User login

Primary Hepatic Lymphoma: A Rare Form of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma of the Liver

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is a rare, malignant lymphoma of the liver. It differs from the predominantly lymph nodal or splenic involvement associated with other types of lymphoma. It is usually detected incidentally on imaging examination, commonly computed tomography (CT), for nonspecific clinical presentation. However, it has important clinical implications for early diagnosis and treatment as indicated in our case.

Case Presentation

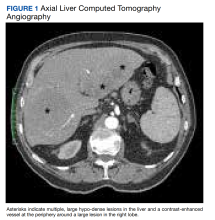

An 84-year-old man presented to the emergency department for evaluation of upper back pain. The patient had a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and was a former smoker. He had normal vital signs, an unremarkable physical examination, and a body mass index of 25. His laboratory studies showed a normal blood cell count and serum chemistry, including serum calcium level and α-fetoprotein, but mildly elevated liver function tests.

The patient’s chest CT angiography showed no evidence of thoracic aortic dissection, penetrating atherosclerotic ulceration, or pulmonary artery embolism. Besides emphysematous changes in the lung, the chest CT was within normal limits.

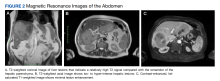

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed hepatomegaly (the liver measured up to 19.3 cm in craniocaudal length) and multiple, large intrahepatic space-occupying lesions, the largest measuring 9.9 cm × 9.5 cm in the right lobe, as well as multiple lesions in the inferior right and left lobe with enhancing capsules surrounding the hepatic lesions (Figure 2).

An ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the liver was performed. Flow cytometry showed a monoclonal B-cell population that was mostly intermediate to large based on forward scattered light characteristics. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD20, BCL2, BCL6, and CD45 in the neoplastic cells. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), CD15, CD30, and CD10 were negative, as were cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and pan-melanoma. CD3 highlighted background T cells. Ki-67 highlighted a proliferative index of approximately 75%, and the MYC stain demonstrated 50% positivity. This was consistent with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). However, there was insufficient tissue on the MUM1-stained slide; therefore, it was inconclusive to distinguish a nongerminal center derived from germinal center–derived DLBCL.

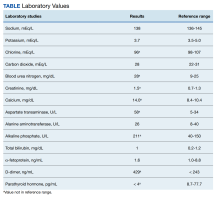

Two weeks after the initial CT examination, the patient’s condition quickly deteriorated, and he was admitted for severe weakness with evidence of severe hypercalcemia, hyperuricemia, and renal insufficiency (Table).

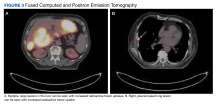

To get additional tissue for further tumor characterization, a repeat liver biopsy was performed along with other diagnostic tests, including head MRI, bone marrow biopsy, and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) full-body positron emission tomography (PET). Repeat liver biopsy showed only necrotic debris with immunostaining positive for CD20 and negative for CD3. B-cell lymphomas tend to retain CD20 expression after necrosis, so the presence of CD20 staining was consistent with a necrotic tumor. Again, there was insufficient tissue on the MUM1-stained slide. Head MRI showed no evidence of tumor involvement. Full-body PET showed abnormally elevated standardized uptake value (SUV) of radioactive tracers in several areas: multifocal, large area uptake within both right (SUV, 19) and left (SUV, 24) hepatic lobe (Figure 3A), retroperitoneal lymph node (SUV, 3.9), and a right lateral pleural-based nodule (SUV, 17.9) (Figure 3B).

The diagnosis was primary DLBCL of the liver with retroperitoneal lymph nodes and right lung metastasis. The patient was started on systemic chemotherapy of R-CHOP (rituximab with reduced cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone).

Discussion

Lymphoma is a tumor that originates from hematopoietic cells typically presented as a circumscribed solid tumor of lymphoid cells.1 Lymphomas are usually seen in the lymph nodes, spleen, blood, bone marrow, brain, gastrointestinal tract, skin, or other normal structures where lymphoreticular cells exist but very rarely in the liver.2 PHL is extremely rare due to the lack of abundant lymphoid tissue in the normal liver.3 It accounts for 0.4% of extra-nodal lymphomas and 0.016% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.4-6 The etiology of PHL is unknown but usually it develops in patients with previous liver disease: viral infection (hepatitis B and C, Epstein-Barr, and HIV), autoimmune disease, immunosuppression, or liver cirrhosis.5-7

The diagnosis of PHL can be challenging due to its rarity, vague clinical features, and nonspecific radiologic findings. The common presenting symptoms are usually vague and include abdominal pain or discomfort, fatigue, jaundice, weight loss, and fever.5 Liver biopsy is essential to its diagnosis. The disease course is usually indolent among most patients with PHL. In our case, the patient presented with upper back pain but his condition deteriorated rapidly, likely due to the advanced stage of the disease. Diagnosis of liver lymphoma depends on a liver biopsy that should be compatible with the lymphoma. The criteria for diagnosis of PHL defined by Lei include (1) symptoms caused mainly by liver involvement at presentation; (2) absence of distant lymphadenopathy, palpable clinically at presentation or detected during staging radiologic studies; and (3) absence of leukemic blood involvement in the peripheral blood smear.7 Other authors define PHL as having major liver involvement without evidence of extrahepatic involvement for at least 6 months.8 In our case, the multiple large lesions of the liver are consistent with advanced stage PHL with retroperitoneal lymph nodes and right lung metastasis. DLBCL is the most common histopathological type of lymphoma (65.9%). Other types have been described less commonly, including diffuse mixed large- and small-cell, lymphoblastic, diffuse histiocytic, mantle cell, and small noncleaved or Burkitt lymphoma.5-7

Currently, there is no consensus on PHL treatment. The therapeutic options include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of therapies.7 Most evidence regarding treatment and tumor response comes from case series, as PHLs are rare. Surgical resection in a series of 8 patients showed a cumulative 1- and 2-year survival rate of 66.7% and 55.6%, respectively.9 Chemotherapy is the recommended treatment option for extra-nodal DLBCL, making it a choice also for the treatment of PHL.10 Page and colleagues demonstrated that combination chemotherapy regimens helped achieve remission for 83.3% of patients.11 Since PHL is chemo-sensitive, most patients are treated with chemotherapy alone or in combination with surgery and radiotherapy. The most common chemotherapy regimen is R-CHOP for CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma. The use of the R-CHOP regimen has been reported to achieve complete remission in primary DLBCL of the liver.12

Conclusions

Primary DLBCL of the liver is a very rare disease without specific clinical manifestations, biochemical indicators, or radiologic features except for space-occupying liver lesions. However, patients’ conditions can deteriorate rapidly at an advanced stage, as demonstrated in our case. DLBCL requires a high level of suspicion for its early diagnosis and treatment and should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any hepatic space-occupying lesions.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Lynne Dryer, ARNP, for her clinical assistance with this patient and in the preparation of the manuscript.

1. Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114(5):937-951. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262

2. Do TD, Neurohr C, Michl M, Reiser MF, Zech CJ. An unusual case of primary hepatic lymphoma mimicking sarcoidosis in MRI. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2014;3(4):2047981613493625. Published 2014 May 10. doi:10.1177/2047981613493625

3. Laroia ST, Rastogi A, Panda D, Sarin SK. Primary hepatic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an enigma beyond the liver, a case report. World J Oncol. 2015;6(2):338-344. doi:10.14740/wjon900W

4. Yousuf S, Szpejda M, Mody M, et al. A unique case of primary hepatic CD-30 positive, CD 15-negative classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting as fever of unknown origin and acute hepatic failure. Haematol Int J. 2018;2(3):1-6. doi:10.23880/hij-16000127

5. Ugurluer G, Miller RC, Li Y, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma: a retrospective, multicenter rare cancer network study. Rare Tumors. 2016;8(3):118-123. doi:10.4081/rt.2016.6502

6. Noronha V, Shafi NQ, Obando JÁ, Kummar S. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;53(3):199-207. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.10.010

7. Lei KI. Primary non-Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma. 1989;29(3-4):293-299. doi:10.3109/10428199809068566

8. Caccamo D, Pervez NK, Marchevsky A. Primary lymphoma of the liver in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110(6):553-555.

9. Yang XW, Tan WF, Yu WL, et al. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of primary hepatic lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(47):6016-6019. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.6016

10. Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Introduction of combined CHP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5027-5033. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.09.137

11. Page RD, Romaguera JE, Osborne B, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma: favorable outcome after combination of chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92(8):2023-2029. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2023::aid-cncr1540>3.0.co;2-b

12. Zafar MS, Aggarwal S, Bhalla S. Complete response to chemotherapy in primary hepatic lymphoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8(1):114-116. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.95187

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is a rare, malignant lymphoma of the liver. It differs from the predominantly lymph nodal or splenic involvement associated with other types of lymphoma. It is usually detected incidentally on imaging examination, commonly computed tomography (CT), for nonspecific clinical presentation. However, it has important clinical implications for early diagnosis and treatment as indicated in our case.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old man presented to the emergency department for evaluation of upper back pain. The patient had a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and was a former smoker. He had normal vital signs, an unremarkable physical examination, and a body mass index of 25. His laboratory studies showed a normal blood cell count and serum chemistry, including serum calcium level and α-fetoprotein, but mildly elevated liver function tests.

The patient’s chest CT angiography showed no evidence of thoracic aortic dissection, penetrating atherosclerotic ulceration, or pulmonary artery embolism. Besides emphysematous changes in the lung, the chest CT was within normal limits.

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed hepatomegaly (the liver measured up to 19.3 cm in craniocaudal length) and multiple, large intrahepatic space-occupying lesions, the largest measuring 9.9 cm × 9.5 cm in the right lobe, as well as multiple lesions in the inferior right and left lobe with enhancing capsules surrounding the hepatic lesions (Figure 2).

An ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the liver was performed. Flow cytometry showed a monoclonal B-cell population that was mostly intermediate to large based on forward scattered light characteristics. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD20, BCL2, BCL6, and CD45 in the neoplastic cells. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), CD15, CD30, and CD10 were negative, as were cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and pan-melanoma. CD3 highlighted background T cells. Ki-67 highlighted a proliferative index of approximately 75%, and the MYC stain demonstrated 50% positivity. This was consistent with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). However, there was insufficient tissue on the MUM1-stained slide; therefore, it was inconclusive to distinguish a nongerminal center derived from germinal center–derived DLBCL.

Two weeks after the initial CT examination, the patient’s condition quickly deteriorated, and he was admitted for severe weakness with evidence of severe hypercalcemia, hyperuricemia, and renal insufficiency (Table).

To get additional tissue for further tumor characterization, a repeat liver biopsy was performed along with other diagnostic tests, including head MRI, bone marrow biopsy, and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) full-body positron emission tomography (PET). Repeat liver biopsy showed only necrotic debris with immunostaining positive for CD20 and negative for CD3. B-cell lymphomas tend to retain CD20 expression after necrosis, so the presence of CD20 staining was consistent with a necrotic tumor. Again, there was insufficient tissue on the MUM1-stained slide. Head MRI showed no evidence of tumor involvement. Full-body PET showed abnormally elevated standardized uptake value (SUV) of radioactive tracers in several areas: multifocal, large area uptake within both right (SUV, 19) and left (SUV, 24) hepatic lobe (Figure 3A), retroperitoneal lymph node (SUV, 3.9), and a right lateral pleural-based nodule (SUV, 17.9) (Figure 3B).

The diagnosis was primary DLBCL of the liver with retroperitoneal lymph nodes and right lung metastasis. The patient was started on systemic chemotherapy of R-CHOP (rituximab with reduced cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone).

Discussion

Lymphoma is a tumor that originates from hematopoietic cells typically presented as a circumscribed solid tumor of lymphoid cells.1 Lymphomas are usually seen in the lymph nodes, spleen, blood, bone marrow, brain, gastrointestinal tract, skin, or other normal structures where lymphoreticular cells exist but very rarely in the liver.2 PHL is extremely rare due to the lack of abundant lymphoid tissue in the normal liver.3 It accounts for 0.4% of extra-nodal lymphomas and 0.016% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.4-6 The etiology of PHL is unknown but usually it develops in patients with previous liver disease: viral infection (hepatitis B and C, Epstein-Barr, and HIV), autoimmune disease, immunosuppression, or liver cirrhosis.5-7

The diagnosis of PHL can be challenging due to its rarity, vague clinical features, and nonspecific radiologic findings. The common presenting symptoms are usually vague and include abdominal pain or discomfort, fatigue, jaundice, weight loss, and fever.5 Liver biopsy is essential to its diagnosis. The disease course is usually indolent among most patients with PHL. In our case, the patient presented with upper back pain but his condition deteriorated rapidly, likely due to the advanced stage of the disease. Diagnosis of liver lymphoma depends on a liver biopsy that should be compatible with the lymphoma. The criteria for diagnosis of PHL defined by Lei include (1) symptoms caused mainly by liver involvement at presentation; (2) absence of distant lymphadenopathy, palpable clinically at presentation or detected during staging radiologic studies; and (3) absence of leukemic blood involvement in the peripheral blood smear.7 Other authors define PHL as having major liver involvement without evidence of extrahepatic involvement for at least 6 months.8 In our case, the multiple large lesions of the liver are consistent with advanced stage PHL with retroperitoneal lymph nodes and right lung metastasis. DLBCL is the most common histopathological type of lymphoma (65.9%). Other types have been described less commonly, including diffuse mixed large- and small-cell, lymphoblastic, diffuse histiocytic, mantle cell, and small noncleaved or Burkitt lymphoma.5-7

Currently, there is no consensus on PHL treatment. The therapeutic options include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of therapies.7 Most evidence regarding treatment and tumor response comes from case series, as PHLs are rare. Surgical resection in a series of 8 patients showed a cumulative 1- and 2-year survival rate of 66.7% and 55.6%, respectively.9 Chemotherapy is the recommended treatment option for extra-nodal DLBCL, making it a choice also for the treatment of PHL.10 Page and colleagues demonstrated that combination chemotherapy regimens helped achieve remission for 83.3% of patients.11 Since PHL is chemo-sensitive, most patients are treated with chemotherapy alone or in combination with surgery and radiotherapy. The most common chemotherapy regimen is R-CHOP for CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma. The use of the R-CHOP regimen has been reported to achieve complete remission in primary DLBCL of the liver.12

Conclusions

Primary DLBCL of the liver is a very rare disease without specific clinical manifestations, biochemical indicators, or radiologic features except for space-occupying liver lesions. However, patients’ conditions can deteriorate rapidly at an advanced stage, as demonstrated in our case. DLBCL requires a high level of suspicion for its early diagnosis and treatment and should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any hepatic space-occupying lesions.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Lynne Dryer, ARNP, for her clinical assistance with this patient and in the preparation of the manuscript.

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is a rare, malignant lymphoma of the liver. It differs from the predominantly lymph nodal or splenic involvement associated with other types of lymphoma. It is usually detected incidentally on imaging examination, commonly computed tomography (CT), for nonspecific clinical presentation. However, it has important clinical implications for early diagnosis and treatment as indicated in our case.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old man presented to the emergency department for evaluation of upper back pain. The patient had a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and was a former smoker. He had normal vital signs, an unremarkable physical examination, and a body mass index of 25. His laboratory studies showed a normal blood cell count and serum chemistry, including serum calcium level and α-fetoprotein, but mildly elevated liver function tests.

The patient’s chest CT angiography showed no evidence of thoracic aortic dissection, penetrating atherosclerotic ulceration, or pulmonary artery embolism. Besides emphysematous changes in the lung, the chest CT was within normal limits.

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed hepatomegaly (the liver measured up to 19.3 cm in craniocaudal length) and multiple, large intrahepatic space-occupying lesions, the largest measuring 9.9 cm × 9.5 cm in the right lobe, as well as multiple lesions in the inferior right and left lobe with enhancing capsules surrounding the hepatic lesions (Figure 2).

An ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the liver was performed. Flow cytometry showed a monoclonal B-cell population that was mostly intermediate to large based on forward scattered light characteristics. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD20, BCL2, BCL6, and CD45 in the neoplastic cells. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), CD15, CD30, and CD10 were negative, as were cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and pan-melanoma. CD3 highlighted background T cells. Ki-67 highlighted a proliferative index of approximately 75%, and the MYC stain demonstrated 50% positivity. This was consistent with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). However, there was insufficient tissue on the MUM1-stained slide; therefore, it was inconclusive to distinguish a nongerminal center derived from germinal center–derived DLBCL.

Two weeks after the initial CT examination, the patient’s condition quickly deteriorated, and he was admitted for severe weakness with evidence of severe hypercalcemia, hyperuricemia, and renal insufficiency (Table).

To get additional tissue for further tumor characterization, a repeat liver biopsy was performed along with other diagnostic tests, including head MRI, bone marrow biopsy, and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) full-body positron emission tomography (PET). Repeat liver biopsy showed only necrotic debris with immunostaining positive for CD20 and negative for CD3. B-cell lymphomas tend to retain CD20 expression after necrosis, so the presence of CD20 staining was consistent with a necrotic tumor. Again, there was insufficient tissue on the MUM1-stained slide. Head MRI showed no evidence of tumor involvement. Full-body PET showed abnormally elevated standardized uptake value (SUV) of radioactive tracers in several areas: multifocal, large area uptake within both right (SUV, 19) and left (SUV, 24) hepatic lobe (Figure 3A), retroperitoneal lymph node (SUV, 3.9), and a right lateral pleural-based nodule (SUV, 17.9) (Figure 3B).

The diagnosis was primary DLBCL of the liver with retroperitoneal lymph nodes and right lung metastasis. The patient was started on systemic chemotherapy of R-CHOP (rituximab with reduced cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone).

Discussion

Lymphoma is a tumor that originates from hematopoietic cells typically presented as a circumscribed solid tumor of lymphoid cells.1 Lymphomas are usually seen in the lymph nodes, spleen, blood, bone marrow, brain, gastrointestinal tract, skin, or other normal structures where lymphoreticular cells exist but very rarely in the liver.2 PHL is extremely rare due to the lack of abundant lymphoid tissue in the normal liver.3 It accounts for 0.4% of extra-nodal lymphomas and 0.016% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.4-6 The etiology of PHL is unknown but usually it develops in patients with previous liver disease: viral infection (hepatitis B and C, Epstein-Barr, and HIV), autoimmune disease, immunosuppression, or liver cirrhosis.5-7

The diagnosis of PHL can be challenging due to its rarity, vague clinical features, and nonspecific radiologic findings. The common presenting symptoms are usually vague and include abdominal pain or discomfort, fatigue, jaundice, weight loss, and fever.5 Liver biopsy is essential to its diagnosis. The disease course is usually indolent among most patients with PHL. In our case, the patient presented with upper back pain but his condition deteriorated rapidly, likely due to the advanced stage of the disease. Diagnosis of liver lymphoma depends on a liver biopsy that should be compatible with the lymphoma. The criteria for diagnosis of PHL defined by Lei include (1) symptoms caused mainly by liver involvement at presentation; (2) absence of distant lymphadenopathy, palpable clinically at presentation or detected during staging radiologic studies; and (3) absence of leukemic blood involvement in the peripheral blood smear.7 Other authors define PHL as having major liver involvement without evidence of extrahepatic involvement for at least 6 months.8 In our case, the multiple large lesions of the liver are consistent with advanced stage PHL with retroperitoneal lymph nodes and right lung metastasis. DLBCL is the most common histopathological type of lymphoma (65.9%). Other types have been described less commonly, including diffuse mixed large- and small-cell, lymphoblastic, diffuse histiocytic, mantle cell, and small noncleaved or Burkitt lymphoma.5-7

Currently, there is no consensus on PHL treatment. The therapeutic options include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of therapies.7 Most evidence regarding treatment and tumor response comes from case series, as PHLs are rare. Surgical resection in a series of 8 patients showed a cumulative 1- and 2-year survival rate of 66.7% and 55.6%, respectively.9 Chemotherapy is the recommended treatment option for extra-nodal DLBCL, making it a choice also for the treatment of PHL.10 Page and colleagues demonstrated that combination chemotherapy regimens helped achieve remission for 83.3% of patients.11 Since PHL is chemo-sensitive, most patients are treated with chemotherapy alone or in combination with surgery and radiotherapy. The most common chemotherapy regimen is R-CHOP for CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma. The use of the R-CHOP regimen has been reported to achieve complete remission in primary DLBCL of the liver.12

Conclusions

Primary DLBCL of the liver is a very rare disease without specific clinical manifestations, biochemical indicators, or radiologic features except for space-occupying liver lesions. However, patients’ conditions can deteriorate rapidly at an advanced stage, as demonstrated in our case. DLBCL requires a high level of suspicion for its early diagnosis and treatment and should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any hepatic space-occupying lesions.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Lynne Dryer, ARNP, for her clinical assistance with this patient and in the preparation of the manuscript.

1. Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114(5):937-951. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262

2. Do TD, Neurohr C, Michl M, Reiser MF, Zech CJ. An unusual case of primary hepatic lymphoma mimicking sarcoidosis in MRI. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2014;3(4):2047981613493625. Published 2014 May 10. doi:10.1177/2047981613493625

3. Laroia ST, Rastogi A, Panda D, Sarin SK. Primary hepatic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an enigma beyond the liver, a case report. World J Oncol. 2015;6(2):338-344. doi:10.14740/wjon900W

4. Yousuf S, Szpejda M, Mody M, et al. A unique case of primary hepatic CD-30 positive, CD 15-negative classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting as fever of unknown origin and acute hepatic failure. Haematol Int J. 2018;2(3):1-6. doi:10.23880/hij-16000127

5. Ugurluer G, Miller RC, Li Y, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma: a retrospective, multicenter rare cancer network study. Rare Tumors. 2016;8(3):118-123. doi:10.4081/rt.2016.6502

6. Noronha V, Shafi NQ, Obando JÁ, Kummar S. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;53(3):199-207. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.10.010

7. Lei KI. Primary non-Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma. 1989;29(3-4):293-299. doi:10.3109/10428199809068566

8. Caccamo D, Pervez NK, Marchevsky A. Primary lymphoma of the liver in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110(6):553-555.

9. Yang XW, Tan WF, Yu WL, et al. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of primary hepatic lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(47):6016-6019. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.6016

10. Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Introduction of combined CHP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5027-5033. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.09.137

11. Page RD, Romaguera JE, Osborne B, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma: favorable outcome after combination of chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92(8):2023-2029. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2023::aid-cncr1540>3.0.co;2-b

12. Zafar MS, Aggarwal S, Bhalla S. Complete response to chemotherapy in primary hepatic lymphoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8(1):114-116. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.95187

1. Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114(5):937-951. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262

2. Do TD, Neurohr C, Michl M, Reiser MF, Zech CJ. An unusual case of primary hepatic lymphoma mimicking sarcoidosis in MRI. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2014;3(4):2047981613493625. Published 2014 May 10. doi:10.1177/2047981613493625

3. Laroia ST, Rastogi A, Panda D, Sarin SK. Primary hepatic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an enigma beyond the liver, a case report. World J Oncol. 2015;6(2):338-344. doi:10.14740/wjon900W

4. Yousuf S, Szpejda M, Mody M, et al. A unique case of primary hepatic CD-30 positive, CD 15-negative classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting as fever of unknown origin and acute hepatic failure. Haematol Int J. 2018;2(3):1-6. doi:10.23880/hij-16000127

5. Ugurluer G, Miller RC, Li Y, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma: a retrospective, multicenter rare cancer network study. Rare Tumors. 2016;8(3):118-123. doi:10.4081/rt.2016.6502

6. Noronha V, Shafi NQ, Obando JÁ, Kummar S. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;53(3):199-207. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.10.010

7. Lei KI. Primary non-Hodgkins lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma. 1989;29(3-4):293-299. doi:10.3109/10428199809068566

8. Caccamo D, Pervez NK, Marchevsky A. Primary lymphoma of the liver in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110(6):553-555.

9. Yang XW, Tan WF, Yu WL, et al. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of primary hepatic lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(47):6016-6019. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.6016

10. Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Introduction of combined CHP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5027-5033. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.09.137

11. Page RD, Romaguera JE, Osborne B, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma: favorable outcome after combination of chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92(8):2023-2029. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2023::aid-cncr1540>3.0.co;2-b

12. Zafar MS, Aggarwal S, Bhalla S. Complete response to chemotherapy in primary hepatic lymphoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8(1):114-116. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.95187

Watching feasible for asymptomatic kidney stones

Many patients with asymptomatic renal stones can qualify for an active surveillance program, Swiss researchers report at the American Urological Association 2023 Annual Meeting.

Kevin Stritt, MD, chief resident in the urology department at Lausanne University Hospital, said kidney stones often pass without symptoms. But until now, data on the frequency of asymptomatic, spontaneous passage of stones have been lacking.

The new data come from the NOSTONE trial, a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial to assess the efficacy of hydrochlorothiazide in the prevention of recurrence in patients with recurrent calcium-containing kidney stones.

Dr. Stritt and colleagues evaluated the natural history of asymptomatic renal stones during a median follow-up of 35 months. “We found for the first time that a relevant number of kidney stone passages [39%] were asymptomatic, spontaneous stone passages,” Dr. Stritt told this news organization.

All asymptomatic spontaneous stone passages were analyzed in a comparison of the total number of kidney stones on low-dose, nonintravenous contrast CT imaging at the beginning and end of the 3-year follow-up.

Of the 403 stones passed spontaneously, 61% (245) were symptomatic stone passages and 39% (158) were asymptomatic stone passages, Dr. Stritt told this news organization.

Asymptomatic stones were a median size of 2.4 mm, and symptomatic stones were 2.15 mm, which was not significantly different (P = .366), according to the researchers. Dr. Stritt said the spontaneous passage of asymptomatic stones was largely influenced by a higher number of stones on CT imaging at randomization (P = .001) and a lower total stone volume (P = .001).

Ephrem Olweny, MD, an assistant professor of urology and section chief of endourology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said previous studies have found that the rate of spontaneous passage of kidney stones ranges from 3% to 29%.

“But this secondary analysis of data from a prior multicenter prospective randomized trial offers higher-quality data that will be of value in guiding patient counseling,” Dr. Olweny said.

“Observation should be initially offered to these patients. However, patients should be informed that 52% are likely to develop symptoms, and some may indeed opt for preemptive surgical removal,” he added.

David Schulsinger, MD, an associate professor in the department of urology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University Hospital, said the incidence of kidney stones has been increasing worldwide, affecting approximately 12% of men and 6% of women. Dehydration and diets high in sodium and calcium are major factors, he said.

Patients with a history of stones have a 50% risk of recurrence in the next 5 years, and an 80% risk in their lifetime, he added.

Dr. Schulsinger said the message from the Swiss study is that urologists can be “comfortable” watching small stones, those averaging 2.4 mm or less in size. “But if a patient has a 7- or 8-mm stone, you might be more inclined to manage that patient a little bit more aggressively.”

Roughly half of patients with stones less than 2 mm will pass it in about 8 days, he said.

Dr. Olweny noted that the study was a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial that evaluated the efficacy of thiazides in preventing the recurrence of calcium stones. “The original study was not specifically designed to look at asymptomatic stone passage rates for small renal stones, and therefore, the observed rates may not reflect the most precise estimates,” he said.

Dr. Stritt said his group has not studied the size limit of stones that pass spontaneously without symptoms. “This study could serve to construct recurrence prediction models based on medical history and stone burden on CT imaging. More well-designed research on this topic is urgently needed,” he said. “These results should encourage urologists to counsel patients about the possibility of an active surveillance strategy when smaller kidney stones are present.”

The author and independent commentators have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many patients with asymptomatic renal stones can qualify for an active surveillance program, Swiss researchers report at the American Urological Association 2023 Annual Meeting.

Kevin Stritt, MD, chief resident in the urology department at Lausanne University Hospital, said kidney stones often pass without symptoms. But until now, data on the frequency of asymptomatic, spontaneous passage of stones have been lacking.

The new data come from the NOSTONE trial, a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial to assess the efficacy of hydrochlorothiazide in the prevention of recurrence in patients with recurrent calcium-containing kidney stones.

Dr. Stritt and colleagues evaluated the natural history of asymptomatic renal stones during a median follow-up of 35 months. “We found for the first time that a relevant number of kidney stone passages [39%] were asymptomatic, spontaneous stone passages,” Dr. Stritt told this news organization.

All asymptomatic spontaneous stone passages were analyzed in a comparison of the total number of kidney stones on low-dose, nonintravenous contrast CT imaging at the beginning and end of the 3-year follow-up.

Of the 403 stones passed spontaneously, 61% (245) were symptomatic stone passages and 39% (158) were asymptomatic stone passages, Dr. Stritt told this news organization.

Asymptomatic stones were a median size of 2.4 mm, and symptomatic stones were 2.15 mm, which was not significantly different (P = .366), according to the researchers. Dr. Stritt said the spontaneous passage of asymptomatic stones was largely influenced by a higher number of stones on CT imaging at randomization (P = .001) and a lower total stone volume (P = .001).

Ephrem Olweny, MD, an assistant professor of urology and section chief of endourology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said previous studies have found that the rate of spontaneous passage of kidney stones ranges from 3% to 29%.

“But this secondary analysis of data from a prior multicenter prospective randomized trial offers higher-quality data that will be of value in guiding patient counseling,” Dr. Olweny said.

“Observation should be initially offered to these patients. However, patients should be informed that 52% are likely to develop symptoms, and some may indeed opt for preemptive surgical removal,” he added.

David Schulsinger, MD, an associate professor in the department of urology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University Hospital, said the incidence of kidney stones has been increasing worldwide, affecting approximately 12% of men and 6% of women. Dehydration and diets high in sodium and calcium are major factors, he said.

Patients with a history of stones have a 50% risk of recurrence in the next 5 years, and an 80% risk in their lifetime, he added.

Dr. Schulsinger said the message from the Swiss study is that urologists can be “comfortable” watching small stones, those averaging 2.4 mm or less in size. “But if a patient has a 7- or 8-mm stone, you might be more inclined to manage that patient a little bit more aggressively.”

Roughly half of patients with stones less than 2 mm will pass it in about 8 days, he said.

Dr. Olweny noted that the study was a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial that evaluated the efficacy of thiazides in preventing the recurrence of calcium stones. “The original study was not specifically designed to look at asymptomatic stone passage rates for small renal stones, and therefore, the observed rates may not reflect the most precise estimates,” he said.

Dr. Stritt said his group has not studied the size limit of stones that pass spontaneously without symptoms. “This study could serve to construct recurrence prediction models based on medical history and stone burden on CT imaging. More well-designed research on this topic is urgently needed,” he said. “These results should encourage urologists to counsel patients about the possibility of an active surveillance strategy when smaller kidney stones are present.”

The author and independent commentators have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many patients with asymptomatic renal stones can qualify for an active surveillance program, Swiss researchers report at the American Urological Association 2023 Annual Meeting.

Kevin Stritt, MD, chief resident in the urology department at Lausanne University Hospital, said kidney stones often pass without symptoms. But until now, data on the frequency of asymptomatic, spontaneous passage of stones have been lacking.

The new data come from the NOSTONE trial, a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial to assess the efficacy of hydrochlorothiazide in the prevention of recurrence in patients with recurrent calcium-containing kidney stones.

Dr. Stritt and colleagues evaluated the natural history of asymptomatic renal stones during a median follow-up of 35 months. “We found for the first time that a relevant number of kidney stone passages [39%] were asymptomatic, spontaneous stone passages,” Dr. Stritt told this news organization.

All asymptomatic spontaneous stone passages were analyzed in a comparison of the total number of kidney stones on low-dose, nonintravenous contrast CT imaging at the beginning and end of the 3-year follow-up.

Of the 403 stones passed spontaneously, 61% (245) were symptomatic stone passages and 39% (158) were asymptomatic stone passages, Dr. Stritt told this news organization.

Asymptomatic stones were a median size of 2.4 mm, and symptomatic stones were 2.15 mm, which was not significantly different (P = .366), according to the researchers. Dr. Stritt said the spontaneous passage of asymptomatic stones was largely influenced by a higher number of stones on CT imaging at randomization (P = .001) and a lower total stone volume (P = .001).

Ephrem Olweny, MD, an assistant professor of urology and section chief of endourology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said previous studies have found that the rate of spontaneous passage of kidney stones ranges from 3% to 29%.

“But this secondary analysis of data from a prior multicenter prospective randomized trial offers higher-quality data that will be of value in guiding patient counseling,” Dr. Olweny said.

“Observation should be initially offered to these patients. However, patients should be informed that 52% are likely to develop symptoms, and some may indeed opt for preemptive surgical removal,” he added.

David Schulsinger, MD, an associate professor in the department of urology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University Hospital, said the incidence of kidney stones has been increasing worldwide, affecting approximately 12% of men and 6% of women. Dehydration and diets high in sodium and calcium are major factors, he said.

Patients with a history of stones have a 50% risk of recurrence in the next 5 years, and an 80% risk in their lifetime, he added.

Dr. Schulsinger said the message from the Swiss study is that urologists can be “comfortable” watching small stones, those averaging 2.4 mm or less in size. “But if a patient has a 7- or 8-mm stone, you might be more inclined to manage that patient a little bit more aggressively.”

Roughly half of patients with stones less than 2 mm will pass it in about 8 days, he said.

Dr. Olweny noted that the study was a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial that evaluated the efficacy of thiazides in preventing the recurrence of calcium stones. “The original study was not specifically designed to look at asymptomatic stone passage rates for small renal stones, and therefore, the observed rates may not reflect the most precise estimates,” he said.

Dr. Stritt said his group has not studied the size limit of stones that pass spontaneously without symptoms. “This study could serve to construct recurrence prediction models based on medical history and stone burden on CT imaging. More well-designed research on this topic is urgently needed,” he said. “These results should encourage urologists to counsel patients about the possibility of an active surveillance strategy when smaller kidney stones are present.”

The author and independent commentators have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Diagnosis of Indolent Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini Infections as Risk Factors for Cholangiocarcinoma: An Unmet Medical Need

Cholangiocarcinoma is a heterogeneous, highly aggressive cancer of the biliary tract epithelium with an overall 5-year relative survival rate of only 9%.1,2 Although surgical resection of localized, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is associated with improved overall survival, most patients present with advanced disease not amenable to surgery due to a late onset of symptoms.2 Recently, an increased incidence of cholangiocarcinoma has been reported in the United States.3 Although relatively rare in the US, cholangiocarcinoma is prevalent across large parts of Asia, including China, Vietnam, Thailand, South Korea, and Taiwan.2

Risk Factors

To date, risk factors for developing cholangiocarcinoma have not been elucidated. 4,5 However, a growing body of literature suggests that chronic infection of genetically susceptible human subjects with Clonorchis sinensis ( C sinensis ) and Opisthorchis viverrini ( O viverrini ) plays a role. 6,7 The life cycle of these food-borne zoonotic trematodes involves eggs discharged in the stool of infected humans, the definitive host. 6,7 In nature, these eggs are ingested by freshwater snails, the intermediate host, where they undergo several developmental stages to form cercariae. Once released from snails into the water, free-swimming cercariae come in contact and penetrate freshwater fish where they encyst as metacercariae. Infection of humans occurs by ingesting undercooked, salted, pickled, or smoked freshwater fish infested with metacercariae. After ingestion, metacercariae excyst in the duodenum and ascend the biliary tract through the ampulla of Vater. They then mature into adult flukes that reside in small- and medium-sized intrahepatic biliary ducts. 6,7

Although most infected people remain asymptomatic, untreated indolent infections with C sinensis and O viverrini may persist in peripheral intrahepatic bile ducts for as long as 30 years, which is the lifespan of the trematodes.6,7 During this prolonged period, C sinensis and O viverrini feeding activities and their excretory-secretory products may damage bile duct epithelium and promote intense local inflammation.6,7 Conceivably, these pathological processes could then provoke the epithelial desquamation, adenomatous hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, periductal fibrosis, and granuloma formation that are conducive to initiation and progression of cholangiocarcinoma in genetically susceptible people.8 Accordingly, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has determined that there is sufficient evidence for the carcinogenicity of chronic infections with C sinensis and O viverrini in humans and that chronic infections with these trematodes cause cholangiocarcinoma.9 The IARC concluded that chronic infections with C sinensis and O viverrini are carcinogenic to humans (Group 1).9

Diagnosis

Presently, the diagnosis of C sinensis and O viverrini infection is based on microscopic identification and enumeration of the parasites’ eggs in weighted stool specimens using a formalin-ethyl acetate sedimentation concentration technique. 6,7 This approach requires a labor-intensive test that is conducted by an experienced technician. The test has low specificity and sensitivity because eggs could be confused with those of nonpathogenic intestinal flukes that are morphologically similar and because eggs are not present in feces during all stages of the infection. Although diffuse dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts by screening sonography is used to diagnose clonorchiasis in endemic areas, it has low sensitivity, particularly in patients with low-level C sinensis and O viverrin i infections. 10

To address the current diagnostic gap, several enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) have been developed for the diagnosis of C sinensis, including monoclonal antibody-based (mAb) ELISA and indirect antibody ELISA.11,12 However, both have important limitations. The mAb ELISA detects only active infections while indirect antibody ELISA cross-reacts with other liver flukes.11,12 Taken together, these data illustrate the difficulties in diagnosing asymptomatic individuals with low-burden C sinensis or O viverrini infections by existing laboratory methods.

Timely serodiagnosis of indolent C sinensis and O viverrini infections is important because these parasites have recently been raised as a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma in veterans who served in Vietnam.13 The American War Library estimates that as of February 28, 2019, about 610,000 Americans who served on land in Vietnam or in the air over Vietnam between 1954 and 1975 are alive, and about 164,000 Americans who served at sea in Vietnam waters are alive.14 To that end, Psevdos and colleagues screened 97 US veterans who served in Vietnam and identified 50 who reported exposure to raw or undercooked fish while there.13 None had evidence of active C sinensis or O viverrini infection. Blood samples obtained from these veterans were analyzed for circulating C sinensis and O viverrini antibodies using an ELISA developed in South Korea and 12 blood samples tested positive for the trematodes. Imaging of extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts was unyielding in all cases. One veteran diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma had repeated negative tests. However, the results of this study were challenged by several experts in this field because the authors did not report the sensitivity and specificity of the ELISA assay used.15

Serologic testing of US veterans who served in C sinensis and O viverrini–endemic countries for indolent infections with these parasites is not recommended at present.15 Nevertheless, there is an urgent need to develop sensitive and specific serologic assays, such as ELISA tests with recombinant antigens, to detect both acute and indolent infections caused by each biliary liver fluke in the US, including in patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma. We posit that testing and treatment of high-risk populations could lead to earlier detection and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma, leading to improved overall survival in the population at risk.

1. American Cancer Society. Survival rates for bile duct cancer. Updated March 1, 2023. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-by-stage.html

2. Vij M, Puri Y, Rammohan A, et al. Pathological, molecular, and clinical characteristics of cholangiocarcinoma: A comprehensive review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;14(3):607-627. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v14.i3.607

3. Yao KJ, Jabbour S, Parekh N, Lin Y, Moss RA. Increasing mortality in the United States from cholangiocarcinoma: an analysis of the National Center for Health Statistics Database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):117. Published 2016 Sep 21. doi:10.1186/s12876-016-0527-z

4. Rustagi T, Dasanu CA. Risk factors for gallbladder cancer and cholangiocarcinoma: similarities, differences and updates. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43(2):137-147. doi:10.1007/s12029-011-9284-y

5. Maemura K, Natsugoe S, Takao S. Molecular mechanism of cholangiocarcinoma carcinogenesis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21(10):754-760. doi:10.1002/jhbp.126

6. Steele JA, Richter CH, Echaubard P, et al. Thinking beyond Opisthorchis viverrini for risk of cholangiocarcinoma in the lower Mekong region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):44. Published 2018 May 17. doi:10.1186/s40249-018-0434-3.

7. Kim TS, Pak JH, Kim JB, Bahk YY. Clonorchis sinensis, an oriental liver fluke, as a human biological agent of cholangiocarcinoma: a brief review. BMB Rep. 2016;49(11):590-597. doi:10.5483/bmbrep.2016.49.11.109

8. Murata M. Inflammation and cancer. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23(1):50. Published 2018 Oct 20. doi:10.1186/s12199-018-0740-1

9. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Biological agents. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100(pt B):1-441.

10. Mairiang E, Laha T, Bethony JM, et al. Ultrasonography assessment of hepatobiliary abnormalities in 3359 subjects with Opisthorchis viverrini infection in endemic areas of Thailand. Parasitol Int. 2012;61(1):208-211. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2011.07.009

11. Li HM, Qian MB, Yang YC, et al. Performance evaluation of existing immunoassays for Clonorchis sinensis infection in China. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11(1):35. Published 2018 Jan 15. doi:10.1186/s13071-018-2612-3

12. Hughes T, O’Connor T, Techasen A, et al. Opisthorchiasis and cholangiocarcinoma in Southeast Asia: an unresolved problem. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:227-237. Published 2017 Aug 10. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S133292

13. Psevdos G, Ford FM, Hong ST. Screening US Vietnam veterans for liver fluke exposure 5 decades after the end of the war. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md). 2018;26(4):208-210. doi:10.1097/IPC.0000000000000611

14. American War Library. In harm’s way... How many real Vietnam vets are alive today? Updated February 28, 2019. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.americanwarlibrary.com/personnel/vietvet.htm

15. Nash TE, Sullivan D, Mitre E, et al. Comments on “Screening US Vietnam veterans for liver fluke exposure 5 decades after the end of the war”. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md). 2018;26(4):240-241. doi:10.1097/IPC.0000000000000659

Cholangiocarcinoma is a heterogeneous, highly aggressive cancer of the biliary tract epithelium with an overall 5-year relative survival rate of only 9%.1,2 Although surgical resection of localized, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is associated with improved overall survival, most patients present with advanced disease not amenable to surgery due to a late onset of symptoms.2 Recently, an increased incidence of cholangiocarcinoma has been reported in the United States.3 Although relatively rare in the US, cholangiocarcinoma is prevalent across large parts of Asia, including China, Vietnam, Thailand, South Korea, and Taiwan.2

Risk Factors

To date, risk factors for developing cholangiocarcinoma have not been elucidated. 4,5 However, a growing body of literature suggests that chronic infection of genetically susceptible human subjects with Clonorchis sinensis ( C sinensis ) and Opisthorchis viverrini ( O viverrini ) plays a role. 6,7 The life cycle of these food-borne zoonotic trematodes involves eggs discharged in the stool of infected humans, the definitive host. 6,7 In nature, these eggs are ingested by freshwater snails, the intermediate host, where they undergo several developmental stages to form cercariae. Once released from snails into the water, free-swimming cercariae come in contact and penetrate freshwater fish where they encyst as metacercariae. Infection of humans occurs by ingesting undercooked, salted, pickled, or smoked freshwater fish infested with metacercariae. After ingestion, metacercariae excyst in the duodenum and ascend the biliary tract through the ampulla of Vater. They then mature into adult flukes that reside in small- and medium-sized intrahepatic biliary ducts. 6,7

Although most infected people remain asymptomatic, untreated indolent infections with C sinensis and O viverrini may persist in peripheral intrahepatic bile ducts for as long as 30 years, which is the lifespan of the trematodes.6,7 During this prolonged period, C sinensis and O viverrini feeding activities and their excretory-secretory products may damage bile duct epithelium and promote intense local inflammation.6,7 Conceivably, these pathological processes could then provoke the epithelial desquamation, adenomatous hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, periductal fibrosis, and granuloma formation that are conducive to initiation and progression of cholangiocarcinoma in genetically susceptible people.8 Accordingly, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has determined that there is sufficient evidence for the carcinogenicity of chronic infections with C sinensis and O viverrini in humans and that chronic infections with these trematodes cause cholangiocarcinoma.9 The IARC concluded that chronic infections with C sinensis and O viverrini are carcinogenic to humans (Group 1).9

Diagnosis

Presently, the diagnosis of C sinensis and O viverrini infection is based on microscopic identification and enumeration of the parasites’ eggs in weighted stool specimens using a formalin-ethyl acetate sedimentation concentration technique. 6,7 This approach requires a labor-intensive test that is conducted by an experienced technician. The test has low specificity and sensitivity because eggs could be confused with those of nonpathogenic intestinal flukes that are morphologically similar and because eggs are not present in feces during all stages of the infection. Although diffuse dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts by screening sonography is used to diagnose clonorchiasis in endemic areas, it has low sensitivity, particularly in patients with low-level C sinensis and O viverrin i infections. 10

To address the current diagnostic gap, several enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) have been developed for the diagnosis of C sinensis, including monoclonal antibody-based (mAb) ELISA and indirect antibody ELISA.11,12 However, both have important limitations. The mAb ELISA detects only active infections while indirect antibody ELISA cross-reacts with other liver flukes.11,12 Taken together, these data illustrate the difficulties in diagnosing asymptomatic individuals with low-burden C sinensis or O viverrini infections by existing laboratory methods.

Timely serodiagnosis of indolent C sinensis and O viverrini infections is important because these parasites have recently been raised as a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma in veterans who served in Vietnam.13 The American War Library estimates that as of February 28, 2019, about 610,000 Americans who served on land in Vietnam or in the air over Vietnam between 1954 and 1975 are alive, and about 164,000 Americans who served at sea in Vietnam waters are alive.14 To that end, Psevdos and colleagues screened 97 US veterans who served in Vietnam and identified 50 who reported exposure to raw or undercooked fish while there.13 None had evidence of active C sinensis or O viverrini infection. Blood samples obtained from these veterans were analyzed for circulating C sinensis and O viverrini antibodies using an ELISA developed in South Korea and 12 blood samples tested positive for the trematodes. Imaging of extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts was unyielding in all cases. One veteran diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma had repeated negative tests. However, the results of this study were challenged by several experts in this field because the authors did not report the sensitivity and specificity of the ELISA assay used.15

Serologic testing of US veterans who served in C sinensis and O viverrini–endemic countries for indolent infections with these parasites is not recommended at present.15 Nevertheless, there is an urgent need to develop sensitive and specific serologic assays, such as ELISA tests with recombinant antigens, to detect both acute and indolent infections caused by each biliary liver fluke in the US, including in patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma. We posit that testing and treatment of high-risk populations could lead to earlier detection and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma, leading to improved overall survival in the population at risk.

Cholangiocarcinoma is a heterogeneous, highly aggressive cancer of the biliary tract epithelium with an overall 5-year relative survival rate of only 9%.1,2 Although surgical resection of localized, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is associated with improved overall survival, most patients present with advanced disease not amenable to surgery due to a late onset of symptoms.2 Recently, an increased incidence of cholangiocarcinoma has been reported in the United States.3 Although relatively rare in the US, cholangiocarcinoma is prevalent across large parts of Asia, including China, Vietnam, Thailand, South Korea, and Taiwan.2

Risk Factors

To date, risk factors for developing cholangiocarcinoma have not been elucidated. 4,5 However, a growing body of literature suggests that chronic infection of genetically susceptible human subjects with Clonorchis sinensis ( C sinensis ) and Opisthorchis viverrini ( O viverrini ) plays a role. 6,7 The life cycle of these food-borne zoonotic trematodes involves eggs discharged in the stool of infected humans, the definitive host. 6,7 In nature, these eggs are ingested by freshwater snails, the intermediate host, where they undergo several developmental stages to form cercariae. Once released from snails into the water, free-swimming cercariae come in contact and penetrate freshwater fish where they encyst as metacercariae. Infection of humans occurs by ingesting undercooked, salted, pickled, or smoked freshwater fish infested with metacercariae. After ingestion, metacercariae excyst in the duodenum and ascend the biliary tract through the ampulla of Vater. They then mature into adult flukes that reside in small- and medium-sized intrahepatic biliary ducts. 6,7

Although most infected people remain asymptomatic, untreated indolent infections with C sinensis and O viverrini may persist in peripheral intrahepatic bile ducts for as long as 30 years, which is the lifespan of the trematodes.6,7 During this prolonged period, C sinensis and O viverrini feeding activities and their excretory-secretory products may damage bile duct epithelium and promote intense local inflammation.6,7 Conceivably, these pathological processes could then provoke the epithelial desquamation, adenomatous hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, periductal fibrosis, and granuloma formation that are conducive to initiation and progression of cholangiocarcinoma in genetically susceptible people.8 Accordingly, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has determined that there is sufficient evidence for the carcinogenicity of chronic infections with C sinensis and O viverrini in humans and that chronic infections with these trematodes cause cholangiocarcinoma.9 The IARC concluded that chronic infections with C sinensis and O viverrini are carcinogenic to humans (Group 1).9

Diagnosis

Presently, the diagnosis of C sinensis and O viverrini infection is based on microscopic identification and enumeration of the parasites’ eggs in weighted stool specimens using a formalin-ethyl acetate sedimentation concentration technique. 6,7 This approach requires a labor-intensive test that is conducted by an experienced technician. The test has low specificity and sensitivity because eggs could be confused with those of nonpathogenic intestinal flukes that are morphologically similar and because eggs are not present in feces during all stages of the infection. Although diffuse dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts by screening sonography is used to diagnose clonorchiasis in endemic areas, it has low sensitivity, particularly in patients with low-level C sinensis and O viverrin i infections. 10

To address the current diagnostic gap, several enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) have been developed for the diagnosis of C sinensis, including monoclonal antibody-based (mAb) ELISA and indirect antibody ELISA.11,12 However, both have important limitations. The mAb ELISA detects only active infections while indirect antibody ELISA cross-reacts with other liver flukes.11,12 Taken together, these data illustrate the difficulties in diagnosing asymptomatic individuals with low-burden C sinensis or O viverrini infections by existing laboratory methods.

Timely serodiagnosis of indolent C sinensis and O viverrini infections is important because these parasites have recently been raised as a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma in veterans who served in Vietnam.13 The American War Library estimates that as of February 28, 2019, about 610,000 Americans who served on land in Vietnam or in the air over Vietnam between 1954 and 1975 are alive, and about 164,000 Americans who served at sea in Vietnam waters are alive.14 To that end, Psevdos and colleagues screened 97 US veterans who served in Vietnam and identified 50 who reported exposure to raw or undercooked fish while there.13 None had evidence of active C sinensis or O viverrini infection. Blood samples obtained from these veterans were analyzed for circulating C sinensis and O viverrini antibodies using an ELISA developed in South Korea and 12 blood samples tested positive for the trematodes. Imaging of extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts was unyielding in all cases. One veteran diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma had repeated negative tests. However, the results of this study were challenged by several experts in this field because the authors did not report the sensitivity and specificity of the ELISA assay used.15

Serologic testing of US veterans who served in C sinensis and O viverrini–endemic countries for indolent infections with these parasites is not recommended at present.15 Nevertheless, there is an urgent need to develop sensitive and specific serologic assays, such as ELISA tests with recombinant antigens, to detect both acute and indolent infections caused by each biliary liver fluke in the US, including in patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma. We posit that testing and treatment of high-risk populations could lead to earlier detection and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma, leading to improved overall survival in the population at risk.

1. American Cancer Society. Survival rates for bile duct cancer. Updated March 1, 2023. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-by-stage.html

2. Vij M, Puri Y, Rammohan A, et al. Pathological, molecular, and clinical characteristics of cholangiocarcinoma: A comprehensive review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;14(3):607-627. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v14.i3.607

3. Yao KJ, Jabbour S, Parekh N, Lin Y, Moss RA. Increasing mortality in the United States from cholangiocarcinoma: an analysis of the National Center for Health Statistics Database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):117. Published 2016 Sep 21. doi:10.1186/s12876-016-0527-z

4. Rustagi T, Dasanu CA. Risk factors for gallbladder cancer and cholangiocarcinoma: similarities, differences and updates. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43(2):137-147. doi:10.1007/s12029-011-9284-y

5. Maemura K, Natsugoe S, Takao S. Molecular mechanism of cholangiocarcinoma carcinogenesis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21(10):754-760. doi:10.1002/jhbp.126

6. Steele JA, Richter CH, Echaubard P, et al. Thinking beyond Opisthorchis viverrini for risk of cholangiocarcinoma in the lower Mekong region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):44. Published 2018 May 17. doi:10.1186/s40249-018-0434-3.

7. Kim TS, Pak JH, Kim JB, Bahk YY. Clonorchis sinensis, an oriental liver fluke, as a human biological agent of cholangiocarcinoma: a brief review. BMB Rep. 2016;49(11):590-597. doi:10.5483/bmbrep.2016.49.11.109

8. Murata M. Inflammation and cancer. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23(1):50. Published 2018 Oct 20. doi:10.1186/s12199-018-0740-1

9. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Biological agents. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100(pt B):1-441.

10. Mairiang E, Laha T, Bethony JM, et al. Ultrasonography assessment of hepatobiliary abnormalities in 3359 subjects with Opisthorchis viverrini infection in endemic areas of Thailand. Parasitol Int. 2012;61(1):208-211. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2011.07.009

11. Li HM, Qian MB, Yang YC, et al. Performance evaluation of existing immunoassays for Clonorchis sinensis infection in China. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11(1):35. Published 2018 Jan 15. doi:10.1186/s13071-018-2612-3

12. Hughes T, O’Connor T, Techasen A, et al. Opisthorchiasis and cholangiocarcinoma in Southeast Asia: an unresolved problem. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:227-237. Published 2017 Aug 10. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S133292

13. Psevdos G, Ford FM, Hong ST. Screening US Vietnam veterans for liver fluke exposure 5 decades after the end of the war. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md). 2018;26(4):208-210. doi:10.1097/IPC.0000000000000611

14. American War Library. In harm’s way... How many real Vietnam vets are alive today? Updated February 28, 2019. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.americanwarlibrary.com/personnel/vietvet.htm

15. Nash TE, Sullivan D, Mitre E, et al. Comments on “Screening US Vietnam veterans for liver fluke exposure 5 decades after the end of the war”. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md). 2018;26(4):240-241. doi:10.1097/IPC.0000000000000659

1. American Cancer Society. Survival rates for bile duct cancer. Updated March 1, 2023. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/bile-duct-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-by-stage.html

2. Vij M, Puri Y, Rammohan A, et al. Pathological, molecular, and clinical characteristics of cholangiocarcinoma: A comprehensive review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;14(3):607-627. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v14.i3.607

3. Yao KJ, Jabbour S, Parekh N, Lin Y, Moss RA. Increasing mortality in the United States from cholangiocarcinoma: an analysis of the National Center for Health Statistics Database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):117. Published 2016 Sep 21. doi:10.1186/s12876-016-0527-z

4. Rustagi T, Dasanu CA. Risk factors for gallbladder cancer and cholangiocarcinoma: similarities, differences and updates. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43(2):137-147. doi:10.1007/s12029-011-9284-y

5. Maemura K, Natsugoe S, Takao S. Molecular mechanism of cholangiocarcinoma carcinogenesis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21(10):754-760. doi:10.1002/jhbp.126

6. Steele JA, Richter CH, Echaubard P, et al. Thinking beyond Opisthorchis viverrini for risk of cholangiocarcinoma in the lower Mekong region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):44. Published 2018 May 17. doi:10.1186/s40249-018-0434-3.

7. Kim TS, Pak JH, Kim JB, Bahk YY. Clonorchis sinensis, an oriental liver fluke, as a human biological agent of cholangiocarcinoma: a brief review. BMB Rep. 2016;49(11):590-597. doi:10.5483/bmbrep.2016.49.11.109

8. Murata M. Inflammation and cancer. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23(1):50. Published 2018 Oct 20. doi:10.1186/s12199-018-0740-1

9. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Biological agents. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100(pt B):1-441.

10. Mairiang E, Laha T, Bethony JM, et al. Ultrasonography assessment of hepatobiliary abnormalities in 3359 subjects with Opisthorchis viverrini infection in endemic areas of Thailand. Parasitol Int. 2012;61(1):208-211. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2011.07.009

11. Li HM, Qian MB, Yang YC, et al. Performance evaluation of existing immunoassays for Clonorchis sinensis infection in China. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11(1):35. Published 2018 Jan 15. doi:10.1186/s13071-018-2612-3

12. Hughes T, O’Connor T, Techasen A, et al. Opisthorchiasis and cholangiocarcinoma in Southeast Asia: an unresolved problem. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:227-237. Published 2017 Aug 10. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S133292

13. Psevdos G, Ford FM, Hong ST. Screening US Vietnam veterans for liver fluke exposure 5 decades after the end of the war. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md). 2018;26(4):208-210. doi:10.1097/IPC.0000000000000611

14. American War Library. In harm’s way... How many real Vietnam vets are alive today? Updated February 28, 2019. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.americanwarlibrary.com/personnel/vietvet.htm

15. Nash TE, Sullivan D, Mitre E, et al. Comments on “Screening US Vietnam veterans for liver fluke exposure 5 decades after the end of the war”. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md). 2018;26(4):240-241. doi:10.1097/IPC.0000000000000659

Study of hospitalizations in Canada quantifies benefit of COVID-19 vaccine to reduce death, ICU admissions

A cohort study of more than 1.5 million hospital admissions in Canada through the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic has quantified the benefit of vaccinations. Unvaccinated patients were found to be up to 15 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than fully vaccinated patients.

Investigators analyzed 1.513 million admissions at 155 hospitals across Canada from March 15, 2020, to May 28, 2022. The study included 51,679 adult admissions and 4,035 pediatric admissions for COVID-19. Although the share of COVID-19 admissions increased in the fifth and sixth waves, from Dec. 26, 2021, to March 19, 2022 – after the full vaccine rollout – to 7.73% from 2.47% in the previous four waves, the proportion of adults admitted to the intensive care unit was significantly lower, at 8.7% versus 21.8% (odds ratio, 0.35; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-0.36).

“The good thing about waves five and six was we were able to show the COVID cases tended to be less severe, but on the other hand, because the disease in the community was so much higher, the demands on the health care system were much higher than the previous waves,” study author Charles Frenette, MD, director of infection prevention and control at McGill University, Montreal, and chair of the study’s adult subgroup, said in an interview. “But here we were able to show the benefit of vaccinations, particularly the boosting dose, in protecting against those severe outcomes.”

The study, published in JAMA Network Open, used the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program database, which collects hospital data across Canada. It was activated in March 2020 to collect details on all COVID-19 admissions, co-author Nisha Thampi, MD, chair of the study’s pediatric subgroup, told this news organization.

“We’re now over 3 years into the pandemic, and CNISP continues to monitor COVID-19 as well as other pathogens in near real time,” said Dr. Thampi, an associate professor and infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario.

“That’s a particular strength of this surveillance program as well. We would see this data on a biweekly basis, and that allows for [us] to implement timely protection and action.”

Tracing trends over six waves

The study tracked COVID-19 hospitalizations during six waves. The first lasted from March 15 to August 31, 2020, and the second lasted from Sept. 1, 2020, to Feb. 28, 2021. The wild-type variant was dominant during both waves. The third wave lasted from March 1 to June 30, 2021, and was marked by the mixed Alpha, Beta, and Gamma variants. The fourth wave lasted from July 1 to Dec. 25, 2021, when the Alpha variant was dominant. The Omicron variant dominated during waves five (Dec. 26, 2021, to March 19, 2022) and six (March 20 to May 28, 2022).

Hospitalizations reached a peak of 14,461 in wave five. ICU admissions, however, peaked at 2,164 during wave four, and all-cause deaths peaked at 1,663 during wave two.

The investigators also analyzed how unvaccinated patients fared, compared with the fully vaccinated and the fully vaccinated-plus (that is, patients with one or more additional doses). During waves five and six, unvaccinated patients were 4.3 times more likely to end up in the ICU than fully vaccinated patients and were 12.2 times more likely than fully vaccinated-plus patients. Likewise, the rate for all-cause in-hospital death for unvaccinated patients was 3.9 times greater than that for fully vaccinated patients and 15.1 times greater than that for fully vaccinated-plus patients.

The effect of vaccines emerged in waves three and four, said Dr. Frenette. “We started to see really, really significant protection and benefit from the vaccine, not only in incidence of admission but also in the incidence of complications of ICU care, ventilation, and mortality.”

Results for pediatric patients were similar to those for adults, Dr. Thampi noted. During waves five and six, overall admissions peaked, but the share of ICU admissions decreased to 9.4% from 18.1%, which was the rate during the previous four waves (OR, 0.47).

“What’s important is how pediatric hospitalizations changed over the course of the various waves,” said Dr. Thampi.

“Where we saw the highest admissions during the early Omicron dominance, we actually had the lowest numbers of hospitalizations with death and admissions into ICUs.”

Doing more with the data

David Fisman, MD, MPH, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto, said, “This is a study that shows us how tremendously dramatic the effects of the COVID-19 vaccine were in terms of saving lives during the pandemic.” Dr. Fisman was not involved in the study.

But CNISP, which receives funding from Public Health Agency of Canada, could do more with the data it collects to better protect the public from COVID-19 and other nosocomial infections, Dr. Fisman said.

“The first problematic thing about this paper is that Canadians are paying for a surveillance system that looks at risks of acquiring infections, including COVID-19 infections, in the hospital, but that data is not fed back to the people paying for its production,” he said.

“So, Canadians don’t have the ability to really understand in real time how much risk they’re experiencing via going to the hospital for some other reason.”

The study was independently supported. Dr. Frenette and Dr. Thampi report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fisman has disclosed financial relationships with Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Seqirus, Merck, the Ontario Nurses Association, and the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A cohort study of more than 1.5 million hospital admissions in Canada through the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic has quantified the benefit of vaccinations. Unvaccinated patients were found to be up to 15 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than fully vaccinated patients.

Investigators analyzed 1.513 million admissions at 155 hospitals across Canada from March 15, 2020, to May 28, 2022. The study included 51,679 adult admissions and 4,035 pediatric admissions for COVID-19. Although the share of COVID-19 admissions increased in the fifth and sixth waves, from Dec. 26, 2021, to March 19, 2022 – after the full vaccine rollout – to 7.73% from 2.47% in the previous four waves, the proportion of adults admitted to the intensive care unit was significantly lower, at 8.7% versus 21.8% (odds ratio, 0.35; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-0.36).

“The good thing about waves five and six was we were able to show the COVID cases tended to be less severe, but on the other hand, because the disease in the community was so much higher, the demands on the health care system were much higher than the previous waves,” study author Charles Frenette, MD, director of infection prevention and control at McGill University, Montreal, and chair of the study’s adult subgroup, said in an interview. “But here we were able to show the benefit of vaccinations, particularly the boosting dose, in protecting against those severe outcomes.”

The study, published in JAMA Network Open, used the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program database, which collects hospital data across Canada. It was activated in March 2020 to collect details on all COVID-19 admissions, co-author Nisha Thampi, MD, chair of the study’s pediatric subgroup, told this news organization.

“We’re now over 3 years into the pandemic, and CNISP continues to monitor COVID-19 as well as other pathogens in near real time,” said Dr. Thampi, an associate professor and infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario.

“That’s a particular strength of this surveillance program as well. We would see this data on a biweekly basis, and that allows for [us] to implement timely protection and action.”

Tracing trends over six waves

The study tracked COVID-19 hospitalizations during six waves. The first lasted from March 15 to August 31, 2020, and the second lasted from Sept. 1, 2020, to Feb. 28, 2021. The wild-type variant was dominant during both waves. The third wave lasted from March 1 to June 30, 2021, and was marked by the mixed Alpha, Beta, and Gamma variants. The fourth wave lasted from July 1 to Dec. 25, 2021, when the Alpha variant was dominant. The Omicron variant dominated during waves five (Dec. 26, 2021, to March 19, 2022) and six (March 20 to May 28, 2022).