Kahlke V, Jongen J, Peleikis HG, Herbst RA. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis in adults: its association with pruritic anorectal diseases is mainly caused by group B Streptococci. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(5):602-607.

- Brilliant LC. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(2):391-393.

- Olson D, Edmonson MB. Outcomes in children treated for perineal group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal dermatitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(11):933-936.

- Case Report: Perianal Streptococcal Infection

- Landolt M, Heininger U. Prevalence of perianal streptococcal dermatitis in children and adolescents [in German]. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2005;94(38):1467-1471.

- Kahlke V, Jongen J, Peleikis HG, Herbst RA. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis in adults: its association with pruritic anorectal diseases is mainly caused by group B Streptococci. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(5):602-607.

- Brilliant LC. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(2):391-393.

- Olson D, Edmonson MB. Outcomes in children treated for perineal group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal dermatitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(11):933-936.

Patient-Directed Valgus Stress Radiograph of the Knee: A New and Novel Technique

Medial-compartment partial knee arthroplasty (unicompartmental replacement) is an accepted surgical intervention for anteromedial osteoarthritis of the knee.1 The radiographic investigations required in the workup of these patients should include weight-bearing standing anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and sunrise (Merchant) views, as well as a valgus stress AP radiograph to assess the functionality of the lateral compartment. The method of properly obtaining the valgus stress film has been well described by the Oxford Group.2 Its recommended radiographic technique requires that a surgeon or a radiologic technologist perform the valgus stress maneuver, manually, while another technologist shoots the film. The 2 consequences of this technique are that it requires 2 individuals to obtain the film, and it subjects the individual who is applying the stress to some level of radiation exposure, which is undesirable. Because of this and the time inconvenience, many surgeons omit the valgus stress radiograph, which can lead to the adverse outcome of missing a lateral compartment that is functionally incompetent, resulting in the potential for early lateral compartment progression of osteoarthritis and the need for revision surgery, usually to a total knee arthroplasty.

In an attempt to mitigate these barriers to obtaining the necessary valgus stress radiograph, Dr. Mauerhan’s team developed a technique that could be done with the assistance of the patient and would require only 1 technologist to perform. Additionally, this project was a quality improvement initiative, because it lowered radiation exposure to all personnel involved in obtaining the correct films.

Materials and Methods

We initiated the project using weight-bearing strategies to impart the valgus stress view of the knee. After trying several different wedges and blocks, and varying patient instructions, we realized a different approach to this problem would be required to find an acceptable solution. We redirected our efforts to effectively performing the stress view with the patient in a supine position on the radiograph table. Ultimately, we decided that a much stiffer wedge and a denser object to squeeze would facilitate obtaining a proper film. Considering all available options, a youth size 4 soccer ball (diameter, 11 in) was introduced along with a slightly larger positioning wedge. The soccer ball was wrapped with 4-in Coban wrap (3M) to create a nonslip surface. This change in patient positioning, along with a standardized 7º to 10º cephalic radiographic tube angulation, helped to correct issues with tibial plateau visualization. Once these changes were enacted, we obtained fairly consistent positive results, and we instituted this patient-directed valgus stress view of the knee, along with a manual valgus stress view for comparison.

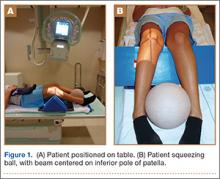

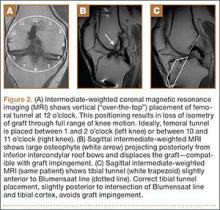

The protocol for obtaining the patient-directed valgus stress view of the knee is as follows: The patient lays supine with a dense 45º spine-positioning wedge (Burlington Medical Supplies) placed under both knees and the patient’s heels on the examining table. The radiographic tube is angled cephalad 7º to 10º centered on the inferior pole of the patella, using a 40-in source to image-receptor distance, collimated to part; the image receptor is placed under the affected knee, below the positioning wedge. The affected knee is rotated to the “true” AP position (the patella will be centered between the femoral condyles on the AP exposure), and the ball is placed between the patient’s legs just above the ankle joint. The technologist demonstrates to the patient how to squeeze the ball while maintaining contact of heels with the table. The technologist can exit the room and obtain the exposure, which is taken while the patient is squeezing the ball, as shown in Figures 1A and 1B. Examples of the standing AP, manual stress, and patient-directed valgus radiographs are shown in Figures 2A-2C. The entire technique is demonstrated in the Video.

Results

During the 9 months of this quality improvement project, 78 examinations were performed. Five studies did not show complete correction of the varus deformity. Of these, 3 showed complete correction on a manual valgus stress radiograph, and 2 did not, contraindicating the use of partial knee replacement. Three patients displayed collapse of the lateral compartment, indicating a nonfunctional lateral compartment, and, therefore, were also a contraindication to partial knee arthroplasty. The remaining 70 patients had identical radiographic results with both the manual and patient-directed valgus stress tests. There was no instance of examination failure or need to repeat as a result of difficulty of the examination for the patient. Repeat films because of positioning errors were very rare, usually early in the learning curve, and no more prevalent than when using the manual stress method. The technique was reproducible and easy to teach and adopt.

Discussion

In total, 73 patients (93.5%) with the patient-directed stress film showed the desired result, either correction of the medial compartment narrowing in conjunction with an intact lateral compartment or narrowing of the lateral compartment. Of the 5 patients (6.5%) whose patient-directed stress films did not show correction of the varus deformity, 3 patients displayed correction with a manually applied stress radiograph and 2 did not. Based on this observation, our recommendation would be for those patients who do not show adequate correction on the patient-directed stress radiograph to have a manual examination to establish the presence or absence of the desired correction.

Performing a valgus stress radiograph is an integral part of the investigation to determine if the patient is an appropriate candidate for partial knee arthroplasty.3 The historical, manually performed valgus stress radiograph requires 2 individuals, 1 to apply the stress with the patient on the table and 1 to shoot the exposure. For the individual or individuals applying this stress, there is an increased radiation exposure that would be undesirable over a long career. The authors developed a new technique using a commercially available spinal positioning wedge and 11-in youth soccer ball wrapped with Coban wrap, as described, which is economical and easy to obtain and use in the clinical setting. We believe this cost-effective method will offer surgeons who perform partial knee arthroplasty a novel method to obtain the important information gleaned from the valgus stress radiograph and to improve surgical outcomes through the preoperative assessment of the lateral compartment. Additionally, as a quality and safety improvement initiative, we believe this technique will reduce radiographic exposure for those performing these studies, and, because the examination can be carried out by a single technologist, it will significantly improve efficiency in the radiology suite.

Conclusion

We have developed a new method of obtaining the important valgus stress radiograph as part of the workup of patients with medial-compartment osteoarthritis of the knee. The technique can be performed with easily obtainable, commercially available products and is reliable 93.5% of the time. It also adds to the efficiency of the radiology suite and reduces radiographic exposure for technologists.

1. White SH, Ludkowski PF, Goodfellow JW. Anteromedial osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(4):582-586.

2. Goodfellow JW, O’Conner JJ, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Unicompartmental Arthroplasty with the Oxford Knee. Woodeaton, Oxford, England: Goodfellow Publishers Limited; 2006:38-39.

3. Gibson PH, Goodfellow JW. Stress radiography in degenerative arthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68(4):608-609.

Medial-compartment partial knee arthroplasty (unicompartmental replacement) is an accepted surgical intervention for anteromedial osteoarthritis of the knee.1 The radiographic investigations required in the workup of these patients should include weight-bearing standing anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and sunrise (Merchant) views, as well as a valgus stress AP radiograph to assess the functionality of the lateral compartment. The method of properly obtaining the valgus stress film has been well described by the Oxford Group.2 Its recommended radiographic technique requires that a surgeon or a radiologic technologist perform the valgus stress maneuver, manually, while another technologist shoots the film. The 2 consequences of this technique are that it requires 2 individuals to obtain the film, and it subjects the individual who is applying the stress to some level of radiation exposure, which is undesirable. Because of this and the time inconvenience, many surgeons omit the valgus stress radiograph, which can lead to the adverse outcome of missing a lateral compartment that is functionally incompetent, resulting in the potential for early lateral compartment progression of osteoarthritis and the need for revision surgery, usually to a total knee arthroplasty.

In an attempt to mitigate these barriers to obtaining the necessary valgus stress radiograph, Dr. Mauerhan’s team developed a technique that could be done with the assistance of the patient and would require only 1 technologist to perform. Additionally, this project was a quality improvement initiative, because it lowered radiation exposure to all personnel involved in obtaining the correct films.

Materials and Methods

We initiated the project using weight-bearing strategies to impart the valgus stress view of the knee. After trying several different wedges and blocks, and varying patient instructions, we realized a different approach to this problem would be required to find an acceptable solution. We redirected our efforts to effectively performing the stress view with the patient in a supine position on the radiograph table. Ultimately, we decided that a much stiffer wedge and a denser object to squeeze would facilitate obtaining a proper film. Considering all available options, a youth size 4 soccer ball (diameter, 11 in) was introduced along with a slightly larger positioning wedge. The soccer ball was wrapped with 4-in Coban wrap (3M) to create a nonslip surface. This change in patient positioning, along with a standardized 7º to 10º cephalic radiographic tube angulation, helped to correct issues with tibial plateau visualization. Once these changes were enacted, we obtained fairly consistent positive results, and we instituted this patient-directed valgus stress view of the knee, along with a manual valgus stress view for comparison.

The protocol for obtaining the patient-directed valgus stress view of the knee is as follows: The patient lays supine with a dense 45º spine-positioning wedge (Burlington Medical Supplies) placed under both knees and the patient’s heels on the examining table. The radiographic tube is angled cephalad 7º to 10º centered on the inferior pole of the patella, using a 40-in source to image-receptor distance, collimated to part; the image receptor is placed under the affected knee, below the positioning wedge. The affected knee is rotated to the “true” AP position (the patella will be centered between the femoral condyles on the AP exposure), and the ball is placed between the patient’s legs just above the ankle joint. The technologist demonstrates to the patient how to squeeze the ball while maintaining contact of heels with the table. The technologist can exit the room and obtain the exposure, which is taken while the patient is squeezing the ball, as shown in Figures 1A and 1B. Examples of the standing AP, manual stress, and patient-directed valgus radiographs are shown in Figures 2A-2C. The entire technique is demonstrated in the Video.

Results

During the 9 months of this quality improvement project, 78 examinations were performed. Five studies did not show complete correction of the varus deformity. Of these, 3 showed complete correction on a manual valgus stress radiograph, and 2 did not, contraindicating the use of partial knee replacement. Three patients displayed collapse of the lateral compartment, indicating a nonfunctional lateral compartment, and, therefore, were also a contraindication to partial knee arthroplasty. The remaining 70 patients had identical radiographic results with both the manual and patient-directed valgus stress tests. There was no instance of examination failure or need to repeat as a result of difficulty of the examination for the patient. Repeat films because of positioning errors were very rare, usually early in the learning curve, and no more prevalent than when using the manual stress method. The technique was reproducible and easy to teach and adopt.

Discussion

In total, 73 patients (93.5%) with the patient-directed stress film showed the desired result, either correction of the medial compartment narrowing in conjunction with an intact lateral compartment or narrowing of the lateral compartment. Of the 5 patients (6.5%) whose patient-directed stress films did not show correction of the varus deformity, 3 patients displayed correction with a manually applied stress radiograph and 2 did not. Based on this observation, our recommendation would be for those patients who do not show adequate correction on the patient-directed stress radiograph to have a manual examination to establish the presence or absence of the desired correction.

Performing a valgus stress radiograph is an integral part of the investigation to determine if the patient is an appropriate candidate for partial knee arthroplasty.3 The historical, manually performed valgus stress radiograph requires 2 individuals, 1 to apply the stress with the patient on the table and 1 to shoot the exposure. For the individual or individuals applying this stress, there is an increased radiation exposure that would be undesirable over a long career. The authors developed a new technique using a commercially available spinal positioning wedge and 11-in youth soccer ball wrapped with Coban wrap, as described, which is economical and easy to obtain and use in the clinical setting. We believe this cost-effective method will offer surgeons who perform partial knee arthroplasty a novel method to obtain the important information gleaned from the valgus stress radiograph and to improve surgical outcomes through the preoperative assessment of the lateral compartment. Additionally, as a quality and safety improvement initiative, we believe this technique will reduce radiographic exposure for those performing these studies, and, because the examination can be carried out by a single technologist, it will significantly improve efficiency in the radiology suite.

Conclusion

We have developed a new method of obtaining the important valgus stress radiograph as part of the workup of patients with medial-compartment osteoarthritis of the knee. The technique can be performed with easily obtainable, commercially available products and is reliable 93.5% of the time. It also adds to the efficiency of the radiology suite and reduces radiographic exposure for technologists.

Medial-compartment partial knee arthroplasty (unicompartmental replacement) is an accepted surgical intervention for anteromedial osteoarthritis of the knee.1 The radiographic investigations required in the workup of these patients should include weight-bearing standing anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and sunrise (Merchant) views, as well as a valgus stress AP radiograph to assess the functionality of the lateral compartment. The method of properly obtaining the valgus stress film has been well described by the Oxford Group.2 Its recommended radiographic technique requires that a surgeon or a radiologic technologist perform the valgus stress maneuver, manually, while another technologist shoots the film. The 2 consequences of this technique are that it requires 2 individuals to obtain the film, and it subjects the individual who is applying the stress to some level of radiation exposure, which is undesirable. Because of this and the time inconvenience, many surgeons omit the valgus stress radiograph, which can lead to the adverse outcome of missing a lateral compartment that is functionally incompetent, resulting in the potential for early lateral compartment progression of osteoarthritis and the need for revision surgery, usually to a total knee arthroplasty.

In an attempt to mitigate these barriers to obtaining the necessary valgus stress radiograph, Dr. Mauerhan’s team developed a technique that could be done with the assistance of the patient and would require only 1 technologist to perform. Additionally, this project was a quality improvement initiative, because it lowered radiation exposure to all personnel involved in obtaining the correct films.

Materials and Methods

We initiated the project using weight-bearing strategies to impart the valgus stress view of the knee. After trying several different wedges and blocks, and varying patient instructions, we realized a different approach to this problem would be required to find an acceptable solution. We redirected our efforts to effectively performing the stress view with the patient in a supine position on the radiograph table. Ultimately, we decided that a much stiffer wedge and a denser object to squeeze would facilitate obtaining a proper film. Considering all available options, a youth size 4 soccer ball (diameter, 11 in) was introduced along with a slightly larger positioning wedge. The soccer ball was wrapped with 4-in Coban wrap (3M) to create a nonslip surface. This change in patient positioning, along with a standardized 7º to 10º cephalic radiographic tube angulation, helped to correct issues with tibial plateau visualization. Once these changes were enacted, we obtained fairly consistent positive results, and we instituted this patient-directed valgus stress view of the knee, along with a manual valgus stress view for comparison.

The protocol for obtaining the patient-directed valgus stress view of the knee is as follows: The patient lays supine with a dense 45º spine-positioning wedge (Burlington Medical Supplies) placed under both knees and the patient’s heels on the examining table. The radiographic tube is angled cephalad 7º to 10º centered on the inferior pole of the patella, using a 40-in source to image-receptor distance, collimated to part; the image receptor is placed under the affected knee, below the positioning wedge. The affected knee is rotated to the “true” AP position (the patella will be centered between the femoral condyles on the AP exposure), and the ball is placed between the patient’s legs just above the ankle joint. The technologist demonstrates to the patient how to squeeze the ball while maintaining contact of heels with the table. The technologist can exit the room and obtain the exposure, which is taken while the patient is squeezing the ball, as shown in Figures 1A and 1B. Examples of the standing AP, manual stress, and patient-directed valgus radiographs are shown in Figures 2A-2C. The entire technique is demonstrated in the Video.

Results

During the 9 months of this quality improvement project, 78 examinations were performed. Five studies did not show complete correction of the varus deformity. Of these, 3 showed complete correction on a manual valgus stress radiograph, and 2 did not, contraindicating the use of partial knee replacement. Three patients displayed collapse of the lateral compartment, indicating a nonfunctional lateral compartment, and, therefore, were also a contraindication to partial knee arthroplasty. The remaining 70 patients had identical radiographic results with both the manual and patient-directed valgus stress tests. There was no instance of examination failure or need to repeat as a result of difficulty of the examination for the patient. Repeat films because of positioning errors were very rare, usually early in the learning curve, and no more prevalent than when using the manual stress method. The technique was reproducible and easy to teach and adopt.

Discussion

In total, 73 patients (93.5%) with the patient-directed stress film showed the desired result, either correction of the medial compartment narrowing in conjunction with an intact lateral compartment or narrowing of the lateral compartment. Of the 5 patients (6.5%) whose patient-directed stress films did not show correction of the varus deformity, 3 patients displayed correction with a manually applied stress radiograph and 2 did not. Based on this observation, our recommendation would be for those patients who do not show adequate correction on the patient-directed stress radiograph to have a manual examination to establish the presence or absence of the desired correction.

Performing a valgus stress radiograph is an integral part of the investigation to determine if the patient is an appropriate candidate for partial knee arthroplasty.3 The historical, manually performed valgus stress radiograph requires 2 individuals, 1 to apply the stress with the patient on the table and 1 to shoot the exposure. For the individual or individuals applying this stress, there is an increased radiation exposure that would be undesirable over a long career. The authors developed a new technique using a commercially available spinal positioning wedge and 11-in youth soccer ball wrapped with Coban wrap, as described, which is economical and easy to obtain and use in the clinical setting. We believe this cost-effective method will offer surgeons who perform partial knee arthroplasty a novel method to obtain the important information gleaned from the valgus stress radiograph and to improve surgical outcomes through the preoperative assessment of the lateral compartment. Additionally, as a quality and safety improvement initiative, we believe this technique will reduce radiographic exposure for those performing these studies, and, because the examination can be carried out by a single technologist, it will significantly improve efficiency in the radiology suite.

Conclusion

We have developed a new method of obtaining the important valgus stress radiograph as part of the workup of patients with medial-compartment osteoarthritis of the knee. The technique can be performed with easily obtainable, commercially available products and is reliable 93.5% of the time. It also adds to the efficiency of the radiology suite and reduces radiographic exposure for technologists.

1. White SH, Ludkowski PF, Goodfellow JW. Anteromedial osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(4):582-586.

2. Goodfellow JW, O’Conner JJ, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Unicompartmental Arthroplasty with the Oxford Knee. Woodeaton, Oxford, England: Goodfellow Publishers Limited; 2006:38-39.

3. Gibson PH, Goodfellow JW. Stress radiography in degenerative arthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68(4):608-609.

1. White SH, Ludkowski PF, Goodfellow JW. Anteromedial osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(4):582-586.

2. Goodfellow JW, O’Conner JJ, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Unicompartmental Arthroplasty with the Oxford Knee. Woodeaton, Oxford, England: Goodfellow Publishers Limited; 2006:38-39.

3. Gibson PH, Goodfellow JW. Stress radiography in degenerative arthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68(4):608-609.

Giant Bone Island of the Tibia in a Child

A bone island is a focus of normal cortical bone located within the medullary cavity. The vast majority of bone islands are small, measuring from 1 mm to 2 cm in size. They are found more frequently in adults than in children. The lesion can be virtually diagnosed on the basis of its characteristic clinical and imaging features. Differential diagnosis may be difficult when the lesion manifests itself uncharacteristically by being symptomatic, very large, and hot on bone scan.1-4

The term giant bone island has been used to describe a large lesion1 that measures more than 2 cm in any dimension.5 Giant bone islands have been described only in adults,1,5-15 and the longest bone island length reported is 10.5 cm.10 They are usually symptomatic and associated with increased radionuclide uptake on bone scintigraphy.14

The history and the clinical and imaging presentation of an even longer, symptomatic, and scintigraphically hot lesion in the tibial diaphysis of a 10-year-old boy is reported. The lesion further exhibited several atypical imaging features necessitating an open biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of a giant bone island. The pertinent differential diagnosis and the clinical and radiographic findings after 15-year follow-up are also presented and discussed. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

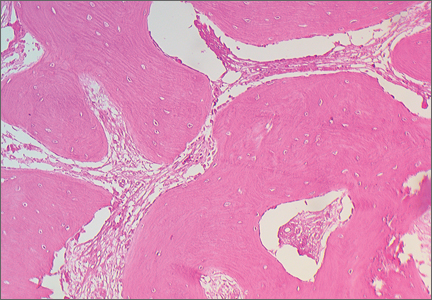

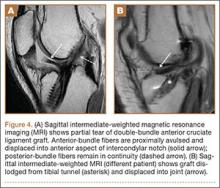

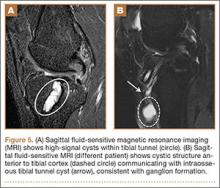

A 10-year-old boy was admitted for surgical repair of an inguinal hernia. Physical examination revealed a painless but tender anterior bowing of the right tibial diaphysis. The patient was a healthy-appearing white male with normal vital signs, gait, and posture. His parents noticed a slight protuberance of the tibia at age 2.5 years. No medical advice was asked for the bone swelling after that time. After recovery from the inguinal hernia repair 3 weeks later, the bone lesion was thoroughly examined. Radiographs showed an oblong, homogenous region of dense sclerosis in the diaphysis of the right tibia. The lesion had relatively well-defined margins and was located in the medullary cavity. Speculations were not obvious in the periphery of the lesion, which exhibited a sharp circumscription (Figures 1A, 1B). A well-defined lytic area was evident at the distal part of the lesion (Figure 1B). There was no periosteal reaction. Blood and serum chemistries were within normal limits, including serum calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase. A conventional 3-phase bone scintigraphy (300 MBq) with technetium-99m HDP (hydroxydiphosphonate) indicated increased uptake in the area of the lesion but no other skeletal abnormality (Figure 2). Computed tomography (CT) showed that the lesion was purely intramedullary and densely blastic. The lesion originated from the medial cortex, which was thickened (Figure 3A). The lesion extended to the anterolateral cortex, which was thinned and included a lytic area. In the distal part of the lesion, the anterolateral cortex was thickened, included lytic areas, and exhibited an anterior portion of cortical destruction (Figure 3B). The fatty marrow adjacent to the region of sclerosis appeared normal. There was no evidence of extraosseous soft-tissue changes. On both T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the lesion exhibited low-signal intensity. The lesion measured 10.8×2.2×1 cm. It originated from the medial cortical bone of the tibia, blended into the medullary cavity, and extended anteriorly towards and through the anterior cortex. The area of cortical destruction was clearly evident on the axial MRI. The periosteum was displaced and eroded anteriorly by focal radiating bony streaks. No enhancement was seen after the intravenous administration of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA) as a contrast medium. There were no extraosseous soft-tissue changes. In the distal part of the lesion, sagittal and axial MRI showed a 1.2×0.8×0.7-cm well-defined ovoid focus, with characteristics of cystic degeneration that exhibited intermediate-signal intensity on T1-weighted MRI (Figure 4) and high-signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI.

An open biopsy was performed. Macroscopically, a wedge of compact bone measuring 3×1.7×0.6 cm was taken. Microscopic examination showed a thinned periphery of lamellar (mature) bone with haversian canals and, beneath it, woven (immature) bone with long-surface processes projecting within adjacent cancellous bone (Figure 5A). The woven bone contained loose vascular fibrous tissue. No osteoclasts were noted, and the very few osteoblasts lining the bone trabeculae were small, single-layered, and flat (Figure 5B). There was no evidence of neoplastic cells. There was no abnormality of the periosteum and the surrounding soft tissues.

The histology was pathognomonic of a giant bone island. No additional surgical intervention was recommended.

The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was discharged 2 weeks later. An above-the-knee plaster was recommended for 3 months and a below-the-knee splint for an additional 2-month period. Full weight-bearing was allowed only after the postsurgical sixth month to prevent an impending fracture. The tibial bowing was tender to pressure or palpation, and the patient reported mild spontaneous pain during follow-up. Radiographs 1 year after surgery indicated that the bone area removed for biopsy was replaced by compact bone. MRI performed 4 years after surgery showed that the volume of the lesion in relation to the host bone was not changed.

At the last follow-up 15 years after surgery, the anterior tibial bowing was not changed (Figure 6A), but the patient additionally complained of skin irritation after intense training wearing boots during military service. The radiographic appearance of the lesion was also not changed, while the periphery of the lesion exhibited scarce radiating bony streaks with rounded contours (Figures 6B, 6C). The clinical symptoms and signs from wearing military boots completely subsided after a couple of weeks’ rest from daily army activities, but the mild spontaneous pain and the local tenderness over the tibial bowing persisted.

Discussion

Giant bone islands are more likely to be associated with clinical symptoms than the usual small-sized bone island. Some degree of pain was detected in 8 of 10 patients with a giant bone island presented in the literature, but it was induced by trauma in 3 of them.14

Radiographic appearance is among the distinguishing diagnostic features of a giant bone island. It appears as an ovoid, round, or oblong, homogenously dense, single or multiple focus of sclerosis within the medullary cavity; it is oriented along the long axis of the host bone, and it exhibits peripheral pseudopodia or radiating spicules producing the typical “thorny” or “paintbrush” appearance.8,16,17 It does not exhibit cortical penetration and it is not associated with periosteal reaction.10

The CT findings include a sclerotic and hyperdense focus with spiculated margins extending into the adjacent cancellous bone. The lack of bone destruction and soft-tissue mass are also diagnostic.3,7 MRI findings will reflect the low-signal intensity characteristics of cortical bone on all pulse sequences.18

Enostoses usually exhibit no activity on skeletal scintigraphy, while giant lesions generally show increased radiotracer uptake.5,9-11,14,19-27 The latter may result from the increased amount of bone turnover, which is seen more often with larger lesions because of active bone deposition and remodeling.20,21,23,28 Histopathology of a giant bone island appears identical to the well-described pathologic appearance of smaller bone islands. The lesion is composed of compact lamellar bone and haversian systems, which blend with the adjacent spongiosa. The surrounding cancellous bone forms thorn-like trabeculae radiating from the lesion and merging with the cancellous bone.1,4,5,8,28

The presumptive diagnosis of a bone island is based on the clinical findings, imaging features, and follow-up examinations. An asymptomatic, isolated, sclerotic bone lesion showing the typical features of a bone island on plain radiography, CT, and MRI, whatever its size, that is nonactive on bone scan may be easily diagnosed. However, a symptomatic patient with a hot lesion on scintigraphy should be carefully observed. In addition, larger lesions may raise the suspicion of a neoplasm, such as a sclerotic variant of osteosarcoma. In such cases, an open biopsy may be undertaken. No specific treatment is required after the diagnosis has been confirmed. There is no literature to suggest that, after adequate biopsy confirmation, excision or resection is necessary. Follow-up radiographic examination of the lesion should be suggested to monitor for any potential growth.2,10,23

The first giant bone island appearing in a child is presented in this report. The lack of a causative factor leading to the anterior tibial bowing indicated that the bone deformity was caused primarily by the lesion. The present case is unusual for the appearance of several atypical features, some of which have not been previously described. Peripheral radiating spiculated margin was absent on the patient’s initial radiographs and CT imaging. MRI indicated only the presence of radiating bony streaks that displaced and eroded the periosteum on the anterior border of the lesion. The CT findings that the lesion likely originated or was in close proximity with the medial cortex of the tibia were also atypical. It has been previously reported that spinal lesions located immediately below the cortex tend to fuse with the endosteal surface, while similar features may also be seen in the appendicular enostoses.4,29 Other CT findings, such as the thinning of the overlying anterolateral cortical bone, as well as the cortical thickening at the periphery of the lesion associated with areas of soft-tissue attenuation and anterior cortical destruction, have not been described even in the atypical features of a giant bone island. The lytic area resembling a nidus that was evident at the distal part of the lesion was more likely consistent with an area of resorption, which, although rare, has been described on giant lesions.2,9,29 The substantial amount of woven bone transforming to lamellar bone that was evident in the present patient’s microscopic features is also an atypical finding, although it may be expected to some degree in scintigraphically hot, large lesions.28 The clinical and imaging progress of the lesion supported the diagnosis of a giant bone island. The degree of the anterior tibial bowing and the volume of the lesion in relation to the host bone were not changed throughout the follow-up period, indicating that the growth of the lesion followed the growth of the normal bone.

The differential diagnosis of a giant bone island includes a variety of benign tumors and tumor-like lesions, as well as malignant bone lesions.2,4,23,28,30,31 In the patient presented in this report, the diagnosis of an atypical sclerotic presentation of a nonossifying fibroma or healing stage of this lesion could be consistent with some of the CT findings, including the eccentric origin from the cortex associated with medial cortical thickening, the anterolateral cortical thinning, and the soft-tissue attenuation of cortical areas. In addition, unifocal osteofibrous dysplasia may also present with a long intracortical diaphyseal lucency within an area of marked cortical sclerosis and cause a bowing deformity. Both diagnoses were excluded, since no fibrous stroma was evident on the histologic examination of the lesion. A large or giant long-bone osteoma would be associated with the outer cortical margin of bone but would not involve the intramedullary space. The scintigraphically increased uptake of radioisotope, as well as the CT and MRI findings, were not consistent with the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, or osteomyelitis. Although most imaging findings were consistent with a benign lesion, and contrast-enhanced MRI showed no increased vascularity, anterior cortical disruption necessitated a bone biopsy to rule out any potential malignancy.

The histopathology in association with the clinical and imaging findings indicated the diagnosis of a giant bone island. The increased proportion of maturing woven bone over lamellar bone indicated an active remodeling lesion that could be related to the patient’s age, since the clinical and radiographic features of the lesion were not changed after 15-year follow-up.

Conclusion

This is the first giant bone island diagnosed in a patient before puberty. Its greatest length was 10.8 cm, which is the longest reported in the literature. The imaging appearance included several atypical features that are very rare or have not been reported. Microscopic features indicated less mature lamellar bone and a prominent proportion of maturing woven bone. The clinical and the radiographic appearance of the lesion were not changed after 15-year follow-up.

1. Smith J. Giant bone islands. Radiology. 1973;7(1):35-36.

2. Mirra JM. Bone Tumors: Clinical, Radiologic and Pathologic Correlations. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1989.

3. Greenspan A. Bone island (enostosis): current concept - a review. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24(2):111-115.

4. Kransdorf MJ, Peterson JJ, Bancroft LW. MR imaging of the knee: incidental osseous lesions. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45(6):943-954.

5. Gold RH, Mirra JM, Remotti F, Pignatti G. Case report 527: Giant bone island of tibia. Skeletal Radiol. 1989;18(2):129-132.

6. Onitsuka H. Roentgenologic aspects of bone islands. Radiology. 1977;123(3):607-612.

7. Ehara S, Kattapuram SV, Rosenberg AE. Giant bone island. Computed tomography findings. Clin Imaging. 1989;13(3):231-233.

8. Greenspan A, Steiner G, Knutzon R. Bone island (enostosis): clinical significance and radiologic and pathologic correlations. Skeletal Radiol. 1991;20(2):85-90.

9. Avery GR, Wilsdon JB, Malcolm AJ. Giant bone island with some central resorption. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24(1):59-60.

10. Brien EW, Mirra JM, Latanza L, Fedenko A, Luck J Jr. Giant bone island of femur. Case report, literature review, and its distinction from low grade osteosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24(7):546-550.

11. Greenspan A, Klein MJ. Giant bone island. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25(1):67-69.

12. Trombetti A, Noël E. Giant bone islands: a case with 31 years of follow-up. Joint Bone Spine. 2002;69(1):81-84.

13. Dhaon BK, Gautam VK, Jain P, Jaiswal A, Nigam V. Giant bone island of femur complicating replacement arthroplasty: a report of two cases. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2004;13(4):220-223.

14. Park HS, Kim JR, Lee SY, Jang KY. Symptomatic giant (10-cm) bone island of the tibia. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(6):347-350.

15. Ikeuchi M, Komatsu M, Tani T. Giant bone island of femur with femoral head necrosis: a case report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(4):447-450.

16. Kim SK, Barry WF Jr. Bone island. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1964;92:1301-1306.

17. Kim SK, Barry WF Jr. Bone islands. Radiology. 1968;90(1):77-78.

18. Cerase A, Priolo F. Skeletal benign bone-forming lesions. Eur J Radiol. 1998;27:S91–S97.

19. Go RT, El-Khoury GY, Wehbe MA. Radionuclide bone image in growing and stable bone island. Skeletal Radiol. 1980;5(1):15-18.

20. Hall FM, Goldberg RP, Davies JA, Fainsinger MH. Scintigraphic assessment of bone islands. Radiology. 1980;135(3):737-742.

21. Greenspan A, Stadalnik RC. Bone island: scintigraphic findings and their clinical application. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1995;46(5):368-379.

22. Sickles EA, Genant HK, Hoffer PB. Increased localization of 99mTc-pyrophosphate in a bone island: case report. J Nucl Med. 1976;17(2):113-115.

23. Dorfman HD, Czerniak B. Bone Tumors. St Louis: Mosby; 1998.

24. Ngan H. Growing bone islands. Clin Radiol. 1972;23(2):199-201.

25. Davies JA, Hall FM, Goldberg RP, Kasdon EJ. Positive bone scan in a bone island. Case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61(6):943-945.

26. Simon K, Mulligan ME. Growing bone islands revisited. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(5):809-811.

27. Blank N, Lieber A. The significance of growing bone islands. Radiology. 1965;85(3):508-511.

28. Greenspan A, Gernot J, Wolfgang R. Differential Diagnosis of Orthopaedic Oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

29. Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD. Osseous tumors. In: Davies AM, Sundaram M, James SLJ, eds. Imaging of Bone Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2009.

30. Mödder B, Guhl B, Schaefer HE. Growing bone islands as differential diagnosis of osteoplastic metastases. Rontgenblatter. 1980;33(6):286-288.

31. Flechner RE, Mills SE. Atlas of Tumor Pathology: Tumors of the Bones and Joints. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1993.

A bone island is a focus of normal cortical bone located within the medullary cavity. The vast majority of bone islands are small, measuring from 1 mm to 2 cm in size. They are found more frequently in adults than in children. The lesion can be virtually diagnosed on the basis of its characteristic clinical and imaging features. Differential diagnosis may be difficult when the lesion manifests itself uncharacteristically by being symptomatic, very large, and hot on bone scan.1-4

The term giant bone island has been used to describe a large lesion1 that measures more than 2 cm in any dimension.5 Giant bone islands have been described only in adults,1,5-15 and the longest bone island length reported is 10.5 cm.10 They are usually symptomatic and associated with increased radionuclide uptake on bone scintigraphy.14

The history and the clinical and imaging presentation of an even longer, symptomatic, and scintigraphically hot lesion in the tibial diaphysis of a 10-year-old boy is reported. The lesion further exhibited several atypical imaging features necessitating an open biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of a giant bone island. The pertinent differential diagnosis and the clinical and radiographic findings after 15-year follow-up are also presented and discussed. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

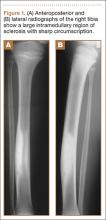

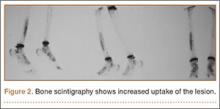

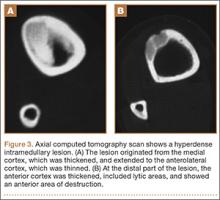

A 10-year-old boy was admitted for surgical repair of an inguinal hernia. Physical examination revealed a painless but tender anterior bowing of the right tibial diaphysis. The patient was a healthy-appearing white male with normal vital signs, gait, and posture. His parents noticed a slight protuberance of the tibia at age 2.5 years. No medical advice was asked for the bone swelling after that time. After recovery from the inguinal hernia repair 3 weeks later, the bone lesion was thoroughly examined. Radiographs showed an oblong, homogenous region of dense sclerosis in the diaphysis of the right tibia. The lesion had relatively well-defined margins and was located in the medullary cavity. Speculations were not obvious in the periphery of the lesion, which exhibited a sharp circumscription (Figures 1A, 1B). A well-defined lytic area was evident at the distal part of the lesion (Figure 1B). There was no periosteal reaction. Blood and serum chemistries were within normal limits, including serum calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase. A conventional 3-phase bone scintigraphy (300 MBq) with technetium-99m HDP (hydroxydiphosphonate) indicated increased uptake in the area of the lesion but no other skeletal abnormality (Figure 2). Computed tomography (CT) showed that the lesion was purely intramedullary and densely blastic. The lesion originated from the medial cortex, which was thickened (Figure 3A). The lesion extended to the anterolateral cortex, which was thinned and included a lytic area. In the distal part of the lesion, the anterolateral cortex was thickened, included lytic areas, and exhibited an anterior portion of cortical destruction (Figure 3B). The fatty marrow adjacent to the region of sclerosis appeared normal. There was no evidence of extraosseous soft-tissue changes. On both T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the lesion exhibited low-signal intensity. The lesion measured 10.8×2.2×1 cm. It originated from the medial cortical bone of the tibia, blended into the medullary cavity, and extended anteriorly towards and through the anterior cortex. The area of cortical destruction was clearly evident on the axial MRI. The periosteum was displaced and eroded anteriorly by focal radiating bony streaks. No enhancement was seen after the intravenous administration of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA) as a contrast medium. There were no extraosseous soft-tissue changes. In the distal part of the lesion, sagittal and axial MRI showed a 1.2×0.8×0.7-cm well-defined ovoid focus, with characteristics of cystic degeneration that exhibited intermediate-signal intensity on T1-weighted MRI (Figure 4) and high-signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI.

An open biopsy was performed. Macroscopically, a wedge of compact bone measuring 3×1.7×0.6 cm was taken. Microscopic examination showed a thinned periphery of lamellar (mature) bone with haversian canals and, beneath it, woven (immature) bone with long-surface processes projecting within adjacent cancellous bone (Figure 5A). The woven bone contained loose vascular fibrous tissue. No osteoclasts were noted, and the very few osteoblasts lining the bone trabeculae were small, single-layered, and flat (Figure 5B). There was no evidence of neoplastic cells. There was no abnormality of the periosteum and the surrounding soft tissues.

The histology was pathognomonic of a giant bone island. No additional surgical intervention was recommended.

The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was discharged 2 weeks later. An above-the-knee plaster was recommended for 3 months and a below-the-knee splint for an additional 2-month period. Full weight-bearing was allowed only after the postsurgical sixth month to prevent an impending fracture. The tibial bowing was tender to pressure or palpation, and the patient reported mild spontaneous pain during follow-up. Radiographs 1 year after surgery indicated that the bone area removed for biopsy was replaced by compact bone. MRI performed 4 years after surgery showed that the volume of the lesion in relation to the host bone was not changed.

At the last follow-up 15 years after surgery, the anterior tibial bowing was not changed (Figure 6A), but the patient additionally complained of skin irritation after intense training wearing boots during military service. The radiographic appearance of the lesion was also not changed, while the periphery of the lesion exhibited scarce radiating bony streaks with rounded contours (Figures 6B, 6C). The clinical symptoms and signs from wearing military boots completely subsided after a couple of weeks’ rest from daily army activities, but the mild spontaneous pain and the local tenderness over the tibial bowing persisted.

Discussion

Giant bone islands are more likely to be associated with clinical symptoms than the usual small-sized bone island. Some degree of pain was detected in 8 of 10 patients with a giant bone island presented in the literature, but it was induced by trauma in 3 of them.14

Radiographic appearance is among the distinguishing diagnostic features of a giant bone island. It appears as an ovoid, round, or oblong, homogenously dense, single or multiple focus of sclerosis within the medullary cavity; it is oriented along the long axis of the host bone, and it exhibits peripheral pseudopodia or radiating spicules producing the typical “thorny” or “paintbrush” appearance.8,16,17 It does not exhibit cortical penetration and it is not associated with periosteal reaction.10

The CT findings include a sclerotic and hyperdense focus with spiculated margins extending into the adjacent cancellous bone. The lack of bone destruction and soft-tissue mass are also diagnostic.3,7 MRI findings will reflect the low-signal intensity characteristics of cortical bone on all pulse sequences.18

Enostoses usually exhibit no activity on skeletal scintigraphy, while giant lesions generally show increased radiotracer uptake.5,9-11,14,19-27 The latter may result from the increased amount of bone turnover, which is seen more often with larger lesions because of active bone deposition and remodeling.20,21,23,28 Histopathology of a giant bone island appears identical to the well-described pathologic appearance of smaller bone islands. The lesion is composed of compact lamellar bone and haversian systems, which blend with the adjacent spongiosa. The surrounding cancellous bone forms thorn-like trabeculae radiating from the lesion and merging with the cancellous bone.1,4,5,8,28

The presumptive diagnosis of a bone island is based on the clinical findings, imaging features, and follow-up examinations. An asymptomatic, isolated, sclerotic bone lesion showing the typical features of a bone island on plain radiography, CT, and MRI, whatever its size, that is nonactive on bone scan may be easily diagnosed. However, a symptomatic patient with a hot lesion on scintigraphy should be carefully observed. In addition, larger lesions may raise the suspicion of a neoplasm, such as a sclerotic variant of osteosarcoma. In such cases, an open biopsy may be undertaken. No specific treatment is required after the diagnosis has been confirmed. There is no literature to suggest that, after adequate biopsy confirmation, excision or resection is necessary. Follow-up radiographic examination of the lesion should be suggested to monitor for any potential growth.2,10,23

The first giant bone island appearing in a child is presented in this report. The lack of a causative factor leading to the anterior tibial bowing indicated that the bone deformity was caused primarily by the lesion. The present case is unusual for the appearance of several atypical features, some of which have not been previously described. Peripheral radiating spiculated margin was absent on the patient’s initial radiographs and CT imaging. MRI indicated only the presence of radiating bony streaks that displaced and eroded the periosteum on the anterior border of the lesion. The CT findings that the lesion likely originated or was in close proximity with the medial cortex of the tibia were also atypical. It has been previously reported that spinal lesions located immediately below the cortex tend to fuse with the endosteal surface, while similar features may also be seen in the appendicular enostoses.4,29 Other CT findings, such as the thinning of the overlying anterolateral cortical bone, as well as the cortical thickening at the periphery of the lesion associated with areas of soft-tissue attenuation and anterior cortical destruction, have not been described even in the atypical features of a giant bone island. The lytic area resembling a nidus that was evident at the distal part of the lesion was more likely consistent with an area of resorption, which, although rare, has been described on giant lesions.2,9,29 The substantial amount of woven bone transforming to lamellar bone that was evident in the present patient’s microscopic features is also an atypical finding, although it may be expected to some degree in scintigraphically hot, large lesions.28 The clinical and imaging progress of the lesion supported the diagnosis of a giant bone island. The degree of the anterior tibial bowing and the volume of the lesion in relation to the host bone were not changed throughout the follow-up period, indicating that the growth of the lesion followed the growth of the normal bone.

The differential diagnosis of a giant bone island includes a variety of benign tumors and tumor-like lesions, as well as malignant bone lesions.2,4,23,28,30,31 In the patient presented in this report, the diagnosis of an atypical sclerotic presentation of a nonossifying fibroma or healing stage of this lesion could be consistent with some of the CT findings, including the eccentric origin from the cortex associated with medial cortical thickening, the anterolateral cortical thinning, and the soft-tissue attenuation of cortical areas. In addition, unifocal osteofibrous dysplasia may also present with a long intracortical diaphyseal lucency within an area of marked cortical sclerosis and cause a bowing deformity. Both diagnoses were excluded, since no fibrous stroma was evident on the histologic examination of the lesion. A large or giant long-bone osteoma would be associated with the outer cortical margin of bone but would not involve the intramedullary space. The scintigraphically increased uptake of radioisotope, as well as the CT and MRI findings, were not consistent with the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, or osteomyelitis. Although most imaging findings were consistent with a benign lesion, and contrast-enhanced MRI showed no increased vascularity, anterior cortical disruption necessitated a bone biopsy to rule out any potential malignancy.

The histopathology in association with the clinical and imaging findings indicated the diagnosis of a giant bone island. The increased proportion of maturing woven bone over lamellar bone indicated an active remodeling lesion that could be related to the patient’s age, since the clinical and radiographic features of the lesion were not changed after 15-year follow-up.

Conclusion

This is the first giant bone island diagnosed in a patient before puberty. Its greatest length was 10.8 cm, which is the longest reported in the literature. The imaging appearance included several atypical features that are very rare or have not been reported. Microscopic features indicated less mature lamellar bone and a prominent proportion of maturing woven bone. The clinical and the radiographic appearance of the lesion were not changed after 15-year follow-up.

A bone island is a focus of normal cortical bone located within the medullary cavity. The vast majority of bone islands are small, measuring from 1 mm to 2 cm in size. They are found more frequently in adults than in children. The lesion can be virtually diagnosed on the basis of its characteristic clinical and imaging features. Differential diagnosis may be difficult when the lesion manifests itself uncharacteristically by being symptomatic, very large, and hot on bone scan.1-4

The term giant bone island has been used to describe a large lesion1 that measures more than 2 cm in any dimension.5 Giant bone islands have been described only in adults,1,5-15 and the longest bone island length reported is 10.5 cm.10 They are usually symptomatic and associated with increased radionuclide uptake on bone scintigraphy.14

The history and the clinical and imaging presentation of an even longer, symptomatic, and scintigraphically hot lesion in the tibial diaphysis of a 10-year-old boy is reported. The lesion further exhibited several atypical imaging features necessitating an open biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of a giant bone island. The pertinent differential diagnosis and the clinical and radiographic findings after 15-year follow-up are also presented and discussed. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 10-year-old boy was admitted for surgical repair of an inguinal hernia. Physical examination revealed a painless but tender anterior bowing of the right tibial diaphysis. The patient was a healthy-appearing white male with normal vital signs, gait, and posture. His parents noticed a slight protuberance of the tibia at age 2.5 years. No medical advice was asked for the bone swelling after that time. After recovery from the inguinal hernia repair 3 weeks later, the bone lesion was thoroughly examined. Radiographs showed an oblong, homogenous region of dense sclerosis in the diaphysis of the right tibia. The lesion had relatively well-defined margins and was located in the medullary cavity. Speculations were not obvious in the periphery of the lesion, which exhibited a sharp circumscription (Figures 1A, 1B). A well-defined lytic area was evident at the distal part of the lesion (Figure 1B). There was no periosteal reaction. Blood and serum chemistries were within normal limits, including serum calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase. A conventional 3-phase bone scintigraphy (300 MBq) with technetium-99m HDP (hydroxydiphosphonate) indicated increased uptake in the area of the lesion but no other skeletal abnormality (Figure 2). Computed tomography (CT) showed that the lesion was purely intramedullary and densely blastic. The lesion originated from the medial cortex, which was thickened (Figure 3A). The lesion extended to the anterolateral cortex, which was thinned and included a lytic area. In the distal part of the lesion, the anterolateral cortex was thickened, included lytic areas, and exhibited an anterior portion of cortical destruction (Figure 3B). The fatty marrow adjacent to the region of sclerosis appeared normal. There was no evidence of extraosseous soft-tissue changes. On both T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the lesion exhibited low-signal intensity. The lesion measured 10.8×2.2×1 cm. It originated from the medial cortical bone of the tibia, blended into the medullary cavity, and extended anteriorly towards and through the anterior cortex. The area of cortical destruction was clearly evident on the axial MRI. The periosteum was displaced and eroded anteriorly by focal radiating bony streaks. No enhancement was seen after the intravenous administration of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA) as a contrast medium. There were no extraosseous soft-tissue changes. In the distal part of the lesion, sagittal and axial MRI showed a 1.2×0.8×0.7-cm well-defined ovoid focus, with characteristics of cystic degeneration that exhibited intermediate-signal intensity on T1-weighted MRI (Figure 4) and high-signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI.

An open biopsy was performed. Macroscopically, a wedge of compact bone measuring 3×1.7×0.6 cm was taken. Microscopic examination showed a thinned periphery of lamellar (mature) bone with haversian canals and, beneath it, woven (immature) bone with long-surface processes projecting within adjacent cancellous bone (Figure 5A). The woven bone contained loose vascular fibrous tissue. No osteoclasts were noted, and the very few osteoblasts lining the bone trabeculae were small, single-layered, and flat (Figure 5B). There was no evidence of neoplastic cells. There was no abnormality of the periosteum and the surrounding soft tissues.

The histology was pathognomonic of a giant bone island. No additional surgical intervention was recommended.

The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was discharged 2 weeks later. An above-the-knee plaster was recommended for 3 months and a below-the-knee splint for an additional 2-month period. Full weight-bearing was allowed only after the postsurgical sixth month to prevent an impending fracture. The tibial bowing was tender to pressure or palpation, and the patient reported mild spontaneous pain during follow-up. Radiographs 1 year after surgery indicated that the bone area removed for biopsy was replaced by compact bone. MRI performed 4 years after surgery showed that the volume of the lesion in relation to the host bone was not changed.

At the last follow-up 15 years after surgery, the anterior tibial bowing was not changed (Figure 6A), but the patient additionally complained of skin irritation after intense training wearing boots during military service. The radiographic appearance of the lesion was also not changed, while the periphery of the lesion exhibited scarce radiating bony streaks with rounded contours (Figures 6B, 6C). The clinical symptoms and signs from wearing military boots completely subsided after a couple of weeks’ rest from daily army activities, but the mild spontaneous pain and the local tenderness over the tibial bowing persisted.

Discussion

Giant bone islands are more likely to be associated with clinical symptoms than the usual small-sized bone island. Some degree of pain was detected in 8 of 10 patients with a giant bone island presented in the literature, but it was induced by trauma in 3 of them.14

Radiographic appearance is among the distinguishing diagnostic features of a giant bone island. It appears as an ovoid, round, or oblong, homogenously dense, single or multiple focus of sclerosis within the medullary cavity; it is oriented along the long axis of the host bone, and it exhibits peripheral pseudopodia or radiating spicules producing the typical “thorny” or “paintbrush” appearance.8,16,17 It does not exhibit cortical penetration and it is not associated with periosteal reaction.10

The CT findings include a sclerotic and hyperdense focus with spiculated margins extending into the adjacent cancellous bone. The lack of bone destruction and soft-tissue mass are also diagnostic.3,7 MRI findings will reflect the low-signal intensity characteristics of cortical bone on all pulse sequences.18

Enostoses usually exhibit no activity on skeletal scintigraphy, while giant lesions generally show increased radiotracer uptake.5,9-11,14,19-27 The latter may result from the increased amount of bone turnover, which is seen more often with larger lesions because of active bone deposition and remodeling.20,21,23,28 Histopathology of a giant bone island appears identical to the well-described pathologic appearance of smaller bone islands. The lesion is composed of compact lamellar bone and haversian systems, which blend with the adjacent spongiosa. The surrounding cancellous bone forms thorn-like trabeculae radiating from the lesion and merging with the cancellous bone.1,4,5,8,28