User login

Children don’t have to belong to the clean plate club

It’s a scene you’re all too familiar with – you’ve gone to a lot of trouble to give your children a well-prepared and nutritious meal, but a lot of it never leaves the plate. It’s frustrating, and you worry about their health, but according to the Cornell Food and Brand Lab, this is not unusual behavior.

When an adult serves him or herself food, it almost all gets eaten, according to a study from Brian Wansink, Ph.D., director of the Cornell Food and Brand Lab in Ithaca, N.Y., with the average adult eating 92% of the food served. However, the same study also found that children eat only about 60% of the food they serve to themselves, indicating a broad difference in how adults and children approach food.

Adults know what they like, and if they try something new, they might only take a little bit in case they don’t like it. Children tend not to fully understand their limits and may take a lot of something they’ve never had before because it looks appetizing, try it, realize they don’t like it, and not finish it. “It’s natural, for them to make some mistakes and take a food they don’t like or to serve too much,” Dr. Wansink said.

Dr. Wansink noted that the children in the study were not eating with their parents, and perhaps they would have eaten more if their parents had been there, but not enough to account for the vast discrepancy between the two groups. Other possible factors in children eating less include uncertainty toward how much will make them full, whether or not they are eating with utensils, the presence of friends, and whether they are introverted or extroverted.

So for all the frustrated parents out there“who want his/her noncooperating children to be vegetable-eating members of the clean plate club,” there is good news in these results. “They show that children who only eat half to two-thirds of the food they serve themselves aren’t being wasteful, belligerent, or disrespectful,” Dr. Wansink concluded. It’s a matter of kids just being kids.

It’s a scene you’re all too familiar with – you’ve gone to a lot of trouble to give your children a well-prepared and nutritious meal, but a lot of it never leaves the plate. It’s frustrating, and you worry about their health, but according to the Cornell Food and Brand Lab, this is not unusual behavior.

When an adult serves him or herself food, it almost all gets eaten, according to a study from Brian Wansink, Ph.D., director of the Cornell Food and Brand Lab in Ithaca, N.Y., with the average adult eating 92% of the food served. However, the same study also found that children eat only about 60% of the food they serve to themselves, indicating a broad difference in how adults and children approach food.

Adults know what they like, and if they try something new, they might only take a little bit in case they don’t like it. Children tend not to fully understand their limits and may take a lot of something they’ve never had before because it looks appetizing, try it, realize they don’t like it, and not finish it. “It’s natural, for them to make some mistakes and take a food they don’t like or to serve too much,” Dr. Wansink said.

Dr. Wansink noted that the children in the study were not eating with their parents, and perhaps they would have eaten more if their parents had been there, but not enough to account for the vast discrepancy between the two groups. Other possible factors in children eating less include uncertainty toward how much will make them full, whether or not they are eating with utensils, the presence of friends, and whether they are introverted or extroverted.

So for all the frustrated parents out there“who want his/her noncooperating children to be vegetable-eating members of the clean plate club,” there is good news in these results. “They show that children who only eat half to two-thirds of the food they serve themselves aren’t being wasteful, belligerent, or disrespectful,” Dr. Wansink concluded. It’s a matter of kids just being kids.

It’s a scene you’re all too familiar with – you’ve gone to a lot of trouble to give your children a well-prepared and nutritious meal, but a lot of it never leaves the plate. It’s frustrating, and you worry about their health, but according to the Cornell Food and Brand Lab, this is not unusual behavior.

When an adult serves him or herself food, it almost all gets eaten, according to a study from Brian Wansink, Ph.D., director of the Cornell Food and Brand Lab in Ithaca, N.Y., with the average adult eating 92% of the food served. However, the same study also found that children eat only about 60% of the food they serve to themselves, indicating a broad difference in how adults and children approach food.

Adults know what they like, and if they try something new, they might only take a little bit in case they don’t like it. Children tend not to fully understand their limits and may take a lot of something they’ve never had before because it looks appetizing, try it, realize they don’t like it, and not finish it. “It’s natural, for them to make some mistakes and take a food they don’t like or to serve too much,” Dr. Wansink said.

Dr. Wansink noted that the children in the study were not eating with their parents, and perhaps they would have eaten more if their parents had been there, but not enough to account for the vast discrepancy between the two groups. Other possible factors in children eating less include uncertainty toward how much will make them full, whether or not they are eating with utensils, the presence of friends, and whether they are introverted or extroverted.

So for all the frustrated parents out there“who want his/her noncooperating children to be vegetable-eating members of the clean plate club,” there is good news in these results. “They show that children who only eat half to two-thirds of the food they serve themselves aren’t being wasteful, belligerent, or disrespectful,” Dr. Wansink concluded. It’s a matter of kids just being kids.

PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors show mettle against relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma

SAN FRANCISCO– PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors, which have shown remarkable efficacy against advanced malignant melanoma, appear to hold similar promise in the treatment of relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma, results from two early studies suggest.

In a phase I study, the PD-1 blocking antibody nivolumab produced an 87% response rate in 23 heavily pre-treated patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL). In a separate phase Ib study, pembrolizumab, which blocks the PD-1 and PD-2 ligands, produced a 66% overall response rate, 21% complete remission rate, and 86% clinical benefit rate among 29 patients with HL for whom therapy with brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) had failed.

The studies were presented at a media briefing prior to the presentation of data in oral sessions at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“Classical Hodgkin lymphoma appears to be a tumor with genetically determined vulnerability to PD-1 blockade. We hope that PD-1 blockade in the future can become an important part of the treatment of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma,” said Dr. Phillipe Armand from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, an investigator for the nivolumab study.

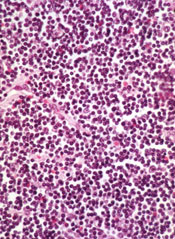

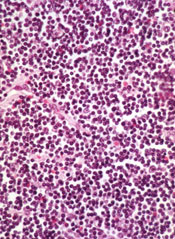

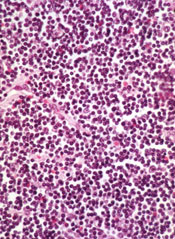

Evidence from preclinical studies suggests that the Reed-Sternberg malignant cells characteristic of HL may use the PD-1 (programmed death 1) pathway to evade detection by immune cells, as suggested by pathologic studies showing the cells surrounded by an extensive but ineffective infiltrate of inflammatory cells.

“We’ve wondered for a long time how Hodgkin lymphoma could attract such a brisk immune response and yet have this immune response fail to kill the tumor,” he said.

Genetic Achilles heel

Genetic analyses had shown that HL frequently has a mutation that results in amplification of a region on chromosome 9 (9p24.1) which leads to increased expression of PD-1 ligands 1 and 2, and leads to a downregulation or weakening of the immune response. The mutation appears to work through the Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator transcription (STAT) signalling. These findings suggested to researchers that classical HL has a genetically driven and, ideally, targetable dependence on the PD-1 pathway for survival, Dr. Armand explained.

To test this idea, he and colleagues studied 23 patients with relapsed or refractory HL that had been heavily pre-treated who were part of an independent expansion cohort of a study of nivolumab in hematologic malignancies. Of these patients, 78% were enrolled after a relapse following autologous stem cell transplantation, and 22% after treatment with brentuximab vedotin had failed.

The patients received nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks until they had either a complete response, tumor progression, or excessive side effects. In all, 20 of the 23 patients (87%) had an objective response to the single-agent therapy, including 4 (17%) complete responses and 16 (70%) partial responses. The remaining three patients (13%) had stable disease.

The longest time on study at the data cutoff point was 72 weeks. Among all responders, 60% had a response by 8 weeks of therapy, 48% are ongoing, and 43% of patients are still on treatment.

Drug-related adverse events were reported in 18 patients, most commonly rash and decreased platelet count. Five patients had grade 3 events. There were no drug-related grade 4 events or deaths.

In an editorial accompanying the study, which was also published online in The New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Mario Sznoll and Dr. Dan L. Longo from the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut write that “with recent data showing impressive clinical activity of PD-1 or PD-L1 antagonists in subgroups of patients with a variety of different cancers, the critical and foundational role of immune interventions in cancer treatment is no longer deniable,” (NEJM, Dec. 6, 2014 [DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087]).

Pembrolizumab trial

Dr. Craig H. Moskowitz from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City discussed results of the second study, dubbed KEYNOTE-013 (A Phase Ib Multi-Cohort Trial of MK-3475 in Subjects With Hematologic Malignancies).

In this study, patients with HL who were not transplant eligible or for whom transplant had failed and who either had a relapse or were refractory to therapy with brentuximab vedotin received 19 mg/kg IV infusion of pembrolizumab every 2 weeks until complete response, partial response/stable disease, or disease progression.

Of the 31 patients enrolled, 29 were available for the analysis. As of the data cutoff in November 2014, 6 patients (21%) had achieved a complete remission, and 13 (45%) had a partial response, for an overall response rate of 66%. The median time to response was 12 weeks, and as of the data cutoff 17 of 19 patients had ongoing responses. The median response duration has not yet been reached. An additional 6 patients (21%) had stable disease, leading to an overall clinical benefit rate (responses plus stable disease) of 86%.

The patients generally tolerated the drug well. There were 4 treatment-related adverse events in 3 patients, including axillary pain, hypoxia, joint swelling, and pneumonitis. There were no grade 4 treatment-related events or deaths.

Of the tumor samples evaluable, all expressed PD-L1, supporting the rationale for PD-1 blockade in this population, Dr. Moskowitz said.

The results of both his and Dr. Armand’s study support the continued development of PD-1 inhibitors in various subsets of patients with classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma, he said.

SAN FRANCISCO– PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors, which have shown remarkable efficacy against advanced malignant melanoma, appear to hold similar promise in the treatment of relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma, results from two early studies suggest.

In a phase I study, the PD-1 blocking antibody nivolumab produced an 87% response rate in 23 heavily pre-treated patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL). In a separate phase Ib study, pembrolizumab, which blocks the PD-1 and PD-2 ligands, produced a 66% overall response rate, 21% complete remission rate, and 86% clinical benefit rate among 29 patients with HL for whom therapy with brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) had failed.

The studies were presented at a media briefing prior to the presentation of data in oral sessions at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“Classical Hodgkin lymphoma appears to be a tumor with genetically determined vulnerability to PD-1 blockade. We hope that PD-1 blockade in the future can become an important part of the treatment of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma,” said Dr. Phillipe Armand from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, an investigator for the nivolumab study.

Evidence from preclinical studies suggests that the Reed-Sternberg malignant cells characteristic of HL may use the PD-1 (programmed death 1) pathway to evade detection by immune cells, as suggested by pathologic studies showing the cells surrounded by an extensive but ineffective infiltrate of inflammatory cells.

“We’ve wondered for a long time how Hodgkin lymphoma could attract such a brisk immune response and yet have this immune response fail to kill the tumor,” he said.

Genetic Achilles heel

Genetic analyses had shown that HL frequently has a mutation that results in amplification of a region on chromosome 9 (9p24.1) which leads to increased expression of PD-1 ligands 1 and 2, and leads to a downregulation or weakening of the immune response. The mutation appears to work through the Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator transcription (STAT) signalling. These findings suggested to researchers that classical HL has a genetically driven and, ideally, targetable dependence on the PD-1 pathway for survival, Dr. Armand explained.

To test this idea, he and colleagues studied 23 patients with relapsed or refractory HL that had been heavily pre-treated who were part of an independent expansion cohort of a study of nivolumab in hematologic malignancies. Of these patients, 78% were enrolled after a relapse following autologous stem cell transplantation, and 22% after treatment with brentuximab vedotin had failed.

The patients received nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks until they had either a complete response, tumor progression, or excessive side effects. In all, 20 of the 23 patients (87%) had an objective response to the single-agent therapy, including 4 (17%) complete responses and 16 (70%) partial responses. The remaining three patients (13%) had stable disease.

The longest time on study at the data cutoff point was 72 weeks. Among all responders, 60% had a response by 8 weeks of therapy, 48% are ongoing, and 43% of patients are still on treatment.

Drug-related adverse events were reported in 18 patients, most commonly rash and decreased platelet count. Five patients had grade 3 events. There were no drug-related grade 4 events or deaths.

In an editorial accompanying the study, which was also published online in The New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Mario Sznoll and Dr. Dan L. Longo from the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut write that “with recent data showing impressive clinical activity of PD-1 or PD-L1 antagonists in subgroups of patients with a variety of different cancers, the critical and foundational role of immune interventions in cancer treatment is no longer deniable,” (NEJM, Dec. 6, 2014 [DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087]).

Pembrolizumab trial

Dr. Craig H. Moskowitz from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City discussed results of the second study, dubbed KEYNOTE-013 (A Phase Ib Multi-Cohort Trial of MK-3475 in Subjects With Hematologic Malignancies).

In this study, patients with HL who were not transplant eligible or for whom transplant had failed and who either had a relapse or were refractory to therapy with brentuximab vedotin received 19 mg/kg IV infusion of pembrolizumab every 2 weeks until complete response, partial response/stable disease, or disease progression.

Of the 31 patients enrolled, 29 were available for the analysis. As of the data cutoff in November 2014, 6 patients (21%) had achieved a complete remission, and 13 (45%) had a partial response, for an overall response rate of 66%. The median time to response was 12 weeks, and as of the data cutoff 17 of 19 patients had ongoing responses. The median response duration has not yet been reached. An additional 6 patients (21%) had stable disease, leading to an overall clinical benefit rate (responses plus stable disease) of 86%.

The patients generally tolerated the drug well. There were 4 treatment-related adverse events in 3 patients, including axillary pain, hypoxia, joint swelling, and pneumonitis. There were no grade 4 treatment-related events or deaths.

Of the tumor samples evaluable, all expressed PD-L1, supporting the rationale for PD-1 blockade in this population, Dr. Moskowitz said.

The results of both his and Dr. Armand’s study support the continued development of PD-1 inhibitors in various subsets of patients with classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma, he said.

SAN FRANCISCO– PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors, which have shown remarkable efficacy against advanced malignant melanoma, appear to hold similar promise in the treatment of relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma, results from two early studies suggest.

In a phase I study, the PD-1 blocking antibody nivolumab produced an 87% response rate in 23 heavily pre-treated patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL). In a separate phase Ib study, pembrolizumab, which blocks the PD-1 and PD-2 ligands, produced a 66% overall response rate, 21% complete remission rate, and 86% clinical benefit rate among 29 patients with HL for whom therapy with brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) had failed.

The studies were presented at a media briefing prior to the presentation of data in oral sessions at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“Classical Hodgkin lymphoma appears to be a tumor with genetically determined vulnerability to PD-1 blockade. We hope that PD-1 blockade in the future can become an important part of the treatment of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma,” said Dr. Phillipe Armand from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, an investigator for the nivolumab study.

Evidence from preclinical studies suggests that the Reed-Sternberg malignant cells characteristic of HL may use the PD-1 (programmed death 1) pathway to evade detection by immune cells, as suggested by pathologic studies showing the cells surrounded by an extensive but ineffective infiltrate of inflammatory cells.

“We’ve wondered for a long time how Hodgkin lymphoma could attract such a brisk immune response and yet have this immune response fail to kill the tumor,” he said.

Genetic Achilles heel

Genetic analyses had shown that HL frequently has a mutation that results in amplification of a region on chromosome 9 (9p24.1) which leads to increased expression of PD-1 ligands 1 and 2, and leads to a downregulation or weakening of the immune response. The mutation appears to work through the Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator transcription (STAT) signalling. These findings suggested to researchers that classical HL has a genetically driven and, ideally, targetable dependence on the PD-1 pathway for survival, Dr. Armand explained.

To test this idea, he and colleagues studied 23 patients with relapsed or refractory HL that had been heavily pre-treated who were part of an independent expansion cohort of a study of nivolumab in hematologic malignancies. Of these patients, 78% were enrolled after a relapse following autologous stem cell transplantation, and 22% after treatment with brentuximab vedotin had failed.

The patients received nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks until they had either a complete response, tumor progression, or excessive side effects. In all, 20 of the 23 patients (87%) had an objective response to the single-agent therapy, including 4 (17%) complete responses and 16 (70%) partial responses. The remaining three patients (13%) had stable disease.

The longest time on study at the data cutoff point was 72 weeks. Among all responders, 60% had a response by 8 weeks of therapy, 48% are ongoing, and 43% of patients are still on treatment.

Drug-related adverse events were reported in 18 patients, most commonly rash and decreased platelet count. Five patients had grade 3 events. There were no drug-related grade 4 events or deaths.

In an editorial accompanying the study, which was also published online in The New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Mario Sznoll and Dr. Dan L. Longo from the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut write that “with recent data showing impressive clinical activity of PD-1 or PD-L1 antagonists in subgroups of patients with a variety of different cancers, the critical and foundational role of immune interventions in cancer treatment is no longer deniable,” (NEJM, Dec. 6, 2014 [DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087]).

Pembrolizumab trial

Dr. Craig H. Moskowitz from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City discussed results of the second study, dubbed KEYNOTE-013 (A Phase Ib Multi-Cohort Trial of MK-3475 in Subjects With Hematologic Malignancies).

In this study, patients with HL who were not transplant eligible or for whom transplant had failed and who either had a relapse or were refractory to therapy with brentuximab vedotin received 19 mg/kg IV infusion of pembrolizumab every 2 weeks until complete response, partial response/stable disease, or disease progression.

Of the 31 patients enrolled, 29 were available for the analysis. As of the data cutoff in November 2014, 6 patients (21%) had achieved a complete remission, and 13 (45%) had a partial response, for an overall response rate of 66%. The median time to response was 12 weeks, and as of the data cutoff 17 of 19 patients had ongoing responses. The median response duration has not yet been reached. An additional 6 patients (21%) had stable disease, leading to an overall clinical benefit rate (responses plus stable disease) of 86%.

The patients generally tolerated the drug well. There were 4 treatment-related adverse events in 3 patients, including axillary pain, hypoxia, joint swelling, and pneumonitis. There were no grade 4 treatment-related events or deaths.

Of the tumor samples evaluable, all expressed PD-L1, supporting the rationale for PD-1 blockade in this population, Dr. Moskowitz said.

The results of both his and Dr. Armand’s study support the continued development of PD-1 inhibitors in various subsets of patients with classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma, he said.

Key clinical point: PD-1 checkpoint inhibition appears to be an effective strategy against treatment-refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Major finding: Nivolumab produced an 87% objective response rate and pembrolizumab a 66% response rate in patients with heavily pre-treated Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Data source: A phase I study with 23 patients and a phase Ib study with 29 patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Disclosures: Dr. Armand’s study is supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb. He reported grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Merck outside the study. Dr. Moskowitz’ study is supported by Merck. He reported receiving research funding from the company. Dr. Sznol reported personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dr. Longo reported no relevant disclosures.

Health Canada approves ibrutinib for CLL

Health Canada recently approved the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The drug can now be used to treat CLL patients, including those with 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy. It can also be used as frontline treatment in CLL patients with 17p deletion.

Health Canada’s approval of ibrutinib is based on results of the phase 3 RESONATE trial, which were presented at this year’s ASCO and EHA meetings.

The trial included 391 previously treated patients, 127 of whom had 17p deletion. Patients were randomized to receive ibrutinib or the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ofatumumab until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The trial was stopped early after a pre-planned interim analysis showed that ibrutinib-treated patients experienced a 78% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death.

At the time of interim analysis, the patients’ median time on study was 9.4 months. The best overall response among evaluable patients was 78% in the ibrutinib arm and 11% in the ofatumumab arm.

Ibrutinib significantly prolonged progression-free and overall survival. The median progression-free survival was 8.1 months in the ofatumumab arm and was not reached in the ibrutinib arm (P<0.0001). The median overall survival was not reached in either arm, but the hazard ratio was 0.434 (P=0.0049).

Of the 127 patients with 17p deletion, those treated with ibrutinib experienced a 75% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death.

Adverse events occurred in 99% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 98% of those in the ofatumumab arm. Grade 3/4 events occurred in 51% and 39%, respectively.

Atrial fibrillation, bleeding-related events, diarrhea, and arthralgia were more common in the ibrutinib arm. Infusion-related reactions, peripheral sensory neuropathy, urticaria, night sweats, and pruritus were more common in the ofatumumab arm.

Ibrutinib is being developed by Cilag GmbH International (a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies) and Pharmacyclics, Inc. Janssen will commercialize the drug in Canada, and Janssen affiliates will commercialize it around the world, except in the US, where Pharmacyclics and Janssen Biotech, Inc. co-market it. ![]()

Health Canada recently approved the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The drug can now be used to treat CLL patients, including those with 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy. It can also be used as frontline treatment in CLL patients with 17p deletion.

Health Canada’s approval of ibrutinib is based on results of the phase 3 RESONATE trial, which were presented at this year’s ASCO and EHA meetings.

The trial included 391 previously treated patients, 127 of whom had 17p deletion. Patients were randomized to receive ibrutinib or the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ofatumumab until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The trial was stopped early after a pre-planned interim analysis showed that ibrutinib-treated patients experienced a 78% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death.

At the time of interim analysis, the patients’ median time on study was 9.4 months. The best overall response among evaluable patients was 78% in the ibrutinib arm and 11% in the ofatumumab arm.

Ibrutinib significantly prolonged progression-free and overall survival. The median progression-free survival was 8.1 months in the ofatumumab arm and was not reached in the ibrutinib arm (P<0.0001). The median overall survival was not reached in either arm, but the hazard ratio was 0.434 (P=0.0049).

Of the 127 patients with 17p deletion, those treated with ibrutinib experienced a 75% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death.

Adverse events occurred in 99% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 98% of those in the ofatumumab arm. Grade 3/4 events occurred in 51% and 39%, respectively.

Atrial fibrillation, bleeding-related events, diarrhea, and arthralgia were more common in the ibrutinib arm. Infusion-related reactions, peripheral sensory neuropathy, urticaria, night sweats, and pruritus were more common in the ofatumumab arm.

Ibrutinib is being developed by Cilag GmbH International (a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies) and Pharmacyclics, Inc. Janssen will commercialize the drug in Canada, and Janssen affiliates will commercialize it around the world, except in the US, where Pharmacyclics and Janssen Biotech, Inc. co-market it. ![]()

Health Canada recently approved the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The drug can now be used to treat CLL patients, including those with 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy. It can also be used as frontline treatment in CLL patients with 17p deletion.

Health Canada’s approval of ibrutinib is based on results of the phase 3 RESONATE trial, which were presented at this year’s ASCO and EHA meetings.

The trial included 391 previously treated patients, 127 of whom had 17p deletion. Patients were randomized to receive ibrutinib or the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ofatumumab until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The trial was stopped early after a pre-planned interim analysis showed that ibrutinib-treated patients experienced a 78% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death.

At the time of interim analysis, the patients’ median time on study was 9.4 months. The best overall response among evaluable patients was 78% in the ibrutinib arm and 11% in the ofatumumab arm.

Ibrutinib significantly prolonged progression-free and overall survival. The median progression-free survival was 8.1 months in the ofatumumab arm and was not reached in the ibrutinib arm (P<0.0001). The median overall survival was not reached in either arm, but the hazard ratio was 0.434 (P=0.0049).

Of the 127 patients with 17p deletion, those treated with ibrutinib experienced a 75% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death.

Adverse events occurred in 99% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 98% of those in the ofatumumab arm. Grade 3/4 events occurred in 51% and 39%, respectively.

Atrial fibrillation, bleeding-related events, diarrhea, and arthralgia were more common in the ibrutinib arm. Infusion-related reactions, peripheral sensory neuropathy, urticaria, night sweats, and pruritus were more common in the ofatumumab arm.

Ibrutinib is being developed by Cilag GmbH International (a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies) and Pharmacyclics, Inc. Janssen will commercialize the drug in Canada, and Janssen affiliates will commercialize it around the world, except in the US, where Pharmacyclics and Janssen Biotech, Inc. co-market it. ![]()

People often dismiss cancer symptoms, survey suggests

Credit: NIH

People could be putting their lives at risk by dismissing potential warning signs of cancer as less serious symptoms, according to a study published in PLOS ONE.

In a survey of about 1700 people, more than half of respondents said they had experienced at least

one red-flag cancer “alarm” symptom—such as persistent, unexplained pain or an unexplained lump—during the previous 3 months, but

only 2% of them thought cancer was a possible cause.

The survey had been sent to people aged 50 and older who were registered with 3 London general practices. The questionnaire listed 17 symptoms, including 10 widely publicized potential cancer warning signs, such as an unexplained cough, bleeding, and a persistent change in bowel or bladder habits.

Cancer was not mentioned, but the survey asked which of the symptoms subjects had experienced, what they thought caused them, if they were concerned that symptoms were serious, and whether they had consulted their doctor.

Of the 1724 subjects who responded, 53% had experienced at least one cancer “alarm” symptom in the previous 3 months.

This included unexplained cough or hoarseness; persistent change in bowel habits; persistent, unexplained pain; persistent change in bladder habits; unexplained lump; a change in the appearance of a mole; a sore that does not heal; unexplained bleeding; unexplained weight loss; and persistent difficulty swallowing.

Persistent cough (20%) and persistent change in bowel habits (18%) were the most common symptoms. Difficulty swallowing and unexplained weight loss (both 4%) were least common.

Overall, subjects appraised the cancer warning “alarm” symptoms as more serious than “non-alarm” symptoms, such as sore throat and feeling tired. Fifty-nine percent of respondents said they contacted a doctor about their “alarm” symptoms.

However, subjects rarely attributed potential signs of cancer to the disease, putting them down to other reasons, such as age, infection, arthritis, piles, and cysts.

“Most people with potential warning symptoms don’t have cancer, but some will, and others may have other diseases that would benefit from early attention,” said study author Katriina Whitaker, PhD, of University College London in the UK.

“That’s why it’s important that these symptoms are checked out, especially if they don’t go away. But people could delay seeing a doctor if they don’t acknowledge cancer as a possible cause. It’s worrying that even the more obvious warning symptoms, such as unexplained lumps or changes to the appearance of a mole, were rarely attributed to cancer, although they are often well recognized in surveys that assess the public’s knowledge of the disease.”

“Even when people thought warning symptoms might be serious, cancer didn’t tend to spring to mind. This might be because people were frightened and reluctant to mention cancer, thought cancer wouldn’t happen to them, or believed other causes were more likely.” ![]()

Credit: NIH

People could be putting their lives at risk by dismissing potential warning signs of cancer as less serious symptoms, according to a study published in PLOS ONE.

In a survey of about 1700 people, more than half of respondents said they had experienced at least

one red-flag cancer “alarm” symptom—such as persistent, unexplained pain or an unexplained lump—during the previous 3 months, but

only 2% of them thought cancer was a possible cause.

The survey had been sent to people aged 50 and older who were registered with 3 London general practices. The questionnaire listed 17 symptoms, including 10 widely publicized potential cancer warning signs, such as an unexplained cough, bleeding, and a persistent change in bowel or bladder habits.

Cancer was not mentioned, but the survey asked which of the symptoms subjects had experienced, what they thought caused them, if they were concerned that symptoms were serious, and whether they had consulted their doctor.

Of the 1724 subjects who responded, 53% had experienced at least one cancer “alarm” symptom in the previous 3 months.

This included unexplained cough or hoarseness; persistent change in bowel habits; persistent, unexplained pain; persistent change in bladder habits; unexplained lump; a change in the appearance of a mole; a sore that does not heal; unexplained bleeding; unexplained weight loss; and persistent difficulty swallowing.

Persistent cough (20%) and persistent change in bowel habits (18%) were the most common symptoms. Difficulty swallowing and unexplained weight loss (both 4%) were least common.

Overall, subjects appraised the cancer warning “alarm” symptoms as more serious than “non-alarm” symptoms, such as sore throat and feeling tired. Fifty-nine percent of respondents said they contacted a doctor about their “alarm” symptoms.

However, subjects rarely attributed potential signs of cancer to the disease, putting them down to other reasons, such as age, infection, arthritis, piles, and cysts.

“Most people with potential warning symptoms don’t have cancer, but some will, and others may have other diseases that would benefit from early attention,” said study author Katriina Whitaker, PhD, of University College London in the UK.

“That’s why it’s important that these symptoms are checked out, especially if they don’t go away. But people could delay seeing a doctor if they don’t acknowledge cancer as a possible cause. It’s worrying that even the more obvious warning symptoms, such as unexplained lumps or changes to the appearance of a mole, were rarely attributed to cancer, although they are often well recognized in surveys that assess the public’s knowledge of the disease.”

“Even when people thought warning symptoms might be serious, cancer didn’t tend to spring to mind. This might be because people were frightened and reluctant to mention cancer, thought cancer wouldn’t happen to them, or believed other causes were more likely.” ![]()

Credit: NIH

People could be putting their lives at risk by dismissing potential warning signs of cancer as less serious symptoms, according to a study published in PLOS ONE.

In a survey of about 1700 people, more than half of respondents said they had experienced at least

one red-flag cancer “alarm” symptom—such as persistent, unexplained pain or an unexplained lump—during the previous 3 months, but

only 2% of them thought cancer was a possible cause.

The survey had been sent to people aged 50 and older who were registered with 3 London general practices. The questionnaire listed 17 symptoms, including 10 widely publicized potential cancer warning signs, such as an unexplained cough, bleeding, and a persistent change in bowel or bladder habits.

Cancer was not mentioned, but the survey asked which of the symptoms subjects had experienced, what they thought caused them, if they were concerned that symptoms were serious, and whether they had consulted their doctor.

Of the 1724 subjects who responded, 53% had experienced at least one cancer “alarm” symptom in the previous 3 months.

This included unexplained cough or hoarseness; persistent change in bowel habits; persistent, unexplained pain; persistent change in bladder habits; unexplained lump; a change in the appearance of a mole; a sore that does not heal; unexplained bleeding; unexplained weight loss; and persistent difficulty swallowing.

Persistent cough (20%) and persistent change in bowel habits (18%) were the most common symptoms. Difficulty swallowing and unexplained weight loss (both 4%) were least common.

Overall, subjects appraised the cancer warning “alarm” symptoms as more serious than “non-alarm” symptoms, such as sore throat and feeling tired. Fifty-nine percent of respondents said they contacted a doctor about their “alarm” symptoms.

However, subjects rarely attributed potential signs of cancer to the disease, putting them down to other reasons, such as age, infection, arthritis, piles, and cysts.

“Most people with potential warning symptoms don’t have cancer, but some will, and others may have other diseases that would benefit from early attention,” said study author Katriina Whitaker, PhD, of University College London in the UK.

“That’s why it’s important that these symptoms are checked out, especially if they don’t go away. But people could delay seeing a doctor if they don’t acknowledge cancer as a possible cause. It’s worrying that even the more obvious warning symptoms, such as unexplained lumps or changes to the appearance of a mole, were rarely attributed to cancer, although they are often well recognized in surveys that assess the public’s knowledge of the disease.”

“Even when people thought warning symptoms might be serious, cancer didn’t tend to spring to mind. This might be because people were frightened and reluctant to mention cancer, thought cancer wouldn’t happen to them, or believed other causes were more likely.” ![]()

Rivaroxaban matches warfarin’s total Afib costs

CHICAGO – Patients with atrial fibrillation who start treatment with a new oral anticoagulant may spend more on their medication than if they were prescribed generic warfarin, but their overall health care costs may wind up being about the same, based on an analysis of health care expense records for more than 4,500 U.S. patients.

“Despite higher anticoagulant costs, total all-cause and atrial fibrillation–related costs remain comparable” between patients prescribed warfarin and those who received the new oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto), said Concetta Crivera, Pharm.D., at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions. Higher drug costs for daily treatment with rivaroxaban were offset by reduced hospital lengths of stays and hence reduced hospitalization costs, said Dr. Crivera, director of cardiovascular health economics and outcomes research at Janssen in Raritan, N.J., the company that markets rivaroxaban along with Bayer.

“I can believe that hospitalized days would be reduced because patients treated with rivaroxaban or any of the other new oral anticoagulants don’t need to remain in the hospital while you wait for their international normalized ratio to enter the therapeutic range,” which is what happens with patients treated with warfarin, commented Dr. Jeffrey Weitz, professor of medicine and director of the Juravinski Hospital and Cancer Centre of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

The new findings by Dr. Crivera “are not definitive on their own, but they add to a growing body of data that indicate that all the new oral anticoagulants are cost effective,” said Dr. Weitz, who specializes in thrombosis and anticoagulants. “The worst time for a patient on warfarin is when they start treatment. You do a disservice to patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation by using warfarin, because some patients will get into the therapeutic range but others never will. That’s why the new oral anticoagulants are better, because everybody gets into therapeutic range,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Crivera and her associates conducted a retrospective study of health records for 2,253 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) who started anticoagulation treatment with rivaroxaban during the period of November 2011 (when the drug received U.S. marketing approval) through December 2012. The data came from the patient records of Humana, a U.S. HMO and insurer that covers both commercially insured patients and those covered by Medicare. The researchers matched each of the patients initiating rivaroxaban treatment with a similar patient from the Humana database with nonvalvular AF who started on warfarin during the same period. The average age of patients in the study was about 74 years, and patients in the two groups were closely matched for their demographic and clinical characteristics, including comorbidities. Data on health care use were available for patients for an average of about 4 months following their start of anticoagulant treatment.

The analysis showed that during the first months on treatment, patients prescribed rivaroxaban averaged 2.11 days of hospitalization for an AF-related episode, compared with 3.02 days for those prescribed warfarin, a statistically significant difference. Hospitalizations for any cause averaged a total of 2.71 days in the rivaroxaban group and 3.87 days in the patients on warfarin, also a significant difference, Dr. Crivera reported.

This difference in days hospitalized translated into reduced hospitalization costs, a roughly $2,000 average difference per patient in actual hospitalization costs in favor of the rivaroxaban patients for all-cause hospitalizations, and an average $1,300 difference per patient for hospitalization costs directly related to AF.

Although the rivaroxaban patients spent an average of $2,700 more per patient on pharmaceuticals for all causes, and an average $2,200 more for AF-related drugs, the total average all-cause and AF-related costs for drugs, hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and emergency department visits were similar in the two subgroups: an average total of $17,590 per patient for the rivaroxaban patients and $18,676 for warfarin patients for all causes, and an average of $7,394 for the rivaroxaban patients and $7,319 for those on warfarin for AF-related care. The between-group differences for both sets of total costs were not statistically significant.

The study was sponsored by Janssen, which along with Bayer markets rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Crivera is a Janssen employee. Dr. Weitz has been an adviser or a consultant to Janssen and Bayer and to Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Pfizer, and Portola.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

CHICAGO – Patients with atrial fibrillation who start treatment with a new oral anticoagulant may spend more on their medication than if they were prescribed generic warfarin, but their overall health care costs may wind up being about the same, based on an analysis of health care expense records for more than 4,500 U.S. patients.

“Despite higher anticoagulant costs, total all-cause and atrial fibrillation–related costs remain comparable” between patients prescribed warfarin and those who received the new oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto), said Concetta Crivera, Pharm.D., at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions. Higher drug costs for daily treatment with rivaroxaban were offset by reduced hospital lengths of stays and hence reduced hospitalization costs, said Dr. Crivera, director of cardiovascular health economics and outcomes research at Janssen in Raritan, N.J., the company that markets rivaroxaban along with Bayer.

“I can believe that hospitalized days would be reduced because patients treated with rivaroxaban or any of the other new oral anticoagulants don’t need to remain in the hospital while you wait for their international normalized ratio to enter the therapeutic range,” which is what happens with patients treated with warfarin, commented Dr. Jeffrey Weitz, professor of medicine and director of the Juravinski Hospital and Cancer Centre of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

The new findings by Dr. Crivera “are not definitive on their own, but they add to a growing body of data that indicate that all the new oral anticoagulants are cost effective,” said Dr. Weitz, who specializes in thrombosis and anticoagulants. “The worst time for a patient on warfarin is when they start treatment. You do a disservice to patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation by using warfarin, because some patients will get into the therapeutic range but others never will. That’s why the new oral anticoagulants are better, because everybody gets into therapeutic range,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Crivera and her associates conducted a retrospective study of health records for 2,253 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) who started anticoagulation treatment with rivaroxaban during the period of November 2011 (when the drug received U.S. marketing approval) through December 2012. The data came from the patient records of Humana, a U.S. HMO and insurer that covers both commercially insured patients and those covered by Medicare. The researchers matched each of the patients initiating rivaroxaban treatment with a similar patient from the Humana database with nonvalvular AF who started on warfarin during the same period. The average age of patients in the study was about 74 years, and patients in the two groups were closely matched for their demographic and clinical characteristics, including comorbidities. Data on health care use were available for patients for an average of about 4 months following their start of anticoagulant treatment.

The analysis showed that during the first months on treatment, patients prescribed rivaroxaban averaged 2.11 days of hospitalization for an AF-related episode, compared with 3.02 days for those prescribed warfarin, a statistically significant difference. Hospitalizations for any cause averaged a total of 2.71 days in the rivaroxaban group and 3.87 days in the patients on warfarin, also a significant difference, Dr. Crivera reported.

This difference in days hospitalized translated into reduced hospitalization costs, a roughly $2,000 average difference per patient in actual hospitalization costs in favor of the rivaroxaban patients for all-cause hospitalizations, and an average $1,300 difference per patient for hospitalization costs directly related to AF.

Although the rivaroxaban patients spent an average of $2,700 more per patient on pharmaceuticals for all causes, and an average $2,200 more for AF-related drugs, the total average all-cause and AF-related costs for drugs, hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and emergency department visits were similar in the two subgroups: an average total of $17,590 per patient for the rivaroxaban patients and $18,676 for warfarin patients for all causes, and an average of $7,394 for the rivaroxaban patients and $7,319 for those on warfarin for AF-related care. The between-group differences for both sets of total costs were not statistically significant.

The study was sponsored by Janssen, which along with Bayer markets rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Crivera is a Janssen employee. Dr. Weitz has been an adviser or a consultant to Janssen and Bayer and to Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Pfizer, and Portola.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

CHICAGO – Patients with atrial fibrillation who start treatment with a new oral anticoagulant may spend more on their medication than if they were prescribed generic warfarin, but their overall health care costs may wind up being about the same, based on an analysis of health care expense records for more than 4,500 U.S. patients.

“Despite higher anticoagulant costs, total all-cause and atrial fibrillation–related costs remain comparable” between patients prescribed warfarin and those who received the new oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto), said Concetta Crivera, Pharm.D., at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions. Higher drug costs for daily treatment with rivaroxaban were offset by reduced hospital lengths of stays and hence reduced hospitalization costs, said Dr. Crivera, director of cardiovascular health economics and outcomes research at Janssen in Raritan, N.J., the company that markets rivaroxaban along with Bayer.

“I can believe that hospitalized days would be reduced because patients treated with rivaroxaban or any of the other new oral anticoagulants don’t need to remain in the hospital while you wait for their international normalized ratio to enter the therapeutic range,” which is what happens with patients treated with warfarin, commented Dr. Jeffrey Weitz, professor of medicine and director of the Juravinski Hospital and Cancer Centre of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

The new findings by Dr. Crivera “are not definitive on their own, but they add to a growing body of data that indicate that all the new oral anticoagulants are cost effective,” said Dr. Weitz, who specializes in thrombosis and anticoagulants. “The worst time for a patient on warfarin is when they start treatment. You do a disservice to patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation by using warfarin, because some patients will get into the therapeutic range but others never will. That’s why the new oral anticoagulants are better, because everybody gets into therapeutic range,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Crivera and her associates conducted a retrospective study of health records for 2,253 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) who started anticoagulation treatment with rivaroxaban during the period of November 2011 (when the drug received U.S. marketing approval) through December 2012. The data came from the patient records of Humana, a U.S. HMO and insurer that covers both commercially insured patients and those covered by Medicare. The researchers matched each of the patients initiating rivaroxaban treatment with a similar patient from the Humana database with nonvalvular AF who started on warfarin during the same period. The average age of patients in the study was about 74 years, and patients in the two groups were closely matched for their demographic and clinical characteristics, including comorbidities. Data on health care use were available for patients for an average of about 4 months following their start of anticoagulant treatment.

The analysis showed that during the first months on treatment, patients prescribed rivaroxaban averaged 2.11 days of hospitalization for an AF-related episode, compared with 3.02 days for those prescribed warfarin, a statistically significant difference. Hospitalizations for any cause averaged a total of 2.71 days in the rivaroxaban group and 3.87 days in the patients on warfarin, also a significant difference, Dr. Crivera reported.

This difference in days hospitalized translated into reduced hospitalization costs, a roughly $2,000 average difference per patient in actual hospitalization costs in favor of the rivaroxaban patients for all-cause hospitalizations, and an average $1,300 difference per patient for hospitalization costs directly related to AF.

Although the rivaroxaban patients spent an average of $2,700 more per patient on pharmaceuticals for all causes, and an average $2,200 more for AF-related drugs, the total average all-cause and AF-related costs for drugs, hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and emergency department visits were similar in the two subgroups: an average total of $17,590 per patient for the rivaroxaban patients and $18,676 for warfarin patients for all causes, and an average of $7,394 for the rivaroxaban patients and $7,319 for those on warfarin for AF-related care. The between-group differences for both sets of total costs were not statistically significant.

The study was sponsored by Janssen, which along with Bayer markets rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Crivera is a Janssen employee. Dr. Weitz has been an adviser or a consultant to Janssen and Bayer and to Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Pfizer, and Portola.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Patients with atrial fibrillation who started on rivaroxaban treatment had total hospitalization and drug costs that were similar to those of patients begun on warfarin.

Major finding: Rivaroxaban-treated patients averaged $17,590 in total all-cause hospitalization and drug costs, compared with $18,676 for warfarin-treated patients.

Data source: A retrospective, matched-cohort study of 4,506 U.S. patients with atrial fibrillation and newly initiated anticoagulant treatment using health records maintained by Humana.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Janssen, which along with Bayer markets rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Crivera is a Janssen employee. Dr. Weitz has been an adviser or a consultant to Janssen and Bayer and to Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Pfizer, and Portola.

Breast cancer drug could treat MPNs, AML

Credit: CDC

Tamoxifen, a drug used to treat breast cancer, may be effective against myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) as well, according to research published in Cell Stem Cell.

The study showed that estrogens regulate the survival, proliferation, and self-renewal of stem cells that give rise to MPNs and AML.

Tamoxifen, which targets estrogen receptors, prevented JAK2V617F-induced MPNs in mice and enhanced the effects of chemotherapy against MLL-AF9-induced AML.

“In this study, we demonstrate that tamoxifen has specific effects on certain cells in the bone marrow: the hematopoietic stem cells and their immediate descendants, known as multipotent progenitors,” explained study author Abel Sánchez-Aguilera, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) in Madrid.

The researchers found that, unlike in breast cancer, where tamoxifen blocks the action of estrogens, in blood cells, the drug acts by imitating the function of the hormone.

Tamoxifen induced apoptosis in short-term hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and multipotent progenitors. But in quiescent, long-term HSCs, the drug prompted proliferation and partial loss of function, which was reversible.

Tamoxifen also prevented polycythemia vera-like MPN from developing in mice with HSCs expressing JAK2V617F. The drug prevented MPN-associated neutrophilia and thrombocytosis; alleviated the early increase in red cell counts, hemoglobin, and hematocrit; decreased bone marrow megakaryocytes; and reduced MPN-associated splenomegaly.

Tamoxifen worked by restoring normal levels of apoptosis in mutant cells. It also prompted apoptosis of human JAK2V617F+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in a xenograft model.

In these models, tamoxifen caused little alteration in the rest of the blood cells, which were maintained at normal levels even after prolonged treatment with the drug.

“Our results suggest that tamoxifen, at a similar dose used for the treatment of other diseases, might be useful to treat myeloproliferative neoplasms at various stages, without being toxic to normal blood cells,” said study author Simón Méndez-Ferrer, PhD, also of CNIC.

In addition, tamoxifen enhanced the effects of conventional chemotherapy on cancerous cells in mice with MLL-AF9-induced AML.

Tamoxifen- and vehicle-treated mice had similar numbers of MLL-AF9+ cells and HSPCs shortly after chemotherapy. But tamoxifen delayed the reappearance of circulating leukemic cells after chemotherapy.

Tamoxifen-treated mice had fewer leukemic cells in the bone marrow, spleen, and blood, although they ultimately died of their disease.

Nevertheless, the researchers concluded that tamoxifen could be a feasible treatment option for patients with MPNs or AML. And the fact that tamoxifen is already approved for clinical use increases the chances of these results leading to a clinical trial. ![]()

Credit: CDC

Tamoxifen, a drug used to treat breast cancer, may be effective against myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) as well, according to research published in Cell Stem Cell.

The study showed that estrogens regulate the survival, proliferation, and self-renewal of stem cells that give rise to MPNs and AML.

Tamoxifen, which targets estrogen receptors, prevented JAK2V617F-induced MPNs in mice and enhanced the effects of chemotherapy against MLL-AF9-induced AML.

“In this study, we demonstrate that tamoxifen has specific effects on certain cells in the bone marrow: the hematopoietic stem cells and their immediate descendants, known as multipotent progenitors,” explained study author Abel Sánchez-Aguilera, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) in Madrid.

The researchers found that, unlike in breast cancer, where tamoxifen blocks the action of estrogens, in blood cells, the drug acts by imitating the function of the hormone.

Tamoxifen induced apoptosis in short-term hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and multipotent progenitors. But in quiescent, long-term HSCs, the drug prompted proliferation and partial loss of function, which was reversible.

Tamoxifen also prevented polycythemia vera-like MPN from developing in mice with HSCs expressing JAK2V617F. The drug prevented MPN-associated neutrophilia and thrombocytosis; alleviated the early increase in red cell counts, hemoglobin, and hematocrit; decreased bone marrow megakaryocytes; and reduced MPN-associated splenomegaly.

Tamoxifen worked by restoring normal levels of apoptosis in mutant cells. It also prompted apoptosis of human JAK2V617F+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in a xenograft model.

In these models, tamoxifen caused little alteration in the rest of the blood cells, which were maintained at normal levels even after prolonged treatment with the drug.

“Our results suggest that tamoxifen, at a similar dose used for the treatment of other diseases, might be useful to treat myeloproliferative neoplasms at various stages, without being toxic to normal blood cells,” said study author Simón Méndez-Ferrer, PhD, also of CNIC.

In addition, tamoxifen enhanced the effects of conventional chemotherapy on cancerous cells in mice with MLL-AF9-induced AML.

Tamoxifen- and vehicle-treated mice had similar numbers of MLL-AF9+ cells and HSPCs shortly after chemotherapy. But tamoxifen delayed the reappearance of circulating leukemic cells after chemotherapy.

Tamoxifen-treated mice had fewer leukemic cells in the bone marrow, spleen, and blood, although they ultimately died of their disease.

Nevertheless, the researchers concluded that tamoxifen could be a feasible treatment option for patients with MPNs or AML. And the fact that tamoxifen is already approved for clinical use increases the chances of these results leading to a clinical trial. ![]()

Credit: CDC

Tamoxifen, a drug used to treat breast cancer, may be effective against myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) as well, according to research published in Cell Stem Cell.

The study showed that estrogens regulate the survival, proliferation, and self-renewal of stem cells that give rise to MPNs and AML.

Tamoxifen, which targets estrogen receptors, prevented JAK2V617F-induced MPNs in mice and enhanced the effects of chemotherapy against MLL-AF9-induced AML.

“In this study, we demonstrate that tamoxifen has specific effects on certain cells in the bone marrow: the hematopoietic stem cells and their immediate descendants, known as multipotent progenitors,” explained study author Abel Sánchez-Aguilera, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) in Madrid.

The researchers found that, unlike in breast cancer, where tamoxifen blocks the action of estrogens, in blood cells, the drug acts by imitating the function of the hormone.

Tamoxifen induced apoptosis in short-term hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and multipotent progenitors. But in quiescent, long-term HSCs, the drug prompted proliferation and partial loss of function, which was reversible.

Tamoxifen also prevented polycythemia vera-like MPN from developing in mice with HSCs expressing JAK2V617F. The drug prevented MPN-associated neutrophilia and thrombocytosis; alleviated the early increase in red cell counts, hemoglobin, and hematocrit; decreased bone marrow megakaryocytes; and reduced MPN-associated splenomegaly.

Tamoxifen worked by restoring normal levels of apoptosis in mutant cells. It also prompted apoptosis of human JAK2V617F+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in a xenograft model.

In these models, tamoxifen caused little alteration in the rest of the blood cells, which were maintained at normal levels even after prolonged treatment with the drug.

“Our results suggest that tamoxifen, at a similar dose used for the treatment of other diseases, might be useful to treat myeloproliferative neoplasms at various stages, without being toxic to normal blood cells,” said study author Simón Méndez-Ferrer, PhD, also of CNIC.

In addition, tamoxifen enhanced the effects of conventional chemotherapy on cancerous cells in mice with MLL-AF9-induced AML.

Tamoxifen- and vehicle-treated mice had similar numbers of MLL-AF9+ cells and HSPCs shortly after chemotherapy. But tamoxifen delayed the reappearance of circulating leukemic cells after chemotherapy.

Tamoxifen-treated mice had fewer leukemic cells in the bone marrow, spleen, and blood, although they ultimately died of their disease.

Nevertheless, the researchers concluded that tamoxifen could be a feasible treatment option for patients with MPNs or AML. And the fact that tamoxifen is already approved for clinical use increases the chances of these results leading to a clinical trial. ![]()

NICE reconsiders obinutuzumab for CLL

Credit: Linda Bartlett

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a draft guidance that recommends obinutuzumab, marketed by Roche as Gazyvaro, for certain patients with untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

In an earlier preliminary guidance, NICE said it could not recommend the drug due to uncertainties in the company’s submission.

In response, Roche submitted revised cost-effectiveness analyses and a patient access scheme.

This prompted NICE to recommend obinutuzumab in combination with chlorambucil as an option for adults with untreated CLL who have comorbidities that make them ineligible for full-dose fludarabine-based therapy.

But NICE is only recommending this as an option if bendamustine-based therapy has been deemed unsuitable and if Roche provides obinutuzumab with the discount agreed in the patient access scheme.

“We are pleased that Roche responded to our consultation and provided further analyses to allow us to propose recommending obinutuzumab as a treatment option for untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia,” said Carole Longson, director of the Centre for Health Technology Evaluation at NICE.

“Half of the people who need treatment for their condition are not able to use the standard first-line treatment of fludarabine combination therapy. NICE recommends alternative treatment with bendamustine, but there are some patients for whom this is also unsuitable. Obinutuzumab is a clinically effective treatment which is associated with fewer adverse events and provides another option to help prevent people’s disease from progressing.”

NICE recommends obinutuzumab on the basis that Roche provides the treatment to the National Health Service (NHS) at a reduced price. The company has agreed with the Department of Health that the size of the discount is to be confidential.

The list price of obinutuzumab is £3312 per 1000 mg vial (excluding value-added tax). According to Roche, a course of treatment costs £26,496 (£9936 for cycle 1 and £3312 for cycles 2 to 6, excluding tax).

Consultees, including the company, healthcare professionals, and members of the public, have until Tuesday, January 6, 2015, to comment on the preliminary recommendations via the NICE website.

NICE has not yet issued the final guidance to the NHS. Until then, NHS bodies should make decisions locally on the funding of specific treatments. ![]()

Credit: Linda Bartlett

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a draft guidance that recommends obinutuzumab, marketed by Roche as Gazyvaro, for certain patients with untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

In an earlier preliminary guidance, NICE said it could not recommend the drug due to uncertainties in the company’s submission.

In response, Roche submitted revised cost-effectiveness analyses and a patient access scheme.

This prompted NICE to recommend obinutuzumab in combination with chlorambucil as an option for adults with untreated CLL who have comorbidities that make them ineligible for full-dose fludarabine-based therapy.

But NICE is only recommending this as an option if bendamustine-based therapy has been deemed unsuitable and if Roche provides obinutuzumab with the discount agreed in the patient access scheme.

“We are pleased that Roche responded to our consultation and provided further analyses to allow us to propose recommending obinutuzumab as a treatment option for untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia,” said Carole Longson, director of the Centre for Health Technology Evaluation at NICE.

“Half of the people who need treatment for their condition are not able to use the standard first-line treatment of fludarabine combination therapy. NICE recommends alternative treatment with bendamustine, but there are some patients for whom this is also unsuitable. Obinutuzumab is a clinically effective treatment which is associated with fewer adverse events and provides another option to help prevent people’s disease from progressing.”

NICE recommends obinutuzumab on the basis that Roche provides the treatment to the National Health Service (NHS) at a reduced price. The company has agreed with the Department of Health that the size of the discount is to be confidential.

The list price of obinutuzumab is £3312 per 1000 mg vial (excluding value-added tax). According to Roche, a course of treatment costs £26,496 (£9936 for cycle 1 and £3312 for cycles 2 to 6, excluding tax).

Consultees, including the company, healthcare professionals, and members of the public, have until Tuesday, January 6, 2015, to comment on the preliminary recommendations via the NICE website.

NICE has not yet issued the final guidance to the NHS. Until then, NHS bodies should make decisions locally on the funding of specific treatments. ![]()

Credit: Linda Bartlett

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a draft guidance that recommends obinutuzumab, marketed by Roche as Gazyvaro, for certain patients with untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

In an earlier preliminary guidance, NICE said it could not recommend the drug due to uncertainties in the company’s submission.

In response, Roche submitted revised cost-effectiveness analyses and a patient access scheme.

This prompted NICE to recommend obinutuzumab in combination with chlorambucil as an option for adults with untreated CLL who have comorbidities that make them ineligible for full-dose fludarabine-based therapy.

But NICE is only recommending this as an option if bendamustine-based therapy has been deemed unsuitable and if Roche provides obinutuzumab with the discount agreed in the patient access scheme.

“We are pleased that Roche responded to our consultation and provided further analyses to allow us to propose recommending obinutuzumab as a treatment option for untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia,” said Carole Longson, director of the Centre for Health Technology Evaluation at NICE.

“Half of the people who need treatment for their condition are not able to use the standard first-line treatment of fludarabine combination therapy. NICE recommends alternative treatment with bendamustine, but there are some patients for whom this is also unsuitable. Obinutuzumab is a clinically effective treatment which is associated with fewer adverse events and provides another option to help prevent people’s disease from progressing.”

NICE recommends obinutuzumab on the basis that Roche provides the treatment to the National Health Service (NHS) at a reduced price. The company has agreed with the Department of Health that the size of the discount is to be confidential.

The list price of obinutuzumab is £3312 per 1000 mg vial (excluding value-added tax). According to Roche, a course of treatment costs £26,496 (£9936 for cycle 1 and £3312 for cycles 2 to 6, excluding tax).

Consultees, including the company, healthcare professionals, and members of the public, have until Tuesday, January 6, 2015, to comment on the preliminary recommendations via the NICE website.

NICE has not yet issued the final guidance to the NHS. Until then, NHS bodies should make decisions locally on the funding of specific treatments. ![]()

FDA approves first drug for polycythemia vera

Credit: AFIP

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the approved use of ruxolitinib (Jakafi) to include treatment of patients with polycythemia vera (PV).

This is the first drug approved by the FDA for this condition.

Ruxolitinib can now be used to treat PV patients who have an inadequate response to hydroxyurea or cannot tolerate the drug.

The FDA said the approval of ruxolitinib for PV patients will help decrease splenomegaly and the need for phlebotomy.

“The approval of Jakafi for polycythemia vera underscores the importance of developing drugs matched to our increasing knowledge of the mechanisms of diseases,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

“The trial used to evaluate Jakafi confirmed clinically meaningful reductions in spleen size and the need for phlebotomies to control the disease.”

Results from that study, the phase 3 RESPONSE trial, were presented at the 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting. RESPONSE was funded by Incyte Corporation, the company developing ruxolitinib.

The trial included 222 patients who had PV for at least 24 weeks. All patients had an inadequate response to or could not tolerate hydroxyurea, had undergone a phlebotomy procedure, and exhibited an enlarged spleen.

They were randomized to receive ruxolitinib at a starting dose of 10 mg twice daily or best available therapy (BAT) as determined by the investigator on a participant-by-participant basis. The ruxolitinib dose was adjusted as needed throughout the study.

The study was designed to measure the reduced need for phlebotomy beginning at week 8 and continuing through week 32, in addition to at least a 35% reduction in spleen volume at week 32.

Twenty-one percent of ruxolitinib-treated patients met this endpoint, compared to 1% of patients who received BAT. At week 32, 77% of patients on ruxolitinib and 20% on BAT achieved hematocrit control or spleen reduction.

Ruxolitinib was generally well-tolerated, but 3.6% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events, compared to 1.8% of patients on BAT.

The most common events associated with ruxolitinib were anemia and thrombocytopenia. The most common non-hematologic events were headache, diarrhea, fatigue, dizziness, constipation, and shingles.

The FDA reviewed ruxolitinib’s use for PV under the agency’s priority review program because, at the time the application was submitted, the drug demonstrated the potential to be a significant improvement over available therapy. Ruxolitinib also received orphan product designation.

Ruxolitinib is currently approved in more than 60 countries for patients with myelofibrosis (MF). In 2011, the FDA approved the drug to treat patients with intermediate or high-risk MF, including primary MF, post-PV MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF. ![]()

Credit: AFIP

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the approved use of ruxolitinib (Jakafi) to include treatment of patients with polycythemia vera (PV).

This is the first drug approved by the FDA for this condition.

Ruxolitinib can now be used to treat PV patients who have an inadequate response to hydroxyurea or cannot tolerate the drug.

The FDA said the approval of ruxolitinib for PV patients will help decrease splenomegaly and the need for phlebotomy.

“The approval of Jakafi for polycythemia vera underscores the importance of developing drugs matched to our increasing knowledge of the mechanisms of diseases,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

“The trial used to evaluate Jakafi confirmed clinically meaningful reductions in spleen size and the need for phlebotomies to control the disease.”

Results from that study, the phase 3 RESPONSE trial, were presented at the 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting. RESPONSE was funded by Incyte Corporation, the company developing ruxolitinib.

The trial included 222 patients who had PV for at least 24 weeks. All patients had an inadequate response to or could not tolerate hydroxyurea, had undergone a phlebotomy procedure, and exhibited an enlarged spleen.

They were randomized to receive ruxolitinib at a starting dose of 10 mg twice daily or best available therapy (BAT) as determined by the investigator on a participant-by-participant basis. The ruxolitinib dose was adjusted as needed throughout the study.

The study was designed to measure the reduced need for phlebotomy beginning at week 8 and continuing through week 32, in addition to at least a 35% reduction in spleen volume at week 32.

Twenty-one percent of ruxolitinib-treated patients met this endpoint, compared to 1% of patients who received BAT. At week 32, 77% of patients on ruxolitinib and 20% on BAT achieved hematocrit control or spleen reduction.

Ruxolitinib was generally well-tolerated, but 3.6% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events, compared to 1.8% of patients on BAT.

The most common events associated with ruxolitinib were anemia and thrombocytopenia. The most common non-hematologic events were headache, diarrhea, fatigue, dizziness, constipation, and shingles.

The FDA reviewed ruxolitinib’s use for PV under the agency’s priority review program because, at the time the application was submitted, the drug demonstrated the potential to be a significant improvement over available therapy. Ruxolitinib also received orphan product designation.

Ruxolitinib is currently approved in more than 60 countries for patients with myelofibrosis (MF). In 2011, the FDA approved the drug to treat patients with intermediate or high-risk MF, including primary MF, post-PV MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF. ![]()

Credit: AFIP

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the approved use of ruxolitinib (Jakafi) to include treatment of patients with polycythemia vera (PV).

This is the first drug approved by the FDA for this condition.

Ruxolitinib can now be used to treat PV patients who have an inadequate response to hydroxyurea or cannot tolerate the drug.

The FDA said the approval of ruxolitinib for PV patients will help decrease splenomegaly and the need for phlebotomy.

“The approval of Jakafi for polycythemia vera underscores the importance of developing drugs matched to our increasing knowledge of the mechanisms of diseases,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

“The trial used to evaluate Jakafi confirmed clinically meaningful reductions in spleen size and the need for phlebotomies to control the disease.”

Results from that study, the phase 3 RESPONSE trial, were presented at the 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting. RESPONSE was funded by Incyte Corporation, the company developing ruxolitinib.

The trial included 222 patients who had PV for at least 24 weeks. All patients had an inadequate response to or could not tolerate hydroxyurea, had undergone a phlebotomy procedure, and exhibited an enlarged spleen.

They were randomized to receive ruxolitinib at a starting dose of 10 mg twice daily or best available therapy (BAT) as determined by the investigator on a participant-by-participant basis. The ruxolitinib dose was adjusted as needed throughout the study.