User login

Pro basketball players’ hearts: LV keeps growing, aortic root doesn’t

For the first time, cardiologists have characterized the adaptive cardiac remodeling in a large cohort of National Basketball Association players, which establishes a normative database and allows physicians to distinguish it from occult pathologic changes that may precipitate sudden cardiac death, according to an imaging study.

“We hope that the present data will help to focus decision making and improve clinical acumen for the purpose of primary prevention of cardiac emergencies in U.S. basketball players and in the athletic community at large,” said Dr. David J. Engel and his associates of Columbia University, New York.

Until now, most of the literature concerning the structural features of the athletic heart has been based on European studies, where comprehensive cardiac screening of all elite athletes is mandatory. The typical sports activities and the demographics of athletes in the U.S. are different, and their cardiologic profiles have not been well studied because detailed cardiac examinations are not compulsory. But the NBA recently mandated that all athletes undergo annual preseason medical evaluations including stress echocardiograms, and allowed the division of cardiology at Columbia to assess the results each year.

“A detailed understanding of normal and expected cardiac remodeling in U.S. basketball players has significant clinical importance given that the incidence of sports-related sudden cardiac death in the U.S. is highest among basketball players and that the most common cause ... in this population is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,” the investigators noted.

Their analysis of all 526 ECGs performed on NBA players during a 1-year period “will provide an invaluable frame of reference to enhance player safety for the large group of U.S. basketball players in training at all skill levels, and in the athletic community at large,” they said.

The study participants were aged 18-39 years (mean age, 25.7 years). Roughly 77% were African American, 20% were white, 2% were Hispanic, and 1% were Asian or other ethnicities. The mean height was 200.2 cm (6’7”).

Left ventricular cavity size was larger than that in the general population, but LV size was proportional to the athletes’ large body size. “Scaling LV size to body size is vitally important in the cardiac evaluation of basketball players, whose heights extend to 218 cm and body surface areas to 2.8 m2,” Dr. Engel and his associates said (JAMA Cardiol. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0252).

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was identified in only 27% of the athletes. African Americans had increased indices of LVH, compared with whites, and had a higher incidence of nondilated concentric hypertrophy, while whites showed predominantly eccentric dilated hypertrophy. These findings should help clinicians recognize genuine hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which is a contraindication to participating in all but the most low-intensity competitive sports.

Most of the participants had a normal left ventricular ejection fraction, and all showed normal augmentation of LV systolic function with exercise.

Aortic root diameter was larger than that in the general population but similar to that in other elite athletes. Surprisingly, aortic root diameter increased with increasing body size only to a certain point, reaching a plateau at 31-35 mm. Fewer than 5% of the participants had an aortic root diameter of 40 mm or more, and the maximal diameter was 42 mm. “These data have important implications in the evaluation of exceptionally large athletes and question the applicability in individuals with significantly increased biometrics of the traditional formula to estimate aortic root diameter that assumes a linear association between [it] and body surface area,” they noted.

“We hope that the results of this study will assist recognition of cardiac pathologic change and provide a framework to help avoid unnecessary exclusions of athletes from competition. We believe that these data have additional applicability to other sports that preselect for athletes with height, such as volleyball, rowing, and track and field,” Dr. Engel and his associates added.

This study was supported by the National Basketball Association as part of a medical services agreement with Columbia University. Dr. Engel and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The most interesting finding of this study was that despite the immense body size of the athletes, aortic root diameter exceeded 40 mm in less than 5%, and when dilation did occur it was of a very small magnitude, with a maximal diameter of 42 mm.

This important finding confirms that only mild aortic dilation should be considered physiologic among athletes, and that even athletes at the extreme end of the height spectrum should not be expected to show proportionally extreme aortic dilation.

Unlike ventricular size, which increases proportionally with body size, aortic dilation has an upper limit. Athletes with aortic dimensions that exceed this limit should be considered at risk for aortopathy and either prohibited from competitive sports or closely monitored if they do participate.

Dr. Aaron L. Baggish of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, made these remarks in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Cardiol. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0289). He reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

The most interesting finding of this study was that despite the immense body size of the athletes, aortic root diameter exceeded 40 mm in less than 5%, and when dilation did occur it was of a very small magnitude, with a maximal diameter of 42 mm.

This important finding confirms that only mild aortic dilation should be considered physiologic among athletes, and that even athletes at the extreme end of the height spectrum should not be expected to show proportionally extreme aortic dilation.

Unlike ventricular size, which increases proportionally with body size, aortic dilation has an upper limit. Athletes with aortic dimensions that exceed this limit should be considered at risk for aortopathy and either prohibited from competitive sports or closely monitored if they do participate.

Dr. Aaron L. Baggish of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, made these remarks in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Cardiol. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0289). He reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

The most interesting finding of this study was that despite the immense body size of the athletes, aortic root diameter exceeded 40 mm in less than 5%, and when dilation did occur it was of a very small magnitude, with a maximal diameter of 42 mm.

This important finding confirms that only mild aortic dilation should be considered physiologic among athletes, and that even athletes at the extreme end of the height spectrum should not be expected to show proportionally extreme aortic dilation.

Unlike ventricular size, which increases proportionally with body size, aortic dilation has an upper limit. Athletes with aortic dimensions that exceed this limit should be considered at risk for aortopathy and either prohibited from competitive sports or closely monitored if they do participate.

Dr. Aaron L. Baggish of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, made these remarks in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Cardiol. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0289). He reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

For the first time, cardiologists have characterized the adaptive cardiac remodeling in a large cohort of National Basketball Association players, which establishes a normative database and allows physicians to distinguish it from occult pathologic changes that may precipitate sudden cardiac death, according to an imaging study.

“We hope that the present data will help to focus decision making and improve clinical acumen for the purpose of primary prevention of cardiac emergencies in U.S. basketball players and in the athletic community at large,” said Dr. David J. Engel and his associates of Columbia University, New York.

Until now, most of the literature concerning the structural features of the athletic heart has been based on European studies, where comprehensive cardiac screening of all elite athletes is mandatory. The typical sports activities and the demographics of athletes in the U.S. are different, and their cardiologic profiles have not been well studied because detailed cardiac examinations are not compulsory. But the NBA recently mandated that all athletes undergo annual preseason medical evaluations including stress echocardiograms, and allowed the division of cardiology at Columbia to assess the results each year.

“A detailed understanding of normal and expected cardiac remodeling in U.S. basketball players has significant clinical importance given that the incidence of sports-related sudden cardiac death in the U.S. is highest among basketball players and that the most common cause ... in this population is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,” the investigators noted.

Their analysis of all 526 ECGs performed on NBA players during a 1-year period “will provide an invaluable frame of reference to enhance player safety for the large group of U.S. basketball players in training at all skill levels, and in the athletic community at large,” they said.

The study participants were aged 18-39 years (mean age, 25.7 years). Roughly 77% were African American, 20% were white, 2% were Hispanic, and 1% were Asian or other ethnicities. The mean height was 200.2 cm (6’7”).

Left ventricular cavity size was larger than that in the general population, but LV size was proportional to the athletes’ large body size. “Scaling LV size to body size is vitally important in the cardiac evaluation of basketball players, whose heights extend to 218 cm and body surface areas to 2.8 m2,” Dr. Engel and his associates said (JAMA Cardiol. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0252).

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was identified in only 27% of the athletes. African Americans had increased indices of LVH, compared with whites, and had a higher incidence of nondilated concentric hypertrophy, while whites showed predominantly eccentric dilated hypertrophy. These findings should help clinicians recognize genuine hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which is a contraindication to participating in all but the most low-intensity competitive sports.

Most of the participants had a normal left ventricular ejection fraction, and all showed normal augmentation of LV systolic function with exercise.

Aortic root diameter was larger than that in the general population but similar to that in other elite athletes. Surprisingly, aortic root diameter increased with increasing body size only to a certain point, reaching a plateau at 31-35 mm. Fewer than 5% of the participants had an aortic root diameter of 40 mm or more, and the maximal diameter was 42 mm. “These data have important implications in the evaluation of exceptionally large athletes and question the applicability in individuals with significantly increased biometrics of the traditional formula to estimate aortic root diameter that assumes a linear association between [it] and body surface area,” they noted.

“We hope that the results of this study will assist recognition of cardiac pathologic change and provide a framework to help avoid unnecessary exclusions of athletes from competition. We believe that these data have additional applicability to other sports that preselect for athletes with height, such as volleyball, rowing, and track and field,” Dr. Engel and his associates added.

This study was supported by the National Basketball Association as part of a medical services agreement with Columbia University. Dr. Engel and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

For the first time, cardiologists have characterized the adaptive cardiac remodeling in a large cohort of National Basketball Association players, which establishes a normative database and allows physicians to distinguish it from occult pathologic changes that may precipitate sudden cardiac death, according to an imaging study.

“We hope that the present data will help to focus decision making and improve clinical acumen for the purpose of primary prevention of cardiac emergencies in U.S. basketball players and in the athletic community at large,” said Dr. David J. Engel and his associates of Columbia University, New York.

Until now, most of the literature concerning the structural features of the athletic heart has been based on European studies, where comprehensive cardiac screening of all elite athletes is mandatory. The typical sports activities and the demographics of athletes in the U.S. are different, and their cardiologic profiles have not been well studied because detailed cardiac examinations are not compulsory. But the NBA recently mandated that all athletes undergo annual preseason medical evaluations including stress echocardiograms, and allowed the division of cardiology at Columbia to assess the results each year.

“A detailed understanding of normal and expected cardiac remodeling in U.S. basketball players has significant clinical importance given that the incidence of sports-related sudden cardiac death in the U.S. is highest among basketball players and that the most common cause ... in this population is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,” the investigators noted.

Their analysis of all 526 ECGs performed on NBA players during a 1-year period “will provide an invaluable frame of reference to enhance player safety for the large group of U.S. basketball players in training at all skill levels, and in the athletic community at large,” they said.

The study participants were aged 18-39 years (mean age, 25.7 years). Roughly 77% were African American, 20% were white, 2% were Hispanic, and 1% were Asian or other ethnicities. The mean height was 200.2 cm (6’7”).

Left ventricular cavity size was larger than that in the general population, but LV size was proportional to the athletes’ large body size. “Scaling LV size to body size is vitally important in the cardiac evaluation of basketball players, whose heights extend to 218 cm and body surface areas to 2.8 m2,” Dr. Engel and his associates said (JAMA Cardiol. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0252).

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was identified in only 27% of the athletes. African Americans had increased indices of LVH, compared with whites, and had a higher incidence of nondilated concentric hypertrophy, while whites showed predominantly eccentric dilated hypertrophy. These findings should help clinicians recognize genuine hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which is a contraindication to participating in all but the most low-intensity competitive sports.

Most of the participants had a normal left ventricular ejection fraction, and all showed normal augmentation of LV systolic function with exercise.

Aortic root diameter was larger than that in the general population but similar to that in other elite athletes. Surprisingly, aortic root diameter increased with increasing body size only to a certain point, reaching a plateau at 31-35 mm. Fewer than 5% of the participants had an aortic root diameter of 40 mm or more, and the maximal diameter was 42 mm. “These data have important implications in the evaluation of exceptionally large athletes and question the applicability in individuals with significantly increased biometrics of the traditional formula to estimate aortic root diameter that assumes a linear association between [it] and body surface area,” they noted.

“We hope that the results of this study will assist recognition of cardiac pathologic change and provide a framework to help avoid unnecessary exclusions of athletes from competition. We believe that these data have additional applicability to other sports that preselect for athletes with height, such as volleyball, rowing, and track and field,” Dr. Engel and his associates added.

This study was supported by the National Basketball Association as part of a medical services agreement with Columbia University. Dr. Engel and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

Key clinical point: Cardiologists characterized normal, adaptive cardiac remodeling in NBA players, allowing physicians to distinguish it from occult pathologic changes that may precipitate sudden cardiac death.

Major finding: Aortic root diameter increased with increasing body size only to a certain point, reaching a plateau at 31-35 mm.

Data source: An observational cohort study in which echocardiograms of 526 professional athletes were analyzed.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Basketball Association as part of a medical services agreement with Columbia University. Dr. Engel and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

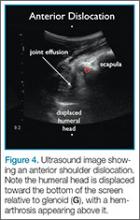

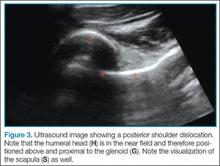

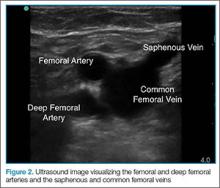

Emergency Ultrasound: Musculoskeletal Shoulder Dislocation

Point-of-care (POC) ultrasound is a great adjunct to the evaluation and treatment of shoulder dislocations. This modality can assist with identification of the dislocation—especially posterior dislocations, which can be notoriously difficult to diagnose on plain radiography.1,2 Moreover, it can aid with reduction by guiding intra-articular anesthetic injection, regional anesthesia with an interscalene brachial plexus nerve block, or suprascapular nerve block. Following treatment, POC ultrasound also can immediately confirm successful reduction.

Imaging Technique

Facilitation of Reduction

Summary

Bedside ultrasound is an excellent adjunct to traditional radiographs in the evaluation of patients presenting with shoulder injuries. In addition to its high sensitivity in detecting dislocation, this modality can be used to guide intra-articular treatment and to confirm successful reduction.

Dr Meer is an assistant professor and director of emergency ultrasound, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. Dr Beck is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. Dr Taylor is an assistant professor and director of postgraduate medical education, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta.

- Abbasi S, Molaie H, Hafezimoghadam P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonographic examination in the management of shoulder dislocation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):170-175. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.01.022.

- Beck S, Chilstrom M. Point-of-care ultrasound diagnosis and treatment of posterior shoulder dislocation. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(2):449.e3-449.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2012.06.017.

- Breslin K, Boniface K, Cohen J. Ultrasound-guided intra-articular lidocaine block for reduction of anterior shoulder dislocation in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(3):217-220. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000095.

Point-of-care (POC) ultrasound is a great adjunct to the evaluation and treatment of shoulder dislocations. This modality can assist with identification of the dislocation—especially posterior dislocations, which can be notoriously difficult to diagnose on plain radiography.1,2 Moreover, it can aid with reduction by guiding intra-articular anesthetic injection, regional anesthesia with an interscalene brachial plexus nerve block, or suprascapular nerve block. Following treatment, POC ultrasound also can immediately confirm successful reduction.

Imaging Technique

Facilitation of Reduction

Summary

Bedside ultrasound is an excellent adjunct to traditional radiographs in the evaluation of patients presenting with shoulder injuries. In addition to its high sensitivity in detecting dislocation, this modality can be used to guide intra-articular treatment and to confirm successful reduction.

Dr Meer is an assistant professor and director of emergency ultrasound, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. Dr Beck is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. Dr Taylor is an assistant professor and director of postgraduate medical education, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta.

Point-of-care (POC) ultrasound is a great adjunct to the evaluation and treatment of shoulder dislocations. This modality can assist with identification of the dislocation—especially posterior dislocations, which can be notoriously difficult to diagnose on plain radiography.1,2 Moreover, it can aid with reduction by guiding intra-articular anesthetic injection, regional anesthesia with an interscalene brachial plexus nerve block, or suprascapular nerve block. Following treatment, POC ultrasound also can immediately confirm successful reduction.

Imaging Technique

Facilitation of Reduction

Summary

Bedside ultrasound is an excellent adjunct to traditional radiographs in the evaluation of patients presenting with shoulder injuries. In addition to its high sensitivity in detecting dislocation, this modality can be used to guide intra-articular treatment and to confirm successful reduction.

Dr Meer is an assistant professor and director of emergency ultrasound, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. Dr Beck is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. Dr Taylor is an assistant professor and director of postgraduate medical education, department of emergency medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta.

- Abbasi S, Molaie H, Hafezimoghadam P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonographic examination in the management of shoulder dislocation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):170-175. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.01.022.

- Beck S, Chilstrom M. Point-of-care ultrasound diagnosis and treatment of posterior shoulder dislocation. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(2):449.e3-449.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2012.06.017.

- Breslin K, Boniface K, Cohen J. Ultrasound-guided intra-articular lidocaine block for reduction of anterior shoulder dislocation in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(3):217-220. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000095.

- Abbasi S, Molaie H, Hafezimoghadam P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonographic examination in the management of shoulder dislocation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):170-175. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.01.022.

- Beck S, Chilstrom M. Point-of-care ultrasound diagnosis and treatment of posterior shoulder dislocation. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(2):449.e3-449.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2012.06.017.

- Breslin K, Boniface K, Cohen J. Ultrasound-guided intra-articular lidocaine block for reduction of anterior shoulder dislocation in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(3):217-220. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000095.

A Guide to Ultrasound of the Shoulder, Part 1: Coding and Reimbursement

Although ultrasound has been around for many years, the technology is underutilized. It has been used primarily by the radiologists and obstetricians-gynecologists. However, orthopedic surgeons and sports medicine doctors are beginning to realize the utility of this imaging modality for their specialties. Ultrasound has classically been used as a diagnostic tool. This usage is beneficial to sports medicine specialists for on-field coverage at sports competitions to efficiently evaluate injuries without the need for taking the athletes back to the locker room for an x-ray or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Ultrasound can quickly assess for damage to soft tissue, joints, and superficial bones. Another of ultrasound’s benefits is its use as an adjunct to treatment. Ultrasound has been shown to vastly increase the accuracy of injections and can be used in surgery to accurately guide percutaneous techniques or to identify structures that previously required radiation-exposing fluoroscopy or large incisions to find by feel or eye.

Ultrasound is a technician-dependent modality. The surgeon and physician must become facile with the use of the probe and how ultrasound works. The use of the probe is similar to an arthroscope, requiring small movements of the hand to reveal the best imaging of the tissues. Rather than relying on just the patient’s position with an immobile machine, the user must use the probe position and the placement of the patient’s limb or body to optimize the use of ultrasound. Doing so saves time, money, and exposure to dangerous radiation. In a retrospective study of 1012 patients treated over a 10-month period, Sivan and colleagues1 concluded that the use of clinic-based musculoskeletal (MSK) ultrasound enables a one-stop approach, reduces repeat hospital appointments, and improves quality of care.With the increased use of ultrasound comes the need to accurately code and bill for the use of ultrasound. According to the College of Radiology, Medicare reimbursements for MSK ultrasound studies has increased by 316% from 2000-2009.2 Paradoxically, ultrasound has still been relatively underutilized when compared to the use of MSK MRI.

Diagnostic Ultrasound

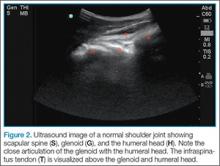

Ultrasound is based off sound waves, emitted from a transducer, which are then bounced back off the underlying structures based on the density of that structure. The computer interprets the returning sound waves and produces an image reflecting the quality and strength of those returning waves. When the sound waves are bounced back strongly and quickly, like when hitting bone, we see an image that is intensely white (“hyperechoic”). When the sound waves encounter a substance that transmits those waves easily and do not return, like air or fluid, the image is dark (“hypoechoic”).

Ultrasound’s fundamental advantages start with every patient being able to have an ultrasound: no interference from metal, pacemakers, claustrophobia, or obesity. Contralateral comparisons, sono-palpation at the site of pathology, and real-time dynamic studies allow for a more comprehensive diagnostic evaluation. Doppler capabilities can further expand the usefulness of the evaluation and guide safer interventions. With the advent of high-resolution portable ultrasound machines, these studies can essentially be performed anywhere, and are typically done in a timely and cost-effective manner.

Ultrasound has many diagnostic uses for soft tissue, joint, and bone disorders. For soft tissues, ultrasound can image tears of muscles, tendons, and ligaments; show inflammation like tenosynovitis; demonstrate masses like hematomas, cysts, solid tumors, or calcific tendonitis; display nerve disorders like Morton’s neuroma; or confirm foreign bodies or infections.3-5 For joint disorders, ultrasound can show erosions on bones, loose bodies, pannus, inflammation, or effusions. For bone disorders, ultrasound can diagnose fractures and, sometimes, even stress fractures. Tomer and colleagues6 compared 51 patients with bone contusions and fractures; they determined that ultrasound was most reliable in the diagnosis of long bone diaphyseal fractures. The one disadvantage, especially when compared to MRI, is ultrasound’s inability to fully evaluate intra-articular or deep structures such as articular cartilage, the glenohumeral labrum, the biceps’ anchor, etc.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

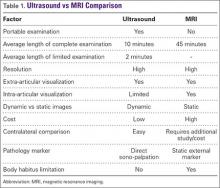

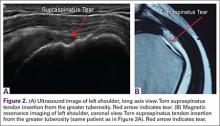

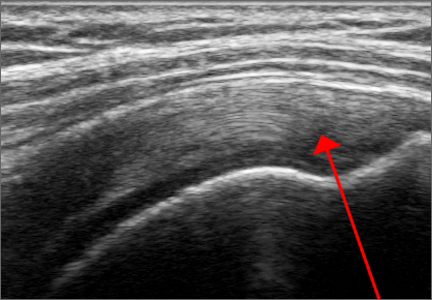

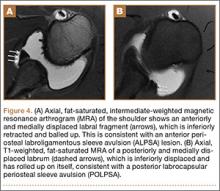

Ultrasound is similar to MRI as it images tissues and gives us ideas whether that tissue is normal, damaged, or diseased (Figures 1A, 1B). MRI is based on magnetics and large machines that cannot be moved. MRI yields planar images that can only be changed by changing the position of the limb or body in the MRI tube. This can create an issue with obese patients or with postoperative patients who cannot maintain the operated body part in one position for the length of the MRI scan. Ultrasound is better tolerated by patients without the need for claustrophobic large machines (Table 1). In 2004, Middleton and colleagues7 surveyed 118 patients who obtained an ultrasound and MRI of the shoulder for suspected rotator cuff pathology; ultrasound had higher satisfaction levels, and 93% of patients preferred ultrasound to MRI.

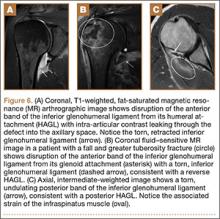

For rotator cuff tears, ultrasound is also comparable diagnostically with MRI (Figures 2A, 2B). In a prospective study of 124 patients, MRI and ultrasound had comparable accuracy for identifying and measuring the size of full-thickness and partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, with arthroscopic findings used as the standard.8 A 2015 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine showed that the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound, MRI, and MR arthrography in the characterization of full thickness rotator cuff tears had >90% sensitivity and specificity. As for partial rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy, overall estimates of specificity were also high (>90%), while sensitivity was as high as 83%. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound was similar whether it was performed by a trained radiologist, sonographer, or orthopedist.9

Medicare reimbursements for MSK ultrasound studies has increased by 316% in the past decade.2 Private practice MSK ultrasound procedures increased from 19,372 in 2000 to 158,351 in 2009.2 In 2010, non-radiologists accounted for more ultrasound-guided procedures than radiologists for the first time.10 MSK ultrasound is still underutilized compared to MRI. This underutilization is also unfortunate economically. The cost of MRIs is significantly higher. According to Parker and colleagues10, the projected Medicare cost for MSK imaging in 2020 is $3.6 billion, with MRI accounting for $2 billion. They also concluded that replacing MSK MRI with MSK ultrasound when clinically indicated could save over $6.9 billion between 2006 and 2020.11

Ultrasound-Guided Procedures

MSK ultrasound has gained significant ground on other imaging modalities when it comes to procedures, both in office and in the operating room. The ability to have a small, mobile, inexpensive machine that can be used in real time has dramatically changed how interventions are done. Most imaging modalities used to perform injections or percutaneous surgery use fluoroscopy machines. This exposes the patients to significant radiation, costs significantly more, and usually requires a secondary consultation with radiologists in a different facility. This wastes time and money, and results in potentially unnecessary exposure to radiation.

Accuracy is the most common reason for referral for guided injections. The guidance can help avoid nerves, vessels, and other sensitive tissues. However, accuracy is also important to make sure the injection is placed in the correct location. When injections are placed into a muscle, tendon, or ligament, it causes significant pain; however, injections placed into a bursal space or joint do not cause pain. Numerous studies have shown that even in the hands of experts, “simple” injections can still miss their mark over 30% of the time.12-19 Therefore, if a patient experiences pain during a bursal space or joint injection, the injection was not placed properly.

The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine Position Paper on MSK ultrasound is based on a systematic review of the literature, including 124 studies. It states that ultrasound-guided joint injections (USGI) are more accurate and efficacious than landmark guided injections (LMGI), with a strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT) evidence rating of A and B, respectively.19 In terms of patient satisfaction, in a randomized controlled trial of 148 patients undergoing knee injections, Sibbitt and colleagues20 showed that USGI had a 48% reduction (P < .001) in procedural pain, a 58.5% reduction (P < .001) in absolute pain scores at the 2-week outcome mark, and a 75% reduction (P < .001) in significant pain and 62% reduction in nonresponder rate.20 From a financial point of view, Sibbitt and colleagues20 also demonstrated a 13% reduction in cost per patient per year, and a 58% reduction in cost per responder per year for a hospital outpatient center (P < .001).

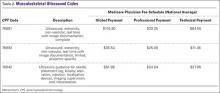

Coding

Coding for diagnostic MSK ultrasound requires an understanding of a few current procedural terminology (CPT) codes (Table 2). Ultrasound usage should follow the usual requirements of medical necessity and the CPT code selected should be based on the elements of the study performed. A complete examination, described by CPT code 76881, includes the examination and documentation of the muscles, tendons, joint, and other soft tissue structures and any identifiable abnormality of the joint being evaluated. If anything less is done, then the CPT code 76882 should be used.

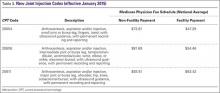

New CPT codes for joint injections became effective January 2015 (Table 3). The new changes affect only the joint injection series (20600-20610). Previously, injections could be billed with CPT code 76942, which was “Ultrasonic guidance for needle placement (eg, biopsy, aspiration, injection, localization device), imaging supervision and interpretation.” This code can still be used, but with only specific injections, when the verbiage “with ultrasound/image guidance” is not included in the injection CPT code descriptor (Table 4).

Under the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI), which sets Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) payment policy as well as that of many private payers, one unit of service is allowed for CPT code 76942 in a single patient encounter regardless of the number of needle placements performed. Per NCCI, “The unit of service for these codes is the patient encounter, not number of lesions, number of aspirations, number of biopsies, number of injections, or number of localizations.”

Per the Radiology section of the NCCI, “Ultrasound guidance and diagnostic ultrasound (echography) procedures may be reported separately only if each service is distinct and separate. If a diagnostic ultrasound study identifies a previously unknown abnormality that requires a therapeutic procedure with ultrasound guidance at the same patient encounter, both the diagnostic ultrasound and ultrasound guidance procedure codes may be reported separately. However, a previously unknown abnormality identified during ultrasound guidance for a procedure should not be reported separately as a diagnostic ultrasound procedure.”

Under the Medicare program, the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) code selected should be based on the test results, with 2 exceptions. If the test does not yield a diagnosis or was normal, the physician should use the pre-service signs, symptoms, and conditions that prompted the study. If the test is a screening examination ordered in the absence of any signs or symptoms of illness or injury, the physician should select “screening” as the primary reason for the service and record the test results, if any, as additional diagnoses.

Modifiers must be used in specific settings. In the office, physicians who own the equipment and perform the service themselves (or the service is performed by an employed or contracted sonographer) may bill the global fee without any modifiers. However, if billing for a procedure on the same day as an office visit, the -25 modifier must be used. This indicates “[a] significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service.” This modifier should not be used routinely. If the service is performed in a hospital, the -26 modifier must be used to indicate that the professional service only was provided when the physician does not own the machine (Tables 2, 3, 4). The payers will not reimburse physicians for the technical component in the hospital setting.

Reimbursement

In general, medical insurance plans will cover ultrasound studies when they are medically indicated. However, we recommend checking with each individual private payer directly, including Medicare. Medicare Part B will generally reimburse physicians for medically necessary diagnostic ultrasound services, provided the services are within the scope of the physician’s license. Some Medicare contractors require that the physician who performs and/or interprets some types of ultrasound examinations be capable of demonstrating relevant, documented training through recent residency training or post-graduate continuing medical education (CME) and experience. Medicare does not differentiate by medical specialty with respect to billing medically necessary diagnostic ultrasound services, provided the services are within the scope of the physician’s license. Some Medicare contractors have coverage policies regarding either the diagnostic study or ultrasound guidance of certain injections, or both.

Payment policies for beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part C, known as the Medicare Advantage plans, will reflect those of the private insurance administrator. The Medicare Advantage plan may be either a health maintenance organization (HMO) or a preferred provider organization (PPO). Private insurance payment rules vary by payer and plan with respect to which specialties may perform and receive reimbursement for ultrasound services. Some payers will reimburse providers of any specialty for ultrasound services, while others may restrict imaging procedures to specific specialties or providers possessing specific certifications or accreditations. Some insurers require physicians to submit applications requesting ultrasound be added to their list of services performed in their practice. Physicians should contact private payers before submitting claims to determine their requirements and request that they add ultrasound to the list of services.

When contacting the private payers, ask the following questions:

- What do I need to do to have ultrasound added to my practice’s contract or list of services?

- Are there any specific training requirements that I must meet or credentials that I must obtain in order to be privileged to perform ultrasound in my office?

- Do I need to send a letter or can I submit the request verbally?

- Is there an application that must be completed?

- If there is a privileging program, how long will it take after submission of the application before we are accepted?

- What is the fee schedule associated with these codes?

- Are there any bundling edits in place covering any of the services I am considering performing? (Be prepared to provide the codes for any non-ultrasound services you will be performing in conjunction with the ultrasound services.)

- Are there any preauthorization requirements for specific ultrasound studies?

- Are there any preauthorization requirements for specific ultrasound studies?

Documentation Requirements

All diagnostic ultrasound examinations, including those when ultrasound is used to guide a procedure, require that permanently recorded images be maintained in the patient record. The images can be kept in the patient record or some other archive—they do not need to be submitted with the claim. Images can be stored as printed images, on a tape or electronic medium. Documentation of the study must be available to the insurer upon request.

A written report of all ultrasound studies should be maintained in the patient’s record. In the case of ultrasound guidance, the written report may be filed as a separate item in the patient’s record or it may be included within the report of the procedure for which the guidance is utilized.

As examples of our documentation in the office, copies of 3 of our standard forms are available: “Ultrasound report of the shoulder” (Appendix 1), “Procedure note for an ultrasound-guided injection of cortisone” (Appendix 2), and “Procedure note for an ultrasound-guided injection of platelet-rich plasma” (Appendix 3).

Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC)

The Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 was an effort to help reduce unnecessary imaging services and reduce costs; the Secretary of Health and Human Services was to establish a program to promote the use of “appropriate use criteria” (AUC) for advanced imaging services such as MRI, computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and nuclear cardiology. AUC are criteria that are developed or endorsed by national professional medical specialty societies or other provider-led entities to assist ordering professionals and furnishing professionals in making the most appropriate treatment decision for a specific clinical condition for an individual. The law also noted that the criteria should be evidence-based, meaning they should have stakeholder consensus, be scientifically valid, and be based on studies that are published and reviewable by stakeholders.

By April 2016, the Secretary will identify and publish the list of qualified clinical decision support mechanisms, which are tools that could be used by ordering professionals to ensure that AUC is met for applicable imaging services. These may include certified health electronic record technology, private sector clinical decision support mechanisms, and others. Actual use of the AUC will begin in January 2017. This legislation applies only to Medicare services, but other payers have cited concerns and may follow in the future.

Conclusion

Ultrasound is being increasingly used in varying specialties, especially orthopedic surgery. It provides a time- and cost-efficient modality with diagnostic power comparable to MRI. Portability and a high safety profile allows for ease of implementation as an in-office or sideline tool. Needle guidance and other intraoperative applications highlight its versatility as an adjunct to orthopedic treatments. This article provides a comprehensive guide to billing and coding for both diagnostic and therapeutic MSK ultrasound of the shoulder. Providers should stay up to date with upcoming appropriate use criteria and adjustments to current billing procedures.

1. Sivan M, Brown J, Brennan S, Bhakta B. A one-stop approach to the management of soft tissue and degenerative musculoskeletal conditions using clinic-based ultrasonography. Musculoskeletal Care. 2011;9(2):63-68.

2. Sharpe R, Nazarian L, Parker L, Rao V, Levin D. Dramatically increased musculoskeletal ultrasound utilization from 2000 to 2009, especially by podiatrists in private offices. Department of Radiology Faculty Papers. Paper 16. http://jdc.jefferson.edu/radiologyfp/16. Accessed January 7, 2016.

3. Blankstein A. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of clinical orthopedics: The orthopedic stethoscope. World J Orthop. 2011;2(2):13-24.

4. Sinha TP, Bhoi S, Kumar S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of bedside emergency ultrasound screening for fractures in pediatric trauma patients. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4(4);443-445.

5. Bica D, Armen J, Kulas AS, Young K, Womack Z. Reliability and precision of stress sonography of the ulnar collateral ligament. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34(3):371-376.

6. Tomer K, Kleinbaum Y, Heyman Z, Dudkiewicz I, Blankstein A. Ultrasound diagnosis of fractures in adults. Akt Traumatol. 2006;36(4):171-174.

7. Middleton W, Payne WT, Teefey SA, Hidebolt CF, Rubin DA, Yamaguchi K. Sonography and MRI of the shoulder: comparison of patient satisfaction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(5):1449-1452.

8. Teefey SA, Rubin DA, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Leibold RA, Yamaguchi K. Detection and quantification of rotator cuff tears. Comparison of ultrasonographic, magnetic resonance and arthroscopic finding in seventy-one consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(4):708-716.

9. Roy-JS, Braën C, Leblond J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography, MRI and MR arthrography in the characterization of rotator cuff disorders: a meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(20):1316-1328.

10. Parker L, Nazarian LN, Carrino JA, et al. Musculoskeletal Imaging: Medicare use, costs, and potential for cost substitution. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5(3):182-188.

11. Eustace J, Brophy D, Gibney R, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. Comparison of the accuracy of steroid placement with clinical outcome in patients with shoulder symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(1):59-63.

12. Partington P, Broome G. Diagnostic injection around the shoulder: Hit and miss? A cadaveric study of injection accuracy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(2):147-150.

13. Rutten M, Maresch B, Jager G, de Waal Malefijt M. Injection of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa: Blind or ultrasound-guided? Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):254-257.

14. Kang M, Rizio L, Prybicien M, Middlemas D, Blacksin M. The accuracy of subacromial corticosteroid injections: A comparison of multiple methods. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1 Suppl):61S-66S.

15. Yamakado K. The targeting accuracy of subacromial injection to the shoulder: An arthrographic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2002;19(8):887-891.

16. Henkus HE, Cobben M, Coerkamp E, Nelissen R, van Arkel E. The accuracy of subacromial injections: A prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282.

17. Sethi PM, El Attrache N. Accuracy of intra-articular injection of the glenohumeral joint: a cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2006;29(2):149-152.

18. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind injection versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

19. Finnoff JT, Hall MM, Adams E, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM) position statement: interventional musculoskeletal ultrasound in sports medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(3):145-150.

20. Sibbitt WL Jr, Peisajovich A, Michael AA, et al. Does sonographic needle guidance affect the clinical outcome of intra-articular injections? J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):1892-1902.

Although ultrasound has been around for many years, the technology is underutilized. It has been used primarily by the radiologists and obstetricians-gynecologists. However, orthopedic surgeons and sports medicine doctors are beginning to realize the utility of this imaging modality for their specialties. Ultrasound has classically been used as a diagnostic tool. This usage is beneficial to sports medicine specialists for on-field coverage at sports competitions to efficiently evaluate injuries without the need for taking the athletes back to the locker room for an x-ray or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Ultrasound can quickly assess for damage to soft tissue, joints, and superficial bones. Another of ultrasound’s benefits is its use as an adjunct to treatment. Ultrasound has been shown to vastly increase the accuracy of injections and can be used in surgery to accurately guide percutaneous techniques or to identify structures that previously required radiation-exposing fluoroscopy or large incisions to find by feel or eye.

Ultrasound is a technician-dependent modality. The surgeon and physician must become facile with the use of the probe and how ultrasound works. The use of the probe is similar to an arthroscope, requiring small movements of the hand to reveal the best imaging of the tissues. Rather than relying on just the patient’s position with an immobile machine, the user must use the probe position and the placement of the patient’s limb or body to optimize the use of ultrasound. Doing so saves time, money, and exposure to dangerous radiation. In a retrospective study of 1012 patients treated over a 10-month period, Sivan and colleagues1 concluded that the use of clinic-based musculoskeletal (MSK) ultrasound enables a one-stop approach, reduces repeat hospital appointments, and improves quality of care.With the increased use of ultrasound comes the need to accurately code and bill for the use of ultrasound. According to the College of Radiology, Medicare reimbursements for MSK ultrasound studies has increased by 316% from 2000-2009.2 Paradoxically, ultrasound has still been relatively underutilized when compared to the use of MSK MRI.

Diagnostic Ultrasound

Ultrasound is based off sound waves, emitted from a transducer, which are then bounced back off the underlying structures based on the density of that structure. The computer interprets the returning sound waves and produces an image reflecting the quality and strength of those returning waves. When the sound waves are bounced back strongly and quickly, like when hitting bone, we see an image that is intensely white (“hyperechoic”). When the sound waves encounter a substance that transmits those waves easily and do not return, like air or fluid, the image is dark (“hypoechoic”).

Ultrasound’s fundamental advantages start with every patient being able to have an ultrasound: no interference from metal, pacemakers, claustrophobia, or obesity. Contralateral comparisons, sono-palpation at the site of pathology, and real-time dynamic studies allow for a more comprehensive diagnostic evaluation. Doppler capabilities can further expand the usefulness of the evaluation and guide safer interventions. With the advent of high-resolution portable ultrasound machines, these studies can essentially be performed anywhere, and are typically done in a timely and cost-effective manner.

Ultrasound has many diagnostic uses for soft tissue, joint, and bone disorders. For soft tissues, ultrasound can image tears of muscles, tendons, and ligaments; show inflammation like tenosynovitis; demonstrate masses like hematomas, cysts, solid tumors, or calcific tendonitis; display nerve disorders like Morton’s neuroma; or confirm foreign bodies or infections.3-5 For joint disorders, ultrasound can show erosions on bones, loose bodies, pannus, inflammation, or effusions. For bone disorders, ultrasound can diagnose fractures and, sometimes, even stress fractures. Tomer and colleagues6 compared 51 patients with bone contusions and fractures; they determined that ultrasound was most reliable in the diagnosis of long bone diaphyseal fractures. The one disadvantage, especially when compared to MRI, is ultrasound’s inability to fully evaluate intra-articular or deep structures such as articular cartilage, the glenohumeral labrum, the biceps’ anchor, etc.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Ultrasound is similar to MRI as it images tissues and gives us ideas whether that tissue is normal, damaged, or diseased (Figures 1A, 1B). MRI is based on magnetics and large machines that cannot be moved. MRI yields planar images that can only be changed by changing the position of the limb or body in the MRI tube. This can create an issue with obese patients or with postoperative patients who cannot maintain the operated body part in one position for the length of the MRI scan. Ultrasound is better tolerated by patients without the need for claustrophobic large machines (Table 1). In 2004, Middleton and colleagues7 surveyed 118 patients who obtained an ultrasound and MRI of the shoulder for suspected rotator cuff pathology; ultrasound had higher satisfaction levels, and 93% of patients preferred ultrasound to MRI.

For rotator cuff tears, ultrasound is also comparable diagnostically with MRI (Figures 2A, 2B). In a prospective study of 124 patients, MRI and ultrasound had comparable accuracy for identifying and measuring the size of full-thickness and partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, with arthroscopic findings used as the standard.8 A 2015 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine showed that the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound, MRI, and MR arthrography in the characterization of full thickness rotator cuff tears had >90% sensitivity and specificity. As for partial rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy, overall estimates of specificity were also high (>90%), while sensitivity was as high as 83%. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound was similar whether it was performed by a trained radiologist, sonographer, or orthopedist.9

Medicare reimbursements for MSK ultrasound studies has increased by 316% in the past decade.2 Private practice MSK ultrasound procedures increased from 19,372 in 2000 to 158,351 in 2009.2 In 2010, non-radiologists accounted for more ultrasound-guided procedures than radiologists for the first time.10 MSK ultrasound is still underutilized compared to MRI. This underutilization is also unfortunate economically. The cost of MRIs is significantly higher. According to Parker and colleagues10, the projected Medicare cost for MSK imaging in 2020 is $3.6 billion, with MRI accounting for $2 billion. They also concluded that replacing MSK MRI with MSK ultrasound when clinically indicated could save over $6.9 billion between 2006 and 2020.11

Ultrasound-Guided Procedures

MSK ultrasound has gained significant ground on other imaging modalities when it comes to procedures, both in office and in the operating room. The ability to have a small, mobile, inexpensive machine that can be used in real time has dramatically changed how interventions are done. Most imaging modalities used to perform injections or percutaneous surgery use fluoroscopy machines. This exposes the patients to significant radiation, costs significantly more, and usually requires a secondary consultation with radiologists in a different facility. This wastes time and money, and results in potentially unnecessary exposure to radiation.

Accuracy is the most common reason for referral for guided injections. The guidance can help avoid nerves, vessels, and other sensitive tissues. However, accuracy is also important to make sure the injection is placed in the correct location. When injections are placed into a muscle, tendon, or ligament, it causes significant pain; however, injections placed into a bursal space or joint do not cause pain. Numerous studies have shown that even in the hands of experts, “simple” injections can still miss their mark over 30% of the time.12-19 Therefore, if a patient experiences pain during a bursal space or joint injection, the injection was not placed properly.

The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine Position Paper on MSK ultrasound is based on a systematic review of the literature, including 124 studies. It states that ultrasound-guided joint injections (USGI) are more accurate and efficacious than landmark guided injections (LMGI), with a strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT) evidence rating of A and B, respectively.19 In terms of patient satisfaction, in a randomized controlled trial of 148 patients undergoing knee injections, Sibbitt and colleagues20 showed that USGI had a 48% reduction (P < .001) in procedural pain, a 58.5% reduction (P < .001) in absolute pain scores at the 2-week outcome mark, and a 75% reduction (P < .001) in significant pain and 62% reduction in nonresponder rate.20 From a financial point of view, Sibbitt and colleagues20 also demonstrated a 13% reduction in cost per patient per year, and a 58% reduction in cost per responder per year for a hospital outpatient center (P < .001).

Coding

Coding for diagnostic MSK ultrasound requires an understanding of a few current procedural terminology (CPT) codes (Table 2). Ultrasound usage should follow the usual requirements of medical necessity and the CPT code selected should be based on the elements of the study performed. A complete examination, described by CPT code 76881, includes the examination and documentation of the muscles, tendons, joint, and other soft tissue structures and any identifiable abnormality of the joint being evaluated. If anything less is done, then the CPT code 76882 should be used.

New CPT codes for joint injections became effective January 2015 (Table 3). The new changes affect only the joint injection series (20600-20610). Previously, injections could be billed with CPT code 76942, which was “Ultrasonic guidance for needle placement (eg, biopsy, aspiration, injection, localization device), imaging supervision and interpretation.” This code can still be used, but with only specific injections, when the verbiage “with ultrasound/image guidance” is not included in the injection CPT code descriptor (Table 4).

Under the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI), which sets Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) payment policy as well as that of many private payers, one unit of service is allowed for CPT code 76942 in a single patient encounter regardless of the number of needle placements performed. Per NCCI, “The unit of service for these codes is the patient encounter, not number of lesions, number of aspirations, number of biopsies, number of injections, or number of localizations.”

Per the Radiology section of the NCCI, “Ultrasound guidance and diagnostic ultrasound (echography) procedures may be reported separately only if each service is distinct and separate. If a diagnostic ultrasound study identifies a previously unknown abnormality that requires a therapeutic procedure with ultrasound guidance at the same patient encounter, both the diagnostic ultrasound and ultrasound guidance procedure codes may be reported separately. However, a previously unknown abnormality identified during ultrasound guidance for a procedure should not be reported separately as a diagnostic ultrasound procedure.”

Under the Medicare program, the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) code selected should be based on the test results, with 2 exceptions. If the test does not yield a diagnosis or was normal, the physician should use the pre-service signs, symptoms, and conditions that prompted the study. If the test is a screening examination ordered in the absence of any signs or symptoms of illness or injury, the physician should select “screening” as the primary reason for the service and record the test results, if any, as additional diagnoses.

Modifiers must be used in specific settings. In the office, physicians who own the equipment and perform the service themselves (or the service is performed by an employed or contracted sonographer) may bill the global fee without any modifiers. However, if billing for a procedure on the same day as an office visit, the -25 modifier must be used. This indicates “[a] significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service.” This modifier should not be used routinely. If the service is performed in a hospital, the -26 modifier must be used to indicate that the professional service only was provided when the physician does not own the machine (Tables 2, 3, 4). The payers will not reimburse physicians for the technical component in the hospital setting.

Reimbursement

In general, medical insurance plans will cover ultrasound studies when they are medically indicated. However, we recommend checking with each individual private payer directly, including Medicare. Medicare Part B will generally reimburse physicians for medically necessary diagnostic ultrasound services, provided the services are within the scope of the physician’s license. Some Medicare contractors require that the physician who performs and/or interprets some types of ultrasound examinations be capable of demonstrating relevant, documented training through recent residency training or post-graduate continuing medical education (CME) and experience. Medicare does not differentiate by medical specialty with respect to billing medically necessary diagnostic ultrasound services, provided the services are within the scope of the physician’s license. Some Medicare contractors have coverage policies regarding either the diagnostic study or ultrasound guidance of certain injections, or both.

Payment policies for beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part C, known as the Medicare Advantage plans, will reflect those of the private insurance administrator. The Medicare Advantage plan may be either a health maintenance organization (HMO) or a preferred provider organization (PPO). Private insurance payment rules vary by payer and plan with respect to which specialties may perform and receive reimbursement for ultrasound services. Some payers will reimburse providers of any specialty for ultrasound services, while others may restrict imaging procedures to specific specialties or providers possessing specific certifications or accreditations. Some insurers require physicians to submit applications requesting ultrasound be added to their list of services performed in their practice. Physicians should contact private payers before submitting claims to determine their requirements and request that they add ultrasound to the list of services.

When contacting the private payers, ask the following questions:

- What do I need to do to have ultrasound added to my practice’s contract or list of services?

- Are there any specific training requirements that I must meet or credentials that I must obtain in order to be privileged to perform ultrasound in my office?

- Do I need to send a letter or can I submit the request verbally?

- Is there an application that must be completed?

- If there is a privileging program, how long will it take after submission of the application before we are accepted?

- What is the fee schedule associated with these codes?

- Are there any bundling edits in place covering any of the services I am considering performing? (Be prepared to provide the codes for any non-ultrasound services you will be performing in conjunction with the ultrasound services.)

- Are there any preauthorization requirements for specific ultrasound studies?

- Are there any preauthorization requirements for specific ultrasound studies?

Documentation Requirements

All diagnostic ultrasound examinations, including those when ultrasound is used to guide a procedure, require that permanently recorded images be maintained in the patient record. The images can be kept in the patient record or some other archive—they do not need to be submitted with the claim. Images can be stored as printed images, on a tape or electronic medium. Documentation of the study must be available to the insurer upon request.

A written report of all ultrasound studies should be maintained in the patient’s record. In the case of ultrasound guidance, the written report may be filed as a separate item in the patient’s record or it may be included within the report of the procedure for which the guidance is utilized.

As examples of our documentation in the office, copies of 3 of our standard forms are available: “Ultrasound report of the shoulder” (Appendix 1), “Procedure note for an ultrasound-guided injection of cortisone” (Appendix 2), and “Procedure note for an ultrasound-guided injection of platelet-rich plasma” (Appendix 3).

Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC)

The Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 was an effort to help reduce unnecessary imaging services and reduce costs; the Secretary of Health and Human Services was to establish a program to promote the use of “appropriate use criteria” (AUC) for advanced imaging services such as MRI, computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and nuclear cardiology. AUC are criteria that are developed or endorsed by national professional medical specialty societies or other provider-led entities to assist ordering professionals and furnishing professionals in making the most appropriate treatment decision for a specific clinical condition for an individual. The law also noted that the criteria should be evidence-based, meaning they should have stakeholder consensus, be scientifically valid, and be based on studies that are published and reviewable by stakeholders.

By April 2016, the Secretary will identify and publish the list of qualified clinical decision support mechanisms, which are tools that could be used by ordering professionals to ensure that AUC is met for applicable imaging services. These may include certified health electronic record technology, private sector clinical decision support mechanisms, and others. Actual use of the AUC will begin in January 2017. This legislation applies only to Medicare services, but other payers have cited concerns and may follow in the future.

Conclusion

Ultrasound is being increasingly used in varying specialties, especially orthopedic surgery. It provides a time- and cost-efficient modality with diagnostic power comparable to MRI. Portability and a high safety profile allows for ease of implementation as an in-office or sideline tool. Needle guidance and other intraoperative applications highlight its versatility as an adjunct to orthopedic treatments. This article provides a comprehensive guide to billing and coding for both diagnostic and therapeutic MSK ultrasound of the shoulder. Providers should stay up to date with upcoming appropriate use criteria and adjustments to current billing procedures.

Although ultrasound has been around for many years, the technology is underutilized. It has been used primarily by the radiologists and obstetricians-gynecologists. However, orthopedic surgeons and sports medicine doctors are beginning to realize the utility of this imaging modality for their specialties. Ultrasound has classically been used as a diagnostic tool. This usage is beneficial to sports medicine specialists for on-field coverage at sports competitions to efficiently evaluate injuries without the need for taking the athletes back to the locker room for an x-ray or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Ultrasound can quickly assess for damage to soft tissue, joints, and superficial bones. Another of ultrasound’s benefits is its use as an adjunct to treatment. Ultrasound has been shown to vastly increase the accuracy of injections and can be used in surgery to accurately guide percutaneous techniques or to identify structures that previously required radiation-exposing fluoroscopy or large incisions to find by feel or eye.

Ultrasound is a technician-dependent modality. The surgeon and physician must become facile with the use of the probe and how ultrasound works. The use of the probe is similar to an arthroscope, requiring small movements of the hand to reveal the best imaging of the tissues. Rather than relying on just the patient’s position with an immobile machine, the user must use the probe position and the placement of the patient’s limb or body to optimize the use of ultrasound. Doing so saves time, money, and exposure to dangerous radiation. In a retrospective study of 1012 patients treated over a 10-month period, Sivan and colleagues1 concluded that the use of clinic-based musculoskeletal (MSK) ultrasound enables a one-stop approach, reduces repeat hospital appointments, and improves quality of care.With the increased use of ultrasound comes the need to accurately code and bill for the use of ultrasound. According to the College of Radiology, Medicare reimbursements for MSK ultrasound studies has increased by 316% from 2000-2009.2 Paradoxically, ultrasound has still been relatively underutilized when compared to the use of MSK MRI.

Diagnostic Ultrasound

Ultrasound is based off sound waves, emitted from a transducer, which are then bounced back off the underlying structures based on the density of that structure. The computer interprets the returning sound waves and produces an image reflecting the quality and strength of those returning waves. When the sound waves are bounced back strongly and quickly, like when hitting bone, we see an image that is intensely white (“hyperechoic”). When the sound waves encounter a substance that transmits those waves easily and do not return, like air or fluid, the image is dark (“hypoechoic”).

Ultrasound’s fundamental advantages start with every patient being able to have an ultrasound: no interference from metal, pacemakers, claustrophobia, or obesity. Contralateral comparisons, sono-palpation at the site of pathology, and real-time dynamic studies allow for a more comprehensive diagnostic evaluation. Doppler capabilities can further expand the usefulness of the evaluation and guide safer interventions. With the advent of high-resolution portable ultrasound machines, these studies can essentially be performed anywhere, and are typically done in a timely and cost-effective manner.

Ultrasound has many diagnostic uses for soft tissue, joint, and bone disorders. For soft tissues, ultrasound can image tears of muscles, tendons, and ligaments; show inflammation like tenosynovitis; demonstrate masses like hematomas, cysts, solid tumors, or calcific tendonitis; display nerve disorders like Morton’s neuroma; or confirm foreign bodies or infections.3-5 For joint disorders, ultrasound can show erosions on bones, loose bodies, pannus, inflammation, or effusions. For bone disorders, ultrasound can diagnose fractures and, sometimes, even stress fractures. Tomer and colleagues6 compared 51 patients with bone contusions and fractures; they determined that ultrasound was most reliable in the diagnosis of long bone diaphyseal fractures. The one disadvantage, especially when compared to MRI, is ultrasound’s inability to fully evaluate intra-articular or deep structures such as articular cartilage, the glenohumeral labrum, the biceps’ anchor, etc.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Ultrasound is similar to MRI as it images tissues and gives us ideas whether that tissue is normal, damaged, or diseased (Figures 1A, 1B). MRI is based on magnetics and large machines that cannot be moved. MRI yields planar images that can only be changed by changing the position of the limb or body in the MRI tube. This can create an issue with obese patients or with postoperative patients who cannot maintain the operated body part in one position for the length of the MRI scan. Ultrasound is better tolerated by patients without the need for claustrophobic large machines (Table 1). In 2004, Middleton and colleagues7 surveyed 118 patients who obtained an ultrasound and MRI of the shoulder for suspected rotator cuff pathology; ultrasound had higher satisfaction levels, and 93% of patients preferred ultrasound to MRI.

For rotator cuff tears, ultrasound is also comparable diagnostically with MRI (Figures 2A, 2B). In a prospective study of 124 patients, MRI and ultrasound had comparable accuracy for identifying and measuring the size of full-thickness and partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, with arthroscopic findings used as the standard.8 A 2015 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine showed that the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound, MRI, and MR arthrography in the characterization of full thickness rotator cuff tears had >90% sensitivity and specificity. As for partial rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy, overall estimates of specificity were also high (>90%), while sensitivity was as high as 83%. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound was similar whether it was performed by a trained radiologist, sonographer, or orthopedist.9

Medicare reimbursements for MSK ultrasound studies has increased by 316% in the past decade.2 Private practice MSK ultrasound procedures increased from 19,372 in 2000 to 158,351 in 2009.2 In 2010, non-radiologists accounted for more ultrasound-guided procedures than radiologists for the first time.10 MSK ultrasound is still underutilized compared to MRI. This underutilization is also unfortunate economically. The cost of MRIs is significantly higher. According to Parker and colleagues10, the projected Medicare cost for MSK imaging in 2020 is $3.6 billion, with MRI accounting for $2 billion. They also concluded that replacing MSK MRI with MSK ultrasound when clinically indicated could save over $6.9 billion between 2006 and 2020.11

Ultrasound-Guided Procedures

MSK ultrasound has gained significant ground on other imaging modalities when it comes to procedures, both in office and in the operating room. The ability to have a small, mobile, inexpensive machine that can be used in real time has dramatically changed how interventions are done. Most imaging modalities used to perform injections or percutaneous surgery use fluoroscopy machines. This exposes the patients to significant radiation, costs significantly more, and usually requires a secondary consultation with radiologists in a different facility. This wastes time and money, and results in potentially unnecessary exposure to radiation.

Accuracy is the most common reason for referral for guided injections. The guidance can help avoid nerves, vessels, and other sensitive tissues. However, accuracy is also important to make sure the injection is placed in the correct location. When injections are placed into a muscle, tendon, or ligament, it causes significant pain; however, injections placed into a bursal space or joint do not cause pain. Numerous studies have shown that even in the hands of experts, “simple” injections can still miss their mark over 30% of the time.12-19 Therefore, if a patient experiences pain during a bursal space or joint injection, the injection was not placed properly.

The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine Position Paper on MSK ultrasound is based on a systematic review of the literature, including 124 studies. It states that ultrasound-guided joint injections (USGI) are more accurate and efficacious than landmark guided injections (LMGI), with a strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT) evidence rating of A and B, respectively.19 In terms of patient satisfaction, in a randomized controlled trial of 148 patients undergoing knee injections, Sibbitt and colleagues20 showed that USGI had a 48% reduction (P < .001) in procedural pain, a 58.5% reduction (P < .001) in absolute pain scores at the 2-week outcome mark, and a 75% reduction (P < .001) in significant pain and 62% reduction in nonresponder rate.20 From a financial point of view, Sibbitt and colleagues20 also demonstrated a 13% reduction in cost per patient per year, and a 58% reduction in cost per responder per year for a hospital outpatient center (P < .001).

Coding

Coding for diagnostic MSK ultrasound requires an understanding of a few current procedural terminology (CPT) codes (Table 2). Ultrasound usage should follow the usual requirements of medical necessity and the CPT code selected should be based on the elements of the study performed. A complete examination, described by CPT code 76881, includes the examination and documentation of the muscles, tendons, joint, and other soft tissue structures and any identifiable abnormality of the joint being evaluated. If anything less is done, then the CPT code 76882 should be used.

New CPT codes for joint injections became effective January 2015 (Table 3). The new changes affect only the joint injection series (20600-20610). Previously, injections could be billed with CPT code 76942, which was “Ultrasonic guidance for needle placement (eg, biopsy, aspiration, injection, localization device), imaging supervision and interpretation.” This code can still be used, but with only specific injections, when the verbiage “with ultrasound/image guidance” is not included in the injection CPT code descriptor (Table 4).

Under the National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI), which sets Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) payment policy as well as that of many private payers, one unit of service is allowed for CPT code 76942 in a single patient encounter regardless of the number of needle placements performed. Per NCCI, “The unit of service for these codes is the patient encounter, not number of lesions, number of aspirations, number of biopsies, number of injections, or number of localizations.”

Per the Radiology section of the NCCI, “Ultrasound guidance and diagnostic ultrasound (echography) procedures may be reported separately only if each service is distinct and separate. If a diagnostic ultrasound study identifies a previously unknown abnormality that requires a therapeutic procedure with ultrasound guidance at the same patient encounter, both the diagnostic ultrasound and ultrasound guidance procedure codes may be reported separately. However, a previously unknown abnormality identified during ultrasound guidance for a procedure should not be reported separately as a diagnostic ultrasound procedure.”

Under the Medicare program, the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) code selected should be based on the test results, with 2 exceptions. If the test does not yield a diagnosis or was normal, the physician should use the pre-service signs, symptoms, and conditions that prompted the study. If the test is a screening examination ordered in the absence of any signs or symptoms of illness or injury, the physician should select “screening” as the primary reason for the service and record the test results, if any, as additional diagnoses.

Modifiers must be used in specific settings. In the office, physicians who own the equipment and perform the service themselves (or the service is performed by an employed or contracted sonographer) may bill the global fee without any modifiers. However, if billing for a procedure on the same day as an office visit, the -25 modifier must be used. This indicates “[a] significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service.” This modifier should not be used routinely. If the service is performed in a hospital, the -26 modifier must be used to indicate that the professional service only was provided when the physician does not own the machine (Tables 2, 3, 4). The payers will not reimburse physicians for the technical component in the hospital setting.

Reimbursement

In general, medical insurance plans will cover ultrasound studies when they are medically indicated. However, we recommend checking with each individual private payer directly, including Medicare. Medicare Part B will generally reimburse physicians for medically necessary diagnostic ultrasound services, provided the services are within the scope of the physician’s license. Some Medicare contractors require that the physician who performs and/or interprets some types of ultrasound examinations be capable of demonstrating relevant, documented training through recent residency training or post-graduate continuing medical education (CME) and experience. Medicare does not differentiate by medical specialty with respect to billing medically necessary diagnostic ultrasound services, provided the services are within the scope of the physician’s license. Some Medicare contractors have coverage policies regarding either the diagnostic study or ultrasound guidance of certain injections, or both.