User login

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Complications of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred modality in the evaluation of complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACL-R).1-3 ACL-R complications may be broadly characterized as those resulting in decreased range of motion (ROM), eg, arthrofibrosis and impingement, and those resulting in increased laxity, ie, graft disruption.4 Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences best minimize artifact related to field inhomogeneity in the presence of metal-containing fixation devices. Patients with contraindications to MRI may undergo high-resolution computed tomographic arthrography of the knee for evaluation of postoperative graft abnormalities.1

Arthrofibrosis refers to focal or diffuse synovial scar tissue, which may limit ROM. Preoperative irritation, preoperative limited ROM, and reconstruction within 4 weeks of trauma may all play a role in the development of arthrofibrosis.5,6 The focal form, cyclops lesion, named for its arthroscopic appearance, has been reported in 1% to 10% of patients with ACL-R.1 On MRI, focal arthrofibrosis may be seen as a focal or diffuse intermediate signal lesion in the anterior intercondylar notch extending linearly along the intercondylar roof1 (Figure 1).

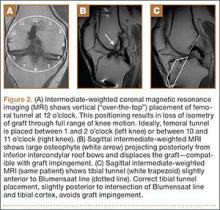

MRI can be used to accurately determine the position of the femoral and tibial tunnels. Correct femoral tunnel position results in isometry of the graft during full ROM of the knee. Graft impingement can occur when the tibial tunnel is placed too far anteriorly such that the graft contacts the roof of the intercondylar notch before the knee is able to fully extend.7 A tibial tunnel placed anterior to the intersection of the Blumensaat line and the tibia is at higher risk for impingement.1,4 Impingement may be accompanied by signal change in the graft on intermediate-weighted and fluid-sensitive sequences. The signal abnormality is usually focal and persists longer than the expected signal changes related to revascularization of immature grafts within the first year (Figure 2). If left untreated, impingement may progress to graft rupture.4

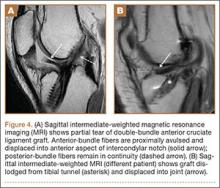

Complete graft rupture is diagnosed on the basis of discontinuity of the graft fibers. MRI findings include fluid-filled defect or absence of intact graft fibers. Other reliable signs include large joint effusion, anterior tibial translation, pivot-shift–type marrow edema pattern, and horizontal orientation, laxity, or resorption of the graft fibers.1,8,9 The diagnosis of partial graft rupture may be challenging, as there are several other causes of increased graft signal, including revascularization (within 12 months after procedure), signal heterogeneity between individual bundles of hamstring grafts, and focal signal changes related to impingment (Figures 3, 4).

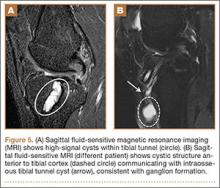

Fluid within the tunnels is a normal finding after surgery and typically resolves within the first 18 months.1 Cyst formation within the tibial tunnel is an uncommon complication of ACL-R and may be incidental to or present with clinical symptoms caused by extension into the pretibial soft tissues or expansion of the tunnel (Figure 5). Communication of cyst with joint space is important, as a noncommunicating cyst requires simple excision without need for bone grafting.7

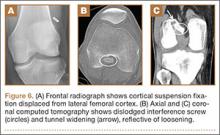

Hardware-related complications (eg, loosening of fixation devices) are uncommon but may require revision surgery (Figure 6). Septic arthritis after ACL-R has a cumulative incidence of 0.1% to 0.9% and may be difficult to diagnose clinically because of the lack of classic symptoms of a septic joint.1 Diagnosis requires joint aspiration.

MRI is reliably and accurately used to assess ACL-R complications. The clinical history helps in stratifying complications that result in decreased ROM or increased laxity.

1. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Feldman MI, Rose DJ. MR imaging of complications of anterior cruciate ligament graft reconstruction. Radiographics. 2009;29(7):2115-2126.

2. Recht MP, Kramer J. MR imaging of the postoperative knee: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):765-774.

3. Papakonstantinou O, Chung CB, Chanchairujira K, Resnick DL. Complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(5):1106-1117.

4. Meyers AB, Haims AH, Menn K, Moukaddam H. Imaging of anterior cruciate ligament repair and its complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(2):476-484.

5. Kwok CS, Harrison T, Servant C. The optimal timing for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with respect to the risk of postoperative stiffness. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):556-565.

6. Mayr HO, Weig TG, Plitz W. Arthrofibrosis following ACL reconstruction—reasons and outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(8):518-522.

7. Ghazikhanian V, Beltran J, Nikac V, Feldman M, Bencardino JT. Tibial tunnel and pretibial cysts following ACL graft reconstruction: MR imaging diagnosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(11):1375-1379.

8. Collins MS, Unruh KP, Bond JR, Mandrekar JN. Magnetic resonance imaging of surgically confirmed anterior cruciate ligament graft disruption. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):233-243.

9. Saupe N, White LM, Chiavaras MM, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction grafts: MR imaging features at long-term follow-up—correlation with functional and clinical evaluation. Radiology. 2008;249(2):581-590.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred modality in the evaluation of complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACL-R).1-3 ACL-R complications may be broadly characterized as those resulting in decreased range of motion (ROM), eg, arthrofibrosis and impingement, and those resulting in increased laxity, ie, graft disruption.4 Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences best minimize artifact related to field inhomogeneity in the presence of metal-containing fixation devices. Patients with contraindications to MRI may undergo high-resolution computed tomographic arthrography of the knee for evaluation of postoperative graft abnormalities.1

Arthrofibrosis refers to focal or diffuse synovial scar tissue, which may limit ROM. Preoperative irritation, preoperative limited ROM, and reconstruction within 4 weeks of trauma may all play a role in the development of arthrofibrosis.5,6 The focal form, cyclops lesion, named for its arthroscopic appearance, has been reported in 1% to 10% of patients with ACL-R.1 On MRI, focal arthrofibrosis may be seen as a focal or diffuse intermediate signal lesion in the anterior intercondylar notch extending linearly along the intercondylar roof1 (Figure 1).

MRI can be used to accurately determine the position of the femoral and tibial tunnels. Correct femoral tunnel position results in isometry of the graft during full ROM of the knee. Graft impingement can occur when the tibial tunnel is placed too far anteriorly such that the graft contacts the roof of the intercondylar notch before the knee is able to fully extend.7 A tibial tunnel placed anterior to the intersection of the Blumensaat line and the tibia is at higher risk for impingement.1,4 Impingement may be accompanied by signal change in the graft on intermediate-weighted and fluid-sensitive sequences. The signal abnormality is usually focal and persists longer than the expected signal changes related to revascularization of immature grafts within the first year (Figure 2). If left untreated, impingement may progress to graft rupture.4

Complete graft rupture is diagnosed on the basis of discontinuity of the graft fibers. MRI findings include fluid-filled defect or absence of intact graft fibers. Other reliable signs include large joint effusion, anterior tibial translation, pivot-shift–type marrow edema pattern, and horizontal orientation, laxity, or resorption of the graft fibers.1,8,9 The diagnosis of partial graft rupture may be challenging, as there are several other causes of increased graft signal, including revascularization (within 12 months after procedure), signal heterogeneity between individual bundles of hamstring grafts, and focal signal changes related to impingment (Figures 3, 4).

Fluid within the tunnels is a normal finding after surgery and typically resolves within the first 18 months.1 Cyst formation within the tibial tunnel is an uncommon complication of ACL-R and may be incidental to or present with clinical symptoms caused by extension into the pretibial soft tissues or expansion of the tunnel (Figure 5). Communication of cyst with joint space is important, as a noncommunicating cyst requires simple excision without need for bone grafting.7

Hardware-related complications (eg, loosening of fixation devices) are uncommon but may require revision surgery (Figure 6). Septic arthritis after ACL-R has a cumulative incidence of 0.1% to 0.9% and may be difficult to diagnose clinically because of the lack of classic symptoms of a septic joint.1 Diagnosis requires joint aspiration.

MRI is reliably and accurately used to assess ACL-R complications. The clinical history helps in stratifying complications that result in decreased ROM or increased laxity.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred modality in the evaluation of complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACL-R).1-3 ACL-R complications may be broadly characterized as those resulting in decreased range of motion (ROM), eg, arthrofibrosis and impingement, and those resulting in increased laxity, ie, graft disruption.4 Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences best minimize artifact related to field inhomogeneity in the presence of metal-containing fixation devices. Patients with contraindications to MRI may undergo high-resolution computed tomographic arthrography of the knee for evaluation of postoperative graft abnormalities.1

Arthrofibrosis refers to focal or diffuse synovial scar tissue, which may limit ROM. Preoperative irritation, preoperative limited ROM, and reconstruction within 4 weeks of trauma may all play a role in the development of arthrofibrosis.5,6 The focal form, cyclops lesion, named for its arthroscopic appearance, has been reported in 1% to 10% of patients with ACL-R.1 On MRI, focal arthrofibrosis may be seen as a focal or diffuse intermediate signal lesion in the anterior intercondylar notch extending linearly along the intercondylar roof1 (Figure 1).

MRI can be used to accurately determine the position of the femoral and tibial tunnels. Correct femoral tunnel position results in isometry of the graft during full ROM of the knee. Graft impingement can occur when the tibial tunnel is placed too far anteriorly such that the graft contacts the roof of the intercondylar notch before the knee is able to fully extend.7 A tibial tunnel placed anterior to the intersection of the Blumensaat line and the tibia is at higher risk for impingement.1,4 Impingement may be accompanied by signal change in the graft on intermediate-weighted and fluid-sensitive sequences. The signal abnormality is usually focal and persists longer than the expected signal changes related to revascularization of immature grafts within the first year (Figure 2). If left untreated, impingement may progress to graft rupture.4

Complete graft rupture is diagnosed on the basis of discontinuity of the graft fibers. MRI findings include fluid-filled defect or absence of intact graft fibers. Other reliable signs include large joint effusion, anterior tibial translation, pivot-shift–type marrow edema pattern, and horizontal orientation, laxity, or resorption of the graft fibers.1,8,9 The diagnosis of partial graft rupture may be challenging, as there are several other causes of increased graft signal, including revascularization (within 12 months after procedure), signal heterogeneity between individual bundles of hamstring grafts, and focal signal changes related to impingment (Figures 3, 4).

Fluid within the tunnels is a normal finding after surgery and typically resolves within the first 18 months.1 Cyst formation within the tibial tunnel is an uncommon complication of ACL-R and may be incidental to or present with clinical symptoms caused by extension into the pretibial soft tissues or expansion of the tunnel (Figure 5). Communication of cyst with joint space is important, as a noncommunicating cyst requires simple excision without need for bone grafting.7

Hardware-related complications (eg, loosening of fixation devices) are uncommon but may require revision surgery (Figure 6). Septic arthritis after ACL-R has a cumulative incidence of 0.1% to 0.9% and may be difficult to diagnose clinically because of the lack of classic symptoms of a septic joint.1 Diagnosis requires joint aspiration.

MRI is reliably and accurately used to assess ACL-R complications. The clinical history helps in stratifying complications that result in decreased ROM or increased laxity.

1. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Feldman MI, Rose DJ. MR imaging of complications of anterior cruciate ligament graft reconstruction. Radiographics. 2009;29(7):2115-2126.

2. Recht MP, Kramer J. MR imaging of the postoperative knee: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):765-774.

3. Papakonstantinou O, Chung CB, Chanchairujira K, Resnick DL. Complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(5):1106-1117.

4. Meyers AB, Haims AH, Menn K, Moukaddam H. Imaging of anterior cruciate ligament repair and its complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(2):476-484.

5. Kwok CS, Harrison T, Servant C. The optimal timing for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with respect to the risk of postoperative stiffness. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):556-565.

6. Mayr HO, Weig TG, Plitz W. Arthrofibrosis following ACL reconstruction—reasons and outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(8):518-522.

7. Ghazikhanian V, Beltran J, Nikac V, Feldman M, Bencardino JT. Tibial tunnel and pretibial cysts following ACL graft reconstruction: MR imaging diagnosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(11):1375-1379.

8. Collins MS, Unruh KP, Bond JR, Mandrekar JN. Magnetic resonance imaging of surgically confirmed anterior cruciate ligament graft disruption. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):233-243.

9. Saupe N, White LM, Chiavaras MM, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction grafts: MR imaging features at long-term follow-up—correlation with functional and clinical evaluation. Radiology. 2008;249(2):581-590.

1. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Feldman MI, Rose DJ. MR imaging of complications of anterior cruciate ligament graft reconstruction. Radiographics. 2009;29(7):2115-2126.

2. Recht MP, Kramer J. MR imaging of the postoperative knee: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):765-774.

3. Papakonstantinou O, Chung CB, Chanchairujira K, Resnick DL. Complications of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(5):1106-1117.

4. Meyers AB, Haims AH, Menn K, Moukaddam H. Imaging of anterior cruciate ligament repair and its complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(2):476-484.

5. Kwok CS, Harrison T, Servant C. The optimal timing for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with respect to the risk of postoperative stiffness. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):556-565.

6. Mayr HO, Weig TG, Plitz W. Arthrofibrosis following ACL reconstruction—reasons and outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(8):518-522.

7. Ghazikhanian V, Beltran J, Nikac V, Feldman M, Bencardino JT. Tibial tunnel and pretibial cysts following ACL graft reconstruction: MR imaging diagnosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(11):1375-1379.

8. Collins MS, Unruh KP, Bond JR, Mandrekar JN. Magnetic resonance imaging of surgically confirmed anterior cruciate ligament graft disruption. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):233-243.

9. Saupe N, White LM, Chiavaras MM, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction grafts: MR imaging features at long-term follow-up—correlation with functional and clinical evaluation. Radiology. 2008;249(2):581-590.

Imaging Evaluation of Superior Labral Anteroposterior (SLAP) Tears

Superior labral anteroposterior (SLAP) tears are common labral injuries. They occur at the attachment of the long head of the biceps tendon on the superior glenoid and extend anterior and/or posterior to the biceps anchor. The mechanism of action for SLAP tears is traction on the superior labrum by the long head of the biceps tendon, resulting in “peeling” of the labrum off the glenoid. Such forces may result from repetitive overhead arm motion (pitching) or from direct trauma.

Clinical diagnosis is challenging with SLAP tears, as they often present with nonspecific shoulder pain and may not be associated with an acute injury. A further complication is that they are often associated with other shoulder pathology, such as rotator cuff tears.1 As physical examination is typically nonspecific, proper diagnostic imaging is essential for diagnosis.

We prefer to assess potential SLAP tears with magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA).2 Dilute (1:200) gadolinium contrast material (12-15 mL) is introduced into the glenohumeral joint under sonographic or fluoroscopic guidance. Capsular distention by dilute intra-articular contrast enables superior imaging resolution of the labroligamentous complex. We think the increase in diagnostic confidence enabled by direct arthrography outweighs the additional invasiveness and cost associated with MRA relative to noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The MRA protocol differs from our routine noncontrast shoulder imaging. We perform a fat-saturated coronal oblique T1 sequence that maximizes the conspicuity of intra-articular contrast in the plane that optimally visualizes the superior labrum. Three planes of intermediate-weighted fast spin echo not only contrast the high-signal intra-articular fluid with the low-signal fibrocartilaginous labrum and the stratified intermediate signal of glenoid articular cartilage, but they also allow optimal assessment of the rotator cuff. In addition, we perform a fat-saturated coronal T2 sequence that highlights all fluid signal structures as well as edema.

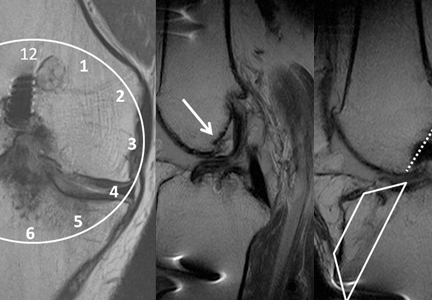

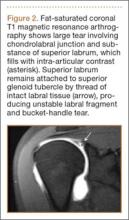

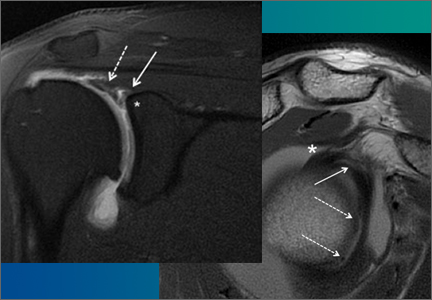

SLAP tears appear on MRA as the insinuation of intra-articular contrast between the articular cartilage and the attachment of the superior labrum,3 within the substance of the labrum, or as detachment of the labrum from the glenoid rim4 (Figure 1). Findings can range from labral fraying to complete detachment with displacement. Tears can extend into other quadrants of the labrum, extend from a Bankart lesion, or involve the biceps tendon and/or the glenohumeral ligaments (Figures 2–4). Up to 10 types of SLAP tears have been described on arthroscopy. This classification scheme, however, is seldom helpful in the interpretation of SLAP tears on MRI. More important in guiding treatment is having a detailed description of the tear, including location, extent, and morphology, along with associated abnormalities.

Several findings can aid in the diagnosis of SLAP tears. Normal anatomical variants of the anterior-superior labrum do not extend posterior to the biceps anchor—an important finding for discerning normal morphologic variants from tears. Therefore, high signal within the posterior third of the superior labrum or extension of high signal laterally within the labrum and away from the glenoid suggests a SLAP tear.5 A paralabral cyst is almost always associated with a labral tear,1 so signal abnormality of the superior labrum with a paralabral cyst suggests a SLAP tear (Figure 5).

MRA is not the only method for diagnosing SLAP tears. Standard 3-Tesla MRI had 83% sensitivity and 99% specificity for diagnosing SLAP tears in a recent study, though MRA had 98% sensitivity and 99% specificity—a statistically significant sensitivity difference.6 In another study, computed tomography arthrography (CTA) had 95% sensitivity and 88% specificity for diagnosing recurrent SLAP tears after surgery.7 CTA is associated with ionizing radiation and is limited in its assessment of other structures that may show concomitant abnormalities, such as the articular cartilage and the rotator cuff. Indirect MRA, wherein magnetic resonance sequences are obtained after intravenous injection of gadolinium contrast and exercise of the affected shoulder, had a high sensitivity of detection of labral tears of all types.8

MRA is most sensitive and specific for diagnosing SLAP tears; 3-Tesla MRI, indirect MRA, and CTA are useful alternative modalities for cases in which MRA cannot be performed.

1. Chang D, Mohana-Borges A, Borso M, Chung CB. SLAP lesions: anatomy, clinical presentation, MR imaging diagnosis and characterization. Eur J Radiol. 2008;68(1):72-87.

2. Jee WH, McCauley TR, Katz LD, Matheny JM, Ruwe PA, Daigneault JP. Superior labral anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions of the glenoid labrum: reliability and accuracy of MR arthrography for diagnosis. Radiology. 2001;218(1):127-132.

3. Fitzpatrick D, Walz DM. Shoulder MR imaging normal variants and imaging artifacts. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010;18(4):615-632.

4. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Rosenberg ZS, et al. Superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions: diagnosis with MR arthrography of the shoulder. Radiology. 2000;214(1):267-271.

5. Tuite MJ, Cirillo RL, De Smet AA, Orwin JF. Superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears: evaluation of three MR signs on T2-weighted images. Radiology. 2000;215(3):841-845.

6. Magee T. 3-T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(1):86-92.

7. De Filippo M, Araoz PA, Pogliacomi F, et al. Recurrent superior labral anterior-to-posterior tears after surgery: detection and grading with CT arthrography. Radiology. 2009;252(3):781-788.

8. Fallahi F, Green N, Gadde S, Jeavons L, Armstrong P, Jonker L. Indirect magnetic resonance arthrography of the shoulder; a reliable diagnostic tool for investigation of suspected labral pathology. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(9):1225-1233.

Superior labral anteroposterior (SLAP) tears are common labral injuries. They occur at the attachment of the long head of the biceps tendon on the superior glenoid and extend anterior and/or posterior to the biceps anchor. The mechanism of action for SLAP tears is traction on the superior labrum by the long head of the biceps tendon, resulting in “peeling” of the labrum off the glenoid. Such forces may result from repetitive overhead arm motion (pitching) or from direct trauma.

Clinical diagnosis is challenging with SLAP tears, as they often present with nonspecific shoulder pain and may not be associated with an acute injury. A further complication is that they are often associated with other shoulder pathology, such as rotator cuff tears.1 As physical examination is typically nonspecific, proper diagnostic imaging is essential for diagnosis.

We prefer to assess potential SLAP tears with magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA).2 Dilute (1:200) gadolinium contrast material (12-15 mL) is introduced into the glenohumeral joint under sonographic or fluoroscopic guidance. Capsular distention by dilute intra-articular contrast enables superior imaging resolution of the labroligamentous complex. We think the increase in diagnostic confidence enabled by direct arthrography outweighs the additional invasiveness and cost associated with MRA relative to noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The MRA protocol differs from our routine noncontrast shoulder imaging. We perform a fat-saturated coronal oblique T1 sequence that maximizes the conspicuity of intra-articular contrast in the plane that optimally visualizes the superior labrum. Three planes of intermediate-weighted fast spin echo not only contrast the high-signal intra-articular fluid with the low-signal fibrocartilaginous labrum and the stratified intermediate signal of glenoid articular cartilage, but they also allow optimal assessment of the rotator cuff. In addition, we perform a fat-saturated coronal T2 sequence that highlights all fluid signal structures as well as edema.

SLAP tears appear on MRA as the insinuation of intra-articular contrast between the articular cartilage and the attachment of the superior labrum,3 within the substance of the labrum, or as detachment of the labrum from the glenoid rim4 (Figure 1). Findings can range from labral fraying to complete detachment with displacement. Tears can extend into other quadrants of the labrum, extend from a Bankart lesion, or involve the biceps tendon and/or the glenohumeral ligaments (Figures 2–4). Up to 10 types of SLAP tears have been described on arthroscopy. This classification scheme, however, is seldom helpful in the interpretation of SLAP tears on MRI. More important in guiding treatment is having a detailed description of the tear, including location, extent, and morphology, along with associated abnormalities.

Several findings can aid in the diagnosis of SLAP tears. Normal anatomical variants of the anterior-superior labrum do not extend posterior to the biceps anchor—an important finding for discerning normal morphologic variants from tears. Therefore, high signal within the posterior third of the superior labrum or extension of high signal laterally within the labrum and away from the glenoid suggests a SLAP tear.5 A paralabral cyst is almost always associated with a labral tear,1 so signal abnormality of the superior labrum with a paralabral cyst suggests a SLAP tear (Figure 5).

MRA is not the only method for diagnosing SLAP tears. Standard 3-Tesla MRI had 83% sensitivity and 99% specificity for diagnosing SLAP tears in a recent study, though MRA had 98% sensitivity and 99% specificity—a statistically significant sensitivity difference.6 In another study, computed tomography arthrography (CTA) had 95% sensitivity and 88% specificity for diagnosing recurrent SLAP tears after surgery.7 CTA is associated with ionizing radiation and is limited in its assessment of other structures that may show concomitant abnormalities, such as the articular cartilage and the rotator cuff. Indirect MRA, wherein magnetic resonance sequences are obtained after intravenous injection of gadolinium contrast and exercise of the affected shoulder, had a high sensitivity of detection of labral tears of all types.8

MRA is most sensitive and specific for diagnosing SLAP tears; 3-Tesla MRI, indirect MRA, and CTA are useful alternative modalities for cases in which MRA cannot be performed.

Superior labral anteroposterior (SLAP) tears are common labral injuries. They occur at the attachment of the long head of the biceps tendon on the superior glenoid and extend anterior and/or posterior to the biceps anchor. The mechanism of action for SLAP tears is traction on the superior labrum by the long head of the biceps tendon, resulting in “peeling” of the labrum off the glenoid. Such forces may result from repetitive overhead arm motion (pitching) or from direct trauma.

Clinical diagnosis is challenging with SLAP tears, as they often present with nonspecific shoulder pain and may not be associated with an acute injury. A further complication is that they are often associated with other shoulder pathology, such as rotator cuff tears.1 As physical examination is typically nonspecific, proper diagnostic imaging is essential for diagnosis.

We prefer to assess potential SLAP tears with magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA).2 Dilute (1:200) gadolinium contrast material (12-15 mL) is introduced into the glenohumeral joint under sonographic or fluoroscopic guidance. Capsular distention by dilute intra-articular contrast enables superior imaging resolution of the labroligamentous complex. We think the increase in diagnostic confidence enabled by direct arthrography outweighs the additional invasiveness and cost associated with MRA relative to noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The MRA protocol differs from our routine noncontrast shoulder imaging. We perform a fat-saturated coronal oblique T1 sequence that maximizes the conspicuity of intra-articular contrast in the plane that optimally visualizes the superior labrum. Three planes of intermediate-weighted fast spin echo not only contrast the high-signal intra-articular fluid with the low-signal fibrocartilaginous labrum and the stratified intermediate signal of glenoid articular cartilage, but they also allow optimal assessment of the rotator cuff. In addition, we perform a fat-saturated coronal T2 sequence that highlights all fluid signal structures as well as edema.

SLAP tears appear on MRA as the insinuation of intra-articular contrast between the articular cartilage and the attachment of the superior labrum,3 within the substance of the labrum, or as detachment of the labrum from the glenoid rim4 (Figure 1). Findings can range from labral fraying to complete detachment with displacement. Tears can extend into other quadrants of the labrum, extend from a Bankart lesion, or involve the biceps tendon and/or the glenohumeral ligaments (Figures 2–4). Up to 10 types of SLAP tears have been described on arthroscopy. This classification scheme, however, is seldom helpful in the interpretation of SLAP tears on MRI. More important in guiding treatment is having a detailed description of the tear, including location, extent, and morphology, along with associated abnormalities.

Several findings can aid in the diagnosis of SLAP tears. Normal anatomical variants of the anterior-superior labrum do not extend posterior to the biceps anchor—an important finding for discerning normal morphologic variants from tears. Therefore, high signal within the posterior third of the superior labrum or extension of high signal laterally within the labrum and away from the glenoid suggests a SLAP tear.5 A paralabral cyst is almost always associated with a labral tear,1 so signal abnormality of the superior labrum with a paralabral cyst suggests a SLAP tear (Figure 5).

MRA is not the only method for diagnosing SLAP tears. Standard 3-Tesla MRI had 83% sensitivity and 99% specificity for diagnosing SLAP tears in a recent study, though MRA had 98% sensitivity and 99% specificity—a statistically significant sensitivity difference.6 In another study, computed tomography arthrography (CTA) had 95% sensitivity and 88% specificity for diagnosing recurrent SLAP tears after surgery.7 CTA is associated with ionizing radiation and is limited in its assessment of other structures that may show concomitant abnormalities, such as the articular cartilage and the rotator cuff. Indirect MRA, wherein magnetic resonance sequences are obtained after intravenous injection of gadolinium contrast and exercise of the affected shoulder, had a high sensitivity of detection of labral tears of all types.8

MRA is most sensitive and specific for diagnosing SLAP tears; 3-Tesla MRI, indirect MRA, and CTA are useful alternative modalities for cases in which MRA cannot be performed.

1. Chang D, Mohana-Borges A, Borso M, Chung CB. SLAP lesions: anatomy, clinical presentation, MR imaging diagnosis and characterization. Eur J Radiol. 2008;68(1):72-87.

2. Jee WH, McCauley TR, Katz LD, Matheny JM, Ruwe PA, Daigneault JP. Superior labral anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions of the glenoid labrum: reliability and accuracy of MR arthrography for diagnosis. Radiology. 2001;218(1):127-132.

3. Fitzpatrick D, Walz DM. Shoulder MR imaging normal variants and imaging artifacts. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010;18(4):615-632.

4. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Rosenberg ZS, et al. Superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions: diagnosis with MR arthrography of the shoulder. Radiology. 2000;214(1):267-271.

5. Tuite MJ, Cirillo RL, De Smet AA, Orwin JF. Superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears: evaluation of three MR signs on T2-weighted images. Radiology. 2000;215(3):841-845.

6. Magee T. 3-T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(1):86-92.

7. De Filippo M, Araoz PA, Pogliacomi F, et al. Recurrent superior labral anterior-to-posterior tears after surgery: detection and grading with CT arthrography. Radiology. 2009;252(3):781-788.

8. Fallahi F, Green N, Gadde S, Jeavons L, Armstrong P, Jonker L. Indirect magnetic resonance arthrography of the shoulder; a reliable diagnostic tool for investigation of suspected labral pathology. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(9):1225-1233.

1. Chang D, Mohana-Borges A, Borso M, Chung CB. SLAP lesions: anatomy, clinical presentation, MR imaging diagnosis and characterization. Eur J Radiol. 2008;68(1):72-87.

2. Jee WH, McCauley TR, Katz LD, Matheny JM, Ruwe PA, Daigneault JP. Superior labral anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions of the glenoid labrum: reliability and accuracy of MR arthrography for diagnosis. Radiology. 2001;218(1):127-132.

3. Fitzpatrick D, Walz DM. Shoulder MR imaging normal variants and imaging artifacts. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010;18(4):615-632.

4. Bencardino JT, Beltran J, Rosenberg ZS, et al. Superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions: diagnosis with MR arthrography of the shoulder. Radiology. 2000;214(1):267-271.

5. Tuite MJ, Cirillo RL, De Smet AA, Orwin JF. Superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears: evaluation of three MR signs on T2-weighted images. Radiology. 2000;215(3):841-845.

6. Magee T. 3-T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(1):86-92.

7. De Filippo M, Araoz PA, Pogliacomi F, et al. Recurrent superior labral anterior-to-posterior tears after surgery: detection and grading with CT arthrography. Radiology. 2009;252(3):781-788.

8. Fallahi F, Green N, Gadde S, Jeavons L, Armstrong P, Jonker L. Indirect magnetic resonance arthrography of the shoulder; a reliable diagnostic tool for investigation of suspected labral pathology. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(9):1225-1233.