User login

Case Report: An Unusual Case of Morel-Lavallée Lesion of the Upper Extremity

Case

A 32-year-old previously healthy woman presented to the ED with right upper arm pain and swelling of 6 days duration. According to the patient, the swelling began 2 days after she sustained a work-related injury at a coin-manufacturing factory. She stated that her right arm had gotten caught inside of a rolling press while she was cleaning it. The roller had stopped over her upper arm, trapping it between the roller and the platform for several minutes before it was extricated. She was brought to the ED by emergency medical services for evaluation immediately following this incident. At this first visit to the ED, the patient complained of mild pain in her right arm. Physical examination at that time revealed mild diffuse swelling extending from her hand to her distal humerus, with mild pain on passive flexion, and extension without associated numbness or tingling. Plain films of her right upper extremity were ordered, the results of which were relatively unremarkable. She was evaluated by an orthopedist, who ruled out compartment syndrome based on her benign physical examination and soft compartments. She was ultimately discharged and told to follow up with her primary care provider.

Over the course of 48 hours from the first ED visit, the patient developed large bullae on the dorsal and volar aspect of her forearm, elbow, and upper arm with associated pain. In addition to dark discolorations of the skin over her affected arm, she noticed that the bullae had become numerous and discolored. These symptoms continued to grow progressively worse, prompting her second presentation to the ED.

The patient was taken to the operating room and underwent debridement and resection of the circumferential necrotic skin and subcutaneous tissue in her right arm, and the placement of a skin graft with overlying wound vacuum-assisted closure. During the procedure, a large amount of serosanguinous fluid was drained and cultured, and was found to be sterile. Due to the size of her injury, she underwent two additional episodes of debridement and graft placement over the course of the next 2 weeks.

Discussion

First described in the 1850s by the French physician Maurice Morel-Lavallée, Morel-Lavallée lesion is a rare, traumatic, soft-tissue injury.1 It is an internal degloving injury wherein the skin and subcutaneous tissue have been forcibly separated from the underlying fascia as a result of shear stress. The lymphatic and blood vessels between the layers are also disrupted in this process, resulting in the accumulation of blood and lymphatic fluid as well as subcutaneous debris in the potential space that forms. Excess accumulation over time can compromise blood supply to the overlying skin and cause necrosis.2 Morel-Lavallée lesion is missed on initial evaluation in up to one-third of the cases and may have a delay in presentation ranging from hours to months after the inciting injury.3

Morel-Lavallée lesions typically involve the flank, hips, thigh, and prepatellar regions as a result of shear injuries sustained from bicycle falls and motor vehicle accidents.4 These lesions are often associated with concomitant acetabular and pelvic fractures.5 Involvement of the upper extremities is unusual. Typically, presentation consists of a fluctuant and painful mass underneath the skin which increases over time. The overlying skin may show the mechanism of the original injury, for example, as abrasions after a crush injury. The excessive skin necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae seen in this particular case is a very rare presentation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes compartment syndrome, coma blisters, a missed fracture, bullous pemphigoid, bullous drug reactions, and linear immunoglobulin A disease. Most of these conditions were easily ruled out in this case as the patient was previously healthy and not on any medications. The lesions in this case could have been confused with coma blisters, which are similar in appearance, self-limiting, and can develop on the extremities. However, coma blisters are classically associated with toxicity from various central nervous system depressants, as well as reduced consciousness from other causes—all of which were readily ruled-out based on the patient’s history. Moreover, the Morel-Lavallée lesion is a degloving injury of the subcutaneous tissue from the fascia underneath, whereas the pathology of coma blisters includes subepidermal bullae formation as well as immunoglobulin and complement deposition.6

Diagnostic Imaging

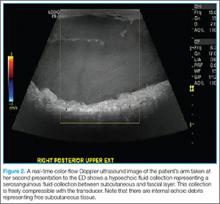

Morel-Lavallée lesion can often be confirmed via several imaging modalities, including ultrasound, CT, 3D CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).3,7 Ultrasound will usually show a well-circumscribed hypoechoic fluid collection with hyperechoic fat globules from the subcutaneous tissue, whereas CT tends to show an encapsulated mass with fluid collection underneath. In MRI, Morel-Lavallée lesion often appears as a hypointense T1-sequence and hyperintense T2-sequence similar to most other fluid collections. There may be variable T1- and T2-intensities with subcutaneous tissues in the fluid collection.2

Management

Despite recognition of this disease entity, controversies still exist regarding management. Case reports have demonstrated a relatively high rate of infected fluid collections depending on the chronicity of the injury.8 A recent algorithm to management described by Nickerson et al4 proposes that for patients with viable skin, percutaneous aspiration of more than 50 cc of fluid from these lesions should be treated with more extensive operative intervention based on the increased likelihood of recurrence. Patients without viable skin require formal debridement with possible skin grafting.

Other treatment options include conservative management, surgical drainage, sclerodesis, and extensive open surgery.8-10 Management is always case-based and dependent upon the size of the lesion and associated injuries.

Conclusion

This case represents an example of Morel-Lavallée lesions in their most severe and atypical form. It also serves as a reminder that vigilance and knowledge of this disease process is important in helping to diagnose this rare but potentially devastating condition. The key to recognizing this injury lies in keeping this disease process in the differential diagnosis of traumatic injuries with suspicious mechanism involving significant shear forces. Significant physical examination findings may not be present initially and evolve over a time period of hours to days. Once this injury is identified, management hinges on the size of the lesion and affected body part. Despite timely interventions, Morel-Lavallée lesions may result in significant morbidity and functional disability.

Dr Ye is an emergency medicine resident at the Brown Alpert Medical School in Providence, Rhode Island. Dr Rosenberg is a clinical assistant professor at Brown Alpert Medical School, and an emergency medicine attending physican at Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island.

- Morel-Lavallée M. Epanchements traumatique de serosite. Arc Générales Méd. 1853;691-731.

- Chokshi F, Jose J, Clifford P. Morel Lavallée Lesion. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2010;39(5): 252-253.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol. 2014;21(1):35-43.

- Nickerson T, Zielinski M, Jenkins D, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014:76(2);493-497.

- Powers ML, Hatem SF, Sundaram M. Morel-Lavallee lesion. Orthopedics. 2007;30(4):322-323.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online Journal. 2012:18(3);10.

- Reddix RN, Carrol E, Webb LX. Early diagnosis of a Morel-Lavallee lesion using three-dimensional computed tomography reconstructions: a case report. J Trauma. 2009;67(2):e57-e59.

- Lin HL, Lee WC, Kuo LC, Chen CW. Closed internal degloving injury with conservative treatment. Am J Emerg Med. 2008:26(2);254.e5-e6.

- Luria S, Applbaum Y,Weil Y, Liebergall M, Peyser A. Talc sclerodhesis of persistent Morel-Lavallée lesions (posttraumatic pseudocysts): case report of 4 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(6):435-438.

- Penaud A, Quignon R, Danin A, Bahé L, Zakine G. Alcohol sclerodhesis: an innovative treatment for chronic Morel-Lavallée lesions. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(10): e262-264.

Case

A 32-year-old previously healthy woman presented to the ED with right upper arm pain and swelling of 6 days duration. According to the patient, the swelling began 2 days after she sustained a work-related injury at a coin-manufacturing factory. She stated that her right arm had gotten caught inside of a rolling press while she was cleaning it. The roller had stopped over her upper arm, trapping it between the roller and the platform for several minutes before it was extricated. She was brought to the ED by emergency medical services for evaluation immediately following this incident. At this first visit to the ED, the patient complained of mild pain in her right arm. Physical examination at that time revealed mild diffuse swelling extending from her hand to her distal humerus, with mild pain on passive flexion, and extension without associated numbness or tingling. Plain films of her right upper extremity were ordered, the results of which were relatively unremarkable. She was evaluated by an orthopedist, who ruled out compartment syndrome based on her benign physical examination and soft compartments. She was ultimately discharged and told to follow up with her primary care provider.

Over the course of 48 hours from the first ED visit, the patient developed large bullae on the dorsal and volar aspect of her forearm, elbow, and upper arm with associated pain. In addition to dark discolorations of the skin over her affected arm, she noticed that the bullae had become numerous and discolored. These symptoms continued to grow progressively worse, prompting her second presentation to the ED.

The patient was taken to the operating room and underwent debridement and resection of the circumferential necrotic skin and subcutaneous tissue in her right arm, and the placement of a skin graft with overlying wound vacuum-assisted closure. During the procedure, a large amount of serosanguinous fluid was drained and cultured, and was found to be sterile. Due to the size of her injury, she underwent two additional episodes of debridement and graft placement over the course of the next 2 weeks.

Discussion

First described in the 1850s by the French physician Maurice Morel-Lavallée, Morel-Lavallée lesion is a rare, traumatic, soft-tissue injury.1 It is an internal degloving injury wherein the skin and subcutaneous tissue have been forcibly separated from the underlying fascia as a result of shear stress. The lymphatic and blood vessels between the layers are also disrupted in this process, resulting in the accumulation of blood and lymphatic fluid as well as subcutaneous debris in the potential space that forms. Excess accumulation over time can compromise blood supply to the overlying skin and cause necrosis.2 Morel-Lavallée lesion is missed on initial evaluation in up to one-third of the cases and may have a delay in presentation ranging from hours to months after the inciting injury.3

Morel-Lavallée lesions typically involve the flank, hips, thigh, and prepatellar regions as a result of shear injuries sustained from bicycle falls and motor vehicle accidents.4 These lesions are often associated with concomitant acetabular and pelvic fractures.5 Involvement of the upper extremities is unusual. Typically, presentation consists of a fluctuant and painful mass underneath the skin which increases over time. The overlying skin may show the mechanism of the original injury, for example, as abrasions after a crush injury. The excessive skin necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae seen in this particular case is a very rare presentation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes compartment syndrome, coma blisters, a missed fracture, bullous pemphigoid, bullous drug reactions, and linear immunoglobulin A disease. Most of these conditions were easily ruled out in this case as the patient was previously healthy and not on any medications. The lesions in this case could have been confused with coma blisters, which are similar in appearance, self-limiting, and can develop on the extremities. However, coma blisters are classically associated with toxicity from various central nervous system depressants, as well as reduced consciousness from other causes—all of which were readily ruled-out based on the patient’s history. Moreover, the Morel-Lavallée lesion is a degloving injury of the subcutaneous tissue from the fascia underneath, whereas the pathology of coma blisters includes subepidermal bullae formation as well as immunoglobulin and complement deposition.6

Diagnostic Imaging

Morel-Lavallée lesion can often be confirmed via several imaging modalities, including ultrasound, CT, 3D CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).3,7 Ultrasound will usually show a well-circumscribed hypoechoic fluid collection with hyperechoic fat globules from the subcutaneous tissue, whereas CT tends to show an encapsulated mass with fluid collection underneath. In MRI, Morel-Lavallée lesion often appears as a hypointense T1-sequence and hyperintense T2-sequence similar to most other fluid collections. There may be variable T1- and T2-intensities with subcutaneous tissues in the fluid collection.2

Management

Despite recognition of this disease entity, controversies still exist regarding management. Case reports have demonstrated a relatively high rate of infected fluid collections depending on the chronicity of the injury.8 A recent algorithm to management described by Nickerson et al4 proposes that for patients with viable skin, percutaneous aspiration of more than 50 cc of fluid from these lesions should be treated with more extensive operative intervention based on the increased likelihood of recurrence. Patients without viable skin require formal debridement with possible skin grafting.

Other treatment options include conservative management, surgical drainage, sclerodesis, and extensive open surgery.8-10 Management is always case-based and dependent upon the size of the lesion and associated injuries.

Conclusion

This case represents an example of Morel-Lavallée lesions in their most severe and atypical form. It also serves as a reminder that vigilance and knowledge of this disease process is important in helping to diagnose this rare but potentially devastating condition. The key to recognizing this injury lies in keeping this disease process in the differential diagnosis of traumatic injuries with suspicious mechanism involving significant shear forces. Significant physical examination findings may not be present initially and evolve over a time period of hours to days. Once this injury is identified, management hinges on the size of the lesion and affected body part. Despite timely interventions, Morel-Lavallée lesions may result in significant morbidity and functional disability.

Dr Ye is an emergency medicine resident at the Brown Alpert Medical School in Providence, Rhode Island. Dr Rosenberg is a clinical assistant professor at Brown Alpert Medical School, and an emergency medicine attending physican at Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island.

Case

A 32-year-old previously healthy woman presented to the ED with right upper arm pain and swelling of 6 days duration. According to the patient, the swelling began 2 days after she sustained a work-related injury at a coin-manufacturing factory. She stated that her right arm had gotten caught inside of a rolling press while she was cleaning it. The roller had stopped over her upper arm, trapping it between the roller and the platform for several minutes before it was extricated. She was brought to the ED by emergency medical services for evaluation immediately following this incident. At this first visit to the ED, the patient complained of mild pain in her right arm. Physical examination at that time revealed mild diffuse swelling extending from her hand to her distal humerus, with mild pain on passive flexion, and extension without associated numbness or tingling. Plain films of her right upper extremity were ordered, the results of which were relatively unremarkable. She was evaluated by an orthopedist, who ruled out compartment syndrome based on her benign physical examination and soft compartments. She was ultimately discharged and told to follow up with her primary care provider.

Over the course of 48 hours from the first ED visit, the patient developed large bullae on the dorsal and volar aspect of her forearm, elbow, and upper arm with associated pain. In addition to dark discolorations of the skin over her affected arm, she noticed that the bullae had become numerous and discolored. These symptoms continued to grow progressively worse, prompting her second presentation to the ED.

The patient was taken to the operating room and underwent debridement and resection of the circumferential necrotic skin and subcutaneous tissue in her right arm, and the placement of a skin graft with overlying wound vacuum-assisted closure. During the procedure, a large amount of serosanguinous fluid was drained and cultured, and was found to be sterile. Due to the size of her injury, she underwent two additional episodes of debridement and graft placement over the course of the next 2 weeks.

Discussion

First described in the 1850s by the French physician Maurice Morel-Lavallée, Morel-Lavallée lesion is a rare, traumatic, soft-tissue injury.1 It is an internal degloving injury wherein the skin and subcutaneous tissue have been forcibly separated from the underlying fascia as a result of shear stress. The lymphatic and blood vessels between the layers are also disrupted in this process, resulting in the accumulation of blood and lymphatic fluid as well as subcutaneous debris in the potential space that forms. Excess accumulation over time can compromise blood supply to the overlying skin and cause necrosis.2 Morel-Lavallée lesion is missed on initial evaluation in up to one-third of the cases and may have a delay in presentation ranging from hours to months after the inciting injury.3

Morel-Lavallée lesions typically involve the flank, hips, thigh, and prepatellar regions as a result of shear injuries sustained from bicycle falls and motor vehicle accidents.4 These lesions are often associated with concomitant acetabular and pelvic fractures.5 Involvement of the upper extremities is unusual. Typically, presentation consists of a fluctuant and painful mass underneath the skin which increases over time. The overlying skin may show the mechanism of the original injury, for example, as abrasions after a crush injury. The excessive skin necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae seen in this particular case is a very rare presentation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes compartment syndrome, coma blisters, a missed fracture, bullous pemphigoid, bullous drug reactions, and linear immunoglobulin A disease. Most of these conditions were easily ruled out in this case as the patient was previously healthy and not on any medications. The lesions in this case could have been confused with coma blisters, which are similar in appearance, self-limiting, and can develop on the extremities. However, coma blisters are classically associated with toxicity from various central nervous system depressants, as well as reduced consciousness from other causes—all of which were readily ruled-out based on the patient’s history. Moreover, the Morel-Lavallée lesion is a degloving injury of the subcutaneous tissue from the fascia underneath, whereas the pathology of coma blisters includes subepidermal bullae formation as well as immunoglobulin and complement deposition.6

Diagnostic Imaging

Morel-Lavallée lesion can often be confirmed via several imaging modalities, including ultrasound, CT, 3D CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).3,7 Ultrasound will usually show a well-circumscribed hypoechoic fluid collection with hyperechoic fat globules from the subcutaneous tissue, whereas CT tends to show an encapsulated mass with fluid collection underneath. In MRI, Morel-Lavallée lesion often appears as a hypointense T1-sequence and hyperintense T2-sequence similar to most other fluid collections. There may be variable T1- and T2-intensities with subcutaneous tissues in the fluid collection.2

Management

Despite recognition of this disease entity, controversies still exist regarding management. Case reports have demonstrated a relatively high rate of infected fluid collections depending on the chronicity of the injury.8 A recent algorithm to management described by Nickerson et al4 proposes that for patients with viable skin, percutaneous aspiration of more than 50 cc of fluid from these lesions should be treated with more extensive operative intervention based on the increased likelihood of recurrence. Patients without viable skin require formal debridement with possible skin grafting.

Other treatment options include conservative management, surgical drainage, sclerodesis, and extensive open surgery.8-10 Management is always case-based and dependent upon the size of the lesion and associated injuries.

Conclusion

This case represents an example of Morel-Lavallée lesions in their most severe and atypical form. It also serves as a reminder that vigilance and knowledge of this disease process is important in helping to diagnose this rare but potentially devastating condition. The key to recognizing this injury lies in keeping this disease process in the differential diagnosis of traumatic injuries with suspicious mechanism involving significant shear forces. Significant physical examination findings may not be present initially and evolve over a time period of hours to days. Once this injury is identified, management hinges on the size of the lesion and affected body part. Despite timely interventions, Morel-Lavallée lesions may result in significant morbidity and functional disability.

Dr Ye is an emergency medicine resident at the Brown Alpert Medical School in Providence, Rhode Island. Dr Rosenberg is a clinical assistant professor at Brown Alpert Medical School, and an emergency medicine attending physican at Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island.

- Morel-Lavallée M. Epanchements traumatique de serosite. Arc Générales Méd. 1853;691-731.

- Chokshi F, Jose J, Clifford P. Morel Lavallée Lesion. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2010;39(5): 252-253.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol. 2014;21(1):35-43.

- Nickerson T, Zielinski M, Jenkins D, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014:76(2);493-497.

- Powers ML, Hatem SF, Sundaram M. Morel-Lavallee lesion. Orthopedics. 2007;30(4):322-323.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online Journal. 2012:18(3);10.

- Reddix RN, Carrol E, Webb LX. Early diagnosis of a Morel-Lavallee lesion using three-dimensional computed tomography reconstructions: a case report. J Trauma. 2009;67(2):e57-e59.

- Lin HL, Lee WC, Kuo LC, Chen CW. Closed internal degloving injury with conservative treatment. Am J Emerg Med. 2008:26(2);254.e5-e6.

- Luria S, Applbaum Y,Weil Y, Liebergall M, Peyser A. Talc sclerodhesis of persistent Morel-Lavallée lesions (posttraumatic pseudocysts): case report of 4 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(6):435-438.

- Penaud A, Quignon R, Danin A, Bahé L, Zakine G. Alcohol sclerodhesis: an innovative treatment for chronic Morel-Lavallée lesions. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(10): e262-264.

- Morel-Lavallée M. Epanchements traumatique de serosite. Arc Générales Méd. 1853;691-731.

- Chokshi F, Jose J, Clifford P. Morel Lavallée Lesion. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2010;39(5): 252-253.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol. 2014;21(1):35-43.

- Nickerson T, Zielinski M, Jenkins D, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014:76(2);493-497.

- Powers ML, Hatem SF, Sundaram M. Morel-Lavallee lesion. Orthopedics. 2007;30(4):322-323.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online Journal. 2012:18(3);10.

- Reddix RN, Carrol E, Webb LX. Early diagnosis of a Morel-Lavallee lesion using three-dimensional computed tomography reconstructions: a case report. J Trauma. 2009;67(2):e57-e59.

- Lin HL, Lee WC, Kuo LC, Chen CW. Closed internal degloving injury with conservative treatment. Am J Emerg Med. 2008:26(2);254.e5-e6.

- Luria S, Applbaum Y,Weil Y, Liebergall M, Peyser A. Talc sclerodhesis of persistent Morel-Lavallée lesions (posttraumatic pseudocysts): case report of 4 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(6):435-438.

- Penaud A, Quignon R, Danin A, Bahé L, Zakine G. Alcohol sclerodhesis: an innovative treatment for chronic Morel-Lavallée lesions. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(10): e262-264.