User login

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Complications of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred modality in the evaluation of complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACL-R).1-3 ACL-R complications may be broadly characterized as those resulting in decreased range of motion (ROM), eg, arthrofibrosis and impingement, and those resulting in increased laxity, ie, graft disruption.4 Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences best minimize artifact related to field inhomogeneity in the presence of metal-containing fixation devices. Patients with contraindications to MRI may undergo high-resolution computed tomographic arthrography of the knee for evaluation of postoperative graft abnormalities.1

Arthrofibrosis refers to focal or diffuse synovial scar tissue, which may limit ROM. Preoperative irritation, preoperative limited ROM, and reconstruction within 4 weeks of trauma may all play a role in the development of arthrofibrosis.5,6 The focal form, cyclops lesion, named for its arthroscopic appearance, has been reported in 1% to 10% of patients with ACL-R.1 On MRI, focal arthrofibrosis may be seen as a focal or diffuse intermediate signal lesion in the anterior intercondylar notch extending linearly along the intercondylar roof1 (Figure 1).

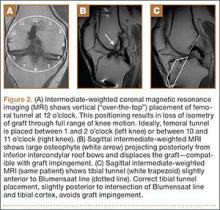

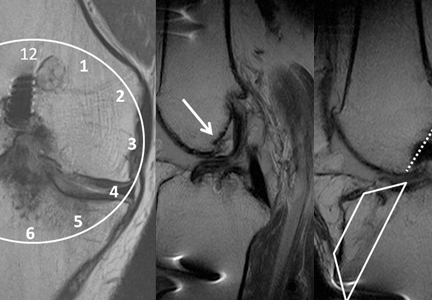

MRI can be used to accurately determine the position of the femoral and tibial tunnels. Correct femoral tunnel position results in isometry of the graft during full ROM of the knee. Graft impingement can occur when the tibial tunnel is placed too far anteriorly such that the graft contacts the roof of the intercondylar notch before the knee is able to fully extend.7 A tibial tunnel placed anterior to the intersection of the Blumensaat line and the tibia is at higher risk for impingement.1,4 Impingement may be accompanied by signal change in the graft on intermediate-weighted and fluid-sensitive sequences. The signal abnormality is usually focal and persists longer than the expected signal changes related to revascularization of immature grafts within the first year (Figure 2). If left untreated, impingement may progress to graft rupture.4

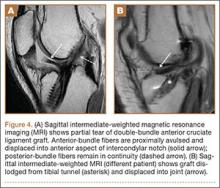

Complete graft rupture is diagnosed on the basis of discontinuity of the graft fibers. MRI findings include fluid-filled defect or absence of intact graft fibers. Other reliable signs include large joint effusion, anterior tibial translation, pivot-shift–type marrow edema pattern, and horizontal orientation, laxity, or resorption of the graft fibers.1,8,9 The diagnosis of partial graft rupture may be challenging, as there are several other causes of increased graft signal, including revascularization (within 12 months after procedure), signal heterogeneity between individual bundles of hamstring grafts, and focal signal changes related to impingment (Figures 3, 4).

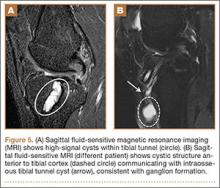

Fluid within the tunnels is a normal finding after surgery and typically resolves within the first 18 months.1 Cyst formation within the tibial tunnel is an uncommon complication of ACL-R and may be incidental to or present with clinical symptoms caused by extension into the pretibial soft tissues or expansion of the tunnel (Figure 5). Communication of cyst with joint space is important, as a noncommunicating cyst requires simple excision without need for bone grafting.7

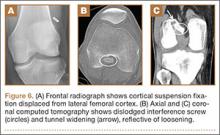

Hardware-related complications (eg, loosening of fixation devices) are uncommon but may require revision surgery (Figure 6). Septic arthritis after ACL-R has a cumulative incidence of 0.1% to 0.9% and may be difficult to diagnose clinically because of the lack of classic symptoms of a septic joint.1 Diagnosis requires joint aspiration.

MRI is reliably and accurately used to assess ACL-R complications. The clinical history helps in stratifying complications that result in decreased ROM or increased laxity.

1. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Feldman MI, Rose DJ. MR imaging of complications of anterior cruciate ligament graft reconstruction. Radiographics. 2009;29(7):2115-2126.

2. Recht MP, Kramer J. MR imaging of the postoperative knee: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):765-774.

3. Papakonstantinou O, Chung CB, Chanchairujira K, Resnick DL. Complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(5):1106-1117.

4. Meyers AB, Haims AH, Menn K, Moukaddam H. Imaging of anterior cruciate ligament repair and its complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(2):476-484.

5. Kwok CS, Harrison T, Servant C. The optimal timing for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with respect to the risk of postoperative stiffness. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):556-565.

6. Mayr HO, Weig TG, Plitz W. Arthrofibrosis following ACL reconstruction—reasons and outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(8):518-522.

7. Ghazikhanian V, Beltran J, Nikac V, Feldman M, Bencardino JT. Tibial tunnel and pretibial cysts following ACL graft reconstruction: MR imaging diagnosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(11):1375-1379.

8. Collins MS, Unruh KP, Bond JR, Mandrekar JN. Magnetic resonance imaging of surgically confirmed anterior cruciate ligament graft disruption. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):233-243.

9. Saupe N, White LM, Chiavaras MM, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction grafts: MR imaging features at long-term follow-up—correlation with functional and clinical evaluation. Radiology. 2008;249(2):581-590.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred modality in the evaluation of complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACL-R).1-3 ACL-R complications may be broadly characterized as those resulting in decreased range of motion (ROM), eg, arthrofibrosis and impingement, and those resulting in increased laxity, ie, graft disruption.4 Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences best minimize artifact related to field inhomogeneity in the presence of metal-containing fixation devices. Patients with contraindications to MRI may undergo high-resolution computed tomographic arthrography of the knee for evaluation of postoperative graft abnormalities.1

Arthrofibrosis refers to focal or diffuse synovial scar tissue, which may limit ROM. Preoperative irritation, preoperative limited ROM, and reconstruction within 4 weeks of trauma may all play a role in the development of arthrofibrosis.5,6 The focal form, cyclops lesion, named for its arthroscopic appearance, has been reported in 1% to 10% of patients with ACL-R.1 On MRI, focal arthrofibrosis may be seen as a focal or diffuse intermediate signal lesion in the anterior intercondylar notch extending linearly along the intercondylar roof1 (Figure 1).

MRI can be used to accurately determine the position of the femoral and tibial tunnels. Correct femoral tunnel position results in isometry of the graft during full ROM of the knee. Graft impingement can occur when the tibial tunnel is placed too far anteriorly such that the graft contacts the roof of the intercondylar notch before the knee is able to fully extend.7 A tibial tunnel placed anterior to the intersection of the Blumensaat line and the tibia is at higher risk for impingement.1,4 Impingement may be accompanied by signal change in the graft on intermediate-weighted and fluid-sensitive sequences. The signal abnormality is usually focal and persists longer than the expected signal changes related to revascularization of immature grafts within the first year (Figure 2). If left untreated, impingement may progress to graft rupture.4

Complete graft rupture is diagnosed on the basis of discontinuity of the graft fibers. MRI findings include fluid-filled defect or absence of intact graft fibers. Other reliable signs include large joint effusion, anterior tibial translation, pivot-shift–type marrow edema pattern, and horizontal orientation, laxity, or resorption of the graft fibers.1,8,9 The diagnosis of partial graft rupture may be challenging, as there are several other causes of increased graft signal, including revascularization (within 12 months after procedure), signal heterogeneity between individual bundles of hamstring grafts, and focal signal changes related to impingment (Figures 3, 4).

Fluid within the tunnels is a normal finding after surgery and typically resolves within the first 18 months.1 Cyst formation within the tibial tunnel is an uncommon complication of ACL-R and may be incidental to or present with clinical symptoms caused by extension into the pretibial soft tissues or expansion of the tunnel (Figure 5). Communication of cyst with joint space is important, as a noncommunicating cyst requires simple excision without need for bone grafting.7

Hardware-related complications (eg, loosening of fixation devices) are uncommon but may require revision surgery (Figure 6). Septic arthritis after ACL-R has a cumulative incidence of 0.1% to 0.9% and may be difficult to diagnose clinically because of the lack of classic symptoms of a septic joint.1 Diagnosis requires joint aspiration.

MRI is reliably and accurately used to assess ACL-R complications. The clinical history helps in stratifying complications that result in decreased ROM or increased laxity.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred modality in the evaluation of complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACL-R).1-3 ACL-R complications may be broadly characterized as those resulting in decreased range of motion (ROM), eg, arthrofibrosis and impingement, and those resulting in increased laxity, ie, graft disruption.4 Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences best minimize artifact related to field inhomogeneity in the presence of metal-containing fixation devices. Patients with contraindications to MRI may undergo high-resolution computed tomographic arthrography of the knee for evaluation of postoperative graft abnormalities.1

Arthrofibrosis refers to focal or diffuse synovial scar tissue, which may limit ROM. Preoperative irritation, preoperative limited ROM, and reconstruction within 4 weeks of trauma may all play a role in the development of arthrofibrosis.5,6 The focal form, cyclops lesion, named for its arthroscopic appearance, has been reported in 1% to 10% of patients with ACL-R.1 On MRI, focal arthrofibrosis may be seen as a focal or diffuse intermediate signal lesion in the anterior intercondylar notch extending linearly along the intercondylar roof1 (Figure 1).

MRI can be used to accurately determine the position of the femoral and tibial tunnels. Correct femoral tunnel position results in isometry of the graft during full ROM of the knee. Graft impingement can occur when the tibial tunnel is placed too far anteriorly such that the graft contacts the roof of the intercondylar notch before the knee is able to fully extend.7 A tibial tunnel placed anterior to the intersection of the Blumensaat line and the tibia is at higher risk for impingement.1,4 Impingement may be accompanied by signal change in the graft on intermediate-weighted and fluid-sensitive sequences. The signal abnormality is usually focal and persists longer than the expected signal changes related to revascularization of immature grafts within the first year (Figure 2). If left untreated, impingement may progress to graft rupture.4

Complete graft rupture is diagnosed on the basis of discontinuity of the graft fibers. MRI findings include fluid-filled defect or absence of intact graft fibers. Other reliable signs include large joint effusion, anterior tibial translation, pivot-shift–type marrow edema pattern, and horizontal orientation, laxity, or resorption of the graft fibers.1,8,9 The diagnosis of partial graft rupture may be challenging, as there are several other causes of increased graft signal, including revascularization (within 12 months after procedure), signal heterogeneity between individual bundles of hamstring grafts, and focal signal changes related to impingment (Figures 3, 4).

Fluid within the tunnels is a normal finding after surgery and typically resolves within the first 18 months.1 Cyst formation within the tibial tunnel is an uncommon complication of ACL-R and may be incidental to or present with clinical symptoms caused by extension into the pretibial soft tissues or expansion of the tunnel (Figure 5). Communication of cyst with joint space is important, as a noncommunicating cyst requires simple excision without need for bone grafting.7

Hardware-related complications (eg, loosening of fixation devices) are uncommon but may require revision surgery (Figure 6). Septic arthritis after ACL-R has a cumulative incidence of 0.1% to 0.9% and may be difficult to diagnose clinically because of the lack of classic symptoms of a septic joint.1 Diagnosis requires joint aspiration.

MRI is reliably and accurately used to assess ACL-R complications. The clinical history helps in stratifying complications that result in decreased ROM or increased laxity.

1. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Feldman MI, Rose DJ. MR imaging of complications of anterior cruciate ligament graft reconstruction. Radiographics. 2009;29(7):2115-2126.

2. Recht MP, Kramer J. MR imaging of the postoperative knee: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):765-774.

3. Papakonstantinou O, Chung CB, Chanchairujira K, Resnick DL. Complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(5):1106-1117.

4. Meyers AB, Haims AH, Menn K, Moukaddam H. Imaging of anterior cruciate ligament repair and its complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(2):476-484.

5. Kwok CS, Harrison T, Servant C. The optimal timing for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with respect to the risk of postoperative stiffness. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):556-565.

6. Mayr HO, Weig TG, Plitz W. Arthrofibrosis following ACL reconstruction—reasons and outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(8):518-522.

7. Ghazikhanian V, Beltran J, Nikac V, Feldman M, Bencardino JT. Tibial tunnel and pretibial cysts following ACL graft reconstruction: MR imaging diagnosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(11):1375-1379.

8. Collins MS, Unruh KP, Bond JR, Mandrekar JN. Magnetic resonance imaging of surgically confirmed anterior cruciate ligament graft disruption. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):233-243.

9. Saupe N, White LM, Chiavaras MM, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction grafts: MR imaging features at long-term follow-up—correlation with functional and clinical evaluation. Radiology. 2008;249(2):581-590.

1. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Feldman MI, Rose DJ. MR imaging of complications of anterior cruciate ligament graft reconstruction. Radiographics. 2009;29(7):2115-2126.

2. Recht MP, Kramer J. MR imaging of the postoperative knee: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):765-774.

3. Papakonstantinou O, Chung CB, Chanchairujira K, Resnick DL. Complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(5):1106-1117.

4. Meyers AB, Haims AH, Menn K, Moukaddam H. Imaging of anterior cruciate ligament repair and its complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(2):476-484.

5. Kwok CS, Harrison T, Servant C. The optimal timing for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with respect to the risk of postoperative stiffness. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):556-565.

6. Mayr HO, Weig TG, Plitz W. Arthrofibrosis following ACL reconstruction—reasons and outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(8):518-522.

7. Ghazikhanian V, Beltran J, Nikac V, Feldman M, Bencardino JT. Tibial tunnel and pretibial cysts following ACL graft reconstruction: MR imaging diagnosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(11):1375-1379.

8. Collins MS, Unruh KP, Bond JR, Mandrekar JN. Magnetic resonance imaging of surgically confirmed anterior cruciate ligament graft disruption. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):233-243.

9. Saupe N, White LM, Chiavaras MM, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction grafts: MR imaging features at long-term follow-up—correlation with functional and clinical evaluation. Radiology. 2008;249(2):581-590.